Open Access

Open Access

LETTER

Semilunar Valve Replacement with a Telescoping Arterial Trunk Valve

1 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, MO 64108, USA

2 Department of Surgery, School of Medicine, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, MO 64108, USA

3 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Little Rock, AR 72202, USA

4 Department of Surgery, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR 72202, USA

* Corresponding Author: Edo Bedzra. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Novel Methods and Techniques for the Management of Congenital Heart Disease)

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(4), 441-446. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.071035

Received 30 July 2025; Accepted 22 August 2025; Issue published 18 September 2025

Abstract

A bicuspid aortic valve, from autologous tissue, with growth potential can be constructed using the simple, and reproducible telescoping arterial trunk technique.Keywords

Approximately one third of congenital heart defects affect the heart valves [1]. When valve repair is not feasible, heart valve replacement becomes necessary. In infants, current valve replacement options include homograft, autografts, mechanical valves and bioprosthetics. Each of these treatment modalities presents significant limitations in the pediatric population.

Despite their widespread use, homografts are acellular and do not retain viable cells, thereby lacking potential for somatic growth [2]. This limitation commits infants to serial valve replacements since they outgrow their prosthesis until an adult-sized valve can be implanted [3]. Mechanical valves offer durability but do not grow and require life-long anticoagulation due to thromobogenicity [4]. These pose significant risk in infants like thromboembolic events [5] and requires risky re-operations to replace outgrown valve [6]. Bioprosthetic valves avoid anticoagulation but suffer from rapid structural degeneration in young patients, an irreversible process leading to valve failure requiring re-operations [7]. Additionally, mechanical and bioprosthetic valves are not manufactured in sizes suitable for neonates, necessitating the exclusive use of homografts (live or cryopreserved) in this population [8].

In pediatric patients, Ross procedure is an attractive option because the autograft is viable, capable of growth, and potentially decreases the need for redo aortic valve replacements [9]. However it is not without drawback, problem that plagues Ross procedures involves a double-valve intervention, introducing the risk of complications at two valve sites [10]. Autograft dilation, regurgitation, and eventual failure are known long-term concerns, particularly when the pulmonary valve is exposed to systemic pressures [11]. Moreover, the need for homograft or conduit replacement in the right ventricular tract remains a major limitation, as these substitutes do not grow and frequently require re-intervention during follow-up [12].

More recently, partial heart transplantation has been proposed to deliver growing heart valve substitutes. While it offers living tissue with growth capacity, this strategy remains constrained by donor availability and necessitates lifelong immunosuppression [13]. Autologous pulmonary valve reconstruction using right atrial appendage has shown early success [14] but require long-term follow-up studies to assess durability and effectiveness [15].

To overcome these challenges, we have developed a simple and reproducible surgical technique for semilunar valve replacement with autologous arterial trunk tissue. This technique avoids the need for immunosuppression, anticoagulation or donor tissue. Most importantly, it uses patient’s own viable arterial tissue, which has a potential for somatic growth. Compared to the Ross procedure, it avoids manipulation of two valve positions and the associated risks, offering a single-site, growth-capable solution that may reduce surgical burden and improve long-term outcomes. Additionally, the biomechanical properties of arterial trunk tissue may offer superior durability and functional integration in semilunar valve positions.

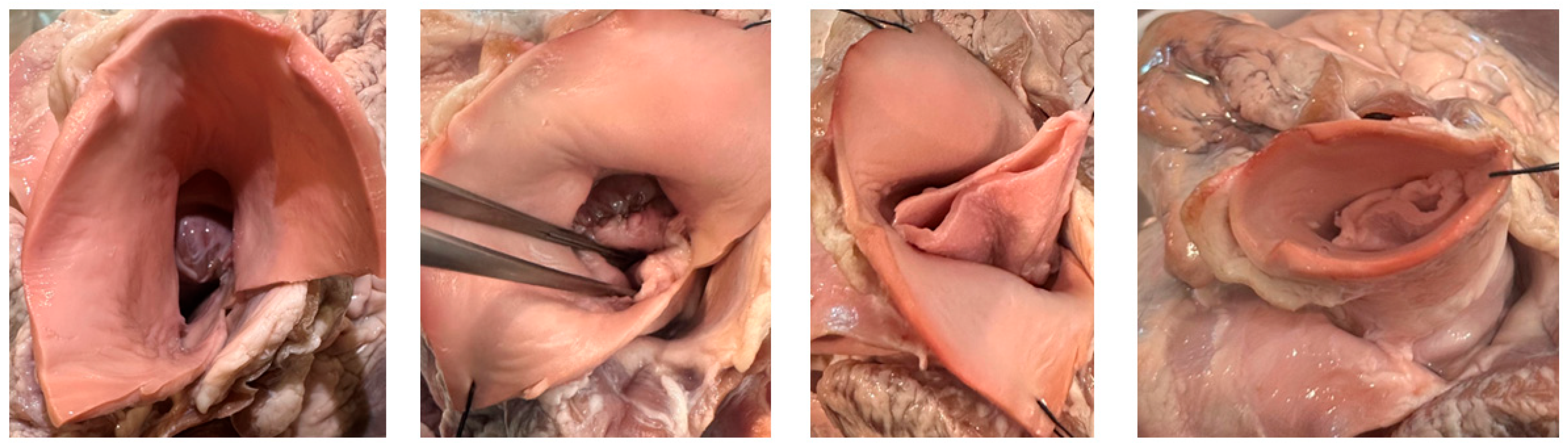

The technique was developed using 2 heart blocks from domestic swine of unknown gender obtained from a local abattoir. Only specimens without anatomical abnormalities grossly were included. As the study was limited to ex vivo experiments. Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approval was not required.

We explored the feasibility for harvesting aortic or pulmonary arterial tissue, assessing structural integrity. Valves were screened for regurgitation using static pressurization of the aortic root with water to identify.

Among the possible vascular tissue, ascending aorta and main pulmonary artery are identified as the most suitable for graft harvesting. We prefer the pulmonary trunk due to ease of harvest and reconstruction. Preoperative imaging can be used to assess the aortic root height, annular size, and the dimensions (length and diameter) of the available donor arterial trunk to ensure anatomical adequacy. This is particularly important with the pulmonary artery as the available tube for harvest is limited by the distance between the sinotubular junction, and the branch pulmonary arteries (particularly the right pulmonary artery) take off. The height of the valve must at least equal to the annular diameter of the valve being replaced, or 10 mm height in early childhood.

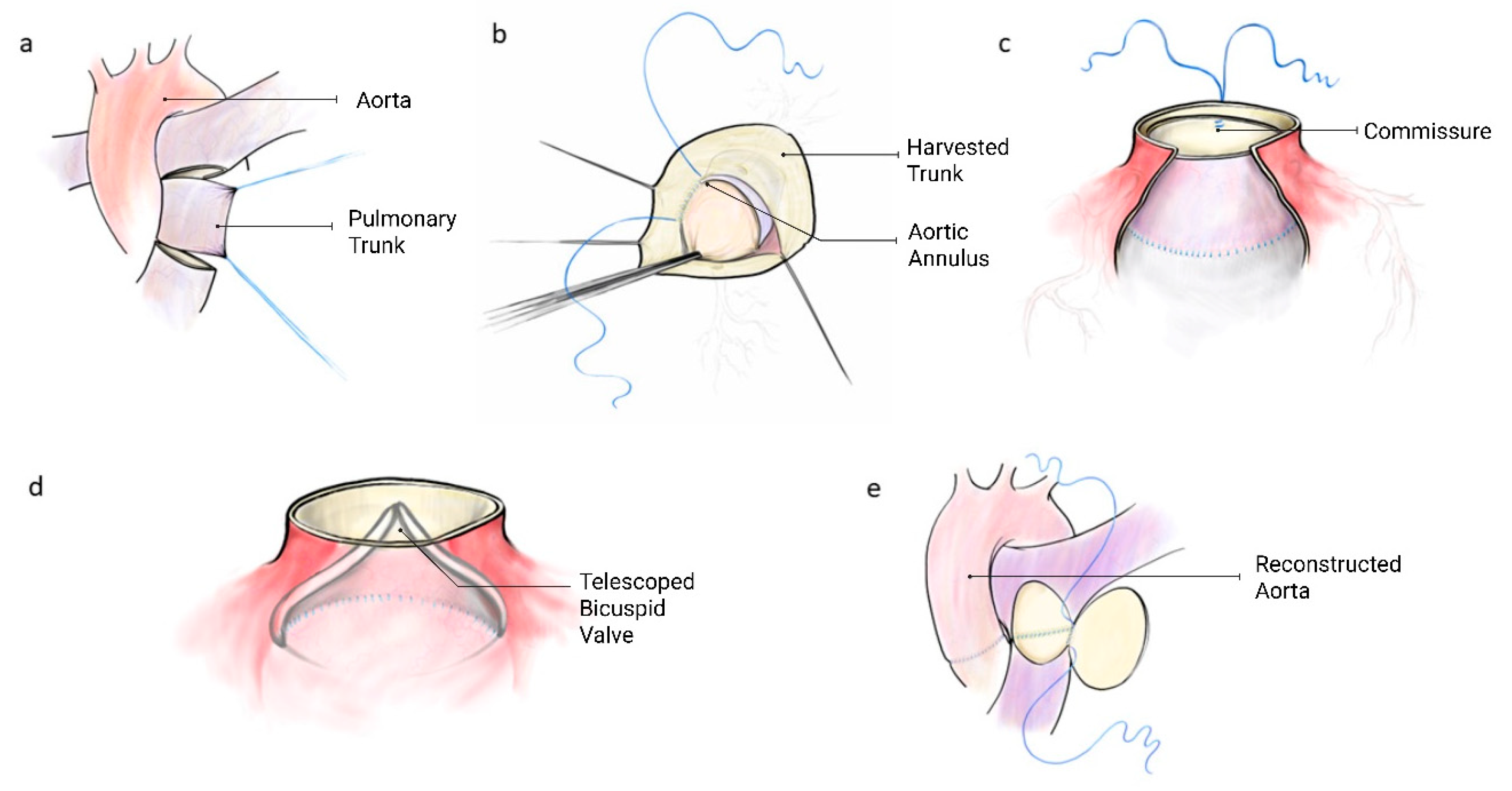

Intraoperatively, the donor vessel is extensively mobilized for a tension-free anastomosis after autograft procurement. Routine venous cannulation is performed via the right atrium using a two-stage cannula, and a left ventricular vent introduced via the right superior pulmonary vein to prevent distention and improve exposure. Cardiopulmonary bypass is initiated, and the pulmonary arterial trunk harvested on a beating heart (Fig. 1a). If using the ascending aorta, the proximal arch needs to be cannulated to preserve room for tissue harvest and reconstruction. Antegrade cardioplegic is delivered to induce cardiac arrest. The aorta is opened transversely just cephalad of the sinotubular junction (STJ). In patients with limited access (small aortic roots) this incision can be extended into the non-coronary sinus. The native aortic valve is excised and the aortic annulus is again measured. If the arterial trunk is larger in diameter than the measured aortic annulus, it can now be downsized using longitudinal plication to achieve an optimal fit or downsizing the tube of tissue over an aortic annulus sized hegar dilator. The tailored harvested trunk is now inverted and intussuscepted into the left ventricular outflow tract for easy, and unobstructed, suturing of the base to the aortic annulus using a running suture technique (Fig. 1b). If an incision is made into the root, this is closed to the STJ. The trunk is now pulled up with the result that the adventitia towards the aortic sinuses. Two vertical anchoring sutures are placed at opposite commissures to fix the graft to the STJ creating commissures (Fig. 1c). These commissures are chosen to bisect the circumference between the coronary arteries. The arterial trunk construct now functions as a telescoped bicuspid aortic valve (Fig. 1d and Fig. 2).

This is followed by aortic reconstruction. The posterior half of the pulmonary bifurcation is now anastomosed to the pulmonary arterial STJ. If necessary, the anterior portion of the vessel is reconstructed with patch material, to relieve anastomotic tension (Fig. 1e).

Valve stability is ensured through two mechanisms: (1) circumferential running suture fixation of the graft base to the aortic annulus, and (2) vertical anchoring sutures placed at opposing commissures at the STJ. These sutures will help prevent migration, rotation or prolapse of the graft.

While the technique is developed using domestic swine heart blocks, it could be adapted for any other large animal models and potentially human applications. The flexibility in modifying the arterial trunk diameter and tailoring the anchor points allows for use in a range of anatomical variations, including pediatric and adult populations. While we discuss harvesting a tube for ease of reproducibility, a patch of pulmonary arterial tissue can also be harvested and shaped into a tube for creating this type of bicuspid valve.

Figure 1: Construction of telescoping arterial trunk valve. (a) pulmonary arterial trunk harvest, (b) aortic annular anastomosis. Valve in left ventricular outflow tract. (c) Commissural suspension at sinotubular junction, (d) bicuspid valve profile (e) pulmonary artery reconstruction.

Figure 2: Ex-vivo porcine valve construction.

Semilunar valve intervention in infants is fraught with problems due to lack of ideal replacement options [16]. Existing prosthetic vales—mechanical, bioprosthetic, homografts—lack growth potential [2] and are often associated with considerable morbidity, necessitating reoperations or lifelong anticoagulation [5]. The Ross procedure, though advantageous in terms of autologous tissue use and growth potential, carries risk of autograft failure [10,11].

In contrast, our proposed approach uses autologous vascular tissue, capitalizing on its direct perfusion from the blood stream and intrinsic growth potential. We have developed a novel surgical technique, to transform arterial tissue into a bicuspid semilunar valve with good hemodynamic outcomes ex-vivo. We note that autologous vascular tissue can also be employed with other more complex surgical techniques, such as leaflet reconstructions and the Ozaki technique. Compared to aforementioned alternatives, our telescoping arterial trunk technique is relatively simple, reproducible and adaptable, particularly in context of small annuli where annular enlargement is often necessary. It does not rely on foreign material or fixed pericardial tissue which may calcify or degenerate over time.

Despite its promise, translating this technique into clinical practice will require careful consideration and faces multiple challenges. First, while the procedure is technically straightforward in the ex-vivo setting, in-vivo application may introduce complexities related to anatomical variability, tissue handling and surgical exposure in the neonates and infants. Second, the long-term durability and functional performance of the telescoped valve under systemic pressures remain to be seen.

Although the use of autologous tissue eliminates concerns regarding immunogenicity and graft rejection, it raises concerns related to tissue harvesting. The use of the vascular tissue must be balanced with the risk of compromising donor vessel integrity and future vessel growth. The altered environment and function of the autologous graft may elicit unforeseen biological responses. Moreover, post-operative complications such as valve insufficiency and outflow tract obstruction due to telescoped valve immobility need to be closely monitored. These considerations will be the focal point for future in-vivo studies.

We are currently initiating preclinical in-vivo studies to evaluate the long-term functionality, durability and growth potential of the telescoping arterial trunk valves. If successful this approach could represent an alternative in semilunar valve replacement for pediatric patients, one that aligns with the unique physiological needs of growing children.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This work was funded by internal grants from the Ward Family Heart Center.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Edo Bedzra; methodology, Edo Bedzra; writing—original draft preparation, Edo Bedzra, James E. O’Brien, Taufiek Konrad Rajab; writing—review and editing, Taufiek Konrad Rajab, Herra Javed; visualization, Edo Bedzra; supervision, James E. O’Brien, Taufiek Konrad Rajab; funding acquisition, Edo Bedzra. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: This article does not involve data availability, and this section is not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable due to the technique was developed using 2 heart blocks from domestic swine of unknown gender obtained from a local abattoir. Only specimens without anatomical abnormalities grossly were included. As the study was limited to ex vivo experiments, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approval was not required for this ex-vivo work.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hoffman JIE, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(12):1890–900. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01886-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Schoen FJ. Evolving concepts of cardiac valve dynamics: the continuum of development, functional structure, pathobiology, and tissue engineering. Circulation. 2008;118(18):1864–80. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.805911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Lounsbury CE, Knott-Craig CJ, Doño A, Allen J, Boston U, Ramakrishnan KV. Midterm to long-term outcomes after aortic valve replacement with homograft in children. Ann Thorac Surg Short Rep. Forthcoming 2025. doi:10.1016/j.atssr.2025.03.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mack CA, Lau C, Girardi LN. There is still no alternative to warfarin for mechanical valves: it remains the most effective anticoagulant. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2025;170(2):489–94. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2024.07.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Soria Jiménez CE, Papolos AI, Kenigsberg BB, Ben-Dor I, Satler LF, Waksman R, et al. Management of mechanical prosthetic heart valve thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81(21):2115–27. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.03.412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Myers PO, Mokashi SA, Horgan E, Borisuk M, Mayer JE Jr, Del Nido PJ, et al. Outcomes after mechanical aortic valve replacement in children and young adults with congenital heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157(1):329–40. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.08.077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kostyunin AE, Yuzhalin AE, Rezvova MA, Ovcharenko EA, Glushkova TV, Kutikhin AG. Degeneration of bioprosthetic heart valves: update 2020. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(19):e018506. doi:10.1161/JAHA.120.018506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Contorno E, Javed H, Steen L, Lowery J, Zaghw A, Duerksen A, et al. Options for pediatric heart valve replacement. Future Cardiol. 2025;21(1):47–52. doi:10.1080/14796678.2024.2445402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Rowe G, Gill G, Zubair MM, Roach A, Egorova N, Emerson D, et al. Ross procedure in children: the society of thoracic surgeons congenital heart surgery database analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2023;115(1):119–25. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2022.06.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Cleveland JD, Bansal N, Wells WJ, Wiggins LM, Kumar SR, Starnes VA. Ross procedure in neonates and infants: a valuable operation with defined limits. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023;165(1):262–72. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2022.04.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Pasquali SK, Cohen MS, Shera D, Wernovsky G, Spray TL, Marino BS. The relationship between neo-aortic root dilation, insufficiency, and reintervention following the Ross procedure in infants, children, and young adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(17):1806–12. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Fernández-Carbonell A, Rodríguez-Guerrero E, Merino-Cejas C, Conejero-Jurado MT, Villalba-Montoro R, Romero-Morales MDC, et al. Predictive factors for pulmonary homograft dysfunction after ross surgery: a 20-year follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;111(4):1338–44. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.06.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Turek JW, Kang L, Overbey DM, Carboni MP, Rajab TK. Partial heart transplant in a neonate with irreparable truncal valve dysfunction. JAMA. 2024;331(1):60–4. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.23823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Amirghofran A, Edraki F, Edraki M, Ajami G, Amoozgar H, Mohammadi H, et al. Surgical repair of tetralogy of Fallot using autologous right atrial appendages: short- to mid-term results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;59(3):697–704. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezaa374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Almousa A, Behrmann A, Miller P, Bhattacharya S, Nath D, Miller JR, et al. Use of right atrial appendage tissue for pulmonary valve reconstruction in tetralogy of fallot. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2025;28:60–7. doi:10.1053/j.pcsu.2025.02.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Henaine R, Roubertie F, Vergnat M, Ninet J. Valve replacement in children: a challenge for a whole life. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;105(10):517–28. doi:10.1016/j.acvd.2012.02.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools