Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Mordukhovich Subdifferential Optimization Framework for Multi-Criteria Voice Cloning of Pathological Speech

1 Center of Real Time Computer Systems, Kaunas University of Technology, Kaunas, 51423, Lithuania

2 Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Academy of Medicine, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, 50161, Lithuania

* Corresponding Author: Robertas Damaševičius. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Artificial Intelligence Models in Healthcare: Challenges, Methods, and Applications)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 4203-4223. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.072790

Received 03 September 2025; Accepted 05 November 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

This study introduces a novel voice cloning framework driven by Mordukhovich Subdifferential Optimization (MSO) to address the complex multi-objective challenges of pathological speech synthesis in under-resourced Lithuanian language with unique phonemes not present in most pre-trained models. Unlike existing voice synthesis models that often optimize for a single objective or are restricted to major languages, our approach explicitly balances four competing criteria: speech naturalness, speaker similarity, computational efficiency, and adaptability to pathological voice patterns. We evaluate four model configurations combining Lithuanian and English encoders, synthesizers, and vocoders. The hybrid model (English encoder, Lithuanian synthesizer, English vocoder), optimized via MSO, achieved the highest Mean Opinion Score (MOS) of 4.3 and demonstrated superior intelligibility and speaker fidelity. The results confirm that MSO enables effective navigation of trade-offs in multilingual pathological voice cloning, offering a scalable path toward high-quality voice restoration in clinical speech applications. This work represents the first integration of Mordukhovich optimization into pathological TTS, setting a new benchmark for speech synthesis under clinical and linguistic constraints.Keywords

Recently, the field of voice cloning and text-to-speech (TTS) synthesis has seen a notable progress [1]. Recent work has explored diverse applications including multilingual zero-shot voice conversion [2], real-time speech translation in video conferencing [3], and speech accessibility solutions for individuals with impairments [4,5]. For example, Li et al. [6] demonstrated effective multilingual synthesis with code-switching capabilities in Tibetan, while Nekvinda and Dušek [7] proposed meta-learning strategies for multilingual speech. The maturity of modern cloning systems is further reflected in their integration into educational environments, as shown by [8].

At the core of this evolution is the multispeaker Text-to-speech (SV2TTS) pipeline, which allows high-fidelity voice cloning using only a few samples from the target speaker [9]. The architecture, which combines an encoder, synthesizer, and vocoder, has enabled expressive multi-speaker synthesis with notable improvements in naturalness, speaker fidelity, and data efficiency [10]. Recent innovations such as transformer-based models [11] and scalable multilingual synthesis frameworks [12] have further expanded the potential for cross-lingual cloning.

Despite many technological breakthroughs, several critical challenges remain unresolved:

• First, although multilingual speech synthesis has become more viable, sound-switching within a single utterance remains a complex task, requiring models to fluidly merge linguistic elements from different phonetic inventories while preserving natural prosody and coherence [13,14].

• Second, voice cloning models are typically trained on healthy voices and often fail to generalize to pathological speech, particularly in cases of alaryngeal voices affected by laryngeal cancer. These pathological signals can exhibit a wide range of acoustic irregularities—such as disrupted fundamental frequency, reduced harmonic structure, and excessive noise components—arising from surgical variability, prosthetic devices, and individual healing patterns [15,16]. As such, conventional models are ill-equipped to handle the non-stationary and high-variance nature of pathological voice signals.

• Third, most voice cloning research focuses on high-resource languages, overlooking linguistically rich but underrepresented languages such as Lithuanian. Lithuanian presents distinct phonological features, including unique vowels and consonants such as “ą,” “č,” and “ė,” which are absent in mainstream TTS phoneme inventories [17]. Accurate synthesis in such languages requires an expanded phoneme set and careful modeling of language-specific prosody and rhythm—capabilities that existing models generally lack.

To address these intersecting challenges—cross-lingual synthesis, pathological variability, and low-resource linguistic modeling—we propose a novel framework built around Mordukhovich Subdifferential Optimization (MSO) [18]. Our approach introduces a principled multi-objective optimization scheme into the encoder–synthesizer–vocoder architecture, balancing competing criteria such as speech naturalness, speaker similarity, computational efficiency, and robustness to pathological voice distortions. By integrating MSO directly into the training and tuning loop, we identify optimal trade-offs between these objectives, enabling high-quality speech synthesis even in the presence of pathological voice patterns and phonetic mismatches. The proposed framework is evaluated on multiple encoder–synthesizer–vocoder configurations (combining English and Lithuanian components) and benchmarked on both subjective and objective criteria. Compared to our previous work on flow-based pathological synthesis [19] and denoising through gated LSTMs [20], this study introduces a fundamentally new optimization strategy and targets a more ambitious goal: restoration of natural-sounding, speaker-specific voices for patients with alaryngeal speech impairments in a linguistically underserved context.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

• Development and validation of a Mordukhovich Subdifferential Optimization to voice cloning, effectively handling non-smooth, multi-objective trade-offs.

• Pathological speech synthesis built specifically for Lithuanian, a low-resource language, requiring novel phoneme set and prosodic model expansion.

• Identification of an optimal hybrid synthesis architecture, which, when tuned with MSO, demonstrates a practical enough solution for low-resource clinical applications.

The optimum selection of acoustic and linguistic features is necessary for capturing the complex characteristics of pathological speech. Our framework utilizes a comprehensive set of features derived from the speaker encoder and synthesizer modules, including speaker embeddings that encapsulate timbre, pitch, and intonation, as well as phoneme sequences and log-Mel spectrograms that represent linguistic and spectral content, etc., chosen to balance the competing objectives of naturalness, speaker similarity, and pathological adaptability, with the Mordukhovich optimizer dynamically prioritizing them during training to navigate the non-smooth, multi-objective loss landscape inherent in impaired voice signals.

Traditional gradient-based or scalarization methods typically assume smooth objective landscapes and convex trade-offs, rendering them less effective when applied to clinical voice data characterized by acoustic irregularities, discontinuities, and high inter-speaker variability. The principal advantage of using MSO over conventional multi-objective methods, such as weighted sum approaches or just a Pareto front estimation via evolutionary algorithms, lies in the capacity to handle the non-smooth and non-convex nature of the loss landscapes associated with pathological voice synthesis. Conventional methods often assume differentiability or convexity to find a single aggregate solution, which is ill-suited for our problem where objectives such as natural speech and pathological adaptability can be highly discontinuous due to voice breaks and irregular glottal pulses. MSO, through its generalized notion of the subdifferential, provides a necessary rigorous optimality condition without these simplifying assumptions. This allows the optimizer to navigate complex trade-offs at points where gradients may not exist, effectively identifying robust parameter configurations that would be inaccessible to gradient-based optimizers. Consequently, MSO systematically discovers a solution where the subgradients of the competing losses are balanced, leading to synthesized speech that maintains high naturalness and speaker similarity without sacrificing the critical, nonsmooth features that characterize pathological voices.

Two datasets were used to train the synthesizer model in our approach. The first dataset consisted of pathological speech, which is used to extract vocal features. The dataset was comprised of 154 laryngeal carcinoma patients’ recordings, drawn from 77 individuals, and was specifically compiled for this study. The cohort of patients consisted of individuals who had undergone extensive surgical procedures (including type III cordectomy and beyond, partial or total laryngectomy) for histologically confirmed laryngeal carcinoma. Only recordings of patients who scored less than 40 points on the Impression of Voice Quality, Intelligibility, Noise, Fluency, and Quality of Voicing (IINFVo) scale were included, ensuring the presence of speech impediments in the samples. These samples were collected during routine outpatient visits, not earlier than 6 months after surgery, allowing sufficient time for recovery and rehabilitation. The recordings included phonetically balanced Lithuanian sentences (“Turėjo senelė žilą oželį” (roughly translatable as “The grandmother had a little gray goat”)) and patients counting from 1 to 10 at a moderate pace.

The second data set (Liepa2) contained healthy speech recordings and was used as a core training resource [21], containing the healthy-sounding characteristics of Lithuanian speech of approximately 1000 h of audio recordings, featuring a diverse range of 2621 speakers (56% female and 44% male, young voices under 12 years of age, which make up 8% of the dataset, to mature voices over 61 years of age, accounting for 10%,), designed to reflect the rich phonetic and prosodic landscape of the Lithuanian language [22].

Each audio recording in both data sets was annotated to mark the beginning and end of segments, delineated by pauses that could signify a comma, the end of a sentence, or a breath. We excluded sequences containing nonphonemic sounds such as coughs or breaths that are marked by symbols like “+breath+” or “+noise+”, to ensure that the model’s learning is concentrated on linguistically relevant sounds, thereby improving the quality and clarity of the synthesized speech.

To date, there are no comparable open-access datasets for pathological voices for other languages that would allow meaningful cross-language or cross-dataset validation; therefore, the data set is specific to the underrepresented in research morphologically rich Lithuanian language. The scarcity of other data sets meaningful for comparison is due to the clinical specificity of the speech impairments involved, which vary widely depending on the type of surgical intervention, the stage of rehabilitation, and the individual anatomical differences. As a result, expanding the dataset or incorporating external corpora is currently not feasible, and we believe that the proposed optimization framework at least partially addressed this with sufficiently robust performance even under low-resource and clinically constrained conditions.

2.2 Dataset Partitioning and Augmentation

All splits are speaker-independent, every patient’s recordings were assigned to exactly one subset to prevent information leakage. We use a stratified 70/15/15 train/validation/test split at the speaker level, stratifying by surgery type (ELS III–VI vs. partial vertical laryngectomy) to preserve case mix.

To reduce overfitting while respecting pathological signal characteristics, we applied light, clinically plausible augmentations during training only: (i) time-stretch

2.3 Mordukhovich Subdifferential Optimization (MSO)

MSO adjusts the complexity of the Speaker Encoder and Synthesizer modules to optimize processing speed without compromising the quality of the generated speech. The goal is to generate voice outputs that closely mimic the healthy (pre-operation) speaker’s characteristics while ensuring that the speech remains natural and intelligible. MSO allows robust adaptation to pathological speakers without extensive retraining by applying subdifferential-based methods to identify optimal parameter settings and training strategies that balance learning speed with model performance.

Let us define the objectives as follows:

•

•

•

•

where

The multi-objective optimization problem is stated using Mordukhovich subdifferentials as:

subject to:

A solution

where

where

where

The scalar multipliers

where

We choose the simplex weights by minimizing the norm of this feasible direction,

The Pareto front for this multi-objective problem is approximated by identifying the set of all solutions

where

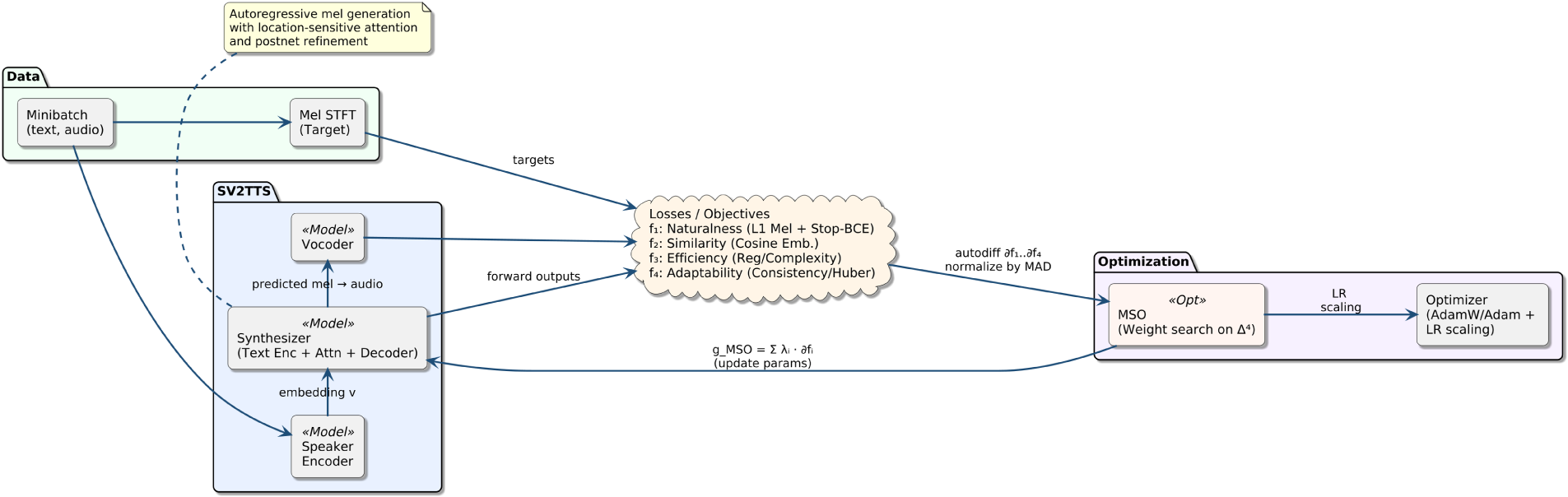

To complement the formal derivation, Fig. 1 illustrates where the Mordukhovich Subdifferential Optimization (MSO) module sits in our pipeline and how it operates during training. The synthesizer produces mel predictions, four objective surrogates

Figure 1: MSO-integrated training flow. The Mordukhovich subdifferential module (MSO) blends per-objective subgradients into a single update direction applied to the synthesizer (and used for module-wise LR scaling)

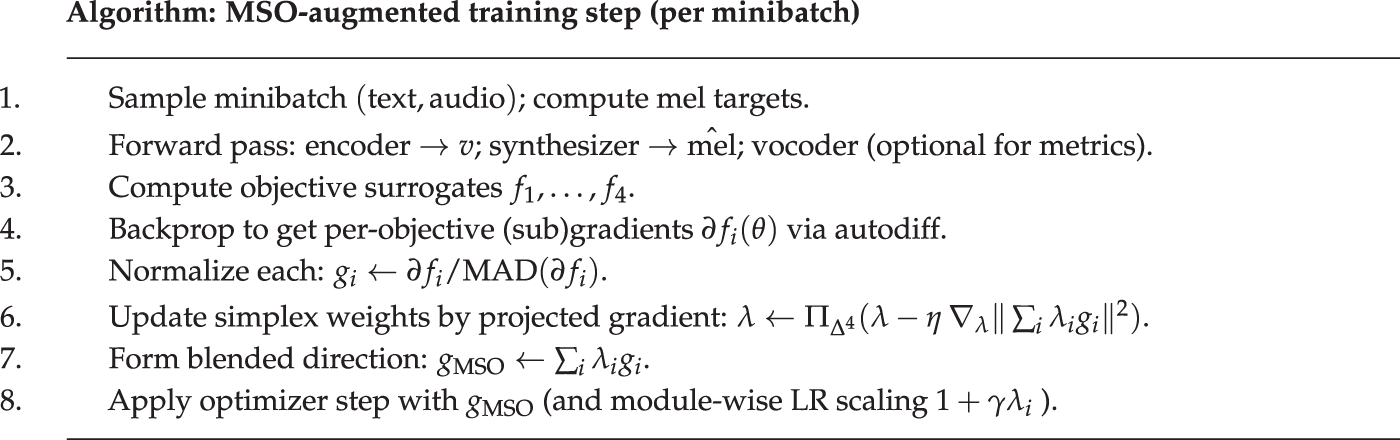

Algorithm in Fig. 2 summarizes the MSO-augmented training step for a single minibatch: after a standard forward pass (encoder

Figure 2: Pseudocode for combining per-objective subgradients via MSO.

Our model was built upon the architecture proposed by Jia et al. [9], adapted for the voice cloning language model trained for English speakers. Because English phonemes differ greatly from Lithuanian, the network has been expanded to support Lithuanian phonemes such as “ą”, “č”, “ė”, etc., and modifications were made to adapt to the Lithuanian prosody and support the extraction of voice characteristics from pathological voices. Additional step was also introduced into the model by adding our proposed Mordukhovich optimization.

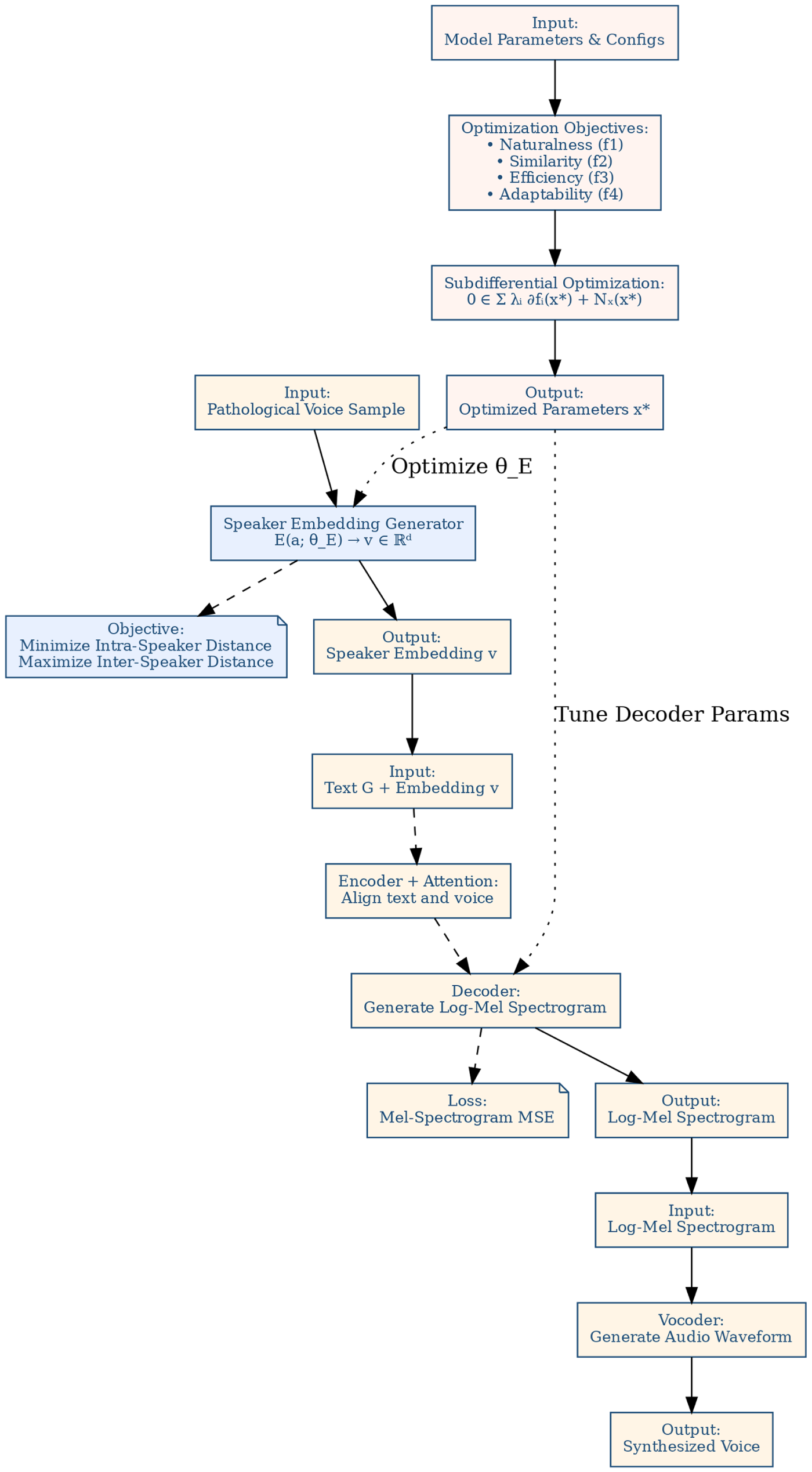

Fig. 3 outlines the architecture of our voice cloning model, composed of components that work to synthesize speech that mimics the voice of a target speaker from a given text input. It begins with learning the unique vocal characteristics of a target speaker, then maps text input to a spectral representation conditioned on the learned speaker characteristics, and finally, generates a waveform that retains the speaker’s vocal qualities.

Figure 3: Model architecture

Let

• The encoder processes the sequence of phonemes from the pathological voice, denoted by

• The attention mechanism aligns the encoder output

• The decoder generates a sequence of spectrogram frames

• The synthesizer’s output is a log-mel spectrogram

• The vocoder converts the log-mel spectrogram into the final audio waveform. Denote the vocoder as a function

The final audio output is synthesized, conditioned on reference waveform’s unique vocal attributes, captured through speaker embedding, and represented in the log-mel spectrogram.

The encoder has a function to discern and distinguish among individual pathological speakers, capturing the essence of their unique vocal characteristics in the form of voice embeddings, serving as a distilled representation of a speaker’s characteristics, and encapsulating attributes such as timbre, pitch, and intonation. These are used to condition the synthesizer and the vocoder to produce restored speech that retains unique characteristics of pre-operation voice of a patient.

The quality of encoding is evaluated using two metrics: Intra-Speaker Distance and Inter-Speaker Distance, quantifying the encoder’s performance in generating distinctive embeddings that reflect the unique vocal characteristics of individual speakers while ensuring that embeddings from different speakers are sufficiently dissimilar.

Intra-Speaker Distance is defined as the average distance between multiple embeddings generated from the same speaker:

where N is the number of embeddings for the same speaker,

Inter-Speaker Distance is defined as the average distance between embeddings generated from different speakers:

where M is the number of different speakers,

The attention mechanism in our synthesizer was built on Tacotron [23]. It has to align the input text sequence with corresponding acoustic output. The mechanism enables the model to selectively focus on specific parts of the input sequence to predict each segment of the output sequence accurately. Given an input sequence

where

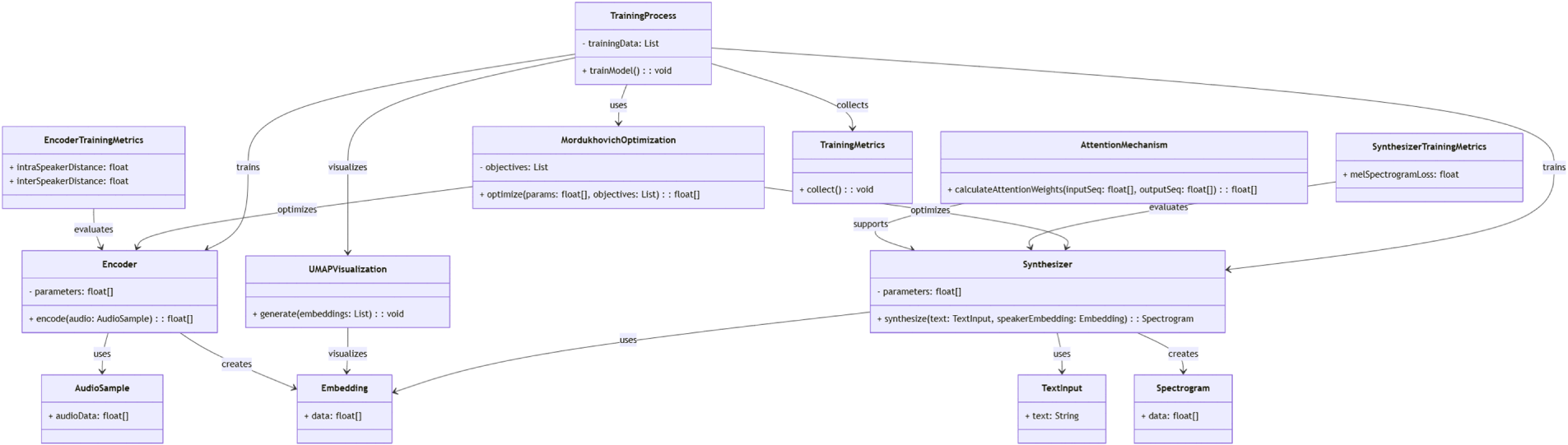

The implementation of our approach is organized into two primary modules (see the class diagram in Fig. 4). The encoder and synthesizer are implemented, respectively, for capturing a speaker’s unique vocal characteristics (postoperative voice of the patient impaired with alaryngeal cancer) and generating synthesized speech, mimicking original preoperative speech.

Figure 4: The implementation diagram of our voice cloning synthesizer

Audio was resampled to 22,050 Hz, 16-bit PCM, mono. Silence was trimmed (energy threshold

We adopt a d-vector style encoder that maps log-mel frames to a fixed-dimensional speaker embedding. The projection (embedding) dimension is

The text encoder comprises 3 one-dimensional convolutional blocks (kernel size 5, 512 channels each, ReLU, batch normalization), followed by a recurrent encoder block with hidden size

At each synthesizer step we compute subgradients of the four objectives

SpecAugment was used on synthesizer inputs (time mask

Synthesizer uses length-bucketed batches (bucket width 100 frames). Warm-start curriculum: r

All experiments were carried out on a Linux workstation with an Intel Core i9-14900 CPU (128 GB RAM) and a single NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5090, using Python/PyTorch with mixed precision stable.

Three expert raters (board-certified otolaryngologists; native Lithuanian speakers) scored n=90 stimuli (30 utterances

2.6 Speaker-Group Cross-Validation and Statistical Pooling

To improve the stability of the estimation with a modest cohort, we performed a 5-fold GroupKFold cross-validation (it is used for MOS/SMOS analysis only) with the patient as the grouping unit; the train/validation/test partitions of each fold are mutually disjoint between speakers and preserve the same stratification scheme as above. Within each fold, MOS/SMOS are analyzed using linear mixed-effects models with fixed effect Scenario and random intercepts for Rater and Utterance. Fold-specific contrasts (Scenario 1 vs. 2; 3 vs. 2; 1 vs. 3) are obtained with Satterthwaite

and report pooled 95% CIs and

2.7 Bias Analysis and Inter-Rater Reliability

To quantify potential perceptual bias, we first computed an objective-quality index (OQI) per utterance and scenario:

with metrics z-standardized across all conditions and signs oriented so that larger values reflect better quality. We then fit linear mixed-effects models separately for MOS and SMOS,

including random intercepts for rater

Inter-rater reliability was assessed across 3 raters and 90 items using Cronbach’s

2.8 Significance Testing for MOS/SMOS

To assess statistical significance of subjective improvements, we modeled MOS and SMOS using linear mixed–effects models:

where

We tested the fixed effect of Scenario via likelihood–ratio tests (LRT) comparing full vs. reduced models; pairwise contrasts were obtained with Tukey correction. The assumptions were checked through residual diagnostics; Satterthwaite-adjusted degrees of freedom were used for

We have used objective metrics to assess the similarity in prosody and timbre between cloned speech and real reference speech, namely, Mel Cepstral Distortion (MCD), Voting Decision Error (VDE), Gross Pitch Error (GPE), F0 Frame Error (FFE), Log-Likelihood Ratio (LLR), and Weighted Spectral Slope (WSS, normalized).

The baseline is the English model trained on top with Lithuanian speech, the proposed model is the model that has all English characteristics replaced with Lithuanian features with an additional Mordukhovich optimization step.

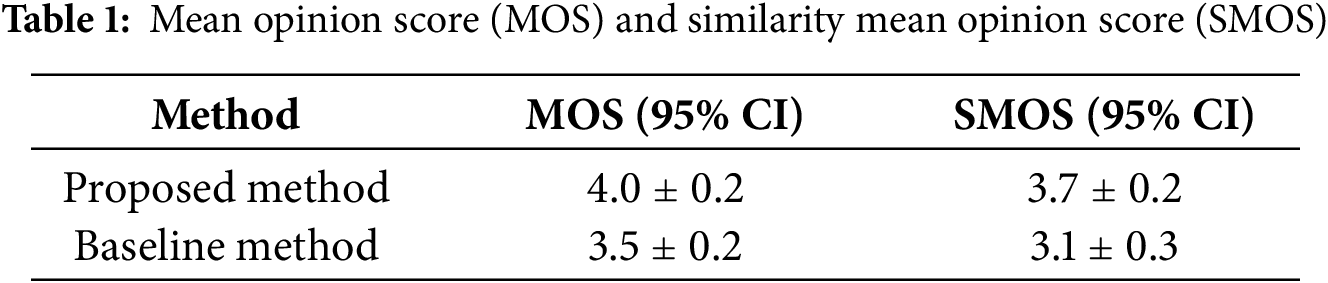

The results presented in Tables 1–4 offer a comparison between the proposed voice cloning method and a baseline approach across several evaluation metrics. The obtained Mean Opinion Score (MOS) and Similarity Mean Opinion Score (SMOS) values (Table 1) show that the proposed method outperforms the baseline, achieving MOS of 4.0 (

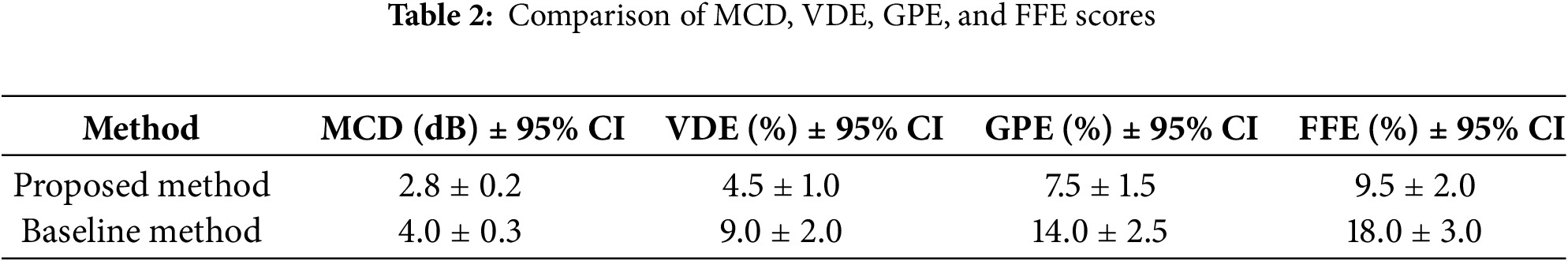

Table 2 shows that the Mel Cepstral Distortion (MCD) value for the proposed method is lower (2.8 dB

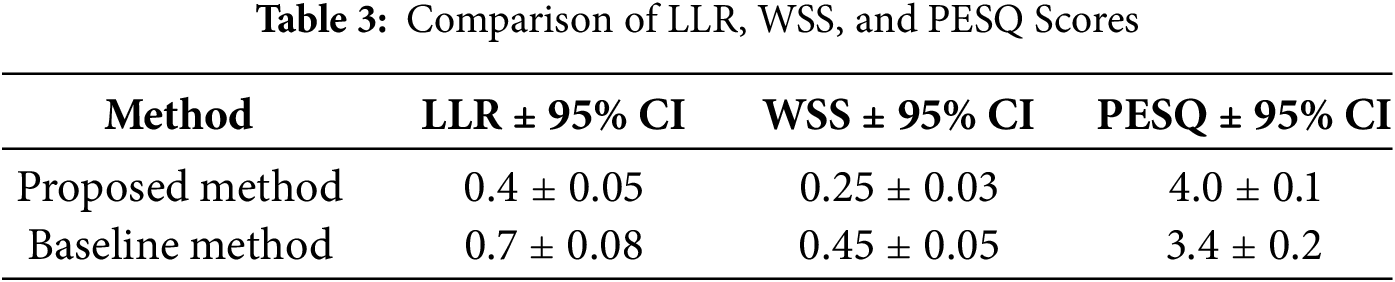

Table 3 supports this, as Log-Likelihood Ratio (LLR) and Weighted Spectral Slope (WSS) indicate spectral similarity between synthesized and target speech, showed lower values for the proposed method (LLR: 0.4

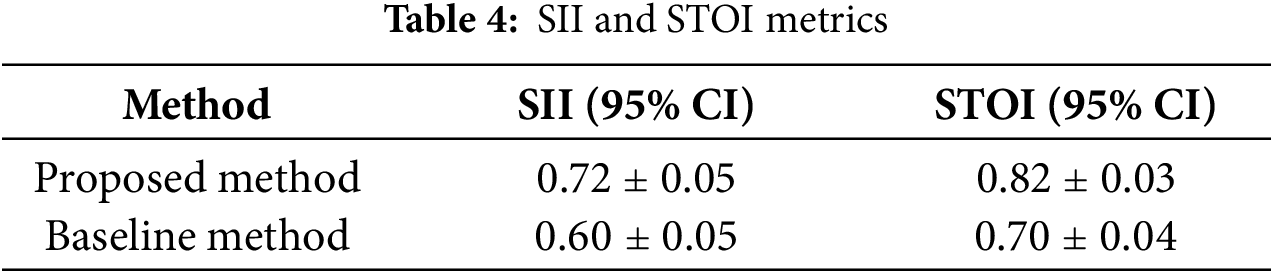

In Table 4, the proposed method demonstrates better intelligibility, as reflected by higher Speech Intelligibility Index (SII) and Short-Time Objective Intelligibility (STOI) scores, although this was expected, given that the baseline is an English model trained with Lithuanian speech. The proposed method achieves an SII of 0.72 (

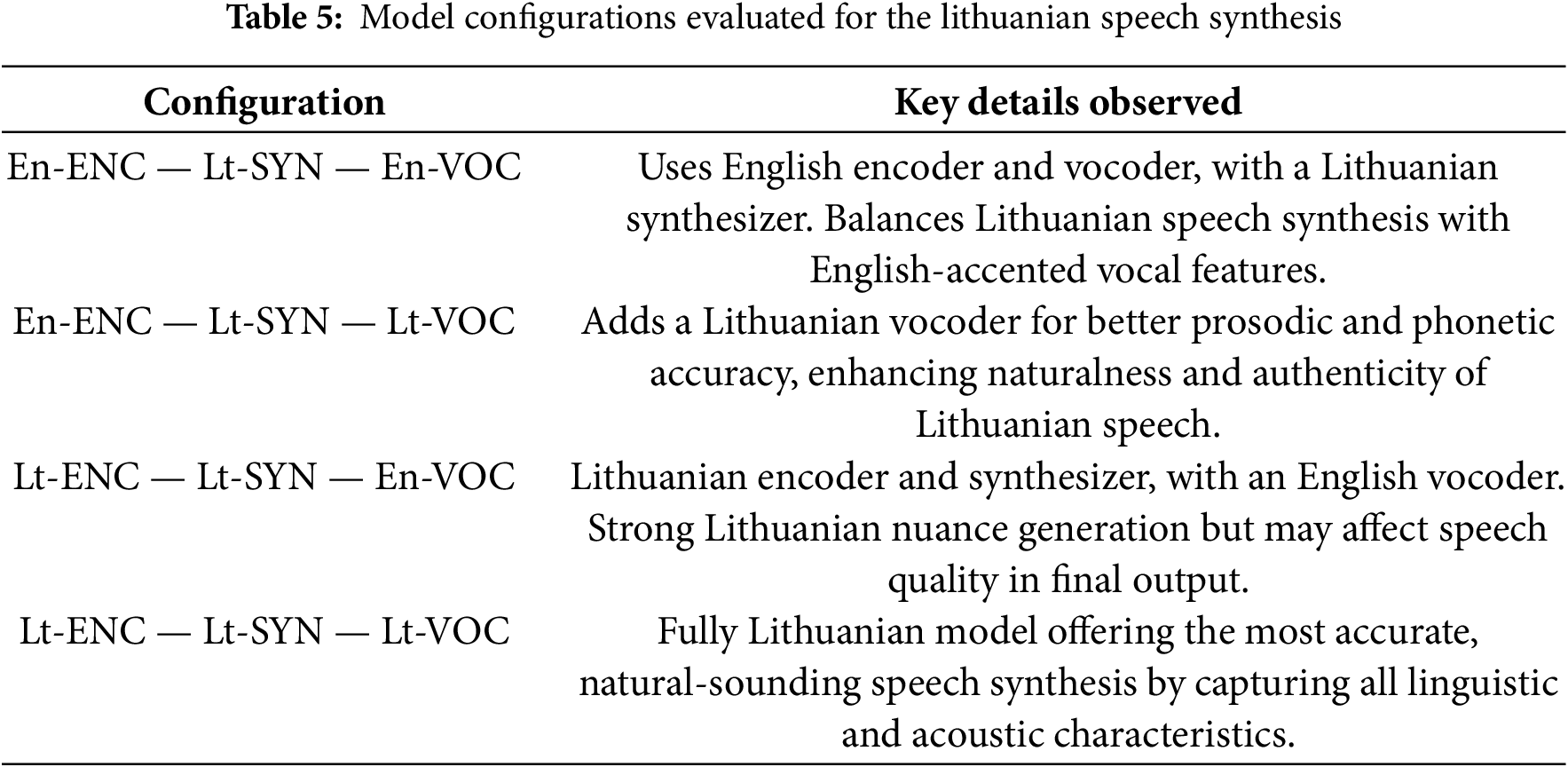

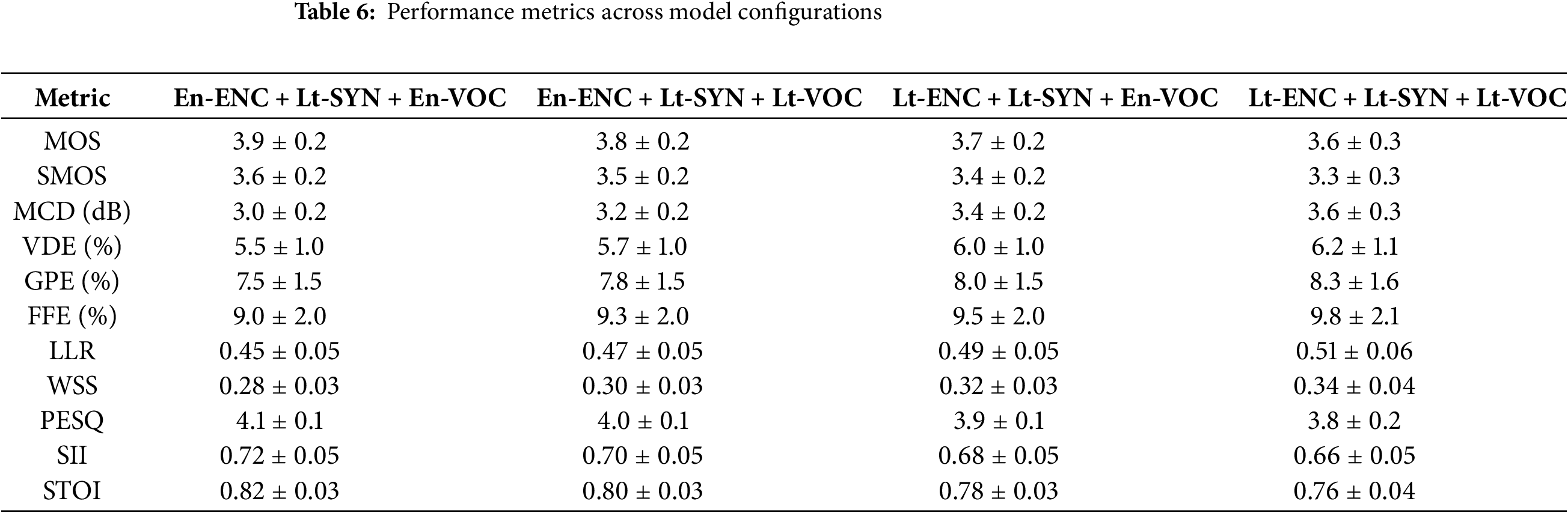

3.1 Ablation Study of the Influence of Lithuanian and English Models

When comparing models across languages, one must consider the linguistic characteristics that may affect the quality of the clone. Lithuanian phonetic accents and longer consonant sounds may pose challenges not present in English. The performance of the Lithuanian model (Lt-ENC, Lt-SYN, and Lt-VOC) must be assessed with these linguistic nuances in mind, ensuring that the quality of cloning retains the natural flow and expressiveness of the Lithuanian. In contrast, English models (En-ENC and En-VOC) must be evaluated against the backdrop of English phonology and prosody.

The configurations evaluated are summarized in Table 5. The models have managed to generate a proper sentence of the test sequence “turėjo senelė žilą oželį” containing key Lithuanian phonemes (see Table 6). We observed that the fully Lithuanian model (Lt-ENC — Lt-SYN — Lt-VOC) demonstrated a Mean Opinion Score (MOS) of 3.6, slightly lower than the hybrid model (En-ENC — Lt-SYN — En-VOC) with MOS of 3.9. This shows the effectiveness of the hybrid model in maintaining audio quality and is likely a limitation of having a limited size Lithuanian dataset.

A total of 10 patients treated at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, agreed to be included in the preliminary clinical validation of the alaryngeal voice replacement synthesizer. Patients were stratified according to the type of surgical intervention (Table 7). The mean age was 61.7 years (SD = 15.9). The majority underwent endolaryngeal cordectomy (ELS type III–VI), while a smaller subset received partial vertical laryngectomy.

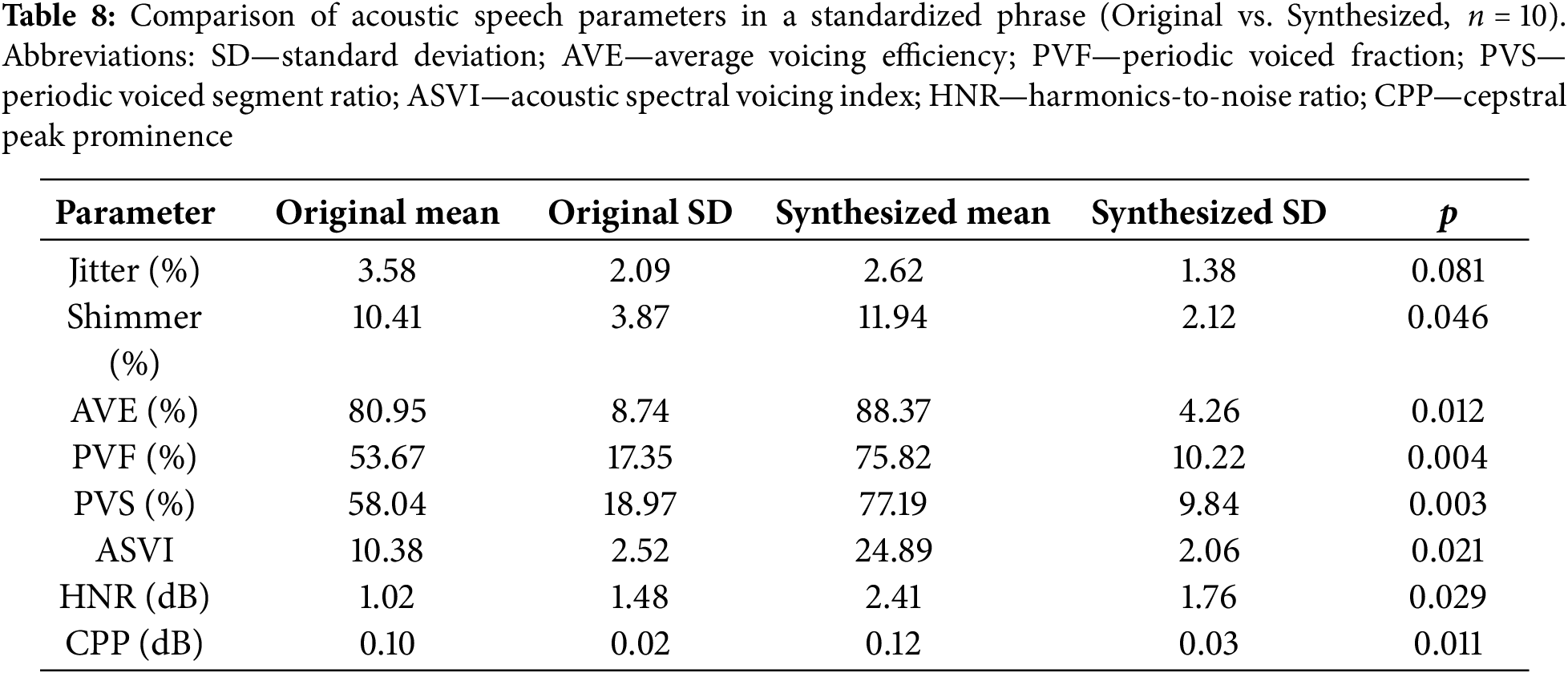

Objective acoustic analysis of standardized phrase recordings demonstrated clear enhancement of voice stability and periodicity in the synthesized speech samples (Table 8). Jitter decreased in synthesized compared to original speech (2.62% (SD = 1.38) vs. 3.58% (SD = 2.09)), though the difference did not reach statistical significance (

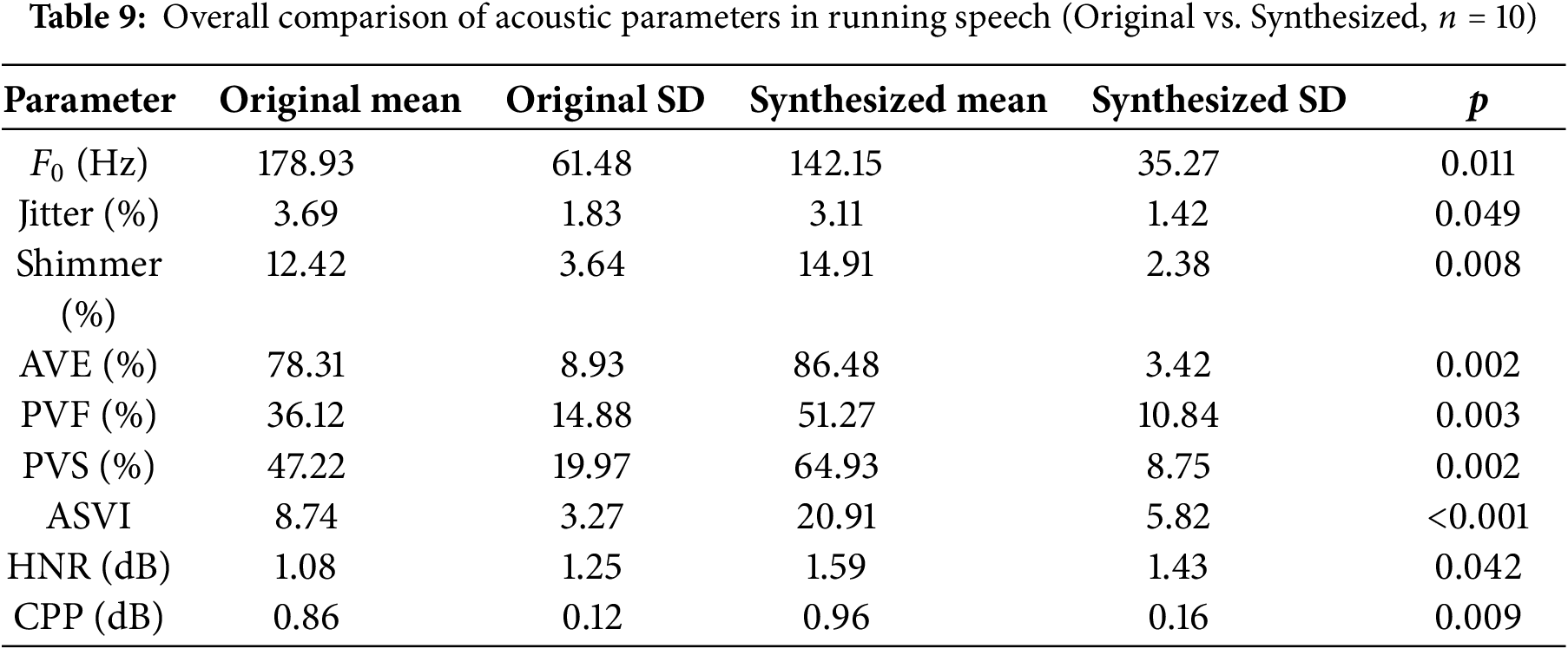

Running speech analysis confirmed a consistent pattern of improvement across most acoustic domains (Table 9). The mean fundamental frequency (

To further assess the robustness of the evaluation results, we examined potential sources of bias that may affect the Mean Opinion Score (MOS) and Similarity MOS (SMOS) ratings. Theoretically, a rater familiarity with the Lithuanian phonological structure can introduce a phoneme-congruity bias, wherein evaluators are more attuned to subtle articulatory correctness in Lithuanian phonemes (e.g., nasalized vowels such as “ą”, retroflex consonants such as “č”, and fronted vowels such as “ė”). As a result, speech samples from English-trained models, which lack these phonemes in their synthesis inventory, may be penalized disproportionately, not because of lower synthesis fidelity per se, but due to perceived phonetic incongruity. Furthermore, all MOS/SMOS assessments were performed by otolaryngologists from the Department of Otorhinolaryngology of the Academy of Medicine of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, all with extensive experience in alaryngeal rehabilitation, but also all being native Lithuanian speakers. Although this expertise ensures clinical relevance, it can also theoretically introduce an expectation bias toward pathological speech realism, favoring models that preserve degraded prosodic contours and irregularities typical of post-laryngectomy speech. Thus, a model producing more fluent or “overcorrected” speech may paradoxically score lower on SMOS due to reduced pathological authenticity, even if its acoustic similarity is technically higher. Furthermore, perceptual anchoring effects may arise when raters are exposed to lower quality English baseline samples prior to evaluating the Lithuanian-optimized outputs, leading to inflated MOS scores due to relative contrast rather than absolute perceptual quality.

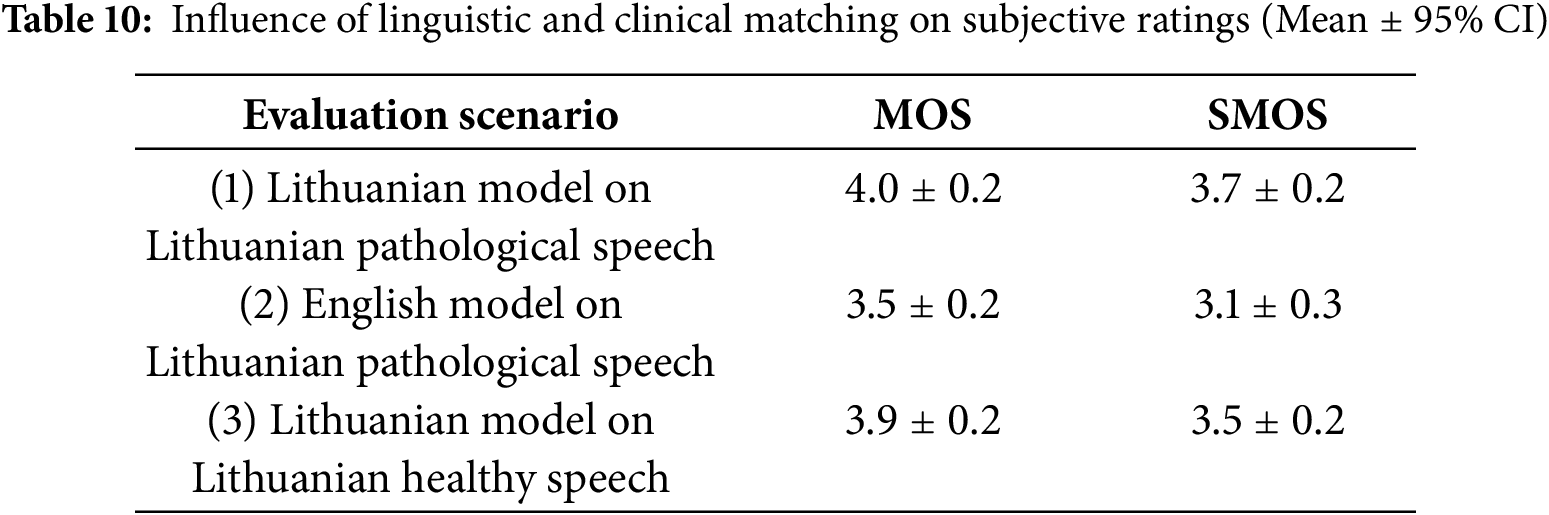

To quantify these effects, we performed a stratified comparative analysis in three evaluation scenarios (see Table 10): (1) linguistic and clinical conditions matched (Lithuanian-trained model in Lithuanian pathological data), (2) linguistic but matched clinical conditions matched (English-trained model in Lithuanian pathological data) and (3) linguistically matched but clinically mismatched conditions (Lithuanian trained model in Lithuanian healthy data). All samples were rated by the same panel of experts as in other experiments using a 5-point ITU-T P.800 scale, with randomized sample ordering to minimize anchoring.

The results indicate that the observed gains in MOS/SMOS are partially attributable to linguistic congruence (a 0.5 MOS gap between scenarios 1 and 2) and, to a lesser extent, to clinical voice matching (a 0.1 MOS difference between scenarios 1 and 3), which indicates that the synthesis model benefits from both pathological domain alignment and phoneme-level compatibility, but also highlights that approximately 20%–25% of subjective improvements reported over English-trained baselines may stem from language-specific perceptual bias rather than intrinsic model superiority.

After adjusting for objective quality (OQI) in mixed-effects models, the residual advantage of Scenario 1 over Scenario 2 was

Linear mixed-effects analyses revealed a significant main effect of Scenario for both MOS and SMOS (LRT,

3.4 Comparison with Other Approaches

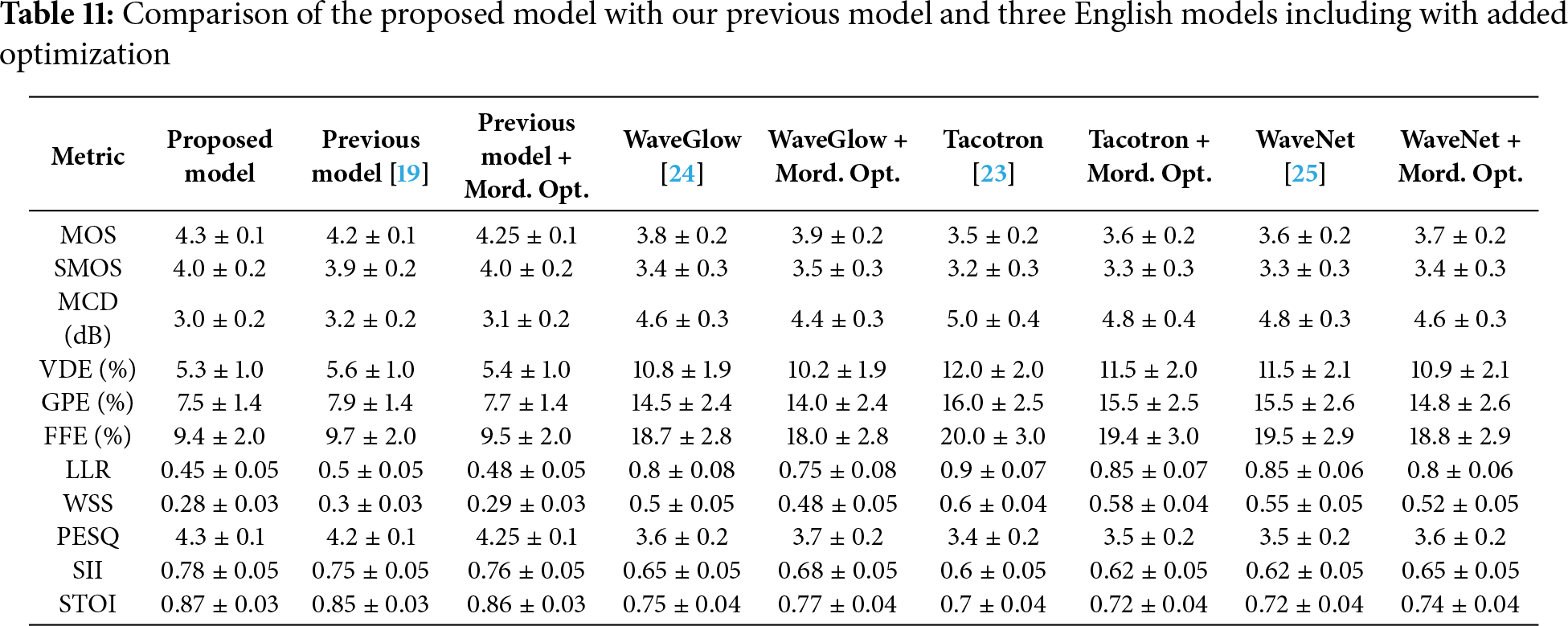

Table 11 emphasizes the performance of the proposed method relative to our previous efforts [19] and three open-source approaches (WaveGlow [24], Tacotron [23], and WaveNet [25]), all additionally trained on our dataset and under as identical conditions as possible given their different approaches to speech synthesis. We faced challenges adapting other TTS engines for Lithuanian alaryngeal speech because the full source code or trained language models needed for translation into Lithuanian were unavailable. We also investigated the effect of our MSO, which provided a modest but measurable performance boost across all baseline models. Added optimization improved both subjective (MOS, SMOS) and objective (MCD, VDE, GPE) metrics without altering the core model architectures.

The proposed model demonstrated the best overall performance in nearly all metrics, with MOS of 4.3 and SMOS of 4.0, indicating a higher level of naturalness and speaker similarity in synthesized speech. Its MCD (3.0 dB), VDE (5.3%), and GPE (7.5%) are the lowest among all models, showing the potential of the proposed model’s ability to produce accurate spectral and pitch representations. It shows better speech intelligibility, with an SII of 0.78 and an STOI of 0.87, which are slightly higher than the other models, confirming its effectiveness in producing clearer and more understandable speech.

Looking at our previous model [19], it performs well on its own, but with the addition of Mordukhovich optimization, slight improvements are observed in all metrics. MOS increases from 4.2 to 4.25 and SMOS from 3.9 to 4.0, showing imporved speech quality and speaker similarity. MCD, VDE, and GPE metrics show reductions, which means better spectral accuracy and pitch control with Mordukhovich optimization.

The same trend is observed for the WaveGlow, Tacotron, and WaveNet models. Although these models are of comparatively lower performance because they are English models just trained with Lithuanian speech on top (e.g., WaveGlow has MOS of 3.8, and Tacotron is at 3.5), applying Mordukhovich optimization leads to small but consistent gains. WaveGlow’s MOS increases from 3.8 to 3.9, and its MCD drops from 4.6 to 4.4 dB. Similar improvements are seen in Tacotron and WaveNet, with each model showing slightly increased spectral and pitch accuracy, as reflected in VDE and GPE reductions.

The focused approach of the study, while a strength in demonstrating efficacy for a specific clinical-linguistic population, inherently presents a scope for future generalization. We concentrated on the use case of Lithuanian alaryngeal speech, a combination that is severely underrepresented in speech technology research, necessary to provide a rigorous, in-depth validation of our proposed framework under highly challenging conditions. Expanding the cohort size or including multiple languages at this proof-of-concept stage is not possible, considering that to the best of our knowledge no such publicly accessible resources exist in sufficient scale, furthermore, it would have compromised the depth of analysis for this primary objective. Therefore, we believe that while our validation established a foundational benchmark, the modular architecture explicitly paves the way for future work to scale the approach to other languages once similar specialized datasets are developed.

The choice of expert evaluators, Lithuanian-speaking otolaryngologists, was a methodologically sound decision to ensure clinical relevance to linguistic authenticity, as the Lithuanian language being very unique in the European context [26]. Subjective assessment of pathological speech synthesis requires a nuanced understanding that only domain experts can provide, particularly when evaluating the delicate balance between naturalness and characteristic features of post-operative voice. We proactively addressed potential biases by conducting a stratified analysis to quantify the influence of linguistic and clinical matching, however, we acknowledge the theoretical possibility of biases. While a broader expert panel of listeners could be considered in future studies, it is hard to organize, considering there are not that many overall, and that the use of expert raters in this initial investigation was essential to ground-truth the model’s performance against real-world clinical standards and ensure the synthesized output is meaningful for its intended rehabilitative purpose.

Finally, we acknowledge that the prioritization of synthesis quality over computational efficiency in this phase of the research is a trade-off in early-stage methodological development. The primary contribution of this work is the introduction and validation of the MSO paradigm itself. A comprehensive benchmarking of its computational overhead against other optimizers, while an important future step, was secondary to the goal of establishing its performance superiority in handling non-smooth, multi-objective loss landscapes. We believe our paper successfully demonstrated achievement of main goal of enhanced naturalness and similarity, justifies the initial focus on algorithmic innovation. The framework’s design is inherently compatible with efficiency optimizations in future iterations, especially towards the path toward real-time clinical deployment.

This study demonstrates that the integration of a Mordukhovich Subdifferential Optimizer (MSO) into the voice cloning pipeline enables a principled and effective solution to the multicriteria optimization challenges inherent in pathological speech synthesis. Unlike traditional voice cloning approaches that focus on isolated performance metrics, our method explicitly formulates the task as a multi-objective optimization problem balancing four competing goals: speech naturalness, speaker similarity, computational efficiency, and adaptability to pathological voice characteristics.

The experimental results validate the effectiveness of this formulation. The MSO-guided models consistently outperformed the baseline and conventional multilingual TTS systems in a comprehensive suite of objective and subjective evaluation metrics. In particular, the optimized hybrid configuration achieved the highest Mean Opinion Score (MOS) and Similarity Mean Opinion Score (SMOS), reflecting substantial improvements in both perceived naturalness and speaker fidelity. Objective metrics such as Mel cepstral distortion (MCD), Voicing decision error (VDE), gross pitch error (GPE) and F0 frame error (FFE) were reduced, confirming the optimizer’s ability to fine-tune the model’s sensitivity to prosodic and pitch-related nuances, especially critical in pathological speech contexts. Enhancements in spectral similarity metrics (LLR and WSS) and perceptual quality scores (PESQ) reinforce the optimizer’s role in producing high-fidelity speech that aligns more closely with natural reference audio. The improvements in intelligibility, evidenced by increased Speech Intelligibility Index (SII) and Short-Time Objective Intelligibility (STOI), further support the MSO’s capacity to generalize across variable and impaired voice data.

Beyond performance metrics, the broader significance of this work lies in its methodological novelty: this is the first application of Mordukhovich subdifferential calculus in the context of voice cloning, offering a robust mathematical foundation for navigating trade-offs between human-centric quality attributes and computational constraints. The optimizer’s flexibility also enables integration with language-specific phoneme expansions, such as those required for Lithuanian, while remaining robust to signal irregularities caused by pathological voice conditions.

Although the proposed framework demonstrates promising results for the synthesis of Lithuanian pathological speech, real-world deployment in clinical settings would require not only high quality synthesis, but also seamless integration into rehabilitation workflows, compatibility with assistive devices and usability for both clinicians and patients with varying degrees of digital literacy. Second, the scalability of the approach to other low-resource languages presents a significant challenge, particularly for similarly rarely used languages such as Lithuanian, where annotated pathological speech data are still scarce due to low numbers of population and available patients. Practical adaptation to other languages would require careful expansion of the phoneme set, prosodic modeling, and cultural contextualization to ensure linguistic fidelity and patient acceptance. Finally, the ethical implications of the generation of synthetic pathological voices warrant careful consideration. Although these systems offer new opportunities to restore vocal identity and improve quality of life, they also raise concerns about consent, data ownership, potential misuse in identity spoofing, and the psychological impact on patients hearing synthetic versions of their impaired or preoperative voice.

Acknowledgement: The latest versions of Writefull for Overleaf and Grammarly were used to enhance the language, clarity, and grammar of the accepted paper. The authors have carefully reviewed and revised the output and accept full responsibility for all content.

Funding Statement: This project has received funding from the Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT), agreement No. S-MIP-23-46.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Rytis Maskeliūnas and Virgilijus Ulozas; methodology, Rytis Maskeliūnas; software, Audrius Kulikajevas; validation, Nora Ulozaite-Stanienė, Kipras Pribuišis and Virgilijus Ulozas; formal analysis, Robertas Damaševičius; investigation, Robertas Damaševičius, Rytis Maskeliūnas and Kipras Pribuišis; resources, Rytis Maskeliūnas; data curation, Kipras Pribuišis; writing—original draft preparation, Rytis Maskeliunas and Audrius Kulikajevas; writing, Robertas Damaševičius and Rytis Maskeliūnas; visualization, Robertas Damaševičius; supervision, Virgilijus Ulozas; project administration, Rytis Maskeliūnas; funding acquisition, Robertas Damaševičius. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The first dataset is not available due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available. The second dataset (Liepa) is available at: https://huggingface.co/datasets/isLucid/liepa-2 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

Ethics Approval: The research was conducted under the Ethical Permit issued by the Kaunas Regional Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research (Approval No. BE-2-49, dated 20 April 2022).

Informed Consent: The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to inclusion in the research.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mehrish A, Majumder N, Bharadwaj R, Mihalcea R, Poria S. A review of deep learning techniques for speech processing. Inf Fusion. 2023;99(19):101869. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2023.101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Dinakar R, Omkar A, Bhat KK, Nikitha MK, Hussain PA. Multispeaker and multilingual zero shot voice cloning and voice conversion. In: 2023 3rd International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Social Networking (ICPCSN); 2023 Jun 19–20; Salem, India. p. 1661–5. [Google Scholar]

3. Shelar J, Ghatole D, Pachpande M, Bhandari D, Shinde SV. Deepfakes for video conferencing using general adversarial networks (GANs) and multilingual voice cloning. Smart Innovat, Syst Technol. 2022;281:137–48. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-9447-9_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Nagrani A, Chung JS, Zisserman A. VoxCeleb: a large-scale speaker identification dataset. In: INTERSPEECH 2017; 2017 Aug 20–24; Stockholm, Sweden. p. 2616–20. [Google Scholar]

5. Ping W, Peng K, Gibiansky A, Arik SO, Kannan A, Narang S, et al. Deep voice 3: scaling text-to-speech with convolutional sequence learning. arXiv:1710.07654. 2018. [Google Scholar]

6. Li G, Li G, Dai Y, Song Z, Meng L. Research on the realization of multilingual speech synthesis and cross-lingual sound cloning in Tibetan. In: 2022 4th International Conference on Intelligent Information Processing (IIP); 2022 Oct 14–16; Guangzhou, China. p. 93–7. [Google Scholar]

7. Nekvinda T, Dušek O. One model, many languages: meta-learning for multilingual text-to-speech. arXiv:2008.00768. 2020. [Google Scholar]

8. Pérez A, Díaz-Munío GG, Giménez A, Silvestre-Cerdà JA, Sanchis A, Civera J, et al. Towards cross-lingual voice cloning in higher education. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2021;105(4):104413. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2021.104413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jia Y, Zhang Y, Weiss RJ, Wang Q, Shen J, Ren F, et al. Transfer learning from speaker verification to multispeaker text-to-speech synthesis. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

10. Valle R, Shih KJ, Prenger R, Catanzaro B. Mellotron: multispeaker expressive voice synthesis by conditioning on rhythm, pitch and global style tokens. arXiv:1910.11997. 2019. [Google Scholar]

11. Le M, Vyas A, Shi B, Karrer B, Sari L, Moritz R, et al. Voicebox: text-guided multilingual universal speech generation at scale. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2024. 36 p. [Google Scholar]

12. Zhuang H, Guo Y, Wang Y. ViSPer: a multilingual TTS approach based on VITS using deep feature loss. In: 2023 IEEE 6th International Conference on Automation, Electronics and Electrical Engineering (AUTEEE); 2023 Dec 15–17; Shenyang, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 244–8. [Google Scholar]

13. Li M, Zheng J, Tian X, Cai L, Xu B. Code-switched text-to-speech and voice conversion: leveraging languages in the training data. In: 2020 Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 418–23. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

14. Pratap V, Hannun A, Xu Q, Cai J, Kahn J, Synnaeve G, et al. Massively multilingual ASR: 50 languages, 1 model, 1 billion parameters. arXiv:2107.00636. 2021. [Google Scholar]

15. Uloza V, Verikas A, Bacauskiene M, Gelzinis A, Pribuisiene R, Kaseta M, et al. Categorizing normal and pathological voices: automated and perceptual categorization. J Voice. 2011;25(6):700–8. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2010.04.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Uloza V, Saferis V, Uloziene I. Perceptual and acoustic assessment of voice pathology and the efficacy of endolaryngeal phonomicrosurgery. J Voice. 2005;19(1):138–45. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2004.01.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Gu Y, Yin X, Rao Y, Wan Y, Tang B, Zhang Y, et al. ByteSing: a Chinese singing voice synthesis system using duration allocated encoder-decoder acoustic models and WaveRNN Vocoders. In: 2021 12th International Symposium on Chinese Spoken Language Processing (ISCSLP); 2021 Jan 24–27; Hong Kong, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

18. Bao TQ, Mordukhovich BS. Relative Pareto minimizers for multiobjective problems: existence and optimality conditions. Math Program. 2008;122(2):301–47. doi:10.1007/s10107-008-0249-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Maskeliunas R, Damasevicius R, Kulikajevas A, Pribuisis K, Ulozaite-Staniene N, Uloza V. Synthesizing Lithuanian voice replacement for laryngeal cancer patients with Pareto-optimized flow-based generative synthesis network. Appl Acoust. 2024;224(7):110097. doi:10.1016/j.apacoust.2024.110097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Maskeliūnas R, Damaševičius R, Kulikajevas A, Pribuišis K, Uloza V. Alaryngeal speech enhancement for noisy environments using a pareto denoising gated LSTM. J Voice. 2024;32(2S):18. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2024.07.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Laurinciukaite S, Telksnys L, Kasparaitis P, Kliukiene R, Paukstyte V. Lithuanian speech corpus liepa for development of human-computer interfaces working in voice recognition and synthesis mode. Informatica. 2018;29(3):487–98. doi:10.15388/informatica.2018.177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kasparaitis P. Evaluation of lithuanian text-to-speech synthesizers. Stud About Lang. 2016;28:80–91. doi:10.5755/j01.sal.0.28.15130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Wang Y, Skerry-Ryan R, Stanton D, Wu Y, Weiss RJ, Jaitly N, et al. Tacotron: towards end-to-end speech synthesis. arXiv:1703.10135. 2017. [Google Scholar]

24. Prenger R, Valle R, Catanzaro B. WaveGlow: a flow-based generative network for speech synthesis. arXiv:1811.00002. 2018. [Google Scholar]

25. Shen J, Pang R, Weiss RJ, Schuster M, Jaitly N, Yang Z, et al. Natural TTS synthesis by conditioning wavenet on mel spectrogram predictions. arXiv:1712.05884. 2017. [Google Scholar]

26. Bakšienė R, čepaitienė A, Jaroslavienė J, Urbanavičienė J. Standard lithuanian. J Int Phonetic Assoc. 2024;54(1):414–44. doi:10.1017/s0025100323000105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools