Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Computational Modeling Approach for Joint Calibration of Low-Deviation Surgical Instruments

1 School of Artificial Intelligence, Guangzhou Huashang College, Guangzhou, 511300, China

2 School of Automation, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, 610054, China

3 Research Institute of AI Convergence, Hanyang University ERICA, Ansan-si, 15577, Republic of Korea

4 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Hanyang University, Ansan-si, 15577, Republic of Korea

5 Department of Biomedical and Electrical Engineering, Marshall University, Huntington, WV 25755, USA

* Corresponding Authors: Jiawei Tian. Email: ; Shan Liu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Recent Advances in Signal Processing and Computer Vision)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 2253-2276. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.072031

Received 18 August 2025; Accepted 23 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

Accurate calibration of surgical instruments and ultrasound probes is essential for achieving high precision in image guided minimally invasive procedures. However, existing methods typically treat the calibration of the needle tip and the ultrasound probe as two independent processes, lacking an integrated calibration mechanism, which often leads to cumulative errors and reduced spatial consistency. To address this challenge, we propose a joint calibration model that unifies the calibration of the surgical needle tip and the ultrasound probe within a single coordinate system. The method formulates the calibration process through a series of mathematical models and coordinate transformation models and employs a gradient descent based optimization to refine the parameters of these models. By establishing and iteratively optimizing a template coordinate system through modeling of constrained spherical motion, the proposed joint calibration model achieves submillimeter accuracy in needle tip localization. Building upon this, an N line based calibration model is developed to determine the spatial relationship between the probe and the ultrasound image plane, resulting in an average pixel deviation of only 1.2373 mm. Experimental results confirm that this unified modeling approach effectively overcomes the limitations of separate calibration schemes, significantly enhancing both precision and robustness, and providing a reliable computational model for surgical navigation systems that require high spatial accuracy without relying on ionizing radiation.Keywords

With the advancement of society, increasing attention to individual health has been accompanied by growing investments in healthcare technologies [1,2]. Engineering and technical professionals increasingly offer technical support to physicians based on specific clinical needs. The close cooperation between technology experts and medical professionals has significantly accelerated the development of medical technology, leading to the emergence of numerous innovative techniques. Among these innovations, image-guided surgical techniques [3–6], a cutting-edge minimally invasive treatment, have become widely adopted.

CT scans, fluoroscopy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or ultrasound images are usually used to guide needle insertion in minimally invasive medical procedures. The use of CT has limitations, primarily due to the high doses of ionizing radiation patients are exposed to during the procedure [7]. Instruments made of non-magnetic and dielectric materials are restricted to permeabilization procedures [8]. Ultrasound is considered a safe and readily available imaging modality for observing needles and targets during surgery [9–11].

Calibration of surgical instruments is essential for surgical navigation before surgery [12–14]. The accuracy of instruments calibration determines the overall precision of surgical navigation, playing a critical role in the effectiveness and safety of surgery. Thus, the positioning and calibration of the probe needle in the surgical navigation systems remains a research focus. Traditional hand-eye calibration methods are challenging to implement in the confined spaces of the body. To address this challenge, researchers have proposed an autonomous instrument calibration method using a monocular camera [15]. This method utilizes visual feedback to track the instrument’s motion trajectory, followed by a two-stage parameter estimation process to achieve autonomous calibration. This approach overcomes the limitations of hand-eye observation, enhancing the safety of minimally invasive surgery. Some researchers have shifted their focus to surgical instruments, such as robotic arms, applying image-guided techniques to track their paths [16,17]. An economical, high-precision optical tracking system has been introduced by researchers. Within this system, Bumblebee2 stereo cameras are utilized to capture images of objects marked with distinctive identifiers. The central pixel coordinates of these markers are extracted, and specialized image processing techniques are applied to reconstruct the coordinates of the surgical instrument’s tip, facilitating tracking. This approach significantly enhances the system’s resilience to interference.

In recent years, the precision of surgical navigation systems has increasingly relied on accurate localization of the needle tip and robust calibration of ultrasound probes. However, most existing methods approach these two processes independently, leading to cumulative spatial errors during interventional procedures. For instance, Beigi et al. [18] developed techniques to enhance needle visibility and localization in ultrasound images, yet their method focuses solely on image-based improvements without addressing hardware alignment or spatial registration. Recent advancements have also proposed calibration schemes for ultrasound probes using either phantoms or robotic assistance. Wang et al. [19] introduced a dual-arm surgical navigation platform with independent ultrasound probe calibration via fiducial phantoms, achieving reasonable precision but at the cost of system complexity and multi-step workflows. Meanwhile, Seitel et al. [20] employed miniaturized electromagnetic tracking to guide needle insertions in real time, demonstrating accuracy improvements but still requiring separate probe-needle calibration steps. More recently, Che et al. [21] utilized deep learning to improve needle tip detection in ultrasound-based navigation, but their framework assumes pre-calibrated devices and does not consider joint optimization. These studies collectively reveal a significant research gap: there remains a lack of integrated calibration models that simultaneously account for both needle tips and ultrasound probe alignment within a unified coordinate system. This fragmentation results in accumulated spatial errors and hinders real-time surgical adaptability.

Despite progress in individual domains of needle tracking and ultrasound probe calibration, a major limitation remains: the absence of a unified, model-driven calibration framework that directly relates the physical space of the surgical instrument to the imaging plane of the ultrasound probe in a mathematically consistent and spatially coherent manner. Existing techniques typically decouple the two processes: first localizing the needle tip through geometric constraints, then calibrating the probe separately using phantoms or empirical image mappings. This two-stage pipeline introduces cumulative transformation errors, increases system complexity, and often requires manual intervention or fiducial markers, which are undesirable in real-time, minimally invasive procedures.

In contrast, our work introduces a joint calibration model that integrates both the needle tip localization and the ultrasound probe-to-image plane calibration within a shared coordinate system, supported by explicit coordinate transformation and optimization models. By leveraging the constrained spherical motion of the instrument during rotation, we formulate a gradient-descent-based solution to estimate the true spatial position of the needle tip. This result is then used as a geometric anchor in an N-line ultrasound calibration model, allowing the system to compute the spatial transformation between the ultrasound image plane and the physical coordinate frame without relying on external phantoms. Our approach thus not only reduces system complexity and accumulated error but also demonstrates submillimeter localization accuracy (0.1644 mm) and low pixel deviation in image alignment (1.2373 mm), validated across 253-frame sequences. These contributions position our method as a practical and precise calibration strategy for real-time ultrasound-guided surgical navigation, especially in scenarios requiring portability, reduced radiation exposure, and high spatial fidelity. It fills a critical gap in the literature by offering an end-to-end mathematical framework that bridges the calibration of hardware (needle and probe) with imaging output in a single optimization loop.

Initially, capturing the tip of the surgical instrument is essential. After the initial capturing of the tip, the next step is to establish the optical positioning systems for both the surgical instrument and its tip. Using optical positioning, the three-dimensional spatial coordinates of three non-collinear feature points on the surgical instrument, along with the coordinates of the tip, are captured. Next, the spatial coordinates of the instrument’s tip point are determined relative to its own coordinate system. As the surgical instrument rotates around its tip, the three non-collinear points trace paths on a concentric spherical surface. Leveraging this spherical motion constraint, the spatial coordinates of the tip can be precisely calibrated within the coordinate system defined by the surgical instrument. This method ensures high accuracy in the calibration process, which is vital for the precision and reliability of surgical navigation systems.

2.1 Optimal Rotation Algorithm

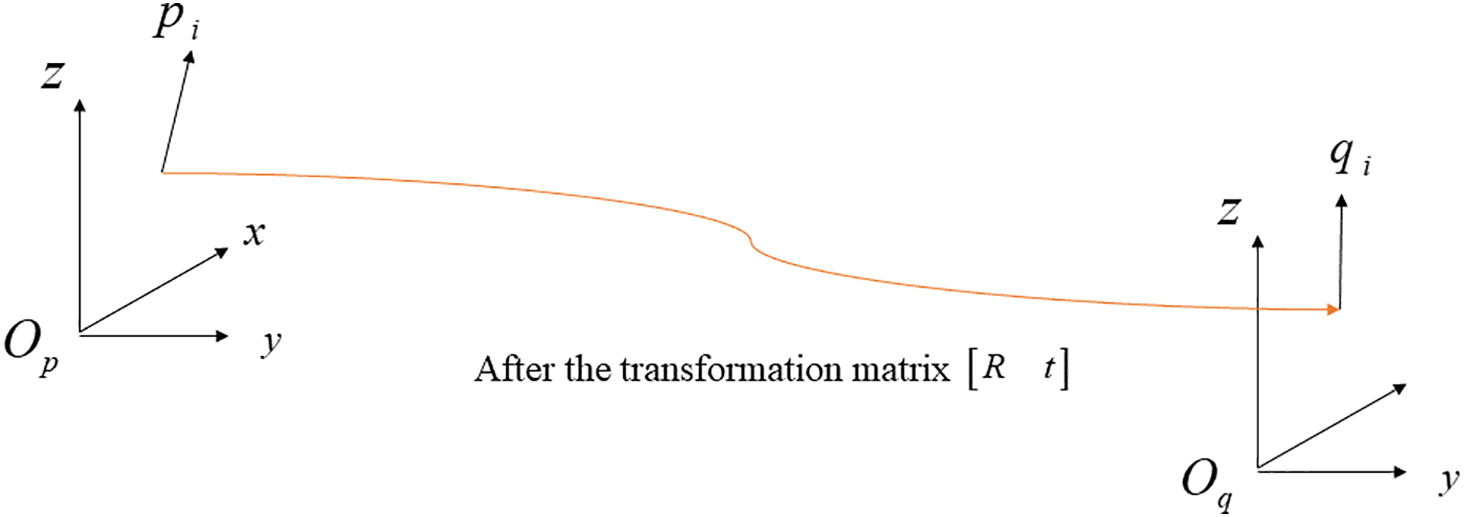

The optimal rotation algorithm [22] is used to determine the rotation and translation matrix between coordinate systems, as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of the optimal rotation algorithm

The optimization objective is shown in Eq. (1):

where

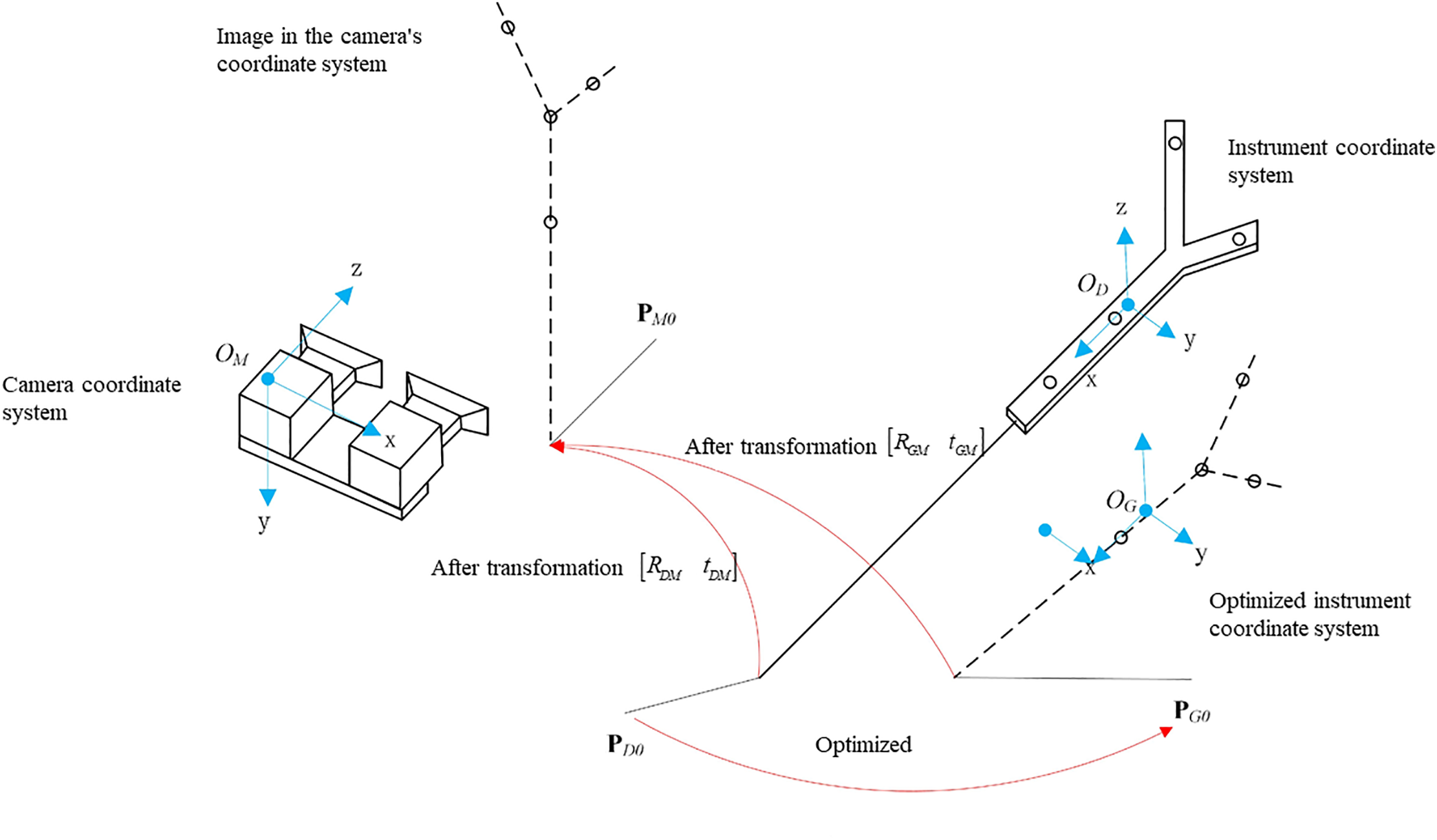

2.2 Calibration of Puncture Needle Tips

Tracking and positioning surgical instruments during surgery is a fundamental task in surgical navigation. The spatial coordinates of these instruments can be accurately determined by referencing non-collinear landmarks on their structure. Fig. 2 clearly demonstrates this calibration process, using four specific marking points on a surgical instrument as an example. Once the instrument’s movement stabilized, the tip of the surgical instrument is established as the center of a sphere, with the four landmarks positioned on its surface. This method provides a robust calibration technique, which is essential for the accuracy and effectiveness of surgical navigation systems.

Figure 2: Needle tip calibration model

To calculate the coordinates of the tip point in the instrument coordinate system, a common method involves fixing the tip of the surgical instrument, rotating the instrument around this fixed point, using an optical tracking system to collect the positions of the surgical instrument’s marking points, and then calculating the transformation matrix

The matrix form of the coordinate system in the instrument coordinate system is shown in the Eq. (2).

where

The matrix form of the coordinate system in the camera coordinate system is shown in the Eq. (3).

where

The transformation of coordinates from the instrument coordinate system to the camera coordinate system is an indirect process. First, the instrument coordinate system

The matrix representation of the optimized instrument coordinate system is shown in Eq. (4).

where

The transformation relationship between optimized instrument coordinate and camera coordinate is shown in the Eq. (5).

where

Since

The calibration formula for the puncture tip is shown in Eq. (6).

where

According to Eq. (6), the needle tip coordinates obtained from the

The Mean Square Error (MSE) of the tip position is shown in Eq. (8):

The optimization problem is shown in Eq. (9).

where

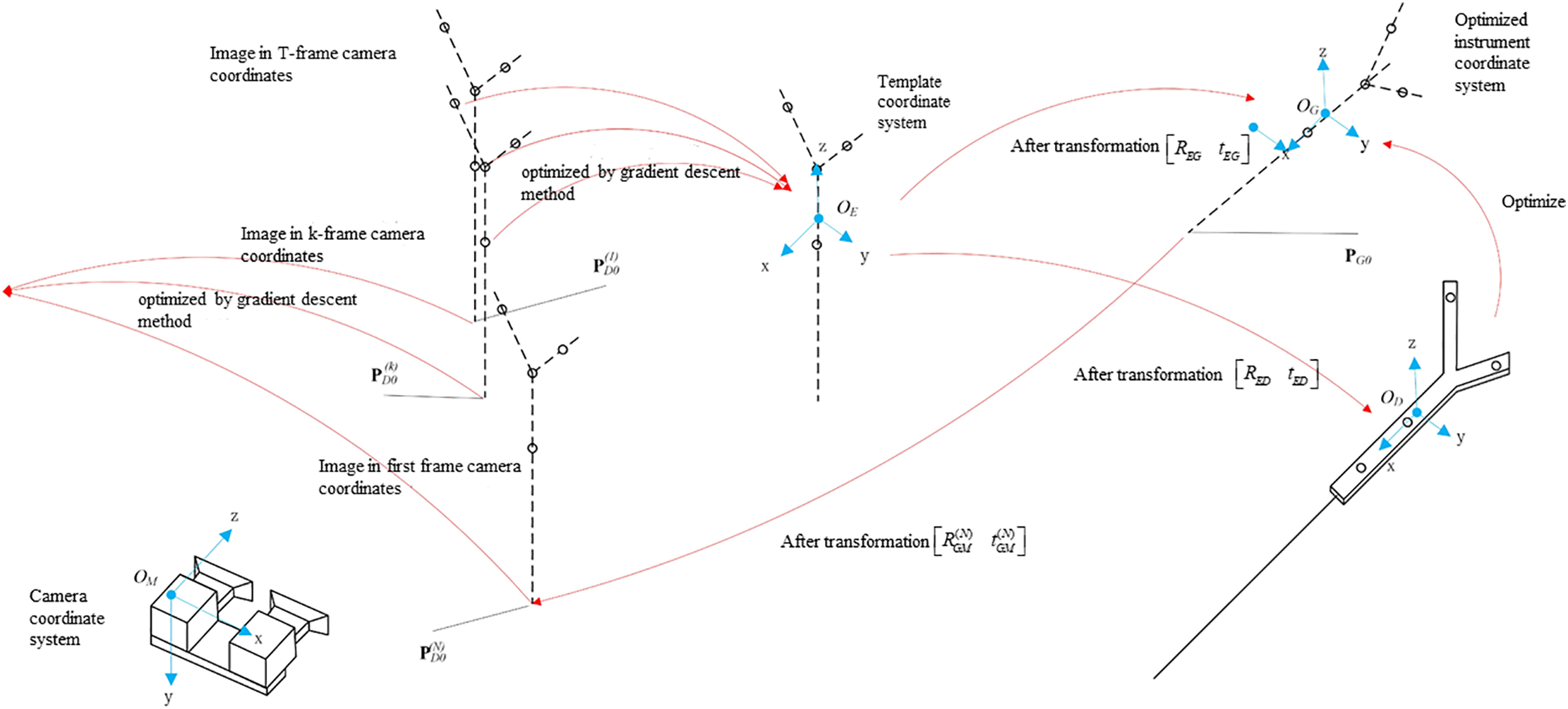

According to the gradient descent method [23,24], the solution to Eq. (9), as illustrated in Fig. 3, can be formulated as follows:

Figure 3: Calibration process of puncture needle tip

The template coordinate system is optimized based on the image of the T-group optical spheres captured in the camera coordinate system.

The coordinates of the optical sphere of the template coordinate system are transformed into the instrument coordinate system, and the rotation transformation matrix

To account for inherent errors in the coordinate system transitions from the optimal rotation algorithm, the template coordinate system’s coordinates are converted to the optimized instrument coordinate system using a rotation transformation matrix

The gradient descent method is used to solve the objective function, yielding the coordinates of the needle tip in the optimized instrument coordinate system.

Initially, we optimized the template coordinate system. By rotating the needle tip around a fixed point, we captured T images, from which we extract the coordinates of T sets of four optically marked spheres. Using binocular vision calibration, we obtain the coordinates of the four optical marker spheres in the coordinate system of

The T groups of optical spheres’ coordinate can be optimized using gradient descent to establish a template coordinate system

where

The objective function of the template coordinate system is obtained as Eq. (11).

where

Taking the image coordinates from the first frame as the initial value:

where

The Jacobi matrix is shown in Eq. (13). Where

The step size was set to

By iteratively updating

We can refine the tip’s coordinates within the instrument’s coordinate system. Initially, the coordinates of the four optical spheres are rotated and translated from the template coordinate system to align with the instrument coordinate system, as indicated in Eq. (15).

where

Due to the error e in the transformation between the coordinate systems as determined by the optimal rotation algorithm, the coordinate

The coordinates in the template coordinate system are first rotated and translated to align with the optimized instrument coordinate system. Subsequently, these coordinates are transformed to the coordinate system of T groups of cameras, resulting in Eq. (17).

We convert the needle tip coordinates from the instrument coordinate system to the camera coordinate system, obtaining eight sets of coordinates in the camera’s frame of reference. Subsequently, the optimized tip coordinates were determined using the gradient descent method.

Solve the Eq. (9) using the objective optimization function illustrated in Eq. (18).

where

The Jacobi matrix is illustrated in Eq. (19).

where

Set step length α = 0.01 based on empirical testing to update the value according to Eq. (20).

The optimal tip coordinate

By using the design coordinates of four optically marked spheres and a series of rotation translation matrices, the minimum value of the objective function is obtained, thus completing the optimization of the design coordinates.

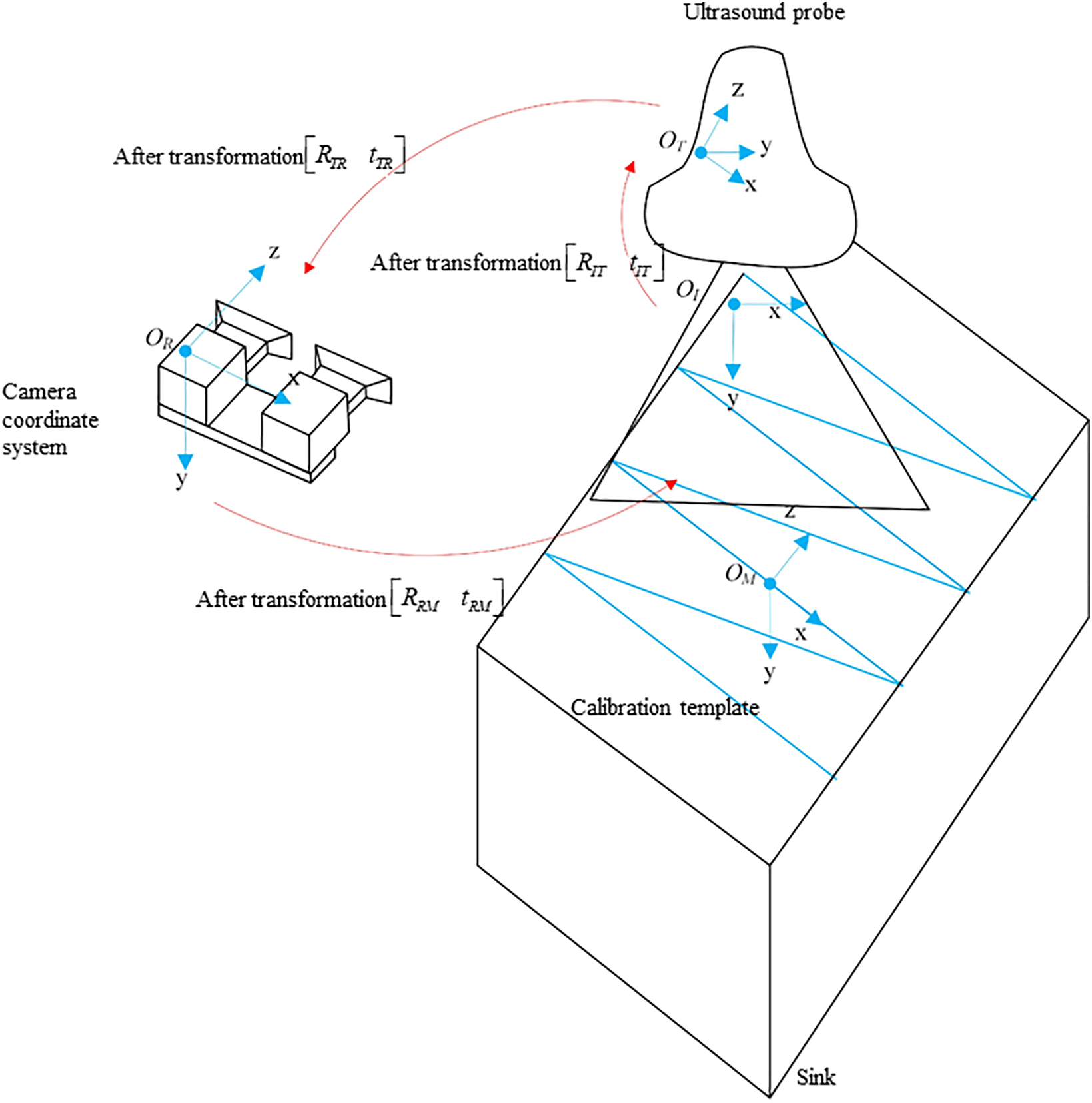

2.3 Calibration of Ultrasound Probe

This study employs an optical tracking system [25,26] and proposes an innovative method for calibrating ultrasound probes based on the N-line method [27]. The method involves first calibrating the coordinates of endpoints of each line in the optical coordinate system using the puncture needle tip as a reference and then mapping the intersections of the N-line with the ultrasound image in the image coordinate system. Finally, the calibration equation is applied to determine the calibration results through substitution.

The principle involves obtaining a transformation matrix that aligns the spatial references of the ultrasound image with the corresponding probe, ensuring accurate spatial mapping across different coordinate systems. This concept is illustrated in the accompanying Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Calibration of ultrasound probes

We establish four coordinate systems: the template coordinate system

Therefore, after obtaining the feature point’s coordinates

where

The above expression indicates that the ultrasound image calibration requires solving for 6 calibration parameters along with

Eq. (21) is simplified as Eq. (24).

where

Then

Substituting

Substituting

It is evident that when the number of calibration ultrasound images

To determine the calibration parameters using the nonlinear optimization method, the objective function is first formulated. For the calibration feature points of each image, Eq. (29) is used.

where

Then we have Eq. (30).

where

The MSE of the distance deviation is Eq. (32).

The optimization problem for the goal is shown in Eq. (33).

The above equation represents the optimization result, where the least squares method is employed in MATLAB to optimize the eight calibration parameters, aiming to minimize the values towards zero. In this study, the least squares method is utilized to solve systems of equations. When the

Then we can obtain the parameters

3.1.1 Experimental Instruments for Needle Tip Calibration

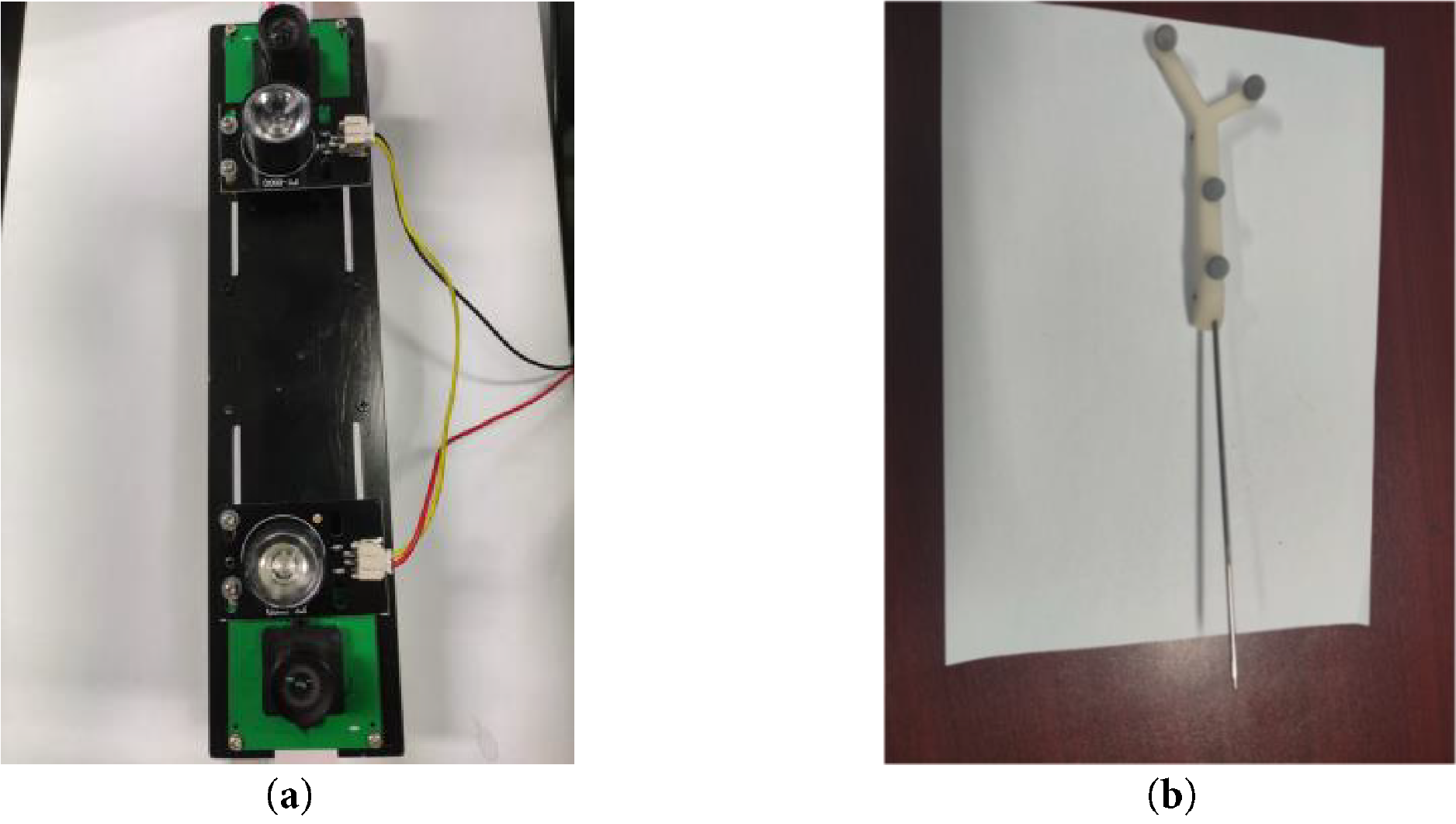

The camera used in this study is a Medvision industrial camera model MV-MSU130GM2-T. The experimental setup includes four optical balls, a puncture needle, and a needle cover, as shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Experimental instrument structure diagram. (a) video camera; (b) puncture needle

The 3D-printed hub of the piercing needle contains four threaded holes designed to attach the optical balls. During the experiment, the camera captures images of these four optical balls attached to the puncture needle, and their coordinates are determined within the camera coordinate system using binocular positioning.

3.1.2 Experimental Instruments for Needle Tip Calibration

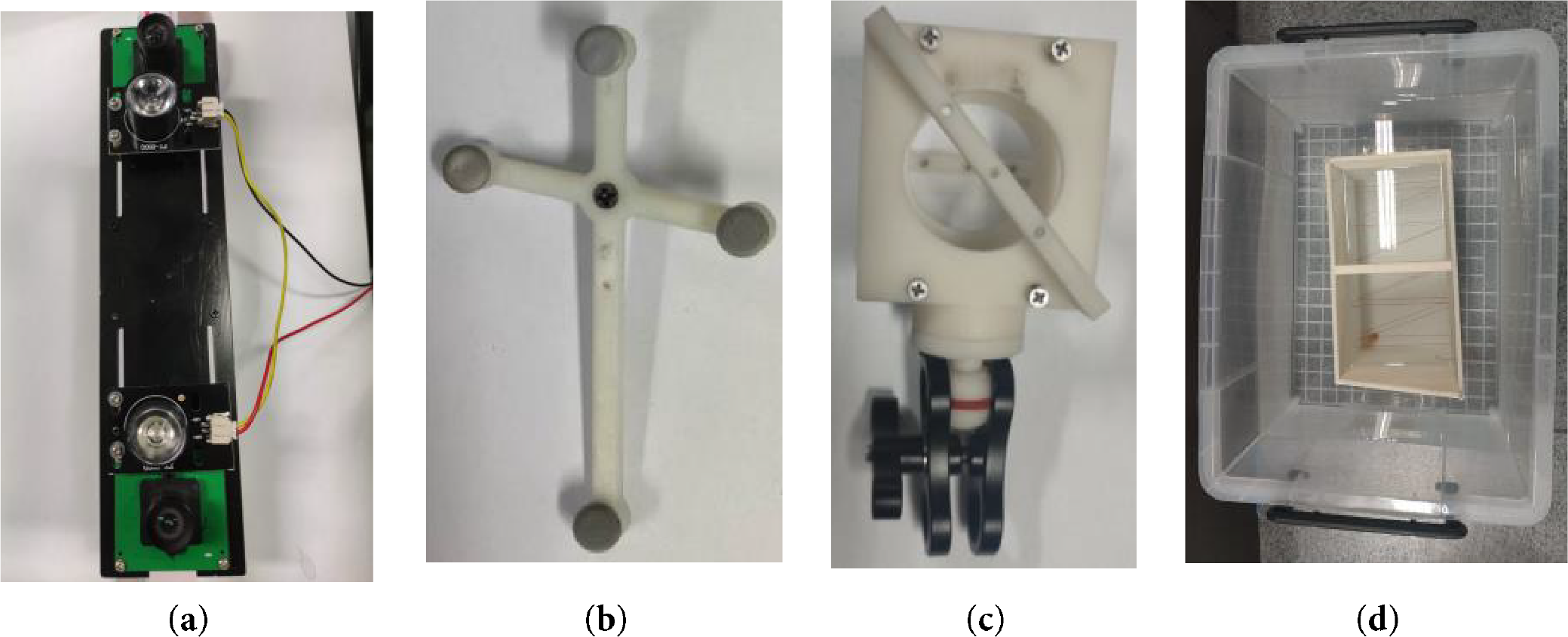

The ultrasound probe used in this experiment is a Sonostar all-digital ultrasound imaging diagnostic instrument, model CProbe. The camera employed is a Medvision industrial camera, model MV-MSU130GM2-T. The robotic arm utilized is the EC63, a lightweight 6-degree-of -freedom modular collaborative robot developed by Suzhou Elite Robot Co. Additional equipment includes ultrasound probe holders, optically marked pellets, N-type nylon wire, and a sink (filled with water maintained at 50°C). The configuration of the camera and the calibration board for the ultrasound probe is shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Schematic diagram of experimental equipment. (a) camera structure; (b) calibration plate structure; (c) fixture structure; (d) sink structure

3.2 Experiments on Needle Tip Calibration

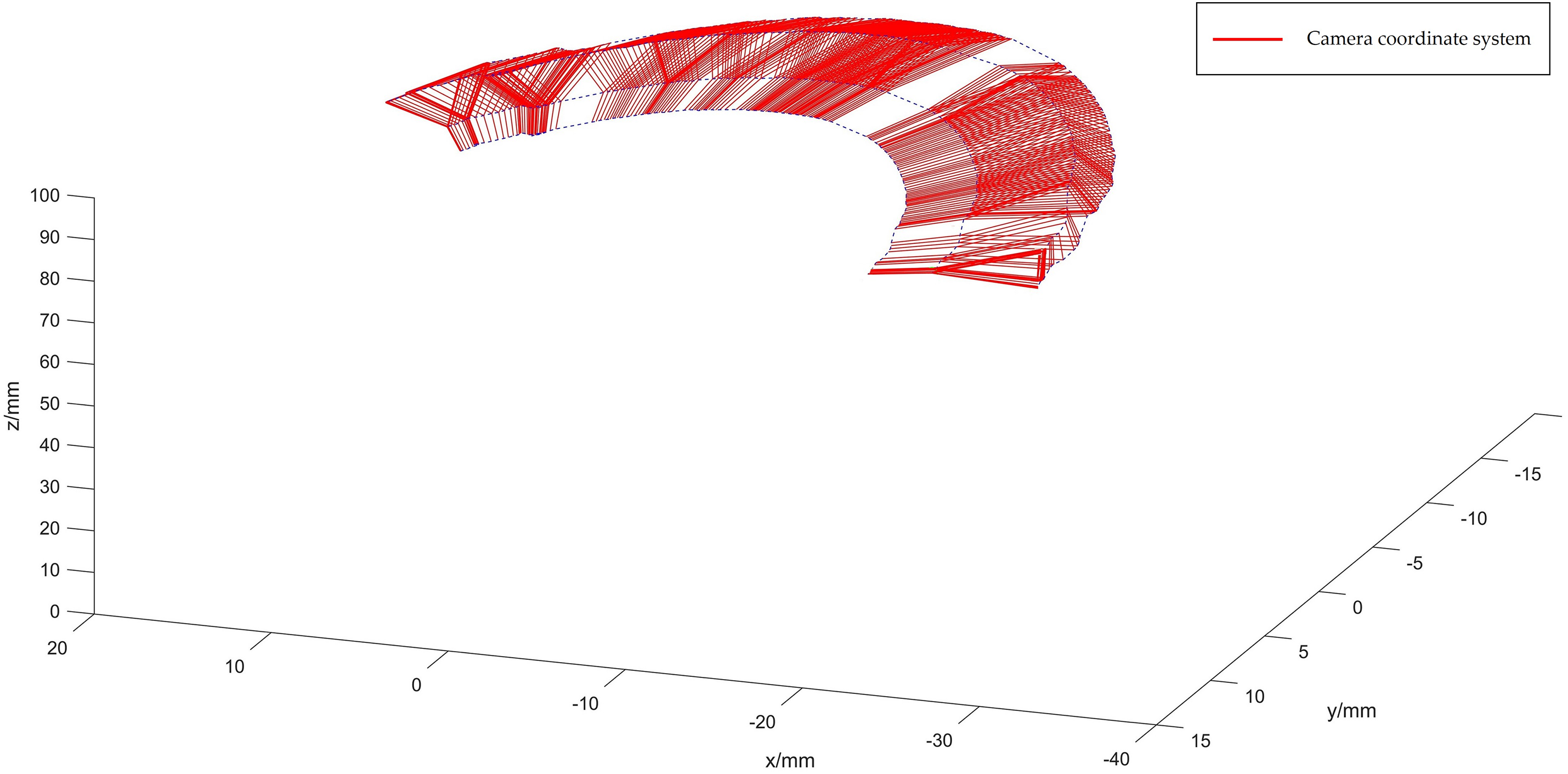

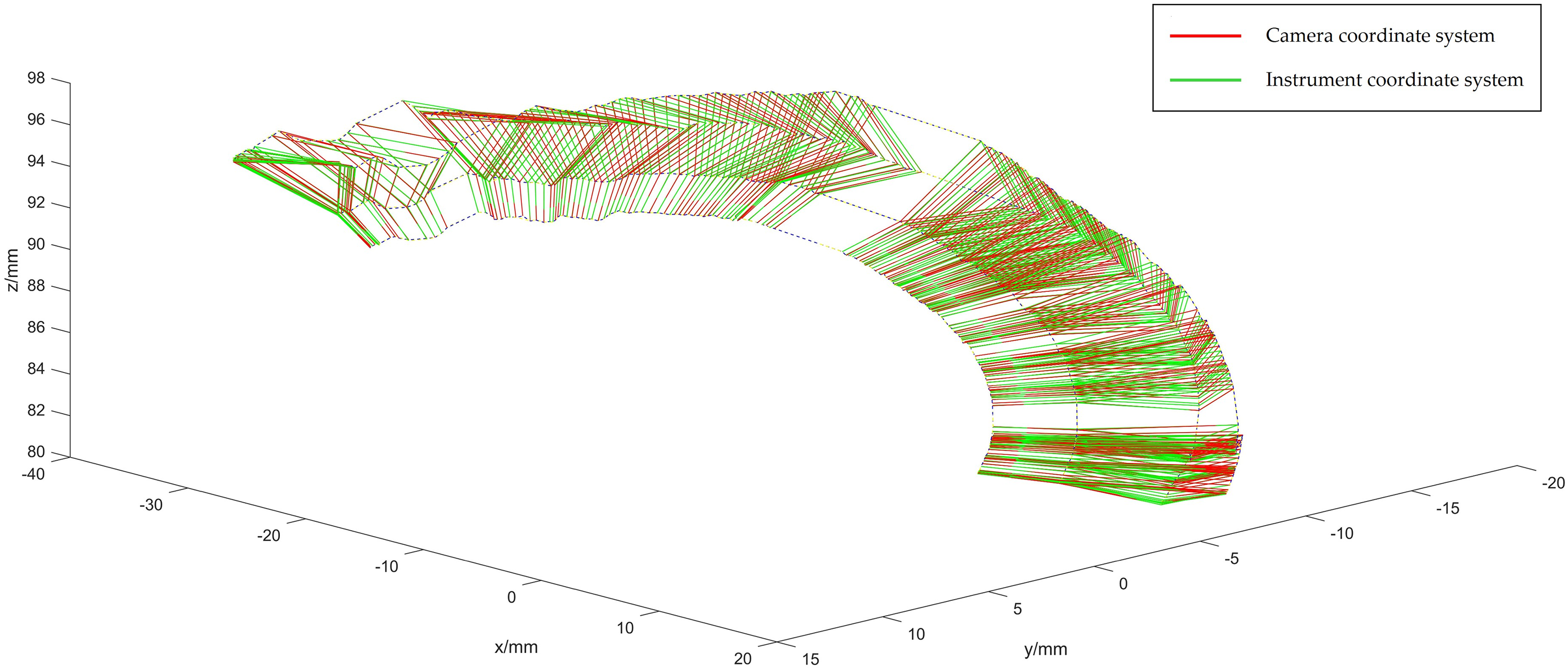

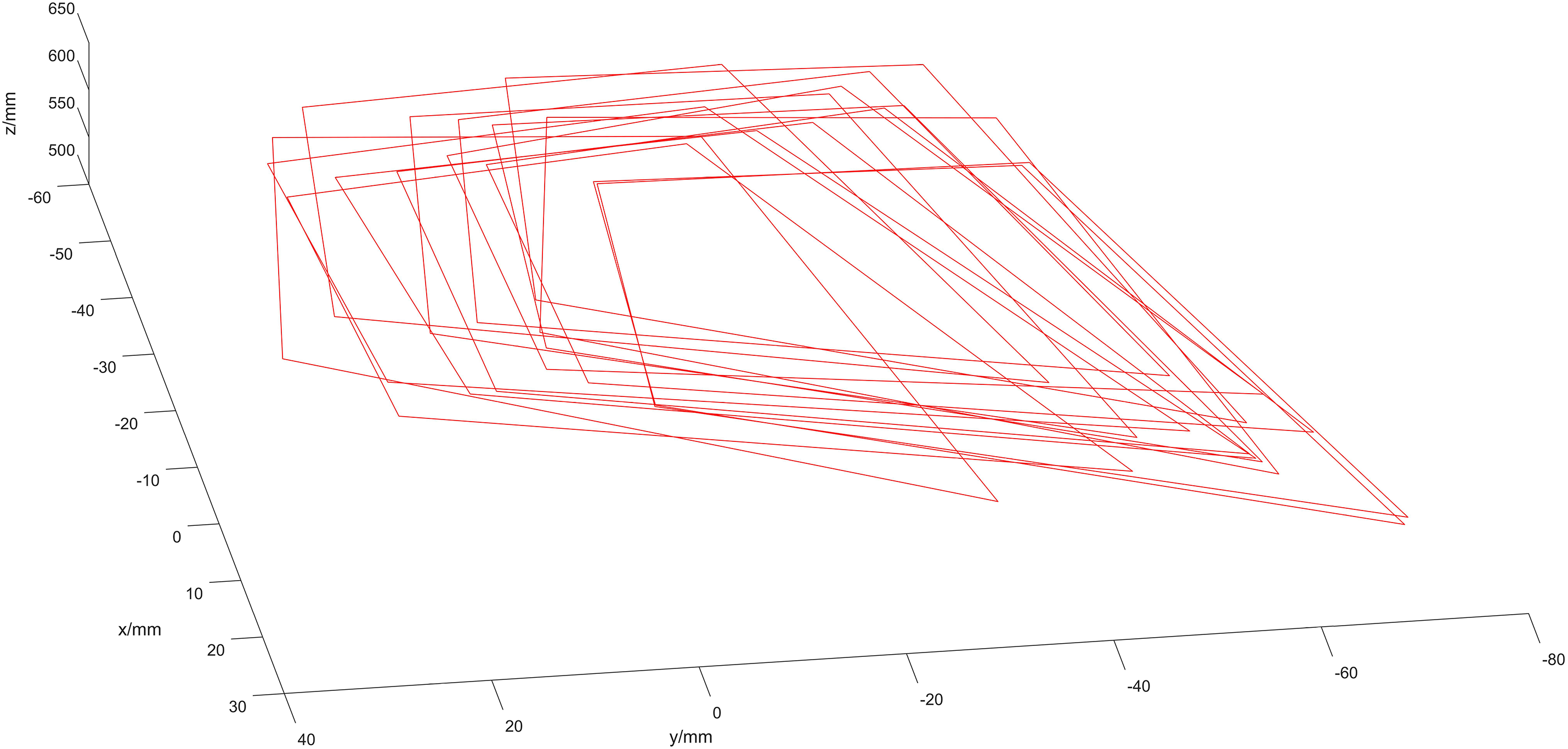

During the experiment, the camera captures images of four optical spheres attached to the puncture needle, and their coordinates are determined in the camera’s coordinate system through using dual targeting. By rotating the puncture needle tip 130 degrees around the calibration plate, we obtained 253 image frames of the 4 optical balls, as depicted in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Optical sphere diagram in the camera coordinate system

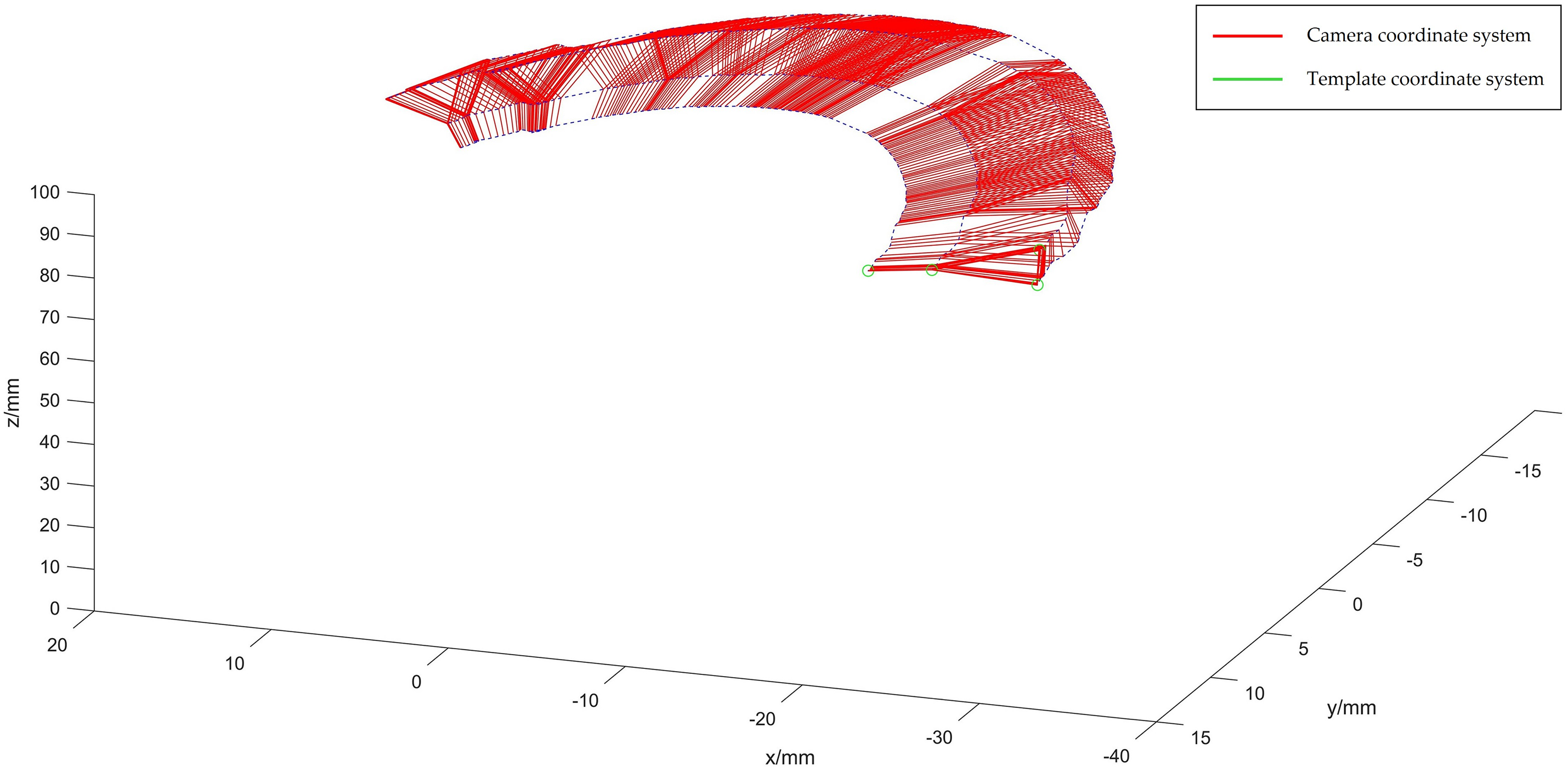

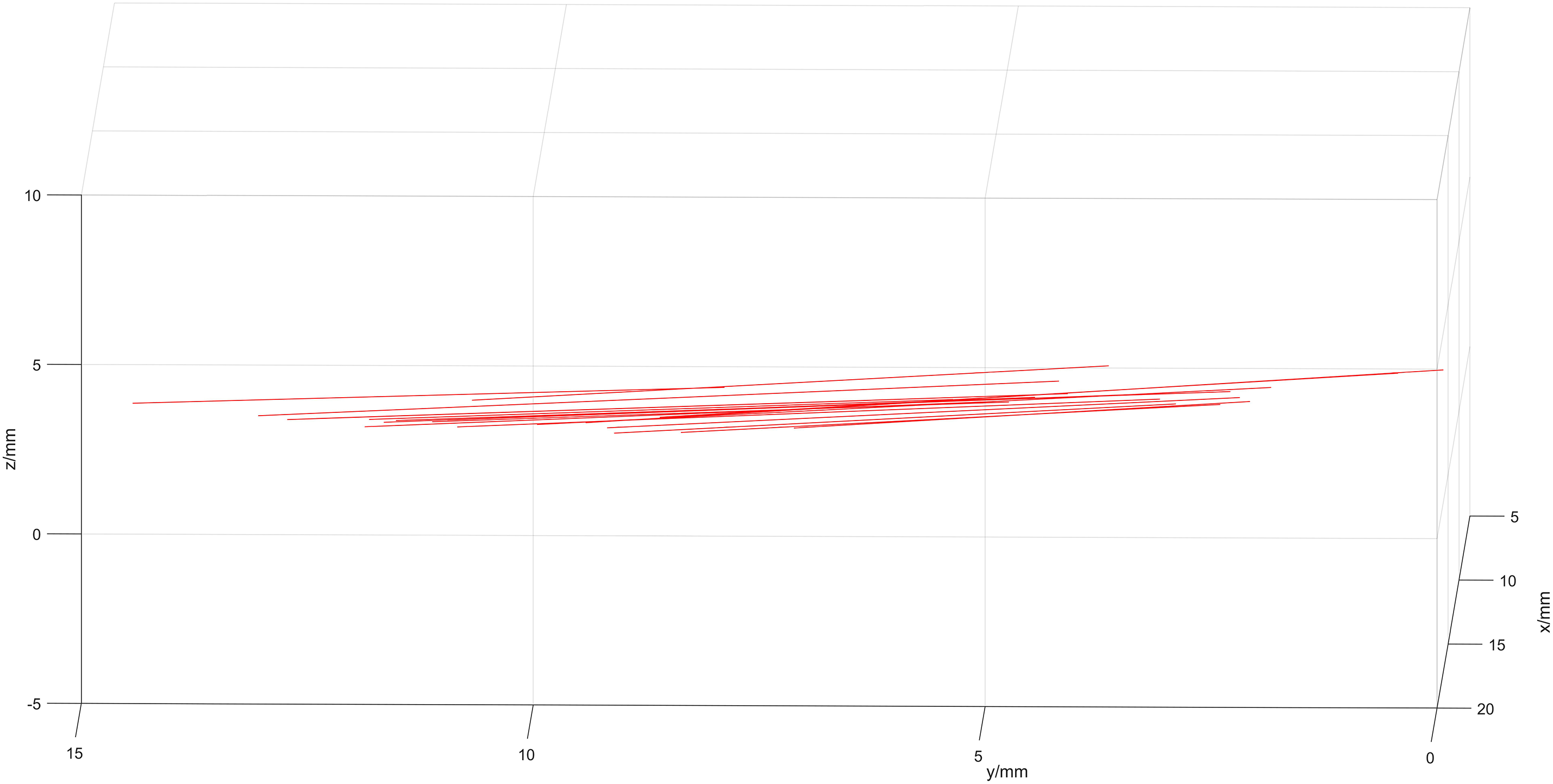

The coordinates in the template coordinate system are determined using gradient descent, applied to the images captured under the 253-frame camera coordinate system, as depicted in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Optical spherical diagram in template coordinate system

The spatial coordinates of the optical sphere, relative to the template coordinate system, are described in Eq. (35).

The spatial coordinates of the four optical spheres within the instrument’s reference coordinate system are described by Eq. (36).

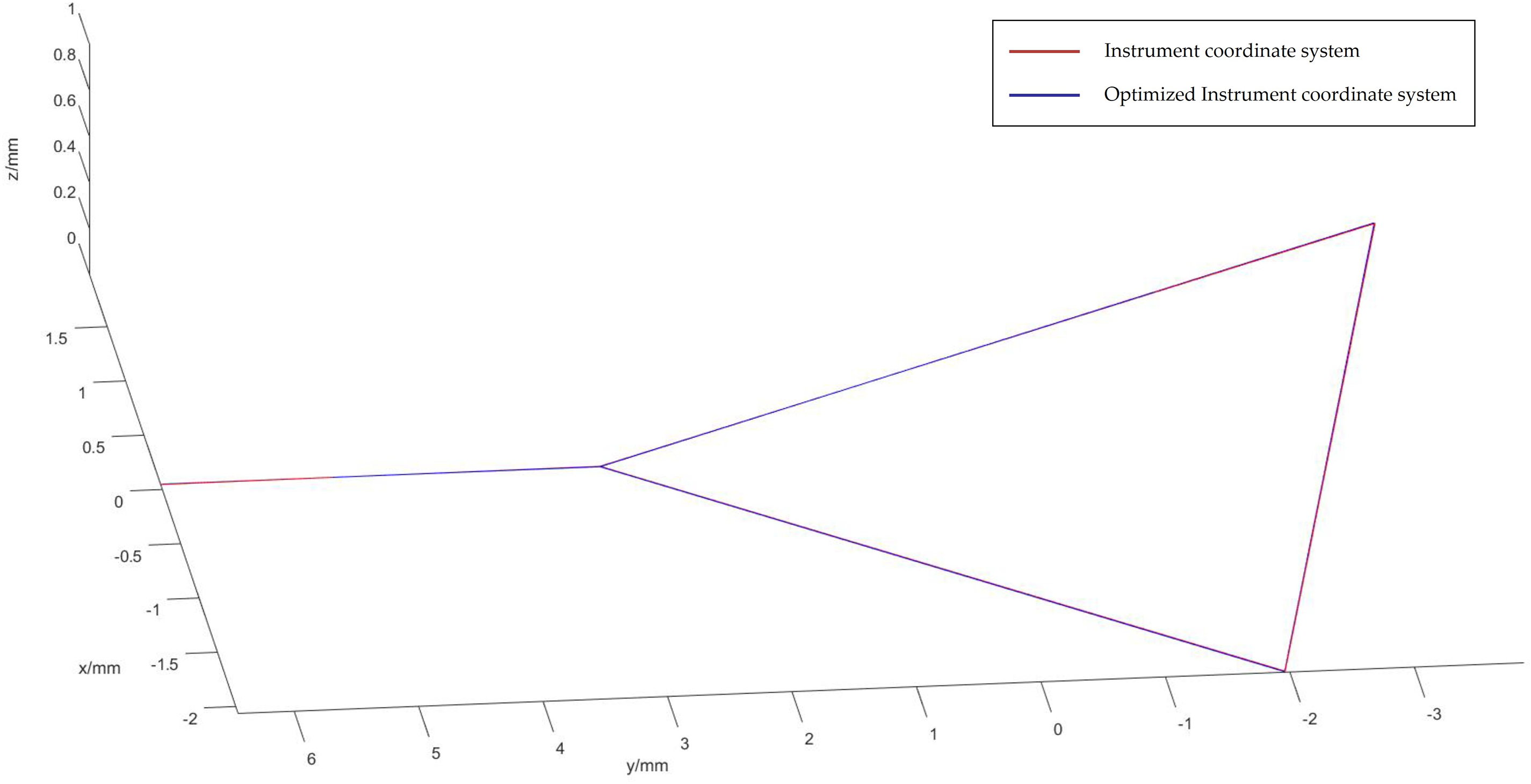

The coordinates in the template coordinate system are converted to the instrument coordinate system using the optimal rotation algorithm, resulting in

Considering the error in the coordinate transformation obtained by the optimal rotation algorithm

Figure 9: Optical spheroids of the optimized instrument coordinate system

The coordinates of the four optical spheres are presented in Eq. (37).

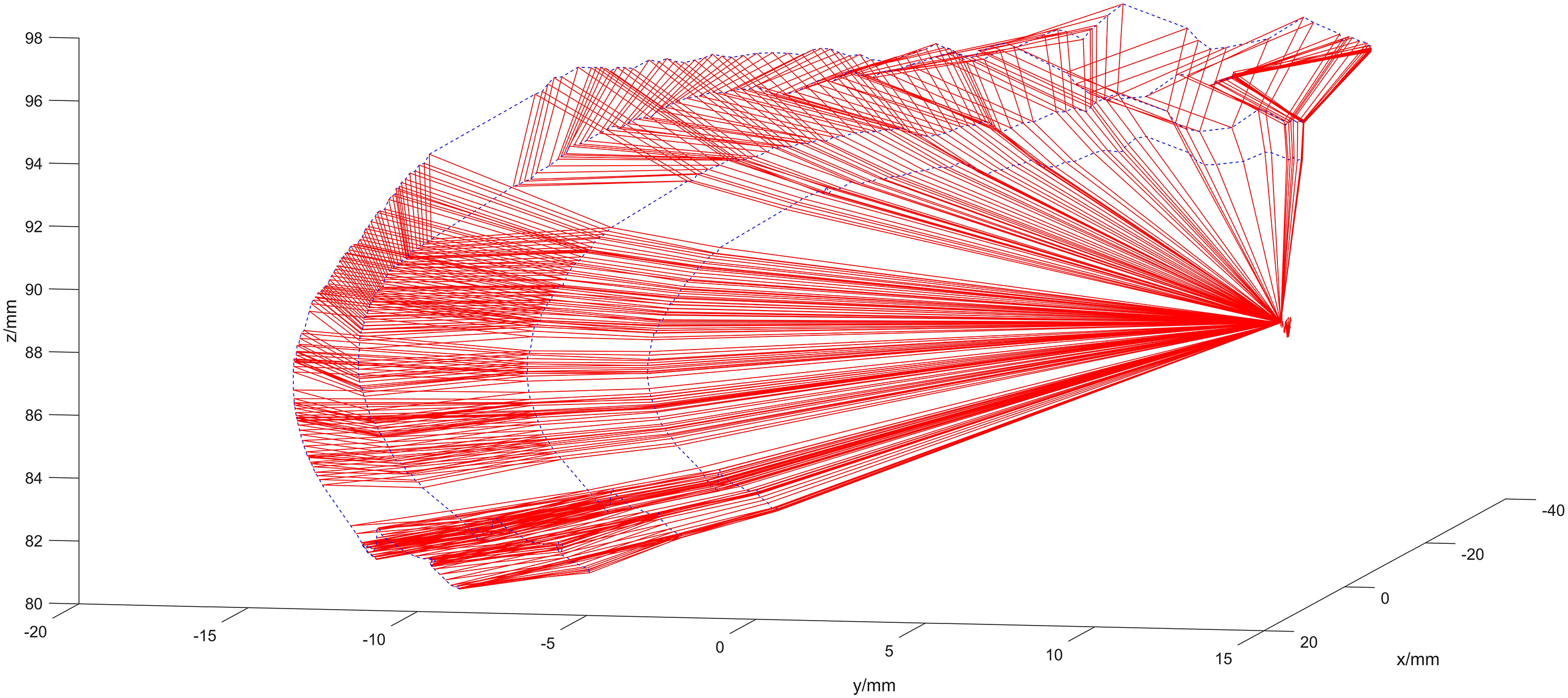

Using the optimal rotation algorithm, the coordinates of the optical spheres in the optimized instrument coordinate system are converted to the 253-frame camera coordinate system, allowing us to obtain the transformation matrix

The coordinate of the needle tip in the instrument coordinate system is

Figure 10: Optical spheroids of the optimized instrument coordinate system

The needle tip and optical sphere coordinates in the instrument coordinate system are transformed using

Figure 11: Optimized calibration scenario

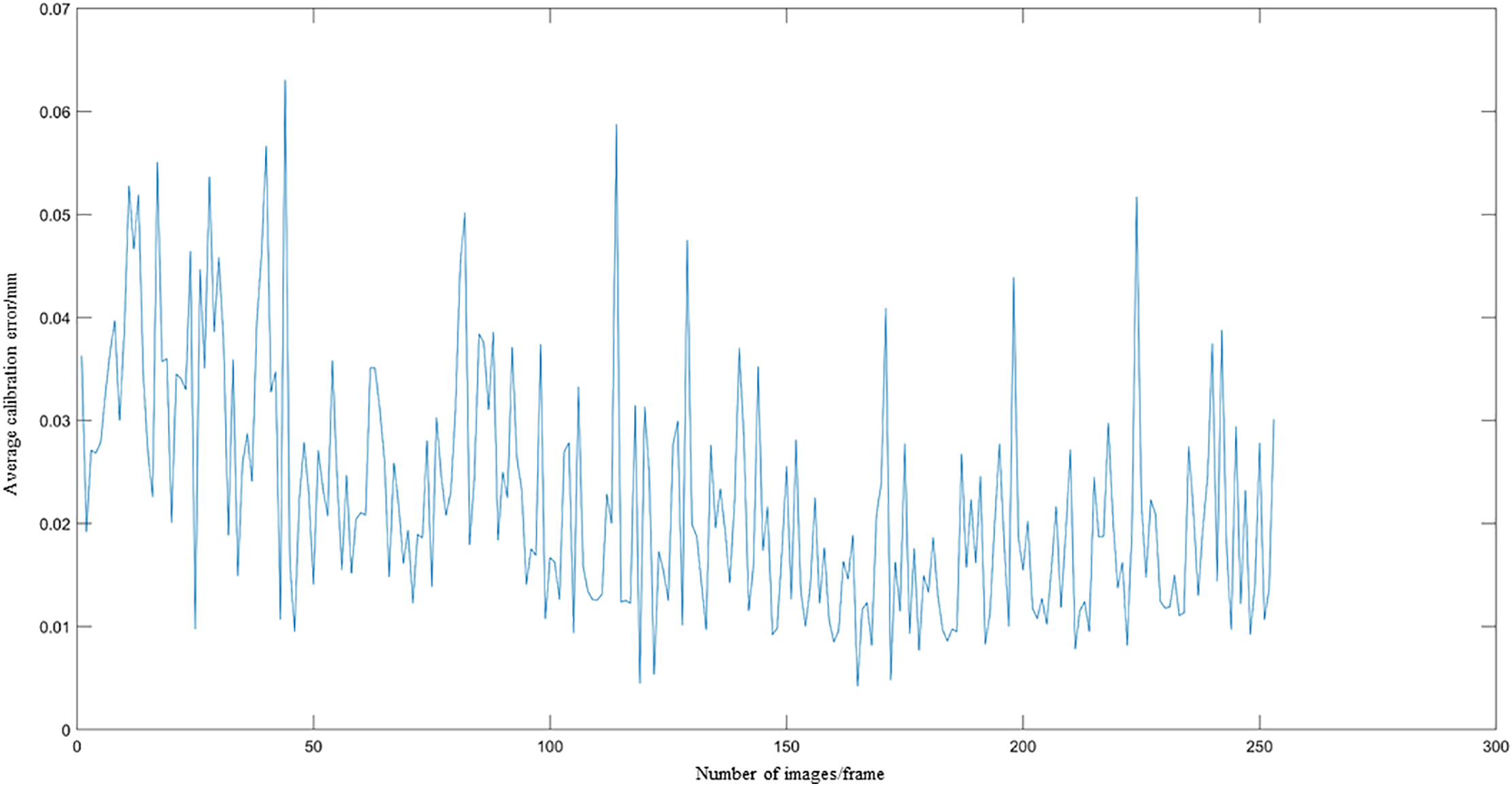

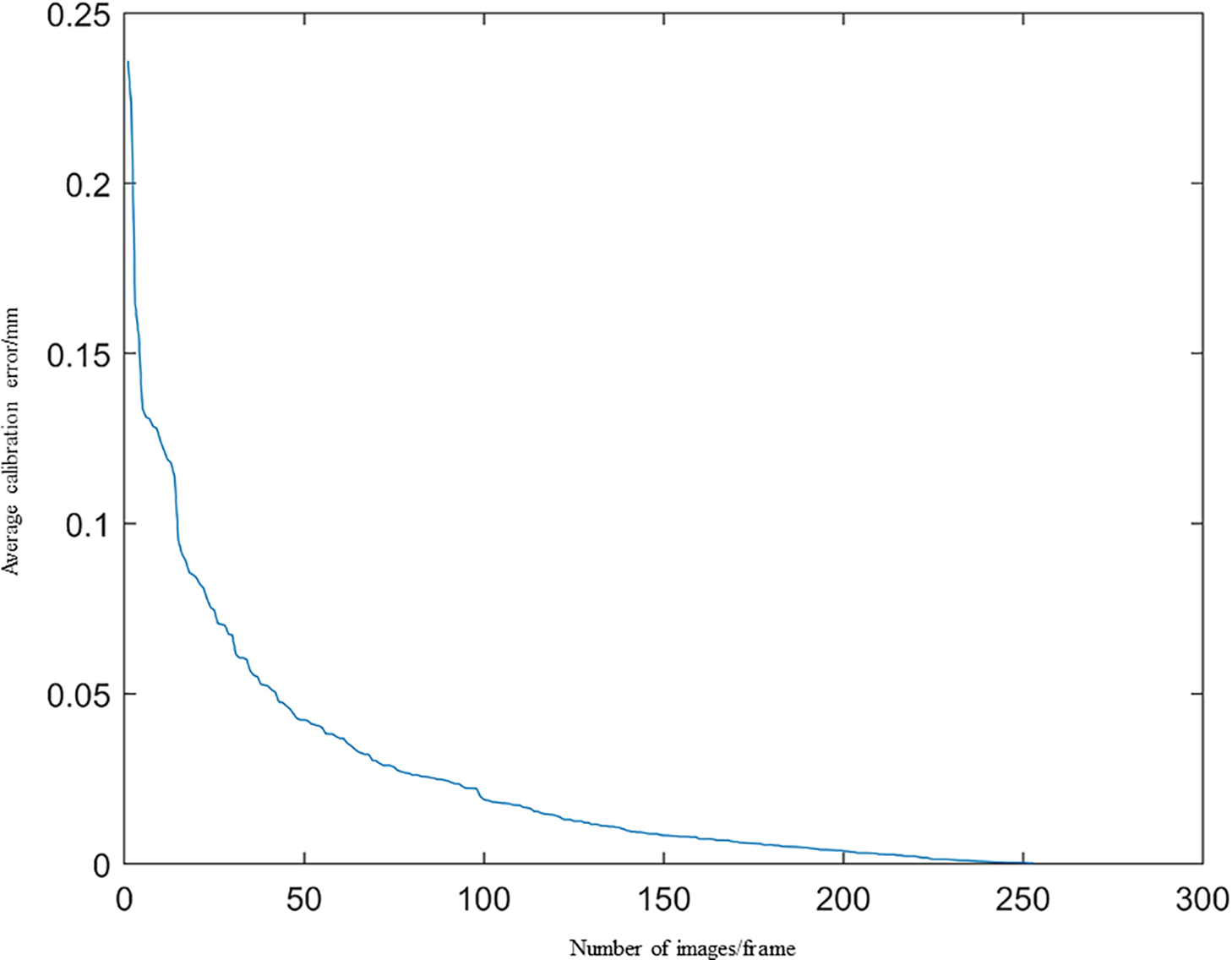

The average offset distance of the four optical spheres per frame, across all 253-frames, is illustrated in Fig. 12.

Figure 12: The average offset distance of the four optical spheroids

Fig. 13 illustrates the calibration error for the tip in each frame of the 253-frame sequence.

Figure 13: Calibration error diagram of the tip of the needle

Fig. 13 demonstrates a consistent decline in calibration error as the number of images increases, with deviations remaining below 0.25 mm throughout.

The gradient descent method is used to optimize the objective function based on 253 tip points, yielding an optimized coordinate for the puncture tip of

3.3 Experiments with Ultrasound Probe Calibration

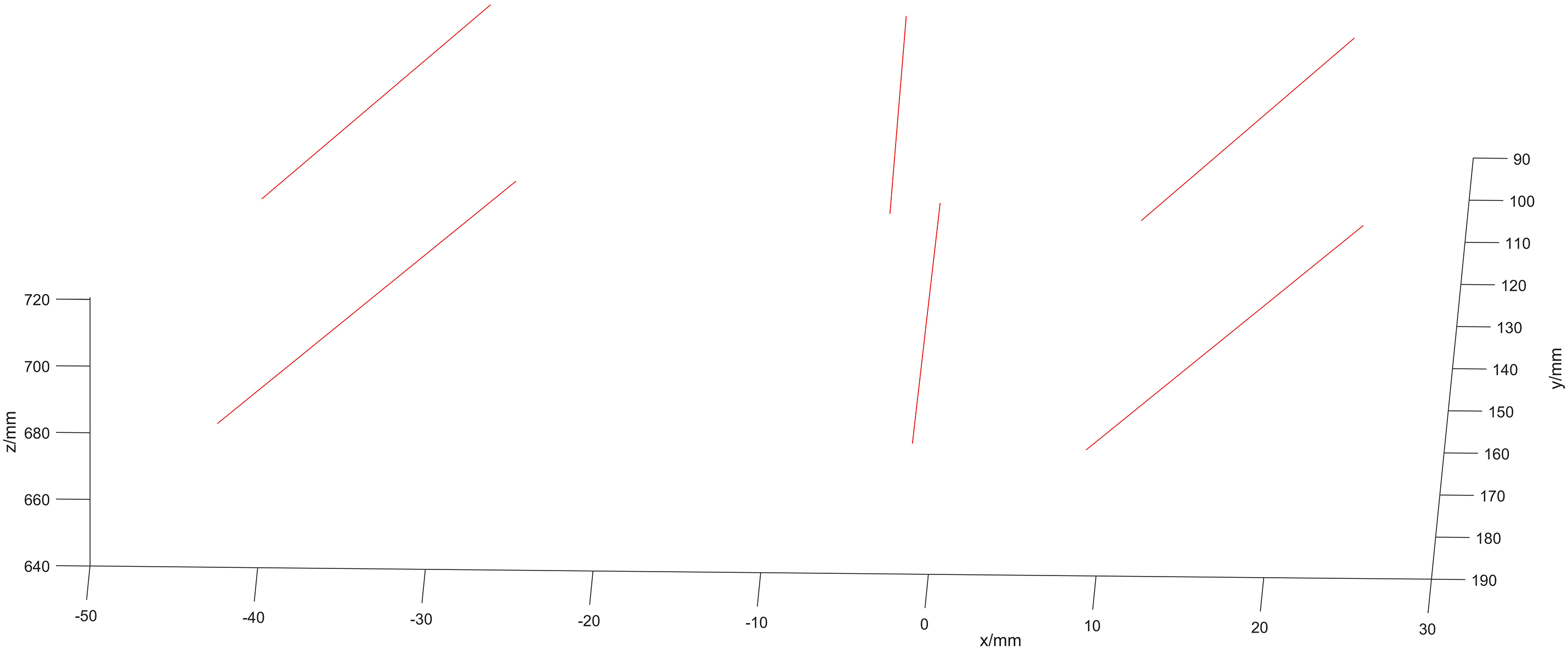

We take M = 30 ultrasound images, each containing L = 4 points. The coordinates of the two endpoints on the N-line are obtained, as shown in the resulting N-line image in Fig. 14.

Figure 14: Image of the N-line

The spatial coordinates of the optical marker in the probe’s reference frame are described by Eq. (38):

Fig. 15 illustrates images of 30 sets of optical spheres held by the ultrasound probe.

Figure 15: Optical spheroids in the camera’s coordinate system

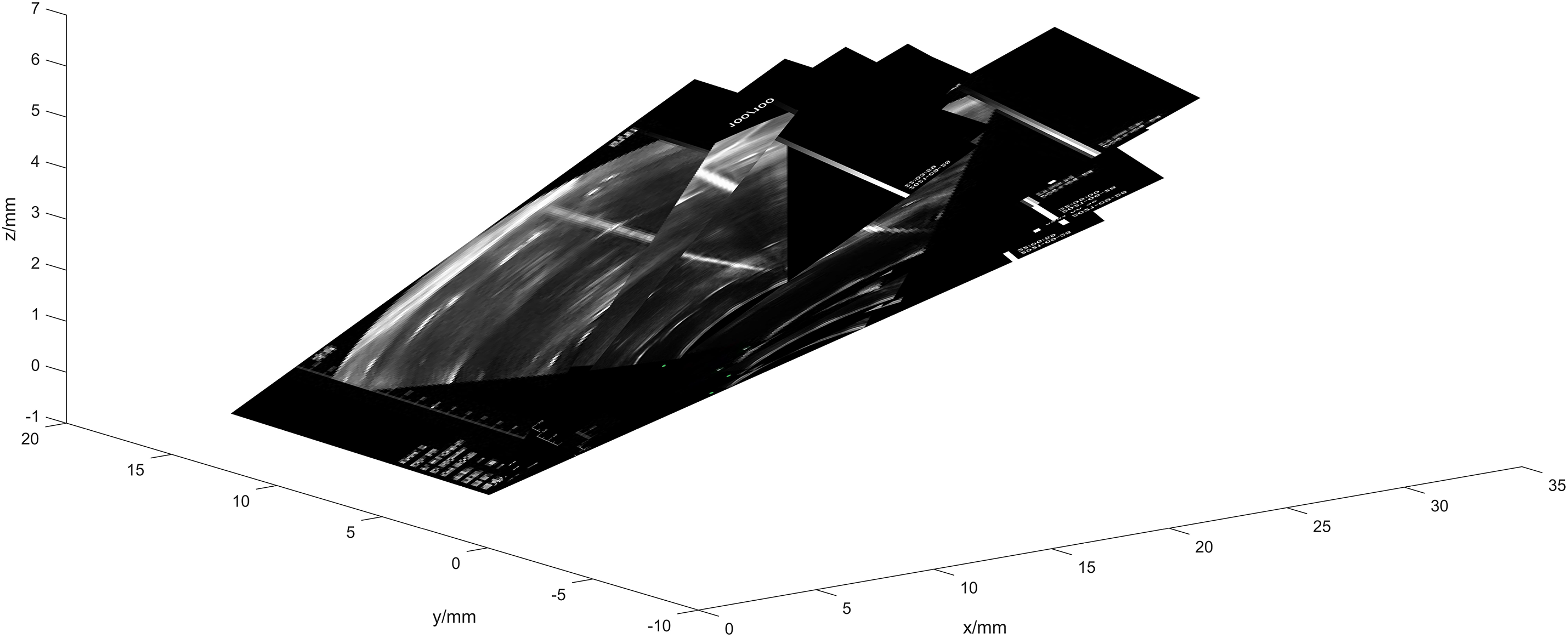

Substituting the initial value

Subsequently, the ultrasound image is transformed into the camera coordinate system, as shown in Fig. 16.

Figure 16: Schematic diagram of ultrasound probe calibration

Two points from the same side wall of the sink were selected from each frame image, and the resulting image of the pipe wall is illustrated in Fig. 17.

Figure 17: Image of the pipe wall

Fig. 17 shows that the pipe wall aligns closely with a single plane, with a deviation of less than 1 mm, thereby improving calibration precision. In this experiment, the value of

Surgical navigation systems have undergone rapid advancements in recent years, particularly in improving intraoperative precision and reducing patient trauma. Nevertheless, traditional navigation methods based on binocular stereovision often suffer from limited visibility in obstructed anatomical regions and lack robustness in dynamic scenarios [28,29]. To address these limitations, our approach integrates optical tracking, robotic manipulation, and real-time ultrasound guidance into a unified calibration framework.

A critical challenge in ultrasound-guided interventions is the accurate spatial registration between the ultrasound probe and the needle tip, which has typically been addressed in isolation. For instance, Kim et al. [30] proposed a calibration procedure for needle-guide systems attached to ultrasound probes, but their method relied on fixed mechanical assumptions and was not applicable to freehand scenarios. Similarly, Paralikar et al. [31] developed a robot-assisted calibration for the probe itself, but without considering the dynamic spatial behavior of the needle tip.

Other studies such as Carbajal et al. [32] utilized N-wire phantoms for ultrasound probe calibration, but treated needle localization as a separate or manually controlled process, introducing potential cumulative error. In contrast, our method achieves joint calibration, in which the accurately optimized needle tip coordinates are directly employed to solve the N-line model of the ultrasound probe. This integration ensures tighter spatial coupling, minimizes registration errors, and eliminates reliance on external fiducial phantoms.

Our experimental results demonstrate that this integrated approach significantly enhances calibration precision. The needle tip localization error remains under 0.25 mm across 253 captured frames, and the ultrasound probe calibration achieves a pixel deviation of only 1.2373 mm. Furthermore, the alignment of the calibrated ultrasound image with a known planar surface shows deviation below 1 mm, reinforcing the spatial accuracy of the proposed method. Compared to previous methods, this represents a substantial improvement in both accuracy and robustness under freehand or robotic setups.

In summary, the proposed joint calibration framework fills a notable gap in the current literature by unifying two previously separate procedures—needle tip and probe calibration—into a single optimization-based workflow. This method has strong potential for application in real-time surgical navigation, especially in 2D ultrasound-based systems that require precise spatial coordination without the aid of ionizing radiation.

Nevertheless, several limitations remain. The current experiments were conducted in a phantom environment using an optical tracking system, industrial camera, and robotic arm, we clarify that the proposed joint calibration method has not yet been deployed or tested on a fully integrated surgical navigation system in clinical or pre-clinical settings. The implementation was performed within a controlled prototype environment designed to simulate real-world constraints, including hardware synchronization and image acquisition workflows that align with those of standard navigation systems. In addition, while gradient descent with a fixed step size proved effective in our study, we acknowledge that more advanced optimization strategies, such as particle swarm optimization or other metaheuristic algorithms, may further enhance robustness in more complex or nonlinear calibration scenarios. Recent reviews and algorithmic studies on robot calibration highlight the effectiveness of data-driven and evolutionary approaches for improving optimization performance, which could inspire future extensions of our framework [33,34].

The entire calibration pipeline was implemented end-to-end, covering both needle tip localization and ultrasound probe-to-image registration. However, real-time integration into a functioning navigation system with user interface, intraoperative imaging, and surgeon feedback loop remains a direction for future development. The current results demonstrate the feasibility and internal consistency of the proposed model, providing a solid computational foundation for future system-level integration. We acknowledge that validation under more complex surgical conditions, such as soft tissue deformation, occlusion, or dynamic anatomical changes, will be necessary to demonstrate robustness in realistic environments. As such, future work will focus on extending the system to animal models or hybrid OR setups, and addressing practical challenges like tracking loss, calibration drift, and probe misalignment through sensor fusion and online error correction methods.

In this research, we introduce an advanced method for precise needle tip localization using a sophisticated rotation algorithm. This technique involves rotating the needle tip by 130 degrees around a fixed pivot, which enables the acquisition of multiple images of four optical spheres within the camera’s coordinate system. These images are then employed to refine the template coordinate system through gradient descent optimization. Subsequently, the coordinates within the template system are transformed into the instrument’s coordinate system. Further optimization of these coordinates is performed within the camera’s coordinate system. Notably, as the number of captured images increases, the calibration error remains consistently low, demonstrating remarkable stability and accuracy.

We then utilize the optimized needle tip coordinates to develop a joint calibration algorithm for the ultrasound probe. This calibration involves identifying the two endpoints of each N-line using the calibrated needle tip and solving the N-line equations based on ultrasound images. Additionally, using data from optical spheres captured by the optical positioning framework, we derive a transformation matrix to facilitate the transition from the probe’s reference system to the camera’s coordinate system. The calibration matrix for the ultrasound probe is formulated using a least-squares methodology, ensuring an optimized solution.

In our experimental setup, we used a Sonostar digital ultrasound imaging system equipped with a CProbe probe. The camera used was the MV-MSU130GM2-T industrial camera from MedViewTech. The mechanical arm used in the experiments was the EC63 intelligent lightweight 6-degree-of-freedom modular collaborative robot developed by Suzhou Eletech Robotics Co. Our experimental results validate the proposed method’s efficacy in achieving high-precision calibration for 2D ultrasound surgical navigation, showing stable calibration errors across different numbers of images.

Overall, the study establishes a practical and accurate calibration strategy that addresses a long-standing gap in ultrasound-guided navigation, offering a streamlined workflow with potential for translation into real-time minimally invasive surgical applications.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: Support by Sichuan Science and Technology Program [2023YFSY0026, 2023YFH0004].

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, Bo Yang and Shan Liu; methodology, Bo Yang and Fupei Guo; software, Bo Yang and Xiang Zhang; validation, Jiawei Tian and Yu Zhou; formal analysis, Fupei Guo; investigation, Xiang Zhang; resources, Jiawei Tian; data curation, Xiang Zhang; writing—original draft preparation, Bo Yang; writing—review and editing, Jiawei Tian; visualization, Yu Zhou; supervision, Jiawei Tian; project administration, Shan Liu; funding acquisition, Shan Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Recker F, Höhne E, Damjanovic D, Schäfer VS. Ultrasound in telemedicine: a brief overview. Appl Sci. 2022;12(3):958. doi:10.3390/app12030958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chandrashekhara SH, Rangarajan K, Agrawal A, Thulkar S, Gamanagatti S, Raina D, et al. Robotic ultrasound: an initial feasibility study. World J Methodol. 2022;12(4):274–84. doi:10.5662/wjm.v12.i4.274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Elmi-Terander A, Burström G, Nachabe R, Skulason H, Pedersen K, Fagerlund M, et al. Pedicle screw placement using augmented reality surgical navigation with intraoperative 3D imaging: a first in-human prospective cohort study. Spine. 2019;44(7):517–25. doi:10.1097/brs.0000000000002876. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Gonzalez LV, Arango A, López JP, Gnecco JP. Technological integration of virtual surgical planning, surgical navigation, endoscopic support and patient-specific implant in orbital trauma. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2021;20(3):459–63. doi:10.1007/s12663-020-01423-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Lartizien R, Zaccaria I, Savoldelli C, Noyelles L, Chamorey E, Cracowski JL, et al. Learning condyle repositioning during orthognathic surgery with a surgical navigation system. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;48(7):952–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2019.01.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Quang TT, Chen WF, Papay FA, Liu Y. Dynamic, real-time, fiducial-free surgical navigation with integrated multimodal optical imaging. IEEE Photonics J. 2021;13(1):1–13. doi:10.1109/jphot.2020.3042269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Granata A, Distefano G, Pesce F, Battaglia Y, Suavo Bulzis P, Venturini M, et al. Performing an ultrasound-guided percutaneous needle kidney biopsy: an up-to-date procedural review. Diagnostics. 2021;11(12):2186. doi:10.3390/diagnostics11122186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Lee JY, Islam M, Woh JR, Mohamed Washeem TS, Ngoh LYC, Wong WK, et al. Ultrasound needle segmentation and trajectory prediction using excitation network. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2020;15(3):437–43. doi:10.1007/s11548-019-02113-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Gueziri HE, Drouin S, Yan CXB, Collins DL. Toward real-time rigid registration of intra-operative ultrasound with preoperative CT images for lumbar spinal fusion surgery. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2019;14(11):1933–43. doi:10.1007/s11548-019-02020-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Jengojan S, Sorgo P, Streicher J, Snoj Ž, Kasprian G, Gruber G, et al. Ultrasound-guided thread versus ultrasound-guided needle release of the A1 pulley: a cadaveric study. Radiol Med. 2024;129(10):1513–21. doi:10.1007/s11547-024-01875-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Li Q, Lin X, Zhang X, Samir AE, Arellano RS. Imaging-related risk factors for bleeding complications of US-guided native renal biopsy: a propensity score matching analysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30(1):87–94. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2018.08.031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Edwards W, Tang G, Tian Y, Draelos M, Izatt J, Kuo A, et al. Data-driven modelling and control for robot needle insertion in deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2022;7(2):1526–33. doi:10.1109/lra.2022.3140458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Hong A, Petruska AJ, Zemmar A, Nelson BJ. Magnetic control of a flexible needle in neurosurgery. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2021;68(2):616–27. doi:10.1109/tbme.2020.3009693. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Jiang Y, Song Q, Gao F, Liu Z, Gupta MK, Hao X. Needle deformation in the process of puncture surgery: experiment and simulation. Procedia CIRP. 2020;89(3):270–6. doi:10.1016/j.procir.2020.05.151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhong F, Wang Z, Chen W, He K, Wang Y, Liu YH. Hand-eye calibration of surgical instrument for robotic surgery using interactive manipulation. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2020;5(2):1540–7. doi:10.1109/lra.2020.2967685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Pavone M, Seeliger B, Teodorico E, Goglia M, Taliento C, Bizzarri N, et al. Ultrasound-guided robotic surgical procedures: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2024;38(5):2359–70. doi:10.1007/s00464-024-10772-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. van Boxel GI, Carter NC, Fajksova V. Three-arm robotic cholecystectomy: a novel, cost-effective method of delivering and learning robotic surgery in upper GI surgery. J Robot Surg. 2024;18(1):180. doi:10.1007/s11701-024-01919-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Beigi P, Salcudean SE, Ng GC, Rohling R. Enhancement of needle visualization and localization in ultrasound. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2021;16(1):169–78. doi:10.1007/s11548-020-02227-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Wang KJ, Chen CH, Lo CY, Lin HH, Jason Chen JJ. Ultrasound calibration for dual-armed surgical navigation system. J Healthc Eng. 2022;2022:3362495. doi:10.1155/2022/3362495. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Seitel A, Groener D, Eisenmann M, Aguilera Saiz L, Pekdemir B, Sridharan P, et al. Miniaturized electromagnetic tracking enables efficient ultrasound-navigated needle insertions. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):14161. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-64530-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Che H, Qin J, Chen Y, Ji Z, Yan Y, Yang J, et al. Improving needle tip tracking and detection in ultrasound-based navigation system using deep learning-enabled approach. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2024;28(5):2930–42. doi:10.1109/JBHI.2024.3353343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Chai Z, Sun Y, Xiong Z. A novel method for LiDAR camera calibration by plane fitting. In: 2018 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics (AIM); 2018 Jul 9–12; Auckland, New Zealand. p. 286–91. doi:10.1109/aim.2018.8452339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Nurbekyan L, Lei W, Yang Y. Efficient natural gradient descent methods for large-scale PDE-based optimization problems. SIAM J Sci Comput. 2023;45(4):A1621–55. doi:10.1137/22m1477805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Masood H, Zafar A, Ali MU, Hussain T, Khan MA, Tariq U, et al. Tracking of a fixed-shape moving object based on the gradient descent method. Sensors. 2022;22(3):1098. doi:10.3390/s22031098. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Sorriento A, Porfido MB, Mazzoleni S, Calvosa G, Tenucci M, Ciuti G, et al. Optical and electromagnetic tracking systems for biomedical applications: a critical review on potentialities and limitations. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. 2019;13:212–32. doi:10.1109/rbme.2019.2939091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Dai H, Zeng Y, Wang Z, Lin H, Lin M, Gao H, et al. Prior knowledge-based optimization method for the reconstruction model of multicamera optical tracking system. IEEE Trans Automat Sci Eng. 2020;17(4):2074–84. doi:10.1109/tase.2020.2989194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Song X, Zhang Y, Wang C, Zhao H, Liu A. Study on calibration method of ultrasonic probe based on electromagnetic positioner in puncture surgical robot. In: Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Robotics, Intelligent Control and Artificial Intelligence; 2022 Dec 16–18; Dongguan, China. p. 161–4. doi:10.1145/3584376.3584404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Teatini A, Kumar RP, Elle OJ, Wiig O. Mixed reality as a novel tool for diagnostic and surgical navigation in orthopaedics. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2021;16(3):407–14. doi:10.1007/s11548-020-02302-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Bi S, Wang M, Zou J, Gu Y, Zhai C, Gong M. Dental implant navigation system based on trinocular stereo vision. Sensors. 2022;22(7):2571. doi:10.3390/s22072571. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Kim C, Chang D, Petrisor D, Chirikjian G, Han M, Stoianovici D. Ultrasound probe and needle-guide calibration for robotic ultrasound scanning and needle targeting. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2013;60(6):1728–34. doi:10.1109/TBME.2013.2241430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Paralikar A, Mantripragada P, Nguyen T, Arjoune Y, Shekhar R, Monfaredi R. Robot-assisted ultrasound probe calibration for image-guided interventions. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2025;20(5):859–68. doi:10.1007/s11548-025-03347-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Carbajal G, Lasso A, Gómez Á, Fichtinger G. Improving N-wire phantom-based freehand ultrasound calibration. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2013;8(6):1063–72. doi:10.1007/s11548-013-0904-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Chen T, Yang W, Li S, Luo X. Data-driven calibration of industrial robots: a comprehensive survey. IEEE/CAA J Autom Sinica. 2025;12(8):1544–67. doi:10.1109/jas.2025.125237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Chen T, Li S, Qiao Y, Luo X. A robust and efficient ensemble of diversified evolutionary computing algorithms for accurate robot calibration. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2024;73(6):7501814. doi:10.1109/TIM.2024.3363783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools