DOI:10.32604/biocell.2021.014441

www.techscience.com/journal/biocell

| Biocell DOI:10.32604/biocell.2021.014441 |  www.techscience.com/journal/biocell |

| Review |

Epigenetic regulation−The guardian of cellular homeostasis and lineage commitment

1Department of Biotechnology, Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Chennai, 600036, India

2Department of Life Sciences, Sharda University, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, 201310, India

3Department of Biotechnology, Campus–Bhimtal, Kumaun University, Nainital, Uttarakhand, 263136, India

4Department of Botany, Mahatma Gandhi Central University, Motihari, Bihar, 845401, India

*Address correspondence to: Kavitha Govarthanan, govarthanan_kavitha@yahoo.co.in; Ram Prasad, rpjnu2001@gmail.com

Received: 27 September 2020; Accepted: 06 January 2021

Abstract: Stem cells constitute the source of cells that replenishes the worn out or damaged cells in our tissue and enable the tissue to carry out the destined function. Tissue-specific stem cells are compartmentalized in a niche, which keeps the stem cells under quiescent condition. Thus, understanding the molecular events driving the successful differentiation of stem cells into several lineages is essential for its better manipulation of human applications. Given the developmental aspects of the cell, the cellular function is greatly dependent on the epigenomics signature that in turn governs the expression profile of the cell. The stable inheritance of the epigenome is crucial for the development, modulation, and maintenance of the cell and its complex tissue-specific function. Emerging evidence suggesting that stem cell chromatin comprises a specialized state in which self-renewing genes and its downstream lineage-specific genes are kept paralleled poised for activation. Thus, the epigenetic regulatory network and pathway dictate lineage commitment and differentiation. It mainly modifies the chromatin landscape to facilitate euchromatin and heterochromatin architecture, which in turn alters the accessibility of transcription factors to the gene loci. DNA methylation and histone marks are the two widely studied epigenetic modifications regulating the transcriptome profile of a specific lineage. Abnormalities in the epigenetic landscape lead to diseases or disorders. Here, we emphasize the prominence of the epigenetic network and its regulation in normal tissue functioning and in the diseased state. Furthermore, we highlighted the emerging role of epigenetic modifiers in lineage differentiation and epigenetic markers as novel druggable targets for cancer therapy.

Keywords: Epigenetics; Chromatin Genome; Methylation; Inheritance; Modulation

The concept of genomic equivalence states that all cells in an organism carry the same genetic material, but the expression profiles may vary according to its destined function. Further, in order to facilitate the differential expression profile, epigenetics plays a central role in modulating the sequential changes in the chromatin landscape that finally leads to the specific chromatin signature for a particular lineage. Epigenetics is classically defined as “the branch of biology which deals with the cross-talk between genes and its products that finally leads to the phenotype into existence” (Waddington, 1942). The current biologist defines epigenetics as collective information about the chromatin landscape resulting in a specific transcriptome profile of cells without the involving changes in the primary DNA sequence (Russo et al., 1996). In a simpler way, it can be described as an alteration in phenotype without alteration in genotype. In the complex mammalian system, epigenetics modulates the chromatin configuration upon which the expression profile of the genes varies. If any aberrations or changes happen in the epigenetic network, then it may lead to the development of a variety of human diseases. Therefore, a stable inheritance of epigenetic state is very crucial for the development, modulation, and maintenance of cells and their complex tissue-specific function.

Chromatin is a multimeric complex made up of domains of histone proteins on which the DNA is tightly wound and well packaged within the cell. An epigenome is a complimentary term connected with the chemical changes occurring in the cytosine moiety of DNA base sequence in the chromatin without altering the sequence of the DNA. This change can be often transferred down to the progeny via transgenerational epigenetic inheritance (Waterland and Michels, 2007). If there is any change in the epigenome, then it may result in the modification of chromatin organization leading to an alteration in the genome’s function (Bannister and Kouzarides, 2011). The epigenome involves gene expression regulation, embryonic and fetal development, tissue differentiation, genomic imprinting, suppression of transposable elements, and inactivation of X-chromosome (Fedoriw et al., 2012; Li et al., 2012). In contrast, the underlying genome remains fundamentally inert within an individual, whereas the epigenome may be constantly altered by cues such as age, diet, and also in the diseased states. The epigenome is highly influenced by environmental factors and external cues, thus studying its fundamental mechanism may help us to enrich our knowledge in stem cell identity, fine-tuning of stem cell differentiation, and other developmental mechanisms related to tissue functioning. In eukaryotes, the gene regulation is tightly bound by the specific epigenetic signatures where the expression and repression of a specific gene are distinct in a particular cell type. Major epigenetic contributing events widely studied in gene regulation are methylation of DNA and histone protein modifications. (Russo et al., 1996; Avgustinova and Benitah, 2016). This current review talks about the highlights of epigenetic variations occurring in the chromatin landscape resulting in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis and differentiation. Also, several epigenetic markers as new druggable targets will be discussed in this review for effective killing of tumorigenic stem cells or CSCs.

Epigenetic Modifications in Chromatin Architecture

DNA packaging and chromatin assembly are tightly organized phenomena that determine the transcriptome profile of cell type. Thus, the cellular identity and its homeostasis principally depend on the epigenetic modifications that widely occur throughout the genome. The conventional chromatin modifications that occur in the mammalian genome are methylation of DNA and modifications in the core histone residues. In DNA methylation, the methyl groups donated from S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) are covalently added cytosine or adenine residues of DNA by the DNMTase family of enzymes. Methyl group is added to the 5th position of cytosine residue in CpG dinucleotide is the most studied and highly heritable modification suggested to maintain the stable genomic integrity (Razin and Shemer, 1995; Lachner and Jenuwein, 2002). The methylated form of cytosine causes the spatial hindrance to the binding of a transcription factor to the promoter region and thereby represses the gene expression. DNA methylation analysis confers stable information about the transcripts, and it is found to be directly coupled with cellular differentiation (Jaenisch and Bird, 2003). Methylation of DNA at the promoter region dictates the transcriptome profile of the cell by impeding the interaction of transcriptional machinery with the gene. Further, the binding of methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins (MDBs) to the methylated DNA, in turn, attracts the ancillary proteins like histone deacetylase and other chromatin remodeling proteins. Therefore, forming an inactive chromatin state called heterochromatin and ultimately hypothesized to involve in the key regulatory processes like genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, transposable elements repression, cellular senescence, and cancer initiation and progression. Thus, methylation positioned at the gene promoter region modifies the function of the DNA, thereby repressing the gene transcription (Wainwright and Scaffidi, 2007).

Histones are proteins made up of basic amino acids and involved in the formation of nucleosome core as octamer complex containing a C-terminal globular domain and N-terminal tail (Luger et al., 1997). Several covalent post-translational alterations, comprising methylation, phosphorylation acetylation, ubiquitination, and sumoylation, occur on particular residues of N-terminal tail regions of histone. These modifications are indispensable in regulating the key cellular processes, including transcription and repair mechanisms (Kouzarides, 2007). Hence, it has been hypothesized that the complementary modifications on histone residues are encoded as “histone code” and it contributes to epigenetic memory inside a cell (Jenuwein and Allis, 2001). Chromatin accessibility is tightly regulated by recruiting non-histone effector proteins that act as a block in decoding the message determined by its modification. In contrast to DNA methylation, histone modifications on the specific type on the specific determine the activation or repression of the downstream molecular events. The mammalian cell is made up of chromatin that presents in two forms, either as euchromatin (open for gene transcription) or heterochromatin (closed for gene transcription), and it is solely dependent on the post-translational modifications on histone.

Presence of heavily acetylated histone residues (H3K9ac, H4K12ac (Hebbes et al., 1988; Liang et al., 2004), and the histone core is enriched with H3K4Me3 (Bernstein et al., 2002) and linked with histone variant H3.3 (Ahmad and Henikoff, 2002; Mcittrick et al., 2004) sorts the Euchromatin. However, heterochromatin is typically contained with repressive methyl marks H3K27Me3, H3K9Me2 (Zhang and Reinberg, 2001, Umlauf et al., 2004; Dong and Weng, 2013). A huge panel of active and repressive histone marks have been identified, forming a complex regulatory network indispensable for various cellular activities (Bernstein et al., 2007). Hence, the compact wrapping of eukaryotic DNA in the form of chromatin determines the accessibility of DNA.

The chromatin remodelers are ATP-dependent multi-enzyme complexes involving in the process of chromatin opening using an ATP dependent manner. According to the configuration and order of the ATPase subunits, the nucleosome remodelers are classified into four classes, such as the SWI/SNF family, the ISWI family, the CHD family and the INO80 family (Munoz et al., 2012). BRM/BAF are human analogs of SWI/SNF classes of remodelers having a role in both activation and repression of genes performing key functions in development (Lessard and Crabtree, 2010). Studies about double conditional knock out of the BAF155 and BAF170 core units in mice showed BAF complex could globally modulate key chromatin marks H3K27Me2 and 3 by direct regulation of Utx and jmjd3, an H3K27 demethylase. Additionally, loss of BAF complexes impaired forebrain development and embryogenesis by upregulating H3K27Me3 (Nguyen et al., 2016). Additionally, knock-out experiments pertaining to BA170 in BAF complex showed loss of pluripotency whereas overexpression showed impaired differentiation to mesoderm and endoderm lineage (Wade et al., 2015).

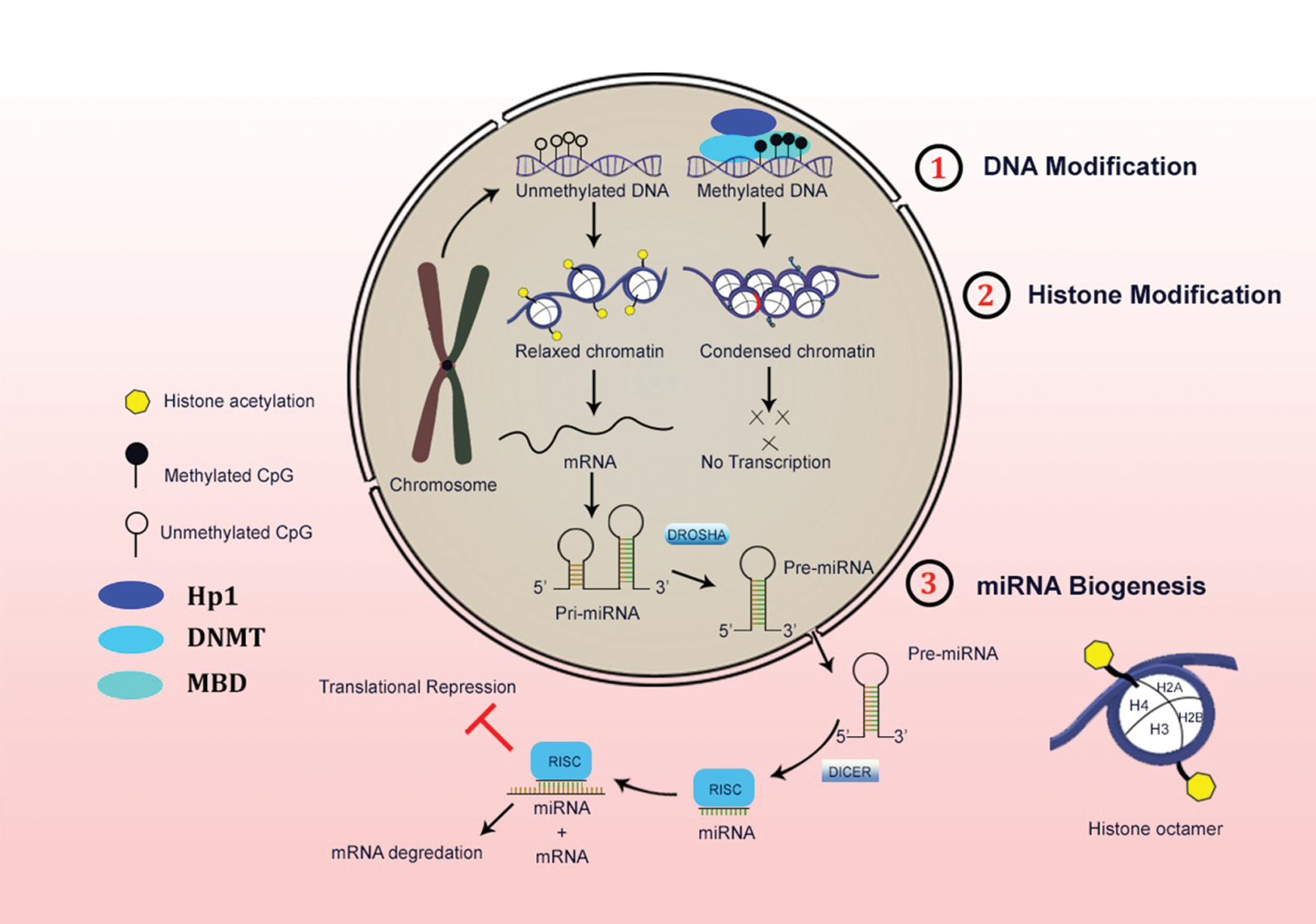

In the central dogma of molecular biology, the information flow from DNA to protein contributes through RNA, which functions to code for a protein with a destined specific function. However, a few exceptions to this paradigm are still present in which RNAs do not code for proteins, which in turn function in the regulation and processing of other RNAs (mRNAs, tRNAs, and rRNAs). It includes in a process such as splicing (snRNAs), nucleotide modification (snoRNAs), processing pre-tRNAs (RNase P, a ribozyme). Other small ncRNAs like miRNAs and siRNAs that involve in gene regulation by targeting mRNAs. LncRNAs are > 200 nucleotides to 2 kb sequence of non-coding transcripts (Carninci et al., 2005; Dinger et al., 2009; Perkel, 2013). These are putative non-coding RNAs lacking an elusive open reading frame (ORF) of 300 nucleotides or longer. (Pang et al., 2006). The hierarchy of epigenetic regulation with respect from the genomic DNA to the transcriptome mRNA is shown in detail in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of three major levels of epigenetic regulations in the mammalian system.

DNA methylation role in stem cell fate

DNA methylation occurs mainly in the CpG dinucleotide region, which is found in clusters called CpG islands. 60% of human gene promoter has CpG islands, which is unmethylated in stem cells and get methylated, leads to tissue-specific expression during early embryonic development or in different specific tissue types in adults. Stem cells unveil a unique gene expression profile that governs cell fate during lineage commitment and differentiation (Straussman et al., 2009). DNA methylation array could give key evidence about hypo-methylation (transcriptionally open state) and hyper-methylation (transcriptionally repressed state) of various target genes (Fouse et al., 2008). DNA methylation negatively controls the gene expression via recruitment of MBD, which in turn recruits histone-modifying and chromatin-remodeling complexes to the specific methylated site. Recruitment of various proteins disables the availability of promoter region for transcription factors, which suppress the gene expression (Protela and Esteller, 2010). GATA2, TAL1, and LMO2 are the oncogenes and myeloid key transcription factors responsible for myeloid lineage commitment.

These genes were highly methylated during lymphoid differentiation demonstrating DNA methylation may not only interfere with gene expression but also block the binding of unwanted myeloid transcription factors, which are of oncogenic nature. DNA methylation parallelly inhibits the activation of TF gene loci, as well as block the binding of TFs across the whole genome to make sure the two-tier epigenetic barrier in regulating the expression of myeloid TFs in lymphoid cells. Thus, a high-resolution global DNA Methylation mapping proved the gain of DNA methylation and its direct correlation in loss of gene expression during the course of differentiation (Shen, 2009). This also suggested that these epigenetic switches were performing the role of surveillance mainly to prevent the aberrant expression of stem cell-related genes after differentiation.

The differentiation potential of MSCs to adipocytes was directly correlated with its long-term culture and demonstrated the methylated status of LEP promoter upon adipogenic stimulation (Digirolamo et al., 1999; Noer et al., 2007; Banfi et al., 2008). Another study suggested that hypermethylation of ADIPOQ in late passages restricted the adipogenic differentiation (Lara-Castro et al., 2007). The core hypermethylated regions in the genome of mesenchymal progenitors showed a common epigenetic marker suggesting that MSCs obtained from adipose tissue, bone marrow and skeletal muscle were having a common origin (Hupkes et al., 2011; Sorrenson et al., 2010; Hakelein et al., 2014). This enabled us to understand that cellular identity is mainly defined by its epigenetic state (switch) and gets modified according to the lineage-committed during differentiation.

The promoter methylation status of NKX 2.5 and sFRP4 in umbilical cord MSCs displayed that both promoters underwent demethylation and further validated with upregulated expression at mRNA level upon cardiac stimulation (Bhuvanalakshmi et al., 2017). Hyper methylated CD31 promoter region showed a restricted differentiation potential to endothelial lineage in MSCs derived from adipose tissue (Bonquest et al., 2007). Any aberrant change in the DNA methylation signature at the enhancer region could lead to inappropriate gene expression and delayed differentiation in intestinal stem cells (Sheaffer et al., 2014). Similarly, a restricted differentiation potential of the C2C12 myoblast cell line to adipogenic and osteogenic lineage was observed due to the promoter hypermethylation (Hupkes et al., 2011). The differentiated methylation patterns were found to be established already in MSCs at its progenitor state, and also the differentiation potential of MSCs directly coupled with the methylation profile of the lineage-specific markers, where hypermethylation representing a barrier to differentiation (Sorrenson et al., 2010).

Histone core modification role in stem cell fate

A specific mark on histone protein contributes to its post-translational modifications governs gene expression patterns and differentiation potential in stem cells (Meissner, 2010; Fisher and Fisher, 2011). Global genome-wide analysis revealed that the presence of ‘‘bivalent or poised’’ chromatin domains in many developmental genes exhibiting both ‘‘active’’ (H3K4me3) and ‘‘repressive’’ (H3K27me3) marks on histone proteins (Azuara et al., 2006; Bernstein, 2006). This intermediate bivalent marked state is anticipated to permit for the further précised and sequential gene expression. Acetylation of lysine (K) residues in H3 (Histone-3) is considered as an active mark on the euchromatin near those genes that are actively transcribed.

PcG protein complex maintains the gene expression of many cells during development. PcG proteins like EZH (EZH1/EZH2), EED and SUZ 12 along with methyltransferase, PRC2 acts on histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27), are very essential for maintenance and control of pluripotency. PRC2, along with jumonji protein, acts as a master regulatory switch by which this protein complex rapidly reprograms the epigenome either by repression or subsequent activation via H3K27me3 (Shen et al., 2009). A specialized chromatin signature is essential for the proper conversion of pluripotent ESCs to multipotent ESCs in which a bivalent chromatin structure was documented in developmental and pluripotent genes. It maintained a gene in a transcriptional open state, which allows the instant transcription activation of specific genes upon induction with differentiation factors and shutting of pluripotency genes (Aranda et al., 2009).

The master regulatory pluripotency triads such as SOX2, OCT4, and NANOG determine the stemness and differentiation potential of embryonic stem cells (Silva et al., 2008; Han et al., 2010). However, MSCs are also shown to express these factors at primary culture conditions and its expression level declines markedly upon successive or repeated passaging (Greco et al., 2007; Li et al., 2011; Yannarelli et al., 2013). Also, the osteogenic and adipogenic genes were expressed at a considerably increased level due to spontaneous differentiation cultured over a longer period of time (Tsai, 2010). However, spheroid conditions increased levels of pluripotent genes were observed with declined expression levels of the osteoblast and adipocyte-specific genes cultured over for several passages. Deposition of acetylation marks in H3K9 and K14 residues in pluripotent genes were consistently observed in in vitro MSCs aging experiments. However, promoter DNA methylation levels of pluripotent master regulatory genes have no correlation with the expression levels. It is then substantiated with another report showing that promoter DNA methylation level has no role in dictating the transcription levels of Oct4 and Nanog in human Wharton’s jelly and bone marrow MSCs model system. Thus, the histone modifications in the promoter’s region of specific genes are to be expected to play a crucial role in channelizing MSC’s stemness and potency (Tan, 2008; Yu et al., 2011).

Histone lysine demethylase (KDM2A) was shown to regulate MSCs proliferation and osteo-/dentinogenic differentiation. Knock-in/Knock out studies on KDM2A has enhanced the SCAP differentiation potential into the adipogenic and chondrogenic lineage. Also demonstrated knockdown of KDM2A, showed cofactor BCOR has considerably increased expression of Sox2 and Nanog by depositing H3K4Me3 marks in the Sox2 and Nanog loci (Dong et al., 2013). Other findings revealed that KDM2A along BCOR showed an increased deposition of histone marks K4/36 methylation in Epiregulin (EREG) gene promoter, thereby inhibited the osteo-/dentinogenic differentiation potential of human MSCs (Du et al., 2013). RNF40 ubiquitinated Histone H2B (H2Bub1) genes, which further triggered the changeover to an active chromatin signature by resolving H3K4Me3/H3K27Me3 bivalent controlled state on the lineage-specific induction of differentiation markers. Thus, RNF40 mediated ubiquitination has significantly increased during hMSCs differentiation into various lineage-committed precursor cells (Karpiuk et al., 2012).

Comprehensive epigenomic profiling between CD44+ and CD24+ in breast epithelial cells showed the crosstalk between K27 and DNA methylation correlated with higher expression of CD24+ genes independent of the K27 mark. But CD44+ cells showed CD44 high dependence of K27 marks. Thus, suggesting a presumed strategy independent of gene body methylation and gene expression and further correlated with an increase of promoter K27 marks (Maruyama et al., 2011).

WGBS of large partially methylated domains study showed signature similar to DPSCs as compared to 30–40% with ICM. DPSCs showed a similar methylation profile with neuronal stem cell lines and placenta-derived cells, as demonstrated by principal component analysis (Dunaway et al., 2017). It was also identified that the loss of chromatin-modifying enzyme HDAC-1 affects early cardiovascular differentiation in mESCs and iPSCs (Hoxha et al., 2012). During the course of differentiation, iPSCs generated by reprogramming erases somatic epigenetic signatures from silent pluripotent loci and establishes alternative epigenetic marks. Nanog and Esrrb loci are considered as the early essential pluripotent loci preceding the induction of methylcytosine and hydroxyl methylcytosine Parp1 and Tet2. Hence Tet2 and Parp1 are needed for activating chromatin state at pluripotent loci and promotes the opening of oct4 promoter for reprogramming (Doege et al., 2012).

The ChIP-on-chip assay revealed that promoters of RUNX, MSX2, and DLK5, early mineralization genes provided with H3K4Me3 active marks whereas repressive marks H3K9Me3 or H3K27Me3 augmented in OSX, IBSP, and BGLAP gene promoters. It also mediated the suppression of dental family genes (DSPP and DMP1 genes) in dental follicular (DF) cells and not in dental pulp (DP) cells. (Gopinathan et al., 2013). Histone demethylase KDM6B (JMJD3) epigenetically regulated by removing H3K27Me3 marks from promoters of osteogenic commitment. In odontogenic lineage, KDM6B was recruited to BMP2 promoters and facilitating the removal/silencing of odontogenic master transcription gene (Xu et al., 2013). A recent study investigation on odontogenic commitment in dental MSC differentiation showed that the ultimate balance between H3K27Me3 and H3K4Me3 marks mediated by JMJD3 and MLL co-activator complex finally regulate transcription activities of Wnt5A during differentiation (Zhou, 2018).

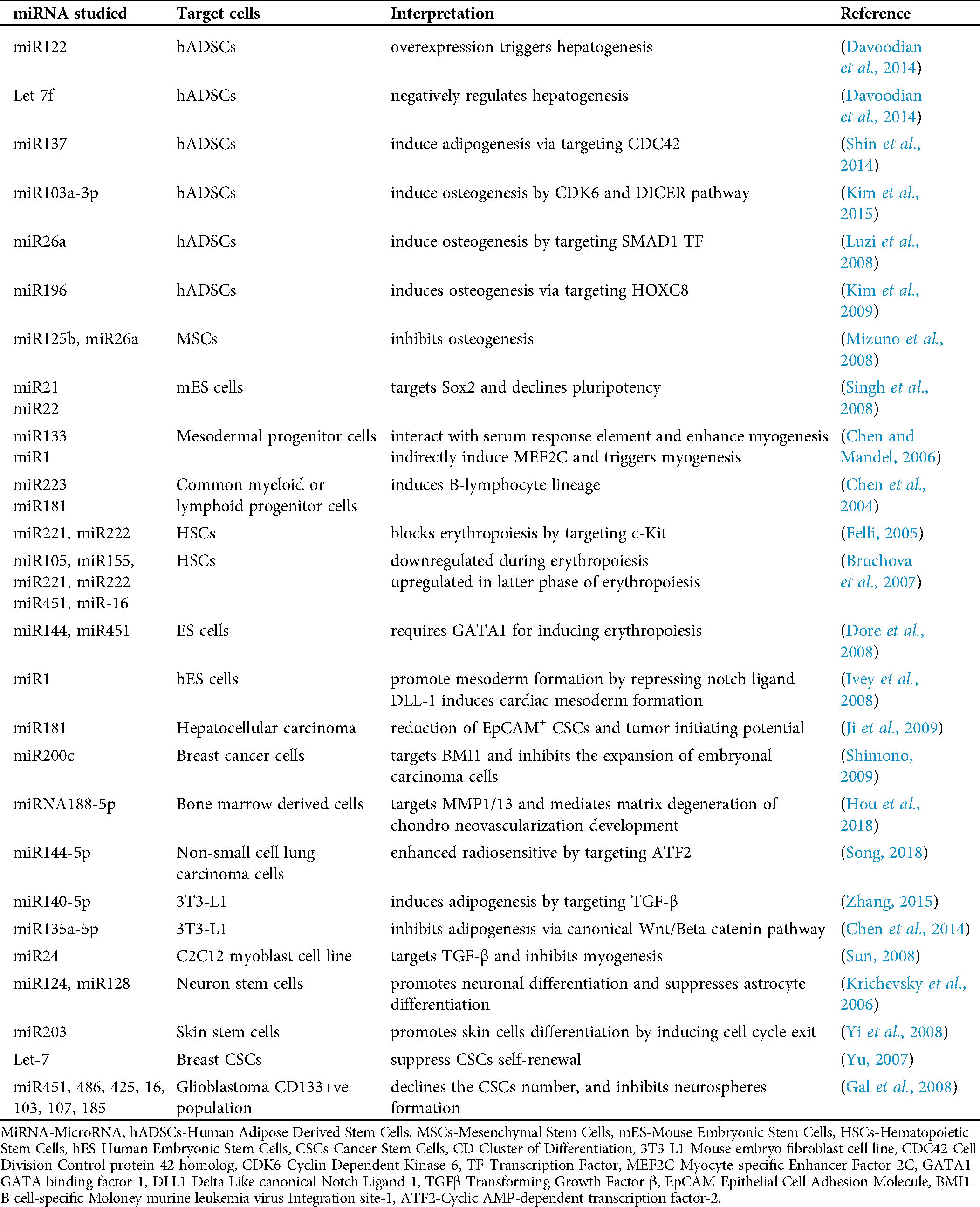

Precise chromatin configuration leads to appropriate gene expression which ensures proper stem cell and progenitor differentiation, lineage commitment. miRNAs are demonstrated to act mainly in RNA silencing and post-transcriptional via base-pairing with complementary sequences within mRNA molecules, which triggers the degradation of mRNA strand (Bartel, 2004). MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNA molecules that play a crucial role in normal biological processes and are commonly dysregulated in human diseases. Cells express different levels of numerous miRNAs that can target at various stages of differentiation or sustaining pluripotency. Given recent studies supported the critical regulatory roles of miRNAs in the stemness and commitment potential of normal and tumor-inducing stem cells. Hence, miRNA signature profiling is very useful for identifying the biomarkers at various developmental stages of specific cell types and is also used for cellular identity. Tab. 1 summarizes various miRNAs and their targeted cells related to their involvement in several regulatory processes of development.

Table 1: Tabulation summarizing the various regulatory processes in both normal stem cells and cancer stem cells

Epigenetics of cancer stem cells

Each mammalian cell differs from the other in the differentiated state but still retains a similar genome, which was inherited from the common precursor ESC. These cells have the potential to de-differentiate and acquire their totipotent character in a specific milieu. However, this process is determined by the expurgation of diverse epigenetic states in the chromatin through various covalent modifications in DNA and histone leads to change of fate by reprogramming. The initiation of CSCs also involves the parallel route during cancer triggering might be hypothesized based on epigenetic reprogramming in which downregulation of differentiation-specific genes and upregulation of stemness property, thereby eventually escapes the natural cell death process. The major cellular event that drives the carcinogenesis is reprogramming of the epigenome initiated by a series of cellular signaling cascades, finally culminating in gaining and maintenance of stem cell properties (Shukla and Meeran, 2014).

The CSCs are a subpopulation of cells present in the tumor niche, which undergo changes in Methylome and chromatin signature that finally transform into CSCs. During the initial phase of cancer initiation, the epigenetic modifiers might facilitate opening up target oncogenic DNA sites by requisite over-expression of oncogenic factors.

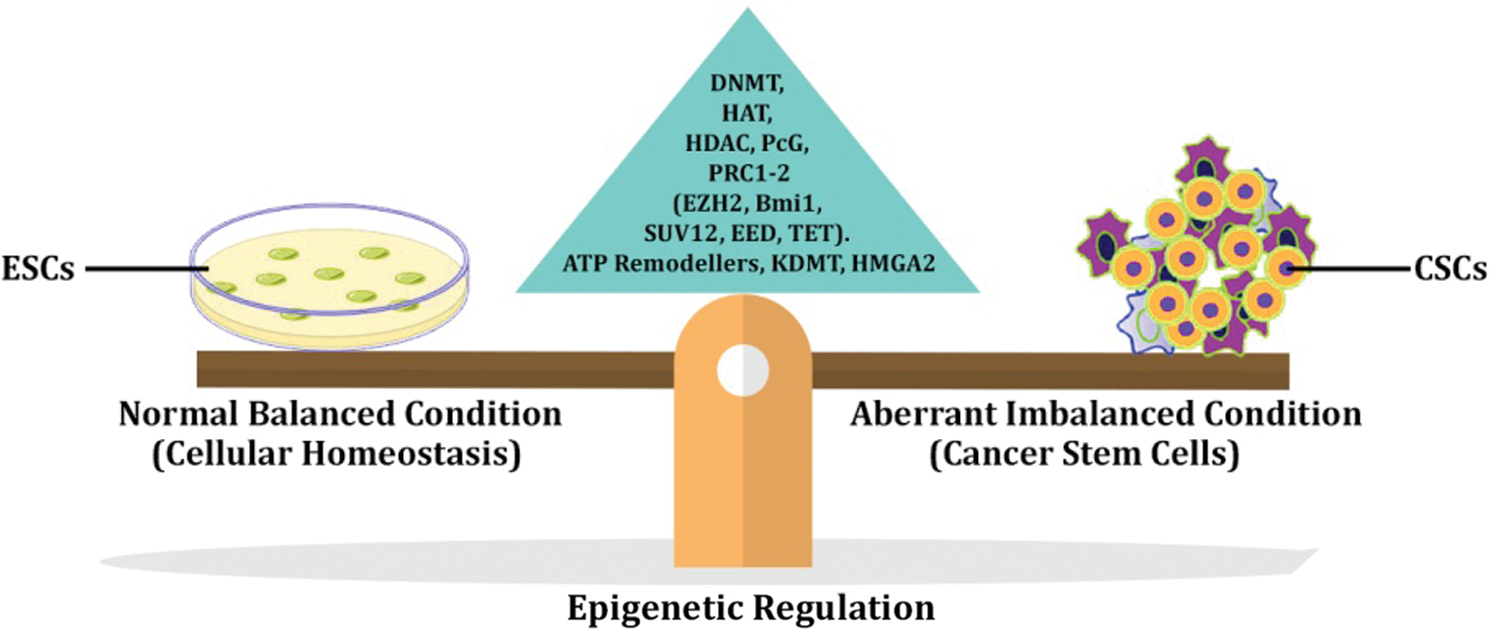

Through epigenetic analysis, various druggable targets are identified and targeted. Some of which are currently in clinical trials. In Fig. 2, the role of epigenetic modifiers in regulating cellular function under the imbalanced state is reversed that finally leads to the transformation of the normal somatic stem cells or progenitor cells into a highly aggressive cancer stem cell.

Figure 2: Carcinogenesis and Epigenetic regulation.

The expression of repressed tumor-promoting factors and silencing tumor-suppressing genes were correlated with the downregulation of DNMT enzyme (Meeran et al., 2011; Meeran et al., 2012; Wang, 2013). Hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes like DKK1, ASCL2, APCDD1, AXIN2, and LGR5A has correlated with poor tumor prognosis in colorectal cancer (CRC) and its elevated levels showed good prognosis in CSCs showed effective treatment in CRC patients (De Sousa et al., 2011). In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), hyper-methylation of tumor suppressor genes is correlated with the prognosis of tumor progression (Deneberg et al., 2011). A previous report demonstrated the occurrence of higher hypomethylation in breast CSCs than in non-CSC populations at differentially methylated regions (DMRs) and correlated with cancer prognosis (El Helou et al., 2014). More hypomethylation in DMR in breast CSCs showed poor prognosis when compared to the non-CSCs population. Knockdown of DNMT showed reduced stem cell properties, which again confirmed that epigenetic imbalances drive carcinogenesis and DNMT1, could be a candidate target for treating breast cancers.

Wnt pathway was epigenetically regulated by Brahma-related gene 1 (BRG1), which is the main tumor-initiating factor in triggering intestinal cancer, and its downregulation prevents adenoma development and decreased TIC population. Also, BRG is involved in leukemia maintenance, as BRG-AML cells are more sensitive to treatments than the BRG+ cells (Holik et al., 2014). Prevalent mutations in BRG1 are observed in the 30–40% non-small cell lung cancer, and thus highlighted BRG1as a significant key regulator in lung tumor development (Medina et al., 2008; Wu, 2012). BRG1 down-regulated Oct4 and Sox2 gene targets and promote self-renewable potential in B-cell lymphomas. Also, the high incidence of Mo-MLV insertion in BMI-1and EZH2 regions of the PcG family have also been linked with poor prediction in many different cancers (Ho et al., 2009; Kidder et al., 2009).

BMI-1 maintains the stemness of CSCs and also intricate in triggering various types of cancers. Overexpression of BMI-1 induced stemness property in CSCs which in turn augmented tumor initiation (Molofsky et al., 2003; Siddique and Saleem, 2012; Proctor et al., 2013). Mutation in chromatin remodeling complex (nearly 20 %) mainly SWI/SNF plays a role in triggering carcinogenesis (Lee and Roberts, 2013). Target abolition of the PRC-1 and PRC-2 complexes components were revealed to have dissimilar effects on the in vitro re-programming competence in the pluripotent cells and somatic cells. Knockdown of H3K27 methyltransferase leads to reduced re-programming competence in pluripotent and somatic cells. Also, downregulation of SUV39H1, DOT1L, and transcription factor YY1 was established to trigger pluripotency (Onder et al., 2012).

Efficient silencing of appropriate chromatin remodeling complexes in differentiated cell types induces pluripotency. Any modifications in the transcriptome profiling of chromatin remodelers are proficient in initiating tumor genesis. Hence, regulating chromatin complexes modifies the capability to induce CSCs phenotype. Ectopic expression of these complexes could cause repression of tumor suppressors or expression of oncogenic promoter genes. EZH2 expression was found higher in side-populations as observed in breast and pancreatic cancer lines than in non-CSC populations. Also, a recent report showed that knockout of EZH2 resulted in decreased CSCs incidence, which supplementary endorses EZH2 as a useful CSC marker and targeting protein for therapeutic purposes. Regulatory genes are often silent in ES cells (Bernstein, 2006). Early developmental studies in fruit flies show that the bithorax locus is co-occupied by Polycomb repressive group proteins (PcG) and trithorax G proteins (trxG), where the trxG protein is essential for gene induction. Chip assays on ES cells revealed that H3K4 methylation within bivalent domains and trxG protein may help the methylated H3K4 (active state) regions in murine ESC cell line. The presence of bothactive and repressed states co-exist at the same locus on the same chromosome.

A chip on-chip studies showed the overlapping of more H3K27 trimethylated (repressed state) regions with few such specific modifications where both active and inactive marks co-exist in the particular gene promoter region is called “Chromatin Bivalency,” which is considered as a unique feature frequently found in the domains of developmental regulatory genes poised for induction. In human primary T cells, both H3K27 and H3K4 methylation co-exhibit in the HOXB7 promoter region, which is as compared analogy to the proposed role of bivalent chromatin in ES cells (Roh et al., 2006). Thus, a similar mechanism is also observed for priming the dynamic gene expression in naive T cells upon antigen triggering.

The well-known PcG group of proteins has two main histone modifiers, PRC1 and PRC2, respectively. PRC1 complexes (BMI1, RING1A, RING1B, PHC) are capable of catalyzing mono-ubiquitination of lysine residues on Histone2A proteins. Any aberrations in PRC1, specifically RING1B, exhibited embryonic lethality in in vivo mouse embryo studies; however, other group members of PRC1 knock-out studies showed a severe developmental defect rather than embryonic lethality. Another familiar member of PcG proteins is PRC2 (SUZ12, EED, EZH2), which is known to catalyze di- or tri-methylation in H3K27 residues. Like PRC1, PRC2 knock out experiments also showed embryonic lethality. Thus, suggesting that PcG complex proteins are very crucial for normal embryo development (Arisan et al., 2005; Chase and Cross, 2011; Yoo and Hennighausen, 2012; Zingg, 2015).

High mobility nuclear proteins regulate the expression of many developmental genes via the formation of chromatin remodeling complexes on the distant promoter regulatory landscapes. Research on knock-in and knock-out model of HMGA2 showed its role in modulating cardiomyogenesis via gain of function induces cardiomyogenesis, and its siRNA mediated knockdown hindered the differentiation of embryonal carcinoma cell line PC19CC6 to cardiomyocyte lineage. Another study also demonstrated HMGA2 along with Smad transcription factor in response with bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) coordinately upregulated NKX 2.5 promoter activity. In Xenopus laevis embryo, morpholino or dominant-negative HMGA2 experiments have been shown to hinder normal heart formation. Thus, HMGA2 can act as an optimistic controller of the Nkx2.5 gene, and its expression is indispensable for in vivo heart development (Monzen et al., 2008).

Active DNA demethylation is the prerequisite obligation for cells to recover self-renewal property and reverts to their pluripotent state. This can be achieved progressively by modification of 5-methyl cytosine to thymine or 5-hydroxy methylcytosine by Ten-Eleven Translocation proteins (TET) and activation-induced deamination (AID), respectively (Klungland and Robertson, 2016). miR combo (miR-1, 133, 208, and 499) were shown to reprogram cardiac fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes directly. It was found that histone methyltransferase and demethylase regulating H3K27 trimethylation were shown to be modified in miR combo treated fibroblasts. Similarly, cardiac TFs showed a decreased H3K27Me3 mark in chip-qRT PCR reaction. Also, knockdown of H3K27 demethylase KDM6A and KDM6B restored the level of H3K27Me3 and inhibited cardiac gene expression in miR combo treated fibroblast (Dal-Pra et al., 2017).

EZH2 in stem cell fate determination

The characteristic property of pluripotency in ESCs is highly dependent on the PcG proteins, where it tends to maintain the balance between repressing markers and pluripotent specific markers by repressing the early differentiation marker genes and maintains the pluripotency genes. Initial days of fate commitments, deposition of PCR2 mediated histone H3K27Me3 makes these cells trigger the early differentiation marker genes, but still, PcG proteins suppress the late differentiation genes for a specific lineage. Consistent high expression of EZH2 in ESCs and early mouse development, which determines the pluripotent state upon declining its level differentiation is triggered. Also, EZH2 is abundantly expressed in progenitor cells of the epidermis region; nevertheless, its level declines upon commitment. Additionally, EZH2 was shown to maintain the multipotency in Mesoderm derived stem cells like myeloid and lymphoid progenitors, muscle progenitors, and neural progenitors.

EZH2 cover-expressed in the HSCs preserves the long-term self-renewing potential, which prevents HSCs depletion after serial transformation. Increased EZH2 expression blocked muscle differentiation from myoblasts due to histone lysine methyltransferase (HKMT) activity in its SET domain. NSCs also expressed high EZH2 level, and further commitment to astrocytes its level declined. Reduced differentiation potential into astrocytes in NSCs on ectopic expression of EZH2 further substantiated the role of EZH2 in preserving pluripotent or multipotent property of stem cells (Birve, 2001; Czermin et al., 2002; Chambers et al., 2003; Erhardt, 2003; Caretti et al., 2004; Cao and Zhang, 2004; Boiani and Scholer, 2005; Boyer et al., 2005; Pasini et al., 2007; Aloia et al., 2013). Transcriptional reprogramming of bone marrow MSCs to hepatocytes mainly depends on the deposition of activation marks (H3K4me3, H3K9Ac) and depletion of repressive marks (H3K9Me3, H3K27Me3) at the promoter binding site of hepatic transcription factors. However, the repressive H3K27 methylation was belligerently regulated by EZH2 and JMJD3, and the promoter activation of epigenetically poised hepatic genes was preceded by restricted nuclear reprogramming (Kochat et al., 2017).

It is well demonstrated that complex coordinated networking between epigenetic mediators and chromatin landscapes facilitates the expression of Glial gene expression and favors glial fate determination in Neuronal Stem Cells (NSCs). Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing analysis data demonstrated that distinct epigenetic signatures leading to three different neuronal sub-populations in NSCs, such as self-renewing neurons stem cells, progenitors consistently expressing neuronal markers actively, and cells switched from neurogenic to gliogenic phase, respectively (Nakagawa et al., 2020). Nuclear factor-1 binding motif nfia expression is highly correlated with the active neurogenesis and facilitates the demethylation of genes specific for astrocyte generation. Similarly, miR153 guides the astrogenesis via targeting the expression of nfia and nfib (Tsuyama et al., 2015).

Small molecule inhibitor-based fate determination

Molecular events associated with lineage decisions are the contemporary area of research in normal stem cells for its better manipulation in clinical use. A large number of evidences is available to depict chemical-based approaches, as a versatile tool in controlling the stem cell properties and their fate, such as stemness, lineage differentiation, reprogramming and regeneration. Our previous study about methylation profiling of cardiac-specific gene (CSG) promoter in human Wharton’s jelly derived MSCs at single-nucleotide resolution mapping (GATA4, SERCA, NKX 2.5, TBX5, MYH6, and MYL7) suggested that no DNA methylation level hindrances were found in native MSCs which underscored that the functional restriction to become competent cardiomyocyte is not due to DNA methylation. Hypo-methylation in CSGs suggested that WJ-MSCs exhibit a permissive methylome for cardiomyocyte lineage differentiation (Govarthanan et al., 2020). Further fine-tuning of differentiation protocol with other small molecule inhibitors like Histone deacetylase inhibitors, voltage channel agonists may yield the fully matured cardiomyocyte differentiation in WJ-MSCs.

CHIR 99021 is one such molecule that is an agonist of the Wnt pathway, widely used to sustain pluripotency in ESCs, induce reprogramming in somatic cells along with few Yamanaka factors, and lineage differentiation in MSCs (Ring et al., 2003; Ying et al., 2008; Li et al., 2015; Cao et al., 2016; Narcisi et al., 2016). An interesting study using WJ-MSCs pretreated with CHIR 99021 showed an increased state of potency, exhibiting enhanced differentiation capabilities with de-methylated OCT 4 promoter region. Thus, suggesting MSCs treated with CHIR 99021 can be potent, alternative sources of stem cells that are well suited to cell-based regenerative therapy (Govarthanan et al., 2020). These crucial evidences have laid down a strong foundation to employ the use of small-molecule inhibitors successfully in the process of fine-tuning the dedifferentiation towards the development of new biological therapies.

Sharma and Bhonde (2020) suggested that the age of stem cells could have a direct impact on cell-based therapy. Effectively, the more the passage number which concomitantly decreases the proliferative state of the cells and finally leads to senescence. This is mainly due to the varying degree of hypermethylation pattern and it is known to cause a direct effect on cell cycle control, DNA replication and repair, differentiation potential, etc. (Sharma and Bhonde, 2020). Intriguingly, several bioactive molecules collectively named “epi-drug” are presently employed in various clinical trials for devising potential cancer management treatments. Similarly, previous drugs shown good efficacy in reversing the aberrant disease-associated epigenetic status such as SWI/SNF, Polycomb, MLL-fusion proteins, jumonji-C domain encompassing histone demethylase, ten eleven translocation are actively recommended for drug repurposing and this strategy mostly improves the transition of epi-drugs towards clinical applications (Chiacchiera et al., 2020).

Current trends in epigenetic research areas

From the above-cited references and reports, it is well apparent that epigenetics is either directly or indirectly involved in the lineage commitment, identity, differentiation potential of the cell. On the other hand, it is playing a predominant role in cancer initiation, tumor progression and dissemination. We found much of the work has been extensively done from 2010 to 2016, and this accelerated us to understand the contribution of the epigenetic regulatory network in the above-mentioned areas of research. Due to this, many avenues of cancer research and basic fundamental research in stem cell biology are started employing epigenetic modifiers in disease management and in vitro differentiation cues respectively. A recent study by Pan et al., 2020 showed lineage-specific gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma-specific master regulatory transcription factor HNF4A promoted cancer proliferation and survival in cancer cells. Here, the group has employed a novel computational algorithm called enhancer linking by methylation/expression relationships (ELMER) to map the key transcription factor associated with the tumor initiation progression, etc. Thus, the group has demonstrated HNF4A could be a common potential target for gastrointestinal groups of carcinomas.

A study by Cakouros et al. (2019) speculated that hydroxyl methylation and enzyme regulating hydroxyl methylation such as DNA hydroxylase TET family of enzymes played a crucial role in bone repair and remodeling via regulating the osteogenesis process. This group showed TET1 enzyme inhibited osteogenesis and adipogenesis via indirect recruitment of epigenetic modifiers like SIN3A and EZH2, while TET2 directly promoted osteogenesis. Additionally, the relevance of TET1 and TET2 enzymes were found to be present in downregulated levels in osteoporosis, therefore targeting TET1 seems to be an ideal target for the new therapeutic strategies to prevent bone loss.

Interestingly screening of small molecules having the potential to rescue MSCs senescence-related concerns under in vitro conditions and boosting its plasticity are currently identified as novel methods to reverse the MSCs aging in aged patients and employed for regenerative therapies further. Here, small molecules such as Gemcitabine and Chidamide hugely 5.9- and 2.3- fold increased osteogenic differentiation potential of aged donors of hMSCs. It also increased the differentiation potential via 2.4- and 2.6- fold in late passaged osteogenic differentiation induced MSCs, respectively (Dhaliwal et al., 2018).

Limitations of epigenetic study

The generation of iPSCs has revelutionized the avenues of stem cell biology, still the concept of reprogramming is not fully understood. Hitherto, the two well-known proposed models of reprogramming such as the elite and stochastic were widely accepted. However, it is still under debate about the mechanism of reprogramming. The elite model proposes that not all the cells were conducive for reprogramming, this often correlated with the reprogramming efficiencies of the source cells employed for reprogramming studies. Whereas the stochastic model proposes that every cell inherently has the potential to undergo the process of reprogramming and become iPSCs (Yamanaka, 2009; Wakao et al., 2011). In any case, the efficiency of cellular reprogramming is highly dependent on its epigenetic state. Therefore, the current advanced reprogramming methods have started to incorporate the small molecule inhibitors targeting epigenetic modifiers, thus greatly influencing its reprogramming efficiencies. However, the probability and the actual phenomenon occurring in the genome and epigenome of the cell undergoing the reprogramming is still unknown. In addition, the status of histone modifications was also found to be associated with the transformation of cells. Therefore, forthcoming studies on the cells having conducive epigenome for reprogramming may give us a clear picture of the factors that hinder the other subset of the population from not responding to the transformation protocols.

Epigenetics plays a significant regulatory role in determining stem cell linage and cellular differentiation. Its predominant function has also been recognized in recruiting the appropriate transcriptional machinery during embryonic development and adult tissue homeostasis. Specialized chromatin structure dictates the unique expression profiles of stem cells intact and regulates its differentiation into various downstream lineages. Numerous epigenetic modifications occur concomitantly during the differentiation of MSCs to respective cell types. However, the knowledge about the epigenetic regulatory mechanism in relation to differentiation towards specific cell lineage is limited. Further investigations of the epigenetic profiling may help us in better understanding the systematic derivation of the physiologically competent cell types for exploitation in the field of various other regenerative therapy pursuits.

The MSCs have been used in preclinical models for various bone and cartilage tissue engineering. The development of tissue-engineered products has given considerable promising use for rebuilding damaged or diseased tissues. Epigenetic regulatory mechanisms are likely to enhance scientific hold on transcriptional regulation, especially critical for stem cells, their potential for self-renewal and differentiation. Classification based on gene expression profiles could help us in segregating stem cells into pluripotent stem cells, multipotent stem cells, and multipotent adult stem cells. Analysis of histone modifications mediated by PcG proteins and promoter histone methylation of a gene have demonstrated that certain marks on the histone bodies are necessary for the self-renewing stem cell populations, and its subsequent loss could deliberately lead to differentiation of a specific lineage. DNA methylation may often correlate with the restricted differentiation potential towards the specific lineage.

Research on the chromatin signature and cellular behavior would be more useful in fishing out the long-term self-renewing potential cells for transplantation and regenerative therapy. Overall, a combination of DNA methylation at gene promoter region and histone core modification marks in gene promoter and gene body contributes to the epigenetic regulations in stem cell state and determines the degree of differentiation impending from pluripotent stem cells to multipotent stem cells and progenitors. Similarly, the epigenetic road map will give us a clear picture of normal and cancerous chromatin organization or architectural difference, which will contribute to identifying new potential druggable targets for cancer treatment regime in the future.

Acknowledgement: KG is thankful to UGC, PKG and BZE to MHRD for their fellowships. All authors are grateful to IIT-Madras, Kumaun University, Mahatma Gandhi Central University, and Department of Life Sciences, SBSR, Sharda University for infrastructure and facility.

Author’s Contributions: KG wrote the manuscript, and responsible for the overall direction of the review, PKG contributed in manuscript writing, editing and graphical designing of figures, BZE, RG & SP contributed in review compilation and manuscript editing, RP contributed for overall final editing and proof read of the manuscript.

Ethics Statement: This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Funding Statement: The author(s) received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ahmad K, Henikoff S. (2002). The histone variant H3.3 marks active chromatin by replication-independent nucleosome assembly. Molecular Cell 9: 1191–1200. DOI 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00542-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Aloia L, Di-Stefano B, Di-Croce L. (2013). Polycomb complexes in stem cells and embryonic development. Development 140: 2525–2534. DOI 10.1242/dev.091553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Aranda P, Agirre X, Ballestar E, Andreu EJ, Roman-Gomez J. (2009). Epigenetic signatures associated with different levels of differentiation potential in human stem cells. PLoS One 4: e7809. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0007809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Arisan S, Buyuktuncer ED, Palavan-Unsal N, Caşkurlu T, Cakir OO, Ergenekon E. (2005). Increased expression of EZH2, a polycomb group protein, in bladder carcinoma. Urologia Internationalis 75: 252–257. DOI 10.1159/000087804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Avgustinova A, Benitah SA. (2016). Epigenetic control of adult stem cell function. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 17: 643–658. DOI 10.1038/nrm.2016.76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Azuara V, Perry P, Sauer S, Spivakov M, Jørgensen HF, John RM, Gouti M, Casanova M, Warnes G, Merkenschlager M, Fisher AG. (2006). Chromatin signatures of pluripotent cell lines. Nature Cell Biology 8: 532–538. DOI 10.1038/ncb1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Banfi A, Muraglia A, Dozin B, Mastrogiacomo M, Cancedda R, Quarto R. (2000). Proliferation kinetics and differentiation potential of ex vivo expanded human bone marrow stromal cells: implications for their use in cell therapy. Experimental Hematology 28: 707–715. DOI 10.1016/S0301-472X(00)00160-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. (2011). Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Research 21: 381–395. DOI 10.1038/cr.2011.22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bartel DP. (2004). MicroRNAs. Cell 116: 281–297. DOI 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, Jaenisch R, Wagschal A, Feil R, Schreiber SL, Lander ES. (2006). A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell 125: 315–326. DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bernstein BE, Meissner A, Lander ES. (2007). The mammalian epigenome. Cell 128: 669–681. DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bernstein BE, Humphrey EL, Erlich RL, Schneider R, Bouman P, Liu JS, Kouzarides T, Schreiber SL. (2002). Methylation of histone H3 Lys 4 in coding regions of active genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99: 8695–8700. DOI 10.1073/pnas.082249499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bhuvanalakshmi G, Arfuso F, Kumar AP, Dharmarajan A, Warrier S. (2017). Epigenetic reprogramming converts Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cells into functional cardiomyocytes on differential regulation of Wnt Mediators. Stem Cells Research & Therapy 8: CD006536. DOI 10.1186/s13287-017-0638-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Birve A. (2001). Su(z)12, a novel Drosophila Polycomb group gene that is conserved in vertebrates and plants. Development 128: 3371–3379. [Google Scholar]

Boiani M, Scholer HR. (2005). Regulatory networks in embryo-derived pluripotent stem cells. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 6: 872–881. DOI 10.1038/nrm1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bonquest AC, Noer A, Sorrensen AL, Vekterud K, Collas P. (2007). CpG methylation profiles of endothelial specific gene promoter regions in adipose tissue stem cells suggest limited differentiation potential toward endothelial cell lineage. Stem Cells 25: 852–861. DOI 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Levine SS, Zucker JP, Guenther MG, Kumar RM, Murray HL, Jenner RG, Gifford DK, Melton DA, Jaenisch R, Young RA. (2005). Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell 122: 947–956. DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bruchova H, Yoon D, Agarwal AM, Mendell J, Prchal JT. (2007). Regulated expression of microRNAs in normal and polycythemia vera erythropoiesis. Experimental Hematology 35: 1657–1667. DOI 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.08.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cakouros D, Hemming S, Gronthos K, Liu R, Zannettino A, Shi S, Gronthos S. (2019). Specific functions of TET1 and TET2 in regulating mesenchymal cell lineage determination. Epigenetics & Chromatin 12: 13. DOI 10.1186/s13072-018-0247-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cao N, Huang Y, Zheng J. (2016). Conversion of human fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by small molecules. Science 352: 1216–1220. DOI 10.1126/science.aaf1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cao R, Zhang Y. (2004). SUZ12 is required for both the histone methyltransferase activity and the silencing function of the EED-EZH2 complex. Molecular Cell 15: 57–67. DOI 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Caretti G, Di-Padova M, Micales B, Lyons GE, Sartorelli V. (2004). The Polycomb Ezh2 methyltransferase regulates muscle gene expression and skeletal muscle differentiation. Genes & Development 18: 2627–2638. DOI 10.1101/gad.1241904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Carninci P, Kasukawa T, Katayama S, Gough J, Frith MC, Maeda N, Oyama R, Ravasi T, Lenhard B, Wells C, Kodzius R, Shimokawa K, Bajic VB, Brenner SE, Batalov S, Forrest AR, Zavolan M, Davis MJ, Wilming LG, Aidinis V, Allen JE, Ambesi-Impiombato A, Apweiler R, Aturaliya RN, Bailey TL, Bansal M, Baxter L, Beisel KW, Bersano T, Bono H, Chalk AM, Chiu KP, Choudhary V, Christoffels A, Clutterbuck DR, Crowe ML, Dalla E, Dalrymple BP, de Bono B, Della Gatta G, di Bernardo D, Down T, Engstrom P, Fagiolini M, Faulkner G, Fletcher CF, Fukushima T, Furuno M, Futaki S, Gariboldi M, Georgii-Hemming P, Gingeras TR, Gojobori T, Green RE, Gustincich S, Harbers M, Hayashi Y, Hensch TK, Hirokawa N, Hill D, Huminiecki L, Iacono M, Ikeo K, Iwama A, Ishikawa T, Jakt M, Kanapin A, Katoh M, Kawasawa Y, Kelso J, Kitamura H, Kitano H, Kollias G, Krishnan SP, Kruger A, Kummerfeld SK, Kurochkin IV, Lareau LF, Lazarevic D, Lipovich L, Liu J, Liuni S, McWilliam S, Madan Babu M, Madera M, Marchionni L, Matsuda H, Matsuzawa S, Miki H, Mignone F, Miyake S, Morris K, Mottagui-Tabar S, Mulder N, Nakano N, Nakauchi H, Ng P, Nilsson R, Nishiguchi S, Nishikawa S, Nori F, Ohara O, Okazaki Y, Orlando V, Pang KC, Pavan WJ, Pavesi G, Pesole G, Petrovsky N, Piazza S, Reed J, Reid JF, Ring BZ, Ringwald M, Rost B, Ruan Y, Salzberg SL, Sandelin A, Schneider C, Schönbach C, Sekiguchi K, Semple CA, Seno S, Sessa L, Sheng Y, Shibata Y, Shimada H, Shimada K, Silva D, Sinclair B, Sperling S, Stupka E, Sugiura K, Sultana R, Takenaka Y, Taki K, Tammoja K, Tan SL, Tang S, Taylor MS, Tegner J, Teichmann SA, Ueda HR, van Nimwegen E, Verardo R, Wei CL, Yagi K, Yamanishi H, Zabarovsky E, Zhu S, Zimmer A, Hide W, Bult C, Grimmond SM, Teasdale RD, Liu ET, Brusic V, Quackenbush J, Wahlestedt C, Mattick JS, Hume DA, Kai C, Sasaki D, Tomaru Y, Fukuda S, Kanamori-Katayama M, Suzuki M, Aoki J, Arakawa T, Iida J, Imamura K, Itoh M, Kato T, Kawaji H, Kawagashira N, Kawashima T, Kojima M, Kondo S, Konno H, Nakano K, Ninomiya N, Nishio T, Okada M, Plessy C, Shibata K, Shiraki T, Suzuki S, Tagami M, Waki K, Watahiki A, Okamura-Oho Y, Suzuki H, Kawai J, Hayashizaki Y, FANTOM Consortium; RIKEN Genome Exploration Research Group and Genome Science Group (Genome Network Project Core Group) (2005). The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science 309: 1559–1563. DOI 10.1126/science.1112014. Erratum in: Science 311: 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chambers I, Colby D, Robertson M, Nichols J, Lee S, Tweedie S, Smith A. (2003). Functional expression cloning of Nanog, a pluripotency sustaining factor in embryonic stem cells. Cell 113: 643–655. DOI 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00392-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chase A, Cross NC. (2011). Aberrations of EZH2 in Cancer: Figure 1. Clinical Cancer Research 17: 2613–2618. DOI 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen C, Peng Y, Peng Y, Peng J, Jiang S. (2014). miR-135a-5p inhibits 3T3-L1 adipogenesis through activation of canonical Wnt/β catenin signaling. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology 52: 311–320. DOI 10.1530/JME-14-0013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP. (2004). MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Provides the first evidence that miRNAs are involved in the differentiation of an adult stem cell lineage. Science 303: 83–86. DOI 10.1126/science.1091903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen JF, Mandel EM, Thomson JM, Wu Q, Callis TE, Hammond SM, Conlon FL, Wang DZ. (2006). The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nature Genetics 38: 228–233. DOI 10.1038/ng1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chiacchiera F, Morey L, Mozzette L. (2020). Epigenetic regulation of stem cell plasticity in tissue regeneration and diseases. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 8: 643. DOI 10.3389/fcell.2020.00082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Czermin B, Melfi R, McCabe D, Seitz V, Imhof A, Pirrotta V. (2002). Drosophila enhancer of Zeste/ESC complexes have a histone H3 methyltransferase activity that marks chromosomal Polycomb sites. Cell 111: 185–196. DOI 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00975-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dal-Pra S, Hodgkinson CP, Mirotsou M, Kriste I, Dzau VJ. (2017). Demethylation of H3K27 is essential for the induction of direct cardiac programming by miR combo. Circulation Research 120: 1403–1413. DOI 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Davoodian N, Lotfi AS, Soleimani M, Mola SJ, Arjmand S. (2014). Let-7f microRNA negatively regulates hepatic differentiation of human adipose tissue-derived stem cells. Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry 70: 781–789. DOI 10.1007/s13105-014-0346-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Davoodian N, Lotfi AS, Soleimani M, Mowla SJ. (2014). MicroRNA-122 overexpression promotes hepatic differentiation of human adipose tissue‐derived stem cells. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 115: 1582–1593. DOI 10.1002/jcb.24822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

de Sousa E Melo F, Colak S, Buikhuisen J, Koster J, Cameron K, de Jong JH, Tuynman JB, Prasetyanti PR, Fessler E, van den Bergh SP, Rodermond H, Dekker E, van der Loos CM, Pals ST, van de Vijver MJ, Versteeg R, Richel DJ, Vermeulen L, Medema JP. (2011). Methylation of cancer stem cell associated Wnt target genes predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Cell Stem Cell 9: 476–485. DOI 10.1016/j.stem.2011.10.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Deneberg S, Guardiola P, Lennartsson A, Qu Y, Gaidzik V, Blanchet O, Karimi M, Bengtzén S, Nahi H, Uggla B, Tidefelt U, Höglund M, Paul C, Ekwall K, Döhner K, Lehmann Sören. (2011). Prognostic DNA methylation patterns in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia are predefined by stem cell chromatin marks. Blood 118: 5573–5582. DOI 10.1182/blood-2011-01-332353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dhaliwal A, Pelka S, Gray DS, Moghe PV. (2018). Engineering lineage potency and plasticity of stem cells using epigenetic molecules. Scientific Reports 8: 16289. DOI 10.1038/s41598-018-34511-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Digirolamo CM, Stokes D, Colter D, Phinney DG, Class R, Prockop DJ. (1999). Propagation and senescence of human marrow stromal cells in culture: A simple colony-forming assay identifies samples with the greatest potential to propagate and differentiate. British Journal of Haematology 107: 275–281. DOI 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01715.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dinger ME, Amaral PP, Mercer TR, Mattick JS. (2009). Pervasive transcription of the eukaryotic genome: Functional indices and conceptual implications. Briefings in Functional Genomics and Proteomics 8: 407–423. DOI 10.1093/bfgp/elp038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Doege CA, Inoue K, Yamashita T, Rhee DB, Travis S, Fujita R, Guarnieri P, Bhagat G, Vanti WB, Shih A, Levine RL, Nik S, Chen EI, Abeliovich A. (2012). Early-stage epigenetic modification during somatic cell reprogramming by Parp1 and Tet2. Nature 488: 652–655. DOI 10.1038/nature11333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dong R, Yao R, Du J, Wang S, Fan Z. (2013). Depletion of histone demethylase KDM2A enhanced the adipogenic and chondrogenic differentiation potentials of stem cells from apical papilla. Experimental Cell Research 319: 2874–2882. DOI 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.07.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dong X, Weng Z. (2013). The correlation between histone modifications and gene expression. Epigenomics 5: 113–116. DOI 10.2217/epi.13.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dore LC, Amigo JD, dos Santos CO, Zhang Z, Gai X, Tobias JW, Yu D, Klein AM, Dorman C, Wu W, Hardison RC, Paw BH, Weiss MJ. (2008). A GATA-1-regulated microRNA locus essential for erythropoiesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105: 3333–3338. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0712312105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Du J, Ma Y, Ma P, Wan S, Fan Z. (2013). Demethylation of epiregulin gene by histone demethylase FBXL11 and BCL6 corepressor inhibits osteo/dentinogenic differentiation. Stem Cells 31: 126–136. DOI 10.1002/stem.1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dunaway K, Goorha S, Matelski L, Urraca N, Lein PJ, Korf I, Reiter LT, LaSalle JM. (2017). Dental pulp stem cells model early life and imprinted DNA methylation pattern. Stem Cells 35: 981–988. DOI 10.1002/stem.2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

El Helou R, Wicinski J, Guille A, Adélaïde J, Finetti P, Bertucci Fçois, Chaffanet M, Birnbaum D, Charafe-Jauffret E, Ginestier C. (2014). A distinct DNA methylation signature defines breast cancer stem cells and predicts cancer outcome. Stem Cells 32: 3031–3036. DOI 10.1002/stem.1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Erhardt S. (2003). Consequences of the depletion of zygotic and embryonic enhancer of zeste 2 during preimplantation mouse development. Development 130: 4235–4248. DOI 10.1242/dev.00625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fedoriw A, Mugford J, Magnuson T. (2012). Genomic imprinting and epigenetic control of development. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 4: a008136. DOI 10.1101/cshperspect.a008136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Felli N, Fontana L, Pelosi E, Botta R, Bonci D, Facchiano F, Liuzzi F, Lulli V, Morsilli O, Santoro S, Valtieri M, Calin GA, Liu CG, Sorrentino A, Croce CM, Peschle C. (2005). MicroRNAs-221 and 222 inhibit normal erythropoiesis and erythroleukemic cell growth via kit receptor down-modulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102: 18081–18086. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0506216102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fisher CL, Fisher AG. (2011). Chromatin states in pluripotent, differentiated, and reprogrammed cells. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 21: 140–146. DOI 10.1016/j.gde.2011.01.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fouse SD, Shen Y, Pellegrini M, Cole S, Meissner A, Van Neste L, Jaenisch R, Fan G. (2008). Promoter CpG methylation contributes to ES cell gene regulation in parallel with Oct4/Nanog, PcG complex, and histone H3 K4/K27 trimethylation. Cell Stem Cell 2: 160–169. DOI 10.1016/j.stem.2007.12.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gal H, Pandi G, Kanner AA, Ram Z, Lithwick-Yanai G, Amariglio N, Rechavi G, Givol D. (2008). miR-451 and imatinib mesylate inhibit tumor growth of glioblastoma stem cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 376: 86–90. DOI 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gopinathan G, Kolokythas A, Luan X, Diekwisch TGH. (2013). Epigenetic marks define the lineage and differentiation potential of two distinct neural crest-derived intermediate odontogenic progenitor population. Stem Cells and Development 22: 1763–1778. DOI 10.1089/scd.2012.0711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Govarthanan K, Gupta PK, Ramasamy D, Kumar P, Mahadevan S, Verma RS (2020). DNA Methylation Microarray uncovers a permissive methylome for cardiomyocyte differentiation in human Mesenchymal stem cells. Genomics 112: 1384–1395. DOI 10.1016/j.ygeno.2019.08.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Govarthanan K, Vidyasekar P, Gupta PK, Lenka N, Verma RS. (2020). Glycogen synthase kinase 303B2; inhibitor- CHIR 99021 augments the differentiation potential of mesenchymal stem cells. Cytotherapy 22: 91–105. DOI 10.1016/j.jcyt.2019.12.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Greco SJ, Liu K, Rameshwar P. (2007). Functional similarities among genes regulated by Oct4 in human mesenchymal and embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 25: 3143–3154. DOI 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Håkelien AM, Bryne JC, Harstad KG, Lorenz S, Paulsen J, Sun J, Mikkelsen TS, Myklebost O, Meza-Zepeda LA. (2014). The regulatory landscape of osteogenic differentiation. STEM CELLS 32: 2780–2793. DOI 10.1002/stem.1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Han DW, Tapia N, Joo JY, Greber B, Araúzo-Bravo MJ, Bernemann C, Ko K, Wu G, Stehling M, Do JT, Schöler HR. (2010). Epiblast stem cell subpopulations represent mouse embryos of distinct pregastrulation stages. Cell 143: 617–627. DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hebbes TR, Thorne AW, Crane-Robinson C. (1988). A direct link between core histone acetylation and transcriptionally active chromatin. EMBO Journal 7: 1395–1402. DOI 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02956.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ho L, Jothi R, Ronan JL, Cui K, Zhao K, Crabtree GR. (2009). An embryonic stem cell chromatin remodeling complex, esBAF, is an essential component of the core pluripotency transcriptional network. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106: 5187–5191. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0812888106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Holik AZ, Young M, Krzystyniak J, Williams GT, Metzger D, Shorning BY, Clarke AR, Hunter KW. (2014). Brg1 loss attenuates aberrant Wnt-signalling and prevents Wnt-dependent tumorigenesis in the murine small intestine. PLoS Genetics 10: e1004453. DOI 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hou H, Gao F, Liang H, Lv Y, Li M, Yao L, Zhang J, Dou G, Wang Y. (2018). miR-188-5p regulates contribution of bone marrow derived cells to choroidal neovascularization by targeting MMP-2/13. Experimental Eye Research 175: 115–123. DOI 10.1016/j.exer.2018.06.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hoxha E, Lambers E, Xie H, De Andrade A, Krishnamurthy P, Wasserstrom JA, Ramirez V, Thal M, Verma SK, Soares MB, Kishore R. (2012). Histone deacetylase 1 deficiency impairs differentiation and electrophysiological properties of cardiomyocytes derived from induced pluripotent cells. Stem Cells 30: 2412–2422. DOI 10.1002/stem.1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hupkes M, Jonsson MKB, Scheenen WJ, Rotterdam W, Sotoca AM, Someren EP, Heyden MAG, Veen TA, Ravestein‐van Os RI, Bauerschmidt S, Piek E, Ypey DL, Zoelen EJ, Dechering KJ. (2011). Epigenetics: DNA Methylation promotes skeletal myotube maturation. The FASEB Journal 25: 3861–3872. DOI 10.1096/fj.11-186122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ivey KN, Muth A, Arnold J, King FW, Yeh RF, Fish JE, Hsiao EC, Schwartz RJ, Conklin BR, Bernstein HS, Srivastava D. (2008). MicroRNA regulation of cell lineages in mouse and human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2: 219–229. DOI 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jaenisch R, Bird A. (2003). Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nature Genetics 33: 245–254. DOI 10.1038/ng1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jenuwein T, Allis CD. (2001). Translating the histone code. Science 293: 1074–1080. DOI 10.1126/science.1063127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ji J, Yamashita T, Budhu A, Forgues M, Jia HL, Li C, Deng C, Wauthier E, Reid LM, Ye QH, Qin LX, Yang W, Wang HY, Tang ZY, Croce CM, Wang XW. (2009). Identification of microRNA-181 by genome wide screening as a critical player in EpCAM positive hepatic cancer stem cells. Hepatology 50: 472–480. DOI 10.1002/hep.22989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Karpiuk O, Najafova Z, Kramer F, Hennion M, Galonska C, König A, Snaidero N, Vogel T, Shchebet A, Begus-Nahrmann Y, Kassem M, Simons M, Shcherbata H, Beissbarth T, Johnsen SA. (2012). The histone H2B monoubiquitination regulatory pathway is required for differentiation of multipotent stem cells. Molecular Cell 46: 705–713. DOI 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kidder BL, Palmer S, Knott JG. (2009). SWI/SNF-Brg1 regulates self-renewal and occupies core pluripotency-related genes in embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 27: 317–328. DOI 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sol Kim D, Young Lee S, Hee Lee J, Chan Bae Y, Sup Jung J. (2015). miRNA-103a-3p controls proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human adipose tissue derived stromal cells. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 47: e172–e172. DOI 10.1038/emm.2015.39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kim YJ, Bae SW, Yu SS, Bae YC, Jung JS. (2009). miR-196a regulates proliferation regulates proliferation and osteogenic differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells derived from human adipose tissue. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 24: 816–825. DOI 10.1359/jbmr.081230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Klungland A, Robertson AB. (2017). Oxidized C5-methyl cytosine base in DNA, 5-hydroxycytosine, 5-Formylcytosine, and 5-carboxycytosine. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 107: 62–68. DOI 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.11.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kochat V, Equbal Z, Baligar P, Kumar V, Srivastava M, Mukhopadhyay A, Laconi E. (2017). JMJD3 aids in reprogramming of bone marrow progenitor cells to hepatic phenotype through epigenetic activation of hepatic transcription factors. PLoS One 12: e0173977. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0173977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kouzarides T. (2007). Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128: 693–705. DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Krichevsky AM, Sonntag KC, Isacson O, Kosik KS. (2006). Specific microRNAs modulate embryonic stem cell-derived neurogenesis. Stem Cells 24: 857–864. DOI 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lachner M, Jenuwein T. (2002). The many faces of histone lysine methylation. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 14: 286–298. DOI 10.1016/S0955-0674(02)00335-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lara-Castro C, Fu Y, Chung BH, Garvey WT. (2007). Adiponectin and the metabolic syndrome: mechanisms mediating risk for metabolic and cardiovascular disease. Current Opinion in Lipidology 18: 263–270. DOI 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32814a645f. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lee RS, Roberts CW. (2013). Linking the SWI/SNF complex to prostate cancer. Nature Genetics 45: 1268–1269. DOI 10.1038/ng.2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lessard JA, Crabtree GR. (2010). Chromatin regulatory mechanisms in pluripotency. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 26: 503–532. DOI 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-051809-102012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li X, Zuo X, Jing J. (2015). Small-molecule-driven direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts into functional neurons. Cell Stem Cell 17: 195–203. DOI 10.1016/j.stem.2015.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li Y, Tan T, Zong L, He D, Tao W, Liang Q. (2012). Study of methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 and H3 lysine 27 during X chromosome inactivation in three types of cells. Chromosome Research 20: 769–778. DOI 10.1007/s10577-012-9311-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li Z, Liu C, Xie Z, Song P, Zhao RCH, Guo L, Liu Z, Wu Y, Abdelhay ESFW. (2011). Epigenetic dysregulation in mesenchymal stem cell aging and spontaneous differentiation. PLoS One 6: e20526. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0020526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liang G, Lin JCY, Wei V, Yoo C, Cheng JC. (2004). Distinct localization of histone H3 acetylation and H3-K4 methylation to the transcription start sites in the human genome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101: 7357–7362. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0401866101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Luger K, Rechsteiner TJ, Flaus AJ, Waye MM, Richmond TJ. (1997). Characterization of nucleosome core particles containing histone proteins made in bacteria. Journal of Molecular Biology 272: 301–311. DOI 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Luzi E, Marini F, Sala SC, Tognarini I, Galli G, Brandi ML. (2008). Osteogenic differentiation of human adipose tissue-derived stem cells is modulated by the miR-26a targeting of the SMAD1 transcription factor. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 23: 287–295. DOI 10.1359/jbmr.071011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Maruyama R, Choudhury S, Kowalczyk A, Bessarabova M, Beresford-Smith B, Conway T, Kaspi A, Wu Z, Nikolskaya T, Merino VF, Lo PK, Liu XS, Nikolsky Y, Sukumar S, Haviv I, Polyak K, Schübeler D. (2011). Epigenetic regulation of cell type-specific expression patterns in the human mammary epithelium. PLoS Genetics 7: e1001369. DOI 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mcittrick E, Gafken PR, Ahmad K, Henikoff S. (2004). Histone H3.3 is enriched in covalent modifications associated with active chromatin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101: 1525–1530. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0308092100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Medina PP, Romero OA, Kohno T, Montuenga LM, Pio R, Yokota J, Sanchez-Cespedes M. (2008). Frequent BRG1/SMARCA4-inactivating mutations in human lung cancer cell lines. Human Mutation 29: 617–622. DOI 10.1002/humu.20730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Meeran S.M. Patel SN, Chan TH, Tollefsbol TO. (2011). A novel prodrug of epigallocatechin-3-gallate: Differential epigenetic hTERT repression in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Prevention Research 4: 1243–1254. DOI 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Meeran SM, Patel SN, Li Y, Shukla S, Tollefsbol TO. (2012). Bioactive dietary supplements reactivate ER expression in ER-negative breast cancer cells by active chromatin modifications. PLoS One 7: e37748. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0037748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Meissner A. (2010). Epigenetic modifications in pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature Biotechnology 28: 1079–1088. DOI 10.1038/nbt.1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mizuno Y, Yagi K, Tokuzawa Y, Kanesaki-Yatsuka Y, Suda T, Katagiri T, Fukuda T, Maruyama M, Okuda A, Amemiya T, Kondoh Y, Tashiro H, Okazaki Y. (2008). miR-125b inhibits osteoblastic differentiation by down-regulation of cell proliferation. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 368: 267–272. DOI 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Molofsky AV, Pardal R, Iwashita T, Park IK, Clarke MF, Morrison SJ. (2003). Bmi-1 dependence distinguishes neural stem cell self-renewal from progenitor proliferation. Nature 425: 962–967. DOI 10.1038/nature02060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Monzen K, Ito Y, Naito AT, Kasai H, Hiroi Y, Hayashi D, Shiojima I, Yamazaki T, Miyazono K, Asashima M, Nagai R, Komuro I. (2008). A crucial role of a high mobility group protein HMGA2 in cardiogenesis. Nature Cell Biology 10: 567–574. DOI 10.1038/ncb1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Munoz P, Iliou MS, Esteller M. (2012). Epigenetic alternations involved in cancer stem cell reprogramming. Molecular Oncology 6: 620–636. DOI 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.10.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nakagawa T, Wada Y, Katada S, Kishi Y. (2020). Epigenetic regulation for acquiring glial identity by neural stem cells during cortical development. Glia 68: 1554–1567. DOI 10.1002/glia.23818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Narcisi R, Ozan A, Johannes L. (2016). Differential effects of small molecule WNT agonists on the multilineage differentiation capacity of human mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Engineering Part A 22: 1264–1273. DOI 10.1089/ten.tea.2016.0081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nguyen H, Sokpor G, Pham L, Rosenbusch J, Stoykova A, Staiger JF, Tuoc T. (2016). Epigenetic remodeling by BAF (mSWI/SNF) chromatin remodeling complexes is indispensable for embryonic development. Cell Cycle 15: 1317–1324. DOI 10.1080/15384101.2016.1160984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Noer A, Bonquest AC, Collas P. (2007). Dynamics of adipogenic promoter DNA Methylation during clonal culture of human adipose stem cells to senescence. BMC Cell Biology 8: 18. DOI 10.1186/1471-2121-8-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Onder TT, Kara N, Cherry A, Sinha AU, Zhu N, Bernt KM, Cahan P, Mancarci BO, Unternaehrer J, Gupta PB, Lander ES, Armstrong SA, Daley GQ. (2012). Chromatin-modifying enzymes as modulators of reprogramming. Nature 483: 598–602. DOI 10.1038/nature10953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pang KC, Frith MC, Mattick JS. (2006). Rapid evolution of noncoding RNAs: lack of conservation does not mean lack of function. Trends in Genetics 22: 1–5. DOI 10.1016/j.tig.2005.10.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pasini D, Bracken AP, Hansen JB, Capillo M, Helin K. (2007). The polycomb group protein Suz12 is required for embryonic stem cell differentiation. Molecular and Cellular Biology 27: 3769–3779. DOI 10.1128/MCB.01432-06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pan J, Silva TC, Gull N, Yang Q, Plummer JT, Chen S, Daigo K, Hamakubo T, Gery S, Ding LW, Jiang YY, Hu S, Xu LY, Li EM, Ding Y, Klempner SJ, Gayther SA, Berman BP, Koeffler HP, Lin DC. (2020). Lineage-specific epigenomic and genomic activation of oncogene HNF4A promotes gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas. Cancer Research 80: 2722–2736. DOI 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-0390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Perkel JM. (2013). Visiting 201C Noncodarnia. BioTechniques 54: 301–304. DOI 10.2144/000114037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Proctor E, Waghray M, Lee CJ, Heidt DG, Yalamanchili M, Li C, Bednar F, Simeone DM, Roemer K. (2013). Bmi1 enhances tumorigenicity and cancer stem cell function in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. PLoS One 8: e55820. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0055820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Protela A, Esteller M. (2010). Epigenetic Modifications and human diseases. Nature Biotechnology 28: 1057–1068. DOI 10.1038/nbt.1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Razin A, Shemer R. (1995). DNA methylation in early development. Human Molecular Genetics 4: 1751–1755. DOI 10.1093/hmg/4.suppl_1.1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ring DB, Johnson KW, Henriksen EJ. (2003). Selective glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibitors potentiate insulin activation of glucose transport and utilization in vitro and in vivo. Diabetes 52: 588–595. DOI 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Roh TY, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Zhao K. (2006). The genomic landscape of histone modifications in human T cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103: 15782–15787. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0607617103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Russo VEA, Martienssen RA, Riggs AD. (1996). Epigenetic Mechanism of Gene Regulation. Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Cold. [Google Scholar]

Sharma S, Bhonde R. (2020). Genetic and epigenetic stability of stem cells: epigenetic modifiers modulate the fate of mesenchymal stem cells. Genomics 112: 3615–3623. DOI 10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.04.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]