Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Shuffled Frog-Leaping Algorithm with Competition for Parallel Batch Processing Machines Scheduling in Fabric Dyeing Process

School of Automation, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, 430070, China

* Corresponding Author: Deming Lei. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Swarm and Metaheuristic Optimization for Applied Engineering Application)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 143(2), 1789-1808. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.064886

Received 26 February 2025; Accepted 22 April 2025; Issue published 30 May 2025

Abstract

As a complicated optimization problem, parallel batch processing machines scheduling problem (PBPMSP) exists in many real-life manufacturing industries such as textiles and semiconductors. Machine eligibility means that at least one machine is not eligible for at least one job. PBPMSP and scheduling problems with machine eligibility are frequently considered; however, PBPMSP with machine eligibility is seldom explored. This study investigates PBPMSP with machine eligibility in fabric dyeing and presents a novel shuffled frog-leaping algorithm with competition (CSFLA) to minimize makespan. In CSFLA, the initial population is produced in a heuristic and random way, and the competitive search of memeplexes comprises two phases. Competition between any two memeplexes is done in the first phase, then iteration times are adjusted based on competition, and search strategies are adjusted adaptively based on the evolution quality of memeplexes in the second phase. An adaptive population shuffling is given. Computational experiments are conducted on 100 instances. The computational results showed that the new strategies of CSFLA are effective and that CSFLA has promising advantages in solving the considered PBPMSP.Keywords

Batch processing is a typical production mode and has been widely applied in the manufacturing processes of textiles, chemicals, minerals, pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, and others. Batch processing machines (BPM) can simultaneously process multiple jobs in a batch. Parallel batch and serial batch are often considered, the processing time of the former being the maximum processing time of all jobs in a batch and the processing time of the latter being the sum of the processing time of all jobs in a batch. BPM scheduling problems have attracted much attention [1–5].

Parallel batch processing machines scheduling problem (PBPMSP) is an extended version of the parallel machines scheduling problem [6] and has attracted much attention in the past decades. Koh et al. [7] designed a genetic algorithm (GA) for the problem in a multi-layer ceramic capacitor production line. Su and Wang [8] proposed weighted nested partitions based on differential evolution (DE) for the problem in semiconductor production lines. Zhou et al. [9] developed a multi-objective DE algorithm to solve the problem considering electricity cost. Zhang et al. [10] solved the problem in cloud manufacturing with an efficient algorithm and improved particle swarm optimization (PSO). Gahm et al. [11] handled parallel serial-batch processing machine scheduling by using some heuristics. Zhang et al. [12] presented a mixed integer linear programming (MILP) model and an improved biased random key GA for the problem with two-dimensional bin packing constraints. Ou et al. [13] considered an efficient polynomial time approximation scheme with near-linear-time complexity. Uzunoglu et al. [14] provided a new multi-start construction heuristic with controlled batch urgencies and a local search mechanism with advanced termination criteria for solution improvement. Kucukkoc et al. [15] dealt with the problem of batch delivery by using a discrete DE algorithm hybridized with GA.

There are some works on uniform PBPMSP. Jula and Leachman [16] gave three algorithms based on linear programming, integer programming, and heuristic for solving the problem in semiconductor manufacturing. Li et al. [17] proposed several heuristics, including an algorithm batching rule and a heuristic assignment rule, to solve the problem of dynamic job arrivals. Some meta-heuristics are applied, which are the Pareto-based ant colony system (Xu et al. [18]), non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm-II (NSGA-II), and multi-objective imperialist competitive algorithm [19], DE [20], ant colony optimization [21,22], artificial immune system [23] and evolutionary algorithm [24].

Non-identical PBPMSP is also solved by PSO [25], GA [26], and fruit fly optimization algorithm [27]. Many results on unrelated PBPMSP were also obtained. Shahidi-Zadeh et al. [28] presented a multi-objective harmony search algorithm. Lu et al. [29] developed a hybrid ABC with tabu search for the problem with maintenance and deteriorating jobs. Zhou et al. [30] solved the problem with different capacities and arbitrary job sizes by a random key GA. Sadati et al. [31] proposed fuzzy multi-objective discrete teaching learning-based optimization and fuzzy NSGA-II. Zarook et al. [32] constructed a MILP model and provided six heuristics and a random key GA. Fallahi et al. [33] studied the problem in production systems under carbon reduction policies, presented a MILP model, NSGA-II and multi-objective gray wolf optimizer. Kong et al. [34] applied a shuffled frog-leaping algorithm (SFLA) with variable neighborhood search for the problem with nonlinear processing time. Xiao et al. [35] proposed a tabu-based adaptive large neighborhood search algorithm, which updates the best-known solutions of 55 instances.

PBPMSP is widely found in various manufacturing processes such as casting [36], food and chemical production [37], semiconductors [38], metal packaging [39], and others. In recent years, PBPMSP in the fabric dyeing process has also received some attention. Zhang et al. [40] proposed a multi-objective artificial bee colony algorithm with an elite retention strategy to simultaneously minimize total tardiness and total completion time. Huynh and Chien [41] studied a hybrid multi-subpopulation GA with heuristic rules. Li et al. [42] proposed a two-objective evolutionary algorithm with the constructive generation of an initial solution and cluster-based environmental selection strategy. Demir [43] developed a lexicographic multi-objective GA to simultaneously minimize total tardiness, total washing times, and total machine fixed costs. Srinath et al. [44] proposed two meta-heuristics to solve multi-objective problems considering SDST and preferences.

Machine eligibility is often investigated in parallel machine scheduling problems [45–47], and there are limited works on PBPMSP with machine eligibility. Li et al. [48] presented a hybrid DE algorithm with chaos theory and two local search algorithms for the problem considering different colors, sequence-dependent setup time (SDST), and machine eligibility. Wang et al. [49] solved a fuzzy energy-efficient problem with machine eligibility and SDST by using a dynamic teaching-learning-based optimization. Lei and Dai [50] dealt with the problem of machine eligibility in the fabric dyeing process by using an adaptive SFLA.

Accordingly, PBPMSP has been studied fully in the last three years, and most of the existing works are related to the usage of heuristics and meta-heuristics; however, PBPMSP with machine eligibility is seldom considered [48–50]. Machine eligibility often exists in real-life manufacturing processes such as fabric dyeing and PBPMSP, with machine eligibility often exhibiting different features compared to the classical PBPMSP. For example, a machine set is used when a machine assignment is done for a job. The inclusion of machine eligibility can make PBPMSP closely resemble the actual situations of manufacturing processes. As a result, the corresponding optimization results hold high application value, so it is necessary to focus on PBPMSP with machine eligibility in fabric dyeing shops.

Compared to PSO, DE, and GA, SFLA has fast convergence speed and effective algorithm structure containing local search and global information exchanges; in addition, as an effective method for BPM scheduling [34,50], distributed scheduling [51,52], flexible job shop scheduling [53], and flow shop scheduling [54], SFLA has been successfully applied to solve PBPMSP [34,50] and the corresponding results show that has advantages on solving PBPMSP. On the other hand, the integration of new optimization mechanisms and SFLA is an effective way to intensify the search ability of SFLA. Q-learning and cooperation are proven to be useful mechanisms and can improve search advantages of SFLA [52,53]; however, competition among memeplexes is seldom considered. After the competition is added to SFLA, parameters or search strategies can be adjusted in the search process, the search ability can be intensified effectively, and optimization results on PBPMSP can be significantly improved. The advantages of SFLA on PBPMSP and the great impact of competition demonstrate that the shuffled frog-leaping algorithm with competition (CSFLA) is particularly suited for PBPMSP, so it is necessary to focus on CSFLA.

This study considers PBPMSP with machine eligibility in the fabric dyeing process, and a new CSFLA is presented to minimize makespan. The competitive search of memeplexes is composed of two phases to produce high-quality solutions, and the initial population is produced in a heuristic and random way. Competition between any two memeplexes is executed in the first phase, then iteration times are adjusted based on competition, and search strategies are adjusted adaptively based on the evolution quality of memeplexes. An adaptive population shuffling is given. Several computational experiments are conducted on 100 instances. The computational results demonstrate that the new strategies of CSFLA are effective and that CSFLA has promising advantages in solving the PBPMSP considered.

The remaining parts of the paper are organized as follows. The problem description is given in Section 2. CSFLA for PBPMSP is shown in Section 3. Computational results and analyses are provided in Section 4. The conclusions are drawn, and the future research topics are reported in the final section.

PBPMSP in fabric dyeing process is composed of

Each

All jobs in a batch are processed simultaneously on BPM. Families are incompatible, and jobs within different families cannot be processed in the same batch. Each batch is formed with jobs in the same family. When jobs of family

The above equation is used described capacity constraint, that is, the sum of weight of job

All jobs in the same batch are processed with the same beginning time and completion time. When BPM is required to switch from one batch with family

There are some constraints on jobs and machines.

Each BPM can only process one batch at a time.

No job can be processed in different batches on more than one BPM.

Operations cannot be interrupted.

All BPMs and jobs are always available.

The goal of the problem is to minimize makespan when all constraints are satisfied and three sub-problems are solved.

where

The above formula is applied to compute

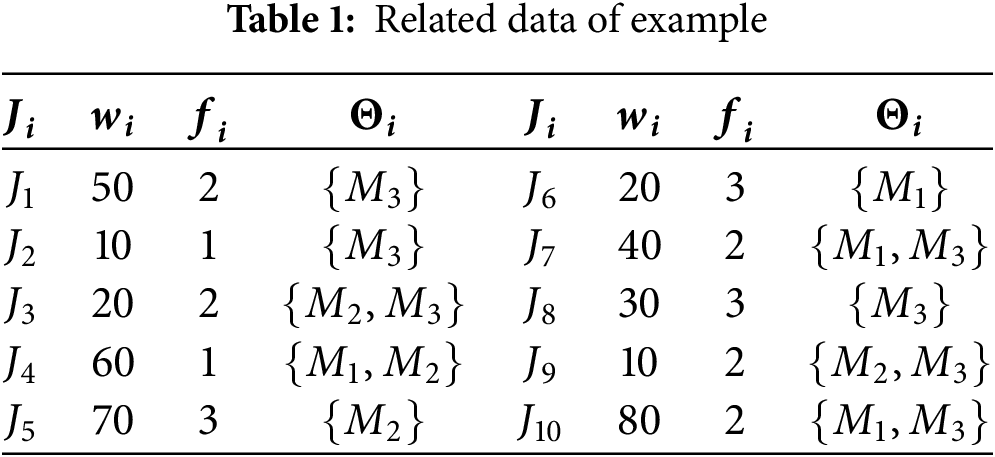

Table 1 lists an illustrative example with 10 jobs, 3 job families and 3 BPMs,

In the above equation,

3 CSFLA for PBPMSP in the Fabric Dyeing Process

There are

Zhang et al. [40] presented a two-string representation. For PBPMSP with

With respect to

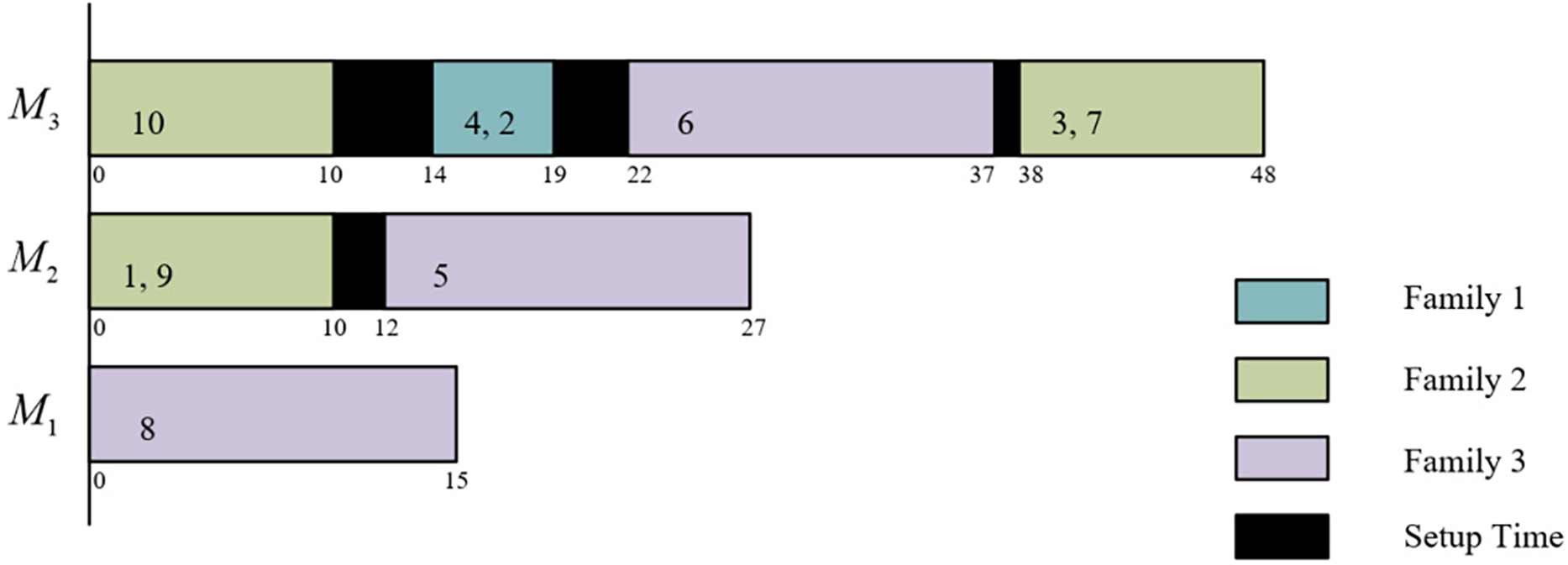

The decoding procedure of [40] is directly adopted. For the example in Table 1, a possible solution is [10, 1, 8, 4, 9, 6, 2, 5, 3, 7] and [2, 1, 3, 3, 2, 3, 3, 1, 1, 2]. After two strings are decoded, a schedule in Fig. 1 is obtained.

Figure 1: A schedule of the example

Initial population

The heuristic is shown below.

(1) Produce scheduling string by sorting all jobs in the ascending order of

(2) Calculate the average weight

(3) Repeat the following steps until

(4) Repeat the following steps until

As stated above, jobs with smaller weight are given higher priority to be assigned into the first half of scheduling string, machines with

Population division is an important step of SFLA. In this study, population

Initially,

Three global search operators

For solution

Three search strategies

When

The initial set

3.3 Competitive Search of Memeplexes

In existing SFLAs [34,53], search within memeplex is often done independently; in CSFLA, the competitive search of memeplexes is composed of two phases. In the first phase, any two memeplexes compete with each other. The second phase is done based on the data from the first phase and the adaptive adjustment of search strategies.

Algorithm 1 describes competitive search of memeplexes, where

In the above equation, for each

In line 9, For

In line 9, with respect to

In line 12,

In lines 17–27, when conditions in lines 17 or 20 are met, evolution difference among memeplexes occurs and is avoided by adjusting search strategies for memeplexes.

In the above procedure, competition can lead to more iteration times and

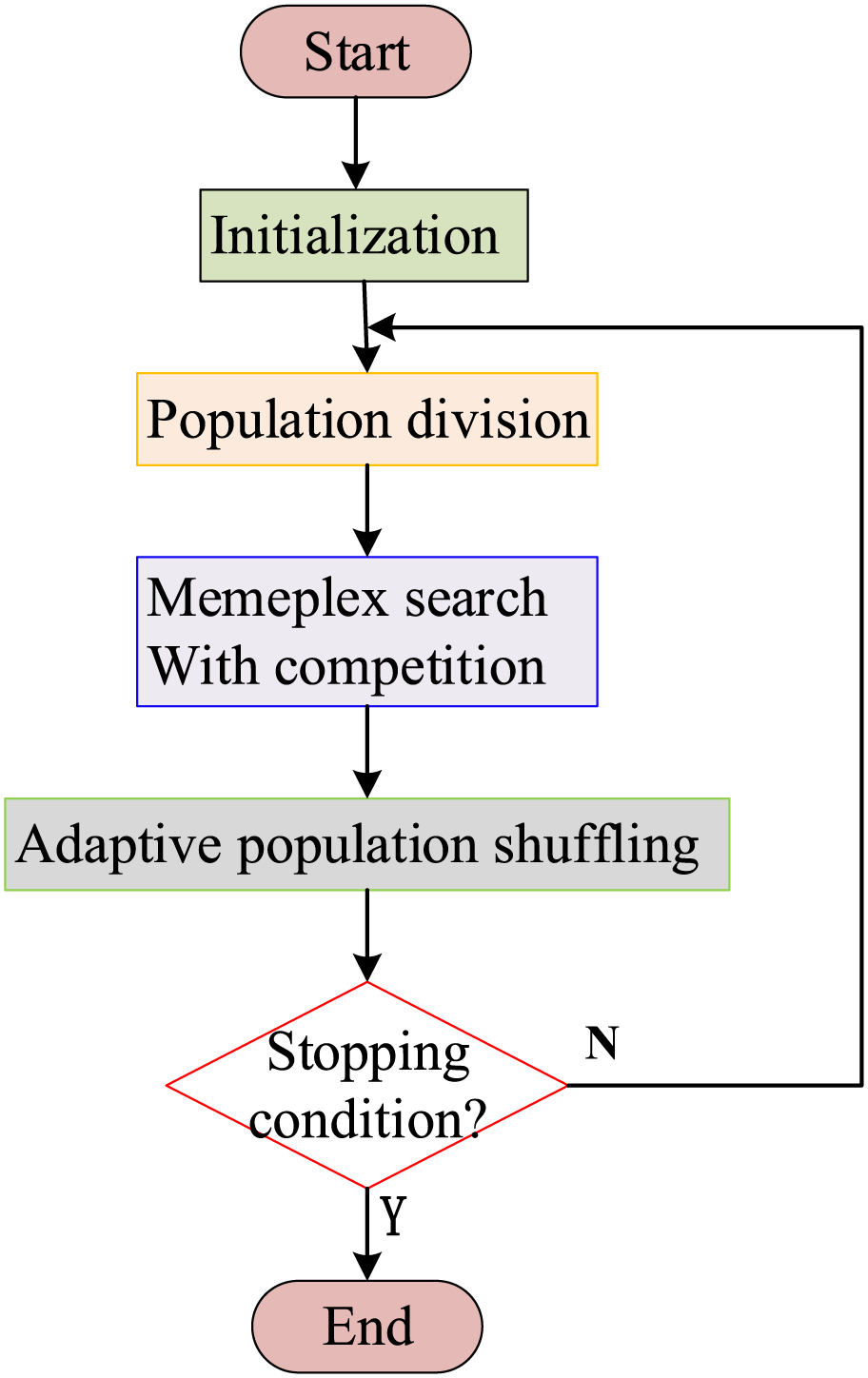

The detailed steps of CSFLA are described as follows.

(1) Produce initial population by using heuristic and random way, for each memeplex

(2) Execute population division.

(3) Perform a competitive search of memeplexes.

(4) Execute adaptive population shuffling.

(5) If the termination condition is not met, then go to step (2); otherwise, stop the search.

The flowchart of CSFLA is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Flowchart of CSFLA

As the main step of SFLA, population shuffling is utilized to form a new population by using all memeplexes, and it is done in each generation. Adaptive population shuffling is proposed and described below. Compute

In the above process, a memeplex is decided with

Unlike the existing SFLA [51–54], CSFLA has the following features: (1) Each memeplex

Competition,

Extensive experiments are conducted to test the performance of CSFLA for the considered PBPMSP. Experiments are implemented by using Microsoft Visual C++ 2019 and run on 8.0 G RAM 2.4 GHz CPU PC.

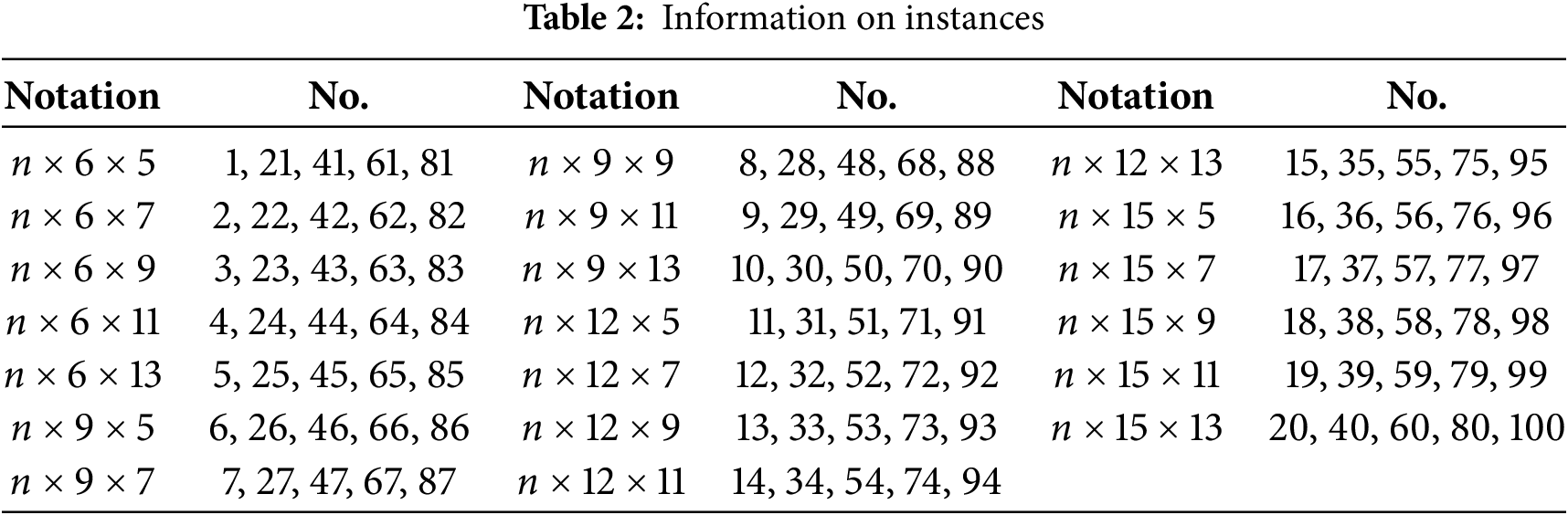

4.1 Instances and Comparative Algorithms

One hundred instances are generated based on the data refined from the dyeing factory in China. The related data are shown below.

CSFLA is compared to three existing methods, which are the random key genetic algorithm (RKGA, [30]), RKGA [32], and orthogonal biased random-key genetic algorithm (OBRKGA, [12]) to show the search advantages of CSFLA. RKGA (Zhou et al. [30]) is called as RKGA1, and RKGA (Zarook et al. [32]) as RKGA2 for convenience. These GAs are utilized to solve PBPMSP with the minimization of makespan and can be directly applied to solve the PBPMSP; in addition, three GAs have promising advantages on solving the problems in references [12,30,32], so they are chosen.

SFLA was constructed to show the impact of new strategies of CSFLA on its performance. The steps of SFLA are identical with the general SFLA, when memeplex search is done, one of

CSFLA has the following parameters:

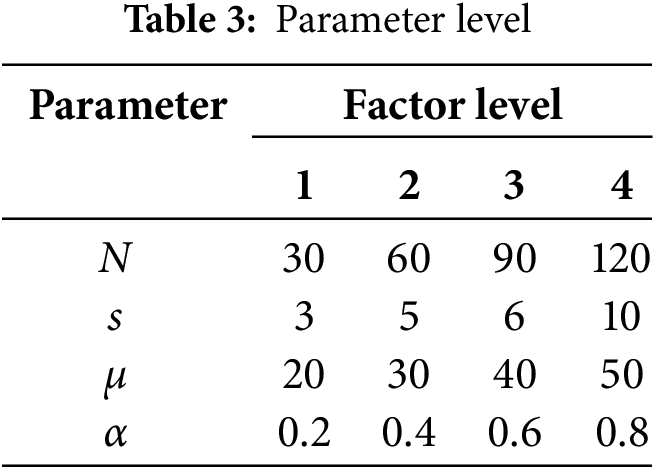

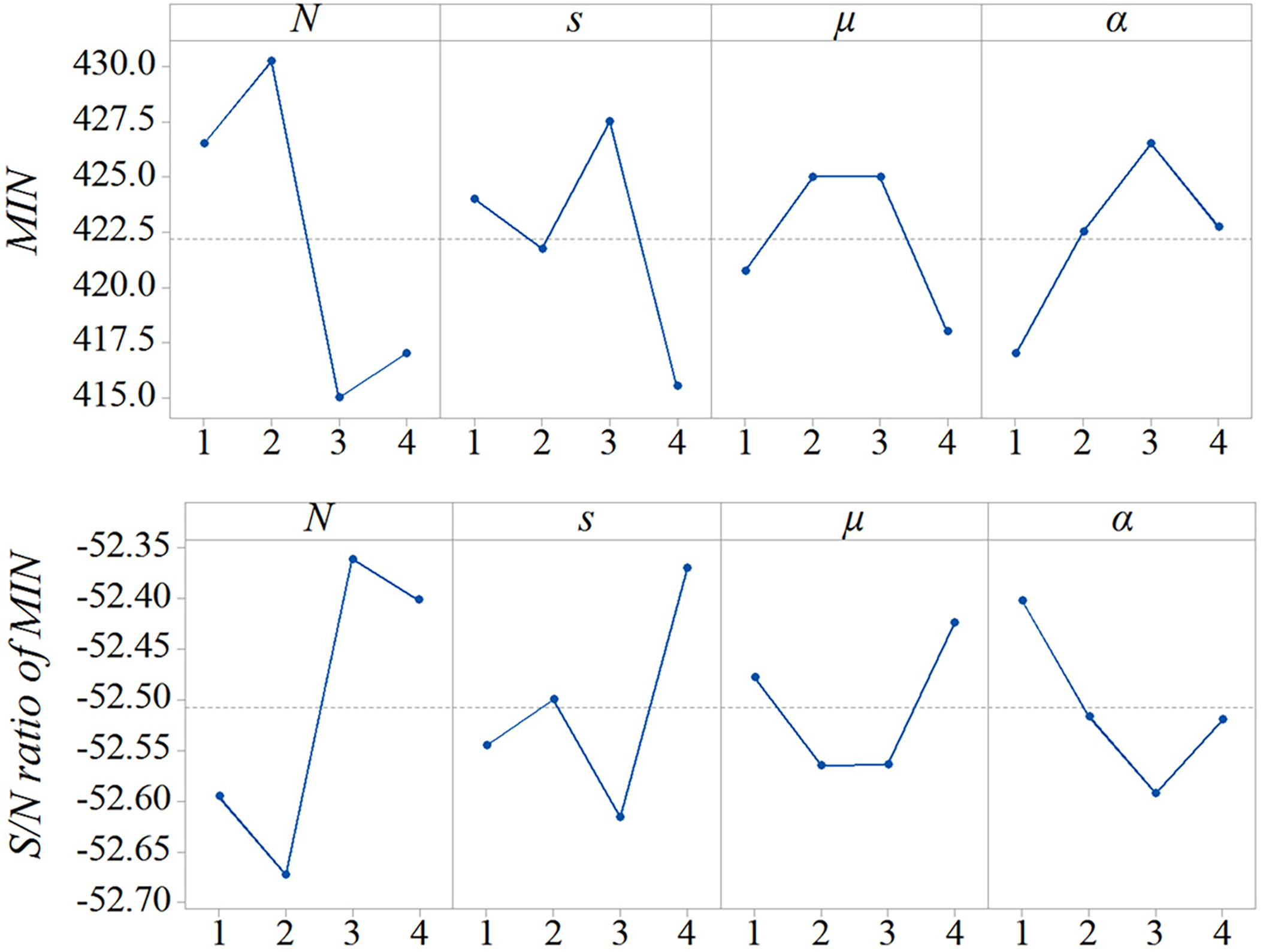

Taguchi method [55] is applied to obtain the settings of parameters. Instance 50 is used. Table 3 describes the levels of each parameter. The orthogonal array

Fig. 3 shows the results of MIN and S/N ratio, which is defined as

Figure 3: Main effect plot for MIN and S/N ratio

SFLA has

With respect to RKGA1, RKGA2, and OBRKGA, their parameter settings, except the stopping condition, are directly used in this study. The experimental results show that these settings of each comparative algorithm are still effective, so they are kept. Three GAs are given the same stopping condition as CSFLA.

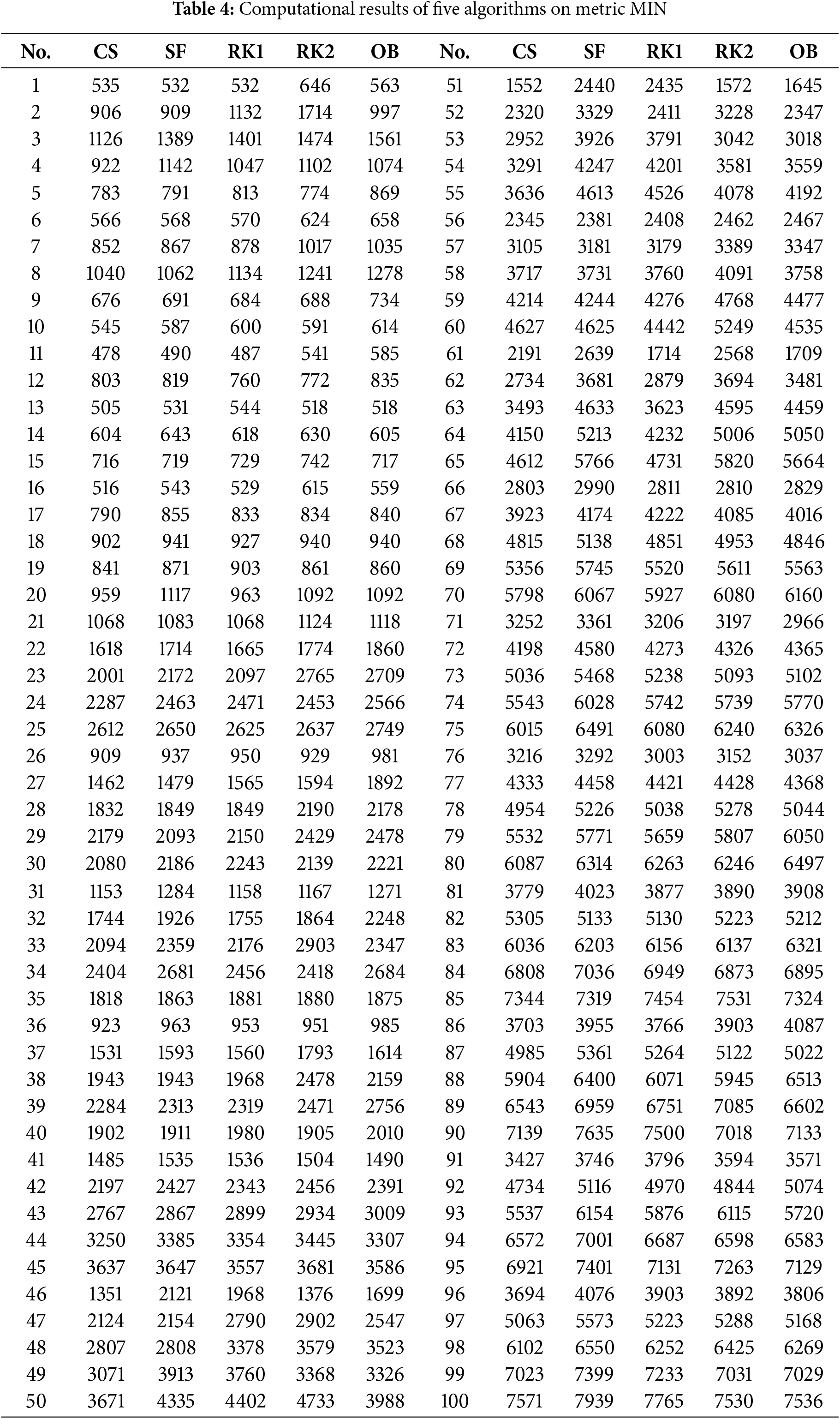

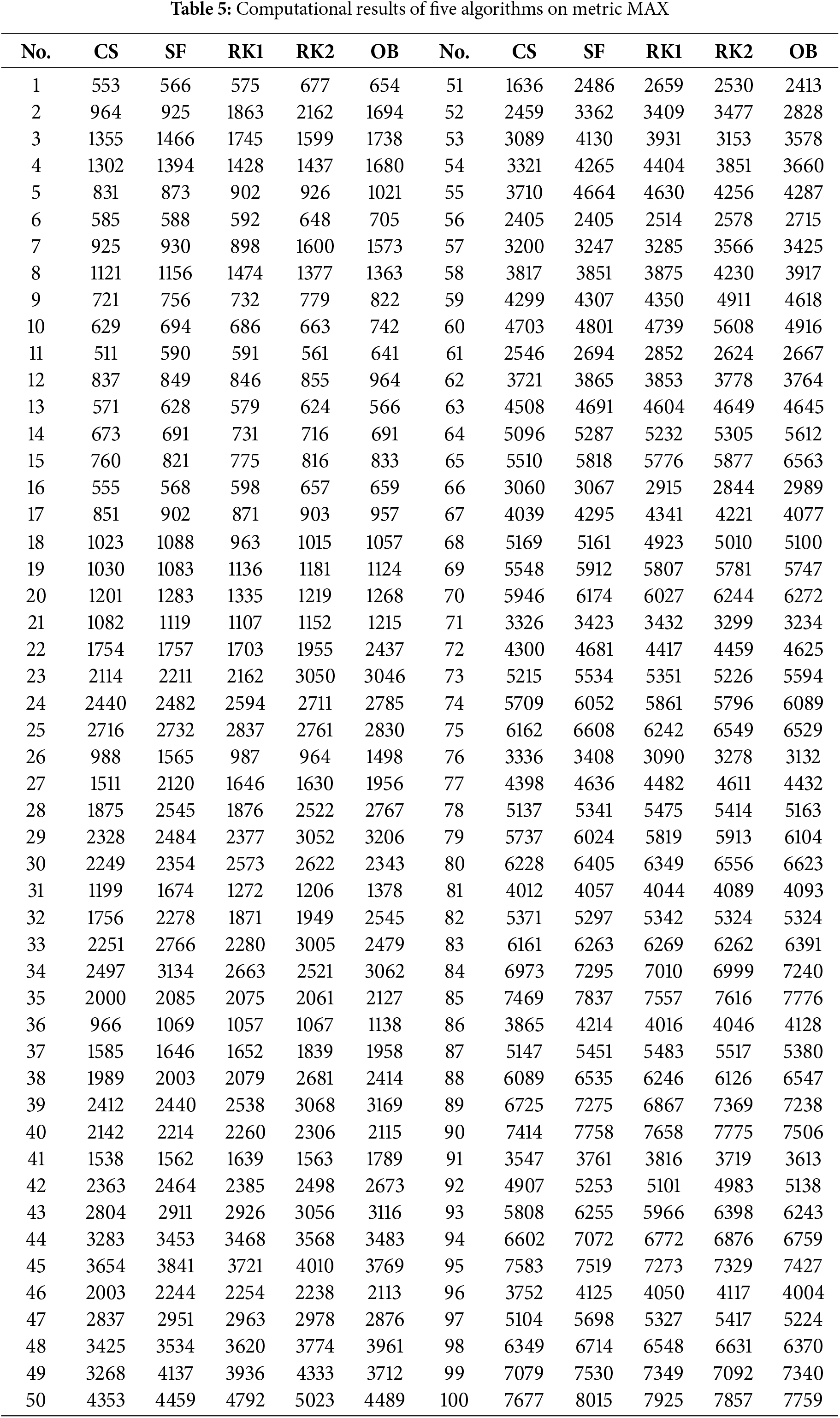

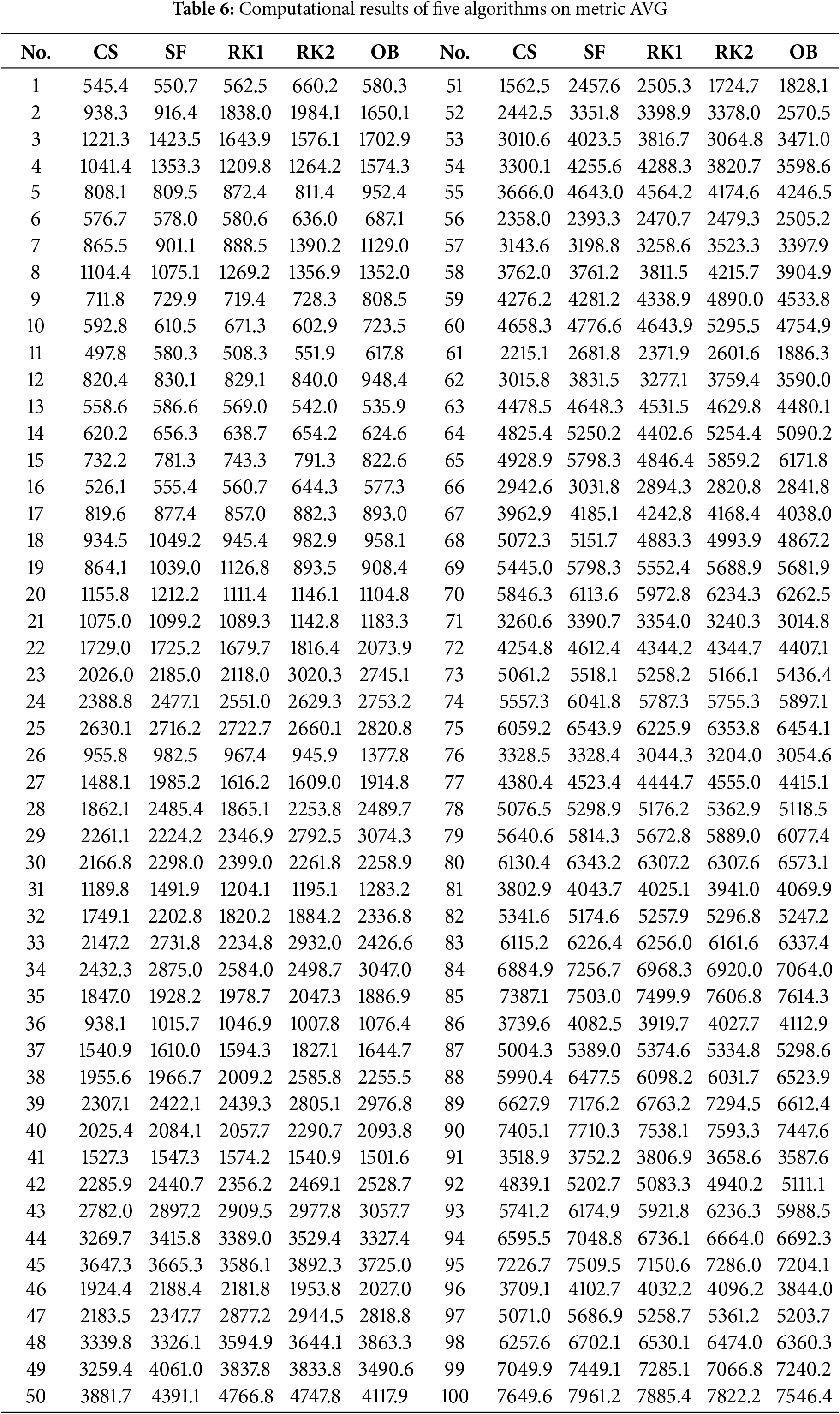

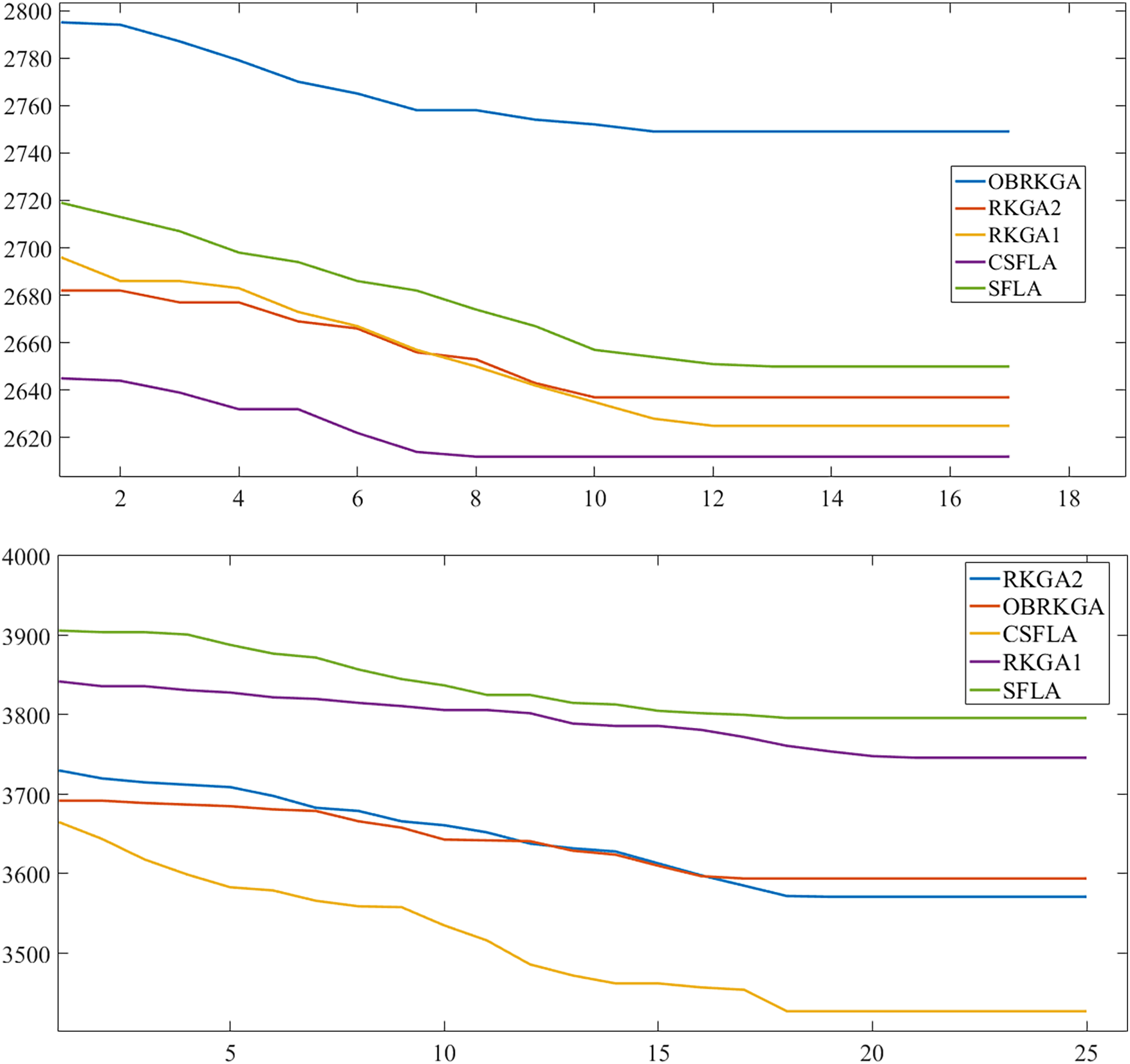

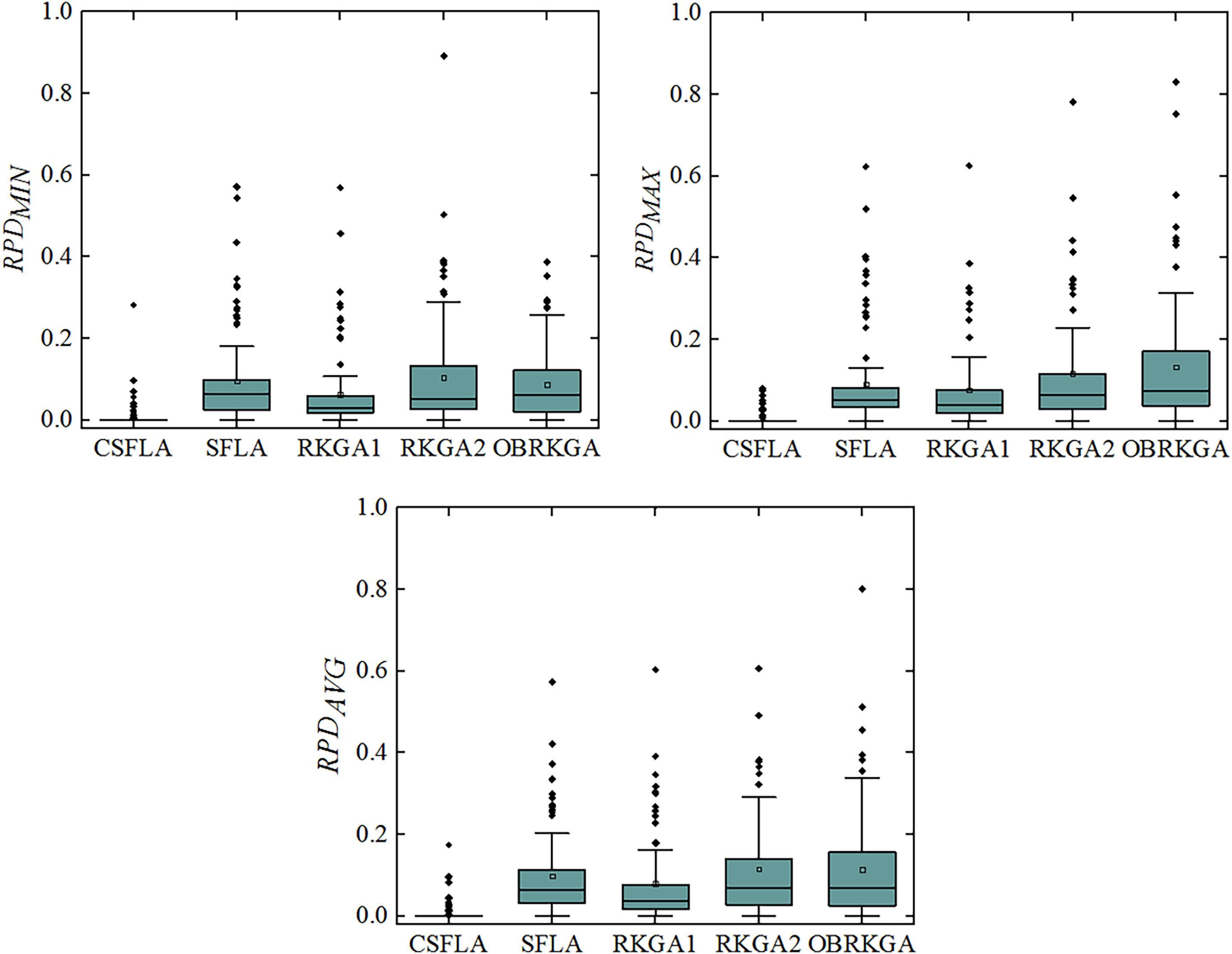

CSFLA, SFLA, and three RKGA are compared, each of which randomly runs 10 times on each instance. In a run, an elite solution is obtained, MAX indicates the worst one of 10 elite solutions, and AVG denotes the average value of 10 elite solutions. Tables 4–6 show the computational results of five algorithms. CS, SF, RK1, RK2, OB indicate CSFLA, SFLA, RKGA1, RKGA2, OBRKGA. Fig. 4 describes the convergence curves of all algorithms, and Fig. 5 provides a box plot.

Figure 4: Convergence curves of five algorithms

Figure 5: Box plot of all algorithms

Table 4 indicates that CSFLA obtains a smaller MIN than SFLA on 94 instances, and the MIN of CSFLA is bigger than that of SFLA just on 5 instances; in addition, the MIN of CSFLA is less than by at least 100 on 57 instances. CSFLA significantly outperforms SFLA on convergence. The convergence curves in Fig. 4 and

Tables 5 and 6 indicate that CSFLA performs better than SFLA on MAX and AVG. SFLA just produces a smaller MAX than CSFLA in 4 instances, and there are differences between the MAX of CSFLA and SFLA. CSFLA obtains smaller AVG on 93 instances. The performance advantages of CSFLA on MAX and AVG also can be observed in Fig. 5. The above analyses show new strategies.

When CSFLA is compared to RKGA1, it can be found that CSFLA produces better results than RKGA1. RKGA1 obtains a smaller MIN than CSFLA in six instances; however, the MIN of RKGA1 is worse than that of CSFLA in 94 of 100 instances. Obviously, CSFLA converges better than RKGA1.

Competition and excessive evolution differences really have a positive impact on the performance of CSFLA. Thus, these new strategies are effective.

Convergence differences between CSFLA and RKGA1 also can be observed in Figs. 4 and 5. Tables 5 and 6 indicate that CSFLA performs better than RKGA1 on MAX, AVG, MAX of CSFLA is less than that of RKGA1 by at least 100 on 54 instances, and CSFLA also obtains smaller AVG than RKGA1 on 93 instances.

Tables 4–6 exhibit that CSFLA has a smaller MIN than RKGA2 and OBRKGA on 89 instances, the MAX of CSFLA is smaller than that of RKGA2 and OBRKGA on 91 instances, and CSFLA has better average results than RKGA2 and OBRKGA more than 85 instances. CSFLA really performs better than RKGA2 and OBRKGA, and this conclusion can also be concluded from Figs. 4 and 5. Based on the above analyses, it can be concluded that CSFLA outperforms three GAs on three metrics.

The above analyses show that the superiority of CSFLA lies in the performance between CSFLA and its comparative algorithm. The advantage of CSFLA results from its adaptive adjustment of search strategies and iteration times by using competition and avoiding excessive evolution differences. With the inclusion of these new strategies, global search ability can be intensified, and a good solution structure can be kept in the memeplex. As a result, search efficiency is significantly improved. Thus, CSFLA is a competitive method for solving PBPMSP.

This study considers PBPMSP with machine eligibility in the fabric dyeing process and presents a new algorithm called CSFLA to minimize makespan. Population initialization is implemented in a heuristic and random way. A competitive search of memeplexes is composed of two phases. Competition between any two memeplexes is done in the first phase, then iteration times are adjusted based on competition, and search strategies are adjusted adaptively based on the evolution quality of memeplexes. An adaptive population shuffling is also given. Computational experiments are conducted, and experimental results validate the effectiveness of new strategies and the promising advantages of CSFLA in solving the considered PBPMSP in the fabric dyeing process.

BPM extensively exists in many real-life manufacturing industries, and the BPM scheduling problem has higher complexity than the classical scheduling problem. Shortly, it will focus on PBPMSP, a hybrid flow shop scheduling problem with BPM. In recent years, learning, cooperation, feedback, and competition have been included in meta-heuristics. Meta-heuristics with new optimization mechanisms for scheduling problems are also future research topics.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to anonymous reviewers and the editors for providing valuable suggestions for the paper.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 61573264).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Deming Lei; methodology, formal analysis, original draft preparation: Mingbo Li; writing—review and editing: Deming Lei. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data generated in this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Azizoglu M, Webster S. Scheduling a batch processing machine with non-identical job sizes. Int J Prod Res. 2000;38(10):2173–84. doi:10.1080/00207540050028034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Shi ZS, Huang ZW, Shi LY. Customer order scheduling on batch processing machines with incompatible job families. Int J Prod Res. 2018;56(1–2):795–808. doi:10.1080/00207543.2017.1401247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Trindade RS, de Araujo OCB, Fampa MHC, Muller FM. Modelling and symmetry breaking in scheduling problems on batch processing machines. Int J Prod Res. 2018;56(22):7031–48. doi:10.1080/00207543.2018.1424371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zheng SX, Xie NM, Wu Q, Liu CJ. Novel mathematical formulations for parallel-batching processing machine scheduling problems. Comput Oper Res. 2025;173(20):106859. doi:10.1016/j.cor.2024.106859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang J, Lei DM, Tang HT. A multi-objective dynamical artificial bee colony for energy-efficient fuzzy hybrid flow shop cheduling with batch processing machines. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;259(2):125244. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Esfandiari S, Mashreghi H, Emami S. Coordination of order acceptance, scheduling, and pricing decisions in unrelated parallel machine scheduling. Int J Ind Eng Prod Res. 2019;30(2):195–205. [Google Scholar]

7. Koh SG, Koo PH, Ha JW, Lee WS. Scheduling parallel batch processing machines with arbitrary job sizes and incompatible job families. Int J Prod Res. 2004;42(19):4091–107. doi:10.1080/00207540410001704041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Su GJ, Wang XH. Weighted nested partitions based on differential evolution (WNPDE) algorithm-based scheduling of parallel batching processing machines (BPM) with incompatible families and dynamic lot arrival. Int J Comput Integ Manuf. 2011;24(6):552–60. doi:10.1080/0951192X.2011.562545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhou SC, Li XL, Du N, Pang Y, Chen HP. A multi-objective differential evolution algorithm for parallel batch processing machine scheduling considering electricity consumption cost. Comput Oper Res. 2018;96(1):55–68. doi:10.1016/j.cor.2018.04.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang H, Li K, Chu CB, Jia ZH. Parallel batch processing machines scheduling in cloud manufacturing for minimizing total service completion time. Comput Oper Res. 2022;146(2):105899. doi:10.1016/j.cor.2022.105899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Gahm C, Wahl S, Tuma A. Scheduling parallel serial-batch processing machines with incompatible job families, sequence-dependent setup times and arbitrary sizes. IntJ Prod Res. 2022;60(17):5131–54. doi:10.1080/00207543.2021.1951446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang XP, Shan MJ, Zeng J. Parallel batch processing machine scheduling under two-dimensional bin-packing constraints. IEEE Trans Reliab. 2023;72(3):1265–75. doi:10.1109/TR.2022.3201333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ou JW, Lu LF, Zhon XL. Parallel-batch scheduling with rejection: structural properties and approximation algorithms. Euro J Oper Res. 2023;310(3):1017–32. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2023.04.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Uzunoglu A, Gahm C, Wahl S, Tuma A. Learning-augmented heuristics for scheduling parallel serial-batch processing machines. Comput Oper Res. 2023;151(3):106122. doi:10.1016/j.cor.2022.106122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kucukkoc I, Keskin GA, Karaoglan AD, Karadag S. A hybrid discrete differential evolution—genetic algorithm approach with a new batch formation mechanism for parallel batch scheduling considering batch delivery. Int J Prod Res. 2024;62(1–2):460–82. doi:10.1080/00207543.2023.2233626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Jula P, Leachman RC. Coordinated multistage scheduling of parallel batch-processing machines under multiresource constraints. Oper Res. 2010;58(4):933–47. doi:10.1287/opre.1090.0788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Li XL, Chen HP, Du B, Tan Q. Heuristics to schedule uniform parallel batch processing machines with dynamic job arrivals. Int J Comput Integ Manuf. 2013;26(5):474–86. doi:10.1080/0951192X.2012.731612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Xu R, Chen HP, Li XP. A bi-objective scheduling problem on batch machines via a Pareto-based ant colony system. Int J Prod Econo. 2013;145(1):371–86. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2013.04.053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Abedi M, Seidgar H, Fazlollahtabar H, Bijani R. Bi-objective optimisation for scheduling the identical parallel batch-processing machines with arbitrary job sizes, unequal job release times and capacity limits. Int J Prod Res. 2015;53(6):1680–711. doi:10.1080/00207543.2014.952795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhou SC, Liu M, Chen HP, Li XP. An effective discrete differential evolution algorithm for scheduling uniform parallel batch processing machines with non-identical capacities and arbitrary job sizes. Int J Prod Econo. 2016;179(1):1–11. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.05.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Jia ZH, Yan JH, Leung JYT, Li K, Chen HP. Ant colony optimization algorithm for scheduling jobs withfuzzy processing times on parallel batch machines with different capacities. Appl Soft Comput. 2019;75(9–10):548–61. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2018.11.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Jia ZH, Huo SY, Li K, Chen HP. Integrated scheduling on parallel batch processing machines with non-identical capacities. Eng Optim. 2020;52(4):715–30. doi:10.1080/0305215X.2019.1613388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li CH, Wang F, Gupta JND, Chung T. Scheduling identical parallel batch processing machines involving incompatible families with different job sizes and capacity constraints. Comput Ind Eng. 2022;169(5):108115. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2022.108115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li K, Zhang H, Chu CB, Jia ZH, Chen JF. Abi-objective evolutionary algorithm scheduled on uniform parallel batch processing machines. Exp Syst Appl. 2022;204(6):117487. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.117487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Liu M, Chu F, He JK, Yang DP, Chu CB. Coke production scheduling problem: a parallel machine scheduling with batch preprocessings and location-dependent processing times. Comput Oper Res. 2019;104(7):37–48. doi:10.1016/j.cor.2018.12.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Hulett M, Damodaran P, Amouie M. Scheduling non-identical parallel batch processing machines to minimize total weighted tardiness using particle swarm optimization. Comput Ind Eng. 2017;113(8):425–36. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2017.09.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wang R, Jia ZH, Li K. Scheduling parallel-batching processing machines problem with learning and deterioration effect in fuzzy environment. J Intel Fuzzy Syst. 2021;40(6):12111–24. doi:10.3233/JIFS-210196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Shahidi-Zadeh B, Tavakkoli-Moghaddam R, Taheri-Moghadam A, Rastgar I. Solving a bi-objective unrelated parallel batch processing machines scheduling problem: a comparison study. Comput Oper Res. 2017;88(6):71–90. doi:10.1016/j.cor.2017.06.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Lu SJ, Liu XB, Pei J, Thai MT, Pardalos PM. A hybrid ABC-TS algorithm for the unrelated parallel-batching machines scheduling problem with deteriorating jobs and maintenance activity. Appl Soft Comput. 2018;66(2):168–82. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2018.02.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhou SC, Xie JH, Du N, Pang Y. A random-keys genetic algorithm for scheduling unrelated parallel batch processing machines with different capacities and arbitrary job sizes. Appl Math Comput. 2018;334(8):254–68. doi:10.1016/j.amc.2018.04.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Sadati A, Moghaddam RT, Naderi B, Mohammadi M. Abi-objective model for a scheduling problem of unrelated parallel batch processing machines with fuzzy parameters by two fuzzy multi-objective meta-heuristics. Iran J Fuzzy Syst. 2019;16(4):21–40. [Google Scholar]

32. Zarook Y, Rezaeian J, Mahdavi I, Yaghini M. Efficient algorithms to minimize makespan of the unrelated parallel batch-processing machines scheduling problem with unequal job ready times. Performa Analy Intel Syst Oper. 2021;55(3):1501–22. doi:10.1051/ro/2021062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Fallahi A, Shahidi-Zadeh B, Niaki STA. Unrelated parallel batch processing machine scheduling for production systems under carbon reduction policies: nSGA-II and MOGWO metaheuristics. Soft Comput. 2023;27(22):17063–91. doi:10.1007/s00500-023-08754-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kong M, Wang WZ, Deveci M, Zhang YJ, Wu XZ, Coffman D. A novel carbon reduction engineering method-based deep Q-learning algorithm for energy-efficient scheduling on a single batch-processing machine in semiconductor manufacturing. Int J Prod Res. 2024;62(18):6449–72. doi:10.1080/00207543.2023.2252932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Xiao X, Ji B, Yu SS, Wu GH. A tabu-based adaptive large neighborhood search for scheduling unrelated parallel batch processing machines with non-identical job sizes and dynamic job arrivals. Flex Serv Manuf J. 2024;36(2):409–52. doi:10.1007/s10696-023-09488-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhang W, Tang HT, Wang WY, Zhuang M, Lei D, Wang XV. A multi-objective hybrid algorithm for the casting scheduling problem with unrelated batch processing machine. Compl Syst Model Simul. 2024;4(3):236–57. doi:10.23919/CSMS.2024.0011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Mageed G, Sharareh T. Dynamic shop-floor scheduling using real-time information: a case study from the thermoplastic industry. Comput Oper Res. 2023;152(4):106134. doi:10.1016/j.cor.2022.106134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Hu KX, Che YX, Ng TS, Deng J. Unrelated parallel batch processing machine scheduling with time requirements and two-dimensional packing constraints. Comput Oper Res. 2024;162(3):106474. doi:10.1016/j.cor.2023.106474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Fu LL, Aloulou MA, Triki C. Integrated production scheduling and vehicle routing problem with job splitting and delivery time windows. Int J Prod Res. 2017;55(20):5942–57. doi:10.1080/00207543.2017.1308572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhang R, Chang PC, Song SJ, Wu C. A multi-objective artificial bee colony algorithm for parallel batch-processing machine scheduling in fabric dyeing processes. Knowl-Based Syst. 2017;116(7):114–29. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2016.10.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Huynh NT, Chien CF. A hybrid multi-subpopulation genetic algorithm for textile batch dyeing scheduling and an empirical study. Comput Ind Eng. 2018;125(2):615–27. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2018.01.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Li K, Zhang H, Chu CB, Jia ZH, Wang Y. A bi-objective evolutionary algorithm for minimizing maximum lateness and total pollution cost on non-identical parallel batch processing machines. Comput Ind Eng. 2022;172(3):108608. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2022.108608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Demir Y. An efficientlexicographic approach to solve multi-objective multi-port fabric dyeing machine planning problem. Appl Soft Comput. 2023;144(2):110541. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2023.110541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Srinath N, Yilmazlar IO, Kurz ME, Taaffe K. Hybrid multi-objective evolutionary meta-heuristics for a parallel machine scheduling problem with setup times and preferences. Comput Ind Eng. 2023;185(5–6):109675. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2023.109675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Lee DH, Park IB, Kim K. An incremental learning approach to dynamical parallel machine scheduling with sequence-dependent setups and machine eligibility restrictions. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;164(21):112002. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.112002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Santoro MC, Junqueira L. Unrelated parallel machine scheduling models with machine avaiability and eligibility constraints. Comput Ind Eng. 2023;179(1–2):109219. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2023.109219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Zheng FF, Jin KY, Xu YF, Liu M. Unrelated parallel machine scheduling with processing cost, machine eligibility and order splitting. Comput Ind Eng. 2022;171(3):108483. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2022.108483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Li DB, Wang J, Qiang R, Chiong R. A hybrid differential evolution algorithm for parallel machine scheduling of lace dyeing considering colour families, sequence-dependent setup and machine eligibility. Int J Prod Res. 2021;59(9):2722–38. doi:10.1080/00207543.2020.1740341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Wang J, Li DB, Tang HT, Li XX, Lei DM. A dynamical teaching-learning-based optimization algorithm for fuzzy energy-efficient parallel batch processing machines scheduling in fabric dyeing process. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;167(9):112413. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.112413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Lei DM, Dai T. An adaptive shuffled frog-leaping algorithm for parallel batch processing machines scheduling with machine eligibility in fabric dyeing process. Int J Prod Res. 2024;62(21):7704–21. doi:10.1080/00207543.2024.2324452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Cai JC, Lei DM. A cooperated shuffled frog-leaping algorithm for distributed energy-efficient hybrid flow shop scheduling with fuzzy processing time. Comple Intel Syst. 2021;7(5):2235–53. doi:10.1007/s40747-021-00400-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Cai JC, Lei DM, Wang J, Wang L. A novel shuffled frog-leaping algorithm with reinforcement learning for distributed assembly hybrid flow shop scheduling. Int J Prod Res. 2022;61(4):1233–51. doi:10.1080/00207543.2022.2031331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Yang YF, Song YH, Guo WF, Lei Q, Sun AH, Fan LH. Guided shuffled frog-leaping algorithm for flexible job shop scheduling with variable sublots and overlapping in operations. Comput Ind Eng. 2023;180(19):109209. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2023.109209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Wu PL, Yang QY, Chen WB, Mao BY, Yu HN. An improved genetic-shuffled frog-leaping algorithm for permutation flowshop scheduling. Complexity. 2020;1(14):3450180. doi:10.1155/2020/3450180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Taguchi G. Introduction to quality engineering: designing quality into products and processes. Tokyo, Japan: Asian Productivity Organization; 1986. 191 p. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools