Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Increased Incidence of Congenital Heart Disease during the COVID-19 Pandemic in 492,662 Newborns: Multicenter Observational Study

1 Heart Center, Children’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, National Clinical Research Center for Child Health, Hangzhou, 310000, China

2 Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, 310000, China

3 Child Health Care Department, Ningbo Women and Children Hospital, Ningbo, 315000, China

4 Department of Health Care, Taizhou Women and Children’s Hospital, Taizhou, 318000, China

5 Department of Health Care, Shaoxing Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, Shaoxing, 312000, China

6 Department of Health Care, Jiaxing Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, Jiaxing, 314000, China

7 Department of Health Care, Huzhou Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, Huzhou, 313000, China

8 Department of Neonatology, Lishui Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, Lishui, 323000, China

9 Department of Health Care, Zhoushan Women and Children Hospital, Zhoushan, 316000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Qiang Shu. Email: ; Weize Xu. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(5), 571-580. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.066258

Received 02 April 2025; Accepted 12 June 2025; Issue published 30 November 2025

Abstract

Background: Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common congenital anomaly, but whether the COVID-19 pandemic affects its prevalence is unknown. We aimed to compare the incidence of CHD during the COVID-19 pandemic with that before the pandemic in China. Methods: This multicenter retrospective observational study involved all newborns in seven representative cities of China between 01 September 2019, and 31 December 2021. All the newborns underwent pulse oximetry monitoring combined with cardiac murmur auscultation in the first 6 h to 72 h after birth for CHD screening. We defined fetuses born in and beyond September 2020 as the exposed group, and before as the non-exposed group. The incidence of CHD and specific heart abnormalities, including atrial septal defect (ASD) and ventricular septal defect (VSD), before and during the COVID-19 pandemic were compared. Results: The study included 492,662 newborns; 217,003 newborns born before September 2020 and 275,659 newborns born in and beyond September 2020. There were 3115 patients with CHD in total during the whole study period. Of those, 1055 (September 2019 to August 2020) and 2060 (September 2020 to December 2021) were less and more affected by the pandemic, respectively. There was a significant increase in the incidence of CHD in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic (7.78 per 1000 births) compared to that before the pandemic (4.86 per 1000 births) (p < 0.001). The birth prevalence of ASD and VSD significantly increased during the pandemic from 3.991 per 1000 births to 4.717 per 1000 births (p = 0.008) and from 1.650 per 1000 births to 3.508 per 1000 births (p < 0.001), respectively. Conclusions: The incidence of CHD increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was possibly related to the reallocation of medical resources, increased psychological pressure, and increased socioeconomic deprivation, though underlying mechanisms remain unclear.Keywords

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is a gross structural and functional abnormality of the heart or intrathoracic great vessels caused by various factors during embryonic development [1]. CHD accounts for nearly one-third of all major birth defects, with a birth prevalence of 9 cases per 1000 live births in China [2,3]. Although advances in diagnosis and treatment in recent decades have yielded favorable results, the CHD mortality rate per 1000 children younger than 1 year is estimated to be 1.20 in countries with a moderate sociodemographic index (SDI) [4].

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way we live, work and socialize. In the face of crises, the negative impact on women is exacerbated by social and gender inequalities [5,6]. Cross-country data from UN Women’s Rapid Assessment Surveys reveal that the burden of unpaid labor and economic pressure have increased for women as a result of the pandemic [7]. Combined with the effects of segregation policies and the redistribution of social security funds, women experience great difficulty seeking family planning services and routine medical care [7,8]. These disruptions have worsened reproductive health outcomes in several countries [9,10].

There is growing evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic’s indirect consequences adversely affect global maternal health and perinatal outcomes, which is possibly related to the reallocation of resources and priorities, elevated psychological pressure, and increased socioeconomic deprivation [11,12,13,14,15]. Between 2019 and 2021, a cohort study (n = 1,654,868) conducted in the US revealed small but significant increases in maternal death during delivery hospitalization (odds ratio [OR], 1.75; 95% CI, 1.19–2.58), gestational hypertension (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.06–1.11), and obstetric hemorrhage (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.04–1.10) during the COVID-19 pandemic [16].

However, studies on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on CHD and other birth defects in newborns are limited. Although COVID-19 no longer constitutes a public health emergency of international concern, it is now an established and ongoing health problem. We should pay close attention to the short- and long-term effects of the COVID-19 epidemic. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the variations in the incidence of CHD before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in a large, population-based retrospective observational study.

2.1 Study Design and Participants

We performed a population-based observational study using Network Platform for Congenital Heart Diseases (NPCHD) data. Supported by the National 12th 5-Year Science and Technology Major Project of China, the National Comprehensive Hospital of Health (NPCHD) is a neonatal CHD screening, diagnosis and treatment surveillance system that includes 517 hospitals in eastern Chinese cities. All the newborns underwent pulse oximetry monitoring combined with cardiac murmur auscultation performed by trained medical staff in the first 6 h to 72 h after birth, and all the newborns’ parents provided informed consent before participating in the screening campaigns for CHD. Newborns with positive screening results were offered further examination. The final diagnosis was based on echocardiography and confirmed by an experienced pediatrician. All the patients with CHD were reported to have NPCHD. The platform commits to reducing mortality and improving the prognosis in children with CHD and is responsible for the quality control of screening and skills training of primary care physicians.

The study consisted of all children born alive in seven representative cities between 01 September 2019, and 31 December 2021. The Ethics Committee of Children’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine approved this retrospective study (2023-IRB-0139-P-01) and waived the requirement for informed consent.

Before and after childbirth, all pregnant women and their families were provided with health education about CHD by trained and qualified clinicians, including the basic concepts and risks of CHD and the necessity, benefits, process, interpretation of results and limitations of CHD screening. All parents signed informed consent forms for their children. The results of screening, diagnosis and demographic characteristic information (e.g., infant sex, birth date, birthweight, gestational age, birthplace and maternal age) were collected and analyzed through the NPCHD.

In the neonate cohort, experienced pediatricians performed universal pulse oximetry plus cardiac murmur auscultation (namely, the dual-index method) for CHD screening. The test was administered to infants between 6 h and 72 h without oxygen or oxygenation ≥12 h. Cardiac murmur auscultation was performed by a trained pediatrician with a stethoscope suitable for infants in a quiet room before pulse oximetry measurement to ensure that the result of cardiac murmur auscultation was not affected by environmental noise or the result of pulse oximetry measurement. Cardiac murmur auscultation was performed using Levine’s grading system for systolic cardiac murmurs. Then, a trained nurse or pediatrician performed pulse oximetry screening with a pulse oximeter and a multisite reusable sensor to measure oxygen saturation (SpO2) from the infants’ right hand and food. Pulse oximetry was repeated 4 h later by the pediatrician if the first pulse oximeter oxygen saturation measurement was between 90% and 95%.

A screening result was considered positive if the murmur was equal to or greater than grade II (a faint murmur heard immediately); an SpO2 of less than 95% was obtained both on the right hand and on either foot on two measurements separated by 4 h; a difference between the two extremities was more than 3% on two measures separated by 4 h; or any measure was less than 90% [17,18].

Newborns screened as positive were recommended to be referred for echocardiography. Patient clinical information was uploaded to the NPCHD. An experienced cardiologist diagnosed the patients secondarily based on echocardiography. We used the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Edition (ICD-10) for CHD diagnosis.

We excluded cardiac physiological changes: (1) patent foramen ovale (PFO); (2) patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) less than 3 mm in diameter or PDA in preterm infants; (3) atrial septal defect (ASD) less than 5 mm in diameter; (4) echocardiographic maximum instantaneous gradient <20 mmHg in pulmonary stenosis (PS) or aortic stenosis (AoS) that does not expand with age; (5) physiological stenosis of the left and right pulmonary arteries; or (6) simple bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) without stenosis or regurgitation [19].

The NPCHD is responsible for the organization and coordination of neonatal CHD screening, diagnosis, treatment, follow-up and referral, as well as information management. Training and on-site supervision are implemented at least twice a year for relevant pediatricians and nurses. The NPCHD regularly examines the reports and data from all partner hospitals. Questionable reports or data were returned for supplementation or correction.

In total, this study included 492,662 newborns. Considering the COVID-19 infection prevention and control program in China, we hypothesized that children born in and beyond September 2020 will be more affected by the pandemic, with gestational age week 3 occurring after 31 December 2019; of those, children es born between September 2020 and December 2020 will be most severely affected, with gestational age 3 occurring during the most severe phase of the pandemic. The newborns were divided into three groups: newborns born before September 2020 were in the non-exposed group, newborns born between September 2020 and December 2020 were in the early-epidemic group, and newborns born after December 2020 were in the late-epidemic group.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (International Business Machines Corporation, New York, NY, USA) version 20.0 was used for descriptive analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to display the birth prevalence of CHD and its subtypes. The chi-square test was used to detect associations in categorical data and to identify differences in birth incidence. A 2-sided p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

We included 492,662 newborns who underwent CHD screening and were born between January 2019 and December 2021 in seven representative cities. Of the 492,662 newborns, 3115 (6.32‰) were diagnosed with CHD after positive screening results (Table 1). The primary clinical data of these patients were uploaded to the NPCHD. There were 1055 patients in the non-exposure group, 572 in the early pandemic group and 1488 in the late pandemic group. The maternal age did not significantly differ among the three groups or in the male/female ratio of children with CHD. The period from 2019 to 2021 witnessed a slight decrease in the gestation period from 38.37 ± 2.00 weeks to 38.04 ± 2.26 weeks. Moreover, the birthweight decreased from 3271.36 ± 612.21 g to 3211.77 ± 655.21 g. The proportion of confirmed CHD diagnoses as a percentage of the overall number of confirmed cases fluctuated in various municipalities before and after the pandemic.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics.

| No Exposure (n = 1055) | Early in the Pandemic (n = 572) | Late in the Pandemic (n = 1488) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, y | 29.69 ± 5.04 | 29.74 ± 4.66 | 29.81 ± 4.96 | |

| Gestation period, w | 38.37 ± 2.00 | 38.10 ± 2.06 | 38.04 ± 2.26** | |

| Birthweight, g | 3271.36 ± 612.21 | 3232.35 ± 645.34 | 3211.77 ± 655.21* | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 493 | 283 | 681 | |

| Female | 562 | 289 | 807 | |

| District | ||||

| Ningbo | 256 (24.3) | 155 (27.1) | 425 (28.6)* | |

| Huzhou | 113 (10.7) | 43 (7.5) | 119 (8.0) | |

| Jiaxing | 167 (15.8) | 85 (14.9) | 171 (11.5)* | |

| Shaoxing | 182 (17.3) | 152 (26.6)* | 454 (30.5)* | |

| Zhoushan | 41 (3.9) | 26 (4.5) | 55 (3.7) | |

| Taizhou | 235 (22.3) | 89 (15.6)* | 163 (11.0)# | |

| Lishui | 61 (5.8) | 22 (3.8) | 101 (6.8)# | |

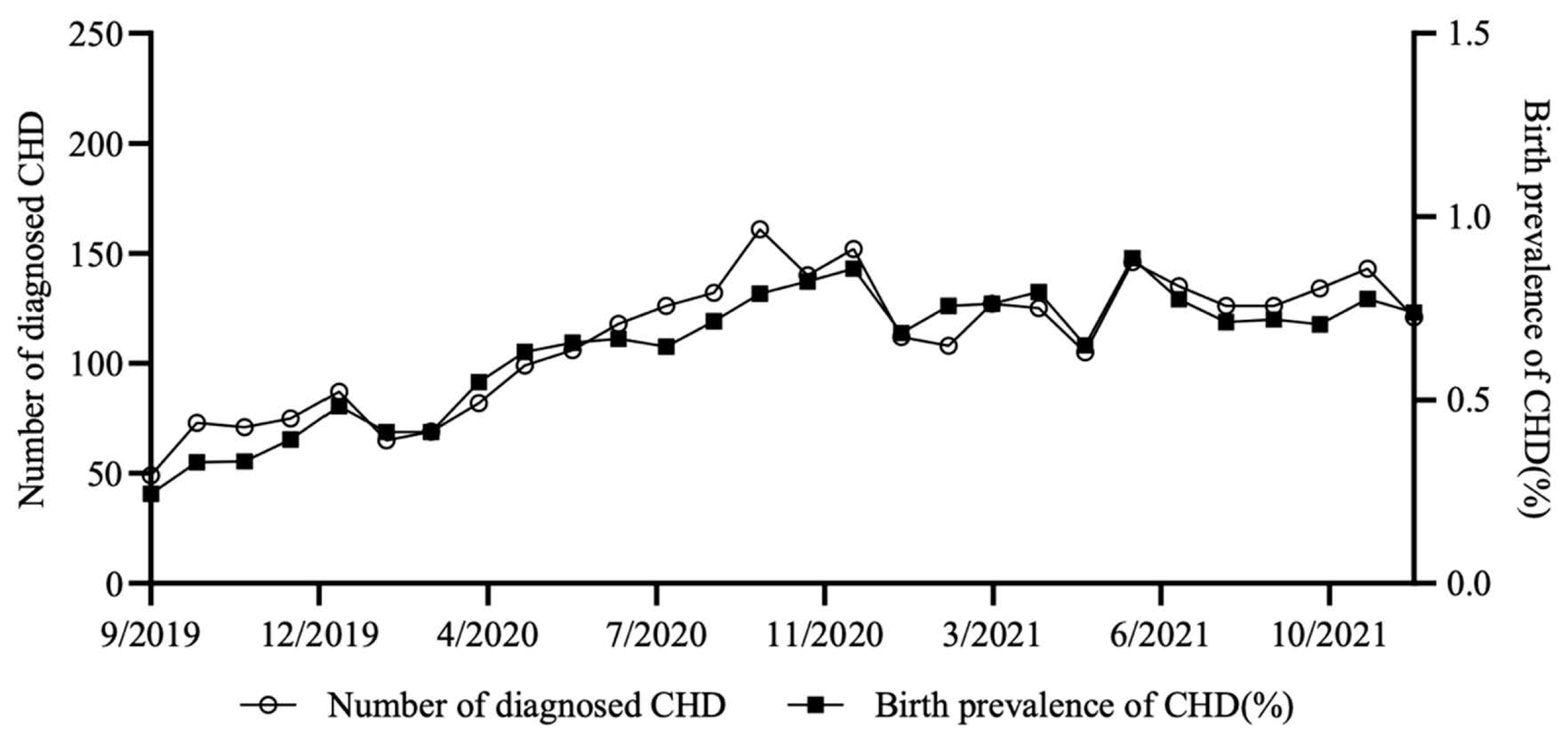

As shown in Fig. 1, there is a significant upward trend in the incidence of CHD during 2020, with the incidence in December 2020 (0.858%) being 1.78 times the incidence in January 2020 (0.483%), a difference of 37.5 per 1000 newborns in absolute terms. In 2021, the second year after the outbreak of COVID-19, the incidence of CHD declines in fluctuation, but remains at a high level (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Temporal trends of CHD in seven representative cities of China from 2019.9 to 2021.12.

There was a significant increase in the total proportion of newborns with CHD born to pregnant women whose first trimester occurred in the early stage of the pandemic (7.78 per 1000 births) compared to that of newborns born before the pandemic (4.86 per 1000 births) (χ2 = 83.815, p < 0.001) (Table 2). The total proportion of newborns with CHD has declined slightly as the pandemic has gone from major outbreak to normalized management (7.36 per 1000 births) (χ2 = 1.245, p = 0.265). Significant differences were found in 7 cities. The increase in the incidence of CHD in the early pandemic group compared with that in the pre-pandemic group was the lowest in Huzhou (5.84 per 1000 births vs 5.58 per 1000 births) (χ2 = 1.359, p = 0.244). Based on the number of people diagnosed with COVID-19 by the Zhejiang Provincial Health Commission and the residential population of each city published in the Announcement of the Seventh National Population Census of Zhejiang Province, Huzhou city had the lowest COVID-19 incidence rate (2.97 per 10,000 population) during the major outbreak of COVID-19 [20].

Table 2: The CHD birth prevalence among 7 administrative districts of China.

| Ningbo | Huzhou | Jiaxing | Shaoxing | Zhoushan | Taizhou | Lishui | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Exposure (n = 1055) | Number of diagnosed CHD | 256 | 113 | 167 | 182 | 41 | 235 | 61 | 1055 |

| Number of live births | 53,506 | 23,833 | 39,975 | 28,995 | 3561 | 49,113 | 18,020 | 217,003 | |

| Birth prevalence of CHD (/1000) | 4.78 | 4.74 | 4.18 | 6.28 | 11.51 | 4.78 | 3.39 | 4.86 | |

| Early in the Pandemic (n = 572) | Number of diagnosed CHD | 155 | 43 | 85 | 152 | 26 | 89 | 22 | 572 |

| Number of live births | 21,745 | 7366 | 12,570 | 10,518 | 1771 | 14,449 | 5137 | 73,556 | |

| Birth prevalence of CHD (/1000) | 7.13* | 5.84 | 6.76* | 14.45* | 14.68 | 6.16* | 4.28 | 7.78* | |

| Late in the Pandemic (n = 1488) | Number of diagnosed CHD | 425 | 119 | 171 | 454 | 55 | 163 | 101 | 1488 |

| Number of live births | 59,390 | 21,376 | 33,818 | 29,363 | 4426 | 40,838 | 12,892 | 202,103 | |

| Birth prevalence of CHD (/1000) | 7.16* | 5.57 | 5.06 | 15.46* | 12.43 | 3.99# | 7.83#* | 7.36* |

3.3 Incidence of Specific CHD Subtypes

The birth prevalence of specific CHD subtypes before and during the pandemic in eastern Chinese cities is shown in Table 3. The incidence of common CHD was significantly greater during the pandemic, with the incidence of ASD increasing from 3.991 per 1000 births in the prepandemic period to 4.717 per 1000 births in the early stage of the pandemic (χ2 = 6.980, p = 0.008); the incidence of VSD increased from 1.650 per 1000 births to 3.508 per 1000 births (χ2 = 89.622, p < 0.001); and the prevalence of PDA increased from 1.889 per 1000 births to 4.486 per 1000 births (χ2 = 145.849, p < 0.001) (Table 3). In regard to complex types of CHD, there was a statistically significant difference in the incidence of PS birth between the pre-pandemic group (0.014 per 1000 births) and the early pandemic group (0.095 per 1000 births) (χ2 = 10.561, p = 0.001). The incidence of PDA decreased significantly in the later stages of the pandemic (3.518 per 1000 births) (χ2 = 13.442, p < 0.001), and the incidence of other CHD subtypes decreased slightly.

Table 3: The birth prevalence of specific CHD subtypes in eastern China.

| No Exposure (n = 1055) | Early in the Pandemic (n = 572) | Late in the Pandemic (n = 1488) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Birth Prevalence (/1000) | Cases | Birth Prevalence (/1000) | Cases | Birth Prevalence (/1000) | |

| ASD | 866 | 3.991 | 347 | 4.717* | 936 | 4.631* |

| VSD | 358 | 1.650 | 258 | 3.508* | 633 | 3.132* |

| PDA | 410 | 1.889 | 330 | 4.486* | 711 | 3.518*# |

| AVSD | 3 | 0.014 | 2 | 0.027 | 3 | 0.015 |

| TGA | 1 | 0.005 | 1 | 0.014 | 0 | 0.000 |

| TOF | 10 | 0.046 | 6 | 0.082 | 7 | 0.035 |

| PS | 3 | 0.014 | 7 | 0.095* | 16 | 0.079* |

In the present study, we selected seven geographically representative municipalities for retrospective analysis. The birth prevalence of CHD and its specific subtypes before and after the COVID-19 pandemic were quantified by analyzing clinical data from the NPCHD, 492,662 newborns and 3115 CHD individuals. We defined the start of the exposure window as the first day of the third week of pregnancy, based on evidence that cardiac development is initiated at gastrulation at the beginning of the third week of human development [21]. Previous literatures have associated increased maternal heat exposure and air pollution during early pregnancy with a higher risk of CHD [22,23].

According to the descriptive statistics of the general data, we found that the mean gestational age, based on the last menstrual period, decreased by less than half a week between 2019 (38.37 weeks) and 2021 (38.04 weeks). Additionally, the mean birth weight decreased sparingly between the three years. According to the data of the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics, birth weight decreased 16 g among term births, and the mean gestational length decreased by more than 2 days from 1990 to 2005 in the U.S [24]. Moreover, preterm birth rates have increased significantly worldwide over the past decade [25]. An observational study between 01 January 2012, and 31 December 2018, in China noted an increase in preterm births for both singleton and multiple pregnancies (8.8% increase; annual rate of increase [ARI] 1.3 [95% CI 0.6 to 2.1]), related to advanced maternal age at delivery, maternal complications, and multiple pregnancies [26]. Our study revealed a downward trend in birth weight and gestational age in the population of newborns with CHD, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the CHD birth incidence (4.86 per 1000 births) in 2019 in eastern China was relatively higher than the national average (4.09 per 1000 births) in 2011. The incidence of CHD during the perinatal period in 2000 was 1.14 per 1000 births, and an upward trend was maintained over the next decade [27]. A meta-analysis (n = 130,758,851) reported that the incidence of CHD in Asia [9.342/1000 (95% CI 8.072–10.704)] was the highest among geographical regions in 2010–2017, which was greater than that in our study [28]. However, between 2017 and 2021, an observational study (n = 801,831) conducted in Shanghai found that the birth incidence of CHD was 4.54 per 1000 births in the coastal city of eastern China [29]. As a result, the birth incidence of CHD in eastern China is slightly lower than the Asian average and is on the rise.

We found a significant increase in the incidence of CHD at birth in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before the pandemic (χ2 = 83.815, p < 0.001). This phenomenon is consistent with previous findings of increased adverse pregnancy outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic, which are possibly related to the reallocation of resources, increased psychological pressure, and increased socioeconomic deprivation during the pandemic [30,31]. The interaction of multiple environmental and genetic factors has been shown to be involved in the development of CHD [32]. Between 2007 and 2012, a population-based cohort study (n = 2,419,651) conducted in California revealed that an increased social deprivation index was associated with a greater incidence of CHD [33]. Another meta-analysis reported that maternal psychological stress and stressful life events during pregnancy may slightly increase the risk of CHD in offspring [34]. Furthermore, maternal obesity, diabetes, alcohol consumption, tobacco use and medication exposure in the first trimester have been repeatedly recognized as potential risk factors for CHD [35]. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a large and sudden shock to the world economy [36]. According to data released by China’s National Bureau of Statistics, gross domestic product (GDP) growth for 2020 as a whole fell by 3.8 percent compared with that of the previous year, and GDP fell by 6.8 percent year-on-year in the first quarter [37]. Additionally, social distancing was one of the signature strategies used to contain the spread of the disease during the COVID-19 pandemic [38]. To achieve ‘zero’ transmission, China implemented stringent social distancing measures, including stay-at-home orders and strict access controls across apartment complexes and subdistricts, which may have amplified indirect adverse effects. A cross-sectional study assessed COVID-19-related health worries and current mental health symptoms in 1123 perinatal women and reported 36.4% of participants had clinically significant levels of depression, 22.7% had generalized anxiety, and 10.3% had post-traumatic stress disorder; these percentages are higher than pre-pandemic levels [39]. In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, women have poorer socioeconomic status, greater psychological stress and less access to medical care due to their assumed roles at home and gender discrimination in society [40,41,42,43]. Moreover, we found that the incidence of morbidities decreased as the impact of the pandemic waned and socioeconomic conditions improved. Therefore, we considered the COVID-19 pandemic to be an indirect risk factor for an increased incidence of CHD.

In our study, the distribution of most CHD subtypes in eastern China differed from that in the world, as reported in previous studies. The worldwide reported birth prevalence of the three most common CHD subtypes was as follows: VSD, 2.62 per 1000 live births; ASD, 1.64 per 1000 live births; and PDA, 0.87 per 1000 live births, which are all less common than those in China. ASD is the most common subtype of CHD in eastern China. Additionally, relatively rare complex CHD subtypes, such as TAGs, have a higher incidence of births worldwide than in eastern China, which may be associated with ethnic, socioeconomic, and environmental differences and with prenatal screening and medical interventions [28].

Our study has several limitations. First, observational database studies based on true-world clinical practice could be limited by the lack of direct control, heterogeneity of the populations and unmeasured confounders such as maternal health, air pollution, and healthcare access. Second, we artificially set grouping standards between the early and late stages of the pandemic, which may have resulted in bias in the research data and results. Third, we do not have standardized scales to assess the extent of the impact of the pandemic on people, which has led us to estimate only the correlation between the COVID-19 pandemic and the incidence rate of CHD. We will conduct prospective studies to explore this further in the future.

Due to the comprehensive coverage of the newborn screening programme for CHD, the birth prevalence of CHD in 7 cities of China was found to be relatively accurate. There was a significant increase in the incidence of CHD at birth in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before the pandemic, and the incidence of CHD decreased as the impact of the pandemic waned and socioeconomic conditions improved. Additionally, the distribution of most CHD subtypes in China differs from that in the world. In summary, birth defects during major public health emergencies should be given attention and prioritized. Our study provides positive evidence for controlling birth defects by guaranteeing women’s basic labor remuneration and medical care in the event of a major public health emergency.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Central Guiding Fund for Local Science and Technology Development Projects (No. 2023ZY1058) and the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 82270309), both awarded to Weize Xu.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, Lanqing Qu; methodology, writing—review and editing, Jinbiao Zhang; formal analysis, Wei Jiang and Jiayu Zhang; data curation, Die Li, Wei Cheng, Linghua Tao, Hongdan Zhu, Jing Li, Min Xue, Feng Chen, and Cuicui Xu; conceptualization, supervision, Qiang Shu and Weize Xu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: The Ethics Committee of Children’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine approved this retrospective study (2023-IRB-0139-P-01) and waived the requirement for informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mitchell SC , Korones SB , Berendes HW . Congenital heart disease in 56,109 births. Incidence and natural history. Circulation. 1971; 43( 3): 323– 32. doi:10.1161/01.cir.43.3.323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. van der Linde D , Konings EEM , Slager MA , Witsenburg M , Helbing WA , Takkenberg JJM , et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 58( 21): 2241– 7. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhao QM , Liu F , Wu L , Ma XJ , Niu C , Huang GY . Prevalence of congenital heart disease at live birth in China. J Pediatr. 2019; 204: 53– 8. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.08.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. GBD 2017 Congenital Heart Disease Collaborators . Global, regional, and national burden of congenital heart disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020; 4( 3): 185– 200. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30402-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. United Nations . The sustainable development goals report 2021. New York, NY, USA: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Statistics Division; 2021. [Google Scholar]

6. Fisseha S , Sen G , Ghebreyesus TA , Byanyima W , Diniz D , Fore HH , et al. COVID-19: the turning point for gender equality. Lancet. 2021; 398( 10299): 471– 4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01651-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Azcona G , Bhatt A , Encarnacion J , Plazaola-Castaño J , Seck P , Staab S , et al. From insights to action: gender equality in the wake of COVID-19. New York, NY, USA: UN Women; 2020. [Google Scholar]

8. Burki T . The indirect impact of COVID-19 on women. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020; 20( 8): 904– 5. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30568-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. De Paz Nieves C , Gaddis I , Muller M . Gender and COVID-19: what have we learnt, one year later? Washington, DC, USA: World Bank; 2021. Report No.: 9709. [Google Scholar]

10. Chmielewska B , Barratt I , Townsend R , Kalafat E , van der Meulen J , Gurol-Urganci I , et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2021; 9( 6): e759– 72. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00079-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wastnedge EAN , Reynolds RM , van Boeckel SR , Stock SJ , Denison FC , Maybin JA , et al. Pregnancy and COVID-19. Physiol Rev. 2021; 101( 1): 303– 18. doi:10.1152/physrev.00024.2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chan CS , Kong JY , Sultana R , Mundra V , Babata KL , Mazzarella K , et al. Optimal delivery management for the prevention of early neonatal SARS-CoV-2 infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2024; 41( 12): 1625– 33. doi:10.1055/a-2253-5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Lucas DN , Bamber JH . Pandemics and maternal health: the indirect effects of COVID-19. Anaesthesia. 2021; 76( Suppl 4): 69– 75. doi:10.1111/anae.15408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Simpson AN , Snelgrove JW , Sutradhar R , Everett K , Liu N , Baxter NN . Perinatal outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2021; 4( 5): e2110104. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Salvatore CM , Han JY , Acker KP , Tiwari P , Jin J , Brandler M , et al. Neonatal management and outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: an observation cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020; 4( 10): 721– 7. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30235-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Molina RL , Tsai TC , Dai D , Soto M , Rosenthal N , Orav EJ , et al. Comparison of pregnancy and birth outcomes before vs during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022; 5( 8): e2226531. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.26531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hu XJ , Ma XJ , Zhao QM , Yan WL , Ge XL , Jia B , et al. Pulse oximetry and auscultation for congenital heart disease detection. Pediatrics. 2017; 140( 4): e20171154. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhao QM , Ma XJ , Ge XL , Liu F , Yan WL , Wu L , et al. Pulse oximetry with clinical assessment to screen for congenital heart disease in neonates in China: a prospective study. Lancet. 2014; 384( 9945): 747– 54. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60198-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Pan F , Li J , Lou H , Li J , Jin Y , Wu T , et al. Geographical and socioeconomic factors influence the birth prevalence of congenital heart disease: a population-based cross-sectional study in Eastern China. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2022; 47( 11): 101341. doi:10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2022.101341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Communiqué on the main data of the seventh population census of Zhejiang province 2021 . [cited 2023 Oct 12]. Available from: https://tjj.zj.gov.cn/art/2021/5/13/art_1229129205_4632764.html. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

21. Buijtendijk MFJ , Barnett P , van den Hoff MJB . Development of the human heart. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2020; 184( 1): 7– 22. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang W , Spero TL , Nolte CG , Garcia VC , Lin Z , Romitti PA , et al. Projected changes in maternal heat exposure during early pregnancy and the associated congenital heart defect burden in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019; 8( 3): e010995. doi:10.1161/JAHA.118.010995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ma Z , Li W , Yang J , Qiao Y , Cao X , Ge H , et al. Early prenatal exposure to air pollutants and congenital heart disease: a nested case-control study. Environ Health Prev Med. 2023; 28: 4. doi:10.1265/ehpm.22-00138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Donahue SMA , Kleinman KP , Gillman MW , Oken E . Trends in birth weight and gestational length among singleton term births in the United States: 1990–2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 115( 2): 357– 64. doi:10.1097/aog.0b013e3181cbd5f5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chawanpaiboon S , Vogel JP , Moller AB , Lumbiganon P , Petzold M , Hogan D , et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019; 7( 1): e37– 46. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30451-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Deng K , Liang J , Mu Y , Liu Z , Wang Y , Li M , et al. Preterm births in China between 2012 and 2018: an observational study of more than 9 million women. Lancet Glob Health. 2021; 9( 9): e1226– 41. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00298-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. The Chinese National Report on Birth Defects 2012. [cited 2023 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.gov.cn/gzdt/2012-09/12/content_2223371.htm. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

28. Liu Y , Chen S , Zühlke L , Black GC , Choy MK , Li N , et al. Global birth prevalence of congenital heart defects 1970–2017: updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 260 studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2019; 48( 2): 455– 63. doi:10.1093/ije/dyz009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ma X , Tian Y , Ma F , Ge X , Gu Q , Huang M , et al. Impact of newborn screening programme for congenital heart disease in Shanghai: a five-year observational study in 801,831 newborns. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023; 33: 100688. doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Jamieson DJ , Rasmussen SA . An update on COVID-19 and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022; 226( 2): 177– 86. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2021.08.054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ciapponi A , Berrueta M , Argento FJ , Ballivian J , Bardach A , Brizuela ME , et al. Safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Saf. 2024; 47( 10): 991– 1010. doi:10.1007/s40264-024-01458-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. van der Bom T , Zomer AC , Zwinderman AH , Meijboom FJ , Bouma BJ , Mulder BJM . The changing epidemiology of congenital heart disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011; 8( 1): 50– 60. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2010.166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Peyvandi S , Baer RJ , Chambers CD , Norton ME , Rajagopal S , Ryckman KK , et al. Environmental and socioeconomic factors influence the live-born incidence of congenital heart disease: a population-based study in California. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020; 9( 8): e015255. doi:10.1161/JAHA.119.015255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Gu J , Guan HB . Maternal psychological stress during pregnancy and risk of congenital heart disease in offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021; 291: 32– 8. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Boyd R , McMullen H , Beqaj H , Kalfa D . Environmental exposures and congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2022; 149( 1): e2021052151. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-052151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Oncology TL . Pandemics and the health of a nation. Lancet Oncol. 2021; 22( 1): 1. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30748-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Stable Recovery of the National Economy in 2020 Better Than Expected Fulfilment of the Main Objectives. [cited 2023 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-01/18/content_5580658.htm. [Google Scholar]

38. Delgado MCM . COVID-19 pandemic. In: Hidalgo J , Rodríguez-Vega G , Pérez-Fernández J , editors. Chapter 4—COVID-19: a family’s perspective. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2022. p. 41– 51. [Google Scholar]

39. Liu CH , Erdei C , Mittal L . Risk factors for depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms in perinatal women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2021; 295: 113552. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Dias FA , Chance J , Buchanan A . The motherhood penalty and the fatherhood premium in employment during COVID-19: evidence from the United States. Res Soc Stratif Mobil. 2020; 69: 100542. doi:10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Salanti G , Peter N , Tonia T , Holloway A , White IR , Darwish L , et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated control measures on the mental health of the general population: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2022; 175( 11): 1560– 71. doi:10.7326/M22-1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Anderson KE , McGinty EE , Presskreischer R , Barry CL . Reports of forgone medical care among US adults during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021; 4( 1): e2034882. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Almeida M , Shrestha AD , Stojanac D , Miller LJ . The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women’s mental health. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020; 23( 6): 741– 8. doi:10.1007/s00737-020-01092-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools