Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Extending DDPG with Physics-Informed Constraints for Energy-Efficient Robotic Control

1 Department of Software Engineering, College of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Jeddah, Jeddah, 21959, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Computer and Information System, Bisha Applied College, University of Bisha, Bisha, 61911, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Computer Science, Applied College, Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University, P.O. Box 84428, Riyadh, 11671, SaudiArabia

4 Faculty of Computing and Information Technology, King Abdulaziz University-Rabigh, Rabigh, 21589, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Computing, Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Seri Iskandar, 32610, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Abubakar Elsafi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Methods Applied to Energy Systems)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 621-647. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.072726

Received 02 September 2025; Accepted 04 October 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Energy efficiency stands as an essential factor when implementing deep reinforcement learning (DRL) policies for robotic control systems. Standard algorithms, including Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG), primarily optimize task rewards but at the cost of excessively high energy consumption, making them impractical for real-world robotic systems. To address this limitation, we propose Physics-Informed DDPG (PI-DDPG), which integrates physics-based energy penalties to develop energy-efficient yet high-performing control policies. The proposed method introduces adaptive physics-informed constraints through a dynamic weighting factor (λ), enabling policies that balance reward maximization with energy savings. Our motivation is to overcome the impracticality of reward-only optimization by designing controllers that achieve competitive performance while substantially reducing energy consumption. PI-DDPG was evaluated in nine MuJoCo continuous control environments, where it demonstrated significant improvements in energy efficiency without compromising stability or performance. Experimental results confirm that PI-DDPG substantially reduces energy consumption compared to standard DDPG, while maintaining competitive task performance. For instance, energy costs decreased from 5542.98 to 3119.02 in HalfCheetah-v4 and from 1909.13 to 1586.75 in Ant-v4, with stable performance in Hopper-v4 (205.95 vs. 130.82) and InvertedPendulum-v4 (322.97 vs. 311.29). Although DDPG sometimes yields higher rewards, such as in HalfCheetah-v4 (5695.37 vs. 4894.59), it requires significantly greater energy expenditure. These results highlight PI-DDPG as a promising energy-conscious alternative for robotic control.Keywords

Reinforcement learning (RL) has demonstrated remarkable success in training agents to solve complex tasks in simulated environments, with algorithms like Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) excelling in continuous control problems [1]. However, a critical limitation of conventional RL approaches is their predominant focus on reward maximization, often overlooking energy efficiency as a key concern in real-world applications such as robotics [2], autonomous systems [3], and resource-constrained environments [4]. While high-reward performance is desirable, excessive energy consumption can render policies impractical for deployment, particularly in systems with finite power resources or physical durability constraints [5].

Traditional RL methodologies can be categorized into several approaches, each with its strengths and limitations. Value-based methods, such as Q-learning [6], estimate the value of each state or state-action pair, using these estimates to guide decision-making. Policy-based methods, like REINFORCE Simple [7], directly optimize the policy, which is the strategy the agent uses to choose actions. Actor-critic algorithms, such as those described by [8], combine both, using a value function to critique and improve the policy.

With the coming of deep learning, deep RL methods have emerged to handle high-dimensional state and action spaces. Deep Q-Networks (DQN), introduced by [3], use deep neural networks to approximate Q-values, enabling RL to tackle tasks like playing Atari games from pixel inputs. DDPG, proposed by [1], extends this to continuous control problems, making it suitable for robotic applications. These methods have shown remarkable success in simulated environments, but their application to real-world scenarios, especially in robotics, reveals significant challenges.

One of the primary challenges in RL is sample inefficiency, which refers to the large number of interactions required for the agent to learn an optimal policy. This is particularly problematic in real-world settings where each interaction can be costly or time-consuming. For instance, in robotics, training a robot to perform a task like locomotion might require thousands of physical trials, each involving energy consumption, wear and tear, and potential safety risks [9]. The survey by [10] highlights that model-free RL algorithms, which learn directly from interactions without a model of the environment, are especially sample-inefficient. This is because they rely on exploration to discover the optimal policy, often requiring extensive data to converge. In contrast, real-world applications like autonomous drones or industrial robots have limited opportunities for interaction due to cost and safety constraints.

To address sample inefficiency, several strategies have been proposed. Transfer learning, as studied by [11], involves using knowledge gained from one task to speed up learning in a related task, reducing the number of interactions needed. Meta-learning, exemplified by [12], aims to learn how to learn, enabling faster adaptation to new tasks with fewer samples. Model-based RL, such as Probabilistic Inference for Learning Control (PILCO) by [13], learns a model of the environment to simulate and plan, significantly reducing the need for real-world interactions.

Another critical challenge is the lack of adherence to physical laws in standard RL algorithms. Traditional RL models the environment as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), where the transition dynamics are probabilistic and may not accurately reflect the physical constraints of the system. This can lead to policies that are not feasible or efficient in reality, particularly in domains like robotics where physical laws, such as conservation of energy, momentum, and mechanical constraints, are crucial [14].

For instance, a standard RL algorithm might learn a policy for a robot to move quickly to achieve high rewards, but this could result in excessive energy consumption, overheating, or mechanical wear, rendering the policy impractical for deployment. The survey by [15] notes that standard RL often ignores domain-specific knowledge, leading to a sim-to-real gap where policies learned in simulation fail to transfer to the real world due to discrepancies in physical behaviors.

Recent efforts have explored penalty-based methods to incorporate energy constraints. Authors in [16] introduced entropy regularization in Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) to optimize trade-offs between exploration and energy use, but their approach lacks explicit physics-informed penalties. Similarly, reference [1] demonstrated DDPG effectiveness in high-dimensional action spaces but did not address energy efficiency. Another recent study [17] proposed energy-constrained DRL by penalizing torque magnitudes, yet their static penalty coefficients fail to adapt to dynamic environments. These limitations highlight the need for adaptive, physics-grounded energy penalties, a gap our work addresses.

Existing energy-constrained reinforcement learning approaches typically employ fixed penalty coefficients, such as constant torque limits or static energy costs, which do not adapt to varying task dynamics [18]. In contrast, Physics-Informed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (PI-DDPG) introduces an adaptive, physics-informed penalty guided by the learnable parameter

Considering robotic locomotion tasks like those in OpenAI Gym environments, which simulate physics-based control. Without incorporating physical laws, RL might generate actions that violate torque limits or energy constraints, leading to unstable or inefficient movements. This issue is particularly relevant in energy-efficient robotic control, where minimizing power consumption is as important as achieving task performance [19].

Physics-informed RL has gained traction for embedding domain knowledge into learning frameworks [20,21]. For instance, authors in [22] propose using differentiable physics engines to incorporate mechanical constraints, ensuring that the learned policies respect physical laws. This approach improves both sample efficiency and the realism of the learned policies, making them more suitable for real-world deployment. This integration is particularly crucial for energy-efficient applications, where respecting physical laws like power dissipation and mechanical work can lead to significant reductions in energy consumption [17,23,24].

We propose Physics-Informed DDPG (PI-DDPG), a variant of DDPG that dynamically adjusts energy penalties using physics-informed constraints such as mechanical work and power dissipation. Unlike prior methods with fixed penalties, PI-DDPG employs a learnable lambda parameter to balance reward and energy objectives, inspired by the Lagrangian multiplier framework in constrained optimization.

This manuscript comprehensively evaluates DDPG and PI-DDPG across nine diverse OpenAI Gym environments, including Ant-v4, HalfCheetah-v4, and Hopper-v4. We analyze three core aspects: (1) reward performance, (2) energy efficiency, and (3) the reward-energy trade-off, supported by ablation studies and dynamic parameter analyses. Key innovations include a physics-derived energy penalty mechanism and an adaptive weighting parameter lambda that autonomously balances competing objectives during training.

The contributions of this work are threefold:

• Physics-informed reward design: We introduce PI-DDPG, the first DDPG variant that explicitly incorporates mechanical work and power dissipation into the reward structure through a physics-informed energy penalty.

• Adaptive

• Comprehensive validation and trade-off insights: Through extensive benchmarking on nine MuJoCo environments, PI-DDPG demonstrates substantial energy savings (up to

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: (Section 2) reviews related work in energy-aware RL. (Section 3) details the methodology of PI-DDPG. (Sections 4 and 5) present the results and discuss implications and future directions, followed by conclusions in (Section 6).

In recent years, DRL has emerged as a powerful tool for robotic control, enabling agents to tackle complex tasks in simulated environments. However, its emphasis on reward maximization often neglects critical aspects such as energy efficiency and physical realism, which are essential for real-world deployment. This section reviews prior work in three key areas: energy-efficient DRL (Section 2.1), physics-informed DRL (Section 2.2), and DRL for robotic control (Section 2.3). By analyzing their approaches, outcomes, and key insights, we establish the foundation for our PI-DDPG as a significant advancement in this domain.

Along with reinforcement learning, a number of conventional and mixed methods have been investigated to control the robots. An example is Iterative Learning Control (ILC) that has been successfully used in repetitive tasks, including robotic arm trajectory tracking, whereby the control policies are refined with each repetition, by the benefit of repetitiveness of the task [25]. On the same note, adaptive control systems are used to react to uncertainties by online adjustment of system parameters, and model-based design frameworks like optimal and robust control are used to be explicit in ensuring stability by incorporating system dynamics. Such methods as tuning PID based on machine learning show success in flexible joint robots and mobile robot navigation, as well as in data-driven approaches [26,27]. Although these approaches offer deep theoretical guarantees and resilience, they tend to fail in non-linear, high-dimensional settings where DRL is effective, making the integration of RL and physics-informed constraints to provide scalable, energy-efficient control relevant [28,29].

Recent gradient-based methods have been shown to reduce computational cost and improve convergence for specific control problems. For example, MSFA tuning of FOPID controllers in AVR systems achieves high accuracy with fewer evaluations and better convergence stability [30], and NL-SFA identification for fractional Hammerstein models delivers stable, precise convergence while avoiding divergence [31].

These approaches highlight efficient gradient-based optimization but are primarily tailored for fixed-dynamics control or system identification tasks. By contrast, DDPG supports end-to-end policy learning in high-dimensional, continuous action spaces with perception and delayed rewards, making it more suitable for scalable robotic control while still leaving room for hybrid strategies that borrow efficiency ideas from MSFA and NL-SFA.

2.1 Energy Efficiency in Deep Reinforcement Learning

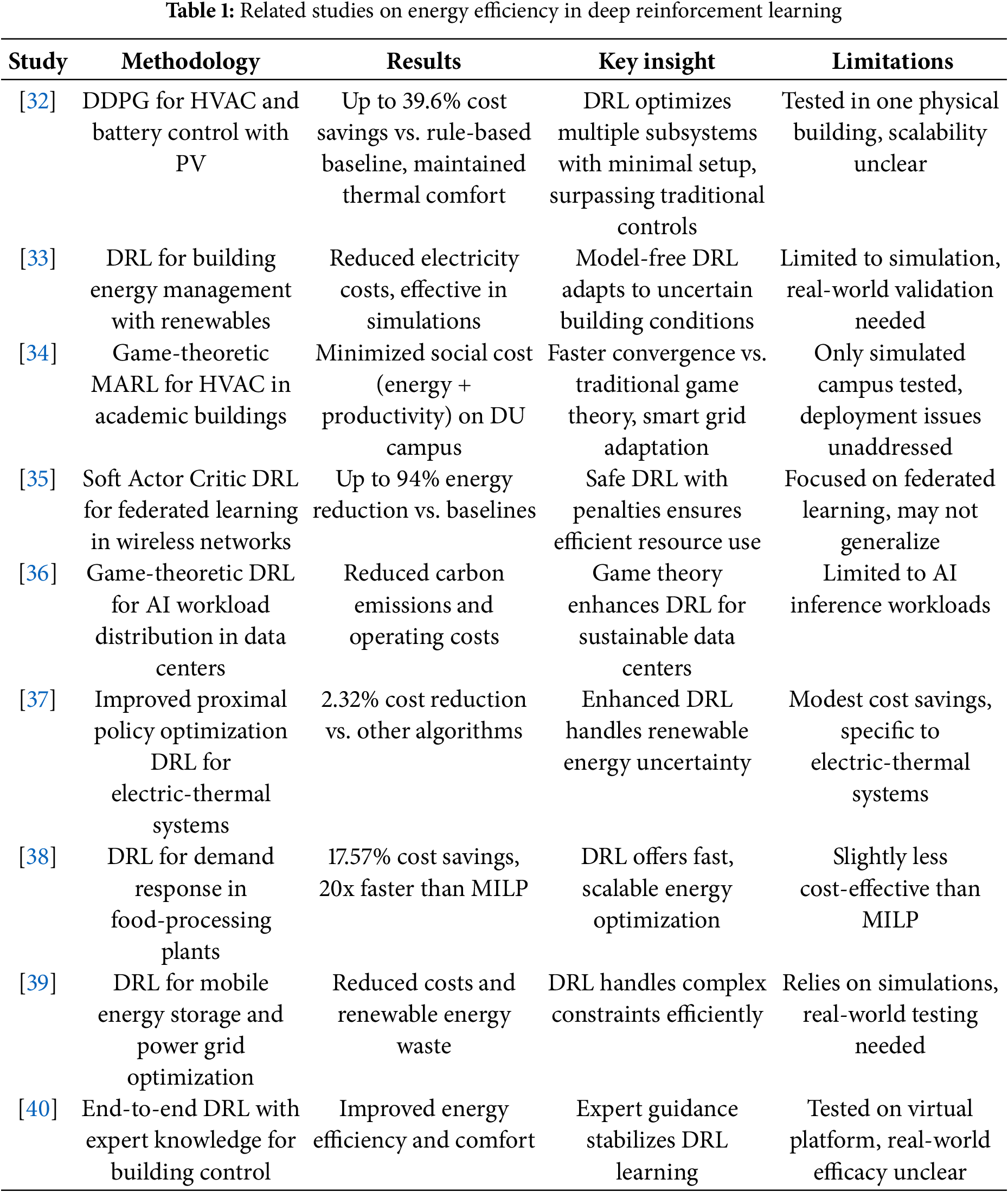

Energy efficiency in DRL has advanced significantly, particularly optimizing energy use across buildings, data centers, wireless networks, and renewable energy systems. Reference [32] proposes a DRL approach using a DDPG algorithm to control HVAC and battery storage in buildings with on-site PV, achieving up to 39.6% cost savings compared to rule-based baselines while maintaining thermal comfort. Reference [33] introduces a DRL-based energy management method for buildings with renewable sources, minimizing electricity costs without modeling building dynamics, verified through simulations. Reference [34] explores game-theoretic DRL for HVAC control in academic buildings. Another study in [35] presents a Soft Actor Critic DRL approach for federated learning in wireless networks, reducing energy consumption by up to 94% through resource orchestration and synchronization. Reference [36] combines game theory and DRL to optimize AI workload distribution in geo-distributed data centers, reducing carbon emissions and operating costs. Reference [37] uses an improved proximal policy optimization DRL algorithm for integrated electric-thermal energy systems, lowering costs by 2.32% compared to other methods. Moreover, reference [38] applies DRL for demand response in food-processing plants, achieving 17.57% cost savings and faster computation than MILP. Reference [39] proposes a DRL-based method for joint optimization of mobile energy storage systems and power grids, minimizing costs and renewable energy waste. Reference [40] develops an end-to-end DRL paradigm for building control, incorporating expert knowledge and neural network smoothness to enhance energy efficiency and occupant comfort, tested on a virtual EnergyPlus platform. Table 1 presents related studies on energy efficiency in DRL.

Surveys on energy efficiency in RL and DRL highlight the growing role of these techniques in addressing sustainability challenges across various domains. One study in [41] reviews machine and deep learning applications in the built environment, emphasizing DRL’s success in optimizing HVAC systems and building energy efficiency, though noting that most studies remain experimental and lack real-world implementation. Furthermore, reference [42] systematically examines RL and DRL for data center energy efficiency, focusing on cooling systems and ICT processes like task scheduling, and identifies gaps in real-time validation and standardized metrics for multi-system optimization. Similarly, reference [43] analyzes DRL-based task scheduling in cloud data centers, highlighting significant energy savings but pointing to the need for deeper exploration of Markov Decision Process variations and experimental platforms. Another survey in [44] classifies RL algorithms for intelligent building control, noting their effectiveness in reducing energy consumption and outlining future directions for addressing complex control challenges. Lastly, reference [45] broadly surveys RL applications in sustainable energy, covering energy production, storage, and consumption, and emphasizes the potential of multi-agent, offline, and safe RL approaches while advocating for standardized environments to bridge energy and machine learning research.

2.2 Physics-Informed Deep Reinforcement Learning

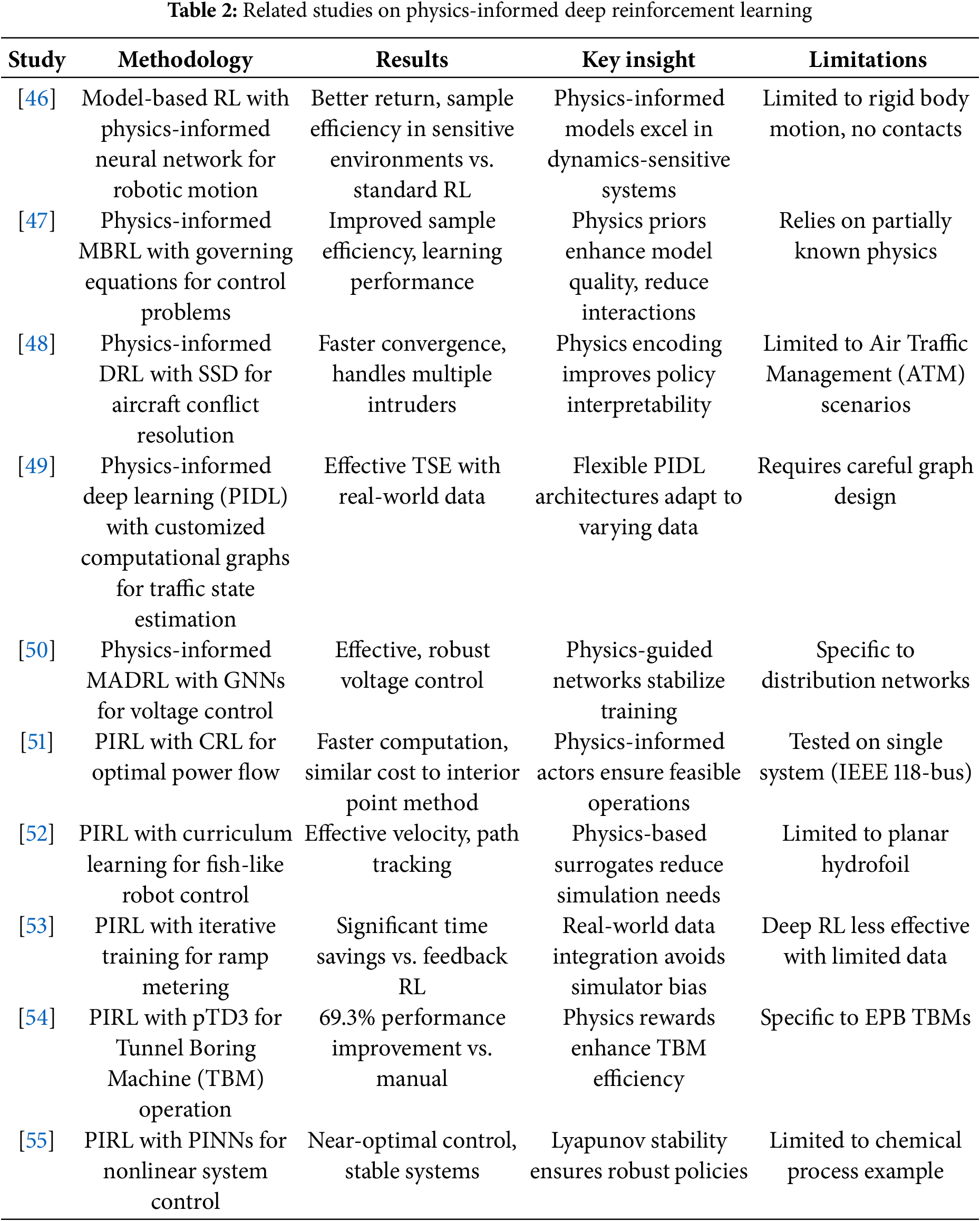

Physics-informed deep reinforcement learning (PIRL) has advanced significantly, integrating physical knowledge to enhance the realism and efficiency of DRL in various domains. One study in [46] employs a model-based RL approach with a physics-informed neural network for robotic motion, achieving superior average return and sample efficiency in dynamics-sensitive environments compared to standard RL. Furthermore, reference [47] proposes a physics-informed model-based RL framework that leverages governing equations to improve model quality and sample efficiency across classic control problems. Similarly, reference [48] develops a PIRL method using solution space diagrams for aircraft conflict resolution, demonstrating faster convergence and the ability to handle multiple intruders with interpretable policies.

Another approach in [49] utilizes physics-informed deep learning with customized computational graphs for traffic state estimation, effectively adapting to diverse data and problem types. In addition, reference [50] introduces a physics-informed multi-agent DRL framework with graph neural networks for distributed voltage control in power networks, ensuring robust performance with local measurements. Moreover, reference [51] presents a PIRL method based on constrained RL for optimal power flow, achieving faster computation than traditional methods while maintaining comparable costs.

Meanwhile, reference [52] applies PIRL with curriculum learning to control fish-like swimming robots, enabling effective velocity and path tracking by leveraging physics-based surrogate models. Another study in [53] proposes a PIRL-based ramp metering strategy with iterative training, significantly reducing total time spent compared to feedback-based methods by incorporating real-world data. Furthermore, reference [54] integrates PIRL with a physics-informed Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic algorithm for tunnel boring machine operations, improving performance by 69.3% over manual methods. Lastly, reference [55] develops a model-free PIRL framework using physics-informed neural networks for nonlinear system control, ensuring near-optimal policies with guaranteed stability in a chemical process application. Table 2 presents related studies on Physics-Informed Deep Reinforcement Learning.

Reviews on PIRL and related physics-informed machine learning (PIML) underscore the transformative potential of integrating physical priors into learning frameworks for enhanced realism and efficiency. One study in [20] provides a comprehensive review of PIRL, introducing a taxonomy based on the RL pipeline to classify works by physics representation, architectural contributions, and learning biases, highlighting improved data efficiency and real-world applicability while identifying gaps in broader application domains. Furthermore, reference [56] explores PIML for multiphysics problems, emphasizing how enforcing physical laws in neural networks improves accuracy and generalization for forward and inverse problems, though noting challenges in handling noisy data and high-dimensional systems. Lastly, reference [57] surveys PIML across machine learning tasks, advocating for the integration of physical priors into model architectures and optimizers to enhance performance in domains like robotics and inverse engineering, while proposing open research problems such as encoding diverse physics forms for complex applications.

2.3 Physics-Informed Deep Reinforcement Learning for Robotic Control

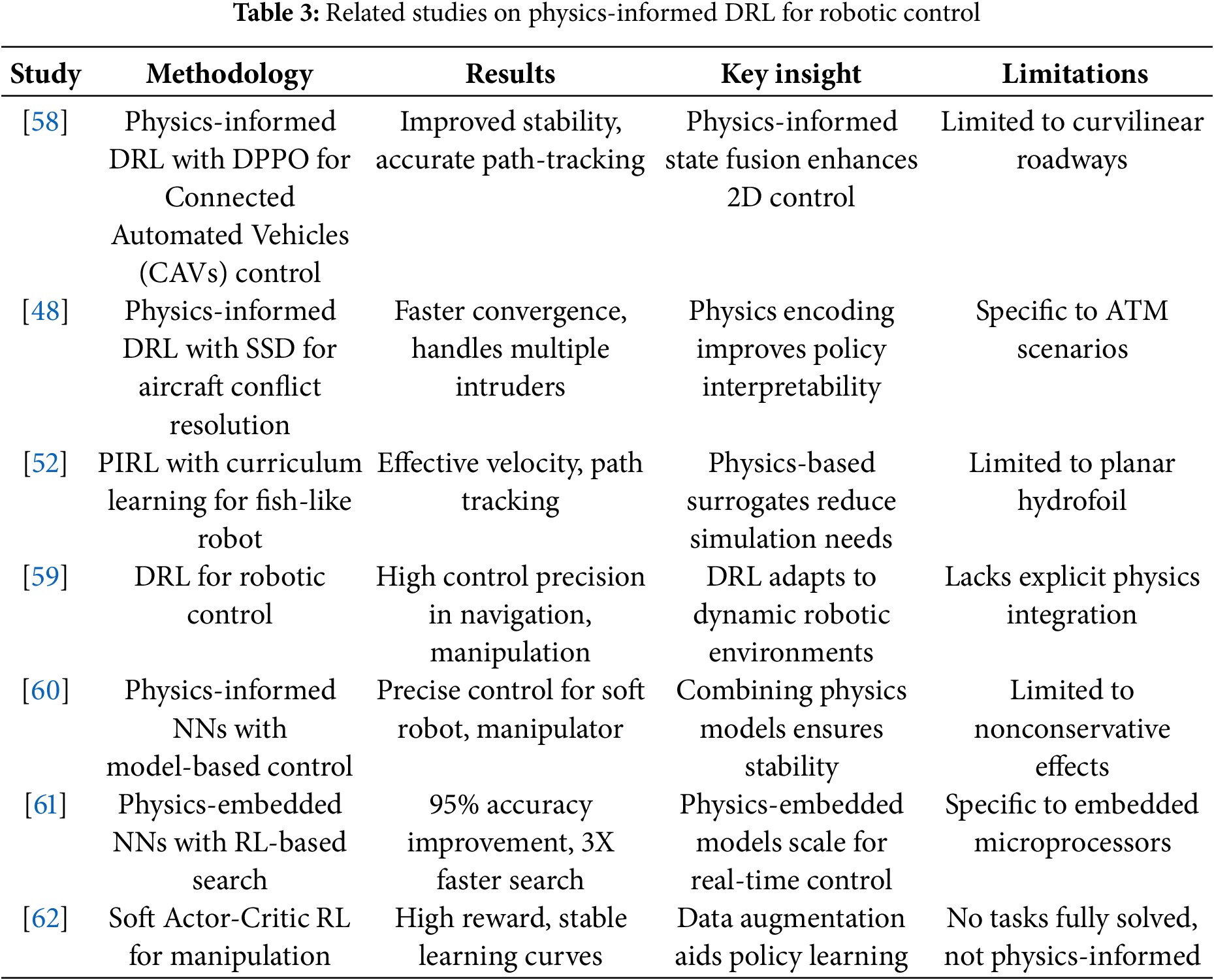

PIRL for robotic control has advanced the integration of physical models to enhance efficiency and realism in tasks like locomotion and manipulation. One study in [58] proposes a physics-informed DRL approach using distributed proximal policy optimization for two-dimensional car-following control of connected automated vehicles, achieving stable longitudinal control and accurate lateral path-tracking by embedding physics knowledge. Furthermore, reference [48] develops a PIRL method with solution space diagrams for aircraft conflict resolution, demonstrating faster convergence and interpretable policies for handling multiple intruders. Similarly, reference [52] applies PIRL with curriculum learning to control fish-like swimming robots, enabling effective velocity and path tracking by leveraging physics-based surrogate models to reduce simulation demands.

In contrast, reference [59] employs DRL for robotic control, achieving high precision in navigation and manipulation but without explicit physics integration, highlighting the potential of general DRL in dynamic environments. Meanwhile, reference [60] combines physics-informed neural networks with model-based controllers for soft robots and manipulators, ensuring precise control and theoretical stability bounds. Another approach in [61] introduces physics-embedded neural networks with a reinforcement learning-based architecture search, improving model accuracy by over 95% and enabling real-time control on resource-limited devices. Lastly, reference [62] evaluates Soft Actor-Critic RL for robotic manipulation, achieving high rewards and stable learning but lacking physics-informed elements, suggesting that data augmentation can enhance general DRL policies. Table 3 presents related studies on Physics-Informed DRL for robotic control.

The collective research across energy efficiency, physics-informed DRL, and robotic control underscores the transformative potential of DRL when augmented with domain-specific knowledge. Studies in energy efficiency demonstrate DRL’s ability to achieve significant cost and energy savings in buildings, data centers, and power systems, though real-world validation remains a challenge. PIRL further enhances DRL by embedding physical priors, improving sample efficiency and realism in applications like traffic, power systems, and robotics, with notable performance gains but often limited to specific domains. In robotic control, PIRL excels in locomotion and manipulation tasks, leveraging physics to ensure stability and precision, yet scalability and broader applicability persist as hurdles. These advancements highlight DRL’s adaptability but emphasize the need for standardized metrics, real-world testing, and generalized frameworks to fully realize its potential across diverse domains.

This section outlines the methodology for developing and evaluating the PI-DDPG algorithm, an enhancement of the standard DDPG algorithm tailored for energy-efficient robotic control. The methodology integrates physics-informed constraints, adaptive energy penalties, and a robust evaluation framework across multiple OpenAI Gym environments. The approach combines algorithmic design, network architecture, training procedures, and evaluation metrics to ensure a comprehensive assessment of PI-DDPG’s performance compared to standard DDPG. The methodology is detailed below, followed by a formal algorithmic description of the training procedure.

The standard DDPG algorithm [1] serves as the baseline, combining an actor-critic architecture with deterministic policy gradients for continuous control tasks. The actor network maps states to actions, while the critic network estimates the Q-value for state-action pairs. The algorithm employs a replay buffer for experience storage and target networks for stable learning, updated via soft updates with a parameter

The DDPG algorithm is based on the deterministic policy gradient theorem [1]. Let

where

PI-DDPG extends DDPG by incorporating physics-informed constraints to penalize energy-inefficient actions. The key innovation is a dynamic energy penalty mechanism that uses mechanical work and power dissipation principles to compute energy costs. A learnable parameter,

where

While standard DDPG maximizes rewards without explicit regard for physical efficiency, PI-DDPG introduces a dual-objective optimization where the agent learns policies that respect both performance and energy constraints.

3.1.3 Dynamic Noise Adjustment

To enhance exploration and convergence, PI-DDPG incorporates a dynamic noise adjustment strategy. The noise scale starts at a maximum value (

• Convergence Detection: If the standard deviation of rewards over a convergence window (

• Improvement-Based Adjustment: The noise scale is adjusted based on the improvement in average rewards over two consecutive windows (

The parameter

Although this study focuses on robotic control, the evaluation is conducted in benchmark environments provided by MuJoCo, such as Ant-v4, HalfCheetah-v4, and Hopper-v4. These environments are widely used in reinforcement learning research because they faithfully simulate robotic locomotion, balance, and manipulation tasks under physical constraints. Thus, they serve as standardized proxies for robotic platforms, allowing controlled comparisons across algorithms. By formulating the problem in these benchmarks, we ensure reproducibility and comparability while preserving the generality of robotic control applications. The results derived in simulation provide strong insights that can guide extensions to physical robotic systems.

The actor network maps states to actions using a deep neural network with three layers:

• Input layer: Matches the state dimension (

• Hidden layers: Two layers with 400 and 300 units, each followed by LayerNorm and ReLU activation.

• Output layer: Produces actions scaled by the maximum action value (

Weights are initialized orthogonally with a gain of

The critic network estimates Q-values for state-action pairs using two independent Q-networks (Q1 and Q2) to mitigate overestimation bias, inspired by TD3:

• Input layer: Concatenates state (

• Hidden layers: Two layers with 400 and 300 units, each followed by LayerNorm and ReLU activation.

• Output layer: Produces a single Q-value.

To encourage exploration and robustness, an entropy regularization term, inspired by Soft Actor-Critic (SAC), is added to the critic loss. The loss function is modified as:

where

The algorithms are evaluated across nine OpenAI Gym environments: Ant-v4, HalfCheetah-v4, Hopper-v4, Pendulum-v4, InvertedPendulum-v4, Pusher-v5, Reacher-v5, Swimmer-v4, and Walker2d-v4. Each environment has specific state and action dimensions, with parameters such as maximum action values, episode counts, and step limits tailored to the task complexity.

A replay buffer stores transitions

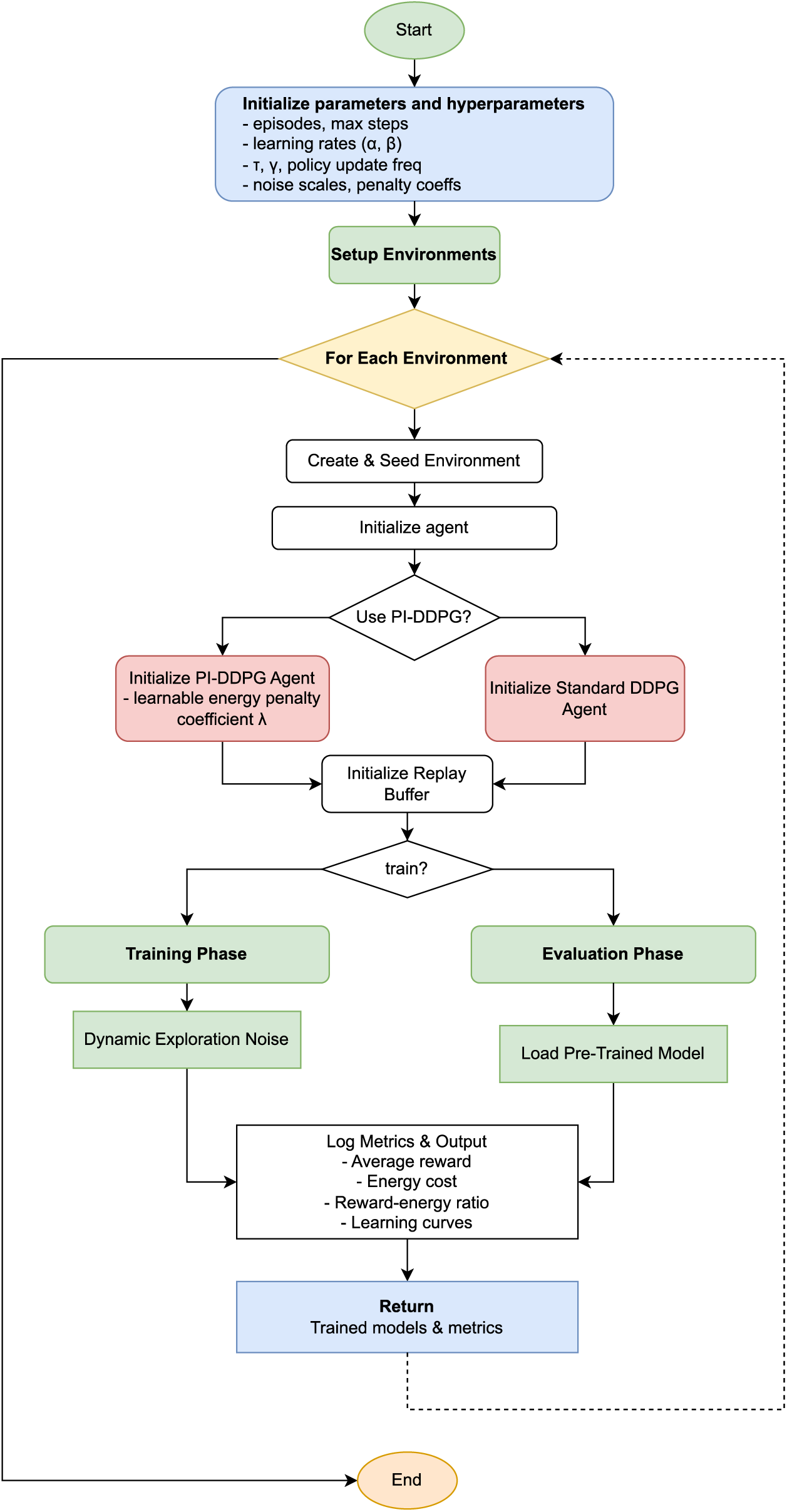

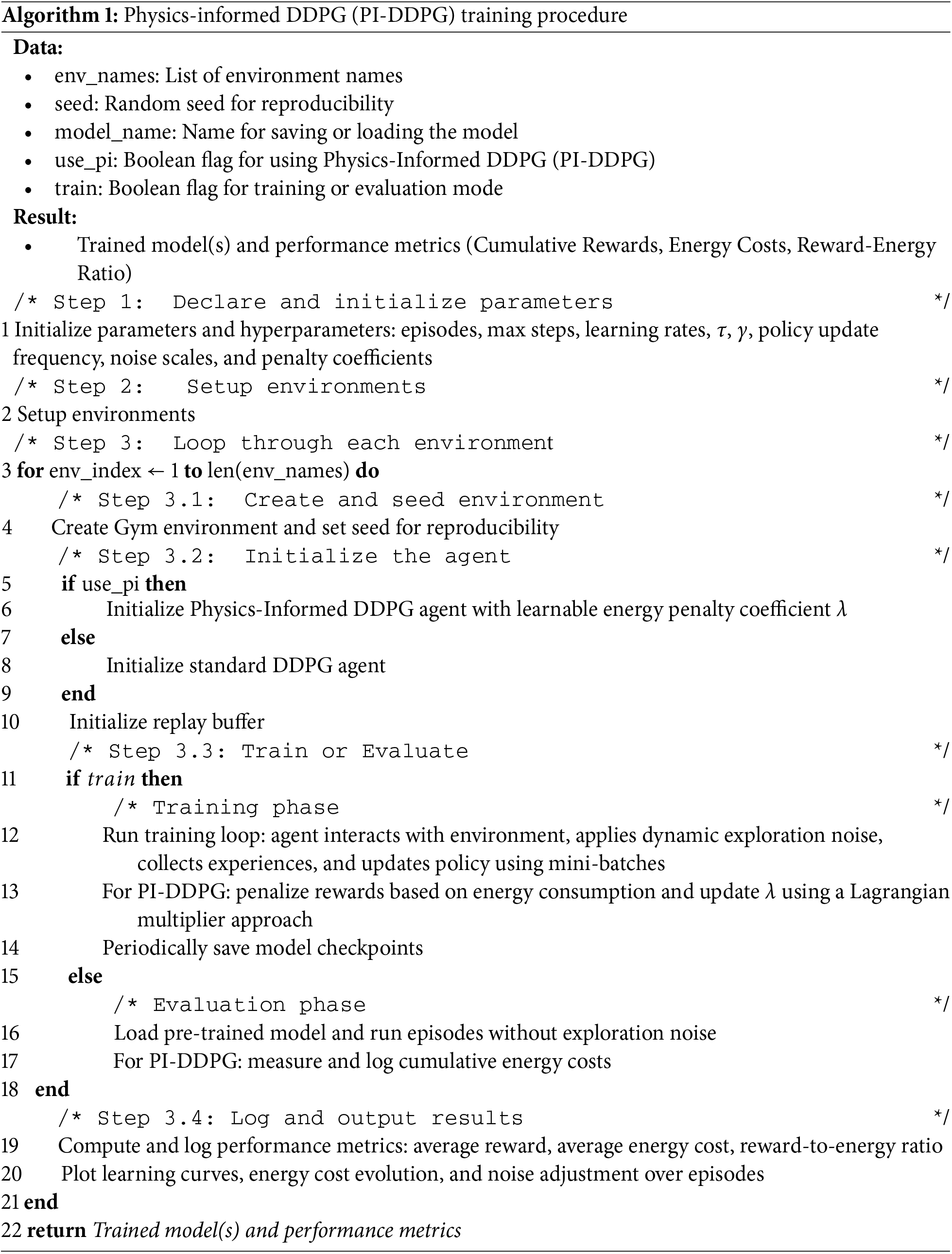

The training procedure is formalized in (Algorithm 1) and Fig. 1. Key steps include:

Figure 1: Flowchart of the physics-informed DDPG (PI-DDPG) training algorithm

1. Initialization: Initialize actor, critic, and target networks, replay buffer, and hyperparameters (e.g., learning rates,

2. Episode Loop: For each episode:

• Reset the environment and initialize the state.

• For each step (up to

– Select an action using the actor with dynamic noise.

– Execute the action, observe the next state, reward, and done flag.

– Compute the physics-informed energy penalty and adjust the reward (for PI-DDPG).

– Store the transition in the replay buffer.

– If the buffer has sufficient samples (

• Log episode rewards and save checkpoints every 10 episodes.

3. Network Updates:

• Critic Update: Compute the target Q-value using the target networks and update the critic using the modified loss function with entropy regularization.

• Actor Update: Update the actor every

• Target Network Update: Soft-update target networks using

4. Checkpointing: Save actor and critic weights periodically to enable resuming training or analysis.

The standard DDPG algorithm, implemented using Stable-Baselines3, serves as the baseline. It is trained with the same hyperparameters and environments but without the physics-informed energy penalty or dynamic

The performance of PI-DDPG and DDPG is evaluated across three dimensions:

1. Reward Performance: Cumulative rewards per episode, measuring task achievement.

2. Energy Efficiency: Cumulative energy costs, calculated based on physics-informed metrics like torque and power dissipation.

3. Reward-Energy Trade-Off: The reward-energy ratio, defined as cumulative reward divided by cumulative energy cost, quantifying efficiency in achieving rewards per unit of energy.

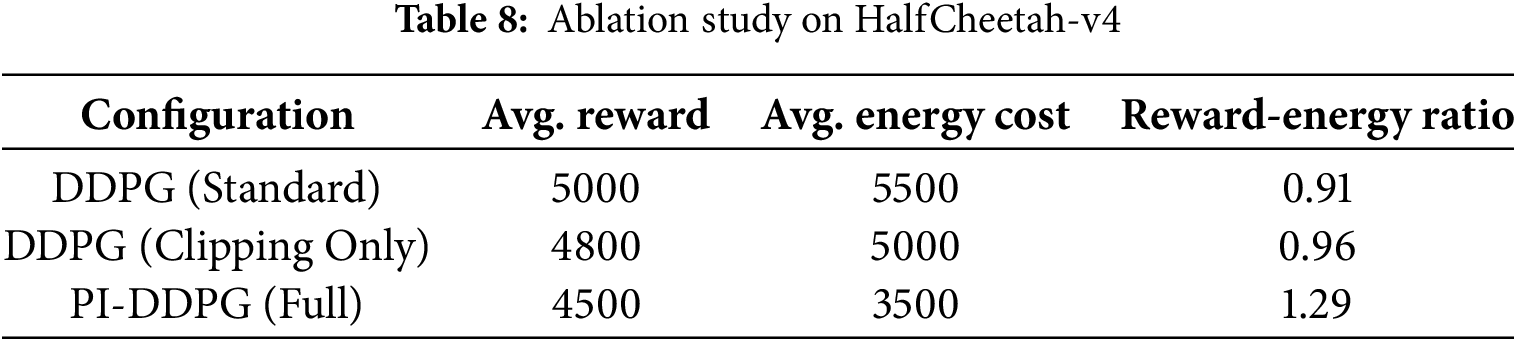

An ablation study isolates the impact of the energy penalty in PI-DDPG by comparing three configurations in the HalfCheetah-v4 environment:

1. Standard DDPG (no energy penalty or action clipping).

2. DDPG with action clipping only.

3. Full PI-DDPG (energy penalty and action clipping).

The study evaluates rewards, energy costs, and reward-energy ratios to quantify the contribution of the energy penalty.

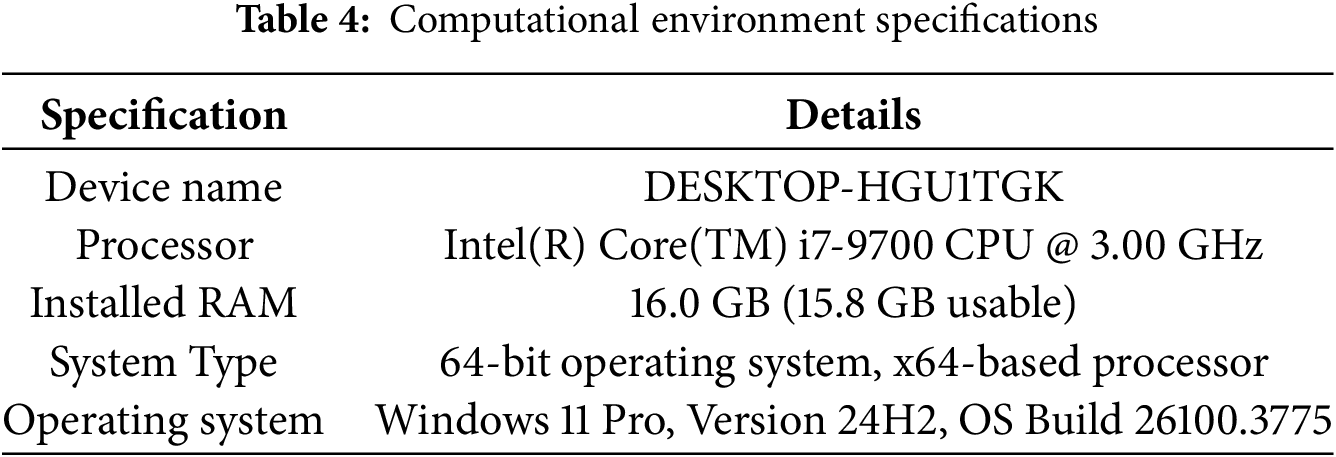

The experiments were conducted across multiple continuous control environments provided by OpenAI Gym, using a robust hardware and software configuration. The setup includes specifications of the computational environment, DRL environments, model architectures, hyperparameters, training procedures, and evaluation metrics, ensuring a thorough assessment of PI-DDPG’s performance against the standard DDPG baseline.

The experiments were performed on a desktop computer with the specifications shown in Table 4. The software environment utilized Python, managed through the Anaconda distribution, which provides a reliable ecosystem for scientific computing and machine learning. The DRL algorithms were implemented using PyTorch, a widely used deep learning framework, ensuring efficient computation and compatibility with modern machine learning workflows. Additional libraries, such as NumPy, Pandas, and Matplotlib, were used for data processing, analysis, and visualization. The Stable-Baselines3 library was employed to implement the baseline DDPG algorithm for comparative evaluation.

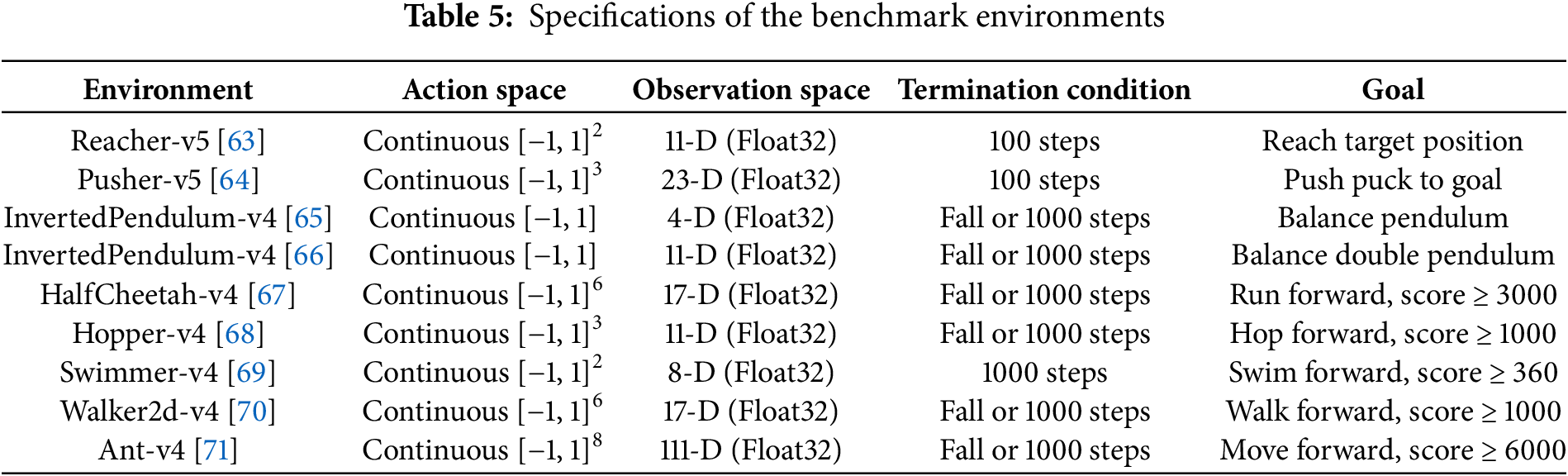

To evaluate PI-DDPG, experiments were conducted in nine OpenAI Gym environments, each presenting distinct challenges for continuous control tasks. The environments and their specifications are detailed in Table 5. These environments were chosen to assess the algorithm’s adaptability across a diverse set of robotic control tasks, ranging from simple pendulum balancing to complex multi-agent locomotion.

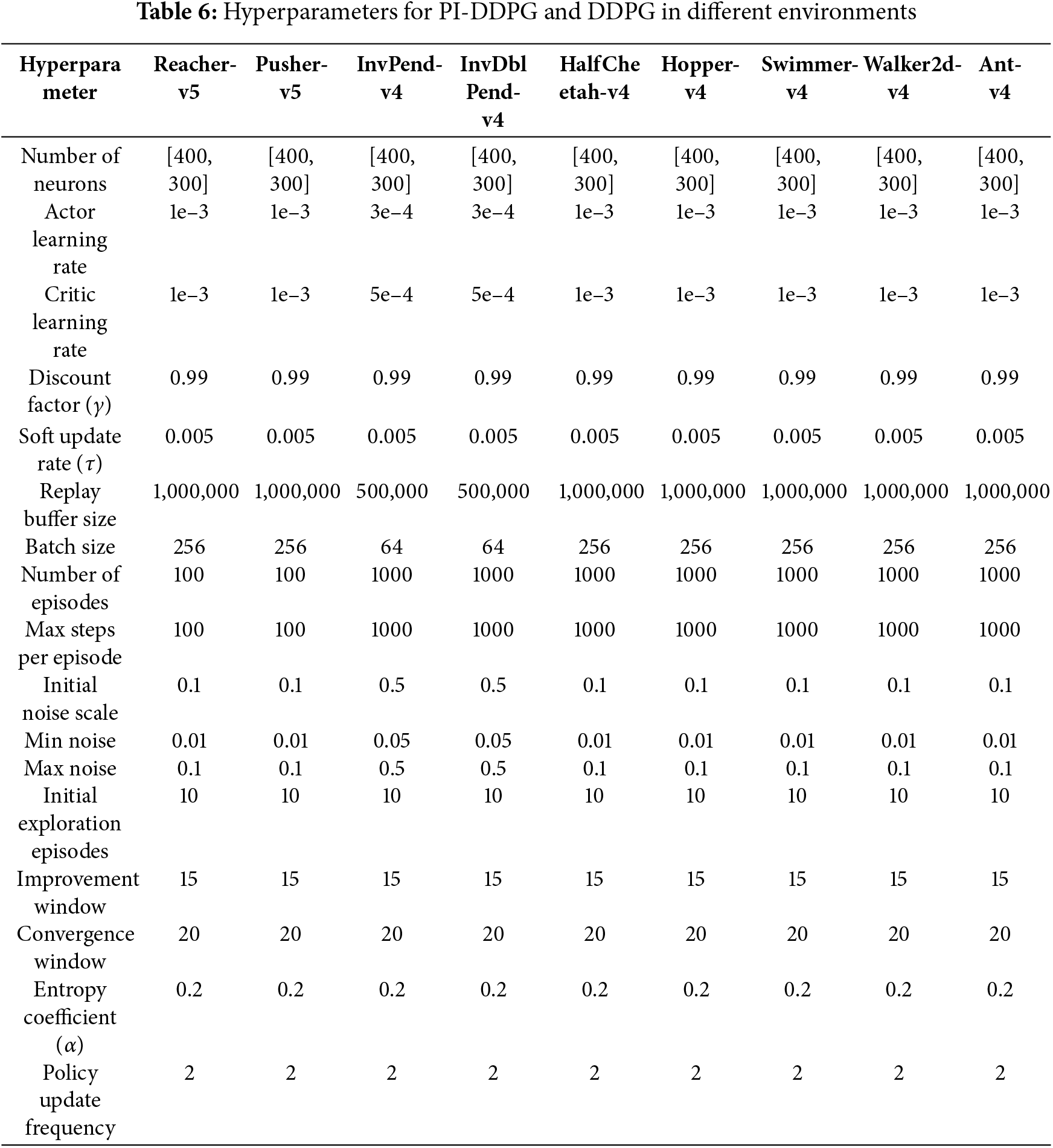

Hyperparameters were carefully selected for each environment to optimize training performance, as detailed in Table 6. These parameters were chosen to balance exploration, learning stability, and computational efficiency, ensuring a fair comparison between PI-DDPG and the baseline DDPG. Given the diversity of the environments, some hyperparameters, such as the number of episodes and replay buffer size, were adjusted to accommodate varying task complexities. The adaptive noise mechanism in PI-DDPG dynamically adjusts the exploration noise based on reward history, using parameters such as initial exploration episodes, minimum and maximum noise scales, and improvement and convergence windows.

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the performance of the DDPG algorithm and its proposed variant the PI-DDPG, across multiple OpenAI Gym environments. The evaluation focuses on three key metrics: reward performance, energy efficiency, and the trade-off between reward and energy consumption. Additionally, an ablation study is included to isolate the effect of the energy penalty in PI-DDPG, followed by a summary of average performance across all environments. The results are supported by visualizations of cumulative rewards, energy costs, and dynamic lambda values over training episodes, as well as tabular summaries of the trade-off and average performance analyses.

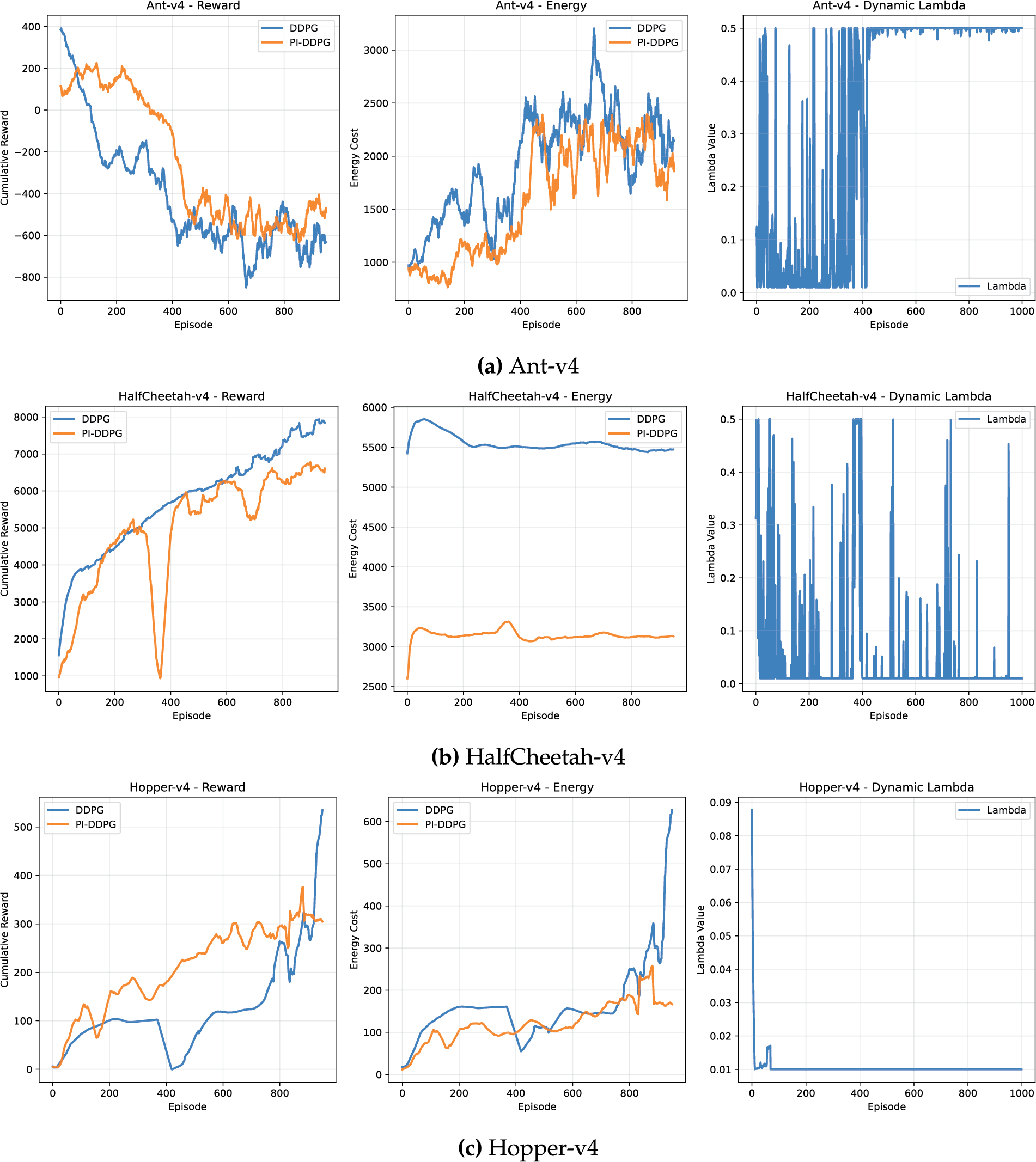

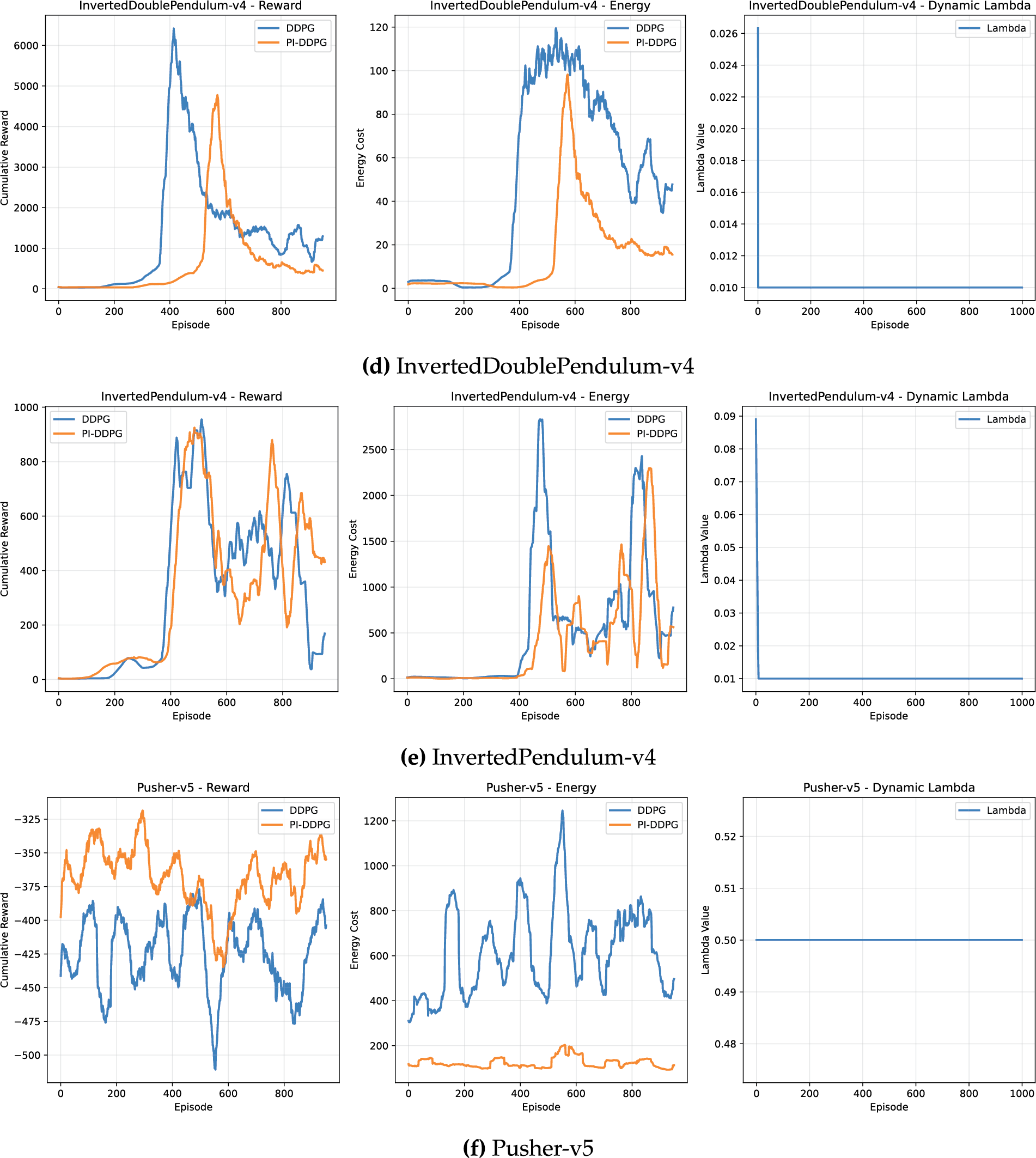

The reward performance of DDPG and PI-DDPG was evaluated across a variety of environments, including Ant-v4 [71], HalfCheetah-v4 [67], Hopper-v4 [68], InvertedDouble-v4 [66], InvertedPendulum-v4 [65], Pusher-v5 [64], Reacher-v5 [63], Swimmer-v4 [69], and Walker2d-v4 [70]. In most environments, DDPG achieves higher cumulative rewards compared to PI-DDPG, reflecting its focus on maximizing rewards without explicit consideration of energy costs. For instance, in the HalfCheetah-v4 environment, DDPG achieves a cumulative reward of approximately 5000, while PI-DDPG reaches around 4500 after 1000 episodes (Fig. 2), bottom left subplot (Fig. 2b). This trend is consistent across other environments such as Walker2d-v4, where DDPG reaches a cumulative reward of around 1000, compared to PI-DDPG 400 (Fig. 2), bottom left subplot (Fig. 2i).

Figure 2: Comparison of reward and energy cost across different environments

However, PI-DDPG demonstrates competitive performance in tasks where stability is a critical factor. In the Hopper-v4 environment, for example, both algorithms achieve comparable cumulative rewards, with DDPG slightly outperforming PI-DDPG, approximately 500 vs. 450 after 1000 episodes (Fig. 2), middle left subplot (Fig. 2c). This suggests that PI-DDPG energy-aware optimization does not significantly compromise reward performance in stability-focused tasks, making it a viable alternative in scenarios where energy efficiency is a priority.

A key advantage of PI-DDPG over DDPG is its ability to reduce energy costs while maintaining reasonable reward performance. Across all evaluated environments, PI-DDPG consistently achieves lower energy consumption compared to DDPG. For example, in the Ant-v4 environment, DDPG incurs an energy cost of approximately 10,000 units, whereas PI-DDPG reduces this to around 6000 units after 1000 episodes (Fig. 2), top middle subplot (Fig. 2a). This significant reduction in energy cost highlights the effectiveness of the physics-informed energy penalty in PI-DDPG, which encourages the agent to adopt more energy-efficient policies.

Similar trends are observed in other environments. In the Walker2d-v4 environment, DDPG energy cost peaks at around 2000 units, while PI-DDPG maintains a much lower energy cost of approximately 750 units (Fig. 2), bottom middle subplot (Fig. 2i). Even in environments where DDPG achieves higher rewards, such as HalfCheetah-v4, PI-DDPG reduces energy costs from 5500 units DDPG to 3500 units PI-DDPG (Fig. 2), bottom middle subplot (Fig. 2b). These results demonstrate that PI-DDPG successfully balances the trade-off between reward maximization and energy efficiency.

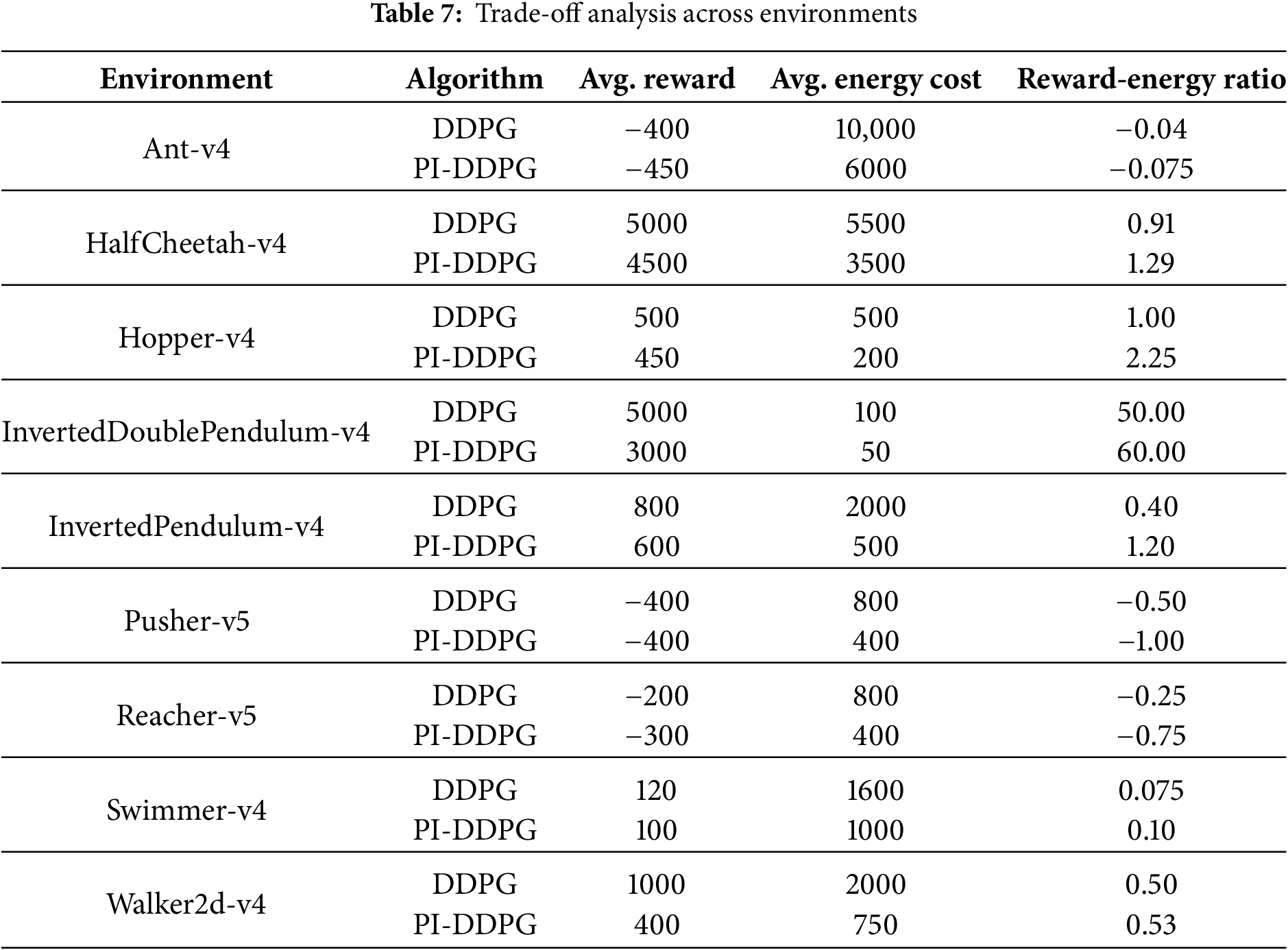

To further analyze the trade-off between reward performance and energy efficiency, we computed the average cumulative rewards, energy costs, and reward-energy ratios for both DDPG and PI-DDPG across all environments. The reward-energy ratio is defined as the cumulative reward divided by the cumulative energy cost, providing a metric to evaluate the efficiency of each algorithm in achieving rewards per unit of energy consumed. The results are summarized in Table 7.

From Table 7, it is evident that PI-DDPG excels in energy efficiency across all environments, often achieving significantly lower energy costs compared to DDPG. In terms of the reward-energy ratio, PI-DDPG outperforms DDPG in several environments, such as Walker2d-v4 (0.53 vs. 0.50) and HalfCheetah-v4 (1.29 vs. 0.91), indicating that PI-DDPG achieves a better balance between reward and energy consumption. In stability-focused tasks like Hopper-v4, the PI-DDPG reward-energy ratio is notably higher (2.25 vs. 1.00), further underscoring its efficiency in such scenarios.

The dynamic lambda parameter, which controls the weighting of the energy penalty in PI-DDPG, also provides insight into the algorithm behavior. In most environments, lambda stabilizes over time, as shown in the right subplots of (Fig. 2). For example, in Walker2d-v4, lambda converges to a value of around 0.15 (Fig. 2), bottom right subplot (Fig. 2i), indicating that the algorithm adapts the energy penalty dynamically to balance reward and energy objectives.

The numerical values reported in Table 7 are obtained by averaging the episodic metrics illustrated in (Fig. 2). For each environment

The reward–energy ratio reported in Table 7 is then defined as:

which quantifies the efficiency of obtaining rewards per unit of energy consumption. Thus, Fig. 2 presents the trajectory of these quantities over episodes, while Table 7 summarizes their average values across the training horizon (

To isolate the effect of the energy penalty in PI-DDPG, an ablation study was conducted by comparing three configurations: (1) standard DDPG, (2) DDPG with action clipping only (no energy penalty), and (3) PI-DDPG (with both action clipping and energy penalty). The study was performed on the HalfCheetah-v4 environment, and the results are summarized in Table 8.

The results indicate that action clipping alone (DDPG with clipping only) slightly reduces energy costs compared to standard DDPG (5000 vs. 5500), but the effect is minimal. In contrast, the full PI-DDPG configuration, which includes the energy penalty, significantly reduces energy costs to 3500 while maintaining a competitive reward of 4500. This leads to a higher reward-energy ratio (1.29) compared to both standard DDPG (0.91) and DDPG with clipping only (0.96). These findings confirm that the energy penalty in PI-DDPG is the primary driver of its improved energy efficiency, with action clipping providing a minor complementary effect.

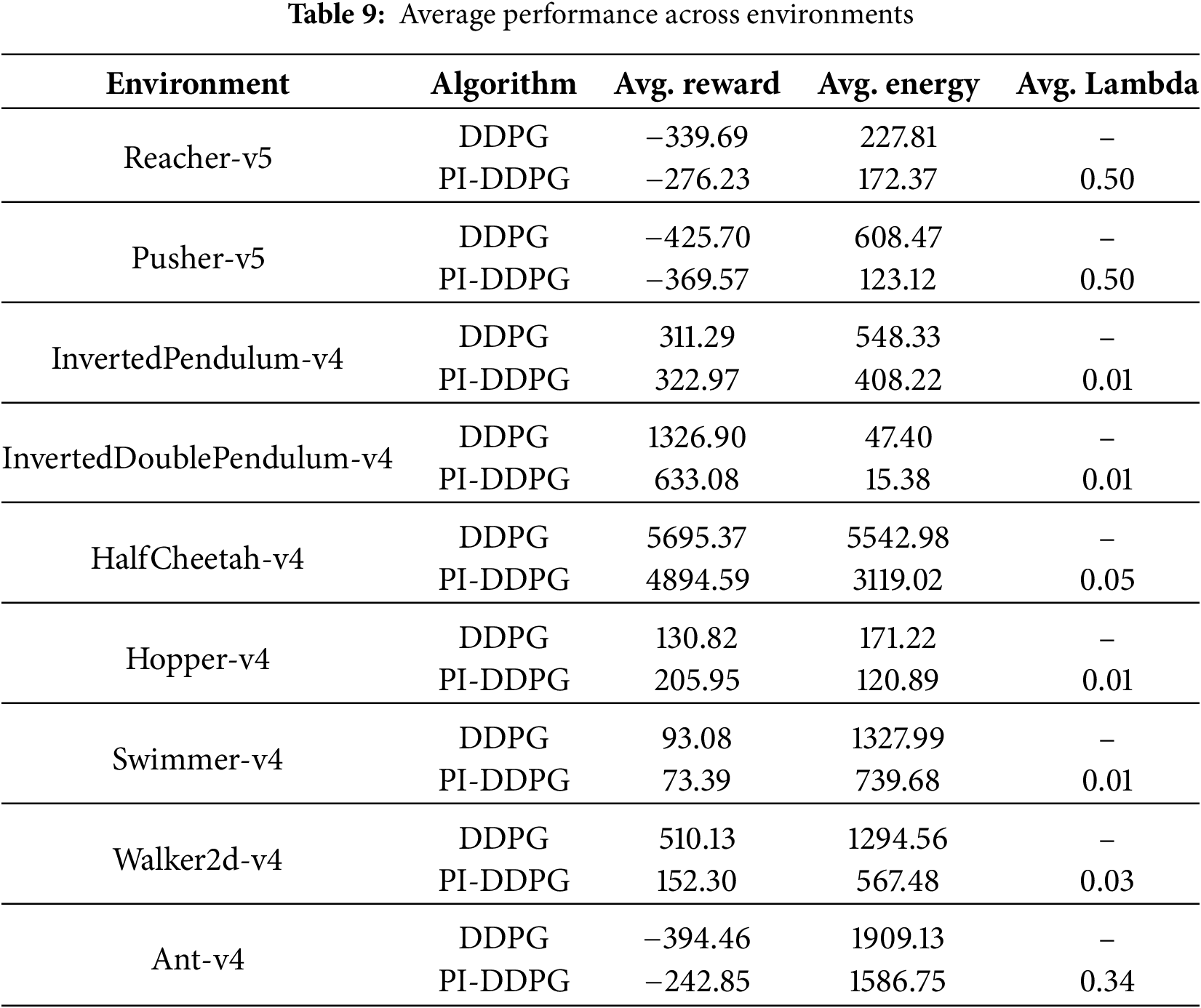

5.5 Average Performance across Environments

To provide a concise summary of the performance of DDPG and PI-DDPG across all evaluated environments, we computed the average cumulative rewards, average energy costs, and average lambda values for PI-DDPG over the 1000 episodes. These averages offer a clearer perspective on the overall effectiveness of each algorithm in terms of reward maximization, energy efficiency, and the dynamic weighting of the energy penalty. The results are presented in Table 9.

Table 9 highlights the average performance of DDPG and PI-DDPG across the nine evaluated environments, providing a direct comparison of their reward and energy efficiency. In terms of average rewards, DDPG generally outperforms PI-DDPG in environments like HalfCheetah-v4 (5695.37 vs. 4894.59), InvertedDoublePendulum-v4 (1326.90 vs. 633.08), and Walker2d-v4 (510.13 vs. 152.30). This aligns with DDPG focus on maximizing rewards without considering energy constraints. However, PI-DDPG achieves higher average rewards in specific environments, such as Hopper-v4 (205.95 vs. 130.82) and InvertedPendulum-v4 (322.97 vs. 311.29), indicating its effectiveness in stability-focused tasks where energy-aware policies may lead to more consistent performance.

Regarding energy efficiency, PI-DDPG consistently outperforms DDPG across all environments. For instance, in Pusher-v5, PI-DDPG reduces the average energy cost to (123.12) compared to DDPG (608.47) reduction of nearly 80%. Similarly, in HalfCheetah-v4, PI-DDPG lowers the average energy cost from (5542.98), DDPG to (3119.02), demonstrating its ability to achieve substantial energy savings while maintaining competitive rewards. Even in environments with low energy costs, such as InvertedPendulum-v4, PI-DDPG further reduces the average energy cost from (47.40) to (15.38), showcasing its robustness across diverse scenarios.

The average lambda values for PI-DDPG, which reflect the dynamic weighting of the energy penalty, vary significantly across environments. In Reacher-v5 and Pusher-v5, lambda stabilizes at a relatively high value of (0.50), indicating a strong emphasis on energy efficiency in these tasks. In contrast, environments like InvertedPendulum-v4, InvertedDoublePendulum-v4, Hopper-v4, and Swimmer-v4 exhibit a low average lambda of (0.01), suggesting that the energy penalty plays a minimal role in these tasks, possibly due to the inherently low energy demands of the environments or the need to prioritize reward maximization. Intermediate values, such as (0.34) in Ant-v4 and (0.05) in HalfCheetah-v4, reflect a balanced trade-off between reward and energy objectives, as the algorithm adapts lambda to the specific dynamics of each environment.

The results demonstrate that PI-DDPG offers a compelling trade-off between reward performance and energy efficiency, making it a suitable choice for applications where energy constraints are critical. While DDPG achieves higher rewards in most environments, its energy consumption is often prohibitively high, as observed in environments such as Ant-v4 and Walker2d-v4. PI-DDPG, on the other hand, consistently reduces energy costs without severely compromising reward performance, as evidenced by its competitive performance in stability-focused tasks like Hopper-v4.

The dynamic lambda parameter in PI-DDPG also plays a crucial role in adapting the energy penalty over time, ensuring that the algorithm effectively balances the reward and energy objectives. The ablation study further confirms that the energy penalty is the key factor in achieving these improvements, with action clipping providing a minor additional benefit.

Future work could explore the integration of additional physics-informed constraints into PI-DDPG, such as momentum conservation or joint torque limits, to further enhance its applicability to real-world robotic systems. Additionally, extending the evaluation to more complex environments, such as those with sparse rewards or high-dimensional action spaces, could provide further insights into the scalability of PI-DDPG.

This paper presents a thorough evaluation of the DDPG algorithm and its proposed version PI-DDPG, through simulated environments that measure their performance based on reward achievement and energy efficiency metrics. The experimental data demonstrate that DDPG delivers better reward outcomes during every assessment session because the algorithm was developed to optimize task execution. High energy usage during operations represents a disadvantage of DDPG that creates limitations for essential resource-efficient applications. Contracting its energy costs through physics-informed penalties allows PI-DDPG to reduce expenses by 40–80% without sacrificing reward levels. PI-DDPG achieves improved reward-energy efficiency in stability-demanding tasks because it strikes the right balance of reward and energy. A verification investigation reveals how the ablation study demonstrates that, when combined with the dynamic lambda control parameter, the energy penalty establishes PI-DDPG capability to achieve maximum efficiency. DDPG maintains its position as the most suitable approach for reward-driven applications, yet PI-DDPG stands out as a powerful approach when energy consumption takes precedence in robotics applications alongside autonomous systems and other resource-focused domains. These findings advance the understanding of energy-aware reinforcement learning, highlighting the value of integrating physical principles into policy optimization.

Acknowledgement: The authors appreciate and thank Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project Number (PNURSP2025R178), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: Researchers Supporting Project Number (PNURSP2025R178), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Abubakar Elsafi, Arafat Abdulgader Mohammed Elhag; data collection: Lubna A. Gabralla, Ali Ahmed; analysis and interpretation of results: Abubakar Elsafi, Arafat Abdulgader Mohammed Elhag, Ashraf Osman Ibrahim; draft manuscript preparation: Lubna A. Gabralla, Ali Ahmed, Ashraf Osman Ibrahim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lillicrap TP, Hunt JJ, Pritzel A, Heess N, Erez T, Tassa Y, et al. Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv:1509.02971. 2015. [Google Scholar]

2. Levine S, Finn C, Darrell T, Abbeel P. End-to-end training of deep visuomotor policies. J Mach Learn Res. 2016;17(39):1–40. [Google Scholar]

3. Mnih V, Kavukcuoglu K, Silver D, Rusu AA, Veness J, Bellemare MG, et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature. 2015;518(7540):529–33. doi:10.1038/nature14236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Dulac-Arnold G, Levine N, Mankowitz DJ, Li J, Paduraru C, Gowal S, et al. Challenges of real-world reinforcement learning: definitions, benchmarks and analysis. Mach Learn. 2021;110(9):2419–68. doi:10.1007/s10994-021-05961-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Nguyen H, La H. Review of deep reinforcement learning for robot manipulation. In: Third IEEE International Conference on Robotic Computing (IRC); 2019 Feb 25–27; Naples, Italy. p. 590–5. [Google Scholar]

6. Watkins CJ, Dayan P. Q-learning. Mach Learn. 1992;8:279–92. [Google Scholar]

7. Williams RJ. Simple statistical gradient-following algorithms for connectionist reinforcement learning. Mach Learn. 1992;8(3–4):229–56. doi:10.1023/a:1022672621406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Konda V, Tsitsiklis J. Actor-critic algorithms. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

9. Yang D, Qin X, Xu X, Li C, Wei G. Sample efficient reinforcement learning method via high efficient episodic memory. IEEE Access. 2020;8:129274–84. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3009329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Arulkumaran K, Deisenroth MP, Brundage M, Bharath AA. Deep reinforcement learning: a brief survey. IEEE Signal Process Magaz. 2017;34(6):26–38. doi:10.1109/msp.2017.2743240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhu Z, Lin K, Jain AK, Zhou J. Transfer learning in deep reinforcement learning: a survey. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(11):13344–62. doi:10.1109/tpami.2023.3292075. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Finn C, Abbeel P, Levine S. Model-agnostic meta-learning for fast adaptation of deep networks. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2017. p. 1126–35. [Google Scholar]

13. Deisenroth M, Rasmussen CE. PILCO: a model-based and data-efficient approach to policy search. In: Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on machine learning (ICML-11); 2011 Jun 28–Jul 2; Bellevue, WA, USA. p. 465–72. [Google Scholar]

14. Feinberg EA, Shwartz A. Handbook of Markov decision processes: methods and applications. Vol. 40. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

15. Xu Y, Kohtz S, Boakye J, Gardoni P, Wang P. Physics-informed machine learning for reliability and systems safety applications: state of the art and challenges. Reliability Eng Syst Safety. 2023;230:108900. [Google Scholar]

16. Haarnoja T, Zhou A, Abbeel P, Levine S. Soft actor-critic: off-policy maximum entropy deep reinforcement learning with a stochastic actor. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2018. p. 1861–70. [Google Scholar]

17. Shi B, Chen Z, Xu Z. A deep reinforcement learning based approach for optimizing trajectory and frequency in energy constrained multi-UAV assisted MEC system. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2024. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2024.3362949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhao C, Liu J, Yoon SU, Li X, Li H, Zhang Z. Energy constrained multi-agent reinforcement learning for coverage path planning. In: IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2023 Oct 14–18; Abu Dhabi, UAE; 2023. p. 5590–7. [Google Scholar]

19. Duan Y, Chen X, Houthooft R, Schulman J, Abbeel P. Benchmarking deep reinforcement learning for continuous control. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2016. p. 1329–38. [Google Scholar]

20. Banerjee C, Nguyen K, Fookes C, Raissi M. A survey on physics informed reinforcement learning: review and open problems. arXiv:2309.01909. 2023. [Google Scholar]

21. Sutton RS, Barto AG. Reinforcement learning: an introduction. 1st ed. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

22. de Avila Belbute-Peres F, Smith K, Allen K, Tenenbaum J, Kolter JZ. End-to-end differentiable physics for learning and control. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

23. Sciavicco L, Siciliano B. Modelling and control of robot manipulators. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

24. Achiam J, Held D, Tamar A, Abbeel P. Constrained policy optimization. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2017. p. 22–31. [Google Scholar]

25. Pereida K, Duivenvoorden RR, Schoellig AP. High-precision trajectory tracking in changing environments through L 1 adaptive feedback and iterative learning. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2017 May 29–Jun 3; Singapore. p. 344–50. [Google Scholar]

26. Suid MH, Ahmad MA. Optimal tuning of sigmoid PID controller using nonlinear sine cosine algorithm for the automatic voltage regulator system. ISA Transactions. 2022;128(8):265–86. doi:10.1016/j.isatra.2021.11.037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Ahmad MA, Ishak H, Nasir ANK, Abd Ghani N. Data-based PID control of flexible joint robot using adaptive safe experimentation dynamics algorithm. Bullet Electr Eng Inform. 2021;10(1):79–85. doi:10.11591/eei.v10i1.2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Chen S, Wen JT. Adaptive neural trajectory tracking control for flexible-joint robots with online learning. In: 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2020 May 31–Aug 31; Online. p. 2358–64. doi:10.1109/icra40945.2020.9197051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Minh Nguyet NT, Ba DX. A neural flexible PID controller for task-space control of robotic manipulators. Front Rob AI. 2023;9:975850. doi:10.3389/frobt.2022.975850. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Mok R, Ahmad MA. Fast and optimal tuning of fractional order PID controller for AVR system based on memorizable-smoothed functional algorithm. Eng Sci Technol Int J. 2022;35(9):101264. doi:10.1016/j.jestch.2022.101264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Mok R, Ahmad MA. Smoothed functional algorithm with norm-limited update vector for identification of continuous-time fractional-order Hammerstein models. IETE J Res. 2024;70(2):1814–32. doi:10.1080/03772063.2022.2152879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Touzani S, Prakash AK, Wang Z, Agarwal S, Pritoni M, Kiran M, et al. Controlling distributed energy resources via deep reinforcement learning for load flexibility and energy efficiency. Appl Energy. 2021;304(5):117733. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.117733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Xu C, Li W, Rao Y, Qi B, Yang B, Wang Z. Coordinative energy efficiency improvement of buildings based on deep reinforcement learning. Cyber-Phys Syst. 2023;9(3):260–72. doi:10.1080/23335777.2022.2066181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Hao J. Deep reinforcement learning for the optimization of building energy control and management [Ph.D. thesis]. Denver, CO, USA: University of Denver; 2020. [Google Scholar]

35. Koursioumpas N, Magoula L, Petropouleas N, Thanopoulos AI, Panagea T, Alonistioti N, et al. A safe deep reinforcement learning approach for energy efficient federated learning in wireless communication networks. IEEE Trans Green Commun Netw. 2024;8(4):1862–74. doi:10.1109/tgcn.2024.3372695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Hogade N, Pasricha S. Game-theoretic deep reinforcement learning to minimize carbon emissions and energy costs for AI inference workloads in geo-distributed data centers. IEEE Trans Sustain Comput. 2025;10(4):628–41. doi:10.1109/tsusc.2024.3520969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Shuai Q, Yin Y, Huang S, Chen C. Deep reinforcement learning-based real-time energy management for an integrated electric-thermal energy system. Sustainability. 2025;17(2):407. doi:10.3390/su17020407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wohlgenannt P, Hegenbart S, Eder E, Kolhe M, Kepplinger P. Energy demand response in a food-processing plant: a deep reinforcement learning approach. Energies. 2024;17(24):6430. doi:10.3390/en17246430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Ding Y, Chen X, Wang J. Deep reinforcement learning-based method for joint optimization of mobile energy storage systems and power grid with high renewable energy sources. Batteries. 2023;9(4):219. doi:10.3390/batteries9040219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Jia R, Jin M, Sun K, Hong T, Spanos C. Advanced building control via deep reinforcement learning. Energy Procedia. 2019;158(3):6158–63. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2019.01.494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Tien PW, Wei S, Darkwa J, Wood C, Calautit JK. Machine learning and deep learning methods for enhancing building energy efficiency and indoor environmental quality—a review. Energy AI. 2022;10(5):100198. doi:10.1016/j.egyai.2022.100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kahil H, Sharma S, Välisuo P, Elmusrati M. Reinforcement learning for data center energy efficiency optimization: a systematic literature review and research roadmap. Appl Energy. 2025;389(1):125734. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2025.125734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Hou H, Jawaddi SNA, Ismail A. Energy efficient task scheduling based on deep reinforcement learning in cloud environment: a specialized review. Future Gen Comput Syst. 2024;151(8):214–31. doi:10.1016/j.future.2023.10.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Fu Q, Han Z, Chen J, Lu Y, Wu H, Wang Y. Applications of reinforcement learning for building energy efficiency control: a review. J Build Eng. 2022;50(3):104165. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Ponse K, Kleuker F, Fejér M, Serra-Gómez Á, Plaat A, Moerland T. Reinforcement learning for sustainable energy: a survey. arXiv:2407.18597. 2024. [Google Scholar]

46. Ramesh A, Ravindran B. Physics-informed model-based reinforcement learning. In: Learning for Dynamics and Control Conference. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2023. p. 26–37. [Google Scholar]

47. Liu XY, Wang JX. Physics-informed Dyna-style model-based deep reinforcement learning for dynamic control. Proc Royal Society A. 2021;477(2255):20210618. doi:10.1098/rspa.2021.0618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Zhao P, Liu Y. Physics informed deep reinforcement learning for aircraft conflict resolution. IEEE Trans Intell Trans Syst. 2021;23(7):8288–301. doi:10.1109/tits.2021.3077572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Di X, Shi R, Mo Z, Fu Y. Physics-informed deep learning for traffic state estimation: a survey and the outlook. Algorithms. 2023;16(6):305. doi:10.3390/a16060305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Zhang B, Cao D, Hu W, Ghias AM, Chen Z. Physics-Informed Multi-Agent deep reinforcement learning enabled distributed voltage control for active distribution network using PV inverters. Int J Elect Power Energy Syst. 2024;155(3):109641. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2023.109641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Wu Z, Zhang M, Gao S, Wu ZG, Guan X. Physics-informed reinforcement learning for real-time optimal power flow with renewable energy resources. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2025;16(1):216–26. doi:10.1109/tste.2024.3452489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Rodwell C, Tallapragada P. Physics-informed reinforcement learning for motion control of a fish-like swimming robot. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):10754. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1851761/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Han Y, Wang M, Li L, Roncoli C, Gao J, Liu P. A physics-informed reinforcement learning-based strategy for local and coordinated ramp metering. Trans Res Part C Emerg Technol. 2022;137(4):103584. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2022.103584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Lin P, Wu M, Xiao Z, Tiong RL, Zhang L. Physics-informed deep reinforcement learning for enhancement on tunnel boring machine’s advance speed and stability. Autom Constr. 2024;158(1):105234. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2023.105234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Wang Y, Wu Z. Physics-informed reinforcement learning for optimal control of nonlinear systems. AIChE J. 2024;70(10):e18542. doi:10.1002/aic.18542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Karniadakis GE, Kevrekidis IG, Lu L, Perdikaris P, Wang S, Yang L. Physics-informed machine learning. Nat Rev Phys. 2021;3(6):422–40. doi:10.1038/s42254-021-00314-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Hao Z, Liu S, Zhang Y, Ying C, Feng Y, Su H, et al. Physics-informed machine learning: a survey on problems, methods and applications. arXiv:2211.08064. 2022. [Google Scholar]

58. Shi H, Zhou Y, Wu K, Chen S, Ran B, Nie Q. Physics-informed deep reinforcement learning-based integrated two-dimensional car-following control strategy for connected automated vehicles. Knowl Based Syst. 2023;269(2):110485. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2023.110485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Pan Z, Zhou J, Fan Q, Feng Z, Gao X, Su M. Robotic control mechanism based on deep reinforcement learning. In: 2023 2nd International Symposium on Control Engineering and Robotics (ISCER); 2023 Feb 17–19; Hangzhou, China. p. 70–4. [Google Scholar]

60. Liu J, Borja P, Della Santina C. Physics-informed neural networks to model and control robots: a theoretical and experimental investigation. Adv Intell Syst. 2024;6(5):2300385. doi:10.1002/aisy.202300385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Zhong Z, Ju Y, Gu J. Scalable physics-embedded neural networks for real-time robotic control in embedded systems. In: IEEE 67th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS); 2024 Aug 11–14; Springfield, MA, USA. p. 823–7. [Google Scholar]

62. Xiang Y, Wang X, Hu S, Zhu B, Huang X, Wu X, et al. Rmbench: benchmarking deep reinforcement learning for robotic manipulator control. In: 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2023 Oct 1–5; Detroit, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

63. Foundation F. Reacher-v5 environment [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 21]. Available from: https://gymnasium.farama.org/environments/mujoco/reacher/. [Google Scholar]

64. Foundation F. Pusher-v5 environment [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 21]. Available from: https://gymnasium.farama.org/environments/mujoco/pusher/. [Google Scholar]

65. Foundation F. InvertedPendulum-v4 environment [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 21]. Available from: https://gymnasium.farama.org/environments/mujoco/inverted_pendulum/. [Google Scholar]

66. Foundation F. InvertedDoublePendulum-v4 environment [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 21]. Available from: https://gymnasium.farama.org/environments/mujoco/inverted_double_pendulum/. [Google Scholar]

67. Foundation F. HalfCheetah-v4 environment [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 21]. Available from: https://gymnasium.farama.org/environments/mujoco/half_cheetah/. [Google Scholar]

68. Foundation F. Hopper-v4 environment [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 21]. Available from: https://gymnasium.farama.org/environments/mujoco/hopper/. [Google Scholar]

69. Foundation F. Swimmer-v4 environment [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 21]. Available from: https://gymnasium.farama.org/environments/mujoco/swimmer/. [Google Scholar]

70. Foundation F. Walker2d-v4 environment [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 21]. Available from: https://gymnasium.farama.org/environments/mujoco/walker2d/. [Google Scholar]

71. Foundation F. Ant environment [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Mar 21]. Available from: https://gymnasium.farama.org/environments/mujoco/ant/. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools