Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

HybridFusionNet with Explanability: A Novel Explainable Deep Learning-Based Hybrid Framework for Enhanced Skin Lesion Classification Using Dermoscopic Images

1 EIAS Data Science Lab, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, 11586, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Information Technology, Faculty of Computers and Information, Menoufia University, Shibin El Kom, 32511, Egypt

3 Information Technology Department, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Authors: Mohamed Hammad. Email: ; Souham Meshoul. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 1055-1086. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.072650

Received 31 August 2025; Accepted 09 October 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Skin cancer is among the most common malignancies worldwide, but its mortality burden is largely driven by aggressive subtypes such as melanoma, with outcomes varying across regions and healthcare settings. These variations emphasize the importance of reliable diagnostic technologies that support clinicians in detecting skin malignancies with higher accuracy. Traditional diagnostic methods often rely on subjective visual assessments, which can lead to misdiagnosis. This study addresses these challenges by developing HybridFusionNet, a novel model that integrates Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) with 1D feature extraction techniques to enhance diagnostic accuracy. Utilizing two extensive datasets, BCN20000 and HAM10000, the methodology includes data preprocessing, application of Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique combined with Edited Nearest Neighbors (SMOTEENN) for data balancing, and optimization of feature selection using the Tree-based Pipeline Optimization Tool (TPOT). The results demonstrate significant performance improvements over traditional CNN models, achieving an accuracy of 0.9693 on the BCN20000 dataset and 0.9909 on the HAM10000 dataset. The HybridFusionNet model not only outperforms conventional methods but also effectively addresses class imbalance. To enhance transparency, it integrates post-hoc explanation techniques such as LIME, which highlight the features influencing predictions. These findings highlight the potential of HybridFusionNet to support real-world applications, including physician-assist systems, teledermatology, and large-scale skin cancer screening programs. By improving diagnostic efficiency and enabling access to expert-level analysis, the model may enhance patient outcomes and foster greater trust in artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted clinical decision-making.Keywords

Skin cancer is one of the most frequent types of cancer worldwide, with melanoma being the most fatal variant [1]. The rising incidence of skin cancer emphasizes the critical need for reliable diagnostic technologies that can help physicians reliably identify and classify skin lesions [2]. Traditional diagnostic methods, which rely heavily on visual inspection and the expertise of trained professionals, can be subjective and prone to human error. Consequently, advanced technologies—most notably artificial intelligence (AI)—are increasingly being explored to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of skin cancer classification [3–5], with a particular emphasis on ensuring explainability and interpretability. Deep learning, a branch of machine learning, has demonstrated exceptional efficacy across numerous domains, including medical imaging [6–8]. Its capacity to autonomously acquire hierarchical characteristics from unprocessed input renders it especially apt for intricate tasks like image categorization [9]. In dermatology, deep learning models can analyze dermoscopic images to identify various skin lesions, including benign and malignant types [10]. However, despite the promising results achieved by existing models, several challenges remain. These include issues related to class imbalance, the need for extensive labeled datasets, and the interpretability of model predictions [11]. This study is motivated by the necessity to enhance the diagnostic precision of skin cancer detection and to overcome the limits of existing approaches. Many existing studies have reported high accuracy rates; however, they often fail to account for the variability in lesion types and the challenges posed by class imbalance. For instance, certain classes of skin lesions, such as melanoma, may be underrepresented in training datasets, leading to biased model performance. Furthermore, the lack of interpretability in deep learning models can hinder their adoption in clinical settings, as healthcare professionals require clear explanations for the decisions made by these systems.

To address these challenges, this study introduces HybridFusionNet, a novel deep learning architecture that integrates Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) with 1D feature extraction techniques. By combining these approaches, we aim to enhance the model’s ability to classify skin lesions accurately while also improving interpretability. Additionally, we apply resampling methods such as SMOTEENN to address class imbalance and employ the Tree-based Pipeline Optimization Tool (TPOT) for automated pipeline optimization. TPOT streamlines feature selection and pipeline optimization, ensuring robust performance across classes while enhancing interpretability. In skin cancer classification, deep learning provides clear advantages over conventional techniques. These models automatically learn discriminative image features, eliminating the need for manual engineering and reducing development effort. To address class imbalance, SMOTEENN generates synthetic samples for minority classes while refining noisy data, improving model stability and fairness. This is crucial in dermatology, where certain skin conditions may be rare, leading to skewed datasets that can adversely affect model performance.

Recent papers in the field have demonstrated the potential of deep learning for skin cancer detection; however, many have limitations. For example, some studies have focused solely on accuracy metrics without considering the broader implications of model interpretability and generalizability [12,13]. Others have not adequately addressed the issue of class imbalance, resulting in models that perform well in majority classes but poorly on minority classes [14–18]. Additionally, the lack of robust validation on diverse datasets raises concerns about the real-world applicability of these models [19–22]. In this study, we propose HybridFusionNet, a novel framework that integrates deep image representations with handcrafted one-dimensional features to address the limitations of single-modality approaches. The CNN branch captures spatial and textural patterns directly from dermoscopic images, while the 1D branch processes statistical descriptors that summarize cancer characteristics. These complementary streams are fused by concatenating their latent representations, enabling the model to jointly learn complex spatial structures and clinically relevant descriptors. This integration enhances classification accuracy and robustness, especially in challenging cases where visual cues alone may be insufficient. To address both class imbalance and noise in the training data, SMOTEENN is employed. Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) oversamples minority lesion types by generating synthetic but realistic examples, while Edited Nearest Neighbors (ENN) removes ambiguous or mislabeled samples. This combined strategy produces a dataset that is both balanced and less noisy, improving the model’s ability to generalize across lesion categories. In addition, we employ TPOT to automate the feature selection and model optimization process. This ensures that only the most informative features are utilized, leading to improved classification accuracy and reduced overfitting. Additionally, the integration of LIME enables us to provide explanations for the model’s predictions, fostering trust and understanding among healthcare professionals. The main novel contributions of this paper include:

• Proposes a novel hybrid classification framework called HybridFusionNet, which combines CNNs with one-dimensional handcrafted feature extraction methods to enhance the representational capacity for skin cancer detection.

• To address class imbalance, SMOTEENN is employed that enables the model to train on a more balanced and representative dataset, which improves its generalizability across different lesion types.

• The use of TPOT to automate the selection of the most informative features and optimize the model pipeline, improving overall classification accuracy.

• To enhance explainability, LIME is integrated as a post-hoc tool, offering transparent, case-specific insights into the decision-making process and supporting clinical trust.

• Comprehensive experiments were carried out using two benchmark datasets, BCN20000 and HAM10000. The results confirm the model’s reliability in practical scenarios and suggest its suitability for clinical use. The implementation code can be provided upon request.

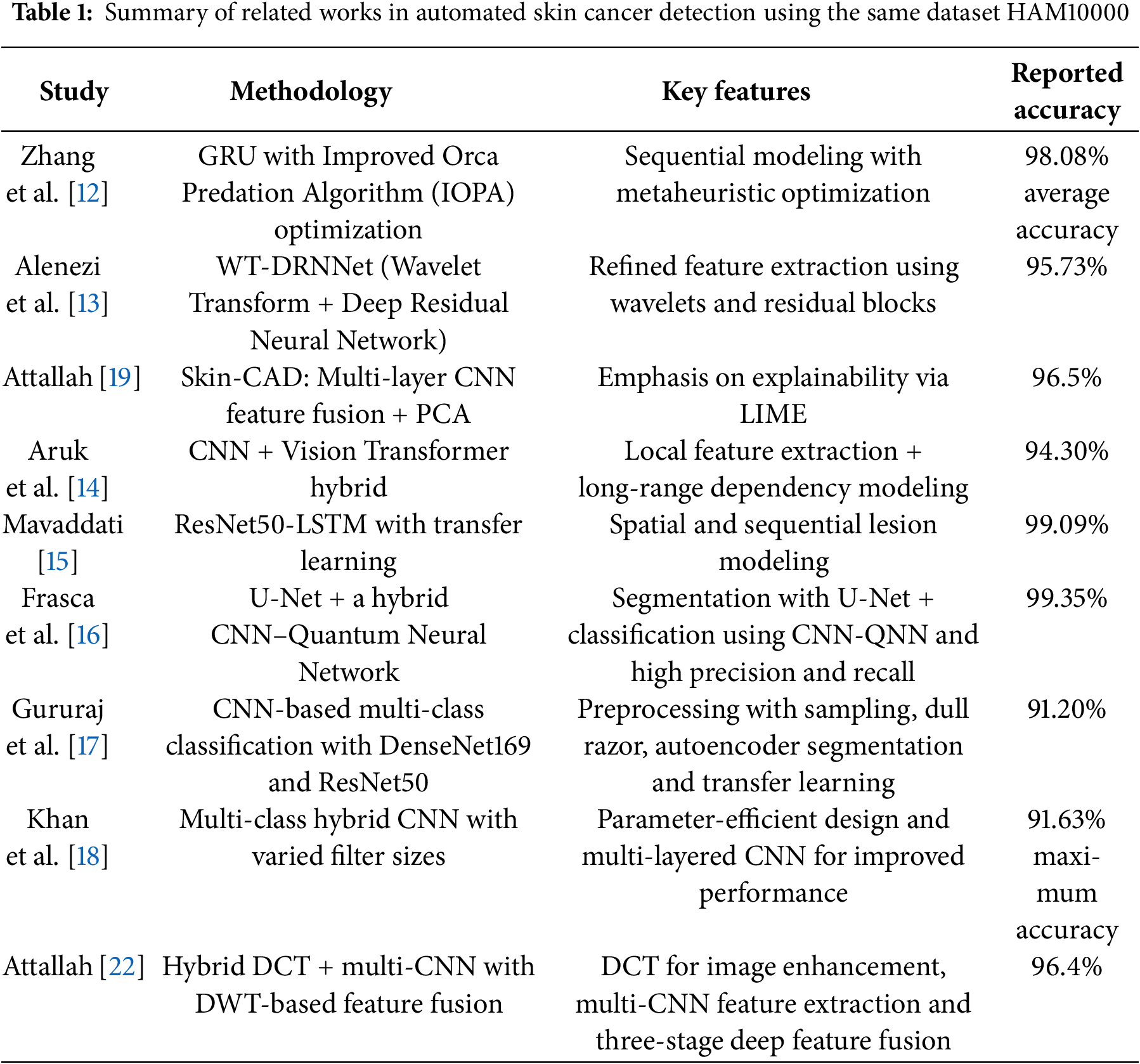

Recent advancements in medical image analysis have led to significant improvements in automated skin cancer detection using deep and machine learning approaches [23,24]. Numerous studies have explored the effectiveness of CNNs [17,20,21] traditional handcrafted features [19,22] and hybrid models [14–16,18] in classifying different types of skin lesions. Zhang et al. [12] preseted a GRU-based model optimized using an improved Orca Predation Algorithm (IOPA). Their method, tested on the HAM10000 dataset, achieved high diagnostic performance across multiple metrics, demonstrating the strength of combining sequential learning with optimization techniques. Alenezi et al. [13] developed a model that integrates wavelet transform and a deep residual neural network (WT-DRNNet), achieving high accuracy on the ISIC2017 and HAM10000 datasets through refined feature extraction and extreme learning. Attallah [19] introduced the Skin-CAD system, an explainable CAD framework using multi-layer CNN feature fusion and PCA-based dimensionality reduction. The model achieved high accuracy on two benchmark datasets and emphasized interpretability through LIME. Lastly, Tuncer et al. [20] proposed TurkerNet, a lightweight CNN designed to reduce computational complexity without sacrificing accuracy. It performed competitively on binary classification tasks, offering a practical solution for real-time or resource-constrained environments.

Aruk et al. [14] introduced a hybrid model combining CNN and Vision Transformer (ViT) to enhance skin cancer classification. CNN layers capture local texture and edge features, while Transformer layers model long-range dependencies. Tested on HAM10000, the model achieved high performance 94.30% accuracy outperforming 20 other deep models. Mavaddati [15] developed a hybrid ResNet50-LSTM model using transfer learning to improve skin cancer detection. ResNet50 extracts spatial features, while LSTM captures sequential lesion structure. Three scenarios were tested, with the combined ResNet50-LSTM-TL model achieving over 99.09% accuracy. Frasca et al. [16] employed a U-Net for segmentation and a hybrid CNN–Quantum Neural Network (CNN-QNN) for classification of skin lesions using the HAM10000 dataset. Their model achieved exceptional performance, with precision and recall at 99.67% and overall accuracy of 99.35%. These results surpass traditional CNN-based classifiers, demonstrating the model’s potential to support dermatologists in clinical decision-making. Gururaj et al. [17] presented a CNN-based framework for multi-class skin lesion classification on the HAM10000 dataset. The approach incorporated preprocessing techniques such as sampling, hair removal, and autoencoder-driven segmentation. Transfer learning with DenseNet169 and ResNet50 was employed to enhance predictive performance. Experimental comparisons demonstrated that the method achieved competitive results with existing state-of-the-art models. Khan et al. [18] developed a multi-class CAD system for automated skin lesion classification. Their hybrid, multilayered CNN model was carefully designed with varied filter sizes and reduced parameters to improve performance. Evaluation on the HAM10000 dataset reported a maximum accuracy of 91.63%, alongside strong precision, recall, and F1-scores. Hammad et al. [21] introduced Derma Care, a deep learning framework for simultaneous detection of eczema and psoriasis. Tested on a large, diverse skin image dataset, the model achieved 96.2% accuracy, 96% precision, 95.7% recall, and 95.8% F1-score. The study highlights the practical application by integrating the model into a mobile phone app, enabling rapid and accurate dermatological diagnosis. Attallah [22] presented a hybrid model combining discrete cosine transform (DCT) and multi-CNN structures for skin cancer classification. The approach uses DCT to enhance image quality, followed by feature extraction from multiple CNN layers. A three-stage deep feature fusion using discrete wavelet transform (DWT) and concatenation generates a comprehensive feature representation. The model achieved 96.4% accuracy, outperforming individual CNNs and recent methods.

While the aforementioned studies demonstrate significant advancements in skin cancer detection, several limitations remain. Many of these methods rely heavily on handcrafted feature extraction or focus on single-modal architecture, which may limit the model’s ability to fully capture the complex patterns present in diverse skin lesion types. For instance, Zhang et al.’s [12] GRU-based model and Alenezi et al.’s [13] wavelet-based approach, though effective, may not generalize well across all skin cancer variations due to limited feature representation. Additionally, while Attallah’s [19] Skin-CAD and Tuncer et al.’s [20] TurkerNet introduce explainability and efficiency, they still depend on fixed feature fusion strategies or simplified network designs that may compromise classification depth or scalability. High-performing hybrid models, such as Frasca et al.’s [16] CNNQNN or Attallah’s [22] multi-CNN fusion, achieve good accuracy but introduce substantial computational complexity, reducing feasibility for real-world clinical deployment. Approaches by Gururaj et al. [17] and Khan et al. [18] depend on extensive pre-processing, transfer learning, or specialized image enhancement, which can affect robustness and scalability. Additionally, models such as Hammad et al.’s [21] focus on a limited set of dermatological conditions, leaving broader skin disease diagnosis underexplored. Interpretability, efficiency, and practical implementation remain concerns across these studies. Our proposed method addresses these gaps by introducing a hybrid multimodal framework that combines CNN and 1D handcrafted features for richer representation. We integrate SMOTEENN to resolve class imbalance, TPOT for automated feature selection, and LIME to enhance interpretability, thereby improving both accuracy and clinical utility of skin cancer classification. Aruk et al.’s [14] model, although effective in combining CNN and Transformer architectures, relies on complex structures that may lead to increased computational costs and require significant training data to generalize well. Additionally, their work does not incorporate traditional handcrafted features, which could further enrich the representation of lesion characteristics. Mavaddati’s approach [15], while achieving very high accuracy through the integration of ResNet50, LSTM, and transfer learning, is primarily focused on sequential modeling without fully leveraging the spatial and textural synergy that can arise from combining deep and handcrafted features. Moreover, the heavy reliance on pre-trained networks may limit adaptability to different medical imaging modalities or lower-resource settings. Our method addresses these limitations by integrating deep learning features with Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG), a powerful handcrafted descriptor. This fusion enables our model to capture both high-level abstract representations and low-level texture details, resulting in a more comprehensive understanding of lesion structures. Unlike purely deep or sequential models, our approach remains computationally efficient while improving generalizability across datasets. Additionally, our method is designed to perform robustly even with limited data, making it more suitable for real-world clinical applications where large-annotated datasets may not always be available. Table 1 summarizes key methodologies, datasets, and performance metrics reported in the literature.

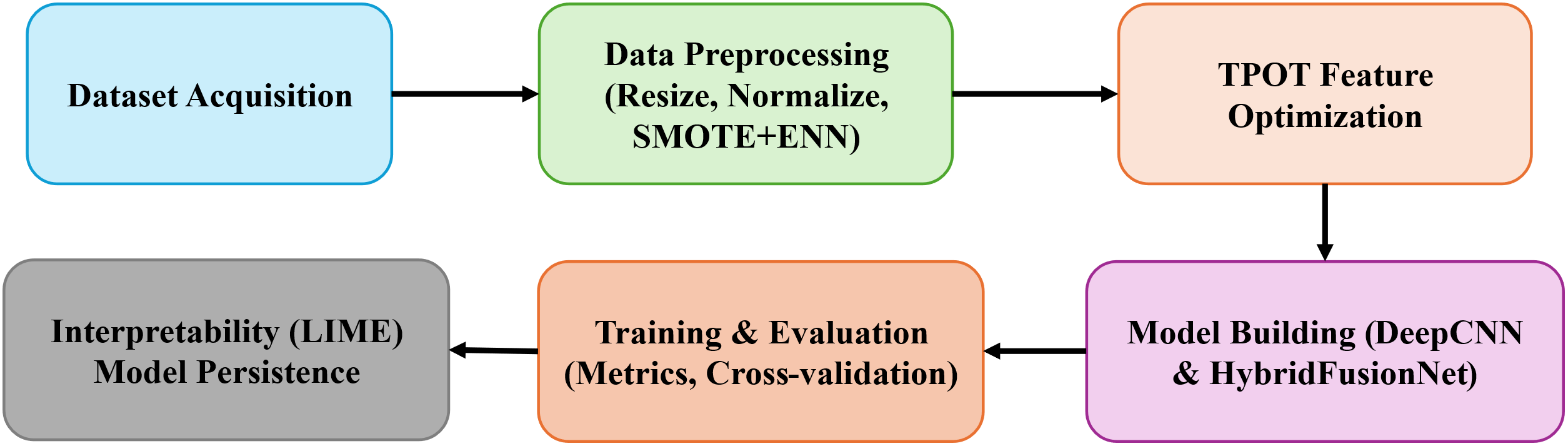

This section outlines the datasets, preprocessing techniques, and modeling strategies employed in developing the proposed skin lesion classification system. The methodology combines conventional deep learning with automated pipeline optimization using the TPOT. Two benchmark dermoscopic image datasets: HAM10000 [25] and BCN20000 [26] were utilized to ensure diversity, robustness, and real-world applicability. The end-to-end workflow shown in Fig. 1 begins with dataset acquisition, followed by preprocessing, feature optimization, and model construction, leading to training, evaluation, interpretability analysis, and final model persistence for deployment. Preprocessing steps included image resolution standardization, label encoding, normalization, and hybrid class balancing via SMOTE combined with ENN. TPOT was used to automate feature selection and pipeline configuration, yielding an optimized foundation for downstream deep learning models. Two neural architectures were explored: a baseline DeepCNN and the proposed HybridFusionNet, which integrates a 2D convolutional feature extractor with a complementary 1D CNN branch to incorporate additional descriptors.

Figure 1: Block diagram of the proposed model

To evaluate the performance of the proposed model, we utilized two well-established dermoscopic image datasets: HAM10000 [25] and BCN20000 [26].

(1) HAM10000

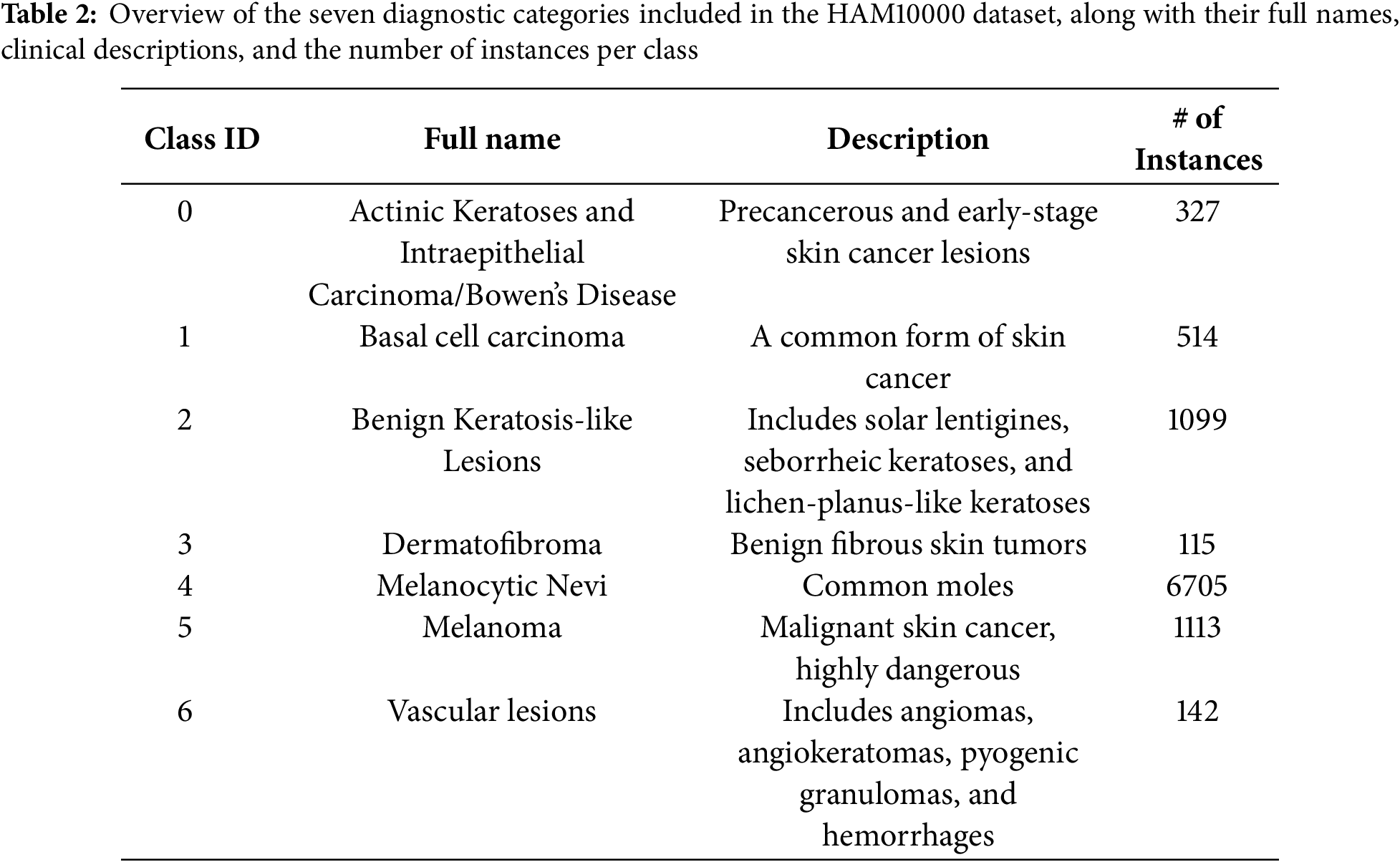

The HAM10000 dataset [25] is a large, publicly available dermatoscopic image dataset designed to support the development and train neural networks to automatically diagnose pigmented skin lesions. Recognizing the limitations posed by small and homogeneous datasets in dermatological AI research, the HAM10000 collection addresses both data quantity and diversity, incorporating images from different sources, populations, and acquisition modalities. The final dataset consists of 10,015 high-quality dermatoscopic images of pigmented lesions. It encompasses a broad and clinically representative range of diagnostic categories, capturing the real-world distribution of cases encountered in dermatology. Each image is labeled with one of seven clinically relevant skin lesion categories as shown in Table 2.

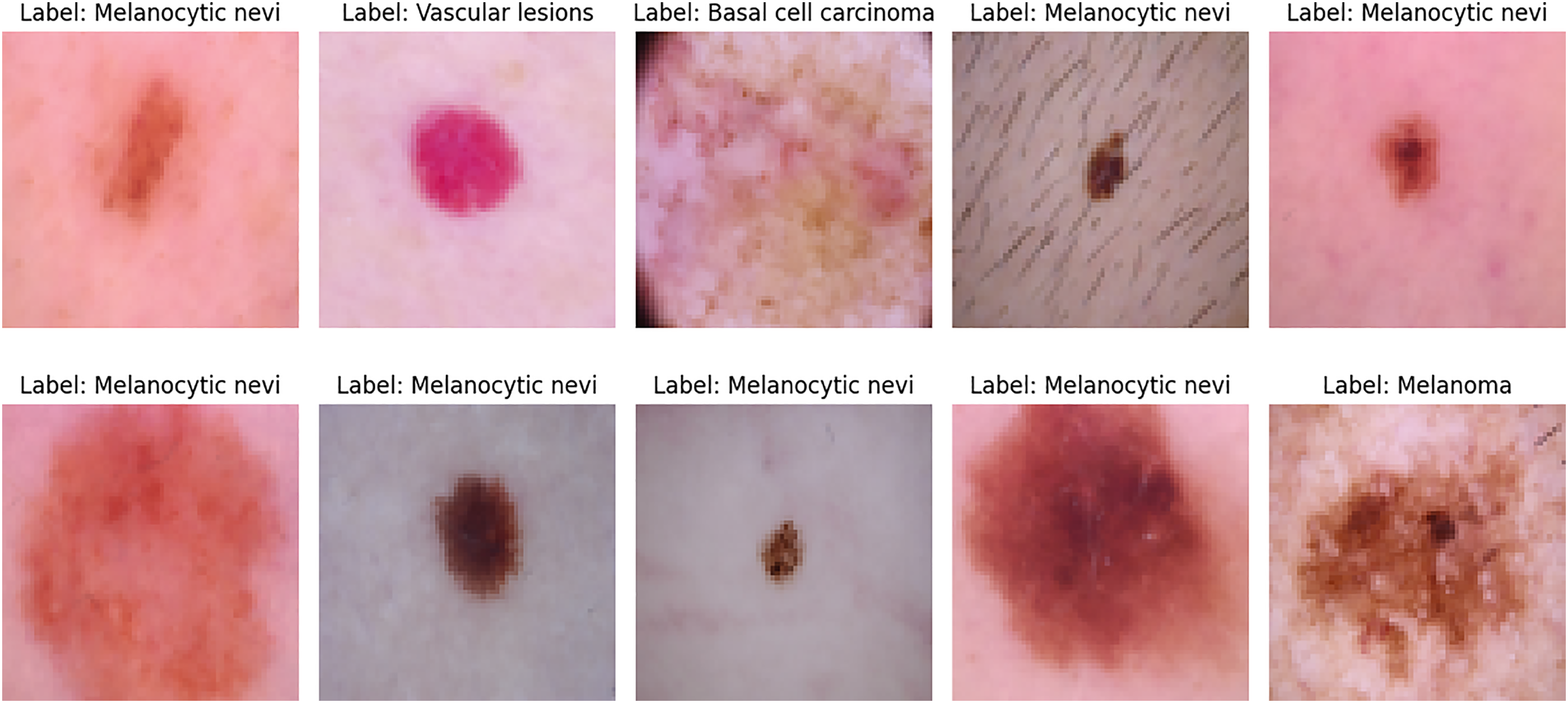

Fig. 2 presents representative dermatoscopic images from the HAM10000 dataset, showcasing a range of lesions across multiple diagnostic categories, including melanocytic nevi, melanoma, vascular lesions, and basal cell carcinoma.

Figure 2: Sample dermatoscopic images from the HAM10000 dataset [25]

(2) BCN20000

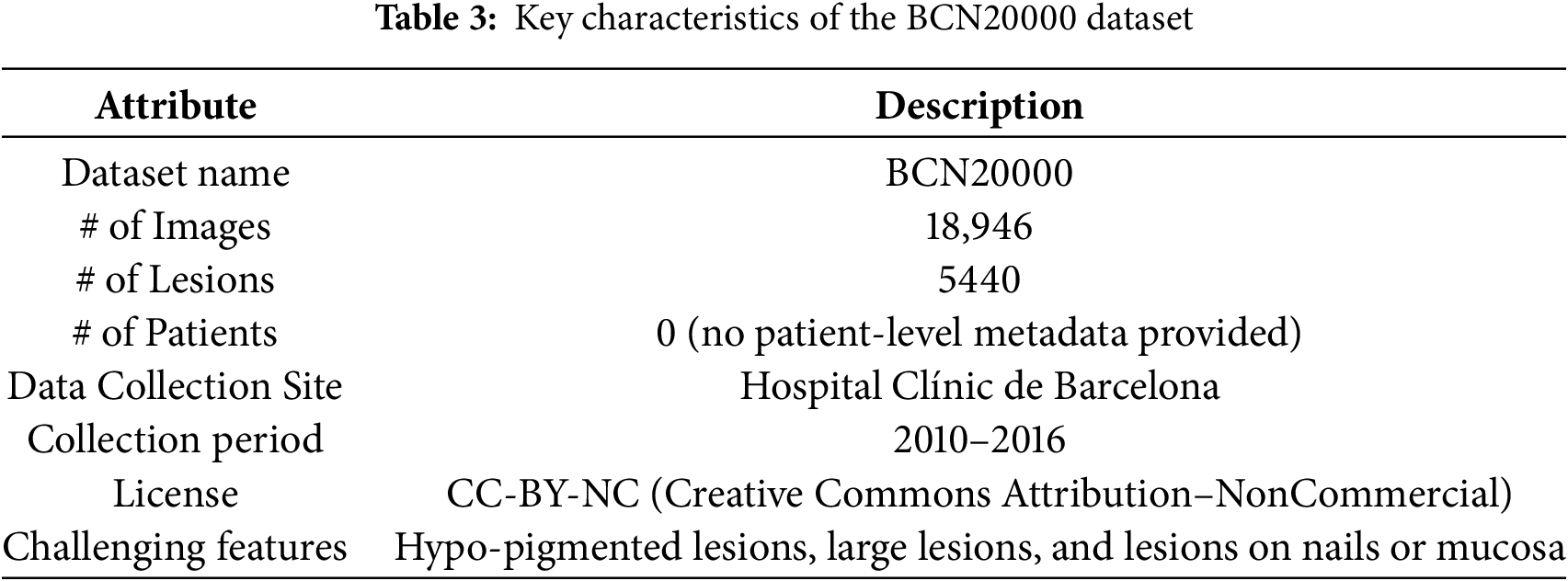

The BCN20000 [26] is a high-resolution dermoscopic image dataset specifically curated for advancing the development of automated skin lesion classification systems. Collected between 2010 and 2016 at the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, the dataset contains a total of 18,946 dermoscopic images representing 5440 unique lesions. Although the dataset does not include patient identifiers or demographic data (i.e., zero patient records are provided), its richness lies in the complexity and variety of the lesion images.

A key strength of the BCN20000 dataset is its clinical diversity, which includes dermoscopic images taken from challenging anatomical sites, such as nails, mucosal areas, and other regions where image acquisition is typically difficult. Moreover, it features:

• Hypo-pigmented lesions, which are harder to diagnose due to minimal coloration.

• Large lesions that exceed the viewing aperture of standard dermatoscopic equipment.

These characteristics make BCN20000 a valuable benchmark for training robust deep learning models capable of handling real-world variability in skin lesion imaging. The dataset is publicly available under a CC-BY-NC license and is attributed to Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. Table 3 shows the key characteristics of this dataset.

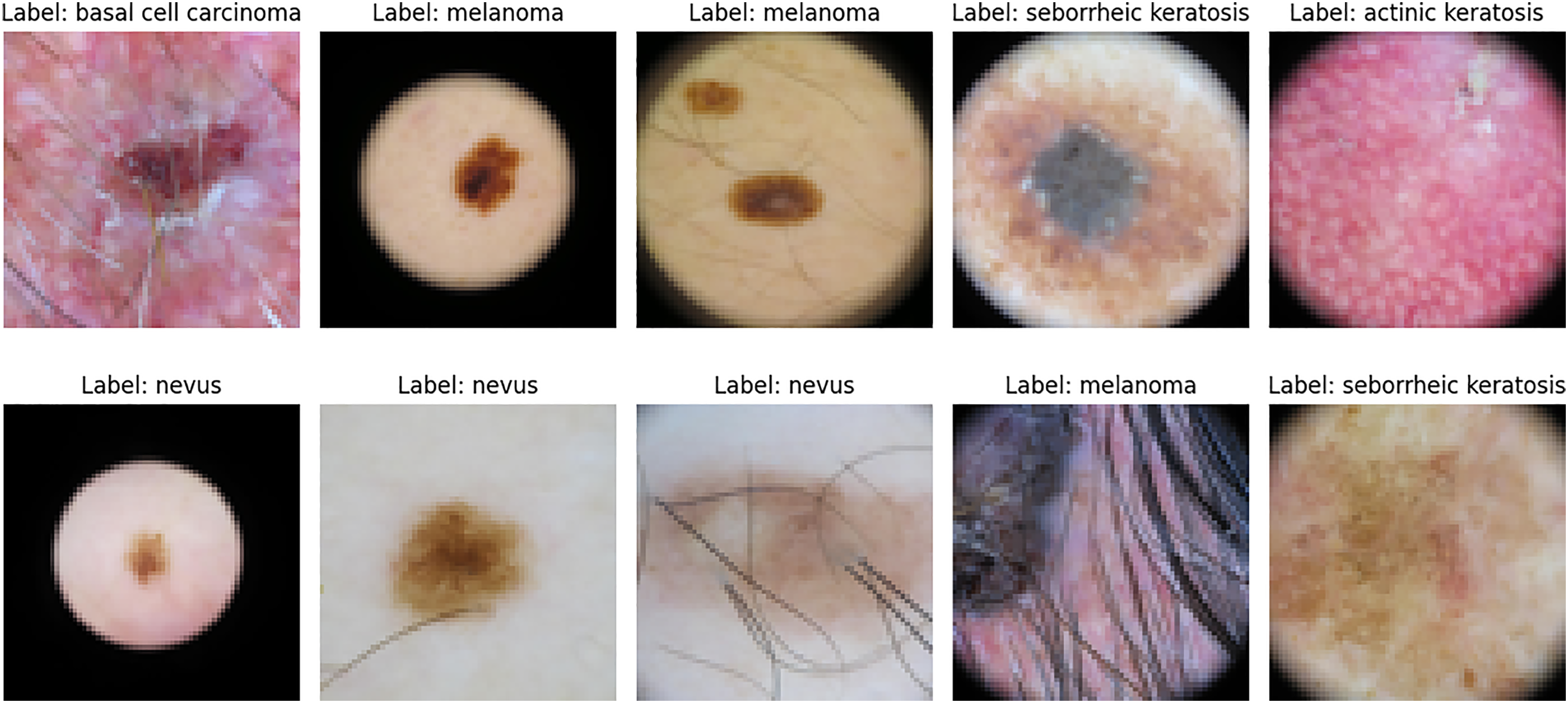

Fig. 3 presents representative dermoscopic images from the BCN20000 dataset, illustrating the diversity of lesion types and anatomical contexts included in this collection.

Figure 3: Sample dermoscopic images from the BCN20000 dataset [26]

3.2 Data Loading and Preprocessing

The images from the datasets were standardized to a resolution of 64 × 64 × 3 pixels to ensure consistent spatial dimensions across all samples. This resizing step reduces computational costs while retaining sufficient visual detail for classification tasks. Metadata files were loaded using the Pandas library to facilitate structured data handling. Lesion types were mapped to descriptive, human-readable labels and then converted into numeric codes using the LabelEncoder from scikit-learn, enabling compatibility with machine learning algorithms. For each image I, normalization was performed as:

where Inorm ∈ [0, 1] ensures uniform pixel intensity scaling, improving convergence during training.

The dataset exhibited class imbalance, with melanocytic nevi dominating the sample distribution. To address this, the SMOTEENN technique was applied to the training set only, after the train–test split, in order to avoid data leakage. Balancing was conducted on a per-class basis. In the SMOTE step, an oversampling ratio of 1.0 was used, generating synthetic minority class examples based on k = 5 nearest neighbors:

where xi is a minority sample and xnn is one of its nearest neighbors. In addition to oversampling, ENN [27] was applied with a 3-nearest neighbor rule to remove ambiguous, mislabeled, or noisy samples that lie close to class boundaries. This dual process ensures that the dataset is not only balanced but also cleaner, reducing class overlap and improving the quality of training samples. In practical implementation, SMOTE and ENN were not applied at the raw pixel level, as directly interpolating between pixel intensities would yield unrealistic “blended” images with limited diagnostic relevance. Instead, each image was first projected into a discriminative feature space using deep learning–based embeddings extracted from intermediate layers of convolutional neural networks. In this lower-dimensional representation, nearest neighbors were identified using Euclidean distance, and synthetic samples were generated as interpolated feature vectors between a minority sample and its neighbor. ENN subsequently pruned ambiguous or mislabeled samples by analyzing neighborhood consistency.

This hybrid strategy therefore achieves two objectives: it balances the dataset by generating synthetic samples for underrepresented classes and simultaneously reduces noise by filtering out unreliable examples. It preserved structural clarity and ensured that the augmented dataset contained meaningful lesion representations. Importantly, balancing was thus achieved in feature space rather than pixel space, allowing downstream models to learn from representations that better capture lesion morphology and texture rather than raw intensity patterns. This hybrid oversampling and undersampling strategy improves the model’s exposure to rare lesion patterns, while reducing the impact of noisy samples, thereby enhancing classification robustness.

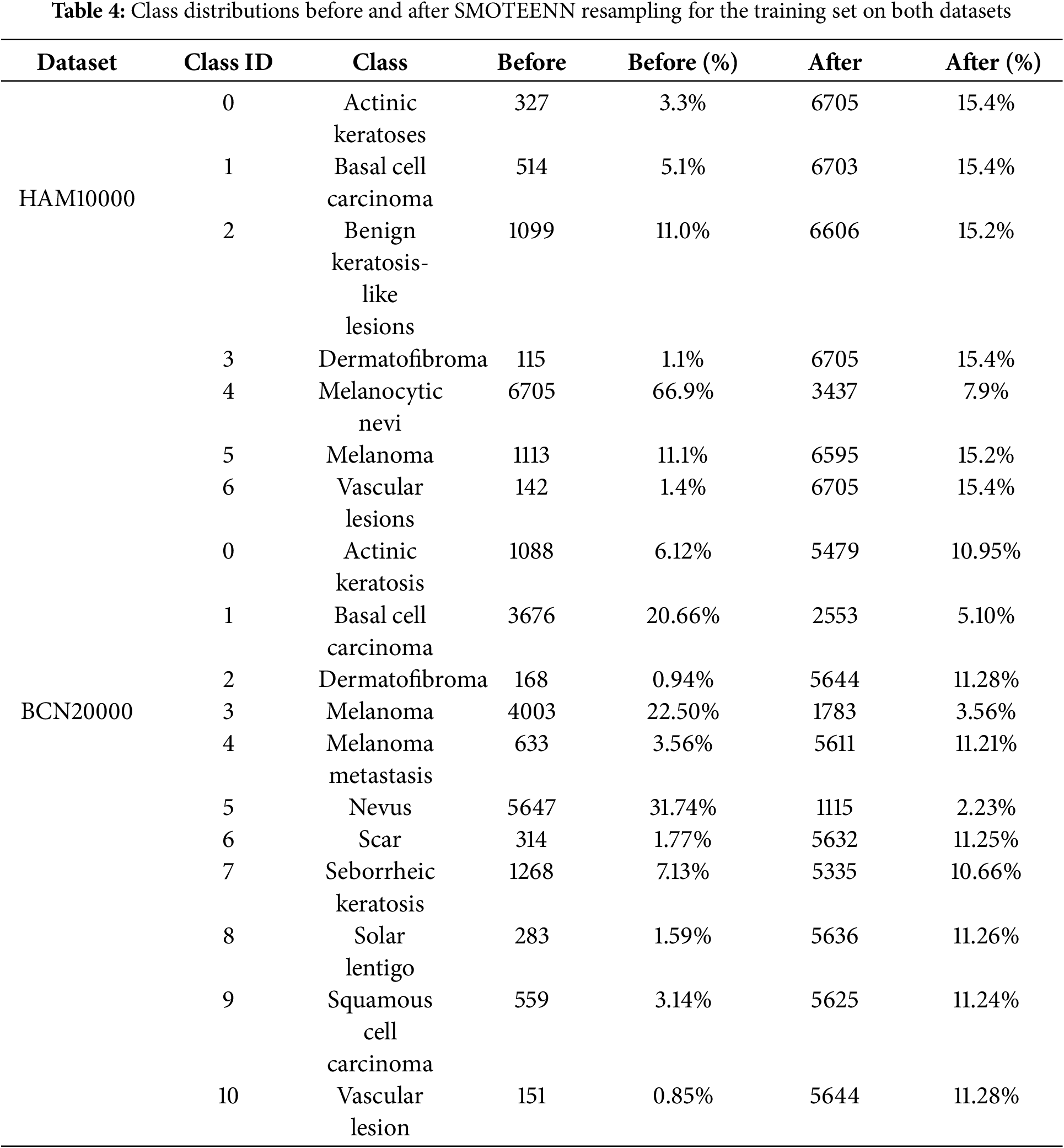

Additionally, Table 4 shows the quantitative class distributions before and after applying SMOTEENN for the training set. The imbalance ratio (IR) and coefficient of variation (CV) are also reported, demonstrating that rare classes such as Melanoma, Dermatofibroma, and Actinic keratoses are substantially better represented after resampling. For HAM10000, IR decreased from 58.30 to 1.95 and CV from 1.53 to 0.18. For BCN20000, IR was reduced from 46.27 to 2.11 and CV from 1.47 to 0.21. This highlights that the proposed approach effectively mitigates class imbalance and improves the model’s generalization to underrepresented lesion types.

3.3 TPOT-Based Feature Optimization

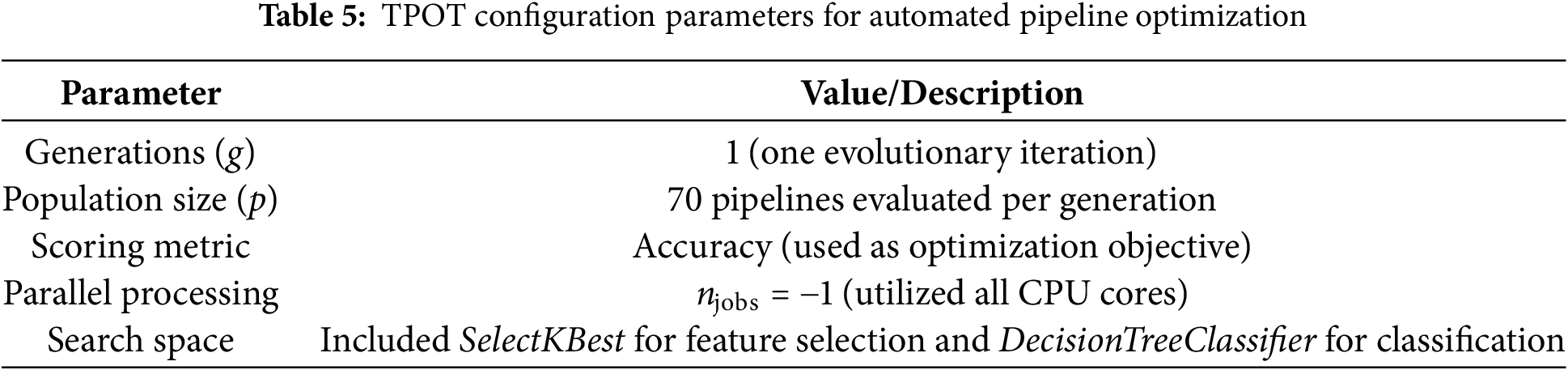

To automate the search for an optimal classification pipeline, we employed the TPOT, which uses genetic programming to automatically explore combinations of models, hyperparameters, and feature selection strategies. Unlike manual tuning, TPOT systematically evaluates candidate pipelines, ensuring that the resulting configuration is both performant and reproducible.

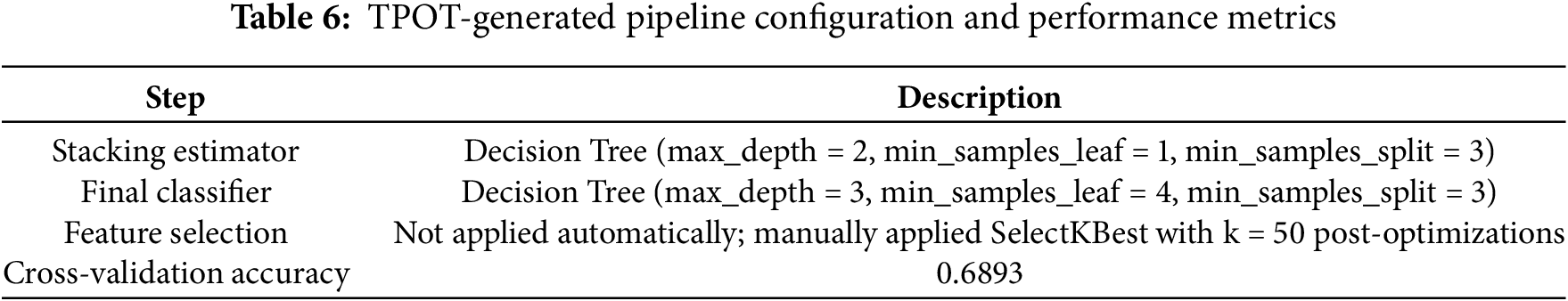

The search space was deliberately constrained to maintain interpretability. For feature selection, we included SelectKBest using f_classif as the scoring function, with k ∈ {10, 20, 50, ‘all’}. For classification, DecisionTreeClassifier was chosen with the following hyperparameters: criterion ∈ {gini, entropy}, max_depth ∈ [2–9], min_samples_split ∈ [2–9], and min_samples_leaf ∈ [1–9]. TPOT was executed with one evolutionary generation (g = 1) and a population size of 70 candidate pipelines per generation (p = 70). Accuracy was used as the scoring metric, and parallel processing was enabled (n_jobs = −1) to maximize computational efficiency. The best pipeline identified by TPOT consisted of two decision tree classifiers:

• Stacking Estimator: DecisionTreeClassifier (criterion = ‘gini’, max_depth = 2, min_samples_split = 3, min_samples_leaf = 1).

• Final Classifier: DecisionTreeClassifier (criterion = ‘gini’, max_depth = 3, min_samples_split = 3, min_samples_leaf = 4). To ensure feature dimensionality reduction and improve interpretability, we manually applied SelectKBest with k = 50 after optimization. The best pipeline selected 32 informative features from the original handcrafted feature set. These features were processed by the 1D branch of HybridFusionNet and fused with CNN-derived features, providing complementary global statistics to the spatial CNN representation.

The configuration used in our study is summarized in Table 5, which defines the evolutionary parameters, search space, and computational setup. Table 6 presents the detailed configuration and performance metrics of the TPOT-generated pipeline.

The significance of using TPOT lies in its automated search capability, which eliminates the need for exhaustive manual tuning. Moreover, the genetic algorithm framework allows exploration of unconventional model configurations that might be overlooked in manual experimentation. By leveraging TPOT, we ensured that the downstream deep learning models started from a data representation already optimized for discriminative performance, increasing their ability to generalize.

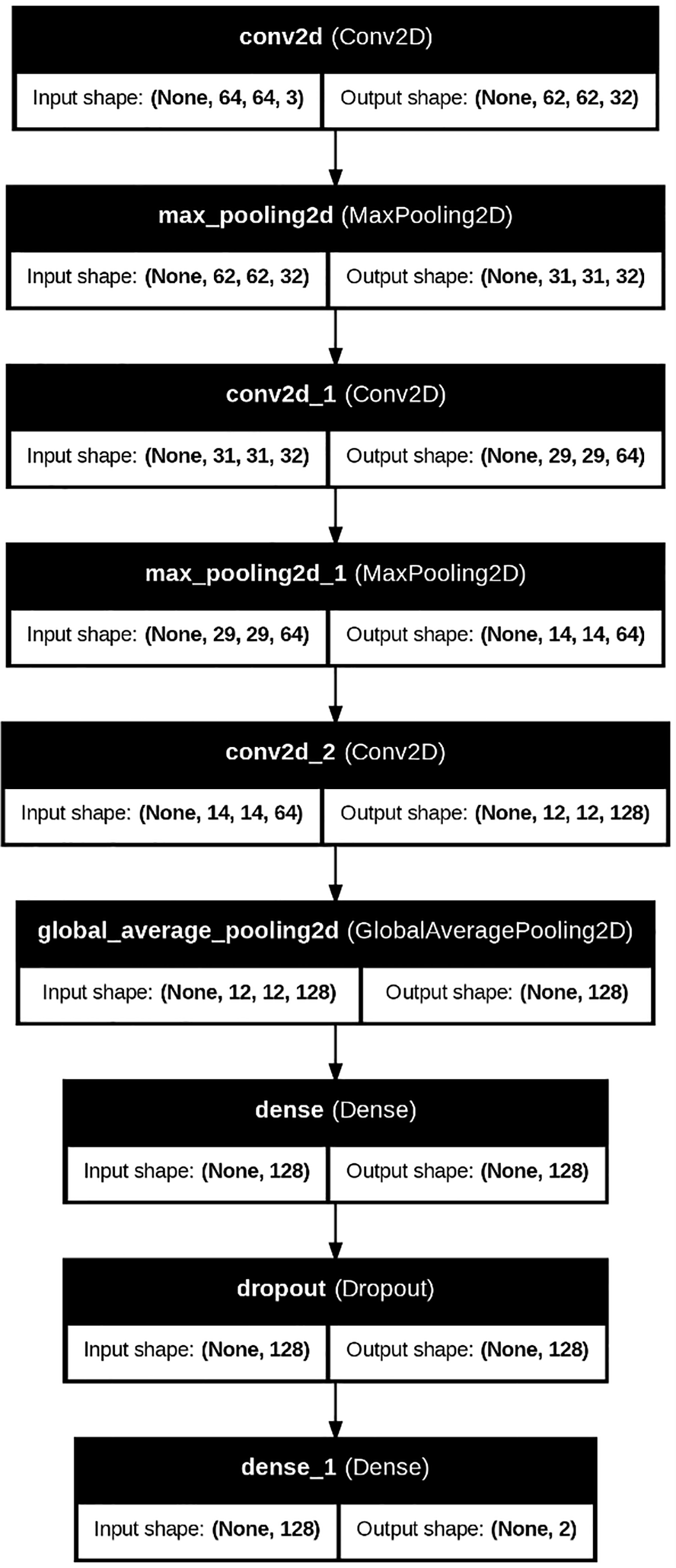

(1) Baseline Model: DeepCNN

The baseline DeepCNN follows a conventional image classification pipeline. It comprises three convolutional layers, each followed by max-pooling operations to reduce spatial resolution. Following the convolutional layers, global average pooling was applied to condense the feature maps. The resulting representations were then passed through fully connected layers, where dropout was introduced to prevent overfitting. The Adam optimizer and sparse categorical cross-entropy loss were employed for efficient multi-class training. Fig. 4 shows the architecture of the DeepCNN model.

Figure 4: DeepCNN model architecture

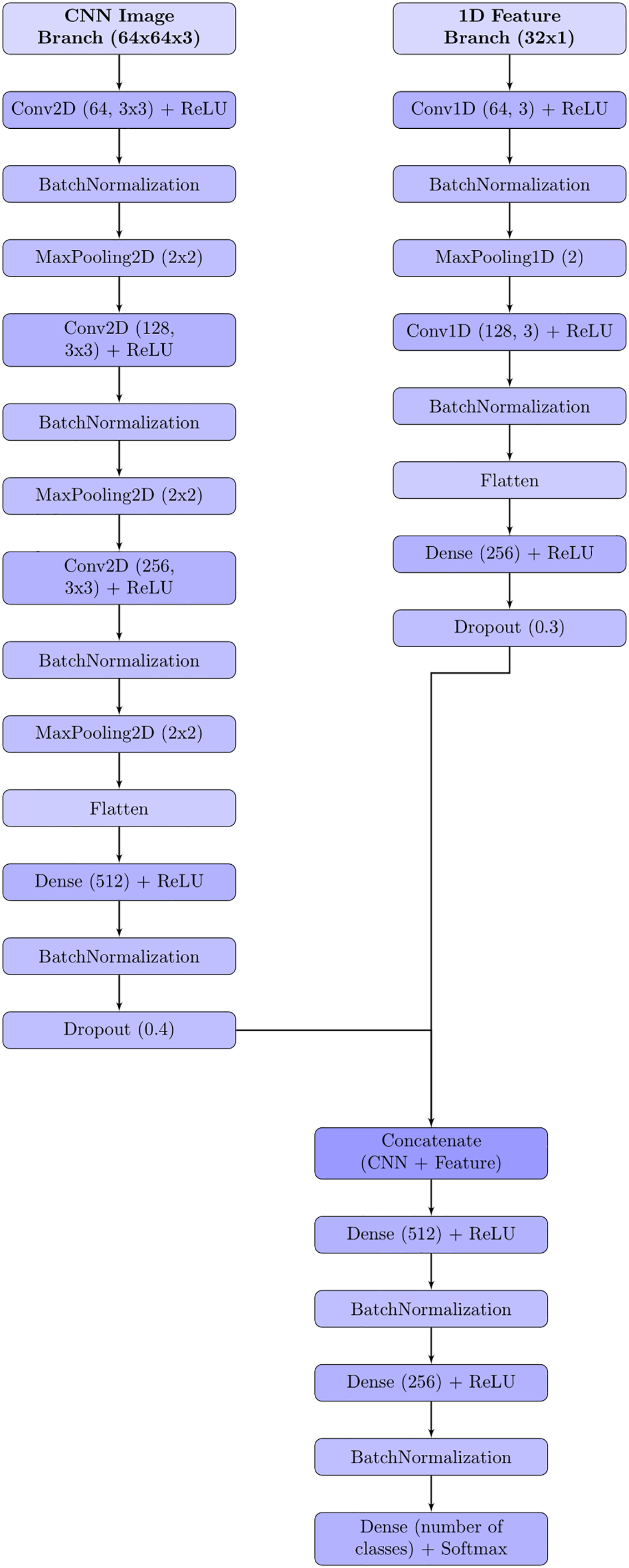

(2) Proposed Model: HybridFusionNet

The proposed HybridFusionNet is designed to combine the strengths of deep learning and handcrafted feature extraction for skin cancer classification. Its architecture follows a dual-branch structure that integrates complementary information before final prediction.

The first branch is a conventional CNN module that extracts hierarchical spatial features from dermoscopic images. Multiple Conv2D layers are used to capture low-level texture patterns and high-level semantic representations. These features provide detailed spatial information that reflects lesion structure, borders, and pigmentation. The second branch processes a set of 1D features derived from TPOT-selected statistical and texture descriptors. Specifically, TPOT selected 32 features from the original handcrafted feature set, which were passed through two dense layers to learn compact representations. This 1D branch runs in parallel to the CNN branch, allowing the model to capture global lesion statistics, such as color distribution, texture homogeneity, and channel-wise correlations, which complement the local spatial patterns learned by the CNN.

The outputs of both branches are fused at the feature level. Specifically, the latent vectors from the CNN and the 1D feature extractor are concatenated into a single feature embedding. This fused representation is then passed through fully connected layers with batch normalization and dropout. Batch normalization stabilizes training by reducing internal covariate shift, while dropout mitigates overfitting by randomly deactivating neurons during training.

This fusion strategy enables the model to jointly exploit deep image features and handcrafted descriptors, resulting in a richer and more discriminative feature space. By leveraging both modalities, HybridFusionNet improves robustness and accuracy in classifying diverse skin lesion types. Fig. 5 illustrates the architecture of the proposed hybrid model.

Figure 5: Proposed hybrid model architecture

The compilation phase serves as a bridge between model design and the commencement of training, translating conceptual architecture into an executable computational graph. During this stage, three key components are defined: the optimization algorithm, the loss function, and the performance metrics. In this study, the Adam optimizer was employed due to its adaptive learning rate mechanism, which efficiently adjusts parameter updates based on gradient history, thereby enhancing convergence stability [28]. The categorical cross-entropy loss function was selected as well-suited for multi-class classification problems, penalizing incorrect predictions more heavily as the confidence in those predictions increases [29]. To monitor performance during training, accuracy was used as the primary evaluation metric, providing a straightforward measure of the proportion of correctly classified samples [30]. In addition, early stopping and learning rate scheduling mechanisms were incorporated to prevent overfitting and improve generalization. The compilation configuration was tailored to strike a balance between convergence speed and stability, ensuring that the model’s parameter space could be explored effectively without overshooting optimal minima.

3.6 Model Training, Evaluation, Interpretability, and Persistence

The training process involved feeding the compiled model with the prepared dataset in mini batches, allowing for efficient gradient updates and improved generalization. A stratified train-test split approach was employed for each experiment (50–50, 60–40, 70–30, and 80–20 ratios) to ensure proportional representation of each class. To prevent overfitting and ensure reliable generalization, all test sets remained completely independent of training, SMOTEENN resampling was applied only to the training set, and feature selection/preprocessing (e.g., SelectKBest) fitted solely on the training data. Early stopping monitored the validation loss with a patience of 10 epochs, halting training when no further improvements were observed. These strategies collectively guarantee that the reported results reflect genuine model generalization rather than memorization of the training data. Training was conducted over multiple epochs, with validation loss and accuracy monitored after each epoch to identify the optimal stopping point. The evaluation phase extended beyond basic accuracy measurements, incorporating metrics such as precision, recall, F1-score, and confusion matrices to provide a more nuanced understanding of classification behavior. These metrics were particularly important given the imbalanced distribution of lesion categories in the dataset, where high accuracy could be misleading if the model simply favored the majority class.

To enhance transparency and trust in model predictions, LIME was employed [31]. LIME works by perturbing the input data and observing changes in predictions, thereby constructing a local, interpretable approximation of the decision boundary. In practice, this meant that for any given dermoscopic image, LIME could highlight the specific pixel regions most influential in the classification decision. It should be emphasized that LIME does not make the model inherently interpretable. Instead, it provides post-hoc explanations. This interpretability layer not only aids in debugging and model refinement but also supports clinical adoption by providing human-readable justifications for automated diagnoses.

Following training and validation, the final model persisted to disk in a serialized format (e.g., HDF5 or Pickle) to enable reproducibility and deployment. Model persistence ensures that the trained parameters, architecture, and metadata can be seamlessly reloaded for further analysis, integration into clinical decision support systems, or future transfer learning tasks.

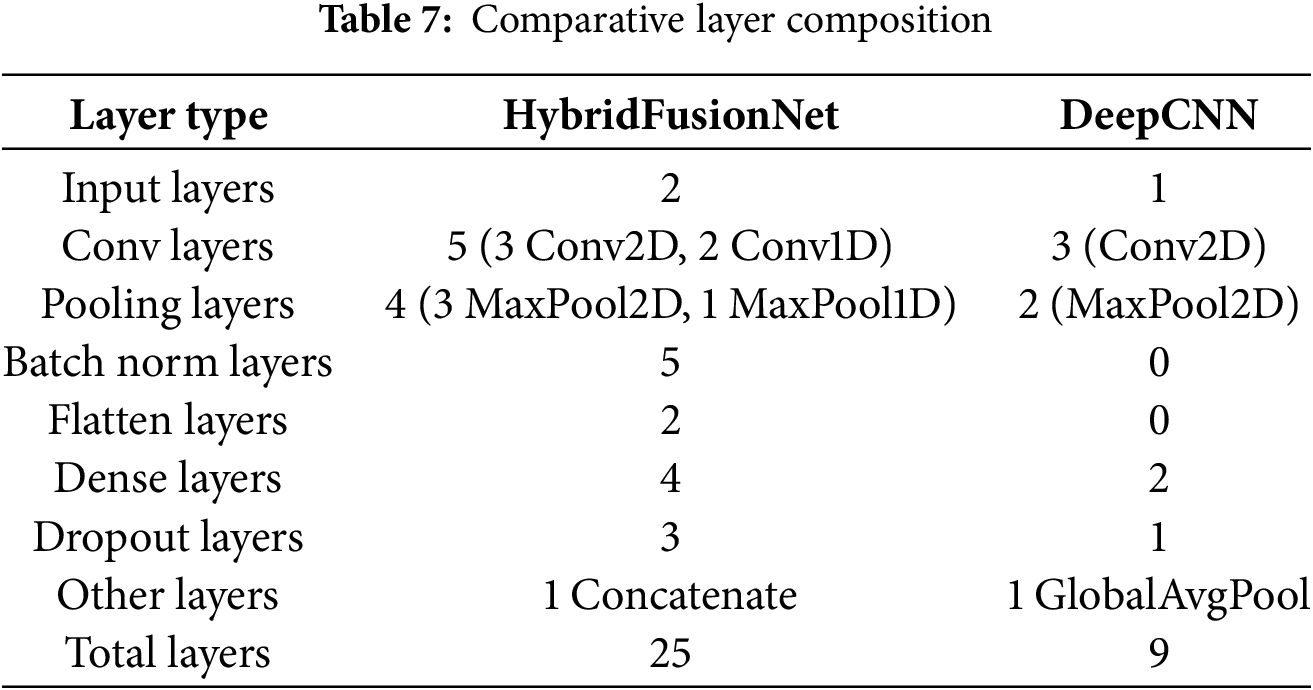

3.7 Model Architecture Overview

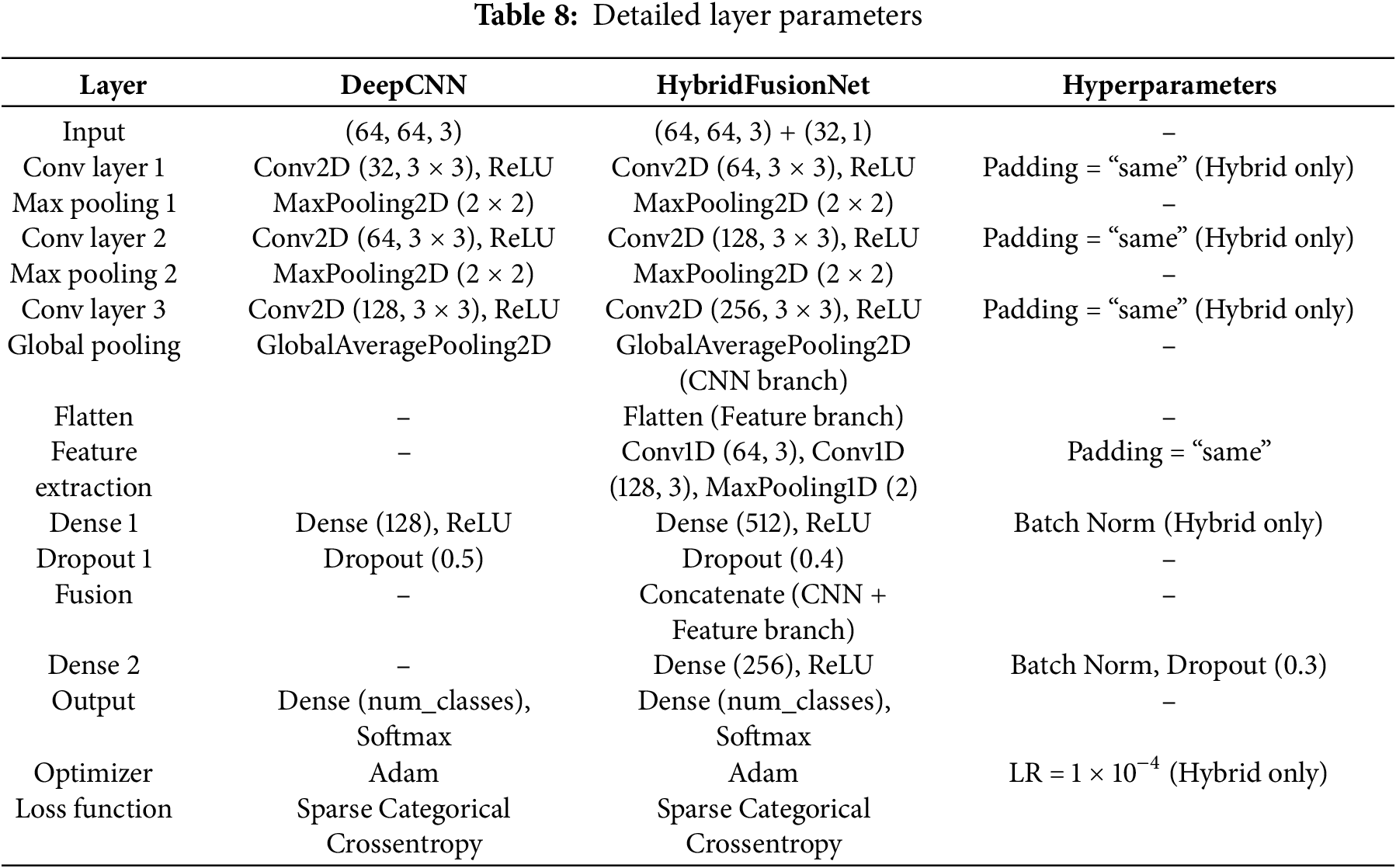

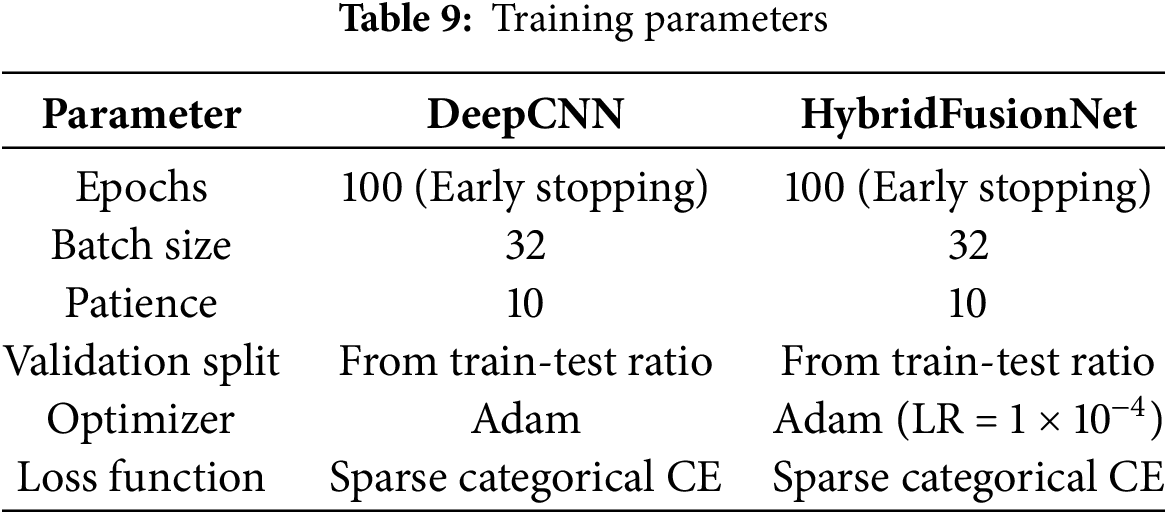

The architecture of the proposed model was carefully designed to balance representational capacity, computational efficiency, and interpretability. A detailed comparison of the architectural composition across the main layers is presented in Table 7, which outlines the progression from early convolutional feature extraction to deeper layers specialized for complex pattern recognition. These layers were deliberately structured to progressively capture low-level spatial features in the initial stages, while later layers extract increasingly abstract semantic representations relevant to the classification task.

Further technical specifications of each layer, including kernel sizes, stride values, activation functions, and parameter counts, are provided in Table 8. This breakdown highlights the rationale for selecting each configuration, such as the use of Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activations [32] to enhance non-linearity and batch normalization to stabilize training and improve convergence. The number of trainable parameters at each stage was monitored to avoid overfitting, especially considering the dataset size.

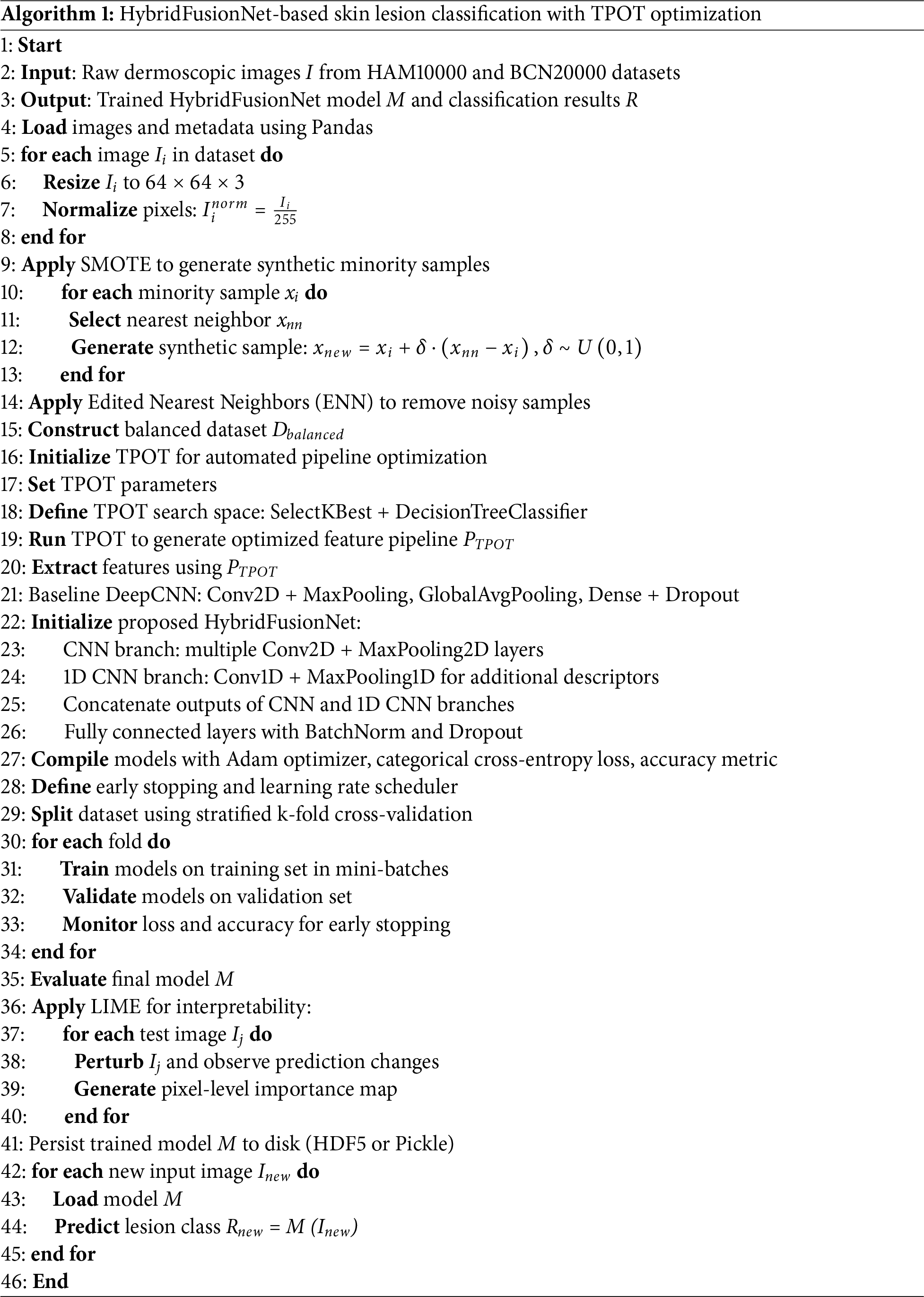

To ensure robust and efficient learning, the model’s training configuration summarized in Table 9 was fine-tuned based on empirical experimentation. Key hyperparameters, such as the learning rate, batch size, and optimizer choice (Adam optimizer [32] with default β-values), were selected to balance convergence speed with model generalization. Additionally, a moderate number of epochs were chosen to mitigate overfitting risks while allowing the network to fully explore the parameter space. The end-to-end workflow of the proposed method is summarized in Algorithm 1.

The experimental evaluation was conducted on two benchmark dermoscopic image datasets, HAM10000 [25] and BCN20000 [26], to assess the performance of the baseline CNN and the proposed HybridFusionNet. Performance was measured using multiple metrics including accuracy, balanced accuracy, Cohen’s kappa [33], precision, recall, and F1-score. These metrics were formally defined as follows:

where TP, TN, FP, and FN denote true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively, and C represents the number of classes. Cohen’s kappa (κ) was also employed to measure inter-rater agreement beyond chance. The models were trained and tested using a computing setup equipped with an Intel CPU (performance score 5.2), a high-performance GPU (score 7), and 24 GB of RAM. All experiments were conducted on cloud-based platforms, including Kaggle and Google Colab, which provided access to advanced computational resources and deep learning frameworks such as TensorFlow and Keras.

4.1 Results on HAM10000 Dataset

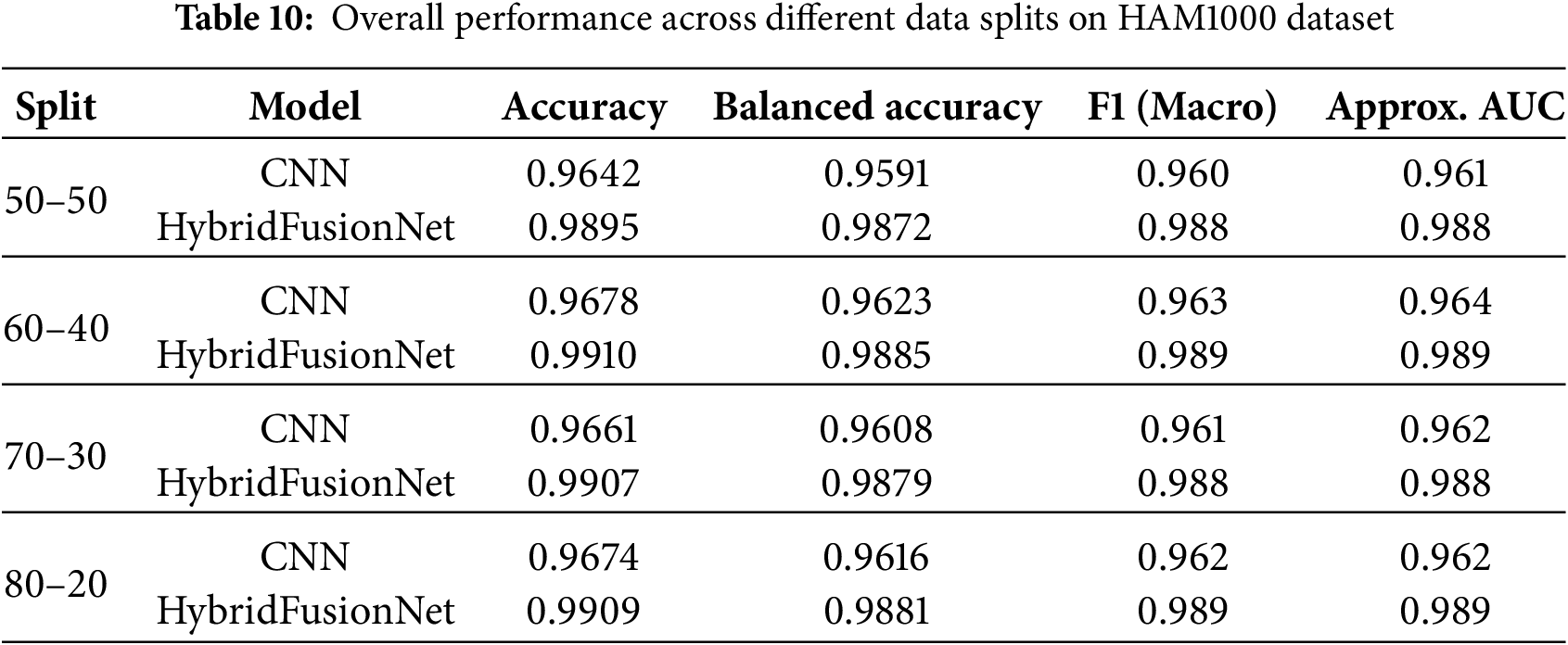

For the HAM10000 dataset, the CNN achieved an accuracy of 0.9674, balanced accuracy of 0.9616, and a kappa of 0.9618, while HybridFusionNet surpassed these results with an accuracy of 0.9909, balanced accuracy of 0.9881, and a kappa of 0.9893. The HybridFusionNet benefited from early stopping at 26 epochs, compared to 100 epochs required by the CNN, indicating higher efficiency.

To provide a more clinically relevant evaluation, we report macro F1-score and approximate Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) in addition to accuracy and balanced accuracy. Across multiple data splits, HybridFusionNet consistently outperformed CNN. For instance, under a 70–30 split, the CNN achieved an accuracy of 0.9661, balanced accuracy of 0.9608, F1 of 0.961, and AUC of 0.962, whereas HybridFusionNet reached an accuracy of 0.9907, balanced accuracy of 0.9879, F1 of 0.988, and AUC of 0.988. Comparable performance gains were observed across the 50–50, 60–40, and 80–20 splits, as summarized in Table 10.

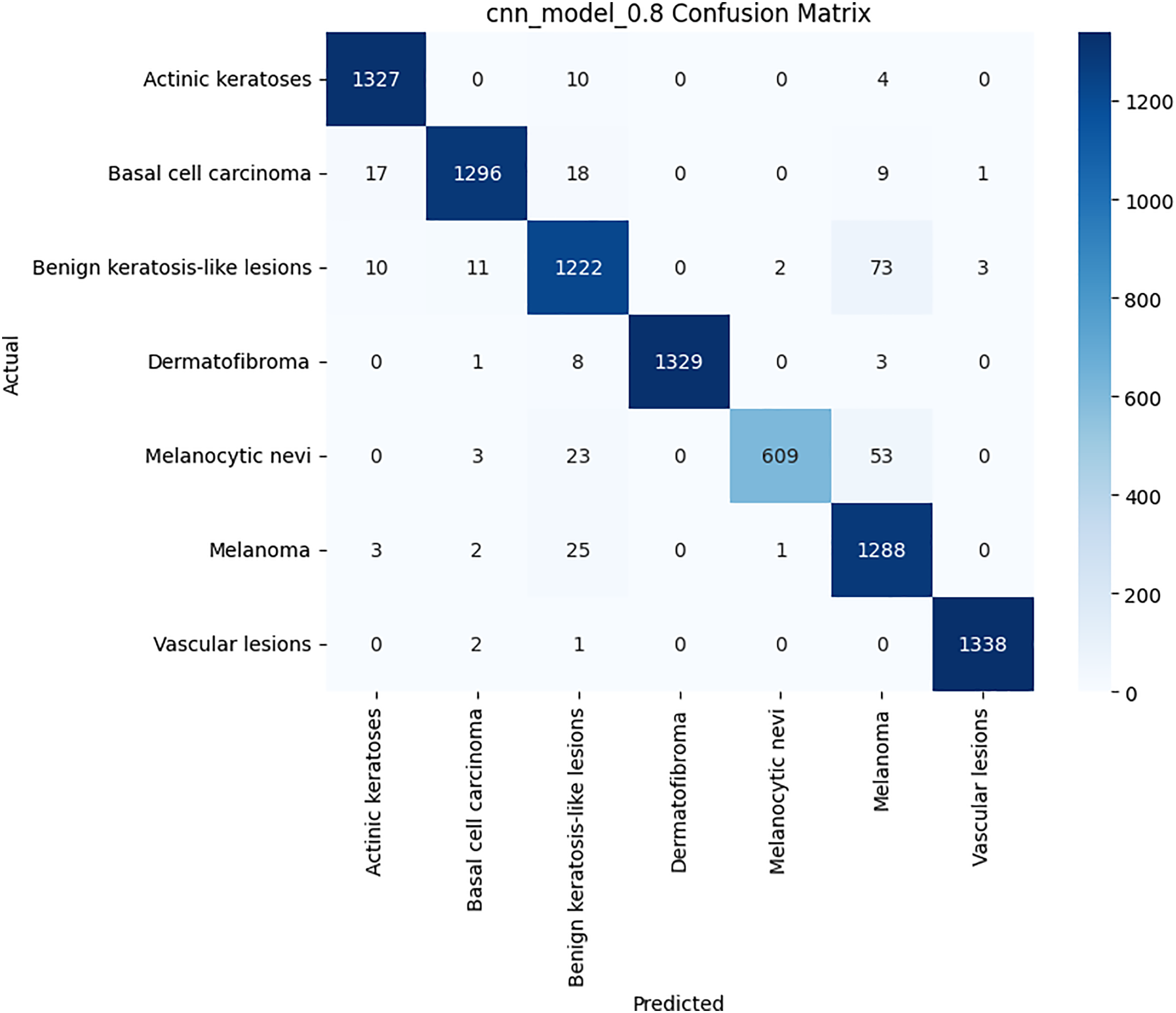

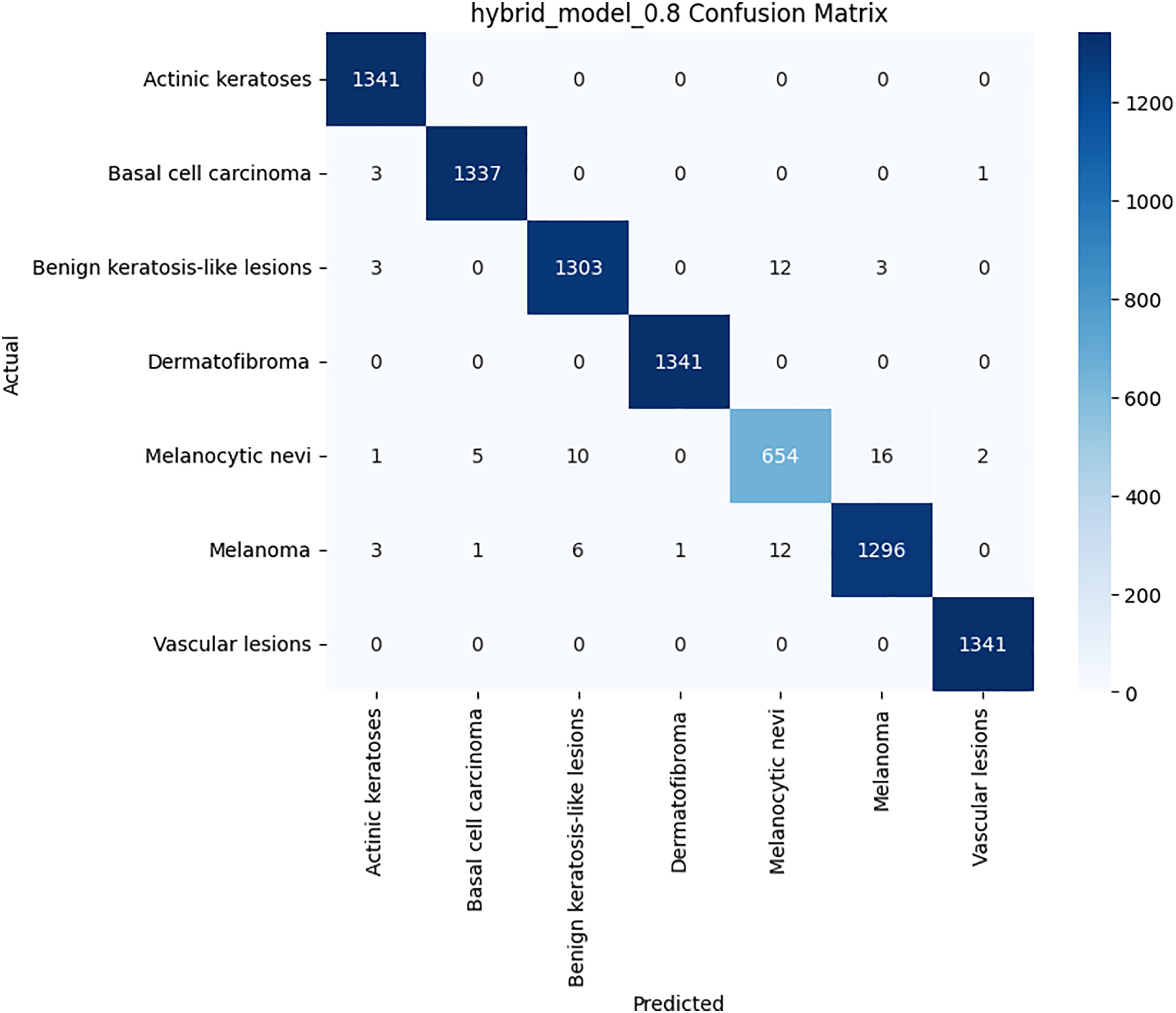

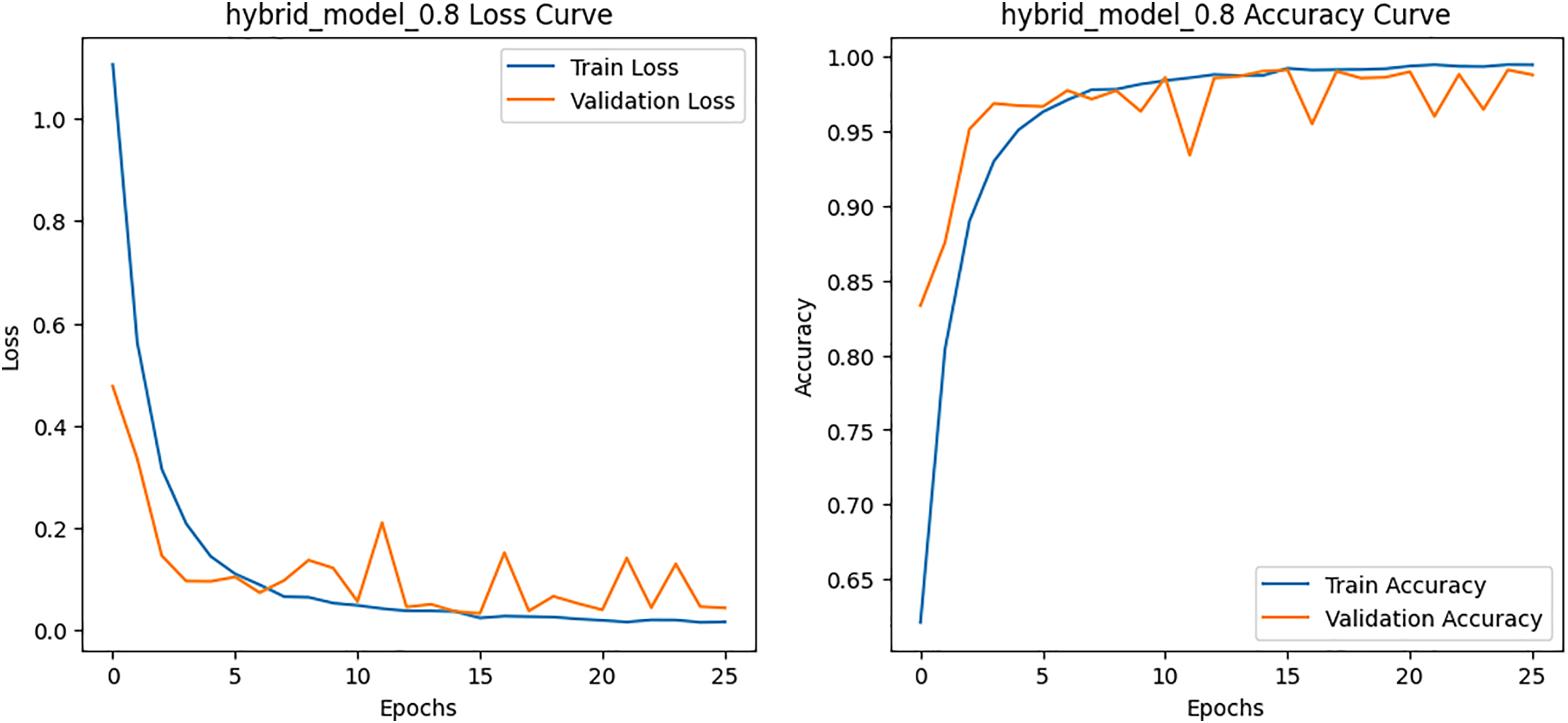

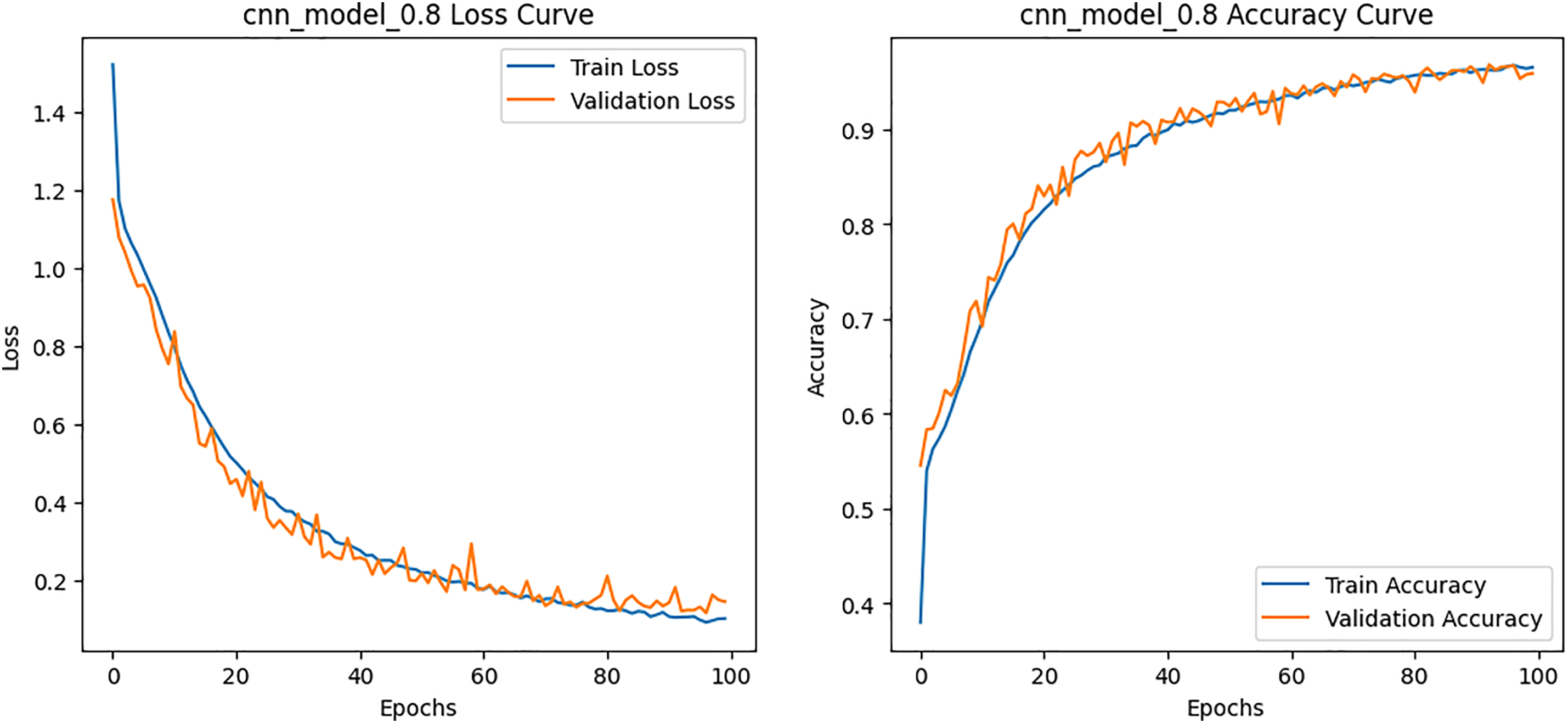

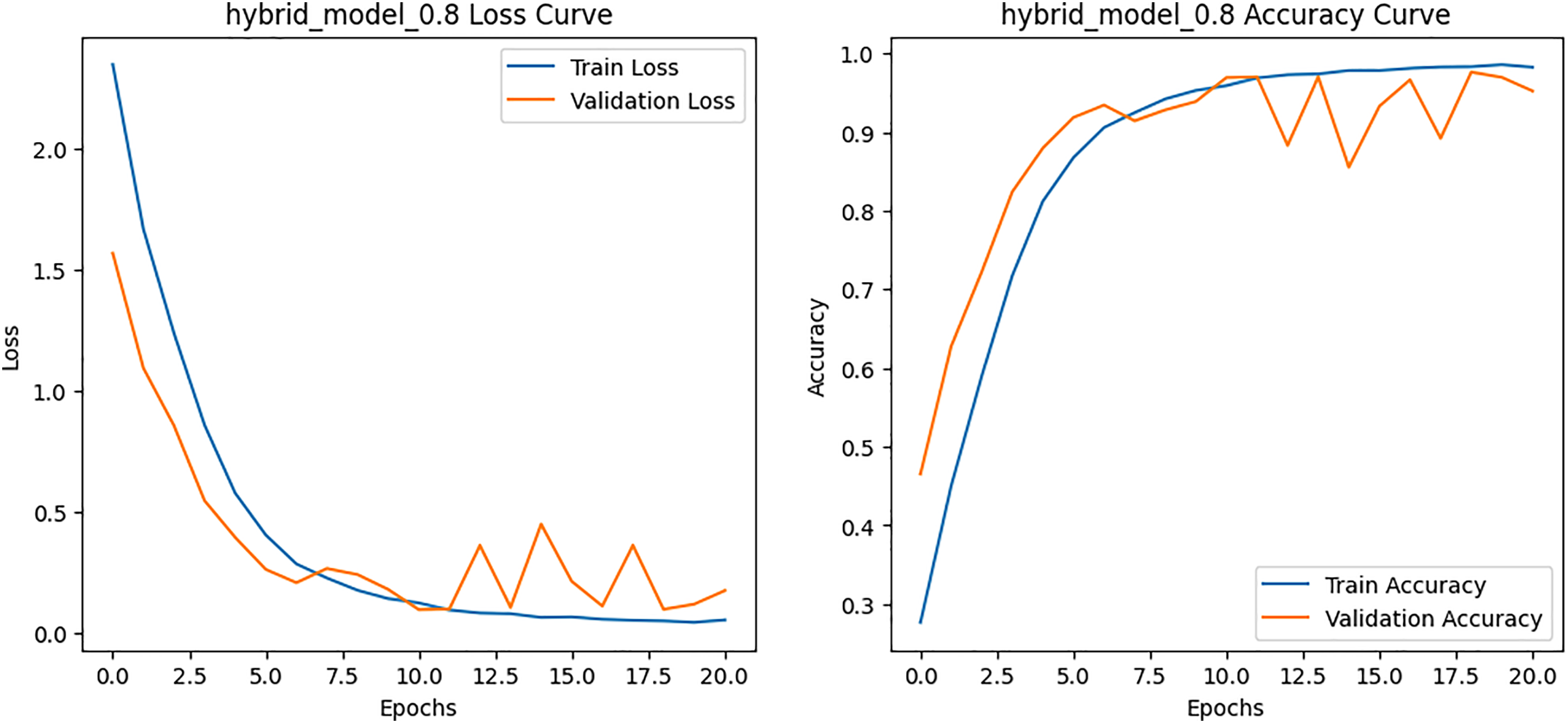

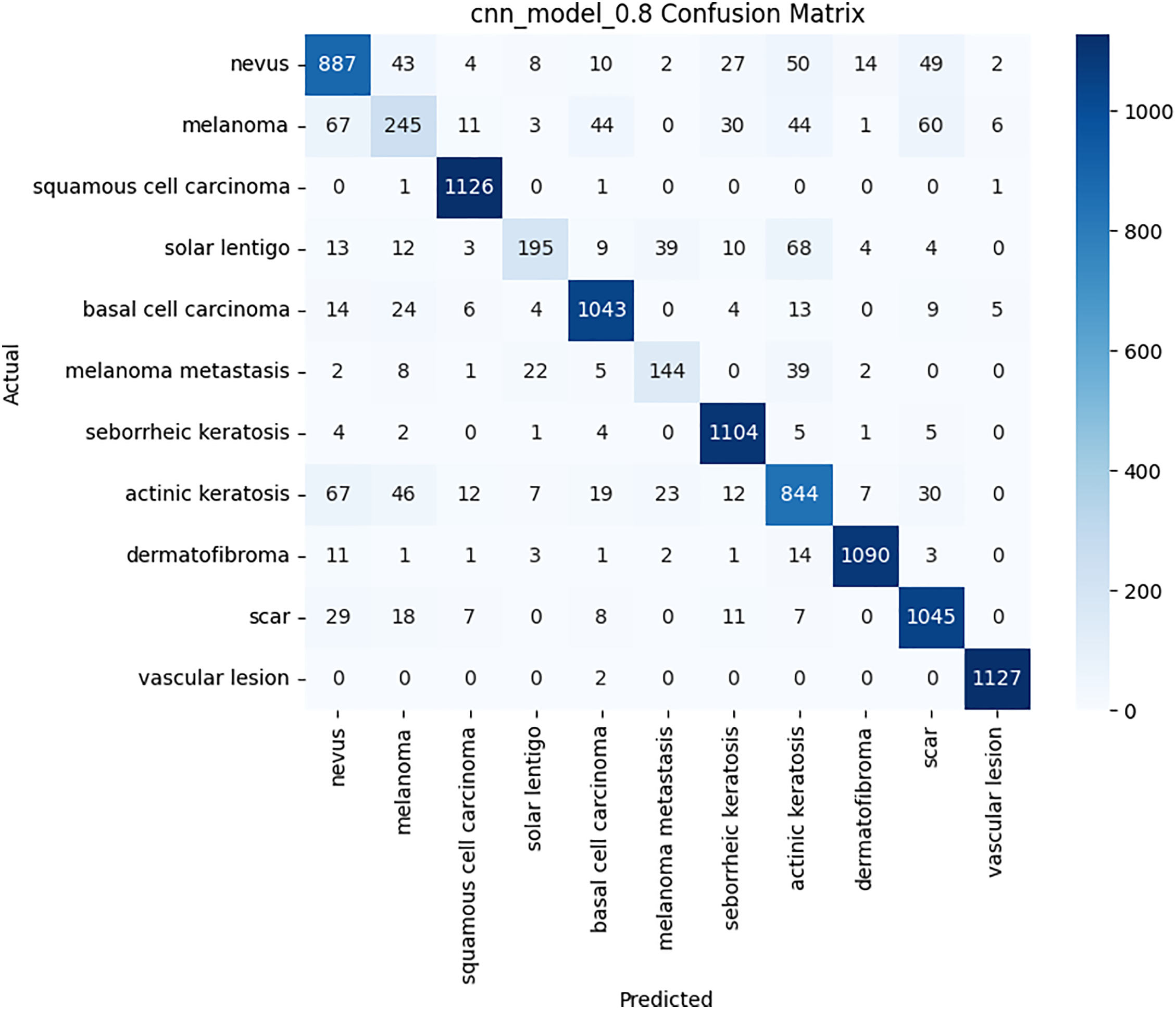

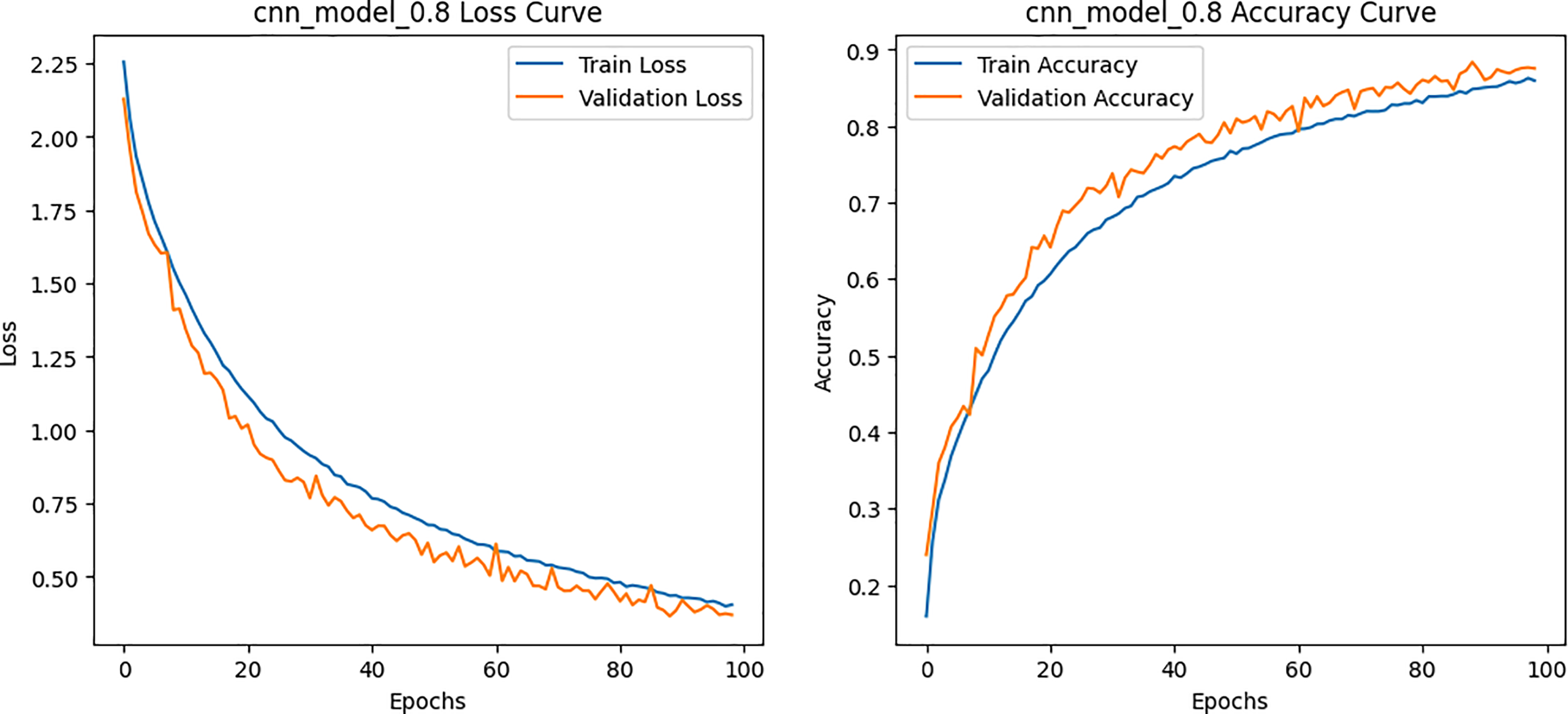

Class-wise evaluation in Table 11 highlighted that HybridFusionNet achieved near-perfect precision and recall across most classes, including Actinic Keratoses, Basal Cell Carcinoma, and Dermatofibroma (F1 = 1.00). The confusion matrix for the CNN shown in Fig. 6 revealed minor misclassifications between Melanocytic Nevi and Melanoma, while HybridFusionNet reduced these errors substantially as shown in Fig. 7. The loss and accuracy curves shown in Fig. 8 further demonstrate faster convergence and reduced overfitting in the hybrid model compared to the baseline CNN as shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 6: Confusion matrix for the CNN model on HAM10000 dataset

Figure 7: Confusion matrix for the proposed hybrid model on HAM10000 dataset

Figure 8: Loss and Accuracy curves for the proposed hybrid model on HAM10000 dataset

Figure 9: Loss and Accuracy curves for the CNN model on HAM10000 dataset

4.2 Results on BCN20000 Dataset

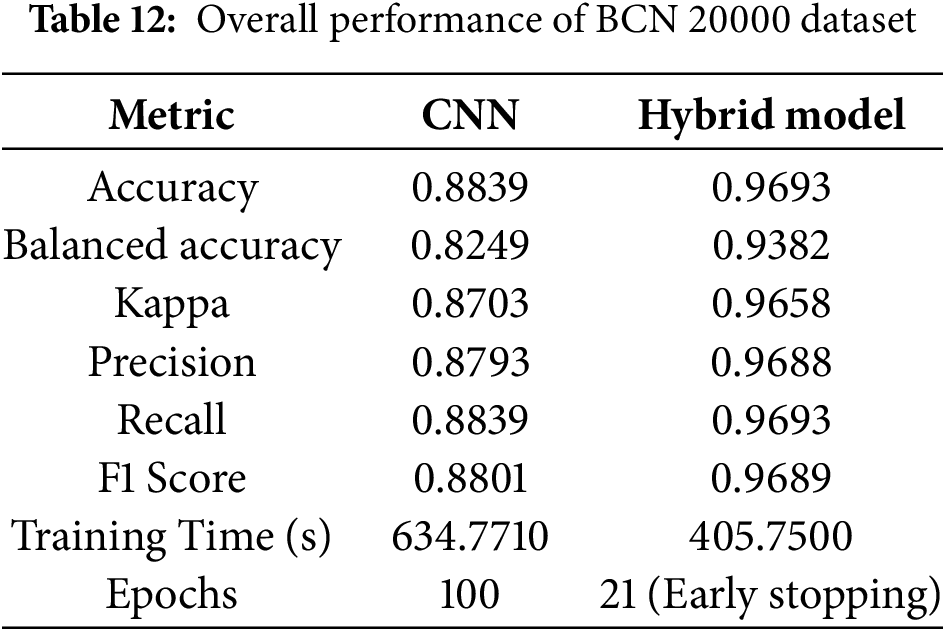

On the larger and more diverse BCN20000 dataset, HybridFusionNet again outperformed the CNN. The hybrid model achieved an accuracy of 0.9693, balanced accuracy of 0.9382, and kappa of 0.9658, compared to 0.8839, 0.8249, and 0.8703, respectively, for the CNN. Importantly, HybridFusionNet converged within 21 epochs, whereas the CNN required the full 100 epochs as shown in Table 12.

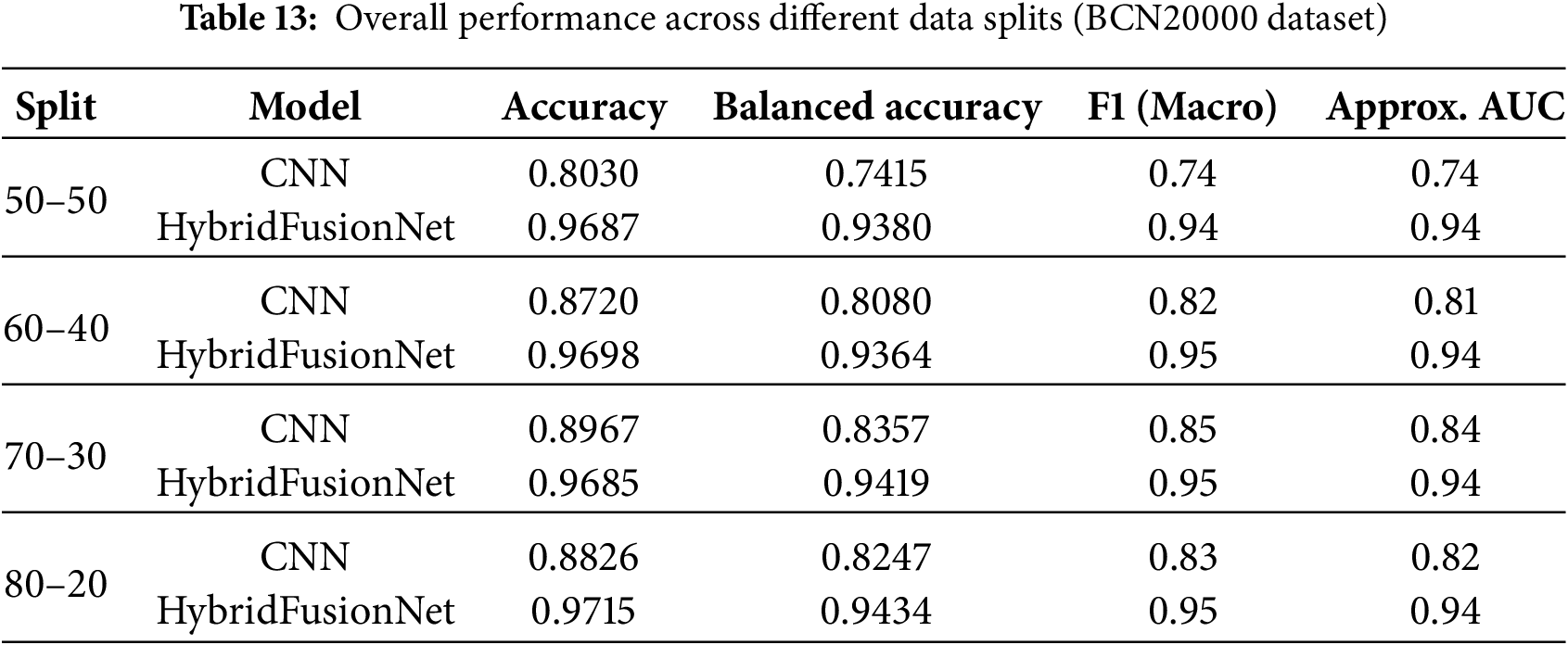

When evaluating macro F1-score and approximate AUC across different data splits, the superiority of HybridFusionNet over the baseline CNN becomes evident as shown in Table 13. For the 50–50 split, CNN achieved an accuracy of 0.8030, balanced accuracy of 0.7415, F1 of 0.74, and AUC of 0.74, whereas HybridFusionNet reached 0.9687, 0.9380, 0.94, and 0.94, respectively. Similar trends were observed for the 60–40, 70–30, and 80–20 splits, with the hybrid model consistently maintaining high F1-scores (0.94–0.95) and AUC values (0.94), while the CNN lagged behind. These results demonstrate that HybridFusionNet reliably captures discriminative features across various training–testing splits, enhancing robustness and generalizability, particularly in challenging classes such as Melanoma and Solar Lentigo.

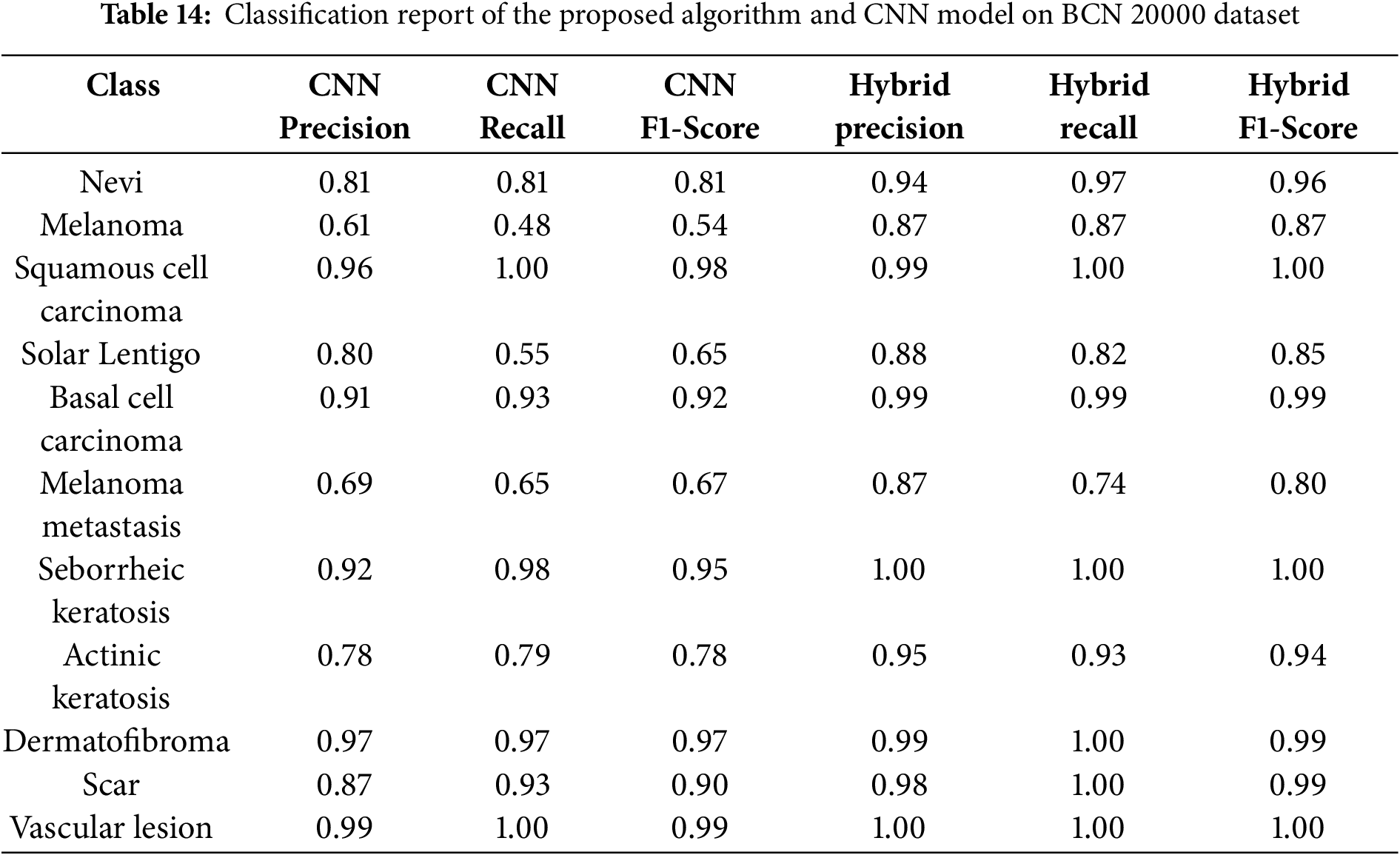

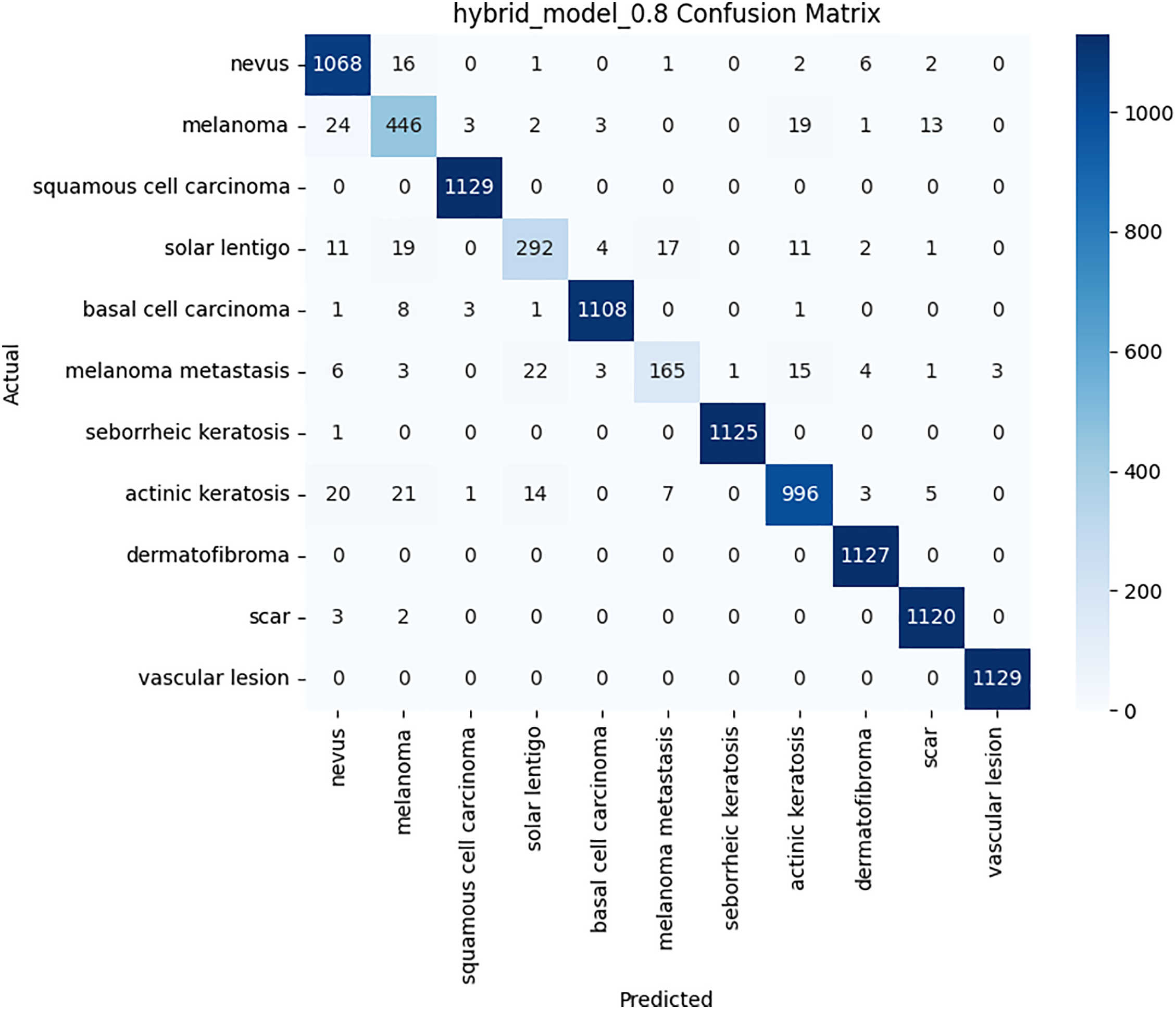

The per-class metrics shown in Table 14 showed notable improvements in challenging categories such as Melanoma (CNN F1 = 0.54 vs. Hybrid F1 = 0.87) and Solar Lentigo (CNN F1 = 0.65 vs. Hybrid F1 = 0.85). These improvements reflect the hybrid model’s ability to capture subtle textural and contextual features overlooked by the CNN. The confusion matrix and learning curves of our hybrid model shown in Figs. 10 and 11 corroborate these findings, illustrating higher classification consistency and more stable learning behavior than CNN model in Figs. 12 and 13.

Figure 10: Confusion matrix for the proposed hybrid model on BCN 20000 dataset

Figure 11: Loss and Accuracy curves for the proposed hybrid model on BCN 20000 dataset

Figure 12: Confusion matrix for the CNN model on BCN 20000 dataset

Figure 13: Loss and Accuracy curves for the CNN model on BCN 20000 dataset

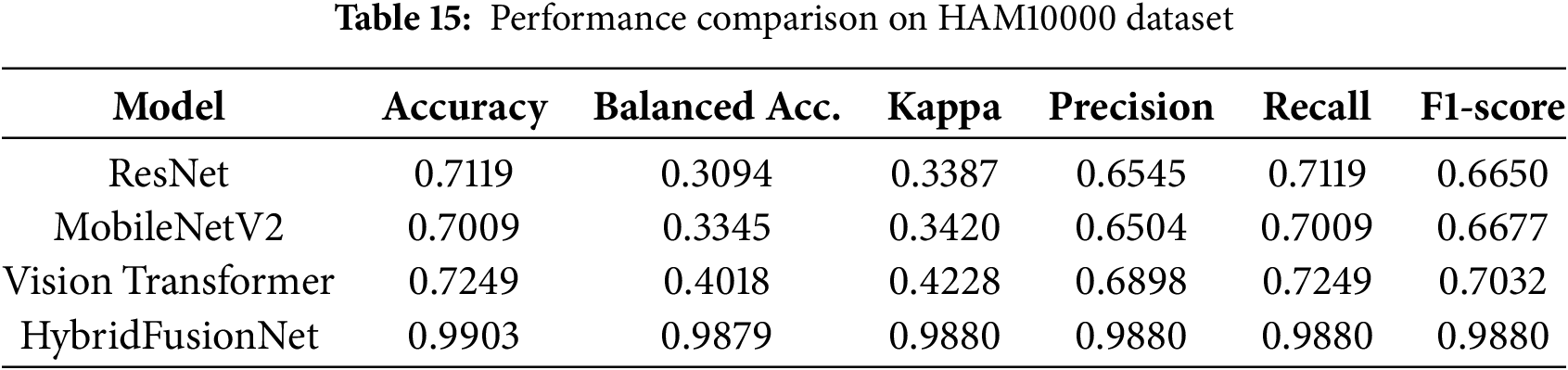

4.3 Comparison with Baseline Models

To strengthen the credibility of our study, we compared HybridFusionNet with several widely adopted architectures, including Baseline ResNet, MobileNetV2, and Vision Transformer (ViT) on both the HAM10000 and BCN20000 datasets.

• HAM10000 Dataset

The results, summarized in Table 15, demonstrate that HybridFusionNet substantially outperforms all baselines across multiple performance metrics.

The comparative evaluation highlights that HybridFusionNet significantly outperforms conventional baselines across all metrics. While baseline ResNet, MobileNetV2, and Vision Transformer models struggled with rare lesion classes, leading to low balanced accuracy and moderate F1-scores, HybridFusionNet achieved accuracy of 0.9903, balanced accuracy of 0.9879, and macro F1-score of 0.988. This improvement reflects the hybrid model’s ability to capture both local and global contextual features, ensuring reliable classification even under class imbalance. The results confirm that HybridFusionNet not only surpasses simple CNNs but also outperforms modern architecture such as ResNet, MobileNetV2 and Vision Transformers on the HAM10000 dataset.

• BCN20000 Dataset

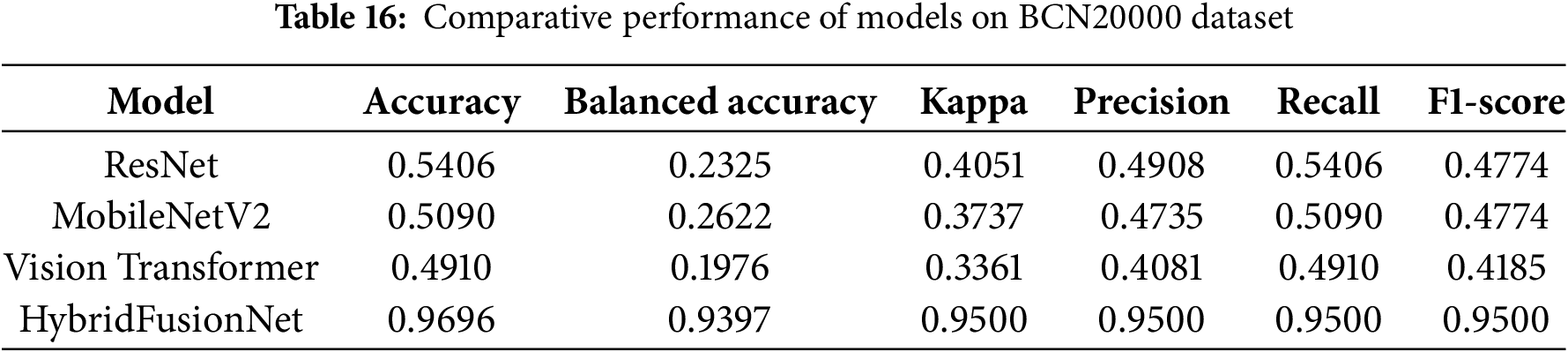

Table 16 presents performance comparisons on the larger BCN20000 dataset.

The BCN20000 dataset demonstrates the robust superiority of HybridFusionNet. While traditional ResNet, MobileNetV2, and Vision Transformer models underperformed due to severe class imbalance and dataset diversity, HybridFusionNet consistently achieved accuracy of 0.9696, balanced accuracy of 0.9397, and macro F1-score of 0.9500. These results highlight its effectiveness in capturing discriminative features across both common and rare lesion classes. The hybrid architecture, combining convolutional and transformer components, allows the model to maintain strong generalization, outperforming both lightweight and transformer-based baselines.

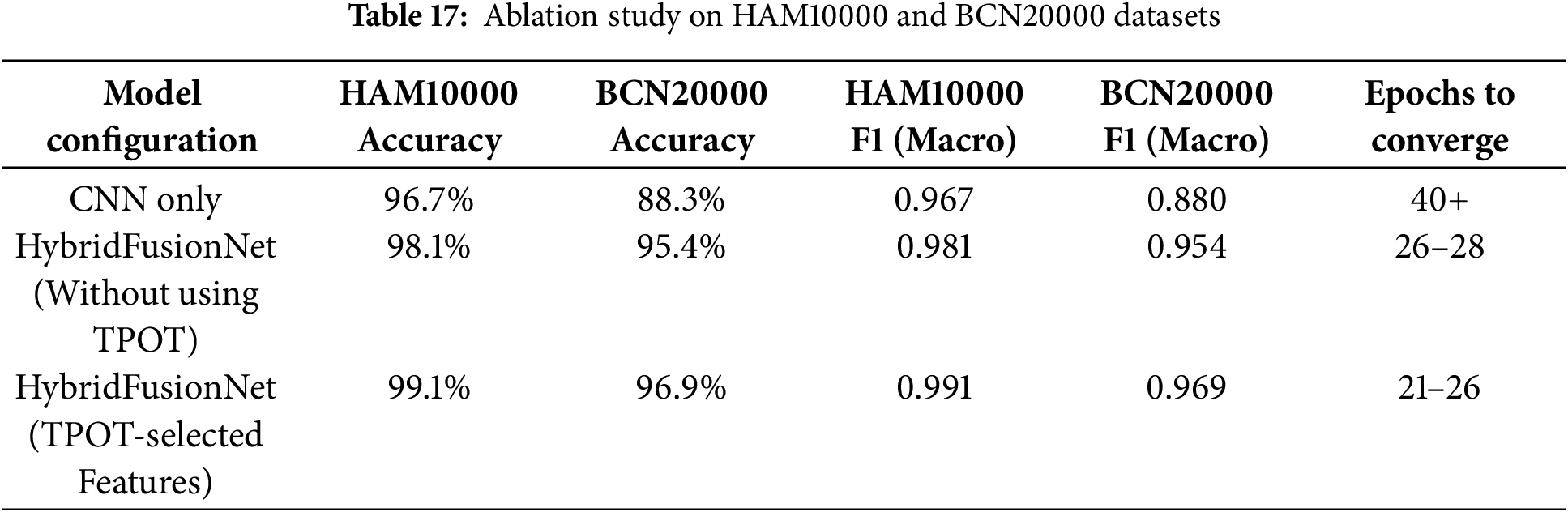

We evaluated the contribution of the 1D handcrafted features and the TPOT selection using an ablation study. Three scenarios were compared:

(1) CNN only: Only the CNN branch was used, no 1D handcrafted features.

(2) HybridFusionNet (Without using TPOT): Both CNN and all handcrafted features were fused.

(3) HybridFusionNet (TPOT-selected features): CNN fused with 32 TPOT-selected 1D features.

The impact of 1D handcrafted features and TPOT-based feature selection on model performance is summarized in Table 17.

Incorporating handcrafted 1D features into the model clearly improved performance compared to using CNN alone. Applying TPOT-based feature selection to identify the most informative features further enhanced accuracy and F1-scores, while also reducing convergence time. Overall, the hybrid model with TPOT-selected features achieved the best results across both datasets, demonstrating that systematic feature selection contributes to greater robustness and generalization in skin lesion classification.

5 Model Interpretability and Discussion

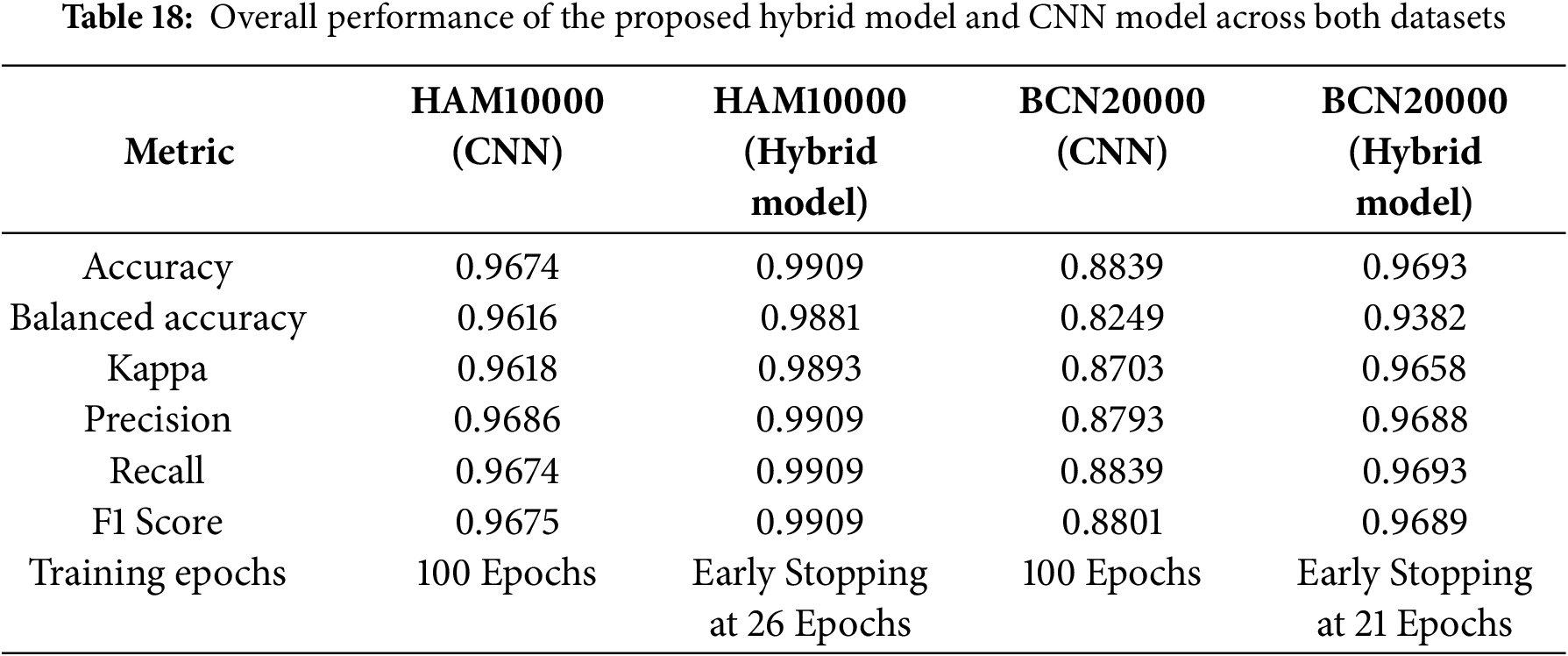

This section provides both quantitative results and qualitative insights, offering a comprehensive understanding of how HybridFusionNet learns, generalizes, and provides reliable predictions across datasets of varying scale and complexity. The results presented in Tables 11 and 14 and in Figs. 7, 8, 10 and 11 highlight the strength of the proposed model in capturing meaningful features and delivering reliable classification outcomes. Compared with traditional CNN, the hybrid architecture demonstrates clear improvements, benefiting from the complementary roles of convolutional layers in learning fine-grained details and transformer blocks in modeling broader contextual relationships. The stability of performance across validation folds further suggests that the model generalizes well and is not overly sensitive to variations in the data. Although slight variations were noted in precision and recall, these remain within acceptable limits and are likely influenced by the inherent complexity and overlap among certain classes.

Table 18 summarizes overall performance across both datasets. HybridFusionNet consistently achieved superior results across all metrics while also demonstrating computational efficiency through early stopping. Specifically, HybridFusionNet reached accuracies of 0.9909 (HAM10000) and 0.9693 (BCN20000), compared to CNN accuracies of 0.9674 and 0.8839, respectively. These findings underline the robustness and generalizability of the proposed hybrid approach across datasets of varying scale and complexity.

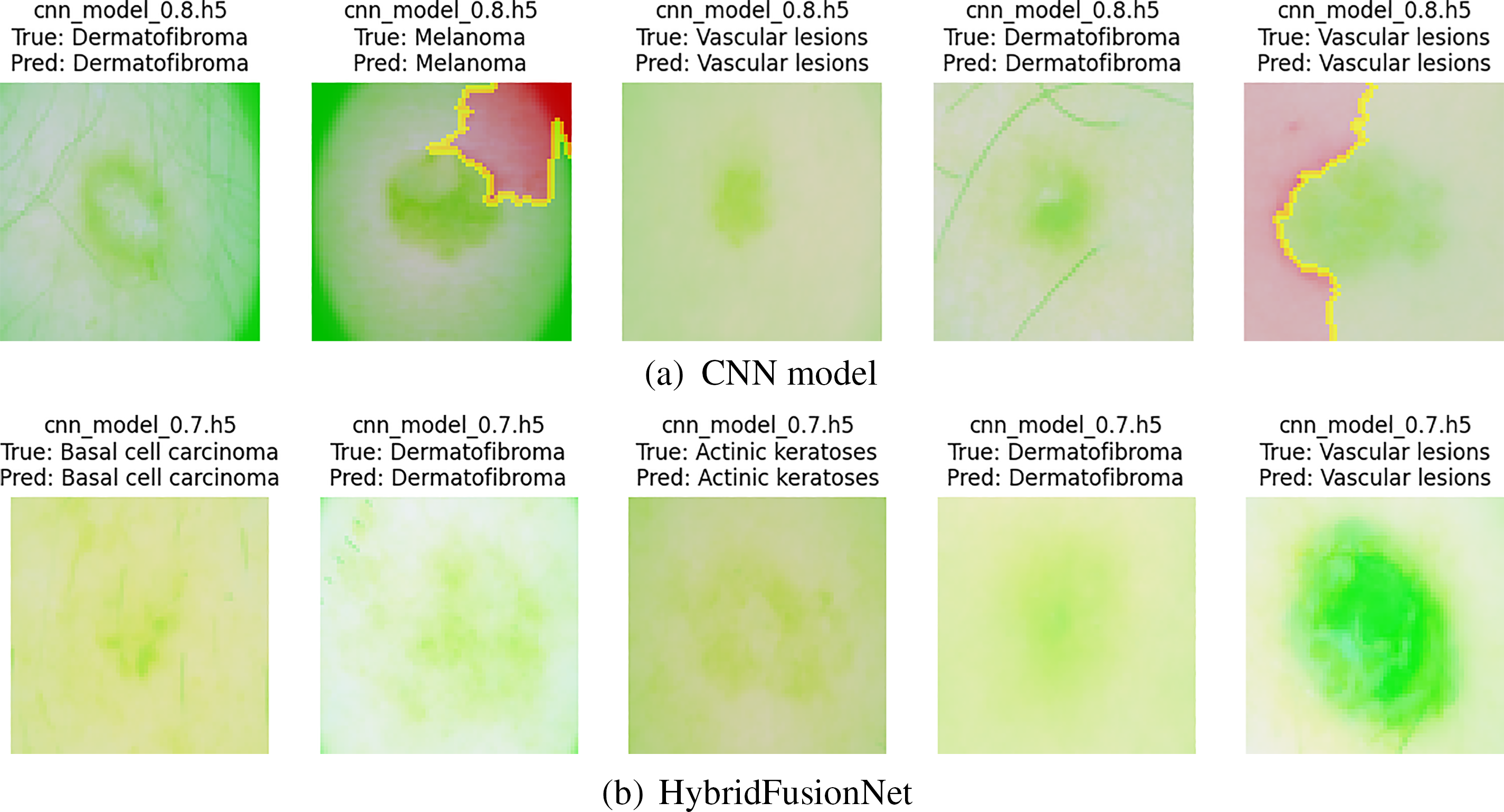

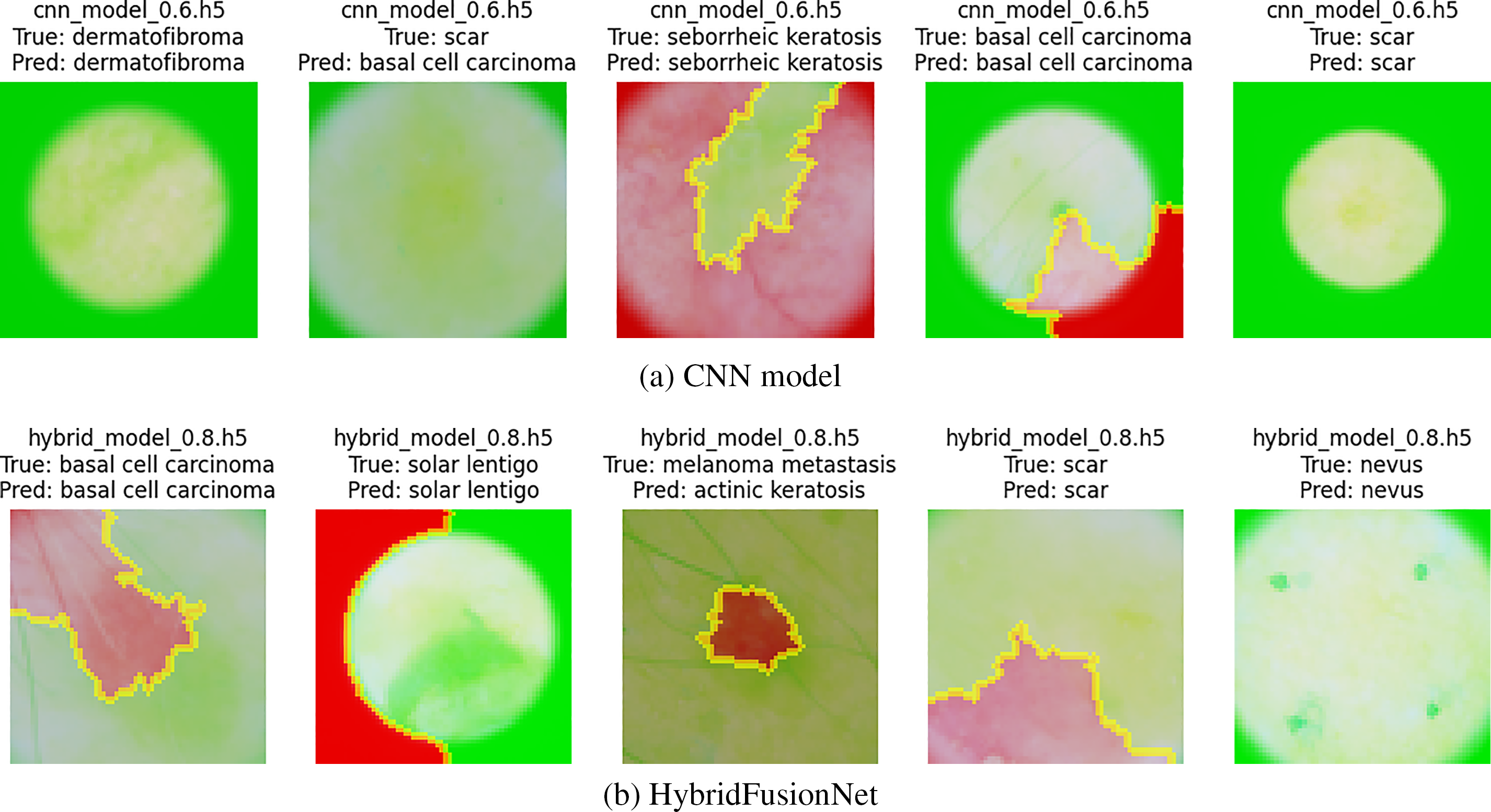

The LIME-based interpretability analysis shown in Figs. 14 and 15 offers a deeper understanding of how the models process and prioritize image features across the two datasets. While both models highlight clinically relevant regions, distinct differences in interpretability can be observed. The CNN model tends to emphasize either localized or fragmented regions, which may capture fine-grained details but occasionally overlook broader contextual structures. In contrast, our proposed HybridFusionNet demonstrates a more balanced focus, integrating both local and global patterns within the highlighted areas. This behavior aligns with its architectural design, which fuses convolutional feature extraction with transformer-based global reasoning, enabling the model to capture detailed textures without losing contextual information. Such interpretability patterns reinforce the superior reliability of HybridFusionNet, as its predictions are grounded in a more comprehensive representation of disease-specific features. Beyond performance metrics, these explanations illustrate how HybridFusionNet provides a more transparent and clinically meaningful decision-making process, thereby strengthening its potential for real-world medical applications.

Figure 14: LIME explanation of both models on HAM10000 dataset

Figure 15: LIME explanation of both models on BCN20000 dataset

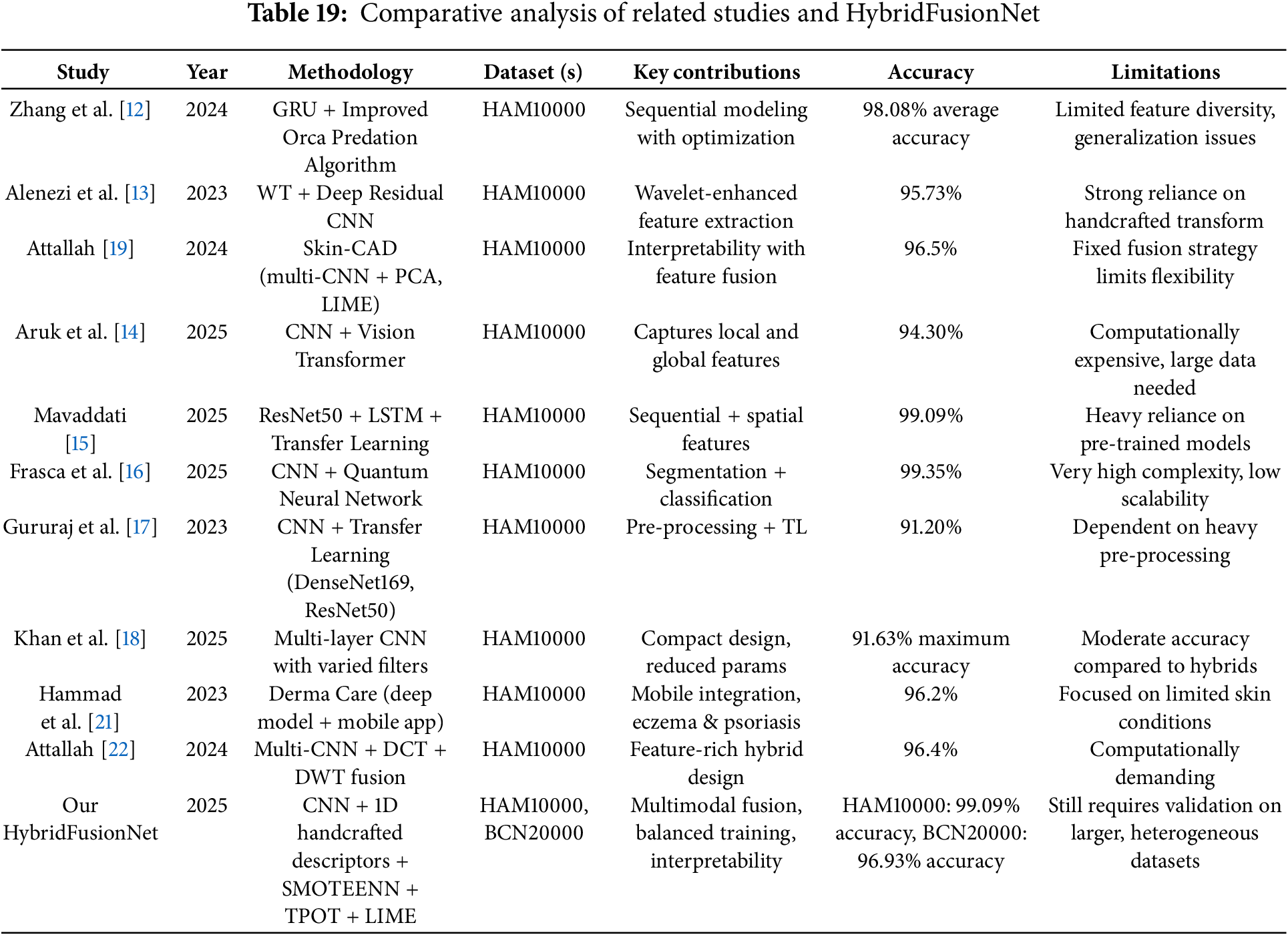

Recent studies have made notable progress in skin cancer detection by employing diverse deep learning architectures, ranging from GRU-based models [12] and wavelet-enhanced CNNs [13] to explainable CAD frameworks [19] and lightweight CNNs [20]. Hybrid approaches, such as CNN–ViT combinations [14], ResNet50–LSTM networks [15], and CNN–QNN models [16], have shown impressive accuracy but often at the expense of computational complexity or scalability. While these models demonstrate strong diagnostic performance, many rely on single-modal architectures, heavy pre-processing, or pre-trained backbones, which may reduce adaptability in real-world clinical settings. In contrast, our proposed HybridFusionNet addresses these limitations by combining CNN-derived deep features with handcrafted 1D descriptors, enhanced through SMOTEENN for class balancing, TPOT for automated feature selection, and LIME for interpretability. This integration enables the model to capture both high-level semantic and fine-grained textural details, leading to superior performance on HAM10000 and BCN20000 datasets. A detailed comparison of related studies with the proposed HybridFusionNet is presented in Table 19.

The proposed HybridFusionNet demonstrates clear advantages over CNN model by achieving superior classification performance across all metrics on both datasets. Notably, it requires fewer epochs and significantly less training time, highlighting its efficiency alongside accuracy. This efficiency stems from its dual-branch fusion of CNN-derived semantic features with handcrafted descriptors, enabling richer representation while reducing overfitting through normalization, dropout, and early stopping. The integration of LIME-based interpretability further enhances its clinical relevance. However, its architectural complexity may still challenge deployment in highly resource-constrained environments. The model’s novelty lies in its fusion-driven design and interpretability emphasis. Future research should explore model compression [34], large-scale clinical validation [35], and adaptation through transfer learning to broaden its practical impact [36].

In this study, we proposed HybridFusionNet, a novel deep learning framework for skin cancer classification that integrates convolutional feature extraction with transformer-based global context modeling. Extensive evaluation on the HAM10000 and BCN20000 datasets demonstrated its superiority over conventional CNN architectures. The proposed HybridFusionNet achieves higher accuracy of 99% and 96.93% for HAM10000 and BCN20000 datasets, respectively, while maintaining robustness across diverse lesion types. The model’s hybrid design addresses limitations of existing single-architecture methods by capturing both fine-grained local features and long-range dependencies, leading to improved diagnostic reliability. Despite its strong performance, challenges remain in terms of generalization across larger, more heterogeneous datasets and the computational demands of training on high-resolution images. The proposed model offers a promising direction for clinical decision support, with future work focusing on optimization for real-time deployment, integration with multimodal patient data, and validation on broader clinical cohorts. The source code for the proposed HybridFusionNet is available upon request.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R196), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors also would like to acknowledge Prince Sultan University for their valuable support.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R196), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Mohamed Hammad, Mohammed ElAffendi and Souham Meshoul; methodology, Mohamed Hammad; software, Mohamed Hammad; validation, Mohammed ElAffendi and Souham Meshoul; formal analysis, Mohamed Hammad, Mohammed ElAffendi and Souham Meshoul; investigation, Mohamed Hammad and Mohammed ElAffendi; resources, Souham Meshoul; data curation, Mohamed Hammad; writing—original draft preparation, Mohamed Hammad and Souham Meshoul; writing—review and editing, Mohamed Hammad, Mohammed ElAffendi and Souham Meshoul; visualization, Mohamed Hammad, Mohammed ElAffendi and Souham Meshoul; supervision, Mohammed ElAffendi; project administration, Souham Meshoul; funding acquisition, Souham Meshoul. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/DBW86T (accessed on 29 August 2025) and https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/radwahashiesh/bcn20000 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Arnold M, Singh D, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Vaccarella S, Meheus F, et al. Global burden of cutaneous melanoma in 2020 and projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(5):495–503. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Kassem MA, Hosny KM, Damaševičius R, Eltoukhy MM. Machine learning and deep learning methods for skin lesion classification and diagnosis: a systematic review. Diagnostics. 2021;11(8):1390. doi:10.3390/diagnostics11081390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Ahmad N, Shah JH, Khan MA, Baili J, Ansari GJ, Tariq U, et al. A novel framework of multiclass skin lesion recognition from dermoscopic images using deep learning and explainable AI. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1151257. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1151257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Tschandl P, Rinner C, Apalla Z, Argenziano G, Codella N, Halpern A, et al. Human-computer collaboration for skin cancer recognition. Nat Med. 2020;26(8):1229–34. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0942-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Nematzadeh H, García-Nieto J, Navas-Delgado I, Aldana-Montes JF. Ensemble-based genetic algorithm explainer with automized image segmentation: a case study on melanoma detection dataset. Comput Biol Med. 2023;155:106613. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.106613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Gao Y, Jiang Y, Peng Y, Yuan F, Zhang X, Wang J. Medical image segmentation: a comprehensive review of deep learning-based methods. Tomography. 2025;11(5):52. doi:10.3390/tomography11050052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Varoquaux G, Cheplygina V. Machine learning for medical imaging: methodological failures and recommendations for the future. npj Digit Med. 2022;5(1):48. doi:10.1038/s41746-022-00592-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Rahman MA, Masum MI, Hasib KM, Mridha MF, Alfarhood S, Safran M, et al. GliomaCNN: an effective lightweight CNN model in assessment of classifying brain tumor from magnetic resonance images using explainable AI. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;140(3):2425–48. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.050760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Mienye ID, Swart TG. A comprehensive review of deep learning: architectures, recent advances, and applications. Information. 2024;15(12):755. doi:10.3390/info15120755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bechelli S, Delhommelle J. Machine learning and deep learning algorithms for skin cancer classification from dermoscopic images. Bioengineering. 2022;9(3):97. doi:10.3390/bioengineering9030097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Brinker TJ, Hekler A, Enk AH, Klode J, Hauschild A, Berking C, et al. Deep learning outperformed 136 of 157 dermatologists in a head-to-head dermoscopic melanoma image classification task. Eur J Cancer. 2019;113:47–54. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.04.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang L, Zhang J, Gao W, Bai F, Li N, Ghadimi N. A deep learning outline aimed at prompt skin cancer detection utilizing gated recurrent unit networks and improved orca predation algorithm. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2024;90:105858. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2023.105858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Alenezi F, Armghan A, Polat K. Wavelet transform based deep residual neural network and ReLU based extreme learning machine for skin lesion classification. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;213:119064. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.119064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Aruk I, Pacal I, Toprak AN. A novel hybrid ConvNeXt-based approach for enhanced skin lesion classification. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;283:127721. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.127721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Mavaddati S. Skin cancer classification based on a hybrid deep model and long short-term memory. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2025;100:107109. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2024.107109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Frasca M, Cutica I, Pravettoni G, La Torre D. Optimizing melanoma diagnosis: a hybrid deep learning and quantum computing approach for enhanced lesion classification. Intell-Based Med. 2025;12:100264. doi:10.1016/j.ibmed.2025.100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Gururaj HL, Manju N, Nagarjun A, Manjunath Aradhya VN, Flammini F. DeepSkin: a deep learning approach for skin cancer classification. IEEE Access. 2023;11:50205–14. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3274848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Khan MA, Rastogi D, Johri P, Al-Taani A, Baghela VS, Kumud. Hybrid deep CNN model for multi-class classification of skin lesion. Neural Comput Appl. 2025;37(23):19479–99. doi:10.1007/s00521-025-11409-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Attallah O. Skin-CAD: explainable deep learning classification of skin cancer from dermoscopic images by feature selection of dual high-level CNNs features and transfer learning. Comput Biol Med. 2024;178:108798. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.108798. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Tuncer T, Barua PD, Tuncer I, Dogan S, Acharya UR. A lightweight deep convolutional neural network model for skin cancer image classification. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;162:111794. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hammad M, Pławiak P, ElAffendi M, El-Latif AAA, Abdel Latif AA. Enhanced deep learning approach for accurate eczema and psoriasis skin detection. Sensors. 2023;23(16):1–17. doi:10.3390/s23167295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Attallah O. A hybrid trio-deep feature fusion model for improved skin cancer classification: merging dermoscopic and DCT images. Technologies. 2024;12(10):190. doi:10.3390/technologies12100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Toumaj S, Heidari A, Jafari Navimipour N. Leveraging explainable artificial intelligence for transparent and trustworthy cancer detection systems. Artif Intell Med. 2025;169:103243. doi:10.1016/j.artmed.2025.103243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Hameed M, Zameer A, Raja MAZ. A comprehensive systematic review: advancements in skin cancer classification and segmentation using the ISIC dataset. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;140(3):2131–64. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.050124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Tschandl P, Rosendahl C, Kittler H. The HAM10000 dataset, a large collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of common pigmented skin lesions. Sci Data. 2018;5:180161. doi:10.1038/sdata.2018.161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Hernández-Pérez C, Combalia M, Podlipnik S, Codella NCF, Rotemberg V, Halpern AC, et al. BCN20000: dermoscopic lesions in the wild. Sci Data. 2024;11(1):641. doi:10.1038/s41597-024-03387-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Husain G, Nasef D, Jose R, Mayer J, Bekbolatova M, Devine T, et al. SMOTE vs. SMOTEENN: a study on the performance of resampling algorithms for addressing class imbalance in regression models. Algorithms. 2025;18(1):37. doi:10.3390/a18010037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang Z. Improved Adam optimizer for deep neural networks. In: 2018 IEEE/ACM 26th International Symposium on Quality of Service (IWQoS); 2018 Jun 4–6; Banff, AB, Canada. doi:10.1109/IWQoS.2018.8624183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Terven J, Cordova-Esparza DM, Romero-González JA, Ramírez-Pedraza A, Chávez-Urbiola EA. A comprehensive survey of loss functions and metrics in deep learning. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(7):195. doi:10.1007/s10462-025-11198-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Sokolova M, Lapalme G. A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Inf Process Manage. 2009;45(4):427–37. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2009.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Hassan SU, Abdulkadir SJ, Zahid MSM, Al-Selwi SM. Local interpretable model-agnostic explanation approach for medical imaging analysis: a systematic literature review. Comput Biol Med. 2025;185:109569. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.109569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Glorot X, Bordes A, Bengio Y. Deep sparse rectifier neural networks. In: Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS); 2011 Apr 11–13; Lauderdale, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

33. Wang TW, Tzeng YH, Wu KT, Liu HR, Hong JS, Hsu HY, et al. Meta-analysis of deep learning approaches for automated coronary artery calcium scoring: performance and clinical utility AI in CAC scoring: a meta-analysis. Comput Biol Med. 2024;183:109295. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.109295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Dantas PV, Sabino da Silva W, Cordeiro LC, Carvalho CB. A comprehensive review of model compression techniques in machine learning. Appl Intell. 2024;54(22):11804–44. doi:10.1007/s10489-024-05747-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Long Q, Tian Y, Pan B, Xu Z, Zhang W, Xu L, et al. Clinical validation of a deep learning model for low-count PET image enhancement. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2025;49:480. doi:10.1007/s00259-025-07370-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Disci R, Gurcan F, Soylu A. Advanced brain tumor classification in MR images using transfer learning and pre-trained deep CNN models. Cancers. 2025;17(1):121. doi:10.3390/cancers17010121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools