Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Systematic Analysis of Latent Fingerprint Patterns through Fractionally Optimized CNN Model for Interpretable Multi-Output Identification

1 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, International Islamic University, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

2 International Graduate School of Artificial Intelligence, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Yunlin, 64002, Taiwan

3 Department of Computer Science and Information Engineering, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, 123 University Road, Section 3, Douliou, Yunlin, 64002, Taiwan

4 Future Technology Research Center, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Yunlin, 64002, Taiwan

5 Department of Electronic Engineering, Fatima Jinnah Women University, Rawalpindi, 46000, Pakistan

6 College of Electrical Engineering, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, 310027, China

7 Department of Computer Engineering, College of Computer, Qassim University, Al-Qassim, 51452, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Zeshan Aslam Khan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovative Applications of Fractional Modeling and AI for Real-World Problems)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 807-855. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.068131

Received 21 May 2025; Accepted 06 August 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Fingerprint classification is a biometric method for crime prevention. For the successful completion of various tasks, such as official attendance, banking transactions, and membership requirements, fingerprint classification methods require improvement in terms of accuracy, speed, and the interpretability of non-linear demographic features. Researchers have introduced several CNN-based fingerprint classification models with improved accuracy, but these models often lack effective feature extraction mechanisms and complex multineural architectures. In addition, existing literature primarily focuses on gender classification rather than accurately, efficiently, and confidently classifying hands and fingers through the interpretability of prominent features. This research seeks to improve a compact, robust, explainable, and non-linear feature extraction-based CNN model for robust fingerprint pattern analysis and accurate yet efficient fingerprint classification. The proposed model (a) recognizes gender, hands, and fingers correctly through an advanced channel-wise attention-based feature extraction procedure, (b) accelerates the fingerprints identification process by applying an innovative fractional optimizer within a simple, but effective classification architecture, and (c) interprets prominent features through an explainable artificial intelligence technique. The encapsulated dependencies among distinct complex features are captured through a non-linear activation operation within a customized CNN model. The proposed fractionally optimized convolutional neural network (FOCNN) model demonstrates improved performance compared to some existing models, achieving high accuracies of 97.85%, 99.10%, and 99.29% for finger, gender, and hand classification, respectively, utilizing the benchmark Sokoto Coventry Fingerprint Dataset.Keywords

The popularity of Machine learning (ML) has been increasing day by day. The researchers have been trying to solve various complex problems by exploiting ML algorithms [1]. ML strategies have been applied in numerous fields such as disease diagnosis [2], smart soil monitoring [3], indoor positioning systems [4], wind power forecasting [5], drug discovery [6], wireless sensor networks [7], and classification [8,9]. Recently, the role of deep learning (DL) strategies has been instrumental in dealing with image classification problems and other applications [10]. DL-based classification models have the capability of extracting prominent features for accurate classification. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) are pioneers in solving image classification tasks [11]. The applications of CNNs include disease diagnosis [12], driver drowsiness monitoring [13], traffic flow prediction [14], intrusion detection [15], and damage diagnosis [16].

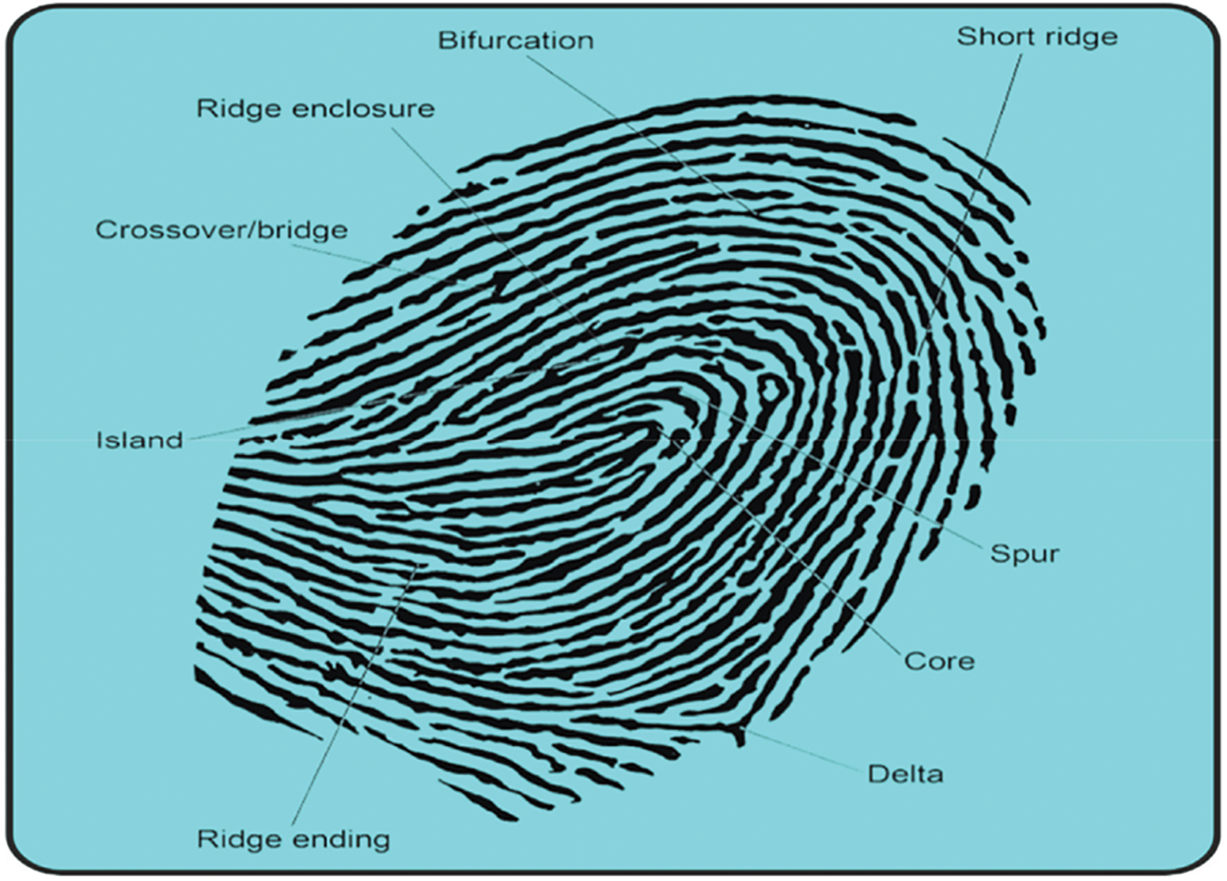

Biometrics utilize physiological, physical, and behavioral characteristics such as iris, voice, face, gait, and fingerprints [17], for the identification of individuals. The minutiae patterns on a standard fingerprint are illustrated in Fig. 1. Biometrics are not only useful for the identification of individuals but also appropriate for determining demographic features such as ethnicity, gender, and age [18]. The applications of light-biometrics include forensics [19], providing customized age and gender assistance [20], access control based on gender and age [21], distributed computing [22], reducing search space in sizable (both non-cloud and cloud) biometric databases, and video recovery [23].

Figure 1: Minutiae patterns on standard fingerprint

Various gender classification methods use biometrics, including face, gait, iris, fingerprints, and voice [24], for the accurate identification of male and female individuals. Gender recognition usually exploits both texture and minutiae attributes of fingerprints [25,26]. Minutiae attributes, such as ridge valley density, valley count, and ridge count, are acquired from high-quality images. Texture characteristics are obtained through various transforms, including Fast Fourier Transforms (FFT) [27] and Discrete Wavelet Transforms (DWT) [28]. Researchers commonly use DWT in combination with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [29] and Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) [30]. In addition, fingerprint matching procedure is usually performed through transforms-based feature extraction [31], but genders have not been identified yet using transforms-based feature extraction mechanisms.

Recently, significant research has been observed in the domain of fingerprint analysis [32], which presents a comprehensive survey on the implications of deep learning in the fingerprint identification task. The conducted survey provides crucial insights into the current challenges in the domain of fingerprint analysis, including the lack of standard databases, existing deep learning solutions, and environmental and algorithmic biases. Similarly, reference [33] presents a study on fingerprint pattern classification using deep learning approaches. The various filtration approaches were employed to extract texture and minutiae-level features from the fingerprint patterns. Afterwards, the configuration of a deep convolutional neural network along with gannet bald optimization approach is utilized to train and validate the performance of the proposed approach for the task at hand. In addition, reference [34] presents an extensive evaluation study on the performance of CNN models with state-of-the-art networks such as AlexNet, LeNet, and VGG-16 for verifying the effectiveness of the designed Fingerprint-Net in the fingerprint classification task.

Several CNN-based models have been designed by researchers for the accurate fingerprint’s classification [35,36]. The existing CNN models provide improved accuracy but lack effective feature extraction techniques. In addition, the proposed models consume more resources due to the inherent complexity in architectures. The complex models fail to give efficient, accurate, and explainable results. In addition, CNN variants place more emphasis on gender classification and compromise the accuracy, interpretability, and speed of hand and finger recognition. The challenges faced in the existing work for fingerprint classification include architectural complexity, classification speed, robustness, accuracy, and interpretability of prominent features.

Accordingly, this study aims to develop a simple, advanced, and fractional-calculus-based CNN model that incorporates a better feature extraction procedure and an innovative optimization strategy for accurate and fast fingerprint classification. In addition, for the interpretable outcomes, explainable artificial intelligence (XAI)-based Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanation (LIME) method is applied to reveal and highlight the contribution of features.

It was noticed from the literature that a few fractional gradients-based stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimizers [37–40] have succeeded in accelerating the speed of convergence for various applications. In addition, the accuracy and speed of recommendations are further enhanced by another fractional SGD variant, titled generalized fractional SGD (GFSGD), as presented in [41]. The TensorFlow-based GFSGD optimizer is also utilized in this study for efficient and accurate fingerprint classification using the proposed FOCNN model.

The primary goals of this research are given as:

• To recognize gender, hands, and fingers through fingerprints correctly through advanced channel-wise attention-driven feature extraction procedures.

• To accelerate the fingerprint identification process by applying an innovative and resource-friendly fractional optimizer within a simple, but effective CNN-based classification architecture.

• To boost the complex feature learning ability of the proposed CNN model through a non-linear activation function.

• To interpret prominent features through an explainable artificial intelligence technique.

• To evaluate the performance of the proposed model for different fractional orders and compare the proposed model with benchmark models such as support vector machine (SVM) + convolutional neural network (CNN), dense dilated convolutional ResNet (DDC-ResNet), visual geometry group (VGG16) + Siamese, Inception-v3, deep CNN and others in terms of accuracy, precision, recall and f1-score through on-hold validation strategy.

• To enhance the robustness of the proposed classification model in comparison to state-of-the-art models through stable and adaptive behavior of the fractional optimizer.

The paper is structured as follows: The related work is presented in Section 2. Section 3 provides the materials and methods linked with the conducted research. Experimentation, results, and analysis are given in Section 4. At last, the study concludes with Section 5, which includes the findings, limitations, and future directions.

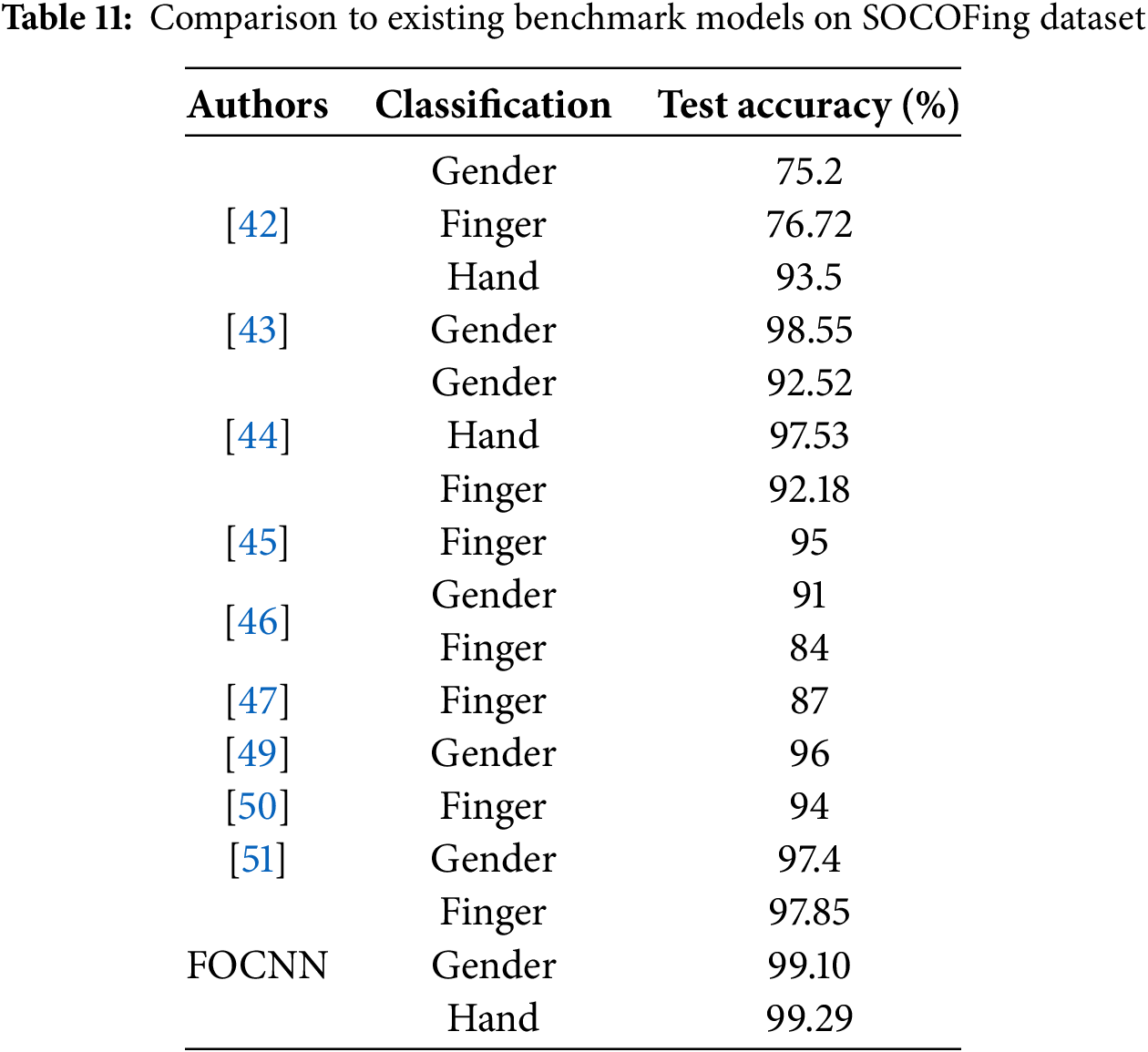

Researchers have proposed several innovative strategies reflecting different perspectives for solving the fingerprint classification problem. This section summarizes existing work related to the fingerprint classification problem. Shehu et al. [42] proposed a transfer learning-based improved CNN model and utilized a benchmark SOCOFing dataset for training. Shehu et al. [43] tested the model’s accuracy for three classes, including gender, finger, and hand. The accuracies achieved by the model are 75.2%, 76.72%, and 93.5%, respectively. They indicated another CNN variant for the identification of fake and real fingerprints using the SOCOFing dataset. In addition, the modified fake fingerprints were also grouped into Z-cut, rotation, and obliteration. The overall accuracy obtained by the model is 98.55%. Giudice et al. [44] introduced a single-architecture and multiple-tasks deep neural network for modified fingerprint analysis. Inception V3 architecture was used in this work. The proposed method used the SOCOFing dataset and recognized gender, hand, finger, alterations, and fakeness with the accuracies 92.52%, 97.53%, 92.18%, 98.21%, and 98.46%, respectively. A Long-Short-Term-Memory-based network (LSTMs) was proposed by Fattahi et al. [45] and the LSTM-based model identified the damaged fingerprints with more than 95% accuracy to identify the damaged fingerprints.

A CNN-based architecture was developed by Iloanusi and Ejiogu (2020) [46] for gender classification using fingerprints of the five fingers. They used two datasets in their study, a custom dataset and the Sokoto fingerprints dataset. They observed that the best accuracies for male and female gender classification were achieved by fusing the thumb and other fingers, such as the middle, ring, and index fingers. The optimal accuracies achieved for the custom and Sokoto datasets were 91% and 84%, respectively. Moga and Filip [47] presented a new solution for fingerprint recognition by proposing a Siamese network consisting of VGG-16 architectures. An average test accuracy of 87% was achieved using this model for fingerprint recognition. In addition, in Gnanasivam and Vijayarajan (2019) [48], CNN was exploited for two activation functions, including ReLU and Tanh. CNN-based models were trained using the NIST-DB4 dataset. They indicated that the model representing CNN-ReLu performed better in terms of accuracy by consuming a smaller number of epochs compared to CNN-Tanh. Ibitayo et al. [49] indicated a fingerprint-based gender indicator system using fingerprint pattern analysis. A CNN+SVM-based model was exploited for fingerprint classification. They obtained outcomes of 96.92%, 96%, and 97.8% with a threshold of 0.25 for precision, accuracy, and sensitivity using the SOCOFing dataset. Another finger type classification model was given by Al-Wajih et al. [50] to classify fingerprints and finger types. The idea was to increase the speed of matching and search space time using two standard datasets, including NIST D4 and SOCOFing. The proposed model achieved an overall finger type prediction accuracy of 94%.

A comparative study was conducted by Qi et al. [51] for the comparative performance analysis of several models, including linear discriminant analysis (LDA), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), J48, AdaBoost, SVM (with polynomial and radial basis function kernels), CNN, and iterative dichotomizer (ID3). Authors explored six feature-extraction mechanisms, such as ResNet, SVD, VGG, DDC-ResNet, FFT, and DWT. They found that the accuracies achieved by SVM for male and female gender classification are 97.43% and 93.24%, respectively, whereas CNN obtained a gender accuracy of around 97.52% and a female accuracy of 95.48%.

The advancement in theoretical concepts of fractional calculus has played a vital role in the development of innovative adaptive algorithms [52]. Researchers have indicated several fractional gradient-based solutions to various problems such as financial systems [53], corruption dynamics [54], disease modeling [55,56], power systems [57], and non-linear systems [58]. Researchers also noticed that the estimated accuracy and rate of convergence of optimizers are increased by replacing integer-order gradients with fractional-order gradients. Fractional-order strategies are already exploited for providing solutions to various domains such as parameter estimation [59], fuzzy functions [60], Laplace transform [61], communication [62], output error model identification [63], and matrix factorization in recommender systems [64].

Scholars with fractional calculus expertise have recently implemented fractional definition-based optimizers, including fractional adaptive moment estimation (FADAM) and fractional stochastic gradient descent (FSGD) [65], in PyTorch for adaptively learning improved weights during the training of deep neural network architectures. In addition, to enhance prediction accuracy and speed, a cost-effective generalized fractional stochastic gradient descent algorithm (GFSGD) was introduced in [41]. In addition, the unexplored GFSGD optimizer not only advances convergence efficiency but also provides an opportunity to exploit a higher fractional order range beyond 1 [41], unlike other fractional-based adaptive algorithms [64]. GFSGD was exploited for solving the recommender systems problem through matrix factorization to make the matrix factorization procedure efficient and effective [66]. Inspired by the consistent behavior of GFSGD in terms of convergence speed and prediction accuracy, this study exploits GFSGD for solving a classification problem with applications to fingerprint recognition for gender, hand, and finger identification.

Based on the detailed review of existing work, the current solutions primarily focus on gender classification by analyzing fingerprint patterns. In addition, the existing networks are architecturally complex, less convergent, computationally expensive, and uninterpretable. Therefore, this research intends to develop a simplified, interpretable, and fractionally optimized CNN architecture for the task at hand. Therefore, the proposed study contributes in the following directions: (1) The proposed fractional calculus-based model identifies genders, hands, and fingers precisely by utilizing unconventional and improved feature extraction processes. (2) The proposed classification model expedites the fingerprint identification activity by implementing an unexploited fractional gradient-based optimizer with a customized and economical classification architecture. (3) The unexplored GFSGD optimizer not only improves the convergence rate substantially but also provides an opportunity to utilize a fractional order range from 1 to 2. (4) The developed CNN model emphasizes latent useful attributes through an XAI-based local interpretable model-agnostic explanation (LIME) method for getting explainable predictions.

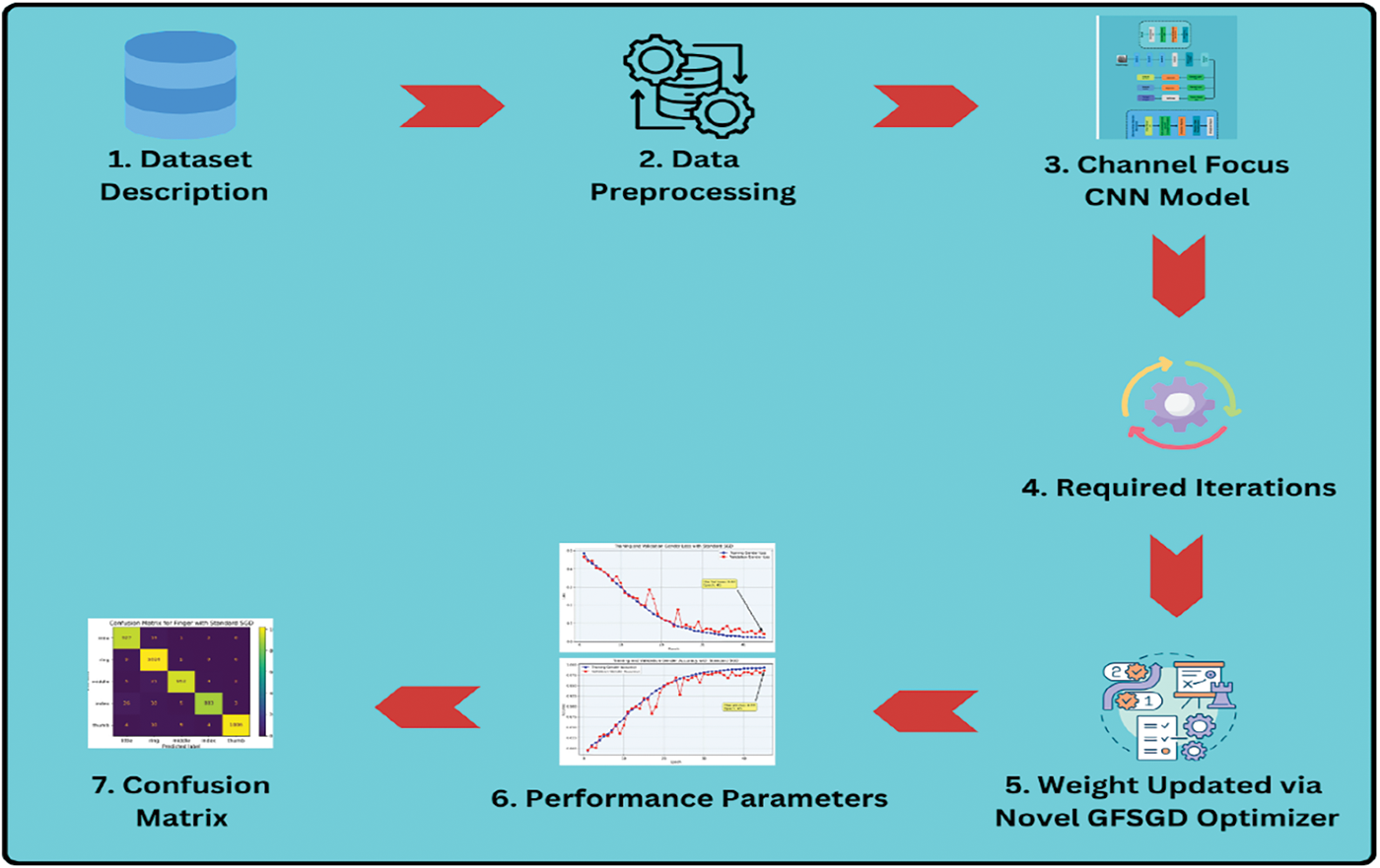

This section provides insights into the dataset used in this study, including the necessary pre-processing steps. The detailed work process of the proposed study is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Graphical abstract of the study

Database Description

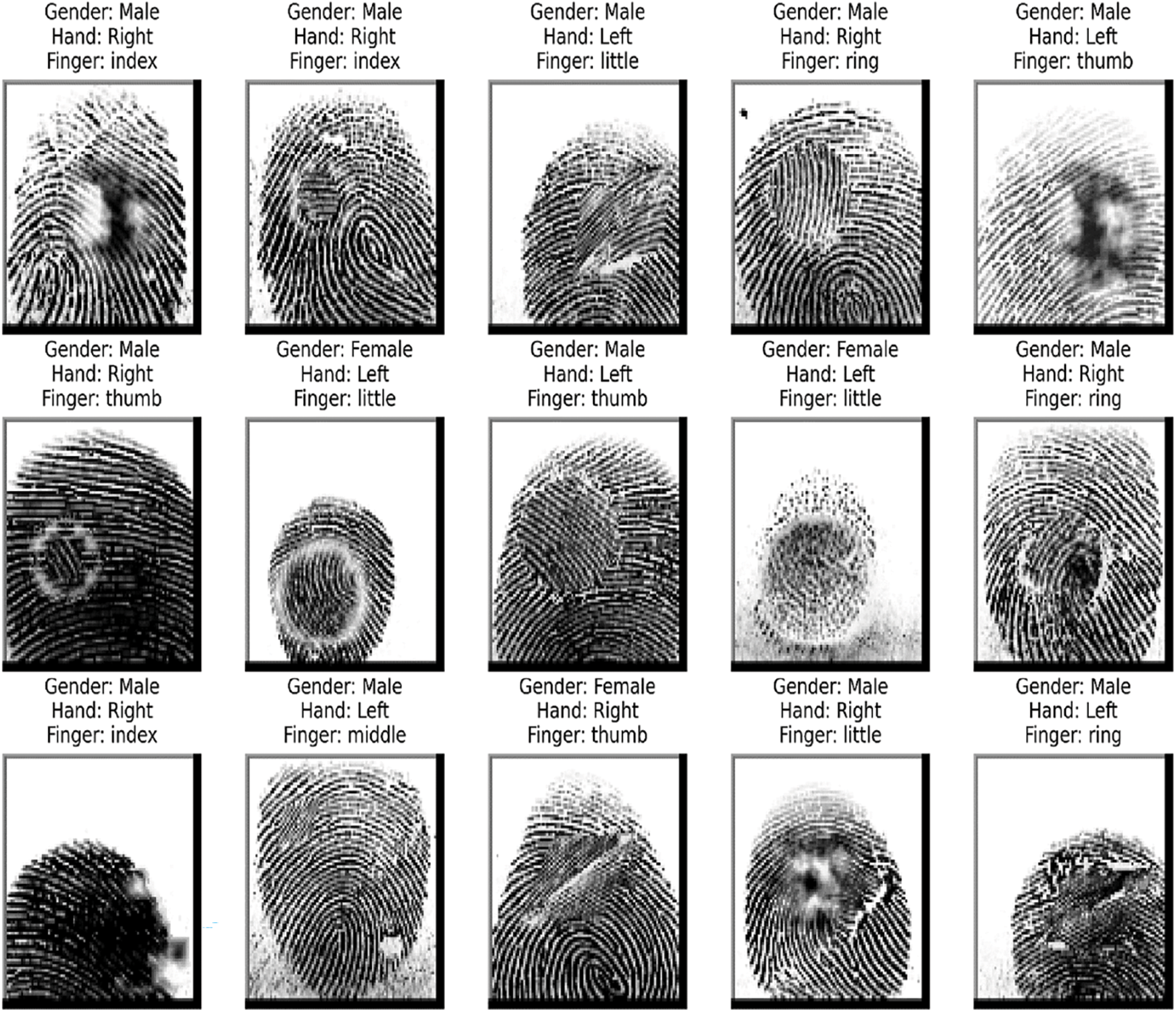

This study utilizes the SOCOFing Database [67] to train and verify the efficiency of the proposed model for fingerprint classification. The SOCOFing database is freely accessible at https://www.kaggle.com/ruizgara/socofing (accessed on 05 August 2025) for research purposes. This dataset comprises 6000 fingerprint samples taken from 600 distinct individuals belonging to the African continent. SOCOFing includes distinctive fingerprint characteristics with varied labels, such as hand, finger, and gender, which confirms the diverse nature of the database. In addition, by exploiting the strange toolbox [68], multiple stages of alteration, such as central rotation, obliteration, and z-cut, are performed on the SOCOFing dataset. After alteration and other operations, the total strength of the database comprises 49,270 grayscale fingerprint images. For the proposed study, these images are converted to RGB color space, with three separate sets created for training, validation, and testing purposes. The training set includes 39,416 fingerprint images. The validation and testing sets consist of 4927 fingerprint images. Fig. 3 shows sample images from the SOCOFing dataset used in this study.

Figure 3: Sample images of fingerprint from benchmark SOCOFing dataset

This section outlines the overall proposed methodology for fingerprint detection, including the working of the proposed algorithm, feature extraction mechanism, explainable operations, and the mathematical foundations of the generalized fractional stochastic gradient descent-based proposed optimization approach.

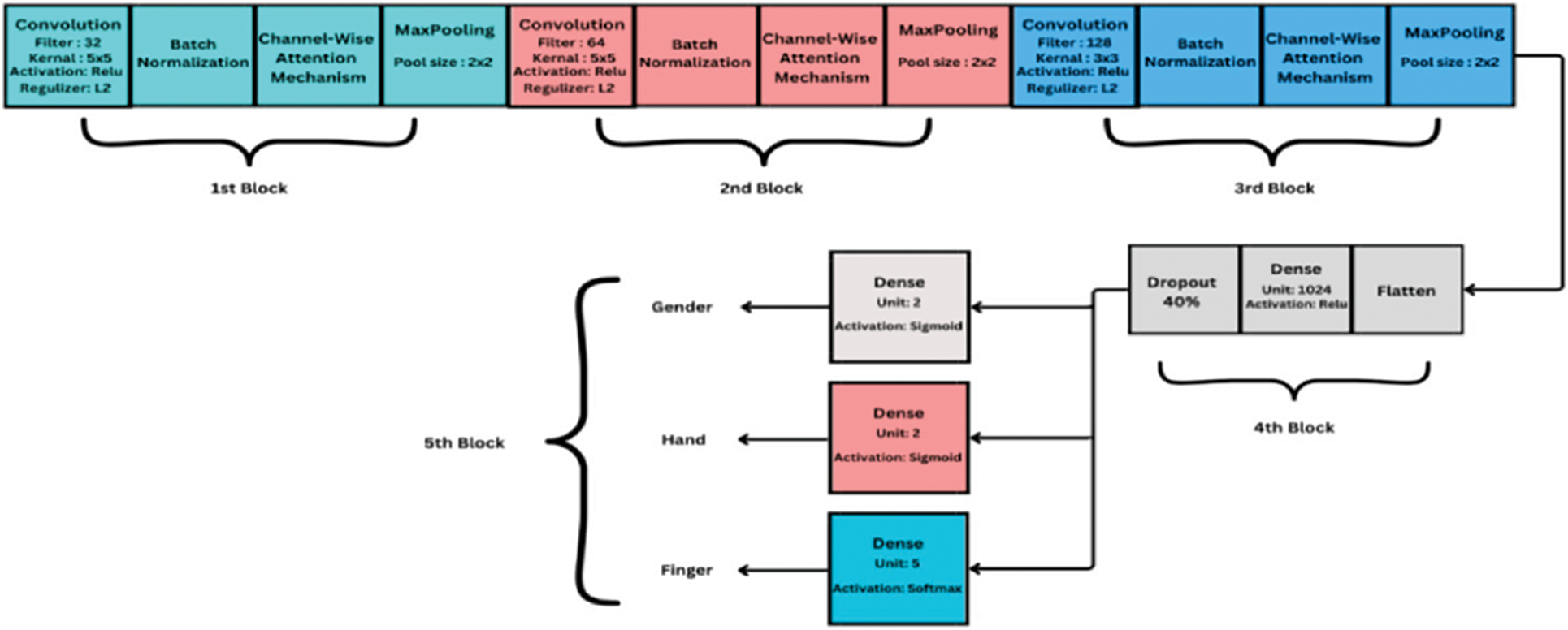

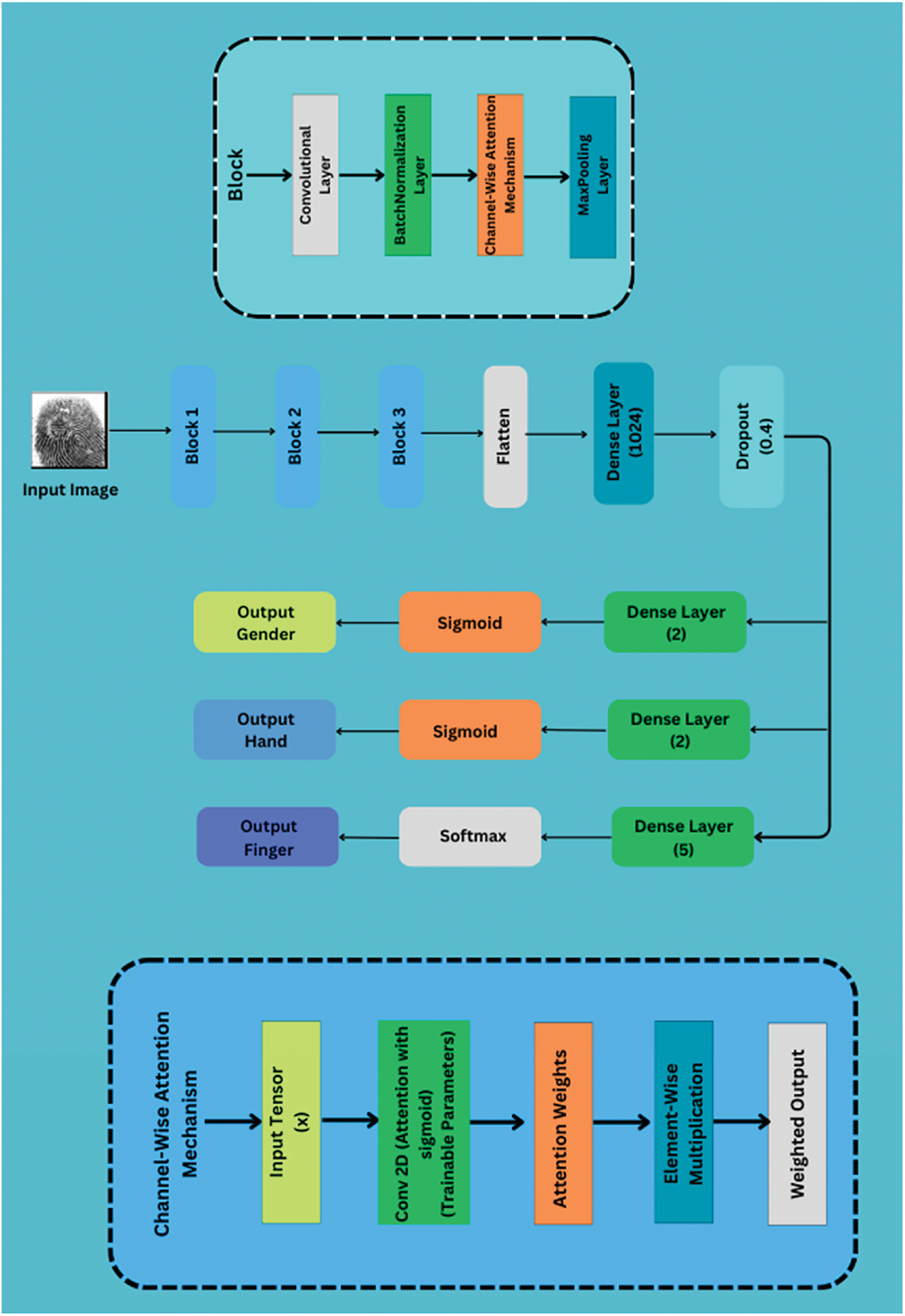

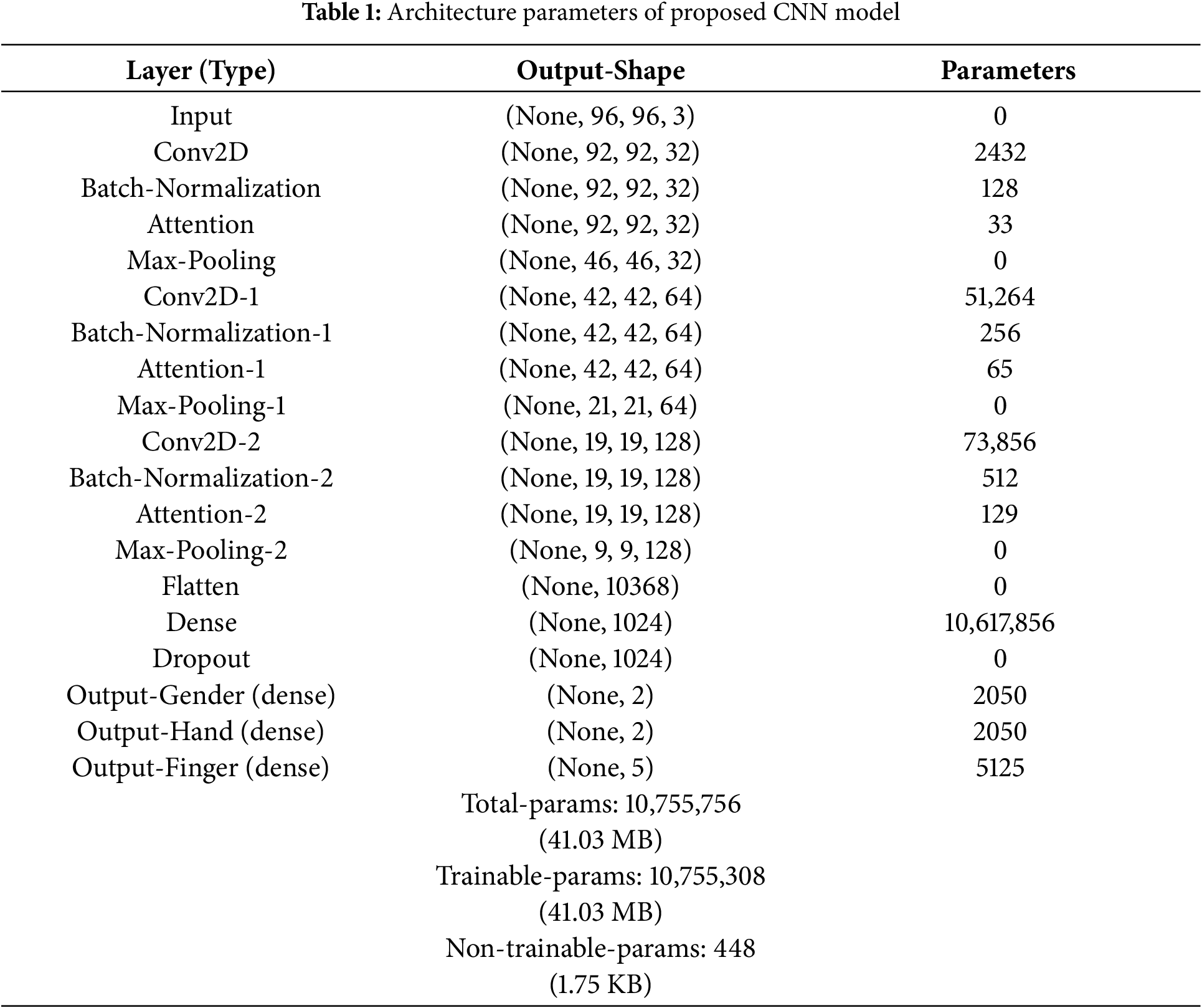

CNNs are widely exploited for image classification tasks due to their versatile capabilities in terms of feature extraction and dimensionality reduction. This study designs a channel-focused CNN model for the accurate and efficient classification of distinct fingerprint attributes. Fig. 4 represents the brief block diagram of the proposed FOCNN model architecture. It indicates that the proposed neural architecture contains five different stages/blocks. The initial three blocks represent the feature extraction and dimensionality reduction section of the proposed model. They contain three convolutional layers with a specified number and size of filters, as shown in Fig. 4, and a ReLU non-linear activation operator to reduce parameter complexity and capture hidden relations between different non-linear features. In addition, a batch-normalization layer is incorporated beyond the convolutional layer to stabilize the model throughout the training process. An effective channel-wise attention-based feature extraction mechanism is exploited within the CNN architecture to emphasize the prominent features in the specified channel regions. Similarly, the max pooling technique is explored after the attention mechanism to extract features for accurate fingerprint classification. The fourth block shows the initial classification part of the proposed architecture, which includes a flatten layer and a first dense layer with 1024 units, followed by a dropout layer with a rate of 0.4. The fifth block in Fig. 4 displays the multi-output fully connected layers with specified attributes of fingerprint classification. The stratified graphical representation of the proposed channel-focused CNN model is provided in Fig. 5. The initial two convolutional layers of the proposed architecture comprise 32 × 5 × 5 and 64 × 5 × 5 filter sizes, whereas the last convolutional layer in the architecture contains 128 × 3 × 3 filter size. The comprehensive summary of architectural parameters for the proposed FOCNN model is listed in Table 1.

Figure 4: Architectural blocks of the proposed FOCNN model for fingerprint detection

Figure 5: Stratified graphical representation of the proposed CNN model

3.2.2 Channel-Wise Attention Mechanism

The channel-wise attention-based feature extraction mechanism emphasizes modifying the prominence of distinct feature maps within the neural architecture. Fig. 5 represents the workflow of the channel-wise attention mechanism. From Fig. 5, the input tensor block refers to the specified input image (x) provided to the mechanism. In addition, Conv2D or Attention block is the layer that computes the attention weights (aw) for the provided image. This block has trainable parameters, which refer to the automatic adaptation of parameters such as biases or weights during the training procedure. The calculated attention weights correspond to the importance of each region in the given input tensor. The element-wise multiplication operation is performed between x and aw, which gives the weighted output (wo). This wo refers to the original x after the channel-wise attention mechanism operation, where regions with prominent features within the provided images are given superior attention weights. The key pros of exploiting channel-wise attention mechanisms within CNN architecture are as follows:

• It enables the model to focus on useful features and ignore the less relevant regions of the image.

• It can enhance the performance of proposed models by adjusting the prominence of distinct channels according to their relevance to the task at hand.

• It provides useful insights into the decision-making process of the proposed model by showing which channel is most prominent for the specified prediction.

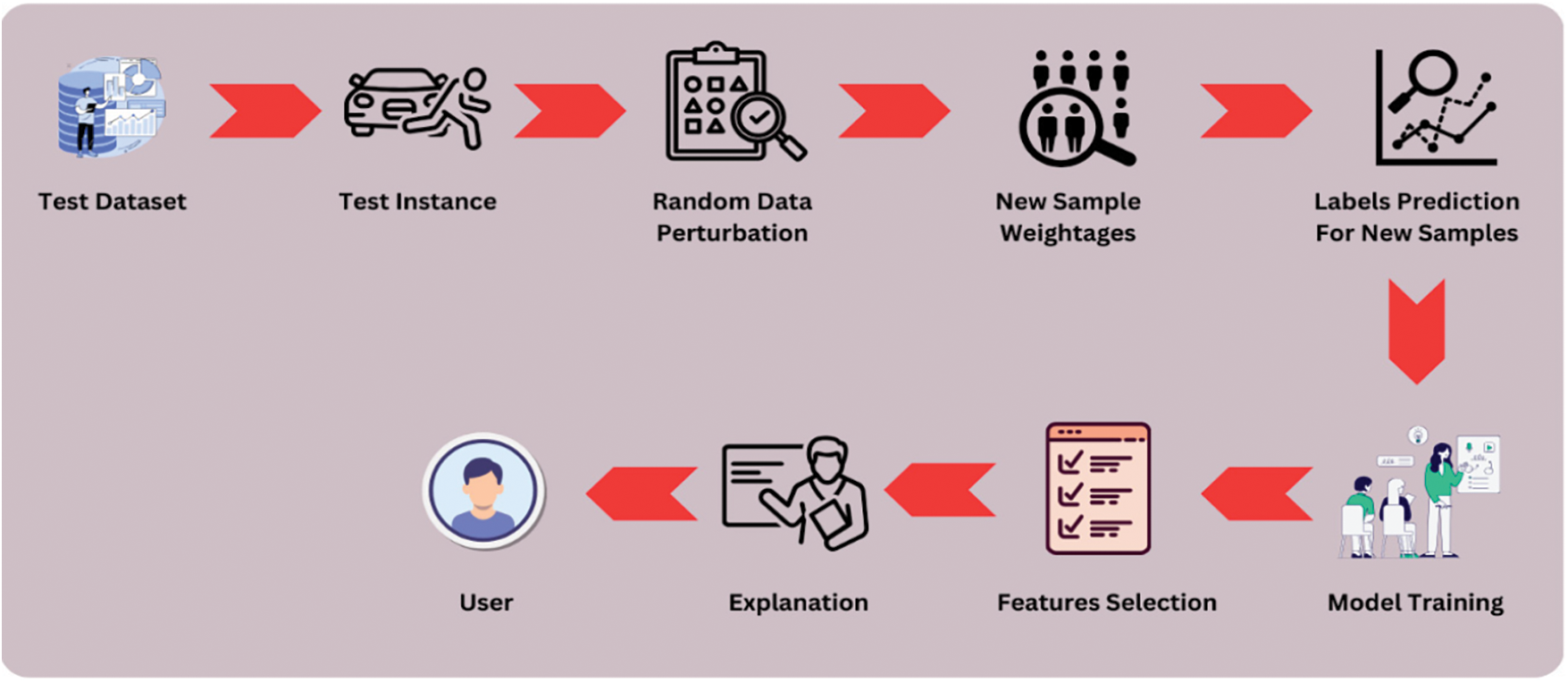

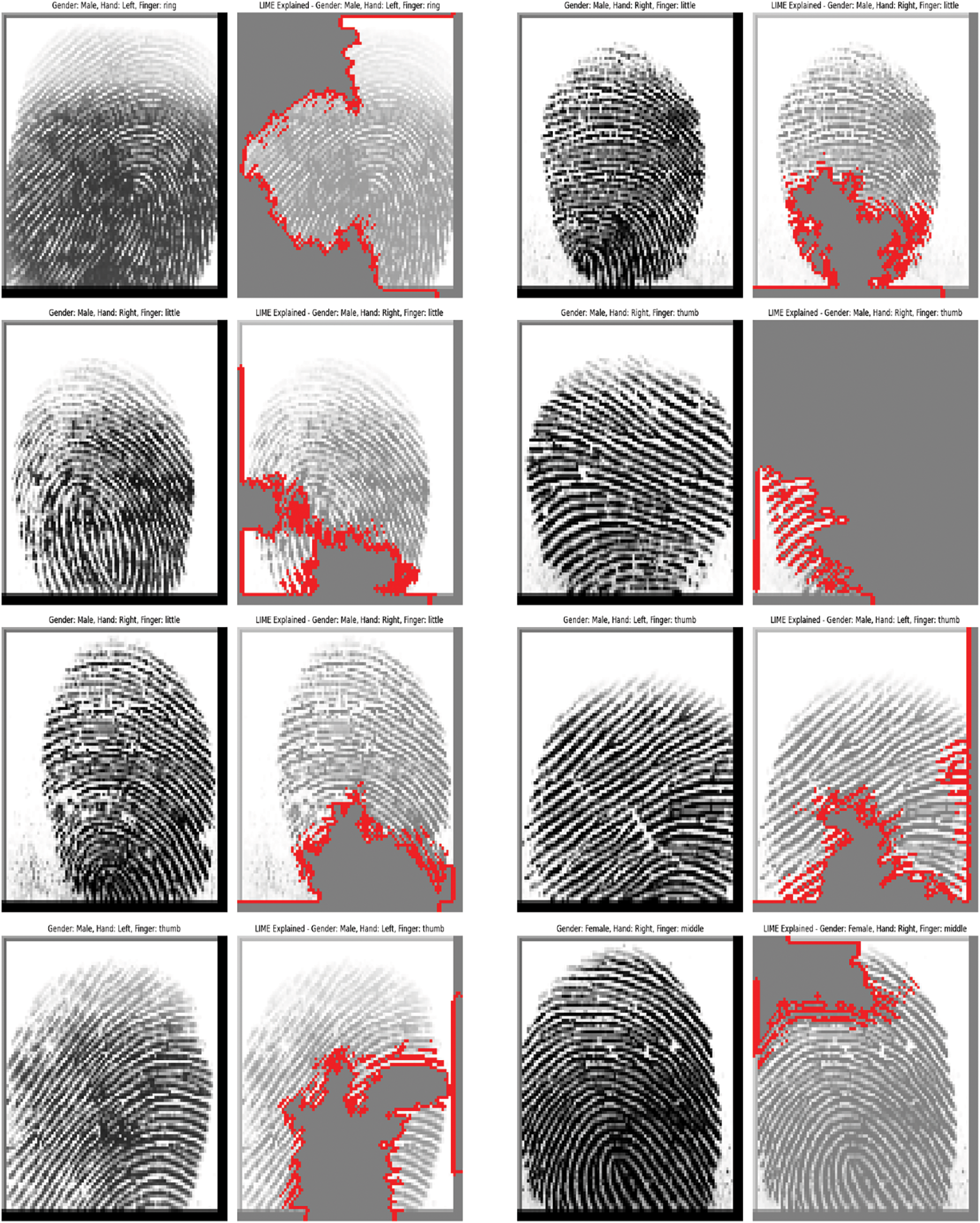

3.2.3 Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI)

This study explores the local interpretable model-agnostic explanation (LIME)-based XAI for human-understandable fingerprint classification. LIME is an approach utilized to demonstrate the predictions of complicated AI-based models in an easy and explainable manner [69]. The complete working procedure of the LIME is shown in Fig. 6. After choosing the specific instance for the explanation, LIME perturbed the selected instance to observe the change in model predictions. In addition, it provides both the perturbed and original selected instances to the simple or interpretable model for prediction. Hence, LIME [70] computes the meaningful insights about the prominent features in the chosen instance. Beyond extensive analysis, LIME encircles the most useful region of the input image that heavily contributed to the given prediction. This interpretability is crucial in disciplines such as healthcare and criminal justice, where implications of predictions can have noteworthy consequences. This interpretability is also essential for building trust in AI-based products.

Figure 6: Graphical work-process of the local interpretable model agnostic (LIME) technique

3.2.4 Generalized Fractional Stochastic Gradient Descent (GFSGD)

This section entails the mathematical intuition behind the Generalized Fractional Stochastic Gradient Descent (GFSGD) algorithm. It knows that every gradient descent method has the standard update rule:

where

For the GFSGD method, the Caputo definition of the fractional derivative serves as the basis:

where

Taylor series expansion is further utilized to simplify the above definition as in [71].

Utilizing the interchangeability of the summation and integral yiels:

The integral can easily be solved by using the power formula:

It is useful for us to reindex the summation as follows:

The following equation can be described by further simplifying using known formulas of fractional calculus:

The short memory principle (SMP) is utilized by replacing the lower bound

The first derivative is only required to be zero (critical point) for an optimization problem

where

Finally, the update rule of the GFSGD method is determined by replacing Eq. (12) in (2).

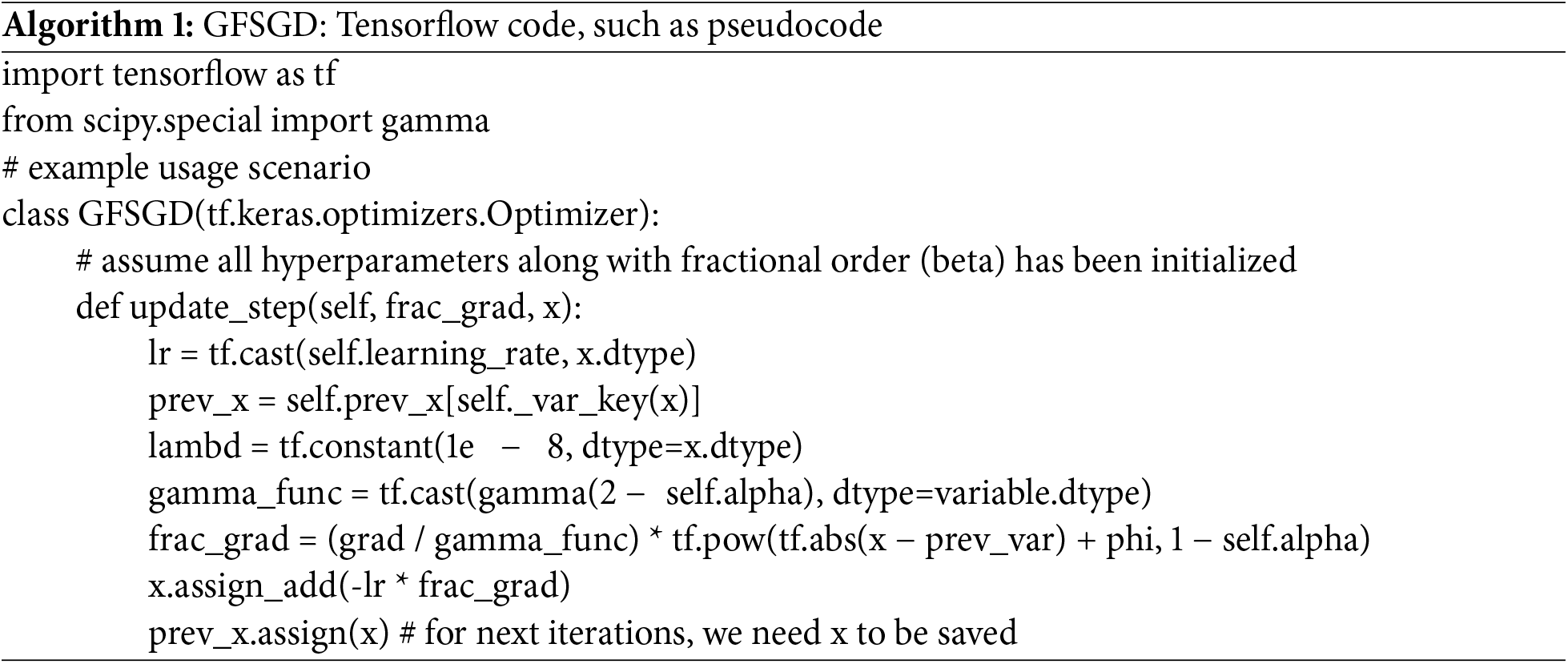

It draws inspiration from Theorem 1 and Theorem 2 of [41] and merges both theorems for its final update step. It utilizes both the fixed memory step and higher-order truncation. A tensor flow pseudo-code (Algorithm 1) can be expressed as follows:

4 Experimentation, Results, and Analysis

This research was conducted using an MSI laptop with an Intel i7 12th generation CPU and RAM of 16 GB, with an octa-core processor. In this formation, the training procedure was optimized, and the model was trained and evaluated satisfactorily. In addition, a Python language-driven TensorFlow framework has been utilized for the development of the proposed deep learning solution.

An extensive performance evaluation of the proposed method was performed at different fractional orders with respect to the evaluation measures, such as accuracy (

This portion of the study summarizes the performance of the proposed CNN model, along with the GFSGD optimizer having distinct fractional order values, for fingerprint classification on the the benchmark SOCOFing dataset. Following the comprehensive tuning of architectural parameters, the FOCNN model is executed with optimal parameters, including a learning rate of 0.001, a batch size of 64, and the model is trained for 45 epochs. During each variation in optimization approaches, the above optimal hyperparameters are used for training the FOCNN model. The results portion is further divided into three studies, which exploit diverse fractional order values for GFSGD to obtain the best possible outcomes.

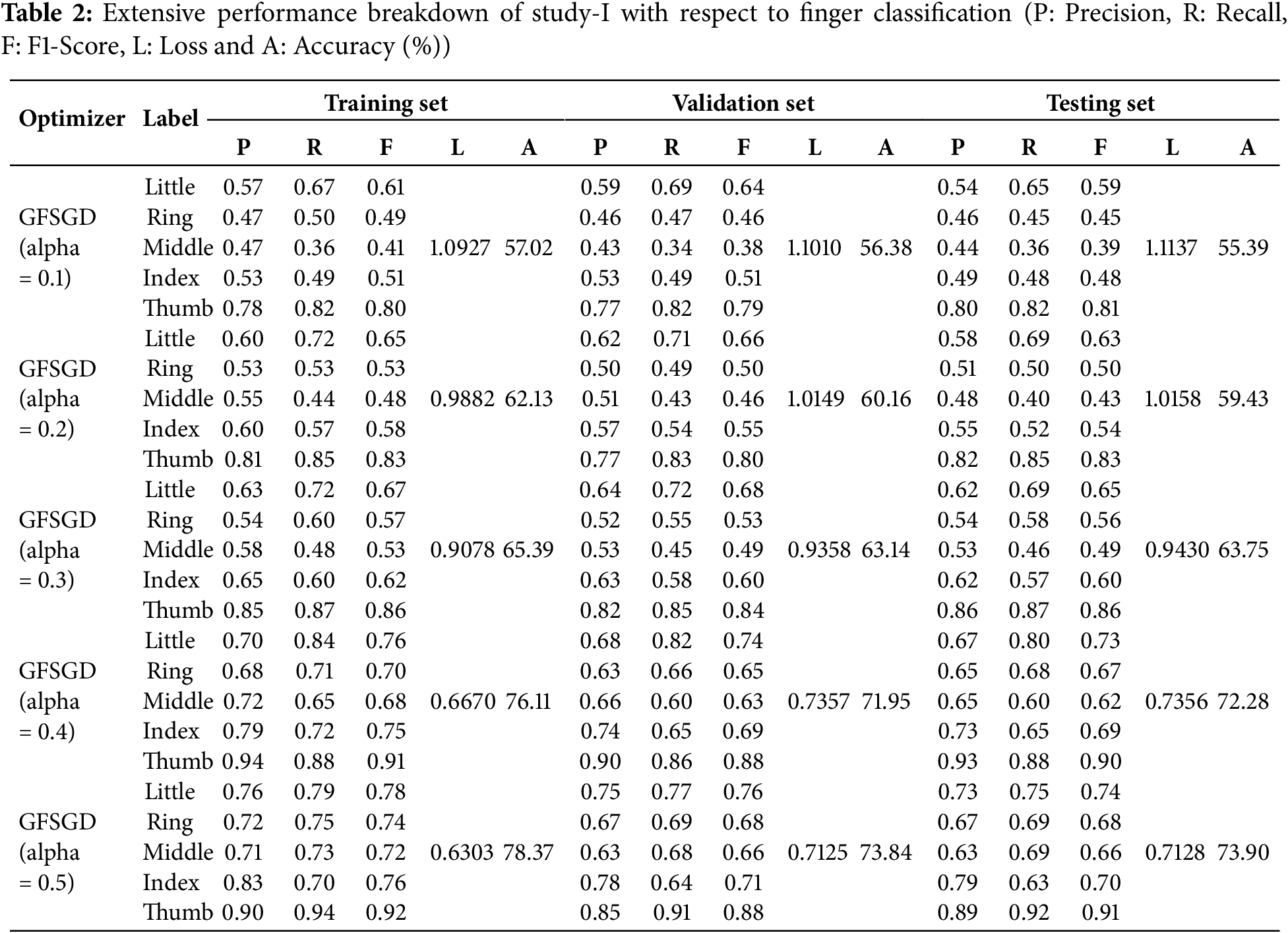

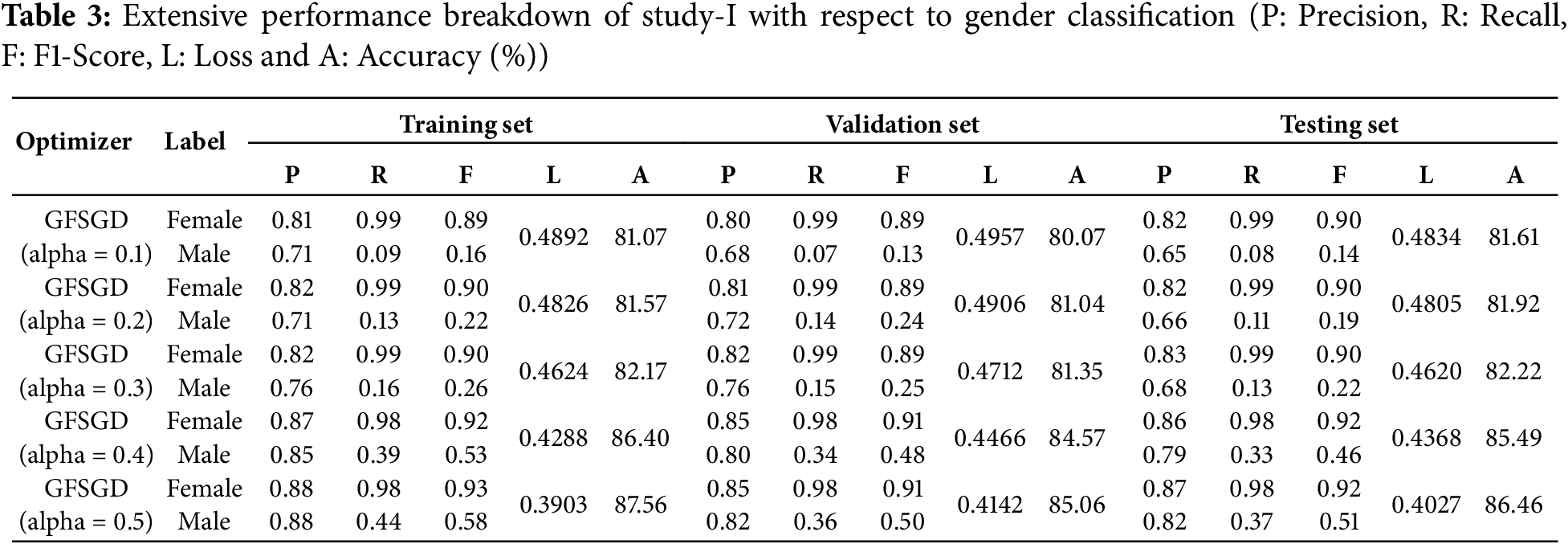

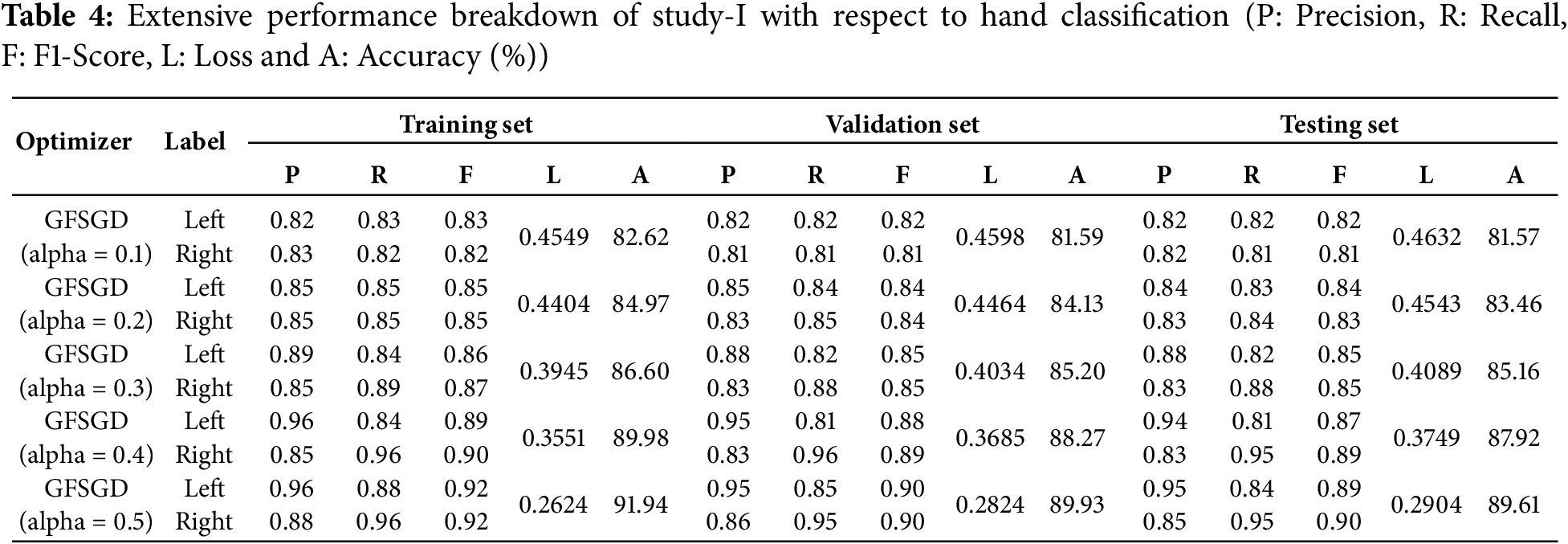

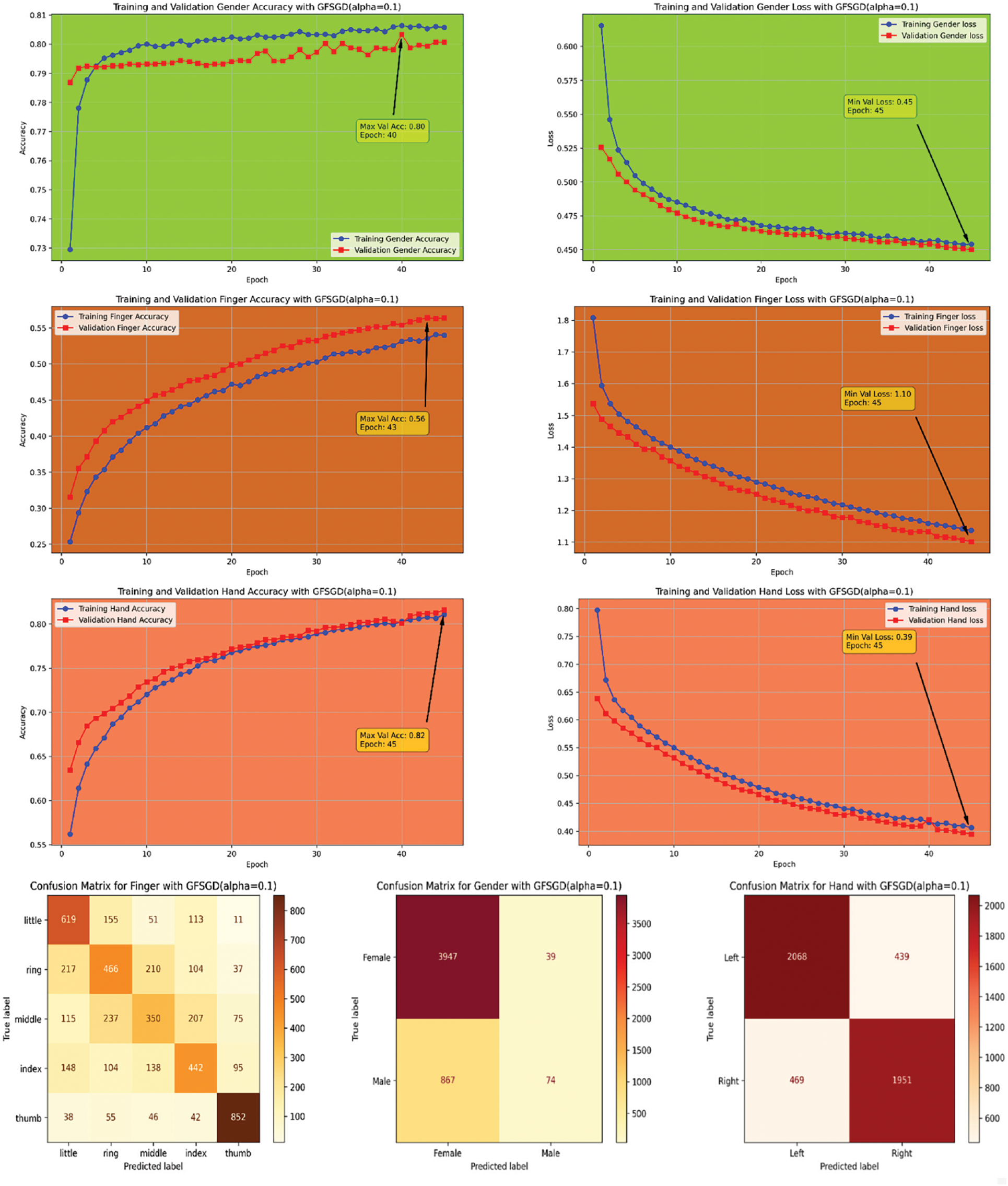

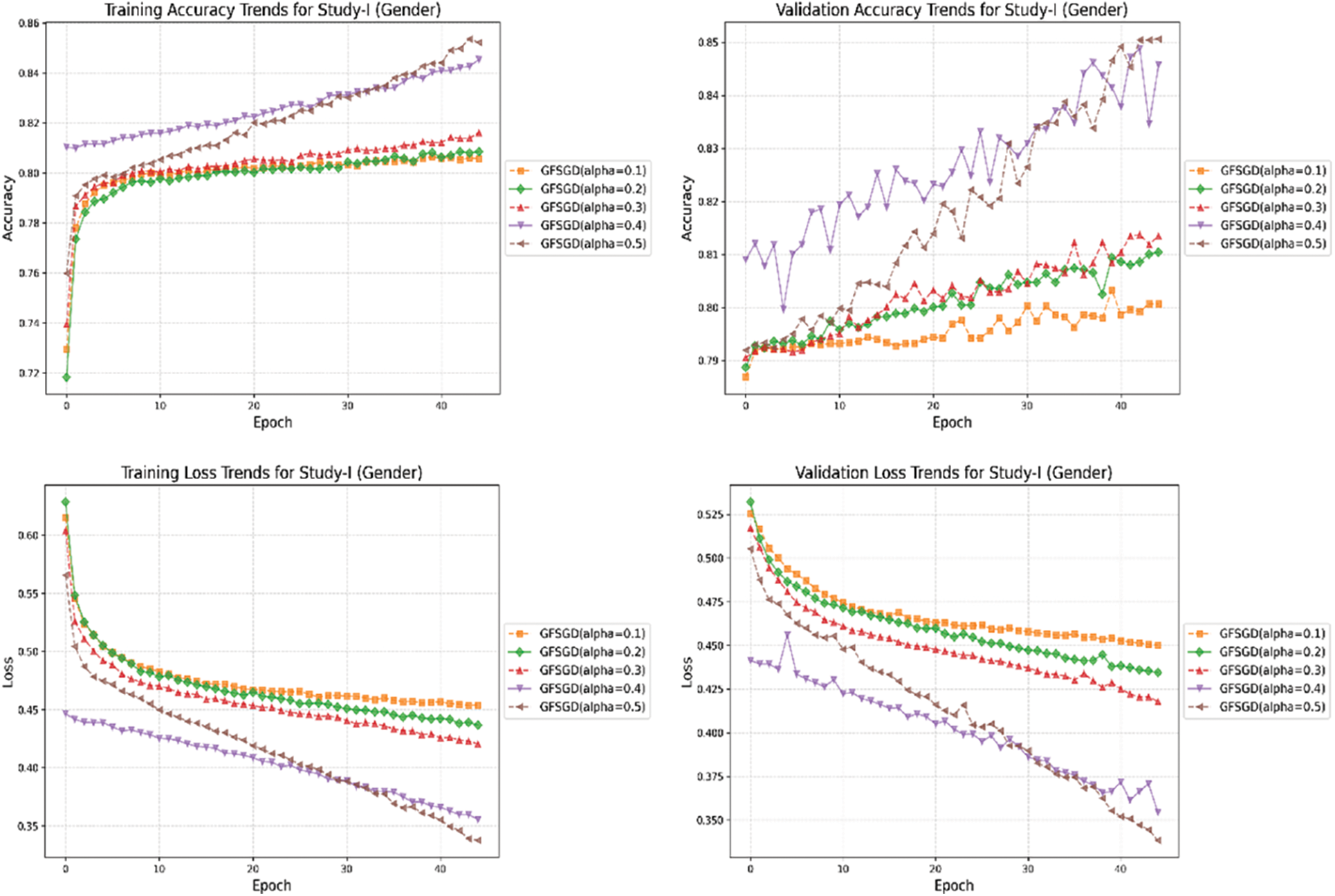

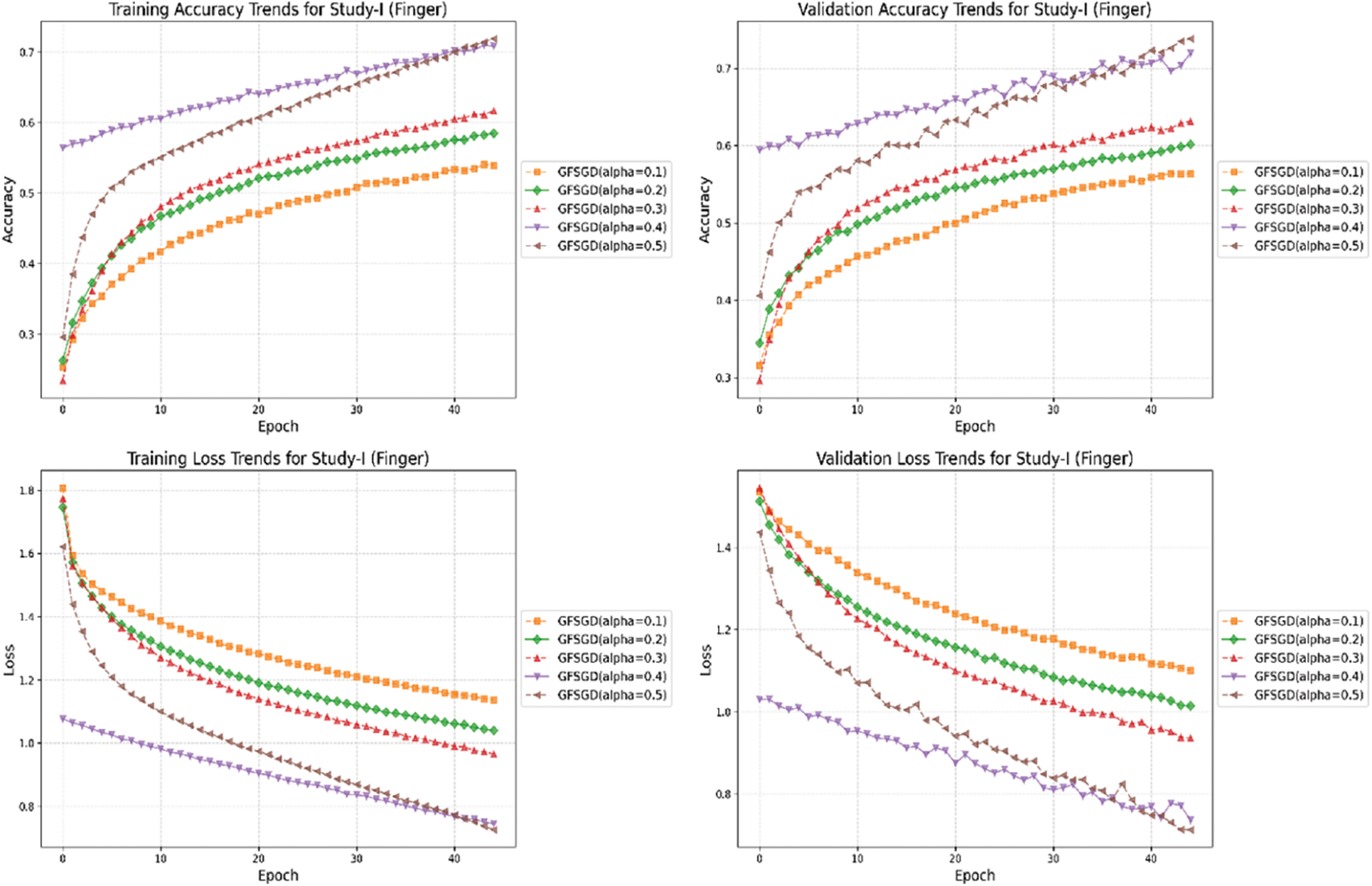

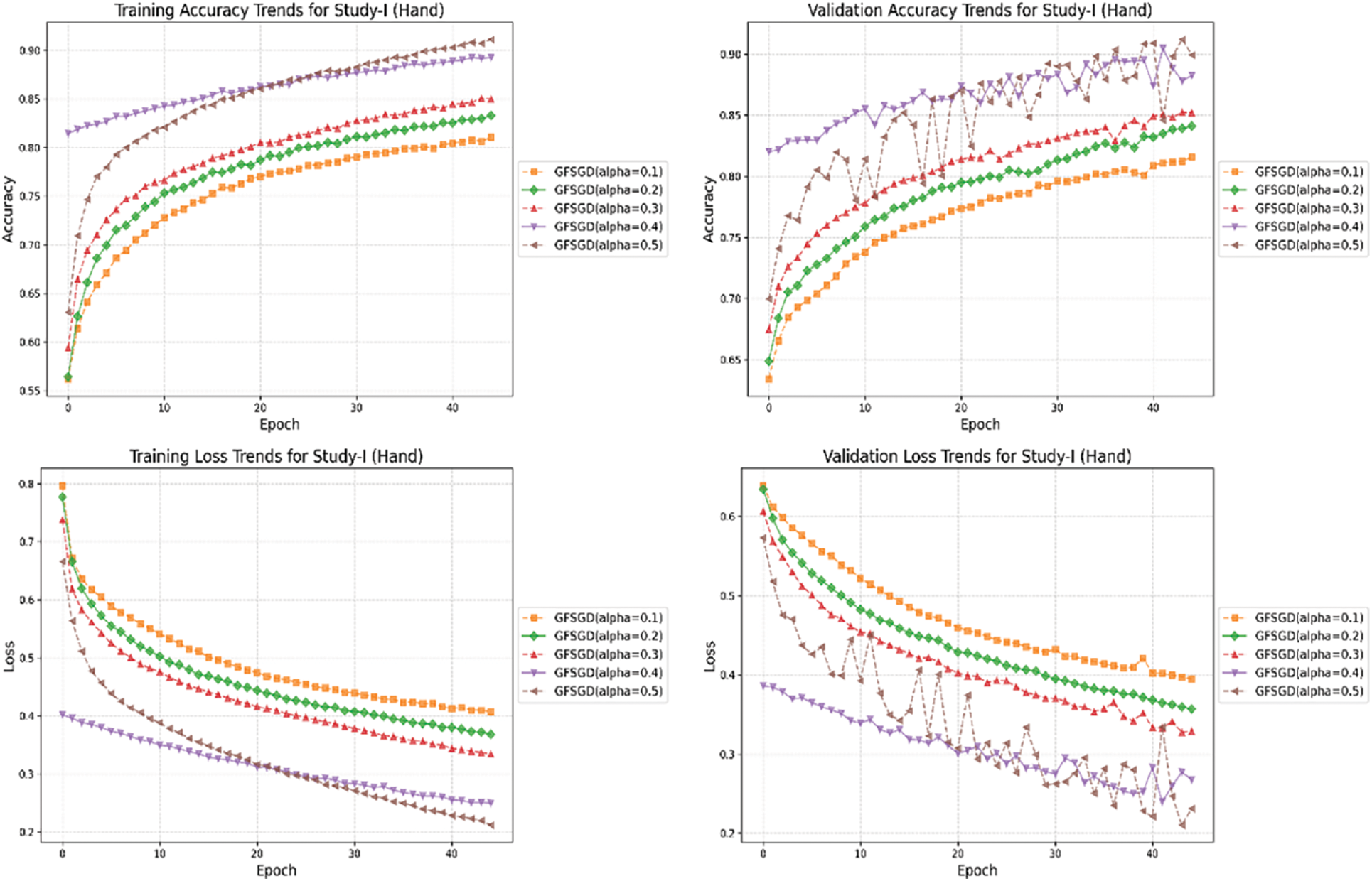

This study presents a performance analysis of the proposed model with GFSGD, which has fractional order values ranging from 0.1 to 0.5. The performance of the proposed model is analyzed through effective evaluation measures, including precision, recall, F1-score, accuracy, bias, and variance. Tables 2–4 demonstrates the comprehensive performance examination of study-I with respect to finger, gender, and hand classification through the benchmark SOCOFing fingerprint dataset. It shows that the proposed CNN model with GFSGD, having an alpha of 0.5, produces the best performance by attaining generalized accuracies of 73.90%, 86.46%, and 89.61% for the classification of finger, gender, and hand, respectively. However, the proposed model along with GFSGD (alpha = 0.1) shows the worst performance in Study-I, achieving low accuracies of 55.39%, 81.61%, and 81.57% for finger, gender, and hand classification, respectively. Study I indicates that the performance of the proposed model improves as the fractional order value of GFSGD increases, which motivates us to explore further fractional values to produce optimal results. The accuracy-loss learning curves and computed confusion matrices related to Study-I are presented in Figs. 7–11. Study-I reveals that the proposed model shows better performance with GFSGD having (alpha = 0.5).

Figure 7: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 0.1)

Figure 8: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 0.2)

Figure 9: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 0.3)

Figure 10: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 0.4)

Figure 11: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 0.5)

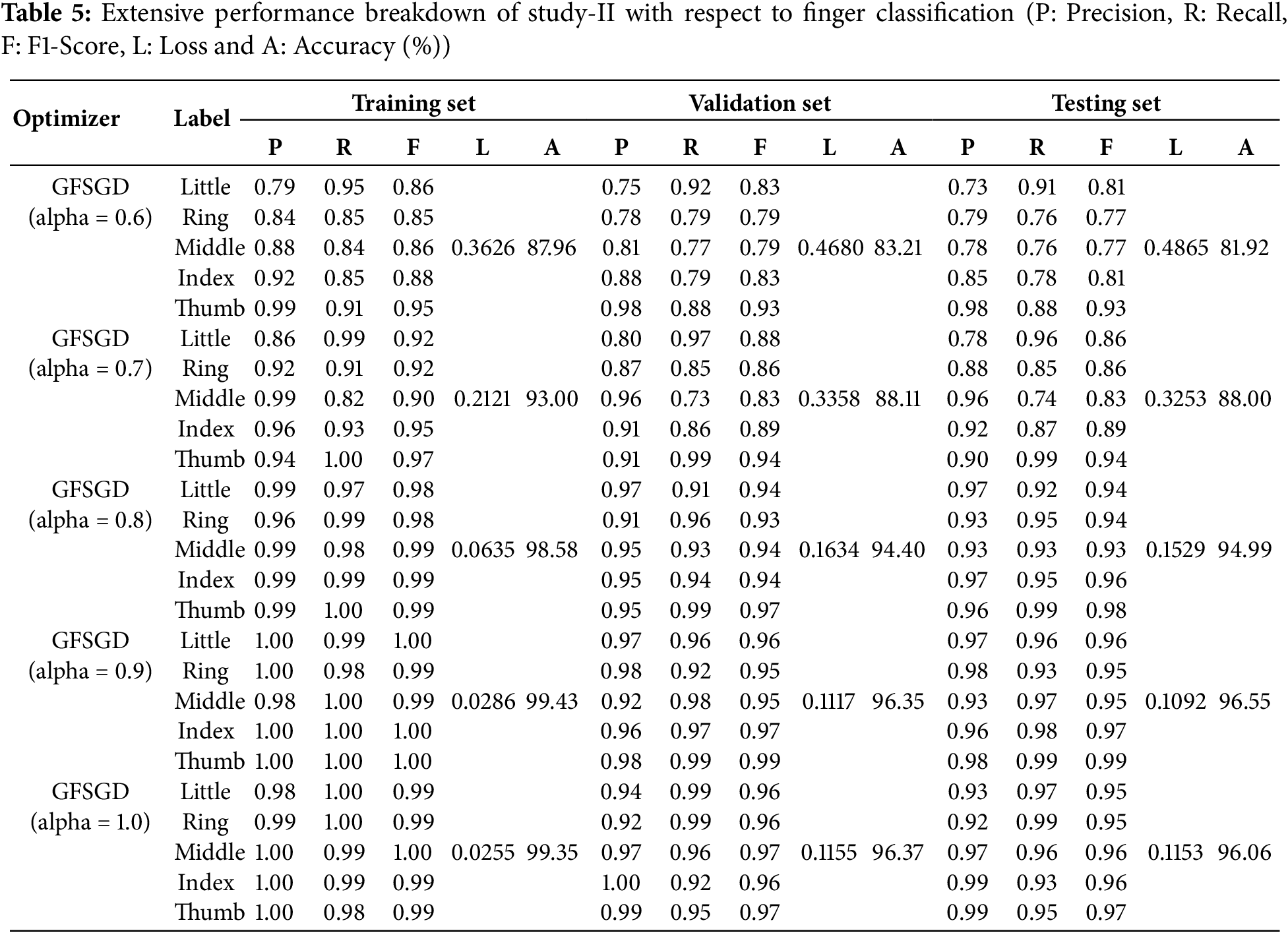

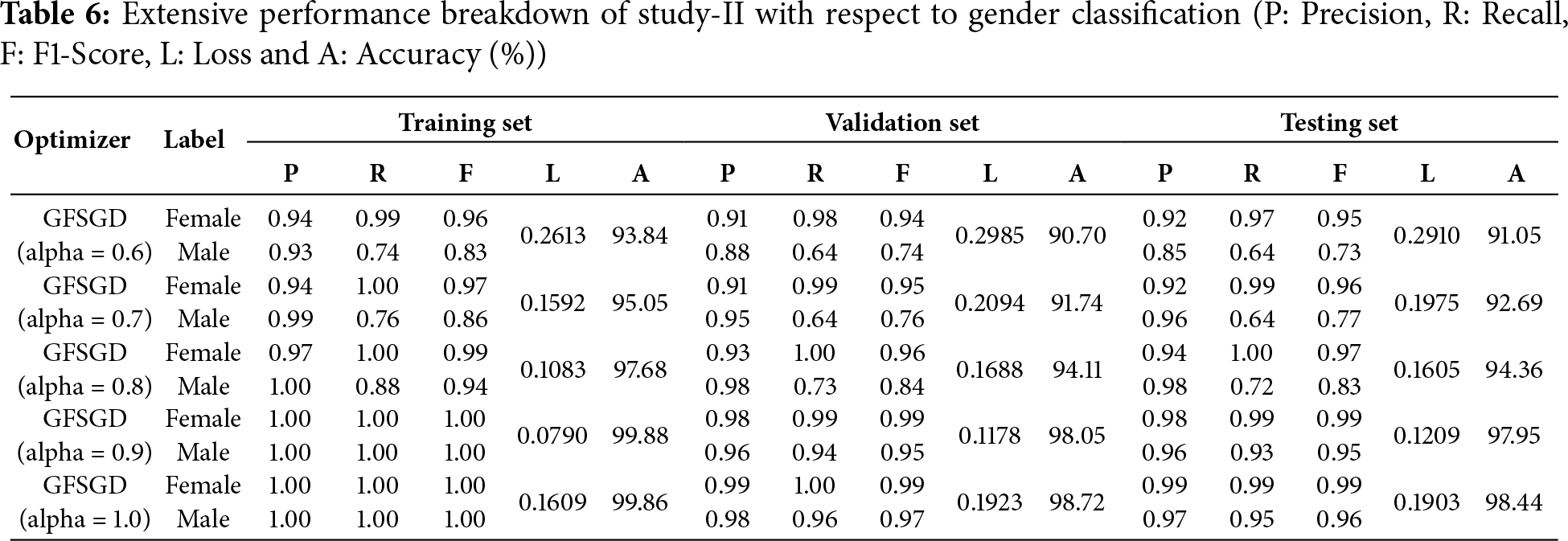

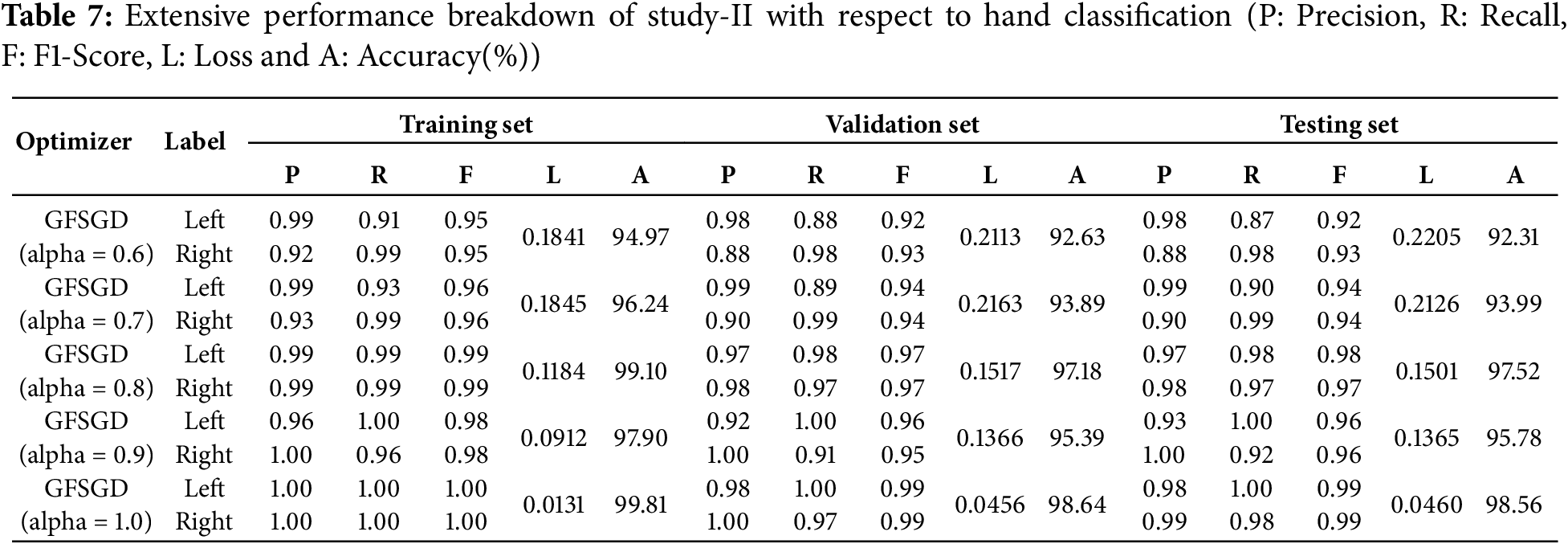

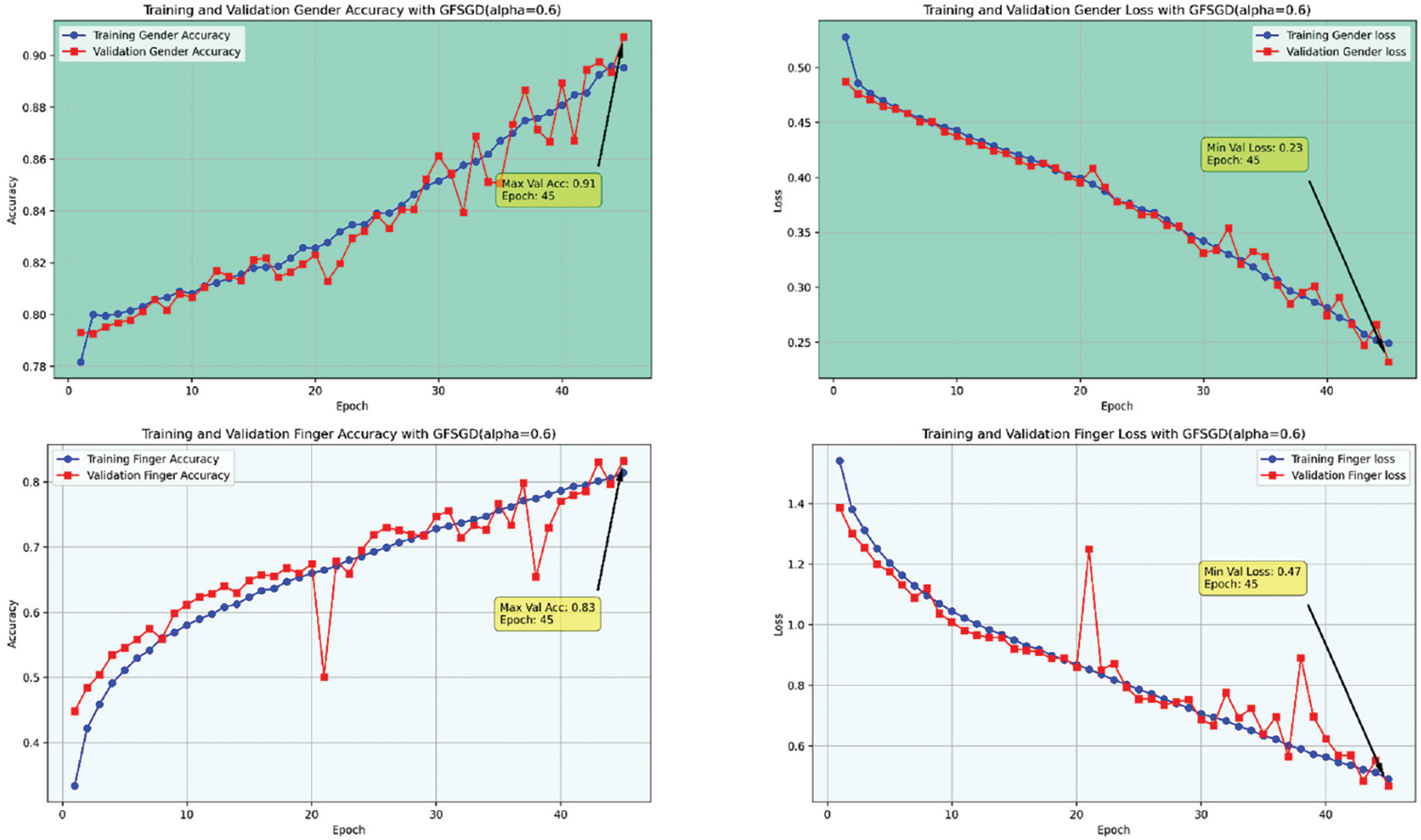

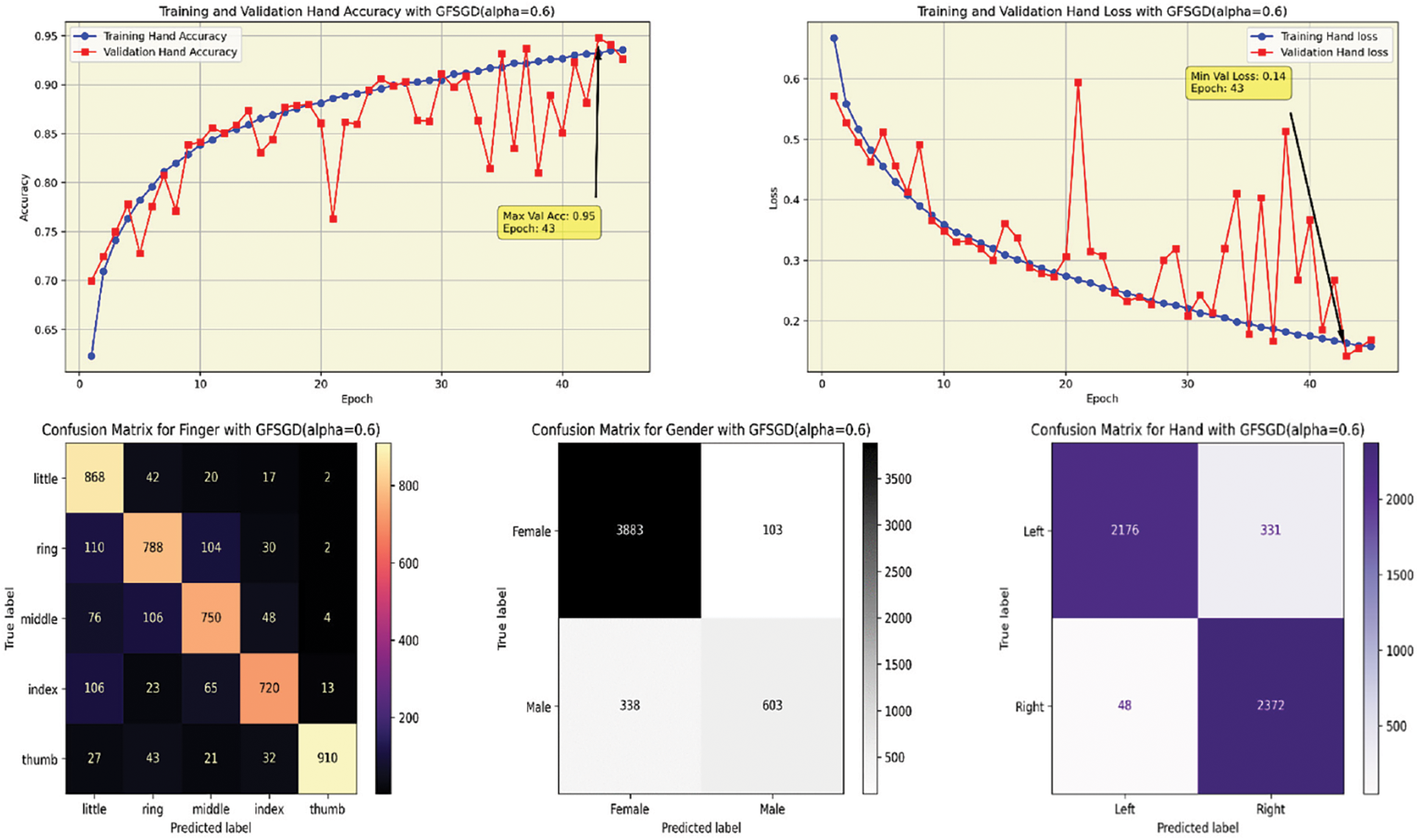

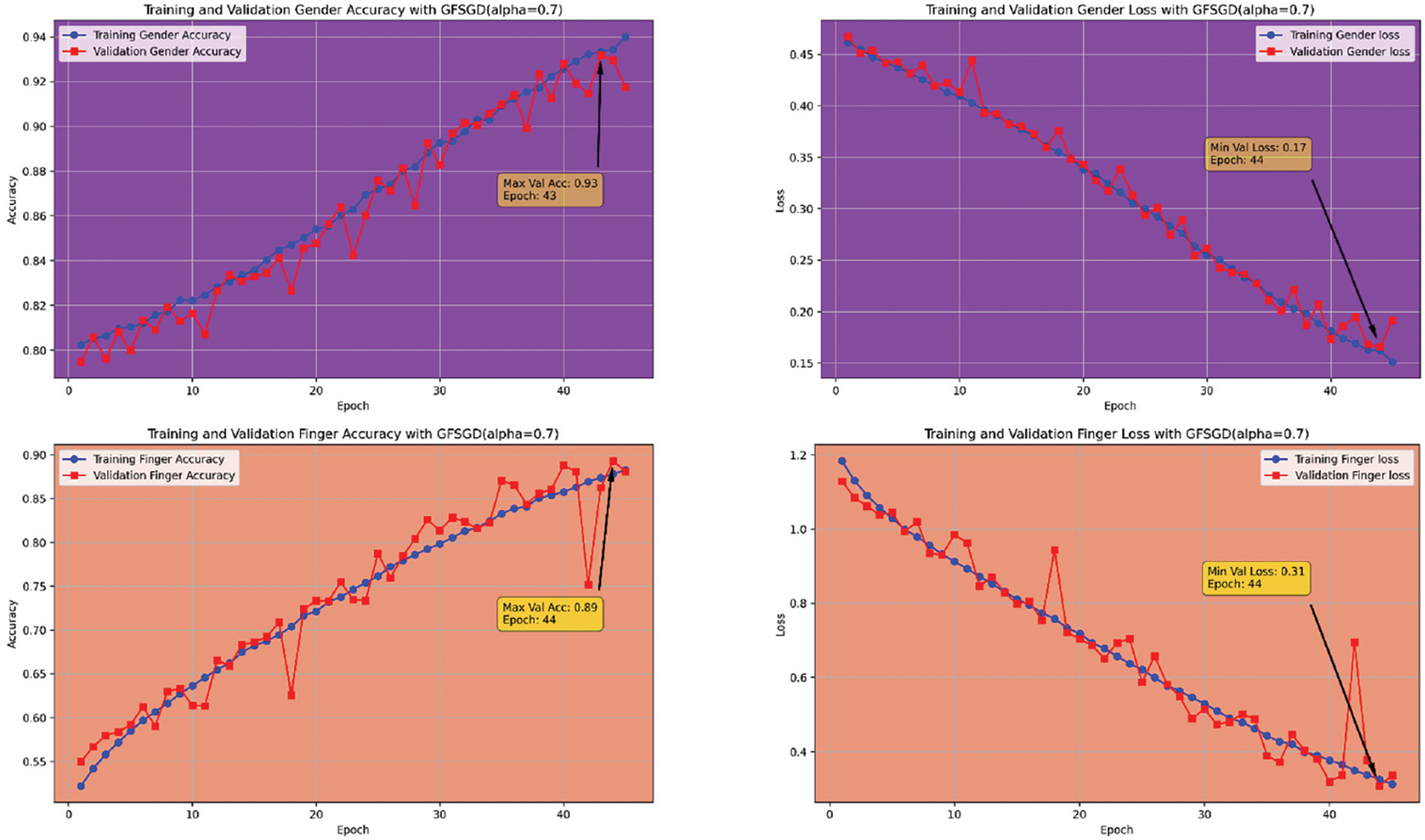

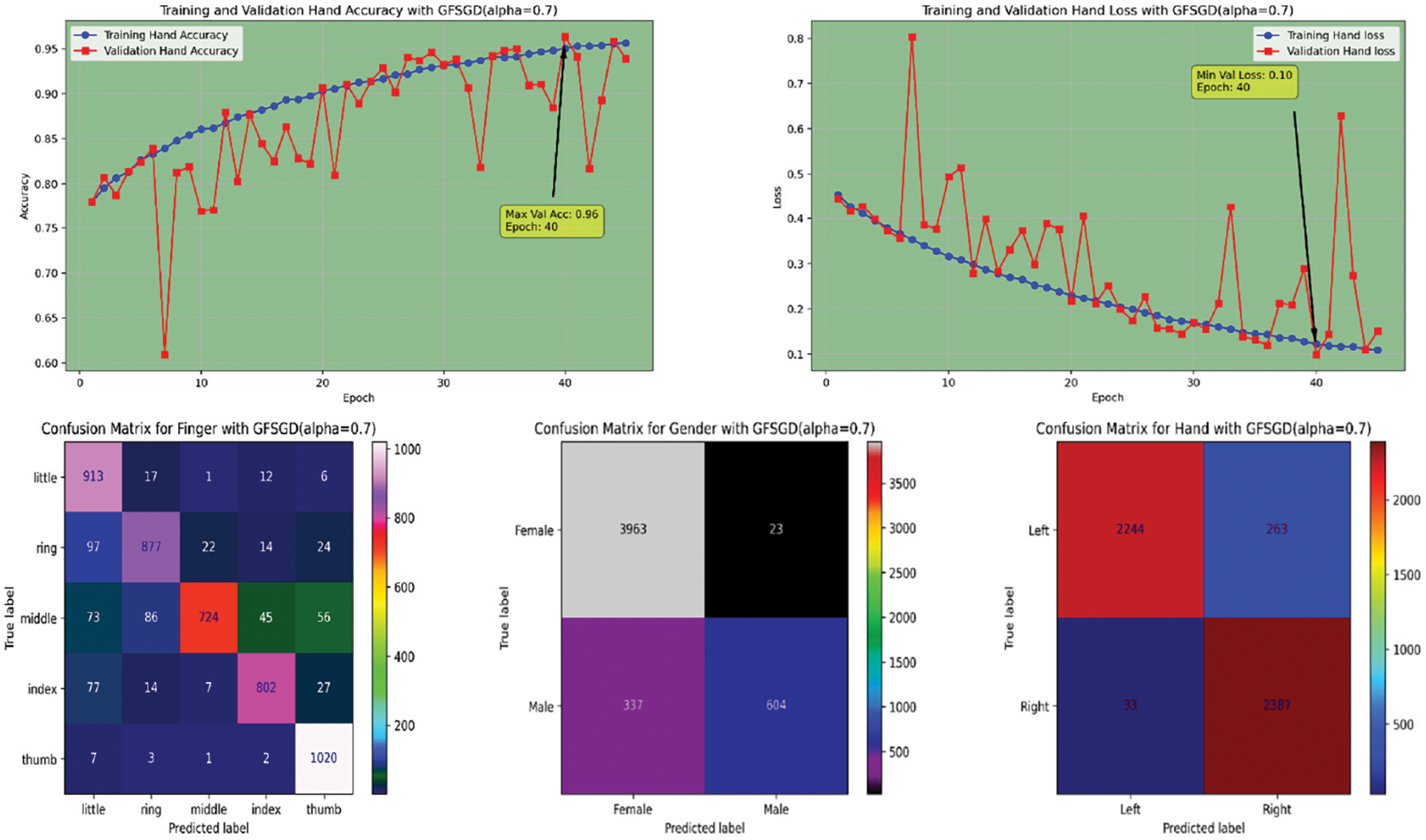

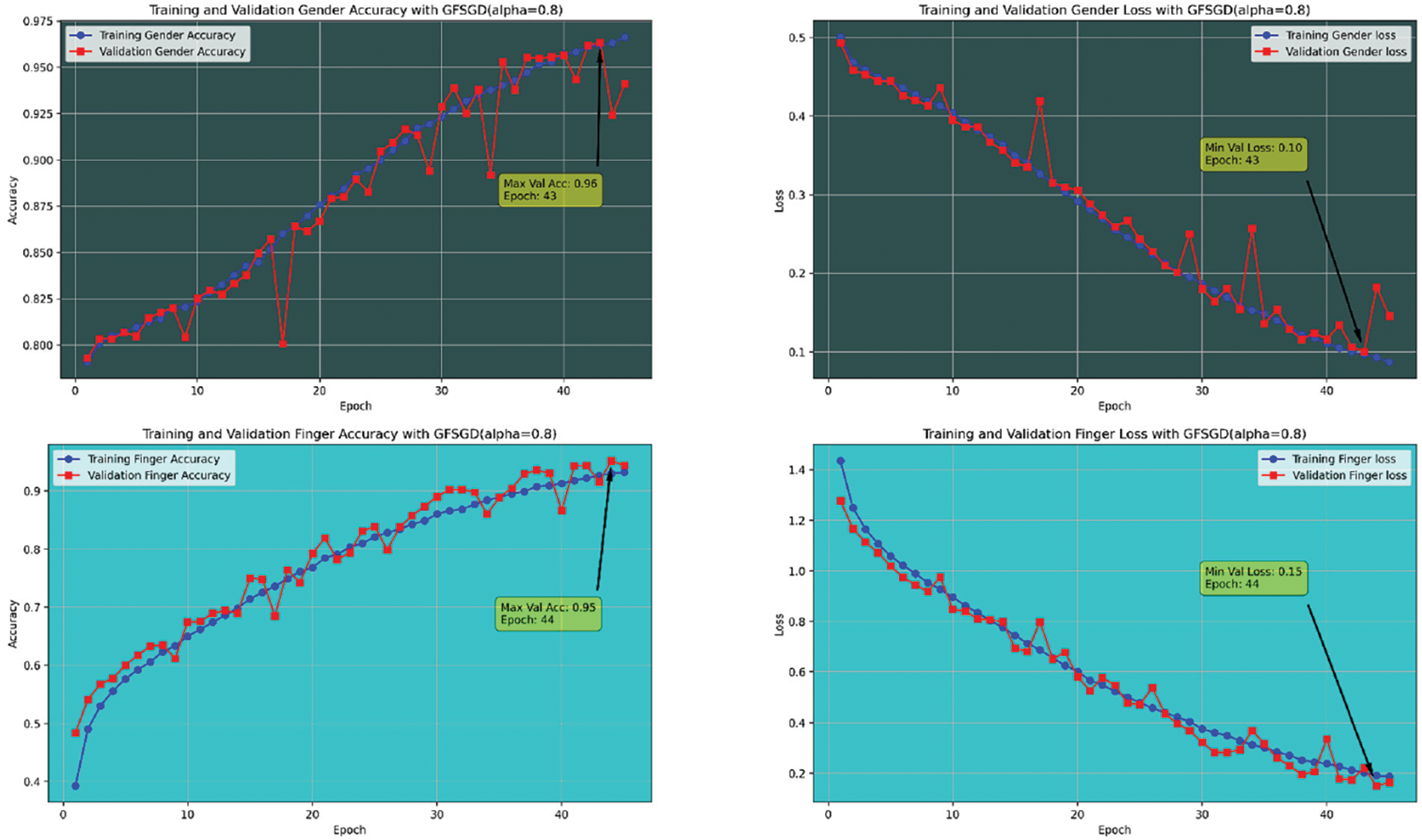

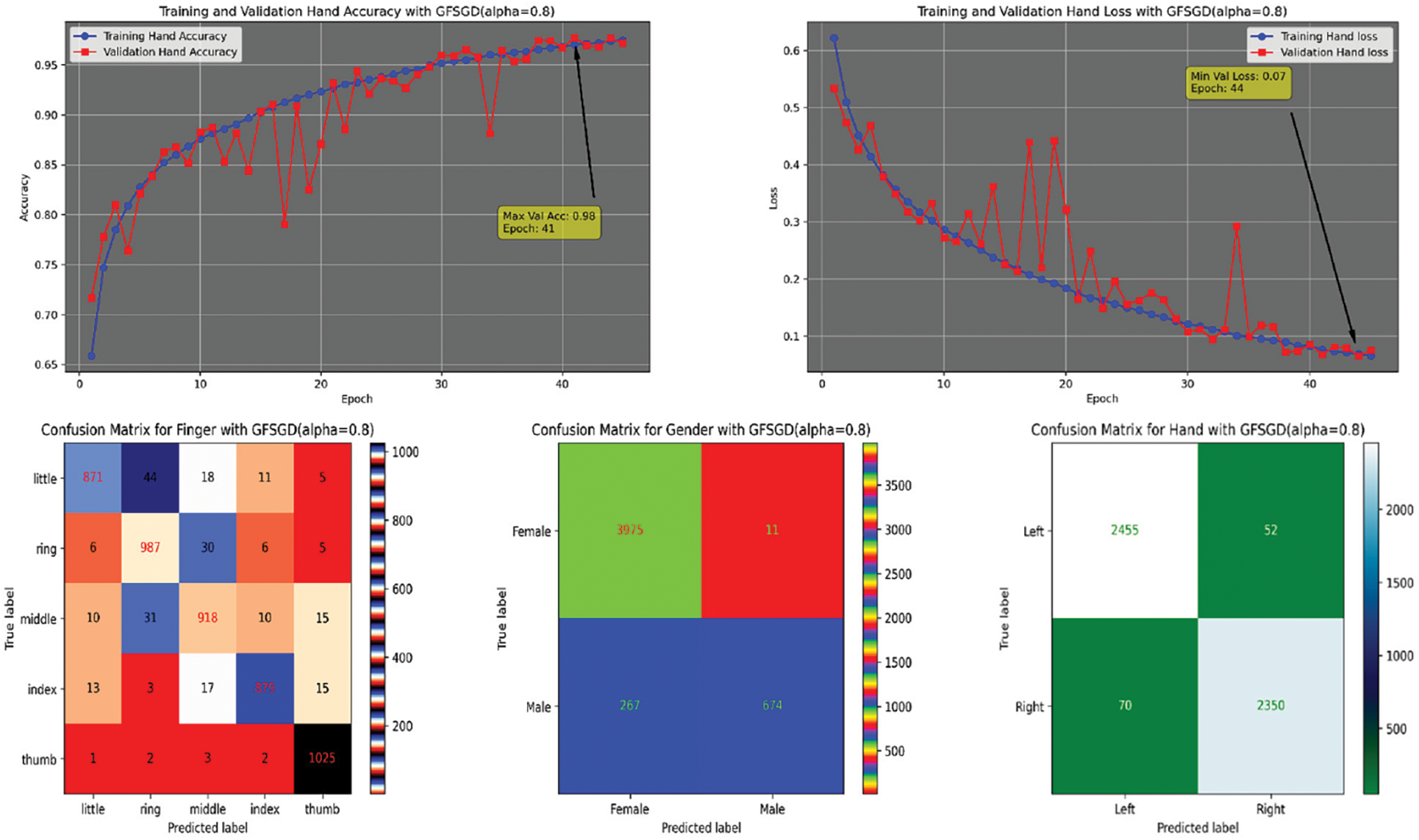

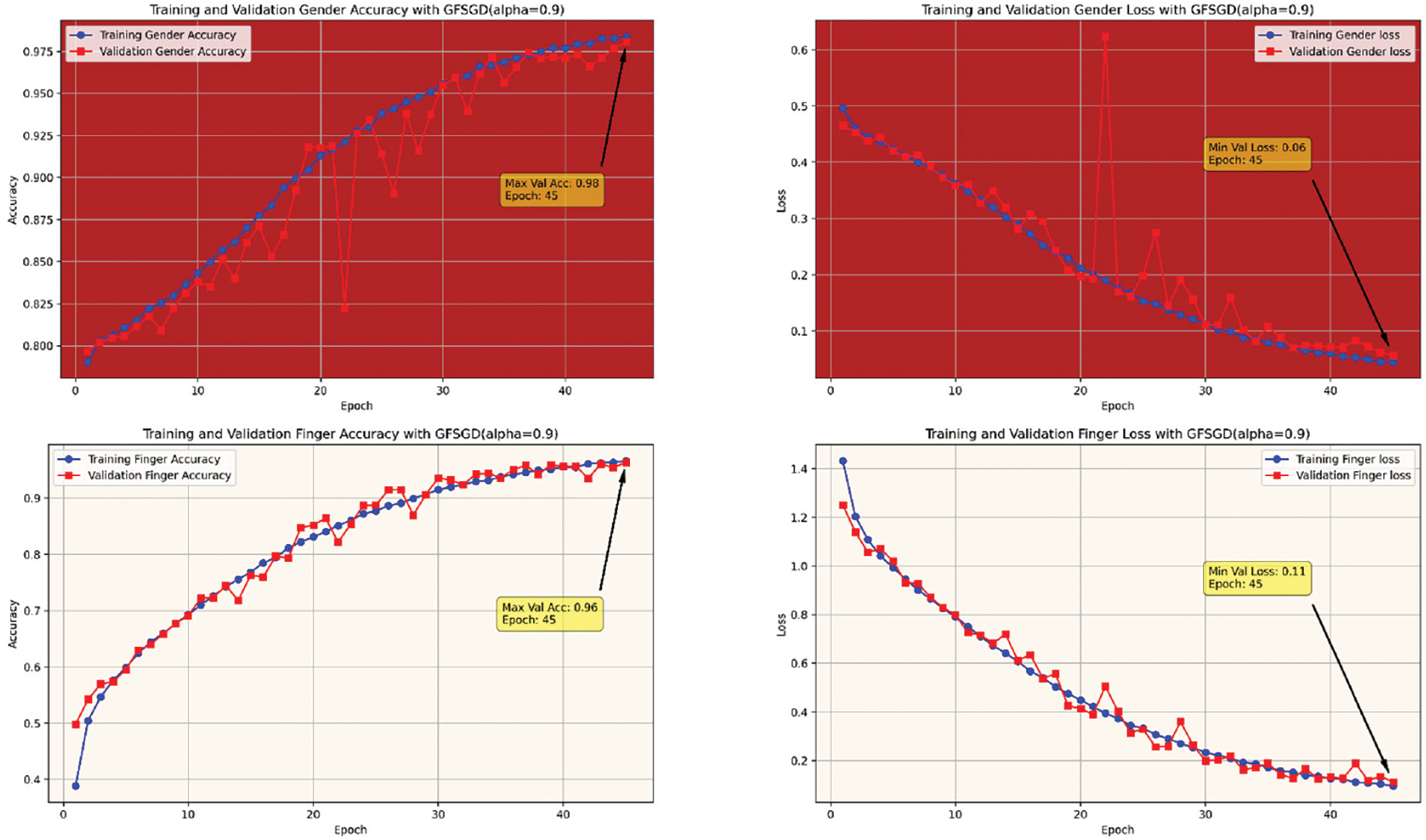

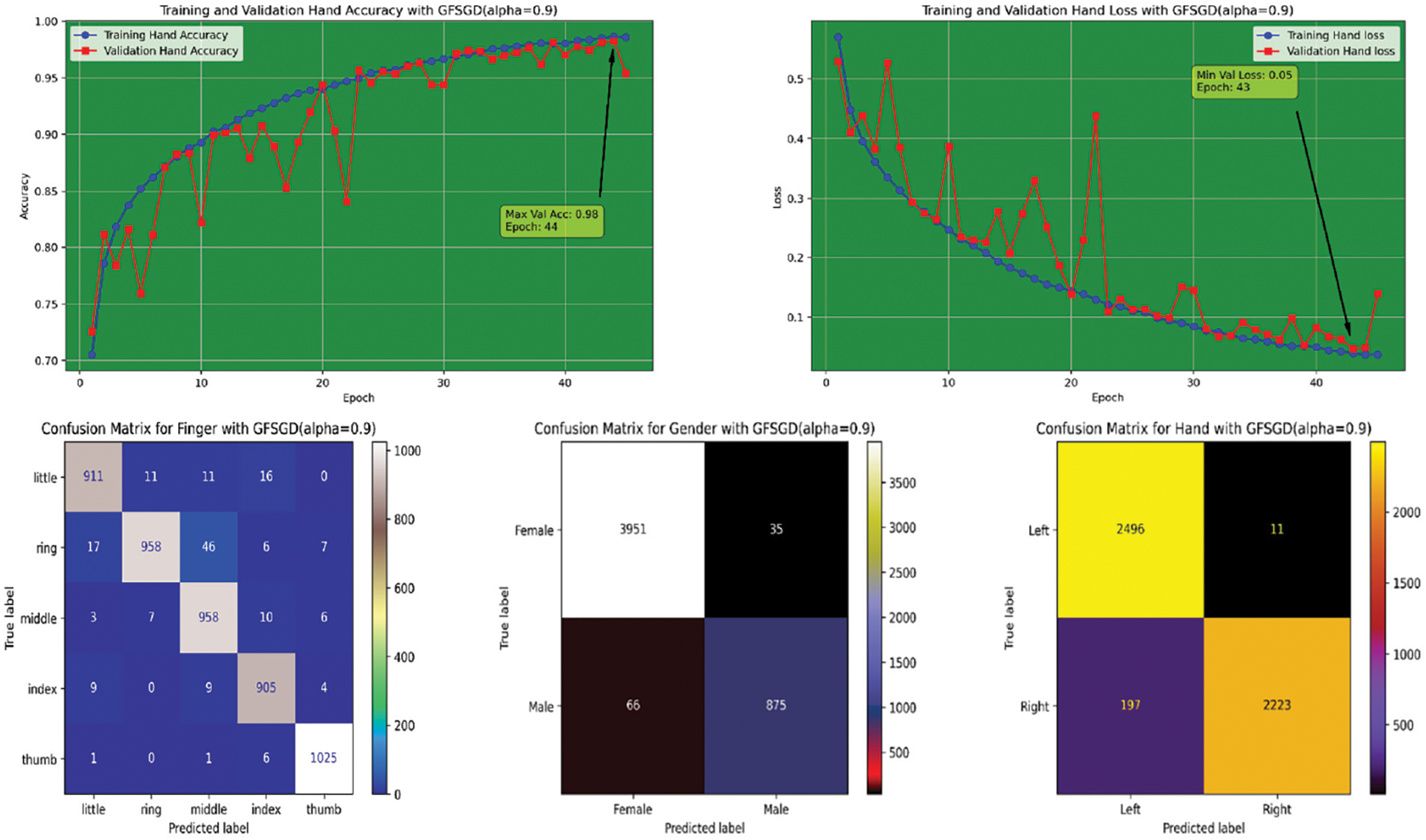

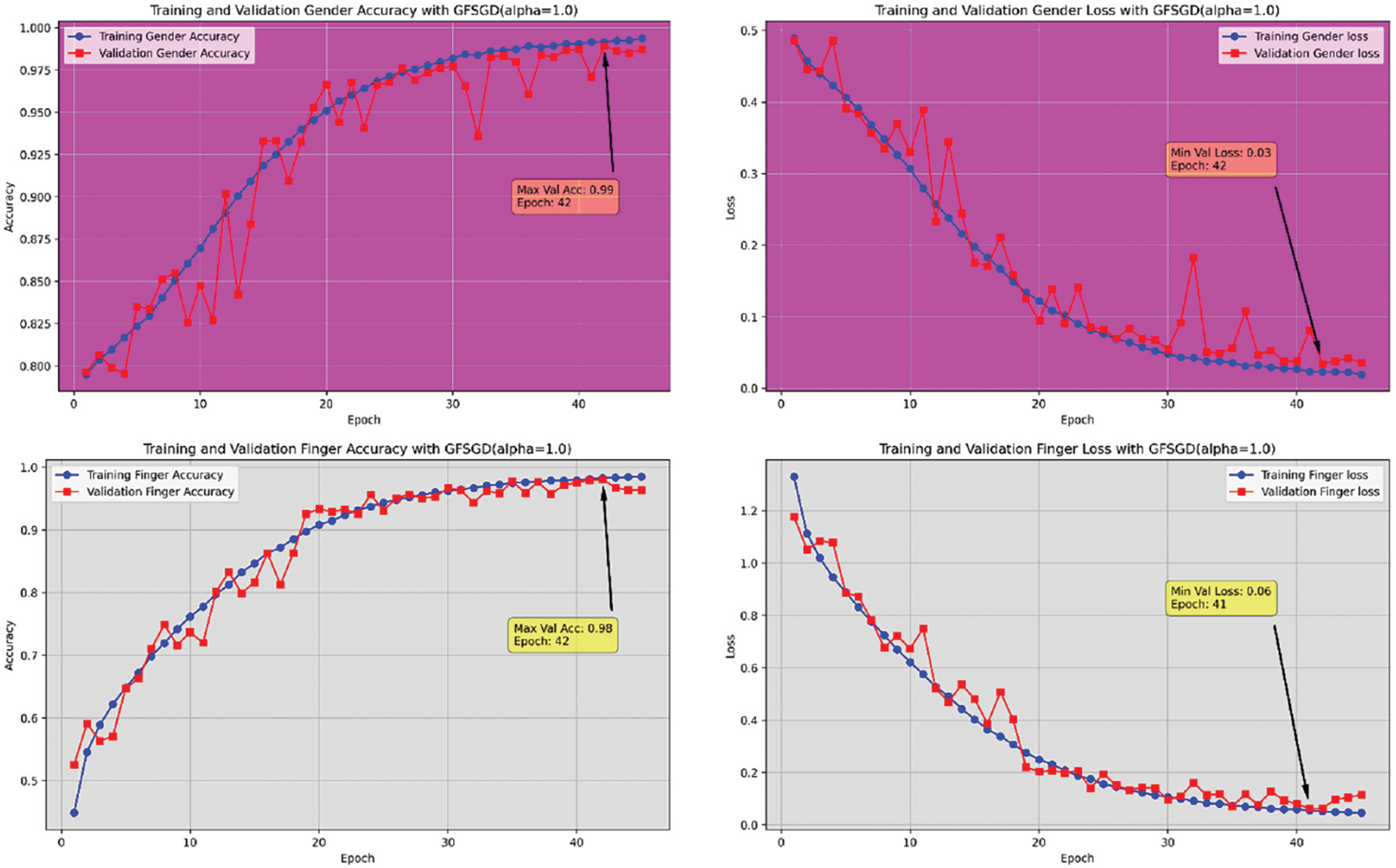

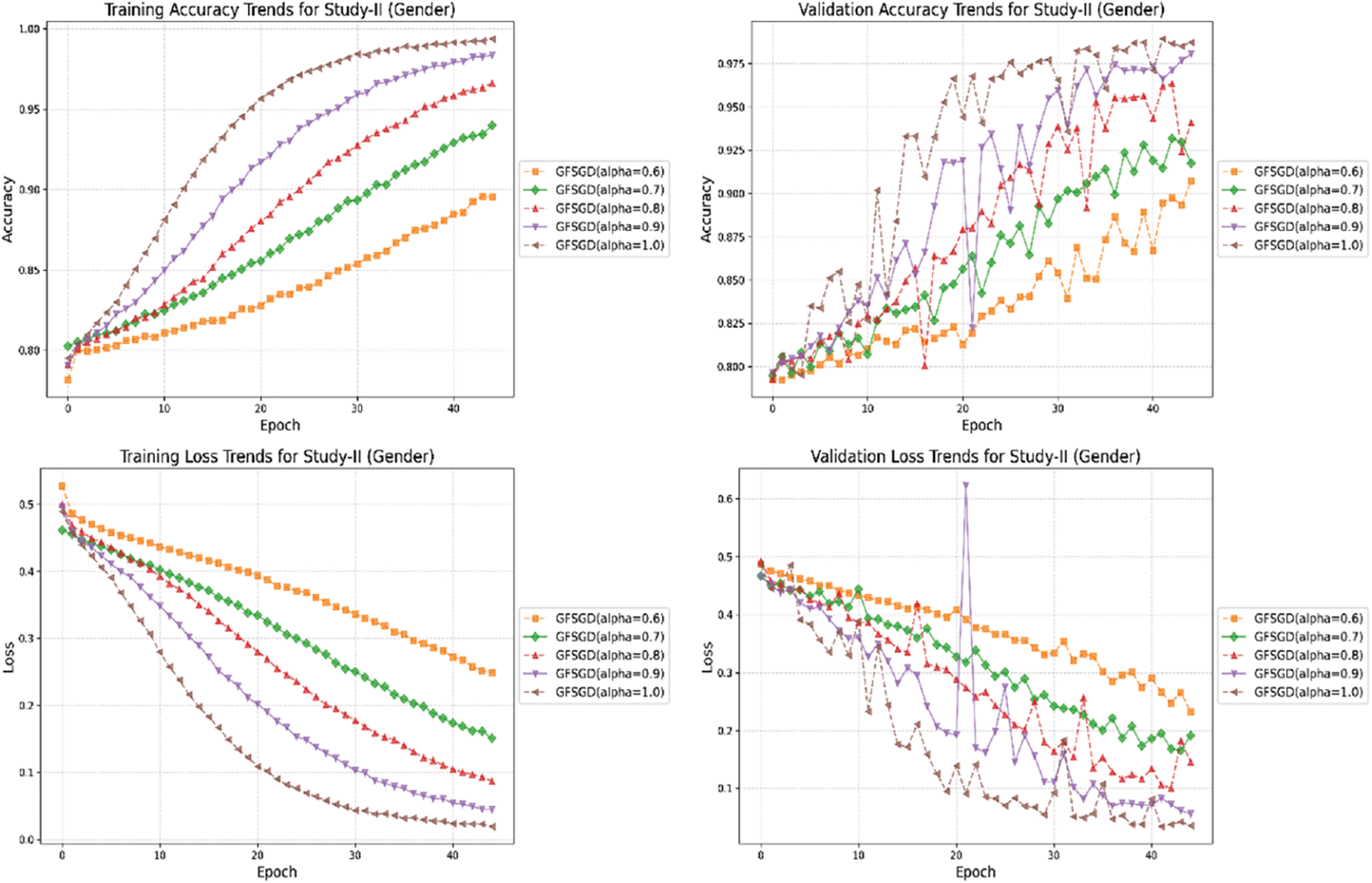

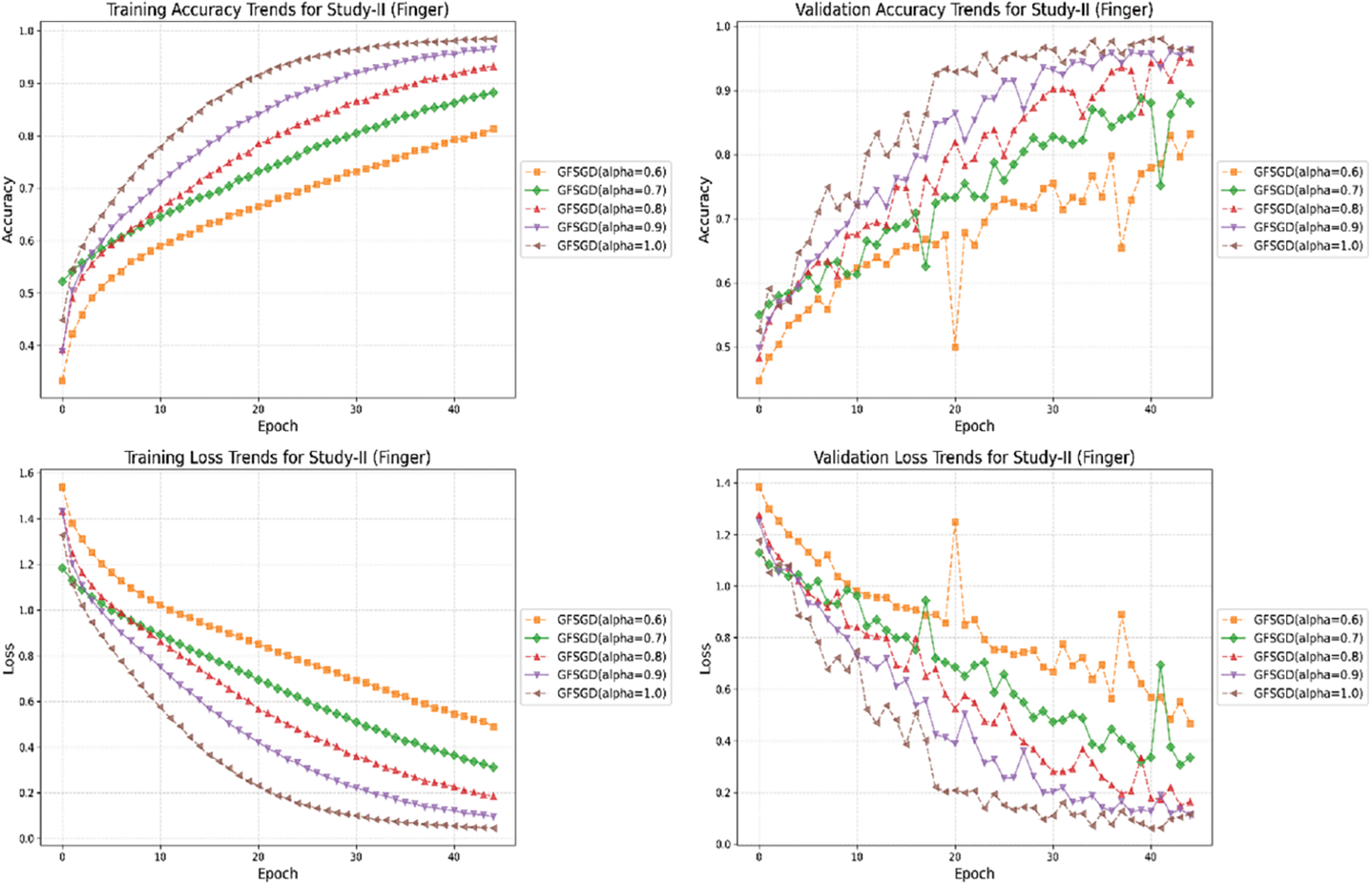

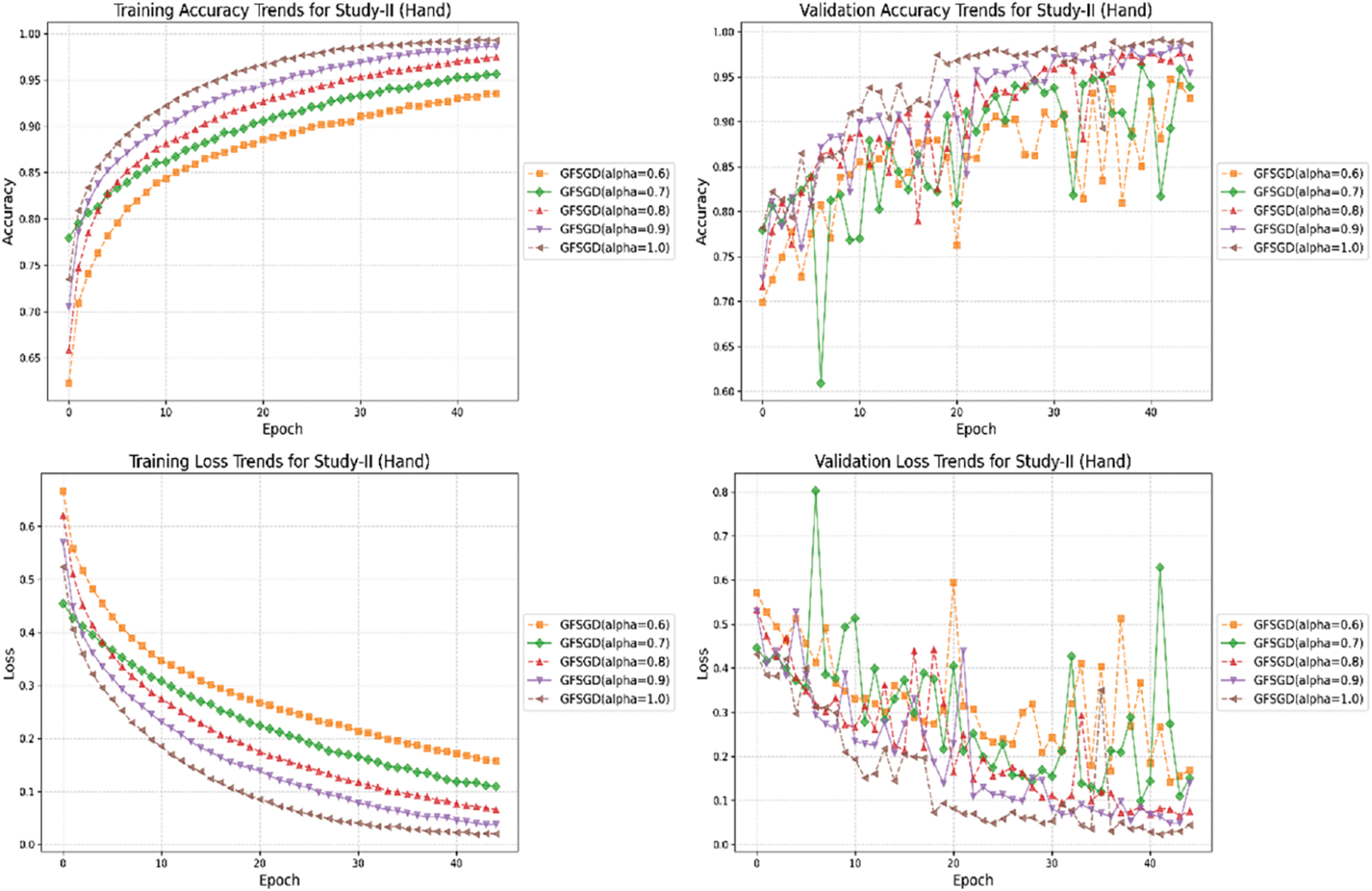

This study shows the performance of the proposed model with the GFSGD optimizer having fractional order values ranging from 0.6 to unity. Tables 5–7 display the extensive performance investigation of Study-II in terms of finger, gender, and hand classification tasks. It shows that the proposed model produces the best performance with GFSGD (alpha = 1.0) for gender and hand classification, achieving an accuracy of 98.44% and 98.56%, respectively. However, with GFSGD (alpha = 0.9), the proposed model shows second-best performance with respect to finger classification by attaining a test accuracy of 96.55%. In addition, the proposed model, along with GFSGD (alpha = 0.6), shows the worst performance in Study-II, achieving low accuracies of 81.92%, 91.05%, and 92.31% for finger, gender, and hand classification, respectively. Tables 5–7 reveal that the performance of the proposed model is further improved with higher fractional order values. Figs. 12–16 present the accuracy-loss learning curves and confusion matrices belonging to Study-II. Study-II demonstrates that the proposed model shows superior performance, with GFSGD having fractional order values of unity, which becomes standard SGD.

Figure 12: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 0.6)

Figure 13: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 0.7)

Figure 14: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 0.8)

Figure 15: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 0.9)

Figure 16: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 1.0)

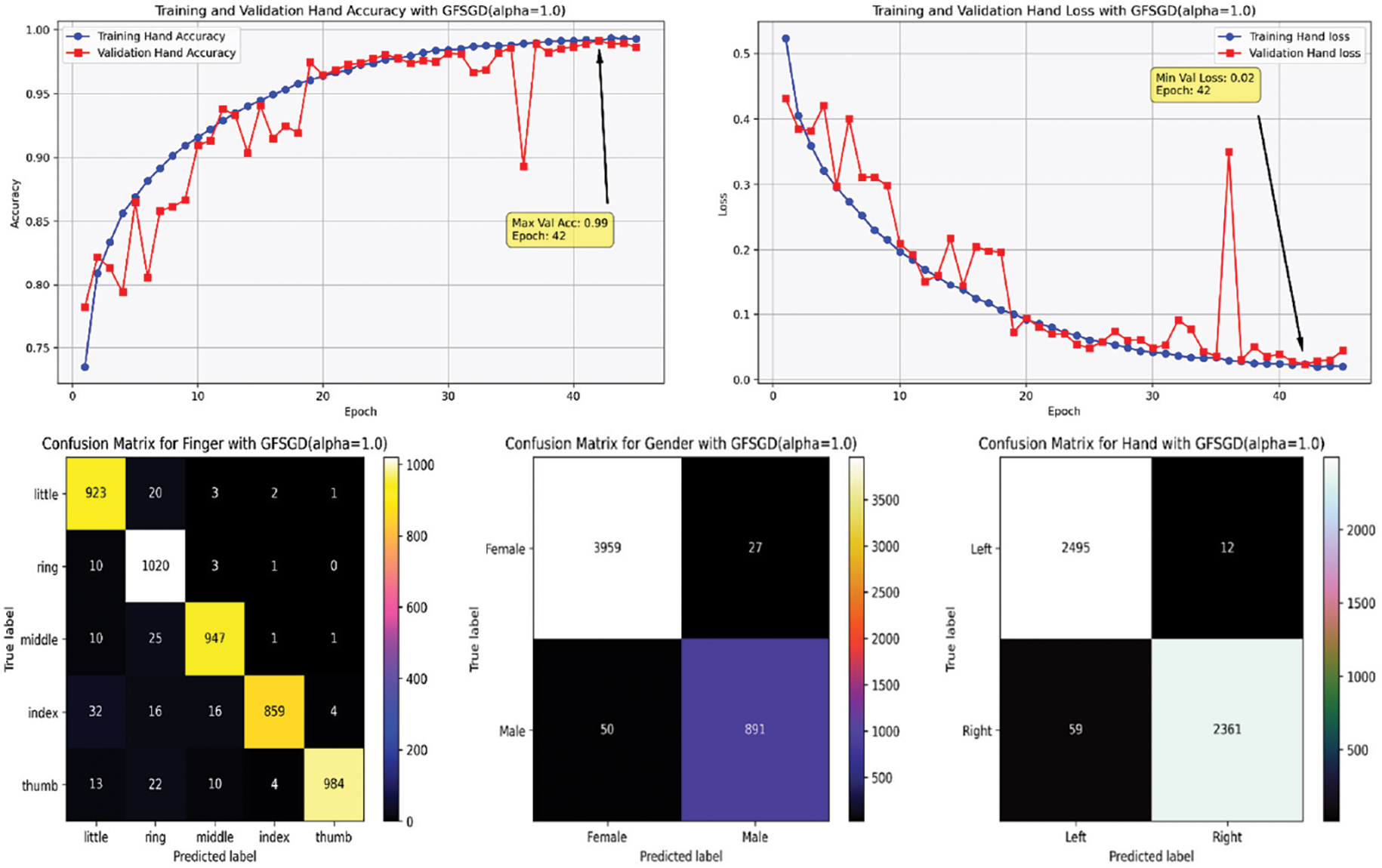

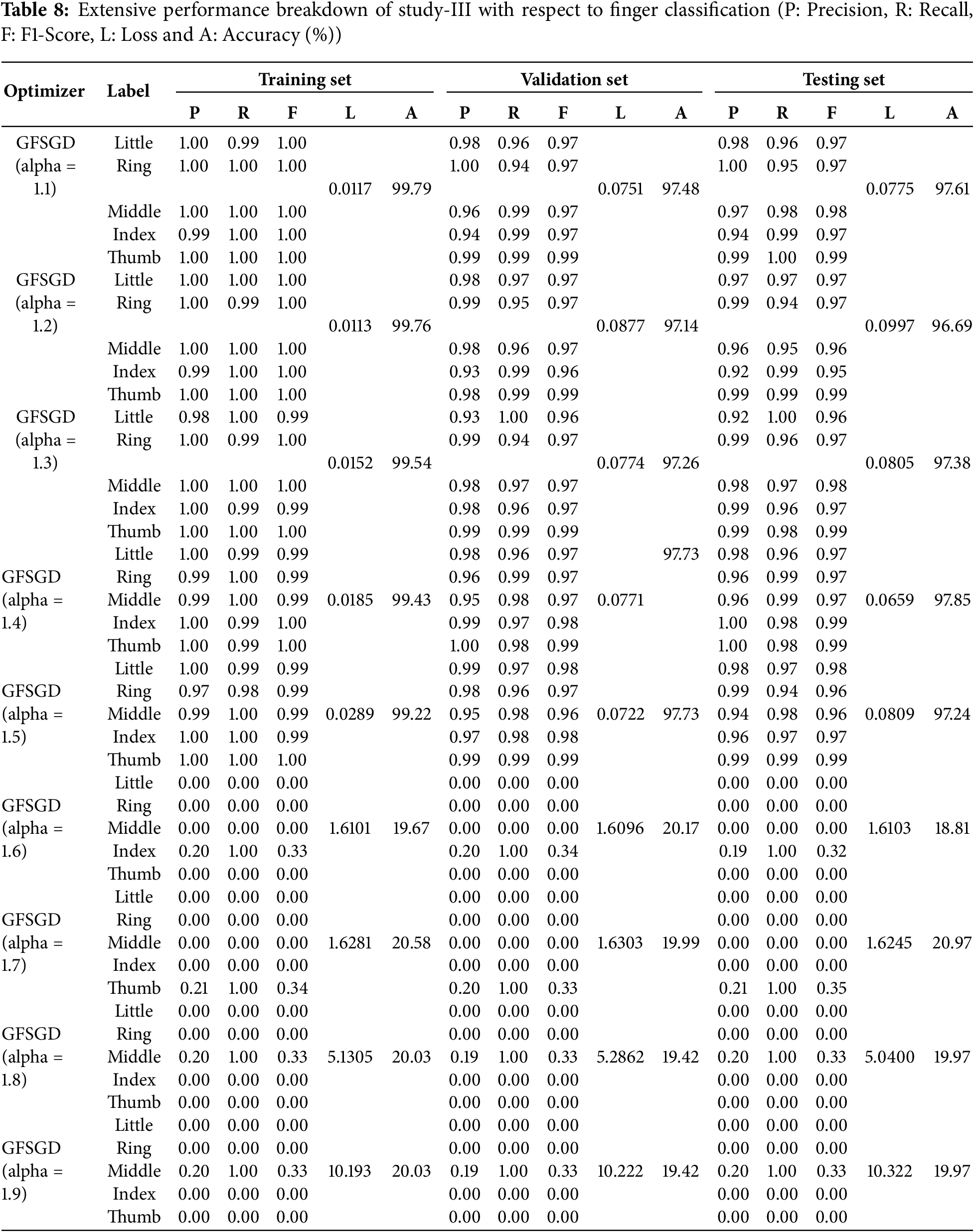

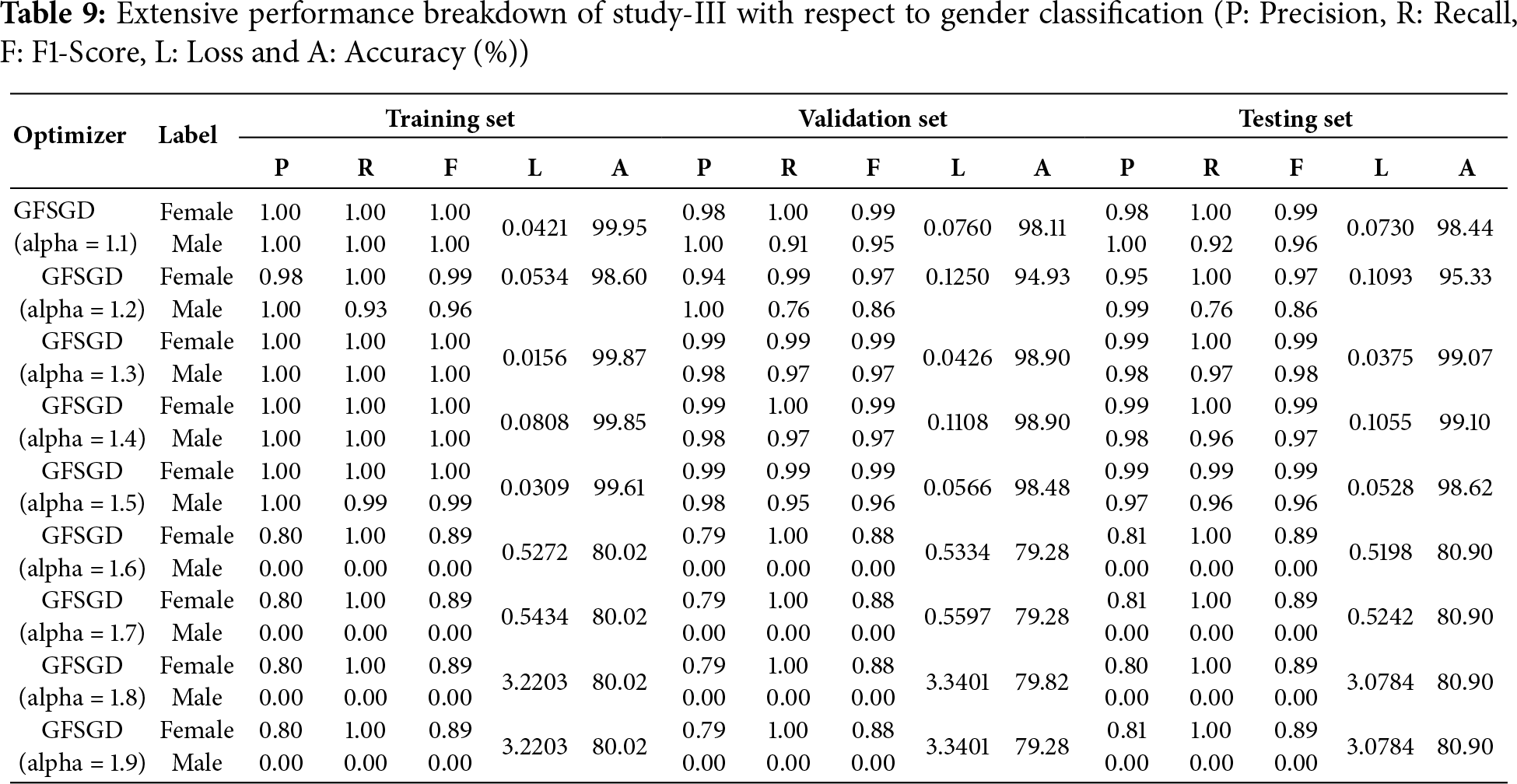

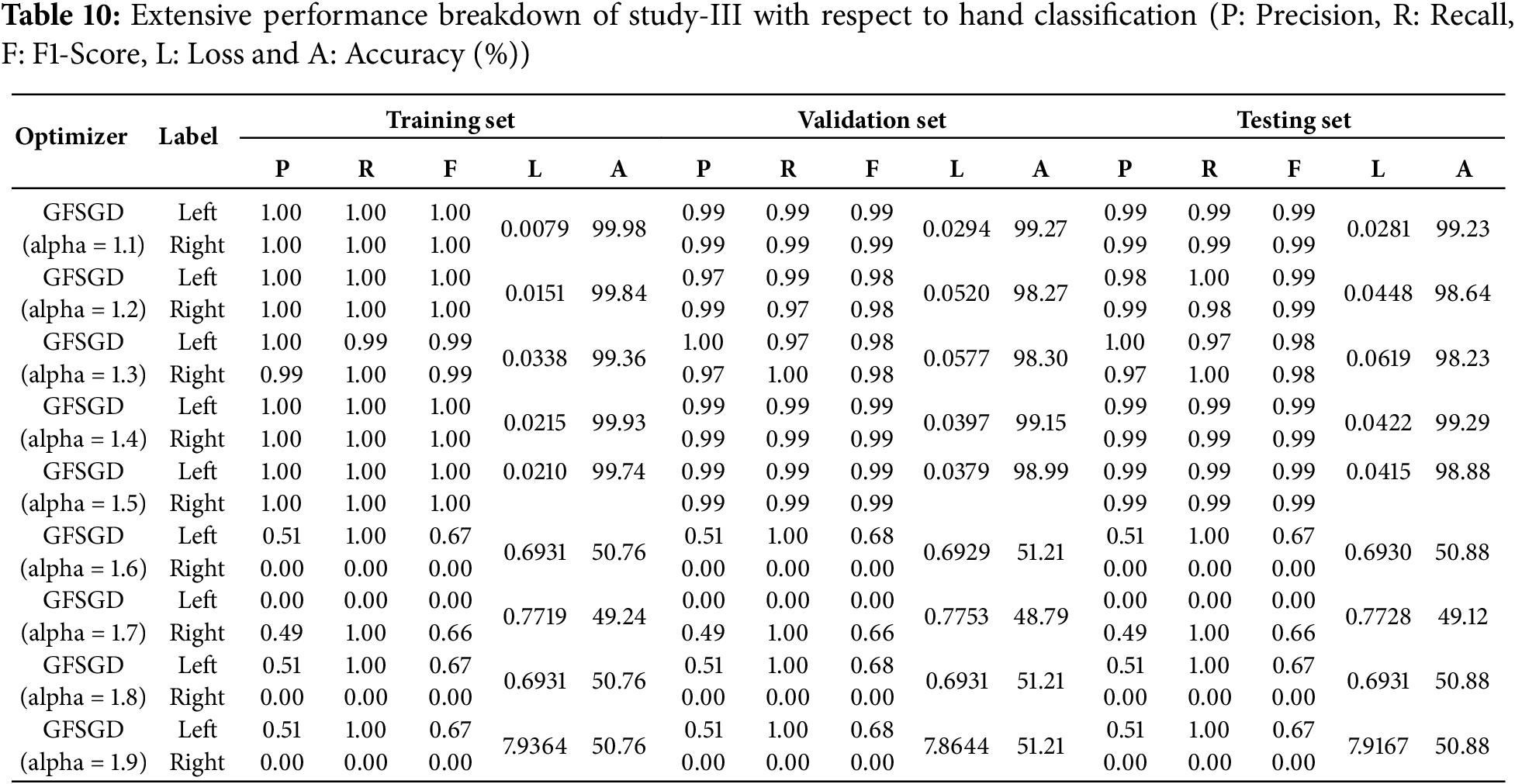

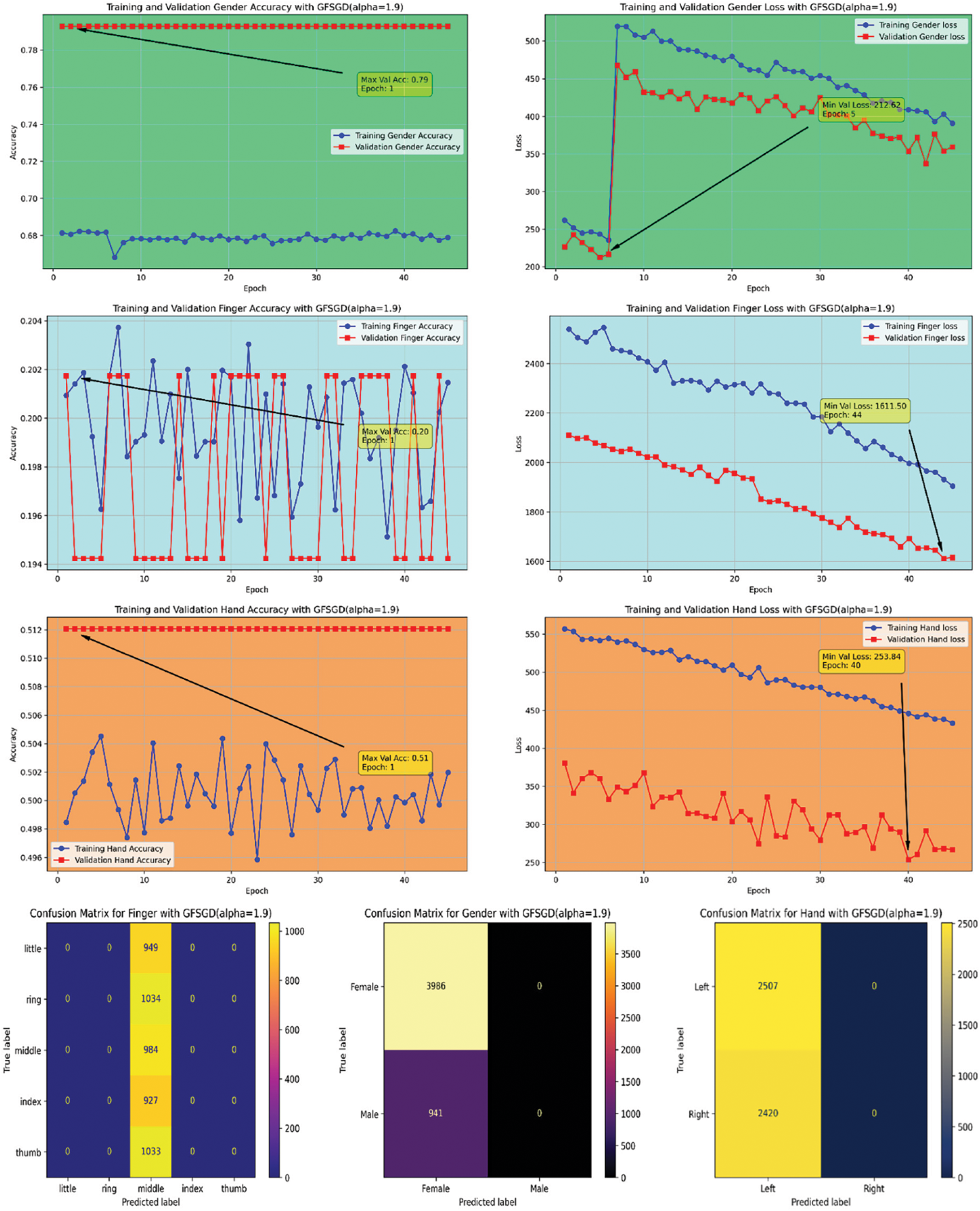

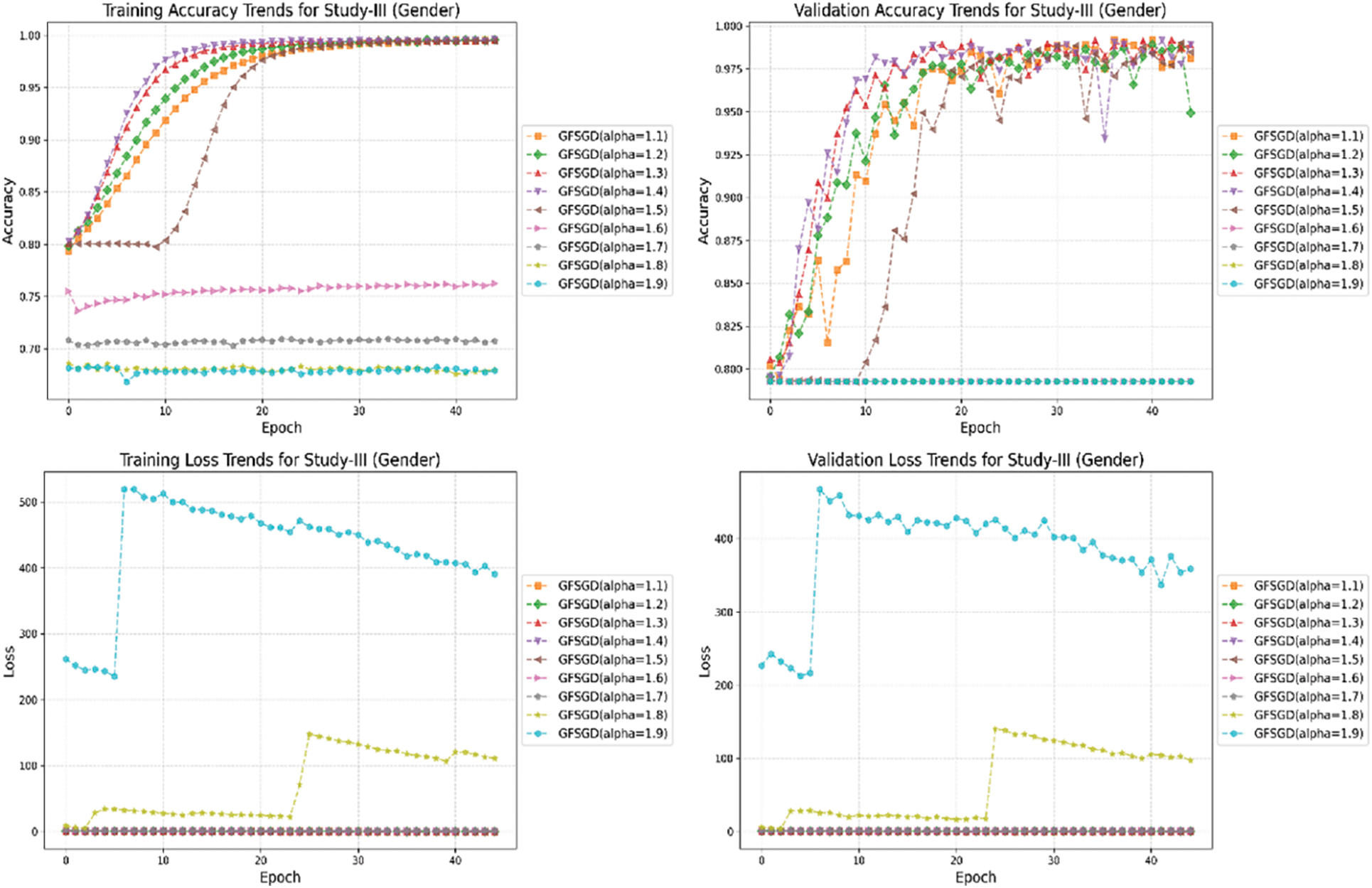

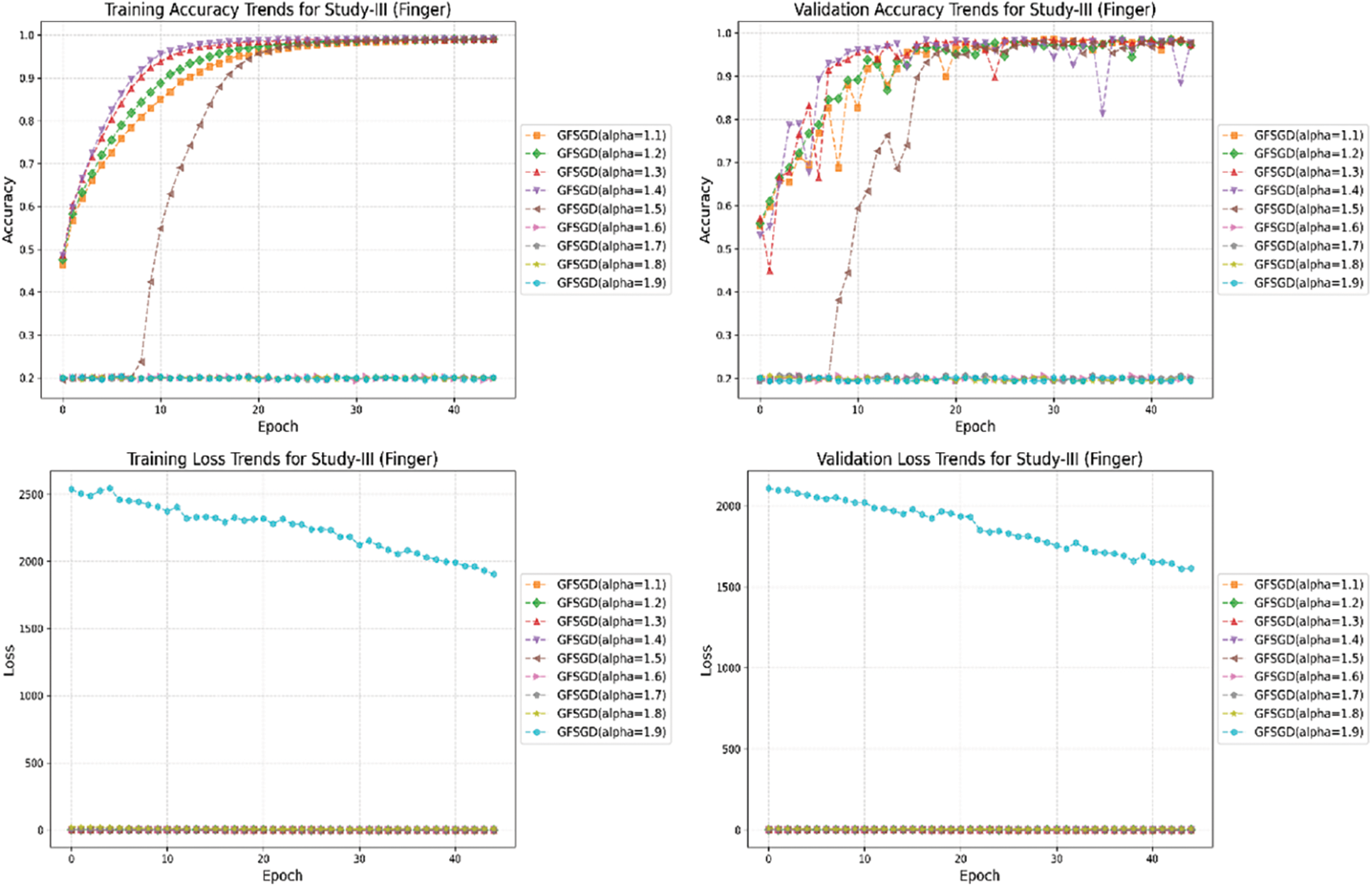

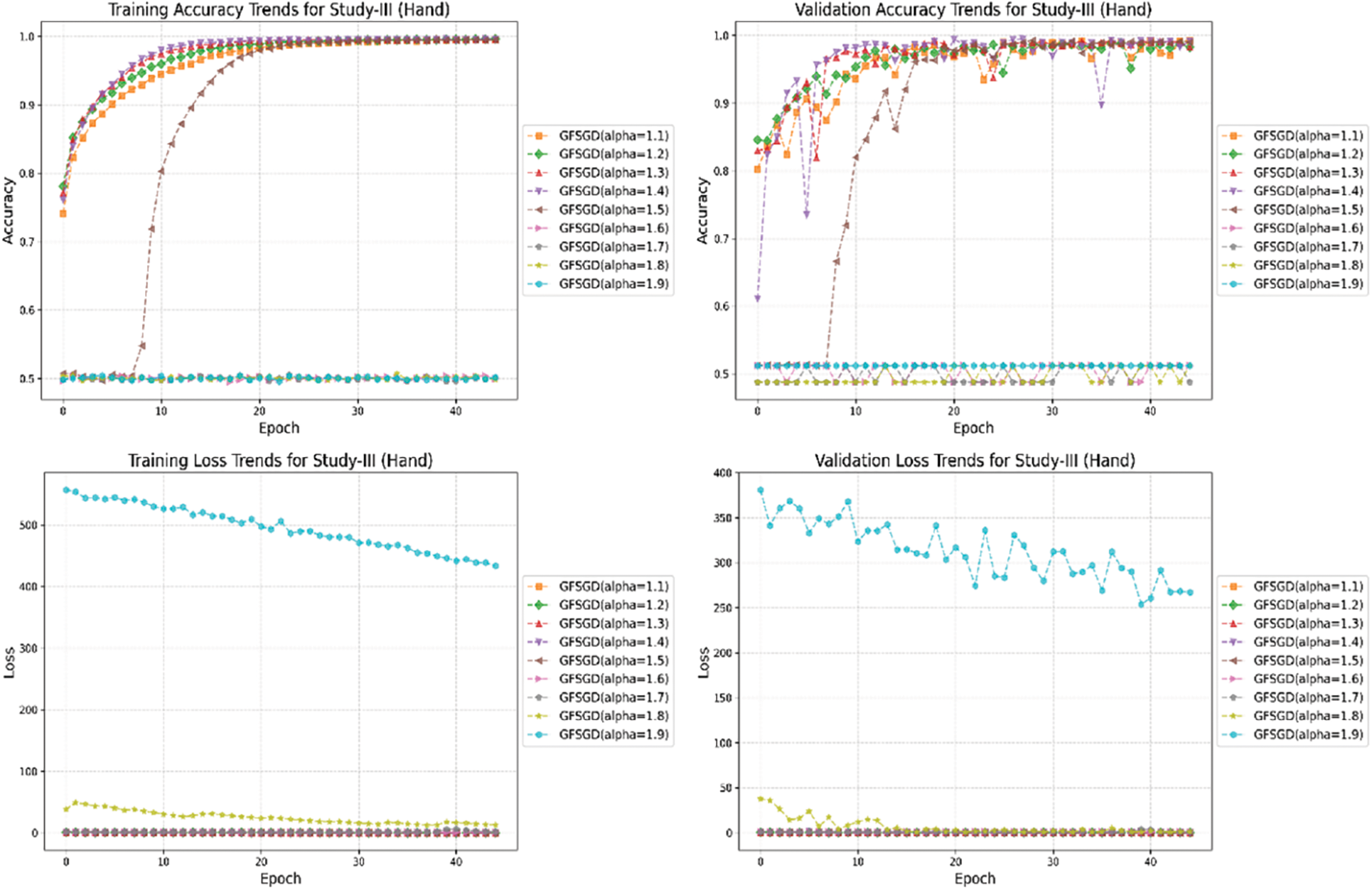

The performance analysis of the proposed CNN model with GFSGD optimization strategy, which has fractional order values beyond unity, is presented in this study. The critical experimental examination in Study-III with respect to finger, gender, and hand classification is presented in Tables 8–10. Similar to Studies I and II, an improving trend is observed in evaluation metrics with higher fractional order values of GFSGD. It indicates that the proposed CNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 1.4) shows optimal performance by achieving a generalized accuracy of 97.85%, 99.10%, and 99.29% for the finger, gender, and hand classification tasks. The proposed CNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 1.4) outperformed the performance of standard SGD (GFSGD (alpha = 1)) in terms of test accuracies for finger, gender, and hand classification tasks. Tables 8–10 exhibit that beyond a fractional order of 1.5, the GFSGD optimizer diverges and produces poor performance for fingerprint classification. The proposed CNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 1.9) exhibits the worst performance, attaining low test accuracies of 19.97%, 80.90%, and 50.88% for finger, gender, and hand classification tasks. The accuracy-loss learning curves and confusion metrics related to Study-III are presented in Figs. 17–25. Through a detailed investigation of the proposed CNN model and a novel GFSGD optimization strategy with diverse fractional order variations, the best performance is achieved with GFSGD (alpha = 1.4) and optimal architectural hyperparameters for fingerprint classification using the standard SOCOFing dataset.

Figure 17: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 1.1)

Figure 18: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 1.2)

Figure 19: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 1.3)

Figure 20: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 1.4)

Figure 21: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 1.5)

Figure 22: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 1.6)

Figure 23: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 1.7)

Figure 24: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 1.8)

Figure 25: Performance evaluation of the FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 1.9)

This research presents the channel-focused CNN model with a novel fractional calculus-driven stochastic gradient descent optimization approach for solving the fingerprint classification problem accurately and efficiently. For a fair comparison, the performance of the proposed CNN model is evaluated with standard SGD (GFSGD (alpha = 1)) and novel GFSGD optimizer under similar optimal hyperparameters. Through a comprehensive performance investigation of the proposed CNN model in Studies I–III, the model with GFSGD, having a fractional order of 1.4, achieves optimal generalized accuracies of 97.85%, 99.10%, and 99.29% for finger, gender, and hand classification, respectively. After extensive hyperparameter tuning, the proposed CNN model is trained along optimal architectural parameters with optimization variations on the benchmark SOCOFing dataset. The combined accuracy and loss learning curve behaviors of each discussed study are presented in Figs. 26–34. Examining the learning curve trends in Figs. 27–35, the proposed CNN model demonstrates superior classification performance, particularly with the novel GFSGD optimizer, especially at an alpha rate of 1.4, compared to the standard SGD optimizer.

Figure 26: Combine accuracy and loss learning curve trends for study-I (gender)

Figure 27: Combine accuracy and loss learning curve trends for study-I (finger)

Figure 28: Combine accuracy and loss learning curve trends for study-I (hand)

Figure 29: Combine accuracy and loss learning curve trends for study-II (gender)

Figure 30: Combine accuracy and loss learning curve trends for study-II (finger)

Figure 31: Combine accuracy and loss learning curve trends for study-II (hand)

Figure 32: Combine accuracy and loss learning curve trends for study-III (gender)

Figure 33: Combine accuracy and loss learning curve trends for study-III (finger)

Figure 34: Combine accuracy and loss learning curve trends for study-III (hand)

Figure 35: Interpretable predictions on unseen images of benchmark SOCOFing dataset

4.5 Comparison to Existing Benchmark Models

The proposed FOCNN model, which incorporates a fractional calculus-based stochastic gradient descent optimization approach, demonstrates robust predictive capabilities by accurately and efficiently classifying finger, gender, and hand attributes using a given fingerprint scan. Through a comprehensive training process on the benchmark SOCOFing dataset, the proposed CNN model demonstrates reliability in finger, gender, and hand classification tasks. Table 11 shows a performance comparison of the proposed model with existing benchmark models for fingerprint classification using the SOCOFing dataset. It demonstrates that significant improvements are attained in terms of test accuracy, and the proposed CNN model outclasses its counterparts in finger, gender, and hand classification tasks. This highlights the efficiency of the proposed fractionally optimized CNN model in accurately classifying key attributes, such as finger, gender, and hand, through fingerprint scans.

4.6 Predictive Capabilities of Proposed FOCNN Model

The proposed model demonstrates generalized predictive capabilities by accurately and efficiently classifying finger, gender, and hand attributes through fingerprint scans. An explainable artificial intelligence (XAI)-based local interpretable model-agnostic (LIME) technique is employed to introduce an interpretable model for the fingerprint classification task to address the challenges related to transparency. The primary goal of exploring LIME is to highlight the region of a fingerprint with the most useful features. Upon visualizing an encircled region, one can gain clear insights into which region of the scan contributed most to the decision-making process of the proposed model. Fig. 35 shows interpretable predictions on unseen images of the benchmark SOCOFing dataset.

This study aims to exploit the novel GFSGD with a proposed CNN model to accomplish the task of fingerprint classification accurately and efficiently. The key findings concluded from this study are as follows:

• The proposed channel-focused and non-linear feature learning-driven CNN model produces remarkable performance for fingerprint classification tasks.

• The fractional calculus-driven GFSGD optimizer provides flexibility in controlling speed and accuracy through distinct fractional order values.

• The improved performance trend, as indicated by evaluation measures, is observed with higher fractional order values.

• For the task at hand, it is depicted that the novel GFSGD optimizer diverges beyond a fractional order value of 1.5 and results in poor classification performance.

• Through critical experimental analysis, the proposed FOCNN model with GFSGD (alpha = 1.4) shows optimal performance for gender, hand, and finger classification using fingerprint scan.

• The proposed approach outperforms the existing benchmark models on the standard SOCOFing dataset, achieving superior classification accuracy for distinct fingerprint attributes.

• This research presents an accurate, efficient, and reliable fractional calculus-driven deep neural architecture for the fingerprint classification task.

The core limitation of this research was the use of a single database due to the unavailability of standard and reliable fingerprint datasets. In the future scope, the authors intend to acquire fingerprint data from the responsible authorities to validate and improve the performance of the proposed method. In addition, the enriching capabilities of generative artificial intelligence will also be exploited for generating the synthetic fingerprint data.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The author contributions to this paper are as follows: writing—original draft and validation: Mubeen Sabir; supervision: Zeshan Aslam Khan, Khizer Mehmood; conceptualization and methodology: Muhammad Waqar, Muhammad Junaid Ali Asif Raja; software and formal analysis: Muhammad Waqar, Naveed Ishtiaq Chaudhary, Khalid Mehmood Cheema; investigation and visualization: Muhammad Farhan Khan, Syed Sohail Ahmed; writing—review & editing & supervision: Muhammad Asif Zahoor Raja. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data exploited in this study can be obtained from the relevant references cited in this paper. Furthermore, the associated data or material can be made available upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author of this paper.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Izhar M, Parwez K, Iftikhar S, Ahmad A, Bawazeer S, Abdullah S. Cyber-integrated predictive framework for gynecological cancer detection: leveraging machine learning on numerical data amidst cyber-physical attack resilience. J Artif Intell. 2025;7(1):55–83. doi:10.32604/jai.2025.062479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Khan ZA, Waqar M, Khan HU, Chaudhary NI, Khan AT, Ishtiaq I, et al. Fine-tuned deep transfer learning: an effective strategy for the accurate chronic kidney disease classification. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2025;11(2):e2800. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.2800. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Vahidi M, Shafian S, Frame WH. Precision soil moisture monitoring through drone-based hyperspectral imaging and PCA-driven machine learning. Sensors. 2025;25(3):782. doi:10.3390/s25030782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Lin Y, Yu K, Zhu F, Bu J, Dua X. The state of the art of deep learning-based Wi-Fi indoor positioning: a review. IEEE Sens J. 2024;24(17):27076–98. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2024.3432154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yang Y, Lou H, Wu J, Zhang S, Gao S. A survey on wind power forecasting with machine learning approaches. Neural Comput Appl. 2024;36(21):12753–73. doi:10.1007/s00521-024-09923-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ani R, Deepa OS, Manju BR. Ligand based virtual screening of molecular compounds in drug discovery using GCAN fingerprint and ensemble machine learning algorithm. Comput Syst Sci Eng. 2023;47(3):3033–48. doi:10.32604/csse.2023.033807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Priyadarshi R. Exploring machine learning solutions for overcoming challenges in IoT-based wireless sensor network routing: a comprehensive review. Wirel Netw. 2024;30(4):2647–73. doi:10.1007/s11276-024-03697-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Shin J, Al Mehedi Hasan M, Miah ASM, Suzuki K, Hirooka K. Japanese sign language recognition by combining joint skeleton-based handcrafted and pixel-based deep learning features with machine learning classification. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;139(3):2605–25. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.046334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Saad Hameed S, Taha Ahmed I, Munthir Al Okashi O. Real and altered fingerprint classification based on various features and classifiers. Comput Mater Contin. 2023;74(1):327–40. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.031622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Raeisi E, Yavuz M, Khosravifarsani M, Fadaei Y. Mathematical modeling of interactions between colon cancer and immune system with a deep learning algorithm. Eur Phys J Plus. 2024;139(4):345. doi:10.1140/epjp/s13360-024-05111-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kim J, Beanbonyka R, Sung NJ, Hong M. Left or right hand classification from fingerprint images using a deep neural network. Comput Mater Contin. 2020;63(1):17–30. doi:10.32604/cmc.2020.09044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Rawashdeh M, Obaidat MA, Abouali M, Salhi DE, Thakur K. An effective lung cancer diagnosis model using pre-trained CNNs. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;143(1):1129–55. doi:10.32604/cmes.2025.063765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Irsan M, Hassan R, Ibrahim AH, Hasan MK, Lam MC, Hussain WMHW. A framework for driver drowsiness monitoring using a convolutional neural network and the Internet of Things. Intell Autom Soft Comput. 2024;39(2):157–74. doi:10.32604/iasc.2024.042193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Promsawat P, Sae-dan W, Kaewsuwan M, Sudsutad W, Aphithana A. Dynamic multi-graph spatio-temporal graph traffic flow prediction in bangkok: an application of a continuous convolutional neural network. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;142(1):579–607. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.057774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Arsalan M, Mubeen M, Bilal M, Abbasi SF. 1D-CNN-IDS: 1D CNN-based intrusion detection system for IIoT. In: 2024 29th International Conference on Automation and Computing (ICAC); 2024 Aug 28–30; Sunderland, UK. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/ICAC61394.2024.10718772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Cai C, Guo X, Xue Y, Ren J. Damage diagnosis of bleacher based on an enhanced convolutional neural network with training interference. Struct Durab Health Monit. 2024;18(3):321–39. doi:10.32604/sdhm.2024.045831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Arman SM, Yang T, Shahed S, Al Mazroa A, Attiah A, Mohaisen L. A comprehensive survey for privacy-preserving biometrics: recent approaches, challenges, and future directions. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;78(2):2087–110. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.047870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Tiwari S, Singh R, Singh SK, Kilak AS, Alkhayyat A, Vidyarthi A. Biometrics recognition of newborn: a review. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(33):80129–59. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-18508-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Horsman G. Sources of error in digital forensics. Forensic Sci Int Digit Investig. 2024;48(2):301693. doi:10.1016/j.fsidi.2024.301693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Park H, Kim J. The use of assistive devices and social engagement among older adults: heterogeneity by type of social engagement and gender. Geroscience. 2024;46(1):1385–94. doi:10.1007/s11357-023-00910-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Ghirardi A, Carobbio A, Guglielmelli P, Rambaldi A, De Stefano V, Vannucchi AM, et al. Age-stratified analysis reveals arterial thrombosis as a predictor for gender-related second cancers in myeloproliferative neoplasms: a case-control study. Blood Cancer J. 2024;14(1):68. doi:10.1038/s41408-024-01052-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Shi Y, Yu W, Zhao Y, Jia Y. A web application fingerprint recognition method based on machine learning. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;140(1):887–906. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.046140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Nallappan M, Velswamy R. Exploring deep learning-based content-based video retrieval with Hierarchical Navigable Small World index and ResNet-50 features for anomaly detection. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;247(4):123197. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.123197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Cho H. Gender classification of Korean personal names: deep neural networks versus human judgments. Lingua. 2024;303(1):103703. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2024.103703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Raghavan R, John Singh K. An enhanced and hybrid fingerprint minutiae feature extraction method for identifying and authenticating the patient’s noisy fingerprint. Int J Syst Assur Eng Manag. 2024;15(1):84–97. doi:10.1007/s13198-022-01674-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kavitha T, Revappa, Handignur SB, Sachin YM, Purandare SS, Rathish CR. FingerPrintInsight: unveiling crime pattern through deep fingerprint analysis. In: 2024 4th International Conference on Data Engineering and Communication Systems (ICDECS); 2024 Mar 22–23; Bangalore, India. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICDECS59733.2023.10502384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li X, Liu R, Yang Y. Infrared image super-resolution reconstruction based on residual fast Fourier transform. Multimed Tools Appl. 2025;84(9):6805–23. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-19236-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wulandari M, Chai R, Basari B, Gunawan D. Hybrid feature extractor using discrete wavelet transform and histogram of oriented gradient on convolutional-neural-network-based palm vein recognition. Sensors. 2024;24(2):341. doi:10.3390/s24020341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Hamidi M, Sohrabi MR, Tehrani MS, Mortazavi Nik S. Continuous wavelet transform and integration of discrete wavelet transform with principal component analysis and fuzzy inference system for the simultaneous determination of ethinyl estradiol and drospirenone in combined oral contraceptives. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2024;320:124541. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2024.124541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. El Maadi A, Loukhaoukha K, Benmami M, Zebbiche K, Mehallegue N. Ambiguity attacks on the digital image watermarking using discrete wavelet transform and singular value decomposition. Multimed Tools Appl. 2025;84(8):5335–48. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-18980-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Song B, Wei P, Wu S, Lin Y, Zhou W. A survey on deep-learning-based image steganography. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;254(7):124390. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Ghalib Muhammad H, Ali Khalaf Z. A survey of fingerprint identification system using deep learning. Int J Comput Digit Syst. 2025;17(1):1–17. doi:10.12785/ijcds/1571022983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Mokal AB, Gupta B. A deep learning approach for effective classification of fingerprint patterns and human behavior analysis. Pattern Recognit. 2025;163(28):111439. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2025.111439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Mahmood SH, Farhan AK. An evaluation of convolutional neural network architectures: alexnet, LetNet, VGG-16, and fingerprint-net for fingerprint classification. In: AIP Conference Proceedings. Moradabad, India: AIP Publishing; 2025. 030021 p. doi:10.1063/5.0255956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ametefe DS, Sarnin SS, Ali DM, Muhammad ZZ. Fingerprint pattern classification using deep transfer learning and data augmentation. Vis Comput. 2023;39(4):1703–16. doi:10.1007/s00371-022-02437-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Chhabra M, Ravulakollu KK, Kumar M, Sharma A, Nayyar A. Improving automated latent fingerprint detection and segmentation using deep convolutional neural network. Neural Comput Appl. 2023;35(9):6471–97. doi:10.1007/s00521-022-07894-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Bajpai A, Chaurasia D, Tiwari N. A novel methodology for anomaly detection in smart home networks via Fractional Stochastic Gradient Descent. Comput Electr Eng. 2024;119(15):109604. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.109604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Khan ZA, Waqar M, Raja MJAA, Chaudhary NI, Khan ATMA, Raja MAZ. Generalized fractional optimization-based explainable lightweight CNN model for malaria disease classification. Comput Biol Med. 2025;185(4):109593. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.109593. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Zhou X, You Z, Sun W, Zhao D, Yan S. Fractional-order stochastic gradient descent method with momentum and energy for deep neural networks. Neural Netw. 2025;181(12):106810. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2024.106810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Khan ZA, Waqar M, Chaudhary NI, Raja MJAA, Khan S, Khan FA, et al. Fractional gradient optimized explainable convolutional neural network for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Heliyon. 2024;10(20):e39037. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e39037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Wei Y, Kang Y, Yin W, Wang Y. Generalization of the gradient method with fractional order gradient direction. J Frankl Inst. 2020;357(4):2514–32. doi:10.1016/j.jfranklin.2020.01.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Shehu YI, Ruiz-Garcia A, Palade V, James A. Detailed identification of fingerprints using convolutional neural networks. In: 2018 17th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA); 2018 Dec 17–20; Orlando, FL, USA. p. 1161–5. doi:10.1109/ICMLA.2018.00187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Shehu YI, Ruiz-Garcia A, Palade V, James A. Detection of fingerprint alterations using deep convolutional neural networks. In: Artificial neural networks and machine learning-ICANN 2018. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 51–60. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-01418-6_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Giudice O, Litrico M, Battiato S. Single architecture and multiple task deep neural network for altered fingerprint analysis. In: 2020 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2020 Oct 25–28; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. p. 813–7. doi:10.1109/icip40778.2020.9191094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Fattahi J, Mejri M. Damaged fingerprint recognition by convolutional long short-term memory networks for forensic purposes. In: 2021 IEEE 5th International Conference on Cryptography, Security and Privacy (CSP); 2021 Jan 8–10; Zhuhai, China. p. 193–9. doi:10.1109/CSP51677.2021.9357588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Iloanusi ON, Ejiogu UC. Gender classification from fused multi-fingerprint types. Inf Secur J A Glob Perspect. 2020;29(5):209–19. doi:10.1080/19393555.2020.1741742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Moga D, Filip I. Study on fingerprint authentication systems using convolutional neural networks. In: 2021 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Applied Computational Intelligence and Informatics (SACI); 2021 May 19–21; Timisoara, Romania. p. 000015–20. doi:10.1109/saci51354.2021.9465628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Gnanasivam P, Vijayarajan R. Gender classification from fingerprint ridge count and fingertip size using optimal score assignment. Complex Intell Syst. 2019;5(3):343–52. doi:10.1007/s40747-019-0099-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Ibitayo FB, Olanrewaju OA, Oyeladun MB. A fingerprint based gender detector system using fingerprint pattern analysis. Ijarcs. 2022;13(4):35–47. doi:10.26483/ijarcs.v13i4.6885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Al-Wajih YA, Hamanah WM, Abido MA, Al-Sunni F, Alwajih F. Finger type classification with deep convolution neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Informatics in Control, Automation and Robotics (ICINCO 2022); 2022 Jul 14–16; Lisbon, Portugal. p. 247–54. [Google Scholar]

51. Qi Y, Qiu M, Jiang H, Wang F. Extracting fingerprint features using autoencoder networks for gender classification. Appl Sci. 2022;12(19):10152. doi:10.3390/app121910152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Yavuz M, Özdemir N,editors. Fractional calculus: new applications in understanding nonlinear phenomena. Vol. 3. Sharjah, United Arab Emirates: Bentham Science Publishers; 2022. [Google Scholar]

53. Wen C, Yang J. Complexity evolution of chaotic financial systems based on fractional Calculus. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2019;128(7):242–51. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2019.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Akgül A, Farman M, Sutan M, Ahmad A, Ahmad S, Munir A, et al. Computational analysis of corruption dynamics insight into fractional structures. Appl Math Sci Eng. 2024;32(1):2303437. doi:10.1080/27690911.2024.2303437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Joshi H, Yavuz M, Taylan O, Alkabaa A. Dynamic analysis of fractal-fractional cancer model under chemotherapy drug with generalized Mittag-Leffler kernel. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2025;260(6859):108565. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2024.108565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Joshi H, Yavuz M, Townley S, Jha BK. Stability analysis of a non-singular fractional-order COVID-19 model with nonlinear incidence and treatment rate. Phys Scr. 2023;98(4):045216. doi:10.1088/1402-4896/acbe7a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Younis RA, Touti E, Aoudia M, Zahrouni W, Omar AI, Elmetwaly AH. Innovative hybrid energy storage systems with sustainable integration of green hydrogen and energy management solutions for standalone PV microgrids based on reduced fractional gradient descent algorithm. Results Eng. 2024;24:103229. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Wang J, Ji Y, Zhang X, Xu L. Two-stage gradient-based iterative algorithms for the fractional-order nonlinear systems by using the hierarchical identification principle. Int J Adaptive Control Signal Process. 2022;36(7):1778–96. doi:10.1002/acs.3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Chaudhary NI, Raja MAZ, He Y, Khan ZA, Tenreiro Machado JA. Design of multi innovation fractional LMS algorithm for parameter estimation of input nonlinear control autoregressive systems. Appl Math Model. 2021;93(9):412–25. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2020.12.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Khan MB, Santos-García G, Noor MA, Soliman MS. Some new concepts related to fuzzy fractional calculus for up and down convex fuzzy-number valued functions and inequalities. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2022;164(3):112692. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2022.112692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Li X, Ma W, Bao X. Generalized fractional Calculus on time scales based on the generalized Laplace transform. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2024;180(3):114599. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2024.114599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Zhou S, Wei Y, Liang S, Cao J. A gradient tracking protocol for optimization over nabla fractional multi-agent systems. IEEE Trans Signal Inf Process Netw. 2024;10:500–12. doi:10.1109/TSIPN.2024.3402354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Chaudhary NI, Khan ZA, Kiani AK, Raja MAZ, Chaudhary II, Pinto CMA. Design of auxiliary model based normalized fractional gradient algorithm for nonlinear output-error systems. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2022;163(3):112611. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2022.112611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Khan ZA, Zubair S, Chaudhary NI, Raja MAZ, Khan FA, Dedovic N. Design of normalized fractional SGD computing paradigm for recommender systems. Neural Comput Appl. 2020;32(14):10245–62. doi:10.1007/s00521-019-04562-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Herrera-Alcántara O, Castelán-Aguilar JR. Fractional gradient optimizers for PyTorch: enhancing GAN and BERT. Fractal Fract. 2023;7(7):500. doi:10.3390/fractalfract7070500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Khan ZA, Chaudhary NI, Raja MAZ. Generalized fractional strategy for recommender systems with chaotic ratings behavior. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2022;160(2):112204. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2022.112204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Adeniyi JK, Ajagbe SA, Adeniyi EA, Mudali P, Adigun MO, Adeniyi TT, et al. A biometrics-generated private/public key cryptography for a blockchain-based e-voting system. Egypt Inform J. 2024;25(24):100447. doi:10.1016/j.eij.2024.100447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Papi S, Ferrara M, Maltoni D, Anthonioz A. On the generation of synthetic fingerprint alterations. In: 2016 International Conference of the Biometrics Special Interest Group (BIOSIG); 2016 Sep 21–23; Darmstadt, Germany. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

69. Angelov PP, Soares EA, Jiang R, Arnold NI, Atkinson PM. Explainable artificial intelligence: an analytical review. WIREs Data Min Knowl. 2021;11(5):e1424. doi:10.1002/widm.1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Ribeiro MT, Singh S, Guestrin C. Why should I trust you?: explaining the predictions of any classifier. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. San Francisco, CA, USA: ACM; 2016. p. 1135–44. doi:10.1145/2939672.2939778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Wei Y, Chen Y, Gao Q, Wang Y. Infinite series representation of functions in fractional calculus. In: 2019 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC); 2019 Nov 22–24; Hangzhou, China. p. 1697–702. doi:10.1109/cac48633.2019.8997499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Chen Y, Gao Q, Wei Y, Wang Y. Study on fractional order gradient methods. Appl Math Comput. 2017;314(1):310–21. doi:10.1016/j.amc.2017.07.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Wei Y, Chen Y, Cheng S, Wang Y. A note on short memory principle of fractional Calculus. Fract Calc Appl Anal. 2017;20(6):1382–404. doi:10.1515/fca-2017-0073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools