Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Evaluating the Association between Acute Postoperative Enteral Nutrition and Clinical Outcomes in Infants after Congenital Heart Surgery: A Retrospective Cohort Study

1 Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Saitama Children’s Medical Center, Saitama, 330-8777, Japan

2 Department of Critical Care Medicine, Osaka City General Hospital, Osaka, 534-0021, Japan

* Corresponding Author: Shun Maki. Email:

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(5), 547-558. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.072277

Received 23 August 2025; Accepted 04 November 2025; Issue published 30 November 2025

Abstract

Background: Considering the limited evidence for acute postoperative nutritional therapy for congenital heart disease (CHD), this study evaluated the effects of achieving enteral nutrition (EN) targets in the acute postoperative phase on clinical outcomes in infants after congenital heart surgery. Methods: This retrospective cohort study, conducted in a multivalent pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), enrolled infants aged ≤6 months following congenital heart surgery between April 2021 and March 2023. Based on the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition guidelines, the EN target was defined as two-thirds of the resting energy expenditure with a protein intake of 1.5 g/kg/day. Clinical outcomes of patients who did and did not achieve the EN target by postoperative day (POD) 7 were compared. The association between EN target achievement and ventilator-free days within 28 days (28-day VFDs) was evaluated. Results: Of 151 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 97 (64%) who achieved the EN target by POD7 had significantly more 28-day VFDs (median [interquartile range]: 25.0 days [24.0, 26.0] vs. 19.0 days [5.3, 21.8], p < 0.001), a shorter length of stay in the PICU, and a lower nosocomial infection incidence than those who did not. In the multivariate analysis, EN target achievement was independently associated with more 28-day VFDs. Conclusions: This is the first study to demonstrate an association between achieving a specific EN target during the acute postoperative phase and improved clinical outcomes in infants undergoing congenital heart surgery. These findings underscore the importance of meticulous postoperative nutritional management in this vulnerable population and highlight the need for prospective interventional studies.Keywords

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is a common congenital anomaly, accounting for approximately 1% of births globally [1]. Patients with CHD often have both cardiac and non-cardiac problems; owing to their vulnerabilities, they have significantly higher morbidity and mortality risks than the general population [2] and therefore require meticulous medical management in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). The complexity of the treatment and care of CHD and its comorbidities result in excessive medical resource consumption, high costs, and prolonged PICU stays, causing significant public health challenges [3,4]. Hence, improving medical management for this population is crucial for enhancing patient outcomes in the PICU and reducing the economic burden on the healthcare system.

Malnutrition prevalence in children with CHD is high. A cohort study reported an acute malnutrition prevalence rate of 51.2% in patients undergoing congenital heart surgery [5]. Preoperative malnutrition is associated with worse postoperative outcomes [6]; moreover, energy requirements further increase in the acute postoperative phase after congenital heart surgery [7]. However, during the acute postoperative phase, hemodynamic instability, concerns about increased gastrointestinal complications, fluid restrictions, and procedures often lead to inadequate nutritional intake [8]. The resulting malnutrition can worsen postoperative outcomes and negatively impact subsequent growth and development [9].

Guidelines for the general population in the PICU recommend the early initiation of enteral nutrition (EN) and the achievement of acute-phase nutritional targets [10,11]. However, no specific recommendations exist for patients after congenital heart surgery. Despite a reported association between achieving acute-phase nutritional targets and improved outcomes among the general PICU population [12,13], the studies included few postoperative patients with CHD. Previous studies targeting cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) patients have reported the association between early EN or the use of high-energy nutritional formulas and improved outcomes [14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. However, the nutritional target in the acute postoperative phase after congenital heart surgery has not been investigated and no studies have demonstrated an association between achieving specific nutritional targets and clinical outcomes. Thus, although these patients are a critically ill population in the PICU and nutritional management in the acute postoperative phase is important, evidence for specific nutritional management strategies remains insufficient.

This study addressed these gaps, investigating the association between achieving specific calorie and protein intake targets through EN during the acute postoperative phase and clinical outcomes in infants aged ≤6 months after congenital heart surgery.

This single-center retrospective cohort study was conducted in the 14-bed multivalent PICU of an urban regional tertiary hospital in Saitama, Japan.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Saitama Children’s Medical Center (refer-ence number: 2023-04-003; approval date: 9 November 2023) and complied with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki principles. The Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects waived the requirement for informed consent, given the use of non-personally identifiable data from electronic patient records.

Patients admitted to the PICU following cardiac surgery for CHD between 1 April 2021, and 31 March 2023, were eligible. Patients aged ≤6 months at PICU admission were included because they are generally exclusively fed baby formula or breast milk; therefore, the calculation of energy intake is more accurate than that in children fed solid foods. Furthermore, infants have a higher mortality rate than other age groups [21]. Patients for whom preoperative height and weight data were unavailable, those who were offered baby food, and those who were already scheduled for a tracheostomy owing to severe airway disease before congenital heart surgery were excluded.

Postoperative EN was initiated at the discretion of the attending intensivist, without a standardized protocol. The attending intensivist at our institution determined the safety of initiating EN by referencing clinical parameters such as hemodynamic stability, inotrope dosage, lactate levels, and central venous oxygen saturation. Early trophic feeding (10–20 mL/kg/day) was initiated within 48 h post-surgery if possible but was delayed in cases requiring high doses of inotropes or in patients with single-ventricle circulation and unstable systemic blood flow. The decision between intermittent or continuous administration of the nutritional formula was left to the discretion of the attending physician. Once EN was initiated, the rate was advanced while monitoring for signs of feeding intolerance (e.g., gastric residuals, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal distension). Abdominal imaging using X-rays was reviewed every morning by the intensivist and a radiologist, and ultrasound screening for necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) was performed as needed. For infants aged ≤6 months, breast milk was preferentially selected, and if unavailable, standard concentration formula was used; high-concentration nutrition was not used during the acute postoperative phase. The target EN intake during the acute postoperative phase was set at two-thirds of the resting energy expenditure (REE) estimated using the Schofield weight–height equation, with a protein intake of 1.5 g/kg/day, in accordance with the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) guidelines [11,22]. Because parenteral nutrition was rarely used within the first postoperative week, parenteral calorie intake was not considered. Patients were subsequently classified into achievement and non-achievement groups according to whether the EN target was reached by postoperative day (POD) 7.

Comorbidities included chromosomal abnormalities and pre-existing gastrointestinal diseases. Body mass index (BMI) for age z-score was calculated using CHILD METRICS to evaluate nutritional status [20]. Preoperative mechanical ventilation was defined as intubation for respiratory or circulatory failure, excluding cases of scheduled intubation for surgery or examinations. The Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery (RACHS)-1 category is a classification system used to stratify the complexity of congenital heart surgery procedures [23,24]. For analysis, patients were categorized into two groups (RACHS-1 category <3 and RACHS-1 category ≥3). Open-chest procedures, including delayed sternal closure, were performed within 1 week postoperatively, and blood transfusion volumes, lactate levels, and muscle relaxant use were assessed within the first 24 h postoperatively. The vasoactive–inotropic score (VIS) quantifies the use of multiple vasoactive drugs [25]. We defined VIS as the maximum score within 24 h postoperatively. Early EN—initiated within 48 h of PICU admission—has been proven feasible in critically ill children [26].

Patient background (age, sex, body weight, BMI, comorbidities, and preoperative mechanical ventilation), perioperative (RACHS-1 category, cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) time, aortic clamping time, VIS, lactate level, blood transfusion volume, and open-chest procedure), nutritional (timing of EN initiation, administration route, and energy and protein intakes on POD7), and clinical outcome data were collected.

The primary outcome was the number of ventilator-free days within 28 days (28-day VFDs) postoperatively. VFDs were defined as the number of days alive and free from mechanical ventilation; patients who remained mechanically ventilated and those who died were coded as having 0 VFDs [27]. In a previous study on nutritional therapy in general PICU patients, 28-day VFDs were evaluated as a clinical outcome [13]. The secondary outcomes were mortality within 28 days, length of stay (LOS) in the PICU, gastrointestinal complications by POD7, and new infections bacteriologically proven during the PICU stay. At our institution, prophylactic antibiotics are typically used for 48 h postoperatively to prevent surgical site infections, with patients under open chest management receiving antibiotics for up to 48 h following delayed sternal closure.

Patient characteristics are described using medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables and numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Between-group differences were compared using the Mann–Whitney U and Fisher’s exact tests. To identify independent factors associated with 28-day VFDs, various modeling strategies were employed. The zero-inflated negative binomial regression (ZINB) model was ultimately adopted (Supplementary Material). The ZINB model accounts for the excess number of zero values and overdispersion in count data. Intuitively, it separates the outcome into two processes: one determining whether patients have zero VFDs (e.g., died or remained intubated) and another modeling the distribution of VFDs among patients with non-zero values. This approach allows a more accurate estimation than conventional count models when many zero values are present. Adhering to the commonly recommended guideline in regression analyses, which suggests including one variable for every 15 cases, we planned to incorporate 10 variables into our model. To ensure a sufficiently robust sample size, data were retrospectively collected, aiming for a target of 150 cases to support the statistical validity of our analysis. To evaluate the independent association between EN target achievement and 28-day VFDs, we adjusted for potential confounders identified in previous studies [12,13,20] and other clinically relevant factors. These included age, BMI, comorbidities, preoperative mechanical ventilation, RACHS-1 category, CPB time, VIS, blood transfusion volume, and open chest procedure. The variance inflation factors for all variables included in the model ranged from 1.1 to 2.3, indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data contained no missing values. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

We conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding patients with RACHS-1 category 6 procedures, who were present only in the non-achievement group, to evaluate the robustness of the primary findings.

3.1 Comparison of Patients with or without EN Target Achievement

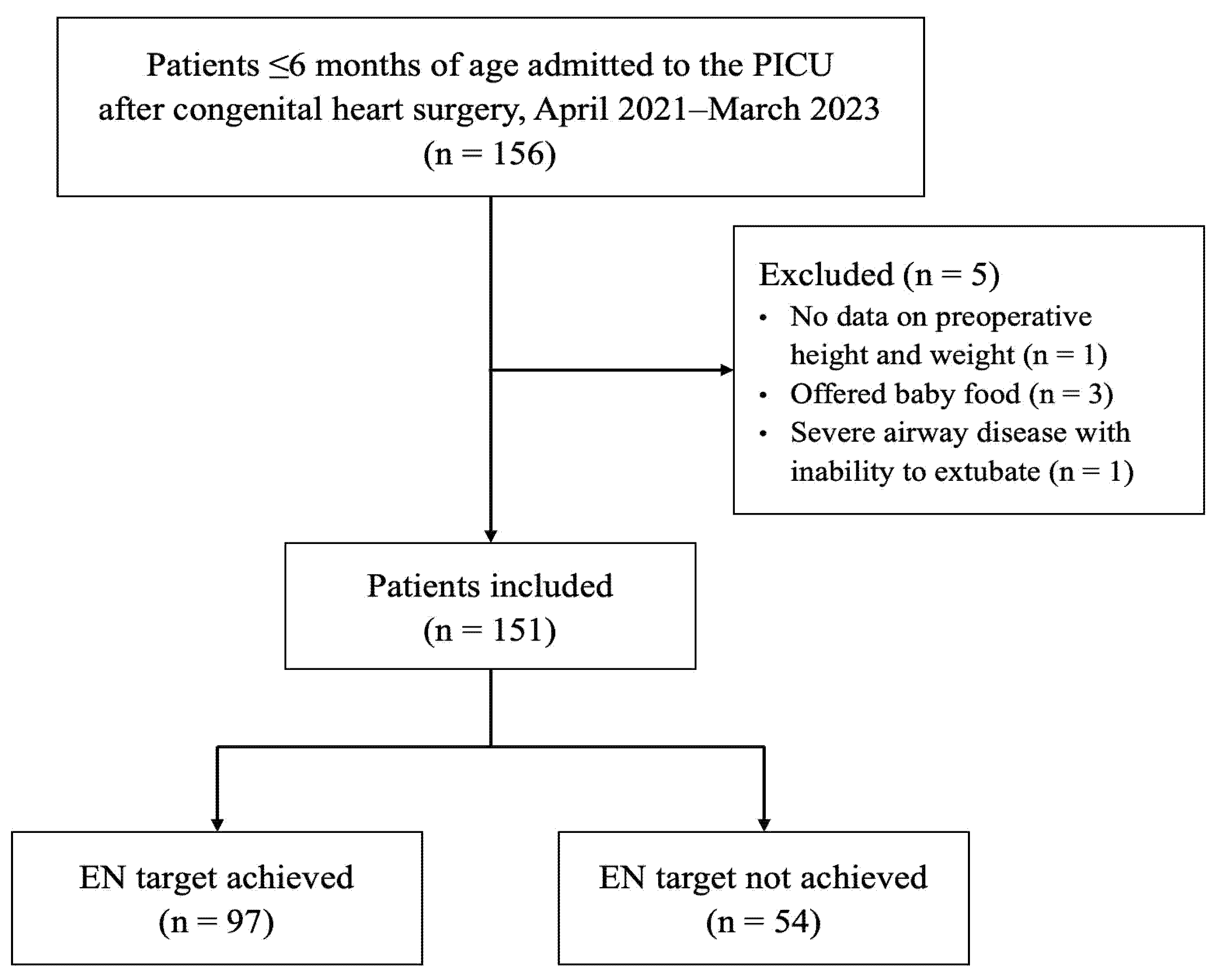

During the study period, 156 patients aged ≤6 months admitted to the PICU after cardiac surgery were identified; 151 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. Of these, 97 patients (64%) achieved the EN target by POD7, whereas 54 patients did not (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Flowchart of patient selection. PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; EN, enteral nutrition.

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics. Age, body weight, and comorbidities did not differ significantly between the groups. A BMI for age z-score <−2 as an indicator of poor nutritional status was observed in 44% and 48% of patients in the achievement and non-achievement groups, respectively (p = 0.78). Although the difference was not significant, the proportion of patients with a RACHS-1 category ≥3 was greater in the non-achievement group than in the achievement group. The surgical procedures performed in this cohort corresponding to each RACHS-1 category are presented in Table S1. The number of patients requiring preoperative mechanical ventilation, CPB time, the proportion of patients who underwent an open-chest procedure by POD7, and the VIS, lactate level, and blood transfusion volume within 24 h postoperatively were significantly higher in the non-achievement group than in the achievement group.

Table 1: Patient demographics and surgical characteristics.

| Characteristics | EN Target Achieved (n = 97) | EN Target not Achieved (n = 54) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | 1 (0, 4) | 1 (0, 3) | 0.29 |

| Sex, male | 52 (54%) | 40 (74%) | 0.02 |

| Body weight (kg) | 3.7 (3.0, 5.4) | 3.3 (2.9, 4.5) | 0.24 |

| BMI | 13.0 (11.7, 14.5) | 12.4 (11.4, 13.8) | 0.15 |

| BMI for age z-score <−2 | 43 (44%) | 26 (48%) | 0.78 |

| Comorbidities | 21 (22%) | 8 (15%) | 0.42 |

| Preoperative mechanical ventilation | 4 (4%) | 12 (22%) | 0.001 |

| RACHS-1 category | <0.001 | ||

| 1 | 6 (6%) | 1 (2%) | |

| 2 | 29 (30%) | 10 (19%) | |

| 3 | 45 (46%) | 19 (35%) | |

| 4 | 17 (18%) | 10 (19%) | |

| 5 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 6 | 0 (0%) | 14 (26%) | |

| RACHS-1 category ≥3 | 62 (64%) | 43 (80%) | 0.07 |

| CPB time (min) | 118 (0, 189) | 210 (139, 350) | <0.001 |

| Aortic clamping time (min) | 48 (0, 121) | 77 (0, 120) | 0.15 |

| VISb | 9.0 (6.0, 10.0) | 9.5 (7.0, 13.0) | 0.01 |

| Lactate (mmol/L)b | 1.9 (1.4, 3.0) | 4.3 (2.7, 6.9) | <0.001 |

| Blood transfusion volume (mL/kg)c | 23 (12, 37) | 55 (24, 114) | <0.001 |

| Open chest procedure within POD 7 | 5 (5%) | 35 (65%) | <0.001 |

Table 2 presents the patients’ nutritional data. Over 90% of the patients in both groups received early EN. Energy and protein intake on POD7 were significantly higher in the achievement group than in the non-achievement group. Patients who achieved the EN target had higher 28-day VFDs after surgery (median [IQR], 25.0 days [24.0, 26.0] vs. 19.0 days [5.3, 21.8], p < 0.001) and a shorter PICU LOS (median [IQR], 8.0 days [6.0, 10.0] vs. 18.5 days [12.0, 28.3], p < 0.001). Mortality within 28 days and gastrointestinal complications within POD7 did not differ significantly between the groups. The incidence of nosocomial infection during the PICU stay was significantly lower in the achievement group than in the non-achievement group (Table 3).

Table 2: Patient nutritional data.

| Characteristics | EN Target Achieved (n = 97) | EN Target not Achieved (n = 54) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early enteral nutrition | 95 (98%) | 49 (91%) | 0.11 |

| Energy intake on POD 7 (kcal/kg/day) | 96 (86, 106) | 35 (20, 53) | <0.001 |

| Protein intake on POD 7 (g/kg/day) | 2.1 (1.8, 2.3) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.2) | <0.001 |

| Tube feeding on POD 7 | 51 (53%) | 46 (85%) | <0.001 |

| Post-pyloric feeding on POD 7 | 3 (3%) | 3 (6%) | 0.02 |

Table 3: Patient outcomes with and without EN target achievement.

| Characteristics | EN Target Achieved (n = 97) | EN Target not Achieved (n = 54) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| 28-day ventilator-free days after surgery | 25.0 (24.0, 26.0) | 19.0 (5.3, 21.8) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation duration (day) | 3.0 (2.0, 4.0) | 8.5 (6.0, 18.5) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay in the PICU (days) | 8.0 (6.0, 10.0) | 18.5 (12.0, 28.3) | <0.001 |

| Death within 28 days | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) | 0.24 |

| Gastrointestinal complications within POD 7 | 5 (5%) | 6 (11%) | 0.31 |

| Intestinal emphysema | 4 (4%) | 6 (11%) | 0.19 |

| Bloody stool | 2 (2%) | 3 (6%) | 0.50 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0.77 |

| New infection during PICU stay | 10 (10%) | 17 (32%) | 0.002 |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 1 (1%) | 5 (9%) | 0.04 |

3.2 Factors Associated with 28-Day VFDs

Factors influencing 28-day VFDs were assessed using a multivariate ZINB model. In the count model, EN target achievement was significantly associated with an increase in 28-day VFDs. Preoperative mechanical ventilation and increased postoperative blood transfusion volume were significantly associated with decreased 28-day VFDs. In the zero-inflation model, only comorbidities were significantly linked to a decreased probability of zero counts. EN target achievement was not associated with the probability of zero counts (Table 4).

Table 4: Factors associated with ventilator-free days within 28 days after congenital heart surgery.

| Part | Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | z-Value | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count model | (Intercept) | 3.167 | 0.084 | 37.76 | <0.001 |

| Age (months) | −0.006 | 0.012 | −0.50 | 0.61 | |

| BMI for age z-score <−2 | 0.015 | 0.039 | 0.37 | 0.71 | |

| Comorbidities | −0.045 | 0.052 | −0.87 | 0.39 | |

| Preoperative mechanical ventilation | −0.195 | 0.078 | −2.51 | 0.01 | |

| RACHS-1 category ≥3 | −0.087 | 0.047 | −1.86 | 0.06 | |

| CPB time (min) | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.57 | 0.57 | |

| VISb | −0.008 | 0.005 | −1.75 | 0.08 | |

| Blood transfusion volume (mL/kg)c | −0.002 | 0.0006 | −3.42 | <0.001 | |

| Open chest procedure within POD 7 | 0.046 | 0.064 | 0.73 | 0.47 | |

| EN target achievement | 0.228 | 0.054 | 4.25 | <0.001 | |

| Zero-inflation model | (Intercept) | −3.102 | 1.758 | −1.76 | 0.08 |

| Age (months) | −0.160 | 0.410 | −0.39 | 0.70 | |

| BMI for age z-score <−2 | −0.352 | 1.030 | −0.34 | 0.73 | |

| Comorbidities | 2.968 | 1.399 | 2.12 | 0.03 | |

| Preoperative mechanical ventilation | 1.765 | 0.971 | 1.82 | 0.07 | |

| RACHS-1 category ≥3 | 0.734 | 1.437 | 0.51 | 0.61 | |

| CPB time (min) | −0.006 | 0.004 | −1.52 | 0.13 | |

| VISb | −0.012 | 0.069 | −0.17 | 0.86 | |

| Blood transfusion volume (mL/kg)c | 0.067 | 0.007 | 1.01 | 0.31 | |

| Open chest procedure within POD 7 | 1.477 | 1.178 | 1.25 | 0.21 | |

| EN target achievement | −19.89 | 4255 | −0.005 | >0.99 |

Multiple analyses using zero-inflated negative binomial regression were performed to identify the factors independently associated with ventilator-free days within 28 days. The variables included in the model were age, BMI, comorbidities, preoperative mechanical ventilation, RACHS-1 category, CPB time, VIS, blood transfusion volume, open chest procedure, and EN target achievement.

3.3 Sensitivity Analysis Excluding RACHS-1 Category 6

When patients with RACHS-1 category 6 procedures (n = 14) were excluded, the association between EN target achievement and 28-day VFDs remained significant. Other covariates that had shown significance in the primary analysis, such as preoperative mechanical ventilation, remained significant, whereas several lost significance. Details are presented in Table S2.

In this retrospective study of acute postoperative EN therapy following congenital heart surgery in infants aged ≤6 months, the EN target was achieved by 64% of patients by POD7. Those meeting the EN target showed significantly higher 28-day VFDs, reduced mechanical ventilation duration, and shorter PICU LOS, with fewer new infections than those who did not. Achieving the EN target was independently associated with higher 28-day VFDs, even after adjusting for patient background and disease severity. Preoperative mechanical ventilation, postoperative transfusion volume, and comorbidities were also independently associated with 28 VFDs; however, the achievement of the EN target is a potentially modifiable factor. The robustness of the association between EN target achievement and 28-day VFDs was confirmed in a sensitivity analysis excluding RACHS-1 category 6 patients, mitigating concerns about potential bias due to a lack of overlap across surgical risk strata.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the association between EN target achievement in the acute postoperative phase and clinical outcomes in patients after congenital heart surgery. Prospective studies in the general PICU population have reported the benefits of achieving acute-phase nutritional targets [12,13]. In these studies, achieving calorie and protein intake targets within 7 days of PICU admission was associated with a decrease in mortality; however, these studies included only a few patients who underwent congenital heart surgery. Conversely, previous studies on EN for patients after congenital heart surgery have been limited to those focusing on early EN or high-energy nutritional formulas. Regarding early EN, Kalra et al. and Du et al. showed that initiating EN within 6 h post-surgery shortens the duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU stay in neonates and infants compared with that initiated 24–48 h post-surgery [14,15]. In systematic reviews by Sigal et al. and Ni et al., the use of high-energy EN has been reported to increase calorie and protein intake without increasing nutritional intolerance [16,17]. Aryafar et al. and Zhang et al. reported that high-energy nutrition promotes postoperative weight gain in infants [18,19]. Additionally, in a randomized controlled trial targeting infants aged <6 months conducted by Ni et al., the high-energy nutrition group had a higher calorie intake, lower incidence of pneumonia, and shorter duration of mechanical ventilation than the regular-energy nutrition group; however, it did not compare outcomes based on whether nutritional targets were achieved during the specific postoperative acute period [20]. Thus, no previous study has demonstrated an association between achieving specific targets for duration, calories, and protein intake and clinical outcomes during the acute postoperative phase. In the present study, the EN target was clearly defined in the acute postoperative phase based on the ASPEN guidelines [11]. Although the appropriate nutritional target for postoperative patients with CHD with increased energy expenditure remains unclear [8,28], this study’s findings are notable because they indicate that clinical outcomes in pediatric CICU patients can be improved by providing essential nutritional intake while preventing underfeeding and overfeeding, similar to those in the general PICU population.

In the present study, the mechanisms whereby achieving nutritional targets were associated with favorable clinical outcomes may be partially explained by the nutrition-associated suppression of the adverse effects of poor prognostic factors in critically ill patients, including ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW) and infection-related complications. ICU-AW is caused by enhanced catabolism owing to inflammatory responses and stress, malnutrition, muscle weakness resulting from prolonged bed rest, and medications, including steroids, in critically ill patients. This condition is associated with worsened outcomes, such as prolonged mechanical ventilation, longer ICU LOS, and increased mortality [29,30]. Few reports on ICU-AW in pediatric populations are available, and its frequency and risk factors are unknown. In children, owing to the absence of a clear ICU-AW definition, the diagnosis is often based on clinical findings such as muscle weakness and difficulty weaning from mechanical ventilation. Factors associated with ICU-AW in children include infections, renal replacement therapy, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation management [30]. However, nutritional therapy in the acute phase of critical illness reduces ICU-AW incidence and improves extubation rates in adults [31,32], which may explain the effectiveness of postoperative nutritional therapy after congenital heart surgery. Additionally, adequate protein intake suppresses muscle loss [33]; thus, specifying the target protein consumption besides calories may have contributed to favorable outcomes through ICU-AW prevention. However, because ICU-AW was not evaluated in the present study, direct associations with these mechanisms could not be demonstrated.

Infectious complications in critically ill patients are associated with worse clinical outcomes, including increased mortality and prolonged PICU LOS [34,35]. Conversely, EN in critically ill patients is associated with fewer infectious complications, attributed to the maintenance of intestinal mucosa and immune function and bacterial translocation prevention [36,37]. Through these mechanisms, in our patients, the reduction in infectious complications by EN may have indirectly contributed to the improvement in 28-day VFDs—a measure of clinical outcome—as patients who achieved the EN target had a significantly lower frequency of infectious complications than the non-achievement group.

Concerns exist regarding the increased incidence of gastrointestinal complications associated with EN in the acute postoperative phase after congenital heart surgery. Previous reports have suggested that single ventricle circulation, duct-dependent circulation, and low birth weight are risk factors for NEC in infants with CHD [38,39]. However, the evidence is inconsistent, with some reports showing no clear association between EN and NEC development [40]. EN can be initiated in patients who are hemodynamically stable, even with inotropic agents [10,41], and nutritional interventions and protocol implementation have been associated with decreased gastrointestinal complications [42]. Herein, although the condition in the non-achievement group tended to be more severe, early EN was initiated in >90% of patients in both groups, and the frequency of gastrointestinal complications did not differ significantly between the groups. Thus, advancing EN therapy during the acute postoperative phase after congenital heart surgery may not necessarily increase gastrointestinal complication risk; however, it is important to identify patients at high risk for gastrointestinal complications. Combining nutrition protocols and support teams with parenteral nutrition might be beneficial for patients at intestinal ischemia risk, such as those with severe heart failure or single ventricle conditions.

This study has some limitations. First, as a single-center study, it is subject to potential selection bias and its generalizability is limited. As the characteristics and treatment strategies of patients with CHD vary across institutions and nutritional practices differ considerably among facilities and countries, validation of these results in multicenter and international cohorts is warranted. Second, measurement bias from the retrospective design could have influenced the accuracy of data on gastric residual volume, EN intolerance, and subjective indicators like abdominal distention, impacting nutrient intake and gastrointestinal complication assessments. Third, inconsistent nutritional management owing to non-standardized EN protocols and physician discretion might have skewed the results. Fourth, REE was calculated using a formula instead of the recommended indirect calorimetry, which is challenging to implement in pediatric cases; thus, estimations were necessary [43]. Fifth, although the EN target in this study was defined according to ASPEN guidelines, infants after congenital heart surgery may have elevated metabolic demands compared with the general PICU population. Thus, our EN target may have underestimated the true nutritional requirements. In this case, some patients in the achievement group may still have received insufficient intake, potentially leading to an overestimation of the proportion of patients with adequate nutrition. Conversely, the observed association between EN achievement and improved outcomes might be conservative and achieving the true requirements could yield an even greater benefit. Future studies are warranted to determine the optimal energy and protein targets in this population. Sixth, as this study was limited to patients aged ≤6 months, future studies should encompass all patients undergoing CHD surgery. Seventh, owing to the retrospective study design, we could not demonstrate a causal relationship between achieving postoperative EN targets and improved outcomes. Eighth, although we adjusted for surgical complexity and perioperative severity indicators, residual confounding cannot be excluded. In particular, patients achieving EN targets tended to have lower severity; therefore, EN achievement may partly represent a surrogate marker of lower illness severity rather than a direct causal factor. To determine whether EN achievement itself exerts a causal effect on clinical outcomes, interventional studies are warranted. To address these limitations, a future multicenter prospective study with standardized nutritional protocols is needed. Finally, this study focused on short-term outcomes, particularly 28-day VFDs. Longer-term endpoints, such as growth, neurodevelopment, and rehospitalization, were not evaluated, although they represent important clinical indicators of early nutritional status. Future studies are warranted to investigate the relationship between postoperative nutritional achievement and these broader developmental outcomes.

Meeting acute postoperative EN targets following congenital heart surgery was independently linked with longer 28-day VFDs in infants ≤6 months old. This implies that achieving at least a certain level of EN target may improve clinical outcomes. We recommend broader prospective interventional studies to determine the optimal energy and protein targets for these patients and explore the mechanisms by which nutritional therapy improves outcomes.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This study was funded by a grant from Saitama Children’s Medical Center (2023-04-003).

Author Contributions: Shun Maki, Satoshi Nakano and Taiki Haga contributed to the conception and design of the study. Shun Maki, Satoshi Nakano and Taiki Haga contributed to the acquisition and analysis of the data. Shun Maki, Satoshi Nakano, Taiki Haga, Takehiro Niitsu and Ikuya Ueta contributed to the interpretation of the data. Shun Maki wrote the first draft of the article, and Satoshi Nakano and Taiki Haga revised the article. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Saitama Children’s Medical Center (reference number: 2023-04-003; approval date: 9 November 2023) and complied with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki principles. The Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects waived the requirement for informed consent, given the use of non-personally identifiable data from electronic pa-tient records.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/chd.2025.072277/s1.

References

1. Pierpont ME , Brueckner M , Chung WK , Garg V , Lacro RV , McGuire AL , et al. Genetic basis for congenital heart disease: revisited: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2018; 138( 21): e653– 711. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000606 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Gilboa SM , Salemi JL , Nembhard WN , Fixler DE , Correa A . Mortality resulting from congenital heart disease among children and adults in the United States, 1999 to 2006. Circulation. 2010; 122( 22): 2254– 63. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.947002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Edelson JB , Rossano JW , Griffis H , Quarshie WO , Ravishankar C , O’Connor MJ , et al. Resource use and outcomes of pediatric congenital heart disease admissions: 2003 to 2016. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021; 10( 4): e018286. doi:10.1161/JAHA.120.018286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Boerman GH , Haspels HN , de Hoog M , Joosten KF . Characteristics of long-stay patients in a PICU and healthcare resource utilization after discharge. Crit Care Explor. 2023; 5( 9): e0971. doi:10.1097/CCE.0000000000000971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Toole BJ , Toole LE , Kyle UG , Cabrera AG , Orellana RA , Coss-Bu JA . Perioperative nutritional support and malnutrition in infants and children with congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis. 2014; 9( 1): 15– 25. doi:10.1111/chd.12064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ross FJ , Radman M , Jacobs ML , Sassano-Miguel C , Joffe DC , Hill KD , et al. Associations between anthropometric indices and outcomes of congenital heart operations in infants and young children: an analysis of data from the society of thoracic surgeons database. Am Heart J. 2020; 224: 85– 97. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2020.03.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Trabulsi JC , Irving SY , Papas MA , Hollowell C , Ravishankar C , Marino BS , et al. Total energy expenditure of infants with congenital heart disease who have undergone surgical intervention. Pediatr Cardiol. 2015; 36( 8): 1670– 9. doi:10.1007/s00246-015-1216-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kerstein JS , Klepper CM , Finnan EG , Mills KI . Nutrition for critically ill children with congenital heart disease. Nutr Clin Pract. 2023; 38( Suppl 2): S158– 73. doi:10.1002/ncp.11046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ravishankar C , Zak V , Williams IA , Bellinger DC , Gaynor JW , Ghanayem NS , et al. Association of impaired linear growth and worse neurodevelopmental outcome in infants with single ventricle physiology: a report from the pediatric heart network infant single ventricle trial. J Pediatr. 2013; 162( 2): 250– 6.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.07.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Tume LN , Valla FV , Joosten K , Jotterand Chaparro C , Latten L , Marino LV , et al. Nutritional support for children during critical illness: European society of pediatric and neonatal intensive care (ESPNIC) metabolism, endocrine and nutrition section position statement and clinical recommendations. Intensive Care Med. 2020; 46( 3): 411– 25. doi:10.1007/s00134-019-05922-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Mehta NM , Skillman HE , Irving SY , Coss-Bu JA , Vermilyea S , Farrington EA , et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the pediatric critically ill patient: society of critical care medicine and American society for parenteral and enteral nutrition. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017; 18( 7): 675– 715. doi:10.1097/pcc.0000000000001134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Misirlioglu M , Yildizdas D , Ekinci F , Ozgur Horoz O , Tumgor G , Yontem A , et al. Evaluation of nutritional status in pediatric intensive care unit patients: the results of a multicenter, prospective study in Turkey. Front Pediatr. 2023; 11: 1179721. doi:10.3389/fped.2023.1179721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Bechard LJ , Staffa SJ , Zurakowski D , Mehta NM . Time to achieve delivery of nutrition targets is associated with clinical outcomes in critically ill children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021; 114( 5): 1859– 67. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqab244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kalra R , Vohra R , Negi M , Joshi R , Aggarwal N , Aggarwal M , et al. Feasibility of initiating early enteral nutrition after congenital heart surgery in neonates and infants. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018; 25: 100– 2. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2018.03.127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Du N , Cui Y , Xie W , Yin C , Gong C , Chen X . Application effect of initiation of enteral nutrition at different time periods after surgery in neonates with complex congenital heart disease: a retrospective analysis. Medicine. 2021; 100( 1): e24149. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000024149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ni P , Wang X , Xu Z , Luo W . Effect of high-energy and/or high-protein feeding in children with congenital heart disease after cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pediatr. 2023; 182( 2): 513– 24. doi:10.1007/s00431-022-04721-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Singal A , Sahu MK , Trilok Kumar G , Kumar A . Effect of energy- and/or protein-dense enteral feeding on postoperative outcomes of infant surgical patients with congenital cardiac disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Clin Pract. 2022; 37( 3): 555– 66. doi:10.1002/ncp.10799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang H , Gu Y , Mi Y , Jin Y , Fu W , Latour JM . High-energy nutrition in paediatric cardiac critical care patients: a randomized controlled trial. Nurs Crit Care. 2019; 24( 2): 97– 102. doi:10.1111/nicc.12400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Aryafar M , Mahdavi M , Shahzadi H , Nasrollahzadeh J . Effect of feeding with standard or higher-density formulas on anthropometric measures in children with congenital heart defects after corrective surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2022; 76( 12): 1713– 8. doi:10.1038/s41430-022-01186-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ni P , Chen X , Zhang Y , Zhang M , Xu Z , Luo W . High-energy enteral nutrition in infants after complex congenital heart surgery. Front Pediatr. 2022; 10: 869415. doi:10.3389/fped.2022.869415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zheng G , Wang J , Chen P , Huang Z , Zhang L , Yang A , et al. Epidemiological characteristics and trends in postoperative death in children with congenital heart disease (CHD): a single-center retrospective study from 2005 to 2020. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2023; 18( 1): 165. doi:10.1186/s13019-023-02224-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Schofield WN . Predicting basal metabolic rate, new standards and review of previous work. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr. 1985; 39( Suppl 1): 5– 41. [Google Scholar]

23. Allen P , Zafar F , Mi J , Crook S , Woo J , Jayaram N , et al. Risk Stratification for Congenital Heart Surgery for ICD-10 Administrative Data (RACHS-2). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022; 79( 5): 465– 75. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.11.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Jenkins KJ , Gauvreau K , Newburger JW , Spray TL , Moller JH , Iezzoni LI . Consensus-based method for risk adjustment for surgery for congenital heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002; 123( 1): 110– 8. doi:10.1067/mtc.2002.119064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Gaies MG , Gurney JG , Yen AH , Napoli ML , Gajarski RJ , Ohye RG , et al. Vasoactive–inotropic score as a predictor of morbidity and mortality in infants after cardiopulmonary bypass. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010; 11( 2): 234– 8. doi:10.1097/pcc.0b013e3181b806fc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chellis MJ , Sanders SV , Webster H , Dean JM , Jackson D . Early enteral feeding in the pediatric intensive care unit. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1996; 20( 1): 71– 3. doi:10.1177/014860719602000171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Schoenfeld DA , Bernard GR . Statistical evaluation of ventilator-free days as an efficacy measure in clinical trials of treatments for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2002; 30( 8): 1772– 7. doi:10.1097/00003246-200208000-00016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Justice L , Buckley JR , Floh A , Horsley M , Alten J , Anand V , et al. Nutrition considerations in the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit patient. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2018; 9( 3): 333– 43. doi:10.1177/2150135118765881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Vanhorebeek I , Latronico N , Van den Berghe G . ICU-acquired weakness. Intensive Care Med. 2020; 46( 4): 637– 53. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-05944-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Field-Ridley A , Dharmar M , Steinhorn D , McDonald C , Marcin JP . ICU-acquired weakness is associated with differences in clinical outcomes in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016; 17( 1): 53– 7. doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000000538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Watanabe S , Hirasawa J , Naito Y , Mizutani M , Uemura A , Nishimura S , et al. Association between intensive care unit-acquired weakness and early nutrition and rehabilitation intensity in mechanically ventilated patients: a multicenter retrospective observational study. Cureus. 2023; 15( 4): e37417. doi:10.7759/cureus.37417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Brierley-Hobson S , Clarke G , O’Keeffe V . Safety and efficacy of volume-based feeding in critically ill, mechanically ventilated adults using the ‘protein & energy requirements fed for every critically ill patient every time’ (PERFECT) protocol: a before-and-after study. Crit Care. 2019; 23( 1): 105. doi:10.1186/s13054-019-2388-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Nakanishi N , Matsushima S , Tatsuno J , Liu K , Tamura T , Yonekura H , et al. Impact of energy and protein delivery to critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. 2022; 14( 22): 4849. doi:10.3390/nu14224849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ping Kirk AH , Sng QW , Zhang LQ , Ming Wong JJ , Puthucheary J , Lee JH . Characteristics and outcomes of long-stay patients in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2018; 7( 1): 1– 6. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1601337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Hatachi T , Tachibana K , Takeuchi M . Incidences and influences of device-associated healthcare-associated infections in a pediatric intensive care unit in Japan: a retrospective surveillance study. J Intensive Care. 2015; 3: 44. doi:10.1186/s40560-015-0111-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Mehta NM , Bechard LJ , Cahill N , Wang M , Day A , Duggan CP , et al. Nutritional practices and their relationship to clinical outcomes in critically ill children—an international multicenter cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2012; 40( 7): 2204– 11. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31824e18a8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Heyland DK , Stephens KE , Day AG , McClave SA . The success of enteral nutrition and ICU-acquired infections: a multicenter observational study. Clin Nutr. 2011; 30( 2): 148– 55. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2010.09.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Jeffries HE , Wells WJ , Starnes VA , Wetzel RC , Moromisato DY . Gastrointestinal morbidity after Norwood palliation for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006; 81( 3): 982– 7. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.09.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Becker KC , Hornik CP , Cotten CM , Clark RH , Hill KD , Smith PB , et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis in infants with ductal-dependent congenital heart disease. Am J Perinatol. 2015; 32( 7): 633– 8. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1390349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Iannucci GJ , Oster ME , Mahle WT . Necrotising enterocolitis in infants with congenital heart disease: the role of enteral feeds. Cardiol Young. 2013; 23( 4): 553– 9. doi:10.1017/S1047951112001370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Panchal AK , Manzi J , Connolly S , Christensen M , Wakeham M , Goday PS , et al. Safety of enteral feedings in critically ill children receiving vasoactive agents. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016; 40( 2): 236– 41. doi:10.1177/0148607114546533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kaufman J , Vichayavilas P , Rannie M , Peyton C , Carpenter E , Hull D , et al. Improved nutrition delivery and nutrition status in critically ill children with heart disease. Pediatrics. 2015; 135( 3): e717– 25. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Jotterand Chaparro C , Moullet C , Taffé P , Laure Depeyre J , Perez MH , Longchamp D , et al. Estimation of resting energy expenditure using predictive equations in critically ill children: results of a systematic review. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2018; 42( 6): 976– 86. doi:10.1002/jpen.1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools