Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Urban Transportation Strategy Selection for Multi-Criteria Group Decision-Making Using Pythagorean Fuzzy N-Bipolar Soft Expert Sets

1 Department of Mathematics, College of Education, University of Zakho, Zakho, 42002, Iraq

2 Department of Computer Science, College of Science, Knowledge University, Kirkuk Road, Erbil, 44001, Iraq

3 Department of Mathematics, College of Science, University of Duhok, Duhok, 42001, Iraq

4 Department of Mathematics and Statistics, College of Science, University of Jeddah, Jeddah, 23445, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Mathematics, College of Science, University of Zakho, Zakho, 42002, Iraq

6 Department of Computer Science, College of Science, Cihan University-Duhok, Duhok, 42001, Iraq

* Corresponding Author: Zanyar A. Ameen. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Algorithms, Models, and Applications of Fuzzy Optimization and Decision Making)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(3), 3493-3529. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.070019

Received 06 July 2025; Accepted 19 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Urban transportation planning involves evaluating multiple conflicting criteria such as accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and environmental impact, often under uncertainty and incomplete information. These complex decisions require input from various stakeholders, including planners, policymakers, engineers, and community representatives, whose opinions may differ or contradict. Traditional decision-making approaches struggle to effectively handle such bipolar and multivalued expert evaluations. To address these challenges, we propose a novel decision-making framework based on Pythagorean fuzzy N-bipolar soft expert sets. This model allows experts to express both positive and negative opinions on a multinary scale, capturing nuanced judgments with higher accuracy. It introduces algebraic operations and a structured aggregation algorithm to systematically integrate and resolve conflicting expert inputs. Applied to a real-world case study, the framework evaluated five urban transport strategies based on key criteria, producing final scores as follows: improving public transit (−0.70), optimizing traffic signal timing (1.86), enhancing pedestrian infrastructure (3.10), expanding bike lanes (0.59), and implementing congestion pricing (0.77). The results clearly identify enhancing pedestrian infrastructure as the most suitable option, having obtained the highest final score of 3.10. Comparative analysis demonstrates the framework’s superior capability in modeling expert consensus, managing uncertainty, and supporting transparent multi-criteria group decision-making.Keywords

Designing successful urban mobility system solutions is a problem of multifaceted complexity driven by competing priorities such as cost, environmental conservation, optimal traffic flow, and social justice. Decision-makers must balance inputs from a broad spectrum of stakeholders with varying concerns and preferences, typically based on personal intuition or untested data. These complexities are compounded further by the dynamic context of cities, where policy must be continuously adapted to respond to shifting demands. As a result, conventional decision-making (DM) models—typically using strict or dichotomous logic—fall short to capture reality-based contexts’ complexities, and hence more and more reliance is being placed on computational models capable of coping with uncertainty and vagueness.

A foundational mathematical approach for modeling such uncertainty and vagueness is fuzzy set (FS) theory, introduced by Zadeh [1], which allows partial membership and captures the imprecision of human reasoning. Intuitionistic FSs (IFSs), developed by Atanassov [2], extend FS by introducing independent membership degrees (MDs) and non-membership degrees (NMDs). Yager’s Pythagorean FSs (PFSs) [3] further generalize IFSs by allowing the squared sum of MDs and NMDs to be at most one, offering enhanced flexibility. PFSs have gained wide recognition in multi-criteria group decision-making (MCGDM) due to their expressive power, with applications in distance measures [4–6], structural modeling [7,8], and decision support systems [9].

Soft set (SS) theory, introduced by Molodtsov [10], provides a parameterized framework for uncertainty modeling, independent of probabilistic or fuzzy principles. By associating elements with parameter sets, SSs effectively handle vague and incomplete data. The framework was further developed by Maji et al. [11] and Ali et al. [12], who formalized core operations. Extensions such as fuzzy SSs [13], intuitionistic fuzzy SSs [14], and Pythagorean fuzzy SSs [15] have broadened its applicability. These hybrid models have been successfully applied in medical diagnosis [16], multi-attribute aggregation [17], structural analysis [18], clustering [19], and biological networks [20], highlighting their suitability for complex MCGDM environments [21].

Bipolarity reflects the dual nature of human reasoning, where evaluations consider both positive and negative dimensions. Shabir and Naz [22] introduced bipolar soft sets (BSSs), extending SSs to accommodate contradictory information. Subsequent refinements by Karaaslan and Karataş [23] and Mahmood and Jaballah [24] improved operational definitions and adaptability. Fuzzy extensions [25,26] have enhanced modeling precision. In particular, the works by Zeb et al. [27,28] stand out by developing advanced aggregation operators for fuzzy and Pythagorean fuzzy BSSs, significantly advancing practical DM methodologies. Applications in decision models [29] and error-reduction frameworks [30] confirm the practical value of these theoretical advances.

Many existing models rely on binary or real-valued evaluations within

In situations that require the active involvement of multiple experts—each contributing unique insights shaped by their individual backgrounds, expertise, and value systems—modeling and aggregating conflicting or diverse opinions becomes a critical component of the DM process. Soft expert sets (SESs), introduced by Alkhazaleh and Salleh [40], provide a foundational structure by embedding expert evaluations directly into SS theory. This integration supports group DM under uncertainty, where collective judgments must be synthesized despite partial knowledge, imprecise preferences, and subjective bias.

To better capture the nuances of expert-based assessments, several fuzzy generalizations have been proposed, including fuzzy SESs (FSESs) [41], intuitionistic fuzzy SESs (IFSESs) [42], and Pythagorean fuzzy SESs (PFSESs) [43], each offering richer semantics for expressing uncertainty through MDs and NMDs. These models have been further extended by incorporating bipolar reasoning, enabling the representation of both favorable and unfavorable expert views within a unified framework. Notable developments in this regard include bipolar SESs (BSESs) [44], fuzzy bipolar SESs (FBSESs) [45], and soft expert models built upon multinary evaluations, such as (fuzzy) N-soft expert sets ((F)NSESs) [46] and their Pythagorean counterparts, Pythagorean fuzzy NSESs (PFNSESs) [47].

Recent advances have combined the expressiveness of N-soft structures and expert and bipolar assessment to generate models like N-bipolar soft expert sets (NBSESs) [48], fuzzy NBSESs (FNBSESs) [49], and intuitionistic fuzzy NBSESs (IFNBSESs) [50]. These enhanced frameworks are designed to handle at the same time symbolic or linguistic scales, bipolar assessments, various expert opinions, and various forms of uncertainty. Collectively, these models constitute a comprehensive and integrated MCGDM methodology that can more effectively represent real-world complexities than can classical methodologies. As they currently exist, SESs and their modern extensions represent a powerful class of tools for implementing consensus-based decision methods under uncertainty and multi-dimensionality conditions.

From a broader methodological standpoint, Kumar and Pamucar [51] presented a large-scale bibliometric analysis of MCGDM developments over the past two decades, highlighting the rise of hybrid fuzzy methods and identifying application gaps across various sectors. The review confirms that while fuzzy MCGDM methods have diversified in terms of structure and application, challenges remain in modeling heterogeneous expert knowledge, symbolic preferences, and bipolar trade-offs.

In parallel, domain-specific applications of fuzzy and MCGDM methods for sustainable DM have gained momentum. For instance, Nayeb-Pashaei et al. [52] applied the fuzzy logarithm methodology of additive weights using triangular fuzzy numbers to identify and rank sustainability criteria in urban transport systems. Their model effectively captures uncertainty in sustainability dimensions such as health, safety, and emissions. However, it does not accommodate expert-level disagreement or contradictory evaluations, which are often critical in sustainability planning.

These gaps motivate the development of Pythagorean fuzzy N-bipolar soft expert set (PFNBSES), which uniquely integrates Pythagorean fuzzy logic with NBSES, allowing for more nuanced, expert-driven, and context-sensitive sustainability DM frameworks.

1.3 Research Gap and Motivation

The motivation for developing the PFNBSES model is that DM environments in the real world are growing more and more complex, particularly those involving multiple experts, uncertainty, bipolarity, and qualitative diversity. Classical SS paradigms, as essential for handling uncertainty, cannot handle at the same time bipolarity, multinary evaluation, and expert-based discrimination. BSSs handle dual-valued information but are usually limited to binary evaluation. NSSs are supportive of multinary symbolic evaluation but are not necessarily supportive of expert consensus or bipolar scales. SESs are supportive of multiple expert opinions but are usually developed from lower-order fuzzy or intuitionistic structures.

This layered design enables PFNBSES to reflect the intrinsic dualities and subjectivities of modern DM problems while maintaining computational rigor and interpretability. Its development is driven by the practical need for a scalable, expressive, and expert-driven framework applicable to domains such as urban planning, medical diagnostics, and cybersecurity.

1.4 Novelties and Advantages of the Proposed Model

The PFNBSES model offers a unified and flexible framework that integrates Pythagorean fuzzy logic, multinary evaluation scales, bipolar reasoning, and multi-expert aggregation. These features collectively enable more nuanced, balanced, and reliable DM compared to existing SS-based models.

A detailed comparative analysis of PFNBSES’s strengths and advantages is provided in Section 5.2, where its superior handling of uncertainty, expert diversity, and bipolarity is rigorously demonstrated.

This succinct overview highlights PFNBSES’s significant contribution to advancing MCGDM methodologies.

1.5 Objectives and Key Contributions

This study aims to develop a comprehensive DM framework for MCGDM environments characterized by uncertainty, bipolar evaluations, and expert diversity. The PFNBSES model unifies and extends several SS-based methodologies to improve flexibility, precision, and applicability. It addresses methodological gaps in SSs, BSSs, and soft expert frameworks by incorporating Pythagorean fuzzy logic, multinary evaluation, and expert consensus within a single model.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

• Formal definition of the PFNBSES model with foundational operations including union, intersection, complement, agreement, and disagreement, supported by algebraic properties.

• Development of a complete algorithmic framework for MCGDM using PFNBSES, enabling systematic processing of expert evaluations involving both positive and negative attributes.

• Application of the proposed model to a real-world case study in urban transportation strategy planning, demonstrating its effectiveness in handling conflicting criteria and supporting transparent DM.

• Comparative analysis benchmarking PFNBSES against existing SS-based models, highlighting its superior capability in addressing bipolarity, multinary evaluations, and expert involvement.

• Critical evaluation of the computational and practical challenges associated with PFNBSES to inform future research and implementation.

These contributions collectively position PFNBSES as a significant advancement in soft computing-based DM, especially in contexts requiring nuanced judgment, expert collaboration, and reconciliation of conflicting objectives.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the foundational background and literature review. Section 3 introduces the proposed PFNBSES model, detailing its formal structure and fundamental operations. Section 4 outlines the complete DM framework based on PFNBSES, including a step-by-step algorithm and a case study in urban transportation planning. Section 5 offers a critical assessment of PFNBSES, covering its advantages, comparative performance, and computational considerations. Section 6 concludes the paper with key findings and directions for future research.

To summarize, the PFNBSES model addresses a critical need for more expressive and integrative DM tools capable of handling symbolic, bipolar, and expert-based evaluations simultaneously. While the model improves over existing frameworks in flexibility and structure, it may introduce computational complexity and practical challenges in large-scale settings. Nonetheless, its potential impact spans multiple domains—such as urban planning, healthcare, and risk analysis—where DM under conflicting, uncertain, and multidimensional criteria is essential.

2 Basic Definitions and Notation

This section presents the key notations and basic concepts used throughout the study. Let

Definition 1. [3] Let

Definition 2. [9] Let

i. Its score value is

ii. Its accuracy value is

Definition 3. [9] Let

i. If

ii. If

• if

• if

Definition 4. [10] An SS is defined as a pair

Definition 5. [40] An SES is defined as a pair

where

Definition 6. [40] The NOT set associated with a set

Definition 7. A quadruple

i. an NBSES [48], if

ii. an FNBSES [49], if

iii. an IFNBSES [50], if

3 Pythagorean Fuzzy N-Bipolar Soft Expert Sets

In this section, we introduce the PFNBSES model and define its fundamental operations, including the null set, the whole set, complement, subset, equality, agree, disagree, union, and intersection. Each of these operations is presented together with its associated algebraic properties.

Definition 8. A quadruple

where

Henceforth, we consider the sets

To demonstrate the structure and functionality of our proposed model, we present the following illustrative example.

Example 1. Suppose a government agency seeks to identify the most secure cloud storage provider among five candidates:

along with their corresponding negative counterparts:

Initially, an internal IT team conducts a detailed assessment of all five providers based on the above parameters and prepares a technical report. This report is then independently reviewed by a panel of cybersecurity experts, denoted by

Each evaluation is expressed using a graded symbolic scale to capture the intensity of satisfaction or risk associated with each parameter. The symbols used in Table 2 are interpreted as follows:

• “

• “

• “

• “

• “

Each symbolic grade is associated with a corresponding numerical value in the set

•

•

•

•

•

According to Definition 7 (ii), the tabular representation of the 5BSES

To achieve a thorough assessment, the experts express their evaluations of the systems in the form of a PF5BSES. Following the predefined grading scheme, they assign MDs and NMDs in accordance with the principles of PFSs, as illustrated in Table 4.

Therefore, the PF5BSES is displayed in Table 5.

We now introduce a set of fundamental operations defined on PFNBSESs. These operations include the null and whole sets, subset relation, equality, agree and disagree notions, complement as well as union and intersection.

Definition 9. A PFNBSES

Definition 10. A PFNBSES

Definition 11. A PFNBSES

1.

2. For every

3. For every

Definition 12. Two PFNBSESs

Definition 13. Let

Definition 14. Let

Definition 15. Consider a PFNBSES

Definition 16. Given a PFNBSES

Definition 17. The complement of

Definition 18. The extended union of

where

Similarly, for all

where

Definition 19. The extended intersection of

where

Similarly, for all

where

Definition 20. The restricted union of

where

Similarly, for all

where

Definition 21. The restricted intersection of

where

Similarly, for all

where

Next, we present several key propositions that describe essential algebraic properties of the PFNBSES model, including complementarity, commutativity, associativity, distributivity, absorption, and De Morgan’s laws, which together establish the foundational structure of the framework.

Proposition 1. Let

1.

2.

3.

Proof. Straightforward. □

Proposition 2. Let

1.

2.

Proof. Straightforward. □

Proposition 3. Let

1.

2.

Proof. Straightforward. □

Proposition 4. Let

1.

2.

3.

4.

Proof. (1) Let

where

Similarly, for all

where

Then, for all

Similarly, for all

On the other hand, let

Similarly, for all

Since

The remaining parts can be demonstrated in a comparable manner. □

Proposition 5. Let

1.

2.

3.

4.

Proof. (1) Suppose that

where

Similarly, for all

where

Now, let

where

Similarly, for all

where

Hence,

and

Therefore,

The other parts can be explained similarly. □

Proposition 6. Let

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Proof. (3) Suppose that

where

Similarly, for all

where

Let

where

Similarly, for all

where

Hence, for all

Similarly, for all

On the other hand, let

Similarly, for all

Next, let

Similarly, for all

Now, suppose that

where

Similarly, for all

where

Since

The other parts can be illustrated similarly. □

4 PFNBSES-Based Approach for Decision-Making: Methodology and Case Study

This section presents a comprehensive framework for MCGDM based on the PFNBSES model. By utilizing expert judgments encoded within the PFNBSES structure, the framework facilitates systematic comparison among alternatives to identify the most suitable option. We first detail the stepwise algorithm that guides the DM process, accompanied by a flowchart to enhance comprehension (see Algorithm 1 and Fig. 1). Following this, we demonstrate the practical utility of the PFNBSES framework through a real-world case study focused on urban transportation planning, showcasing how the model supports balanced and transparent evaluation of competing strategies across multiple positive and negative criteria.

Figure 1: Flowchart of the proposed PFNBSES algorithm (Algorithm 1)

In this subsection, we outline the step-by-step procedure for performing DM using the PFNBSES model. The proposed algorithm systematically processes expert evaluations encoded in the PFNBSES to calculate comparative scores for each alternative, enabling the selection of the most appropriate choice. To aid understanding, each stage of the procedure is visually depicted with a flowchart immediately following the algorithm.

To make the calculations easier, we first organize expert evaluations as ordered triples like

4.2 Planning Strategies for Urban Transportation: A Case Study

Several recent studies have explored sustainable urban transportation using MCGDM frameworks. To contextualize our case study and highlight the added value of PFNBSES, we compare it with recent approaches. Nayeb-Pashaei et al. [52] employed a fuzzy additive weighting method to identify key sustainability criteria, focusing on social and environmental aspects but lacking multi-expert aggregation and symbolic scale handling. Romero-Ania et al. [53] classified urban public transport vehicles based on economic and environmental criteria, emphasizing expert judgment but relying on threshold-based sorting. Alkharabsheh et al. [54] addressed uncertainty in transport quality assessment, focusing on user satisfaction and pollution control but depending on non-expert input and lacking bipolar reasoning. Kundu et al. [55] proposed a fuzzy group DM model for transit mode selection, offering robustness checks yet relying on fuzzy membership values without explicit bipolar logic. Zeb et al. [56] introduced a q-rung orthopair fuzzy SS approach for urban housing location, enhancing membership flexibility and stability analysis, though their model centers on spatial growth rather than expert-driven transport strategy evaluation.

In comparison, the PFNBSES framework uniquely integrates Pythagorean fuzzy logic with NBSES theory to address complex evaluations involving multilevel symbolic scales, expert disagreement, and nuanced criteria interpretation, offering a more robust and flexible solution for sustainable transport planning.

To demonstrate the practical advantages of PFNBSES in this domain, we now apply it to a real-world-inspired case involving urban transportation strategies. This application illustrates how the model manages multidimensional criteria, integrates diverse expert judgments, and supports sustainable planning under uncertainty.

Urban transportation planning is a critical component of sustainable city development, directly impacting economic vitality, environmental health, and residents’ quality of life. As cities grow and populations increase, planners face mounting challenges to design transportation systems that are efficient, accessible, and environmentally responsible. Key concerns include mitigating traffic congestion, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, ensuring safety for all users, and making transportation affordable and equitable across diverse communities. The set of alternatives and attributes were collaboratively defined by the expert panel based on current urban planning priorities, stakeholder needs, and sustainability goals outlined by the metropolitan city council’s transport division.

Effective urban transportation planning requires a holistic approach that balances multiple criteria simultaneously. These criteria often conflict: for example, a strategy that significantly improves accessibility might involve high costs or potential environmental trade-offs. Moreover, the social impact of transportation initiatives must be considered alongside technical and economic factors. To navigate this complexity, decision-makers rely on multidisciplinary panels of experts, including urban planners, environmental scientists, economists, and public safety officials.

Experts assess proposed transportation strategies through a rigorous evaluation process considering a variety of performance metrics. The objective is to identify strategies that not only deliver optimal mobility solutions but also align with broader urban sustainability goals. These evaluations must weigh positive attributes such as improved accessibility and reduced emissions against potential negative consequences such as increased costs or safety risks.

In this context, we consider five distinct transportation strategies currently under review for a mid-sized metropolitan area:

Each strategy

•

•

•

•

•

To evaluate these strategies, a set of core criteria is defined, representing the primary goals of the transportation plan:

where:

•

•

•

Importantly, planners must also consider complementary aspects — the risks and limitations that may accompany each strategy. These negative criteria are captured as:

highlighting issues such as limited accessibility in certain neighborhoods, excessive costs beyond budget, and potential environmental hazards that might undermine overall effectiveness.

A group of transportation experts,

comprising professionals with the following expertise:

•

•

•

each examines every transportation strategy

The experts’ initial evaluations use symbolic notations to indicate performance levels:

•

• Multiple

This symbolic system allows nuanced expert evaluations to be captured succinctly, accommodating the inherent uncertainty and gradation in real-world assessments.

The expert assessments for each strategy, criterion, and opinion are compiled in Table 6, forming the basis for applying the PFNBSES framework. This framework integrates these evaluations to support robust MCGDM, enabling planners to rank strategies by balancing benefits and risks. Note that the ratings are illustrative and assumed for demonstration; in practice, they should be obtained through structured expert elicitation or real data, which the PFNBSES framework can readily incorporate.

The symbolic evaluations are converted into numerical values from 0 to 4 following the approach outlined in Example 1, and the results are interpreted based on the grading intervals defined in Table 4. The PF5BSES matrix is presented in Table 7.

The following steps outline the PFNBSES DM procedure applied to the case study:

• Step 1: After specifying the inputs—alternatives, decision parameters, and expert group—we identify each of the PFNBSES evaluation categories:

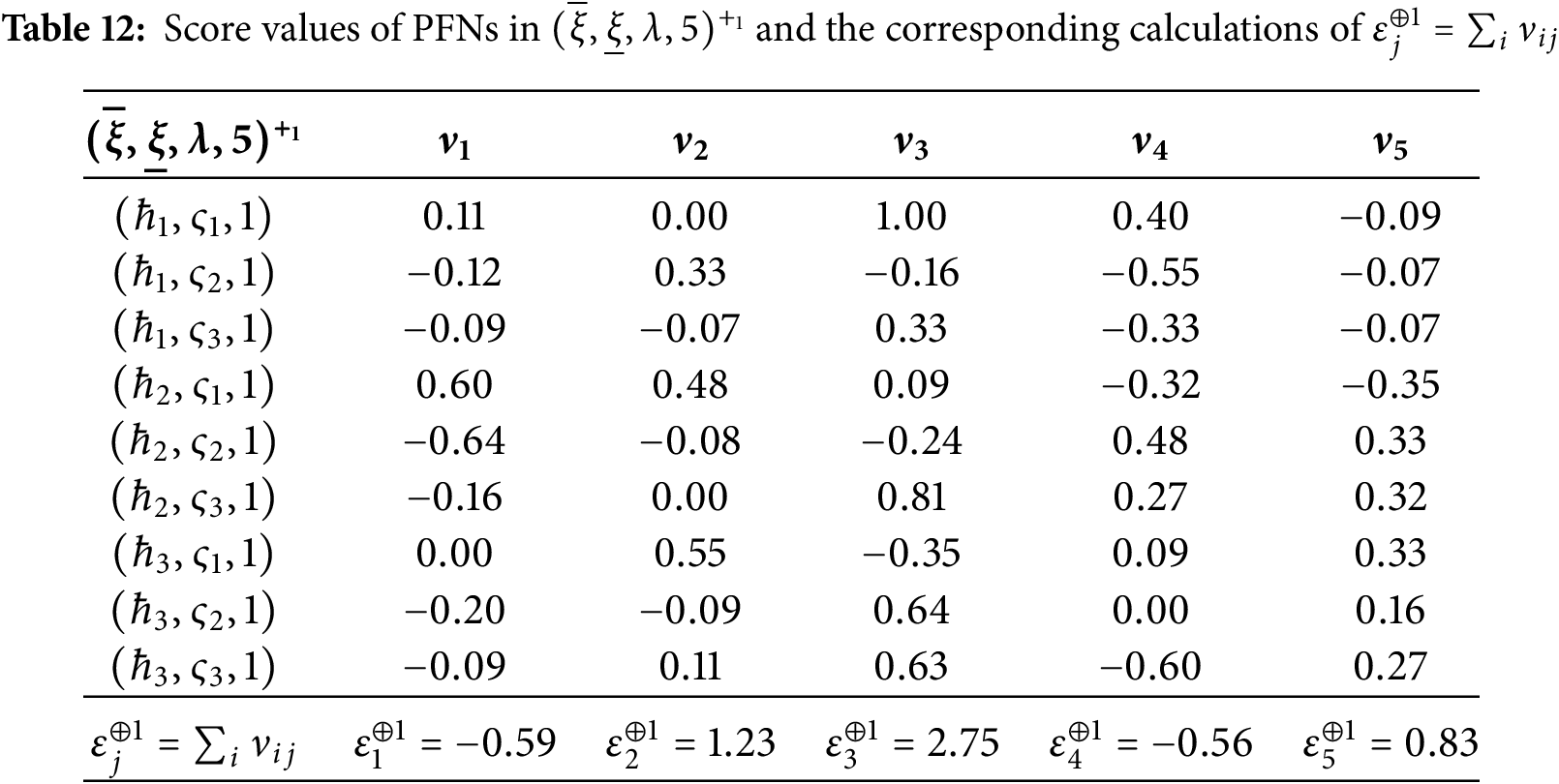

• Step 2: We extract the PFNs from each subset identified in Step 1 and compute their score values using Definition 2. Results are summarized in Tables 12 through 15.

• Step 3: Using the computed PFN scores, we aggregate positive and negative scores separately to form intermediate summary tables (Tables 16 and 17).

• Step 4: Finally, we compute the net score for each alternative by subtracting the aggregated negative scores from the aggregated positive scores. The alternative with the highest net score is identified as optimal. The computed scores are summarized in Table 18.

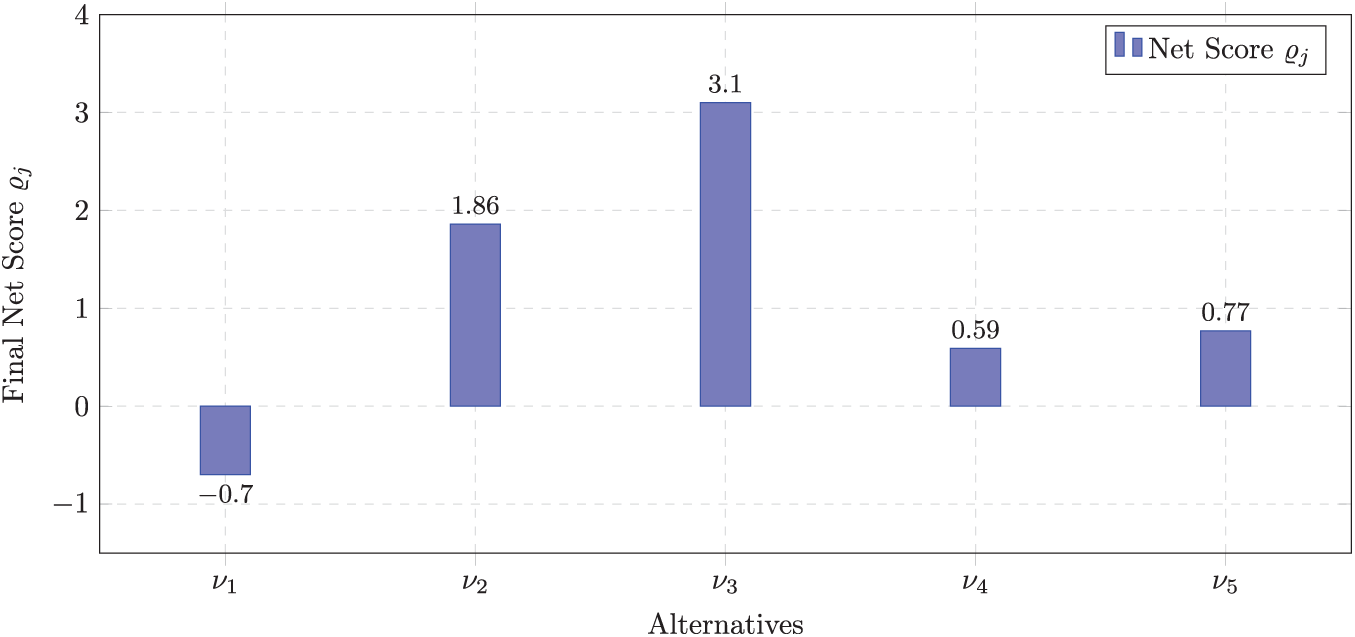

As shown in Table 18, the highest net score is

This result highlights the effectiveness of the PFNBSES model in addressing conflicting criteria and varied expert opinions. Urban transportation planning inherently involves trade-offs—for example, balancing cost-effectiveness against accessibility. Experts from different fields may place differing emphasis on these aspects. The bipolar structure of PFNBSES simultaneously captures positive and negative evaluations, while its Pythagorean fuzzy scale allows for degrees of agreement, disagreement, and hesitation. This dual consideration preserves diverse viewpoints and integrates them into a balanced DM process, better reflecting real-world complexities. Thus, PFNBSES supports planners in making nuanced, data-driven decisions amid uncertainty and diverse expert judgments.

Fig. 2 visually depicts the positive (

Figure 2: Positive and negative score components for each transportation strategy

Fig. 3 shows the final net scores

Figure 3: Final overall net scores

5 Assessment and Analysis of the PFNBSES Model

This section evaluates the proposed PFNBSES model by benchmarking it against existing SS-based frameworks, analyzing its distinctive strengths, and discussing its limitations and future research directions. In particular, we demonstrate how PFNBSES builds upon and complements recent DM methods reported in the literature, as shown in both the benchmarking table and the case study application. This structured analysis illustrates how PFNBSES advances the state of the art in MCGDM under uncertainty and conflicting expert opinions.

5.1 Benchmarking PFNBSES against Existing SS Models

To clearly demonstrate the advancements of the proposed PFNBSES model, this subsection presents a detailed benchmarking analysis against a comprehensive set of existing SS-based frameworks. The models are grouped into four main categories: Soft Sets, Bipolar Soft Sets, N-Soft Sets, and N-Bipolar Soft Sets. Within each category, we include both foundational models and their subsequent extensions.

The evaluation criteria focus on several critical dimensions relevant to DM complexity, including membership type and superiority, parameterization support, evaluation type and scale, bipolar reasoning capability, and expert involvement. Table 19 provides a concise yet comprehensive overview, highlighting how PFNBSES synthesizes and extends desirable features from prior models.

This structured comparison underscores the evolutionary progression in SS theory and decisively positions PFNBSES at the intersection of these developments. By accommodating richer evaluation schemes, managing simultaneous positive and negative opinions, and integrating multi-expert input, PFNBSES resolves previous limitations and better aligns with the multifaceted nature of modern decision environments.

5.2 Key Features and Strengths of the PFNBSES Model

Building upon the detailed benchmarking analysis, this subsection synthesizes the core advantages that distinguish PFNBSES and underpin its superior performance in MCGDM contexts.

• Pythagorean Fuzzy Representation: Leveraging PFSs provides enhanced modeling capacity to capture uncertainty more flexibly and expressively than classical FSs or IFSs.

• Multinary Evaluation Scale: Supporting continuous and symbolic evaluation schemes empowers experts to provide more granular and nuanced judgments compared to binary or discrete scales.

• Comprehensive Bipolar Reasoning: PFNBSES fully incorporates bipolarity, enabling simultaneous modeling of positive and negative expert evaluations—a critical capability for addressing the inherent duality of complex decision problems.

• Robust Multi-Expert Involvement: By facilitating aggregation and conflict reconciliation among multiple experts, PFNBSES enhances consensus reliability and better reflects diverse perspectives.

• Scalability and Interpretability: Designed to balance computational efficiency with transparent reasoning, the model is well-suited for practical applications requiring clear and justifiable decision support.

• Conflict Resolution via Bipolar Pythagorean Fuzzy Logic: Uniquely, PFNBSES combines bipolar reasoning with Pythagorean fuzzy logic to effectively reconcile contradictory evaluations within and across expert opinions, enhancing decision robustness.

• Sensitivity to Expert Inputs: Since PFNBSES uses binary expert opinions (i.e., 1 = agree and 0 = disagree) for each parameter, its sensitivity mainly arises from shifts in the number of agreeing or disagreeing experts per criterion. While minor changes in individual opinions do not drastically alter outcomes, changes in group consensus can impact final rankings, highlighting the importance of balanced and well-selected expert involvement.

Collectively, these strengths equip PFNBSES to tackle the increasing complexity, uncertainty, and diversity of real-world MCGDM challenges, establishing it as a significant advancement over prior SS-based approaches.

5.3 Computational and Practical Challenges of PFNBSES

While the PFNBSES model offers significant advantages in expressiveness and DM accuracy, it also presents some computational and practical challenges. The application of Pythagorean fuzzy operations increases computational complexity, which may require substantial processing power for large-scale problems. Furthermore, obtaining detailed continuous-scale evaluations from multiple experts can be time-intensive and demands careful coordination. The model’s sensitivity to variations in group consensus further underscores the importance of expert selection and balanced participation to ensure stable and reliable DM outcomes. Despite these challenges, the ability of PFNBSES to capture nuanced expert input and manage uncertainty effectively supports its continued development and optimization.

6 Conclusions and Future Direction

This paper introduced the PFNBSES model as an innovative and comprehensive framework for urban transportation strategy planning. The model effectively addresses DM scenarios characterized by conflicting criteria, uncertainty, and the integration of multiple expert opinions. By facilitating graded bipolar evaluations on a continuous multinary scale, PFNBSES captures the subtle trade-offs inherent in complex assessments. Key operations—such as union, intersection, complement, and agreement—were formalized to provide a solid algebraic foundation. Additionally, a stepwise DM algorithm was developed and demonstrated through a case study on sustainable urban transportation planning, showcasing the model’s practical applicability. Comparative analysis confirms that PFNBSES surpasses existing SS approaches in flexibility, expressiveness, and support for multi-expert evaluations.

Nevertheless, certain computational and practical challenges remain to be addressed in future research. The inherent complexity of Pythagorean fuzzy operations may lead to increased computational demands, highlighting the need to develop more efficient algorithms or approximation techniques that reduce processing time without significant loss of accuracy. Additionally, collecting detailed continuous-scale evaluations from multiple experts can be time-consuming and may introduce coordination difficulties; hence, future work could explore streamlined elicitation methods or expert consensus techniques–such as grouping or weighting schemes–to facilitate scalable and reliable data acquisition. Addressing these challenges will further enhance the applicability and effectiveness of PFNBSES in large-scale and real-time DM scenarios. Moreover, integrating machine learning algorithms–such as clustering, pattern recognition, or predictive modeling–could help automatically learn from historical data to refine parameter weights, expert consensus, and recommendations. Finally, extending the framework to other FS types, such as q-rung orthopair FSs, represents a promising direction to increase its flexibility and applicability.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research received no external funding.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Sagvan Y. Musa, Wafa Alagal, Zanyar A. Ameen; data collection: Sagvan Y. Musa, Baravan A. Asaad, Wafa Alagal; analysis and interpretation of results: Sagvan Y. Musa, Baravan A. Asaad, Zanyar A. Ameen, Wafa Alagal; draft manuscript preparation: Baravan A. Asaad, Wafa Alagal, Zanyar A. Ameen; funding acquisition and support: Wafa Alagal. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: This study did not involve human participants or animals, and therefore ethics approval was not required.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zadeh LA. Fuzzy sets. Inf Control. 1965;8(3):338–53. doi:10.1016/s0019-9958(65)90241-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Atanassov KT. Intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1986;20(1):87–96. doi:10.1016/s0165-0114(86)80034-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Yager RR. Pythagorean fuzzy subsets. In: 2013 Joint IFSA World Congress and NAFIPS Annual Meeting (IFSA/NAFIPS2013 Jun 24–28. Edmonton, AB, Canada. p. 57–61. [Google Scholar]

4. Thakur P, Paradowski B, Gandotra N, Thakur P, Saini N, Sałabun W. A study and application analysis exploring Pythagorean fuzzy set distance metrics in decision making. Information. 2024;15(1):28. doi:10.3390/info15010028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang Q, Hu J, Feng J, Liu A, Li Y. New similarity measures of Pythagorean fuzzy sets and their applications. IEEE Access. 2019;7:138192–202. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2942766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Mahanta J, Panda S. Distance measure for Pythagorean fuzzy sets with varied applications. Neural Comput Appl. 2021;33(24):17161–71. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-06308-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Bozyigit MC, Olgun M, Ünver. M. Circular Pythagorean fuzzy sets and applications to multi-criteria decision making. Informatica. 2023;34(4):713–42. doi:10.15388/23-infor529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Khan MJ, Alcantud JCR, Kumam W, Kumam P, Alreshidi NA. Expanding Pythagorean fuzzy sets with distinctive radii: disc Pythagorean fuzzy sets. Compl Intell Syst. 2023;9(6):7037–54. doi:10.1007/s40747-023-01062-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang X, Xu Z. Extension of TOPSIS to multiple criteria decision making with Pythagorean fuzzy sets. Int J Intell Syst. 2014;29(12):1061–78. doi:10.1002/int.21676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Molodtsov D. Soft set theory-first results. Comput Math Appl. 1999;37:19–31. [Google Scholar]

11. Maji PK, Biswas R, Roy AR. Soft set theory. Comput Math Appl. 2003;45:555–62. [Google Scholar]

12. Ali MI, Feng F, Liu X, Min WK, Shabir M. On some new operations in soft set theory. Comput Math Appl. 2009;57:1547–53. [Google Scholar]

13. Maji PK, Biswas R, Roy R. Fuzzy soft sets. J Fuzzy Math. 2001;9:589–602. [Google Scholar]

14. Maji PK, Biswas R, Roy R. Intuitionistic fuzzy soft sets. J Fuzzy Math. 2001;9:677–92. [Google Scholar]

15. Peng X, Yang Y, Song J, Jiang Y. Pythagorean fuzzy soft set and its application. Comput Eng. 2015;41(7):224–9. [Google Scholar]

16. Kirişci M. Group-based Pythagorean fuzzy soft sets with medical decision-making applications. J Experim Theoret Artif Intell. 2022;36(1):27–45. [Google Scholar]

17. Zulqarnain RM, Siddique I, Jarad F, Hamed YS, Abualnaja KM, Iampan A. Einstein aggregation operators for Pythagorean fuzzy soft sets with their application in multiattribute group decision-making. J Funct Spaces. 2022;2022(6):1358675. doi:10.1155/2022/1358675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Riaz M, Naeem K, Aslam M, Afzal D, Almahdi FAA, Jamal SS. Multi-criteria group decision making with Pythagorean fuzzy soft topology. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. 2020;39(5):6703–20. [Google Scholar]

19. Athira TM, John SJ, Garg H. Similarity measures of Pythagorean fuzzy soft sets and clustering analysis. Soft Comput. 2023;27(6):3007–22. doi:10.1007/s00500-022-07463-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Nawaz HS, Akram M. Granulation of protein–protein interaction networks in Pythagorean fuzzy soft environment. J Appl Math Comput. 2023;69(1):293–320. doi:10.1007/s12190-022-01749-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Khan A, Farman M, Akgül A. Decision making under Pythagorean fuzzy soft environment. Int J Uncertainty Fuzz Knowl Based Syst. 2023;31(5):773–93. doi:10.1142/s0218488523500368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Shabir M, Naz M. On bipolar soft sets. arXiv:1303.1344. 2013. [Google Scholar]

23. Karaaslan F, Karataş S. A new approach to bipolar soft sets and its applications. Discrete Math Algorithms Appl. 2015;7(4):1550054. doi:10.1142/s1793830915500548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mahmood T. A novel approach towards bipolar soft sets and their applications. J Math. 2020;2020(5):4690808. doi:10.1155/2020/4690808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Naz M, Shabir M. On fuzzy bipolar soft sets, their algebraic structures and applications. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. 2014;26:1645–56. [Google Scholar]

26. Asaad BA, Musa SY, Ameen ZA. Fuzzy bipolar hypersoft sets: a novel approach for decision-making applications. Math Comput Appl. 2024;29(4):50. doi:10.3390/mca29040050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zeb A, Khan A, Izhar M, Hila K. Aggregation operators of fuzzy bi-polar soft sets and its application in decision making. J Multiple-Valued Logic Soft Comput. 2021;36(6):569–99. [Google Scholar]

28. Zeb A, Khan A, Fayaz M, Izhar M. Aggregation operators of Pythagorean fuzzy bi-polar soft sets with application in multiple attribute decision making. Granul Comput. 2022;7(4):931–50. doi:10.1007/s41066-021-00307-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Mahmood T, Hussain K, Ahmmad J, Rehman UU, Aslam M. A novel approach toward TOPSIS method based on lattice ordered T-bipolar soft sets and their applications. IEEE Access. 2022;10(2):69727–69740. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3184783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Dalkılıç O. A decision-making approach to reduce the margin of error of decision makers for bipolar soft set theory. Int J Syst Sci. 2022;53(2):265–74. doi:10.1080/00207721.2021.1949644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Fatimah F, Rosadi D, Hakim RBF, Alcantud JCR. N-soft sets and their decision making algorithms. Soft Comput. 2018;22(12):3829–42. doi:10.1007/s00500-017-2838-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Alcantud JCR. The semantics of N-soft sets, their applications, and a coda about three-way decision. Inf Sci. 2022;606(23):837–52. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2022.05.084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Alcantud JCR, Santos-García G, Akram M. OWA aggregation operators and multi-agent decisions with N-soft sets. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;203(253):117430. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.117430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Alcantud JCR, Santos-García G, Akram M. A novel methodology for multi-agent decision-making based on N-soft sets. Soft Comput. 2023. doi:10.1007/s00500-023-08522-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Kamacı H, Palpandi B, Petchimuthu S, Fathima M. m-polar N-soft set and its application in multi-criteria decision-making. Comput Appl Math. 2025;44(1):1–46. doi:10.1007/s40314-024-03029-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Riaz M, Razzaq A, Aslam M, Pamucar D. M-parameterized N-soft topology-based TOPSIS approach for multi-attribute decision making. Symmetry. 2021;13(5):748. doi:10.3390/sym13050748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Musa SY, Asaad BA. Bipolar M-parametrized N-soft sets: a gateway to informed decision-making. J Math Comput Sci. 2025;36(1):121–41. [Google Scholar]

38. Shabir M, Fatima J. N-bipolar soft sets and their application in decision making. Res Sq. 2021. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-755020/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Musa SY, Asaad BA, Alohali H, Ameen ZA, Alqahtani MH. Fuzzy N-bipolar soft sets for multi-criteria decision-making: theory and application. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;143(1):911–43. doi:10.32604/cmes.2025.062524 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Alkhazaleh S, Salleh A. Soft expert sets. Adv Decis Sci. 2011;2011(72):757868. doi:10.1155/2011/757868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Alkhazaleh S, Salleh A. Fuzzy soft expert set and its application. Appl Math. 2014;5(09):1349–68. doi:10.4236/am.2014.59127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Broumi S, Smarandache F. Intuitionistic fuzzy soft expert sets and its application in decision making. J New Theory. 2015;1:89–105. [Google Scholar]

43. Ihsan M, Saeed M, Rahman AU. Multi-attribute decision-making application based on Pythagorean fuzzy soft expert set. Int J Inf Decis Sci. 2024;16(4):383–408. doi:10.1504/ijids.2024.142637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Dalkilic O, Demirtaş N. Combination of the bipolar soft set and soft expert set with an application in decision making. Gazi Univ J Sci. 2022;35:644–57. [Google Scholar]

45. Ali G, Muhiuddin G, Adeel A, Abidin MZU. Ranking effectiveness of COVID-19 tests using fuzzy bipolar soft expert sets. Math Probl Eng. 2021;2021(3):5874216. doi:10.1155/2021/5874216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Ali G, Akram M. Decision-making method based on fuzzy N-soft expert sets. Arab J Sci Eng. 2020;45(12):10381–400. doi:10.1007/s13369-020-04733-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Akram M, Ali G, Alcantud JCR. A novel group decision-making framework under Pythagorean fuzzy N-soft expert knowledge. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;120(4):105879. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.105879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Musa SY, Alajlan AI, Asaad BA, Ameen ZA. N-bipolar soft expert sets and their applications in robust multi-attribute group decision-making. Mathematics. 2025;13(3):530. doi:10.3390/math13030530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Ameen ZA, Musa SY, Saeed MM, Asaad BA. Optimizing healthcare facility allocation using a novel fuzzy N-bipolar soft expert decision approach. Contemp Math. Forthcoming 2025. [Google Scholar]

50. Musa SY, Ameen ZA, Alagal W, Asaad BA. A robust methodology for multi-criteria group decision-making: intuitionistic fuzzy N-bipolar soft expert sets in cybersecurity risk assessment for financial institutions. Complex Intell Syst (under Review). 2025. [Google Scholar]

51. Kumar R, Pamucar D. A comprehensive and systematic review of multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods to solve decision-making problems: two decades from 2004 to 2024. Spectr Decis Making Appl. 2025;2(1):178–97. doi:10.31181/sdmap21202524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Nayeb-Pashaei K, Vahabzadeh S, Hosseinian-Far A, Ghoushchi SJ. Sustainable urban transportation: key criteria for a greener future. Spect Operat Res. 2026;3(1):103–27. [Google Scholar]

53. Romero-Ania A, Rivero Gutiérrez L, De Vicente Oliva MA. Multiple criteria decision analysis of sustainable urban public transport systems. Mathematics. 2021;9(16):1844. doi:10.3390/math9161844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Alkharabsheh A, Moslem S, Oubahman L, Duleba S. An integrated approach of multi-criteria decision-making and grey theory for evaluating urban public transportation systems. Sustainability. 2021;13(5):2740. doi:10.3390/su13052740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Kundu P, Görçün ÖF, Garg CP, Küçükönder H, Çanakçıoğlu M. Evaluation of public transportation systems for sustainable cities using an integrated fuzzy multi-criteria group decision-making model. Environ Develop Sustain. 2024;26(11):27655–84. doi:10.1007/s10668-023-03776-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Zeb A, Ahmad W, Asif M, Senapati T, Simic V, Hou M. A decision analytics approach for sustainable urbanization using q-rung orthopair fuzzy soft set-based Aczel–Alsina aggregation operators. Socio-Econ Plan Sci. 2024;95(3):101949. doi:10.1016/j.seps.2024.101949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools