Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Numerical Study on Hemodynamic Characteristics and Distribution of Oxygenated Flow Associated with Cannulation Strategies in Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Support

1 Department of Engineering Mechanics, School of Ocean and Civil Engineering, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, 200240, China

2 Division of Vascular Surgery, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, 610041, China

3 Department of General Surgery 1 (Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgery & Vascular Surgery), West China Tianfu Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, 610065, China

4 State Key Laboratory of Ocean Engineering, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, 200240, China

5 Institute for Computer Science and Mathematical Modeling, Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Moscow, 119991, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Fuyou Liang. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 143(3), 2867-2882. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.066444

Received 08 April 2025; Accepted 11 June 2025; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

Veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) is a life support intervention for patients with refractory cardiogenic shock or severe cardiopulmonary failure. However, the choice of cannulation strategy remains contentious, partly due to insufficient understanding of hemodynamic characteristics associated with the site of arterial cannulation. In this study, a geometrical multiscale model was built to offer a mathematical tool for addressing the issue. The outflow cannula of ECMO was inserted into the ascending aorta in the case of central cannulation, whereas it was inserted into the right subclavian artery (RSA) or the left iliac artery (LIA) in the case of peripheral cannulation. Numerical simulations conducted on three patient-specific aortas demonstrated that the central cannulation outperformed the two types of peripheral cannulation in evenly delivering ECMO flow to branch arteries. Both the central and RSA cannulations could maintain an approximately normal hemodynamic state in the aortas, although the area of aortic walls exposed to abnormal wall shear stress (WSS) was considerably enlarged in comparison with the normal physiological condition. In contrast, the LIA cannulation not only led to insufficient delivery of ECMO flow to the right upper body (with ECMO flow fractions < 0.5), but also induced marked flow disturbance in the aorta, causing about 40% of the abdominal aortic wall and over 65% of the resting aortic wall to suffer from high time-averaged WSS (>5 Pa) and low time-averaged WSS (<0.4 Pa), respectively. The LIA cannulation also resulted in significantly prolonged blood residence time (>40 s) in the ascending aorta, which, along with abnormal WSS, may considerably increase the risk of thrombosis. In summary, our numerical study elucidated the impact of arterial cannulation site in VA-ECMO intervention on aortic hemodynamics and ECMO flow distribution. The findings provide compensatory biomechanical information for traditional clinical studies and may serve as a theoretical reference for guiding the evaluation and selection of cannulation strategies in clinical practice.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileVeno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) is a temporary life support technique that diverts venous blood through an oxygenator and reperfuses the oxygenated blood into the arterial system, thereby providing support for both the cardiac and pulmonary functions in patients with refractory cardiogenic shock (CS) or severe cardiorespiratory failure [1]. In the implementation of VA-ECMO, the ascending aorta and several peripheral arteries (e.g., the femoral, subclavian, or axillary arteries) are potential candidates for ECMO outflow cannulation [2]. The aortic cannulation forms the central VA-ECMO configuration, while the cannulation to a peripheral artery constitutes the peripheral VA-ECMO configuration. Clinically, central VA-ECMO requires more complex surgical procedures than peripheral VA-ECMO [3]. In the past decades, the trade-off between the benefits and risks of central vs. peripheral cannulation strategy has long been a critical issue of debate. Some clinical studies suggested that central cannulation is associated with higher in-hospital mortality compared to peripheral cannulation, with an increased rate of bleeding and infection [4–6]. Conversely, other studies have reported no significant differences in in-hospital mortality between patients receiving central and peripheral VA-ECMO supports [7,8], although peripheral VA-ECMO was found to be associated with a higher incidence of vascular complications, lower-limb ischemia, or cerebrovascular events. So far, the exact mechanisms underlying the differential outcomes of clinical studies remain incompletely understood, although the differences in patient cohort and limitations in available clinical data for in-depth analysis are important factors of concern [9,10].

From the biomechanical point of view, the reinjection of blood from the VA-ECMO system into the arterial system will induce significant changes in blood flow patterns, especially those in the aorta [11]. Another important issue associated with VA-ECMO support is the distribution of the ECMO-oxygenated blood in the body via the aorta and its branch arteries [2]. As a useful means for overcoming the limitations of clinical studies in collecting detailed hemodynamic data, computational modeling methods have been widely employed to address biomechanical problems associated with ECMO support [12,13]. Studies focused on peripheral VA-ECMO have demonstrated the presence of strong retrograde blood flow in the aorta, which interacts with the forward flow originating from the heart to induce marked flow disturbance and abnormality of wall shear stress (WSS) [14,15]. In comparison with central cannulation, peripheral cannulation has also been found to have poor performance in evenly distributing ECMO-oxygenated blood in the body, leading to hypoxemia of certain organs/tissues, such as the brain and upper limbs [16]. At this point, numerical studies have proposed some strategies, such as placing the cannula tip closer to the aortic arch or increasing the power of the ECMO pump, to enhance oxygen delivery to the upper body and coronary circulation in the context of peripheral VA-ECMO [17,18]. While these studies offered valuable insights, many of them employed stand-alone three-dimensional (3D) models and incorporated simplifications or assumptions in model development, such as the use of idealized aortic models, the prescription of fixed flow conditions at the aortic inlet and the ECMO outlet, and the neglection of the dynamic interaction between the heart and ECMO. These simplifications/assumptions might considerably compromise the physiological relevance of numerical results. The limitations of stand-alone 3D models in assessing the impact of VA-ECMO on cardiac load, systemic hemodynamics and oxygen transport can be effectively addressed by employing reduced-order models, such as one-dimensional or lumped parameter models, which integrate the ECMO and cardiovascular systems into a unified framework [19–21]. These kinds of models, however, lack the ability to provide spatially high-resolution hemodynamic information in specific aortic segments or arteries of interest. Given the limitations of existing studies, it remains unclear how varying the arterial cannulation site of VA-ECMO would affect aortic hemodynamics and the distribution of ECMO-oxygenated blood over the body.

In the present study, we developed a geometrical multiscale model by coupling a closed-loop lumped parameter (0D) model of the cardiovascular system supported by a VA-ECMO with a three-dimensional (3D) model of the aorta and its major branch arteries. The multiscale modeling approach ensured that the boundary conditions of the 3D model could dynamically adapt to systemic hemodynamic changes [22], thereby minimizing the artifacts associated with prescribed boundary conditions in stand-alone 3D models. The multiscale model also allowed for flexible connection of the ECMO outflow cannula to any artery of interest, thereby offering a practical tool for simulating and comparing the hemodynamic impacts of various VA-ECMO cannulation strategies. In addition, the blood flows originated from the heart and ECMO were modeled as two fluids with the same physical properties for purpose of tracing the distribution of ECMO flow, and the ‘virtual ink’ technique was employed to quantify the residence time of blood in the aorta.

2.1 Model Development and Numerical Methods

A 0D model of the cardiovascular system was firstly constructed by representing the vascular resistances, compliances, and blood inertances of the major cardiovascular portions (i.e., heart, pulmonary circulation, arterial system, and venous system) with lump parameters, which was then coupled to a 3D model of an aorta and its major branch arteries to form a geometrical multiscale model (see Fig. 1). In addition, a 0D model of the ECMO system was coupled to the multiscale model by connecting its inflow cannula to the vena cava and outflow cannula to the aorta or a branch artery, thereby forming a flow pathway running in parallel with the cardiopulmonary circulation. In order to represent the CS condition, the peak systolic elastances of the left ventricle (LV) and right ventricle in the 0D model were reduced by 83% relative to the normal values, resulting in a LV ejection fraction of 20% that fulfills the diagnostic threshold for CS [23,24]. The ECMO pump was modeled as a mathematical function relating pump output to the rotation speed and trans-pump pressure gradient [25]. More detailed descriptions of the cardiovascular and ECMO models are provided in the Supplementary Material, while the assigned parameter values have been reported in a recent study by our group [14]. To determine the optimal VA-ECMO work state under the CS condition, the rotation speed of the ECMO blood pump was adjusted via numerical experiments so that the total cardiac output (i.e., the sum of the native cardiac flow rate and ECMO flow rate) was 5.25 L/min. The total cardiac output aligns with most clinical guidelines on targeted cardiac output (5.25–6.06 L/min) in VA-ECMO support and is close to the typical cardiac output in healthy adults [1].

Figure 1: Geometrical multiscale model of the cardiovascular system supported by VA-ECMO. The 3D model of the aorta and its branch arteries is connected to the 0D cardiovascular model via exchange of hemodynamic quantities at the inlet and outlets and to the ECMO outflow cannula at a specific cannulation site (i.e., ascending aorta, right subclavian artery (RSA), or left iliac artery (LIA))

The 3D geometric models of three aortas and their branch arteries were reconstructed from the computed tomography angiography (CTA) images of three patients upon the approval of the Ethical Review Committee of the West China Hospital (No. 2020309). A 3D straight tube model with a diameter of 19F was built to represent the distal portion of the ECMO outflow cannula that was inserted into the ascending aorta to represent central cannulation or into a branch artery (herein, the left iliac artery (LIA), or the right subclavian artery (RSA)) to represent peripheral cannulation. The reconstructed geometric models were meshed in Ansys ICEM with a hybrid meshing method. Specifically, the entire domain was firstly divided by tetrahedral elements, with local refinements applied to regions with abrupt geometrical changes or narrow fluid space, such as the origins of branch arteries and the ECMO outflow cannula. In the near-wall regions, five layers of prism elements were created, which were mapped along the inner wall and grew toward the internal fluid domain. The thickness of the first prism layer was set to 0.005 mm, which increased toward the internal layers at a ratio of 1.2. To ensure the acquirement of mesh-independent numerical solutions, grid sensitivity analysis was conducted on a randomly selected model. The results showed that setting the maximum tetrahedral element size at 1.5 mm in the aortic domain and 0.15 mm in the branch arteries was sufficient to guarantee mesh-independent solutions, as evidenced by less than 0.5% change in time-averaged WSS (TAWSS) following further mesh refinement by reducing the aortic and branch arterial element sizes to 1.0 mm and 0.1 mm, respectively. A total of nine mesh models were generated for the three cannulation strategies (central, RSA, and LIA) implemented on the three aortas, with the total element numbers ranging from 7,789,367 to 7,917,524.

Blood was assumed to be a homogeneous, incompressible, and Newtonian fluid, and the blood flow was governed by the continuity and Navier-Stokes equations. The arterial wall was assumed rigid, with a no-slip boundary condition imposed. In addition, to facilitate the tracing of the ECMO flow in the aorta and branch arteries, the bloods originated from the heart and the ECMO were treated as two fluids using the two-phase mixture model, but with the same physical properties. The continuity equation for the mixture model is expressed as

where

where

The volume fraction of ECMO-originated blood is governed by a ‘mass’ conservation equation.

where subscripts ‘p’ and ‘q’ denote the ECMO-originated and heart-originated bloods (same physical properties), respectively.

Hemodynamic variables in the 0D model were governed by ordinary differential equations that were solved using a fourth-order Runge-Kutta method. The 3D equations of blood flow were discretized and numerically solved with second-order schemes for both the temporal and spatial terms in Ansys Fluent. Hemodynamic quantities in the 0D and 3D models were coupled via bidirectional data exchange at their interfaces, as described in detail in our previous work [14]. In brief, the inlets and outlets of the 3D model were connected to the ‘Q’ (flow rate) and ‘P’ (pressure) nodes of the 0D model, respectively (see Fig. 1), forming 0–3D model interfaces where the solutions of the two models are linked to each other. At an inlet of the 3D model, the flow rate computed by the 0D model was imposed as the inflow boundary condition, while the computed inlet pressure by the 3D model was in turn used to set the pressure boundary condition of the 0D model. At an outlet of the 3D model, the 0D model transmitted the computed blood pressure to the 3D model as the outlet pressure boundary condition, while the 3D model returned the updated outlet flow rate to the 0D model. Herein, to facilitate the data exchange between the two models, the computer program of the 0D model was embedded into Fluent in form of user-defined functions. The coupled solution of the 0D and 3D models was implemented in a time-marching manner by iteratively exchanging hemodynamic data (i.e., pressure and flow rate) at the 0D–3D model interfaces at each numerical time step (fixed at 0.0005 s). Each set of numerical simulation was run continuously for 60 cardiac cycles (the duration of a cardiac cycle is 0.75 s) so that the distribution of ECMO flow and the blood residence time could be fully evaluated.

2.2 Design of Numerical Experiments and Data Analysis

For each aortic model, the ECMO outflow cannula was connected to the ascending aorta, RSA, and LIA, respectively, forming three cannulation modes, including one central cannulation and two peripheral cannulations. In total, nine sets of numerical simulation were performed for the three aortic models.

Data analysis was focused on the fraction of ECMO flow that characterizes the distribution of oxygenated blood in the body, and WSS metrics (herein, TAWSS and oscillatory shear index (OSI)) that evaluate hemodynamic characteristics. For the definitions of TAWSS and OSI, please refer to previous studies [14,26]. In addition, blood residence time (RT), which measures the severity of flow stagnation, was evaluated by tracing the blood with the ‘virtual ink’ technique [27]. To implement the technique, hypothetical massless dye was introduced to the full 3D fluid domain at the beginning of numerical simulation. The motion of dye in the blood stream followed the advection-diffusion equation, which was numerically solved with the blood flow velocities from the hemodynamic model as the input. The governing equation is expressed as

where

3.1 Influence of Cannulation Sites on Hemodynamic Characteristics

Fig. 2 presents the simulated aortic and ECMO flow waveforms and flow streamlines (at peak velocity) in the three aortas under different cannulation conditions. A jet flow from the ECMO outflow cannula was predicted in all the cases, but it had differential impacts on the native aortic flow depending on the site of cannulation. Specifically, the most remarkable changes in aortic flow patterns were predicted in the case of LIA cannulation, as characterized by the presence of a strong retrograde swirling flow in the abdominal aorta. The central cannulation could better preserve cardiac output, as evidenced by the higher aortic flow rate than those under the peripheral cannulation conditions. The cannulation site also affected the distributions of aortic flow to branch arteries. In the case of central cannulation, approximately 31% of the total aortic flow (sum of flows originated from the heart and ECMO) was delivered to the aortic arch branches, 39% to the abdominal branches, and 30% to the iliac arteries, which changed into 32%, 38%, and 30% in the case of RSA cannulation, and into 30%, 47%, and 23% in the case of LIA cannulation. The anatomical structure of the aorta only had minimal influence on flow distribution, as indicated by less than 0.5% differences among the three models.

Figure 2: Flow streamlines in three aortas at the moment of peak flow velocity (left panels) and heart-and ECMO-generated flow waveforms (right panels) under central (ascending aorta) and peripheral (LIA or RSA) cannulation conditions of VA-ECMO

Fig. 3 shows the distributions of TAWSS and OSI in the three aortas. Under the control (normal physiological) condition, most values of TAWSS and OSI in the aortas fell in the normal ranges (0.4 Pa < TAWSS < 5 Pa, OSI < 0.35), although abnormal values in some local regions or the branch arteries were observed. Under the CS condition supported by VA-ECMO, regional high TAWSS (>5 Pa) was predicted, which was present in the inner wall of the ascending aorta and aortic arch in the central cannulation mode, the outer wall of the ascending aorta and the brachiocephalic artery in the RSA cannulation mode, and the abdominal aorta in the LIA cannulation mode. Quantitatively, the area ratios of walls exposed to high TAWSS in the ascending aorta and aortic arch segments of Model 1, Model 2, and Model 3 were 45.38%, 49.90%, and 47.65% in the case of central cannulation, and were 19.11%, 15.32%, and 7.88% in the case of RSA cannulation. In the case of LIA cannulation, high TAWSS appeared in the abdominal aorta, occupying 38.11%, 43.29%, and 43.58% of the wall area in Model 1, Model 2, and Model 3, respectively. These regions corresponded to the wall regions subjected to the impingement of the jet flow from the ECMO. Large area of low TAWSS (<0.4 Pa) appeared in the aortic segments distal to the aortic arch in the cases of central and RSA cannulations, and in the aortic segments proximal to the abdominal aorta in the case of LIA cannulation. Quantitatively, in the case of central cannulation, the area ratios of low TAWSS in the abdominal aorta segments of Models 1, 2, and 3 were 31.84%, 24.62%, and 33.59%, respectively, which became 30.76%, 20.97%, and 31.81% when the cannulation site was switched to the RSA. In contrast, the LIA cannulation caused a large portion of the aortic segments proximal to the abdominal aorta to suffer from low TAWSS, with the area ratios of low TAWSS reaching 87.45%, 65.55%, and 80.91% in Models 1, 2, and 3, respectively. As for OSI, high OSI (>0.35) distributed widely in the aortic segments proximal to the abdominal aorta under the LIA cannulation condition, with the area ratios of high OSI being 35.41%, 29.28%, and 40.93% in Model 1, Model 2, and Model 3, respectively. Relatively, high OSI was predicted to appear only in some focal regions in the cases of central and RSA cannulations. The three aortas exhibited overall similar hemodynamic characteristics, although they differed in the details of flow field and WSS distribution owing to the different anatomical structures.

Figure 3: Contour maps of TAWSS (left panels) and OSI (right panels) in three aortas under the control (i.e., normal physiological) condition and various VA-ECMO cannulation conditions

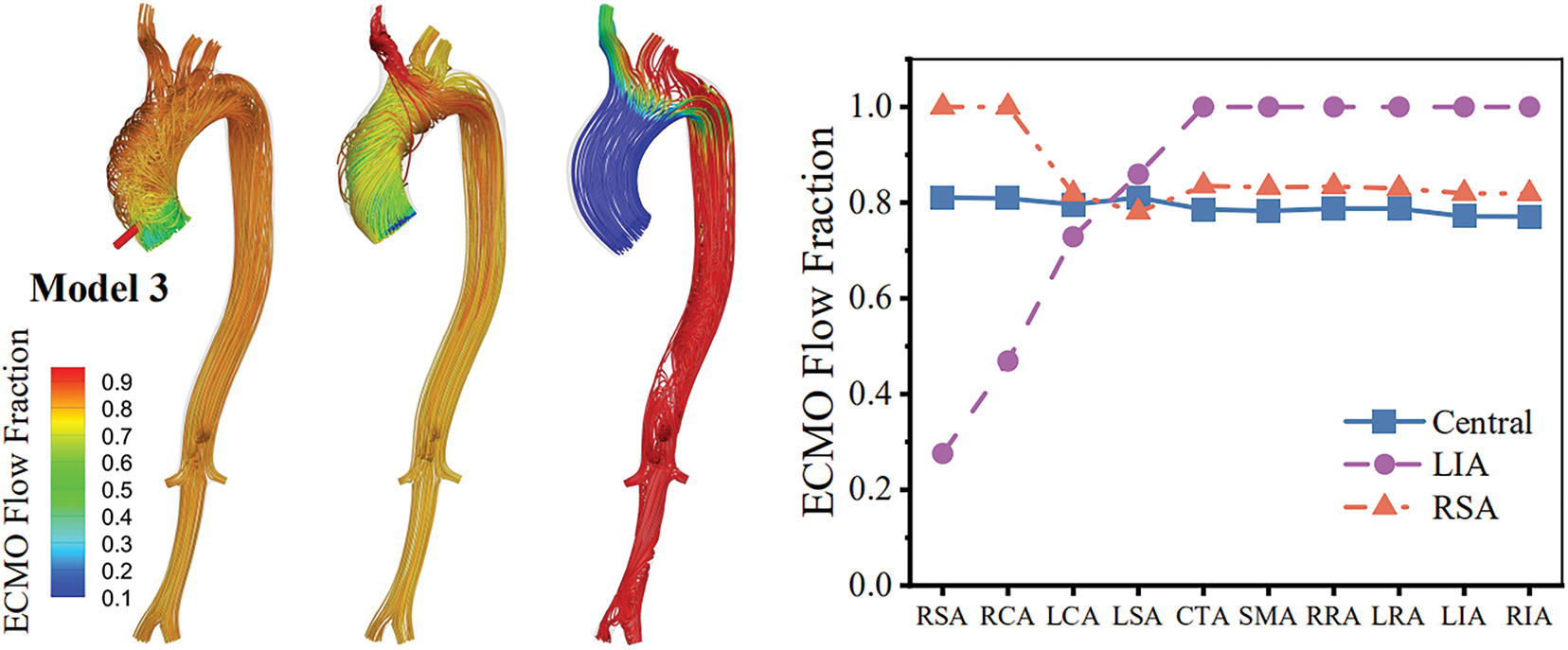

The distribution of ECMO flow was quantified by the fraction of the ECMO-originated blood in the fluid domain. Fig. 4 shows the flow streamlines colored by the fraction of ECMO flow at peak velocity as well as the plots of ECMO flow fractions in the branch arteries averaged over a cardiac cycle. The central cannulation and RSA cannulation enabled an overall uniform distribution of ECMO flow in the aorta, whereas the LIA cannulation led to insufficient delivery of the ECMO flow to the ascending aorta, which is consistent with the imaging data reported in a previous clinical study [28] (see Fig. 5). All the branch arteries exhibited a ECMO flow fraction of over 0.8 in the cases of central cannulation and RSA cannulation, whereas only the branch arteries located distal to the descending aorta were sufficiently perfused by the ECMO flow in the case of LIA cannulation. The fractions of ECMO flow in the RSA and right carotid artery (RCA) were most sensitive to cannulation site, which were close to 1 with the RSA cannulation, but dropped to lower than 0.5 as the cannulation site was changed to the LIA. In addition, the left and right carotid arteries suffered from unbalanced ECMO flow perfusion under the conditions of RSA and LIA cannulations. In particular, with the LIA cannulation, the ECMO flow fractions in the RSA and RCA (which perfuse the right upper body) were only about 50% of those in the left subclavian artery (LSA) and left carotid artery (LCA) (which perfuse the left upper body).

Figure 4: Distributions of ECMO flow fraction (visualized on flow streamlines) in three aortas at peak velocity (left panels) and time-averaged ECMO flow fractions in branch arteries (right panels) under various cannulation conditions of VA-ECMO. Abbreviations: RSA, right subclavian artery; RCA, right carotid artery; LCA, left carotid artery; LSA, left subclavian artery; CTA, celiac trunk artery; SMA, superior mesenteric artery; RRA, right renal artery; LRA, left renal artery; LIA, left iliac artery; RIA, right iliac artery

Figure 5: CTA image of ECMO-originated blood flow in the aorta of a patient undergoing VA-ECMO support with femoral cannulation [28]. The blue arrow shows the heart-originated antegrade flow directed to the ascending aorta and right-sided branch arteries, while the red arrow indicates the retrograde flow stemming from the ECMO, which perfuses the left subclavian artery better than the ascending aorta and right-sided branch arteries

In order to highlight the changes in blood residence time in the aorta following the implementation of VA-ECMO support, numerical simulations were also carried out under the normal physiological (control) condition in the absence of VA-ECMO support. The simulated values of NRT for the three aortas under all the conditions are displayed in Fig. 6. It is noted that RT can be readily derived from the data presented in Fig. 6 by multiplying NRT by the time moment of visualization. Under the normal physiological condition, the residence time of blood in the aorta was less than 2.25 s in all three models, indicating the absence of evident flow stagnation. Under the CS condition, the implementation of VA-ECMO led to prolonged retention of blood in the aorta. For the three models, the computed blood residence times in the aorta ranged from 12.19 s to 21.34 s in the case of central cannulation and from 12.22 s to 23.48 s in the case of RSA cannulation. The LIA cannulation further prolonged the blood residence time in the proximal portion of the aorta, especially the ascending aorta where the blood residence time was over 40 s.

Figure 6: Contour maps of normalized blood residence time (NRT) in three aortas under the normal physiological condition and the CS condition supported by VA-ECMO of various cannulation modes. NRT is calculated for each specific time moment for visualization (e.g., 10, 20, 30, and 40 s), i.e., the simulated residence time is divided by the time moment

VA-ECMO establishes a dual blood circulation wherein the blood flows in the native and extracorporeal circuits interact complexly [11], imposing great influence on hemodynamic characteristics in the aorta. In the present study, we developed a geometrical multiscale model to offer a mathematical tool for quantitatively investigating the hemodynamic impact of VA-ECMO and its sensitivity to the arterial cannulation site under the CS condition. The numerical results demonstrated the marked changes in aortic hemodynamics and distribution of ECMO flow following the variations in cannulation site. In general, the distributions of TAWSS and OSI in the aorta under the CS condition supported by VA-ECMO differed considerably from those under the normal physiological condition. Relatively, the central cannulation could better preserve physiological flow patterns in the aorta and evenly distribute ECMO-oxygenated blood to branch arteries that perfuse various organs/tissues. In contrast, the LIA cannulation led to marked disturbance of aortic flow, prolonged blood residence time, and inadequate delivery of ECMO flow to the upper body. The RSA cannulation was basically comparable to the central cannulation, although the details of hemodynamic characteristics under the two cannulation conditions were different. In addition, it was found that inter-patient differences in aortic anatomical structure led to regional differences in flow patterns and WSS metrics, but did not qualitatively alter the major hemodynamic characteristics associated with cannulation sites.

Thrombosis is one of the major complications associated with VA-ECMO support [1,3,29]. Previous studies have extensively demonstrated the association of hemodynamic environment with thrombosis. For instance, high WSS can activate platelets, while low oscillatory WSS (indicated by low TAWSS and high OSI) can cause endothelial dysfunction/injury to enhance platelet activation and induce coagulation cascade [30–32]. In addition, the risk of thrombosis can be significantly elevated in vascular regions with severe flow stagnation that facilitates the accumulation of platelets and clotting factors [27]. Based on the results of our hemodynamic analysis, the LIA cannulation is most likely to induce thrombosis in the ascending aorta where TAWSS is low, OSI is high, and flow stagnation is severe as indicated by the long blood residence time. The risk may be further increased by the extremely high WSS present in the abdominal aorta, because part of the activated platelets by high WSS there can transport to and stay in the ascending aorta according to the distribution of ECMO flow fraction shown in Fig. 4. These numerical results may theoretically explain the clinically observed high risk of aortic root thrombosis in patients supported by VA-ECMO in the LIA cannulation mode [33]. Relatively, the central and RSA cannulations have lower risk of triggering thrombosis given the small area of aortic walls exposed to low oscillatory WSS and the absence of aortic segments with severe flow stagnation. Nevertheless, the presence of high WSS in the ascending aorta and aortic arch and the larger NRT than that in the normal physiological condition (see Fig. 6) still imply an increased risk of thrombosis in comparison with the normal physiological state, which justifies the necessity of preventive antithrombotic therapy for patients undergoing VA-ECMO intervention regardless of the cannulation mode as suggested by clinical guidelines [3].

The distribution of ECMO flow plays a pivotal role in delivering oxygenated blood to organs/tissues, especially the metabolically active ones, such as the brain and heart [2]. Our numerical results indicate that the central and RSA cannulations can both enable a large portion of ECMO flow to be distributed throughout the body. A specific weakness of the RSA cannulation compared with the central cannulation is that it tends to deliver more ECMO flow to the RSA and RCA while relatively less to the LSA and LCA, leading to unbalanced perfusion of the left and right brain hemispheres (see Fig. 4). Unlike the central and RSA cannulations, the LIA cannulation causes evidently nonuniform distribution of ECMO flow, and cannot deliver sufficient ECMO flow to the upper body, especially the right-side part supplied by the RSA and RCA (see Fig. 4). These results indicate that the LIA cannulation has inherent limitations in supporting cerebral and upper-limb perfusion, and provide theoretical evidence for explaining the clinical finding that ‘Harlequin Syndrome’ (or ‘North-South Syndrome’), characterized by hypoxemia of the upper body, frequently occurs in patients suffering from pulmonary failure and receiving peripheral VA-ECMO intervention [28,34].

While the study provides useful insights into the hemodynamic characteristics associated with the arterial cannulation site of VA-ECMO, the findings must be considered in the context of certain limitations. Despite the use of patient-specific aortic models, the hemodynamic analyses were not conducted for patients receiving VA-ECMO intervention, because CTA scanning of the entire aorta is not a routine examination for the patient cohort. In addition, the measurement of hemodynamic data in the aortas of patients supported by VA-ECMO is technically restricted given the special environment of intensive care unit where the patients are admitted to. For these reasons, validating the numerical results with patient-specific clinical data remains highly challenging. To solve this problem, in-vitro experiments may be a feasible approach [35]. Another limitation is due to the fixed pathological condition represented by the models (herein, the CS condition characterized by a LV ejection fraction of 20%). In reality, patients receiving VA-ECMO intervention may exhibit large variability and high complexity in impairment of the cardiac and/or the pulmonary function. These patient-specific characteristics may significantly affect the behavior of cardiac-ECMO interaction and the distribution of oxygenated blood in the body, and thereby compromise the applicability of the findings of the present study. To address the limitation, large-scale numerical simulations covering a wide range of pathological conditions are warranted.

The multiscale model developed in the study enabled quantitative analysis and comparison of hemodynamic characteristics associated with arterial cannulation sites in VA-ECMO support. The central cannulation was proven as the best approach for preserving physiological flow patterns, minimizing the risk of thrombosis, and evenly distributing ECMO flow in the body. While the RSA cannulation offers a potential alternative to the central cannulation, unbalanced perfusion of the left and right brain hemispheres may be an issue of concern. Relatively, the LIA cannulation, though having the advantage of easier access to the cannulation artery and simpler surgical procedure, is most risky because it induces pronounced flow disturbance that may considerably increase the probability of thrombus formation and result in insufficient perfusion of the upper body. These findings deepen our understanding of the hemodynamic impact of VA-ECMO and provide theoretical insights to guide the optimization of cannulation strategies depending on patient-specific pathological conditions.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 12372309; 12061131015).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Da Li and Fuyou Liang; methodology, Da Li and Yuqing Tian; software, Da Li and Yuqing Tian; validation, Chengxin Weng, Fuyou Liang and Da Li; formal analysis, Da Li and Yuqing Tian; investigation, Chengxin Weng; resources, Chengxin Weng; data curation, Da Li and Fuyou Liang; writing—original draft preparation, Da Li and Fuyou Liang; writing—review and editing, Fuyou Liang; visualization, Da Li and Yuqing Tian; supervision, Fuyou Liang; project administration, Fuyou Liang and Chengxin Weng; funding acquisition, Fuyou Liang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Fuyou Liang, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This research was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the West China Hospital of Sichuan University (No. 2020309). Since the study involved the collection of de-identified retrospective data, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cmes.2025.066444/s1.

References

1. Guglin M, Zucker MJ, Bazan VM, Bozkurt B, El Banayosy A, Estep JD, et al. Venoarterial ECMO for adults: JACC scientific expert panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(6):698–716. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Gajkowski EF, Herrera G, Hatton L, Velia Antonini M, Vercaemst L, Cooley E. ELSO guidelines for adult and pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation circuits. Asaio J. 2022;68(2):133–52. doi:10.1097/mat.0000000000001630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Lorusso R, Shekar K, MacLaren G, Schmidt M, Pellegrino V, Meyns B, et al. ELSO interim guidelines for venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adult cardiac patients. Asaio J. 2021;67(8):827–44. doi:10.1097/mat.0000000000001510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Antonopoulos M, Koliopoulou A, Elaiopoulos D, Kolovou K, Doubou D, Smyrli A, et al. Central versus peripheral VA ECMO for cardiogenic shock: an 8-year experience of a tertiary cardiac surgery center in Greece. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2024. doi:10.1016/j.hjc.2024.09.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Mariscalco G, Salsano A, Fiore A, Dalén M, Ruggieri VG, Saeed D, et al. Peripheral versus central extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for postcardiotomy shock: multicenter registry, systematic review, and meta-analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;160(5):1207–16.e44. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.10.078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Biancari F, Kaserer A, Perrotti A, Ruggieri VG, Cho SM, Kang JK, et al. Central versus peripheral postcardiotomy veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2022;11(24):7406. doi:10.3390/jcm11247406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Djordjevic I, Eghbalzadeh K, Sabashnikov A, Deppe AC, Kuhn E, Merkle J, et al. Central vs. peripheral venoarterial ECMO in postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock. J Card Surg. 2020;35(5):1037–42. doi:10.1111/jocs.14526. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Raffa GM, Kowalewski M, Brodie D, Ogino M, Whitman G, Meani P, et al. Meta-analysis of peripheral or central extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in postcardiotomy and non-postcardiotomy shock. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107(1):311–21. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.05.063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. El Sibai R, Bachir R, El Sayed M. Outcomes in cardiogenic shock patients with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use: a matched cohort study in hospitals across the United States. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:2428648. doi:10.1155/2018/2428648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Zavalichi MA, Nistor I, Nedelcu AE, Zavalichi SD, Georgescu CMA, Stătescu C, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in cardiogenic shock due to acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:6126534. doi:10.1155/2020/6126534. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Badulak J, Abrams D, Luks AM, Zakhary B, Conrad SA, Bartlett R, et al. Position paper on the physiology and nomenclature of dual circulation during venoarterial ECMO in adults. Intensive Care Med. 2024;50(12):1994–2004. doi:10.1007/s00134-024-07645-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Xi YF, Li Y, Wang HY, Wang XF, Feng WT, Chen ZS. The impact of traditional vs parallel venous-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation on the intra-aortic hemodynamic environment: a numerical study. Phys Fluids. 2025;37(2):025175. doi:10.1063/5.0254456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Seetharaman A, Keramati H, Ramanathan K,Cove EM,Kim S,Chua KJ, et al. Vortex dynamics of veno-arterial extracorporeal circulation: a computational fluid dynamics study. Phys Fluids. 2021;33(6):061908. doi:10.1063/5.0050962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Li D, Li X, Xia Y, Weng C, Liang F. Impact of peripheral venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for heart failure on systemic hemodynamics and aortic blood flow. Phys Fluids. 2024;36(10):101916. doi:10.1063/5.0232133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Xi Y, Li Y, Wang H, Sun A, Deng X, Chen Z, et al. Effect of veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation lower-extremity cannulation on intra-arterial flow characteristics, oxygen content, and thrombosis risk. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2024;251(2):108204. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2024.108204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Gu K, Zhang Y, Gao B, Chang Y, Zeng Y. Hemodynamic differences between central ECMO and peripheral ECMO: a primary CFD study. Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:717–26. doi:10.12659/msm.895831. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Wickramarachchi A, Burrell AJC, Stephens AF, Šeman M, Vatani A, Khamooshi M, et al. The effect of arterial cannula tip position on differential hypoxemia during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Phys Eng Sci Med. 2023;46(1):119–29. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1939080/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Neidlin M, Amiri A, Hugenroth K, Steinseifer U. Investigations of differential hypoxemia during venoarterial membrane oxygenation with and without impella support. Cardiovasc Eng Technol. 2024;15(5):623–32. doi:10.1007/s13239-024-00739-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Feiger B, Kochar A, Gounley J, Bonadonna D, Daneshmand M, Randles A. Determining the impacts of venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation on cerebral oxygenation using a one-dimensional blood flow simulator. J Biomech. 2020;104:109707. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2020.109707. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Feiger B, Jensen CW, Bryner BS, Segars WP, Randles A. Modeling the effect of patient size on cerebral perfusion during veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Perfusion. 2024;39(7):1295–303. doi:10.1177/02676591231187962. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Cui W, Wang T, Xu Z, Liu J, Simakov S, Liang F. A numerical study of the hemodynamic behavior and gas transport in cardiovascular systems with severe cardiac or cardiopulmonary failure supported by venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11:1177325. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2023.1177325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Li XY, Zhang Z, Simakov S, Gamilov T, Vassilevski Y, Wang Y, et al. Influence of pressure guidewire on coronary hemodynamics and fractional flow reserve. Phys Fluids. 2025;37(3):031920. doi:10.1063/5.0256403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Reynolds HR, Hochman JS. Cardiogenic shock: current concepts and improving outcomes. Circulation. 2008;117(5):686–97. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.106.613596. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Sundermeyer J, Kellner C, Beer BN, Besch L, Dettling A, Bertoldi LF, et al. Association between left ventricular ejection fraction, mortality and use of mechanical circulatory support in patients with non-ischaemic cardiogenic shock. Clin Res Cardiol. 2024;113(4):570–80. doi:10.1007/s00392-023-02332-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Shi Y, Korakianitis T. Impeller-pump model derived from conservation laws applied to the simulation of the cardiovascular system coupled to heart-assist pumps. Comput Biol Med. 2018;93(1):127–38. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2017.12.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Lee SW, Antiga L, Steinman DA. Correlations among indicators of disturbed flow at the normal carotid bifurcation. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131(6):061013. doi:10.1115/1.3127252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Rayz VL, Boussel L, Ge L, Leach JR, Martin AJ, Lawton MT, et al. Flow residence time and regions of intraluminal thrombus deposition in intracranial aneurysms. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38(10):3058–69. doi:10.1007/s10439-010-0065-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Pasrija C, Bedeir K, Jeudy J, Kon ZN. Harlequin syndrome during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2019;1(2):e190031. doi:10.1148/ryct.2019190031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Olson SR, Murphree CR, Zonies D, Meyer AD, McCarty OJT, Deloughery TG, et al. Thrombosis and bleeding in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) without anticoagulation: a systematic review. Asaio J. 2021;67(3):290–6. doi:10.1097/mat.0000000000001230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Samady H, Eshtehardi P, McDaniel MC, Suo J, Dhawan SS, Maynard C, et al. Coronary artery wall shear stress is associated with progression and transformation of atherosclerotic plaque and arterial remodeling in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2011;124(7):779–88. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.111.021824. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Meng H, Tutino VM, Xiang J, Siddiqui A. High WSS or low WSS? Complex interactions of hemodynamics with intracranial aneurysm initiation, growth, and rupture: toward a unifying hypothesis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35(7):1254–62. doi:10.3174/ajnr.a3558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Chatzizisis YS, Coskun AU, Jonas M, Edelman ER, Feldman CL, Stone PH. Role of endothelial shear stress in the natural history of coronary atherosclerosis and vascular remodeling: molecular, cellular, and vascular behavior. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(25):2379–93. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Hireche-Chikaoui H, Grübler MR, Bloch A, Windecker S, Bloechlinger S, Hunziker L. Nonejecting hearts on femoral veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: aortic root blood stasis and thrombus formation-a case series and review of the literature. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(5):e459–64. doi:10.1097/ccm.0000000000002966. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Al Hanshi SAM, Al Othmani F. A case study of Harlequin syndrome in VA-ECMO. Qatar Med J. 2017;2017(1):39. doi:10.5339/qmj.2017.swacelso.39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Vignali E, Gasparotti E, Mariotti A, Haxhiademi D, Ait-Ali L, Celi S. High-versatility left ventricle pump and aortic mock circulatory loop development for patient-specific hemodynamic in vitro analysis. Asaio J. 2022;68(10):1272–81. doi:10.1097/mat.0000000000001651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools