Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Multivariate Lithium-ion Battery State Prediction with Channel-Independent Informer and Particle Filter for Battery Digital Twin

Department of Industrial and Management Systems Engineering, Kyung Hee University, Yongin-si, 17104, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Younghoon Kim. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 3723-3745. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.073030

Received 09 September 2025; Accepted 13 November 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

Accurate State-of-Health (SOH) prediction is critical for the safe and efficient operation of lithium-ion batteries (LiBs). However, conventional methods struggle with the highly nonlinear electrochemical dynamics and declining accuracy over long-horizon forecasting. To address these limitations, this study proposes CIPF-Informer, a novel digital twin framework that integrates the Informer architecture with Channel Independence (CI) and a Particle Filter (PF). The CI mechanism enhances robustness by decoupling multivariate state dependencies, while the PF captures the complex stochastic variations missed by purely deterministic models. The proposed framework was evaluated using the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) battery dataset against benchmark deep learning models. Results demonstrate that CIPF-Informer consistently achieves superior performance, in multivariate and long sequence forecasting scenarios. By effectively synergizing a model-based method with a data-driven model, CIPF-Informer provides a more reliable pathway for advancing Battery Management System (BMS) technologies, contributing to the development of safer and more sustainable energy storage systems.Keywords

The proliferation of lithium-ion batteries (LiBs) in critical applications like electric vehicles (EVs) and energy storage systems (ESSs) necessitates advanced Battery Management Systems (BMS) to ensure safety and longevity [1–4]. Accurate State-of-Health (SOH) estimation is a cornerstone of BMS for predicting battery degradation and enabling preventive maintenance [5,6], yet it remains a significant challenge due to the battery’s complex, nonlinear degradation dynamics influenced by various factors [1].

While many methods exist, they face critical limitations. Model-based approaches struggle with nonlinearities [7], while purely data-driven models often lack generalizability and ignore physical principles [8–11]. Hybrid methods show promise [12], but most remain focused on univariate SOH prediction, overlooking the coupled dynamics between voltage, current, and temperature that are vital for a comprehensive Digital Twin (DT) [13]. Furthermore, many deep learning models, including the Transformer [14], suffer from high computational complexity, limiting their utility for long-horizon forecasting of battery lifecycle data.

This paper argues that a truly effective battery DT requires a model that is simultaneously multivariate, robustly hybridized, and computationally efficient for long-term prediction. To this end, we propose CIPF-Informer, a novel framework integrating Channel Independence (CI) and a Particle Filter (PF) with the efficient Informer architecture. This study aims to answer the following key research questions:

• How can a model simultaneously predict multiple battery state variables (voltage, current, temperature, SOH) without sacrificing the accuracy of the primary SOH prediction task?

• Can the systematic integration of a model-based filter (PF) and a channel-independent deep learning architecture (CI-Informer) yield a synergistic effect that surpasses the performance of each individual component?

• Does the proposed multivariate, hybrid framework (CIPF-Informer) achieve state-of-the-art performance against established deep learning models in long-horizon battery forecasting tasks?

By addressing these questions, we seek to demonstrate a more holistic and robust pathway for developing next-generation battery digital twins. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews related work, Section 3 describes our methodology, Section 4 details the experimental setup, Section 5 reports and analyzes the results, Section 6 discusses the practical implications, and Section 7 concludes the study by answering our research questions.

State-of-Health (SOH) estimation is a key application of time-series analysis in battery research. Methodologies have evolved from model-based to data-driven and hybrid approaches, each presenting a trade-off between physical interpretability, accuracy, and computational cost. Recently, Digital Twin (DT) technology has emerged as a demanding application area, requiring models that are not only accurate but also computationally efficient for long-term, multivariate forecasting in real-time. This section critically reviews the evolution of prognostic models, analyzing their limitations in the context of these demanding DT requirements to establish the motivation for our proposed approach.

2.1 Model-Based, Data-Driven, and Hybrid Methods

Model-based approaches rely on mathematical representations of battery electrochemical processes. The Kalman Filter (KF) is widely used due to its interpretability [15,16], but is limited by linear assumptions. To address this, nonlinear variants such as the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) [17], Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) [18], and Particle Filter (PF) [19] were introduced. While the PF excels in modeling highly nonlinear systems, this accuracy comes at a significant computational cost, with a complexity of approximately

Data-driven methods emerged to model complex patterns without requiring detailed physical knowledge [21]. Traditional machine learning algorithms such as Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) [8], Support Vector Machines (SVM) [10], Fuzzy Logic [22], and Random Forests [9] have demonstrated robust performance but often depend on manual feature engineering. Deep learning models, particularly Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [23] and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks [24], automated this process and improved accuracy. However, their sequential nature, with a time complexity of

A recent innovation that enhances robustness, particularly in multivariate tasks, is Channel Independence. This approach processes each variable independently and has shown strong performance in various backbones, including CNNs [27], linear models [28], and Transformers [29,30].

Hybrid approaches combine the strengths of both paradigms [12]. For instance, Shi [31] used a KF for pre-processing before an Transformer, achieving a 25% improvement in Mean Squared Error. However, a critical analysis reveals two persistent limitations. First, many existing hybrid models create a significant computational bottleneck by naively combining two computationally expensive models, such as a standard Transformer (

The Digital Twin (DT) paradigm, originally introduced by NASA [33], aims to create a real-time, virtual replica of a physical battery system for predictive diagnostics and optimized control [34,35]. However, a high-fidelity DT, often integrated into EVs [1], ESSs [4], and smart grids [36] to enhance reliability [3], imposes stricter requirements that reveal limitations in the prognostic models described above.

First, a true DT requires a comprehensive, multivariate understanding of the battery’s state. As noted, most studies focus on univariate predictions, a critical shortcoming for a holistic system view. Second, the real-time nature of a DT makes computational efficiency paramount, as high-frequency data updates create significant computational demands [37]. The quadratic complexity of standard Transformers, for example, is often too slow. Finally, the reliability of a DT depends on its physical plausibility. The battery’s operational complexity makes accurate modeling difficult [38], and purely data-driven models, even efficient ones, can produce physically unrealistic predictions, reducing the reliability of AI-driven control strategies [39].

The preceding review highlights a clear research gap for a framework that can satisfy the demanding requirements of a practical battery DT. This gap can be summarized by two key needs:

1. Computational efficiency for LSTF: While standard Transformers are too slow (

2. A shift from univariate to multivariate forecasting: A comprehensive DT requires moving beyond single-variable SOH prediction to a multivariate approach where multiple key battery state variables are forecasted simultaneously.

To address these specific gaps, this study makes the following contributions:

• We propose a multivariate time-series prediction model that extends beyond SOH estimation, enhancing the scope and interpretability of battery digital twins.

• We develop an efficient hybrid architecture that combines a Particle Filter (PF) and Channel Independence (CI) with the computationally efficient Informer (

• We empirically demonstrate the superior performance of our proposed model in both prediction accuracy and robustness compared to state-of-the-art models in multivariate, long-horizon forecasting tasks.

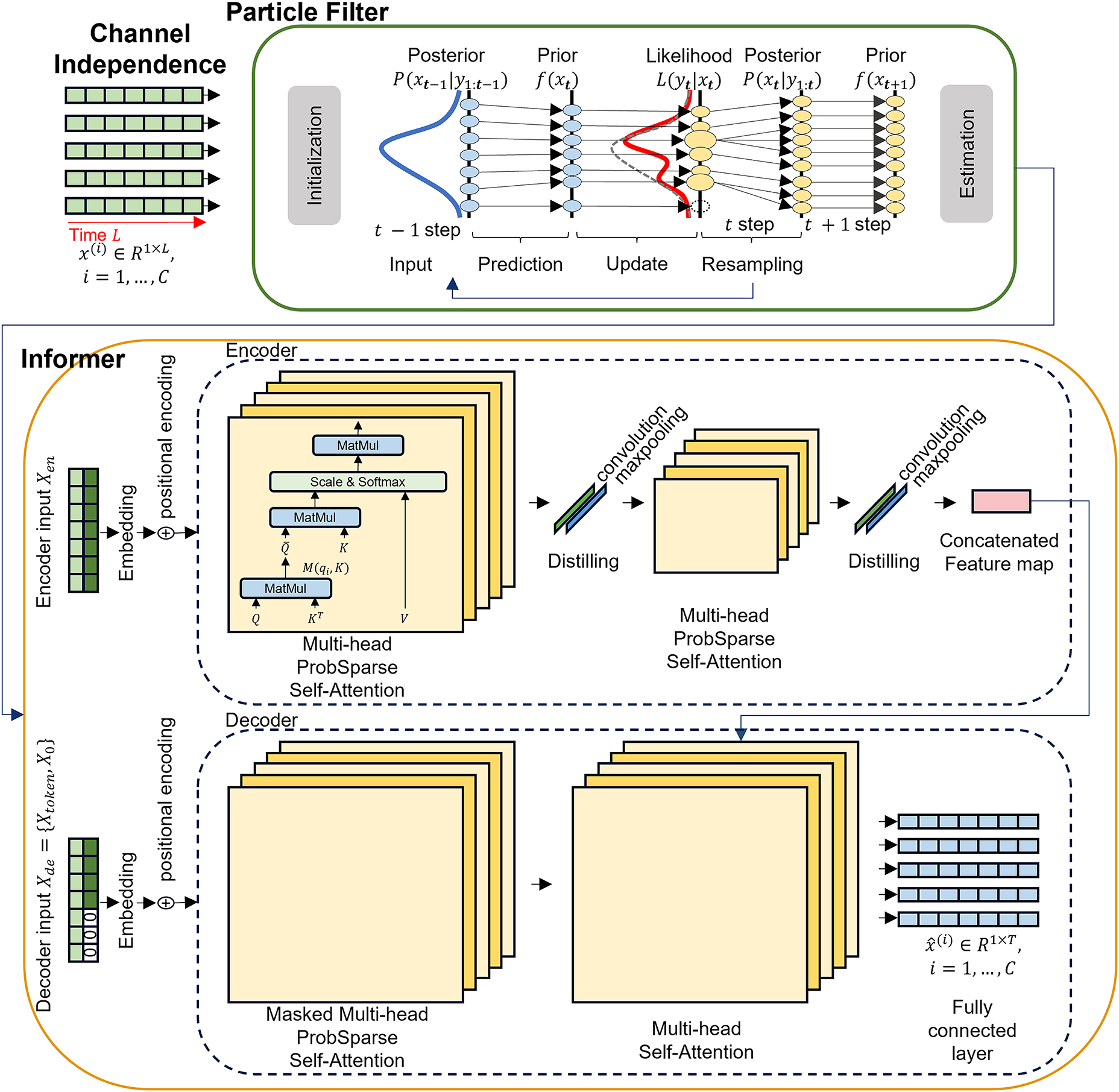

In this study, we propose the CIPF-Informer model for the digital twin of lithium-ion batteries (LiBs). The proposed method integrates Channel Independence (CI) and Particle Filter (PF) into an Informer-based time series forecasting model to effectively capture the nonlinear and dynamic characteristics of batteries. This approach aims to enhance the accuracy of battery state estimation and improve the stability of long-term forecasting. Fig. 1 illustrates the overall architecture of the CIPF-Informer model, where each component is designed to process input time-series data and optimize battery state prediction performance.

Figure 1: CIPF-Informer architecture. The backbone, represented by the blue border, is used for training the data. The green border represents the particle filter, and the yellow border represents the informer

3.1 Long Sequence Time-Series Forecasting

This study addresses the Long Sequence Time-series Forecasting (LSTF) problem. Using a fixed-size sliding window approach, the objective is to predict a sequence of

where

Multivariate time-series data in batteries consist of multiple independent time-series channels. Given a lookback window:

where C represents the total number of channels and L is the length of the observation window. Each univariate time-series of length L for channel

Each input sequence

where

In this study, the input variables are set as

Each univariate time series of length L starting from time index 1 is denoted as

The Particle Filter (PF) is an algorithm used for state estimation in nonlinear and non-Gaussian systems. In this study, the PF is applied as a preprocessing step to incorporate the physical characteristics of the input data and filter out noise before it is fed into the deep learning model. The main steps of the Particle Filter algorithm, as applied in our framework, are detailed below.

First, a set of N weighted particles

The state of the system is governed by a state transition model, generally defined as:

where

where the parameters

where

The PF algorithm then proceeds iteratively. The prediction step propagates each particle forward using the system dynamics. The posterior probability density function

The update step adjusts the particle weights based on the new observation

where

To prevent particle degeneracy where a few particles have all the weight, a resampling step is performed. This step redistributes the particles, eliminating those with low weights and replicating those with high weights, typically resetting all weights to

Finally, the estimated state at time

In this study, the Particle Filter is applied to the input time-series data

The processed data, with filtered noise and enhanced physical characteristics, is then fed into the Informer-based data-driven model. The core mechanisms of Informer used in the proposed method are outlined below.

Model Input The output

Subsequently,

ProbSparse Self-attention The Self-attention mechanism in Informer exploits the long-tail distribution property of self-attention scores in Transformers. Instead of computing all attention scores, ProbSparse Self-attention selects only the most dominant queries, reducing computational complexity:

where Q, K and V represent the query, key, and value matrices, respectively, and

Encoder input

where

where

Encoder’s Distilling Operation The distilling operation in the encoder filters out important information from the input sequence. It assigns higher weights to dominant features, reducing the length of the input sequence by half and decreasing spatial complexity. The distilling process propagates from the

where

Decoder’s Generating Structure The output is obtained using the decoder’s generating structure, which reduces decoding time and prevents cumulative error propagation during the prediction period. The start token is a sequence of length

where

In this study, the decoder input is defined as follows:

where

Subsequently,

where

The performance of a battery gradually deteriorates over time, potentially preventing it from fulfilling its expected operational lifespan. Therefore, monitoring the State of Health (SOH) of a battery is essential [40]. SOH is defined as the ratio of the currently available capacity to the initial capacity, serving as an indicator of battery degradation and overall health status over time:

where

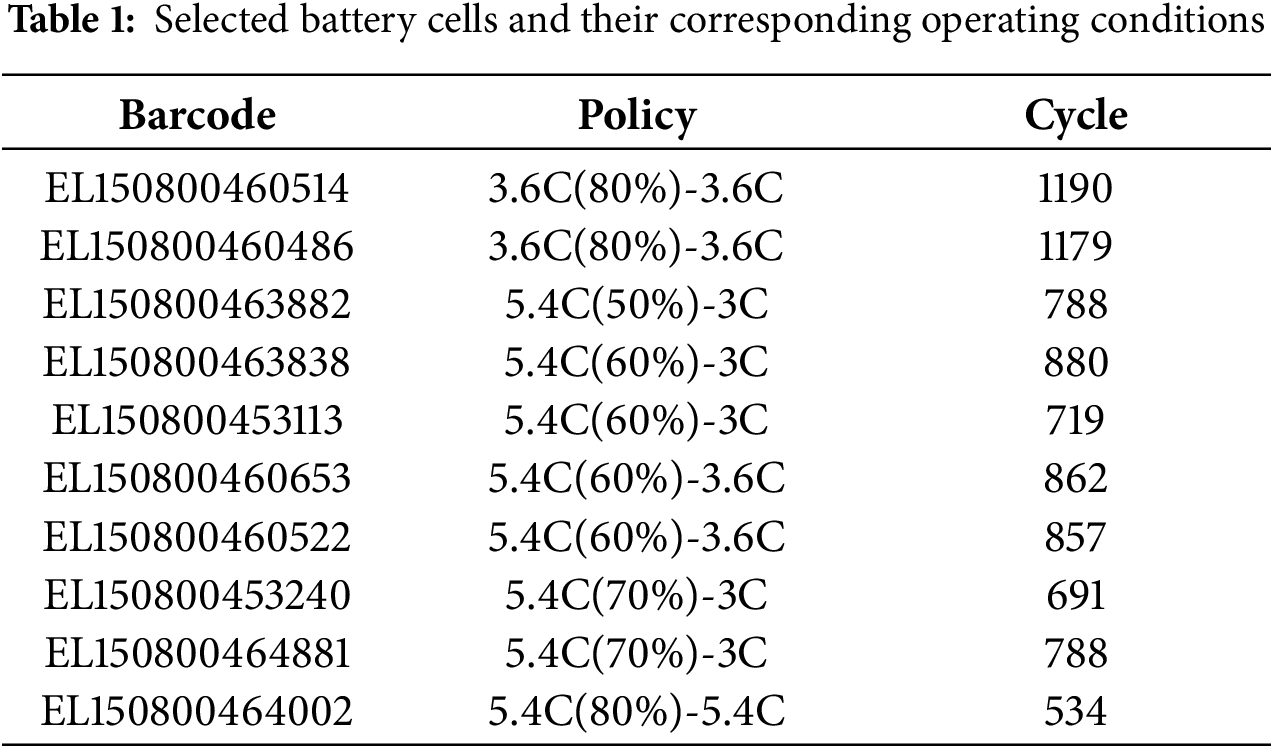

The dataset used in this study is obtained from a publicly available dataset provided by MIT [41]. It consists of 124 lithium iron phosphate (LFP) battery cells, which have been cycled under 72 different operating conditions. Among them, 10 battery cells were selected for evaluation of the proposed method. The nominal capacity of these cells is 1.1 Ah, and the batteries were charged using a two-step fast-charging protocol. This charging protocol follows the format C1(Q1)-C2, where C1 and C2 are the first and second constant current (CC) charging phases, respectively, and Q1 represents the state of charge (SOC; %) at which the current transition occurs. The second current phase is terminated at 80% SOC, after which the cells are charged using a 1-C CC-CV mode. A 4-C constant current discharge is applied until the battery reaches its lower cutoff voltage. All battery tests were conducted in a temperature-controlled chamber at

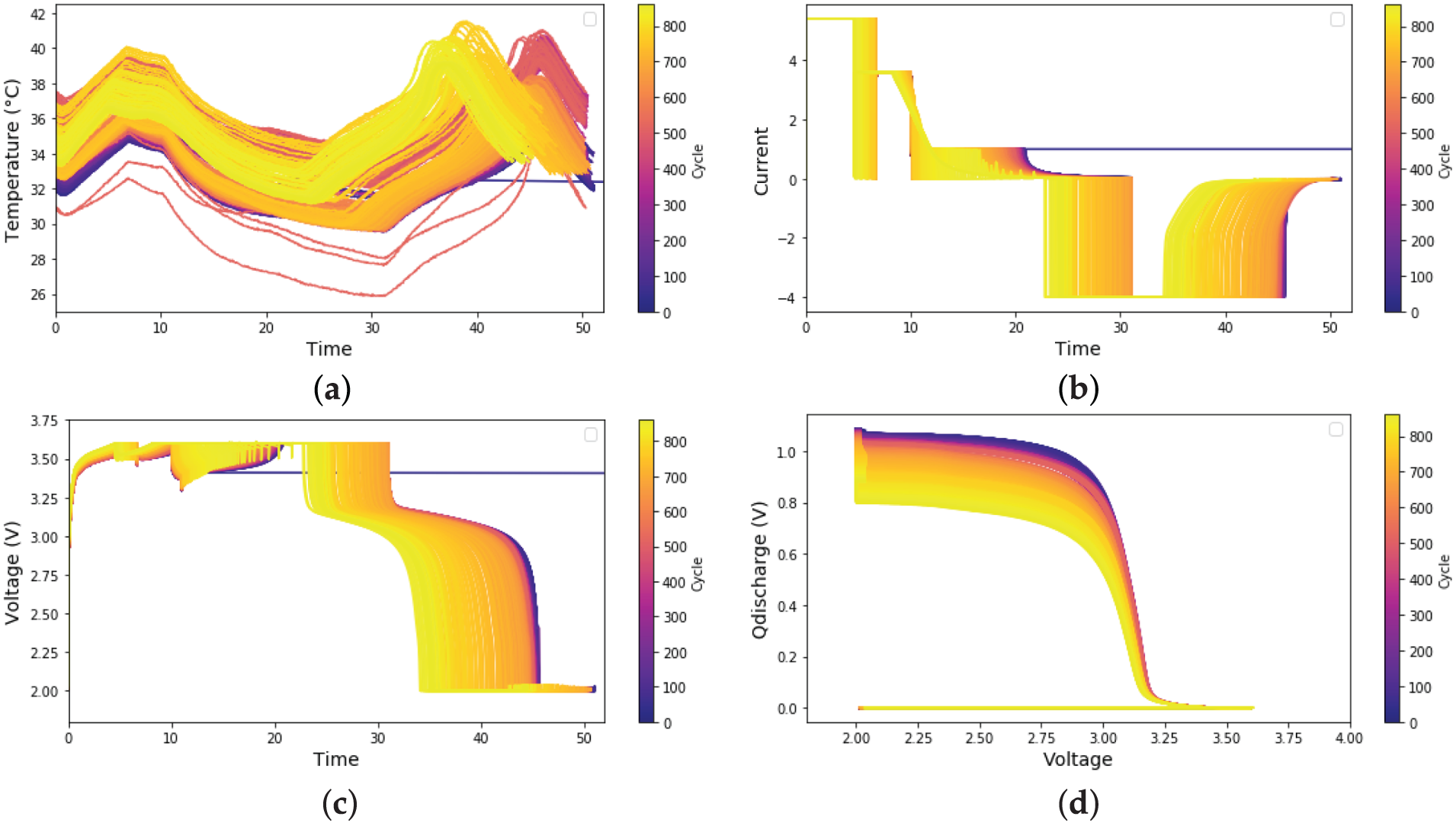

The dataset provides detailed records of battery degradation trends over different cycles. Fig. 2 illustrates the aging trends of battery variables over increasing cycles. As the cycle count increases, distinct patterns can be observed across different variables. For instance, temperature-related variables tend to shift toward higher values as the cycle count increases. This indicates that, as the battery degrades, it reaches a higher surface temperature more rapidly during operation. Such trends provide valuable insights into battery dynamics and degradation mechanisms, which can be utilized for battery state estimation and predictive maintenance.

Figure 2: Aging trends according to the cycle of each variable. (a) Represents the temperature over time for each cycle, (b) shows the current over time for each cycle, (c) illustrates the voltage over time for each cycle, and (d) depicts the relationship between voltage and Qdischarge across cycles. The purple color represents earlier cycles, while the yellow color indicates later cycles

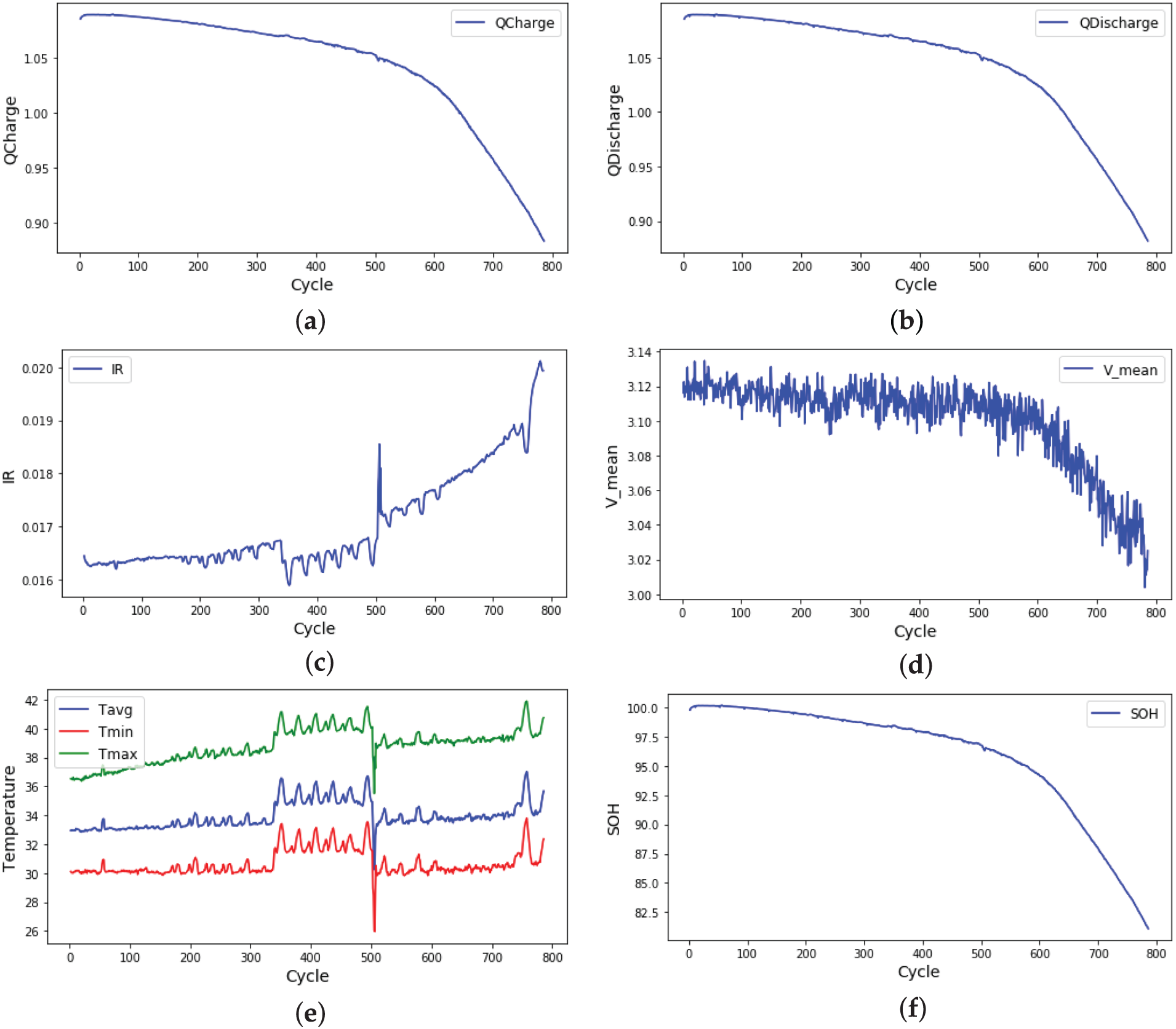

Fig. 3 demonstrates how each battery variable evolves over cycles until the SOH reaches 80%. These observed trends highlight the progressive degradation of lithium-ion batteries, which is crucial for developing accurate SOH estimation models.

Figure 3: Trends of battery cell variables across cycles. (a) charge capacity(Qcharge), (b) discharge capacity Qdischarge), (c) internal resistance (IR), (d) mean voltage (Vmean), (e) average (Tavg), minimum (Tmin), and maximum (Tmax) temperatures, and (f) state of health (SOH)

This study analyzed data using the battery dataset provided by MIT, which includes cycle-level information on Qcharge (charge capacity), Qdischarge (discharge capacity), IR (internal resistance), Tavg (average temperature), Tmin (minimum temperature), Tmax (maximum temperature), V (mean voltage per cycle), and SOH (State of Health).

This study was conducted using data from 10 distinct battery cells. To ensure a rigorous evaluation of the model’s generalization capabilities and to prevent any data leakage, we employed a 10-fold cross-validation (CV) scheme based on the battery cell IDs.

Specifically, in each of the 10 folds, one unique battery cell was designated as the test set, while the remaining 9 cells were used for training and validation (maintaining a 6-cell training/3-cell validation split ratio within these 9 cells). This process was repeated 10 times, ensuring that each cell served as the test set exactly once. This cell-level, leave-one-out cross-validation approach guarantees that the model is always evaluated on entirely unseen cells, fundamentally preventing data leakage and providing a robust assessment of generalization performance by capturing variance across different test cells.

The final performance metrics reported in Section 5.1 (Table 2) represent the mean and standard deviation calculated across these 10 folds.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we selected Transformer, DeepVAR, DLinear, and NLinear as benchmark models. All models were trained and evaluated under the same experimental settings, including the 10-fold CV procedure, to ensure a fair comparison.

4.3.1 Model Parameter Settings

To optimize the performance of the proposed method, we experimented with various hyperparameter settings and adopted the following final configuration: input length = 20, predict length =

4.3.2 Training Parameter Settings

All models were trained using the same training settings to ensure a fair comparison. Additionally, hyperparameter values were fixed to maintain experimental reproducibility. The training settings are as follows: dropout rate = 0.05, batch size = 50, epoch = 100, optimizer = Adam, learning rate = 0.0001, early stop = 3.

To quantitatively evaluate the predictive performance of the proposed method, we used three commonly employed evaluation metrics: Mean Squared Error (MSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Coefficient of Determination (

Based on these settings, we compared the performance of the proposed method with benchmark models. The experimental results demonstrate the superiority of the proposed method in battery state estimation.

5.1 Comparison of Overall and Variable-Specific Performance of the Proposed Method and Baselines

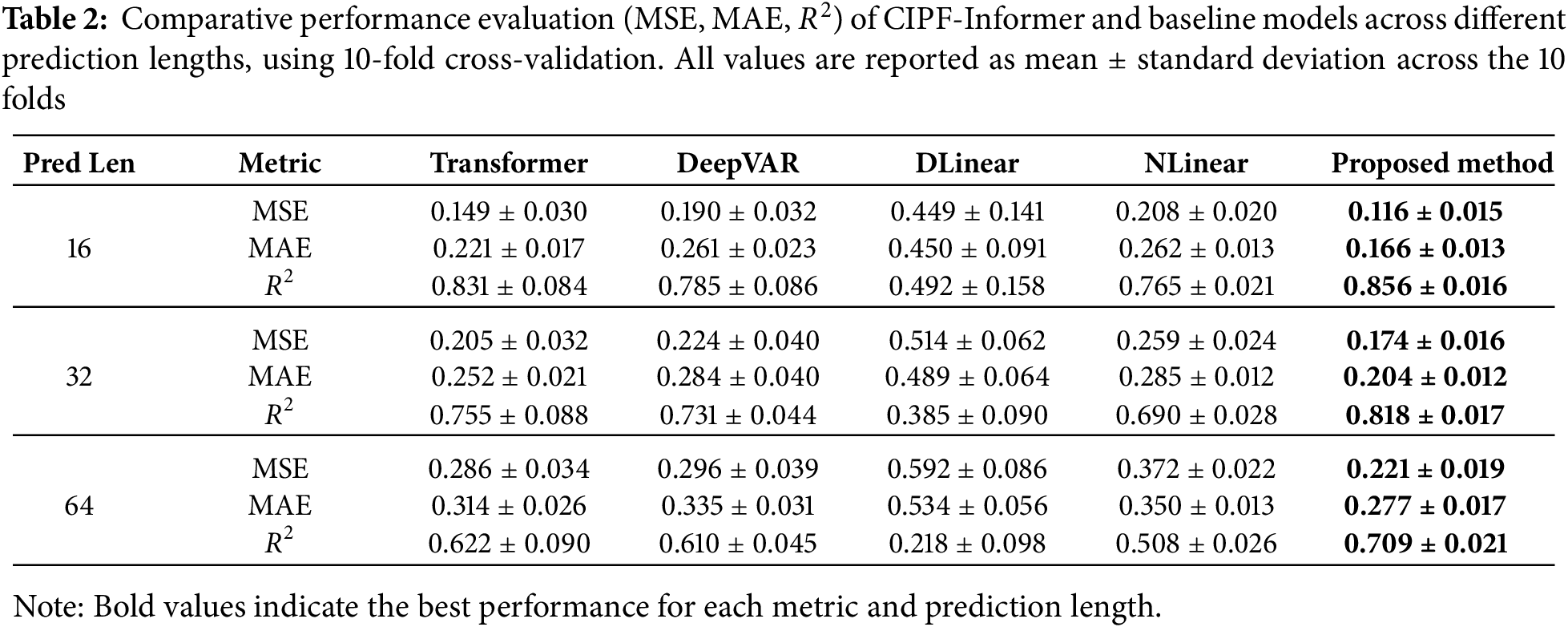

To evaluate the performance of the proposed CIPF-Informer model, we compared it with state-of-the-art models (Transformer, DeepVAR, DLinear, NLinear) across various prediction lengths (16, 32, 64). As detailed in Section 4.3, we employed a 10-fold cross-validation scheme to ensure a robust evaluation. The results, summarized in Table 2, represent the mean and standard deviation (

As shown in Table 2, the proposed model, CIPF-Informer, consistently achieved the lowest mean MSE and MAE values and the highest mean

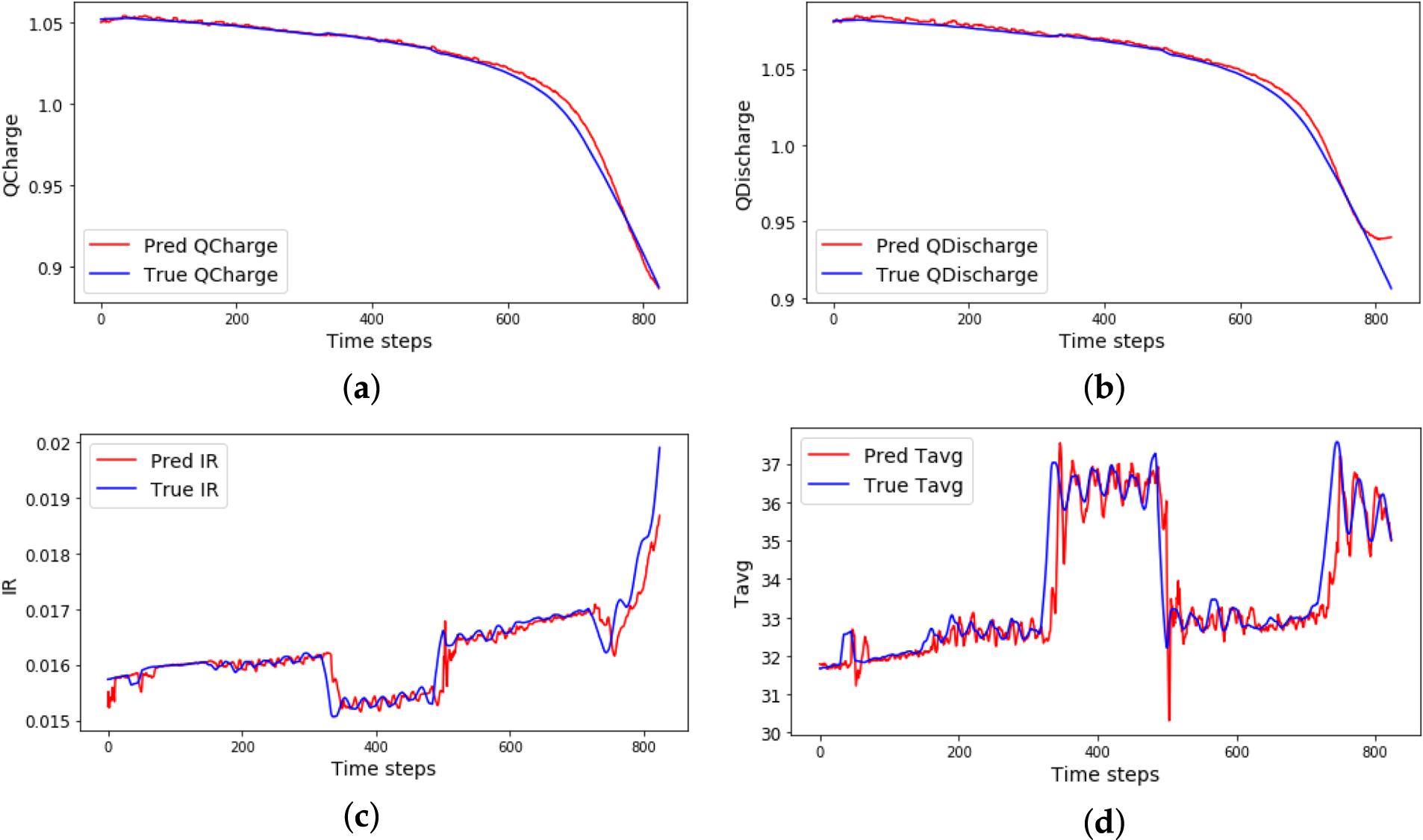

Fig. 4 presents a plot illustrating the performance of the proposed method for each variable.

Figure 4: Variable-specific prediction performance of the proposed method. The x-axis of the graph represents cycles, while the y-axis represents various variables. The blue line represents the actual values of the variable, while the red line represents the predicted values. (a) Charge capacity (Qcharge), (b) discharge capacity (Qdischarge), (c) internal resistance (IR), (d) average temperature (Tavg), (e) minimum temperature (Tmin), (f) maximum temperature (Tmax), (g) mean Voltage (Vmean), (h) state of health (SOH)

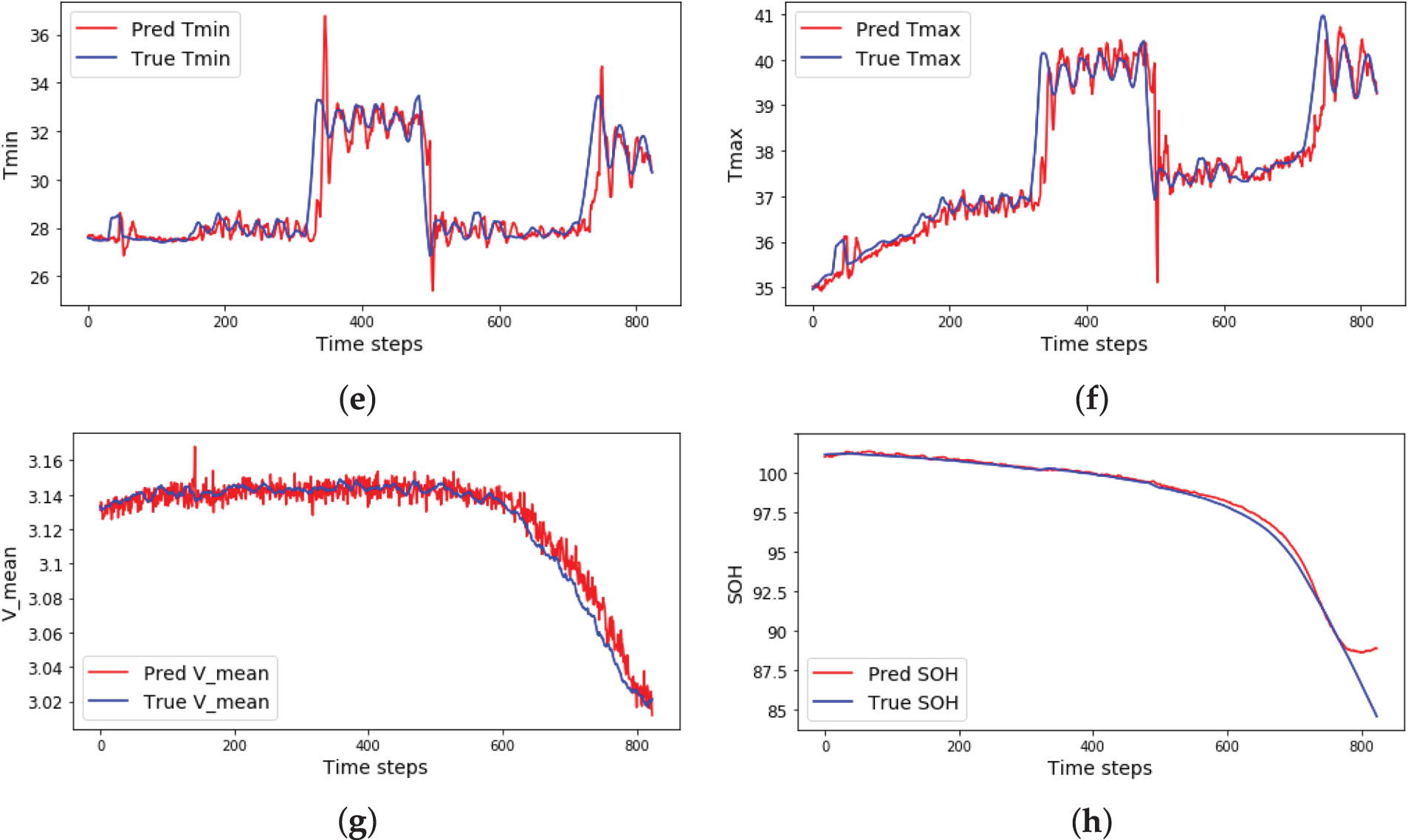

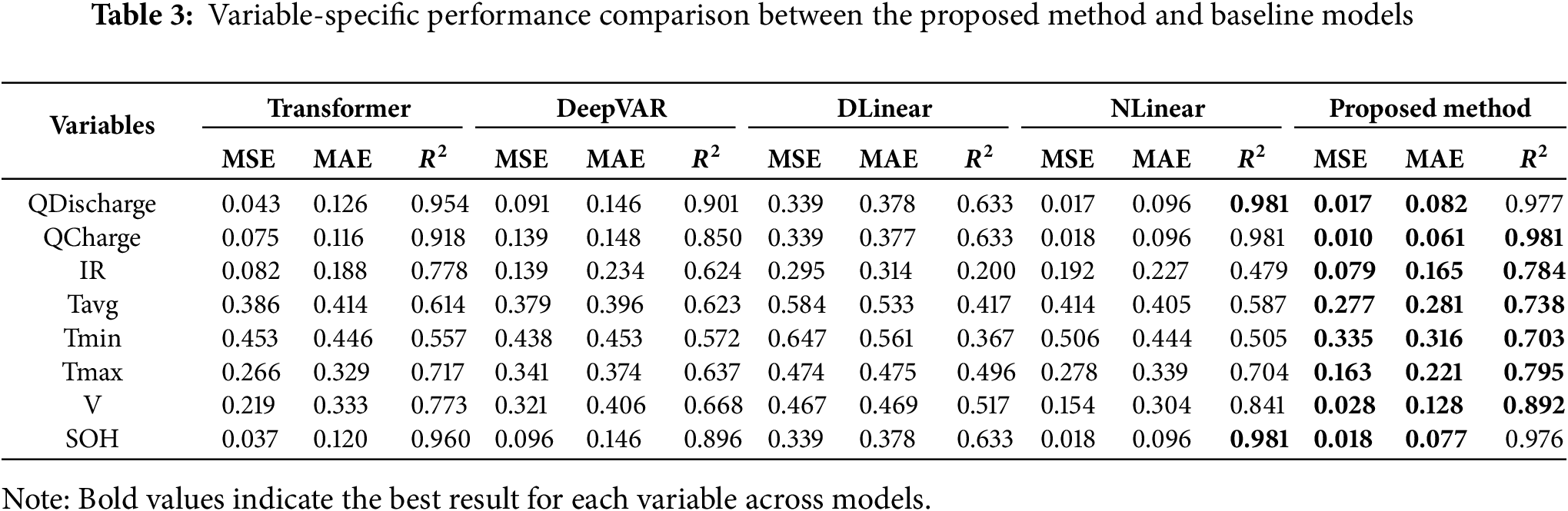

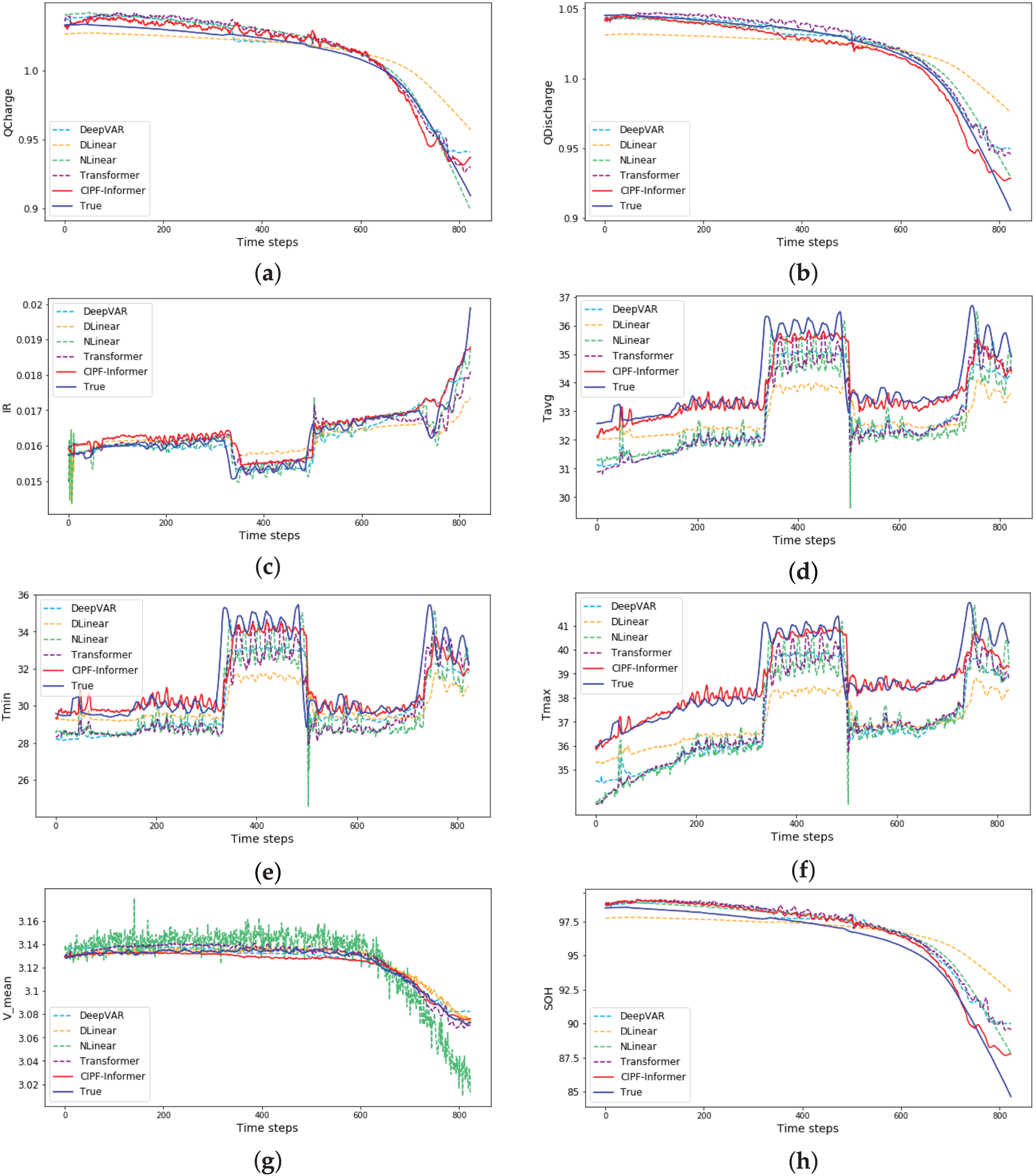

Table 3 and Fig. 5 present the variable-specific prediction performance of the proposed method compared to state-of-the-art baselines (Transformer, DeepVAR, DLinear, and NLinear) under a prediction length of 16.

Figure 5: Comparison of variable-wise prediction results (QCharge, QDischarge, IR, Tavg, etc.) across CIPF-Informer and baseline models. The x-axis of the graph represents cycles, while the y-axis represents various variables. The colors represent different models: true values are shown in blue, CIPF-Informer in red, Transformer in purple, DLinear in orange, NLinear in light green, and DeepVAR in bright sky blue. (a) Charge capacity (Qcharge), (b) discharge capacity (Qdischarge), (c) internal resistance (IR), (d) average temperature (Tavg), (e) minimum temperature (Tmin), (f) maximum temperature (Tmax), (g) mean Voltage (Vmean), (h) state of health (SOH)

The evaluation metrics used are MSE, MAE, and

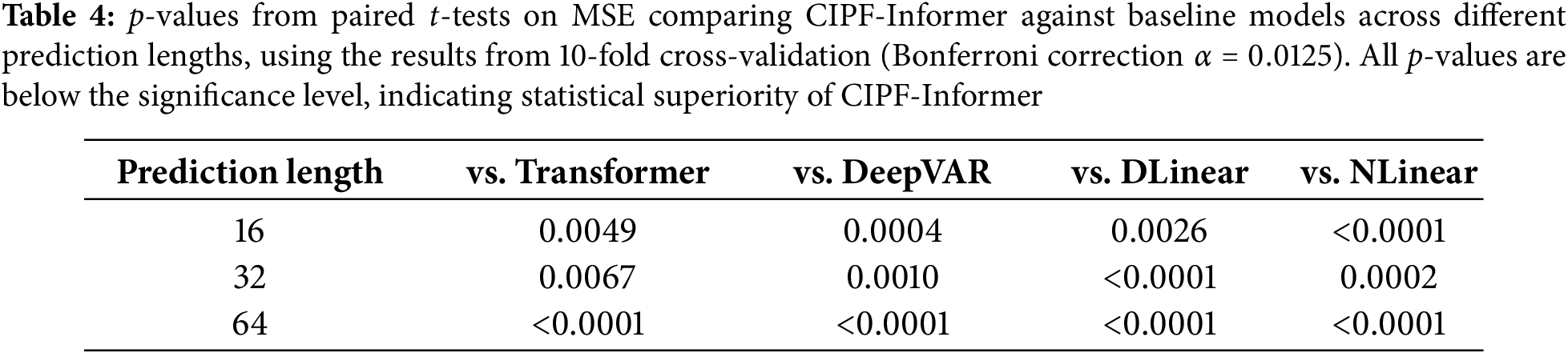

To formally validate the statistical significance of these improvements, we conducted a series of paired t-tests on the 10 averaged fold results (one for each fold) for the MSE metric. The Bonferroni correction was applied to account for multiple comparisons, setting the significance level at

These results, supported by statistical significance testing, demonstrate that CIPF-Informer robustly outperforms all baseline models across all prediction horizons. In particular, the model maintains stable and superior performance in long-term forecasting, demonstrating its effectiveness with significantly less performance degradation compared to existing methods.

5.2.1 Channel Independence and Particle Filter

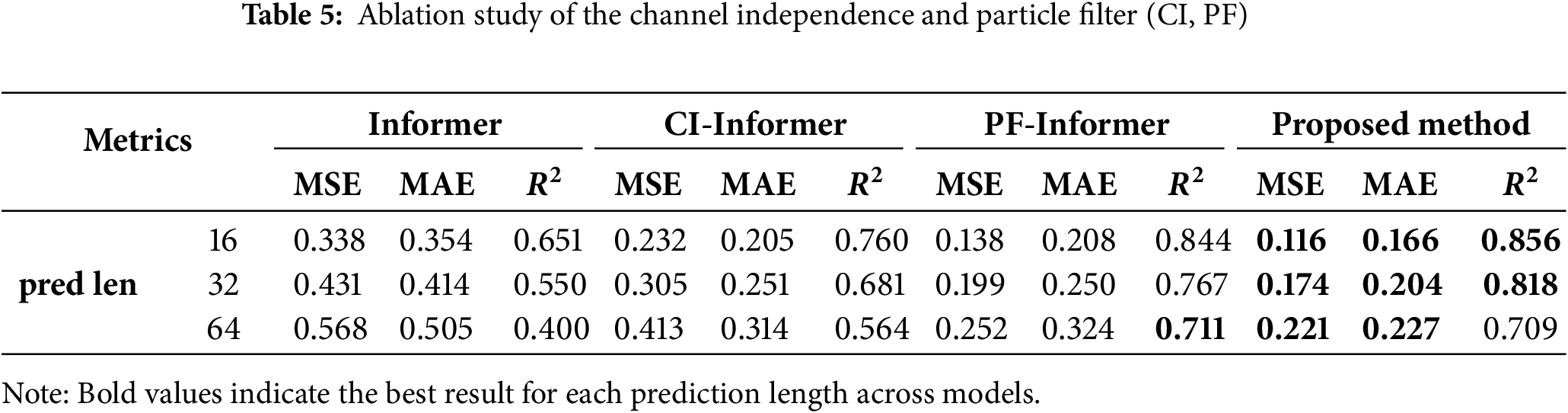

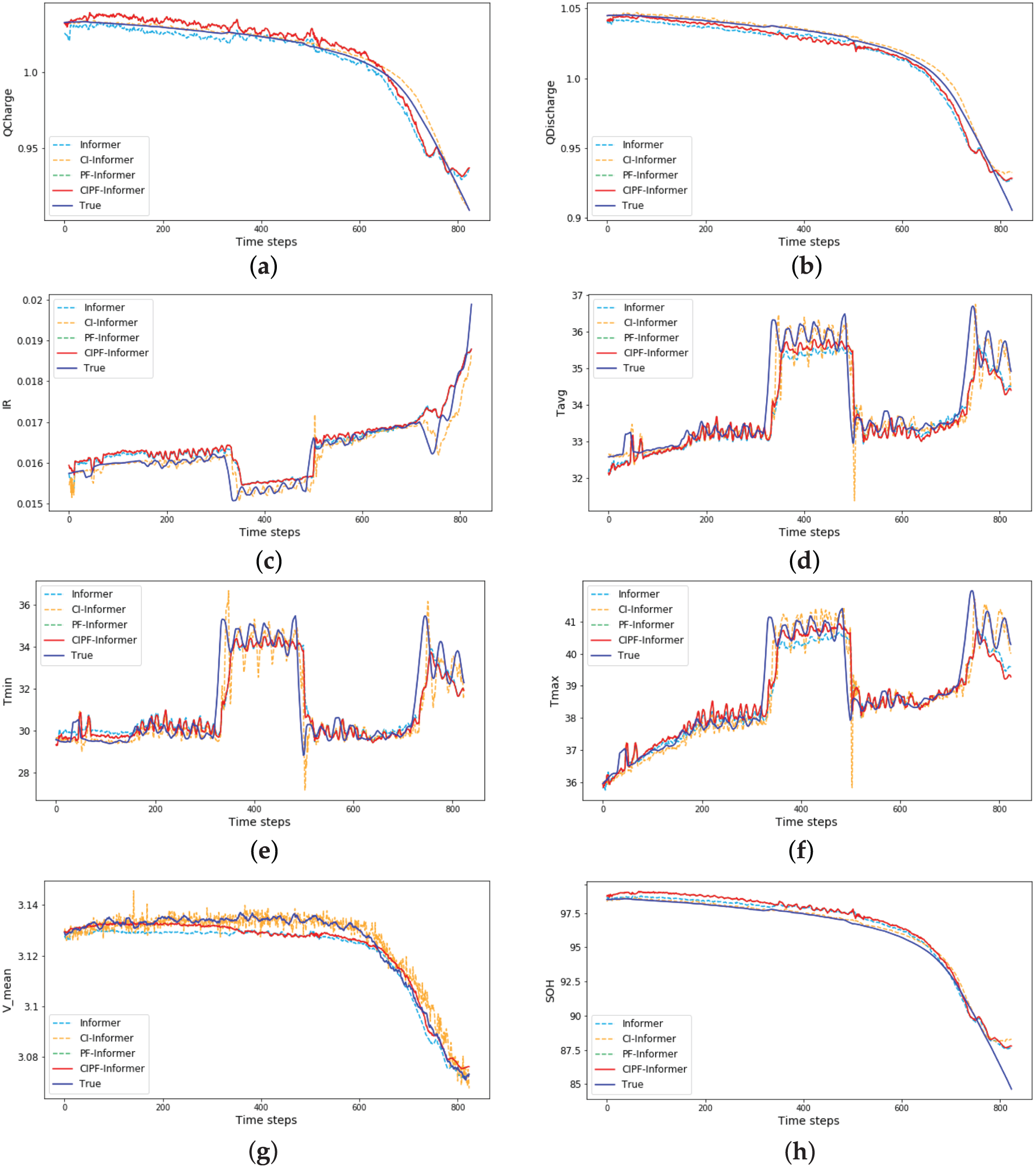

To assess the contributions of Channel Independence (CI) and Particle Filter (PF) to the proposed method, an ablation study was conducted. Table 5 and Fig. 6 present the performance of the base Informer model, CI-Informer, PF-Informer, and the proposed method.

Figure 6: Variable-wise prediction results from the ablation study, comparing four model configurations against the ground truth. The x-axis represents cycles, and the y-axis represents various variables. The colors represent different models: true values are shown in blue, the final CIPF-Informer in red, the baseline Informer in sky blue, CI-Informer in orange, and PF-Informer in light green. (a) Charge capacity (Qcharge), (b) discharge capacity (Qdischarge), (c) internal resistance (IR), (d) average temperature (Tavg), (e) minimum temperature (Tmin), (f) maximum temperature (Tmax), (g) mean Voltage (Vmean), (h) state of health (SOH)

1. Base Model: Informer

2. CI-Informer: Informer with Channel Independence

3. PF-Informer: Informer with Particle Filter

4. Proposed Method: Informer with both Channel Independence and Particle Filter

Effect of Channel Independence: The CI-Informer, which incorporates channel independence, demonstrates an overall improvement compared to the baseline model across all forecast horizons. For instance, when the forecast length is 16, the MSE decreases from 0.338 to 0.232 (31.4% reduction), and the

Effect of Particle Filter: The PF-Informer, which integrates a particle filter, shows significant improvements, particularly in longer forecast horizons. For example, at a forecast length of 64, the MSE decreases from 0.568 to 0.252 (55.6% reduction), and the

Superiority of the Proposed Method: By combining CI and PF, the proposed CIPF-Informer achieves the best performance in most cases. At prediction length 16, it records an MSE of 0.116, reducing error by 50.0% and 15.9% compared to CI-Informer and PF-Informer, respectively. Its

In summary, ablation studies verify that both CI and PF components significantly contribute to performance gains, and their integration is essential for maximizing accuracy. CIPF-Informer demonstrates robust and consistent forecasting, making it a powerful tool for battery state prediction and intelligent BMS deployment.

5.2.2 Univariate vs. Multivariate

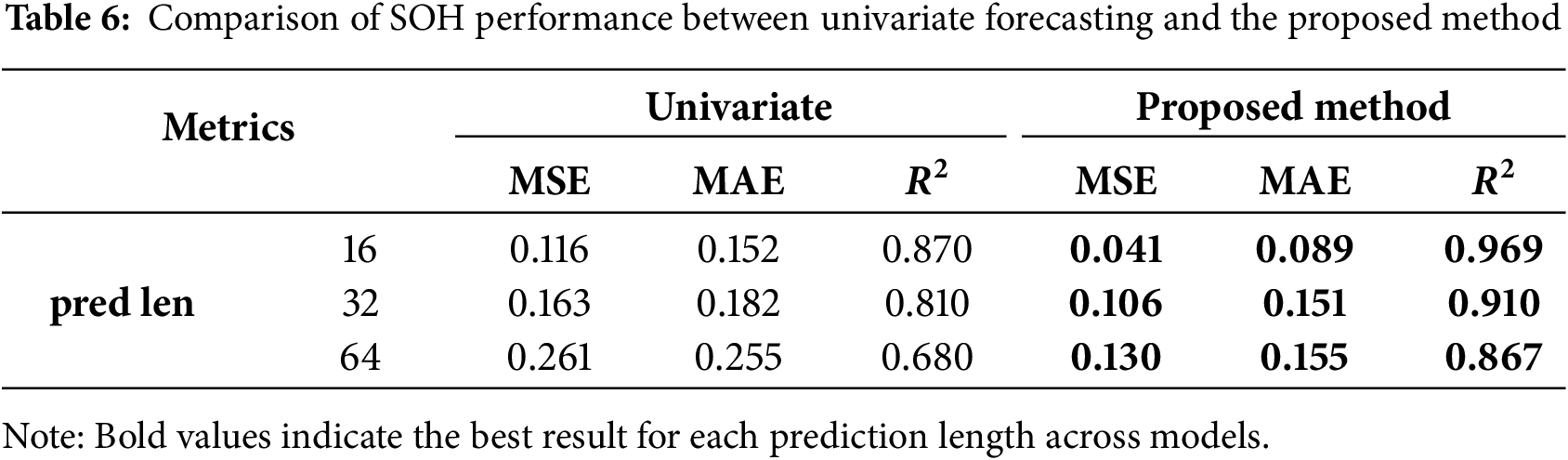

Table 6 presents a comparative analysis of SOH prediction performance between existing univariate approaches and the proposed multivariate method.

Conventional studies typically predict SOH as a single target variable using features such as current, voltage, and temperature. In contrast, the proposed method utilizes the same input variables to predict not only SOH but also all relevant state variables. This enables a direct and fair comparison of SOH prediction accuracy under equivalent input conditions. According to Table 6, the proposed method consistently achieved the lowest MSE and MAE across all prediction lengths, while also exhibiting higher

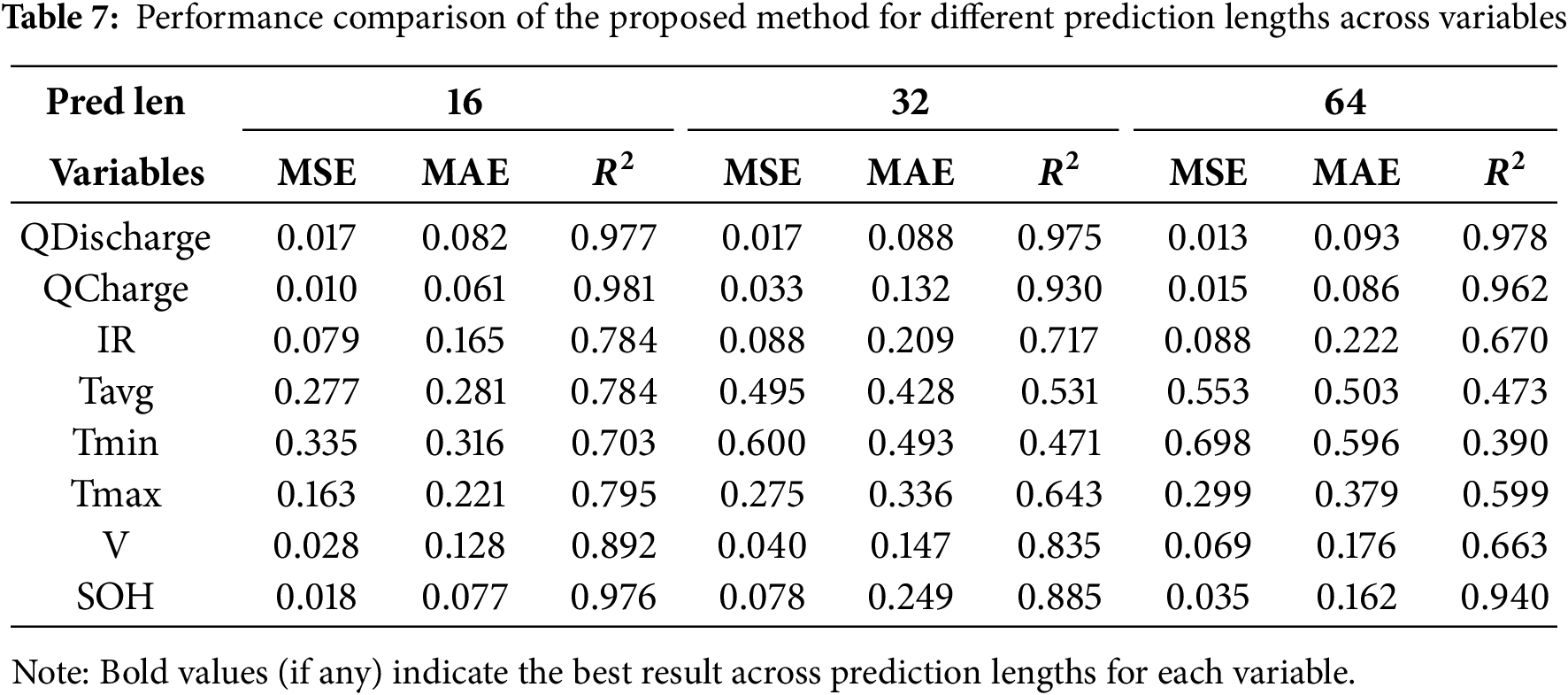

Table 7 presents a comparison of the predictive performance of the proposed method for different forecast lengths across various variables.

In general, as the prediction length increases, MSE and MAE tend to increase, while

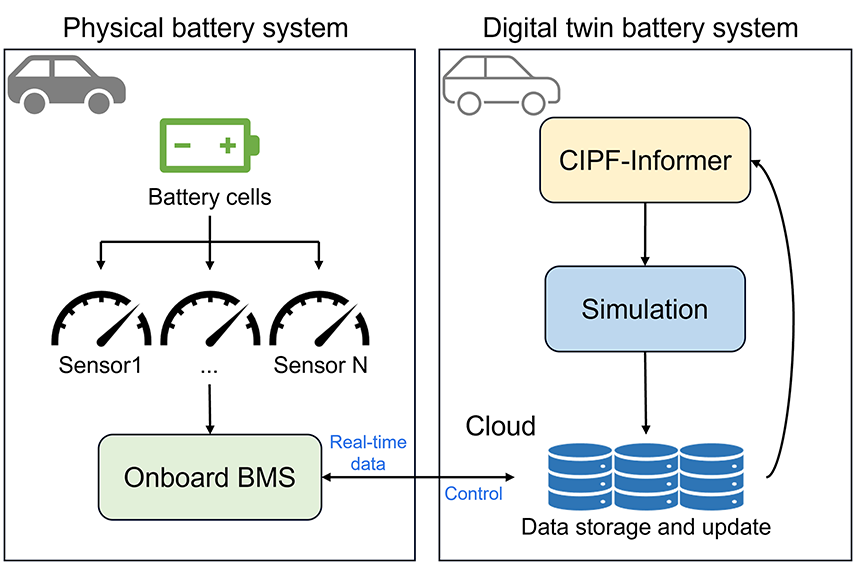

This study introduced CIPF-Informer, a hybrid multivariate prediction model. To address its real-world applicability beyond theoretical performance, this section details the specific Digital Twin (DT) architecture our model is designed for, explains the mechanism for bidirectional feedback as illustrated in Fig. 7, and analyzes its computational cost.

Figure 7: Digital twin architecture. The physical system (left) transmits ‘Real-time data’ to the Virtual Twin (right) for prediction and simulation, which in turn sends ‘Control’ commands back to the Onboard BMS for operational optimization

Our proposed framework operates within a DT ecosystem composed of two main domains, as shown in Fig. 7: a Physical System (the real-world asset, including the battery pack, sensors, and the Onboard BMS) and a Virtual Digital Twin (a cloud-based computational environment containing Cloud Storage, the CIPF-Informer predictive engine, and a Simulation and Decision Logic module). The true value of the DT is realized through a continuous, bidirectional feedback loop between these physical and virtual twins.

This process begins with the Physical-to-Virtual (‘Real-time data’) flow, where the Onboard BMS collects real-time sensor data and transmits it to the Cloud Storage. This allows for early detection of degradation patterns and anomalies [42] and provides the CIPF-Informer model with the necessary information for both real-time predictions and periodic retraining to adapt to the battery’s aging characteristics. The loop is completed by the Virtual-to-Physical (‘Control’) flow, which is the action-oriented part where intelligence from the virtual twin optimizes the operation of the physical asset. For instance, in an intelligent charging scenario, the CIPF-Informer might predict that a standard fast-charging profile will cause excessive future temperatures. The Simulation and Decision Logic module would then determine an optimal, safer charging current to prevent thermal risks [43] and even assess risks for extreme conditions like thermal runaway [44]. This is translated into a Control command, which is sent from the cloud back to the Onboard BMS to adjust the charging process in real-time.

6.2 Computational Cost and Practicality

A critical aspect for practical deployment is the model’s computational cost. All experiments were conducted on a single NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU. The average training time for the proposed CIPF-Informer was approximately 42.7 min per epoch. While this introduces a significant overhead compared to a non-PF baseline, we argue it represents a highly favorable trade-off between cost and performance, as the PF’s contribution to accuracy and stability is substantial (see Section 5.2). In terms of inference, a single prediction can be processed in approximately 76.2 milliseconds, which is sufficient for many near-real-time monitoring applications in a cloud-based DT.

This study proposed CIPF-Informer, a hybrid prediction model that integrates a model-based approach (Particle Filter) and a data-driven approach (Informer) to support digital twin applications for lithium-ion batteries. By incorporating Channel Independence and multivariate time-series forecasting, the model effectively captures complex battery dynamics and enhances long-term predictive performance.

Our primary goal was to answer the research questions posed in the introduction. We conclude by providing direct answers based on our experimental findings.

Answers to the Research Questions:

• Multivariate Prediction): Our results confirm that a multivariate approach is not only feasible but beneficial. The CIPF-Informer, by modeling key variables concurrently, achieved a lower SOH prediction error than its univariate counterpart (see Section 5.2.2). This suggests that contextual information from other variables provides valuable constraints for more accurate degradation modeling.

• Synergistic Integration): The ablation studies (Section 5.2.1) provided a clear affirmative answer. Removing either the Particle Filter (PF) or the Channel Independence (CI) mechanism resulted in a significant performance drop. This demonstrates a true synergistic effect.

• Performance Comparison): The proposed CIPF-Informer consistently outperformed state-of-the-art models (Transformer, DeepVAR, DLinear, NLinear) across all evaluation metrics, as shown in Section 5.1. Its performance, validated by statistical significance testing (p < 0.0125), was particularly dominant in long-horizon forecasting scenarios.

In summary, this research successfully demonstrates that the proposed hybrid architecture offers a superior solution for comprehensive battery digital twins. By moving beyond univariate SOH prediction and creating a synergistic fusion of probabilistic filtering and efficient deep learning, CIPF-Informer provides a robust and scalable framework.

Despite strong results, several challenges remain:

1. Generalizability: The model was tested only on the MIT dataset, and its performance on other battery types remains uncertain.

2. Computational Cost: Particle Filter adds computational burden, requiring optimization for real-time deployment.

3. Inter-variable Correlation: While CI improves performance, real-world BMS often exhibit inter-variable dependencies that must be better modeled.

Future work will focus on improving generalization, optimizing real-time performance, and adapting to diverse battery systems, moving toward more reliable digital twin-based BMS.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Human Resources Development of the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) grant funded by the Korea government Ministry of Knowledge Economy (No. RS-2023-00244330) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. NRF RS-2023-00219052).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Changyu Jeon; Methodology, Changyu Jeon; Software, Changyu Jeon; Formal analysis, Changyu Jeon; Data Curation, Changyu Jeon; Writing—original draft preparation, Changyu Jeon; Visualization, Changyu Jeon; Supervision, Younghoon Kim; Writing—review and editing, Younghoon Kim; Project administration, Younghoon Kim; Funding acquisition, Younghoon Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The dataset that supports the findings of this study is openly available at the MIT Battery Dataset repository [41].

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lipu MH, Hannan MA, Hussain A, Hoque M, Ker PJ, Saad MHM, et al. A review of state of health and remaining useful life estimation methods for lithium-ion battery in electric vehicles: challenges and recommendations. J Clean Prod. 2018;205:115–33. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.09.065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Cuma MU, Koroglu T. A comprehensive review on estimation strategies used in hybrid and battery electric vehicles. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2015;42:517–31. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2014.10.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Safavi V, Bazmohammadi N, Vasquez JC, Guerrero JM. Battery state-of-health estimation: a step towards battery digital twins. Electronics. 2024;13(3):587. doi:10.3390/electronics13030587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mitali J, Dhinakaran S, Mohamad A. Energy storage systems: a review. Energy Storage Sav. 2022;1(3):166–216. doi:10.1016/j.enss.2022.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Xia G, Cao L, Bi G. A review on battery thermal management in electric vehicle application. J Power Sources. 2017;367(3):90–105. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2017.09.046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhou X, Stein JL, Ersal T. Battery state of health monitoring by estimation of the number of cyclable Li-ions. Control Eng Pract. 2017;66(7):51–63. doi:10.1016/j.conengprac.2017.05.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Singirikonda S, Obulesu Y. Advanced SOC and SOH estimation methods for EV batteries—a review. In: International Conference on Automation, Signal Processing, Instrumentation and Control. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 1963–77. [Google Scholar]

8. Fei Z, Yang F, Tsui KL, Li L, Zhang Z. Early prediction of battery lifetime via a machine learning based framework. Energy. 2021;225(4):120205. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2021.120205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yang N, Song Z, Hofmann H, Sun J. Robust state of health estimation of lithium-ion batteries using convolutional neural network and random forest. J Energy Storage. 2022;48(4):103857. doi:10.1016/j.est.2021.103857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Nuhic A, Terzimehic T, Soczka-Guth T, Buchholz M, Dietmayer K. Health diagnosis and remaining useful life prognostics of lithium-ion batteries using data-driven methods. J Power Sources. 2013;239(3):680–8. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2012.11.146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Eleftheriadis P, Giazitzis S, Leva S, Ogliari E. Data-driven methods for the state of charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries: an overview. Forecasting. 2023;5(3):576–99. doi:10.3390/forecast5030032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yang B, Qian Y, Li Q, Chen Q, Wu J, Luo E, et al. Critical summary and perspectives on state-of-health of lithium-ion battery. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2024;190(40):114077. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2023.114077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Li W, Rentemeister M, Badeda J, Jöst D, Schulte D, Sauer DU. Digital twin for battery systems: cloud battery management system with online state-of-charge and state-of-health estimation. J Energy Storage. 2020;30(1–2):101557. doi:10.1016/j.est.2020.101557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hannan MA, How DN, Lipu MH, Mansor M, Ker PJ, Dong Z, et al. Deep learning approach towards accurate state of charge estimation for lithium-ion batteries using self-supervised transformer model. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):19541. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-687515/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Demirci O, Taskin S, Schaltz E, Demirci BA. Review of battery state estimation methods for electric vehicles-Part II: SOH estimation. J Energy Storage. 2024;96:112703. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.112703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Andre D, Appel C, Soczka-Guth T, Sauer DU. Advanced mathematical methods of SOC and SOH estimation for lithium-ion batteries. J Power Sources. 2013;224(1–2):20–7. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2012.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Plett GL. Extended Kalman filtering for battery management systems of LiPB-based HEV battery packs: part 3. State and parameter estimation. J Power Sources. 2004;134(2):277–92. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2004.02.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhu F, Fu J. A novel state-of-health estimation for lithium-ion battery via unscented Kalman filter and improved unscented particle filter. IEEE Sens J. 2021;21(22):25449–56. doi:10.1109/jsen.2021.3102990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Elfring J, Torta E, Van De Molengraft R. Particle filters: a hands-on tutorial. Sensors. 2021;21(2):438. doi:10.3390/s21020438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Gustafsson F. Particle filter theory and practice with positioning applications. IEEE Aerosp Electron Syst Mag. 2010;25(7):53–82. doi:10.1109/maes.2010.5546308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wang S, Jin S, Bai D, Fan Y, Shi H, Fernandez C. A critical review of improved deep learning methods for the remaining useful life prediction of lithium-ion batteries. Energy Rep. 2021;7:5562–74. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2021.08.182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Li SG, Sharkh SM, Walsh FC, Zhang CN. Energy and battery management of a plug-in series hybrid electric vehicle using fuzzy logic. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2011;60(8):3571–85. doi:10.1109/tvt.2011.2165571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Raman M, Champa V, Prema V. State of health estimation of lithium ion batteries using recurrent neural network and its variants. In: 2021 IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Computing and Communication Technologies (CONECCT). New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

24. Ma Y, Shan C, Gao J, Chen H. A novel method for state of health estimation of lithium-ion batteries based on improved LSTM and health indicators extraction. Energy. 2022;251(2):123973. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.123973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kong Y, Wang Z, Nie Y, Zhou T, Zohren S, Liang Y, et al. Unlocking the power of LSTM for long term time series forecasting. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2025. Vol. 39. p. 11968–76. [Google Scholar]

26. Zhou H, Zhang S, Peng J, Zhang S, Li J, Xiong H, et al. Informer: beyond efficient transformer for long sequence time-series forecasting. In: Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2021. Vol. 35. p. 11106–15. [Google Scholar]

27. Zheng Y, Liu Q, Chen E, Ge Y, Zhao JL. Time series classification using multi-channels deep convolutional neural networks. In: International Conference on Web-Age Information Management. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2014. p. 298–310. [Google Scholar]

28. Zeng A, Chen M, Zhang L, Xu Q. Are transformers effective for time series forecasting? In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2023. Vol. 37. p. 11121–8. [Google Scholar]

29. Nie Y, Nguyen NH, Sinthong P, Kalagnanam J. A time series is worth 64 words: long-term forecasting with transformers. arXiv:2211.14730. 2023. [Google Scholar]

30. Han L, Ye HJ, Zhan DC. The capacity and robustness trade-off: revisiting the channel independent strategy for multivariate time series forecasting. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2024;36(11):7129–42. doi:10.1109/tkde.2024.3400008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Shi Z. Incorporating transformer and LSTM to Kalman filter with EM algorithm for state estimation. arXiv:2105.00250. 2021. [Google Scholar]

32. Zhao H, Chen Z, Shu X, Shen J, Lei Z, Zhang Y. State of health estimation for lithium-ion batteries based on hybrid attention and deep learning. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2023;232(8):109066. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2022.109066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Glaessgen E, Stargel D. The digital twin paradigm for future NASA and US air force vehicles. In: 53rd AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics and Materials Conference 20th AIAA/ASME/AHS Adaptive Structures conference 14th AIAA; 2012 April 23-26; Honolulu, HI, USA. No. AIAA 2012-1818. [Google Scholar]

34. Wu B, Widanage WD, Yang S, Liu X. Battery digital twins: perspectives on the fusion of models, data and artificial intelligence for smart battery management systems. Energy AI. 2020;1:100016. doi:10.1016/j.egyai.2020.100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Tao F, Zhang H, Liu A, Nee AY. Digital twin in industry: state-of-the-art. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2018;15(4):2405–15. [Google Scholar]

36. Jafari M, Kavousi-Fard A, Chen T, Karimi M. A review on digital twin technology in smart grid, transportation system and smart city: challenges and future. IEEE Access. 2023;11:17471–84. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3241588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Chen Z, Mi CC, Fu Y, Xu J, Gong X. Online battery state of health estimation based on Genetic Algorithm for electric and hybrid vehicle applications. J Power Sources. 2013;240:184–92. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2013.03.158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Zhang Y, Wu J, Sun S, Ye T. Research on modeling method of digital twin of lithium battery based on data-model hybrid drive. In: 2024 IEEE 4th International Conference on Power, Electronics and Computer Applications (ICPECA). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 716–20. [Google Scholar]

39. Alamin KSS, Chen Y, Macii E, Poncino M, Vinco S. A machine learning-based digital twin for electric vehicle battery modeling. In: 2022 IEEE International Conference on Omni-layer Intelligent Systems (COINS). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

40. Tao T, Ji C, Dai J, Rao J, Wang J, Sun W, et al. Data-based health indicator extraction for battery SOH estimation via deep learning. J Energy Storage. 2024;78(3):109982. doi:10.1016/j.est.2023.109982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Severson KA, Attia PM, Jin N, Perkins N, Jiang B, Yang Z, et al. Data-driven prediction of battery cycle life before capacity degradation. Nat Energy. 2019;4(5):383–91. doi:10.1038/s41560-019-0356-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Tao F, Cheng J, Qi Q, Zhang M, Zhang H, Sui F. Digital twin-driven product design, manufacturing and service with big data. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2018;94(9–12):3563–76. doi:10.1007/s00170-017-0233-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Naseri F, Gil S, Barbu C, Cetkin E, Yarimca G, Jensen A, et al. Digital twin of electric vehicle battery systems: comprehensive review of the use cases, requirements, and platforms. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2023;179(4):113280. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2023.113280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Liu K, Li K, Peng Q, Zhang C. A brief review on key technologies in the battery management system of electric vehicles. Front Mech Eng. 2019;14(1):47–64. doi:10.1007/s11465-018-0516-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools