Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Long-Term Follow-Up of Percutaneous Stent Implantation for Residual Pulmonary Artery Stenosis in Pediatric Patients after Surgical Repair of Complicated Congenital Heart Diseases

1 Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Guangdong Cardiovascular Institute, Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences), Southern Medical University, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of South China Structural Heart Disease, Guangzhou, 510100, China

2 Department of Cardiology, Wuhan Children’s Hospital (Wuhan Maternal and Child Healthcare Hospital), Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science & Technology, Wuhan, 430016, China

3 Department of Pediatrics, Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, 510120, China

* Corresponding Author: Yumei Xie. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(4), 463-475. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.068286

Received 24 May 2025; Accepted 29 August 2025; Issue published 18 September 2025

Abstract

Objective: The aim of the present study was to investigate long-term efficacy and safety of percutaneous stent implantation for residual pulmonary artery stenosis (PAS) in pediatric patients after surgical repair of complicated congenital heart diseases (CHDs). Methods: All pediatric patients diagnosed with residual PAS after surgical repair of complicated CHDs between 1996 and 2020 were retrospectively enrolled in the study. Results: A total of 41 patients (30 males, 11 females; median age 5.0 years, median weight 17 kg) were followed-up for a median of 7.1 years. Follow-up echocardiography results demonstrated that the target vessel diameter increased from (3.4 ± 1.1) mm preoperatively to (6.2 ± 1.9) mm one year post-procedure and (6.0 ± 1.5) mm at the final follow-up (p < 0.05). The pressure gradient across the stenosis decreased from (52.6 ± 15.8) mmHg preoperatively to (35.8 ± 19.1) mmHg one year post-procedure and (33.1 ± 19.7) mmHg at the final follow-up (p < 0.05). Cardiac computed tomography scans indicated that target vessel/distal vessel diameter ratio increased from (0.4 ± 0.2) pre-operatively to (0.8 ± 0.2) one year post-procedure and (0.9 ± 0.3) at the final follow-up (p < 0.05). A total of six adverse events were documented, comprising two cases of in-stent restenosis requiring surgical reintervention, three cases of in-stent restenosis managed with regular clinical surveillance, and one case of percutaneous pulmonary valve replacement due to severe pulmonary regurgitation. Kaplan-Meier event-free survival analysis demonstrated that elevated preprocedural right ventricular systolic pressure (>72 mmHg) was significantly associated with long-term adverse events (p = 0.024). Conclusion: Percutaneous stent implantation for residual PAS after surgical repair of complicated CHDs effectively relieves vessel stenosis, stabilizes cardiac function, and improves long-term prognosis in pediatric patients. In-stent restenosis remains an unresolved complication, necessitating further advancements in interventional strategies.Keywords

Pulmonary artery stenosis (PAS) in children may present as an isolated congenital lesion or coexist with congenital heart diseases (CHDs), such as tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), pulmonary atresia (PA), transposition of the great arteries (TGA), and double outlet right ventricle (DORV). Residual PAS may occur post-surgery for CHDs due to hypertrophic scarring at the anastomotic site and fibrous tissue traction [1,2]. PAS pathophysiology involves elevated RV pressure and increased pressure in the proximal pulmonary artery due to stenosis, which may progress to RV failure and unbalanced lung perfusion if left untreated [3]. PAS treatments include surgery and transcatheter intervention. Surgery carries inherent procedural risks, including perioperative complications, prolonged hospitalization periods, extended recovery duration, and technical challenges in addressing stenotic lesions within distal pulmonary artery branches [4,5]. Transcatheter intervention is a preferred therapeutic option that is characterized by minimal invasiveness, avoids thoracotomy and cardiopulmonary bypass, and is unrestricted by stenotic lesion location [6,7]. Interventional therapies include percutaneous balloon angioplasty and percutaneous stent implantation. The restenosis rate after balloon angioplasty is relatively high, often requiring multiple dilations to achieve satisfactory outcomes [8]. Percutaneous stent implantation for PAS demonstrates a lower restenosis rate of 1.5%–4.0% and a more complete stenosis resolution, solidifying its status as a routine interventional procedure [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Limited data are currently available for long-term follow-up results of percutaneous stent implantation for PAS mainly due to the minority of patients. The present study retrospectively analyzed clinical data for pediatric patients with PAS treated by percutaneous stent implantation at Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital and evaluated the long-term safety and efficacy of this treatment strategy.

Pediatric patients (<18 years old) who underwent percutaneous stent implantation for residual PAS following surgical repair of complex CHDs between January 1996 and June 2020 were included in the present retrospective analysis. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (KY-Q-2022-336-03). Written informed consent was obtained from the guardians of all participants prior to the procedure. The study protocol was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

The indications for percutaneous stent implantation for PAS included one of the following criteria [16]: (i) pressure gradient across the stenosis of ≥20 mmHg as measured by catheterization; (ii) degree of PAS of ≥50% as determined by pulmonary angiography (calculated using the following formula: (diameter of adjacent normal segment—residual lumen diameter of stenosis segment)/(diameter of adjacent normal segment × 100%)); and (iii) ratio of RV systolic pressure to aortic systolic pressure of ≥50% as measured by catheterization.

Contraindications for stent implantation were as follows: (i) presence of other anatomical malformations requiring surgical intervention; (ii) cardiopulmonary dysfunction, such as severe heart failure (NYHA class III or higher) despite optimal medical therapy; (iii) hemorrhagic disorders; (iv) contraindications to antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy; and (v) severe stenosis, tortuous vessels, or anatomical abnormalities that preclude easy access of the device to the lesion site.

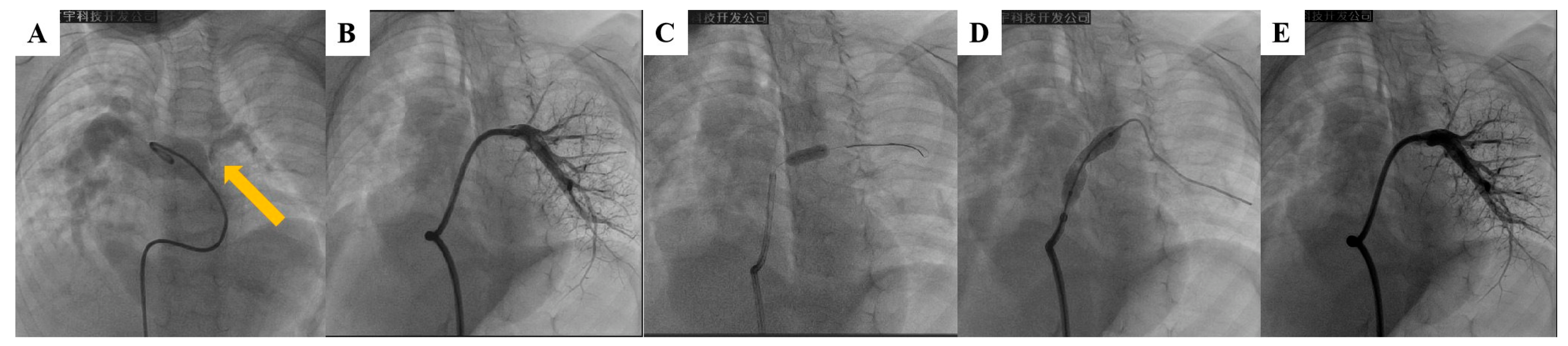

The percutaneous stent implantation procedure for PAS has been described in detail in previous reports [14,15,16]. The operation was performed under general anesthesia in all patients. Intravenous heparin (100 IU/kg) and prophylactic antibiotic (cefazolin 50 mg/kg) were administered. A diagnostic catheterization was performed to evaluate hemodynamic and morphological data using the femoral veins as access vessels. RV and pulmonary artery angiography were performed to obtain the following measurements: stenosis segment diameter, diameter of the segment adjacent to the stenosis, and distance from the stenosis to the opening of the left or right pulmonary artery and to the lower branch vessels. An appropriate stent was selected based on the angiographic findings. The stent size did not exceed the diameter of the normal pulmonary artery adjacent to the stenosis, while its length did not exceed the distance from the opening of the left or right pulmonary artery to the lower branch vessels. Angiography was performed after the stents were delivered to the stenotic lesion to confirm the correct position. The balloon was then inflated to expand the stent to the desired diameter. Coronary balloon pre-dilation was performed prior to stent implantation if the target vessel exhibited severe stenosis (Fig. 1). Repeat angiography and hemodynamic measurements were carried out to evaluate the acute outcome of stent implantation.

All patients received aspirin therapy (3–5 mg/kg/day) after stent implantation for a minimum duration of six months. Additionally, patients with complex pulmonary artery anatomy (including long-segment stenosis or multiple stenoses) were concurrently administered clopidogrel (1 mg/kg/day) for 1–3 months. Advanced anticoagulation medication (warfarin) was prescribed to patients with prior conduit implantation or valve replacement.

Figure 1: Percutaneous stent implantation in a case of left pulmonary artery (LPA) stenosis. (A) Proximal stenosis of LPA (arrow); (B) Distal LPA segment adjacent to the narrowing site as shown on pulmonary angiography. (C) Pre-dilation of stenosis with a 3-mm coronary balloon; (D) Implantation of 8 mm × 27 mm stent at stenosis; (E) Repeat pulmonary angiography demonstrating stenosis resolution and pulmonary perfusion improvement after stent implantation.

All patients underwent a comprehensive postoperative evaluation that included a clinical assessment, chest X-ray (anteroposterior and lateral views), electrocardiography (ECG), and transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) within 24 h after the procedure. Repeat X-ray, ECG and TTE evaluations were scheduled 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after hospital discharge and then yearly thereafter. Z-scores of the right atrium (RA) and right ventricle (RV) were examined using TTE at each follow-up timepoint as previously described [17]. Cardiac computed tomography (CT) was routinely performed to evaluate stent morphology at the 12-month follow-up. Furthermore, cardiac CT was performed if stent restenosis was suspected at any follow-up timepoint based on the TTE findings (defined as either a reduction in stent lumen diameter to less than half of the inner diameter at the restenosis segment or a 50% increase in pressure gradient across the stent compared to post-implantation baseline values) [14]. Additional catheterization and angiography were recommended after stent restenosis was also suggested by cardiac CT results. In-stent stenosis was defined as neointimal proliferation between the stent and contrast-filled lumen showing >25% narrowing of the lumen on angiography [18].

All analyses were performed using SPSS software for Windows (version 26.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were described as means ± standard deviations for normally distributed data or medians (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were described as counts and percentages. Statistical comparisons were conducted using appropriate parametric and non-parametric tests as follows: independent or paired samples t-tests for two-group comparisons and one-way ANOVA (F-test) or Kruskal-Wallis H test for multiple-group comparisons. Freedom from adverse events was determined using Kaplan-Meier curves. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

A total of 41 patients (30 males, 11 females) were included in the study. The median age and weight of the study population at stent implantation were 5.0 (range, 1.1 to 14.2) years and 17 (range, 8.0 to 43) kg, respectively. All patients exhibited postoperative residual PAS following surgical procedures for complex CHDs. The underlying primary diagnoses were TOF in 19 cases (46.3%), PA in 15 cases (36.6%), TGA in three cases (7.3%), DORV in three cases (7.3%), and isolated aortopulmonary septal defect (APSD) in one case (2.4%). TTE results indicated the mean target vessel diameter and the mean pressure gradient across the narrow segment of (3.4 ± 1.1) mm and (52.6 ± 15.8) mmHg, respectively. A total of 70.7% of patients had at least moderate pulmonary regurgitation (PR), while moderate or severe tricuspid valve regurgitation (TR) was observed in 24.4% of the patients. The mean target vessel diameter measured using cardiac CT was (2.8 ± 1.3) mm. Patient demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Patient characteristics.

| Patients | N = 41 |

| Male | 30 (73.2) |

| Age (years) | 5.0 (1.1–14.2, 5.6 ± 3.7) |

| Weight (kg) | 17 (8.0–43.0, 18.9 ± 9.3) |

| Height (cm) | 110 (69–164, 110.6 ± 24.3) |

| Type of CHD | |

| TOF | 19 (46.3) |

| PA | 15 (36.6) |

| TGA | 3 (7.3) |

| DORV | 3 (7.3) |

| APSD | 1 (2.4) |

| Unilateral PAS | 34 (82.9) |

| Bilateral PAS | 7 (17.1) |

| Clinical symptoms | |

| Cyanosis | 10 (24.4) |

| Exertional dyspnea | 16 (39) |

| Palpitation | 8 (19.5) |

| Heart function (NYHA Class) | |

| Class I | 25 (61) |

| Class II | 14 (34.1) |

| Class III | 2 (4.9) |

| Target vessel diameter measured by TTE (mm) | 3.3 (1.4–5.6, 3.4 ± 1.1) |

| Pressure gradient measured by TTE (mmHg) | 51 (22–91, 52.6 ± 15.8) |

| RVSP measured by TTE (mmHg) | 65 (35–89, 62.5 ± 14.3) |

| Degree of TR | |

| Mild | 20 (48.8) |

| Moderate | 9 (22.0) |

| Severe | 1 (2.4) |

| Degree of PR | |

| Mild | 7 (17.1) |

| Moderate | 20 (48.8) |

| Severe | 9 (22.0) |

| Target vessel diameter measured by cardiac CT (mm) | 2.9 (0.8–7.0, 2.8 ± 1.3) |

All patients underwent cardiac catheterization and intervention on the stenotic pulmonary artery. A total of 41 stents were successfully deployed at the site of PAS during the procedure. The stents were implanted in the left pulmonary artery (LPA) in 33 cases and the right pulmonary artery (RPA) in the remaining eight cases. The most frequently utilized stent sizes were 8 mm (41.5%, n = 17), 7 mm (24.4%, n = 10), and 9 mm (14.6%, n = 6). Procedure data are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Procedure data.

| Patients | N = 41 |

|---|---|

| Target vessel diameter (mm) by angiography | 3.1 (0.5–5.4, 3 ± 1.2) |

| Pressure gradient (mmHg) | 48 (24–90, 51.3 ± 16.7) |

| RVSP (mmHg) | 72 (33–121, 72.5 ± 20.8) |

| Implantation site | |

| LPA | 33 (80.5) |

| RPA | 8 (19.5) |

| Size of delivery sheath | |

| 6F | 20 (48.8) |

| 7F | 14 (34.1) |

| 8F | 6 (14.6) |

| 12F | 1 (2.4) |

| Implanted stent | |

| Express Vascular LDTM balloon expanded stents [Boston Scientific, United States] | |

| 7 mm × 19 mm | 1 (2.4) |

| 7 mm × 37 mm | 8 (19.5) |

| 8 mm × 17 mm | 1 (2.4) |

| 8 mm × 27 mm | 8 (19.5) |

| 8 mm × 37 mm | 8 (19.5) |

| 9 mm × 25 mm | 6 (14.6) |

| 10 mm × 25 mm | 2 (4.9) |

| 10 mm × 37 mm | 2 (4.9) |

| HIPPOCAMPUS peripheral artery stent [Medtronic, United States] | |

| 6 mm × 20 mm | 1 (2.4) |

| 7 mm × 20 mm | 1 (2.4) |

| Wallstent ballon expanded stent [Boston Scientific, United States] | |

| 12 mm × 18 mm | 1 (2.4) |

| CP-stent self-expansion bare stent [NuMED, United States] | |

| 14 mm × 22 mm | 1 (2.4) |

| Cordis ballon expanded stent [Johnson, United States] | |

| 6 mm × 18 mm | 1 (2.4) |

Technical success was achieved in all 41 patients. A significant angiographic improvement was observed in the vessel diameter at the stenotic region [increase from (3.0 ± 1.2) mm pre-intervention to (7.4 ± 1.8) mm post-intervention, p < 0.05], while a significant decrease was noted in the peak pressure gradient across the stenotic pulmonary artery [decrease from (51.3 ± 16.7) mmHg pre-intervention to (19.2 ± 10.2) mmHg post-intervention, p < 0.05]. A significant decrease in right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) [decrease from (72.5 ± 20.8) mmHg pre-intervention to (40.3 ± 14.0) mmHg post-intervention, p < 0.05] was also present immediately after stent implantation. There were no significant echocardiographic changes in the degree of PR or TR after the procedure.

All patients underwent serial clinical assessments and imaging evaluations at least one year after stent implantation. The median follow-up time was 7.1 years (range, 3.1 years to 13.8 years). Baseline assessment revealed peripheral arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) of <90% in 10 patients (24.4%). All affected patients demonstrated complete resolution of hypoxemia, achieving SpO2 levels of ≥95% at the final follow-up evaluation.

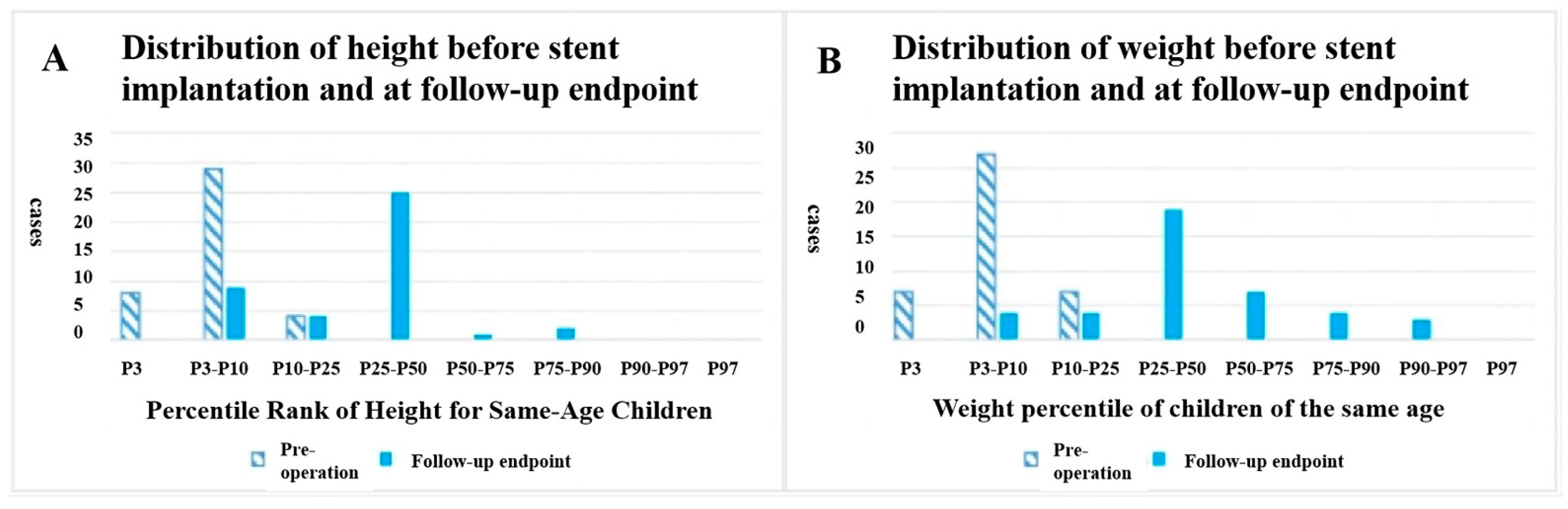

Patients demonstrated anthropometric parameters within age-specific norms [height: 150.0 cm ± 17.8 cm (range, 112–180 cm); weight: 40.0 kg ± 12.6 kg (range, 18–74 kg)] at the final follow-up evaluation. Patients exhibited significant improvements in growth and developmental parameters following stent implantation, with a marked increase in both height-for-age and weight-for-age percentiles compared to preoperative baseline measurements (Fig. 2). Cardiac functional status showed an improvement, with Grade I function present in 39 cases (95.1%) compared to 25 preoperative cases (61.0%, p < 0.05) and Grade II function reduced to two cases (4.9%) from 14 preoperative cases (34.1%, p < 0.05). NT-proBNP levels significantly decreased to a median of 123 pg/mL (Interquartile range, 46.9–324 pg/mL) from preoperative values of 880 pg/mL (Interquartile range, 104.2–35,001 pg/mL; p < 0.05).

Figure 2: Distribution of (A) height-for-age percentile and (B) weight-for-age percentile before stent implantation and at the follow-up endpoint.

Target vessel diameter measured by TTE demonstrated sustained improvement, increasing from (3.4 ± 1.1) mm at baseline to (6.2 ± 1.9) mm one year post-stent implantation, with a slight decrease to (6.0 ± 1.5) mm at final follow-up (p < 0.05 for pairwise comparisons between baseline and follow-up intervals; Table 3). Right atrial diameter (RAD) remained stable at the one-year follow-up, while a significant reduction in RAD and Z-score at the final follow-up was observed [baseline: (33.6 ± 15.7) mm, Z-score: 3.3 ± 1.4; one-year: (31.4 ± 12.3) mm, Z-score: 3.1 ± 1.7; final follow-up: (22.3 ± 11.1) mm, Z-score: 2.3 ± 1.1]. Right ventricular diameter stabilization was demonstrated during long-term follow-up [baseline: (28.1 ± 9.6) mm, Z-score: 2.7 ± 0.9; one-year: (21.5 ± 8.4) mm, Z-score: 2.2 ± 0.8; final follow-up: (26.4 ± 8.5) mm, Z-score: 2.6 ± 0.9], with no statistically significant differences observed between assessments (p > 0.05). On the other hand, although RVSP decreased significantly following the procedure, it subsequently rebounded to levels close to the preoperative baseline at the final follow-up [baseline: (62.5 ± 14.3) mmHg; one-year: (47.0 ± 18.6) mmHg; final follow-up: (59.6 ± 23.1) mmHg].

Cardiac CT scan at the final follow-up demonstrated stent patency with a mean diameter of (6.4 ± 1.3) mm, showing a statistically significant increase compared to pre-implantation measurements (2.8 ± 1.3 mm; p < 0.05). However, no significant difference was observed between the final follow-up and one-year postoperative stent dimensions (6.5 ± 1.8 mm; p > 0.05). Stent-to-distal vessel diameter ratio improved from 0.4 ± 0.2 at baseline to 0.8 ± 0.2 at follow-up (p < 0.05), with sustained stability noted one year post-implantation (0.9 ± 0.3; p > 0.05).

Table 3: Follow-up results for various parameters after stent implantation for PAS.

| Variables | Pre-Operation (Group 1) | One-Year Follow-Up (Group 2) | Follow-Up Endpoint (Group 3) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTE parameters | ||||

| Target vessel diameter (mm) | 3.4 ± 1.1 | 6.2 ± 1.9 | 6.0 ± 1.5 | p1–2 < 0.001 |

| p1–3 < 0.001 | ||||

| p2–3 = 0.055 | ||||

| RAD (mm) | 33.6 ± 15.7 | 31.4 ± 12.3 | 22.3 ± 11.1 | p1–2 = 0.605 |

| p1–3 < 0.001 | ||||

| p2–3 < 0.001 | ||||

| Z-score of RAD | 3.3 ± 1.4 | 3.1 ± 1.7 | 2.3± 1.1 | p1–2 = 0.938 |

| p1–3 < 0.001 | ||||

| p2–3 = 0.003 | ||||

| RVD (mm) | 28.1 ± 9.6 | 21.5 ± 8.4 | 26.4 ± 8.5 | p1–2 = 0.056 |

| p1–3 = 0.914 | ||||

| p2–3 = 0.151 | ||||

| Z-score of RVD | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | p1–2 = 0.058 |

| p1–3 = 0.488 | ||||

| p2–3 = 0.180 | ||||

| Pressure gradient across stenosis (mmHg) | 52.6 ± 15.8 | 35.8 ± 19.1 | 33.1 ± 19.7 | p1–2 < 0.001 |

| p1–3 < 0.001 | ||||

| p2–3 = 0.169 | ||||

| RVSP (mmHg) | 62.5 ± 14.3 | 47.0 ± 18.6 | 59.6 ± 23.1 | p1–2 < 0.001 |

| p1–3 = 0.366 | ||||

| p2–3 < 0.001 | ||||

| Cardiac CT parameters | ||||

| Target vessel diameter (mm) | 2.8 ± 1.3 | 6.4 ± 1.3 | 6.5 ± 1.8 | p1–2 < 0.001 |

| p1–3 < 0.001 | ||||

| p2–3 = 0.964 | ||||

| Target-to-distal vessel diameter ratio | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | p1–2 < 0.001 |

| p1–3 < 0.001 | ||||

| p2–3 = 0.304 |

Five patients (12.2%) exhibited significant in-stent restenosis during the follow-up. The target vessel diameter in these five patients decreased significantly from (8.58 ± 2.18) mm immediately after the procedure to (5.68 ± 0.91) mm at the last visit (p = 0.023). The pressure gradient across the target vessel increased from (21.5 ± 5.8) mmHg immediately after the procedure to (75.0 ± 16.6) mmHg at the last visit (p = 0.003). Two of these five patients eventually underwent surgical stent removal, while the remaining three patients remained on the regular follow-up schedule, exhibiting stable cardiac function with absence of clinically significant dyspnea or exercise intolerance. No other major complications, such as death, stent fracture, pulmonary artery dissection, pulmonary embolism, or pulmonary aneurysm formation, were found.

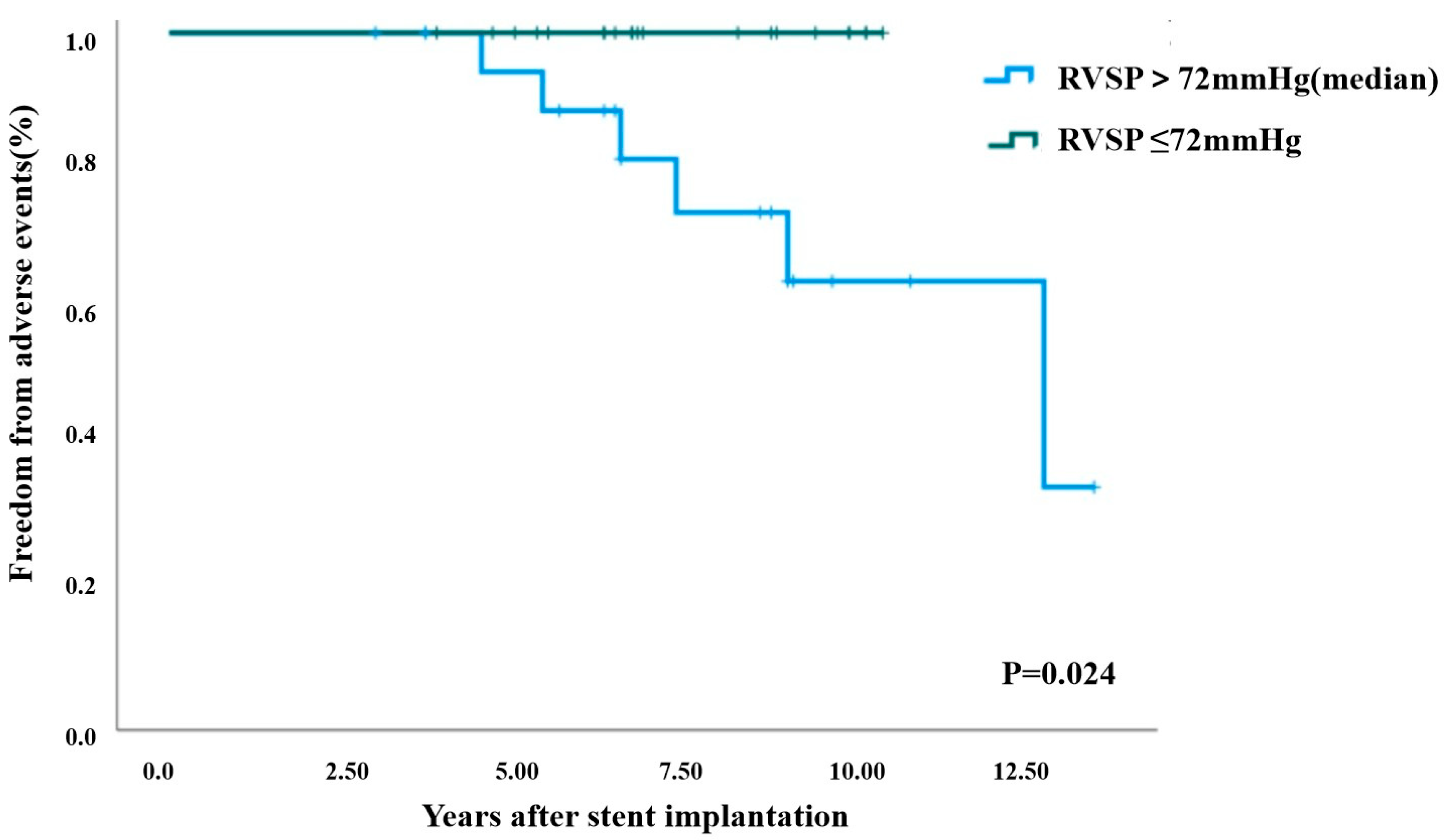

The primary endpoint comprised cardiovascular mortality, in-stent restenosis (regardless of requirement for further intervention), stent fracture, and need for repeat intervention excluding in-stent restenosis. A total of six adverse events were documented during the follow-up period, comprising two cases of in-stent restenosis requiring surgical reintervention, three cases of in-stent restenosis managed with regular clinical surveillance, and one case of percutaneous pulmonary valve replacement due to severe PR. Kaplan-Meier event-free survival analysis was carried out based on the baseline clinical parameters, including age, body mass index, invasively measured RVSP, catheterization-derived pressure gradient across stenosis, and CT-assessed target-to-distal vessel diameter ratio. The results demonstrated that elevated preprocedural RVSP (>72 mmHg) was the only factor that was significantly associated with long-term adverse events (p = 0.024; Fig. 3). Patients with higher baseline RVSP developed adverse events at a median follow-up of 7.16 years, whereas no adverse events were observed in those with lower RVSP.

Figure 3: Freedom from adverse events after initial stent implantation by RVSP (Kaplan-Meier survival analysis). RVSP: right ventricular systolic pressure.

The present study demonstrated that stent implantation in pediatric PAS populations achieved favorable long-term clinical outcomes, evidenced by consistent procedural efficacy, sustained cardiac function preservation, and normal somatic growth patterns. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest series evaluating prognosis of stent implantation for PAS with the longest follow-up period in a selected cohort of pediatric patients in China. Hiremath et al. [3] revealed that successful relief of branch PAS with balloon angioplasty and stenting resulted in significant improvements in exercise capacity and symptoms. Notably, Takao et al. [19] showed that stent implantation was beneficial in promoting pulmonary artery growth. The present study findings corroborate these observations, revealing significant improvements in cardiac function status and serum NT-proBNP levels after stent implantation.

The initial baseline screening and follow-up assessment of pulmonary anatomical characteristics, including target vessel diameter and transstenotic pressure gradient, primarily relied on TTE in the present study. However, prior research has shown that preoperative cardiac CT outperforms TTE and demonstrates non-inferiority to cardiac catheterization and angiography in the accurate quantification of pulmonary vascular parameters in TOF patients [20]. Consequently, cardiac CT was systematically performed in each patient prior to catheterization and at one-year follow-up and was specifically recommended when TTE findings suggested possible in-stent restenosis. Furthermore, the analysis revealed concordant trends between echocardiographic and cardiac CT evaluations during follow-up, demonstrating a statistically significant improvement in target vessel diameter from baseline to the one-year post-procedural assessment, with subsequent stabilization observed starting at one-year evaluation and until the final follow-up. Thus, TTE and cardiac CT may have complementary roles in the preoperative assessment and follow-up of stent implantation in PAS patients.

Follow-up TTE showed that RVSP exhibited a significant reduction at the one-year assessment. However, this beneficial effect was not maintained through the final follow-up evaluation. This phenomenon may be due to several underlying reasons. (1) A previous study has demonstrated that transcatheter therapy achieved smaller hemodynamic improvements than surgical reconstruction for PAS, especially in long-term follow-up [21]. (2) The sustained high prevalence of significant pulmonary valve regurgitation both before and after stent implantation may exert persistent adverse effects on RV afterload [22]. (3) The pathophysiological mechanisms involving chronic endothelial hyperplasia, in-stent thrombosis, and vascular remodeling may influence the long-term efficacy of pulmonary artery stenting in PAS patients. Optimal antithrombotic therapy may serve as a critical factor affecting in-stent restenosis following pulmonary artery stent implantation. However, antiplatelet/anticoagulation regimens were empirically administered due to the lack of standardized antithrombotic protocols in the present study, making definitive evaluation challenging. Previous studies have indicated that postprocedural antiplatelet therapy with aspirin administered for six months constituted the standard treatment strategy, except in patients with univentricular circulation, for whom intensified anticoagulation (warfarin) was recommended [14,23]. In the present study, the primary antithrombotic regimen consisted of aspirin monotherapy administered for six months. A dual antiplatelet therapy regimen combining aspirin with clopidogrel was additionally employed for a duration of one to three months for patients at elevated thrombotic risk [16,24]. Although no recommendation can be made based on these observations, it makes sense that patients with complex pulmonary artery anatomy receive a more active antithrombotic treatment.

Kaplan-Meier event-free survival analysis identified preprocedural RVSP (measured by cardiac catheterization) as a significant factor associated with poor prognosis in PAS patients after stent implantation in the present study. In this cohort of patients, elevated RVSP correlated with advanced pulmonary vascular pathophysiology, characterized by progressive PAS severity after surgical repair of complex CHDs. This hemodynamic burden exacerbated RV dysfunction over time, manifesting as myocardial contractility impairment, diastolic dysfunction, and reduced pulmonary perfusion. These pathophysiological changes increased the risk of adverse events, underscoring the clinical imperative for timely intervention in high-risk PAS patients.

The present study population exhibited several risk factors for stent-related complications, including young age [mean age (5.6 ± 3.7) years] and low body weight [mean body weight (18.9 ± 9.3) kg] at intervention. The observed in-stent restenosis rate of 12.2% (5/41) aligns with previous studies with relatively high incidence of stenting reintervention for PAS, especially in patients <2 years old and individuals diagnosed with TOF [17]. Notably, peripheral vascular stents were predominantly utilized (38 cases, 92.7%) in the present study. These stents have a small to medium diameter, are typically deployed via 6–7 F delivery systems, and feature modular designs and flexibility suitable for peripheral vascular anatomy [18]. However, their application in pulmonary arteries presents challenges. Peripheral vascular stents often exceed 30 mm in length, resulting in excessive longitudinal placement within the pulmonary artery branches in the pediatric population. This anatomical mismatch predisposes to partial stent protrusion into the main pulmonary artery, potentially increasing the risks of restenosis and embolization. This phenomenon was observed more frequently in patients with ostial PAS, resulting in a higher stent malposition incidence and the need for reintervention compared to other PAS types that do not involve the ostium [25]. Therefore, a more precise anatomical PAS assessment is recommended to optimize interventional therapy through appropriate stent sizing and length selection in the future.

An additional limitation of peripheral stents is their inability to undergo post-implantation expansion. Recent clinical evidence demonstrates that dedicated pulmonary re-expandable stents, exemplified by the Pul-stent system (Med-Zenith Medical Scientific Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), have achieved favorable short- and medium-term clinical outcomes in pediatric populations [13]. This new technology provides a biomechanically rational solution for pediatric pulmonary artery stenting by eliminating mechanical mismatch between static stent geometry and dynamic vascular growth patterns and reducing reintervention rates through programmed staged dilation protocols. The Pul-stent was not available at our center at the time of the study and thus no patients receiving this stent were included in the study cohort.

There were several limitations in the present study. First, it was a retrospective study that involved a relatively small number of selected patients from a single center, rendering the results susceptible to certain biases. Second, the heterogeneous patient population included various PAS types, potentially confounding the results. Third, there were several operators with varying practice habits, which likely contributed to data heterogeneity. Finally, the limited follow-up catheterization rate restricted comprehensive evaluation of stent morphology and long-term performance.

Percutaneous stent implantation for residual PAS after surgical repair of complicated CHDs effectively relieves vessel stenosis, stabilizes cardiac function, and improves tong-term prognosis of pediatric patients. In-stent restenosis remains an unresolved complication, necessitating further advancements in interventional strategies.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 82300268) and Guangzhou Science and Technology Project (grant number 2023A04J0485).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yumei Xie; administrative support: Zhiwei Zhang, Shushui Wang, Yumei Xie; provision of study materials or patients: Zhiwei Zhang, Shushui Wang, Yumei Xie, Yifan Li, Ling Sun; data collection and assembly of data: Yifan Li, Xu Huang; data analysis and interpretation: Yifan Li, Xu Huang, Bingyu Ma; draft manuscript preparation: Yifan Li, Xu Huang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Yumei Xie, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (KY-Q-2022-336-03).

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the guardians of all participants prior to the procedure. The study protocol was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kumar N, Hussain N, Kumar J, Essandoh MK, Bhatt AM, Awad H, et al. Evaluating the impact of pulmonary artery obstruction after lung transplant surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplantation. 2021;105(4):711–22. doi:10.1097/tp.0000000000003407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Martin E, Mainwaring RD, Collins RT 2nd, MacMillen KL, Hanley FL. Surgical repair of peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis in patients without williams or alagille syndromes. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;32(4):973–9. doi:10.1053/j.semtcvs.2020.01.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hiremath G, Qureshi AM, Prieto LR, Nagaraju L, Moore P, Bergersen L, et al. Balloon angioplasty and stenting for unilateral branch pulmonary artery stenosis improve exertional performance. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12(3):289–97. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2018.11.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Nielsen EA, Hjortdal VE. Surgically treated pulmonary stenosis: over 50 years of follow-up. Cardiol Young. 2016;26(5):860–6. doi:10.1017/S1047951115001158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Patel AB, Ratnayaka K, Bergersen L. A review: percutaneous pulmonary artery stenosis therapy: state-of-the-art and look to the future. Cardiol Young. 2019;29(2):93–9. doi:10.1017/S1047951118001087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Feltes TF, Bacha E, Beekman RH 3rd, Cheatham JP, Feinstein JA, Gomes AS, et al. Indications for cardiac catheterization and intervention in pediatric cardiac disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(22):2607–52. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31821b1f10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Flores-Umanzor E, Alshehri B, Keshvara R, Wilson W, Osten M, Benson L, et al. Transcatheter-based interventions for tetralogy of fallot across all age groups. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17(9):1079–90. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2024.02.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Xia S, Li J, Ma L, Cui Y, Liu T, Wang Z, et al. Ultra-high pressure balloon angioplasty for pulmonary artery stenosis in children with congenital heart defects: short- to mid-term follow-up results from a retrospective cohort in a single tertiary center. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:1078172. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.1078172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Gritti MN, Farid P, Hassan A, Marshall AC. Cardiac catheterization interventions in the right ventricular outflow tract and branch pulmonary arteries following the arterial switch operation. Pediatr Cardiol. 2025;46(2):339–48. doi:10.1007/s00246-024-03408-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Cao BL, Mervis J, Adams P, Roberts P, Ayer J. Branch pulmonary artery stent angioplasty in infants less than 10 kg. Int J Cardiol Congenit Heart Dis. 2022;8:100368. doi:10.1016/j.ijcchd.2022.100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Girija H, Muthukumaran CS, Ganesan R, Ramkishore S, Arun V, Mahitha V, et al. Early and midterm results of Cook Formula stent in children with right heart disease: a single-center experience. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2024;17(5):347–55. doi:10.4103/apc.apc_176_24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zampi JD, Loccoh E, Armstrong AK, Yu S, Lowery R, Rocchini AP, et al. Twenty years of experience with intraoperative pulmonary artery stenting. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;90(3):398–406. doi:10.1002/ccd.27094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ooi YK, Kim SIH, Gillespie SE, Kim DW, Vincent RN, Petit CJ. Premounted stents for branch pulmonary artery stenosis in children: a short term solution. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;92(7):1315–22. doi:10.1002/ccd.27800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Xu X, Guo Y, Huang M, Fu L, Li F, Zhang H, et al. Stenting of branch pulmonary artery stenosis in children: initial experience and mid-term follow-up of the pul-stent. Heart Vessels. 2023;38(7):975–83. doi:10.1007/s00380-023-02246-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ma I, El Arid JM, Neville P, Soule N, Dion F, Poinsot J, et al. Long-term evolution of stents implanted in branch pulmonary arteries. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;114(1):33–40. doi:10.1016/j.acvd.2020.05.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sun L, Li JJ, Xu YK, Xie YM, Wang SS, Zhang ZW. Initial status and 3-month results relating to the use of biodegradable nitride iron stents in children and the evaluation of right ventricular function. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:914370. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.914370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang SS, Zhang YQ, Chen SB, Huang GY, Zhang HY, Zhang ZF, et al. Regression equations for calculation of z scores for echocardiographic measurements of right heart structures in healthy Han Chinese children. J Clin Ultrasound. 2017;45(5):293–303. doi:10.1002/jcu.22436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Hallbergson A, Lock JE, Marshall AC. Frequency and risk of in-stent stenosis following pulmonary artery stenting. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(3):541–5. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.10.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Takao CM, El Said H, Connolly D, Hamzeh RK, Ing FF. Impact of stent implantation on pulmonary artery growth. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;82(3):445–52. doi:10.1002/ccd.24710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kumar A, Sahu AK, Goel PK, Jain N, Garg N, Khanna R, et al. Comparison of non-invasive assessment for pulmonary vascular indices by two-dimensional echocardiography and cardiac computed tomography angiography with conventional catheter angiocardiography in unrepaired Tetralogy of Fallot physiology patients weighing more than 10 kg: a retrospective analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023;24(3):383–91. doi:10.1093/ehjci/jeac078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Lan IS, Yang W, Feinstein JA, Kreutzer J, Collins RT 2nd, Ma M, et al. Virtual transcatheter interventions for peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis in williams and alagille syndromes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(6):e023532. doi:10.1161/JAHA.121.023532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Prati F, Sirico D, Di Salvo G, Castaldi B, Pozza A, Cattapan I, et al. Transcatheter pulmonary valve implantation: a state of the art review. Congenit Heart Dis. 2024;19(5):513–33. doi:10.32604/chd.2025.058053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Fagan TE, Ahluwalia N. Pulmonary artery stent implantation. Interv Cardiol Clin. 2024;13(3):409–20. doi:10.1016/j.iccl.2024.03.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Qin L, Zhang G, Sun L, Yu Z, Zhang Z, Sun L, et al. A novel iron bioresorbable scaffold: a potential strategy for pulmonary artery stenosis. Regen Biomater. 2025;12:rbaf041. doi:10.1093/rb/rbaf041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Patel ND, Sullivan PM, Takao CM, Badran S, Ing FF. Stent treatment of ostial branch pulmonary artery stenosis: initial and medium-term outcomes and technical considerations to avoid and minimise stent malposition. Cardiol Young. 2020;30(2):256–62. doi:10.1017/S1047951119003032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools