Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Side-Scan Sonar Image Synthesis Based on CycleGAN with 3D Models and Shadow Integration

1 Department of Artificial Intelligence Convergence, Pukyong National University, Busan, 48513, Republic of Korea

2 Marine Domain Research Division, Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology (KIOST), Busan, 49111, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Won-Du Chang. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Machine Learning and Deep Learning-Based Pattern Recognition)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 1237-1252. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.073530

Received 19 September 2025; Accepted 16 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

Side-scan sonar (SSS) is essential for acquiring high-resolution seafloor images over large areas, facilitating the identification of subsea objects. However, military security restrictions and the scarcity of subsea targets limit the availability of SSS data, posing challenges for Automatic Target Recognition (ATR) research. This paper presents an approach that uses Cycle-Consistent Generative Adversarial Networks (CycleGAN) to augment SSS images of key subsea objects, such as shipwrecks, aircraft, and drowning victims. The process begins by constructing 3D models to generate rendered images with realistic shadows from multiple angles. To enhance image quality, a shadow extractor and shadow region loss function are introduced to ensure consistent shadow representation. Additionally, a multi-resolution learning structure enables effective training, even with limited data availability. The experimental results show that the generated data improved object detection accuracy when they were used for training and demonstrated the ability to generate clear shadow and background regions with stability.Keywords

Water, covering 71% of the Earth’s surface, presents unique challenges for exploration since electromagnetic waves, including lasers, are heavily absorbed, limiting their effective range [1]. While airborne bathymetric Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) systems offer some capability for marine surveys, they struggle with limited resolution and shallow depth penetration [2]. As a result, sound waves are preferred for underwater applications because they can travel farther and are ideal for tasks such as detailed seafloor mapping, imaging, and communication [3]. Side-scan sonar (SSS), which utilizes sound waves, is a powerful tool for quickly acquiring high-resolution images of the seafloor across large areas, enabling the detection of subsea objects. Although more advanced technologies such as synthetic aperture sonar (SAS) can provide higher resolution and broader coverage [4], their deployment is constrained by high cost and limited accessibility. Consequently, side-scan sonar (SSS) remains the predominant modality for efficient wide-area seafloor imaging and constitutes the focus of this study. However, despite its practicality, SSS data remain difficult to acquire at scale due to military security, cultural heritage restrictions, and the scarcity of underwater objects [5]. Additionally, the accuracy of SSS image interpretation can vary depending on the expertise of surveyors and environmental conditions. In some cases, divers or remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) are necessary to capture optical images for precise identification [6,7]. Automating the analysis of SSS images through artificial intelligence (AI) offers the potential for rapid and expert-level object detection or recognition. This, however, relies on training AI models with large datasets, which are often difficult to acquire.

Generative techniques, such as generative adversarial networks (GANs), offer a practical way to address data scarcity by creating realistic and diverse datasets that support effective model training [8]. These techniques ensure recognition models are well-trained to identify underwater objects, even with limited real-world SSS data. Karjalainen et al. (2019) validated an automatic target recognition (ATR) system using GANs [9], while Reed et al. (2019) synthesized SAS images by combining GANs with an optical renderer [10]. Jiang et al. (2020) developed a GAN-based method for synthesizing multi-frequency SSS images [11], and Tang et al. (2023) leveraged CycleGAN for augmenting SSS image samples [12].

This study presents an SSS image synthesis method based on CycleGAN, with a focus on accurately incorporating shadow characteristics to enhance the quality of generated images. The shadow characteristics in SSS images provide crucial 3D cues about the height and shape of objects [13,14]. These cues are essential for accurate analysis of SSS images, helping to interpret spatial information that might otherwise be lost. Despite the importance of shadows, previous research on synthetic SSS images has not thoroughly addressed how to generate them realistically. To bridge this gap, we employed 3D models to generate SSS images with shadows from multiple angles. A shadow extractor and shadow region loss function were integrated into the CycleGAN framework to ensure correct shadow generation. Additionally, a multi-resolution learning structure was incorporated to facilitate effective training with limited data. Compared to existing approaches that neglect shadow information, the proposed method incorporates accurate shadow characteristics into the CycleGAN framework to enhance the quality of generated SSS images. By leveraging 3D models and integrating a shadow extractor and shadow region loss function, the framework ensures realistic shadow generation, capturing essential spatial details. This improves the model’s ability to generate high-quality images and enhances the effectiveness of recognition models, leading to more reliable underwater object detection even with limited training data.

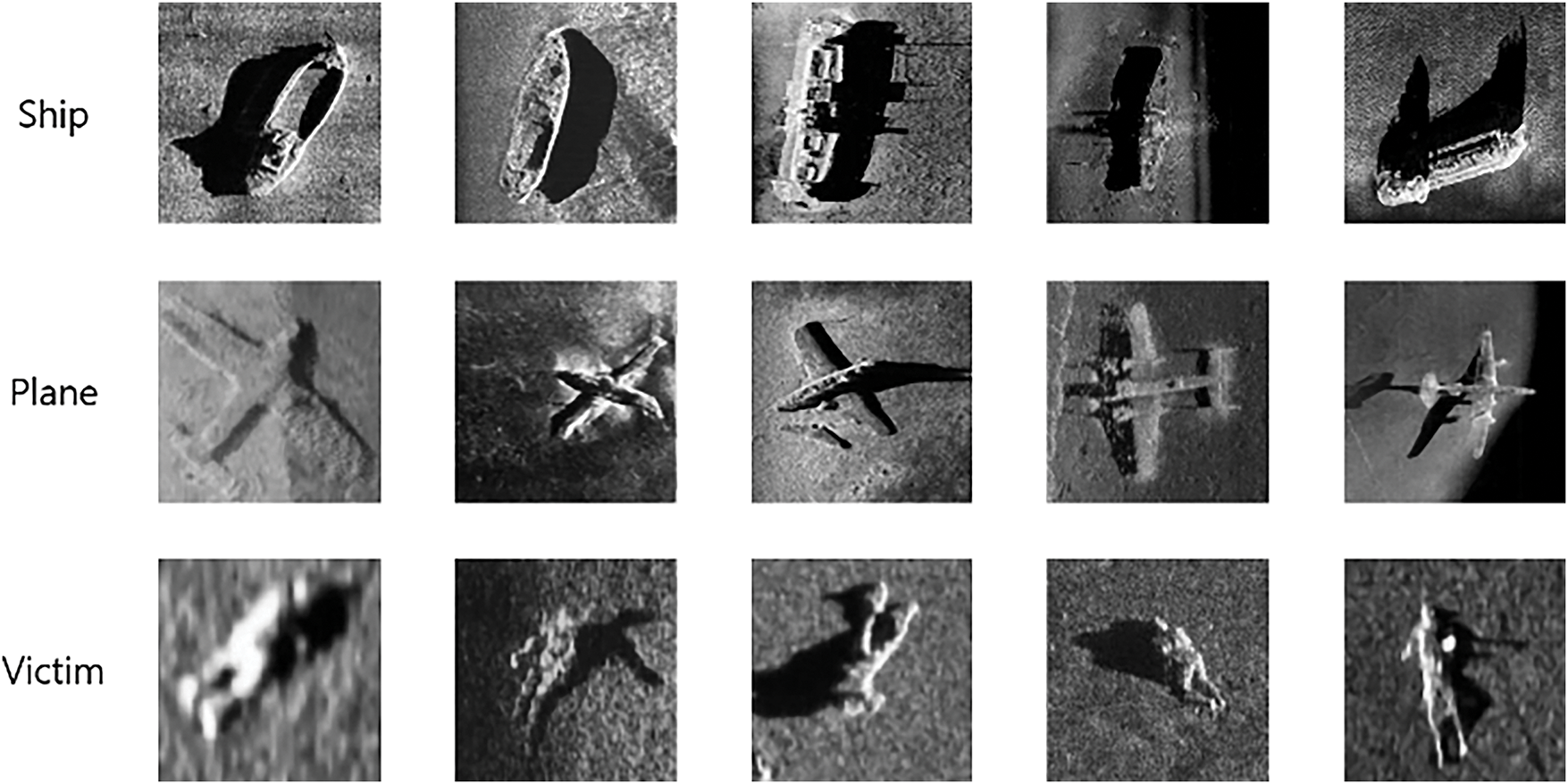

In this study, style transformation based on CycleGAN was performed to generate SSS images, utilizing datasets from two domains: real-world SSS images and synthetic images for style transformation. The SeabedObjects-KLSG dataset, published by Huo et al., is a publicly available collection of 1190 underwater SSS images gathered over 10 years [15]. These images are categorized into five groups—shipwrecks, aircraft, drowning victims, mines, and seafloor—to support automatic underwater object detection research. For this study, 402 images from three categories—334 shipwrecks, 34 aircraft, and 34 drowning victims—were selected, while other categories such as mines and seafloor were excluded. Mines were excluded because their specifications vary widely across different types, and the shadows they cast are generally small, making them less relevant to the objectives of this study. The seafloor category was also omitted, since the focus of this study is on object-level representation rather than background modeling. Fig. 1 presents sample images from the SeabedObjects-KLSG dataset, showcasing real-world examples of SSS imagery.

Figure 1: Samples of seabedObjects-KLSG dataset

Beyond the SeabedObjects-KLSG dataset, the availability of public SSS datasets containing object instances is extremely limited. Due to security restrictions and data sensitivity, most existing studies have relied on private datasets, which makes reproducibility difficult. Moreover, many works have primarily focused on mine or mine-like objects [16–18], while comparatively little attention has been given to objects with more complex structural features. The SeabedObjects-KLSG dataset remains one of the few publicly accessible resources and has therefore been widely adopted in related research [19,20]. Other available datasets mainly contain categories unrelated to this study, including glaciers and walls [21], pipes, mounds, and platforms [22], walls [23], pipelines [24], and seagrass, rocks, and sand [25]. Consequently, the SeabedObjects-KLSG dataset was selected as the most suitable basis for the experiments in this work.

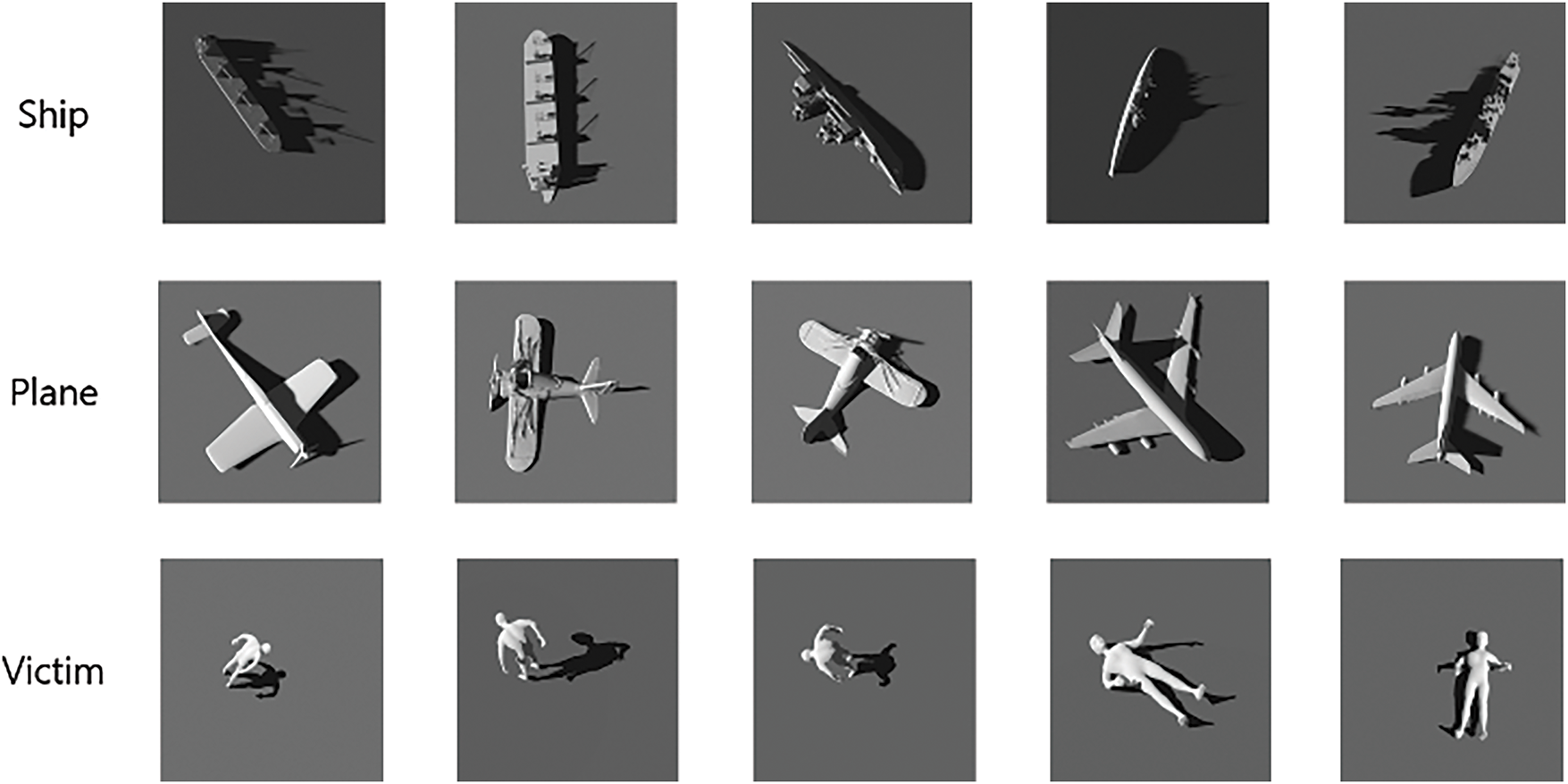

To complement real-world data, a rendering image dataset was created using Blender, a 3D computer graphics software. This dataset includes 3D models of ships, aircraft, and human figures, transformed through rotation, deformation, and other adjustments. Camera angles were varied to capture different perspectives, while light sources were altered to generate diverse shadow effects. The rendering dataset comprises 117 shipwreck images, 104 aircraft images, and 100 drowning victim images. Fig. 2 illustrates examples from this dataset, demonstrating the variety achieved through controlled 3D rendering.

Figure 2: Samples of rendering image dataset

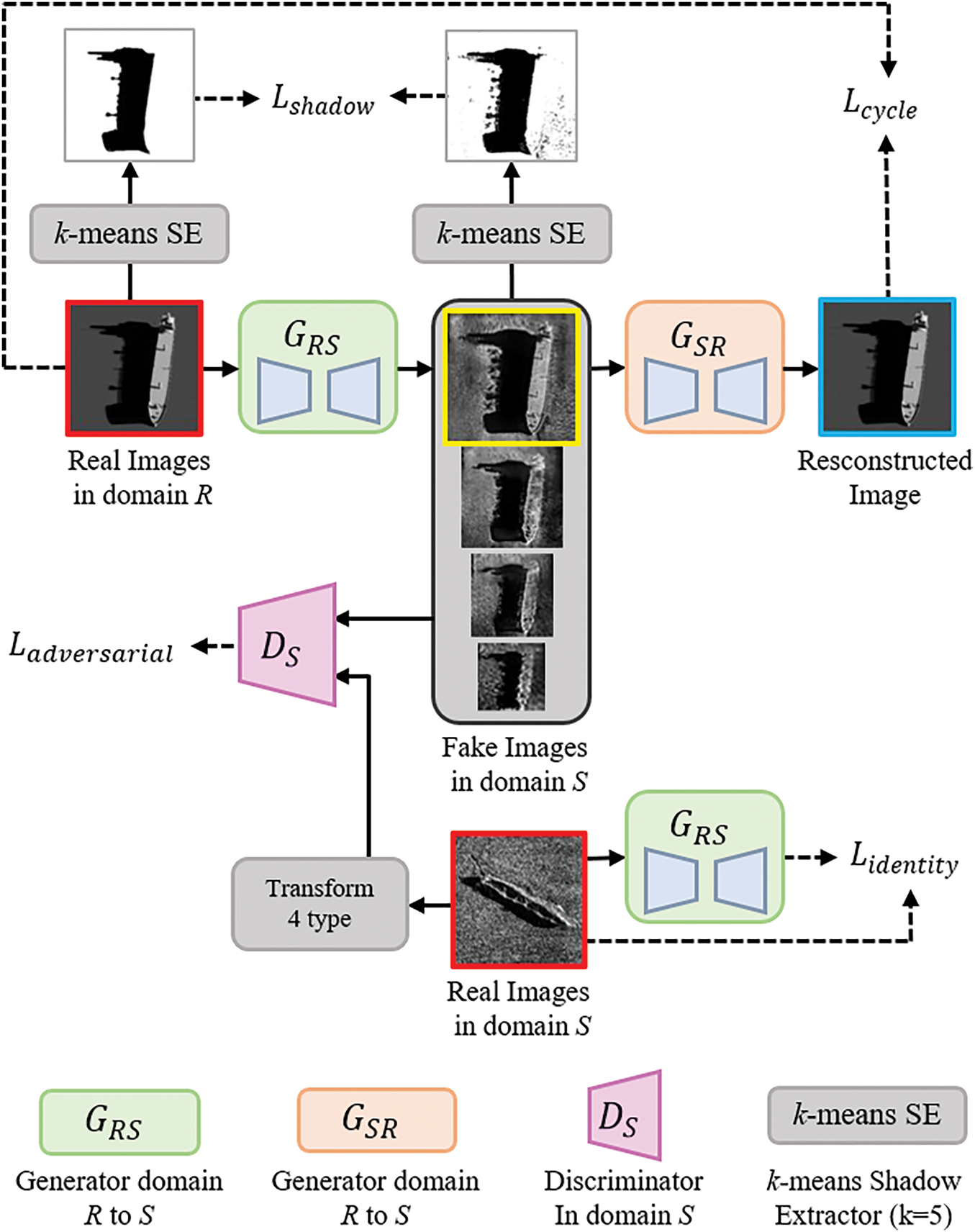

This study implements a style transformation model based on CycleGAN to generate SSS images from rendered images of various 3D models. A limitation of the traditional CycleGAN structure is that, with a small amount of data, the generated images may not sufficiently reflect the characteristics of real SSS images. To address this issue, we introduced a multi-resolution training structure and a shadow area loss function. The multi-resolution training method enables the model to simultaneously learn from images of varying resolutions, allowing the network to learn diverse features effectively. The shadow area loss function compares the shadow regions extracted from the original and generated images, training the network to preserve the original object’s shadow shape while accurately reflecting the shadow characteristics of SSS images. The network structure used for generating SSS images based on CycleGAN in this study is presented in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Structure for the SSS image domain for the proposed network

CycleGAN is a GAN-based model designed to learn image translation between two different domains. It is composed of two generators and two discriminators. These two neural networks, the generators, and discriminators, interact with each other, progressively learning to generate and discriminate realistic images. A key advantage of CycleGAN is its ability to learn image translation between two domains through unsupervised learning without requiring a one-to-one matched dataset. Additionally, cycle consistency helps minimize distortions and information loss during the translation process, enabling more consistent and reliable image transformations [26]. Moreover, the lack of paired ground-truth supervision does not guarantee the preservation of high-frequency structures (e.g., edges and shadow boundaries). Adversarial loss primarily enforces distribution-level realism, while cycle-consistency loss emphasizes reversibility of content rather than exact edge fidelity; as a result, generated images may not consistently retain fine details.

Fig. 3 illustrates the training structure for the domain

2.4 Multi-Resolution Training Structure

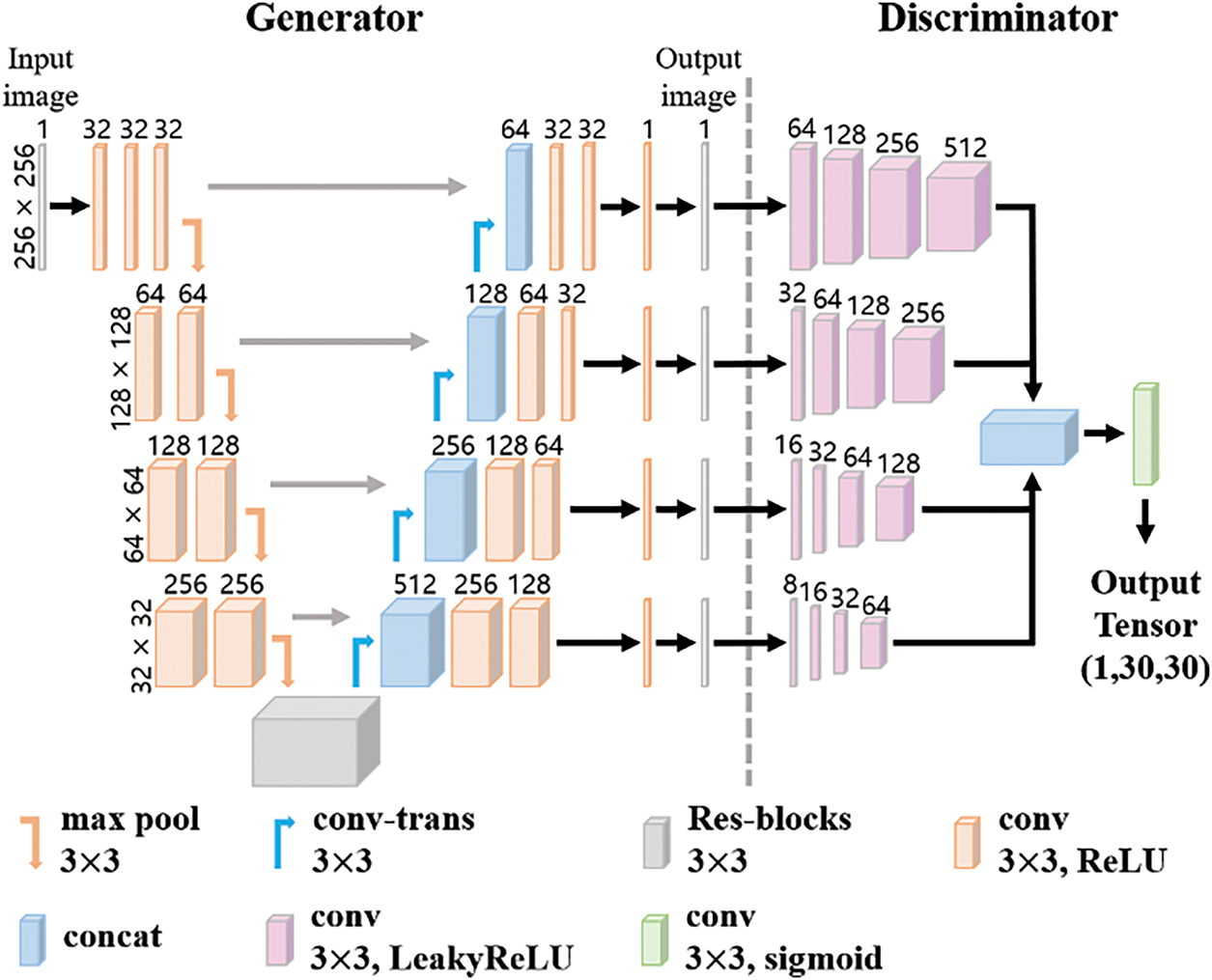

Due to the limited number of available SSS images, the conventional CycleGAN structure faced limitations in generating SSS images. To address this limitation, this study proposes a multi-resolution training structure. The multi-resolution learning structure refers to a structure in which the generator and discriminator are trained at multiple resolutions for a single image, allowing for more diverse and efficient learning [27]. This study conducts training at four resolutions: 256 × 256, 128 × 128, 64 × 64, and 32 × 32. Fig. 4 provides a detailed overview of the generator and discriminator structure used for multi-resolution training.

Figure 4: Detailed structure of constructors and discriminators

The generator is based on the U-net structure employed in the traditional CycleGAN generator, with an added feature that generates images at the four specified resolutions from each decoder layer. The four generated images at different resolutions are passed to the discriminator, which extracts features from each resolution and then combines them to produce a decision value. The real images are also converted into four resolutions to match the discriminator’s input format. The output of the discriminator adopts a PatchGAN structure, where the image is divided into small patches, and each patch is evaluated, resulting in an output of (1, 30, 30) shape. This enables the model to learn more detailed and localized information across the image [28].

2.5 Loss Functions Used for Training

In this study, four loss functions—adversarial loss, cycle consistency loss, identity loss, and shadow area loss—are used to train the model.

Adversarial loss is the fundamental loss function used in GANs and plays a role in training the generator to produce images indistinguishable from the target domain images. In traditional GANs, the discriminator learns to output 1 for real data and 0 for fake data. However, in this study, we employ the Least Squares Generative Adversarial Network (LSGAN) loss function, to ensure more stable training and higher-quality image generation [29]. The discriminator is trained to classify real images as genuine and generated images as fake. The formulation is as follows:

The generator is trained to ensure the discriminator classifies the generated images as real. Here, s represents the SSS image domain, and r denotes the rendered image domain. The formulation is as follows:

The Adversarial Loss is defined by Eqs. (1) and (2). Since CycleGAN consists of two generators and two discriminators, the loss is defined for each domain as follows:

Cycle Consistency Loss ensures that a transformed image remains similar to the original image when it is converted back to its original domain. This criterion, when applied to each domain, is represented as follows:

This minimizes distortions or information loss that may arise during the transformation process, resulting in more consistent and reliable image translations. Cycle Consistency Loss is defined as follows:

Identity Loss ensures the generator does not introduce unnecessary distortions or alterations to the input image. Identity Loss is defined as follows:

Shadow Area Loss ensures that the generator preserves the shadow shapes of objects in the input image and accurately reflects the overall shadow characteristics of SSS images. A shadow extractor based on the K-Means algorithm is utilized to extract the shadow areas from both the input and generated images for comparison. Based on empirical results, the value of K is set to 8 in this study. The Shadow Area Loss is defined as follows, where SE represents the shadow extractor:

The overall loss function of the proposed model is formulated as follows, building upon the losses in Eqs. (3) and (5)–(7):

where

This study conducted experiments using both the SSS and rendered image datasets. The SSS image dataset consisted of 403 images, including 334 shipwrecks, 34 aircraft, and 35 drowning victims. The Blender-generated image dataset comprised 321 images, 117 shipwrecks, 104 aircraft, and 100 drowning victims.

The model was trained for 1000 epochs, and data augmentation techniques such as CenterCrop, HorizontalFlip, and VerticalFlip were applied. CenterCrop is a technique that crops the central part of the image to adjust its size, while HorizontalFlip and VerticalFlip flip the image horizontally and vertically, respectively. The input data was normalized with a mean of 0.5 and a standard deviation of 0.5. The learning rate was set to 0.0001, and optimization was performed using Adam with β = (0.5, 0.999), consistent with the settings reported in the original CycleGAN study.

Weighted loss functions were applied with the following values:

To analyze the impact of each loss weight (

Figure 5: Qualitative comparison of generated SSS images under different configurations. From left to right: Proposed method, cycle loss min (λ1 = 0.1), identity loss min (λ2 = 0.1), shadow loss min (λ3 = 0.1), without multi-resolution training, and rendered input

The generated images exhibit the features of SSS imagery, as presented in Fig. 6. The highlights are caused by the direct reflection of sound waves off objects, and the shadows formed in areas where objects obstruct sound waves are prominently displayed. The overall noise in the images, resulting from various sources of underwater interference, is also effectively represented. These features demonstrate that the model effectively captures the distinctive properties of SSS imagery.

Figure 6: SSS images generated by the proposed method

To evaluate the generated SSS images against other generative models, we trained existing CycleGAN models—Unet128, Unet256, Resnet-06, and Resnet-09—and compared their generated outputs with those from the proposed model. When analyzing the outputs of these existing models, we observed that traditional models struggled to preserve object structure, with significant distortions occurring in the background and shadows, resulting in unsuccessful image generation. In some cases, the images lacked typical SSS characteristics, presenting only irregular patterns in place of the original features. In contrast, the model proposed in this study consistently preserved the shape of the objects, background, and shadow while also effectively capturing key characteristics of SSS images, such as the highlights of object surfaces, shadow details, and noise (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: SSS images generated by different methods

To evaluate the computational requirements of the proposed model, we compared the number of parameters, multiply-accumulate operations (MACs) and floating-point operations (FLOPs) with those of the baseline CycleGAN. Table 1 summarizes the results for an input size of 1 × 256 × 256. The proposed model contains 15.45 M parameters, which is comparable to the 14.12 M parameters of CycleGAN. The total MACs decreased from 59.16 to 17.06 G, and the total FLOPs decreased from 118.32 to 34.11 G, representing reductions of approximately 71.2% in both metrics.

This result is attributed to structural design differences. Conventional CycleGAN applies nine residual blocks on relatively high-resolution feature maps, which considerably increases computational cost despite having a similar number of parameters. Because MACs/FLOPs scale with the spatial dimensions of feature maps and the number of convolutional operations, repeated residual blocks substantially amplify the overall computational load in CycleGAN. In contrast, the proposed model distributes computation across multiple resolutions, executes a substantial portion at lower resolutions, and uses an optimized discriminator that avoids redundant operations. As a result, the proposed framework maintains a similar parameter scale while reducing MACs and FLOPs by more than two-thirds.

3.3 Performance Comparison Of YOLOv5 Using Generated Images

In this study, we used the YOLOv5 model [30] to evaluate the performance of ATR when trained with SSS images generated by different models, including Unet128, Unet256, ResNet-06, ResNet-09, and the proposed CycleGAN-based method. The experiment was conducted over 200 epochs, using real SSS data split into training and testing sets in a 50:50 ratio. The YOLOv5n model, known for its lightweight structure and fast inference speed, was trained from scratch without pre-trained weights. Following initial training, we augmented the training dataset by adding 117 shipwreck images, 104 aircraft images, and 100 drowning victim images generated by the model described above. A comparative analysis was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of these generated datasets in improving ATR performance.

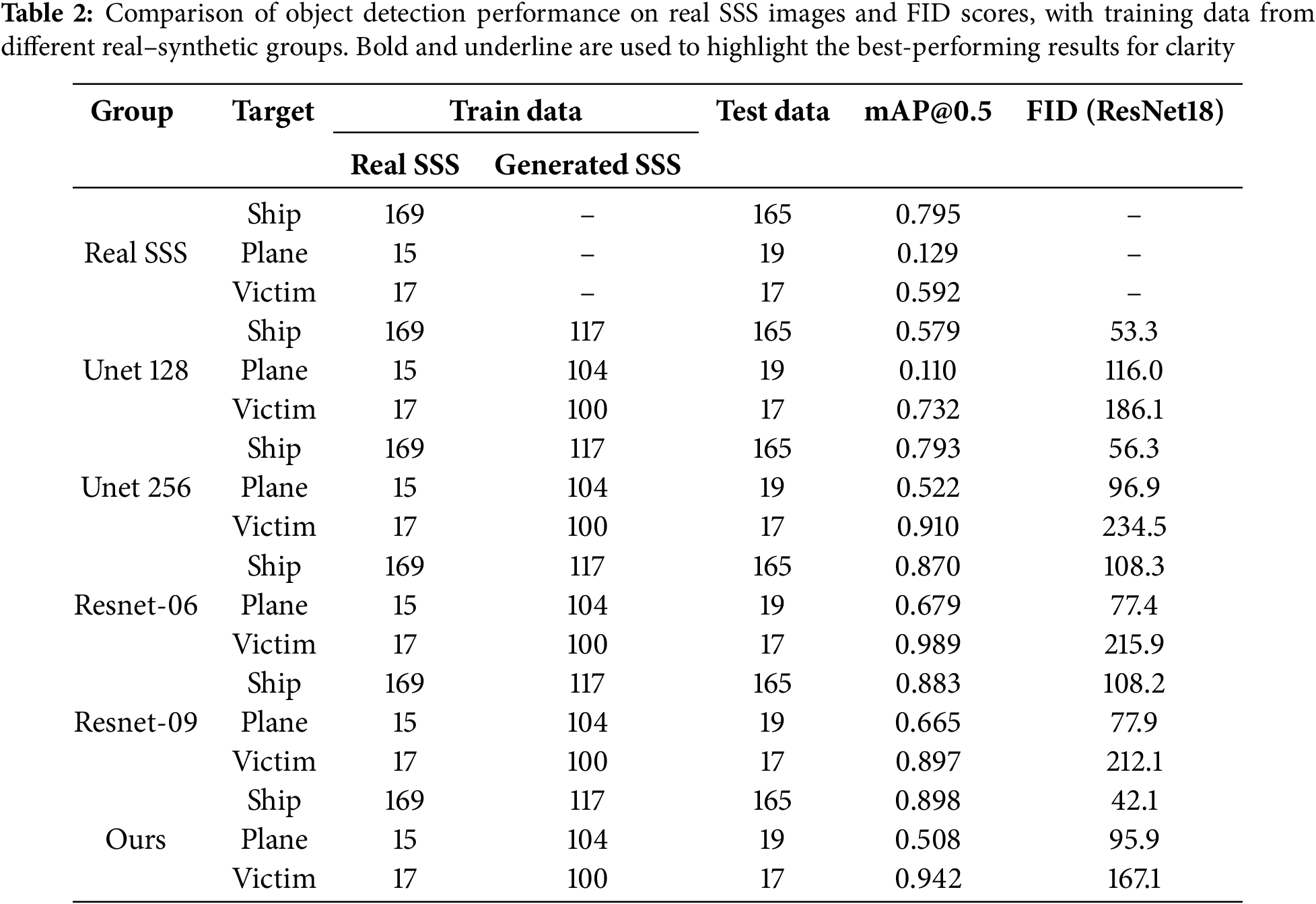

Table 2 summarizes the quantitative evaluation results, including object detection performance evaluated with YOLOv5 and image quality assessed using Fréchet inception distance (FID). The proposed method yielded the highest mAP for shipwreck (0.898) and drowning victim (0.942) detection, demonstrating superior performance in these categories compared with other models. For aircraft detection, ResNet-06 achieved the highest mAP (0.679), while the proposed method obtained a lower mAP of 0.508. To further evaluate image quality, we employed FID as an objective image similarity metric. Since the conventional InceptionV3 model used for FID is trained on natural images and thus unsuitable for sonar imagery evaluation, we replaced it with a ResNet18 model fine-tuned on sonar images. The FID results obtained using this approach are summarized in Table 2. The experimental results show that our method achieved the lowest FID scores for the Ship and Victim classes, while ResNet-06 yielded the lowest FID for the Plane class. Upon further analysis, we observed that the real sonar Plane images used in training contained numerous complex and cluttered signals. These signals likely resulted from structural damage during crashes or from prolonged underwater exposure, which caused corrosion and deformation of the fuselage and wings, producing intricate internal structural patterns. In contrast, the images generated by our method were derived from 3D models without surface damage or corrosion, leading to cleaner representations where the acoustic responses of the fuselage and wings were expressed with reduced noise. This seems to imply that the ResNet-based model, which was trained to emphasize irregular and noisy features, assigned relatively lower FID values to real Plane images compared with our generated counterparts.

3.4 Role of the Shadow Area Loss Function

To evaluate the impact of the shadow area loss function on training, the proposed model was trained with the weight of the shadow area loss function set to 0, and the generated results were compared.

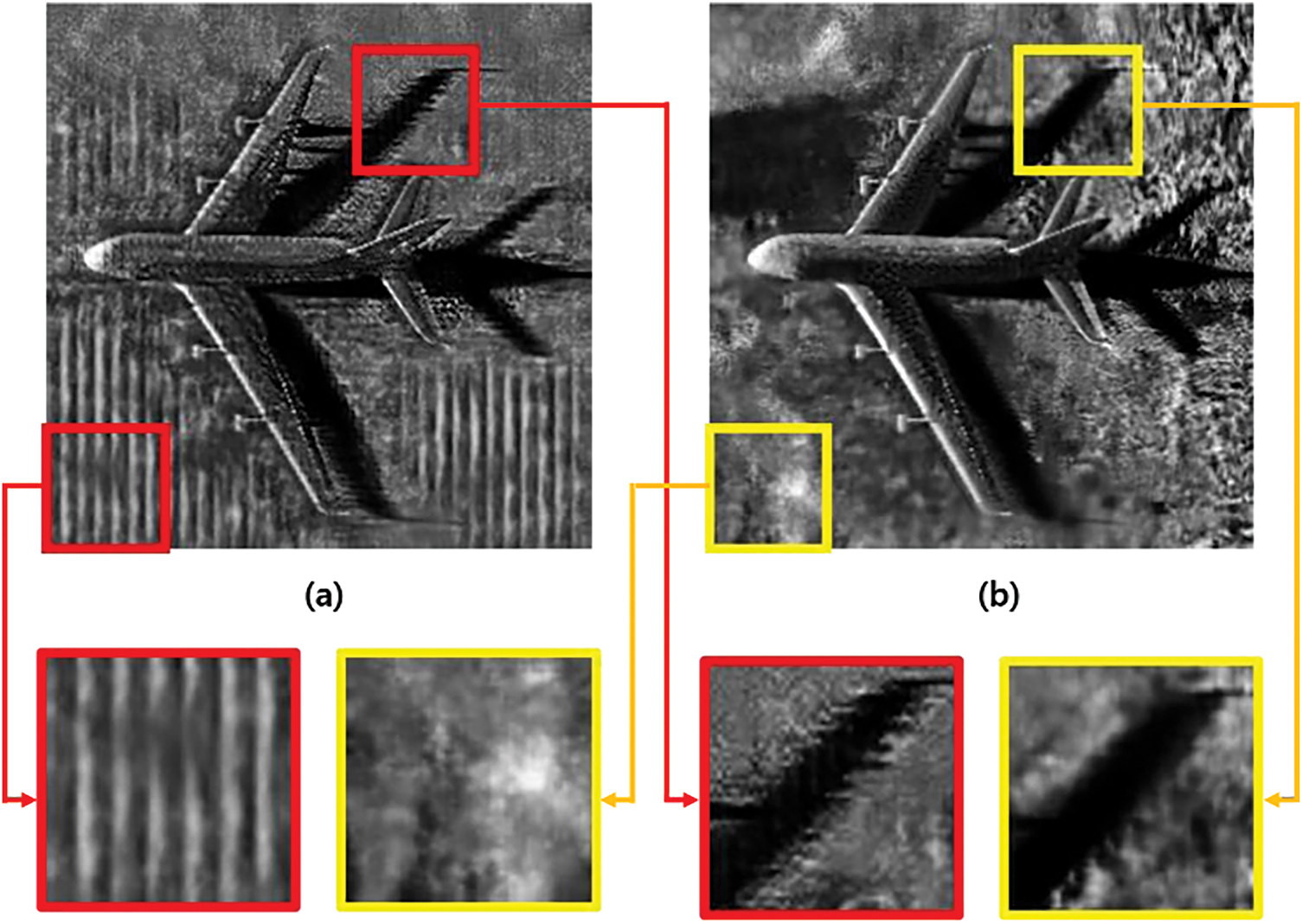

The experimental results, shown in Fig. 8, reveal that abnormal shadow patterns appeared in the background in the model without the shadow area loss function. Additionally, the shapes of the object shadows were unstable. These findings indicate that the shadow area loss function plays a crucial role in preserving the shadow shapes of objects in the input images and ensuring that the overall shadow characteristics of SSS images are represented consistently and accurately.

Figure 8: (a) The result of training without the shadow loss function, (b) The result of training with the shadow loss function

This study proposed a CycleGAN-based model for augmenting SSS images, introducing a multi-resolution learning structure, a shadow extractor, and a shadow region loss function. These innovations address limitations in conventional CycleGAN models by ensuring consistent shadow preservation and stable image generation. In particular, the shadow region loss function compares highlight and shadow patterns between the original and generated images, preserving the critical structural information unique to SSS images while realistically representing underwater noise.

Performance evaluation using the YOLOv5 model demonstrated the effectiveness of the proposed model, achieving an average precision improvement of 10.3% in shipwreck detection, 37.9% in aircraft detection, and 35% in drowning victim detection. These results highlight the model’s capability to overcome the limitations of limited SSS datasets, significantly enhancing AI-driven marine exploration and seabed monitoring through the generation of diverse SSS images under various conditions.

However, the study faced limitations in generalization due to the constrained size and variety of the dataset, with aircraft images being particularly underrepresented (34 samples compared to 334 shipwreck images). Future research should prioritize securing larger, more diverse datasets and developing objective, quantitative evaluation metrics. In particular, incorporating data from varied seabed textures, sonar angles, and occlusion scenarios would be valuable for improving the model’s robustness and real-world applicability. Furthermore, integrating the model with various marine exploration equipment will be essential to validate its robustness and applicability, thereby advancing its potential for underwater exploration. Building on this, it is also important to consider how the proposed approach could be integrated into real-world operational pipelines.

The synthetic images themselves are not directly integrated into real sonar systems. Instead, they are used to train automatic target recognition (ATR) systems that operate on board sonar platforms. The trained ATR models can subsequently be deployed in autonomous sonar systems, where they detect critical targets for further investigation. They can also provide essential information for applications such as mission planning with Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs), autonomous object recognition, and military operations. Nevertheless, potential challenges such as domain drift in operational environments should be carefully addressed to ensure reliable performance when transferring from training datasets to real-world scenarios.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the members of the Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology (KIOST) and the Pattern Recognition & Machine Learning Lab at Pukyong National University for their valuable technical advice on sonar data acquisition and preprocessing. The authors also acknowledge the open-access contributors of the SeabedObjects-KLSG dataset for making their side-scan sonar imagery publicly available, which served as an essential foundation for this study. Finally, the authors express their appreciation to all individuals who assisted in the preparation and verification of 3D models and provided valuable insights into sonar image interpretation and dataset validation.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00334159), and the Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology (KIOST) project entitled “Development of Maritime Domain Awareness Technology for Sea Power Enhancement” (PEA0332).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Byeongjun Kim, Won-Du Chang; data collection: Byeongjun Kim; analysis and interpretation of results: Byeongjun Kim, Seung-Hun Lee, Won-Du Chang; draft manuscript preparation: Byeongjun Kim, Seung-Hun Lee; supervision: Won-Du Chang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The SeabedObjects-KLSG dataset used in this study is publicly available and can be accessed from the original open-access publication by Huo et al. (2020). This dataset contains real-world side-scan sonar images collected over a 10-year period for underwater object detection research. The synthetic SSS images generated in this study were produced using 3D modeling and a CycleGAN-based style transformation framework. These images were created solely for experimental purposes and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lunkenheimer P, Emmert S, Gulich R, Köhler M, Wolf M, Schwab M, et al. Electromagnetic-radiation absorption by water. Phys Rev E. 2017;96(6):062607. doi:10.1103/physreve.96.062607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Yeu Y, Yee JJ, Yun HS, Kim KB. Evaluation of the accuracy of bathymetry on the nearshore coastlines of western Korea from satellite altimetry, multi-beam, and airborne bathymetric LiDAR. Sensors. 2018;18(9):2926. doi:10.3390/s18092926. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Murad M, Sheikh AA, Manzoor MA, Felemban E, Qaisar S. A survey on current underwater acoustic sensor network applications. Int J Comput Theory Eng. 2015;7(1):51–6. doi:10.7763/ijcte.2015.v7.929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhang X, Yang P, Cao D. Synthetic aperture image enhancement with near-coinciding nonuniform sampling case. Comput Electr Eng. 2024;120:109818. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.109818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Bai Y, Bai Q. Subsea engineering handbook. Oxford, UK: Gulf Professional Publishing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

6. Olejnik C. Visual identification of underwater objects using a ROV-type vehicle: graf Zeppelin wreck investigation. Pol Marit Res. 2008;15(1):72–9. doi:10.2478/v10012-007-0055-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Neves G, Ruiz M, Fontinele J, Oliveira L. Rotated object detection with forward-looking sonar in underwater applications. Expert Syst Appl. 2020;140(1):112870. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2019.112870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Dai Z, Liang H, Duan T. Small-sample sonar image classification based on deep learning. J Mar Sci Eng. 2022;10(12):1820. doi:10.3390/jmse10121820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Karjalainen AI, Mitchell R, Vazquez J. Training and validation of automatic target recognition systems using generative adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Sensor Signal Processing for Defence Conference (SSPD); 2019 May 9–10; New York, NY, USA. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/sspd.2019.8751666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Reed A, Gerg ID, McKay JD, Brown DC, Williamsk DP, Jayasuriya S. Coupling rendering and generative adversarial networks for artificial SAS image generation. In: Proceedings of the OCEANS, 2019 MTS/IEEE Seattle; 2019 Oct 27–31; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 1–10. doi:10.23919/oceans40490.2019.8962733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Jiang Y, Ku B, Kim W, Ko H. Side-scan sonar image synthesis based on generative adversarial network for images in multiple frequencies. IEEE Geosci Remote Sens Lett. 2020;18(9):1505–9. doi:10.1109/LGRS.2020.3005679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tang Y, Wang L, Bian S, Jin S, Dong Y, Li H, et al. SSS underwater target image samples augmentation based on the cross-domain mapping relationship of images of the same physical object. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2023;16:6393–410. doi:10.1109/JSTARS.2023.3292327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Grządziel A. The impact of side-scan sonar resolution and acoustic shadow phenomenon on the quality of sonar imagery and data interpretation capabilities. Remote Sens. 2023;15(23):5599. doi:10.3390/rs15235599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zou L, Liang B, Cheng X, Li S, Lin C. Sonar image target detection for underwater communication system based on deep neural network. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2023;137(3):2641–59. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.028037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Huo G, Wu Z, Li J. Underwater object classification in sidescan sonar images using deep transfer learning and semisynthetic training data. IEEE Access. 2020;8:47407–18. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2978880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Pessanha Santos N, Moura R, Sampaio Torgal G, Lobo V, de Castro Neto M. Side-scan sonar imaging data of underwater vehicles for mine detection. Data Brief. 2024;53:110132. doi:10.1016/j.dib.2024.110132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Li S, Li T, Wu Y. Side-scan sonar mine-like target detection considering acoustic illumination and shadow characteristics. Ocean Eng. 2025;336:121711. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2025.121711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Bouwman F, Ecclestone DW, Gabriëlse AL, van Oers AM. Synthetic side-scan sonar data for detecting mine-like contacts. Artif Intell Secur Def Appl II. 2024;13206:437–41. doi:10.1117/12.3031150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ge Q, Ruan F, Qiao B, Zhang Q, Zuo X, Dang L. Side-scan sonar image classification based on style transfer and pre-trained convolutional neural networks. Electronics. 2021;10(15):1823. doi:10.3390/electronics10151823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Peng Y, Li H, Zhang W, Zhu J, Liu L, Zhai G. Underwater sonar image classification with image disentanglement reconstruction and zero-shot learning. Remote Sens. 2025;17(1):134. doi:10.3390/rs17010134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Sugiyama S, Minowa M, Schaefer M. Underwater ice terrace observed at the front of glaciar grey, a freshwater calving glacier in Patagonia. Geophys Res Lett. 2019;46(5):2602–9. doi:10.1029/2018GL081441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Du X, Sun Y, Song Y, Dong L, Tao C, Wang D. Recognition of underwater engineering structures using CNN models and data expansion on side-scan sonar images. J Mar Sci Eng. 2025;13(3):424. doi:10.3390/jmse13030424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Aubard M, Antal L, Madureira A, Ábrahám E. Knowledge distillation in YOLOX-ViT for side-scan sonar object detection. arXiv:2403.09313. 2024. [Google Scholar]

24. Álvarez-Tuñón O, Marnet LR, Aubard M, Antal L, Costa M, Brodskiy Y. SubPipe: a submarine pipeline inspection dataset for segmentation and visual-inertial localization. In: Proceedings of the OCEANS 2024; 2024 Apr 15–18; Singapore. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/OCEANS51537.2024.10682150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Burguera A, Bonin-Font F. On-line multi-class segmentation of side-scan sonar imagery using an autonomous underwater vehicle. J Mar Sci Eng. 2020;8(8):557. doi:10.3390/jmse8080557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhu JY, Park T, Isola P, Efros AA. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 2242–51. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Sauer A, Chitta K, Müller J, Geiger A. Projected GANs converge faster. Adv Neural Inf Process. 2021;34:17480–92. doi:10.5555/3540261.3541598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Isola P, Zhu JY, Zhou T, Efros AA. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Piscataway, NJ, USA. p. 5967–76. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Mao X, Li Q, Xie H, Lau RYK, Wang Z, Smolley SP. Least squares generative adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV)2017 Oct 22–29; Piscataway, NJ, USA. p. 2813–21. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 779–88. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools