Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Human Behaviour Classification in Emergency Situations Using Machine Learning with Multimodal Data: A Systematic Review (2020–2025)

1 Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Computing, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Bahawalpur, 63100, Pakistan

2 Fakulti Kecerdasan Buatan dan Keselamatan Siber, Universiti Teknikal Malaysia, Melaka, 76100, Malaysia

3 Department of AI and SW, Gachon University, Seongnam, 13557, Republic of Korea

4 Fakulti Pengurusan Teknologi Dan Teknousahawanan, Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melaka, Kampus Teknologi, Melaka, 76100, Malaysia

* Corresponding Authors: Muhammad Rehan Faheem. Email: ; Lal Khan. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 2895-2935. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.073172

Received 12 September 2025; Accepted 13 November 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

With growing urban areas, the climate continues to change as a result of growing populations, and hence, the demand for better emergency response systems has become more important than ever. Human Behaviour Classification (HBC) systems have started to play a vital role by analysing data from different sources to detect signs of emergencies. These systems are being used in many critical areas like healthcare, public safety, and disaster management to improve response time and to prepare ahead of time. But detecting human behaviour in such stressful conditions is not simple; it often comes with noisy data, missing information, and the need to react in real time. This review takes a deeper look at HBC research published between 2020 and 2025 and aims to answer five specific research questions. These questions cover the types of emergencies discussed in the literature, the datasets and sensors used, the effectiveness of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models, and the limitations that still exist in this field. We explored 120 papers that used different types of datasets, some were based on sensor data, others on social media, and a few used hybrid approaches. Commonly used models included CNNs, LSTMs, and reinforcement learning methods to identify behaviours. Though a lot of progress has been made, the review found ongoing issues in combining sensors properly, reacting fast enough, and using more diverse datasets. Overall, from the findings we observed, the focus should be on building systems that use multiple sensors together, gather real-time data on a large scale, and produce results that are easier to interpret. Proper attention to privacy and ethical concerns needs to be addressed as well.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileAs time passes and the population is continuously rising and ageing, various challenges like urban growth, climate change, and unpredictable geopolitical conditions are paving the way for emergencies to happen more often. Because of this, the need for fast, responsive, and human-centred management systems is becoming more critical than ever. Defined formally, HBC is an automatic process for the identification and categorisation of human activities and their behavioural patterns based on data from sensors, video, or multimodal sources in order to support decision-making in real-world scenarios. In this study, HBC is specifically used for emergencies, which cover activities such as fall detection, running, crouching, reactions during panic, and evacuation movements in case of disaster. HBC systems are helpful tools that can connect real-life incidents with timely and targeted actions. These systems detect behaviour patterns by processing data from various sources that may lead to or indicate emergency conditions [1,2]. This is the reason why HBC is now being applied in many areas such as healthcare, surveillance, public safety, assisted living, environmental monitoring, and evacuation strategies [3].

As this need becomes stronger, the role of HBC systems becomes more visible and essential, and because of that, it becomes important to explore how exactly these systems function and what kind of situations they are meant to address. When we deeply understand their core workings, their role in emergency response becomes even more convincing and impactful. To assume the understanding of human behaviour in such emergencies, the use of intelligence-based systems is important [4]. HBC systems have become vital tools to address these issues. For example, ref. [5] detected leg postural abnormalities, which can be helpful to identify people with such abnormalities during any emergency, so that the required response can be generated that could save lives. These calamities can refer to personal incidents, such as falls (natural or deliberate) and sudden health concerns [6,7], as well as large-scale disasters, such as fires, earthquakes, and even terrorist attacks [8,9]. An important contribution of this review is the identification and analysis of multimodal sensing frameworks. Datasets like KFall, which combine inertial data with synchronised video, are excellent examples of multimodal input sources designed to improve both accuracy and interpretability [10]. These datasets combine inputs such as RGB video, thermal imaging, inertial data from wearables, physiological signals, environmental measurements, and contextual data. The integration of these modalities not only improves accuracy but also provides robustness to missing or degraded data, a common issue in real-world emergency scenarios [1].

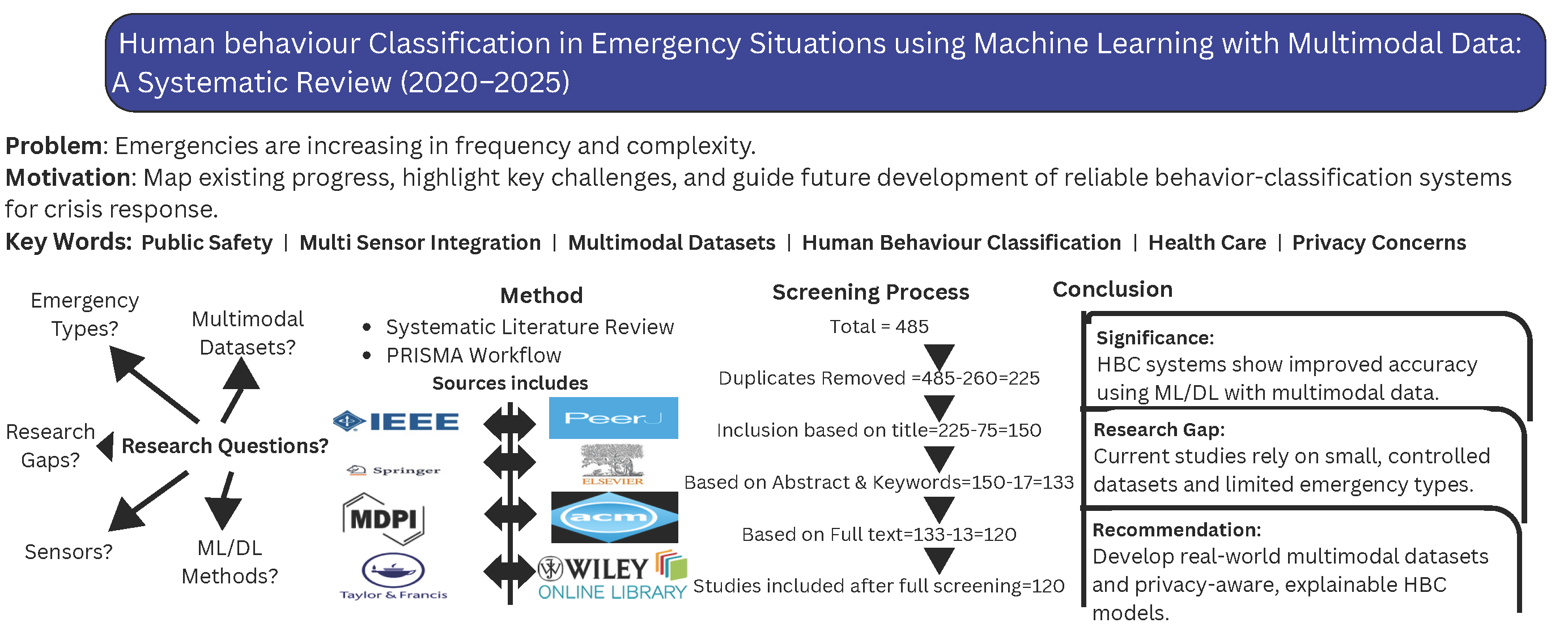

As the world becomes more complex and unpredictable, it has become the need of the time to recognise and respond to emergencies more effectively and logically than ever [11]. This supports public safety, strengthens healthcare systems, and increases the level of preparedness for such calamities [12]. By accepting the importance of timely detection and response, it becomes essential to understand how the systems are built and what types of data they need to work on. Their importance is often dependent on the variety and richness of the information they can process. Comparing data from various sources such as visual, auditory, physiological, inertial, and environmental sensors [2,6,8,9,10]. HBC systems have greatly improved their ability to quickly recognise and efficiently respond during emergencies, giving more accurate interpretations [13]. On the other hand, single-sensor systems that rely only on visual or motion data tend to be less robust and computationally heavy, depending on the quality of images or video used [3,9]. For example, vision-based fall detection often fails under poor lighting or occlusions [14], whereas inertial-sensor-based systems may misclassify rapid but harmless movements [8,15]. Multimodal approaches combining both (through different levels of modality fusion as shown in Fig. 1) tend to reduce such errors [16]. They often lack context awareness and struggle to adapt across different situations. Multimodal systems, however, bring together diverse data inputs to form a more complete and reliable understanding and prediction of human actions and intent [17]. Between the single-sensor and multimodal systems, the difference clearly illustrates how much potential lies in combining data streams.

Figure 1: An overview of different levels of modalities fusion as described in [16]

This study explores how researchers have employed state-of-the-art architectures to overcome the limitations of traditional ML models. Various smart techniques like convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [6], LSTMs [8], BiLSTMs and attention mechanisms [13] have been explored to check their success in recognising behaviour during emergencies. Each of these methods is tested for how well it handles mixed data sources and performs in real-world conditions. When these systems are actually used in emergencies, they bring extra challenges [9].

The model must not only work well, but it also needs to respect human values, social norms, and ethical boundaries. As movement analysis for determining behavioural patterns has raised privacy concerns when relying on continuous video monitoring [1]. Wearable-based systems are often preferred due to their less intrusive nature [18]. A single missed signal or a false alert can lead to serious outcomes in any emergency [19]. That’s why it’s not just about accuracy anymore; we also need systems that can clearly explain why they acted a certain way, especially when lives are on the line. Another important aspect is how well these systems behave in different situations, like with different people, changing surroundings, and unpredictable conditions. To build genuine trust and ensure that practices remain responsible, privacy-first measures have to be part of the design right from the beginning. Methods like on-device processing, anonymising data and even federated learning should not be treated as optional add-ons but as necessary ethical requirements [20]. By including these safeguards in the core, we can ensure that systems not only work intelligently but also remain accountable and responsible when applied in real-world settings.

While human activity recognition (HAR) has advanced significantly in domains like smart homes and fitness applications, including wearable sensors [21], its use in emergencies is still relatively limited and inconsistent. Emergencies present distinct challenges for HBC systems. These ongoing challenges make it clear that emergency systems must aim for high accuracy, respond in real time, tolerate noise, respect user privacy, and adapt easily to different environments and people. This study builds a strong and purposeful base for future research by closely examining what earlier research missed or struggled with. The selected studies mainly explore how machine learning and deep learning models are being used for HBC, especially in emergency settings that deal with diverse and multimodal data inputs [22]. The review is based on selected peer-reviewed papers from respected journals and conferences. These works cover different types of emergencies, sensor technologies and analytical techniques. Continued advancements and improvements in computing-related resources, access to large datasets [10] and the development of advanced intelligent architectures like CNNs, RNNs [2] and attention-based hybrids have effectively and greatly accelerated progress in this domain. Some of the remarkable strengths of these models are that they can now extract detailed spatiotemporal patterns from multiple data sources [6,8].

As a result, they can recognise subtle behaviours even in unpredictable, real-time, or noisy conditions. Even though the number of research studies and practical applications is steadily increasing, several critical points still remain unresolved. One major concern is that many algorithms are still tested mainly on simulated datasets, which usually fall short of reflecting the true complexity and unpredictability of real-life scenarios. For example, which types of emergencies are most often studied in HBC research? What sensor combinations and data types are typically used? Which learning models demonstrate the greatest effectiveness? What limitations still hinder practical deployment? A significant contribution in this area is the introduction of the KFall dataset, which includes synchronised sensor and video data to support more accurate labelling and evaluation [10]. This review organises and examines existing studies based on specific research questions. Through this structured approach, it presents a broad view of both the technological developments and the methodological patterns found in emergency-focused HBC research. The key research questions driving this analysis are outlined below:

• RQ1: What types of emergencies are being addressed using human behaviour classification?

• RQ2: What multimodal datasets are commonly used?

• RQ3: Which sensors are commonly used?

• RQ4: Which ML/DL algorithms are most effective for HBC in emergencies?

• RQ5: What are the main limitations and gaps in current research?

These questions aim to uncover both the breadth and depth of the field, including applications such as fall detection for elderly individuals, evacuation monitoring in public buildings, violence or assault detection in surveillance footage and the prediction of large-scale environmental disasters like wildfires.

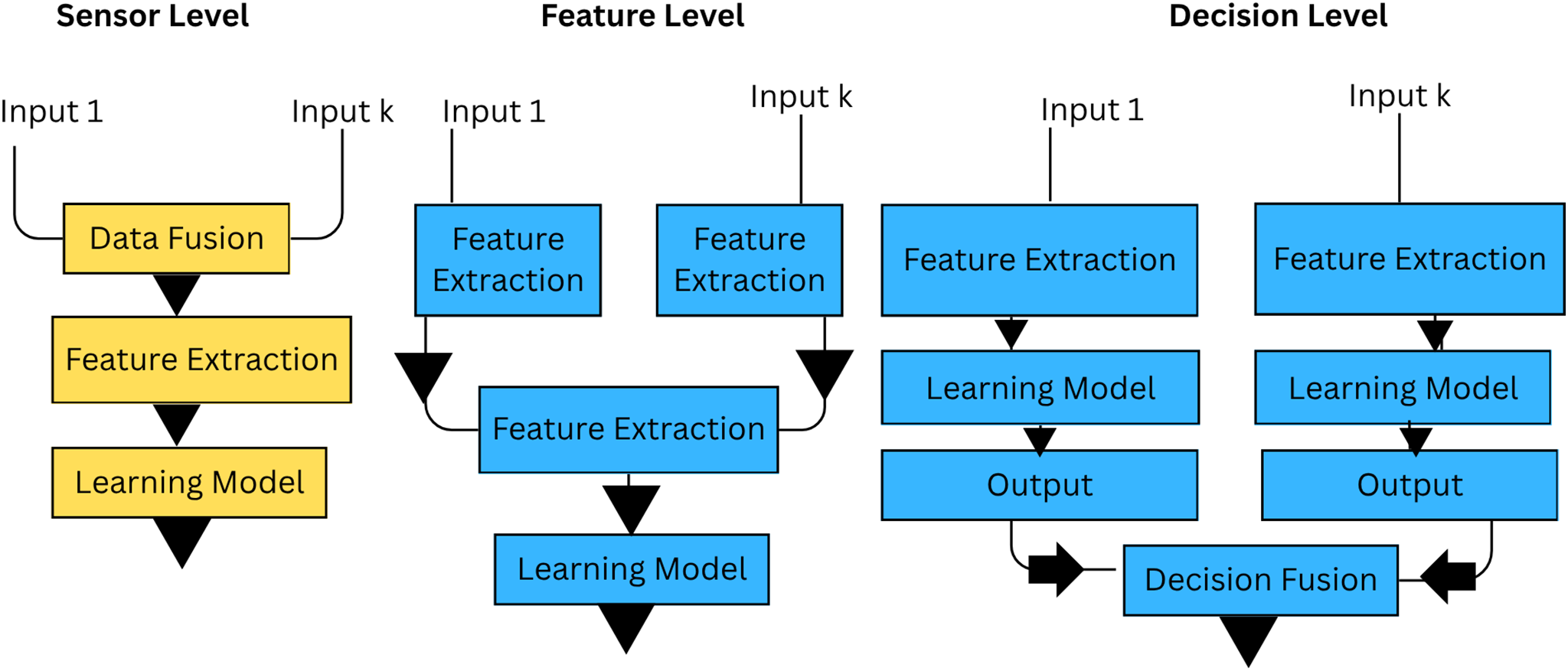

Understanding human behaviour during emergencies has long intrigued researchers across disciplines such as psychology, biology and cognitive science [23]. Efforts have been made to classify behavioural patterns, particularly walking behaviours, by drawing on conceptual frameworks like rational thinking, habitual and impulsive reactions [24]. To build a more accurate and practical taxonomy, walking behaviour has also been interpreted through parallels with animal behaviours and further examined under both normal and high-stress conditions, such as those found in disaster scenarios [25]. Understanding how people make decisions when facing risk and uncertainty has long been a central challenge in behavioural science, psychology and economics [26]. Despite the structured nature of many experimental tasks, human choices often deviate from rational models. This unpredictability highlights the complexity of human behaviour across different disciplines [27]. HAR has gained much attraction in various smart home environments, especially to continuously monitor human behaviours in ambient assisted living to provide elderly care and rehabilitation [28]. In recent years, there has been a growing trend in the medical domain to explore methods for predicting human behaviour, particularly in the context of patient behaviour analysis [29]. Simulation of human behaviour has emerged as a critical component across various applications, especially in healthcare and social behaviour research. In addition, achieving accurate predictions is equally important to identify and understand the contributing factors behind human behaviour [30]. HAR in videos has long stood as an active area of research in computer vision and pattern recognition; steps for human activity recognition are represented in Fig. 2 from [31].

Figure 2: Steps for human action recognition process as described in [31]

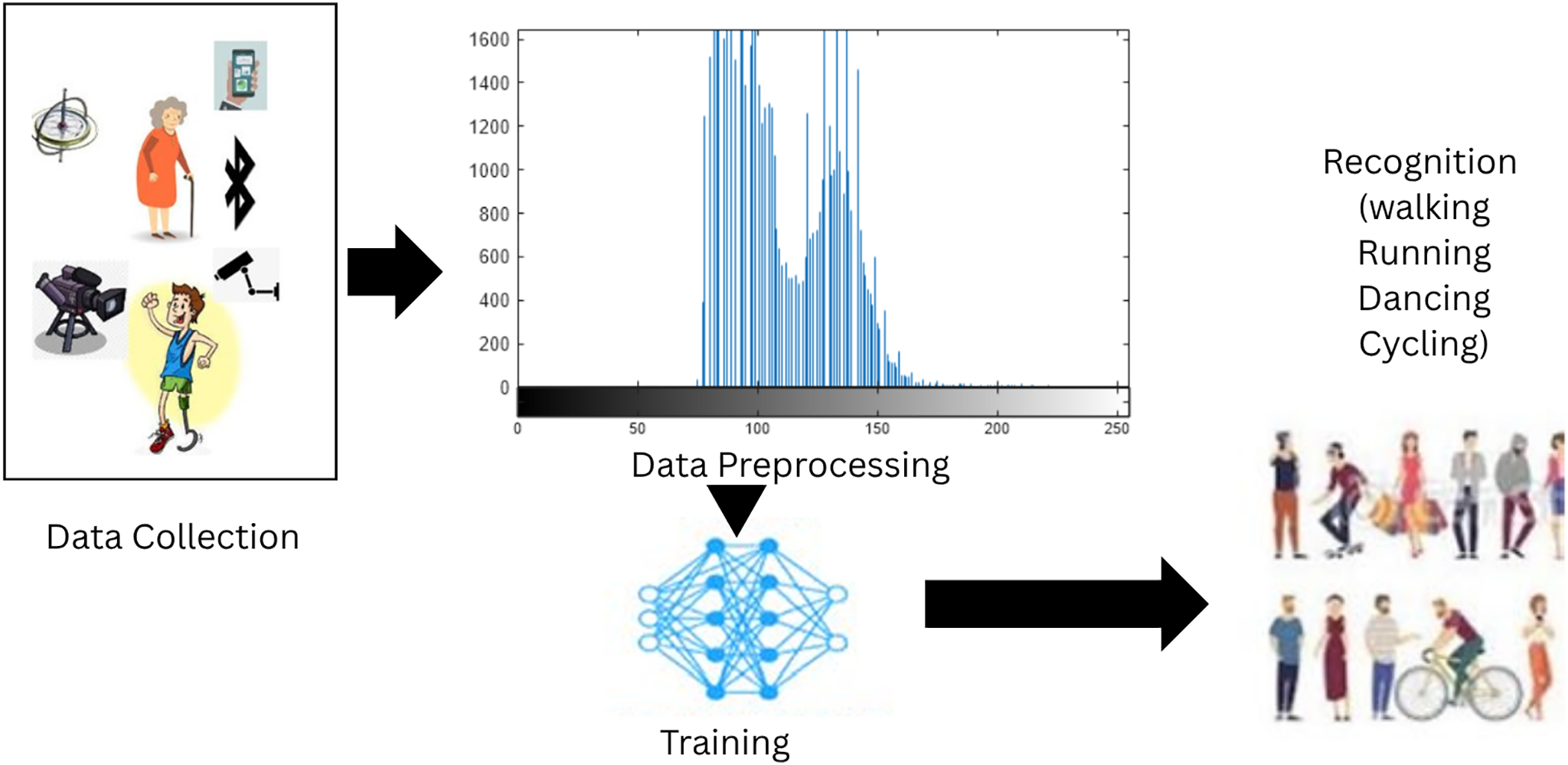

Initially, the challenge was understanding how to detect and identify people, their behaviour and suspicious activities [32]. Over time, researchers discovered that spatial and temporal information played a crucial role in accurately recognising different human actions in complex scenes [33]. However, despite these advancements, precise recognition in real-world videos remained difficult. Factors such as motion style, occlusion and background clutter often hinder the correct identification of human actions under uncontrolled or crowded conditions [34]. A comprehensive and challenging benchmark shall be able to promote the research on human behaviour understanding, including action recognition, pose estimation, re-identification and attribute recognition [35]. Machine learning (ML) algorithms have emerged as a powerful tool for managing and interpreting Emergency situations, whether natural or human-made disasters [36]. Over the years, ML techniques have been increasingly applied in emergency management systems to support first responders and decision-makers, enhancing the overall capabilities in disaster prevention, preparedness, response and recovery [37]. Emergency management and response are critical aspects of ensuring public safety and security. Emergencies can take many forms, including natural disasters such as hurricanes, earthquakes and wildfires, as well as human-caused emergencies like terrorist attacks, industrial accidents [38] and pandemics [39]. Effective emergency response efforts during an emergency or natural disaster, as in Fig. 3, play a vital role in mitigating the impact of such events, helping to save lives and minimise property damage [40]. In recent years, there has been a surge in research focused on utilising social media for disaster response. This includes platforms like Facebook and “X” when used for communication during emergencies [41]. Many of these studies explore automated machine learning approaches to identify disaster-related posts [42], which play a crucial role in facilitating coordination and timely response. Besides physical sensors and other technical sources, individuals using smart mobile devices, often referred to as human sensors, generate vast amounts of multimodal data during crises, including text, audio, video and images. These datasets are typically categorised as multimodal, reflecting the diverse formats in which critical information is shared during emergencies [43]. The main challenges faced by emergency responders is effective extraction, analysis and interpretation of this multimodal data within a limited time frame for timely and informed decision-making.

Figure 3: Types of Natural Disasters and the mitigating technologies as described in [40]

One of the key challenges in disasters is combining the excess of available information, ranging from social media data to satellite imagery and turning it into concrete and actionable insight [44]. This requires multi-modal data on disaster impact, location-based risk and spatial conditions [45], for disaster response. Although multimodal data fusion for disaster response has been applied to social media data, a research gap remains in incorporating other sources, such as satellite imagery or statistical data, to better capture the spatial context and exposure. During the occurrence of natural disasters, people heavily use social media for communication by posting multimedia information in the form of texts and images. In such critical situations, it becomes imperative to use all modalities of information sources to better capture vital knowledge related to the crisis [46]. Ignoring either modality (text or image) can lead to a partial understanding of the content.

In the year 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic drastically disrupted both private and public life [47], forcing many sectors around the world to shift to online modes of operation with little to no preparation time. The study of human behaviour, whether in daily life [48] or under high-stress conditions, shows how complex it truly is when viewed across different disciplines.

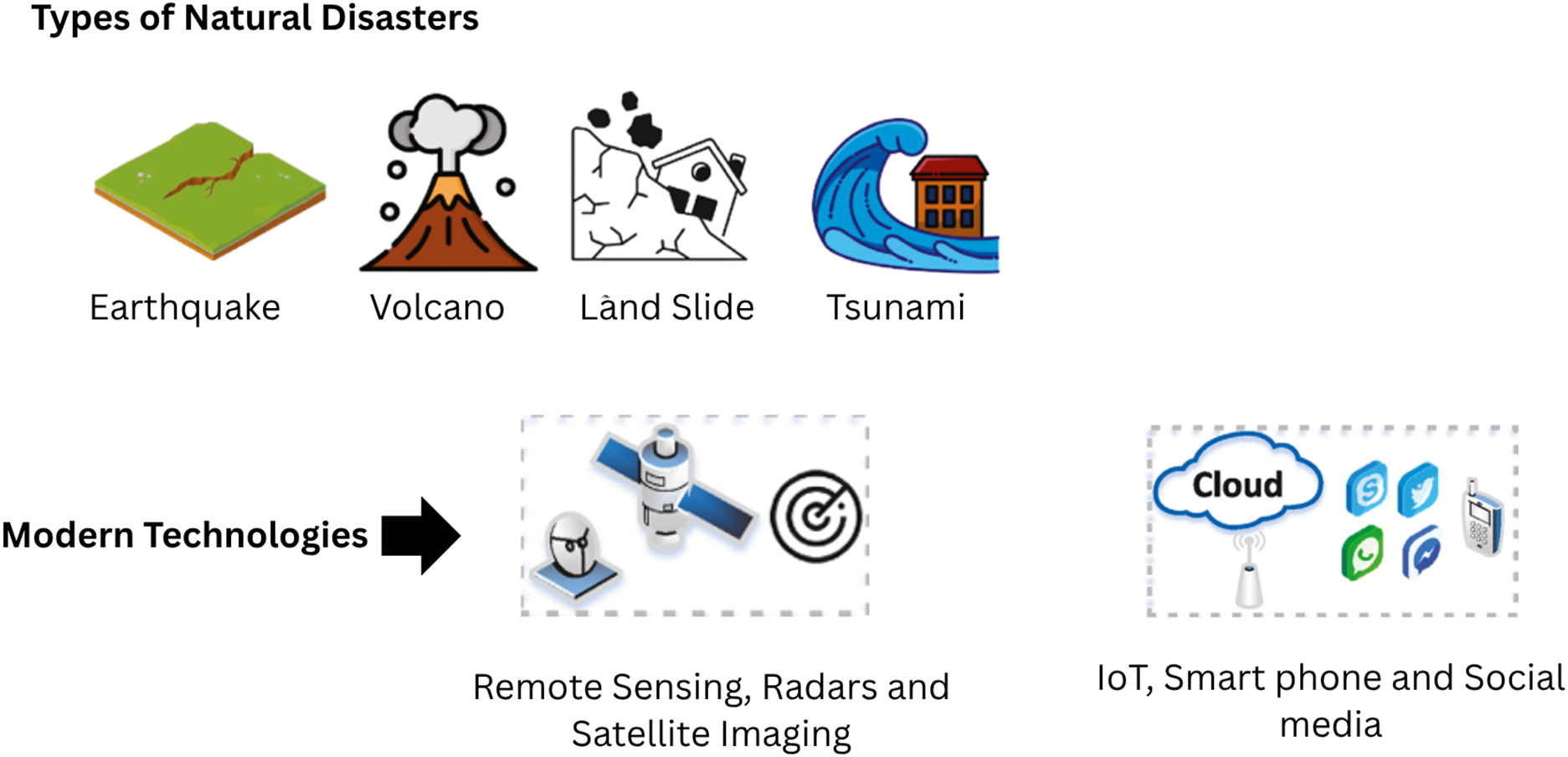

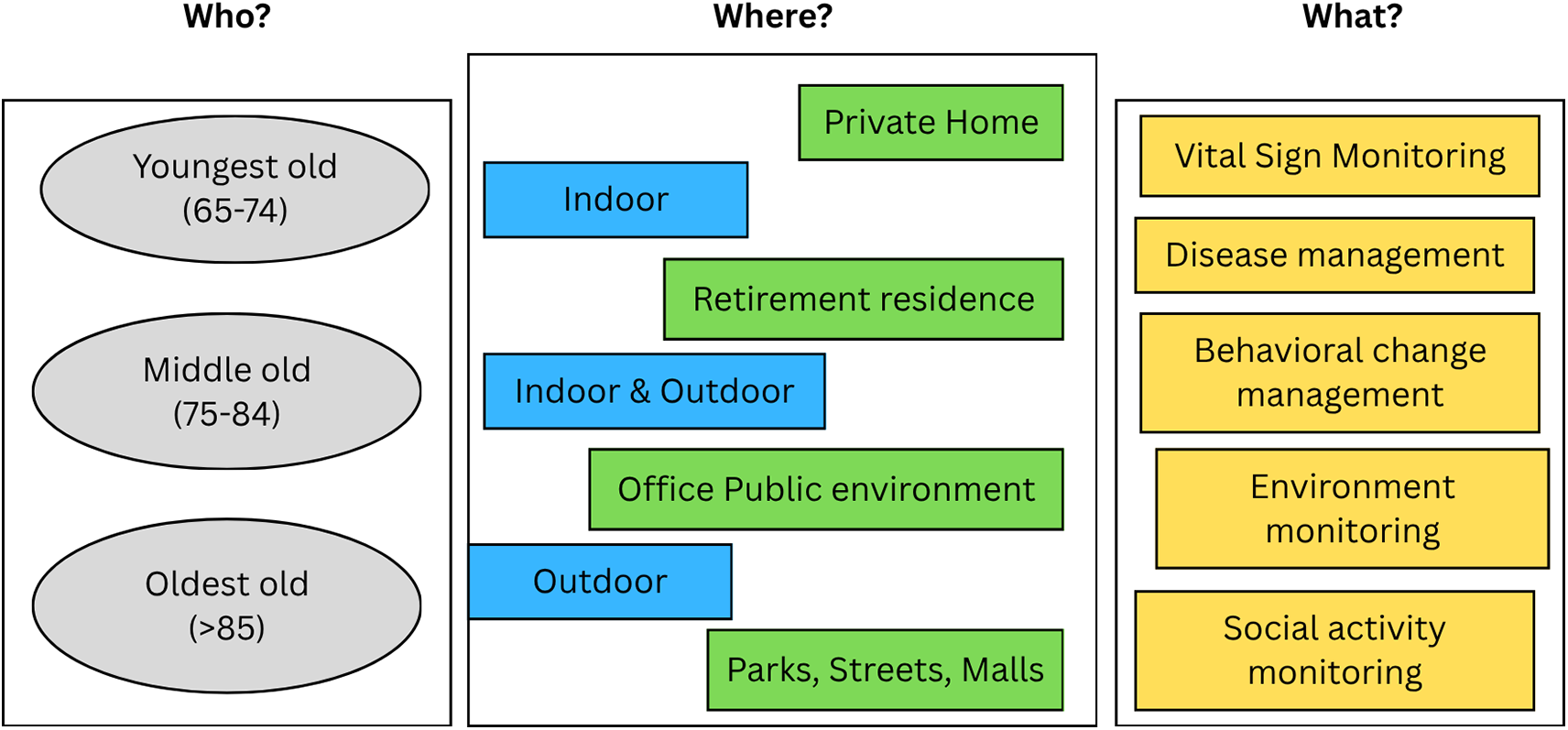

Over the years, progress has been made in areas like assisted living, healthcare and predictive behaviour systems, which have improved both the reliability and interpretability of results [49]. Fundamental aspects to be considered in the design of such systems are shown in Fig. 4. Yet, challenges are still there, especially in uncontrolled or crowded environments, where achieving accuracy becomes much more difficult. Even with the support of benchmarks and multimodal approaches, the success of disaster management still depends a lot on quick decision-making and proper preparedness. The rapid digital shift during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic also reminds us of the growing need for adaptive and resilient systems that can truly support emergency response.

Figure 4: Fundamental aspects to be considered in the design and development of an AAL system: possible users (who?), environments (where?) and functionalities (what?) as described in [49]

As a result of the new technological advancements and emergencies becoming more complex, there has been a noticeable rise in SLRs and meta-analyses exploring how human behaviour can be modelled and managed through AI systems. These recent studies have laid a strong foundation by discussing methods, approaches and highlighting the research gaps, like [50]. This current review shifts its focus towards classifying human behaviour during emergencies, especially by using machine learning (ML) and diverse data types. Comparing some of the most relevant recent studies to help place this work in the larger research picture and understand where it stands. One of the most comprehensive studies [51] presented a literature review focused on human behaviour during disaster evacuation processes. Their analysis synthesised 177 studies from 1954–2022 and emphasised the necessity of understanding individual and group behaviour for successful evacuation planning. The review highlighted several behavioural modelling techniques, including route choice behaviour, decision-making models, virtual reality simulations and agent-based approaches. Especially, the study pointed out the lack of focus on transportation evacuations, suggesting a gap in representing real-world urban scenarios. The authors also identified the key role of psychological, demographic and social characteristics in determining evacuee behaviour, aligning with the motivations behind HBC in our own study. The authors in [52] reviewed 134 papers from 2013–2023 and their work outlined challenges associated with current agent-based modelling (ABM) approaches, including computational limitations, scarcity of real-time behavioural data and the limited complexity of decision-making architectures. Their review highlights the importance of simulating adaptive and autonomous human-like behaviour in emergencies, which is a challenge directly addressed through ML-based HBC models and multimodal fusion techniques [53].

A broader perspective on decision-making support in emergency contexts is provided in [54], along with the use of decision support systems (DSS) in search and rescue (SAR) operations. Their study evaluated a wide range of AI-driven tools, including geospatial information systems, optimisation models and intelligent data fusion platforms used in SAR planning and response. While their work does not focus directly on behaviour classification, it reinforces the critical role of real-time, context-aware decision-making tools, of which HBC systems are a natural complement. A unique contribution from this review was the identification of knowledge transfer possibilities across domains such as environmental monitoring and maritime safety domains, where behaviour classification has emerging relevance. Like [55], localisation is provided as an essential tool to ensure readiness, response, and coordination between first responders and affected individuals. They also worked on emerging sixth-generation (6G) wireless technologies such as integrated sensing and localisation. Their reviewed technologies can play an effective role in device localisation and are presented to serve as a base for others to further investigate and conduct research in this domain.

Reference [56] conducted an SLR on driver behaviour classification (DBC), an adjacent domain that similarly seeks to model and predict human actions in real-time and high-risk environments. Their analysis highlighted the types of behaviours classified (e.g., aggressive, distracted, abnormal) and categorised the use of ML/DL algorithms such as SVMs, CNNs and LSTMs across datasets like SHRP2 and NGSIM. Although the context is different in vehicular safety and emergency responses, the challenges in feature extraction, multimodal fusion and real-world deployment are very similar. This provides a conceptual bridge for applying DBC techniques to broader emergency HBC models.

Another study [57] focused on big data analytics (BDA) in humanitarian and disaster operations. Although this study was not centred purely on HBC, it strongly highlights the importance of large-scale multimodal data in managing crises. A critical insight from this review is the identification of persistent gaps in preventive modelling and early-warning systems, areas where predictive HBC systems using multimodal sensing could make substantial contributions. Together, these related reviews demonstrate the depth and interdisciplinarity of the field, covering evacuation modelling, pedestrian dynamics, SAR coordination, driver behaviour and humanitarian logistics.

However, none of these works provide a comprehensive and focused synthesis of HBC specifically in emergency situations using multimodal data and machine learning methods. Our review emphasises the live classification and real-time understanding of human actions, especially in high-risk, time-sensitive environments. It also bridges methodologies from adjacent fields and connects them through the lens of multimodal fusion and ML-enhanced behavioural modelling. Reference [58] provided a detailed overview of the latest advancements in real-time fall prediction using wearable sensors. A comprehensive review was carried out on various studies that employed different machine learning techniques and sensor modalities to predict falls in real time. It describes the problems and limitations associated with wearable sensor-based fall prediction. It identifies the possible future research directions in this field and provides a comprehensive narrative review of the recent research on fall risk assessment using wearable sensors and gait analysis. The importance of Radio frequency (RF) spectrum sensing is key for the purpose of precise object posture detection and its classification. Reference [59] aims for a focused review of context-aware RF-based sensing, emphasising its principles, advancements and issues. Reference [60] highlighted the importance of abnormal behaviour detection (ABD) in activities of daily life (ADL). The author compared and contrasted the formation of the ABD system in ADL from input data types (sensor-based input and vision-based input) to modelling techniques (conventional and deep learning approaches). Review [61], comprising 424 studies, investigates the integration of machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), computer vision, IoT-enabled predictive analytics and AI-powered robotics in shifting emergency response mechanisms. It also investigates the integration of machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), computer vision, IoT-enabled predictive analytics and AI-powered robotics in shifting emergency response mechanisms. It comprehensively examines AI applications in disaster management, real-time incident detection, healthcare emergency response, industrial hazard prevention, cybersecurity frameworks and intelligent traffic control, which provides a comprehensive assessment of advancements and problems in AI adoption.

• This study classifies the various types of emergencies, including falls, evacuation scenarios, violent incidents, wildfires and medical crises.

• It examines the application of multimodal datasets, emphasising the frequent use of publicly accessed datasets like SisFall [62] and UCI-HAR [63], along with custom-built and synthetic data sources for emergency-related studies.

• This study analyses and records the range of sensors employed in the selected studies. These include inertial measurement units (IMUs), thermal and RGB cameras, environmental detectors and different wearable systems equipped with multiple sensors.

• Various ML and DL approaches were reviewed and compared to assess how good they perform in behaviour classification tasks during emergency situations.

• Some of the major research challenges and gaps, which include the lack of real-world generalizability, inconsistent dataset standards, difficulties in integrating multimodal inputs and limited focus on vulnerable or at-risk populations.

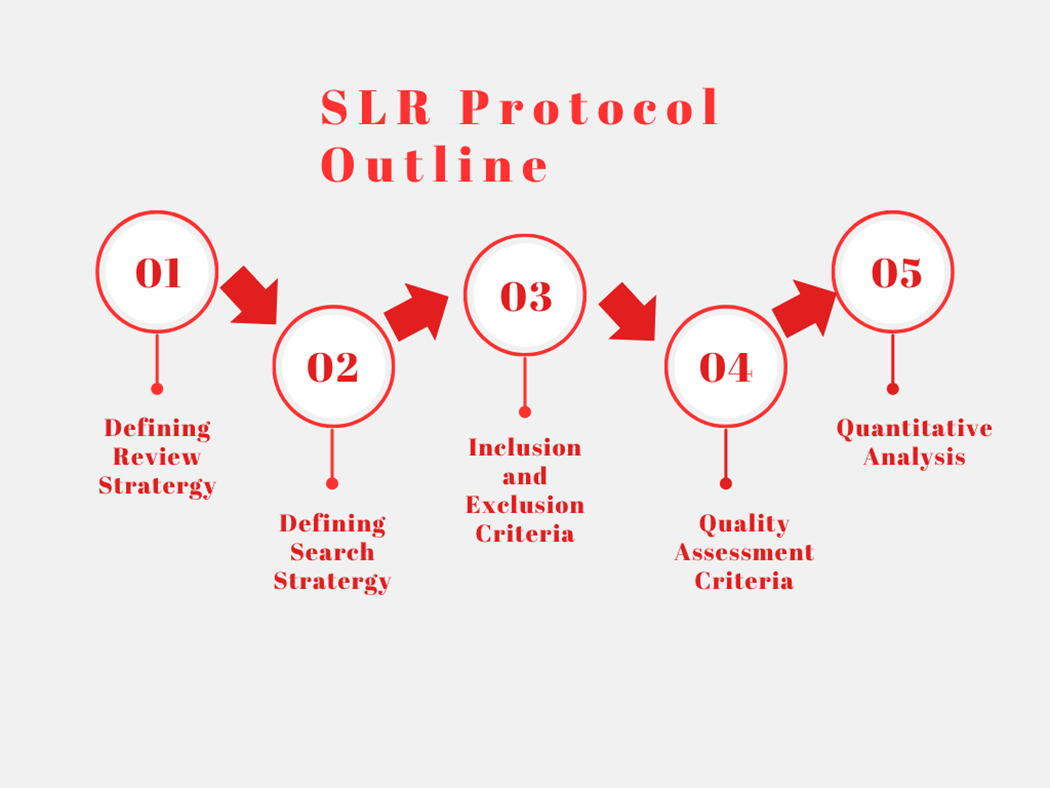

This review follows the PRISMA framework, which is recognised as the most reliable approach to conduct a systematic review, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The PRISMA checklist is provided as Supplementary Material attached to this paper. A structured approach was maintained, examining peer-reviewed studies published between 2020 and 2025, and stating five key research questions (RQ1–RQ5). These questions were carefully formulated to ensure alignment with the main theme and to refine the specific focus of the study.

Figure 5: SLR review protocol

The search strategy involved querying multiple digital databases, including IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, MDPI, and Elsevier, using a predefined set of keywords accompanied by Boolean operators and wildcard characters for the sake of expanding search scope. Main search terms included combinations of:

• “Human behaviour classification” or “activity recognition”

• “Emergency” or “disaster” or “evacuation” or “fall detection”

• “Multimodal data” or “sensor fusion”

• “Machine learning” or “deep learning”

The time range was restricted to 2020–2025. Only English-language, peer-reviewed journals and conference papers were included.

3.4 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

In order to ensure the relevance and quality. We applied following criteria.

Inclusion Criteria:

• Studies published between 2020 and 2025.

• Focus on human behaviour recognition/classification in emergency contexts.

• Use of machine learning or deep learning models.

• Utilisation of multimodal or multi-sensor data (vision, inertial, environmental, etc.).

• Peer-reviewed journal or conference publications.

Exclusion Criteria:

• Papers outside the specified date range.

• Studies focusing solely on non-emergency activities.

• Articles lacking ML/DL or sensor-based approaches.

• Non-peer-reviewed work (e.g., preprints, editorials, theses).

• Duplicate or redundant studies.

3.5 Quality Assessment Criteria

Each included study was given a quality score, assigning binary number (0 or 1) across the following dimensions:

• Relevance: Is the study focused on HBC in emergencies?

• Technical Rigour: Does the study present a valid and replicable ML/DL methodology?

• Data Modality: Does the study use more than one modality or sensor type?

• Results and Evaluation: Are the model performance metrics clearly reported?

• Contribution: Does the study present a novel architecture, dataset, or insight?

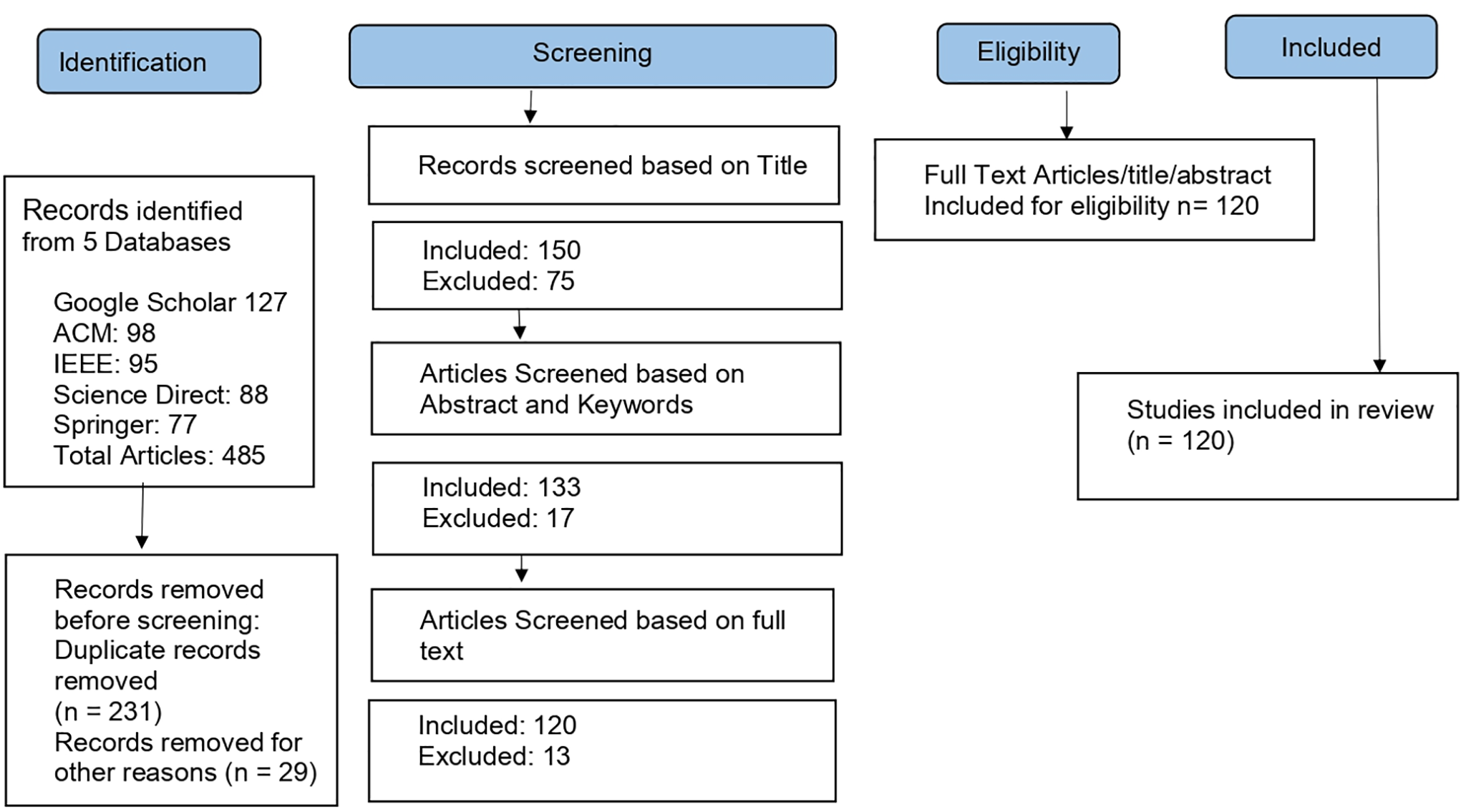

Fig. 6 presents a thorough overview of our screening and assessment method for the statistical analysis of our literature.

Figure 6: Flow diagram of screening

A total of 120 papers were selected as a result of a detailed review, subsequently applying the inclusion, exclusion and quality criteria. Quantitative analysis was conducted to identify:

• Publication trends by year (2020–2025)

• Frequency of emergency types addressed (e.g., fall detection, evacuation, fire, violence)

• Sensor distribution (e.g., IMU, camera, thermal, environment)

• Modalities used (vision-only, wearable-only, multimodal fusion)

• ML/DL algorithm usage (e.g., CNN, LSTM, hybrid models)

• Dataset types (public, custom, simulated)

This structured approach ensured the reliability, reproducibility and thematic alignment of the review with the defined research objectives.

RQ1: What types of emergencies are being addressed using human behaviour classification?

The above-mentioned question highlights the wide spectrum of emergencies studied under human behaviour classification. Starting from personal health crises to societal scale disasters as represented in Table 1. The outcomes state that broader integration of multimodal data, real-world deployment and context-aware generalisation remain key directions for future research. Emphasising the importance of detecting fall-related events in vulnerable populations such as the elderly, disabled, or patients in assisted living. It is demonstrated that social media, environmental data and multimodal fusion are vital for rapid situational awareness. Extending human behaviour classification to include help-seeking behaviours, evacuation monitoring and even wildfire prediction. The literature addressed physical hazards in workplace environments. The use of wearable sensors and motion analysis reflects their practical use in high-risk industries. Both physical cues (e.g., “hands up” poses, frantic running) and digital signals (e.g., misinformation on social media) as indicators of emergencies. However, privacy concerns, scalability in crowded scenarios and real-time deployment challenges remain open issues.

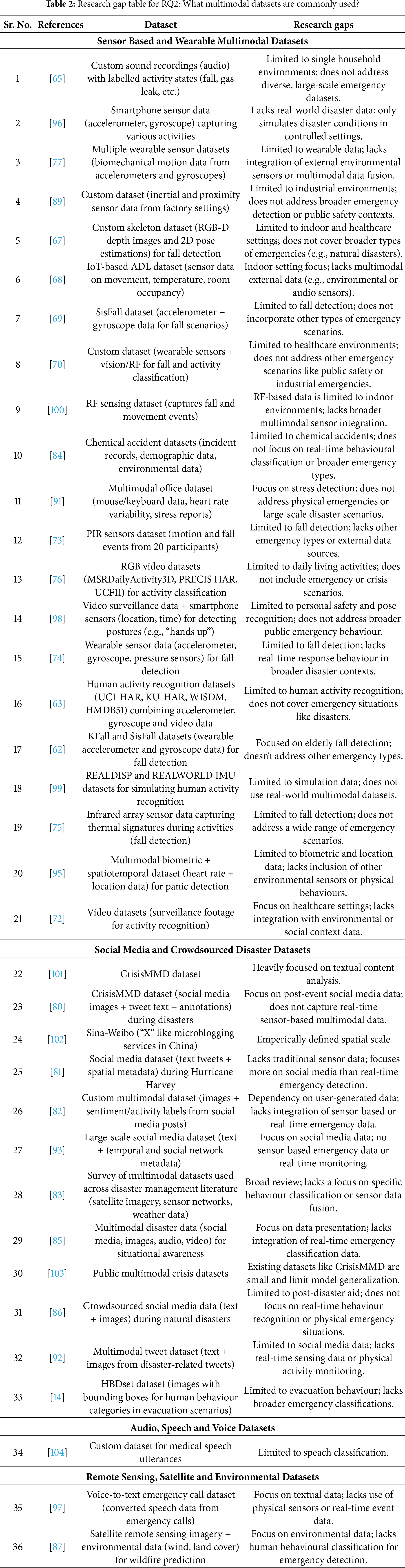

RQ2: What multimodal datasets are commonly used?

For the demonstration, that progress in human behaviour classification for emergencies is shaped by the diversity and availability of datasets. The discussed above Datasets enable crisis monitoring, fall detection, evacuation analysis and disaster forecasting. Still, there exist some issues, including noisy or incomplete annotations, limited real-world generalisation, imbalance across event types and ethical concerns related to privacy and surveillance are also discussed. Efforts are concentrated on fall detection, activity recognition and stress monitoring. Public benchmarks such as SisFall and KFall played a central role, while custom datasets addressed workplace, smart home and clinical environments. CrisisMMD and Hurricane Harvey collections have been widely applied for crisis informatics. They capture help-seeking behaviours, misinformation and rumour propagation, providing rapid situational awareness. It has been shown that emergency call recordings and speech-to-text conversions serve as valuable multimodal resources. These datasets provide unique real-time communication cues, with challenges in noisy environments, caller variability and limited availability due to privacy constraints. Lastly, by fusing imagery, climate and geospatial data, these datasets enable large-scale forecasting and evacuation planning. However, they lack fine-grained human-level behavioural details, limiting their integration with micro-scale human activity datasets as shown in Table 2. The fusion of multimodal data enables richer context awareness, reduces ambiguity and enhances model robustness under complex conditions, while a single source data stream alone might fail. But for, the integration of multimodal sources may require overcoming challenges like synchronisation across modalities, differing sampling rates, data imbalance and computational overhead.

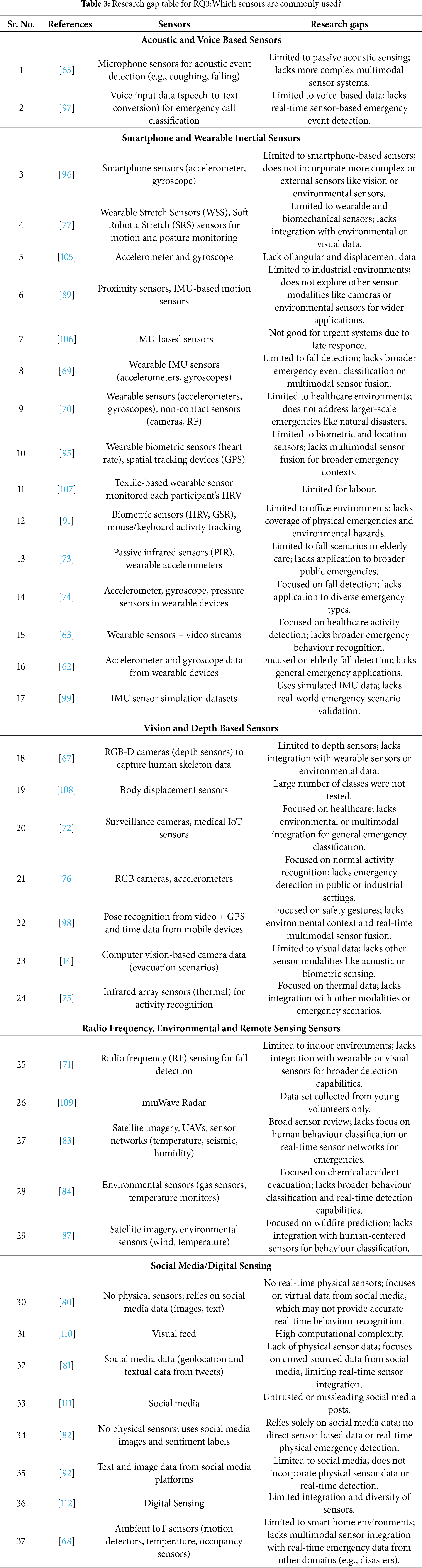

RQ3: Which sensors are commonly used?

The human behaviour classification in emergencies relies on a highly diverse spectrum of sensing modalities, ranging from traditional to fully digital, as shown in Table 3. This diversity reflects both the complexity of emergency contexts and the complementary strengths of different sensor types. Microphones and speech-to-text pipelines are advantageous for unobtrusive monitoring in households or dispatch systems, but remain sensitive to environmental noise and caller variability. Accelerometers, gyroscopes, magnetometers and stretch sensors dominate fall detection and activity recognition. But issues such as body placement, user compliance and energy efficiency remain open. Vision and Depth-based Sensors discussed above provide rich spatial-temporal information but face scalability, occlusion and privacy-related concerns, particularly in public monitoring scenarios. Radio Frequency, Environmental and Remote Sensing Sensors extend emergency monitoring to larger environmental and infrastructural scales, but they often lack fine-grained individual-level details helpful for behaviour classification. Social Media/Digital Sensing are treated as “virtual sensors” where human posts, images and geolocation data act as dynamic signals. This paradigm supports real-time situational awareness with a high risk of incomplete data and misinformation. Ambient IoT and Contextual Sensors. While effective for localised monitoring, they require dense deployment and may lack portability across diverse environments.

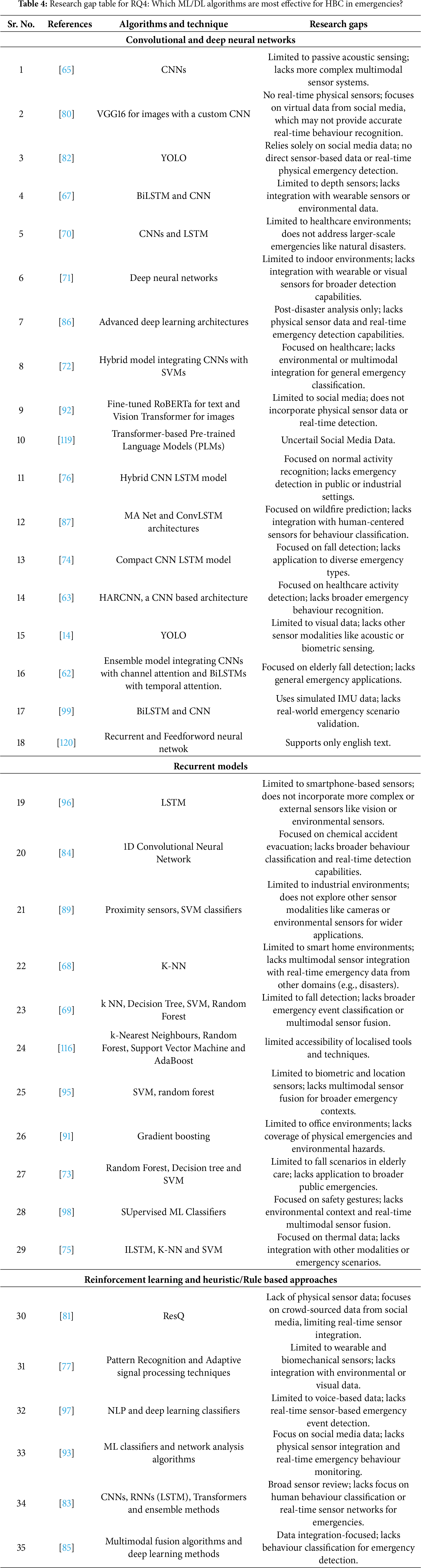

RQ4: Which ML/DL algorithms are most effective for HBC in emergencies?

Convolutional and Deep Neural Networks:

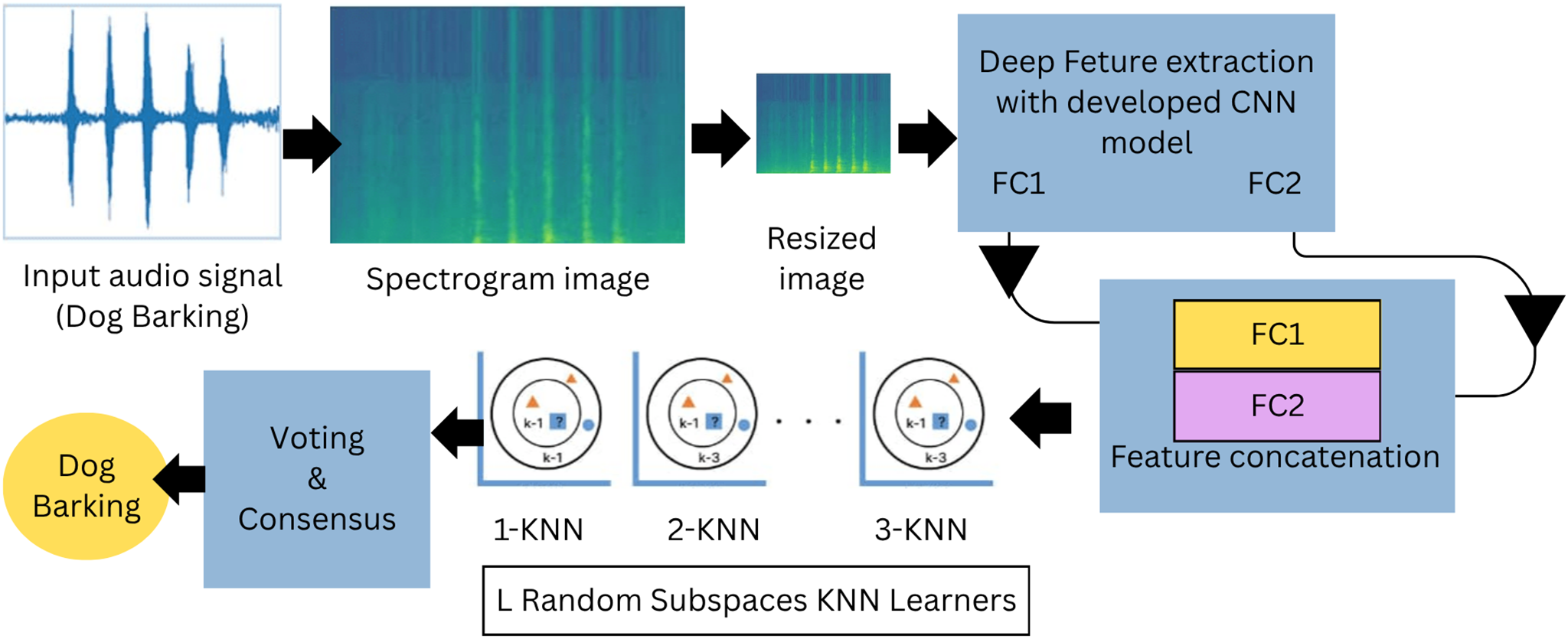

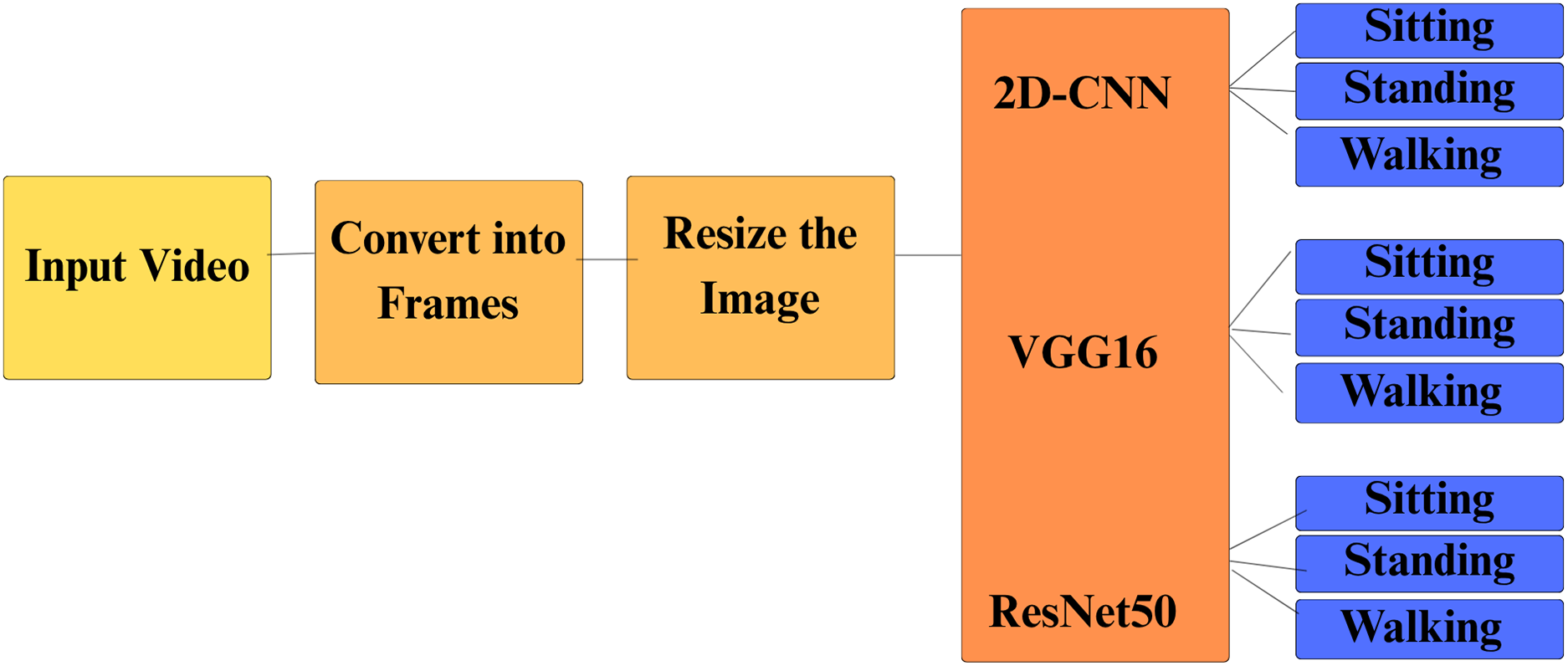

Reference [65] demonstrated the effectiveness of CNNs for emergency sound recognition. Fig. 7 uses spectrogram-based representations and data augmentation techniques to achieve strong performance in real-time classification [113]. Study [114] showed that combining VGG16 for images with a custom CNN, as shown in Fig. 8, significantly outperformed unimodal baselines when classifying disaster-related text in a multimodal architecture [80].

Figure 7: A Deep CNN model for environmental sound classification by [113]

Figure 8: Block diagram of human behaviour classification system with training the 2D CNN model, VGG16 and ResNet50 by [114]

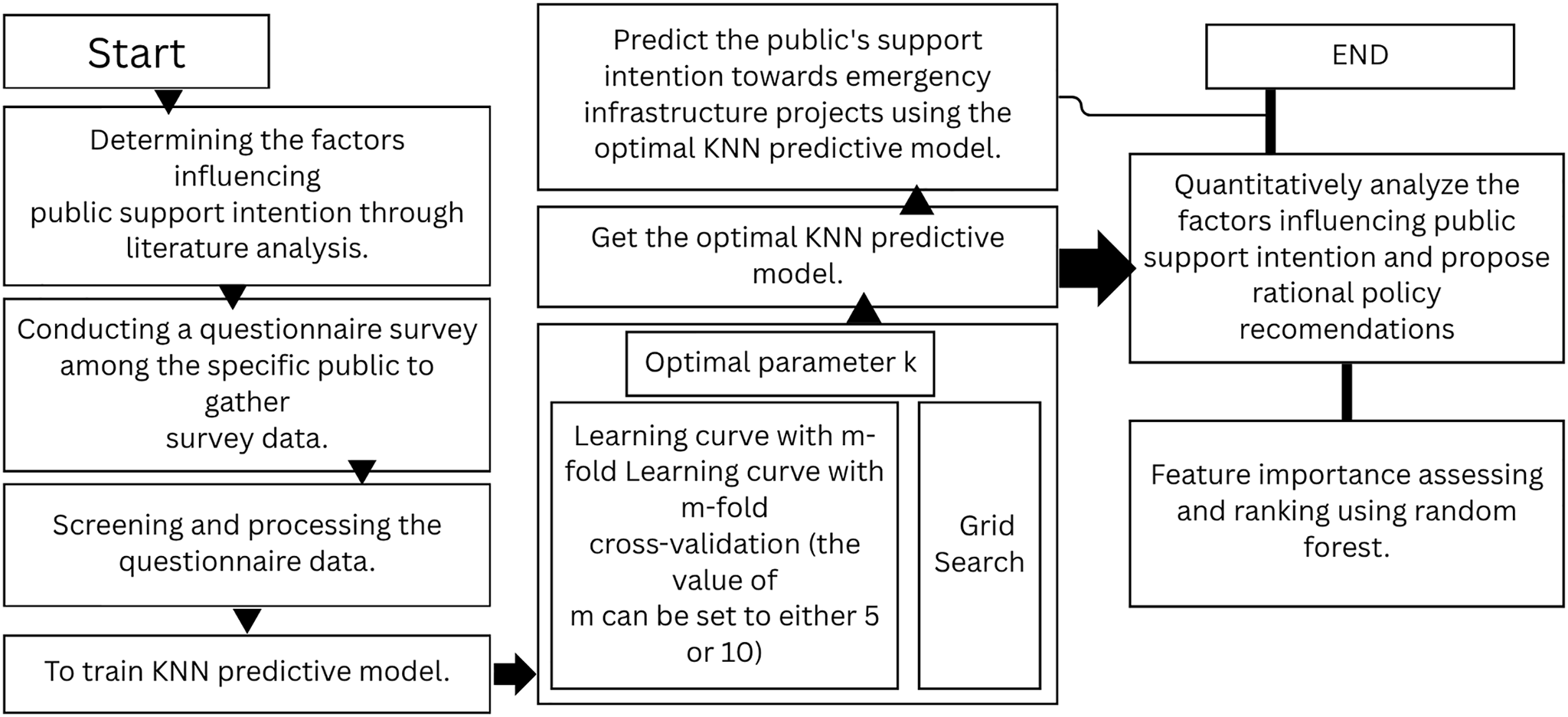

The use of a k-nearest neighbour classifier for behaviour recognition and anomaly detection is shown in Fig. 9 [115]. In [68], the authors used an ADL dataset and achieved up to 83.87% accuracy in detecting anomalies in user behaviour that could constitute an emergency.

Figure 9: Division of research framework into a three-step process [115]

In Fig. 9, data collection and processing were conducted in Stage 1. In Stage 2, an optimised K Nearest Neighbour prediction model was constructed to make predictions of new sample data. Stage 3 is the quantitative analysis of the influencing factors of public support.

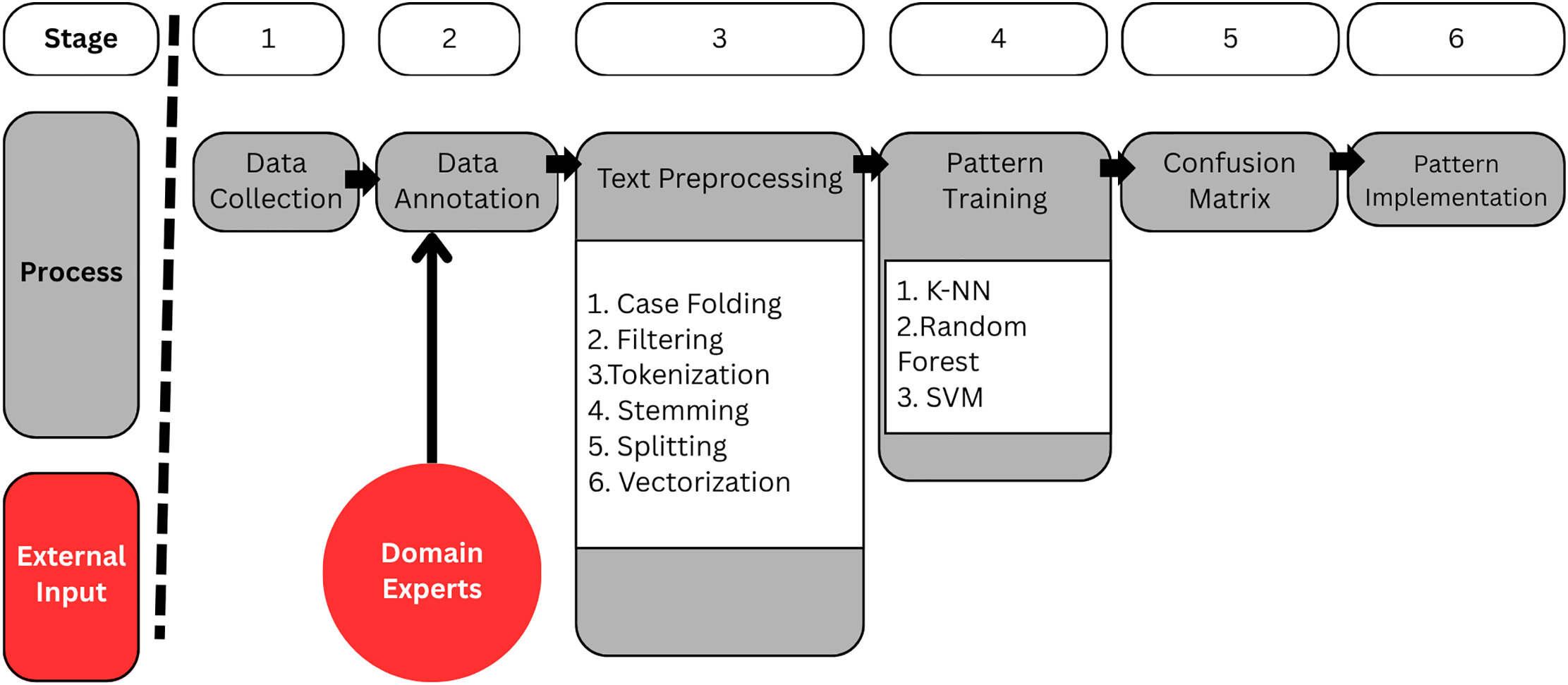

Reference [69] compared multiple ML algorithms, including kNN, Decision Tree, SVM, Random Forest and Gradient Boosting. Fig. 10 finds that Random Forest and Gradient Boosting achieved the highest sensitivity and specificity.

Figure 10: Stage-wise process division and comparison of algorithms by [116]

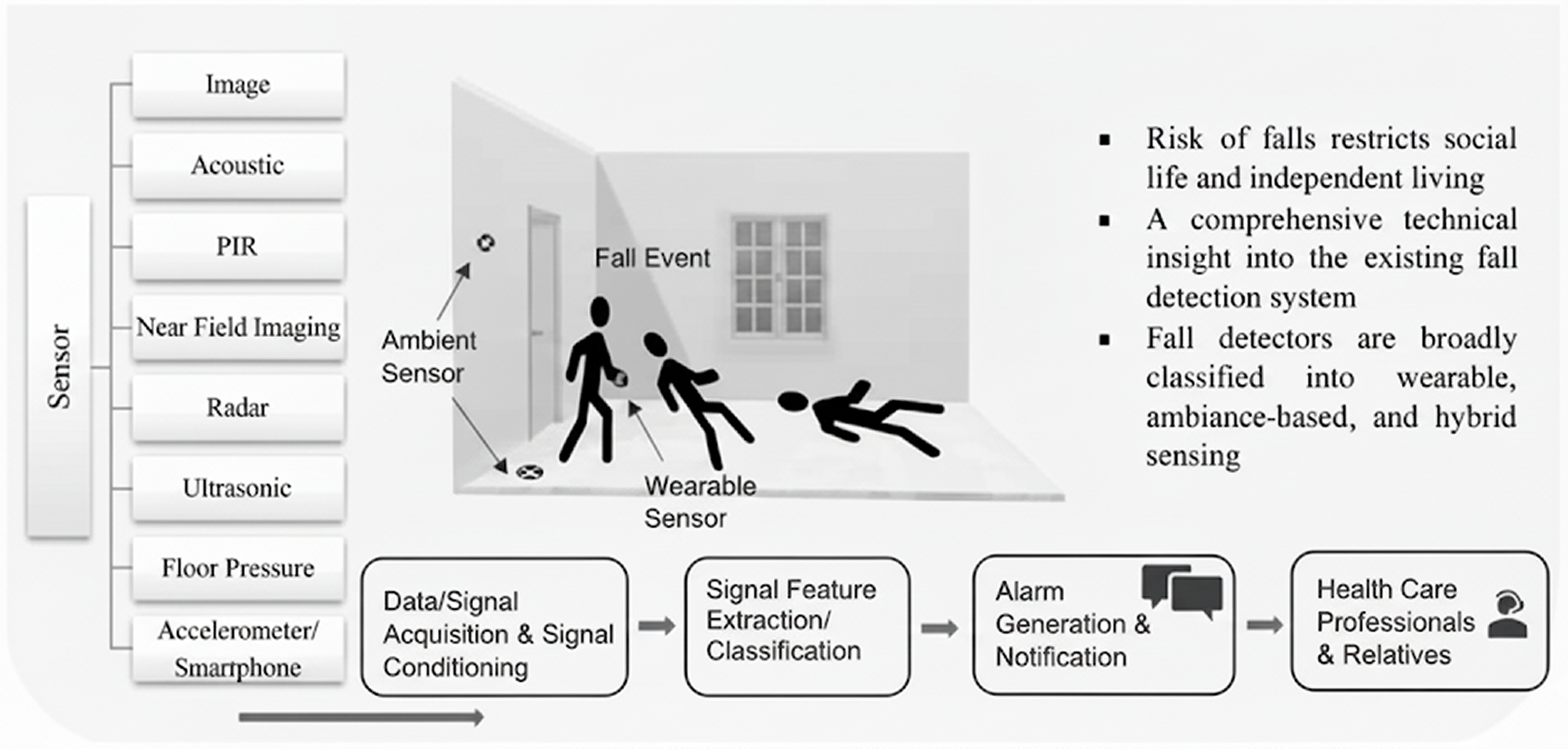

Chander et al. (2020) and Singh et al. (2020) presented a review highlighting pattern recognition and adaptive signal processing techniques for interpreting WSS sensor data in fall detection systems [77], as represented in Fig. 11.

Figure 11: Fall Detectors classification and alarm generation by [117]

Linardos et al. (2022) highlighted CNNs, RNNs (LSTM), Transformers and ensemble methods as effective techniques for prediction, classification and early warning in disaster management Fig. 12, as discussed in the review by [83].

Figure 12: Review of disaster management system approaches by [118]

The research question in consideration shows that deep learning models dominate human behaviour classification in emergencies, as shown in Table 4, with CNNs, LSTMs and hybrid CNN-LSTM frameworks consistently outperforming traditional ML approaches. Transformer-based models and ensemble architectures are emerging as promising alternatives, particularly for multimodal text-image classification and interpretability. Convolutional and Deep Neural Networks are highly effective for spatial and multimodal feature learning. Hybrids such as CNN-LSTM and CNN-SVM further enhance classification accuracy by utilising complementary strengths. Recurrent Models demonstrate clear advantages for sequential data, outperforming feedforward and CNN-only models in capturing temporal dynamics for falls, postures and evacuation monitoring. Classical ML Algorithms still hold value in domains requiring interpretability or constrained computation. However, they often underperform compared to DL models, except in structured or low-dimensional sensor datasets where Random Forest and AdaBoost achieve strong accuracy. Reinforcement Learning and Heuristic Approaches extend the field beyond recognition toward adaptive coordination, decision making and rumour detection.

RQ5: What are the main limitations and gaps in current research?

This question highlights several limitations which persist across sensing, data quality and modelling dimensions, that can be seen in Table 5. Sensor-related challenges are among the most critical and face robustness issues in uncontrolled environments. Hardware constraints further restrict scalability. Data-related challenges emphasise the lack of comprehensive and diverse datasets. Vulnerable groups such as the elderly and disabled populations remain underrepresented, limiting generalisation to real-world emergencies. Large-scale multimodal datasets are needed to improve robustness, cross-domain adaptability and inclusivity. Model and algorithmic limitations include reliance on computationally expensive deep learning models. The literature indicates that future research must balance model accuracy with interpretability and address data diversity gaps.

This systematic literature review has offered a broad overview of human behaviour classification in emergency situations, highlighting the variety of methods, datasets, and challenges within the field. The main aim was to examine how human behaviour classification is implemented across various types of emergencies, for the identification of commonly experimented datasets and sensors, to evaluate the performance of machine learning and deep learning algorithms, and to point out the existing gaps and limitations in current research.

The reviewed studies cover a wide range of emergency types, including health-related crises, natural disasters, and industrial accidents. Additionally, emergency scenarios like panic detection in crowds, disaster response coordination, and health crises in single-person households were explored. However, despite the wide array of emergencies discussed, several gaps exist in terms of coverage. Many studies focused primarily on falls, especially in elderly populations, neglecting other critical emergencies such as public safety incidents or large-scale natural disasters. The focus on single emergency types restricts the ability of models to generalise to different contexts, which could limit their real-world applicability.

Multimodal Datasets:

The studies involved various multimodal datasets where the common data types are sensor data (from wearables and environmental sensors), images, video footage and social media content (Posts or comments). Social media data is useful but likely to suffer from issues such as incompleteness and bias, which affect the accuracy of the models. If we now consider the sensor-based datasets (such as those derived from accelerometers, gyroscopes and RF sensing), they are promising but frequently encounter challenges with data fusion, sensor calibration and environmental factors intervention. Most of the datasets are limited to controlled environments, and there is an empty space left for real-time and dynamic datasets capturing real-world emergencies. This limits the ability to generalise findings and apply models in different uncontrolled settings.

Sensors and Technology:

Sensors such as wearable sensors, RF sensing, video surveillance and social media platforms were utilised to detect and classify human behaviour. Many sensors have limitations in terms of accuracy and robustness, particularly in noisy or uncontrolled environments. It is a common observation that RF sensors and video surveillance show sensitivity to environmental interference and often face problems such as occlusions or poor camera placement, respectively; their performance tends to decline in real-world conditions. Issues like user compliance and battery life are usually encountered in wearable devices, restricting their effectiveness in continuous real-world monitoring. The fact that sensors play a crucial role in emergency detection, their integration with multimodal data from social media or environmental sources is still not widely explored.

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms:

The machine learning and deep learning algorithms used in the studies are quite diverse, with CNNs, LSTMs, SVMs, and Random Forests being the most frequently employed models. These algorithms have proven particularly effective for tasks such as activity recognition (including falls and panic detection) and event classification. Deep learning models like CNNs and LSTMs have demonstrated strong potential in managing sequential and spatial data, whereas traditional ML models such as SVMs and Random Forests are generally applied to simpler classification tasks, as presented in Table 6. Many of these models face significant challenges in terms of real-time applicability, scalability and generalizability to different emergency contexts. For instance, models trained on specific emergency types (like falls or fire accidents) often fail to generalise to broader scenarios, which limits their robustness in handling real-world emergencies. Lack of interpretability in deep learning models can make it difficult to understand model decisions, particularly in critical emergency response situations.

5.2 Gaps and Future Recommendations

Integration of Multimodal Sensor Data:

Identified gap in this review is the scarce integration of multimodal sensor data. Several studies have employed different sensors, most have not successfully combined these data streams, impacting the accuracy and robustness of the developed models. Future research should focus on fusion techniques which are capable of integrating multiple sensor modalities in real time and allowing for more dependable emergency detection under diverse conditions.

Real World Dynamic Datasets:

There is a strong need for real-world dynamic datasets that cover a wider range of emergencies, including public safety, natural disasters and industrial accidents. Most of the reviewed works rely on controlled settings or simulated data, which may not truly reflect the complexity and diversity of real emergency conditions. Datasets that collect real-time information from real incidents would support better accuracy, scalability and generalisation of the models. Especially, open source multimodal datasets containing different kinds of emergencies should be given priority.

Improved Sensor Technologies:

Sensor technologies encounter significant challenges concerning accuracy, power consumption, and adaptability in different environments. For example, wearable sensors rely heavily on user compliance, whereas video surveillance systems are influenced by obstacles and changes in camera angles. Future studies should aim to develop robust and adaptable sensors that can operate efficiently wherever deployed, provide longer battery life, and remain easy to deploy in real-world settings. Hybrid sensors that combine environmental and human-centred data would further contribute to offering a more holistic understanding of emergency situations.

Hybrid and Explainable Models:

Although deep learning models such as CNNs and LSTMs are widely used, their interpretability remains a significant challenge. In emergency situations, understanding the logic behind a model’s decision is crucial, especially when human safety is at risk. Future studies should prioritise integrating explainable AI (XAI) approaches with deep learning models to enhance both transparency and dependability. Combining traditional machine learning techniques with deep learning within hybrid frameworks could also improve the robustness and adaptability of emergency classification systems.

Addressing Privacy and Ethical Concerns:

Several studies have examined the privacy and ethical implications of using personal data in the context of wearable sensors and video surveillance. There is a need to preserve any sensitive data in case of any emergency in order to avoid any potential danger and help maintain the privacy of individuals. There is a need to develop a framework that respects the privacy of the person and ensures that ethical standards are followed because sensor data from personal devices and public areas play a key role in such studies.

5.3 Limitations of Review Study

The areas that need attention include improving real-time detection, enhancing model performance, and making sure that data protection is strong enough to address ethical and privacy concerns in system design. One of the most important issues for this SLR is that the inclusion criteria are limited to studies published between 2020 and 2025, which narrows down the scope of this analysis. Methodologies used in the reviewed studies must also be examined for further understanding of limitations. This analysis lacks broader domains such as emergency planning, disaster response, and preparedness strategies. Another issue that needs attention is the unauthorised use of proprietary datasets and closed methodologies. This can be the cause of unclear direct comparisons of algorithms and reduce reproducibility. The absence of consistent benchmarks and standardised evaluation criteria across the reviewed literature presents an added challenge. These issues, if incorporated, would result in a more robust and trusted system.

The review found that HBC has become more accurate with time by the use of advanced sensors, with intelligent machine learning and deep learning models. These models have shown potential in the classification of human behaviour when aided with multimodal datasets. The majority of research still focuses on controlled environments and limited emergency types, indicating that a gap between experimental and real-world performance. One of the major problems is that the existing research only focuses on very few types of emergencies, particularly fall detection in elderly people. Other challenges include small datasets, biased samples, and loosely coordinated sensor setups. In some cases, the integration of different data streams is either weak or missing altogether. Recently, there has been a growing trend to mix different data types like sensors, videos, and even social media posts. Many studies still rely on datasets created in controlled environments, which do not represent the real emergency conditions. Most of the current research is dependent on wearable devices like accelerometers, gyroscopes, or RF sensors. Their dependency on user cooperation becomes a limiting factor. Social media and video surveillance, in some cases, may not always give real-time or ground-level detail. Dependency on the intelligence of the models and how well we understand their outputs is also an important factor that cannot be ignored for making such systems.

For future needs, it is necessary to concentrate on generating richer, real-world datasets and optimizing multimodal integration between different datasets, such as sensors, vision, and social media data. There is a Need to make these systems explainable, observing privacy concerns, and ethically grounded for deployment in actual emergency scenarios. The need for focus is in several key areas, such as the nature of emergencies under consideration, including the role of diverse types of datasets or sensors, and how machine learning or deep learning techniques are proving their abilities in this context.

Acknowledgement: We thank UTeM and IUB for all support during this research.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: writing—original draft preparation, Mirza Murad Baig; writing—review and editing, Mirza Murad Baig; supervision and paper collection, Muhammad Rehan Faheem; conceptualization and monitoring, Lal Khan, Syed Asim Ali Shah; writing supervision, Hannan Adeel. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: As this is a review paper and does not include any kind of computational experimentation on any kind of data. Hence there is no data available. However, the studies reviewed in this articles and the data sets used by them are cited in the text.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cmes.2025.073172/s1.

References

1. Kidziński Ł., Yang B, Hicks JL, Rajagopal A, Delp SL, Schwartz MH. Deep neural networks enable quantitative movement analysis using single-camera videos. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4054. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17807-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Waheed M, Afzal H, Mehmood K. NT-FDS—a noise tolerant fall detection system using deep learning on wearable devices. Sensors. 2021;21(6):2006. doi:10.3390/s21062006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Hernández Ó.G, Morell V, Ramon JL, Jara CA. Human pose detection for robotic-assisted and rehabilitation environments. Appl Sci. 2021;11(9):4183. doi:10.3390/app11094183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sethu M, Kotla B, Russell D, Madadi M, Titu NA, Coble JB, et al. Application of artificial intelligence in detection and mitigation of human factor errors in nuclear power plants: a review. Nuclear Technology. 2023;209(3):276–94. doi:10.1080/00295450.2022.2067461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Potharaju S, Tambe SN, Srikanth N, Tirandasu RK, Amiripalli SS, Mulla R. Smartphone based real-time detection of postural and leg abnormalities using deep learning techniques. J Current Sci Technol. 2025;15(3):112–2. doi:10.59796/jcst.v15n3.2025.112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Shi J, Chen D, Wang M. Pre-impact fall detection with CNN-based class activation mapping method. Sensors. 2020;20(17):4750. doi:10.3390/s20174750. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Usmani S, Saboor A, Haris M, Khan MA, Park H. Latest research trends in fall detection and prevention using machine learning: a systematic review. Sensors. 2021;21(15):5134. doi:10.3390/s21155134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Yu X, Qiu H, Xiong S. A novel hybrid deep neural network to predict pre-impact fall for older people based on wearable inertial sensors. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:63. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2020.00063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Casilari E, Álvarez-Marco M, García-Lagos F. A study of the use of gyroscope measurements in wearable fall detection systems. Symmetry. 2020;12(4):649. doi:10.3390/sym12040649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Yu X, Jang J, Xiong S. A large-scale open motion dataset (KFall) and benchmark algorithms for detecting pre-impact fall of the elderly using wearable inertial sensors. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:692865. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2021.692865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Soyege OS, Nwokedi CN, Tomoh BO, Mustapha AY, Mbata AO, Balogun OD, et al. Public health crisis management and emergency preparedness: strengthening healthcare infrastructure against pandemics and bioterrorism threats. J Front Multidiscip Res. 2024;5(2):52–68. [Google Scholar]

12. Gooding K, Bertone MP, Loffreda G, Witter S. How can we strengthen partnership and coordination for health system emergency preparedness and response? Findings from a synthesis of experience across countries facing shocks. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1441. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1800832/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Jiang Y, Ye Y, Gopinath D, Won J, Winkler AW, Liu CK. Transformer inertial poser: real-time human motion reconstruction from sparse imus with simultaneous terrain generation. In: SIGGRAPH Asia 2022 Conference; 2022 Dec 6–9; Daegu, Republic of Korea. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2022. p. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

14. Ding Y, Chen X, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Huang X. Human behaviour detection dataset (HBDset) using computer vision for evacuation safety and emergency management. J Safety Sci Resil. 2024;5(3):355–64. doi:10.1016/j.jnlssr.2024.04.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Oh H, Yoo J. Real-time detection of at-risk movements using smartwatch IMU sensors. Appl Sci. 2025;15(4):1842. doi:10.3390/app15041842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ni J, Tang H, Haque ST, Yan Y, Ngu AH. A survey on multimodal wearable sensor-based human action recognition. arXiv:2404.15349. 2024. [Google Scholar]

17. Dritsas E, Trigka M, Troussas C, Mylonas P. Multimodal interaction, interfaces, and communication: a survey. Multimodal Technol Interact. 2025;9(1):6. doi:10.3390/mti9010006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ramanujam E, Perumal T, Padmavathi S. Human activity recognition with smartphone and wearable sensors using deep learning techniques: a review. IEEE Sens J. 2021;21(12):13029–40. doi:10.1109/jsen.2021.3069927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Sadiq AA, Dougherty RB, Tyler J, Entress R. Public alert and warning system literature review in the USA: identifying research gaps and lessons for practice. Natural Hazards. 2023;117(2):1711–44. doi:10.1007/s11069-023-05926-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Dhatterwal JS, Malik K, Kaswan KS, Elngar AA. Federated learning: overview, challenges, and ethical considerations. In: Artificial intelligence using federated learning. 1st ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2025. [Google Scholar]

21. Uddin MZ, Soylu A. Human activity recognition using wearable sensors, discriminant analysis, and long short-term memory-based neural structured learning. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):16455. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-95947-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Ray-Dowling A, Hou D, Schuckers S, Barbir A. Evaluating multi-modal mobile behavioral biometrics using public datasets. Comput Secur. 2022;121:102868. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2022.102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Cianconi P, Hanife B, Grillo F, Zhang K, Janiri L. Human responses and adaptation in a changing climate: a framework integrating biological, psychological, and behavioural aspects. Life. 2021;11(9):895. doi:10.3390/life11090895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Lee J, Yook D. Characterizing human behavior in emergency situations. J Soc Disaster Inform. 2022;18(3):495–506. [Google Scholar]

25. Shipman A, Majumdar A, Feng Z, Lovreglio R. A quantitative comparison of virtual and physical experimental paradigms for the investigation of pedestrian responses in hostile emergencies. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):6892. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-55253-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Plonsky O, Apel R, Ert E, Tennenholtz M, Bourgin D, Peterson JC, et al. Predicting human decisions with behavioural theories and machine learning. Nat Hum Behav. 2025;22:23. doi:10.1038/s41562-025-02267-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Box-Steffensmeier JM, Burgess J, Corbetta M, Crawford K, Duflo E, Fogarty L, et al. The future of human behaviour research. Nature Human Behav. 2022;6(1):15–24. doi:10.1038/s41562-021-01275-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Bibbò L, Carotenuto R, Della Corte F. An overview of indoor localization system for human activity recognition (HAR) in healthcare. Sensors. 2022;22(21):8119. doi:10.3390/s22218119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Sirapangi MD, Gopikrishnan S. Predictive health behavior modeling using multimodal feature correlations via Medical Internet-of-Things devices. Heliyon. 2024;10(15):e34429. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Gulhane M, Sajana T. Human behavior prediction and analysis using machine learning–a review. Turkish J Comput Mathem Educat. 2021;12(5):870–6. doi:10.17762/turcomat.v12i5.1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Bhola G, Vishwakarma DK. A review of vision-based indoor HAR: state-of-the-art, challenges, and future prospects. Multim Tools Applicat. 2024;83(1):1965–2005. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-15443-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Muhammad K, Ullah A, Imran AS, Sajjad M, Kiran MS, Sannino G, et al. Human action recognition using attention based LSTM network with dilated CNN features. Future Generat Comput Syst. 2021;125(3):820–30. doi:10.1016/j.future.2021.06.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wang H. Deeply-learned and spatial-temporal feature engineering for human action understanding. Future Generat Comput Syst. 2021;123:257–62. doi:10.1016/j.future.2021.04.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kong Y, Fu Y. Human action recognition and prediction: a survey. Int J Comput Vis. 2022;130(5):1366–401. [Google Scholar]

35. Li T, Liu J, Zhang W, Ni Y, Wang W, Li Z. Uav-human: a large benchmark for human behavior understanding with unmanned aerial vehicles. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 16266–75. [Google Scholar]

36. Kyrkou C, Kolios P, Theocharides T, Polycarpou M. Machine learning for emergency management: a survey and future outlook. Proc IEEE. 2022;111(1):19–41. doi:10.1109/jproc.2022.3223186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Shoyama K, Cui Q, Hanashima M, Sano H, Usuda Y. Emergency flood detection using multiple information sources: integrated analysis of natural hazard monitoring and social media data. Sci Total Environ. 2021;767(1):144371. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Bekios-Calfa J, Manzano-Munizaga E, Alvarez-Rojas M, Araya-Vidal J, Rojas-Castillo V, Mayo-Mena F. Risk prediction of hazardous materials emergencies in industrial areas using machine learning and expert knowledge. In: 2024 43rd International Conference of the Chilean Computer Science Society (SCCC); 2024 Oct 28–30; Temuco, Chile. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

39. Damaševičius R, Bacanin N, Misra S. From sensors to safety: internet of Emergency Services (IoES) for emergency response and disaster management. J Sens Actuator Netw. 2023;12(3):41. doi:10.3390/jsan12030041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Krichen M, Abdalzaher MS, Elwekeil M, Fouda MM. Managing natural disasters: an analysis of technological advancements, opportunities, and challenges. Internet Things Cyber-Phys Syst. 2024;4(1):99–109. doi:10.1016/j.iotcps.2023.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Dwarakanath L, Kamsin A, Rasheed RA, Anandhan A, Shuib L. Automated machine learning approaches for emergency response and coordination via social media in the aftermath of a disaster: a review. IEEE Access. 2021;9:68917–31. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3074819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Sufi FK, Khalil I. Automated disaster monitoring from social media posts using AI-based location intelligence and sentiment analysis. IEEE Transact Computat Soci Syst. 2022;11(4):4614–24. doi:10.1109/tcss.2022.3157142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Algiriyage N, Prasanna R, Stock K, Doyle EE, Johnston D. Multi-source multimodal data and deep learning for disaster response: a systematic review. SN Comput Sci. 2022;3:92. doi:10.1007/s42979-021-00971-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Erokhin D, Komendantova N. Social media data for disaster risk management and research. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024;114(1):104980. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2024.104980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Ochoa KS, Comes T. A Machine learning approach for rapid disaster response based on multi-modal data. The case of housing & shelter needs. arXiv:2108.00887. 2021. [Google Scholar]

46. Ahmad Z, Jindal R, Mukuntha NS, Ekbal A, Bhattachharyya P. Multi-modality helps in crisis management: an attention-based deep learning approach of leveraging text for image classification. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;195(5):116626. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.116626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Hofer SI, Nistor N, Scheibenzuber C. Online teaching and learning in higher education: lessons learned in crisis situations. Comput Human Behav. 2021;121(3):106789. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2021.106789. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Yuh AH, Kang SJ. Real-time sound event classification for human activity of daily living using deep neural network. In: 2021 IEEE International Conferences on Internet of Things (iThings) and IEEE Green Computing & Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical & Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData) and IEEE Congress on Cybermatics (Cybermatics); 2021 Dec 6–8; Melbourne, VIC, Australia. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 83–8. [Google Scholar]

49. Cicirelli G, Marani R, Petitti A, Milella A, D’orazio T. Ambient assisted living: a review of technologies, methodologies and future perspectives for healthy aging of population. Sensors. 2021;21(10):3549. doi:10.3390/s21103549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Manakitsa N, Maraslidis GS, Moysis L, Fragulis GF. A review of machine learning and deep learning for object detection, semantic segmentation, and human action recognition in machine and robotic vision. Technologies. 2024;12(2):15. doi:10.3390/technologies12020015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Bakhshian E, Martinez-Pastor B. Evaluating human behaviour during a disaster evacuation process: a literature review. J Traffic Transport Eng (English Edition). 2023;10(4):485–507. doi:10.1016/j.jtte.2023.04.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Senanayake GP, Kieu M, Zou Y, Dirks K. Agent-based simulation for pedestrian evacuation: a systematic literature review. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024;111:104705. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2024.104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Hafeez S. Robust vital-sign monitoring of human attention through deep multi-modal sensor fusion [master’s thesis]. Islamabad, Pakistan: Air University; 2022. [Google Scholar]

54. Nasar W, Da Silva Torres R, Gundersen OE, Karlsen AT. The use of decision support in search and rescue: a systematic literature review. ISPRS Int J Geo Inf. 2023;12(5):182. doi:10.3390/ijgi12050182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Alnoman A, Khwaja AS, Anpalagan A, Woungang I. Emerging ai and 6g-based user localization technologies for emergencies and disasters. IEEE Access. 2024;12(3):197877–906. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3521005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Bouhsissin S, Sael N, Benabbou F. Driver behavior classification: a systematic literature review. IEEE Access. 2023;11:14128–53. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3243865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Kondraganti A, Narayanamurthy G, Sharifi H. A systematic literature review on the use of big data analytics in humanitarian and disaster operations. Ann Operat Res. 2024;335(3):1015–52. doi:10.1007/s10479-022-04904-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Velusamy A, Akilandeswari J, Prabhu R. A comprehensive review on machine learning models for real time fall prediction using wearable sensor-based gait analysis. In: 2023 5th International Conference on Inventive Research in Computing Applications (ICIRCA); 2023 Aug 3–5; Coimbatore, India. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 601–7. [Google Scholar]

59. Casmin E, Oliveira R. Survey on context-aware radio frequency-based sensing. Sensors. 2025;25(3):602. doi:10.3390/s25030602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Tay NC, Connie T, Ong TS, Teoh ABJ, Teh PS. A review of abnormal behavior detection in activities of daily living. IEEE Access. 2023;11(4):5069–88. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3234974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Bajwa A. AI-based emergency response systems: a systematic literature review on smart infrastructure safety. American J Adv Technol Eng Solut. 2025;1(1):174–200. [Google Scholar]

62. Sahni S, Jain S, Saritha SK. A novel ensemble model for fall detection: leveraging CNN and BiLSTM with channel and temporal attention. Automatika. 2025;66(2):103–16. doi:10.1080/00051144.2025.2450553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Abdellatef E, Al-Makhlasawy RM, Shalaby WA. Detection of human activities using multi-layer convolutional neural network. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):7004. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-90307-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Hernández-Fernández C, Meneses-Falcón C. Nobody should die alone. Loneliness and a dignified death during the COVID-19 pandemic. Omega-J Death Dying. 2023;88(2):550–69. doi:10.1177/00302228211048316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Kim J, Min K, Jung M, Chi S. Occupant behavior monitoring and emergency event detection in single-person households using deep learning-based sound recognition. Build Environ. 2020;181:107092. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Fernandes A, Leithardt V, Santana JF. Novelty detection algorithms to help identify abnormal activities in the daily lives of elderly people. IEEE Latin America Transact. 2024;22(3):195–203. doi:10.1109/tla.2024.10431423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Ramirez H, Velastin SA, Meza I, Fabregas E, Makris D, Farias G. Fall detection and activity recognition using human skeleton features. IEEE Access. 2021;9:33532–42. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3061626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Thakur N, Han CY. An ambient intelligence-based human behavior monitoring framework for ubiquitous environments. Information. 2021;12(2):81. doi:10.3390/info12020081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Zurbuchen N, Wilde A, Bruegger P. A machine learning multi-class approach for fall detection systems based on wearable sensors with a study on sampling rates selection. Sensors. 2021;21(3):938. doi:10.3390/s21030938. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Chandak A, Chaturvedi N, Dhiraj. Machine-learning-based human fall detection using contact-and noncontact-based sensors. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2022;2022(1):9626170. doi:10.1155/2022/9626170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Ji S, Xie Y, SiFall Li M. Practical online fall detection with RF sensing. In: Proceedings of the 20th ACM Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems; 2022 Nov 6–9; Boston MA, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2022. p. 563–77. [Google Scholar]

72. Noor TH. Human action recognition-based IoT services for emergency response management. Mach Learn Know Extract. 2023;5(1):330–45. doi:10.3390/make5010020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Hassan CAU, Karim FK, Abbas A, Iqbal J, Elmannai H, Hussain S, et al. A cost-effective fall-detection framework for the elderly using sensor-based technologies. Sustainability. 2023;15(5):3982. doi:10.3390/su15053982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Campanella S, Alnasef A, Falaschetti L, Belli A, Pierleoni P, Palma L. A novel embedded deep learning wearable sensor for fall detection. IEEE Sens J. 2024;24(9):15219–29. doi:10.1109/jsen.2024.3375603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Newaz NT, Hanada E. An Approach to fall detection using statistical distributions of thermal signatures obtained by a stand-alone low-resolution IR array sensor device. Sensors. 2025;25(2):504. doi:10.3390/s25020504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Hossain S, Deb K, Sakib S, Sarker IH. A hybrid deep learning framework for daily living human activity recognition with cluster-based video summarization. Multim Tools Applicat. 2025;84(9):6219–72. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-19022-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Chander H, Burch RF, Talegaonkar P, Saucier D, Luczak T, Ball JE, et al. Wearable stretch sensors for human movement monitoring and fall detection in ergonomics. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10):3554. doi:10.3390/ijerph17103554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Krogh AH, Røiseland A. Urban governance of disaster response capacity: institutional models of local scalability. J Homeland Secur Emerg Manag. 2024;21(1):27–47. doi:10.1515/jhsem-2022-0005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Sathianarayanan M, Hsu PH, Chang CC. Extracting disaster location identification from social media images using deep learning. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024;104(3):104352. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2024.104352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Ofli F, Alam F, Imran M. Analysis of social media data using multimodal deep learning for disaster response. arXiv: 2004.11838. 2020. [Google Scholar]

81. Yang Z, Nguyen L, Zhu J, Pan Z, Li J, Jin F. Coordinating disaster emergency response with heuristic reinforcement learning. In: 2020 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM); 2020 Dec 7–10; Virtual Event, The Netherlands. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 565–72. [Google Scholar]

82. Sadiq AM, Ahn H, Choi YB. Human sentiment and activity recognition in disaster situations using social media images based on deep learning. Sensors. 2020;20(24):7115. doi:10.3390/s20247115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Linardos V, Drakaki M, Tzionas P, Karnavas YL. Machine learning in disaster management: recent developments in methods and applications. Mach Learn Knowl Extract. 2022;4(2):446–73. doi:10.3390/make4020020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Phark C, Kim S, Jung S. Development to emergency evacuation decision making in hazardous materials incidents using machine learning. Processes. 2022;10(6):1046. doi:10.3390/pr10061046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. AlAbdulaali A, Asif A, Khatoon S, Alshamari M. Designing multimodal interactive dashboard of disaster management systems. Sensors. 2022;22(11):4292. doi:10.3390/s22114292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Khanmohammadi S, Golafshani E, Bai Y, Li H, Bazli M, Arashpour M. Multi-modal mining of crowd-sourced data: efficient provision of humanitarian aid to remote regions affected by natural disasters. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023;96(2):103972. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Shadrin D, Illarionova S, Gubanov F, Evteeva K, Mironenko M, Levchunets I, et al. Wildfire spreading prediction using multimodal data and deep neural network approach. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):2606. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-52821-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Cvetković VM, Renner R, Jakovljević V. Industrial disasters and hazards: from causes to consequences—A holistic approach to resilience. Int J Disaster Risk Manag. 2024;6(2):149–68. [Google Scholar]

89. Nwakanma CI, Islam FB, Maharani MP, Lee JM, Kim DS. Detection and classification of human activity for emergency response in smart factory shop floor. Appl Sci. 2021;11(8):3662. doi:10.3390/app11083662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Cheng MY, Vu QT, Teng RK. Real-time risk assessment of multi-parameter induced fall accidents at construction sites. Autom Constr. 2024;162(3):105409. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Naegelin M, Weibel RP, Kerr JI, Schinazi VR, La Marca R, Von Wangenheim F, et al. An interpretable machine learning approach to multimodal stress detection in a simulated office environment. J Biomed Inform. 2023;139(4):104299. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2023.104299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Koshy R, Elango S. Multimodal tweet classification in disaster response systems using transformer-based bidirectional attention model. Neural Comput Applicat. 2023;35(2):1607–27. doi:10.1007/s00521-022-07790-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Ding X, Zhang X, Fan R, Xu Q, Hunt K, Zhuang J. Rumor recognition behavior of social media users in emergencies. J Manag Sci Eng. 2022;7(1):36–47. doi:10.1016/j.jmse.2021.02.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Ammar H, Cherif A. DeepROD: a deep learning approach for real-time and online detection of a panic behavior in human crowds. Mach Vision Appl. 2021;32(3):57. doi:10.1007/s00138-021-01182-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Lazarou I, Kesidis AL, Hloupis G, Tsatsaris A. Panic detection using machine learning and real-time biometric and spatiotemporal data. ISPRS Int J Geo Inf. 2022;11(11):552. doi:10.3390/ijgi11110552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. Han YK, Choi YB. Detection of emergency disaster using human action recognition based on LSTM model. IEIE Transact Smart Process Comput. 2020;9(3):177–84. [Google Scholar]

97. Lazuko A, Gui X, Arshad A, Khan NA, Quershi I. Reduce emergency response time using machine learning technique. In: 2023 International Conference on Communication Technologies (ComTech); 2023 Mar 15–16; Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 48–52. [Google Scholar]

98. Velychko D, Osukhivska H, Palaniza Y, Lutsyk N, Sobaszek Ł. Artificial intelligence based emergency identification computer system. Adv Sci Technol Res Jo. 2024;18(2):296–304. doi:10.12913/22998624/184343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Oishi N, Birch P, Roggen D, Lago P. WIMUSim: simulating realistic variabilities in wearable IMUs for human activity recognition. Front Comput Sci. 2025;7:1514933. doi:10.3389/fcomp.2025.1514933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Khunteta S, Saikrishna P, Agrawal A, Kumar A, Chavva AKR. RF-sensing: a new way to observe surroundings. IEEE Access. 2022;10:129653–65. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3228639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Jain T, Gopalani D, Meena YK. Classification of humanitarian crisis response through unimodal multi-class textual classification. In: 2024 International Conference on Emerging Systems and Intelligent Computing (ESIC); 2024 Feb 9–10; Bhubaneswar, India. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 151–6. [Google Scholar]

102. Han X, Wang J, Zhang X, Wang L, Xu D. Mining public behavior patterns from social media data during emergencies: a multidimensional analytical framework considering spatial-temporal–semantic features. Transact GIS. 2024;28(1):58–82. doi:10.1111/tgis.13125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Abavisani M, Wu L, Hu S, Tetreault J, Jaimes A. Multimodal categorization of crisis events in social media. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 14679–89. [Google Scholar]

104. Kumar Y, Koul A, Mahajan S. A deep learning approaches and fastai text classification to predict 25 medical diseases from medical speech utterances, transcription and intent. Soft Comput-A Fusion Foundat Methodol Appl. 2022;26(17):8253–72. doi:10.1007/s00500-022-07261-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. Jalal A, Quaid MAK, Tahir SBUD, Kim K. A study of accelerometer and gyroscope measurements in physical life-log activities detection systems. Sensors. 2020;20(22):6670. doi:10.3390/s20226670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

106. Park S, Youm M, Kim J. IMU sensor-based worker behavior recognition and construction of a cyber-physical system environment. Sensors. 2025;25(2):442. doi:10.3390/s25020442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Anwer S, Li H, Umer W, Antwi-Afari MF, Mehmood I, Yu Y, et al. Identification and classification of physical fatigue in construction workers using linear and nonlinear heart rate variability measurements. J Constr Eng Manag. 2023;149(7):04023057. doi:10.1061/jcemd4.coeng-13100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

108. Hg Chi, Ha MH, Chi S, Lee SW, Huang Q, Ramani K. Infogcn: representation learning for human skeleton-based action recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 20186–96. [Google Scholar]

109. Rezaei A, Mascheroni A, Stevens MC, Argha R, Papandrea M, Puiatti A, et al. Unobtrusive human fall detection system using mmwave radar and data driven methods. IEEE Sens J. 2023;23(7):7968–76. doi:10.1109/jsen.2023.3245063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

110. Sajjad M, Zahir S, Ullah A, Akhtar Z, Muhammad K. Human behavior understanding in big multimedia data using CNN based facial expression recognition. Mobile Netw Appl. 2020;25(4):1611–21. doi:10.1007/s11036-019-01366-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]