Materials Processing

| Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing |  |

DOI: 10.32604/fdmp.2021.012789

ARTICLE

Buoyancy driven Flow of a Second-Grade Nanofluid flow Taking into Account the Arrhenius Activation Energy and Elastic Deformation: Models and Numerical Results

1Department of Mathematics, Vivekananda College, Madurai, 625234, India

2PG and Research Department of Mathematics, Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda College, Chennai, 600004, India

3Department of Mathematical Sciences, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

*Corresponding Author: Qasem M. Al-Mdallal. Email: q.almdallal@uaeu.ac.ae

Received: 12 July 2020; Accepted: 11 January 2021

Abstract: The buoyancy driven flow of a second-grade nanofluid in the presence of a binary chemical reaction is analyzed in the context of a model based on the balance equations for mass, species concentration, momentum and energy. The elastic properties of the considered fluid are taken into account. The two-dimensional slip flow of such non-Newtonian fluid over a porous flat material which is stretched vertically upwards is considered. The role played by the activation energy is accounted for through an exponent form modified Arrhenius function added to the Buongiorno model for the nanofluid concentration. The effects of thermal radiation are also examined. A similarity transformations is used to turn the problem based on partial differential equations into a system of ordinary differential equations. The resulting system is solved using a fourth order RK and shooting methods. The velocity profile, temperature profile, concentration profile, local skin friction, local Nusselt number and local Sherwood number are reported for several circumstances. The influence of the chemical reaction on the properties of the concentration and momentum boundary layers is critically discussed.

Keywords: Arrhenius activation energy; buoyancy effects; chemical reaction; elastic deformation; nanofluid; nonlinear thermal radiation

Nanofluids are artificially synthesized novel fluids, which are colloidal mixtures of 1–100-nm-sized inorganic solid particles and conventional base liquids. These fluids were initially popularized by Choi et al. [1]. They have various important applications in many engineering and medical fields, which can be attributed to their tri-biological, chemical, thermal, biological, mechanical, and magnetic properties. The choice of base fluids (water, molten salts, oil, glycols, etc.) and nanoparticles (carbon nanotubes, metals, metallic oxides, etc.) is mainly dependent on the industrial requirements. Recently, numerous studies have focused on nanofluid heat transfer in different geometries [2–10]. Researchers have introduced various theoretical models to thoroughly examine the properties of nanofluids. It is vital to study the non-Newtonian fluid behavior because of its numerous biological and industrial applications, including in food, mineral suspensions, cosmetics, pharmaceutical, and personal care products. The investigations on the boundary-layer flow characteristics of incompressible non-Newtonian fluids over a stretchable material are paramount in various engineering processes such as polymer processing, drawing of plastic films and wires, metallic plate cooling, glass fiber processing, food processing, and crystal growth. Outstanding performances can be achieved in the aforementioned processes by replacing ordinary fluids with nanofluids. Buongiorno proposed a non-Newtonian flow model of a nanofluid with important slip mechanisms [11]. Nield et al. [12] investigated the natural convective nanofluid flow with active control of the nanoparticle fraction and the temperature at the boundary (the nanoparticle volume fraction can be actively controlled without considering any mass flux boundary condition and other nanofluid parameters at the boundary). They considered the Darcian porous medium model in their study. Kuznetsov et al. [13,14] remodeled the above problem and the convective transport of nanofluids over a vertical plate with the passive control of nanoparticles (the nanoparticle volume fraction can be controlled passively at the wall by including Brownian motion and thermophoresis at the boundary). They reported that the use of the passive control of nanoparticles with respect to the boundary condition is physically realistic. This model is applicable to second-grade nanofluids with two types of nanoparticle controls: active and passive controls. Recently, various studies have been conducted on non-Newtonian second-grade nanofluids [15–20].

Arrhenius first observed the concept of activation energy in heat and mass transport problems in 1889. The energy obtained from molecules or atoms was employed to initiate a reaction in the chemical processes. The study of a chemical reaction along with the activation energy is useful in food processing, chemical engineering of emulsions of various suspensions, oil reservoirs, etc. The amount of activation energy required for a chemical reaction is mainly dependent on the application of the mass transport problem. There may be no need to activate a reaction with additional energy in some situations. The buoyancy forces play a crucial role in controlling the boundary layer in many practical situations involving convection problems, e.g., the boundary layer flows in the atmosphere, petroleum extraction, and solar collectors. The influences of the Arrhenius activation energy have been considered in the absence of the buoyancy effect in recent nanofluid studies [21–28].

Maleque [29] reported the impacts of the Arrhenius activation energy on the flat plate fluid flow problem and viscous dissipation, heat generation, and buoyancy. The local similar flow of a magnetonanofluid with activation energy and buoyancy effects was solved by Mustafa et al. [30]. They reported that the activation energy is directly proportional to the Brownian motion and inversely proportional to the occurrence of thermophoresis. Mustafa et al. [31] inspected the buoyant heat transport in Maxwell’s non-Newtonian fluid flow model and obtained an “S”-shaped temperature profile function for a large temperature difference in the presence of activation energy. Ramzan et al. [32] explored micropolar nanofluid flow when considering the buoyancy and activation energy impacts. They observed that the concentration profile diminished with increasing solute stratification. Khan et al. [33] documented the buoyancy and activation energy impacts on entropy generation in the magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) Casson nanofluid model with heat generation/absorption and thermal radiation. Their work mainly focused on entropy generation and the effects of Bejan number. A computational assessment of the Jeffery nanofluid flow with the Arrhenius activation energy and buoyancy effects was performed by Ahmad et al. [34]. Dhalmini et al. [35] studied the impacts of the activation energy and buoyancy on the time-dependent flow of nanofluids over a heated surface with an infinite boundary length and concluded that the Biot number increases with the increasing concentration of the chemical species. Irfan et al. [36] analyzed the three-dimensional (3D) flow of the Carreau non-Newtonian nanofluid with the Arrhenius activation energy and buoyancy effects and reported that the activation energy was considerably influential. The same problem along with the thermal radiation impacts was analyzed in another study [37]. The Darcy–Forchheimer flow over a curved stretching surface with buoyancy, entropy generation, and activation energy was discussed by Muhammad et al. [38]. Alghamdi [39] focused on the MHD nanofluid flow using a rotating disk in three dimensions with assumptions of activation energy and buoyancy. An entropy generation analysis of the Casson nanofluid, which passed over a stretchable surface with activation energy, buoyancy, and viscous dissipation effects, was conducted by Khan et al. [40]. Recently, Ijaz et al. [41] examined the MHD stagnation point flow of the Walter-B nanofluid flow with activation energy under convective boundary conditions.

This study mainly focuses on the integrated impacts of the Arrhenius activation energy, elastic deformation, chemical reaction, and buoyancy on the MHD second-grade non-Newtonian nanofluid flow. This is an important problem that has not yet been investigated. Further, a computational model is developed by considering the second-grade nanofluid two-phase model, magnetic field, nonlinear thermal radiation, Arrhenius activation energy, binary-order chemical reaction, buoyancy effects, and active and passive control of nanoparticles. The notable results obtained via a numerical experiment are discussed in this study.

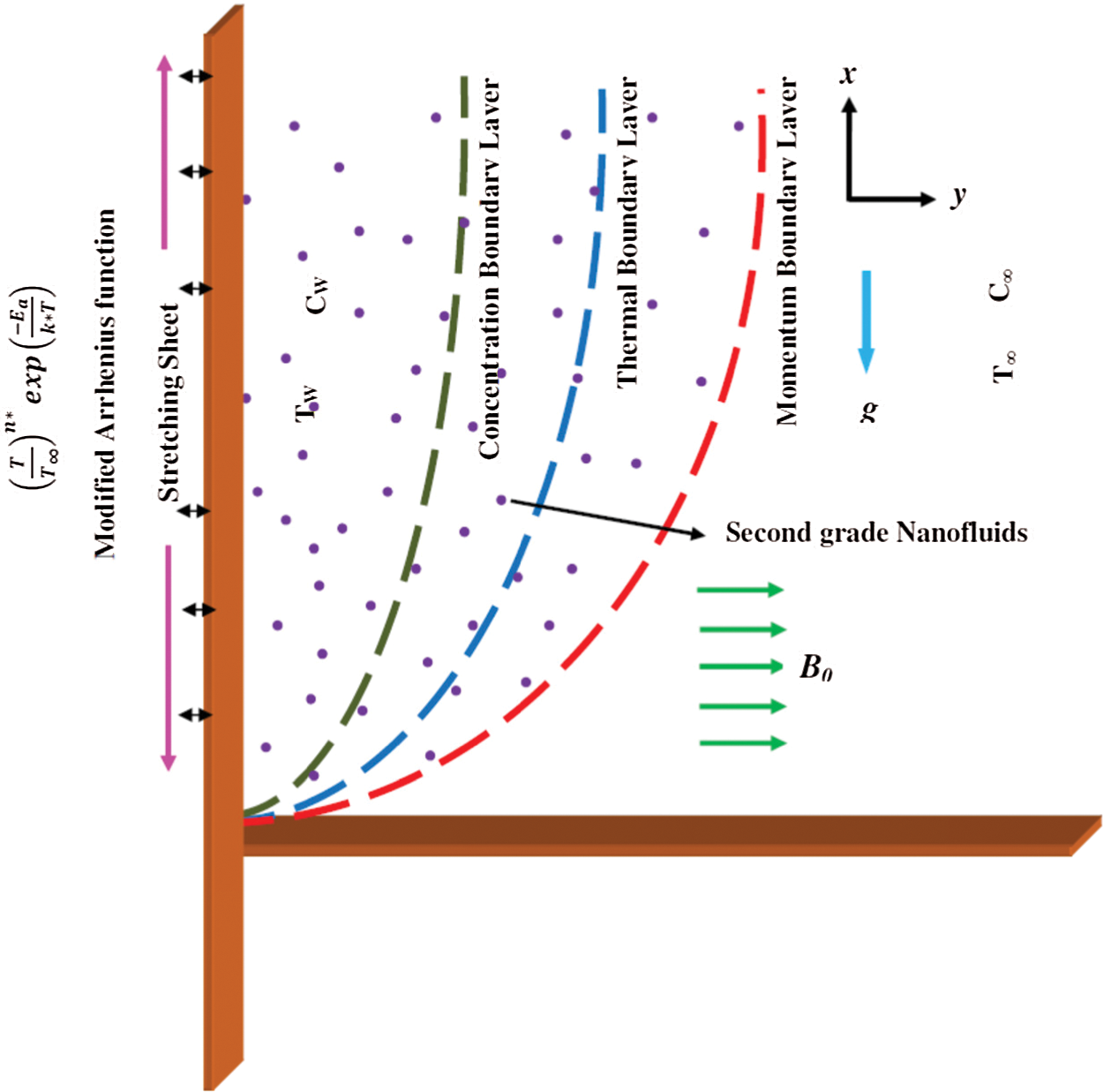

Let us consider a time-independent two-dimensional (2D) slip flow of a non-Newtonian nanofluid over a porous flat material that is stretched vertically upward. The nanofluid flow is considered to be laminar and incompressible. Heat transport analysis is conducted with a nonlinear form of thermal radiation, elastic deformation, and internal heat generation/absorption. The Arrhenius activation energy is assumed to initiate the chemical reaction. The binary-order chemical reaction is assumed to preserve the surface temperature. The flow is subjected to the combined effects of the magnetic field of strength

Figure 1: Physical layout of the model considered in this study

The governing equations of the present problem can be modeled using the following partial differential equations, as presented in previous studies [17–19].

where V1 and V2 are the velocities along the x and y axes, respectively.

The radiation term

where

The boundary conditions are given below.

At the stretching material wall (

Here,

The following condition can be observed far away from the stretching material wall, where the flow attains free stream velocity (

2.3 Similarity Transformations and Dimensionless Forms

To perform a similarity analysis, similarity transformations based on dimensionless nanofluid temperature and nanofluid concentration are introduced.

When considering the nonlinear thermal radiation, the nanofluid temperature is assumed to be

By invoking the above assumptions into Eqs. (1)–(4) and Eq. (6), the similarity transformations in Eq. (7) are proved to satisfy the continuity in Eq. (1). Further, Eqs. (2)–(4) are transformed into the following dimensionless forms based on the physical parameters that govern the flow.

Consequently, the BCs in Eq. (6) adopt the following dimensionless form.

where the parameters are as follows:

The following essential expressions are derived for the interest of engineering and industrial processes.

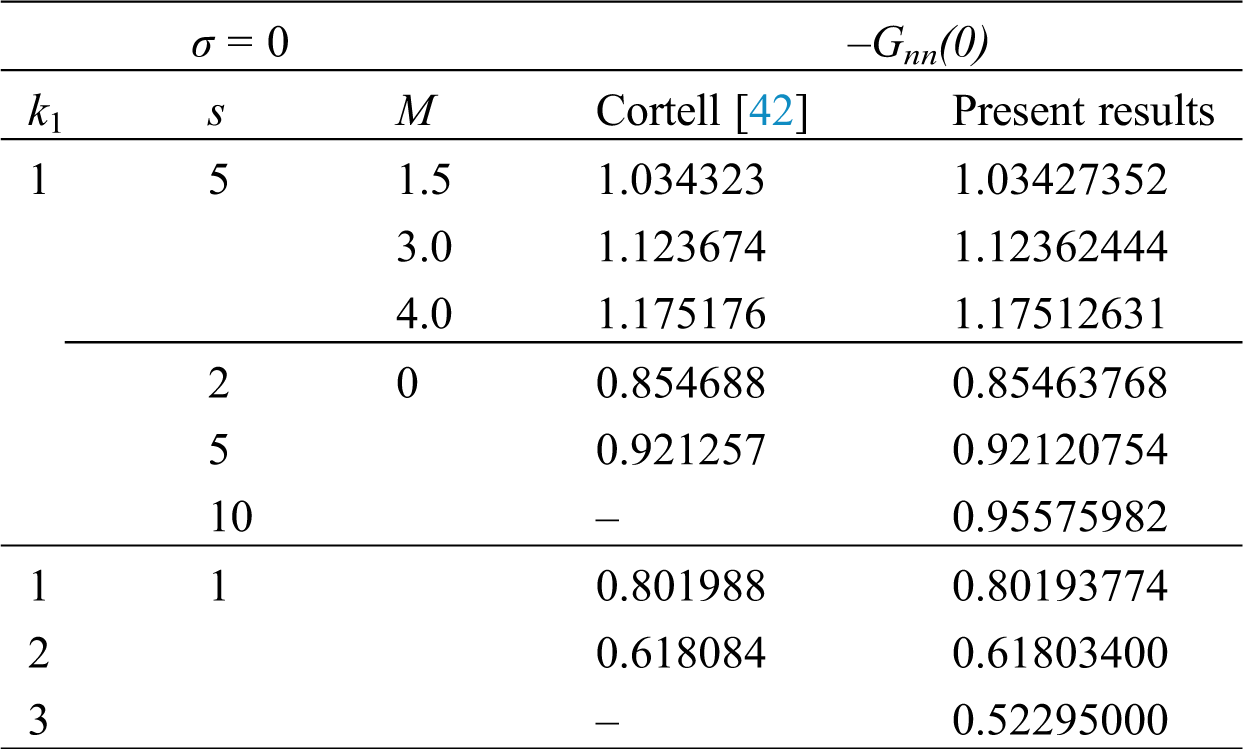

To solve the nonlinear ordinary differential equations (Eqs. (9)–(11)) along with the BCs in Eqs. (12)–(14) using an iterative power-series method with a shooting strategy [42,43], the higher-order BVP equations must be converted into first-order IVP equations; additionally, an appropriate finite value of

To solve Eq. (19) by considering Eq. (20) as an IVP equation, the values for

The performance of the dimensionless parameters is analyzed by solving Eq. (19) based on Eq. (20) using the above numerical method. The following values are fixed throughout the investigation:

Table 1: Validation of −Gηη(0) based on the study of Cortell [44]

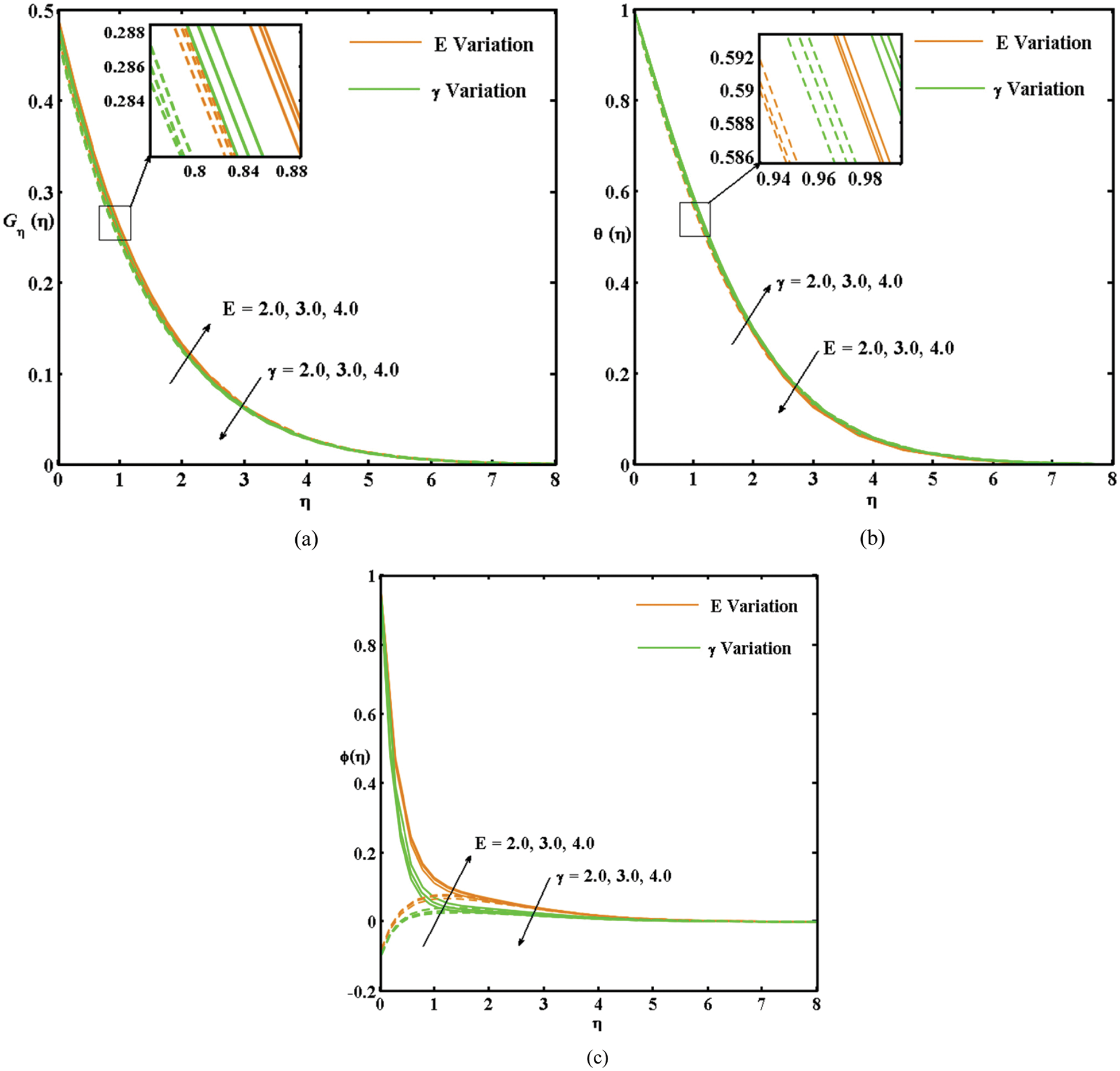

This study mainly explores the impact of the activation energy and chemical reaction on

The activation energy, chemical reaction, radiation, and elastic deformation parameters have an impact on

Figure 2: (a) Variation in the Gη(η) curves with

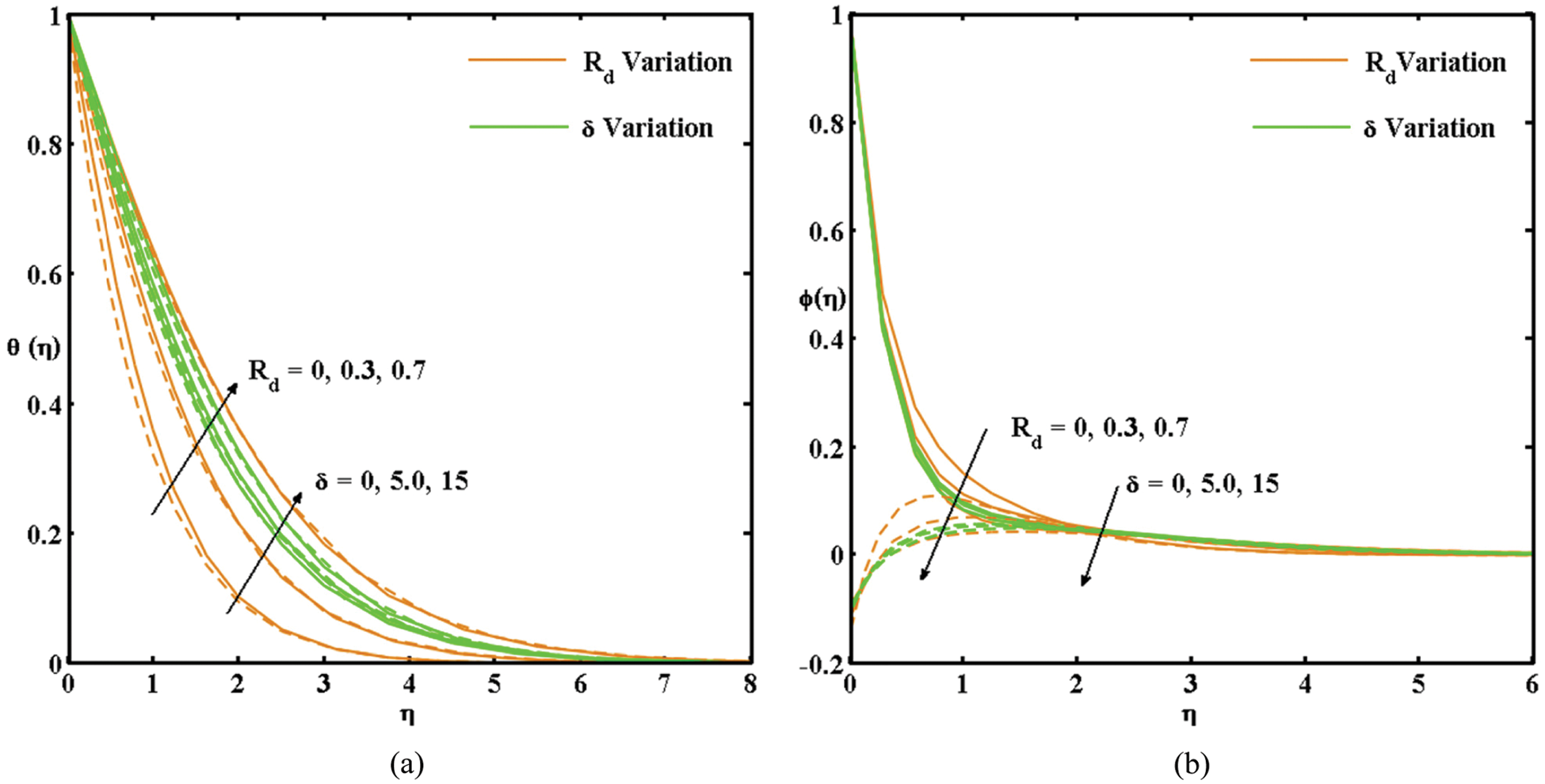

Fig. 3 presents the impacts of Rd and δ on the

Figure 3: (a) Variation in the θ(η) curves with Rd and δ (solid and dashed lines represent the active and passive control of nanoparticles, respectively). (b) Variation in the θ(η) curves with Rd and δ (solid and dashed lines represent the active and passive control of nanoparticles, respectively)

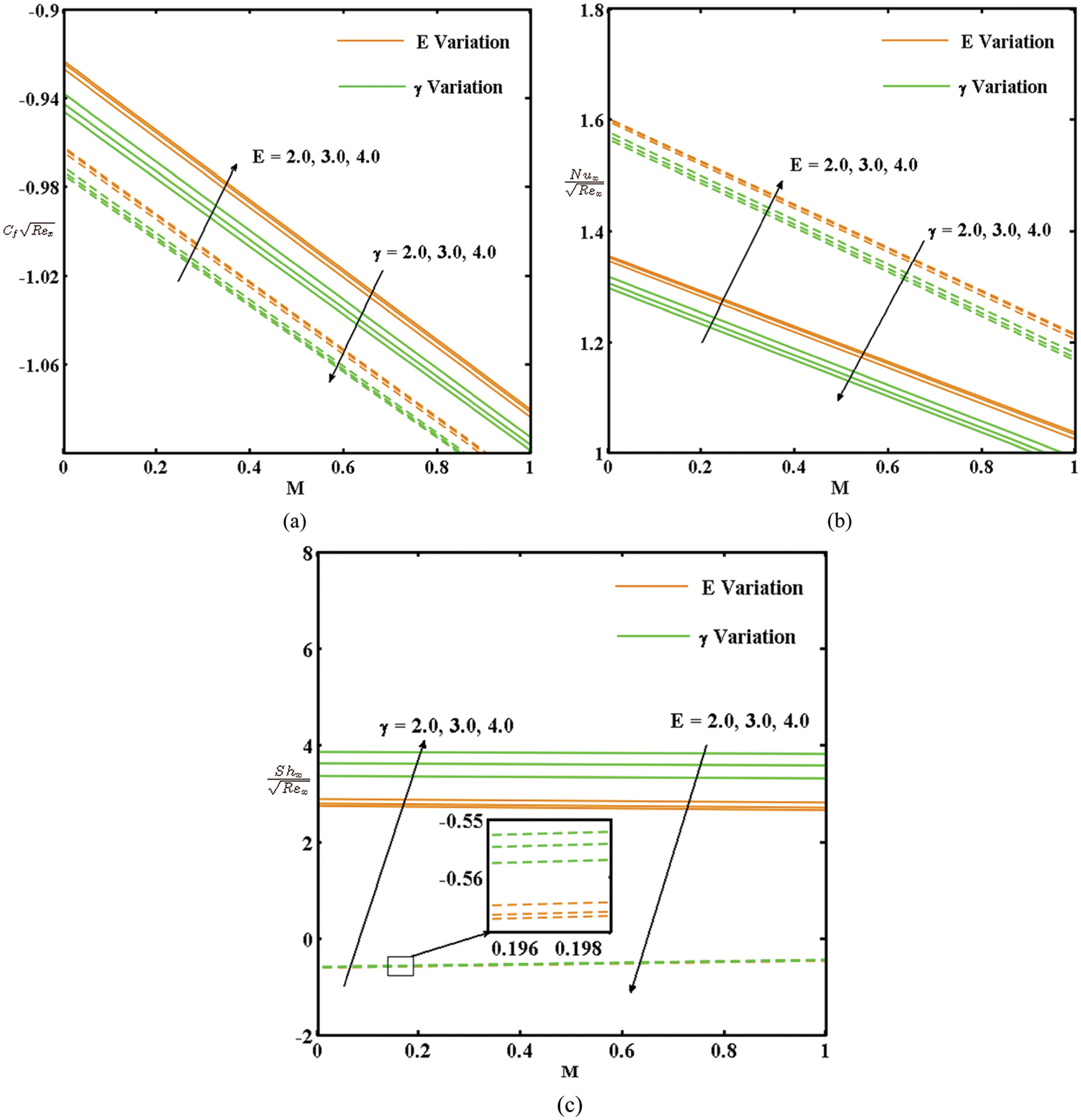

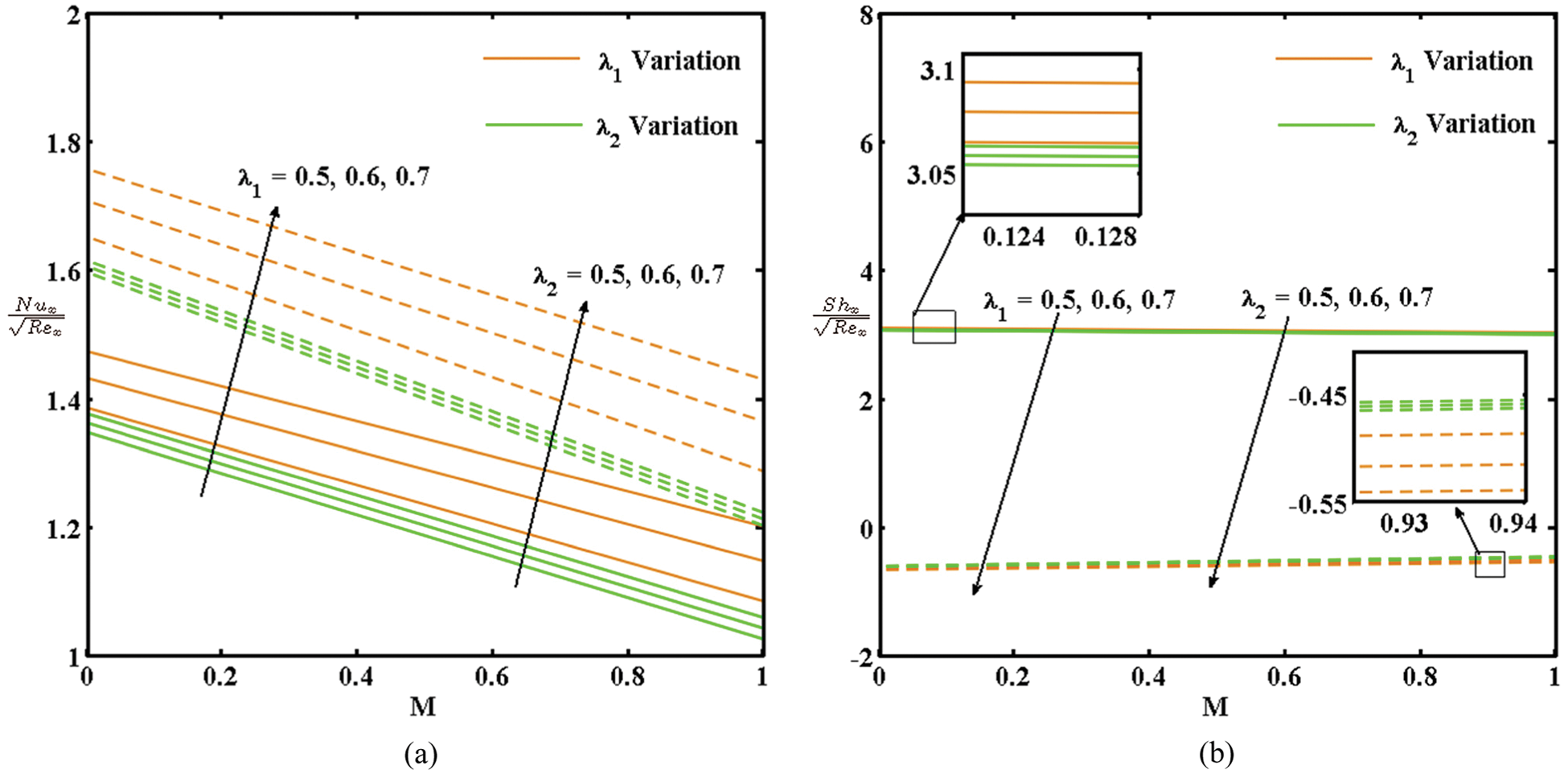

The impacts of E, γ, λ1, and λ2 with M on the local skin friction (

Figure 4: (a) Variation in

Figure 5: (a) Variation in

By comparing the active and passive control of the nanoparticles, high heat and mass transfer rates can be observed in the passive control case and a high surface drag can be observed in the active control case.

In this study, the effects of the Arrhenius activation energy on the momentum, energy, and mass transport of a second-grade magneto nanofluid flow with elastic deformation effects were analyzed. The governing parameters of the flow include the thermal buoyancy, concentration buoyancy, magnetic field, elastic deformation, nonlinear thermal radiation, binary-order chemical reaction, and Arrhenius activation energy. Further, numerical results were obtained and discussed. The notable findings are given below:

• The Arrhenius activation energy significantly increases the thickness of the second-grade nanoconcentration boundary layer, whereas the chemical reaction reduces it. A slight increase is observed in the second-grade nano momentum boundary layer thickness as the Arrhenius activation energy increases. The opposite trend is observed in the second-grade nanothermal boundary layer with the activation energy.

• The elastic deformation and nonlinear thermal radiation increase the nanothermal boundary layer thickness and shrink the nanoconcentration boundary layer.

• The numerical amount of skin friction and the local Nusselt number increase with the activation energy and decrease with the chemical reaction rate. An increase in the thermal and concentration buoyancy increases the local Nusselt number and decreases the local Sherwood number.

• The thickness of the nanoboundary layers can be increased via active control of the nanoparticles in the boundary.

• The Nusselt and local Sherwood numbers increase in the passive control case, and the skin friction increases in the active control case.

Acknowledgement: The authors wish to express their sincere thanks to the honorable referees for their valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of the paper. In addition, the authors would like to express their gratitude to the United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, UAE for providing financial support with Grant No. 31S363-UPAR (4) 2018.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, UAE with Grant No. 31S363-UPAR (4) 2018.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. Choi, S. U. S., Jeffrey, A. E. (1995). Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles. No. ANL/MSD/CP-84938; CONF-951135-29. Argonne National Laboratory, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

2. Sheikholeslami, M., Rashidi, M. M., Ganji, D. D. (2015). Effect of non-uniform magnetic field on forced convection heat transfer of Fe3O4–water nanofluid. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 294(3), 299–312. DOI 10.1016/j.cma.2015.06.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ganesh, N. V., Al-Mdallal, Q. M., Al Fahel, S., Dadoa, S. (2019). Riga-Plate flow of γ Al2O3-water/ethylene glycol with effective Prandtl number impacts. Heliyon, 5(5), e01651. DOI 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ganesh, N. V., Al-Mdallal, Q. M., Kameswaran, P. K. (2019). Numerical study of MHD effective Prandtl number boundary layer flow of γ Al2O3 nanofluids past a melting surface. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, 13(1), 100413. DOI 10.1016/j.csite.2019.100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ganesh, N. V., Al-Mdallal, Q. M., Ali, J. C. (2019). A numerical investigation of Newtonian fluid flow with buoyancy, thermal slip of order two and entropy generation. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, 13(3), 100376. DOI 10.1016/j.csite.2018.100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hayat, T., Ahmad, M. W., Khan, M. I., Alsaedi, A. (2020). Entropy optimization in CNTs based nanomaterial flow induced by rotating disks: A study on the accuracy of statistical declaration and probable error. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 184, 105105. DOI 10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.105105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Torkaman, S., Heydari, M., Loghmani, G. B., Ganji, D. D. (2020). Barycentric rational interpolation method for numerical investigation of magnetohydrodynamics nanofluid flow and heat transfer in nonparallel plates with thermal radiation. Heat Transfer—Asian Research, 49(1), 565–590. DOI 10.1002/htj.21627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Waini, I., Anuar, I., Ioan, P. (2020). Transpiration effects on hybrid nanofluid flow and heat transfer over a stretching/shrinking sheet with uniform shear flow. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 59(1), 91–99. DOI 10.1016/j.aej.2019.12.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Bhandari, A. (2019). Radiation and chemical reaction effects on nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet. Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing, 15(5), 557–582. DOI 10.32604/fdmp.2019.04108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Jalali, H., Abbassi, H. (2019). Analysis of the influence of viscosity and thermal conductivity on heat transfer by Al2O3-water nanofluid. Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing, 15(3), 253–270. DOI 10.32604/fdmp.2019.03896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Buongiorno, J. (2006). Convective transport in nanofluids. Journal of Heat Transfer, 128(3), 240–250. DOI 10.1115/1.2150834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Nield, D. A., Kuznetsov, A. V. (2009). The Cheng–Minkowycz problem for natural convective boundary-layer flow in a porous medium saturated by a nanofluid. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 52(25–26), 5792–5795. DOI 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2009.07.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kuznetsov, A. V., Nield, D. A. (2013). The Cheng–Minkowycz problem for natural convective boundary layer flow in a porous medium saturated by a nanofluid: A revised model. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 65, 682–685. DOI 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2013.06.054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kuznetsov, A. V., Nield, D. A. (2014). Natural convective boundary-layer flow of a nanofluid past a vertical plate: A revised model. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 77, 126–129. DOI 10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2013.10.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Hayat, T., Aziz, A., Muhammad, T., Alsaedi, A., Mustafa, M. (2016). On magnetohydrodynamic flow of second grade nanofluid over a convectively heated nonlinear stretching surface. Advanced Powder Technology, 27(5), 1992–2004. DOI 10.1016/j.apt.2016.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Saif, R. S., Hayat, T., Ellah, R., Muhammad, T., Alsaedi, A. (2017). Stagnation-point flow of second grade nanofluid towards a nonlinear stretching surface with variable thickness. Results in Physics, 7, 2821–2830. DOI 10.1016/j.rinp.2017.07.062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sithole, H., Hiranmoy, M., Precious, S. (2018). Entropy generation in a second grade magnetohydrodynamic nanofluid flow over a convectively heated stretching sheet with nonlinear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation. Results in Physics, 9(3), 1077–1085. DOI 10.1016/j.rinp.2018.04.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Hakeem, A. K., Kalaivanan, R., Ganga, B., Ganesh, N. V. (2018). Effect of elastic deformation on nano-second grade fluid flow over a stretching surface. Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer, 10, 10.5098/hmt.10.20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hakeem, A. K. A., Kalaivanan, R., Ganga, B., Ganesh, N. V. (2019). Nanofluid slip flow through porous medium with elastic deformation and uniform heat source/sink effects. Computational Thermal Sciences: An International Journal, 11(3), 269–283. DOI 10.1615/ComputThermalScien.2018024409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Waqas, H., Khan, S. U., Hassan, M., Bhatti, M. M., Imran, M. (2019). Analysis on the bioconvection flow of modified second-grade nanofluid containing gyrotactic microorganisms and nanoparticles. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 291(1), 111231. DOI 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Alsaadi, F. E., Hayat, T., Khan, S. A., Alsaadi, F. E., Khan, M. I. (2020). Investigation of physical aspects of cubic autocatalytic chemically reactive flow of second grade nanomaterial with entropy optimization. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 183, 105061. DOI 10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.105061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Khan, M., Salahuddin, T., Malik, M. Y., Khan, F. (2019). Arrhenius activation in MHD radiative Maxwell nanoliquid flow along with transformed internal energy. European Physical Journal Plus, 134(5), 198. DOI 10.1140/epjp/i2019-12563-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Reddy, S. R. R., Bala, A. R. P., Krishnendu, B. (2019). Effect of nonlinear thermal radiation on 3D magneto slip flow of Eyring-Powell nanofluid flow over a slendering sheet with binary chemical reaction and Arrhenius activation energy. Advanced Powder Technology, 30(12), 3203–3213. DOI 10.1016/j.apt.2019.09.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kalaivanan, R., Ganesh, N. V., Al-Mdallal, Q. M. (2020). An investigation on Arrhenius activation energy of second grade nanofluid flow with active and passive control of nanomaterials. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, 22, 100774. [Google Scholar]

25. Alsaadi, F. E., Hayat, T., Khan, M. I., Alsaadi, F. E. (2020). Heat transport and entropy optimization in flow of magneto-Williamson nanomaterial with Arrhenius activation energy. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 183, 105051. DOI 10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.105051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ullah, M. Z., Ali, S. A., Metib, A. (2020). Significance of Arrhenius activation energy in Darcy-Forchheimer 3D rotating flow of nanofluid with radiative heat transfer. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 550, 124024. DOI 10.1016/j.physa.2019.124024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ramesh, G. K. (2020). Analysis of active and passive control of nanoparticles in viscoelastic nanomaterial inspired by activation energy and chemical reaction. Physica A, 550(2), 123964. DOI 10.1016/j.physa.2019.123964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kumar, A., Rajat, T., Ramayan, S. (2019). Entropy generation and regression analysis on stagnation point flow of Casson nanofluid with Arrhenius activation energy. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering, 41(8), 306. DOI 10.1007/s40430-019-1803-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Maleque, K. H. (2013). Effects of binary chemical reaction and activation energy on MHD boundary layer heat and mass transfer flow with viscous dissipation and heat generation/absorption. ISRN Thermodynamics, 2013(8), 1–9. DOI 10.1155/2013/284637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Mustafa, M., Khan, J. A., Hayat, T., Alsaedi, A. (2017). Buoyancy effects on the MHD nanofluid flow past a vertical surface with chemical reaction and activation energy. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 108(9), 1340–1346. DOI 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2017.01.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Mustafa, M., Mushtaq, A., Hayat, T., Alsaedi, A. (2017). Numerical study of MHD viscoelastic fluid flow with binary chemical reaction and Arrhenius activation energy. International Journal of Chemical Reactor Engineering, 15(1), 233. DOI 10.1515/ijcre-2016-0131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Ramzan, M., Ullah, N., Chung, J. D., Lu, D., Farooq, U. (2017). Buoyancy effects on the radiative magneto Micropolar nanofluid flow with double stratification, activation energy and binary chemical reaction. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1–15. DOI 10.1038/s41598-017-13140-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Khan, M. I., Qayyum, S., Hayat, T., Waqas, M., Khan, M. I. et al. (2018). Entropy generation minimization and binary chemical reaction with Arrhenius activation energy in MHD radiative flow of nanomaterial. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 259, 274–283. DOI 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.03.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ahmad, S., Ijaz, K. M., Waleed, A. K. M., Khan, T. A., Hayat, T. et al. (2018). Impact of Arrhenius activation energy in viscoelastic nanomaterial flow subject to binary chemical reaction and nonlinear mixed convection. Thermal Science, 24(2), 1143–1155. [Google Scholar]

35. Dhlamini, M., Kameswaran, P. K., Sibanda, P. M., Mondal, S. H. et al. (2019). Activation energy and binary chemical reaction effects in mixed convective nanofluid flow with convective boundary conditions. Journal of Computational Design and Engineering, 6(2), 149–158. DOI 10.1016/j.jcde.2018.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Irfan, M., Khan, W. A., Khan, M., Gulzar, M. M. (2019). Influence of Arrhenius activation energy in chemically reactive radiative flow of 3D Carreau nanofluid with nonlinear mixed convection. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids, 125, 141–152. DOI 10.1016/j.jpcs.2018.10.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Irfan, M., Anwar, M. S., Rashid, M., Waqas, M., Khan, W. A. (2020). Arrhenius activation energy aspects in mixed convection Carreau nanofluid with nonlinear thermal radiation. Applied Nanoscience, 10, 4403–4413. [Google Scholar]

38. Muhammad, R., Khan, M. I., Jameel, M., Khan, N. B. (2020). Fully developed Darcy-Forchheimer mixed convective flow over a curved surface with activation energy and entropy generation. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 188, 105298. DOI 10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.105298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Alghamdi, M. (2020). Significance of Arrhenius activation energy and binary chemical reaction in mixed convection flow of nanofluid due to a rotating disk. Coatings, 10(1), 86. DOI 10.3390/coatings10010086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Khan, M. I., Khan, M. W. A., Alsaedi, A., Hayat, T., Khan, M. I. (2020). Entropy generation optimization in flow of non-Newtonian nanomaterial with binary chemical reaction and Arrhenius activation energy. Physica A, 538, 122806. DOI 10.1016/j.physa.2019.122806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ijaz, K. M., Alzahrani, F. (2020). Activation energy and binary chemical reaction effect in nonlinear thermal radiative stagnation point flow of Walter-B nanofluid: Numerical computations. International Journal of Modern Physics B, 34(13), 2050132. [Google Scholar]

42. Al Khawaja, U., Al-Mdallal, Q. M. (2018). Convergent power series of sech(x) and solutions to nonlinear differential equations. International Journal of Differential Equations, 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

43. Al Sakkaf, L. Y., Al-Mdallal, Q. M., Al Khawaja, U. (2018). A numerical algorithm for solving higher-order nonlinear BVPs with an application on fluid flow over a shrinking permeable infinite long cylinder. Complexity, 2018, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

44. Cortell, R. (2006). Effects of viscous dissipation and work done by deformation on the MHD flow and heat transfer of a viscoelastic fluid over a stretching sheet. Physics Letters A, 357(4–5), 298–305. DOI 10.1016/j.physleta.2006.04.051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |