| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/ijmhp.2022.017484

ARTICLE

Influence of Blocking-Stressors on Post-90s Employees’ Occupational Mobility: The Chain Mediating Effect of Psychological Contracts and Negative Emotion

1School of Business and Management, Liaoning Technical University, Huludao, 125100, China

2School of Economics and Management, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Beijing, 100876, China

*Corresponding Author: Lixia Niu. Email: nlx8941@yeah.net

Received: 13 June 2021; Accepted: 10 October 2021

Abstract: To clarify the mechanism of blocking-stressors, psychological contracts, and negative emotions on post-90s employees’ occupational mobility, based on the literature study, a hypothetical model of the relationship was established. Using the blocking-stressor, psychological contract, negative emotion, and occupational mobility scales, 317 post-90s employees were selected to investigate their status. It used correlation analysis and intermediary effect tests to verify the hypothesis model. The results showed that: first, there were significant positive correlations between blocking-stressors, negative emotions, and occupational mobility, while indicating a significant negative correlation with the psychological contract; second, blocking-stressors can directly and significantly predict occupational mobility; and third, blocking-stressors can indirectly affect occupational mobility through the mediating role of negative emotions and the chain-mediating role of psychological contracts and negative emotions. The effective intervention of blocking-stressors, psychological contracts, and negative emotions can reduce the rate of occupational mobility and provide some guidance for enterprises in making rational use of human resources.

Keywords: Occupational mobility; post-90s; blocking-stressors; psychological contract; negative emotion

In recent years, post-90s employees have entered the workplace, accounting for 60% of e-commerce enterprises. In the Internet age, these new generations undoubtedly become the main force of modern enterprises in terms of quantity, scale, and value creation, and are, therefore, an important part of the talent strategies of modern enterprises [1]. The growth environment of the post-90s exhibits distinct characteristics of current times—economic transformation, information diversity, and educational reform have prompted them to form a strong self-consciousness in pursuing their individuality and advocating spiritual independence, which also makes their attitude towards their careers more changeable [2]. According to the latest survey of the China News Network, 90% of the employees interviewed said that many post-90s graduates have been employed for less than three years. The turnover rate of undergraduates is 40% within three years, and the average turnover is once every seven months [3]. This phenomenon is driven by social factors and individual factors. Compared to the post-70s and 80s, post-90s employees pay more attention to the career development mode driven by personal value orientation. Traditional management modes hinder their personalized career development and break the psychological contract between them and the organization, resulting in high occupational mobility [4], which not only brings great challenges to individual careers and enterprise human resource planning, but also negatively affects the social employment climate. This has been widely studied in theoretical and practical circles domestically and abroad [5]. Practically, it is of great practical significance to explore the mechanism of blocking-stressors on occupational mobility perceived by the post-90s, which can effectively reduce their mobility and improve their career management style.

Currently, most research on occupational mobility is carried out from the perspective of social systems and industrial structures, but few from the perspective of social psychology. Additionally, previous studies mainly focused on (urban) migrant workers with strong mobility and doctors with specific professional attributes [6]; however, insufficient attention has been paid to the post-90s generation. Some scholars have only analyzed the objective reasons—such as intergenerational differences—that affect occupational mobility [7] with little research on the specific mechanism between this and individual subjective perception. A few studies have found that blocking-stressors have a positive impact on employee occupational mobility [8], but the mechanism and boundary conditions between them have not been fully revealed. Therefore, based on the literature analysis, this study focuses on the blocking-stressors perceived by the post-90s generation, and the changes in psychological feelings and internal coping resources after it acts on individuals, and introduces two mediating variables: psychological contracts and negative emotions. A psychological contract is a personal belief created by the organization; its stability depends on the cognition of the relationship between dedication and income by individuals and the organization. Deviation from expectation refers to the violation of a psychological contract, which will affect individuals’ work attitudes and behavior [9]. Therefore, based on the theory of resource preservation, this study explores the mediating role of psychological contracts between blocking-stressors and occupational mobility. In addition, negative emotion, as a stable emotional trait, is a form of negative emotional change that often affects individual decision-making along with negative behavior [10]. This tendency is closely related to individuals’ work and psychological contracts under blocking pressure for a long time, and has a profound impact on occupational mobility [8].

This study uses a structural equation modeling method to construct the relationship model of blocking-stressors, psychological contracts, negative emotions, and occupational mobility of the post-90s generation, while revealing the mechanism and conditions of action from blocking-stressors on occupational mobility, and the chain-mediating role of psychological contracts and negative emotions. The research results provide a new way to improve the career management styles for the generation of new enterprise ideas.

2 Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1 Blocking-Stressors and Occupational Mobility

According to the theory of resource conservation, when the demands of an individual’s work excessively consume their coping resources, this may result in their inability to deal with residual pressures and demands, and their psychological feelings and behavioral decisions will be negatively affected [11]. Post-90s employees reflect the distinct characteristics of our times, with the most significant intergenerational differences to previous employees are self-awareness and values. Post-90s employees have strong self-awareness and pursue the realization of their self-worth, career development, and working environment. Therefore, the blocking-stressors perceived by the post-90s are specific to these times, such as their power distance perception [12]. The post-90s tend to change their career interests; hence the key to accepting a job is often the charisma and sense of mission associated with the profession [13]. In addition, the post-90s are a generation with a strong sense of self-identity and are eager for enterprises to provide self-expression. My stage is even less willing to work in no use, lack of space. Therefore, the alienated leadership relationship, the extinction of self-work value, and the status quo of companies with no prospects for promotion or development may become the blocking-stressors faced by these post-90s employees, leading to a generation characterized by occupational mobility. Empirical research shows that the post-90s are more daring and passionate in dealing with issues than the previous generation. Dissatisfaction or disapproval at work may stimulate negative attitudes, to the point where, in their view, “firing” the boss is a “cool behavior” [3]. Due to different personal views on the current work state, the nature of the work itself and the future work state, different forms of stress will be caused. Therefore, based on the most prevalent blocking-stressors faced by post-90s employees, and combined with the characteristics and current situation of the research object, this study divides the potential dimensions of this variable into the perception of power distance, career charisma, and career development expectations. Accordingly, we propose hypothesis H1.

H1: Blocking-stressors positively affect occupational mobility.

2.2 Mediating Role of the Psychological Contract

Social exchange theory emphasizes that the foundation of maintaining a good psychological contract between individuals and organizations is the equality and mutual benefit of material and spirit [14]. If employees feel that the blocking pressure is beyond their scope of coping, psychological contract violation may occur based on a social exchange relationship. Robinson and Rousseau defined psychological contract breach as the organization’s perception of employees’ failure to fulfill their commitments [15]. Due to the low development of the labor market, information asymmetry persists, and unfulfilled commitments deprive employees of expected results, which contribute to the perception of unfair distribution [16]. Post-90s employees resist the cognitive bias of the contrast effect before and after their employment. The attitude of those in leadership, working environment, and even entertainment facilities in the company will become their links in establishing a psychological contract. Therefore, the “feeling of being deceived” has become an important factor in the turnover intention of post-90s employees. When there are not enough coping resources to deal with and accept this bad feeling, the sense of contract with the organization will decline. Conversely, as long as it is the company or their leaders recognize and can meet their needs, post-90s will commit with absolute sincerity to working diligently. Empirical research also shows that strong psychological contracts have a positive effect on the work behavior of university teachers and medical staff [17,18]. Therefore, we propose hypotheses H2, H2a, and H2b.

H2: The psychological contract is a mediating variable between blocking-stressors and occupational mobility;

H2a: Blocking-stressors negatively affect psychological contracts;

H2b: Psychological contracts have a negative impact on occupational mobility.

2.3 Mediating Effect of Negative Emotions

The stressor emotion model of counterproductive work behavior emphasizes that individuals should evaluate a large number of their organization- and context-specific stressors. Once a sense of pressure is formed, it leads to the generation of negative emotions [19]. That is, when the required work ability exceeds its own work ability, it will lead to active or passive career mobility. Empirical research shows that there is an intimate relationship between stress and anger. If individuals cannot actively deal with these pressures, negative consequences will occur [20]. Weiss and Cropanzano’s affective events theory suggests that employees’ emotional experiences will further affect their attitudes and behaviors; for example, the long-term accumulation of negative emotions will reduce employee satisfaction and organizational commitment, and ultimately affect career choice [21]. Based on the particularity of the post-90s style, the consequences of negative emotions will be further magnified. The reason is that they are far less worried than the post-70s and 80s, and do not need to bear excessive family responsibilities. At the same time, they hate the occupation of their private time because in the post-90s concept—making money for a better life—they sacrifice the time to enjoy life. Empirical studies also show that negative emotions can narrow the cognitive range, reduce the perception of consequences, and have a negative impact on individual occupational mobility [9]. Based on this, we propose hypotheses H3, H3a, and H3b.

H3: Negative emotion is the mediating variable between blocking-stressors and occupational mobility;

H3a: Blocking-stressors positively affect negative emotions;

H3b: Negative emotions positively affect occupational mobility.

2.4 Multiple Mediating Effects of Psychological Contract and Negative Emotions

Based on the frustration-aggression theory, an important reason for post-90s employees to show aggressive behavior in their work is that they feel pressure or depression brought on by work, and then affects their psychological changes [22]. Most of the setbacks in the general working situation arise from unfair treatment regarding personal rights and interests. However, for new employees, their ability to solve such problems is limited, and they do not perceive management to be humanizing or kind, which may lead to occupational mobility. Empirical research shows that distrust of superiors, misunderstanding of colleagues, heavy tasks, and disappointment in the organization will lead to a deviation in employees’ emotional commitment or a breach of the psychological contract. Organizational commitment will be impacted, and negative emotions will accelerate employees’ aggressive behavior [15]. As the post-90s pay more attention to the special qualities of self-esteem and happiness, such aggressive behavior will have a significant negative impact on occupational mobility. Therefore, hypothesis H4 is proposed.

H4: Psychological contracts negatively affect negative emotions. Psychological contracts and negative emotions play multiple mediating roles between blocking-stressors and occupational mobility.

In summary, the hypotheses model is shown in Fig. 1:

Figure 1: Hypotheses model

To test the hypotheses and clarify the relationship among blocking-stressors, psychological contracts, negative emotions, and occupational mobility, a sample of post-90s employees were selected for data collection, and the SPSS and Amos software packages were used for the correlation analysis and mediating effect testing.

From the alumni circle, random sampling was conducted on the post-90s employees. The sample covered four first tier cities: Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Guangzhou, as well as 15 new first tier cities such as Chengdu, Hangzhou, Chongqing and Xi’an, with a total of 19 cities with leading economy, advanced technology and commercial resources. For this reason, these first tier cities have become the favorite places for post-90s graduates, with fierce competition, rising pressure and frequent personnel flow among enterprises, so they are used as the sample source. In order to ensure the authenticity of the questionnaire, at the beginning of the questionnaire, clearly inform the participants of the anonymity and confidentiality of the questionnaire. The survey results will be only for scientific research, and the survey will not have any adverse impact on the respondents themselves and their units. In order to effectively control the representativeness of the sample, a total of 380 online questionnaires were distributed according to the proportion of graduates received by first tier cities in recent ten years. Excluding the questionnaires that did not answer carefully, 317 were recovered—a recovery rate was 83.4%. Among the participants, the ratio of male to female was 1.17:1; the age was mainly 24 to 30-year-old (89.6% of the total sample); the education level was mainly undergraduate or above (80.8%); the marital status was mainly unmarried (66.7%); and the working year was mainly 1–6 (86.4%).

3.2.1 Blocking-Stressors Source Scale

The power distance orientation scale [12] developed by Erez was used for reference in the perception of power distance items; the career appeal scale [13] developed by Tong Jing for Chinese employees was used as a reference in the design of career appeal items; the career expectation scale [23] developed by Zhijin Hou was used as a reference for the design of career appeal items. Thus, there were 12 items in the blocked-stressor scale which was scored on a 5-point likert scale—higher scores denoted greater pressure. The results showed that Cronbach’s Alpha value of the scale was 0.802.

3.2.2 Psychological Contract Scale

In this study, the measurement of psychological contract variables mainly refers to the scale [15] designed by Rousseau, including 10 items such as “the superior gives me the power to make decisions on my work”. Lower scores imply a greater violation of the psychological contract is, with these results reflecting a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.931.

The scale of negative psychology developed by Piao Li was used, including eight common emotions: guilt, fear, hostility, anger, shyness, disappointment, disgust, and anxiety [20]. A higher score reflects increased levels of the subjective feelings of perplexity and pain of the participants. Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.884.

3.2.4 Occupational Mobility Scale

The mobile willingness scale published by Fan Jingli has four items in total, including “I often have the idea of quitting my current job”, and “I may be about to leave my present company and find another job” [5]. A high score means that employees have a strong desire for career mobility; the result of Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.933.

According to the sample situation, this study selected gender, age, education level, marital status, and working years of post-90s employees as control variables. A descriptive statistical analysis was used for the classification and analysis of sample data. By calculating averages, standard deviation, and frequency of the samples, we preliminarily understood the basic situation of the post-90s employees investigated enabling us to conduct further detailed analyses with explanations.

In this study, Excel 2010 was used to input the survey data, SPSS 26.0 and AMOS22.0 were used for correlation analysis and the mediating effect test to verify the hypothesis model, and the bootstrap method was used to estimate the confidence interval.

4 Data Analysis and Inspection

4.1 Common Method Deviation Test

The common method deviation test [24] showed that the characteristic roots of the six factors were all greater than 1, and the first factor explained 22.45% (less than the critical value of 40%), indicating that the survey data passed the test.

4.2 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation among Variables

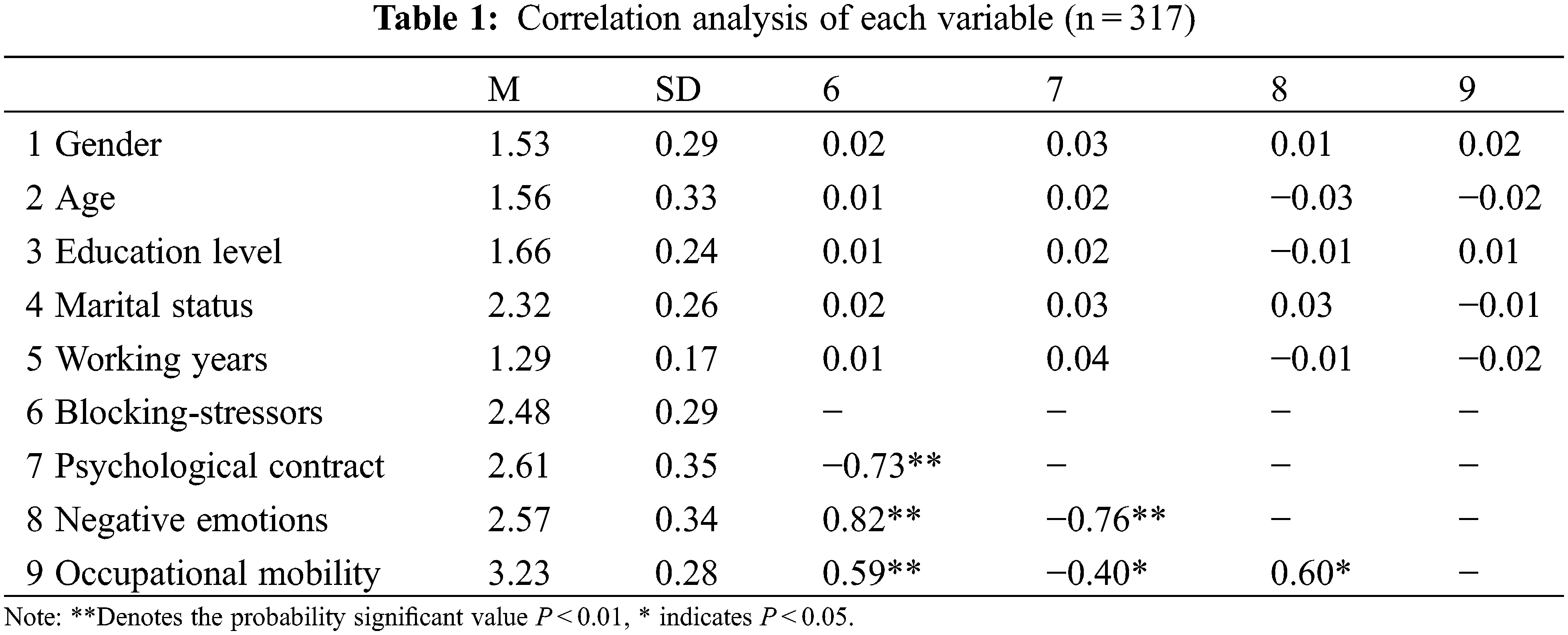

Because the correlation coefficient of demographic variables was much smaller than that of influencing factors and occupational mobility, we took demographic variables as control variables and focused on the relationship between influencing factors. The results showed that there were significant positive correlations among blocking-stress, negative emotion, and occupational mobility, while psychological contracts were negatively correlated with blocking-stress (r = −0.73, P < 0.01), negative emotion (r = −0.76, P < 0.01), and occupational mobility (r = −0.40, P < 0.05), as per Table 1.

4.3 The Relationship between Blocking-Stressors and Occupational Mobility: A Chain Mediated Effect Test

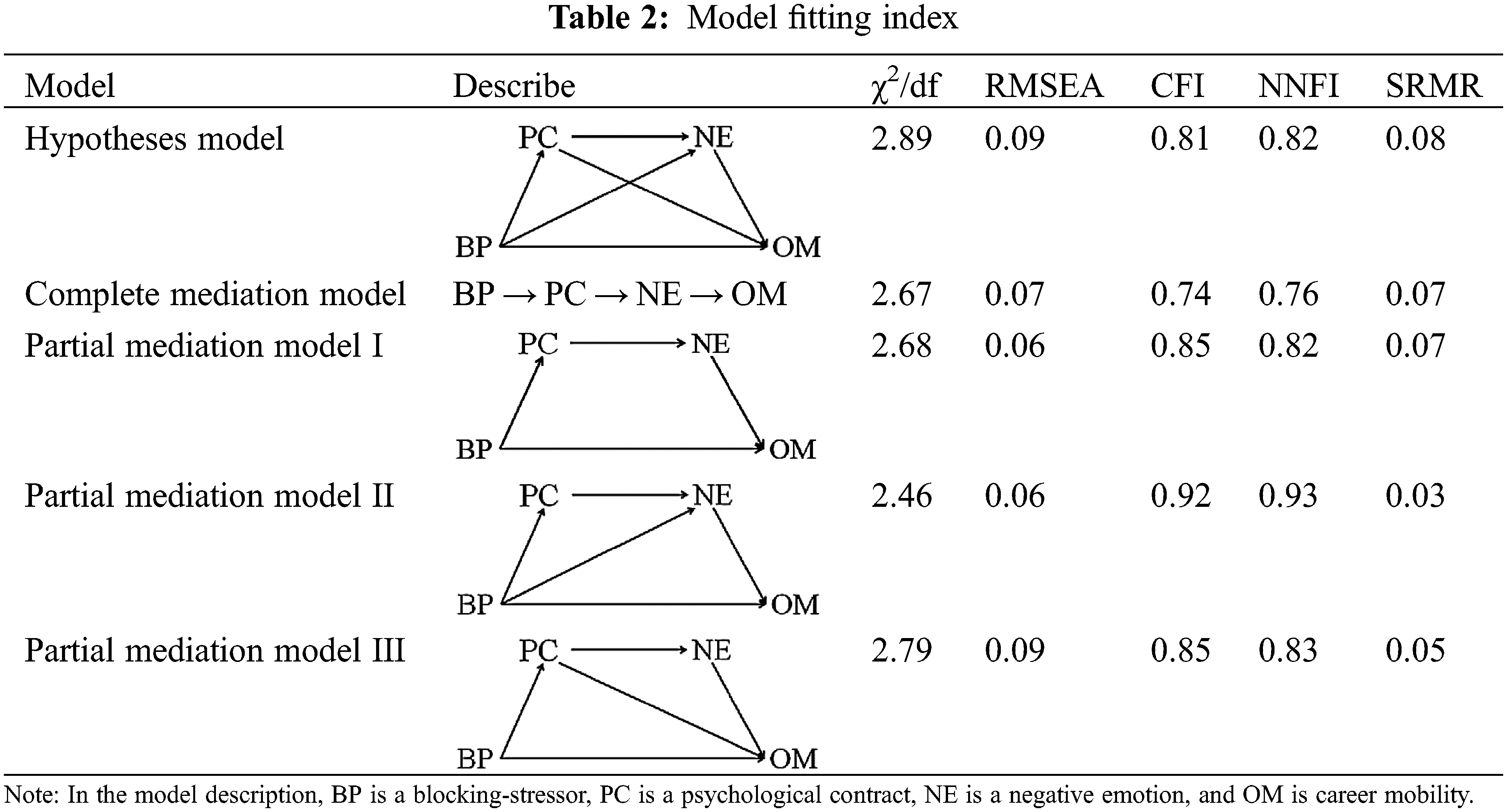

The mediating effect of psychological contracts and negative emotions on occupational mobility was examined by structural equation modeling (SEM). First, five possible competition models were proposed, as shown in Table 2. They were the hypotheses, complete mediation, and three partial mediation models. According to the analysis of test results, the observation data and partial mediation model II had the best fitting effect, and hypothesis 2 was not verified.

Second, we test the chain mediating effect. It can be seen from Fig. 2 that blocking-stressors have a significant positive impact on occupational mobility (γ = 0.60, t = 2.23, P < 0.001), and hypothesis 1 holds. Blocking-stressors significantly negatively affected psychological contracts (γ = −0.73, t = 7.45, P < 0.001), psychological contracts significantly negatively affected negative emotions (γ = −0.61, t = −1.78, P < 0.001), and negative emotions significantly negatively affected occupational mobility (γ = 0.82, t = 1.28, P < 0.001) In other words, higher blocking-stressors caused lower levels of psychological contract, which increases negative emotions and ultimately enhances the occupational mobility of employees.

Figure 2: Chain mediation model

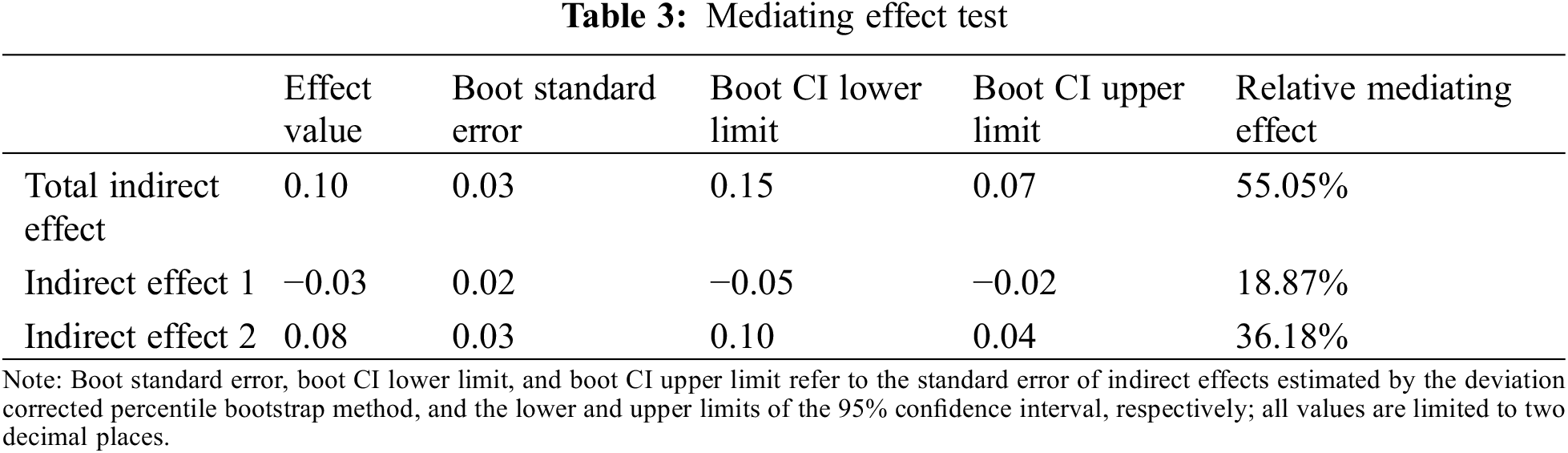

Thereafter, the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method was employed to test [25], which showed that the mediating effect of psychological contract and negative emotion was significant, including two mediating chains. The first mediating chain verified hypothesis 3: blocking-stressors → negative emotions → occupational mobility. The confidence interval of the mediating effect does not contain 0.00, indicating that the indirect mediating effect of negative emotions is significant. The second intermediary chain verifies that hypothesis 4 is tenable: blocking-stress → psychological contract → negative emotion → occupational mobility, and the confidence interval of the mediating effect does not contain 0.00, indicating psychological contract is significant. The indirect effects of mobility and negative emotions were significant, as shown in Table 3.

This study explored the mechanism of blocking-stressors on occupational mobility and explored the mediating role of psychological contracts and negative emotions. The mediating effect is produced through the independent mediating effect of negative emotion and the chain-mediating effect of psychological contracts and negative emotions.

5.1 Blocking-Stressors and Occupational Mobility

According to the fitted model, the path coefficient of blocking-stressors on occupational mobility is 0.77, which indicates that blocking-stressors have a significant positive impact on employees’ occupational mobility; that is, the more blocked-stressors experienced by post-90s employees, the higher the possibility of occupational mobility. This research result is consistent with those of previous studies [26]. The data in Fig. 2 show that the direct effect (β = 0.60) of blocking-stressors on post-90s’ occupational mobility is greater than the mediating effect (

5.2 The Independent Mediating Effect of Negative Emotions

The path coefficient of negative emotion on occupational mobility is 0.69, and the path coefficient is positive, which indicates that employees with high a negative emotion experience are prone to occupational mobility. The independent mediating effect of negative emotions was 0.566 (β = 0.82 × 0.69), indicating that blocking-stressors can affect the post-90s employees’ occupational mobility through the mediating effect of negative emotions. Some studies have found that individuals’ emotional coping, processing, and expression have different predictive effects on behavioral outcomes under different stress scenarios. The more acute the stress event, the more obvious is the expression of negative emotion [27]. According to the theory of resource preservation, the level of blocking-stress determines the lack of coping resources and the inability to deal with work pressure actively and effectively, resulting in negative emotions such as fear and even hostility. The handling of these negative emotions is closely related to an individual’s cognitive processing ability and comprehensive psychological quality [28]. When encountering stressful events, people with high psychological quality can cope with emotional reactions more quickly by effectively mobilizing cognitive resources to reinterpret and analyze emotional situations. Thus they weaken their negative emotions, reduce the interference and destructive effects of negative emotions, and have a higher level of social adaptation [29]. The emotional event theory also suggests that this will reduce the individual’s perception of consequences. To balance emotional resources, we cannot overemphasize the behavioral consequences, which lead to an increase in the possibility of occupational mobility—this is consistent with previous research results [30]. Therefore, negative emotions can indirectly affect the effect of blocking-stress on occupational mobility.

5.3 The Chain Mediating Effect of Psychological Contracts and Negative Emotion

For the two latent variables of blocking-stressors and psychological contracts, the path coefficient is −0.73, which indicates that more blocking-stress events increase the possibility of a psychological contract being broken. For the two latent variables of blocking-stressors and negative emotions, the path coefficient is 0.82, which indicates that higher levels of blocking pressure lead to greater perceived negative emotion; for psychological contracts and negative emotion, the path coefficient is 0.82. The path coefficient of the two latent variables is −0.61, which indicates that psychological contract violation will exacerbate the negative emotional experience. The path shows that blocking-stressors not only directly affect employees’ negative emotional experiences, but also their negative emotional experiences through psychological contracts. In this study, the chain mediating effect was 0.307 (β = 0.73 × 0.61 × 0.69), which indicates that blocking-stressors can affect employees’ occupational mobility through the chain-mediating effect of psychological contracts and negative emotions. Based on the resource preservation theory, the occurrence of psychological contract violations stems from the mismatch between employees’ perceived work pressure and their coping mechanisms as well as the imbalance between work input and returns. In terms of its impact on results, this mismatch and imbalance can trigger employees’ own negative emotional reflection, while also causing a negative self-evaluation and of others [31]. Emotion consistency theory emphasizes that this negative emotion arouses negative memory in the individual’s subconscious, which will continue to strengthen negative emotion, and lead to turnover intention and even occupational mobility behavior, which is consistent with previous studies [32]. The combination of psychological contracts and negative emotions fully reflects the formation mechanism of internal psychological characteristics of individual behavior performance. Focusing on the mechanism of chain mediation, an increase in the blocking pressure level will increase the risk of a breach in the psychological contract. The weakening of psychological contracts is accompanied by an increase in negative emotion, which causes the post-90s employees’ occupational mobility to occur. This analysis supports the frustration-aggression theory, which emphasizes that when individuals are disturbed by negative emotions for a long time, they will act to alleviate the situation [22]. Compared to improving their competence, it is easier to change their work content or environment. Therefore, blocking-stressors easily lead to psychological contract violations and increase the accumulation of negative emotions, which leads to occupational mobility.

Contrary to the research hypothesis, psychological contracts do not directly affect employee occupational mobility except through negative emotions. The reason may be that negative emotion, as a passive emotional trait, and is often accompanied by a series of passionate behaviors that can easily affect an individual’s state of consciousness and actions. As typical spontaneous thinking, psychological contracts are mainly determined by the cognitive resources and cost to individuals. When there is a state of violation that is beyond the scope of acceptance, negative emotions will be aroused, thus affecting individual behavior. Therefore, the direct prediction effect of psychological contracts on occupational mobility is not significant.

The following conclusions can be drawn from this study:

1. This study discusses the influence of blocking-stressors on the occupational mobility of post-90s employees and the mediating effect of psychological contracts and negative emotion. Among them, blocking-stressors have a significant positive impact on occupational mobility; negative emotions play an independent mediating role between blocking-stressors and occupational mobility; psychological contracts and negative emotions play a chain mediating role between blocking-stressors and occupational mobility. Therefore, blocking-stressors not only directly and positively affect occupational mobility, but also indirectly affect occupational mobility through psychological contracts and negative emotions—this enriches the research results of blocking-stressors and occupational mobility.

2. The research results have important practical value for effectively reducing the occupational mobility of post-90s employees. First, blocking-stressors have a positive impact on employees’ occupational mobility. Managers should pay attention to the blocking-stressors that are more sensitive to the perception of post-90s employees, improve the effectiveness of management systems, build employee assistance systems, strengthen employees’ positive perceptions and responses, and reduce the channels and negative experience of blocking-stressors. Second, the study found that psychological contracts and negative emotions indirectly affect occupational mobility. Therefore, effective management communication, especially during emergencies, can effectively reduce the breach of psychological contracts and the negative emotions of employees, improve the post-90s employees’ sense of happiness and value, and reduce occupational mobility.

5.5 Research Limitations and Prospects

Due to the limitations of subjectivity and social expectations arising from a questionnaire survey, future research may consider using behavioral experiments, among others, as future auxiliary methods, combined with a questionnaire survey to obtain more objective research results. Additionally, this study selects the dimension of blocking-stressors that are more sensitive to the perceptions of post-90s employees for future research—we can thus explore the deep relationship between each variable and its dimensions.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to this work. Specifically, L.N. developed the original idea for the study and designed the methodology. Y.L. completed in the survey and drafted the manuscript, which was revised by L.N., Y.L., J.L. and R.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the Liaoning Provincial Education Department Project (No. LJ2020JCW002), Liaoning Provincial Social Science Planning Fund Project (No. L20BGL030), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52174184, 51504126), Humanities and Social Science Foundation of Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (No. 19YJA630038) and Discipline Innovation Team of Liaoning Technical University (LNTU20TD-04). These supports are gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1. Huang, Y. L. (2021). The study on social participation among “post-90s” young people in China. Youth Studies, 439(4), 11–23+94. [Google Scholar]

2. Zhou, Y. X. (2020). Analysis of the characteristics and causes of the post-90s population in China. China Youth Study, (11), 43–51. DOI 10.19633/j.cnki.11-2579/d.2020.0163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Meng, X. L., Chai, P. F., Huang, Z. W. (2020). A research on the relationship among work values, organizational justice and turnover intentions and their intergenerational differences. Science Research Management, 41(6), 219–227. DOI 10.19571/j.cnki.1000-2995.2020.06.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bachmann, R., Bechara, P., Vonnahme, C. (2020). Occupational mobility in Europe: Extent, determinants and consequences. De Economist, 168(1), 79–108. DOI 10.1007/s10645-019-09355-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Goswami, S., Bhaduri, G. (2021). Investigating the direct and indirect effects of perceived corporate hypocrisy on turnover intentions. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 12, 214–228. DOI 10.1080/20932685.2021.1893782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Nicole, L. (2020). Mobility for healthcare professional workforce continues to soar. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 10(4), 54–56. DOI 10.1016/S2155-8256(20)30015-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Cheng, S., Song, X. (2019). Linked lives, linked trajectories: Intergenerational association of intergenerational income mobility. American Sociological Review, 84, 1037–1068. DOI 10.1177/0003122419884497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li, Z., Lin, M., Li, Y. L. (2020). A study on the employees turnover behaviors and causes based on grounded theory. Human Resource Development of China, 37(7), 21–33. DOI 10.16471/j.cnki.11-2822/c.2020.7.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Dixon-Fowler, H., O’Leary-Kelly, A., Johnson, J., Waite, M. (2020). Sustainability and ideology infused psychological contracts: An organizational- and employee-level perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 30(3), 100690. DOI 10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Pan, Z. X., Li, B. B. (2019). Differences in the effectiveness of negative emotion regulation among college students: The role of psychological quality and gender. Journal of Southwest University (Social Science Edition), 45(1), 113–119. DOI 10.13718/j.cnki.xdsk.2019.01.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Duan, J. Y., Yang, J., Zhu, Y. L. (2020). Resource conservation theory: Content, theoretical comparison and research prospect. Psychological Research, 13(1), 49–57. DOI 10.3969/j.issn.2095-1159.2020.01.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liu, G. F. (2020). The influence of psychological ownership on post-90s new generation employees. CO-Operative Economy & Science, 4, 156–157. DOI 10.13665/j.cnki.hzjjykj.2020.04.062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ugwu, F. O., Onyishi, I. E. (2018). Linking perceived organizational frustration to work engagement: The moderating roles of sense of calling and psychological meaningfulness. Journal of Career Assessment, 26(2), 220–239. DOI 10.1177/1069072717692735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Roch, S. G., Shannon, C. E., Martin, J. J., Swiderski, D., Agosta, J. P. et al. (2019). Role of employee felt obligation and endorsement of the just world hypothesis: A social exchange theory investigation in an organizational justice context. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 49(4). DOI 10.1111/jasp.12578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhou, Y. (2015). Employee psychological contract violation and turnover intention: A literature review. China Collective Economy, 27, 104–105. DOI 10.3969/j.issn.1008-1283.2015.27.058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhu, H. (2019). Review on the influence of social network on individual employment decision. China Price, 6, 73–75. [Google Scholar]

17. Liu, J. J., Wang, Y. (2019). Research on organizational citizenship behavior of university teachers based on psychological contract. Economic Research Guide, 22, 129–130. DOI 10.3969/j.issn.1673-291X.2019.22.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhou, P., Shi, J. W., Zhang, Y., Bai, F., Wei, X. F. et al. (2016). Relationships between physicians’ psychological contract and job satisfaction, intention to leave medical practice, and professionalism: A cross-sectional survey in China. The Lancet, 388, 12. DOI 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31939-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ma, L., Li, W. (2019). The relationship between stress and counterproductive work behavior: Attachment orientation as a moderate. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 7, 413–423. DOI 10.4236/jss.2019.74033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Garefelt, J., Platts, L. G., Hyde, M., Hanson, L. L. M., Westerlund, H. et al. (2020). Reciprocal relations between work stress and insomnia symptoms: A prospective study. Journal of Sleep Research, 29(2), 129–139. DOI 10.1111/jsr.12949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Cheng, J., Cao, T. (2018). Research on the mechanism of employees’ irrational external exposure based on emotional event theory. Human Resource Development of China, 35(2), 6–18. DOI 10.16471/j.cnki.11-2822/c.2018.02.001. [Google Scholar]

22. Azemi, Y., Ozuem, W., Howell, K. E. (2020). The effects of online negative word-of-mouth on dissatisfied customers: A frustration–aggression perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 37(4), 564–577. DOI 10.1002/mar.21326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu, T., Shen, H. W., Chau, K. Y., Wang, X. (2019). Measurement scale development and validation of female employees’ career expectations in mainland China. Sustainability, 11(10), 32–46. DOI 10.3390/su11102932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhou, H., Long, L. (2014). Statistical test and control method of common method deviation. Advances in Psychological Science, 12(6), 942–950. DOI 10.3969/j.issn.1671-3710.2004.06.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Erceg-Hurn, D. M., Mirosevich, V. M. (2008). Modern robust statistical methods: An easy way to maximize the accuracy and power of your research. The American Psychologist, 63(7), 591–601. DOI 10.1037/0003-066X.63.7.591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhou, F., Chen, L., Su, Q. (2019). Understanding the impact of social distance on users’ broadcasting intention on live streaming platforms: A lens of the challenge-hindrance stress perspective. Telematics and Informatics, 41, 46–54. DOI 10.1016/j.tele.2019.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Sandner, M., Zeier, P., Lois, G., Wessa, M. (2021). Cognitive emotion regulation withstands the stress test: An fMRI study on the effect of acute stress on distraction and reappraisal. Neuropsychologia, 10, 76–78. DOI 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2021.107876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Tse, W. S., Bond, A. J., Baumann, N. (2021). Focusing too much on individualistic achievement may generate stress and negative emotion: Social rank theory perspective. Journal of Health Psychology, 26, 1271–1281. DOI 10.1177/1359105319864650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Yu, H. Y., Lee, L., Popa, L., Madera, J. M. (2021). Should I leave this industry? the role of stress and negative emotions in response to an industry negative work event. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102–112. DOI 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Sarker, R. I., Kaplan, S., Mailer, M., Timmermans, H. (2019). Applying affective event theory to explain transit users’ reactions to service disruptions. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 130(12), 593–605. DOI 10.1016/j.tra.2019.09.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Kong, D. T., Jolly, P. M. (2019). A stress model of psychological contract violation among ethnic minority employees. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(3), 424–438. DOI 10.1037/cdp0000235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yao, Z., Zhang, X. (2020). Research on the influence of congruence in time pressure on employees turnover intention—Emotional exhaustion as a mediator. Soft Science, 34(9), 109–115. DOI 10.13956/j.ss.1001-8409.2020.09.17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |