Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Review and Comparative Analysis of System Identification Methods for Perturbed Motorized Systems

School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 14300 Nibong Tebal, Penang, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Nur Syazreen Ahmad. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Swarm and Metaheuristic Optimization for Applied Engineering Application)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 143(2), 1301-1354. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.063611

Received 19 January 2025; Accepted 08 May 2025; Issue published 30 May 2025

Abstract

This paper reviews recent advancements in system identification methods for perturbed motorized systems, focusing on brushed DC motors, brushless DC motors, and permanent magnet synchronous motors. It examines data acquisition setups and evaluates conventional and metaheuristic optimization algorithms, highlighting their advantages, limitations, and applications. The paper explores emerging trends in model structures and parameter optimization techniques that address specific perturbations such as varying loads, noise, and friction. A comparative performance analysis is also included to assess several widely used optimization methods, including least squares (LS), particle swarm optimization (PSO), grey wolf optimizer (GWO), bat algorithm (BA), genetic algorithm (GA) and neural network for system identification of a specific case of a perturbed DC motor in both open-loop (OL) and closed-loop (CL) settings. Results show that GWO achieves the lowest error overall, excelling in OL scenarios, while PSO performs best in CL due to its synergy with feedback control. LS proves efficient in CL settings, whereas GA and BA rely heavily on feedback for improved performance. The paper also outlines potential research directions aimed at advancing motor modeling techniques, including integration of advanced machine learning methods, hybrid learning-based methods, and adaptive modeling techniques. These insights offer a foundation for advancing motor modeling techniques in real-world applications.Keywords

Motorized systems are fundamental to a wide range of advanced applications, driving a diverse array of devices including industrial machinery, semiconductor wafer production, robotics, and electric vehicles. The crux of leveraging these systems lies in the development of computational or mathematical models that faithfully emulate their dynamic behavior. Such motor models are tailored to meet the varying degrees of sophistication and accuracy required by their application domains, empowering researchers and engineers to simulate, predict, and fine-tune system performance with high precision [1]. These models are informed by data sourced from an array of sensors and other inputs, translating into precise mathematical representations of the motors’ dynamics [2]. Through this modeling, intricate insights into the functioning of motorized systems under diverse conditions are unearthed [3].

The challenge becomes even more critical when dealing with perturbed motorized systems-those subjected to disturbances, noise, and environmental variations—which directly impact their efficiency, reliability, and overall performance. In such systems, precise system identification is essential, as it enables the detection, quantification, and modeling of perturbation effects. Accurate identification lays the foundation for developing robust and adaptive control strategies capable of anticipating and mitigating unpredictable operational disruptions [4]. Without a well-structured approach to system identification, control mechanisms may struggle to maintain stability and efficiency, particularly in dynamic environments.

This becomes especially crucial in high-precision industries such as aerospace, automotive engineering, and industrial automation, where even minor deviations can lead to significant performance degradation or safety risks. By integrating perturbation models into system identification, motorized systems can achieve enhanced resilience, stability, and adaptability, even under fluctuating operating conditions. Thus, advancing system identification techniques for perturbed motorized systems is not just an academic pursuit but a practical necessity for ensuring reliable and high-performance operation in increasingly complex and demanding applications.

Modeling approaches for dynamic systems can be broadly categorized into two principal types: data-driven modeling and first-principle modeling. First-principle modeling, also referred to as white-box modeling, relies entirely on fundamental physical laws, such as Ohm’s law and Newton’s laws of motion, to describe system dynamics without the need for experimental data [5]. In contrast, data-driven modeling constructs system representations using input-output data and includes black-box and grey-box approaches [6,7]. Black-box modeling develops models solely from input-output data without any knowledge of internal system structures, while grey-box modeling integrates both empirical data and partial system knowledge to improve model accuracy [8]. A thorough understanding of these modeling paradigms is crucial for building accurate system representations and designing effective control strategies.

In recent years, advanced nonlinear modeling techniques have been proposed to capture complex system behaviors with greater precision. Block-oriented models, including Hammerstein and Wiener models, are particularly prominent due to their capability to represent nonlinear systems through a combination of linear dynamic components and static nonlinearities [9–11]. Furthermore, neural networks and neuro-fuzzy systems have gained considerable attention owing to their powerful approximation capabilities and adaptive learning features, rendering them suitable for modeling highly nonlinear and time-varying systems [12]. These methodologies have been extensively investigated in the literature to enhance modeling accuracy and robustness.

The optimization of motor parameters through grey- and black-box modeling has been extensively studied in prior research, employing various algorithms. Least square (LS) serves as a foundational method for this purpose. An extension of LS, the Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) algorithm [13], enhances the traditional approach by incorporating mechanisms to improve convergence speed and robustness, especially in nonlinear optimization problems. Additionally, metaheuristic algorithms are pivotal in optimizing parameters based on selected cost functions. These algorithms are categorized into four main types: swarm intelligence, evolutionary, physics-based, and human-inspired algorithms. Swarm intelligence algorithms emulate cooperative behaviors among agents to tackle complex problems, drawing inspiration from social organisms such as ants and birds [14,15]. Notable examples include particle swarm optimization (PSO), where particles adjust their positions in the solution space based on personal and collective experiences [16]. Other prominent algorithms in this category include whale optimization algorithm (WOA), grey wolf optimization (GWO), ant colony optimization (ACO), artificial bee colony (ABC), bat algorithm (BA), and cuckoo search (CS) [17,18]. There are also novel swarm algorithms proposed including marine predator algorithm, artificial circulation system algorithm (ACSA), wolverine optimization algorithm (WoOA), and synergistic swarm optimization algorithm (SSOA) [19–21]. These techniques harness natural dynamics and social structures to enhance search efficiency effectively.

Evolutionary algorithms on the other hand imitate the evolutionary process to search for the optimal solutions in challenging situations. These algorithms, including differential evolution (DE) [22] and genetic algorithms (GA) maintain a population of potential solutions that evolve across generations through mutation, crossover, and selection methods. Human-based algorithms use human judgment and knowledge to address optimization challenges [23]. These algorithms often require the development of rule-based systems, manual optimization, and expert judgment, such as the jaya algorithm (JA), teaching–learning–based optimization (TLBO). Physics-based algorithms, in contrast, model the physical behaviors of systems through the application of physics and mathematics principles. These methods are crucial for precise simulation and analysis, commonly employing tools like computational fluid dynamics and finite element analysis [24]. Utilized extensively in engineering and scientific research, physics-based algorithms enable detailed investigation and optimization of complex physical phenomena, facilitating advanced developments in motor parameter optimization and other areas of applied mechanics.

Recent surveys in the field have predominantly focused on electromagnetic field modeling perspectives [25], laboratory testing methodologies [26], and parameter identification approaches tailored to specific types of motors such as permanent magnet synchronous motors (PMSM) [27], inverter-fed induction motors [28], three-phase induction motor drives [29], and permanent magnet DC motors [30]. While some surveys, such as [31], have addressed model structures, they often lack comprehensive discussions on model parameter optimization. None have systematically explored the relationship between different model structure types and parameter optimization methods concerning perturbations. A thorough exploration of parameter optimization methods and state-of-the-art techniques for managing perturbations remains underrepresented in the existing literature. This paper aims to fill these gaps with the following primary contributions:

• Providing a comprehensive review of recent advancements in system identification methods for perturbed motorized systems, including data acquisition processes and setups, with a focus on brushed DC motors, brushless DC motors (BLDC), and PMSMs.

• Systematically evaluating both conventional and metaheuristic algorithms as parameter optimization strategies, analyzing their strengths, limitations, and practical applications in system modeling.

• Investigating emerging trends in model structures and optimization techniques, specifically in the context of perturbations such as varying loads, noise, and friction, to understand their impact on system identification accuracy.

• Introducing a comparative analysis of grey-box and black-box system identification methods, including grey-box modeling using metaheuristic algorithms (PSO, GWO, and GA) and black-box modeling with neural networks, for a perturbed DC motor under both open-loop and closed-loop conditions. This study uniquely evaluates their generalization ability and robustness in handling system perturbations.

• Identifying key research gaps and proposing future directions to enhance system identification methodologies, including the integration of advanced machine learning techniques and adaptive optimization strategies for improved performance in real-world applications.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 describes an organized research framework that help to ensure the transparency of systematic review reporting. Section 3 provides a comprehensive examination of motor mathematical models. Section 4 delves into the synthesized findings from the preceding systematic review of the literature concerning system identification techniques for motorized systems under various perturbations. Section 5 reviews various parameter optimization methods in optimizing motor model parameters and performance. Section 6 provides a systematic analysis and discussion of the literature reviewed in Sections 4 and 5. Section 7 presents a comparative performance analysis of several widely used optimization methods for system identification, applied to a perturbed DC motor under both open-loop and closed-loop settings. Section 8 outlines potential directions for future research. Finally, Section 9 concludes the study by summarizing the key findings and highlighting their significance.

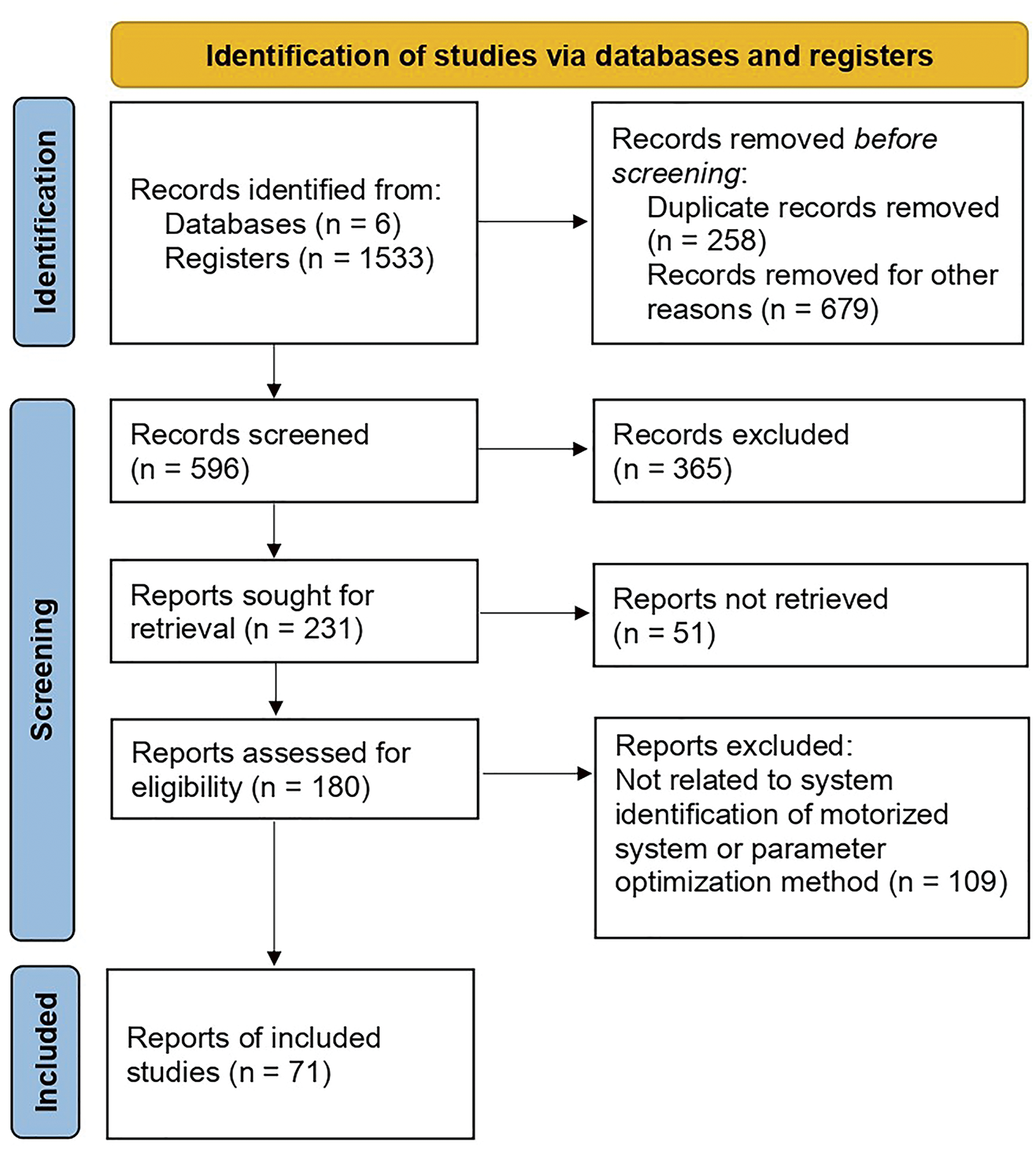

In this section, an organized research framework was developed. Fig. 1 shows the flow diagram of preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses PRISMA 2020 as a graphical representation of the study screening and selection process. The flow diagram can be expressed in three major steps, namely, identification, screening, and included.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram

In the identification phase, research area and goal were first defined. The research areas are the system identification of perturbed motorized systems and parameter optimization methods. The research goal is to provide a systematic research scheme for existing modeling and optimization methods. The articles were gathered as references by using key terms, such as system identification, motor modeling, motor parameter optimization, LS parameter estimation, motor identification using PSO, etc. Online journal database used for searching research articles based on key terms as listed as Web of Science, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, Taylor & Francis, and Springer.

In screening phase, the articles are screened for eligibility and relevancy with the research area and goal. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are specified to ease the screening phase. Inclusion criteria such as relevance to system identification, motor modeling, and parameter optimization. Exclusion criteria such as low citation, irrelevant to motorized systems, reports before 2010, etc. In third phase which is the included phase, the remaining articles are selected for review and analysis.

This section describes modeling methods for brushed DC motors, BLDC, and PMSM based on first principles, which is also known as white-box modeling. The models of these motors, which detail their structural and functional aspects, are in some cases crucial for applying both grey-box and black-box modeling techniques. Grey-box modeling strikes a balance between theoretical physical models and empirical data, allowing for predictions that account for known behaviors and measured data simultaneously. This approach is particularly useful when some system parameters are unknown or difficult to measure directly but where some theoretical knowledge about the system’s behavior is available. The black-box modeling, on the other hand, which relies solely on input-output data without any presumption about the system’s internal workings, benefits from the detailed model structures to better interpret the data patterns and relationships that emerge during the modeling process.

3.1 Mathematical Model of Brushed Motor

A DC motor is a common actuator utilized in control systems, primarily for generating rotational motion. Its key components comprise the housing and bearings, the stator (which may consist of a magnet, permanent magnet, or electromagnet), the rotor, the commutator, and the brushes. Upon the application of voltage to the motor terminals, current flows through the armature windings, establishing an electromagnetic field. This field interacts with the magnetic field generated by either stationary magnets or field coils, generating a force that initiates armature rotation. As the armature turns, the commutator segments make contact with the brushes, thereby reversing the current direction in the windings to sustain continuous rotation. The mathematical modeling of a DC motor circuit integrates both electrical and mechanical aspects, providing a fundamental tool for control system design. Accurate determination of model parameters is crucial as they significantly influence the motor’s behavior. Fig. 2 illustrates a schematic diagram of a DC motor on no load condition [32].

Figure 2: Brushed DC motor schematic diagram for no load condition

In general, a DC motor’s torque is directly correlated with its armature current and magnetic field intensity. Assuming a constant magnetic field, the motor’s torque,

The back electromotive force (EMF),

From Fig. 2, equations can be formulated using Newton’s Second Law for the mechanical aspect and Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law for the electrical aspect as follows:

where

The armature voltage is regarded as the input and the motor shaft’s position as the output, the transfer function (TF) of the DC motor position,

At no load condition, the armature current is zero, and the angular speed will try to reach infinite speed. For load condition as depicted in Fig. 3, an additional load mechanical equation is added for calculation by assuming

where

By substituting (10) into (1), (11) is obtained, then followed by substituting (11) into (9), (12) is obtained:

DC motor position with respect to the voltage source at load condition can then be expressed as:

Figure 3: Brushed DC motor schematic diagram for load condition

3.2 Mathematical Model of Brushless DC Motors (BLDC)

Fig. 4 depicts a schematic diagram of a BLDC motor [33]. While both brushed DC and BLDC motors adhere to similar principles, BLDC motors operate with more precision. Leveraging rotor position feedback from Hall sensors, the motor controller of a BLDC motor determines the optimal timing and sequence of current pulses to the stator coils. By energizing the coils in the stator in the correct sequence, the motor controller generates a rotating magnetic field. This field interacts with the fixed magnetic field of the rotor, resulting in torque generation and motor rotation. The circuit equation of the three windings in phase variables is given by:

where R is the stator resistance,

Figure 4: BLDC motor schematic diagram

All windings are assumed to have equal resistance, and the rotor reluctance is assumed to remain constant with angle. The simplication of stator phase voltages,

The induced EMF equation of the BLDC motor is all assumed to be trapezoidal and can be written as:

The electromagnetic torque,

where

where J is moment of inertia, B is frictional coefficient,

where

where

where

3.3 Mathematical Model of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (PMSM)

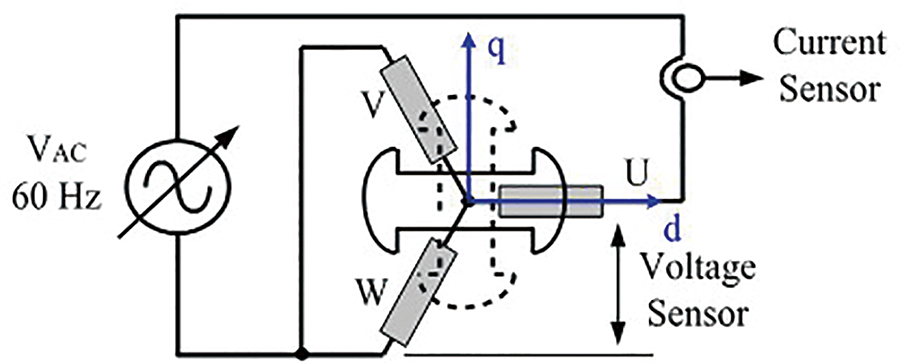

The PMSM is a brushless machine with sinusoidal flux distribution and has very high reliability and efficiency. It is also known as a brushless AC machine. The dynamic model of PMSM was first derived using equivalent two-phase motor system formulated in direct (d) and quadrature (q) axes. Fig. 5 shows the equivalent circuit at d- and q-axes PMSM model in rotor reference frame is obtained as [34]:

where the saliency ratio is

Figure 5: Equivalent circuit of PMSM: (a) q-axis (b) d-axis

PMSMs with three-phase are prevalent but two-phase machines are rarely used in industrial applications. A dynamic model for three-phase PMSM can be derived from two-phase machine. Assume that each of the stator three-phase windings has equal current magnitude and

where

where

where

In the context of a perturbed motorized system, where factors like friction, varying loads, and other disturbances introduce complexities that challenge traditional first principles modeling, system identification emerges as a powerful solution. By leveraging observed input-output data, system identification enables the creation of accurate models that capture the dynamic behavior of the system amidst perturbations. These models not only adapt to changing conditions but also provide insights into the underlying dynamics, facilitating the design of robust control strategies tailored to mitigate the effects of disturbances.

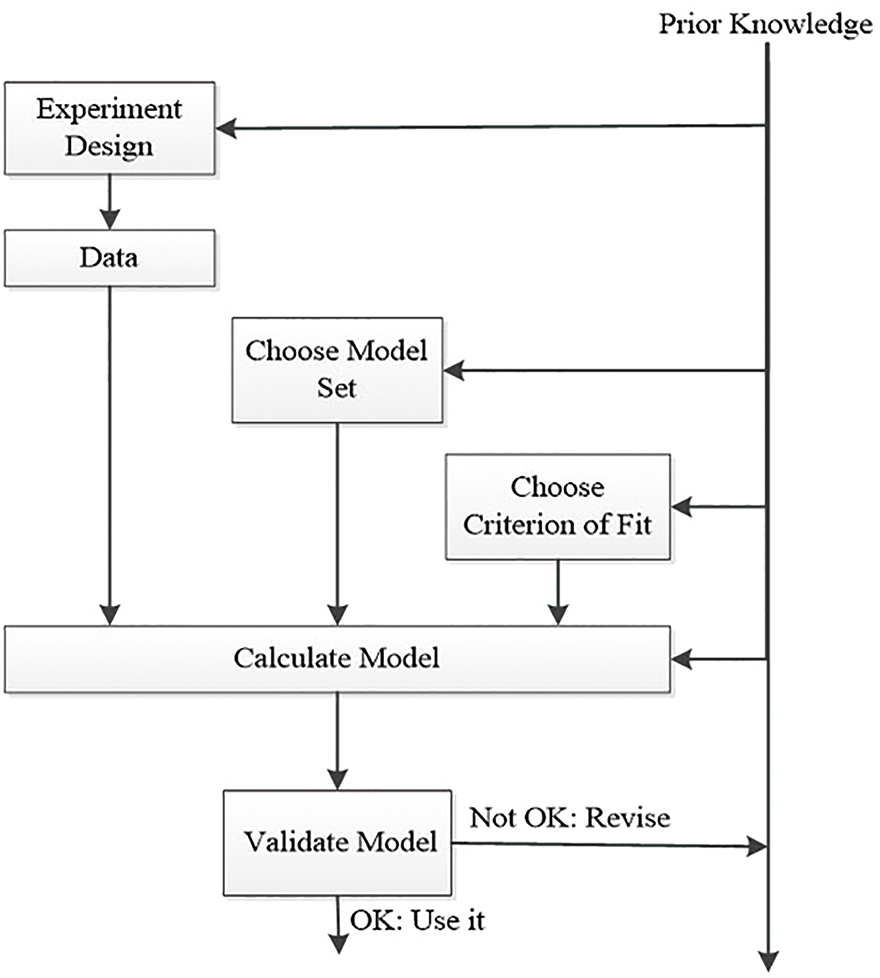

The diagram in Fig. 6 outlines a standard procedure in system identification, starting from “Experiment Design” which is informed by “Prior Knowledge” [35]. Here, data is gathered and used to “Choose Model Set” based on a selected “Criterion of Fit.” This stage ensures the model aligns well with the collected data and system dynamics. The motor model structures based on first principles as described in the previous section can usually serve as hypotheses or initial guesses on the model structure. Next, the “Calculate Model” step involves applying the chosen model to predict or simulate system behavior. If the model predictions do not align with the expectations or further data (“Not OK”), the process includes a “Revise” loop, indicating iterative refinement of the model. Upon successful validation (“Validate Model”), where the model sufficiently represents the system under study, it is deemed acceptable for use (“OK: Use it”). This structured approach emphasizes iterative refinement and validation, leveraging both empirical data and theoretical knowledge to develop an accurate model of the system.

Figure 6: System identification’s standard procedure [35]

In [36], the study employs system identification to model a perturbed BLDC motor to achieve precise speed control. It introduces an ideal back EMF for enhanced precision in speed control in the face of varying load torques ranging from 0 to 20 Nm. The work in [37] utilizes system identification to design a proportional-integral-derivative (PID) control with auto-tuning. In [38], the system identification method is used to estimate both static and dynamic characteristics of a DC motor using starting rheostat as the starting current limiter.

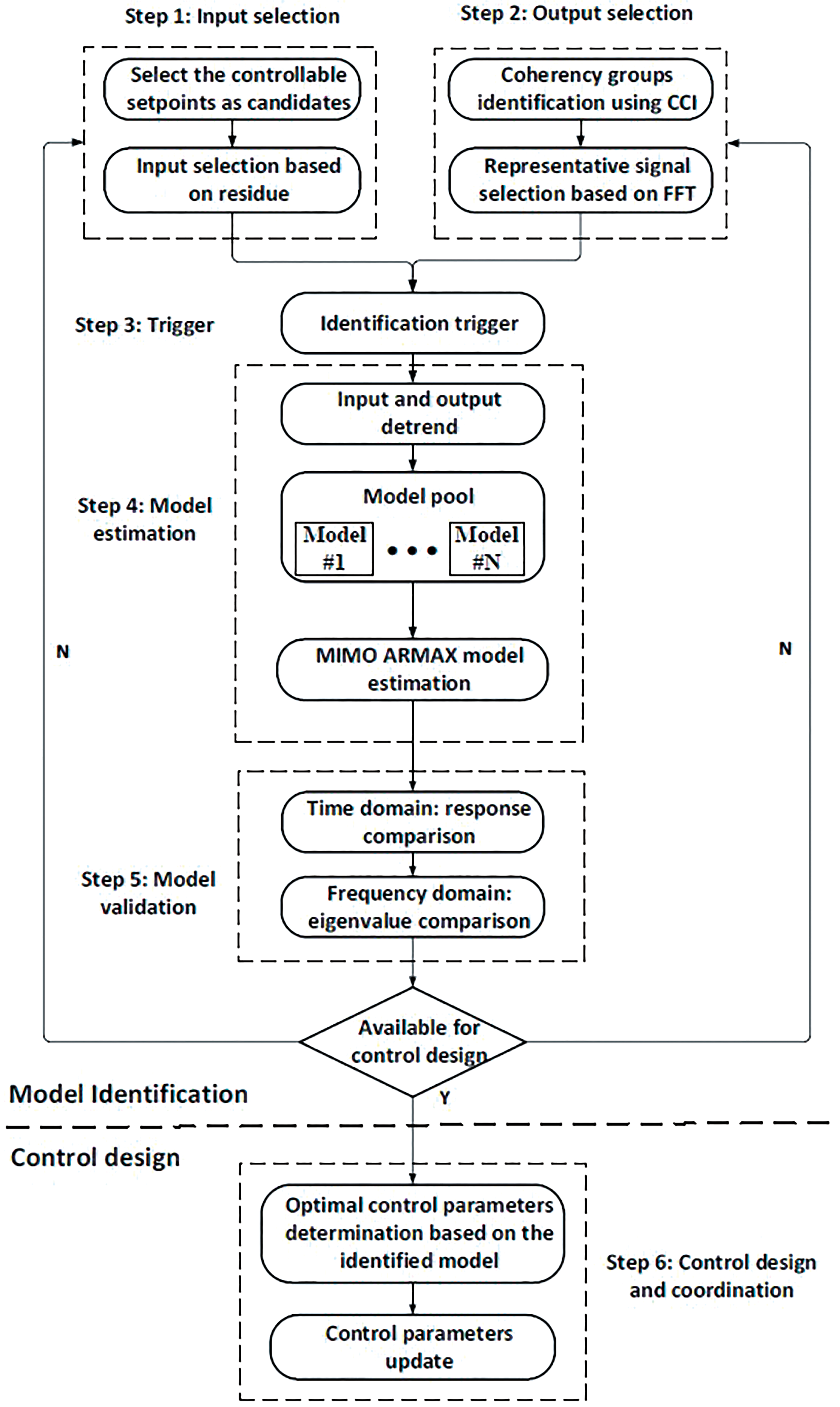

A recent comparative study in [39] demonstrates that AutoRegressive with eXogenous input (ARX) and second-order continuous-time TF models offer a more accurate representation of the mathematical model of a DC motor under varying payloads. Additionally, in a separate study [40], it was demonstrated that the Autoregressive Moving Average Exogenous (ARMAX) structure provides a superior representation of the mathematical model of a DC servo motor compared to the ARX structure. In [41], a subspace-aided closed-loop system identification method is introduced for a DC motor system which demonstrates superior performance in pole estimation compared to a class of subspace identification methods utilizing principal component analysis algorithms. The study in [42] employs system identification to establish a low-order TF model of a physiological system (PSys) using a Multi-Input Multi-Output (MIMO) ARMAX model. Fig. 7 illustrates the flow chart of the proposed method where the model obtained from the system identification is then used to optimize the control parameters.

Figure 7: Methodology of model identification to build MIMO ARMAX model using measurement data as proposed in [42]

Batool et al. [43] discussed three estimation techniques for multi-domain DC servo motor model parameters: the Compare Coefficient Method, MATLAB Parameter Estimation Toolbox, and System Identification Toolbox. Experimental data is used to compare the accuracy of these methods, with the parameter estimation technique proving to be the most accurate and computationally efficient, guiding researchers in preference for DC servo motor simulation model parameter estimation. The proposed method in [44] optimizes accuracy and reliability of permanent magnet DC (PMDC) motor models while considering dynamic characteristics and operational conditions. Eight parameters were identified, such as brush current constant, back EMF constant, motor resistance, brush voltage current, motor inertia, viscous friction, motor inductance, and stiffness constant.

The study in [45] utilized system identification to estimate load torque and moment of inertia in PMSM drives based on sliding mode observer (SMO), which offered precise estimation and quick convergence. In [46], various estimators for PMSM electrical parameter identification were compared where the finding revealed that the moving horizon estimation outperformed the rest in accuracy. The Kalman filter (KF) of extended KF (EKF) and unscented KF (UKF) performed similarly, while the model reference adaptive system (MRAS) was sensitive to disturbances and required extensive tuning recursive LS yielded inaccurate results.

The method proposed in [47] utilizes motor impedance characteristics for parameter estimation, suitable for both offline and online environments. It achieves high accuracy even at low or zero current and speed, minimizing the influence of identification errors on different parameters. A KF-based approach discussed in [48] enables continuous updates of motor parameters, effectively handling noisy measurements for improved accuracy. EKF and dual EKF (DEKF) are compared, with DEKF performing better in estimation quality and resilience to initial states. In [49], a deadbeat control is introduced for tracking reference currents with zero steady-state error, adapting PMSM parameters during control. It effectively eliminates control offsets caused by parameter errors. The study in [50] enhances control robustness, minimizes torque ripples, and improves disturbance rejection, mainly integrating deadbeat control while addressing torque oscillations and noise reduction.

The system identification method is employed in [51] to model the inertia of a PMSM drive. It uses a sinusoidal perturbation torque with a DC offset to drive the PMSM, and then measures the amplitudes of the torque and speed response to calculate the system’s inertia. This method is robust and provides accurate inertia values quickly compared to other approaches. The studies in [52–56] utilized a black-box modeling approach for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), PSys stabilizer, flexible maneuvering systems (FMS), ground robots, and fuel control unit, respectively. This approach allows for adaptability to system changes without requiring extensive recalibration.

In system identification, after selecting or obtaining the model structure, the subsequent step involves parameter optimization. This section explores diverse parameter optimization methods utilized in the literature, which have shown promising results. In optimization algorithms, the error-or more specifically, the fitness value, a standard term in metaheuristic algorithms-serves as a quantitative measure of how well the identified model represents the actual system dynamics. Commonly used metrics include Sum of Squared Errors (SSE), Mean Squared Error (MSE), Integral of Absolute Errors (IAE), and Integral of Time-weighted Absolute Error (ITAE). These metrics are calculated by comparing the observed outputs (

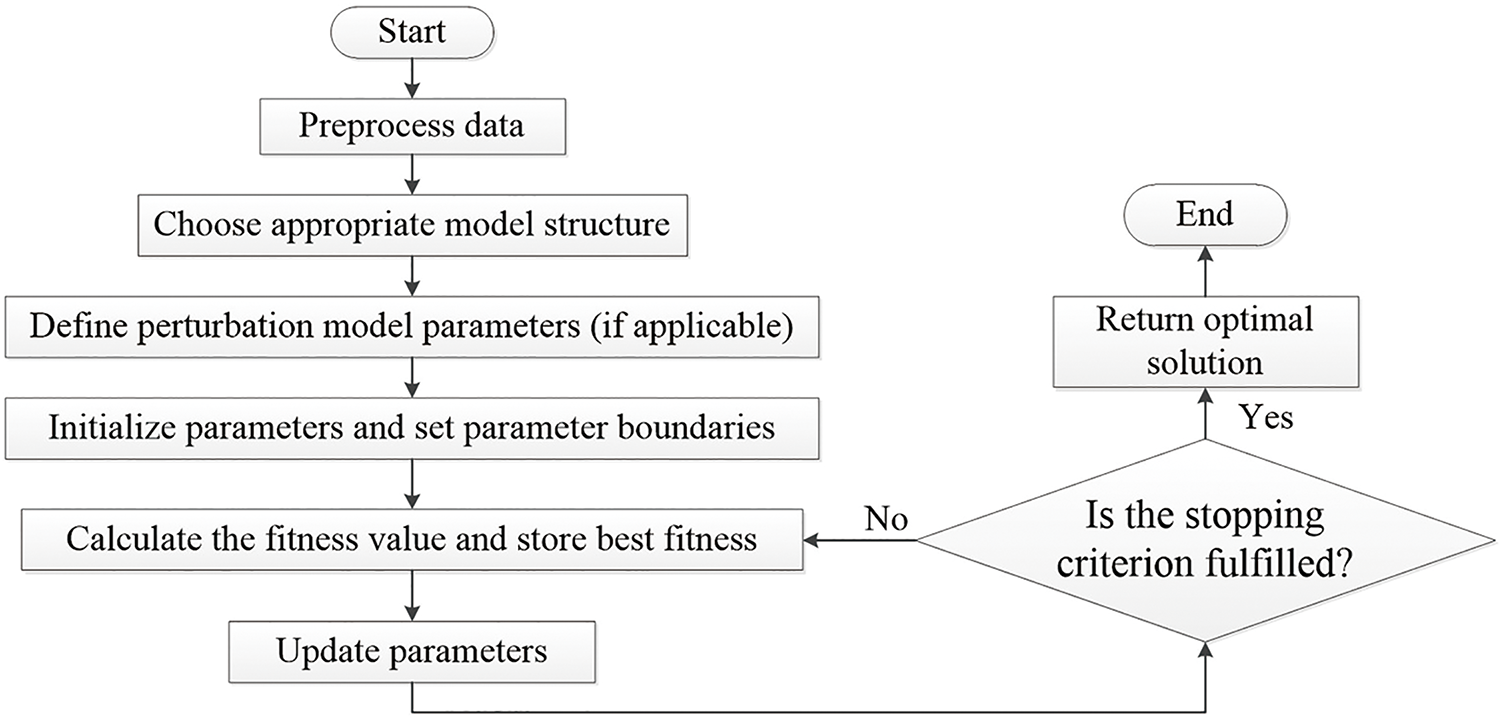

Fig. 8 illustrates the general framework for parameter optimization. The process of tuning model coefficients using metaheuristic optimization algorithms begins with preprocess data, followed by the identification of the model structure and the selection of parameters to be optimized. In the context of electric motor systems, key parameters such as armature resistance (

Figure 8: Generic parameter optimization procedure

The optimization problem is formulated by defining decision variables, selecting an appropriate objective function, and imposing relevant constraints based on system dynamics and performance requirements. The choice of the objective function significantly influences the optimization outcome, with commonly used objective functions including the IAE, ITAE, MSE and SSE. The optimization algorithm is then initialized by generating a population of candidate solutions in population-based methods. Each candidate solution is evaluated through model simulation, where the objective function quantifies system performance based on predefined criterion. The algorithm iteratively refines the solutions by leveraging exploration mechanisms to enhance global search capabilities and exploitation mechanisms to fine-tune local optima. Convergence is assessed based on predefined stopping criterion, such as a maximum number of iterations or a threshold for minimal improvement in the objective function. Once an optimal solution is identified, its validity can be examined through several methods such as step response analysis, frequency response evaluation, and robustness testing against parametric variations and external disturbances. Finally, the optimized parameters are implemented, and key performance metrics are analyzed to ensure a comprehensive and unbiased comparison across different optimization algorithms.

The LS method is commonly used for parameter optimization by minimizing the SSE between the observed output data and the model predictions [57]. This involves formulating an objective function that represents the difference between the actual output and the model’s output. LS is suitable for linear problems, whereas LM is more effective at handling nonlinearity. In [58], the MATLAB System Identification Toolbox, which uses LS as the default search algorithm, is employed to identify a DC motor model. The resulting error between the real and estimated data for transfer function prediction is less than 2%. Let

This objective function is typically minimized by solving the following equation:

Once

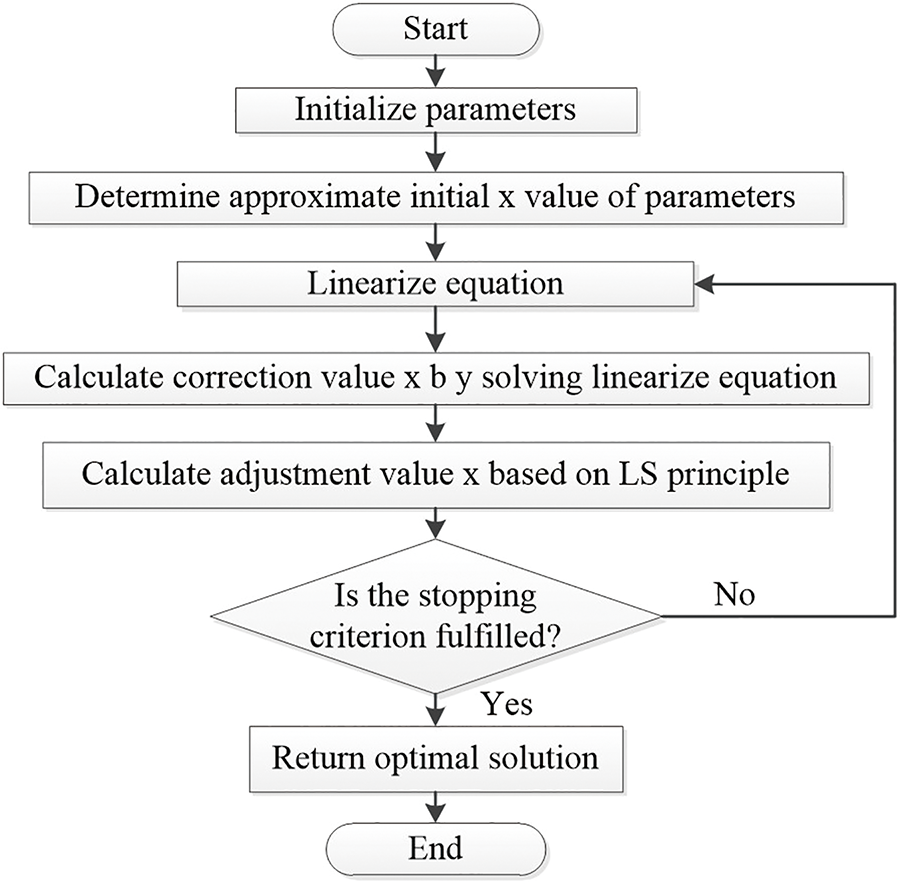

Fig. 9 demonstrates the working principle of LS. It begins by initializing the parameters to be optimized, then transforms the equation into a linear form to simplify the solution process. The next step is to check whether the adjustment value is below a specified threshold and if the stopping criteria are met to obtain the parameter solution. The LS approach is particularly useful when dealing with linear models or when the objective function can be linearized, as it provides a computationally efficient and statistically robust way to estimate model parameters. In [59], the LS method is utilized to derive both static and dynamic models for DC motors. Fig. 10 depicts the experimental setup proposed in [59] for estimating motor parameters, implemented using Arduino and Python. The results indicate that motor models adopting the ARX structure achieve greater accuracy when optimized using the LS method compared to pattern search (PS) and nonlinear LS (NLS) methods, particularly in terms of angular velocity responses.

Figure 9: LS flowchart

Figure 10: Experiment setup for system identification in [59]

For perturbed BLDC motors, the LS method can be employed to estimate cogging torque as it effectively approximates the true nonlinear dynamics of the systems. Fig. 11 illustrates the approach introduced in [60] for cogging torque estimation which leverages an ideal model derived from the linear mechanical dynamics of the BLDC motor without any external load torque. In the work, a combination of frequency domain identification of linear terms and time domain estimation method is used to estimate unknown parameters. The study in [61] employs a DC motor with a minimum-phase mathematical model controlled by a self-tuning regulator without model pole cancellation. The standard system identification process is then detailed by parameterizing the system for LS estimation, incorporating exponential forgetting to address time-varying plants.

Figure 11: Cogging torque estimation technique using LS for nonlinear BLDC modeling [60]

In perturbed motor modeling, various LS variants have been proposed in the literature to either lessen computational burden or tailor it to specific applications. One such method is the recursive LS (RLS) approach, which updates parameter estimates recursively as new data is acquired in order to enable efficient adaptation to changing system dynamics and time-varying parameters [62]. Thus, instead of constructing

where

This method generally demands fewer computational resources than batch LS estimation, rendering it well-suited for online and real-time applications [63]. The work in [64] for instance, utilizes the RLS method for online identification of the dynamic model of a differential drive mobile robot, while employing the LM method for offline identification. A similar approach is adopted in [65] for PMSM with sensorless control technique. LM is an optimization technique which is particularly effective when dealing with NLS problems. It can handle situations in which the underlying relationship between variables is nonlinear.

In [66], the RLS is employed to estimate the disturbance voltage in voltage source inverter operation in a PMSM system. It proposes two methods to reduce this estimation error; one uses an iterative learning controller to suppress d-axis current harmonics, and the other bases the disturbance voltage estimation on the average value of the q-axis equation variables, making it immune to current harmonics and enhancing motor parameter identification accuracy. Such a method is illustrated in Fig. 12. The work in [67] presents a methodology combining finite-control-set model predictive control with online LS system identification, which can maintain optimal performance despite changes in motor dynamics or external disturbances. This approach enhances the control performance of PMSM drives by integrating predictive control with real-time system identification. It is capable of handling constraints on control inputs and system states, making it suitable for applications with strict operational requirements or safety constraints.

Figure 12: Iterative learning controller in the d-axis current control loop for a perturbed PMSM system [66]

In [68], the RLS method is utilized for a PMDC motor with an ARX model structure. Subsequently, an adaptive discrete pole placement controller is proposed and designed to regulate the motor’s rotational speed. Another LS variant, termed sequential LS, is proposed in [69] which is specifically tailored for ARMAX dynamic network identification. This approach offers advantages in terms of accuracy, convergence speed, robustness, and improved approximation by introducing new criteria to refine the parameter estimates. The study in [70] introduced ordinary LS (OLS) for BLDC motor modeling, but it has limited ability to handle complex or noisy data and not suitable for systems with highly dynamic behavior or significant uncertainties. Palpacelli et al. [71] employed OLS for the identification of industrial robots. This method utilizes motor current measurements obtained during numerous slow-motion tests. This study takes into consideration the Coulomb friction and gravity contributions to motor torques. The model incorporates and analyzes the effect of external pressures applied at the end-effector. A combination of RLS and OLS has been introduced in [72] to improve the system identification of a DC motor while minimizing computational burden. This approach is suitable for relatively well-behaved systems with low noise levels.

The study in [73] proposed a combination of EKF and LS to optimize parameters of both kinematic and dynamic models for a tracked mobile robot. The findings illustrate the effectiveness and reliability of the proposed approach in identifying terrain parameters, which could prove valuable for future path planning efforts. Li and Ma [74] proposed a compound LS (CLS) for DC motor parameter identification, aiming to address the volatility of fault-prone results in forgetting factor LS (FFLS) identification. By integrating selection control, this method offers faster, more accurate, and stable real-time identification of DC motor parameters, even as these parameters change. Simulation results demonstrate that the hybrid least square parameter identifier outperforms the FFLS method by offering faster identification speed, higher accuracy, better stability, and effective online identification of motor parameters across different speeds.

5.2.2 Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

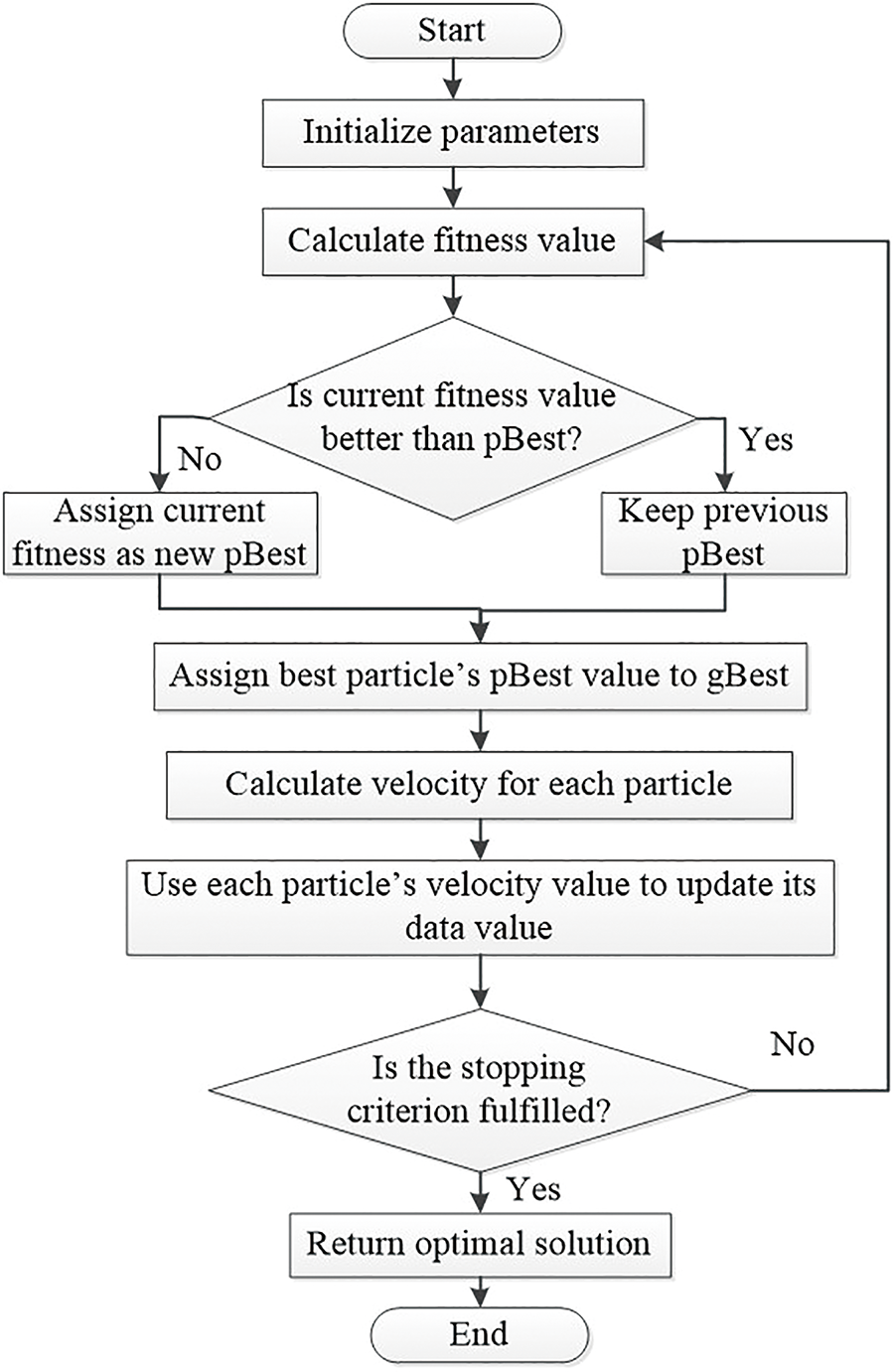

PSO is modeled after the social behavior of schools of fish or flocks of birds, in which single particles cooperate to find the utmost solution. The PSO approach was first introduced by social psychologist James Kennedy and electrical engineer Eberhart and Kennedy [75]. In the domain of identification, PSO is used to iteratively change the locations of a population of particles in a multidimensional search space to identify the ideal model parameters or structures [76]. Each particle in the PSO represents a possible solution, which could be a set of model parameters or even a DC motor model. Each particle keeps track of its position and speed inside the search space while assessing its fitness using a predetermined objective function. On the basis of their individual knowledge, which is also known as local best, and the aggregate wisdom of the entire swarm, which is global best, particles modify their positions and velocities [77,78]. The results possess improved accuracy in parameter estimation and enhanced model performance for dynamic systems.

Fig. 13 indicates the working principle of PSO, which optimizes solutions by simulating the movement and interactions of particles in a solution space. Each particle starts by calculating its fitness value based on an objective function. The algorithm then checks if each particle’s current fitness is better than its best previous fitness, known as pBest. If it is, pBest is updated; if not, it remains the same. The best pBest among all particles is then assigned to the gBest, representing the best solution found so far. The particles’ velocities are updated based on both their distance from pBest and gBest, guiding them towards potentially better solutions. Each particle then uses its updated velocity to move to a new position in the solution space. The algorithm repeats this process until the maximum number of iterations is reached or the solution stabilizes, ultimately yielding the best solution found by the swarm.

Figure 13: PSO flowchart

PSO can be mathematically described as:

where

In [79], a systematic evaluation of the influence of the swarm size parameter on the effectiveness of the PSO-based Nonlinear ARX (NARX) structure selection is proposed. By doing so, it offers insights into optimizing the swarm size for better model performance. The findings show that a swarm size of 20 to 30 was best for optimizing the DC motor structure selection because it required a minimum of iterations to converge and had high fitness values. A comparison study discussed in [80] indicates good fitting results using the orthogonal LS approach and PSO for the NARX parameter estimation of a DC motor. The plots of autocorrelation and cross-correlation showed minor correlations between the output and the residual as well as between the residual and itself.

The cognitive coefficient (

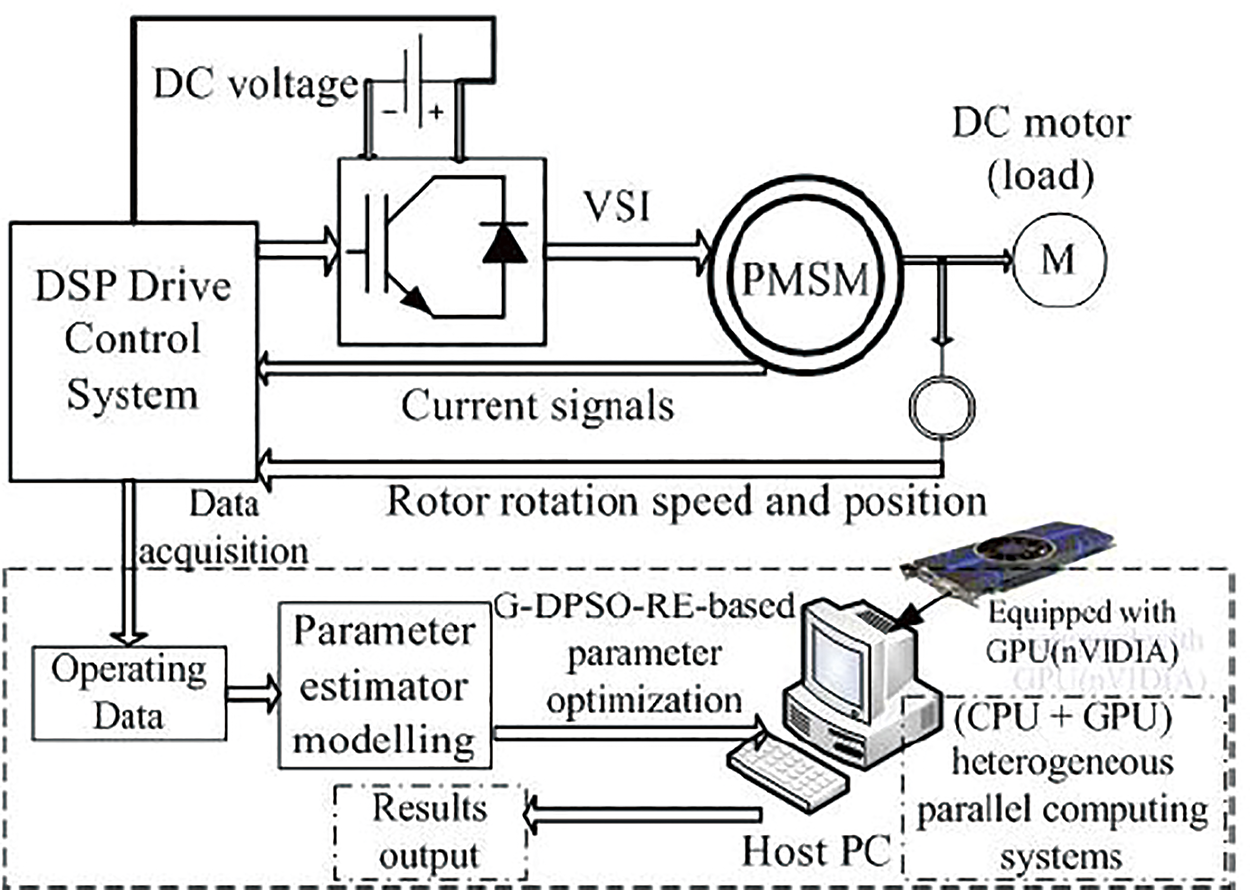

Liu et al. [81] employed parallel computing on a graphics processing unit (GPU) to enhance the efficiency, speed of parameter identification, and temperature monitoring. Parameter estimation was carried out under a variation of temperature conditions. A heater is used to heat the prototype for twenty minutes before the identification experiment is carried out. The data indicates that the parallel co-evolutionary immune PSO accelerated by GPU (G-PCIPSO), performs better with respect to mean, standard deviations, and t-values. The confidence level of G-PCIPSO reached 98% compared to other hybrid PSOs. In terms of speed and computing efficiency, this method can perform noticeably better than conventional central processing unit based techniques, enabling real-time and increased accuracy.

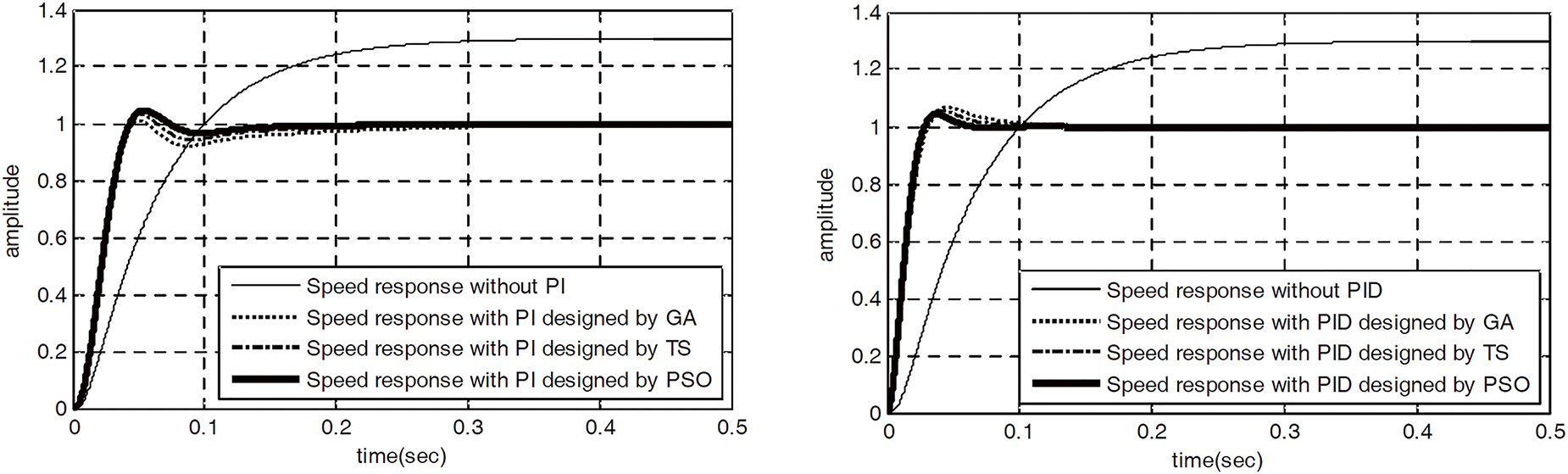

Another study in [82] critically evaluates the use of PSO for optimizing control parameters to improve motor control performance. Utilization of back EMF detection for feedback can provide information about the motor’s actual speed and position, contributing to more accurate and responsive control. Fig. 14 illustrates the resulting system responses of proportional-integral (PI) and PID controllers optimized via PSO against other optimization methods. From the findings, PSO consumed the smallest search time, providing the fastest response with the shortest rise and settling time. The optimized controller can be applied to various BLDC motor control scenarios, making it versatile and adaptable to different applications. Thus, it enhances the capability to deal with non-linear models and dynamic behavior with more accurate parameter identification.

Figure 14: System response of PI (left) and PID (right) controllers with GA, TS and PSO [82]

In [83], the results suggest that PSO offers a unified and potentially more efficient method for accurately predicting the behavior of a DC motor, while the modified KF successfully reduces noise in measurement. This approach is particularly well-suited for nonlinear and dynamic systems. Meanwhile, Ref. [84] focuses on enhancing the precision and efficiency of parameter estimation, crucial for improving system control and performance. The study explores various PSO variants, including Constricted PSO (CI PSO), Standard PSO (STD PSO), Chaos Initialized PSO (CIW PSO), and Adaptive Inertia Weight Factor PSO (AIWF PSO), to identify the best-performing algorithm. CIW PSO emerges as the top performer, surpassing other algorithms by avoiding local optima, achieving close-to-actual values, and minimizing the cost function. With its collective intelligence and exploration-exploitation balance, PSO proves to be an effective method for identifying motor parameters.

Kanojiya and Meshram [85] proposed an automated tuning process that reduces manual parameter adjustment, introducing a hybrid topology PSO concept advantageous for solving optimal control problems due to its convergence, flexibility, and adaptability. Another study conducted by Abedinifar et al. [86] focused on nonlinear model identification and statistical verification of UR5 manipulator joint parameters using experimental data, resulting in improved accuracy and reliability in capturing dynamic behavior. The PSO algorithm facilitated parameter determination for nonlinear terms, achieving a high R2 value of 97.1% and precise computation of joint torques, with a maximum identification error as low as 5%. Additionally, Sandre-Hernandez et al. [87] employed PSO to identify stator inductances of a PMSM using experimental measurements, demonstrating fast and stable convergence characteristics without complex control strategies, as depicted in Fig. 15. Experimental validation confirmed the effectiveness of the proposed method, showing feasibility with a commercial PMSM and real-time microcontroller.

Figure 15: Connection scheme for identification of the stator inductances using PSO as proposed in [87]

The study in [88] aims to estimate the parameters of a PMDC motor for a wheelchair, utilizing standard PSO and dynamic PSO (DPSO), ACO, and ABC, alongside experimental methods. Parameters such as torque constant, back-EMF constant, moment of inertia, friction coefficient, armature inductance, and resistance are estimated and compared using both experimental and optimization approaches, with simulations showing that DPSO with varying inertia weight and ABC algorithm yield motor parameters with significantly lower speed and current errors compared to other methods. The work in [89] introduces the G-DPSO-RE method, which combines fast DPSO with a receptor editing strategy, leveraging GPU acceleration to establish an accurate parameter estimation model for surface PMSMs while considering voltage-source-inverter (VSI) nonlinearity. The method demonstrates effectiveness in estimating PMSM parameters and disturbance voltage from experimental data and analyzing the impact of VSI nonlinearity on estimation accuracy. In [90,91], the dynamic self-learning feature enhances the algorithm’s adaptability to changes in operating conditions. Fig. 16 illustrates the schematic of the parameter estimation system as proposed in [91], which utilizes a prototype of a PMSM and a DSP vector control hardware platform as the experimental setup.

Figure 16: The schematic of the parameter estimation system as proposed in [91], which utilizes a prototype of a PMSM and a DSP vector control hardware platform as the experimental setup

GA, drawing inspiration from natural selection, is an influential optimization method widely applied in parameter identification tasks for motorized systems. It aims to determine crucial parameters like friction coefficients, moment of inertia, and back EMF constant to accurately model the behavior and dynamics of DC motors for control, simulation, and system analysis. It begins with a population of potential solutions, each evaluated by a fitness function that indicates how well it meets the objective.High-fitness solutions are selected to reproduce, creating new solutions through crossover by combining traits of two solutions and mutation by introducing random changes. This process iterates, with each generation evolving toward better solutions.

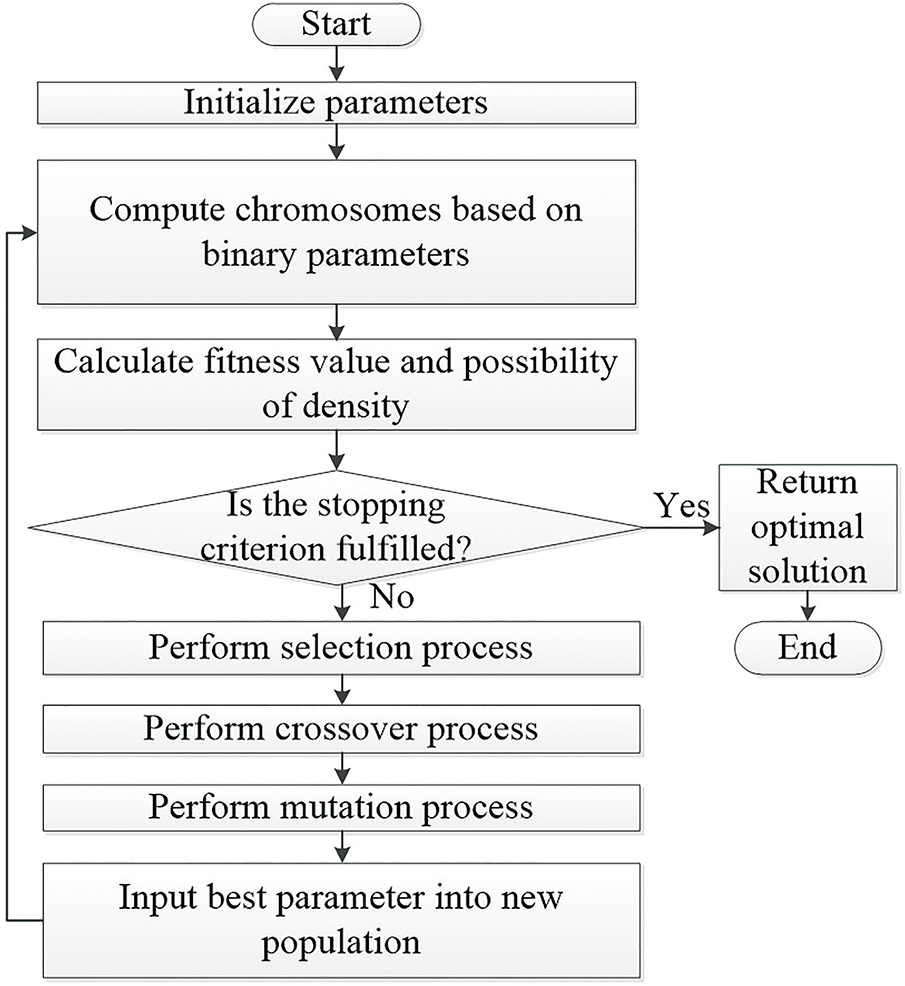

For instance, in [92], GA is employed for parameter estimation of a geared DC motor, while in [93], it is used to estimate the PMDC motor used in a wheelchair. The study in [94] explores the application of GA for parameter identification in PMSMs under information interference. It assesses the algorithm’s effectiveness by comparing the motor’s response with its dynamic model under disturbing influences, demonstrating successful parameter identification despite resource-intensive computational requirements. Fig. 17 depicts the GA working principle. Each chromosome’s fitness is evaluated and best chromosomes are chosen for reproduction. Following selection, crossover and mutation processes are applied to introduce variation and explore new solutions. Crossover combines parts of selected chromosomes, while mutation slightly alters them to maintain genetic diversity. After these operations, the best parameters are added to a new population, replacing the old one.

Figure 17: GA flowchart

In [95], a multi-objective GA (MOGA) is utilized for dynamic modeling and parameter estimation of a hydraulic robot manipulator, facilitating simultaneous evaluation of performance objectives such as accuracy, speed, and energy efficiency, leading to improved convergence of estimated parameters compared to single-objective approaches. Similarly, in [96], GA, MOGA, and Niched Pareto GA (NPGA) are employed for analyzing magnetic flux distribution, with NPGA demonstrating superior performance in providing optimal solutions due to its enhanced growth and convergence characteristics compared to proportionate selection.

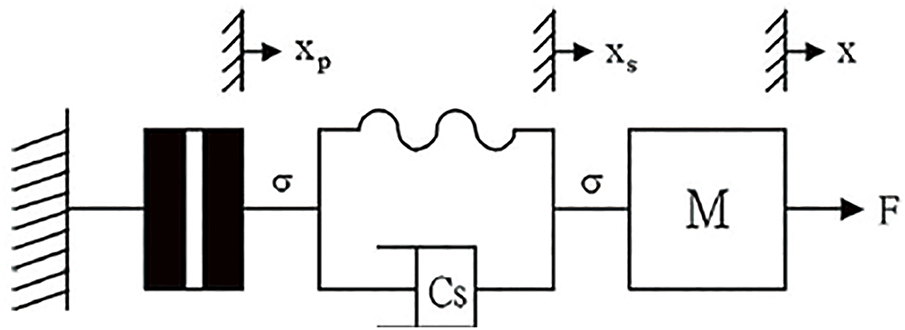

The study in [97] aims to enhance the tracking accuracy of a BLDC-based linear motor stage used in printing applications by addressing nonlinear friction dynamics. The Hsieh-Pan model [98] is used to account for friction-induced behaviors, such as stick-slip motion, which can disrupt motor precision. GA iteratively adjust parameters by evolving a population of possible solutions and minimizes these friction effects. Through selection and mutation, GA finds an optimal parameter set to counteract static friction, ensuring smoother, more accurate motor performance. This model has been employed to describe the nonlinear static friction as depicted in Fig. 18, and GA is used to identify its parameters. Additionally, PSO-based optimization is applied to fine-tune parameters in a disturbance-observer-based variable structure controller, resulting in improved tracking response. The PSO with constriction coefficient is used to aid particles in converging quickly over time by reducing their oscillation amplitude as the particles focus on nearby points that have yielded optimal results previously. To incorporate the constriction factor, the PSO’s velocity update equation is modified as follows [99]:

where

with

Figure 18: Static friction based on Hsieh-Pan model employed in [97] where

The work in [100] addresses the challenge of system identification in process industries when open-loop data is unavailable, emphasizing the importance of selecting an appropriate model structure. It compares a first-order integer model with four different fractional models for closed-loop identification of a DC motor, optimizing fractional model parameters using GA to minimize the sum of squared errors (SSE). The results indicate that fractional order (FO) models generally provide a better fit than the first-order integer model, with the fractional model featuring the fewest parameters demonstrating the best performance among the identified models.

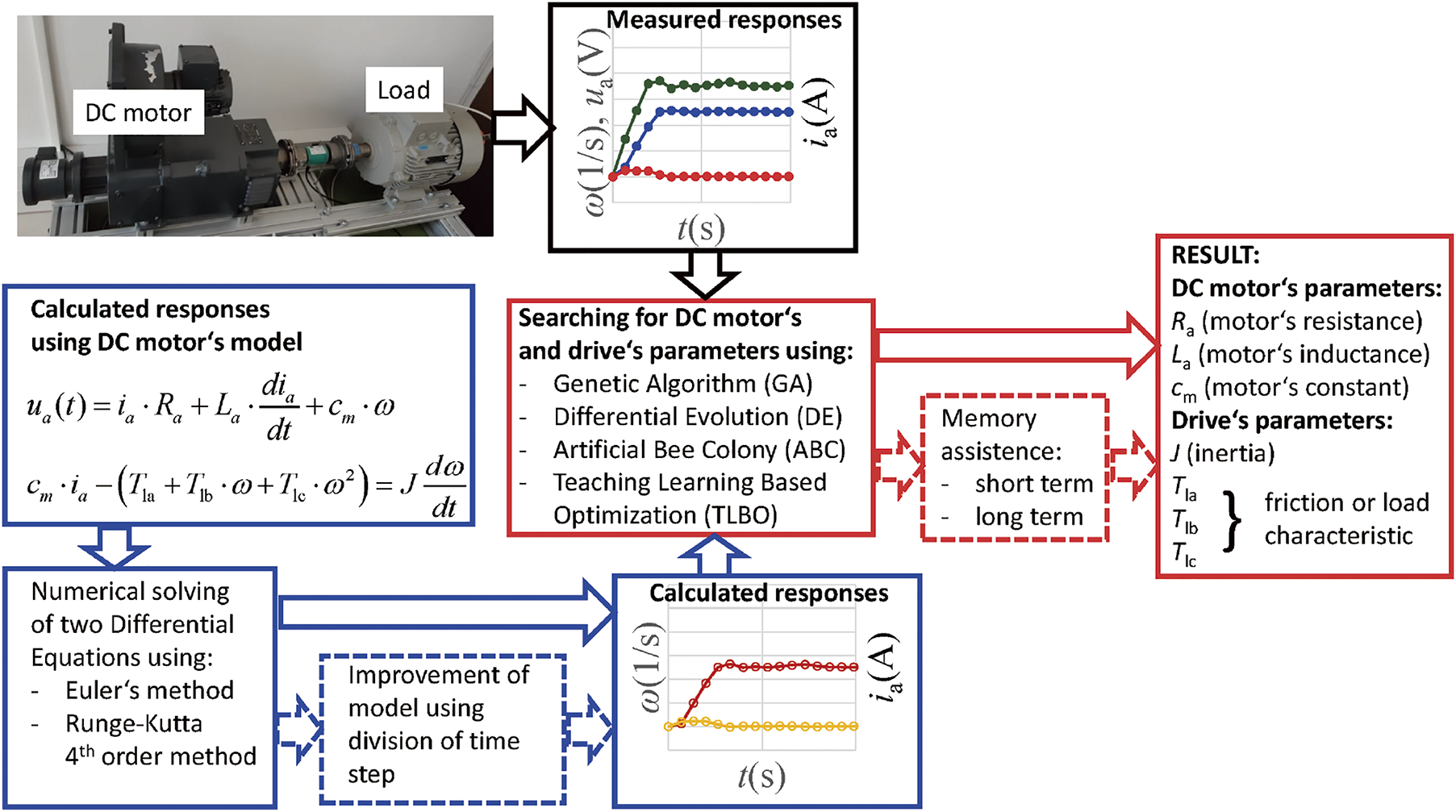

In [101], a technique for identifying seven parameters of a DC motor and drive is outlined, taking into account speed and current step responses. Fig. 19 depicts the system identification workflow. Various evolutionary methods, such as GA, DE, TLBO, and ABC, are utilized and compared, with DE/rand/1/exp demonstrating superior performance for this task. Additionally, strategies such as dividing the motor model simulation time and employing short-term memory assistance are suggested to improve results and decrease computation time, respectively.

Figure 19: The system identification process in [101]

5.2.4 Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO)

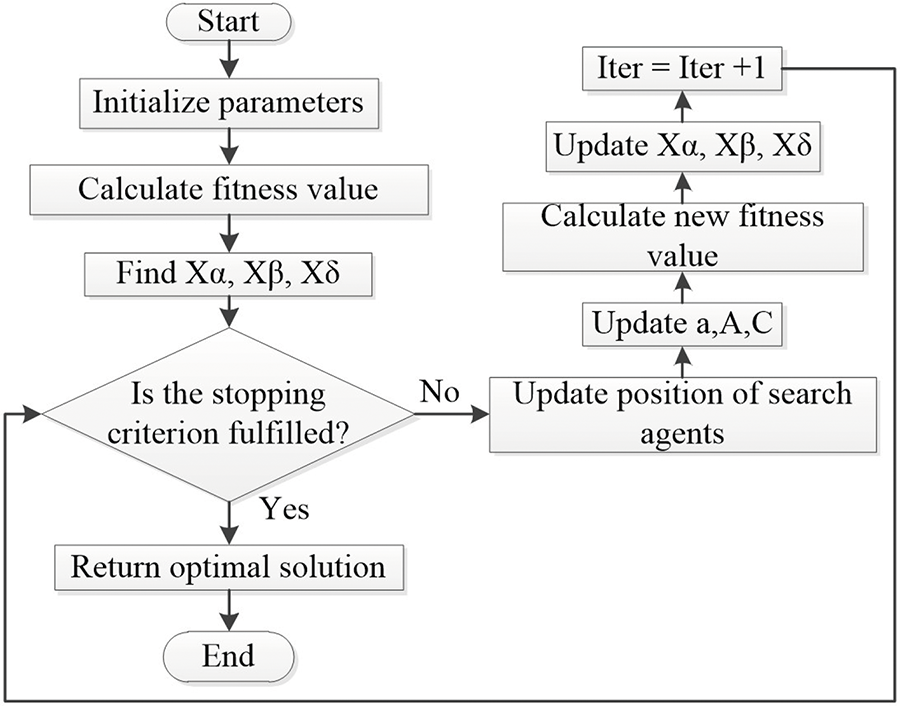

GWO, a metaheuristic optimization algorithm developed in 2014, seeks optimal solutions by mimicking the hierarchical hunting behavior of grey wolves in nature [18]. The algorithm begins by generating a set of random candidate solutions. The grey wolf population is divided into four categories: alpha (

where

where

Throughout the optimization process, the

where

Figure 20: GWO flowchart

The work in [102] utilized GWO, JA, and CS to identify the parameters of DC motors, focusing on their dynamic responses to step inputs and employing steady-state and transient-state relationships as search constraints. The data acquisition setup for system identification is depicted in Fig. 21 where a PIC18F4550 with a sampling period of 0.001 s is used as the main controller. The three algorithms were tested using real-world signals to assess their performance under practical conditions. Unlike synthetic data, real-world signals typically contain noise and higher uncertainty due to factors like measurement system characteristics and environmental conditions. In this scenario, each algorithm was evaluated with a population size of 30 individuals and a maximum of 50 iterations. The results showed that all three algorithms performed competitively, with GWO slightly outperforming the others.

Figure 21: Illustration of the data acquisition setup for DC motor system identification in [102]

The work in [103] addresses the challenge of choosing the correct parameters for motor controllers in a wheeled mobile robot’s design. It emphasizes the importance of accurately tuning these controllers based on known parameters of the robot’s PMDC motors to improve its dynamics. The approach combines the GWO algorithm with initial parameter estimates from the characteristic point method (CPM), resulting in CPM-GWO. Findings indicate that CPM-GWO outperforms its individual components in terms of RMSE. Another approach in [104] using GWO attained the lowest MSE of 0.43%, demonstrating superior accuracy in parametric estimation compared to Steiglitz-McBride, JA, and GA. The algorithms were evaluated using real current and velocity signals containing inherent noise. To mitigate its impact on parameter estimation, the velocity signal was processed using a Chebyshev software filter, while the current signal underwent hardware-based filtering.

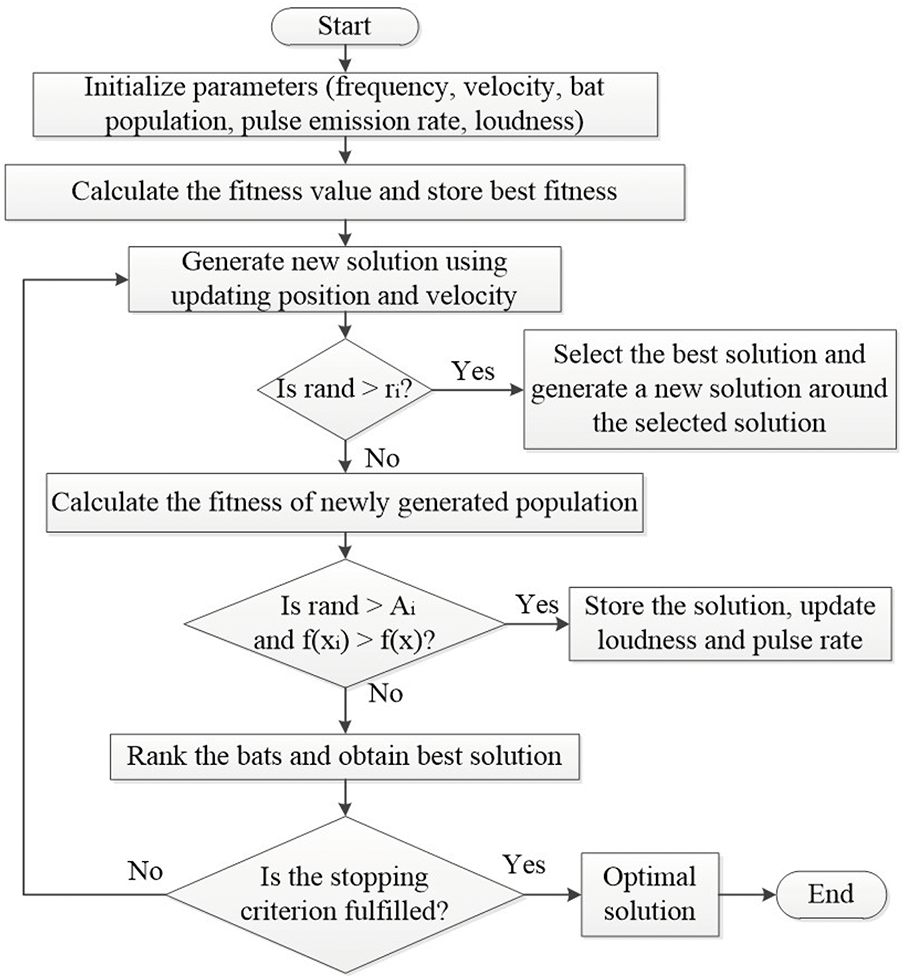

BA is an metaheuristic optimization algorithm which mimics the echolocation behavior of bats to solve complex optimization problems [105]. Bats use echolocation to navigate and hunt prey by emitting sound waves and listening to the echoes that bounce back from obstacles and prey. To identify the most optimal solution, the algorithm generates a bat population and allows the bats to roam randomly within a restricted space. Each bat discovers the best answer, followed by rating the bats to choose the best option among them. BA often exhibits strong convergence properties which leads to faster and more reliable parameter estimation.

Fig. 22 presents the working principle of BA. The algorithm begins by initializing parameters such as frequency, velocity, position, pulse emission rate, and loudness for each bat in the population. The fitness of each bat is then evaluated, and the best solution is recorded. If a random number exceeds a threshold, the best solution is selected to explore nearby areas for refinement. After generating a new population, the fitness of the bats is recalculated. The bats are then ranked to identify the best solution in the current iteration. This method balances exploration and exploitation to find the best solution efficiently.

Figure 22: BA flowchart

Each bat is represented as a solution in the search space and the algorithm updates its position and velocity to move towards better solutions. Velocity, position and frequency update can be expressed as:

where

where

where

In [106], the Bat Algorithm (BA) is utilized to tackle BLDC wheel motor challenges, encompassing 5 design parameters and 6 constraints for the mono-objective problem, and 2 objectives, 5 design parameters, and 5 constraints for the multiobjective version. Additionally, the results are compared with the Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm—Version II (NSGA-II), which stands as one of the most efficient multiobjective algorithms in the literature. The findings reveal promising outcomes for the mono-objective BA, with efficiency consistently nearing 95.23% when addressing the BLDC motor problem. The study outlined in [107] applies the BA to estimate parameters of a closed-loop operating DC servo motor in a robot. This approach proves particularly valuable for robots or machines lacking complete information.

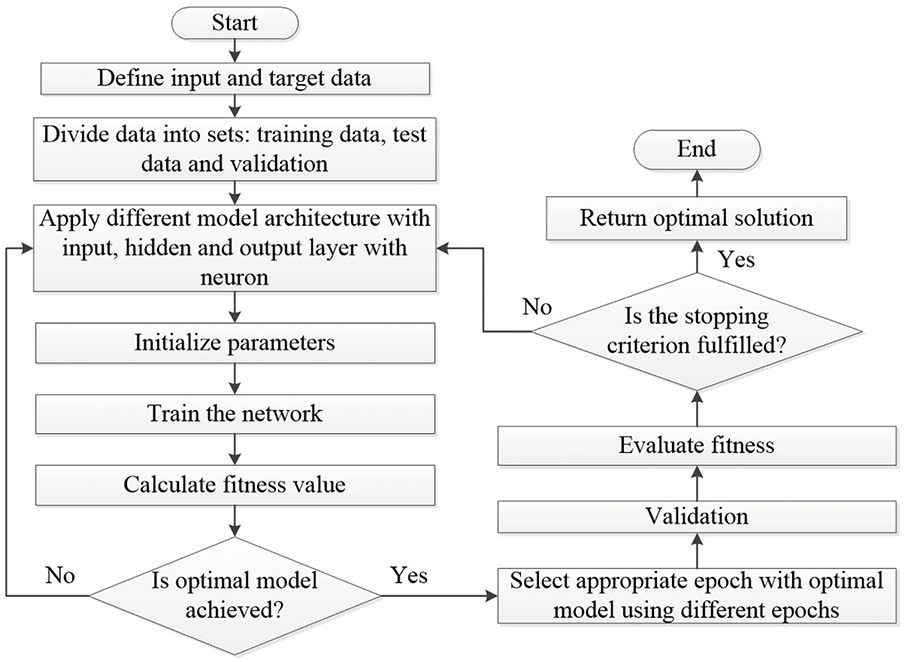

A neural network (NN) can model motor behavior using input parameters like voltage, current, temperature, and load conditions, learning nonlinear relationships with motor performance metrics such as speed, torque, and efficiency through historical data or simulations. NN can be effectively used to model the behavior of DC motors by learning the relationships between the motor’s input and output variables. The inputs required for training include a dataset of historical input-output data, network architecture specifications (such as the number of neurons and layers), weights, biases, learning rate, step size, loss function, batch size, and the number of epochs. The core idea is to treat the DC motor as a black-box system and leverage the neural network to approximate its dynamics. By doing so, the neural network can capture the motor’s nonlinear characteristics without the need for a detailed mathematical model, making it a powerful tool for system identification and control.

Fig. 23 shows the NN working principle. It begins by defining input and target data, which is then divided into three sets: training, testing, and validation data. Next, different model architectures are applied, consisting of input, hidden, and output layers with neurons. The weights and biases are initialized for these layers, and the network begins training by adjusting weights based on the data. During training, the model calculates the error, which represents the difference between the network’s output and the target data. If the error is within acceptable limits, training ends, otherwise, adjustments are made and training continues.

Figure 23: NN flowchart

In [108], a novel method is introduced for identifying robot arm manipulators driven by DC motors with a 131.25 to 1 reduction gearbox, employing convolutional NN (CNN) for efficient feature extraction and pattern recognition. This approach optimizes network architecture, hyperparameters, and training procedures to enhance accuracy and generalization, ensuring reliable parameter identification across varied operating conditions. However, the CNN’s effectiveness heavily relies on high-quality, representative training data, as insufficient or biased data can result in inaccurate parameter identification and compromised performance.

The study in [109] highlights the improvement of the accuracy of modeling PMSMs by integrating computational simulations with experimental data, which combines finite element calculations with data-based system identification techniques. Integrating computational simulations with experimental data offers a holistic understanding of PMSM behavior. This approach can capture both electromagnetic phenomena and real-world operating conditions. Another work in [110] investigated data-driven approaches for diagnosing incipient faults in DC motors. The methods used in this research analyze operational data and find patterns suggestive of impending DC motor problems using machine learning algorithms. For instance, decision trees, artificial NN (ANN), and support vector machines (SVMs). This involves preprocessing the operational data, selecting appropriate features, tuning hyperparameters, and evaluating model performance using suitable metrics.

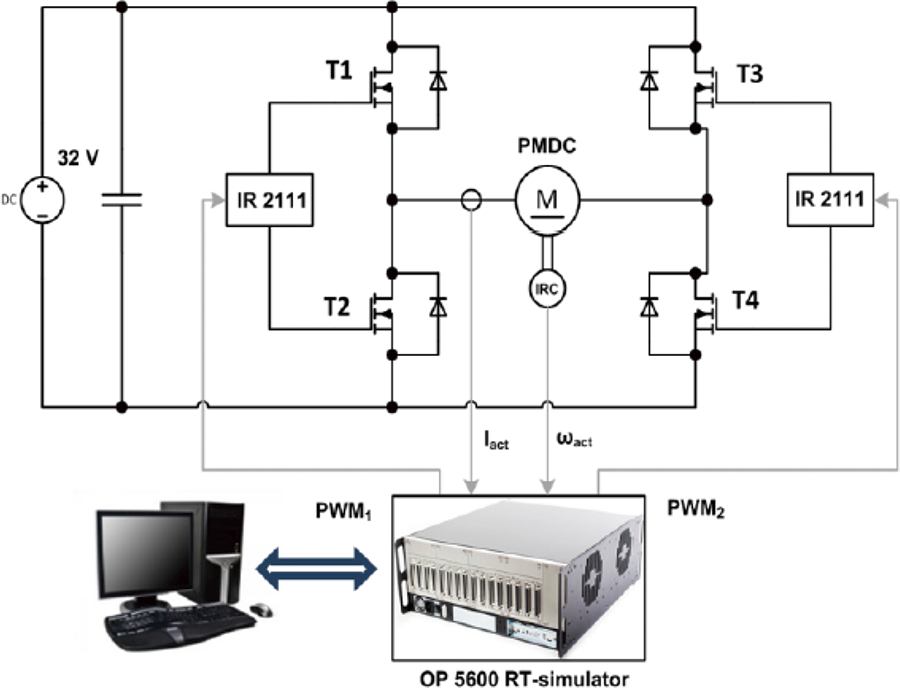

In [111], a recurrent neural network (RNN) is utilized to identify PMDC motors. RNNs are specialized for processing sequential data by retaining past input memory, allowing them to learn directly from input-output data without the need for complex models or extensive experimentation. This approach saves time by reducing the requirement for manual experimentation and iterative model tuning. The experimental setup, illustrated in Fig. 24, involves supplying the PMDC machine with an H-bridge converter controlled using a bipolar control strategy. Two PWM signals generated by the control system OP5600 regulate IR2111 drivers, which control MOSFET transistors (T1–T4). Current sensing is facilitated by a ACS712T sensor in the armature circuit, while speed sensing is conducted using an IRC sensor LARM, providing 1000 impulses per revolution.

Figure 24: Experimental setup for PMDC motor identification via RNN [111]

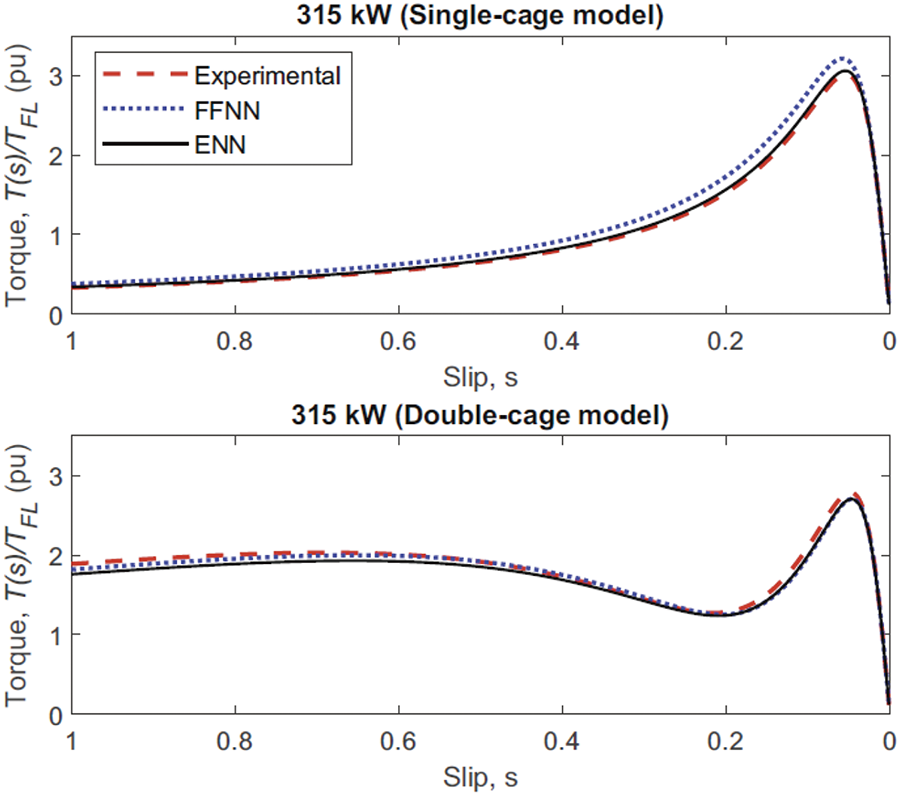

In [112], a novel feedforward neural network (FFNN) and Elman neural network (ENN) are proposed for parameter estimation of induction motors. The training process of these neural network structures was conducted with unmemorized training, demonstrating better performance for the single-cage model, which has 5 parameters compared to the double-cage model with 7 parameters. Fig. 25 illustrates successful convergence and improved estimation for the single-cage model using both ENN and FFNN networks.

Figure 25: Torque-speed curves for 315 kW motor comparing single and double cage model [112]

Additionally, in [113], an approach employing artificial neural networks (ANN), support vector machines (SVM), and extreme learning machines (ELM) for power consumption estimation of UAVs is presented. The mean absolute percentage error values for ANN, ELM, and SVM are reported as 0.389%, 1.258%, and 0.269%, respectively, with SVM outperforming ANN and ELM. This approach enables the determination of safe flight routes by adjusting the speed and pulse degree of the UAV based on predicted battery life during strategic flights.

5.2.7 Other Metaheuristic Methods

In [114], the WOA is employed to identify unknown parameters of a nonlinear PMSM, with validation against known parameter values. Comparative analysis with other algorithms such as BA, Self Adaptive Learning BA (SALBA), and PSO demonstrates superior convergence rates of the proposed WOA-based approach. While its mean square error performance is better than BA and PSO but not SALBA, the scheme shows promise for real-time implementation in hardware.

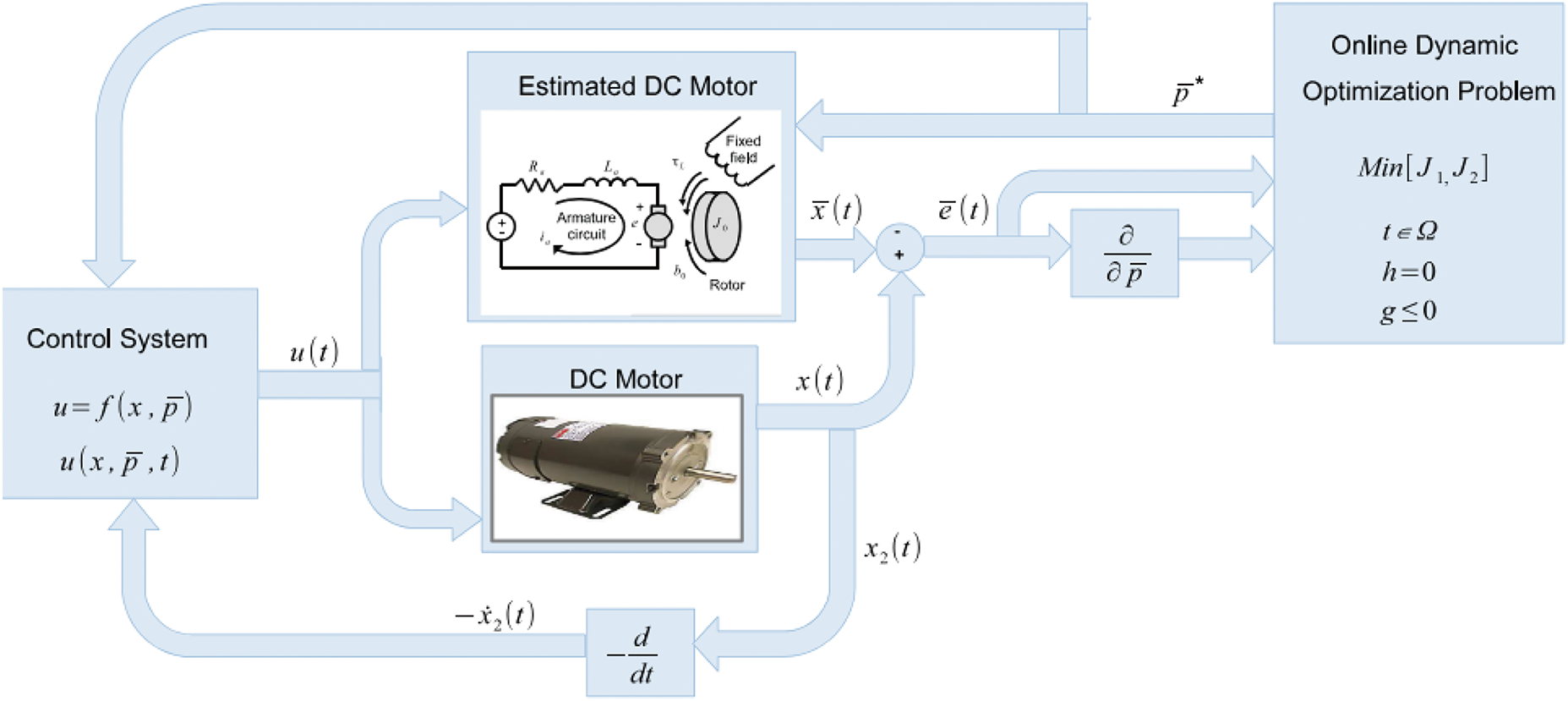

This study in [115] proposes a multi-objective online tuning optimization method for adaptively adjusting the velocity control parameters of a PMDC motor as illustrated in Fig. 26. By considering both modeled error and sensitivity, it selects the best compromise solution through a Pareto dominance-based selection process, while introducing modifications to the DE algorithm. Simulation results show improved velocity regulation control under parametric uncertainties and discontinuous dynamic loads compared to other optimization algorithms such as multi-objective DE, PSO, and NSGA-II.

Figure 26: Schematic diagram of the dynamic optimization process for the on-line PMDC control parameter estimation in [115]

Another approach presented in [116] focuses on applying the Flower Pollination Algorithm (FPA) to parameter identification for a DC motor model. FPA reduces the likelihood of getting trapped in local minima and provides accurate identification of eight ideal DC motor model parameters that capture system dynamics effectively.

Rodriguez-Abreo et al. [117] focused on motor parameter identification using CS, leveraging steady-state relations for precise parameter identification under stable operating conditions. The modifications made to the original CS algorithm allowed for the determination of motor parameter settings with minimal root mean square error, ensuring accurate results for both real signals and simulation data.

In [118], PMSM parameter identification using chaotic Gaussian-Cauchy RAO (CGCRAO) algorithm employs Tent chaotic mapping for population initialization, improving population diversity and promoting a more uniform distribution of initial solutions across the search space. CGCRAO algorithm retains the simplicity of the original RAO-1 algorithm, with fewer parameters and a concise core formula [119]. The CGCRAO algorithm achieved identification errors of less than 1% for resistance and flux while maintaining an error of only 1.0547% for inductance, demonstrating superior performance compared to other algorithms. CGCRAO attained the lowest fitness value (0.02411), outperforming PSO (0.03682), DE (0.03845), GWO (0.02661), and RAO-1 (0.02935).

The study in [120] focuses on identifying the continuous-time Hammerstein model under conditions of sparse measurement data using random average marine predators algorithm (RAMPA) with a tunable step-size adaptive coefficient(CF) (RAMPA-TCF). MPA utilizes Lévy flight and Brownian motion to improve global search efficiency while incorporating adaptive mechanisms for local refinement. This dynamic search strategy facilitates faster convergence and mitigates the risk of premature stagnation [121]. The main challenge was incomplete data affecting parameter estimation accuracy. The piecewise affine function improves nonlinear subsystem modeling, enhancing robustness against noise. Performance was assessed under sparse measurement data conditions of 5%, 15%, 35%, and 50% missing data. Even with 50% missing data, RAMPA-TCF demonstrated the highest accuracy in identifying the Hammerstein model compared to other algorithms.

In [122], a hybrid algorithm combining the Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm (AOA) [123] and the Harris Hawk Optimization (HHO) algorithm [124] is proposed for more efficient exploitation mechanisms. The results indicate that the AOA-HHO hybrid outperforms both AOA and other algorithms in terms of minimizing the IAE while achieving reasonable overshoot, settling time, and rise time. Hybridization of PSO and gravitational search algorithm (PSOGSA) demonstrates the ability to achieve its global optimal solution within a reduced number of iterations [125]. Hybridizing metaheuristic methods typically offers the advantage of combining the strengths of multiple algorithms to enhance optimization performance and address the limitations inherent in individual approaches. However, achieving a more effective hybrid requires careful design and technique to ensure it performs better than its individual components [126–128].

The hybrid PSO and Sine Cosine Algorithm (SCA) optimization algorithm (HPSOA) proposed in [129] attained a minimal error of 0.0013, which is approximately ten times lower than the minimal errors produced by PSO and seven times lower than those obtained by SCA. The parameters estimated using HPSOA were validated against real motor data, demonstrating a high degree of accuracy. The steady-state speed error was measured at 0.58%, while the steady-state current error was 3.75%. These minimal errors substantiate the robustness and effectiveness of HPSOA in real-world applications.

Another approach in [130] employs simulated annealing adaptive particle swarm optimization (SAAPSO) to optimize the position control parameters. A Hammerstein-Wiener model based on a backpropagation neural network is developed. It integrates both linear and nonlinear modules to effectively capture the system’s linear and nonlinear characteristics. The proposed model achieves a substantial improvement in accuracy compared to traditional linear models help to reduce the maximum absolute position errors by 44.801% along the X-axis and 45.876% along the Y-axis. The symmetrical mean absolute percentage errors (SMAPEs) decreased by 86.804% along the X-axis and 85.996% along the Y-axis. Hybrid algorithms tend to produce more accurate results because they combine the best features of multiple optimization techniques [131].

This section delves into the synthesized findings from the preceding systematic review of literature concerning system identification techniques for motorized systems under various perturbations. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the system identification techniques employed for perturbed DC and AC motors, respectively. Each table organizes the studies according to the modeling method, motor structure, parameter optimization method, source of perturbations, and their respective applications or use cases. The diverse range of studies documented in the tables has been graphically represented below to offer a clearer overview of prevalent trends and distinct methodologies in both DC and AC motor applications.

Such perturbations can significantly impact real-time control applications by affecting system stability, accuracy, and overall performance. Load variations cause sudden torque demands, leading to speed deviations that can destabilize the system if not properly managed. Speed fluctuations, often resulting from external disturbances or supply inconsistencies, introduce tracking errors that reduce the precision of motion control. Friction, particularly at low speeds, leads to nonlinear effects such as stick-slip motion and increased energy losses, making precise control difficult. Hysteresis, commonly found in magnetic materials and mechanical systems, results in lagging system responses and inconsistent behavior, which complicates accurate control. Additionally, noise, both mechanical and electrical, interferes with sensor measurements and control signals, leading to erroneous feedback and degraded system performance.

These perturbations collectively challenge the reliability and responsiveness of motorized systems, particularly in high-precision and high-speed applications. Variations in load and speed can cause oscillations, overshooting, or delays in response, reducing efficiency and increasing wear on components. Friction and hysteresis introduce unwanted nonlinearities that make modeling and prediction difficult, leading to unpredictable deviations in system behavior. Noise further compounds these issues by distorting control signals, potentially causing instability or reduced sensitivity to actual system dynamics. In critical applications such as robotics, industrial automation, and electric vehicles, these perturbations can lead to performance degradation, increased energy consumption, and even system failures if not properly accounted for in the control design.

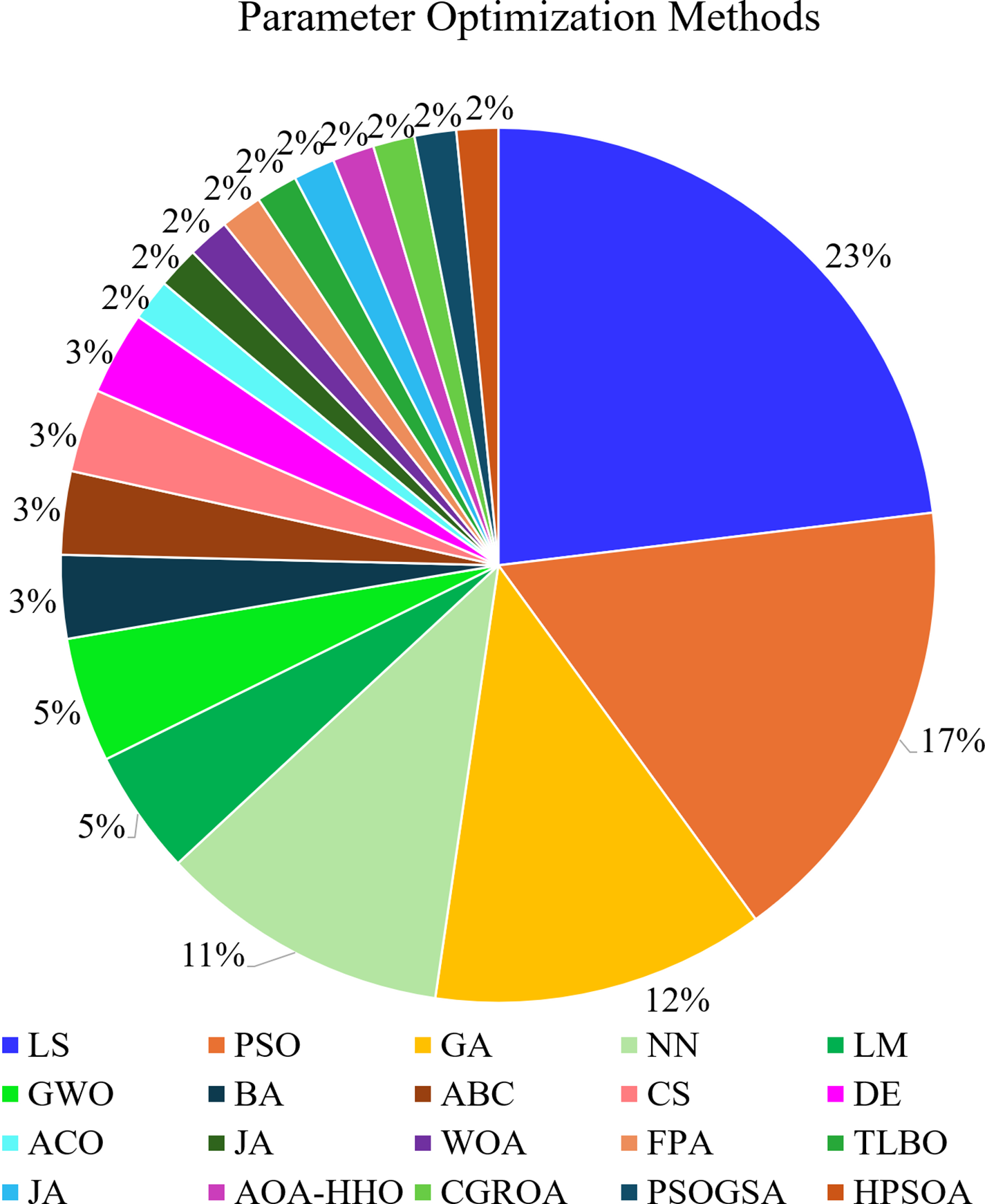

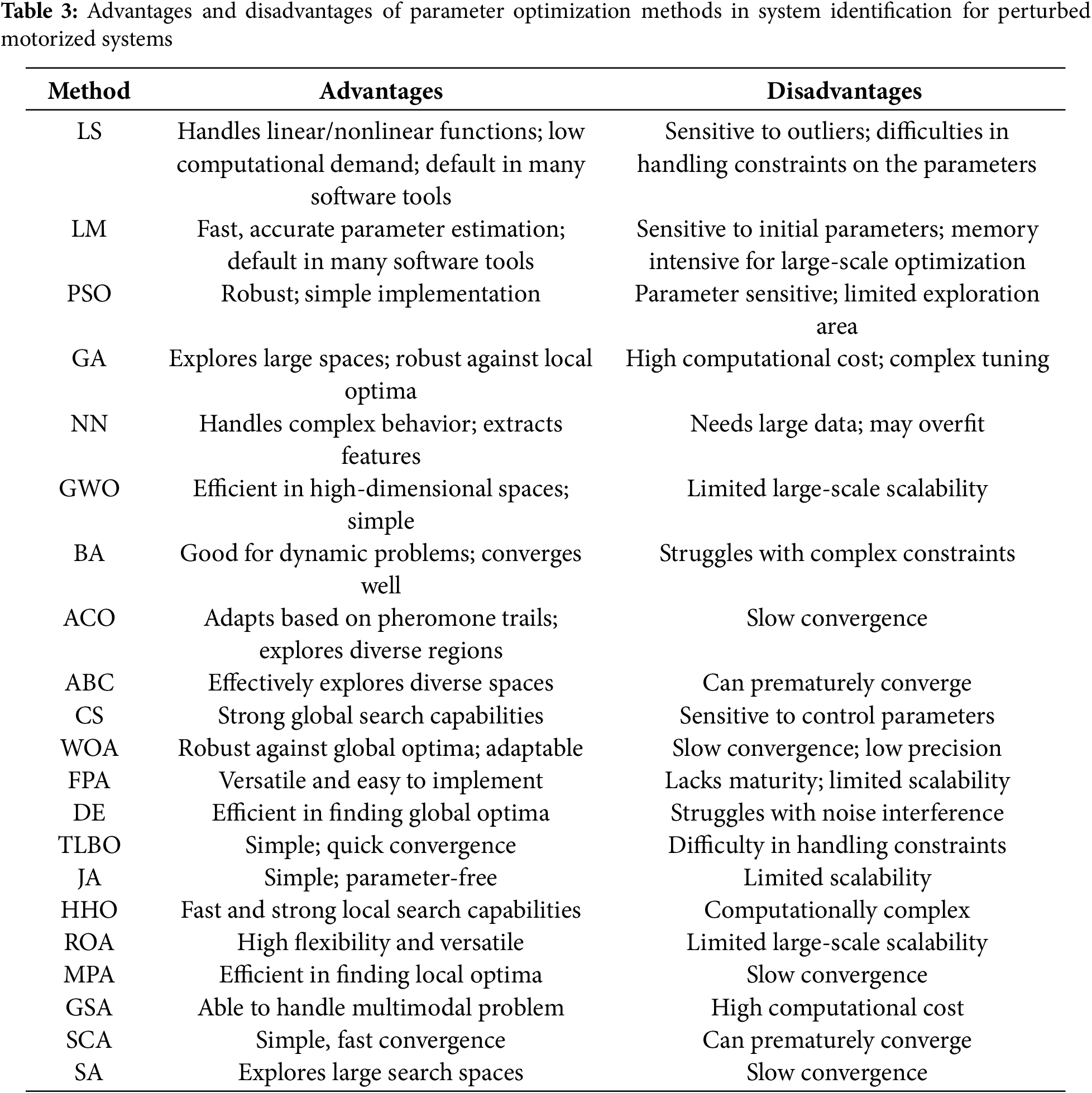

Fig. 27 demonstrates the distribution of parameter optimization methods utilized in the reviewed articles, where LS and PSO emerge as the most frequently used techniques. As detailed in Table 3, LS is widely adopted due to its versatility in handling both linear and nonlinear functions and its adaptability to real-time applications, although it remains sensitive to data outliers which can affect parameter estimation. In addition, the preference for LS can be attributed to its widespread availability in system identification tools and its designation as a default technique in popular software applications like MATLAB, which enhances its accessibility and ease of use. PSO is favored for its robustness and efficient control parameter tuning but can struggle with exploring certain regions of the search space. Additionally, the table highlights other methods like GA and NN, which excel in exploring large search spaces and extracting relevant features from complex data, respectively. However, these methods also face challenges such as high computational demand and overfitting. The diversity of other population-based optimization strategies such as TLBO, GWO, DE, and CS, reflects ongoing innovation in the field to address the unique challenges posed by different motor configurations and perturbation types. Hybrid algorithms integrate the advantages of multiple optimization techniques, enhancing both exploration and exploitation capabilities, thereby achieving superior performance. This analysis underscores the importance of selecting an optimization method that not only aligns with the specific dynamics and challenges of motor system perturbations but also balances between computational efficiency and the ability to handle complex data structures.

Figure 27: Distribution of parameter optimization methods used in system identification for motorized systems

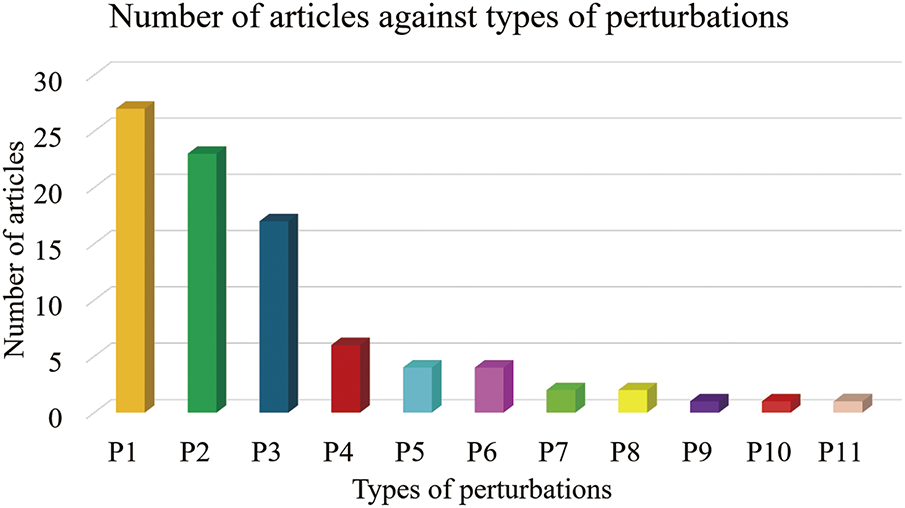

Figs. 28 and 29 offer insights into the types of perturbations and their correlation with modeling methods for both DC and AC motors. From Fig. 28, it is clear that fluctuations in loads and speed are extensively studied in the literature concerning system identification. These variations present challenges in accurately modeling motor behavior due to their dynamic and unpredictable nature. System identification methods enable researchers to derive meaningful insights from data collected during perturbed operation, facilitating the development of models that capture the intricate interactions between motor dynamics and external influences. Understanding how motors respond to these perturbations is essential for optimizing performance across various operational scenarios, ranging from industrial applications to consumer electronics. Furthermore, the precise characterization and simulation of these behaviors contribute to advancements in control algorithms designed to mitigate the impacts of load and speed fluctuations, thereby enhancing overall motor efficiency and reliability in diverse environments.

Figure 28: Number of articles against type of perturbations (Note: P1: Speed, P2: Load, P3: Noise, P4: Friction, P5: Voltage, P6: Disturbance, P7: Current, P8: Position & Orientation, P9: Heat, P10: Discontinuities, P11: Hysterisis)

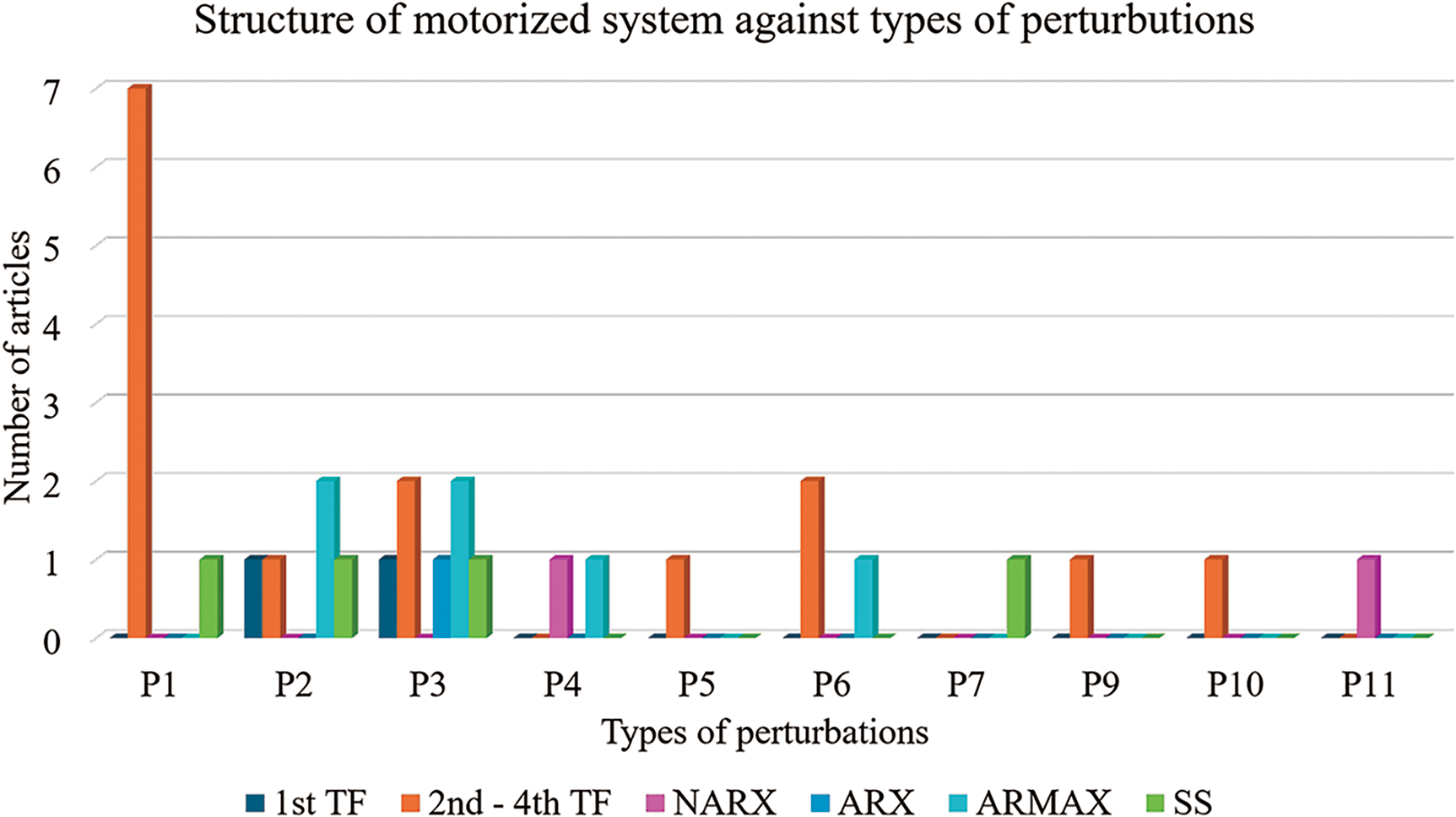

Figure 29: Number of articles for structure of motorized systems against types of perturbations (Note: P1: Speed, P2: Noise, P3: Load, P4: Friction, P5: Disturbance, P6: Voltage, P7: Current, P9: Heat, P10: Discontinuities, P11: Hysterisis)

The model structure selection procedure in system identification is a critical step that determines the accuracy and effectiveness of the identified model in representing system dynamics. The first step involves data analysis, where the system’s input-output behavior is examined to determine whether it follows a linear or nonlinear trend. This initial assessment guides the choice between simpler linear models, such as ARX, or more complex nonlinear models, such as NARX. A TF model is an appropriate choice for system identification when the system is linear time-invariant and its behavior can be effectively described by input-output relationships without explicitly modeling internal states. TF models are also beneficial when data availability is limited, as TF allow system characterization based solely on input-output measurements. To ensure model reliability, validation techniques such as Mean Squared Error (MSE), R-squared values, and residual analysis are employed to compare different models and identify the one that achieves the best balance between accuracy and generalization. Additionally, cross-validation is essential to assess the model’s performance on unseen data by dividing the dataset into training and validation sets. This step helps mitigate overfitting and enhances the model’s robustness for real-world applications.

Based on the plot in Fig. 29, it is clear that the TF structures of order two to four were the most commonly employed across different types of perturbations, particularly excelling in addressing speed and voltage fluctuations. This is followed by ARMAX models, which also show significant usage, particularly effective in handling noise and load perturbations. SS models, although not as prevalent, are notably utilized for handling friction and voltage disturbances. The ARX model appears to be favored for disturbances like load and voltage, whereas NARX models are selectively applied, mainly for noise and current perturbations. First-order TF models, while less common compared to higher-order TFs, are still relevant in scenarios involving heat and hysteresis perturbations. This distribution of modeling techniques illustrates a targeted approach where specific models are chosen based on their efficacy in handling particular disturbances in motorized systems, ensuring optimal performance and robustness under varying operational conditions.

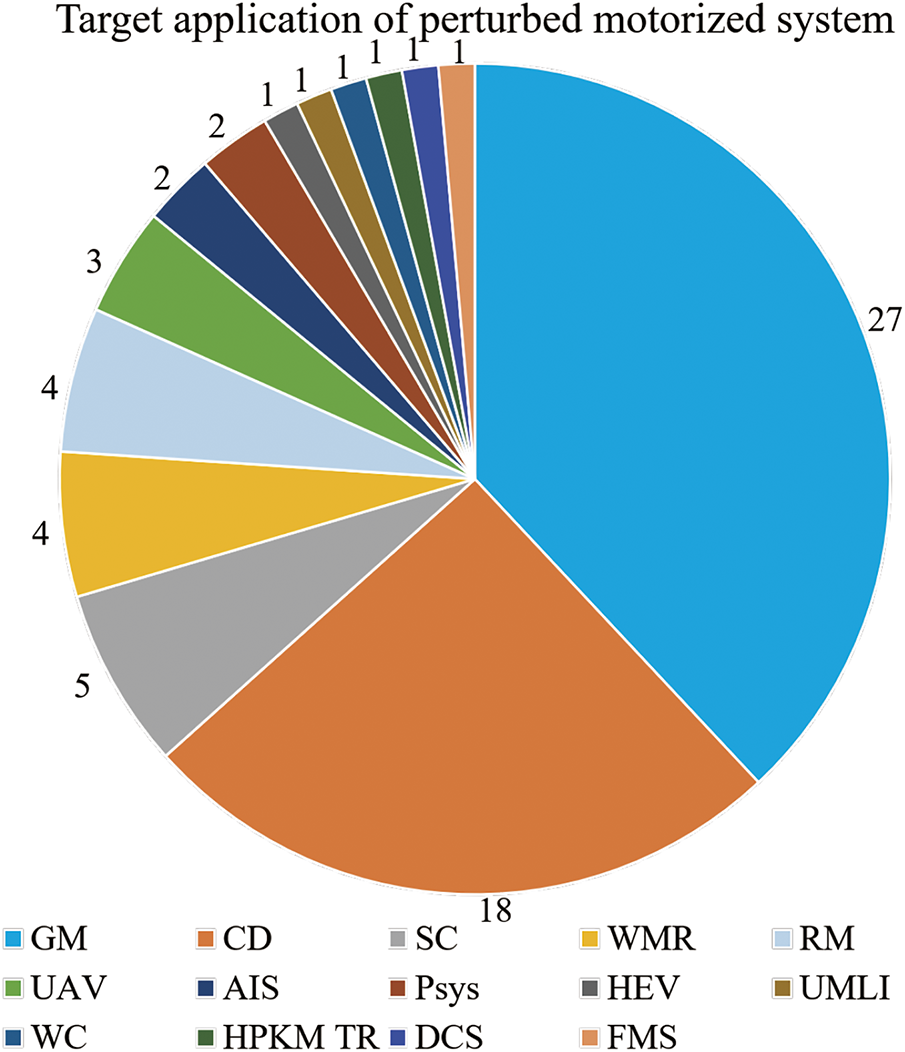

Fig. 30 illustrates the distribution of research articles focused on the target applications for modeling perturbed motorized systems. Control development (CD) emerges as a primary area, underscoring the importance of capturing motor uncertainties and unmodeled dynamics for designing robust and adaptive controllers. Following closely is generic modeling (GM), which provides foundational insights into various motor types, offering substantial benefits for those seeking to deepen their understanding of motor behaviors. Additional target applications span a diverse range of fields, including UAV, wheeled mobile robots (WMR), robot manipulators (RM), speed control (SC), hybrid electric vehicles (HEV), artificial immune systems (AIS), underground mine lifting installations (UMLI), wheelchairs (WC), DC servomotors (DCS), PSys, FMS, and hybrid parallel kinematic machines tricept robots (HPKM TR). Each application highlights different challenges and requirements, demonstrating the extensive reach and relevance of system identification methods across varied motorized systems.

Figure 30: Distribution of articles by target application of perturbed motorized systems

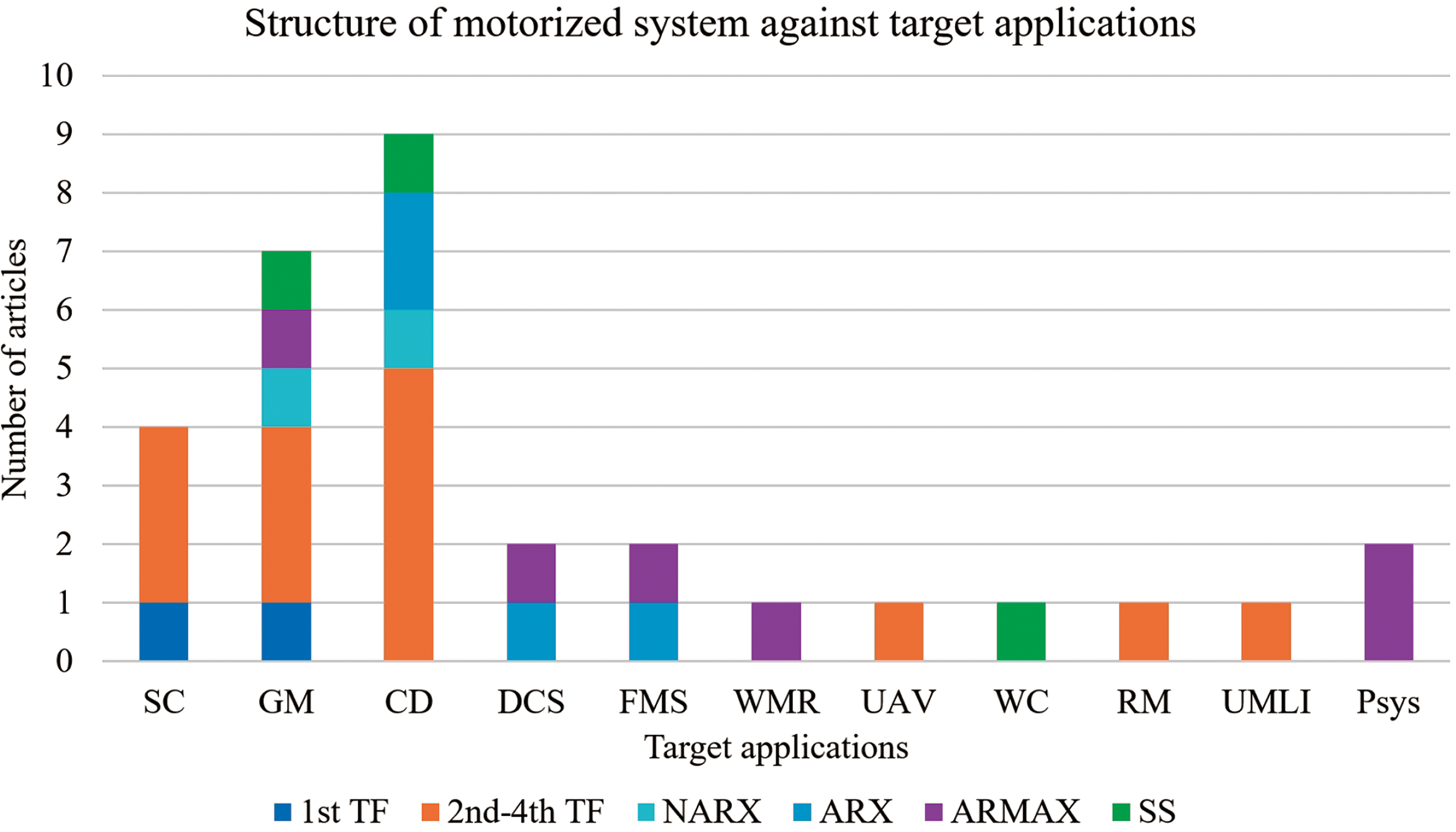

Fig. 31 complements this by presenting a comparative analysis of the model structures employed across various applications, indicating that different models are tailored to the unique challenges of each application. The standard forms of perturbed motor models, specifically TF and SS structures, are prevalently used in GM and CD. The figure highlights the dominance of 2nd–4th order TF models in CD, reflecting their capability to handle the complexities and dynamic behaviors inherent in control systems. SS models are also prominently used in CD and other applications such as DCS, demonstrating their versatility and effectiveness in capturing system dynamics.

Figure 31: Comparative analysis of model structure of motorized systems across different applications. The bar chart displays the number of articles categorized by target applications such as SC, GM, CD and DCS

Additionally, the figure reveals that other modeling techniques like ARMAX and NARX are applied across various applications, although less frequently. These methods are valuable for their ability to model nonlinear behaviors and handle a variety of perturbations. The diversity in modeling approaches underscores the necessity of selecting appropriate models based on the specific requirements of each application, such as the precision needed in SC, the robustness required in HEV, and the adaptability crucial for WMR. This tailored approach ensures that the unique challenges of each application are effectively addressed, optimizing the performance and reliability of motorized systems in different operational contexts.

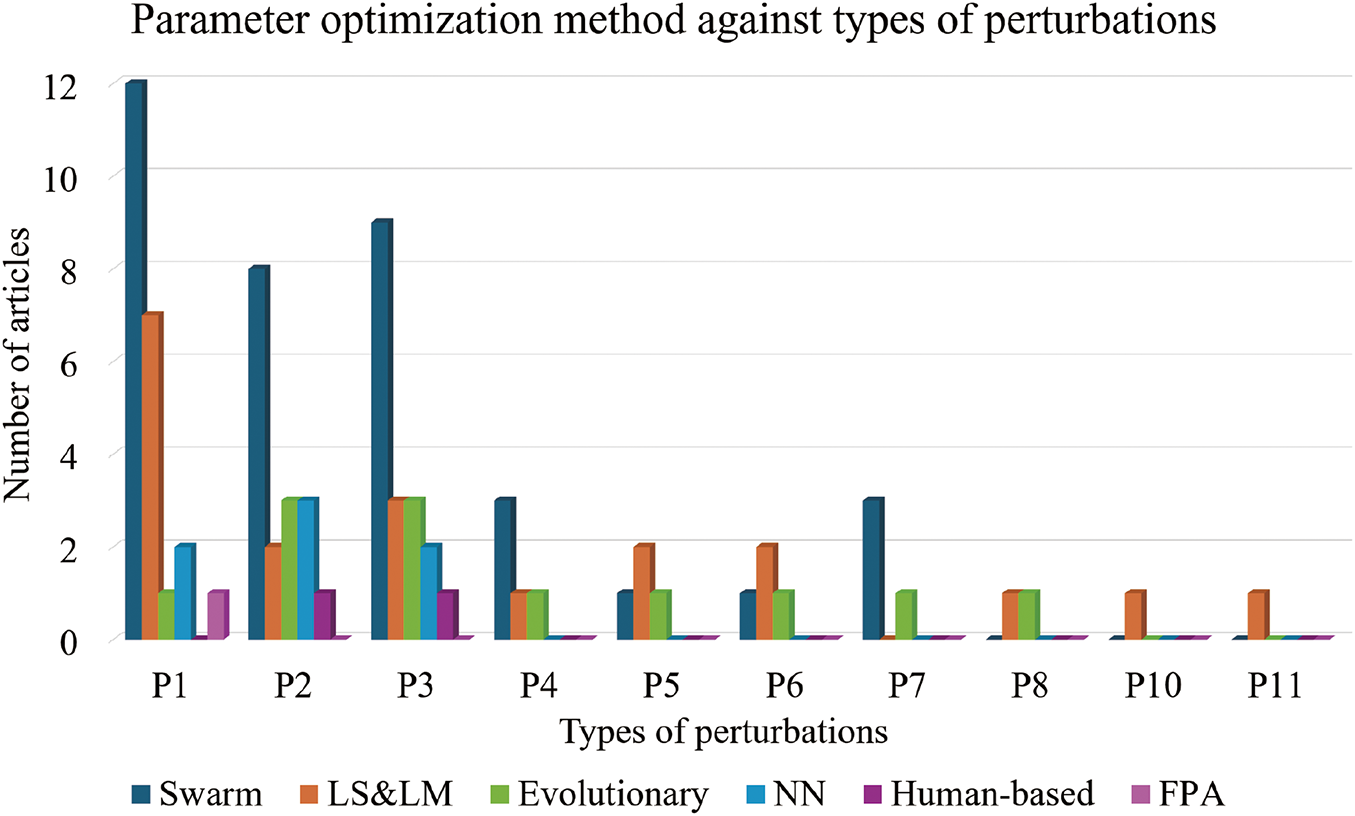

Fig. 32 displays the distribution of parameter optimization methods used across various types of perturbations in motorized systems. From the figure, it is evident that parameter optimization methods are selectively utilized across various types of perturbations in motorized systems. LS and LM are commonly used for various perturbations including speed, noise, load, disturbance, and voltage, leveraging their respective capabilities in minimizing residuals and efficiently exploring parameter spaces.

Figure 32: Number of articles for parameter optimization methods against type of perturbations (Note: P1: Speed, P2: Load, P3: Noise, P4: Friction, P5: Voltage, P6: Disturbance, P7: Current, P8: Position & Orientation, P10: Discontinuities, P11: Hysterisis)

Swarm intelligence algorithms, such as PSO, GWO, ACO, ABC, BA, WOA, CS, AOA, HHO, ROA, MPA, GSA, SCA, and SA are prominently employed for managing perturbations. PSO is favored for its adaptability in systems affected by speed, noise, load, disturbance, friction, current, and voltage, despite its slower convergence speed. GWO is effective in handling noise and friction-related challenges through iterative optimization processes. BA, AOA and HHO are specialized for speed-perturbed systems, while CS is applied to noise-related systems. These algorithms cater to specific perturbation types, adapting their strategies to optimize performance in motorized systems.

Evolutionary algorithms which include GA and DE find application across diverse perturbations such as speed, noise, load, friction, voltage, and current, demonstrating their adaptability in optimizing motorized systems. Human-based algorithms such as TLBO and JA are deployed for load and noise systems, respectively, offering streamlined parameter requirements and effective optimization strategies. NN excel in handling noise, speed, and load systems by learning from extensive data, providing robust solutions to complex perturbations. Finally, methods like FPA specialize in accurately estimating motor model parameters under speed-related perturbations. These trends illustrate a strategic use of optimization methods tailored to specific challenges encountered in perturbed motorized systems.

7 Comparative Performance Analysis

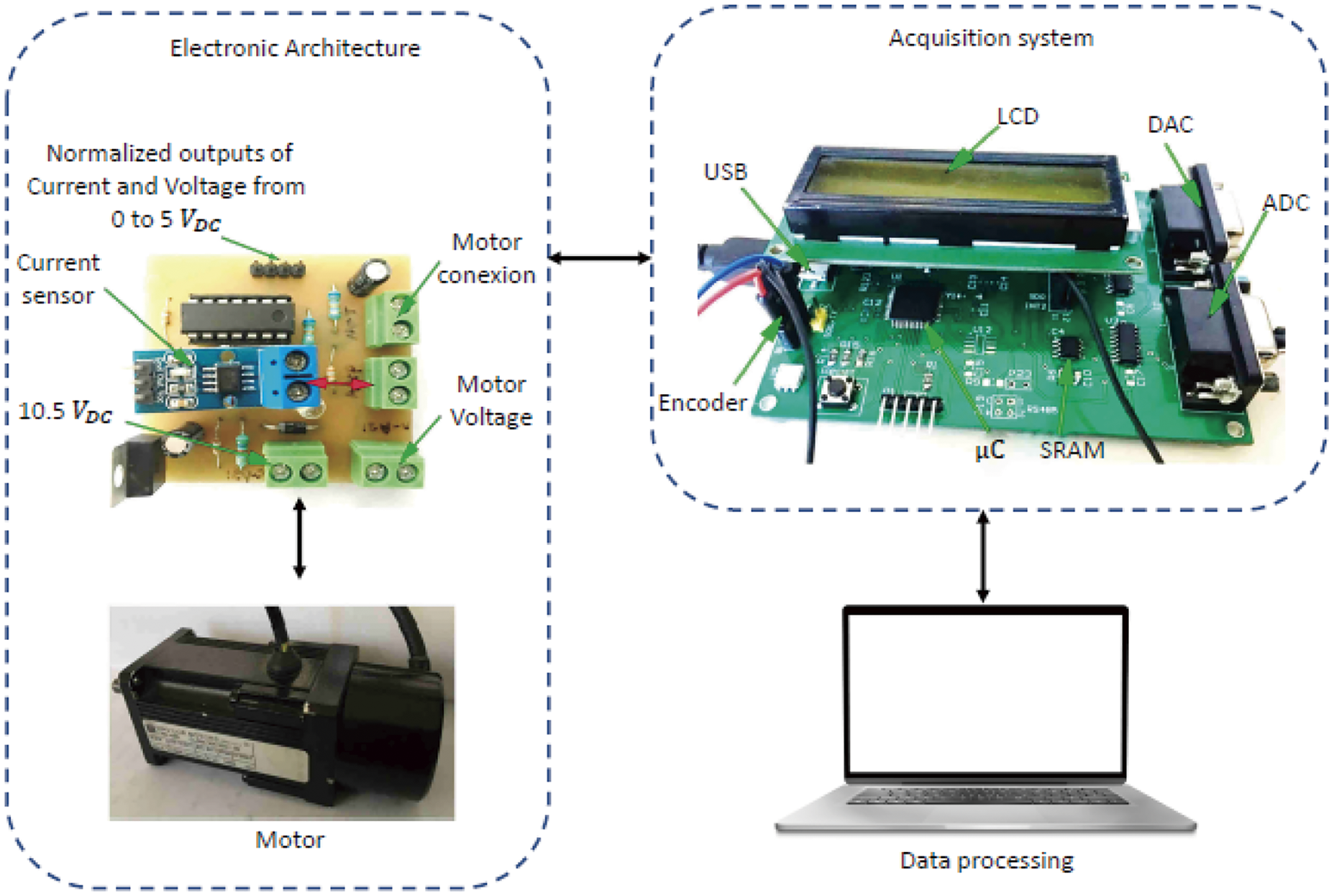

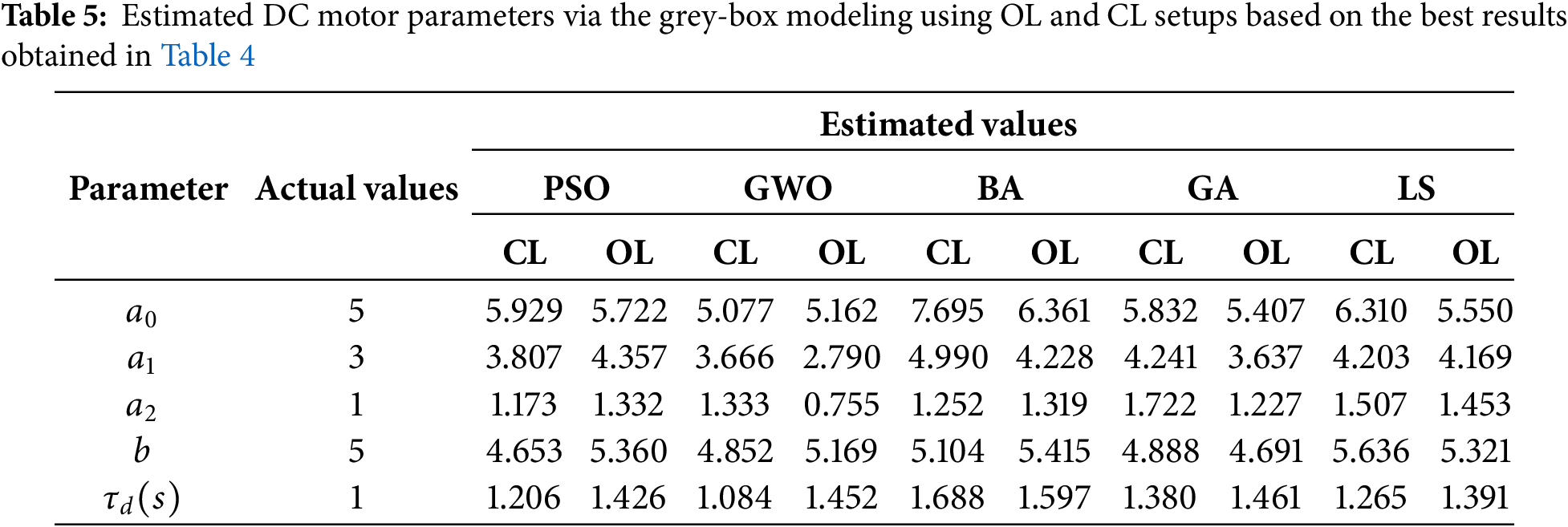

This section compares the performance of several widely used methods identified via the analysis in the previous section, which include grey-box modeling using LS, PSO, GWO, BA, GA, and black-box modeling using NN, to parameterize the DC motor shown in Fig. 3, which is perturbed by a time delay,