Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Preoperative ECMO Bridging in Pediatric Heart Transplantation: A Cohort Study on Graft Remodeling, Inflammatory Biomarkers and Survival

1 Division of Pediatric Cardiology, Department of Pediatric Medicine, The Seventh Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, 100700, China

2 Chinese PLA Medical School, Beijing, 100853, China

3 Department of Radiology, Hospital of Jiangxi Provincial Corps, Chinese People’s Armed Police Force, Nanchang, 330030, China

4 Department of Health, Beijing Garrison Security Bureau of the Chinese PLA, Beijing, 100009, China

5 Department of Health Service, The Seventh Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, 100700, China

6 Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, The First Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, 100853, China

* Corresponding Authors: Ran Zhang. Email: ; Gengxu Zhou. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(4), 519-530. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.067164

Received 26 April 2025; Accepted 06 August 2025; Issue published 18 September 2025

Abstract

Background: To investigate the impact of preoperative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) on clinical outcomes in pediatric heart transplantation (PHT). Methods: This retrospective cohort analysis was conducted on 19 pediatric heart transplant recipients, divided into two groups: ECMO and non-ECMO, based on whether preoperative ECMO was utilized. We evaluated the patients’ surgical conditions, postoperative complications, and survival rates. Additionally, the analysis focused on the differences and correlations in clinical characteristics, inflammatory markers, and long-term survival outcomes. Results: There was no statistically significant difference in perioperative survival rates between the ECMO group (85.7%) and the non-ECMO group (83.3%). However, the ECMO group exhibited significantly higher levels of inflammatory markers, including Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Interleukin-8 (IL-8), Interleukin-6 (IL-10), Tumor Necrosis Factor-a (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein (CRP), compared to the non-ECMO group (p < 0.05). Notably, IL-6, IL-8, and CRP levels in the ECMO group were found to normalize to the levels of the non-ECMO group 24 h after the operation. The cohort demonstrated a mean donor-recipient weight ratio of 1.38 ± 0.39, with successful cardiac remodeling observed in recipients of oversized grafts, with the highest Donor-Recipient Weight Ratio (DRWR) reaching 3.0. Conclusions: The donor-recipient size mismatch plays a significant role in influencing the success rate of PHT. Despite the inflammatory response and perioperative complications, ECMO proves to be an effective bridging strategy, ultimately enhancing overall outcomes in PHT.Keywords

Pediatric heart transplantation (PHT) remains the gold-standard treatment for end-stage heart failure in children, with over 500 cases performed annually worldwide and a one-year survival rate exceeding 87.2% [1,2,3]. Despite significant advancements in the field, several challenges continue to impede clinical progress, particularly concerning donor-recipient size mismatch, prolonged waitlist times, and suboptimal outcomes in high-risk cohorts requiring preoperative mechanical circulatory support [4,5,6,7]. Additionally, waitlist mortality remains unacceptably high, with an estimated mortality rate of slightly more than 20% for patients who are not transplanted within one year of listing [8]. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), as a key component of extracorporeal life support, plays a critical role in bridging critically ill patients to heart transplantation [6,9]. Reports indicate that the one-year survival rate for those bridged with ECMO to transplant is 73.5% [10]. However, the optimal timing for ECMO initiation and the various complications associated with its use are key factors that limit its widespread application. In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the data of 19 pediatric heart transplant cases at a single center, focusing on donor-recipient clinical data, perioperative conditions, postoperative complications, and the impact of preoperative ECMO use on patients’ clinical characteristics and inflammatory status. Our aim is to provide valuable insights that could enhance the clinical outcomes of PHT.

All donor hearts were procured through organ donation and allocated via the China Organ Allocation and Sharing Computer System.

A total of 19 pediatric patients who underwent heart transplantation at the Seventh Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, from May 2022 to December 2024, were included in this study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Seventh Medical Center of the Chinese PLA General Hospital (S2024-044-01). The requirement for informed patient consent was waived by the Board due to the retrospective nature of the research. Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of receptors and donors are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographics and clinical characteristics of receptors and donors.

| Receptor Information (n = 19) | Numerical Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (case) | ||

| Male | 10 (52.6%) | |

| Female | 9 (47.4%) | |

| Age (y) | 0.6~16.0 (median: 12.0; IQR: 10.0–13.0) | |

| Body mass (kg) | 7.0~67.5 (41.6 ± 16.2) | |

| Blood type (case) | ||

| A | 4 (21.1%) | |

| B | 6 (31.6%) | |

| O | 7 (36.8%) | |

| AB | 2 (10.5%) | |

| Clinical diagnosis | ||

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 16 (84.2%) | |

| Hypertrophic nonobstructive cardiomyopathy | 1 (5.3%) | |

| Fulminant myocarditis | 1 (5.3%) | |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 1 (5.3%) | |

| NYHA Class IV (case) | 19 | |

| PRA < 10% | 100% | |

| Donor Information (n = 19) | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 13 (68.4%) | |

| Female | 6 (31.6%) | |

| Age (y) | 1.3~59.0 (28.3 ± 16.8) | |

| Body mass (kg) | 9.5~80.0 (median: 60.0; IQR: 39.0–70.0) | |

| Donor-recipient weight ratio | 0.74~3.0 (median: 1.36; IQR: 1.11–1.67) | |

| Blood type (case) | ||

| A | 2 (10.5%) | |

| B | 5 (26.3%) | |

| O | 12 (63.2%) | |

| ABOi (case) | 5 (21.1%) | |

2.2 Heart Transplantation Procedure

The bicaval anastomosis technique was used in all cases. Immunosuppressive induction therapy was initiated with basiliximab (an Interleukin-2 receptor antagonist) and methylprednisolone. For postoperative maintenance immunosuppression, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone acetate were used. Conventional postoperative support, including mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit (ICU), was provided as required.

Perioperative conditions and postoperative complications of the patients were carefully monitored and recorded. Follow-up records were maintained to track postoperative survival times. The duration of postoperative ICU stays, length of mechanical ventilation, aortic cross-clamp time during surgery, and cardiopulmonary bypass time were documented. Additional factors such as recipient body surface area (BSA), preoperative left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), preoperative left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), cardiothoracic ratio on chest X-ray, donor heart cold ischemia time, and Donor-Recipient Weight Ratio (DRWR) were collected and calculated. All imaging studies were obtained within two weeks prior to cardiac transplantation. Based on preoperative use of ECMO, the patients were divided into two groups: ECMO group (n = 12) and non-ECMO group (n = 7) (Table 2). The donor-recipient weight ratio (DRWR) ranged from 0.74 to 3.0 (median: 1.36; interquartile range (IQR): 1.11–1.67), with the highest DRWR being 3.0. Serum levels of inflammatory cytokines, including Interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-17, Tumor Necrosis Factor-a (TNF-α), Interferon-a (IFN-α), IFN-γ, and C-reactive protein (CRP), were measured at 24 h preoperatively, and at 24 and 72 h postoperatively (Table 3).

Table 2: The surgery-related characteristics of patients receiving pediatric heart transplantation.

| Covariate | Total | ECMO Group | Non-ECMO Group | t/U | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative ICU stay duration (d) | 14.0 (6.0, 29.0) | 7.0 (0.0, 22.0) | 14.0 (0.0, 52.0) | 25.000** | 0.419 |

| Postoperative duration of Mechanical ventilation (h) | 165.0 (42.0, 292.0) | 75.0 (0.0, 468.0) | 109.0 (0.0, 267.0) | 38.000** | 0.615 |

| Aortic cross-clamp time (min) | 64.89 ± 13.87 | 63.64 ± 14.70 | 61.83 ± 11.91 | −0.257* | 0.801 |

| CPB time (min) | 186.40 ± 69.11 | 199.09 ± 65.19 | 177.83 ± 86.24 | −0.575* | 0.574 |

| BSA (m2) | 1.27 ± 0.36 | 1.34 ± 0.30 | 1.11 ± 0.48 | −1.238* | 0.235 |

| Graft preoperative LVEF (%) | 29.32 ± 10.97 | 24.64 ± 9.32 | 34.0 ± 6.29 | 2.188* | 0.045 |

| Preoperative LVEDD (mm) | 57.05 ± 12.45 | 61.50 ± 10.68 | 49.43 ± 12.18 | 2.260* | 0.037 |

| Cardiothoracic ratio | 0.61 ± 0.09 | 0.63 ± 0.09 | 0.61 ± 0.05 | −0.632 | 0.537 |

| Cold ischemic time (min) | 201.30 ± 90.88 | 179.27 ± 74.44 | 223.17 ± 118.43 | 0.945* | 0.359 |

| Donor-to-recipient body weight ratio | 1.36 (1.11, 1.67) | 1.29 (0.95, 1.63) | 1.76 (0.36, 3.16) | 14.500** | 0.063 |

Table 3: Preoperative serum inflammatory cytokines in patients receiving pediatric heart transplantation.

| Covariate | ECMO Group | Non-ECMO Group | t/U | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | 2.12 ± 0.93 | 1.43 ± 1.03 | −1.494* | 0.154 |

| IL-2 (pg/mL) | 1.49 (0.48, 2.77) | 1.32 (0.78, 1.74) | 42.000** | 0.999 |

| IL-4 (pg/mL) | 1.63 (0.85, 2.21) | 1.93 (1.09, 5.73) | 28.500** | 0.254 |

| IL-5 (pg/mL) | 0.70 (0.30, 1.33) | 0.72 (0.60, 1.00) | 43.000** | 0.933 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 226.80 (159.90, 298.50) | 10.27 (9.38, 38.00) | 82.000** | 0.001 |

| IL-8 (pg/mL) | 257.50 (175.40, 392.60) | 28.40 (26.09, 63.84) | 81.000** | 0.001 |

| IL-10 (pg/mL) | 19.08 (7.37, 25.05) | 3.92 (3.23, 7.18) | 68.000** | 0.028 |

| IL-12P70 (pg/mL) | 1.10 (0.01, 2.01) | 0.20 (0.02, 0.41) | 22.000** | 0.088 |

| IL-17 (pg/mL) | 4.07 (2.61, 7.15) | 1.48 (1.00, 8.40) | 61.500** | 0.099 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 4.46 ± 2.18 | 1.67 ± 0.59 | −3.277* | 0.004 |

| IFN-α (pg/mL) | 1.57 ± 1.14 | 2.78 ± 1.61 | 1.926* | 0.071 |

| IFN-γ (pg/mL) | 6.40 ± 3.26 | 8.32 ± 3.62 | 1.190* | 0.250 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 49.70 (3.45, 131.80) | 1.90 (0.80, 3.20) | 69.000** | 0.022 |

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Inc., Armonk, USA). The normality of the data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and homogeneity of variance was assessed using Levene’s test. Normally distributed continuous data are presented as mean ± SD (x̄ ± s) and were compared between two groups using the t-test or repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Non-normally distributed continuous data are presented as median (IQR) and were compared between two groups using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data are expressed as percentages and were analyzed using the chi-square test. Correlation analysis was performed using the Spearman’s rho test. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to estimate survival rates, with all-cause mortality or re-transplantation as the primary endpoint events. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.1 Surgery-Related Characteristics and Complications

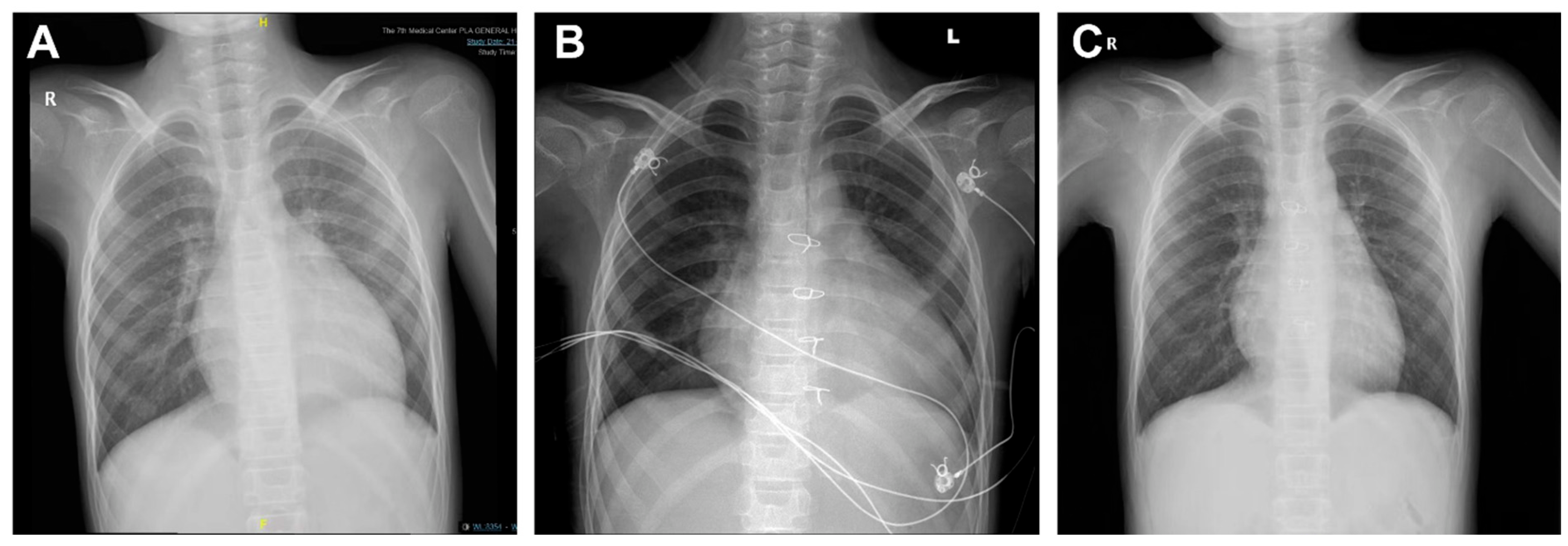

All transplantations were successfully performed. 5 patients underwent ABO-incompatible (ABOi) heart transplants, including one Type B recipient who received a Type O donor heart, 1 Type AB recipient who received a Type A donor heart, and 3 Type A recipients who received Type O donor hearts. Among these, 1 case had the highest DRWR of 3.0. This patient was discharged on postoperative day 28 and returned for a follow-up two months later, with the transplanted heart having resized to fit the recipient’s body (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Digital radiography (DR) images of patients with maximum donor-recipient weight ratio (DRWR). (A) Pre-transplant DR imaging showing an enlarged heart with an increased cardiothoracic ratio of approximately 0.63. (B) Transplantation of a 19-year-old donor heart (DRWR of 3.0), with a cardiothoracic ratio of 0.75, at 13 days postoperatively. (C) Repeat DR imaging at 2 months post-transplantation, demonstrating the heart restored to the adapted recipient’s size, with a cardiothoracic ratio of approximately 0.57.

In the ECMO group, 12 patients were included, all undergoing ECMO-bridged transplantation (including 1 case with ECMO plus left ventricular drainage). Of these, 3 patients continued ECMO support postoperatively. In the non-ECMO group, 3 out of 7 patients required ECMO support postoperatively, 1 patient received continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) preoperatively, and 4 patients required CRRT postoperatively, including 2 patients who received both ECMO and CRRT.

Postoperative complications included acute kidney injury and pericardial effusion in 3 cases, delayed chest closure and sternum infection with poor wound healing in 2 cases, and ECMO cannulation site infection in 2 cases. One of these cases was complicated by femoral nerve injury, leading to flaccid paralysis of both lower limbs. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection occurred in 2 cases, one of which was also complicated by Pneumocystis jirovecii infection. Pleural effusion was observed in 2 cases, and 1 patient experienced severe cerebral edema with difficulty weaning from the ventilator, necessitating a tracheostomy. Other complications included pneumothorax in 1 case, hypertension in 2 cases, and hyperglycemia in 1 case. All complications improved or were resolved with appropriate treatments.

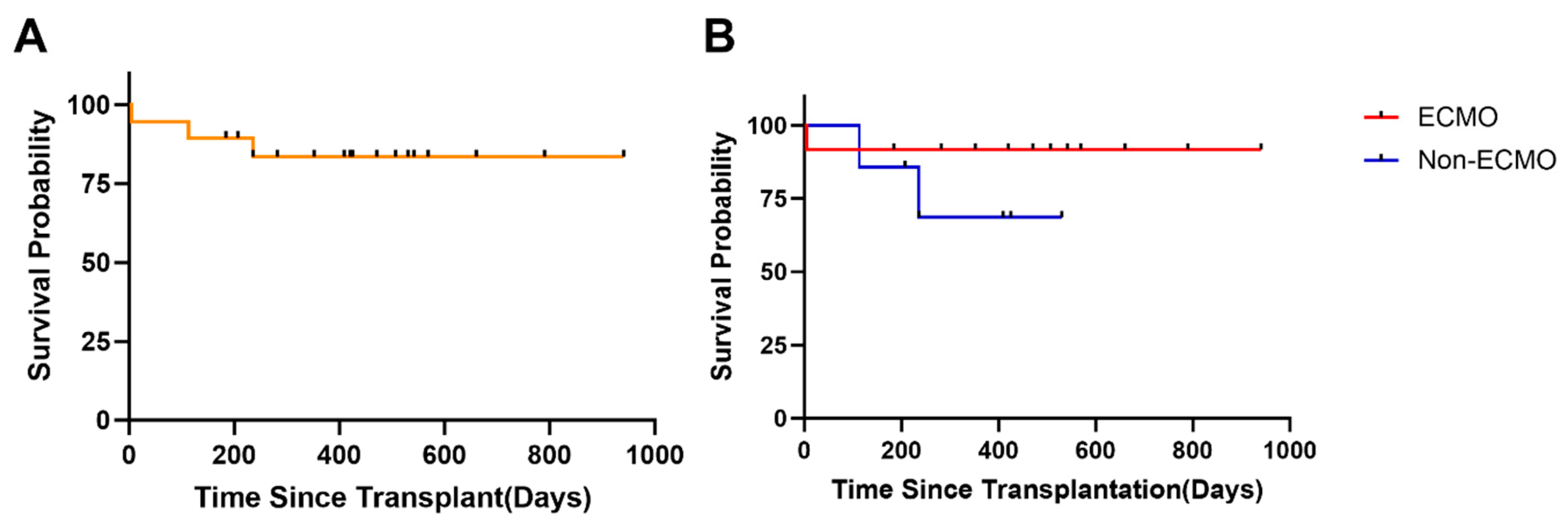

Among the 19 pediatric patients, 3 deaths were recorded. 1 death occurred in the ECMO group, involving a patient who underwent ABOi heart transplantation and died of multi-organ failure due to graft dysfunction on postoperative day 5. The other two deaths occurred in the non-ECMO group: one patient died of cerebral infarction 3 months postoperatively, and another died of acute rejection 6 months postoperatively. Among the 5 patients who underwent ABOi heart transplantation, 4 survived to the end of the follow-up period, apart from the aforementioned death. The follow-up duration for the 16 surviving patients ranged from 5 to 870 days (335.0 ± 225.3 days). All school-age and adolescent children who were discharged have returned to school and maintained a high quality of life. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to estimate survival rates, with all-cause mortality or re-transplantation as the primary endpoint events. The survival rates of the 19 pediatric patients and the impact of preoperative ECMO use on survival are shown in Fig. 2. The overall cumulative survival rate was 84.2% (Fig. 2A), with a cumulative survival rate of 85.7% in the ECMO group and 83.3% in the non-ECMO group (Fig. 2B). There was no statistically significant difference in perioperative survival rates between the ECMO and non-ECMO groups (p = 0.275, Fig. 2B).

Figure 2: Survival analysis of patients receiving pediatric heart transplantation. (A) Kaplan-Meier actuarial curve displaying survival probability (up to 941 days of follow-up) following PHT. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing children with preoperative ECMO support to those without ECMO support.

3.3 The Effects of ECMO on PTH Clinical Outcomes

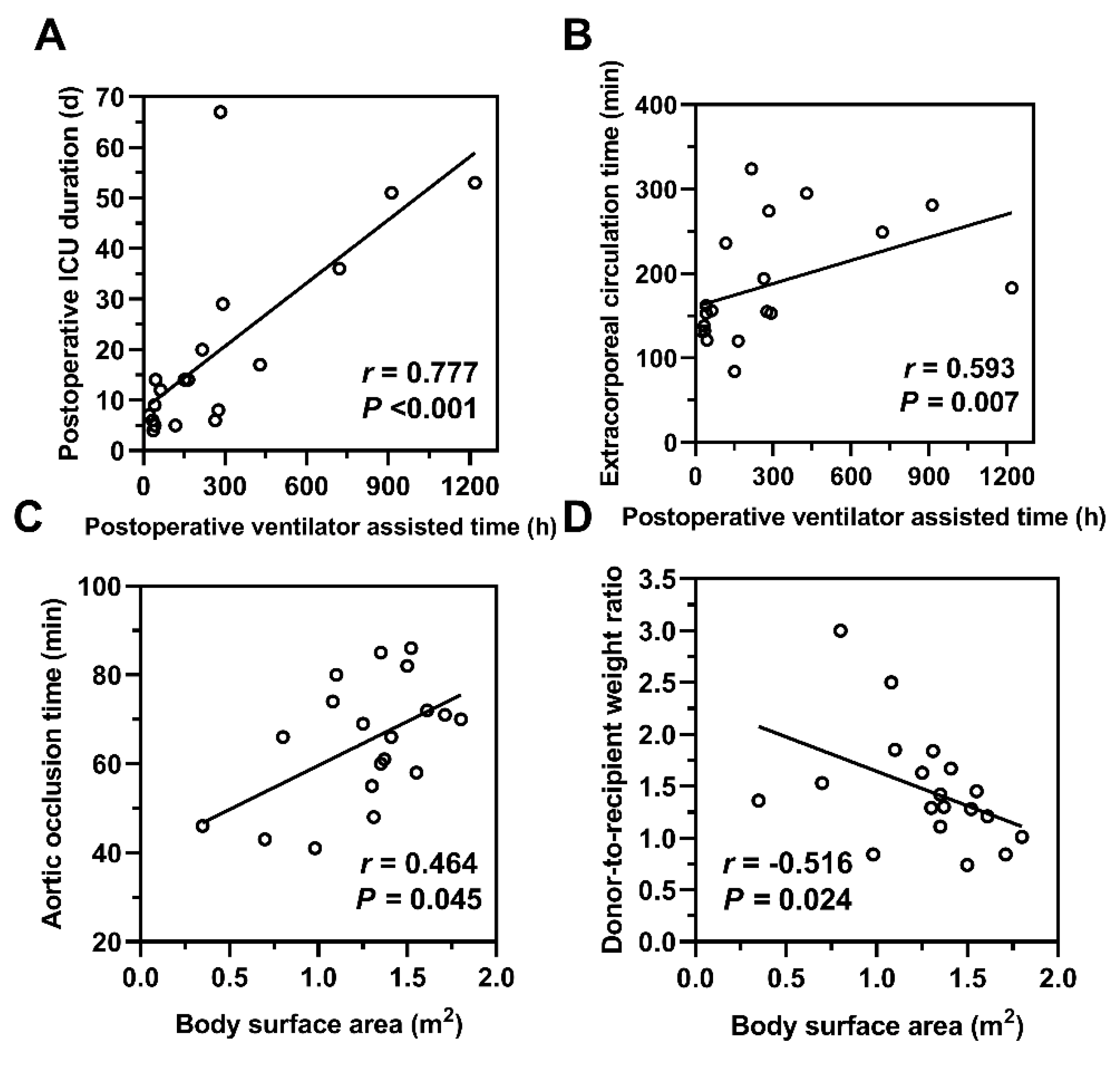

The demographics and clinical characteristics of receptors and donors were shown in Table 1, and the surgery-related characteristics of patients receiving pediatric heart transplantation were shown in Table 2. The LVEF was significantly lower in the ECMO group than in the non-ECMO group (t = 2.188, p = 0.040). The LVEDD was significantly higher in the ECMO group than in the non-ECMO group (t = 2.260, p = 0.037). Correlation analysis of these clinical indicators between the two groups showed that the postoperative duration of mechanical ventilation was positively correlated with postoperative ICU stay duration (r = 0.777, p < 0.001) and cardiopulmonary bypass time (r = 0.593, p = 0.007). Recipient BSA was positively correlated with aortic cross-clamp time (r = 0.593, p = 0.045) and negatively correlated with the DRWR (r = −0.516, p = 0.024) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Correlation analysis of perioperative clinical characteristics. (A,B) The postoperative duration of mechanical ventilation was positively correlated with both the postoperative ICU stay duration and cardiopulmonary bypass time. (C,D) The recipient’s body surface area was positively correlated with aortic cross-clamp time and negatively correlated with the donor-to-recipient weight ratio. r: Correlation coefficient; p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

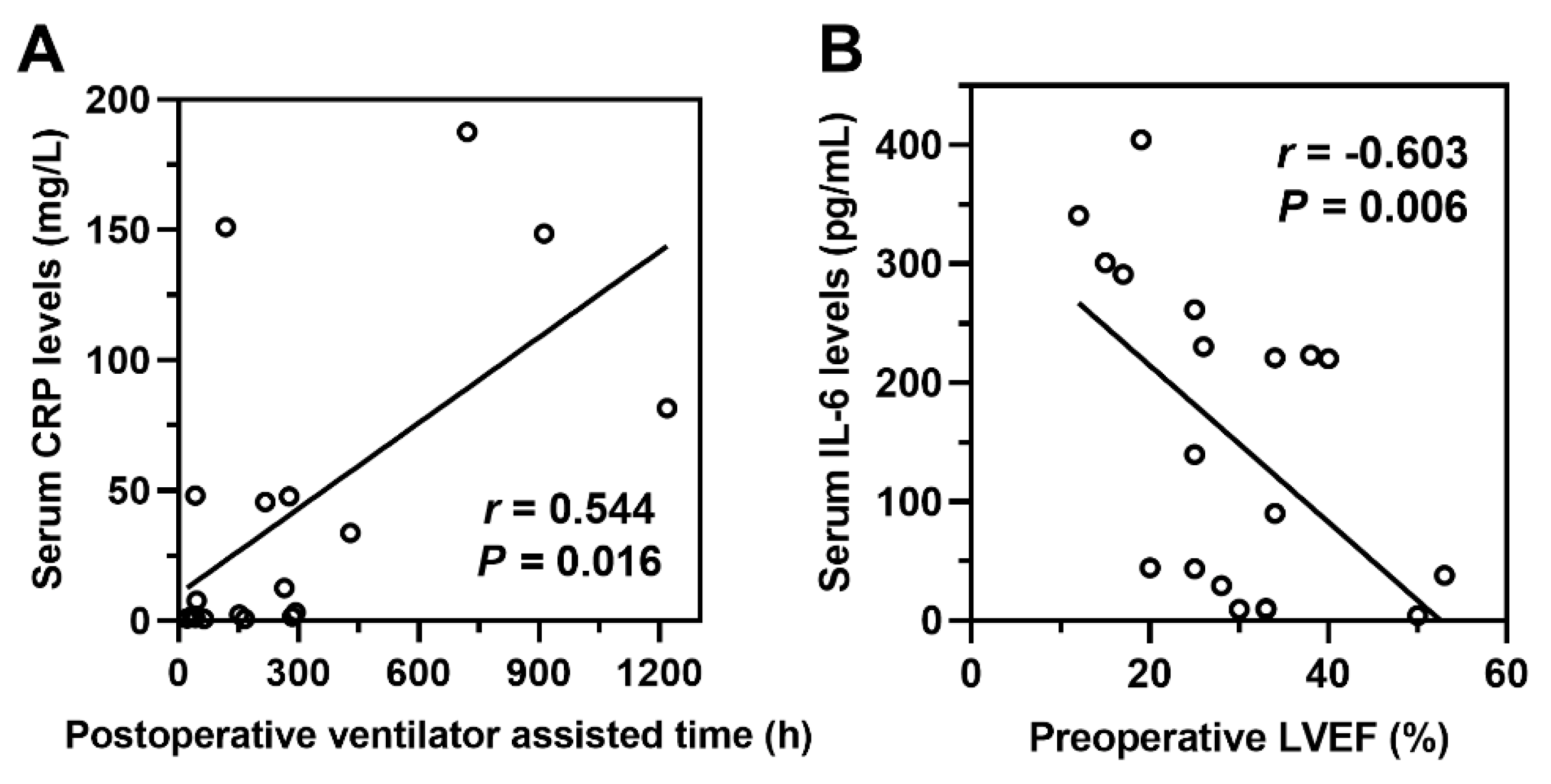

3.4 The Effects of ECMO on Perioperative Inflammatory Markers

Preoperative levels of inflammatory markers, including IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-17, TNF-α, IFN-α, IFN-γ, and CRP were compared between the two groups (Table 3). The ECMO group had significantly higher levels of IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, and CRP compared to the non-ECMO group (p < 0.05). Correlation analysis between postoperative ICU stay duration, postoperative duration of mechanical ventilation, preoperative LVEF, preoperative LVEDD, and serum levels of IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, and CRP revealed that the postoperative duration of mechanical ventilation was positively correlated with serum CRP levels (r = 0.544, p = 0.016), and preoperative LVEF was negatively correlated with serum IL-6 levels (r = −0.603, p = 0.006) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Correlation analysis of perioperative clinical characteristics and inflammatory cytokines. (A) The postoperative duration of mechanical ventilation is positively correlated with serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. (B) Preoperative left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is negatively correlated with serum IL-6 levels. r: Correlation coefficient; p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

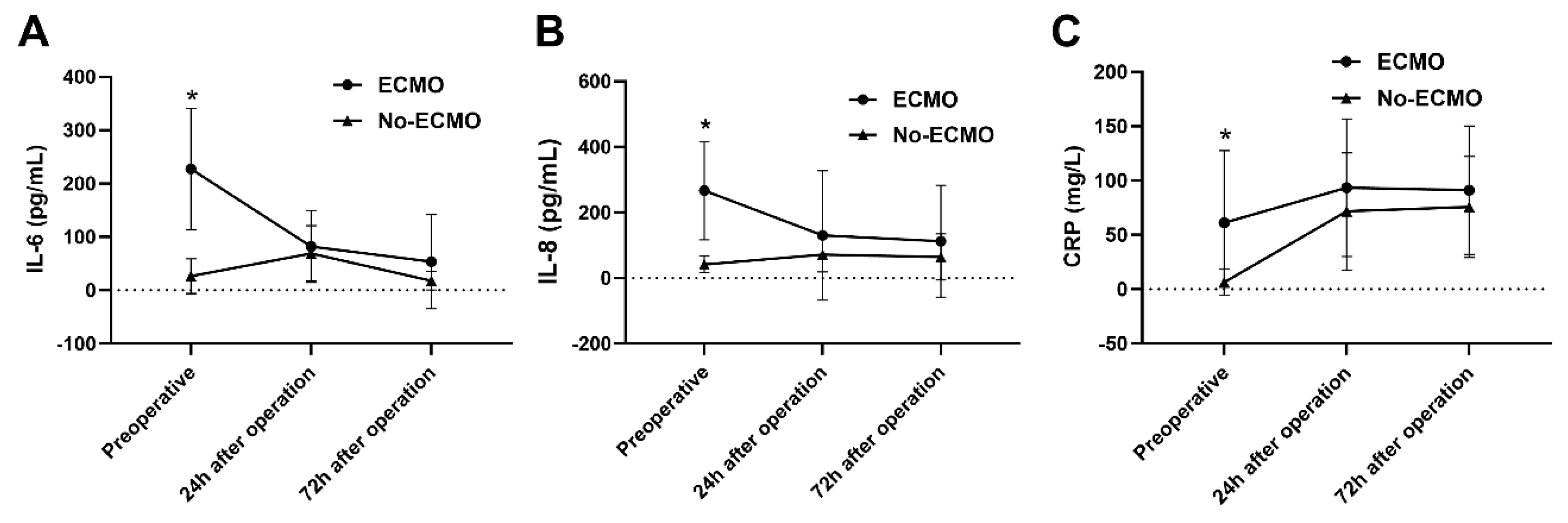

The serum levels of IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-17, TNF-α, IFN-α, IFN-γ, and CRP at 24 and 72 h postoperatively were assayed. IL-6 levels decreased over time in both groups (F within-group = 9.107, p within-group = 0.004). Between-group comparisons showed that IL-6 levels were significantly higher in the ECMO group compared to the non-ECMO group (F between-group = 7.256, p between-group = 0.017). Interaction analysis indicated a statistically significant interaction between ECMO use and time (F interaction = 11.49, p interaction < 0.001) (Fig. 5A). IL-8 (F between-group = 6.111, p between-group = 0.025) and CRP (F within-group = 13.51, p within-group < 0.001) levels were significantly higher in the ECMO group than in the non-ECMO group (Fig. 5B,C).

Figure 5: Analysis of inflammatory cytokines pre- and post-pediatric heart transplantation. (A) IL-6 levels decreased over time in both groups (p within-group = 0.004). Between-group comparisons showed that IL-6 levels were significantly higher in the ECMO group compared to the non-ECMO group (p between-group = 0.017). Interaction analysis indicated a statistically significant interaction between ECMO use and time (p interaction < 0.001). (B,C) IL-8 (p between-group = 0.025) and CRP (p within-group < 0.001) levels were significantly higher in the ECMO group than in the non-ECMO group. *p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

PHT has emerged as a definitive therapeutic intervention for patients with end-stage heart failure that is unresponsive to conventional pharmacological and surgical treatments [11]. Due to the shortage of donor hearts, patients often face prolonged waiting times for a suitable donor. During this waiting period, some patients become critically ill and require intensive life support. ECMO and left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) can stabilize hemodynamics, mitigate end-organ dysfunction, and provide essential support during acute graft failure or cardiogenic shock, playing a pivotal role in bridging critically ill patients to heart transplantation. ECMO is primarily divided into two types: veno-venous ECMO (VV-ECMO) and veno-arterial ECMO (VA-ECMO). In PHT, due to the prevalence of heart failure in patients, VA ECMO, which provides circulatory support, is more commonly used. Our center exclusively employs VA ECMO. Over the past decade, with the successful clinical application of ventricular assist devices (VADs), the use of VA-ECMO as a sole pre-transplant bridging therapy has steadily declined. However, ECMO remains indispensable in acute settings due to its rapid deployability and biventricular support capabilities. Simultaneously, the demographic of VA-ECMO-treated patients has shifted toward younger, more critically ill children [12]. LVADs, while effective for chronic support, have limitations in pediatric and congenital heart disease populations due to anatomical constraints and increased thrombotic risks. Additionally, the limited availability of small-sized pediatric VADs in China, due to weight constraints, means that VA-ECMO remains the primary option for mechanical circulatory support in children awaiting heart transplantation. A retrospective study analyzed pediatric heart transplant cases from 2005 to 2017, including 240 cases that utilized ECMO for preoperative bridging therapy. The early postoperative, 1-year, and 5-year mortality rates were 25.43%, 32.57%, and 45.51%, respectively, demonstrating favorable survival rates [13]. However, despite ECMO’s significant role in PHT management, there is still controversy regarding the optimal timing for its initiation, as well as various cannulation and management strategies. Complications, such as bleeding, infection, and neurological injury, remain a major concern [12,14,15,16]. In the present study, we found that the ECMO group had significantly lower LVEF and higher LVEDD. This suggests that baseline ventricular dysfunction predisposes patients to risk factors that necessitate ECMO, highlighting the importance of ventricular impairment as a key factor in determining the need for ECMO. These findings align with previous studies that have identified ventricular dysfunction as a critical determinant in the decision to initiate ECMO [17].

The initiation of ECMO triggers systemic inflammatory response that involves the activation of coagulation cascades, endothelial dysfunction, and interactions between leukocytes and platelets [18,19,20,21], which leads to cytokine release and potentially multiorgan injury [20]. Key inflammatory mediators, such as IL-6, play a significant role in the acute-phase response, promoting myocardial injury and endothelial activation, which could worsen graft dysfunction [22]. Elevated levels of TNF-α and IL-8 further contribute to endothelial permeability and neutrophil recruitment, exacerbating ischemia-reperfusion injury. CRP, often used as a marker for systemic inflammation, has been shown to correlate with prolonged ventilator dependence, indicating that a higher preoperative inflammatory burden may impair postoperative recovery. In this study, the levels of IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, and CRP were significantly higher in the ECMO group. However, it was observed that 24 h after the operation, the levels of IL-6, IL-8, and CRP had returned to similar levels as those in the non-ECMO group, with no significant difference in mortality between the two groups. This suggests that while ECMO activates an inflammatory response in patients undergoing PTH, it provides crucial life support for critically ill patients, particularly during the perioperative period. Therefore, ECMO can improve the overall prognosis for individuals with PHT.

Children face unique challenges related to growth and weight changes during development, which often lead to size mismatches between donor and recipient hearts in PHT [23,24]. The DRWR is generally accepted to fall within the range of 0.8 to 1.2. However, the use of larger donor hearts (with DRWR > 1.2) is common in PHT, with studies indicating that more than 50% of pediatric recipients receive hearts from larger donors [25]. Smaller donor hearts, on the other hand, are associated with increased mortality within the first-year post-transplantation. In this study, the average DRWR was 1.38 ± 0.39, with two cases having a DRWR of 0.84. The remaining cases had a DRWR > 1.00, with the highest DRWR reaching 3.0. Notably, the patient with the highest DRWR experienced a successful postoperative recovery and was discharged without complications. Follow-up two months later revealed that the transplanted heart had adapted in size to fit the recipient, demonstrating the heart’s ability to remodel post-transplantation. This finding aligns with other studies, which suggest that donor-recipient size mismatch may not preclude successful outcomes when proper post-transplant management and support are provided [26].

A total of five ABOi heart transplants have been performed at our center, with 4 of these recipients surviving to date. This highlights the potential for successful outcomes in ABOi heart transplantation, despite the inherent immunological challenges associated with this procedure. ABOi heart transplantation presents a viable option for pediatric patients, especially in situations where donor availability is limited. It offers the opportunity to reduce waiting list times without compromising long-term survival, making it an important strategy in addressing the ongoing challenges in PHT [2,27].

This study has several limitations: The single-center retrospective design and small ECMO cohort limit generalizability. Lack of longitudinal cytokine monitoring restricts precise guidance on anti-inflammatory management during ECMO support. Unmeasured confounders like immunosuppression variability may influence outcomes. These constraints highlight the need for multicenter studies to validate ventricular parameter thresholds for ECMO initiation and establish cytokine-guided management protocols.

In conclusion, ECMO delivers essential hemodynamic stabilization for critically ill pediatric patients despite provoking transient inflammatory responses, facilitating successful transplantation with outcomes equivalent to non-ECMO recipients. Clinically, our findings validate three key applications: ventricular dysfunction markers (LVEF/LVEDD) should inform ECMO initiation decisions; donor-recipient size matching demonstrates flexibility within a DRWR range of 0.8–3.0 when supported by intensive postoperative monitoring; and ABO-incompatible transplantation emerges as a viable strategy to mitigate waitlist mortality.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant Nos. 2021YFC2701700 & 2021YFC2701703) and Special Research Project on Family Planning of the Logistics Support Department of the Military Commission (20JSZ15).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Hui Yi, Ran Zhang and Gengxu Zhou; data collection: Hui Yi, Lei Wan, Xiaoyang Hong, Junjie Shao, Gang Wang, Hui Wang, Hua Yan and Xiujuan Shi; analysis and interpretation of results: Hongjian Shi, Fuquan Kan, Fan Han and Zhe Zhao; drafting manuscript preparation: Hui Yi and Hongjian Shi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Seventh Medical Center of the Chinese PLA General Hospital (S2024-044-01). The requirement for informed patient consent was waived by the Board due to the retrospective nature of the research.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kirk R, Butts RJ, Dipchand AI. The first successful pediatric heart transplant and results from the earliest era. Pediatr Transplant. 2019;23(2):e13349. doi:10.1111/petr.13349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Urschel S, McCoy M, Cantor RS, Koehl DA, Zuckerman WA, Dipchand AI, et al. A current era analysis of ABO incompatible listing practice and impact on outcomes in young children requiring heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39(7):627–35. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2020.02.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Lin Y, Davis TJ, Zorrilla-Vaca A, Wojcik BM, Miyamoto SD, Everitt MD, et al. Neonatal heart transplant outcomes: a single institutional experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;162(5):1361–8. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.01.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Patel ND, Weiss ES, Nwakanma LU, Russell SD, Baumgartner WA, Shah AS, et al. Impact of donor-to-recipient weight ratio on survival after heart transplantation: analysis of the united network for organ sharing database. Circulation. 2008;118(14 Suppl):S83–8. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.756866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chambers DC, Cherikh WS, Harhay MO, Hayes D Jr, Hsich E, Khush KK, et al. The international thoracic organ transplant registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: thirty-sixth adult lung and heart-lung transplantation report-2019; focus theme: donor and recipient size match. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019;38(10):1042–55. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2019.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Barbaro RP, Paden ML, Guner YS, Raman L, Ryerson LM, Alexander P, et al. Pediatric extracorporeal life support organization registry international report 2016. ASAIO J. 2017;63(4):456–63. doi:10.1097/MAT.0000000000000603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Deshpande S, Sparks JD, Alsoufi B. Pediatric heart transplantation: year in review 2020. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;162(2):418–21. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.04.073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Butts RJ, Toombs L, Kirklin JK, Schumacher KR, Conway J, West SC, et al. Waitlist outcomes for pediatric heart transplantation in the current era: an analysis of the pediatric heart transplant society database. Circulation. 2024;150(5):362–73. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.068189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Godown J, Smith AH, Thurm C, Hall M, Dodd DA, Soslow JH, et al. Mechanical circulatory support costs in children bridged to heart transplantation—analysis of a linked database. Am Heart J. 2018;201:77–85. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2018.04.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. DeFilippis EM, Clerkin K, Truby LK, Francke M, Fried J, Masoumi A, et al. ECMO as a bridge to left ventricular assist device or heart transplantation. JACC Heart Fail. 2021;9(4):281–9. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2020.12.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. D’Addese L, Joong A, Burch M, Pahl E. Pediatric heart transplantation in the current era. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2019;31(5):583–91. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Dalton HJ, Reeder R, Garcia-Filion P, Holubkov R, Berg RA, Zuppa A, et al. Factors associated with bleeding and thrombosis in children receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(6):762–71. doi:10.1164/rccm.201609-1945OC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Edelson JB, Huang Y, Griffis H, Huang J, Mascio CE, Chen JM, et al. The influence of mechanical circulatory support on post-transplant outcomes in pediatric patients: a multicenter study from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Registry. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;40(11):1443–53. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2021.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Popugaev KA, Bakharev SA, Kiselev KV, Samoylov AS, Kruglykov NM, Abudeev SA, et al. Clinical and pathophysiologic aspects of ECMO-associated hemorrhagic complications. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0240117. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Thomas J, Kostousov V, Teruya J. Bleeding and thrombotic complications in the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2018;44(1):20–9. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1606179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Fletcher K, Chapman R, Keene S. An overview of medical ECMO for neonates. Semin Perinatol. 2018;42(2):68–79. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2017.12.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kobashigawa J, Zuckermann A, MacDonald P, Leprince P, Esmailian F, Luu M, et al. Report from a consensus conference on primary graft dysfunction after cardiac transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(4):327–40. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2014.02.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Siegel PM, Barta BA, Orlean L, Steenbuck ID, Cosenza-Contreras M, Wengenmayer T, et al. The serum proteome of VA-ECMO patients changes over time and allows differentiation of survivors and non-survivors: an observational study. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):319. doi:10.1186/s12967-023-04174-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Raasveld SJ, Volleman C, Combes A, Broman LM, Taccone FS, Peters E, et al. Knowledge gaps and research priorities in adult veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a scoping review. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2022;10(1):50. doi:10.1186/s40635-022-00478-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Al-Fares A, Pettenuzzo T, Del Sorbo L. Extracorporeal life support and systemic inflammation. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2019;7(Suppl 1):46. doi:10.1186/s40635-019-0249-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Siegel PM, Orlean L, Bojti I, Kaier K, Witsch T, Esser JS, et al. Monocyte dysfunction detected by the designed ankyrin repeat protein F7 predicts mortality in patients receiving veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:689218. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.689218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Watts RP, Thom O, Fraser JF. Inflammatory signalling associated with brain dead organ donation: from brain injury to brain stem death and posttransplant ischaemia reperfusion injury. J Transplant. 2013;2013:521369. doi:10.1155/2013/521369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Szugye NA, Moore RA, Dani A, Ollberding NJ, Villa C, Lorts A, et al. Comparing donor and recipient total cardiac volume predicts risk of short-term adverse outcomes following heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2022;41(11):1581–9. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2022.06.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Lee JY, Kidambi S, Zawadzki RS, Rosenthal DN, Dykes JC, Nasirov T, et al. Weight matching in infant heart transplantation: a national registry analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2023;116(6):1241–8. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2022.05.067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Brown G, Moynihan KM, Deatrick KB, Hoskote A, Sandhu HS, Aganga D, et al. Extracorporeal life support organization (ELSO): guidelines for pediatric cardiac failure. ASAIO J. 2021;67(5):463–75. doi:10.1097/mat.0000000000001431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Su JA, Kelly RB, Grogan T, Elashoff D, Alejos JC. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support after pediatric orthotopic heart transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2015;19(1):68–75. doi:10.1111/petr.12382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Kozik D, Sparks J, Trivedi J, Slaughter MS, Austin E, Alsoufi B. ABO-incompatible heart transplant in infants: a UNOS database review. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;112(2):589–94. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.06.073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools