| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/ijmhp.2022.018516

ARTICLE

Do Personality Variables Predict Job Embeddedness and Proclivity to Be Absent from Work?

Faculty of Tourism, Eastern Mediterranean University, TRNC, Gazimagusa, Via Mersin 10, 99628, Turkey

*Corresponding Author: Osman M. Karatepe. Email: osman.karatepe@emu.edu.tr

Received: 02 August 2021; Accepted: 05 November 2021

Abstract: The current knowledge base lacks evidence about situational- and surface-level personality variables and their impacts on job embeddedness and proclivity to be absent from work. With this recognition, drawing from the hierarchical personality model and fit theory as well as job embeddedness theory, our paper explores the influences of job resourcefulness (JR) and customer orientation (CO) on job embeddedness and propensity to be absent from work. We tapped time-lagged data gathered from hotel customer-contact employees in the United Arab Emirates to assess the aforementioned linkages via structural equation modeling. CO is a complete mediator between JR and job embeddedness, while job embeddedness completely mediates the linkage between CO and absence intentions. Specifically, hotel employees who can work under a resource-depleted environment are high on CO and therefore display job embeddedness at elevated levels. In addition, customer-oriented hotel employees have higher job embeddedness and therefore exhibit lower absence intentions.

Keywords: Absence intentions; hotel workers; customer orientation; job embeddedness; job resourcefulness

In today’s market environment where there is strict competition, customer-contact employees (CCEs) who manage customer requests [1] are supposed to deliver service quality and achieve customer satisfaction as well as maintain strong relationships with customers [2]. However, they are likely to suffer from stressors and mental health problems [3]. These stressors and problems directly and negatively influence employees’ behaviors [4]. In addition, management expects such employees to “do more with less” in the workplace [5,6]. Under these conditions, management has to hire individuals who can work effectively under resource constraints, are customer-oriented, and can cope with problems arising at work [3,6]. It appears that management may retain these employees who display positive outcomes such as diminished burnout, creativity, job satisfaction, reduced withdrawal cognition, and effective work-related performance [6–10].

Two of the personality variables considered important in customer-contact positions are job resourcefulness (JR) and customer orientation (CO) [11]. JR highlights “… the enduring disposition to garner scarce resources and overcome obstacles in pursuit of job-related goals” [11]. Workers high on JR can meet formal performance requirements in a company where resources are scarce [12]. CO refers to “…an employee’s tendency or predisposition to meet customer needs in an on-the-job context” [13]. CO is considered either a personality trait or a behavioral outcome [9,14]. In the present empirical work, it is used as a personality trait.

Job embeddedness enables managers to retain employees who are resourceful and customer-oriented. To retain such employees, management should focus on links, fit, and sacrifice, which represent both on-the-job and off-the-job embeddedness. Fit is related to “…an employee’s perceived compatibility or comfort with an organization and with his or her environment”, while links are associated with “…formal or informal connections between a person and institutions or other people” [15]. Sacrifice describes “…the perceived cost of material or psychological benefits that may be forfeited by leaving a job” [15].

The ones with high JR and CO may be enmeshed in their jobs because they may find that management offers an environment where they can improve their skills and knowledge, maintain strong connections with managers and coworkers, and take advantage of a number of benefits. Such environment should also be supported by the leadership style such as servant leadership practiced in the organization [16]. Consequently, job embeddedness can mitigate unscheduled or unauthorized absenteeism as well as other negative outcomes such as intent to quit and voluntary turnover [17,18].

Against the above background, our paper examines the interrelationships of JR, CO, job embeddedness, and absence intentions. More precisely, our paper tests: (a) the influence of JR on CO; (b) the impact of CO on job embeddedness; (c) CO as a complete mediator of the influence of JR on job embeddedness; and (d) job embeddedness as a full mediator between CO and absence intentions.

This study identifies three voids in the relevant literature. First, JR and CO are relevant and significant personality traits in frontline service jobs. CCEs high on JR can work in an organization where job resources are scarce [19]. CO mitigates burnout and fosters job satisfaction, service interaction quality, and task performance [20–23]. Despite this recognition and these findings, empirical research testing JR and CO simultaneously is still scanty. This is noticeable in the relevant pieces [6–9].

Second, job embeddedness is still a timely and an important topic [24–26]. It enables managers to acquire and retain talented individuals in their company and enhances employees’ life satisfaction [27–29]. This is significant because high employee turnover results in substantial costs in the hospitality industry [30]. Although there are studies about job embeddedness and its consequences, the relevant literature seems to lack evidence about its potential antecedents [31–34]. To this end, our paper explores the direct/indirect effects of JR and CO on CCEs’ job embeddedness.

Third, employees may exhibit absence from work. This can be in the form of unauthorized or unscheduled absence [35]. Such absence threatens employment status [18]. According to Kocakulah et al. [36], unplanned service worker absence is responsible for a loss of 2.3% of all scheduled labor hours in the United States. This leads to ample costs in the whole service industry. However, there is still a lack of research about the factors influencing CCEs’ absence intentions [3,37].

2.1 Studies on Job Resourcefulness and Customer Orientation

There are empirical pieces, which have explored the impacts of JR and CO on employees’ work outcomes, CO as a mediator, or JR/CO as a moderator. Broadly speaking, Donavan et al.’s [38] study conducted in the financial and food service industries documented that CO enhanced work outcomes such as organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behaviors. In a sample of employees who had direct contact with patients in a hospital setting, Harris et al. [5] reported that openness to experience and conscientiousness were significant predictors of JR. Yagil et al. [39] found that CO strengthened the negative linkage between core self-evaluations and negative customer behaviors among different service providers (e.g., bank tellers, food serves, salespeople) in Israel. In another study, it was shown that role clarity fostered CCEs’ CO, while role conflict diminished their CO [40].

Using a sample of hotel employees in Northern Cyprus, Yavas et al. [41] found that JR heightened quitting intentions, while CO activated organizational commitment and job satisfaction and alleviated quitting intentions. A study of hotel employees in Iran disclosed that CO completely mediated the effect of JR on in-role performance [12]. Karatepe et al. [42] found that work engagement completely mediated the impacts of both JR and CO on outcomes such as job satisfaction and quitting intentions among bank employees in Northern Cyprus. A study of bank employees in New Zealand denoted that person-job fit partly mediated the influence of CO on job performance and quitting intentions [43]. The same study further indicated that CO strengthened the positive association between training and person-job fit, while the negative effect of service technology on person-job fit was weaker at higher levels of CO.

Chen [7] reported that work engagement partly mediated the influence of JR on hotel employees’ individual and collaborative job crafting in China. Semedo et al.’s [44] study indicated that both JR and affective commitment partly mediated the association between authentic leadership and creativity. A study illustrated that both supervisor support and person-job fit fostered bank employees’ JR [45]. Hughes et al. [46] showed that the effect of brand extra-role behavior on sales performance was weakened by CO. Recently, Harris et al. [6] indicated that JR reduced burnout among restaurant employees, while it boosted job performance among restaurant and bank employees.

Kim et al. [47] reported that CO mediated the impact of customer-employee exchange on restaurant employees’ task and contextual performances. Anosike et al. [48] highlighted that internal service quality, empowerment, and job satisfaction predicted bank employees’ CO. The findings associated with a study carried out in South Korea highlighted that CO partly mediated the linkage between emotional exhaustion and service recovery performance [49]. A study of hospitality employees in Portugal documented that affective organizational commitment completely mediated the linkage between authentic leadership and CO [50]. Another study illustrated that the positive impact of service workers’ CO on deep acting was mediated by perspective taking and emotional sensitivity [51]. In addition, Wu et al.’s [52] research documented that surface and deep acting as well as genuine emotions partly mediated the linkage between CO and burnout among hotel employees in China. Anaza et al. [53] found that service workers’ CO linked both employee and customer identification to work engagement.

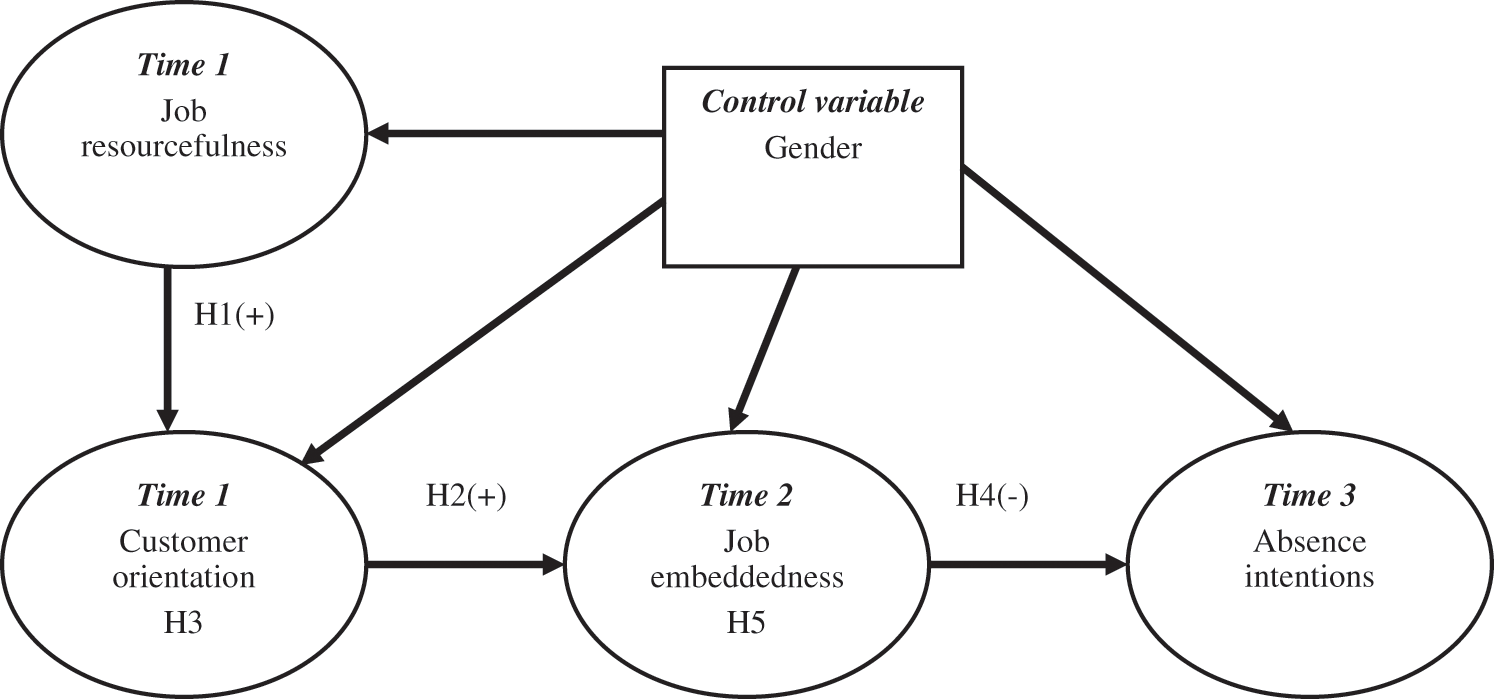

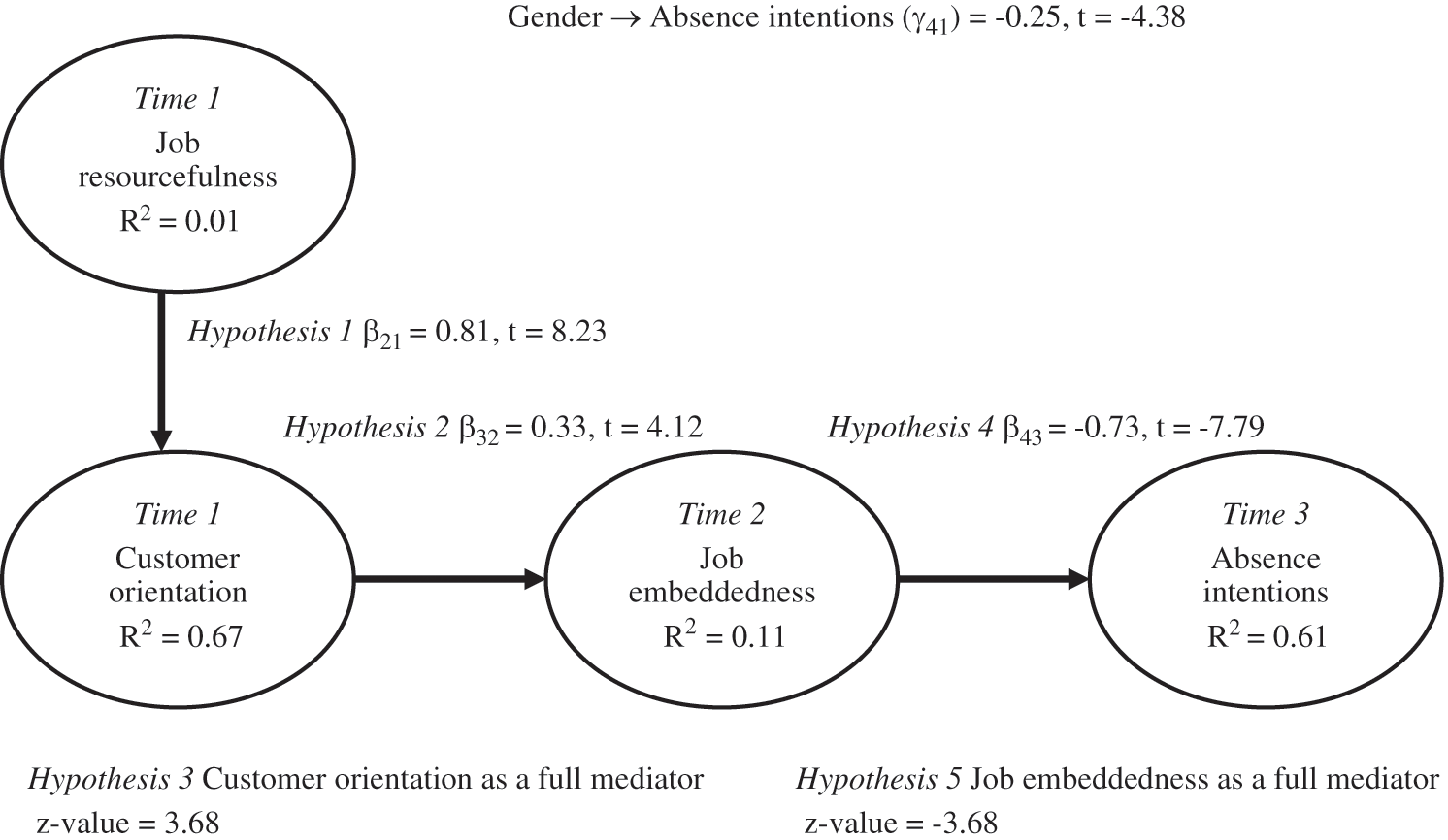

The aforementioned empirical investigations have illustrated that job resourceful employees can work under resource constraints, are work-engaged, and are susceptible to lower burnout [6,7,42]. Such employees are also high on creativity [44]. Surprisingly, the findings of an empirical study have denoted a positive linkage between JR and withdrawal cognition [41]. Lack of sufficient job resources might be responsible for such a result. Studies have revealed that customer-oriented employees are work-engaged [7,42] and exhibit desirable outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction and reduced proclivity to quit). These employees have also been shown as effective task and service recovery performers [43,49]. Studies conducted in different settings have enhanced current knowledge about situational- and surface-level personality variables. However, it seems that no empirical study has examined the interrelationships of JR, CO, job embeddedness, and absence intentions so far. Based on this, the present study proposes a conceptual model (Fig. 1), which aims to fill in this void. Specifically, the conceptual model that includes the hypotheses is shown in Fig. 1. As the model proposes, JR fosters CO, which in turn gives rise to job embededdness at elevated levels. The model further contends that job embeddedness acts as a complete mediator between CO and proclivity to be absent from work. Female employees are more relationship-oriented than male employees and value social interactions at elevated levels when compared with male employees [21]. Therefore, gender is treated as a control variable to ascertain whether it acts as a confounding variable.

Figure 1: Conceptual model

The hierarchical personality model contends that personality traits can be organized on the basis of the level of abstraction of traits [11]. JR is a situational-level trait and influenced by elemental (e.g., openness) and compound (e.g., competitiveness) traits, which in turn engender CO, a surface-level personality trait [11]. It appears that CCEs high on JR can work under resource constraints and can still be customer-oriented. Job resourceful employees possess “…an innate problem-solving disposition” [19, p. 339] and carry out their tasks in a resource-depleted environment by displaying elevated levels of CO [12].

Few empirical pieces have gauged the relationship between JR and CO so far. Specifically, Karatepe et al.’s [12] study documented that JR exerted a strong positive influence on CO among hotel employees in Iran. Karatepe et al. [42] also reported a similar finding among bank employees in Northern Cyprus. Harris et al.’s [5] study showed a strong positive linkage between the two constructs in a sample of retail bank employees. In an earlier study, JR was found to increase CO [11]. In light of the hierarchical personality model and the evidence given above, it is postulated that:

Hypothesis 1: CCEs’ perceptions of JR have a positive influence on their CO.

According to fit theory, the person and the situation combine to affect the behavior [38]. The demands-abilities fit and needs-supplies fit represent person-job fit [54]. The demands-abilities fit occurs when employees’ knowledge, skills, and abilities match with the requirements of the job [54]. The needs-supplies fit takes place when employees’ needs and preferences are commensurate with the job they are expected to carry out [54]. The person-organization fit highlights the compatibility between the employee and the organization (e.g., organizational culture, values). In addition, the person-group fit is associated with the interpersonal compatibility between the employee and his or her group, while the person-supervisor fit is related to the supervisor-subordinate value congruence, supervisor-subordinate personality similarity, and supervisor-subordinate value congruence [54].

In light of fit theory, it is argued that management is in need of employees who can work in customer-contact positions by displaying genuine emotions, enjoying serving customers, taking a problem-solving approach, and responding to customer requests promptly [38]. When the skills, abilities, and preferences of employees high on CO are commensurate with these requirements, they are likely to be enmeshed in their jobs. When these employees’ values and career expectations match with what their company offers, they are likely to exhibit higher job embeddedness. Customer-oriented employees work with others effectively when there is an interpersonal compatibility between them and their coworkers. Under these circumstances, management can retain such employees. They can also work under the supervision of a manager productively when there are supervisor-subordinate value congruence, supervisor-subordinate personality similarity, and supervisor-subordinate value congruence. Consequently, they display elevated levels of job embeddedness.

The discussion given above leads to the conclusion that CO fosters job embeddedness. Accordingly, it is advanced that:

Hypothesis 2: CCEs’ perceptions of CO have a positive influence on their job embeddedness.

The previously mentioned hypotheses refer to the association between JR and job embeddedness, as mediated by CO. CCEs who are able to carry out their tasks effectively and manage customer problems despite the absence of or limited various high-performance work systems (e.g., empowerment, teamwork) are both job resourceful and customer-oriented [12]. As a result, such employees are embedded in their jobs.

JR, combined with CO, makes CCEs become embedded in their jobs. Although limited, several studies focused on CO as a mediator. For instance, Karatepe et al. [12] highlighted that JR positively influenced role-prescribed customer service only via CO. In Licata et al.’s [11] study, CO was found to completely or partly mediated the influence of JR on self-rated and/or supervisor-rated performance. Harris et al.’s [5] research documented that JR influenced job satisfaction and propensity to quit only through CO. However, it seems that the relevant literature is devoid of evidence pertaining to the JR → CO →.job embeddedness relationship among CCEs. Accordingly, it is postulated that:

Hypothesis 3: CO completely mediates the influence of JR on job embeddedness.

Job embeddedness theory suggests that employees are enmeshed in their jobs when they possess good connections with supervisors and coworkers within the company. They are embedded in their jobs since their values and career expectations fit with what the organization offers. These employees also display job embeddedness because they know they have a lot to lose as a result of quitting [15,55]. It seems that leading service companies (e.g., Four Seasons Hotels and Marriott International) are able to retain their talented employees by creating an environment where individuals develop and possess good connections with others, and whether their values and career expectations are met [56].

It can be concluded that job embeddedness is a potential antidote to CCEs’ absence intentions [18]. However, little is known about the influence of job embeddedness on absence intentions among service workers. This is also underscored in a recent study that not much is known about the negative job outcomes of job embeddedness [26]. Therefore, it is advanced that:

Hypothesis 4: CCEs’ perceptions of job embeddedness have a negative influence on their absence intentions.

CCEs are the ones who can work productively by delivering quality services to customers, dealing with service failure severity, and managing customer expectations. Customer-oriented employees are more predisposed to responding to the needs of customers. They possess higher predisposition to enjoy serving the customers and meeting their needs [57,58]. As stated by Babakus et al. [21], “These behaviors are expected to emanate from the crystallization of deeper personality traits at the surface as high levels of customer orientation and become automatic response tendencies” (p. 483). Employees high on CO are unlikely to display frequent unscheduled or unauthorized absence from work because they enjoy working in frontline service jobs and remain with the organization as a result of job embeddedness.

In short, CO is a critical personality trait in customer-contact positions and employees high on CO can make significant contributions to the entire organization in terms of retention of satisfied customers [21]. In addition, they remain with their company and display lower propensity to be absent from work when they find that the person-job fit, person-organization fit, person-group fit, and person-supervisor fit are accomplished. Based on the above discussion, it is postulated that:

Hypothesis 5: Job embeddedness completely mediates the effect of CO on absence intentions.

3.1 Participants and Procedure

The hypotheses were assessed with data obtained from hotel CCEs in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates. The purposive sampling technique was applied through three criteria. First, CCEs do emotional labor and have a crucial role in the provision of service quality. This is highlighted in recent studies [9,59]. Therefore, these employees, due to their boundary-spanning roles, were included in the sample. Second, we selected full-time CCEs. Third, the sample of this study consisted of Arab CCEs.

Data were gathered via a senior researcher in a marketing research firm. Permission for data collection was obtained from 10 hotels. Respondents were assured of anonymity and confidentiality. The researcher received strong support from management of hotels. Participation in this study was voluntary. These practices helped the researcher to reduce common method variance [60]. Moreover, data were obtained from CCEs in three waves (i.e., two weeks apart at each wave) to minimize such risk [60]. The researcher matched the questionnaires through identification codes.

The three types of surveys were prepared in English. This was followed by translating them into Arabic through the back-translation technique. All types of the surveys used in this study were pretested with three different samples of five CCEs. As a result of these studies, no amendments were made in the questionnaires.

Four items were tapped to gauge JR [5]. Sample items are “When it comes to completing tasks at my job I am very clever and enterprising” and “I am able to make things happen in the face of scarcity at my job”. The participants tapped a 5-point scale (“1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree”). Coefficient alpha (α) for JR was 0.82.

Four items from Licata et al. [11] were deployed to assess CO. Example items are “I try to help customers achieve their goals” and “I try to get customers to discuss their needs with me”. The participants utilized a 5-point scale (“1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree”). α for CO was 0.88.

Seven items were used to assess job embeddedness. These items came from Crossley et al. [17]. Example items are “I feel attached to this hotel” and “It would be difficult for me to leave this hotel”. All items were rated on a 5-point scale (“1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree”). α for job embeddedness was 0.90.

The measure of absence intentions was adopted from Baba et al. [61] and had three items. Sample items are “How important do you think never missing a day’s work is?” and “How important is having a good attendance record to you?” These items were assessed via a 7-point scale (“1 = not at all important” and “7 = extremely important”). α for job embeddedness was 0.89.

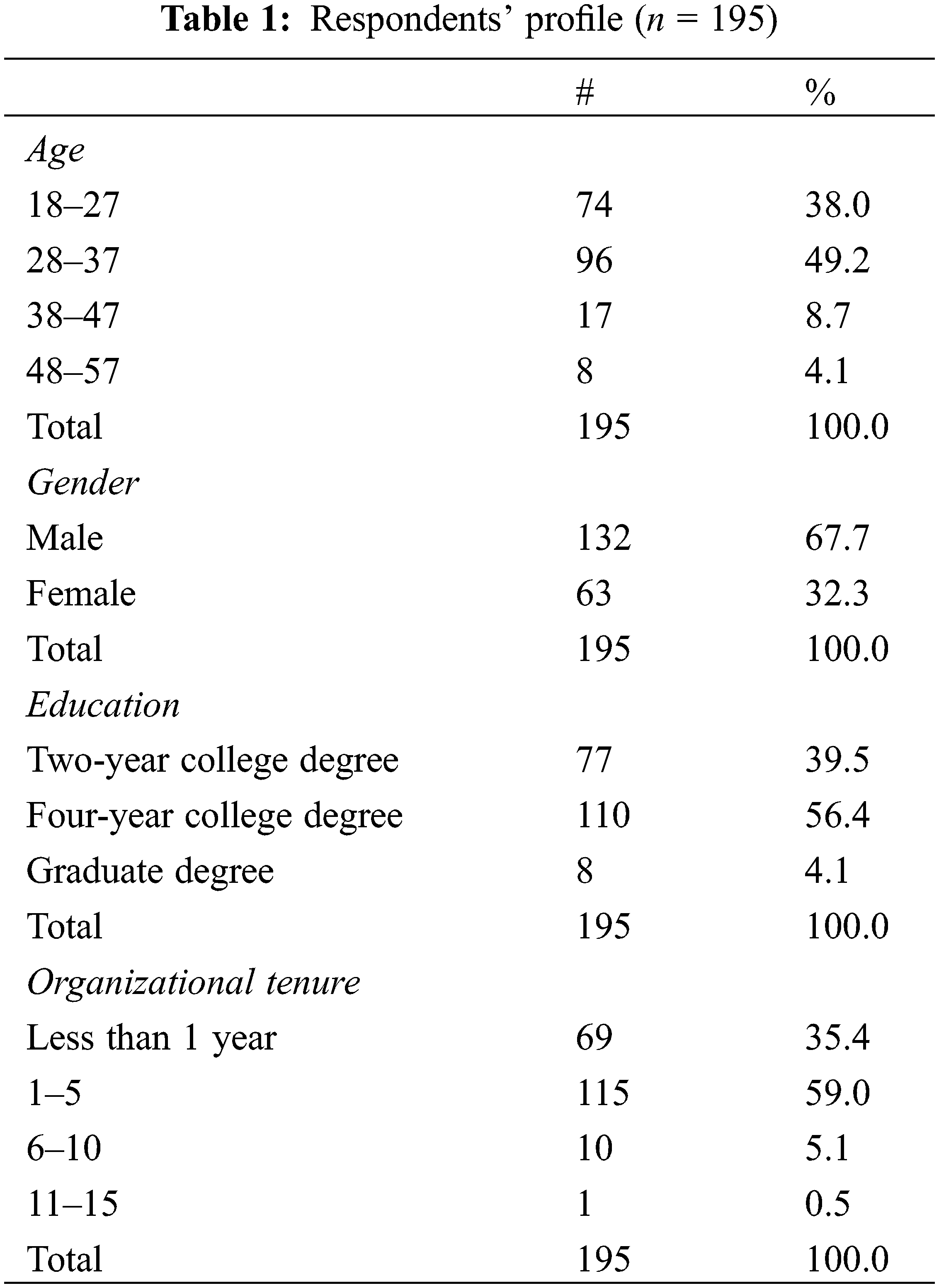

4.1 Respondents and Their Profile

Two hundred and ten CCEs were invited to complete the surveys (Time 1). All CCEs responded to the items in the survey at Time 1. The same employees were requested to complete the surveys at Time 2. Two hundred and nine surveys were received. In the third wave of this study (Time 3), 209 CCEs were asked to complete the surveys. One hundred and ninety-five surveys were obtained, providing a response rate of 92.9%. The previously mentioned practices during data collection helped the researcher to achieve such a response rate. Similar response rates are also accomplished and reported in other empirical pieces [62]. Table 1 presents respondents’ profile.

The overall measurement quality was tested through confirmatory factor analysis in LISREL 8.30 [63]. Specifically, the fit statistics emanating from confirmatory factor analysis was satisfactory: χ2 = 282.16, df = 127, χ2/df = 2.22; “Comparative Fit Index” (CFI) = 0.94; “Parsimony Normed Fit Index” (PNFI) = 0.74; “Root Mean Square Error of Approximation” (RMSEA) = 0.079; “Standardized Root Mean Square Residual” (SRMR) = 0.062. Sixteen out of 18 loadings were > than 0.70. The average variance extracted (AVE) by JR, CO, job embeddedness, and absence intentions was 0.54, 0.64, 0.57, and 0.66, respectively. Each AVE was > than 0.50. The results reported above supported convergent validity [64].

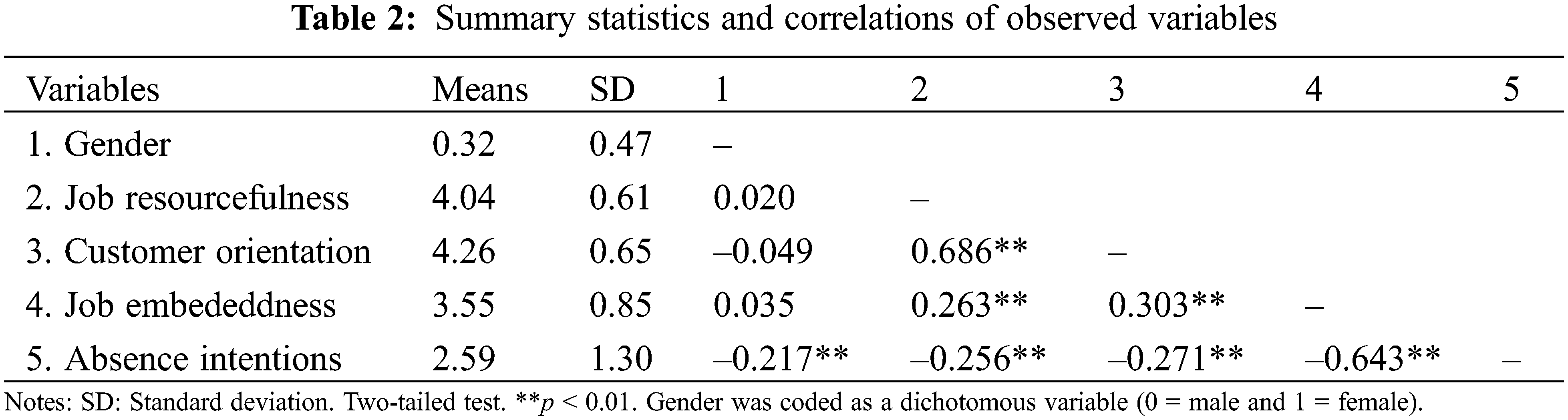

The AVE for each latent construct was larger than the respective squared correlation between constructs. However, this was not the case for the JR and CO measures. Therefore, discriminant validity of these measures was reassessed. A two-factor model (χ2 = 58.52, df = 19) was compared with a single-factor model (χ2 = 115.97, df = 20) via the Δχ2 test. The result was significant (Δχ2 = 57.45, df = 1, p < 0.05). Consequently, discriminant validity was corroborated [64,65]. In addition, the composite reliability for JR, CO, job embeddedness, and absence intentions was 0.82, 0.88, 0.90, and 0.85, respectively. All the measures (>0.60) were reliable [2]. Table 2 provides descriptive statistics and correlations of observed variables.

The associations among the study constructs were tested with structural equation modeling (Fig. 2). Before moving to this stage, the hypothesized model (χ2 = 305.99, df = 144) was compared with the partially mediated model (χ2 = 301.46, df = 141). The finding was not significant (Δχ2 = 4.53, df = 3, p > 0.05). The completely mediated model fit the data well (χ2 = 305.99, df = 144; χ2/df = 2.13; CFI = 0.93; PNFI = 0.74; RMSEA = 0.076; SRMR = 0.066).

Figure 2: Structural model test results

Note: The skewness value for job resourcefulness, customer orientation, job embeddedness, and absence intentions was –0.169, –0.852, –0.378, and 0.960, respectively. Therefore, there was no evidence of non-normality of data [2].

Hypothesis 1 predicts that JR portrays a positive association with CO. The data supported hypothesis 1 since JR portrayed a strong positive linkage with CO (β21 = 0.81, t = 8.23). Hypothesis 2 predicts that CO has a positive impact on job embeddedness. Hypothesis 2 was supported since CO positively influenced job embeddedness (β32 = 0.33 t = 4.12). Hypothesis 3 suggests that CO completely mediates the influence of JR on job embeddedness. The Sobel test finding revealed that CO was a complete mediator between JR and job embeddedness (z = 3.68). Therefore, hypothesis 3 was supported.

Hypothesis 4 suggests that job embeddedness is negatively associated with absence intentions. The data supported hypothesis 4 since job embeddedness exerted a strong negative influence on proclivity to be absent from work (β43 = –0.73 t = –7.79). Hypothesis 5 proposes that job embeddedness completely mediates the linkage between CO and absence intentions. The Sobel test finding revealed that the indirect effect of CO on absence intentions via job embeddedness was negative (z = –3.68). Hence, hypothesis 5 was supported.

The findings showed that gender was negatively linked to absence intentions (γ41 = –0.25, t = –4.38). Accordingly, female employees displayed lower intentions to be absent from work. The findings accounted for 1% of the variance in JR, 67% in CO, 11% in job embeddedness, and 61% in absence intentions. The findings pertaining to the significance of the direct and indirect effects did not change with or without gender.

This study investigated CO as a complete mediator between JR and job embeddedness and job embeddedness as a complete mediator of the effect of CO on absence intentions. The theoretical linkages proposed above were assessed using data gathered from hotel CCEs in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates. All hypotheses were supported. Key findings are discussed below.

Path estimates suggest that JR is a significant personality trait activating employees’ CO. In accordance with the hierarchical personality model, JR is impacted by elemental and compound traits, which in turn boost CO. The finding regarding the strong positive effect of JR on CO supports the proposition that CCEs high on JR can perform their jobs successfully in a resource-depleted setting by being highly customer-oriented [5,12].

The findings delineated in this study suggest that CO boosts employees’ job embeddedness. Customer-oriented employees are high on job embeddedness because they see that their skills, knowledge, and abilities are commensurate with what is expected from the job. This is also true for these employees’ needs and preferences which are in accordance with the job they perform. They have higher job embeddedness due to the compatibility between them and the organization (e.g., organizational culture). They are also embedded in their jobs when there is interpersonal compatibility between them and their coworkers and when there are supervisor-subordinate value and goal congruence and supervisor-subordinate personality similarity.

The findings point to CO as a mediator of the impact of JR on job embeddedness. That is, employees who are capable of carrying out their routine and nonroutine tasks are customer-oriented and therefore stay in the organization. Not surprisingly, employees high on JR can work in a company where there are problems arising from plenty of challenging service encounters. Employees high on CO can also meet customers’ expectations by displaying genuine emotions despite the difficulties inherent in customer-contact positions.

Job embeddedness is an antidote to absence intentions. Consistent with Lee et al.’s [18] work, path estimates suggest that CCEs are less likely to have intent to be absent from work. In accordance with job embeddedness theory, employees stay in the organization due to the presence of fit and links. They stay in the organization when they see that leaving the organization will cost a lot to them. The findings further suggest that job embeddedness is a complete mediator between CO and proclivity to be absent from work. Broadly speaking, employees with high CO exhibit job embeddedness at elevated levels, which in turn engender reduced intentions to be absent from work.

One of the strengths of the present study is related to the investigation of JR and CO simultaneously in customer-contact positions. This is significant because evidence about the antecedents and outcomes of these two critical personality traits in the current literature is still scarce. This void is observed in various writings [6,7,9]. The other strength of this study refers to the examination of the left side of job embeddedness. There is much evidence about the outcomes of job embeddedness. However, empirical research about the factors affecting job embeddedness is still scanty [33,34]. Therefore, this study adds to the existing knowledge base by gauging the impacts of JR and CO on job embeddedness. The last strength of this study refers to the investigation of CCEs’ absence intentions. Despite the acknowledgment that absenteeism leads to substantial costs for the organization [2,36], evidence concerning the influences of CO and job embeddedness on absence intentions is hard to find.

The current study delineates three recommendations for managerial action. First, hiring the right individuals requires selective staffing practices. The ones who do not fit with the requirements of the job are not customer-oriented and are unlikely to work in an environment which is not resourceful. If such individuals are hired and are expected to work under the mandate of ‘do more with less’, they erode service delivery process and hinder effective service recovery [5]. Therefore, managers and peers should be involved in the hiring process and have a voice in the decision process. This practice enables them to have an understanding of the candidates’ intellectual background and observe their interaction style and demeanor. This is important because such managers and peers will work with the ones to be hired for the vacant posts [56]. As a result, they can hire the ones high on JR and CO [66]. Though selective staffing may be used in some of the international chain hotels as well as other successful service companies, its effective implementation is still in its infancy stage.

Second, management should take advantage of job embeddedness to retain the current talented individuals. Consistent with the internal marketing perspective, management has to take care of employees who are expected to take care of customers. Offering a resourceful environment to such employees is a potential solution. This solution can consist of relevant and significant high-performance work systems such as training [67]. CCEs who find that management invests in their well-being via human resource practices will be embedded in their jobs.

Third, management can organize workshops to demonstrate that absenteeism is a significant problem, leading to substantial costs for the organization. To reduce absenteeism or absence intentions, management can gather feedback from CCEs in these workshops about how to mitigate it. If management finds that CCEs experience problems in terms of person-supervisor fit and/or person-group fit, it should arrange training programs that highlight the improvement of the interpersonal compatibility between employees and their coworkers and the supervisor-subordinate value and goal congruence.

5.4 Methodological Concerns and Directions for Future Research

It is acknowledged that this empirical investigation conducted with hotel employees has several limitations that draw attention to suggestions for future research. First, this study centered on JR and CO influencing job embeddedness and absence intentions. This is due to the dearth of research about these personality variables in the relevant literature [7,8]. In future research, testing the antecedents of both JR and CO among CCEs would expand the current understanding.

Second, job embeddedness is a relatively emerging variable and there is limited research about its antecedents [33]. In addition to JR and CO, investigating the effects of the relevant and significant high-performance work systems as well as work and nonwork social support on job embeddedness would pay dividends. Third, future research may consider psychological contract breach as a moderator. Specifically, future research may examine psychological contract breach as a moderator of the influence of job embeddedness on employees’ proclivity to be absent. Lastly, conducting a cross-national study that would lead to test of the linkages proposed in this model would add to current knowledge.

Acknowledgement: Data came from part of a larger project. The extended abstract of this paper was presented in the 7th Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Marketing and Management (AHTMM) Conference, July 10–15, 2017, in Famagusta in Northern Cyprus and was published in the proceedings of this conference.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. Rezapouraghdam, H., Karatepe, O. M. (2020). Applying health belief model to unveil employees’ workplace COVID-19 protective behaviors: Insights for the hospitality industry. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 22(4), 234–247. DOI 10.32604/IJMHP.2020.013214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Etehadi, B., Karatepe, O. M. (2019). The impact of job insecurity on critical hotel employee outcomes: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 28(6), 665–689. DOI 10.1080/19368623.2019.1556768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Karatepe, O. M., Saydam, M. B., Okumus, F. (2021). COVID-19, mental health problems and their detrimental effects on hotel employees’ propensity to be late for work, absenteeism, and life satisfaction. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(7), 934–951. DOI 10.1080/13683500.2021.1884665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zeng, Y., Qiu, S., Alizadeh, A., Liu, T. (2021). How challenge stress affects mental health among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: The moderating role of self-efficacy. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 23(2), 167–175. DOI 10.32604/IJMHP.2021.015937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Harris, E. G., Artis, A. B., Walters, J. H., Licata, J. W. (2006). Role stressors, service worker job resourcefulness, and job outcomes: An empirical analysis. Journal of Business Research, 59(4), 407–415. DOI 10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Harris, E. G., Fleming, D. E., Dapko, J. L. (2021). A holistic examination of the antecedents and outcomes of frontline employee job resourcefulness. Journal of Managerial Issues, 33(2), 174–190. [Google Scholar]

7. Chen, C. Y. (2019). Does work engagement mediate the influence of job resourcefulness on job crafting? An examination of frontline hotel employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1684–1701. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-05-2018-0365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Joello, M., Coelho, A. M. (2019). The impact of a spiritual environment on performance mediated by job resourcefulness. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 12(4), 267–286. DOI 10.1108/IJWHM-05-2018-0058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Karatepe, O. M., Yavas, U., Babakus, E., Deitz, G. D. (2018). The effects of organizational and personal resources on stress, engagement, and job outcomes. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 74(5), 147–161. DOI 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.04.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Silva, D., Coelho, A. (2019). The impact of emotional intelligence on creativity, the mediating role of worker attitudes and the moderating effects of individual success. Journal of Management and Organization, 25(2), 284–302. DOI 10.1017/jmo.2018.60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Licata, J. W., Mowen, J. C., Harris, E. G., Brown, T. J. (2003). On the trait antecedents and outcomes of service worker job resourcefulness: A hierarchical model approach. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31(3), 256–271. DOI 10.1177/0092070303031003004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Karatepe, O. M., Douri, B. G. (2012). Does customer orientation mediate the effect of job resourcefulness on hotel employee outcomes? Evidence from Iran. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 19(1), 1–9. DOI 10.1017/jht.2012.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Brown, T. J., Mowen, J. C., Donavan, D. T., Licata, J. W. (2002). The customer orientation of service workers: Personality trait effects on self- and supervisor performance ratings. Journal of Marketing Research, 39(1), 110–119. DOI 10.1509/jmkr.39.1.110.18928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wu, X., Shie, A. J., Gordon, D. (2017). Impact of customer orientation on turnover intention: Mediating role of emotional labor. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 25(5), 909–927. DOI 10.1108/IJOA-06-2017-1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Mitchell, T. R., Holtom, B. C., Lee, T. W., Sablynski, C. J., Erez, M. (2001). Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 44(6), 1102–1121. DOI 10.5465/3069391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Brownell, J. (2010). Leadership in the service of hospitality. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 51(3), 363–378. DOI 10.1177/1938965510368651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Crossley, C. D., Bennett, R. J., Jex, S. M., Burnfield, J. L. (2007). Development of a global measure of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1031–1042. DOI 10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lee, T. W., Mitchell, T. R., Sablynski, C. J., Burton, J. P., Holtom, B. C. (2004). The effects of job embeddedness on organizational citizenship, job performance, volitional absences, and voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 47(5), 711–722. DOI 10.2307/20159613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ashill, N. J., Rod, M., Thirkell, P., Carruthers, J. (2009). Job resourcefulness, symptoms of burnout and service recovery performance: An examination of call center frontline employees. Journal of Services Marketing, 23(5), 338–350. DOI 10.1108/08876040910973440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ashill, N. J., Gibbs, T., Gazley, A. (2020). Personality trait determinants of frontline employee customer orientation and job performance: A Russian study. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 38(5), 1215–1234. DOI 10.1108/IJBM-11-2019-0407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Babakus, E., Yavas, U., Ashill, N. J. (2009). The role of customer orientation as a moderator of the job demand-burnout-performance relationship: A surface-level trait perspective. Journal of Retailing, 85(4), 480–492. DOI 10.1016/j.jretai.2009.07.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Jha, S., Balaji, M. S., Yavas, U., Babakus, E. (2017). Effects of frontline employee role overload on customer responses and sales performance. European Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 282–303. DOI 10.1108/EJM-01-2015-0009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lindblom, A., Lindblom, T., Wechtler, H. (2020). Retail entrepreneurs’ exit intentions: Influence and mediations of personality and job-related factors. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 54(3), 102055. DOI 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Chen, H., Ayoun, B. (2021). Does national culture matter? Restaurant employees’ workplace humor and job embeddedness. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research. DOI 10.1177/10963480211027927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Dechawatanapaisal, D. (2018). The moderating effects of demographic characteristics and certain psychological factors on the job embeddedness-turnover relationship among Thai health-care employees. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 26(1), 43–62. DOI 10.1108/IJOA-11-2016-1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Singh, R. (2019). Engagement as a moderator on the embeddedness-deviance relationship. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 27(4), 1004–1016. DOI 10.1108/IJOA-08-2018-1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Afsar, B., Shahjehan, A., Shah, S. I. (2018). Frontline employees’ high-performance work practices, trust in supervisor, job embeddedness and turnover intentions in hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(3), 1436–1452. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-11-2016-0633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ampofo, E. T., Coetzer, A., Poisat, P. (2018). Extending the job embeddedness-life satisfaction relationship: An exploratory relationship. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 5(3), 236–258. DOI 10.1108/JOEPP-01-2018-0006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Shehawy, Y. M., Elbaz, A., Agag, G. M. (2018). Factors affecting employees’ job embeddedness in the Egyptian airline industry. Tourism Review, 73(4), 548–571. DOI 10.1108/TR-03-2018-0036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Chen, H., Ayoun, B., Eyoun, K. (2018). Work-family conflict and turnover intentions: A study comparing China and U.S. hotel employees. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, 17(2), 247–269. DOI 10.1080/15332845.2017.1406272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Self, T. T., Gordon, S. (2019). The impact of coworker support and organizational embeddedness on turnover intention among restaurant employees. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, 18(3), 394–423. DOI 10.1080/15332845.2019.1599789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yam, L., Raybould, M., Gordon, R. (2018). Employment stability and retention in the hospitality industry: Exploring the role of job embeddedness. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, 17(4), 445–464. DOI 10.1080/15332845.2018.1449560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Rahiminia, F., Nosrati, S., Eslami, G. (2021). Antecedents and outcomes of job embeddedness among nurses. The Journal of Social Psychology, 56(4), 1–16. DOI 10.1080/00224545.2021.1920360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Saghih, A. M. F., Nosrati, S. (2021). The antecedents of job embeddedness and their effects on cyberloafing among employees of public universities in eastern Iran. International Journal of Islamic and Middles Eastern Finance and Management, 14(1), 77–93. DOI 10.1108/IMEFM-11-2019-0489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Pizam, A., Thornburg, S. W. (2000). Absenteeism and voluntary turnover in Central Florida hotels: A pilot study. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 19(2), 211–217. DOI 10.1016/S0278-4319(00)00011-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kocakulah, M. C., Galligan, A., Mitchell, K. M., Ruggieri, M. P. (2009). Absenteeism problems and costs: Causes, effects and cures. International Business and Economics Research Journal, 8(5), 81–88. DOI 10.19030/iber.v8i5.3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Deery, S., Walsh, J., Zatzick, C. D., Hayes, A. F. (2017). Exploring the relationship between compressed work hours satisfaction and absenteeism in frontline service work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(1), 42–52. DOI 10.1080/1359432X.2016.1197907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Donavan, T. D., Brown, T. J., Mowen, J. C. (2004). Internal benefits of service-worker customer orientation: Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 128–146. DOI 10.1509/jmkg.68.1.128.24034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Yagil, D., Luria, G., Gal, I. (2008). Stressors and resources in customer service roles: Exploring the relationship between core self-evaluations and burnout. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 19(5), 575–595. DOI 10.1108/09564230810903479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Coelho, F. J., Augusto, M. G., Coelho, A. F., Sá, P. M. (2010). Climate perceptions and the customer orientation of frontline service employees. The Service Industries Journal, 30(8), 1343–1357. DOI 10.1080/02642060802613525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Yavas, U., Karatepe, O. M., Babakus, E. (2011). Efficacy of job and personal resources across psychological and behavioral outcomes in the hotel industry. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, 10(3), 304–314. DOI 10.1080/15332845.2011.555881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Karatepe, O. M., Aga, M. (2012). Work engagement as a mediator of the effects of personality traits on job outcomes: A study of frontline employees. Services Marketing Quarterly, 33(4), 343–362. DOI 10.1080/15332969.2012.715053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Sengupta, A. S., Yavas, U., Babakus, E. (2015). Interactive effects of personal and organizational resources on frontline bank employees’ job outcomes: The mediating role of person-job fit. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 33(7), 884–903. DOI 10.1108/IJBM-10-2014-0149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Semedo, A. S., Coelho, A., Ribeiro, N. (2018). The relationship between authentic leaders and employees’ creativity: What are the roles of affective commitment and job resourcefulness? International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 11(2), 58–73. DOI 10.1108/IJWHM-06-2017-0048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Harris, E. G. (2018). Exploring the influence of supervisor support, fit, and job attractiveness on service employee job resourcefulness: An abstract. In: Krey, N., Rossi, P. (Ed.Boundary blurred: A seamless customer experience in virtual and real spaces. Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science, pp. 115. Springer, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

46. Hughes, D. E., Richards, K. A., Calantone, R., Baldus, B., Spreng, R. A. (2019). Driving in-role and extra-role brand performance among retail frontline salespeople: Antecedents and the moderating role of customer orientation. Journal of Retailing, 95(2), 130–143. DOI 10.1016/j.jretai.2019.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Kim, H., Qu, H. (2020). Effects of employees’ social exchange and the mediating role of customer orientation in the restaurant industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 89(4), 102577. DOI 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Anosike, U. P., Eid, R. (2011). Integrating internal customer orientation, internal service quality, and customer orientation in the banking sector: An empirical study. The Service Industries Journal, 31(14), 2487–2505. DOI 10.1080/02642069.2010.504822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Choi, C. H., Kim, T., Lee, G., Lee, S. K. (2014). Testing the stressor-strain-outcome model of customer-related social stressors in predicting emotional exhaustion, customer orientation and service recovery performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36(3), 272–285. DOI 10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.09.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Ribeiro, N., Duarte, P., Fidalgo, J. (2020). Authentic leadership’s effect on customer orientation and turnover intention among Portuguese hospitality employees: The mediating role of affective commitment. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(6), 2097–2116. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-06-2019-0579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Huang, Y. S., Brown, T. J. (2016). How does customer orientation influence authentic emotional display? Journal of Services Marketing, 30(3), 316–326. DOI 10.1108/JSM-12-2014-0402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Wu, X., Shie, A.J. (2017). The relationship between customer orientation, emotional labor and job burnout. Journal of Chinese Human Resource Management, 8(2), 54–76. DOI 10.1108/JCHRM-03-2017-0005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Anaza, N. A., Rutherford, B. (2012). How organizational and employee-customer identification, and customer orientation affect job engagement. Journal of Service Management, 23(5), 616–639. DOI 10.1108/09564231211269801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281–342. DOI 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Wheeler, A. R., Harris, K. J., Sablynski, C. J. (2012). How do employees invest abundant resources? The mediating role of work effort in the job embeddedness/job performance relationship. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(S1), E224–E266. DOI 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.01023.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Hinkin, T. R., Tracey, J. B. (2010). What makes it so great? An analysis of human resources practices among Fortune’s best companies to work for. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 51(2), 158–170. DOI 10.1177/1938965510362487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Rod, M., Ashill, N. J. (2010). The effect of customer orientation on frontline employees’ job outcomes in a new public management context. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 28(5), 600–624. DOI 10.1108/02634501011066528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Yoo, J. J., Arnold, T. J. (2014). Customer orientation, engagement, and developing positive emotional labor. The Service Industries Journal, 34(16), 1272–1288. DOI 10.1080/02642069.2014.942653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Kim, W. G., Han, S. J., Kang, S. (2019). Individual and group level antecedents and consequence of emotional labor of restaurant employees. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, 18(2), 145–171. DOI 10.1080/15332845.2019.1558479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. DOI 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Baba, V. V., Harris, M. J. (1989). Stress and absence: A cross-cultural perspective. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 12, 483–493. [Google Scholar]

62. Liu, X. Y., Kwan, H. K., Chiu, R. K. (2014). Customer sexual harassment and frontline employees’ performance in China. Human Relations, 67(3), 333–356. DOI 10.1177/0018726713493028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Joreskog, K., Sorbom, D. (1996). LISREL 8: User’s reference guide. Chicago: Scientific Software International, Inc. [Google Scholar]

64. Fornell, C., Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. DOI 10.1177/002224378101800104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Anderson, J. C., Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. DOI 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Cheng, J. C., Chen, C. Y. (2017). Job resourcefulness, work engagement and prosocial service behaviors in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(10), 2668–2687. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-01-2016-0025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Thakur, S. J., Bhatnagar, J. (2017). Mediator analysis of job embeddedness: Relationship between work-life balance practices and turnover intentions. Employee Relations, 39(5), 718–731. DOI 10.1108/ER-11-2016-0223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |