DOI:10.32604/biocell.2021.017581

| BIOCELL DOI:10.32604/biocell.2021.017581 |  |

| Article |

Identification of PtGai (a DELLA protein) in trifoliate orange and expression patterns in response to drought stress

1College of Horticulture and Gardening, Yangtze University, Jingzhou, 434025, China

2Botany and Microbiology Department, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, 11451, Saudi Arabia

3Mycology and Plant Disease Survey Department, Plant Pathology Research Institute, ARC, Giza, 12511, Egypt

4Plant Production Department, Faculty of Food and Agricultural Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, 11451, Saudi Arabia

5Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Hradec Kralove, Hradec Kralove, 50003, Czech Republic

*Address correspondence to: Qiangsheng Wu, wuqiangsh@163.com; Kamil Kuča, kamil.kuca@uhk.cz

Received: 21 May 2021; Accepted: 29 June 2021

Abstract: Gibberellins (GAs) are an important hormone in regulating plant growth and development, and DELLA protein is an essential negative regulator of GA signal transduction. The aim of the study was to clone a GA-inhibiting protein DELLA from trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf.) and to analyze the bioinformations and expression patterns of the protein gene in tissues and in response to drought stress. A DELLA protein was isolated from trifoliate orange and named as PtGai (Genebank number: MZ170959). The PtGai protein had 1731 bp open reading frames, along with 576 amino acid codes, and also grouped with sweet orange (XM_006430552.4). The PtGai protein sequence was 65% homology with the sequences of DELLA proteins in other plant families. PtGai protein existed in the nucleus based on the prediction of subcellular localization. PtGai protein could be expressed in roots, stems, and leaves, along with the highest expression in stems. PtGai was upregulated by drought stress in leaves and roots, along with the decrease of root total GA concentration and the inhibition of shoot and root biomass production. It indicated the characteristics of PtGai protein and the roles of PtGai in GA synthesis and plant growth.

Keywords: Abiotic stress; Citrus; DELLA protein; Gibberellin; Phytohormone

Due to the abnormal global climate change, various abiotic stresses have caused tremendous damage to ecosystems and crop production, whilst drought stress as a kind of abiotic stress has become a major factor for limiting crop growth (Cheng et al., 2021; Zou et al., 2021a). To mitigate the damaging effects of drought and to enhance plant vigor in the face of abiotic stress, plants adopt various strategies to cope with soil water deficit, including osmoregulator accumulation, stomatal closure, and accumulation of stress proteins, in order to maintain normal plant growth and development (Natanella et al., 2020). As an important endogenous hormone, the hormonal network of gibberellins (GAs) regulates plant growth processes and responses to abiotic stress (Stirk et al., 2019). GAs regulate the plant growth cycle and developmental processes through a variety of mechanisms (Theo et al., 2020). It has been found that under certain drought levels, GAs enhanced plant growth and mitigated the negative effects of drought stress (Shan et al., 2019).

DELLA proteins are a group of independent transcription regulators of GRAS, mainly present in plant cell nuclei, and are also key inhibitory proteins for the signal transduction of GAs, inhibition of GA responses, and plant growth (Floss et al., 2013; Bai et al., 2019). The result of Zhou and Underhill (2020) showed that the GA signaling pathway could relieve the inhibition of DELLA protein during plant growth and development, and the decrease of GA biosynthetic gene expression was accompanied by the increase of DELLA protein expression. Bilova et al. (2016) also observed that under the condition of low GA concentration, DELLA protein was closely linked with specific transcription factors, complementing each other and blocking plant DNA activity, thus inhibiting plant growth. Therefore, the removal of DELLA proteins can effectively eliminate the inhibitory function on GA activity and promote plant growth (Harberd et al., 2009). On the contrary, more stable proteins may be the result of mutations in DELLA proteins or an important functional domain of GA signal transduction (Bilova et al., 2016), which reflects the malleability of the GA signal. During plant growth and development, DELLA forms a huge regulatory network pathway, thus, suggesting an interaction between GA signals and DELLA (Arro et al., 2019).

DELLA proteins interact with numerous transcription factors in different signaling pathways and emit functions associated with plant regulation of drought (Park et al., 2013; Bai et al., 2019). The results from Nir et al. (2017) showed that the tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) DELLA protein PROCERA (PRO) regulated plant stomata and reduced water loss by increasing abscisic acid (ABA) sensitivity. In Oryza sativa, the DELLA protein Slender Rice1 (SLR1) had an important role on four pathogens (Vleesschauwer et al., 2016). Jusovic et al. (2018) reported that the altered structure of the wheat DELLA mutant contributed to the mitigation of photosynthetic tissue damage under salt stress. The yield increase in wheat under drought stress was closely linked to the DELLA protein gene encoding a reduced Rht gene (Kocheva et al., 2014). These results indicate that DELLA proteins are linked to the stress responses of plants.

Citrus is one of the most widely cultivated fruit crops in the world (Wu et al., 2019), and citrus yield and fruit quality are seriously impacted by drought stress (He et al., 2020; Zou et al., 2021b). Trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf.) is the principal rootstock used in Southeast Asia and is also drought-sensitive (Zhang et al., 2020). Studies on DELLA proteins mainly focused on model plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana, rice, and wheat (Jusovic et al., 2018; Noel et al., 2020), whereas the information regarding DELLA proteins in woody plants such as citrus is scarce. The aim of this study was to clone DELLA protein from trifoliate orange and to analyze the characteristics and basic functions of the protein gene in response to drought stress and the relationship with plant GAs concentrations and plant growth.

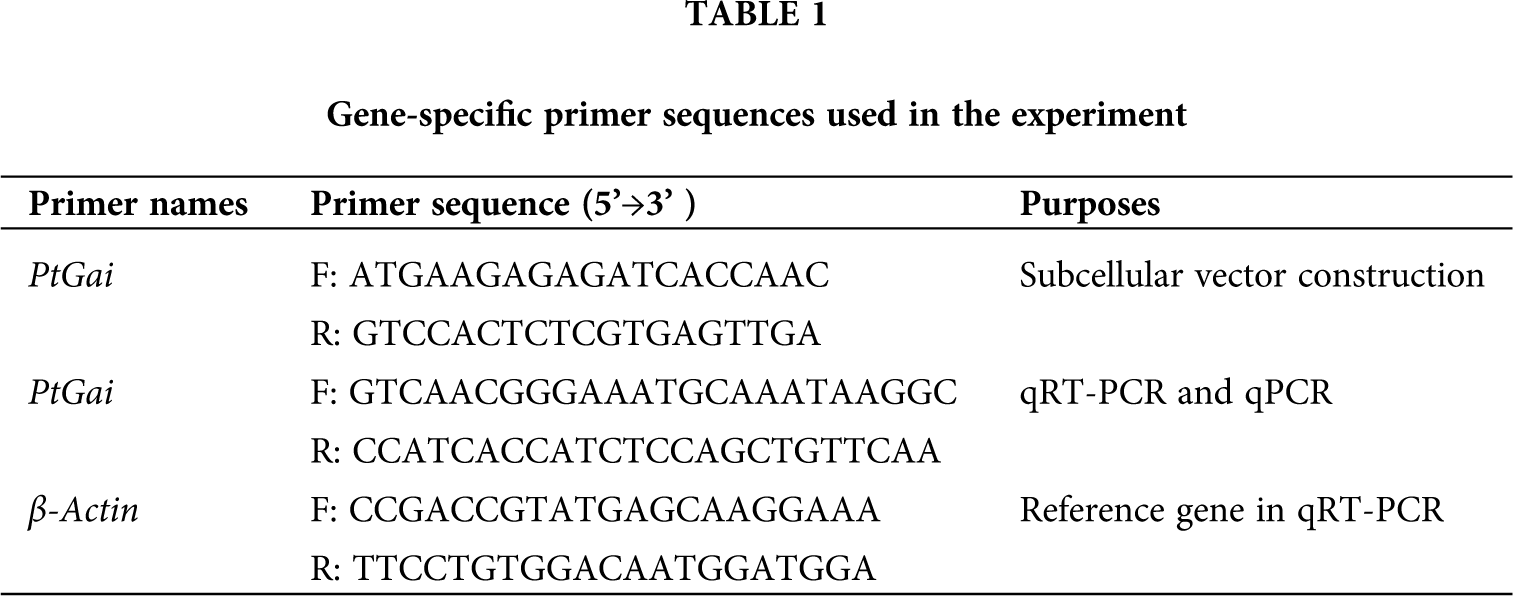

Cloning and sequence analysis of PtGai protein

The roots of trifoliate orange were pre-treated with liquid nitrogen to avoid DNA degradation. The PrimeScriptTM RT Master Mix (Baori Medical Biotechnology Beijing Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was used to extract total RNA. The PrimeScriptM RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Baori Medical Biotechnology Beijing Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was used to reverse the RNA into cDNA. On the basis of sweet orange database (http://citrus.hzau.edu.cn/orange/index.php) and our transcriptome data (SRR10413223, SRR10413224, SRR10413225, and SRR10413226), the specificity primer of DELLA protein was designed (Tab. 1). The PCR product (cDNA) was purified and ligated into the 1300-35S-YFP vector. The PCR product (cDNA) was purified and ligated into the 1300-35S-YFP vector, and the ligated product was transferred into Escherichia coli for cloning and sequencing to obtain the cloned full-length sequence. Sequence alignment was carried out using NCBI (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) in combination with Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) to download the sequences of different plant DELLA proteins. The amino acid sequence evolutionary tree of plant DELLA protein was constructed using the MEGA-X software. Gene structures were predicted using the online SWISS-MODEL tool (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/). Evolutionary tree construction was obtained using the Neighbor-joining (NJ) method (Saitou and Nei, 1987), and the bootstrap method with a repetition number of 500 was used to validate the evolutionary tree (Felsenstein, 1985). Evolutionary tree distances were achieved using the p-distance method (Nei and Kumar, 2000), with the number of amino acid differences per locus as a unit. Subcellular structural localization analyses were performed online using the WoLF-PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/).

Plant culture and drought treatment

Seeds of trifoliate orange were soaked in 10% NaOH for 10 min, washed with distilled water for three times, disinfected with 75% alcohol for 15 min, and then placed in sterilized sands in 28/20°C (day/night temperature), 1200 Lux light intensity, and 80% relative air humidity. Five-leaf-old seedlings with consistent growth were transplanted into a plastic pot with autoclaved (0.11 MPa, 121°C, 2 h) mixture of soil and sand (5:2). Three seedlings were planted in each pot, with a total of 24 pots. After transplanting, the plants were grown in 75% of the maximum field capacity (WW) for 8 weeks. Subsequently, half of the plants were exposed to 55% of the maximum field capacity (DS) for 10 weeks, and the other plants were kept in WW status for another 10 weeks. The soil moisture was controlled by weighting. After the drought treatment lasted for 10 weeks, the experiment was ended, and the seedlings were harvested. Plant samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for further study on the response of DELLA protein to drought stress.

The obtained cDNA products were used to design primers for the clone of the DELLA sequence in combination with Olige-7 software (Tab. 1). After the successful primer was obtained, qRT-PCR analysis was performed using the Chamq™ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China). The CFX96 Real-time PCR Analyzer (BIO-RAD, Hercules, California, USA) was used to analyze the quantitative results. Three biological replicates were performed on each sample, and the 2-ΔΔCT method was used to calculate the relative quantification (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). The β-actin was used as a reference gene.

The experimental data such as the relative expression of PtGai, root total GA concentrations, and shoot and root biomass were statistically analyzed by the analysis of variance (ANOVA) based on the SAS software. We used Duncan’s Multiple Range test to compare the significant (P < 0.05) difference between treatments.

Full length and bioinformatics analysis of PtGai protein

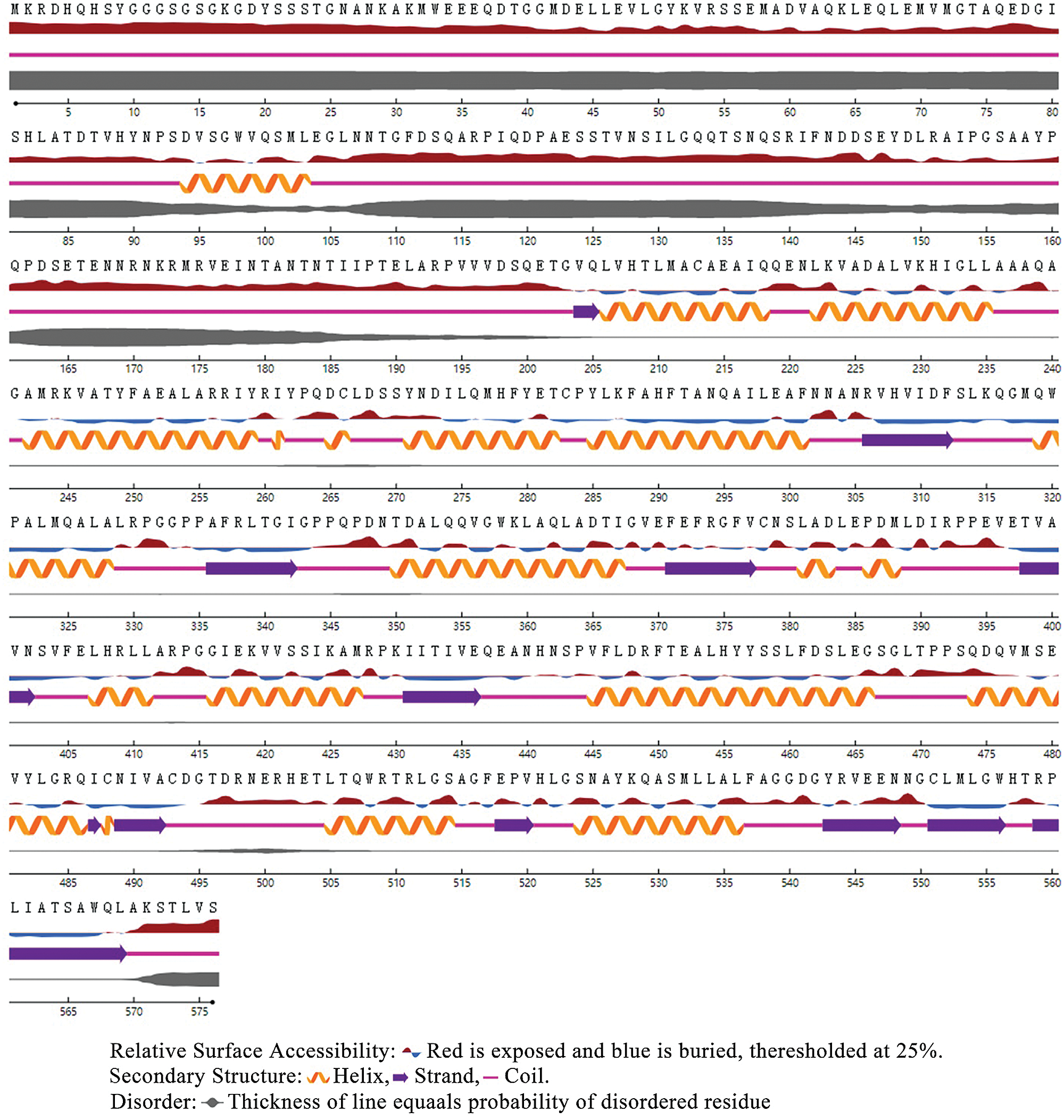

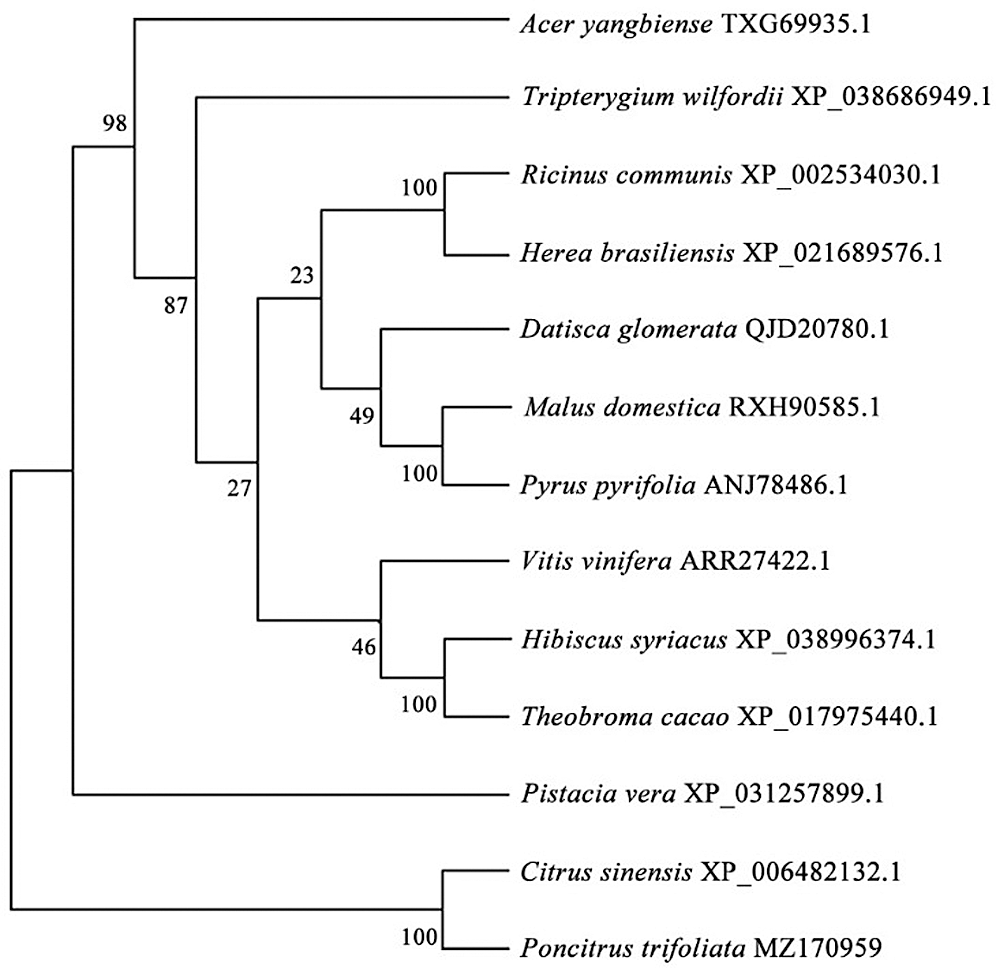

Based on the Transcription Factor Database (http://planttfdb.gao-lab.org/), phylogenetic relationships between DELLA proteins of the GRAS family and their homologous proteins indicate that all proteins have different families. PtGai protein (registration number: MZ170959) has a 1731 bp open reading frame, 576 amino acid coding, oligo-state monomer structure and its molecular weight is 63.49 kDa. The amino acid contents analyzed by WoLF-PSORT were alanine 70, cysteine 45, glutamine 94, histidine 78, isoleucine 32, leucine 63, serine 46, and valine 30. Within iPSORT range, the first 30 has N-terminal residues, and under the condition of 12 of the maximum hydrophilic value, the protein value of PtGai is 1; the first 20 n has N-terminal residues, and the protein value of PtGai is 45 when the maximum total negative charge is 12 (Fig. 1). Secondary structure predictions indicated that approximately 46.88% of the PtGai protein sequence was α-helix, and 9.72% of the extended chain, and 43.40% of the coil, with a threshold of 25% (Fig. 2). The average hydrophobicity of the PtGai protein was −0.49. Phylogenetic tree analysis of DELLA proteins showed that PtGai protein grouped with Citrus sinensis and also closely related to Pistacia vera L. (Fig. 3). The WoLF-PSORT predicted that PtGai protein was localized in the nucleus.

Figure 1: The three-dimensional structure of the PtGai protein.

Figure 2: PtGai protein secondary structure and relative solvent accessibility.

Figure 3: Phylogenetic trees of PtGai and other DELLA proteins.

Sequences of PtGai proteins blast

The published amino acid sequences of DELLA proteins from other seven plants were compared with the amino acid sequences of PtGai proteins by MEGA-X software. The results showed that the PtGai protein sequence was 65% homology with the sequences of DELLA proteins of different plant families (Fig. 4).

Expression of PtGai protein in different tissues and in response to drought stress

Tissue-specific quantitative expression of PtGai protein was detected by qRT-PCR. PtGai was expressed in roots, stems, and leaves, and the highest expression of PtGai was observed in stems, followed by the roots and leaves in the decreasing order (Fig. 5a). PtGai protein in roots and stems was 4.36 and 4.79 times higher than that in leaves (Fig. 5a). Leaf and root PtGai protein could be induced by drought stress, by 2.98 times and 1.26 times, respectively (Fig. 5b).

Changes in root total GA concentrations and biomass production

The drought treatment significantly reduced the total GA content of roots in trifoliate orange by 22.06%, compared to the well-watered treatment (Fig. 6a). On the other hand, the drought treatment also strongly suppressed shoot and root biomass production of trifoliate orange by 3.28% and 6.24%, respectively (Fig. 6b).

The present study cloned a DELLA protein from P. trifoliata, having a registration number MZ170959. Phylogenetic tree structure showed that the PtGai protein was close to that of sweet orange (C. sinensis), consistent with the species evolution. The results also indicated that the DELLA protein of P. trifoliata had highly homologous (65%) with other plants. Li et al. (2018a) found that the RcDELLA protein of Ricinus communis had a typical conserved DELLA domain, which was most similar to the plants with a genetic relationship. DELLA protein sequences of different plants showed that DELLA proteins mainly existed in the nucleus. The results of subcellular localization of PtGai in this study showed that PtGai protein was mainly localized in the nucleus, which was also consistent with the previous results (Li et al., 2018b).

Figure 4: Multiple sequence alignments between PtGai protein and other plant DELLA proteins. The conserved amino acids in all proteins are identified in purple.

Figure 5: Tissue-specific expressions (a) and drought stress response (b) of PtGai protein gene. Data (mean ± SD, n = 3) with different letter at the bar indicated the significant difference among treatments at 0.05 levels.

Figure 6: Root total GA concentrations (a) and shoot and root biomass production (b) of trifoliate orange under well-watered and drought stress. Data (mean ± SD, n = 12) with different letter at the bar indicated the significant difference among treatments at 0.05 levels.

PtGai protein gene had tissue-specific expression characteristics, and the high expression of PtGai was found in stems. Jia et al. (2019) also found that whole-genome DELLA proteins (BNA A06G34810D, BNA A09G18700D, and BNA C09G52270D) of Brassica napus showed the highest expression in stem tissue. It may be that DELLA proteins controlled the establishment of shoot rip tissue (Benavent, 2017). DELLA proteins might regulate the expression of the SPL gene in stem tissues and thus delay the flowering of stem tissues (Galvao et al., 2012). However, Song et al. (2016) reported the highest expression of JrGAI gene in flower buds at the dormant stage. A higher expression of PaGAI gene was found in flowers and phloem of cherry plum than in fruits and leaves (Zhang et al., 2012). Such tissue-specific expression of PtGai showed the regulatory dependence and tissue-specific function of PtGai protein (Grimplet et al., 2016; Arro et al., 2019).

In our study, PtGai protein gene was induced in leaves and roots of trifoliate orange in response to drought stress, showing a stressed responsive pattern, which was consistent with the results of Arro et al. (2019) and An et al. (2015). DELLA protein genes negatively regulated plant growth (Liu et al., 2021). Our study further showed that drought stress markedly inhibited root total GA content and shoot and root biomass production, which was contrary to the induced expression of PtGai under drought stress. Therefore, it was concluded that the overexpression of PtGai under drought conditions inhibited plant GA content, which thus inhibited plant growth performance. Karel et al. (2017) also found that the decrease of GA synthesis led to the up-regulation of DELLA protein genes. Guo et al. (2014) revealed that DELLA protein genes regulated the remodeling of plant development and improved the degradation of harmful substances under long-term Mg stress. However, Joanna et al. (2020) observed the increase of the active GA20 under drought conditions. As a result, more work needs to be done around the types of GAs, along with the expression of DELLA genes.

In this study, a DELLA protein PtGai was cloned from trifoliate orange. Bioinformatics analysis revealed that PtGai proteins were grouped with sweet orange, highly homologous (65%) with DELLA proteins from other plants, and localized in the nucleus, with tissue-specific expression and drought-induced expression. Coupled with the changes of biomass and total GAs content, PtGai protein as the GA inhibitor modulated GA biosynthesis to regulate plant growth. These results provide a basis for further analysis of the function of PtGai protein gene and its regulatory network in response to drought stress. More work is needed to further uncover the upstream transcription factors.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in this published article.

Author Contribution: The authors confirm the contribution of the paper as follows: study conception and design: Q-SW and KK; data collection: X-FC and Q-SW; analysis and interpretation of results: X-FC, AH, EFAA, and Q-SW; draft manuscript preparation: X-FC and Q-SW. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the 2020 Joint Projects between Chinese and CEECs’ Universities (202019), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFD1000303), and the UHK Project VT2019-2021. The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project No. (RSP-2021/134), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

An J, Hou L, Li C, Wang CX, Xia H et al. (2015). Cloning and expression analysis of four DELLA genes in peanut. Russian Journal of Plant Physiology 62: 116–126. [Google Scholar]

Arro J, Yang YZ, Song GQ, Zhong GY (2019). RNA-Seq reveals new DELLA targets and regulation in transgenic GA-insensitive grapevines. BMC Plant Biology 19: 80. [Google Scholar]

Bai YH, Zhu XD, Fan XC, Wang C, Zhang WY et al. (2019). Research progress of plant DELLA proteins and its response to gibberellin signal regulating plant growth and development. Molecular Plant Breeding 17: 2509–2516. [Google Scholar]

Benavent AF (2017). Modulation of primary meristem activity by gibberellins through DELLA-TCP interaction in Arabidopsis. (Ph.D. Thesis). Universitat Politecnica de Valencia, Valencia, Italty. [Google Scholar]

Bilova TE, Ryabova DN, Anisimova IN (2016). Molecular basis of the dwarfism character in cultivated plants. II. DELLA-proteins: Structure and functions. Agricultural Biology 51: 571–584. [Google Scholar]

Cheng XF, Wu HH, Zou YN, Wu QS, Kuča K (2021). Mycorrhizal response strategies of trifoliate orange under well-watered, salt stress, and waterlogging stress by regulating leaf aquaporin expression. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 162: 27–35. [Google Scholar]

Felsenstein J (1985). Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39: 783–791. [Google Scholar]

Floss DS, Levy JG, Véronique LT, Pumplin N, Harrison MJ (2013). DELLA proteins regulate arbuscule formation in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110: E5025−E5034. [Google Scholar]

Galvao VC, Horrer D, Kuttner F, Schmid M (2012). Spatial control of flowering by DELLA proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 139: 4072–4082. [Google Scholar]

Grimplet J, Agudelo-Romero P, Teixeira RT, Martinez-Zapater JM, Fortes AM (2016). Structural and functional analysis of the GRAS gene family in grapevine indicates a role of GRAS proteins in the control of development and stress responses. Frontiers in Plant Science 7: 353. [Google Scholar]

Guo WL, Cong YX, Hussain N, Wang Y (2014). The remodeling of seedling development in response to long-term magnesium toxicity and regulation by ABA-DELLA signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiology 55: 1713–1726. [Google Scholar]

Harberd NP, Belfield E, Yasumura Y (2009). The angiosperm gibberellin-GID1-DELLA growth regulatory mechanism: How an inhibitor of an inhibitor enables flexible response to fluctuating environments. Plant Cell 21: 1328–1339. [Google Scholar]

He JD, Zou YN, Wu QS, Kuča K (2020). Mycorrhizas enhance drought tolerance of trifoliate orange by enhancing activities and gene expression of antioxidant enzymes. Scientia Horticulturae 262: 108745. [Google Scholar]

Jia YP, Li KX, Zan LX, Yao YM, Du DZ (2019). Genome-wide identification and expression of DELLA protein family in Brassica napus. Chinese Journal of Oil Crop Sciences 41: 360–368. [Google Scholar]

Joanna G, Michał D, Agnieszka O, Katarzyna H, Tomasz H (2020). Phytohormone synthesis pathways in sweet briar rose (Rosa rubiginosa L.) seedlings with high adaptation potential to soil drought. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 154: 745–750. [Google Scholar]

Jusovic M, Velitchkova MY, Misheva SP, Börner A, Apostolova EL, Dobrikova AG (2018). Photosynthetic responses of a wheat mutant (Rht-B1c) with altered DELLA proteins to salt stress. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 37: 645–656. [Google Scholar]

Kocheva K, Nenova V, Karceva T, Petrov P, Georgiev GI et al. (2014). Changes in water status, membrane stability and antioxidant capacity of wheat seedlings carrying different Rht-b1 dwarfing alleles under drought stress. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 200: 83–91. [Google Scholar]

Li W, Li GR, Huang FL, Cong AQ, Li XC et al. (2018a). Cloning and sequence analysis of RcDELLA gene in castor. Acta Agriculturae Boreali-Sinica 33: 14–19. [Google Scholar]

Li WJ, Zhang JX, Sun HY, Wang SM, Chen KQ et al. (2018b). FveRGA1, encoding a DELLA protein, negatively regulates runner production in Fragaria vesca. Planta 247: 941–951. [Google Scholar]

Liu YY, Wen J, Ke XC, Zhang J, Sun XD et al. (2021). Gibberellin inhibition of taproot formation by modulation of DELLA-NAC complex activity in turnip (Brassica rapa var rapa). Protoplasma. 1–10. DOI 10.1007/s00709-021-01609-1. [Google Scholar]

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25: 402–408. [Google Scholar]

Natanella IE, Idan N, Ido N, Uria R, Hagai S, David W (2020). Mutations in the tomato gibberellin receptors suppress xylem proliferation and reduce water loss under water-deficit conditions. Journal of Experimental Botany 71: 3603–3612. [Google Scholar]

Nei M, Kumar S (2000). Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Nir I, Shohat H, Panizel I, Olszewski NE, Aharoni A, Weiss D (2017). The tomato DELLA protein procera acts in guard cells to promote stomatal closure. Plant Cell 29: 3186–3197. [Google Scholar]

Noel BT, Legris M, Minguet EG, Costigliolo-Rojas C, Alabad D (2020). Cop1 destabilizes DELLA proteins in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117: 13792–13799. [Google Scholar]

Park J, Nguyen KT, Park E, Jeon JS, Choi G (2013). DELLA proteins and their interacting ring finger proteins repress gibberellin responses by binding to the promoters of a subset of gibberellin-responsive genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 927–943. [Google Scholar]

Saitou N, Nei M (1987). The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 4: 406–425. [Google Scholar]

Shan XD, Zhang R, Maiwulidai K, Gulinaer N, Xu LX (2019). Effect of gibberellin soaking on seed germination of perennial ryegrass under polyethylene glycol simulated drought conditions. Pratacultural Science 36: 2304–2311. [Google Scholar]

Song XB, Wang HX, Zhang ZH (2016). Cloning and expression analysis of JrGAI gene in DELLA protein from ‘Liaoning 2’. Journal of Agricultural University of Hebei 39: 29–34. [Google Scholar]

Stirk WA, Tarkowská D, Gruz J, Strnad M, Ördög V, Staden JV (2019). Effect of gibberellins on growth and biochemical constituents in Chlorella minutissima (Trebouxiophyceae). South African Journal of Botany 126: 92–98. [Google Scholar]

Theo L, Carolin K, Maria JPL (2020). The class III gibberellin 2-oxidases AtGA2ox9 and AtGA2ox10 contribute to cold stress tolerance and fertility. Plant Physiology 184: 478–486. [Google Scholar]

Karel VDV, Philip R, Koen G, Antje R, Dominique VDS (2017). Exploiting DELLA signaling in cereals. Trends in Plant Science 22: 880–893. [Google Scholar]

Vleesschauwer DD, Seifi HS, Filipe O, Haeck A, Huu SN et al. (2016). The DELLA protein SLR1 integrates and amplifies salicylic acid-and jasmonic acid-dependent innate immunity in rice. Plant Physiology 170: 1831–1847. [Google Scholar]

Wu QS, He JD, Srivastava AK, Zou YN, Kuča K (2019). Mycorrhizas enhance drought tolerance of citrus by altering root fatty acid compositions and their saturation levels. Tree Physiology 39: 1149–1158. [Google Scholar]

Zhang F, Shen XJ, Liu F, Yuan HZ, Liu LY et al. (2012). Cloning and expression analysis of PaGAI gene of DELLA protein from Prunus avium. Acta Horticulturae Sinica 39: 143–150. [Google Scholar]

Zhang F, Zou YN, Wu QS, Kuča K (2020). Arbuscular mycorrhizas modulate root polyamine metabolism to enhance drought tolerance of trifoliate orange. Environmental and Experimental Botany 171: 103962. [Google Scholar]

Zhou YC, Underhill SJR (2020). Expression of gibberellin metabolism genes and signalling components in dwarf phenotype of breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis) plants growing on marang (Artocarpus odoratissimus) rootstocks. Plants 9: 634. [Google Scholar]

Zou YN, Wu QS, Kuča K (2021a). Unravelling the role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in mitigating the oxidative burst of plants under drought stress. Plant Biology 23: 50–57. [Google Scholar]

Zou YN, Zhang F, Srivastava AK, Wu QS, Kuča K (2021b). Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi regulate polyamine homeostasis in roots of trifoliate orange for improved adaptation to soil moisture deficit stress. Frontiers in Plant Science 11: 600792. [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |