| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/IJMHP.2021.017492

ARTICLE

The Effect of Online Wellness Coaching for Nursing Students during the COVID-19 Lockdown on Well-Being: A Qualitative Study

Department of Public Health Nursing, Gulhane Faculty of Nursing, University of Health Sciences Turkey, Etlik, 06010, Turkey

*Corresponding Author: Şeyma Zehra Altunkurek. Email: serifezehra.altunkurek@sbu.edu.tr

Received: 14 May 2021; Accepted: 09 July 2021

Abstract: Aim: The aim of this study was to explore and describe the lived experience of 3rd-year nursing students who participated in an online wellness coaching program during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Methods: This qualitative research study on an online wellness coaching program included 30 female students, aged 21 to 30 years, who were confined to their home during the COVID-19 outbreak for two months. The students were asked to describe their feelings and responses during the COVID-19 lockdown. Results: Four thematic clusters emerged in the data analysis: what the students felt during the quarantine period, what the wellness coaching practice added to the students’ lives, what changes resulted from the application and whether the students would like the application to continue and recommend the application. The study showed that students had a high level of stress, fear and anxiety at home during the COVİD-19 outbreak. With the online wellness coaching application, they experienced a decrease in social isolation, an improved ability to cope with stress, and improved positivity and well-being. Conclusion: Findings from this study demonstrate that online wellness coaching during the COVID-19 quarantine has a positive effect on students’ well-being.

Keywords: Wellness coaching; mental health; nursing; COVID-19; anxiety; lockdown

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) [1] announced that it considered the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak a pandemic. A pandemic is not only a medical phenomenon but also affects individuals and society and can cause depression, anxiety, and stress [2]. With the rapidly changing situation following the emergence of COVID-19, governments around the world have made the decision to quarantine individuals in their homes [3]. The concept of lockdowns is new for the public and affects segments of the world’s population, resulting in physical, mental, interpersonal, economic, social and educational challenges [4]. In particular, regarding educational status, this pandemic represents a threat to the progress of education worldwide and the global closure of schools at all levels, with more than 1.5 billion students in 197 countries having to switch to home schooling [5]. In Turkey, in accordance with the decision made after the first case was seen on March 10, 2020, it was announced that education was suspended for 3 weeks as of March 16, 2020, in all higher education institutions. Subsequently, it was decided that education will continue as distance education at all levels for the spring semester [6]. Later, various scientific, cultural and other events were impacted by restrictions on in-person gatherings the work of barbers and hairdressers was stopped, and only takeaway services from restaurants were approved. Additionally, people aged 65 and over and those with chronic diseases were restricted from going outside and walking around in open areas such as parks and gardens. On March 22, some restrictions were imposed on working in public institutions and organizations. The curfews imposed toward the middle of April ended at the end of May 2020 [7]. Associated with social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic, many people are experiencing high levels of psychological problems due to stress, which may include but are not limited to mental distress, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and fear of infection [8]. For example, one study investigated the prevalence of depressive symptoms among adults living in the US during COVID-19 and showed that symptoms were three times more prevalent than before the pandemic [9]. Moreover, during the lockdown process, due to changes in habits, such as socializing, physical activity, eating and entertainment, it is natural to see anxiety and depression among people in quarantine, including college students [10]. The strict quarantine imposed in China, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, led to more psychological stress, anxiety, depression, anger and emotional exhaustion in university students staying at home to take online courses [11]. College students who seem to experience higher levels of stress appear to be more susceptible to mental health issues [12]. An important health promotion strategy is to participate in leisure activities, as leisure participation has been found to reduce stress levels, increase positive emotions, and promote overall health and well-being [13]. World Health Organization [14] recommends that children and young people engage in moderate to vigorous physical activity for at least 60 min a day. However, the COVID-19 epidemic has affected people of all ages, especially university students who are away from school, and restricted physical activity [15]. In many countries, indoor and outdoor sports and recreational facilities, such as gyms, public swimming pools and playgrounds, have been closed due to the lockdown [15]. It has been stated that an unhealthy diet, sedentary behavior and reduced time spent outdoors may have unexpected medium- and long-term mental and physical health consequences [16]. In one study, it was stated that from a public health and preventive care perspective, there is an urgent need to provide information and interventions to individuals, communities, and students to promote the healthiest lifestyle possible during the lockdown process [17].

Wellness is defined as an optimal health-oriented lifestyle that promotes well-being, whereby the body, mind, and spirit of an individual are nurtured to facilitate optimized functioning of the individual in their social and natural environments [18]. Wellness coaching is thought to be closely related to the attainment of positive health behaviors and changes of individuals and has attracted great attention [19,20]. Wellness coaching is becoming an increasingly common strategy to help people improve their well-being and physical and mental health [21]. Mettler et al. [20] found that wellness coaching participants exhibited positive behavioral health changes, such as increased motivation and life satisfaction, increased energy levels and physical activity, healthier weight, better nutrition, and better management of physical and mental health. In their study in the field of nursing, Altunkürek et al. [18] found that participants who received wellness coaching had an improved sense of well-being and mental health and made significant progress in adopting healthy lifestyle behaviors. Schmittdiel et al. [22] examined the effect of wellness coaching on weight loss by phone and showed that it was effective in weight loss of the participants. Although wellness coaching is very popular and effective, there are limited published studies on its potential effectiveness [18,21,22]. Wellness coaching is important for nursing students who have to stay at home during the COVID-19 lockdown to maintain the healthiest lifestyle possible.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the results of online wellness coaching to improve health and the ability to cope with the situation during the COVID-19 lockdown process in a university nursing facility in Ankara, according to the opinions of the students participating in the practice.

A qualitative research technique was used in this study. The study was designed and carried out in a holistic single case pattern, which is a qualitative research method, in accordance with the study’s aim [23,24]. The study investigated an application that was developed to help students acquire healthy lifestyle behaviors during the COVID-19 lockdown process in a university nursing facility in Ankara in the 2019–2020 academic year. The researcher has a wellness coaching certificate. This application includes activities that improve health both physically, mentally and socially. For physical health, an online exercise plan for 45 min was created with the researcher five days a week. In accordance with this purpose, an online class was created to improve physical, mental and social health; courses were given to meet the needs of the students. Each student was asked to create a thank-you book during the quarantine process and to write a note in the gratitude book for the first 10 things she had in her life each morning. Apart from the online classroom, a WhatsApp group was also created, and posts were made about coping with negative situations during the COVID-19 process, stress management, healthy eating and hours of exercise time. This application was used for 8 weeks. In the groups, the wellness coach researcher provided assistance individually in accordance with the request of the students.

The study population was from the province surrounding Turkey’s capital of Ankara has and included 160 established Class 3 students at a university nursing faculty. To obtain the research sample, the typical sampling method was used for the purpose of determining the subject situation, event and person and to obtain in-depth data. Accordingly, the study sample consisted of 30 students who volunteered to participate in the study. The students who agreed to participate in the study had online internet access at home and had no limitations in their ability to perform physical activity. Students of the nursing faculty who continued their education remotely due to the lockdown were informed about the study online, and written and verbal consent was obtained from the students who volunteered to participate. The study aimed to help students with a holistic approach in the quarantine process. The average age of the sample, which consisted of female students, ranged from 21–30 years.

2.2 Data Collection and Analysis

Semistructured interviews were conducted to obtain the results. In a semistructured interview, the topic and some of the questions are planned before it begins, but the format is flexible to offer the possibility to change or add new questions as the interview and/or research work progresses. It is the most frequently used interview type in qualitative research on health. The data were collected between 31 March and 20 June 2020. All of the interviews were individual and were conducted online via electronic resources, with the day and time decided. The interviews were recorded, and notes were taken after each interview. All interviews were conducted by the researcher with sufficient knowledge. The data were collected between 31 March and 20 June 2020. The researcher conducted face-to-face interviews with each participant online. After the online face-to-face interview, the results were conveyed to the researcher in writing by the students. Before the interviews, the students were asked to reflect on the positive and negative effects of the COVID-19 lockdown process and their experiences of the wellness coaching that was offered to help them cope with the process.

The students were asked the following questions: ‘How did the corona virus pandemic affect your life at first?’, ‘How did the sudden distant education affect you?’, ‘Did you have any methods of coping with the negativity of the lockdown process before this wellness coaching?’, ‘Did you participate in physical activity before this practice?’ and ‘Did you take the time to be thankful first?’ Interviews were recorded in audio and written format with the consent of the participants. Each meeting lasted at least one to two hours and continued until a new theme was determined. Participants chose the online classroom as the interview venue due to the lockdown situation. Ethical approval was obtained from the relevant university human research ethics committees. Before the interviews, informed consent was obtained from the participants. Data were analyzed using the content analysis method [24]. In the study, interview data of the participants were recorded, and their responses were transcribed. Numbers were assigned to the interview papers. Using NVivo 8.0, a computer-aided qualitative data analysis program, the interview papers were transferred to the resources section of the program, and the necessary coding was made. The data were prepared for analysis by matching the themes created in the context of the research problems with the interview content. Subthemes/categories were created to better understand the identified themes. The categories were the following: how students felt during the quarantine process, what the Wellness coaching practice added to their life, what were the changes resulting from the application, would they like the application to continue, and would they recommend the application? A research protocol was created to ensure the transparency and consistency of data [25].

The researcher participated in the research by providing views and suggestions on data collection, coding, analysis, interview text, coding and themes. In addition, the researcher has been involved in the research as both an application participant and observer, although it is the application that is the subject of the study. In this way, the application could be described in detail and entered into the relevant research topic [24]. A detailed explanation of the application and data collection process was provided by the researcher, who’s opinions on the interview text, themes and codings have been important for ensuring the reliability of the research.

In addition, the findings obtained regarding the validity of the study were shared with ten students who participated in the interview, and participant confirmation was obtained. However, the opinions of the participants supporting the findings were conveyed by using direct quotations. Detailed quotations are provided to create a picture in the mind of the reader about the environment from which the data are obtained and to enable the reader to draw conclusions about the results more easily.

Four main themes were defined: how students felt during the quarantine process, what the Wellness coaching practice added to students’ lives, what changes resulted from the application, whether students would like the application to continue and whether students would recommend the application. Subthemes are given under each theme.

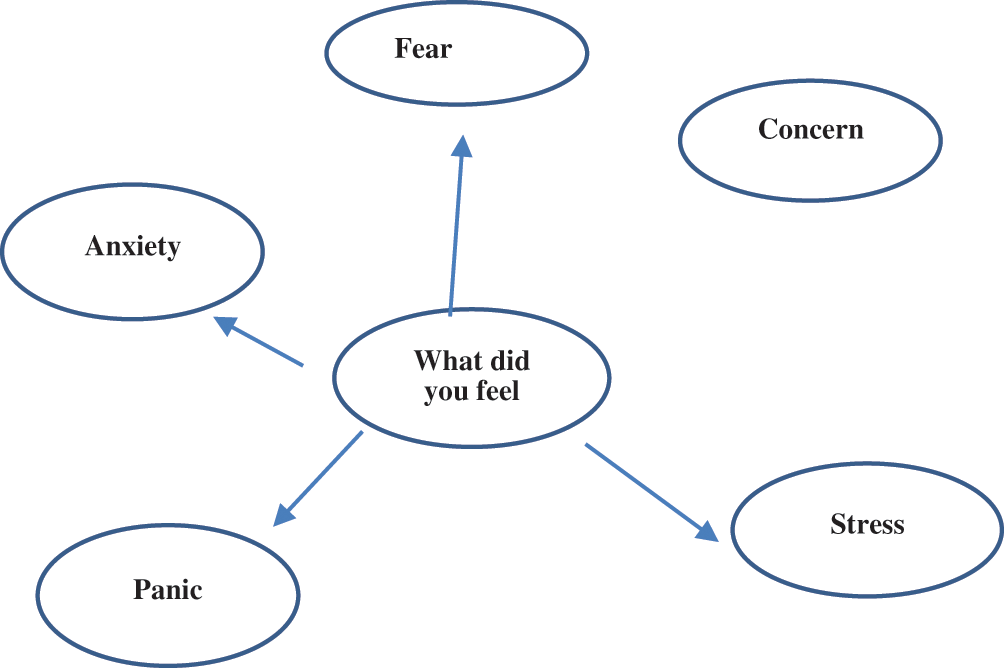

3.1 How Did You Feel during the COVID-19 Lockdown Process?

The theme and subthemes of this finding defined by the participants are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: What did you find in the COVID-19 lockdown process?

One of the emotions that students felt during the transition to distance education and lockdown at home due to the pandemic was fear. The reason for the fear is that a pandemic was encountered for the first time and the measures taken were very restrictive, so they had to quarantine at home. The views referring to this feeling are as follows:

“…… Our daily routines have changed, our active school life had to continue from home, we could not do our social activities, we could not meet our friends and loved ones, and we were very afraid that we would catch the disease.” P1

“…… I was very scared. Thought we’d live a life like a science fiction movie.” P2

Students stated that they experienced anxiety due to the announcement of the COVID-19 epidemic as a pandemic, the quarantine measures implemented in their country, the transition from formal education to distance education in education and uncertainty. Supporting statements are provided below.

“…… You buy the fish in the ocean and put it in a tiny aquarium, that is how it affected. I felt like I was trapped between four walls. I thought I could not breathe, I would drown. This situation created anxiety in me.” P3

“…… It caused serious chaos in my life. While I was a planned person, not knowing what will happen tomorrow during this period caused me great anxiety and chaos.” P4

Another emotion that students convey regarding what they feel during the pandemic process is anxiety, and sample views expressing this feeling are as follows:

“…… I didn’t panic much at first. I knew that it would not be a problem if I took the necessary precautions. My only concern was my family. I was worried about their health as they are over a certain age and working individuals.” P5

“…… At first, I was much more worried, afraid that I was going to get infected from everywhere anytime.” P6

Another feeling expressed was panic, as supported by the following statement:

“…… I did not know what to do at first, I panicked. Since I am away from my family, how is the health condition of my family? I had hundreds of questions in my mind in case they get sick and die due to COVID-19. Because of this, I was constantly experiencing panic.” P7

Another of the transferred feelings is stress, as supported by the following statements:

“…… I had turned into a stressful person. The events and uncertainties affected me negatively in a psychological way. I didn’t know what to do.” P8

“…… The uncertainty of this process was very difficult not knowing anything about what to expect, the change in education was stressful.” P9

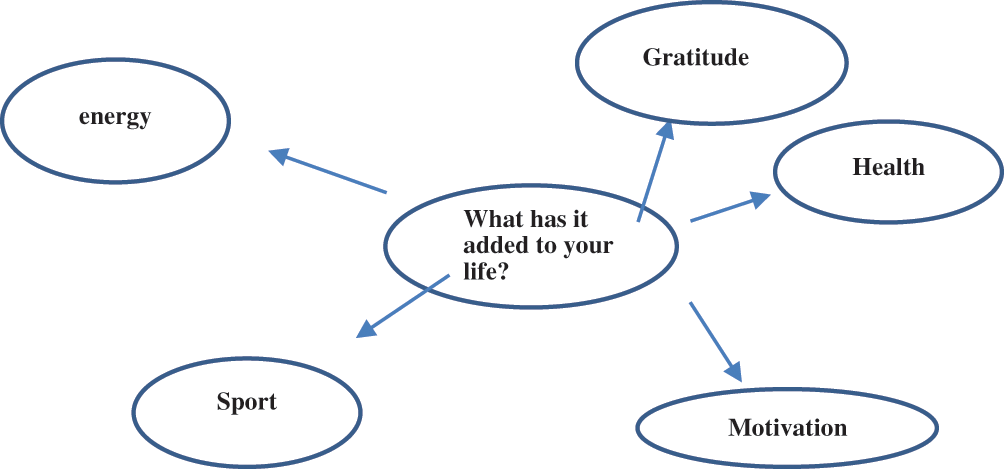

3.2 What Has the Wellness Coaching Practice Added to Your Life?

The themes created for the contribution of the application to the students’ lives were determined by descriptive analysis and are modeled in Fig. 2. Explanations of the themes and subthemes are detailed below.

Figure 2: What has wellness coaching added to your life?

The students stated that they had never been grateful for this theme before, they did not spare time to be thankful, and they realized that they had many things to be thankful for in their lives as a result of this practice. Some of the opinions conveyed support this theme.

“…… There were things that I was verbally grateful for before, but I never thought of writing them down or creating a diary. When I put these in writing, my soul became more relaxed and I felt a spiritual satisfaction.” P10

“…… It actually made me see that I have so much gratitude in my life.” P11

“…… I have found many things to be thankful for in such negativities, which increased my hope.” P12

In the students’ interviews, they stated that one of the most important contributions of this application was to gain the habit of participating in sports. Below are some comments supporting the theme:

“…… It helped me deal with stress during the sports lockdown process.” P13

“…… It helped me understand that exercising makes you feel happy, not torment. Impossible, I saw that I could actually do it when I said I don’t do sports.” P14

“…… This application proved to me that you can do sports while staying at home. And with this application, we have taught my siblings that sports are fun and the importance of being able to step into life more solidly.” P15

When the opinions about the theme were evaluated, the students stated that participating in the application created a source of motivation for them and that they were excited while waiting for the application hours. Some of the participant expressions supporting the theme are provided below:

“…… This application has definitely added motivation to my life. I realized how important and beautiful it is to value my body, to do something for it every day. This affected my self-confidence positively.” P16

“…… It added gratitude, happiness, peace, love, motivation and energy. He taught the importance of the concept of time, and taught that the taste of drinking water cannot be changed for anything. Made me love myself.” P17

Students stated that the application improved their health. Some of the participant expressions supporting the theme are as follows:

“…… Most importantly, it added health. I learned new information to give to my environment.” P18

“…… I have learned by experience how important health is and that the only issue where the whole world is united is human health.” P19

The students stated that they felt energetic due to this application. Some of the supporting views are as follows:

“…… It energized my boring and monotonous life. It energized me to cope with depression, the ugly feelings created by the quarantine.” P20

“…… It enabled me to look at life more energetically and positively.” P21

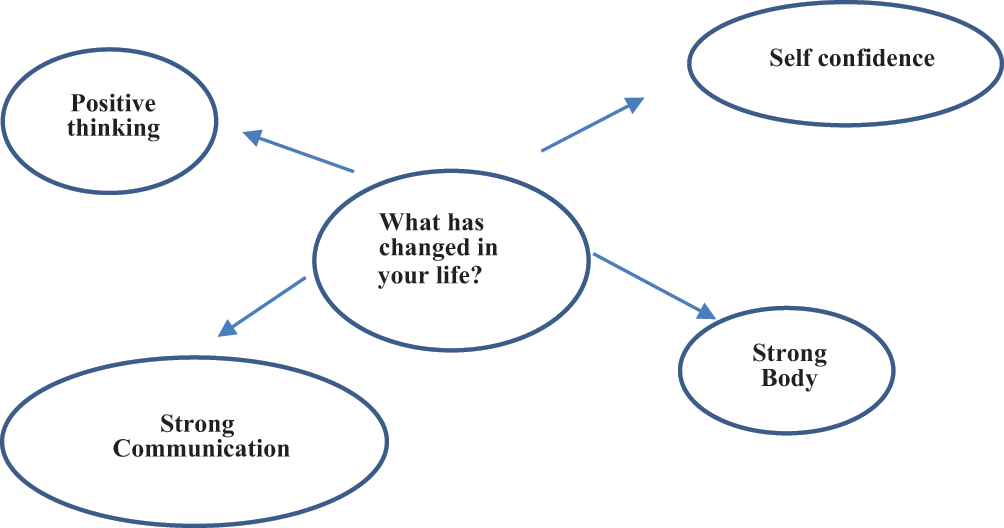

3.3 What are the Changes that the Application Has Created for You?

The model obtained as a result of the analysis of participant views on this theme is presented in Fig. 3. After use of the application, the participants stated that they experienced mental, spiritual and physical changes. As an example of these changes, the students stated that they became physically stronger, lost weight, experienced an increase in their self-confidence, and started to think positively. Subthemes are detailed below.

Figure 3: What are the changes caused by the application?

Students stated that this practice strengthened their communication by allowing them to express their opinions among themselves more often and showing more tolerance. Some examples of the participant responses support this theme.

“…… It reminded us of the feeling of unity, togetherness and socialization that we lost in the classroom. It caused us to communicate even better and stronger with many of our friends”. P22

“…… Thanks to our whatsapp group we share, it has added color to my life these days when we are isolated from social life. And after the group was formed, I didn’t feel so isolated. Communication between me and my friends has also strengthened.” P23

The students stated that the application was especially effective for this theme, as it created the opportunity for them to feel stronger and happier and contributed to their development. Some of the supporting opinions regarding this theme are as follows:

“…… Before this practice, I could not think positively and had no enthusiasm to do anything. I started to look positive to the day. I started to see the positive side of everything.” P24

“…… I became a depressed person because of the negativities COVID-19 brought to our lives. Thanks to this application, I got rid of depression by seeing the positive things in my life.” P25

Students stated that their bodies became stronger, they lost weight and their existing pain was reduced due to online exercise they participated in five days a week. Statements in support of the views are given below:

“…… I found peace in sports, I was physically tightened and lost weight, my back pain decreased, I feel physically healthier and stronger.” P26

“…… My body, which was physically inactive, recovered. My body has begun to recover. I constantly moved from a horizontal position to a vertical position.” P27

One change that the practice created in students was self-confidence. The views representing this feeling are as follows:

“…… I realized how important and beautiful it is to value my body, to do something for it every day. This increased my self-confidence.” P28

“…… If you have a coach who motivates you and I wouldn’t really believe that with her sports would change so much in my life, but seeing the changes in my body increased my self-confidence.” P29

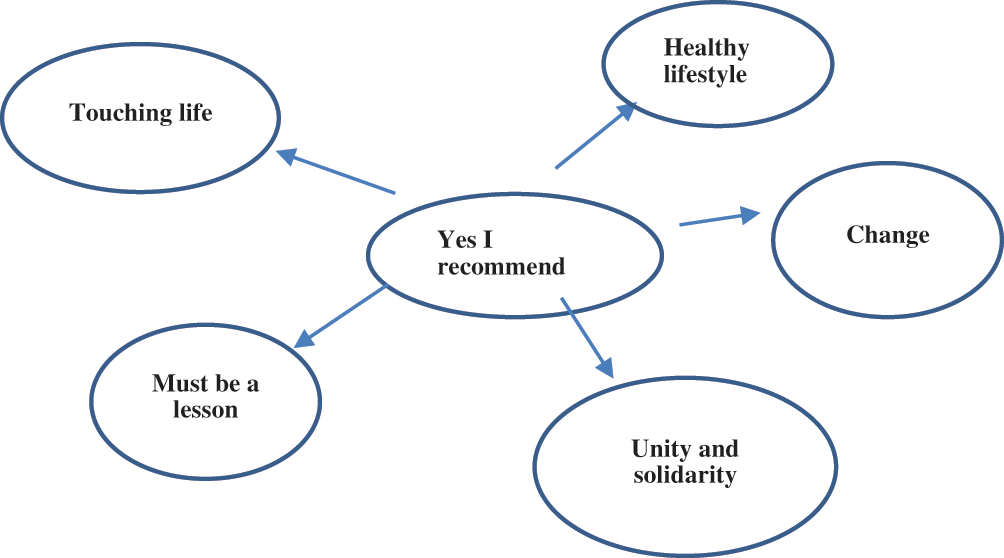

3.4 Would you Like the Application to Continue? and Would You Recommend the Application?

Participants stated that they were in favor of the continuation of the application and expressed their views that they would also recommend the application to others. The model generated based on their opinions is shown in Fig. 4. The students noted that they would suggest this practice because it supported healthy living behaviors, touched their life, yielded great changes, and increased unity and solidarity, and they felt that such a course must be in the curriculum.

Figure 4: Do you want the application to continue? And would you recommend the application?

Some of the participants’ responses are as follows:

“…… I highly recommend it. I think, with this application, participants will definitely notice both physical and psychological changes in themselves” P30

“…… I opened the door and let the sun in with this app” P1

“…… Wellness is the happiness of someone who seeks and finds a glass of water in the desert” P3

“…… It will be very good for those who want to change something in their life but do not feel that power.” P5

“…… Absolutely yes, even if we don’t have a course next year, I still want it to continue under the leadership of the researcher.” P10

Nursing has always utilized information from a wide variety of sources and areas to achieve the best possible results for clients. Coaching emerged as one of the ways to structure nursing in a way that improves client interactions and client-nurse partnerships. Wellness coaching is one of the roles of nurses and provides various health services to facilitate lifestyle behavior changes and improve the mental health of individuals and society. This study was a preliminary investigation of how wellness coaching is associated with the psychological, physiological, and mental health benefits of college students during a public health crisis. While the COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to decreased mental health (e.g., depression, loneliness, isolation) and limited opportunities to participate in activities, this study highlighted the importance of wellness coaching as a way to improve mental and physical health among college students. Overall, the results showed that wellness coaching contributes to psychological and mental health benefits among students. In particular, it serves as a powerful indicator of happiness, life satisfaction, and perceptions of health, reducing the impact of loneliness, anxiety, and depression caused by social isolation during the quarantine period. These findings show that the application of wellness coaching online is likely to increase students’ psychological and mental health during the COVID-19 era.

In this study, it was determined that the emotional states of the students were negatively affected by the onset of the pandemic. Savitsky et al. [26] showed that the level of anxiety of nursing students during the quarantine period during the pandemic process was high. In a different study, they found that 71% of students showed increased stress and anxiety due to the COVID-19 outbreak and fear and anxiety about their own health and the health of loved ones. In addition, 91% of them reported the negative effects of the pandemic and stated that they had difficulty concentrating, disturbances in sleep patterns, and a decrease in social interactions [27]. In a study conducted in India, a significant difference was found in the symptoms of depression; specifically, quarantine negatively affected students and employees, and the participants experienced anxiety and worry [28]. The literature results support our study findings.

Studies have shown that during the COVID-19 quarantine period, there was an increase in unhealthy living behaviors, such as a decrease in physical activity and malnutrition, an increase in weight gain, and an increase in smoking [29–31]. In addition, one study noted that school closures would have a lasting impact on nutritional and lifestyle behavior and long-term challenges for children. The same study noted that intervention studies that integrate a certain diet and lifestyle during school closures are necessary by encouraging healthy living every day [32]. In this study, students showed similar unhealthy lifestyle behaviors during the quarantine process; however, with the wellness coaching health promotion intervention study, it has been observed that they have coped with the situation easily and, fortunately, experienced improvements in physical activity, motivation, energy and health in their lives. During the COVID-19 quarantine process, it was observed that individuals had sleep problems and decreased physical activity, social interactions and communication [33]. In this study, students also experienced similar problems and stated that the social isolation caused by quarantine was mitigated by the improvements in communication, positive thinking, self-confidence and physical health afforded by the wellness coaching. In a study investigating the effect of wellness coaching on improving quality of life, it was shown that participants experienced increased social activity and mental and emotional well-being and decreased depression symptoms after use of the application [21]. In another study conducted in students, it was determined that a wellness coaching practice was more effective in improving health than health education, and the health promotion total scores of the students who received wellness coaching were significantly higher [18]. The results of the study show that wellness coaching is an effective practice for health promotion.

This study has several important limitations. First, this was a single-arm study without a control group; therefore, no comparison could be made. Qualitative participant data were obtained, as the study was conducted during the COVID-19 quarantine process. No causality statement can be made regarding the findings. Other limitations are that the sample consists mainly of individuals composed of women and university students. How these findings apply to more diverse or different populations is unknown. Direct measurement of health behaviors (e.g., activity level, diet) was not performed. Measuring these health behaviors together with qualitative and quantitative data could strengthen the findings. All participants agreed to participate in 8 weeks of face-to-face health coaching; therefore, the effects of different lengths of wellness coaching (8 vs. 12 weeks) or the manner in which wellness coaching is presented (over the phone or in person) could not be studied.

This study demonstrated positive improvements in the physical, mental and spiritual health of students during the quarantine process. In addition, it has been observed that providing wellness coaching in a group setting as well as individual delivery online is successful in improving both physical and mental health. These four components, which are determined to be important public health initiatives for mental and physical health promotion, can be used as a guide to address the remaining gaps in services to be provided.

Acknowledgement: I would like to thank all the students.

Funding Statement: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. World Health Organization (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report-62. Geneva, CH: WHO. [Google Scholar]

2. Javed, B., Sarwer, A., Soto, E. B., Mashwani, Z. U. R. (2020). The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic’s impact on mental health. International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 35(5), 993–996. DOI 10.1002/hpm.3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Lades, L. K., Laffan, K., Daly, M., Delaney, L. (2020). Daily emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. British Journal of Health Psychology, 25(4), 902–911. DOI 10.1111/bjhp.12450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. AlMughamis, N., AlAsfour, S., Mehmood, S. (2020). Poor eating habits and predictors of weight gain during the COVID-19 quarantine measures in Kuwait: A cross sectional study. F1000Research, 9, 914. DOI 10.12688/f1000research.25303.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Cano-Hila, A. B., Argemí-Baldich, R. (2021). Early childhood and lockdown: The challenge of building a virtual mutual support network between children, families and school for sustainable education and increasing their well-being. Sustainability, 13(7), 3654. DOI 10.3390/su13073654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Erdem, I. (2020). Koronavirüse (COVID-19) karşı Türkiye’nin karantina ve tedbir politikalari. Electronic Turkish Studies, 15(4), 377–388. DOI 10.7827/TurkishStudies.43703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Varol, G., Varol, B. T. (2020). Halk sağliği boyutuyla Türkiye’de COVID-19 pandemisinin değerlendirmesi. Namık Kemal Tıp Dergisi, 8(3), 364–379. DOI 10.37696/nkmj.776032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kim, J., Byon, K. K., Kim, J. (2021). Leisure activities, happiness, life satisfaction, and health perception of older Korean adults. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 23(2), 155–166. DOI 10.32604/IJMHP.2021.015232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ettman, C. K., Abdalla, S. M., Cohen, G. H., Sampson, L., Vivier, P. M. et al. (2020). Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2019686. DOI 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Rosen, Z., Weinberger-Litman, S. L., Cheskie, R., Rosmarin, D. H., Muennig, P. et al. (2020). Anxiety and distress among the first community quarantined in the US due to COVID-19: Psychological implications for the unfolding crisis. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 53, 1689–1699. DOI 10.31234/osf.io/7eq8c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yan, Z., Qiu, S., Alizadeh, A., Liu, T. (2021). How challenge stress affects mental health among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: The moderating role of self-efficacy. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 2(23), 167–175. DOI 10.32604/IJMHP.2021.015937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Lee, J. S., Koeske, G. F., Sales, E. (2004). Social support buffering of acculturative stress: A study of mental health symptoms among Korean International students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 28(5), 399–414. DOI 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2004.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Menec, V. H. (2003). The relation between everyday activities and successful aging: A 6-year longitudinal study. Journals of Gerontology Series B, 58(2), S74–S82. DOI 10.1093/geronb/58.2.s74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. World Health Organization (2010). World health organization global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva, CH: WHO. [Google Scholar]

15. Shahidi, S. H., Williams, J. S., Hassani, F. (2020). Physical activity during COVID-19 quarantine. Acta Paediatrica, 109(10), 2147–2148. DOI 10.1111/apa.15420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Lippi, G., Henry, B. M., Sanchis-Gomar, F. (2020). Physical inactivity and cardiovascular disease at the time of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 27(9), 906–908. DOI 10.1177/2047487320916823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Balanzá-Martínez, V., Atienza-Carbonell, B., Kapczinski, F., de Boni, R. B. (2020). Lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19 time to connect. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 141(5), 399–400. DOI 10.1111/acps.13177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Altunkurek, S. Z., Bebis, H. (2019). The effects of wellness coaching on the wellness and health behaviors of early adolescents. Public Health Nursing, 36(4), 488–497. DOI 10.1111/phn.12608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Huffman, M. H. (2016). Advancing the practice of health coaching: Differentiation from wellness coaching. Workplace Health & Safety, 64(9), 400–403. DOI 10.1177/2165079916645351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Passey, D. G., Hammerback, K., Huff, A., Harris, J. R., Hannon, P. A. (2018). The role of managers in employee wellness programs: A mixed-methods study. American Journal of Health Promotion, 32(8), 1697–1705. DOI 10.1177/0890117118767785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Clark, M. M., Bradley, K. L., Jenkins, S. M., Mettler, E. A., Larson, B. G. et al. (2014). The effectiveness of wellness coaching for improving quality of life. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 89(11), 1537–1544. DOI 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.04.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Schmittdiel, J. A., Adams, S. R., Goler, N., Sanna, R. S., Boccio, M. et al. (2017). The impact of telephonic wellness coaching on weight loss: A “natural experiments for translation in diabetes (NEXT-D)” study. Obesity, 25(2), 352–356. DOI 10.1002/oby.21723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Storey, L. (2007). Analysing qualitative data in psychology. In: Lyons, E., Coyle, A. (eds.Analysing qualitative data in psychology, pp. 51–64. London, UK: SAGE Publications, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

24. Yıldırım, A., Şimşek, H. (2006). Sosyal bilimlerde nitel araştırma yöntemleri. Ankara, TR: Seçkin Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

25. Graneheim, U. H., Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. DOI 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Savitsky, B., Findling, Y., Ereli, A., Hendel, T. (2020). Anxiety and coping strategies among nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurse Education in Practice, 46, 102809. DOI 10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., Sasangohar, F. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), e21279. DOI 10.2196/21279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Majumdar, P., Biswas, A., Sahu, S. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: Cause of sleep disruption, depression, somatic pain, and increased screen exposure of office workers and students of India. Chronobiology International, 37(8), 1191–1200. DOI 10.1080/07420528.2020.1786107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Radwan, H., Al Kitbi, M., Hasan, H., Al Hilali, M., Abbas, N. et al. (2020). Diet and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown in the United Arab Emirates: Results of a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 1. DOI 10.21203/rs.3.rs-76807/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Haddad, C., Zakhour, M., Bou Kheir, M., Haddad, R., Al Hachach, M. et al. (2020). Association between eating behavior and quarantine/confinement stressors during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 8, 40. DOI 10.1186/s40337-020-00317-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Sidor, A., Rzymski, P. (2020). Dietary choices and habits during COVID-19 lockdown: Experience from Poland. Nutrients, 12(6), 1657. DOI 10.3390/nu12061657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Allabadi, H., Dabis, J., Aghabekian, V., Khader, A., Khammash, U. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on dietary and lifestyle behaviours among adolescents in Palestine. Dynamic Health and Human Movement, 7(2), 2170. [Google Scholar]

33. Giuntella, O., Hyde, K., Saccardo, S., Sadoff, S. (2020). Lifestyle and mental health disruptions during COVID-19. SSRN Electronic Journal, 13569. DOI 10.2139/ssrn.3666985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |