| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/IJMHP.2021.012787

ARTICLE

Mindfulness Associates Life Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Internal Control and the Presence of Meaning in Life

1Department of Psychology, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, China

2Cognition and Human Behavior Key Laboratory of Human Province, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, China

*Corresponding Author: Yanhui Xiang. Email: xiangyh@hunnu.edu.cn

Received: 13 July 2020; Accepted: 26 August 2020

#The author is the first author

Abstract: This study explored the internal mechanism of the effect of mindfulness on life satisfaction from the perspective of logotherapy theory and achievement attribution theory. We recruited 1021 college students using a combination of random sampling and cluster sampling. They completed the relevant questionnaire. The results showed that, from the perspective of logotherapy theory, we find that the presence of meaning in life is an important intermediary between mindfulness and life satisfaction. From the perspective of achievement attribution theory, we found that internal control was an important intermediary between mindfulness and life satisfaction. In addition, we also found the chain mediating path that mindfulness positively predicted life satisfaction by influencing internal control and then influencing the presence of meaning in life. This study proves for the first time that the theory of logotherapy and achievement attribution explain the internal mechanism of the relation of mindfulness on life satisfaction. This study provides an important reference for how to effectively improve life satisfaction from the perspective of mindfulness.

Keywords: Mindfulness; life satisfaction; the presence of meaning in life; internal control; structural equation model

Life satisfaction is a subjective assessment of the overall quality of life and considered a key indicator of subjective well-being [1]. In recent years, with the development of positive psychology, life satisfaction as an important concept in positive psychology [2] has attracted more and more attention from researchers. Generally, positive evaluations of life are associated with happiness and the realization of the “good life”, while negative evaluations of life are associated with depression and unhappiness. In addition, a healthy psychological state of being happy and satisfied with life is two-way related to access to social and economic resources and success [3]. Thus it can be seen that life satisfaction plays the vital role in the good self-development of individuals and the realization of the “good life”. Much research has been done on the relationship between mindfulness and other factors. For example, the research of Kong et al. [4] and the study of Wang et al. [5] have proved the mediating role of emotional intelligence between mindfulness and life satisfaction; the research of Stolarski et al. [6] illustrates the concept of the Balanced Time Perspective (BTP) may be one of the potential links between mindfulness and life satisfaction. At the same time, a large number of previous studies have proved that mindfulness can positively predict life satisfaction [7–11]. Unlike the predecessors, this article explores the internal mechanism between mindfulness and life satisfaction from the perspective of logotherapy theory and achievement attribution theory. Therefore, this study aims to explore the specific mechanism between mindfulness and life satisfaction from the perspective of logotherapy theory and achievement attribution theory, so as to enrich the theoretical research in the field of life satisfaction and provide intervention suggestions for individual life satisfaction.

From the view of logotherapy theory, one of the ways to discover the meaning of life is to realize the creative value, that is, to engage in all kinds of work in a down-to-earth way, and to realize the meaning of life from creative work or artistic creation [12]. And mindfulness refers to the conscious, non-judgmental state of focusing on the present [13], which means mindful individuals are more likely to perceive the important value of the work they are doing and to find meaning in their lives. Also related studies have also demonstrated that mindfulness is an enhanced attention and awareness of current experience or reality [7], which means that mindfulness may associate an individual’s the presence of meaning in life. Previous studies have also directly proved that mindfulness can positively predict the meaning in life [14]. When the individual has the will to meaning, it can protect the mental and physical health, and it can also help the individual to overcome extreme conditions such as physical pain and sadness, so that the individual has the positive emotional state [12], which leads to a higher life satisfaction. Previous studies have also proved that life meaning positively predicts life satisfaction [15–18], which means that people are more likely to make positive comments on life when they experience the sense of life meaning and pursue life meaning. Therefore, we speculate that mindfulness affects life satisfaction through the mediation of the presence of meaning in life. So we propose hypothesis 1: mindfulness positively predicts life satisfaction through the presence of meaning in life.

From the perspective of achievement attribution theory, individuals’ causal explanation of their behavior is influenced by three dimensions: attribution point, stability and controllability, and the attribution of results with different properties will have different effects. Attributing negative results to internal, stable and uncontrollable abilities will lead to more self-condemnation and decreased sense of self-worth, which will easily lead to depression and other bad emotions [19]. Locus of control refers to the degree to which a person thinks he can command his own destiny, and internal control makes people feel that they can control their own destiny [20]. The internal control believes that everything is done to themselves [21], and tend to interpret the reasons as controllable, thereby reducing the impact of negative events on the individual’s subjective feelings, and improving the individual’s life satisfaction. Hence, based on achievement attribution theory, we speculate that internal control may be used to explain the mechanism by which mindfulness associates life satisfaction. Research supports this conjecture as well. Former studies have shown that individuals with higher levels of mindfulness are more inclined to internal control [22]. At the same time, according to the research of Mirowsky et al. [23], those who prefer external control often suffer more than others, so their life satisfaction may be lower. A stronger sense of personal control leads to greater self-confidence and hope. On the contrary. the feeling of being unable to control the outcomes of life can make people feel depressed, and will also weaken the will and motivation to settle and avert problems [23]. People with external control may be more likely to feel helpless [24]. Thereout, we propose hypothesis 2: Mindfulness associates life satisfaction through internal control.

Additionally, the theory of logotherapy mentioned that another way to discover the meaning of life is attitudinal value. This means that people’s spiritual attitudes determine their choice of fate. Even in the face of force majeure, we can still decide our own attitudes and positions [12]. Internal control is just an attitude that everything is controlled by me [21], which can further promote the presence of meaning in life. Indirect studies have concluded that external control sources can positively predict depression [25], and depression is a state of low meaningful presence. Therefore, we speculate that the internally-controlled individuals are more likely to realize the meaning of life and thus improve life satisfaction. And direct studies have also demonstrated the relationship between life meaning and internal control [26]. To sum up, we propose hypothesis 3: Mindfulness positively predicts life satisfaction by associating internal control and then the presence of meaning in life.

In conclusion, from the perspective of logotherapy theory and achievement attribution theory, this study explores the mediating effects of internal control and the presence of meaning in life on the relationship between mindfulness and life satisfaction. This study proposes the following hypotheses: 1) According to the logotherapy theory, mindfulness can positively predict life satisfaction through the presence of meaning in life; 2) According to the achievement attribution theory, mindfulness improves life satisfaction through internal control; 3) According to the logotherapy theory, Mindfulness can positively predict life satisfaction by associating internal control and then the presence of meaning in life.

A total of 1021 valid subjects were extracted from a university in South China using random sampling and cluster sampling methods. There were 315 males and 706 females, aged between 17 to 26 years old. The average age of students was 19.04 ± 1.52 years old. The handwritten informed consent was given to all participants before they filled out the questionnaire, and they were paid a certain amount of money after completing the questionnaire. This study had been approved by the academic committee of the department of psychology.

2.2.1 Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS)

The mindfulness scale is a fifteen-question Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) compiled by Brown et al. in 2003 [7]. Items describe the experience of mindfulness (e.g., “I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present”). Respondents used a six-point Likert-type scale (1 = almost always, 6 = almost never), and the score indicates the level of mindfulness. This paper adopted the Chinese version of MAAS, which has been proved to be a credible and effective method to assess the level of mindfulness of Chinese people [27]. The coefficient of internal consistency was 0.794.

2.2.2 The Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ)

The original questionnaire, compiled by Steger et al. in 2006 [28,29] consists of ten questions and used a seven-point Likert-type scale (1 = total disagreement, 7 = total agreement) to measure two dimensions of life meaning (the presence of meaning in life and search for meaning in life). This paper adopted the presence of meaning in life dimension in the life meaning scale. The higher the score, the stronger the presence of meaning in life of the respondents. We adopted the revised Chinese version by Dai et al. [30], which has been testifyied by them to have high credibility and effectiveness in Chinese groups. The consistency of internal coefficient of the scale was 0.863.

2.2.3 Internality, Powerful Others and Chance Questionnaire (IPC)

This scale was compiled by Levenson [31], and is divided into three dimensions (internality, powerful others and chance). In this paper, the dimensions of internal control were adopted. There are eight questions in total, and a score of six-point is adopted. This study used the Chinese version of the IPC scale compiled by the Mental Health Assessment Scale Manual [32], which has been shown to have high reliability and validity within the Chinese population [33,34]. The consistency of internal coefficient of the scale was 0.769.

2.2.4 The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

The life satisfaction scale consists of five short statements [35], including such items as “The conditions of my life are excellent” and “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing”. The higher the score, the higher the life satisfaction. The Chinese version of SWLS has demonstrated to be a reliable and valid measure of life satisfaction among Chinese people [36–39]. The consistency of internal coefficient of SWLS was 0.841.

We used the Harman single factor method to test whether there is a common method bias. After performing unrotated principal component factor analysis on all items, it was found that the first common factor could only explain 32.520% of the total variation. This ratio is less than 40% of the total variation. Therefore, the common method bias is not obvious and will not cause a significant impact on the research results.

AMOS 26.0 was used for data analysis. First, we built a measurement model in AMOS26.0 according to the research hypothesis, in order to test whether the observed variables could predict the latent variables well. The questions in the mindfulness scale were divided into three factors, the questions in the life satisfaction scale into two factors, the questions in the life meaning experience scale into two factors, and the questions in the internal control scale into two factors, as their corresponding observation variables [40]. If the fitting degree of the measurement model was good, we would further construct the structural model, and took the approximate error root mean square (RMSEA), the standardized mean square residual (SRMR) and the comparison fitting index (CFI) as the indexes to test the model fitting degree [41]. Meanwhile, the expected cross validity index (ECVI) was also used to evaluate the possibility of replicating the model in different samples [42]. Subsequently, we used Bootstrap to test the mediating effect of internal control and life meaning experience between mindfulness and life satisfaction.

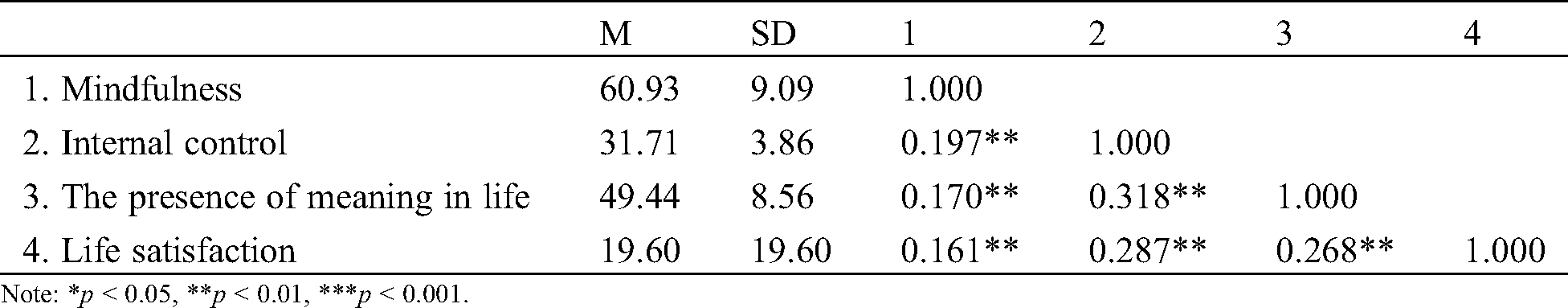

Mindfulness, internal control, the presence of meaning in life, and life satisfaction were the underlying variables in the measurement model. The results showed that the measurement model fitted well [χ2 (21, N = 1021) = 33.107, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.024; SRMR = 0.022; CFI = 0.993]. The standardized load of each indicator on its corresponding factor was significant (p < 0.001), indicating that the observed variables could represent the corresponding latent variables. In addition, as illustrated in Tab. 1, there was a significant correlation between all latent variables.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations of all variables

3.2 Rationality of Structural Model

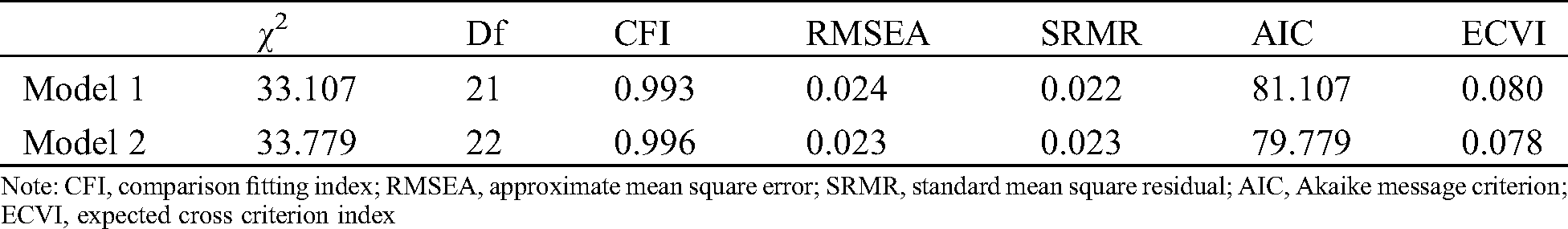

According to the results of correlation analysis, mindfulness, internal control, life meaning experience and life satisfaction were correlated in two ways, which met the requirements of multi-mediation model test. Then, on the basis of the research hypothesis, we first built model 1, in which mindfulness could directly predict life satisfaction, indirectly predict life satisfaction through life meaning experience and internal control, and indirectly related life satisfaction through life meaning experience and internal control. The results showed that the fitting degree of model 1 was good [χ2 (21, N = 1021) = 33.107, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.024; SRMR = 0.022; CFI = 0.993]. But “mindfulness → life satisfaction” (Beta = 0.03, p < .001) was not significant, so we controlled the regression coefficient of this path to be 0, and further constructed model 2. The results showed that model 2 had better fitting degree than model 1 [χ2 (21, N = 1021) = 33.779, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.023; SRMR = 0.023; CFI = 0.996]. Finally, we chose model 2 as the final structural model. The specific fitting indexes of model 1 and model 2 are shown in Tab. 2.

Table 2: Fitting index of model 1 and model 2

Figure 1: A standardized mediation model

3.3 Mediation Variable Significance Test

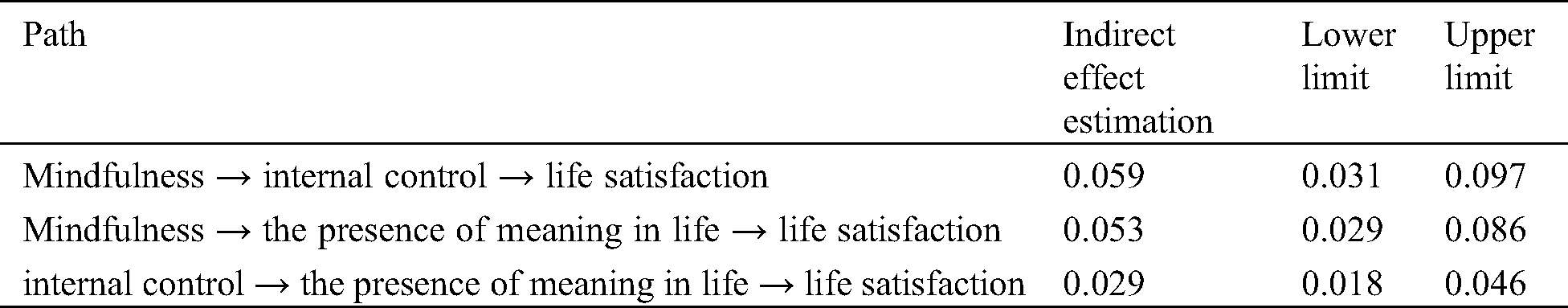

We further the Bootstrap method was used to model 2 test in internal control and meaning of life experience in mindfulness and life satisfaction intermediary effect between us in the original data (N = 1021) randomly selected 5000 Bootstrap sample. Results show that the 95% confidence interval, sexual (0.031~0.097) and the meaning of life experience [0.029~0.086] between mindfulness and life satisfaction were a significant intermediary role. At the same time, the internal control sex could also through the meaning of life experience to the mediation effect on life satisfaction [0.018~0.046] (Tab. 3).

Table 3: Indirect effects of normalization of 95% confidence intervals

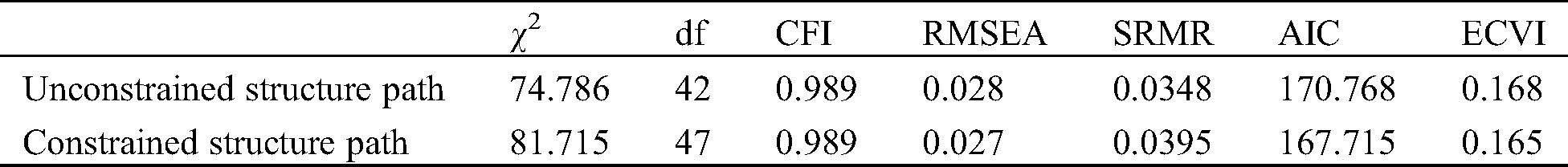

3.4 Transgender Stability Analysis

For verifying the stability of the structural model, the stability of the model was further analyzed. Firstly, the gender differences of the four latent variables were tested. The results indicated that there were no significant gender differences in the four potential variables mindfulness [t(1021) = 0.002, p > 0.05], internal control [t(1021) = 0.683, p > 0.05], the presence of meaning in life [t(1021) = 0.931, p > 0.05] and life satisfaction [t(1021) = −0.033, p > 0.05]. Then we used multi-group analysis to explore its stability in the model. Based on Byrne research [43], this study factors in keeping the basic parameters of the load, error variance and covariance structure remains the same, on the basis of establishing the two models, one allows for the path of the transgender free estimate (unconstrained structure path), and the other limit the path coefficient of two kinds of gender equal (path) constraint structure, results showed that the two models of the fitting of indicators had reached the standard of the fitness (Tab. 4), and the edge of a significant difference in two models [χ2(5, 1021) = 6.292, p = 0.226]. There may be differences between the two models, so the Critical Ratios of Differences (CRD) of the standard deviations of the two models were used as an indicator to further investigate the cross-gender stability of the structural model. According to the decision rules, if the absolute value of CRD is greater than 1.96, it indicates that there is a significant difference between the two parameters [44]. The results showed that there was no significant difference in the structural paths of the other variables except the presence meaning in life → life satisfaction (CRD = −2.530). CRD Mind → LS = −0.130, CRD Mind → IC = −0.875, CRD IC → LS = −0.153, CRDIC → PMI = −1.425, this suggested that the model had transgendered stability. The specific model is shown in Fig. 1.

Table 4: Comparison of transgender constrained and unconstrained structural path models

This study explored the internal mechanism of mindfulness associateing life satisfaction based on the logotherapy theory and achievement attribution. In view of the logotherapy theory, we found that the presence of meaning in life mediates the effect of mindfulness on life satisfaction. In view of achievement attribution theory, we found that mindfulness contributes to life satisfaction by associateing internal control. In addition, life meaning experience positively associated life satisfaction by associateing internal control. The results of this study are the first to confirm the impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction from the perspective of meaning therapy theory and achievement attribution theory, and to reveal its mechanism.

First of all, the results of correlation analysis proved that mindfulness can positively predict life satisfaction, which is consistent with previous research results [4,7–11]. However, in this study, the direct path coefficient between mindfulness and life satisfaction was not significant, which further indicates that internal control and the presence of meaning in life are important mediators of mindfulness associateing life satisfaction. And, through the study of the intermediary effect of model test, we found there is a significant intermediary role under the path: Mindfulness → the presence of meaning in life → life satisfaction. It proved that the presence of meaning in life for the intermediary role between mindfulness and life satisfaction, verified our hypothesis 1, that mindfulness will enhance the individual experience of meaning of life, and raise the life satisfaction of the individual. According to the logotherapy theory, the search for the meaning of life is the core motivation of human individuals [12]. In this process, individuals can realize the meaning of life. Mindfulness is considered to be a state in which a person is able to give uninterrupted attention to ongoing physical, cognitive and psychological experiences in a non-judgmental manner over a period of time [45]. This means a high level of mindfulness orientation means a more focused awareness of the present moment and a greater commitment to the process of realization. So mindfulness enhances the presence of meaning in life. Meanwhile, Frankl [12] proposed that if individuals can understand the meaning of their lives from life, it will change their outlook on life, face the reality better, and live a positive and optimistic life, the individual’s psychological and behavioral problems will also disappear. Physical and mental health is an important indicator of life satisfaction [46–49,29]. Furthermore, a high level of the presence of meaning in life can improve life satisfaction. And the presence of meaning in life provides a holistic, conceptual framework for how people understand themselves, how they understand the world, and how they see themselves in relation to the world [50]. The presence of meaning in life, as a cognitive dimension of life meaning, means to understand that one is a unique individual and to identify what one is trying to achieve in life [51]. That one of the core of the presence of meaning in life is an understanding of oneself, and the mindfulness process supports a more flexible and objective response to external stimuli and a clearer understanding of one’s internal processes [7,52], which means increasing the understanding of the real self, and only when people can live according to their real selves can they experience happiness [53]. Therefore, we believe that from the perspective of logotherapy, mindfulness can improve the life satisfaction of individuals by influencing their level of the presence of meaning in life.

Secondly, we also found another significant mediating path: Mindfulness→internal control→life satisfaction, it proved the mediating role of internal control between mindfulness and life satisfaction, and verified our hypothesis 2, that mindfulness improves the internal control of individuals, and thereby increasing life satisfaction. According to the theory of achievement attribution [54,55], high self-concept has important significance for attribution change. For example, if an individual with a high self-concept believes that he or she has a high probability of success on a task, he or she is more likely to attribute failure to unstable causes, such as luck or emotion. The influence of mindfulness on internal control may be that individuals with a high level of mindfulness can keep a clearer understanding of body feelings, thoughts, emotions, etc. [13], so as to have a more correct cognition of their own ability level, which is more conducive to the formation of a high self-concept, and then may form internal attribution, which is more inclined to internal control. At the same time, Weiner et al. [56] found that if a person believes that success is caused by ability, i.e., internal attribution, then ability and confidence lead to a strong positive experience, which leads to a higher evaluation of life. Therefore, we believe that from the perspective of achievement attribution theory, mindfulness can improve the life satisfaction of individuals by influencing their tendency of internal control.

Thirdly, this study also found a significant chain mediating path: Mindfulness→internal control→the presence of meaning in life → life satisfaction, proving that internal control and life meaning experience play a chain mediating role between mindfulness and life satisfaction, and verifying hypothesis 3. Rotter [57] proposed that external control means that the result of behavior is determined by external forces not controlled by individuals, while internal control, on the contrary, believes that the outcome is dominated by one’s own efforts. A person inclined to internal control will show a strong ability to resist pressure [58], and Frankl [12] proposed that overcoming difficulties is also one of the ways to realize the meaning of life. Therefore, mindfulness can improve the individual’s life meaning experience by influencing the internal control, thus promoting the improvement of life satisfaction.

Finally, we carried out the stability analysis of trans gender, and the results showed that the model had the stability of trans gender, and only the path of “life meaning experience→life satisfaction” had gender difference, that is, the life meaning experience of boys had more significant prediction effect on life satisfaction. One of the ways to find the meaning of life is to engage in all kinds of work in a down-to-earth way, from creative work or artistic creation to realize the meaning of life [12]. When individuals succeed in these work, they will inevitably gain an understanding of the meaning of life. However, men are more motivated to achieve than women and experience more positive emotions in the pursuit of success [59,17], which means that men are more likely than women to have positive emotional experiences after success and thus have higher life satisfaction. Therefore, we believe that the prediction effect of “life meaning experience→life satisfaction” of male students is more significant than that of female students, but the model still has transgender stability.

However, this study also has several limitations. First, the data was completely dependent on self-reporting measures. Although these scales were chosen because of their good reliability and validity, self-report scales are susceptible to biases, such as social desirability. Second, the cross-sectional design used in this study cannot determine causality. Therefore, the interpretation of the results of the intermediary analysis of cross-sectional data must always be carried out carefully. Future research can use longitudinal or experimental research to provide additional insights into the relationship between mindfulness, internal control, the presence of meaning in life, and life satisfaction. Finally, because a sample of Chinese college students was used, the current findings cannot be generalized to the entire population.

In conclusion, this research provides an important perspective for understanding the complex interactions among Chinese college students’ mindfulness, internal control, meaning in life and life satisfaction. It from the logotherapy theory and achievement attribution theory of mechanism of the effect of mindfulness to life satisfaction was investigated, and for the first time, this paper discusses the meaning of life experience and the internal control in mindfulness and intermediary role between life satisfaction, further improved promotes mindfulness the specific mechanism of action of positive relation on life satisfaction, enriches the theoretical research related to life satisfaction, has a strong theoretical significance. At the same time, the research results of this study also have a strong practical significance. It provides valuable guidance on how to implement psychological interventions aimed at improving life satisfaction, and provides enlightenment for the establishment of scientific and effective programs to improve life satisfaction.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful for the support and grant funding contributed by General Program of the National Social Science Foundation of China (19BSH114).

Author Contributions Statement: Yanhui Xiang: Study designing, data collection, paper revising; Zihui Yuan: Data collection, paper writing, paper revising, data analysis; Ziyuan Chen: Data collection, paper revising.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the General Program of the National Social Science Foundation of China (19BSH114)

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. Diener, E., Diener, M. (1995). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(4), 653–663. DOI 10.1037/0022-3514.68.4.653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Gilman, R., Huebner, S. (2003). A review of life satisfaction research with children and adolescents. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(2), 192–205. DOI 10.1521/scpq.18.2.192.21858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803–855. DOI 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kong, F., Wang, X., Zhao, J. (2014). Dispositional mindfulness and life satisfaction: The role of core self-evaluations. Personality and Individual Differences, 56, 165–169. DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2013.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang, Y., Kong, F. (2014). The role of emotional intelligence in the impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction and mental distress. Social Indicators Research, 116(3), 843–852. DOI 10.1007/s11205-013-0327-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Stolarski, M., Vowinckel, J., Jankowski, K. S., Zajenkowski, M. (2016). Mind the balance, be contented: Balanced time perspective mediates the relationship between mindfulness and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 93, 27–31. DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Brown, K., Ryan, R. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. DOI 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Brown, K., Kasser, T., Ryan, R., Linley, P., Orzech, K. (2009). When what one has is enough: Mindfulness, financial desire discrepancy, and subjective well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(5), 727–736. DOI 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Falkenström, F. (2010). Studying mindfulness in experienced meditators: A quasi-experimental approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(3), 305–310. DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2009.10.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Howell, A. J., Digdon, N. L., Buro, K., Sheptycki, A. R. (2008). Relations among mindfulness, well-being, and sleep. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(8), 773–777. DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2008.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M. (2011). Emotional intelligence mediates the relationship between mindfulness and subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(7), 1116–1119. DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2011.01.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Viktor E. Frankl. (2005). Man’s search for meaning. Pocket Books, 67, 671–677. [Google Scholar]

13. Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. DOI 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Bowen, S., Witkiewitz, K., Dillworth, T. M., Chawla, N., Simpson, T. L. et al. (2006). Mindfulness meditation and substance use in an incarcerated population. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20(3), 343–347. DOI 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Cohen, K., Cairns, D. (2012). Is searching for meaning in life associated with reduced subjective well-being? Confirmation and possible moderators. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(2), 313–331. DOI 10.1007/s10902-011-9265-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Doğan, T., Sapmaz, F., Tel, F. D., Sapmaz, S., Temizel, S. (2012). Meaning in life and subjective well-being among Turkish university students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 55, 612–617. DOI 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sahin, M., Aydin, B., Sari, S. V., Kaya, S., Pala, H. (2012). Öznel iyi oluşu açiklamada umut ve yaşamda anlamin rolü [The role of hope and the meaning in life in explaining subjective well-being]. Kastamonu Education Journal, 20(3), 827–836. [Google Scholar]

18. Shrira, A., Palgi, Y., Ben-Ezra, M., Shmotkin, D. (2011). How subjective well-being and meaning in life interact in the hostile world? Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(4), 273–228. DOI 10.1080/17439760.2011.577090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Weiner, B. (1979). A theory of motivation for some classroom experiences. Journal of Educational Psychology, 71(1), 3–25. DOI 10.1037/0022-0663.71.1.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Goodman, S. H., Cooley, E. L., Sewell, D. R., Leavitt, N. (1994). Locus of control and self-esteem in depressed, low-income African-American women. Community Mental Health Journal, 30(3), 259–269. DOI 10.1007/BF02188886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographical Monographs, 80(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar]

22. Xu, W., Wang, Y. Z., Fu, Z. F. (2018). The moderating role of dispositional mindfulness and locus of control in the impact of perceived stress on negative emotions in daily life. Psychological Science, 41(3), 749–754. [Google Scholar]

23. Mirowsky, J., Ross, C. E. (2003). Education, social status, and health. Social institutions and social change. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

24. Perlmuter, L., Monty, R. (1977). The importance of perceived control: fact or fantasy? American Scientist, 65, 759–765. [Google Scholar]

25. Benson, L., Deeter, T. (1992). Moderators of the relation between stress and depression in adolescents. School Counselor, 39, 189–194. [Google Scholar]

26. Chen, Q., Li, X. Q. (2015). Relationships between the meaning in life, social support, locus of control and subjective well-being among college students. China Journal of Health Psychology, 23(1), 96–99. [Google Scholar]

27. Bao, X., Xue, S., Kong, F. (2015). Dispositional mindfulness and perceived stress: The role of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 78, 48–52. DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2015.01.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93. DOI 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zullig, K. J., Valois, R. F., Huebner, E. S., Drane, J. W. (2005). Adolescent health-related quality of life and perceived satisfaction with life. Quality of Life Research, 14(6), 1573–1584. DOI 10.1007/s11136-004-7707-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wang, M. C., Dai, X. Y. (2008). Chinese meaning in life questionnaire revised in college students and its reliability and validity test. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 16(5), 459–461. [Google Scholar]

31. Levenson, H. (1981). Differentiating among internality. Powerful others and chance. In: Lefcourt, H. M. (ed.Research with the locus of control construct, pp. 15–63. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

32. Wang, X. D., Wang, X. L., Ma, H. (1999). Mental health rating scale manual (updated version). Chinese Mental Health Journal, 31–194. [Google Scholar]

33. Li, Z. S. (2004). A research on the psychological control sense of undergraduates and their mental health. Psychological Science, 27(5), 1100–1102. [Google Scholar]

34. Mo, S. L., Shen, C. X., Zhou, Z. K. (2009). Research on the relationship among subjective well-being, locus of control and coping style of college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 17(3), 292–294. [Google Scholar]

35. Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. DOI 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kong, F., You, X. (2013). Loneliness and self-esteem as mediators between social support and life satisfaction in late adolescence. Social Indicators Research, 110(1), 271–279. DOI 10.1007/s11205-011-9930-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kong, F., Zhao, J. (2013). Affective mediators of the relationship between trait emotional intelligence and life satisfaction in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(2), 197–201. DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2012.08.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Kong, F., Zhao, J., You, X. (2012). Emotional intelligence and life satisfaction in Chinese university students: The mediating role of self-esteem and social support. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(8), 1039–1043. DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2012.07.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kong, F., Zhao, J., You, X. (2013). Social support mediates the impact of emotional intelligence on mental distress and life satisfaction in Chinese young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(4), 513–517. DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2012.04.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 151–173. DOI 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. International Journal of Testing, 1(1), 55–86. DOI 10.1207/S15327574IJT0101_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Akaike, H. (1987). Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika, 52(3), 317–332. DOI 10.1007/BF02294359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Byrne, B. M., Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. (2009). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming/Routledge. [Google Scholar]

44. Arbuckle, J. L. (2003). AMOS 5.0 update to the AMOS user’s guide. Chicago, IL: Smallwaters. [Google Scholar]

45. Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion. [Google Scholar]

46. Greenspoon, P. J., Saklofske, D. H. (2001). Toward an integration of subjective well-being and psychopathology. Social Indicators Research, 54(1), 81–108. DOI 10.1023/A:1007219227883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Headey, B., Kelley, J., Wearing, A. (1993). Dimensions of mental health: Life satisfaction, positive affect, anxiety and depression. Social Indicators Research, 29(1), 63–82. DOI 10.1007/BF01136197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Huebner, E. S., Alderman, G. L. (1993). Convergent and discriminant validation of a children’s life satisfaction scale: Its relationship to self- and teacher-reported psychological problems and school functioning. Social Indicators Research, 30(1), 71–82. DOI 10.1007/BF01080333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Roberts, R., Alegria, M., Roberts, C., Chen, I. (2005). Concordance of reports of mental health functioning by adolescents and their caregivers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 193(8), 528–534. DOI 10.1097/01.nmd.0000172597.15314.cb. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Heine, S., Proulx, T., Vohs, K. (2006). The meaning maintenance model: On the coherence of social motivations. Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 10(2), 88–110. DOI 10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Steger, M. F., Kashdan, T. B., Sullivan, B. A., Lorentz, D. (2008). Understanding the search for meaning in life: Personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. Journal of Personality, 76(2), 199–228. DOI 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00484.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry: An International Journal for the Advancement of Psychological Theory, 18(4), 211–237. [Google Scholar]

53. Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141166. [Google Scholar]

54. Sullivan, T., Weiner, B. (1975). Achievement motivation and attribution theory. Contemporary Sociology, 4(4), 425. DOI 10.2307/2062395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Weiner, B. (1976). 5: An attributional approach for educational psychology. Review of Research in Education, 4, 179–209. [Google Scholar]

56. Weiner, B., Russell, D., Lerman, D. (1978). Affective consequences of causal ascriptions. In: Harvey, J. H., Ickes, W. J., Kidd, F. R. (eds.New directions in attribution research, vol. 2, pp. 59–90. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

57. Rotter, J., Chance, J., Phares, E. (1972). Application of a social learning theory of personality. Holt, Rinehart & Winston. [Google Scholar]

58. Vasiliu, D. (2016). Correlations between locus of control and hardiness. Romanian Journal of Experimental Applied Psychology, 8/2017(1). DOI 10.15303/rjeap.2017.si1.a1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Fan, X. H. (2006). Relationship between undergraduates’, achievement motivation, emotion and behavior problem. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 14(1), 75–76. [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |