Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Probabilistic Rock Slope Stability Assessment of Heterogeneous Pyroclastic Slopes Considering Collapse Using Monte Carlo Methodology

1ETS Arquitectura, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, 28040, Spain

2ETSI Caminos, C. y P., Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, 28040, Spain

* Corresponding Author: Miguel A. Millán. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(3), 2923-2941. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.069356

Received 21 June 2025; Accepted 29 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Volcanic terrains exhibit a complex structure of pyroclastic deposits interspersed with sedimentary processes, resulting in irregular lithological sequences that lack lateral continuity and distinct stratigraphic patterns. This complexity poses significant challenges for slope stability analysis, requiring the development of specialized techniques to address these issues. This research presents a numerical methodology that incorporates spatial variability, nonlinear material characterization, and probabilistic analysis using a Monte Carlo framework to address this issue. The heterogeneous structure is represented by randomly assigning different lithotypes across the slope, while maintaining predefined global proportions. This contrasts with the more common approach of applying probabilistic variability to mechanical parameters within a homogeneous slope model. The material behavior is defined using complex nonlinear failure criteria, such as the Hoek–Brown model and a parabolic model with collapse, both implemented through linearization techniques. The Discontinuity Layout Optimization (DLO) method, a novel numerical approach based on limit analysis, is employed to efficiently incorporate these advances and compute the factor of safety of the slope. Within this framework, the Monte Carlo procedure is used to assess slope stability by conducting a large number of simulations, each with a different lithotype distribution. Based on the results, a hybrid method is proposed that combines probabilistic modeling with deterministic design principles for the slope stability assessment. As a case study, the methodology is applied to a 20-m-high vertical slope composed of three lithotypes (altered scoria, welded scoria, and basalt) randomly distributed in proportions of 15%, 60%, and 25%, respectively. The results show convergence of mean values after approximately 400 simulations and highlight the significant influence of spatial heterogeneity, with variations of the factor of safety between 5 and 12 in 85% of cases. They also reveal non-circular and mid-slope failure wedges not captured by traditional stability methods. Finally, an equivalent normal probability distribution is proposed as a reliable approximation of the factor of safety for use in risk analysis and engineering decision-making.Keywords

Slope stability has been extensively studied in the literature due to its critical importance for human safety and economic consequences. There are methods available to predict the safety coefficient of a slope with a fixed structure (uniform, layered, etc.) that vary in accuracy, as discussed in general geotechnical treatises [1–3]. The main variables defining the problem are the soil or rock structure and properties (resistance, self-weight), the height and angle of the slope, the existence of a water table, the top plane inclination, etc. The concepts defined years ago remain commonly used in engineering practice. These concepts are applied through a variety of classic and modern methodologies. Analytical methods, such as limit analysis and the Limit Equilibrium Method—for example, the Bishop method—are frequently employed. Additionally, numerical methods like the Finite Element Method (FEM), the Finite Difference Method (FDM), and, more recently, the Discrete Element Method (DEM) are also in use [4,5]. All of them consider a homogeneous terrain in the slope.

However, some terrains exhibit spatial variability, indicating that the distribution of geomechanical properties or material components across the slope is not uniform. Additionally, this distribution cannot be defined deterministically because it varies randomly within the slope mass. In volcanic environments, it is common to encounter an alternation of lithotypes with a highly heterogeneous spatial distribution, resulting from eruptive processes that typically occur in successive waves. This complex stratigraphic arrangement significantly complicates the geotechnical design of slopes and cuttings in linear infrastructure projects, as there is neither continuity nor homogeneity in the materials. As a result, numerous slope instabilities are observed without a clear pattern of occurrence, which increases the level of uncertainty in geotechnical risk assessment and the planning of stabilization measures.

Addressing this spatial variability requires the use of probabilistic analysis, which has been widely used for this type of problem since the 1970s ([6,7], among others). Followed by many researchers, the use of spatial correlation of statistical geotechnical properties has become standard in the analysis of the statistical variation of the characteristics of soil over the domain of the slope or foundation. Two primary methods exist for modeling uncertain soil properties: the “single random variable” (SRV) approach and the “random field” approach. The first approach assumes that a single property of the soil has the same value across the slope, selecting this value randomly from the probability distribution of the variable [8]. On the contrary, the random field approach assumes that the different soil variables change spatially, and a correlation coefficient is selected to define the range of these variations [9–13].

Regarding the calculation of slope stability with spatial variability, traditional Limit Equilibrium Methods (LEM) and Limit Analysis (LA), in combination with probabilistic analysis, have been used to address this problem. However, they may not be sufficient to represent the behavior of complex slope problems. These methods typically require an assumed failure surface and allow the calculation of the influence of the random field only along this predefined failure line. Often, this line is assumed to be circular, which may not always be accurate in nonhomogeneous slopes [14]. Moreover, an additional shortcoming of limit equilibrium methods is that they only satisfy the static equation and do not include strain and displacement compatibility [15]. Examples of the use of LE with random fields are [16–18].

Numerical methods, such as the Finite Element Method (FEM), have been successfully applied to slope stability analysis using the Shear Strength Reduction (SSR) approach for calculating the factor of safety, with numerous examples of application. Due to their versatility, these models can represent a wide variety of both continuous and discontinuous terrains without prior assumptions about failure mechanisms, offering a clear advantage over traditional LEM and LA methods. Despite this fact, recent results have been presented using LEM in combination with the Bishop technique, and including weathering effect [19,20]. One advanced option was the Random Finite Element Method (RFEM) [21], which combines the use of random fields with the classical strength reduction method.

Other methods have also been applied to successfully represent spatial variability, such as the Discrete Element Method (DEM) [22,23]. Moreover, the recent development of the Discontinuity Layout Optimization Method (DLO) by Smith and Gilbert [24] has enabled the solution of limit analysis problems without any previous assumption about the failure mode. However, no publication has been found on the use of DLO applied to spatial variability problems. Alternatively, Limit FEM was also developed [25] with similar capabilities to DLO techniques, including random fields and considering the limit analysis of the slope.

Despite the ability of numerical methods to represent complex slopes, they use deterministic parameters in their calculations, requiring a sensitivity analysis to incorporate the uncertainties, usually involving a large number of runs. The inclusion of nonhomogeneities is possible through different probabilistic methods [26–28]. One of the most used is the Monte Carlo method [29,30], involving running numerous simulations with randomly varied input parameters to estimate the probability of slope failure and the factor of safety.

Regarding rock slope stability, a thorough review of the application of probabilistic analysis is presented by Rusydy et al. [31]. Most recent advances in the field are centered on considering advanced criteria, such as combining stratigraphic uncertainty with spatial variability [32], modeling rotated anisotropy in soil–rock mixtures [33], and including multiple simultaneous instability factors (water, rainfall, and seismicity) in probabilistic analysis [34]. Other research lines have a strong emphasis on computational efficiency, in complex models considering slope reinforcement [35], applying machine learning to accelerate Monte Carlo [36], or using improved statistical tools [37]. There are also some studies considering spatial variability and 3D boundary effects [38,39].

Although many references exist on the analysis of rock slopes considering spatial variability, no previous works including volcanic rocks have been found. The distinct behavior of pyroclastic rocks requires including their specific failure criteria along with the consideration of nonhomogeneity in the slope.

In volcanic geology, it is well known that pyroclastic deposits, lava flows, and other volcanic products are typically generated in intermittent episodes, resulting in pronounced lithological heterogeneity. This variability can lead to localized or widespread slope failures, even in the absence of a predictable stratigraphic sequence. In this research, a probabilistic methodology is proposed and applied to a specific case study where three distinct materials with appreciable contrasts in geomechanical properties have been identified.

The objective of this research is to develop a probabilistic analysis of a nonhomogeneous volcanic slope, considering a random distribution of different lithotypes in the slope mass and including the parabolic failure criterion with collapse, using the DLO method in combination with Monte Carlo simulation.

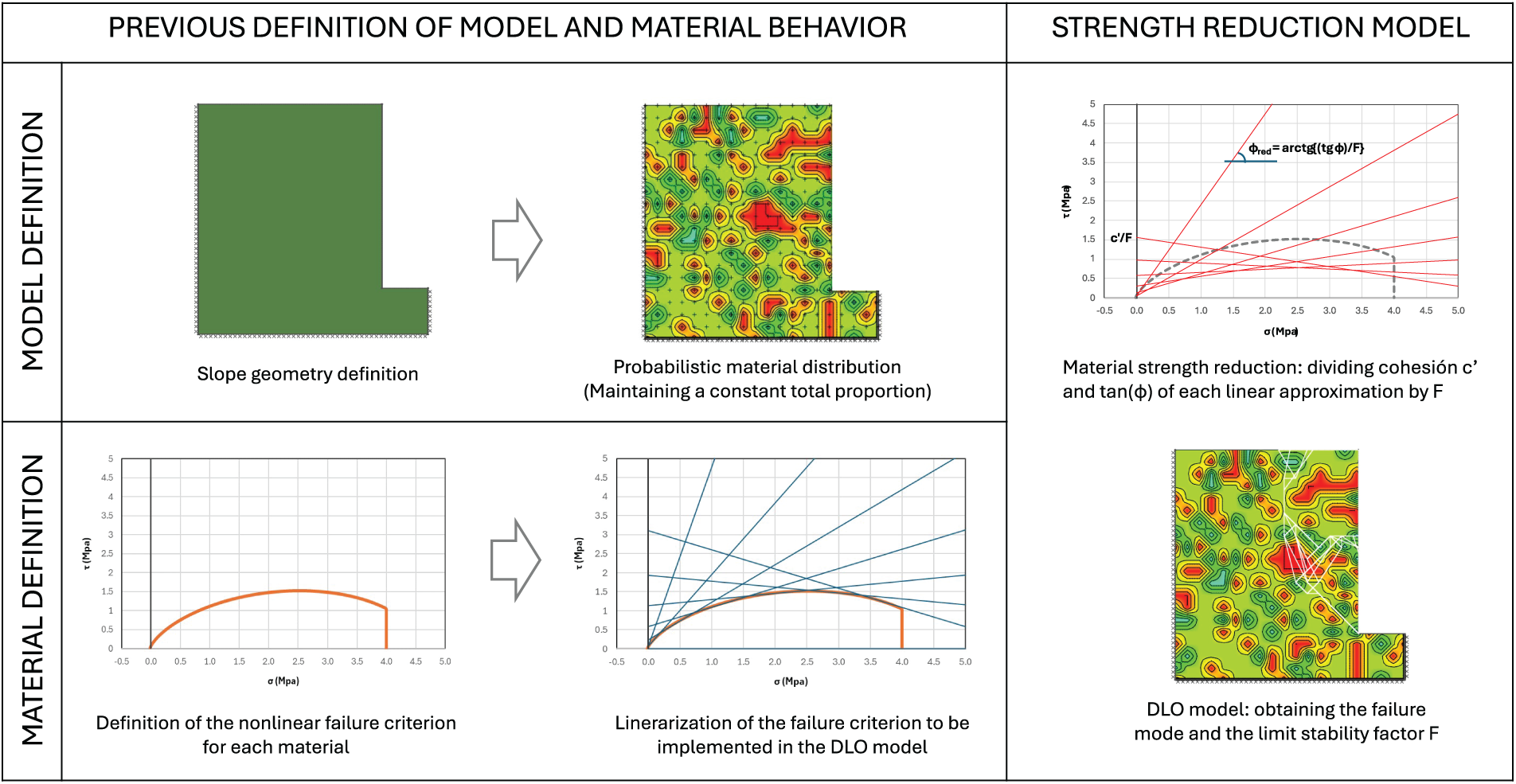

The detailed definition, hypotheses adopted, and methods employed to solve the proposed problem are outlined in the following subsections.

2.1 Problem Definition and Case Study

The problem under study corresponds to a nonhomogeneous volcanic rock slope composed of three different volcanic materials with a random spatial distribution.

This research aims to develop a methodology to address a specific problem characteristic of volcanic terrains, where various materials are expelled by a volcano and deposited without adhering to an established or predictable pattern, being applicable to various rock distributions and slope geometries. To demonstrate the effectiveness of this method, we have selected a specific case study based on a recognized volcanic terrain profile [40], which features a vertical rock slope with a height of 20 m. A comprehensive analysis of the effects of different rock combinations and slope geometries is not within the scope of this research and will be explored in future investigations.

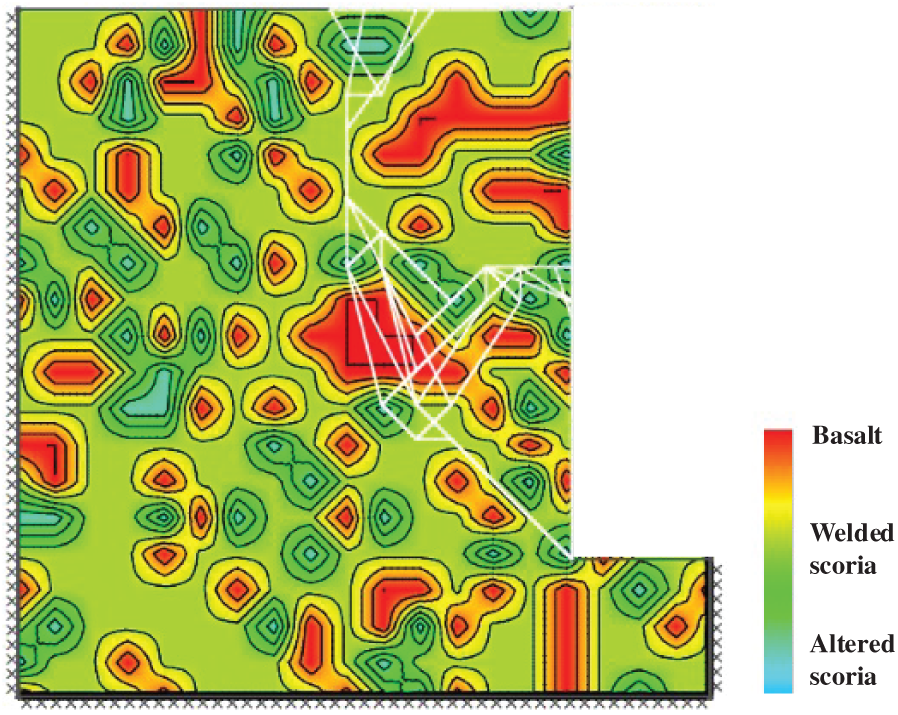

Fig. 1 presents the rock slope considered in this research. The material properties of the different rocks considered in the massif are randomly assigned following the percentage proportions registered in the terrain profile. These proportions are imposed to be maintained in the reference volume described in Figure.

Figure 1: Geometric definition of the rock slope

2.2 Material Definition and Failure Criteria

One key contribution of this research is the exploration of various non-linear failure criteria, rather than relying solely on the widely used Mohr-Coulomb characterization of materials. Three different materials are considered in the slope mass of the case study: basalt, welded scoria, and altered scoria. Two different failure criteria are assigned to those materials: the Hoek and Brown criterion for basalt and the parabolic collapse criterion for scoria. Both are briefly introduced in the following.

2.2.1 Hoek & Brown Failure Criterion

The Hoek and Brown failure criterion, following the last modification [41], is written as:

where

where

2.2.2 Parabolic Failure Criterion with Collapse

Serrano et al. [43] proposed a parabolic strength criterion to describe the mechanical behavior of low-density pyroclastic materials, based on experimental data. This approach is grounded in earlier developments on collapsible soils formulated by Serrano [44], which laid the foundation for the current model.

The initial formulation of the criterion is expressed as:

where t∗ is the isotropic tensile strength and

This expression can be simplified using dimensionless variables, resulting in the following form:

where

Figure 2: Parabolic criterion for volcanic pyroclasts in Cambridge dimensionless variables (

The exponent λ introduces nonlinearity into the strength envelope, extending the classical Mohr–Coulomb model. When λ = 0, Eq. (6) simplifies to the linear Mohr–Coulomb form. Empirically, λ varies between 0 and 1, with λ = 1 being the most commonly observed and, therefore, generally used as a reference value.

The parameters t* (isotropic tensile strength) and

Starting from the case λ = 1, the instantaneous friction angle (ρ) can be evaluated as proposed by Low et al. [35], using the Hill-Lambe variables. This relationship is expressed as:

The value of the instantaneous friction angle depends on the parameter

– If

– If

The type of destructuring that develops is governed by the value of M. Two distinct modes can be identified:

– Compression-induced destructuring (CID): Occurs when M > 1.5.

– Tension-induced destructuring (TID): May coexist with CID if M > 3.

However, as noted by Conde [45] and Serrano et al. [44,46], the experimental values of M are typically between 1.5 and 3, without exceeding this upper limit. Therefore, compression-induced destructuring (CID) is the most relevant mechanism from a practical engineering perspective.

Triaxial tests conducted at low stress levels were used to determine the failure law parameters for various types of pyroclasts in the Canary Islands. Conde [45] and Serrano [44] discovered that welded lapilli had lower average values for the parameter t (around 10% of the collapse load) when compared to pumice, which had values around 20%. In contrast, most other pyroclasts exhibited significantly lower average values below 1%.

This study provides an important foundation for understanding the mechanical behavior of volcanic rock masses and for developing more accurate and reliable slope stability models in volcanic environments.

It is relevant to note that collapse occurs when the isotropic compressive stress p reaches the value Pc at any point in the solid. When the parameter

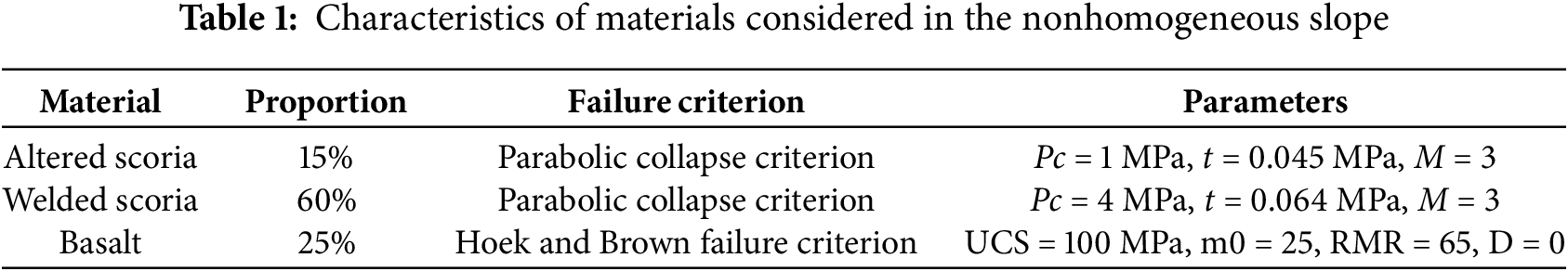

The assumed proportions in the whole mass (following a case reported in [29]) and geotechnical parameters associated with the failure criteria [43] are described in Table 1.

The previous criteria are represented in Fig. 3, where the compressive cap in the parabolic criteria is shown when the normal stress is equal to the collapse pressure.

Figure 3: Failure criteria used in the rock slope modeling. The parabolic failure criteria include the collapse pressure vertical caps

2.3 Discontinuity Layout Optimization Method

The Discontinuity Layout Optimization (DLO) method is a modern computational approach for stability analysis that improves classical limit analysis techniques, developed by Smith and Gilbert in 2007 [24]. Rather than assuming a predefined failure mechanism, DLO identifies the critical failure mode through a systematic search among all possible configurations of discontinuities within a defined domain.

The method operates by discretizing the problem domain into a set of uniformly distributed nodes. From these nodes, potential discontinuity lines, representing possible failure planes, are generated by connecting pairs of nodes. The failure mechanism is then formulated as a problem of relative displacements across these discontinuities, with both tangential and normal components considered. At junctions where discontinuities intersect, compatibility conditions for displacement are enforced to ensure a physically consistent solution.

An optimization problem is then established, where the objective is to minimize the total energy dissipation associated with the movement along the discontinuities. Solving this problem identifies a subset of discontinuities that together form the critical failure mechanism. Importantly, this mechanism corresponds to the lowest energy configuration and thus provides an upper-bound estimate of the true collapse load.

One of DLO’s strengths is its robustness and efficiency. It avoids the convergence issues often encountered in numerical simulations, particularly in problems involving weak confinement or complex failure paths. Moreover, the accuracy of the results can be systematically improved by refining the node density, allowing for high-resolution modeling of the failure pattern.

In this research, DLO is applied using the LimitState: GEO software [47], which can incorporate linearized versions of advanced failure criteria, including the modified Hoek–Brown criterion and the collapse criterion for pyroclastic rocks developed by Serrano et al.

The approximation procedure outlined in [48] defines several intervals, within each of which a linear yield surface is utilized to represent the corresponding non-linear failure criterion. The limit analysis optimization procedure of DLO will automatically select the line associated with the lowest load work needed for the system to reach a state of collapse. When multiple linear yield surfaces are defined, several linear Mohr-Coulomb materials are assigned to the system. A new set of DLO equations is established for each material, and all these equations are addressed simultaneously in the optimization problem. As this optimization seeks to minimize load work, the Mohr-Coulomb line that provides the lowest values of normal stress and shear stress at each discontinuity will be selected.

This allows for the realistic modeling of complex geological materials such as volcanic soils. Fig. 4 demonstrates the tangent approximation used to represent the failure behavior of low-density pyroclastic rocks with mechanical collapse.

Figure 4: Linear approximation to the parabolic failure criterion including collapse. Welded scoria with parameters Pc = 4 MPa; t = 0.064 MPa; M = 3

Due to its flexibility, low computational cost, and strong theoretical foundation, DLO is particularly well-suited for analyzing slope stability in geotechnical engineering.

When different linear criteria are superimposed at the same discontinuity of a solid, DLO writes down the optimization equation for every single one, and the optimization process will select the one with the least dissipation energy. This natural organization of the calculations allows us to define a procedure for randomly assigning several materials in a solid and choosing the one to be considered at that point by forcing its failure criterion to be the lower one.

The slope domain is characterized by a 20 by 20 reference points where the material is assigned randomly. This assumes that the size of the minimum portion of each material is around 1 m, which is consistent with field observations. In the DLO software, only one domain is defined, and the three materials are assigned to it simultaneously. The effective material assignment at each specific location is made by ensuring that the lowest failure criterion in this area corresponds to the actual material. For example, when the material at one specific point is the weakest, the optimization procedure will automatically consider it for failure, and no action is needed. If the actual material in the slope is an intermediate type, we should artificially increase the failure criterion for the weaker material at that location. This will make the intermediate material the weakest in that area, prompting the optimization procedure to select it instead. By applying this procedure to all materials within the solid, the spatial variability of the material can be incorporated into the standard DLO method.

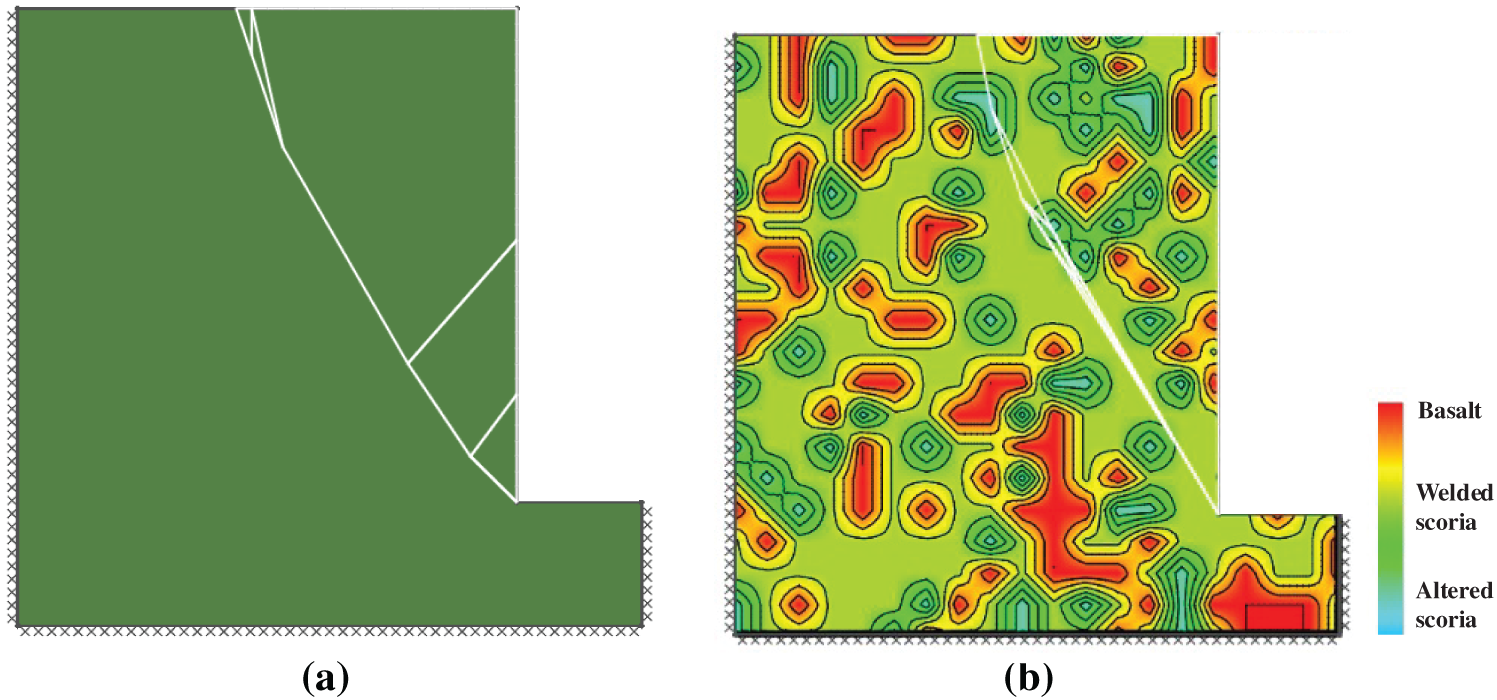

Fig. 5 shows the random distribution of the three materials assigned to the reference volume of the rock slope. This assignment fulfills the criterion of rock type percentage defined for each lithotype in the whole reference volume before performing the excavation.

Figure 5: Random distribution of the three materials considered in the reference volume of the rock slope

The Monte Carlo method for slope stability analysis is a probabilistic approach that involves running a large number of simulations to account for the uncertainty and variability in soil or rock properties or, as in this research, for the spatial variability of rock lithotypes. In the first case, instead of using fixed values, input parameters such as cohesion, friction angle, or unit weight are defined as statistical distributions (e.g., normal, lognormal). In the second case, a random distribution of material types is defined, maintaining a global proportion of each one throughout the entire domain.

The conventional procedure in a Monte Carlo simulation includes the following steps [28]. The first step is to identify the deterministic model, with fixed parameters and materials, that will be used to obtain a single output (in this research, that would correspond to the reference model in Fig. 1). The second step is to identify all the parameters with uncertainty. Third, a probability distribution is assigned to each variable, or a random position is determined for each material (as shown in Fig. 5). Finally, a random trial procedure is established to determine the probability distribution function for the deterministic situation being modeled. For each simulation (or iteration), the method randomly samples values from these distributions and calculates the factor of safety using a deterministic stability analysis (limit analysis by DLO numerical modeling in this study). After many iterations (in this case, 1000 simulations), the results are used to estimate the probability of failure, the distribution function of safety factors, and reliability metrics.

However, this study introduces an innovative variation of the method. Instead of applying randomness to the mechanical properties of the soil, the Monte Carlo approach is used to simulate the spatial variability of lithological materials within the slope. This is particularly relevant in highly heterogeneous geological environments lacking well-defined stratigraphy, such as volcanic terrains. In these settings, pyroclastic deposition and subsequent sedimentary processes produce irregular lithological sequences with little lateral continuity and no clear patterns, making traditional geotechnical characterization and modeling difficult.

This approach starts from data obtained during a geotechnical field campaign (e.g., boreholes, test pits, and in-situ tests), which provide relative percentages of the occurrence of each lithotype. Based on these data, random spatial distributions of soil materials are generated in the model, where each node or cell in the analysis domain is randomly assigned a lithotype according to the observed proportions. This assignment is randomized for each simulation while maintaining the global lithotype ratios across the domain. No stratigraphic order is imposed, reflecting the extreme heterogeneity typical of some complex volcanic formations.

The general procedure for the Monte Carlo simulation under this framework involves the following steps:

1. Definition of a base deterministic model (reference model), with fixed material distribution and constant mechanical properties.

2. Identification of the source of uncertainty, which in this case is the spatial positioning of different lithotypes.

3. Generation of random slope configurations, assigning materials to each domain point randomly, but preserving the global proportions observed.

4. Calculation of the safety factor (F) using a deterministic analysis for each simulation (in this study, a limit analysis via the DLO method is used).

5. Execution of a large number of iterations (1000 simulations in this case) to construct a statistical distribution of safety factors.

This methodology offers a more realistic representation of geotechnical uncertainty in contexts where lithological heterogeneity governs ground behavior, surpassing the limitations of deterministic models or those that only vary material parameters. By simulating multiple spatial configurations, the method captures the natural complexity of the slope, helps identify unexpected critical scenarios, and supports more robust and risk-informed design decisions.

A fundamental distinction exists between the conventional Monte Carlo method, which applies variability to geotechnical parameters, and the spatial variability-based approach proposed in this study. In the former, continuous probability distributions (e.g., normal, log-normal) create an infinite theoretical range of values, allowing the model to explore even extreme scenarios, albeit with low probability. This results in tails in the safety factor distribution, allowing failure probabilities to approach values near zero or one, as is typical when modeling rare but physically possible events (e.g., extremely low cohesion or friction angles). In such cases, there is always a small, non-zero probability (e.g., 10−6 or 10−9) that the safety factor falls below 1.0.

In contrast, the spatial randomization approach limits uncertainty to a finite number of possible configurations, defined by the domain’s discretization and the combination of lithotypes assignable to each cell. As a result, the number of unique safety factor values is also finite, and the resulting distribution lacks continuous tails. This means the estimated probability of failure cannot approach 0 or 1 arbitrarily, unless all configurations lead to failure, or none do.

This limitation has direct implications for the safety criterion. Since “rare but possible” events cannot be captured through statistical tails, it is not advisable to rely solely on an acceptable failure probability threshold (e.g., Pf < 10−3, as proposed by Santamarina et al. [49]). Instead, the proposed approach requires all Monte Carlo-generated configurations to yield safety factors above the stability threshold (F > 1.0), and it additionally introduces a safety margin (e.g., F > 1.5) to account for residual uncertainty in constant mechanical properties.

This hybrid approach, combining spatial probabilistic assessment with reinforced deterministic design, provides a more robust evaluation in line with traditional geotechnical engineering principles. Given the novelty of this spatial Monte Carlo methodology in geotechnical engineering, there are no established acceptable failure probabilities, which must be informed by engineering judgment and experience. Therefore, a conservative criterion has been adopted for volcanic slope stability, taking the deterministic design threshold (F > 1.5) as a baseline requirement in all Monte Carlo simulations.

The cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the safety factor describes the probability that a random variable takes on a value less than or equal to a given number. It is a fundamental concept in probability and statistics, and in slope stability analysis, it is used to assess the probability that the safety factor falls below a critical threshold. Its graphical representation helps to evaluate the probability distribution.

This method offers a more realistic evaluation of slope stability by taking into account the natural variability in geotechnical conditions, helping in making risk-informed decisions.

The proposed methodology addresses the stability of a slope characterized by the spatial variability of the volcanic rocks it comprises.

The slope stability calculations used the so-called Strength Reduction Method (SRM) [50]. This method defines a resistance reduction factor F that applies to an equivalent Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion of the terrain, represented by both the friction angle and the cohesion. Since the Hoek and Brown and the parabolic failure criteria of the different rocks were approximated with linear equivalent limits, the procedure applies as follows:

being

The DLO model will obtain a value of the coefficient F in such a way that the resistant properties of the terrain (c′ and tg

Since the failure criteria, either the Hoek & Brown or the parabolic with collapse criterion, are defined in terms of linear approximations, the strength reduction method is simultaneously applied to all the equivalent parameters c′ and tg

Regarding the rock spatial variability, a systematic calculation procedure was used to define a terrain profile with material proportions of 15% altered scoria, 60% welded scoria, and 25% basalt, similar to what is shown in Fig. 5. This procedure generates a terrain profile for each calculation, maintaining the previous material proportions while randomly assigning the location of the different materials, as explained in Section 2.3. A simplified flowchart to show the full workflow of the SRM is outlined in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Flowchart of the SRM procedure, including the model preparation and material failure criterion linearization before using the strength reduction method in DLO

Considering the previously described procedures, a total of 1000 calculations are conducted, with each calculation corresponding to a specific spatial configuration of the material. For each configuration, a safety coefficient is determined. Following this, the Monte Carlo method is applied to determine the safety characteristics of the slope.

To define a reference value, the factor of safety of the non-homogeneous slope F can be compared with the safety factor of the rock slope composed only of the weakest material (altered scoria), which in this case is Fmin = 2.053. If the slope is composed only of the intermediate material (a reasonable simplification, since its amount is 60%), the factor of safety obtained is Fmed = 2.131. The small difference obtained between the two configurations is due to their failure criteria being very close in the low normal stress range (see Fig. 3), which is present at the slope failure wedges.

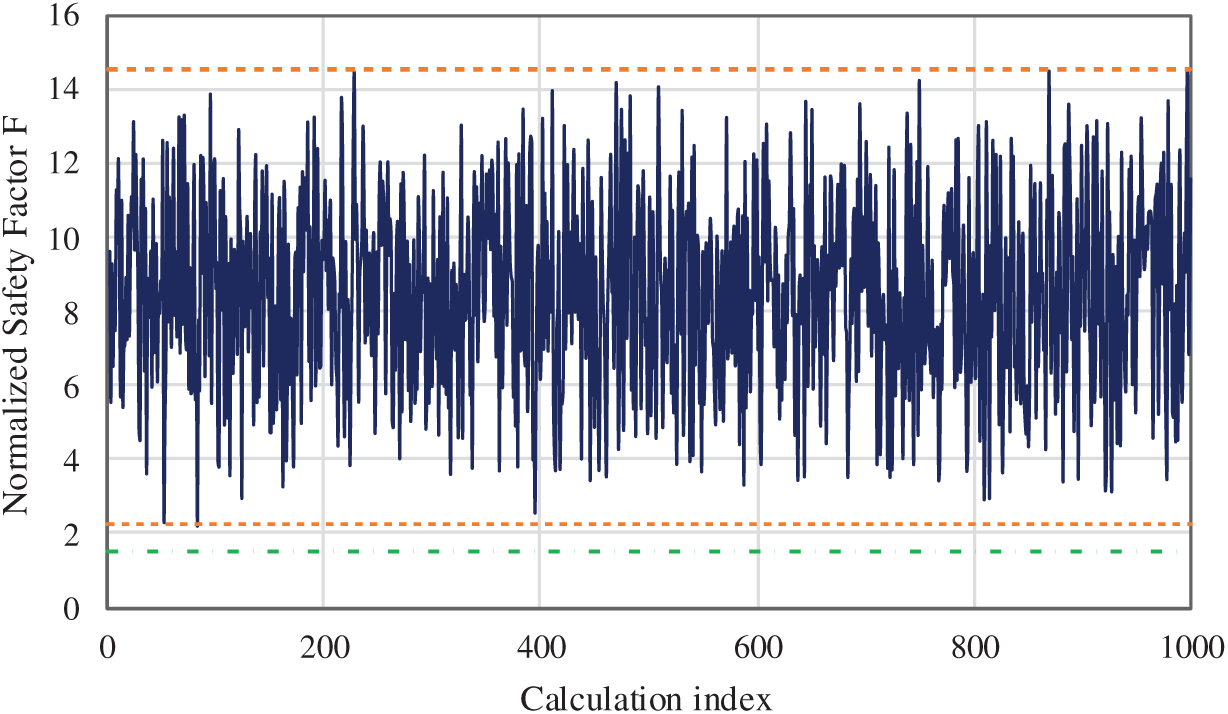

The value of the safety factor F, obtained for the entire set, is graphically presented in Fig. 7, where the range of variation between the material configurations that induce failure and those that prevent it reaches a value of 12, making clear the need for a statistical analysis of the lithotype distribution. This means that adopting a unique, specific spatial configuration in a slope analysis may produce a very unsafe result.

Figure 7: Results for the safety factor F for the whole set of calculations. The minimum and maximum values are marked in red. The green line represents the reference value F = 1.5

To better understand the slope behavior shown in Fig. 7, the wedge configurations of the limit analysis for the lower and highest safety factor are represented in Figs. 8 and 9.

Figure 8: Failure mode with minimum factor of safety. (a) Homogeneous slope with the weakest rock and Fmin = 2.053; (b) Nonhomogeneous slope with the lowest factor of safety F = 2.24

Figure 9: Failure mode with maximum factor of safety in a nonhomogeneous slope

Fig. 8 presents a comparison of the failure modes for two types of rock slopes. The first slope, illustrated in Fig. 8a, is uniform and composed of the weakest material analyzed, which is altered scoria. In contrast, Fig. 8b shows a non-homogeneous slope that has the lowest safety factor, with F = 2.24. As can be observed, the material nonhomogeneity allows for a distribution of discontinuities like that of the weakest case in this instance.

A different distribution of materials in the slope can prevent the previous failure from occurring, necessitating that the discontinuities follow a more complex path in order to initiate the failure. This is illustrated in Fig. 9, which presents the scenario with a maximum factor of safety of F = 14.50.

Intermediate geometric configurations of the materials in the slope present failures that are unusual in a homogeneous slope, but are characteristic of a nonhomogeneous one, as the mid-slope failure presented in Fig. 10. The model’s ability to identify unusual solutions is a highlight of the proposed procedure, especially since traditional techniques using homogeneous slopes often overlook them.

Figure 10: Mid-slope failure mode in nonhomogeneous rock. (a) Simulation number 1, F = 9.64. (b) Simulation number 2, F = 5.57

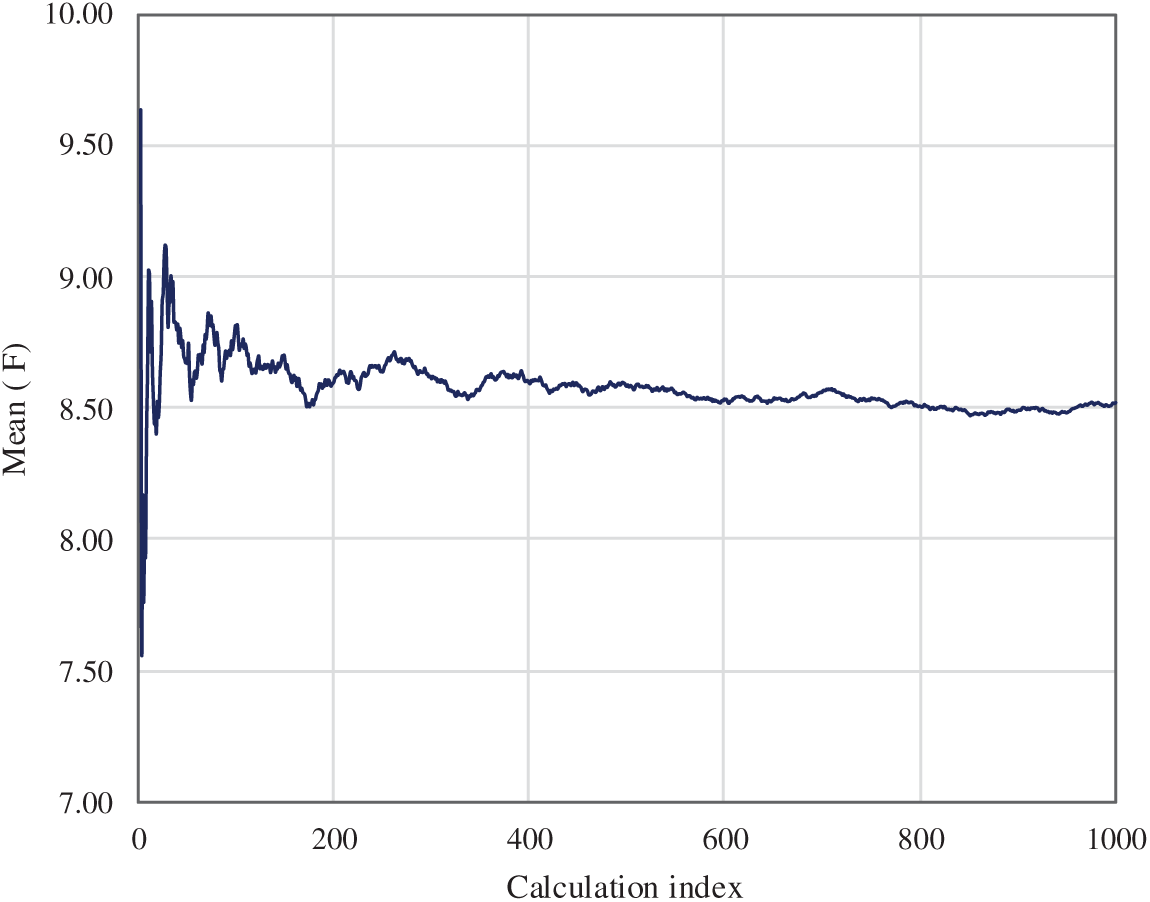

Regarding the Monte Carlo procedure, a set of 1000 simulations was initially defined, and this decision should be verified. Analyzing the convergence of the safety factor F mean along the set of simulations is particularly important since it determines the optimum number of simulations. For this case, we obtain the curve presented in Fig. 11.

Figure 11: Convergence of the mean of the factor of safety, F

As observed in Fig. 11, after 400 simulations, the cumulative mean stabilizes, showing little deviation from the final value of F = 8.50. The indicated preselection of 1000 calculations is therefore overall adequate.

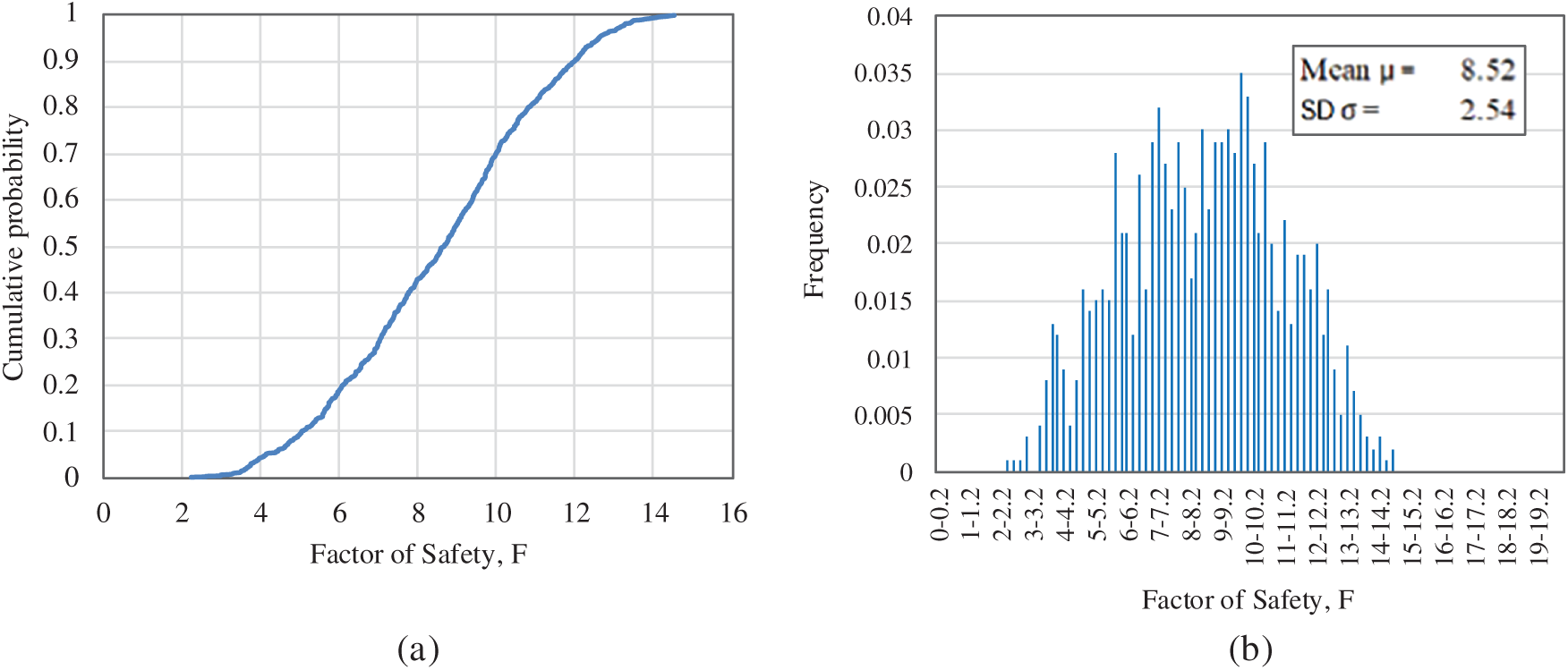

Though not properly defined since it is not a continuous function in this research, it is of interest to represent the discrete approach to the probability distribution function (PDF) and the cumulative distribution function (CDF). The PDF shows the different percentages of simulations where the safety factor reaches a threshold value. The CDF of the safety factor describes the probability that a random variable takes on a value less than or equal to a given number. It is a fundamental concept in probability and statistics, and in slope stability analysis, it is used to assess the probability that the safety factor falls below a critical threshold. Its graphical representation helps to evaluate the probability distribution.

The results, in terms of probability distributions of the normalized factor of safety, are shown in Fig. 12. The probability distribution function (PDF) is presented in Fig. 12a, and the cumulative distribution function (CDF) in Fig. 12b.

Figure 12: Probability distributions of the factor of safety. (a) Frequency histogram of the factor of safety (PDF); (b) Cumulative probability distribution (CDF)

The variability of F is relatively high, with about 85% of all realizations falling in the relatively wide interval of 5 < F < 12. After estimating the parameters, it is important to evaluate how well the assumed distribution fits the sample. This process of checking the goodness of fit can provide valuable insights [26].

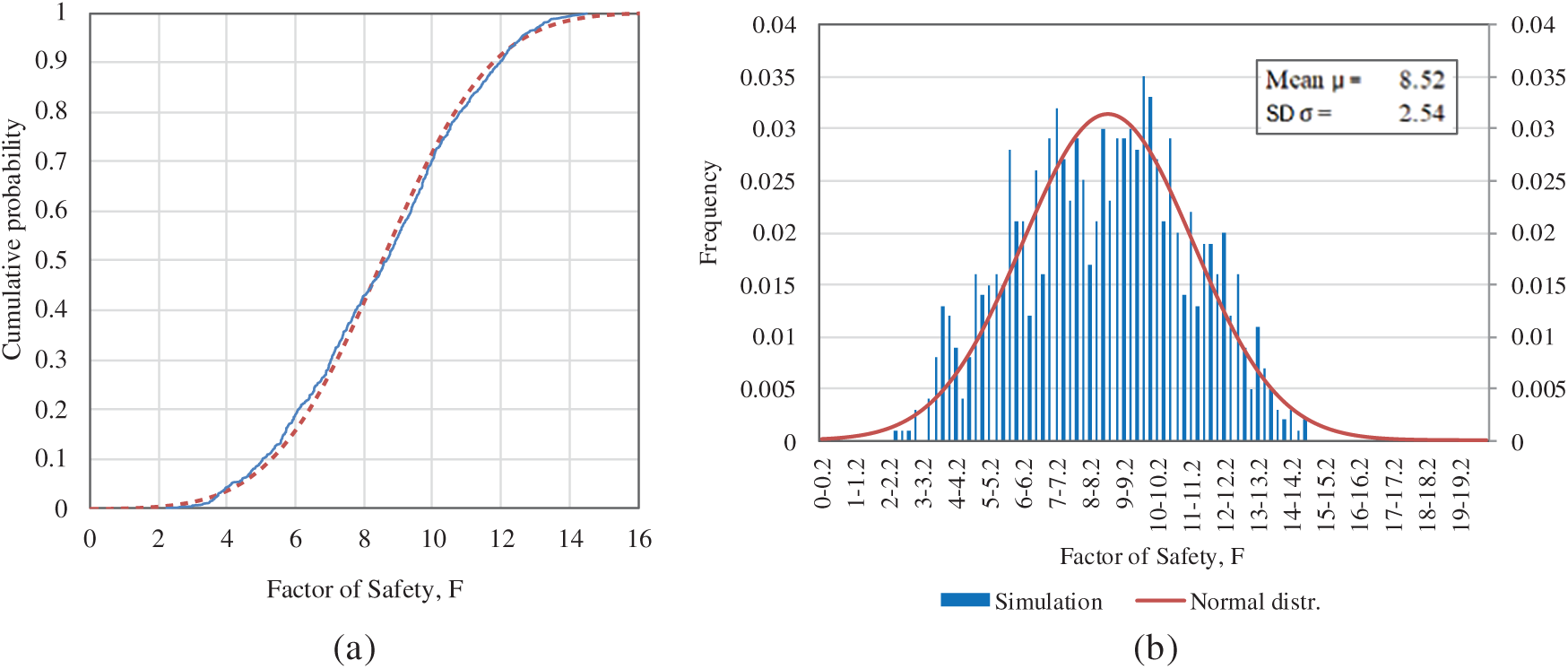

Fig. 13 shows the agreement between the sample distribution obtained from calculations and a normal distribution fitted with the same mean and standard deviation. The discontinuity observed in the frequency representation of the factor of safety (see Fig. 13b) occurs because it is calculated from a limited set of 1000 individual cases. The gaps or sudden changes in the curve indicate the intervals where insufficient results were obtained for these specific frequencies. Ideally, if an infinite number of cases were analyzed, the resulting frequency curve would be continuous, resembling the red curve.

Figure 13: Comparison between the probability distribution of the simulation and a normal distribution with the same parameters. Factor of safety, F. (a) Cumulative probability of F; (b) Frequency of F

A general good agreement is observed between the probability distributions in Fig. 13, despite occasional variations such as the low probability registered for F = 8–8.2, for example.

While the previous probabilistic approach to the Monte Carlo results is valuable as a reference to the traditional probabilistic approach, it may not provide adequate safety on its own, as discussed in Section 2.4. As noted, the discrete distribution used in Monte Carlo simulations does not effectively capture “rare but possible” events due to its lack of defined tails, making standard thresholds potentially unreliable. Therefore, for this case study, the proposed hybrid approach stipulates that all Monte Carlo simulations must yield a safety factor (F) greater than 1.5 to be considered safe, which is indeed the case.

This study presents a novel probabilistic framework for volcanic slope stability analysis, shifting the focus from spatial variability in mechanical parameters to spatial variability in lithological distributions. The main result is a more realistic and robust stability evaluation that better reflects the heterogeneous nature of pyroclastic terrains. The Monte Carlo approach is used, assigning randomized lithotype configurations to the slope model while preserving global field proportions.

A key innovation is the integration of this spatial variability with the Discontinuity Layout Optimization (DLO) method, enabling the identification of complex failure mechanisms, including non-circular and mid-slope surfaces, typically missed by traditional techniques in homogeneous slopes. It also facilitates the inclusion of non-linear failure criteria by linearization, without the numerical instabilities or convergence problems of other methods. This approach, based on finite material localization instead of continuous distribution of properties, also poses some questions. The spatially randomized approach limits the probability of extreme outcomes, unlike traditional Monte Carlo simulations that rely on continuous parameter distributions and produce infinite variation and statistical tails. It is inappropriate to define safety based solely on failure probabilities. Instead, the study advocates for all simulated configurations to meet a minimum safety factor (e.g., F > 1.0) and proposes a higher threshold (e.g., F > 1.5) to account for unmodeled uncertainties. This hybrid strategy combines probabilistic spatial modeling with conservative deterministic thresholds, improving both the accuracy and reliability of stability assessments.

Current research concentrated on establishing a consistent methodology, evaluating its applicability, and discussing the findings from a case study. However, further research is needed to consider other important factors, such as the presence of a water table and the stratification structures typically found in volcanic terrains, coherent with secondary spatial variability. The approach is especially applicable to volcanic slopes with irregular stratigraphy, where homogeneous models fail to capture critical failure scenarios. Furthermore, the introduction of an equivalent normal distribution for the factor of safety enhances its use in engineering risk analysis and decision-making. Overall, the method offers a significant advancement for both scientific understanding and practical geotechnical design in heterogeneous slope conditions.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This publication is part of the project PID2022-139202OB-I00, Neural Networks and Optimization Techniques for the Design and Safe Maintenance of Transportation Infrastructures: Volcanic Rock Geotechnics and Slope Stability (IA-Pyroslope), funded by the Spanish State Research Agency of the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain and the European Regional Development Fund, MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/FEDER, EU.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Miguel A. Millán, Rubén A. Galindo; methodology, Miguel A. Millán, Rubén A. Galindo; software, Miguel A. Millán; validation, Rubén A. Galindo; formal analysis, Miguel A. Millán; investigation, Fausto Molina‐Gómez; resources, Fausto Molina‐Gómez; data curation, Fausto Molina‐Gómez; writing—original draft preparation, Miguel A. Millán; writing—review and editing, Rubén A. Galindo; visualization, Fausto Molina‐Gómez; supervision, Rubén A. Galindo; project administration, Miguel A. Millán, Rubén A. Galindo; funding acquisition, Miguel A. Millán, Rubén A. Galindo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Huang YH. Stability analysis of earth slopes. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1983. 316 p. [Google Scholar]

2. Hoek E, Bray JW. Rock slope engineering. London, UK: Institution of Mining and Metallurgy; 1997. 364 p. [Google Scholar]

3. Wyllie DC. Rock slope engineering: civil applications. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Taylor & Francis Inc.; 2017. 620 p. [Google Scholar]

4. Boruah PP, Chakraborty A. Deterministic and probabilistic approach of seismic slope stability analysis—a state-of-the-art review. Geotech Eng J SEAGS AGSSEA. 2024;53(3):31–8. doi:10.14456/seagj.2022.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gael CN, Luc Leroy MN, Christian FB. Research on slope stability assessment methods: a comparative analysis of limit equilibrium, finite element, and analytical approaches for road embankment stabilization. AI Civ Eng. 2025;4(1):2. doi:10.1007/s43503-024-00046-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Matsuo M, Kuroda K. Probabilistic approach to design OF embankments. Soils Found. 1974;14(2):1–17. doi:10.3208/sandf1972.14.2_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Alonso EE. Risk analysis of slopes and its application to slopes in Canadian sensitive clays. Géotechnique. 1976;26(3):453–72. doi:10.1680/geot.1976.26.3.453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Low BK, Tang WH. Efficient reliability evaluation using spreadsheet. J Eng Mech. 1997;123(7):749–52. doi:10.1061/(asce)0733-9399(1997)123:7(749). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Vanmarcke EH. RandomFields: analysis and synthesis. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

10. Griffiths DV, Fenton GA. Bearing capacity of spatially random soil: the undrained clay Prandtl problem revisited. Géotechnique. 2001;51(4):351–9. doi:10.1680/geot.51.4.351.39396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Jiang SH, Li DQ, Zhang LM, Zhou CB. Slope reliability analysis considering spatially variable shear strength parameters using a non-intrusive stochastic finite element method. Eng Geol. 2014;168(13):120–8. doi:10.1016/j.enggeo.2013.11.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Li XY, Zhang LM, Li JH. Using conditioned random field to characterize the variability of geologic profiles. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng. 2016;142(4):04015096. doi:10.1061/(asce)gt.1943-5606.0001428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kasama K, Whittle AJ. Effect of spatial variability on the slope stability using random field numerical limit analyses. Georisk Assess Manag Risk Eng Syst Geohazards. 2016;10(1):42–54. doi:10.1080/17499518.2015.1077973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Griffiths DV, Huang J, Fenton GA. Influence of spatial variability on slope reliability using 2-D random fields. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng. 2009;135(10):1367–78. doi:10.1061/(asce)gt.1943-5606.0000099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Krahn J. The 2001 R.M. Hardy Lecture: the limits of limit equilibrium analyses. Can Geotech J. 2003;40(3):643–60. doi:10.1139/t03-024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sivakumar Babu GL, Mukesh MD. Effect of soil variability on reliability of soil slopes. Géotechnique. 2004;54(5):335–7. doi:10.1680/geot.2004.54.5.335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Low BK, Lacasse S, Nadim F. Slope reliability analysis accounting for spatial variation. Georisk Assess Manag Risk Eng Syst Geohazards. 2007;1(4):177–89. doi:10.1080/17499510701772089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Cho SE. Effects of spatial variability of soil properties on slope stability. Eng Geol. 2007;92(3–4):97–109. doi:10.1016/j.enggeo.2007.03.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Rezaei M, Seyed Mousavi SZ, Esmaeili K. Combination of Monte Carlo simulation and bishop technique for the slope stability analysis of the Gol-E-Gohar iron open pit mine. J Min Environ. 2025;16(2):613–32. doi:10.22044/jme.2024.14470.2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Rezaei M, Seyed Mousavi SZ. Slope stability analysis of an open pit mine with considering the weathering agent: field, laboratory and numerical studies. Eng Geol. 2024;333(8):107503. doi:10.1016/j.enggeo.2024.107503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Griffiths DV, Fenton GA. Probabilistic slope stability analysis by finite elements. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng. 2004;130(5):507–18. doi:10.1061/(asce)1090-0241(2004)130:5(507). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Liu DY, Che HQ, Wang C, Chen Y. Assessing the effect of layered spatial variability on soil behavior via DEM simulation. Comput Part Mech. 2025;12(1):59–80. doi:10.1007/s40571-024-00779-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Gonen S, Pulatsu B, Erdogmus E, Lourenço PB, Soyoz S. Effects of spatial variability and correlation in stochastic discontinuum analysis of unreinforced masonry walls. Constr Build Mater. 2022;337(3):127511. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Smith C, Gilbert M. Application of discontinuity layout optimization to plane plasticity problems. Proc R Soc A. 2007;463(2086):2461–84. doi:10.1098/rspa.2006.1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sloan SW. Lower bound limit analysis using finite elements and linear programming. Int J Numer Anal Meth Geomech. 1988;12(1):61–77. doi:10.1002/nag.1610120105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Dyson AP, Tolooiyan A. Comparative approaches to probabilistic finite element methods for slope stability analysis. Simul Model Pract Theory. 2020;100(1):102061. doi:10.1016/j.simpat.2019.102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. El-Ramly H, Morgenstern NR, Cruden DM. Probabilistic slope stability analysis for practice. Can Geotech J. 2002;39(3):665–83. doi:10.1139/t02-034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Mostyn GR, Li KS. Probabilistic slope analysis—state-of-play. In: Probabilistic methods in geotechnical engineering. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2020. p. 89–109. doi:10.1201/9781003077749-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Tobutt DC. Monte Carlo simulation methods for slope stability. Comput Geosci. 1982;8(2):199–208. doi:10.1016/0098-3004(82)90021-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Jiang SH, Li DQ, Cao ZJ, Zhou CB, Phoon KK. Efficient system reliability analysis of slope stability in spatially variable soils using Monte Carlo simulation. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng. 2015;141(2):04014096. doi:10.1061/(asce)gt.1943-5606.0001227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Rusydy I, Canbulat I, Zhang C, Wei C, McQuillan A. The development and implementation of design flowchart for probabilistic rock slope stability assessments: a review. Geoenviron Disasters. 2024;11(1):28. doi:10.1186/s40677-024-00290-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Deng ZP, Pan M, Niu JT, Jiang SH. Full probability design of soil slopes considering both stratigraphic uncertainty and spatial variability of soil properties. Bull Eng Geol Environ. 2022;81(5):195. doi:10.1007/s10064-022-02702-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Qu C, Liu Y, Guo H, Fang H, Cheng K, Yuan H, et al. Probabilistic assessment of soil–rock mixture slope failure considering two-phase rotated anisotropy random fields. Int J Numer Anal Meth Geomech. 2025;49(4):1113–25. doi:10.1002/nag.3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhang W, Ran B, Gu X, Sun G, Zou Y. Probabilistic stability analysis of a layered slope considering multi-factors in spatially variable soils. Nat Hazards. 2024;120(12):11209–38. doi:10.1007/s11069-024-06640-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Low BK, Boon CW. Probability-based design of reinforced rock slopes using coupled FORM and Monte Carlo methods. Rock Mech Rock Eng. 2024;57(2):1195–217. doi:10.1007/s00603-023-03607-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Aminpour M, Alaie R, Kardani N, Moridpour S, Nazem M. Slope stability predictions on spatially variable ran-dom fields using machine learning surrogate models. arXiv:2204.06097. 2022. [Google Scholar]

37. Renaud V, Al Heib M. Probabilistic slope stability analysis: a novel distribution for soils exhibiting highly variable spatial properties. Probab Eng Mech. 2024;76(5):103586. doi:10.1016/j.probengmech.2024.103586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Sun Z, Ding J, Yang X, Wang Y, Dias D. Probabilistic analysis of width-limited 3D slope considering spatial variability of Hoek-Brown rock masses. Rock Mech Rock Eng. 2024;57(11):9759–80. doi:10.1007/s00603-024-04059-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Nguyen PMV, Marciniak M. Stochastic rock slope stability analysis: open pit case study with adjacent block caving. Geotech Geol Eng. 2024;42(7):5827–45. doi:10.1007/s10706-024-02862-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Menéndez MM, González-Gallego FJ. Las clasificaciones geomecánicas en macizos rocosos volcánicos. In: Hernández LE, Santamarta JC, editors. Ingeniería geológica en terrenos volcánicos. Madrid, Spain: Ilustre Colegio Oficial de Geólogos; 2015. p. 61–94. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

41. Hoek E, Carranza-Torres C, Corkum B. Hoek-Brown failure criterion—2002 edition. In: Hammah R, Bawden W, Curran J, Telesnicki M, editors. Proceedings of NARMS-TAC, Mining Innovation and Technology; 2020 Jul 10; Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 267–73. [Google Scholar]

42. Bieniawski ZT. Rock mass classification in rock engineering. In: Proceedings of the Symposium on Exploration for Rock Engineering. Rotterdam. The Netherlands: Balkema; 1976. p. 97–106. [Google Scholar]

43. Serrano A, Perucho A, Conde M. Yield criterion for low-density volcanic pyroclasts. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2016;86(1):194–203. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2016.04.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Serrano A. Aglomerados volcánicos en las Islas Canarias. In: Proceedings of Memoria del Simposio Nacional de Rocas Blandas; 1976 Nov 17–18; Madrid, Spain. p. 47–53. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

45. Conde M. Caracterización geotécnica de materiales volcánicos de baja densidad [master’s thesis]. Madrid, Spain: Universidad Complutense de Madrid; 2013. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

46. Serrano A, Galindo R, Perucho Á. Ultimate bearing capacity of low-density volcanic pyroclasts: application to shallow foundations. Rock Mech Rock Eng. 2021;54(4):1647–70. doi:10.1007/s00603-020-02341-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. LimitState: GEO Manual Version [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.limitstate.com/geo-documentation. [Google Scholar]

48. Millán MA, Galindo R, Alencar A. Application of discontinuity layout optimization method to bearing capacity of shallow foundations on rock masses. ZAMM J Appl Math Mech/Z Für Angew Math Und Mech. 2021;101(10):e201900192. doi:10.1002/zamm.201900192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Santamarina JC, Altschaeffl AG, Chameau JL. Reliability of slopes: incorporating qualitative information (abridgment). Transp Res Rec. 2024;2024:1–5. [Google Scholar]

50. Dawson EM, Roth WH, Drescher A. Slope stability analysis by strength reduction. Géotechnique. 1999;49(6):835–40. doi:10.1680/geot.1999.49.6.835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools