Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Online Estimation Method of Train Wheel-Rail Adhesion Coefficient Based on Parameter Estimation

1 School of Urban Rail Transportation, Shanghai University of Engineering Science, Shanghai, 201620, China

2 School of Transportation, Tongji University, Shanghai, 201834, China

* Corresponding Author: Wenliang Zhu. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(3), 2873-2891. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.068951

Received 10 June 2025; Accepted 05 September 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Aiming to address the challenge of directly measuring the real-time adhesion coefficient between wheels and rails, this paper proposes an online estimation algorithm for the adhesion coefficient based on parameter estimation. Firstly, a force analysis of the single-wheel pair model of the train is conducted to derive the calculation relationship for the wheel-rail adhesion coefficient in train dynamics. Then, an estimator based on parameter estimation is designed, and its stability is verified. This estimator is combined with the wheelset force analysis to estimate the wheel-rail adhesion coefficient. Finally, the approach is validated through joint simulations on the MATLAB/Simulink and AMESim platforms, as well as a hardware-in-the-loop semi-physical simulation experimental platform that accounts for system delay and noise conditions. The results indicate that the proposed algorithm effectively tracks changes in the adhesion coefficient during train braking, including the decrease in adhesion when the train brakes and slides, and the overall increase as the train speed decreases. The effectiveness of the algorithm was verified by setting different test conditions. The results show that the estimation algorithm can accurately estimate the adhesion coefficient, and through error analysis, it is found that the error between the estimated value of the adhesion coefficient and the theoretical value of the adhesion coefficient is within 5%. The adhesion coefficient obtained through the online estimation method based on the parameter estimation proposed in this paper demonstrates strong followability in both simulation and practical applications.Keywords

The traction and braking of trains are achieved through the transmission of tangential forces at the wheel-rail contact patch. The wheel-rail adhesion coefficient is a critical parameter influencing train traction, braking, and control stability. When the adhesion coefficient lies within an appropriate range, trains can efficiently transmit tractive and braking forces, ensuring stable operation [1]. However, due to the complexity of the wheel-rail contact interface and the variability of operating conditions, the adhesion coefficient is difficult to measure directly. This limitation restricts the precision of train operational safety monitoring and control systems. Insufficient adhesion during train operation significantly reduces traction and braking performance, leading to wheel slip at the wheel-rail interface, extended braking distances, and potentially causing rear-end collisions and derailments in severe cases, thereby jeopardizing operational safety [2]. Therefore, accurately estimating the wheel-rail adhesion coefficient has become a key technical challenge for ensuring safe train operation and improving operational efficiency.

In countries with advanced railway technology, research into the adhesion coefficient commenced relatively early, leading to the establishment of a well-developed theoretical framework and a range of application technologies. Notably, significant achievements have been made in adhesion estimation, control, and optimization. Existing research methods for adhesion estimation can be broadly classified into two main categories: conventional methods and novel methods.

Traditional methods primarily rely on theoretical modeling, experimental measurement, and numerical simulation to investigate the adhesion coefficient. In terms of theoretical model development, scholars have proposed various adhesion coefficient calculation models based on tribology theory and wheel-rail contact mechanics, such as adhesion models derived from tribological theories and computational methods based on wheel-rail contact mechanics. These models have, to a certain extent, revealed the variation patterns of the adhesion coefficient [3,4]. For instance, Abdulkadir and Altan [5] proposed an algorithm that combines a Proportional-Integral controller with a swarm intelligence-based tractive force estimator to determine the optimal adhesion coefficient on the adhesion-slip curve; however, the real-time performance of this method faces challenges. Krishnan et al. [6] introduced a torque modulation method that estimates the adhesion coefficient by using the phase difference between the angular velocity of the wheelset and the modulated torque. In the realm of experimental measurement and analysis, researchers have conducted extensive laboratory and field trials to measure and analyze the adhesion coefficient, acquiring data under various operating conditions. This provides a critical basis for adhesion coefficient modeling and estimation [7]. For example, Yuan et al. [8] compared and analyzed the performance of four common adhesion models in calculating the wheel-rail adhesion coefficient, offering new insights for model selection and development. Regarding numerical simulation, with the advancement of computer technology, numerical methods such as multi-body dynamics simulation [9] and state estimation observers [10] have been widely applied to simulate the wheel-rail contact process, enabling more accurate prediction of adhesion coefficient variations [11]. For instance, Zhao et al. [12] designed an intelligent adhesion coefficient sensor based on a sliding mode observer, which transforms the perception of the adhesion coefficient into the observation of the traction motor’s load torque to subsequently calculate the coefficient. However, the performance of this method in noisy environments requires further improvement. Chen et al. [13] proposed a wheel-rail adhesion identification method based on an improved recursive Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm, employing the Polach model to fit the nonlinear tangential force. In recent years, progress has also been made in refined wheel-rail contact simulations using the Finite Element Method and studies that combine vehicle-track coupled dynamics [14], further enhancing the accuracy of numerical simulations.

With the rapid development of artificial intelligence and data-driven technologies, adhesion coefficient estimation techniques based on new methods such as neural networks, Kalman filtering, and machine learning have become a research hotspot. These methods are typically applied innovatively within the framework of or in conjunction with traditional approaches, aiming to address the challenges of adhesion estimation under complex operating conditions and demonstrate promising application prospects [15]. In the field of deep learning, Abdurahman et al. [16] proposed an adhesion coefficient estimation algorithm based on a multi-channel deep convolutional neural network combined with the Short-Time Fourier Transform. Verified through experiments under various rail surface conditions and speeds, the method can accurately estimate the adhesion coefficient under normal operating conditions, but it suffers from high computational complexity. To reduce this complexity, Zhang [17] explored the application of the Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN) structure for adhesion estimation, achieving preliminary success. In the realm of state estimation and filtering, Zhao et al. [18] developed an adhesion controller that incorporated an indirect method for measuring the adhesion coefficient using a Kalman filter. While the Kalman filter exhibits good estimation performance in noisy environments, its accuracy is highly dependent on the fidelity of the model. To address this issue, Chen et al. [19] applied an improved Square-root Cubature Kalman Filter (SCKF) to adhesion estimation, which enhanced the robustness against variations in model parameters. Regarding machine learning, Zirek and Uysal [20] introduced a voting regression model based on machine learning to effectively estimate the wheel-rail adhesion coefficient by averaging the predictions of multiple individual models with weights. However, this method shows limited adaptability to dynamic changes in speed. To improve dynamic adaptability, Zhu et al. [21] investigated a hybrid approach that combines traditional time-domain dynamic loads with machine learning for adhesion estimation.

Driven by the widespread application of adhesion estimation algorithms, adhesion control methods in engineering have shown a trend of multifaceted development in recent years. For instance, Zhao et al. [22] proposed a cooperative adhesion control method applicable to multi-electric locomotives. This method achieves optimal adhesion utilization for each axle and consequently the optimal torque distribution among multiple motors by optimizing the output torque of each motor. Sun et al. [23] established a co-simulation dynamics model that incorporates adhesion control to study stick-slip vibration behavior, with parameters such as rail surface conditions and track curve radius. Ni et al. [24] introduced a neural network controller based on the Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) algorithm, and its capability for optimizing wheel-rail adhesion was experimentally validated under various operating conditions. Furthermore, Liu et al. [25] achieved precise train operation at the optimal adhesion point by combining a machine learning algorithm with a torque controller.

Currently, despite the existence of various methods for estimating train wheel-rail adhesion, some existing approaches exhibit low sensitivity to parameter variations in dynamic environments and a strong reliance on historical data, making them difficult to adapt to the rapid changes in wheel-rail contact conditions during train operation. Another group of methods, based on complex dynamic models, although offering high accuracy, suffer from significant computational complexity, failing to meet real-time requirements. Additionally, certain methods struggle with robustness issues. To address these limitations of current adhesion estimation techniques, this paper proposes an online estimation method for wheel-rail adhesion coefficient based on parameter estimation. A key innovation of this method is the adoption of a time-varying parameter adaptive identification technique, which enhances its adaptability to dynamic conditions. It is verified through the MATLAB/Simulink and AMESim co-simulation platform and the hardware-in-the-loop semi-physical simulation experimental platform, which can estimate the wheel-rail adhesion coefficient in real-time and accurately in complex environments. The aim is to offer a novel approach for the real-time monitoring of train wheel-rail adhesion coefficient and provide technical support for improving the effective utilization of adhesion between the wheel and rail.

2 Wheel-Rail Adhesion and Wheel-Pair Force Analysis

During the operation of the rail vehicle, traction is transmitted through the adhesive-creep between the wheel and the rail contact spot. Tests have shown that the tangential force between the wheel and the rail is proportional to the normal force exerted by the wheel on the rail, and the proportional coefficient is called the adhesion coefficient, that is:

where

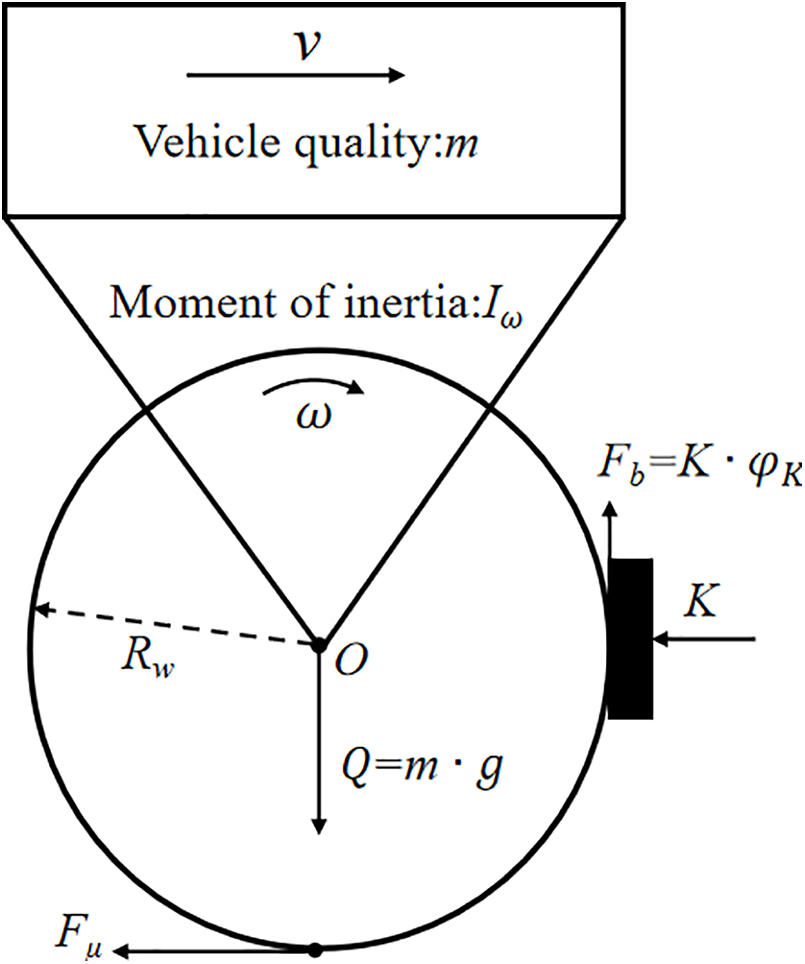

Fig. 1 shows the one-eighth model of the vehicle body. Under the action of the normal force

Figure 1: Force analysis of wheel sets in braking state

The braking force Fb can be calculated by Eq. (2):

where

Based on the force analysis in Fig. 1, the differential equation for the rotation of the pair of wheels can be obtained as:

where

The braking force

3 Online Estimation Algorithm and Implementation Method for the Coefficient of Adhesion

3.1 Online Parameter Estimator

Before calculating the wheel-rail tangential force

where the n-dimensional vector

Firstly, the design method of the online estimator is based on error prediction. Assuming that at time

The difference between the predicted output

Calculate the error using the least squares method with the forgetting index. Based on the prediction error

In Eq. (7),

The purpose of the online parameter estimator is to find the estimated value

Thus there is:

After differentiating

make

If

3.2 Stability Analysis of Parameter Estimator

Denoted

Eq. (13) can be regarded as a first-order filter with input of

If the parameter

Therefore, the parameter estimation error

Select Lyapunov function:

Taking the derivative of Eq. (17), it is known that its derivative satisfies:

From this, it is known that the online parameter estimator is stable.

3.3 Online Estimation Implementation Based on Parameter Estimation

Currently, on rail vehicles such as high-speed trains or urban rail transit trains, the rotational speed of the wheel sets is measured by the axle speed pulse sensor installed at the axle end. For the angular acceleration of the wheels, there is no direct means for measurement. Considering the influence of measurement noise and various interferes, in order to eliminate the differential of the diagonal velocity of the wheels in Eq. (3) and convert it into the form of linearized parameters, The two sides of Eq. (3) are filtered with a first-order filter

During the braking anti-skid process, although

Denoted

make

Then the estimation error

Based on the estimation error

The differential equation for the online real-time update of the estimation parameter

The tangential force

4 Simulation Analysis and Semi-Physical Platform Validation

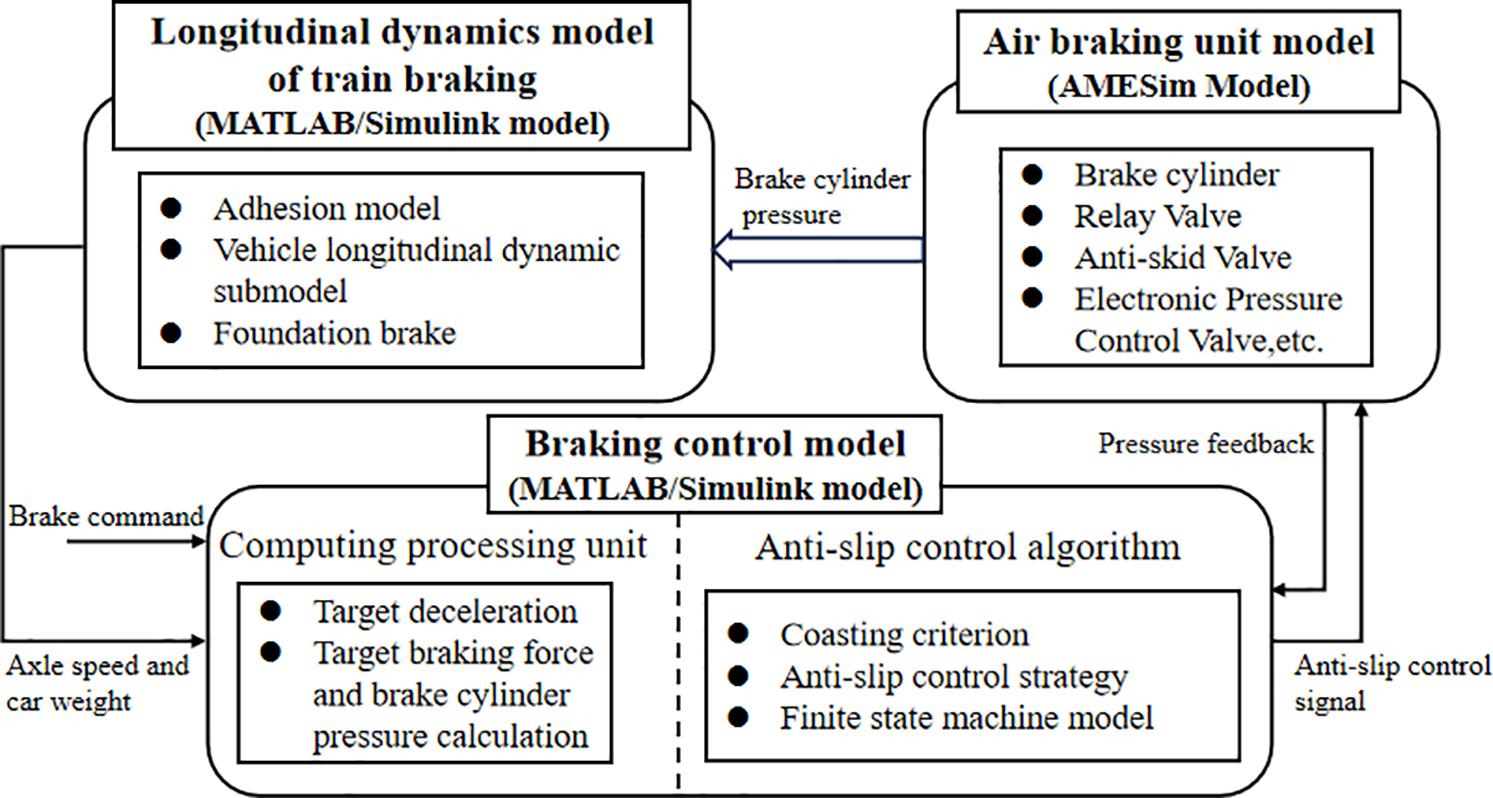

To verify the effectiveness of the adhesive coefficient estimation method, this paper divides the system into three parts based on the working principle of the rail vehicle braking system: the longitudinal dynamic model of train braking, the braking control model, and the air braking unit model. The estimation method is verified through joint simulation under braking anti-skid conditions and a semi-physical test bench.

4.1 Construction of the Joint Simulation Platform

First, the longitudinal braking dynamics model of a single four-axle train was established using MATLAB/Simulink. The vehicle model incorporates sub-models for the car body, bogie, wheelset, and suspension system. The wheelset sub-model further includes dynamics, wheel-rail adhesion, and basic braking device components. The friction coefficient of the basic braking device varies with the train’s initial and instantaneous speeds. According to the Polach nonlinear contact theory model, the adhesion curve represents the changing adhesion state as the wheelset slips. A braking control model was developed based on a finite state machine. This control module calculates and allocates the target braking force and brake cylinder pressure according to the specified target deceleration and the train’s mass. The anti-slip control module primarily determines the wheels’ state based on external input signals. When the slip condition reaches a threshold, it actuates the anti-slip valve to reduce brake cylinder pressure, thereby restoring the wheels to an adhesive state.

The train’s pneumatic braking system comprises components like braking commands, transmission units, microcomputer braking control systems, pneumatic control units, anti-slip valves, and basic braking devices. Upon receiving a braking command, the microcomputer braking control unit adjusts the target braking pressure in real-time, considering factors such as air spring pressure. The pneumatic control unit then receives signals from this control unit and generates compressed air at the required pressure. This air flows through the anti-slip valve into the brake cylinders of the basic braking devices. There, it actuates the pistons, causing brake blocks or shoes to press against the wheel treads or discs, resulting in vehicle deceleration. Following the principles of the rail train braking system and its operation, the pneumatic braking unit model—including elements such as Electro-Pneumatic (EP) valves, relay valves, and anti-slip valves—was constructed using AMESim’s pneumatic component library. A co-simulation platform integrating MATLAB/Simulink and AMESim was established via their simulation interfaces (refer to Fig. 2). The modeling approaches for these individual components are detailed in related literature [26,27] and are not elaborated upon here. Simulations were performed according to the described modeling principles. The estimated adhesion was derived using the online wheel-rail adhesion coefficient estimation method based on parameter estimation.

Figure 2: Train braking system model and the relationship between the systems

In the simulation, Polach nonlinear contact theory model is used to simulate the wheel-rail tangential force [28], and its calculation formula is:

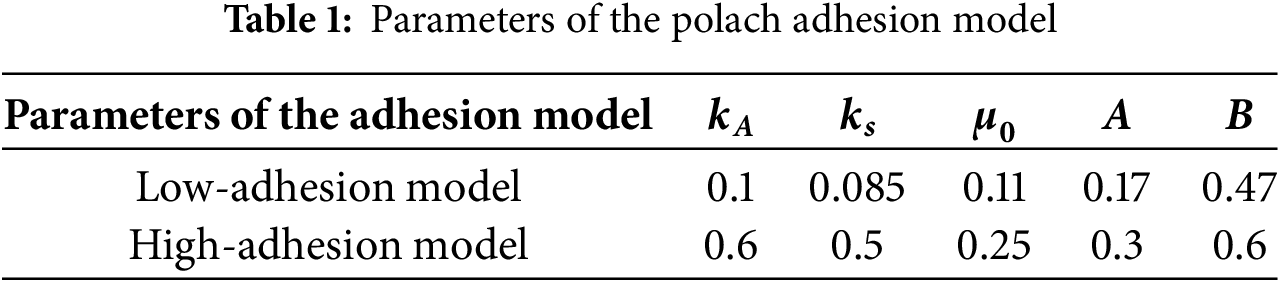

where

The Polach model is adjusted by tuning five parameters—

4.2 Analysis of Simulation Results

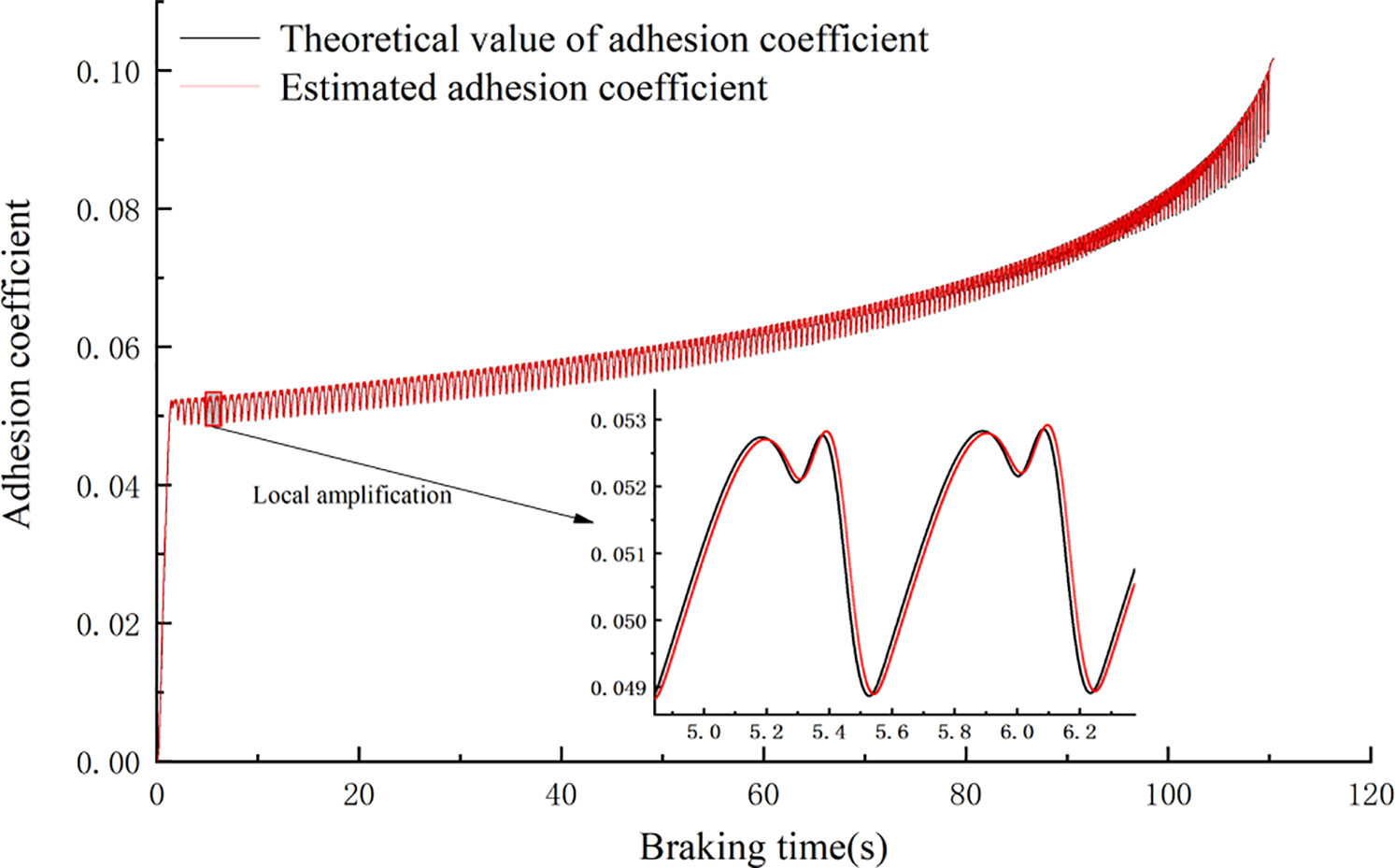

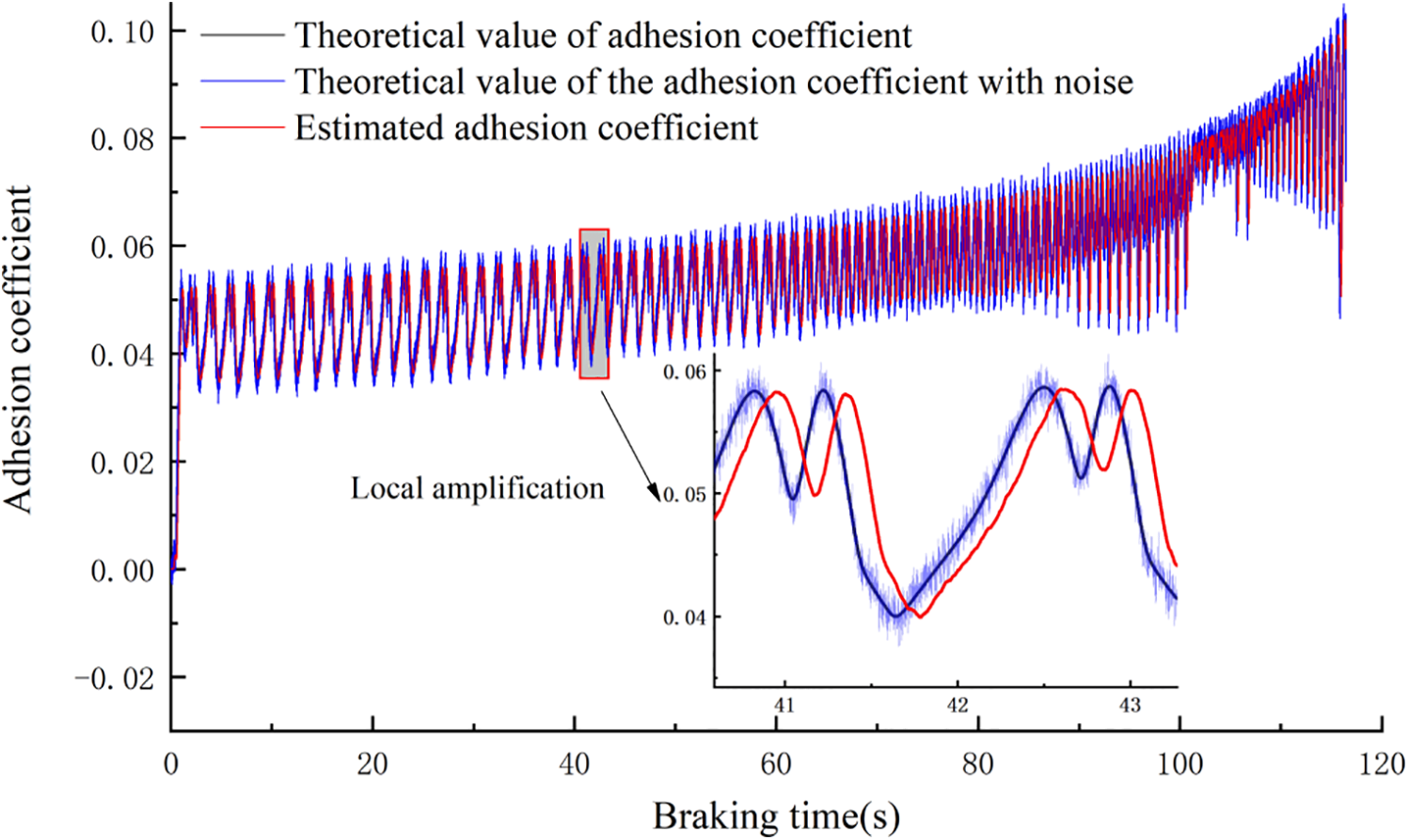

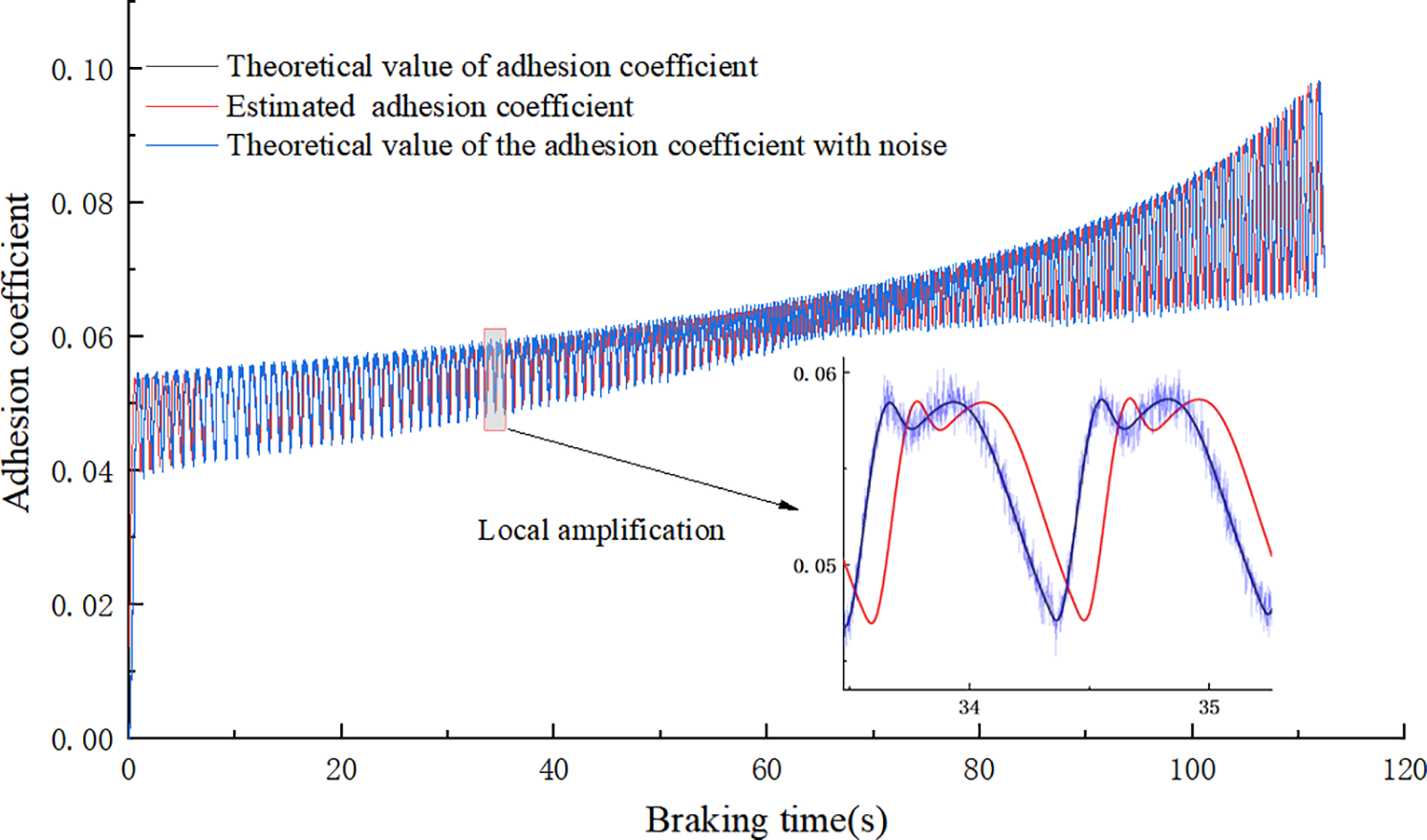

The coasting condition caused by emergency braking with an initial speed v0 of 250 km/h is simulated. Fig. 3 shows the estimator’s estimation of the adhesion coefficient, where the theoretical value of the adhesion coefficient is obtained from the Polach model and the estimated value of the adhesion coefficient is obtained from the adhesion estimation algorithm.

Figure 3: Comparison of the theoretical and estimated values of the adhesion coefficient

As can be seen from Fig. 3, during the braking process of the train, the adhesive coefficient shows an overall upward trend as the speed decreases. Due to the complex state of the rail surface, when traveling on a low-adhesion road, if the maximum tangential force that can be provided between the wheels of a certain pair is less than the braking force, sliding occurs. The train’s anti-skid control system has to judge the state of the wheels based on the external input signal. When it is determined that wheel slip occurs, the anti-slip valve is actuated to reduce the brake cylinder pressure, restoring the wheel to a re-adhesion state. It can be seen that within a slip cycle, the process of the estimated adhesion decreasing due to slip and then increasing after the train’s anti-slip action can maintain tracking with the theoretical adhesion coefficient value. Throughout the entire anti-slip process, as the train speed decreases, during the overall rise in the theoretical adhesion coefficient value, the estimated adhesion coefficient value also maintains tracking. This indicates that the adhesion coefficient prediction value is relatively accurate, and the use of the estimated adhesion coefficient value exhibits good tracking performance relative to the theoretical value.

However, during the actual operation of the train, there will be system delay, noise interference and measurement noise from signal acquisition. To further verify the train adhesion coefficient estimation algorithm based on the parameter estimation proposed in this paper, the proposed adhesion estimation algorithm will be tested in a hardware-in-the-loop simulation with delay and noise environment.

4.3 Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation Validation

4.3.1 Hardware-in-Loop Simulation Test Platform

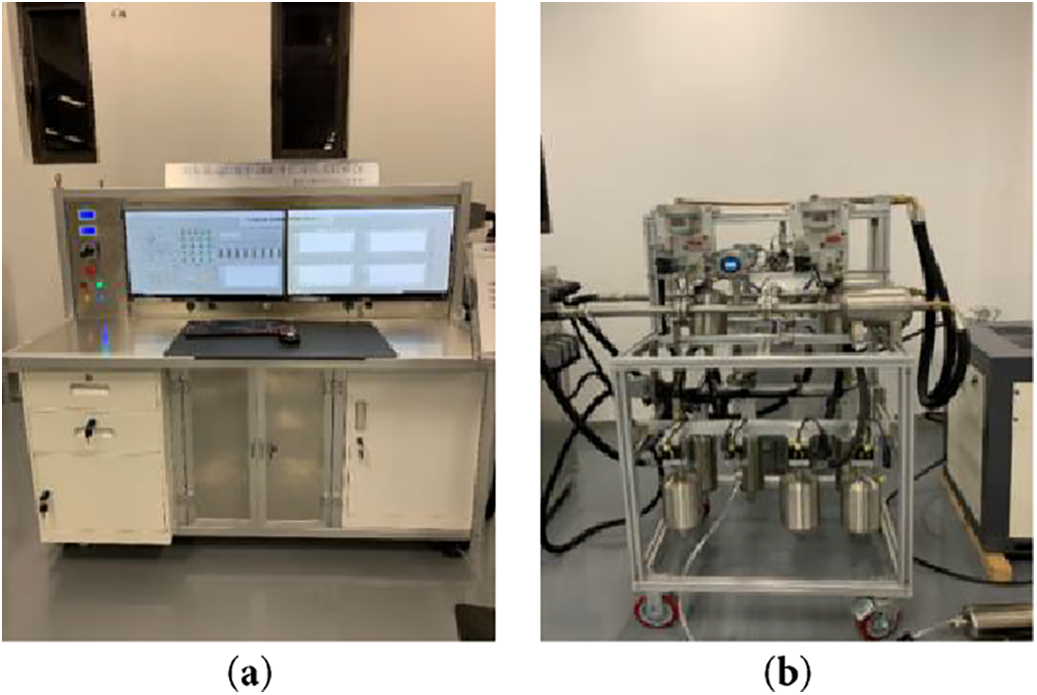

Fig. 4 shows the physical structure of the hardware-in-loop simulation platform. The test platform is mainly composed of test bench simulation software and physical hardware. The simulation software runs in the industrial control computer on the test bench, including the human-machine interaction interface and the train braking model. The simulation software comprises the longitudinal dynamics model of train braking and the braking control model in the Matlab/Simulink model in Section 4.1, as shown in Fig. 4a. The hardware physical object is the air braking unit, as shown in Fig. 4b. Its braking performance meets the requirements of the international standards for rail vehicle anti-slip control, UIC541-05 and EN15595-2018. The information exchange between the virtual train and the hardware of the hardware-in-the-loop test platform is achieved through the Multiple Vehicle Bus (MVB) bus and data acquisition and conversion circuits. Among them, the signals transmitted via the MVB bus include the brake commands generated by the driver’s controller, the virtual train’s load, and the requests and feedback of electric braking force. The signals hardwired through the data acquisition and conversion circuits include the virtual train’s axle speed and the brake cylinder pressure of the braking mechanism.

Figure 4: Train brake anti-skid control hardware-in-the-loop simulation test bench. (a) The longitudinal dynamics model of train braking and the braking control model. (b) The air braking unit

4.3.2 Test Results and Analysis

This section verifies the adhesion estimation algorithm through hardware-in-the-loop semi-physical simulation experiments. System delay and noise interference from harsh environments during train operation are important factors affecting train performance and safety. During the test on the test bench, there were system delays and interference noises in the acquisition and transmission of brake signals and valve signals in the hardware physical part, which made the input signals of train-related parameters received by the model more in line with the actual train operation environment.

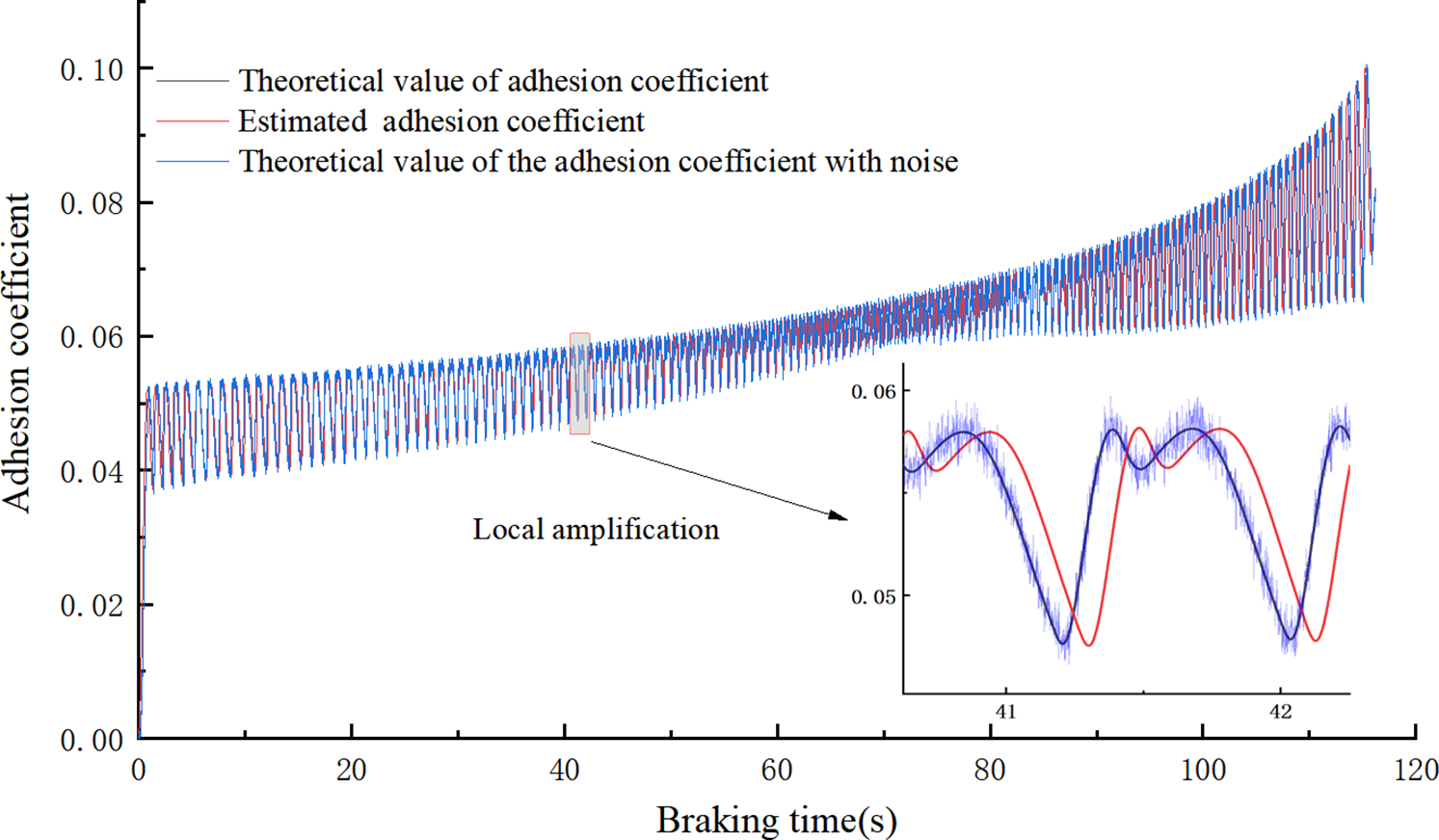

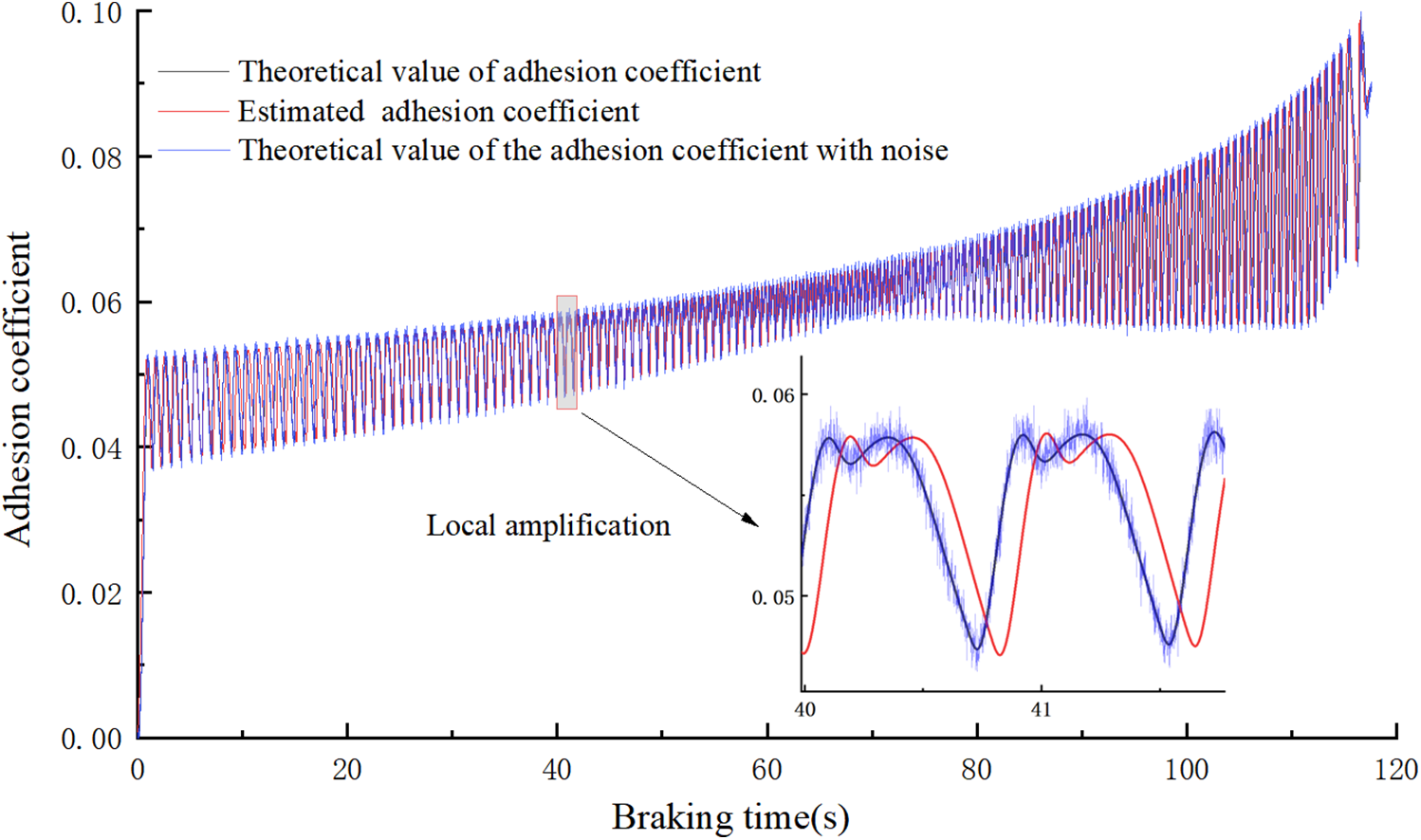

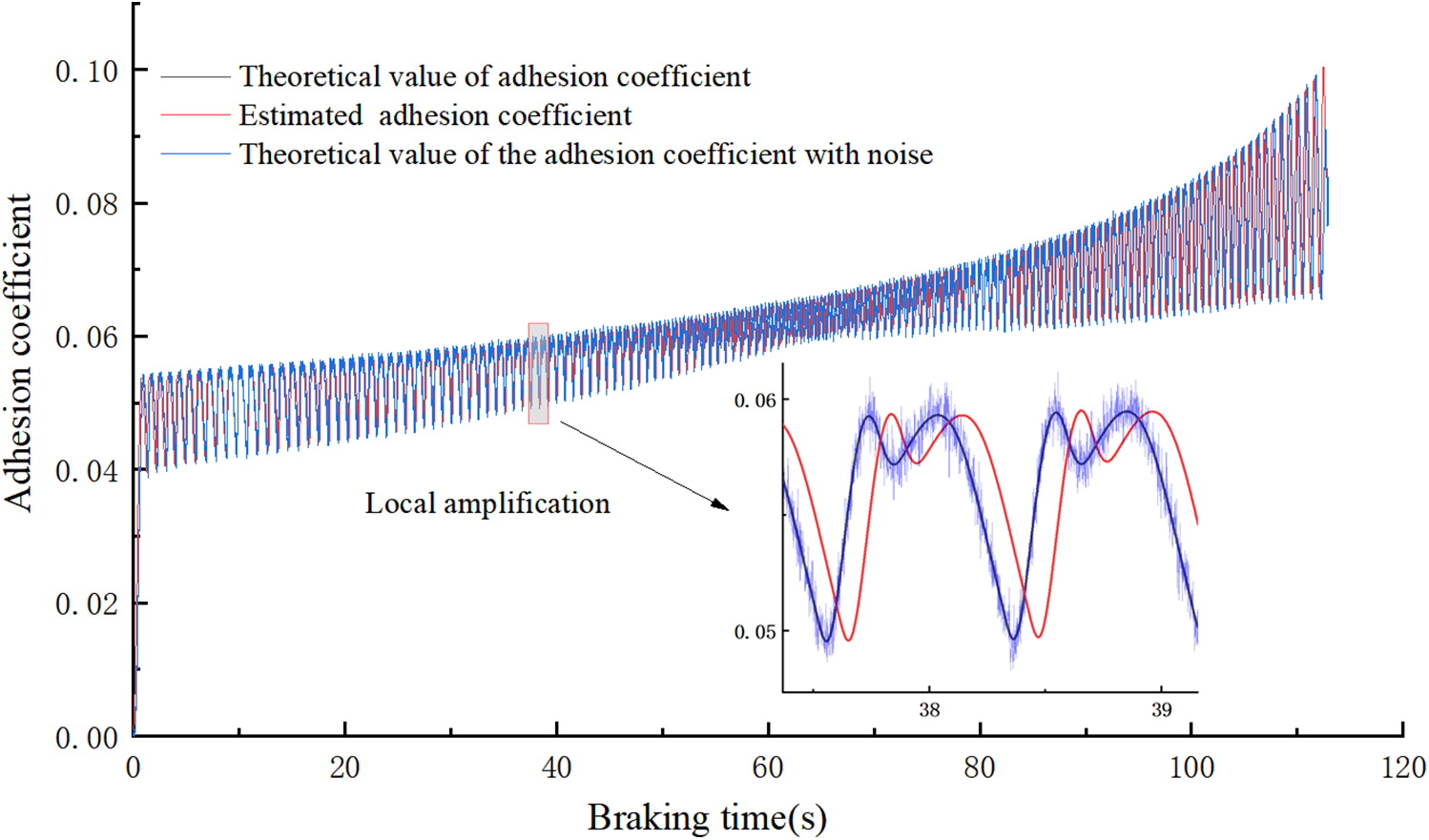

As shown in Fig. 5, due to noise interference during the process of collecting input signals from the hardware physical part, the theoretical value of the adhesion coefficient will have some noise during the test process. The estimated value of the adhesion coefficient lags slightly and fluctuates compared to the theoretical value. This lag and fluctuation are caused by delays in the physical system, signal acquisition time, and other reasons. Within a slip cycle, the process where train slip causes the adhesion coefficient to decrease and the adhesion coefficient to rise after the train’s anti-slip, and as the train speed decreases and the overall adhesion coefficient rises, the estimated adhesion can maintain good tracking with the theoretical value of the adhesion coefficient. This indicates that this method also has good inhibitory effects on noise.

Figure 5: Comparison of the adhesion coefficient based on the semi-physical simulation test bench

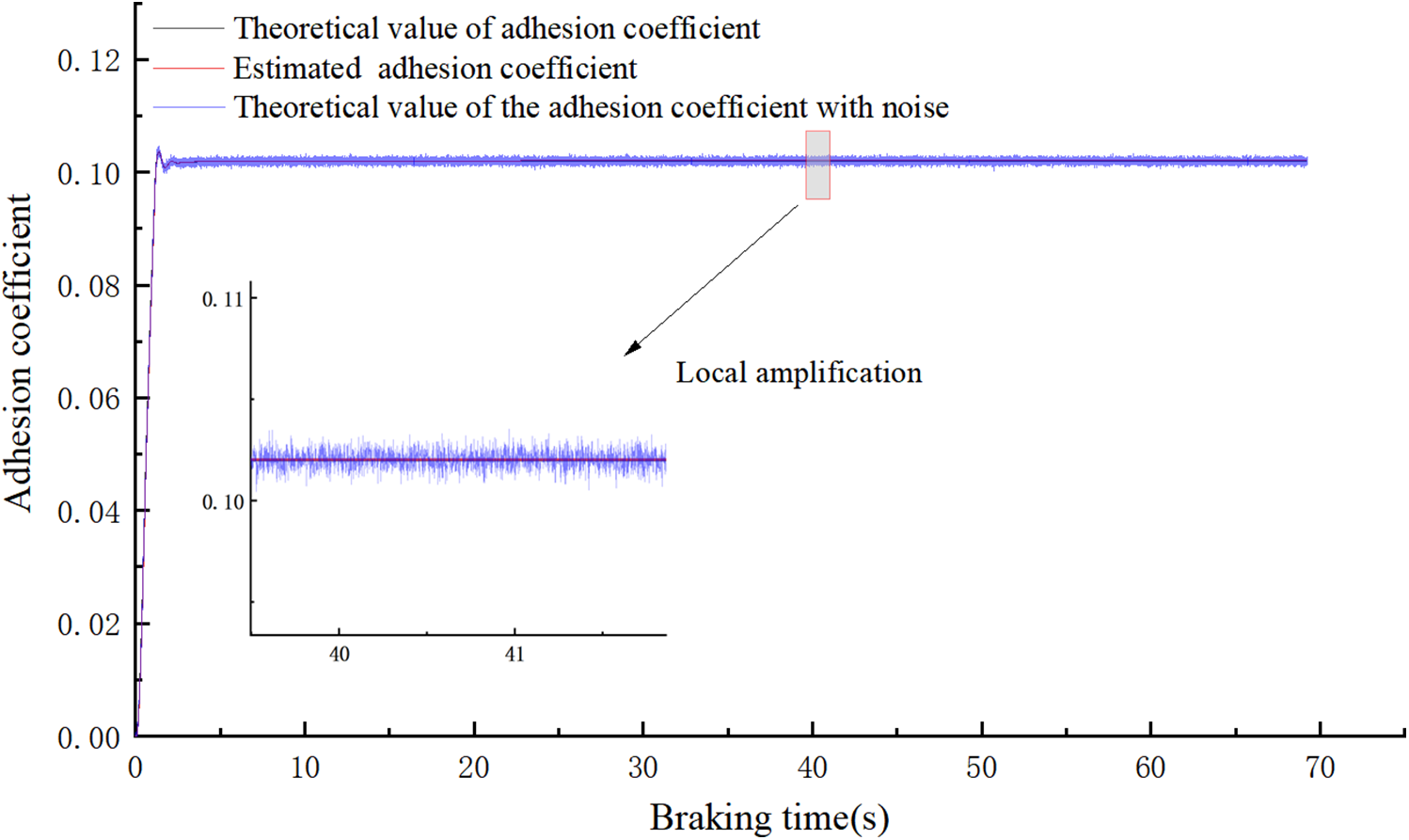

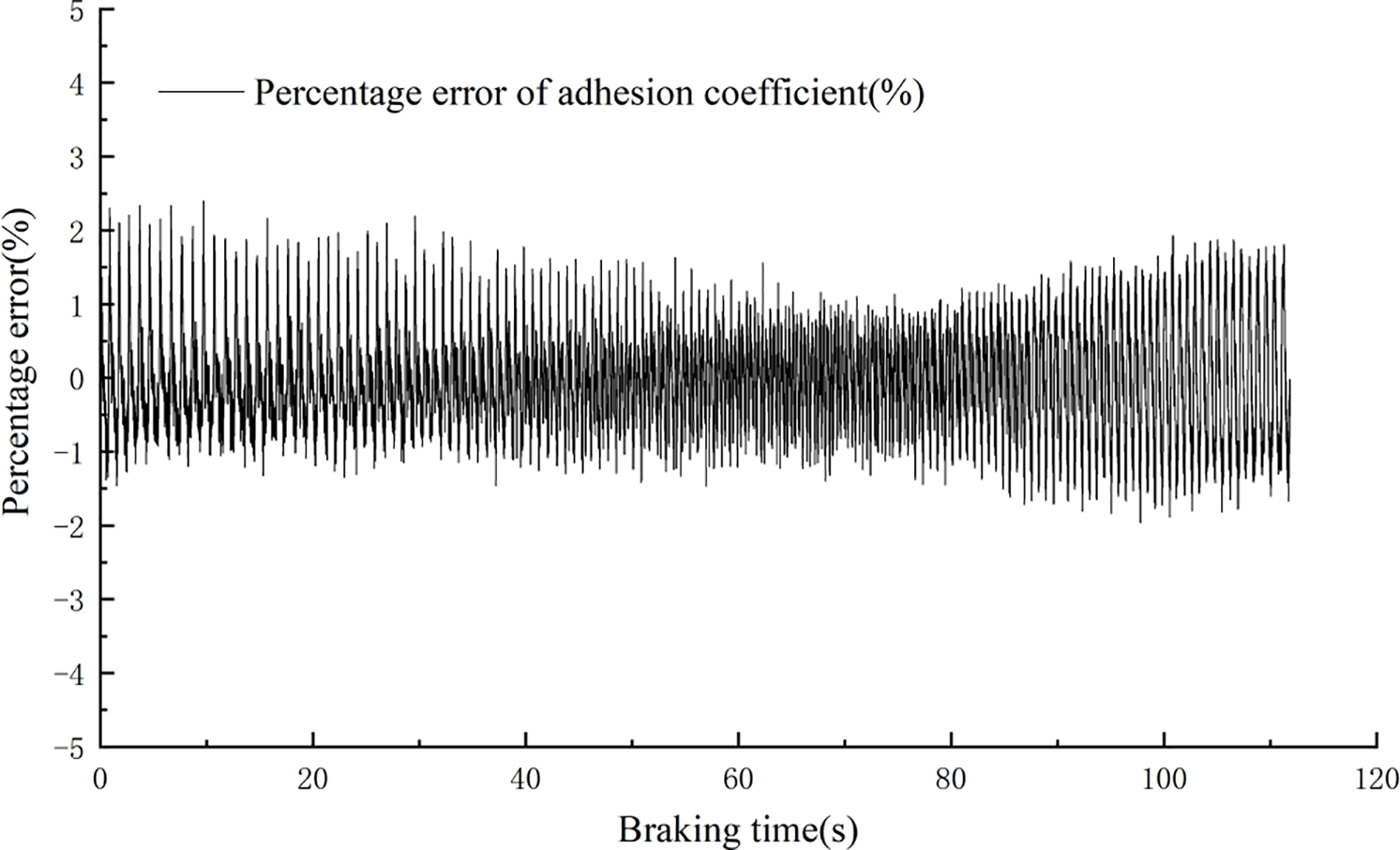

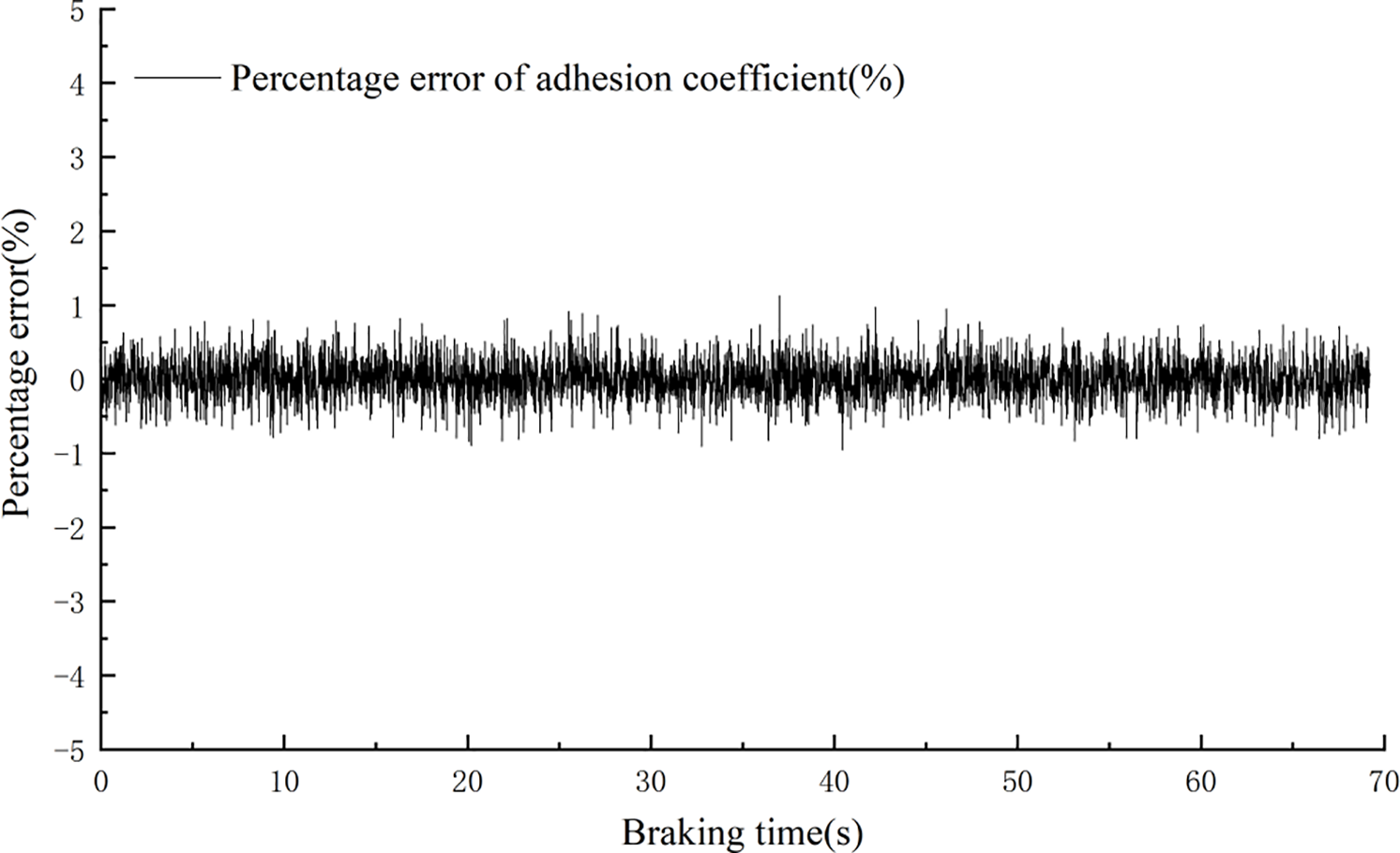

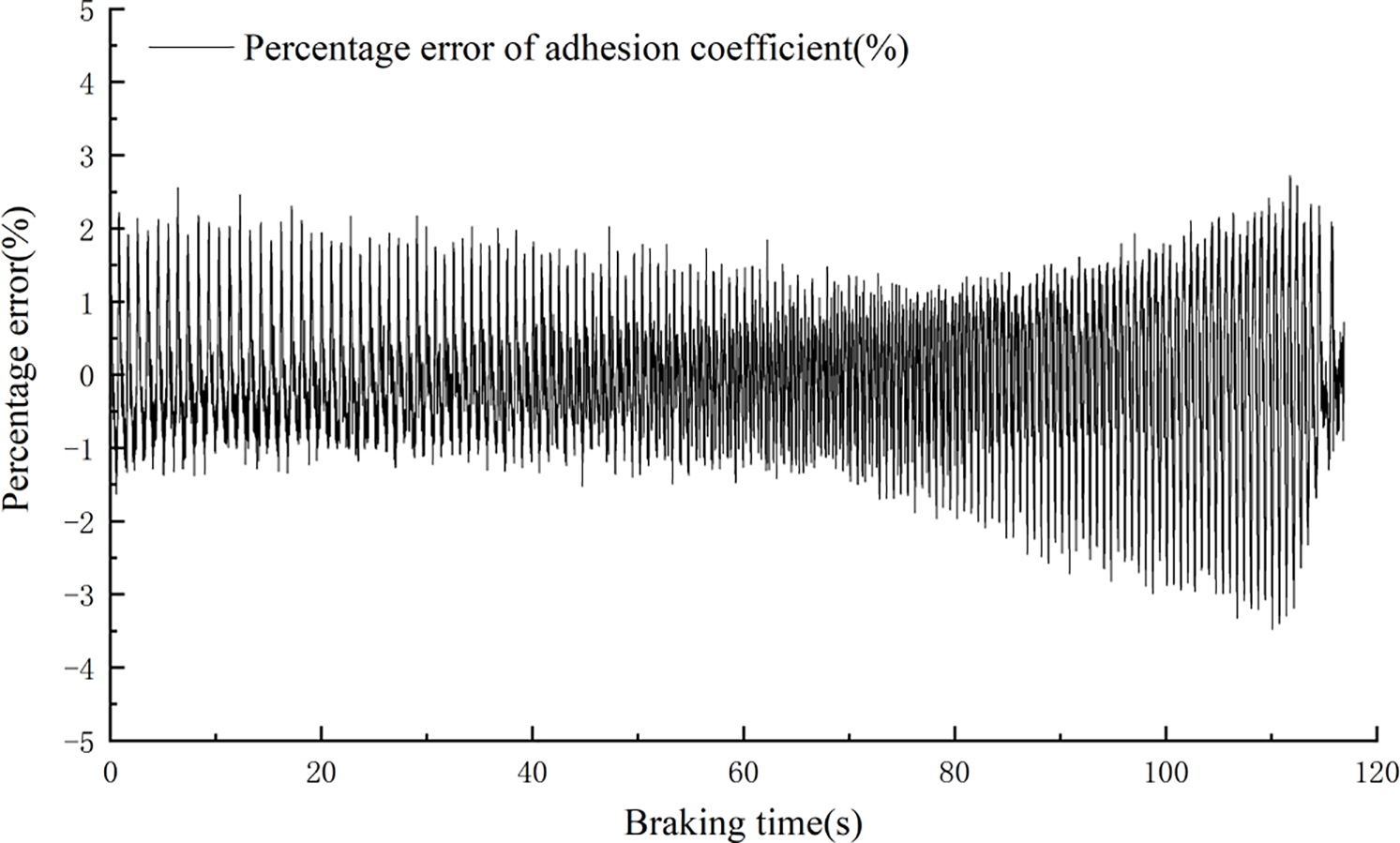

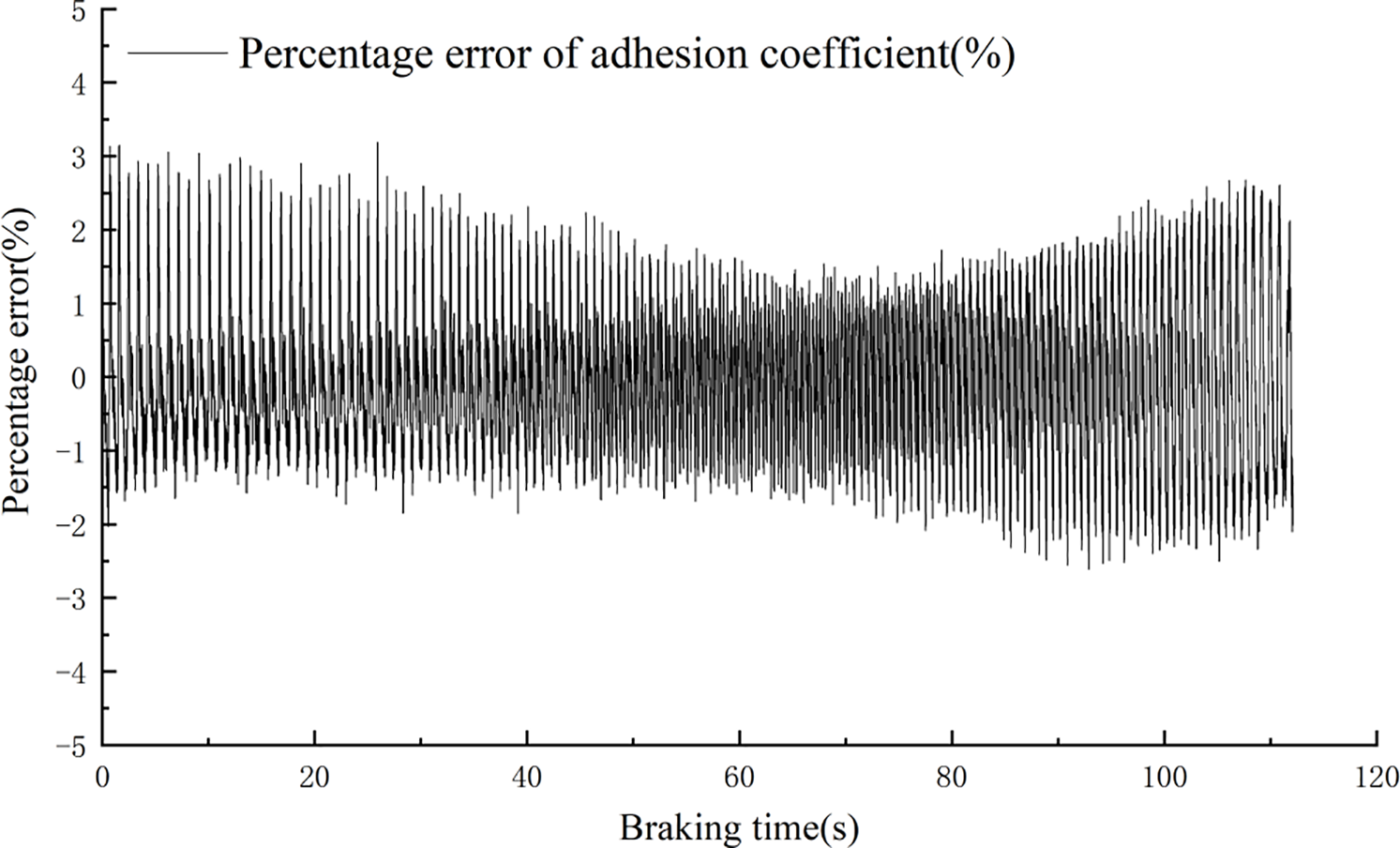

To further verify the effectiveness of the adhesion estimation method, this paper conducted multiple test conditions on the hardware-in-the-loop simulation testbed, analyzing conditions such as different rail surface adhesion conditions, different braking levels, and different train loads. Tests were conducted under both low adhesion conditions and high adhesion conditions, i.e., tests where wheel slip occurs during braking and tests where it does not. As shown in Figs. 6 and 7, these are Condition 1: low adhesion, emergency braking, full load test and Condition 2: high adhesion, emergency braking, full load test. Error analysis was performed for these two conditions. Because there is a delay effect between the theoretical value of the adhesion coefficient and the estimated value of the adhesion coefficient, the delay effect should be eliminated before error analysis. By comparing the adhesion coefficient estimation value from pure simulation tests with that from the hardware-in-the-loop platform tests, it was found that the system delay is approximately 100 ms. After eliminating the delay, the theoretical value of the adhesion coefficient is subtracted by the estimated value of the adhesion coefficient to obtain the difference, and then the difference is divided by the theoretical value of the adhesion coefficient to obtain the percentage error. The percentage errors for the two test conditions are shown in Figs. 8 and 9, respectively:

Figure 6: Comparison chart of adhesion coefficients under low adhesion conditions

Figure 7: Comparison chart of adhesion coefficients under high adhesion conditions

Figure 8: Percentage error of the adhesion coefficient under low adhesion conditions

Figure 9: Percentage error of the adhesion coefficient under high adhesion conditions

Fig. 6 is the adhesion coefficient comparison diagram under low adhesion conditions. The estimated adhesion coefficient can still maintain tracking during train slip. Fig. 7 is the adhesion coefficient comparison diagram under high adhesion conditions. Because the train does not experience slip under high adhesion, the axle speed is basically equal to the train speed, so the adhesion coefficient does not change due to variations in slip ratio. Compared to Fig. 6, the adhesion coefficient in Fig. 7 remains basically constant during braking. Additionally, the estimated adhesion coefficients in both test conditions can maintain tracking with the theoretical adhesion coefficient values. An error analysis was conducted for the two test conditions. The error for Condition 1 is shown in Fig. 8, and its error is basically maintained within 5%. The error for Condition 2 is shown in Fig. 9, where the theoretical adhesion coefficient remains basically constant during braking, resulting in smaller error fluctuations, which are basically maintained around 1%. This result is acceptable for engineering applications.

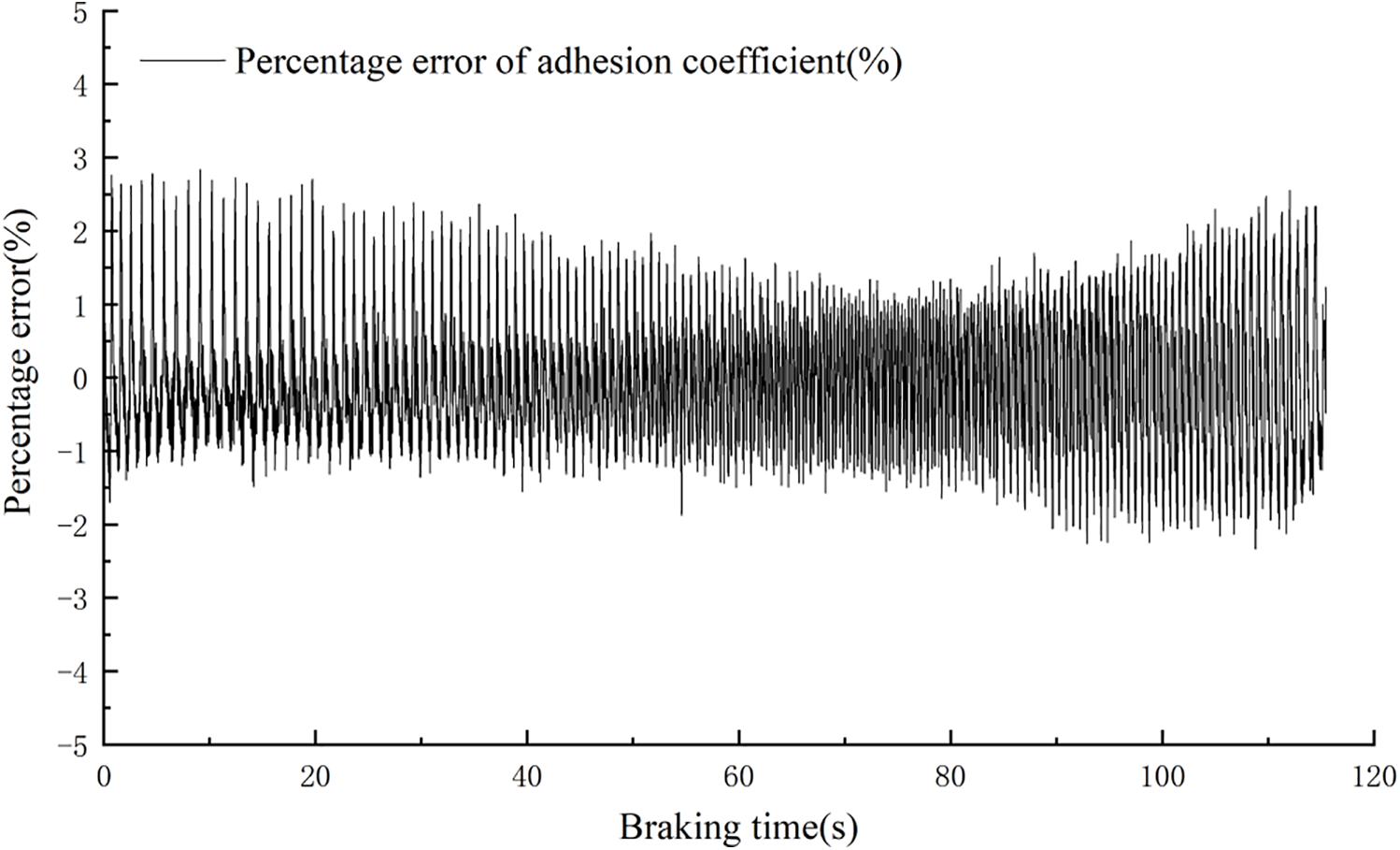

Using Condition 1: low adhesion, emergency braking, full load test as the control group, Fig. 10 is the test diagram for Condition 3: low adhesion, normal braking, full load test; Fig. 11 is the test for Condition 4: low adhesion, emergency braking, empty load test. The percentage errors for the two test scenarios are shown in Figs. 12 and 13, respectively:

Figure 10: Comparison chart of commonly used braking adhesion coefficients

Figure 11: Comparison chart of no-load adhesion coefficients

Figure 12: Percentage error of commonly used braking adhesion coefficients

Figure 13: Percentage error of no-load adhesion coefficient

As shown in Figs. 10 and 11, under normal braking conditions and different load test conditions, the estimated adhesion coefficient and the theoretical adhesion coefficient can also basically maintain tracking. An error analysis is performed on the theoretical and estimated adhesion coefficients. The errors for the two conditions are shown in Figs. 12 and 13, respectively. The percentage error between the theoretical adhesion coefficient and the estimated adhesion coefficient is basically maintained within 5%, proving the effectiveness of the adhesion coefficient estimation method proposed in this paper.

4.4 Analysis of the Impact of Changes in Constant Parameters on Estimation Results

Although experiments under different conditions were conducted and analyzed in this paper, and the algorithm shows good effectiveness, some parameters in the aforementioned research can be regarded as constants during short-term operation but will change over long-term operation. For example, parameters such as wheel radius, moment of inertia, and the friction coefficient between the friction pair and the wheel may affect the adhesion coefficient estimation value due to wear. This section takes the wheel radius parameter as an example for experimental analysis. By changing the wheel radius parameter, the condition after wheel wear is simulated. Using Condition 1 as the experimental control group, Condition 5 was tested after changing the wheel radius parameter. The wheel radius parameter in Condition 1 was 0.42 m, and in Condition 5, the wheel radius parameter was set to 0.4 m. The test results are shown in Fig. 14. An error analysis was performed on Condition 5 after eliminating the delay, and the percentage error is shown in Fig. 15:

Figure 14: Comparison chart of adhesion coefficients with a radius of 0.4 m

Figure 15: Percentage error of the adhesion coefficient with a radius of 0.4 m

As shown in Fig. 14, after the wheel radius wears down, the estimated adhesion coefficient can still maintain tracking during train slip. An error analysis was performed on it, and the results are shown in Fig. 15. Compared with the error diagram before radius wear Fig. 8, wheelset wear does indeed have a certain impact on the estimated adhesion. However, over time, the error does not gradually increase, and the percentage error can still be maintained within 5%, indicating that the wear variation of the wheel radius has a relatively small impact on the adhesion estimation.

In this paper, an adhesive estimation algorithm based on parameter estimation is proposed for the adhesive coefficient that has an important influence during train braking. The designed adhesion estimation algorithm is experimentally verified by using the joint simulation of MATLAB/Simulink and the hardware-in-the-loop semi-physical simulation test platform. It provides a new technical approach for the real-time monitoring of the wheel-rail adhesion coefficient of trains and offers more reliable technical support for the safe operation of trains.

Conduct a force analysis on the wheel set under braking conditions to obtain the motion equation of the wheel set. Subsequently, the research on the online parameter estimator was carried out. The theoretical basis for the implementation of the online parameter estimator method was given, and its stability was verified. The estimation method of the wheel-rail adhesion coefficient is given by combining the online estimator with the force analysis of the wheel pair.

A co-simulation platform based on MATLAB/Simulink and AMESim was established. The effectiveness of the adhesion estimation algorithm was verified through co-simulation. The results show that during train braking, as the speed decreases, the adhesion coefficient shows an overall upward trend. Among these, the estimated adhesion, within a slip cycle, due to the drop in the adhesion coefficient caused by slip and the rise after the train’s anti-slip action, can maintain tracking with the theoretical adhesion coefficient value. Throughout the entire anti-slip process, as the train speed decreases and the theoretical adhesion coefficient value shows an overall upward trend, the estimated adhesion can also ensure tracking.

The adhesion estimation algorithm was verified based on the hardware-in-the-loop semi-physical simulation test platform. The semi-physical simulation platform collects the physical part of the hardware input signal with noise interference, so the input of the adhesion coefficient has noise fluctuations. Although the estimated value of the adhesion coefficient has a certain lag and fluctuation compared with the theoretical value, it still has good followability, a good noise suppression effect, and has high engineering application value. The effectiveness of the estimation algorithm was verified through four groups of experiments under different conditions. The results show that in the four groups of experiments, the percentage error between the theoretical adhesion coefficient and the estimated adhesion coefficient is basically within 5%, proving the effectiveness of the algorithm proposed in this paper.

The limitation of this paper is that some parameters that may change over time, such as wheelset radius and friction coefficient of the friction pair, were treated as constant parameters in this study. The goal of future research is to estimate some parameters that may vary over time, such as the friction coefficient of the friction pair, using multi-parameter estimation methods, and to include research on the influence of the suspension system on adhesion estimation.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant/award number 52072266).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yi Zhang, Wenliang Zhu; data collection: Yi Zhang, Hanbin Wang; analysis and interpretation of results: Wenliang Zhu, Chun Tian, Jiajun Zhou; draft manuscript preparation: Yi Zhang, Wenliang Zhu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All the data used and analyzed are available in the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Xue MS, Qiang JL, Lan L, Xin SL, Ying CM. Adhesion and damage behaviour of wheel-rail rolling-sliding contact suffering intermittent airflow with different humidities and ambient temperatures. Tribol Lett. 2024;72(1):18. doi:10.1007/S11249-023-01817-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Gan WW, Zhao XF, Wei D, Bai ZH, Ding RJ, Liu K, et al. Research on the identification of nonlinear wheel-rail adhesion characteristics model parameters in electric traction system based on the improved TLBO algorithm. Electronics. 2024;13(9):1789. doi:10.3390/ELECTRONICS13091789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Yang Y, Wu B, Xiao G, Shen Q. Numerical investigation on wheel-rail adhesion under water-lubricated condition during braking. Ind Lubr Tribol. 2023;75(5):568–77. doi:10.1108/ILT-02-2023-0040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wu B, Yang Y, Xiao G. A transient three-dimensional wheel-rail adhesion model under wet condition considering starvation and surface roughness. Wear. 2024;540:205263. doi:10.1016/J.WEAR.2024.205263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Abdulkadir Z, Altan O. A novel anti-slip control approach for railway vehicles with traction based on adhesion estimation with swarm intelligence. Railw Eng Sci. 2020;28(4):346–64. doi:10.1007/s40534-020-00223-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Krishnan GJ, Yang Z, Li ZL, Dollevoet R. A concept for torque modulation-based train-borne measurement of coefficient of friction. Adv Dyn Veh Roads Tracks III. 2025;1:546–54. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-66971-2_57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Shrestha S, Wu Q, Spiryagin M. Review of adhesion estimation approaches for rail vehicles. Int J Rail Transp. 2019;7(2):79–102. doi:10.1080/23248378.2018.1513344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yuan Z, Wu M, Tian C, Zhou J, Chen C. A review on the application of friction models in wheel-rail adhesion calculation. Urban Rail Transit. 2021;7(1):1–11. doi:10.1007/S40864-021-00141-Y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hubbard P, Harrison T, Ward C, Abduraxman B. Creep slope estimation for assessing adhesion in the wheel/rail contact. IET Intell Transp Syst. 2024;18(10):1931–42. doi:10.1049/ITR2.12561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Yin S, Peng T, Yang C, Yang C, Chen Z, Gui W, et al. Dynamic hybrid observer-based early slipping fault detection for high-speed train wheelsets. Control Eng Pract. 2024;142(3):105736. doi:10.1016/J.CONENGPRAC.2023.105736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Tahmasbi M. A model-based proportional-integral observer design for adhesion estimation in the wheel-rail interface: LMI approach. Veh Syst Dyn. 2025;63(4):631–49. doi:10.1080/00423114.2024.2351032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhao K, Li P, Zhang C, He J, Li Y, Yin T. Online accurate estimation of the wheel-rail adhesion coefficient and optimal adhesion antiskid control of heavy-haul electric locomotives based on asymmetric barrier lyapunov function. J Sens. 2018;2018(3):1–12. doi:10.1155/2018/2740679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Chen QH, Ge X, Wang KY. Identification of wheel-rail adhesion status using an improved recursive levenberg-marquardt algorithm. Adv Dyn Veh Roads Tracks III. 2025;1(8):343–52. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-66971-2_37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Liu W, Huang S, Qi H, Zhao X, Liang S, Jin X. Explicit finite element simulations of dynamic low adhesion behavior between wheel and rail in the presence of high-frequency vibrations. Eng Comput. 2024;41(5):1185–202. doi:10.1108/EC-01-2024-0028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Mal K, Memon TD, Kalwar IH, Junejo AR, Memon MH, Memon TR, et al. Functional verification of extended Kalman filter on FPGA for railway wheelset parameters estimation. IEEE Access. 2025;13(1):96646–59. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3563643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Abdurahman B, Hubbard P, Harrison T, Ward C, Fletcher D, Lewis R, et al. Estimation of wheel-rail friction coefficient using deep CNN on axlebox accelerations. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2025;232(2):112756. doi:10.1016/J.YMSSP.2025.112756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang YY, Yang XW, Sun Z, Mao K, Xiang KW, Ye Z, et al. Prediction of wheel-rail force and vehicle safety index using genetic algorithm-based backpropagation neural network with physics-based inversion model. Meas Sci Technol. 2025;36(2):026010. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/ad9e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhao Y, Shen L, Jiang Z, Zhang B, Liu G, Shu Y, et al. Real-time wheel-rail friction coefficient estimation and its application. Veh Syst Dyn. 2023;61(10):2598–612. doi:10.1080/00423114.2022.2159846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chen Q, Gong J, Ge X, Chen S, Wang K. Estimation of wheel-rail forces based on the STF-SCKF-NE algorithm. Measurement. 2024;236(8):114974. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2024.114974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zirek A, Uysal C. A machine learning based voting regression method for adhesion estimation in wheel-rail contact. Veh Syst Dyn. 2024;30:1–18. doi:10.1080/00423114.2024.2390578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhu T, Wang X, Wu J, Zhang J, Xiao S, Lu L, et al. Comprehensive identification of wheel-rail forces for rail vehicles based on the time domain and machine learning methods. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2025;222:111635. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2024.111635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhao L, Wang Y, Liu K, Li L, Zhan J, Liu Q. Cooperative maximum adhesion tracking control for multi-motor electric locomotives. Railw Sci. 2025;4(1):22–36. doi:10.1108/RS-11-2024-0049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Sun L, Yang Z, Ma W, Luo S, Wang B. Investigating the stick-slip vibration behavior of a locomotive with adhesion control in a curve. Proc Inst Mech Eng. 2024;238(7):804–13. doi:10.1177/09544097241233039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ni ZP, Wu BP, Xiao GW, Shen Q, Yao LQ. Wheel-rail adhesion control model by integrating neural network and direct torque control during traction under low adhesion. J Vib Control. 2025;31(11–12):2328–39. doi:10.1177/10775463241257576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Liu W, Qi H, Huang J, Chen Y, He S, Feng H. Rail surface identification and adhesion control based on dynamic adhesion characteristics. Discov Appl Sci. 2025;7(7):657. doi:10.1007/S42452-025-07218-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhu WL, Zhu WJ, Zheng S, Wu N. An improved degraded adhesion model for wheel-rail under braking conditions. Ind Lubr Tribol. 2021;73(3):450–6. doi:10.1108/ILT-07-2020-0244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Chen PW, Zhu WL, Yu CG, Sun NY, Xue WS. Research on train braking model by improved Polach model considering wheel-rail adhesion characteristics. IET Intell Transp Syst. 2023;17(12):2432–43. doi:10.1049/ITR2.12422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Polach O. Creep forces in simulations of traction vehicles running on adhesion limit. Wear. 2004;258(7):992–1000. doi:10.1016/j.wear.2004.03.046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools