Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Pulmonary Hypertension Associated with Congenital Heart Disease: A Clinical Primer

1 Department of Pediatrics, Heart Institute, Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital, St. Petersburg, FL 33701, USA

2 Department of Pediatrics, Division of Critical Care, The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK 73014, USA

* Corresponding Author: Lily M. Landry. Email:

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(3), 325-339. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.066142

Received 31 March 2025; Accepted 03 June 2025; Issue published 11 July 2025

Abstract

Pulmonary hypertension associated with congenital heart disease represents a significant challenge for clinicians due to its complex pathophysiology and diverse presentation. This patient population exhibits a broad spectrum of anatomical and hemodynamic abnormalities, with congenital heart disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH-CHD) comprising a significant proportion of pediatric pulmonary hypertension (PH) cases. Although progress in diagnostic methods and treatment options has been made, PH continues to be a major contributor to illness and death among affected pediatric patients, especially when diagnosis or treatment is postponed. This review aims to equip non-specialist clinicians with a better understanding of PH associated with congenital heart disease, focusing on its pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and diagnostic criteria. Key recommendations for evaluating and managing this fragile population are presented, emphasizing the importance of early recognition and multidisciplinary collaboration. As an increasing number of congenital heart disease patients reach adulthood, understanding its lifelong impacts becomes crucial for improving outcomes and creating tailored treatment approaches.Keywords

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) associated with congenital heart disease encompasses a unique patient population, one that involves a variety of complex anatomic and hemodynamic abnormalities [1]. This group is increasingly common, with recent epidemiological research indicating an incidence of 2.2 cases per million and a prevalence of 15.6 cases per million for congenital heart disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH-CHD) [1,2]. Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), classified as Group 1 PH, ranks as the second most common cause of PH among pediatric patients [3,4]. Furthermore, PAH-CHD comprises nearly 60–75% of all patients classified in the World Symposium of Pulmonary Hypertension (WSPH) Group 1 [3,4,5].

In the past, classifying patients with PH associated with congenital heart disease has been complex, and the classification system for PH has evolved to better describe biventricular and single-ventricle circulations [1,6,7,8,9]. Despite the revised classification from the 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension in 2018, it is increasingly acknowledged that patients with complex congenital heart disease may span multiple categories, exhibiting characteristics of various PH groups at different points in their condition’s progression [1,7,9].

The prognosis for PH associated with congenital heart disease differs widely and is primarily influenced by the type of defect, age at diagnosis, and available therapeutic approaches [4]. With limited prospective trial data available for this group, therapeutic strategies are commonly informed by clinical expertise and smaller retrospective analyses, adapted to the patient’s unique cardiac defects [1,4].

This review focuses on delineating the major PH groups linked to congenital heart disease, elucidating the underlying pathophysiology, and summarizing the latest clinical guidelines for assessing and managing this varied and vulnerable patient cohort.

2 Classification of Pulmonary Hypertension Associated with Congenital Heart Disease

PH associated congenital heart disease may be classified into one of four World Health Organization pathogenic categories: Group 1, PAH; Group 2, PH caused by left-sided heart conditions; Group 4, PH resulting from pulmonary artery blockages; and Group 5, PH with uncertain or multifactorial causes, encompassing complex congenital heart disease [1,4]. See Table 1. PAH is specifically characterized by a mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) greater than 20 mmHg, a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) of 15 mmHg or lower, and a pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) of 3 Wood units or greater [1,10,11,12]. PAH-CHD is a sub-group of Group 1 PAH and can be further broken down into four clinical sub-categories: Eisenmenger syndrome, PAH associated with systemic to pulmonary shunts, PAH with small cardiac defects (such as atrial septal defects and ventricular septal defects), and PAH after cardiac defect closure [12,13]. As a growing number of individuals with CHD survive into adulthood, we can expect a corresponding rise in the prevalence of PAH-CHD [3,4,14].

Table 1: Pulmonary Hypertension Associated with Congenital Heart Disease.

| WHO PH Category: | Examples: | |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | PAH-Congenital Heart Disease | ▪ Eisenmenger syndrome ▪ PAH due to large persistent left to right shunts ▪ PAH with coincidental congenital heart disease (small defects) ▪ PAH after cardiac defect closure |

| Group 2 | Left-Sided Heart Disease | ▪ Left heart obstructive disease ▪ Ventricular dysfunction (systolic or diastolic) ▪ Mitral of Aortic valve disease ▪ Pulmonary vein stenosis |

| Group 4 | Pulmonary Artery Obstruction | ▪ Congenital pulmonary artery stenosis |

| Group 5 | Unclear or Multifactorial Mechanisms | ▪ Complex congenital heart disease ▪ Single ventricle after BDG or Fontan ▪ Segmental PH |

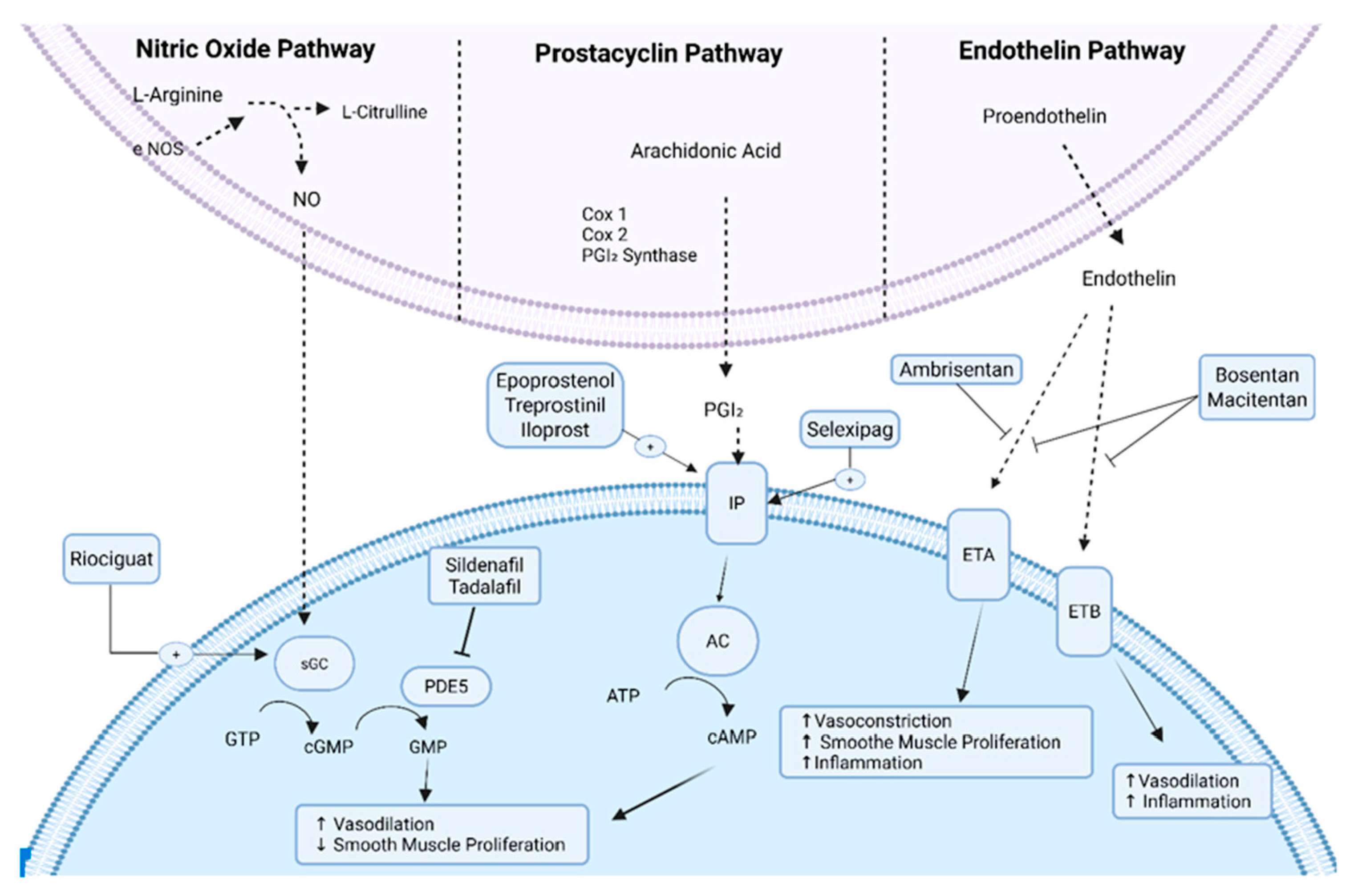

The pathophysiology of PH in congenital heart disease is complex but largely involves a series of vascular changes that result in increased PVR and eventually right heart failure [15,16]. The three primary mechanisms contributing to PAH involve the nitric oxide pathway, endothelin pathway, and prostacyclin pathway [4,15]. See Fig. 1 for pathway details. Heart defects involving systemic-to-pulmonary shunts contribute to volume and pressure overload in the pulmonary circulation, triggering shear stress, circumferential stretching, and damage to the endothelium [13,17,18]. These vascular alterations result in the overexpression of vasoactive mediators (endothelin-1) that lead to vasoconstriction and under expression of mediators (nitric oxide and prostacyclin) that result in vasodilation [13,17]. Sustained vasoconstriction, coupled with the release of growth factors that foster intimal thickening, smooth muscle cell growth, and in situ thrombus formation, contributes to elevated PVR and progressive, irreversible vascular pathology [13,14].

Figure 1: Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Pathophysiology, eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; NO, nitric oxide; sGC, soluble guanylate cyclase; GTP, guanosine triphosphate; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate; GMP, guanosine monophosphate; PDE5, phosphodiesterase type 5; Cox, cyclooxygenase; PGI2, prostaglandin I2; IP, prostaglandin I2 receptor; AC, adenylate cyclase; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; ETA, endothelin type A receptor; ETB, endothelin type B receptor.

In the setting of increased afterload, the right ventricle undergoes a series of maladaptive changes to enhance contractility and preserve cardiac output. This process, known as right ventricular-to-pulmonary artery coupling, results in concentric hypertrophy [19,20,21]. The right ventricle is capable of immense adaptation; however, ultimately, it becomes so dilated that it fails to eject properly [19,20,21]. Additionally, a dilated and pressure-overloaded right ventricle can displace the intraventricular septum toward the left ventricle, obstructing left ventricular outflow, leading to inadequate left ventricular filling, and potentially causing fatal outcomes [19,20,21,22].

A combination of genetic and environmental influences likely contributes to the development of PAH-CHD. Over twenty genes associated with risk have been identified, connected to progressive PAH in pediatric and young adult populations [23]. Several of the most widely reported of these genes include the BMPR2, TBX4, BMP10, EIF2AK4, CAV1, ENG, KCNK3, and SMAD9 genes [23,24,25,26,27,28]. BMPR2 is a protein that inhibits smooth muscle and endothelial cell proliferation, and prevents neointimal formation; therefore, disruption of the BMPR2 signaling pathway leads to increased inflammation and hyperproliferation [29]. At the endothelial level, mutated BMPR2 fails to activate protein kinase A (PKA), resulting in inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation and decrease in nitric oxide production [29]. Pathogenic mutations in the BMPR2 gene contribute to roughly 70% of familial PAH cases, but they are less commonly associated with PAH-CHD [30]. Pediatric patients with congenital heart disease who also have coexisting genetic syndromes often experience a more rapid disease progression and poorer clinical outcomes [1].

4 Clinical Evaluation and Testing

Diagnosing patients with PH and congenital heart disease begins with a thorough medical history and physical. Although early symptomology is often subtle and non-specific, early diagnosis and treatment is imperative for improved survival [12,31,32]. For infants, early symptoms can include tachypnea, tachycardia, poor feeding, and growth failure. For older children, dyspnea on exertion and unexplained fatigue are the most common presenting symptoms at the time of diagnosis [1,12]. Less common symptoms are syncope, near-syncope, and chest pain [12].

Early in the disease progression, physical exam findings may be unclear, but certain examination techniques have been shown to serve as effective diagnostic tools. In particular, a prominent second heart sound, jugular venous distension, and right ventricular heave are recognized as the most reliable physical examination findings for identifying PH [31]. Additionally, as right ventricular dysfunction progresses, patients may exhibit signs of right ventricular failure, such as peripheral edema, ascites, and abdominal discomfort or distension [12].

Chest radiographic findings are usually non-specific and do not correlate with disease severity; however, they may provide insight to the degree of left-to-right shunting in patients with PAH-CHD [1,33]. Pulmonary venous congestion, pulmonary artery enlargement, and right heart enlargement can all be seen in patients with large left-to-right shunts. Conversely, oligemia can be seen in patients with limited pulmonary blood flow secondary to cardiac disease states such Eisenmenger syndrome or certain forms of complex single ventricle physiology [1].

N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) is commonly used to help determine the severity or progression of PH. The rationale for this is that the pressure/volume load on the right heart will cause activation of the natriuretic peptide system and thus increase cardiomyocyte production of B-type natiuretic peptide and its N-terminal cleavage product, NT-proBNP [34]. In terms of risk stratification, redefined cut-off values for NT-proBNP (<300, 300–649, 650–1100, and >1100 ng/L) for low, intermediate-low, intermediate-high, and high risk have been recently introduced in the four-strata model published in the 2022 European Society of Cardiology–European Respiratory Society (ESC/ERS) treatment guidelines [35]. Even though brain natriuretic peptide levels have been found to correlate with the New York Heart Association functional class strongly, the 6-min walk distance test, and various hemodynamic parameters, caution must be excised when attempting to ascertain the relevance of NT-proBNP in the setting of pediatric patients with PAH-CHD. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide is highly variable and rarely studied in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease [34,36,37]. Many clinicians will use the NT-proBNP as a marker of right ventricular health and response to therapy. Additionally, C-reactive protein (CRP) can be elevated in PH patients and likely represents inflammation. Care must be taken in PAH-CHD patients, as CRP can be elevated after surgery or in other inflammatory conditions.

Noninvasive echocardiography is a highly effective screening technique for PH and is typically the initial imaging approach for individuals with congenital heart disease [1,31,33,38]. Echocardiography is used to estimate the probability of PH by assessing chamber dimensions in 2D, estimating hemodynamics using spectral Doppler, and assessing right and left ventricular function using tissue Doppler imaging, speckle tracking, and measurements such as tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion and fractional area change [33]. Of note, recent guidelines suggest that echocardiographic-derived systolic pulmonary artery pressure measurements are imprecise and should not be used in guiding treatment [12,33,39]. Any patient with evidence of elevated pulmonary artery pressure by echocardiography (such as increased tricuspid regurgitation velocity, right ventricle/left ventricular basal diameter ratio of greater than 1.0, right ventricular dysfunction, flattening of the interventricular septum or pulmonary artery enlargement) should undergo diagnostic testing via cardiac catheterization [12,39,40]. In areas where cardiac catheterization is not easily accessible, echocardiography may serve as the primary diagnostic method [41].

Right and left-sided cardiac catheterization and acute vasoreactivity testing constitute the definitive approach for diagnosis, treatment stratification, and prognostication of PH in patients with congenital heart disease [33,42,43]. The initial cardiopulmonary hemodynamic assessment should include right and left heart pressure measurements to determine PVR, transpulmonary gradient (TPG), and severity of disease [42]. Additionally, other causes of PH including pulmonary vein stenosis and bronchopulmonary dysplasia should be ruled out and pre-capillary PH should be distinguished from post-capillary PH (see Table 2).

Table 2: Hemodynamic Criteria for Pulmonary Hypertension.

| Type of PH | mPAP (mmHg) | PAWP or LVEDP (mmHg) | PVRI (WU·m2) | Diastolic TPG (mmHg) | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precapillary PH | >20 | <15 | ≥3 | ≥7 | - |

| Mixed Pre-Post Capillary PH | >20 | >15 | >3 | - | - |

| Post-capillary PH | >20 | >15 | <3 | <7 | - |

| Pulmonary Hypertensive Vascular Disease (Biventricular patients) | >20 | - | >3 | - | - |

| Pulmonary Hypertensive Vascular Disease (Cavopulmonary Anastomosis) | - | - | >3 | - | or mean TPG > 6 mmHg |

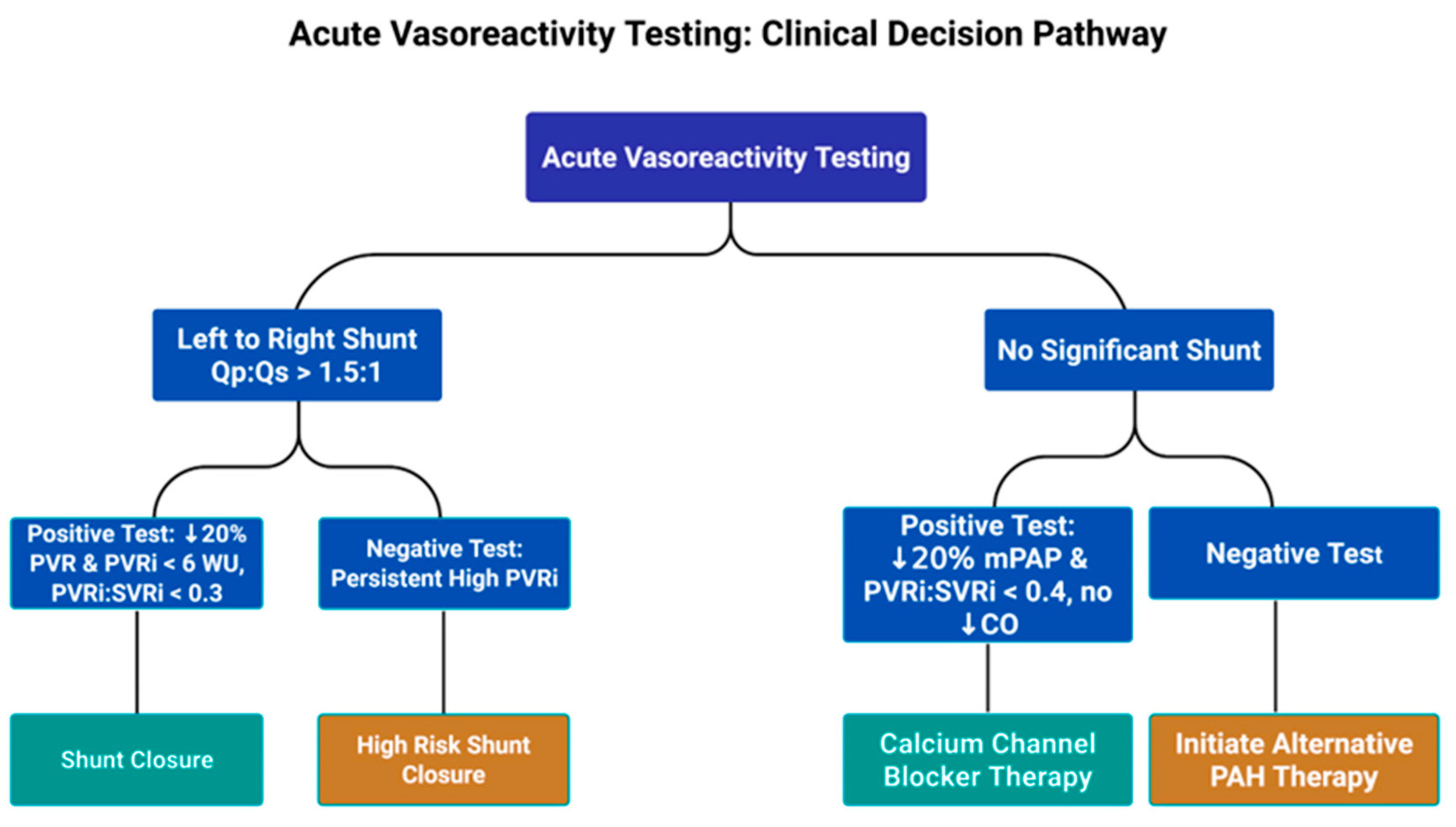

Acute vasoreactivity should be performed in all patients to help guide treatment strategy and determine suitability for operability in patients with significant left-to-right shunts [1,42,44]. See Fig. 2. Inhaled nitric oxide (20–40 parts per million) alone or in combination with oxygen are the preferred agents used for testing [1,42]. For patients without significant cardiac shunts, a positive test per the modified Barst criteria is a 20% decrease in mPAP and indexed pulmonary vascular resistance to indexed systemic vascular resistance ratio (PVRi:SVRi) without a decrease in cardiac output [42,44,45]. In the presence of a positive test, a fall in the ratio of PVRi:SVRi below 0.4 may be an indication for calcium channel blocker therapy [42,44,46]. For patients with significant left-to-right shunts (Qp:Qs > 1.5), vasoreactivity testing is used to distinguish reversible PAH from irreversible/progressive PAH and determine whether or not shunt closure may be undertaken safely [44,45]. The suggested definition for a positive test in this population is a 20% decrease in indexed PVR, an indexed PVR value below 6 Wood units, and a PVRi:SVRi ratio less than 0.3 [45].

Figure 2: Acute Vasoreactivity Testing Clinical Decision Pathway, Qp:Qs, ratio of pulmonary blood flow to systemic blood flow; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance: PVRi, indexed pulmonary vascular resistance; WU, Woods unit; PVRi:SVRi, indexed pulmonary vascular resistance to indexed systemic vascular resistance ratio; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; CO, cardiac output; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension.

In patients with single ventricle physiology, cardiac catheterization can be a useful surveillance tool, providing a detailed hemodynamic assessment that may or may not guide transcatheter and medical therapies [47]. For this specific population, a low PVR is necessary to sustain adequate pulmonary blood flow and provide optimal cardiac output. There is growing evidence to suggest that a mPAP greater than 15 mmHg may be associated with early and late mortalities after Fontan operation [42]. The Pulmonary Vascular Research Institute Panama classification defines pulmonary hypertensive vascular disease following a cavopulmonary anastomosis as an indexed PVR greater than 3.0 Wood units or a transpulmonary gradient (TPG) greater than 6 mmHg, even if the mPAP is less than 25 mmHg [42,48]. See Table 2.

5 Pharmacological and Surgical Treatment Considerations

In comparison to other Group 1 subgroups, limited data exists on drug treatment options for patients with PAH-CHD [15]. Treatment strategies for these patients vary depending on clinical scenario and operability. The most recent PH treatment guidelines published by the ESC/ERS describe an updated four-strata treatment algorithm that stratifies patients based on risk (low, intermediate-low, intermediate-high or high risk) and adjusts management accordingly [35,49]. High risk features include the presence of clinical symptoms (syncope, exercise testing intolerance, 6-min walking distance <165 m), elevated NT-proBNP (>1100 ng/L), and evidence of right ventricular failure by echocardiogram, MRI, and right heart catheterization [35]. This treatment algorithm may prove to be useful for the general practitioner; however, it should be noted that the majority of risk stratification models have been validated primarily in patients with idiopathic PAH, not specifically PAH-CHD [49]. Therefore, case by case evaluation is warranted in patients with PAH-CHD, especially those with high-risk features and other comorbidities (genetic syndromes, complex congenital heart disease, etc.). In high-risk patients or patients with cardiac lesions that are deemed inoperable, pharmacotherapy may be the only available option [4]. Currently, drugs used by PH specialists to treat PAH target the endothelin, nitric oxide, and prostacyclin pathways [4,13,15]. See Fig. 1.

5.1 Endothelin Receptor Antagonists (ERA)

Bosentan, an oral dual antagonist of endothelin receptor type A (ET-A) and type B (ET-B), suppresses smooth muscle proliferation by attaching to receptors on vascular smooth muscle endothelial cells and blocking endothelin-1 function [16,50,51]. It is one of the most well-studied drugs to treat Eisenmenger syndrome and has been associated with hemodynamic improvements, increased survival, improved WHO functional class, and six-minute walking distances [16,50,51,52]. On the other hand, Bosentan has been associated with increased hepatic transaminase levels; therefore, monthly liver function testing is recommended [52]. If there is a mild to moderate increase in the hepatic transaminase levels, the clinician could consider decreasing the dose in half for a week and then rechecking the levels. If the levels are significantly increased, discontinuation of the medication is likely warranted. Based on the current data, the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology and European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend Bosentan as first-line medical therapy in patients with PAH-CHD who are not eligible for defect closure [13,15,35,53].

Ambrisentan is an oral selective endothelin receptor antagonist that preferentially blocks ET-A receptors and can be administered in a single daily dose. In patients with PAH, it has demonstrated efficacy in improving exercise capacity, lowering plasma B-type natriuretic peptide levels, and reducing rates of clinical worsening [35,54]. Additionally, Ambrisentan carries a lower risk of aminotransferase abnormalities and only requires laboratory monitoring once every three months [35,54].

Macitentan is another dual endothelin receptor antagonist that is relatively new to the drug market but has shown to be a safe and efficacious option for the treatment of PAH-CHD [52,55,56]. The SERAPHIN (Study with an Endothelin Receptor Antagonist in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension to Improve Clinical Outcome) multicenter randomized control trial, which included 62 PAH-CHD patients, showed a significant improvement in mortality and morbidity with drug use [52,55,57]. Macitentan has been shown to have better tissue properties and remains an appealing option due to its once-daily dosing and lack of associated liver toxicity [35,52,55]. Macitentan is currently not approved for use in children [35]; however, several reports of its off-label use in children (used either as monotherapy or adjunct therapy) for severe cases have shown that this drug is rather well-tolerated with minimal side effects, such as hepatotoxicity and hypotension [58,59,60]. The TOMORROW study—a large multicenter placebo controlled trial investigating the use of Macitentan in 148 pediatric PAH patients—is currently in process and should provide more data to validate these preliminary findings [58].

5.2 Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) Inhibitors

Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors are a subclass of drug that elicit pulmonary vasodilation and inhibit smooth muscle proliferation by increasing levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate in the nitric oxide-cyclic guanosine monophosphate-protein kinase G signaling pathway [52,61]. Utilization of PDE-5 inhibitors in patients with PAH have shown clear clinical and statistical benefits in regards to WHO functional class, six-minute walking distance, mean pulmonary artery pressure, and cardiac index, irrespective of the underlying etiology [61,62].

Sildenafil is an oral PDE-5 inhibitor that is widely used in the PAH population due to its ease of use and low cost [52]. The most commonly reported side effects include vomiting, headache, bronchitis, pyrexia and diarrhea [13,52].

Tadalafil is a longer-acting oral PDE-5 inhibitor that has been shown to improve WHO functional class, increase six-minute walking distance and reduce PVR in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome [52,63]. Additionally, Tadalafil is given once daily; therefore, compliance may better than Sildenafil.

5.3 Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Stimulators

Soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators are a relatively new class of drugs that act directly on the nitric oxide pathway to promote vasodilation and inhibit cellular proliferation. Riociguat is the first FDA-approved drug for the treatment of adults with PAH and patients with chronic thromboembolic PH (Group 4). The drug works via two mechanisms: It sensitizes soluble guanylate cyclase to endogenous nitric oxide, and it directly stimulates soluble guanylate cyclase receptors, independent of nitric oxide availability [13,64]. This is in contrast to PDE-5 inhibitors that depend on endogenous nitric oxide to work [13,64]. The PATENT-1 trial, a global multi-center clinical study, assessed the safety and efficacy of Riociguat in symptomatic PAH patients who were either treatment-naive or receiving therapy with an endothelin receptor antagonist or a non-inhaled prostanoid [64,65]. The study found that patients treated with Riociguant in both groups had significantly improved exercise intolerance and consistently improved pulmonary hemodynamics, WHO functional class, and time to clinical worsening [64,65]. Coadministration of Riociguat and PDE-5 inhibitors is contraindicated due to an additive hypotensive effect [64].

5.4 Prostacyclin Analogs and Non-Prostacyclin Receptor Agonists

Prostacyclin analogs are fast-acting, potent pulmonary vasodilators that also inhibit platelet aggregation, inhibit smooth muscle proliferation, and induce smooth muscle relaxation [13,66]. Synthetic prostacyclin analogs such as Epoprostenol, Iloprost and Treprostanil have been clinically proven to confer benefits in function, morbidity, and mortality in patients with PAH [67]. Additionally, they offer an array of parenteral and non-parenteral (inhaled or oral) treatment options. Their use in patients with PAH-CHD has been limited due to their adverse side effects and the need for central venous access which carries the additional risk of infection and thrombosis. For this reason, prostacyclin analogs are reserved for more symptomatic patients (WHO functional class III or IV) and/or lack response to oral therapies [52].

Selexipag is a new oral non-prostanoid IP receptor agonist that entered the drug market in 2015 and has vasodilatory and antiproliferative effects on the pulmonary vasculature [68]. Unlike other prostacyclin analogs, it does not cause receptor desensitization. The randomized controlled Prostacyclin (PGI2) Receptor Agonist In Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (GRIPHON) study showed that Selexipag, added as a third agent, was shown to increase cardiac index and significantly reduce PVR in PAH patients who were already receiving treatment with an ERA and a PDE-5i [69,70]. Common side effects include headache, nausea, jaw pain, diarrhea, and myalgia. In some cases, a patient can first be stabilized on a prostacyclin and then transitioned to Selexipag.

According to the ESC/ERS guidelines, patients with PAH-CHD who are deemed low or intermediate-risk should be offered dual-combination therapy upfront (ERA and PDE-5 inhibitor). This recommendation is based off results of the AMBITION study, which showed significant improvements in the six-minute walking distance and NT—proBNP levels with combination therapy (Ambrisentan and Tadalafil) [35,71]. Interestingly, the TRITON study showed no benefit of oral triple-combination therapy (Macitentan, Tadalafil, Selexipeg) versus oral dual-combination therapy (Macitentan and Tadalafil) for this group [35,72]. For PAH-CHD patients who fall into the high-risk category, upfront triple therapy is recommended (ERA, PDE-5 inhibitor, and prostanoid analog) due to the highest likelihood of success [35,49].

5.6 Surgical Treatment Considerations

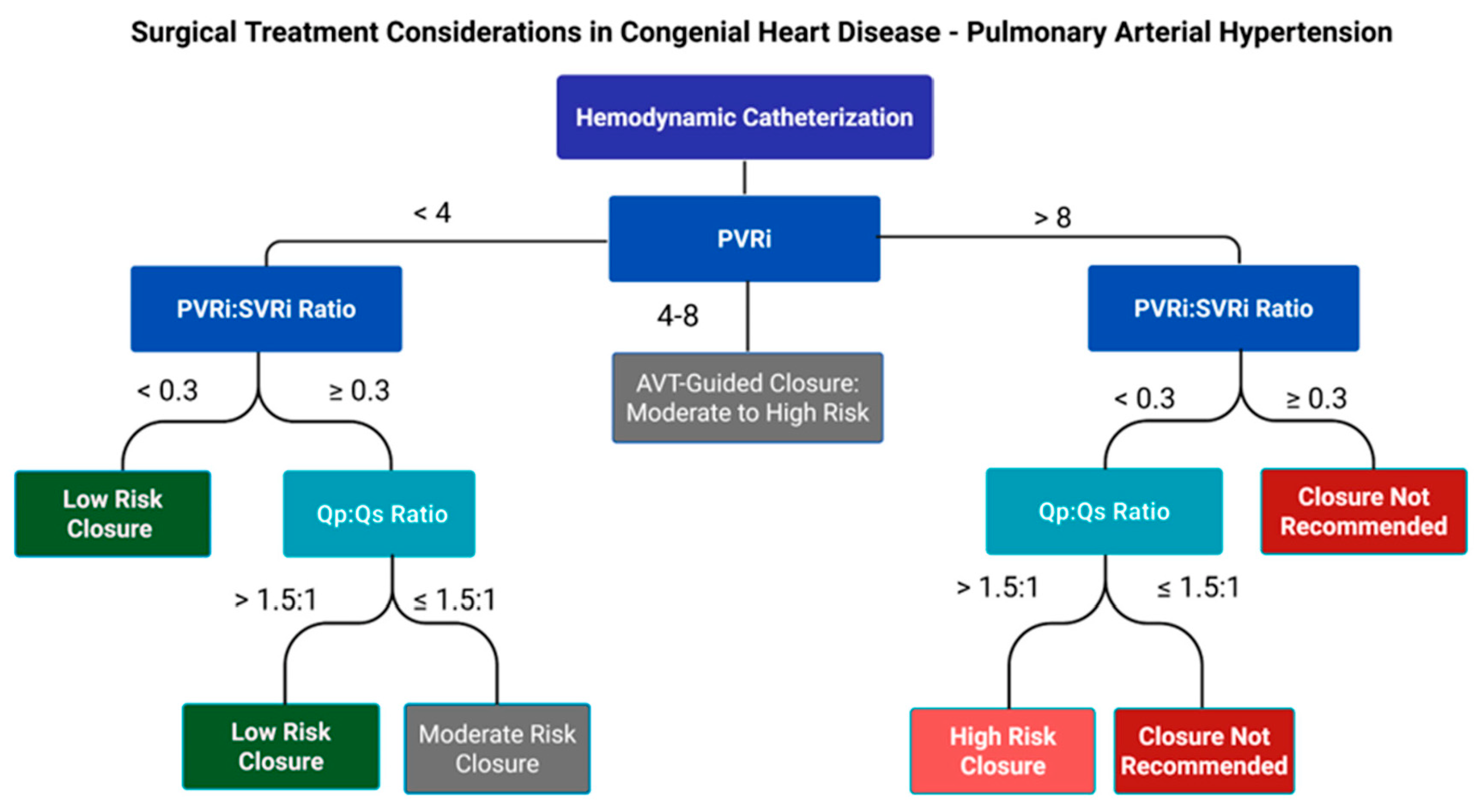

Surgical or percutaneous closure of congenital heart defects is generally contraindicated when significant pulmonary vascular disease is present. Patients with PAH-CHD with persistent systemic-to-pulmonary shunts and mild-to-moderately elevated PVR require a more complex management strategy and should undergo careful evaluation for consideration of shunt closure. The decision to close a shunt depends on several factors including the size and location of the defect and the severity of PAH determined by cardiac catheterization [13]. See Fig. 3. In general, shunt closure is recommended when there is net left-to-right shunting (Qp:Qs > 1.5), a PVR index < 4 WU·m2), and a PVRi:SVRi ratio less than 0.3. Conversely, closure is discouraged when the PVR index is >8 WU·m2 and/or the PVRi:SVRi ratio is greater than 0.5 [13,49]. See Fig. 3. The grey area in between (PVR index between 4–8 WU·m2 or PVRi:SVRi ratio 0.3–0.5) requires case-by-case evaluation and should also take into account patient risk factors and associated comorbidities (genetics syndromes such as Trisomy 21) [13,42,49]. Although long-term supportive data is lacking, the “treat-and-repair” approach can be an option for selective patients that fall into this ambiguous grey area. This approach utilizes PAH-targeted pharmacotherapy with 1–2 medications to lower PVR as a bridge to partial or complete defect closure [13,49,73]. It has also been considered for patients with a PVR index > 8 WU·m2, where the goal is to decrease the PVR index < 8 WU·m2 [73]. No matter the situation, the treat-and-repair approach is risky and warrants close follow-up and hemodynamic re-evaluation.

Figure 3: Surgical Treatment Considerations in Congenital Heart Disease—Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. PVRi:SVRi, indexed pulmonary vascular resistance to indexed systemic vascular resistance ratio; Qp:Qs, ratio of pulmonary blood flow to systemic blood flow; PVRi, indexed pulmonary vascular resistance; AVT, acute vasoreactivity testing.

5.7 Single Ventricle Circulation

Succeeding significant surgical improvements in patients with single ventricle physiology over the years, there is now a growing interest in improving quality of life in these patients by optimizing their PVR with the use of pulmonary vasodilators. PVR plays a key role in determining total cardiac output for these patients, and even the slightest increase can result in significant morbidity [74]. In a recent meta-analysis by Wang et. al, nine randomized control trials involving 381 patients with Fontan physiology were reviewed and results indicated that pulmonary vasodilators (mainly PDE-5 inhibitors and ERA’s) were generally well-tolerated and their use led to significantly improved hemodynamics, reduced the NYHA functional class, increased six-minute walking distance, and improved peak oxygen consumption during exercise testing [75]. However, no significant change in mortality or BNP/pro-NT BNP levels was seen [75]. Despite these promising results, the level of evidence to support routine recommendation of pulmonary vasodilators for Fontan patients is limited and careful review of each patient’s hemodynamic profile is recommended prior to initiating therapy.

Managing PH in patients with congenital heart disease is an intricate process that requires both a deep understanding of the underlying pathophysiology and a tailored approach to treatment. The diversity in clinical presentations and disease progression highlights the necessity for personalized care strategies. Non-specialist clinicians are essential in the early identification of symptoms and the prompt start of diagnostic evaluations, which are vital for enhancing long-term patient outcomes. Treatment paradigms continue to evolve with the introduction of advanced pharmacological therapies targeting specific pathways and, when feasible, surgical interventions. These efforts collectively aim to mitigate disease progression, improve quality of life, and extend survival.

Further research is essential to refine diagnostic tools, develop novel therapies, and optimize management guidelines. In particular, the SV-INHIBITION study, a nationwide multicenter, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study, currently in process, may provide more supporting evidence for the use of Sildenafil therapy in single ventricle adolescent and adult patients [76]. Multidisciplinary collaboration among pediatricians, cardiologists, pulmonologists, and other specialists is paramount to achieving the best outcomes for this growing population. By promoting collaboration and prioritizing a patient-focused approach, healthcare providers can more effectively meet the intricate needs of individuals with congenital heart disease and associated PH.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Both authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Lily M. Landry and Christopher L. Jenks; draft manuscript preparation: Lily M. Landry and Christopher L. Jenks. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: No new data were generated or analyzed for this study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Jone PN, Ivy DD, Hauck A, Karamlou T, Truong U, Coleman RD, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in congenital heart disease: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circ Heart Fail. 2023;16(7):e00080. doi:10.1161/HHF.0000000000000080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. van Riel ACMJ, Schuuring MJ, van Hessen ID, Zwinderman AH, Cozijnsen L, Reichert CLA, et al. Contemporary prevalence of pulmonary arterial hypertension in adult congenital heart disease following the updated clinical classification. Int J Cardiol. 2014;174(2):299–305. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Abman SH, Mullen MP, Sleeper LA, Austin ED, Rosenzweig EB, Kinsella JP, et al. Characterisation of paediatric pulmonary hypertensive vascular disease from the PPHNet Registry. Eur Respir J. 2021;59(1):2003337. doi:10.1183/13993003.03337-2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sullivan RT, Raj JU, Austin ED. Recent advances in pediatric pulmonary hypertension: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Clin Ther. 2023;45(9):901–12. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2023.07.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. del Cerro Marín MJ, Rotés AS, Ogando AR, Soto AM, Jiménez MQ, Gavilán Camacho JL, et al. Assessing pulmonary hypertensive vascular disease in childhood. Data from the Spanish registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(12):1421–9. doi:10.1164/rccm.201406-1052OC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Galiè N, McLaughlin VV, Rubin LJ, Simonneau G. An overview of the 6th world symposium on pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(1):1802148. doi:10.1183/13993003.02148-2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Rosenzweig EB, Abman SH, Adatia I, Beghetti M, Bonnet D, Haworth S, et al. Paediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension: updates on definition, classification, diagnostics and management. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(1):1801916. doi:10.1183/13993003.01916-2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Simonneau G, Gatzoulis MA, Adatia I, Celermajer D, Denton C, Ghofrani A, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D34–41. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Simonneau G, Montani D, Celermajer DS, Denton CP, Gatzoulis MA, Krowka M, et al. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(1):1801913. doi:10.1183/13993003.01913-2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Velayati A, Valerio MG, Shen M, Tariq S, Lanier GM, Aronow WS. Update on pulmonary arterial hypertension pharmacotherapy. Postgrad Med. 2016;128(5):460–73. doi:10.1080/00325481.2016.1188664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Mukherjee D, Konduri GG. Pediatric pulmonary hypertension: definitions, mechanisms, diagnosis, and treatment. Compr Physiol. 2021;11(3):2135–90. doi:10.1002/cphy.c200023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ruopp NF, Cockrill BA. Diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: a review. JAMA. 2022;327(14):1379–91. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Mahmoud AK, Abbas MT, Kamel MA, Farina JM, Pereyra M, Scalia IG, et al. Current management and future directions for pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease. J Pers Med. 2023;14(1):5. doi:10.3390/jpm14010005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Rosenzweig EB, Krishnan U. Congenital heart disease-associated pulmonary hypertension. Clin Chest Med. 2021;42(1):9–18. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2020.11.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Humbert M, Sitbon O, Guignabert C, Savale L, Boucly A, Gallant-Dewavrin M, et al. Treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: recent progress and a look to the future. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11(9):804–19. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00264-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Landry LM, Burks AC, Osakwe O, Knudson JD, Jenks CL. Bosentan is associated with a reduction in right ventricular systolic pressure N-terminal pro-hormone B-type natriuretic peptide levels in young patients with pulmonary hypertension. OJPed. 2023;13(1):32–42. doi:10.4236/ojped.2023.131004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Gursoy M, Salihoglu E, Hatemi AC, Hokenek AF, Ozkan S, Ceyran H. Inflammation and congenital heart disease associated pulmonary hypertension. Heart Surg Forum. 2015;18(1):E38–41. doi:10.1532/hsf.1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Pektaş A, Olguntürk R, Kula S, Çilsal E, Oğuz AD, Tunaoğlu FS. Biomarker and shear stress in secondary pediatric pulmonary hypertension. Turk J Med Sci. 2017;47(6):1854–60. doi:10.3906/sag-1609-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Vonk Noordegraaf A, Westerhof BE, Westerhof N. The relationship between the right ventricle and its load in pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(2):236–43. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. He Q, Lin Y, Zhu Y, Gao L, Ji M, Zhang L, et al. Clinical usefulness of right ventricle-pulmonary artery coupling in cardiovascular disease. J Clin Med. 2023;12(7):2526. doi:10.3390/jcm12072526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Guo J, Wang J, Wang L, Li Y, Xu Y, Li W, et al. Left ventricular underfilling in PAH: a potential indicator for adaptive-to-maladaptive transition. Pulm Circ. 2023;13(4):e12309. doi:10.1002/pul2.12309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Bernier ML, Romer LH, Bembea MM. Spectrum of current management of pediatric pulmonary hypertensive crisis. Crit Care Explor. 2019;1(8):e0037. doi:10.1097/CCE.0000000000000037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Castaño JAT, Hernández-Gonzalez I, Gallego N, Pérez-Olivares C, Ochoa Parra N, Arias P, et al. Customized massive parallel sequencing panel for diagnosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Genes. 2020;11(10):1158. doi:10.3390/genes11101158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhu N, Pauciulo MW, Welch CL, Lutz KA, Coleman AW, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, et al. Correction to: novel risk genes and mechanisms implicated by exome sequencing of 2572 individuals with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Genome Med. 2022;14(1):12. doi:10.1186/s13073-022-01014-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Welch CL, Chung WK. Genetics and genomics of pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension. Genes. 2020;11(10):1213. doi:10.3390/genes11101213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Taha F, Southgate L. Molecular genetics of pulmonary hypertension in children. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2022;75:101936. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2022.101936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Galambos C, Mullen MP, Shieh JT, Schwerk N, Kielt MJ, Ullmann N, et al. Phenotype characterisation of TBX4 mutation and deletion carriers with neonatal and paediatric pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(2):1801965. doi:10.1183/13993003.01965-2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Eyries M, Montani D, Nadaud S, Girerd B, Levy M, Bourdin A, et al. Widening the landscape of heritable pulmonary hypertension mutations in paediatric and adult cases. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(3):1801371. doi:10.1183/13993003.01371-2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Tatius B, Wasityastuti W, Astarini FD, Nugrahaningsih DAA. Significance of BMPR2 mutations in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir Investig. 2021;59(4):397–407. doi:10.1016/j.resinv.2021.03.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Welch CL, Austin ED, Chung WK. Genes that drive the pathobiology of pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56(3):614–20. doi:10.1002/ppul.24637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Shellenberger RA, Imtiaz K, Chellappa N, Gundapanneni L, Scheidel C, Handa R, et al. Physical examination for the detection of pulmonary hypertension: a systematic review. Cureus. 2021;13(9):e18020. doi:10.7759/cureus.18020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Constantine A, Dimopoulos K, Haworth SG, Muthurangu V, Moledina S. Twenty-year experience and outcomes in a national pediatric pulmonary hypertension service. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206(6):758–66. doi:10.1164/rccm.202110-2428OC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, Badagliacca R, Berger RMF, Brida M, et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2023;61(1):2200879. doi:10.1183/13993003.00879-2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Berghaus TM, Kutsch J, Faul C, von Scheidt W, Schwaiblmair M. The association of N-terminal pro-brain-type natriuretic peptide with hemodynamics and functional capacity in therapy-naive precapillary pulmonary hypertension: results from a cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(1):167. doi:10.1186/s12890-017-0521-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, Badagliacca R, Berger RMF, Brida M, et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(38):3618–731. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehac237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Cowley CG, Bradley JD, Shaddy RE. B-type natriuretic peptide levels in congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2004;25(4):336–40. doi:10.1007/s00246-003-0461-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Santos-Gomes J, Gandra I, Adão R, Perros F, Brás-Silva C. An overview of circulating pulmonary arterial hypertension biomarkers. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:924873. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.924873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ploegstra MJ, Roofthooft MTR, Douwes JM, Bartelds B, Elzenga NJ, van de Weerd D, et al. Echocardiography in pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Imag. 2015;8(1):e000878. doi:10.1161/circimaging.113.000878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Augustine DX, Coates-Bradshaw LD, Willis J, Harkness A, Ring L, Grapsa J, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of pulmonary hypertension: a guideline protocol from the British society of echocardiography. Echo Res Pract. 2018;5(3):G11–24. doi:10.1530/ERP-17-0071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Mandras SA, Mehta HS, Vaidya A. Pulmonary hypertension: a brief guide for clinicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(9):1978–88. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Hasan B, Hansmann G, Budts W, Heath A, Hoodbhoy Z, Jing ZC, et al. Challenges and special aspects of pulmonary hypertension in middle- to low-income regions: jacc state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(19):2463–77. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Apitz C, Hansmann G, Schranz D. Hemodynamic assessment and acute pulmonary vasoreactivity testing in the evaluation of children with pulmonary vascular disease. Expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of paediatric pulmonary hypertension. The European Paediatric Pulmonary Vascular Disease Network, endorsed by ISHLT and DGPK. Heart. 2016;102(Suppl 2):ii23–9. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2014-307340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Hill KD, Lim DS, Everett AD, Ivy DD, Moore JD. Assessment of pulmonary hypertension in the pediatric catheterization laboratory: current insights from the Magic registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;76(6):865–73. doi:10.1002/ccd.22693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Del Cerro MJ, Moledina S, Haworth SG, Ivy D, Al Dabbagh M, Banjar H, et al. Cardiac catheterization in children with pulmonary hypertensive vascular disease: consensus statement from the Pulmonary Vascular Research Institute, Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease Task Forces. Pulm Circ. 2016;6(1):118–25. doi:10.1086/685102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Kaestner M, Apitz C, Lammers AE. Cardiac catheterization in pediatric pulmonary hypertension: a systematic and practical approach. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2021;11(4):1102–10. doi:10.21037/cdt-20-395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Barst RJ, McGoon MD, Elliott CG, Foreman AJ, Miller DP, Ivy DD. Survival in childhood pulmonary arterial hypertension: insights from the registry to evaluate early and long-term pulmonary arterial hypertension disease management. Circulation. 2012;125(1):113–22. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.026591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Patel ND, Sullivan PM, Sabati A, Hill A, Maedler-Kron C, Zhou S, et al. Routine surveillance catheterization is useful in guiding management of stable fontan patients. Pediatr Cardiol. 2020;41(3):624–31. doi:10.1007/s00246-020-02293-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Cerro MJ, Abman S, Diaz G, Freudenthal AH, Freudenthal F, Harikrishnan S, et al. A consensus approach to the classification of pediatric pulmonary hypertensive vascular disease: report from the PVRI Pediatric Taskforce, Panama 2011. Pulm Circ. 2011;1(2):286–98. doi:10.4103/2045-8932.83456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Brida M, Nashat H, Gatzoulis MA. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: closing the gap in congenital heart disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2020;26(5):422–8. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Avitabile CM, Vorhies EE, Ivy DD. Drug treatment of pulmonary hypertension in children. Paediatr Drugs. 2020;22(2):123–47. doi:10.1007/s40272-019-00374-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Wang Y, Chen S, Du J. Bosentan for treatment of pediatric idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: state-of-the-art. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:302. doi:10.3389/fped.2019.00302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Liew N, Rashid Z, Tulloh R. Strategies for the management of pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with congenital heart disease. J Congenit Cardiol. 2020;4(1):21. doi:10.1186/s40949-020-00052-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, Bozkurt B, Broberg CS, Colman JM, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(12):1494–563. [Google Scholar]

54. Galiè N, Olschewski H, Oudiz RJ, Torres F, Frost A, Ghofrani HA, et al. Ambrisentan for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2008;117(23):3010–9. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.107.742510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Blok IM, van Riel ACMJ, van Dijk APJ, Mulder BJM, Bouma BJ. From bosentan to macitentan for pulmonary arterial hypertension and adult congenital heart disease: further improvement? Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:51–2. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Herbert S, Gin-Sing W, Howard L, Tulloh RR. Early experience of macitentan for pulmonary arterial hypertension in adult congenital heart disease. Heart Lung Circ. 2017;26(10):1113–6. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2016.12.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Pulido T, Adzerikho I, Channick RN, Delcroix M, Galiè N, Ghofrani HA, et al. Macitentan and morbidity and mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(9):809–18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1213917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Albinni S, Pavo I, Kitzmueller E, Michel-Behnke I. Macitentan in infants and children with pulmonary hypertensive vascular disease. Feasibility, tolerability and practical issues—a single-centre experience. Pulm Circ. 2021;11(1):2045894020979503. doi:10.1177/2045894020979503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Aypar E, Alehan D, Karagöz T, Aykan H, Ertugrul İ. Clinical efficacy and safety of switch from bosentan to macitentan in children and young adults with pulmonary arterial hypertension: extended study results. Cardiol Young. 2020;30(5):681–5. doi:10.1017/S1047951120000773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Flores M, Caro AT, Mendoza A. Initial experience in children with the use of macitentan in pulmonary arterial hypertension after side effects with other endothelin receptor antagonists. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2019;52:55–6. doi:10.1016/j.ppedcard.2018.11.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Karedath J, Dar H, Ganipineni VDP, Gorle SA, Gaddipati S, Bseiso A, et al. Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors on clinical outcomes in patients with pulmonary hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Cureus. 2023;15(1):e33363. doi:10.7759/cureus.33363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Barnes H, Brown Z, Burns A, Williams T. Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors for pulmonary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1(1):CD012621. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012621.pub2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Mukhopadhyay S, Nathani S, Yusuf J, Shrimal D, Tyagi S. Clinical efficacy of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor tadalafil in Eisenmenger syndrome—a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover study. Congenit Heart Dis. 2011;6(5):424–31. doi:10.1111/j.1747-0803.2011.00561.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Khaybullina D, Patel A, Zerilli T. Riociguat (adempas): a novel agent for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. P T. 2014;39(11):749–58. [Google Scholar]

65. Ghofrani HA, Galiè N, Grimminger F, Grünig E, Humbert M, Jing ZC, et al. Riociguat for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(4):330–40. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1209655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Swisher JW, Weaver E. The evolving management and treatment options for patients with pulmonary hypertension: current evidence and challenges. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2023;19:103–26. doi:10.2147/VHRM.S321025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. LeVarge BL. Prostanoid therapies in the management of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2015;11:535–47. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S75122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Rothman A, Cruz G, Evans WN, Restrepo H. Hemodynamic and clinical effects of selexipag in children with pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2020;10(1):2045894019876545. doi:10.1177/2045894019876545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Coghlan JG, Channick R, Chin K, Di Scala L, Galiè N, Ghofrani HA, et al. Targeting the prostacyclin pathway with selexipag in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension receiving double combination therapy: insights from the randomized controlled GRIPHON study. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2018;18(1):37–47. doi:10.1007/s40256-017-0262-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Sitbon O, Channick R, Chin KM, Frey A, Gaine S, Galiè N, et al. Selexipag for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(26):2522–33. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1503184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Galiè N, Barberà JA, Frost AE, Ghofrani HA, Hoeper MM, McLaughlin VV, et al. Initial use of ambrisentan plus tadalafil in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):834–44. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1413687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Chin KM, Sitbon O, Doelberg M, Feldman J, Gibbs JSR, Grünig E, et al. Three- versus two-drug therapy for patients with newly diagnosed pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(14):1393–403. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.07.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Hansmann G, Koestenberger M, Alastalo TP, Apitz C, Austin ED, Bonnet D, et al. 2019 updated consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric pulmonary hypertension: the European Pediatric Pulmonary Vascular Disease Network (EPPVDN), endorsed by AEPC, ESPR and ISHLT. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019;38(9):879–901. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2019.06.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Handler SS, Feinstein JA. Pulmonary vascular disease in the single-ventricle patient: is it really pulmonary hypertension and if so, how and when should we treat it? Adv Pulm Hypertens. 2019;18(1):14–8. doi:10.21693/1933-088x-18.1.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Wang W, Hu X, Liao W, Rutahoile WH, Malenka DJ, Zeng X, et al. The efficacy and safety of pulmonary vasodilators in patients with Fontan circulation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pulm Circ. 2019;9(1):2045894018790450. doi:10.1177/2045894018790450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Amedro P, Gavotto A, Abassi H, Picot MC, Matecki S, Malekzadeh-Milani S, et al. Efficacy of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in univentricular congenital heart disease: the SV-INHIBITION study design. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7(2):747–56. doi:10.1002/ehf2.12630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools