Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

LLM-Based Enhanced Clustering for Low-Resource Language: An Empirical Study

1 Department of Computer Science, The University of Faisalabad, Faisalabad, 38000, Pakistan

2 Department of Computer Science, The University of Southern Punjab, Multan, 60000, Pakistan

3 Department of AI and SW, Gachon University, Seongnam, 13120, Republic of Korea

4 Department of Artificial Intelligence, Chang Gung University, Linkou, Taoyuan, 333, Taiwan

5 Department of Computer Science and Information Engineering, Chang Gung University, Linkou, Taoyuan, 333, Taiwan

6 Center for Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Linkou, Linkou, Taoyuan, 333, Taiwan

* Corresponding Authors: Lal Khan. Email: ; Hsien-Tsung Chang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Applied NLP with Large Language Models: AI Applications Across Domains)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 3883-3911. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.073021

Received 09 September 2025; Accepted 24 November 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

Text clustering is an important task because of its vital role in NLP-related tasks. However, existing research on clustering is mainly based on the English language, with limited work on low-resource languages, such as Urdu. Low-resource language text clustering has many drawbacks in the form of limited annotated collections and strong linguistic diversity. The primary aim of this paper is twofold: (1) By introducing a clustering dataset named UNC-2025 comprises 100k Urdu news documents, and (2) a detailed empirical standard of Large Language Model (LLM) improved clustering methods for Urdu text. We explicitly evaluate the behavior of the 11 multilingual and Urdu-specific embeddings on 3 different clustering algorithms. We carefully evaluated our performance based on a set of internal and external measurements of validity. We discover the best configuration of the mBERT embedding with the HDBSCAN algorithm that attains a new state-of-the-art performance with a high score of external validity of 0.95. This new LLM method has created a new strong standard of Urdu text clustering. Importantly, the results confirm the strength and high scalability of the LLM-generated embeddings towards the ability to generalise the fine, subtle semantics needed to discover topics in low-resource settings and open the door to novel NLP applications in underrepresented languages.Keywords

The rapid increase in digital text and the widespread use of online communication have greatly amplified the importance of effective text clustering and organization. Text clustering, a fundamental task in Natural Language Processing (NLP), enables the automatic grouping of similar documents without predefined labels [1]. This capability is crucial for various applications, including news categorization, spam detection, topic modeling, sentiment analysis [2,3], and document retrieval systems. While extensive research has been conducted on text clustering for well-resourced languages such as English, a considerable gap remains for low-resource languages such as Urdu [4]. The main challenges include the scarcity of linguistic resources, limited availability of annotated datasets, high linguistic complexity, and underdeveloped NLP tools [5]. Consequently, researchers often rely on multilingual models that may not fully capture the unique semantic and structural characteristics of Urdu, unlike the rich linguistic tools and large datasets available for high-resource languages.

Urdu is the national language of Pakistan, and it is one of the leading languages belonging to the Indo-Aryan family, with over 230 million speakers all over the world but it has not been adequately researched in computational linguistics despite its prominence in the government, literature, and digital communication. One of the reasons for this underrepresentation is that its morphological and syntactic complexity is very different from that of high-resource languages such as English Unlike analytical languages, whose word forms are relatively stable, Urdu is an agglutinative language which means that its word forms are created through the concatenation of several morphemes, meaning that there are large amounts of word variations that are created from the same roots. This complexity makes tokenization, stemming, and lemmatization significantly more difficult than in English. Moreover, the script of Urdu, written from right to left, features context-sensitive letter forms, heavy use of diacritics. These characteristics make it extremely challenging to perform text Processing in Urdu using traditional NLP methods. Moreover, Urdu has complex syntactic dependencies, phonetic variations, and lexical ambiguity, all of which make the clustering task challenging [6]. Although standard clustering algorithms such as K-Means, hierarchical clustering, and DBSCAN have been widely used for English and other well-resourced languages, their use for Urdu is still little explored due to linguistic challenges and the absence of high-quality pre-trained embeddings [7,8]. These constraints underlay the importance of specialized research over embedding-based clustering methods in Urdu to overcome existing resource inequalities in NLP.

With the advent of deep learning and transformer-based architectures, the text representation has been much improved using contextualized embeddings [9,10]. Different from the traditional feature extraction schemes like Bag-of-Words (BoW) and Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF), the recent word embeddings are capable of reflecting the semantic relationships and the contextual information. The advent of pre-trained language models like mBERT, XLM-RoBERTa, and UrduBERT, as well as the proprietary embeddings like OpenAI’s text-embedding, has created new opportunities for better accuracy in clustering of texts [11]. Although the state-of-the-art clustering frameworks, such as BERTopic, HDBSCAN, and K-Means, have been extensively tested for high-resource languages. However, there is no systematic study performed to investigate the impact of modern LLM-based embeddings for the Urdu text clustering using various clustering algorithms. It is still unclear if such frameworks will be effective for clustering Urdu text. To address this research gap, to the best of our knowledge, we are first performing this comparative study for the low-resource Urdu language.

Although there are very few task- and domain-specific Urdu datasets publicly available, some valuable contributions have been made, such as those by Rasheed et al. [12] and Khan et al. [3,6]. These limited available corpora are specifically designed for particular tasks such as information retrieval and sentiment analysis. More importantly, they are usually coarsely grouped by topic, with comparatively little fine-grained distinction and minimal manual labeling—both of which are essential for conducting rigorous evaluations of state-of-the-art unsupervised clustering models. This paper bridges that gap by introducing the UNC-2025 corpus, which is specifically designed and deemed representative for benchmarking clustering performance. The corpus provides a reliable ground truth for external validation measures such as the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) and Normalized Mutual Information (NMI).

Word embedding models have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance across various NLP tasks for many resource-rich languages. However, these embeddings have not been thoroughly investigated for resource-deprived languages such as Urdu. Several major roadblocks still exist for Urdu NLP development. Firstly, there is a lack of dedicated, high-quality word embedding models tailored specifically for the Urdu dialect. Secondly, only a few small Urdu datasets are available to fine-tune existing English-based embedding models for the Urdu language. This limitation hinders the ability of embedding models to capture the finer linguistic nuances and contextual richness of Urdu. Furthermore, traditional clustering algorithms often fail to account for the morphological richness and structural complexity inherent in the Urdu language. To the best of our knowledge, there is no published study that provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of different embedding and clustering methods for Urdu. Consequently, best practices for Urdu text clustering remain underexplored due to the absence of such comparative evaluations. In light of these challenges, it is essential to conduct a robust empirical study that integrates LLM-based embeddings with state-of-the-art clustering methods, thereby advancing NLP research for this under-resourced language and establishing an initial benchmark standard. Our proposed study has answered the following research questions:

1. Which embedding models (e.g., UrduBERT, mBERT, XLM-RoBERTa, OpenAI embeddings) provide the most effective vector representations for Urdu text clustering?

2. How do different clustering techniques (BERTopic, HDBSCAN, K-Means) perform when applied to Urdu text embeddings in terms of topic coherence and clustering quality?

3. Which embedding-clustering combination yields the best performance based on key cluster evaluation metrics?

4. Can LLM-based embeddings significantly improve the quality of topic modeling and clustering in low-resource languages such as Urdu?

To address these research questions, this study presents a comprehensive benchmarking of embedding-based clustering techniques for Urdu text processing. The main contributions of this research are as follows:

1. A systematic and comprehensive empirical benchmark of eleven advanced LLM-derived embedding models for Urdu text clustering, including UrduBERT, mBERT, XLM-RoBERTa, MIXEDBREAD AI, Nomic Embed Text, and Open’s embedding models.

2. A detailed comparative analysis of three major clustering techniques (BERTopic, HDBSCAN, and K-Means) applied to Urdu text embeddings, assessing their performance in topic modeling and unsupervised document classification.

3. The adoption of a rigorous evaluation framework using multiple external cluster validity metrics, including Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) and Normalized Mutual Information (NMI), to objectively assess performance against ground-truth labels.

4. The identification of the most effective LLM-based embedding and clustering combination for Urdu text, establishing a new benchmark for low-resource language NLP research.

5. The first comprehensive benchmarking study on Urdu text clustering that provides data-driven insights into embedding quality, clustering effectiveness, and evaluation metrics, thereby contributing significantly to the advancement of Urdu NLP.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the literature review, covering existing research on embedding techniques, clustering algorithms, and topic modeling for low-resource languages. Section 3 describes the corpus, preprocessing steps, and experimental setup. Section 4 details the proposed methodology, including the Large Language Model (LLM)-based embedding and clustering techniques experimented in this study. Section 5 discusses the experimental results, comparative analyses, evaluation metrics, and key findings, along with the study’s limitations and implications. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines potential directions for future research.

Recently, the exponential trends of unstructured data in various fields and domains, including social media tools and multilingual corpora, have sped up the development of more enhanced clustering methods to partition, process, and make sense of complicated data to serve diverse functions, such as topic discovery, document reconstruction, and user behavior analysis [13,14]. The combination of traditional clustering algorithms, such as K-Means and DBSCAN, with embeddings, domain-specific adaptations, and scalable models has created new opportunities in text mining, low-resource language processing, and real-time analytics [15].

In the case of low-resource languages such as Urdu, unique and complex linguistic features—such as rich agglutinative morphology, the intricate Nastaliq script, and the lack of annotated digital resources—pose serious roadblocks for Urdu NLP tasks, including text clustering [16]. In addition, it uses inflected word forms and complicated syntactic dependencies, which makes its tokenization and parsing more difficult and complex, which are fundamental to most NLP pipelines [17]. These issues complicate the Urdu text processing and, in most cases, cause poor algorithm performance relative to high-resource languages. This paper specifically tackles these problems by using a systematic empirical analysis of the clustering of Urdu text with LLM additions, which will offer important references on the understudied field.

2.1 Traditional Clustering Algorithms and Hybrid Frameworks

Traditional clustering methods such as K-Means [18] and DBSCAN are widely used for clustering tasks. K-Means, a centroid-based algorithm, partitions data points into

In study [20], the hierarchical clustering technique was used to construct a sequence of clusters from the original high-dimensional space by successively merging or splitting based on distance metrics. This method minimized noise sensitivity in large-scale text corpus segmentation, increasing thematic correctness by 15%. Similarly, in study [21], density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) has proven very effective in detecting outlier clusters, but its optimal parameter setting is still difficult to achieve. DBSCAN identifies the data points that form dense clusters and isolates data points as outliers. The main strength of DBSCAN is the ability to find clusters of arbitrary shape. On this basis HDBSCAN (Hierarchical Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise) generalizes DBSCAN into a hierarchy, able to discover clusters of various densities as well, and to automatically detect the number of clusters.

Similarly, the RFM (Recency, Frequency, Monetary) model with K-Means [22] is traditionally utilized for customer segmentation tasks, but it can be extended to text analysis, as it clusters documents according to inferred interaction patterns (i.e., document access frequency, downloading, and recency). This method helps identify groups of highly engaged content. In another study [23], spectral clustering in combination with Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) using the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm was employed to capture the dynamic nature of textual data streams and achieved an F1 score of 0.89 on online review datasets.

2.2 NLP-Driven Segmentation for Short Texts

Clustering short texts poses different problems because of lexical sparsity and polysemy. The Vector Space Model (VSM) of the early models [24] treated text as vectors of word frequency but lacked semantic interpretation. The Word2Vec neural network-based embedding model revolutionized the entire NLP field, as it learns to predict surrounding words and has been found to be more precise in syntactic representation, but it still faces issues with polysemy [25].

The introduction of BERT revolutionized text representation by employing bidirectional transformers to generate context-aware word embeddings. BERT’s ability to model entire sentences allowed it to capture richer semantic nuances and reduce ambiguity. Hybrid approaches such as BERT-BTM (Biterm Topic Model) further enhanced topic modeling by integrating topic vectors with contextual embeddings, outperforming Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) in topic coherence (0.64 vs. 0.52) on Weibo datasets.

For news classification, the combination of Doc2Vec and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) achieved 94%–96% accuracy on Turkish and English datasets [26]. Similarly, ClusTop [27], which employs co-word networks, surpassed LDA in topic coherence for Twitter data. These studies highlight how contextual embeddings help overcome the limitations of short text clustering. Study [28] specifically focused on topic discovery in Urdu, comparing statistical models, clustering algorithms, and embedding methods. Their findings underscore the morphological richness and limited resources that challenge Urdu NLP, providing valuable insights aligned with the objectives of the present study.

2.3 Low-Resource Language Adaptations

Text clustering for low-resource languages such as Uzbek and Arabic requires language-specific adaptations. In [13], FP-Trees (Frequent Pattern Trees) were employed to address Uzbek’s morphological complexity by identifying frequent word patterns, while the use of BERT embeddings improved topic detection accuracy by 22% [29]. Large-scale systems such as TensorFlow [30] have also been utilized to scale processing of terabyte-sized corpora, reducing runtime by 40%.

For Arabic, graph-based approaches and PageRank algorithms [31] improved text summarization, while GPT-3.5 [32] achieved a 70% compression ratio on the AGS dataset. Hybrid frameworks combining BERTopic and hierarchical clustering further improved topic stability for morphologically complex languages, reinforcing the importance of customized embeddings for Urdu and similar languages.

Advanced embedding models prevail in news and social media topic modeling. A hybrid BERT-LDA-UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) model [33] reduced the feature dimensionality before LDA which resulted in a Silhouette Score of 0.52 for the CORD-19 dataset. Further, Kernel PCA in conjunction with K-Means achieved a topic coherence score of 0.85 over 959,000 banking tweets, whereas Doc2Vec for TaxoGen [34] and for unsupervised news topic detection gives 87% accuracy in classification.

2.4 Evaluation Metrics and Scalability Challenges

Robust evaluation is essential for validating clustering results. Internal validity indices such as the Silhouette Score [19] and the Davies-Bouldin Index [21] measure cluster compactness and separation. For datasets with ground-truth labels, external validity indices provide a more objective evaluation by comparing clustering outputs with true class labels. The Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) and Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) [35] are among the most widely used external metrics for assessing clustering quality.

Topic Coherence and ROUGE-L [32] are also employed to assess semantic consistency in topic models and summarization systems, respectively. Scalability challenges in high-dimensional datasets [30] are increasingly addressed through distributed computing frameworks such as Apache Spark and parameter-efficient large language models [36].

Overall, these advancements underscore the growing role of embedding-based clustering in enabling effective analysis for both high- and low-resource languages, while emphasizing the continued need for empirical benchmarking—particularly for underrepresented languages like Urdu.

The increasing volume of digital Urdu content, particularly across mainstream news platforms, presents a valuable opportunity for advancing Natural Language Processing (NLP) research in low-resource language contexts. To support deep semantic modeling and clustering, we developed a robust and large-scale benchmark dataset titled Urdu News Corpus 2025 (UNC-2025). The corpus comprises 100,000 manually validated Urdu news articles, curated and augmented from an existing Kaggle dataset introduced by Shahane [37], which originally contained 44,000 samples.

The main goal was to train a diverse, high-volume dataset that can be used for downstream tasks such as semantic clustering, representation learning, and document classification. For comparative experimental purposes and scalability, two versions were created: the full corpus-based version (100K) and the subset version (50K). Both variants are categorized into six major groups: politics, sports, entertainment, health, technology, and business. Tables 1 and 2 present the summary of article distribution and word counts across the categories in the UNC-2025 Subset Corpus (100K and 50K).

Although several datasets have contributed to Urdu NLP research [2,3,12], most of them are created for supervised tasks like classification rather than unsupervised clustering evaluation. Our research needed a specific corpus with two key characteristics: (1) with an evenly distributed category within the same corpus in order to reduce the algorithm bias; (2) Labelled corpora with high enough coherence to enable the calculation of external clustering validation metrics such as ARI and NMI. The creation of UNC-2025 is a necessary precursor to this benchmarking study because there is no existing public corpus that is constructed with such strict methodological requirements.

3.1 Ethical Considerations and Data Collection

The construction of UNC-2025 was strictly conducted in compliance with ethical principles in research. All articles were gathered from open-access digital news sites, in full accordance with fair-use and academic research codes of practice. Information was not sought from the paywall or subscription services. The articles were not adjusted for sentiment, bias, or content; however, normalization and cleaning of the format were performed.

All sources are actual news organizations and news opinions, so that the dataset is a correct representation of the diversity of languages and topics found in real news. Copyright and attributes policies were reviewed to ensure the legal allowability of reuse for non-commercial, research-oriented purposes.

The UNC-2025 corpus was constructed using a semi-automated pipeline that combined data augmentation, category balancing, and manual validation.

1. Initial Dataset: The Kaggle dataset [37] served as the foundation, providing approximately 44,000 news articles across multiple domains.

2. Augmentation: To extend the dataset to one hundred thousand documents, we used Python-based web scrapers based on BeautifulSoup and Selenium. From the popular Urdu news portals such as BBC Urdu, Jang News, and UrduPoint, the tools used extracted titles, timestamps, categories, and descriptions from the news archives.

3. Balancing and Deduplication: All the articles were classified into one of the six predetermined topics. There was equal representation of each category in the 50K and 100K versions so that the corpus was stratified. This balanced design was a methodological decision to promote fairness in the comparison of the LLM embeddings and clustering algorithms to avoid the artificial influx of evaluation metrics by class imbalance. Automated content validation scripts were used to remove duplicate or incomplete entries.

4. Data Validation and Inter-Rater Agreement: Three Urdu NLP experts were taken to review 3000 articles (500 articles in each category) to guarantee a high level of label reliability. The Kappa reported by Fleiss was calculated to assess the inter-rater agreement among the six categories, and its value was 0.87, which is close to perfect agreement. This proves the consistency and reliability of the category labels applied to the external cluster validation (ARI and NMI).

All the data were screened manually to eliminate code-mixed (Urdu English) texts, malformed Unicode or category ambiguities. The posts that were less than 85 words were filtered out to maintain a high enough semantic depth, and a limit was not put on the word count to maintain richness in the context.

The raw corpus underwent a multi-stage preprocessing pipeline to ensure text consistency, normalization, and compatibility for downstream NLP applications. The steps included:

• Unicode Normalization: Converted all text to UTF-8 and standardized Arabic-script encoding variants common in Urdu.

• Noise Removal: Removed HTML tags, emojis, special characters, and embedded URLs.

• Punctuation and Diacritic Handling: Eliminated redundant punctuation and optional Urdu diacritics to focus on lexical content.

• Stopword Filtering: Removed high-frequency, semantically void words using a custom Urdu stopword list.

• Length Validation: Excluded articles with fewer than 85 words to maintain semantic completeness.

3.4 Data Distribution Statistics

Two corpus versions were finalized for experimental comparison:

• Subset Dataset: 50,000 articles (8333 per category)

• Full Dataset: 100,000 articles (16,667 per category)

Each version was analyzed for word count, article length, and category representation to confirm suitability for semantic clustering and deep embedding tasks.

The UNC-2025 corpus thus represents one of the largest, most balanced, and methodologically rigorous Urdu news datasets available. While earlier works [1] utilized portions of the 44K dataset for classification, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first effort to curate and employ a large-scale, augmented, and semantically enriched Urdu corpus explicitly designed for deep clustering and representation learning.

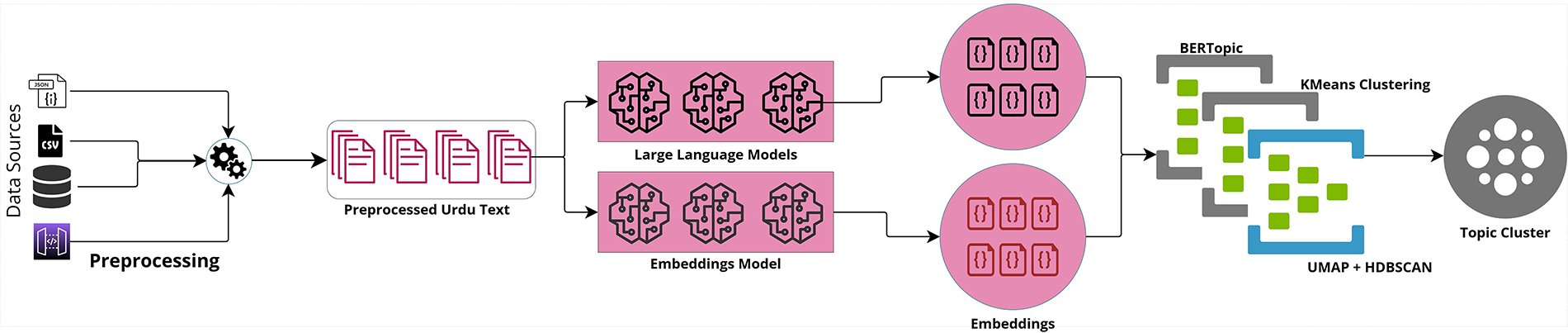

This section describes a detailed methodology, which is used to test the performance of different LLM embedding algorithms for clustering Urdu text. The proposed study investigates a total of 33 different configurations, comprising 11 multilingual word embedding models and 3 clustering algorithms. The primary aim of these extensive experiments is to identify the most efficient approach for generating semantically coherent and scalable clusters of Urdu textual information, considering linguistic complexity and limited computational resources. Fig. 1 illustrates the overall methodological pipeline of this study.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the proposed LLM-based clustering framework for Urdu text

The initial step is to obtain a contextualized representation of Urdu text as a set of vectors through a chosen set of embedding models based on LLM. The architectural strength and pre-training goals of each of these models can affect the quality of the resulting embeddings to solve clustering tasks. The clustering algorithms use these embeddings as input and cluster semantically related Urdu documents. The results of each of the 33 model-clustering combinations are then compared with various quantitative measures so that a rigorous and objective comparison can be conducted.

The structure of this section is divided into 3 subsections. Section 4.1 describes the 11 embedding models that were experimented with to generate Urdu text embeddings. Section 4.2 explains the principles and implementation specifics of the three clustering algorithms, which include K-Means, HDBSCAN, and BERTopic. Section 4.3 provides details on the evaluation metrics used to determine the quality of clustering.

After due preprocessing steps, the proposed model is converts Urdu text into dense numerical representations using eleven pre-trained multilingual embedding models. These models are designed to capture semantic and contextual relationships across multiple languages, including Urdu. The embedding of a sentence S is represented as

DeepSeek is a multilingual embedding model optimized for cross-lingual understanding. Its architecture captures complex semantic relationships, making it potentially suitable for the morphological richness of Urdu. The embedding for a sentence S is computed as in the following equation.

LLaMA 3.2 (1B) [38] is a large language model capable of modeling long-range dependencies and rich contextual semantics. We examine its ability to produce meaningful Urdu embeddings for clustering.

MIXEDBREAD [39] AI is a hybrid transformer-based model designed for multilingual NLP tasks. It integrates multiple architectural strengths to produce accurate, transferable embeddings:

Nomic [40] Embed Text is optimized for clustering and information retrieval, providing high-dimensional embeddings suitable for distinguishing subtle semantic differences.

XLM-RoBERTa [41] is a transformer-based multilingual model pre-trained on a massive corpus covering multiple languages, including Urdu. It effectively preserves cross-lingual semantic meaning.

mBERT [42] is a well-known multilingual model trained on 100+ languages. It handles complex morphology and syntax, making it a solid baseline for Urdu text representation.

The Paraphrase Multilingual model [43] is fine-tuned to capture semantic similarity across languages, making it particularly relevant for clustering semantically similar Urdu texts.

Text-Embedding-3-Large [44] is a high-dimensional embedding model optimized for retrieval-augmented generation (RAG). Its detailed representations support fine-grained Urdu text clustering:

Text-Embedding-3- Small is a compact model from the same family, optimized for efficiency in resource-constrained environments [44]:

Text-Embedding-Ada-002 [45], developed by OpenAI, has shown strong performance across diverse NLP tasks and is included to test its ability to generate robust Urdu embeddings:

UrduBERT [46] is a transformer model trained exclusively on large Urdu corpora. Its Urdu-specific pre-training allows it to capture linguistic nuances effectively:

K-Means, HDBSCAN, and BERTopic were used for Urdu text clustering. These three algorithms represent different clustering approaches: centroid-based, density-based, and topic modeling methods. Each was combined with Large Language Model (LLM) embeddings to capture semantic similarities in the text.

K-Means [47] partitions

where

The other clustering algorithm utilized is HDBSCAN [48], a density-based clustering method that extends DBSCAN into a hierarchical approach and automatically extracts stable clusters. Unlike K-Means, it does not require a predefined number of clusters. The neighborhood of a point

Key parameters such as min_cluster_size (5–50) and min_samples (1–10) were optimized using grid search for stable and meaningful clusters.

The third algorithm used for clustering is BERTopic [49], a transformer-based topic modeling approach that combines embeddings, dimensionality reduction (UMAP), and density-based clustering (HDBSCAN). It applies class-based TF-IDF to extract representative topic terms. For Urdu text, the UMAP parameters were set to

Clustering performance evaluation is crucial, particularly for domain-specific datasets like the UNC-2025 Urdu News Corpus, which includes ground truth annotations for benchmarking. Given Urdu’s morphological richness and low-resource nature, this study prioritizes external validity metrics—Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) and Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) [50] as they better reflect semantic alignment with true labels than internal measures. Although internal indices such as the Silhouette Score [51], Davies-Bouldin Index (DBI) [52], and Calinski-Harabasz Index (CHI) [53] provide insights into cluster cohesion and separation, they are biased toward spherical clusters and thus less suitable for density-based methods like HDBSCAN and BERTopic. Therefore, our evaluation framework primarily relies on ARI and NMI for unbiased and accurate assessment of clustering quality.

The Silhouette Score quantifies how similar a sample is to its own cluster compared to other clusters. It is defined as:

where

Similarly, the DBI measures the average similarity between each cluster and its most similar counterpart. A lower DBI indicates better clustering performance:

where

The CHI evaluates clustering quality by comparing between-cluster dispersion to within-cluster dispersion. A higher CHI value suggests more distinct and compact clusters:

where

The ARI measures the similarity between predicted and true cluster labels, adjusting for chance agreement. A score of

where RI is the Rand Index, and

where

All the experiments were performed on a high-performance computing server with an Nvidia A100 GPU (80 GB VRAM), an Intel Xeon Gold 6248R CPU, and 512 GB of RAM. This configuration was required to cope with the computational requirements of large-scale models such as LLaMA 3.2. For the entire 100K corpus, it took about 4.5 h to generate embeddings using LLaMA 3.2, and it took less than 15 min per algorithm for clustering and evaluation using UMAP dimensionality reduction for BERTopic.

Each of the 33 model configurations was developed by taking 11 embedding models and 3 clustering algorithms. Performance was evaluated by using Silhouette Score, DBI, CHI, ARI, and NMI. Each configuration was repeated 5 times, and the average results are reported. Statistical significance tests (t-tests or ANOVA) were used to compare the best-performing configurations. This approach ensures the robustness and the most effective combinations of embeddings and clustering algorithms for Urdu text.

5.1 Qualitative and Error Analysis

In addition to quantitative evaluation, qualitative inspection was performed on the top three LLM clustering combinations (based on ARI and NMI). This analysis consisted of two steps:

1. Error Inspection: A random sample of 50 misclassified documents, which were placed in clusters other than their ground truth label, were manually reviewed to identify common linguistic or semantic challenges.

2. Cluster Coherence Assessment: For the top performing models, 10 most representative documents from six clusters have been analyzed in order to assess the semantic coherence and interpretability of the found topics, which serve as contextual evidence to support the quantitative results.

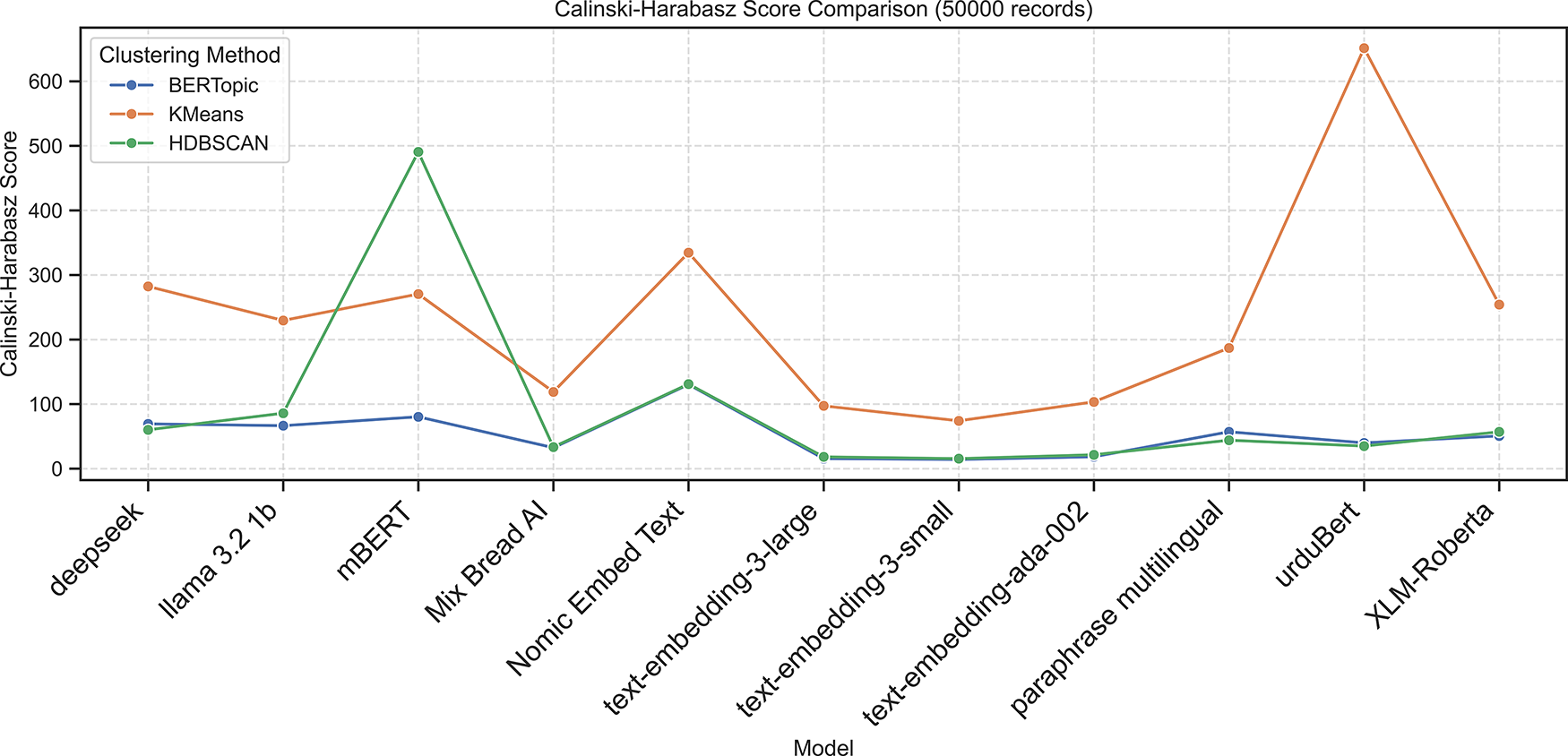

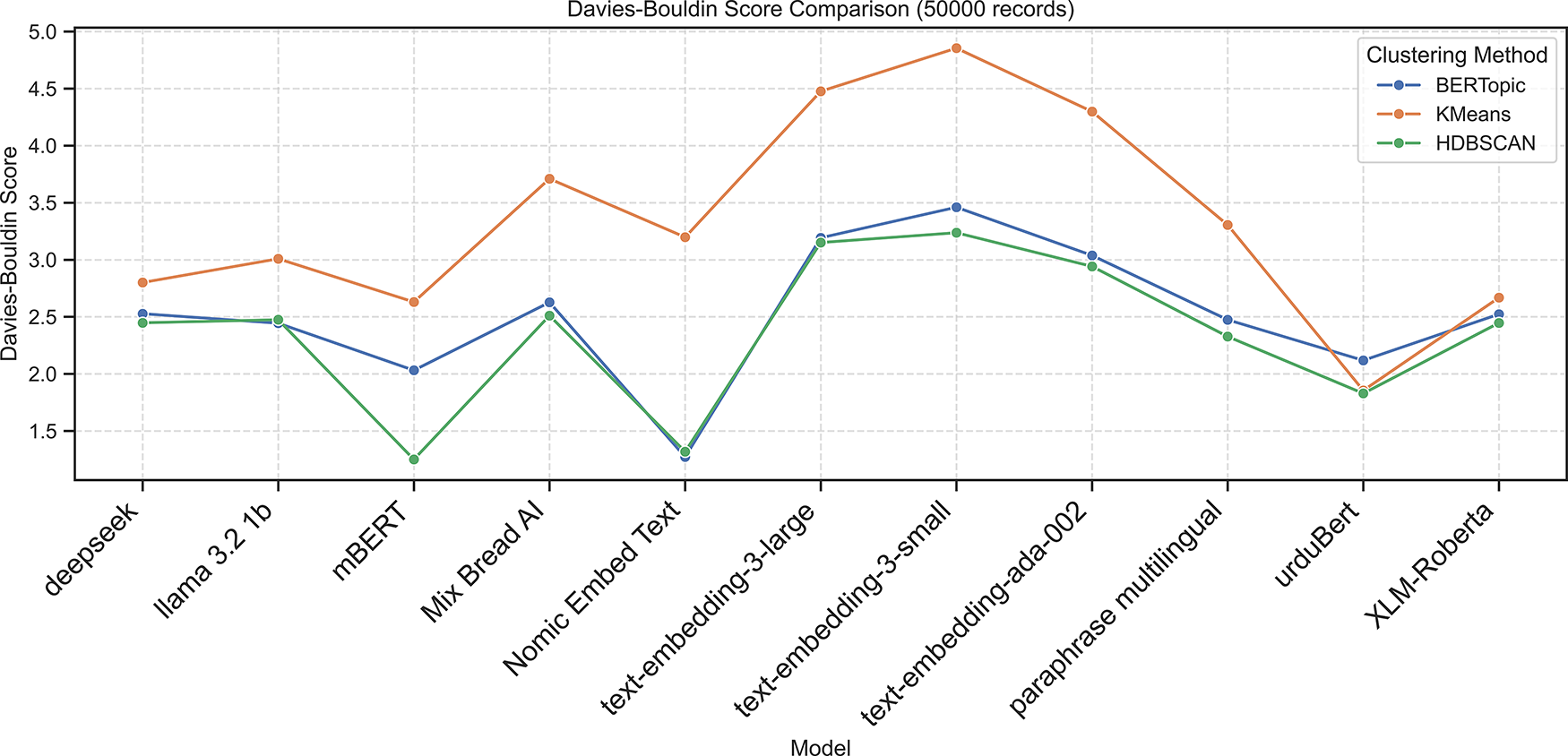

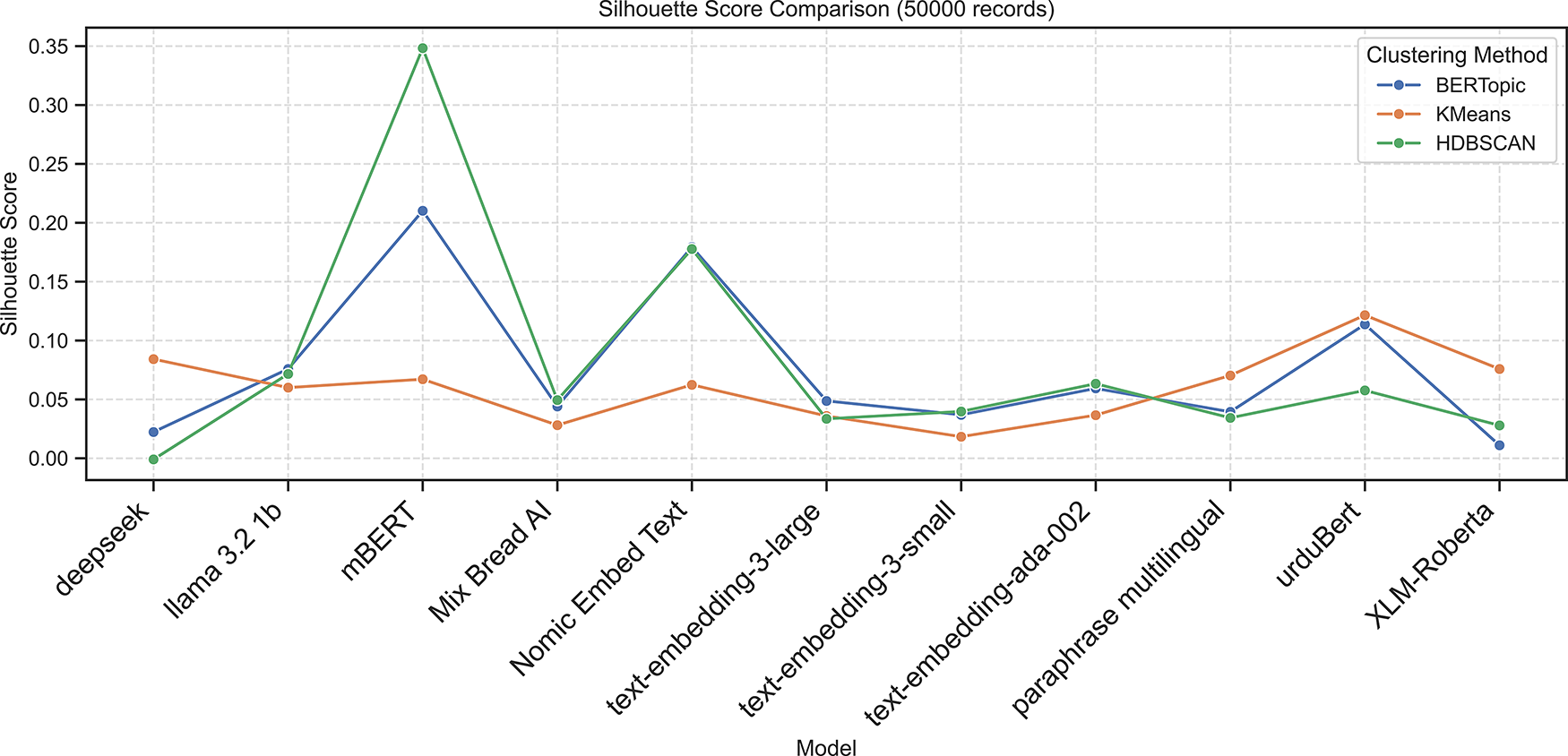

This section presents the results and analysis of clustering experiments conducted on the 50K- and 100K document subsets of the UNC-2025 Urdu News Corpus. Three clustering algorithms—BERTopic, K-Means, and HDBSCAN were evaluated using eleven embedding models. The clustering quality was assessed using the evaluation metrics described earlier.

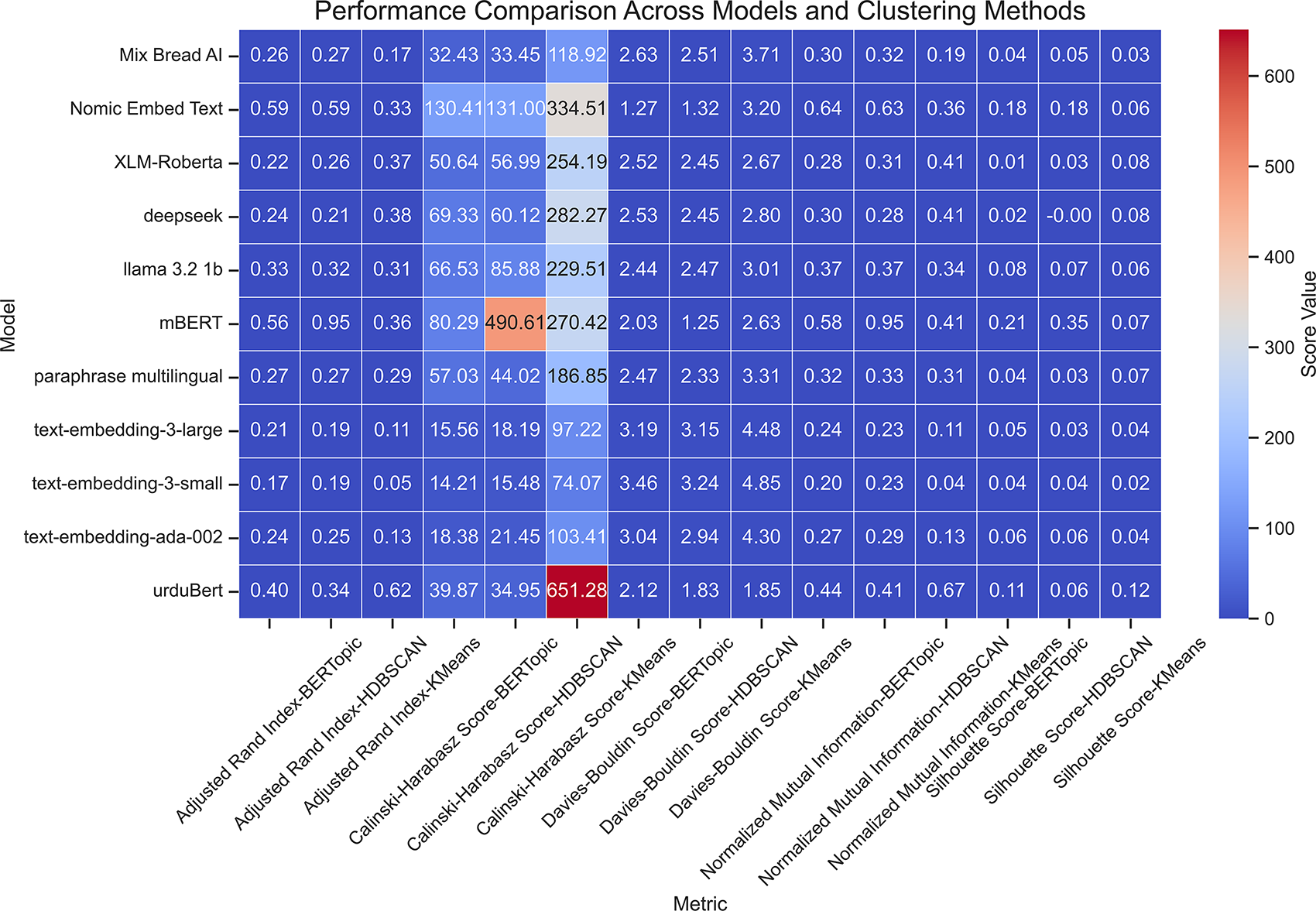

Applying BERTopic to the 50K dataset revealed strong dependence on the semantic richness of embeddings. As shown in Table 4, Nomic Embed Text achieved the best results with an ARI of 0.5929 and NMI of 0.6406, reflecting close alignment with ground truth topics. It also yielded the highest Silhouette Score (0.1794) and lowest DBI (1.2723), indicating compact and well-separated clusters.

mBERT was ranked second with an ARI of 0.5580 and NMI of 0.5759. However, its internal measures (Silhouette Score = 0.2102, DBI = 2.0313) indicate clusters with slightly less cohesion. UrduBERT obtained an ARI of 0.4000 and NMI of 0.4431, indicating meaningful topic organization and Deepseek performed moderately with an ARI of 0.2443 and NMI of 0.3022. Other embeddings, such as LLaMA 3.2, Mixedbread AI, and XLM-RoBERTa, showed low Silhouette Scores (0.011–0.075) and high DBI values, indicating poor topic separation. Overall, BERTopic was unable to form dense Urdu clusters across most embeddings; however, the Nomic Embed Text model performed the best among them.

Using K-Means, UrduBERT embeddings clearly performed better than all others (Table 5). It got the highest ARI (0.6250) and NMI (0.6732) and better internal metrics, Silhouette Score 0.1215, DBI 1.8547, and CHI 651.27. These results validate that the contextual representations of UrduBERT are suitable for the partition-based clustering.

DeepSeek, mBERT, and XLM-RoBERTa also received moderate test results (ARI 0.36–0.41), and models like LLaMA 3.2 and Paraphrase Multilingual were worse. The OpenAI and Mixedbread embeddings had the worst results, with text-embedding-3-small getting an ARI of only 0.0464 and NMI of 0.0409. Overall, UrduBERT showed the most cohesive and semantically interpretable clusters with the help of K-means.

As shown in Table 6, mBERT with HDBSCAN achieved exceptional results, producing an ARI and NMI of 0.9496 and a Silhouette Score of 0.3483. It also had the lowest DBI (1.2502), confirming its ability to form compact and well-separated clusters. This indicates that HDBSCAN, with its ability to capture clusters of varying densities, pairs effectively with mBERT’s dense semantic space.

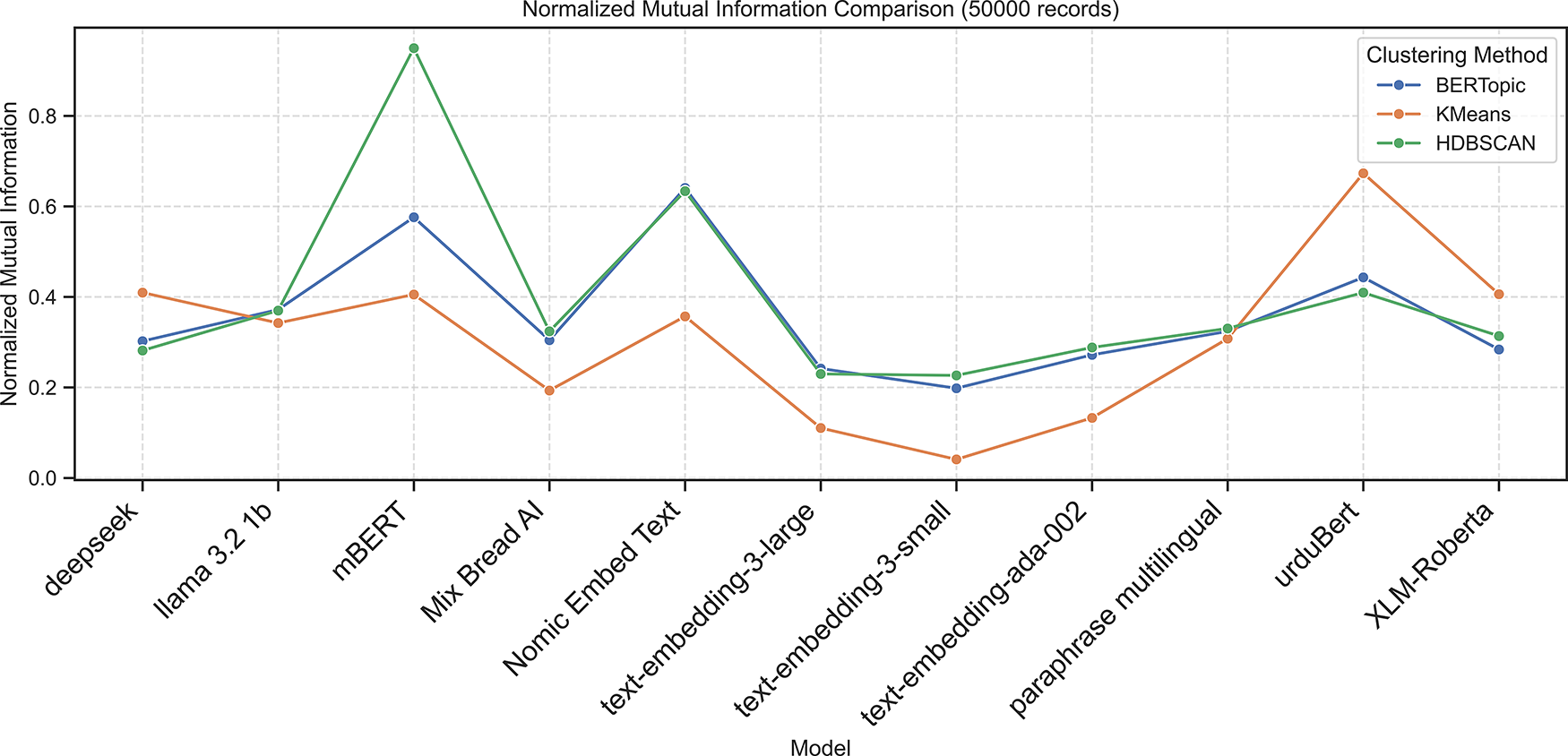

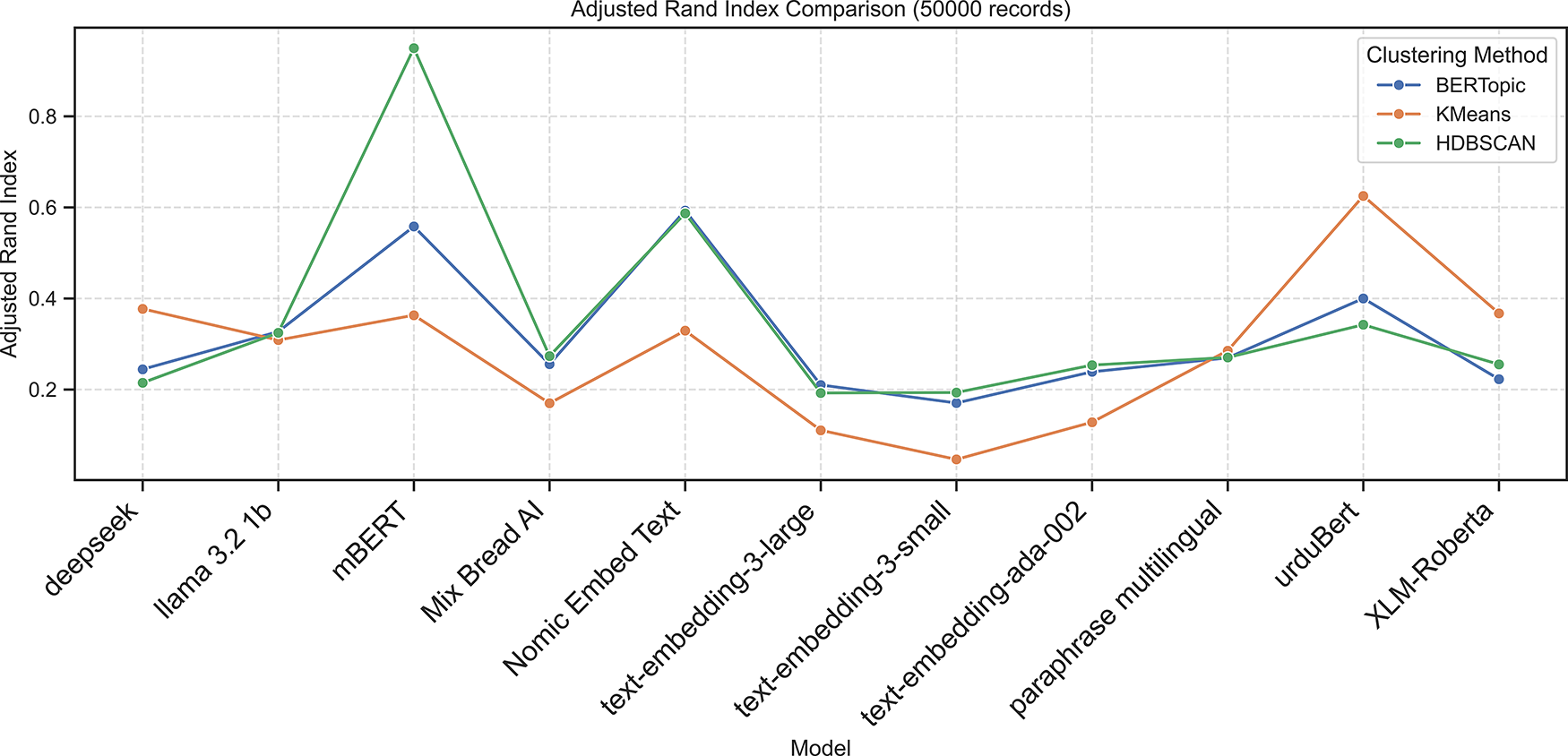

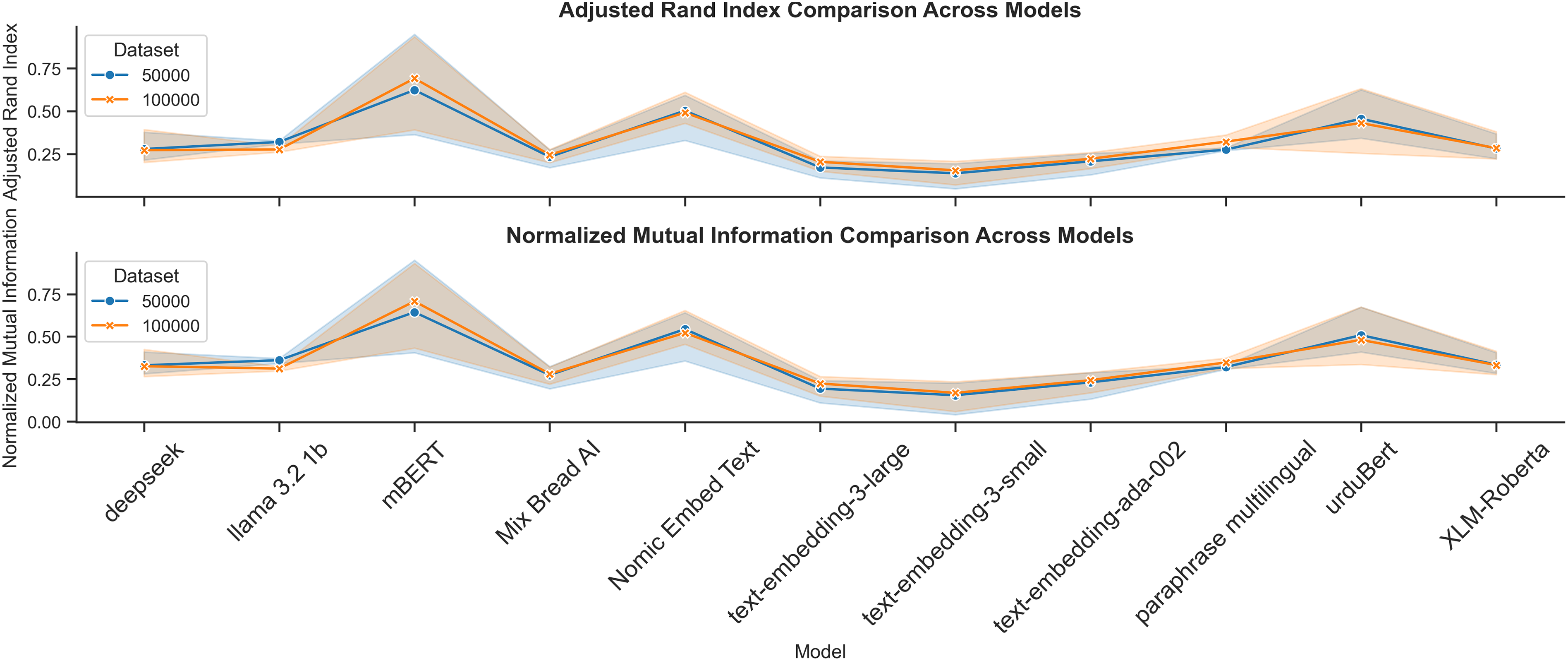

Nomic Embed Text also performed well (ARI = 0.5868, NMI = 0.6337), followed by UrduBERT (ARI = 0.3422, NMI = 0.4094). In contrast, Deepseek and other embeddings (e.g., LLaMA 3.2, Mixedbread AI, and OpenAI embeddings) exhibited near-zero or negative Silhouette Scores, indicating weak internal cohesion. The following Figs. 2–6 present the Calinski-Harabasz, Davies-Bouldin, Silhouette, Normalized Mutual Information, and Adjusted Rand Index scores, respectively, across embedding models using BERTopic, KMeans, and HDBSCAN on the 50K dataset.

Figure 2: Calinski-Harabasz scores across embedding models using BERTopic, KMeans, and HDBSCAN on 50K dataset

Figure 3: Davies-Bouldin scores across embedding models using BERTopic, KMeans, and HDBSCAN on 50K dataset

Figure 4: Silhouette scores across embedding models using BERTopic, KMeans, and HDBSCAN on 50K dataset

Figure 5: Normalized mutual information scores across embedding models using BERTopic, KMeans, and HDBSCAN on 50K dataset

Figure 6: Adjusted rand index scores across embedding models using BERTopic, KMeans, and HDBSCAN on 50K dataset

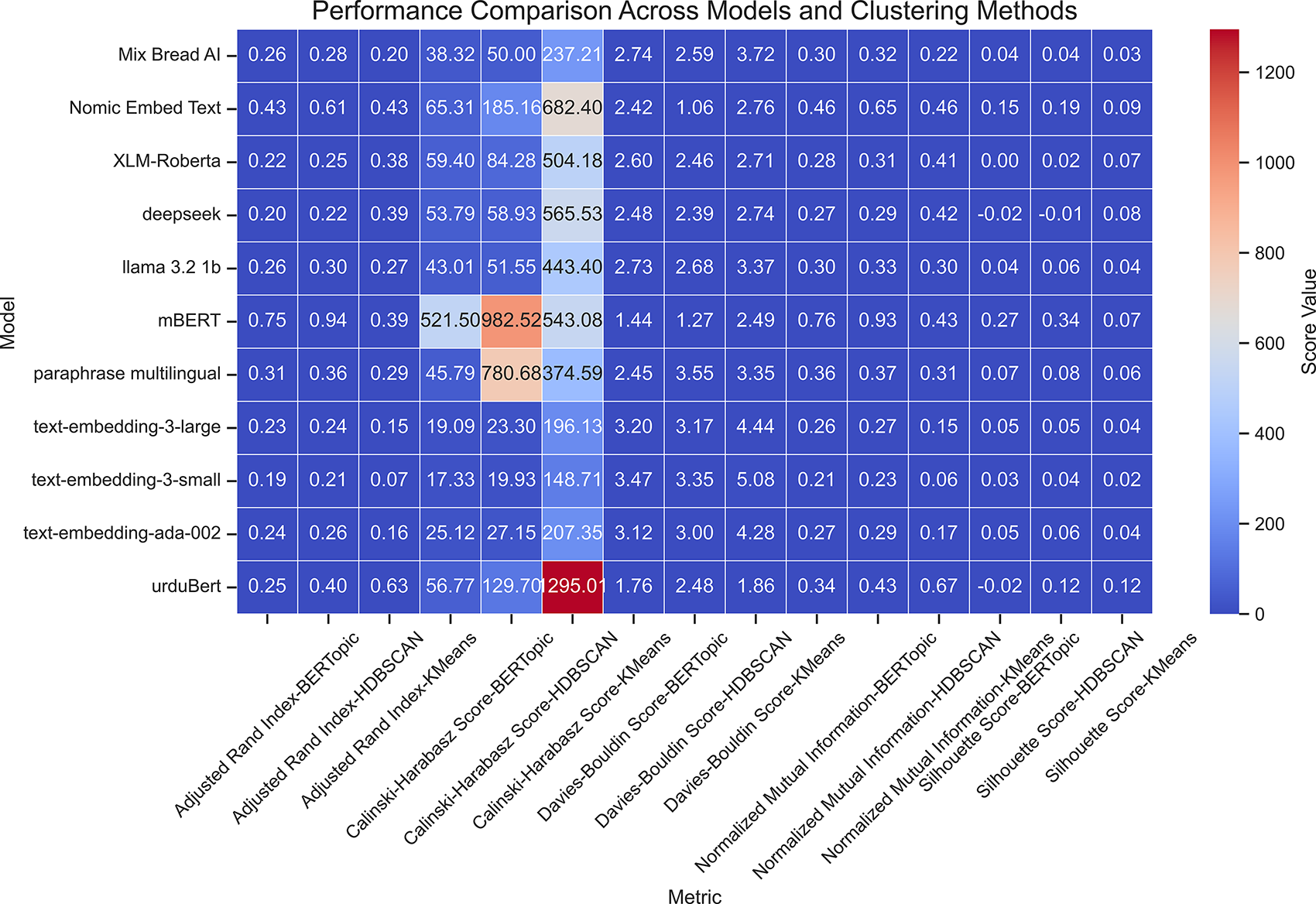

The trends on the larger 100K data were similar to the 50K data trends, which proved the robustness of the results. mBERT remained the leader in performance with HDBSCAN, while UrduBERT proved to be the best-performing model for K-Means. Nomic Embed Text also showed good and consistent results in both subsets, indicating Urdu text clustering’s scalability and stability.

Applying BERTopic to the larger dataset Table 7 showed that mBERT achieved the best clustering performance, with the highest external validity (ARI = 0.7481, NMI = 0.7593) and strong internal metrics (Silhouette = 0.2699, DBI = 1.4392, CHI = 521.50). Nomic Embed Text showed moderate results (ARI = 0.4342, NMI = 0.4551). In contrast, Deepseek and UrduBERT recorded negative Silhouette Scores (−0.0161 and −0.0165) and low external validity, indicating weak topic separation. Other embeddings, including LLaMA 3.2, Mixedbread AI, and XLM-RoBERTa, yielded low Silhouette Scores (0.0048–0.0653) and high DBI values, confirming BERTopic’s general difficulty in forming distinct Urdu clusters.

On the 100k-document dataset, the K-Means results in Table 8 showed that UrduBERT achieved the best performance with the highest ARI (0.6321), NMI (0.6741), CHI (1295.0138), and Silhouette Score (0.1215), along with the lowest DBI (1.8581), indicating strong semantic representation for Urdu text. Nomic Embed Text ranked second with solid internal (Silhouette: 0.0929, CHI: 682.4048) and external (ARI: 0.4292, NMI: 0.4567) metrics. Deepseek, mBERT, and XLM-RoBERTa showed competitive ARI/NMI scores (

On the 100k-document dataset Table 9, HDBSCAN achieved its highest performance with mBERT embeddings, revealing near-perfect agreement with ground truth (ARI = 0.9355, NMI = 0.9303) and the strongest internal validity (Silhouette = 0.3440, DBI = 1.2727, CHI = 982.52). Nomic Embed Text ranked second (ARI = 0.6109, NMI = 0.6540), followed by UrduBERT (ARI = 0.4045, NMI = 0.4308). Other embeddings, such as Deepseek, LLaMA 3.2, and OpenAI models, showed weak clustering with low ARI/NMI and poor separation. Overall, mBERT gives the most coherent and stable Urdu topic clusters.

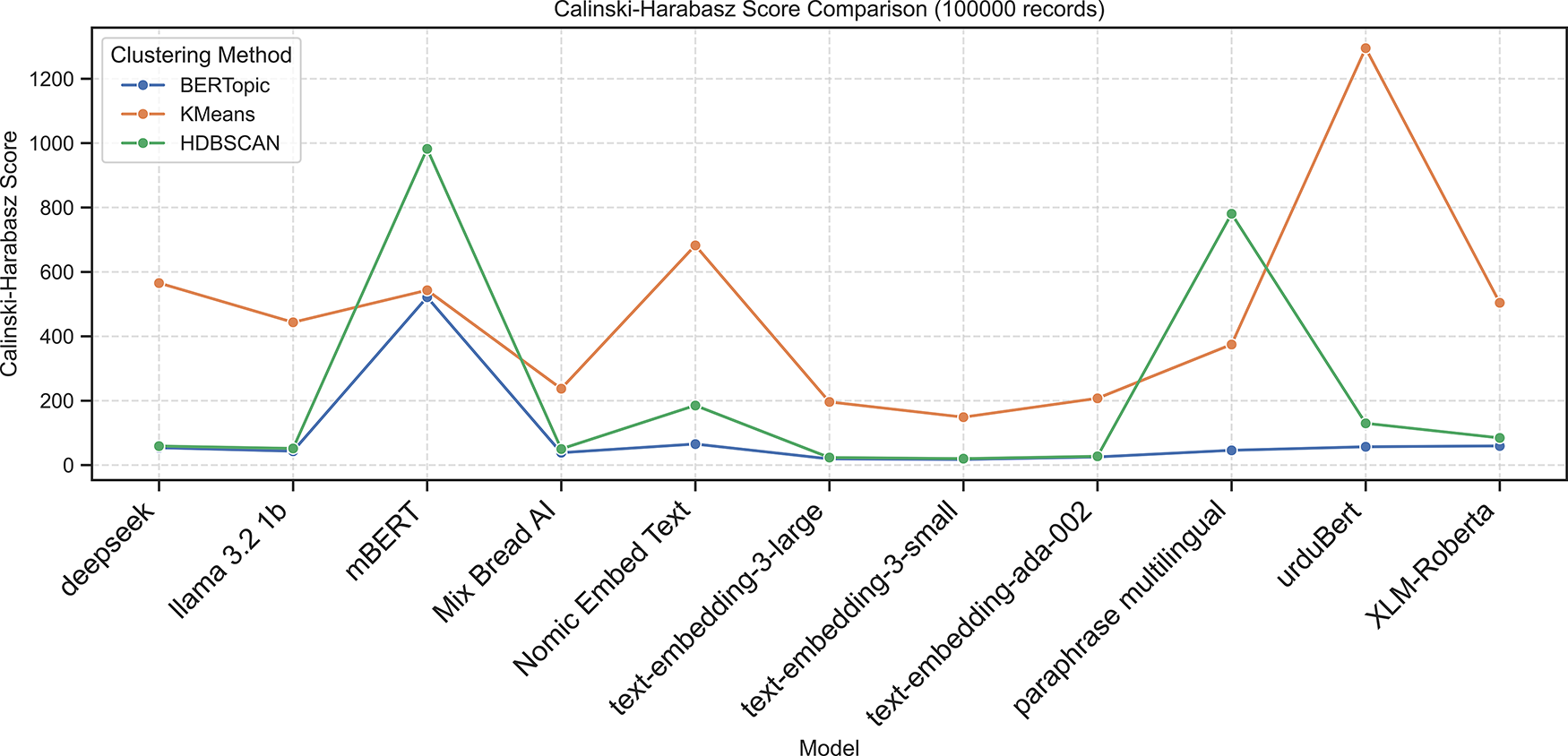

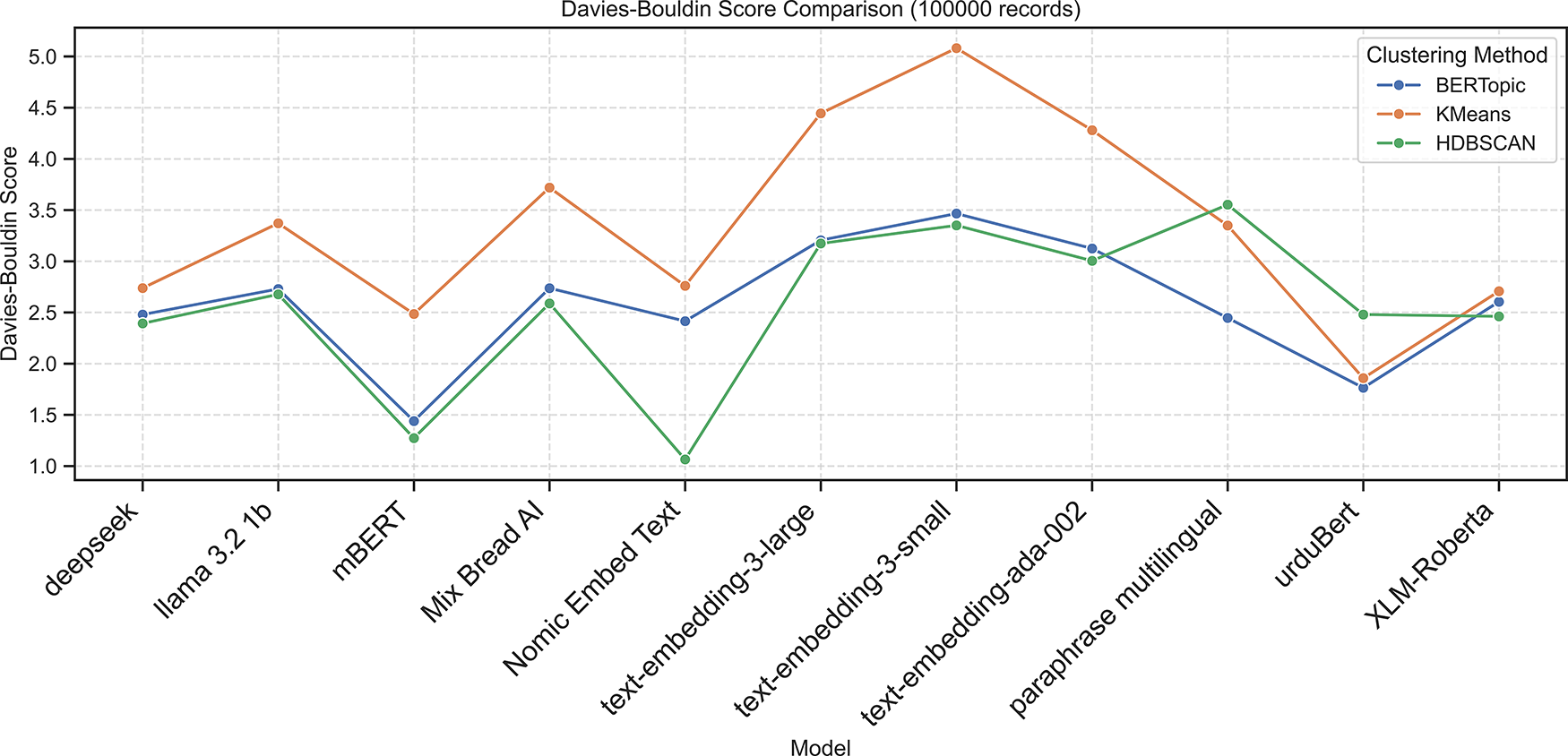

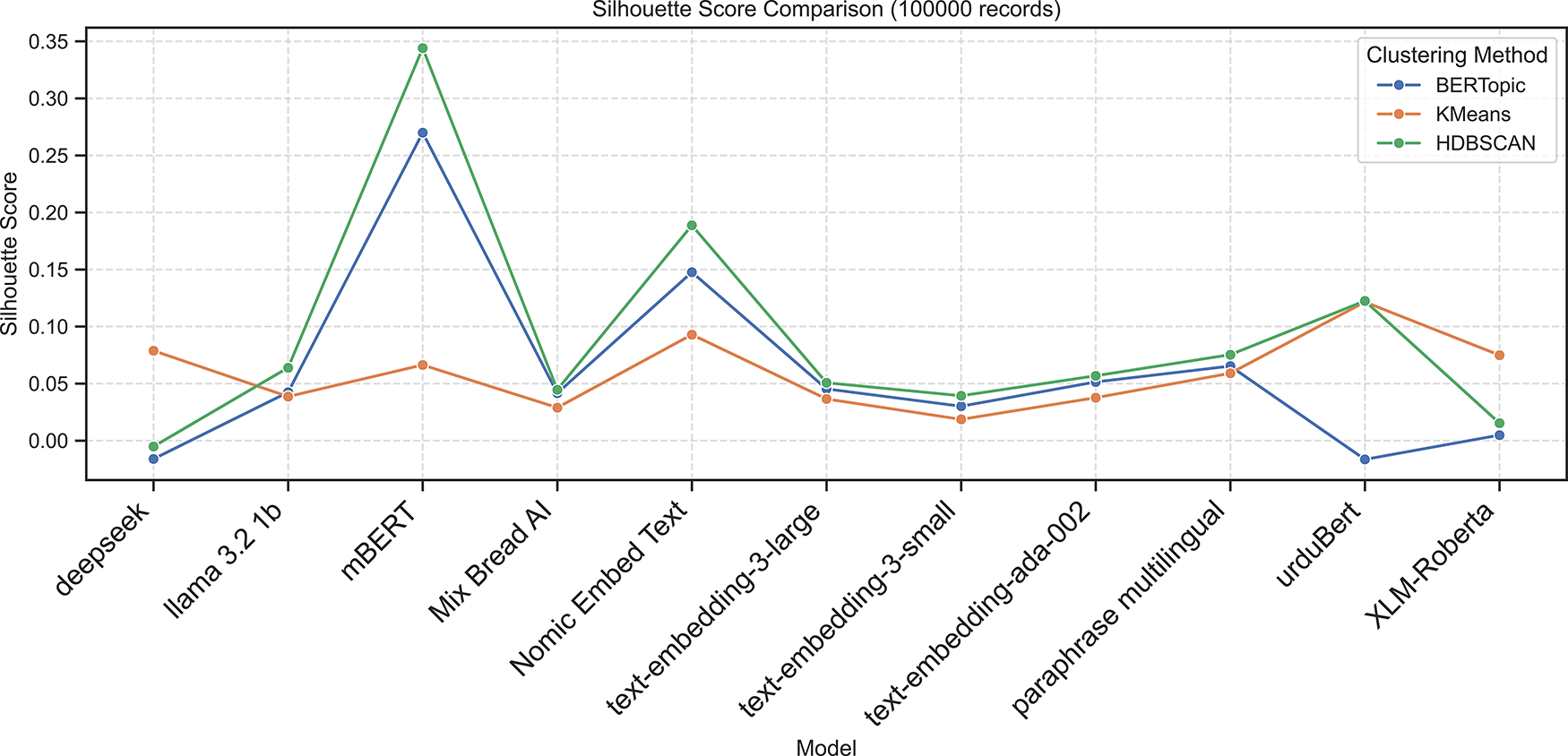

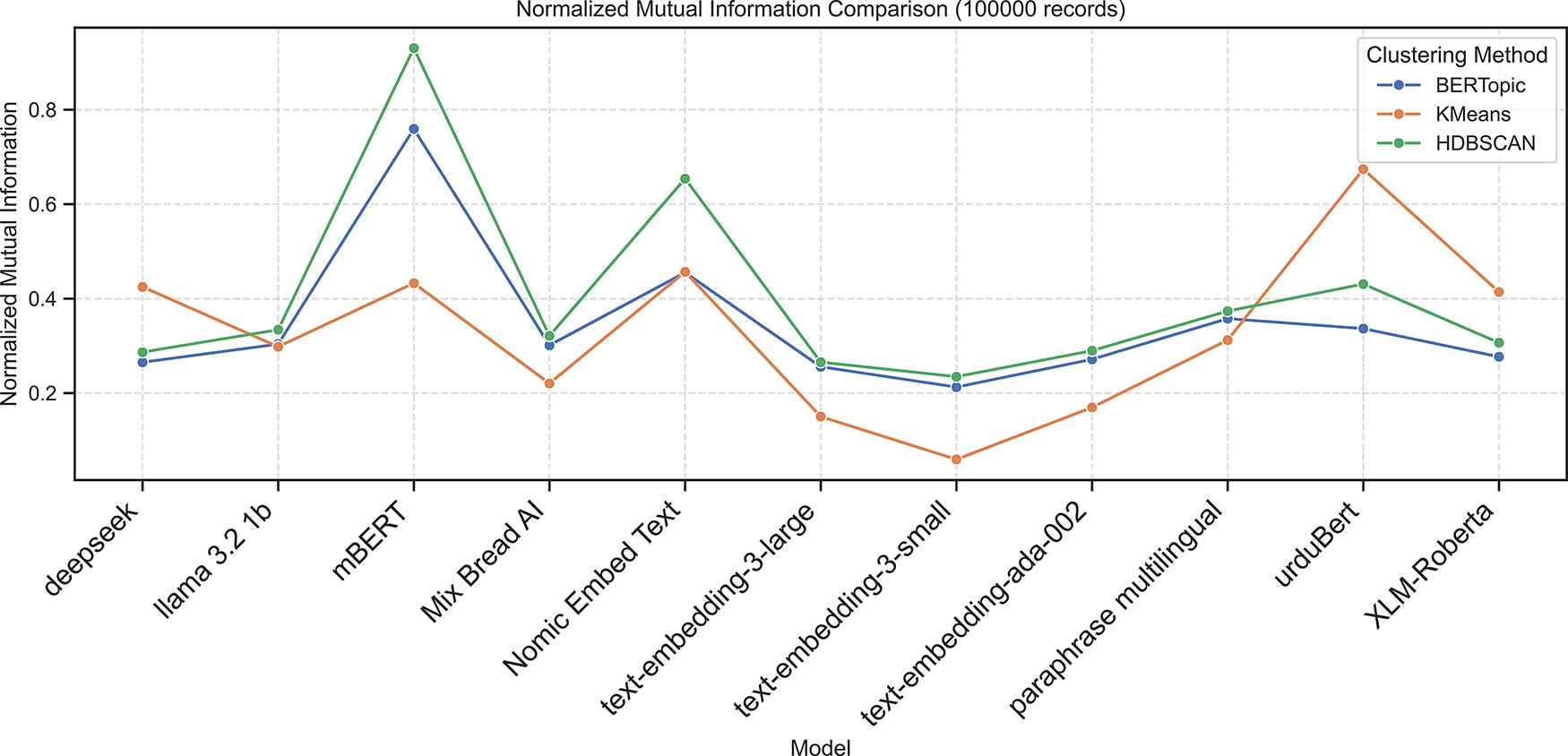

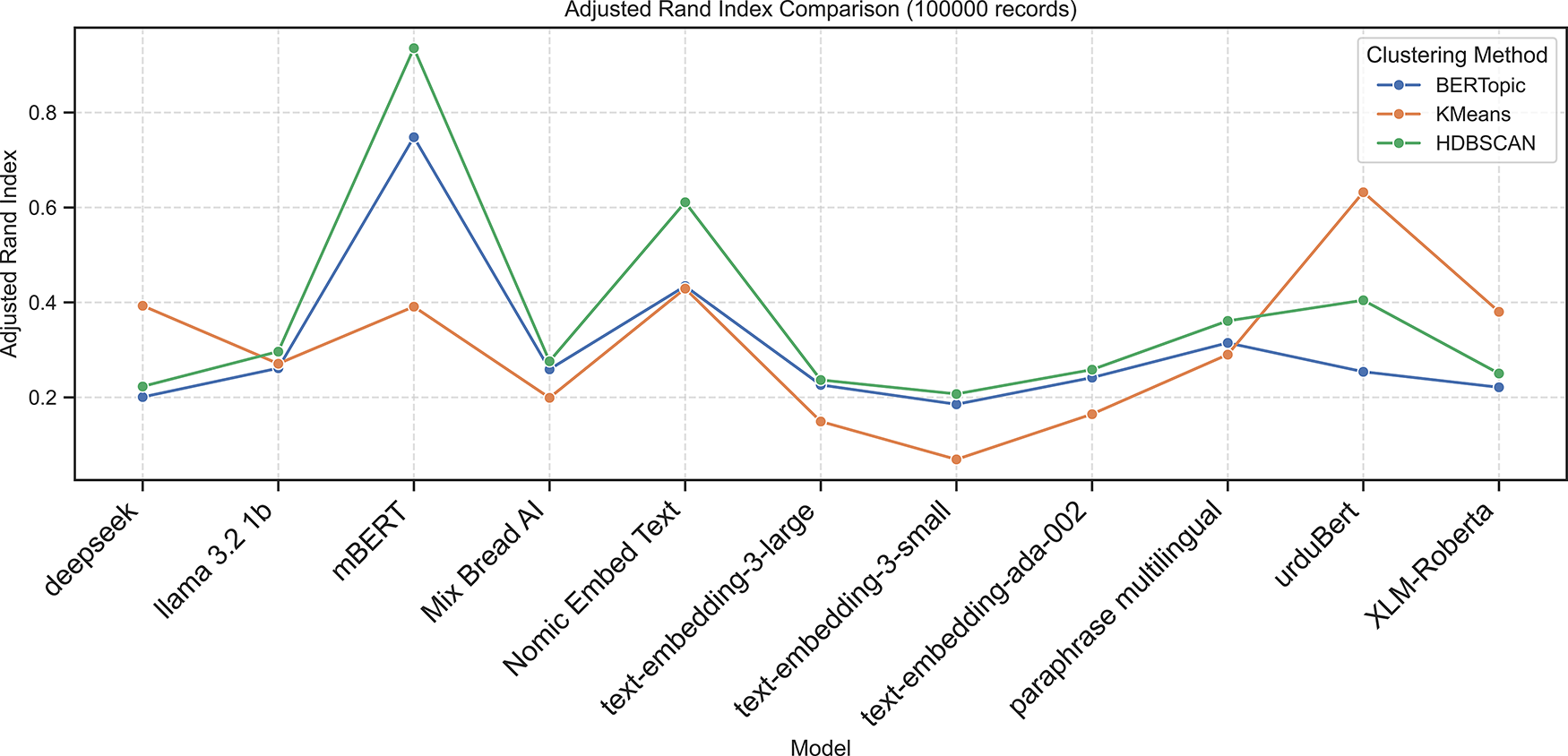

The following Figs. 7–11 present the Calinski–Harabasz, Davies–Bouldin, Silhouette, Normalized Mutual Information, and Adjusted Rand Index scores, respectively, across embedding models using BERTopic, KMeans, and HDBSCAN on the 100K dataset.

Figure 7: Calinski-Harabasz scores across embedding models using BERTopic, KMeans and HDBSCAN on 100K dataset

Figure 8: Davies-Bouldin scores across embedding models using BERTopic, K-Means, and HDBSCAN on the 100K dataset

Figure 9: Silhouette scores across embedding models using BERTopic, K-Means, and HDBSCAN on the 100K dataset

Figure 10: Normalized mutual information scores across embedding models using BERTopic, KMeans, and HDBSCAN on 100K dataset

Figure 11: Adjusted rand index scores across embedding models using BERTopic, KMeans, and HDBSCAN on 100K dataset

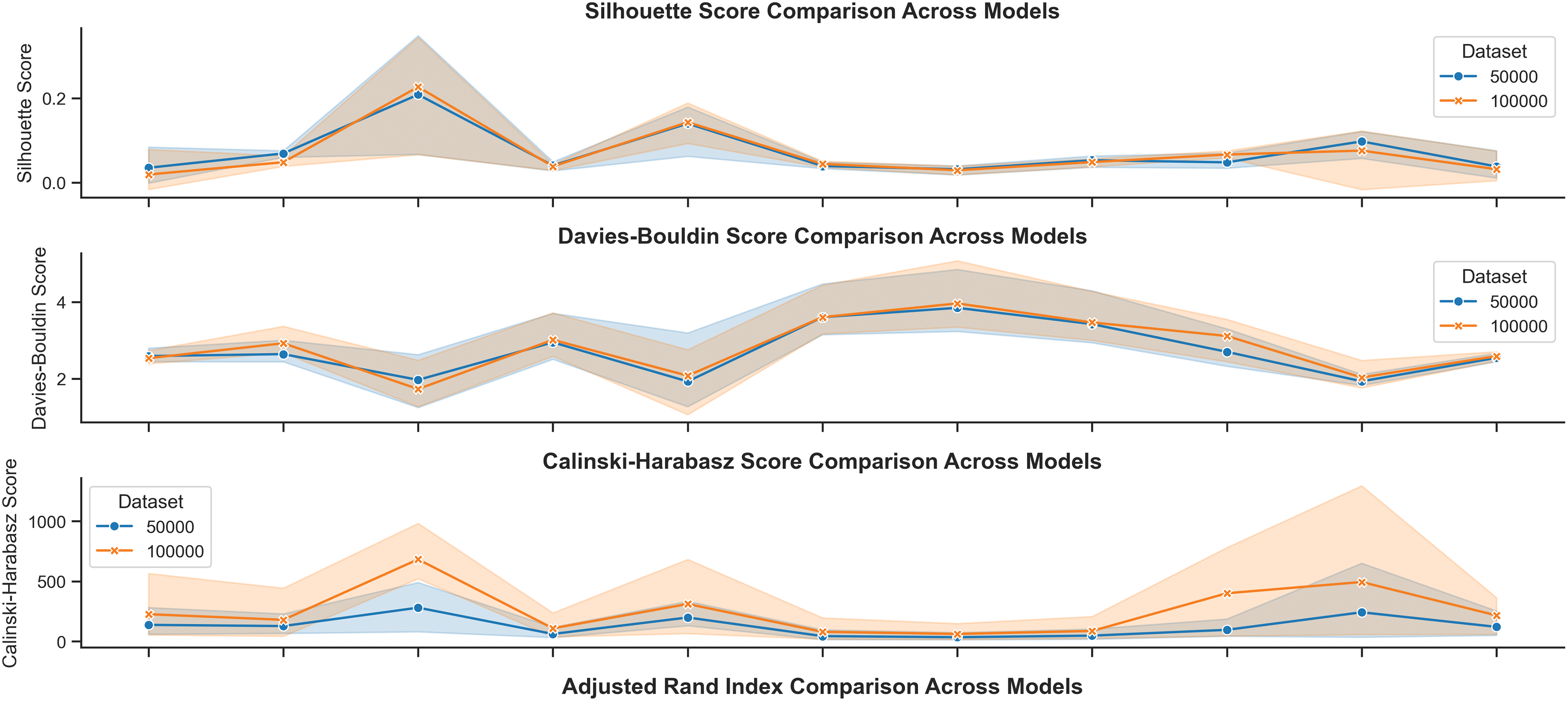

5.3 Comparative Analysis of Clustering Models across Embeddings and Datasets

The comparative analysis of clustering results across embeddings and dataset sizes provides important insights into the relationship between linguistic representation, clustering algorithms, and data scale. Fig. 12 and the corresponding heatmaps Figs. 13 and 14 explain variations in Silhouette Score, DBI, CHI, ARI, and NMI across both the 50K and 100K datasets. Tables 10 and 11 present the summary of key performance metrics across datasets.

Figure 12: Comparison of performance metrics (Silhouette, DBI, CHI) across clustering methods and embedding models

Figure 13: Heatmap of clustering performance across embedding models and clustering methods for the 50K dataset

Figure 14: Heatmap of clustering performance across embedding models and clustering methods for the 100K dataset

BERTopic performed best for obtaining semantic coherence, especially with mBERT and Nomic Embed Text. On the 100K dataset, mBERT with BERTopic recorded an ARI of 0.7481 and NMI of 0.7593, showing substantial scalability and stable topic formation. On the 50K dataset, the best external validity (ARI = 0.5929, NMI = 0.6406) was obtained with Nomic Embed Text. This consistency highlights the ability of these models to capture the contextual richness of Urdu, which is crucial for topic modeling. In contrast, UrduBERT demonstrated mixed performance when paired with BERTopic with positive Silhouette Score (0.1137) on 50K dataset but a negative one (−0.0165) on the 100K dataset, indicating less coherence for a larger amount of data.

On both datasets, HDBSCAN, especially with mBERT proved to be the most effective clustering method. This combination achieved the highest ARI and NMI values (up to 0.95 and 0.93, respectively), along with strong Silhouette and CHI scores, showing dense and clearly separated clusters. Nomic Embed Text also performed well with HDBSCAN, maintaining stable results across datasets. UrduBERT, when paired with K-Means, achieved very high CHI values (651.28 on 50K, 1295.01 on 100K, confirming its ability to capture Urdu’s morphological richness using centroid-based clustering.

Figs. 13 and 14 visualize these trends, indicating that mBERT and Nomic Embed Text consistently produce high-quality clusters. The performance becomes more uniform on the 100K dataset, suggesting that larger datasets help mitigate embedding limitations. While smaller or general-purpose embeddings like text-embedding-3-small underperformed, models such as mBERT and Nomic Embed Text showed scalability, semantic precision, and robustness, making them particularly suitable for low-resource languages like Urdu.

5.4 Technical and Linguistic Rationale for Optimal Performance

The results of the Multilingual BERT (mBERT) embeddings in combination with the HDBSCAN clustering algorithm in terms of the highest ARI and NMI scores (around 0.95) are due to a complementary interaction of the embedding and clustering methods. This combination matches very well with the linguistic features of Urdu and the structure of the news corpus.

• Multilingual Representation Learning (mBERT): The advantage of mBERT is that it has a greater multilingual pre-training that builds a common semantic space that spans over a hundred languages. Even though Urdu is relatively underrepresented in the original training corpus, the model works very well to transfer contextual knowledge between typologically related languages. This common display aids in extracting semantic significance out of the complicated orthography and morphology of Urdu (e.g., Nastaliq script and inflectional richness). As a result, mBERT produces dense language-agnostic embeddings that are able to retain topical similarity and semantic coherence despite a low-resource setting.

• Density-Aware Clustering (HDBSCAN): The HDBSCAN algorithm is a finding of clusters in high-dimensional and skewed embedding space. In contrast to K-Means, which assumes the homogeneity and sphericity of cluster shapes, HDBSCAN is able to detect clusters of any shape and density. This is necessary in real-life corpora like the Urdu news, where topical boundaries can be diffuse and interdependent, e.g., an article about Politics and an article about Policy may have the same vocabulary but differ in semantics. Besides, the ability of HDBSCAN to handle ambiguous or low-represented documents as noise is beneficial to maintain cluster purity and avoid semantic drift.

The integration of mBERT’s multilingual, semantically rich embeddings with HDBSCAN’s density-sensitive clustering approach thus provides an effective and scalable framework for Urdu text analysis, yielding robust and interpretable clusters in a linguistically challenging environment.

5.5 Qualitative Cluster and Error Analysis

In addition to the quantitative results (ARI and NMI), a qualitative assessment on clusters generated by the best-performing setup (mBERT + HDBSCAN) and a relatively weak baseline (text-embedding-3-small + HDBSCAN) was performed. This analysis was performed to evaluate topic cohesion in the real world and to determine the main causes of clustering error.

5.5.1 Cluster Cohesion and Strength (mBERT + HDBSCAN)

The optimal configuration achieved clear topic boundaries and strong intra-cluster coherence. It effectively separated closely related topics that frequently co-occur in news reporting.

• High Cohesion in Distinct Domains (Sports): The Sports cluster had a high internal consistency. For example, news items such as ‘National Cricket Team’s tour of Australia: Preparations complete’ and ‘Selection of players for upcoming matches’ were clustered together, but there was no mixing of unrelated political or economic content.

• Fine-Grained Thematic Separation (Policy): The model was able to distinguish between “Political Instability” and “Government Policy,” which is a known challenge in Urdu news data. Articles relating to international conflicts were kept apart from those relating to domestic legislation so as to indicate fine semantic discrimination.

5.5.2 Sources of Confusion and Weaknesses

Residual errors where ARI values fell short of 1.0 were primarily observed in semantically overlapping domains and in embeddings lacking Urdu-specific contextual understanding.

• Political-Economic Overlap: The misclassification between political and economic clusters was most frequent. Articles on fiscal policies or budget announcements were sometimes listed under “Politics” instead of “Economy.” For instance, the headline “Fear of inflation increases after budget approval” has a strong political element (“budget approval”) but is economically focused in content (“inflation”).

• Limitations of General-Purpose Embeddings: Low-performance models such as text-embedding-3-small were found to employ lexical over semantic similarity. In most cases, these embeddings group documents with the same Urdu words (e.g., country, region) without any contextual knowledge. For instance, the article “Rapid deforestation in the northern regions of Pakistan” (ground truth: Environment) was misclassified with regional development news (ground truth: Regional Affairs) due to the presence of the common word “regions.”

The qualitative analysis is also in agreement with the quantitative results: the combination of mBERT and HDBSCAN shows its power to capture subtle semantic differences and maintain the purity of the clusters. Its efficacy in overcoming the ambiguity in resolving the topical boundaries makes it suitable for the large-scale Urdu text classification and topic modeling tasks.

This research work was planned to address the natural challenges of text clustering in the Urdu language, which is a language that has morphological limitations of morphology complexity and the lack of adequate computational resources. By thoroughly experimenting with 33 configurations involving a variety of multilingual LLM-based embeddings and clustering algorithms (K-Means, HDBSCAN, and BERTopic), we tried to come up with a robust and scalable solution. Our analysis converged upon a singular and outstanding result: that the combination of Multilingual BERT (mBERT) embeddings with the HDBSCAN algorithm showed an unparalleled performance with a near-perfect clustering score (Adjusted Rand Index 0.94 and NMI 0.93) on the large UNC-2025 corpus. The success of this pipeline is due to a unique synergy. We attribute this high quality of the clusters to the fact that mBERT can go beyond the linguistic surface complexity of Urdu due to its cross-lingual training, which then produced a dense and semantic-centric vector space. HDBSCAN then effectively exploited this density and was able to discover arbitrarily shaped topic manifolds and robustly filter out noise, a mechanism that is of great importance in real-world news data because such data has semantic overlap. This finding was both quantitatively and qualitatively validated, showing the power of the pipeline in distinguishing even in cases of ambiguous political and economic topics. Furthermore, while the UrduBERT model was very much effective when coupled with the centroid-based K-Means algorithm (very good separation as denoted by CHI 1295), the mBERT+HDBSCAN setup is certainly able to set the new state-of-the-art benchmark for unsupervised Urdu text classification. Despite the strong overall clustering performance, the model still faces challenges in domains with high semantic overlap, particularly between political and economic news. Additionally, general-purpose embeddings lacking Urdu-specific contextual understanding limit the system’s ability to accurately differentiate nuanced categories, highlighting the need for more culturally and linguistically adapted representations in future work.

In the future, the research will be focused on further refining the semantic representation. Specifically, fine-tuning general-purpose embeddings in Urdu-specific content can help to address the failure modes directly, leading to improved accuracy across dialectal texts and code-mixed texts. Investigating lightweight variants of LLMs and hybrid clustering approaches are also important and serves as a way to balance performance, interpretability, and computational cost for practical, large-scale deployment. In conclusion, this research has been capable of bridging the resource gap of Urdu NLP by offering a scalable and highly accurate solution leading to fair progress in language technologies all over the world.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Department of Computer Science, The University of Faisalabad, for their support and resources. We also thank our colleagues for their insightful discussions and guidance throughout this study.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), Taiwan under grant number 114-2221-E-182-041-MY3, and by Chang Gung University and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital under project number NERPD4Q0021.

Author Contributions: Talha Farooq Khan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft, Data Curation. Majid Hussain: Data Preprocessing, Software Implementation, Validation. Muhammad Arslan: Experiment Design, Results Analysis, Visualization. Muhammad Saeed: Literature Review, Writing—Review & Editing. Lal Khan: Supervision, Project Administration, Editing, and Writing. Hsien-Tsung Chang: Supervision, Methodology Guidance, Reviewing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used in this study, including the UNC-2025 Urdu news corpus, cannot be made publicly available due to copyright and licensing restrictions associated with the original news sources. As the corpus contains content collected from third-party publishers, open redistribution is not permitted. However, the dataset can be shared for non-commercial research purposes upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants or animals, and no ethical approval was required.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Dhir S, Rastogi N, Sinha A, Rani R, Goel N. News in vectors: optimizing news analysis through advanced embeddings and clustering. In: 2024 2nd International Conference on Advancement in Computation & Computer Technologies (InCACCT); 2024 May 2–3; Gharuan, India. p. 40–5. [Google Scholar]

2. Khan L, Amjad A, Ashraf N, Chang HT, Gelbukh A. Urdu sentiment analysis with deep learning methods. IEEE Access. 2021;9:97803–12. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3093078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Khan L, Amjad A, Ashraf N, Chang HT. Multi-class sentiment analysis of Urdu text using multilingual BERT. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):5436. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-09381-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hassan ME, Maab I, Hussain M, Habib U, Matsuo Y. Polarity classification of low resource roman Urdu and movie reviews sentiments using machine learning-based ensemble approaches. IEEE Open J Comput Soc. 2024;5(3):599–611. doi:10.1109/ojcs.2024.3476378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Anwar W, Bajwa IS, Choudhary MA, Ramzan S. An empirical study on forensic analysis of Urdu text using LDA-based authorship attribution. IEEE Access. 2019;7:3224–34. doi:10.1109/access.2018.2885011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Khan L, Amjad A, Afaq KM, Chang HT. Deep sentiment analysis using CNN-LSTM architecture of English and Roman Urdu text shared in social media. Appl Sci. 2022;12(5):2694. doi:10.3390/app12052694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Khan TF, Anwar W, Arshad H, Abbas SN. An empirical study on authorship verification for low resource language using hyper-tuned CNN approach. IEEE Access. 2023;11:80403–15. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3299565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ashraf N, Khan L, Butt S, Chang HT, Sidorov G, Gelbukh A. Multi-label emotion classification of Urdu tweets. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2022;8(3):e896. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jamjoom AA, Karamti H, Umer M, Alsubai S, Kim T-H, Ashraf I. Enhanced RoBERTa transformer based model for cyberbullying detection with GloVe features. IEEE Access. 2024;12(1):58950–9. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3386637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Kumar M, Khan L, Choi A. RAMHA: a hybrid social text-based transformer with adapter for mental health emotion classification. Mathematics. 2025;13(18):2918. doi:10.3390/math13182918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Siino M, Falco M, Croce D, Rosso P. Exploring LLMs applications in law: a literature review on current legal NLP approaches. IEEE Access. 2025;13(9):18253–76. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3533217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Rasheed HM, Banka I, Khan H. A hybrid feature selection approach based on LSI for classification of Urdu text. In: Machine learning algorithms for industrial applications. Cham, Swizterland: Springer; 2021. p. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

13. Svetlana U, Bakhtiyor K, Suyun K, Mamura N. Automatic topic detection in large text data in uzbek using clustering methods. In: 2024 9th International Conference on Computer Science and Engineering (UBMK); 2024 Oct 26–28; Antalya, Turkiye. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

14. Alomari E. Unlocking the potential: a comprehensive systematic review of ChatGPT in natural language processing tasks. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;141(1):43–85. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.052256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Karim AA, Ibrahim MA, Hosny MM, Ibrahim AH. A comparative analysis of Arabic text summarization techniques: evaluating word frequency, K-means clustering, and PageRank algorithm. In: 2024 International Mobile, Intelligent, Ubiquitous Computing Conference (MIUCC); 2024 Nov 13–14; Cairo, Egypt. p. 257–64. [Google Scholar]

16. Ullah K, Aslam M, Khan MUG, Alamri FS, Khan AR. UEF-HOCUrdu: unified embeddings ensemble framework for hate and offensive text classification in Urdu. IEEE Access. 2025;13(1):21853–69. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3532611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ali S, Jamil U, Younas M, Zafar B, Hanif MK. Optimized identification of sentence-level multiclass events on Urdu-language text using machine learning techniques. IEEE Access. 2025;13:1–25. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3522992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Hartigan J, Wong M. Algorithm AS 136: a K-means clustering algorithm. J Royal Stat Soc Ser C Appl Stat. 1979;28(1):100–8. [Google Scholar]

19. Mim SS, Logofatu D. A cluster-based analysis for targeting potential customers in a real-world marketing system. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 18th International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing (ICCP); 2022 Sep 22–24; Cluj-Napoca, Romania. p. 159–66. [Google Scholar]

20. Pitchayaviwat T. A study on clustering customer suggestions on online social media about insurance services by using text mining techniques. In: 2016 Management and Innovation Technology International Conference (MITicon); 2016 Oct 12–14; Bang-San, Thailand. MIT-148MIT151. [Google Scholar]

21. Mehta V, Mehra R, Verma SS. A survey on customer segmentation using machine learning algorithms to find prospective clients. In: 2021 9th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions) (ICRITO); 2021 Sep 3–4; Noida, India. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

22. Ling SS, Too CW, Wong WY, Hoo MH. Customer relationship management system for retail stores using unsupervised clustering algorithms with RFM modeling for customer segmentation. In: 14th IEEE Symposium on Computer Applications and Industrial Electronics (ISCAIE 2024); 2024 May 24–25; Penang, Malaysia. p. 550–5. [Google Scholar]

23. Regmi SR, Meena J, Kanojia U, Kant V. Customer market segmentation using machine learning algorithm. In: 6th International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI 2022); 2022 Apr 28–30; Tirunelveli, India; 2022. p. 1348–54. [Google Scholar]

24. Salton G, Wong A, Yang CS. A vector space model for automatic indexing. Commun ACM. 1975;18(11):613–20. doi:10.1145/361219.361220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Khomsah S. Sentiment analysis on YouTube comments using Word2Vec and random forest. Telematika. 2021;18(1):61. doi:10.31315/telematika.v18i1.4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Dogru HB, Tilki S, Jamil A, Hameed AA. Deep learning based classification of news texts using Doc2Vec model. In: 2021 1st International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Data Analytics (CAIDA); 2021 Apr 6–7; Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. p. 91–6. [Google Scholar]

27. Mu W, Lim KH, Liu J, Karunasekera S, Falzon L, Harwood A. A clustering-based topic model using word networks and word embeddings. J Big Data. 2022;9(1):1–38. doi:10.1186/s40537-022-00585-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Mustafa M, Zeng F, Manzoor U, Meng L. Discovering coherent topics from Urdu text: a comparative study of statistical models, clustering techniques and word embedding. In: 2023 6th International Conference on Information and Computer Technologies (ICICT); 2023 Mar 24–26; Raleigh, NC, USA. p. 127–31. [Google Scholar]

29. Ogunleye B, Maswera T, Hirsch L, Gaudoin J, Brunsdon T. Comparison of topic modelling approaches in the banking context. Appl Sci. 2023;13(2):797. doi:10.3390/app13020797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Abadi M, Barham P, Chen JM, Chen ZF, Davis A, Dean J, et al. TensorFlow: a system for large-scale machine learning. In: Proceedings of the 12th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI). 2016 Nov 2–4; Savannah, GA, USA. p. 265–83. [Google Scholar]

31. Elbarougy R, Behery G, El Khatib A. Extractive Arabic text summarization using modified PageRank algorithm. Egyptian Inf J. 2020;21(2):73–81. doi:10.1016/j.eij.2019.11.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Atef A, Seddik F, Elbedewy A. AGS: Arabic GPT summarization corpus. In: 2023 International Conference on Electrical, Communication and Computer Engineering (ICECCE); 2023 Dec 30–31; Dubai, UAE. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

33. George L, Sumathy P. An integrated clustering and BERT framework for improved topic modeling. Int J Inf Technol. 2023;15(4):2187–95. doi:10.1007/s41870-023-01268-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Budiarto A, Rahutomo R, Putra HN, Cenggoro TW, Kacamarga MF, Pardamean B. Unsupervised news topic modelling with doc2vec and spherical clustering. Procedia Comput Sci. 2021;179(1):40–6. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2020.12.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Lytvynenko V, Olszewski S, Osypenko V, Lurie I, Demchenko V, Dontsova D. Comparing the effectiveness of generative adversarial networks for clustering tasks. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 19th International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technologies (CSIT); 2024 Oct 16–19; Lviv, Ukraine. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

36. Karim AA, Usama M, Ibrahim MA, Hatem Y, Wael W, Mazrua AT, et al. Arabic abstractive summarization using the multilingual T5 model. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computing and Informatics (ICCI); 2024 Mar 6–7; Cairo, Egypt. p. 223–8. [Google Scholar]

37. Shahane S. Urdu news dataset; 2020. [cited 2025 Aug 7]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/saurabhshahane/urdu-news-dataset. [Google Scholar]

38. Petukhova A, Matos-Carvalho JP, Fachada N. Text clustering with large language model embeddings. Int J Cogn Comput Eng. 2025;6(11):100–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijcce.2024.11.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Lee S, Shakir A, Koenig D, Lipp J. Open source strikes bread-new fluffy embeddings model. Vancouver, BC, Canada: Mixedbread AI Inc.; 2024. [Google Scholar]

40. nomic-embed-text-v1.5—Hugging face model card; 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 9]. Available from: https://huggingface.co/nomic-ai/nomic-embed-text-v1.5. [Google Scholar]

41. Conneau A, Khandelwal K, Goyal N, Chaudhary V, Wenzek G, Guzmán F, et al. Unsupervised cross-lingual representation learning at scale. arXiv:1911.02116. 2019. [Google Scholar]

42. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2019 Jun 2–7; Minneapolis, MN, USA. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

43. Reimers N, Gurevych I. Sentence-BERT: sentence embeddings using siamese BERT-networks; arXiv:1908.10084.2019. [Google Scholar]

44. OpenAI. New embedding models and API updates; 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 6]. Available from: https://platform.openai.com/docs/models/text-embedding-3-small. [Google Scholar]

45. OpenAI. Text-embedding-Ada-002 model documentation; 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 6]. Available from: https://platform.openai.com/docs/models/text-embedding-ada-002. [Google Scholar]

46. UrduBERT. Hugging face model card; 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 9]. Available from: https://huggingface.co/mahwizzzz/UrduBert. [Google Scholar]

47. McQueen JB. Some methods of classification and analysis of multivariate observations. Berkeley Symp on Math Statist and Prob. 1967;5(1):281–97. [Google Scholar]

48. Campello RJGB, Moulavi D, Sander J. Density-based clustering based on hierarchical density estimates. In: Pacific-Asia Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2013 Apr 14–17; Gold Coast, QLD, Australia. p. 160–72. [Google Scholar]

49. Grootendorst M. BERTopic: neural topic modeling with a class-based TF-IDF procedure. arXiv:2203.05794. 2022. [Google Scholar]

50. Strehl A, Ghosh J, Mooney R. Impact of similarity measures on web-page clustering. In: Workshop on Artificial Intelligence for Web Search (AAAI 2000); 2000 Jul 30–31; Austin, TX, USA. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

51. Peter J, Rousseeuw S. Silhouettes: a graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J Comput Appl Math. 1987;20:53–65. doi:10.1016/0377-0427(87)90125-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Davies DL, Bouldin DW. A cluster separation measure. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2009;2(2):224–7. doi:10.1109/tpami.1979.4766909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Caliński T, Harabasz J. A dendrite method for cluster analysis. Commun Stat—Methods. 1974;3(1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools