Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

GLM-EP: An Equivariant Graph Neural Network and Protein Language Model Integrated Framework for Predicting Essential Proteins in Bacteriophages

1 College of Information Science and Technology, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, Beijing, 100029, China

2 School of Computer Science and Technology, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, 150001, China

* Corresponding Author: Jing Wan. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 4089-4106. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.074364

Received 09 October 2025; Accepted 19 November 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

Recognizing essential proteins within bacteriophages is fundamental to uncovering their replication and survival mechanisms and contributes to advances in phage-based antibacterial therapies. Despite notable progress, existing computational techniques struggle to represent the interplay between sequence-derived and structure-dependent protein features. To overcome this limitation, we introduce GLM-EP, a unified framework that fuses protein language models with equivariant graph neural networks. By merging semantic embeddings extracted from amino acid sequences with geometry-aware graph representations, GLM-EP enables an in-depth depiction of phage proteins and enhances essential protein identification. Evaluation on diverse benchmark datasets confirms that GLM-EP surpasses conventional sequence-based and independent deep-learning methods, yielding higher F1 and AUROC outcomes. Component-wise analysis demonstrates that GCNII, EGNN, and the gated multi-head attention mechanism function in a complementary manner to encode complex molecular attributes. In summary, GLM-EP serves as a robust and efficient tool for bacteriophage genomic analysis and provides valuable methodological perspectives for the discovery of antibiotic-resistance therapeutic targets. The corresponding code repository is available at: https://github.com/MiJia-ID/GLM-EP (accessed on 01 November 2025).Keywords

Bacteriophages, viruses that specifically infect bacteria, have garnered renewed attention in recent years due to their potential in combating multidrug-resistant bacteria and advancing synthetic biology. A critical step toward the therapeutic and engineering applications of phages is the accurate identification of essential proteins. Essential proteins refer to those indispensable for the survival and replication of an organism or virus. For instance, in bacteriophages, capsid proteins and tail fiber proteins are typically considered essential because they are required for viral assembly and host infection. Understanding and identifying such essential proteins are crucial for elucidating viral life cycles and developing phage-based therapeutic strategies. Traditional experimental methods such as amber mutagenesis, gene knockout, and CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) [1,2] screening can be used to identify essential proteins but are limited by their complexity, duration, and small sample sizes [3,4]. To date, only a few model phages have been systematically annotated through such approaches.

In response to these challenges, researchers have increasingly turned to computational methods, particularly deep learning-based frameworks for predicting essential proteins. For example, models such as JDC [5] and DeepCellEss [6] employ multilayer perceptrons or convolutional neural networks trained on handcrafted features, including physicochemical properties and position-specific scoring matrices, or on features extracted from curated gene essentiality databases [7]. More recently, the Bingo model [8] introduced the use of sequence embeddings generated by protein language models such as ESM-2. These embeddings capture contextual information within the protein sequence and have been shown to improve predictive accuracy. This development reflects a broader shift from rule-based toward data-driven approaches in functional prediction [9] and illustrates the application potential of pretrained models in protein bioinformatics.

Although the prediction of protein essentiality is often formulated as a binary classification task, the underlying modeling process occurs at the level of protein representation. Recent studies have demonstrated that protein language models such as ESM [10], ProtBert and ProtTrans [11], and related approaches like UniRep [12] and TAPE [13] are capable of learning rich semantic features from sequences alone. These features include structural, evolutionary, and functional signals [14]. At the same time, progress in protein structure prediction has made it possible to obtain high-quality three-dimensional structures at large scale. Representative tools in this domain include AlphaFold [15] and RoseTTAFold [16], as well as earlier comparative modeling frameworks such as I-TASSER [17]. In parallel, graph neural networks have become powerful tools for modeling proteins as residue-level graphs. For example, models such as GraphQA [18] and MaSIF [19] have shown effectiveness in functional annotation and binding site identification, while early work such as ProteinGNN [20] introduced the application of graph neural networks to protein structural learning. More recent approaches, such as equivariant graph models represented by EGNN [21], SE3-Transformer [22], and related methods in geometric deep learning [23], are capable of preserving rotational and translational symmetry in three-dimensional space, allowing for more accurate modeling of global geometric features. These advances highlight the importance of integrating global sequence semantics with spatial structural modeling [24] and have informed the design of the predictive model proposed in the present study.

Despite recent progress, existing essential protein prediction methods suffer from key limitations in both data and modeling dimensions. At the data level, most current datasets are constructed for eukaryotic or bacterial systems, with limited coverage of phage proteins. These datasets are often non-standardized, sparsely labeled, or unavailable to the public. For instance, models such as JDC [5] and DeepCellEss [6] rely on private or heterogeneous sources, with unclear annotation criteria and inconsistent definitions of essentiality. Moreover, viral protein datasets are rarely well-defined, and negative sample construction often lacks biological justification [25], undermining the reproducibility and generalizability of these models. At the modeling level, existing approaches typically depend on single-modality inputs, such as handcrafted sequence features or embeddings from protein language models. However, they neglect the intrinsic structural complexity of proteins, including local residue interactions and global 3D topology [21]. As a result, these models struggle to capture the multi-scale biological context that underlies essentiality, especially in phage genomes where compact coding and spatial organization are functionally critical.

To address these limitations, we present a deep learning framework named GLM-EP, which integrates pretrained protein language model embeddings with an equivariant graph neural network for the accurate prediction of essential proteins in bacteriophages. At the data level, we systematically curated experimental literature indexed in PubMed between 1960 and 2023. Based on this collection, we constructed a high-quality dataset covering eleven representative phages. We then validated the dataset using independent genetic evidence and CRISPR-based knockout experiments. In addition, we incorporated results from three large-scale CRISPR screening studies to build a rigorously filtered dataset of human essential proteins [26], which was used to evaluate the cross-species generalization performance of the model. At the modeling level, the GLM-EP framework adopts a dual-branch architecture. The first branch extracts semantic representations using ProtTrans and ESM-2 language models. The second branch constructs residue-level protein graphs from predicted structures and encodes them using GCNII [27] and EGNN modules to capture local neighborhood and global topological features, respectively. A gated multi-head attention mechanism is then used to integrate the features from both branches. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed model significantly outperforms baseline methods, including multilayer perceptrons, convolutional networks, residual networks, and the Bingo model. Ablation studies further confirm the complementary advantages of handcrafted features and deep sequence representations, as well as the synergistic benefits of combining GCNII and EGNN for protein structure modeling.

To address the scarcity of essential protein data in bacteriophages, we developed a systematic dataset using a literature-mining strategy. The PubMed core literature database was used as the primary source. Professional search queries such as “bacteriophage essential protein”, “viral core gene”, and “phage genome essentiality” were constructed to comprehensively collect experimental studies published between 1960 and 2024. Based on the availability of experimental evidence on essentiality, eleven model bacteriophages were selected and processed through a multi-dimensional data integration framework as follows:

• Classical Model Phages (T4, T7, P2): These phages have been extensively studied for over sixty years. Their genome-wide essentiality has been systematically validated through classical genetic methods, including amber mutations and temperature-sensitive deletions. Essentiality annotation for these genomes is considered complete [28–31].

• Dual-Validated Phages (Lambda, P1): For these two phages, we adopted a dual-validation strategy. First, we reviewed the literature-mining results of Piya and colleagues published in 2024. Second, we cross-referenced these findings with results from CRISPR-Cas9 whole-genome knockout screens. For the Lambda phage, 64 out of 68 proteins (94.1 percent) had consistent essentiality annotations, while for the P1 phage, 101 out of 104 proteins (97.1 percent) showed agreement. Only a few accessory proteins showed inconsistent labeling. Proteins without disagreement were retained for dataset construction based on the principle of annotation conservatism [31–33].

• Partially Annotated Phages (SPO1, Mu, N15, T1, P22, Phi29): For these phages with incomplete functional studies, we adopted a strict data inclusion criterion and selected only proteins with experimentally verified essentiality [34–38].

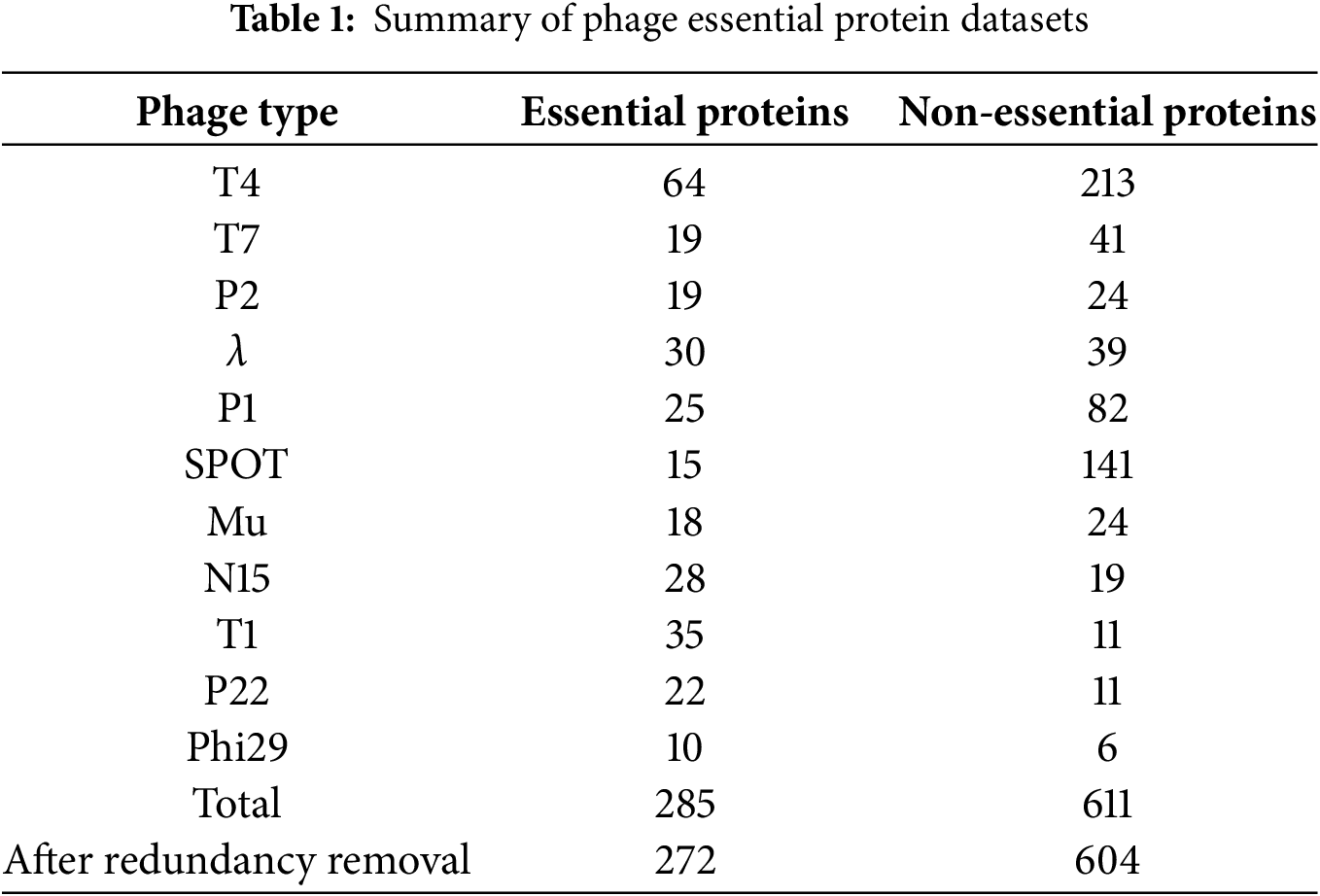

Following this methodology, we constructed a bacteriophage essential protein dataset comprising eleven tailed phages (Table 1). The dataset includes 285 experimentally validated essential proteins and 611 non-essential proteins. To enhance reproducibility, we have supplemented this section with additional details regarding dataset construction and quality control. Essential proteins were identified from experimentally validated studies, including amber mutation, temperature-sensitive deletion, and CRISPR-Cas9 knockout experiments, while non-essential proteins were extracted from corresponding genome annotations of the same phages. To ensure data quality, redundant sequences were filtered using CD-HIT with a sequence identity threshold of 0.8, and ambiguous annotations were resolved through cross-reference verification among multiple literature sources. After redundancy removal, the final dataset contained 272 essential proteins and 604 non-essential proteins. These additions make the dataset construction process transparent, standardized, and fully reproducible.

To evaluate the biological generalizability of the model, we collected human essential protein data from the Database of Essential Genes. The phage essential protein dataset serves as the main dataset for model training and evaluation, while the human essential protein dataset is used as an independent validation set to examine the model’s cross-species generalization capability. We integrated data from three independent studies [39,40] that employed CRISPR-Cas9 and gene-trap technologies. Strict filtering criteria were applied, retaining only proteins consistently identified as essential across all three studies and excluding conditionally essential proteins. Non-essential proteins were obtained from the study by Guo [41] and colleagues and supplemented with complete sequence information from the UniProt database. Ambiguous proteins appearing in both essential and non-essential lists were removed. CD-HIT was again applied with a sequence identity threshold of 0.8. The final human essential protein dataset contains 1574 essential proteins and 9846 non-essential proteins. The full dataset used in this study is publicly available at our GitHub repository: https://github.com/MiJia-ID/GLM-EP/tree/main/data/pdb_dir (accessed on 01 November 2025).

2.2 Network Architecture Design

The prediction of essential proteins in phages is essentially a functional classification task. Since protein function is largely determined by three-dimensional conformation and most phage proteins lack experimentally resolved structural data, we relied on predicted structures to support functional modeling. Each protein sequence was transformed into a residue-level graph representation. This representation retains sequence semantics while capturing spatial topology, providing a more biologically meaningful basis than sequence-only approaches.

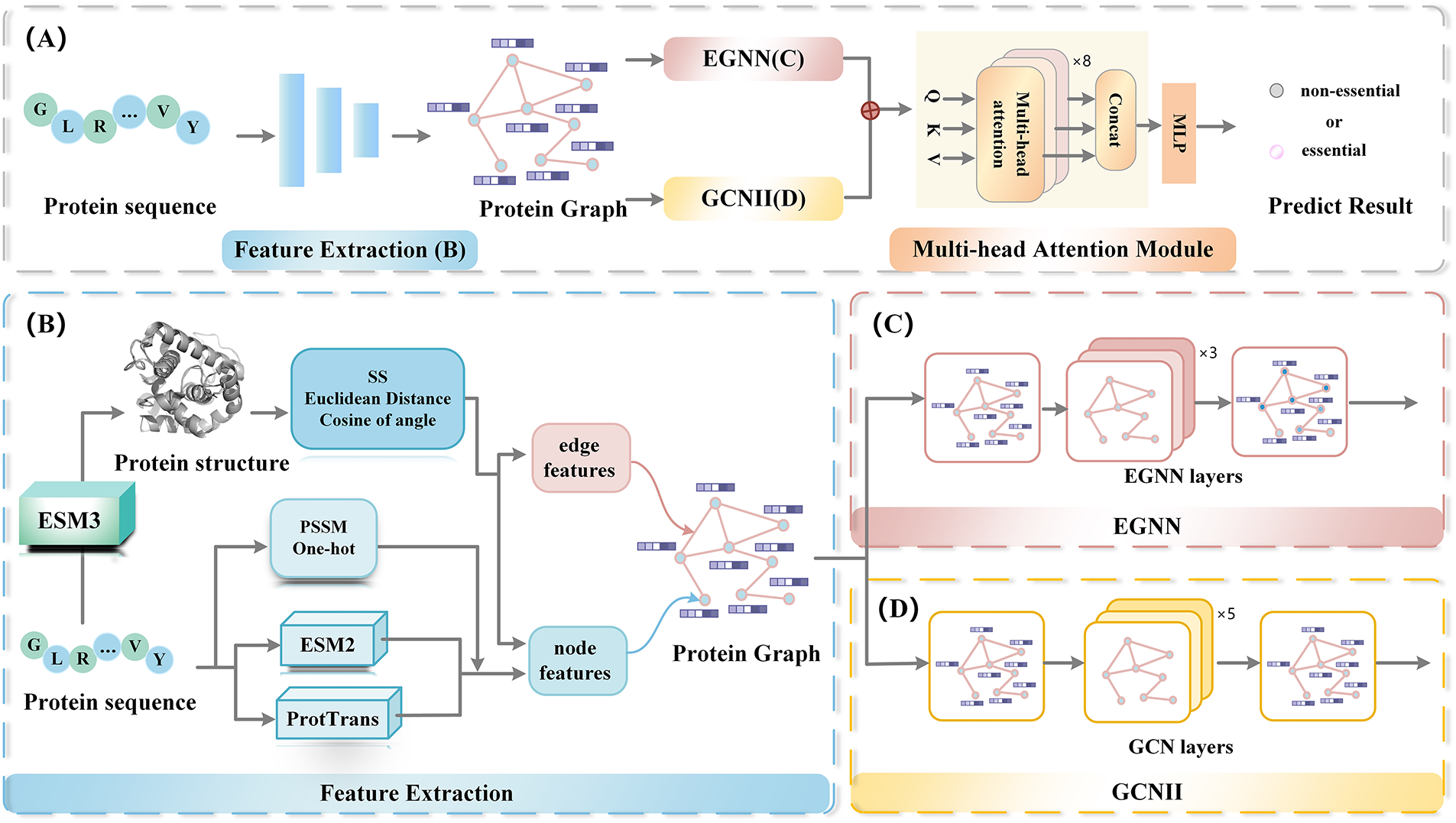

In the overall design of the framework, as illustrated in Fig. 1, each protein sequence is transformed into a residue-level graph representation. In this graph, amino acids are represented as nodes, with node features composed of both handcrafted descriptors and embeddings derived from protein language models. Edges are constructed according to predicted structural coordinates, where two residues are connected in the adjacency matrix if the Euclidean distance between their C-alpha atoms is less than 17 angstroms. The resulting node and edge features are then processed by two complementary modules. The GCNII module aggregates local neighborhood information, while the EGNN module captures the global spatial topology of the protein structure. Finally, these two types of embeddings are fused through a gated multi-head attention mechanism, yielding an integrated representation suitable for downstream classification.

Figure 1: The overall architecture of GLM-EP

Each protein sequence is represented as a graph, defined as

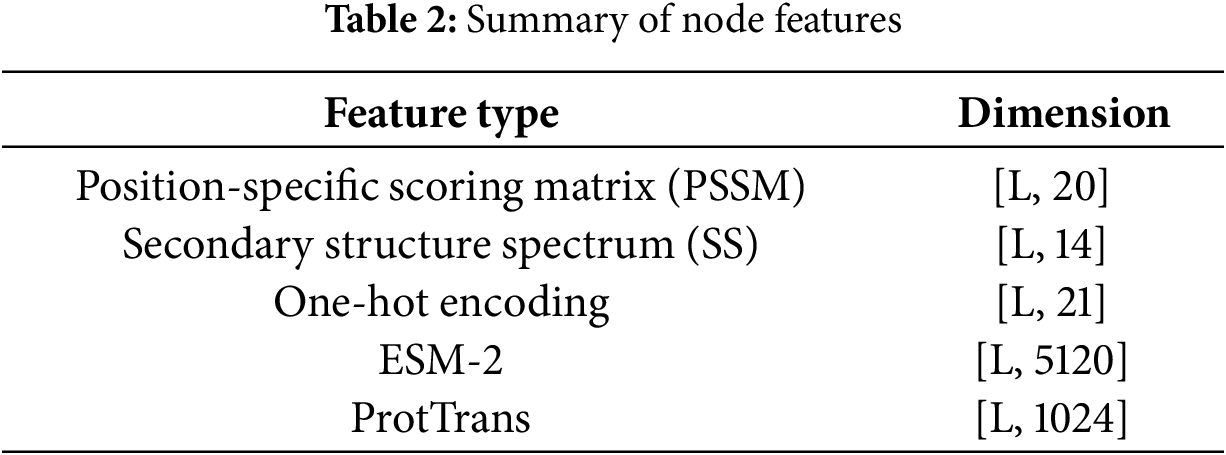

2.4 Node Feature Representation

Node features consist of two components: handcrafted features and protein language model features. The handcrafted features include the position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM) [43], secondary structure profiles (SS) [44], and one-hot encoding [42]. The protein language model features are derived from ESM-2 and ProtTrans (as shown in Table 2).

The PSSM is generated using PSI-BLAST version 2.10.1, reflecting the amino acid preferences at each position, with a feature dimension of 20 per site. SS are calculated using DSSP version 2.1.0, describing the secondary structure class of each residue (such as alpha helix, beta sheet, or coil), with a dimensionality of 14. The one-hot encoding represents amino acid types, with a total of 21 dimensions, covering 20 standard amino acids and one unknown residue.

In the deep representation part, two protein language models are used: ESM-2 (15B version, with 5120 dimensions per residue) and ProtTrans (with 1024 dimensions per residue), both employed to capture high-dimensional semantic information from sequences. To further clarify how the ESM-2 and ProtTrans embeddings represent protein sequences, we provide a mathematical formulation of the encoding process. Let a protein sequence be defined as:

where

(1) ESM-2 Embedding. The pretrained ESM-2 model maps each residue

The resulting embedding matrix for the entire protein can be represented as

Each embedding vector

(2) ProtTrans Embedding. Similarly, the pretrained ProtTrans encoder generates a 1024-dimensional embedding vector for each residue based on a transformer-based architecture:

The embedding matrix for the entire protein sequence is

ProtTrans embeddings emphasize evolutionary and contextual dependencies within sequences, providing complementary information to the ESM-2 representations.

(3) Feature Fusion. Finally, both embeddings are concatenated along the feature dimension to form the unified residue-level representation:

where X and Y denote the ESM-2 and ProtTrans embedding matrices, respectively, and “

2.5 Edge Feature Representation

Edge features mainly consist of two components: the Euclidean distance between nodes and the cosine value of the angle between nodes.

To compute the Euclidean distance between amino acid nodes in the predicted 3D protein structure, the C

Here,

The cosine value of an angle is commonly used to describe the angle formed by three atoms, which frequently appears in analyses of protein 3D structures, including backbone or side-chain angles. Specifically, given three atoms A, B, and C with coordinates

Graph convolutional networks and their variants, particularly GCNII [46], have achieved remarkable success in recent graph node classification tasks. GCNII is an improved model based on GCN, designed to address the training difficulties of deep graph neural networks. Its core innovation lies in the introduction of two mechanisms: initial residual connections and identity mapping, which enhance information preservation and representation capabilities in deep networks. The node

Here,

GCNII introduces two improvements: (1)Initial residual connection: the residual connection directly combines with the initial input

EGNN [21] extends standard graph neural networks by integrating spatial coordinate features, allowing it to maintain equivariance under geometric transformations such as translation, rotation, and reflection in three-dimensional molecular structures. This property facilitates richer structural representation learning from protein data. Moreover, EGNN differs from conventional GNNs in its ability to process both equivariant and invariant representations.

EGNN is constructed by stacking multiple Equivariant Graph Convolution Layers (EGCL). EGCL updates the coordinate features

The relative distance between nodes

The node feature

First, the node gathers aggregation information

In GLM-EP, the EGNN module consists of 3 layers, with hidden dimensionality of 512.

2.8 Gate-Controlled Multi-Head Attention Module

To focus on the extraction of key features, we introduce an attention mechanism to integrate the graph embedding representations generated by the GCNII and EGNN modules. First, the graph embeddings from different perspectives are concatenated, and the fused feature matrix

where

In this work,

To maintain consistency, we have standardized all notations related to the attention mechanism throughout the manuscript. Specifically,

To further regulate global information flow, we incorporate a gating control mechanism inspired by the concept of LSTM, that mathematically formulated as:

where

Considering the complex spatial configuration of protein structures, a single gate-controlled attention head may not adequately capture the full set of local or global features. Therefore, we perform concatenation over

In our GLM-EP framework, the tensor dimension of the output from the gate-controlled multi-head attention block is

3 Experimental Results and Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed model GLM-EP, we introduce a variety of baseline methods for comparison, covering three typical neural network architectures and three traditional essential protein prediction algorithms, ensuring the broad applicability and comparability of the results.

First, we select commonly used general neural network architectures in deep learning as reference models, including MLP, one-dimensional convolutional neural network (CONV1D), and residual network (RESNET) [47,48]. At the input level, each protein sequence is encoded as a one-dimensional numerical array representing amino acid indices (ranging from 0 to 21) and zero-padded to a fixed length of 1200. The MLP consists of a feedforward neural network with two hidden layers, whose hidden dimensions are 640 and 64, respectively. ReLU is used as the activation function [49], with Sigmoid applied at the output layer and Dropout (rate = 0.5) used for regularization. CONV1D adopts two convolutional layers, with the first layer’s kernel size set to 1

In addition, to verify the advancement of GLM-EP in essential protein prediction tasks, we also compare it with three mainstream traditional machine learning methods: EP-GBDT is a gradient boosting decision tree algorithm based on handcrafted features [50]; DeepCellEss uses deep learning to automatically extract features from manually constructed biological characteristics for classification [6]. To ensure fairness and reproducibility, all baseline models were implemented and tested using the same experimental settings as the proposed method, and the training set was enhanced using adversarial sample generation [51].

All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with four NVIDIA A6000 GPUs (48 GB memory each). We used Python as the programming language, and major dependencies include PyTorch, NumPy, and Scikit-learn. Although GLM-EP integrates multiple modules—GCNII, EGNN, and gated multi-head attention—the overall computational cost remains reasonable. On the NVIDIA A6000 platform, the training time per epoch is approximately 1.1

The complete list of Python packages and their versions can be found in our GitHub repository: https://github.com/MiJia-ID/GLM-EP (accessed on 01 November 2025).

Since the essential protein prediction task for phages is an instance of a binary classification problem, this paper employs several widely used evaluation indicators to comprehensively evaluate model performance, including accuracy, precision, recall (or sensitivity), specificity, F1-score, G-mean, and AUROC. The specific definitions of these metrics are provided below.

Here, TP, FP, TN, and FN are employed to denote the counts of true and false positives and negatives, respectively. The F1-score, which serves as a balance between precision and recall, is expressed as their harmonic mean. G-mean balances classification performance between positive and negative samples. AUROC reflects the overall discriminative ability of the model across different thresholds. Given that high precision for identifying essential proteins is particularly important, this study emphasizes F1-score, AUROC, and G-mean to ensure the reliability and robustness of the model predictions.

3.4 Performance Comparison Experiment

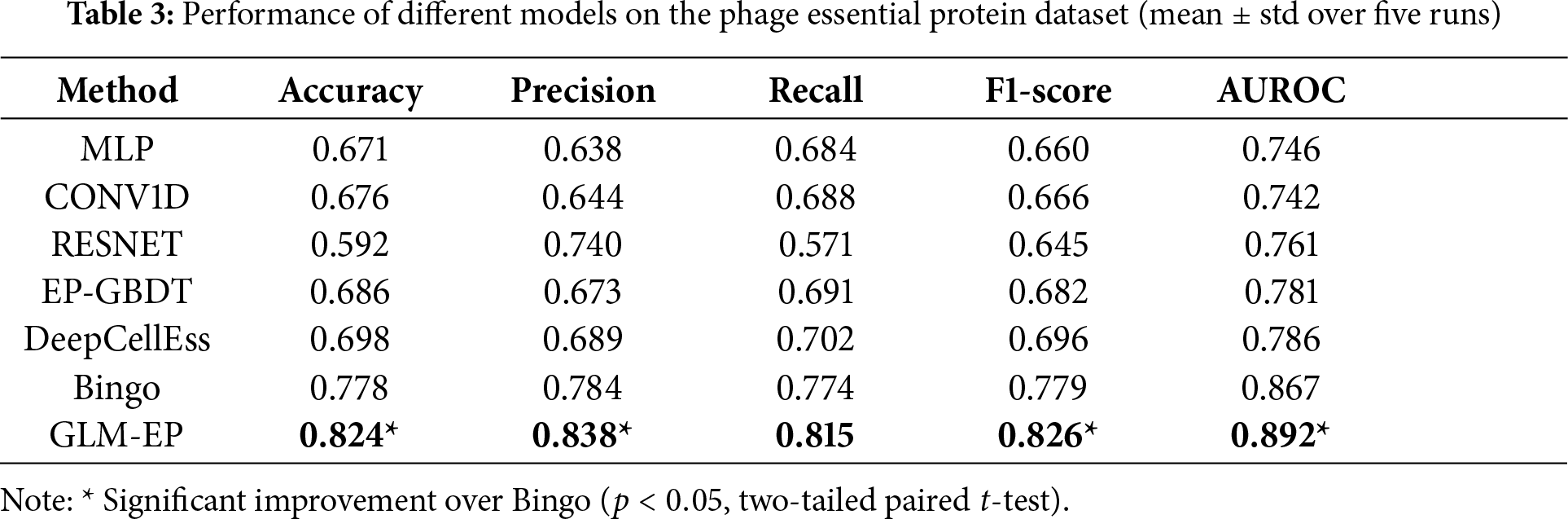

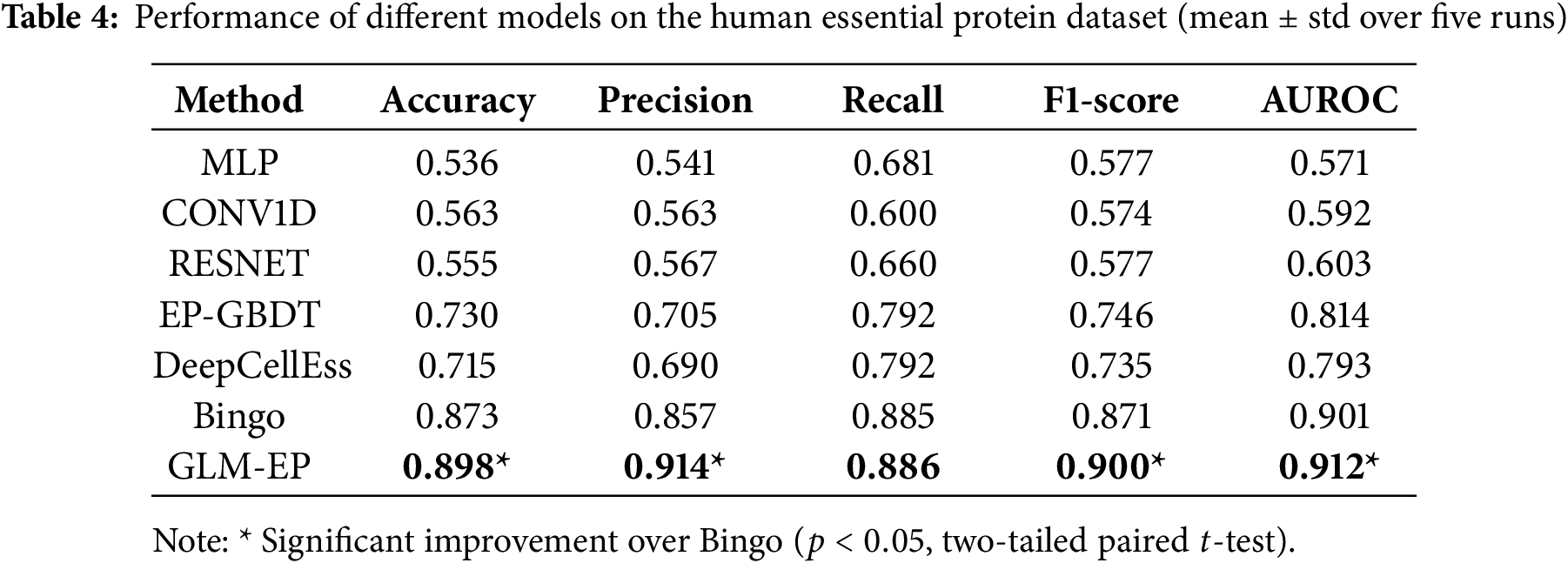

This section verifies through ablation experiments that GLM-EP exhibits superior performance in the task of predicting essential proteins, while also demonstrating the influence regularity of different model components on prediction performance. The experimental design adopts a dual-dataset validation framework, and experiments are conducted on both human essential protein datasets and phage essential protein datasets. The experimental results (Tables 3 and 4) show that compared with baseline models, GLM-EP achieves better performance on all five evaluation metrics. Specifically, on the human essential protein dataset, compared with Bingo, GLM-EP improves accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and AUROC by 2.5%, 5.7%, 0.1%, 2.9%, and 1.1%, respectively; on the phage essential protein dataset, GLM-EP improves these five metrics by 4.6%, 5.4%, 4.1%, 4.7%, and 2.5%, respectively. This demonstrates the good generalizability of GLM-EP.

As shown in Table 3, GLM-EP achieves competitive or superior performance compared with existing baseline models. Among them, Bingo performs relatively well due to its graph-based architecture, which can capture local connectivity patterns between residues. Both Bingo and GLM-EP, which integrate protein language representations and graph neural networks, exhibit strong predictive capabilities, reflecting the effectiveness of combining semantic and structural features. However, GLM-EP consistently outperforms Bingo across all evaluation metrics. Moreover, we conducted a two-tailed paired

In-depth analysis reveals three main factors contributing to this performance gap: (1) Feature representation: Bingo uses only ESM-2 (3B) protein embeddings, whereas GLM-EP integrates ESM-2 and ProtTrans dual-encoder features along with handcrafted evolutionary features, yielding richer input representations. (2) Graph module: Bingo employs CNN-based feature graphs, while GLM-EP adopts a GCNII—EGNN hybrid architecture, enhancing the expressiveness of local structural information. (3) Feature fusion: GLM-EP designs a gated multi-head attention fusion module that dynamically assigns weights to sequence and structure inputs, achieving more adaptive and informative integration than Bingo’s simple concatenation strategy.

Although the two models perform comparably in some metrics, they are fundamentally different in modeling paradigms. Bingo is a topology-driven GNN focusing on residue connectivity, whereas GLM-EP incorporates an equivariant geometric mechanism through EGNN, which preserves geometric consistency and captures fine-grained spatial dependencies. This enables GLM-EP to utilize 3D structural information more effectively, resulting in more stable and accurate predictions even under similar feature conditions.

To further evaluate the cross-species generalization ability of GLM-EP, we applied it to an independent human essential protein dataset, as shown in Table 4. Although the model was not specifically fine-tuned on human data, it showed consistent predictive performance, indicating that the learned embeddings and graph representations capture common biological principles of essential proteins across different species. Furthermore, GLM-EP achieved statistically significant improvements over the strongest baseline Bingo (

3.5 Feature Ablation Experiment

To verify the influence of different types of protein representations on the performance of essential protein prediction, we designed a feature ablation experiment aimed at comparing the contributions of traditional biological information features, protein language model features, and their fused features within the model. Specifically, the three feature combination schemes are as follows: (1) handcrafted features based on position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM), One-hot encoding, and secondary structure spectra; (2) protein language model (PLM) features embedded from ESM-2 and ProtTrans; and (3) fusion features that combine the above two types of features.

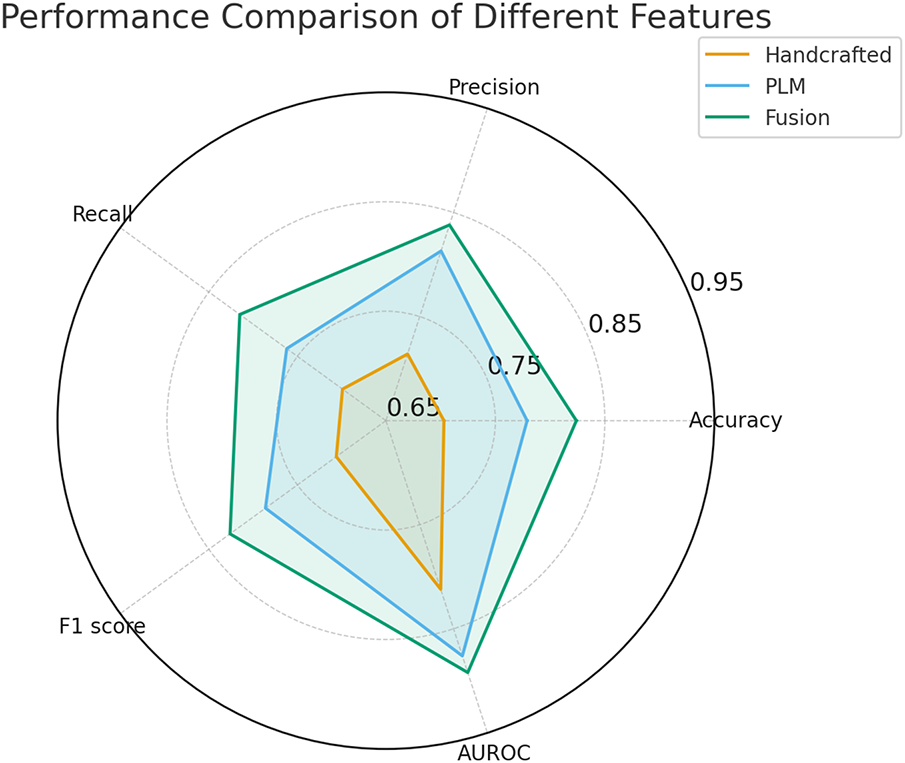

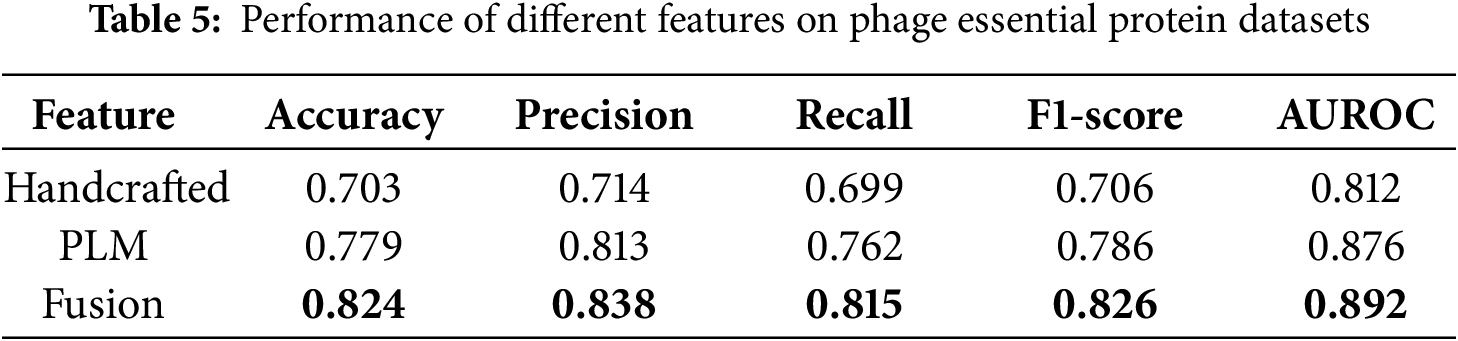

Fig. 2 and Table 5 present the performance of the three feature types on the phage protein dataset. The results indicate that fusion features achieve the best performance across all five evaluation metrics, including Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1 score, and AUROC, demonstrating comprehensive superiority.

Figure 2: Performance comparison of different features

Compared with using handcrafted features alone, the fusion features improved the F1 score by 12% and the AUROC by approximately 8%. Compared with using protein language model features alone, the fusion features led to a 4% increase in F1 score and a 1.6% increase in AUROC.

These findings highlight the effectiveness and stability of the feature fusion strategy. From the perspective of representation mechanism analysis, protein language model features are trained on large-scale protein sequences and possess strong cross-species and cross-task transferability, capable of capturing both structural information and higher-level functional attributes. In contrast, handcrafted features incorporate prior biological knowledge, such as PSSM and secondary structure elements, which complement the protein language model in encoding physicochemical properties that are otherwise difficult to capture. These two types of features are complementary in their representation dimensions, and their fusion significantly enhances the model’s discriminative capability and generalization ability.

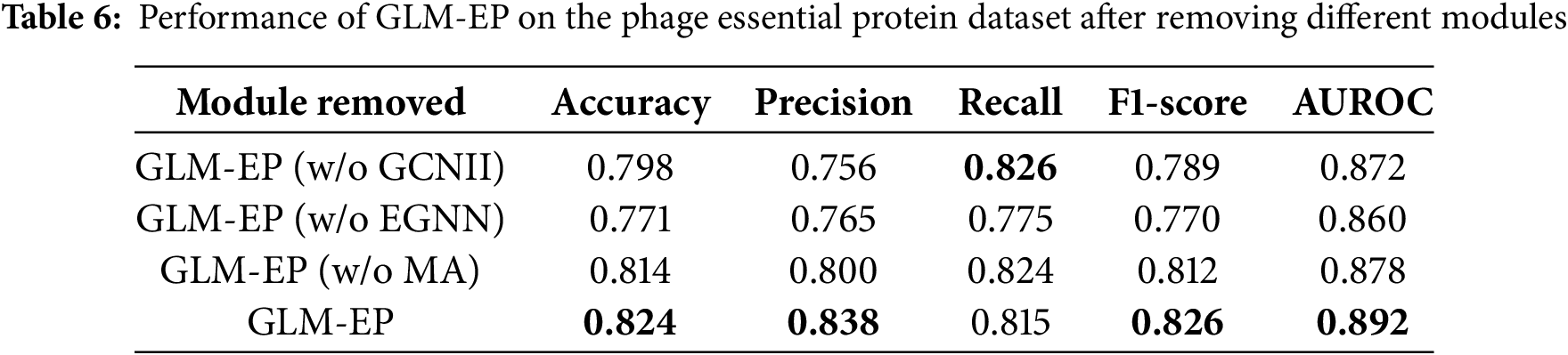

3.6 Module Ablation Experiment

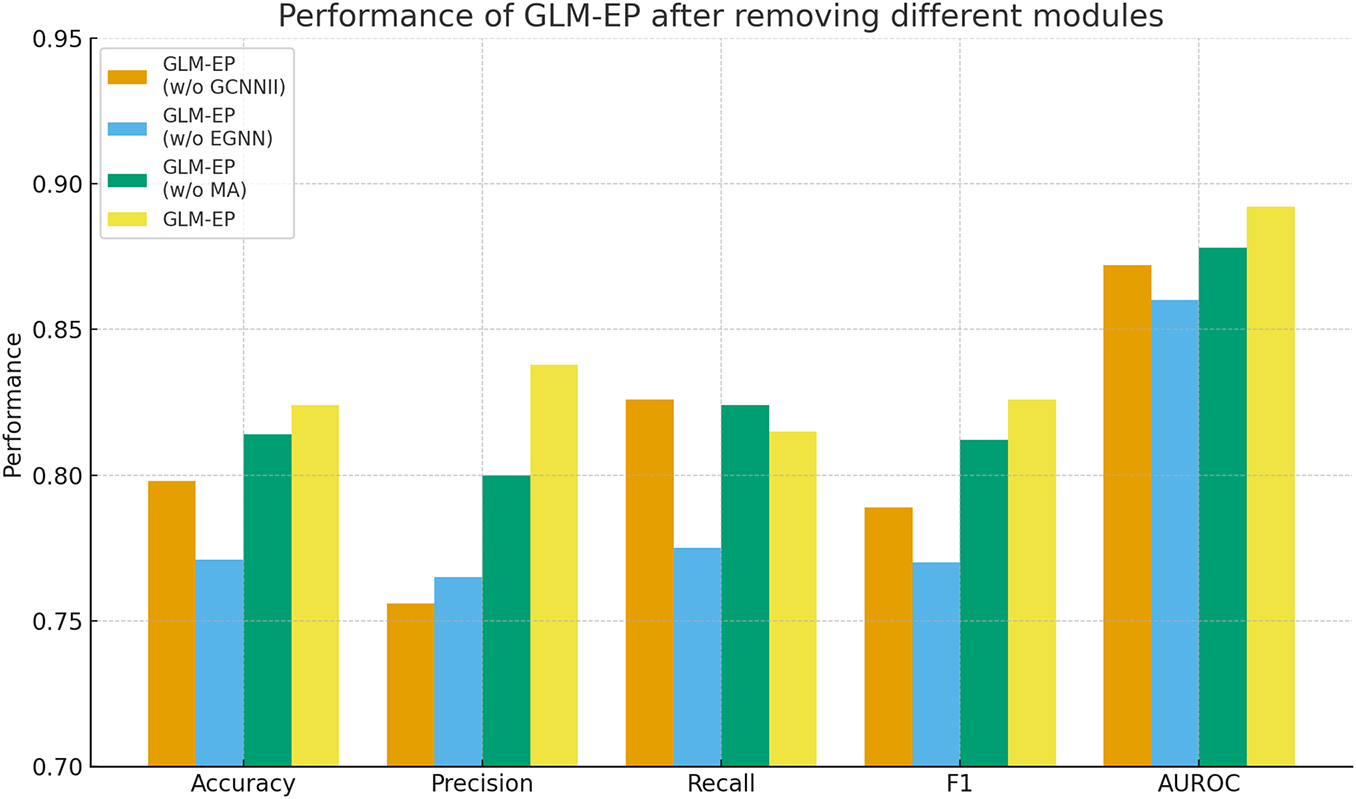

To evaluate the contribution of key structural modules in the GLM-EP model, we designed a module ablation experiment by successively removing the GCNII, EGNN, and multi-head attention (MA) modules, and analyzing their impact on prediction performance. All experiments were conducted on the standard phage essential protein dataset. The evaluation metrics include Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1 score, and AUROC, and the results are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 6.

Figure 3: Performance of GLM-EP after removing different modules

The experimental results demonstrate that the complete GLM-EP model achieves optimal performance, with an F1 score of 0.826 and AUROC of 0.892. Removing any of the key modules leads to a decline in performance, indicating that each module plays an important role. Specifically, removing the EGNN module results in the most significant decline, with F1 decreasing by 5.6% and AUROC decreasing by 3.2%. Removing the GCNII module leads to a decrease of 3.7% in F1 and 2.0% in AUROC. Removing the multi-head attention module has a relatively smaller effect, with both F1 and AUROC decreasing by 1.4%.

These results reflect the complementarity of the EGNN and GCNII graph neural network modules in the process of feature construction. Further observation shows that even after removing the MA module while retaining GCNII and EGNN, the simplified model can still achieve an F1 score of 0.812, which verifies the effectiveness of hierarchical graph learning. The GCNII module focuses on aggregating local neighborhood information, whereas the EGNN module captures structural characteristics at the global graph level. The two modules cooperate to enable the model to integrate both local and global semantic representations, thereby enhancing classification performance.

We proposed an integrated framework, GLM-EP, that combines protein language models with equivariant graph neural networks to predict essential phage proteins. By integrating the semantic representation capabilities of language models with the spatial modeling strengths of geometric networks, GLM-EP is able to capture high-level protein features that are difficult to model using traditional sequence-based approaches. Experimental results on both bacteriophage and human benchmark datasets demonstrate that our method consistently outperforms classical machine learning and recent deep learning baselines across multiple metrics. These results verify the effectiveness of GLM-EP’s architectural innovations and multi-modal feature fusion mechanism, which combines language embeddings, structural topology, and handcrafted evolutionary descriptors.

From a biological perspective, accurately identifying essential proteins is key to understanding the core mechanisms governing phage viability. The features learned by GLM-EP capture biologically meaningful patterns such as conserved residues, structural rigidity, and inter-residue dependencies, which align with known molecular characteristics of essential proteins. This connection between model representations and biochemical properties not only enhances predictive performance but also facilitates biological interpretation. GLM-EP thus provides a computational tool for uncovering therapeutic targets in phage genomics and contributes to broader research on phage-based antibacterial strategies and cross-species essentiality analysis.

Despite these strengths, our study has limitations. The model’s performance still depends on the scale and diversity of benchmark datasets, and generalization to evolutionarily distant or sparsely annotated phages remains challenging. Future work will incorporate residue-level structural priors predicted by AlphaFold to improve spatial modeling and will construct a phage-centered knowledge graph that integrates structural, functional, and interaction data. These enhancements aim to increase model interpretability and support cross-species transfer. By unifying geometric reasoning with external biological knowledge, future versions of GLM-EP are expected to achieve better generalization, biological applicability, and utility in downstream experimental validation.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their gratitude to all individuals who provided helpful comments and support during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding Statement: This work is supported in part by funds from the Ministry of Science and Technology (2022FY101104).

Author Contributions: The study was conceptualized and designed by Jia Mi, who also conducted data analysis and manuscript writing. Experimental procedures were performed by Zhikang Liu. Contributions from Chang Li included partial experimental validation, statistical assistance, and refinement of the draft. Jing Wan supported the work by providing reagents, materials, and analytical tools. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The source code can be found at: https://github.com/MiJia-ID/GLM-EP (accessed on 01 November 2025).

Ethics Approval: This study did not involve human or animal subjects.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Deveau H, Garneau JE, Moineau S. CRISPR/Cas system and its role in phage-bacteria interactions. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64(1):475–93. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Hatoum-Aslan A. Phage genetic engineering using CRISPR–Cas systems. Viruses. 2018;10(6):335. doi:10.3390/v10060335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Fage C, Lemire N, Moineau S. Delivery of CRISPR-Cas systems using phage-based vectors. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2021;68:174–80. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2020.11.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Altamirano FLG, Barr JJ. Phage therapy in the postantibiotic era. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32(2):e00066-18. [Google Scholar]

5. Zhong J, Tang C, Peng W, Xie M, Sun Y, Tang Q, et al. A novel essential protein identification method based on PPI networks and gene expression data. BMC Bioinform. 2021;22:248. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-55902/v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Li Y, Zeng M, Zhang F, Wu FX, Li M. DeepCellEss: cell line-specific essential protein prediction with deep learning. Bioinformatics. 2022;23(1):e2. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btac779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Xu W, Dong Y, Guan J, Zhou S. Identifying essential proteins from protein–protein interaction networks based on influence maximization. BMC Bioinform. 2022;23(S8):339. doi:10.1186/s12859-022-04874-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Fang T, Liu J, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Zeng J. Bingo: a protein essentiality prediction framework based on pretrained protein language models. Bioinformatics. 2023;39(Suppl 1):i575–83. doi:10.1093/bib/bbad472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Radivojac P, Clark WT, Oron TP, Schnoes AM, Wittkop T, Sokolov A, et al. A large-scale evaluation of computational protein function prediction. Nat Methods. 2013;10:221–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

10. Rives A, Meier J, Sercu T, Goyal S, Lin Z, Liu J, et al. Biological structure and function emerge from scaling unsupervised learning to 250 million protein sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2021;118(15):e2016239118. doi:10.1101/622803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Elnaggar A, Heinzinger M, Dallago C, Rehawi G, Wang Y, Jones L, et al. ProtTrans: towards cracking the language of life’s code through self-supervised deep learning and high performance computing. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2021;44(10):7112–27. doi:10.1101/2020.07.12.199554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Alley EC, Khimulya G, Biswas S, AlQuraishi M, Church GM. Unified rational protein engineering with sequence-based deep representation learning. Nat Methods. 2019;16:1315–22. doi:10.21203/rs.2.13774/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Fenoy E, Edera AA, Stegmayer G. Transfer learning in proteins: evaluating novel protein learned representations for bioinformatics tasks. Brief Bioinform. 2022;23(4):bbac232. doi:10.1093/bib/bbac232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Bepler T, Berger B. Learning protein sequence embeddings using information from structure. arXiv:1902.08661. 2019. [Google Scholar]

15. Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nat. 2021;596(7873):583–9. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Baek M, DiMaio F, Anishchenko I, Dauparas J, Ovchinnikov S, Lee GR, et al. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Sci. 2021;373(6557):871–6. doi:10.1530/ey.19.15.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yang J, Yan R, Roy A, Xu D, Poisson J, Zhang Y. The I-TASSER Suite: protein structure and function prediction. Nat Methods. 2015;12(1):7–8. doi:10.1038/nmeth.3213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Gligorijevic V, Renfrew PD, Kosciolek T, Leman JK, Berenberg D, Vatanen T, et al. Structure-based function prediction using graph convolutional networks. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1–14. doi:10.1101/786236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Gainza P, Sverrisson F, Monti F, Rodolà E, Boscaini D, Bronstein MM, et al. Deciphering interaction fingerprints from protein molecular surfaces using geometric deep learning. Nat Methods. 2020;17(2):184–92. doi:10.1038/s41592-019-0666-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Gao H, Ji S. Graph U-nets. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2022;44(9):4948–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

21. Nehil-Puleo K, Quach CD, Craven NC, McCabe C, Cummings PT. E(n) equivariant graph neural network for learning interactional properties of molecules. J Phys Chem B. 2024;128(4):1108–17. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.3c07304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Fuchs FB, Worrall DE, Fischer V, Welling M. SE(3)-transformers: 3D roto-translation equivariant attention networks. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2020;33:1970–81. [Google Scholar]

23. Bronstein MM, Bruna J, Cohen T, Veličković P. Geometric deep learning: grids, groups, graphs, geodesics, and gauges. arXiv:2104.13478. 2021. [Google Scholar]

24. Senior AW, Evans R, Jumper J, Kirkpatrick J, Sifre L, Green T, et al. Improved protein structure prediction using potentials from deep learning. Nat. 2020;577(7792):706–10. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1923-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang Z, Ruan J, Gao J, Wu FX. Predicting essential proteins from protein-protein interactions using order statistics. J Theor Biol. 2019;480:274–83. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2019.06.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Hart T, Chandrashekhar M, Aregger M, Steinhart Z, Brown KR, MacLeod G, et al. High-resolution CRISPR screens reveal fitness genes and genotype-specific cancer liabilities. Cell. 2015;163(6):1515–26. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Chen M, Wei Z, Huang Z, Ding B, Li Y. Simple and deep graph convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2020 Jul 13–18; Online. p. 1725–35. [Google Scholar]

28. Miller ES, Kutter E, Mosig G, Arisaka F, Kunisawa T, Ruger W. Bacteriophage T4 genome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67(1):86–156. doi:10.1128/mmbr.67.1.86-156.2003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Studier FW. Bacteriophage T7: genetic and biochemical analysis of this simple phage provides information about basic genetic processes. Science. 1972;176(4033):367–76. doi:10.1126/science.176.4033.367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Molineux IJ. The T7 group. In: The bacteriophages. Vol. 2. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2006. 277 p. [Google Scholar]

31. Bertani LE, Bertani G. Genetics of P2 and related phages. Adv Genet. 1971;16(3):199–237. doi:10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60359-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Casjens SR, Hendrix RW. Bacteriophage lambda: early pioneer and still relevant. Virology. 2015;479–480(Part 5):310–30. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Hatfull GF. Bacteriophage genomics. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11(5):447–53. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2008.09.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Klumpp J, Lavigne R, Loessner MJ, Ackermann HW. The SPO1-related bacteriophages. Arch Virol. 2010;155(10):1547–61. doi:10.1007/s00705-010-0783-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Stewart CR, Casjens SR, Cresawn SG, Houtz JM, Smith AL, Ford ME, et al. The genome of Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage SPO1. J Mol Biol. 2009;388(1):48–70. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Harshhey RM. Transposable phage Mu. Mob DNA. 2015;6(1):18. [Google Scholar]

37. Roberts MD, Martin NL, Kropinski AM. The genome and proteome of coliphage T1. Virology. 2004;318(1):245–66. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2003.09.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Ravin NV. N15: the linear plasmid prophage. Bacteriophages. 2006;2:448–56. doi:10.1093/oso/9780195148503.003.0028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Silva JM, Marran K, Parker JS, Silva J, Golding M, Schlabach MR, et al. Profiling essential genes in human mammary cells by multiplex RNAi screening. Science. 2008;319(5863):617–20. doi:10.1126/science.1149185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Wang T, Birsoy K, Hughes NW, Krupczak KM, Post Y, Wei JJ, et al. Identification and characterization of essential genes in the human genome. Science. 2015;350(6264):1096–101. doi:10.1126/science.aac7041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Guo FB, Dong C, Hua HL, Liu S, Luo H, Zhang H, et al. Accurate prediction of human essential genes using only nucleotide composition and association information. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(12):1758–64. doi:10.1101/084129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zheng M, Sun G, Li X, Fan Y. EGPDI: identifying protein—DNA binding sites based on multi-view graph embedding fusion. Brief Bioinform. 2024;25(4):bbae330. doi:10.1093/bib/bbae330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Kelley LA, MacCallum RM, Sternberg MJE. Enhanced genome annotation using structural profiles in the program 3D-PSSM. J Mol Biol. 2000;299(2):501–22. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2000.3741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Lüthy R, McLachlan AD, Eisenberg D. Secondary structure-based profiles: use of structure-conserving scoring tables in searching protein sequence databases for structural similarities. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinf. 1991;10(3):229–39. doi:10.1002/prot.340100307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Connolly ML. Measurement of protein surface shape by solid angles. J Mol Graph. 1986;4(1):3–6. doi:10.1016/0263-7855(86)80086-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Zhang S, Tong H, Xu J, Maciejewski R. Graph convolutional networks: a comprehensive review. Comput Soc Net. 2019;6(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

47. LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature. 2015;521(7553):436–44. doi:10.1038/nature14539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 770–8. [Google Scholar]

49. Wang Z, Zhu J, Chen J. Remoe: fully differentiable mixture-of-experts with relu routing. arXiv:2412.14711. 2024. [Google Scholar]

50. Zeng M, Wang N, Wu Y, Li Y, Wu FX, Li M. Improving human essential protein prediction using only protein sequences via ensemble learning. In: 2021 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM); 2021 Dec 9–12; Houston, TX, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 98–103. [Google Scholar]

51. Wang L, Zheng X. Improving grammatical error correction models with purpose-built adversarial examples. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2020 Nov 16–20; Online. New York, NY, USA: ACL; 2020. p. 2858–69. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools