Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Development of a Multi-Resolution SPH-PD Model for Simulating Ice Sheet Fragmentation under Underwater Explosion Loads

1 School of Ocean Engineering and Technology, Sun Yat-sen University & Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai), Zhuhai, 519000, China

2 Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Information Technology for Deep Water Acoustics, Zhuhai, 519080, China

3 College of Shipbuilding Engineering, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, 150001, China

* Corresponding Author: Peng-Nan Sun. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Recent Developments in Nonlocal Meshfree Particle Methods for Solids and Fluids )

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 3405-3431. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.072496

Received 28 August 2025; Accepted 18 November 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

A multi-resolution smoothed particle hydrodynamics and peridynamics (SPH-PD) coupling model is proposed in this study for simulating the fracture characteristics of ice plates exposed to underwater blast loads. The SPH model employs a volume adaptive scheme (VAS) and a multi-resolution particle technique to accurately simulate explosive charge detonation and shock wave propagation. This approach addresses numerical challenges from charge expansion and significant size disparity between the charge and the fluid particles. The model captures the full underwater explosion process, covering both the shock wave phase and the bubble expansion stage, by applying appropriate equations of state for each respective phase. To analyze ice plate damage and crack propagation influenced by temperature changes, an ordinary state-based PD (OSB-PD) formulation with coupled mechanical and thermodynamic models is used. Numerical results show that the proposed coupling method demonstrates good agreement with reference solutions and experimental data.Keywords

Ice jams are physical blockages resulting from the accumulation of ice in cold regions, such as rivers, lakes, and oceans. These blockages typically form during winter and spring, coinciding with periods of freezing and thawing. Ice jams pose significant threats to both the natural environment and infrastructure. They can trigger extreme flooding events [1], jeopardizing human safety and property. Additionally, excessive accumulated weight or impact loads may cause structural damage [2], leading to the destruction of specialized facilities. Therefore, effective removal of ice jams is essential to mitigate these risks. Underwater explosions are widely regarded as a top technique for breaking up ice and clearing blockages. In ice-covered regions, ocean submersibles may encounter thick ice layers [3] that cannot be penetrated by physical impact alone, resulting in operational delays. Underwater explosive icebreaking provides a prompt and reliable solution to overcome such blockades. Investigating the behavior of various types of ice under dynamic loads [4,5] is crucial for understanding the fracture mechanisms of ice sheets and advancing underwater explosive icebreaking technology.

The mechanisms of ice damage caused by shock waves and bubble pulsations generated by blast loads remain insufficiently understood due to limited research. Most studies on this topic rely on experimental tests. Although experimental tests [6,7] provide authentic and reliable data, they are limited in terms of data collection, safety, repeatability, and visualization. With the rapid development of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) [8–11] and computational solid mechanics (CSM) [12–15], numerical methods have become increasingly prevalent for addressing these challenges. In computational mechanics, modeling the complex failure mechanisms of ice sheets subjected to concurrent shock wave and bubble pulsation loading [16,17] presents significant computational challenges. These challenges stem from difficulties in multiphysics field coupling, material nonlinearities, uncertainties in the constitutive behavior of ice, shock wave dissipation, and bubble evolution. In simulations, mesh-based, particle-based, and hybrid methods are widely employed in explosive icebreaking projects due to their algorithmic strengths.

For simulating underwater explosions, the accurate prediction of shock wave propagation is paramount. Liu et al. [18] achieved high-fidelity simulation of both shock wave and bubble pulsation loads by employing the Eulerian finite element method (EFEM) coupled with the volume of fluid (VOF) algorithm. To solve the six-equation multiphase model with uniform pressure for compressible two-phase flows, Li et al. [19] developed an interface sharpening technique within the finite volume method (FVM) framework, successfully applying it to underwater explosion scenarios. Among particle-based methods, smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) excels at accurately tracking the gas-liquid interface motion. Pioneering the application of SPH to underwater explosions, Liu et al. [20] implemented modifications (e.g., to smoothing length and boundary conditions) within the weakly compressible SPH (WCSPH) framework. The adaptive volume scheme (VAS) proposed by Sun et al. [21] further enhanced SPH’s capability for strongly compressible flows, significantly improving the simulation of rapid gas expansion/compression from detonating charges. However, the significant computational cost inherent in particle-based methods, stemming from the absence of a grid-like topology, remains a challenge. This is particularly acute when simulating detonations, as the characteristic size of the explosive charge is typically much smaller than that of the surrounding water domain; discretizing the entire domain at the particle size required for the charge resolution incurs prohibitive computational expense.

To simulate the mechanical characteristics of ice under dynamic loading, numerous numerical methods are available, such as the finite element method (FEM), discontinuous Galerkin method (DGM), discrete element method (DEM), and peridynamics (PD). Utilizing the arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian (ALE) method, Wang et al. [22] examined ice plate failure and fluid dynamics caused by underwater explosions, analyzing influencing factors and deriving a predictive formula for the damaged area. The rupture of ice sheets with varying thicknesses under underwater explosion was investigated by Luo et al. [23] using an ALE-FEM-SPH coupled approach, which allowed for a comparison of crack propagation patterns. Employing the commercial software LS-DYNA, Yu et al. [24] assessed the damaging effects of underwater explosion bubbles and highly pressurized gas bubbles on ice. Sand [25] studied ice forces on offshore structures via nonlinear finite element simulations. Based on DGM, Miryaha et al. [26] simulated ice floe impact on an upright cylindrical offshore pillar and discussed ice failure patterns and structural pressure distributions. A DEM-based computer code was presented by Jang et al. [27] for analyzing the dynamic interaction of moored floating platforms with drifting level ice. Vazic et al. [28] performed a numerical study of ice failure modes using PD, successfully predicting both in-plane and out-of-plane fracture of ice sheets. Collectively, these numerical methods demonstrate efficacy in modeling ice failure. The PD method’s intrinsic non-local nature [29,30] offers a theoretical advantage, providing a more natural and flexible framework for simulating crack initiation and propagation without the need for predefined fracture paths.

In fluid-structure interaction (FSI) problems concerning explosive ice-breaking, fluid solvers based on the Eulerian perspective and solid solvers based on the Lagrangian algorithm have been widely employed owing to their computational efficiency and accuracy. By coupling the EFEM and PD methods, He et al. [31] studied the overall icebreaking properties induced by underwater explosion bubbles. Kan et al. [32] established an FSI solver based on BEM and PD to model crack evolution and fracture modes in ice subjected to dynamic loads from high-pressure bubbles. Regarding the application of fully particle-based solvers, Fan et al. [33] employed PD with the Drucker-Prager (DP) constitutive model for soil media, coupled with SPH using a state equation for explosive charges, to investigate blast-induced soil fragmentation and ejection dynamics. Huang et al. [34] integrated a rate-dependent concrete model into a PD-SPH framework, accounting for fluid-structure interaction effects, to systematically simulate the complete physical process from explosive detonation to structural failure. Rabczuk and Belytschko [35] proposed a meshfree cracking particles method that models crack evolution through particle-level displacement field enrichment. This approach eliminates explicit crack topology representation, enabling efficient simulation of complex crack patterns and branching phenomena. Subsequently, they developed an immersed particle method [36] that naturally accommodates fluid flow through cracks, simplifying FSI simulations, particularly under high-pressure, low-velocity conditions. In these numerical simulations involving explosive loads, thermodynamic effects were neglected, despite temperature changes being a significant factor influencing structural response. Furthermore, algorithms did not incorporate particle splitting/merging during gas expansion/compression in SPH-PD simulations of explosion problems. This results in insufficient particle resolution for the expanding gas, potentially compromising computational accuracy. The employed state equation for the charge remained unchanged; it is suitable only for simulating the shockwave phase of an explosion and cannot model the subsequent bubble pulsation. Additionally, for fully particle-based solvers, their computational cost is prohibitively high, and without high-performance parallel acceleration, a single-resolution scheme cannot realistically simulate large-scale three-dimensional (3D) explosion problems.

This work develops a fully particle-based solver coupling SPH and PD to examine the damage response of ice sheets under underwater blast loading. A multi-resolution technique is implemented within the Riemann SPH (RSPH) framework, enabling discretization and computation of different components using varied particle sizes, thus reducing computational expense. Within the SPH formulation, VAS and distinct equations of state are employed during different phases of underwater explosions, effectively simulating the transition from shockwave propagation to bubble expansion dynamics. To characterize failure patterns and crack evolution in ice sheets under blast loading, an ordinary state-based PD (OSB-PD) model coupling mechanical and thermal effects is adopted.

The subsequent sections are structured as follows. In Section 2, the utilized SPH and PD models are briefly introduced. In Section 3, some numerical benchmark tests are simulated by the present method. The effectiveness of the SPH-PD coupling scheme for solving the dynamic behavior of ice by underwater explosion is investigated and discussed in detail. Finally, conclusions and prospects are drawn in the last part of this paper.

2.1 Fluid Modeling Based on SPH

SPH is a Lagrangian meshfree method that discretizes continuous media into a collection of particles carrying physical attributes such as density, pressure, and velocity. Using kernel and particle approximations, the discretized forms of variables and their divergence/gradient can be obtained as follows:

where

RSPH is an ideal method for simulating underwater explosion shock wave propagation, bubble evolution, and multiphysics responses of ice-water-structure interactions. This is due to its ability to effectively solve the Riemann problem for compressible flows, which can accurately capture shock wave fronts and pressure discontinuities. Furthermore, through multiphase flow modeling and its inherent meshless nature, it can flexibly handle gas-liquid-solid multiphase interactions and complex geometric boundary conditions. Simultaneously, the VAS and multi-resolution techniques are employed to balance computational accuracy and efficiency. When conducting numerical simulations of underwater explosions using RSPH [37], the continuity, momentum, and energy equations can be discretized as follows:

where

For the above equations, the primitive variable Riemann solver (PVRS) [38] is adopted owing to its accuracy and stability for simulating multiphase flows. In this way,

where

Usually, the traditional RSPH carries a dissipation problem, resulting in a significant decrease in computational accuracy. As in most of the literature [39], in this paper, a dissipation limiter is used to limit the unphysical loss of momentum. Thus,

where

To enhance computational accuracy, the second-order monotone upwind centered scheme for conservation laws (MUSCL) reconstruction technique [40,41] is employed to reconstruct the left and right states required for solving the Riemann problem. For two interacting particles

where

To preserve distinct phase interfaces and avoid spurious intermixing in the multi-phase flow simulation, an interface sharpness force [42],

where

To close and decouple system (1), the introduction of an equation of state establishing the relationship between pressure, density, and energy is required. The propagation process of underwater explosion shock waves is typically calculated using the Mie-Gruneisen (MG) equation of state [20] for water particle pressure. When water particles are in a state of expansion or compression, their pressure can be determined by the following formula:

and

where the parameters

The pressure of the TNT explosion products is calculated using the Jones-Wilkins-Lee (JWL) equation of state [20], as follows:

where the fitting coefficients

When an underwater explosion transitions from the shock wave phase to the bubble pulsation phase, the pressure of water and gas is calculated using the Tait equation of state. Their expressions [43] are as follows:

where

The pseudo sound speed

where

2.2 Particle Splitting Based on VAS

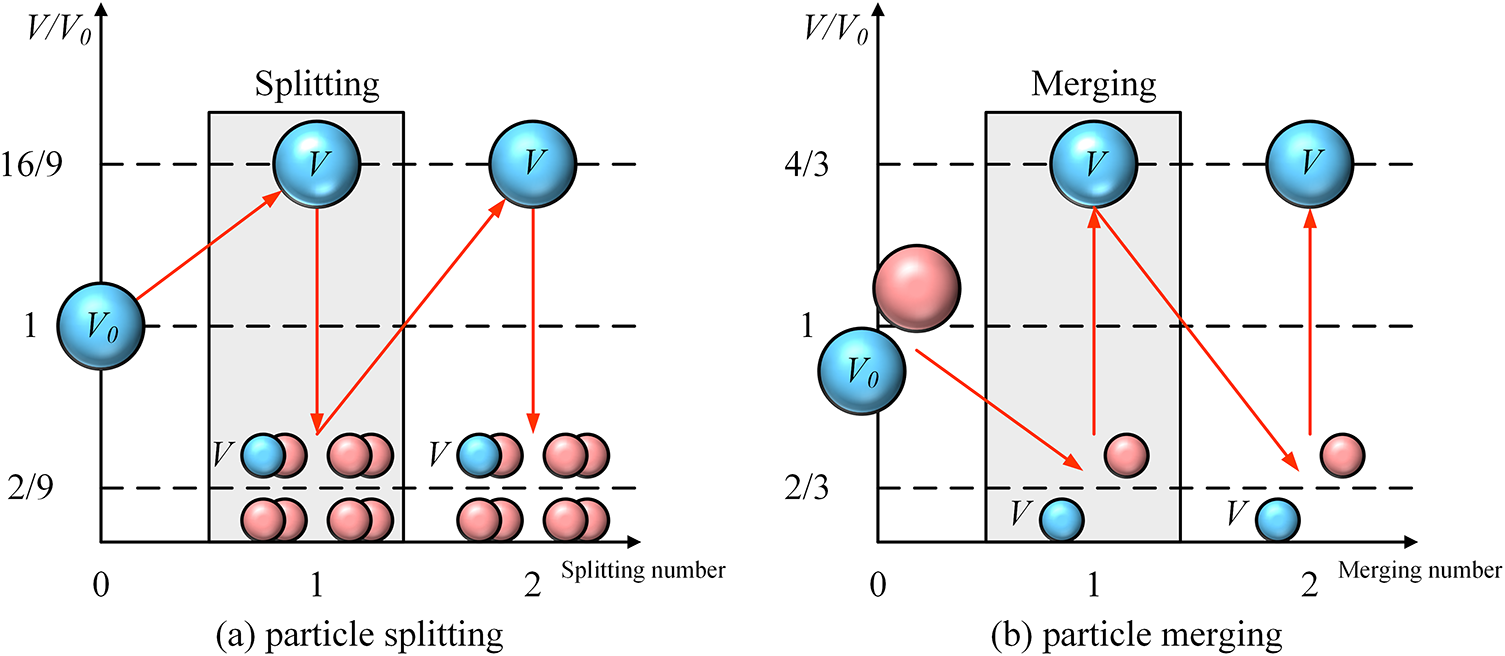

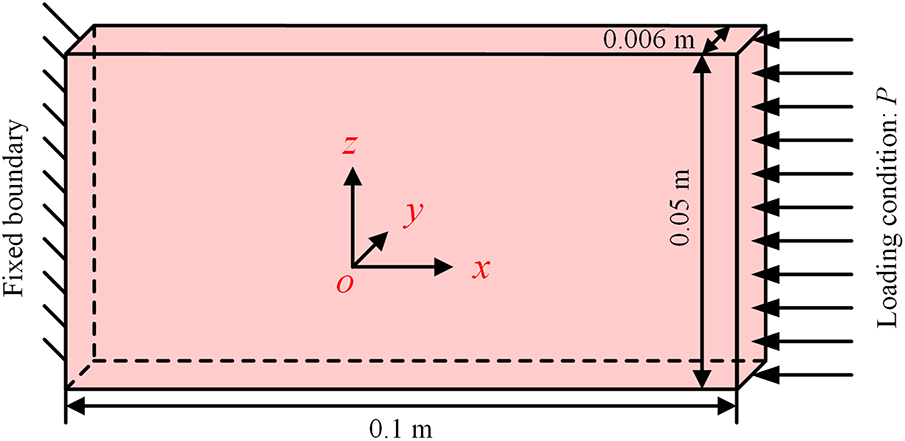

During the propagation of shock waves from an underwater explosion, the rapid expansion of high-pressure gas leads to a significant increase in the volume of explosive particles. Traditional SPH methods maintain a uniform particle distribution, but they suffer from reduced accuracy and stability when particles become overly sparse. To address this, the present study employs a VAS [21] to dynamically refine particle distribution in regions requiring higher accuracy (e.g., the explosive charge zone) and coarsen particles in less dense areas, thereby balancing computational efficiency and precision. The core principle of VAS is to control the particle refinement and coarsening through volume-based thresholds, ensuring adaptive particle distribution. This approach originates from the adaptive refinement techniques pioneered by Bonet and Lok [44], who introduced the concept of dynamically adjusting particle density based on local physical gradients or geometric features to enhance resolution in critical regions. Fig. 1 illustrates the principle of the VAS algorithm in 3D scenarios. As shown in Fig. 1a, if a particle’s volume

where

Figure 1: A sketch showing the 3D VAS scheme

During the process of splitting, subject to the conservation of mass, momentum, and energy, the variables of daughter particles shall inherit or derive from their mother particle values. In 3D scenarios, a daughter particle’s variables (with subscript

in which the variables

Similarly, to obtain the merging threshold,

in which

When the particle merging algorithm is triggered, two daughter particles will merge into one mother particle. The relationship between the physical quantities before and after merging is as follows:

2.3 Particle Shifting Technique Applicable to Highly Compressible Flows

In SPH simulations of highly compressible flows, the particle shifting technique (PST) is typically applied to improve numerical stability, accuracy, and consistency through the regularization of particle distribution. This is accomplished by applying a small shift to particle positions during each computational step. In this work, the PST proposed by Mokos et al. [45] is employed, which has been proven effective for modeling underwater explosions in a similar SPH framework. The following equation defines the particle repositioning vector:

where

2.4 Structure Simulating Based on PD

PD is a meshfree method based on a nonlocal theory proposed by Silling [46,47]. This theory reformulates the equations of motion for objects using integral forms instead of differential equations in traditional continuum mechanics theory; therefore, PD can still be applied at spatial discontinuities. In PD theory, the concept of a horizon is introduced. Within the horizon, material points interact via bonds, while beyond the horizon, interactions cease. The equation of motion can be expressed as follows, considering the temperature change of material points:

where

Following the OSB-PD model utilized by Gao et al. [48] for solving the fully coupled thermoelastic problems, Eq. (18) can be discretized as:

where the indices

In the above equation,

The PD material parameters, e.g.,

where K and

To close and decouple Eq. (19), the heat conduction equation must be incorporated within the fully coupled thermomechanical PD model. Its discretized form is:

where

From Eq. (24), the analytical expressions for the local thermal modulus,

Once the deformation between material points reaches a threshold, specifically when the stretch exceeds its critical value,

In the above equation, the relationship between the critical energy release rate,

According to the experimental study by Ji et al. [49], the fracture toughness of ice material is related to temperature as follows:

To assess material damage, a history-aware function,

Notably, when considering material failure, Eq. (30) must be incorporated into Eq. (19) for computation to assess the influence of bond states on the force density vector, thereby avoiding the inclusion of interaction points associated with broken bonds.

Local damage measures the weighted magnitude of fracture interactions at a point, normalized by their total count. Consequently, the path of crack propagation is characterized by the locally defined damage variable,

2.6 Coupling between the SPH and PD Models for FSI Problems

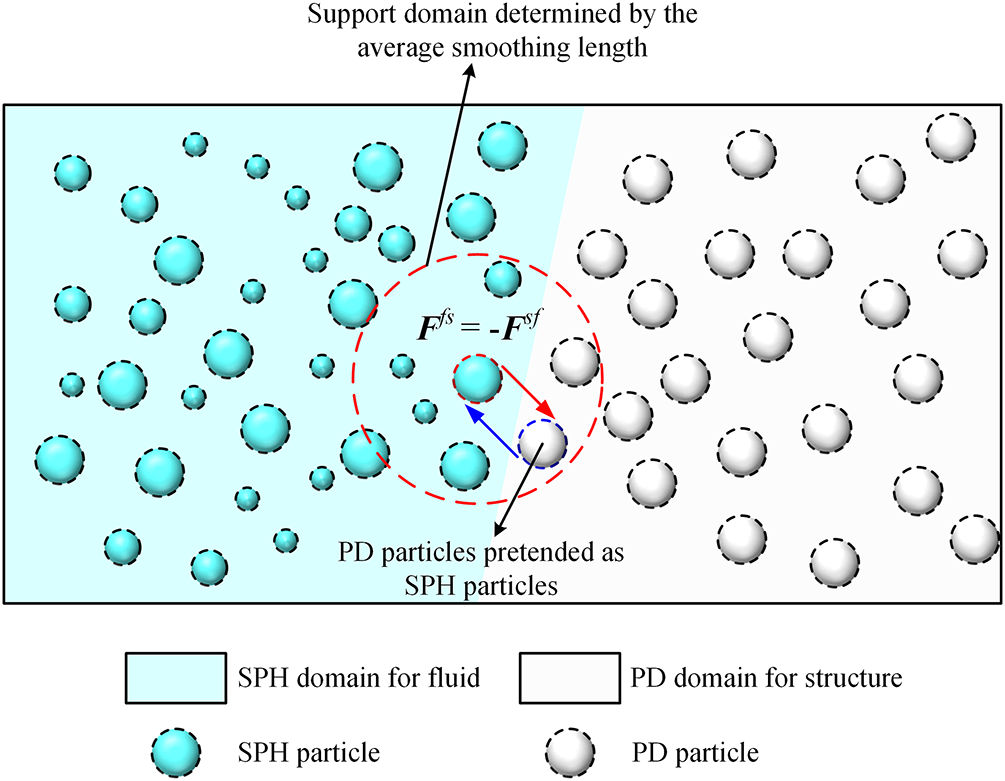

In the FSI simulation, as illustrated in Fig. 2, structural particles are discretized into PD particles. These particles serve a dual purpose: (1) They contribute to solving PD equations of motion to simulate structural responses; (2) They function as pseudo-SPH particles in solving fluid governing equations, applying fluid-structure coupling forces (i.e.,

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of the multi-resolution SPH-PD coupling scheme

Through the dummy particle boundary proposed by Adami et al. [51], the pressure of the structural particles can be obtained using the following interpolation formulation:

where

For time integration, the scheme is: fourth-order Runge-Kutta for the fluid; central difference for the structure. The time steps are taken according to the following criteria:

where

Before applying the SPH-PD coupling model to underwater explosive icebreaking problems, it is necessary to conduct rigorous and comprehensive validation in terms of stability, accuracy, and feasibility based on fundamental benchmark tests. First of all, the propagation process of shock waves from underwater explosions is simulated using the SPH model to observe the implementation effects of the multi-resolution scheme. Subsequently, a case of fully coupled thermoelasticity is calculated based on the PD model to assess the functionality of the structural solver. More importantly, the stability at the fluid-structure interface will be examined and the feasibility of the fluid-structure coupling scheme will be verified through a classic benchmark test. After that, an underwater explosive icebreaking case will be modeled, and numerical results will be discussed and analyzed by comparing them with reference solutions.

3.1 Propagation of Shock Waves in a Free-Field Underwater Explosion

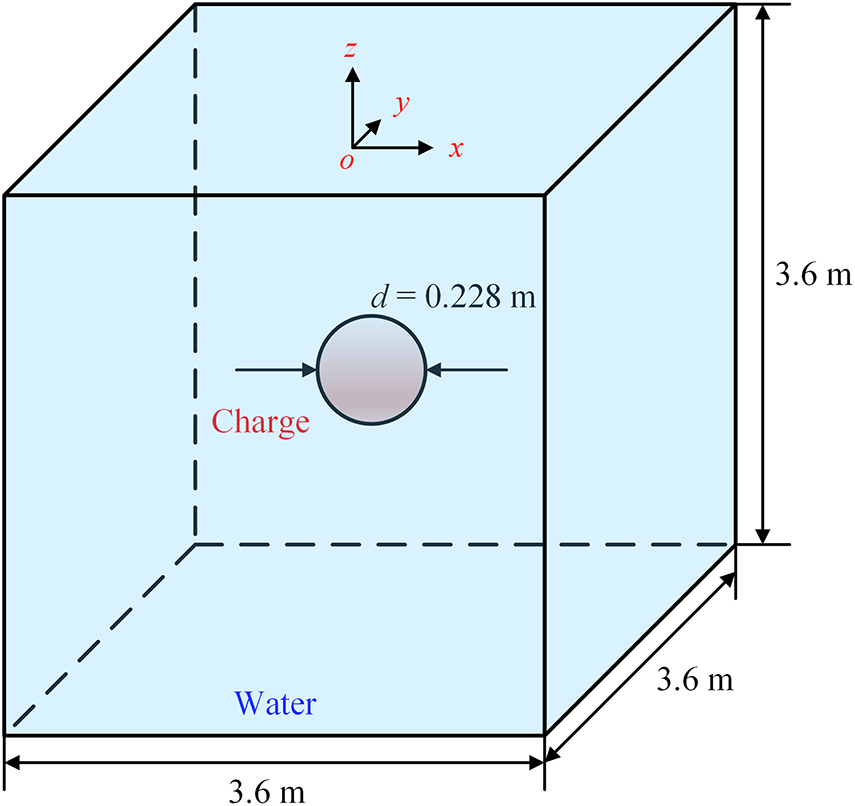

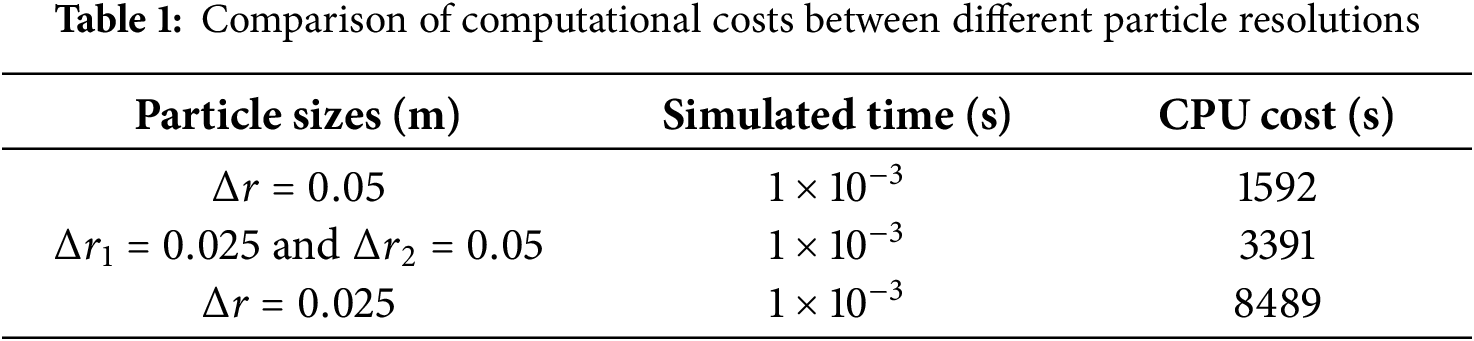

In this section, to test the performance of the multi-resolution SPH model proposed in this paper, the propagation process of shock waves from an underwater explosion was simulated. The numerical setup is depicted in Fig. 3, featuring a cubic water domain measuring

Figure 3: A schematic of a 3D free-field underwater explosion

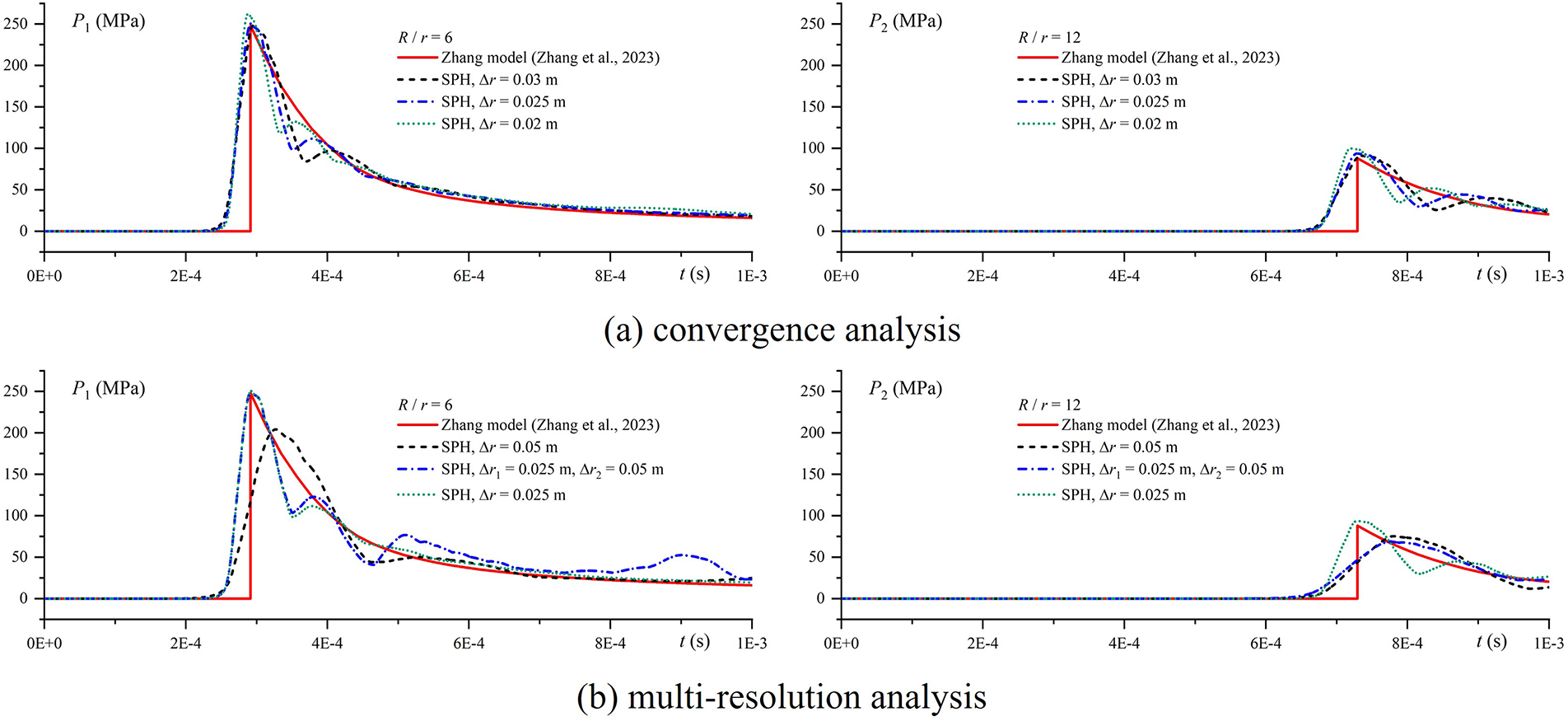

To quantitatively verify the accuracy of the shock wave simulation using the present SPH model, the pressure results derived by the numerical method at two scaled distances of

Figure 4: Pressure time-history curves of underwater explosion shock waves at two stand-off distances

After the charge detonation, the expansion process of the explosion bubble and the propagation process of the shock wave at different time instants are illustrated in Fig. 5. Following the initiation of the charge, the explosive material instantaneously transforms into high-pressure gas, gradually expanding outward. The underwater shock wave propagates spherically at the speed of sound, with its peak pressure decreasing as it travels. The overall pressure profile is smooth, and the wavefront is narrow. Although the multi-resolution scheme introduces slight numerical oscillations at the interface between coarse and fine particles, leading to local pressure fluctuations, it has a negligible impact on the overall accuracy of shock wave propagation.

Figure 5: Propagation process of the shock wave from an underwater explosion (Top:

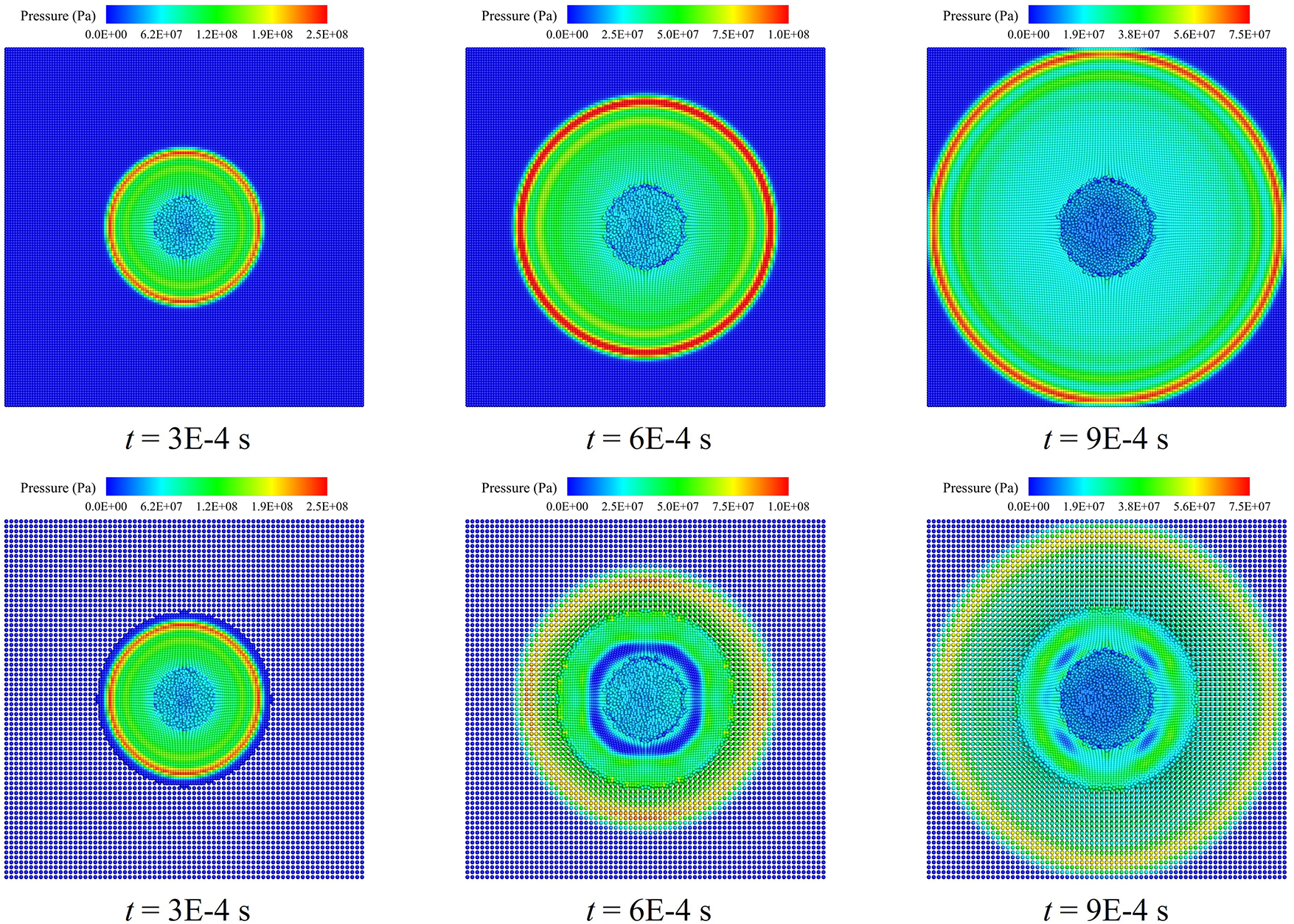

To highlight the importance of PST and VAS techniques for underwater explosion simulation, Fig. 6 presents the comparison results of different numerical schemes. Without PST implementation (Fig. 6(a1)), gas particles show uneven clustering or dispersion, causing simulation instability. The displacement correction forced by PST (Fig. 6(a2)) ensures uniform particle distribution, improving accuracy and stability. Additionally, without VAS (Fig. 6(b1)), particle spacing increases during charge expansion, complicating neighbor search and reducing precision. VAS application (Fig. 6(b2)) splits or merges particles based on conservation criteria, maintaining density to minimize kernel errors.

Figure 6: Comparison of underwater explosion simulations under different numerical schemes (Top: PST; Bottom: VAS)

3.2 Plate under Pressure Loading

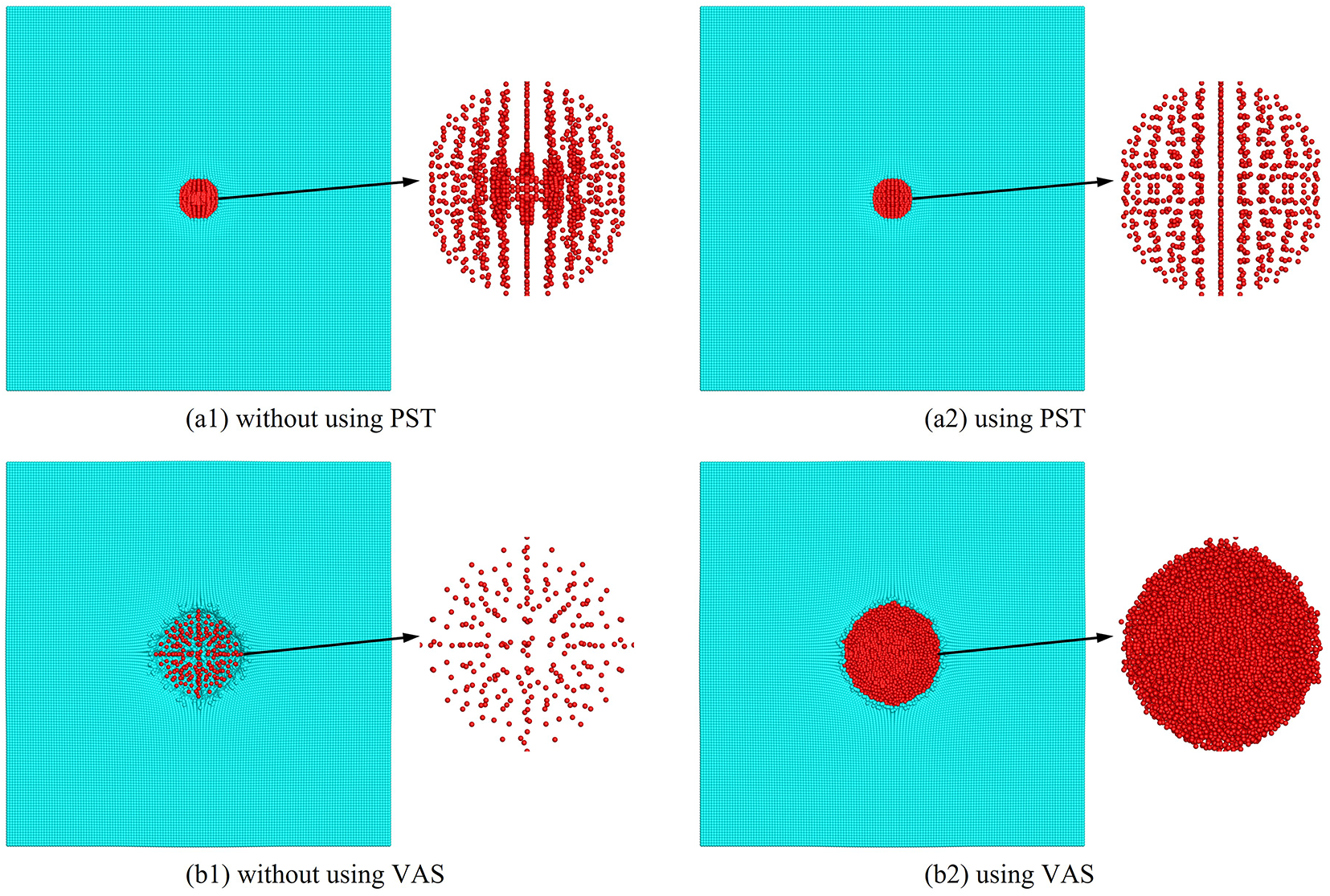

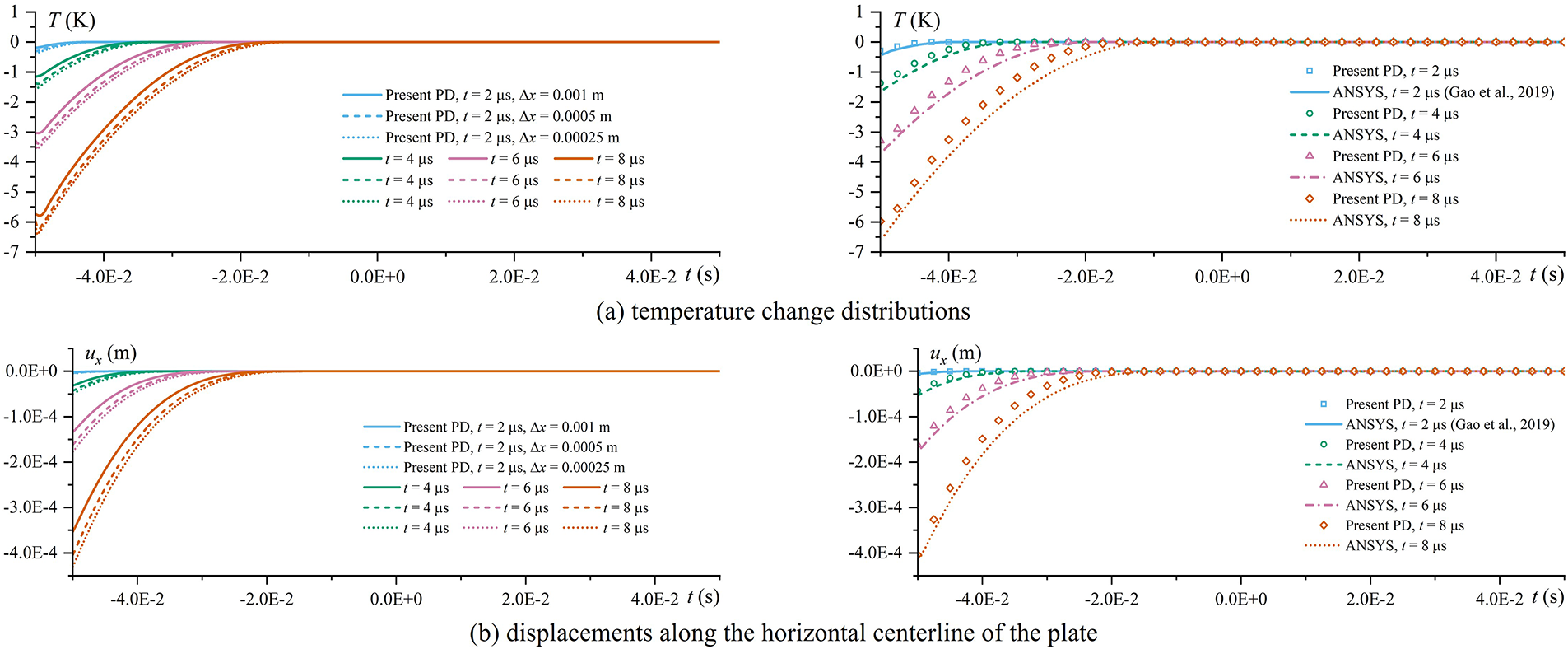

In this part, the structural solver based on the PD model is validated using a typical benchmark test, i.e., deformation and thermal behavior of a square plate subjected to pressure shock loading. The numerical setting is illustrated in Fig. 7. The plate measures

Figure 7: Diagram of a plate under pressure loading

Fig. 8 presents the temperature and deformation behavior measured along the plate’s horizontal centerline during shock loading. Since only mechanical loads were applied, the temperature variation arises from the coupling terms in the heat transfer equation. The left portion of Fig. 8 indicates that with increasing particle resolution, the simulation curves for temperature and displacement variations progressively converge, signifying good convergence. As illustrated in the right side of Fig. 8, both the temperature changes and displacement fields obtained through PD at

Figure 8: Comparison of numerical results (Left: Convergence analysis; Right: Analysis of ANSYS [48] and PD solutions)

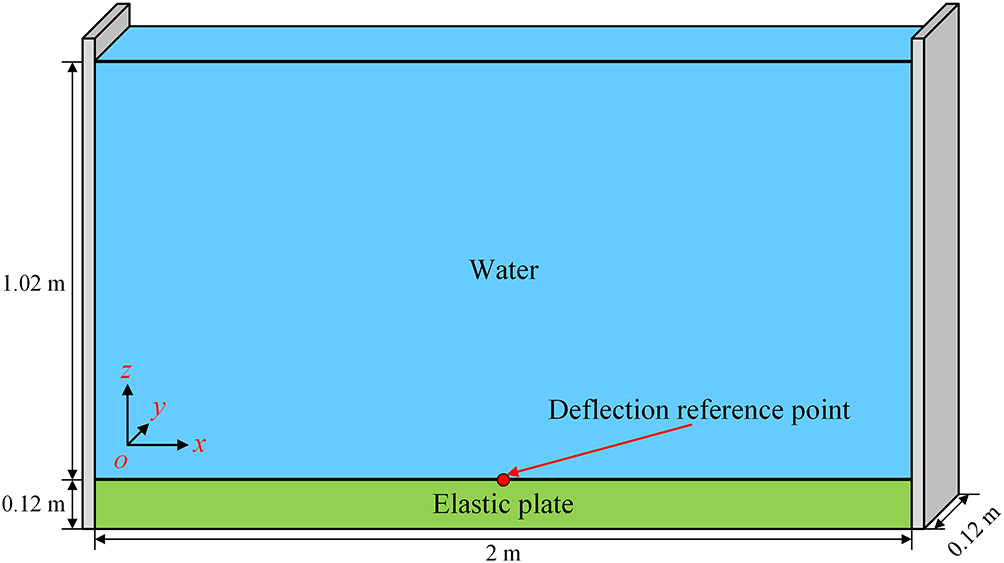

3.3 Water Column in Hydrostatic Equilibrium over an Elastic Plate

A classical case of hydrostatic pressure acting on an elastic plate is simulated in this section. This benchmark test possesses an analytical solution and has been widely employed by numerous researchers [53,54] to validate the stability and effectiveness of their developed FSI algorithms. As illustrated in Fig. 9, a

Figure 9: Numerical model for a hydrostatic water column over an elastic plate

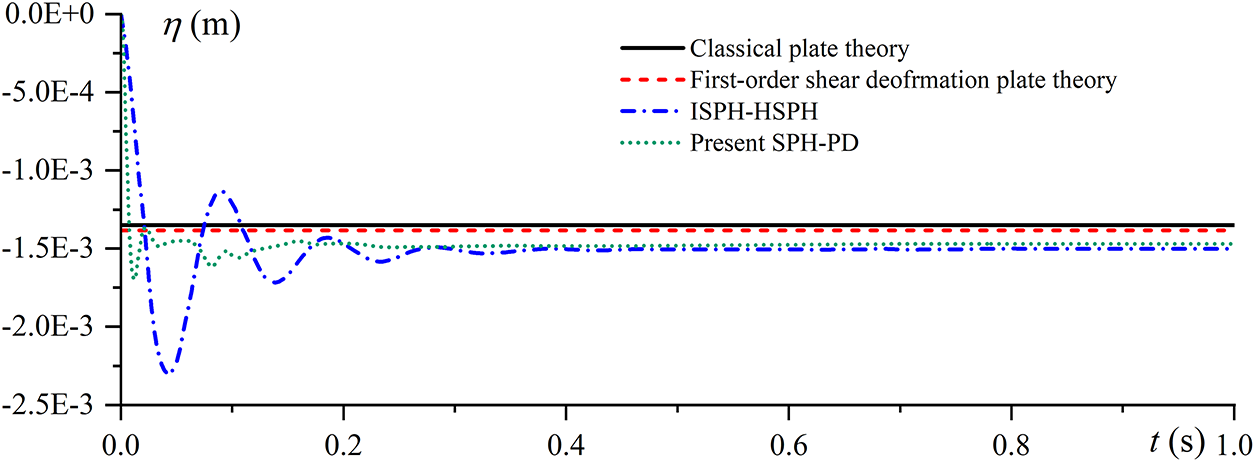

Fig. 10 presents a comparison between the simulated mid-point displacement curve of the elastic plate and the analytical solutions [54], along with other numerical results. The elastic plate, subjected to an abrupt application of hydrostatic pressure, undergoes deformation and violent oscillation, subsequently stabilizing rapidly to reach an equilibrium state. The agreement between the simulation results and the reference solutions is favorable. This case validates the accuracy of the fluid-structure coupling solver.

Figure 10: Deflection histories at the center of the plate

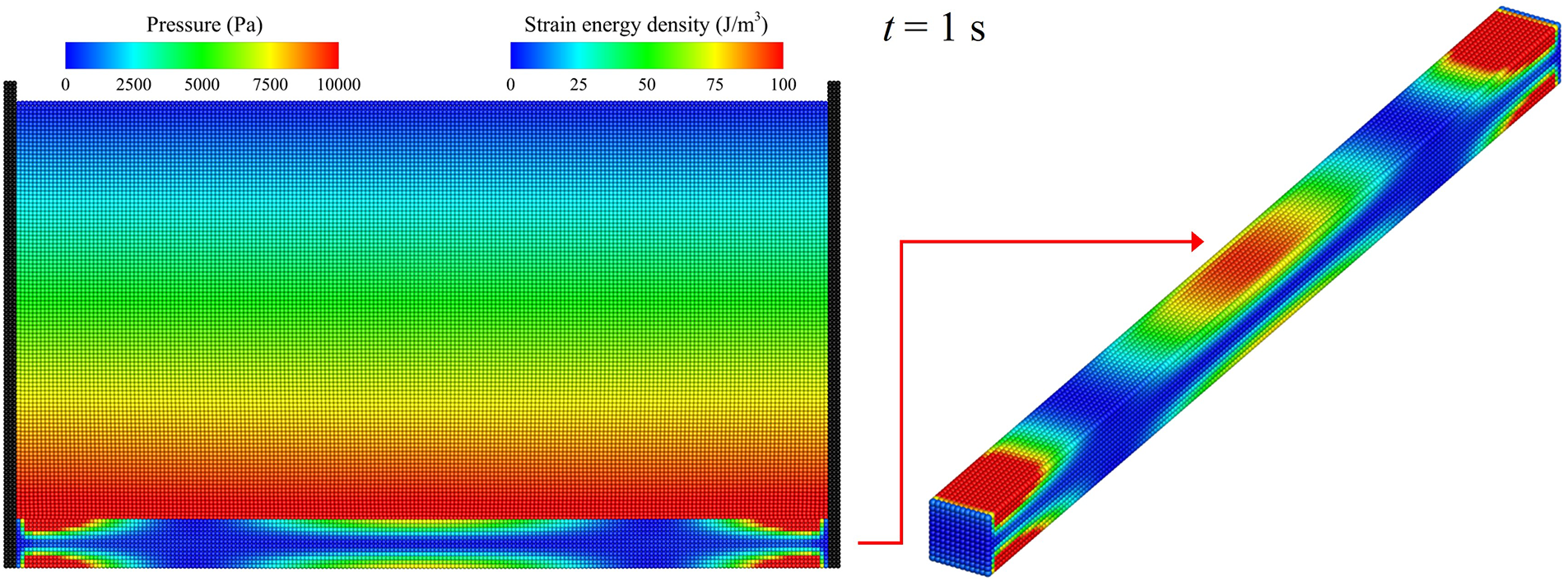

Representative particle snapshots, along with their corresponding pressure/strain energy density distributions at

Figure 11: Pressure contours and strain energy density distributions reproduced by the SPH-PD solver

3.4 Ice Sheet Exposed to Explosive Loading

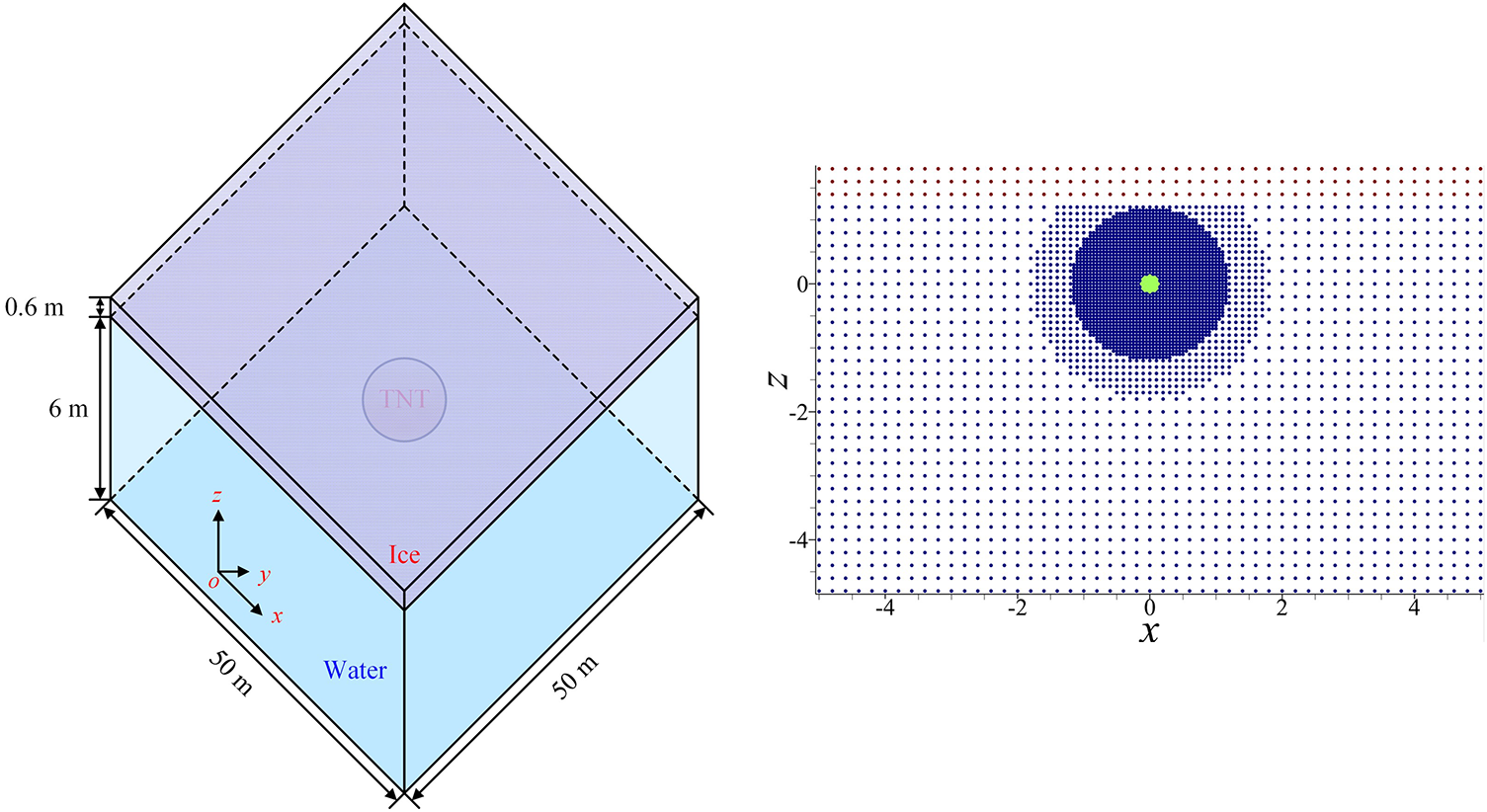

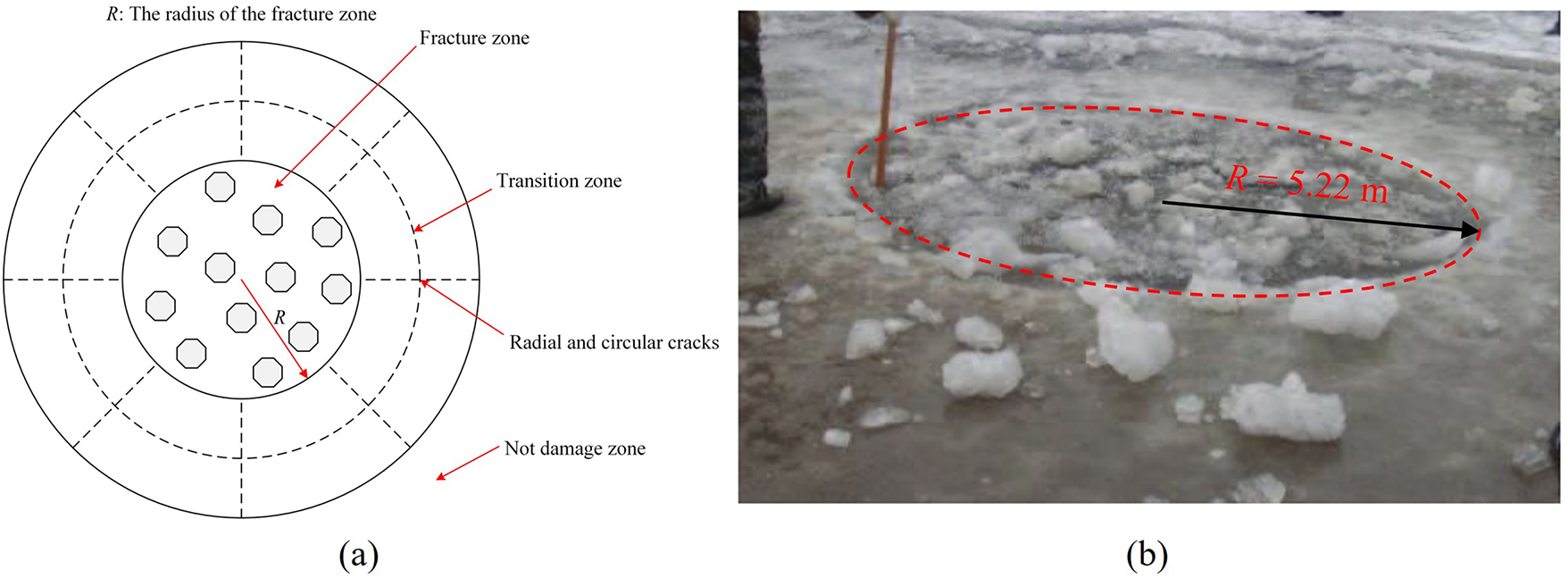

In this section, the fragmentation of ice sheet caused by explosive loads is investigated by the SPH-PD coupling method, which has been modeled by Wang et al. [55] and Zhang et al. [56] using the BB-PD and OSB-PD schemes, respectively. Numerical settings are shown in Fig. 12. The computational domain has dimensions of

Figure 12: Sketch of the numerical setup for an ice sheet subjected to explosive loads

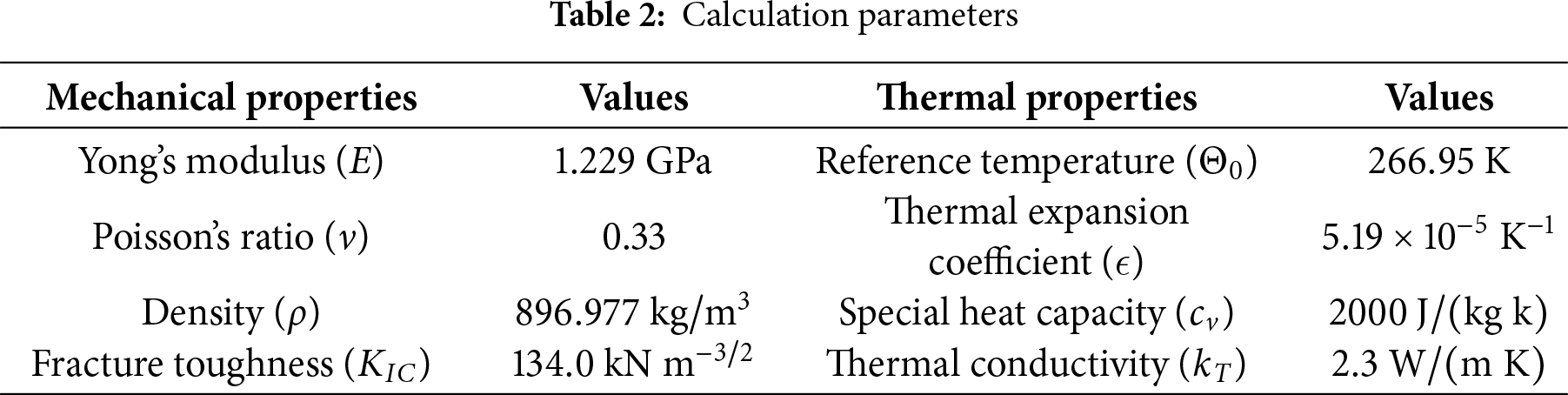

In terms of mechanics, ice, as an anisotropic crystalline material, exhibits mechanical properties closely related to its crystal structure. This implies that the choice of discretization method for ice may significantly affect numerical results. To investigate differences between the so-called “structured” and “unstructured” mesh schemes in underwater explosive icebreaking simulations, we adopted both approaches to discretize the ice domain. Nodal information from these discretizations was then extracted to initialize PD particles as computational physical quantities. Fig. 13 illustrates the discretization processes and simulation results for the two schemes. It can be observed that, while the simulated ice failure patterns produced by both schemes are broadly similar, the unstructured mesh scheme reproduces a greater degree of damage at the center of the ice plate (i.e., the bar of the contour plot is darker). Furthermore, the damage zone exhibits a more circular shape, aligning more closely with the actual observed failure morphology. Consequently, the unstructured mesh discretization scheme is adopted in this case study to yield more accurate predictions of ice failure.

Figure 13: Compariosn of different discrete schemes

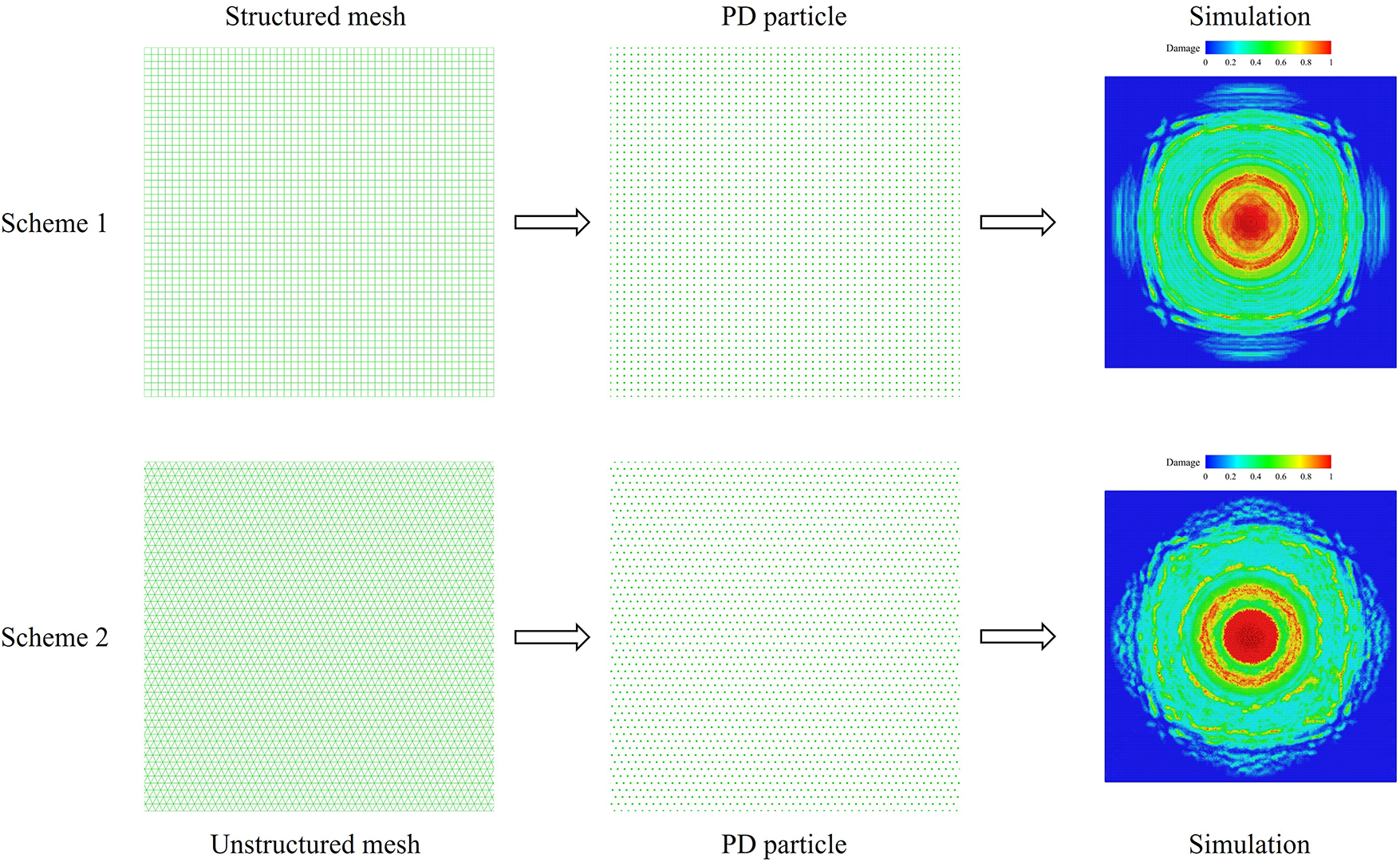

Fig. 14 illustrates the theoretical and experimental failure modes of the ice zone. It can be observed that the ice plate primarily forms a rupture above the center of the explosive, which is largely consistent with numerical simulations, thereby verifying the accuracy of the results presented in this paper. To quantitatively assess the accuracy of the numerical model presented herein, Fig. 15 and Table 3 show a comparison of the destruction radii of ice plates at different standoff distances. As the standoff distance increases, the destruction radius predicted by the SPH-PD method initially increases and then decreases, consistent with experimental observations and other numerical results. Furthermore, the predicted destruction radius errors in this study are all controlled within

Figure 14: Sketch of the damage zone under different results: (a) damage mode and (b) experimental test [57]

Figure 15: Destruction radius at different standoff distances, from left to right:

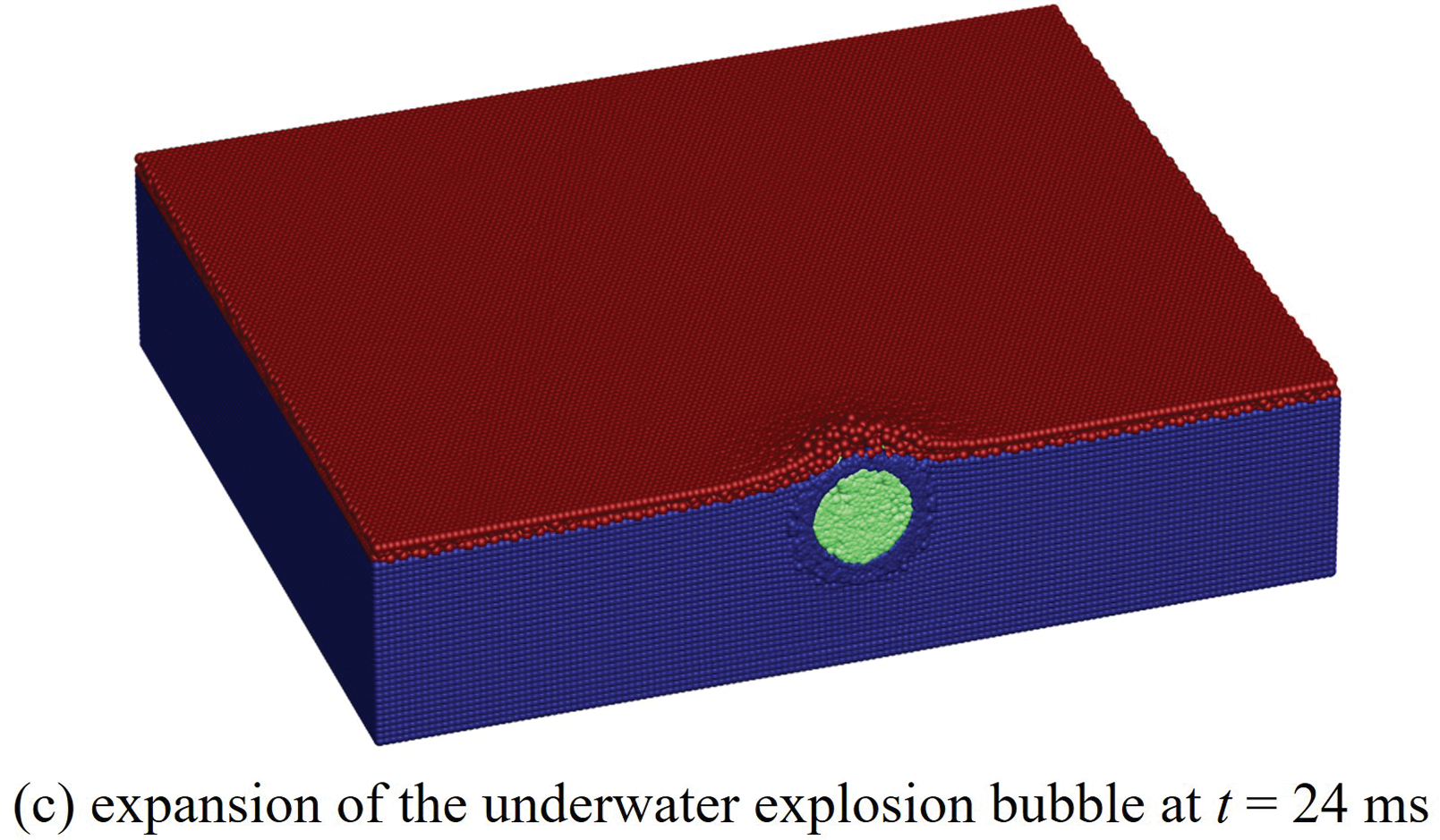

Fig. 16 presents the numerical simulation results of ice-breaking. Over time, the radius of the damaged zone (the red central region) rapidly increases from

Figure 16: Snapshots of damage in an ice plate at different time instants

Fig. 17 illustrates the temperature variations within the ice plate during the underwater explosion ice-breaking process. Compared with Fig. 16, it is evident that in areas experiencing severe damage, the temperature consistently maintains an upward trend throughout the entire process. This phenomenon occurs because the PD particles in these regions are almost entirely disrupted by the shock wave and bubble expansion, undergoing significant displacement from their original positions, consequently leading to a temperature rise. Conversely, throughout the cracked zone, the temperature consistently exhibits a decreasing trend. This is because when cracks begin to propagate, the crack tips experience a localized temperature drop due to mechanical energy dissipation and an imbalance in heat conduction. Furthermore, crack propagation causes the separation of ice material, forming new crack surfaces. The lack of an effective thermal conduction pathway prevents heat within the cracked zone from dissipating through the continuous heat conduction network of the surrounding material. Consequently, the overall temperature in the cracked zone remains lower than that of the intact ice layer.

Figure 17: Snapshots of temperature change in an ice plate at different time instants

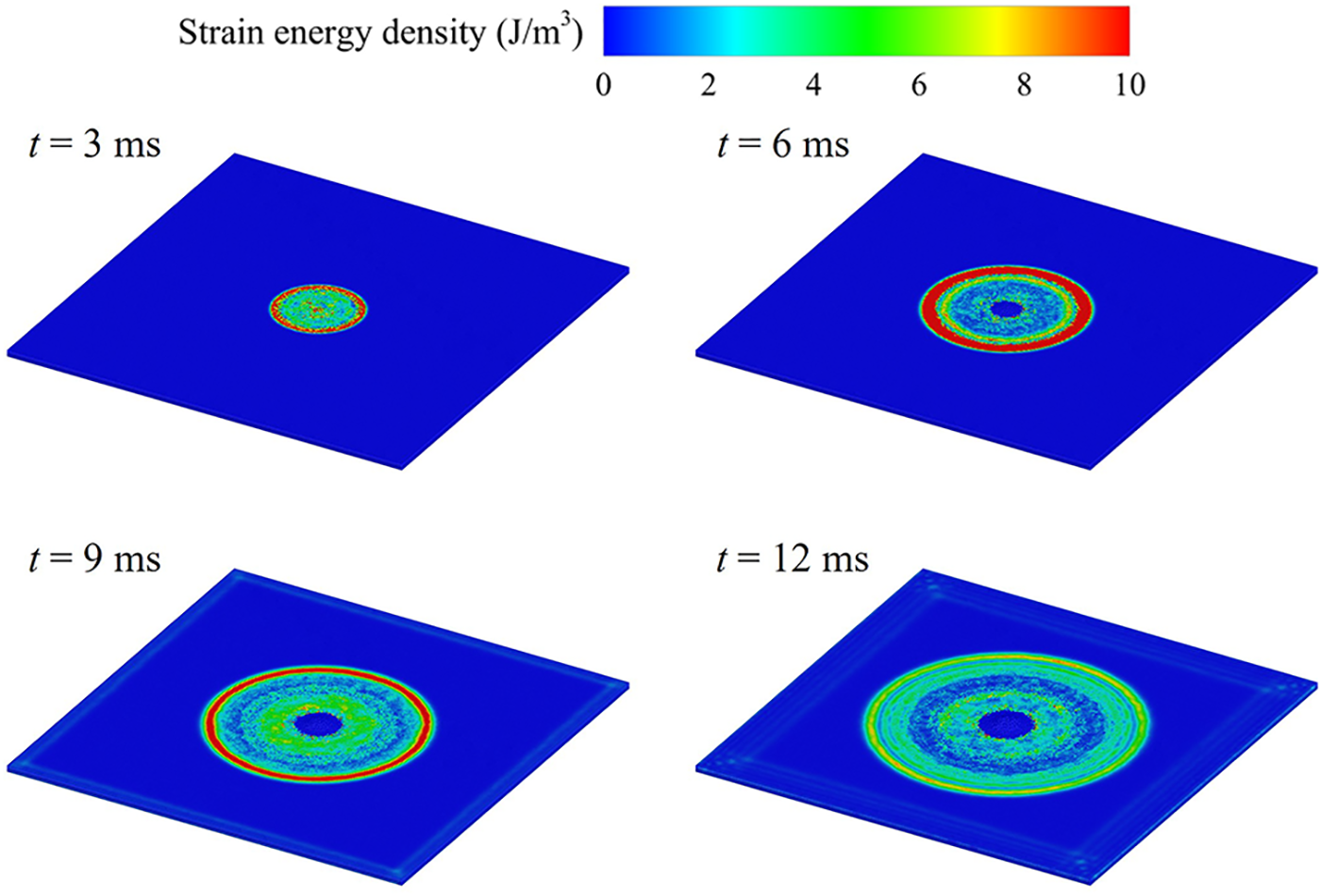

The distribution of strain energy density in the ice plate during the underwater explosion is shown in Fig. 18. It can be observed that as the shock wave propagates outward, the strain energy density in the ice plate gradually increases from the center towards the periphery. This indicates that the shock wave is the primary source of loading causing the ice plate’s failure, initiating damage from the interior and extending to the edges. Furthermore, the strain energy density at the center of the ice plate undergoes a process of first increasing, then decreasing, and finally reaching nearly zero. This demonstrates that the central region experiences severe damage, where the bond connections between PD particles are almost entirely broken, rendering it unable to maintain basic mechanical and physical properties.

Figure 18: Strain energy density distribution of the ice plate at four specific time instants

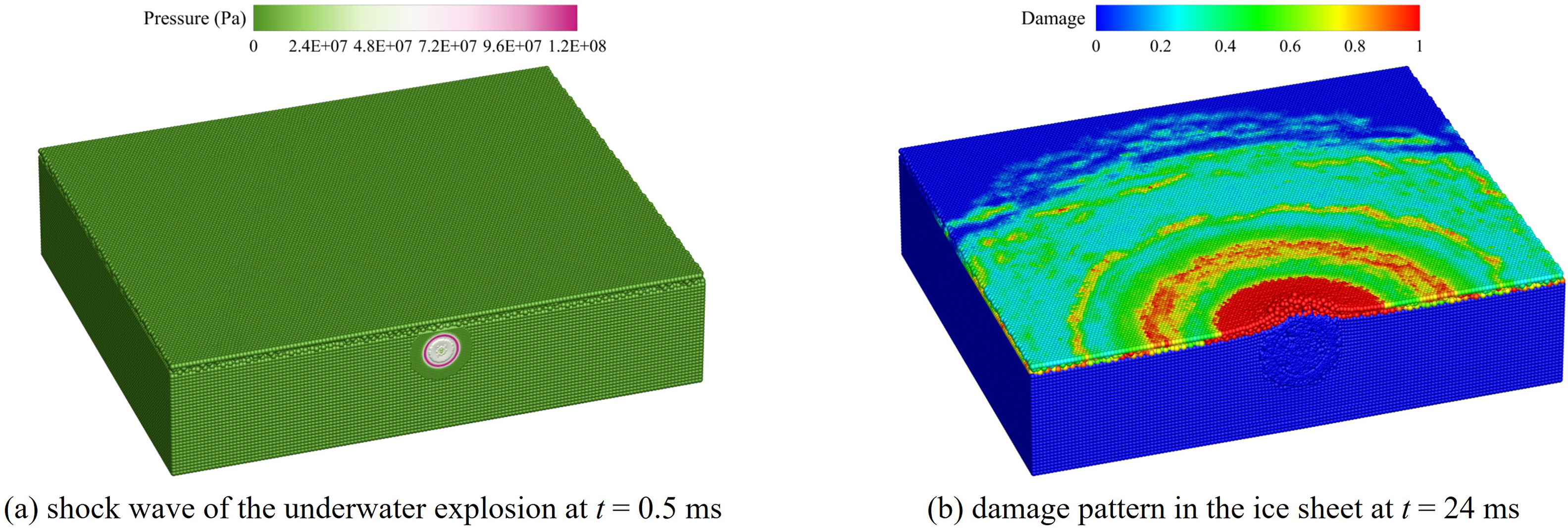

Fig. 19 illustrates the propagation of shock waves, ice plate failure, and bubble expansion during underwater explosive ice-breaking. It can be observed that the pressure generated by the shock waves is smoothly transmitted to the edge of the ice plate, causing certain damage. Under the action of bubbles, the ice plate bulges upward, resulting in compressive failure. Through the application of the SPH method, the continuous expansion process of the bubbles is also clearly demonstrated.

Figure 19: Different features involved in underwater explosive ice-breaking process

A coupled SPH-PD model was developed and utilized in predicting the dynamic response of an ice sheet exposed to underwater explosive loading. This numerical model, validated against benchmark cases, handles the coupled mechanical and thermal effects of underwater explosion shock waves, bubble expansion, and ice damage across both surfaces of the ice sheet.

The Riemann SPH model was validated against a free-field underwater explosion case to verify its accuracy and performance in simulating shock wave propagation. Subsequently, the solid solver’s performance was tested using a plate-under-pressure-load case. Moreover, the stability and accuracy of the FSI solver were comprehensively assessed using the case of a water column impacting an elastic plate. Finally, the SPH and PD methods were coupled and applied to the underwater explosion ice-breaking problem, yielding highly encouraging results.

Drawing on multiple perspectives here improves our study. Currently, the proposed numerical model has only been used for validation and has not been extended to broader applications. Future work will consider investigating a wider range of ice-breaking scenarios under different conditions, such as ice thickness, stand-off distance, and charge weight, to analyze the influence of various parameters on the ice failure modes.

Acknowledgement: Authors thank for the support of OceanConnect High-Performance Computing Cluster.

Funding Statement: This work was partially funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52171329), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2024B1515020107), the Young Elite Scientist Sponsorship Program by CAST (Grant No. 2022QNRC001) and Characteristic Innovation Project of Universities in Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2023KTSCX005).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Peng-Nan Sun and A-Man Zhang; methodology, Guang-Qi Liang; software, Guang-Qi Liang; validation, Peng-Nan Sun, A-Man Zhang and Guang-Qi Liang; formal analysis, Guang-Qi Liang; investigation, Guang-Qi Liang; resources, Peng-Nan Sun; data curation, Peng-Nan Sun and Guang-Qi Liang; writing—original draft preparation, Guang-Qi Liang; writing—review and editing, Peng-Nan Sun and A-Man Zhang; visualization, Guang-Qi Liang; supervision, Peng-Nan Sun and A-Man Zhang; project administration, Peng-Nan Sun; funding acquisition, Peng-Nan Sun. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data will be made available on request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Beltaos S, Prowse TD. Climate impacts on extreme ice-jam events in Canadian rivers. Hydrol Sci J. 2001;46(1):157–81. doi:10.1080/02626660109492807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Newton B, Beltaos S, Burrell BC. Ice regimes, ice jams, and a changing hydroclimate, Saint John (Wolastoq) River, New Brunswick, Canada. Nat Hazards. 2024;120(14):12613–42. doi:10.1007/s11069-024-06736-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zemlyak VL, Kozin VM, Baurin NO, Ipatov KI, Kandelya MV. The study of the impact of ice conditions on the possibility of the submarine vessels surfacing in the ice cover. J Phys Conf Ser. 2017;919:012004. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/919/1/012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Yuan G, Song J, Yang Y, Ni B, Yang D, Xue Y. Experimental study on icebreaking mechanism and failure modes of submerged high-pressure water jets. Ocean Eng. 2025;323(1):120586. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2025.120586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yuan G, Wang X, Ni B, Xu W, Yang D, Xue Y. Experimental study on load characteristic and icebreaking process of submerged Venturi cavitating water jets. J Fluids Struct. 2025;137:104374. doi:10.1016/j.jfluidstructs.2025.104374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Orlova YN, Orlov MY. The study of the process of explosive loading of ice. Tomsk State Univ J Mathem Mech. 2015;38(6):81–9. doi:10.17223/19988621/38/10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wang Y, Qin Y, Yao X. A combined experimental and numerical investigation on damage characteristics of ice sheet subjected to underwater explosion load. Appl Ocean Res. 2020;103:102347. doi:10.1016/j.apor.2020.102347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lai X, Li S, Yan J, Liu L, Zhang AM. Multiphase large-eddy simulations of human cough jet development and expiratory droplet dispersion. J Fluid Mech. 2022;942:A12. doi:10.1017/jfm.2022.334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yan J, Li S, Kan X, Lv P, Zhang AM, Duan H. Updated Lagrangian particle hydrodynamics (ULPH) modeling for free-surface fluid flows. Comput Mech. 2024;73(2):297–316. doi:10.1007/s00466-023-02368-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhan Y, Luo M, Khayyer A. DualSPHysics+: an enhanced DualSPHysics with improvements in accuracy, energy conservation and resolution of the continuity equation. Comput Phys Commun. 2025;306:109389. doi:10.1016/j.cpc.2024.109389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sun YH, Huang YM, Chen Z. On the freely falling circular cylinder with a splitter plate. J Fluid Mech. 2025;1019:A26. doi:10.1017/jfm.2025.10590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhan Y, Luo M, Khayyer A. An enhanced SPH-based hydroelastic FSI solver with structural dynamic hourglass control. J Fluids Struct. 2025;135:104295. doi:10.1016/j.jfluidstructs.2025.104295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Fan H, Li S. A Peridynamics-SPH modeling and simulation of blast fragmentation of soil under buried explosive loads. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2017;318:349–81. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2017.01.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Lai X, Ren B, Fan H, Li S, Wu CT, Regueiro RA, et al. Peridynamics simulations of geomaterial fragmentation by impulse loads: peridynamics simulations of geomaterial fragmentation by impulse loads. Int J Numer Anal Meth Geomech. 2015;39(12):1304–30. doi:10.1002/nag.2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Liang GQ, Sun PN, Lyu HG, Zhang GY. Establishment of a 3D numerical ice tank and its applications to ice-water-structure interactions based on a multi-resolution SPH-PD coupled method. Comput Struct. 2025;316:107862. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2025.107862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhao Z, Li S, Xiong C, Cui P, Wang S, Zhang AM. New insights into the cavitation erosion by bubble collapse at moderate stand-off distances. J Fluid Mech. 2025;1015:A33. doi:10.1017/jfm.2025.10331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang AM, Li SM, Xu RZ, Pei SC, Li S, Liu YL. A theoretical model for compressible bubble dynamics considering phase transition and migration. J Fluid Mech. 2024;999:A58. doi:10.1017/jfm.2024.954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu Y, Zhang AM, Tian Z, Wang S. Investigation of free-field underwater explosion with Eulerian finite element method. Ocean Eng. 2018;166(1):182–90. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2018.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Li L, Löhner R, Pandare AK, Luo H. A vertex-centered finite volume method with interface sharpening technique for compressible two-phase flows. J Comput Phys. 2022;460(1):111194. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2022.111194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu MB, Liu GR, Lam KY, Zong Z. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics for numerical simulation of underwater explosion. Comput Mech. 2003;30(2):106–18. doi:10.1007/s00466-002-0371-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Sun PN, Le Touzé D, Oger G, Zhang AM. An accurate SPH Volume Adaptive Scheme for modeling strongly-compressible multiphase flows. Part 1: numerical scheme and validations with basic 1D and 2D benchmarks. J Comput Phys. 2021;426(2):109937. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2020.109937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wang Y, Qin Y, Wang Z, Yao X. Numerical study on ice damage characteristics under single explosive and combination explosives. Ocean Eng. 2021;223:108688. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2021.108688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Luo X, Zhong ZX, Huang X, Chen XP. The icebreaking characteristics of underwater explosions based on the ALE-FEM-SPH coupled method. Eng Anal Bound Elem. 2025;179:106381. doi:10.1016/j.enganabound.2025.106381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yu Z, Ni BY, Wu Q, Wang Z, Liu P, Xue Y. Numerical simulation of icebreaking by underwater-explosion bubbles and compressed-gas bubbles based on the ALE method. J Mar Sci Eng. 2024;12(1):58. doi:10.3390/jmse12010058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sand B. Nonlinear finite element simulations of ice forces on offshore structures [dissertation]. Luleå, Sweden: Luleå Tekniska Universitet; 2008. [Google Scholar]

26. Miryaha VA, Petrov IB. Discontinuous Galerkin method for simulating an ice floe impact on a vertical cylindrical offshore structure. Math Models Comput Simul. 2019;11(3):400–14. doi:10.1134/s2070048219030153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Jang H, Kim M. Kulluk-shaped Arctic floating platform interacting with drifting level ice by discrete element method. Ocean Eng. 2021;236:109479. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2021.109479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Vazic B, Oterkus E, Oterkus S. In-plane and out-of plane failure of an ice sheet using peridynamics. J Mech. 2020;36(2):265–71. doi:10.1017/jmech.2019.65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Cheng W, Cao Q, Yuan B, Yan J. Experimental and peridynamic numerical study on the opening process of the soft PSD in pulse solid rocket motors. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;143(3):3197–214. doi:10.32604/cmes.2025.065041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Li T, Gu X, Zhang Q. A coupled thermomechanical crack propagation behavior of brittle materials by peridynamic differential operator. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;140(1):339–61. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.047566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. He M, Yan J, Lv P, Duan H, Zhang AM. Research on ice-breaking characteristics of underwater explosion bubbles based on an effective coupled model. Appl Ocean Res. 2024;153:104259. doi:10.1016/j.apor.2024.104259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kan X, Wang J, Yan J, Wang C, Wang Y. Numerical analysis of ice-breaking effects induced by two interacting bubbles using the coupled boundary element method and peridynamics model. Phys Fluids. 2024;36(9):097110. doi:10.1063/5.0218632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Fan H, Bergel GL, Li S. A hybrid peridynamics-SPH simulation of soil fragmentation by blast loads of buried explosive. Int J Impact Eng. 2016;87:14–27. doi:10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2015.08.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Huang X, Zhu B, Chen Y. A rate-dependent peridynamic-SPH coupling model for damage and failure analysis of concrete dam structures subjected to underwater explosions. Int J Impact Eng. 2025;200:105270. doi:10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2025.105270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Rabczuk T, Belytschko T. Cracking particles: a simplified meshfree method for arbitrary evolving cracks. Num Meth Eng. 2004;61(13):2316–43. doi:10.1002/nme.1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Rabczuk T, Gracie R, Song JH, Belytschko T. Immersed particle method for fluid-structure interaction. Num Meth Eng. 2010;81(1):48–71. doi:10.1002/nme.2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Roubtsova V, Kahawita R. The SPH technique applied to free surface flows. Comput Fluids. 2006;35(10):1359–71. doi:10.1016/j.compfluid.2005.08.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Toro EF. Riemann solvers and numerical methods for fluid dynamics: a practical introduction. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2009. doi:10.1007/b79761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhang C, Hu XY, Adams NA. A weakly compressible SPH method based on a low-dissipation Riemann solver. J Comput Phys. 2017;335:605–20. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2017.01.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Koukouvinis PK, Anagnostopoulos JS, Papantonis DE. An improved MUSCL treatment for the SPH-ALE method: comparison with the standard SPH method for the jet impingement case. Int J Numer Meth Fluids. 2013;71(9):1152–77. doi:10.1002/fld.3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Fang XL, Wang PP, Meng ZF, Ming FR, Chen H. Load characteristics of large-scale underwater explosion bubble pair near a wall using the smoothed particle hydrodynamics method. Phys Fluids. 2025;37(2):023388. doi:10.1063/5.0257686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Grenier N, Antuono M, Colagrossi A, Le Touzé D, Alessandrini B. An Hamiltonian interface SPH formulation for multi-fluid and free surface flows. J Comput Phys. 2009;228(22):8380–93. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2009.08.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Zhang A, Sun P, Ming F. An SPH modeling of bubble rising and coalescing in three dimensions. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2015;294:189–209. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2015.05.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Bonet J, Lok TSL. Variational and momentum preservation aspects of Smooth Particle Hydrodynamic formulations. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 1999;180(1–2):97–115. doi:10.1016/S0045-7825(99)00051-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Mokos A, Rogers BD, Stansby PK. A multi-phase particle shifting algorithm for SPH simulations of violent hydrodynamics with a large number of particles. J Hydraul Res. 2017;55(2):143–62. doi:10.1080/00221686.2016.1212944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Silling SA. Reformulation of elasticity theory for discontinuities and long-range forces. J Mech Phys Solids. 2000;48(1):175–209. doi:10.1016/S0022-5096(99)00029-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Silling SA, Epton M, Weckner O, Xu J, Askari E. Peridynamic states and constitutive modeling. J Elast. 2007;88(2):151–84. doi:10.1007/s10659-007-9125-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Gao Y, Oterkus S. Ordinary state-based peridynamic modelling for fully coupled thermoelastic problems. Continuum Mech Thermodyn. 2019;31(4):907–37. doi:10.1007/s00161-018-0691-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Ji SY, Liu HL, Xu N, Ma HY. Experiments on sea ice fracture toughness in the Bohai Sea. Adv Water Sci. 2013;24(3):386–91. (In Chinese). doi:10.14042/j.cnki.32.1309.2013.03.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Bouscasse B, Colagrossi A, Marrone S, Antuono M. Nonlinear water wave interaction with floating bodies in SPH. J Fluids Struct. 2013;42:112–29. doi:10.1016/j.jfluidstructs.2013.05.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Adami S, Hu XY, Adams NA. A generalized wall boundary condition for smoothed particle hydrodynamics. J Comput Phys. 2012;231(21):7057–75. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2012.05.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Zhang AM, Li SM, Cui P, Li S, Liu YL. A unified theory for bubble dynamics. Phys Fluids. 2023;35(3):033323. doi:10.1063/5.0145415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Fourey G, Hermange C, Le Touzé D, Oger G. An efficient FSI coupling strategy between Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics and Finite Element methods. Comput Phys Commun. 2017;217(2):66–81. doi:10.1016/j.cpc.2017.04.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Khayyer A, Shimizu Y, Gotoh H, Hattori S. A 3D SPH-based entirely Lagrangian meshfree hydroelastic FSI solver for anisotropic composite structures. Appl Math Model. 2022;112(1):560–613. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2022.07.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Wang Q, Wang Y, Zan Y, Lu W, Bai X, Guo J. Peridynamics simulation of the fragmentation of ice cover by blast loads of an underwater explosion. J Mar Sci Technol. 2018;23(1):52–66. doi:10.1007/s00773-017-0454-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Zhang Y, Tao L, Wang C, Sun S. Peridynamic analysis of ice fragmentation under explosive loading on varied fracture toughness of ice with fully coupled thermomechanics. J Fluids Struct. 2022;112:103594. doi:10.1016/j.jfluidstructs.2022.103594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Ma W, Xie W, Liu D, Zhang D. Analysis of the dynamic response of the icecap structure under the action of explosion wave. In: 2011 International Conference on Electric Technology and Civil Engineering (ICETCE); 2011 Apr 22–24; Lushan, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2011. p. 95–8. doi:10.1109/ICETCE.2011.5776175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools