Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A New Dataset for Network Flooding Attacks in SDN-Based IoT Environments

1 Innov’COM Laboratory, Higher School of Communication of Tunis, University of Carthage, Technopark Elghazala, Raoued, Ariana, 2083, Tunisia

2 Department of Computer Sciences, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, P.O. Box 84428, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Imen Filali. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Next-Generation Intelligent Networks and Systems: Advances in IoT, Edge Computing, and Secure Cyber-Physical Applications)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 4363-4393. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.074178

Received 04 October 2025; Accepted 26 November 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

This paper introduces a robust Distributed Denial-of-Service attack detection framework tailored for Software-Defined Networking based Internet of Things environments, built upon a novel, synthetic multi-vector dataset generated in a Mininet-Ryu testbed using real-time flow-based labeling. The proposed model is based on the XGBoost algorithm, optimized with Principal Component Analysis for dimensionality reduction, utilizing lightweight flow-level features extracted from OpenFlow statistics to classify attacks across critical IoT protocols including TCP, UDP, HTTP, MQTT, and CoAP. The model employs lightweight flow-level features extracted from OpenFlow statistics to ensure low computational overhead and fast processing. Performance was rigorously evaluated using key metrics, including Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, False Alarm Rate, AUC-ROC, and Detection Time. Experimental results demonstrate the model’s high performance, achieving an accuracy of 98.93% and a low FAR of 0.86%, with a rapid median detection time of 1.02 s. This efficiency validates its superiority in meeting critical Key Performance Indicators, such as Latency and high Throughput, necessary for time-sensitive SDN-IoT systems. Furthermore, the model’s robustness and statistically significant outperformance against baseline models such as Random Forest, k-Nearest Neighbors, and Gradient Boosting Machine,validating through statistical tests using Wilcoxon signed-rank test and confirmed via successful deployment in a real SDN testbed for live traffic detection and mitigation.Keywords

The rapid expansion of the IoT [1] has brought about transformative changes across industries, enabling seamless connectivity between devices and fostering innovative services such as machine-to-machine, machine-to-cloud, machine-to-edge, machine-to-human, and machine-to-infrastructure communication, vehicle-to-vehicle. However, this exponential growth has also introduced significant security challenges [2]. IoT devices, often resource-constrained and deployed in diverse environments using multiple communication protocols, are particularly vulnerable to cyberattacks targeting their data [3], networks [4], or the devices themselves [5]. In this paper, we emphasize the critical role of network infrastructure as the primary target in cybersecurity threats [6–8] due to its fundamental role in ensuring connectivity. Network infrastructure serves as the backbone of digital communication, enabling data exchange between IoT devices, cloud services, and enterprise systems. This high level of interconnectivity makes it a prime target for various cyberattacks, including MITM [9,10], botnet attacks [11], DDoS [12], and Sybil attacks [13], which exploit vulnerabilities in protocols, routing mechanisms, and traffic management. Among these, DDoS attacks stand out as one of the most prevalent and damaging threats. These attacks can disrupt services, compromise critical infrastructure, and lead to substantial financial and operational losses. The dynamic nature of IoT networks, coupled with the evolving tactics of attackers, necessitates robust, adaptive, and intelligent security mechanisms. SDN [14] offers a promising solution to address these challenges. By decoupling the control and data planes, SDN provides centralized control, programmability, and flexibility, making it an ideal architecture for managing IoT networks.

Our work in the field of cybersecurity for IoT in SDN-based environments emphasizes the growing importance of defending IoT networks from DDoS attacks. We highlight the broader implications of our study by showing how a realistic IoT-specific dataset can enable more reliable ML–based intrusion detection and support the deployment of practical security solutions in real SDN-managed IoT infrastructures. The motivation for creating this synthetic dataset is that existing DDoS datasets are largely derived from traditional IT networks and fail to capture the unique traffic characteristics, constraints, and vulnerabilities of IoT devices in SDN-managed environments. This gap motivates the creation of a new dataset that accurately reflects IoT-specific protocols (MQTT, CoAP, etc.), realistic attack vectors, and flow-level features that are lightweight yet expressive enough for real-time detection. We explicitly discuss the technical gap between traditional datasets and well-known SDN-specific DDoS datasets such as InSDN [15], SDN-SlowRate-DDoS [16], and HLD-DDoSD [17], noting that existing datasets lack protocol diversity, real-time labeling, and IoT-specific traffic characteristics, and cannot be effectively deployed in real live traffic with high accuracy.

Our Contributions:

• We propose a novel SDN-IoT-specific DDoS dataset generated in a Mininet-based environment with a Ryu controller and IoT protocols (TCP, UDP, ICMP, HTTP, MQTT, CoAP).

• We provide real-time flow-level labeling of normal and attack traffic using SDN’s controller logic, ensuring higher accuracy and practical relevance.

• We introduce a comprehensive multi-vector attack simulation including both volumetric and slow-rate flooding attacks across multiple IoT communication protocols.

• We evaluate the dataset using well-established ML algorithms (RF, kNN, XGB, GBM), achieving high detection performance with XGBoost (accuracy of 98.93%, precision of 99.76%, recall of 99.20%, F1-score of 99.48%, and low FAR of 0.86%).

• We implement and test the proposed detection framework in a real SDN testbed, demonstrating real-time attack detection, low computational overhead, and effective mitigation.

• We make the dataset publicly available (via Kaggle) to support the research community in developing and benchmarking SDN-IoT security solutions.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides background information on SDN, DDoS datasets, and various types of DDoS attacks that specifically target IoT devices. Section 3 reviews related work. Section 4 details the implementation methodology, while Section 5 presents the experimental results. Section 6 evaluates the model’s performance by deploying it on a real SDN testbed. Section 7 offers a discussion, and Section 8 concludes the paper with future research directions. By providing a high-quality dataset tailored to the needs of SDN and IoT researchers, this paper aims to foster the development of advanced, intelligent security solutions capable of protecting IoT networks against the escalating threat of DDoS attacks.

After presenting the related works section, which analyzes and contrasts prior research to contextualize our contribution, we place our study within the framework of its objectives. To establish this context, the background section begins with a detailed definition of SDN. We then analyze DDoS attack protocols and methods that pose significant threats to IoT devices and are represented in our dataset. Finally, we explain the motivation for developing our SDN-IoT synthetic dataset and compare it with existing datasets.

As shown in Fig. 1, DDoS attacks in SDN environments disrupt network operations by overwhelming the SDN controller with excessive traffic, exploiting its centralized architecture. In this paper, Mininet is used to simulate these attacks, collect datasets, and evaluate detection and mitigation strategies.

Figure 1: DDoS attacks in an SDN environment

An overview of SDN is presented in the following subsection, including how the dataset was collected, and how SDN-based ML is applied for attack detection and mitigation. This information supports a better understanding of the motivation behind this work and highlights why previous datasets are insufficient for the objectives of this research.

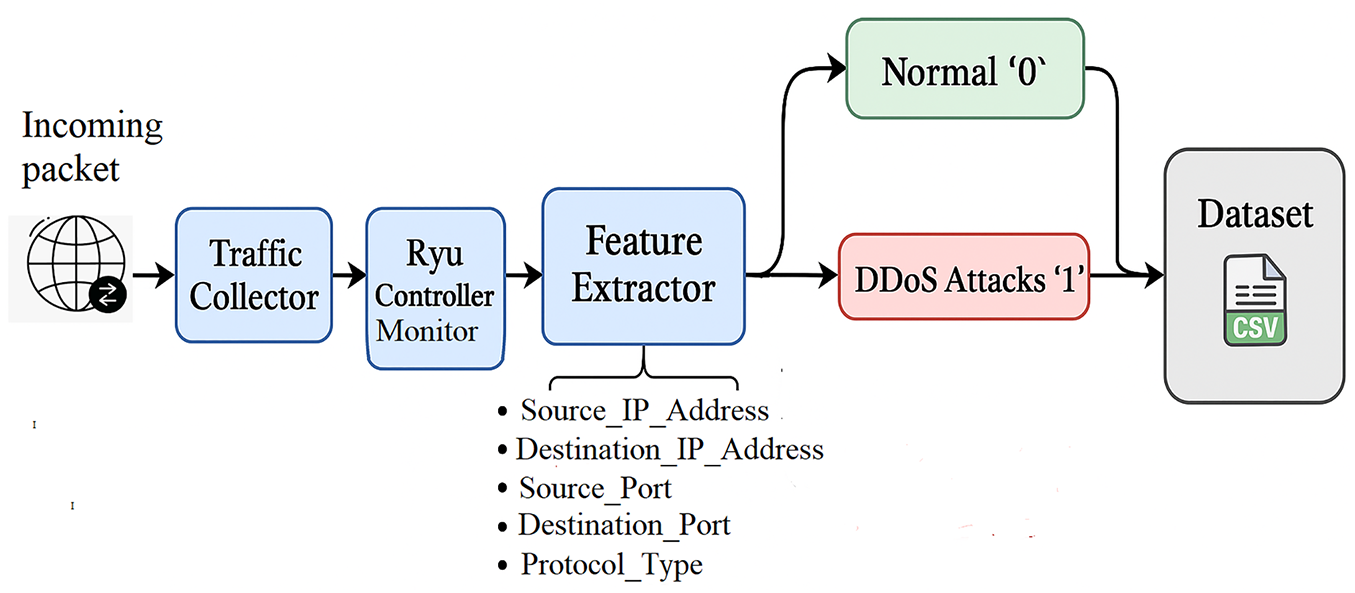

To generate the network traffic required for ML-based detection, a testbed was developed using Mininet, a lightweight SDN emulator capable of simulating different topologies composed of hosts and OpenFlow switches. The Ryu controller was used to manage the SDN environment and collect real-time flow statistics. The dataset collection process involved designing multiple network topologies in Mininet including single, ring, linear, tree, and mesh structures followed by the generation of both benign and malicious traffic between the participating hosts. During these experiments, the Ryu controller monitored the network and retrieved flow-level statistics such as Source_IP_Address, Destin ation_IP_Address, Source_Port, Destination_Port, and Protocol_Type. All captured information was then exported into a structured dataset suitable for machine learning training and evaluation.

2.1.2 SDN-Based ML for Attack Detection and Mitigation

Machine learning models can be trained on the collected SDN traffic to classify flows as either normal or malicious. In a real-time SDN deployment, the controller integrates the trained model into its decision-making pipeline. The controller receives flow information through packet_in events or periodic flow-statistic requests, then extracts relevant features such as Source_IP_Address, Destination _IP_Address, Source_Port, Destination_Port, and Protocol_Type. Based on these features, the ML model predicts the behavior of the traffic flow. When a flow is identified as malicious, the controller initiates mitigation actions by issuing Flow-Mod commands to the appropriate switches, instructing them to drop or redirect the offending traffic. This reactive control mechanism enables SDN to dynamically respond to threats and maintain robust network security.

2.2 DDoS Attack Methods in IoT Networks

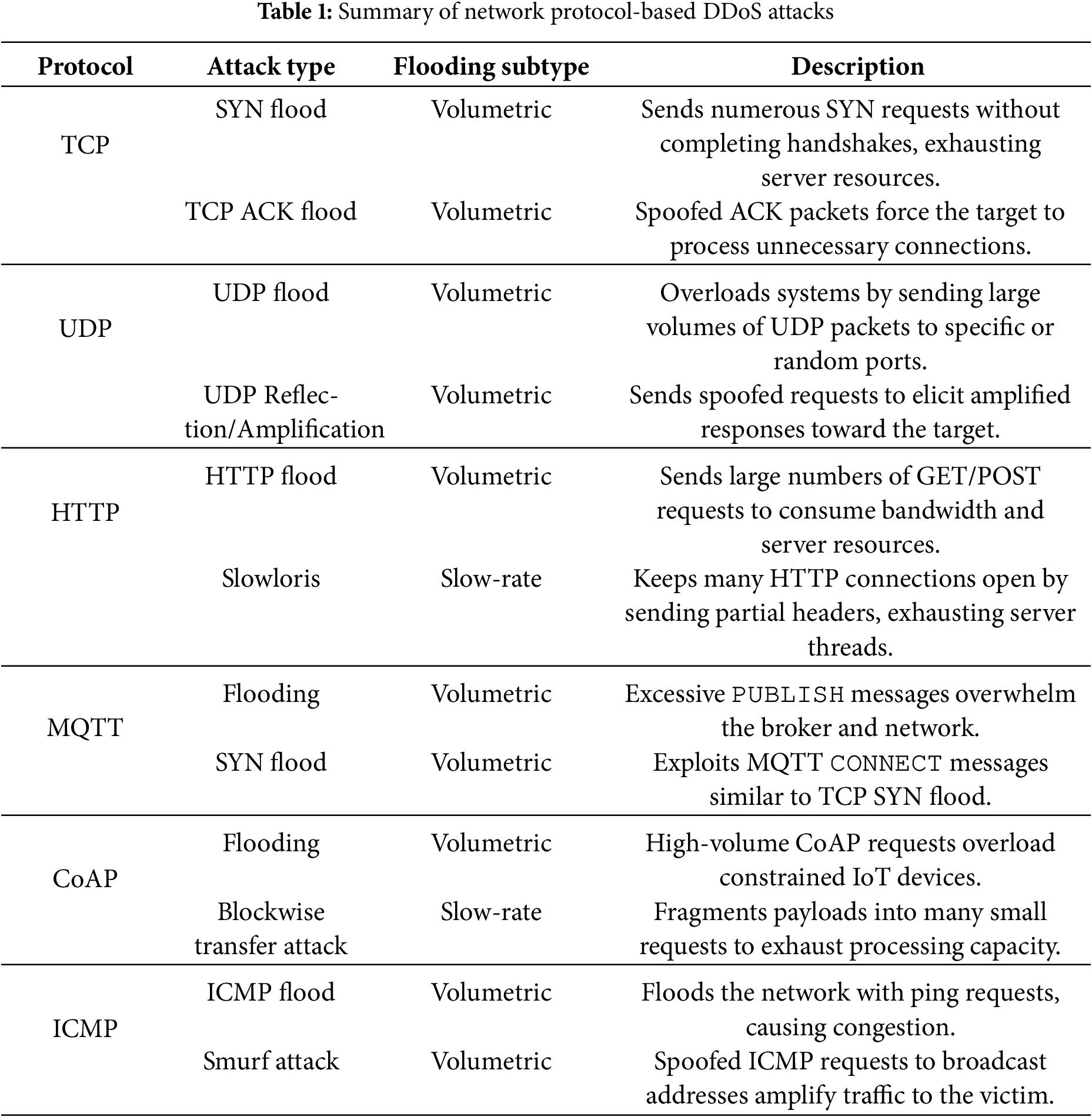

In IoT environments, various DDoS attack methods exploit vulnerabilities in different network protocols. Common DDoS attack methods target protocols such as TCP, UDP, HTTP, MQTT, CoAP, and ICMP, leveraging their inherent weaknesses to disrupt network operations. Our proposed dataset has been meticulously collected by simulating DDoS attacks specifically targeting these protocols, ensuring comprehensive coverage of real-world IoT attack scenarios.

TCP-based attacks in this study included SYN Flood and TCP ACK Flood scenarios. In a SYN Flood attack, the adversary initiates a large number of incomplete TCP handshakes by sending numerous SYN packets without completing the connection, thereby exhausting server resources and degrading service availability. In the TCP ACK Flood attack, attackers transmit a high volume of ACK packets, often with spoofed source IP addresses, forcing the target system to process each packet and quickly overwhelming its computational capacity.

UDP-based attack scenarios consisted of UDP Flood and UDP Reflection/Amplification attacks. In a UDP Flood attack, the adversary sends a continuous stream of UDP packets to random or predefined ports, saturating network bandwidth and overloading target devices. UDP Reflection and Amplification attacks exploit open or misconfigured UDP services by sending requests with spoofed victim IP addresses to servers that generate disproportionately larger responses, amplifying the attack’s impact and significantly increasing the volume of malicious traffic directed toward the target.

The HTTP-layer attack simulations comprised HTTP Flood and Slowloris attacks. During HTTP Flood attacks, adversaries generate large numbers of HTTP GET or POST requests to consume server processing power and bandwidth, leading to service degradation or downtime. The Slowloris attack, in contrast, maintains numerous open HTTP connections by sending partial or incomplete headers, preventing the server from releasing resources and causing a gradual exhaustion of available threads.

MQTT-based attacks were represented by MQTT Flooding and MQTT SYN Flood scenarios. In an MQTT Flooding attack, the adversary sends a large volume of MQTT PUBLISH messages to overwhelm the broker, disrupt message dissemination, and consume network bandwidth. The MQTT SYN Flood attack mirrors the logic of TCP SYN flooding but targets MQTT connection establishment by repeatedly sending excessive CONNECT messages, preventing legitimate clients from establishing sessions with the broker.

CoAP-layer threats included CoAP Flooding and Blockwise Transfer attacks. In CoAP Flooding, attackers transmit excessive volumes of CoAP requests toward constrained IoT devices or CoAP servers, saturating their limited resources and degrading application-layer performance. The Blockwise Transfer attack operates by fragmenting payloads into many small CoAP blocks and sending them in rapid succession, forcing devices to allocate significant processing and memory resources, ultimately leading to resource exhaustion and service instability.

Table 1 summarizes common network protocol-based DDoS attacks, detailing their types and mechanisms across TCP, UDP, HTTP, MQTT, CoAP, and ICMP. These attacks aim to exhaust resources, disrupt services, or amplify traffic using methods like flooding, interruption, or slow request techniques.

Our proposed dataset has been meticulously collected by simulating DDoS attacks specifically targeting these protocols. It includes both volumetric flooding (high-throughput) and slow-rate flooding (connection exhaustion) subtypes, ensuring comprehensive coverage of real-world IoT attack scenarios. The flooding subtype not only improves the interpretability of the dataset but also supports the development of protocol-specific ML models by providing finer distinctions between attack vectors with potentially unique traffic patterns. We believe this improved labeling granularity will significantly aid researchers and practitioners in designing more accurate and robust intrusion detection systems.

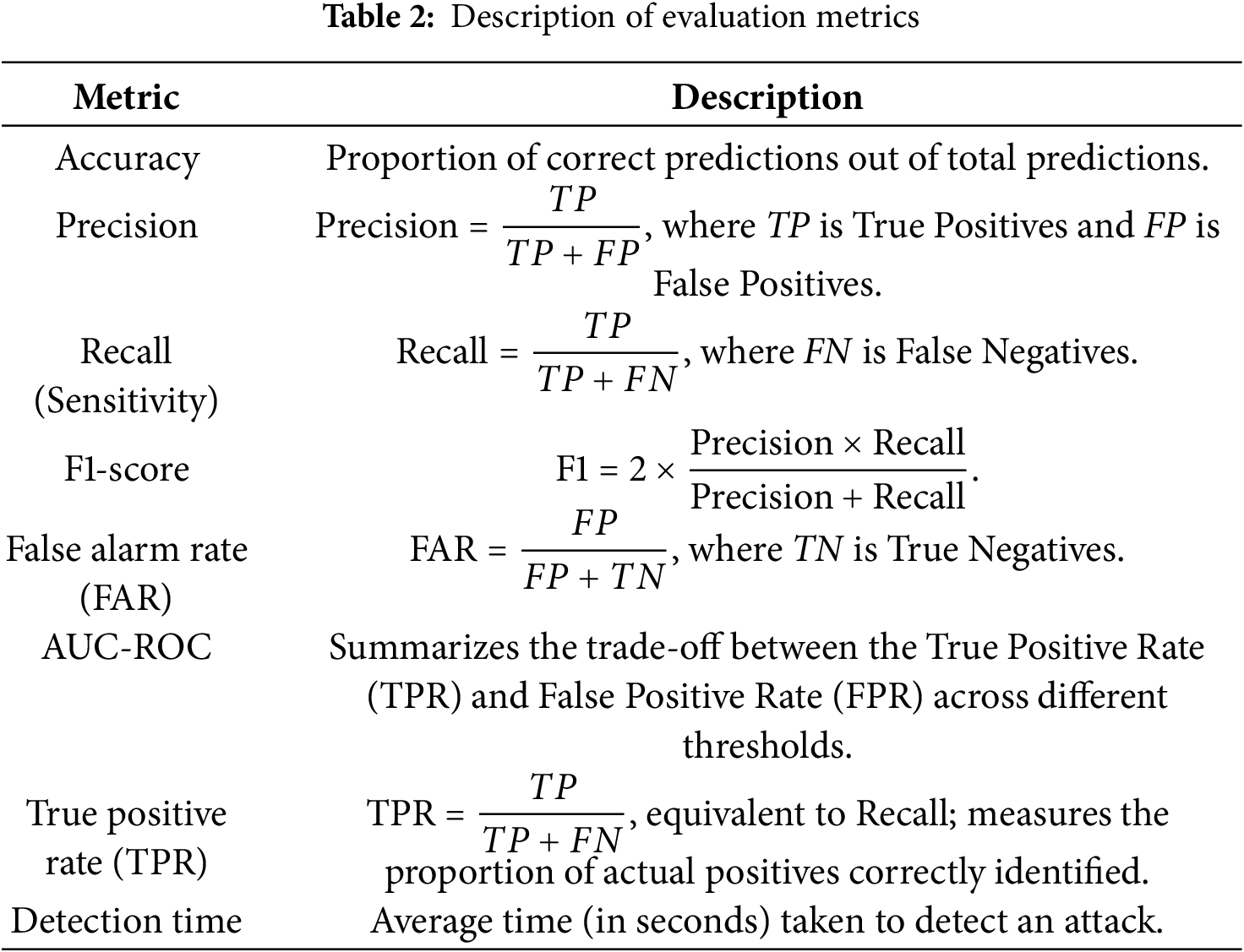

To assess the effectiveness of the ML models in detecting DDoS attacks within IoT–SDN environments, we employ two complementary evaluation approaches: (1) performance metrics analysis and (2) key performance indicators.

We consider the following key evaluation metrics. These metrics, along with their descriptions and corresponding mathematical formulas, are summarized in Table 2.

2.3.2 Key Performance Indicators

Effective key metrics utilized across recent literature, including the probabilistic approach proposed by Srinivasu et al. [18], are essential for benchmarking novel methodologies in SDN–IoT environments. In this context, several performance indicators play a pivotal role. Network lifetime reflects the operational duration of the SDN–IoT system from deployment until a critical node, such as an IoT device or switch, depletes its resources, thereby indicating the system’s long-term energy sustainability. Energy consumption quantifies the average power usage across IoT nodes and SDN components during each communication cycle, typically accounting for transmission, reception, and control-plane overhead. Throughput characterizes the rate of successful data packet delivery across the SDN-managed IoT network and serves as a measure of communication efficiency and reliability under varying traffic loads. Finally, computational delay, or latency, denotes the time required for data to traverse from an IoT device through the OpenFlow switches to the SDN controller or cloud service, a critical metric for latency-sensitive IoT applications that demand rapid and consistent decision-making.

This subsection describes the motivation behind generating the SDN-IoT synthetic datasets, both in the general context of IoT security and specifically within the framework of SDN.

Developing a synthetic DDoS attack dataset specifically for IoT devices using Mininet and the Ryu controller in an SDN environment represents a significant advancement in our cybersecurity research. Unlike many existing datasets, which primarily focus on traditional network environments and often overlook IoT-specific threats, our dataset addresses the unique security challenges faced by IoT ecosystems. Furthermore, many publicly available datasets contain attack types that are not relevant to IoT environments. Additionally, large datasets, due to their higher data volume, significantly increase processing and training time complexity, requiring substantial CPU resources. This results in higher CPU utilization during both the training and detection phases.

Our dataset captures real-world complexities and vulnerabilities unique to IoT ecosystems. By simulating live traffic scenarios across protocols such as TCP, UDP, ICMP, HTTP, MQTT, and CoAP, it provides a comprehensive view of the potential attack vectors IoT devices face daily. Leveraging the advantages of SDN such as centralized control, programmability, and dynamic network reconfiguration, this dataset facilitates real-time network monitoring and adaptive security mechanisms, making it ideal for testing defense strategies. SDN’s capability to quickly isolate and mitigate attacks by dynamically modifying network behavior at the controller level enhances the dataset’s relevance for real-world IoT environments.

This dataset can be utilized to develop and validate robust intrusion detection and prevention systems tailored for IoT, thereby strengthening overall network security in dynamic, IoT-driven environments. Its synthetic nature ensures controlled experimentation while accurately reflecting the diversity and intensity of DDoS attacks targeting IoT devices. This fosters more precise and effective cybersecurity solutions. Ultimately, our dataset serves as a crucial resource for advancing the state-of-the-art in IoT security, offering insights and benchmarks that are often unavailable in more generalized datasets.

Our proposed dataset has been benchmarked against well-known SDN-specific DDoS datasets, including InSDN, SDN-IoT, SDN-SlowRate-DDoS, and HLD-DDoSDN, and several distinguishing characteristics clearly set it apart. Unlike most existing SDN datasets, it incorporates diverse IoT communication protocols such as MQTT and CoAP, which remain largely absent or underrepresented in prior work. Furthermore, the dataset provides a comprehensive multi-protocol and multi-vector attack simulation, capturing a wide spectrum of DDoS attack types across several network layers within a controlled Mininet–Ryu environment that simultaneously generates legitimate and malicious IoT traffic. Another distinguishing aspect is the use of real-time flow-based labeling, performed dynamically by the SDN controller rather than through offline or post-capture annotation, thereby improving the contextual accuracy and usefulness of the data for machine learning applications. The dataset also relies exclusively on lightweight and expressive flow-level features extracted directly from OpenFlow statistics, making it suitable for real-time ML-based intrusion detection on resource-constrained SDN controllers. Finally, it reflects realistic IoT communication behavior—including bursty flows, lightweight payloads, low-latency constraints, and protocol-specific vulnerabilities—elements that are insufficiently represented in conventional SDN datasets.

While our proposed dataset offers a targeted solution for addressing the distinct challenges in securing IoT environments, it is important to position this contribution within the context of existing research. Numerous recent works have attempted to detect and mitigate DDoS attacks using ML approaches and public datasets, with varying degrees of effectiveness. To highlight the novelty and impact of our synthetic SDN-IoT dataset and detection model, we now present a highlight related works that are similar to our synthetic dataset and approach, and conduct a comparative analysis after presenting the implementation and experimental details.

To address the motivations outlined in Section 2.4, it is important to explore how previous research has utilized existing datasets to study DDoS attacks. Several datasets have been widely used for detection and mitigation studies, categorized into three key types: general, SDN-specific, and IoT-specific. In this section, we highlight recent studies that use these datasets, discuss the results obtained, and identify their limitations.

In [19], the authors explored ML techniques to detect DDoS attacks targeting IoT devices in Energy Hub [20] systems. Using the CICDDOS2019 [21] and KDD-CUP datasets [22], several classifiers, including Gradient Boosting [23], Support Vector Machine [24], and RF [25], were evaluated. Gradient Boosting emerged as the most effective, achieving high accuracy across datasets, particularly with the CICDDOS2019. Hybrid models integrating Gradient Boosting with SVM or DT [26] further enhanced predictive performance. However, the study highlights limitations such as reduced precision and recall with smaller training datasets and the need for improved model generalization to diverse real-world scenarios.

The authors of [27] evaluated the effectiveness of various ML algorithms for detecting DDoS attacks using the UNSW-NB15 dataset [28]. Eight algorithms were compared, including Logistic Regression [29], kNN [30], SVM, RF, DT, Long Short-Term Memory [31], Multi-Layer Perceptron [32], and Gated Recurrent Unit [33]. RF outperformed the others with the highest accuracy of 97.68%, followed by neural network models (Long Short-Term Memory, Gated Recurrent Unit, and Multi-Layer Perceptron) and DT with accuracies around 96%. The study emphasizes the potential of RF for DDoS detection. However, limitations include the reliance on a single dataset, which may affect the model’s generalizability to diverse real-world scenarios.

Hnamte et al. in [34] introduced a deep neural network-based approach [35] for detecting and mitigating DDoS attacks within SDN environments. Using three datasets (InSDN [36], CICIDS2018 [37], and Kaggle DDoS), the proposed model achieved detection accuracy rates of 99.98%, 100%, and 99.99%, respectively, with low loss rates, showcasing its efficacy over traditional detection methods. The framework demonstrates scalability and adaptability in identifying intricate patterns in network traffic. However, the study highlights practical challenges, including computational complexity and the potential difficulty of deploying DNNs in real-world SDN scenarios.

The paper [38] proposes a hybrid IoT DDoS defense framework that combines CNN-based deep feature extraction, traditional ML classifiers (kNN, SVM, RF), and a permissioned blockchain for automated mitigation using smart contracts. CNN features fused with statistical features significantly enhance detection, with the CNN+RF model achieving the best performance. Tests on the BoT-IoT [39] and IoT-23 [40] datasets show up to 97.5% F1-score, 1.8% false-positive rate, and 92 ms mitigation latency, confirming high accuracy and fast response. Advantages include improved detection, decentralized and tamper-proof mitigation, and scalability for real-time IoT systems, while limitations involve computational overhead and difficulty detecting very low-rate stealth attacks.

Sangodoyin et al. [41] investigated ML-based detection of DDoS flooding attacks in SDNs using emulated traffic metrics (throughput, jitter, and response time) and four classifiers: Gaussian Naive Bayes, Quadratic Discriminant Analysis, kNN, and Classification and Regression Tree. Their results showed that all models achieved >95% accuracy, with CART performing best (98.7% accuracy, fastest training with 12.4 ms and prediction with 5.3

The paper [42] aimed to enhance the detection of diverse DDoS attack types with high accuracy and efficiency. It employs a hybrid model integrating a Selective Deep Autoencoder for feature selection, Convolutional Neural Networks for spatial feature extraction, and Self-Attention mechanisms for temporal dependencies, using the CIC-DDoS2019 dataset [43] with SMOTE for balancing. Results show an overall accuracy of 99.14%, with F1-scores of 97.97% or higher across categories, and an inference time of 1.86 seconds, outperforming existing methods. Advantages include robust noise handling, fast real-time detection, and effective multi-class classification, while limitations may involve potential performance drops for attack types resembling normal traffic, requiring further validation on diverse datasets.

The paper named Real-Time DDoS Attack Detection in SDN Based on En-CNN and OptiLGBM [44] aimed to enhance the detection and mitigation of DDoS attacks in Software-Defined Networks (SDN) by improving accuracy, reducing latency, and minimizing false positives. It employs an adaptive Borderline-SMOTE method to balance the CICDDoS2019 dataset, an Enhanced Convolutional Neural Network (En-CNN) for efficient traffic feature extraction with low latency, and an Optimized LightGBM (OptiLGBM) for rapid and accurate classification, integrated within the Ryu SDN controller for real-time detection and mitigation. The results show an accuracy of 99.98%, an average response time under 1 s, and the ability to block attacks and restore normal traffic within 3 s, outperforming baseline models. Advantages include high detection accuracy, fast real-time response, effective mitigation through a closed-loop mechanism, and practical applicability in SDN environments, while limitations may involve potential challenges in adapting to unseen attack types or large-scale deployments due to reliance on the specific dataset and controller performance.

In this section, we first describe the working environment used for our research. We then describe the dataset details after outlining the methodology employed to create the dataset and to detect/mitigate DDoS attacks using a trained model with this dataset. Before presenting the results and selecting the best model, we detail the preprocessing steps. These steps are crucial as they transform raw data into a clean, understandable format suitable for training ML models. The quality of the input data directly impacts the performance and accuracy of the model.

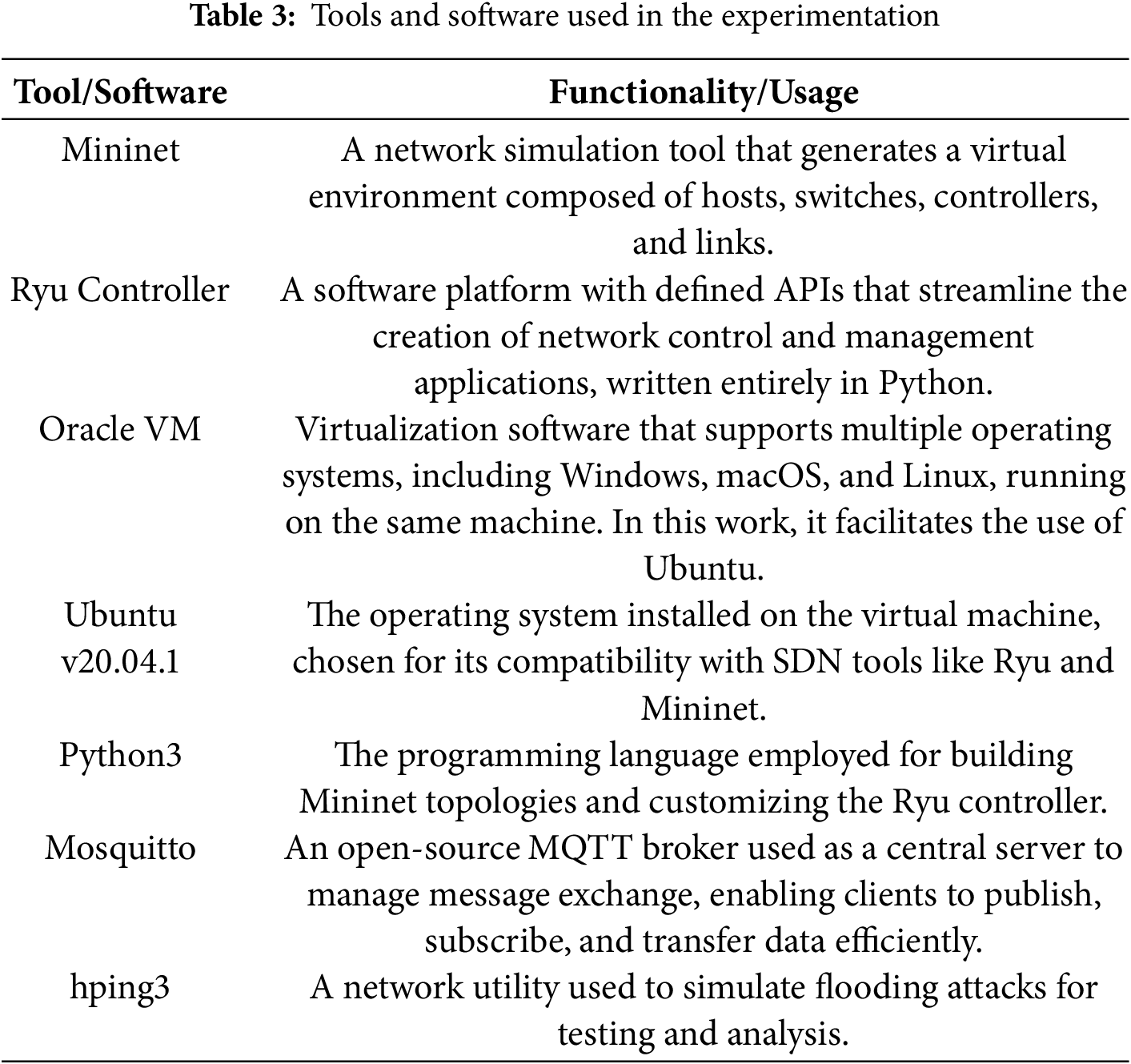

As shown in Table 3 of Tools, the dataset was developed using Mininet, an SDN emulator, on a virtualized setup hosted by Oracle VM VirtualBox with Ubuntu 20.04.1 LTS. Mininet simulated various network topologies (e.g., tree, mesh) featuring OpenFlow-enabled switches and IoT-like hosts, managed by the Ryu controller (v4.34) implemented in Python 3.8. The Ryu controller facilitated real-time collection of flow statistics (e.g., Source IP, Destination Port, Packet Rate) via the OpenFlow protocol, ensuring accurate traffic representation. The hardware comprised an Intel i5-12400F CPU with 16 GB RAM, supporting the simulation of 4,644,465 flows. Tools such as hping3, aiocoap, mosquitto_pub, and wrk were employed to simulate both normal and attack traffic.

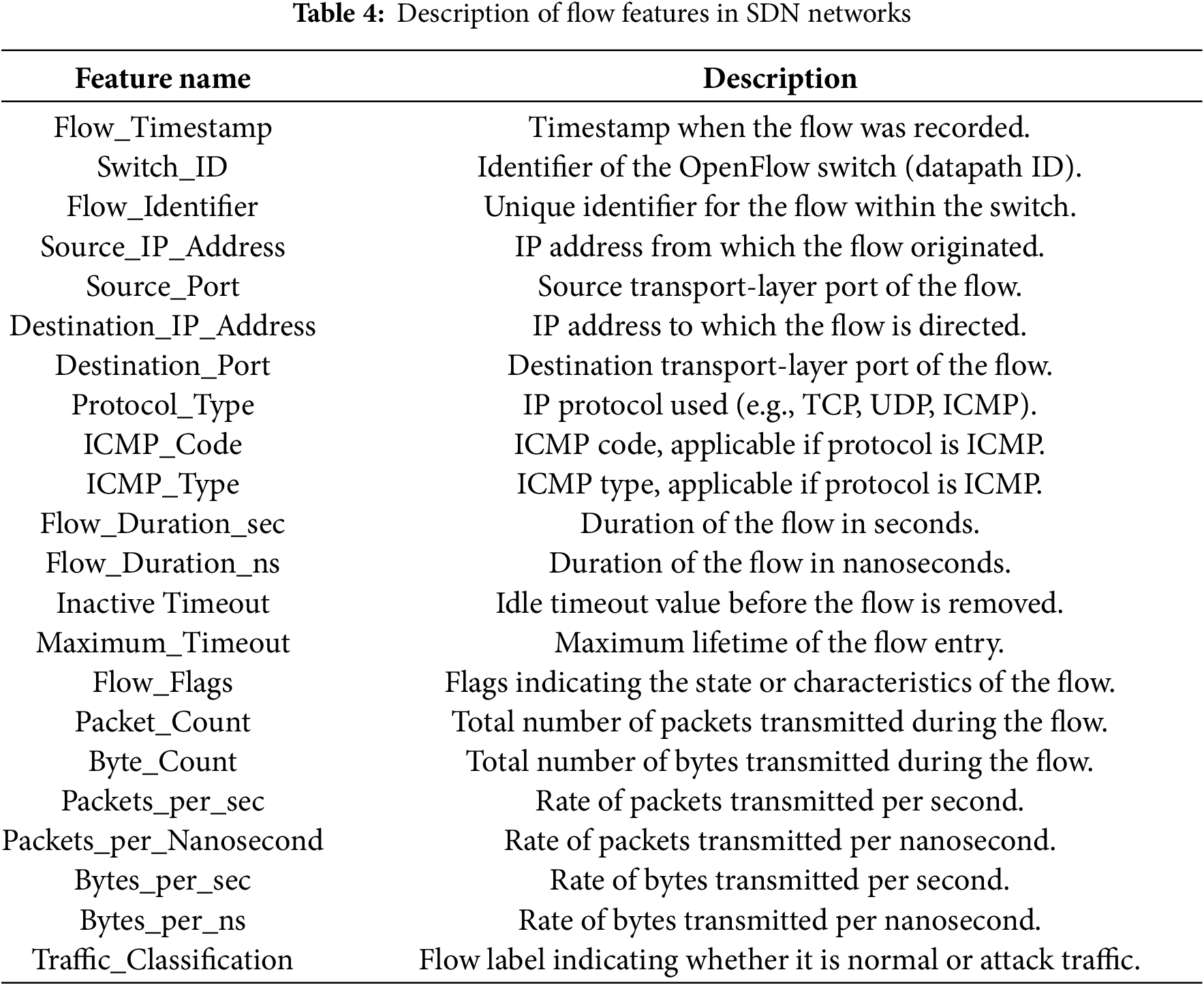

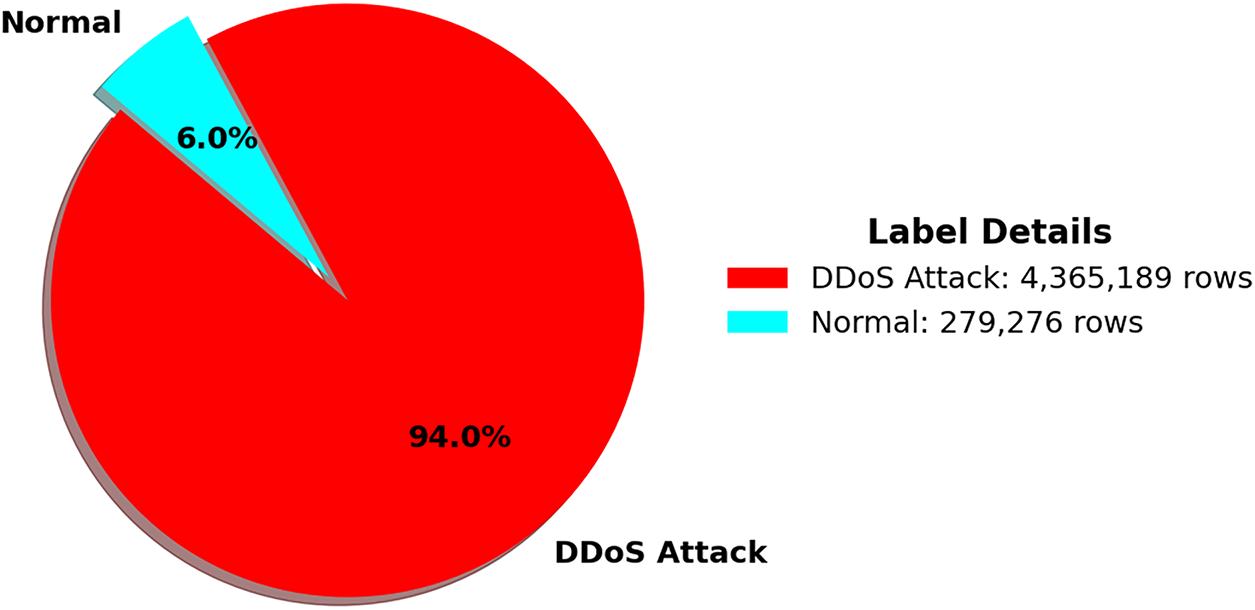

The dataset, accessible at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/nedernido/sdn-ddos-dataset (accessed on 20 November 2025), contains 4,644,465 flows with a total size of 662.06 MB, comprising a training set (6,985,276 flows post-SMOTE) and a test set (928,893 flows). It includes 22 features, as shown in Table 4, and two classes: normal (0, 278,668 flows, 6%) and DDoS (1, 4,365,797 flows, 94%) in the original dataset, as shown in Fig. 2. The training set, initially imbalanced with 3,492,638 DDoS (94%) and 222,934 normal (6%) flows, was balanced post-SMOTE to 6,985,276 flows (3,492,638 each, 50% each). The test set retains the original distribution with 873,159 DDoS (94%) and 55,734 normal (6%) flows. The dataset captures diverse IoT protocols (TCP, UDP, HTTP, MQTT, CoAP, ICMP) and attack types (SYN Flood, Slowloris, etc.), making it versatile for ML-based detection in SDN-IoT contexts.

Figure 2: Distribution of label counts

4.3 Pipeline for Dataset Preparation and Model Implementation

In this subsection, we provide a detailed explanation of the steps involved in implementing our proposed methodology. Fig. 3 illustrates the processing architecture for dataset collection. In this step, traffic data is collected using a controller-based monitoring system, and relevant features are extracted and stored in a .csv format for training purposes.

Figure 3: Dataset collection process

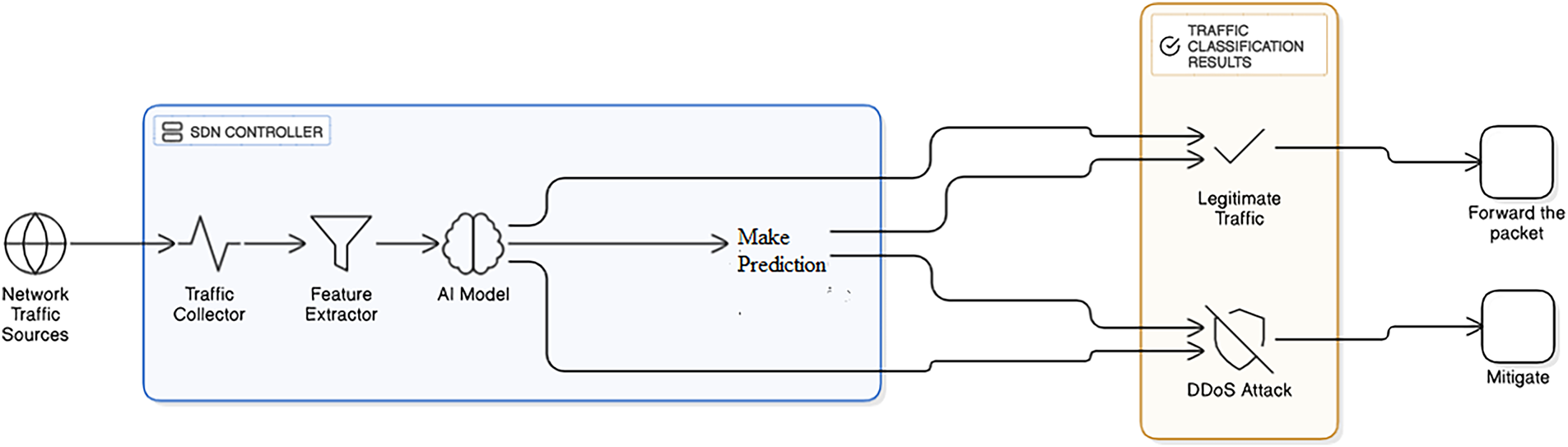

Fig. 4 presents the block diagram illustrating the implementation steps of the proposed IDPS in a real SDN testbed environment. In this process, a sample of network traffic (unseen dataset) is collected using the Ryu controller monitor. The captured traffic undergoes feature extraction and is subsequently analyzed by the proposed AI-based selector model to determine whether the traffic is legitimate or indicative of a DDoS attack.

Figure 4: Block diagram for detection and mitigation of DDoS attacks using an SDN-based AI model

If the selector model classifies the traffic as normal, it is forwarded to the appropriate destination host. Conversely, if the traffic is identified as a DDoS attack, it is dropped based on the source port information, thereby mitigating the attack,this approach enables the collection and real-time classification of SDN traffic using our selector model, supporting effective detection and mitigation of DDoS attacks while allowing legitimate traffic to flow uninterrupted and forwarding the packets to the appropriate host. The process illustrated in Fig. 4 will be used in Section 6, which focuses on testing the performance in a real SDN testbed environment.

4.4 Generating the Synthetic Dataset

To generate the synthetic dataset, we followed the methodology outlined in Section 2.1.1 for feature extraction, with the Ryu controller writing flow data into a .csv file in real time using Python’s csv library. Normal traffic was simulated by configuring multiple IoT devices within the Mininet environment to exchange benign packets using protocols such as TCP, UDP, HTTP, ICMP, MQTT, and CoAP. Tools like wget, ping, iperf, aiocoap, mosquitto_pub, and mosquitto_sub were used to emulate realistic IoT communication patterns, including periodic sensor updates, control signals, and device-to-host interactions. For malicious traffic, we simulated various DDoS attack scenarios targeting these protocols, with specific configuration parameters to ensure comprehensive coverage of both volumetric and slow-rate attacks.

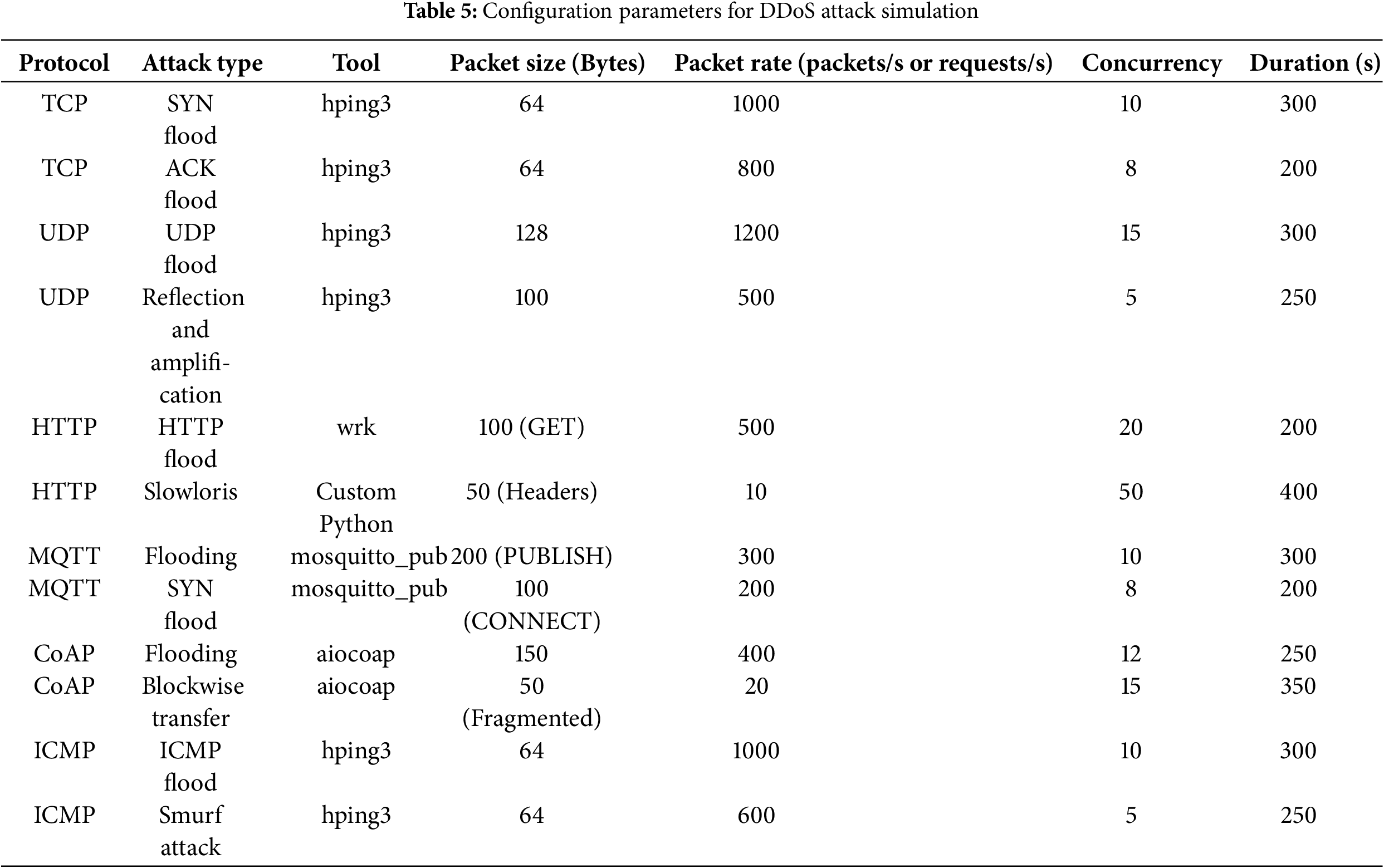

A diverse set of attack scenarios was generated to evaluate the robustness of the proposed IDPS under realistic SDN-IoT threat conditions. TCP-based attacks were produced using hping3, where SYN Flood traffic consisted of 64-byte packets transmitted at 1000 packets/s with 10 concurrent connections over 300 s, while TCP ACK Flood attacks used the same packet size but at 800 packets/s and 8 concurrent connections for 200 s. UDP-based attacks included UDP Flood traffic generated with 128-byte packets at a rate of 1200 packets/s and 15 concurrent connections for 300 s, as well as UDP reflection/amplification attacks targeting DNS servers using spoofed IP addresses, with 100-byte packets at 500 packets/s and 5 concurrent connections for 250 s. Application-layer attacks were also simulated: HTTP Flood traffic was created using wrk with 100-byte GET requests at 500 requests/s and 20 concurrent connections for 200 s, and Slowloris attacks were crafted via a custom Python script that transmitted partial 50-byte HTTP headers at 10 requests/s with 50 concurrent connections over 400 s. MQTT-based attacks were produced using mosquitto_pub, where MQTT Flooding relied on 200-byte PUBLISH messages sent at 300 messages/s with 10 concurrent connections for 300 s, while MQTT SYN Flood attacks used 100-byte CONNECT messages at 200 messages/s with 8 concurrent connections for 200 s. For CoAP traffic, aiocoap was used to generate CoAP Flood requests of 150 bytes at 400 requests/s with 12 concurrent connections for 250 s, and blockwise transfer attacks fragmented 500-byte payloads into 50-byte request segments sent at 20 requests/s with 15 concurrent connections for 350 s. Finally, ICMP-based attacks included ICMP Flood traffic composed of 64-byte ping requests at 1000 packets/s with 10 concurrent connections for 300 s, as well as Smurf attacks using 64-byte ICMP requests directed to broadcast addresses at 600 packets/s with 5 concurrent connections for 250 s.

These parameters were chosen to reflect realistic attack scenarios, with packet sizes and rates designed to stress IoT devices and SDN controllers while maintaining compatibility with the Mininet testbed. The dataset was labeled in real time using the Ryu controller’s flow statistics, distinguishing normal (0) and attack (1) traffic for ML training and testing. The tools and their configurations are detailed below and summarized in Table 5.

To ensure the accuracy and robustness of the ML model for DDoS attack detection, a comprehensive data preprocessing pipeline was implemented. This step was essential to address the raw dataset’s quality, balance, and dimensionality before feeding it into the learning algorithms. The preprocessing pipeline involved the following key steps, with each technique carefully selected based on the dataset characteristics and ML requirements:

4.5.1 Handling Missing and Inconsistent Values

The dataset was first examined for missing values or inconsistencies, which could distort the learning process. Entries with missing values were either imputed using statistical methods (mean/mode for numerical/categorical features) or removed if they were incomplete. This step ensured the dataset’s integrity and eliminated noise, improving the generalizability of the model.

4.5.2 Label Encoding of Categorical Features

Since ML models require numerical input, the categorical attributes in the dataset were converted into numerical values using label encoding. This method assigns a unique integer to each distinct category, allowing the model to process non-numerical attributes without inflating the feature space. In this work, the features Flow_Timestamp, Flow_Identifier, Source_IP_Address, and Destination_IP_Address were label-encoded. The Flow_Timestamp was encoded to preserve the order of time instances, while Flow_Identifier was transformed to distinguish individual flows within the SDN network. Similarly, the source and destination IP addresses were encoded to treat each network node as a distinct categorical entity. Label encoding was preferred over one-hot encoding to prevent the curse of dimensionality, given the high cardinality of these features.

4.5.3 Normalization of Numerical Features

Feature scaling was performed using Min-Max normalization to rescale numerical values to a [0, 1] range. This step ensures that no feature dominates due to its scale and facilitates faster convergence during training. Normalization is particularly beneficial for gradient-based models and distance-based algorithms.

4.5.4 Balancing the Dataset Using the SMOTE Approach

Our synthetic dataset exhibited class imbalance, with a higher number of attack instances compared to normal traffic. This imbalance can bias the ML model toward the majority class (attacks labeled as 1). To address this, SMOTE [45] was employed. SMOTE generates synthetic samples of the minority class using kNN interpolation, effectively balancing the ‘normal’ label (0) with all attack types labeled as (1), which include protocols such as TCP, UDP, ICMP, HTTP, MQTT, and CoAP. This approach enhances the model’s ability to recognize attack patterns without simply duplicating existing samples, leading to improved performance metrics, especially in imbalanced classification tasks.

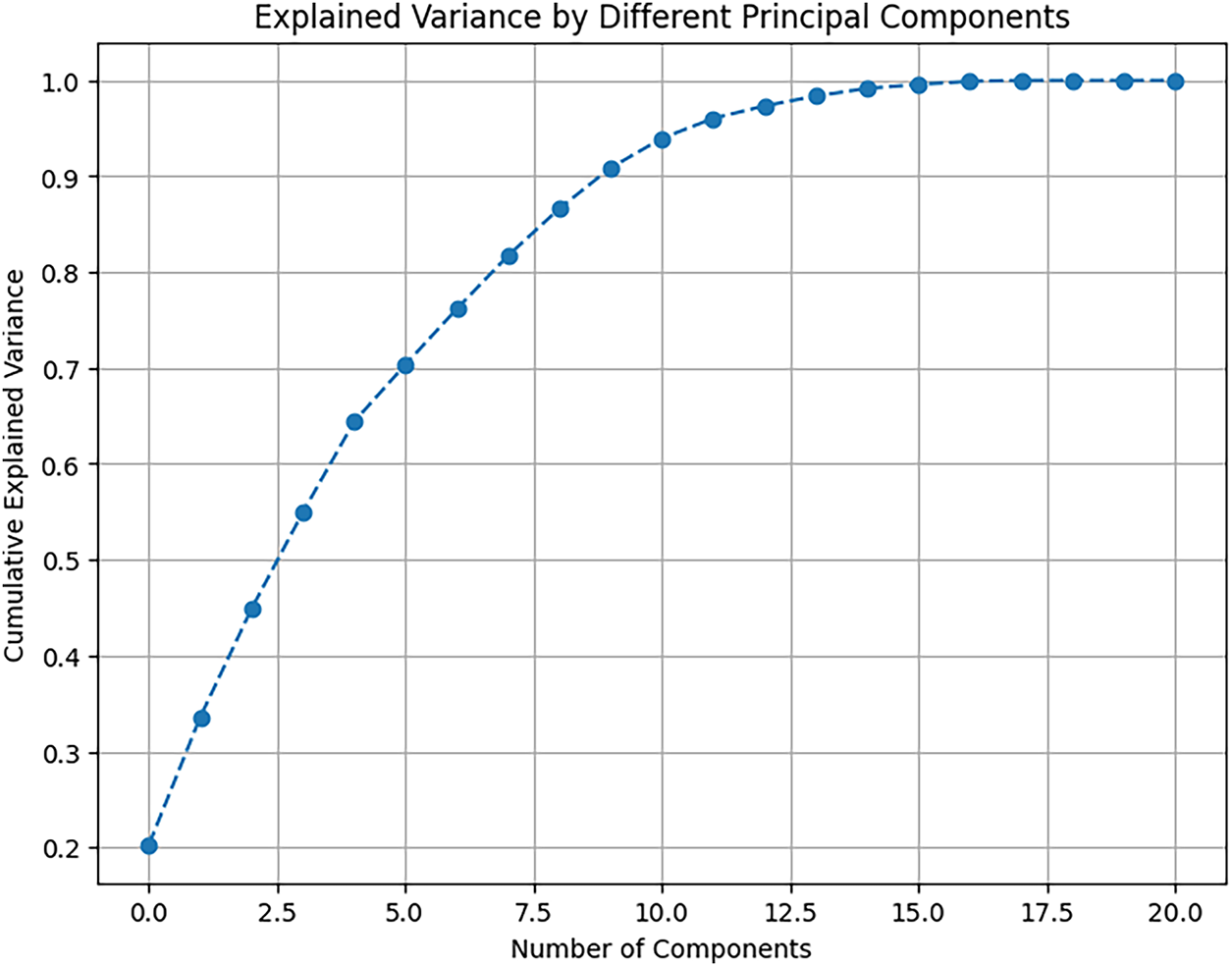

4.5.5 Dimensionality Reduction with PCA

To reduce computational complexity and mitigate multicollinearity among features, PCA was applied. PCA transforms the original features into a set of linearly uncorrelated components while preserving the maximum variance. Ten principal components were retained, as shown in Fig. 5, capturing the majority of the information in the dataset. This step is important not only because it speeds up model training but also because it improves robustness by removing redundant features, reducing overfitting, and decreasing the number of features in the dataset while preserving the most important information.

Figure 5: Principal component analysis

Finally, the dataset was randomly divided into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets. This split ensures that the model is evaluated on unseen data, providing an unbiased estimation of its real-world performance. The hold-out method remains a widely adopted strategy in supervised ML evaluation.

5 Experiments and Analysis of Results

In this section, we evaluate the performance of our trained model on the synthetic dataset using various ML metrics to select the best model for deployment in a real SDN testbed environment.

5.1 Performance of Each Classification Model

The test results were evaluated using both the evaluation metrics and the key performance indicators to comprehensively assess the model’s performance.

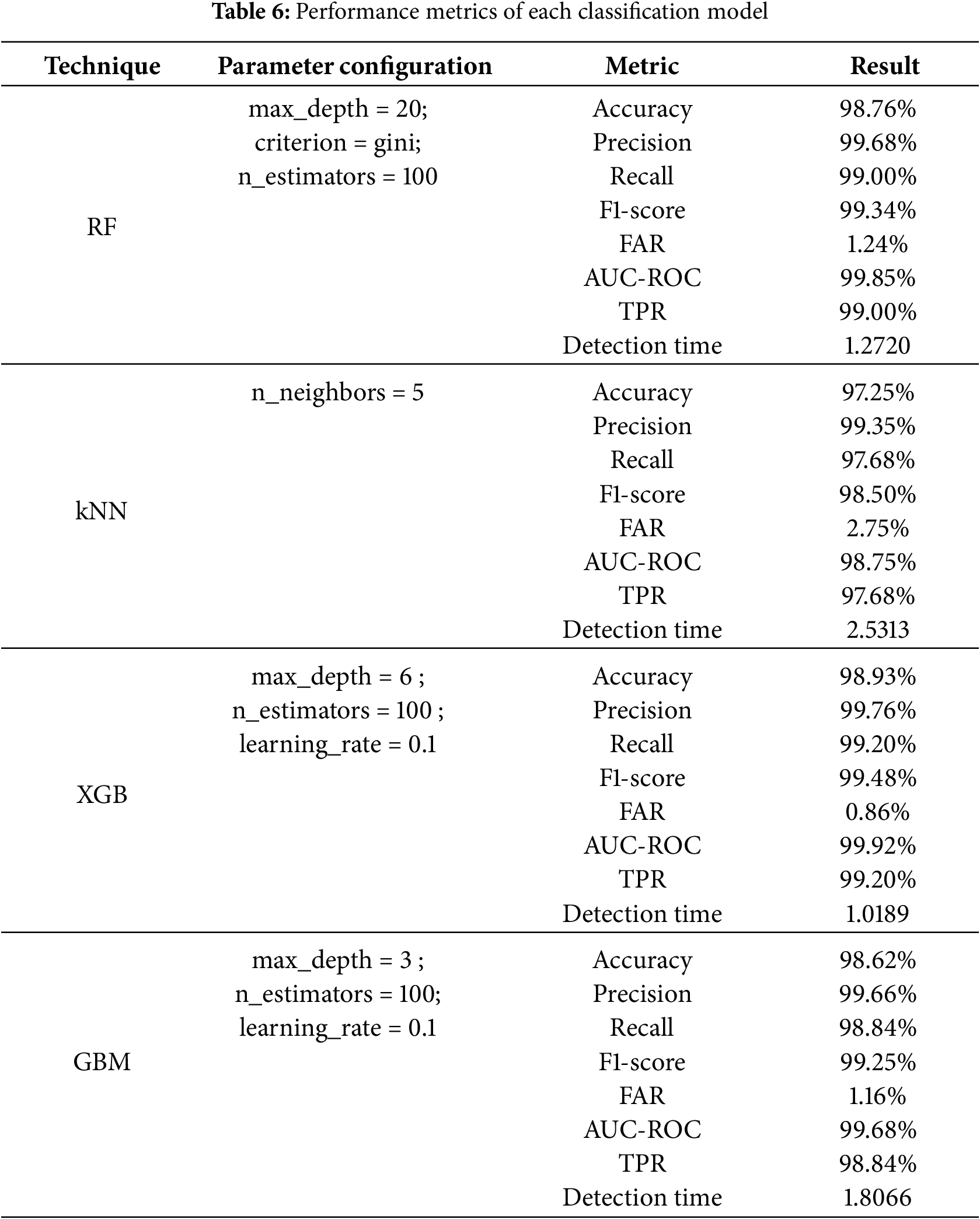

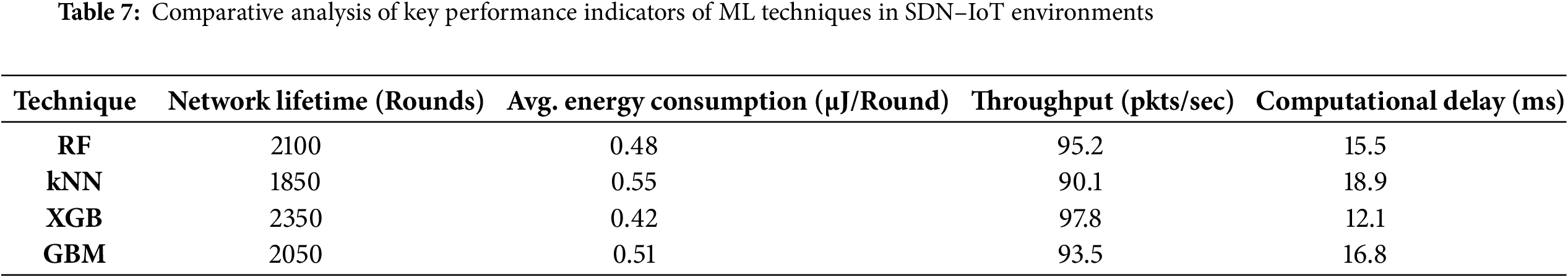

To evaluate the performance of the models, we used ML algorithms including RF, kNN, XGB, and GBM, because they have demonstrated their effectiveness and efficiency in intrusion detection systems in IoT environments [46–48].

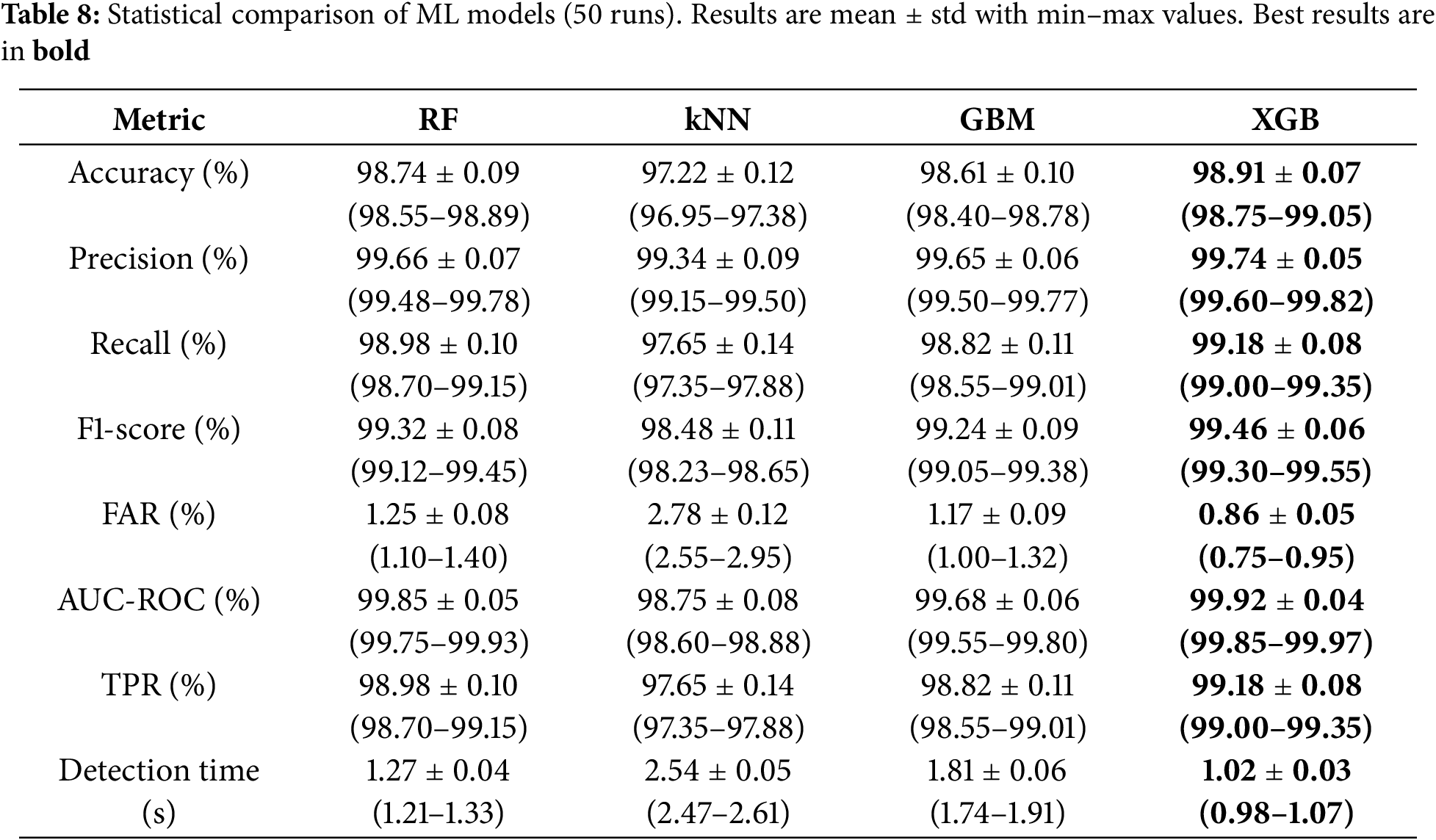

Using the optimal ML hyperparameters, as presented in Table 6. The results highlight the performance of each classification model. Among the models tested, XGB achieved the highest accuracy of 98.93%, with excellent precision (99.76%), recall (99.20%), and TPR of 99.20%, as well as a high F1-score of 99.48%. It also displayed the lowest FAR of 0.86% and a strong AUC-ROC value of 99.92%, with a detection time of 1.02 s. RF followed closely with an accuracy of 98.76%, precision of 99.68%, recall and TPR of 99.00%, along with a low FAR of 1.24% and a detection time of 1.27 s. GBM and kNN showed relatively lower performance, with GBM having an accuracy of 98.62%, TPR of 98.84%, and KNN achieving 97.25% accuracy and TPR of 97.68%. The detection times for GBM and kNN were 1.81 and 2.53 s, respectively. Overall, XGB outperformed the other models in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and TPR, while also maintaining the fastest detection time.

5.1.2 The Key Performance Indicators

Table 7 presents the comparative analysis of four ML techniques: RF, kNN, XGB, and GBM benchmarked against four critical distributed network performance indicators. The empirical results demonstrate that the proposed protocol utilizing the XGB algorithm consistently yields superior overall performance across all measured criteria. Specifically, the XGB-based scheme achieved the maximum Network Lifetime of 2350 rounds and concurrently recorded the minimum Average Energy Consumption at 0.42 μJ per round, highlighting its excellent energy management capabilities. Furthermore, XGB attained the highest Throughput (97.8 packets per second) and exhibited the lowest latency, with a Computational Delay of only 12.1 ms, validating its robustness for real-time operations within the SDN-IoT environment. These findings confirm the effectiveness of XGBoost’s ensemble approach in optimizing critical network metrics compared to the other tested methodologies.

5.2 Robustness Assessment through Multiple Independent Experimental Runs

1. Multiple Independent Runs: Each classifier (RF, kNN, GBM, and XGB) was retrained and tested across 50 independent runs with different random seeds to ensure reproducibility and robustness.

2. Descriptive Statistics: For each metric, we report the mean

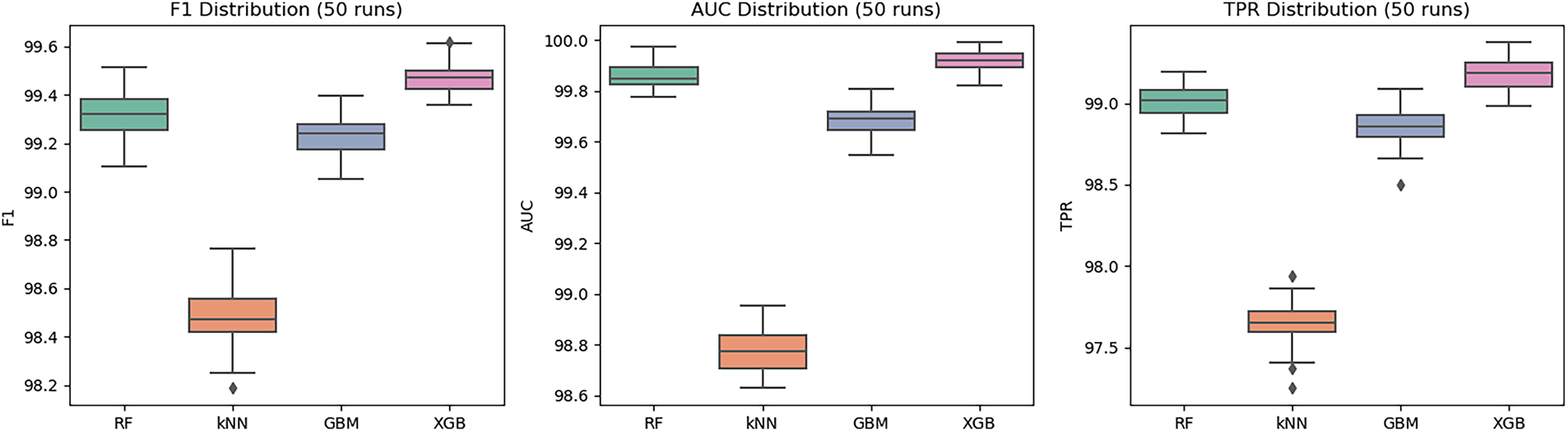

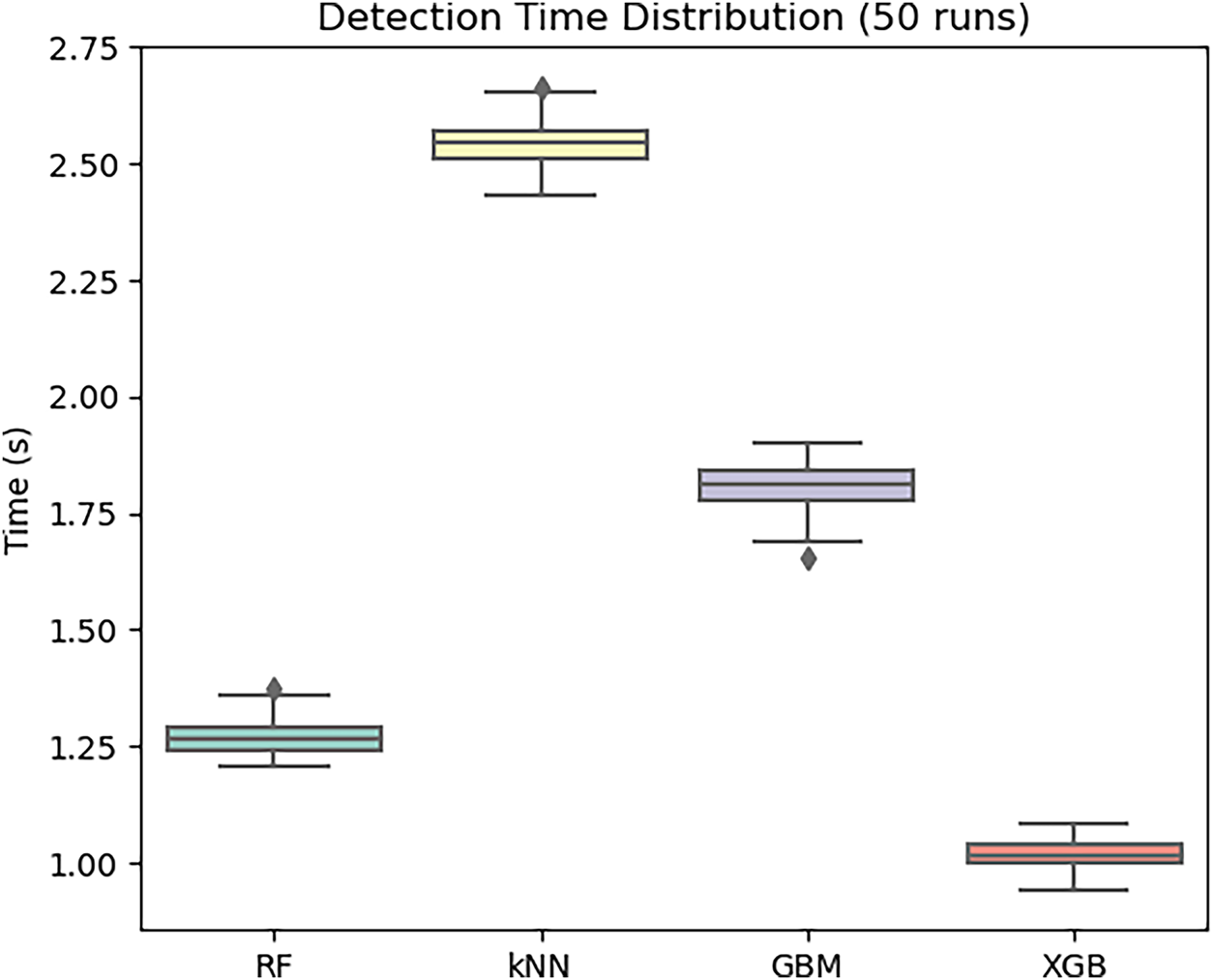

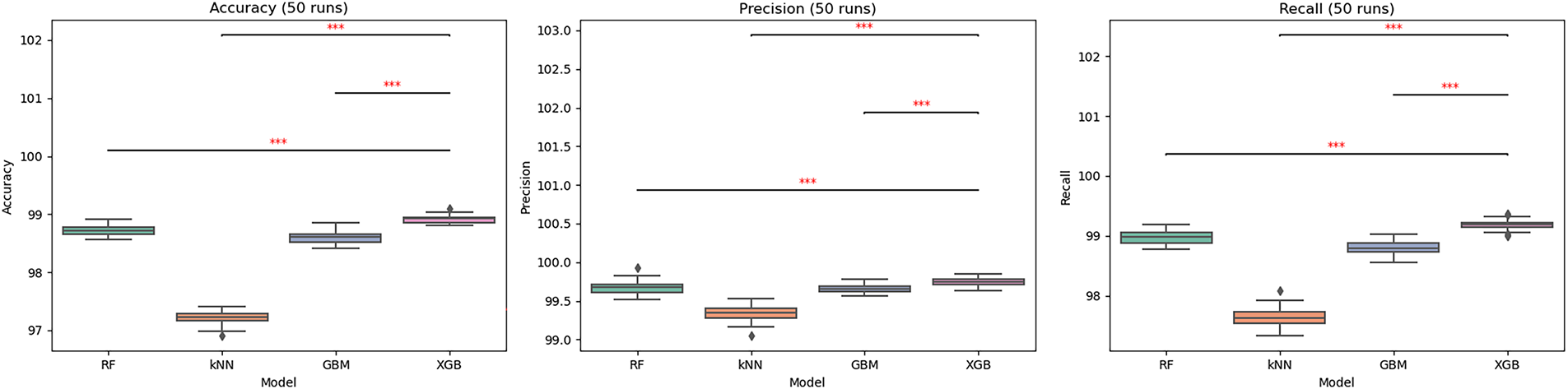

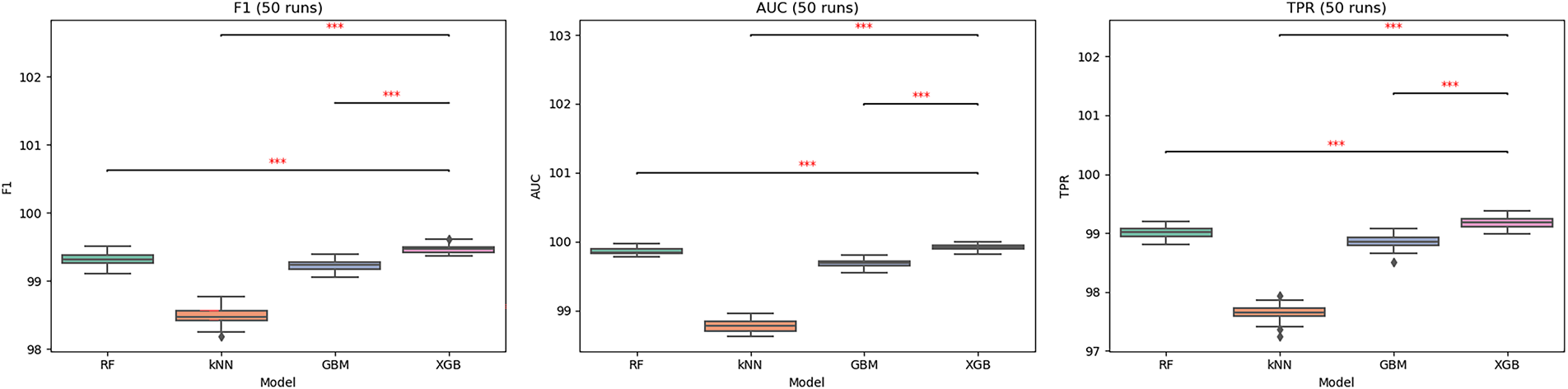

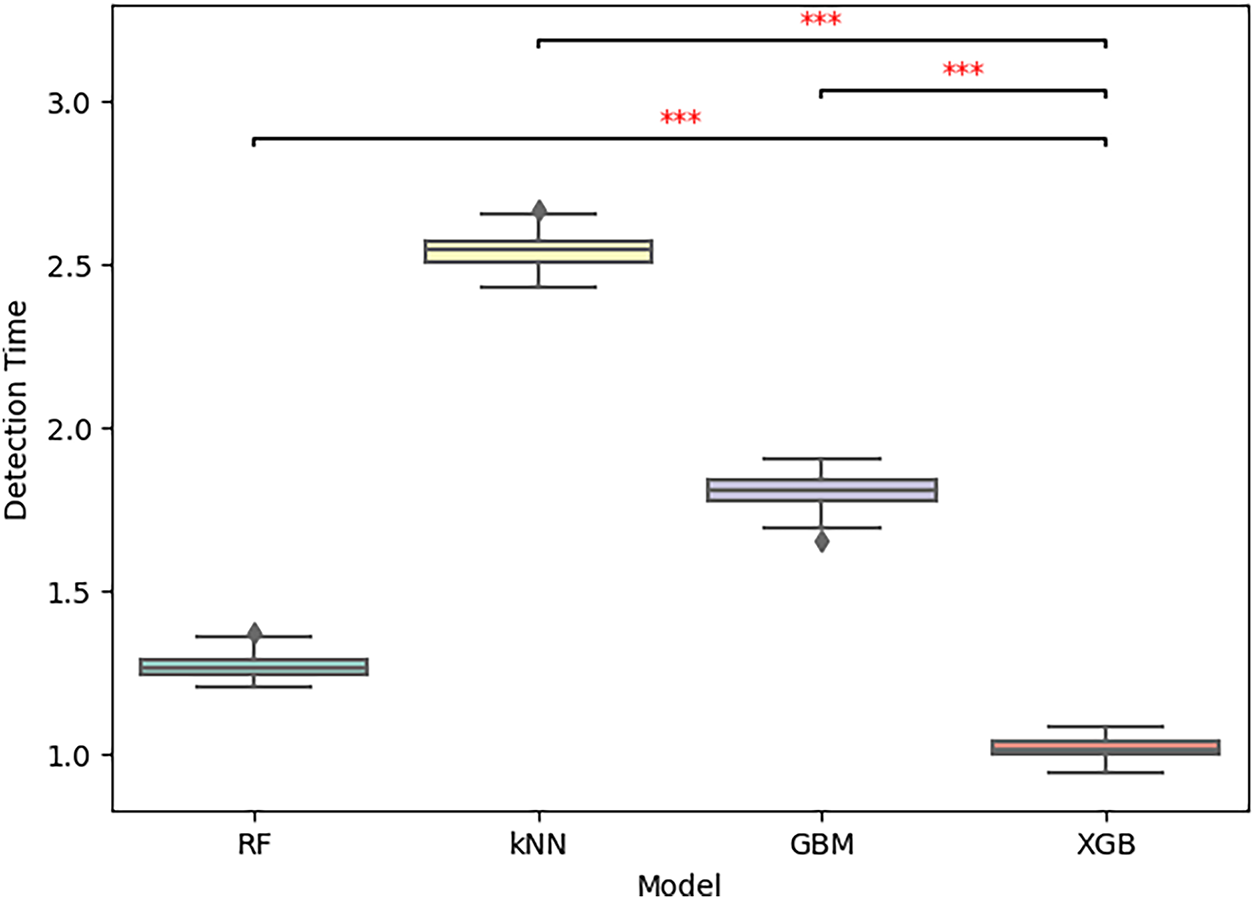

3. Box Plot Visualization: Fig. 6 illustrates the distributions of Accuracy, Precision, and Recall across 50 runs, while Fig. 7 shows the distributions of F1-score, AUC-ROC, and TPR. XGB achieves the highest medians with the smallest variance, confirming its robustness. RF and GBM remain competitive but slightly below XGBoost, whereas kNN exhibits the largest variability. Fig. 8 presents the Detection Time distributions, where XGBoost achieves the lowest detection time (

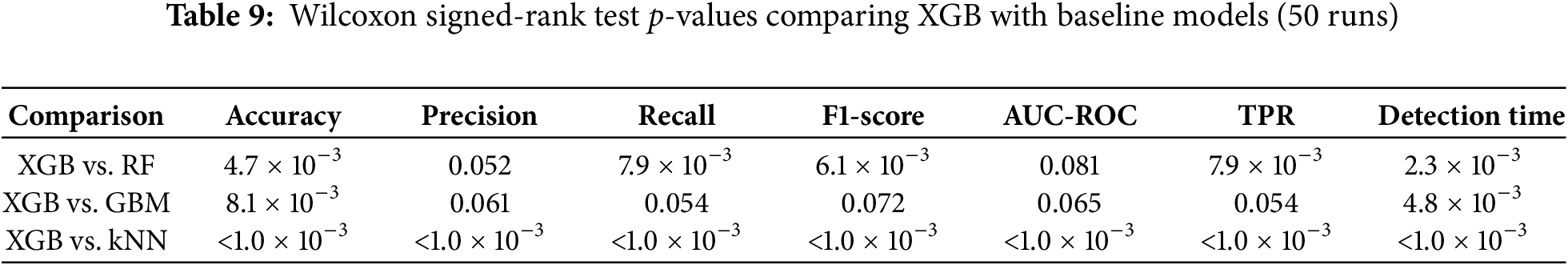

4. Hypothesis Testing with Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test: To validate the observed differences, we conducted Wilcoxon signed-rank tests across the 50 runs. The results are presented in the Table 9, with p-values reported in scientific notation.

• XGB vs. RF: significant differences (

• XGB vs. GBM: significant differences (

• XGB vs. kNN: highly significant differences (

Fig. 9 illustrates the boxplot distributions of Accuracy, Precision, and Recall across 50 runs, while Fig. 10 presents the corresponding distributions of F1-score, AUC-ROC, and TPR. XGBoost consistently achieves the highest medians with the smallest variance, whereas RF and GBM perform slightly lower with moderate spread, and kNN shows the widest variability with several outliers.

Fig. 11 presents the Detection Time distributions, showing that XGBoost attains the lowest median detection time (

Figs. 9–11 are annotated with significance stars (*

5. Alignment with Best Practices: Our methodology ensuring adherence to rigorous standards for stochastic ML-based attack detection in SDN environments. Our evaluation robust, reproducible, and statistically validated. The results confirm with strong statistical evidence that the XGBoost-based model significantly outperforms RF, GBM, and kNN, both in terms of detection accuracy and efficiency.

Figure 6: Distributions of accuracy, precision, and recall across 50 runs

Figure 7: Distributions of F1-score, AUC-ROC, and TPR across 50 runs

Figure 8: Distributions of detection time across 50 runs

Figure 9: Boxplot distributions and Wilcoxon signed-rank test results for Accuracy, Precision, and Recall (50 runs). The red Asterisks (***) indicate statistically significant differences with p < 0.001 according to the Wilcoxon signed-rank test

Figure 10: Boxplot distributions and Wilcoxon signed-rank test results for F1-score, AUC-ROC, and TPR (50 runs). The red Asterisks (***) indicate statistically significant differences with p < 0.001 according to the Wilcoxon signed-rank test

Figure 11: Boxplot distributions and Wilcoxon signed-rank test results for detection Time (50 runs). The red Asterisks (***) indicate statistically significant differences with p < 0.001 according to the Wilcoxon signed-rank test

6 Performance in SDN Environments for DDoS Attack Detection

In this section, we implement our ML-based XGBoost model in a real SDN testbed environment to evaluate its performance in detecting DDoS attacks in live traffic. To achieve this, we first describe the characteristics of our machine, ensuring adaptability and flexibility with SDN. Next, we set up our SDN environment on this machine using the Ryu controller and Mininet to create our network topology. Finally, we test the performance of our model in live traffic using our synthetic dataset to detect DDoS attacks in real time. Additionally, we analyze the impact of our XGBoost model on CPU usage and memory consumption to assess its efficiency with our synthetic dataset.

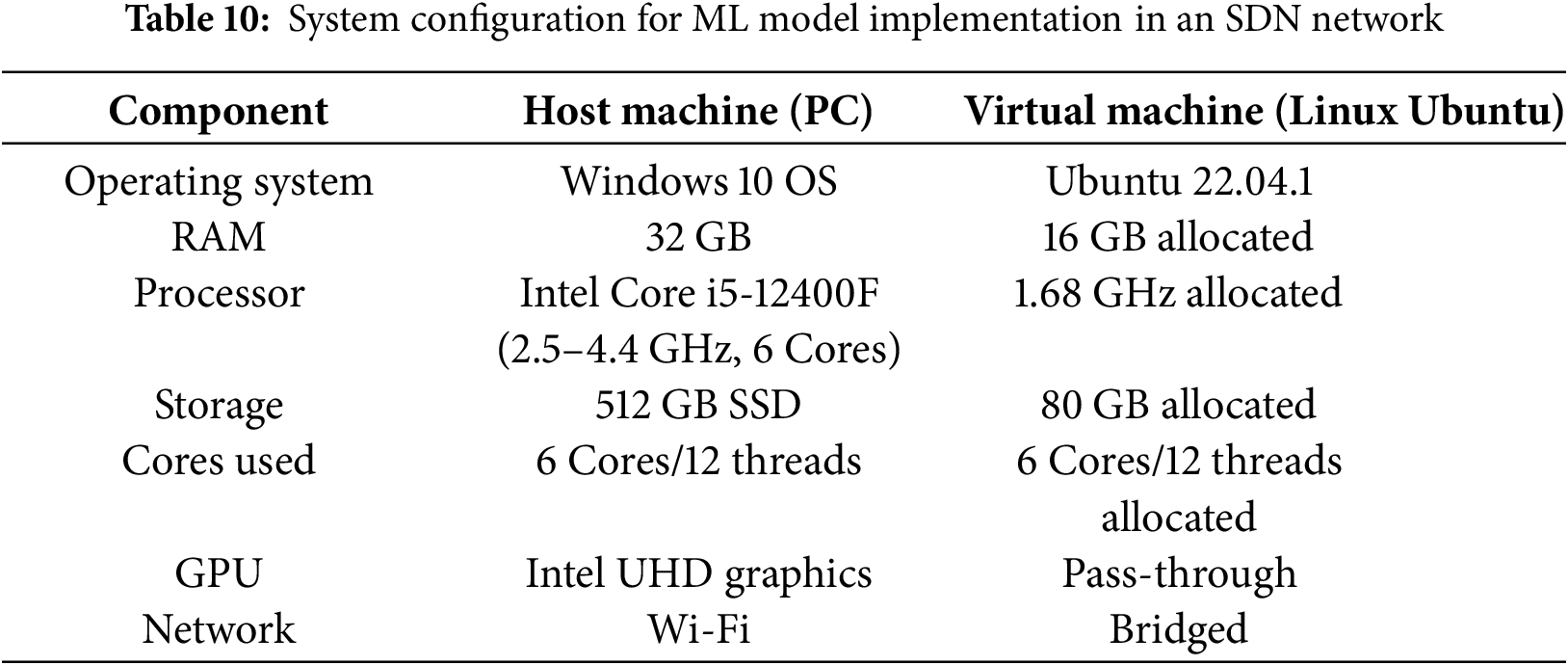

To implement our ML model, which is based on XGB algorithms and feature selection using PCA for our synthetic dataset in an SDN network, we configured a virtual machine as shown in Table 10, running Ubuntu 22.04.1. The VM is allocated 12 GB of RAM out of the total 16 GB available on the host machine, ensuring sufficient memory for ML model execution. The processor, an Intel Core i5-12400F with six cores, has a base frequency of 2.5 GHz, with 1.68 GHz allocated to the VM to balance performance and resource availability. Storage is configured with an 80 GB allocation from the host’s 512 GB SSD, ensuring fast read/write operations. The VM utilizes Intel UHD Graphics for basic visual processing, while the network is set to bridged or NAT mode for seamless communication in the SDN environment.

As shown in Fig. 12, we selected for our test the performance of an SDN network using a medium-sized tree topology with 16 hosts, 15 switches, and a single Ryu controller. The tree topology was chosen because it offers a hierarchical and scalable structure, making it ideal for simulating real-world network environments while ensuring efficient data flow and minimized latency. This setup, combined with the flexibility and programmability of the Ryu controller, allows for effective management and optimization of network resources, making it well-suited for evaluating SDN performance in medium-sized networks, which are commonly found in enterprise environments.

Figure 12: OpenFlow-based tree topology with medium size

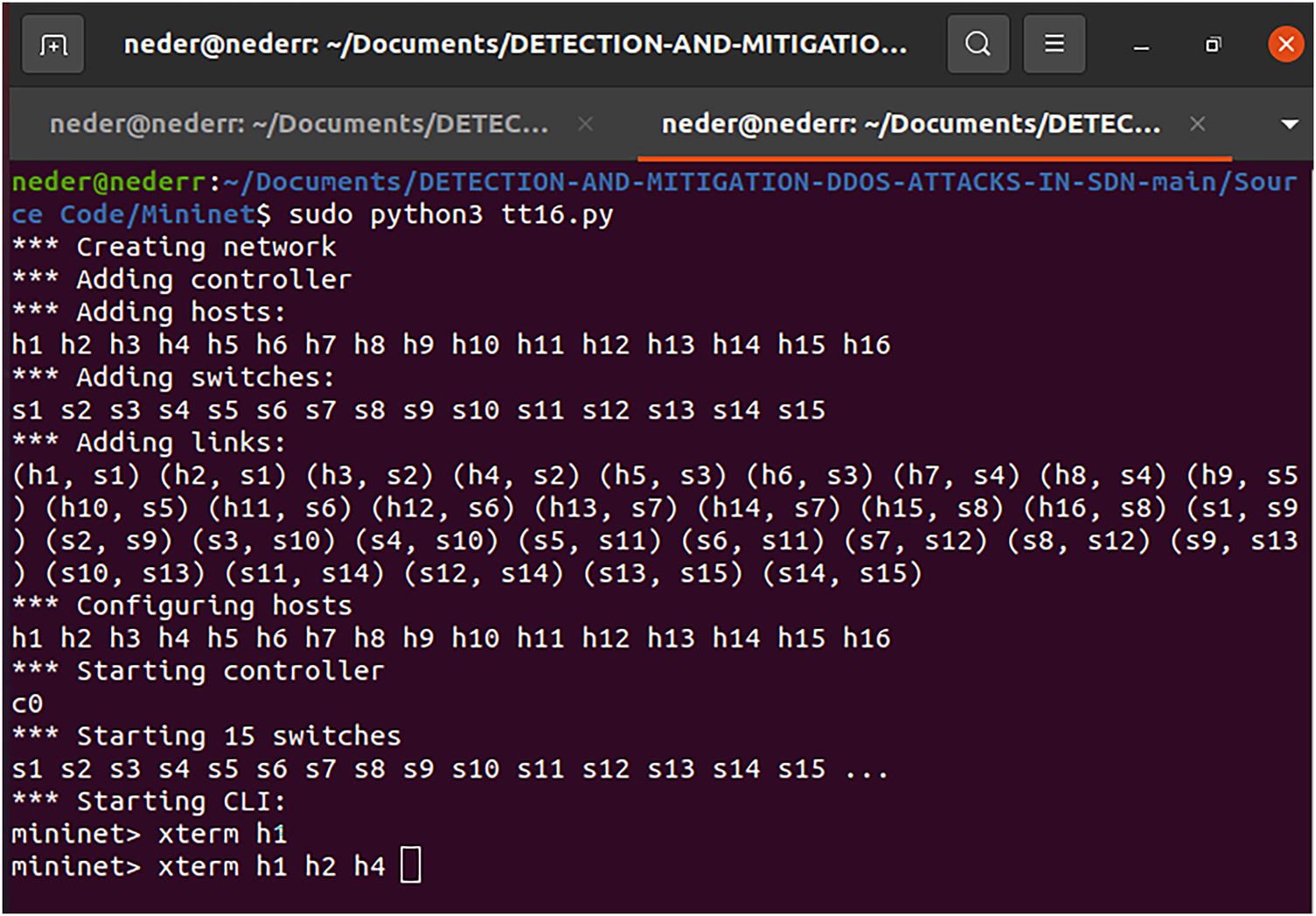

We launch our SDN topology using Mininet, which creates a tree network with a medium size of 16 hosts and 15 switches, with a single Ryu controller, as shown in Fig. 13 below:

Figure 13: Tree topology network creation using Mininet tools

6.2.2 Normal Traffic Condition

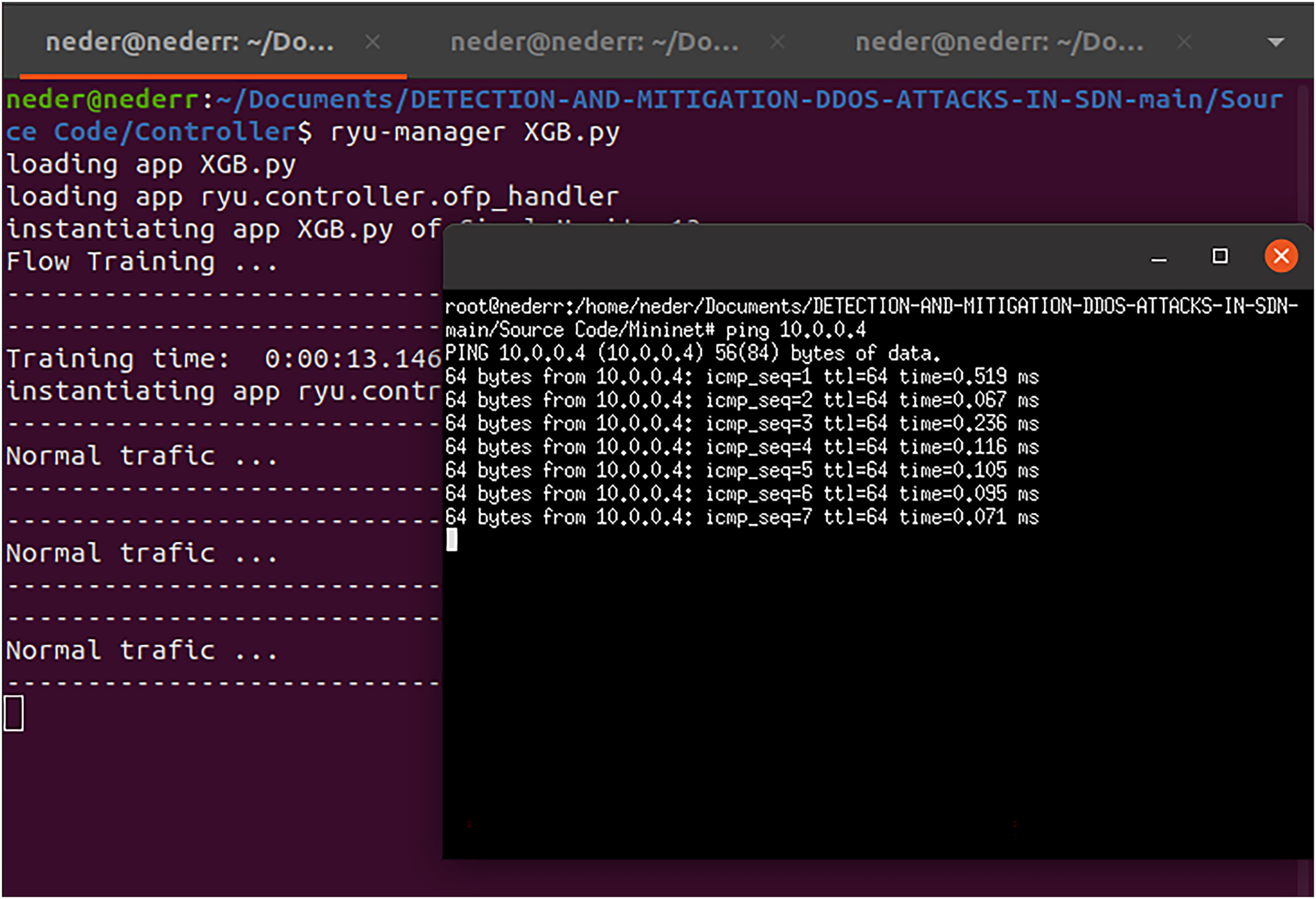

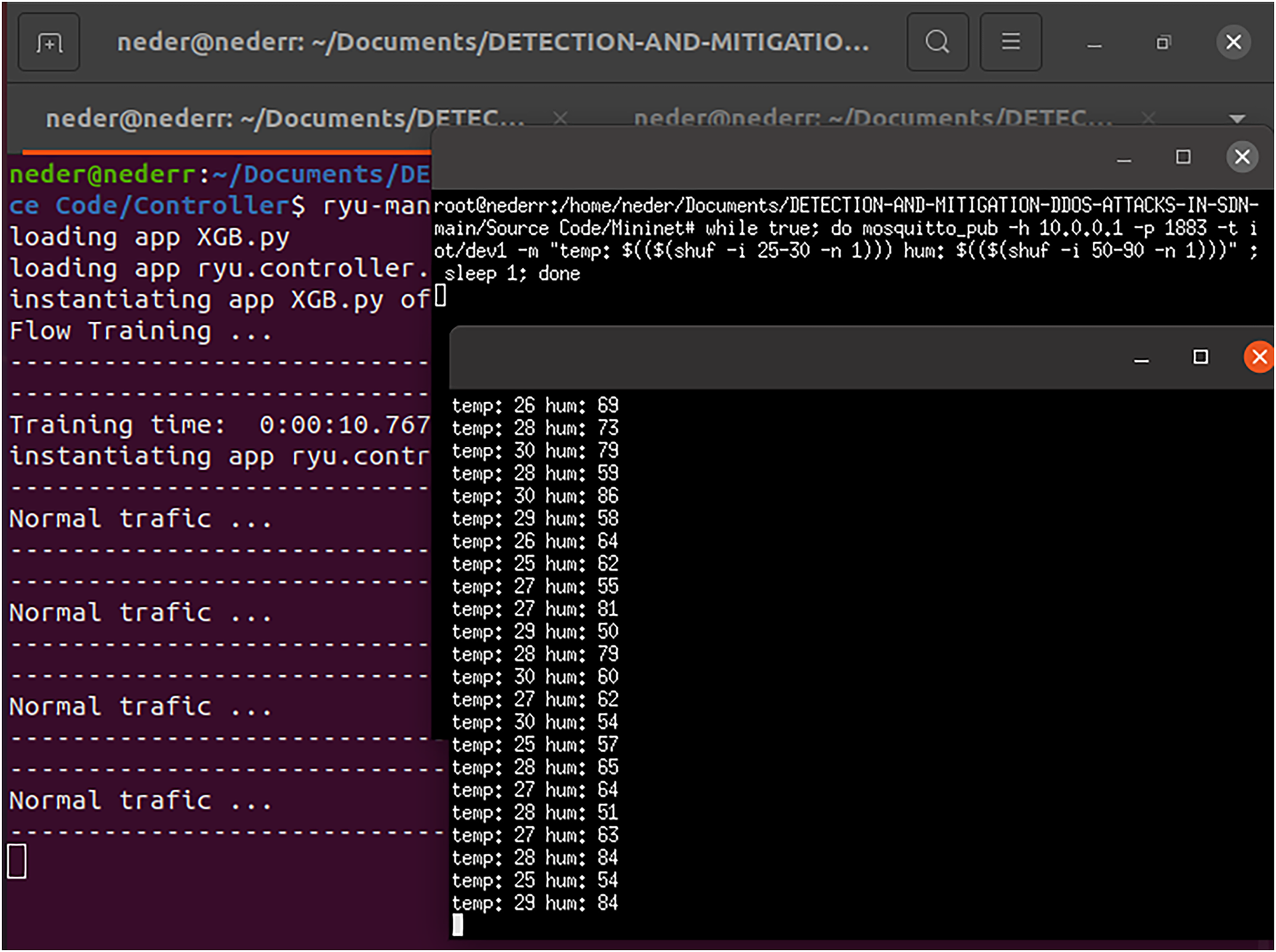

We used two protocols, ICMP and MQTT, to launch legitimate traffic. Host 1 (h1) pings Host 4 (h4) to assess reachability. As shown in Fig. 14, our XGB model detects the traffic as normal (legitimate). We also used the MQTT protocol, with h1 acting as a publisher IoT device that sends temperature and humidity data on a specific topic to an MQTT broker, which forwards the data to h4. As shown in Fig. 15, the XGB model also detects this traffic as normal (legitimate).

Figure 14: Normal traffic using ICMP protocol

Figure 15: Normal traffic using MQTT protocol

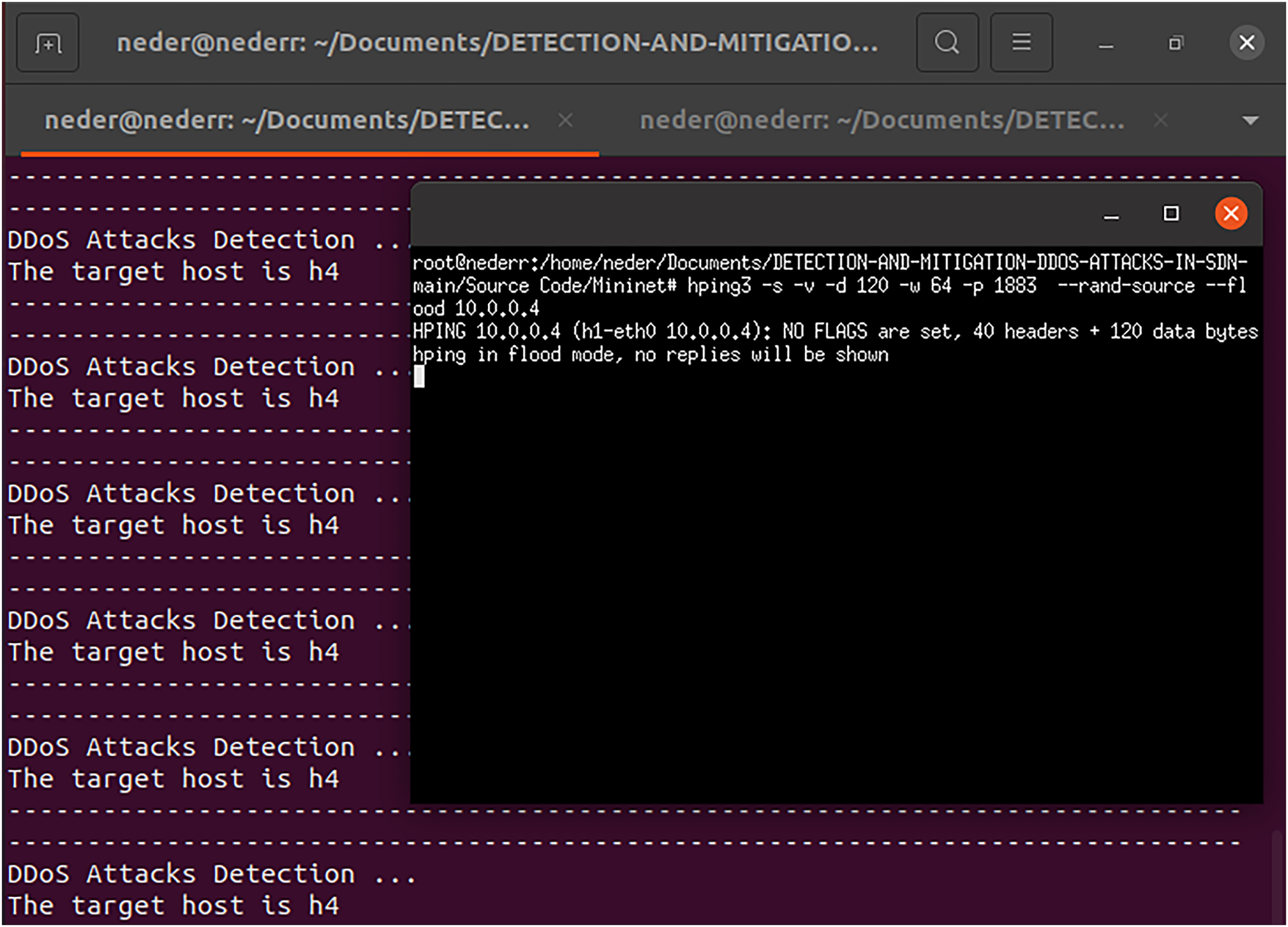

As shown in Fig. 16, we used the hping tool to launch DDoS attacks. h2 is simulated as a DDoS attacker targeting IoT devices on the MQTT protocol of h1. Our XGB model effectively detects the DDoS attacks in real-time.

Figure 16: Real-time DDoS attack detection using the proposed XGBoost model

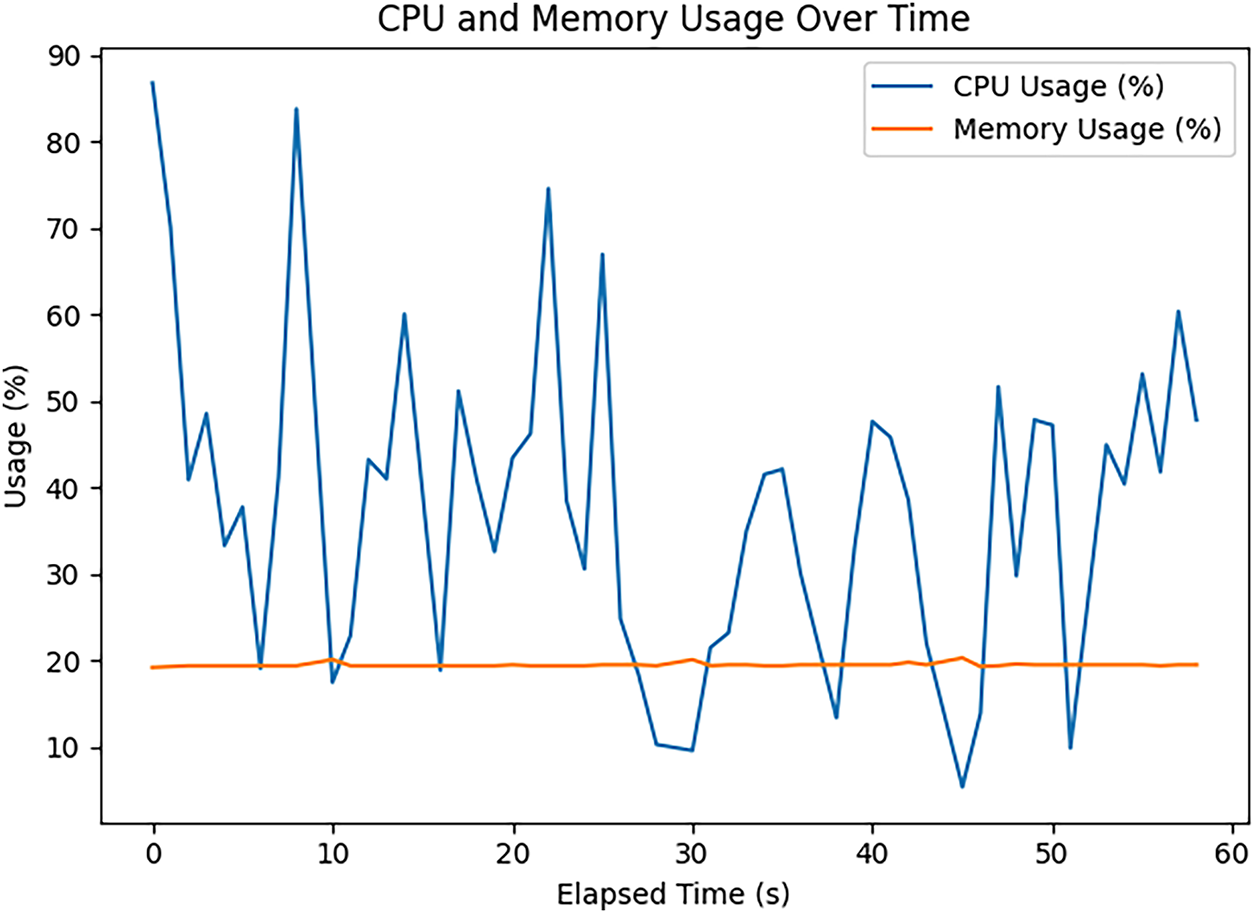

Fig. 17 shows the CPU usage average during DDoS attacks, with an average CPU usage of 45.62%, which could slow down the publisher’s data transmission from IoT device h1 to legitimate subscriber hosts, along with a memory consumption average of 18.27%.

Figure 17: CPU usage during DDoS attacks

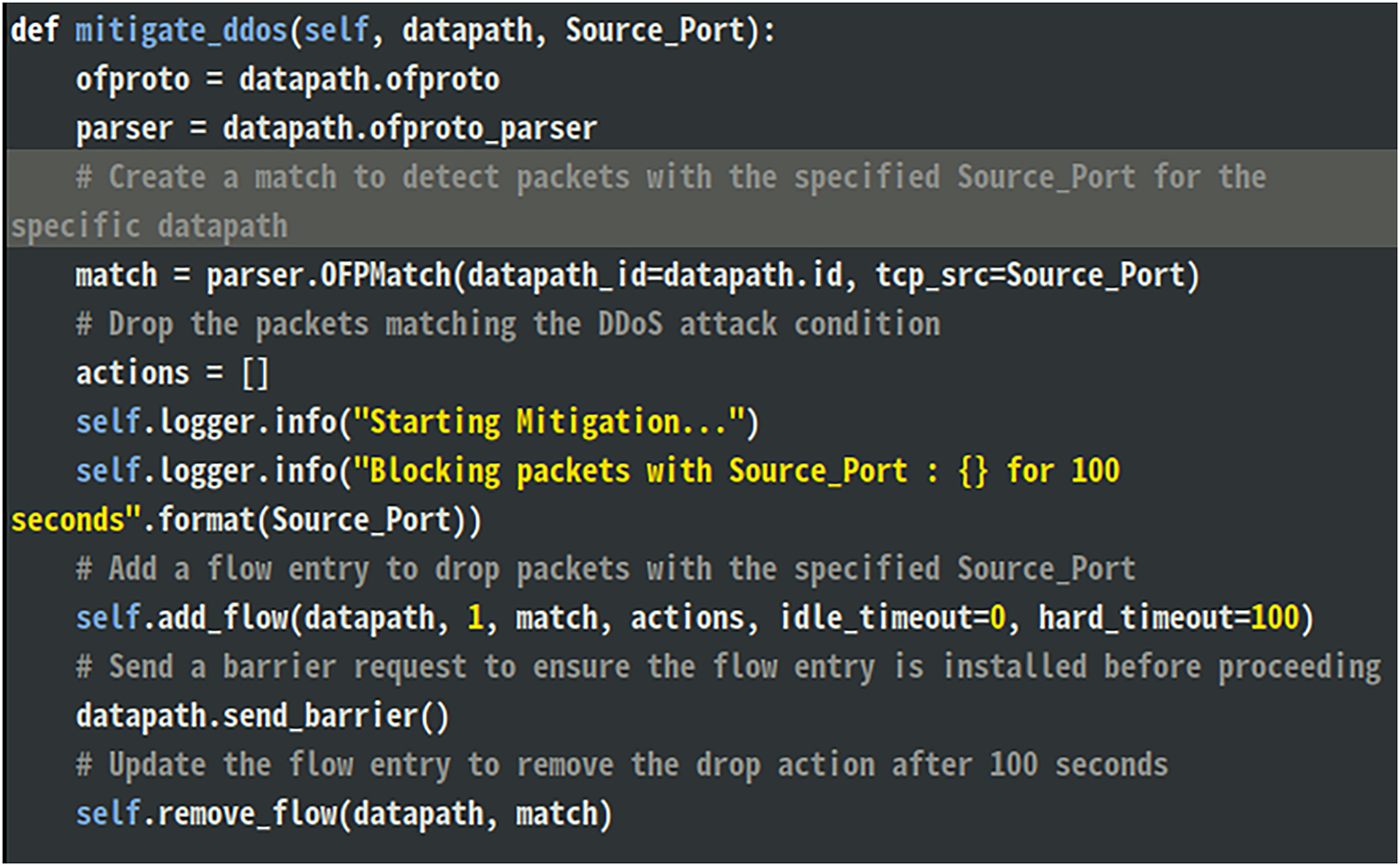

Fig. 18 shows the provided code, which is a function designed to mitigate DDoS attacks in an SDN environment by blocking traffic based on the source port (Source_Port). It uses OpenFlow to create a flow rule on the switch that matches packets originating from a specified source port and drops them. The function first constructs a match condition using the source port, then installs a flow entry with no actions (which results in dropping the packets). The flow rule has a hard timeout of 100 s, after which it is automatically removed. Logging messages are included to track the mitigation process, and a barrier request ensures the flow rule is installed before proceeding. This approach effectively blocks malicious traffic from the specified source port for a defined duration.

Figure 18: Mitigating DDoS attacks using Python code in an OpenFlow switch

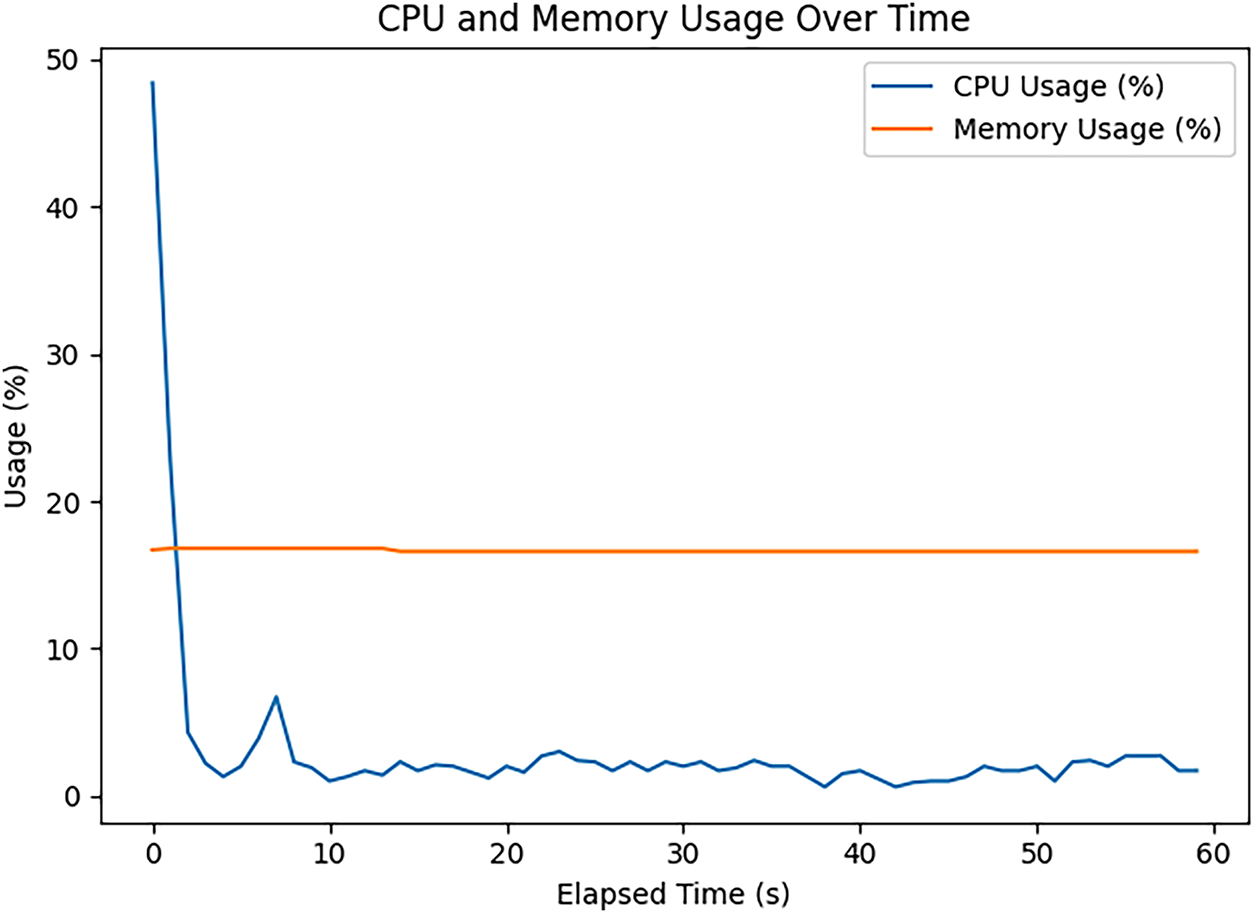

After mitigating the DDoS attacks, as shown in Fig. 19, the CPU average usage decreased from 45.62% to 3.16%, ensuring the availability of the IoT device for continuous data publishing without interruption or delay. Additionally, the memory consumption average dropped from 18.27% to 16.65%.

Figure 19: CPU usage after mitigating DDoS attacks

7 Discussion and Comparative Analysis

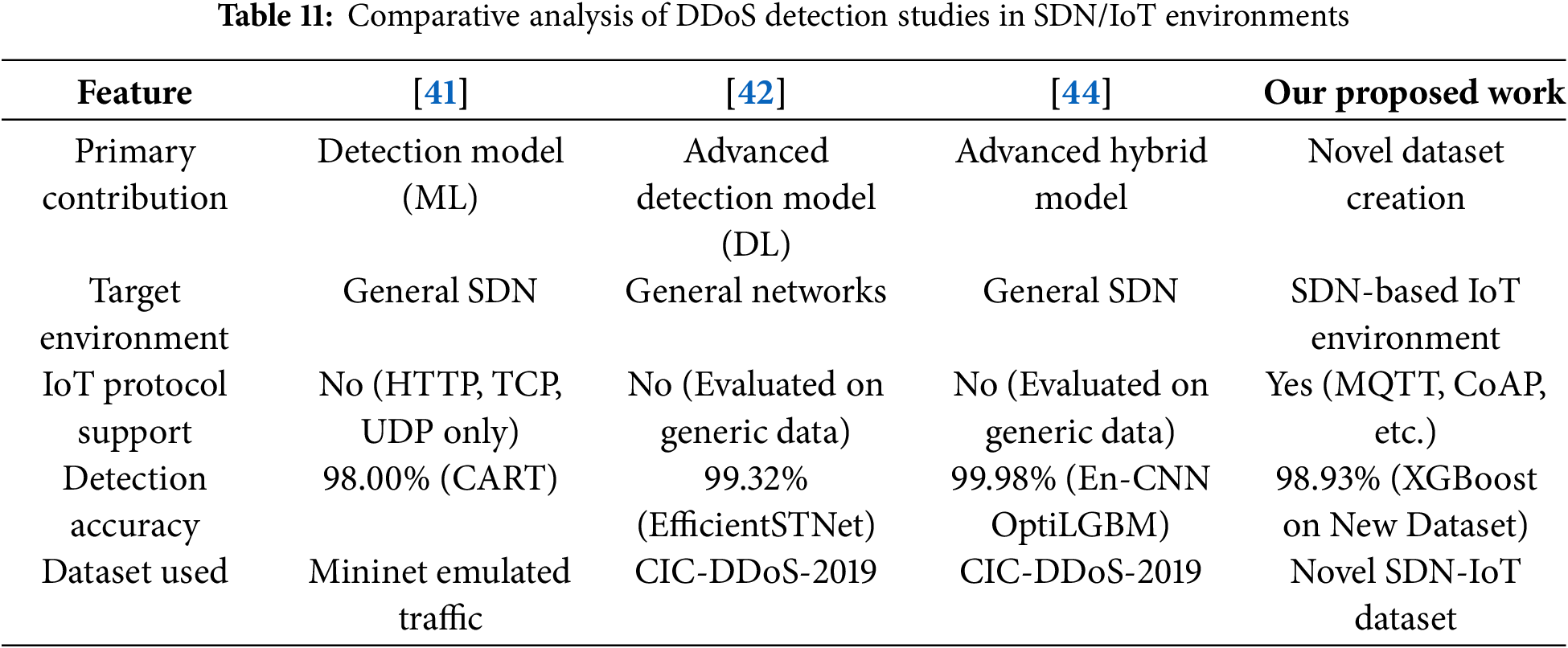

Our research is fundamentally driven by the need for domain-specific security resources to safeguard the complex, resource-constrained architecture of SDN and IoT. This section rigorously compares our contributions the novel SDN-IoT dataset and its XGBoost validation against the current state-of-the-art in DDoS detection.

The work by Sangodoyin et al. (2021) [41] served as a vital benchmark, establishing the feasibility of using classic ML models, such as the Classification and Regression Tree classifier, to achieve high accuracy (98%) for DDoS detection in a simulated SDN environment.

The Key Differentiation: This study presented a general SDN security model whose scope is limited to detecting attacks carried out through conventional network protocols (HTTP, TCP, and UDP). However, it fails to capture the distinctive, often low-rate, and protocol-specific traffic patterns of IoT-oriented protocols such as MQTT and CoAP, which represent the primary targets and attack vectors in integrated SDN-IoT environments. Our contribution addresses this fundamental protocol gap by providing a domain-specific and context-aware security resource. The work by Zhang et al. (2025) [42] proposed the EfficientSTNet model that showcases the remarkable power of advanced deep learning by combining a Convolutional Neural Network with a Self-Attention mechanism to achieve a high multi-class classification accuracy of 99.32%. However, its evaluation and subsequent high performance are rooted in the generic CIC-DDoS-2019 dataset.

The Key Differentiation:EfficientSTNet is a model built for general network security, not specific to the constraints of SDN-IoT. The CIC-DDoS-2019 dataset lacks the low-rate, protocol-specific flow statistics of MQTT and CoAP. Therefore, while EfficientSTNet demonstrates superior performance metrics, its real-world effectiveness in an SDN-IoT environment remains unproven without a domain-specific resource like our proposed dataset for rigorous validation. The work by Yang et al. (2025) [44] proposed the En-CNN and OptiLGBM framework that addresses the need for high-speed, real-time detection in SDN, achieving an exceptional accuracy of 99.98% with sub-second response times. This model, explicitly designed for SDN controllers, is arguably the most relevant competitor to our approach.

The Key Differentiation: Despite its highly optimized architecture and deployment focus, the En-CNN/OptiLGBM model also relies on the CIC-DDoS-2019 dataset for its core training and validation. This demonstrates a persistent research gap: the detection architecture is mature, but the underlying training data is insufficient for the target application (IoT). Our work provides the essential, high-quality, protocol-aware data infrastructure that is necessary to translate the proven performance of models like En-CNN/OptiLGBM from laboratory results on generic data to reliable security solutions in industrial SDN-IoT deployments.

Table 11 consolidates the comparative analysis, highlighting the unique features and contributions of each study, with emphasis on the domain-specific novelty of our proposed dataset.

The pervasive integration of IoT devices into SDN architectures necessitates adaptive and robust security mechanisms, a need that existing general-purpose datasets and detection models have largely failed to meet. This study addressed this critical security gap by delivering two key contributions: first, a novel, realistic, and publicly available SDN-IoT DDoS dataset featuring real-time flow-based labeling and comprehensive multi-vector attack simulation across core IoT protocols (TCP, UDP, HTTP, MQTT, and CoAP); second, a highly efficient DDoS detection framework based on the XGB classifier, optimized using PCA for low-overhead operation. The experimental results definitively validate the model’s efficacy. The XGB model achieved a remarkable 98.93% Accuracy, a FAR of 0.86%, and a rapid median Detection Time of 1.02 s. From an engineering perspective, this performance is highly significant, as it successfully meets critical Key Performance Indicators for real-world SDN-IoT systems. Specifically, the low detection latency ensures minimal Computational Delay in the control plane, which is essential for time-sensitive IoT applications, while the high accuracy and low FAR guarantee high network Throughput and reliable service availability during attack scenarios. Furthermore, our comparative analysis, statistically validated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, proved that the XGB-based framework is significantly superior to traditional classifiers, including RF, GBM, and kNN, across all performance metrics. In summary, this work provides a statistically validated, high-performing, and computationally lightweight defense mechanism, offering a crucial resource for real-time security mitigation in the growing landscape of SDN-managed IoT networks. While highly accurate models exist, they rely on generic datasets like CIC-DDoS-2019, lacking the IoT protocol specificity (MQTT, CoAP) essential for deployment. Our work uniquely provides the necessary domain-specific data infrastructure and a validated model, successfully addressing this key protocol gap that limits the real-world deployment of other state-of-the-art methods.

First, future work could focus on enhancing the computational efficiency of the proposed framework by integrating lightweight ML models or edge computing techniques, reducing the resource overhead while maintaining high detection accuracy. Additionally, the framework could be extended to support more complex and large-scale IoT environments, such as smart cities or industrial IoT, by testing it on larger and more diverse network topologies, including mesh and hybrid architectures.

Acknowledgement: Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R904), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R904), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Nader Karmous, Wadii Jlassi, Mohamed Ould-Elhassen Aoueileyine, Imen Filali and Ridha Bouallegue; methodology, Nader Karmous, Wadii Jlassi, Mohamed Ould-Elhassen Aoueileyine, Imen Filali and Ridha Bouallegue; software, Nader Karmous, Wadii Jlassi, Mohamed Ould-Elhassen Aoueileyine, Imen Filali and Ridha Bouallegue; validation, Nader Karmous, Wadii Jlassi, Mohamed Ould-Elhassen Aoueileyine, Imen Filali and Ridha Bouallegue; formal analysis, Nader Karmous, Wadii Jlassi, Mohamed Ould-Elhassen Aoueileyine, Imen Filali and Ridha Bouallegue; investigation, Nader Karmous, Wadii Jlassi, Mohamed Ould-Elhassen Aoueileyine, Imen Filali and Ridha Bouallegue; resources, Nader Karmous, Wadii Jlassi, Mohamed Ould-Elhassen Aoueileyine, Imen Filali and Ridha Bouallegue; data curation, Nader Karmous, Wadii Jlassi, Mohamed Ould-Elhassen Aoueileyine, Imen Filali and Ridha Bouallegue; writing—original draft preparation, Nader Karmous, Wadii Jlassi, Mohamed Ould-Elhassen Aoueileyine, Imen Filali and Ridha Bouallegue; writing—review and editing, Nader Karmous, Wadii Jlassi, Mohamed Ould-Elhassen Aoueileyine, Imen Filali and Ridha Bouallegue; visualization, Nader Karmous, Wadii Jlassi, Mohamed Ould-Elhassen Aoueileyine, Imen Filali and Ridha Bouallegue; supervision, Nader Karmous, Wadii Jlassi, Mohamed Ould-Elhassen Aoueileyine, Imen Filali and Ridha Bouallegue; project administration, Nader Karmous, Wadii Jlassi, Mohamed Ould-Elhassen Aoueileyine, Imen Filali and Ridha Bouallegue; funding acquisition, Imen Filali. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in [sdn-ddos-dataset] at [https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/nedernido/sdn-ddos-dataset] (accessed on 20 November 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations:

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACK | Acknowledgment |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CoAP | Constrained Application Protocol |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| DDOS | Distributed Denial of Service |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| FAR | False Alarm Rate |

| GBM | Gradient Boosting Machine |

| HTTP | Hypertext Transfer Protocol |

| ICMP | Internet Control Message Protocol |

| IDPS | Intrusion Detection and Prevention System |

| IDS | Intrusion Detection System |

| IOT | Internet of Things |

| KNN | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| MITM | Man-in-the-Middle |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SDN | Software-Defined Networking |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| SYN | Synchronize |

| TCP | Transmission Control Protocol |

| TPR | True Positive Rate |

| UDP | User Datagram Protocol |

| XGB | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

References

1. Sun P, Shen S, Wan Y, Wu Z, Fang Z, Gao XZ. A survey of IoT privacy security: architecture, technology, challenges, and trends. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(21):34567–91. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3372518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Sasi T, Lashkari AH, Lu R, Xiong P, Iqbal S. A comprehensive survey on IoT attacks: taxonomy, detection mechanisms and challenges. J Inf Intell. 2024;2(6):455–513. doi:10.1016/j.jiixd.2023.12.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Yan L, Ma M, Li D, Huang X, Ma Y, Xie K. Certrust: an SDN-based framework for the trust of certificates against crossfire attacks in IoT scenarios. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2023;134(3):2137–62. doi:10.32604/cmes.2022.022462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sharma R, Pandey N, Khatri SK. Analysis of IoT security at network layer. In: Proceedings of the 2017 6th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions) (ICRITO); 2017 Sep 20–22; Noida, India. p. 585–90. [Google Scholar]

5. Alsoufi MA, Siraj MM, Ghaleb FA, Al-Razgan M, Al-Asaly MS, Alfakih T, et al. Anomaly-based intrusion detection model using deep learning for IoT networks. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;141(1):823–45. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.052112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. AlAali AM, AlAteeq A, Elmedany W. Cybersecurity threats and solutions of IoT network layer. In: Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Innovation and Intelligence for Informatics, Computing, and Technologies (3ICT); 2022 Nov 20–21; Sakheer, Bahrain. p. 250–7. [Google Scholar]

7. Alam MZ, Reegu F, Dar AA, Bhat WA. Recent privacy and security issues in internet of things network layer: a systematic review. In: Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Data Communication Systems (ICSCDS); 2022 Apr 7–9; Erode, India. p. 1025–31. [Google Scholar]

8. Jahangeer A, Bazai SU, Aslam S, Marjan S, Anas M, Hashemi SH. A review on the security of IoT networks: from network layer’s perspective. IEEE Access. 2023;11(12):71073–87. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3246180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Aoueileyine MOE, Karmous N, Bouallegue R, Youssef N, Yazidi A. Detecting and mitigating MitM attack on IoT devices using SDN. In: Advanced Information Networking and Applications: Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications (AINA-2024). Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2024. p. 320–30. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-57942-4_31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Tamayo J, López LIB, Caraguay ÁLV. Detection of distributed denial of service attacks carried out by botnets in software-defined networks. arXiv:2401.09358. 2024. [Google Scholar]

11. Karmous N, Ben Dhiab Y, Ould-Elhassen Aoueileyine M, Youssef N, Bouallegue R, Yazidi A. Deep learning approaches for protecting IoT devices in smart homes from MitM attacks. Front Comput Sci. 2024;6:1477501. doi:10.3389/fcomp.2024.1477501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Bårli EM, Yazidi A, Viedma EH, Haugerud H. DoS and DDoS mitigation using variational autoencoders. Comput Netw. 2021;199(11):108399. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2021.108399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Jlassi W, Haddad R, Bouallegue R, Shubair R. A novel dynamic authentication method for sybil attack detection and prevention in wireless sensor networks. In: Advanced Information Networking and Applications: Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications (AINA-2021). Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 531–41. [Google Scholar]

14. Mishra SR, Shanmugam B, Yeo KC, Thennadil S. SDN-enabled IoT security frameworks—a review of existing challenges. Technologies. 2025;13(3):121. doi:10.3390/technologies13030121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Elsayed MS, Le-Khac N-A, Jurcut AD. InSDN: SDN intrusion detection dataset. Kaggle. [cited 2025 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/badcodebuilder/insdn-dataset. [Google Scholar]

16. Yungaicela-Naula NM, Vargas-Rosales C, Perez-Diaz JA, Jacob E, Martinez-Cagnazzo C. Physical Assessment of an SDN-based security framework for DDoS attack mitigation: introducing the SDN-SlowRate-DDoS dataset. IEEE Access. 2023;11:46820–31. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3274577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Bahashwan AA, Anbar M, Manickam S, Issa G, Aladaileh MA, Alabsi BA, et al. HLD-DDoSDN: high and low-rates dataset-based DDoS attacks against SDN. PLoS One. 2024;19(2):e0297548. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0297548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Srinivasu PN, Panigrahi R, Singh A, Bhoi AK. Probabilistic buckshot-driven cluster head identification and accumulative data encryption in WSN. J Circuit Syst Comput. 2022;31(17):2250303. doi:10.1142/s0218126622503030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Sakr HA, Fouda MM, Ashour AF, Abdelhafeez A, El-Afifi MI, Abdellah MR. Machine learning-based detection of DDoS attacks on IoT devices in multi-energy systems. IEEE Egypt Inform J. 2024;28(4):100540. doi:10.1016/j.eij.2024.100540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. El-Afifi MI, Sedhom BE, Padmanaban S, Eladl AA. A review of IoT-enabled smart energy hub systems: rising, applications, challenges, and future prospects. Renew Energy Focus. 2024;51(5):100634. doi:10.1016/j.ref.2024.100634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Talukder MA, Uddin MA. CIC-DDoS2019 dataset. Mendeley data, Version 1. [cited 2025 May 17]. Available from: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/ssnc74xm6r/1. [Google Scholar]

22. Tavallaee M, Bagheri E, Lu W, Ghorbani AA. A detailed analysis of the KDD CUP 99 data set. In: Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence for Security and Defense Applications; 2009 Jul 8–10; Ottawa, ON, Canada. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/CISDA.2009.5356528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Manoharan A, Begam KM, Aparow VR, Sooriamoorthy D. Artificial neural networks, gradient boosting and support vector machines for electric vehicle battery state estimation: a review. J Energy Storage. 2022;55(1):105384. doi:10.1016/j.est.2022.105384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Abdullah DM, Abdulazeez AM. Machine learning applications based on SVM classification a review. Qubahan Acad J. 2021;1(2):81–90. doi:10.48161/qaj.v1n2a50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Antoniadis A, Lambert-Lacroix S, Poggi JM. Random forests for global sensitivity analysis: a selective review. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2021;206(5):107312. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2020.107312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Priyanka NA, Kumar D. Decision tree classifier: a detailed survey. Int J Inf Decis Sci. 2020;12(3):246–69. doi:10.1504/ijids.2020.108141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Janivasya RP, Rachmawati IDA. DDoS detection using machine learning approach. Procedia Comput Sci. 2024;245:1157–64. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2024.10.345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Moustafa N, Slay J. UNSW-NB15: a comprehensive data set for network intrusion detection systems (UNSW-NB15 network data set). In: Proceedings of the Military Communications and Information Systems Conference (MilCIS); 2015 Nov 10–12; Canberra, ACT, Australia. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

29. Akram Z, Majid M, Habib S. A systematic literature review: usage of logistic regression for malware detection. In: 2021 International Conference on Innovative Computing (ICIC); 2021 Nov 9–10. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/icic53490.2021.9693035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Peng H, Xu Z, Mo W, Wang Y, Huang Q. Survey on kNN. In: CAIBDA 2022; 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Big Data and Algorithms; 2022 Jun 17–19; Nanjing, China. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

31. Lindemann B, Maschler B, Sahlab N, Weyrich M. A survey on anomaly detection for technical systems using LSTM networks. Comput Ind. 2021;131(3):103498. doi:10.1016/j.compind.2021.103498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Naskath J, Sivakamasundari G, Begum AAS. A study on different deep learning algorithms used in deep neural nets: MLP SOM and DBN. Wirel Pers Commun. 2023;128(4):2913–36. doi:10.1007/s11277-022-10079-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Shiri FM, Perumal T, Mustapha N, Mohamed R. A comprehensive overview and comparative analysis on deep learning models: CNN, RNN, LSTM, GRU. arXiv:2305.17473. 2023. [Google Scholar]

34. Hnamte V, Najar AA, Nhung-Nguyen H, Hussain J, Sugali MN. DDoS attack detection and mitigation using deep neural network in SDN environment. Comput Secur. 2024;138(21):103661. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2023.103661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Borisov V, Leemann T, Seßler K, Haug J, Pawelczyk M, Kasneci G. Deep neural networks and tabular data: a survey. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2022;35(6):7499–519. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2022.3229161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Elsayed MS, Le-Khac N-A, Jurcut AD. InSDN: a novel SDN intrusion dataset. IEEE Access. 2020;8:165263–84. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3022633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Sharafaldin I, Lashkari AH, Ghorbani AA. Toward generating a new intrusion detection dataset and intrusion traffic characterization. In: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2018); 2018 Jan 22–24; Madeira, Portugal. p. 108–16. [Google Scholar]

38. Krishnapriya S, Singh S. A hybrid machine learning and blockchain framework for IoT DDoS mitigation. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;144(2):1849–81. doi:10.32604/cmes.2025.068326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. U.N.S.W. Research. BOT IoT dataset. Sydney, Australia: University of New South Wales. [cited 2025 Nov 19]. Available from: https://research.unsw.edu.au/projects/bot-iot-dataset. [Google Scholar]

40. Stratosphere Research Laboratory. IoT23 dataset. Stratosphere IPS. [cited 2025 Nov 19]. Available from: https://www.stratosphereips.org/datasets-iot23. [Google Scholar]

41. Sangodoyin AO, Akinsolu MO, Pillai P, Grout V. Detection and classification of DDoS flooding attacks on software-defined networks: a case study for the application of machine learning. IEEE Access. 2021;9:122495–508. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3109490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zhang L, Bai Y, Xue T, Feng G, Zhang H. EfficientSTNet: a deep learning approach for multi-class DDoS detection. IEEE Access. 2025;13(12):157587–99. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3606644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Sharafaldin I, Lashkari AH, Hakak S, Ghorbani AA. Developing realistic distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack dataset and taxonomy. In: Proceedings of the IEEE 53rd International Carnahan Conference on Security Technology (ICCST); 2019 Oct 1–3; Chennai, India. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

44. Yang G, Wang X, Li C, Li X, Zhang J, Cui F, et al. Real-time DDoS attack detection in SDN based on en-CNN and OptiLGBM. IEEE Access. 2025;13(2):161453–71. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3608205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Liaw LCM, Tan SC, Goh PY, Lim CP. A histogram SMOTE-based sampling algorithm with incremental learning for imbalanced data classification. Inf Sci. 2025;686(9):121193. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.121193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Abdaljabar ZH, Ucan ON, Alheeti KMA. An intrusion detection system for IoT using KNN and decision-tree based classification. In: Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference of Modern Trends in Information and Communication Technology Industry (MTICTI); 2021 Dec 4–6; Sana’a, Yemen. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

47. Zhao G, Wang Y, Wang J. Intrusion detection model of Internet of Things based on LightGBM. IEICE Trans Commun. 2023;E106.B(8):622–34. doi:10.1587/transcom.2022ebp3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Faysal JA, Mostafa ST, Tamanna JS, Mumenin KM, Arifin MM, Awal MA, et al. XGB-RF: a hybrid machine learning approach for IoT intrusion detection. Telecom. 2022;3(1):52–69. doi:10.3390/telecom3010003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools