Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Topology Optimization of Lattice Structures through Data-Driven Model of M-VCUT Level Set Based Substructure

School of Mechanical Science and Engineering, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, 430074, China

* Corresponding Authors: Qi Xia. Email: ; Shiyuan Liu. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(3), 2685-2703. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.068078

Received 20 May 2025; Accepted 18 July 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

A data-driven model of multiple variable cutting (M-VCUT) level set-based substructure is proposed for the topology optimization of lattice structures. The M-VCUT level set method is used to represent substructures, enriching their diversity of configuration while ensuring connectivity. To construct the data-driven model of substructure, a database is prepared by sampling the space of substructures spanned by several substructure prototypes. Then, for each substructure in this database, the stiffness matrix is condensed so that its degrees of freedom are reduced. Thereafter, the data-driven model of substructures is constructed through interpolation with compactly supported radial basis function (CS-RBF). The inputs of the data-driven model are the design variables of topology optimization, and the outputs are the condensed stiffness matrix and volume of substructures. During the optimization, this data-driven model is used, thus avoiding repeated static condensation that would require much computation time. Several numerical examples are provided to verify the proposed method.Keywords

Lattice structures have excellent mechanical properties, for instance, the high specific strength and stiffness, and their rich geometric characteristics give a large design space [1]. Therefore, it is used in various engineering applications [2–4].

Because many microscale features exist in the lattice structures, an accurate finite element analysis (FEA) calls for a fine mesh to capture their mechanical behavior, and this is time-consuming [5]. To improve the computational efficiency of FEA and sensitivity analysis in the topology optimization of lattice structures, scholars often use homogenization to obtain the effective properties of microscale features and view them as homogeneous materials [6–10]. In addition to compliance problem [11–13], scholars have also done a lot of work in other fields such as stress constraint [14–16]. The use of homogenization, however, requires two conditions to be met: (1) the microstructures should be periodically distributed; (2) the scale of the microstructure should be much smaller than that of the macrostructure. However, the two conditions can not be strictly satisfied in many engineering applications. In such circumstances, to improve the computational efficiency, the extended multiscale finite element method [17–19] and substructure method [20–24] are often used.

In the present study on the topology optimization of lattice structures, the substructure method is also used. The lattice structure is divided into multiple substructures. Each substructure is converted to a super element through static condensation that retains only the boundary nodes. By this means, the degrees of freedom of the stiffness matrix is reduced [24]. The key ideas of the present study is explained as follows.

First, the M-VCUT level set method is used to generate substructures with various configurations [25–27], and this diversity of configuration is important for obtaining a large design space of topology optimization. In addition, the M-VCUT level set method also ensures the connectivity between neighboring substructures [26].

Second, in order to avoid time-consuming static condensation once the configurations of substructures are changed during the optimization, a data-driven model is constructed. In an offline stage, a database is prepared by sampling the space of substructures spanned by several prototypes of substructures, and for each substructure in this database, static condensation is used to obtain its stiffness matrix. Meanwhile, the volume of the substructure is also computed. Then, a data-driven model of substructures is constructed through interpolation with CS-RBF [28–30]. The inputs of the data-driven model are the design variables of topology optimization, and the outputs are the condensed stiffness matrix and volume of substructures. In the online optimization stage, this data-driven model is used in the FEA and sensitivity analysis.

The remaining part of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the representation of lattice structures and substructures. Section 3 introduces the data-driven model. Section 4 presents the optimization problem and sensitivity analysis. Section 5 presents several examples of topology optimization. The conclusion is presented in Section 6.

2 Geometric and Mechanical Models of Substructure

The geometry of substructure is modeled by using the M-VCUT level set method [25,26]. The mechanical model of substructures, i.e., the stiffness matrix in the present study, is obtained by static condensation [20,21].

2.1 Geometry Model of Substructure Based on M-VCUT Level Set

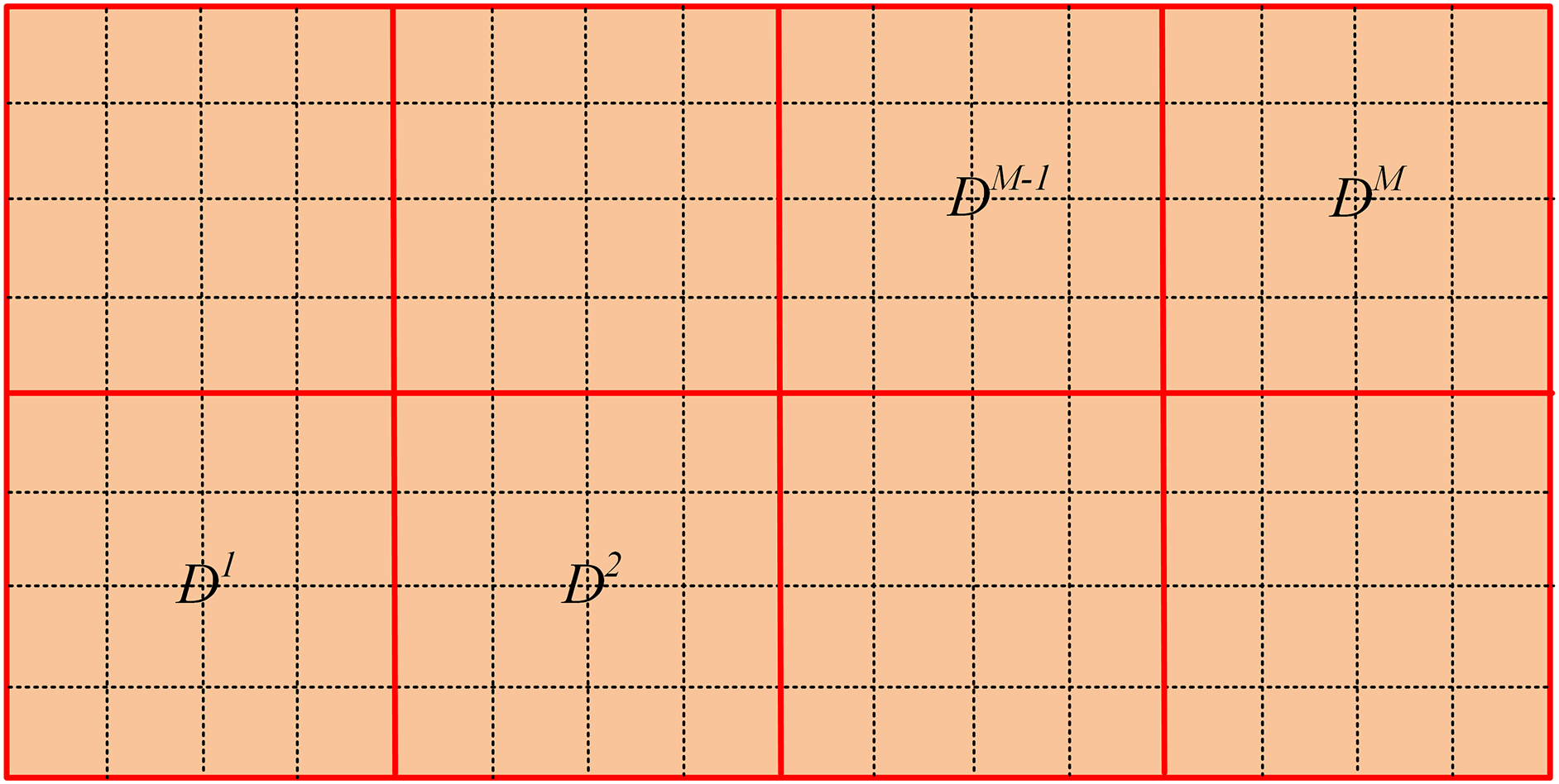

In the optimization, the lattice structure

Figure 1: Design domain of lattice structure is divided into multiple cells

According to the M-VCUT level set method, a substructure

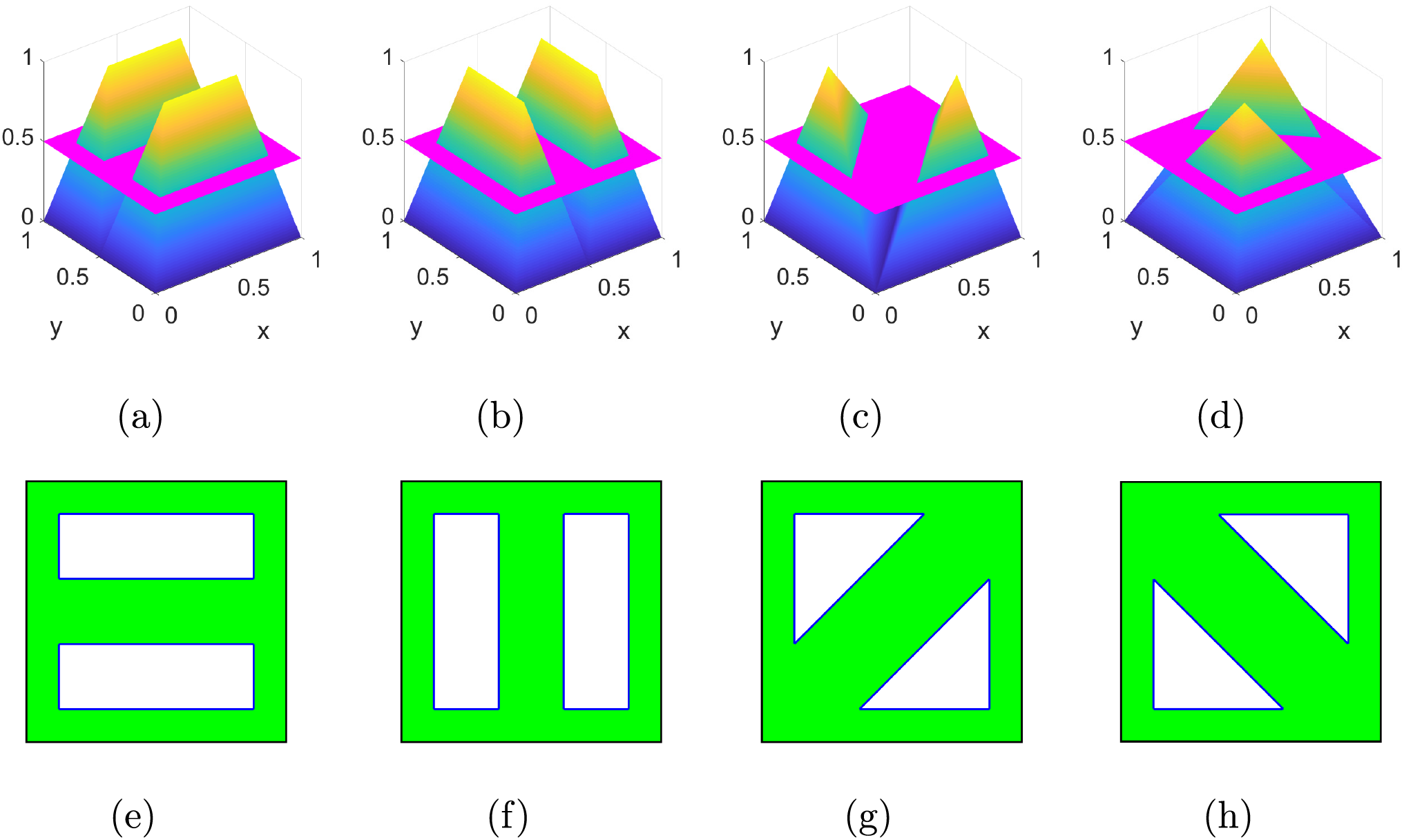

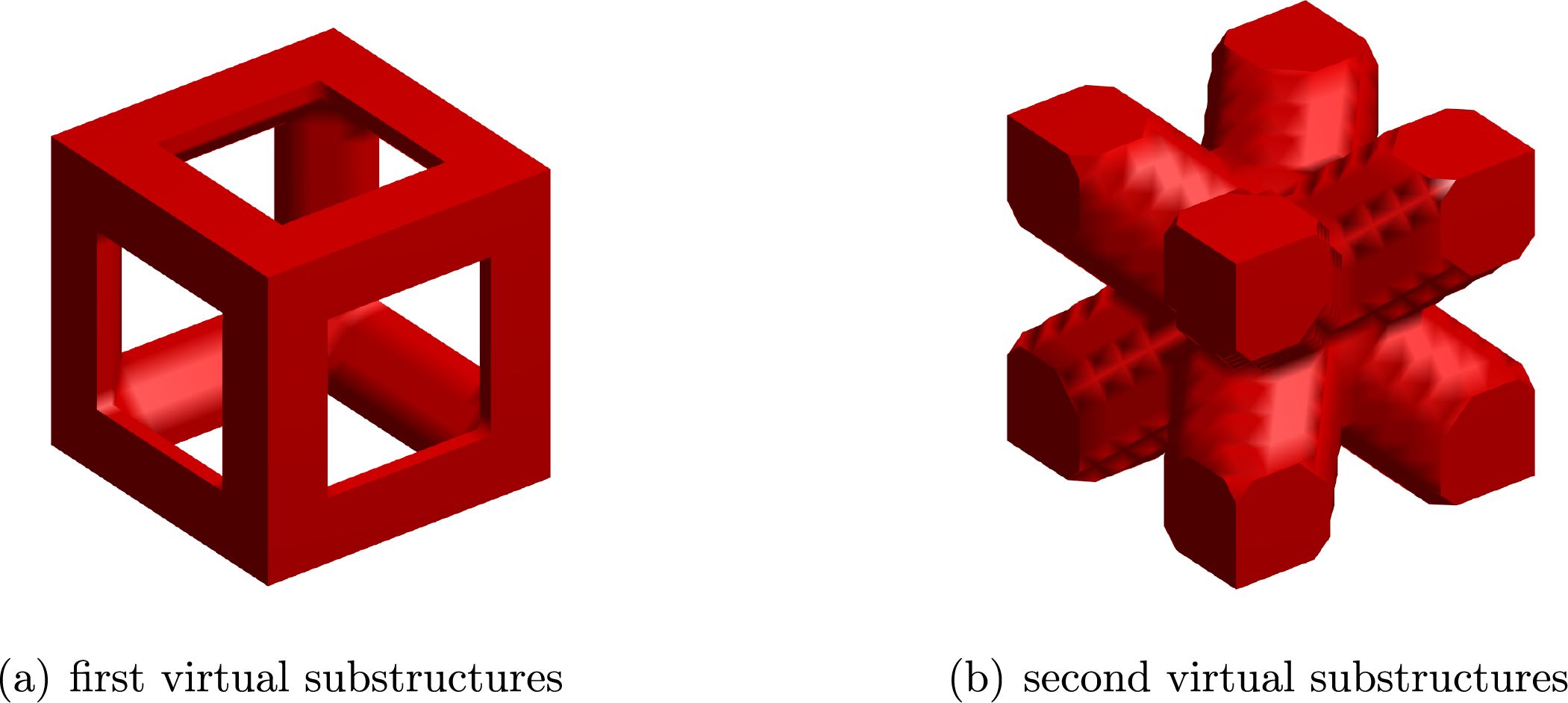

Fig. 2 shows four basic level set functions, cutting planes, and corresponding virtual substructures. During the optimization, the basic level set functions are fixed, and the height of cutting planes is changed. The admissible ranges of cutting heights are set to ensure the virtual substructures can change from full void to full solid.

Figure 2: Four basic level set functions and cutting planes (purple horizontal plane), corresponding virtual substructures. (a)–(d) are four basic level set functions and cutting planes with the cutting height of 0.5, while (e)–(h) are the corresponding virtual substructures

The choice of basic level set functions determines the basic configuration of virtual substructures and gives a set of bases that span a space of substructures. In the virtual substructures

The combination of virtual substructures

Then,

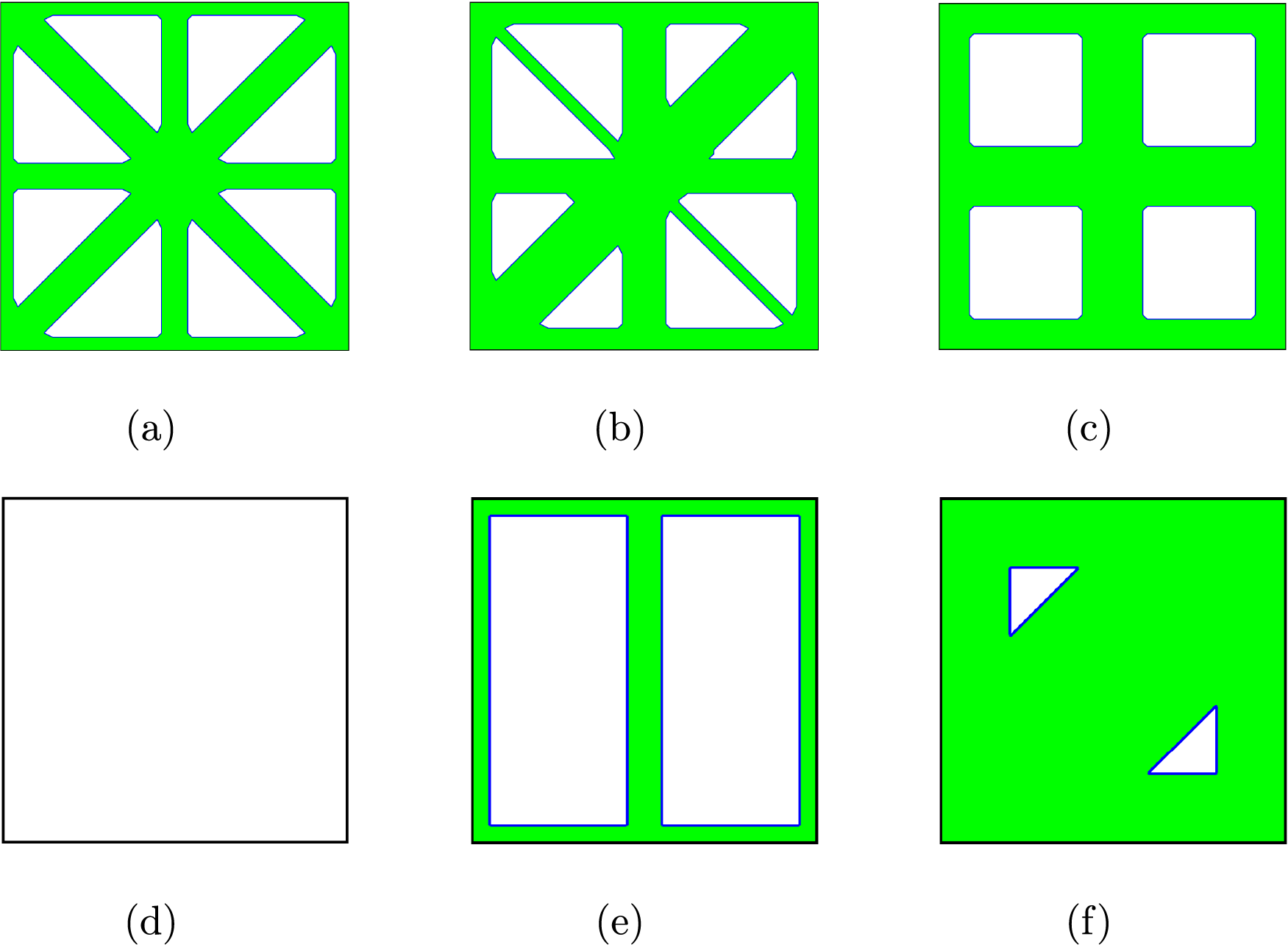

Fig. 3 shows six examples of actual substructures obtained by combining virtual substructures.

Figure 3: Six examples of actual substructure. (a)

2.2 Static Condensation of Substructure

In the finite element analysis, the stiffness matrix of the lattice structure is obtained by assembling the stiffness matrices of substructures, which are obtained by static condensation [20,21].

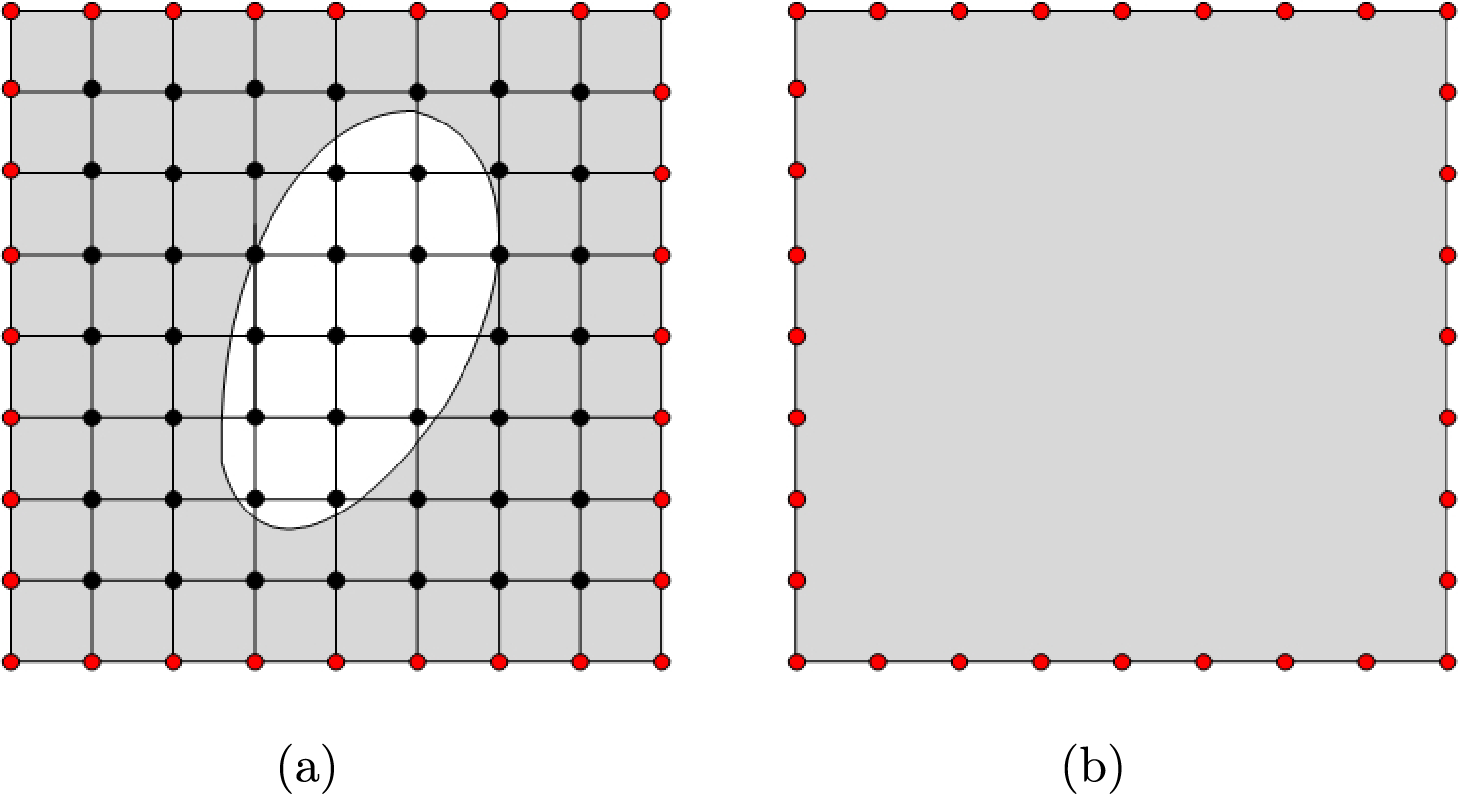

The concept of static condensation is shown in Fig. 4. Before condensation, the equilibrium equation of a substructure is written as

where the subscript

Figure 4: Static condensation of substructure. (a) substructure before static condensation, (b) substructure after static condensation

According to second row of Eq. (6),

Substitute Eq. (7) into the first row of Eq. (6), the condensed equation can be obtained as

where the coefficient matrix is the condensed stiffness matrix

Similarly, the force vector of the condensed substructure is given by

3 Data-Driven Model of Substructure

The static condensation can reduce the degrees of freedom in the stiffness matrices of substructures, thus improving computational efficiency. However, as the topology optimization progresses, the configurations of substructures will be changed in every iteration; thus, the stiffness matrices need to be condensed again. This process is still time-consuming. In order to avoid repeated static condensation during the optimization, a data-driven model of substructure is proposed in this study.

In order to establish a data-driven model, a database of substructures is first prepared by sampling the space of substructures, i.e., the substructures are obtained by sampling the cutting heights

3.2 Mapping Model of Substructure

The CS-RBF interpolation is used to construct the mapping model. When an evaluation point is inputted to the mapping model, we search the database for several nearest data points, and the CS-RBF interpolation is used to obtain the condensed stiffness matrix

The evaluation point

where

where

where

The coefficients

where

where

Similarly, Eq. (16) can be rewritten in a matrix form.

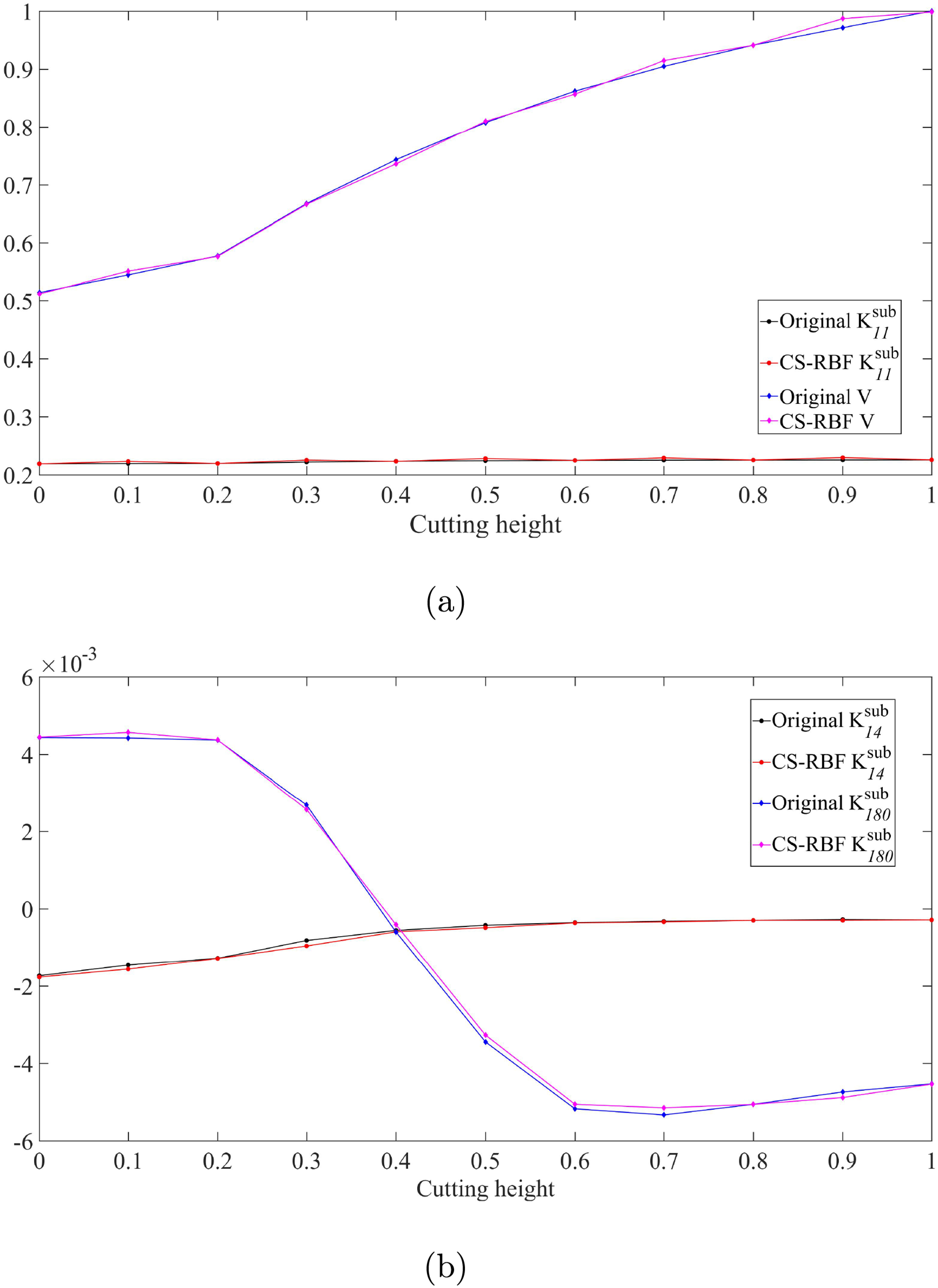

The accuracy of the CS-RBF interpolation function is verified. Fig. 5 shows the value of

Figure 5: Comparison of interpolation accuracy. (a) is the curve of

4 Topology Optimization and Sensitivity Analysis of Lattice Structure

The topology optimization problem is defined as

where C represents the objective function, i.e., the compliance in the present study;

The design variables of the optimization problem are the cutting heights

where

According to Eq. (13), we have [30]

where

The derivatives of the volume constraint are also computed. The volume V is obtained from the mapping model, and its sensitivity is calculated similarly to the stiffness matrix.

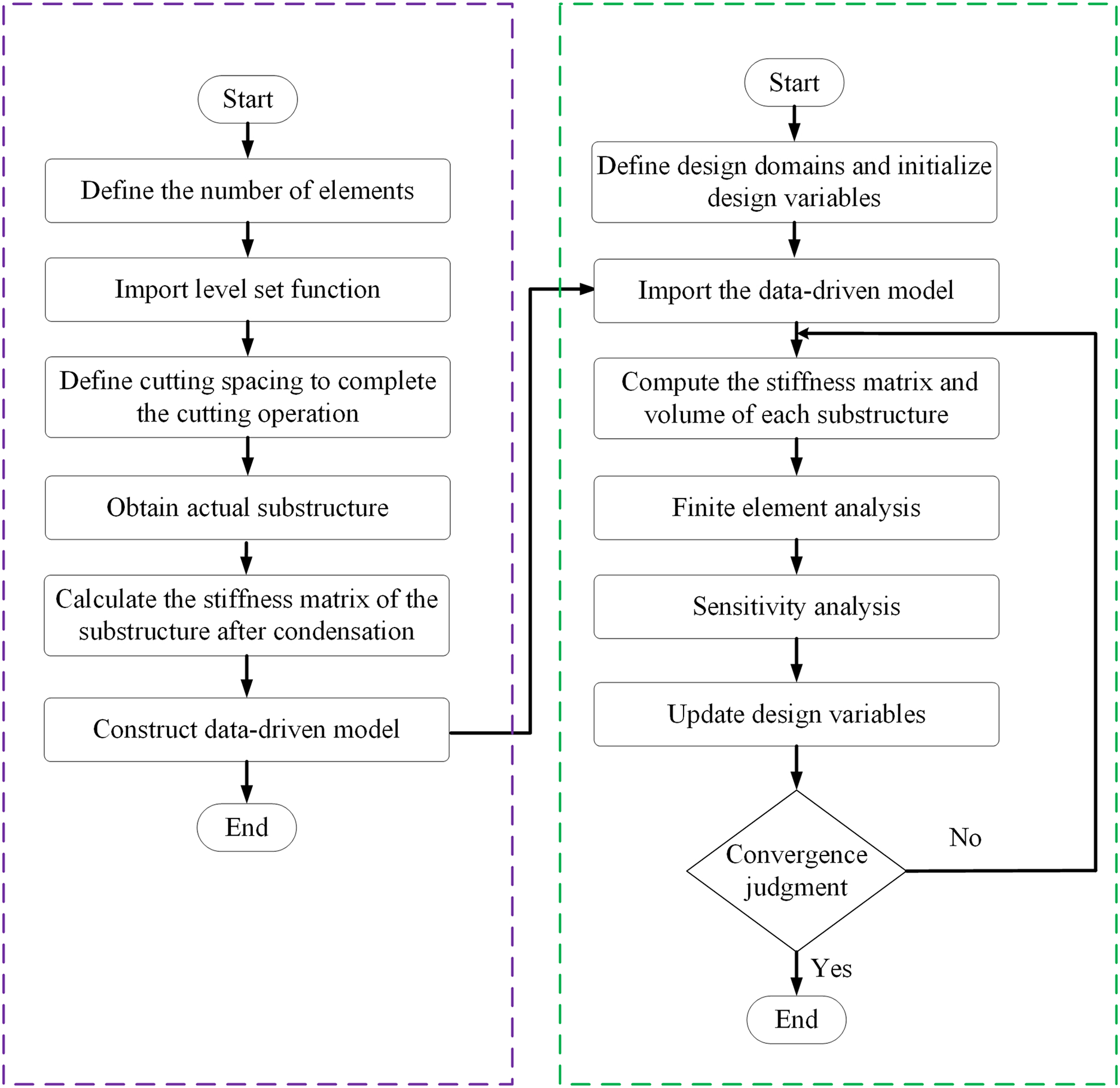

In the present study, the method of moving asymptote (MMA) is used to solve the optimization problem [31]. Set the move limit parameter to 0.05. The procedure of optimization is shown in Fig. 6. It comprises two stages: the offline stage and the online stage. The purple box represents the construction of the data-driven model of substructure in the offline stage, while the green box represents the online optimization stage.

Figure 6: Flowchart of optimization procedure

In this section, several examples of topology optimization were presented. For the topology optimization of two-dimensional lattice structures, Young’s modulus

The following convergence criteria Eq. (24) is used in all optimizations that include both the method proposed in this paper and the Solid Isotropic Material with Penalization (SIMP) method.

where

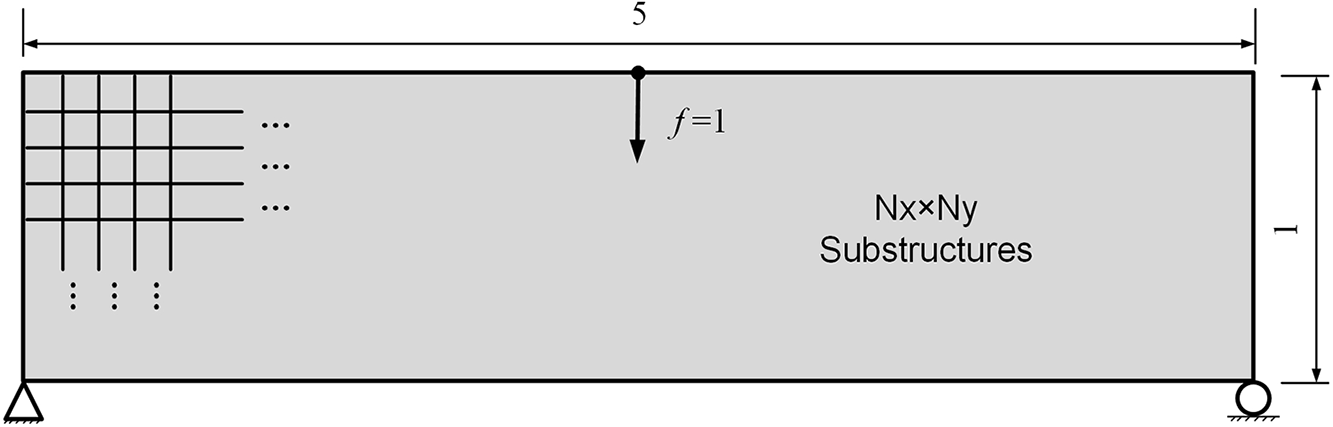

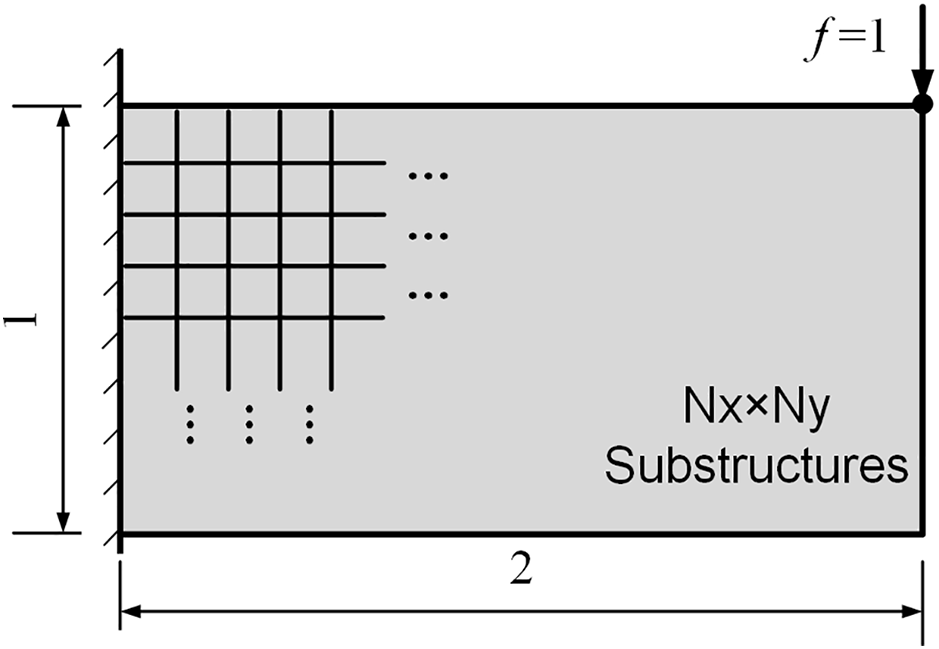

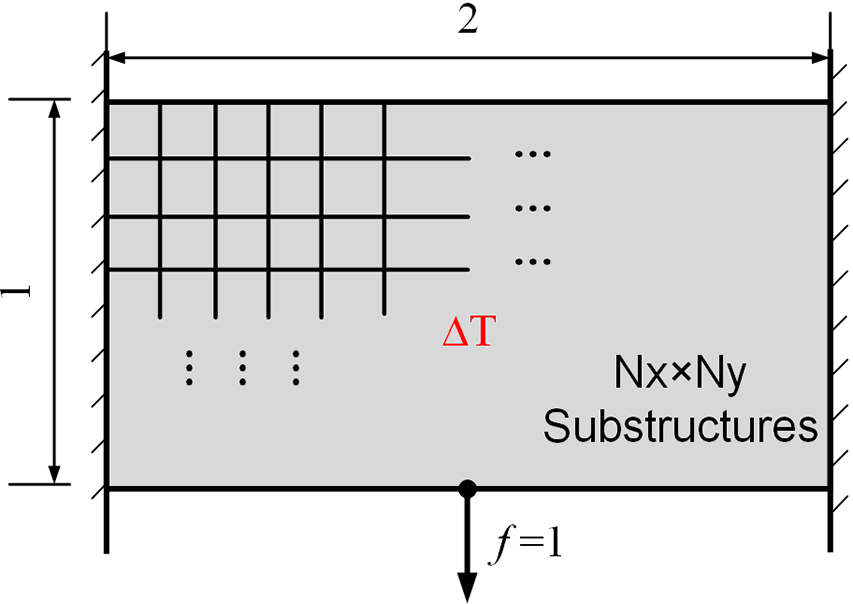

The optimization problem of the first example is shown in Fig. 7. The reference design domain is a

Figure 7: Design problem of the first example

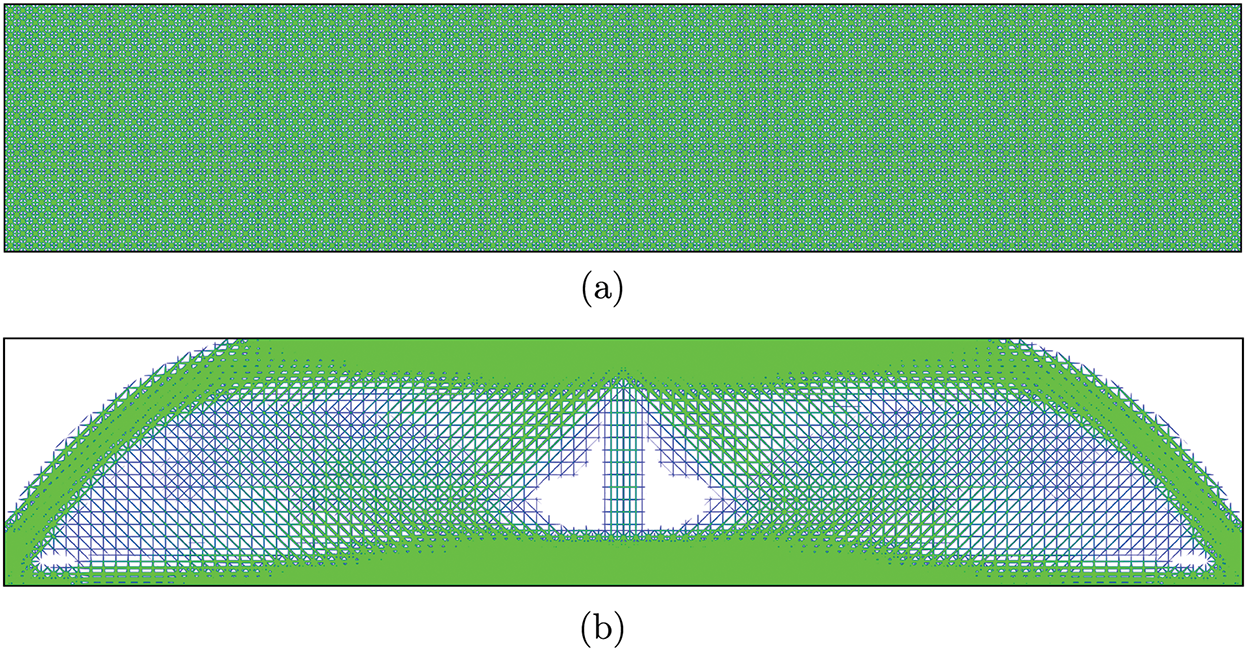

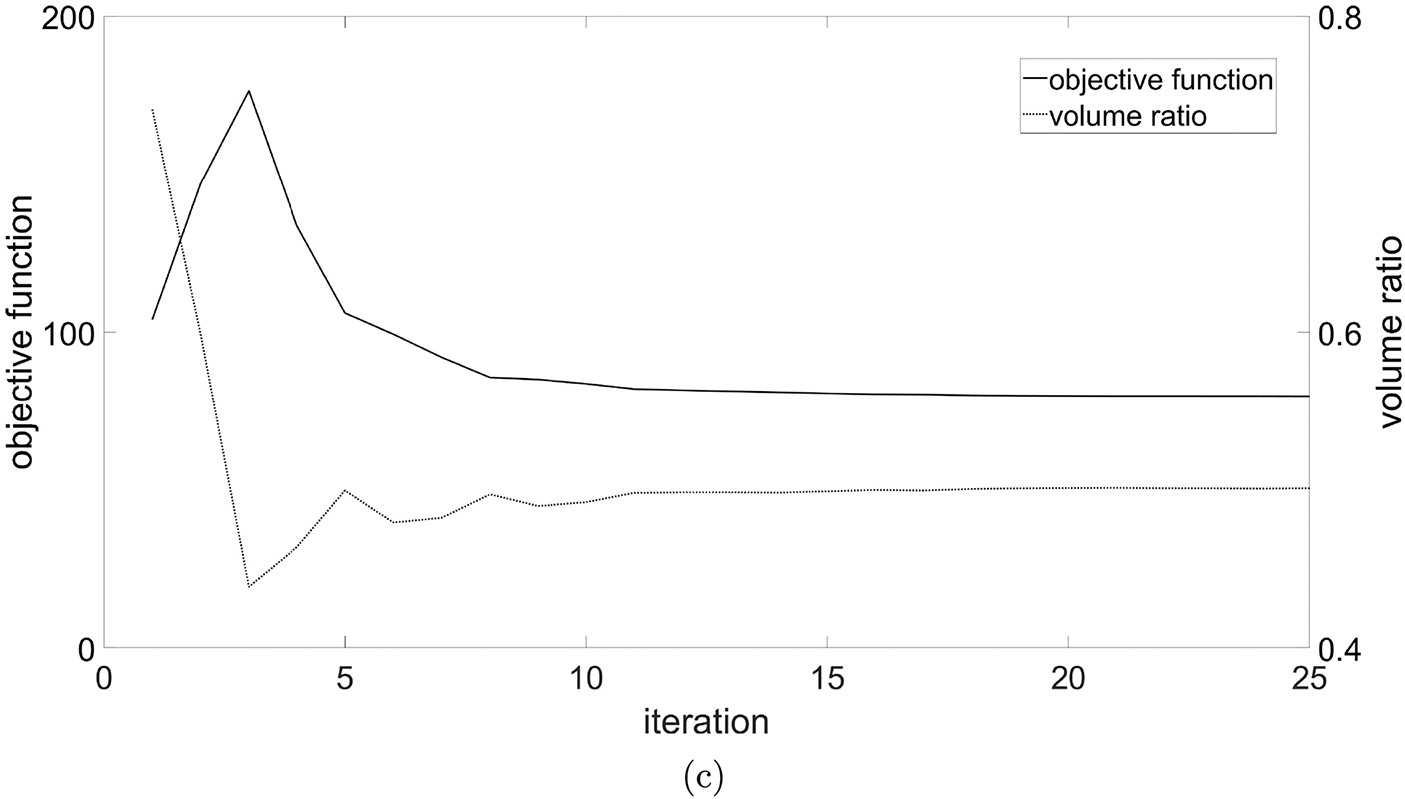

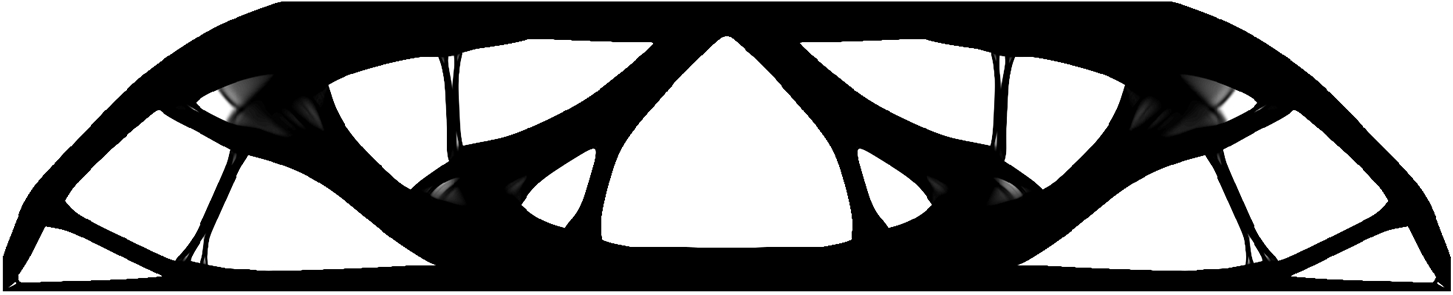

The initial design is shown in Fig. 8a, the compliance is 104.01. The optimized design is shown in Fig. 8b, with a compliance of 79.72. The convergence history is shown in Fig. 8c, it can be seen that the optimization converged smoothly.

Figure 8: Initial and optimized designs and convergence curve with simply supported beam. Compliance of (a) is 104.01, (b) is 79.72, (c) is the convergence curve

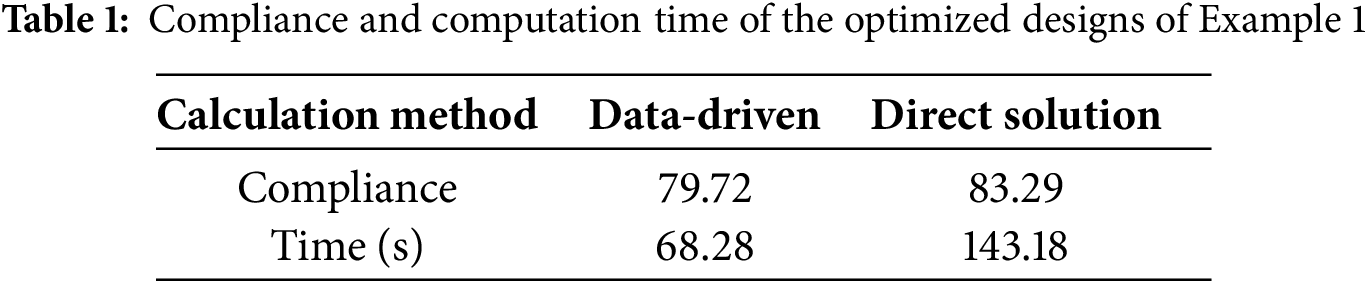

For comparison, a method for directly solving the stiffness matrix of substructures through online condensation has also been considered. As shown in Table 1, it can be found that when directly solving the simply supported beam example online, the finite element calculation time, including calculation of substructure stiffness matrix, is 143.18 s for one iteration, and the final compliance is 83.29. When considering the use of the method proposed in this paper, the finite element calculation time is shortened to 68.28 s, and the compliance is 79.72. Comparison shows that the data-driven approach proposed in this paper can effectively improve the computational efficiency, and the compliance is very close. Besides, a macroscale optimization is also conducted by using the SIMP method [33,34]. Considering that each substructure in this example contains

Figure 9: Optimized design by SIMP method with

As shown in Fig. 10, the second example has a

Figure 10: Design problem of the second example

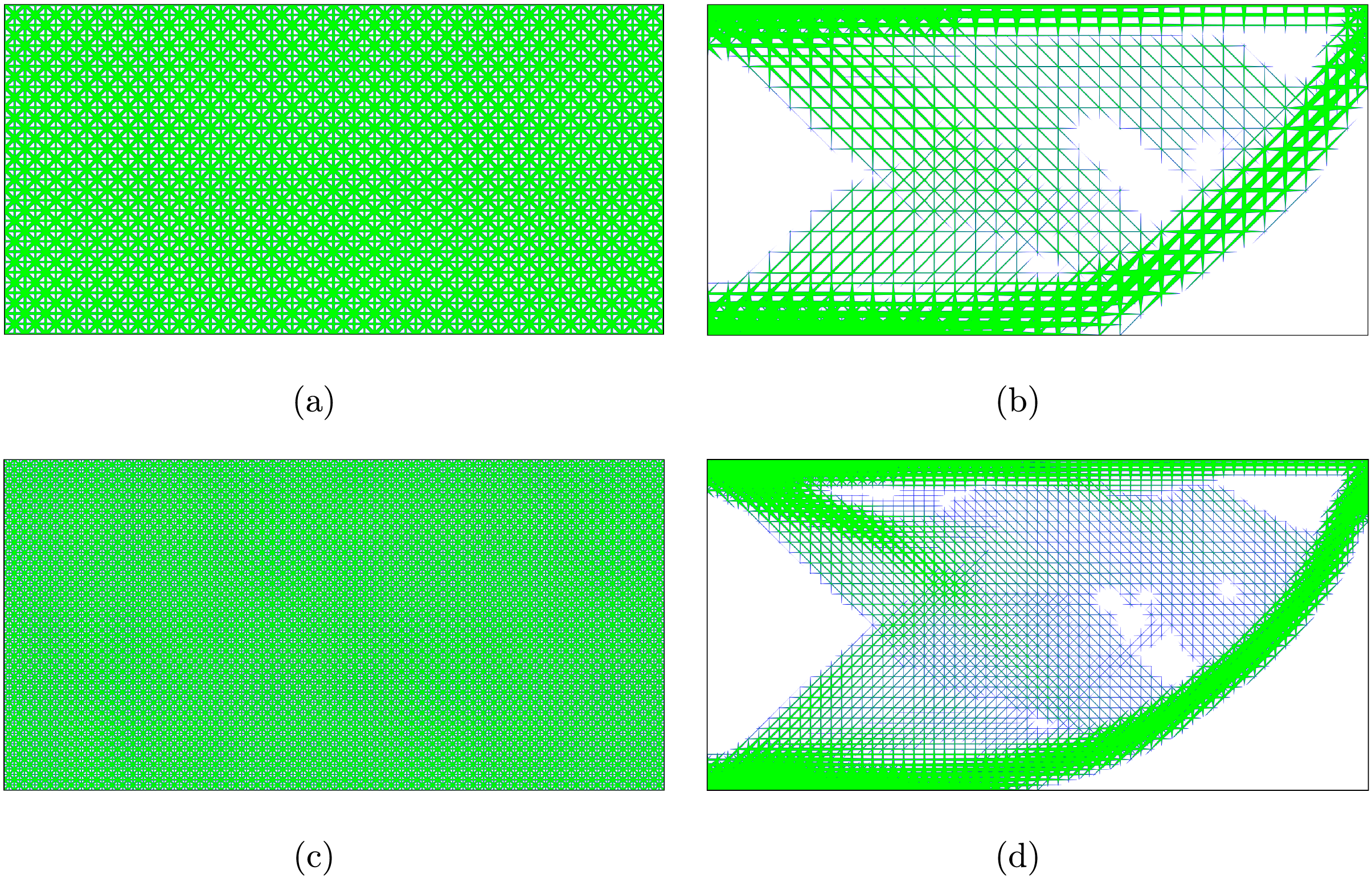

Firstly, the design domain is discretized into

Figure 11: Initial and optimized designs with

Secondly, the optimization is done with the number of substructures being increased to

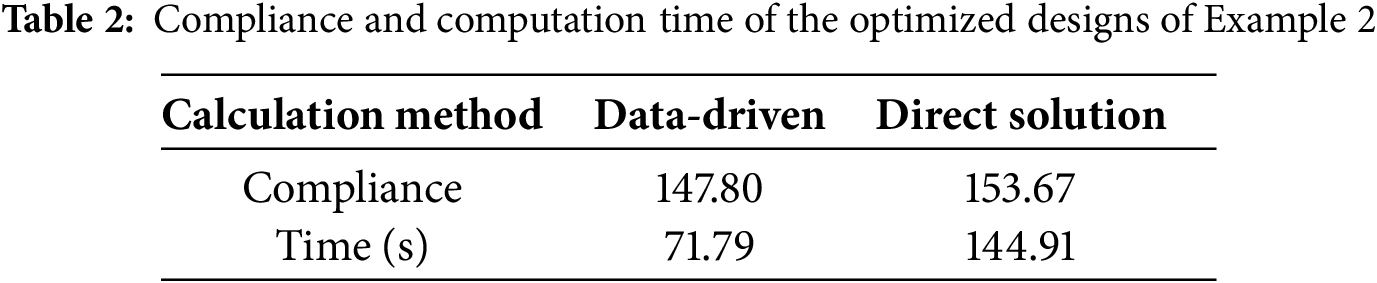

Similar to Example 1, the method of directly calculating the substructure stiffness matrix online is also considered here. As shown in Table 2, for the same

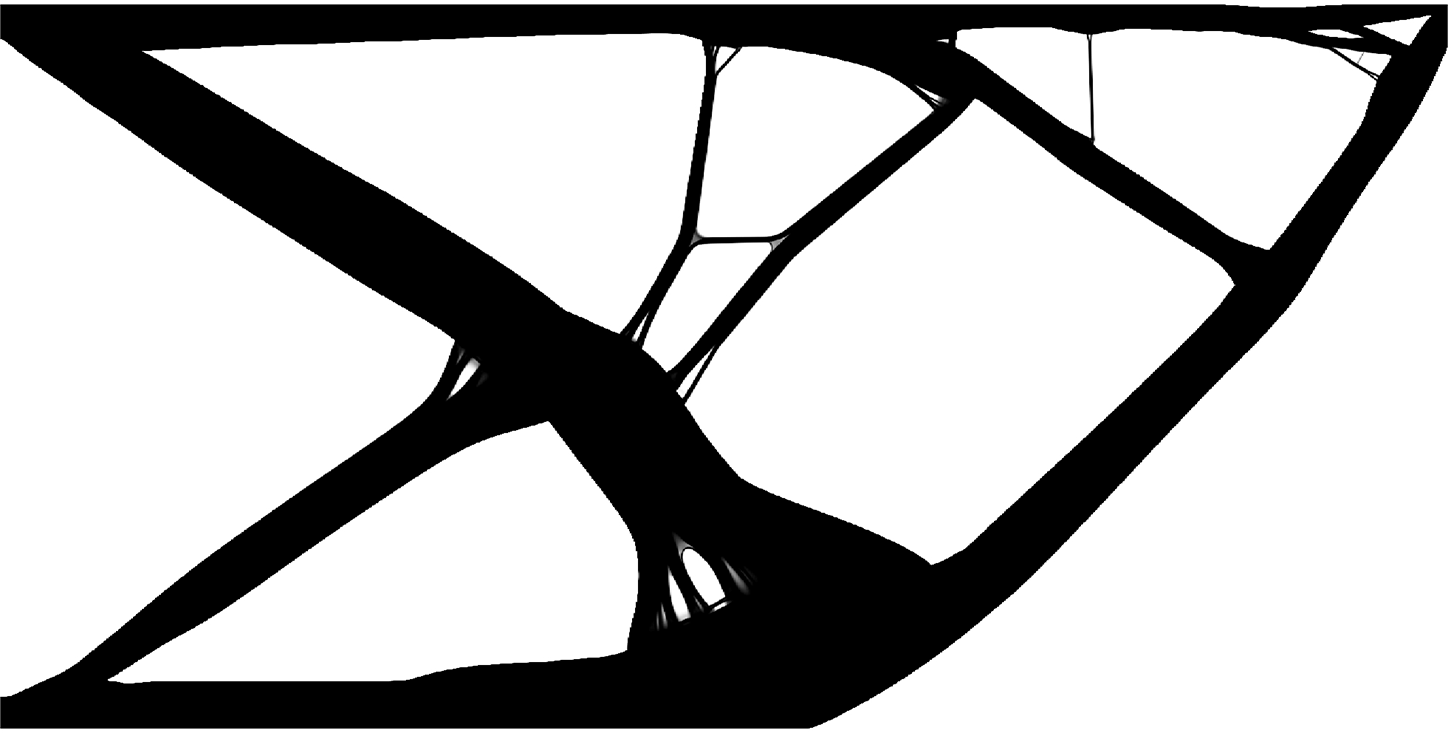

Figure 12: Optimized design by SIMP method with

In the third example, the proposed method is applied to the topology optimization of a thermoelastic lattice structure. The reference design domain is a

Figure 13: Design problem of the third example

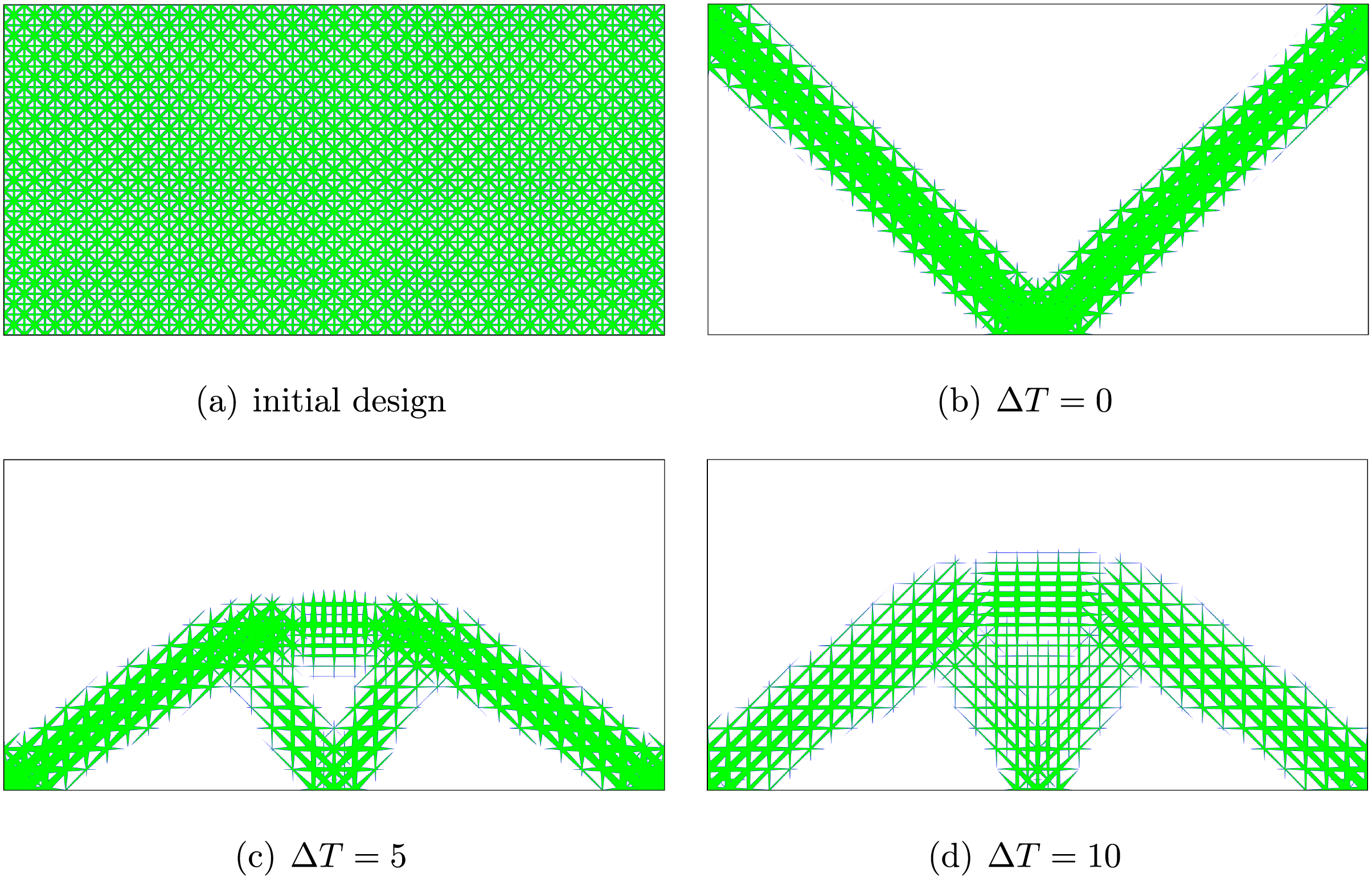

Fig. 14a shows the initial design of the thermoelastic lattice structure. Fig. 14b–d shows the optimized designs at

Figure 14: Initial and optimized designs with

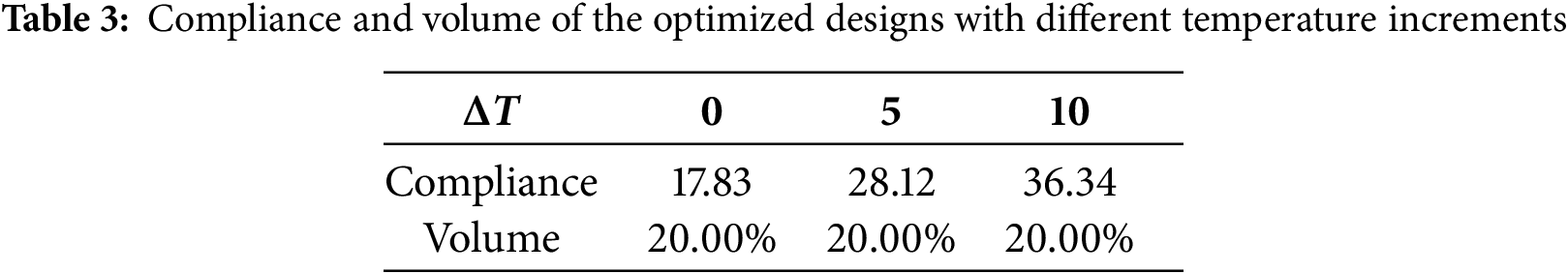

Similarly, the structure is optimized by using the SIMP method with

Figure 15: Optimized design by SIMP method with

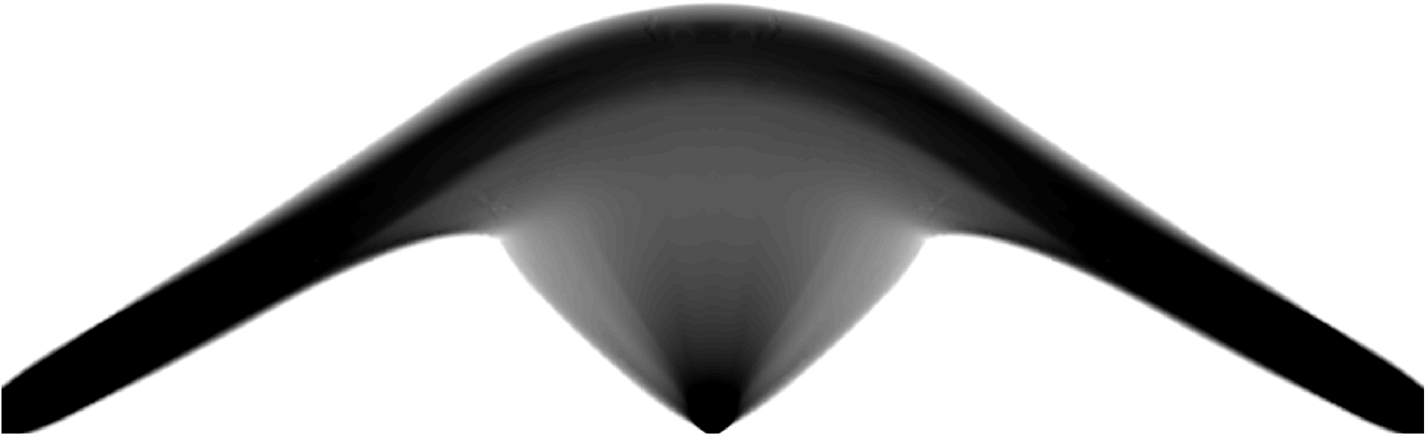

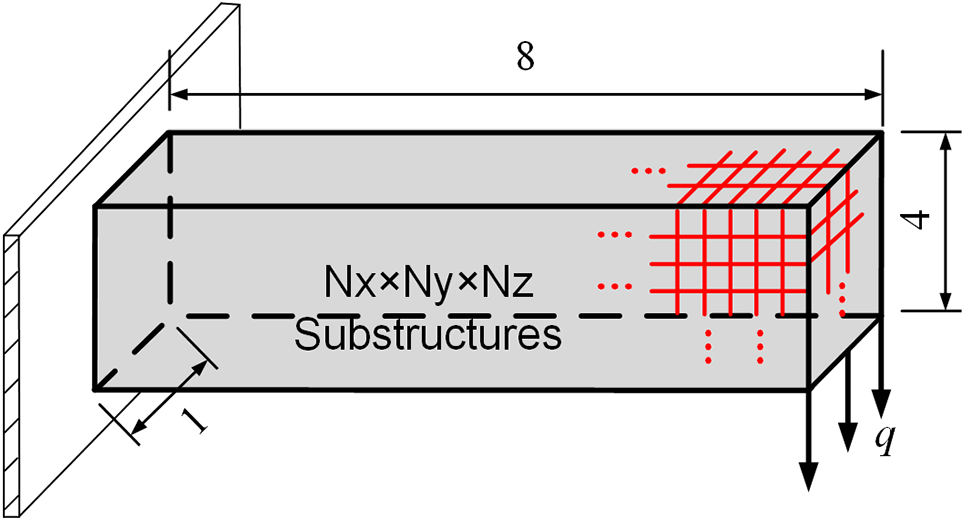

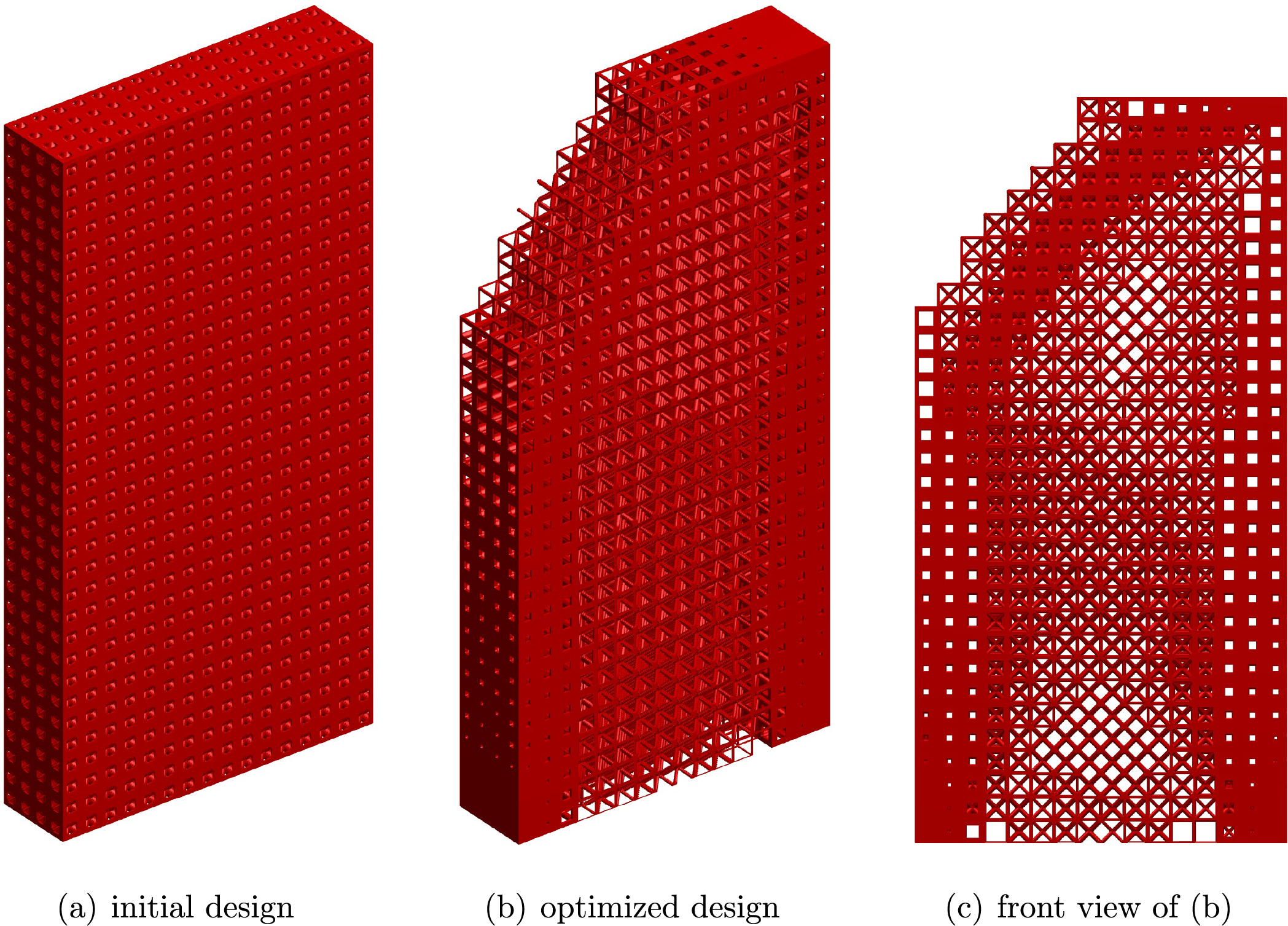

The fourth example considers a three-dimensional lattice structure, as shown in Fig. 16. The reference design domain is an

Figure 16: Design problem of the fourth example

Two virtual substructures shown in Fig. 17 are used in the optimization. The initial and optimized designs are shown in Fig. 18, whose compliance is respectively 1544.42 and 2185.53, the volume fraction has decreased from

Figure 17: Two 3D virtual substructures. Cutting height (a)

Figure 18: Initial and optimized designs with

In this paper, a data-driven model of M-VCUT level set-based substructure is proposed for the topology optimization of lattice structures. The geometries of substructures are described by using the M-VCUT level set method. The condensed stiffness matrix of substructures is obtained by a data-driven model during the optimization, which is computationally efficient, and they are used in the finite element analysis and sensitivity analysis. The data-driven model is constructed by using the CS-RBF interpolation method. The numerical examples demonstrate that the proposed method is effective and efficient for the topology optimization of lattice structures.

In current research, CS-RBF interpolation itself involves computational overhead, especially in solving 3D problems, which is very time-consuming, and the optimization results often contain slim beams that cannot be manufactured. Therefore, in our future work, we will consider multi-scale optimization results that meet manufacturing conditions and more efficient methods.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully thank Zhen Liu for providing the code of the substructuring method and Krister Svanberg for providing MMA code support.

Funding Statement: This research work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12272144).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Minjie Shao, Qi Xia; data collection: Minjie Shao; analysis and interpretation of results: Minjie Shao, Tielin Shi; draft manuscript preparation: Minjie Shao, Qi Xia, Tielin Shi, Shiyuan Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wu J, Sigmund O, Groen JP. Topology optimization of multi-scale structures: a review. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2021;63(3):1455–80. doi:10.1007/s00158-021-02881-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wang C, Zhu JH, Wu MQ, Hou J, Zhou H, Meng L, et al. Multi-scale design and optimization for solid-lattice hybrid structures and their application to aerospace vehicle components. Chinese J Aeronaut. 2021;34(5):386–98. doi:10.1016/j.cja.2020.08.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Aage N, Andreassen E, Lazarov BS, Sigmund O. Giga-voxel computational morphogenesis for structural design. Nature. 2017;550(7674):84–6. doi:10.1038/nature23911. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zhu JH, Zhou H, Wang C, Zhou L, Yuan SQ, Zhang WH. A review of topology optimization for additive manufacturing: status and challenges. Chinese J Aeronaut. 2021;34(1):91–110. doi:10.1016/j.cja.2020.09.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Mukherjee S, Lu DC, Raghavan B, Breitkopf P, Dutta S, Xiao MY, et al. Accelerating large-scale topology optimization: state-of-the-art and challenges. Arch Computat Methods Eng. 2021;28(7):1–23. doi:10.1007/s11831-021-09544-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Bendsoe MP, Kikuchi N. Generating optimal topologies in structural design using a homogenization method. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 1988;71(2):197–224. doi:10.1016/0045-7825(88)90086-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Dong GY, Tang YL, Zhao YYF. A 149 line homogenization code for three-dimensional cellular materials written in matlab. J Eng Mater-T ASME. 2019;141(1):011005. doi:10.1115/1.4040555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Groen JP, Sigmund O. Homogenization-based topology optimization for high-resolution manufacturable microstructures. Int J Numer Methods Eng. 2018;113(8):1148–63. doi:10.1002/nme.5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Allaire G, Geoffroy-Donders P, Pantz O. Topology optimization of modulated and oriented periodic microstructures by the homogenization method. Comput Math Appl. 2019;78(7):2197–229. doi:10.1016/j.camwa.2018.08.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wang YJ, Xu H, Pasini D. Multiscale isogeometric topology optimization for lattice materials. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2017;316:568–85. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2016.08.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chen WJ, Tong LY, Liu ST. Concurrent topology design of structure and material using a two-scale topology optimization. Comput Struct. 2017;178:119–28. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2016.10.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang YG, Kang Z. Concurrent two-scale topological design of multiple unit cells and structure using combined velocity field level set and density model. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2019;347:340–64. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2018.12.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang YJ, Li XQ, Long K, Wei P. Open-source codes of topology optimization: a summary for beginners to start their research. Comp Model Eng. 2023;137(1):1–34. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.027603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wei GK, Chen Y, Li Q, Fu KK. Multiscale topology optimisation for porous composite structures with stress-constraint and clustered microstructures. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2023;416:116329. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2023.116329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Cheng L, Bai JX, To AC. Functionally graded lattice structure topology optimization for the design of additive manufactured components with stress constraints. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2019;344(5):334–59. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2018.10.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wang YJ, Arabnejad S, Tanzer M, Pasini D. Hip implant optimization design with three-dimensional porous material of graded density. AMSE J Mech Des. 2018;140(11):111406. doi:10.1115/1.4041208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen XL, Liu H, Wei P. Extended multiscale fem-based concurrent optimization of three-dimensional graded lattice structures with multiple microstructure configurations. Compos Struct. 2024;341:118186. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2024.118186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wu TY, Li S. An efficient multiscale optimization method for conformal lattice materials. Struct Multidiscip O. 2021;63(3):1063–83. doi:10.1007/s00158-020-02739-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Huang MC, Du ZL, Liu C, Zheng YG, Cui TC, Mei Y, et al. Problem-independent machine learning (piml)-based topology optimization-a universal approach. Extreme Mech Lett. 2022;56:101887. doi:10.1016/j.eml.2022.101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wu ZJ, Xia L, Wang ST, Shi TL. Topology optimization of hierarchical lattice structures with substructuring. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2019;345(2):602–17. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2018.11.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Liu Z, Xia L, Xia Q, Shi TL. Data-driven design approach to hierarchical hybrid structures with multiple lattice configurations. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2020;61(6):2227–35. doi:10.1007/s00158-020-02497-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Huang MC, Liu C, Guo YL, Zhang LF, Du ZL, Guo X. A mechanics-based data-free problem independent machine learning (piml) model for large-scale structural analysis and design optimization. J Mech Phys Solids. 2024;193(7674):105893. doi:10.1016/j.jmps.2024.105893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Wu ZJ, Fan F, Xiao RB, Yu LQ. The substructuring-based topology optimization for maximizing the first eigenvalue of hierarchical lattice structure. Int J Numer Meth Eng. 2020;121(13):2964–78. doi:10.1002/nme.6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Fu JJ, Xia L, Gao L, Xiao M, Li H. Topology optimization of periodic structures with substructuring. J Mech Design. 2019;141(7):071403. doi:10.1115/1.4042616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Liu H, Zong HM, Shi TL, Xia Q. M-VCUT level set method for optimizing cellular structures. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2020;367(8):113154. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2020.113154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Xia Q, Zong HM, Shi TL, Liu H. Optimizing cellular structures through the m-vcut level set method with microstructure mapping and high order cutting. Compos Struct. 2021;261(3):113298. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.113298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhou J, Shao MJ, Tian Y, Xia Q. Concurrent two-scale topology optimization of thermoelastic structures using a m-vcut level set based model of microstructures. Comp Model Eng. 2024;141(2):1327–45. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.054059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Buhmann MD. Radial basis functions: theory and implementations. In: Cambridge monographs on applied and computational mathematics. Vol. 12. New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

29. Wang SY, Wang MY. Radial basis functions and level set method for structural topology optimization. Int J Numer Meth Eng. 2006;65(12):2060–90. doi:10.1002/nme.1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wei P, Li Z, Li X, Wang MY. An 88-line Matlab code for the parameterized level set method based topology optimization using radial basis functions. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2018;58(2):831–49. doi:10.1007/s00158-018-1904-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Svanberg K. The method of moving asymptotes-a new method for structural optimization. Int J Numer Methods Eng. 1987;24(2):359–73. doi:10.1002/nme.1620240207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Liu H, Chen LX, Bian H. Data-driven m-vcut topology optimization method for heat conduction problem of cellular structure with multiple microstructure prototypes. Int J Heat Mass Tran. 2022;198(7646):123421. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2022.123421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Andreassen E, Clausen A, Schevenels M, Lazarov BS, Sigmund O. Efficient topology optimization in matlab using 88 lines of code. Struct Multidiscip O. 2011;43(1):1–16. doi:10.1007/s00158-010-0594-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Sigmund O. A 99 line topology optimization code written in matlab. Struct Multidiscip O. 2001;21(2):120–7. doi:10.1007/s001580050176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools