| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/ijmhp.2022.018187

ARTICLE

Why Insisting in Being Volunteers? A Practical Case Study Exploring from Both Rational and Emotional Perspectives

1Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, 510006, China

2Chaoyang University of Technology, Taichung, 413, Taiwan

3WuFeng University, Chiayi, 621, Taiwan

*Corresponding Author: I-Tung Shih. Email: itungshih99@gmail.com

Received: 06 July 2021; Accepted: 10 September 2021

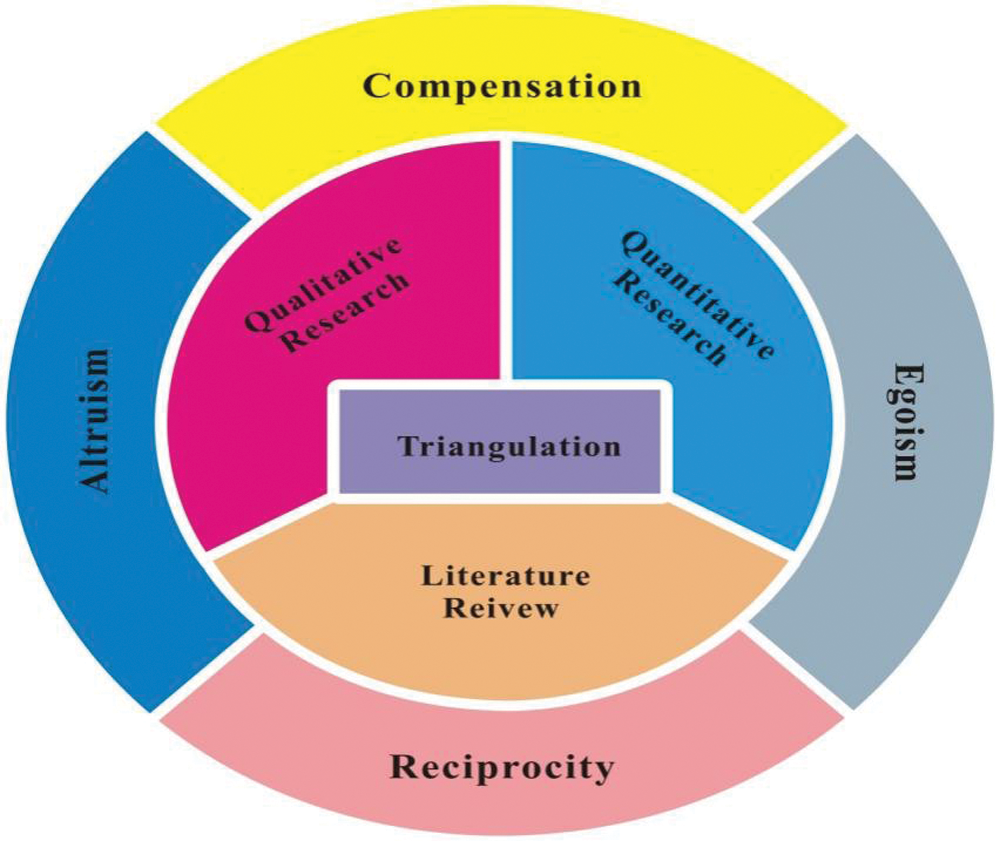

Abstract: This study explored the mechanism on how volunteers as rationalists use rationalism during their cognitive appraisal process when dealing with emotional events in their social helping behavior such as international rescue events. The authors used the triangulation method to include three studies (Study 1 is a qualitative research which explored ways of TCF leader’s inspiring their volunteer workers; Study 2 is a quantitative research on the decision-making process of volunteer individuals involving in international rescue activities; Study 3 is a quantitative research on individuals’ motivation for joining social helping behavior) for validation of Tzu Chi Foundation (TCF), which is a famous non-profit organization worldwide, to prove that volunteers as rationalists rely on the reasonable cognitive appraisal method to substantially evaluate the necessity of social helping behavior, including their emotional responses and arousals. Economic evaluation theory was used to depict volunteers as volunteers as rationalists’ way of cognitive appraisal perspective towards emotional events such as international rescue cases or when participating in activities by non-profit organizations. Accordingly, this study found that volunteers as rationalists adhere to the principles of altruism, egoism, compensation, and reciprocity as part of their cognitive appraisal when responding to emotional situations. The research findings of this study depicted the volunteers’ behavioral intention as volunteers as rationalists in responding to emotional events in the form of NPO helping behaviors and international rescue events. Social helping behaviors often rely on people’s emotional compassion and empathy at the beginning, but social helping behaviors cannot rely solely on emotional support. To create long-term support for non-profit organizations’ action plans, it is still necessary to plan rationally, turning the actions of volunteers into reasonable plans. In this way, even if the volunteers have experienced many difficulties during devotion, hindrance, and stress afterward, they can still keep in a rationalist’ mindset continuously. This paper provided directions for volunteer training for non-profit organizations.

Keywords: Altruism; compensation; egoism; NPO; reciprocity; rationalism; volunteer; Tzu Chi

Human decisions are made in accordance with emotions, sometimes with reasons. However, this study aims to prove that volunteers as rationalists are always reasonable even when confronting with emotional events.

Individuals perform certain behaviors based on their evaluation of the rewards and the resources. Homans [1] suggested that individuals perform a behavior when the reward is greater than the resources used. Moreover, individuals first determine the association of probable costs and rewards before performing a certain behavior [2]. People experience negative internal emotions mainly due to the influence of the norm (rational thinking), and the intensity of the emotion is mainly due to the influence of economic evaluation. The Economic Evaluation Theory [3] was applied to depict volunteers as rationalists’ cognitive appraisal process when deciding whether to perform a behavior or not during an emotional event such as in aiding in relief operations.

On the other hand, the Cognitive Appraisal Theory developed by Arnold [4] and was later expounded by Lazarus [5], who defined cognitive appraisal as the individuals’ response to a situation after evaluating the stimuli present in the environment. Lazarus [5] proposed that appraisal occurs in primary appraisal and secondary appraisal, and explained how individuals cope with situations in terms of self-centered benefit and attribution of the event causes. The primary appraisal can be considered emotional appraisal. Since it takes into account the situational factors that affect personal well-being and self-centered benefit. The secondary appraisal can be considered as the rational appraisal since it considers how one should cope with the situation cognitively and rationally in order to solve the problem, hindrance, or challenge being confronted.

This study aimed to determine whether volunteers think and act as rationalists who continuously use rationalism even when dealing with emotional events during social helping behaviors such as international rescue activities, and cognitively appraise with a reasonable mind to motive their behavioral and social intention when acting upon social situations; so that the social helping behavior can be executed continuously and thus volunteers as stress takers tend to become easier in viewing rescue tasks as challenge stressor, instead of hindrance in the long term [6]. Further, we proposed that volunteers as rationalists use four principles of rational cognitive appraisal when dealing with an emotional event which is: (1) altruism, (2) egoism, (3) compensation, and (4) reciprocity. To achieve its goal, the current study performed three case studies. Study 1 examined the Tzu Chi Foundation and their overseas relief activities and explored how a large religious group uses rationalism to encourage their volunteers to continue helping in rescue operations. Meanwhile, Study 2 explored social norms’ effect over empathic emotions, and Study 3 investigated altruistic and egoism motives through economic evaluation and behavioral motivation in relieving others’ distress by joining NPO’s international rescue operations.

2 Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Volunteering was defined as “an activity in which time is given freely to another person, group or organization” [7]. Since volunteers can help develop valuable social capital, contribute to the community, and civic awareness [8] by reducing costs of non-profit organizations at the same time; attracting and retaining volunteers with fascinating value systems becomes an important part of the operations of non-profit organizations. Dunn et al. [9] suggested that the common motivation of volunteers is to help others and be socialized; thus, gaining friendship and acquire knowledge and desired information through educational activities of the non-profit organization was found to be ways of increasing the possibility of volunteering; stronger religious beliefs also increase the level of volunteerism [10]. Grube et al. [11] explored volunteers’ self-definition (from the perspective of role identification, which is derived from the volunteer’s experience in the organizational environment); it implied that the volunteer believes that “his or her role is essential to the success of a valuable organization” [11].

Based on the above-mentioned past research, we understand that past researchers believed that the role identity formed by volunteers is related to (1) the personal experiences in the organization, (2) the prestige of non-profit organizations, (3) and homogeneity of personal values with value systems of NPO. Through interactions with members of the organization, the volunteers tend to have feelings of being proud and enthusiastic and view volunteering tasks as a means of self-identification [12], which helps volunteers to have a sense of belonging to their NPO, as the organization seems to promise to realize the value of volunteers.

However, this study extensively started from another perspective. The role of the volunteer is often a job that requires mental toughness in the long term. In the absence of any income, individual volunteers achieve the meaningful life goals of friendship, the feeling of pride and enthusiasm, and prestige from the process of volunteering. However, except for the volunteerism mentioned above, being consistent with their role and value identification and positioning sometimes volunteers have to consider volunteers’ family time spent together with their family members, stress from family members and relatives in the financial aspects. Under such pressure, the authors of this study explored the mechanism to engage in volunteer work and still handle it properly and for a long time from both emotional and rational prospects. This study specifically classified the motives of volunteers: in addition to the existing literature review that has been emphasizing more towards the discussion of emotional phases, this study extensively went deeper in exploring the rational behavior of volunteers. The authors expected that the augmented discussion of the rational behaviors and rationalism motives of volunteers help develop more comprehensive literature in the field of volunteering.

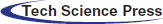

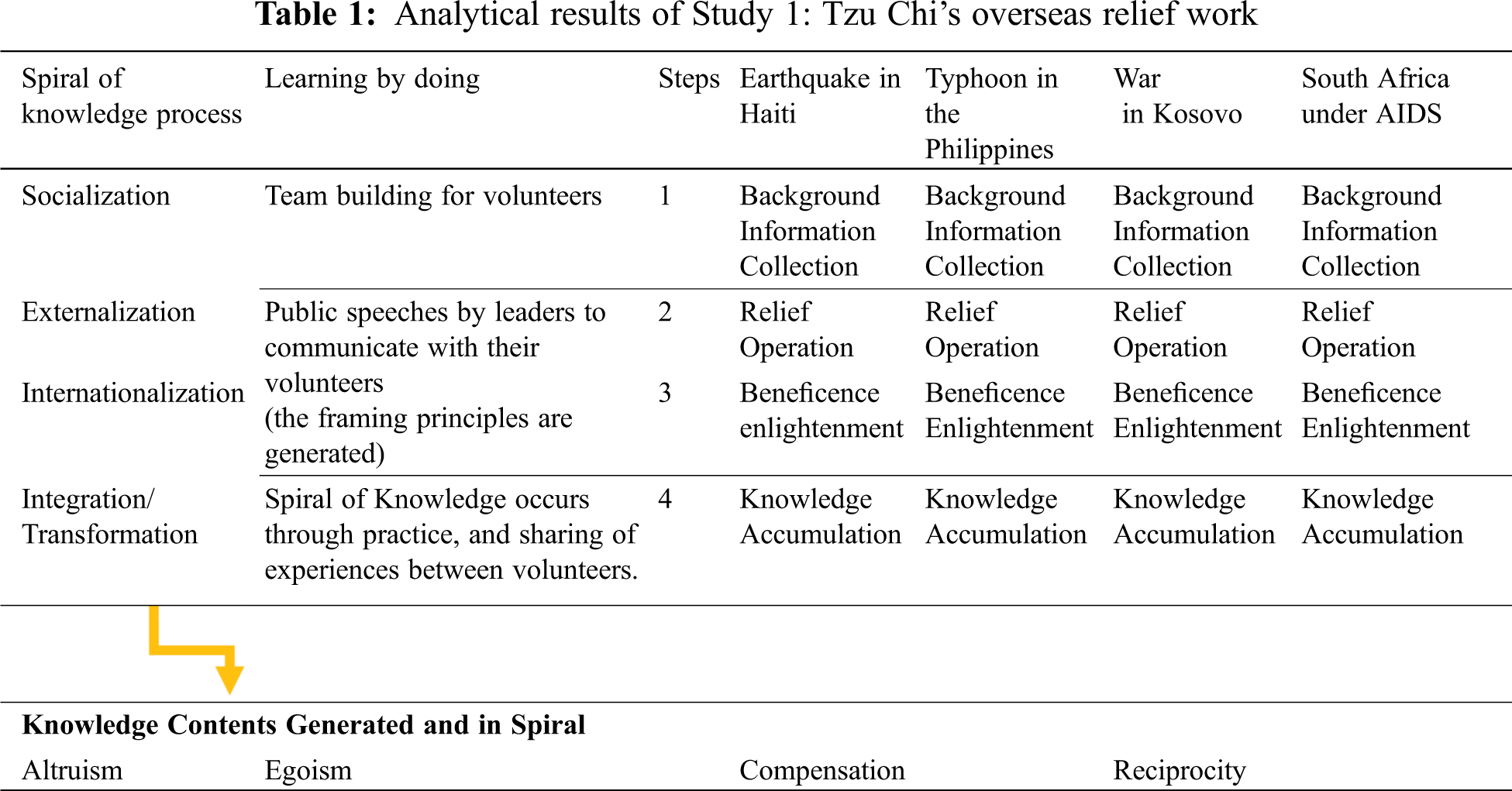

In short, they are the four critical emotional and cognitive appraisal factors supporting volunteers to join NPO, as suggested in this study: reciprocity, altruism, compensation, and egoism, as well as rational concerns for meeting social demands in the form of social norms, economic evaluation, and empathy expressed to the same group of society, which the authors believe empathy belong to the spirit of social helping behavior: to help each other in one society in order to ensure one group of society is protected as a whole. And these four critical factors are also like the glue in attaching organizational values and individual values together. From following Table 1, we can see that TCF also used these four factors as the principles to process the spiral of knowledge within their NPO in order to input valued beliefs to volunteers so that to increase their life meanings, which is one of the factors of positive thinking and life of learned happiness and optimism [13].

2.2 Cognitive Appraisal into Motives of Social Helping Behavior for Volunteers as Rationalists

Hsu et al. [14] distinguished the four types of motives of social helping behavior which are: (1) altruism, (2) egoism, (3) compensation and (4) reciprocity. These four types of motives in social helping behavior reflect the volunteers as rationalists’ thinking pattern of why they perform social helping behaviors.

According to Monroe [15], altruism is a selfless behavior for the welfare of others. Altruism regards the happiness of others as one’s own happiness, and satisfies the needs of others as the criterion of their behavior.

Compensation is the behavior concerned with correcting an individual’s previous wrong deeds.

This involves behavior that is beneficial to both the doer and the receiver. The issue related to oneself and others is the key to this appeal.

Egoism entails benefits to one’s own welfare. In the background of the appeal, the audience must be informed of the benefits of performing the behavior.

Behavior is influenced by people’s concerns on norms. Social norms are acquired through social learning and role models; this typically includes “reciprocity” which suggests that individuals should help those who helped them; and “responsibility” norms which dictate that a person should be of help to those who depend on him [16].

Ajzen [17] interpreted subjective norm as perceived social pressure, indicating that people worry about how others perceive them; thus, normative factors have substantial influence and utility in the social intention and behaviors of people. In addition, normality in society represents accepted standards of behavior. Deviancy leads to social sanctions [18]. Those who follow the norms expect to gain social approval, self-approval, and rewards from behaving according to the standards of the group [19]. These norms create a circle of influence among individuals’ behavior. Based on the above, the following is proposed:

H1: Norms have a positive and significant effect on social behavioral intention.

2.4 Economic Evaluation on Emotions

Homans [1] suggested that individuals consider an outcome as favorable when the reward is greater than the resources used. According to Piliavin et al. [2], individuals also assess the negative consequences of the action, such as loss of time or the effort required. The internal aversive emotion experienced by an individual is mainly due to the influence of the norm, and the emotional intensity is the effect of economic evaluation. Accordingly, the following are proposed:

H2: Norms have a positive and significant effect on economic evaluation.

H3: Economic evaluation has a positive and significant effect on individuals’ cognitive appraisal towards social behavioral intention.

2.5 Actual Control Factors on Emotions

According to Ajzen [20], motives lead to factors that affect certain acts. Further, the strength of the intention determines the success of the outcome. The possibility of a good outcome also depends on non-motivational factors such as resources available (e.g., finances, time, capabilities, etc.). An individual who has the capacity and intention to act has higher chances of performing the behavior. Therefore, the following are proposed:

H4: Actual control factors have a positive and significant effect on social behavioral intention.

H5: Economic evaluation has a positive and significant effect on actual control factors.

The study by Olsen et al. [21] found that empathy may influence an individual’s willingness to help. Allred et al. [22] indicated that empathy serves a mediating role between negative images and donation intentions. According to Riess [23], reasons, morals, and informational knowledge are involved during the cognitive appraisal process of individuals. Based on the above, the following are proposed:

H6: Individuals’ perception of norms has a positive and significant effect on empathy.

H7: Empathy has a positive and significant effect on social behavioral intention.

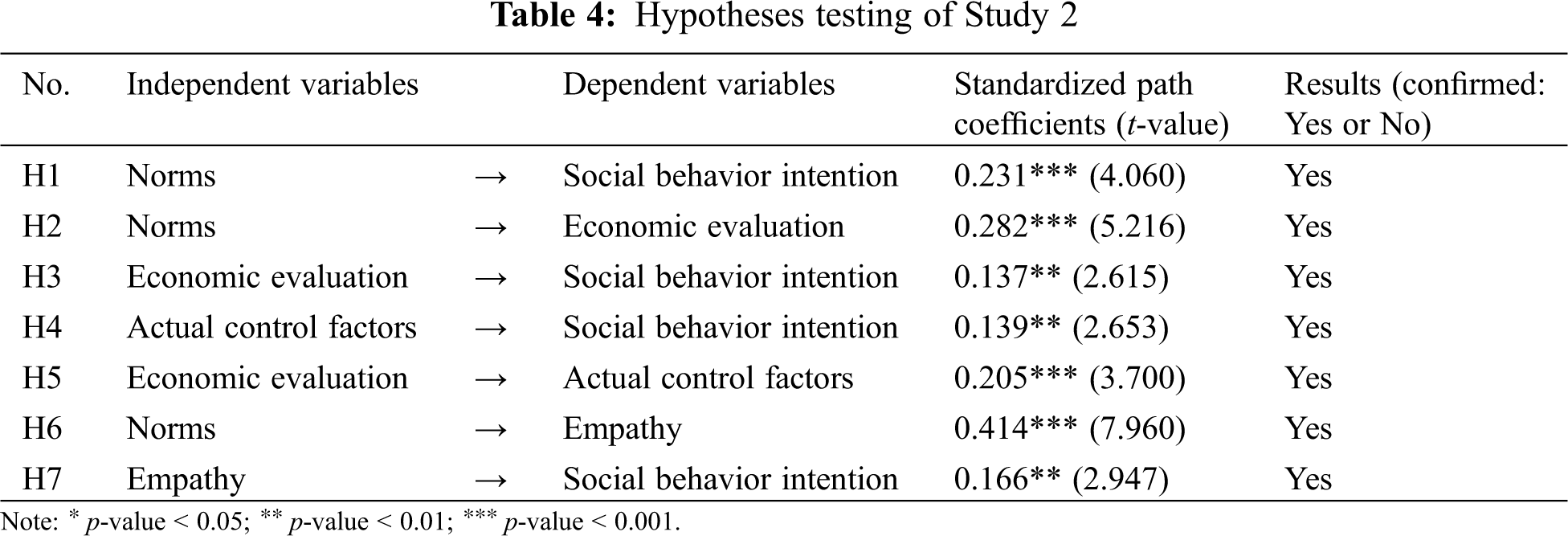

Above H1~H7 were tested in Study 2.

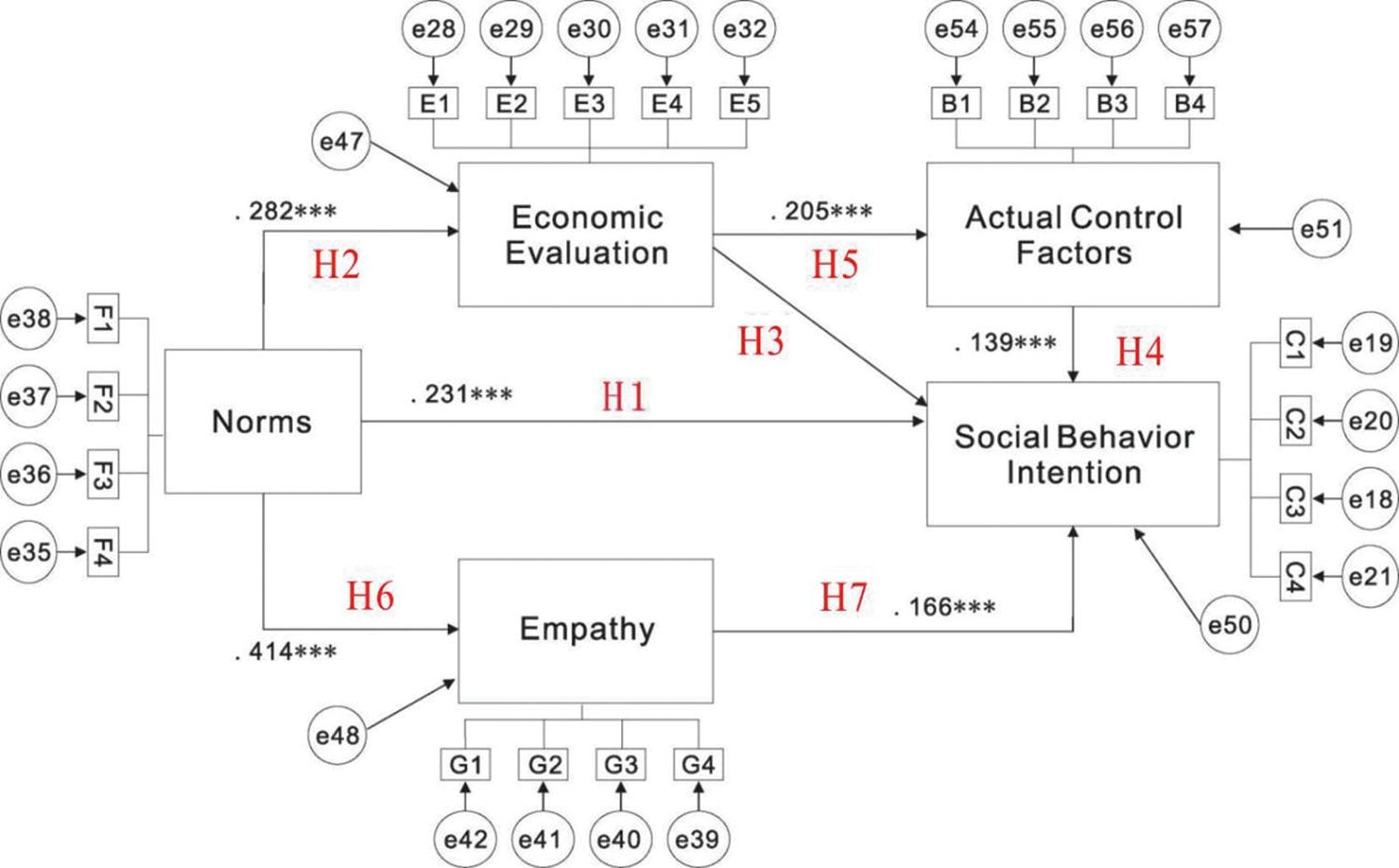

With respect to the literature review and the proposed hypotheses, Study 2 developed its research framework presented in Fig. 1 below.

Figure 1: Volunteers as rationalists’ cognitive appraisal upon emotional events: Helping behavior (Study 2)

2.7 Altruism and Egoism as Motives for Relieving Others’ Distress

2.7.1 Social Exchange and Economic Evaluation

Batson [24] suggested that helping behavior has altruistic and egoistic motivations and that there are three paths in helping behavior: an altruistic path and two egoistic paths. The first path is activated by a motivational state, a unique combination of instigating situations, a final behavior response, a consequent internal response and a cost-reward analysis of potential behavior responses, the perception of helping someone in need, and the expected recompense for assisting or avoiding punishment for not assisting others. The second path involves the individual’s control of his state of mind on seeing people suffer. Lastly, the third path results from an altruistic motivation that comes from another’s positive perspective, which results in empathy and sympathy.

Bar-Tal [25] indicated that prosocial behavior occurs when one acts for his own good, and when one gives back what was lost or stolen. The former is called altruism and the latter is restitution which includes reciprocity and compensatory behaviors.

Social exchange theory holds that the majority of people’s behavior is based on the possible increase in interest and the desire to reduce the payment. If people can be attracted to the remuneration of helping behavior, they will approach altruistic behavior and will work hard in order to maximize the reward. Bar-Tal [25] pointed out that based on the definition of altruism, those who help others will not expect any interests from the outside world; however, they will look forward to the internal rewards such as enhancement of pride, self-esteem, and mood.

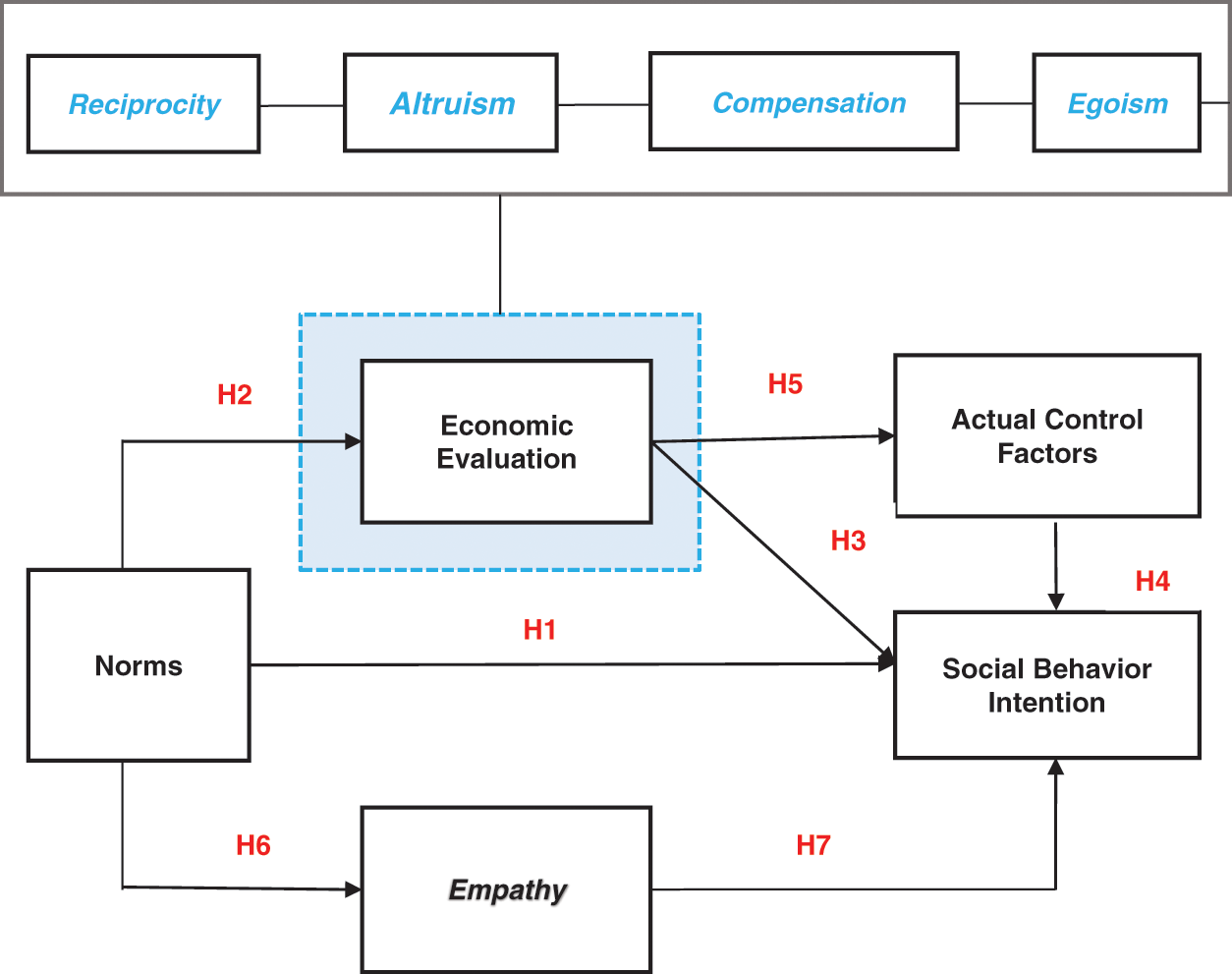

People look forward and make expectations about the rewards they will receive from helping others, and if it is lower than expected, the helping behavior will decrease or end. If this exchange relationship is stable, it results in both sides benefitting from each other; but if there is an unequal exchange remuneration, it means that there is an unequal exchange of power. Hsu et al. [14] stated that successful human interaction is the effect of individuals’ economic evaluation. The present study divided economic evaluation into two constructs: (1) rewards of participation, and (2) costs of non-participation. The former indicates that people engage in international rescue to relieve others’ distress to obtain the rewards, while the latter indicates that people participate in international rescue to relieve personal distress or avoid the costs of non-participation.

2.7.2 Intention of Being Volunteers

In the process of work assignments in international disaster relief activities, the best way is to assign tasks based on volunteers’ interests and work experience; for example, regarding the involvement in capacity-building efforts, volunteer physicians’ surgical tasks are assigned appropriately, and thus lower-level providers are adequately [26]. This study described the intention of being volunteers of non-profit organizations (NPO) for international rescue as the tendency of to participate in international aids, which is affected by personal behavioral motivation including, relieving personal and others’ distress.

Accordingly, the concept of reward to participation includes egoism, compensation, and reciprocity. The cost of non-participation pushes individuals to consider economic evaluation before acting on the behaviour. Lastly, relieving others’ distress entails altruism. Based on the above, the following are proposed:

H8: Rewards of participation have a positive effect in decreasing others’ suffering.

H9: Costs of non-participation have a positive effect in decreasing personal suffering.

H10: Relieving others’ suffering has a positive effect on the intention of being volunteers of NPO for international rescue.

H11: Relieving personal suffering has a positive effect on the intention of being volunteers of NPO for international rescue.

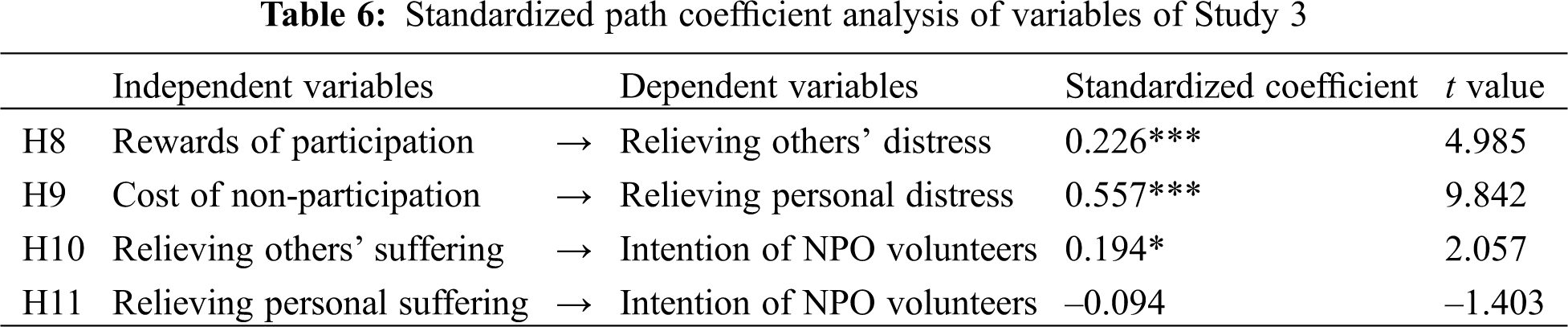

Above H8~H11 were tested in Study 3. Conceptual Framework of Study 3 is proposed as of below.

2.8 Background Information of the Research Object: Tzu Chi Foundation (TCF)

Tzu Chi Foundation (TCF) is a famous non-profit organization (NPO) worldwide, and located their headquarter in Taiwan. One of the specialties of TCF is that: there is a close interaction between Master Zheng Yen and the volunteers through morning meetings on a daily basis. When volunteers are engaged in overseas disaster relief work, multi-party video conference is held to formulate a long-term and visionary action plan. Master Zheng Yen not only collects all kinds of materials from all resources she had to provide victims with necessary living equipment but also thinks in an innovative and visionary way to encourage local victims to take an active part in the relief work themselves. One of the innovative practices is to encourage victims to help in the relief work to earn food or money by themselves so that they can pick up the confidence for life.

Figure 2: Conceptual framework of Study 3

Criteria for selection of TCF as the sample objection for investigation is that: TCF is a world-renowned and fully functional NPO; Its branches are all over the world, including various countries and races. Organizational types include hospitals, educational institutions, universities, medical schools, rescue organizations, etc. TCF welcomes researchers, scholars, and professors to join them. Therefore, the planning of various NPO activities is always very well-organized, well-documented, easy to obtain, and the interviewees have a high degree of cooperation. This is the main reason that this study can obtain three studies for validating on the conceptual framework suggested by this study at the same time.

This paper described ways of inducting theory via case studies, which are specifically appropriate for new types of topics in order to reach closure with features of the process, such as problem definition and construct validation [27].

This research performed three case studies: Study 1, a qualitative research on how Tzu Chi Foundation’s leaders inspire their volunteer workers; Study 2, a quantitative research on the decision-making process of individuals when engaging in international rescue activities; and Study 3, a quantitative research on individuals’ motivation for helping behavior. The overall research method is shown in Fig. 3 and was based on the results of Study 1.

Figure 3: The overall research method of this research

Consequently, the five main sources of literature utilized in this paper include research papers, file records, interviews, direct observations, and physical objects, among which no single one has a complete advantage over the other. These sources are highly supplementary with each other and all are needed to improve the study’s validity and reliability.

In order to obtain in-depth knowledge on the operation of Tzu Chi Foundation’s overseas disaster relief work, this research utilized the qualitative method. Data on the disaster relief operation of Tzu Chi Foundation in Haiti, Philippines, Kosovo, and South Africa were gathered. Based on inductive and integrated analyses of the information, the impact of knowledge accumulation and transformation on organizational leadership and disaster relief operations was explored.

3.1.1 Steps Implemented in Study 1

To ensure the case study is effective, logical, and research-oriented, the following steps were implemented:

Step One: Background information on the disaster-hit areas and on the leadership of Master Zheng Yen were collected. In each area, data on the geographical environment and cultural characteristics were collected to better analyze the disaster and the needed assistance. Next, the role of Master Zheng Yen in the whole operation was explained. Master Zheng Yen shares a strong bond with her followers; continuous communication, and her warm and encouraging persona make her a trustworthy leader. The foundation always prioritizes the safety and well-being of volunteers and upholds Buddhist values above all; this is why volunteers always feel the love and care and are able to promote the concept and deeds of great love all over the world.

Step Two: Tzu Chi volunteers’ overseas relief work. Depending on the geographical, social, cultural, political, and religious background of the disaster-stricken area and the foundation’s experience, different modes of relief operation are adopted, including Taiwan Tzu Chi directed operation, international cooperation, native Tzu Chi directed operation, and nearby Tzu Chi directed operation. The first is the most common mode with direct investigation and assessment, and relief material being directly given to people in need by Taiwan-based volunteers. For severe disasters like the Kosovo wars, Tzu Chi cooperates with other NPOs. For areas with solid experiences, they serve as a powerful leading force for relief operations. However, for areas where there are no Tzu Chi volunteers, nearby help is necessary.

Step Three: Beneficence enlightenment. The foundation has two phases of relief work: the first phase involves assessment of the disaster, and provision of medical and material aids; the second, the more challenging phase, involves area restoration, helping locals to return to their normal life. This phase can be easily achieved with the participation and support of the local people; thus, volunteers’ kindness plays a fundamental role in inspiring residents to help in the restoration work.

Step Four: Knowledge accumulation and transformation from overseas relief work. Overseas volunteers learn about the relief operations through participation. Reports and accumulated relief experiences, including material distribution, transportation safety, venue planning and construction, manpower arrangement, respect for differences, children’s education, and skill training and home visits help volunteers complete their job. Through sharing of experiences and personal participation, volunteers are able to transform their tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge and set up a whole new set of operation for the next task.

3.1.2 Analytical Perspectives: Spiral of Knowledge Theory

Polanyi [28] divided knowledge into tacit and explicit knowledge; the former can only be produced through interpersonal interaction and consensus; the latter can be transmitted through formal, standardized, and systematic language. Nonaka et al. [29] developed the Spiral of Knowledge Theory based on Polanyi’s research, and noted that the creation and accumulation of knowledge is a process of continuous transformation and interaction of tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge. Based on the different types of the interaction process, four models of knowledge transformation can be derived: (1) socialization, (2) externalization, (3) combination, and (4) internalization of [29].

The four models enable individuals to develop knowledge assets and apply them to promote the operation of the organization. A new round of spiral of knowledge will unfold in another round of process of socialization when the internalized knowledge is interacted and communicated with others. In the present research, a knowledge transformation pattern based on the Spiral of Knowledge Theory was applied to explore the beneficence enlightenment-knowledge accumulation cycle model. It is believed that volunteers do not only have ideals for helping others, but also chase maximum material interests in actions; this is one of the reasons why Tzu Chi can quickly develop into a worldwide Asian Help Association [30].

After determining how leaders, like those of Tzu Chi’s, influence its volunteers in Study 1, Study 2 was implemented to examine individuals’ decision-making process when engaging in international relief activities. This study considered economic evaluation, actual control and other actors as basic variables that affect rational decision-making, and empathy as the major emotional variable. The conceptual framework for Study 2 is shown in Fig. 1.

As opposed to Study 1, Study 2 is a quantitative research. A survey questionnaire, adapted from the research of Hsu et al. [14], was utilized for data collection. Individuals from Taiwan who joined an international relief operation were recruited as participants of Study 2. They were asked to rate the items in the questionnaire using a 7-point Likert scale (1 for strongly disagree and 7 for strongly agree).

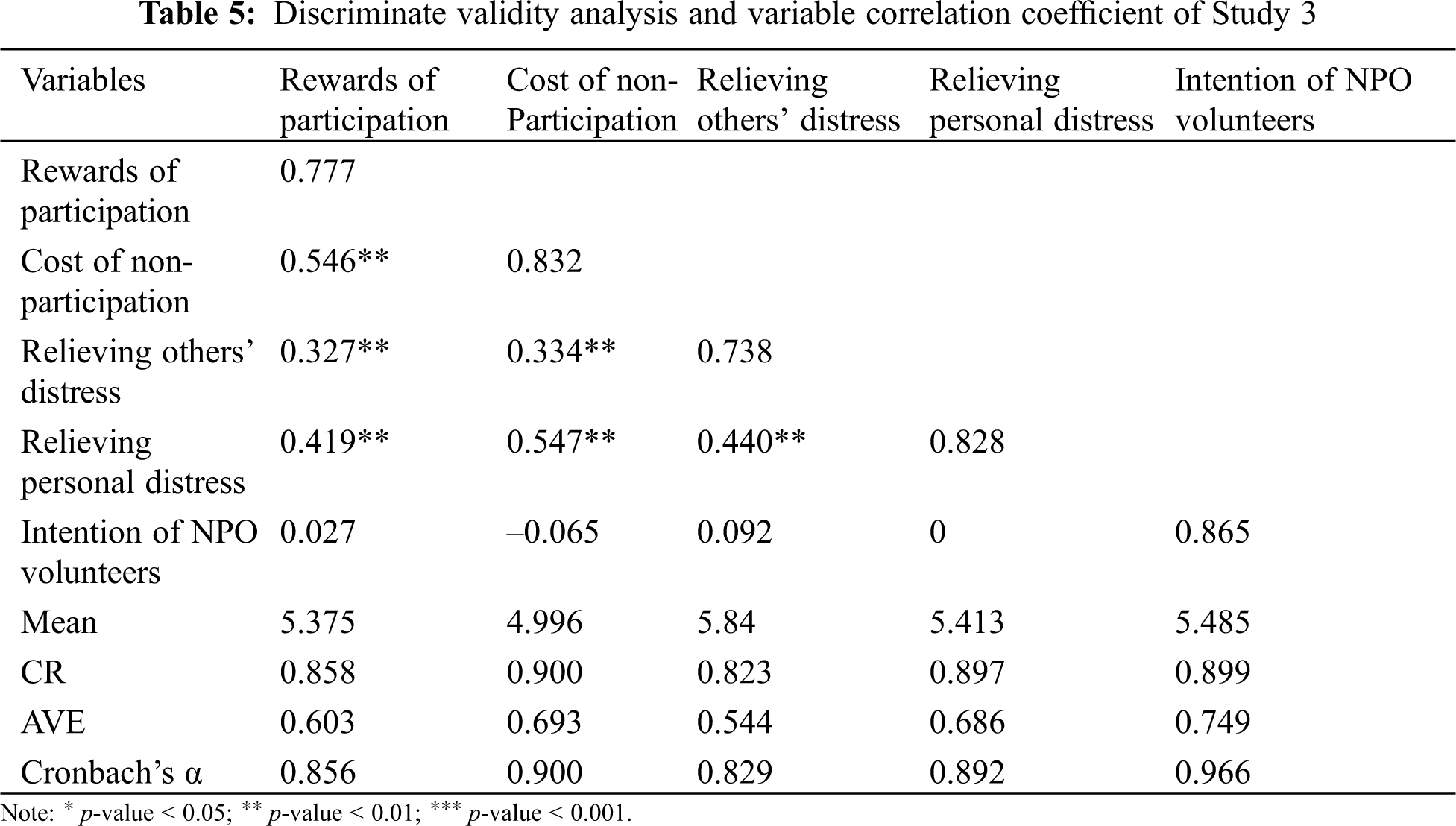

Similar to Study 2, Study 3 is a quantitative research done to determine the motivations of individuals’ helping behaviors, which is illustrated in Fig. 2. For this study, 311 individuals who joined in the operation for victims of Japan’s earthquake were selected as participants. To understand the factors that affect people’s intention to help, this research was divided into two models. The survey questionnaire was consisted of 32 items. The participants were asked to answer the items using a 7-point Likert scale (1 for strongly disagree and 7 for strongly agree).

The results found that leaders communicate with the volunteers using the principles of altruism, egoism, compensation, and reciprocity. Tzu Chi’s overseas relief activities work in four countries Fig. 1. The knowledge spiral mostly took place in Step 2 beneficence enlightenment and Step 3 knowledge accumulations.

Both the elements of emotions and rational logic for helping behaviors were integrated into the routines and public speeches of leaders and volunteers. More importantly, it was found that rational logic was the first to guide emotional responses when participating in international operations.

Formed in 1966 by Master Zheng Yen with the spirit of overcoming self-weakness and all difficulties, promoting frugality and diligence, the Tzu Chi Foundation has held charitable activities in the fields of healthcare, education, and humanitarianism all over the world, having affiliation or liaison offices in 47 countries.

To achieve an ultimate purpose of spreading happiness and eliminating suffering, its members and followers are expected to be merciful, empathic, joyful, and ready to sacrifice to build a worldwide community. They must act on sincerity, integrity, faithfulness, and truth in order to encourage more followers with the same aspiration. Transcending ethnicity, nation, language, color, and religion, the foundation engages itself in secular charity work while steeps itself in immortal spirit. At present, Tzu Chi Foundation is engaged in four main areas, including philanthropy, healthcare, education, and humanitarian work, carrying out charitable activities such as international disaster relief work, bone marrow donation, community volunteering, and environmental protection [31].

4.2.2 Tzu Chi’s Overseas Relief Work

In its overseas development, Master Zheng Yen has always provided intangible “seeds of love” and encouraged volunteers to collect resources from native areas to help local victims. Overseas liaison offices are also encouraged to cooperate with native charity organizations to carry out more prompt and effective relief work, especially in acute disasters like fire accidents, hurricanes, and earthquakes. In addition to the emergency mobilization of volunteers to provide assistance and supplies to disaster-stricken areas, arousing the participation of local people for charitable activities is another focus of the foundation.

Most of the foundation’s aid operations follow the five principles of focus, direct, respect, pragmatic, and timely, from which the three models of overseas disaster relief work were derived.

Directed by Tzu Chi Foundation in Taiwan. The foundation takes full responsibility in relief operations in certain areas such as Turkey, North Korea, Iran, and Myanmar, from the initial investigation and analyses, to resource delivery, and the building of shelters and schools.

Cooperation with International Charity Organizations. Through knowledge of other experienced international charity organizations on disaster-stricken areas and the already established communication contacts and transportation channels, Tzu Chi saves its time and energy in carrying out an effective relief plan, mobilizing funds, and reporting relief operations.

Directed by Native Tzu Chi Affiliated Foundation. This overseas disaster relief model encourages native affiliated foundations to inspire residents to join local relief work. Examples include those in Indonesia, India, and South Africa.

Natural disasters all over the world prompted Tzu Chi to further extend its help outside Taiwan; thus, its volunteers have transformed Zheng Yen’s idea of “working for Buddhism and for all sentient beings” into concrete and perceivable actions. This practice is of special value, especially at the beginning of Tzu Chi’s overseas relief work when the organization had neither familiarity nor religious common ground with the rest of the world. By using appropriate communication tools such as holding seminars, TV programs, and videos, leaders of Tzu Chi were able to deliver both emotional and reasonable content to volunteer workers using the principle of altruism, egoism, compensation, and reciprocity.

4.2.3 Communicative and Persuasive Styles Used by Tzu Chi

Recent disasters have shown that inter-organizational collaboration is often fraught with complexity [32]. Different types of disasters and different degrees of destruction may require different relief modes, and that cultural, religious, geographical, and customary variance between countries and regions may require adjustments in practice from time to time. For example, when faced with huge disasters where Tzu Chi has no relevant experiences or effective contacts for entry, the foundation chooses to cooperate with other NPOs. Therefore, communicative and persuasive styles and contents for volunteers are important to train them in generating beliefs (framing principals) for taking future helpful actions during international disasters.

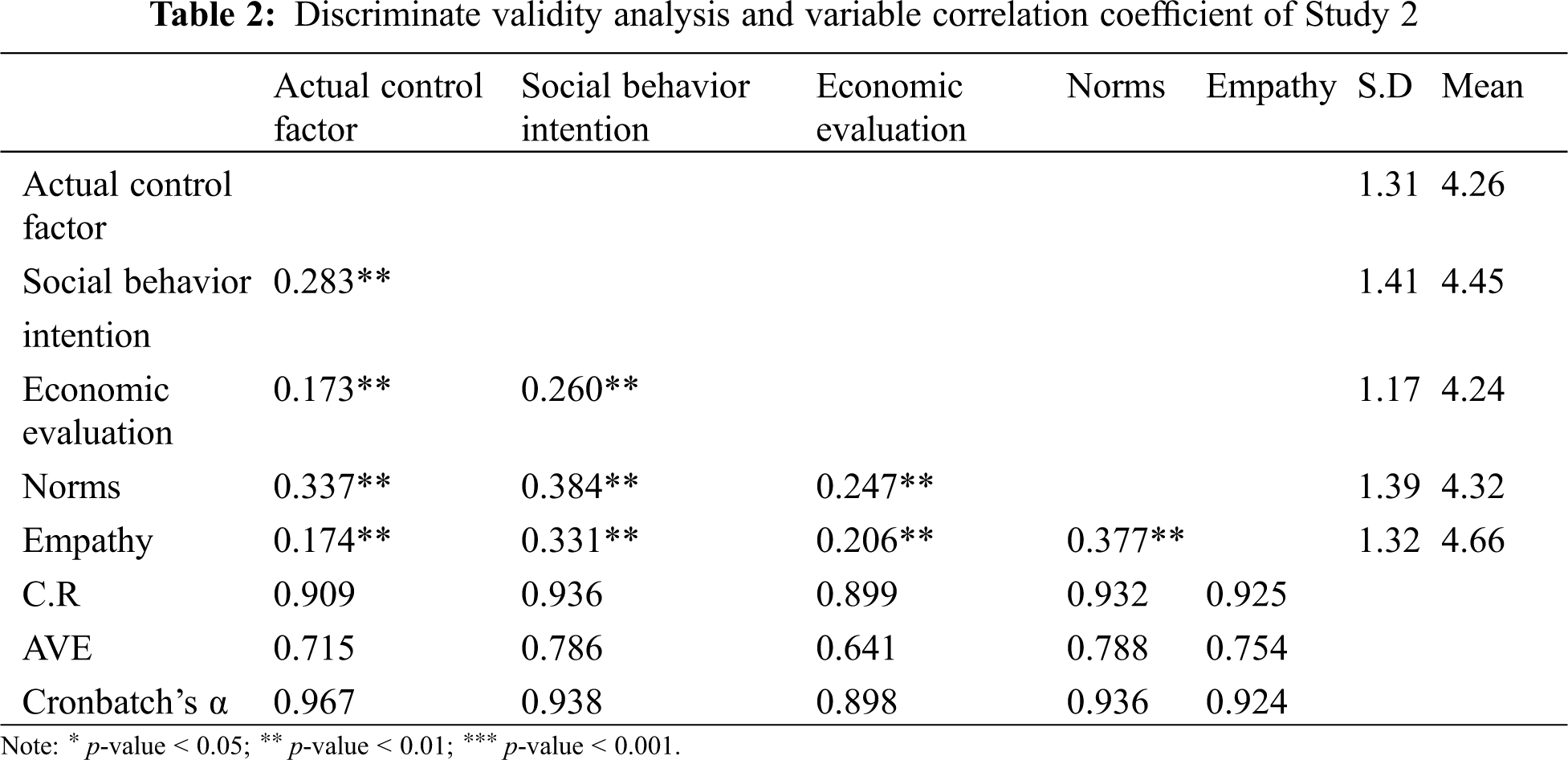

For Study 2, a total of 398 valid questionnaires were collected. The models were tested using a two-stage approach [21]: first, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was done to evaluate the construct, convergent, and discriminate validity; for the second stage, structural equation modeling (SEM) [33] using AMOS 5.0 was done to analyze the relationships among variables (Fig. 4), test the research hypotheses (H1 to H7), and obtain the goodness-of-fit. The measurement model in the CFA was revised by dropping items that shared a high degree of residual variance with other items, which was based on the standard AMOS methodology [21], and Scale Development Paradigm [34].

Before analyzing the path model using SEM, several analyses were used to test its reliability and validity. A Cronbach’s α greater than 0.7 indicates high reliability [35]. Table 2 shows the items, reliability values, and intercorrelations of the main study constructs (N = 398). Factor analysis was also done to identify the scale items’ convergent validity. To ensure the reliability of scales, principal components factor analysis (PCA) was utilized to assess the factor loading of each item. The results are summarized in Appendix A. The testing and structural models were evaluated using the AMOS 7.0 program. The researchers utilized CFA to determine the convergent validity of each item and showed that all had values higher than 0.7 (see Table 2).

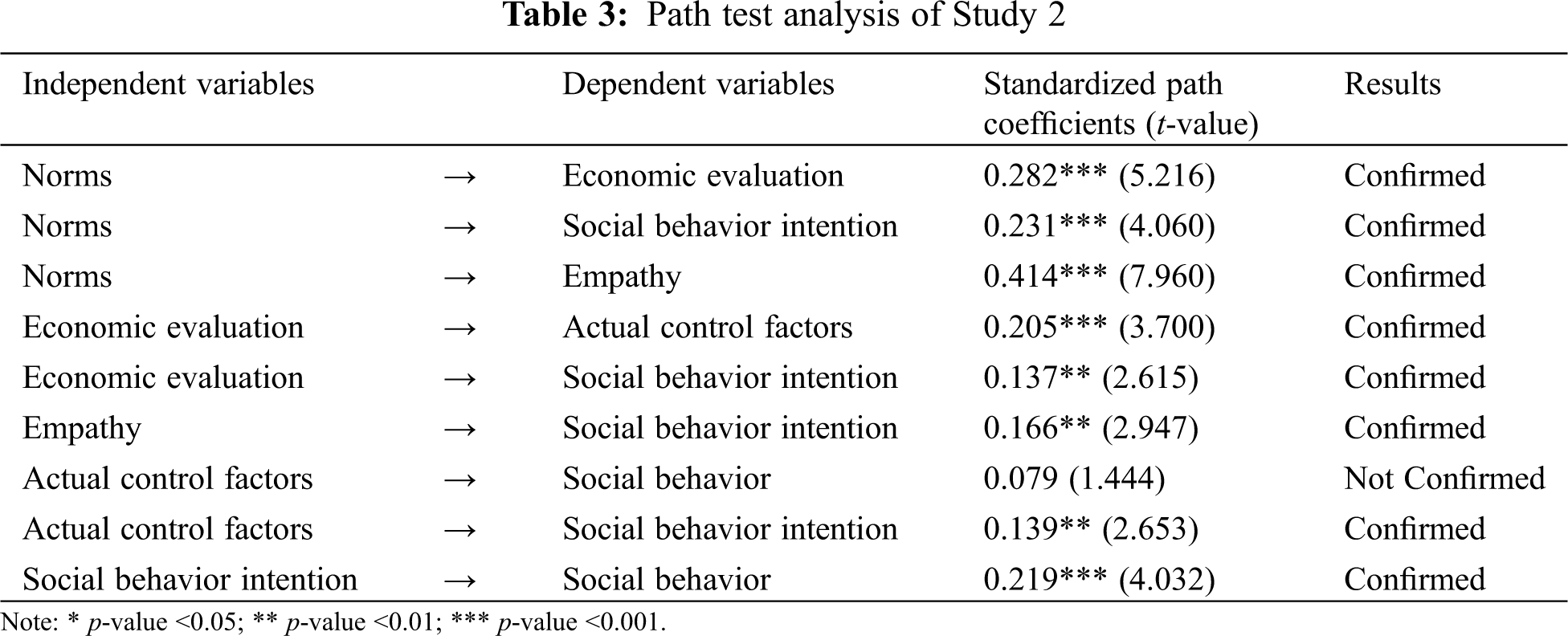

The composite reliability (CR) reports the internal consistency of the indicators evaluating a particular factor [36], and is calculated using the formula provided by Fornell et al. [37]; a CR value higher than 0.7 is considered acceptable. The average variances extracted (AVE) represents the amount of variance captured by the construct’s measures relative to the measurement error and the correlations among the latent variables. As shown in Table 2, all of the AVE values were larger than 0.5, indicating good convergent and discriminant validity [37]. Additionally, Table 3 shows the results of the path test for Study 2, which indicates there was a good fit between the data and the model, in which * means p-value is less than 0.05; ** means p-value is less than 0.01; *** means p-value is less than 0.001.

Figure 4: Structural Path Analysis of Study 2.

Notes: Number on path: standardized parameter estimation; *p-value <0.05; ** p-value <0.01; *** p-value <0.001

The results indicated that norms had a greater positive significant effect on empathy than on economic evaluation. During the decision-making process, people are affected by external (social expectations) and internal factors (personal responsibility) more than the economic evaluation of the behavior (costs and rewards). Also, in irrational decision-making, norms had a significant positive influence on empathy. Individuals who used to be victims of international disasters develop a strong sense of empathy to help others. Further, those who have learned empathy as a child are more likely to participate actively in rescue activities. Consequently, in rational decision-making, norms had a significant positive influence on actual control factors through economic evaluation; however, actual control factor did not have a significant positive effect on social behavior. When joining international rescue activities entails minimum cost, individuals with high opportunities and resources are most likely to participate (due to a high degree of certainty and reduced self-restless) and organize one. In addition, consumers who have the chance and resources, but have not been directly involved in aiding activities, may also become encouraged to join relief operations.

For Study 3, a total of 330 out of 350 survey questionnaires were collected from volunteers of NPO residing in four main cities (Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Taipei, and Kaohsiung). CFA was also performed to assess the constructs, convergent, and discriminate validity. Except for the moderator variable, the CR and Cronbach’s α for the seven constructs were greater than 0.78, and the value of AVE was greater than 0.5, exceeding the recommended threshold [37,38]. These indicate that the questionnaire has acceptable convergent and discriminate validity. Table 4 shows the test results of Study 2; and Table 5 shows the test results of Study 3. The SEM using AMOS18.0 was done to analyze the relationship among variables and obtain the goodness-of-fit model.

The results of the hypotheses testing shown in Table 6 indicated that all paths were confirmed. In terms of economic evaluation, it was found that rewards of participation had a positive and significant influence on relieving others’ distress (β = 0.226, p < 0.05), and the cost of non-participation also had a positive and significant influence on relieving personal distress (β = 0.557, p < 0.01); therefore, H3 and H4 are supported. Also, relieving others’ distress had a positive and significant influence on the intention of being volunteers of NPO for international rescue (β = 0.194, p < 0.01); therefore, H5 is supported, while H6 is not.

In Study 1, it can be seen that leaders play a major role in motivating volunteers to participate in overseas disaster relief work, which in turn could influence the residents of disaster-stricken areas also to volunteer and offer help. In addition, it was found that knowledge and experience accumulated through continuous participation in relief works can be shared within members of the foundation. This could be beneficial during the next relief operation, and could also be used as a way to encourage others to volunteer in the future. Master Zheng Yen’s sincere desire to help demonstrates pure altruism and is also reflected in her pure concern towards volunteers of the foundation; because of this, volunteers are more inspired to extend their help to others in need.

In Study 2, it was found that in irrational decision-making, norms provided significant positive influence through empathy. This indicates that individuals are willing to be volunteers in international relief operations not only for having the resources and empathy, but also for follow the effect of social norms.

The results of Study 3 indicate that without the influence of national interest, people’s motivation to participate in international rescue operations is mainly altruistic. Moreover, volunteers as rationalists rely on the reasonable cognitive appraisal to substantially evaluate the necessity for social helping behavior, which even involves volunteers as rationalists’ emotional responses and arousals. Individuals may feel sad for the victims of disasters and may find happiness when they are able to reduce the pain and suffering of others. This indicates that the motivation to help may come from egoism; that is, people help those who are in need because they perceive that it is also beneficial for them due to the relief it brings.

Consequently, it was found that when the motivation to help is mainly due to egoism, that is, for self-interest, an individual’s willingness to help will be high. Therefore, when promoting a social behavior for self-interest, the benefits of helping should be highlighted to increase their willingness to participate. Meanwhile, when people are engaged in altruistic social behavior, willingness to participate will be high when emphasis is given on the possible adverse outcomes of non-participation.

When photos and audio presentations depicting the suffering of international disaster victims were shown, individuals who have experienced the same developed a strong sense of empathy for the survivors and want to provide help. In addition, individuals who have learned empathy as a child are more likely to participate actively in rescue activities.

Moreover, norms provided positive significant influence on actual control factors through economic evaluation. Economic evaluation theory can be a good application depicting volunteers as rationalists’ way of cognitive appraisal perspective towards events. And the content of cognitive appraisal of volunteers as rationalists, as proposed by this study is: altruism, compensating, egoism, and reciprocity, which could become four important critical elements for investigation for researchers in the future in terms of cognitive principles to increase volunteers’ resistence [6].

That is to say, reciprocity, altruism, compensation, and egoism are the four key emotional and cognitive evaluation factors that support volunteers to join the NPO, as well as the rational concerns of volunteers in meeting social needs in the form of social norms, economic evaluation, and expression social empathy. Reciprocity, altruism, compensation, and egoism are also the glue that connects organizational value and personal value. TCF used these four factors as the principle to process the knowledge spiral within its NPO, making it a value with meaning in life, so that volunteers’ lives become more meaningful with learned happiness [13].

5.2 Managerial Implications for International Rescue Activities

Foundation can arise the motivation of volunteers’ participation in overseas disaster relief work, which in turn has a positive influence on local people who can interact and identify with volunteers’ actions and minds and thus be aroused to contribute their own power to help in the relief work. On the other hand, the knowledge and experience accumulated through the relief work by volunteers can be shared within the foundation and accumulated as a common asset of Tzu Chi, which cannot only enlighten the next relief operation, but also enlighten those who were helped before to be helpers in the future.

Critical factors for Tzu Chi to quickly respond to the national disasters and quickly found enough volunteer workers are that Tzu Chi reaches out to understand more of the disaster through reports, news and other available information. That is why Tzu Chi would never hesitate to offer its hand. A practical problem faced is what Tzu Chi planned beforehand to carry out relief work might need certain adjustments or complete changes due to the actual situation of the disaster-hit area and the change of the disaster. In that situation, accumulating of experience and knowledge through actual participation in the relief work would be valuable wealth for the foundation.

The results of this study suggested that social helping behavior can be integrated more with the reasonable appraisal in the long run. Because social helping behavior requires organized behaviors in the long run; it cannot rely solely on emotional support: Perhaps volunteers have empathy and compassion at the beginning, but for long-term support such as the execution of the action plans, rational planning is still needed for the nonprofit organization. TCF is a good example. At first, it was because of religious beliefs and beliefs, which led to self-efficacy and confidence [6] and finally insist on being involved in volunteer behavior. After that, through many difficulties, hindrances, and stress, some volunteers may feel hard and decide to drop joining social helping behaviors. That is to say, such an insisting power cannot only be explained by emotional support. Behind the power of action, rational support is still needed for social helping behavior to last in the long term. This paper provided conceptual support for feasible solutions and mechanisms behind the training of many non-profit organizations for volunteers.

Based on the overall results, altruistic behavioral motivation is more effective in evoking people to participate in overseas relief operations.

Situational involvement is the temporary concern for a special situation to achieve an external target [39]. Although both rewards of participation and situational involvement have a positive influence on relieving others’ distress, the influence of situational involvement is greater than the influence of rewards of participation. When people receive astonishing disaster information unexpectedly, a feeling of sympathy will be generated, arousing one’s willingness to participate in international rescue; the motivation behind participation is simply altruistic. During information dissemination or formation of appeal strategy, it is therefore necessary to communicate the specific situation to the audience.

Further, it was found that it is easier to use the cost of non-participation to encourage volunteerism; therefore, using egoism by highlighting the helping behavior as a way to reduce personal suffering could be used to promote participation in international relief.

Government organizations or public welfare groups can reward individuals involved in international rescue through praise. They can also encourage others to actively participate in disaster relief operations through mass media, where the real situation of the victims could be shown to the public. This may arouse feelings of guilt and shame, encouraging them to volunteer to eliminate the uncomfortable feeling.

5.3 Suggestions for Future Studies and Research Limits

From the literature review section of this study, we understand that this article attempted to discuss from a different perspective, not just the positive emotions influencing volunteers’ being involved in volunteer work. For example, it is the volunteers’ pride and enthusiasm, other emotional factors, NPO’s reputation, value consistency between volunteers and the organization, self-identification in roles of being volunteers, and even the four critical emotional factors supporting volunteers to join NPO, which are the four critical emotional factors supporting volunteers to join NPO (reciprocity, altruism, compensation, and egoism).

On the other hand, investigating from the volunteers as rationalists’ perspective, the source of pressure that workers may face, which may affect their long-term influential factors for volunteer work. To be able to understand the stressors of volunteers, and help them to solve the stressors so that volunteers can help in the social helping activities such as the international rescue event mentioned in this study, the authors of this study suggest that for future studies, researchers are encouraged to investigate stressors that could be confronted by volunteers when they executing their tasks for NPO, and try to solve those hindrances and discuss the relevant issues in volunteers’ training programs, which could help increase mental toughness for volunteers in insisting on being volunteers in the long run and devoting themselves to global society.

This study obtained three studies for validating the conceptual framework suggested by this study at the same time; however, this also forms the research limitation of this study.

Even though the author has used three research triangulation methods to test the conceptual framework proposed by this study, it is still the same TCF after all. Therefore, the authors of this article suggested that researchers for future studies may use different NPOs as research objects for extensive verification of the theoretical concepts proposed by this study.

Author Contributions: Kuei-Feng Chang (1st author): Dr. Chang is responsible for building up the conceptual research framework, confirmation and inferring the hypothesis of these three studies, as well as the formation of abstracts and introduction, and supervising on the progress of the research. Wen-Goang Yang (2nd author): Dr. Yang is responsible for helping revise the manuscript according to the journal’s requirement in terms of conceptual framework’s presentation and discussion of issues in connecting literature review and practical and theoretical implications. Ya-Wen Cheng (3rd author): Dr. Cheng is responsible for helping Dr. Chang in data collection and analysis, as well as statistical analysis, writing on the analytical result, and the presentation of the statistical results on the manuscript; she is mainly focusing on the method parts. I-Tung Shih (4th and corresponding author): Dr. Shih is responsible for corresponding and writing of the literature review, theoretical contributions, theoretical implications and practical implications of these three studies, as well as translation, checking, formation, submission, and revising the manuscript according to the journal’s requirement.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. Homans, G. C. (1958). Social behavior as exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 63(6), 597–606. DOI 10.1086/222355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Piliavin, I. M., Rodin, J., Piliavin, J. A. (1969). Good samaritanism: An underground phenomenon? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13(4), 289–299. DOI 10.1037/h0028433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Raftery, J. (1998). Economics notes: Economic evaluation: An introduction. BMJ Clinical Research, 316(7136), 1013–1014. DOI 10.1136/bmj.316.7136.1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Arnold, M. B. (1960). Emotion and personality. In Psychological aspects, vol. 1; Neurological and physiological aspects, vol. 2. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

5. Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

6. Fan, S. C., Shih, H. C., Tseng, H. T., Chang, K. F., Li, W. C. et al. (2021). Self-efficacy triggers psychological appraisal mechanism for mindset shift. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 23(1), 57–73. DOI 10.32604/IJMHP.2021.012177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wilson, J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 215–240. DOI 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Malinen, S., Harju, L. (2017). Volunteer engagement: Exploring the distinction between job and organizational engagement. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 28(1), 69–89. DOI 10.1007/s11266-016-9823-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Dunn, J., Chambers, S., Hyde, M. (2016). Systematic review of motives for episodic volunteering. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27(1), 425–464. DOI 10.1007/s11266-015-9548-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Forbes, K. F., Zampelli, E. M. (2014). Volunteerism: The influences of social, religious, and human capital. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43(2), 227–253. DOI 10.1177/0899764012458542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Grube, J. A., Piliavin, J. A. (2000). Role identity, organizational experiences, and volunteer performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(9), 1108–1119. DOI 10.1177/01461672002611007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Curran, R., Taheri, B., MacIntosh, R., O’Gorman, K. (2016). Nonprofit brand heritage: Its ability to influence volunteer retention, engagement, and satisfaction. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45(6), 1234–1257. DOI 10.1177/0899764016633532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Learned optimism: How to change your mind and your life. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

14. Hsu, T. H., Chang, K. F. (2007). The taxonomy, model and message strategies of social behavior. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 37(3), 279–294. DOI 10.1111/j.1468-5914.2007.00338.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Monroe, K. R. (1996). The heart of altruism: Perceptions of a common humanity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

16. Berkowitz, L., Connor, W. H. (1966). Success, failure and social responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4(6), 664–669. DOI 10.1037/h0023990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl, J., Beckman, J. (Eds.Action-control: From cognition to behavior (11–39). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

18. Fehr, B. (2004). Intimacy expectations in same-sex friendships: A prototype interaction-pattern model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 265–284. DOI 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Goranson, R. E., Berkowize, L. (1966). Reciprocity and responsibility reactions to prior help. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(2), 227–232. DOI 10.1037/h0022895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ajzen, I. (1989). Attitude structure and behavior. In: Pratkanis, A., Breckler, S., Greenwaald, A. (Eds.Attitude structure and function (241–269). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum and Associates. [Google Scholar]

21. Olsen, J. E., Granzin, K. L., Biswas, A. (1993). Influencing consumers’ selection of domestic versus imported products: Implications for marketing based on a model of helping behavior. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 21(4), 307–321. DOI 10.1007/BF02894523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Allred, A., Amos, C. (2018). Disgust images and nonprofit children’s causes. Journal of Social Marketing, 8(1), 120–140. DOI 10.1108/JSOCM-01-2017-0003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Riess, H. (2017). The science of empathy. Journal of Patient Experience, 4(2), 74–77. DOI 10.1177/2374373517699267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Batson, C. D. (1987). Prosocial motivation: Is it ever truly altruistic? In: Berkowitz, L. (Ed.Advances in experimental social psychology. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

25. Bar-Tal, D. (1976). Prosocial behavior: Theory and research. Washington: Hemisphere. [Google Scholar]

26. Aliu, O., Pannucci, C. J., Chung, K. C. (2013). Qualitative analysis of the perspectives of volunteer reconstructive surgeons on participation in task-shifting programs for surgical-capacity building in low-resource countries. World Journal of Surgery, 37(3), 481–487. DOI 10.1007/s00268-012-1885-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. DOI 10.2307/258557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Polanyi, M. (1966). The logic of tacit inference. Philosophy, 41(155), 1–18. DOI 10.1017/S0031819100066110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Nonaka, I., Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge creating company: How japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

30. Chang, K. F., Shih, H. C., Yu, Z., Pi, S., Yang, H. (2019). A study on perceptual depreciation and product rarity for online exchange willingness of second-hand goods. Journal of Cleaner Production, 241(1), 118315. DOI 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Tzu Chi granted special UN status (2010). Taiwan Today. https://taiwantoday.tw/news.php?unit=10&post=16875#:~:text=The%20U.N.,in%20more%20than%2070%20coun. [Google Scholar]

32. Curnin, S., O’Hara, D. (2019). Nonprofit and public sector interorganizational collaboration in disaster recovery: Lessons from the field. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 30(2), 277–297. DOI 10.1002/nml.21389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Anderson, J. C., Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. DOI 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Churchill, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73. DOI 10.1177/002224377901600110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Nunnally, J. C., Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd Ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Inc. [Google Scholar]

36. Hatcher, L. (1994). A step-by-step approach to using the SAS system for factor analysis and structural equation modeling, pp. 325–339. Cary, NC: The SAS Institute. [Google Scholar]

37. Fornell, C., Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. DOI 10.1177/002224378101800104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Bagozzi, R., Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. DOI 10.1007/BF02723327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Bloch, P. H. (1982). Involvement beyond the purchase process: Conceptual issue and empirical investigation. In: Mitchel, A. (Ed.Advance in consumer research, association for consumer research, pp. 413–417. Ann Arbor, MI. [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |