DOI:10.32604/biocell.2021.015363

www.techscience.com/journal/biocell

| Biocell DOI:10.32604/biocell.2021.015363 |  www.techscience.com/journal/biocell |

| Article |

Zinc oxide nanoparticles and epibrassinolide enhanced growth of tomato via modulating antioxidant activity and photosynthetic performance

1Collaborative Innovation Center of Sustainable Forestry in Southern China, College of Forest Science, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, 210037, China

2School of Life Sciences, Glocal University, Saharanpur, 247121, India

3Plant Physiology Laboratory, Department of Botany, Faculty of Life Sciences, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, 202002, India

4State Key Laboratory for Crop Genetics and Germplasm Enhancement, College of Agriculture, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, 210095, China

*Address correspondence to: Javaid A. Bhat, javid.akhter69@gmail.com; Fangyuan Yu, fyyu@njfu.edu.cn

Received: 13 December 2020; Accepted: 08 February 2021

Abstract: Nanotechnology has greatly expanded the applications of nanoparticles (NPs) domain in the scientific field. In this context, the zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) and 24-epibrassinolide (EBL) has been revealed to positively regulate plant metabolism and growth. In the present study, we investigated the role of ZnO-NPs and EBL in the regulation of plant growth, photosynthetic efficiency, enzymes activities and fruit yield in tomato. Foliar treatment of ZnO-NPs at three levels (10, 50 or 100 ppm) and EBL (10−8 M) were applied separately or in combination to the foliage of plant at 35–39 days after sowing (DAS); and the control plants were treated with double distilled water (DDW) only at the same time interval. Among different tested concentrations of ZnO-NPs and/or EBL, the combined spray of 50 ppm of ZnO-NPs and 10−8 M of EBL proved to be best, and considerably increased the growth, photosynthetic efficiency, biochemical enzymes activities as well as fruit yield. Besides, the performance of the antioxidant enzymes viz catalase, peroxidase and superoxide dismutase were also increased after the combined application of ZnO-NPs and EBL in Lycopersicon esculentum. Therefore, it is suggested that combined application of 50 ppm of ZnO-NPs and 10−8 M of EBL is the best combination can be applied to increase the performance and yield of L. esculentum.

Keywords: Antioxidant enzymes; 24-epibrassinolide; Lycopersicon esculentum; Zinc oxide nanoparticles

Nanotechnology is a promising field of science that has been applied in plant production in the form of nanoparticles (NPs), which have been used as fertilizers to increase plant growth and development, as pesticides to achieve pest and disease management, and as sensors to monitor plant health and soil superiority (Duhan et al., 2017). Materials with a particle size of less than 100 nm in at least one dimension are generally classified as NPs. NPs are absorbed 15–20 times more than their bulk particles by plants (Srivastav et al., 2016). It has been estimated that 260000–309000 metric tons of NPs were produced globally in 2010 (Yadav et al., 2014), and worldwide consumption of NPs is likely to grow from 225060 metric tons to nearly 585000 metric tons from 2014 to 2019 (BCC Research, 2014). In recent times, NPs are the most advanced way of supplying mineral nutrients to plants as compared to conventional fertilizers (Shang et al., 2019). NPs are mainly absorbed by plant leaves and roots and subsequently transported to all the plant parts via cellular structures and ground organs (Wang et al., 2016).

Zinc (Zn) is an essential micronutrient and plays an important role in the activity of enzymes like dehydrogenases, tryptophan synthetase, aldolases, iso- merases, transphosphorylases, superoxide dismutase, and DNA and RNA polymerases (Marschner, 2011). Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) are one of the most important NPs because of their interesting and unique physical and chemical properties. Due to its unique properties including high thermal conductivity, refractive index, binding energy, ultraviolet protection, and antibacterial capabilities, ZnO-NPs are widely applied in various products and materials including medicine, cosmetics, solar cells, rubber, concrete, and foods (Uikey and Vishwakarma, 2016). ZnO-NPs have also been used in several fields such as sun-protective lotions, wall paints, ceramic manufactures, and catalysis (Akir et al., 2016). ZnO-NPs, with an estimated global annual production of between 550 and 33400 tons, are the third most commonly used metal-containing nanomaterial (Peng et al., 2017; Connolly et al., 2016). Environmental levels of ZnO-NPs were reported to be in the range of 3.1–31 µg/kg of soil and 76–760 µg/L in water (Ghosh et al., 2016). In addition, ZnO-NPs are excellent candidates for application in the agriculture and food sector as pesticides, fungicides, and fertilizer (Kah and Hofmann, 2014). In recent years, the use of ZnO-NPs has received great attention due to the increase in the nutrient accumulation by plants for enhancing the capacity of agronomic zinc biofortification (Rizwan et al., 2019; Hussain et al., 2018). Exogenous application of ZnO-NPs increased the growth in Vigna radiata and Cicer arietinum seedlings (Mahajan et al., 2011). Ejaz et al. (2011) revealed that Zn deficiency declined the yield of the tomato plant. ZnO-NPs increased the chlorophyll content, photosynthetic pigments, activity of antioxidant enzymes, and uptake of micronutrients in Cucumis sativus and Helianthus annuus (Rajiv et al., 2018). Similarly, in Moringa peregrina, ZnO-NPs increased the proline and total carbohydrate levels, antioxidant non-enzymes (vitamins A and C), and enzymes (POX and SOD) level (Soliman et al., 2015). In addition, ZnO-NPs increased the growth characteristic, photosynthetic activity, and biomass of Triticum aestivum (Munir et al., 2018) and soybean plants (Ahmad et al., 2020). Venkatachalam et al. (2017) also proved that ZnO-NPs encouraged the growth, chlorophyll, protein content and CAT, POX and SOD activities in Gossypium hirsutum. The effect of NPs was dependent on the size of NPs, plant species, mode of application, and their time of exposure (Rico et al., 2014).

Brassinosteroids (BRs) are a group of naturally occurring steroidal plant hormones that play important roles in several developmental processes in plants, such as cell division and elongation in stem and roots, photo-morphogenesis, reproductive development, leaf senescence, and also mitigate stress (Nazir et al., 2019). It has been reported that exogenous application of BRs in tomato plant increased the photosynthetic efficiency, pollen germination, and pollen tube growth (Singh and Shono, 2005) soluble sugars, lycopene contents, and ethylene production (Zhu et al., 2015). Positive effects of BRs have also been studied in mung bean (Fariduddin et al., 2008), mustard (Sharma et al., 2017; Hayat et al., 2012), grapes (Babalik et al., 2019), soybean (Ribeiro et al., 2019), and lavandin (Asci et al., 2019).

This study was thus designed to explore the interactive effect of ZnO-NPs and 24-epibrassinolide (EBL) in strengthening plant growth, photosynthesis, antioxidant defense system, and yield. To the best of our knowledge, almost no research has been conducted to evaluate the combined effects of ZnO-NPs and EBL on the performance of the tomato plant. The hypothesis tested is that how the efficacy of ZnO-NPs will increase with EBL in the tomato plant.

Location and growth conditions

The experiment was performed at the Department of Botany of Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India, under natural environmental conditions. The minimum, maximum, and median temperatures were 15, 30, and 22°C, respectively. The relative humidity during the experimental period varied between 55 and 80%.

Seeds of tomato var. PKM-1 were procured from Department of Horticulture of Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi, India. The seeds were sterilized with 1% sodium hypochlorite solution for 10 min and rinsed thoroughly with double distilled water (DDW) and sown in containers for germination. At the stage of 20 days, the seedlings were transferred to the main containers, filled with soil and farmyard manure (6:1). Both the regulators were applied as foliar spray in the various combinations: T1–control (only water); T2–EBL (10−8 M); T3–ZnO-NPs (10 ppm); T4–ZnO-NPs (50 ppm); T5–ZnO-NPs (100 ppm); T6–ZnO-NPs (10 ppm) + EBL (10−8 M); T7–ZnO-NPs (50 ppm) + EBL (10−8 M); T8–ZnO-NPs (100 ppm) + EBL (10−8 M). The ZnO-NPs and EBL were applied to the foliage of tomato at 35–39 DAS. Each plant was sprayed thrice at a time, and the nozzle of the sprayer was adjusted in such a way that it pumped out about 1 cm3 of the solution in a single spray. Therefore, each plant received about 3 cm3 of DDW, ZnO-NPs, and EBL solution. Each treatment was replicated five times with three plants per replicate, and plants were sampled at 45 and 60 DAS to assess various growth parameters, photosynthetic attributes, biochemical characteristics as well as yield.

Zinc oxide nanoparticles and 24-epibrassinolide

ZnO-NP was procured from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals Pvt. Ltd., India. A stock solution of 100 ppm was prepared by dissolving the required amounts of ZnO-NPs in 10 mL DDW in a 100 mL-volumetric flask and made the volume to 100 mL by adding the DDW. Other required concentrations were prepared by diluting the stock solution. EBL was obtained from Sigma Chemicals Co., St. Louis, USA. The EBL was separately dissolved in a sufficient quantity of ethanol, and the stock solution of 10−8 M was prepared by adding DDW and 0.05% Tween-20 as a surfactant. The concentrations of ZnO-NPs and EBL were selected on the basis of our previous studies, ZnO-NP was selected on the basis of Faizan and Hayat (2019) and EBL was selected on the basis of Faizan et al. (2018).

Determination of growth parameters

Length of shoot and root was measured using a meter scale. After recording the fresh weight, plants were dried in an oven at 80°C for 24 h to assess the dry weight of plants. Leaf-area was measured by leaf area meter (ADC Bio Scientific, Hoddesdon, UK).

The SPAD value of chlorophyll was measured in fully expanded uppermost leaves of plants in each treatment using SPAD chlorophyll meter (SPAD-502; Konica, Minolta sensing, Inc., Japan). During measurement, the leaves are placed in the SPAD chlorophyll meter, and the top portion of the meter is slightly closed; after that, reading is visible on the screen of the meter.

Determination of gas exchange characteristics

Leaf gas exchange characteristics (PN, gs, Ci, and E) were measured in fully expanded leaves of the plants in each treatment using an infrared gas analyzer (LI-6400, LI COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) on clear days. The values were expressed as µmol CO2 m−2s−1 (PN); mol H2O m−2s−1 (gs); ppm (Ci); and mmol H2O m−2s−1 (E), respectively. The measurement was done between 11:00 and 12:00 h at light saturating intensity and the air temperature (25°C), relative humidity (85%), CO2 concentration (600 ppm), and photosynthetic photon flux density (800 µmol mol−2s−1).

CA activity in leaves was measured by the procedure of Dwivedi and Randhawa (1974). Leaf was slash into minute pieces in a cysteine hydrochloride solution. They were blotted and conveyed in a test tube, pursue phosphate buffer addition (pH = 6.8), 0.2 M NaHCO3, bromothymol blue, and red indicator of methyl. 0.5 N HCl used for titrating. The unit in which the values were measured is mol CO2 g-1 (FM) s−1. The activity of NR was assayed by Jaworski (1971). A mixture of newly form leaf (0.1 g), phosphate buffer (pH = 7.5), KNO3, isopropanol was placed in an incubator run at 30°C for 2 h. Sulfanilamide and N-1-napthyl ethylenediamine hydrochloride mixture were added to the incubated mixture. The absorbance was read at 540 nm by the spectrophotometer (Spectronic 20D; Milton Roy, USA), and the value was expressed in nmol NO2 g−1 (FM) s−1.

For the estimation of antioxidant enzymes, the leaf tissue (0.5 g) was homogenized in a 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH = 7.0) containing 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone. These mixtures were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the resulting supernatant was used as a source of enzymes like CAT, POX, and SOD. A method described by Zhang (1992) was used to estimate SOD and POX activities. The activity of CAT was evaluated by the method of Aebi (1984).

Estimation of proline and protein contents

The method of Bates et al. (1973) was used for the identification of proline content in the newly formed leaves. Leaves were extracted in sulfosalicylic acid, and an equal volume of glacial acetic acid and ninhydrin solutions was also added. The sample was heated at 100°C, to which 5 mL of toluene was added. The absorbance of the aspired layer was read at 528 nm on a spectrophotometer. The proline was expressed as µg g−1 FW. Protein content was measured by the method of Bradford (1976). 1 g newly formed leaves were homogenized in buffer consisted of 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH = 7.5), 0.07% β-mercaptoethanol, 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM phenyl methane sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and 1 mM EDTA by pestle and mortar and mixture was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected, and the Bradford reagent was added for color development. The intensity of color was read at a spectrophotometer. The protein was expressed as mg g−1 FW.

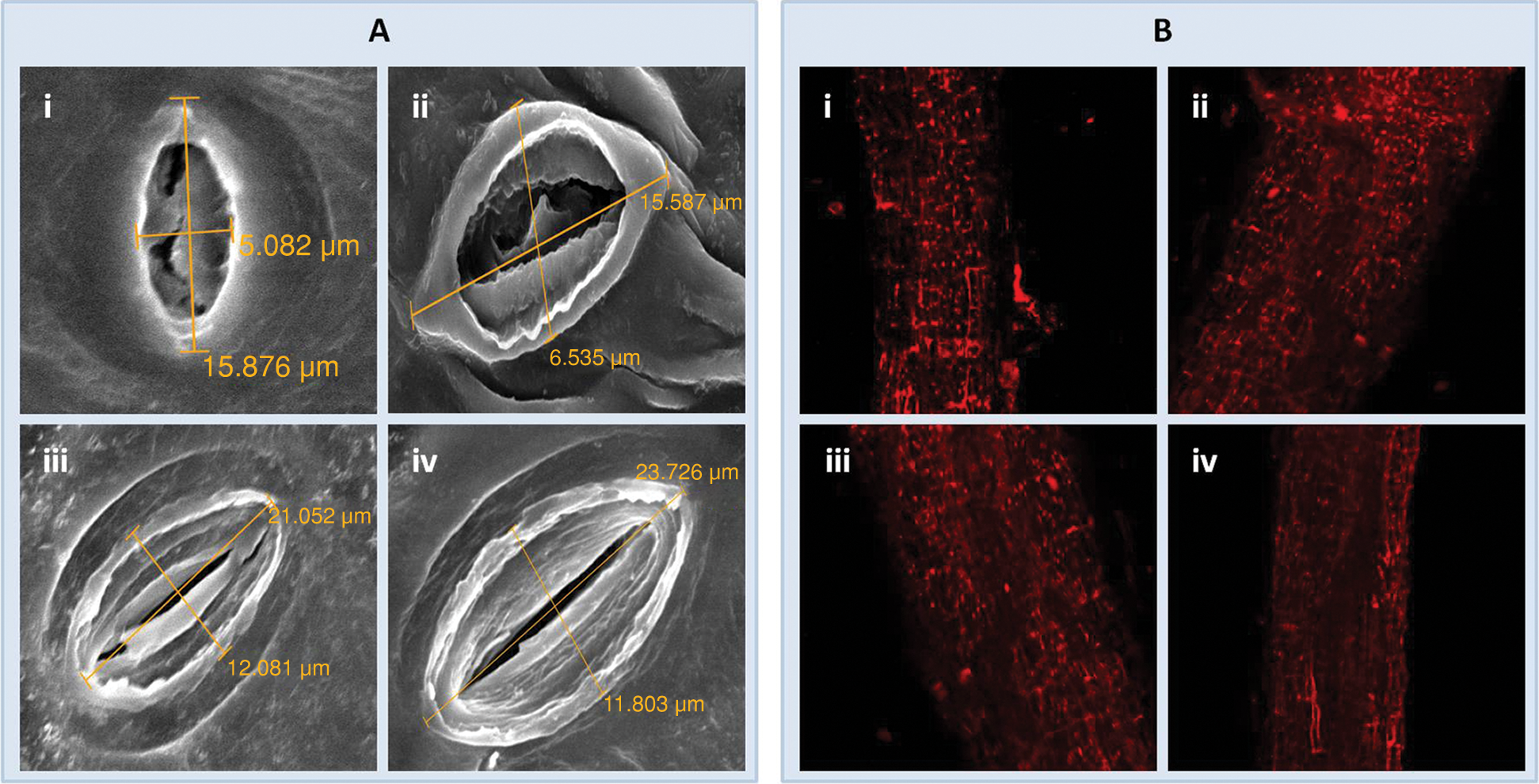

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Effect of ZnO-NPs with EBL on the structure of stomata was examined by SEM (JEOL, JSM-6510LV, Japan) at the Ultra Sophisticated Instrumentation Facility Centre, AMU, Aligarh, India. Leaf sample was fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.01 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3) for 2 h and dehydrated in an ethanol series. The surface characteristic of the sample (Fig. 6) was evaluated at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

Cell viability tests were conducted using the method of Rattan et al. (2017). Roots were dipped in a solution containing 25 µM propidium iodide for 10 min. The samples were then washed twice with DDW and placed on glass slides for viewing in a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss, LSM 780) at 20 × magnifications with maximum excitation of 535–617 nm.

Estimation of lycopene, β-carotene, and ascorbic acid content

Lycopene and β-carotene contents in the ripe fruits were determined by the procedure described by Ranganna (1976) and Sadasivam and Manickam (1997), respectively, whereas ascorbic acid content in the fruits was determined following the procedure applied by Raghuramula et al. (1983).

The yield parameters (number of fruits and fruit yield) were measured at harvest (180 DAS). The units in which values were measured are g of fruits/plant.

The experiment was conducted according to a simple randomized block design. Each treatment was replicated five times. Data were statistically analyzed with the analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS, 17.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The least significant difference (LSD) was calculated to separate the means.

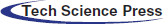

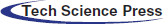

The growth (shoot and root length, fresh and dry weight, and leaf area) of the tomato plants were increased by the foliar application of ZnO-NPs (10, 50 or 100 ppm) or EBL (10−8 M) at 45 and 60 days after sowing (DAS) (Figs. 1A, 1B and 2A–2E). On the other hand, the combined application of EBL and ZnO-NPs proved better than that of the individual application. The optimal increase for all the growth characteristics was observed in the plants sprayed with 50 ppm of ZnO-NPs with 10−8 M of EBL over the untreated control plants, and the respective increase was 39 and 44% (shoot length), 28 and 33% (root length), 32 and 41% (shoot fresh mass), 32 and 35% (root fresh mass), 37 and 46% (shoot dry mass), 36 and 45% (root dry mass) and 39 and 45% (leaf area) at 45 and 60 DAS, over their respective controls.

Figure 1: Effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) and epibrassinolide (EBL) on the (A) shoot length and (B) root length of tomato plant at 45 and 60-day stage. All the data are mean of 5 replicates (N = 5), and the vertical bar shows standard error (SE). Different letters in graphs denote significant differences between control and treatment (p < 0.05). T1–control (only water); T2–EBL (10−8 M); T3–ZnO-NPs (10 ppm); T4–ZnO-NPs (50 ppm); T5–ZnO-NPs (100 ppm); T6–ZnO-NPs (10 ppm) + EBL (10−8 M); T7–ZnO-NPs (50 ppm) + EBL (10−8 M); T8–ZnO-NPs (100 ppm) + EBL (10−8 M). Abbreviations: LSD–Least Significant Difference; DAS–days after sowing.

Figure 2: Effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) and epibrassinolide (EBL) on the (A) shoot fresh mass, (B) root fresh mass, (C) shoot dry mass, (D) root dry mass, (E) leaf area, and (F) SPAD value of tomato plant at 45 and 60-day stage. All the data are mean of 5 replicates (N = 5), and the vertical bar shows standard error (SE).

The SPAD value (chlorophyll) was increased as the growth progressed and also with the application of ZnO-NPs and EBL alone or in combination (Fig. 2F). Among the different tested concentrations (10, 50 or 100 ppm) of ZnO-NPs, the spray of 50 ppm of ZnO-NPs along with 10−8 M of EBL proved to be most effective and increased the SPAD by 32 and 36% over their respective control at 45 and 60 DAS.

Other concentrations of ZnO-NPs (10 or 100 ppm) along with EBL also increased the leaf area over the control but not to a significant level.

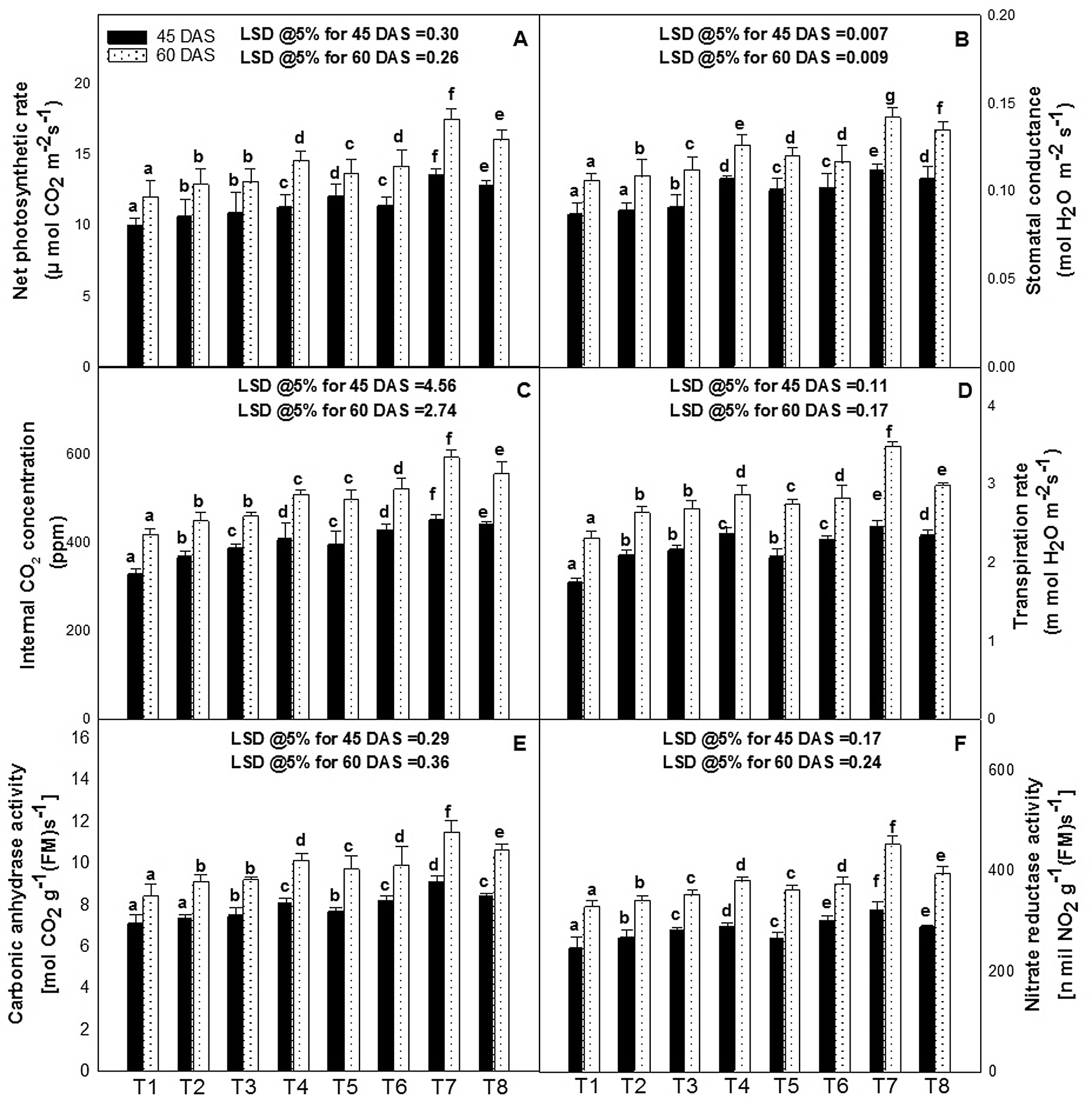

Net photosynthetic rate and related attributes

The values for net photosynthetic rate (PN) and its related attributes, i.e., stomatal conductance (gs), internal CO2 concentration (Ci), and transpiration rate (E), were increased significantly by the foliar application of ZnO-NPs alone and with EBL at 45 and 60 DAS (Figs. 3A–3D). However, the foliar application of 50 ppm of ZnO-NPs along with 10−8 M of EBL proved best and increased the values of PN by 36%, 45%; gs by 28%, 34%; Ci by 37%, 42%; and E by 40%, 51% respectively at 45 and 60 DAS, over their respective control. Furthermore, other concentrations of ZnO-NPs (10 or 100 ppm) with EBL (10−8 M) also increased the values over their control but less than the combination of ZnO-NPs (50 ppm) and EBL (10−8 M).

Carbonic anhydrase (CA) and nitrate reductase (NR) activities

The values of CA and NR were higher in the leaves of the plant that received ZnO-NPs and EBL alone as well as in combination as foliar spray (Figs. 3E, 3F). However, plants received 50 ppm of ZnO-NPs and also of 10−8 M of EBL had significantly higher activity of CA and NR at 45 and 60 DAS, and the increase was about 28%, 36% for CA and 31%, 38% for NR over non treated control at 45 and 60 DAS.

Figure 3: Effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) and epibrassinolide (EBL) on the (A) carbonic anhydrase activity, (B) nitrate reductase activity, (C) net photosynthetic rate, (D) stomatal conductance, (E) internal CO2 concentration, and (F) transpiration rate of tomato plant at 45 and 60-day stage. All the data are mean of 5 replicates (N = 5), and the vertical bar shows standard error (SE). Different letters in graphs denote significant differences between control and treatment (P < 0.05). T1–control (only water); T2–EBL (10−8 M); T3–ZnO-NPs (10 ppm); T4–ZnO-NPs (50 ppm); T5–ZnO-NPs (100 ppm); T6–ZnO-NPs (10 ppm) + EBL (10−8 M); T7–ZnO-NPs (50 ppm) + EBL (10−8 M); T8–ZnO-NPs (100 ppm) + EBL (10−8 M). Abbreviations: LSD–Least Significant Difference; DAS–days after sowing.

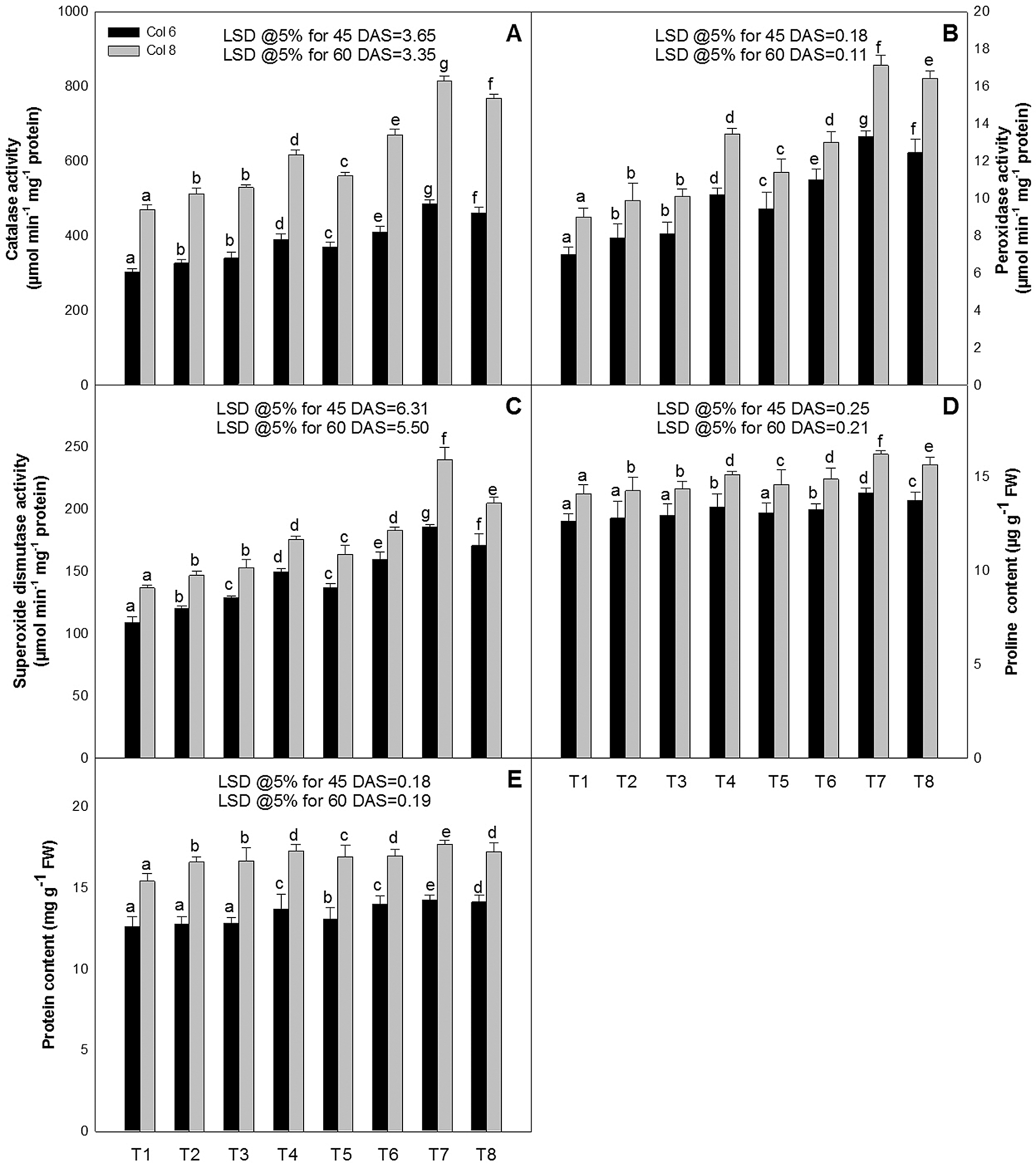

The activity of antioxidant enzymes [catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POX), and superoxide dismutase (SOD)] increased as the growth progressed and also in the plants sprayed with ZnO-NPs and EBL alone as well as in combination (Figs. 4A–4C). The maximum activity of these enzymes was recorded in the plants of the leaves sprayed with 50 ppm of ZnO-NPs and 10−8 M of EBL. The activity of CAT was increased by 60 and 72%, POX by 70 and 76%, and SOD by 63 and 68%, at 45 and 60 DAS, over their respective controls. Other concentrations of ZnO-NPs (10 or 100 ppm) along with EBL (10−8 M) also increased the values for all the enzymes over their control.

Figure 4: Effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) and epibrassinolide (EBL) on the activities of (A) catalase, (B) peroxidase, (C) superoxide dismutase, (D) proline content, and (E) protein content of tomato plant at 45 and 60-day stage. All the data are mean of 5 replicates (N = 5), and the vertical bars show standard error (SE).

Levels of proline accumulation in leaves of tomato plants were increased in response to foliar application of ZnO-NPs and/or EBL (Fig. 4D). However, the combined application of ZnO-NPs (50 ppm) and EBL (10−8 M) possessed the highest proline content at both the stages of growth (Fig. 4D) and the increase was about 12 and 15% at 45 and 60 DAS, respectively, over the control plants.

The plants treated with ZnO-NPs and/or EBL alone or in combination had higher protein content than the control. The prominent increase was noted in the combination of ZnO-NPs (50 ppm) along with EBL (10−8 M), which was about 13 and 15 % higher as compared to the control plants at 45 and 60 DAS, respectively (Fig. 4E).

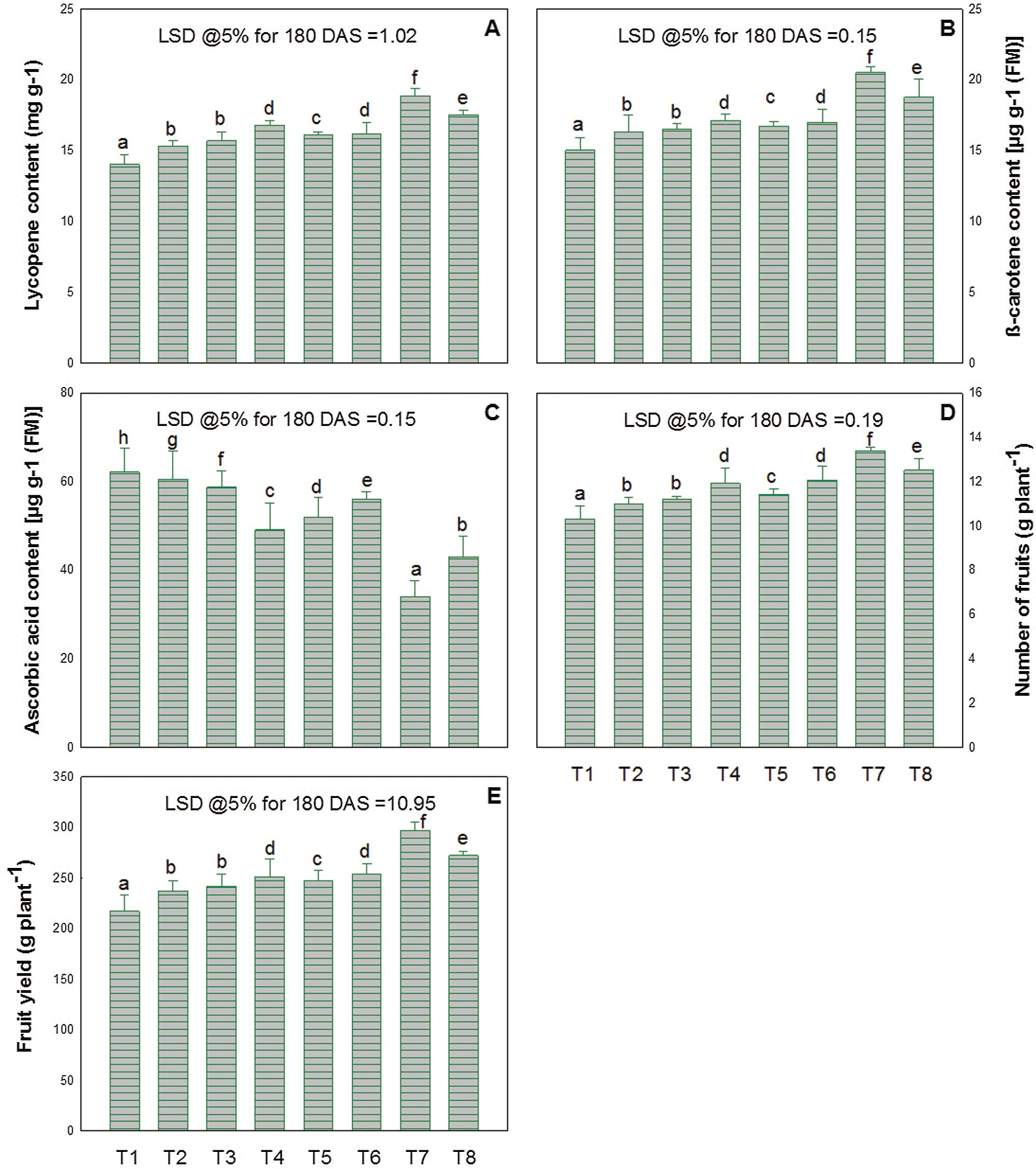

Lycopene, β-carotene, and ascorbic acid content

The fruits obtained from the application to plants of ZnO-NPs and/or EBL alone or in combination showed a marked increase in the content of lycopene and β-carotene, compared to the control plants. In addition, the optimum increase was noted in the treatment of 50 ppm of ZnO-NPs with 10−8 M of EBL and it was about 35% (lycopene content) and 36% (β-carotene) over the control plants (Figs. 5A–5B).

Figure 5: Effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) and epibrassinolide (EBL) on the contents of (A) lycopene, (B) β-carotene, (C) ascorbic acid, (D) number of fruits, and (E) fruit yield of tomato plant at the 180-day stage. All the data are mean of 5 replicates (N = 5), and the vertical bar shows standard error (SE).

Plants treated with ZnO-NPs and/or EBL had a minimum content of ascorbic acid in fruit (Fig. 5C). The lowest value of ascorbic acid was noted in the plants that received 50 ppm of ZnO-NPs and 10−8 M of EBL as a foliar spray, and it was about 49% less as compared to the control.

Number of fruits and fruit yield

The data presented in Figs. 5D–5E reveals that the plants treated with ZnO-NPs and/or EBL had a significantly higher number of fruits and fruit yield at harvest.

However, the maximum increase was noted in the plants sprayed with 50 ppm of ZnO-NPs and 10−8 M of EBL. The increase was about 29 and 37% for fruit number and fruit yield respectively over their control.

Scanning electron microscopic analysis revealed a distinguished effect in the stomatal orifice of the plants sprayed with ZnO-NPs (50 ppm) and EBL (10−8 M) alone as well as in combination as compared to the control (Fig. 6A). Stomatal pore size, which was less than 6 µm in the controls, increased to more than 6 µm upon combined application of ZnO-NPs (50 ppm) and EBL (10−8 M) in the tomato plant.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

Cell viability could be examined visually by observing nucleic acid staining. Viability shows antagonistic effects with stained nuclei. In the present study, exogenous application of ZnO-NPs and EBL increased cell viability, which was evident from the lesser number of stained nuclei (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6: The figure represents scanning electron microscopic images of stomata (A), confocal micrographic images of root cell (B) of a 60-day-old plant of tomato; (i), (ii), (iii), and (iv) represent control, treated with EBL (10−8 M); ZnO-NPs (50 ppm) and ZnO-NPs (50 ppm) + EBL (10−8 M) images, respectively.

The positive effects of individual ZnO-NPs (Rawat et al., 2018; Prasad et al., 2012; Garcia-Lopez et al., 2018) and EBL (Bajguz and Hayat, 2009; Babalik et al., 2019) on plants are known where their exogenous application change the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics, as well as their catalytic properties, which in turn influence the physiological and biochemical activities in plants. In the present study, plants sprayed with the combination of EBL and ZnO-NPs improved the growth attributes such as shoot and root length, fresh and dry mass of plant and leaf area (Figs. 1A, 1B and 2A–2E). The positive effects of ZnO-NPs on the growth indicators were mainly associated with the enhanced photosynthetic rate which leads to higher cell division, biomass, and length (Garcia-Lopez et al., 2019; Mahajan et al., 2011). In addition, EBL also acts as an important growth-promoting hormone (Zhabinskii et al., 2015), and its transcription factors BZR1 (BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT) and BES1/BZR2 along with other genes could have induced the activity of expansions and xyloglucanases (Gudesblat and Russinova, 2011), which leads to better growth of the plants. Therefore, it is assumed that the combined application of ZnO-NPs and EBL proved to be more effective. Individual application of ZnO-NPs (Raliya and Tarafdar, 2013; Prasad et al., 2012) and EBL (Bajguz and Tretyn, 2003; Ali et al., 2008) has already been reported to enhance plant growth.

Exogenous application of ZnO-NPs and EBL significantly induced the activities of CA and NR enzymes (Figs. 3A, 3B). Among the different concentrations of ZnO-NPs used, 50 ppm of ZnO-NPs with 10−8M of EBL optimized the activities of CA and NR. There are various factors that decide the proper activity of CA, viz. intensity of light, hormonal signaling, accessibility of Zn, and regulation of gene expression of transcript (Tiwari et al., 2005). Moreover, ZnO-NPs with EBL increased the CO2 assimilation (Fig. 3D), which leads to an increase in the activity of CA. Increased CA activity was also recorded in the several plants treated with ZnO-NPs (Faizan et al., 2018; Faizan and Hayat, 2019), SiO2-NPs (Siddiqui et al., 2014), and EBL (Fariduddin et al., 2003). The cumulative spray of ZnO-NPs and EBL also increases the NR activity (Fig. 3F). It was reported that NR activity modulates the various physiological functions and activates specific photosynthetic machinery. The increased activity of NR by exogenous application of ZnO-NPs and EBL speculated to be the ability of ZnO-NPs and EBL as in plants NR plays a key role in the synthesis of nitric oxide (NO). NR-mediated NO production was induced by various abiotic stresses. It has also been reported that NO can regulate the activity of NR, thereby upregulate the activity of other substances, including that of nitrate, which has the capability of activating specific genes of NR (Campbell, 1999).

SPAD value (chlorophyll content) is used to indicate the plant’s photosynthetic capacity. In the current study, the combined application of ZnO-NPs (50 ppm) and EBL (10−8 M) as a foliar spray increased the chlorophyll index to a maximum level in the tomato plant (Fig. 2F). The rise in chlorophyll content by ZnO-NPs and EBL could be an articulation of an improvement in the translation of chlorophyll biosynthetic genes (Bajguz and Asami, 2005) and also due to the disruption of chlorophyll destruction pace and other related proteins, mainly those linked to the antenna complex (Sadeghi and Shekafandeh, 2014; Bajguz, 2000).

The photosynthetic efficiency of the plants under exogenous application of ZnO-NPs and EBL was increased through the attenuation of different gas exchange attributes like PN, gs, Ci, and E (Figs. 3C–3F). It is claimed that enhanced photosynthetic efficiency after the exogenous use of EBL could be due to the improved activity of the water-splitting system, photochemical quenching, non-photosynthetic quenching, maximum PSII efficiency, and enhanced activity of rubisco enzyme (Siddiqui et al., 2018). In addition, modification of photosynthetic rate due to exogenously application of ZnO-NPs manifested the enhanced assimilation of atmospheric CO2, synthesis and/or activation of the enzymes involved in the chlorophyll biosynthesis and also associated with photosynthesis (Yu et al., 2004). Elevated values of E after treatment can be attributed to enhanced gs (Fig. 3C), which leads to the higher absorption of water and nutrients (Sharma et al., 2020; Ali et al., 2008). Moreover, higher chlorophyll content (Fig. 2F) and CA activity (Fig. 3E) after application of ZnO-NPs and EBL leads to higher PN (Fig. 3A).

The higher production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is a consequence of the non-functioning of cellular metabolism, which leads to oxidative damage to macromolecules and ultimately causes cell death (Tripathy and Oelmuller, 2012). Oxidative stress, caused by an elevated accumulation of ROS coincided with the higher amount of H2O2 reflecting the damage to lipids and proteins and adverse effects on metabolic processes, which in turn declined the biomass of the plant (Gill and Tuteja, 2010). Plant cells are normally protected against such effects by a complex non-enzymatic and enzymatic antioxidant system (Ali et al., 2008). The earlier study demonstrated that the exogenous application of ZnO-NPs elevated the enzymatic defense mechanisms by increasing the CAT, POX, and SOD (Faizan and Hayat, 2019; Faizan et al., 2018), but this rise was further boosted by the follow-up treatment of EBL and the prominent increase in the activities of CAT, POX and SOD were observed in the plants (Figs. 4A–4C). The EBL-induced increase in antioxidant enzymes could be due to increased det2 gene expression, which confers endurance to oxidative damage in Arabidopsis through an enhanced antioxidant defense system (Cao et al., 2005). This can be supported by the results of Hu et al. (2013) and Hayat et al. (2007). This view was also further supported by the study of Javadi et al. (2018).

Proline plays a role as an osmoprotectant, membrane stabilizer, and ROS scavenger (Bandurska, 2001). The osmotic adjustment stabilizes the antioxidant system, protecting the integrity of the cell membrane and reducing the impacts of free radicals (Sharma et al., 2019). The present study disclosed that foliar application of ZnO-NPs along with EBL substantially enhanced the accumulation of proline (Fig. 4D). EBL has the potential to elicit proline accumulation by expressing genes associated with the biosynthesis of proline (Bajguz, 2000). These findings are in tune with the study of Helaly et al. (2014) and Ozdemir et al. (2004) with ZnO-NPs and EBL, respectively.

In the current study, foliar application of ZnO-NPs and EBL to the tomato plant resulted in a higher content of protein (Fig. 4E). This may be due to the fact that ZnO-NPs with EBL can regulate the activity of proteins and other enzymes in the membrane, either by affecting configuration or protein activity through direct associations of proteins and sterols, leading to the maintenance of protein structure and regulation of enzymes responsible for protein synthesis (Guzel and Terzi, 2013). This result further finds support from the observation of Raliya and Tarafdar (2013) and Mukherjee et al. (2016).

The transformation in color during the ripening of tomato fruit is principally due to the accumulation of lycopene and β-carotene (Karlova et al., 2011) and is included as the most abundant carotenoid in the tomato plant (Liu et al., 2014). In the present observation, ZnO-NPs with EBL significantly increased the content of lycopene and β-carotene in a concentration-dependent manner, and 50 ppm of ZnO-NPs + 10−8 M of EBL was proved to be best (Figs. 5A, 5B). The reason behind the increase of lycopene and β-carotene may be associated with the ethylene-mediated gene expression during ripening (Giovannoni, 2001). Our outcomes are well supported by Ke et al. (2019), who reported that carotene and lycopene were increased due to oxidative stress. Unlike lycopene and β-carotene, the application of ZnO-NPs with EBL significantly decreased the ascorbic acid content in mature fruits (Fig. 5C). A similar decrease in ascorbic acid was also reported by Vardhini and Rao (2002) and Ali et al. (2006) by the individual application of BRs.

The increase in plant yield in the form of number of fruits and fruit yields depends on the flower formation, flower survival, fruit setting, and maturation (Faizan et al., 2018). The present study revealed that treatment of ZnO-NP along with EBL significantly increased the number of fruits and fruit yield (Figs. 5D, 5E). This enhancement in yield is maybe due to the slow process of senescence before and/or after pollination (Iwahori et al., 1990).

Based on the results obtained from this study, we can conclude that individual and synergistic effects of ZnO-NPs and EBL significantly increased the morpho-physiological and biochemical traits of tomato plants. Such improvements can easily be observed in photosynthetic pigments, antioxidant defense systems, and yield characteristics. The response of exogenous application of 50 ppm of ZnO-NPs with 10−8 M of EBL proved best than the other treatments. Overall, this study could provide a clear understanding for researchers to find out the actual molecular mechanism behind the ZnO-NPs and EBL-based enhancement mechanism in tomato, by which they can carry further investigation at the cellular level.

Availability of Data and Material: All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in this published article.

Author Contribution: The authors confirm contribution of the paper as follows: study conception and design: Shamsul Hayat, Fangyuan Yu; data collection: Mohammad Faizan, Ahmad Faraz; analysis and interpretation of results: Mohammad Faizan, Javaid Akhter Bhat; draft manuscript preparation: Shamsul Hayat, Javaid Akhter Bhat, and Fangyuan Yu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (3197140894), A Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Aebi H (1984). Catalase in vitro. Methods in Enzymology 105: 121–126. [Google Scholar]

Ahmad P, Alyemeni MN, Al-Huqail AA, Alqahtani MA, Wijaya L, Ashraf M, Kaya C, Bajguz A (2020). Zinc oxide nanoparticles application alleviates arsenic (As) toxicity in soybean plants by restricting the uptake of as and modulating key biochemical attributes, antioxidant enzymes, ascorbic-glutathione cycle and glyoxalase system. Biomolecules 9: 825. [Google Scholar]

Akir S, Barras A, Coffinier Y, Bououdina M, Boukherroub R, Omrani AD (2016). Eco-friendly synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with different morphologies and their visible light photocatalytic performance for the degradation of Rhodamine B. Ceramics International 42: 10259–10265. DOI 10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.03.153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ali B, Hasan SA, Hayat S, Hayat Q, Yadav S, Fariduddin Q, Ahmad A (2008). A role for brassinosteroids in the amelioration of aluminium stress through antioxidant system in mung bean (Vigna radiata L. Wilczek). Environmental and Experimental Botany 62: 153–159. DOI 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2007.07.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ali B, Hayat S, Hasan SA, Ahmad A (2006). Effect of root applied 28 homobrassinolide on the performance of Lycopersicon esculentum. Scientia Horticulturae 110: 267–273. DOI 10.1016/j.scienta.2006.07.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Asci ÖA, Deveci H, Erdeger A, Özdemir KN, Demirci T, Baydar NG (2019). Brassinosteroids promote growth and secondary metabolite production in lavandin (Lavandula intermedia Emeric ex Loisel.). Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants 22: 254–263. DOI 10.1080/0972060X.2019.1585298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Babalik Z, Demirci T, Asci OA, Baydar NG (2020). Brassinosteroids Modify Yield, Quality, and Antioxidant Components in Grapes (Vitis vinifera cv. Alphonse Lavallée). Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 39: 147–156. DOI 10.1007/s00344-019-09970-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bajguz A (2000). Effect of brassinosteroids on nucleic acid and protein content in cultured cells of Chlorella vulgaris. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 38: 209–215. DOI 10.1016/S0981-9428(00)00733-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bajguz A, Asami T (2005). Suppression of Wolffiaarrhiza growth by brassinazole, an inhibitor of brassinosteroid biosynthesis and its restoration by endogenous 24-epibrassinolide. Phytochemistry 66: 1787–1796. DOI 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.06.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bajguz A, Hayat S (2009). Effects of brassinosteroids on the plant responses to environmental stresses. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 47: 1–8. DOI 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.10.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bajguz A, Tretyn A (2003). The chemical characteristics and distribution of brassinosteroids in plants. Phytochemistry 62: 1027–1046. DOI 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00656-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bandurska H (2001). Does proline accumulated in the leaves of water deficit stressed barley plants confine cell membrane injuries? II. Proline accumulation during hardening and its involvement in reducing membrane injuries in leaves subjected to severe osmotic stress. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 23: 483–490. DOI 10.1007/s11738-001-0059-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bates LS, Waldren RP, Teare ID (1973). Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant and Soil 39: 205–207. DOI 10.1007/BF00018060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

BCC Research (2014). Global markets for nanocomposites, nanoparticles, nanoclays, and nano-tubes. https://www.bccresearch.com/market-research/nanotechnology/nanocomposites-mar-. [Google Scholar]

Bradford MM (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry 72: 248–254. DOI 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Campbell WH (1999). Nitrate reductase structure, function and regulation: bridging the gap between biochemistry and physiology. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 50: 277–303. DOI 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cao S, Xu Q, Cao Y, Qian K, An K, Zhu Y, Hu BZ, Zhao HF, Kuai BK (2005). Loss-of-function mutations in DET2 gene lead to an enhanced resistance to oxidative stress in Arabidopsis. Physiologia Plantarum 123: 57–66. DOI 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2004.00432.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Connolly M, Fernandez M, Conde E, Torrent F, Navas JM, Fernandez-Cruz ML (2016). Tissue distribution of zinc and subtle oxidative stress effects after dietary administration of ZnO nanoparticles to rainbow trout. Science of the Total Environment 551-552: 334–343. DOI 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.01.186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Duhan JS, Kumar R, Kumar N, Nehra K, Duhan S (2017). Nanotechnology: The new perspective in precision agriculture. Biotechnology Reports 15: 11–23. DOI 10.1016/j.btre.2017.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dwivedi RS, Randhawa NS (1974). Evaluation of rapid test for hidden hunger of zinc in plants. Plant and Soil 40: 445–451. DOI 10.1007/BF00011531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ejaz M, Waqas R, Butt M, Rehman SU, Manan A (2011). Role of macro-nutrients and micro-nutrients in enhancing the quality of tomato. International Journal for Agro Veterinary and Medical Sciences 5: 401–404. DOI 10.5455/ijavms.20110815111114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Faizan M, Faraz A, Hayat S (2018). Dose dependent response of epibrassinolide on the growth, photosynthesis and antioxidant system of tomato plants. Indian Horticulture Journal 8: 68–76. [Google Scholar]

Faizan M, Hayat S (2019). Effect of foliar spray of ZnO-NPs on the physiological parameters and antioxidant systems of Lycopersicon esculentum. Polish Journal of Natural Sciences 34: 87–105. [Google Scholar]

Fariduddin Q, Ahmad A, Hayat S (2003). Photosynthetic response of Vigna radiata to presowing seed treatment with 28-homobrassinolide. Photosynthetica 41: 307–310. DOI 10.1023/B:PHOT.0000011968.78037.b1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fariduddin Q, Hasan SA, Ali B, Hayat S, Ahmad A (2008). Effect of modes of application of 28-homobrassinolide on mung bean. Turkish Journal of Biology 32: 17–21. [Google Scholar]

Garcia-Lopez JI, Nino-Medina G, Olivares-Saenz E, Lira-Saldivar RH, Barriga-Castro ED, Vazquez-Alvarado R, Rodriguez-Salinas PA, Zavala-Garcia F (2019). Foliar application of zinc oxide nanoparticles and zinc sulfate boosts the content of bioactive compounds in habanero peppers. Plants 8: 254. DOI 10.3390/plants8080254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Garcia-Lopez JI, Zavala-Garcia F, Olivares-Saenz E, Saldivar RHL, Barriga-Castro ED, Ruiz-Torres NA, Ramos-Cortez E, Vazquez-Alvarado R, Nino-Medina G (2018). Zinc oxide nanoparticles boosts phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of Capsicum annuum L. during germination. Agronomy 8: 215. DOI 10.3390/agronomy8100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ghosh M, Jana A, Sinha S, Jothiramajayam M, Nag A, Chakraborty A, Mukherjee A, Mukherjee A (2016). Effects of ZnO nanoparticles in plants: cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, deregulation of antioxidant defenses, and cell-cycle arrest. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis 807: 25–32. DOI 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2016.07.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gill SS, Tuteja N (2010). Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 48: 909–930. DOI 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.08.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Giovannoni J (2001). Molecular regulation of fruit ripening. Annual Review of Plant Biology 52: 725–749. DOI 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gudesblat GE, Russinova E (2011). Plants grow on brassinosteroids. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 14: 530–537. DOI 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Guzel S, Terzi R (2013). Exogenous hydrogen peroxide increases dry matter production, mineral content and level of osmotic solutes in young maize leaves and alleviates deleterious effects of copper stress. Botanical Studies 54: 1182. DOI 10.1186/1999-3110-54-26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hayat S, Ali B, Hasan SA, Ahmad A (2007). Brassinosteroid enhanced the level of antioxidants under cadmium stress in Brassica juncea. Environmental and Experimental Botany 60: 33–41. DOI 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2006.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hayat S, Alyemini MN, Hasan SA (2012). Foliar application of brassinosteroids enhances yield and quality of Solanum lycopersicum under cadmium stress. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 19: 325–335. DOI 10.1016/j.sjbs.2012.03.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Helaly MN, El-Metwally MA, El-Hoseiny H, Omar SA, El-Sheery NI (2014). Effect of nanoparticles on biological contamination of in vitro cultures and organogenic regeneration of banana. Australian Journal of Crop Science 8: 612–624. [Google Scholar]

Hu C, Liu Y, Li X, Li M (2013). Biochemical responses of duckweed (Spirodela polyrhiza) to zinc oxide nanoparticles. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 64: 643–651. DOI 10.1007/s00244-012-9859-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hussain A, Ali S, Rizwan M, Rehman MZ, Javed MR, Imran M, Chatha SAS, Nazir R (2018). Zinc oxide nanoparticles alter the wheat physiological response and reduce the cadmium uptake by plants. Environmental Pollution 242: 1518–1526. DOI 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.08.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Iwahori S, Tominaga S, Higuchi S (1990). Retardation of abscission in citrus leaf and fruitlet explants by brassinolide. Plant Growth Regulation 9: 119–125. DOI 10.1007/BF00027439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Javadi A, Khomari S, Esmaeilpour B, Asghari A (2018). Exogenous application of 24-epibrassinolide and nano-zinc oxide at flowering improves osmotic stress tolerance in harvested tomato seeds. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 16: 4401–4417. DOI 10.15666/aeer/1604_44014417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jaworski EG (1971). Nitrate reductase assay in intact plant tissue. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 43: 1274–1279. DOI 10.1016/S0006-291X(71)80010-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kah M, Hofmann T (2014). Nanopesticide research: current trends and future priorities. Environment International 63: 224–235. DOI 10.1016/j.envint.2013.11.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Karlova R, Rosin FM, Busscher-Lange J, Parapunova V, Do PT, Fernie AR, Fraser PD, Baxter C, Angenent GC, de Maagd RA (2011). Transcriptome and metabolite profiling show that APETALA2a is a major regulator of tomato fruit ripening. Plant Cell 23: 923–941. DOI 10.1105/tpc.110.081273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ke Q, Kang L, Kim HS, Xie T, Liu C, Ji CY, Kim SH, Park WS, Ahn M, Wang S, Li H, Deng X, Kwak S (2019). Down regulation of lycopene ε-cyclase expression in transgenic sweetpotato plants increases the carotenoid content and tolerance to abiotic stress. Plant Science 281: 52–60. DOI 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.01.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu L, Jia C, Zhang M, Chen D, Chen S, Guo RF, Guo D, Wang Q (2014). Ectopic expression of a BZR1-1D transcription factor in brassinosteroid signalling enhances carotenoid accumulation and fruit quality attributes in tomato. Plant Biotechnology Journal 12: 105–115. DOI 10.1111/pbi.12121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mahajan P, Dhoke SK, Khanna AS (2011). Effect of nano-ZnO particle suspension on growth of mung (Vigna radiata) and gram (Cicer arietinum) seedlings using plant agar method. Journal of Nanotechnology 2011: 1–7. DOI 10.1155/2011/696535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Marschner H (2011). Marschner’s mineral nutrition of higher plants. San Diego, CA, USA 651: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

Mukherjee A, Sun Y, Morelius E, Tamez C, Bandyopadhyay S, Niu G, White JC, Peralta-Videa JR, Gardea-Torresdey JL (2016). Differential toxicity of bare and hybrid ZnO nanoparticles in Green Pea (Pisum sativum L.a life cycle study. Frontiers in Plant Science 12: 1242. [Google Scholar]

Munir T, Rizwan M, Kashif M, Shahzad A, Ali S, Amin N, Zahid R, Alam MFE, Imran M (2018). Effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles on the growth and Zn uptake in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) by seed priming method. Digest Journal of Nanomaterials & Biostructures 13: 315–323. [Google Scholar]

Nazir F, Hussain A, Fariduddin Q (2019). Interactive role of epibrassinolide and hydrogen peroxide in regulating stomatal physiology, root morphology, photosynthetic and growth traits in Solanum lycopersicum L. under nickel stress. Environmental and Experimental Botany 162: 479–495. DOI 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2019.03.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ozdemir F, Bor M, Demiral T, Turkan I (2004). Effects of 24-epibrassinolide on seed germination, seedling growth, lipid peroxidation, proline content and antioxidative system of rice (Oryza sativa L.) under salinity stress. Plant Growth Regulation 42: 203–211. DOI 10.1023/B:GROW.0000026509.25995.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Peng YH, Tsai YC, Hsiung CE, Lin YH, Shih Y (2017). Influence of water chemistry on the environmental behaviors of commercial ZnO nanoparticles in various water and wastewater samples. Journal of Hazardous Materials 322: 348–356. DOI 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.10.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Prasad TNVKV, Sudhakar P, Sreenivasulu Y, Latha P, Munaswamy V, Reddy KR (2012). Effect of nanoscale zinc oxide particles on the germination, growth and yield of peanut. Journal of Plant Nutrition 35: 905–927. DOI 10.1080/01904167.2012.663443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Raghuramula H, Madhavan NK, Sundaram K (1983). A manual of laboratory technology, national institute of nutrition, Indian Council of Medical Research, Hyderabad. [Google Scholar]

Rajiv P, Vanathi P, Thangamani A (2018). An investigation of phytotoxicity using Eichhornia mediated zinc oxide nanoparticles on Helianthus annuus. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 16: 419–424. DOI 10.1016/j.bcab.2018.09.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Raliya R, Tarafdar JC (2013). ZnO nanoparticle biosynthesis and its effect on phosphorous-mobilizing enzyme secretion and gum contents in cluster bean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba L.). Agricultural Research 2: 48–57. DOI 10.1007/s40003-012-0049-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ranganna S (1976). Manual of analysis of fruit and vegetable products. New Delhi: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

Rattan A, Kapoor N, Kapoor D, Bhardwaj R (2017). Salinity induced damage overwhelmed by the treatment of brassinosteroids in Zea mays seedlings. Advances in Bioresearch 8: 87–102. [Google Scholar]

Rawat PS, Kumar R, Ram P, Pandey P (2018). Effect of nanoparticles on wheat seed germination and seedling growth. International Journal of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering 12: 13–16. [Google Scholar]

Ribeiro DGS, Silva BRS, Lobato AKS (2019). Brassinosteroids induce tolerance to water deficit in soybean seedlings: contributions linked to root anatomy and antioxidant enzymes. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 41: 27. DOI 10.1007/s11738-019-2873-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rico CM, Lee SC, Rubenecia R, Mukherjee A, Hong J, Peralta-Videa JR, Gardea-Torresdey JL (2014). Cerium oxide nanoparticles impact yield and modify nutritional parameters in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 62: 9669–9675. DOI 10.1021/jf503526r. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rizwan M, Ali S, Ali B, Adrees M, Arshad M, Hussain A, Rehman MZ, Waris AA (2019). Zinc and iron oxide nanoparticles improved the plant growth and reduced the oxidative stress and cadmium concentration in wheat. Chemosphere 214: 269–277. DOI 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.09.120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sadasivam S, Manickam A (1997) Carotenes, In: A. Manickam and S. Sadasivam (eds.pp. 187–188. Biochemical Methods. New Delhi: New Age International Publishers. [Google Scholar]

Sadeghi F, Shekafandeh A (2014). Effect of 24-epibrassinolide on salinity-induced changes in loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindi). Journal of Applied Botany and Food Quality 87: 182–189. [Google Scholar]

Shang Y, Hasan MK, Ahammed GJ, Li M, Yin H, Zhou J (2019). Applications of nanotechnology in plant growth and crop production: a review. Molecules 24: 2558. DOI 10.3390/molecules24142558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sharma A, Shahzad B, Kumar V, Kohli SK, Sidhu GPS, Bali AS, Handa N, Kapoor D, Bhardwaj R, Zheng B (2019). Phytohormones regulate accumulations of osmolytes under abiotic stress. Biomolecules 9: 285. DOI 10.3390/biom9070285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sharma A, Kumar V, Shahzad B, Ramakrishanan M, Sidhu GPS, Bali AS, Handa N, Kapoor D, Yadav P, Khanna K, Bakshi P, Rehman A, Kohli SK, Khan EA, Parihar RD, Yuan H, Thukral AK, Bhardwaj R, Zheng B (2020). Photosynthetic response of plants under different abiotic stresses: a review. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 39: 509–531. DOI 10.1007/s00344-019-10018-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sharma A, Thakur S, Kumar V, Kesavan AK, Thukral AK, Bhardwaj R (2017). 24-epibrassinolide stimulates imidacloprid detoxification by modulating the gene expression of Brassica juncea L. BMC Plant Biology 17: 5336. DOI 10.1186/s12870-017-1003-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Siddiqui H, Hayat S, Bajguz A (2018). Regulation of photosynthesis by brassinosteroids in plants. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 40: 334. DOI 10.1007/s11738-018-2639-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Siddiqui MH, Al-Whaibi MH, Faisal M, Al-Sahli AA (2014). Nanosilicon dioxide mitigates the adverse effects of salt stress on Cucurbita pepo L. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 33: 2429–2437. DOI 10.1002/etc.2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Singh I, Shono M (2005). Physiological and molecular effects of 24-epibrassinolide, a brassinosteroid on thermotolerance of tomato. Plant Growth Regulation 47: 111–119. DOI 10.1007/s10725-005-3252-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Soliman AS, El-feky SA, Darwish E (2015). Alleviation of salt stress on Moringa peregrina using foliar application of nanofertilizers. Journal of Horticulture and Forestry 7: 36–47. DOI 10.5897/JHF2014.0379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Srivastav AK, Kumar M, Ansari NG, Jain AK, Shankar J, Arjaria N, Jagdale P, Singh D (2016). A comprehensive toxicity study of zinc oxide nanoparticles versus their bulk in wistar rats: toxicity study of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Human & Experimental Toxicology 35: 1286–1304. DOI 10.1177/0960327116629530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tiwari SB, Wang S, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ (2005). Transfection assays with Arabidopsis protoplasts containing integrated reporter genes. In: Salinas J, Sanchez-Serrano JJ (eds.Arabidopsis Protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; (in press). [Google Scholar]

Tripathy BC, Oelmuller R (2014). Reactive oxygen species generation and signaling in plants. Plant Signaling & Behavior 7: 1621–1633. DOI 10.4161/psb.22455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Uikey P, Vishwakarma K (2016). Review of zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles applications and properties. International Journal of Emerging Technology in Computer Science & Electronics 21: 239. [Google Scholar]

Vardhini BV, Rao SSR (2002). Acceleration of ripening of tomato pericarp disc by brassinosteroids. Phytochemistry 61: 843–847. DOI 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00223-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Venkatachalam P, Jayaraj M, Manikandan R, Geetha N, Rene ER, Sharma NC, Sahi SV (2017). Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs) alleviate heavy metal induced toxicity in Leucaena leucocephala seedlings: a physiochemical analysis. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 110: 59–69. DOI 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.08.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang P, Lombi E, Zhao FJ, Kopittke PM (2016). Nanotechnology: a new opportunity in plant sciences. Trends in Plant Science 21: 699–712. DOI 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.04.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yadav T, Mungray AA, Mungray AK (2014). Fabricated nanoparticles. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 230: 83–110. [Google Scholar]

Yu JQ, Huag LF, Hu WH, Zhou YH, Mao WH, Ye SF, Nogues S (2004). A role of brassinosteroids in the regulation of photosynthesis in Cucumis sativus. Journal of Experimental Botany 55: 1135–1143. DOI 10.1093/jxb/erh124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhabinskii VN, Gulyakevich OV, Kurman PV, Shabunya PS, Fatykhava SA, Khripach VA (2015). An improved synthesis of [26-2H3] castasterone. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals 58: 469–472. DOI 10.1002/jlcr.3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhu T, Tan WR, Deng X, Zheng T, Zhang DW, Lin HH (2015). Effects of brassinosteroids on quality attributes and ethylene synthesis in postharvest tomato fruit. Postharvest Biology and Technology 100: 196–204. DOI 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2014.09.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang XZ (1992). The measurement and mechanism of lipid peroxidation and SOD POD and CAT activities in biological system. In: Zhang XZ (ed.pp. 208–211. Research Methodology of Crop Physiology. Beijing Agriculture Press. [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |