Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Global Trends, Health Inequalities, and Relationship with Socio-Demographic Index in Congenital Heart Disease: An Analysis from 1990 to 2021

1 Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Nanjing Lishui People’s Hospital, Zhongda Hospital Lishui Branch, Southeast University, Nanjing, 211200, China

2 Department of Respiratory Medicine, Nanjing Lishui People’s Hospital, Zhongda Hospital Lishui Branch, Southeast University, Nanjing, 211200, China

* Corresponding Author: Xia Zhang. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(3), 383-400. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.064790

Received 24 February 2025; Accepted 20 June 2025; Issue published 11 July 2025

Abstract

Background: Congenital heart disease (CHD) remains a significant global health concern, with considerable heterogeneity across age groups, genders, and regions. Objective: This study aimed to investigate the global epidemiological patterns, inequalities, and socio-demographic determinants of CHD burden from 1990 to 2021 to inform targeted interventions. Methods: This study aimed to investigate the global epidemiological patterns, inequalities, and socio-demographic determinants of CHD burden from 1990 to 2021 to inform targeted interventions. Results: CHD burden increased with age, peaking among individuals aged 70 years and older. This does not reflect new-onset disease, but rather the accumulation of late diagnoses, long-term complications, and healthcare encounters in aging individuals with CHD. Males consistently exhibited higher incidence and mortality rates than females. From 1990 to 2010, global age-standardized prevalence and incidence rates increased steadily and declined slightly thereafter. Joinpoint and age-period-cohort analyses revealed inflection points post-2010 and suggested cohort-related effects. Although SII trends indicated rising inequality over time, that disease burden has become more concentrated in low-SDI regions. ARIMA projections estimated a stable or marginally declining CHD burden by 2030. Regional analyses showed that high-SDI countries experienced significant reductions in CHD mortality, whereas low-SDI regions continued to bear a disproportionate burden. Conclusions: CHD burden has shifted in recent decades, influenced by demographic transitions, healthcare access, and socio-economic development. Despite progress, persistent health inequalities remain. Continued investment in early detection, maternal care, and public health infrastructure is essential to reduce CHD disparities globally.Keywords

Congenital Heart Disease (CHD) is a condition caused by abnormal development of the heart and major blood vessels during fetal life. It’s the most common heart disease in children and significantly contributes to the global disease burden [1,2,3]. According to the 2019 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, there are 13 million CHD cases worldwide, with over 210,000 deaths, ranking seventh among causes of death in children under one year and fourth in countries with a medium socio-demographic index (SDI). In China, the incidence of CHD is about 0.7%~0.8%, and since 2004, it has become the leading cause of birth defects [4]. Despite advancements in medical technology improving detection rates, CHD remains a major cause of neonatal mortality and imposes a substantial economic burden on families and society.

With global aging and medical advancements, the epidemiological characteristics of CHD are changing. Understanding CHD trends, identifying health inequalities, and analyzing their relationship with SDI are crucial for effective public health strategies and resource allocation [5,6].

Over the past decades, the GBD study has provided vital data on CHD epidemiology. However, significant differences in CHD prevalence and mortality exist across regions and populations, influenced by factors like economic development, access to and quality of healthcare, and public health policies. This study aims to explore global CHD trends from 1990 to 2021, assess health inequalities among different socio-demographic groups, and examine their association with SDI.

We used various analytical methods, including Joinpoint regression, age-period-cohort models and autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models, to gain a deeper understanding of CHD trends. We also employed the slope index of inequality (SII) and the concentration index (CI) to quantify and track changes in CHD health inequalities. This research aims to provide scientific evidence for global public health policymakers, helping them better understand CHD epidemiology, identify high-risk groups, and develop targeted interventions. This is crucial for reducing the global CHD burden and improving patient survival and quality of life.

GBD 2021 data are accessible through a portal at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, United States. All disease burden data were obtained from the GBD 2021 database (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2021, accessed on 01 January 2025), which used modeling to estimate the burden of 369 diseases or injuries for 204 countries and territories worldwide between 1990 and 2021, stratified by factors such as cause, location, age, and sex [7].

We extracted CHD-specific data from the GBD 2021 database using ICD-10 codes Q20–Q28, which is a well-defined subset of the broader Q00–Q99 range that covers all congenital malformations.

We extracted and analyzed data specifically related to CHD, including incidence, prevalence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), from the GBD 2021 dataset. Metrics included number, rate, and age-standardized rate with 95% uncertainty intervals. Data were stratified by region (China, global, high-, middle-, low-SDI), age, sex, and CHD. SDI is a comprehensive indicator of a country’s lag-distributed income per capita, average years of schooling, and the fertility rate in females under the age of 25 years [8,9]. The data from China included in global, and China is classified as a high-middle SDI according to the SDI calculation rules. Although data were extracted for early neonatal (0–6 days), late neonatal (7–27 days), and post-neonatal (28–364 days) periods, these subgroups were not included in the main analysis due to limited data robustness and the focus on age-standardized burden.

Data were sorted and analyzed using Excel 2021 software. The rate of change in incidence, mortality, and DALYs for CHD between 1990 and 2021 was calculated as (2021 indicator value − 1990 indicator value)/1990 indicator value × 100%. Trend analyses were conducted using the Joinpoint Regression Program, which is developed by the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI) (https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/, accessed on 01 January 2025) [10,11,12]. The number and location of segmentation points and corresponding p values were determined by the Monte Carlo permutation test, and the annual percentage change and average annual percentage change were calculated using log-linear regression. Joinpoint regression was used to identify significant changes in temporal trends by detecting ‘inflection points’—years at which the slope of the trend changes significantly. This method provides annual percentage change estimates for each segment and is particularly suitable for evaluating disease burden trends over time. We used ARIMA models to forecast the incidence and mortality trends of CHD up to 2030. Time series forecasting was performed using ARIMA models, fitted to the annual CHD burden data from 1990 to 2021. Given the limited number of data points and potential structural changes in the time series, this analysis is exploratory. Age-standardized incidence and death rates were modeled using autoregressive integrated moving average models. Model parameters (p, d, q) were selected based on the lowest Akaike information criterion and Bayesian information criterion values. Model adequacy was evaluated through residual plots and the Ljung–Box test to ensure white noise properties. Forecasts were presented with 95% prediction intervals to reflect uncertainty. The incidence rate of CHD between 2021 and 2030 in China was predicted using R-4.2.2 software. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To maintain consistency and accuracy, all epidemiological indicators are presented to two decimal places.

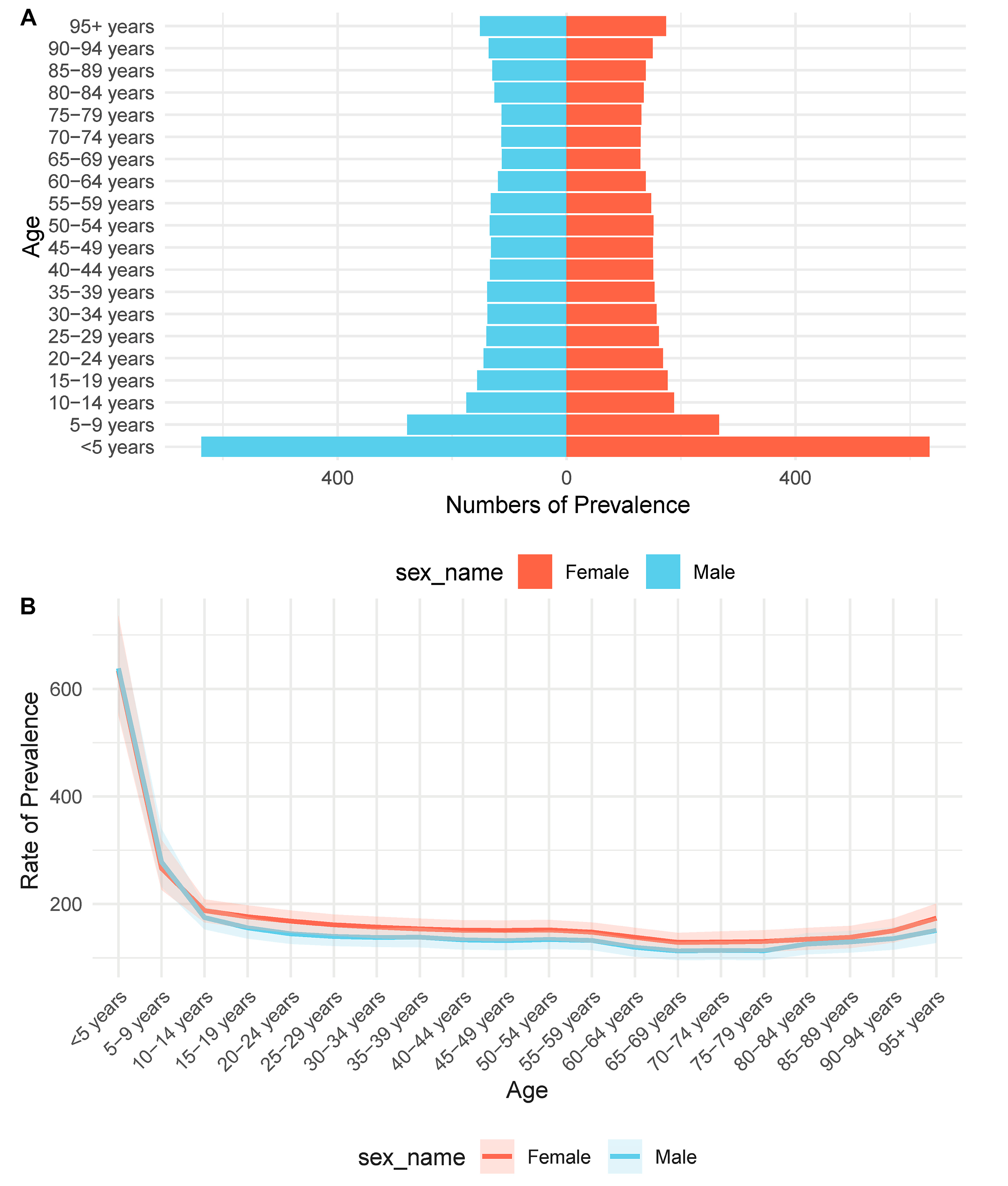

3.1 Age- and Sex-Specific Patterns in the Prevalence of CHD

The analysis of CHD prevalence across age and sex groups reveals distinct demographic patterns. As shown in Fig. 1A, the number of prevalent cases is highest in the <5 years age group for both males and females, indicating the early onset and diagnosis of CHD in childhood. The prevalence then declines sharply and remains relatively stable through adulthood before slightly increasing again in older age groups. Notably, the distribution is symmetric across sexes, although slight differences are observed in certain age intervals, such as 10–14 and 25–29 years. Fig. 1B illustrates the age-specific prevalence rates, demonstrating a steep decline from infancy through adolescence. The rate plateaus in adulthood and rises again in the elderly population. This trend suggests a dual burden of CHD: early-onset cases diagnosed in infancy and a secondary peak in older adults, potentially reflecting accumulated comorbidities or late diagnoses. Overall, males exhibit slightly higher prevalence rates than females across most age groups, although the sex difference narrows in the elderly.

Figure 1: Age- and sex-specific prevalence of CHD. (A) The number of prevalent cases of CHD across age groups for males (blue) and females (red). A clear peak is observed in the <5 years age group, followed by a gradual decline with age. (B) The prevalence rate per 100,000 population plotted against age groups, stratified by sex. Males consistently show slightly higher rates than females across most age categories. A sharp decline from infancy to adolescence is followed by a plateau during adulthood and a slight increase in older age.

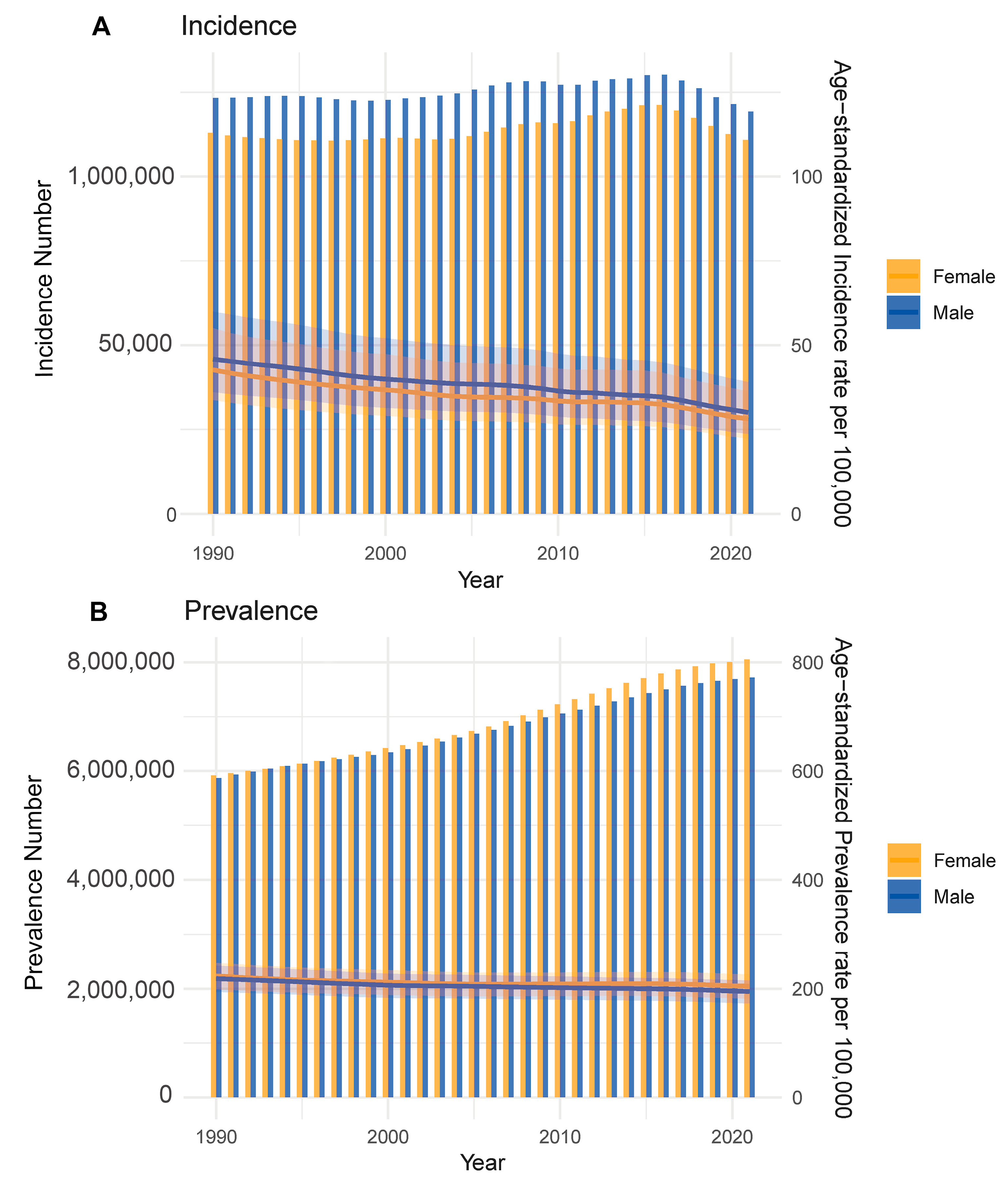

From 1990 to 2021, CHD demonstrated notable changes in both incidence and prevalence worldwide. The total number of new CHD cases steadily increased during this period, with males consistently exhibiting slightly higher case counts compared to females. Although the absolute numbers rose, the age-standardized incidence rate showed a gradual decline for both sexes (Fig. 2A), suggesting improvements in early screening, diagnostic accuracy, and possibly primary prevention strategies. In contrast, the total number of prevalent cases continued to rise throughout the study period, with male prevalence again marginally exceeding that of females. Importantly, the age-standardized prevalence rate also exhibited a continuous upward trend from 1990 to 2021 (Fig. 2B), likely reflecting enhanced survival, better disease management, and the accumulation of cases over time.

Figure 2: Trends in CHD incidence and prevalence by sex (1990–2021). (A) Annual new case numbers (bars) and age-standardized incidence rates (lines) of CHD in males and females from 1990 to 2021. (B) Total prevalent cases (bars) and age-standardized prevalence rates (lines) over the same period. Males consistently show higher case counts, with both sexes exhibiting rising prevalence.

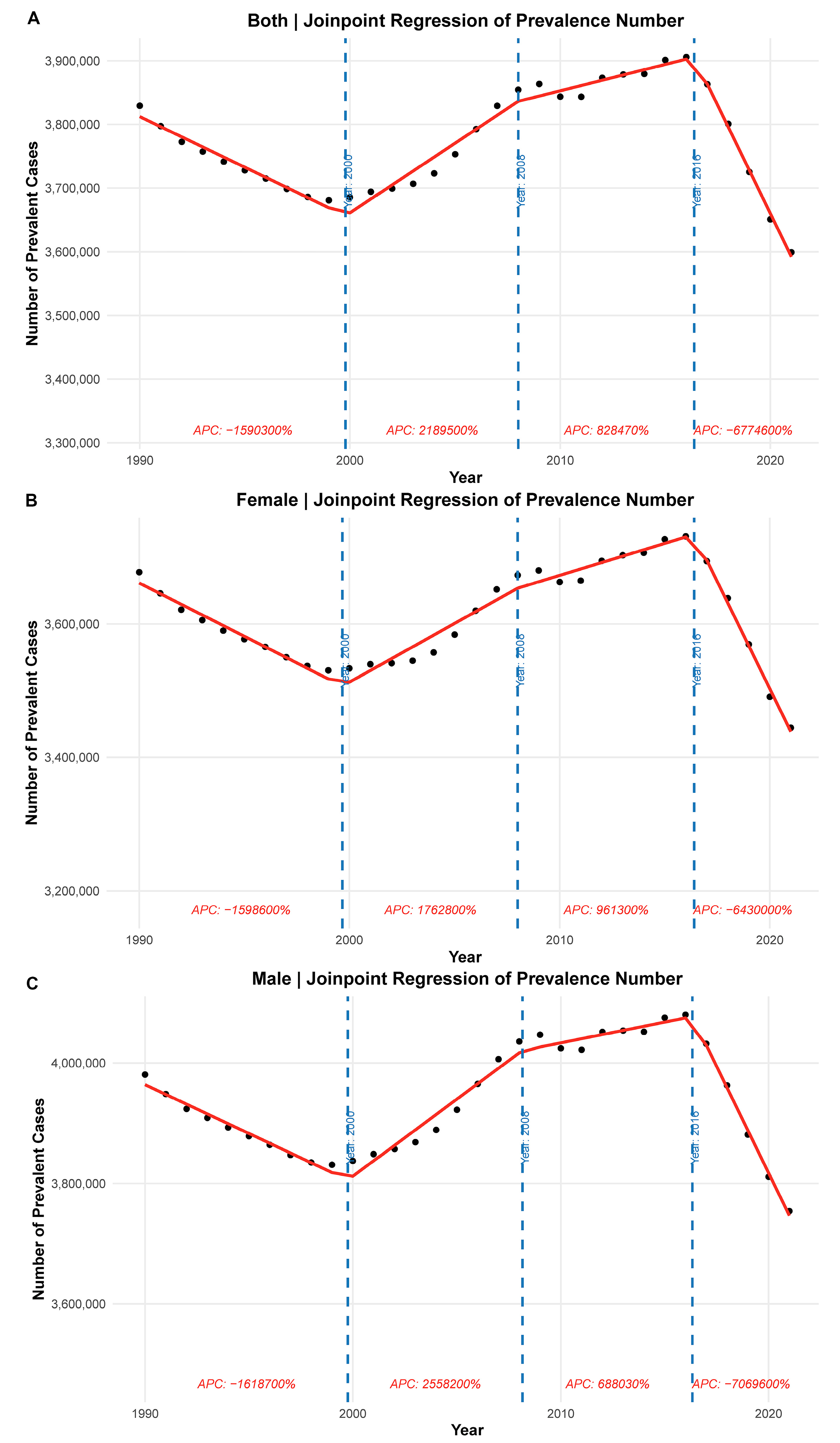

3.3 Joinpoint Regression Analysis of CHD Prevalence (1990–2021)

Joinpoint regression analysis revealed distinct temporal patterns in the number of prevalent cases of CHD across different sex groups. Among the overall population, the prevalence initially declined from 1990 to approximately 1999, followed by a period of sharp growth until around 2010. From 2010 to 2017, the prevalence growth slowed. After 2017, a notable decline was observed (Fig. 3A). Sex-stratified analysis showed similar trends. In females, prevalence decreased from 1990 to 1999 with an annual percent change (APC) of −1.60% (95% CI: −1.68% to −1.52%), then increased steadily from 1999 to 2010 with an APC of 1.77% (95% CI: 1.69% to 1.86%), and from 2010 to 2017 with an APC of 0.96% (95% CI: 0.87% to 1.04%), followed by a sharp drop from 2017 to 2021 with an APC of −6.43% (95% CI: −6.56% to −6.29%) (Fig. 3B). In males, the turning points occurred at slightly different years. From 1999 to 2010, there was a more pronounced increase with an APC of 2.56% (95% CI: 2.47% to 2.66%) and after 2017, a significant decline was observed with an APC of −7.07% (95% CI: −7.22% to −6.92%) (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3: Joinpoint regression of number of prevalent CHD cases from 1990 to 2021. (A) The overall prevalence trajectory with inflection points highlighting three distinct phases of growth and decline. (B) The Joinpoint regression for females, illustrating a turning point around 1999 with subsequent increases and recent declines. (C) The trend in males, with a stronger increase in prevalence before 2010 and a steeper decline in the most recent period. Each segment is annotated with the corresponding annual percent change.

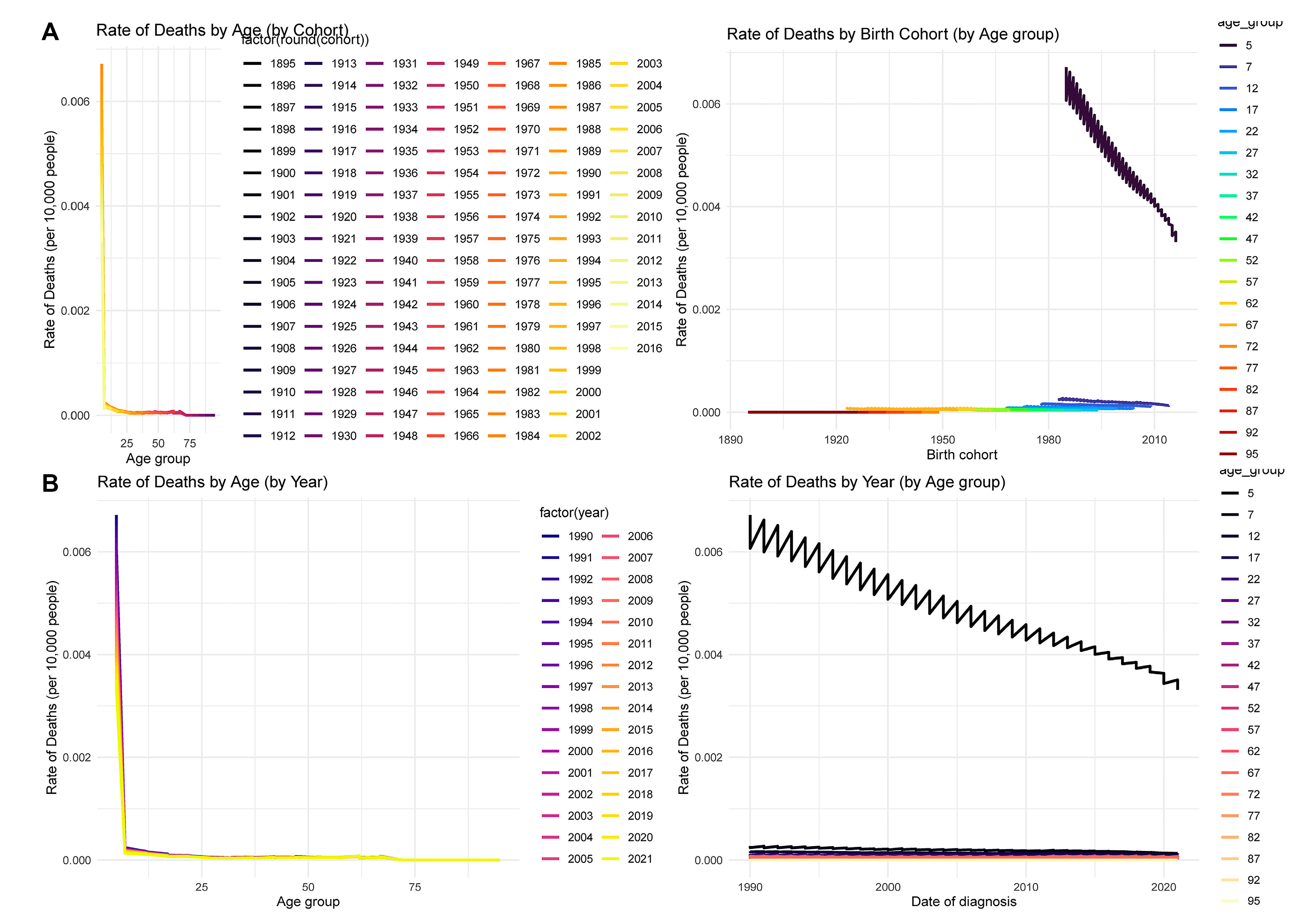

3.4 Age-Period-Cohort Analysis of CHD Mortality

The age-period-cohort analysis reveals complex patterns in CHD mortality across birth cohorts, age groups, and calendar years. In Fig. 4A, mortality rates are highest in early childhood and decline steeply with age, demonstrating a classic age effect. Stratification by birth cohort further shows that more recent cohorts exhibit notably lower mortality, highlighting generational improvements in healthcare and disease management. Meanwhile, Fig. 4B indicates that across all calendar years (1990–2021), the highest mortality burden remains concentrated in young children, but age-specific death rates have gradually decreased over time, suggesting period effects such as enhanced medical technology and access to pediatric care.

Figure 4: Age-period-cohort analysis of CHD mortality from 1990 to 2021. (A) The rate of deaths by age and cohort, and by cohort and age group, indicating that younger birth cohorts have experienced lower mortality, with the highest rates consistently in infancy and early childhood. (B) Death rates by age and year, and by year and age group, demonstrating that while mortality rates are highest in younger ages, they have declined over time across nearly all groups. This supports the influence of both period and cohort effects on CHD mortality trends.

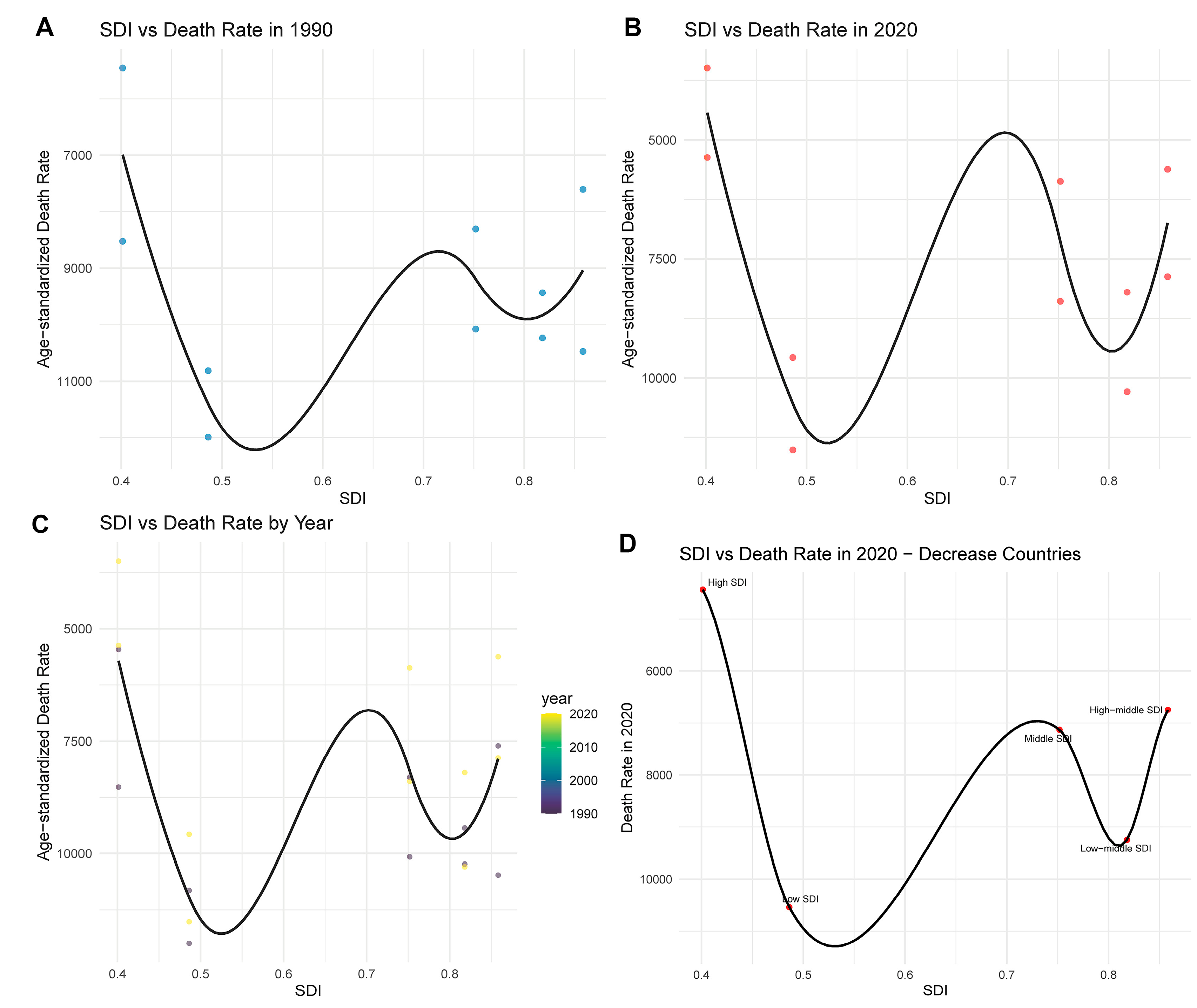

3.5 Relationship between SDI and CHD Mortality

The association between SDI and CHD mortality has evolved over time. In 1990 (Fig. 5A), a U-shaped relationship was observed, with both low- and high-SDI countries exhibiting relatively higher age-standardized death rates, while countries with middle SDI showed lower mortality. By 2021 (Fig. 5B), although overall death rates had declined, the U-shaped pattern remained, suggesting persistent disparities in CHD outcomes related to development levels. A longitudinal analysis across years (Fig. 5C) revealed that although the SDI-mortality relationship fluctuated, countries with low SDI consistently experienced higher death rates, indicating limited progress in healthcare access and CHD management. In contrast, countries with higher SDI levels showed a continued decrease in mortality over time.

Figure 5: Relationship between SDI and age-standardized death rate from CHD. (A) The SDI-death rate curve in 1990, showing a U-shaped relationship with elevated mortality at both low and high SDI levels. (B) The SDI-death rate relationship in 2021, where the U-shaped pattern persists despite an overall reduction in mortality. (C) The SDI-death rate pattern over time (1990–2021), revealing consistent high rates in low-SDI regions and declines in higher SDI countries. (D) The 2021 SDI-death rate association among countries with decreasing mortality trends, highlighting persistent inequalities across SDI tiers (low, middle, high).

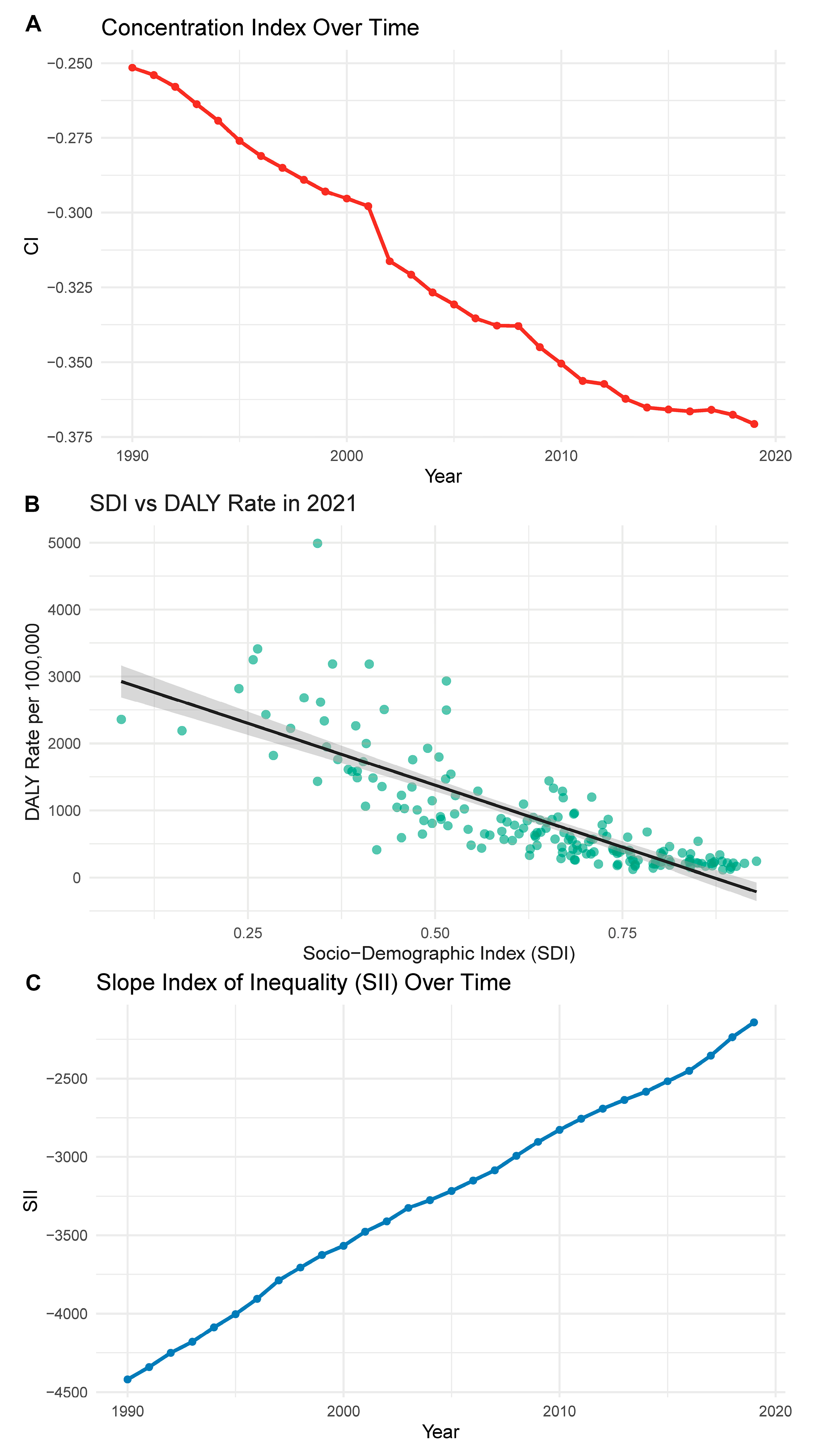

3.6 Inequality Trends in CHD Burden

From 1990 to 2021, the concentration index for CHD burden decreased from −0.25 (95% CI: −0.28 to −0.22) to −0.37 (95% CI: −0.41 to −0.34), indicating an increasing concentration of disease burden among low-SDI populations. This suggests that inequality has worsened over time, with low-income countries disproportionately affected by CHD-related disability and mortality (Fig. 6A). Fig. 6B further supports this pattern by showing a strong inverse relationship between SDI and CHD-related DALY rate in 2021. Countries with lower SDI experienced significantly higher DALY rates, highlighting persistent gaps in healthcare access and outcomes. SII, which quantifies the absolute disparity in burden across the SDI continuum, also exhibited a steadily increasing trend over time (Fig. 6C). From approximately −4500 (95% CI: −5000 to −4000) in 1990 to −2500 (95% CI: −3000 to −2000) in 2021, the less negative slope indicates a relative reduction in absolute disparity, despite the persistent concentration of burden in disadvantaged populations. These findings verify the need for more equitable healthcare strategies aimed at reducing socio-demographic disparities in CHD burden.

Figure 6: Trends in inequality of CHD burden based on SDI. (A) CI from 1990 to 2021, showing a decline that indicates increased concentration of CHD burden among lower-SDI countries. (B) The inverse association between SDI and DALY rate in 2021, with lower-SDI countries facing higher disease burden. (C) SII over time, suggesting a gradual reduction in absolute disparity, though inequities remain substantial.

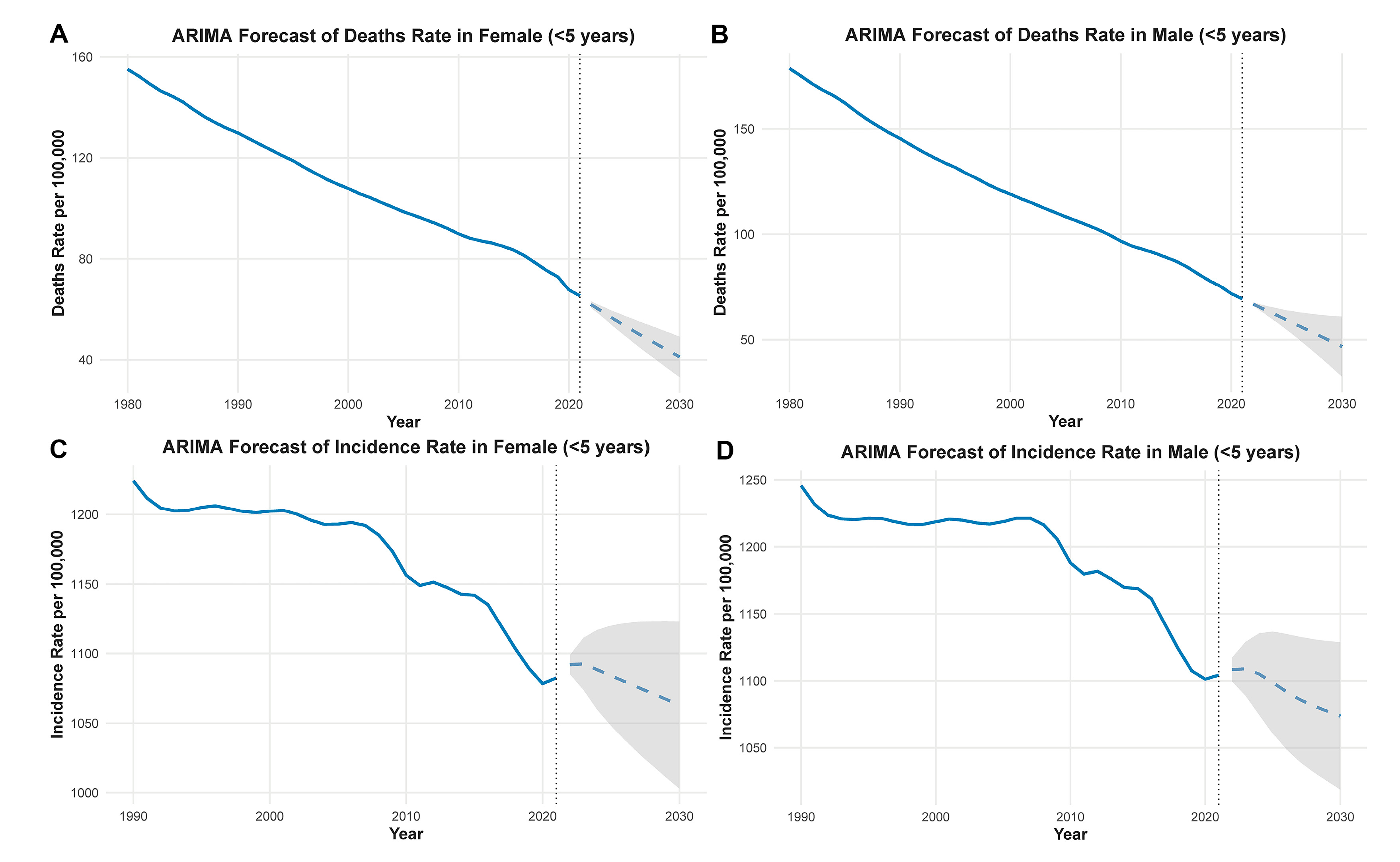

3.7 ARIMA Forecast of CHD in Children under 5 Years Old

The ARIMA forecast models for CHD in children under 5 years old predict continued reductions in both mortality and incidence rates through 2030. As shown in Fig. 7A,B, the age-standardized death rates have steadily declined from the 1990s to 2021 in both females and males. This downward trend is projected to continue, with female mortality rates dropping below 50 per 100,000 and male rates similarly declining, suggesting ongoing improvements in early diagnosis and pediatric care. For incidence, Fig. 7C,D reveals a modest decrease between 2000 and 2021, particularly after 2010. The projections suggest that incidence rates may stabilize or slightly decrease by 2030, with female and male incidence rates predicted to remain below 1100 and 1150 per 100,000, respectively. These findings reflect improved perinatal screening, early interventions, and possibly environmental or genetic risk management in recent decades. However, given potential structural breaks, these forecasts should be interpreted with caution.

Figure 7: ARIMA-based forecasts of CHD burden in children under 5 years old. Predicted age-standardized incidence and mortality rates of CHD from 2021 to 2030. Solid lines indicate point forecasts; shaded areas represent 95% prediction intervals. AIC and BIC values for each fitted ARIMA model are provided in the Methods section. (A) The predicted decline in age-standardized death rate in females under 5 years old, continuing a long-term downward trend. (B) A similar trend in males, with projections indicating further mortality reductions by 2030. (C) The forecasted incidence rate in females, which shows stabilization after a previous decline. (D) The projected incidence in males, suggesting a leveling-off of rates in the coming decade. The shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals for the forecasted values.

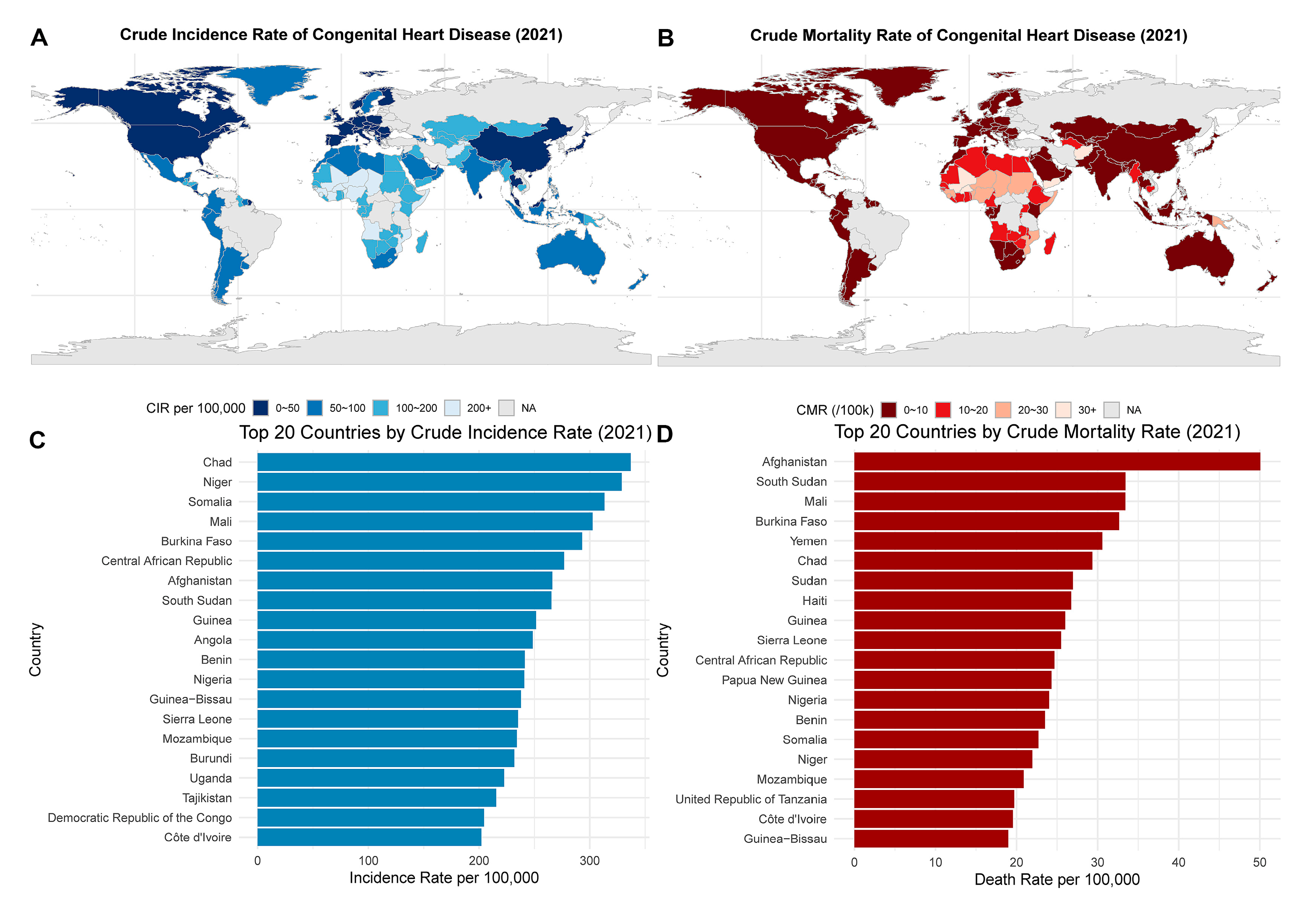

3.8 Global Distribution of CHD Incidence and Mortality (2021)

Fig. 8 illustrates the global patterns of CHD burden in 2021, highlighting significant regional disparities in both incidence and mortality. Fig. 8A shows that the crude incidence rate of CHD was highest in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and parts of the Middle East, with some countries exceeding 200 per 100,000 population. Notably, Chad, Niger, and Somalia ranked among the highest in incidence (Fig. 8C), suggesting a possible association with underdeveloped healthcare systems, limited prenatal screening, and high birth rates. In contrast, Fig. 8B reveals that the crude mortality rate was also disproportionately elevated in these same regions, particularly in Afghanistan, South Sudan, and Burkina Faso. As shown in Fig. 8D, the top 20 countries by crude mortality rate were predominantly low-income countries with constrained access to specialized cardiac care and pediatric surgery.

Figure 8: Global distribution of CHD incidence and mortality in 2021. (A) The global map of crude incidence rates of CHD, with darker shades representing higher rates. (B) The crude mortality rates across countries, where deep red shading indicates high death burdens. (C) The top 20 countries by crude incidence rate per 100,000, with Chad, Niger, and Somalia leading. (D) The top 20 countries by crude mortality rate, with Afghanistan, South Sudan, and Mali showing the highest values.

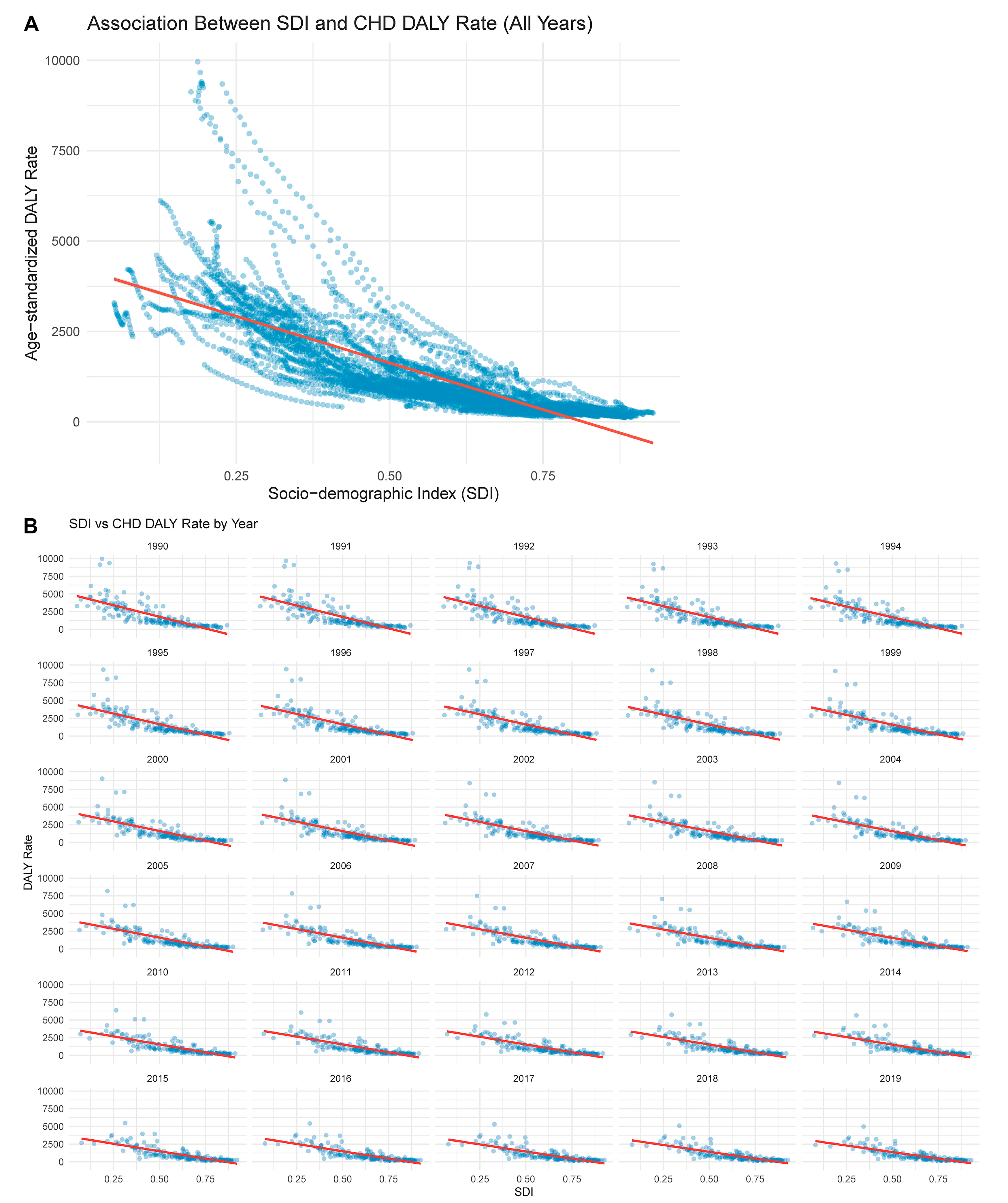

3.9 Association between SDI and CHD Burden (1990–2019)

Fig. 9 explores the relationship between SDI and the age-standardized DALY rate of CHD across countries and over time. As shown in Fig. 9A, there is a strong overall negative correlation between SDI and CHD burden: countries with lower SDI values tend to exhibit significantly higher age-standardized DALY rates. This pattern proves the impact of socioeconomic development on reducing CHD-related disability and mortality. Notably, countries with SDI below 0.5 consistently cluster in the higher DALY range. To further understand this relationship longitudinally, Fig. 9B presents the year-by-year association between SDI and DALY rate from 1990 to 2019. Across all years, the inverse association remains evident, with slight variations in slope and dispersion, indicating a globally consistent yet dynamically shifting inequality landscape. The downward trend becomes more uniform after 2005, possibly reflecting international progress in maternal and child health, congenital disease screening, and treatment access.

Figure 9: Association between SDI and CHD DALY rate. (A) shows the pooled association between SDI and age-standardized DALY rates across all years (1990–2019), highlighting a strong inverse correlation. (B) breaks down this association by year, showing year-specific scatterplots with regression lines indicating the consistent negative relationship between SDI and DALY rate over time.

CHD is one of the most common congenital defects, referring to structural abnormalities of the heart or great vessels that occur during the fetal period. It is a congenital disorder with a high incidence rate in newborns and is also the most common cause of death in infants due to birth defects, imposing a significant economic burden on society and families [13,14,15]. Globally, the prevalence of CHD has been increasing year by year. Between 1970 and 2017, the average rate of CHD at birth worldwide was 8.2 cases per 1000 newborns. In China, since 2004, the incidence of CHD has risen to the top among birth defects. Despite the continuous development of medical technology and increased detection rates, CHD remains a significant cause of neonatal death [16,17,18].

From 1990 to 2021, CHD exhibited distinct age- and sex-related epidemiological characteristics. Males consistently demonstrated slightly higher age-standardized prevalence and incidence rates than females, particularly in early childhood and late adulthood. This pattern is consistent with previous population-based studies that reported a modest male predominance in CHD incidence, especially in severe subtypes such as ventricular septal defects [19,20]. However, this sex gap diminished with increasing age, which may reflect sex-specific differences in biological and social factors, as also reported by previous research [21]. On the other hand, the temporal trend in CHD also demonstrated a critical turning point. While the total number of cases rose steadily, age-standardized incidence rates peaked around 2010 and began to decline thereafter. This finding aligns with prior analyses by Pan et al., which attributed declining incidence to the great improvements achieved in early screening, diagnostic criteria, and possibly primary prevention measures [22]. The post-2010 decline contrasts with the continued growth in absolute case counts and prevalence, which is likely attributable to improved survival and population aging. The observed patterns underscore the dual burden of early-onset CHD and an expanding cohort of adults living with the condition, reflecting the success of pediatric cardiac care over the past three decades. Our observation of higher CHD burden among elderly males aligns with reports highlighting gender-specific disparities in long-term survival and late diagnosis in adults with congenital heart defects [23].

This study utilizes data from the GBD 2021, offering new insights into the epidemiology of CHD. Compared to existing research, the innovation of this study lies in not only analyzing the trends of CHD but also delving into the relationship between CHD and SDI, as well as the health inequalities between different regions and countries. This multidimensional analysis provides a richer perspective for understanding the global distribution of CHD. Existing epidemiological studies face issues such as data limitations, especially in low- and middle-income countries where lower diagnostic levels may lead to delayed diagnosis of mild CHD. Additionally, the etiology of CHD is still unclear, and in most cases, no specific cause can be identified, which limits the formulation and implementation of preventive measures. This study’s global perspective analysis helps to reveal the differences and trends in the epidemiology of CHD worldwide, providing important epidemiological evidence for the prevention and control of CHD globally.

From 1990 to 2021, SII shows an upward trend, indicating increasing disparities. CI illustrates that in 1990, CHD was more concentrated among lower SDI populations, as seen in countries like China and India. By 2021, CI has shifted, showing a reduction in inequality with a more even distribution across SDI levels. The bottom graph highlights that while disparities persist, there is a general trend towards reducing inequality, with higher SDI countries experiencing lower DALY rates. This emphasizes the need for targeted health policies to address these disparities. The worsening concentration of CHD burden in lower-SDI settings, as indicated by our CI and SII analysis, is consistent with findings in other non-communicable diseases [24]. We have emphasized how structural barriers in healthcare access contribute to these trends.

GBD 2021 provides global health data from 1990 to 2021, covering 204 countries and regions, including data on the coverage rate of 11 types of childhood vaccinations. This offers us a comprehensive and up-to-date data perspective to assess the global prevalence of CHD and health inequalities. Our findings reveal persistent disparities in CHD burden across SDI levels. To mitigate these inequities, multi-level and region-specific strategies are needed. Scaling up prenatal screening programs can facilitate early diagnosis and timely interventions, especially in low-resource settings where diagnostic delays are common [25]. Investing in maternal and neonatal health infrastructure, including delivery of essential cardiac services, is critical for improving survival outcomes. Additionally, the establishment of national CHD registries would enhance data quality and allow for better tracking of disease trends, particularly in countries with currently limited surveillance. Telemedicine and task-shifting approaches, such as training primary care providers to perform basic cardiac screening, may further reduce urban–rural disparities in access to pediatric cardiology services [26,27]. Collectively, these evidence-based interventions can help address the structural causes of CHD health inequities.

We employed various statistical methods, including the Joinpoint regression model, SII, and CI, which can more accurately capture the trends of CHD and health inequalities. The application of these methods enhances the scientific and accuracy of the study. This study not only analyzes the trends of CHD but also delves into the relationship between CHD and SDI, as well as the health inequalities between different regions and countries. The study further clarifies the impact of human societal development on the burden of CHD, exploring the relationship between the level of socio-economic development and the burden of CHD, which is significant for understanding the global distribution of CHD and formulating public health strategies.

Data analysis reveals a significant relationship between CHD ASMR and SDI across different regions. Globally, as SDI increases, mortality rates decrease, indicating the positive impact of economic development and social welfare on health. High-income regions, such as the Asia-Pacific, North America, and Western Europe, show the lowest mortality rates, likely due to better healthcare facilities, public health policies, and living standards. In contrast, middle- and low-income regions, like South Asia and Eastern Europe, face higher mortality rates, possibly due to insufficient medical resources, lack of health education, and poorer socio-economic conditions [28]. The observed higher burden of CHD in elderly males may be attributable to a combination of biological and social factors. Biologically, estrogen is believed to confer cardioprotective effects in females, potentially delaying the progression or complications of congenital anomalies [29]. In contrast, elderly males often exhibit a greater burden of comorbidities, such as hypertension and diabetes, which can exacerbate the clinical manifestation of congenital heart defects [30]. Social determinants, including disparities in access to cardiac care and lower health-seeking behavior among males, may also contribute to the observed differences. The decline in CHD incidence rates after 2010 may reflect the global expansion of prenatal screening programs, improved access to fetal echocardiography, and wider implementation of early surgical interventions. For example, in countries such as China and Brazil, nationwide maternal health initiatives and congenital disease registries have strengthened early diagnosis and management, potentially reducing late-stage incidence [31,32]. Continued investment in screening infrastructure and public awareness may further contribute to the declining trend.

Nevertheless, this study has limitations. This study did not further analyze the burden of CHD in specific neonatal subgroups (e.g., 0–6 days, 7–27 days) due to small sample sizes and high uncertainty intervals in many countries. Future studies are required to assess neonatal CHD burden in more detail. Although the GBD 2021 database offers a comprehensive estimation of global disease burden, it is important to acknowledge potential underestimations of CHD prevalence and mortality, particularly in low-SDI regions. These underestimations may arise from diagnostic limitations, lack of access to medical care, and underreporting in health surveillance systems. Such biases can impact inequality measures such as SII, potentially exaggerating disparities by inflating the apparent disease burden in high-SDI regions while underrepresenting the burden in low-resource settings. Moreover, GBD modeling relies on various covariates and assumptions that may not fully capture subnational heterogeneities. Therefore, our findings should be interpreted with caution, especially regarding the magnitude of disparities. Strengthening diagnostic capacity and data collection systems in low-SDI regions remains essential for accurately monitoring CHD burden and informing equitable health policies. While ARIMA provided short-term projections, the presence of structural breaks and limited data points constrain the reliability of long-term forecasts. These limitations underscore the need for more robust modeling frameworks in future studies, especially those incorporating exogenous variables or structural break detection [33]. The projected decline in mortality aligns with long-term outcomes from CHD surgical cohorts in Europe and North America, supporting the model’s plausibility [34].

In conclusion, CHD mortality rates show significant regional differences, highlighting the importance of socio-economic factors in health outcomes. Strengthening public health policies and improving economic conditions could further reduce CHD incidence and mortality rates. By analyzing the relationship between CHD and SDI, this study provides scientific evidence for the formulation of targeted public health strategies, especially in terms of resource allocation and health policy formulation. This study utilizes GBD 2021 data to provide new insights into the trends of CHD, offering important epidemiological evidence for the prevention and control of CHD worldwide. Through these findings, we can better understand the global burden of CHD and guide future research and public health practices.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Jingdong Qi and Fei Zhang; methodology, Jingdong Qi and Fei Zhang; software, Jingdong Qi and Fei Zhang; validation, Jingdong Qi and Fei Zhang; formal analysis, Xia Zhang; investigation, Xia Zhang; data curation, Jingdong Qi and Fei Zhang; writing—Xia Zhang; writing—review and editing, Xia Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Xia Zhang, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Butto A, Mercer-Rosa L, Teng C, Daymont C, Edelson J, Faerber J, et al. Longitudinal growth in patients with single ventricle cardiac disease receiving tube-assisted feeds. Congenit Heart Dis. 2019;14(6):1058–65. doi:10.1111/chd.12843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Delgado Y, Gaytan C, Perez N, Miranda E, Morales BC, Santos M. Association of congenital heart defects (CHD) with factors related to maternal health and pregnancy in newborns in Puerto Rico. Congenit Heart Dis. 2024;19(1):19–31. doi:10.32604/chd.2024.046339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Foote HP, Wu H, Balevic SJ, Thompson EJ, Hill KD, Graham EM, et al. Using pharmacokinetic modeling and electronic health record data to predict clinical and safety outcomes after methylprednisolone exposure during cardiopulmonary bypass in neonates. Congenit Heart Dis. 2023;18(3):295–313. doi:10.32604/chd.2023.026262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi M, Abbasifard M, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–22. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Liu Q, Deng J, Yan W, Qin C, Du M, Wang Y, et al. Burden and trends of infectious disease mortality attributed to air pollution, unsafe water, sanitation, and hygiene, and non-optimal temperature globally and in different socio-demographic index regions. Glob Health Res Policy. 2024;9(1):23. doi:10.1186/s41256-024-00366-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Meadows RJ, Paskett ED, Bower JK, Kaye GL, Lemeshow S, Harris RE. Socio-demographic differences in the dietary inflammatory index from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2018: a comparison of multiple imputation versus complete case analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2024;27(1):e184. doi:10.1017/S1368980024001800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Gaur K, Mohan I, Kaur M, Ahuja S, Gupta S, Gupta R. Erratum to “escalating ischemic heart disease burden among women in India: insights from GBD, NCDRisC and NFHS Reports” [American journal of preventive cardiology 2C (2020) 100035]. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2021;5:100154. doi:10.1016/j.ajpc.2021.100154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Guo Z, Ji W, Yan M, Shi Y, Chen T, Bai F, et al. Global, Regional and national burden of maternal obstructed labour and uterine rupture, 1990–2021: global burden of disease study 2021. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2025;39(2):135–45. doi:10.1111/ppe.13156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhu YS, Sun ZS, Zheng JX, Zhang SX, Yin JX, Zhao HQ, et al. Prevalence and attributable health burdens of vector-borne parasitic infectious diseases of poverty, 1990–2021: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Infect Dis Poverty. 2024;13(1):96. doi:10.1186/s40249-024-01260-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. de Roo AM, Vondeling GT, Boer M, Murray K, Postma MJ. The global health and economic burden of chikungunya from 2011 to 2020: a model-driven analysis on the impact of an emerging vector-borne disease. BMJ Glob Health. 2024;9(12):e016648. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2024-016648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Mokdad AH, Bisignano C, Hsu JM, Bryazka D, Cao S, Bhattacharjee NV, et al. Burden of disease scenarios by state in the USA, 2022–50: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;404(10469):2341–70. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)02246-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Dou Z, Lai X, Zhong X, Hu S, Shi Y, Jia J. Global burden of non-rheumatic valvular heart disease in older adults (60–89 years old), 1990–2019: systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2025;130:105700. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2024.105700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Bhende VV, Bhatt MH, Patel VB, Tandon R, Krishnakumar M. A tale of two congenital lesions: a case report of congenital diaphragmatic hernia and congenital heart disease managed by successful surgical outcome with review of the literature (Bhende-Pathak hernia). Cureus. 2024;16(12):e75238. doi:10.7759/cureus.75238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Shahid S, Khurram H, Lim A, Shabbir MF, Billah B. Prediction of cyanotic and acyanotic congenital heart disease using machine learning models. World J Clin Pediatr. 2024;13(4):98472. doi:10.5409/wjcp.v13.i4.98472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Thomas AR, Bowen C, Abdulhayoglu E, Brennick E, Woo K, Everett MF, et al. Structured pre-delivery huddles enhance confidence in managing newborns with critical congenital heart disease in the delivery room. J Perinatol. 2024:1–8. doi:10.1038/s41372-024-02196-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hu D, Lan T, Chen Y, Chen L, Li J, Sun X, et al. An 18-year evolution of congenital heart disease in China: an echocardiographic database-based study. Int J Cardiol. 2023;391:131286. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2023.131286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang X, Li S, Huo D, Zhu Z, Wang W, He H, et al. Nosocomial infections after pediatric congenital heart disease surgery: data from national center for cardiovascular diseases in China. Infect Drug Resist. 2024;17:1615–23. doi:10.2147/IDR.S457991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhou S, Yang Y, Wang L, Liu H, Wang X, Ouyang C, et al. Study on the trend of congenital heart disease inpatient costs and its influencing factors in economically underdeveloped areas of China, 2015–2020: a case study of Gansu Province. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1303515. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1303515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Majani NG, Koster JR, Kalezi ZE, Letara N, Nkya D, Mongela S, et al. Spectrum of heart diseases in children in a national cardiac referral center Tanzania, Eastern Africa: a six-year overview. Glob Heart. 2024;19(1):61. doi:10.5334/gh.1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Haider A, Khan S, Tafweez R, Yaqoob M. Gender and its association with cardiac defects in down syndrome population at Children Hospital & Institute of Child Health, Lahore, Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci. 2024;40(3Part-II):371–5. doi:10.12669/pjms.40.3.7346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Cook NL. Eliminating the sex and gender gap and transforming the cardiovascular health of all women. Ethn Dis. 2019;29(Suppl 1):65–70. doi:10.18865/ed.29.S1.65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Pan F, Xu W, Li J, Huang Z, Shu Q. Trends in the disease burden of congenital heart disease in China over the past three decades. J Zhejiang Univ Med Sci. 2022;51(3):267–77. doi:10.3724/zdxbyxb-2022-0072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Moons P, Marelli A. Born to age: when adult congenital heart disease converges with geroscience. JACC Adv. 2022;1(1):100012. doi:10.1016/j.jacadv.2022.100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Comfort H, McHugh TA, Schumacher AE, Harris A, May EA, Paulson KR, et al. Global, regional, and national stillbirths at 20 weeks’ gestation or longer in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2021: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;404(10466):1955–88. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01925-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mattia D, Matney C, Loeb S, Neale M, Lindblade C, Scheller McLaughlin E, et al. Prenatal detection of congenital heart disease: recent experience across the state of Arizona. Prenat Diagn. 2023;43(9):1166–75. doi:10.1002/pd.6409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Borrelli N, Grimaldi N, Papaccioli G, Fusco F, Palma M, Sarubbi B. Telemedicine in adult congenital heart disease: usefulness of digital health technology in the assistance of critical patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(10):5775. doi:10.3390/ijerph20105775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. McGrath L, Taunton M, Levy S, Kovacs AH, Broberg C, Khan A. Barriers to care in urban and rural dwelling adults with congenital heart disease. Cardiol Young. 2022;32(4):612–7. doi:10.1017/S1047951121002766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zimmerman MS, Smith AG, Sable CA, Echko MM, Wilner LB, Olsen HE, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of congenital heart disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(3):185–200. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30402-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Hou L, Liu W, Sun W, Cao J, Shan S, Feng Y, et al. Lifetime cumulative effect of reproductive factors on ischaemic heart disease in a prospective cohort. Heart. 2024;110(3):170–7. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2023-322442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Sigala EG, Vaina S, Chrysohoou C, Dri E, Damigou E, Tatakis FP, et al. Sex-related differences in the 20-year incidence of CVD and its risk factors: the ATTICA study (2002–2022). Am J Prev Cardiol. 2024;19:100709. doi:10.1016/j.ajpc.2024.100709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Lu X, Li G, Wu Q, Ni W, Pan S, Xing Q. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease and voluntary termination of pregnancy: a population-based study in Qingdao, China. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2024;17:205–12. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S447493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Gomes JA, Cardoso-dos-Santos AC, Bremm JM, Alves RS, Bezerra AB, Araújo VE, et al. Congenital anomalies in Brazil, 2010 to 2022. Pan Am J Public Health. 2025;49:e9. doi:10.26633/RPSP.2025.9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Fan MC, Geng BC, Li KR, Wang XQ, Varshney PK. Interpretable data fusion for distributed learning: a representative approach via gradient matching. In: 27th International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION); 2024 Jul 7–11; Venice, Italy. doi:10.23919/FUSION59988.2024.10706324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Franklin BA, Thompson PD, Al-Zaiti SS, Albert CM, Hivert MF, Levine BD, et al. Exercise-related acute cardiovascular events and potential deleterious adaptations following long-term exercise training: placing the risks into perspective-an update: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(13):e705–36. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools