Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effects of Normalised SSIM Loss on Super-Resolution Tasks

Department of Information Engineering, Faculty of Economics and Management, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague (CZU), Prague, 165 00, Czech Republic

* Corresponding Author: Adéla Hamplová. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Applied Artificial Intelligence: Advanced Solutions for Engineering Real-World Challenges)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 143(3), 3329-3349. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.066025

Received 27 March 2025; Accepted 06 June 2025; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

This study proposes a new component of the composite loss function minimised during training of the Super-Resolution (SR) algorithms—the normalised structural similarity index loss , which has the potential to improve the natural appearance of reconstructed images. Deep learning-based super-resolution (SR) algorithms reconstruct high-resolution images from low-resolution inputs, offering a practical means to enhance image quality without requiring superior imaging hardware, which is particularly important in medical applications where diagnostic accuracy is critical. Although recent SR methods employing convolutional and generative adversarial networks achieve high pixel fidelity, visual artefacts may persist, making the design of the loss function during training essential for ensuring reliable and naturalistic image reconstruction. Our research shows on two models—SR and Invertible Rescaling Neural Network (IRN)—trained on multiple benchmark datasets that the function significantly contributes to the visual quality, preserving the structural fidelity on the reference datasets. The quantitative analysis of results while incorporating shows that including this loss function component has a mean 2.88% impact on the improvement of the final structural similarity of the reconstructed images in the validation set, in comparison to leaving it out and 0.218% in comparison when this component is non-normalised.Keywords

In this research, we investigate the effect of incorporating a normalised Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) as a component of the composite loss function used in the training of deep learning-based Super-Resolution (SR) models. The proposed approach is applied to two model architectures: a conventional Super-Resolution convolutional neural network (CNN) and an Invertible Rescaling Neural Network (IRN). Both models are trained on three commonly used benchmark datasets. We evaluate three training configurations—excluding SSIM, including SSIM in its non-normalised form, and including SSIM in its normalised form—to examine the influence of normalisation on the reconstruction quality. The results are evaluated using Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), SSIM and LPIPS metrics, allowing for a comparative analysis of the reconstruction performance across all configurations.

Super-Resolution (SR) is a very demanding but fundamental artificial intelligence algorithm that is used in many practical computer vision algorithms, e.g., noise removal [1], increasing resolution on smartphones [2], person identification [3], upscaling images from laboratory measurements from micrometres to millimetres [4] and many others. In recent years, researchers have proposed various methods for solving the SR task, which is often based on deep learning, in contrast to the initially used bicubic interpolation [5], e.g., Super-Resolution generative adversarial network (SRGAN) for the task of semantic segmentation of geographic data [6], digital elevation model (DEM) for the task of flood mapping [7], full resolution class activation maps (F-CAM) based on a parametric decoder in the form of a U-net as an alternative to the previously used interpolation in this task [8], convolutional neural network (CNN) based on short-term caching for ultra-high definition (UHD) in real-time [9] and others.

The latest research Refs. [10–12] includes the principle of invertibility in the training of these models, where the image in the original size is mapped to a 4× (or even more, but with significantly worse results) reduced image using a downscale neural network, from which the upscale neural network tries to obtain an image as similar as possible to the original. The same procedure can also be used to reconstruct colours. This procedure of reducing and enlarging the image is not dissimilar in principle to an encoder and decoder or generative neural networks. Still, it uses different training and structures and layers of neural networks in all steps.

The existing results of the methods presented have shown a significant improvement in the quality of reconstructed images compared to earlier mathematical methods. However, there is still room for improvement.

It is a well-known fact that the loss function plays a key role in the overall quality of artificial intelligence algorithms, next to constructing a suitable neural network architecture, selecting a suitable optimiser and choosing an optimal learning rate value. This is no different in SR tasks. In existing published research, the choice of the loss function is given a growingly decisive role; usually, it is the Mean Square Error (MSE) comparing the original and output image, or a combination of MSE with one or more other components is used. In the research as mentioned above Refs. [10–12], the networks are trained using a combined loss function consisting of three elements—forward MSE loss, backward MSE loss and perceptual loss [13] based on feature extraction using selected layers of the pre-trained VGG19 (Visual Geometry Group) classifier.

Inverse scattering research [14] is the first research that presents

where

The component of the

where the definition of similarity index

where

where

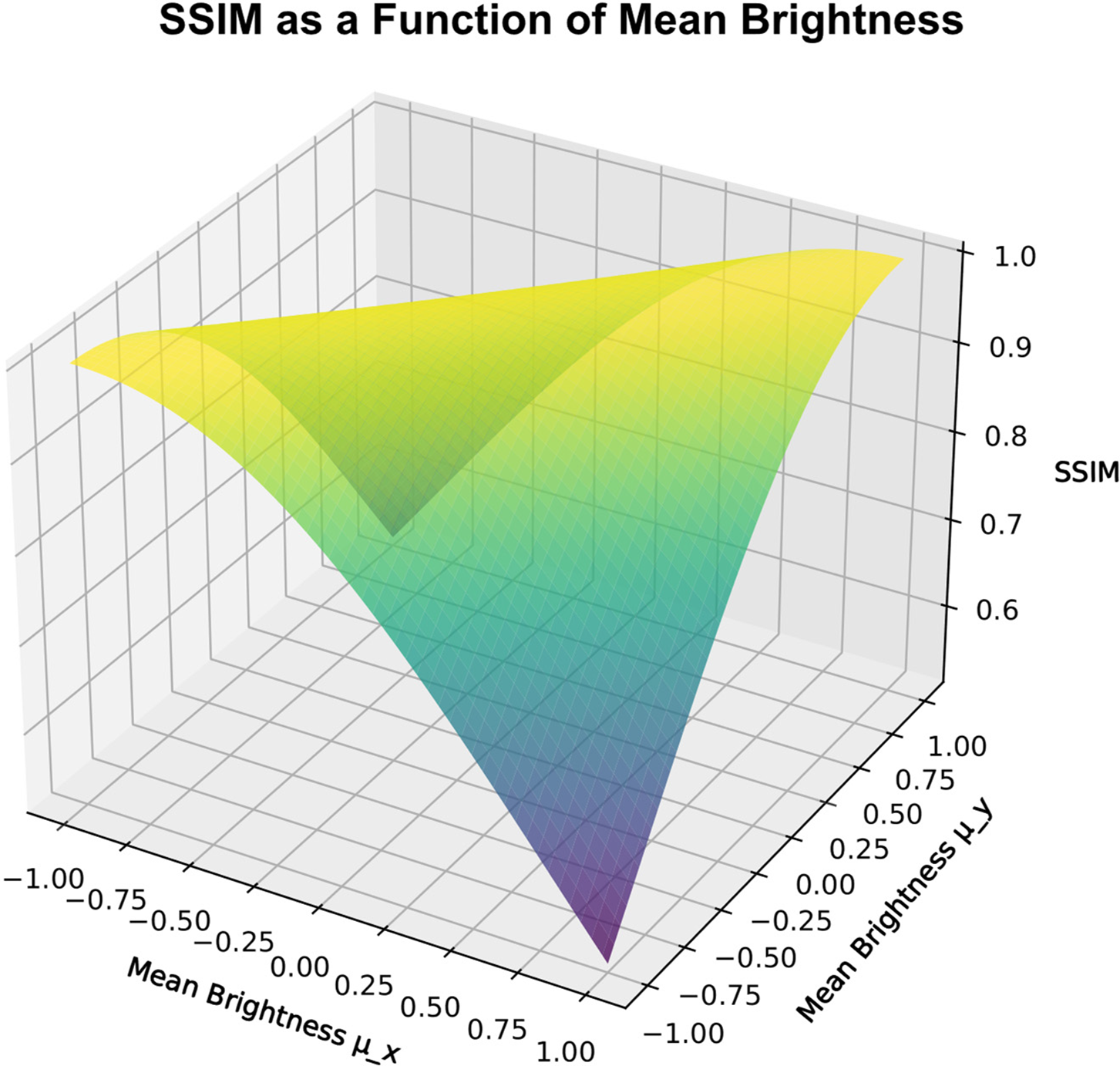

whereas the value 1 indicates structural identity of the compared images, 0 indicates dissimilarity, and negative values indicate anti-correlation, although it occurs quite rarely. As shown in Fig. 1 below, the

Figure 1: SSIM visualisation as a function of mean brightness

However, with a simple definition of the loss function as

2.1 Description of the Experiment

In this research, let us assume a simultaneous training of two neural networks used for image reconstruction—downscaler and upscaler—the final purpose of which is the ability to enlarge small images with high reliability for further use in theoretical and applied research and to compare the influence of loss function components on the quality of the reconstructed image. We present an updated loss function component, the normalised similarity index loss

To build the downscaler and upscaler neural network architectures, we use the Keras and Tensorflow-GPU frameworks, and for training, we use the NVIDIA GeForce GTX 970 hardware with 1664 CUDA cores. As a dataset, we chose the standard DIV2K dataset [20] rescaled to 1000 × 1000 px, General100 [21], and BSDS300 [22] resized to 500 px on longer side.

We train an Invertible Rescaling Neural Network with specific blocks from VGG19 models in the perceptual loss definition as per Eq. (9). and using the same selected specific layers, we train a Super-Resolution network on all the above-mentioned benchmark datasets based on standard metrics, and we examine the influence of the loss function component

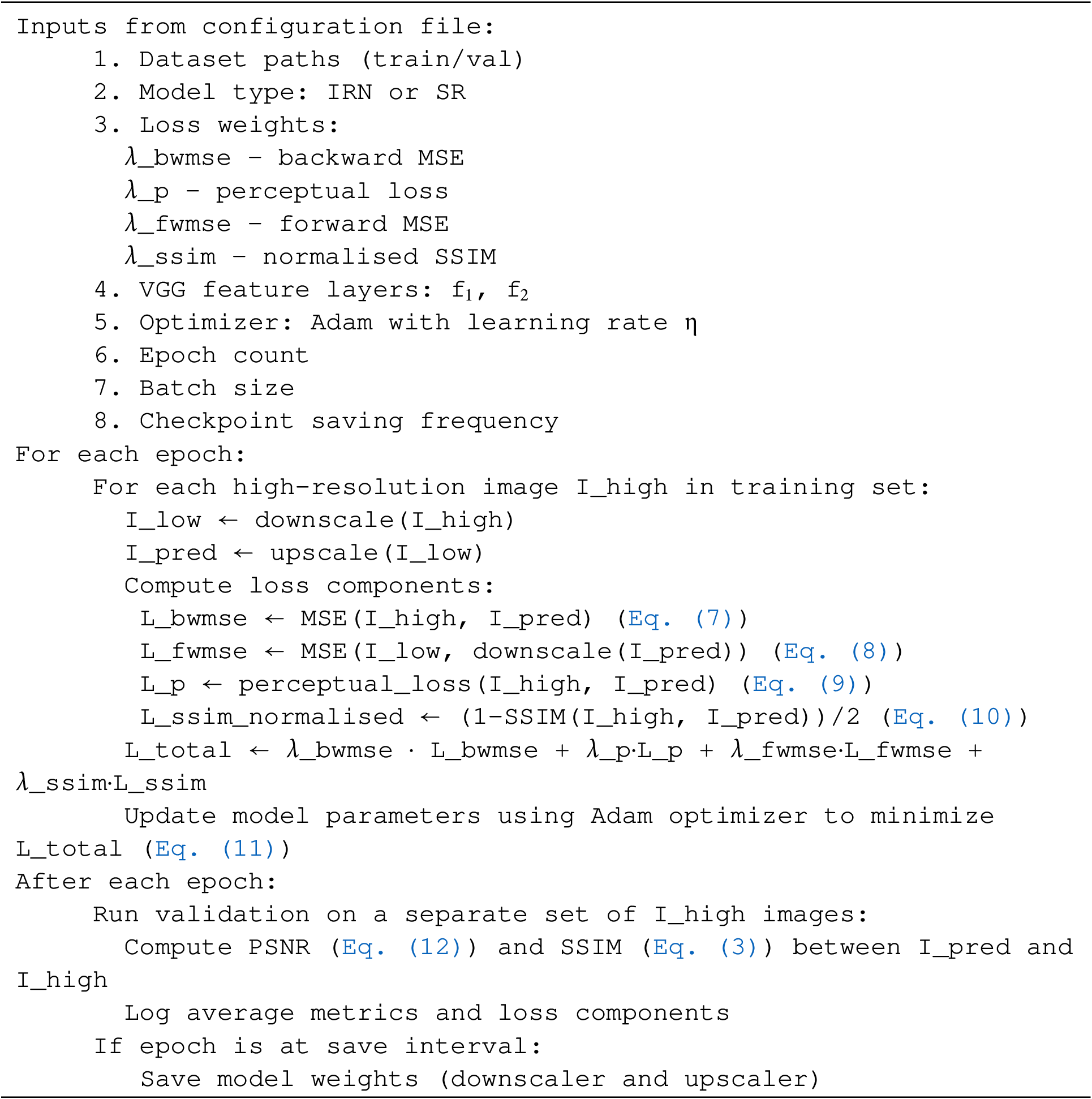

Pseudocode of the Experiment

The experimental workflow is described in the following pseudocode:

2.2 Neural Network Architectures

2.2.1 Invertible Rescaling Neural Network

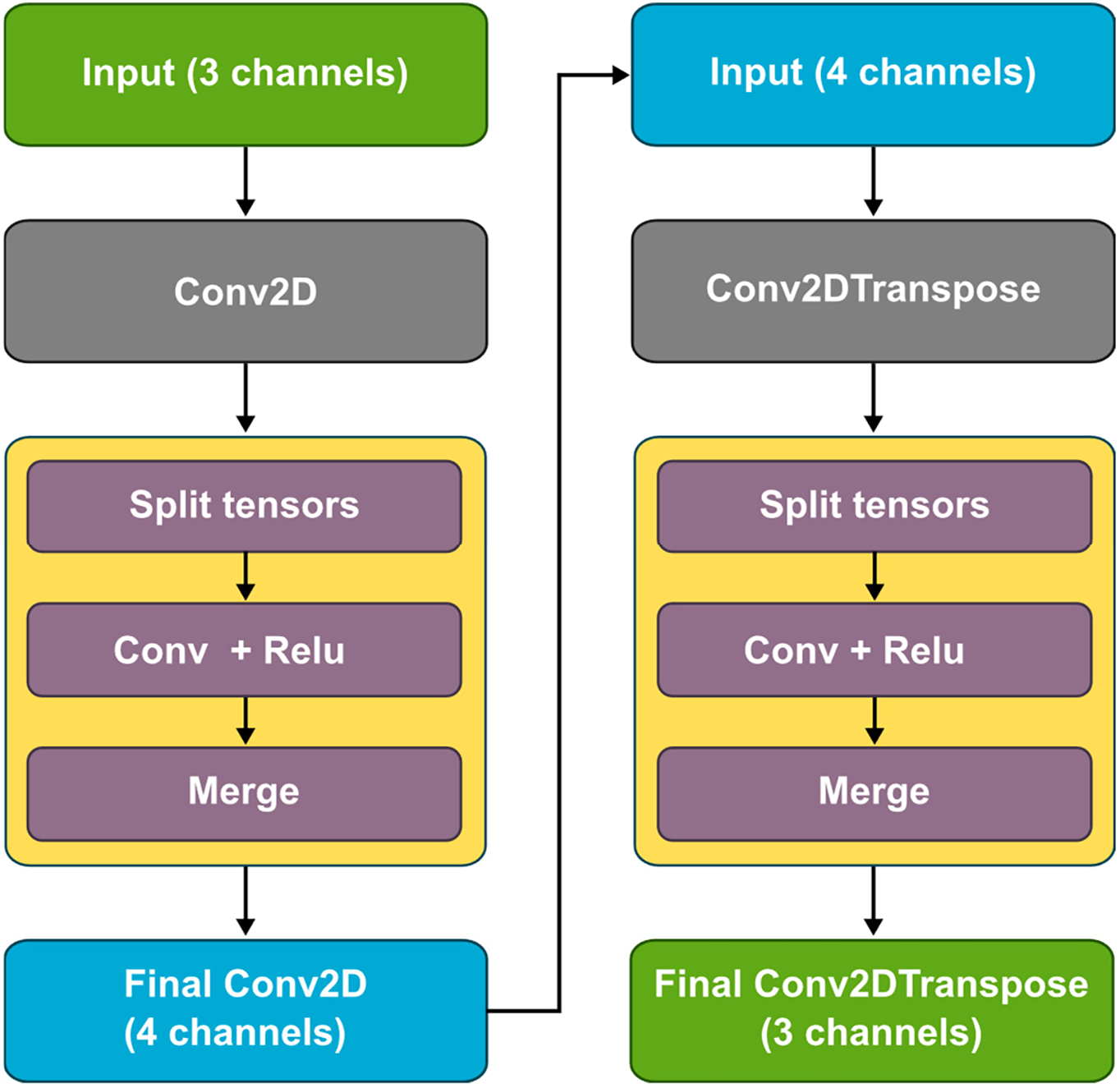

Our Invertible Rescaling Neural Network uses invertible blocks in its architecture, similar to previous research Refs. [10–12]. The network consists of two subnetworks, a downscaler and an upscaler, which can be called separately during inference.

The invertible block divides the input function tensor, along the channel dimension, into two equal parts, see Fig. 2 below. The first half goes through a sequence of transformations consisting of two convolutional layers. The first convolutional layer applies a nonlinear activation function (Rectified Linear Unit—ReLU), while the second is a linear transformation. The output of this transformation is then added to the second, unchanged part of the input. This makes the transformation invertible—the original input can be reconstructed by reversing the operations.

Figure 2: Invertible rescaling neural network architecture

The downscaler takes a three-channel tensor representing a normalised input image between 0 and 1 and reduces the resolution of the input image by 4×. It then applies a convolutional layer, in which the spatial resolution is reduced by a factor of two. After the convolution operation, an invertible block is applied. The number of channels in the output convolutional layer is reduced to four.

The upscaler applies reconstruction using the inverse operation of the downscaler. It takes a four-channel tensor as input, and its first layer is a transposed convolutional layer, which increases the spatial resolution by a factor of four. This is followed by an invertible block and an output layer—a transposed convolution—creating a three-channel output that matches the structure of the original image entering the downscaler.

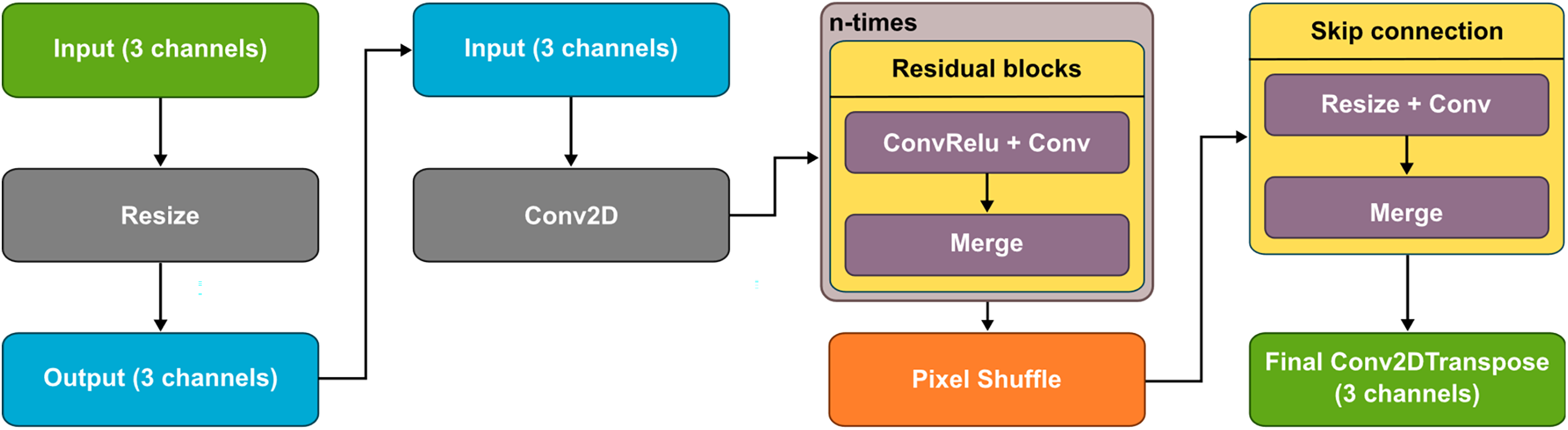

2.2.2 Super-Resolution Network

Our Super-Resolution Network differs from the Invertible Rescaling Network primarily in that the downscaler has no trainable parameters—it is only used to reduce the image to a fractional size according to the parametric number of layers. It repeatedly applies the downscaling operation for a specified number of steps.

The upscaler transforms a 3-channel input image using a convolutional layer with 64 filters and ReLU activation, followed by a sequence of eight residual blocks, each consisting of two 3 × 3 convolutional layers, where the second layer does not apply an activation function, for explanation see Fig. 3 below. After feature extraction, the number of feature maps is increased to 256 channels, preparing the data for resampling using a pixel shuffle operation that reorganises the dimensions of the feature maps to increase spatial resolution. To improve the reconstruction, a skip join is incorporated, where the original input image is resampled using nearest neighbour interpolation, processed using a 1 × 1 convolution, and then added to the resampled feature representation. The output convolution layer adjusts the output to three channels and generates an image dimensionally corresponding to the original input to the downscaler.

Figure 3: Super-resolution neural network architecture

The selected loss function is composed of four components. Three of them correspond with the traditional invertible training and this work newly introduces the normalised

While there are many possible studies in this field, we wanted to focus our analysis on the effects of normalisation on the

Backward

where

Forward

where

The perceptual loss

where

The novel normalised

where

As quantitative evaluation metrics of reconstruction quality, we chose standard metrics used for this type of task, namely

where

We also incorporated Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (

where

3.1 Invertible and Super-Resolution Networks Results

We trained two architectures, Super-Resolution and Invertible-Rescaling-Network, whose structures are described in detail in Sections 2.2.1 and 2.2.2. Training was performed by minimising the loss function defined by Eq. (11), with the weights of the individual components set as follows:

In the first variant, we set

For all experiments, training was conducted using the Adam optimiser with a fixed learning rate of 0.0005, as higher learning rates could skip over optimal solutions during convergence. No learning rate schedule or decay strategy was applied. The batch size was set to 1 due to varying image dimensions across the datasets, which made batch processing impractical without image resizing. The number of iterations per epoch corresponded to the dataset size (e.g., 100 iterations for General100, 250 for BSDS300, and 800 for DIV2K). No data augmentation techniques were used, all images were used in their original orientation and resolution. These settings, along with the associated codes and configurations, are available in the Availability of Data and Materials statement of this manuscript.

In Table 1, the columns denoted with “(start)” indicate results on the validation subset after Epoch 1, the columns denoted with “(end)” indicate results on validation subset after the epoch number specified in the column Epochs. The best results of the monitored metrics after the last epoch are marked in bold. In the table, we use colours to group related experiments together for a better interpretability. Each colour group corresponds to a specific combination of model architecture, dataset, and loss function configuration comparing different experimental conditions. The table describes how the presence or absence of the

Across the majority of configurations, the inclusion of normalised

The results support the hypothesis that normalised

We performed a separate validation using the BSDS300 models on BSDS validation subset (The Berkeley Segmentation Dataset) that contains 50 images. We conducted a statistical paired t-test analysis and measured the p-value, mean difference, confidence interval and Cohen’s d. We paired the reconstruction results of the model which was trained by minimising normalised

Tables 2 and 3 report detailed statistical analyses comparing validation performance across two conditions—normalised (

Table 3 presents a statistical comparison of the model variants trained with normalised

These findings suggest that the benefit of including the

In all examined cases, the quantitative results confirm that the inclusion of the composite loss function component

Although in case of omitting the

Figure 4: Image of a baseball from General100 validation subset (im_100.png) and corresponding contrast-enhanced difference maps (original minus SR reconstruction) using models trained on the BSDS300 dataset: (a) original image, (b) SR reconstruction—model trained with

Figure 5: Image of an author’s photo of a bike (20250220_121442.png) and corresponding contrast-enhanced difference maps (original minus SR reconstruction) using models trained on the BSDS300 dataset: (a) original image, (b) SR reconstruction with

Figure 6: Image of an author’s photo of a cross in front of the church of John the Baptist in Velké Losiny (20250220_150700.png) and corresponding contrast-enhanced difference maps (original minus SR reconstruction) using models trained on the BSDS300 dataset: (a) original image, (b) SR reconstruction with

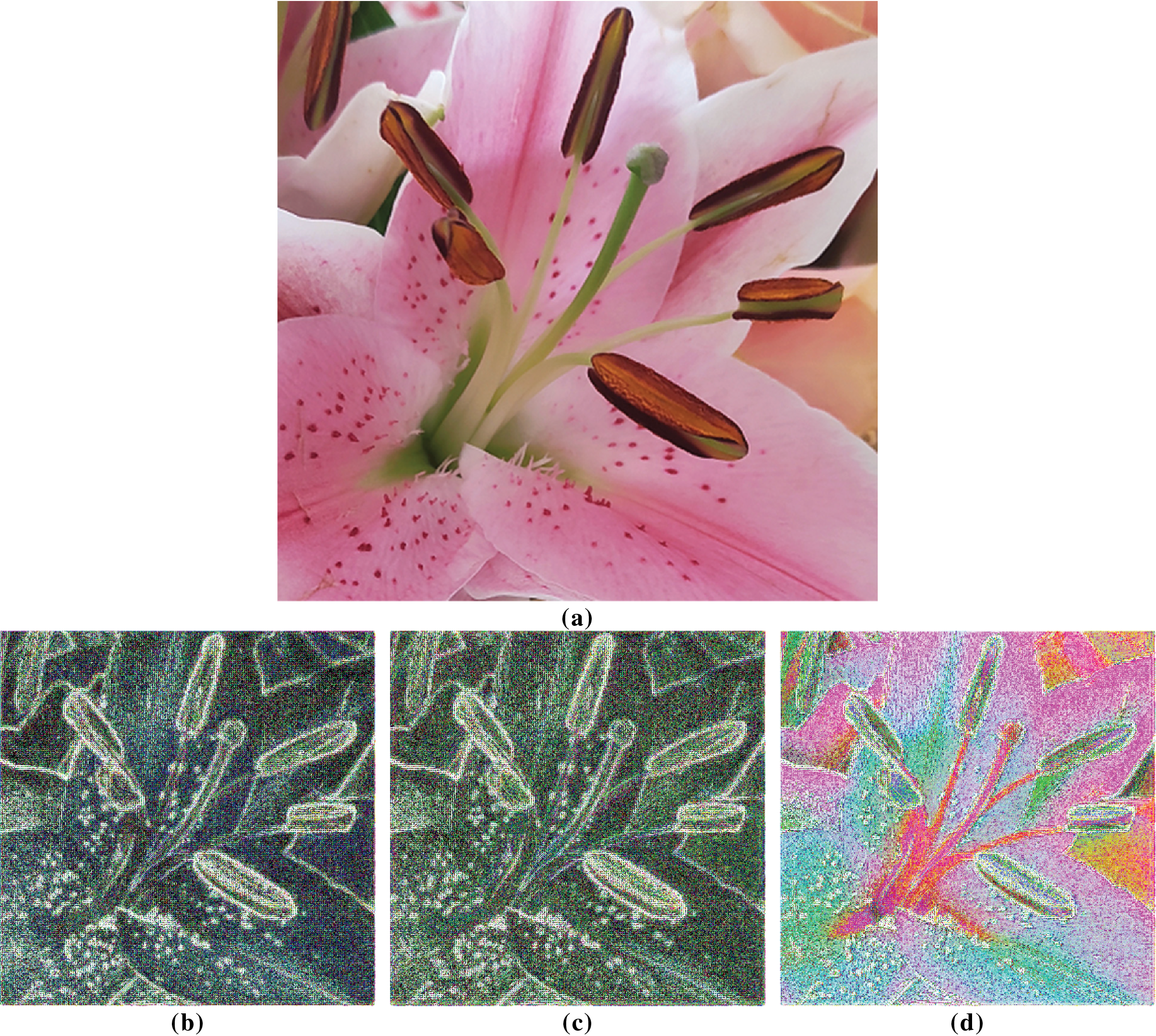

Figure 7: Image of an author’s photo of a pink flower (20250217_151002.png) and corresponding contrast-enhanced difference maps (original minus SR reconstruction) using models trained on the BSDS300 dataset: (a) original image, (b) SR reconstruction with

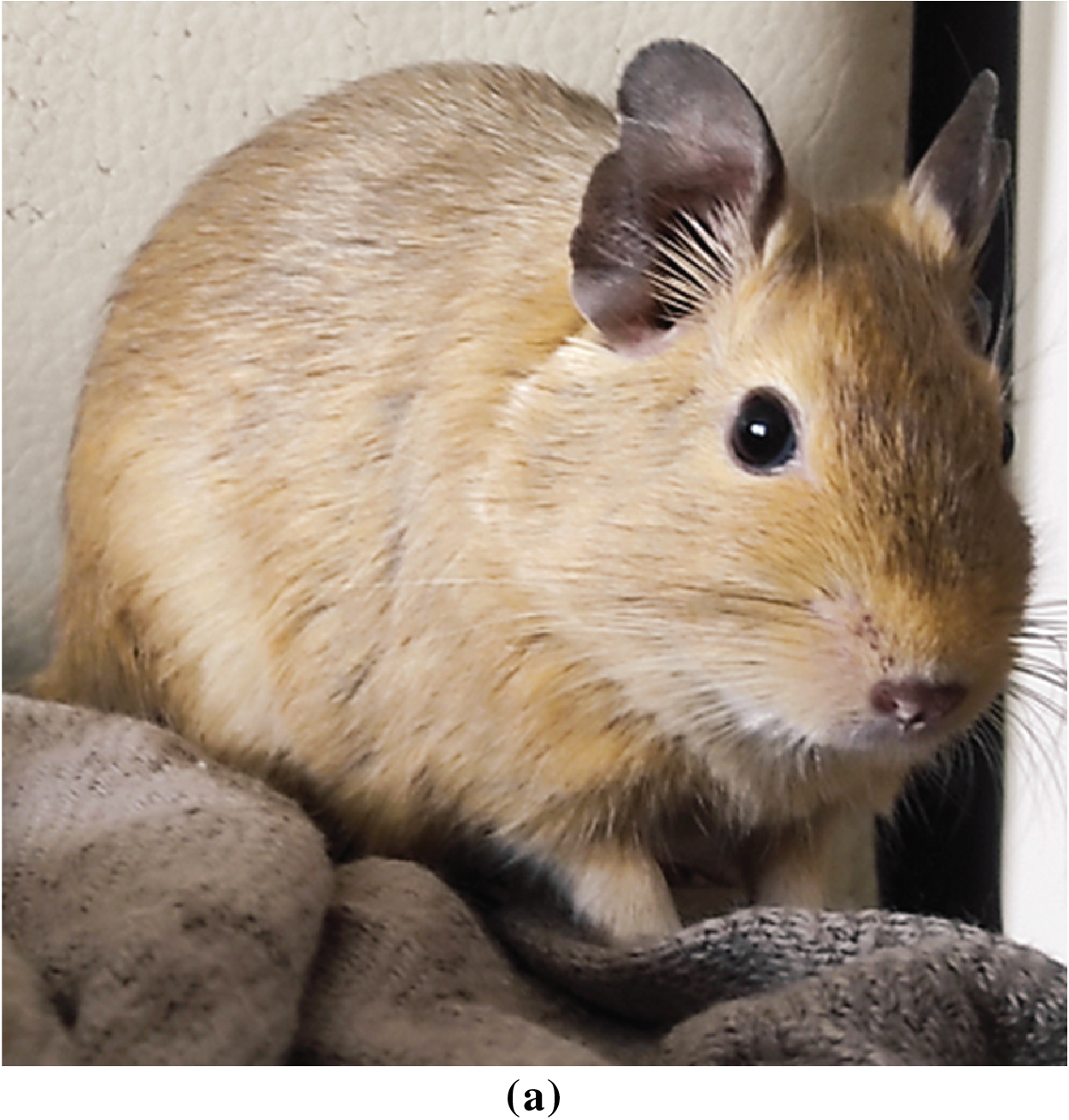

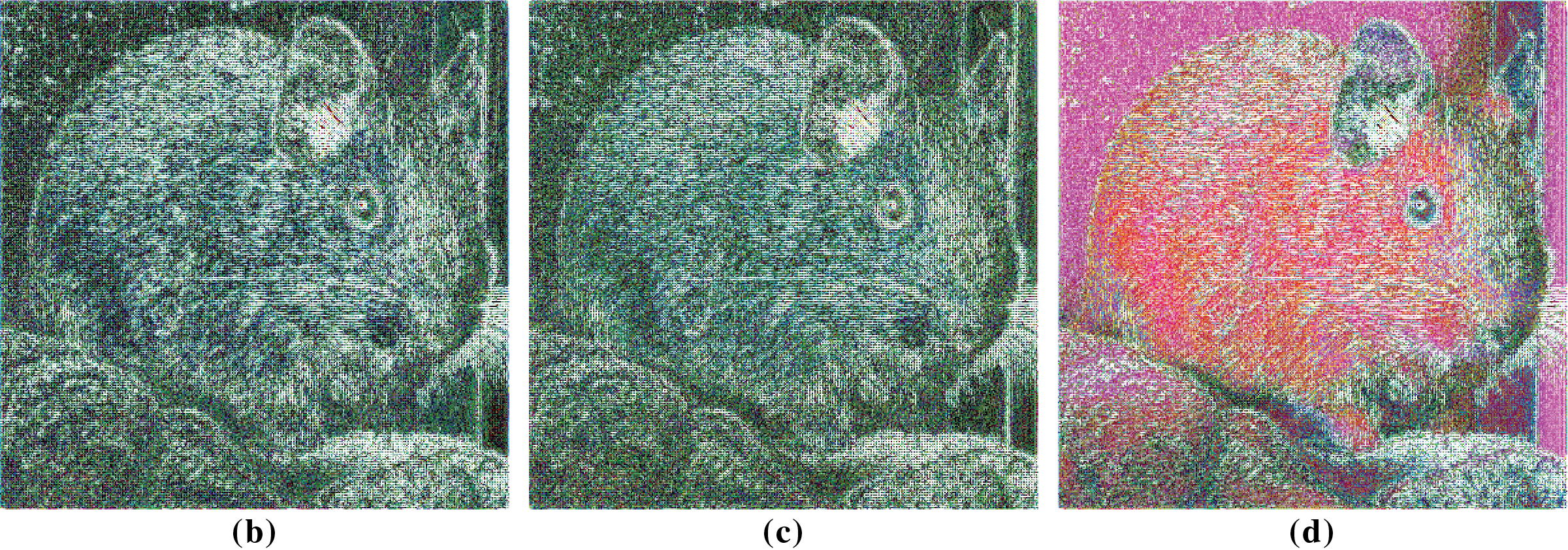

Figure 8: Image of an author’s photo of a common degu (20250503_141137.png) and corresponding contrast-enhanced difference maps (original minus SR reconstruction) using models trained on the BSDS300 dataset: (a) original image, (b) SR reconstruction with

Figure 9: Image of an author’s photo of an orange flower (20230622_175044.png) and corresponding contrast-enhanced difference maps (original minus SR reconstruction) using models trained on the BSDS300 dataset: (a) original image, (b) SR reconstruction with

Models not including the

The highest

Since the nominal difference in

The highest value of each metric for each image is highlighted in bold. The

While all three of the Super-Resolution models achieve high-quality results, subtle differences can be observed, especially in rendering edges and fine details like a continuation of lines. Figs. 4–9 present qualitative comparisons using test images that were included in neither the training nor validation subsets of the BSDS300 SR model to make sure that the evaluation is unbiased and does not suffer from data leakage. Selection was made manually to cover different visual characteristics, and no quantitative criteria or ranking were applied in the selection process. Fig. 4 is picked and cropped from the General100 validation dataset and Figs. 5–9 are photographs by the authors of this article, all of them are cropped to 400 × 400 px.

Figs. 4(b–d)–9(b–d) show contrast-enhanced difference images, i.e., pixel difference maps between reference images 4a–9a and corresponding reconstructions—outputs of SR algorithms trained with different

4.2 Comparison with Related Works

Huang’s research [14] that introduced

From the perspective of using this loss function component, its importance has already been proven in Huang’s research. Still, the importance of normalisation, which ensures that the individual components of the loss function are in the same range of values, has not been considered before. Another recent contribution to the development of SR methods is the work by Gao et al. [26], who proposed a robust symmetrical and recursive transformer network for image super-resolution (SRTNet) and tested it on multiple benchmark datasets. Their model integrates a recursive feedback mechanism and a dual-branch design to improve the reconstructed images and to address the problem of computational cost. While their focus is on architectural innovation rather than loss function design, they also emphasise structural preservation as a key objective, indirectly aligning with our goal of

Further research steps may be aimed at experimenting with the setting of the

In this paper, we investigated the impact of loss function components on the outcome of Super-Resolution tasks. We newly presented the loss function component

When training Super-Resolution models, it is evident that including the normalised loss component

If the goal is to achieve a reconstruction that looks natural and is structurally consistent with the original images,

Although the normalisation of the SSIM component is mathematically straightforward, our experiments demonstrate that it improves the compatibility between loss components and contributes to more efficient training and slightly better image reconstruction. The contribution of our research lies in the systematic analysis within a controlled experimental environment, which has not been explicitly addressed in previous works. We believe that our observations are relevant for future studies of loss function design in image reconstruction tasks.

Acknowledgement: We would like to hereby thank doc. Ing. Arnošt Veselý, CSc. for invaluable advice during writing this article.

Funding Statement: The results and knowledge included herein have been obtained owing to support from the following institutional grant. Internal Grant Agency of the Faculty of Economics and Management, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, grant no. 2023A0004 (https://iga.pef.czu.cz/, accessed on 6 June 2025). Funds were granted to T. Novák, and A. Hamplová from the author team.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualisation, Adéla Hamplová; methodology, Adéla Hamplová; software, Adéla Hamplová; validation, Adéla Hamplová; formal analysis, Adéla Hamplová; investigation, Adéla Hamplová; resources, Adéla Hamplová, Tomáš Novák; data curation, Adéla Hamplová; writing—original draft preparation, Adéla Hamplová; writing—review and editing, Tomáš Novák, Miroslav Žáček, Jiří Brožek; visualisation, Adéla Hamplová, Jiří Brožek; supervision, Adéla Hamplová; project administration, Adéla Hamplová; funding acquisition, Adéla Hamplová. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The code generated for this research is openly available on [normalised-SSIM-loss-SR] GitHub repository at [https://github.com/adelajelinkova/normalised-SSIM-loss-SR]. The datasets used for training the models are openly available at URL addresses: DIV2K [20] [https://data.vision.ee.ethz.ch/cvl/DIV2K/], BSDS300 [22] [https://www2.eecs.berkeley.edu/Research/Projects/CS/vision/bsds/] and General 100 [21] [https://mmlab.ie.cuhk.edu.hk/projects/FSRCNN.html]. Pre-trained models and logs, from which results were calculated, are available at [https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1-lvrKZ9koByt323fN2yCqt7pqJf9oK4L?usp=sharing] (accessed on 6 June 2025.)

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Perceptual Loss Block Grid Search: Appendix A provides a list of options and an interpretation guide to the convolutional blocks available in VGG19 network that can be selected during minimising perceptual loss. Each block extracts features at a different level of abstraction—lowest layers capture low-level features such as lines, edges, etc., and last layer interprets the whole objects.

The list of blocks and their interpretations is as follows:

To identify the most suitable layer configuration for our task, we performed a grid search over multiple block combinations using the IRN model and the DIV2K_1000 dataset. We evaluated combinations of VGG19 feature layers that correspond to different levels of the network hierarchy, including the pairs block1_conv2–block4_conv4 combining lower-middle feature with higher-middle feature, block2_conv2–block5_conv2 combining lower-middle feature with the highest-level feature, block3_conv2–block4_conv4 combining two middle-level features, and block4_conv4–block5_conv4 combining higher-middle features with top-level features. The results of this comparison are provided in Table A2.

References

1. Li W, Liu H, Wang J. A deep learning method for denoising based on a fast and flexible convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2021;60(2):1–13. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2021.3073001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ignatov A, Romero A, Kim H, Timofte R, Ho CM, Meng Z, et al. Real-time video super-resolution on smartphones with deep learning, mobile AI 2021 challenge: report. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2021 Jun 19–25; Nashville, TN, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPRW53098.2021.00287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang Z, Ye M, Yang F, Bai X, Satoh S. Cascaded SR-GAN for scale-adaptive low resolution person re-identification. In: Proceedings of the 27th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI); 2018 Jul 13–19; Stockholm, Sweden. doi:10.24963/ijcai.2018/541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Yu X, Butler SK, Kong L, Milbeck BAF, Barajas-Olalde C, Burton-Kelly ME, et al. Machine learning-assisted upscaling analysis of reservoir rock core properties based on micro-computed tomography imagery. J Pet Sci Eng. 2022;219(9):1–26. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2022.111087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Tsai RY, Huang TS. Multiframe image restoration and registration for spaceborne sensors. Adv Comput Vis Image Process. 1984;1:317–39. doi:10.1016/j.rinp.2021.103991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Crivellari A, Wei H, Wei C, Shi Y. Super-resolution GANs for upscaling unplanned urban settlements from remote sensing satellite imagery—the case of Chinese urban village detection. Int J Digit Earth. 2023;16(1):2623–43. doi:10.1080/17538947.2023.2230956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Tan W, Qin N, Zhang Y, McGrath H, Fortin M, Jonathan L. A rapid high-resolution multi-sensory urban flood mapping framework via DEM upscaling. Remote Sens Environ. 2024;301(4):113956. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2023.113956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Belharbi S, Sarraf A, Pedersoli M, Ayed I, McCaffrey L, Granger EF. CAM: full resolution class activation maps via guided parametric upscaling. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2022 Jan 3–8; Waikoloa, HI, USA. doi:10.1109/WACV51458.2022.00378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Anh HK, Lee S, Jung SO. A CNN-based super-resolution processor with short-term caching for real-time UHD upscaling. IEEE Trans Circuits Sys I Reg Pap. 2024;71(3):1198–207. doi:10.1109/TCSI.2023.3346440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Xiao M, Zheng S, Liu C, Wang Y, He D, Ke G, et al. Invertible image rescaling. In: Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58452-8_8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Xiao M, Zheng S, Liu C, Lin Z, Liu TY. Invertible rescaling network and its extensions. Int J Comput Vis. 2022;131(9):1–26. doi:10.1007/s11263-022-01688-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xu BN, Guo Y, Jiang LQ, Yu MJ, Chen J. Downscaled representation matters: improving image rescaling with collaborative downscaled images. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. doi:10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.01124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Johnson J, Alahi A, Li FF. Perceptual losses for real-time style transfer and super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46475-6_43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Huang Y, Song R, Xu K, Ye X, Li C, Chen X. Deep learning-based inverse scattering with structural similarity loss functions. IEEE Sens J. 2021;21(4):4900–7. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2020.3030321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wang Z, Bovik AC, Sheikh HR, Simoncelli EP. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2004;13(4):600–12. doi:10.1109/TIP.2004.819325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chollet F. Deep learning with python. 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: Simon and Schuster; 2021. p. 73–80. [Google Scholar]

17. Ledig C, Theis L, Huszar F, Caballero J, Cunningham A, Acosta A, et al. Photo-realistic single image super-resolution using a generative adversarial network. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2015 May 7–9; San Diego, CA, USA. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1409.1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Singla S, Bohat VK, Aggarwal M, Mehta Y. Hybrid perceptual structural and pixelwise residual loss function based image super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference for Innovation in Technology (INOCON); 2024 Mar 1–3; Bangalore, India. doi:10.1109/INOCON60754.2024.10511465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Augustsson E, Timofte R. NTIRE 2017 challenge on single image super-resolution: dataset and study. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2017; Honululu, HI, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPRW.2017.150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zeyde R, Elad M, Protter M. Dataset: General100. doi:10.57702/m4tsd5mf. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Martin D, Fowlkes C, Tal D, Malik J. A database of human segmented natural images and its application to evaluating segmentation algorithms and measuring ecological statistics. In: Proceedings of the Eighth IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2001 Jul 7–14; Vancouver, BC, Canada. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2001.937655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhang R, Isola P, Efros AA, Shechtman E, Wang O. The unreasonable effectiveness of deep features as a perceptual metric. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2018 Jun 18–22; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Barron JT. A general and adaptive robust loss function. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 16–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1701.03077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Blau Y, Michaeli T. The perception-distortion tradeoff. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Gao M, Sun J, Li Q, Khan MA, Shang J, Zhu X, et al. Towards trustworthy image super-resolution via symmetrical and recursive artificial neural network. IEEE Img Vis Comput. 2025;158(21):105519. doi:10.1016/j.imavis.2025.105519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools