Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Nationwide Trends in Congenital Heart Disease Surgery in Korea, 2002–2018: Volume, Age-Standardized Incidence, and Lesion-Based Case-Mix

1 Department of Pediatrics, Konkuk University Medical Center, Konkuk University School of Medicine, Seoul, 05030, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Pediatrics, Sejong General Hospital, Sejong Heart Institute, Bucheon-si, 14754, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Soo-Jin Kim. Email:

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(4), 421-440. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.070250

Received 11 July 2025; Accepted 03 September 2025; Issue published 18 September 2025

Abstract

Background: Advancements in diagnostic tools, surgical techniques, and long-term management have significantly improved survival among individuals with congenital heart disease (CHD), leading to an evolving epidemiologic profile characterized by increasing procedural complexity and a growing adult CHD population. This study aimed to examine nationwide trends in CHD surgeries over a 17-year period, with a focus on temporal shifts in surgical volume, procedural complexity, and age-specific incidence. Methods: A total of 41,608 CHD surgeries and 85,417 surgical procedures performed between 2002 and 2018 were identified from a nationwide health insurance database. Temporal trends were evaluated using segmented linear regression, and age-specific standardized incidence rates were calculated per 100,000 population across three age groups: infants (<1 year), children (1–18 years), and adults (≥19 years). Results: Despite a decline in overall surgical volume (from 2523 in 2002 to 1624 in 2018), the number of surgical procedures rose markedly (from 2936 to 5402), indicating higher claims-based procedural volume per patient (i.e., more billed procedure codes per operation), a proxy for operative intensity rather than a direct measure of clinical or system burden. This divergence was particularly notable in infants and adults, while pediatric surgical rates declined sharply. Age-specific incidence rates of surgical procedures showed a continuous rise in infants and a moderate increase in adults, whereas children demonstrated stable or declining trends. Breakpoints in temporal trends were identified in 2015 for surgeries and 2011 for procedures. Conclusions: The landscape of CHD surgery is undergoing a demographic and clinical transformation, with a shift toward early, complex operations in infants and reoperations in adults. These findings underscore the growing need for age-tailored, resource-intensive care models and long-term strategic planning to accommodate the evolving burden of CHD across the lifespan.Keywords

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common major congenital malformation, affecting approximately 1% of live births globally [1,2,3]. It remains a leading cause of mortality from birth defects, despite significant advancements over the past six decades in diagnostics, surgical techniques, and management. These advancements have dramatically improved prognosis, with survival rates for CHD patients reaching adulthood now exceeding 90% in high-income countries, compared to less than 20% in the presurgical era [4,5,6]. Consequently, the population of adults with congenital heart disease (ACHD) has grown substantially, now surpassing the number of children with CHD in many regions.

While surgical outcomes for simpler lesions, such as atrial septal defects (ASD) and ventricular septal defects (VSD), are excellent, more complex conditions like hypoplastic left heart syndrome continue to pose challenges, though outcomes are improving [7,8]. The advent of percutaneous interventions, such as transcatheter ASD and patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) closures, has transformed CHD management, reducing surgical volumes for simpler defects while increasing the complexity of surgical cases [9]. Most prior studies on CHD surgery have been institution-specific, limiting their generalizability. Population-based studies using national registries offer broader insights crucial for healthcare planning and resource allocation.

In Korea, the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) covers nearly the entire population, providing a comprehensive dataset for epidemiological research [10]. However, nationwide data on CHD surgical trends are scarce, particularly in the context of Korea’s demographic shifts, including low birth rates and an aging population, which are likely to increase the ACHD burden. This study investigates nationwide trends in CHD surgeries in Korea over a 17-year period (2002–2018), with a particular focus on changes in surgical volume and procedural complexity across age groups. These findings aim to support strategic planning for the optimization of CHD care in response to shifting clinical demands and demographic dynamics.

Since 1989, the Korean government has implemented a single-payer mandatory health insurance system known as NHIS, which covers approximately 97% of the Korean population—around 50 million individuals. The remaining 3% of the population is covered under the government-funded Medical Aid program, designed for low-income individuals. Since 2006, data from the Medical Aid program have been integrated into the unified NHIS database. For this study, we retrospectively extracted data from the NHIS claims database, which includes nearly the entire Korean population. Diagnoses and procedures related to CHD were identified using the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). The NHIS database includes detailed information on patient demographics (e.g., age, sex, region, socioeconomic status), disease characteristics (major and minor diagnoses), treatment specifics (prescriptions, surgeries, medical devices), and records of inpatient care.

This nationwide, population-based study investigated patients who underwent CHD surgery in Korea from January 2002 to December 2018. Diagnostic and procedural data were obtained from the NHIS database. CHD cases were identified using the ICD-10 and its Korean modification, the Korean Standard Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (KCD-10). Only surgical procedures were included in this study; interventional procedures such as catheter-based treatments were not considered. The detailed ICD-10/KCD-10 diagnostic codes and NHIS Electronic Data Interchange surgical procedure codes are available on request. These included CHD diagnoses such as ASD, VSD, PDA, tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), and other congenital anomalies, with corresponding surgical procedure codes such as shunt procedures, pulmonary artery banding, septal defect repair, valve repair or replacement, and Fontan-type operations. In this study, “CHD surgeries” refers to the number of distinct operations, while “CHD surgical procedures” denotes the total number of procedure codes per year, reflecting multiple procedures within a single operation. To enhance analytic clarity, ASD, VSD, and PDA closures were included only when performed as isolated procedures, not as components of complex cases. We classified congenital heart surgeries into two categories: simple (ASD, VSD, PDA) and non-simple (all other surgeries). Due to the limitations of the NHIS dataset under strict personal information protection regulations, conventional complexity classifications used in prior literature could not be directly applied. Instead, we adopted this indirect definition as a surrogate measure of procedural complexity. Patients were stratified into three age groups: infants (<1 year), children (1–18 years), and adults (≥19 years). Accordingly, we refer to this metric as claims-based procedural volume. Trends in surgical volume and claims-based procedural volume were analyzed across age groups throughout the study period.

We used segmented linear regression (one breakpoint per series) to allow for slope changes over time, relaxing the single-slope assumption of ordinary least squares. Model assumptions (independence, homoscedasticity, normality) were checked, and candidate breakpoints were compared using information criteria; this is mathematically equivalent to joinpoint methods widely used in epidemiology [11]. To account for population change, we also computed age-specific standardized incidence rates per 100,000 using Korean Statistical Information Service, Republic of Korea—KOSIS mid-year denominators. Analyses were implemented in Python 3.11 (statsmodels 0.14.0; scikit-learn 1.3.0); statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

A total of 41,608 CHD surgeries were performed in Korea from 2002 to 2018, based on data from the NHIS. Among these, 22,915 surgeries (55.1%) were performed in infants under the age of 1 year, 8991 (21.6%) in children aged 1–18 years, and 9702 (23.3%) in adults aged 19 years or older. The sex distribution was nearly equal, with 21,007 males (50.5%) and 20,601 females (49.5%), and the mean age at surgery was 9.8 years for males and 13.5 years for females. The most common diagnosis was ASD, accounting for 11,568 cases (27.8%), followed by VSD (9320 cases, 22.4%), TOF (4452 cases, 10.7%), and atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD, 2871 cases, 6.9%). Other commonly treated conditions included pulmonary atresia or stenosis (PA/PS, 2205 cases, 5.3%), coarctation of the aorta (CoA, 1997 cases, 4.8%), double outlet right ventricle (DORV, 1664 cases, 4.0%), and transposition of the great arteries (TGA, 1331 cases, 3.2%). The mean age at surgery varied significantly by diagnosis, with ASD typically corrected at a later age (mean 16.7 years) and hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS, 416 cases, 1.0%) corrected at the youngest average age (mean 2.1 years). Single ventricle (SV, 1290 cases, 3.1%) was also treated at a very young age (mean 3.3 years). Detailed demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients Undergoing Surgical Treatment for Congenital Heart Disease in Korea (2002–2018).

| Variables | Number (%) | Age at Operation (Years) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 41,608) | Mean ± SD | ||

| Main congenital heart defects | |||

| ASD | 11,568 (27.8) | 16.7 ± 23.5 | |

| VSD | 9320 (22.4) | 7.1 ± 15.8 | |

| TOF | 4452 (10.7) | 6.7 ± 12.4 | |

| AVSD | 2871 (6.9) | 9.3 ± 17.9 | |

| PA/PS | 2205 (5.3) | 4.3 ± 9.6 | |

| CoA | 1997 (4.8) | 3.0 ± 9.9 | |

| DORV | 1664 (4.0) | 3.7 ± 9.0 | |

| TGA | 1331 (3.2) | 4.0 ± 10.3 | |

| SV | 1290 (3.1) | 3.3 ± 7.8 | |

| HLHS | 416 (1.0) | 2.1 ± 9.4 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 21,007 (50.5) | 9.8 ± 18.5 | |

| Female | 20,601 (49.5) | 13.5 ± 21.5 | |

| Patient age categories (years) | |||

| <1 yr | 22,915 (55.1) | ||

| 1~18 yr | 8991 (21.6) | 5.3 ± 5.1 | |

| 19~30 yr | 2015 (4.8) | 23.9 ± 3.4 | |

| 31~40 yr | 1869 (4.5) | 35.7 ± 2.9 | |

| 41~50 yr | 2169 (5.2) | 45.7 ± 2.9 | |

| 51~60 yr | 2013 (4.8) | 55.2 ± 2.9 | |

| 61~70 yr | 1138 (2.7) | 65.9 ± 5.1 | |

| ≥71 yr | 496 (1.2) | 76.4 ± 5.1 | |

3.2 Distribution of CHD Surgeries by Diagnosis

ASD was the most frequently operated defect throughout the study period, particularly in adults, suggesting delayed diagnosis or elective repair later in life. In contrast, VSD and TOF were predominantly treated during infancy and early childhood, in accordance with current clinical practice favoring early intervention. Other diagnoses, including AVSD, PA/PS, CoA, TGA, and DORV, showed relatively stable trends and were primarily managed in younger patients due to their severity. While complex CHD was generally corrected in early life, simpler defects such as ASD were more evenly distributed across age groups. These age- and diagnosis-specific trends underscore the heterogeneity in clinical presentation and treatment timing for CHD across the population, as summarized in Table 1.

3.3 Temporal Trends in Surgical Volume

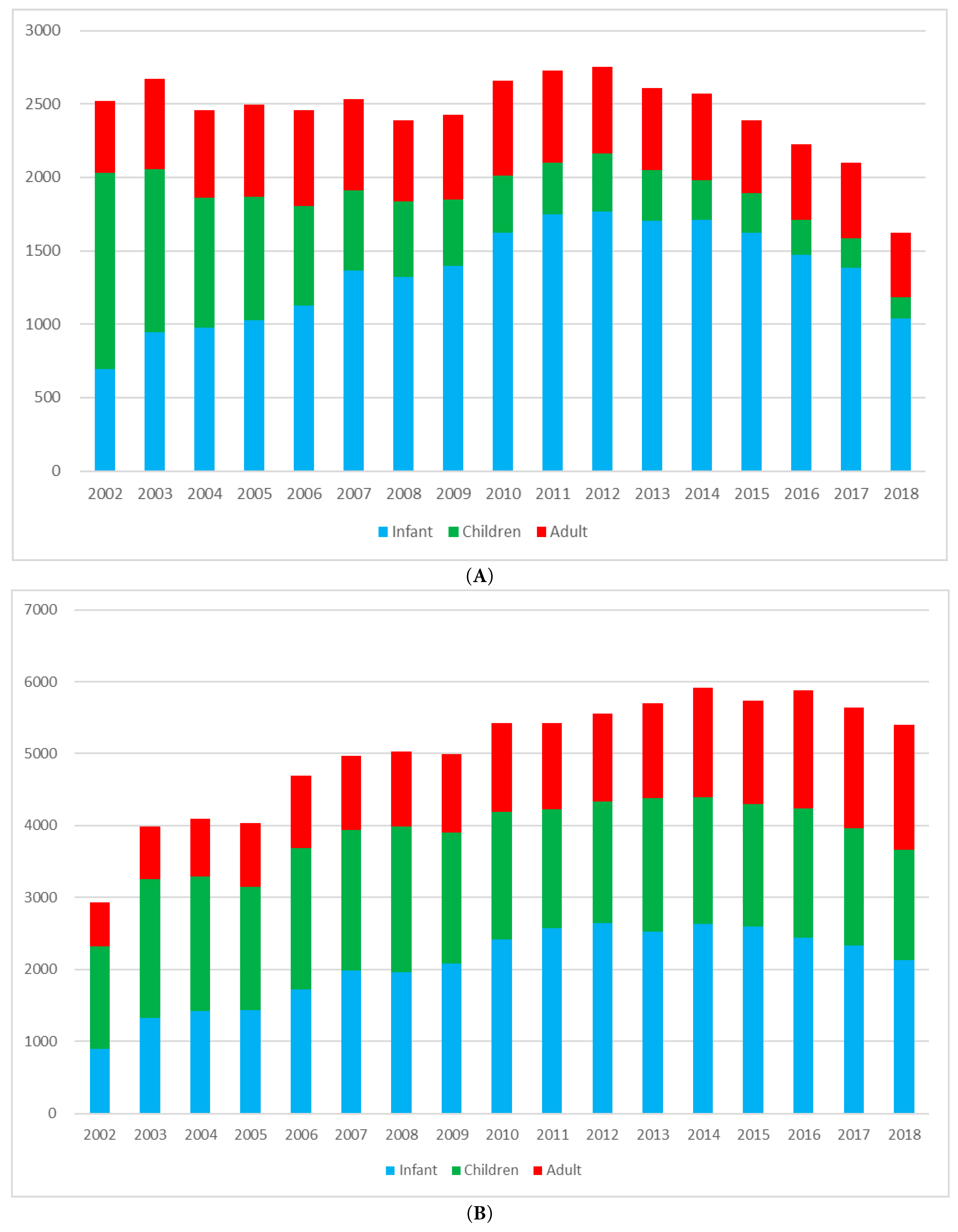

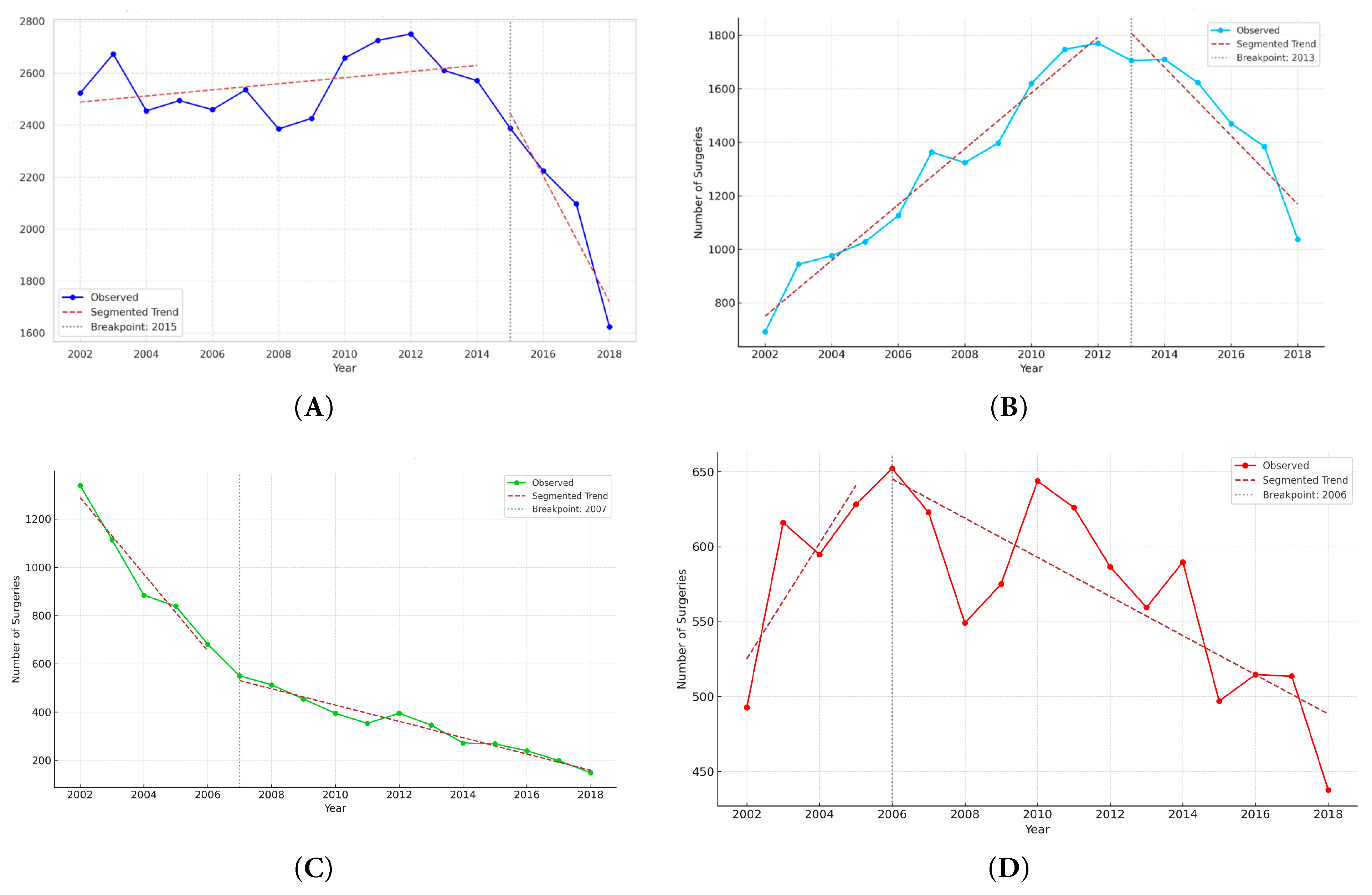

The annual number of CHD surgeries by age group is shown in Fig. 1A. Over 17-year study period, the total number of surgeries remained relatively stable, starting at 2523 in 2002 and ending at 1624 in 2018, with fluctuations during the intervening years. Infants consistently accounted for the highest volume of surgeries throughout the study period, increasing from 692 in 2002 to 1770 in 2012 before declining slightly. Surgeries in children declined steadily from 1338 in 2002 to 471 in 2018. In contrast, adult surgeries increased from 493 in 2002 to 652 in 2006, reflecting expanding adult CHD care. Segmented regression analysis revealed a statistically significant breakpoint in 2015 for the total population (p < 0.001), with a change in slope from an increase of +11.8 cases/year (95% CI, +3.2 to +20.5) to a decrease of −242.0 cases/year (95% CI, −275.1 to −208.9) (Fig. 2A). We interpret this not as an isolated statistical artifact but as a reflection of cumulative real-world transitions, including the maturation and widespread adoption of transcatheter closure techniques, the expansion of insurance reimbursement for catheter-based procedures after 2009, and the concurrent demographic shift due to declining birth rates in Korea. Thus, the segmented regression breakpoint provides a quantitative marker of these multifactorial influences, supporting the model’s clinical plausibility. While we acknowledge that breakpoints may not correspond to a single causative event, they represent the aggregate impact of clinical and policy dynamics, thereby enhancing the explanatory power of time-trend analysis in CHD. In age-stratified analyses, infants showed an increasing trend until 2013 (slope +104.3 cases/year; p < 0.001), followed by a sharp decline thereafter (slope −127.8 cases/year; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2B). For children, a breakpoint was identified in 2007, with the slope changing from −158.9 cases/year (p < 0.001) to −33.8 cases/year (p < 0.001), indicating a more gradual decline (Fig. 2C). In adults, a breakpoint in 2006 marked a shift from a moderate increase (+38.5 cases/year; p < 0.001) to a slight decrease (−13.1 cases/year; p = 0.028) (Fig. 2D).

Figure 1: Trends in the annual number of congenital heart disease (CHD) surgeries and surgical procedures in Korea, 2002–2018. (A) CHD surgeries are defined as discrete surgical operations performed for CHD, regardless of the number of hospital admissions. (B) CHD surgical procedures represent the total number of procedural codes recorded annually, including multiple components that may be performed within a single operation.

Figure 2: Segmented regression analysis of annual CHD surgery volume by age group, 2002–2018. (A) overall population, (B) infants, (C) children, and (D) adults.

3.4 Trends in the Number and Type of CHD Surgical Procedures

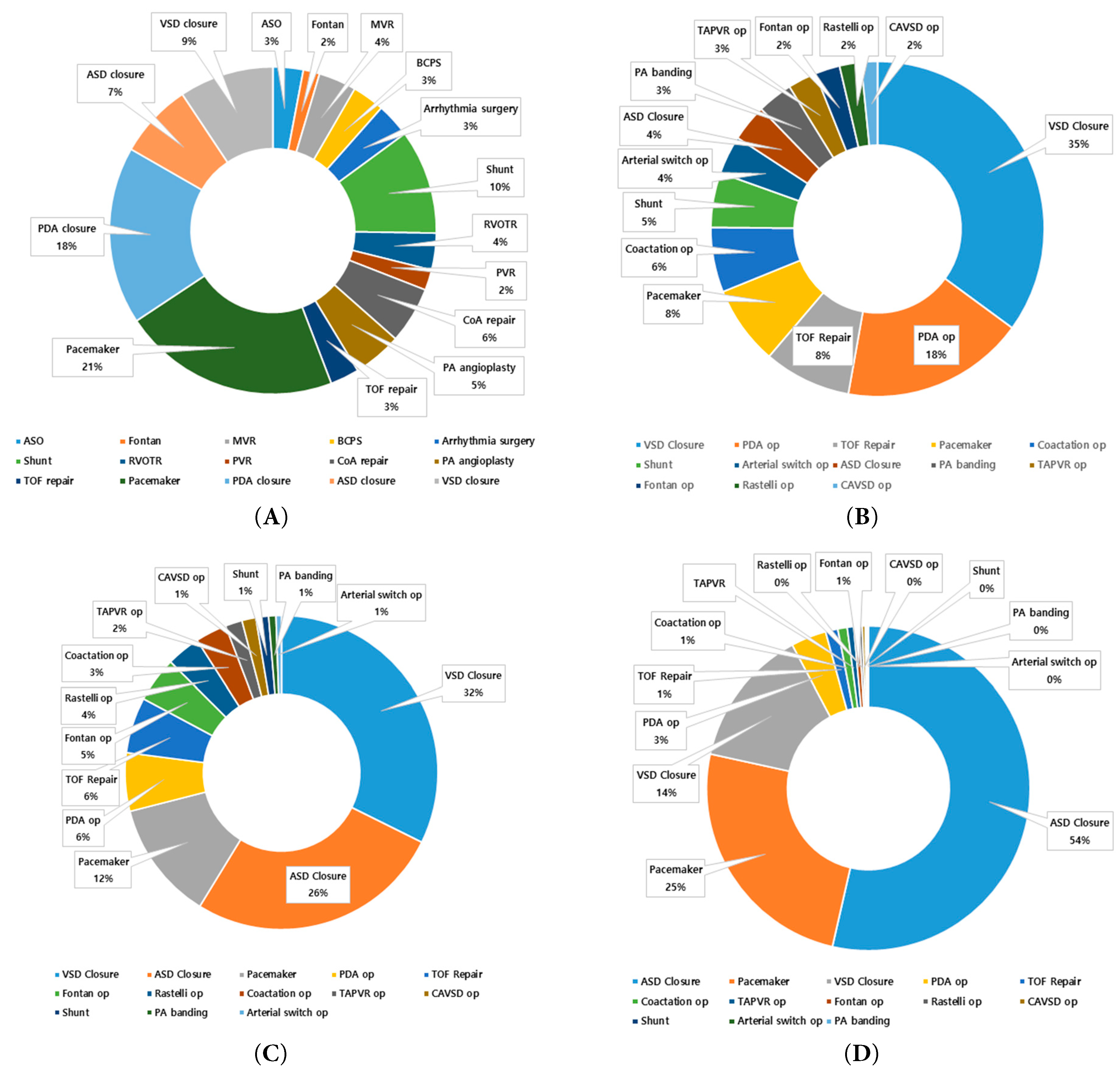

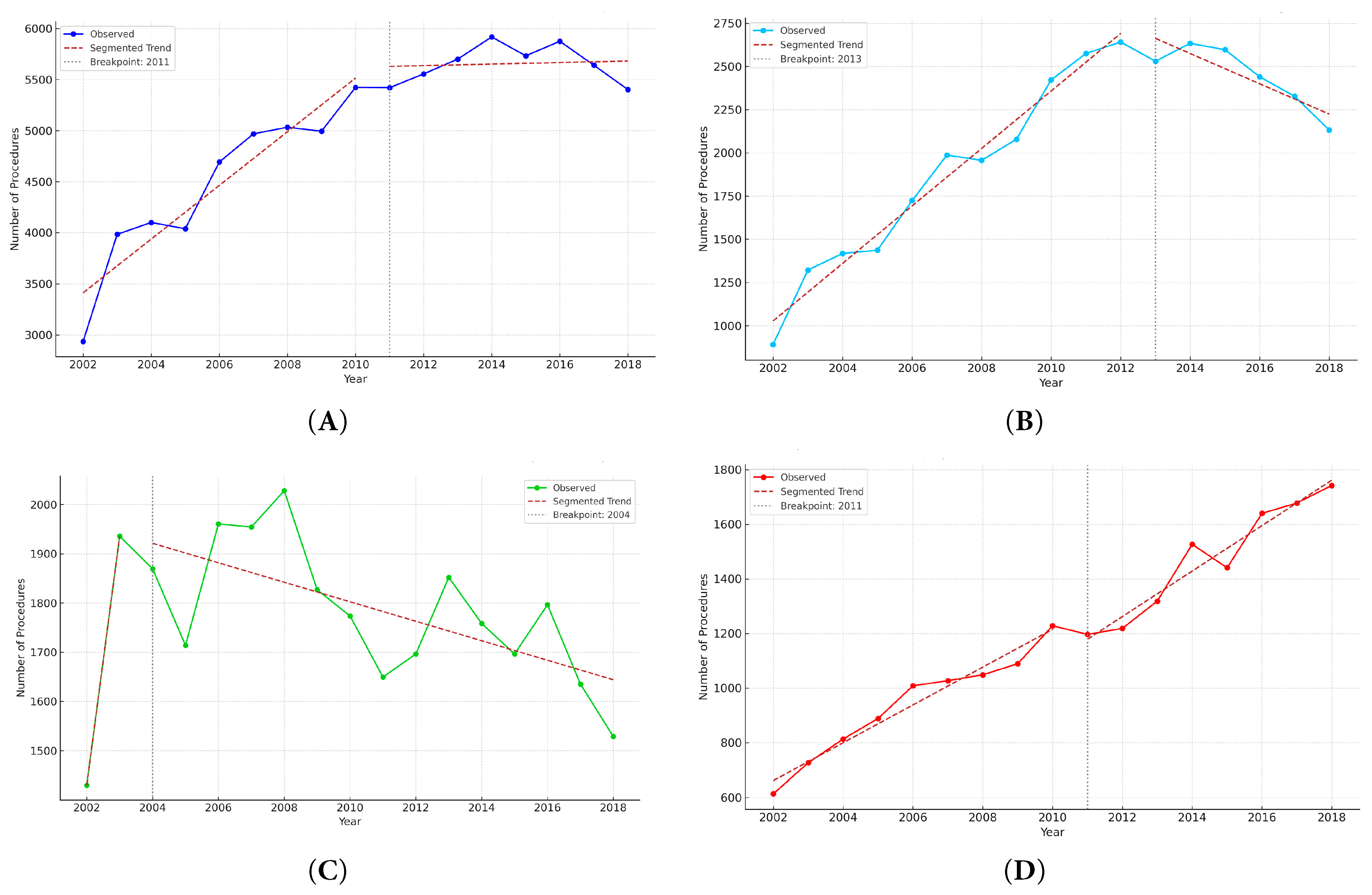

The annual number of CHD surgical procedures—including multiple procedures per surgery—increased steadily from 2936 in 2002 to 5402 in 2018, reflecting growing procedural complexity and a higher frequency of staged or combined surgical procedures (Fig. 1B). Unlike the number of surgeries, which corresponds to individual patients, the number of surgical procedures captures all distinct operative components performed during a single operation, allowing multiple procedures to be identified per patient based on claims coding. As shown in Fig. 3A, the most frequently performed procedures across the entire cohort were pacemaker implantation (21%), PDA closure (18%), systemic-to-pulmonary shunt operations (10%), VSD closure (9%), and ASD closure (7%). This distribution reflects the importance of both device implantation and structural repair in the surgical management of CHD. The high proportion of pacemaker and shunt procedures likely reflects repeated operations for rhythm disturbances or staged palliation in patients with complex anatomy. Age-specific distributions varied markedly. In infants, VSD and ASD closures were common, along with complex neonatal surgeries such as the Norwood procedure, arterial switch operation, and pulmonary artery banding (Fig. 3B). In children, residual defect corrections, valve repairs, and septal closures predominated (Fig. 3C). Among adults, ASD closure alone accounted for more than half of all procedures, followed by pacemaker implantation and operations for valvular disease or late complications (Fig. 3D). Segmented regression identified a significant breakpoint in 2011 for the overall population (p < 0.001), with a slope change from +223.2 procedures/year (95% CI, +188.7 to +257.7) to −45.7 procedures/year (95% CI, −83.2 to −8.2) (Fig. 4A). A significant breakpoint in 2011 for total procedures and in 2015 for total surgeries was identified. These inflection points coincide with (i) modality substitution following national reimbursement for transcatheter ASD device closure in 2009 and (ii) a contemporaneous contraction in the pediatric population, both of which were previously documented in a nationwide analysis of CHD interventions. In infants, the number of procedures increased until 2013 (+174.8/year; p < 0.001), followed by a decline (−122.7/year; p < 0.001) (Fig. 4B). Among children, a breakpoint was observed in 2004, with the slope shifting from −28.0/year (p = 0.052) to −55.7/year (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4C). In adults, the slope increased from +40.6/year before 2011 to +78.9/year after 2011 (p < 0.001), reflecting a rapid rise in adult CHD procedures (Fig. 4D).

Figure 3: Distribution of CHD surgical procedures by age group, 2002–2018. (A) overall population, (B) infants (<1 year), (C) children (1–18 years), and (D) adults (≥19 years).

Figure 4: Segmented regression analysis of annual CHD surgical procedures by age group, 2002–2018. (A) overall population, (B) infants, (C) children, and (D) adults.

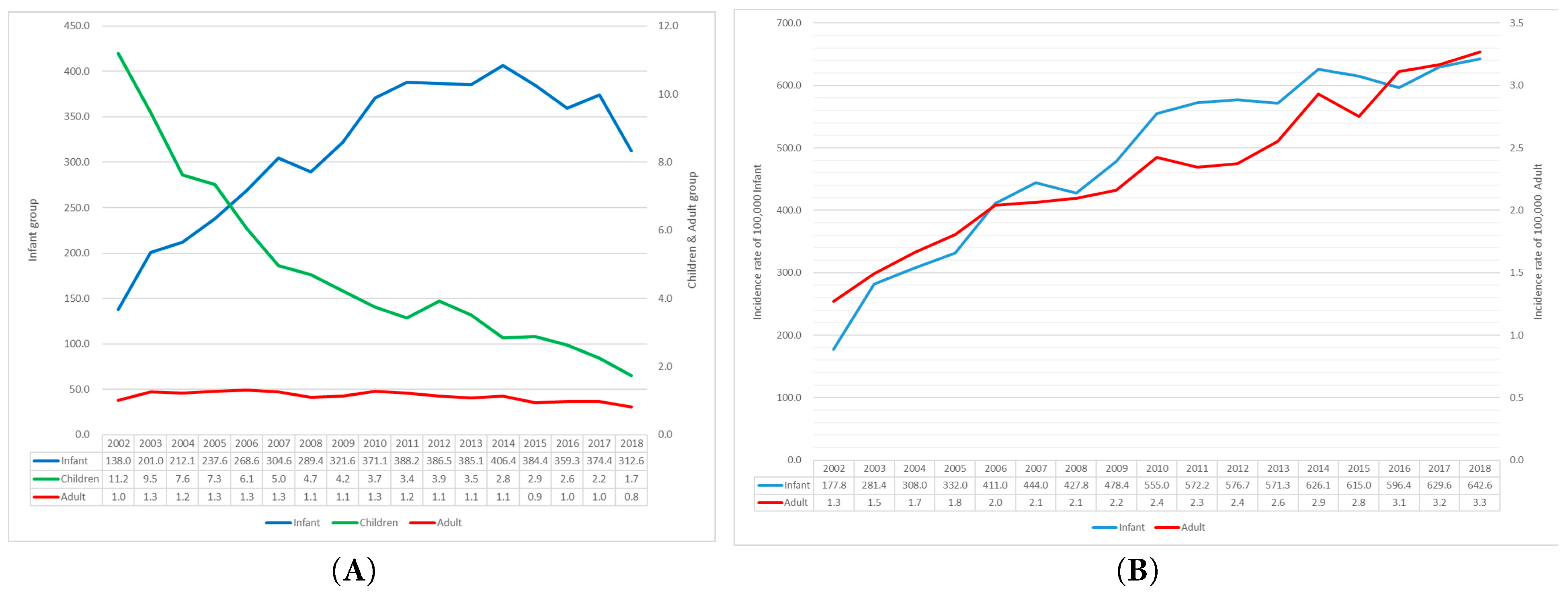

3.5 Age-Specific Trends in Standardized CHD Surgery and Procedure Incidence Rates

To adjust for changes in population size, we calculated age-specific incidence rates of CHD surgeries and surgical procedures per 100,000 individuals during the study period (Fig. 5). We used direct age standardization (applying age-specific rates to a fixed reference population) to remove confounding from Korea’s rapidly changing age structure (2002–2018) and to enable valid comparisons over time. In Fig. 5A, infants (<1 year) consistently demonstrated the highest incidence of CHD surgeries, which rose from 138.0 per 100,000 in 2002 to a peak of 406.4 in 2014, then declined to 312.6 in 2018. Among children (1–18 years), the incidence steadily declined from 11.2 to 1.7 per 100,000 over the same period. In adults (≥19 years), the incidence remained low, peaking at 1.3 per 100,000 in 2005 and decreasing to 0.8 by 2018. Fig. 5B illustrates the incidence of CHD surgical procedures for infants and adults. Children were intentionally excluded to enhance visual clarity, given the substantial scale differences among age groups. The incidence in infants rose sharply from 177.0 per 100,000 in 2002 to 642.0 in 2018. For adults, the rate increased gradually from 1.3 to 3.3 per 100,000. Although not depicted due to scale differences, the incidence among children ranged from 12.0 to 19.8 per 100,000 and remained relatively stable throughout the period.

Figure 5: Age-specific standardized incidence of CHD surgeries and surgical procedures per 100,000 population, 2002–2018. (A) Incidence of CHD surgeries across all age groups. (B) Incidence of surgical procedures in infants and adults; children were excluded due to scale differences that would hinder visual clarity.

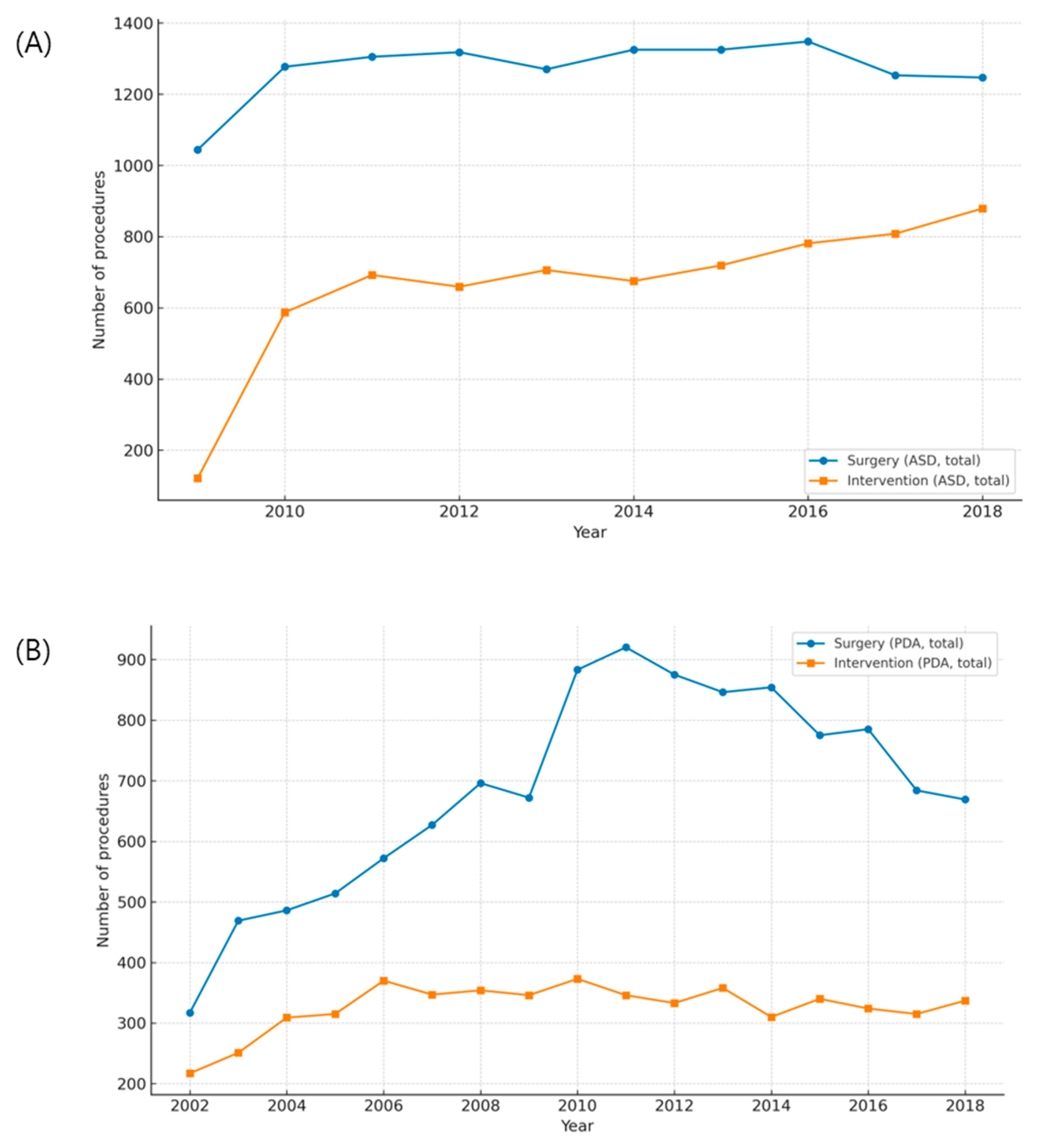

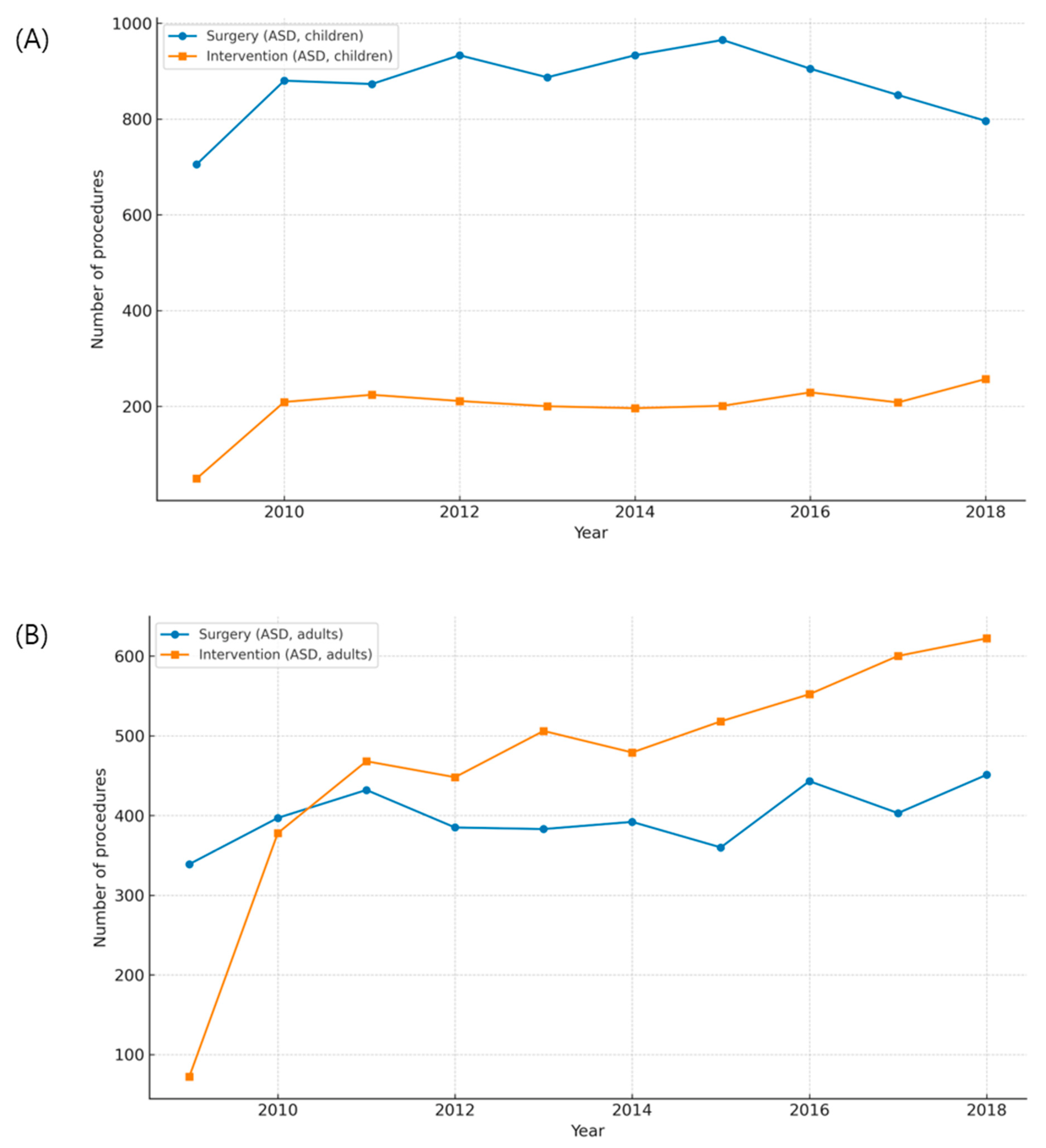

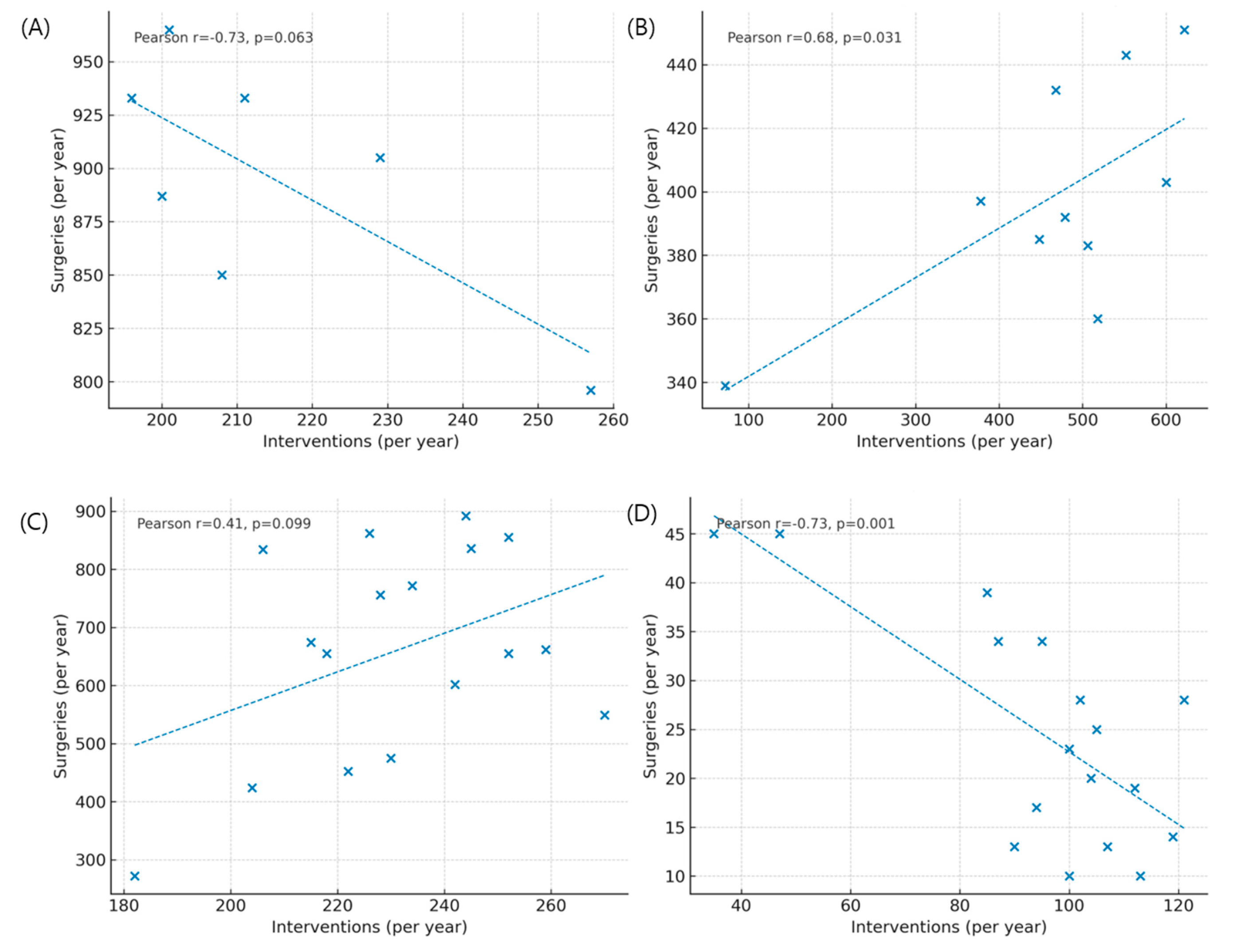

3.6 Lesion-Specific Temporal Trends in ASD and PDA

Quantitative comparisons between surgery and catheter-based interventions demonstrated a clear treatment shift for ASD, but only a partial shift for PDA (Fig. A1 in Appendix A). For ASD, the introduction of reimbursement for device closure in 2009 was followed by a sharp rise in transcatheter procedures and a corresponding decline in surgical repair among children, while adult surgical volumes remained largely stable (Fig. A1A,B and Fig. A3A,B). Correlation scatterplots confirmed a significant inverse relationship between annual surgical and transcatheter volumes in children during the diffusion-stabilized period (2012–2018), with Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) indicating strong negative concordance (Fig. A4A). In adults, transcatheter closure became the dominant modality by the end of follow-up, and scatter analysis demonstrated a similar but less pronounced inverse association (Fig. A4B). For PDA, adults were treated almost exclusively with transcatheter closure, with scatter analysis showing a robust inverse correlation between interventions and surgeries, supported by Pearson’s r values (Fig. A4D). In children, however, both modalities declined modestly, and the inverse association was weak, consistent with the continued necessity of neonatal surgical ligation despite widespread catheter adoption (Fig. A2A,B and Fig. A4C). These findings indicate that the decline in pediatric surgical volume after 2010 was largely driven by the uptake of ASD device closure following national reimbursement, whereas PDA displayed age-dependent heterogeneity, with surgical ligation retaining an essential role in infancy.

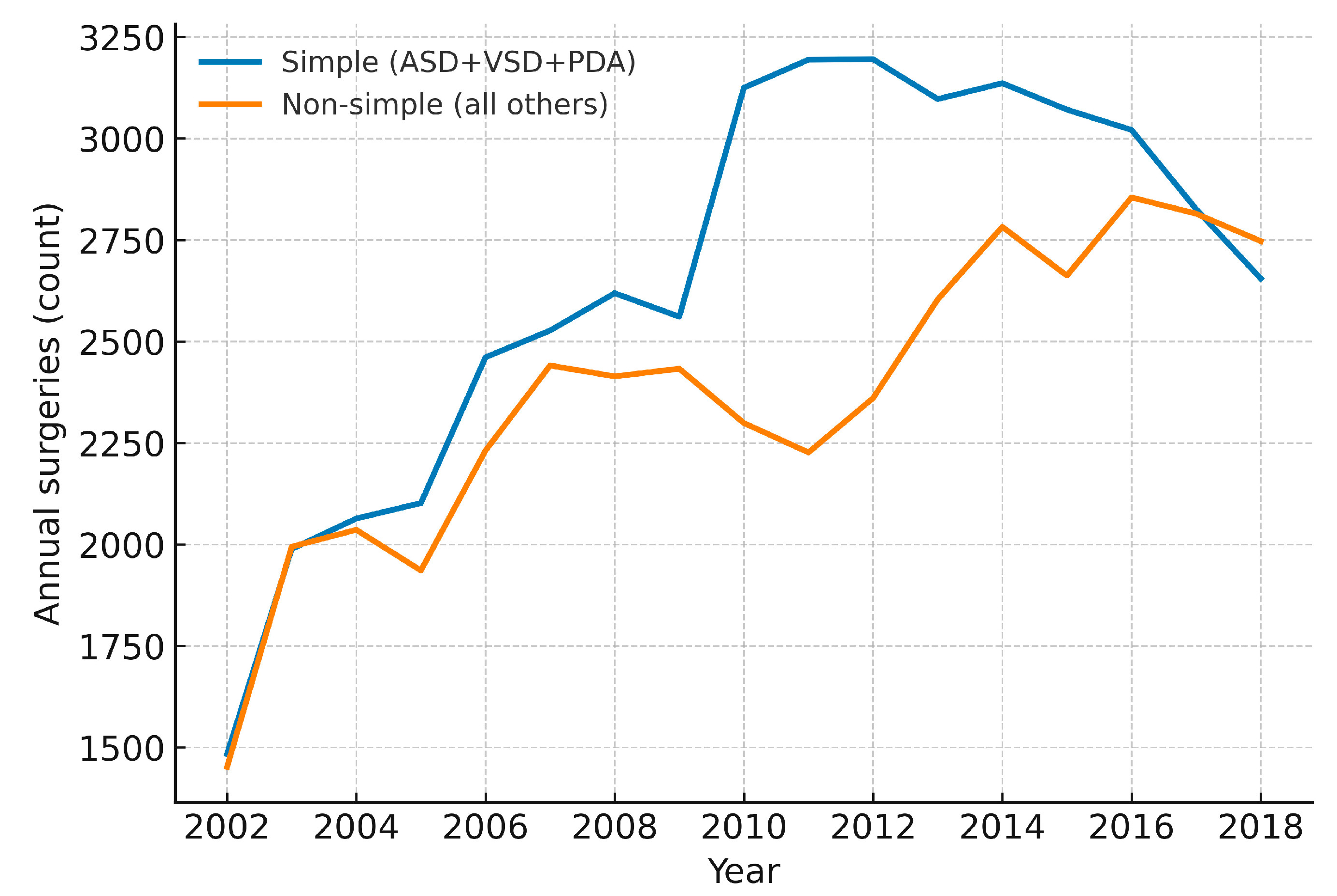

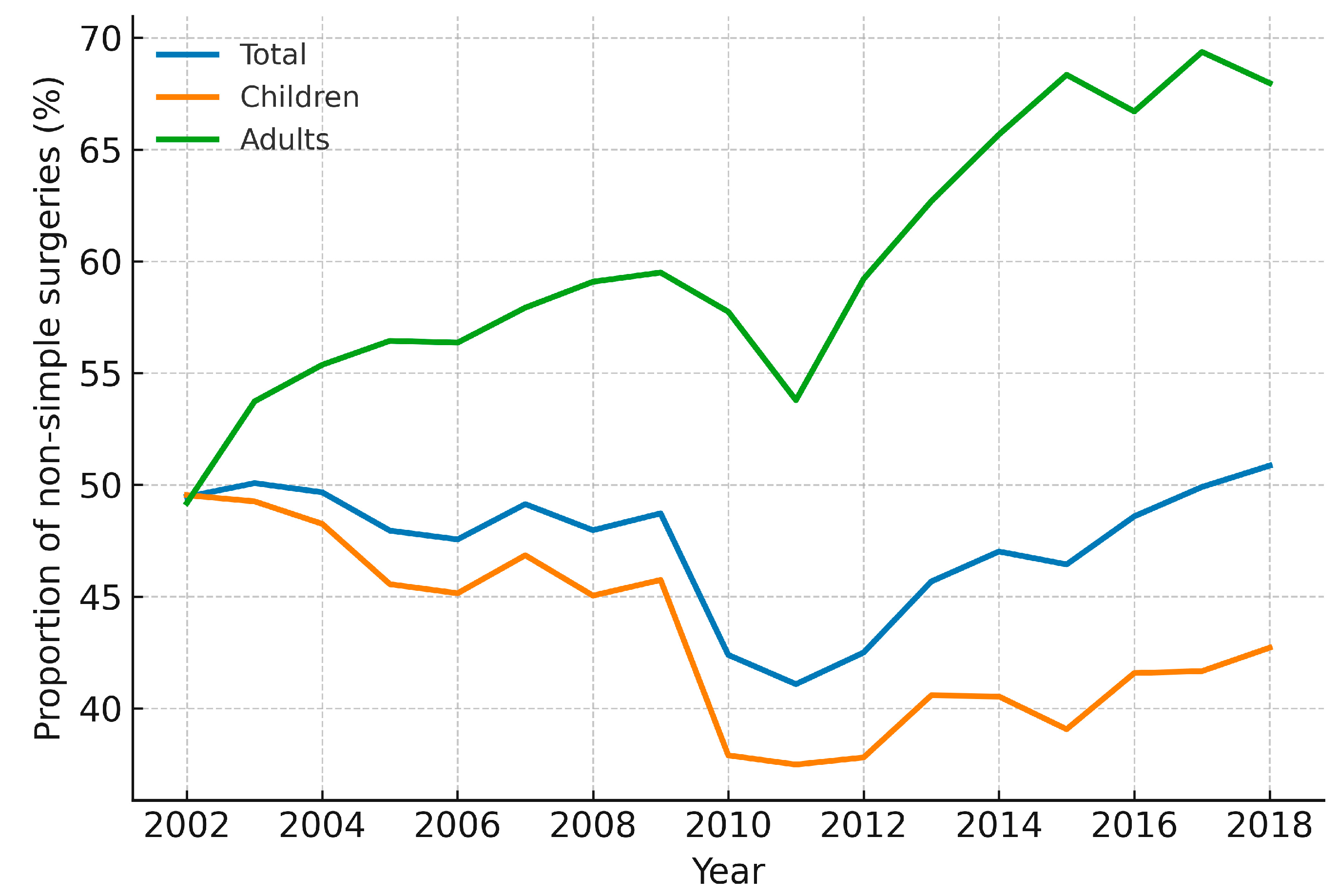

3.7 Proxy Trends in Operative Mix: Simple Versus Non-Simple Lesions

Across 2002–2018, annual counts of simple (ASD + VSD + PDA) versus non-simple operations are displayed in Fig. A5. While simple repairs declined in parallel with the overall reduction in pediatric volume, non-simple operations were comparatively sustained, indicating a relative shift in the surgical portfolio toward more complex lesions. Consistently, the yearly proportion of non-simple surgery increased over time in the total cohort and when stratified by children (<18 years) and adults (≥19 years), with modest year-to-year variability (Fig. A6). Taken together with the lesion-specific ASD/PDA analyses in Section 3.6, these patterns suggest that declining demand for simple repairs—partly displaced by transcatheter closure—co-occurred with a persistently high need for non-simple operations, thereby enriching the surgical case-mix in relative terms.

This nationwide, population-based study, encompassing 41,608 CHD surgeries and 85,417 surgical procedures from 2002 to 2018, elucidates substantial shifts in the landscape of CHD surgery in Korea. A pivotal observation is the divergence between the relatively stable or slightly declining annual number of patients undergoing surgery (from 2523 in 2002 to 1624 in 2018) and the marked increase in surgical procedures (from 2936 to 5402 over the same period). This discrepancy suggests an escalating procedural burden per patient, likely attributable to more frequent staged repairs, reoperations, or multiple interventions within a single surgical session. These trends resonate with findings from the Korea Heart Foundations, which reported a decline in early mortality from 8.6% (1984–1999) to 3.8% (2000–2014), alongside an increase in neonatal surgeries, reflecting earlier and more complex interventions [12,13]. A significant redistribution of surgical volume across age groups was also observed. Infant surgeries peaked in 2014 before declining, while adult surgeries exhibited a gradual increase followed by a modest decline. Conversely, surgical volumes in children (1–18 years) consistently decreased. These shifts were accompanied by a greater concentration of procedural volume in infants and adults, with a corresponding reduction in children. These age-specific trends align with global patterns, driven by advancements in diagnostic imaging, earlier detection, enhanced perioperative care, and the evolving demographics of the CHD population, particularly the growing cohort of ACHD [7,14]. Importantly, lesion-specific analyses demonstrated that these age patterns were strongly influenced by treatment modality substitution: ASD device closure expanded rapidly following the 2009 reimbursement policy, coinciding with declining pediatric surgeries, whereas PDA showed age-dependent heterogeneity with persistent neonatal ligation. Correlation scatterplots further corroborated these relationships, with significant inverse associations in ASD (particularly in children) and in PDA among adults (Fig. A3 and Fig. A4).

4.2 Dynamic Shifts in Congenital Heart Surgery: Volume and Procedural Complexity

From 2002 to 2018, the annual number of CHD surgeries in Korea remained relatively stable, declining from 2523 to 1624 (Fig. 1A). A notable breakpoint in 2015 marked a sharper decline, likely reflecting Korea’s declining birth rate and reduced pediatric CHD incidence. In contrast, the number of surgical procedures—including multiple procedures per patient—rose steadily from 2936 to 5402, with a significant breakpoint in 2011 (Fig. 1B and Fig. 4A). This divergence highlights the growing procedural complexity of CHD surgery, although billed procedure codes function as a proxy and may not fully capture clinical or system-level complexity. Corroborating this, our lesion-based proxy shows a progressive rise in the proportion of non-simple operations (Fig. A6) despite declining totals for simple repairs (Fig. A5). In other words, even as overall pediatric surgical counts fell, the relative contribution of non-simple lesions increased, consistent with a case-mix shift toward more resource-intensive surgery. These data-driven breakpoints should not be read as single causal dates but as quantitative markers of aggregate clinical and policy dynamics—rapid uptake of transcatheter ASD closure after 2009 and sustained declines in births—consistent with our nationwide analysis of CHD interventions. Such trends mirror those observed in high-income countries, as reported in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database (STS-CHSD) and the European Congenital Heart Surgeons Association (ECHSA) databases, where procedural complexity has risen due to advancements in surgical techniques and patient survival [7,15,16]. Approximately 30% of CHD surgeries involve staged procedures, and up to 15% of patients require reoperations for issues such as valve dysfunction, conduit exchange, or acquired complications [17,18]. The increasing survival of CHD patients into adulthood has amplified the demand for re-interventions, even as new CHD cases decline due to demographic shifts [19,20]. By age group, earlier and more complex infant surgery has been enabled by perinatal screening/fetal echocardiography and expanded neonatal surgical/ICU capacity; fewer procedures in children likely reflect effective infant repairs and catheter alternatives; and increasing adult surgery mirrors the expanding ACHD cohort and structured transition-of-care and surveillance in tertiary centers [9,17,18,21]. Advances in imaging and operative techniques have broadened operability, raising per-patient procedural burden and emphasizing needs for infrastructure, specialized training, and long-term care planning in the context of population aging and low birth rates [19].

4.3 Age-Specific Trends in Surgical Volume: A Demographic and Clinical Phenomenon

Age-stratified analysis revealed that infants (<1 year) accounted for the majority of surgeries (55.1%), peaking in 2012 with an incidence rate of 406.4 per 100,000 in 2014 (Fig. 1A and Fig. 5A). This reflects advances in prenatal screening and neonatal care, which have facilitated earlier diagnosis and timely surgical correction of critical lesions. National policies promoting fetal echocardiography and neonatal intensive care infrastructure have further supported this trend [22,23]. Conversely, surgical volume in children (1–18 years) declined sharply from 1338 in 2002 to 471 in 2018, with incidence rates dropping from 11.2 to 1.7 per 100,000 (Fig. 1A and Fig. 5A). This reduction is likely multifactorial: improved early detection and definitive repairs during infancy reduce the need for surgeries later in childhood, while the increasing use of percutaneous interventions—particularly for isolated defects such as ASD and PDA—has shifted treatment away from surgical correction [24,25,26]. Consistent with this interpretation, lesion- and age-specific time series demonstrate a post-2009 rise in ASD device closure with a concomitant decline in pediatric ASD surgery, and a predominantly transcatheter approach for PDA in adults with persistent neonatal ligation in children (Fig. A1A,B and Fig. A3A,B for ASD; Fig. A2A,B for PDA). These inverse modality patterns are further supported by correlation scatterplots, which show a negative association for ASD in children and a strong inverse relationship for PDA in adults (Fig. A4A–D). This shift towards less invasive modalities represents a significant advancement in CHD management, reducing surgical morbidity in pediatric populations. Adult surgeries initially increased from 493 to 652 by 2006 but subsequently declined, with incidence rates falling from 1.3 to 0.8 per 100,000 (Fig. 5A). This trajectory is compatible with the growing ACHD population and with greater availability of catheter-based options—particularly ASD device closure following national reimbursement in 2009—contributing to reduced surgical demand in selected adult lesions [27]. Additionally, Korea’s low birth rate and aging population may contribute to a reduced incidence of new CHD cases, shifting the clinical burden towards adults requiring re-interventions for residual defects, valve dysfunction, or arrhythmias [9,17,18]. Taken together, the bimodal distribution—higher surgical volumes in infancy and adulthood with a trough in childhood—reflects demographic forces and differential modality substitution rather than demographic change alone, and it underscores the need for age-specific policy responses. Priority areas include enhancing neonatal surgical capacity, establishing structured ACHD transition programs, and maintaining long-term registries for surveillance and timely re-intervention [19].

Lesion-specific analyses refine these conclusions. In children, the sharp decline in surgical ASD repair after 2010 coincided with a marked rise in catheter closures temporally aligned with the 2009 reimbursement decision (Fig. A3A), yielding an inverse relationship between modalities (Fig. A4A). In contrast, PDA showed age-dependent heterogeneity: adults were almost uniformly treated percutaneously (Fig. A2B and Fig. A4D), whereas neonatal ligation remained indispensable despite broad catheter adoption (Fig. A2A and Fig. A4C). Thus, the observed pediatric surgical decline reflects differential modality substitution—strongest for ASD—beyond demographic trends alone.

The use of age-standardized rates in our analysis was instrumental in disentangling true clinical trends from the powerful confounding influence of Korea’s demographic transition. The raw counts of surgeries (Fig. 1A) reflect a shifting absolute workload on the healthcare system, primarily driven by a shrinking pool of newborns due to low fertility rates. This metric is vital for administrative planning and resource allocation. However, the age-standardized rates (Fig. 5A,B) reveal the underlying epidemiological reality that the propensity for a patient within a given age group to undergo complex CHD surgery has not diminished and, in some cases, has increased. The rising incidence in infants is consistent with advances in prenatal screening and neonatal intensive care, while the stable or rising incidence of procedures in adults directly reflects the growing cohort of ACHD patients who require specialized, lifelong care for residual lesions or late complications. This dual analysis, combining both crude and standardized metrics, provides a comprehensive picture of the CHD landscape in Korea, capturing both the administrative burden and the fundamental epidemiological shifts. Consistent with this interpretation, the timing aligns with modality substitution after national reimbursement for ASD device closure in 2009 and contemporaneous declines in births demonstrated in a nationwide intervention analysis [26], supporting the epidemiologic rationale for age standardization.

4.4 The Transformative Impact of Percutaneous Interventions

The landscape of CHD management in Korea has undergone a substantial transformation, driven by the widespread adoption of percutaneous interventions. ASD provides the clearest example: transcatheter closure expanded rapidly after the 2009 reimbursement decision, while pediatric surgical repair declined in parallel (Fig. A1A and Fig. A3A). Scatter analyses confirm a strong inverse relationship between modalities (Fig. A4A,B).

Interventions for ACHD now encompass a wide range of transcatheter procedures, the use of which has grown markedly in recent years due to technological advances, improved imaging, and increasing recognition of favorable long-term outcomes. A parallel nationwide study reported 18,800 catheter-based procedures from 2002 to 2018, with ASD and PDA closures comprising over 60% of interventions, underscoring this transition [12]. Korea’s demographic context further shapes these trends. Declining birth rates and an aging population have reduced the incidence of new CHD cases, contributing to lower surgical volumes. However, improved survival rates have expanded the ACHD population, necessitating re-interventions for residual defects, valvular dysfunction, or arrhythmias. Despite this, the overall surgical burden in adults has decreased, reflecting the efficacy of less invasive alternatives. Globally, many studies report an increase in ACHD surgeries, driven by enhanced survival and the growing prevalence of adults requiring re-interventions [17,18,27]. For instance, Marelli et al. [28] estimated that the ACHD population in high-income countries has surpassed pediatric cases, with approximately 1.2 million adults in Europe and 1 million in the United States living with CHD. This rise is attributed to advancements in diagnostics and surgical techniques, enabling long-term survival exceeding 90%. However, Korea’s distinct trajectory may stem from its early adoption of percutaneous interventions and favorable insurance policies, which have shifted simpler cases away from surgery. Notably, no large-scale studies explicitly report a decline in adult CHD surgeries akin to our findings. A targeted literature search identified limited population-based studies directly addressing this phenomenon, suggesting Korea’s trends may be unique due to its healthcare infrastructure and demographic shifts. The absence of reported declines in other settings may reflect differences in healthcare systems, insurance coverage, and demographic profiles. For example, regions with less access to interventional cardiology may rely more heavily on surgical approaches for ACHD management. In Korea, the robust integration of catheter-based techniques, coupled with a declining birth rate, likely reduces the surgical burden while increasing procedural specialization. This hypothesis is supported by the observed increase in procedural complexity, as surgical teams focus on intricate cases requiring open-heart procedures. These observations collectively argue for integrated, lesion- and age-specific care pathways in which surgical and transcatheter options are jointly evaluated by multidisciplinary heart teams and supported by hybrid operating environments.

4.5 Trends in Specific CHD and Management Strategies

Surgical patterns in CHD vary significantly by lesion type and patient age, reflecting differences in clinical urgency and disease progression. In our cohort, ASD was the most prevalent diagnosis (27.8%), with a mean surgical age of 16.7 years, suggesting elective treatment or late diagnosis in adulthood. In contrast, VSD (22.4%) and TOF (10.7%) were typically repaired in infancy or early childhood, with mean surgical ages of 7.1 and 6.7 years, respectively, aligning with clinical guidelines for early intervention in hemodynamically significant or cyanotic lesions [16]. Complex anomalies, such as SV physiology (mean age 3.3 years) and HLHS (mean age 2.1 years), necessitated surgery almost exclusively in infancy, often involving staged palliative procedures requiring specialized expertise and intensive care. Among adults, common surgeries included ASD closure, valve replacements, and reoperations for residual or progressive lesions, often stemming from prior childhood interventions. This reflects the long-term surgical burden in the ACHD population, where re-interventions are driven by evolving hemodynamics, prosthetic material failure, or acquired complications [17,27]. The high prevalence of ASD in adults may also be attributed to improved diagnostic capabilities, identifying previously undetected defects, or elective management of hemodynamically stable lesions [29]. These findings are consistent with global data, where ASD and VSD remain the most common CHD diagnoses, while complex lesions like HLHS require early, resource-intensive interventions [7]. The variation in surgical timing underscores a stratified treatment strategy: urgent interventions for life-threatening lesions in infancy, elective repairs for simpler defects, and re-interventions for ACHD patients. Long-term surveillance is critical to address the evolving needs of CHD patients across their lifespan, particularly in the context of Korea’s aging population, which may amplify the demand for ACHD care [19].

4.6 Strengths and Acknowledged Limitations of the Study

This study leverages a comprehensive, nationwide dataset covering nearly the entire Korean population over a 17-year period, providing robust insights into age-specific trends and procedural burdens in CHD surgery. The large sample size and extended observation window enhance generalizability, while standardized coding ensures consistency across institutions and time. However, limitations include the absence of detailed clinical data, such as anatomical complexity, intraoperative variables, and postoperative outcomes, precluding analysis of morbidity and mortality or direct comparisons with clinical registries. Age was recorded only in whole years due to legal restrictions, making the “0 years old” category span from birth to nearly one year and limiting precision in distinguishing neonatal from late infancy trends. Although the NHIS framework includes demographic and treatment variables, access is restricted by privacy regulations; thus, only age and sex were consistently available for analysis. ASD interventions before 2009 were often non-reimbursed and under-captured, so analyses were restricted to 2009 onward to avoid misclassification. Our measure of procedural burden, based solely on billed codes, should be viewed as a proxy for operative complexity rather than a direct indicator of patient- or system-level burden. Segmented regression models with a single breakpoint were used to reduce overfitting, but multiple inflection points may have existed over the 17-year span due to technological, policy, and demographic shifts.

Because NHIS claims do not include detailed anatomic or operative risk variables, validated surgical risk strata, such as the Society of Thoracic Surgeons–European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery Congenital Heart Surgery Mortality Categories, and the Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery, could not be applied. Our classification of simple versus non-simple procedures (ASD/VSD/PDA vs. all others) should therefore be interpreted as a pragmatic claims-based proxy rather than a true clinical risk stratification, though the rising share of non-simple cases still indicates increasing surgical complexity.

These limitations highlight the inherent constraints of administrative claims data, which lack the clinical granularity required for outcome analysis and risk adjustment. Future studies should link NHIS data with clinical registries or electronic medical records to enhance validity and allow finer subgroup analyses, particularly for neonatal cases.

4.7 Implications for Healthcare Planning and Future Research Directions

The evolving trends in CHD surgery in Korea—characterized by increasing procedural complexity and a growing ACHD population—carry significant implications for healthcare planning. These shifts necessitate resource reallocation to support two critical groups: infants requiring intensive perioperative care for complex conditions and adults with residual lesions needing lifelong follow-up and specialized re-interventions. Health systems must adapt by investing in infrastructure, workforce training, and care models tailored to both ends of the age spectrum. Given Korea’s low birth rate and aging population, the future burden of CHD is likely to shift towards adults, amplifying the need for specialized ACHD services and structured transition-of-care protocols. Consistent with our lesion-specific analyses—showing strong post-2009 uptake of ASD device closure and age-dependent PDA patterns—these demographic and modality shifts together argue for deliberate system redesign rather than incremental adjustments [30]. Based on our findings, policy priorities should include the establishment of regional neonatal cardiac surgical hubs with advanced intensive care unit capability, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation readiness, and congenital anesthesia support; the maturation of dedicated ACHD centers that integrate cardiology, cardiac surgery, electrophysiology, maternal–fetal medicine, and advanced imaging within formal transition programs; workforce planning to expand training positions in complex neonatal surgery and ACHD subspecialties; investment in hybrid operating rooms and catheter–surgical collaborative pathways for lesion- and age-specific care; and the development of a national outcomes registry linking administrative claims with clinical data for risk adjustment, benchmarking, and longitudinal surveillance. This demographic transition, coupled with the increasing prevalence of percutaneous interventions, suggests that surgical volumes may continue to decline for simpler defects, while complex cases and re-interventions dominate surgical practice. From a research perspective, the growing complexity of CHD care demands more granular data to inform clinical and policy decisions. Administrative data, while valuable for identifying trends, lack the clinical detail required for outcome evaluation and risk stratification. Linking NHIS data with clinical registries or electronic medical records could enhance data validity, support precise subgroup analyses, and enable long-term outcome monitoring. In parallel, health-economic evaluations—including the comparative cost-effectiveness of surgical versus interventional approaches and hybrid strategies—should guide resource allocation.

Future research should also explore the impact of emerging technologies, such as 3D/4D imaging, artificial intelligence, and regenerative medicine, on CHD management. Collectively, these strategies provide a pragmatic roadmap to sustain high-quality, equitable care as Korea’s CHD population continues to evolve.

This nationwide study of CHD surgeries in Korea from 2002 to 2018 illuminates a transformative shift in CHD care. While surgical volumes have declined, procedural complexity has increased, reflecting advancements in surgical techniques and the need for staged repairs. Age-specific trends reveal high surgical burdens in infants and adults, underscoring the importance of early intervention and lifelong care. These findings highlight the need for specialized healthcare services for pediatric and adult CHD patients and strategic resource reallocation. Future research should aim to integrate clinical data to enhance understanding of long-term outcomes and optimize CHD management.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Soo-Jin Kim; data collection: Soo-Jin Kim; analysis and interpretation of results: Jae Sung Son; draft manuscript preparation: Jae Sung Son. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data collection and editing were conducted within the National Health Insurance Service. Due to data confidentiality and privacy concerns, the export of raw data is strictly prohibited. Only edited data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request with appropriate permissions.

Ethics Approval: This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision). It was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Konkuk University Hospital, Konkuk University, Seoul, Republic of Korea (approval No. KUH 1090068), and the requirement for informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective design and use of de-identified data. All investigators adhered to applicable ethical and legal standards. All data were de-identified prior to analysis and obtained under a formal data-sharing agreement with the National Health Insurance Service; no individual-level identifiable information was accessed. The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| Congenital heart disease | |

| Atrial septal defect | |

| Ventricular septal defect | |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | |

| Atrioventricular septal defect | |

| Pulmonary atresia/pulmonary stenosis | |

| Coarctation of aorta | |

| Double outlet right ventricle | |

| Transposition of the great arteries | |

| Single ventricle | |

| Hypoplastic left heart syndrome | |

| Adults with congenital heart disease | |

| National Health Insurance Service | |

| 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases | |

| Korean Standard Classification of Diseases, 10th revision | |

| Arterial switch operation | |

| Mitral valve replacement | |

| Pulmonary valve replacement | |

| Bidirectional cavopulmonary shunt | |

| Right ventricular outflow tract reconstruction | |

| Complete atrioventricular septal defect | |

| Total anomalous pulmonary venous return |

Figure A1: Trends in surgical and transcatheter treatment of atrial septal defect (ASD) and patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). (A) Annual numbers of surgical repair and device closure for ASD between 2009 and 2018. (B) Annual numbers of surgical ligation and transcatheter closure for PDA between 2002 and 2018.

Figure A2: Age-stratified trends in patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) treatment. (A) Annual numbers of surgical ligation and transcatheter closure in children. (B) Annual numbers of surgical and transcatheter procedures in adults.

Figure A3: Age-stratified trends in atrial septal defect (ASD) treatment. (A) Annual numbers of surgical repair and device closure in children. (B) Annual numbers of surgical and transcatheter procedures in adults.

Figure A4: Correlation between surgical and transcatheter volumes for atrial septal defect (ASD) and patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). (A) Correlation between annual surgical repair and device closure for ASD in children. (B) Correlation between surgical and transcatheter procedures for ASD in adults. (C) Correlation between surgical ligation and transcatheter closure for PDA in children. (D) Correlation between surgical and transcatheter procedures for PDA in adults.

Figure A5: Annual counts of simple versus non-simple congenital heart surgeries in Korea, 2002–2018 (total cohort). Year-by-year absolute numbers are displayed for simple lesions (ASD, VSD and PDA) and for all other (non-simple) surgeries. Absolute totals for each group are provided to contextualize proportional changes over time.

Figure A6: Annual proportion of non-simple congenital heart surgeries in Korea, 2002–2018. Line plots show the yearly percentage of surgeries classified as non-simple (i.e., all procedures other than ASD, VSD, and PDA), stratified by total cohort, children (<18 years, including infants), and adults (≥19 years). Increasing values indicate a higher relative contribution of complex operations within the annual surgical mix.

References

1. van der Linde D, Konings EE, Slager MA, Witsenburg M, Helbing WA, Takkenberg JJM, et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(21):2241–7. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Marelli AJ, Mackie AS, Ionescu-Ittu R, Rahme E, Pilote L. Congenital heart disease in the general population: changing prevalence and age distribution. Circulation. 2007;115(2):163–72. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.627224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hoffman JIE, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(12):1890–900. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01886-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Dellborg M, Giang KW, Eriksson P, Liden H, Fedchenko M, Ahnfelt A, et al. Adults with congenital heart disease: trends in event-free survival past middle age. Circulation. 2023;147(12):930–8. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.060834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Brida M, Gatzoulis MA. Adult congenital heart disease: past, present, future. Int J Cardiol Congenit Heart Dis. 2020;1:100052. doi:10.1016/j.ijcchd.2020.100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Moons P, Meijboom FJ. Healthcare provision for adults with congenital heart disease in Europe: a review. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22(5):573–8. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833e1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Jacobs JP, Mayer JE Jr, Mavroudis C, O’Brien SM, Austin EH III, Pasquali SK, et al. The society of thoracic surgeons congenital heart surgery database: 2016 update on outcomes and quality. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(3):850–62. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.01.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ooi YK, Kelleman M, Ehrlich A, Glanville M, Porter A, Kim DW, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical closure of atrial septal defects in children: a value comparison. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9(1):79–86. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2015.09.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Baumgartner H, De Backer J, Babu-Narayan SV, Budts W, Chessa M, Diller GP, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(6):563–645. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Lee D, Park M, Chang S, Ko H. Protecting and utilizing health and medical big data: policy perspectives from Korea. Healthc Inform Res. 2019;25(4):239. doi:10.4258/hir.2019.25.4.239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335–51. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Shin HJ, Park YH, Cho BK. Recent surgical outcomes of congenital heart disease according to Korea Heart Foundation data. Korean Circ J. 2020;50(8):677–90. doi:10.4070/kcj.2019.0364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kiraly L. Current outcomes and future trends in paediatric and congenital cardiac surgery: a narrative review. Pediatr Med. 2022;5:35. doi:10.21037/pm-21-47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Protopapas E, Padalino M, Tobota Z, Ebels T, Speggiorin S, Horer J, et al. The European Congenital Heart Surgeons Association congenital cardiac database: a 25-year summary of congenital heart surgery outcomes. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2025;67(4):ezaf119. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezaf119 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kumar SR, Gaynor JW, Heuerman H, Mayer JE Jr, Nathan M, O’Brien JE Jr, et al. The society of thoracic surgeons congenital heart surgery database: 2023 update on outcomes and research. Ann Thorac Surg. 2024;117(5):904–14. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2024.03.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Egidy Assenza G, Krieger EV, Baumgartner H, Cupido B, Dimopoulos K, Louis C, et al. AHA/ACC vs ESC guidelines for management of adults with congenital heart disease: JACC guideline comparison. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(19):1904–18. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Budts W, Prokšelj K, Lovrić D, Kačar P, Gatzoulis MA, Brida M. Adults with congenital heart disease: what every cardiologist should know about their care. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(45):4783–96. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehae716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lee JY. Global burden of congenital heart disease: experience in Korea as a potential solution to the problem. Korean Circ J. 2020;50(8):691–4. doi:10.4070/kcj.2020.0216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Guo Z, Xie L, Zhao J, Hao X, Hou X, Wang W. Temporal and regional differences in congenital heart surgery in China (2017–2022): trends and implications. Congenit Heart Dis. 2024;19(4):341–50. doi:10.32604/chd.2024.057403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Giannakoulas G, Vasiliadis K, Frogoudaki A, Ntellos C, Tzifa A, Brili S, et al. Adult congenital heart disease in Greece: preliminary data from the challenge registry. Int J Cardiol. 2017;245:109–13. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.07.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Bonnet D. Impacts of prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart diseases on outcomes. Transl Pediatr. 2021;10(8):2241–9. doi:10.21037/tp-20-267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Cattapan C, Jacobs JP, Bleiweis MS, Sarris GE, Tobota Z, Guariento A, et al. Outcomes of neonatal cardiac surgery: a European congenital heart surgeons association study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2025;119(4):880–9. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2024.07.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Dos Santos Melchior C, Neves GR, de Oliveira BL, Toguchi AC, Lopes JC, Pavione MA, et al. Percutaneous closure of patent ductus arteriosus versus surgical treatment in low-birth-weight preterms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiol Young. 2024;34(4):705–12. doi:10.1017/S1047951123004353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Turner ME, Bouhout I, Petit CJ, Kalfa D. Transcatheter closure of atrial and ventricular septal defects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(22):2247–58. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.08.082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Butera G, Romagnoli E, Saliba Z, Chessa M, Sangiorgi G, Giamberti A, et al. Percutaneous closure of multiple defects of the atrial septum: procedural results and long-term follow-up. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;76(1):121–8. doi:10.1002/ccd.22435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Son JS, Kim SJ, Ha KS, Kim JY. Population-based study on epidemiological trends in interventions for congenital heart disease in Korea using nationwide big data. J Interv Cardiol. 2025;2025:8815137. doi:10.1155/joic/8815137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Bhatt AB, Foster E, Kuehl K, Alpert J, Brabeck S, Crumb S, et al. Congenital heart disease in the older adult: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(21):1884–931. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Marelli AJ, Ionescu-Ittu R, Mackie AS, Guo L, Dendukuri N, Kaouache M. Lifetime prevalence of congenital heart disease in the general population from 2000 to 2010. Circulation. 2014;130(9):749–56. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. van der Bom T, Mulder BJM, Meijboom FJ, van Dijk APJ, Pieper PG, Vliegen HW, et al. Contemporary survival of adults with congenital heart disease. Heart. 2015;101(24):1989–95. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Jacobs JP, Jacobs ML, Mavroudis C, Backer CL, Lacour-Gayet FG, Tchervenkov CI, et al. Nomenclature and databases for the surgical treatment of congenital cardiac disease—an updated primer and an analysis of opportunities for improvement. Cardiol Young. 2008;18(Suppl 2):38–62. doi:10.1017/S1047951108003028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools