Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Artificial Neural Network-Based Risk Assessment for Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device Complications

1 School of Nursing, National Taipei University of Nursing and Health Sciences, Taipei City, 112303, Taiwan

2 Department of Nursing, MacKay Junior College of Medicine, Nursing, and Management, Taipei City, 112021, Taiwan

3 Department of Artificial Intelligence and Medical Application, MacKay Junior College of Medicine, Nursing, and Management, Taipei City, 112021, Taiwan

4 Cardiovascular Medicine, MacKay Memorial Hospital, Taipei City, 104217, Taiwan

5 Department of Medicine, MacKay Medical University, New Taipei City, 251404, Taiwan

6 Department of Electrical and Mechanical Technology, National Changhua University of Education Bao-Shan Campus, Changhua City, 500208, Taiwan

7 NCUE Alumni Association, National Changhua University of Education Jin-De Campus, Changhua County, Changhua City, 500207, Taiwan

* Corresponding Authors: Ying-Hsiang Lee. Email: ; Wei-Sho Ho. Email:

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(5), 601-612. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.072431

Received 27 August 2025; Accepted 04 November 2025; Issue published 30 November 2025

Abstract

Background: Cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) are essential for preventing sudden cardiac death in patients with cardiovascular diseases, but implantation procedures carry risks of complications such as infection, hematoma, and bleeding, with incidence rates of 3–4%. Previous studies have examined individual risk factors separately, but integrated predictive models are lacking. We compared the predictive performance and interpretability of artificial neural network (ANN) and logistic regression models to evaluate their respective strengths in clinical risk assessment. Methods: This retrospective study analyzed data from 180 patients who underwent cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) implantation in Taiwan between 2017 and 2018. To address class imbalance and enhance model training, the dataset was augmented to 540 records using the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE). A total of 13 clinical risk factors were evaluated (e.g., age, body mass index (BMI), platelet count, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR), hemoglobin (Hb), comorbidities, and antithrombotic use). Results: The most influential risk factors identified by the ANN model were platelet count, PT/INR, LVEF, Hb, and age. In the logistic regression analysis, reduced LVEF, lower hemoglobin levels, prolonged PT/INR, and lower BMI were significantly associated with an increased risk of complications. ANN model achieved a higher area under the curve (AUC = 0.952) compared to the logistic regression model (AUC = 0.802), indicating superior predictive performance. Additionally, the overall model quality was also higher for the ANN model (0.93) than for logistic regression (0.76). Conclusions: This study demonstrates that ANN models can effectively predict complications associated CIED procedures and identify critical preoperative risk factors. These findings support the use of ANN-based models for individualized risk stratification, enhancing procedural safety, improving patient outcomes, and potentially reducing healthcare costs associated with postoperative complications.Keywords

According to a US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the United States [1]. In Taiwan, cardiovascular disease is the second leading cause of death among Chinese people. In 2024, the standardized death rate per 100,000 populations in cardiovascular disease in Taiwan was 45.5 [2]. The cause of death associated with heart disease may be due to cardiomyopathy, arrhythmia, or sudden cardiac death.

Cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIED) are often implanted in patients with cardiovascular diseases to prevent sudden cardiac death [3]. However, the implantation procedure is invasive and can result in unwanted complications, such as infection, hematoma, subcutaneous emphysema, and pocket bleeding. The incidence rate of procedure-associated complications is about 3–4% [4,5]. These complications can cause pain, prolong hospital stay, and increase medical expenses. Thus, a preoperative risk assessment is important for preventing postoperative complications [6].

Several factors are associated with CIED procedure complications, including demographics (age, gender), body weight, comorbidities (e.g., diabetes mellitus [DM], renal insufficiency, end-stage renal disease [ESRD], heart failure), and fever and leukocytosis within 24 h before the procedure [7,8,9,10,11]. CIED-related complications are associated with technical factors, patient factors, and periprocedural factors [12,13]. well as postoperative monitoring and care [13,14,15]. Oral antithrombotic agents and corticosteroid use [16,17,18,19] are also associated with hematoma and pocket bleeding. However, most of these previous studies have investigated each complication and their respective risk factors separately, without an integrated analysis of the risks of multiple interacting factors for all CIED procedure complications.

Among the many quantitative analysis methods available, artificial neural network (ANN) models have gained increasing attention and have been used in a considerable number of clinical and nursing analysis and prediction applications. ANN can perform basic human brain functions, such as learning, memory, and induction. An ANN model is made up of many neurons, and the path of signal transmission between neurons is called a link. Every link has a weight value, which can be considered the impact of the variable. The neural network continuously adjusts weights through learning, and the process of adjusting the weights is the process of learning. Neural-like networks can construct non-linear models with high accuracy [20]. ANNs are widely used in the medical field and can be used for establishing predictive factors [21,22,23].

Imbalanced data is a common issue in medical research, particularly when adverse outcomes such as complications are relatively rare. This imbalance can limit the performance of machine learning models by providing insufficient training signals for the minority class, thereby increasing the risk of overfitting and reducing generalizability. To address this challenge, several techniques have been proposed in the literature, including synthetic class generation, the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE), stratified batch sampling, and ensemble learning approaches. In this study, we integrated ANN models with appropriate data balancing strategies to enhance predictive accuracy and model robustness in the context of complication risk following CIED procedures.

While logistic regression remains a widely used method for analyzing binary outcomes, it has limitations in modeling complex nonlinear relationships and interactions among predictors. Moreover, in scenarios with imbalanced or limited sample sizes, logistic models may produce unstable or biased estimates. Therefore, this study also compares the performance of logistic regression with that of ANN models to evaluate their respective strengths in identifying and interpreting risk factors for CIED-related complications. The comparative analysis aims to highlight the advantages of ANN in capturing intricate patterns within high-dimensional clinical data [24,25,26,27].

This study was a retrospective study utilizing secondary data analysis. The data were obtained from the electronic medical records of patients who underwent CIED implantation procedures at a hospital in Taiwan between July 2017 and July 2018. To address class imbalance in our dataset where complication cases were significantly fewer than non-complication cases, we applied the SMOTE. For each minority instance, we identified its k = 5 nearest neighbors and generated synthetic samples via linear interpolation. This process continued until the minority class accounted for 40% of the total dataset. Synthetic data were merged with original training data, while the test set remained untouched to preserve external validity. Overall, the sample size was expanded from 180 to 540 records in accordance with established modeling principles for ANN. This augmentation was aligned with the Events Per Variable (EPV) rule, which recommends a minimum of 10 outcome events per predictor to avoid model overfitting and ensure statistical stability [28,29].

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) patients aged 20 years or older, and (b) patients who were admitted for a CIED implantation procedure, including one of the following device types: permanent pacemaker (PPM), implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator (CRT-D), or cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker (CRT-P) (3) Patients with complete follow-up data for at least 12 months after the CIED implantation procedure. The exclusion criteria included the following: (a) patients with any signs of active infection prior to the procedure, including fever within 24 h or localized skin conditions such as pocket infection or cellulitis at the intended CIED implantation site; (b) diagnosis of a hematologic disorder (e.g., leukemia, lymphoma); (c) incomplete medical records, specifically missing key baseline laboratory results or imaging necessary for clinical assessment; (d) death occurring within 24 h after the CIED procedure, as outcomes could not be evaluated; (e) current use of chronic oral immunosuppressive therapy, which may confound post-procedural complication risk.

The study was approved by 17MMHIS054e. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The data were encoded and input into a computer and the data and patient privacy are protected by encryption. All research materials are for research use only and will be destroyed after the research is terminated.

Data on CIED implant procedure-related complications and potential risk factors for these complications were collected from the patients’ electronic medical records. The data showed that pocket hematomas, pocket bleeding, skin erosion, and subcutaneous emphysema were recorded within seven days of the procedure, and pocket infections were recorded within one year following the procedure. Data collected on the potential risk factors of CIED implant procedure-related complications according to the evidence-based clinical trial, literature review [7,8,9,10,11,16,17,18,19], and discussion process are shown in Table 1 and include age, gender, body mass index (BMI), non-permanent pacemaker (Non-PPM) CIED (including ICDs/CRT-Ds/CRT-Ps), antithrombotic agents, Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF), hemoglobin (Hb), prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR), platelet count, and comorbidities.

The data on comorbidities included the presence of diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HTN), chronic kidney disease (CKD; including the stage of disease), and structural heart disease (SHD).

Table 1: Attribute description.

| Attribute Name | Clinical Threshold | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Age in years | |

| Gender | Male/Female | |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 18.5 ≦ BMI < 24 kg/m | A value to calculated from height and weight to measure the patient’s degree of obesity |

| Antithrombotic agents | Treatment of antithrombotic agents, including: Antiplatelet agents, Anticoagulant | |

| Non-PPM CIED | Non-permanent pacemaker (Non-PPM) CIED (including ICDs/CRT-Ds/CRT-Ps) | |

| Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF) | 50%–70% | A physiological indicator that refers to the percentage of output per stroke in the end-diastolic volume of the ventricle |

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | Male:13.0–17.0 gm/dL Female: 12.0–16.0 gm/dL | A blood examination for judging of anemia |

| Prothrombin Time/International Normalized Ratio (PT/INR) | 0.8–1.2 | An indicator of coagulation function |

| Platelet Count | 150,000–450,000/μL | A blood examination for judging of coagulation function |

| Comorbidities | Including: diabetes mellitus (DM) hypertension (HTN), structure heart disease (SHD), chronic kidney disease, (CKD) | |

| Post-procedure complications | Including: skin erosion, pocket bleeding, pocket hematoma, pocket infection and subcutaneous emphysema |

2.4 Network Model and Logistic Model

As the ANN statistical analysis method was used for the prediction, the data were divided into two parts: training data and testing data. Data were collected from 540 patients, with 70% and 30% of the data being training and testing data, respectively. The model is first established with the training data, and then the testing data is substituted into the completed model to confirm the data and predictive power. The basic structure of the ANN comprises the input layer, hidden layer, and output layer [30]. The data characteristics and complex nonlinear relationships among input and output variables were examined and detected by adding hidden layers between the input/output layers.

Logistic regression is a widely used statistical method in medical research, particularly suitable for analyzing binary outcome variables, such as the presence or absence of complications. This method estimates the probability of an event based on a set of independent variables and provides interpretable results in the form of odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), which help quantify the strength and direction of each predictor’s effect. Given that the outcome variable in this study was binary (complication vs. no complication), logistic regression offered both robustness and interpretability for constructing a clinically relevant risk assessment model. Furthermore, the predictive performance of the logistic regression model was compared with that of the ANN model to evaluate their relative strengths and enhance the overall explanatory power of the findings.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). To identify significant predictors of complications following CIED implantation, both ANN and logistic regression models were developed. The predictive performance of both models was compared using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, with the area under the curve (AUC) serving as the key performance metric. ROC curves were plotted to visualize and compare model discrimination.

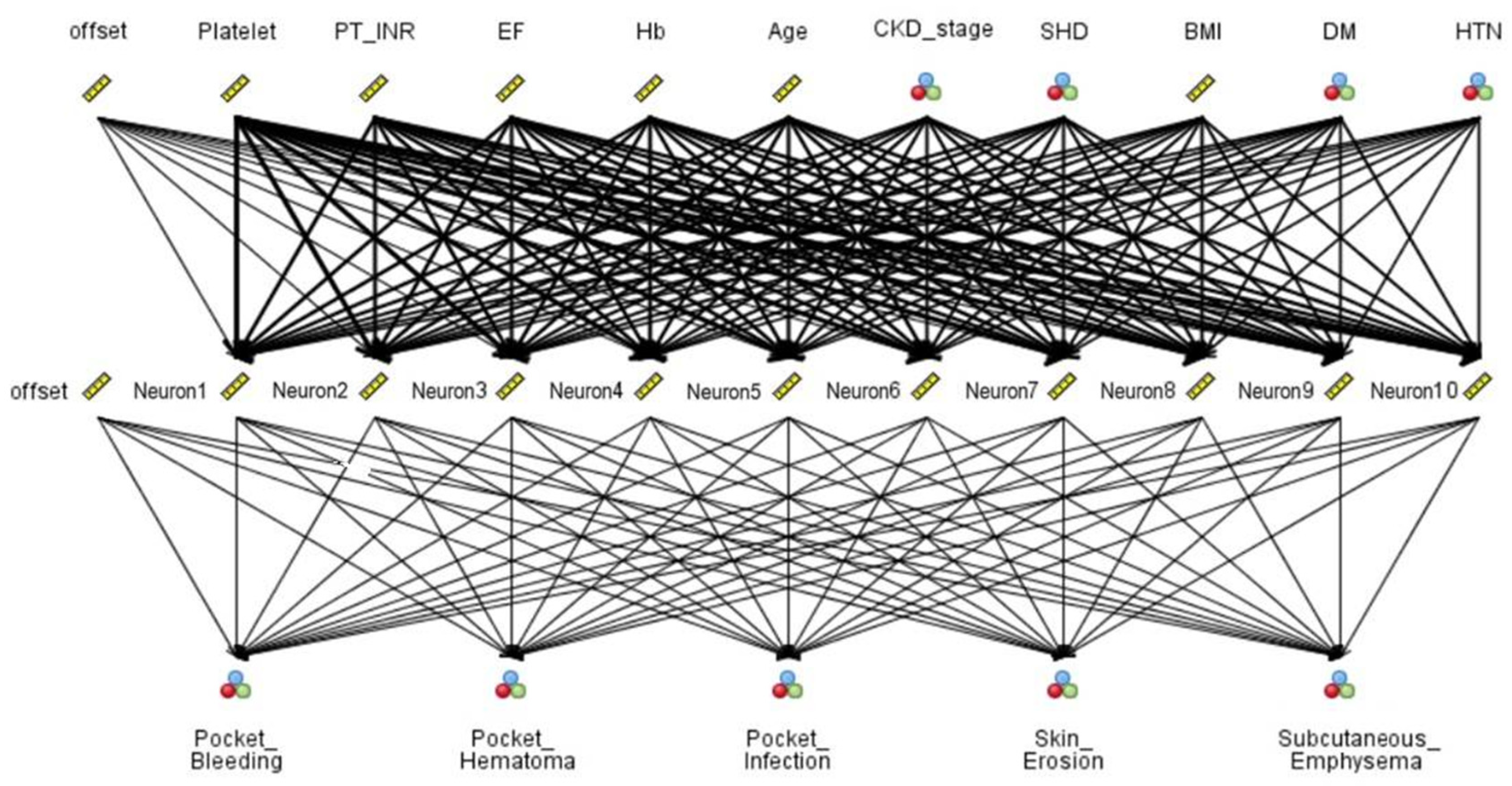

Data with 19 features were collected from 540 patients. Table 2 summarizes the top-ranked risk factors for five CIED-related complications as identified by the ANN model, based on each variable’s contribution to predictive accuracy. Distinct leading predictors were observed for each complication type. Platelet count was consistently identified as the most influential factor for skin erosion, pocket bleeding, and pocket hematoma, underscoring the key role of hemostasis in wound healing and post-procedural outcomes. For subcutaneous emphysema, the LVEF was the top-ranked predictor, suggesting that impaired cardiac function may increase the risk of tissue hypoperfusion. In contrast, pocket infection was most strongly associated with PT INR, indicating that patients with abnormal coagulation profiles may be more susceptible to infectious complications after CIED implantation. The ANN model, comprising 10 risk factors, a single hidden layer with 10 neurons, and five output nodes representing CIED-related complications: pocket bleeding, pocket hematoma, pocket infection, skin erosion, and subcutaneous emphysema. The network maps complex, nonlinear relationships between input variables and clinical outcomes in Fig. 1.

Table 2: Ranked importance of risk factors for each post-procedure complications in the ANN Model.

| Risk Factor | Post-Procedure Complications | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pocket Bleeding | Pocket Hematoma | Pocket Infection | Skin Erosion | Subcutaneous Emphysema | Total | |

| Platelet | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| PT INR | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| LVEF | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Hb | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| Age | 4 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

Figure 1: Artificial Neural Network (ANN) of risk factors associated with post-procedure complications.

Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify risk factors associated with complications following CIED procedures in Table 3. The results indicated that several variables demonstrated statistically significant associations (p < 0.05). Specifically, reduced LVEF (OR = 0.258, p = 0.018), lower Hb levels (OR = 0.422, p = 0.008), prolonged prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (PT INR) (OR = 4.137, p < 0.001), and decreased BMI (OR = 0.541, p = 0.034) were significantly associated with an increased risk of complications. These findings underscore the critical role of hemodynamic and coagulation factors in post-procedural outcomes. In addition, SHD (OR = 3.106, p = 0.001) and DM (OR = 0.387, p = 0.003) were also identified as significant predictors. In contrast, other variables such as age, gender, and comorbidities did not reach statistical significance (Table 3). These results highlight the importance of assessing cardiac function and coagulation status when evaluating the risk of adverse outcomes following CIED implantation.

Table 3: Logistic Regression Analysis of Risk Factors for CIED-Related Complications.

| Variable | P | OR | 95% CI (Lower–Upper) | PR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 83.5 | |||

| Age | 0.170 | 1.614 | 0.814–3.199 | |

| Gender | 0.271 | 1.278 | 0.506–1.211 | |

| BMI | 0.034* | 0.541 | 0.306–0.956 | |

| Antithrombotic Agents | 0.784 | 1.092 | 0.582–2.047 | |

| Non-PPM CIED | 0.826 | 1.079 | 0.547–2.129 | |

| LVEF | 0.018* | 0.285 | 0.101–0.805 | |

| Hb | 0.008* | 0.422 | 0.224–0.797 | |

| PT/INR | <0.001* | 4.137 | 2.271–7.536 | |

| Platelet Count | 0.169 | 1.537 | 0.833–2.834 | |

| Comorbidities | 0.594 | 1.35 | 0.447–4.083 | |

| DM | 0.003* | 0.387 | 0.208–0.720 | |

| HTN | 0.879 | 0.931 | 0.369–2.343 | |

| CKD | 0.062 | 0.537 | 0.416–1.021 | |

| SHD | 0.001* | 3.106 | 1.558–6.191 |

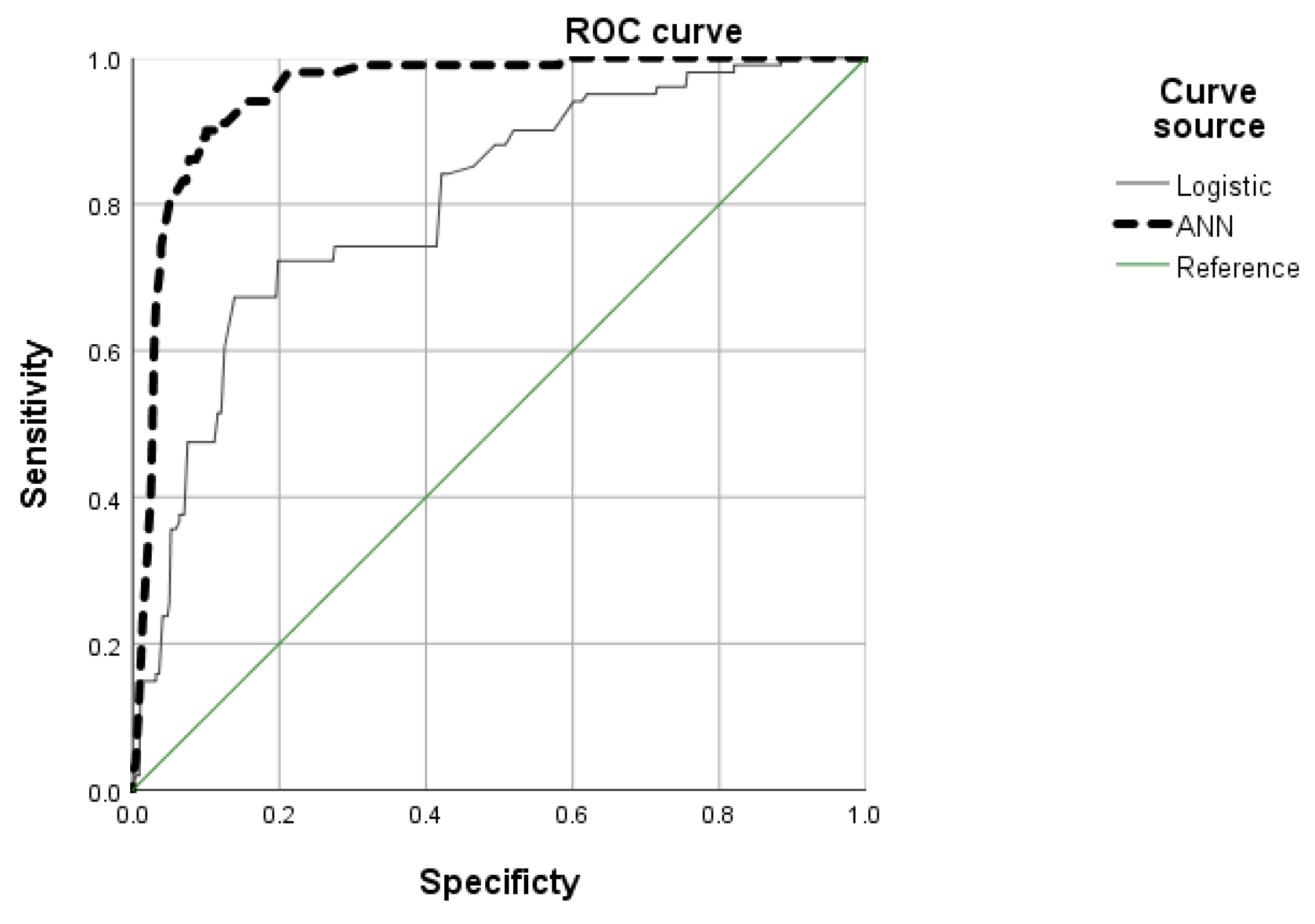

Compares the predictive performance of logistic regression and ANN models using ROC analysis in Table 4. The AUC was significantly higher for the ANN model (AUC = 0.952, 95% CI: 0.933–0.972, p < 0.001) compared to the logistic regression model (AUC = 0.802, 95% CI: 0.755–0.850, p < 0.001). The smaller standard error (SE = 0.010) for the ANN model further indicates greater precision and stability. These results suggest that the ANN model outperformed logistic regression in predicting CIED-related complications, offering superior discrimination and robustness.

Table 4: Model Performance Between Logistic Regression and ANN.

| Model | AUC | Std Error | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Logistic | 0.802 | 0.024 | 0.000* | 0.755 | 0.850 |

| ANN | 0.952 | 0.010 | 0.000* | 0.933 | 0.972 |

Fig. 2 illustrates the ROC curves comparing the classification performance of the ANN and logistic regression models in predicting complications following CIED implantation. The ROC curve plots sensitivity (true positive rate) against 1-specificity (false positive rate), and the AUC serves as a summary measure of overall model performance. The ANN model (thick dashed line) demonstrated superior discriminative ability, with an AUC of 0.952, as compared to the logistic regression model (solid line) with an AUC of 0.802. The greater curvature of the ANN line toward the top-left corner reflects improved sensitivity and specificity, suggesting that ANN provides a more accurate and robust prediction of CIED-related complications.

Figure 2: Area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of two models.

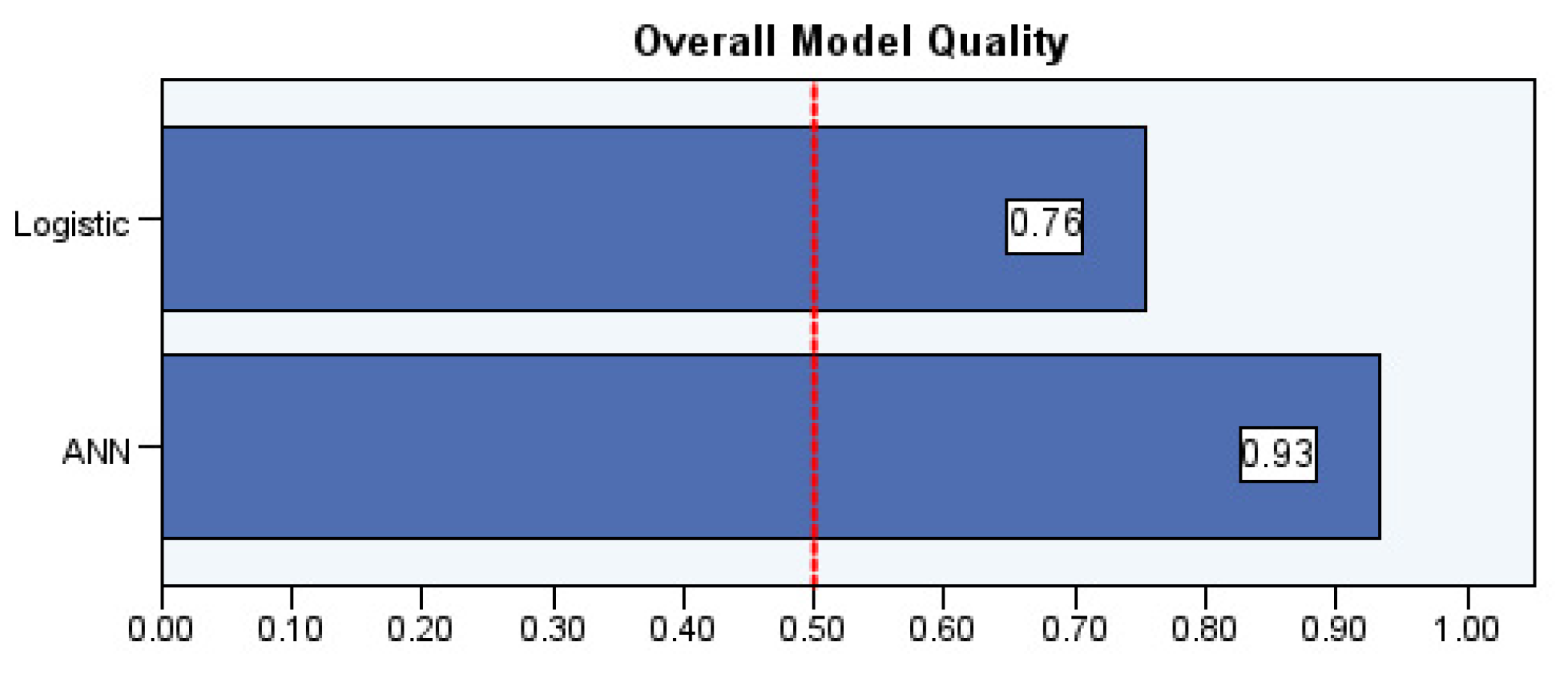

The overall model quality scores for the ANN and logistic regression models used to predict complications associated with cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) in Fig. 3. Model quality was assessed using normalized performance scores, where a value of 1.0 indicates perfect prediction and 0.5 represents random guessing. The ANN model demonstrated superior performance with a score of 0.93, compared to 0.76 for the logistic regression model. These results suggest that the ANN model better captures nonlinear relationships among risk factors, offering improved predictive accuracy for identifying high-risk patients following CIED implantation.

Figure 3: Overall model quality between ANN and logistic regression models.

While the ANN model demonstrated strong predictive performance identified key risk factors (e.g., platelet count, PT/INR, LVEF, Hb and age), its application is limited by the retrospective, single-center design. Potential biases from EMR-based data may affect model generalizability. To overcome these limitations, future prospective, multi-center studies with broader inclusion criteria are essential for robust external validation and calibration. These steps will enhance the clinical utility of the ANN model for individualized risk prediction in CIED procedures.

In terms of patient characteristics, age is recognized as a significant risk factor for complications such as pocket bleeding, pocket infection, and skin erosion following CIED implantation [7]. In this study, the mean age of patients undergoing the CIED procedure was over 70 years. Elderly patients often present with fragile skin, reduced immune function, and underlying chronic conditions (e.g., DM), which may impair wound healing and increase the risk of skin injury and infection [14,15]. Polyzos et al. (2015) have also noted that age has been identified in multiple studies as an important predictor of CIED-related complications [13]. Our ANN analysis confirmed the high importance of age across various complication types. However, logistic regression analysis did not find age to be a statistically significant predictor, highlighting potential differences in variable sensitivity between analytical methods. These findings underscore the need for comprehensive preoperative assessment of elderly patients, considering their overall health status and potential susceptibility to postoperative complications.

Guo et al. (2014) have indicated that a lower BMI may be associated with an increased risk of pocket hematoma complications following CIED procedures [30]. In our study, logistic regression analysis supported these findings, patients with lower BMI values exhibited a higher likelihood of developing complications. Nonetheless, BMI remains a relevant variable that should be carefully evaluated during preoperative risk assessment for CIED candidates. One study reported a potential association between female gender and postoperative pneumothorax complications [11]. However, in our study, gender was not identified as a significant risk factor in either the ANN model or logistic regression analysis. This aligns with previous literature [10,13], which concluded that gender plays a minimal role in the development of CIED-related complications.

The ANN model identified clotting function as the most critical risk factor for complications following CIED implantation, with key indicators including platelet count, PT/INR, and Hb. While the literature [16,17,18,19] often highlights the role of antithrombotic therapy in pocket bleeding and hematoma formation, there remains ongoing debate regarding whether antithrombotic agents should be discontinued before CIED procedures.

In our ANN analysis, the use of antithrombotic agents did not emerge as a top-ranking risk factor for CIED-related postoperative complications. Similarly, logistic regression analysis demonstrated no statistically significant association between antithrombotic therapy and the risk of complications. In contrast, coagulation function indicators—specifically platelet count and PT/INR—showed greater statistical relevance. These findings are consistent with previous studies [16,17,18,19], which highlight the strong association between hematoma and bleeding risk and the use of antithrombotic agents, recommending careful risk stratification before CIED procedures.

Our results suggest that while the pharmacological use of antithrombotic agents should not be disregarded, laboratory parameters of coagulation function may serve as more objective and robust indicators of bleeding risk. For example, Wang et al. [16] reported that for every 10,000/μL increase in platelet count, the risk of bleeding decreases by approximately 8%. This underscores the importance of correcting thrombocytopenia prior to device implantation to minimize procedural risk.

Furthermore, existing literature has shown that pocket hematoma and bleeding can significantly increase the likelihood of subsequent pocket infections, with odds ratios reported as high as 8.46 [13,14,31]. Our ANN model supports this pathway, identifying PT/INR as the most important risk factor for pocket infection, while platelet count emerged as the top predictor for pocket bleeding and hematoma. These findings reinforce the clinical value of preoperative coagulation assessment.

From a healthcare economics perspective, effective risk stratification and early intervention may reduce the incidence of complications, thereby shortening hospital stays and lowering medical costs. In the context of long-term patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness, individualized preoperative planning based on coagulation function remains a critical component of CIED procedural care.

Although chronic kidney disease (CKD), SHD, DM, and HTN have been widely reported as important risk factors for post-CIED complications [7,8,10,12], the ANN model in this study assigned relatively low predictive weights to these comorbidities, none of which were among the top five ranked predictors. In contrast, logistic regression analysis revealed SHD as a significant risk factor [8,12], while DM showed an inverse association with complications, potentially reflecting stricter patient selection, better glycemic control, or statistical adjustment [7,10].

In particular, the relatively low importance of CKD in the ANN model may be attributable to the preoperative exclusion of ESRD patients from CIED eligibility [32]. Since ESRD affects platelet function and alters drug metabolism, its impact may have been captured indirectly by laboratory indicators such as platelet count and PT/INR. This may have diluted the direct predictive weight of CKD in the ANN model.

These findings highlight a key difference between machine learning and traditional regression methods in evaluating variable importance. They also underscore the importance of understanding the clinical context and sample selection criteria when interpreting predictive models. While ANN offers enhanced accuracy in handling nonlinear patterns and imbalanced data, prospective multicenter studies are needed to validate these associations and to explore how clinical comorbidity management may influence long-term CIED outcomes.

Current literature provides limited evidence regarding LVEF as a risk factor for complications following CIED implantation [8]. In our study, LVEF was identified as an important predictor of complications in both ANN analysis and logistic regression models. A lower LVEF was significantly associated with an increased risk of postoperative complications. This association may be attributed to impaired tissue perfusion and the overall compromised health status of patients with reduced cardiac function. Therefore, maintaining adequate LVEF prior to CIED implantation may enhance systemic physiological function, improve prognosis, and reduce the likelihood of postoperative complications.

The result also shows the importance of device-related factors is not high. Polyzos et al. (2015) mentioned that different leads and dual-chamber catheters contribute to the occurrence of CIED complications, with an odds ratio (OR) in the range of 1.42–8.09 [13]. In the ANN analysis, indicating that these devices are not the most important risk factor. Similarly, the logistic regression results did not demonstrate statistical significance for these variables. This finding differed from the conclusion from the statistical results of the study [7,13]. A possible explanation for this result is that the medical team’s proficiency in the procedure in our study meant that the patients experienced few issues. Therefore, the risk factors for CIED devices can be taken into account, and the selection of an appropriate device, according to the standard procedures and the patient’s needs, forms part of the decision analysis that clinical professional teams need to perform before conducting the CIED procedure.

This study applied an ANN model to identify predictive risk factors associated with complications following CIED implantation. Among the 13 variables analyzed, five key predictors—platelet count, PT/INR, LVEF, Hb, and age—were found to have the highest importance and should be integrated into routine preoperative assessments. Impaired coagulation function, anemia, or reduced cardiac function prior to surgery may elevate the risk of complications, underscoring the importance of optimizing anticoagulation management and improving preoperative perfusion and hematologic status.

Compared to logistic regression, the ANN model demonstrated superior predictive performance across five major postoperative complications: skin erosion, pocket bleeding, pocket hematoma, pocket infection, and subcutaneous emphysema. These results support the ANN model as a promising tool for individualized risk stratification and preoperative decision-making in patients undergoing CIED implantation.

However, several limitations must be acknowledged. This analysis was conducted using a retrospective dataset from a single center, which may introduce selection bias and limit external validity. Moreover, potential confounding factors during the postoperative follow-up period—such as changes in medication adherence, post-discharge care, and infection control practices—may have influenced the occurrence and detection of complications. Although the ANN model exhibited strong predictive performance, the risks of overfitting and limited generalizability remain.

Therefore, future prospective, multicenter studies are warranted to externally validate the model, assess its clinical utility across diverse patient populations, and determine its effectiveness in real-world settings. These efforts will be essential before the model can be routinely implemented in clinical practice.

In this study, we used an ANN predictive analysis model to explore the risk factors for complications related to the CIED implant procedure. In particular, careful evaluation and management of preoperative coagulation profiles, as well as correction of anemia and optimization of blood perfusion, establishment of standardized physical assessment indicators may help reduce postoperative complications. The results provide valuable data to clinical staff that allow a thorough assessment of the risk factors for patients undergoing CIED treatment, thus supporting informed decisions for better patient care.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Chih-Yin Chien, Ying-Hsiang Lee and Wei-Sho Ho; Methodology, Chih-Yin Chien, Tsae-Jyy Wang and Pei-Hung Liao; Formal analysis, Chih-Yin Chien, Tsae-Jyy Wang and Ying-Hsiang Lee; Data management, Chih-Yin Chien, Ying-Hsiang Lee and Pei-Hung Liao; Writing—original draft preparation, Chih-Yin Chien, Wei-Sho Ho and Tsae-Jyy Wang; Writing—review and editing, Chih-Yin Chien, Wei-Sho Ho and Tsae-Jyy Wang; Supervision, Wei-Sho Ho. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request due to restrictions regarding privacy, legal and ethical concerns. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Ethics Approval: The procedures used in this study adhere to the ethical standards of the relevant institutional and national research committees and comply with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 1964) and its subsequent amendments or comparable ethical guidelines. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of MacKay Memorial Hospital on 07 July 2017, with the clinical trial and IRB registration number 17MMHIS054e. The approval permitted the conduct of the clinical trial from 07 July 2017 to 06 July 2018, at MacKay Memorial Hospital in Taipei and Tamsui MacKay Memorial Hospital. All participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, and their rights, and provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ahmad FB , Anderson RN . The leading causes of death in the US for 2020. JAMA. 2021; 325( 18): 1829. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ministry of Health and Welfare . 2024 Taiwan life and death report. Taipei City, Taiwan: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/lp-5069-113-xCat-y109.html. [Google Scholar]

3. Hawkins NM , Virani SA , Sperrin M , Buchan IE , McMurray JJV , Krahn AD . Predicting heart failure decompensation using cardiac implantable electronic devices: a review of practices and challenges. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016; 18( 8): 977– 86. doi:10.1002/ejhf.458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Richardson CJ , Prempeh J , Gordon KS , Poyser TA , Tiesenga F . Surgical techniques, complications, and long-term health effects of cardiac implantable electronic devices. Cureus. 2021; 13( 1): e12567. doi:10.7759/cureus.13001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Asad M , Khan QH , Baloch MW , Khan KA , Naseem MA , Hayat A , et al. Implantable cardiac device infection—a clinical audit. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2020; 70( 6): S871– 75. doi:10.51253/pafmj.v70isuppl-4.6046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Mahrous Ali Ismaeil K , Hussein Nasr M , Mostafa Mahrous F , Faltas Marzouk S . Nurses’ performance for patients with implantable cardiac devices. Egypt J Health Care. 2024; 15( 1): 625– 37. doi:10.21608/ejhc.2024.343034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Han HC , Hawkins NM , Pearman CM , Birnie DH , Krahn AD . Epidemiology of cardiac implantable electronic device infections: incidence and risk factors. EP Eur. 2021; 23( Suppl_4): iv3– 10. doi: 10.1093/europace/euab042 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Rahman R , Saba S , Bazaz R , Gupta V , Pokrywka M , Shutt K , et al. Infection and readmission rate of cardiac implantable electronic device insertions: an observational single center study. Am J Infect Control. 2016; 44( 3): 278– 82. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2015.10.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Sohail MR , Eby EL , Ryan MP , Gunnarsson C , Wright LA , Greenspon AJ . Incidence, treatment intensity, and incremental annual expenditures for patients experiencing a cardiac implantable electronic device infection: evidence from a large US payer database 1-year post implantation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016; 9( 8): e003929. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.116.003929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ngiam JN , Liong TS , Sim MY , Chew NWS , Sia CH , Chan SP , et al. Risk factors for mortality in cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2022; 11( 11): 3063. doi:10.3390/jcm11113063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Moore K , Ganesan A , Labrosciano C , Heddle W , McGavigan A , Hossain S , et al. Sex differences in acute complications of cardiac implantable electronic devices: implications for patient safety. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019; 8( 2): e010869. doi:10.1161/JAHA.118.010869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Rennert-May E , Chew D , Lu S , Chu A , Kuriachan V , Somayaji R . Epidemiology of cardiac implantable electronic device infections in the United States: A population-based cohort study. Heart Rhythm. 2020; 17( 7): 1125- 1131. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.02.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Polyzos KA , Konstantelias AA , Falagas ME . Risk factors for cardiac implantable electronic device infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2015; 17( 5): 767– 77. doi:10.1093/europace/euv053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kiuchi K , Okajima K , Tanaka N , Yamamoto Y , Sakai N , Kanda G , et al. Novel compression tool to prevent hematomas and skin erosions after device implantation. Circ J. 2015; 79( 8): 1727– 32. doi:10.1253/circj.cj-15-0341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lakkireddy D , Bartus K , Nagarajan V , Afzal R , Atkins D , Gunasekaran V , et al. Use of novel compression device reduces the incidence of pocket hematoma in anticoagulated patients receiving implantable electronic cardiac devices: a pilot study. Circulation. 2016; 134( Suppl_1): A20633. [Google Scholar]

16. Wang B , Yao J , Sethwala A , Hawson J , Stevenson I . Risk factors of haematoma formation following cardiac implantable electronic device procedures. Heart Lung Circ. 2022; 31( 11): 1539– 46. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2022.07.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ezenna C , Pereira V , Abozenah M , Franco AJ , Gbegbaje O , Zaidi A , et al. Perioperative direct oral anticoagulant management during cardiac implantable electronic device surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2025; 68( 4): 845– 56. doi:10.1007/s10840-024-01947-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. He H , Ke BB , Li Y , Han FS , Li X , Zeng YJ . Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy in patients receiving cardiovascular implantable electronic devices: a network meta-analysis. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2017; 50( 1): 65– 83. doi:10.1007/s10840-017-0280-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Di Biase L , Lakkireddy DJ , Marazzato J , Velasco A , Diaz JC , Navara R , et al. Antithrombotic therapy for patients undergoing cardiac electrophysiological and interventional procedures: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024; 83( 1): 82– 108. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.09.831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Shafiq A , Çolak AB , Sindhu TN . Development of an intelligent computing system using neural networks for modeling bioconvection flow of second-grade nanofluid with gyrotactic microorganisms. Numer Heat Transf Part B Fundam. 2024; 85( 12): 1749– 66. doi:10.1080/10407790.2023.2273512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Bonde A , Varadarajan KM , Bonde N , Troelsen A , Muratoglu OK , Malchau H , et al. Assessing the utility of deep neural networks in predicting postoperative surgical complications: a retrospective study. Lancet Digit Health. 2021; 3( 8): e471– 85. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00084-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Porche K , Maciel CB , Lucke-Wold B , Robicsek SA , Chalouhi N , Brennan M , et al. Preoperative prediction of postoperative urinary retention in lumbar surgery: a comparison of regression to multilayer neural network. J Neurosurg Spine. 2021; 36( 1): 32– 41. doi:10.3171/2021.3.SPINE21189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Parab J , Sequeira M , Lanjewar M , Pinto C , Naik G . Backpropagation neural network-based machine learning model for prediction of blood urea and glucose in CKD patients. IEEE J Transl Eng Health Med. 2021; 9: 1– 8. doi:10.1109/JTEHM.2021.3079714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Gao J , Zagadailov P , Merchant AM . The use of artificial neural network to predict surgical outcomes after inguinal hernia repair. J Surg Res. 2021; 259: 372– 8. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2020.09.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chen X , Pan Y , Tang T , Fu J , Chen X , Bao C . Machine learning-guided one-step fabrication of targeted emodin liposomes via novel micromixer for ulcerative colitis therapy. Nano Res. 2025; 18( 8): 94907713. doi:10.26599/nr.2025.94907713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Yadav DC , Pal S . An experimental study of diversity of diabetes disease features by bagging and boosting ensemble method with rule based machine learning classifier algorithms. SN Comput Sci. 2021; 2( 1): 50. doi:10.1007/s42979-020-00446-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ogundimu EO , Altman DG , Collins GS . Adequate sample size for developing prediction models is not simply related to events per variable. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016; 76: 175– 82. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.02.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Riley RD , Ensor J , Snell KIE , Harrell FE Jr , Martin GP , Reitsma JB , et al. Calculating the sample size required for developing a clinical prediction model. BMJ. 2020; 368: m441. doi:10.1136/bmj.m441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sakthivel KM , Rajitha CS . Artificial neural network for decision making. In: Artificial intelligence theory, models, and applications. Boca Raton, FL, USA: Auerbach Publications; 2021. p. 451– 66. doi:10.1201/9781003175865-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Guo JP , Shan ZL , Guo HY , Yuan HT , Lin K , Zhao YX , et al. Impact of body mass index on the development of pocket hematoma: a retrospective study in Chinese people. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2014; 11( 3): 212– 7. doi:10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2014.03.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zerbo S , Perrone G , Bilotta C , Adelfio V , Malta G , Di Pasquale P , et al. Cardiovascular implantable electronic device infection and new insights about correlation between pro-inflammatory markers and heart failure: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021; 8: 602275. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.602275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Herrmann FEM , Ehrenfeld F , Wellmann P , Hagl C , Sadoni S , Juchem G . Thrombocytopenia and end stage renal disease are key predictors of survival in patients with cardiac implantable electronic device infections. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020; 31( 1): 70– 9. doi:10.1111/jce.14270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools