Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Multi-Stage Centralized Energy Management for Interconnected Microgrids: Hybrid Forecasting, Climate-Resilient, and Sustainable Optimization

1 Department of Scientific Systems, University of Toulouse, University of Technology Tarbes-UTTOP, LGP, Tarbes, 65000, France

2 Department of Physics, College of Science and Humanities Studies, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Kharj, 16278, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Computer Engineering and Information, College of Engineering in Wadi Alddawasir, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Kharj, 16278, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Kafrelsheikh University, Kafrelsheikh, 33516, Egypt

5 Department of Electronic Engineering, Higher Institute of Engineering and Technology at Manzala, Manzala, 66412, Egypt

6 Sustainability Competence Centre, Szechenyi Istvan University, Egyetem tér 1., Győr, H9026, Hungary

* Corresponding Author: Ragab A. El-Sehiemy. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 3783-3811. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.071964

Received 16 August 2025; Accepted 10 November 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

The growing integration of nondispatchable renewable energy sources (PV, wind) and the need to cutKeywords

Abbreviations and Symbols

| ACO | Ant Colony Optimization |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Networks |

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage System |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional LSTM |

| DERs | Distributed Energy Resources |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DQN | Deep Q-Networks |

| DP | Dynamic Programming |

| DRMPC | Dist. Robust MPC |

| EMS | Energy Management System |

| ESS | Energy Storage System |

| ICTs | Infor. and Communication Technologies |

| IMM | Interconnected Multi Microgrids |

| LSTM | Long Short Term Memory |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MG | Microgrid |

| MILP | Mixed Integer Linear Programming |

| MIQP | Mixed-Integer Quadratic Programming |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| PCC | Point of Common Coupling |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| RES | Renewable Energy Source |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| SGs | Smart Grids |

| SoC | State of Charging |

| SSA | Salp Swarm Algorithm |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| TCN | Temporal Convolutional Networks |

| Equality matrices for FLP optimization | |

| PV surface area [ | |

| Real-time power cost [$] | |

| Total daily cost [$] | |

| Input/output energy of BESS [ | |

| Max energy capacity of BESS [ | |

| Min energy capacity of BESS [ | |

| Input/output energy of grid [ | |

| Nominal BESS capacity [ | |

| Objective function | |

| Identity matrix for LP/FLP modeling | |

| K | Time step |

| Power flow MG1 | |

| Power flow MG1 | |

| Power flow MG2 | |

| Power flow MG2 | |

| Power flow MG3 | |

| Power flow MG3 | |

| Power of BESS [kW] | |

| Max charge power of BESS [kW] | |

| Min discharge power of BESS [kW] | |

| Grid active power [kW] | |

| Max grid output power [kW] | |

| Min grid output power [kW] | |

| Total load [kW] | |

| PV system active power [kW] | |

| Solar Irradiation [ | |

| Degree of membership | |

| PV panel efficiency | |

| Charge/discharge efficiency | |

| Membership function | |

| Time between optimization calls [sec] |

EMS play a critical role in the efficient operation of microgrids, which are distributed energy systems capable of operating autonomously or in coordination with the main power grid [1,2]. The primary objectives of an EMS are to optimize energy generation, distribution, and consumption while minimizing operational costs, reducing

The rapid increase in carbon dioxide emissions and environmental pollution has made the transition to sustainable energy systems a global imperative [8,9]. Currently, advances in ICT are transforming modern societies, enabling smart applications in healthcare, transportation, finance, data centers, and, most importantly, SGs. Modern energy systems are expected to achieve high efficiency, resilience, and environmental friendliness by integrating advanced control, automation, and optimization technologies [10]. According to the International Energy Agency, intermittent RES is projected to account for 57% of global electricity generation by 2050, and certain regions experience instantaneous levels of penetration of RES of up to 100% during specific periods [11,12]. These trends exacerbate challenges such as poor power quality, complexity of scheduling, and reliability risks [12].

SGs supported by ICT infrastructure are a cornerstone of next-generation energy systems. They integrate communication and control technologies to achieve secure, efficient, and flexible operation of DERs [10]. Within this paradigm, MGs and IMM have emerged as promising decentralized energy systems that offer autonomy, self-containment, and improved reliability [10]. MGs and IMM improve the integration of renewable energy, reduce dependence on fossil fuels, and improve resilience, particularly in regions with limited or no connection to the utility grid [10]. Furthermore, MGs can be isolated (noninterconnected) or interconnected. Non-interconnected microgrids provide greater autonomy, but face several limitations, including energy imbalances when local generation cannot meet demand, higher operational costs due to fossil fuel dependency of backup, reduced reliability during interruptions, and under-utilization of RES due to limited local demand [8,9]. In contrast, IMM offer benefits such as optimized power flows, resource sharing, and increased reliability, but introduces additional challenges, including scalability issues, managing RES uncertainties, ensuring power flow stability, and maintaining fault tolerance to prevent cascading failures [10]. To address these challenges, Zhao et al. developed and discussed in [13] a new methodology for the energy management of IMM based on DRMPC to handle the variability of DERs. The proposed strategy reduced the daily operating cost of each microgrid by 5.3%, 8.9%, and 6.9%, respectively, compared with independent operation. However, the impact of forecast uncertainty was not considered in this work, and although the obtained results are promising, the proposed methodology remains computationally expensive for real-time implementation. In [14], the authors proposed a distributed energy trading framework for microgrids based on a game-theoretic model. Although the proposed approach is efficient, it remains limited in certain aspects, such as ensuring equilibrium among interconnected microgrids to achieve a truly optimal solution. Moreover, the real-time implementation of such computational methodologies remains costly and complex. The authors of [15] introduced a new method based on a simple fuzzy-logic technique. This methodology is efficient and achieves good accuracy; however, several important factors were not considered, including the distance between connected microgrids, power losses in transmission lines, and the forecast stage, which could significantly affect system performance. In [16], Moazzen et al. developed a methodology based on MIQP to provide an optimal solution for interconnected microgrids. The obtained results demonstrate significant improvements in energy management and coordination between interconnected systems. However, although the proposed method is accurate and effective, the forecasting aspect was not analyzed, which may influence the reliability of the results. Furthermore, the use of MIQP remains computationally demanding, especially for a large number of IMM, and issues related to scalability and robustness against disturbances were not considered.

Although these studies with other [15,17–19] have contributed significantly to advancing energy management strategies for IMM, most of them primarily focus on optimization and coordination aspects, often neglecting the critical role of accurate forecasting in overall system performance [20–22]. In practice, the effectiveness of any EMS strongly depends on the quality of short-term forecasts for renewable generation, load demand, and market prices. Without reliable forecasting, even the most advanced optimization algorithms may lead to suboptimal or unstable operation under uncertainty. Consequently, the integration of accurate forecasting models into EMS frameworks has become a crucial research direction for improving the reliability, cost-efficiency, and resilience of IMM operation.

Accurate short-term forecasting is essential for EMS performance. Conventional stochastic approaches (e.g., Monte Carlo simulations, probabilistic models, scenario-based methods) have been widely used to model uncertainty but often struggle to capture nonlinear temporal dependencies [1,6,7]. ML and DL approaches, such as SVR, RF, ANN, and LSTM networks [23–25], have shown significant promise in capturing complex patterns from historical data [26,27].

Hybrid forecasting models, which combine stochastic and ML/DL techniques, leverage the strengths of both approaches and have demonstrated superior performance in highly uncertain RES environments [28,29]. Recent works show that hybrid models improve EMS operation by providing more reliable forecasts for scheduling and optimization [30–33]. On the optimization side, conventional methods (LP, MILP, DP) offer mathematical rigor and computational efficiency, particularly in deterministic settings [6,34]. Heuristic/metaheuristic algorithms (GA, PSO, ACO, IARO, BWO, COATI) handle multi-objective and nonlinear problems but face convergence and scalability issues [6,35–37]. AI-based methods (Fuzzy logic, RL, DQN, ANN, LSTM) are adaptive and effective under dynamic [23–25], uncertain conditions but require large, high-quality datasets and computational resources [26,27,31,33].

Despite extensive research on EMS for microgrids, several challenges remain. Real-time implementation is still difficult due to the inherent complexity of both the system and the optimization methods [16–18,45]. Developing a novel framework that ensures optimal solutions in both simulation and real-time execution [15,19,21,22], while reducing computational complexity, is therefore crucial for practical deployment in interconnected microgrids [4,20,46].

Most existing studies rely on deterministic models for power generation and load demand, even though real-time energy systems are subject to significant uncertainties, particularly from PV output, wind variability, and load fluctuations. Accurate short-term forecasting is essential to ensure efficient and reliable energy management under these volatile conditions. Incorporating stochastic elements into the EMS is necessary to better address such uncertainties. In addition, the adoption of advanced hybrid forecasting methods, which combine statistical models with machine learning or deep learning techniques, can significantly improve prediction accuracy. Choosing a robust uncertainty modeling and forecasting approach is therefore vital to optimize resource allocation, improve the balance between energy production and consumption, and enhance system resilience.

Furthermore, a new mathematical formulation of the energy management problem is needed to account for power flows and transmission losses between interconnected microgrids. While several optimization frameworks have been proposed for multi-objective energy scheduling in IMM systems, challenges remain regarding real-time implementation and the trade-off between competing objectives. A straightforward, computationally efficient formulation is needed to minimize operational costs while simultaneously reducing

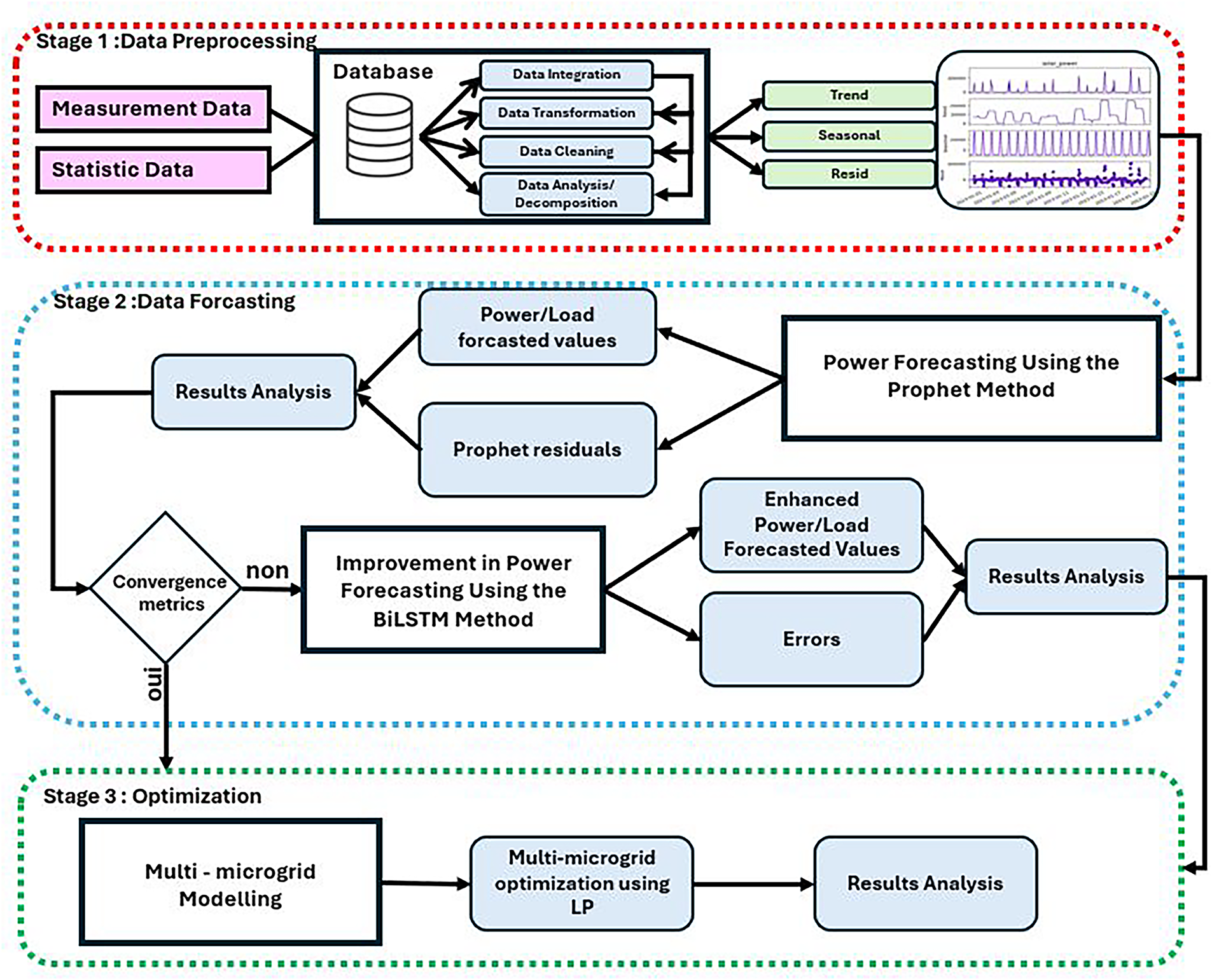

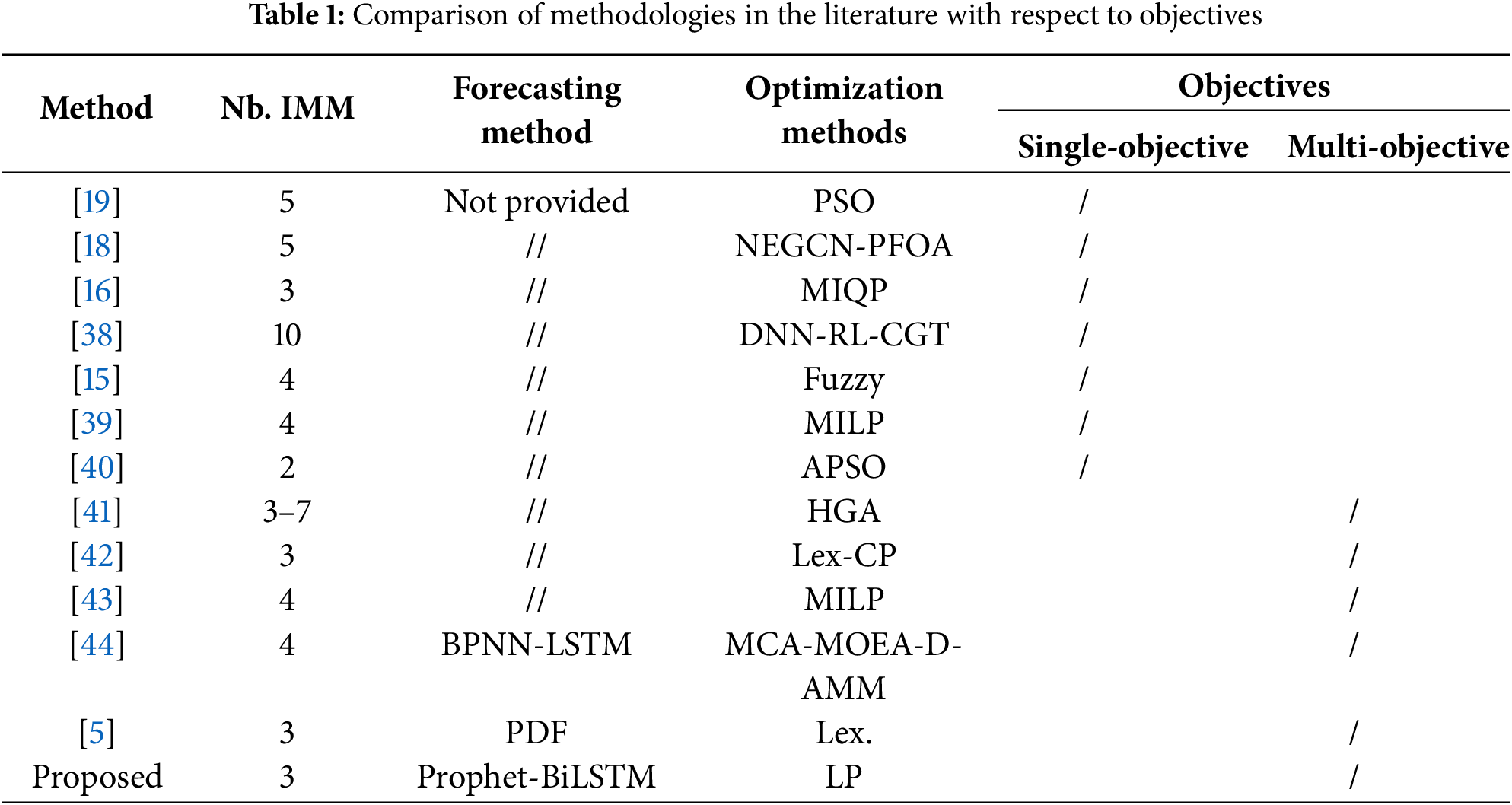

Table 1 provides a comparative overview of existing methodologies in the context of energy management for interconnected microgrids. It summarizes key aspects such as the number of interconnected micro-microgrids (Nb of IMM), the forecasting methods employed, the optimization techniques utilized, and whether the approaches target single-objective or multi-objective problems. The analysis highlights that most studies address both single- and multi-objective optimization problems using advanced methodologies that account for multiple constraints, thereby increasing the complexity of the problem. Compared to the existing literature, the proposed methodology introduces a comprehensive three-stage framework (Fig. 1) for EMS in interconnected microgrids. This framework integrates data analysis, forecasting, and optimized decision-making, leveraging the Prophet-BiLSTM hybrid model for load/production prediction and LP for optimization. The proposed approach facilitates efficient power exchange among microgrids while minimizing operational costs and

Figure 1: Structure of centralized EMS of interconnected microgrids

The first stage involves robust data processing, including cleaning, transformation, integration, and analysis. Next, a hybrid forecasting model, combining stochastic techniques and deep learning, accurately predicts power production under uncertainty. Forecasts are then fed into an improved LP-based optimization framework for reliable energy management across the IMM. The main features of this work are summarized as follows:

• An exponential formulation of uncertainty is applied in the data processing stage to capture sudden variations and all forms of uncertainty.

• A hybrid forecasting approach combines the stochastic Prophet model to capture seasonal patterns with a BiLSTM network for residual correction, improving PV generation and demand predictions [47–49].

• A multi-objective LP-based optimization framework minimizes operational costs and

• Power flow constraints are incorporated to ensure an accurate and balanced energy exchange within the IMM.

In this work, the Prophet model is selected as the baseline instead of more complex architectures such as TCN, Seq2Seq, or Transformer models. This choice is motivated by Prophet’s ability to explicitly decompose time series into trend and seasonality components, providing high interpretability and robustness for energy forecasting tasks dominated by such patterns. Unlike deep learning methods that require large datasets and substantial computational resources, Prophet performs reliably on smaller datasets while maintaining transparency. By combining Prophet with BiLSTM, we take advantage of Prophet’s strength in modeling deterministic components and BiLSTM’s ability to learn non-linear residuals, achieving both interpretability and precision in the resulting forecasts.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 defines the formulation of the problem. Section 3 outlines the key tools and techniques used in this study. Section 4 describes the proposed methodology and offers an in-depth discussion. Section 5 presents the simulation results. Section 6 provides a dedicated discussion. Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines potential directions for future research.

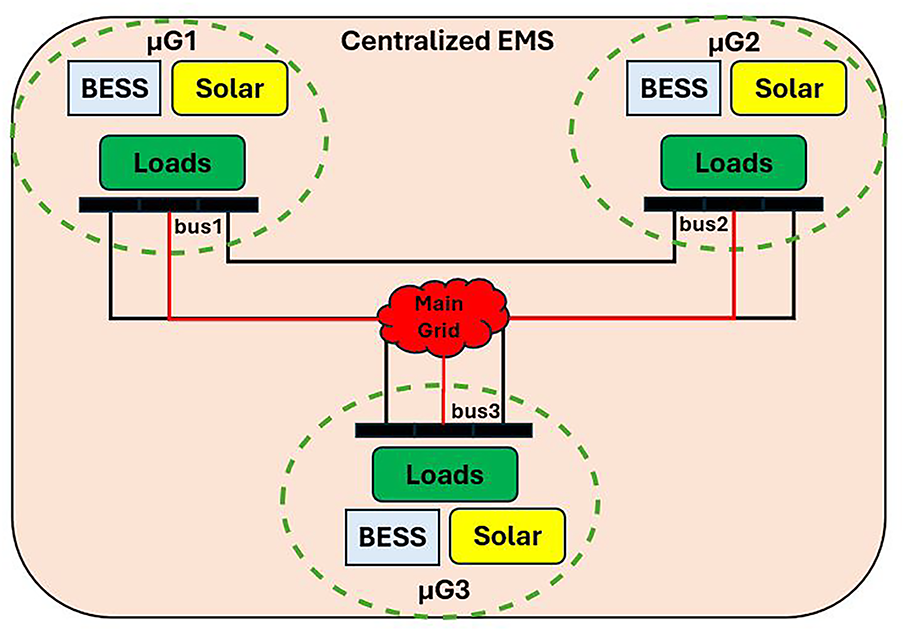

This paper presents a novel energy management framework based on a LP approach for the day-to-day planning of IMM. In the IMM structure, the microgrids are connected to the main grid and are distributed in nearby and distant geographical areas, as illustrated in Fig. 2. These microgrids collaborate by sharing local generation and storage resources to reduce reliance on the main grid, minimize

Figure 2: Structure of centralized EMS of interconnected microgrids

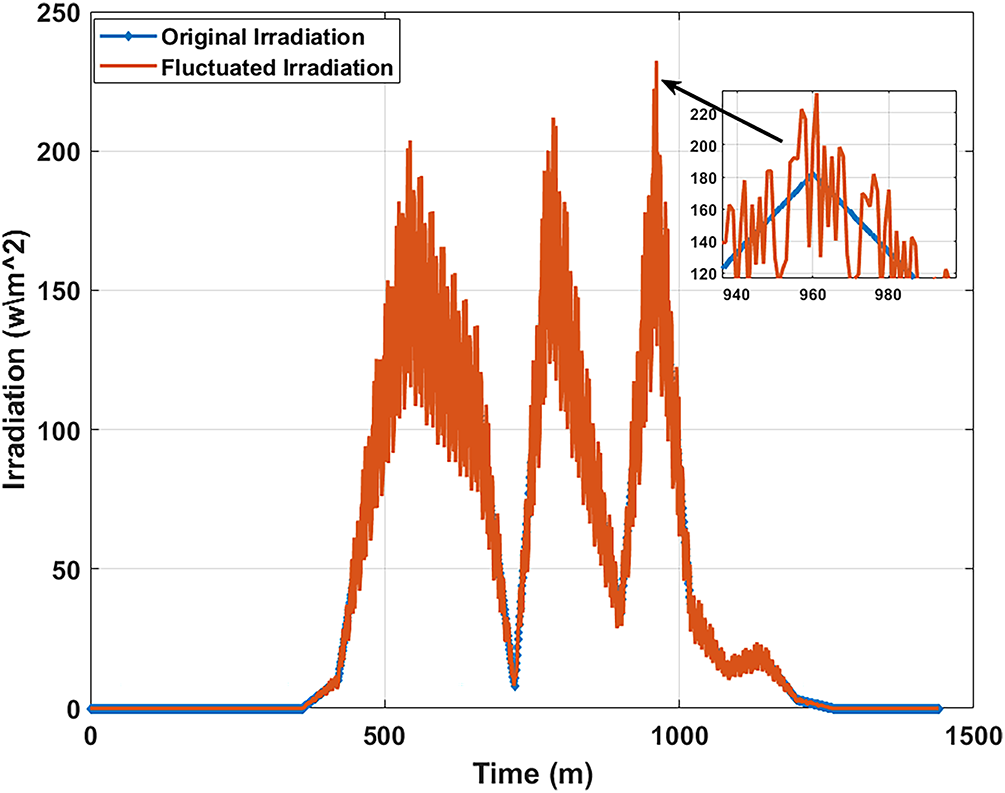

In the following, the architecture of the IMM, as illustrated in Fig. 2, will be used for the analysis and validation of the proposed methodology. The initial data used for the IMM are detailed in Table 2.

3 Mathematical Formulation of the Proposed Model

The output active power of a PV system depends primarily on the size of the PV farm, the available solar irradiation, the system’s efficiency, and the ambient temperature. According to [50], the PV power generation

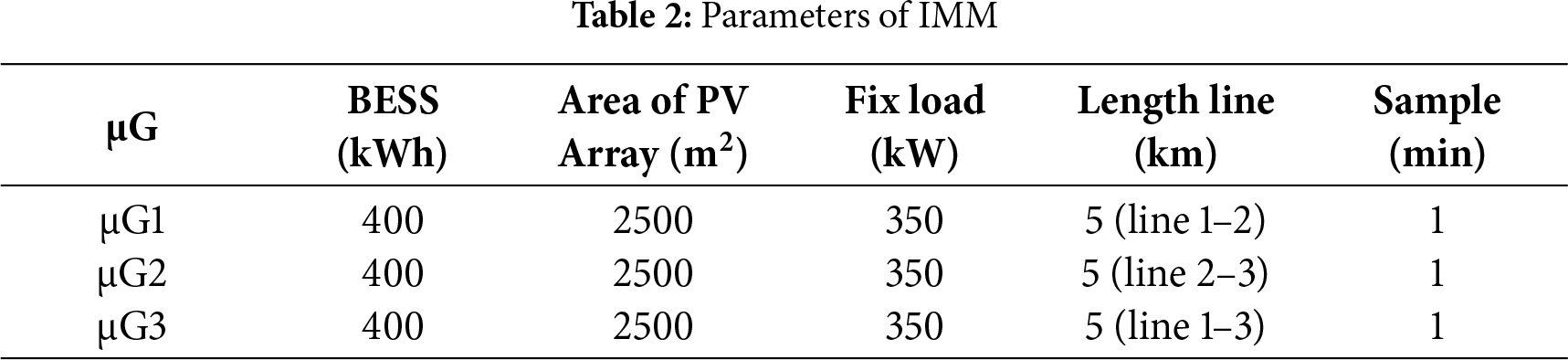

To incorporate stochastic uncertainty-which represents inherent variability in the system or environment and cannot be reduced through data augmentation -randomness is introduced. This uncertainty stems from stochastic processes such as fluctuations in weather conditions (e.g., cloud cover, dust, atmospheric changes, and sudden irradiance variations), as well as sensor noise. As a result, random fluctuations are applied to obtain modified irradiance

Here,

where

By applying this fluctuation to the irradiance dataset used for the validation of our methodology, we simulate real-time weather variability. The resulting fluctuated irradiance profile is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Direct irradiation on 21 April 2025—Original vs. Fluctuated (Cairo Area)

Consequently, the uncertain PV power model is updated as given in Eq. (4).

3.2 Battery Energy Storage System

The BESS model accounts for the charging/discharging power, the battery’s nominal capacity, and the charge/discharge efficiency. It can be expressed in both continuous and discrete forms as described in Eqs. (5) and (6).

• Continuous form

where,

• Discrete form

where,

For interconnected microgrids, the transmission line is modeled using the

The line current and voltage drop between nodes can be expressed using standard

where,

3.4.1 Deterministic Load Model

In the deterministic case, the load is assumed to follow a known and fixed demand profile over time:

This model neglects random fluctuations or forecasting errors.

3.4.2 Uncertainty-Based Load Model

To reflect the variability and unpredictability of real-time load profiles, we introduce a stochastic component to the load:

where,

This uncertainty model is used to test the robustness of energy management algorithms under variable demand conditions.

This study addresses the optimization problem as a multi-objective optimization task, aiming to minimize several conflicting objectives simultaneously. Since LP is traditionally applied to single-objective problems, the weighted sum method is adopted to transform the problem into a form compatible with LP. The total objective function, denoted as

where, f1, represents the total cost vector as:

Notice that the weights in the multi-objective formulation were determined through a trial-and-error approach. Initially, equal weights were assigned to all objectives, and the optimization results were visualized to assess their influence. Subsequently, each weight was slightly adjusted to analyze its effect on the convergence of the solution. In some cases, these variations caused divergence, indicating that the selection of weights significantly impacts the convergence toward the optimal solution. Therefore, efforts were made to identify a suitable set of weights that yield stable and satisfactory results. Although the current approach relies on manual tuning, further improvements could be achieved through adaptive tuning using an optimization algorithm. Nevertheless, the results obtained are considered good and acceptable for the proposed framework.

4 Proposed Energy Management Framework

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the proposed methodology is structured into three main stages. The first stage involves data preprocessing. In our case, the raw data was extracted from the website [51] with an original sampling rate of 1 h. To enhance realism, the data were resampled at a frequency of 1 min, and random variations were introduced to account for various types of fluctuation, including weather-related and technical uncertainties, as detailed in section 3.1. Consequently, this section focuses solely on the prediction and optimization stages.

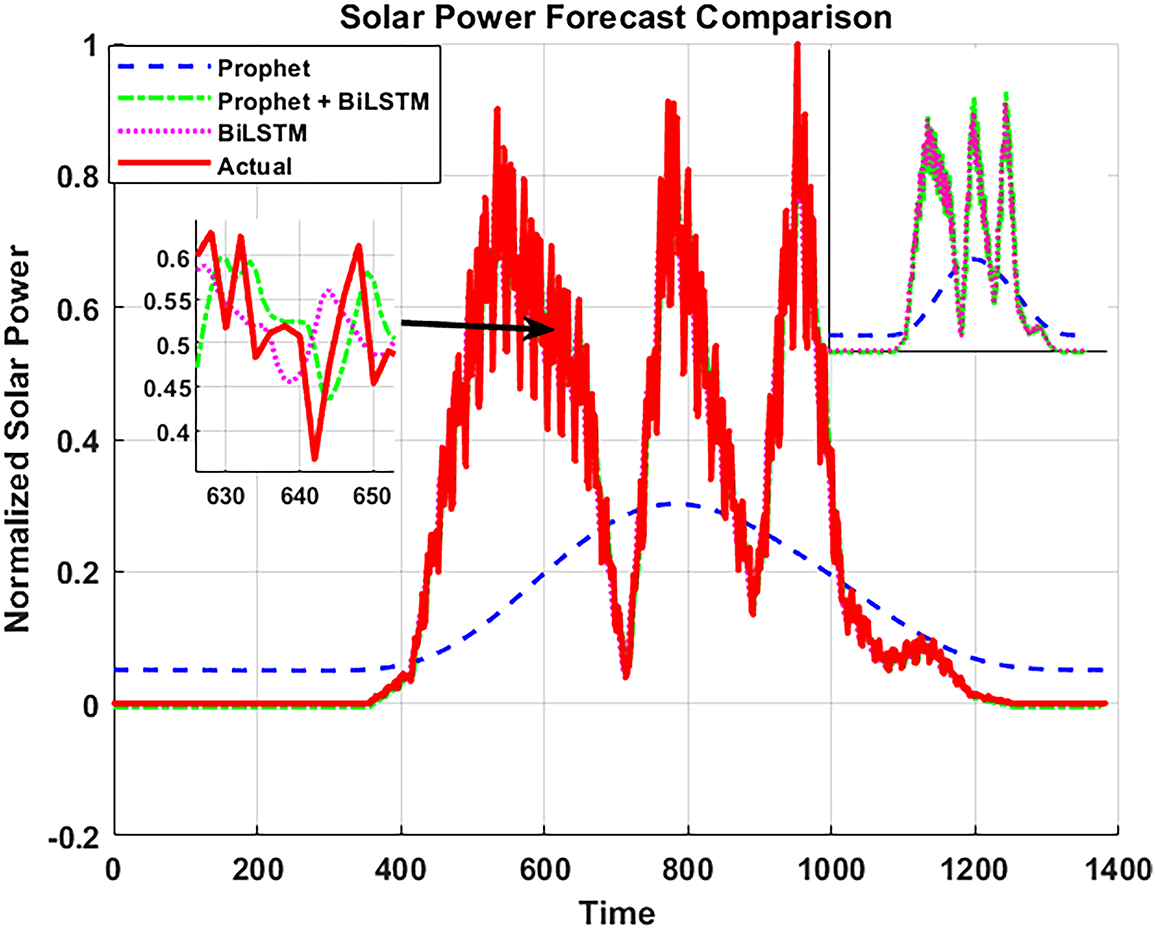

With the increasing integration of RES, the rapid growth in power consumption, and the pressing impacts of climate change, accurately forecasting PV power production has become a critical yet complex task. This complexity arises from the stochastic nature of solar irradiance, weather variability, and other environmental factors influencing PV output. To address this challenge, this paper proposes a hybrid forecasting approach that integrates the Prophet model, well-suited for capturing trend and seasonality components-with the BiLSTM neural network, which excels at modeling nonlinear dependencies and temporal patterns in time series data. By leveraging both models’ strengths, the proposed method improves forecasting accuracy and robustness compared to individual models as given in Fig. 4. The framework uses key independent variables such as historical PV output, temperature, solar irradiance, and cloud cover to enhance prediction performance.

Figure 4: Solar power forecast provided by the proposed methodology and comparison with individual models

Residual Forecasting with Prophet

In the first stage, the Prophet model is applied to the cleaned dataset. It generates the fitted values for the training set (

where

In the second stage, a BiLSTM model is applied to the residuals generated by the Prophet model. The objective of the BiLSTM is to capture complex temporal dependencies in the residuals and to improve the overall forecasting performance by reducing the global error between the predicted and actual values. The final prediction result is obtained by combining the outputs of both the Prophet and BiLSTM models. Prophet models time series as [49,52]:

where,

Trend Function (Piecewise Linear)

where

Seasonal Component (Fourier Series)

As the forecasting task focuses on the short term, hourly seasonality is addressed using the Fourier series representation, as shown in Eq. (16). Additionally, due to the significant fluctuations in the weather data, daily, weekly, and yearly seasonalities are implicitly and automatically handled by the internal mechanisms of the Prophet model.

here, P denotes the seasonal period (equal to 1 for hourly seasonality), and N represents the number of Fourier terms—i.e., pairs of sine and cosine functions—used to model the seasonal pattern. In this context, a value of

Holiday Component

In this work, to enhance forecasting performance using homogeneous variables, additional components such as holidays and external regressors are incorporated. For example, to improve the forecast of power generation, relevant external factors, such as wind speed and humidity, are included in the training process as regressors. The influence of these variables is modeled as:

where

Residual Forecasting with BiLSTM

Due to the strong uncertainty associated with weather conditions, the standalone Prophet model is still insufficient to deliver highly accurate and robust forecasts. To overcome this limitation, an additional stage based on BiLSTM is introduced. The BiLSTM technique is particularly suited for time series forecasting as it can capture both past dependencies and future contextual information through its forward and backward recurrent structure.

In the proposed hybrid framework, the BiLSTM is used to model and correct residual errors resulting from the initial Prophet forecast. This approach enables the capture of complex temporal behaviors that Prophet, based on additive components and piecewise linear trend, might not fully represent. To give a mathematical formulation of BiLSTM, let us start with the formulation of simple LSTM as defined in Eq. (18).

where,

As the BiLSTM based on the past and future dependencies, so the simple LSTM computation should occurs in two direction as describe in Eq. (19).

The final BiLSTM output is:

Based on the output of the BiLSTM and the Prophet output, the corrected forecast becomes as expressed in Eq. (21).

To rigorously assess the prediction performance of the proposed hybrid methodology, three widely recognized evaluation metrics are used: the RMSE, the MAE, and the coefficient of determination (

where,

Data description and analysis

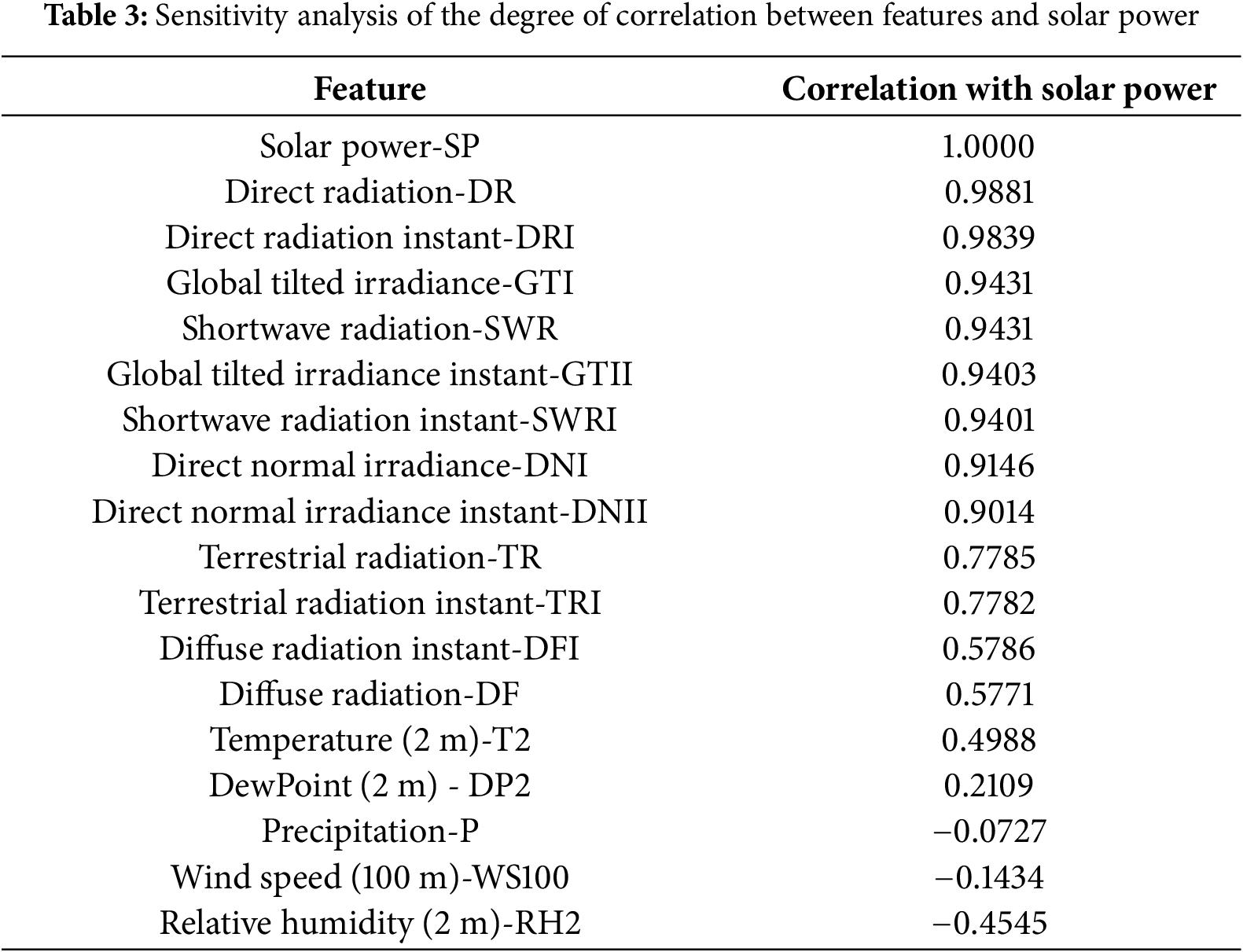

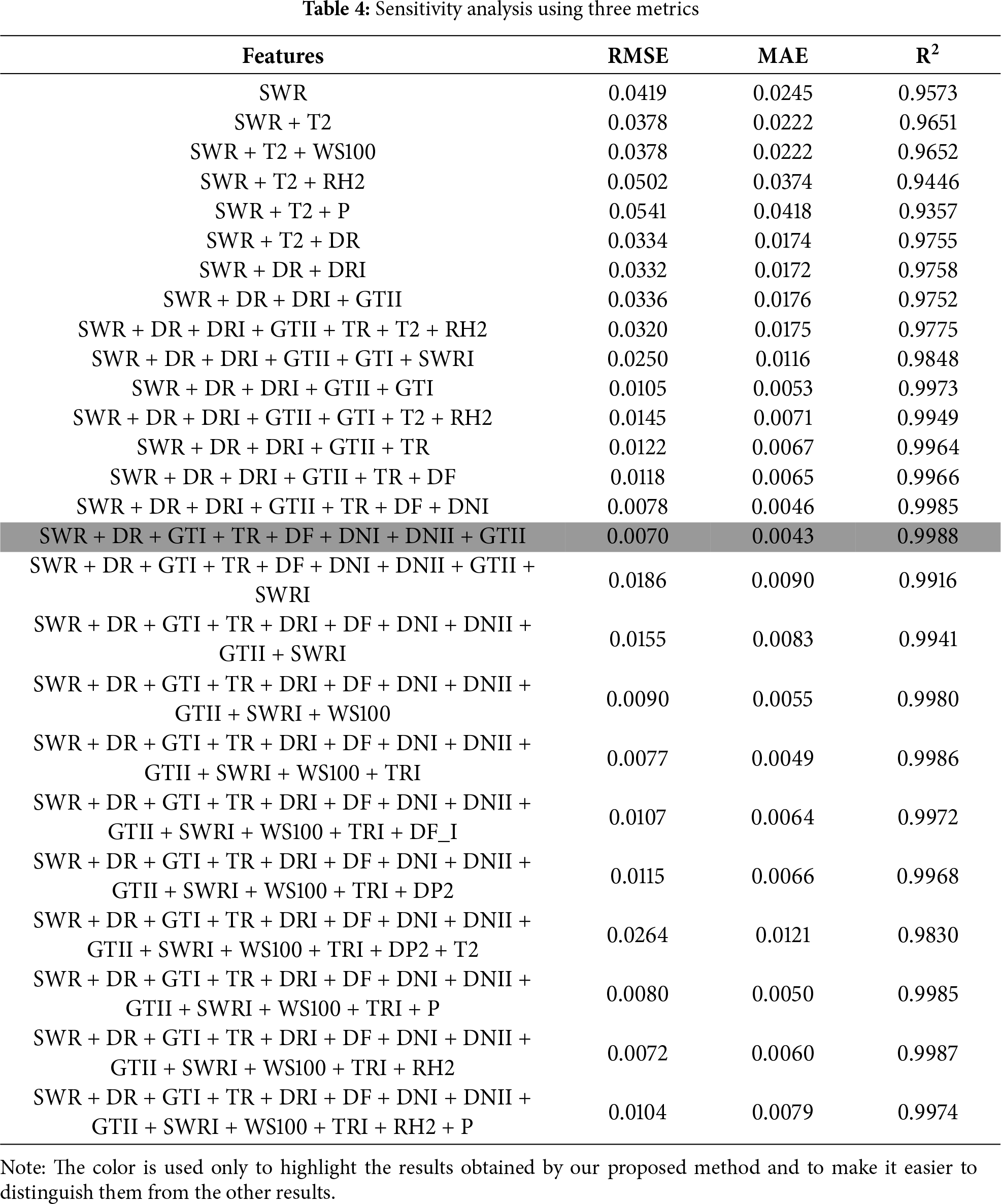

The meteorological dataset used in this simulation was extracted from a publicly available web platform providing high-resolution environmental data. The available data include a variety of meteorological parameters measured or estimated over approximately three years, with a temporal resolution of five minutes. In total, 18 meteorological and environmental features were extracted, as summarized in Table 3. These variables include shortwave and direct radiation, diffuse and global tilted irradiance, air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed (at 10 and 100 m), dew point temperature, precipitation, and terrestrial radiation, among others. To more realistically simulate microgrid operation, uncertainty was incorporated into the dataset, reflecting the stochastic nature of solar irradiance, weather conditions, and measurement errors. Specifically, the hourly data were first resampled to one-minute intervals to capture high-resolution variability. For each day, a fluctuation vector was generated, representing relative changes in the measured variables. The fluctuations were randomly sampled from a uniform distribution between 10% and 30% and assigned a positive or negative sign. This vector was applied multiplicatively to all meteorological features, with radiation-related variables clipped to remain non-negative. This method introduces day-to-day stochastic variations while preserving the overall daily trend of the variables. The same fluctuation vector was reused for all days to maintain a controlled yet realistic level of variability. Following this, solar power output was computed based on panel area, efficiency, and the fluctuated direct radiation. All meteorological features were preprocessed to serve as potential predictors for solar power generation. This preprocessing included normalization using the Min-Max scaling method, transforming all variables into the [0, 1] range to improve numerical stability and convergence of the forecasting algorithms. A correlation analysis between the target variable (solar power) and each feature was performed to identify the most relevant predictors. The analysis revealed that variables such as shortwave radiation, direct irradiance, and temperature have the strongest relationships with solar power. In contrast, others, such as humidity and wind speed, have a weaker influence. Based on these results, the most significant features were retained for model training, reducing redundancy and enhancing the learning process. Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the impact of each selected feature on forecast accuracy. This step helps determine the optimal subset of features that balances model complexity with predictive reliability. The resulting feature configuration, combined with the stochastic dataset, is then used in the subsequent hybrid Prophet + BiLSTM forecasting framework.

From the results provide in Table 4, it is clear that radiation-related features are the most critical for accurate solar power prediction. Using only SWR provides a baseline

Optimization

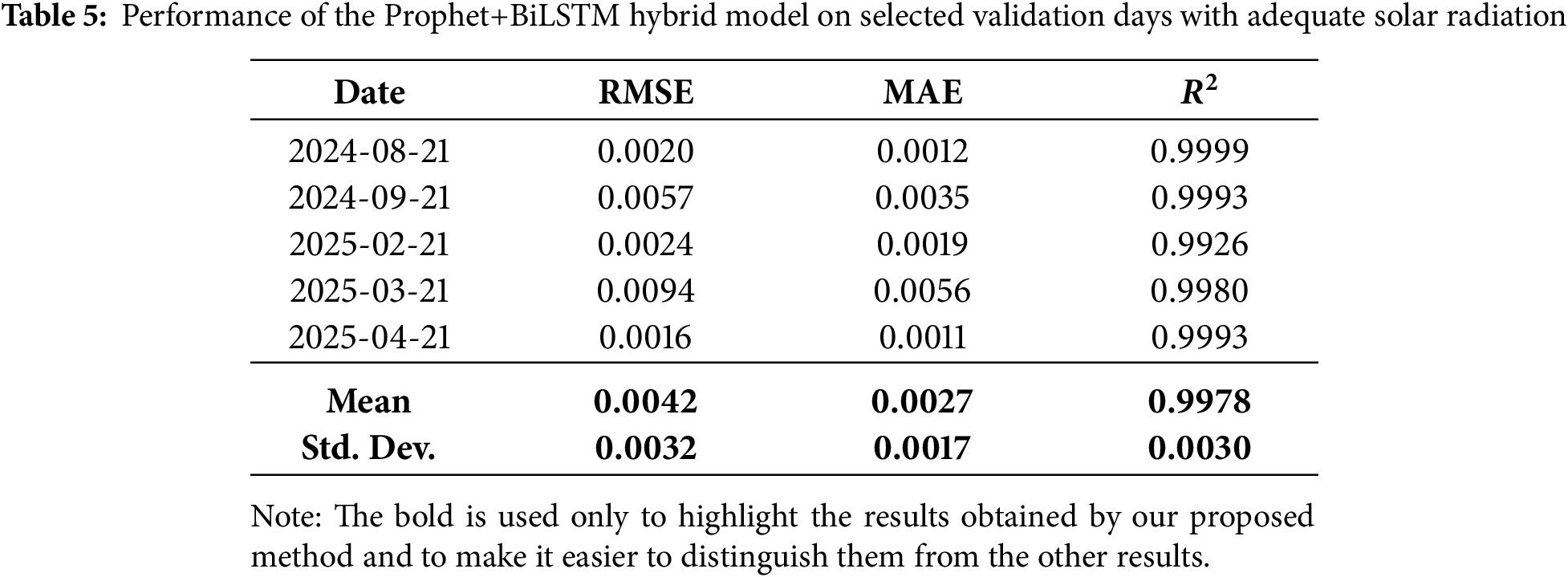

Based on the result provided in Table 5 the proposed hybrid model demonstrates robust performance across typical solar generation days. The RMSE ranges from 0.0016 to 0.0094 and MAE remains below 0.01, while

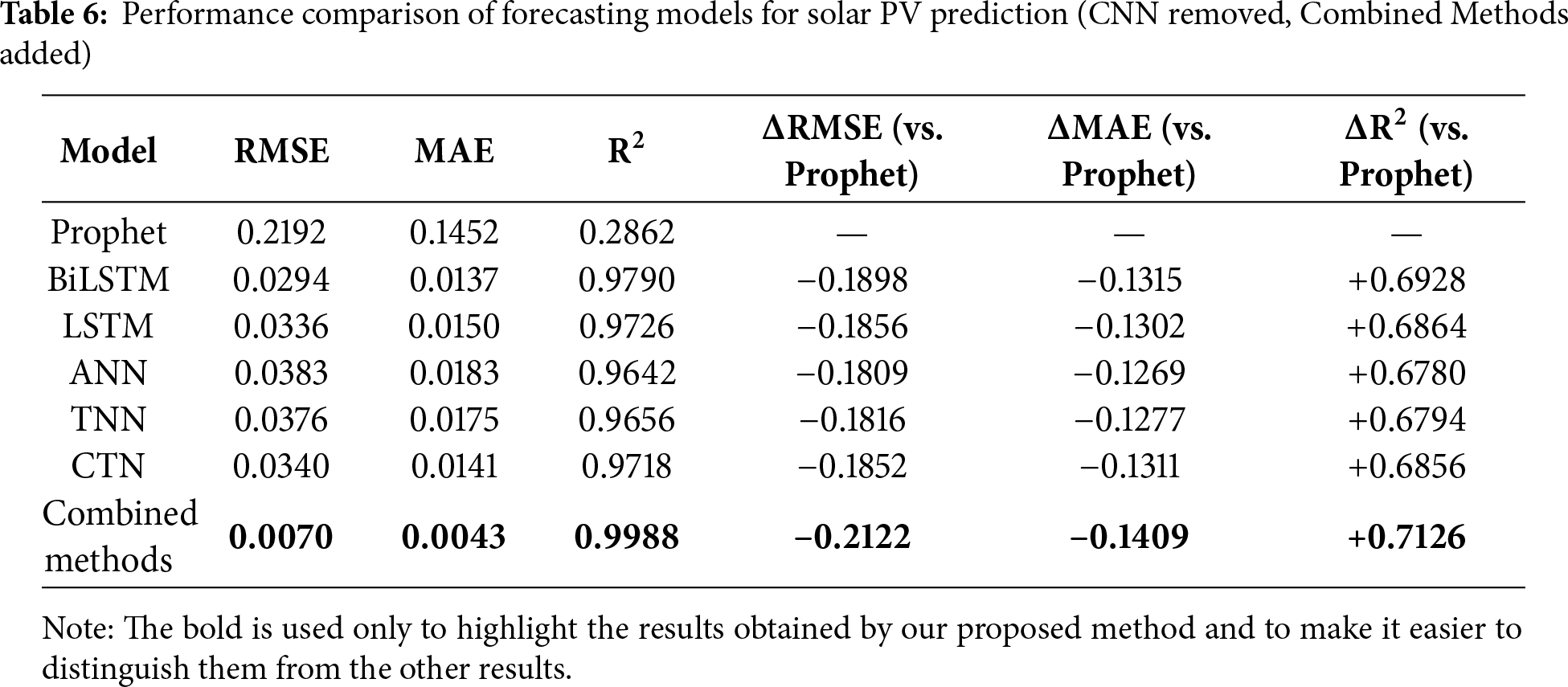

Table 6 presents a comparative evaluation of several forecasting models for solar PV prediction. The results clearly demonstrate that both the Prophet + BiLSTM hybrid and the BiLSTM-only models significantly outperform the standalone Prophet model. Specifically, the Prophet + BiLSTM hybrid achieves the lowest RMSE (0.007) and MAE (0.0043) while attaining a high

Optimization

Based on the forecasting results obtained using the hybrid Prophet-BiLSTM method, an LP-based optimization approach will be implemented to manage the IMM system described in the previous section. This LP approach is designed to address a centralized energy management problem with multiple objectives, such as minimizing operational costs, optimizing power flows, and ensuring the reliability of the system. To this end, the standard formulation of the linear programming problem has been adapted accordingly. The equality constraints, which typically represent energy balance equations in interconnected microgrids, are defined by Eq. (27). Furthermore, inequality constraints, which capture system limitations such as generation capacities, storage limits, and grid exchange limits, are presented in Eq. (28). This formulation allows for integrating accurate load and generation forecasts into the decision-making process. By incorporating forecasts derived from the hybrid Prophet-BiLSTM method, the optimization framework can effectively reflect the microgrid system’s temporal dynamics and operational constraints. This ensures that the decisions made are grounded in realistic expectations of future energy demand and generation capabilities. In order to solve this problem, MATLAB’s linprog solver is utilized due to its efficiency in handling large-scale linear programming problems. The decision vector

As in this paper three interconnected microgrids are used for the validation, the vector of decision variables

The matrices

This formulation ensures that the optimization model captures the temporal coupling of decisions, such as battery state-of-charge dynamics and inter-microgrid power exchanges, over the forecast horizon. Consequently, the LP-based strategy facilitates economically optimal and technically feasible operation of the interconnected microgrid system by leveraging accurate predictions from the hybrid Prophet-BiLSTM model.

with

To validate the proposed methodology, four scenarios are analyzed and implemented in three interconnected microgrids that integrate renewable energy generation and storage systems, as illustrated in Fig. 1. A comprehensive validation is carried out by evaluating power exchange between microgrids using three distinct load profiles. In addition, similar and varying production levels are considered to assess the adaptability of the system under different operating conditions. To account for fluctuations in renewable generation and load demand, uncertainty is systematically incorporated into the analysis. In addition, to quantify the impact of transmission lines on system performance, various line lengths are evaluated.

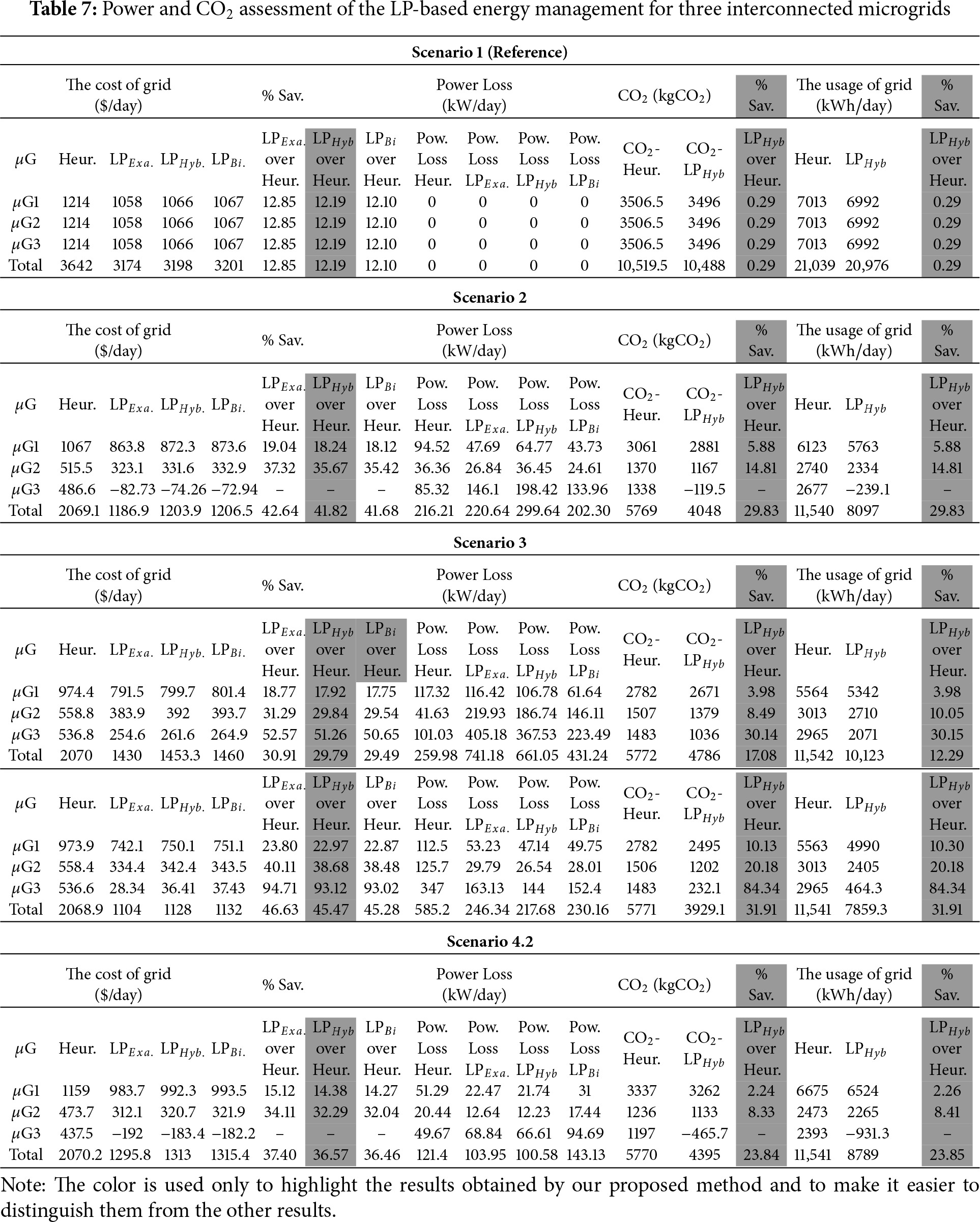

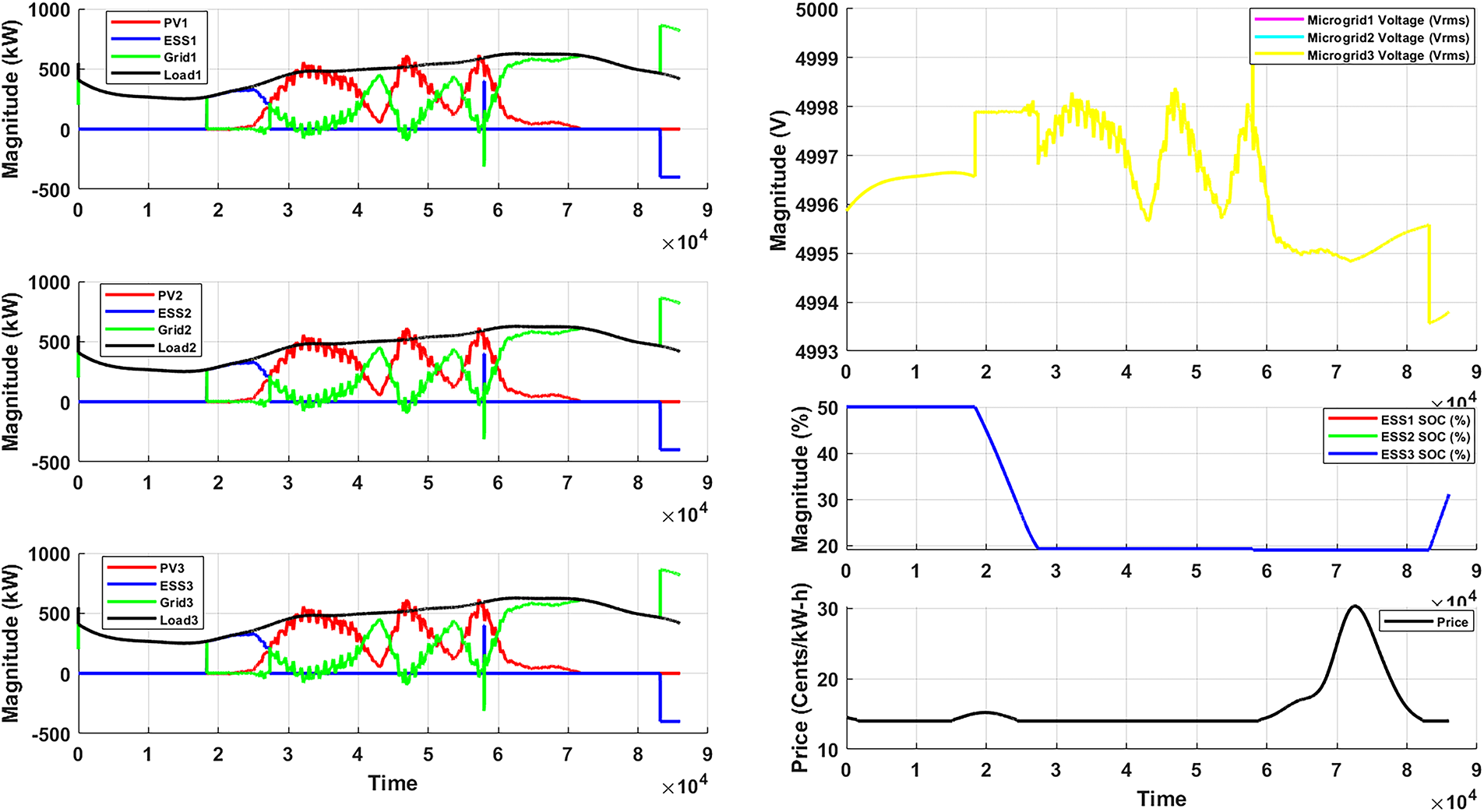

• Scenario 1 (Reference Case). Three interconnected microgrids, each with identical generation and demand profiles, energy storage systems of equal size, and separated by a uniform distance of 5 km. Table 7 compares the proposed approach with the Heuristic, BiLSTM, and LP methods using four key performance indicators: (i) day-ahead operating cost, (ii) total grid energy purchased, (iii) total

• Scenario 2. In this scenario, the three microgrids have identical PV production and are interconnected via transmission lines of equal length (2.5 km). However, their load profiles differ to illustrate how the surplus energy of one microgrid can support another. Specifically, Microgrid 1 is assigned a fixed load of 350 kW plus a variable load; Microgrid 2 has a fixed load of 150 kW plus the same variable component; while Microgrid 3 is subjected only to the variable load. The results in Table 2 show that the proposed methodology outperforms both the Heuristic and BiLSTM-based methods, and its performance is nearly equivalent to the case where the exact PV profile is known. Compared to Scenario 1, the total cost savings increases to approximately 25%, demonstrating the benefit of energy sharing between micro-grids. However, this improvement comes at the expense of increased power losses, which confirms that active energy exchange is taking place across the network in a coordinated and beneficial manner.

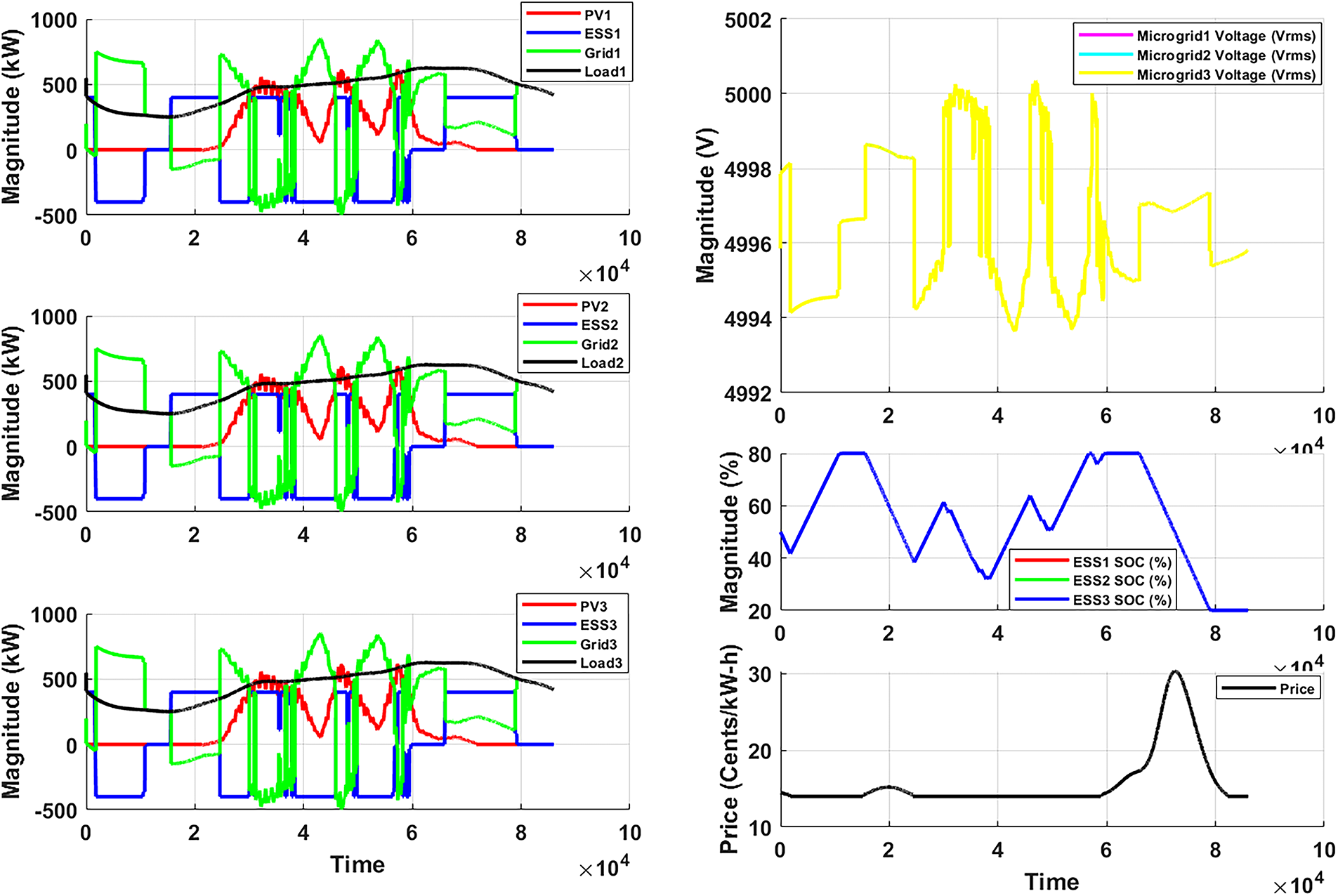

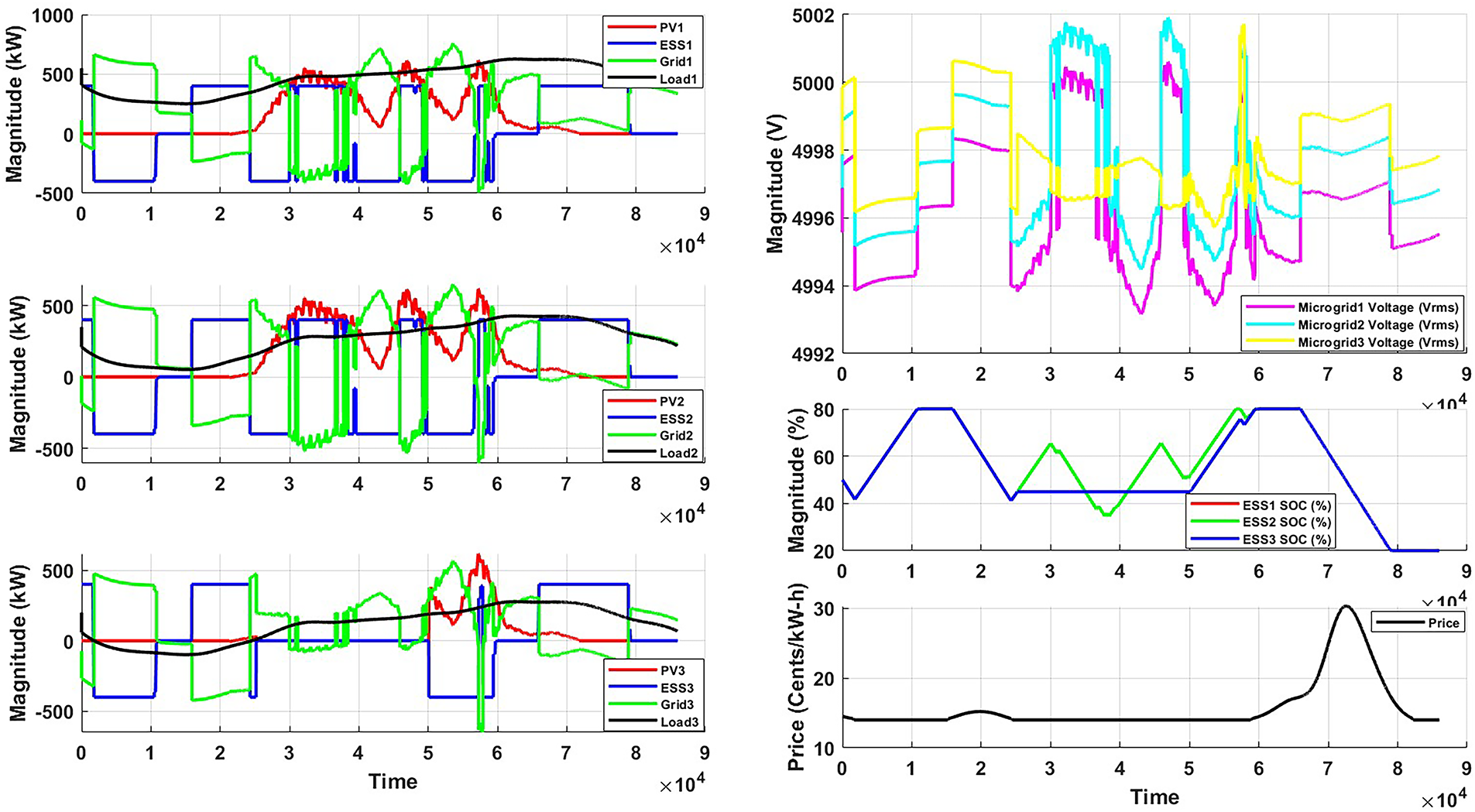

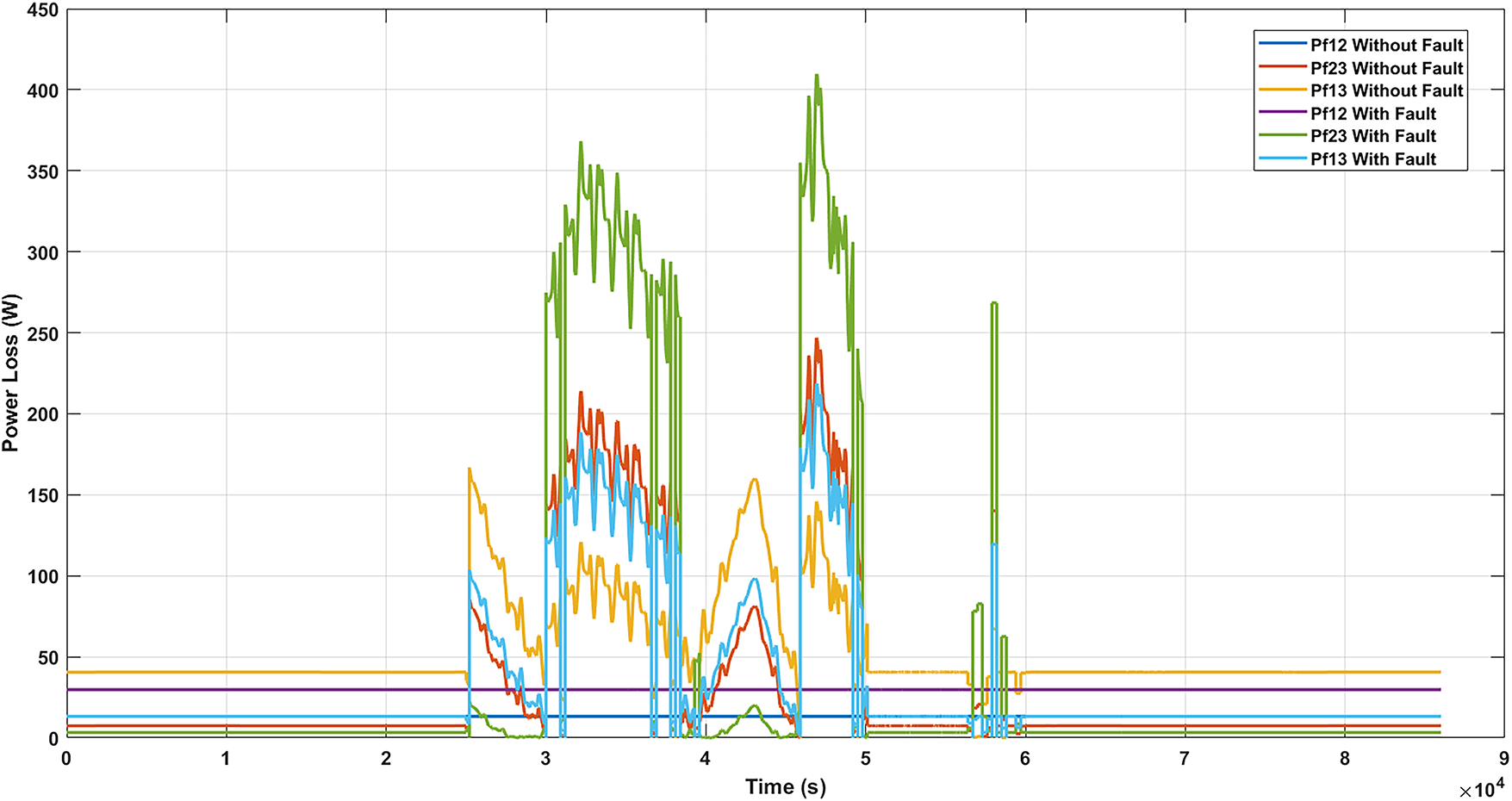

• Scenario 3. To assess the robustness of the proposed methodology, this scenario introduces a fault condition in Microgrid 3 by disconnecting both its battery and PV generation between time steps 25,000 and 50,000, as illustrated in Figs. 7 and 8. The transmission lines between the microgrids are 2.5 km in length. Similar to Scenario 2, the load profiles differ across the microgrids, allowing the system to demonstrate how surplus energy in one microgrid can compensate for deficits in another. This setup evaluates the system’s ability to maintain efficient and coordinated operation under partial failure conditions. It is observed that the total power exchange increases in this scenario, as the optimization algorithm seeks to compensate for the loss of renewable generation in Microgrid 3 while still meeting the defined objectives. The results show that the proposed methodology continues to outperform the competing approaches, confirming its robustness and adaptability in the presence of faults.

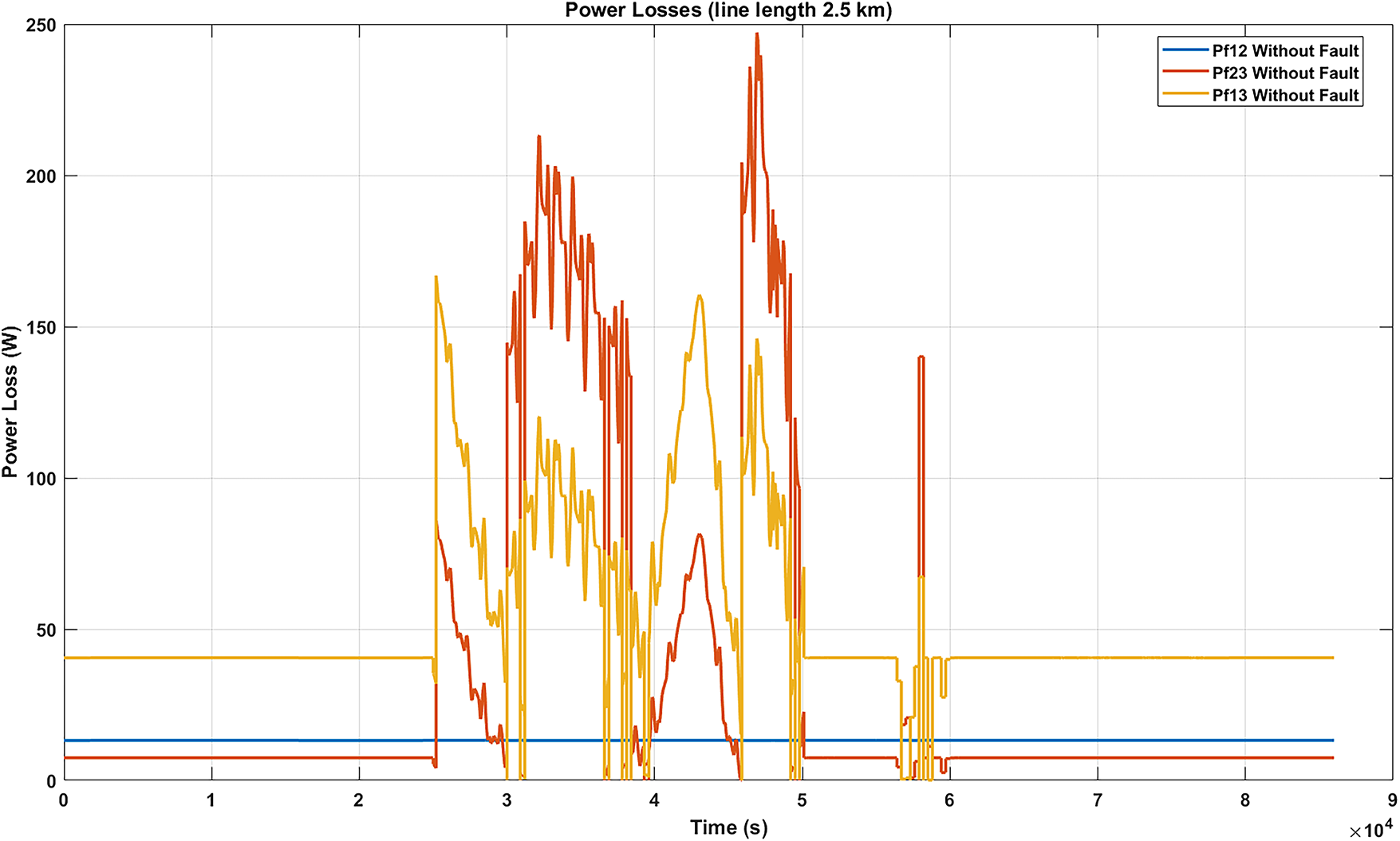

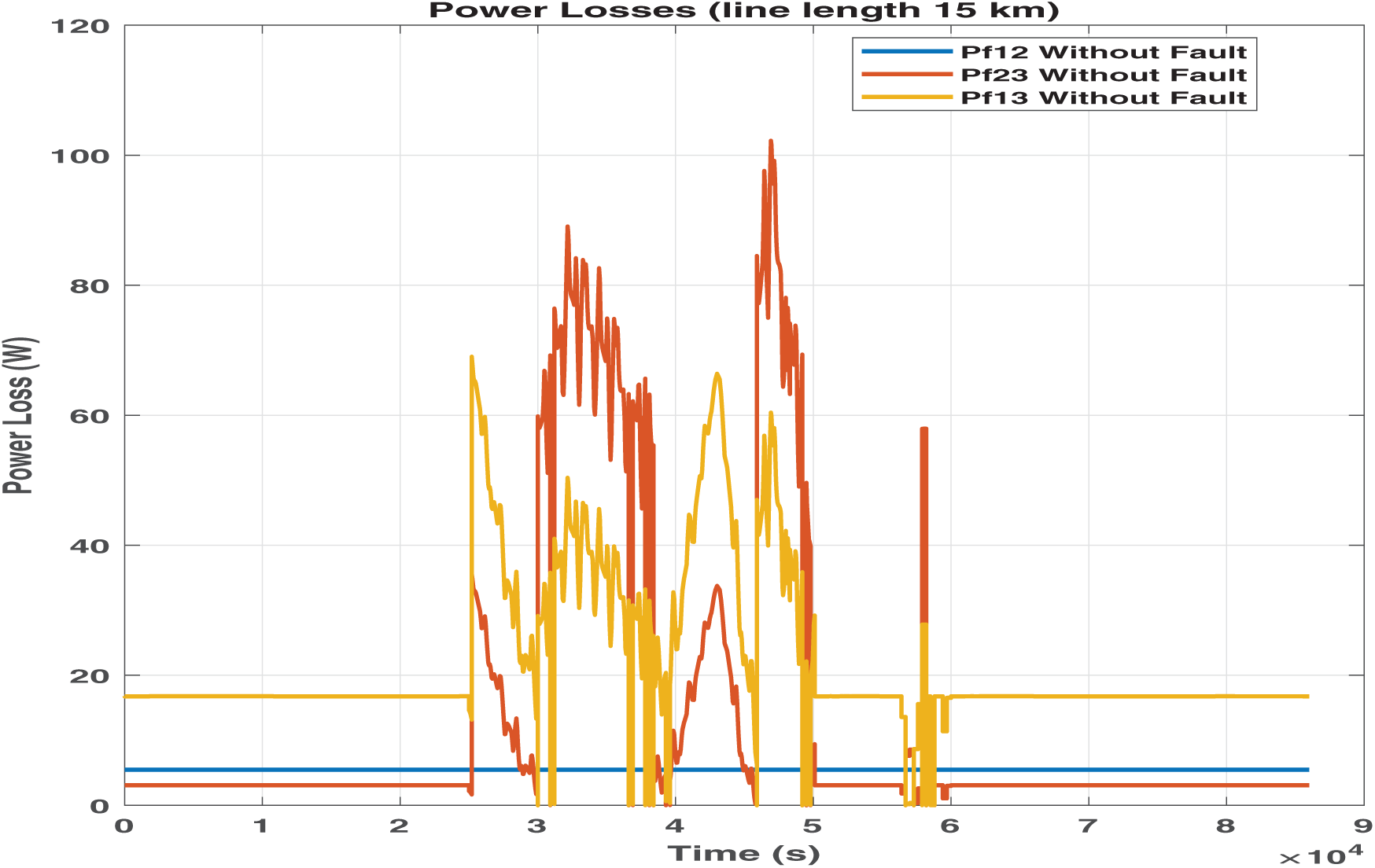

• Scenario 4. This scenario evaluates the impact of the length of the transmission line on the global optimization problem. The microgrid parameters are identical to those in Scenario 3, with the exception that the transmission line length between each pair of microgrids is decreased to 2.5 km for Scenario 4.1 and increased from 5 to 15 km for scenario 4.2. The results indicate that power losses are significantly reduced compared to Scenarios 4.2 as given in Figs. 9 and 10. This suggests a decrease in power exchange between microgrids, as the longer transmission distance discourages energy sharing. In this case, the surplus energy, primarily generated in Microgrid 3, is not fully utilized by the neighboring microgrids. Due to the increased line length and the voltage limitation of 5 kV, a substantial portion of this surplus is instead injected directly into the main grid, which is assumed to be geographically closer to Microgrid 3.

Figure 5: Optimized energy management visualization (Scenario 1 Heuristic-based methodology)

Figure 6: Optimized energy management visualization (Scenario 1 proposed methodology)

Figure 7: Optimized energy management visualization under fault (Scenario 3 proposed methodology)

Figure 8: Interconnection line power losses with and without fault

Figure 9: Optimized energy management visualization (Scenario 4.1 proposed methodology)

Figure 10: Optimized energy management visualization (Scenario 4.2 proposed methodology)

The integration of a hybrid Prophet–BiLSTM forecasting model with a Linear Programming (LP)-based energy management framework improves the operational efficiency and economic performance of interconnected microgrid systems. By leveraging accurate, high-resolution forecasts of renewable energy generation, the proposed architecture enables proactive and informed decision-making within the optimization horizon. Specifically, the LP optimizer dynamically coordinates power exchanges with the main grid, schedules battery charging and discharging cycles with high precision, and optimally manages inter-microgrid power flows. This is achieved while strictly adhering to system-level technical constraints, such as battery SoC thresholds, power flow capacity limits, and grid interconnection rules. The empirical results of Scenario 1, as summarized in Table 3, demonstrate that the LP-based control strategy consistently outperforms conventional heuristic approaches, achieving an average cost reduction of approximately 12%. In addition to economic benefits, the optimization-based strategy yields measurable reductions in grid energy consumption and associated

This paper presents a comprehensive three-stage energy management methodology that encompasses both prediction and decision-making. The first stage emphasizes data pre-processing, ensuring high-quality input for subsequent analysis. The second stage builds upon this foundation to achieve accurate forecasting, employing an iterative hybrid method that integrates BiLSTM and stochastic models. Finally, the third stage introduces an optimization framework based on a modified LP approach, validated for three interconnected microgrids.

The proposed LP-based multi-objective optimization strategy, applied to forecasts generated through the Prophet-BiLSTM hybrid model, demonstrates mathematical simplicity, computational efficiency, and superior performance compared to alternative methodologies. Nevertheless, integration of the ESS remains somewhat limited due to the centralized control structure. In some cases, battery operation control signals exhibit uniformity across microgrids, restricting operational flexibility. To address this, future enhancements could incorporate adaptive fuzzy logic within the LP framework, improving ESS responsiveness, reducing dependence on the main grid, and minimizing overall energy costs.

Looking forward, several avenues will be explored to further strengthen the methodology. The integration of battery degradation costs will be considered to better capture the economic impact of frequent charging and discharging cycles, enhancing model realism and providing a more reliable assessment of ESS operation. The framework will also be extended to larger networks of interconnected microgrids, focusing on coordination among multiple systems and the scalability of the optimization strategy. Advanced approaches, including fuzzy logic and intelligent optimization techniques, will be investigated to improve flexibility, robustness, and operational efficiency. Furthermore, transitioning from a centralized LP framework to distributed or ADMM-based optimization will be explored to efficiently manage clusters of microgrids while maintaining computational tractability. Finally, real-time implementation in practical microgrid testbeds will provide additional validation and insights into real-world performance.

Overall, the proposed methodology offers a robust foundation for predictive and optimization-based energy management, with clear pathways for enhancement and practical deployment in future research.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their appreciation to Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for funding their research work through the project number PSAU/2024/01/31821.

Funding Statement: The authors extend their appreciation to Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for funding their research work through the project number PSAU/2024/01/31821.

Author Contributions: Mohamed Kouki, Nahid Osman, Mona Gafar, and Ragab A. El-Sehiemy confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Mohamed Kouki and Nahid Osman; methodology, Mohamed Kouki; software, Mohamed Kouki; validation, Mohamed Kouki, Nahid Osman, Mona Gafar, and Ragab A. El-Sehiemy; formal analysis, Mohamed Kouki; investigation, Mohamed Kouki; resources, Mohamed Kouki; data curation, Mohamed Kouki; writing—original draft preparation, Mohamed Kouki; writing—review and editing, Mohamed Kouki; visualization, Mohamed Kouki and Ragab A. El-Sehiemy; supervision, Mohamed Kouki and Ragab A. El-Sehiemy; project administration, Mohamed Kouki; funding acquisition, Nahid Osman and Mona Gafar. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Alizadeh A, Kamwa I, Moeini A, Mohseni-Bonab SM. Energy management in microgrids using transactive energy control concept under high penetration of Renewables; a survey and case study. Renew Sustain Energ Rev. 2023;176:113161. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2023.113161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Fathima AH, Palanisamy K. Optimization in microgrids with hybrid energy systems—a review. Renew Sustain Energ Rev. 2015;45:431–46. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.01.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Khan NH, Wang Y, Jamal R, Iqbal S, Elbarbary ZMS, Alshammari NF, et al. A novel modified artificial rabbit optimization for stochastic energy management of a grid-connected microgrid: a case study in China. Energy Rep. 2024;11:5436–55. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2024.05.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Tian M, Zhu L, Alattas KA, Shakibjoo AD, Khandakar A, Muyeen SM, et al. Energy management of multi-carrier microgrids including electric vehicles: a self-structuring type-3 fuzzy approach. Energy Rep. 2025;14:539–51. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2025.05.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Karimi H, Gharehpetian GB, Ahmadiahangar R, Rosin A. Optimal energy management of grid-connected multi-microgrid systems considering demand-side flexibility: a two-stage multi-objective approach. Elect Power Syst Res. 2023;214:108902. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2022.108902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ahmethodžić L, Musić M, Huseinbegović S. Microgrid energy management: classification, review and challenges. CSEE J Power Energy Syst. 2022;9(4):1425–38. [Google Scholar]

7. Aatabe M, El Abbadi R, Vargas AN, Bouzid AEM, Bawayan H, Mosaad MI. Stochastic energy management strategy for autonomous PV-microgrid under unpredictable load consumption. IEEE Access. 2024;12:84401–19. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3414297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Benhamaid S, Bouabdallah A, Lakhlef H. Recent advances in energy management for Green-IoT: an up-to-date and comprehensive survey. J Netw Comput Appl. 2022;198:103257. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2021.103257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yu XE, Xue Y, Sirouspour S, Emadi A. Microgrid and transportation electrification: a review. In: Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo (ITEC); 2012 Jun 18–20; Dearborn, MI, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2012. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

10. Xing X, Jia L. Energy management in microgrid and multi-microgrid. IET Renew Power Gener. 2024;18(15):3480–508. doi:10.1049/rpg2.12816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Oree V, Hassen SZS, Fleming PJ. Generation expansion planning optimisation with renewable energy integration: a review. Renew Sustain Energ Rev. 2017;69:790–803. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.11.120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Mlilo N, Brown J, Ahfock T. Impact of intermittent renewable energy generation penetration on the power system networks—a review. Technol Econ Smart Grids Sustain Energy. 2021;6(1):25. doi:10.1007/s40866-021-00123-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhao Z, Guo J, Luo X, Lai CS, Yang P, Lai LL, et al. Distributed robust model predictive control-based energy management strategy for islanded multi-microgrids considering uncertainty. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2022;13(3):2107–20. doi:10.1109/tsg.2022.3147370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Lee J, Guo J, Choi JK, Zukerman M. Distributed energy trading in microgrids: a game-theoretic model and its equilibrium analysis. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2015;62(6):3524–33. doi:10.1109/tie.2014.2387340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Rodriguez M, Arcos-Aviles D, Guinjoan F. Simple fuzzy logic-based energy management for power exchange in isolated multi-microgrid systems: a case study in a remote community in the Amazon region of Ecuador. Appl Energy. 2024;357:122522. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.122522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Moazzen F, Hossain MJ. A two-layer strategy for sustainable energy management of microgrid clusters with embedded energy storage system and demand-side flexibility provision. Appl Energy. 2025;377:124659. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.124659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Merabet A, Al-Durra A, El-Fouly T, El-Saadany EF. Optimization and energy management for cluster of interconnected microgrids with intermittent non-polluting and diesel generators in off-grid communities. Elect Power Syst Res. 2025;241:111319. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2024.111319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Annamalai T, Uthaya Kumar GS, Sivarajan S, Rao DSNM. Optimized energy management for interconnected networked microgrids: a hybrid NEGCN-PFOA approach with demand response and marginal pricing. Energy. 2024;308:132987. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.132987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Moungos KA, Kyriakou DG, Kanellos FD. Towards the integration of interconnected microgrids to deregulated electricity markets. Elect Power Syst Res. 2025;239:111264. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2024.111264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Yassim HM, Abdullah MN, Gan CK, Ahmed A. A review of hierarchical energy management system in networked microgrids for optimal inter-microgrid power exchange. Elect Power Syst Res. 2024;231:110329. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2024.110329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Srivastava A, Das DK. An interactive class topper optimization with energy management scheme for an interconnected microgrid. Elect Eng. 2024;106(2):2069–86. doi:10.1007/s00202-023-02048-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Rodriguez-Gil JA, Mojica-Nava E, Vargas-Medina D, Arevalo-Castiblanco MF, Cortes CA, Rivera S, et al. Energy management system in networked microgrids: an overview. Energy Syst. 2024;130:216. doi:10.1007/s12667-024-00676-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Cheng Y, Zhang J, Al Shurafa M, Liu D, Zhao Y, Ding C, et al. An improved multiple adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system based on genetic algorithm for energy management system of Island Microgrid. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):17988. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-5730540/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Alarcón RG, Alarcón MA, González AH, Ferramosca A. Artificial neural networks for energy demand prediction in an economic MPC-based energy management system. Int J Robust Nonlinear Control. 2025;35(2):642–58. doi:10.1002/rnc.7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chinnadurrai CL, Ravindran S, Udaiyakumar S. Energy management of a microgrid based on LSTM deep learning prediction model. In: Proceedings of the 2021 Smart Technologies, Communication and Robotics (STCR); 2021 Oct 9–10; Sathyamangalam, India. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

26. Hoummadi MA, Bossoufi B, Karim M, Althobaiti A, Alghamdi TAH, Alenezi M. Advanced AI approaches for the modeling and optimization of microgrid energy systems. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):12599. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-96145-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Mahmoudabadi ND, Khalaj M, Jafari D, Herat AT, Ahranjani PM. Energy management of microgrid coalitions considering renewable energy prediction based on machine learning algorithms. AIP Adv. 2025;15(4):045323. doi:10.1063/5.0236597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang Y, Gu P, Li Y, Zhang C, Duan B. An informed-physic fused data-driven approach based on GRU for accurate SOC estimation. In: Proceedings of the 2024 8th CAA International Conference on Vehicular Control and Intelligence (CVCI); 2024 Oct 25–27; Chongqing, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

29. Tajjour S, Chandel SS. A comprehensive review on sustainable energy management systems for optimal operation of future-generation of solar microgrids. Sustain Energy Technol Assess. 2023;58:103377. doi:10.1016/j.seta.2023.103377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Srikanth D, Sukumar GD, Sobhan PVS. A convolutional neural network based energy management system for photovoltaic/battery systems in microgrid using enhanced coati optimization approach. J Energy Storage. 2025;119:116252. doi:10.1016/j.est.2025.116252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Singh AR, Kumar RS, Bajaj M, Khadse CB, Zaitsev I. Machine learning-based energy management and power forecasting in grid-connected microgrids with multiple distributed energy sources. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):19207. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-70336-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wang H, Zhang S, Liu B. Hybrid physical-data driven model for denoising of generator state measurements. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2025;74:2509912. doi:10.1109/tim.2025.3545981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Qi N, Huang K, Fan Z, Xu B. Long-term energy management for microgrid with hybrid hydrogen-battery energy storage: a prediction-free coordinated optimization framework. Appl Energy. 2025;377:124485. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.124884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kouki M, Vidal P-E, El-Sehiemy RA. Generic fuzzy-based optimal energy management strategy for efficient performance of realistic micro-grids with battery lifetime enhancement under climate changes. J Energy Storage. 2025;128:116977. doi:10.1016/j.est.2025.116977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Balavignesh S, Kumar C, Sripriya R, Senjyu T. An enhanced coati optimization algorithm for optimizing energy management in smart grids for home appliances. Energy Rep. 2024;11:3695–720. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2024.03.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ayub MA, Hussan U, Rasheed H, Liu Y, Peng J. Optimal energy management of MG for cost-effective operations and battery scheduling using BWO. Energy Rep. 2024;12:294–304. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2024.05.071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ahmadi B, Hoogsteen G, Zawadzki P, Gerards MET, Radziszewska W, Bykuć S, et al. A novel multi-objective approach to user-centric energy management systems. Energy Rep. 2025;14:185–204. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2025.05.084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Sarmadi BK, Shayeghi H, Seyedshenava S, Shafie-khah M. Multiple microgrids intelligent energy management with capacity constraint using hybrid deep neural network and reinforcement learning. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst. 2025;172:111179. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2025.111179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Mazidi M, Rezaei N, Ardakani FJ, Mohiti M, Guerrero JM. A hierarchical energy management system for islanded multi-microgrid clusters considering frequency security constraints. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst. 2020;121:106134. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2020.106134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Mirzaei M, Keypour R, Savaghebi M, Golalipour K. Probabilistic optimal bi-level scheduling of a multi-microgrid system with electric vehicles. J Electr Eng Technol. 2020;15(6):2421–36. [Google Scholar]

41. Lu T, Wang Z, Ai Q, Lee W-J. Interactive model for energy management of clustered microgrids. IEEE Trans Ind Appl. 2017;53(3):1739–50. doi:10.1109/tia.2017.2657628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Karimi H, Jadid S. Two-stage economic, reliability, and environmental scheduling of multi-microgrid systems and fair cost allocation. Sustain Energy Grids Netw. 2021;28:100546. doi:10.1016/j.segan.2021.100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Jiang W, Yang K, Yang J, Mao R, Xue N, Zhuo Z. A multiagent-based hierarchical energy management strategy for maximization of renewable energy consumption in interconnected multi-microgrids. IEEE Access. 2019;7:169931–45. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2955552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Tan B, Chen H. Multi-objective energy management of multiple microgrids under random electric vehicle charging. Energy. 2020;208:118360. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2020.118360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Gasca MV, Rigo-Mariani R, Debusschere V, Sidqi Y. Energy communities typologies and performances: impact of members configurations, system size and management. Energy Rep. 2025;14:173–84. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2025.05.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Toquica D, Agbossou K, Henao N. Multi-agent reinforcement learning for energy management in microgrids with shared hydrogen storage. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2025;144:1019–27. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2025.01.413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Pan M, Fu C, Cao X, Guan W, Liang L, Li D, et al. An energy management strategy for fuel cell hybrid electric vehicle based on HHO-BiLSTM-TCN-self attention speed prediction. Energy. 2024;307:132734. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.132734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Nie Z, Song H, Lian Y, Shi Z. BiLSTM-ATTENTION-CNN predictive energy management based on ISSA optimization for intelligent fuel cell hybrid vehicle platoon. Energy. 2025;324:135860. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.135860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Rituraj R, Ali S, Várkonyi-Kóczy AR. Modeling of a microgrid and its time-series analysis using the prophet model. In: Recent advances in intelligent engineering: volume dedicated to Imre J. Rudas’ Seventy-Fifth Birthday. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2024. p. 139–76. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-58257-8_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Shufian A, Mohammad N. Modeling and analysis of cost-effective energy management for integrated microgrids. Cleaner Eng Technol. 2022;8:100508. doi:10.1016/j.clet.2022.100508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Open-Meteo. Historical Weather API [Online]. [cited 2025 Jun 12]. Available from: https://open-meteo.com/en/docs/historical-weather-api. [Google Scholar]

52. Saeed N, Nguyen S, Cullinane K, Gekara V, Chhetri P. Forecasting container freight rates using the Prophet forecasting method. Transp Policy. 2023;133:86–107. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2023.01.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools