Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Precision Pharmacology in Pediatric Congenital Heart Disease: Gene Editing and Organoid Models Addressing Developmental Challenges

1 Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory of Regional Hereditary Birth Defects Prevention and Control, Changsha Hospital for Maternal & Child Health Care Affiliated to Hunan Normal University, Changsha, 410007, China

2 College of Life Science, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, 410081, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yanling Wang. Email: ; Dai Zhou. Email:

; Shuanglin Xiang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Novel Methods and Techniques for the Management of Congenital Heart Disease)

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(5), 613-623. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.071773

Received 12 August 2025; Accepted 24 November 2025; Issue published 30 November 2025

Abstract

Pediatric congenital heart disease (CHD) pharmacotherapy faces three fundamental barriers: developmental pharmacokinetic complexity, anatomic-genetic heterogeneity, and evidence chain gaps. Traditional agents exhibit critical limitations: digoxin’s narrow therapeutic index (0.5–0.9 ng/mL) is exacerbated by ABCB1 mutations (toxicity risk increases 4.1-fold), furosemide efficacy declines by 35% in neonates due to NKCC2 immaturity, and β-blocker responses vary by CYP2D6 polymorphisms (poor metabolizers require 50–75% dose reduction). Novel strategies demonstrate transformative potential—CRISPR editing achieves 81% reversal of BMPR2-associated pulmonary vascular remodeling, metabolically matured cardiac organoids replicate adult myocardial energy metabolism for drug screening, and SGLT2 inhibitors activate triple mechanisms (calcium overload mitigation, mitophagy, fibrosis reversal). However, clinical translation requires overcoming developmental barriers: age-dependent enzyme expression (infant CYP2D6 = 30–60% adult activity), post-Fontan hepatotoxicity (bosentan trough concentrations elevates 1.8-fold), and AI model limitations (32% error in complex CHD). Future integration of placental transfer models, disease-specific organoids, and multi-omics mapping of FOXO/CRIM1 pathways will shift paradigms from symptom control to curative repair.Keywords

Congenital heart disease affects 1% of global births, with 20% requiring lifelong pharmacotherapy [1,2,3,4,5]. While contemporary surgical interventions achieve >90% survival into adulthood, developmental pharmacokinetic barriers significantly compromise therapeutic efficacy: neonates demonstrate 4- to 5-fold prolonged digoxin half-lives (up to 170 h in premature infants) compared to toddlers (18–35h) due to immature renal function and reduced clearance capacity [6]; cyanotic patients require 20% higher digoxin loading doses due to polycythemia-induced volume expansion; diminished myocardial β-receptor density blunts catecholamine responses, favoring phosphodiesterase inhibitors like milrinone [7]. Critically, 38.7% of adult CHD mortality originates from childhood-initiated myocardial fibrosis and metabolic dysfunction—processes beginning as early as infancy [8].

The heterogeneity of CHD phenotypes demands stratified management: hemodynamically insignificant lesions (such as small muscular ventricular septal defects) may only require surveillance, while complex malformations necessitate staged interventions [9,10,11,12,13,14]. For high-risk patients with pneumonia, endocarditis, or severe pulmonary hypertension, pharmacotherapy serves as a bridge to surgery. Emerging technologies now transform this paradigm—gene-edited cardiac organoids predict individual drug susceptibility, while placental transfer models (experimental models used to study the passage of drugs from the mother to the fetus) allow for in utero digoxin therapy in cases of fetal tachyarrhythmia, shifting interventions from emergent postnatal rescue to planned prenatal correction [15].

2 The Limitations of Traditional Pediatric Agents

2.1 Therapeutic Challenges of Cardiotonic Agents

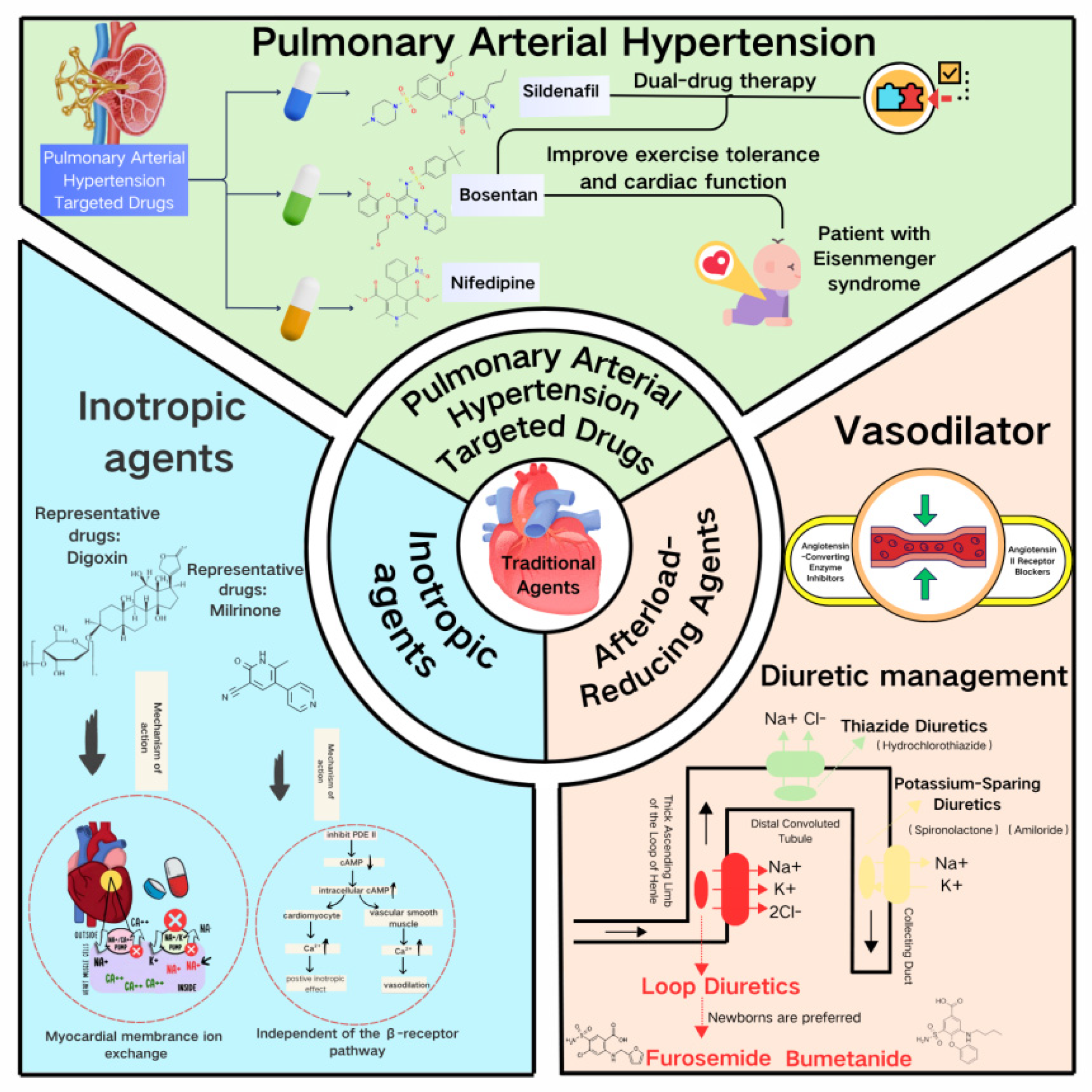

Digoxin, a classical cardiotonic drug, enhances myocardial contractility by inhibiting sarcolemmal Na+/K+-ATPase to increase intracellular calcium concentration (Fig. 1). It is widely used for chronic heart failure management in children. However, its narrow therapeutic window (the concentration range of a drug that is both effective and safe) poses amplified risks in specific genotypes—homozygous carriers of the ABCB1 3435C > T mutation exhibit significantly increased bioavailability and a 4.1-fold higher risk of intoxication, clinically manifesting as life-threatening arrhythmias [16,17]. Equally critical are drug interactions: Varela-Chinchilla et al. specifically caution that digoxin’s narrow therapeutic index is further compromised by drug interactions, particularly with β-blockers, which can precipitate severe conduction abnormalities [18]. Coadministration with β-blockers like carvedilol may induce third-degree atrioventricular block, while baseline β-blocker therapy diminishes inotropic response in pediatric cardiogenic shock [7]. Milrinone, as an alternative, enhances contractility via phosphodiesterase III inhibition and cAMP elevation. Although it reduces postoperative mortality in congenital heart disease [19], optimal dosing for complex anatomical variants lacks robust evidence, hindering standardized clinical application [8].

Figure 1: The limitations of traditional pediatric Agents. This figure was created using Canva (Online version: https://www.canva.cn/).

2.2 Dual Challenges of Afterload-Reducing Agents

In diuretics, furosemide rapidly alleviates volume overload by specifically inhibiting the NKCC2 transporter in the thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop. However, transitions from euvolemia to volume expansion in heart failure trigger intrarenal hemodynamic abnormalities—medullary hypoxia downregulates NKCC2 expression, causing diuretic resistance [20,21]. It is noteworthy that in pediatric post-cardiac surgery patients who do not respond to long-term furosemide use, ethacrynic acid can serve as an effective alternative [22]. As a non-sulfonamide loop diuretic, it is particularly suitable for patients with furosemide resistance or sulfonamide allergies, with an initial intravenous dose of 1 mg/kg [22]. However, its significant risk of ototoxicity necessitates strict therapeutic drug monitoring and hearing assessment during clinical use [23]. For refractory edema patients complicated with metabolic alkalosis, concomitant administration of acetazolamide (5–10 mg/kg) may be considered. By inhibiting carbonic anhydrase, it promotes HCO3− excretion, corrects alkalosis, and enhances the diuretic effect. However, vigilance is required for the potential risks of hyperchloremic acidosis and hypokalemia [23]. Spironolactone, an aldosterone antagonist, achieves potassium-sparing diuresis by blocking renal tubular ENaC channels. Yet it is strictly contraindicated in post-Fontan patients with protein-losing enteropathy (Fontan-PLE)—its antagonism disrupts intestinal ENaC-mediated sodium-water transport, increasing mucosal protein leakage by 2.4-fold [24,25].

Among vasodilators, ACE inhibitors (such as, captopril) reduce afterload by suppressing the renin-angiotensin system. However, children’s glomerular filtration rate (GFR)—only 25%–30% of adult values—heightens acute kidney injury risk [26,27]. Notably, when eGFR falls below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, ARNI (sacubitril/valsartan) shows no renal outcome advantage over ACE inhibitors [28,29]. For β-blockers (e.g., metoprolol), CYP2D6 polymorphisms cause metabolic variability: poor metabolizers require 50%–75% dose reductions to avoid toxicity from elevated plasma concentrations [30,31].

2.3 Specific Limitations of Pulmonary Hypertension-Targeted Therapies

Sildenafil selectively dilates pulmonary vasculature by augmenting the NO-cGMP pathway, improving vascular remodeling in persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn [32]. However, its nonselective vasodilation may provoke systemic hypotension—particularly perilous in single-ventricle physiology, where cardiopulmonary balance depends on precise vascular resistance regulation [8,33]. Bosentan, an endothelin receptor antagonist endorsed in heart failure guidelines for patients with right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF) <45% [34], faces hepatotoxicity challenges in Fontan circulation: hepatic congestion reduces CYP3A4 activity, decreasing clearance and elevating trough concentrations by 1.8-fold, with a 37% higher risk of liver enzyme abnormalities (Table 1) [35]. Crucially, while cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR)-defined RVEF thresholds guide therapy [36], over 30% of young children cannot undergo accurate assessment due to sedation challenges.

Table 1: The limitations of traditional pediatric Agents.

| Drug Class | Representative Agents | Core Pharmacological Action | Pediatric-Specific Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiotonic Agents | Digoxin | Inhibits Na+/K+-ATPase → Increases intracellular Ca2+ → Enhances contractility. | Narrow therapeutic index (0.5–0.9 ng/mL); ABCB1 3435C > T mutation: Increases bioavailability by 29.7%, elevates toxicity risk 4.1-fold; Interaction with β-blockers: Higher AV block risk (OR = 6.3). |

| Milrinone | Inhibits PDE-III → Elevates cAMP → Enhances contractility & vasodilation. | Lack of pediatric RCTs for complex CHD;Reduced efficacy with baseline β-blocker use (HR = 1.82). | |

| Diuretics | Furosemide | Inhibits NKCC2 transporter → Reduces Na+ reabsorption by 25%. | Furosemide response: initial intravenous/intramuscular dose: 1 mg/kg; may increase by 1 mg/kg every 2 h to a max of 6 mg/kg/day. Diuretic Resistance: Medullary hypoxia from heart failure can downregulate NKCC2 expression; Nephrocalcinosis: Long-term use in infants is a major risk factor for kidney calcium deposits. Ototoxicity: Risk increases with rapid IV injection (>4 mg/min) and concurrent use of other ototoxic drugs. |

| Ethacrynic Acid | Loop diuretic; acts on the ascending limb and proximal/distal tubules—Oral: 0.5–1 mg/kg/day. | Furosemide response: initial intravenous/intramuscular dose: 0.5–1mg/kg/dose. Effective in patients with renal insufficiency. Ototoxicity: Potent risk, especially when combined with other ototoxic drugs. Electrolyte Depletion: Can cause profound water and electrolyte loss due to potent diuresis. | |

| Acetazolamide | Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor; reduces aqueous humor production and promotes diuresis. | Furosemide response: initial intravenous/intramuscular dose: 5–10 mg/kg/dose. Used for glaucoma, epilepsy, and altitude sickness. Rarely as primary diuretic for heart failure. Metabolic Acidosis: Causeshigh-chloride metabolic acidosis. Nephrolithiasis: Increases risk of kidney stones. Electrolyte Imbalance: Can cause significant hypokalemia. | |

| Spironolactone | Blocks ENaC channels → Potassium-sparing diuresis. | Contraindicated in Fontan-PLE: Disrupts intestinal ENaC function → Protein leakage increases 2.4-fold. | |

| Vasodilators | ACEI (such as Captopril) | Inhibits RAAS → Reduces afterload. | Elevated AKI risk: GFR only 25–30% of adult values; No renal benefit of ARNI when eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2. |

| β-blockers (such as Metoprolol) | Blocks β-receptors → Reduces heart rate & myocardial O2 demand. | CYP2D6 polymorphisms: Poor metabolizers require 50–75% dose reduction. | |

| PAH-Targeted Therapies | Sildenafil | Augments NO-cGMP → Pulmonary vasodilation. | • Systemic hypotension: High risk in single-ventricle physiology. • CMR dependency: RVEF < 45% threshold difficult in young children (30% unassessable). |

| Bosentan | Blocks ET-1 receptors →Reduces Pulmonary vascular. | Hepatotoxicity in Fontan: Hepatic congestion reduces CYP3A4 activity → Trough concentration increases 1.8-fold, liver enzyme abnormality risk rises 37%. |

3 Breakthroughs in Novel Therapeutic Strategies

The recognized shortcomings of conventional pharmacotherapy—characterized by narrow therapeutic indices, unpredictable pharmacodynamic variability, and off-target organ exposure—create an urgent, unmet clinical need. This imperative to transcend the limitations of imprecise dosing regimens has served as a catalyst for the transformative innovations detailed in this section. Consequently, a paradigm shift is emerging, moving beyond symptomatic control to directly address the fundamental molecular and anatomical bases of pediatric heart disease. This transition is spearheaded by three pivotal strategies: gene editing for direct mutational correction and functional restoration; physiologically relevant organoids for patient-specific phenotyping and drug screening; and advanced delivery platforms for spatially precise therapeutic targeting. Collectively, these advances are revolutionizing precision intervention, thereby inaugurating an era of mechanism-driven therapy in pediatric cardiology.

3.1 Revolutionizing Precision Intervention through Gene Editing Technologies

3.1.1 Genotype-Guided Therapy for Pediatric Pulmonary Hypertension

Children with idiopathic/heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension (I/HPAH) exhibit significant variation in treatment response based on genotype. Pathogenic mutations in BMPR2 are strongly associated with disease severity. Patients harboring BMPR2 mutations demonstrate significantly elevated pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI) at diagnosis (20.55 WU·m2 vs. 16.83 WU·m2 in non-carriers; p < 0.01). Despite intensive triple-combination therapy (endothelin receptor antagonists, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, and prostacyclin analogs), 29% of mutation carriers remain high-risk, substantially exceeding the 16% observed in non-carriers (p = 0.008) [37,38].

To address BMPR2 dysfunction, CRISPR-Cas9-mediated in vivo gene editing shows therapeutic promise. In murine models, AAV9-delivered base editors correcting the BMPR2 c.1472G > T (p.Arg491Leu) mutation achieved 81% reversal of pulmonary vascular remodeling and reduced right ventricular systolic pressure by 32% [39,40]. Validation using patient-derived iPSC-pulmonary endothelial cells confirmed restoration of normal expression for endothelial dysfunction markers, including endothelin-1 and interleukin-6 [33,37].

3.1.2 Targeted Treatment of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy through Genotyping-Based Precision Therapy

In hereditary hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), MYH7 R403Q mutations disrupt β-myosin heavy chain function, leading to sarcomere hypercontraction and calcium dysregulation. This is mechanistically evidenced by impaired sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase activity [41,42]. To therapeutically address this mutation, we established a dose-dependent gene editing protocol: A single low-dose AAV-SaCas9 administration achieved 40–50% target allele modification in cardiomyocytes, while three consecutive high-dose (25×) transductions increased efficiency to 80%. This restored sarcomere ultrastructure and significantly improved calcium handling [43,44]. Further optimization via split intein-mediated dual-vector delivery elevated editing rates to 92%, with whole-genome sequencing confirming off-target frequencies below 0.05% [44]. Critically, edited animals exhibited markedly reduced myocardial fibrosis compared to untreated controls (p < 0.001) and β-blocker therapy groups, demonstrating superior therapeutic efficacy of precision gene editing [45,46].

3.1.3 Targeted Delivery Breakthrough for Diuretic Resistance

Innovations in delivery systems are accelerating clinical translation. Recently developed ultrasound microbubble-liposome composite carriers (lipid-shelled carriers used for ultrasound-mediated targeted drug delivery), combined with focused ultrasound-targeted activation technology, achieve 74.5% myocardial editing efficiency while reducing off-target delivery to the liver by 3.8-fold [47,48]. This technology demonstrates significant clinical potential in diuretic-resistant models: targeted silencing of the TGF-β1gene markedly alleviates myocardial fibrosis-associated edema, increasing urine output by 2.3-fold compared to furosemide-treated groups [48,49]. These findings validate the therapeutic efficacy of precision gene targeting in refractory heart failure, establishing a foundation for mechanism-driven interventions.

3.2 Leap in Physiological Functionality of Organoid Models

Cardiac organoid technology has achieved transformative breakthroughs through metabolic maturation. The metabolically mature medium developed by Feyen’s team significantly enhances the electrophysiological function of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs), bringing action potential duration and calcium transient amplitude (the magnitude of rapid cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration changes in cardiomyocytes during depolarization) close to adult myocardial levels [2]. Building on this foundation, researchers in Sydney constructed “metabolically matured” cardiac organoids that successfully replicate key energy metabolism features of adult myocardium, including fatty acid oxidation-dominated energy supply. These organoids were applied to model desmoplakin cardiomyopathy, and a BET inhibitor screened through this platform demonstrated reversal of myocardial pump dysfunction, advancing to Phase I clinical trials.

Critically, these matured organoids overcome predictive limitations of traditional models that rely on metabolically immature cells or animal systems with non-human cardiac signaling pathways. This technological advance proved essential in uncovering the stromal-cardiomyocyte SLIT3/ROBO1 signaling axis as a key regulator of pressure-overload hypertrophy. Specifically, organoids revealed how SLIT3-activated ROBO1 signaling suppresses pathological calcineurin/NFAT activation and collagen deposition, with experimental restoration reducing fibrosis by 34% (p < 0.001)—establishing a new paradigm for targeting intercellular crosstalk in cardiac remodeling research [8,50].

3.3 Multi-Mechanism Synergy in Targeted Delivery Systems

Metabolic reprogramming therapy reshapes therapeutic logic through multi-target interventions. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors such as empagliflozin target myocardial sodium-hydrogen exchanger-1 (NHE-1), operating via a triple synergistic mechanism: alleviating calcium overload through reduced sodium influx via NHE-1 inhibition and decreased sodium-calcium exchanger activity; activating mitophagy to clear dysfunctional mitochondria; and reversing fibrosis by suppressing TGF-β2 expression to reduce collagen deposition [51,52,53].

Compared to traditional diuretics that merely relieve volume overload while exacerbating electrolyte imbalances (illustrated by furosemide’s 35% hypokalemia risk) [21], or RAAS inhibitors like ACEIs that carry renal injury risks in children with low glomerular filtration rate [26,27], this multi-target strategy concurrently improves energy metabolism and myocardial remodeling. The pediatric subgroup analysis in the DAPA-HF study confirmed a 26% reduction in congenital heart disease-related heart failure hospitalizations. Concurrently developed selective PPARγ modulators inhibit fibrotic gene transcription by blocking PPARγ-Ser273 phosphorylation, circumventing critical limitations of traditional PPARγ agonists such as rosiglitazone, which is contraindicated in heart failure patients due to fluid retention (the abnormal accumulation of fluid in bodily tissues) [32,54,55].

4 Integrated Analysis of Clinical Translation Challenges

The clinical translation of pediatric cardiovascular therapies faces three interconnected barriers: Developmental pharmacokinetic complexity creates age-dependent drug responses—CYP2D6 activity in infants is only 30–60% of adult levels, causing a 2.3-fold increase in blood concentration fluctuations when digoxin is co-administered with carvedilol (elevating bradycardia risk, p < 0.05), while NKCC2 immaturity in neonates reduces furosemide diuretic efficiency by 35% and increases electrolyte risks by 40% [20,31]. Anatomic-genetic interactions critically impact safety and efficacy: perimembranous ventricular septal defects exhibit a 3.2% post-occlusion conduction block rate due to anatomical variations (versus 0.7% in muscular defects) [1], and TBX5/NKX2–5 mutations reduce β-blocker response to 52% (vs. 78% in non-mutants) by dysregulating channels like SCN5A [10]. Additionally, SLIT3/ROBO1 axis activation in adult congenital heart disease patients accelerates fibrosis and diminishes vasodilator sensitivity [8]. Systemic evidence gaps persist, with only 12% of pediatric heart failure drugs having ≥5-year follow-up data (for example, unknown long-term renal safety of sacubitril/valsartan) [56], while AI prediction models trained on datasets containing <15% complex congenital heart disease cases show 32% error rates when applied to critical patients [57]. Integrating developmental pharmacology with individualized anatomic-molecular profiling is essential to overcome these translational barriers.

5 Conclusion: Overcoming Three Critical Barriers

The advancement of pharmacotherapy for pediatric congenital heart disease necessitates overcoming three critical barriers. Developmental pharmacokinetic variations demand the establishment of fetal-child-adult cross-life pharmacokinetic databases, exemplified by placental transfer models for digoxin dosing in fetal supraventricular tachycardia. Anatomical complexity requires leveraging cardiac organoid technology to construct disease-specific models (such as, single-ventricle physiology, Fontan circulation) for accelerated targeted drug screening. Evidence chain gaps must be addressed through international collaborations like the ACTION network to generate pediatric-specific guidelines and secure regulatory approvals for agents such as SGLT2 inhibitors.

Looking toward the next decade, a transformative vision emerges: single-cell multi-omics will map CHD developmental trajectories, identifying pivotal nodes in PDK4 and FOXO/CRIM1 pathways. Convergent innovations in base editing and targeted delivery technologies promise to catalyze a historic leap from symptomatic control to curative repair, fundamentally redefining therapeutic paradigms for children with congenital heart disease.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This work was financially supported by Funding was provided by grants from the Changsha Chinese Medicine Foundation (Grant No. B202314), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (Grant No. 2024JJ8224), Changsha Municipal Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. kq2403187), Hunan Province Children’s Safe Medication Clinical Medical Technology Demonstration Base (Grant No. 2023SK4083).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Yanling Wang, Dai Zhou, Shuanglin Xiang. Writing—original draft preparation, Yanling Wang, Jun He. Data curation, Yanling Wang. Writing—review and editing, Yanling Wang, Dai Zhou, Shuanglin Xiang, Jianli Luo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Koneti NR , Azad S , Bakhru S , Dhulipudi B , Sitaraman R , Kumar RK . Transcatheter closure of perimembranous ventricular septal defect using KONAR-MFTM: a multicenter experience. Pediatr Cardiol. 2025; 46( 4): 853– 61. doi:10.1007/s00246-024-03505-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Feyen DAM , McKeithan WL , Bruyneel AAN , Spiering S , Hörmann L , Ulmer B , et al. Metabolic maturation media improve physiological function of human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes. Cell Rep. 2020; 32( 3): 107925. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Winger T , Ozdemir C , Narasimhan SL , Srivastava J . Time-adaptive machine learning models for predicting the severity of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Diagnostics. 2025; 15( 6): 715. doi:10.3390/diagnostics15060715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Tang LWT , Varma MVS . Hepatic impairment and the differential effects on drug clearance mechanisms: analysis of pharmacokinetic changes in disease state. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2025; 118( 3): 673– 81. doi:10.1002/cpt.3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Baumgartner H , De Backer J , Babu-Narayan SV , Budts W , Chessa M , Diller GP , et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease: the task force for the management of adult congenital heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2021; 42( 6): 563– 645. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ratnapalan S , Griffiths K , Costei AM , Benson L , Koren G . Digoxin-carvedilol interactions in children. J Pediatr. 2003; 142( 5): 572– 4. doi:10.1067/mpd.2003.160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Di Santo P , Mathew R , Jung RG , Simard T , Skanes S , Mao B , et al. Impact of baseline beta-blocker use on inotrope response and clinical outcomes in cardiogenic shock: a subgroup analysis of the DOREMI trial. Crit Care. 2021; 25( 1): 289. doi:10.1186/s13054-021-03706-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Liu X , Li B , Wang S , Zhang E , Schultz M , Touma M , et al. Stromal cell-SLIT3/cardiomyocyte-ROBO1 axis regulates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2024; 134( 7): 913– 30. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.122.321292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Amdani S , Conway J , George K , Martinez HR , Asante-Korang A , Goldberg CS , et al. Evaluation and management of chronic heart failure in children and adolescents with congenital heart disease: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2024; 150( 2): e33– 50. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Diab NS , Barish S , Dong W , Zhao S , Allington G , Yu X , et al. Molecular genetics and complex inheritance of congenital heart disease. Genes. 2021; 12( 7): 1020. doi:10.3390/genes12071020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. van Genuchten WJ , Helbing WA , Ten Harkel ADJ , Fejzic Z , Md IMK , Slieker MG , et al. Exercise capacity in a cohort of children with congenital heart disease. Eur J Pediatr. 2023; 182( 1): 295– 306. doi:10.1007/s00431-022-04648-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Udholm LF , Arendt LH , Knudsen UB , Ramlau-Hansen CH , Hjortdal VE . Congenital heart disease and fertility: a Danish nationwide cohort study including both men and women. J America Heart Assoc. 2023; 12( 2): e027409. doi:10.1161/JAHA.122.027409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Budts W , Prokšelj K , Lovrić D , Kačar P , Gatzoulis MA , Brida M . Adults with congenital heart disease: what every cardiologist should know about their care. Eur Heart J. 2024; 45( 45): 4783– 96. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehae716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Sandberg M , Fomina T , Macsali F , Greve G , Øyen N , Leirgul E . Preeclampsia and neonatal outcomes in pregnancies with maternal congenital heart disease: a nationwide cohort study from Norway. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2024; 103( 9): 1847– 58. doi:10.1111/aogs.14902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Du X , Chang Y , Song J . Use of brain death recipients in xenotransplantation: a double-edged sword. Xenotransplantation. 2025; 32( 1): e70010. doi:10.1111/xen.70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhu Z , Qian C , Su C , Tao H , Mao J , Guo Z , et al. The impact of ABCB1 and CES1 polymorphisms on the safety of dabigatran in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022; 22( 1): 481. doi:10.1186/s12872-022-02910-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Madejczyk AM , Canzian F , Góra-Tybor J , Campa D , Sacha T , Link-Lenczowska D , et al. Impact of genetic polymorphisms of drug transporters ABCB1 and ABCG2 and regulators of xenobiotic transport and metabolism PXR and CAR on clinical efficacy of dasatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia. Front Oncol. 2022; 12: 952640. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.952640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Varela-Chinchilla CD , Sánchez-Mejía DE , Trinidad-Calderón PA . Congenital heart disease: the state-of-the-art on its pharmacological therapeutics. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2022; 9( 7): 201. doi:10.3390/jcdd9070201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Burkhardt BE , Hummel J , Rücker G , Stiller B . Inotropes for the prevention of low cardiac output syndrome and mortality for paediatric patients undergoing surgery for congenital heart disease: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024; 11( 11): CD013707. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013707.pub2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ares GR , Caceres PS , Ortiz PA . Molecular regulation of NKCC2 in the thick ascending limb. America J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2011; 301( 6): F1143– 59. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00396.2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Nijst P , Martens P , Dupont M , Wilson Tang WH , Mullens W . Intrarenal flow alterations during transition from euvolemia to intravascular volume expansion in heart failure patients. JACC Heart Fail. 2017; 5( 9): 672– 81. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2017.05.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ricci Z , Haiberger R , Pezzella C , Garisto C , Favia I , Cogo P . Furosemide versus ethacrynic acid in pediatric patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2015; 19( 1): 2. doi:10.1186/s13054-014-0724-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kassamali R , Sica DA . Acetazolamide: a forgotten diuretic agent. Cardiol Rev. 2011; 19( 6): 276– 8. doi:10.1097/CRD.0b013e31822b4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wernovsky G , Lihn SL , Olen MM . Creating a lesion-specific “roadmap” for ambulatory care following surgery for complex congenital cardiac disease. Cardiol Young. 2017; 27( 4): 648– 62. doi:10.1017/S1047951116000974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Dotson A , Covas T , Halstater B , Ragsdale J . Congenital heart disease. Prim Care Clin Off Pract. 2024; 51( 1): 125– 42. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2023.07.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zarei H , Azimi A , Ansarian A , Raad A , Tabatabaei H , Roshdi Dizaji S , et al. Incidence of acute kidney injury-associated mortality in hospitalized children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2025; 26( 1): 117. doi:10.1186/s12882-025-04033-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Robinson CH , Jeyakumar N , Luo B , Askenazi D , Deep A , Garg AX , et al. Long-term kidney outcomes after pediatric acute kidney injury. J America Soc Nephrol. 2024; 35( 11): 1520– 32. doi:10.1681/asn.0000000000000445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Li J , Liu Q , Lian X , Yang S , Lian R , Li W , et al. Kidney outcomes following angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor vs angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker therapy for thrombotic microangiopathy. JAMA Netw Open. 2024; 7( 9): e2432862. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.32862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Chatur S , Beldhuis IE , Claggett BL , McCausland FR , Neuen BL , Desai AS , et al. Sacubitril/valsartan in patients with heart failure and deterioration in eGFR to <30 min/1.73 m2. JACC Heart Fail. 2024; 12( 10): 1692– 703. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2024.03.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Duarte JD , Thomas CD , Lee CR , Huddart R , Agundez JAG , Baye JF , et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guideline (CPIC) for CYP2D6, ADRB1, ADRB2, ADRA2C, GRK4, and GRK5 genotypes and beta-blocker therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2024; 116( 4): 939– 47. doi:10.1002/cpt.3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Lee CM , Kang P , Cho C , Park HJ , Lee YJ , Bae J , et al. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modelling to predict the pharmacokinetics of metoprolol in different CYP2D6 genotypes. Arch Pharmacal Res. 2022; 45( 6): 433– 45. doi:10.1007/s12272-022-01394-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kang L , Liu X , Li Z , Li X , Han Y , Liu C , et al. Sildenafil improves pulmonary vascular remodeling in a rat model of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2023; 81( 3): 232– 9. doi:10.1097/FJC.0000000000001373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Widjaja SL , Anniazi ML , Artiko B , Moelyo AG , Ahmadwirawan MT . BMPR-II, caspase-3, HIF-1α, and VE-cadherin profile in Down syndrome children with and without congenital heart disease and pulmonary hypertension. Narra J. 2025; 5( 1): e1244. doi:10.52225/nrj.v5i1.1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. McDonagh TA , Metra M , Adamo M , Gardner RS , Baumbach A , Böhm M , et al. 2023 Focused update of the 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure:developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European society of cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution of the Heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2023; 44( 37): 3627– 39. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehad195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Cashen K , Saini A , Brandão LR , Le J , Monagle P , Moynihan KM , et al. Anticoagulant medications: the pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation anticoagulation CollaborativE consensus conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2024; 25( 7 Suppl 1): e7– 13. doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000003495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Lewis RA , Johns CS , Cogliano M , Capener D , Tubman E , Elliot CA , et al. Identification of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging thresholds for risk stratification in pulmonary arterial hypertension. America J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020; 201( 4): 458– 68. doi:10.1164/rccm.201909-1771oc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Austin ED , Elliott CG . TBX4 syndrome: a systemic disease highlighted by pulmonary arterial hypertension in its most severe form. Eur Respir J. 2020; 55( 5): 2000585. doi:10.1183/13993003.00585-2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Bajolle F , Malekzadeh-Milani S , Lévy M , Bonnet D . Multifactorial origin of pulmonary hypertension in a child with congenital heart disease, Down syndrome, and BMPR-2 mutation. Pulm Circ. 2021; 11( 3): 20458940211027433. doi:10.1177/20458940211027433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Cuthbertson I , Morrell NW , Caruso P . BMPR2 mutation and metabolic reprogramming in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Res. 2023; 132( 1): 109– 26. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.122.321554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Talati M , Brittain E , Agrawal V , Fortune N , Simon K , Shay S , et al. A potential adverse role for leptin and cardiac leptin receptor in the right ventricle in pulmonary arterial hypertension: effect of metformin is BMPR2 mutation-specific. Front Med. 2023; 10: 1276422. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1276422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Guo X , Huang M , Song C , Nie C , Zheng X , Zhou Z , et al. MYH7 mutation is associated with mitral valve leaflet elongation in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heliyon. 2024; 10( 14): e34727. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Lee S , Vander Roest AS , Blair CA , Kao K , Bremner SB , Childers MC , et al. Incomplete-penetrant hypertrophic cardiomyopathy MYH7 G256E mutation causes hypercontractility and elevated mitochondrial respiration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024; 121( 19): e2318413121. doi:10.1073/pnas.2318413121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Wang XJ , Xu XQ , Sun K , Liu KQ , Li SQ , Jiang X , et al. Association of rare PTGIS variants with susceptibility and pulmonary vascular response in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. JAMA Cardiol. 2020; 5( 6): 677– 84. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Morsy SG , Tonne JM , Zhu Y , Lu B , Budzik K , Krempski JW , et al. Divergent susceptibilities to AAV-SaCas9-gRNA vector-mediated genome-editing in a single-cell-derived cell population. BMC Res Notes. 2017; 10( 1): 720. doi:10.1186/s13104-017-3028-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Margara F , Psaras Y , Wang ZJ , Schmid M , Doste R , Garfinkel AC , et al. Mechanism based therapies enable personalised treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Sci Rep. 2022; 12: 22501. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-26889-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Krause AA , Kelty TJ , Meers GM , Russell AJ , Evanchik MJ , Barthel B , et al. Heterozygous MYH7 R403Q mutation impairs left atrial mitochondrial function in a Yucatan mini-pig model of genetic nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Appl Physiol. 2025; 139( 1): 265– 74. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00339.2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Nitta Y , Kurioka T , Mogi S , Sano H , Yamashita T . Suppression of the TGF-β signaling exacerbates degeneration of auditory neurons in kanamycin-induced ototoxicity in mice. Sci Rep. 2024; 14( 1): 10910. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-61630-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Inoue T , Hisamichi M , Ichikawa D , Shibagaki Y , Yazawa M . The effect of add-on acetazolamide to conventional diuretics for diuretic-resistant edema complicated with hypercapnia: a report of two cases. Intern Med. 2022; 61( 3): 373– 8. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.7896-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zhang M , Wang H , Wang X , Bie M , Lu K , Xiao H . MG53/CAV1 regulates transforming growth factor-β1 signaling-induced atrial fibrosis in atrial fibrillation. Cell Cycle. 2020; 19( 20): 2734– 44. doi:10.1080/15384101.2020.1827183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Pocock MW , Reid JD , Robinson HR , Charitakis N , Krycer JR , Foster SR , et al. Maturation of human cardiac organoids enables complex disease modeling and drug discovery. Nat Cardiovasc Res. 2025; 4( 7): 821– 40. doi:10.1038/s44161-025-00669-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Osaka N , Mori Y , Terasaki M , Hiromura M , Saito T , Yashima H , et al. Luseogliflozin inhibits high glucose-induced TGF-β2 expression in mouse cardiomyocytes by suppressing NHE-1 activity. J Int Med Res. 2022; 50( 5): 03000605221097490. doi:10.1177/03000605221097490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Endo S , Kanamori H , Yoshida A , Naruse G , Komura S , Minatoguchi S , et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor empagliflozin enhances autophagy and reverses remodeling in hearts with large, old myocardial infarctions. Eur J Pharmacol. 2025; 992: 177355. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2025.177355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Cheng CI , Chou MH , Shih IL , Chen PH , Kao YH . Empagliflozin mitigates high glucose-disrupted mitochondrial respiratory function in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts: a comparative study with NHE-1 andROCK inhibition. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2025; 17: E18761429360640. doi:10.2174/0118761429360640250227054103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Wu X , Liu H , Brooks A , Xu S , Luo J , Steiner R , et al. SIRT6 mitigates heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in diabetes. Circ Res. 2022; 131( 11): 926– 43. doi:10.1161/circresaha.121.318988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Zhang N , Ma Q , You Y , Xia X , Xie C , Huang Y , et al. CXCR4-dependent macrophage-to-fibroblast signaling contributes to cardiac diastolic dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Int J Biol Sci. 2022; 18( 3): 1271– 87. doi:10.7150/ijbs.65802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Shaddy R , Burch M , Kantor PF , Solar-Yohay S , Garito T , Zhang S , et al. Sacubitril/valsartan in pediatric heart failure (PANORAMA-HF): a randomized, multicenter, double-blind trial. Circulation. 2024; 150( 22): 1756– 66. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.066605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Mohammadi I , Rajai Firouzabadi S , Hosseinpour M , Akhlaghpasand M , Hajikarimloo B , Zeraatian-Nejad S , et al. Using artificial intelligence to predict post-operative outcomes in congenital heart surgeries: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2024; 24( 1): 718. doi:10.1186/s12872-024-04336-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools