Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Real-Time Deep Learning Approach for Electrocardiogram-Based Cardiovascular Disease Prediction with Adaptive Drift Detection and Generative Feature Replay

1 Department of Mathematics and Computer Sciences, University of Oum El Bouaghi, Oum El Bouaghi, 04000, Algeria

2 Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Things Laboratory, University of Oum El Bouaghi, Oum El Bouaghi, 04000, Algeria

3 Department of Information Technology, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, P.O. Box 84428, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Networks and Telecommunications, University of Oum El Bouaghi, Oum El Bouaghi, 04000, Algeria

* Corresponding Authors: Soumia Zertal. Email: ; Souham Meshoul. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Exploring the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Healthcare: Insights into Data Management, Integration, and Ethical Considerations)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(3), 3737-3782. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.068558

Received 31 May 2025; Accepted 20 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) continue to present a leading cause of mortality worldwide, emphasizing the importance of early and accurate prediction. Electrocardiogram (ECG) signals, central to cardiac monitoring, have increasingly been integrated with Deep Learning (DL) for real-time prediction of CVDs. However, DL models are prone to performance degradation due to concept drift and to catastrophic forgetting. To address this issue, we propose a real-time CVDs prediction approach, referred to as ADWIN-GFR that combines Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) layers, for spatial feature extraction, with Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), for temporal modeling, alongside adaptive drift detection and mitigation mechanisms. The proposed approach integrates Adaptive Windowing (ADWIN) for real-time concept drift detection, a fine-tuning strategy based on Generative Features Replay (GFR) to preserve previously acquired knowledge, and a dynamic replay buffer ensuring variance, diversity, and data distribution coverage. Extensive experiments conducted on the MIT-BIH arrhythmia dataset demonstrate that ADWIN-GFR outperforms standard fine-tuning techniques, achieving an average post-drift accuracy of 95.4%, a macro F1-score of 93.9%, and a remarkably low forgetting score of 0.9%. It also exhibits an average drift detection delay of 12 steps and achieves an adaptation gain of 17.2%. These findings underscore the potential of ADWIN-GFR for deployment in real-world cardiac monitoring systems, including wearable ECG devices and hospital-based patient monitoring platforms.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The human cardiac system is essential for sustaining life, by continuously pumping blood to maintain the body’s normal physiological functions. Any impairment in cardiac function disrupts these vital processes and can result in fatal outcomes. The term “CVD” broadly encompasses disorders that interfere with the cardiac’s normal operation [1]. Today, CVDs remain a major global public health concern, requiring coordinated international efforts to reduce their impact. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), CVDs account for approximately 18 million deaths annually, making them a foremost cause of mortality worldwide [2].

One of the biggest drawbacks towards relieving this burden is the lack of timely and accurate diagnosis, together with reliable continuous monitoring technologies. Chest pain, dyspnea, ankle edema, and general weakness are some of the associated symptoms, but their absence does not necessarily imply a symptom-free cardiac system. Timely and accurate identification is therefore crucial to allow timely clinical interventions and improved patient outcomes [2]. It is in this sense that the ECG has emerged as a crucial diagnostic tool in cardiac function assessment. By capturing the cardiac’s electrical activity via non-invasive surface electrodes, the ECG provides a means of making almost precise diagnoses of abnormal cardiac rhythm, ischemic episodes, and structural cardiac disease [3]. It provides a real-time, precise, and non-invasive technique for the identification of dysfunctions that would otherwise remain clinically silent, making it indispensable for both preventive screening and emergency cardiovascular care, where timely diagnosis is critical [4,5].

Building upon the fundamental role of ECG in cardiac assessment, recent years have witnessed the emergence of wearable ECG monitoring systems that enable continuous, real-time heart monitoring beyond traditional clinical environments. These innovations are transforming cardiovascular care by allowing for early arrhythmia and other cardiac abnormality diagnosis in different settings like telmedicine, home-based care, post-operative monitoring, and sports medicine, where timely intervention is crucial.

There have been several research exploring the integration of AI-driven ECG monitoring into real-time, wearable or low-power devices: Hassan et al. (2018) [6] proposed a neuromorphic computing platform for arrhythmia detection based on ECG signals. Gu et al. (2023) [7] presented a hardware-accelerated CNN for real-time optimized ECG classification in wearable devices; Poh et al. (2023) [8] demonstrated real-time atrial fibrillation (AF) detection using photoplethysmography (PPG)-based systems. Xu et al. (2024) [9] introduced a multi-channel electrode system to enhance weak ECG signal detection; and Rahman and Morshed (2024) [10] embedded lightweight Artificial Intelligence (AI) models directly into wearable devices for on-device ECG analysis. Additionally, Panwar et al. (2025) [11] designed a low-cost, Arduino-based ECG monitoring system. While these advances highlight the increasing potential of wearable cardiac monitoring, they also reveal persistent challenges in handling noisy signals, managing physiological variability, and ensuring the adaptability and robustness of predictive models in real-world conditions. To address these challenges and unlock the full potential of continuous cardiac monitoring, there is an increasing reliance on AI.

The emergence of AI represents a major turning point in healthcare, fundamentally transforming decision-making processes and human interaction with medical environments. AI has become integral to the development of intelligent and reliable systems, particularly through Machine Learning (ML) models, which enables computers to learn autonomously without explicit programming. A notable advancement within ML is DL, inspired by the structure of the human brain, where multi-layered neural networks facilitate advanced data processing and representation [12]. Several recent studies have applied ML models to predict CVDs, leveraging publicly available datasets such as UCI, IEEE, and Kaggle [13,14]. These studies have explored a wide range of models, including Random Forest, XGBoost, CNN, SVM, MLPs, and various ensemble methods [14–16], often coupled with extensive data preprocessing, feature selection, clustering, and hyperparameter optimization strategies [17,18]. Although these approaches have achieved good results, they primarily rely on static datasets and lack mechanisms for dynamic model adaptation. Despite their initial successes, these approaches encounter significant limitations in achieving real-time prediction and generalization over dynamic patient data, primarily due to their dependence on manual feature extraction, restricted scalability to huge datasets, and lack the capacity to harness the complexity of medical data [19].

In contrast, DL approaches obviate these shortcomings by learning abstractions of hierarchical features from raw data, facilitating scalable and more accurate solutions in advanced medical environments: This capability makes it feasible to make more intricate and accurate predictions, facilitates efficient management of large numbers of datasets, and improve the adaptability of models to evolving and advanced data environments [20,21]. Recent studies have highlighted the effectiveness of DL models in CVDs prediction. Early efforts employed multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) [19], followed by approaches integrating statistical χ χ2-tests [22], principal component analysis (PCA), and logistic regression [23]. More recent studies leveraged deep neural networks (DNNs) [24–26], demonstrating improved accuracy and robustness across both binary and multi-class classification tasks. At the same time, growing attention has been directed toward ECG-based detection, where DL models have been employed to automatically extract and learn temporal features from raw signals, achieving notable improvements in detection accuracy and reliability [27,28]. Although DL models have demonstrated promising results in CVDs prediction, current approaches present significant limitations when applied to dynamic, real-world ECG data. Existing DL models are typically trained under the assumption of a stationary data distribution and often lack mechanisms to detect or adapt to data drift and distributional changes over time. However, ECG signals in clinical practice are highly susceptible to variability caused by factors such as patient aging, evolving comorbidities, medication effects, and variations in acquisition devices, all of which can substantially alter signal morphology, baseline levels, and wave amplitudes. Recent studies have shown that dataset shift can critically impair the performance of predictive models deployed in healthcare environments, emphasizing the urgent need to address such variability to ensure clinical reliability [29]. Furthermore, practical challenges such as device-induced drift and data imbalance in ECG signals have been documented in large-scale benchmarks like the PhysioNet/Computing in Cardiology Challenge [30]. Despite achieving high performance on static datasets, DL-based systems often fail to generalize when confronted with these evolving conditions, resulting in degraded accuracy and reduced practical applicability. This limitation is further intensified by the phenomenon of catastrophic forgetting, where models lose previously acquired knowledge when fine-tuned on new data. Nonetheless, a major limitation persists in real-world CVDs prediction systems: the inability to dynamically adapt to temporal shifts while preserving previously learned knowledge.

Drift refers to the change in the statistical properties of input data or target variables over time, which can significantly deteriorate the predictive performance of CVDs models. In medical data streams, various types of drift can arise: Covariate Drift, occurs when the distribution of input features changes while the relationship with the target remains stable [31]; Label Drift, involving changes in output label distributions [32]; Feature Drift, linked to the evolution of input structures such as new ECG devices [33]; Concept Drift, referring to changes in the relationship between inputs and outputs [34]; and Data Drift, encompassing general shifts in both features and labels [35]. A concrete example is provided by the clinical adoption of new wearable ECG monitoring devices, which can introduce subtle yet impactful changes in signal resolution, noise levels, and waveform shapes, thereby altering the input space and invalidating models trained on traditional clinical ECG datasets [29,30]. These drift phenomena create serious challenges for real-time health monitoring systems. They can lead to errors in diagnosis, missed health issues, and reduced confidence in AI-based tools, especially in fast changing environments like remote patient monitoring or emergency care. Consequently, addressing drift through detection and adaptive learning strategies is crucial to building robust and clinically reliable CVDs prediction systems.

This paper focuses on real-time CVDs prediction using DL models applied to ECG signals. The proposed approach particularly addresses the challenge of data drift by detecting and adapting to changes in ECG data over time, ensuring consistent and accurate predictions. By strengthening the model’s ability to adapt to evolving patient conditions and non-stationary data distributions, this work aims to improve the reliability and clinical applicability of ECG-based prediction systems in dynamic healthcare environments.

In the domain of real-time CVD prediction based on ECG signals, existing approaches can be broadly classified into three major categories. The first category comprises traditional ML and DL approaches that have made notable strides in CVD prediction. Classical ML models such as ensemble MLPs [36], XGBoost [37], and LightGBM [38] have demonstrated efficient performance, particularly in addressing class imbalance. In parallel, some studies have explored data fusion strategies to improve robustness across heterogeneous sources [39]. On the DL side, CNN-based architectures [40,41] have effectively captured spatial patterns within ECG signals and performed well in low-supervision scenarios. More recent efforts incorporating BiLSTM and attention mechanisms [42,43] have further enhanced the detection of minority classes by modeling temporal dependencies and contextual relationships. Over time, there has been a notable transition from early, rigid ML techniques to more flexible and expressive DL architectures. While these advancements have significantly improved modeling capacity and performance, they remain limited in critical aspects. Most of these models are not designed for real-time adaptation, lack mechanisms for long-term knowledge retention, and struggle to maintain robust performance under dynamic, non-stationary clinical conditions.

The second category includes hybrid and adaptive approaches, which attempt to integrate adaptability and robustness into cardiovascular monitoring frameworks. Recent efforts have explored various adaptive and hybrid approaches for CVD prediction. ML–DL ensembles integrating models like etc-XGB, CNN, and RNNs have shown improved accuracy and specificity [44,45]. Real-time learning frameworks, including OS-ELM [46], Spark MLlib pipelines [47], and MLP- or GRU-based architectures [48,49], support online updates and enhance temporal modeling. To address concept drift and catastrophic forgetting, various continual learning strategies have been proposed, including incremental learners like VFDT [50], memory replay with regularization in CNNs [51], and adaptive regression ensembles [52]. More advanced solutions integrate reinforcement learning with GFR to enable efficient and robust sequential learning [53]. These studies represent meaningful progress toward more intelligent systems. However, a key challenge persists: the inability to simultaneously achieve real-time responsiveness, concept drift adaptation, and continual learning within a lightweight, generalizable architecture suitable for deployment on edge or wearable devices.

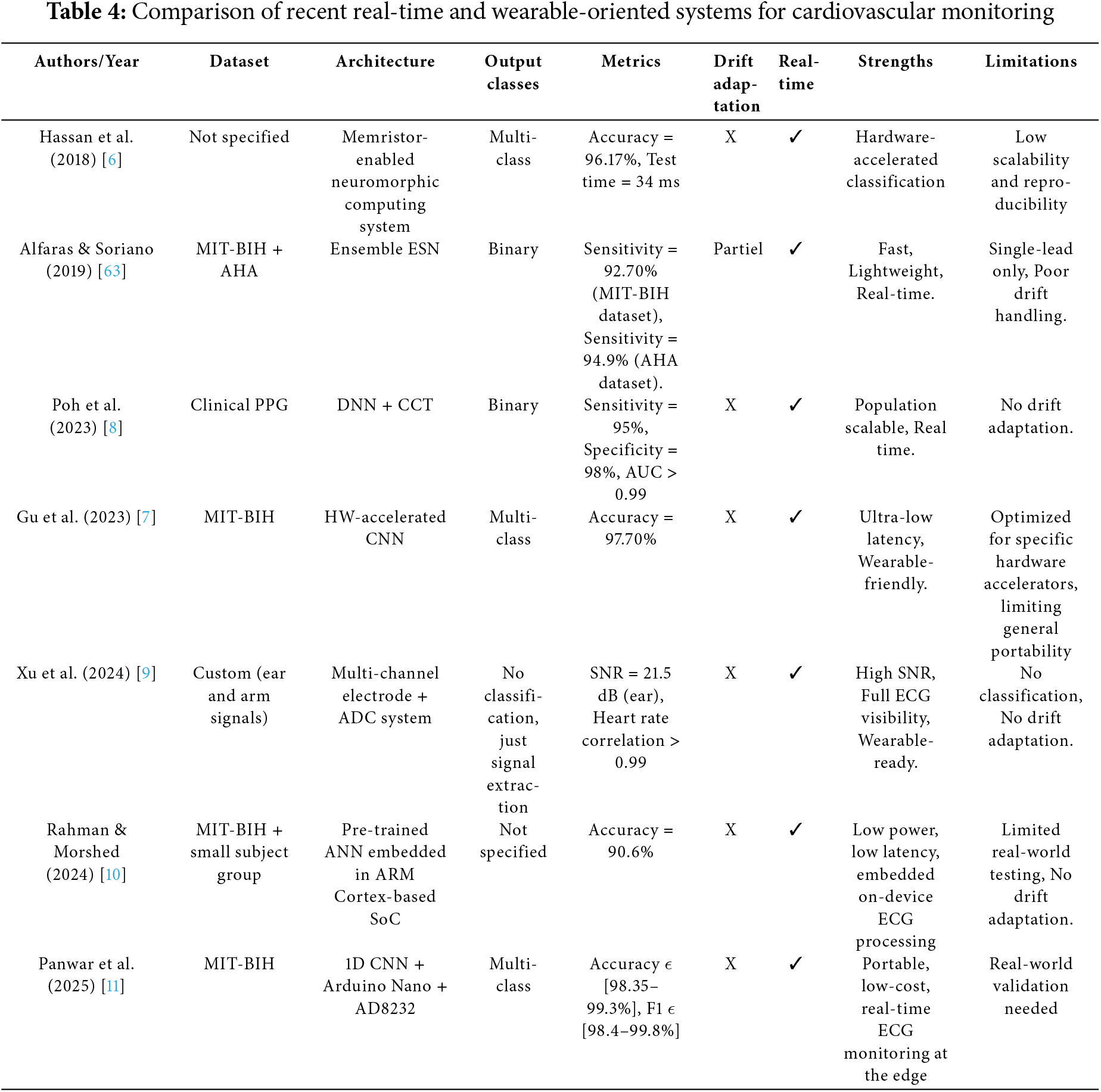

The third category focuses on real-time embedded systems for wearable cardiovascular monitoring, integrating a range of approaches such as neuromorphic and reservoir computing [6], hardware-accelerated CNNs [7], DL models applied to PPG signals [8], multi-channel electrode arrays [9], low-power system-on-chip (SoC) implementations [10], and Arduino-based CNN architectures [11]. These solutions emphasize efficiency, offering low power consumption, compact form factors, and fast on-device inference, all of which are essential for continuous health tracking. Despite these strengths, most of these systems fall short in their ability to adapt to evolving data streams, address concept drift, or preserve learned knowledge over time. This significantly limits their effectiveness in long-term, personalized, and clinically relevant applications.

Overall, most existing approaches for drift detection and adaptation in CVD prediction remain limited by their slow adaptation speed and vulnerability to prior knowledge forgetting, ultimately resulting in suboptimal and inconsistent model performance in dynamic clinical environments. To overcome these limitations, the present work addresses two key challenges in real-time CVD prediction using ECG data streams:

(1) The timely detection of data drift and the adaptive response to changes in ECG signal distributions, and

(2) The preservation of previously acquired knowledge during the adaptation process to avoid catastrophic forgetting.

By addressing these challenges, the proposed ADWIN-GFR approach aims to improve the robustness, adaptability, and long-term predictive accuracy of DL models deployed in dynamic and non-stationary healthcare environments, particularly those involving continuous ECG monitoring.

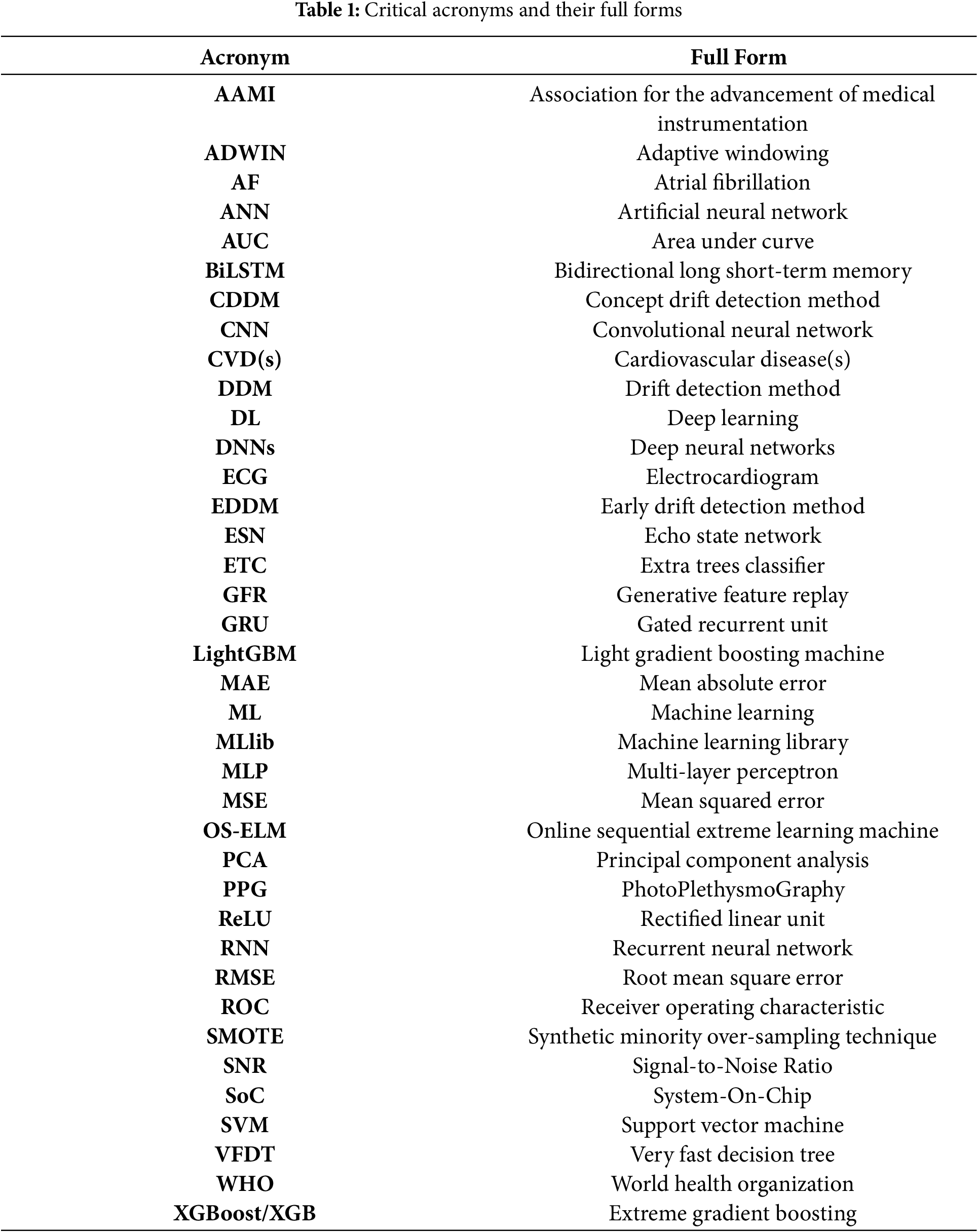

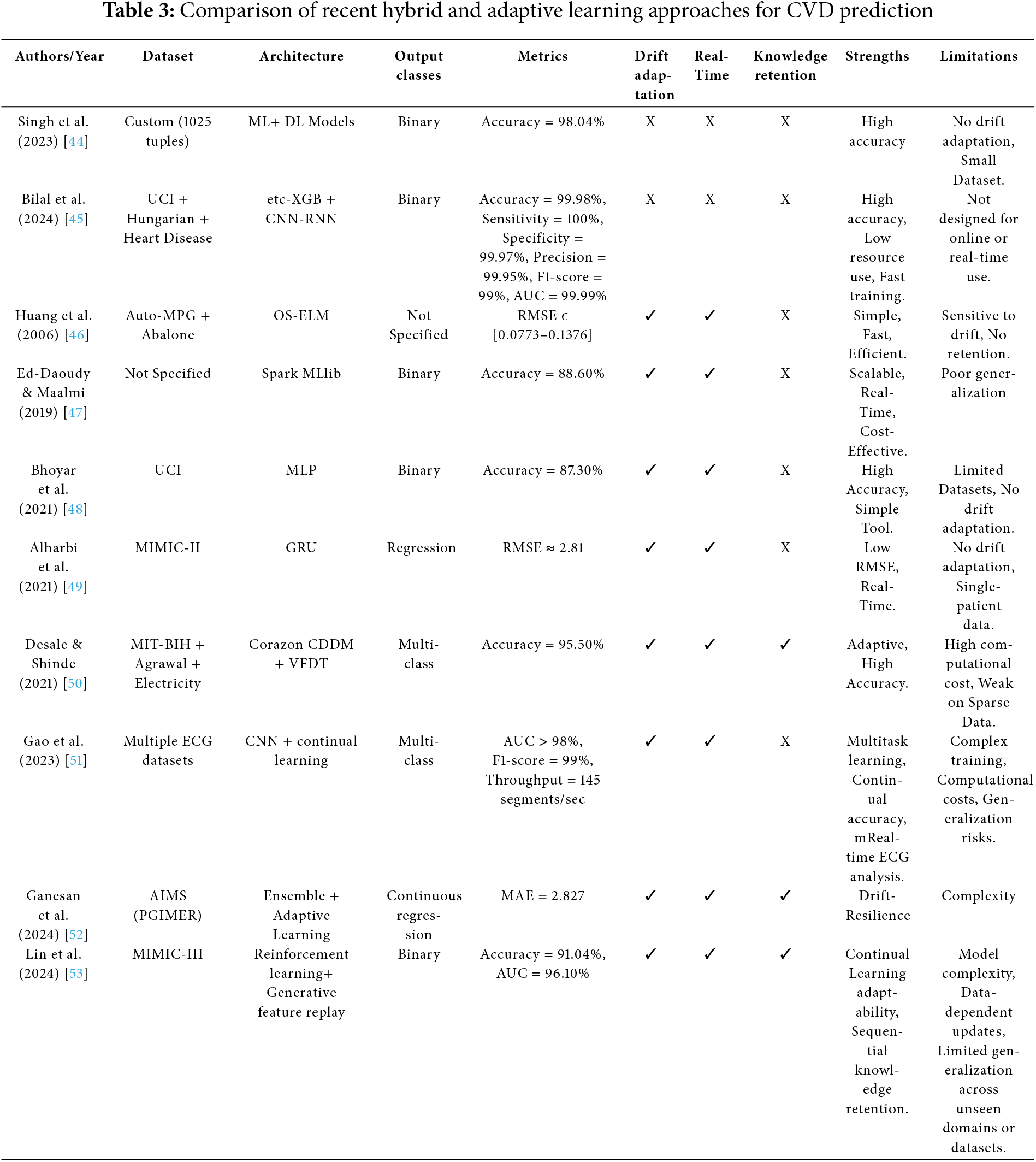

All acronyms listed in Table 1 reflect the interdisciplinary nature of research in this domain, where cardiovascular heart disease prediction and real-time drift adaptation techniques converge.

In this paper, we propose a CVDs prediction approach that combines CNN and GRU models. CNNs are well-suited for extracting local spatial features from complex biomedical signals such as ECGs, allowing the model to detect key patterns and abnormalities in cardiac activity [41,44]. Meanwhile, GRUs are specifically designed to capture sequential and temporal dependencies, which are vital for interpreting the time-series nature of ECG signals [44]. By integrating CNN and GRU architectures, our approach effectively exploits both spatial and temporal dimensions of the data, leading to more accurate and resilient predictions, even in non-stationary ECG streams.

The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

• Dynamic Drift Detection: The proposed method incorporates the ADWIN algorithm, which adaptively resizes its detection window based on statistical variations in prediction errors. ADWIN provides strong theoretical guarantees for detecting both abrupt and gradual drift with low false alarm rates [35]. It has outperformed traditional methods like DDM [54] and EDDM [55], particularly in real-time, noisy environments [32]. Its adaptability makes it highly suitable for ECG-based CVDs prediction, where continuous data variability requires robust model performance.

• Real-Time Adaptation to Drift and Knowledge Preservation: To maintain predictive performance after drift detection, we propose a real-time adaptation strategy based on fine-tuning with a GFR mechanism. Specifically, a dynamic replay buffer is continuously updated to preserve representative features from previous data distributions, with selection driven by variance maximization, feature diversity, and consistency with the data distribution. Alongside, the GFR technique is integrated into the fine-tuning process to mitigate catastrophic forgetting. This dual mechanism enables the model to adapt rapidly to new data while preserving critical knowledge acquired from past distributions, thereby ensuring long-term model stability.

Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed approach improves prediction accuracy, robustness, and adaptability under real-time, non-stationary ECG conditions.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews existing approaches for real-time CVDs prediction and concept drift adaptation. Section 3 provides a comprehensive description of the proposed ADWIN-GFR approach, detailing its core components and operational workflow. Section 4 presents the experimental setup, followed by a comprehensive analysis and discussion of the results. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and highlights the limitations and potential directions for future research.

This review surveys key contributions from 2006 to 2025, a period characterized by accelerated innovation in healthcare monitoring technologies. Advances in ML, DL, online learning, and embedded signal processing have enabled to the emergence of intelligent systems for real-time disease detection and physiological monitoring. Across various medical domains, recent studies have demonstrated the integration of smart sensors with AI models for continuous respiratory monitoring [56,57], epileptic seizure prediction [58,59], sleep apnea detection [60], and breast cancer diagnosis [61,62]. These cross-domain applications illustrate both the versatility and the evolving potential of AI-driven health technologies.

In this context, the proposed approach specifically focuses on ECG signal analysis for CVD prediction, a domain that has gained significant momentum due to the growing availability of wearable ECG sensors and the high prevalence of cardiac conditions. ML and DL architectures, particularly CNNs and GRUs, have shown promise in extracting temporal and spatial features from ECG data. To better reflect the diversity of methodologies and support a structured comparison, the following review is organized into three thematic categories: Classical ML and DL Approaches, Hybrid and Adaptive Approaches, and Real-Time Embedded Systems for Wearable Cardiovascular Monitoring. Each category highlights key contributions, strengths, and limitations of existing models, setting the stage for our proposed solution.

2.1 Traditional Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches

Traditional ML and DL approaches for cardiovascular signal classification, as summarized in Table 2, have shown promising results but share key limitations. Ihsanto et al. (2019) [36] used an ensemble MLP model achieving high accuracy with low computational cost, yet its reliance on hand-crafted features and lack of temporal modeling restrict performance in dynamic contexts. Bertsimas et al. (2021) [37] employed XGBoost for efficient classification on imbalanced data, but it lacks support for streaming adaptation. Similarly, Wang & Cao (2025) [38] used LightGBM with bootstrap sampling to address class imbalance, though it remains a static model requiring retraining. Martinez-Rodrigo et al. (2025) [39] enhanced robustness through multi-source data fusion, but their approach also lacked real-time adaptability. On the DL side, Kwon et al. (2020) [40] applied a CNN-MLP that captured spatial ECG features well, yet CNNs alone fail to model long-term dependencies. Singh & Cironne (2023) [41] introduced a CNN-Transformer model improving performance in low-supervision scenarios, though the architecture was computationally demanding. Finally, Ramesh et al. (2025) [42] and Goretti et al. (2025) [43] leveraged BiLSTM and attention for better detection of minority classes but required static offline training, limiting their applicability in real-time, evolving environments.

Traditional ML approaches, such as decision trees, SVMs, and gradient boosting methods like XGBoost and LightGBM, have shown success in static ECG classification but are limited in real-time applications due to their reliance on batch training and assumption of data stationarity. These models lack inherent mechanisms for continual learning and are vulnerable to concept drift, requiring manual retraining to maintain accuracy. DL architectures, including CNNs, LSTMs, GRUs, and CNN-MLP models, offer improved performance by capturing complex spatial and temporal patterns from raw ECG signals. However, their offline training and computational demands limit adaptability in dynamic, resource-constrained settings such as wearable devices. These limitations have spurred growing interest in hybrid and adaptive approaches that incorporate continual learning to enhance resilience and maintain performance in evolving real-world healthcare environments.

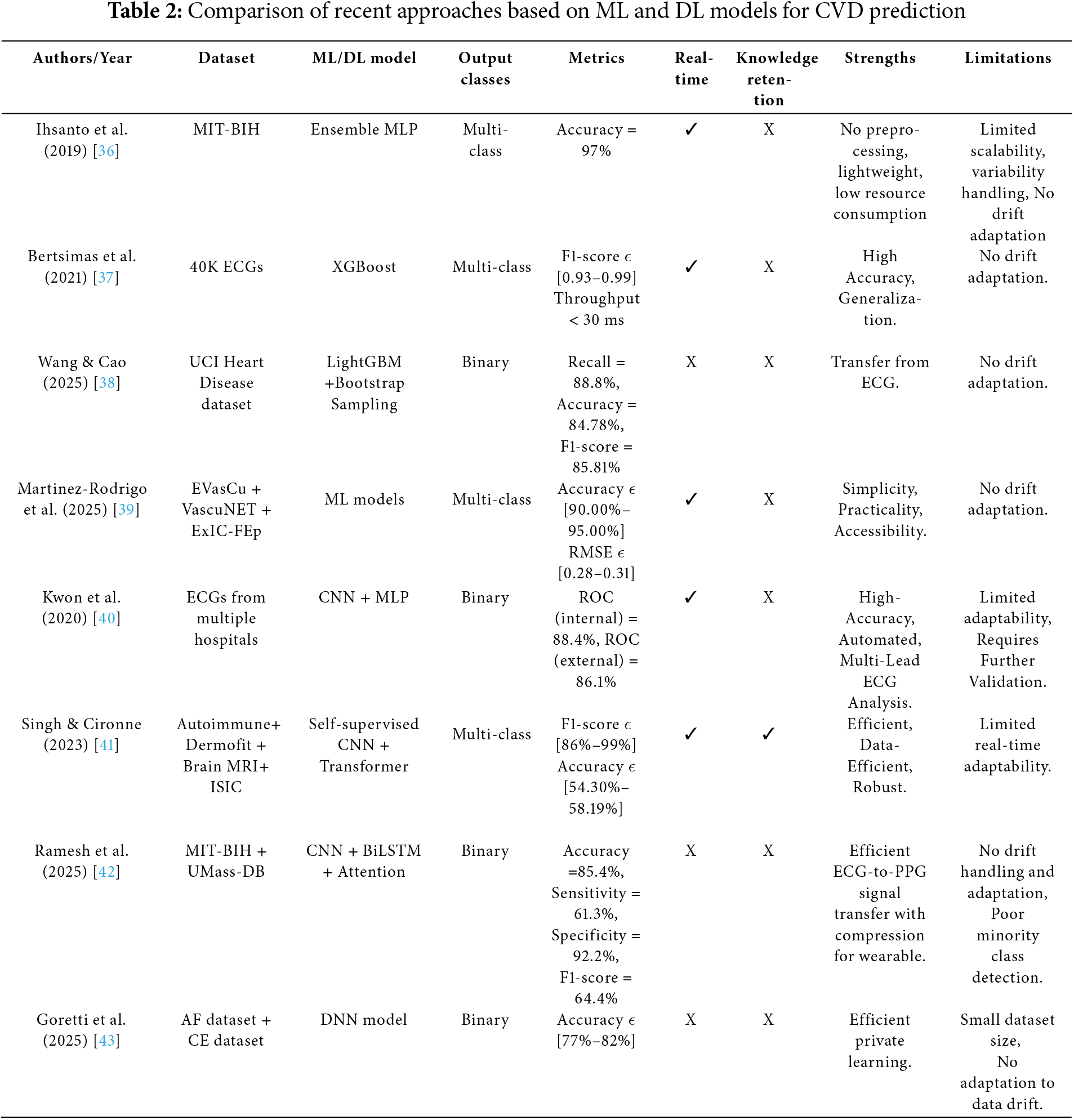

2.2 Hybrid and Adaptive Approaches

This category covers both hybrid learning architectures, which combine ML and DL models, and adaptive systems designed to address evolving data distributions and support knowledge retention. The reviewed approaches are summarized in Table 3. Hybrid learning models combine the strengths of ML and DL to enhance classification performance. Singh et al. (2023) [44] proposed an ML-DL architecture that achieved high accuracy but lacked real-time processing and adaptability. Bilal et al. (2024) [45] combined etc-XGB with CNN-RNN components to improve sensitivity and specificity. The ensemble structure provided diversity in prediction. However, the hybrid was static and not built for continual updates.

Adaptive systems emerged to handle evolving data distributions. Huang et al. (2006) [46] introduced OS-ELM, a fast updating model that performed well in static segments but suffered from instability under drift. Ed-Daoudy & Maalmi (2019) [47] used Spark MLlib in a streaming environment, but the system lacked DL capabilities and was limited in generalization. Bhoyar et al. (2021) [48] and Alharbi et al. (2021) [49] utilized MLP and GRU respectively in real-time pipelines. GRUs offered better temporal modeling, but both models lacked explicit drift detection or retention strategies. More sophisticated systems have incorporated continual learning. Desale & Shinde (2021) [50] introduced Corazon CDDM with VFDT, that performs incremental updates and handles concept drift using statistical splits. However, its reliance on decision trees may limit its ability to model complex, non-linear ECG patterns, especially in high-dimensional data. Gao et al. (2023) [51] integrated continual learning into a CNN-based pipeline, using memory replay or regularization to prevent catastrophic forgetting. Despite its improved adaptability, the approach incurs significant memory overhead, making it less suitable for real-time or embedded applications. Ganesan et al. (2024) [52] applied adaptive regression ensembles to enhance robustness under drift, but the complexity and retraining requirements remained high. Lin et al. (2024) [53] combined reinforcement learning with GFR, enabling memory-preserving updates during sequential learning. Despite these advances, most methods were not optimized for edge devices due to their computational demands.

Hybrid and adaptive learning approaches have been proposed to overcome the limitations of static models by enabling dynamic learning and continual adaptation. While architectures like etc-XGB combined with CNN-RNN [45] achieve high accuracy in controlled environments, they lack incremental learning capabilities and remain unsuitable for memory and energy-constrained platforms such as wearable or embedded systems. More adaptive solutions, including Corazon CDDM with VFDT [50] and reinforcement learning combined with GFR [53], offer continual update mechanisms but often rely on computationally intensive retraining, which risks overwriting prior knowledge and exacerbates catastrophic forgetting. Even methods employing continual learning strategies, such as GFR, are typically evaluated on offline datasets, limiting their generalizability to real-time applications.

These challenges highlight a critical gap: no existing approach fully satisfies the combined requirements of efficient real-time drift adaptation, long-term knowledge retention, and lightweight deployment on edge or embedded clinical systems. This limitation underscores the growing need for intelligent health monitoring solutions that balance adaptability with operational efficiency in real-world physiological data environments.

2.3 Real-Time, Embedded Systems for Wearable Cardiovascular Monitoring

This category includes real-time embedded systems that prioritize low latency and energy efficiency, which are essential for continuous wearable monitoring. The analysis of these systems is presented in Table 4. Hassan et al. (2018) [6] and Alfaras et al. (2019) [63] proposed neuromorphic and reservoir computing-based architectures, offering fast inference speeds. However, these systems lacked adaptability and were not capable of online learning. Poh et al. (2023) [8] applied DNNs to PPG data, achieving high classification accuracy, though the model remained fixed after deployment. Gu et al. (2023) [7] advanced this direction by implementing CNNs on hardware accelerators, enabling ultra-low latency through circuit-level optimization. Nevertheless, these architectures were not designed for post-deployment retraining or model updates. Xu et al. (2024) [9] focused on improving signal quality rather than classification by using multi-channel electrode arrays, which enhanced input fidelity but did not address adaptability. Rahman & Morshed (2024) [10] embedded pre-trained ANNs into low-power SoC platforms, demonstrating edge-readiness but with no mechanisms for handling concept drift. Panwar et al. (2025) [11] developed an Arduino-based CNN system that combined affordability with reasonable performance; however, it still lacked support for online learning or incremental model updates.

Real-time embedded systems for cardiovascular monitoring prioritize speed, low latency, and energy efficiency, essential traits for continuous operation in wearable healthcare devices. However, this focus on efficiency often limits adaptability. Most implementations rely on lightweight or pre-trained models that lack support for online learning or real-time updates. Resource-constrained platforms like Arduino, while cost-effective, cannot accommodate complex or drift-aware models. More critically, the absence of lifelong learning mechanisms poses a significant limitation. ECG signals are inherently dynamic, influenced by aging, health variations, medications, and sensor drift. Without adaptive updates or concept drift detection, static models degrade in accuracy over time, compromising the reliability and long-term effectiveness of continuous monitoring systems.

To address these persistent gaps, this study introduces a novel adaptive classification framework, ADWIN-GFR, specifically designed for real-time cardiovascular monitoring. By integrating drift-aware updating via ADWIN and GFR mechanisms. The proposed model offers real-time responsiveness, resilience to data distribution shifts, and long-term knowledge preservation. This design directly responds to the shortcomings identified in the literature, aiming to deliver a scalable and robust solution suitable for wearable health systems. The following section provides a detailed description of the proposed approach, including its core components and operational mechanisms.

3 The Proposed ADWIN-GFR Approach

The proposed approach targets the prediction of CVDs based on ECG signals, which represents a critical, non-invasive modality for the early detection of cardiac abnormalities. This method employs a hybrid DL architecture that combines CNNs and GRUs to effectively extract and model the spatial and temporal characteristics inherent in ECG data. To enhance model robustness in dynamic and non-stationary environments, the ADWIN algorithm is utilized for real-time concept drift detection. Upon the identification of drift, model adaptation is conducted through a fine-tuning mechanism augmented by GFR, enabling continuous learning while alleviating the effects of catastrophic forgetting.

To effectively evaluate the performance and adaptability of the ADWIN-GFR under realistic clinical conditions, it is essential to test it on a benchmark dataset that exhibits the complexities of real-world ECG signals. This includes dealing with irregular rhythms, temporal variability, and class imbalance, factors that are critical in continuous monitoring scenarios. For evaluation, we use a clinically validated and widely recognized ECG dataset, which provides a solid foundation for meaningful and fair performance comparison. The following section first provides a comprehensive description of the dataset used for training and evaluation, emphasizing its suitability for ECG-based cardiac risk assessment. Thereafter, the proposed model architecture is detailed, followed by a systematic explanation of the entire adaptive learning framework.

The dataset used in this study consists of physiological signals. It includes ECG, obtained from the MIT-BIH Arrhythmia Database (https://physionet.org/content/mitdb/1.0.0/, accessed on 15 January 2025). This database provides high-resolution ECG recordings annotated by medical experts, they capturevariability of real-world cardiac conditions. Its inherent challenges, such as substantial class imbalance and temporal signal variability, closely reflect the dynamic nature of continuous patient monitoring. These characteristics make it particularly suitable for evaluating the complex adaptive DL models in non-stationary environments, aligning well with the goals of this study. The MIT-BIH dataset has served as a foundational benchmark in the development of both classical ML methods [36,49,50] and more recent DL architectures [11,42,43], further reinforcing its value for validating the proposed approach.

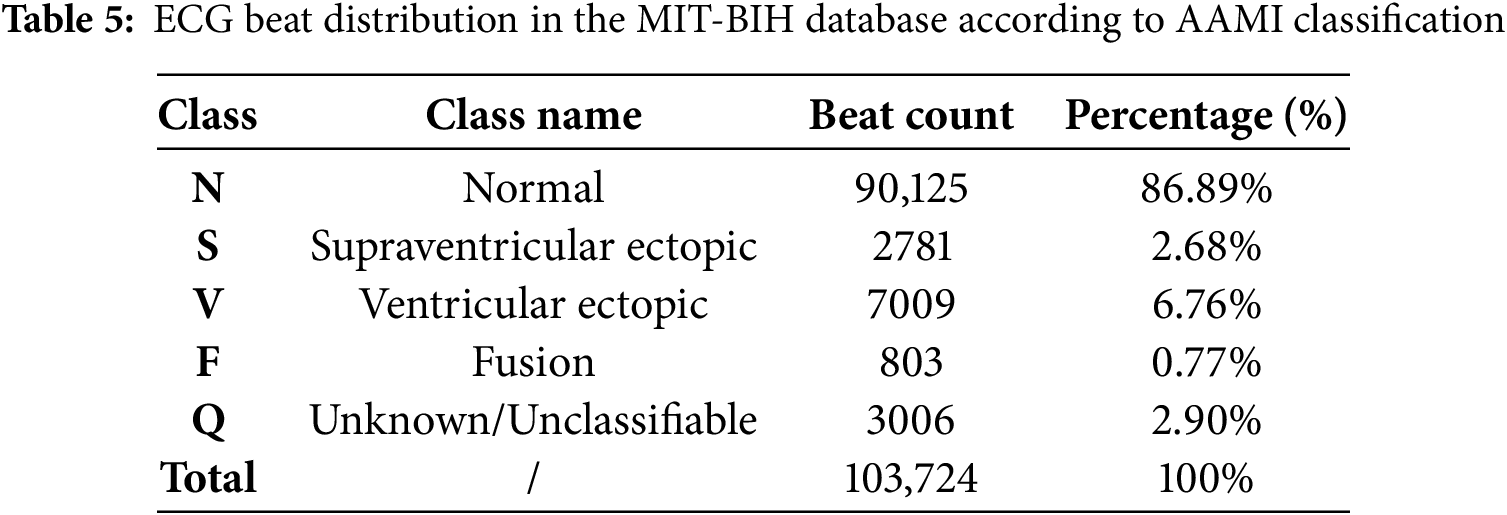

The MIT-BIH Arrhythmia Database comprises 48 two-channel ECG recordings, each approximately 30 min long, collected from 47 subjects [52]. The signals are sampled at 360 Hz with 11-bit resolution, providing high temporal precision suitable for both time-domain and frequency-domain analyses. Each record includes signal file (.dat), header file (.hea), and expert-labeled annotations (.atr or .ann) that conform to the AAMI EC57 standard. This standard classifies heartbeat types into five clinically meaningful categories: Normal beats (N), Supraventricular ectopic beats (S), Ventricular ectopic beats (V), Fusion beats (F), and Unclassifiable rhythms (Q).

For the purpose of this study, a curated subset of 44 records was selected, excluding those with paced beats (records 102, 104, 107, and 217) to ensure data consistency. Each heartbeat was mapped to one of the five AAMI classes, and the total number of beats per class was computed along with their respective percentages. This class distribution analysis is essential for assessing the impact of class imbalance, a known challenge in arrhythmia classification systems. The detailed beat distribution is summarized in Table 5.

The structural and statistical properties of the MIT-BIH Arrhythmia Database directly motivated the design of the ADWIN-GFR framework. Its high temporal resolution and sequential beat annotations necessitate a model capable of capturing both spatial and temporal dynamics within ECG signals, thereby justifying the use of a hybrid CNN-GRU architecture. Moreover, the pronounced class imbalance required the integration of a two-stage SMOTE-based resampling strategy to enhance classification reliability, particularly for underrepresented heartbeat categories. These design choices are technically aligned with the dataset’s inherent challenges and are further detailed in the subsequent sections.

3.2 Description of the Proposed Approach

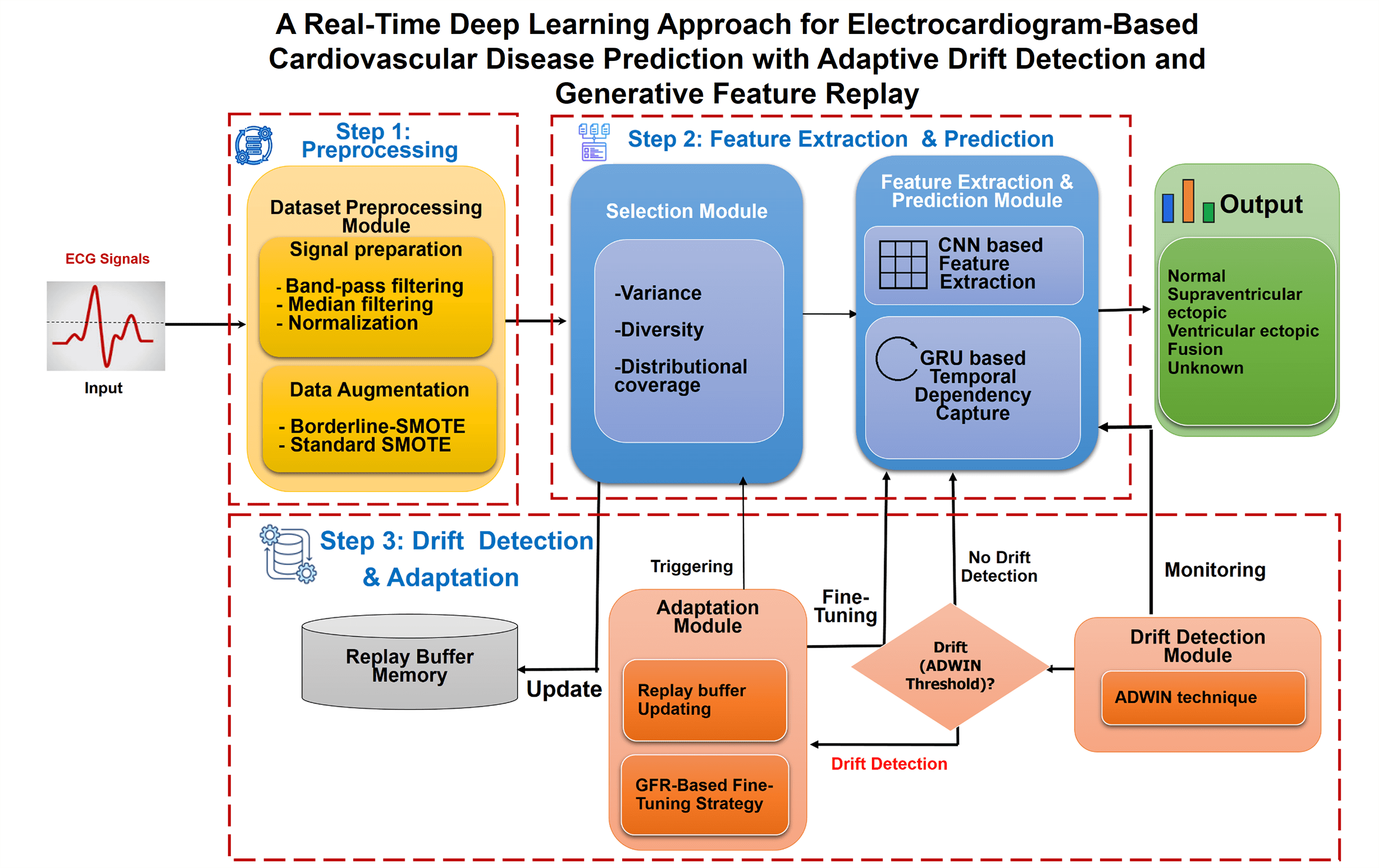

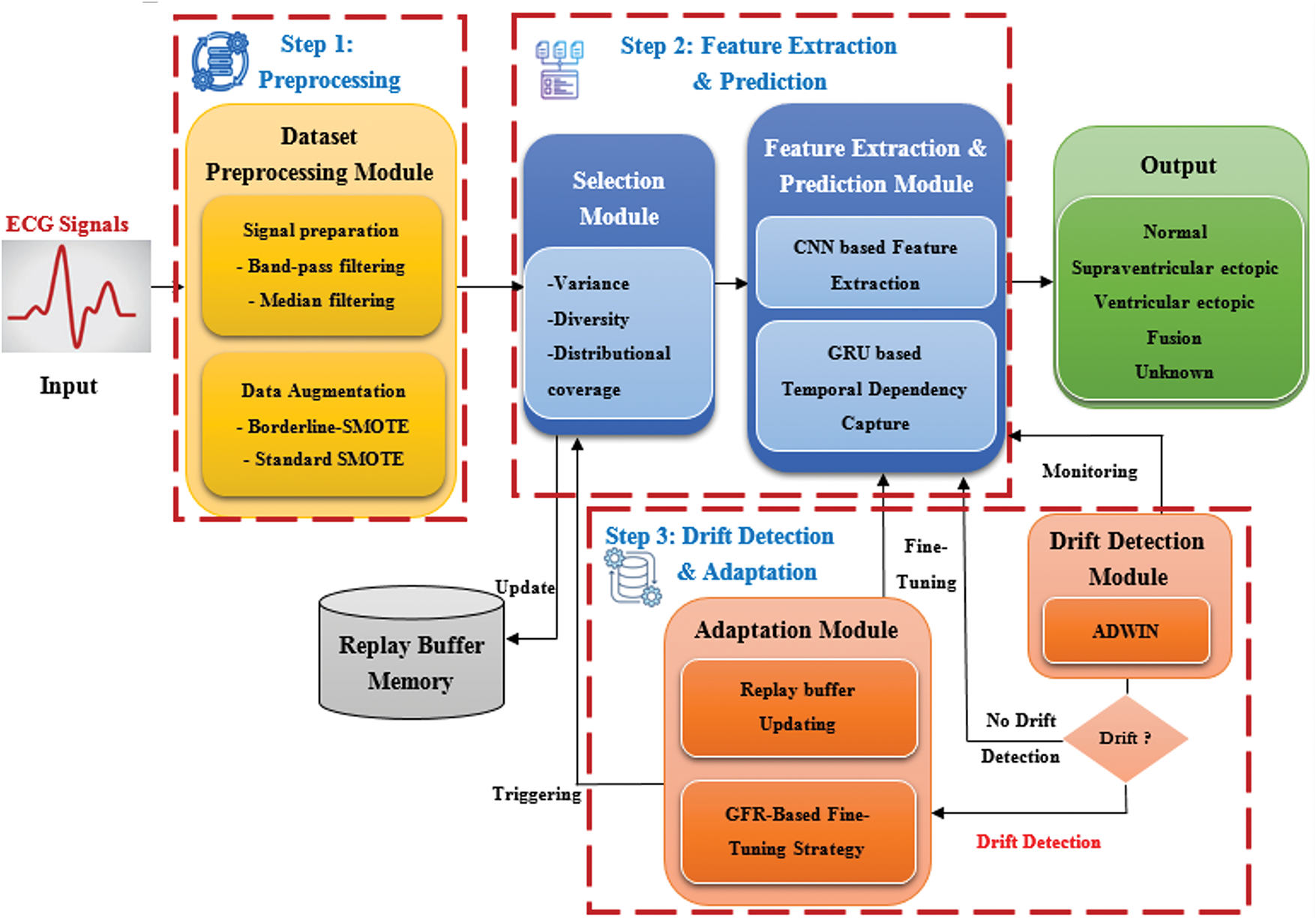

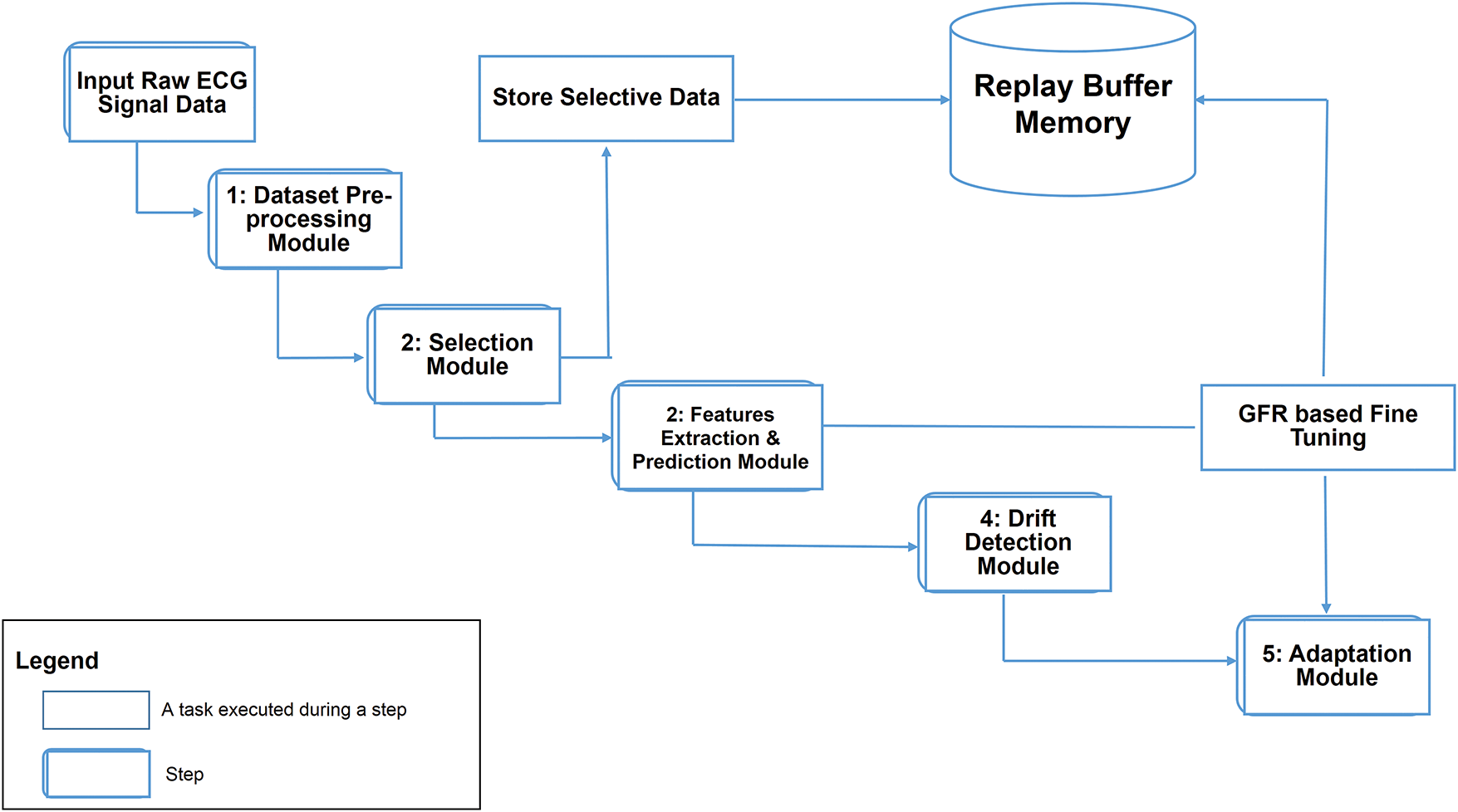

Fig. 1 illustrates the high-level architecture of ADWIN-GFR, specifically designed for CVD prediction using ECG signals. ECG monitoring provides a crucial, non-invasive means for continuous cardiac health assessment, particularly in real-time and dynamic environments where data distributions may evolve over time. To ensure robust and consistent predictive performance under such non-stationary conditions, the proposed system is structured into three main steps, complemented by a Replay Buffer Memory that facilitates continual learning and knowledge preservation.

Figure 1: High-level architecture of the ADWIN-GFR framework for real-time CVD prediction using ECG signals

1. The first step involves Data Pre-processing, managed by a dedicated “Dataset Pre-Processing module” responsible for enhancing signal fidelity and addressing class imbalance. Such two critical factors directly impact the accuracy of arrhythmia classification models.

2. The second step, Data Extraction and Prediction, involves two interconnected modules:

• The “Selection Module” systematically identifies and selects representative data instances based on key criteria including variance, distribution, and diversity. These selected instances are stored in the Replay Buffer Memory, which plays a vital role in mitigating catastrophic forgetting during incremental model updates.

• The “Feature Extraction and Prediction Module” leverages both CNNs and GRUs to capture spatial features and long-range temporal dependencies from sequential ECG data.

3. The third step, focusing on drift detection and adaptation, integrates:

• A “Drift Detection module” based on the ADWIN technique, enabling timely identification of distributional changes; and

• An “adaptation module” employing a fine-tuning strategy enriched with GFR, facilitating continuous learning without degrading prior knowledge.

Alongside this process, the system makes use of a Replay Buffer Memory. It maintains a carefully selected subset of past data instances, identified by the Selection Module. Its function is to enable continual learning by strategically reintroducing representative historical samples during model updates. By preserving essential and diverse information from earlier concepts, the Replay Buffer plays a critical role in mitigating catastrophic forgetting and supporting robust model adaptation over time.

Collectively, these modules enable the proposed ADWIN-GFR framework to achieve robust adaptability, maintaining diagnostic accuracy even under evolving operational conditions. To facilitate a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms and the interplay between components, the following subsections provide a detailed description of each module, supported by schematic representations illustrating the overall workflow of the framework.

The Dataset Preprocessing Module is the initial component of the ADWIN-GFR framework, responsible for preparing raw ECG signals for accurate feature extraction and prediction. Given the presence of physiological noise and the pronounced class imbalance typical of clinical ECG data, this module is specifically designed to enhance signal fidelity and ensure balanced class representation. These preprocessing steps are essential to support the reliability of downstream components, particularly the CNN-GRU architecture and adaptive learning mechanisms. The following subsections detail the signal preparation step and the Data Augmentation strategy implemented to address these challenges.

3.2.1 Dataset Preprocessing Module

The purpose of this module is to clean, prepare, and balance the ECG data to ensure high-quality inputs for the CNN-GRU model. The data pre-processing module consists of two main steps: The Signal Preparation and Data Augmentation Step. In the following, we detail the Signal Preparation Step, which applies the following techniques:

• Signal preparation step: The signal preparation consists of three main stages: band-pass filtering, median filtering, and normalization, each serving a specific purpose in enhancing signal quality for predictive modeling. Band-pass filtering removes undesired frequency components; median filtering reduces noise while preserving signal features, and normalization standardizes the ECG data for improved model performance. This step is defined as follows:

1. Initially, a sixth-order Butterworth band-pass filter with a 0.5–50 Hz pass-band is applied to suppress irrelevant frequencies while preserving essential ECG features, including P waves signify atrial depolarization and ventricular priming [64], QRS complexes represent rapid ventricular depolarization leading to contraction and blood ejection [4], and T waves reflect ventricular repolarization in preparation for the next cardiac cycle [65]. To define the band-pass filter frequency bounds, we have used the following formulas:

where: fs: represents Sampling frequency.

2. Thereafter, a median filter with a kernel size of five is applied to suppress transient noise while preserving essential waveform features. This step effectively reduces artifacts caused by electrode motion or external disturbances without altering the signal’s integrity.

3. Finally, min–max normalization scales the signal values to the range [−1, 1] (Eq. (4)), promoting numerical stability, improving model convergence, and ensuring balanced feature scaling:

where:

- median_filtered_signal: Refers to the ECG signal after processing with a median filter. This step reduces noise while preserving important waveform features and edges.

- min(median_filtered_signal): Indicates the smallest value within the median-filtered signal. It is used during normalization to shift the signal so that its minimum value becomes zero, facilitating consistent scaling.

- max(median_filtered_signal): represents the maximum value of the median-filtered signal, used to scale the signal so that the maximum becomes one during normalization.

- (∗2 − 1): This final operation rescales the normalized values from the range [0, 1] to [−1, 1], centering the signal around zero, which improves numerical stability for many ML models.

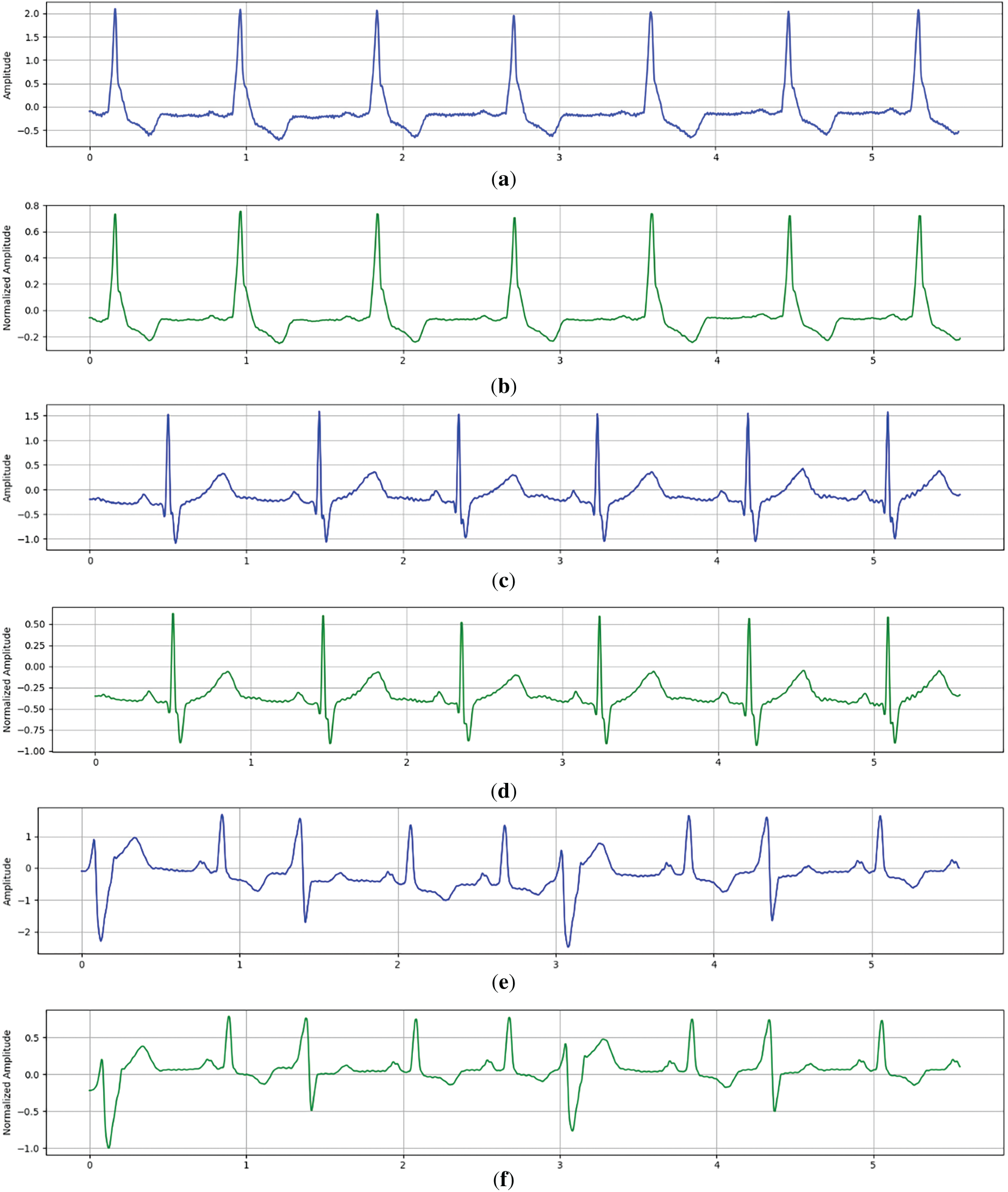

Together, these steps deliver denoised and standardized ECG signals that retain diagnostic integrity, facilitating more accurate feature extraction and improved DL performance. The effect of the signal preparation step is illustrated in Fig. 2, which displays representative ECG signals both before and after the application of this step.

Figure 2: Representative ECG signals before and after the Signal Preparation Step. (a) Raw ECG signal (record 214) Before Signal Preparation Step. (b) Raw ECG signal (record 214) After Signal Preparation Step. (c) Raw ECG signal (record 231) Before Signal Preparation Step. (d) Raw ECG signal (record 231) After Signal Preparation Step. (e) Raw ECG signal (record 233) Before Signal Preparation Step. (f) Raw ECG signal (record 233) After Signal Preparation Step

These samples (records 214−231−233) were selected to highlight common waveform patterns across subjects and illustrate the consistency of Signal Preparation Step effects on ECG signal clarity.

After ECG signals have been filtered, denoised, and normalized, they are segmented into fixed-length windows of 500 samples, approximately 1.39 s at a 360 Hz sampling rate. This duration is sufficient to capture a full cardiac cycle, including the P wave, QRS complex, and T wave, which are essential for accurate arrhythmia detection. Each segment is then reshaped into a three-dimensional tensor with the format (batch_size, 500, 1), where 500 represents time steps and 1 indicates a single channel corresponding to the amplitude of a single-lead ECG signal. This standardized input structure aligns with the CNN-GRU architecture and ensures that the model receives clinically meaningful and computationally optimized data for reliable feature extraction and classification. However, due to the pronounced class imbalance inherent in the dataset, additional data augmentation is required to promote generalization and reliable classification across minority heartbeat categories. The following subsection describes “Data Augmentation Step” employed to address this challenge.

• Data augmentation Step: This step constitutes the second phase of the Data Pre-processing module, following the Signal Preparation Step. To address class imbalance within the training dataset, a two-step resampling strategy based on the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) was employed, combining Borderline-SMOTE [66] and standard SMOTE [67] techniques:

- Initially, the Borderline-SMOTE algorithm (with “k_neighbors = 3” and kind set to “borderline-2”) was applied to generate synthetic samples near the decision boundaries, thus reinforcing minority classes where misclassification risk is highest.

- Subsequently, standard SMOTE was used to further balance all classes to the level of the initial majority class size, ensuring a fully uniform distribution.

This technique was chosen over traditional oversampling or undersampling approaches for several reasons. Although SMOTE may be less effective in highly dimensional spaces [68], our feature space remains moderate, with each ECG segment represented by 500 amplitude values across a fixed window. Thus, the dimensionality remains within the range where SMOTE retains reliable performance [67].

Furthermore, the dataset employed in this study is relatively large, comprising 103,724 heartbeats across five classes (Normal: 90,125 beats, Supraventricular ectopic: 2781 beats, Ventricular ectopic: 7009 beats, Fusion: 803 beats, and Unknown: 3006 beats). Given the critical need for accurate cardiovascular anomaly detection and robustness against data drift, it was crucial to enhance the diversity and representativeness of minority classes.

The two-step application of SMOTE enabled both reinforcement near decision boundaries [69] and complete class balancing [70], ensuring improved model generalization without lousing critical information, an essential requirement for reliable CVD prediction from ECG signals. Enhancing minority classes in this way is particularly important in medical datasets, where imbalance can significantly bias model predictions [71,72].

Upon completion of the preprocessing phase, which ensures high-quality and class-balanced ECG inputs, the ADWIN-GFR framework advances to a critical intermediate stage: the management of memory to support continual learning in non-stationary environments. As new data are introduced over time, it becomes essential to retain a carefully selected subset of past instances that can guide future model updates without introducing unnecessary redundancy. To meet this requirement, the Selection Module governs the construction and maintenance of the replay buffer using a principled sampling strategy. Rather than storing historical data indiscriminately, the module prioritizes instances that are most representative of the underlying and evolving data distribution. This selective approach ensures that the memory remains both computationally efficient and semantically informative, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to adapt incrementally while preserving prior knowledge. The following section provides a detailed account of the methodological foundations and operational mechanisms of this component within the overall adaptive learning framework.

The Selection Module is responsible for maintaining a compact yet informative subset of past ECG samples within the replay buffer. To ensure the selected instances contribute significantly to continual learning, the module evaluates each candidate sample using three complementary criteria: prediction variance, feature diversity, and distributional coverage.

Prediction variance: is measured as the uncertainty of the model’s output for a sample xi. It is calculated as the variance of the predicted class probabilities produced by the softmax layer. The variance is computed as follows:

where:

• C is the number of classes.

• pij is the softmax probability of class “j” for sample “xi”

• μi is the mean probability across all C classes, it is calculated as follows:

Samples with higher prediction variance indicate uncertain model decisions and are prioritized for storage.

Diversity ensures heterogeneity within the buffer by favoring samples that are dissimilar from existing ones. Given a feature embedding f(x), cosine similarity between the candidate and existing buffer embedding is computed between xi and all samples xj in the buffer (B). The diversity score is defined as:

Higher values imply greater dissimilarity, helping the buffer avoid redundancy.

Distributional coverage: ensures that the buffer spans the input space effectively. For this, the Euclidean distance between a candidate xi and the centroid μB of the buffer is computed as follows:

where:

Candidates that expand the feature space coverage are prioritized.

The final selection score for each sample is obtained by a weighted combination of these three metrics, and the top-K scoring samples are retained in the buffer. This principled, multi-objective selection strategy ensures that the replay buffer remains both representative of past data and responsive to new distributions, thereby strengthening the model’s ability to adapt under concept drift.

After the replay buffer has been populated by the Selection Module, the ADWIN-GFR framework advances to its primary predictive component. At this stage, the curated set of representative instances serves as input to “Feature Extraction and Prediction Module” designed to extract meaningful features and perform multi-class arrhythmia classification. The following section provides a detailed exposition of the CNN-GRU model, outlining its hierarchical structure and its critical role in achieving high predictive performance and adaptability in non-stationary, real-world data environments.

3.2.3 Feature Extraction and Prediction Module

At the core of the ADWIN-GFR framework lies a DL model specifically designed to extract both spatial and temporal features from ECG signals. This hybrid architecture combines one-dimensional CNNs and GRUs, leveraging the CNN’s ability to capture local morphological patterns and the GRU’s strength in modeling sequential dependencies. Such a design is particularly well suited for time-series biomedical data, where both waveform shape and signal continuity are diagnostic significance.

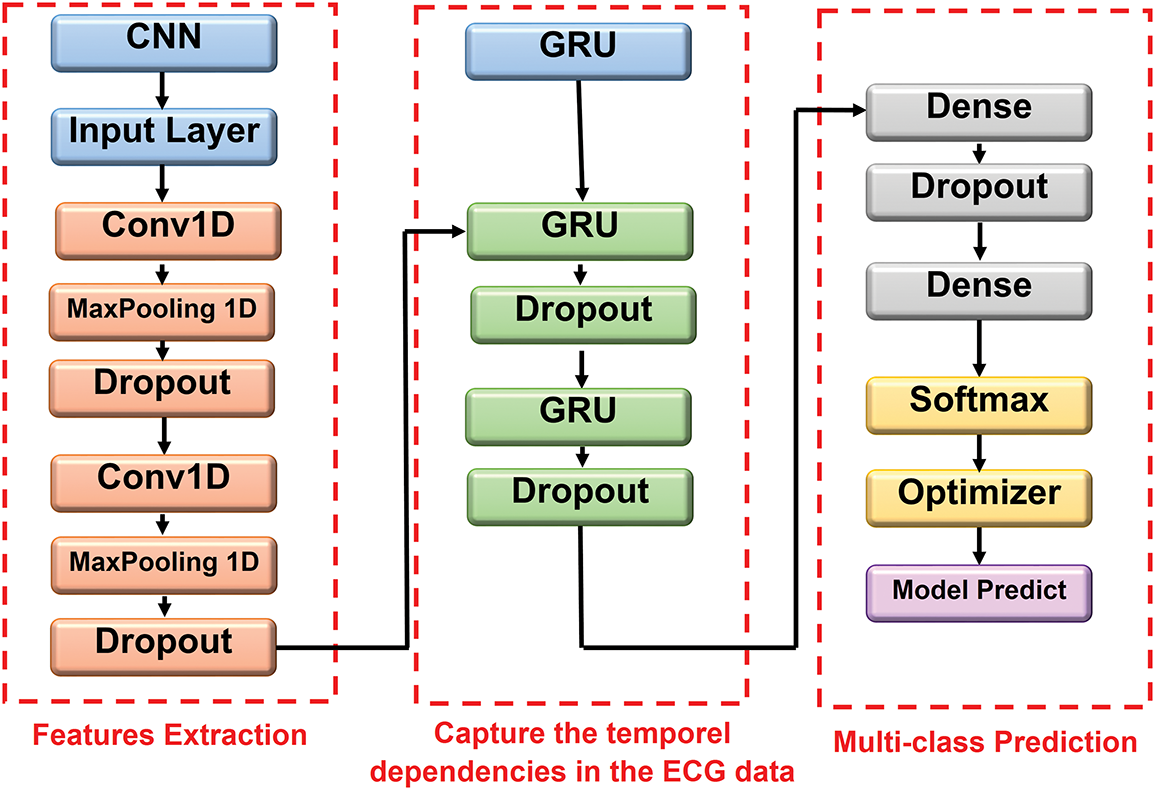

The model processes preprocessed ECG segments. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the architecture consists of three major stages:

• Feature Extraction via Convolution: Two Conv1D layers with 64 and 128 filters (kernel size = 5) are applied to detect short-term temporal features. Each convolution is followed by max pooling (pool size = 2) for down sampling and dropout for regularization.

• Temporal Modeling with GRUs: The resulting feature maps are passed through two GRU layers containing 128 and 64 units, respectively. The first GRU retains the full temporal sequence, while the second summarizes it into a compact representation. Dropout layers are also applied to both GRUs to improve generalization.

• Classification: The final representation is passed to a fully connected (Dense) layer with 32 neurons and ReLU activation, followed by an output Dense layer with softmax activation. The output layer produces class probabilities across five heartbeat types: Normal, Supraventricular ectopic, Ventricular ectopic, Fusion, and Unknown.

Figure 3: Illustrative representation of CNN-GRU architecture

This architectural design balances local feature extraction, temporal coherence, and nonlinear classification, ensuring robustness through systematic dropout regularization at multiple abstraction levels.

The features extraction and prediction module is first trained offline to extract key spatial and temporal features from clean ECG signals, providing a robust initial representation of cardiac patterns. During deployment, this model is incrementally updated using a GFR-based fine-tuning strategy to adapt to new data without forgetting prior knowledge. As this module is the core prediction engine of the ADWIN-GFR framework, its Softmax outputs are continuously monitored to assess performance stability. In particular, the ADWIN-based Drift Detection Module plays a critical role in identifying significant shifts in data distribution that may impact model accuracy. The following section provides an explanation of this component and its integration within the adaptive learning pipeline.

This module involves continuous monitoring and dynamic adjustment of the model’s components to maintain system accuracy and adaptability over time. To achieve this, the ADWIN technique is employed to detect changes in the data distribution and trigger timely updates of the model.

The core mechanism of ADWIN relies on tracking prediction error over time through a dynamically adjusted sliding window. This window is continuously divided into two segments: one capturing recent observations and the other representing earlier data. Concept drift is flagged when the difference between the average errors in these segments surpasses a statistically defined threshold, as determined by the following formula:

where:

• μ sign: represents the average prediction error in the most recent data segment.

• μ sign_prev: denotes the average prediction error in the earlier data segment.

• n sign: indicates the number of data points in each sub-window (i.e., the window size used for comparison).

• δ: is the confidence level (ranging from 0 to 1) that defines the likelihood of error detection. Lower values of δ correspond to higher confidence and stricter detection criteria for drift.

Upon detecting a concept drift, the Adaptation Module responds by selectively updating the model in a way that maintains both accuracy and stability. Rather than simply replacing previous knowledge, it enables the model to integrate new information while preserving what has already been learned. The next section offers a detailed explanation of how this module operates and how it supports continual learning in dynamic, non-stationary environments.

The Adaptation Module constitutes a critical element of the ADWIN-GFR framework, designed to activate automatically in response to concept drift identified by the ADWIN-based detection component. Its principal role is to ensure that the CNN-GRU model remains both accurate and responsive to evolving ECG data streams, while also preserving previously learned knowledge, an essential requirement for reliable, real-time cardiovascular monitoring systems. This module achieves its objective through two fundamental processes:

1. Replay Buffer Updating: This mechanism updates and preserves a well-balanced mix of older and more recent data samples. It ensures that the model’s retraining process can access to both established patterns and newly variations in the data stream.

2. GFR-Feature Relay (GFR) Fine-Tuning: This phase performs targeted model updates, it uses a regularization techniques to minimize catastrophic forgetting and retain critical information from prior learning phases.

Together, these two processes operate in collaboration to handle not only the concept drift but also to ensure model stability over time within a continual learning setting.

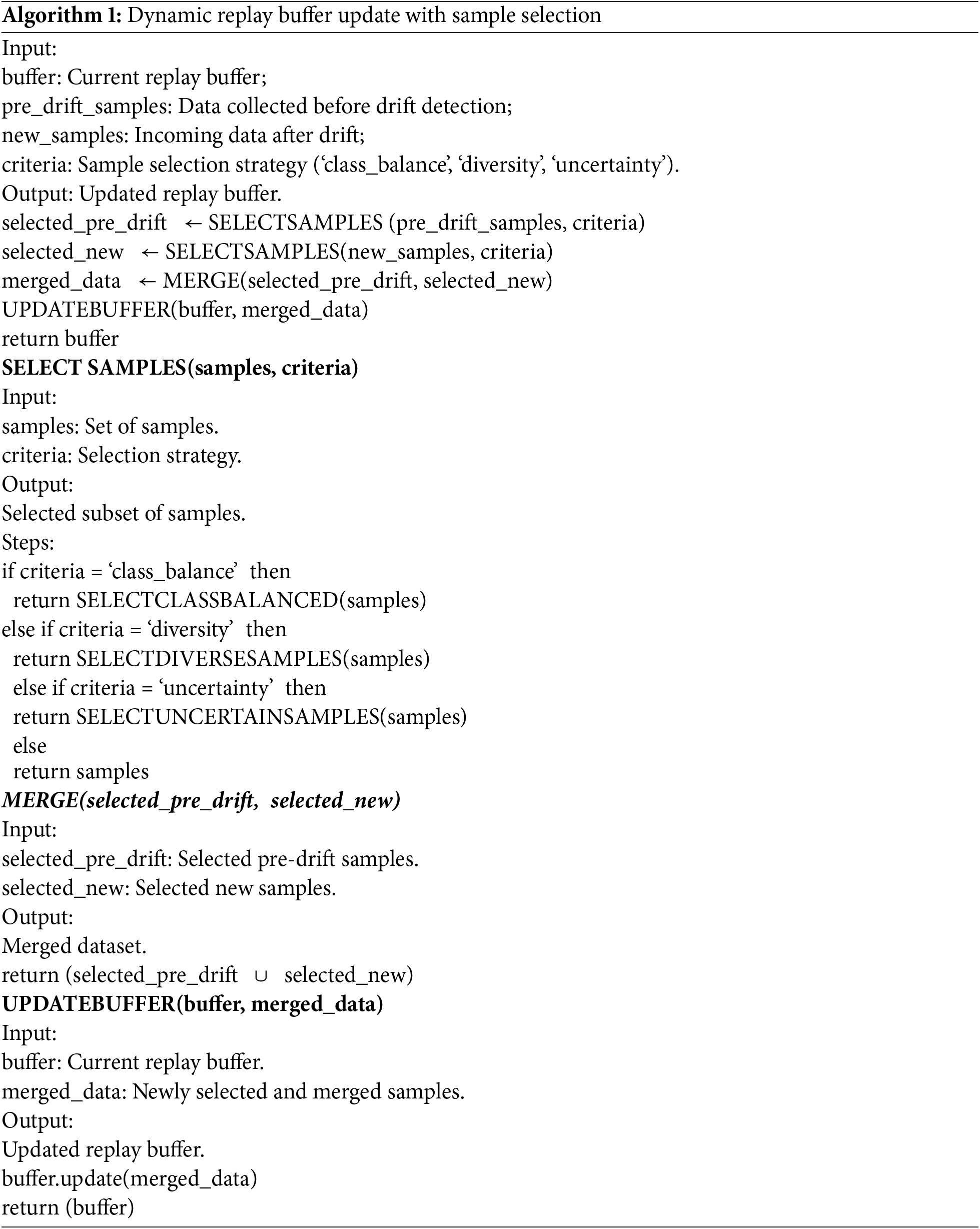

1. Replay Buffer Updating

To maintain alignment with the evolution of data distribution, the replay buffer memory is periodically updated. This process is triggered when the Drift Detection Module detects a distributional shift, prompting the activation of the selection module, which identifies a limited set of the most informative and representative instances from the new data stream. Older representations in the buffer are replaced with these selected examples, ensuring the buffer remains compact yet reflective of both historical and current experiences. This updated buffer serves as a robust foundation for stable and effective continual model adaptation. The following algorithm (Algorithm 1) presents the detailed steps for updating the replay buffer.

Although the replay buffer update mechanism ensures that the memory remains synchronized with the evolving data distribution, it is not sufficient to guarantee robust model adaptation in non-stationary environments. To address this limitation, the ADWIN-GFR framework integrates a complementary fine-tuning module designed to optimize the model’s internal parameters while preserving critical representations learned prior to the drift. This module enables the framework to incorporate new data patterns effectively, mitigating the risk of catastrophic forgetting. The following subsection provides a detailed overview of the GFR-based fine-tuning strategy, emphasizing its dual-objective optimization process and its essential role in sustaining both predictive accuracy and feature stability throughout the continual learning process.

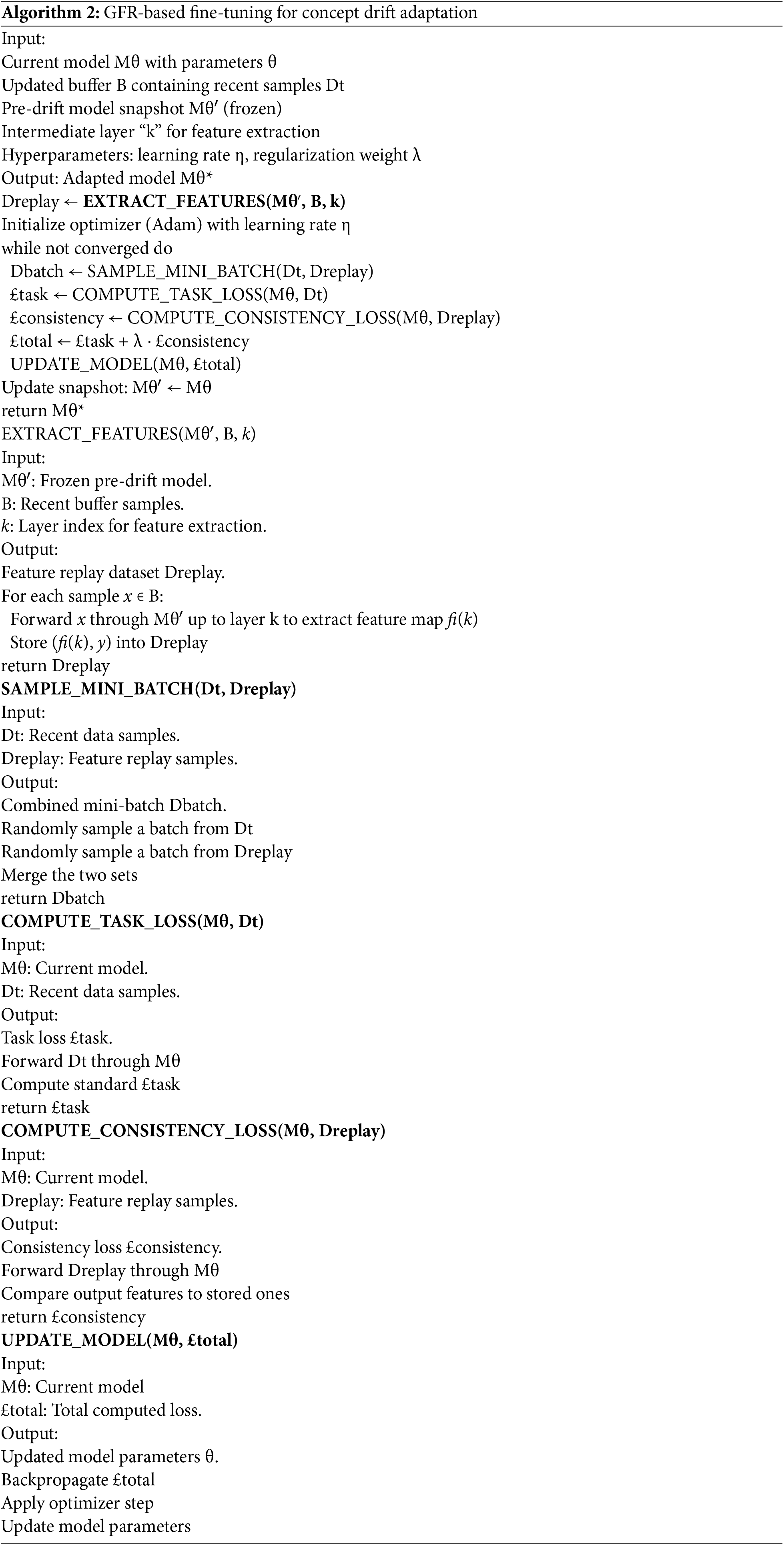

2. GFR-Based Fine-Tuning Strategy

Following updating the replay buffer, ADWIN-GFR frameworks use a GFR-based fine-tuning strategy to adapt the CNN-GRU model to non-stationary data distributions that change over time while simultaneously mitigating the risk of catastrophic forgetting. In contrast to conventional fine tuning methods, which may overwrite the previously learned knowledge, the two-phase optimization of the GFR-based approach enables new information to be integrated while still preserving the essential semantic representations made by earlier training steps.

The central idea of GFR is to store the intermediate feature representations derived from a frozen snapshot of our CNN-GRU model just before it captures the concept drift. These cached activations serve as a generative memory, providing a stable reference that guides the model’s adaptation process and supports continuity in learning without compromising previously acquired knowledge. The full adaptation process using GFR unfolds in two main phases:

• Features Extraction and Buffer Management

Upon the detection of concept drift, the ADWIN-GFR framework initiates its fine-tuning pipeline by leveraging a frozen snapshot of the CNN-GRU model, captured immediately prior to the drift event. This snapshot preserves the semantic knowledge learned under the previous data distribution and serves as a stable reference for guiding the adaptation process.

To extract historically meaningful representations, samples from the updated replay buffer, which includes both pre-drift and post-drift instances, are passed through the frozen model. Feature extraction is performed at an intermediate layer selected for its ability to encode high-level, task-invariant abstractions without being overly specialized to the original class boundaries. In the current implementation, we empirically select layer k = 3 corresponding to the output of the second Conv1D layer. This layer effectively captures a balance between local spatial features and global sequential dependencies, making it ideal for semantic preservation across drift.

For each input sample xi in the buffer, the frozen model computes a feature representation at layer k, yielding an activation tensor fi(k) ∈ RT×C, where:

• T is the number of time steps remaining after convolution and pooling operations (e.g., T = 125 after two Conv1D layers and stride−2 max pooling),

• C is the number of filters in layer k (e.g., C = 128 for Conv1D_2), resulting in a high-dimensional feature map of shape 125 × 128.

To minimize memory consumption and computational load during fine-tuning, these feature maps are compressed using channel-wise Principal Component Analysis (PCA). In this step, each channel is treated as a separate variable, and PCA is applied across time to reduce redundancy.

Given a matrix of flattened activations across N samples, F ∈ RN×d, where d = T × C, PCA projects the data into a lower-dimensional subspace. The reduced dimensionality is selected such that it retains at least 95% of the cumulative explained variance, preserving the most informative components while optimizing storage.

The resulting compressed features are temporarily cached in memory and used as generative replay targets. During fine-tuning, the updated model is encouraged to produce internal activations that remain aligned with these pre-drift representations, thereby enforcing feature-level consistency. This alignment is crucial for maintaining representational stability and reducing the risk of catastrophic forgetting, as it ensures that the updated model preserves essential semantic knowledge while adapting to newly observed patterns.

• Dual-Objective Optimization

During the fine-tuning phase, the model is trained using joint optimization over two complementary objectives:

• Task-Specific Supervised Loss (£ task):

A cross-entropy objective computed on newly observed samples

where:

- Zi(L) denotes the logits for sample Xi at the final layer L.

- N represents the total number of samples in the batch Dt.

- SoftMax(Zi(L)) denotes the softmax function applied to the logits Zi(L), which converts them into a probability distribution over the output classes.

- Log is a natural logarithm, used within the cross-entropy to penalize incorrect predictions.

This loss function encourages the model to increase the probability assigned to the correct labels, thereby improving prediction accuracy over time.

• Feature-Level Consistency Loss (£ consistency)

A MSE loss is introduced to quantifies deviations between the current model’s intermediate activations

where k indexes the selected intermediate layer and M is the replay batch size. This component explicitly regularizes the model to preserve semantic relationships encoded in prior tasks. Thus, GFR directly intervenes by injecting feature-level memory constraints during fine-tuning, explicitly forcing the model to maintain consistency with past internal representations.

The final optimization objective combines both components, as follows:

The hyperparameter λ modulates the relative influence of knowledge preservation by adjusting the weight of the feature-level consistency loss (£ consistency) against the task-specific supervised loss (

The GFR-Based Fine-Tuning Strategy iterates until convergence, periodically updating the replay buffer with incoming data and refreshing the pre-drift model snapshot to reflect stabilized representations. The overall workflow is formalized in Algorithm 2.

Each component of the ADWIN-GFR framework is carefully designed to work together as part of a cohesive and adaptive learning pipeline. Following signal preprocessing and class balancing, the Selection Module identifies a representative subset of ECG samples using a principled strategy based on prediction uncertainty and distributional coverage. These samples are stored in a replay buffer, which plays a central role in supporting the CNN-GRU model’s ability to learn spatial and temporal features critical for accurate heartbeat classification. The model’s Softmax outputs are continuously monitored by the ADWIN-based Drift Detection Module, which detects significant shifts in the input data distribution. Upon drift detection, the framework initiates a targeted adaptation phase that updates the replay buffer and applies GFR-based fine-tuning to preserve prior knowledge while integrating new patterns. The close coordination of these components enables continual learning and ensures stable performance in dynamic, real-world ECG environments. This end-to-end process is visually summarized in Fig. 4, which illustrates the core modules and workflow of the ADWIN-GFR framework.

Figure 4: Workflow diagram of the ADWIN-GFR framework

The proposed ADWIN-GFR approach was implemented and evaluated using Google Colab (https://colab.research.google.com, accessed on 09 March 2025), which offers a virtualized computing environment suitable for DL experiments. The hardware configuration includes an NVIDIA P100 GPU, 12 GB of RAM, and temporary storage of up to 100 GB. Persistent data storage and model checkpoints were managed through Google Drive to facilitate seamless integration and experimental reproducibility.

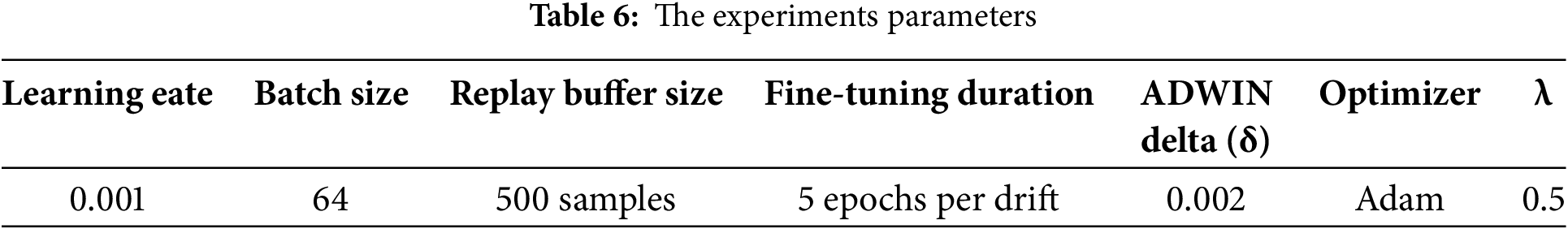

The experimental setup and hyperparameter configurations are summarized in Table 6. The following key parameters were selected to ensure stable convergence, efficient learning, and effective model adaptation:

• Learning Rate (0.001): Selected as a standard configuration for the Adam optimizer, ensuring stable convergence without instability during training. A ReduceLROnPlateau scheduling strategy was implemented, wherein the learning rate was reduced by a factor of 0.5, if the validation loss did not improve over five consecutive epochs, with the minimum learning rate constrained to 1 × 10−4.

• Batch Size (64): Chosen to provide an optimal trade-off between computational efficiency and model generalization, ensuring stable gradient updates while maintaining adequate training speed.

• Replay Buffer Size (500 samples): Chosen to store a diverse subset of previous data while preventing memory overload, ensuring effective retention of important information.

• Fine-Tuning Duration (5 epochs per drift): ensures adequate model adaptation to new data distribution while preventing overfitting to recent drift occurrence.

• ADWIN Delta (δ = 0.002): A delta value of 0.002 was selected to provide balanced sensitivity for detecting concept drifts without introducing excessive false positives.

• Optimizer (Adam): The Adam optimizer was selected for its adaptive learning rates and effectiveness in training deep neural networks, ensuring efficient optimization.

• Regularization Factor (λ = 0.5): This factor ensures an appropriate balance between preserving previously acquired knowledge (stability) and enabling rapid adaptation to new concepts (plasticity), thus mitigating catastrophic forgetting.

The model’s performance was evaluated using the following key metrics:

• Accuracy: measures the proportion of correct predictions made by the model relative to the total number of predictions. It is calculated using the following formula:

• Macro-F1-score: represents the average of the F1-score calculated separately for each class. It is calculated using the following formula:

where:

– N is the total number of classes,

– F1i is the F1-score for class i, and each F1i is computed as:

with:

where: TPi, FPi, FNi are the True Positives, False Positives, and False Negatives for class “i”.

• Forgetting score: measures the extent to which the model forgets previously acquired knowledge (pre-drift performance) after learning new data (post-drift). It is calculated using the following formula:

• Detection Delay: refers to the time interval (or number of steps) between the actual occurrence of concept drift and its detection by the model. It reflects the responsiveness of the drift detection mechanism., where lower values indicate faster adaptation to changes.

• Adaptation Gain (%): refers to the improvement in model performance (typically in terms of accuracy or F1-score) after adaptation to drift, compared to a Naive Fine-Tuning or pre-adaptation performance.

4.4 Experiment 1: Robustness Evaluation under Diverse Concept Drift Scenarios

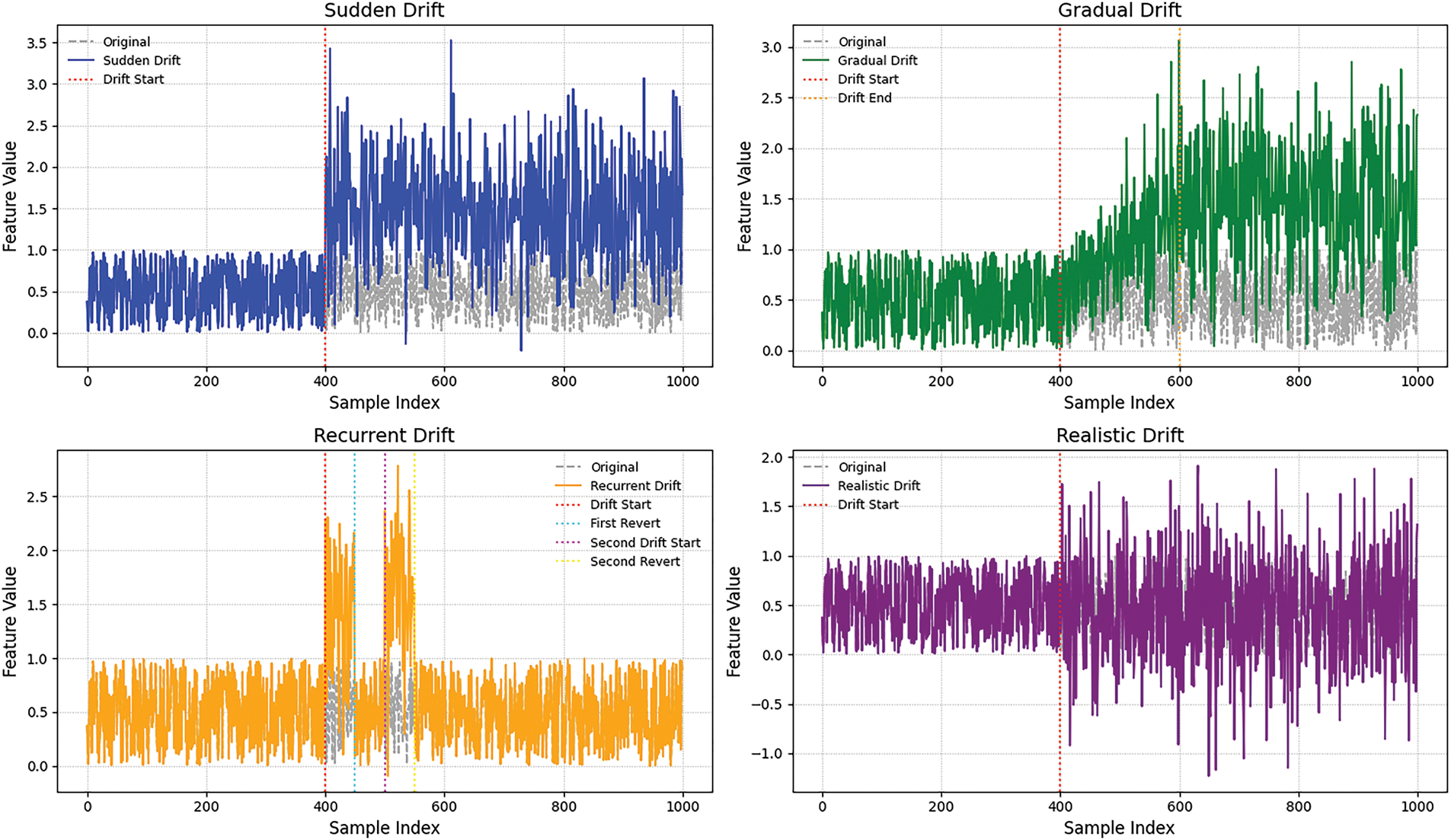

To evaluate the robustness of the ADWIN-GFR framework under diverse real-world drift conditions, we conducted experiments across four representative scenarios: sudden, gradual, recurrent, and realistic drifts. Sudden drift is characterized by an abrupt and complete change in the data distribution, while gradual drift represents a progressive shift where the new concept gradually replaces the old one. Recurrent drift involves the reappearance of a previously observed drift, testing the model’s memory retention. Realistic drift is simulated through ECG noise injection, sensor signal corruption, and domain-specific variability, reflecting practical data challenges.

Fig. 5 illustrates the temporal evolution of a selected feature across four distinct concept drift scenarios.

Figure 5: Visualization of drift types

• The sudden drift scenario, an abrupt shift in feature values occurs, indicating an immediate change in data distribution.

• The gradual drift shows a smooth transition where feature values progressively diverge.

• Recurrent drift demonstrates a temporary shift followed by a return to the original distribution.

• Realistic drift introduces irregular variations due to noise injection and partial feature corruption, effectively simulating real-world data variability.

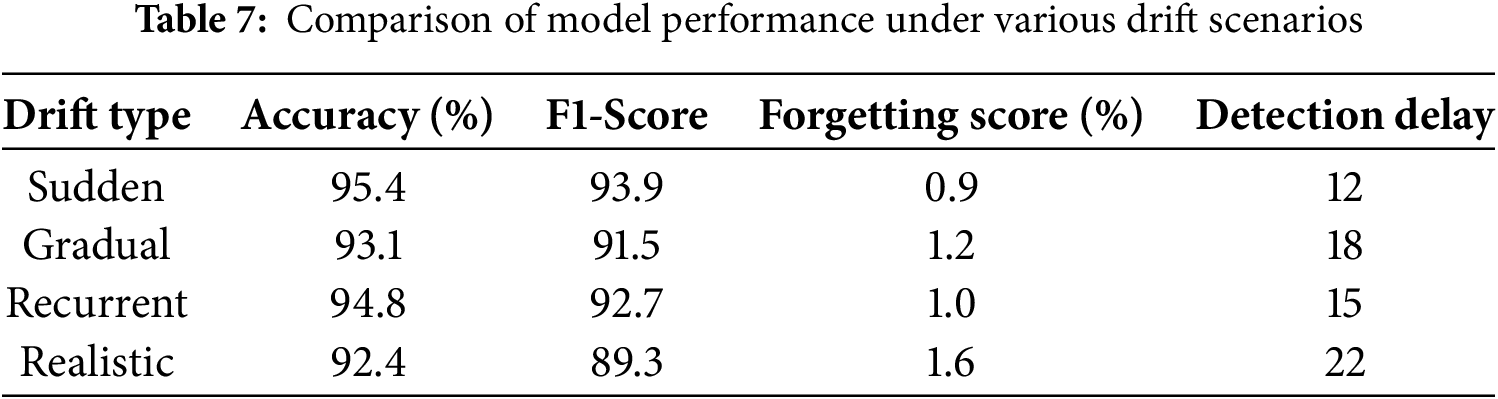

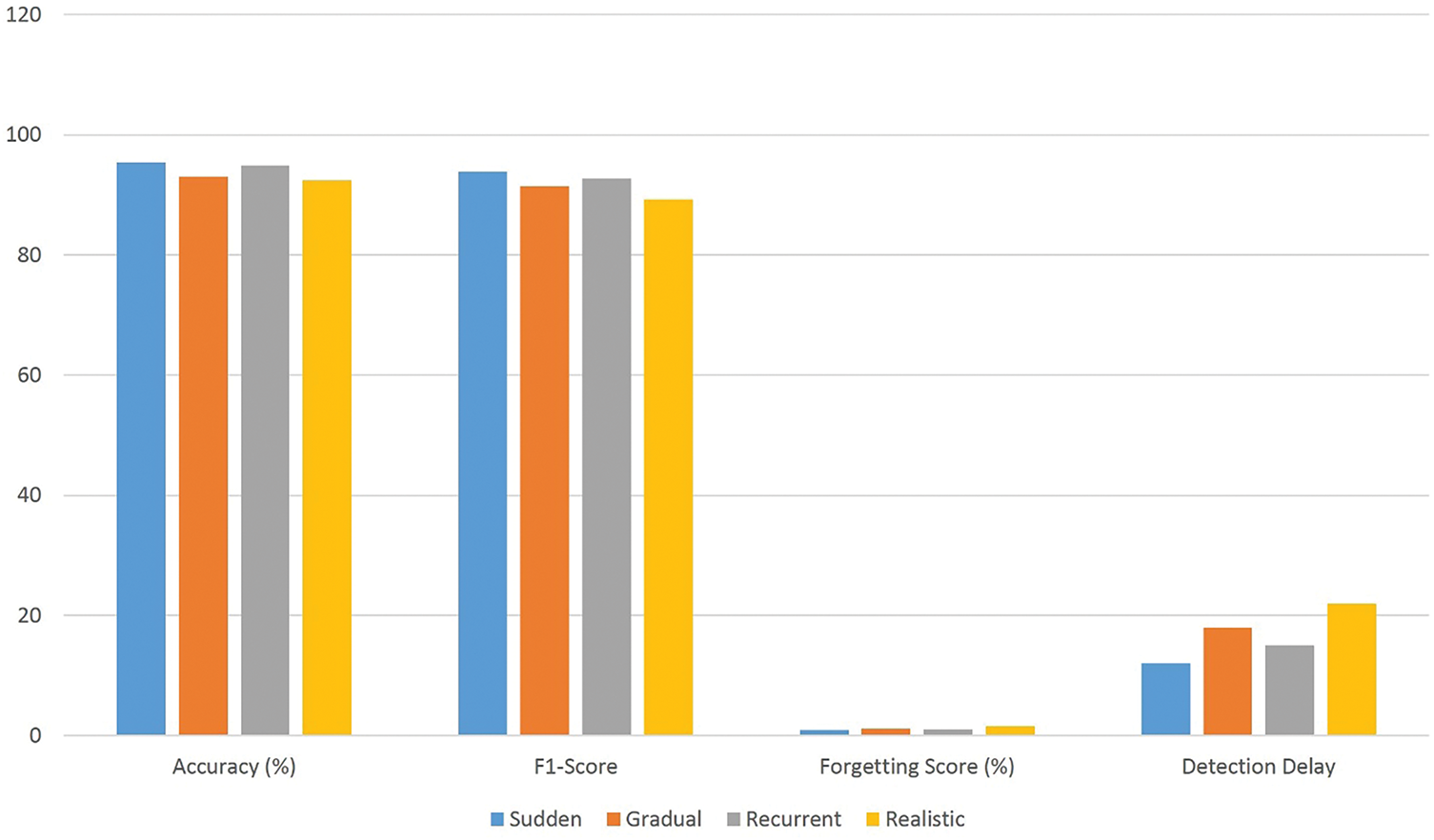

The drift types were injected into the test data, and each scenario was evaluated using the previously described metrics, as summarized in Table 7 and illustrated in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Comparison of model performance under various drift scenarios

According to the results obtained in Table 7 and Fig. 6:

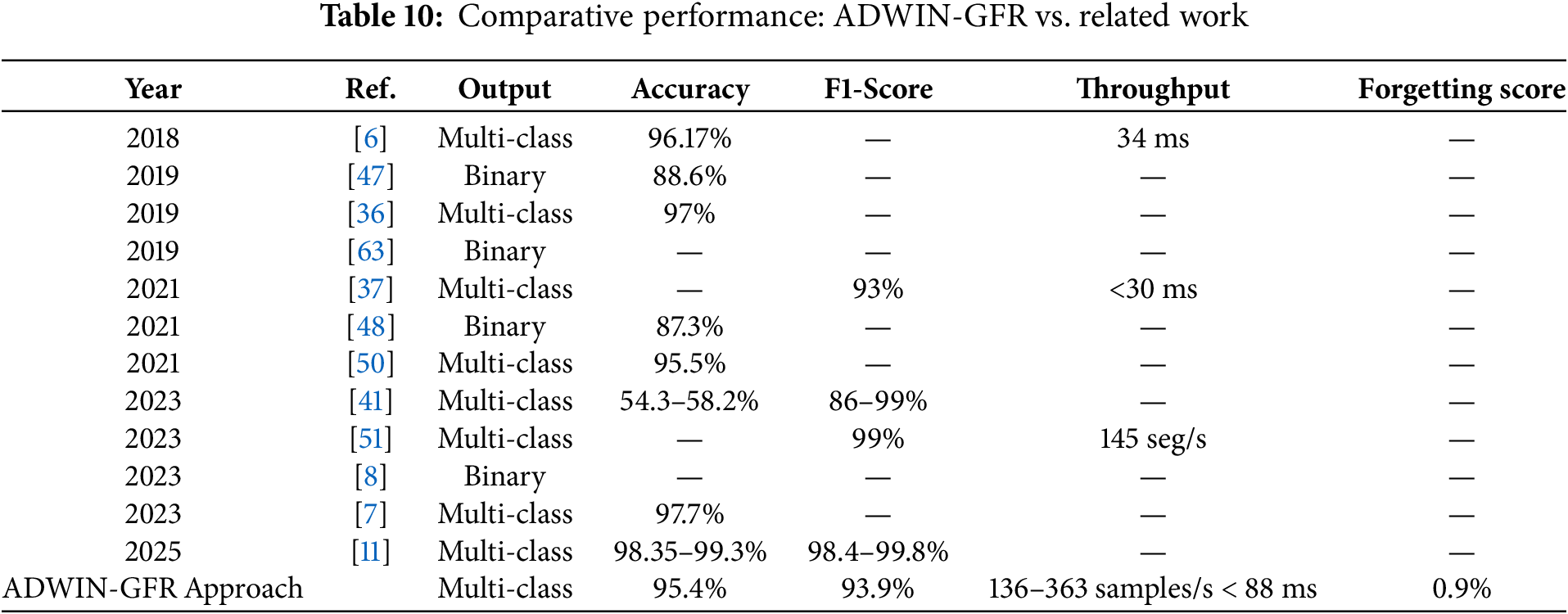

• In the sudden drift scenario, where data distributions shift instantly, the model achieves high accuracy (95.4%) and macro F1-score (93.9%), with low forgetting score (0.9%) and minimal detection delay (12 steps). These results highlight the effectiveness of the ADWIN-based drift detection mechanism and the GFR-enhanced fine-tuning in. enabling rapid model adaptation while preserving the knowledge it has previously learned.

• In the gradual drift setting, where the data distribution shifts progressively over time, the model maintains strong performance with a post-drift accuracy of 93.1% and a macro F1-score of 91.5%. The slightly increased drift detection delay (18 steps) is expected due to the slower nature of change. The low forgetting score (1.2%) confirms the framework’s capacity to remain tuned to track changing patterns without substantial performance degradation.

• Under the recurrent drift scenario, where previously encountered distributions reappear, the model demonstrates excellent knowledge retention and generalization. The accuracy remains high at 94.8% with F1-score of 92.7%, and a minimal forgetting score of 1.0%, indicating that the replay strategy effectively reinforces earlier knowledge without overfitting to recent data segments.

• In the realistic drift scenario, involving signal noise, sensor variation, and simulation of real ECG disturbances, the proposed method still performs robustly, achieving 92.4% accuracy and 89.3% macro F1-score. Although the forgetting score (1.6%) and delay detection (22 steps) are slightly higher, the results confirm the framework’s resilience under real-world changeability.

These results not only demonstrate robustness to various forms of drift but also reflect the model’s responsiveness and low-latency adaptation, key properties for real-time ECG signal monitoring.

4.5 Experiment 2: Comparative Evaluation of Drift Detection Techniques

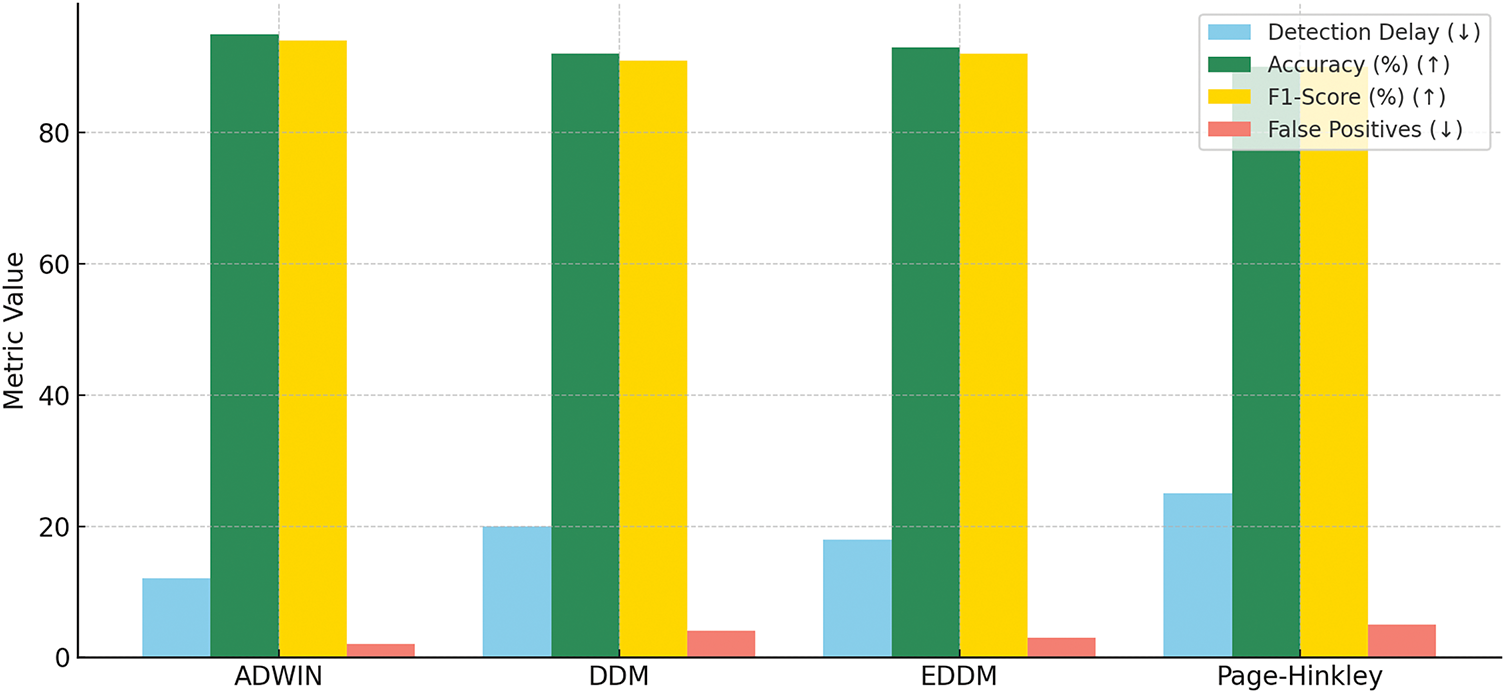

This experiment assesses the effectiveness and efficiency of the proposed drift detection module; ADWIN; by comparing it against well-established alternatives, including DDM [54], EDDM [55], and Page-Hinkley [68]. The goal is to validate that ADWIN provides a good balance between detection speed, model performance post-adaptation, and false positives, thereby reinforcing its relevance for real-time ECG signal monitoring.

Drift Scenario: A stream of ECG data is constructed with known drift points (sudden, gradual, recurrent and realistic drift types). The same stream is processed independently with the different drift detectors (ADWIN, DDM, EDDM and Page-Hinkley).

To compare the performance of each drift detection technique, we compute the average of various evaluation metrics including detection delay, accuracy, macro F1-score, and false positives, across different types of drift (sudden, recurrent, gradual, and realistic).

These were aggregated across all drift types to provide a comprehensive view of each detector’s strengths and limitations under dynamic ECG signal conditions.

Fig. 7 represents a comparative visualization of various drift detection methods, ADWIN, DDM, EDDM, and Page-Hinkley, across several performance criteria:

• Post-Drift Accuracy: ADWIN achieves the highest accuracy (95.4%), followed by Page-Hinkley (92.3%).

• Macro F1-Score: ADWIN also maintains the most balanced class-wise performance (93.9%).

• Detection Delay: ADWIN detects drifts faster (12 steps), while others, such as Page-Hinkley, show higher delays (up to 20 steps).

• False Positives: ADWIN generates the fewest false positives (1), outperforming others in detection reliability.

Figure 7: Comparison of drift detection methods on ECG signal data

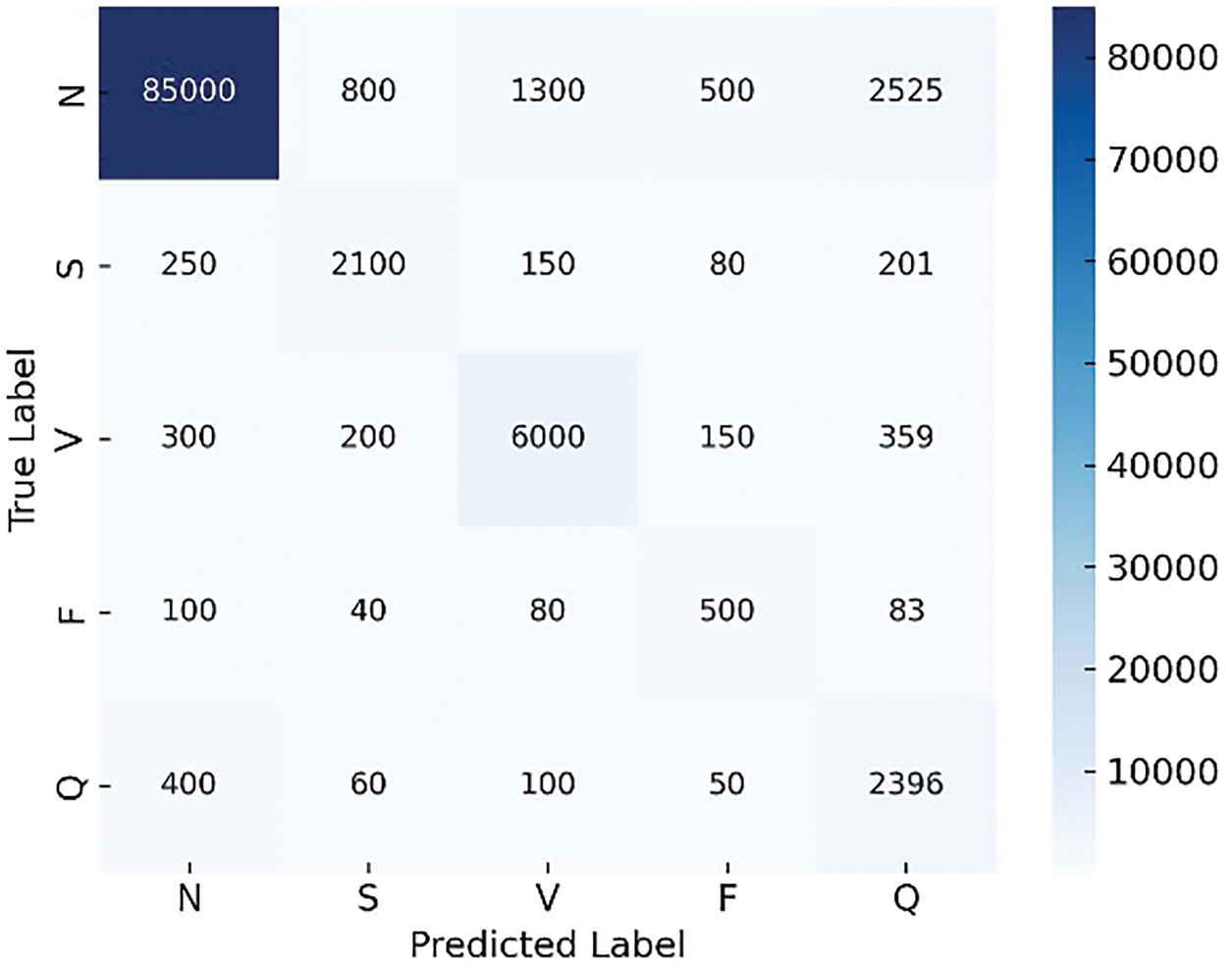

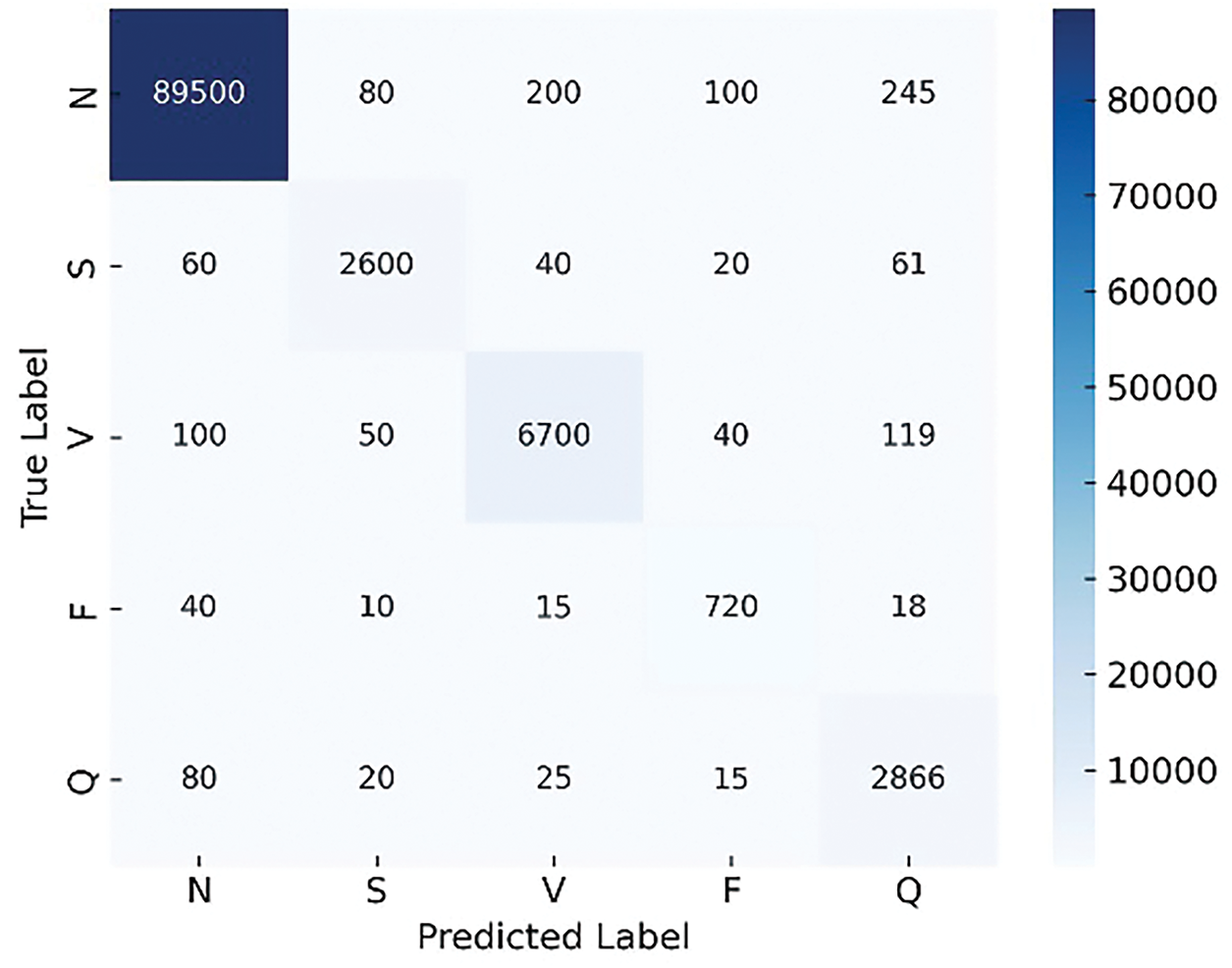

4.6 Experiment 3: Class-Wise Performance Comparison Using Confusion Matrices: GFR-Based Fine-Tuning vs. Standard Fine-Tuning

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed ADWIN-GFR framework, we present a comparative analysis of GFR-based fine-tuning and the standard fine-tuning approaches, using confusion matrices. These matrices provide detailed insights into class-wise performance, especially in the presence of class imbalance. To achieve this, we injected a sudden drift into the data.

As illustrated in Figs. 8 and 9, the ADWIN-GFR clearly outperforms standard fine-tuning, particularly for minority classes such as S and F, which are often challenging to classify. ADWIN-GFR maintains high true positive rates across all classes while significantly reducing misclassifications, especially for the majority N class.

Figure 8: Confusion matrix generated using standard fine-tuning

Figure 9: Confusion matrix generated using GFR-based fine-tuning

In contrast, the standard fine-tuning approach suffers from considerable performance degradation, with many beats misclassified across all classes. This observation aligns with the global performance metrics, confirming the superiority of the proposed GFR-based fine-tuning strategy in handling drift scenarios effectively while preserving class-wise balance and accuracy.

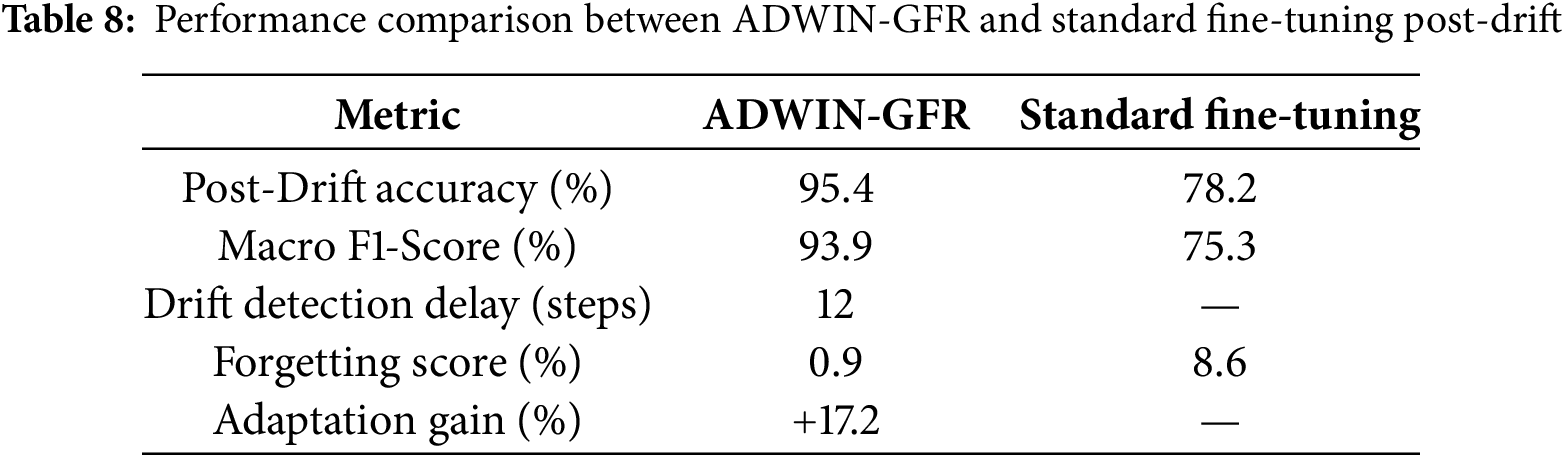

4.7 Experiment 4: Benchmarking ADWIN-GFR against Standard Fine-Tuning

To further substantiate the effectiveness and adaptability of ADWIN-GFR under non-stationary conditions, we present a benchmarking experiment against a baseline strategy employing standard fine-tuning. In this baseline, the model is updated solely using newly observed data following the occurrence of concept drift, without leveraging any form historical memory or adaptive learning mechanisms. This comparative analysis aims to emphasize the limitations of standard fine-tuning approaches and demonstrate the superior performance of ADWIN-GFR in preserving previously acquired knowledge, reducing drift-induced degradation, and achieving faster and more stable adaptation to evolving data distributions. In this experiment, we injected a sudden drift into the data.

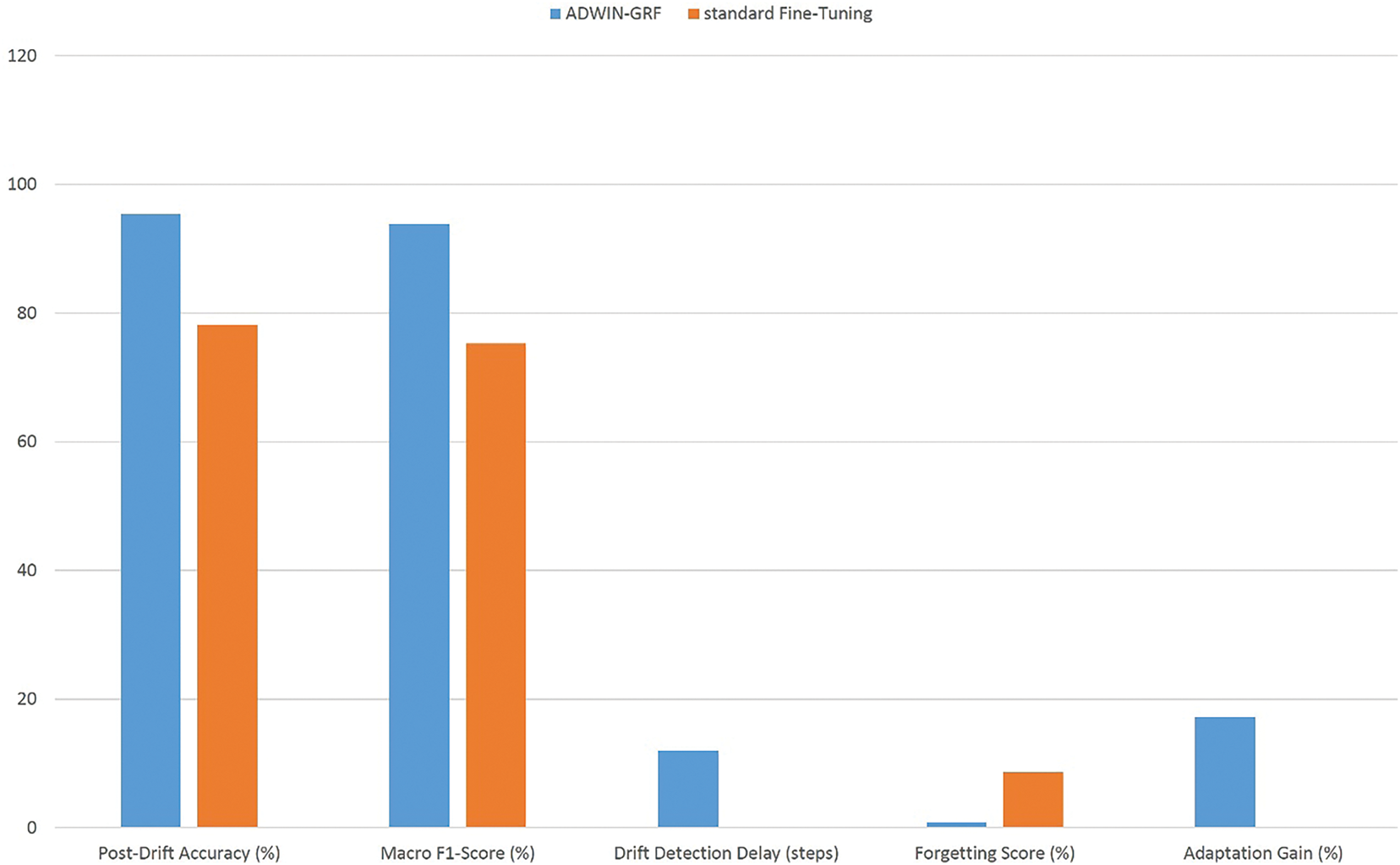

As summarized in Table 8 and Fig. 10, the ADWIN-GFR approach consistently outperforms the standard fine-tuning strategy across several key metrics. The following analysis provides a detailed interpretation of these results:

• Accuracy Improvement: The proposed method achieved a post-drift accuracy of 95.4%, representing a 17.2% improvement over the standard fine-tuning approach, which yielded only 78.2% accuracy post-drift. This significant difference highlights the benefit of integrating drift detection and feature replay into the adaptation process, ensuring the model remains aligned with the evolving data distribution.

• Macro F1-Score: The macro F1-score also showed a substantial increase in the proposed method (93.9%), compared to 75.3% for the standard fine-tuning approach. This improvement indicates that the model is better at maintaining balanced performance across all classes after drift, especially in cases of imbalanced class distributions following drift.

• Forgetting Score: One of the key advantages of the proposed method is its ability to reduce catastrophic forgetting. The forgetting score for the proposed method was only 0.9%, indicating minimal performance degradation on old tasks despite the introduction of drift. On the other hand, the standard fine-tuning approach exhibited a high forgetting score of 8.6%, as retraining from scratch causes the model to overwrite previously learned representations, resulting in a loss of accuracy on older data.

• Adaptation Speed: The drift detection delay for the proposed method was 12 steps, which is relatively low, demonstrating the system’s ability to respond promptly to the detection of drift. In contrast, the standard fine-tuning method has no such adaptive mechanism and is reactive only after retraining, leading to slower adaptation.

Figure 10: Performance comparison between ADWIN-GFR and standard fine-tuning post-drift

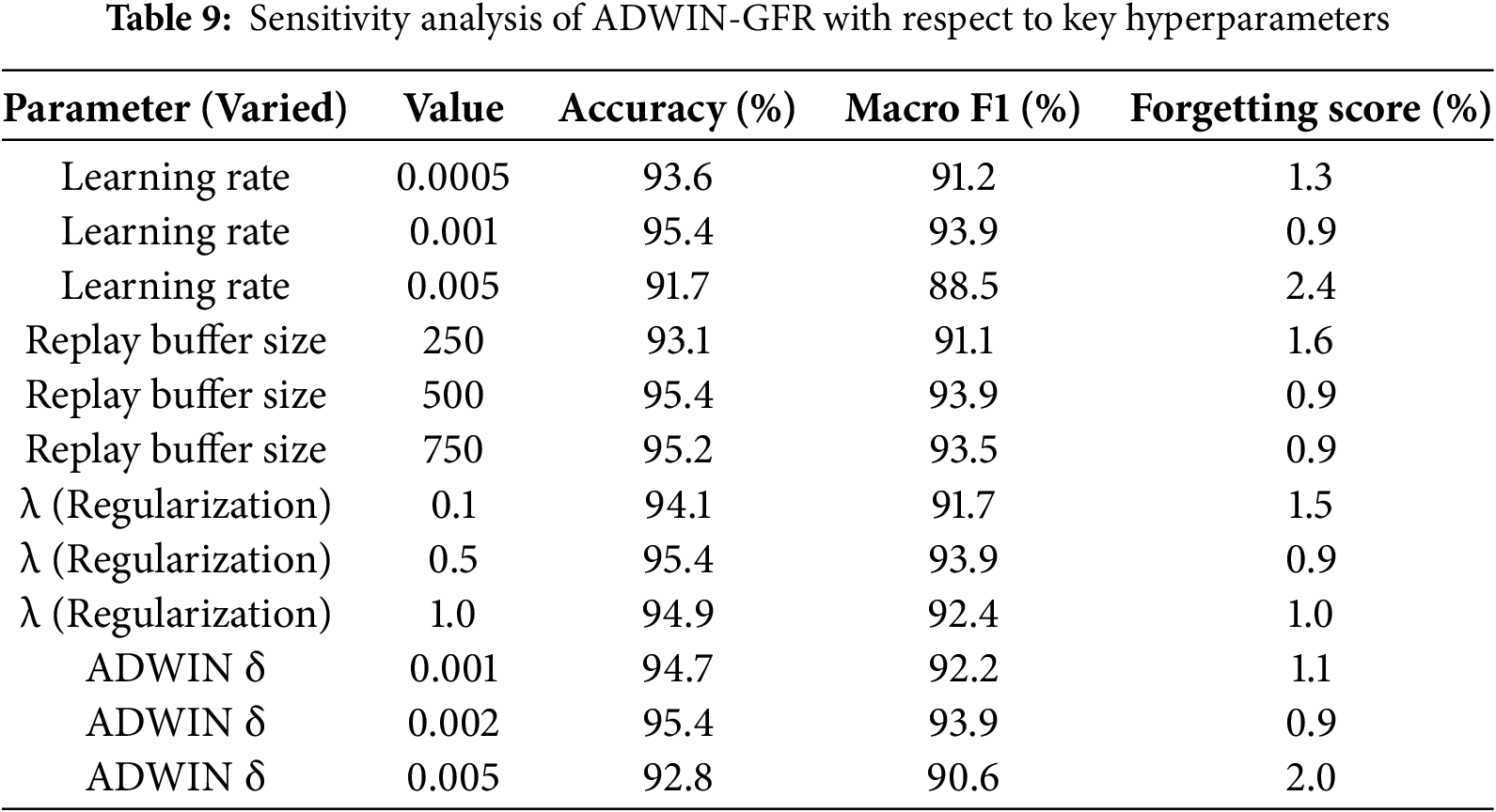

4.8 Experiment 5: Hyperparameter Sensitivity Evaluation under Concept Drift Scenarios

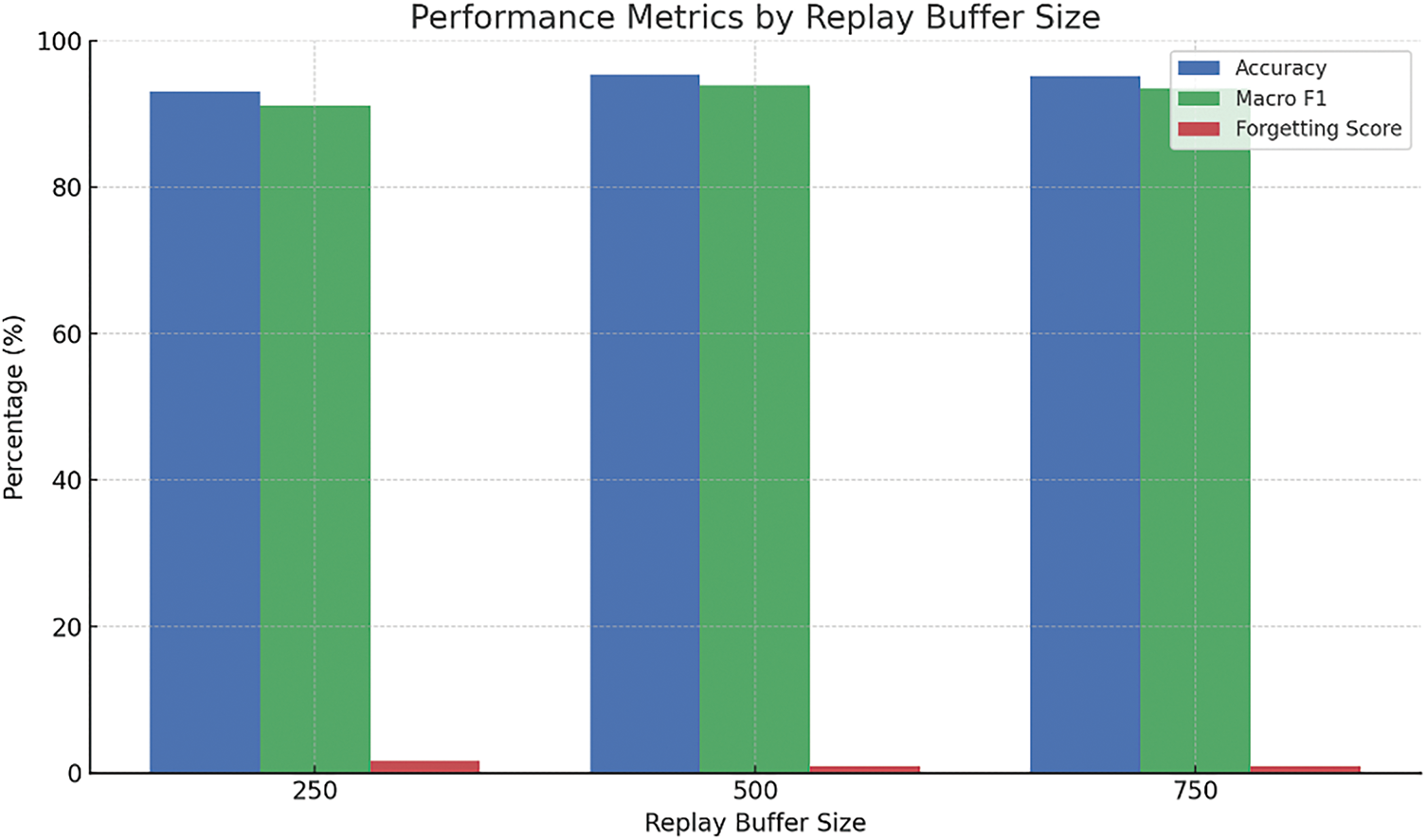

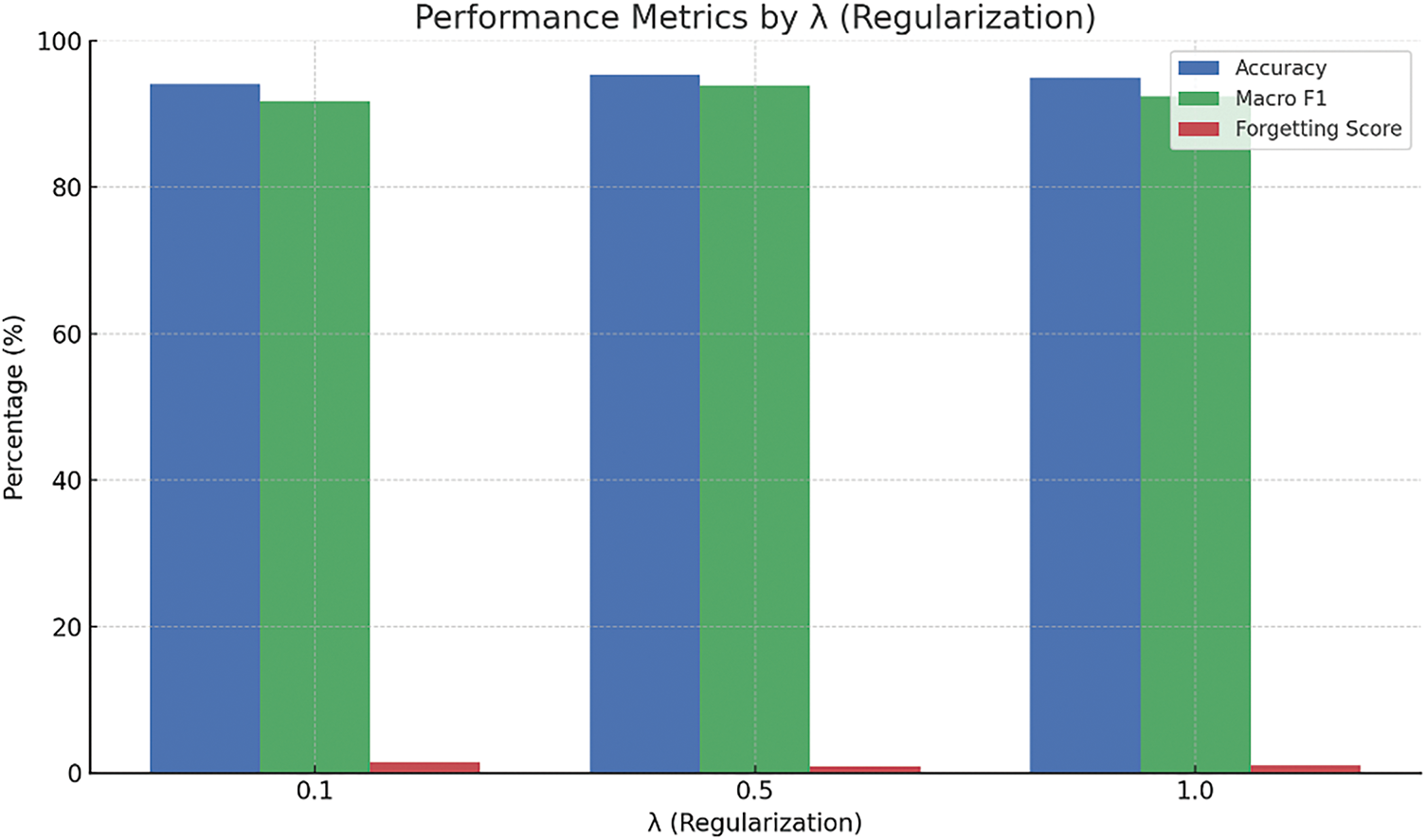

To strengthen the evaluation of the ADWIN-GFR framework, we conducted a detailed sensitivity analysis focusing on four key hyperparameters: learning rate, replay buffer size, regularization factor (λ), and the ADWIN drift detection threshold (δ). Each parameter was varied independently across three representative values, while the remaining parameters were held constant at their empirically optimal settings (learning rate = 0.001, buffer size = 500, λ = 0.5, δ = 0.002). This setup allowed for an isolated and fair assessment of each parameter’s influence on the model’s post-drift performance.

To reflect realistic and clinically relevant scenarios, the experiments were performed on ECG data streams incorporating two types of concept drift: sudden drift, which simulates abrupt physiological events (e.g., arrhythmias), and complex (realistic) drift, which models gradual or irregular changes typical of patients with comorbidities or evolving cardiac conditions. These drift types were deliberately selected to evaluate the model’s ability to handle both fast-acting anomalies and slow, progressive data shifts, challenges frequently encountered in real-world healthcare applications.

For each hyperparameter configuration, we report the mean performance across both drift types, using Accuracy, Macro F1-score, and Forgetting Score as evaluation metrics. To ensure statistical reliability, each experiment was repeated five times, and the results were averaged.

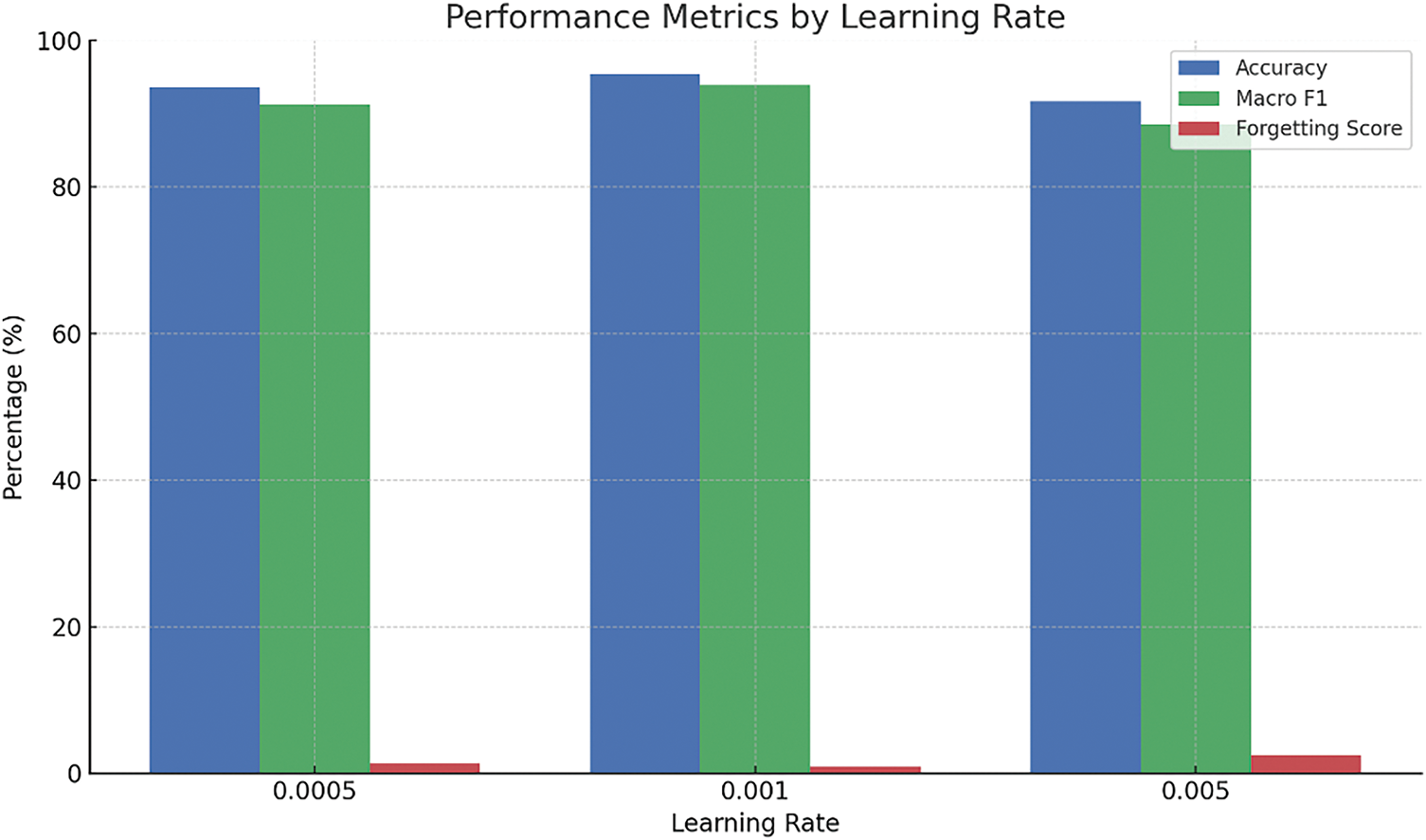

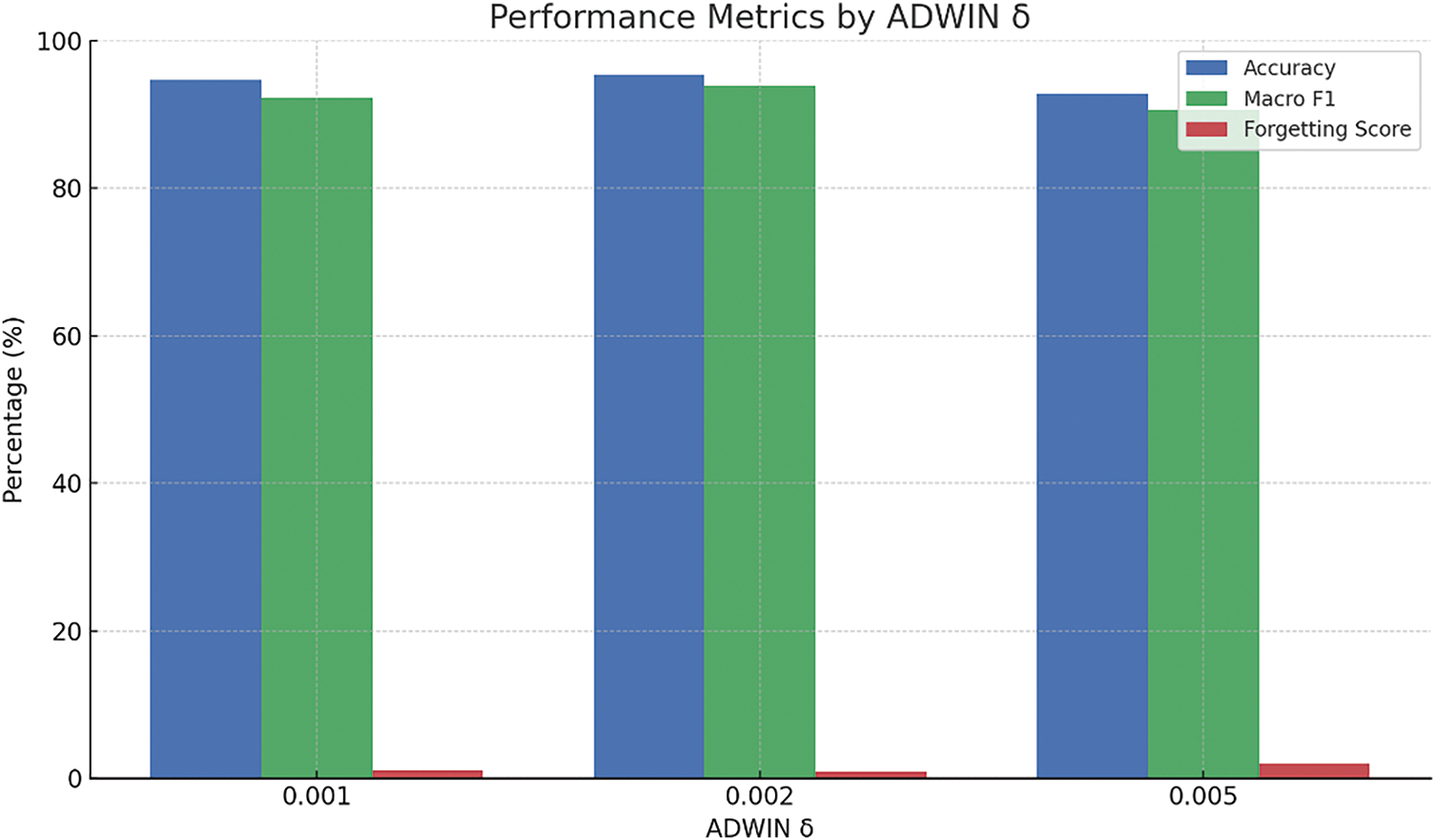

As shown in Table 9 and Figs. 11–14, the sensitivity analysis provides meaningful insights into how the ADWIN-GFR model responds to variations in its key hyperparameters. Among them, the learning rate stands out as particularly influential. A moderate setting of 0.001 delivers the strongest performance, achieving a high accuracy of 95.4%, a Macro F1-score of 93.9%, and the lowest forgetting score of 0.9%. However, when the learning rate is increased to 0.005, the model’s stability is noticeably affected, accuracy drops to 91.7%, and the forgetting score climbs to 2.4%, indicating a trade-off between fast adaptation and long-term reliability.

Figure 11: Impact of varying the learning rate on model performance

Figure 12: Influence of the ADWIN drift detection threshold (δ) on the model’s adaptability

Figure 13: Evaluation of replay buffer size on performance metrics

Figure 14: Effect of the regularization parameter λ on learning stability

The replay buffer size shows a similar trend. A buffer of 500 samples strikes the best balance between memory usage and performance, while increasing it further to 750 brings no meaningful gain. Conversely, reducing the size to 250 results in slightly poorer retention (forgetting score of 1.6%), suggesting that both under- and over-allocation can be suboptimal.

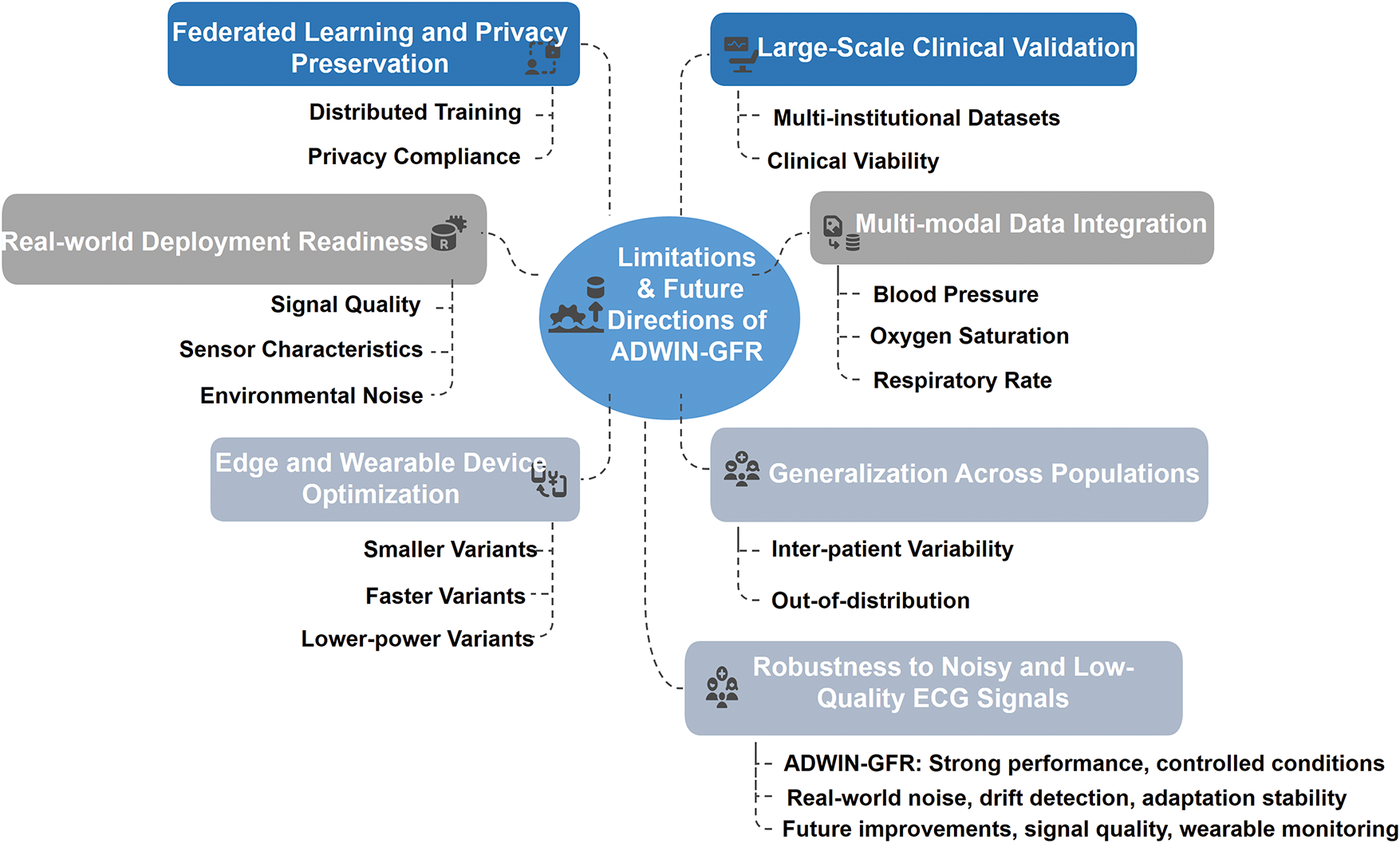

When examining the regularization parameter (λ), the model appears relatively stable across a moderate range. A value of 0.5 leads to optimal outcomes, while lower values (e.g., 0.1) lead to higher forgetting due to insufficient constraint on parameter updates. On the other hand, higher values (e.g., 1.0) tend to slightly suppress the model’s responsiveness to new information.