Open Access

Open Access

CASE REPORT

Case Report: A Rare Case of Left Atrial Aneurysm Following Isolated Staphylococcal Pericarditis in a Paediatric Patient Presenting as Constrictive Pericarditis

Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, National Heart Institute, Kuala Lumpur, 50400, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Sivakumar Sivalingam. Email:

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(3), 341-346. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.066461

Received 09 April 2025; Accepted 27 June 2025; Issue published 11 July 2025

Abstract

Left atrial aneurysm is an exceptionally rare condition, particularly in the pediatric population, and even more so as a sequela of bacterial pericarditis. We present the case of a 16-month-old girl who developed a left atrial aneurysm following isolated Staphylococcus aureus pericarditis. She initially presented in decompensated shock and was later diagnosed with constrictive pericarditis. Despite undergoing pericardiectomy, she subsequently developed a left atrial aneurysm, necessitating surgical closure. This case highlights the aggressive nature of bacterial pericarditis and its potential to cause rare structural cardiac complications.Keywords

Left atrial aneurysm is a rare cardiac abnormality, first described as an isolated congenital pathology by Semans and Taussig in 1938 [1]. However, acquired left atrial aneurysms have also been reported, typically occurring secondary to inflammatory, degenerative, or pressure-related changes. Acquired left atrial aneurysms are more common than congenital cases and have been associated with conditions such as rheumatic heart disease, tuberculosis, and syphilitic myocarditis [2]. These aneurysms are most frequently found in the left atrial appendage but can also occur in the atrial wall.

Here, we present a case of acquired left atrial aneurysm following an isolated Staphylococcal pericarditis, emphasizing its clinical course, diagnostic challenges, and surgical management.

This is a case of a 1 year 4 months old girl, with an uneventful neonatal history. She was born at term via spontaneous vaginal delivery, with a birth weight of 3.3 kg. At presentation, she weighed 8 kg and measured 75 cm in height, placing her between the 3rd and 5th percentiles on WHO growth charts for her age. However, she was not fully immunized, having received only the Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) and first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine at birth as her parents refused subsequent vaccinations.

The child was previously well until she was admitted to the hospital for a simple febrile seizure. She was monitored for one day and discharged home after stabilization. Following her discharge, she developed a persistent fever accompanied by a cough, runny nose, rapid breathing, loose stools, poor oral intake, and increasing lethargy.

One week later, she presented to the emergency department in a state of decompensated shock. On examination, she was lethargic, tachypnea with cold peripheries. She was hemodynamically unstable and was stabilized with Bilevel-positive airway pressure (BiPAP) support, fluid boluses at 40 mL/kg, and intravenous noradrenaline infusion at 0.1 mcg/kg/min.

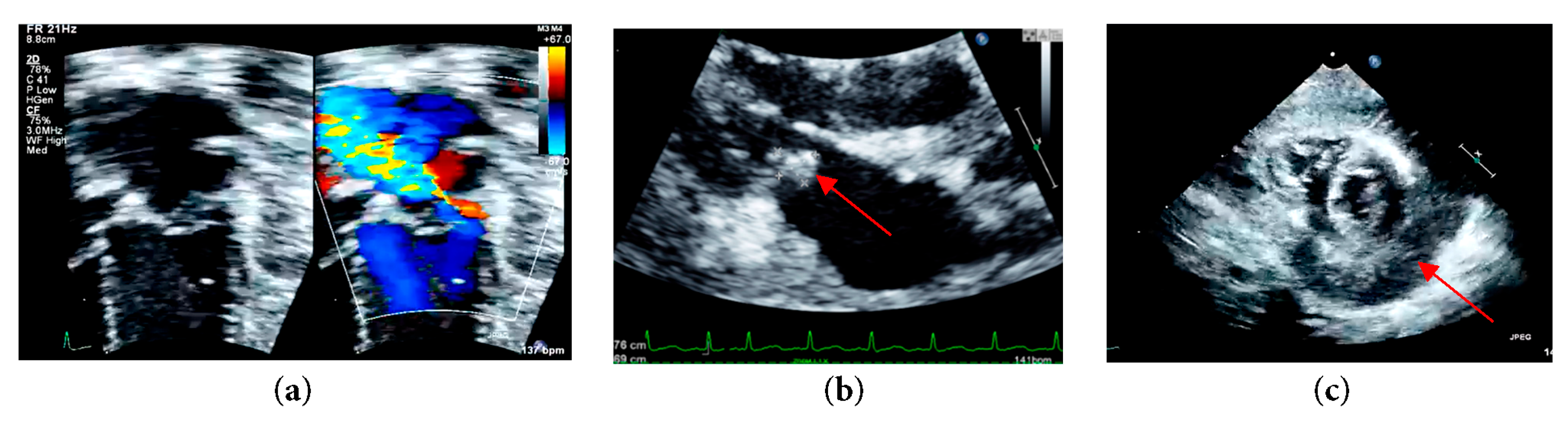

Upon stabilization, her blood pressure was 88/40 mmHg, and her heart rate is 140 beats per minute with an oxygen saturation of 100%. Both cardiovascular and respiratory examinations were normal. The abdomen was soft. Full blood count showed increased white cell count and platelet count at 19.1 × 109/L and 523 × 109/L, respectively. C-reactive protein (CRP) was also raised at 210.9 mg/L. Otherwise, blood, tracheal and urine culture and sensitivity show no growth. An electrocardiogram was done showing sinus rhythm, and normal axis deviation but ST elevation was seen at lead II, III, AVF, V3–V6, consistent with pericarditis. Bedside echocardiogram reveals moderate mitral regurgitation with vegetation of 5 × 7 mm seen at the posterior mitral valve annulus. The left atrium and left ventricle were dilated with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 68%. Global pericardial empyema of 10 to 14 mm was seen (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: (a) Left apical four chamber echocardiographic view with color Doppler at the level of mitral valve demonstrating moderate mitral regurgitation; (b) Parasternal long axis echocardiographic view demonstrating mitral valve vegetation; (c) Parasternal short axis echocardiographic view at mid papillary level demonstrating a global pericardial empyema.

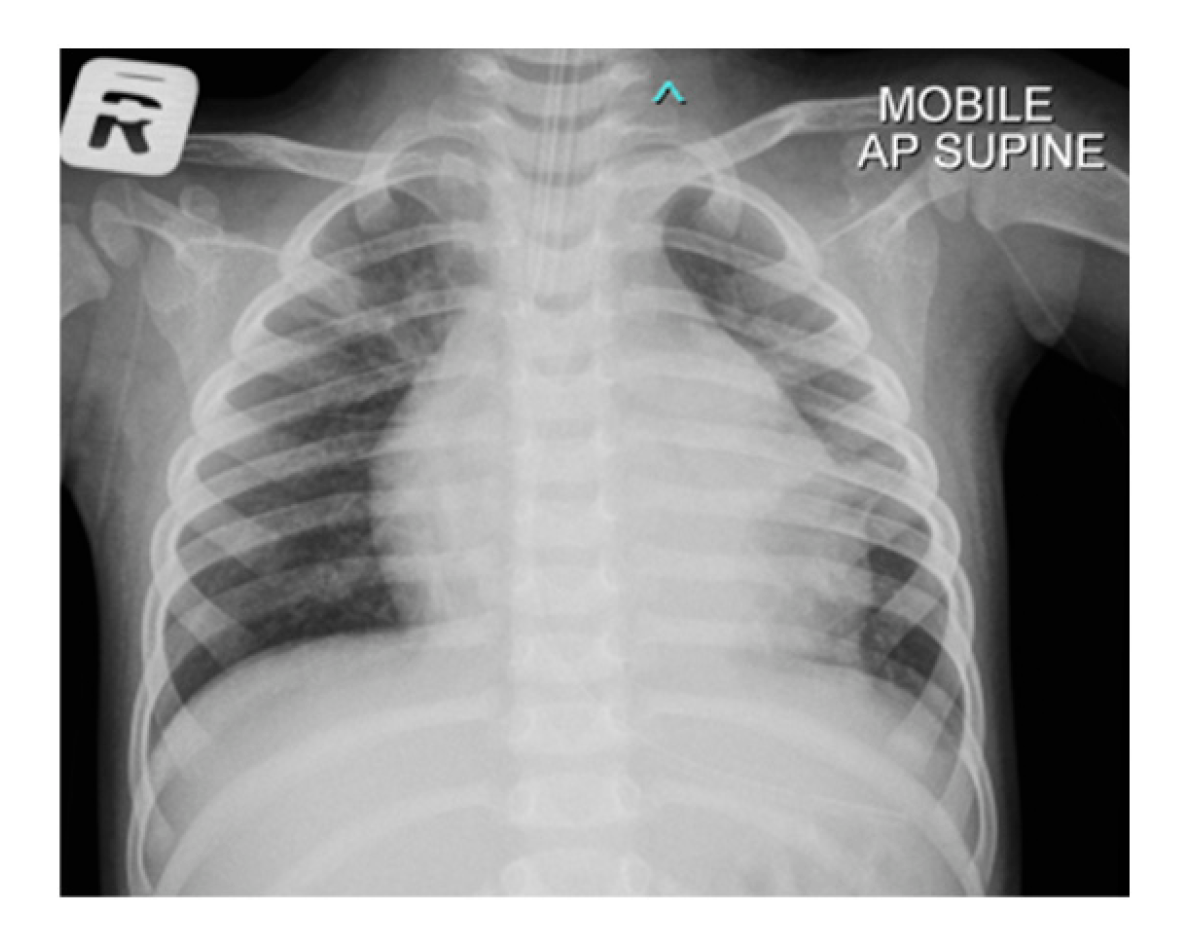

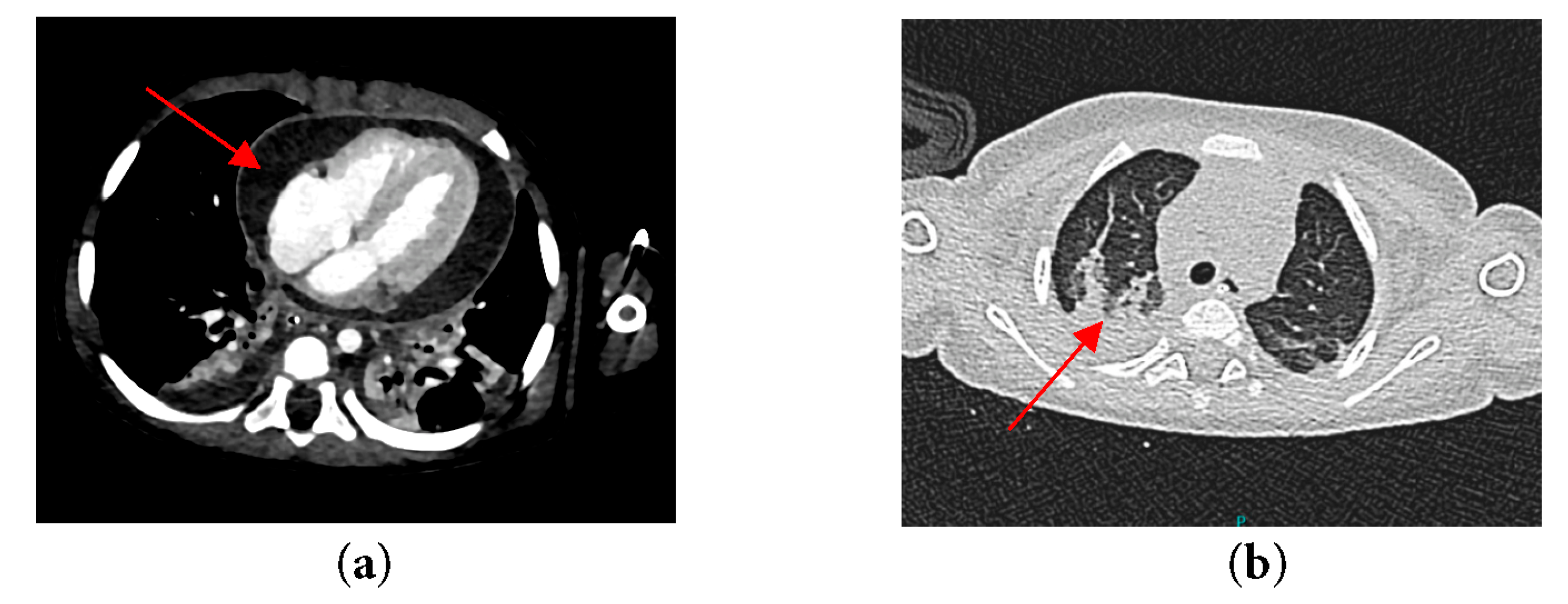

In anticipation of urgent surgical intervention for pericardial washout due to constrictive pericarditis, and to prevent cardiovascular collapse during transfer, the patient was electively intubated. Following intubation, a chest radiograph was performed, which demonstrated significant cardiomegaly with an endotracheal tube (ETT) seen in situ (Fig. 2). Computed tomography (CT) of thorax, abdomen and brain was also done and revealed bilateral pleural effusion with segmental collapse consolidation of both lower lobes. Pericardial effusion was seen and multiple mediastinal lymphadenopathy is identified, measuring 0.8 cm. Otherwise, no focal lesion such as space occupying lesions (SOL) was seen (Fig. 3).

Figure 2: Chest radiograph of the patient with cardiomegaly with bilateral plethoric lung fields.

Figure 3: CT thorax of the patient revealing (a) Constrictive pericardial effusion; (b) Segmental collapse consolidation of both lower lobes.

Subsequently, she was started on intravenous Meropenem 150 mg (20 mg/kg) QID infuses over 4 h for perioperative infective coverage and underwent a median sternotomy as well as total pericardiectomy in view of constrictive pericarditis which had led to globular pericardial empyema. Operation findings revealed a thickened pericardial, particularly along the parietal pericardium, which was adherent to the epicardium but was easily separated without resistance. There was a large amount of pericardial slough, fibrin and empyema surrounding the heart surface. Upon completion of the pericardiectomy, there was no evidence of bleeding or visible wall disruption, and the patient remained hemodynamically stable throughout. Pus from pericardial tissue was sent for the culture and sensitivity. Culture of the pus yielded Methicillin Sensitive Staph Aureus (MSSA) following which antibiotic was tailored to intravenous Cloxacillin 400 mg (50 mg/kg) QID infuse over 4 h. Pericardium histopathological results show inflamed hemorrhagic and thickened pericardium with inflamed granulation tissue and necrotic abscess.

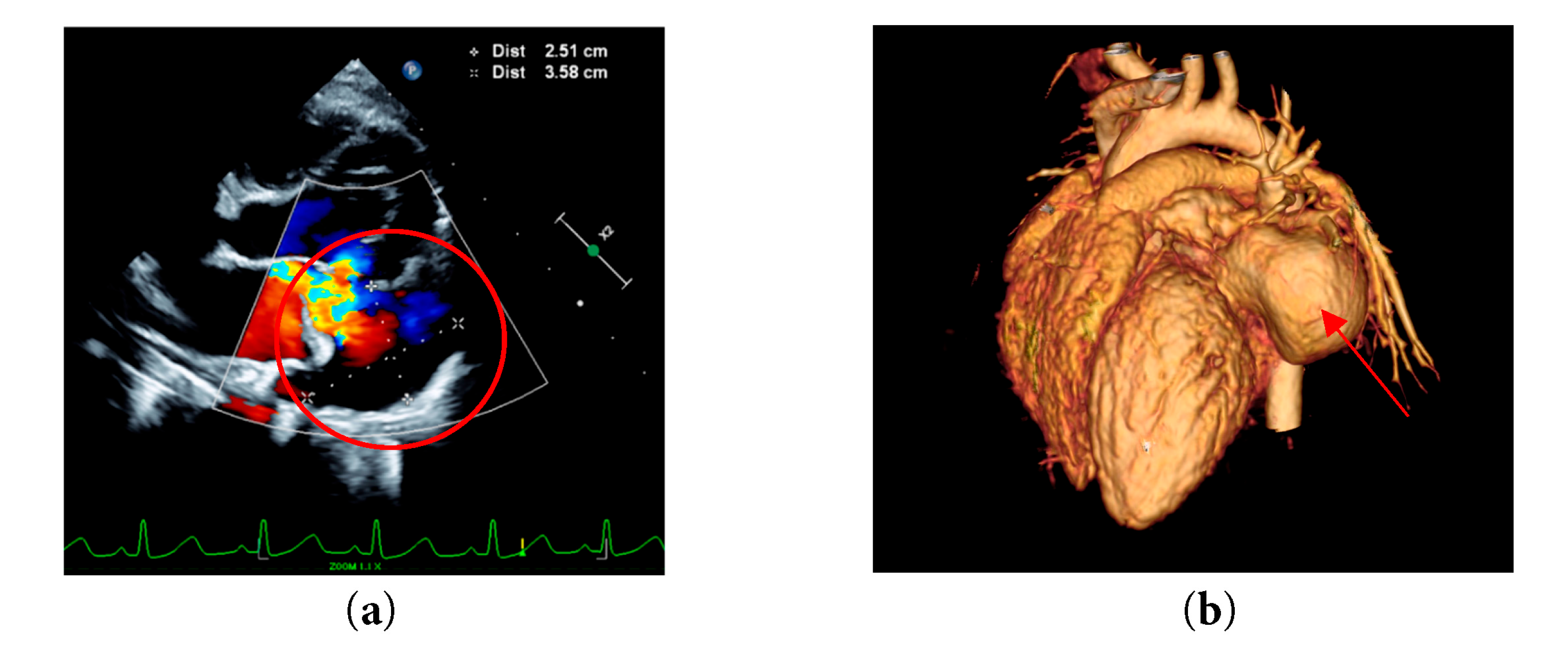

A month later, she came back for a post-pericardiectomy follow-up and assessment, echocardiogram noted a left atrial aneurysm as well as moderate to severe mitral regurgitation (Fig. 4a). Computed Tomography angiography (CTA) was done to assess the extension of the aneurysm and revealed a large left atrial aneurysm measuring 4.5 mm × 29.2 mm × 26.5 mm in size (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4: (a) Left apical four chamber echocardiographic view with color Doppler demonstrating a large intrapericardial left atrial aneurysm (b) CTA of patient’s heart demonstrating a left atrial aneurysm.

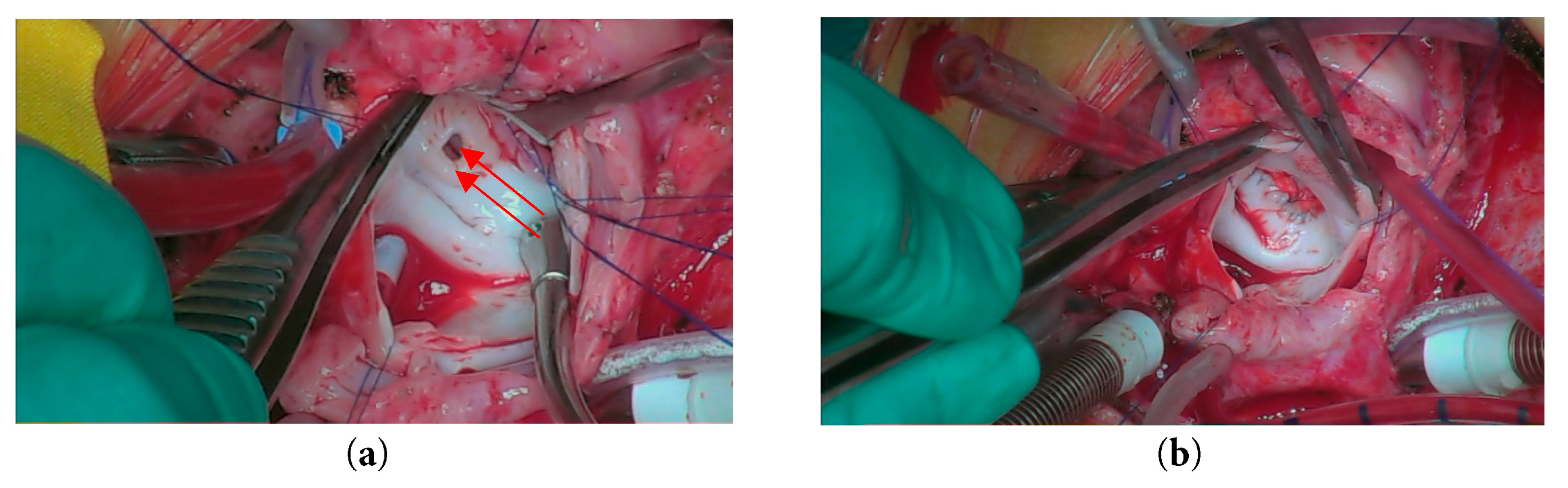

She then underwent an emergency surgery of redo median sternotomy and closure of aneurysm. The right atrium was opened, and a trans-septal approach was made to access the left atrium and mitral valve. Intraoperative inspection revealed that the mitral valve was structurally intact, and the previously noted vegetation had resolved. An atrial aneurysm was identified. A pericardial patch was fashioned and secured to the entry hole using pledgeted 6-0 Cardionyl sutures in an interrupted manner (Fig. 5). The exit hole was closed with a continuous suture technique. The atrial septum was subsequently repaired, and the right atrium was closed using 6-0 Prolene sutures. The chest was closed in the standard fashion, utilizing six stainless steel sternal wires, with mediastinal and pleural drains in situ. The skin and subcutaneous tissue were approximated and closed routinely. The patient was transferred intubated to the cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) with stable hemodynamics for further monitoring and care.

Figure 5: Intraoperative view showing (a) Opening of the left atrial aneurysm; (b) Closure of the aneurysm using a pericardial patch.

Acute pericarditis is predominantly viral or idiopathic, accounting for approximately 90% of cases. In contrast, bacterial pericarditis represents only 1–2% of cases. The organisms most frequently associated with purulent pericarditis include Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Haemophilus, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis [3].

Purulent pericarditis most commonly arises from hematogenous dissemination or direct extension of infection. Given the patient’s recent admission for febrile seizures and suspected staphylococcal septicemia when she presented in a state of decompensated shock, hematogenous spread was considered the most likely route of infection. Besides, due to the pericardium’s ligamentous connections to the sternum, vertebral column, diaphragm, pleura, and anterior mediastinum, infections can propagate along these attachments. The most common mechanism of spread is contiguous extension from the lungs or pleura via the pleuropericardial ligaments. It can also be a direct spread to the pericardium from an intracardiac infection. In this case, the presence of vegetation at the posterior mitral valve annulus on echocardiogram raises concern for infective endocarditis, which could serve as a source of direct extension to the pericardium [4]. Key risk factors for bacterial pericarditis include immunosuppression, recent cardiothoracic surgery, trauma, presence of preexisting catheters in the pericardial cavity, and underlying pericardial effusion [3].

It is often challenging to diagnose acute pericarditis in the pediatric population, as it is a relatively uncommon condition in children. According to 2015 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines, the diagnosis of acute pericarditis requires the presence of any two of chest pain, pericardial rub, saddle-shaped ST-elevation and/or PR-depression, non-trivial new or worsening pericardial effusion. Additional findings of raised inflammatory marker such as CRP, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and white blood cell count as well as evidence of pericardial inflammation through imaging modalities like CT and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) may support the diagnosis of an acute pericarditis [5].

In this patient, the rapid progression from febrile illness to decompensated shock highlights the fulminant nature of bacterial pericarditis. Despite initial stabilization and subsequent pericardiectomy, the patient developed an aneurysm at left lateral atrial wall, which required emergency surgery to prevent life-threatening complications such as risk of rupture, systemic embolization, and tachyarrhythmia [6]. Our literature search found no reported cases of true left atrial aneurysm following pericarditis, though one case of left atrial pseudoaneurysm has been documented.

While cardiac aneurysms most often involve the left ventricle, less often the right ventricle, and atria being the rarest of all. Causes of cardiac aneurysm are ischaemic, congenital, surgical, and infectious. Myocardial infarction is the most common cause, and true aneurysms develop in 5 to 10% of patients with acute myocardial infarction [7]. Left atrial aneurysms, while rare, may arise as congenital anomalies or as acquired pathologies linked to inflammatory or degenerative processes [2]. We postulate that the persistent inflammation and tissue weakening from both the infective endocarditis and constrictive pericarditis may have contributed to aneurysm formation. Meanwhile, given the presence of vegetation at the posterior mitral valve annulus, it is highly likely that the mitral regurgitation resulted from infective endocarditis.

This case highlights the need for vigilant follow-up, despite successful pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis, because atrial aneurysm, though rare, may arise as a delayed sequela requiring early detection and timely intervention to prevent life-threatening complications.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Ji Lam Leong contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and literature review. Sivakumar Sivalingam provided clinical supervision and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All relevant data are included in the manuscript. Additional information can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was reviewed by the National Heart Institute, Institut Jantung Negara Research Ethics Committee (IJNREC) and was waived from full ethical review. Approval to proceed was granted.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Semans JH, Taussig HB. Congenital aneurysmal dilatation of the left auricle. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1938;63:404. [Google Scholar]

2. Morales JM, Patel SG, Jackson JH, Duff JA, Simpson JW. Left atrial aneurysm. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71(2):719–22. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(00)02244-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kondapi D, Markabawi D, Chu A, Gambhir HS. Staphylococcal pericarditis causing pericardial tamponade and concurrent empyema. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2019;2019:3701576. doi:10.1155/2019/3701576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Rubin RH, Moellering RC Jr. Clinical, microbiologic, and therapeutic aspects of purulent pericarditis. Am J Med. 1975;59(1):68–78. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(75)90323-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, Badano L, Barón-Esquivias G, Bogaert J, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: the task force of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2015;36(42):2921–64. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sarioglu CT, Turkekul Y, Arnaz A, Sisli E, Yalcinbas YK, Sarioglu A. Surgical repair of congenital left atrial aneurysm and mitral valve insufficiency in a four-year-old child. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2018;9(3):357–9. doi:10.1177/2150135116678416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Jefferson K, Rees S, editors. Cardiac aneurysm, tumour, and cyst. In: Clinical cardiac radiology. 2nd ed. London, UK: Butterworth; 1980. p. 272–7. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools