DOI:10.32604/biocell.2022.016822

| BIOCELL DOI:10.32604/biocell.2022.016822 |  |

| Review |

MicroRNA regulation and host interaction in response to Aspergillus exposure

1Department of Biomedical Sciences, Bundelkhand University, Jhansi, 284128, India

2Department of Zoology, Indira Gandhi National Tribal University, Amarkantak, 484886, India

3Department of Horticulture, Aromatic and Medicinal Plants, Mizoram University, Aizawl, 796004, India

*Address correspondence to: Rambir Singh, rambirsingh@mzu.edu.in

Received: 30 March 2021; Accepted: 13 August 2021

Abstract: Aspergillus is a group of conidial fungi, isolated from soil and litter, cause serious diseases in humans and animals. This ubiquitous fungus is prevalent in the air and inhalation of fungal spores is common. Fungal diseases from Aspergillus became a major health problem and are difficult to manage because they tend to be chronic and invasive, hard to diagnose and difficult to exterminate with antifungal drugs. Although, immune responses play vital roles in monitoring the fate of fungal infections and regulation of the immune responses against fungal infections might be an effective approach for controlling and reducing the pathological damages. Recent studies have shown that microRNAs (miRNAs) are assembly of regulators which modulates the immune responses during fungal infections through diversified cellular mechanisms. These small non-coding RNA sequences regulate gene expression, mostly at the post-transcriptional level and have emerged as the controller of gene expression of at least 30% human genes. Therefore, miRNAs might be considered as one of the potential goals in immunotherapy for fungal infections. The objective of this review is to explore the role of miRNAs in host recognition processes and understanding the modulation of regulatory pathways in response to Aspergillus exposure.

Keywords: Fungal exposure; Aspergillus; microRNA; Immune response

Fungi are eukaryotic and ubiquitous microorganisms found in soil, animals, faeces, water, plant debris or other surfaces and are present in almost all the surroundings. It is estimated that out of 1.5 million of fungal species, mostly are saprophytes obtaining their nutrients from organic material, among which some are primary or opportunistic pathogens (Hawksworth, 2001). Fungi have a complex cellular organization that is surrounded by a firm cell wall; and its complexity and functionality is crucial to the development of new therapeutic and prophylactic strategies. The cell wall plays several key functions in fungal pathobiology as varied factors, such as cell shape, encapsulation, and rigidity, influence measures during interaction with the host (Gow et al., 2017).

The fungal cell wall has a flexible and an indispensable structure that is highly complex and intricately organized of α- and β- linked glucans, chitin, glycoproteins, and pigments (Gow et al., 2017). Fungal life forms broadly diverge from unicellular yeasts to multicellular filamentous hyphae that collectively form mycelium. Most fungi are adapted to aerial dispersion and replicate by non-motile asexual and sexual spores. Fungal spores and hypha fragments are ubiquitous components of the atmosphere and impact human health as triggers of allergic reactions or as the cause of infectious disease. Fungal spores can be aerosolized when agitated and in some occupational settings the airborne concentration may exceed from 1 × 105 spores/m3 (Eduard, 2009).

Fungi are one of the acknowledged biological factors and those who are pathogenic in nature have a destructive impact on human health (Hardin et al., 2003). The airborne spores of these microorganisms, when inhaled, are alleged to contribute to negating conditions from pulmonary sinus, and subcutaneous infections to respiratory ailments that may consist of hypersensitivity pneumonitis, allergy, and asthma (Eduard, 2009), in individuals who are susceptible to irritant effects of exposure, and immunocompromised patients susceptible to infections. Generally fungi cause mild infections consequences in immunocompetent hosts, but immunocompromised patients face occurrence of pathological indices that can be a substantial cause to a mortality up to 40% (Brown et al., 2012). The frequency of fungal infections also shows variations with socioeconomic conditions, geographic region, and cultural habits. Superficial infections of the skin and nails are communal fungal diseases in humans and affect approximately 25% of the general population globally (Havlickova et al., 2009) that are primarily caused by dermatophytes, which give rise to well-known conditions such as athlete’s foot, and ringworm of the scalp. Mucosal infections of the oral and genital tracts are also common in the regions with limited health care provisions and in individuals who take steroids for asthma, have leukaemia, received transplant or undergoing chemotherapy or radiotherapy (Cornely et al., 2017; Enoch et al., 2017; Lien et al., 2018).

Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) are of greater concern than superficial infections because they are associated with inadmissibly high mortality rates and annually impose large costs, involving 2 million people every year globally (Brown et al., 2012). Many species of fungi are responsible for these invasive infections and the most emphasized species that are gaining importance are Candida albicans (candidiasis), Pneumocyctis jirovecii (pneumocyctosis), Cryptococcus neoformans/gattii (cryptococcosis), and Aspergillus fumigatus (aspergillosis). According to the World Health Organization (WHO; http://www.who.org), candidiasis, pneumocyctosis, cryptococcosis and aspergillosis are among the top 20 significant and deadly fungal infections in AIDS patients worldwide. Aspergillus species are the primary reason of health apprehension in immunocompromised beings, and this ubiquitous and opportunistic fungi cause invasive to allergic aspergillosis. Among the Aspergillus species, A. fumigatus has been found to be the most pathogenic to humans and accountable for more than 90% of Aspergillus induced infections. The morphotypes of Aspergilli such as conidia, mycelia or hyphae provide virulence and pathogenicity to fungi and help them to invade into hosts by secreting enzymes, proteins or toxins. The global burden of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) obscuring asthma likely to be 5 million, out of which 0.4 million are estimated to have chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) (Denning et al., 2013). The mortality rates for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) exceed 90% if not treated and when treated aggressively with antifungals, fatality rates of 50% are common in intensely immunosuppressed individuals such as people with leukaemia and transplant recipient. This high mortality rate subsequent to A. fumigatus infection is a consequence of the availability of suboptimal diagnostic tool, delay in diagnosis and comparative ineffectiveness and toxicity of antifungal drugs against Aspergillus induced infections. The various combinations of antifungals are used but they can only lessen the fungal load in the hosts and the cure from the infection can rarely be achieved. Therefore, it is extremely difficult to treat aspergillosis and hence, the treatment and management of pulmonary aspergillosis has become the most importance topic of concern.

The immune system of healthy individuals has effective mechanisms for preventing fungal infections, and the hefty incidence of invasive diseases is largely a result of extensive escalations over the last few decades in immunosuppressive infections, such as HIV/AIDS, and modern immunosuppressive and invasive medical intrusions. The surge of broad-spectrum antibiotic usage and other medical and therapeutic approaches, concern has been raised towards invasive opportunistic fungal infections as nosocomial infections in the hospital site that may be life-threatening for dangerously ill persons (Bajwa and Kulshrestha, 2013). Therefore, fungal life-threatening infections are the major challenge to the health system in both developed and developing countries. Due to cross-reactivity of many fungal allergens that complicate the diagnosis of fungal sensitization, it is very important to characterize compromised innate and adaptive immune responses (Crameri et al., 2009). Moreover, earlier research has engrossed on host reactions in exposed fungal models by examining immunological, functional, and histological parameters, and also considerable studies have been conducted on the design of antifungal vaccines (Nami et al., 2019). Also, during the recent decade, novel immunotherapeutic strategies are under development such as cytokine/pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) ligand therapy, and antigen trained dendritic cells (DCs) (Goncalves et al., 2016; Datta and Hamad, 2015). In this direction, many studies have been published that have explored the role of microRNAs (miRNAs) in pulmonary immunological responses to acute and chronic exposures to fungal spores. Therefore, understanding the role of miRNAs as the major immune regulators would be beneficial. This review compiles the state-of-knowledge of regulatory role of miRNAs in relation to the host response following Aspergillus exposure, with the emphasis placed on the mechanistic insights.

Host Immune Responses to Aspergillus Exposure

Aspergillus spp. encompasses a diversity of environmental filamentous fungus found in miscellaneous ecological niches worldwide. Among this genus, A. fumigatus is the most predominant species and is mainly accountable for the increased frequency of invasive aspergillosis with high mortality tolls in immunocompromised patients (Garcia-Rubio et al., 2017). A. fumigatus is accountable for a hefty ratio of nosocomial opportunistic fungal infections in immunocompromised hosts, specifically during cytotoxic chemotherapy and after bone marrow transplantation, and is currently a foremost cause of death in leukaemia patients. Aspergillus conidia (resting spores) are ubiquitous in the environment, often inhaled and quickly phagocytised by alveolar macrophages and neutrophils of an immunocompetent host. However, the consequences of failure of immunocompromised individuals to immaculate germinating conidia can be invasive pneumonia and disseminated infection (Marr et al., 2002). Due to its clinical significance; it has become a model for studying filamentous fungus cell wall and understanding its role in evolution and pathogenesis.

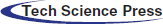

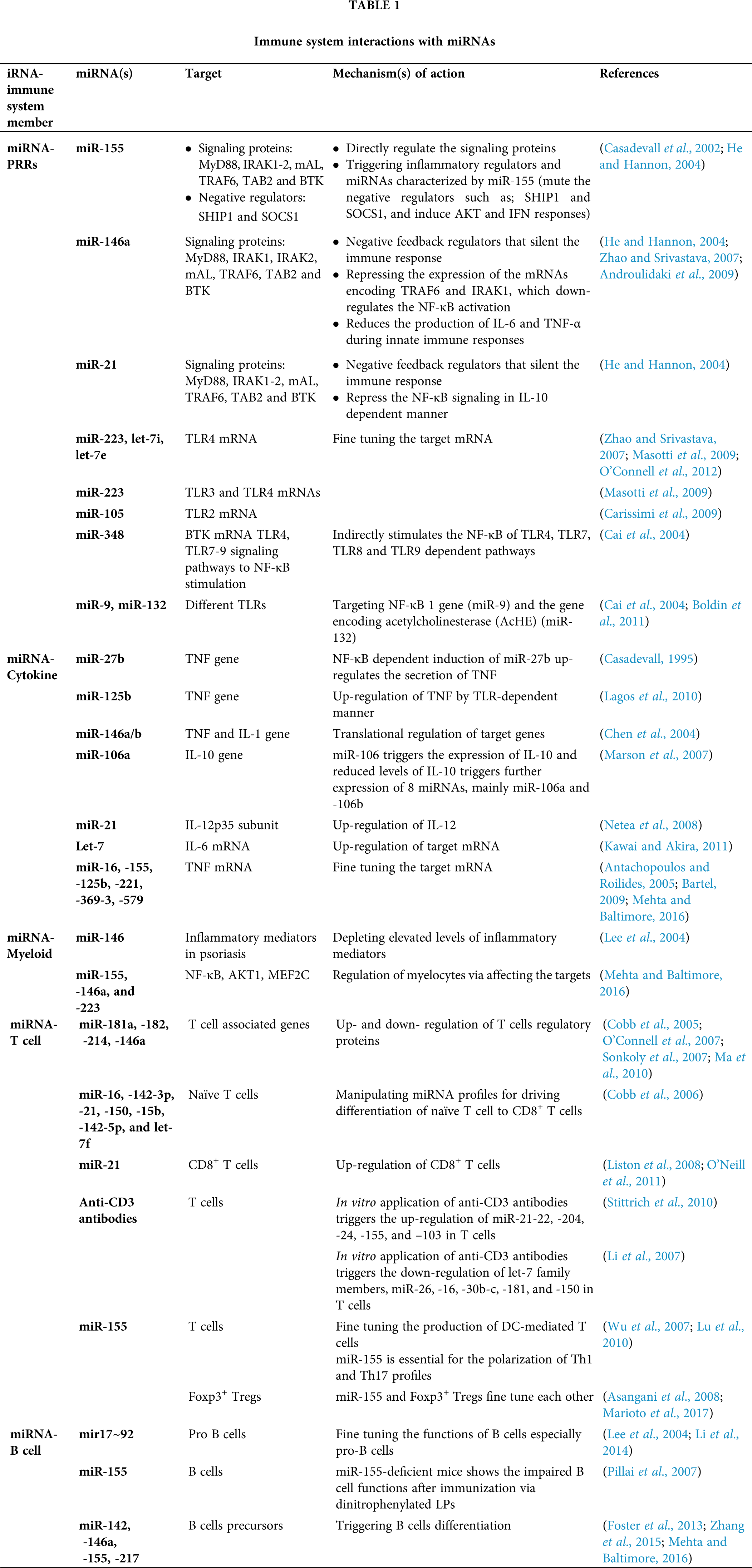

A. fumigatus releases abundant conidia in air which are constantly inhaled by humans. The first barrier for A. fumigatus conidia is airway mucociliary cells followed by the alveolar macrophages in the alveolar lumen before they undergo germination (Latgé, 1999). The host’s innate immune system, consists of mononuclear monocytes and macrophages (MQs), polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), epithelial cells (EPs), dendritic cells (DCs) and soluble mediators such as complement cascade and defensins battle against fungal particles, and PRRs such as TLRs recognize the PAMPs such as zymosan and glucans (Netea et al., 2008). Following the recognition of Aspergillus antigens, specific signaling pathways are triggered through different molecules (Fig. 1), which eventually lead to stimulation of adaptive immune responses through cytokines and chemokines (Kawai and Akira, 2011) (Fig. 3). The host’s immune response varies with the erratic composition of the cell wall that depends on different stages of fungal growth (Lee and Sheppard, 2016). Dormant conidia have an outer layer formed of immunologically inert proteins such as RodA hydrophobins and dihydroxynaphthalene-melanin that mask the inner components of the fungi cell wall and protects conidia from phagocytic activity (Amin et al., 2014; Bayry et al., 2014). After phagocytosis of conidia by alveolar macrophages, hydrophobins are degraded and the cell wall polysaccharides become exposed to trigger a potent immune response.

The β-1,3-glucan has a stimulatory effect on the host immune system and is recognized by a PRR, Dectin-1, expressed on phagocytic cells including macrophages and neutrophils (Goodridge et al., 2009). After inhalation, the conidia swell and, if they are not cleared, produce germ tubes that eventually extend to form filamentous hyphae, thereby exposing β-glucan on the surface of Aspergillus germ tubes and hyphae and thus detected by Dectin-1 (Goodridge et al., 2009). Consistent with this, germinating spores induce neutrophil recruitment to the airways and cytokine and chemokine production by alveolar macrophages. These Dectin-1-dependent responses are more pertinent in germinating conidia and young hyphae that are exposing higher levels of β-1,3-glucans than in mature hyphae where it is covered by exopolysaccharides (Gravelat et al., 2013). Galactosaminogalactan is an important exopolysaccharide and an adhesin that facilitates binding of hyphae to macrophages, neutrophils, and platelets (Fontaine et al., 2011; Rambach et al., 2015). It has been additionally related to an immunosuppressive activity concealing cell wall β-glucans from recognition by Dectin-1, diminished polymorphonuclear neutrophil apoptosis via an NK cell–dependent mechanism and ROS production (Gravelat et al., 2013; Robinet et al., 2014) and stimulated fungal development in immunocompetent mice due to its immunosuppressive activity associated with reduced neutrophil infiltrates (Fontaine et al., 2011). These polysaccharides inhibit Th1 and Th17 shielding response towards Th2 in humans, thus upholding IL-1Ra secretion by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Gresnigt et al., 2014).

Dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN), type II C-type lectin, is an adhesion receptor and used by viral and bacterial pathogens to gain admittance to human DC (Fig. 1). It is reported that DC-SIGN unambiguously interacts with clinical isolates of A. fumigatus. The binding and internalization of A. fumigatus conidia is associated with DC-SIGN cell surface expression levels and is abolished with the occurrence of A. fumigatus-derived cell wall galactomannans (Serrano-Gómez et al., 2004). Thus, galactomannan also has a damaging effect in the host immune system by favouring fungal infection. There is an another receptor, Dectin-2, (Fig. 1) that recognizes α-mannans of cell wall and has an important role in conidia and hyphae binding by THP-1 macrophages which leads to TNF-α (Tumor necrosis factor) and IFN-α (Interferon) release as well as heightened antifungal activity by plasmacytoid DC (Loures et al., 2015).

Figure 1: Innate immune responses to the Aspergillus and miRNA interactions. Different PRRs, mainly TLRs and dectins which expressed on the APCs, recognize fungal PAMPs, and their interaction triggers the stimulation of downstream signaling pathways such as MyD-88, CARD-9, IRAK, TRAF. This further stimulates transcription factor (NF-κB, AP-1) which secrete inflammatory cytokines IL-1, IL-6, IL-17, TNF-α. Several miRNAs interact with these processes (presented by two-way arrows) and double-ended arrows by green and red colour represents up-regulation and down-regulation of target mRNAs. MicroRNA-155, -146 and -21 are the most known miRNAs that fine-tune the innate immune response to ubiquitous fungal pathogen.

However, no host receptor for chitin, the inner component of the Aspergillus cell wall, has yet demonstrated. The immune response to chitin is disputatious and the exact mechanisms determining its inflammatory response are poorly understood. It was shown to have pro-inflammatory as well as anti-inflammatory properties subject to the presence of co-stimulatory pathogen-associated molecular patterns and immunoglobulins (Becker et al., 2016).

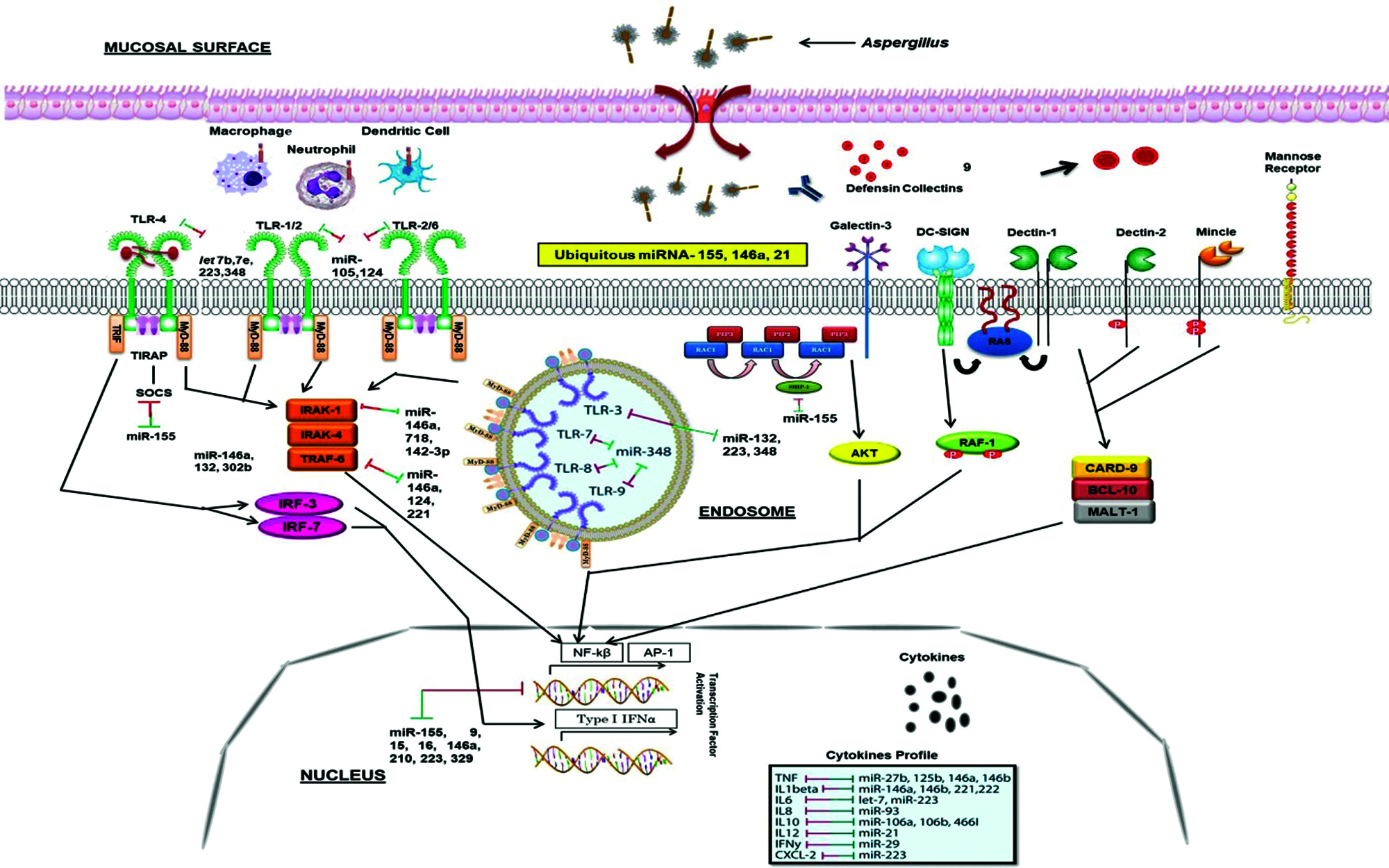

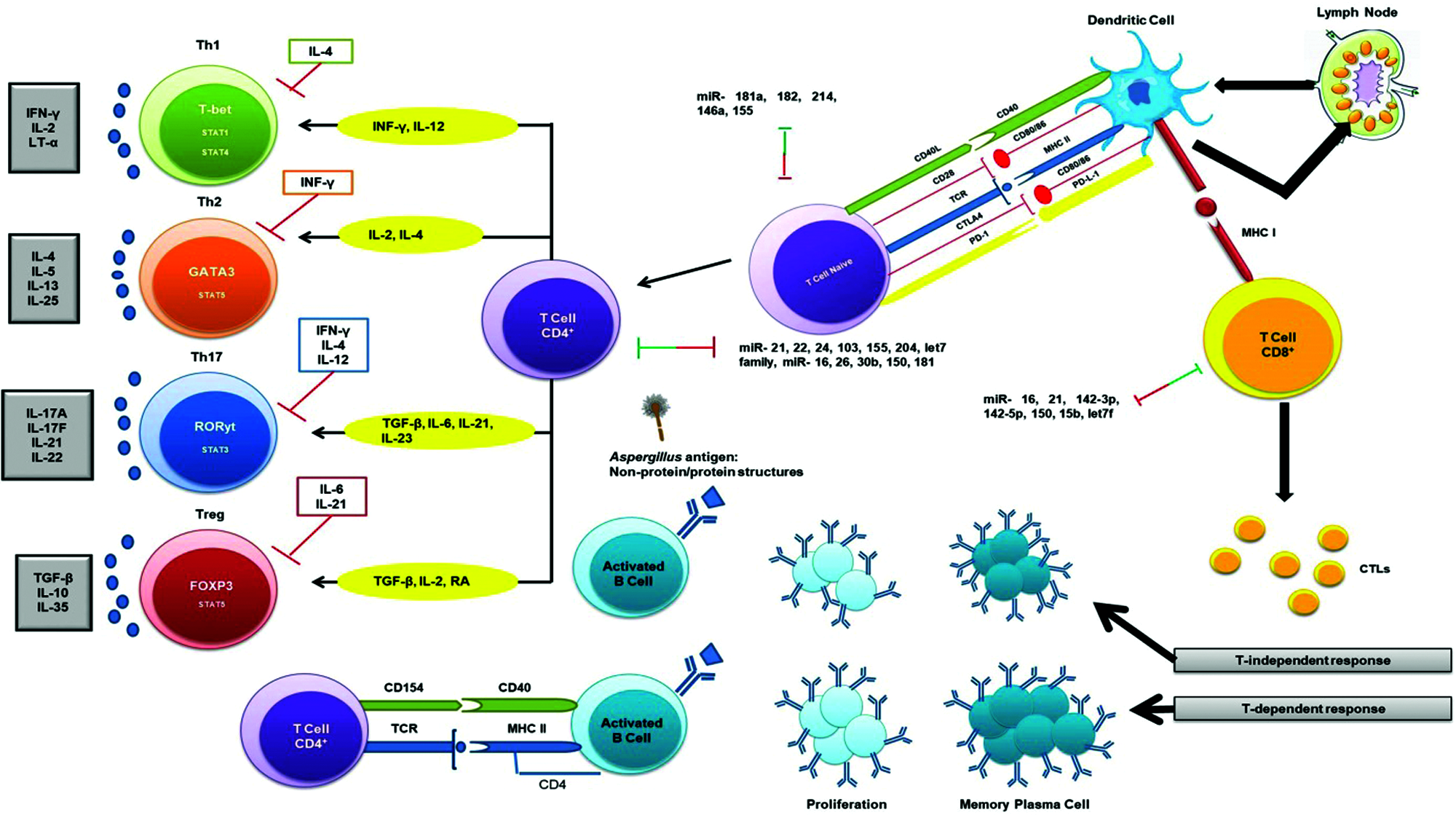

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a complex of about 18–23 bp non-coding single stranded ribose nucleic acids (RNAs) that are involved in the regulation of nearly every basic molecular or cellular process by governing the levels of mRNA and post-transcriptional gene expression (Pakshir et al., 2020). The first miRNA was discovered over 20 years ago has led to a new era in molecular biology (Hammond, 2015). Now, there are over 2000 miRNAs that have been discovered in humans, collectively control one third of the genes in the genome (Hammond, 2015). Most miRNAs are transcribed from DNA sequences and following the reception of stimulatory signals at the cell nucleus, RNA polymerase II (RNA pol II) triggers the generation of primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) that further administered in the nucleus by the microprocessor complex Drosha-DGCR8 to release hairpin structured precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) (O’Brien et al., 2018; Pakshir et al., 2020) (Fig. 2). Then these pre-miRNAs are exported into the cytoplasm via Exportin-5 where they are further transformed by Dicer and catalysed the production of mature miRNA duplex that subsequently loaded onto the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), final functional tuner complex, which transcriptionally/post-transcriptionally regulates the target mRNA (O’Brien et al., 2018; Pakshir et al., 2020) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Biogeneis and mechanism of action of miRNAs.

MicroRNAs function to regulate gene expression in animals, plants and protozoa, and function post-transcriptionally through base-pairing to the mRNA 3’-untranslated regions (Fabian et al., 2010). Depending on the level of complementarity of base-pairing, target mRNA molecules are silenced or gene expression is repressed by one or more of the processes such as cleavage of the mRNA strand into two pieces, destabilization of the mRNA strand through shortening of its polyA tail, no effective translation of mRNA into proteins by ribosomes (Bartel, 2009), affecting DNA methylation or histone acetylation, or targeting transcription factors (Iorio et al., 2010; Sato et al., 2011; Feng et al., 2011), as observed in humans, animals and plants. These single-stranded tuners are endogenously articulated by all metazoan eukaryotes and have emerged as the master gene expression controllers of at least 30% human genes (Mehta and Baltimore, 2016; Masotti et al., 2009; He and Hannon, 2004). The human genome is predicted to encode as many as 1000 miRNAs in a large variety of physiological environments (Zeng, 2006; O’Connell et al., 2012). Studies have shown that a single miRNA can be regulated from one to multiple genes, and also multiple miRNAs can regulate the same gene (Bartel, 2009; Friedman et al., 2009; Rajewsky, 2006; Krek et al., 2005). Few studies have also indicated that miRNA can also trigger the translation of certain target mRNA (Li et al., 2006; Janowski et al., 2007; Vasudevan et al., 2007). Several miRNAs have been broadly examined and characterized in cancer models, aging, heart disease, apoptosis and immune responses to inflammatory provocations (Place et al., 2008; Lu and Rothenberg, 2013; Van Rooij and Olson, 2007; Hackl et al., 2010; Leopold and Maron, 2016; Posch et al., 2017).

In general, post-transcriptional mechanisms of miRNAs are supposed to regulate around two thirds of all human genes (Filipowicz et al., 2008; Esteller, 2011). Recently, amplified information of proteomics has established that single miRNAs function can edge the production of numerous proteins via reduction of mRNA levels and limiting the translational disarray (Filipowicz et al., 2008; Baek et al., 2008; Selbach et al., 2008).

This mechanism indicates that miRNAs do not extinguish gene expression, but instead they are fine-tuners of the key regulatory proteins. Also, under specific circumstances, miRNAs unpredictably govern the upregulation of the target mRNAs (Vasudevan et al., 2007) or directly intervene the target gene transcription (Kim et al., 2008).

MicroRNAs and Immune Responses

MicroRNAs are referred to as key controllers for animal development and many biological processes (Fu et al., 2013), and play pivotal roles in regulating immune reactions to fungi. The importance of miRNA roles has been demonstrated by investigations on Dicer-knockout model of mice, that enforce a cell mediated immune deficiency (Muljo et al., 2005), and also micro-array analysis (Gantier et al., 2007; Taganov et al., 2006). Additionally, miRNAs are shown to be detectable in cell-free body fluids like serum and plasma samples (Chen et al., 2008; Zen and Zhang, 2012) and these circulating miRNAs are shielded from blood RNAses either by prevailing membrane-derived vesicles like exosomes or by making complex with lipid-protein carriers such as high-density lipoprotein (HDL) (Valadi et al., 2007; Gallo et al., 2012; Vickers et al., 2011). Also, the majority of miRNAs in plasma is protected from degradation due to their complex formation with the AGO2 protein which is required for RNA-mediated gene silencing by the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) (Arroyo et al., 2011; Li et al., 2012). Therefore, these circulating miRNAs might be ideal biomarker attributable to their disease-specific dysregulation and their relative stability compared with mRNAs. Hence, we categorize and discuss the potential miRNAs in each sort of the immune response against the fungal pathogen, innate and acquired immunity (Tab. 1).

Influence of miRNA on allergic reactions

Allergic inflammatory responses include a wide range of conditions including asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and more recently eosinophilic esophagitis (Maddox and Schwartz, 2002; Broide, 2008; Blanchard and Rothenberg, 2008; Boguniewicz and Leung, 2011; Gelfand, 2004). Each of these diseases involves continued inflammation that is linked with visible histological changes as well as molecular alterations in gene and protein expression. The pathway employed in regulating and fine-tuning these practices represents a striking area for microRNA studies.

The let-7 family is the substantial respiratory miRNAs and has been recognized in studies examining cancer, diabetes, and aging (Frost and Olson, 2011; Su et al., 2012; Jun-Hao et al., 2016; Brennan et al., 2017; Pal and Kasinski, 2017). Let-7 is a vital tumor suppressor miRNA, which is articulated across various animal species from worms to flies, to humans (Pasquinelli et al., 2000; Ruby et al., 2006). The human let-7 family of miRNA comprises 12 members of miRNA and is highly conserved in human tissues (Su et al., 2012). The let-7 miRNAs target interleukin (IL)-13 in in vivo and in vitro fungal exposed models (Lu and Rothenberg, 2013). Also, miR-21 is another broadly studied miRNA and has been known to take part in the inflammatory response elicited by different stimuli, comprising of doxycycline-induced allergic airway inflammation (Lu et al., 2009). miR-21 is one of the firsts identified cancer-promoting oncomiRs, affecting numerous tumour suppressor genes associated with proliferation, apoptosis and invasion (Feng and Tsao, 2016). The recent studies are focusing on the diagnostic and prognostic value of miR-21 as well as its implication in the drug resistance of human malignancies. miR-21 is also one of the most up-regulated miRNAs in patients suffering from allergic eosinophilic esophagitis (Lu et al., 2012a; Lu et al., 2012c), which is related to the investigations that stated miR-21 and miR-223 as controllers of development of eosinophil in an ex vivo specimen of bone-derived eosinophils (Lu et al., 2013a; Lu et al., 2013b). Down regulation in miR-375 in epithelial cells from patients with eosinophilic esophagitis has been reported. This leads to modulation of IL-13 associated immunoinflammatory pathways in epithelial cells demonstrating the role of miR-375 as a fine-tuner of IL-13-mediated responses (Lu et al., 2012b).

The studies on rodent models, that allowed to expose to house dust mite allergen, have been reported the increased expression of microRNAs miR-126, miR-106a and miR-145 which ultimately contribute to allergic inflammation (Mattes et al., 2009; Collison et al., 2011; Sharma et al., 2012). The airborne pollutants such as cigarette smoke, contribute to pulmonary inflammation in rodent models through down-regulation of let-7c and 7f, miR-34b, -34c and miR-222 (Izzotti et al., 2005; Izzotti et al., 2009a; Izzotti et al., 2009b). Research scrutinizing anomalous miRNA depiction in asthmatic patients also showed new miRNAs that give rise to allergic airway infection. In a study, CD4+ T cells have been isolated from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from human patients with asthma and showed that miR-19a had the extreme expression stimulating a cell response mediated through Th2, a known reaction furnishing to allergic asthma (Simpson et al., 2014). In an another study, upregulation of miR-221 and miR-485-3p in peripheral blood of pediatric asthmatic patients indicated that these miRNAs add to the development of asthma (Liu et al., 2012). A chemical allergen murine model on dermal exposure to toluene 2,4-diisocyanate showed increased dermal expressions of miR-21, -22, -27b, -31, -126, -155, -210 and miR-301a. This study showed miRNAs that are known to be related to immune responses with asthmatic host (miR-21, -31, -126, and miR-155), and also proposed new miRNAs as potential biomarkers (miR-22, -27b, -301a, and miR-210) for allergic sensitization to toluene 2, 4-diisocyanate (Anderson et al., 2014).

miRNA regulation on B-cell and T-cell

In the immune system, microRNAs give the impression to have a key role in the stimulation, function and maintenance of the regulatory T-cell lineage, and differentiation of B cells, dendritic cells and macrophages via toll-like receptors. The miR-17/92 cluster is among the broadly studied microRNA clusters, important in cell cycle, proliferation, apoptosis and other crucial processes and is often dysregulated in cardiovascular, immune and neurodegenerative diseases. The miR-17~92 cluster induces immune responses from Th1 type together with impeding regulatory T-cell differentiation (Jiang et al., 2011) and the consequences of overexpression of miR-17~92 are enhanced B-cell proliferation and survival (Xiao et al., 2008). Similarly, miR-181 and miR-150 has also been shown to regulate B-cell differentiation and responses. Ectopic expression of miR-181 has been shown to decrease T-cell numbers as well as substantial increase in CD19+ B-cells (Chen et al., 2004). The miR-150 is generally expressed at low quantity in initial B-cell progenitors and its aberrant expression marks a developmental block at the pro-B to pre-B transition by targeting the transcription factor c-Myb (Xiao et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2007). In B-cell malignancies in humans, miR-155 has been found to be highly expressed that control important aspects of B-cells but not their early differentiation (van den Berg et al., 2003; Metzler et al., 2004). There is also the requirement of miR-155 for regular and active working of B and T lymphocytes, and dendritic cells (Rodriguez et al., 2007).

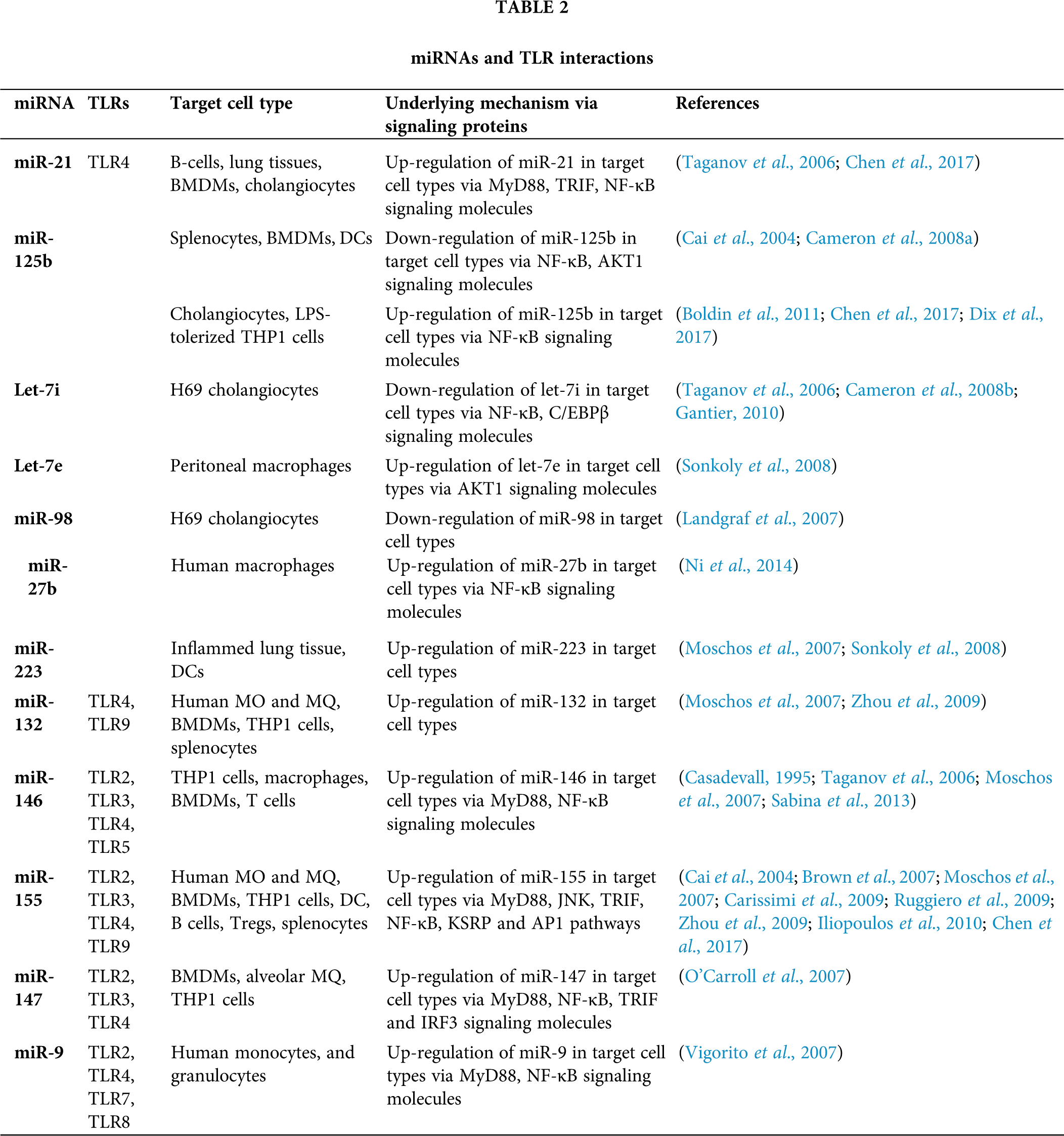

MiRNAs play significant roles in T-cell growth by knocking down of Dicer/Drosha in immature thymocytes that leads to a severe reduction in total thymocytes as well as in peripheral CD4+ numbers (Cobb et al., 2005). Following PAMP-PRR interactions and stimulation of different cytokines, fungal antigens are also presented to TCD4+/TCD8+ (via MHC-TCR interaction) (Fig. 3). Moreover, fungal antigens trigger humoral immune responses through interaction between B and TCD4+ cells and these responses are in two forms: T-dependent and T-independent (Fig. 3). There are several studies suggested the effect of miR-181a, -182, -214, and miR-146a in regulating the T-cell responses (Li et al., 2007; Stittrich et al., 2010; Jindra et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2010; Boldin et al., 2011). The pivotal roles of miR-21, -16, -142-5p, -142-3p, -15b, -150, and let-7 family miRNAs has been studied in manipulating the differentiation of naïve T cells to effector and memory CD8+ T cells (Wu et al., 2007). Also, several studies have indicated the chief roles of miR-21 in the effector CD+ T cells (Asangani et al., 2008; Li et al., 2014; Sonkoly et al., 2008). It is also mentioned that miRNAs also have the same interactions with CD4+ T cells and regulatory T cells (Cobb et al., 2005). A study revealed that mice with miR-155 deficiency were unable to unveil T cell response through dendritic cells signaling onsets (Rodriguez et al., 2007). Since deficit miR-155 did not distress the Th2 profiles, therefore, miR-155 elicits the polarization of Th1 profile and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, considering that (Rodriguez et al., 2007). Additionally, miR-155 activates the polarization of Th17 cell that are the main operators to compel inflammatory responses, and DCs deficient with miR-155, causes lower levels of IL-6 and IL-23 (O’Connell et al., 2010a). Both the thymic and peripheral stimulation of regulatory T cells are enhanced by miRNAs (Lu and Liston, 2009).

Figure 3: Adaptive immune response to the fungal pathogen (Aspergillus) and miRNA interactions. Several miRNAs interact with T-dependent and T-independent processes shown via two-way arrows and these double-ended arrows by green and red indicate up-regulation and down-regulation of miRNAs on target mRNAs, respectively.

Studies indicated the diminution of specific miRNA profiles causes the compromised function of regulatory T cells, which ultimately leads to autoimmunity (Liston et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2008). Also, miR-155 is directly regulated by Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Marson et al., 2007; Zheng et al., 2007). In an animal model of eosinophilic rhinosinusitis, the expression of miR-125b is greater than before that further resulted in amplified interferon IF-γ and a Th1 type immune response (Zhang et al., 2012) and also, miR-125b overexpression persuaded macrophage surface activation (Chaudhuri et al., 2011). MiR-19a has also been critical in modifying Th1 type responses through the production of IF-γ succeeding antigen induction in a mouse model (Jiang et al., 2011).

MiR-19a is a member of miR-17-92 cluster and its up-regulation has been shown to cause increased inflammation and promoted a Th2 type response (Simpson et al., 2014). MiR-106-363 cluster has been found to regulate Th17 cell differentiation (Kästle et al., 2017) and also, Th17 cell-mediated inflammation was induced by miR-326 and miR-21 in an experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (Liston et al., 2008; Murugaiyan et al., 2015).

Toll like receptors (TLRs) have been reported to detect the pathogen invasion and induce either immuno-stimulatory or immune-modulatory biological response (Dwivedi et al., 2011). TLRs perform a fundamental role in the innate immunity by distinguishing pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) expressed on pathogens and signaling for the production of cytokine to excite an immune reaction. These TLRs contribute in macrophage activation and have been shown to persuade miR-155, -146, -147, -9, and -21 (O’Connell et al., 2010b; O’Neill et al., 2011). MicroRNAs administer the TLR signaling by directly targeting specific signaling proteins, mainly MyD88, mAL, IRAK1, IRAK2 and TRAF6 (O’Neill et al., 2011) (Fig. 1). An up-regulation of miR-21 has been noticed in both primary human airway epithelial cells (Lu et al., 2009), and through an IL-13Rα1-dependent mechanism in an IL-13 transgenic mouse model (Case et al., 2011). A study showed that miR-21 expression has inhibited murine pulmonary inflammation by subduing TLR2 signaling (Case et al., 2011). It has also been reported that miR-21 and miR-29a interact with TLR7 and TLR8 on secretion from tumour cells (Chen et al., 2013).

Upon lipopolysaccharide stimulation, miR-146a/b was made known to regulate TLR and cytokine signaling, and TNF and IL-1 through targeting their receptors (Taganov et al., 2006). It has been remarkably specified that miR-146a is a key tuner of TLRs through TRAF6 and IRAK1 signaling pathways and NF-κB (O’Connell et al., 2012; Boldin et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2011) (Fig. 1). The pivotal roles of miR-146 has been studied on diminishing the over elevated levels of inflammatory mediators that were strongly associated with psoriasis, chronic inflammatory disease of skin which is strengthened by Malassezia species (Sonkoly et al., 2007). However, miR-146a decreases the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines during innate immune responses (Boldin et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2011). In TLR signaling, miR-21 is a key player which is induced by MyD88-dependent signaling of NF-κB during TLR4 induction of macrophages and also, accelerates repression of NF-κB signaling in IL-10 dependent manner (O’Connell et al., 2012). Moreover, it has been indicated that TLR signaling and TNF-α lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-triggered mechanism are targeted and modulated by miR-9 and miR-27b (Jennewein et al., 2010). Similarly, TLR-signaling-mediated expression of TNF-α was elicited by miR-125b (Tili et al., 2007). In addition, studies showed that miR-223 was involved in TLR4 and TLR3 expression (Chen et al., 2007), and miR-105 regulated TLR2 mRNA (Benakanakere et al., 2009) (Fig. 1). Further investigation suggested that the gene encoding acetylcholinesterase (AChE) targeted by miR-132 to regulate TLR signaling (O’Connell et al., 2012; Sonkoly et al., 2008; O’Neill et al., 2011) (Tab. 2). Another study showed that miR-106 controlled the expression of IL-10 gene, and the reduced levels of IL-10 triggers added expression of miR-106a and miR-106b (Sharma et al., 2009).

MicroRNAs Profiles Following Aspergillus Exposure

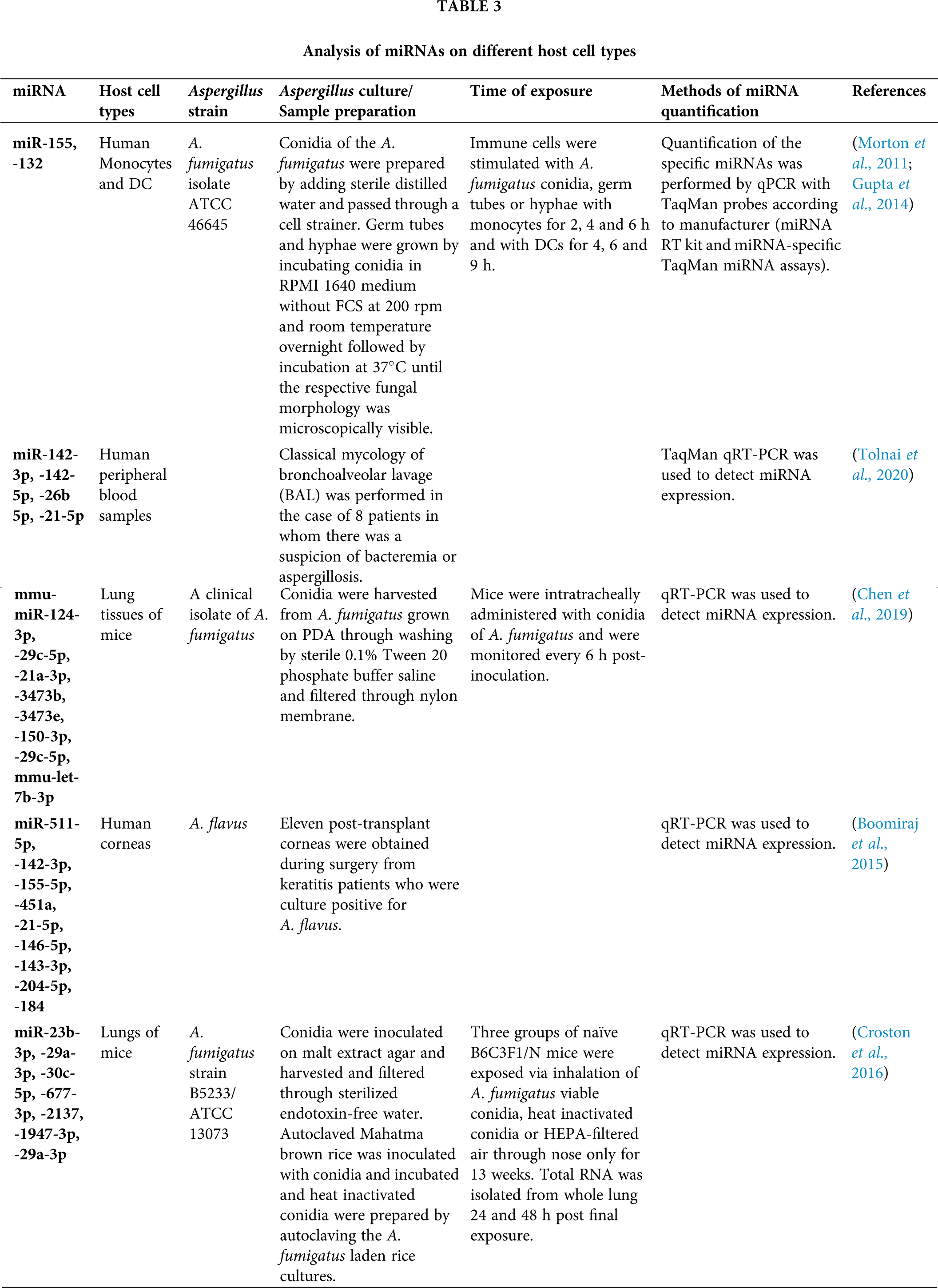

Although the role of miRNA has been explored and established in a number of disorders, their utility in understating the immunological response on pulmonary and systemic exposure to fungus is in nascent state. It has been assumed that fungal pathogen may manipulate the miRNA genetic network signaling and change their expression profiles during the progression of disease. Members of Aspergillus are prominent etiological agents and in the past decades the occurrence of aspergillosis has increased (Ruhnke et al., 2018; Badiee and Hashemizadeh, 2014). MicroRNAs emerged as significant endogenous regulators of almost all basic biological processes. Recent researches have estimated the potential of free circulating miRNAs in diagnostic approaches as biomarkers in extrapolative diseases. During infection, hypoxia related miRNAs, miR-26a, -26b, -21 and -101 were considered when lung hypoxia has been established by an ischemic microenvironment, vascular invasion, thrombosis, antiangiogenic factors such as gliotoxin, that were significantly considered as virulence factor of A. fumigatus (Dix et al., 2017; Saliminejad et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2017). For the investigation of miRNAs role during A. fumigatus infection, a study has been conducted for the analysis of two major miRNAs expression, miR-132 and miR-155 in human monocytes and dendritic cells (Gupta et al., 2014). It was demonstrated that miR-132 and miR-155 were differentially articulated in monocytes and DCs upon induction with A. fumigatus or bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Surprisingly, miR-132 was stimulated by A. fumigatus but not by LPS in both monocytes and DCs and hence, suggested that miR-132 may be a substantial regulator of the immune response focussed against A. fumigatus (Gupta et al., 2014) (Tab. 3).

The immune response against A. fumigatus is dependent on the morphology of fungus that is conidia are covered by hydrophobins that prevent the immune sensing but upon germination, the loss of this rodlet layer leads to the fungal recognition by immune cells (Aimanianda et al., 2009). MiR expression was supported by stimulating monocytes and DCs with different A. fumigatus morphologies (Gupta et al., 2014). Conidia were unable to induce miR-132 expression in both cell types, whereas both germ tubes and hyphae amplified miR-132 levels.

In a study (Tab. 3), a significant association was confirmed between invasive aspergillosis and miRNAs, miR-142-3p, -142-5p, -26b-5p and miR-21-5p (Tolnai et al., 2020). A research identified 23 miRNAs that were associated with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA), a severe opportunistic infection caused by A. fumigatus with high mortality in patients with compromised immunity (Chen et al., 2019). IPA-related miRNAs encompassed upregulated mmu-miR-124-3p, mmu-let-7b-3p, mmu-miR-29c-5p, mmu-miR-21a-3p, mmu-miR-3473b and mmu-miR-3473e, and downregulated mmu-miR-150-3p and mmu-miR29c-5p (Chen et al., 2019) (Tab. 3). As per miRNA target prediction, all IPA-associated miRNAs possibly involve a cooperative regulation of main elements in the NF-κB signaling pathway.

Boomiraj et al. (2015) investigated the miRNA expression profiles and their immune regulatory roles in fungal keratitis caused by A. flavus. They collected the corneas from normal donors and 11 post-transplant patients suffering from fungal keratitis, and evaluated and identified the miRNAs/mRNA expression levels with their targets and regulatory roles by applying real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) followed by bioinformatics analysis. They showed that 43 miRNAs were found to be up-regulated (miR-21-5p, -146b-5p, -143-3p, -204-5p and miR-184 were highly expressed) and 32 miRNAs were down-regulated (miR-142-3p, -155-5p, -511-5p, and miR-451a were the most down-regulated) (Tab. 3).

It was predicted that miR-451a as a potential factor in would healing via regulating macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) gene, and suppressing inflammation by triggering TLR pathway (Gilliver et al., 2010). Also, two novel miRNAs, miR-cornea-5p and miR-cornea-3p were suggested to play major roles in disease pathogenesis by A. flavus.

The interactions between immune responses and pulmonary miRNA, mRNA profiles and some prominent signaling pathways in mice were evaluated by Croston et al. (Croston et al., 2016) after 24 and 48 h of exposure to different forms of inhaled A. fumigatus conidia, particularly viable and heat-inactivated conidia (HIC) (Tab. 3).

Approximately, 50% of all 415 identified miRNAs were controlled following viable and HIC forms of conidia. They observed that six miRNAs (miR-23b-3p, -29a-3p, -30c-5p, -677-3p, -2137 and miR-1947-3p) had prevalent fold change, and miR-29a-3p was down-regulated that may play significant roles in shaping innate responses via regulating TGF-β3, Clec7a and IFN-β genes. Also, miR-23b-3p was observed to be down-regulated and involved in fine-tuning of TGF-β by regulating SMAD2 signaling pathway, IL-13 and IL-33. On the other hand, miR-1947-3p and miR-2137 were involved in triggering chemokine or TCR signaling. Hence, they established that these down-regulated miRNAs played major roles in pulmonary inflammatory response to inhaled conidia.

Application of immunotherapy of fungal infections has recently been the foremost subject in treating invasive fungal infections (IFIs) through various methods, such as cytokine therapy including CSF and IFN-γ, monoclonal antibody therapy, vaccines, ligand therapy via pattern recognition receptor (PRR) agonists, and positioning DCs as critical modulators of immune tolerance. Immune regulation is considered one of the chief approaches in order to control IFIs, therefore, better understanding of interactions between miRNA and immune responses to fungal pathogens is required. This might lead to attain new methods in miRNA-mediated immunotherapeutic against fungal infections, especially pathogenic and ubiquitous fungus such as Aspergillus, and also facilitate their application as biomarkers of specific phases of infection establishment and progression.

According to the potential regulatory roles of miR-155, miR-132, miR-142-5p, miR-142-3p, miR-21-5p, miR-26b-5p, miR-21, let-7 family, and miR-451a on exposure to Aspergillus particles, they can be applied as therapeutics in order to manipulate the immune players to optimize the immune responses against Aspergillus infection. When compared with available datasets probing miRNA profiles in allergic and inflammatory models infected on exposure of Aspergillus, some common differentially expressed miRNAs were recognized. Among these the purpose of miR-132 is to uphold a normal hematopoietic output during an immune reaction and normalizes genes at the commencement of an immune response to recover homeostasis of the immune system.

Another miRNA such as miR-155 induces both Th1 and Th17 immune reactions and persuades classical activation of macrophages. The investigations directed towards miRNA biology have highlighted the curiosity of research community in scrutinizing the transformed genetic profiles in different disease models (Pakshir et al., 2020). The functionality of miRNA in governing diverse gene expression makes miRNA an ideal candidate for therapeutic applications, however, there only a few studies available that have scrutinized miRNA profiles following fungal exposure especially Aspergillus. Also, few data examined that the miRNA expression is transformed in various human diseases and its discriminating modulation through antisense inhibition (Fabani et al., 2010) or replacement (Bader et al., 2010; Bader, 2012) could ominously distress the prognosis of a disease. Although, there are some major challenges ahead in investigating miRNAs profiles such as multiple roles and functions of miRNA molecule leads to no selective and specific target for miRNAs. Also, the efficiency of a miRNA molecule is dose-dependent that is the effect of a miRNA molecule depends on the target mRNA level and its final product. Herein, involvement of miRNAs in the various immunological responses, and their importance and efficiency in fine-tuning the immunity to Aspergillus were discussed. Despite being hot spots in governing the immune responses by miRNAs against fungal pathogens, little studies have been done in this regard. More understanding and exploration is necessary about miRNAs interactions with immune responses and their therapeutic potential as an immunotherapy. Further investigation of miRNA profiles is required to provide greater mechanistic vision into the immunological response to clinically and environmentally relevant fungal species, and establish a treatment approach by conducting further studies. With the growing research, miRNA will have a bright future and become an innovative therapeutic tool.

Acknowledgement: Authors are thankful to Innovation Centre, Bundelkhand University, Jhansi, India for providing necessary facility.

Author Contribution: The author confirms contribution to the review article as follows: study conception and design: Rambir Singh, Mansi Shrivastava; data collection: Mansi Shrivastava, Diksha Pandey; draft manuscript preparation: Poonam Sharma, Mansi Shrivastava. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Aimanianda V, Bayry J, Bozza S, Kniemeyer O, Perruccio K et al. (2009). Surface hydrophobin prevents immune recognition of airborne fungal spores. Nature 460: 1117–1121. DOI 10.1038/nature08264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Amin S, Thywissen A, Heinekamp T, Saluz HP, Brakhage AA (2014). Melanin dependent survival of Apergillus fumigatus conidia in lung epithelial cells. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 304: 626–636. DOI 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.04.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Anderson SE, Beezhold K, Lukomska E, Richardson J, Long C et al. (2013). Expression kinetics of miRNA involved in dermal toluene 2,4-diisocyanate sensitization. Journal of Immunotoxicology 11: 250–259. DOI 10.3109/1547691X.2013.835891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Androulidaki A, Iliopoulos D, Arranz A, Doxaki C, Schworer S et al. (2009). The kinase Akt1 controls macrophage response to lipopolysaccharide by regulating MicroRNAs. Immunity 31: 220–231. DOI 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Antachopoulos C, Roilides E (2005). Cytokines and fungal infections. British Journal of Haematology 129: 583–596. DOI 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05498.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Arroyo JD, Chevillet JR, Kroh EM, Ruf IK, Pritchard CC et al. (2011). Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108: 5003–5008. DOI 10.1073/pnas.1019055108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Asangani IA, Rasheed SAK, Nikolova DA, Leupold JH, Colburn NH et al. (2008). MicroRNA-21 (miR-21) post-transcriptionally downregulates tumor suppressor Pdcd4 and stimulates invasion, intravasation and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Oncogene 27: 2128–2136. DOI 10.1038/sj.onc.1210856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bader AG (2012). miR-34-a microRNA replacement therapy is headed to the clinic. Frontiers in Genetics 3: 120–128. DOI 10.3389/fgene.2012.00120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bader AG, Brown D, Winkler M (2010). The promise of MicroRNA replacement therapy. Cancer Research 70: 7027–7030. DOI 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Badiee P, Hashemizadeh Z (2014). Opportunistic invasive fungal infections: Diagnosis & clinical management. Indian Journal of Medical Research 139: 195–204. [Google Scholar]

Baek D, Villen J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP et al. (2008). The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature 455: 64–71. DOI 10.1038/nature07242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bajwa SJ, Kulshrestha A (2013). Fungal infections in intensive care unit: Challenges in diagnosis and management. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research 3: 238–244. DOI 10.4103/2141-9248.113669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Barbato C, Arisi I, Frizzo ME, Brandi R, Da Sacco L, Masotti A. (2009). Computational challenges in miRNA target predictions: To be or not to be a true target? Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology 2009: 1–9. DOI 10.1155/2009/803069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bartel DP (2009). MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136: 215–233. DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bayry J, Beaussart A, Dufrêne YF, Sharma M, Bansal K et al. (2014). Surface structure characterization of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia mutated in the melanin synthesis pathway and their human cellular immune response. Infection and Immunity 82: 3141–3153. DOI 10.1128/IAI.01726-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Becker KL, Aimanianda V, Wang X, Gresnigt MS, Ammerdorffer A et al. (2016). Aspergillus cell wall chitin induces anti- and proinflammatory cytokines in human PBMCs via the Fc-gamma receptor/Syk/PI3K pathway. mBio 7: e01823. DOI 10.1128/mBio.01823-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Benakanakere MR, Li Q, Eskan MA, Singh AV, Zhao J et al. (2009). Modulation of TLR2 protein expression by miR-105 in human oral keratinocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry 284: 23107–23115. DOI 10.1074/jbc.M109.013862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Blanchard C, Rothenberg ME (2008). Basic pathogenesis of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America 18: 133–143. DOI 10.1016/j.giec.2007.09.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Boguniewicz M, Leung DYM (2011). Atopic dermatitis: A disease of altered skin barrier and immune dysregulation. Immunological Reviews 242: 233–246. DOI 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01027.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Boldin MP, Taganov KD, Rao DS, Yang L, Zhao JL et al. (2011). miR-146a is a significant brake on autoimmunity, myeloproliferation, and cancer in mice. Journal of Experimental Medicine 208: 1189–1201. DOI 10.1084/jem.20101823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Boomiraj H, Mohankumar V, Lalitha P, Devarajan B (2015). Human corneal microRNA expression profile in fungal keratitis. Investigative Opthalmology and Visual Science 56: 7939–7946. DOI 10.1167/iovs.15-17619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Brennan E, Wang B, McClelland A, Mohan M, Marai M et al. (2017). Protective effect of let-7 miRNA family in regulating inflammation in diabetes-associated atherosclerosis. Diabetes 66: 2266–2277. DOI 10.2337/db16-1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Broide DH (2008). Immunologic and inflammatory mechanisms that drive asthma progression to remodeling. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 121: 560–570. DOI 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.01.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Brown BD, Gentner B, Cantore A, Colleoni S, Amendola M et al. (2007). Endogenous microRNA can be broadly exploited to regulate transgene expression according to tissue, lineage and differentiation state. Nature Biotechnology 25: 1457–1467. DOI 10.1038/nbt1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NAR, Levitz SM, Netea MG et al. (2012). Hidden killers: Human fungal infections. Science Translational Medicine 4: 165rv13. DOI 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cai X, Hagedorn CH, Cullen BR (2004). Human microRNAs are processed from capped, polyadenylated transcripts that can also function as mRNAs. RNA 10: 1957–1966. DOI 10.1261/rna.7135204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cameron JE, Fewell C, Yin Q, McBride J, Wang X et al. (2008a). Epstein-Barr virus growth/latency III program alters cellular microRNA expression. Virology 382: 257–266. DOI 10.1016/j.virol.2008.09.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cameron JE, Yin Q, Fewell C, Lacey M, McBride J et al. (2008b). Epstein-barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces cellular MicroRNA miR-146a, a modulator of lymphocyte signaling pathways. Journal of Virology 82: 1946–1958. DOI 10.1128/JVI.02136-07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Carissimi C, Fulci V, Macino G (2009). MicroRNAs: Novel regulators of immunity. Autoimmunity Reviews 8: 520–524. DOI 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.01.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Casadevall A (1995). Antibody immunity and invasive fungal infections. Infection and Immunity 63: 4211–4218. DOI 10.1128/iai.63.11.4211-4218.1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Casadevall A, Feldmesser M, Pirofski LA (2002). Induced humoral immunity and vaccination against major human fungal pathogens. Current Opinion in Microbiology 5: 386–391. DOI 10.1016/S1369-5274(02)00337-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Case SR, Martin RJ, Jiang D, Minor MN, Chu HW (2011). MicroRNA-21 inhibits toll-like receptor 2 agonist-induced lung inflammation in mice. Experimental Lung Research 37: 500–508. DOI 10.3109/01902148.2011.596895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chaudhuri AA, So AYL, Sinha N, Gibson WSJ, Taganov KD et al. (2011). MiR-125b potentiates macrophage activation. Journal of Immunology 187: 5062–5068. DOI 10.4049/jimmunol.1102001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP (2004). MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science 303: 83–86. DOI 10.1126/science.1091903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen F, Xu X, Zhang M, Chen C, Shao H, Shi Y (2019). Deep sequencing profiles MicroRNAs related to Aspergillus fumigatus infection in lung tissues of mice. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection 52: 90–99. DOI 10.1016/j.jmii.2016.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen H, Jin Y, Chen H, Liao I, Yan W, Chen J (2017). MicroRNA-mediated inflammatory responses induced by Cryptococcus neoformans are dependent on the NF-κB pathway in human monocytes. International Journal of Molecular Medicine 39: 1525–1532. DOI 10.3892/ijmm.2017.2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen X, Ba Y, Ma L, Cai X, Yin Y et al. (2008). Characterization of microRNAs in serum: A novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Research 18: 997–1006. DOI 10.1038/cr.2008.282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen X, Liang H, Zhang J, Zen K, Zhang CY (2013). microRNAs are ligands of Toll-like receptors. RNA 19: 737–739. DOI 10.1261/rna.036319.112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen XM, Splinter PL, O’Hara SP, LaRusso NF (2007). A cellular micro-RNA, let-7i, regulates toll-like receptor 4 expression and contributes to cholangiocyte immune responses against Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Journal of Biological Chemistry 282: 28929–28938. DOI 10.1074/jbc.M702633200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cobb BS, Hertweck A, Smith J, O’Connor E, Graf D et al. (2006). A role for Dicer in immune regulation. Journal of Experimental Medicine 203: 2519–2527. DOI 10.1084/jem.20061692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cobb BS, Nesterova TB, Thompson E, Hertweck A, O’Connor E et al. (2005). T cell lineage choice and differentiation in the absence of the RNase III enzyme Dicer. Journal of Experimental Medicine 201: 1367–1373. DOI 10.1084/jem.20050572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Collison A, Mattes J, Plank M, Foster PS (2011). Inhibition of house dust mite-induced allergic airways disease by antagonism of microRNA-145 is comparable to glucocorticoid treatment. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 128: 160–167.e4. DOI 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cornely OA, Lass-Flörl C, Lagrou K, Arsic-Arsenijevic V, Hoenigl M (2017). Improving outcome of fungal diseases–Guiding experts and patients towards excellence. Mycoses 60: 420–425. DOI 10.1111/myc.12628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Crameri R, Zeller S, Glaser AG, Vilhelmsson M, Rhyner C (2009). Cross-reactivity among fungal allergens: A clinically relevant phenomenon? Mycoses 52: 99–106. DOI 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01644.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Croston TL, Nayak AP, Lemons AR, Goldsmith WT, Gu JK et al. (2016). Influence of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia viability on murine pulmonary microRNA and mRNA expression following subchronic inhalation exposure. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 46: 1315–1327. DOI 10.1111/cea.12783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Datta K, Hamad M (2015). Immunotherapy of fungal infections. Immunological Investigations 44: 738–776. DOI 10.3109/08820139.2015.1093913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Denning DW, Pleuvry A, Cole DC (2013). Global burden of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with asthma and its complication chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in adults. Medical Mycology 51: 361–370. DOI 10.3109/13693786.2012.738312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dix A, Czakai K, Leonhardt I, Schäferhoff K, Bonin M et al. (2017). Specific and novel microRNAs are regulated as response to fungal infection in human dendritic cells. Frontiers in Microbiology 8: 5645. DOI 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dwivedi L, Singh DD, Singh R (2011). Toll like receptors: The immunomodulatory agents and novel target of immunotherapeutic research. International Journal of Current Research and Review 03: 19–27. [Google Scholar]

Eduard W (2009). Fungal spores: A critical review of the toxicological and epidemiological evidence as a basis for occupational exposure limit setting. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 39: 799–864. DOI 10.3109/10408440903307333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Enoch DA, Yang H, Aliyu SH, Micallef C (2017). The changing epidemiology of invasive fungal infections. Human Fungal Pathogen Identication 1508: 17–65. DOI 10.1007/978-1-4939-6515-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Esteller M (2011). Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nature Reviews Genetics 12: 861–874. DOI 10.1038/nrg3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fabani MM, Abreu-Goodger C, Williams D, Lyons PA, Torres AG et al. (2010). Efficient inhibition of miR-155 function in vivo by peptide nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Research 38: 4466–4475. DOI 10.1093/nar/gkq160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fabian MR, Sonenberg N, Filipowicz W (2010). Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annual Review of Biochemistry 79: 351–379. DOI 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060308-103103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Feng YH, Tsao CJ (2016). Emerging role of microRNA-21 in cancer (Review). Biomedical Reports 5: 395–402. DOI 10.3892/br.2016.747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Feng Z, Zhang C, Wu R, Hu W (2011). Tumor suppressor p53 meets microRNAs. Journal of Molecular Cell Biology 3: 44–50. DOI 10.1093/jmcb/mjq040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N (2008). Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: Are the answers in sight? Nature Reviews Genetics 9: 102–114. DOI 10.1038/nrg2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fontaine T, Delangle A, Simenel C, Coddeville B, van Vliet SJ et al. (2011). Galactosaminogalactan, a new immunosuppressive polysaccharide of Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathogens 7: e1002372. DOI 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Foster PS, Plank M, Collison A, Tay HL, Kaiko GE et al. (2013). The emerging role of microRNAs in regulating immune and inflammatory responses in the lung. Immunological Reviews 253: 198–215. DOI 10.1111/imr.12058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Friedman RC, Farh KKH, Burge CB, Bartel DP (2008). Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Research 19: 92–105. DOI 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Frost RJA, Olson EN (2011). Control of glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity by the Let-7 family of microRNAs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108: 21075–21080. DOI 10.1073/pnas.1118922109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fu G, Brkić J, Hayder H, Peng C (2013). MicroRNAs in human placental development and pregnancy complications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14: 5519–5544. DOI 10.3390/ijms14035519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gallo A, Tandon M, Alevizos I, Illei GG (2012). The majority of microRNAs detectable in serum and saliva is concentrated in exosomes. PLoS One 7: e30679. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0030679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gantier MP (2010). New perspectives in MicroRNA regulation of innate immunity. Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research 30: 283–289. DOI 10.1089/jir.2010.0037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gantier MP, Sadler AJ, Williams BRG (2007). Fine-tuning of the innate immune response by microRNAs. Immunology & Cell Biology 85: 458–462. DOI 10.1038/sj.icb.7100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Garcia-Rubio R, Cuenca-Estrella M, Mellado E (2017). Triazole resistance in aspergillus species: An emerging problem. Drugs 77: 599–613. DOI 10.1007/s40265-017-0714-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gelfand EW (2004). Inflammatory mediators in allergic rhinitis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 114: S135–S138. DOI 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.08.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gilliver SC, Emmerson E, Bernhagen J, Hardman MJ (2011). MIF: A key player in cutaneous biology and wound healing. Experimental Dermatology 20: 1–6. DOI 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01194.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Goncalves SS, Carolina A, Souza R, Chowdhary A, Meis JF et al. (2016). Epidemiology and molecular mechanisms of antifungal resistance in Candida and Aspergillus. Mycoses 59: 198–219. DOI 10.1111/myc.12469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Goodridge HS, Wolf AJ, Underhill DM (2009). B2;-glucan recognition by the innate immune system. Immunological Reviews 230: 38–50. DOI 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00793.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gow NAR, Latge JP, Munro CA (2017). The fungal cell wall: Structure, Biosynthesis, and Function. Fungal Kingdom 5: 267–292. DOI 10.1128/9781555819583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gravelat FN, Beauvais A, Liu H, Lee MJ, Snarr BD et al. (2013). Aspergillus galactosaminogalactan mediates adherence to host constituents and conceals hyphal β-glucan from the immune system. PLoS Pathogens 9: e1003575. DOI 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gresnigt MS, Bozza S, Becker KL, Joosten LAB, Abdollahi-Roodsaz S et al. (2014). A polysaccharide virulence factor from aspergillus fumigatus elicits anti-inflammatory effects through induction of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. PLoS Pathogens 10: e1003936. DOI 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gupta MD, Fliesser M, Springer J, Breitschopf T, Schlossnagel H et al. (2014). Aspergillus fumigatus induces microRNA-132 in human monocytes and dendritic cells. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 304: 592–596. DOI 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.04.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hackl M, Brunner S, Fortschegger K, Schreiner C, Micutkova L et al. (2010). miR-20a, and miR-106a are down-regulated in human aging. Aging Cell 9: 291–296. DOI 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00549.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hammond SM (2015). An overview of microRNAs. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 87: 3–14. DOI 10.1016/j.addr.2015.05.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hardin B, Kelman B, Saxon A (2003). Adverse human health effects associated with molds in the indoor environment. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 45: 470–478. DOI 10.1097/00043764-200305000-00006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M (2008). Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses 51: 2–15. DOI 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01606.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hawksworth DL (2001). The magnitude of fungal diversity: The 1.5 million species estimate revisited. Mycological Research 105: 1422–1432. DOI 10.1017/S0953756201004725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

He L, Hannon GJ (2004). MicroRNAs: Small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nature Reviews Genetics 5: 522–531. DOI 10.1038/nrg1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Struhl K (2009). An epigenetic switch involving NF-κB, Lin28, let-7 microRNA, and IL6 links inflammation to cell transformation. Cell 139: 693–706. DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Iorio MV, Piovan C, Croce CM (2010). Interplay between microRNAs and the epigenetic machinery: An intricate network. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 1799: 694–701. DOI 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.05.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Izzotti A, Bagnasco M, Cartiglia C, Longobardi M, Balansky RM et al. (2005). Chemoprevention of genome, transcriptome, and proteome alterations induced by cigarette smoke in rat lung. European Journal of Cancer 41: 1864–1874. DOI 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.04.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Izzotti A, Calin GA, Arrigo P, Steele VE, Croce CM et al. (2009a). Downregulation of microRNA expression in the lungs of rats exposed to cigarette smoke. FASEB Journal 23: 806–812. DOI 10.1096/fj.08-121384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Izzotti A, Calin GA, Steele VE, Croce CM, de Flora S (2009b). Relationships of microRNA expression in mouse lung with age and exposure to cigarette smoke and light. FASEB Journal 23: 3243–3250. DOI 10.1096/fj.09-135251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Janowski BA, Younger ST, Hardy DB, Ram R, Huffman KE et al. (2007). Activating gene expression in mammalian cells with promoter-targeted duplex RNAs. Nature Chemical Biology 3: 166–173. DOI 10.1038/nchembio860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jennewein C, von Knethen A, Schmid T, Brüne B (2010). MicroRNA-27b contributes to lipopolysaccharide-mediated peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) mRNA destabilization. Journal of Biological Chemistry 285: 11846–11853. DOI 10.1074/jbc.M109.066399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jiang S, Li C, Olive V, Lykken E, Feng F et al. (2011). Molecular dissection of the miR-17-92 cluster’s critical dual roles in promoting Th1 responses and preventing inducible Treg differentiation. Blood 118: 5487–5497. DOI 10.1182/blood-2011-05-355644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jindra PT, Bagley J, Godwin JG, Iacomini J (2010). Costimulation-dependent expression of MicroRNA-214 increases the ability of T cells to proliferate by targeting Pten. Journal of Immunology 185: 990–997. DOI 10.4049/jimmunol.1000793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jun-Hao ET, Gupta RR, Shyh-Chang N (2016). Lin28 and let-7 in the metabolic physiology of aging. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 27: 132–141. DOI 10.1016/j.tem.2015.12.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kästle M, Bartel S, Geillinger-Kästle K, Irmler M, Beckers J et al. (2017). microRNA cluster 106a~363 is involved in T helper 17 cell differentiation. Immunology 152: 402–413. DOI 10.1111/imm.12775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kawai T, Akira S (2011). Toll-like receptors and their crosstalk with other innate receptors in infection and immunity. Immunity 34: 637–650. DOI 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kim DH, Sætrom P, Snøve O, Rossi JJ (2008). MicroRNA-directed transcriptional gene silencing in mammalian cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105: 16230–16235. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0808830105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Krek A, Grün D, Poy MN, Wolf R, Rosenberg L et al. (2005). Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nature Genetics 37: 495–500. DOI 10.1038/ng1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lagos D, Pollara G, Henderson S, Gratrix F, Fabani M et al. (2010). miR-132 regulates antiviral innate immunity through suppression of the p300 transcriptional co-activator. Nature Cell Biology 12: 513–519. DOI 10.1038/ncb2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Landgraf P, Rusu M, Sheridan R, Sewer A, Iovino N et al. (2007). A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell 129: 1401–1414. DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Latgé JP (1999). Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 12: 310–350. DOI 10.1128/CMR.12.2.310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lee MJ, Sheppard DC (2016). Recent advances in the understanding of the Aspergillus fumigatus cell wall. Journal of Microbiology 54: 232–242. DOI 10.1007/s12275-016-6045-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, Yeom KH, Lee S et al. (2004). MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO Journal 23: 4051–4060. DOI 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Leopold JA, Maron BA (2016). Molecular mechanisms of pulmonary vascular remodeling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17: 761–774. DOI 10.3390/ijms17050761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li L, Zhu D, Huang L, Zhang J, Bian Z et al. (2012). Argonaute 2 complexes selectively protect the circulating MicroRNAs in cell-secreted microvesicles. PLoS One 7: e46957. [Google Scholar]

Li LC, Okino ST, Zhao H, Pookot D, Place RF et al. (2006). Small dsRNAs induce transcriptional activation in human cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103: 17337–17342. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0607015103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li QJ, Chau J, Ebert PJR, Sylvester G, Min H et al. (2007). miR-181a is an intrinsic modulator of T cell sensitivity and selection. Cell 129: 147–161. DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li X, Xin S, He Z, Che X, Wang J et al. (2014). MicroRNA-21 (miR-21) post-transcriptionally downregulates tumor suppressor PDCD4 and promotes cell transformation, proliferation, and metastasis in renal cell carcinoma. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 33: 1631–1642. DOI 10.1159/000362946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lien MY, Chou CH, Lin CC, Bai LY, Chiu CF et al. (2018). Epidemiology and risk factors for invasive fungal infections during induction chemotherapy for newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One 13: e0197851. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0197851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liston A, Lu LF, O’Carroll D, Tarakhovsky A, Rudensky AY (2008). Dicer-dependent microRNA pathway safeguards regulatory T cell function. Journal of Experimental Medicine 205: 1993–2004. DOI 10.1084/jem.20081062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu F, Qin HB, Xu B, Zhou H, Zhao DY (2012). Profiling of miRNAs in pediatric asthma: Upregulation of miRNA-221 and miRNA-485-3p. Molecular Medicine Reports 6: 1178–1182. DOI 10.3892/mmr.2012.1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Loures FV, Röhm M, Lee CK, Santos E, Wang JP et al. (2015). Recognition of aspergillus fumigatus hyphae by human plasmacytoid dendritic cells is mediated by Dectin-2 and results in formation of extracellular traps. PLoS Pathogens 11: e1004643. DOI 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lu LF, Liston A (2009). MicroRNA in the immune system, microRNA as an immune system. Immunology 127: 291–298. DOI 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03092.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lu LF, Boldin MP, Chaudhry A, Lin LL, Taganov KD et al. (2010). Function of miR-146a in controlling treg cell-mediated regulation of Th1 responses. Cell 142: 914–929. DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lu S, Mukkada VA, Mangray S, Cleveland K, Shillingford N et al. (2012a). MicroRNA profiling in mucosal biopsies of eosinophilic esophagitis patients pre and post treatment with steroids and relationship with mRNA targets. PLoS One 7: e40676. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0040676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lu TX, Rothenberg ME (2013). Diagnostic, functional and therapeutic roles of MicroRNA in allergic diseases. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 132: 3–13. DOI 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lu TX, Lim E-J, Besse JA, Itskovich S, Plassard AJ et al. (2013a). MiR-223 deficiency increases eosinophil progenitor proliferation. Journal of Immunology 190: 1576–1582. DOI 10.4049/jimmunol.1202897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lu TX, Lim EJ, Itskovich S, Besse JA, Plassard AJ et al. (2013b). Targeted ablation of miR-21 decreases murine eosinophil progenitor cell growth. PLoS One 8: e59397. DOI 10.1317/journal.pone.0059397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lu TX, Lim EJ, Wen T, Plassard AJ, Martin LJ et al. (2012b). MiR-375 is down-regulated in epithelial cells after IL-13 stimulation and regulates an IL-13 induced epithelial transcriptome. Mucosal Immunology 5: 388–396. DOI 10.1038/mi.2012.16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lu TX, Munitz A, Rothenberg ME (2009). MicroRNA-21 is up-regulated in allergic airway inflammation and regulates IL-12p35 expression. Journal of Immunology 182: 4994–5002. DOI 10.4049/jimmunol.0803560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lu TX, Sherrill JD, Wen T, Plassard AJ, Besse JA et al. (2012c). MicroRNA signature in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, reversibility with glucocorticoids, and assessment as disease biomarkers. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 129: 1064–1075.e9. DOI 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ma F, Liu X, Li D, Wang P, Li N et al. (2010). MicroRNA-466l upregulates IL-10 expression in TLR-triggered macrophages by antagonizing RNA-binding protein Tristetraprolin-mediated IL-10 mRNA degradation. Journal of Immunology 184: 6053–6059. DOI 10.4049/jimmunol.0902308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Maddox L, Schwartz DA (2002). The Pathophysiology of Asthma. Annual Reviews of Medicine 53: 477–498. DOI 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.103921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Marioto DTG, Dos Santos Ferraro ACN, De Andrade FG, Oliveira MB, Itano EN et al. (2017). Study of differential expression of miRNAs in lung tissue of mice submitted to experimental infection by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. Medical Mycology 55: 774–784. DOI 10.1093/mmy/myw135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Marr KA, Patterson T, Denning D (2002). Aspergillosis pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and therapy. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America 16: 875–894. DOI 10.1016/S0891-5520(02)00035-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Marson A, Kretschmer K, Frampton GM, Jacobsen ES, Polansky JK et al. (2007). Foxp3 occupancy and regulation of key target genes during T-cell stimulation. Nature 445: 931–935. DOI 10.1038/nature05478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mattes J, Collison A, Plank M, Phipps S, Foster PS (2009). Antagonism of microRNA-126 suppresses the effector function of T H2 cells and the development of allergic airways disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106: 18704–18709. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0905063106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mehta A, Baltimore D (2016). MicroRNAs as regulatory elements in immune system logic. Nature Reviews Immunology 16: 279–294. DOI 10.1038/nri.2016.40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Metzler M, Wilda M, Busch K, Viehmann S, Borkhardt A (2004). High expression of precursor MicroRNA-155/BIC RNA in children with Burkitt Lymphoma. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer 39: 167–169. DOI 10.1002/(ISSN)1098-2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Morton CO, Varga JJ, Hornbach A, Mezger M, Sennefelder H et al. (2011). The temporal dynamics of differential gene expression in sspergillus fumigatus interacting with human immature dendritic cells in vitro. PLoS One 6: e16016. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0016016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Moschos SA, Williams AE, Perry MM, Birrell MA, Belvisi MG et al. (2007). Expression profiling in vivo demonstrates rapid changes in lung microRNA levels following lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation but not in the anti-inflammatory action of glucocorticoids. BMC Genomics 8: 240. DOI 10.1186/1471-2164-8-240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Muljo SA, Mark Ansel K, Kanellopoulou C, Livingston DM, Rao A et al. (2005). Aberrant T cell differentiation in the absence of Dicer. Journal of Experimental Medicine 202: 261–269. DOI 10.1084/jem.20050678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Murugaiyan G, da Cunha AP, Ajay AK, Joller N, Garo LP et al. (2015). MicroRNA-21 promotes Th17 differentiation and mediates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of Clinical Investigation 125: 1069–1080. DOI 10.1172/JCI74347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nami S, Mohammadi R, Vakili M, Khezripour K, Mirzaei H et al. (2019). Fungal vaccines, mechanism of actions and immunology: A comprehensive review. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 109: 333–344. DOI 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Netea MG, Brown GD, Kullberg BJ, Gow NAR (2008). An integrated model of the recognition of Candida albicans by the innate immune system. Nature Reviews Microbiology 6: 67–78. DOI 10.1038/nrmicro1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ni B, Rajaram MVS, Lafuse WP, Landes MB, Schlesinger LS (2014). Mycobacterium tuberculosis Decreases Human Macrophage IFN-γ responsiveness through miR-132 and miR-26a. Journal of Immunology 193: 4537–4547. DOI 10.4049/jimmunol.1400124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

O’Brien J, Hayder H, Zayed Y, Peng C (2018). Overview of microRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and circulation. Frontiers in Endocrinology 9: 843. DOI 10.3389/fendo.2018.00402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

O’Carroll D, Mecklenbrauker I, Das PP, Santana A, Koenig U et al. (2007). A Slicer-independent role for Argonaute 2 in hematopoiesis and the microRNA pathway. Genes and Development 21: 1999–2004. DOI 10.1101/gad.1565607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

O’Connell RM, Kahn D, Gibson WSJ, Round JL, Scholz RL et al. (2010a). MicroRNA-155 promotes autoimmune inflammation by enhancing inflammatory T cell development. Immunity 33: 607–619. DOI 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

O’Connell RM, Rao DS, Baltimore D (2012). MicroRNA regulation of inflammatory responses. Annual Review of Immunology 30: 295–312. DOI 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

O’Connell RM, Rao DS, Chaudhuri AA, Baltimore D (2010b). Physiological and pathological roles for microRNAs in the immune system. Nature Reviews Immunology 10: 111–122. DOI 10.1038/nri2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

O’Connell RM, Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Cheng G, Baltimore D (2007). MicroRNA-155 is induced during the macrophage inflammatory response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104: 1604–1609. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0610731104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

O’Neill LA, Sheedy FJ, McCoy CE (2011). MicroRNAs: the fine-tuners of Toll-like receptor signalling. Nature Reviews Immunology 11: 163–175. DOI 10.1038/nri2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pakshir K, Badali H, Nami S, Mirzaei H, Ebrahimzadeh V et al. (2020). Interactions between immune response to fungal infection and MicroRNAs; the pioneer tuners. Mycoses 63: 4–20. DOI 10.1111/myc.13017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pal AS, Kasinski AL (2017). Animal models to study microRNA function. Advances in Cancer Research 135: 53–118. DOI 10.1016/bs.acr.2017.06.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pasquinelli AE, Reinhart BJ, Slack F, Martindale MQ, Kuroda MI et al. (2000). Conservation of the sequence and temporal expression of let-7 heterochronic regulatory RNA. Nature 408: 86–89. DOI 10.1038/35040556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pillai V, Ortega SB, Wang C, Karandikar NJ (2007). Transient regulatory T-cells: A state attained by all activated human T-cells. Clinical Immunology 123: 18–29. DOI 10.1016/j.clim.2006.10.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Place RF, Li LC, Pookot D, Noonan EJ, Dahiya R (2008). MicroRNA-373 induces expression of genes with complementary promoter sequences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105: 1608–1613. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0707594105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Posch W, Heimdörfer D, Wilflingseder D, Lass-Flörl C (2017). Invasive candidiasis: Future directions in non-culture based diagnosis. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy 15: 829–838. DOI 10.1080/14787210.2017.1370373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rajewsky N (2006). microRNA target predictions in animals. Nature Genetics 38: S8–S13. DOI 10.1038/ng1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rambach G, Blum G, Latge JP, Fontaine T, Heinekamp T et al. (2015). Identification of Aspergillus fumigatus surface components that mediate interaction of conidia and hyphae with human platelets. Journal of Infectious Diseases 212: 1140–1149. DOI 10.1093/infdis/jiv191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Robinet P, Baychelier F, Fontaine T, Picard C, Debré P et al. (2014). A polysaccharide virulence factor of a human fungal pathogen induces neutrophil apoptosis via NK cells. Journal of Immunology 192: 5332–5342. DOI 10.4049/jimmunol.1303180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rodriguez A, Vigorito E, Clare S, Warren MV, Couttet P et al. (2007). Requirement of bic/microRNA-155 for normal immune function. Science 316: 608–611. DOI 10.1126/science.1139253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Van Rooij E, Olson EN (2007). MicroRNAs: Powerful new regulators of heart disease and provocative therapeutic targets. Journal of Clinical Investigation 117: 2369–2376. DOI 10.1172/JCI33099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ruby JG, Jan C, Player C, Axtell MJ, Lee W et al. (2006). Large-scale sequencing reveals 21U-RNAs and additional MicroRNAs and endogenous siRNAs in C. elegans. Cell 127: 1193–1207. DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ruggiero T, Trabucchi M, De Santa F, Zupo S, Harfe BD et al. (2009). LPS induces KH-type splicing regulatory protein-dependent processing of microRNA-155 precursors in macrophages. FASEB Journal 23: 2898–2908. DOI 10.1096/fj.09-131342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]