Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Learning from Scarcity: A Review of Deep Learning Strategies for Cold-Start Energy Time-Series Forecasting

Department of Data Science, Duksung Women’s University, Seoul, 01369, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Jihoon Moon. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Deep Learning for Energy Systems)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 2 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.071052

Received 30 July 2025; Accepted 10 December 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

Predicting the behavior of renewable energy systems requires models capable of generating accurate forecasts from limited historical data, a challenge that becomes especially pronounced when commissioning new facilities where operational records are scarce. This review aims to synthesize recent progress in data-efficient deep learning approaches for addressing such “cold-start” forecasting problems. It primarily covers three interrelated domains—solar photovoltaic (PV), wind power, and electrical load forecasting—where data scarcity and operational variability are most critical, while also including representative studies on hydropower and carbon emission prediction to provide a broader systems perspective. To this end, we examined trends from over 150 predominantly peer-reviewed studies published between 2019 and mid-2025, highlighting advances in zero-shot and few-shot meta-learning frameworks that enable rapid model adaptation with minimal labeled data. Moreover, transfer learning approaches combined with spatiotemporal graph neural networks have been employed to transfer knowledge from existing energy assets to new, data-sparse environments, effectively capturing hidden dependencies among geographic features, meteorological dynamics, and grid structures. Synthetic data generation has further proven valuable for expanding training samples and mitigating overfitting in cold-start scenarios. In addition, large language models and explainable artificial intelligence (XAI)—notably conversational XAI systems—have been used to interpret and communicate complex model behaviors in accessible terms, fostering operator trust from the earliest deployment stages. By consolidating methodological advances, unresolved challenges, and open-source resources, this review provides a coherent overview of deep learning strategies that can shorten the data-sparse ramp-up period of new energy infrastructures and accelerate the transition toward resilient, low-carbon electricity grids.Keywords

The rapid decarbonization of global energy systems is transforming power grids into highly dynamic and data-intensive networks, with renewable sources, including solar photovoltaic (PV) and wind power, now steadily dominating the global energy landscape [1]. Although these systems offer substantial environmental advantages, they also introduce significant operational uncertainty and nonstationarity into modern power systems, necessitating advanced predictive models to manage the increased complexity [2]. Consequently, accurate and timely forecasting of both energy generation and consumption is necessary to ensure system reliability, facilitate efficient market operations, and effectively allocate resources [3]. However, a persistent and often underestimated obstacle, termed the “cold-start problem,” has been identified during the initial deployment phase of new energy installations [4]. This challenge stems from the scarcity or absence of historical data, which delays the rapid development of reliable forecasting models and the effective integration of new renewable assets into the grid.

Conventional forecasting methods, encompassing classical statistical techniques such as autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) and regression-based models, rely on the availability of sufficiently long and stable historical time-series data [5,6]. In scenarios where operational records are limited or incomplete, these methods tend to generalize poorly, often resulting in large forecasting errors and unstable performance [7]. Conversely, deep learning (DL) techniques have been recognized for their enhanced predictive capability in energy forecasting tasks, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), transformer architectures, and hybrid models that combine CNN and RNN structures [8,9]. However, these DL models typically require large, representative datasets for effective training, presenting a substantial limitation in cold-start contexts where only minimal data are available at the time of deployment [10].

Recent advancements in DL have facilitated the development of practical solutions to overcome the cold-start problem, enabling precise predictions even with limited historical data [11,12]. These advancements include zero-shot and few-shot meta-learning, transfer learning (TL), spatiotemporal graph neural networks (ST-GNNs), and synthetic-data generation [13–16]. If implemented effectively in industrial contexts, these methods have the potential to reduce the ramp-up time for newly deployed renewable assets, enhance short-term grid reliability, and inform early operational planning—well before conventional models can be calibrated with sufficient data. However, despite the promising prospects associated with these methods, their adoption remains fragmented across research communities and application domains, hindering their seamless integration into operational energy systems and limiting their broader influence on practical deployment.

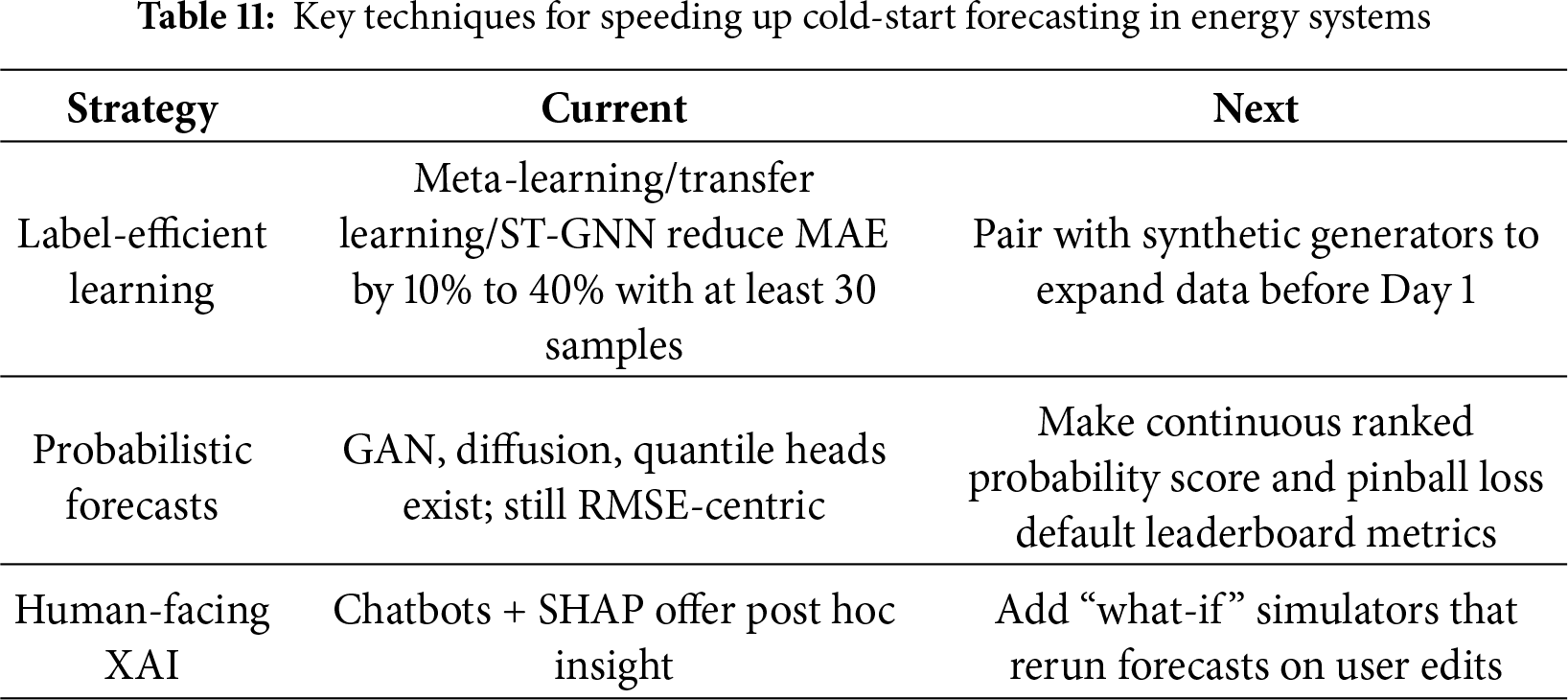

As shown in Table 1, several recent surveys have sought to organize the rapid progress of DL applications in renewable energy forecasting. Ying et al. [17] provided a structural taxonomy of models, and Klaiber and Van Dinther [18] summarized computational trends across variable renewable sources. Domain-focused works such as Paletta et al. [19] and Chu et al. [20] explored vision-based and remote-sensing approaches for solar forecasting, while Eren and Küçükdemiral [21] and Biswal et al. [22] focused on load and demand prediction frameworks. In parallel, Bouquet et al. [23] emphasized operational optimization, and Verdone et al. [24] compared single- and multi-site forecasting performance. Collectively, these studies have contributed substantially to understanding DL architecture and application-specific performance. Yet, most remain confined to descriptive taxonomies—categorizing models or domains—without examining how learning strategies themselves can adapt when data are scarce, incomplete, or imbalanced. This omission leaves a critical methodological gap between architectural innovation and practical deployment.

To bridge this gap, the present review adopts a strategy-centered and cross-domain perspective that treats the cold-start problem as a learning challenge rather than a mere data limitation. By synthesizing insights from meta-learning, transfer adaptation, synthetic data generation, and explainable large language model (LLM)-based forecasting, it establishes a unified analytical framework for adapting DL models under data scarcity. This approach is vital because real-world renewable systems rarely possess abundant, stable data—especially during early-stage deployment—precisely when forecasting accuracy is most needed. Existing reviews have largely overlooked this intersection between data constraints and learning adaptability, which defines the actual boundary of model usability. By connecting fragmented progress—from Wazirali et al. [25] on microgrid forecasting to Bouquet et al. [23] and Verdone et al. [24] on scalability and adaptation—this study advances a cohesive research agenda for robust, scalable, and generalizable cold-start forecasting across renewable energy domains.

This review primarily examines three interrelated domains—solar PV, wind power, and electrical load forecasting—where data scarcity and operational variability make cold-start conditions particularly critical. These sectors capture the most data-challenged and operationally sensitive components of modern power systems. Selected studies on hydropower and carbon-emission prediction are also included to illustrate how learning strategies can extend beyond variable renewables. In contrast, geothermal and bioenergy systems are generally dispatchable and supported by long, stable operational records [26,27], while tidal resources are highly predictable owing to astronomical cycles such as the 18.6-year nodal period [28]. This focus aligns with international classifications that identify solar and wind as variable renewables with the highest operational uncertainty [29,30].

This study makes the following contributions:

• Bridging a critical methodological gap: This review provides the first foundational guide that consolidates fragmented research on cold-start forecasting. By aligning learning strategies with real-world deployment contexts, it helps researchers and practitioners make informed methodological choices and accelerates the operational readiness of renewable forecasting systems under data scarcity.

• Establishing a strategy-oriented synthesis: Beyond architectural taxonomies, this review presents a concise synthesis of key DL paradigms—including TL, meta-learning, ST-GNNs, synthetic data generation, and LLM-assisted explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) [31]—tailored for cold-start forecasting. This synthesis establishes a unified framework for adaptive learning across domains.

• Delivering an evidence-based comparative evaluation: Over 120 peer-reviewed studies are critically analyzed to assess forecasting accuracy, computational cost, generalizability, and implementation feasibility. This comparative approach highlights which strategies perform best under different constraints and provides actionable insights for both research and industrial deployment.

• Defining the forward research agenda: The review identifies persistent research gaps and technical challenges—including interpretability, uncertainty-aware learning, and cross-domain adaptation—and outlines clear directions toward robust, scalable, and transparent cold-start forecasting frameworks for next-generation renewable energy systems.

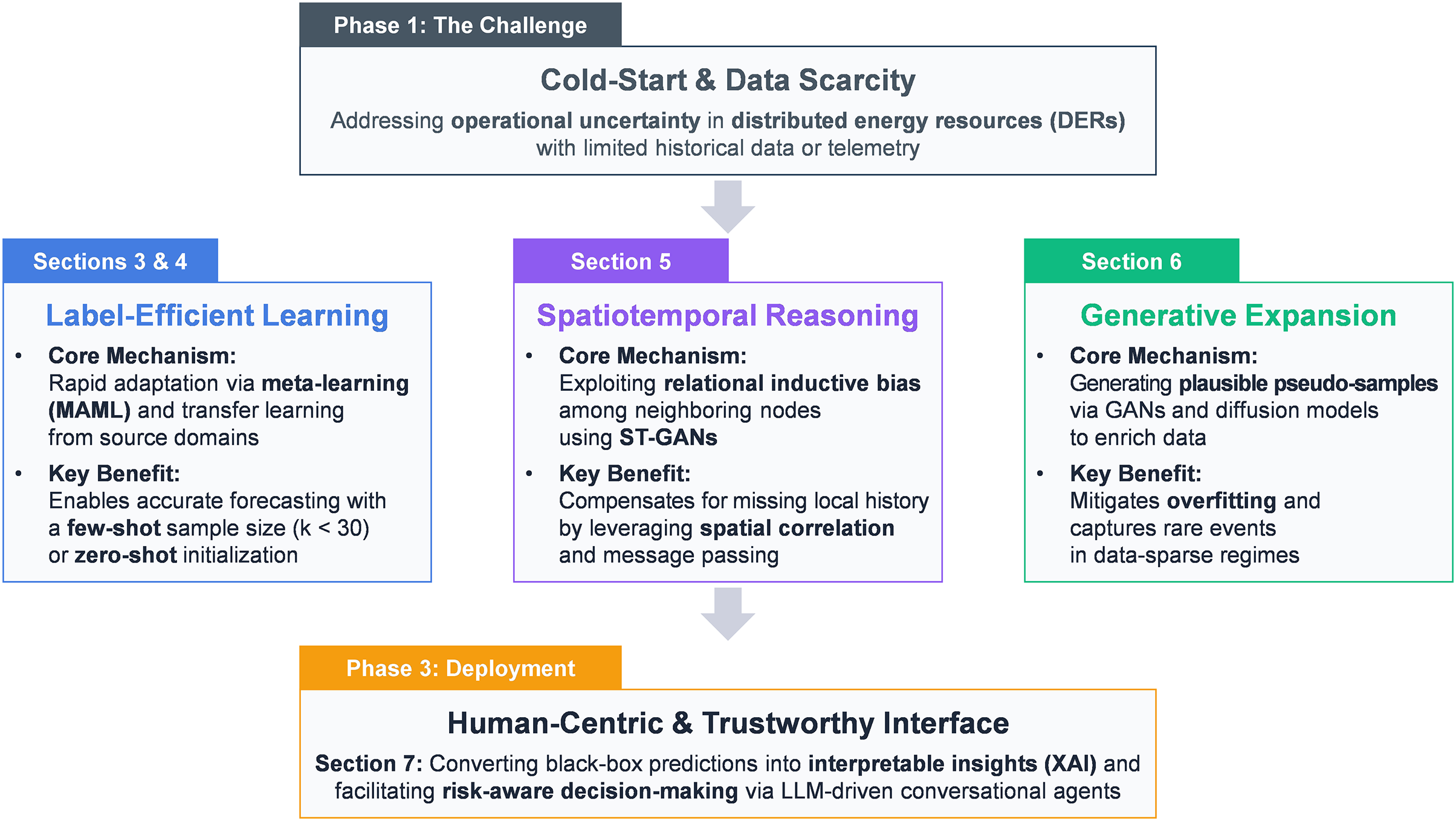

To help readers make sense of the heterogeneous methods surveyed in this work, Fig. 1 consolidates them into a single, coherent conceptual map. Rather than functioning as a simple summary, the figure illustrates how the three methodological strands—label-efficient learning, spatiotemporal modeling, and generative data augmentation—interact to alleviate the data scarcity inherent in cold-start scenarios. By linking each strand to the relevant sections of the review and showing how these ideas ultimately converge in a reliable, human-centered deployment framework, the figure provides a navigational guide that ties the paper’s theoretical arguments to their practical ramifications.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework of the review illustrating the flow of deep learning strategies for cold-start energy forecasting. The diagram highlights the four main contributions analyzed in this paper: (1) Label-efficient learning (meta/transfer learning, Sections 3 and 4) for rapid adaptation; (2) Spatiotemporal modeling (ST-GNNs, Section 5) for leveraging spatial correlations; (3) Generative augmentation (synthetic data, Section 6) for enriching sparse datasets; and (4) Explainable interfaces (XAI/LLMs, Section 7) for operator trust. These components collectively bridge the gap between data scarcity and operational reliability

The rest of this review is structured as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of forecasting models and their cold-start limitations, and Section 3 covers meta-learning for rapid generalization with few examples. Then, Section 4 examines TL for cross-site adaptation, and Section 5 reviews ST-GNNs for spatiotemporal dependency modeling. Next, Section 6 highlights data augmentation as a cold-start solution, and Section 7 discusses LLMs and XAI in relation to transparency and user interaction. Finally, Section 8 outlines open challenges and future work, and Section 9 concludes with practical guidelines for data-scarce forecasting.

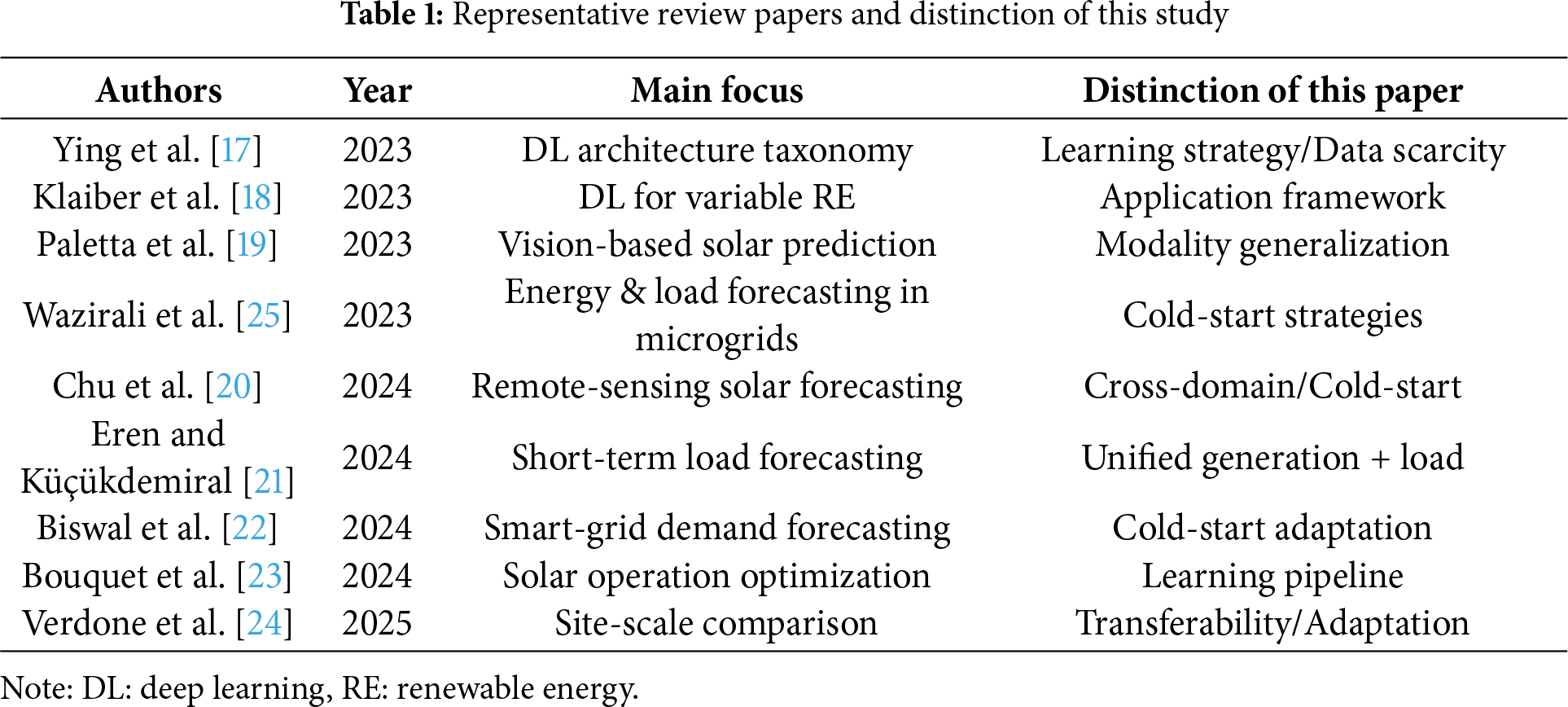

2 Forecasting Approaches and Cold-Start Limitations in Deep Learning

Short-term energy forecasting, ranging from intra-hour to day-ahead projections, is pivotal across all layers of contemporary power systems, encompassing the bulk grid load, building-level demand, PV output, solar irradiance, and wind-farm generation [32]. Although DL can achieve state-of-the-art accuracy in these domains, most prominent studies have relied on months or years of meticulously curated historical data. However, when a newly commissioned asset enters the grid with only a few days of operational history, these models often have critical blind spots. This problem has often been overlooked in the literature. This issue is most pronounced in variable renewables—especially solar PV and wind—because their output shifts quickly with weather changes, unlike the steadier behavior of dispatchable resources [33,34]. Table 2 presents a representative, highly cited DL study of each forecasting domain, highlighting their influence on current practice and examining how its performance degrades under limited historical data conditions.

2.1 Recurrent Neural Architectures under Cold-Start Constraints

The RNN methods, including long short-term memory (LSTM) and gated recurrent units (GRU), were among the first architectures to gain widespread use in energy forecasting [43]. The appeal of these systems stems from their capacity to manage temporal patterns, including the ability to adapt to daily cycles, seasonality, and other temporal correlations that define electricity demand and renewable generation. When trained on extensive datasets encompassing multiple months, these models typically yield highly accurate results [44,45]. However, this success is predicated on the constant availability of substantial, pristine historical data [46].

This success is also predicated on the assumption that months or years of consistent operational data are readily available, which is often not the case in practice. For instance, a newly commissioned solar plant or microgrid node may initiate operations with only a few days of monitoring. In such circumstances, the efficacy of LSTM-based architectures diminishes. These networks require massive datasets to mitigate the risk of overfitting, given their extensive number of trainable parameters, which range from thousands to millions [47]. When confronted with the challenge of training on limited datasets, these models often prioritize memorizing noise over discerning meaningful patterns [48].

In the DrivenData “Power Laws” challenge [49], participants had to predict building energy use with just 1 to 14 days of data for each site. Both organizers and competitors observed that standard LSTM models struggled under these constraints, with DL approaches often failing to generalize when historical data were scarce. This underscores a common cold-start problem: when faced with very short consumption records, LSTMs are prone to overfitting or weak performance. Ahmed et al. [50] showed that PV forecasting with LSTM improves as more historical data become available, while performance drops when data are limited. Their results make it clear that LSTMs struggle to converge and generalize in cold-start or short-history scenarios.

These cases exemplify a more extensive concern: the incongruity between the intricacy of the model and data accessibility during the preliminary implementation phases. Although these architectures remain valuable, their fragility during initialization requires complementary approaches. Section 2.3 presents a comparative synthesis of these limitations across model families.

2.2 Transformer-Based Forecasting in Data-Scarce Environments

Transformer-based models have transformed the landscape of time-series forecasting by capturing distant temporal dependencies that earlier architectures have struggled to represent [51]. Zhou et al. [52] introduced an influential contribution called the informer model, which integrates ProbSparse self-attention with a novel generative decoding mechanism. This design reduces computational complexity to O(LlogL) and delivers consistently strong performance across a range of public energy datasets, including transformer oil temperature and electricity consumption, surpassing LSTM and standard transformer baselines.

However, these models are not immune to the challenges posed by sparse data. Transformers require a considerable volume of data for optimal performance [53]. The mechanisms employed by these systems to identify reliable key-value pairs depend on high token density. The efficacy of this mechanism is compromised in scenarios characterized by scarce input sequences, referred to as cold-start conditions. Although optimized for efficiency, the architecture of the informer model still displays deficiencies when the volume of historical records is inadequate to anchor attention patterns [54].

This limitation becomes problematic in day-ahead forecasting tasks, where the model must relate future weather patterns to energy output with minimal context. In such circumstances, transformer-based architectures often yield uncertainty estimates that are not readily applicable in practice. While these models are technically advanced, they demonstrate fragility when applied to early-stage deployments with sparse data. Section 2.3 further contextualizes this limitation via a comparative analysis.

2.3 Comparative Analysis of Deep Learning Architectures under Cold-Start Constraints

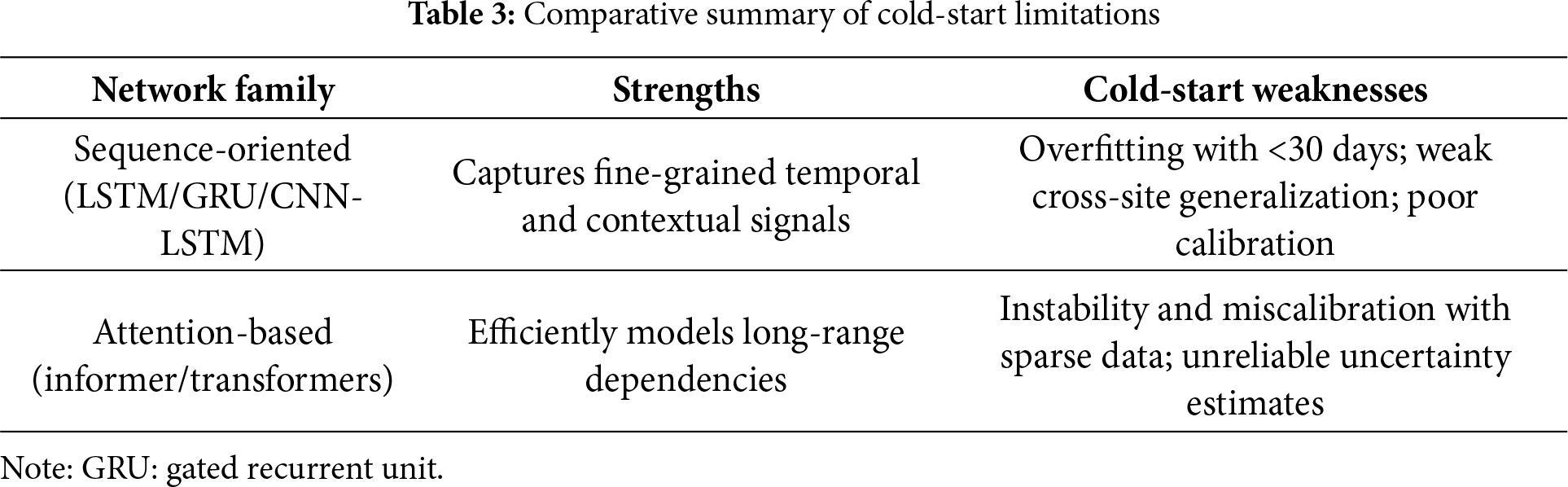

Although individual case studies can explain model behavior under cold-start conditions, a broader comparison across architectural families reveals recurring patterns. Table 3 provides a comparative analysis of two widely adopted model classes: sequence-oriented networks (e.g., LSTM and GRU) and attention-based architectures (e.g., informer). This analysis underscores the primary strengths of the mentioned models in data-rich settings and their failure modes when historical records are scarce.

Despite their strong empirical performance on long-horizon benchmarks, these models are fundamentally designed for data abundance. In practice, the early deployment of energy systems often furnishes only limited operational history. Under such conditions, complex architectures tend to overfit, display poor generalization, and produce unreliable uncertainty estimates. These architectures have been broadly incorporated into residential load forecasting and building-energy modeling pipelines [35,36,44,45], while also supporting forecasting in renewable-energy domains such as solar PV and wind generation [38,40,42]. Their extension to long-sequence time-series forecasting [52] reflects their growing methodological reach. Nonetheless, empirical evidence increasingly points to structural weaknesses, including overfitting under sparse historical data, limited spatial transferability across climates, and instability in modeling multi-scale meteorological drivers, that warrant careful examination.

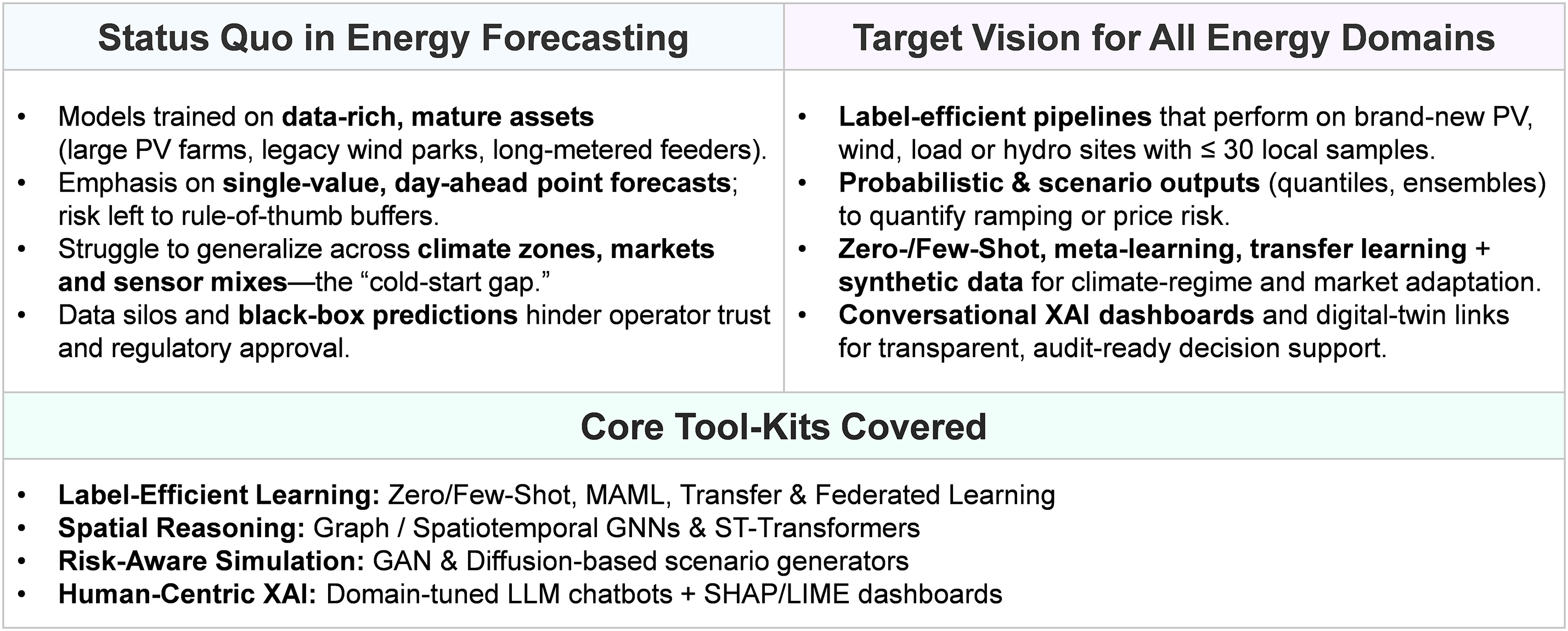

This diagnostic comparison underscores the need for specialized cold-start solutions. Various approaches, including TL, few-shot meta-learning, and physics-informed pretraining, help resolve the mismatch between model complexity and sparse real-world data. To clarify the shift required for next-generation forecasting, Fig. 2 outlines the field’s evolving trajectory. In contrast to the static methodological map in Fig. 1, this diagram places emphasis on how operational workflows diverge between traditional, data-intensive architectures and the cold-start pipelines introduced in this review. It highlights the pivotal movement away from point-based forecasting—effective only when ample historical records exist—toward risk-aware and label-efficient strategies designed to function during the earliest stages of deployment. By presenting this comparison, the roadmap offers a strategic bridge between the limitations of existing models and the adaptive techniques explored in the sections that follow.

Figure 2: Road map from data-rich forecast models to label-efficient, risk-aware, and explainable pipelines for cold-start energy forecasting across energy domains (photovoltaics, wind, load, etc.). The roadmap is centered on PV and wind—where cold-start conditions are most severe—but the principles can extend to other renewables with appropriate domain considerations (see Section 8)

3 Zero-, Few-Shot, and Meta-Learning Strategies for Cold-Start Forecasting

Although short-term energy variables (e.g., solar irradiance and wind speed) follow certain physical regularities, accurate forecasting still typically relies on extensive historical records [55]. However, these data are often unavailable during the initial deployment of new energy systems [56]. In low-data contexts, conventional DL models commonly underperform due to their high parameter count relative to the limited training input.

Recent work has applied meta-learning techniques that enable models to generalize rapidly by drawing on prior experience from related tasks to address this limitation [13]. Rather than learning from scratch, these methods aim to identify shared structures that can be reused across settings. A representative example is the model-agnostic meta-learning (MAML) pipeline [57]. In this framework, a model is trained on multiple source tasks to obtain a generalized initialization, which is subsequently fine-tuned using only a few samples from the target site [58].

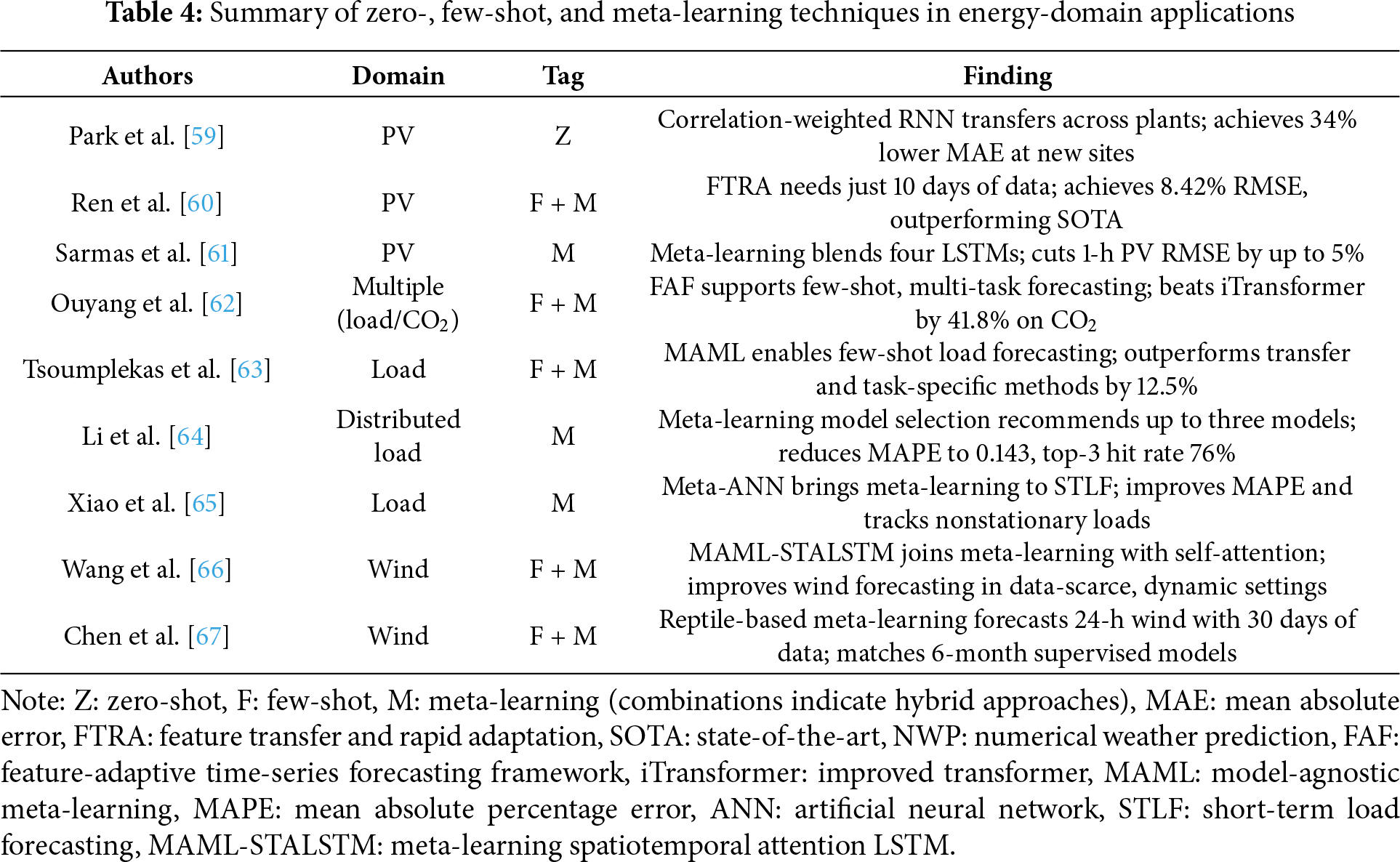

This section outlines the design principles of such approaches and explains why they are well-suited to cold-start forecasting. Moreover, this section synthesizes the findings from recent studies that evaluate meta-learners under limited data conditions. In Table 4, various meta-learning strategies have demonstrated substantial performance gains across energy domains, even when fewer than 50 training examples are available. These results reinforce their potential as a viable solution to the data sparsity challenge in early-stage deployments.

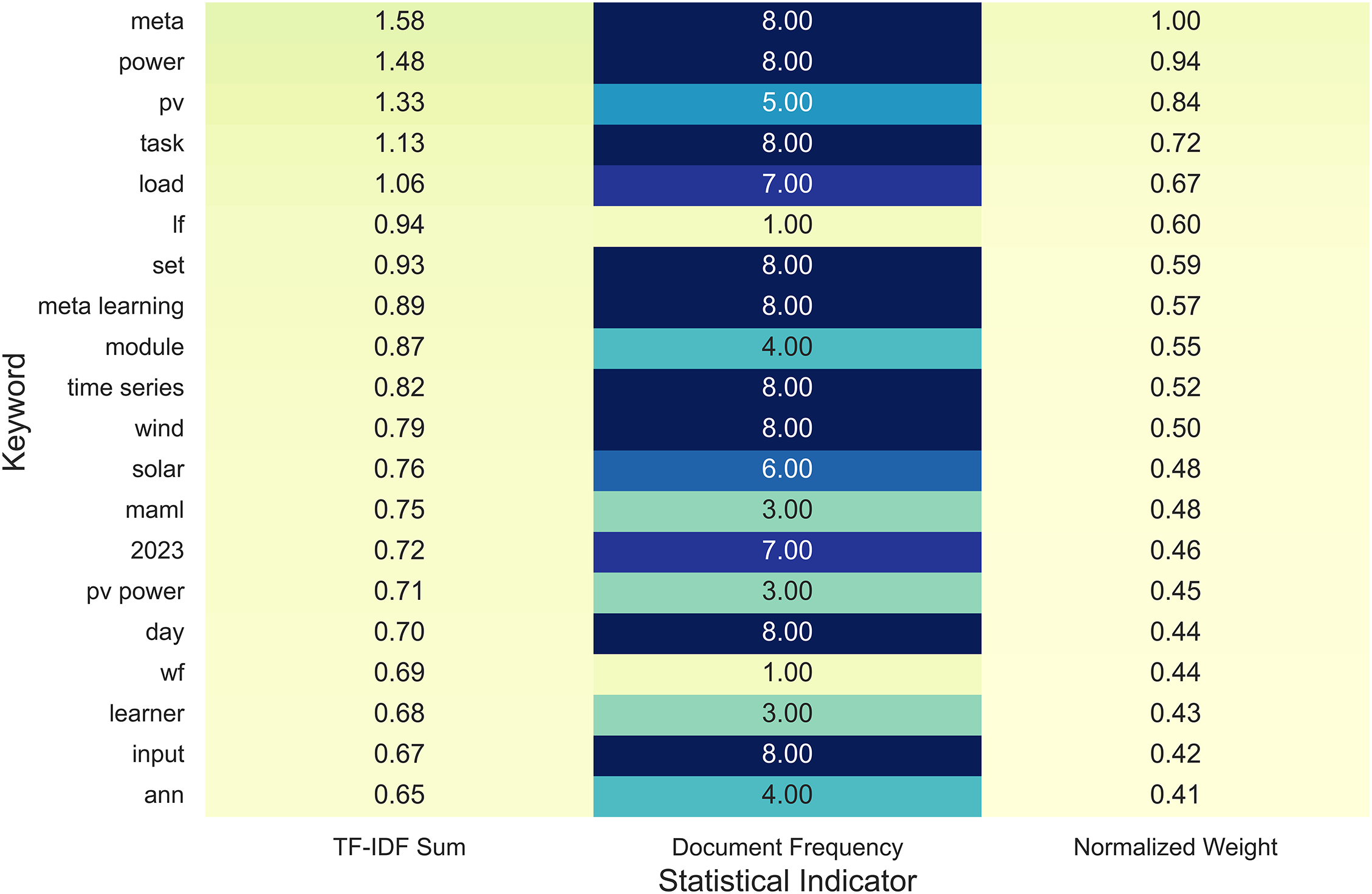

To quantitatively interpret the linguistic structure of recent zero-, few-shot, and meta-learning studies in energy forecasting, a statistical text-mining procedure based on term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) weighting was conducted. Each token’s contribution to the corpus was measured as TF-IDF(t, d) = TF(t, d) × log(N/DF(t)), where N denotes the number of reviewed documents and DF(t) the document frequency of term.

Fig. 3 summarizes the 20 most dominant keywords, presenting their total TF-IDF sum, document frequency, and normalized weight. The results show that meta, power, PV, task, and load consistently achieve the highest statistical relevance across the analyzed corpus. These terms correspond to central methodological trends reported in Table 4, where meta-learning and few-shot strategies repeatedly appear as key mechanisms for addressing data sparsity in cold-start forecasting.

Figure 3: Quantitative summary of dominant keywords in meta-learning literature (TF-IDF analysis)

The quantitative distribution in Fig. 3 thus provides empirical evidence that recent energy-domain literature has converged on meta-learning paradigms such as MAML, feature-adaptive frameworks, and correlation-weighted transfer schemes. By linking statistical keyword dominance with reported physical mechanisms and forecasting outcomes, this analysis reinforces the scientific consistency between textual emphasis and methodological advancement—thereby enhancing the analytical rigor of the study beyond purely descriptive reporting.

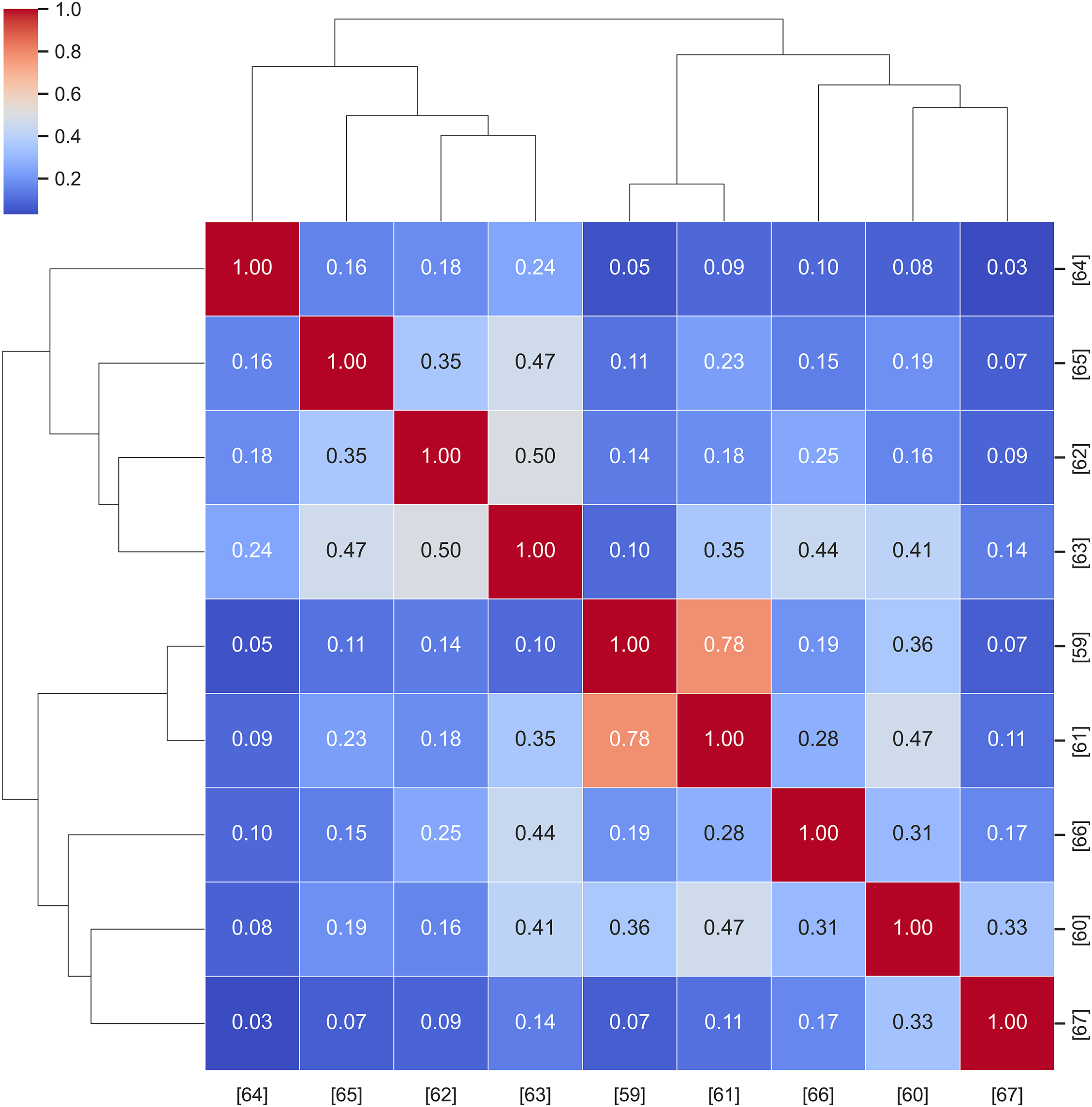

To assist readers in identifying conceptual proximity among recent studies, a hierarchical similarity map was constructed using the cosine similarity of TF-IDF representations for each reference document. This analytical approach measures the directional alignment between documents as Sim(A, B) = (A⋅B)/(∥A∥∥B∥), and applies Ward’s hierarchical linkage to cluster studies that share lexical or thematic overlap.

Fig. 4 visualizes this relationship as a dendrogram-integrated heatmap, where closer branches indicate stronger textual coherence and methodological alignment. For instance, studies [59,61] exhibit high cosine similarity (>0.75), reflecting their shared emphasis on meta-learning frameworks for few-shot forecasting. In contrast, works such as [64,67] occupy more distant clusters, indicating distinctive problem formulations or domain focuses (e.g., distributed load vs. wind prediction).

Figure 4: Hierarchical similarity map among meta-learning studies (TF-IDF cosine + Ward linkage)

This hierarchical structure not only validates the internal consistency of the reviewed corpus but also helps readers systematically explore related research directions, enabling targeted comparison among studies with similar methodological orientations. Such interpretive visualization enhances the transparency, reproducibility, and analytical depth of the literature synthesis, demonstrating the robustness of the present study’s quantitative framework.

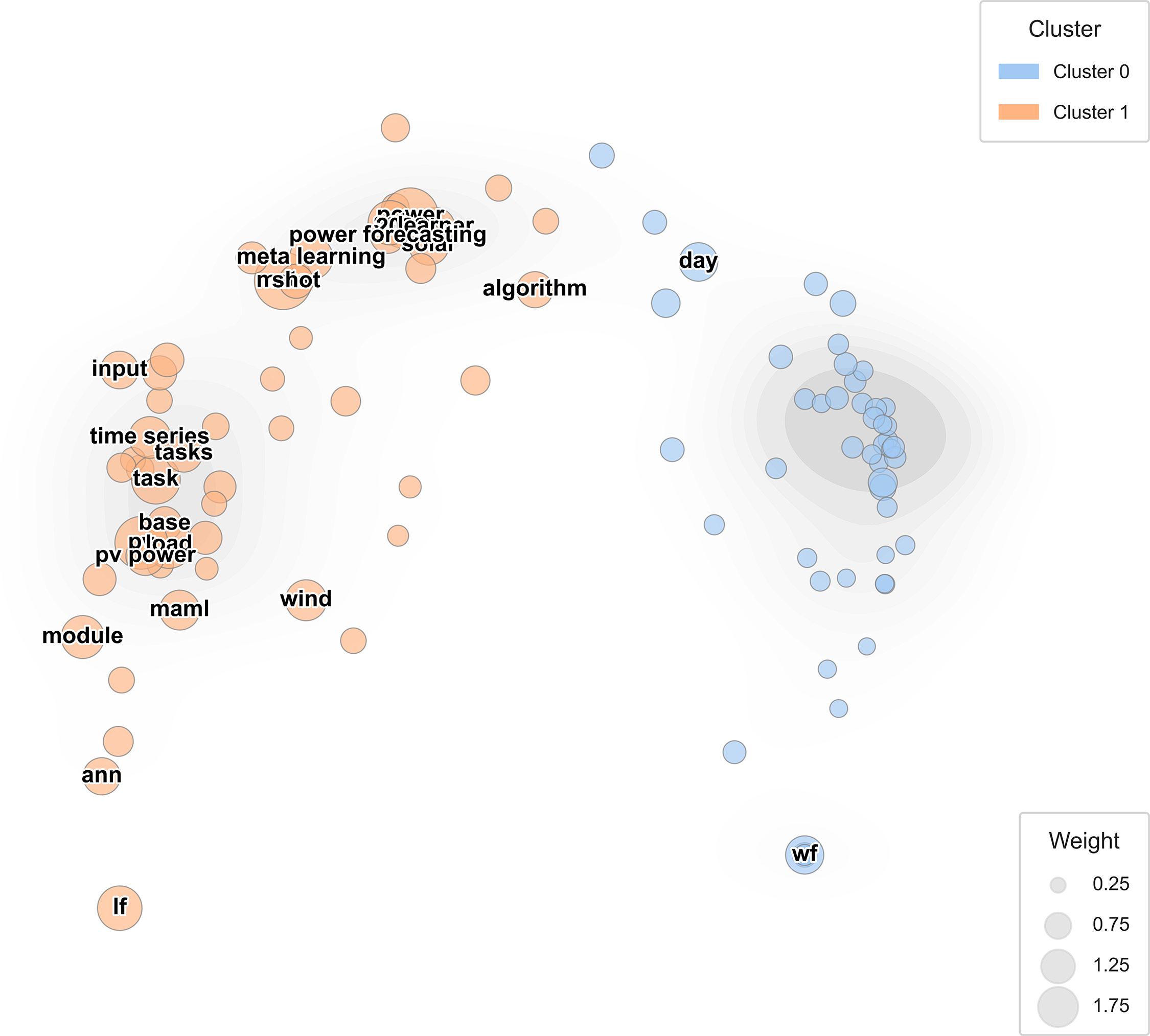

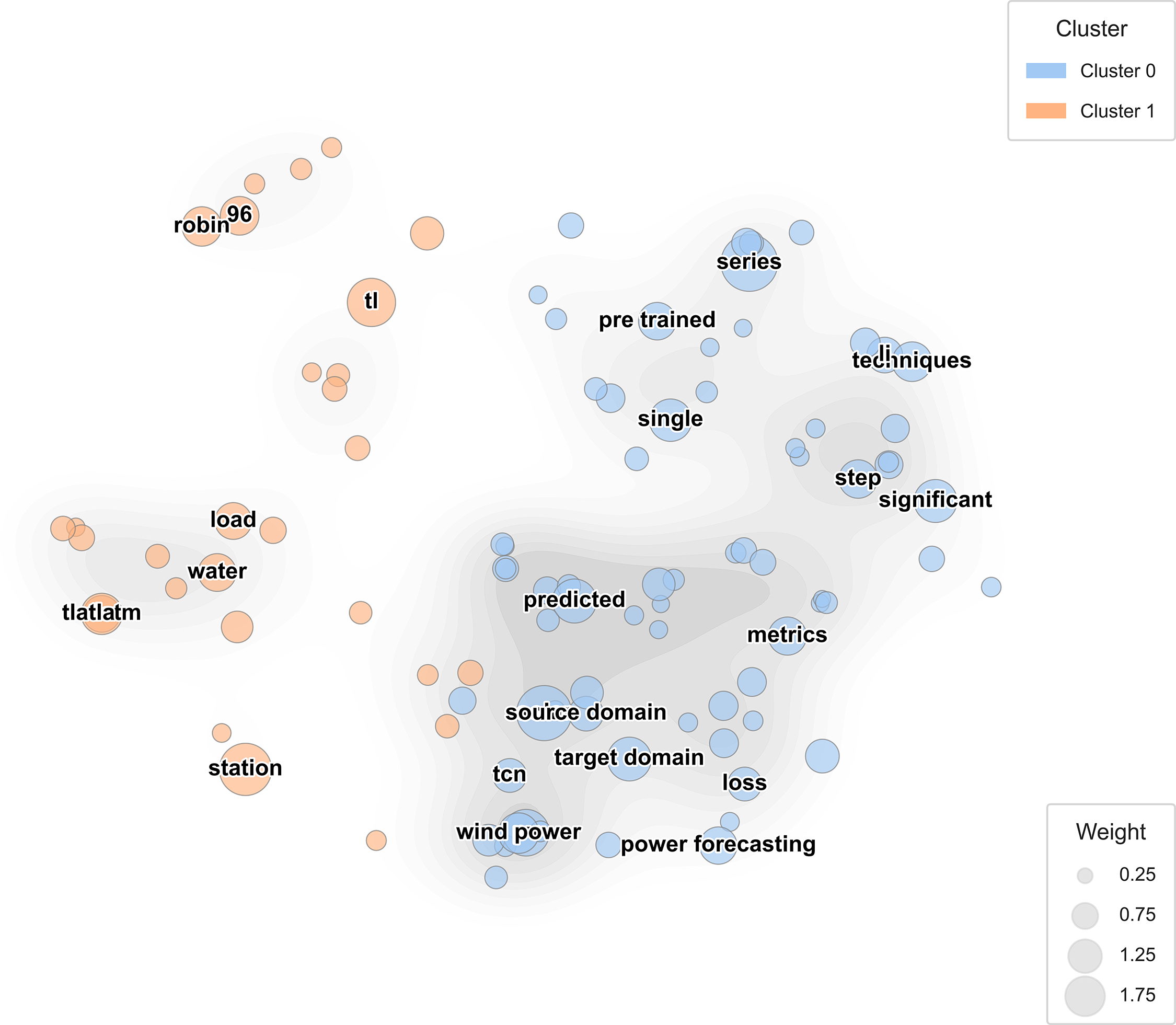

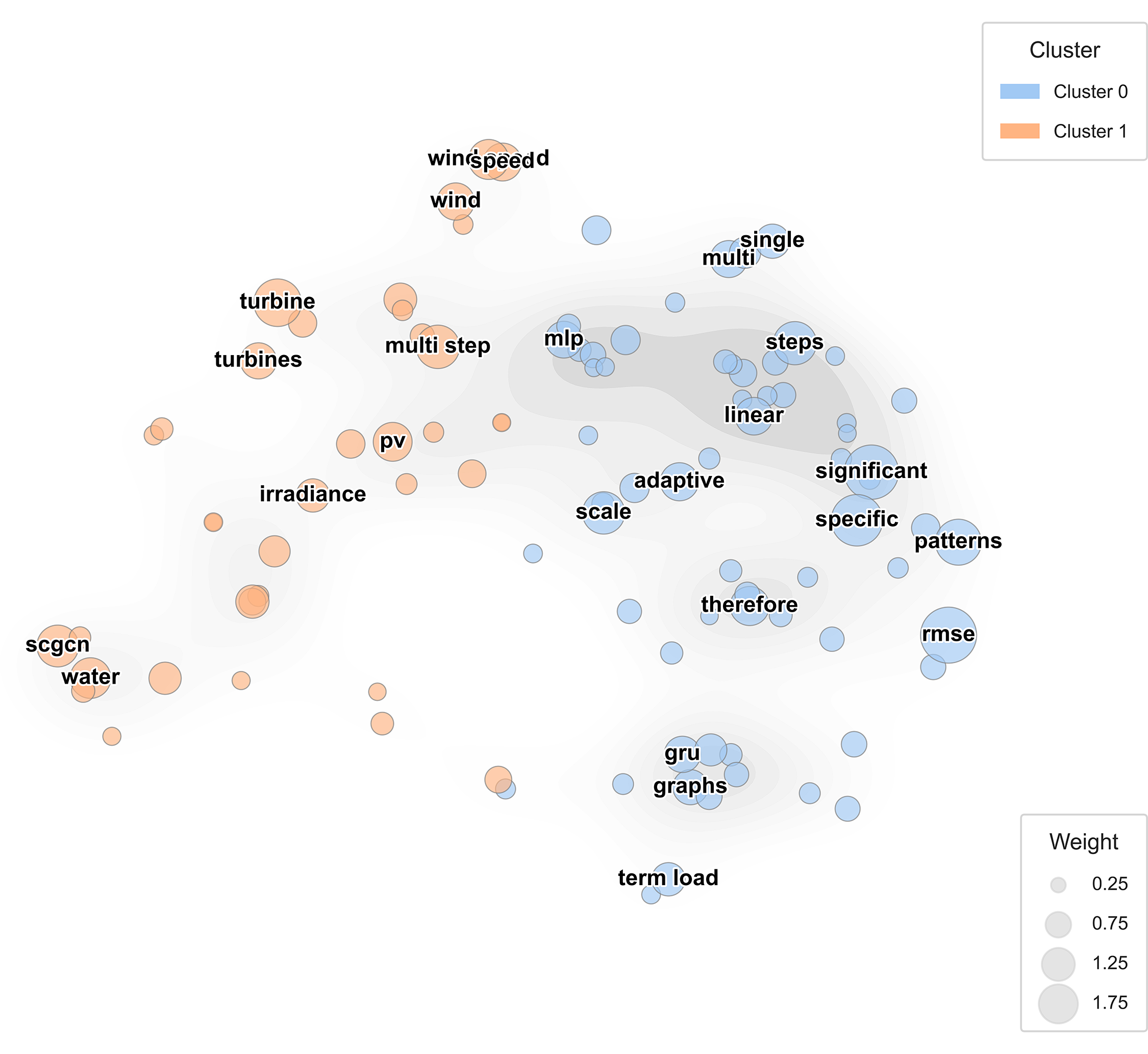

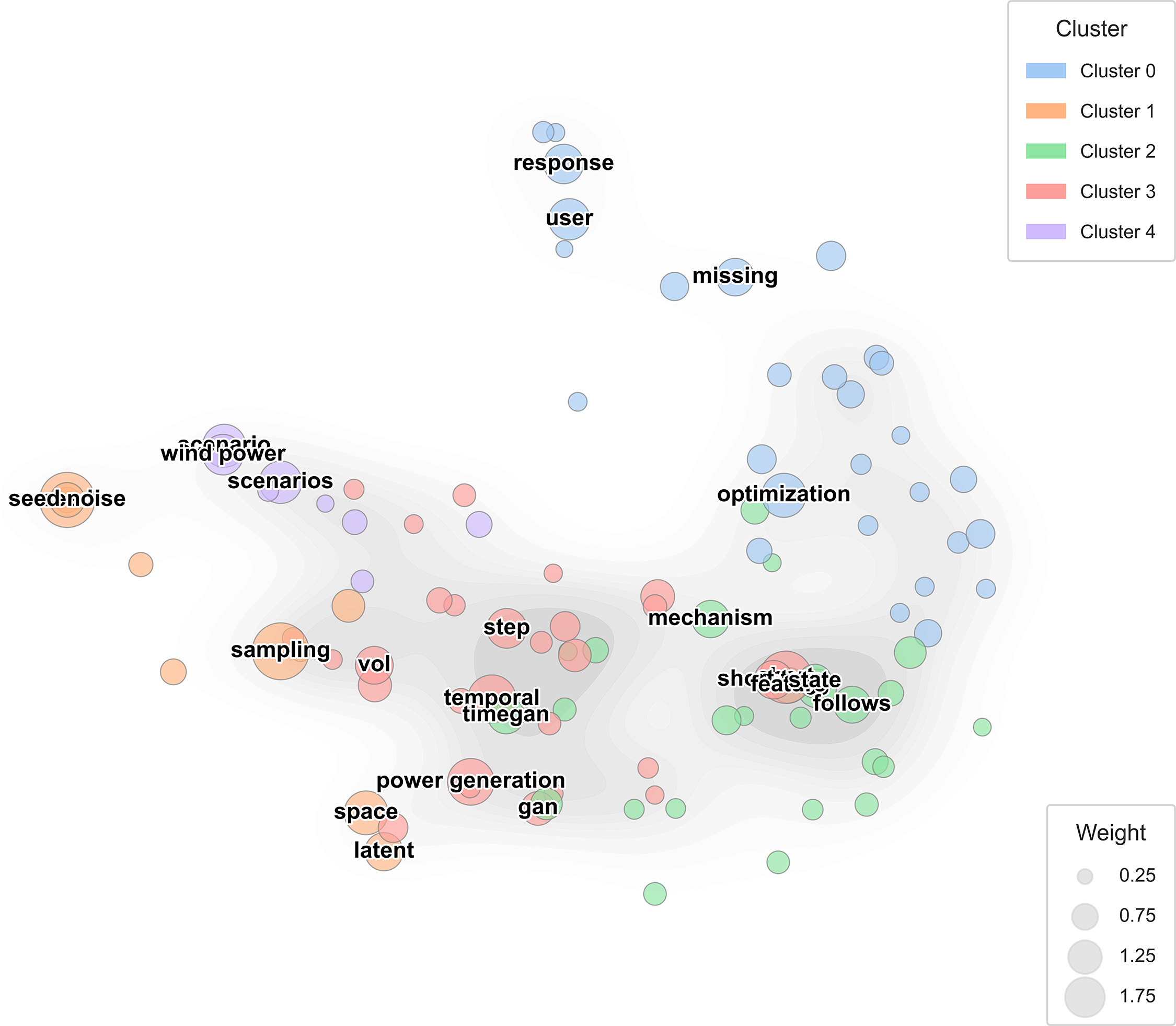

To provide an interpretable overview of how research themes are distributed across the meta-learning corpus, a keyword landscape was constructed using principal component analysis (PCA) on the cosine similarity matrix of TF-IDF term vectors. This deterministic approach projects high-dimensional keyword representations into an orthogonal two-dimensional plane defined by the leading eigenvectors of the covariance matrix XTX.

Fig. 5 visualizes the resulting semantic topology. Each circle represents a keyword, sized according to its normalized TF-IDF weight and colored by its assigned cluster. The use of cosine-based PCA ensures that the spatial distance between terms directly reflects their lexical and contextual similarity, enabling a quantitative yet intuitive understanding of the thematic structure.

Figure 5: Keyword landscape of meta-learning literature (PCA + cosine similarity)

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the spatial organization of the semantic topology highlights a notable pattern: the close proximity of “MAML” and “PV power” within the high-density subregion (Cluster 1) suggests a concentrated body of work where meta-learning is increasingly applied to solar forecasting challenges. This clustering implies that MAML has evolved from a primarily conceptual technique into a frequently adopted operational tool for managing solar-driven variability, particularly in settings where rapid cross-task adaptation is required.

This visualization helps readers navigate the conceptual landscape of meta-learning studies by identifying clusters of recurring research patterns and highlighting transitions between task-level optimization and domain-level adaptation. Unlike heuristic word maps, this PCA-based analysis is fully reproducible and statistically grounded, thus reinforcing the analytical rigor of the literature synthesis.

3.1 Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning

Energy time series, encompassing the grid load and PV output, are subject to fluctuations influenced by meteorological conditions, policy, and user behavior [68]. However, acquiring new labeled data is often time-consuming. Conventional DL models require retraining from the outset to maintain precision, which is costly and occurs after operations have begun. Meta-learning has emerged as a remedy for the label scarcity and distribution drift that plague operational energy forecasting [69]. Rather than requiring the extensive retraining of a deep network from its fundamental components, a meta-learner first identifies a generic representation. This representation can undergo recalibration in real time with a limited number of new data points. The most prominent instantiation of this concept is MAML, which is compatible with any gradient-based model and fits naturally into the CNN, LSTM/GRU, and transformer toolkits already familiar to energy analysts.

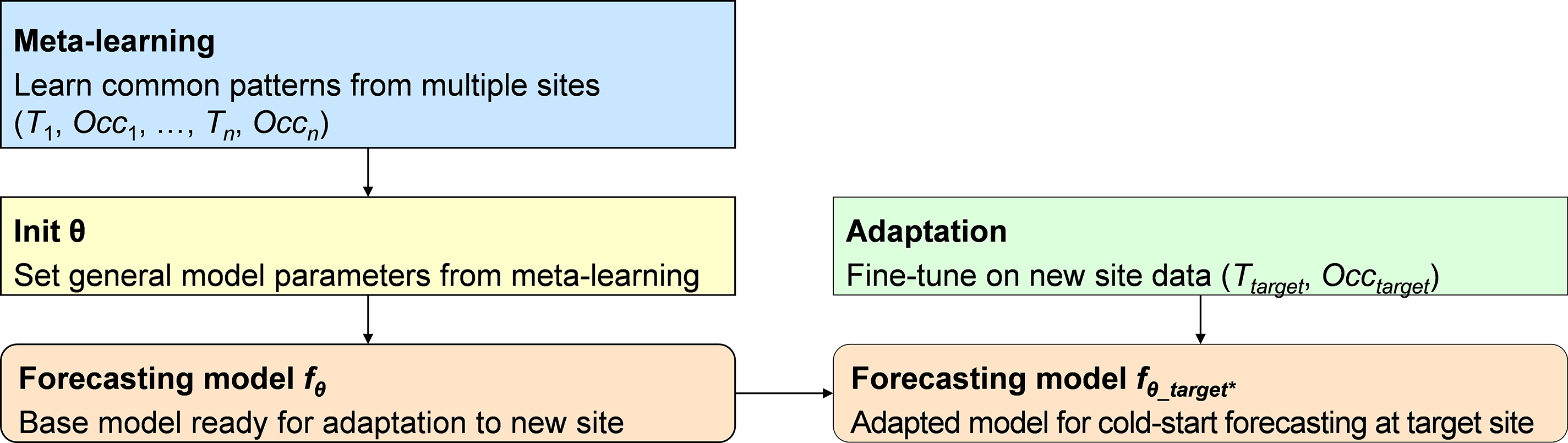

Finn et al. [70] introduced MAML by explicitly optimizing Eqs. (1) and (2) with convolutional classifiers, sinusoid regressors, and policy-gradient agents. Because Eq. (1) uses only one to five examples per task, the tasks could demonstrate state-of-the-art few-shot image classification and markedly faster fine-tuning of reinforcement-learning policies. Crucially, the algorithm is model-agnostic (i.e., any network that admits backpropagation can be integrated into the two-line loop), making the method a standard benchmark for research on rapid adaptation. The algorithmic structure of this approach is visualized in Fig. 6, which explicitly maps the transition from global initialization to task-specific parameters.

Figure 6: Model-agnostic meta-learning-based cold-start forecasting pipeline. A model is trained on source tasks to learn a general initialization θ, θ yield an adapted forecaster fθ∗target

As illustrated in the figure, the MAML algorithm consists of two alternating optimization steps that cycle between task-specific adaptation and global refinement:

Eq. (1) represents the inner-loop adaptation shown in the diagram, where the global initialization (

Ssekulima et al. [55] employed the same mechanics in short-term electric load forecasting using the meta-artificial neural network (Meta-ANN). A long-horizon base ANN first absorbs multiyear Belgian grid data to capture trends and seasonality. Just before each daily forecast, an error-correction module applies Eq. (1) to the previous day’s residuals, recalibrating the model with only a few fresh observations. Joint training via Eq. (2) allows Meta-ANN to outperform the conventional ANN and statistical baselines consistently, confirming that the fast-adaptation principle of MAML extends smoothly from controlled vision benchmarks to nonstationary energy time-series.

This study demonstrates that the inner/outer-loop paradigm of MAML transfers from vision and reinforcement learning to real-world energy time series, achieving meaningful accuracy increases with minimal daily adaptation. Meta-learning remains effective using only simple, interpretable input (calendar and lagged load) even in low-dimensional settings, supporting zero- or few-shot learning, as real deployments often lack sufficient labeled data per site or day, but demand rapid adaptation from limited recent observations.

Zero-shot forecasting refers to the application of a pretrained model to a new domain without additional fine-tuning or local gradient updates [71]. Rather than retraining, the model relies on patterns learned from previous datasets, assuming that the structural characteristics of the new task are sufficiently represented in the original training space. This method draws inspiration from the behavior of LLMs, which can often respond to novel prompts by generalizing from prior knowledge alone [72]. When structural alignment exists, zero-shot forecasts can yield credible output even without site-specific data.

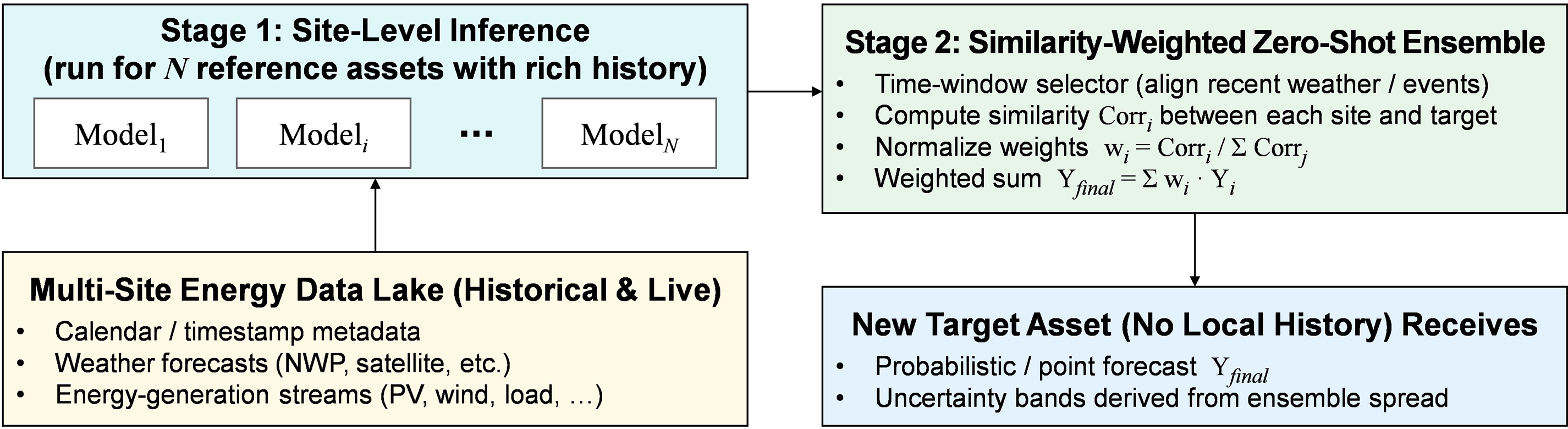

Crucially, performance tends to degrade gracefully, rather than fail completely, when the target domain differs from the source [73]. The operational logic of the zero-shot procedure is illustrated in detail in Fig. 7 [59]. As depicted, the framework begins by evaluating similarity scores between the target site and a library of reference locations using meta-level descriptors. These similarity measures act as adaptive weights, enabling the model to assemble a target-aware predictor through a selective aggregation of the most relevant source models. By constructing this weighted ensemble, the system can produce actionable forecasts even in the absence of initial on-site telemetry, thereby circumventing the conventional data accumulation period required by standard approaches.

Figure 7: Correlation-weighted zero-shot ensemble for rapid, cold-start energy forecasting

Park et al. [59] illustrated this phenomenon (i.e., zero-shot forecasting) in the energy domain by implementing a correlation-weighted RNN trained on eight PV sites for a ninth site, without local data use. Without target samples, the mean absolute error (MAE) of the model was reduced by 34% compared to the baseline. In a broader context, Oreshkin et al. [74] introduced a residual-meta architecture based on N-BEATS (short for Neural Basis Expansion Analysis for interpretable Time-Series forecasting), trained across a collection of diverse univariate time-series (e.g., electricity demand and commodity indices) and demonstrated that, even in zero-shot mode, their framework matched or outperformed classical methods (e.g., ARIMA and exponential smoothing) on many of these datasets.

Such zero-shot capabilities are relevant in operational settings where data may be sparse or temporarily unavailable. This outcome underscores the efficacy of structured, multisite pretraining. For instance, during natural disasters that disrupt supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) connectivity, a pretrained model can be rapidly deployed to maintain forecast continuity until local telemetry is restored [75]. In scenarios where even minimal local data collection is feasible, few-shot adaptation offers a compelling compromise, retaining most of the efficiency of zero-shot transfer while significantly increasing accuracy with just a few target-specific observations.

Few-shot forecasting is the process of applying a model that has been exposed to a limited number of labeled instances from the target domain [76]. In most cases, the number of labeled instances is less than 30, and the model uses these instances to perform a form of lightweight adaptation, often updating only a subset of parameters. Mathematically, this process can be interpreted as an empirical Bayes update, where the pretrained model provides a strong prior and a few steps of stochastic gradient descent refine the posterior toward the target distribution [77].

A substantial body of recent research has validated the efficacy of this approach. Ren et al. [60] proposed FTRA (short for Feature Transfer and Rapid Adaptation), a hybrid of TL and Reptile meta-learning, which achieved a maximum reduction of up to 19% in MAE with as few as 10 days of training data in solar power forecasting. Ouyang et al. [62] developed a feature-adaptive framework (FAF) with a modular architecture that disentangles global and local features via a rank-based adaptation layer, yielding a 42% generalization gain across five public datasets, including electricity, carbon emissions, and traffic flows. Tsoumplekas et al. [63] introduced a MAML-GRU framework that enhanced forecasting accuracy by 12.5% on 96 residential load time-series and proposed a novel evaluation metric tailored to the demand-side variability.

From an engineering perspective, few-shot methods are preferred in settings with microgrids or behind-the-meter devices capable of uploading limited daily data [78]. For example, a 10-day period of hourly measurements results in 240 labeled rows, which is sufficient for collection during a single site visit. This measurement volume is sufficient for a meta-trained model to reduce the error by nearly half compared to zero-shot deployment. Hence, few-shot learning offers a pragmatic intermediate solution by maintaining the plug-and-play nature of zero-shot models while achieving substantially higher accuracy when a modest amount of local supervision is accessible.

3.4 Advanced Meta-Learning Frameworks

Meta-learning has advanced beyond parameter initialization to richer architectures that explicitly model the structure of temporal forecasting tasks. A notable example is FAF, which separates knowledge into two components: a generalized module capturing global patterns shared across tasks and a task-specific module tailored to local characteristics [62]. During adaptation, a lightweight ranker selectively activates the most relevant functional regions, allowing the model to integrate both generalized and task-specific knowledge. FAF achieved substantial accuracy gains across diverse datasets—including electricity, CO2, and traffic—outperforming the best baseline (iTransformer) by up to 41.8% on CO2 data, underscoring its effectiveness for few-shot, multi-task forecasting.

A different approach treats meta-learning as an automated model selection rather than as a parameter adaptation. Li et al. [64] introduced a meta-learning-based model selection framework that recommends up to three optimal load forecasting models per task using input series summary features. This automated approach streamlines deployment and reduces average MAPE from 0.188 to 0.143, making it highly practical for real-world applications with diverse forecasting needs.

Another innovation lies in spatially aware meta-learning. Wang et al. [66] combined a self-attention–enhanced spatiotemporal LSTM with MAML, enabling efficient adaptation to new wind farm conditions with minimal training data. Their framework outperformed baselines on both onshore and offshore wind datasets, demonstrating significant gains in forecasting accuracy and robustness, particularly under data-scarce conditions.

Together, these frameworks reveal how meta-learning can be extended beyond initialization to architecture-level design, model selection, and spatial reasoning. In practice, these frameworks indicate a hybrid deployment strategy: begin with zero-shot forecasting when no target data are available, adopt few-shot updates as small batches accumulate, and shift to full retraining once sufficient historical data and computational resources permit it [79]. This layered approach balances accuracy, responsiveness, and operational constraints in real-world forecasting systems.

4 Transfer Learning in Cold-Start Forecasting

Real-world energy forecasting projects often begin in a data-poor regime. New sites may have no or only a few days of telemetry. In such cold-start settings, full meta-training across dozens of related tasks, as required by MAML, is rarely practical. However, TL offers a compelling alternative: it applies a forecasting model pretrained on a single, well-instrumented source domain (e.g., a decade of SCADA data from a utility-scale PV site) and repurposes it for new targets via simple strategies (e.g., weight freezing, gradual fine-tuning, or inserting lightweight adapters) [14]. Thus, TL provides a low-barrier path to meaningful accuracy, even when labeled target data are extremely limited.

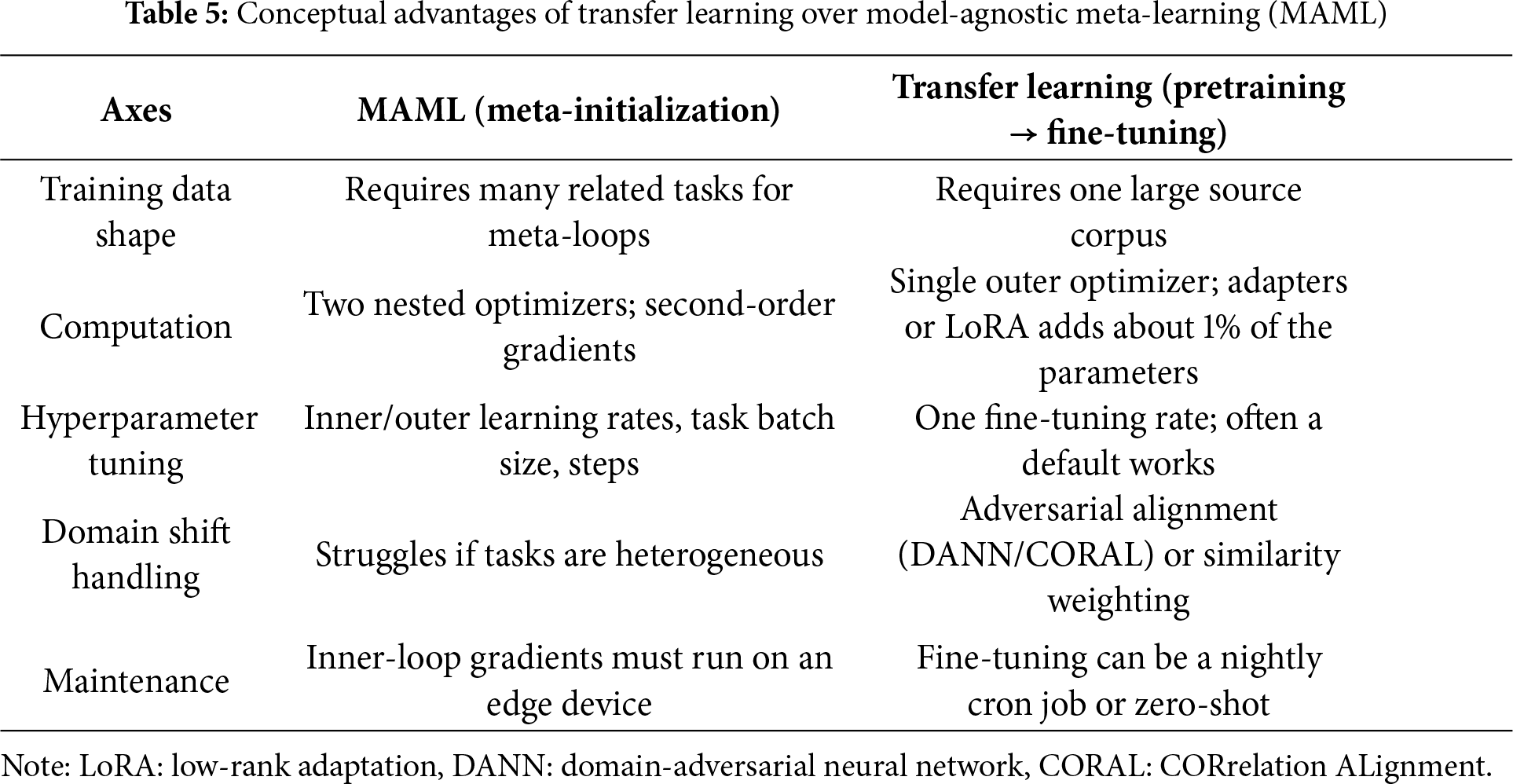

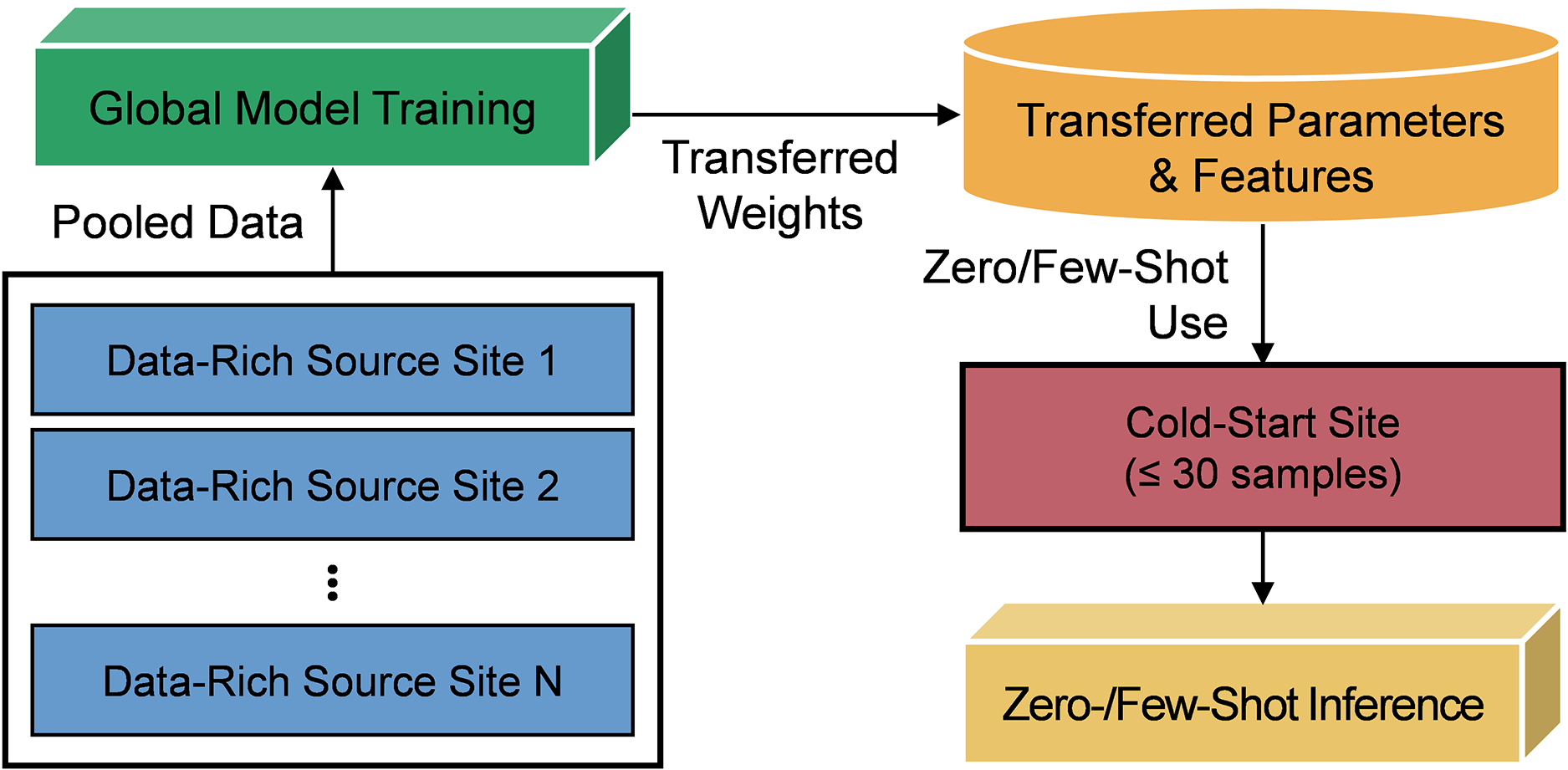

Table 5 contrasts the two paradigms across operational axes (e.g., data requirements, computational demands, and update flexibility) to clarify how TL differs from meta-learning in real-world deployments [80]. While MAML excels when task diversity is available and adaptation speed is critical, TL minimizes complexity by working with a single source dataset, avoiding inner-loop gradient calculations, and requiring minimal hyperparameter tuning. Fig. 8 maps the trade-offs between TL and MAML by situating both methods along the axes of data availability and computational burden [81]. The visualization makes it clear that MAML sits in the high-adaptability region, reflecting its strength in rapidly generalizing across heterogeneous tasks, yet this advantage comes with considerable computational expense. TL, by contrast, occupies a more resource-efficient region of the diagram, making it a practical choice when computational budgets are tight—even when only a modest number of training samples are available. This contrast establishes a straightforward decision boundary for practitioners weighing flexibility against efficiency in cold-start forecasting settings.

Figure 8: Operational tradeoffs between transfer learning and model-agnostic meta-learning in cold-start energy forecasting

4.1 Mathematical Formulation of Fine-Tuning

To formalize the mechanics of TL, we define the standard fine-tuning step commonly employed in cold-start energy forecasting scenarios. In Eq. (3), a model pretrained on a source domain is updated via a single gradient descent step on the target-site loss:

In this formulation,

This simplicity is advantageous in energy forecasting, where computational constraints often preclude complex meta-learning pipelines. Fine-tuning can be performed by fully updating all weights, partially unfreezing selected layers, or inserting lightweight modules, including adapters or low-rank adaptation (LoRA) [82]. Because the procedure is efficient and scalable, it enables routine on-device updates as new measurements arrive, making it suitable for incremental personalization in grid operations, building-control systems, or remote energy assets.

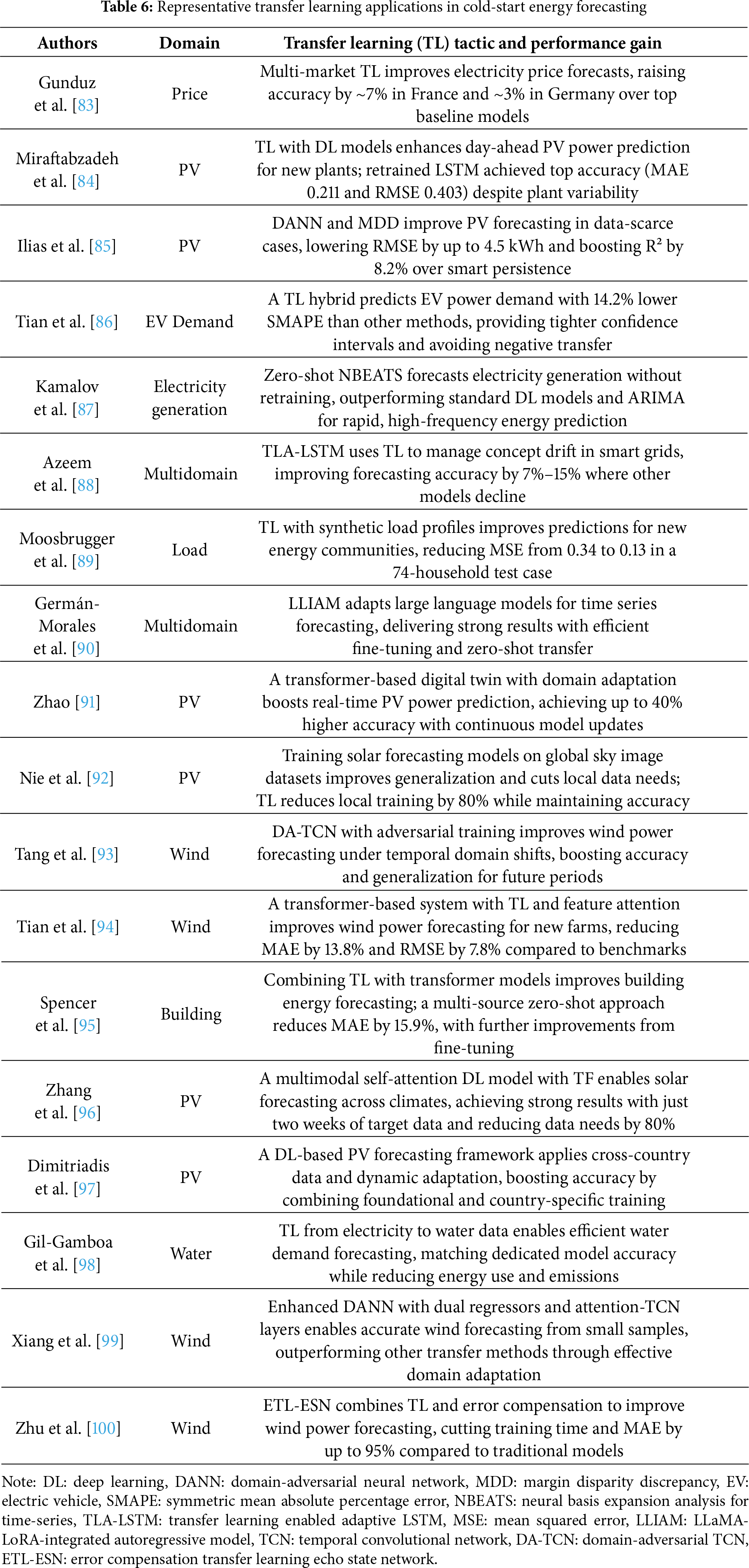

4.2 Representative Case Studies

To ground the conceptual differences highlighted in Table 6 with practical evidence, we present recent studies that apply TL across diverse energy forecasting domains. These case studies demonstrate how TL techniques, from classic fine-tuning to advanced domain adaptation, yield tangible performance gains under real-world constraints.

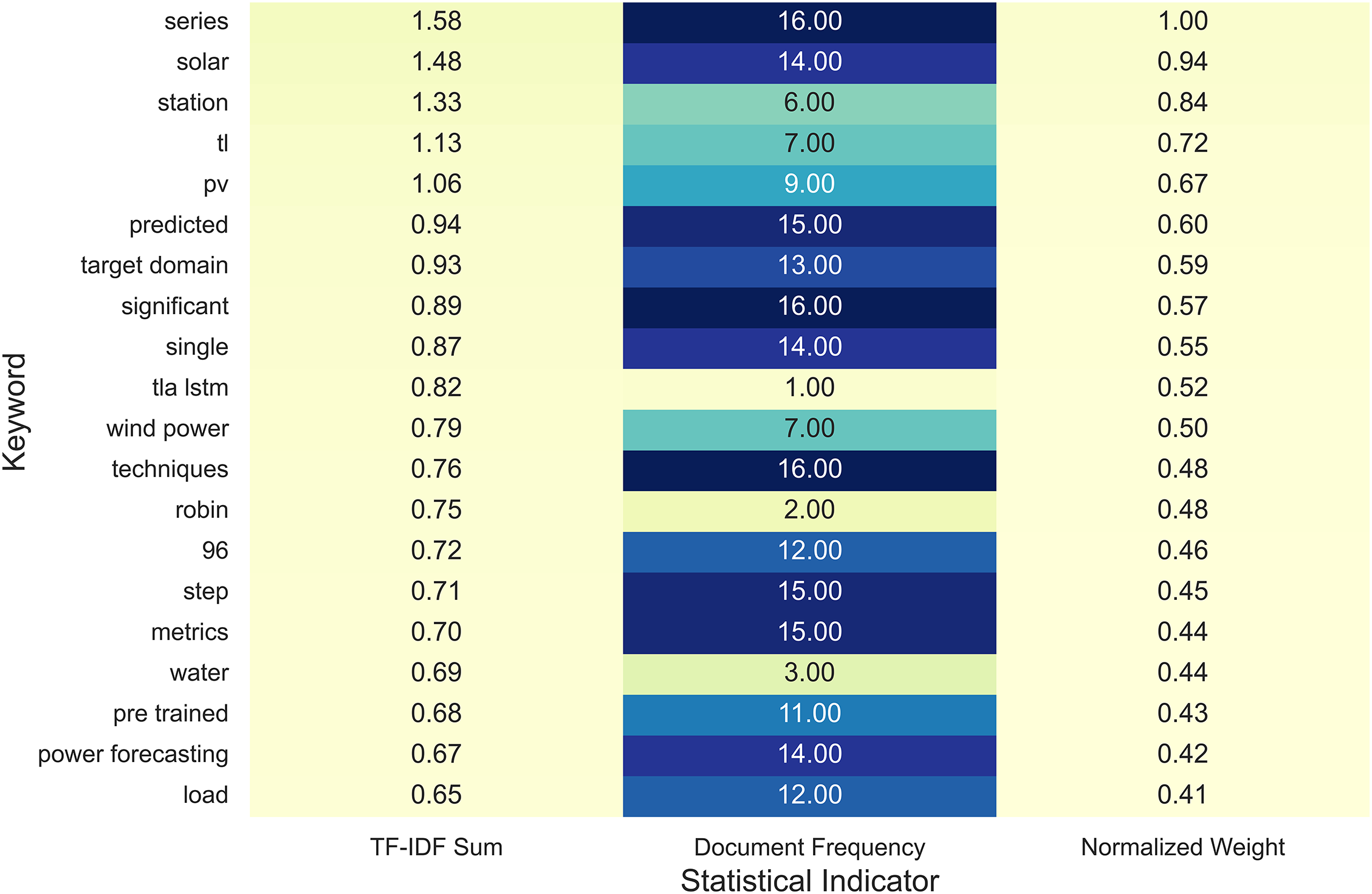

To connect the conceptual overview in Table 6 with practical linguistic evidence, Fig. 9 illustrates the distribution of high-frequency terms that characterize recent TL studies in energy forecasting. This figure serves as a complementary perspective, showing how researchers across different domains—such as PV, wind, load, and water forecasting—tend to share a common technical vocabulary when applying TL in data-scarce or cold-start conditions.

Figure 9: Representative keyword distribution in transfer learning-based energy forecasting studies

The most salient keywords, including series, solar, station, and predicted, emphasize TL’s focus on structured time-series modeling and site-level forecasting. In addition, words like domain, adaptation, and fine-tuning frequently appear, suggesting that modern TL research increasingly targets domain shift mitigation, temporal robustness, and lightweight model reuse rather than simple parameter transfer. Such trends echo the findings in Table 6, where TL has been successfully employed across a wide range of energy applications—from photovoltaic and wind prediction to water demand and building load forecasting—each achieving measurable accuracy gains under constrained data environments.

Taken together, the linguistic distribution in Fig. 9 highlights a clear shift toward transferable, resource-efficient modeling practices. By linking language usage to observed methodological outcomes, this analysis underscores TL’s growing relevance as a pragmatic approach for real-world energy forecasting, offering fast adaptability and reliable performance without excessive retraining.

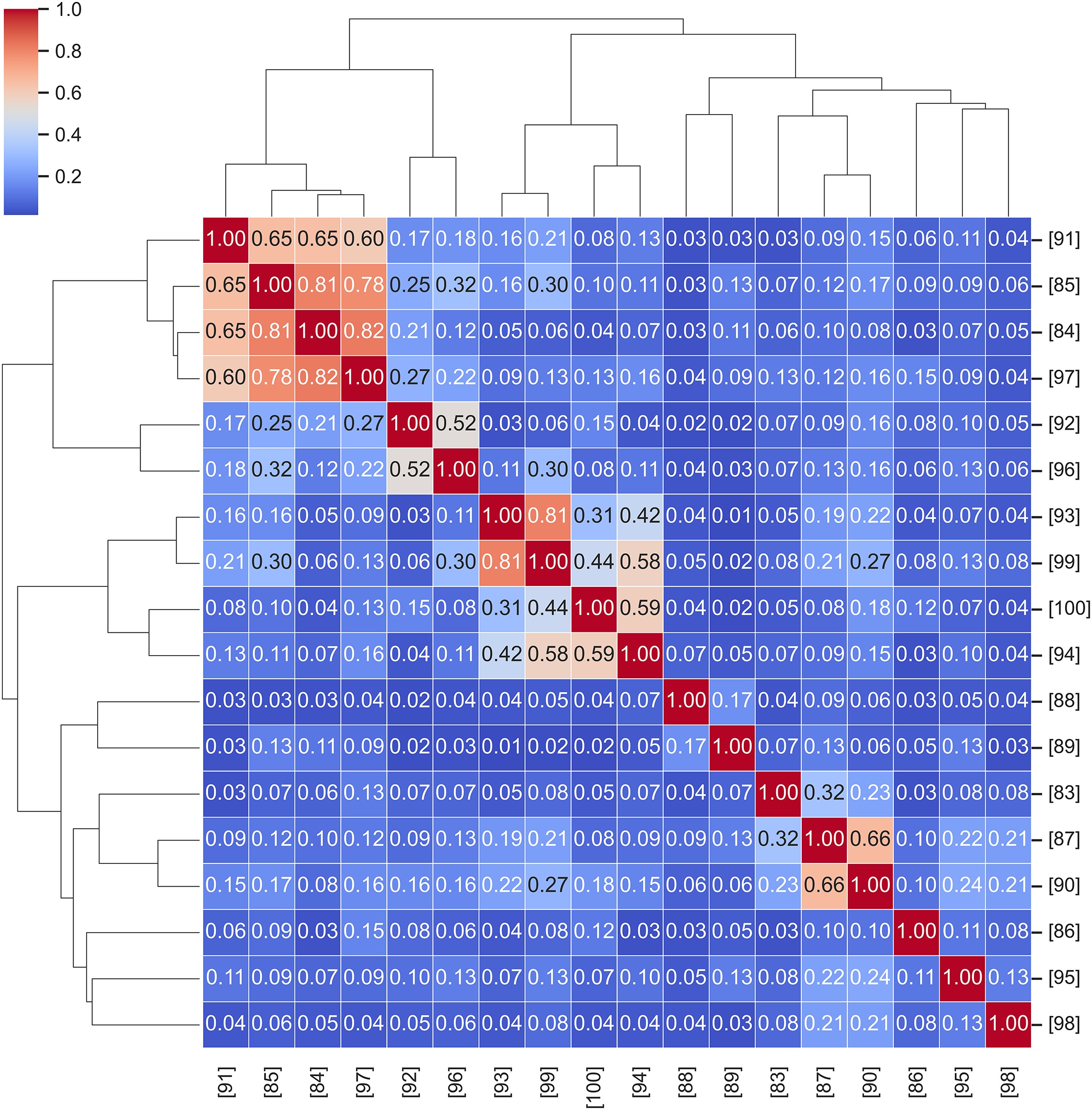

To further interpret the shared structure among recent TL studies, Fig. 10 visualizes their pairwise similarity using a hierarchical clustering approach based on cosine distance and Ward linkage. This analysis provides a document-level perspective, grouping publications that exhibit comparable linguistic and methodological patterns derived from their full-text content.

Figure 10: Hierarchical similarity map among transfer learning studies

As illustrated, several clusters emerge with clear topical coherence. For example, studies [84,85,91] form a tight cluster, reflecting their focus on PV power forecasting with domain adaptation and digital-twin frameworks. Similarly, [93,94,99,100] align under wind forecasting applications, where adversarial or temporal adaptation techniques (e.g., DA-TCN, attention-based transfer) dominate. In contrast, papers such as [94,97] display moderate linkage to both wind and PV groups, suggesting hybrid or cross-domain architectures that integrate features from multiple forecasting contexts.

This hierarchical organization quantitatively reinforces the narrative outlined in Table 6—showing that TL studies, despite their diversity of datasets and architectures, tend to converge around a few dominant methodological axes: domain adaptation, temporal generalization, and cross-modal transferability. By mapping textual coherence to research themes, the figure helps readers identify conceptually related works and navigate the literature more effectively. It also demonstrates that the reviewed corpus forms a consistent and interconnected body of research rather than a set of isolated case studies.

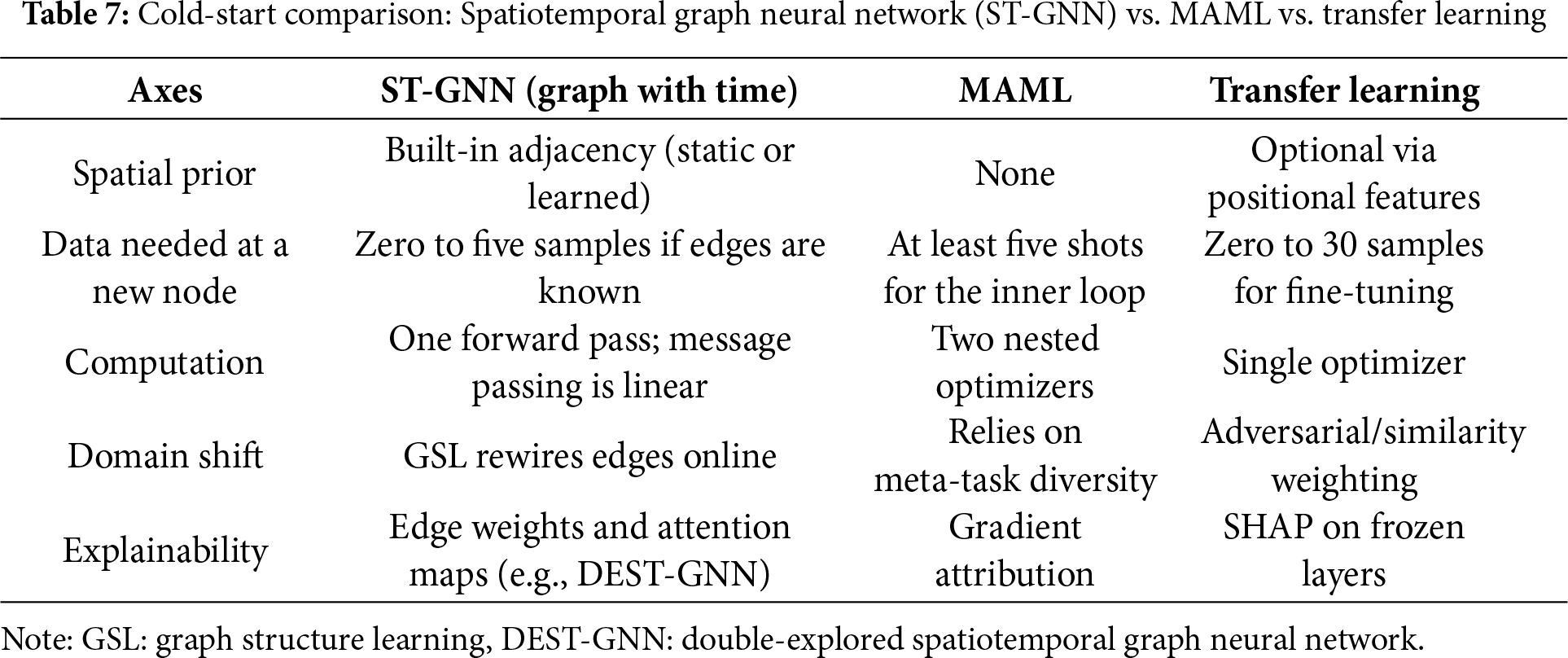

To provide a more intuitive view of the conceptual space formed by recent TL studies, Fig. 11 projects the major keywords into a two-dimensional landscape using PCA combined with cosine similarity. This visualization reveals how methodological and application-level terms co-locate, indicating shared thematic structures within the reviewed literature.

Figure 11: Keyword landscape of transfer learning studies in energy forecasting

The figure separates two broad clusters. The right-hand group (Cluster 0) centers on series, techniques, metrics, and power forecasting, capturing the statistical and procedural language typical of TL implementations for predictive modeling. In contrast, the left-hand group (Cluster 1) gathers around TL, TLA-LSTM, load, water, and station, reflecting studies emphasizing domain adaptation, resource management, and cross-modal transfer between heterogeneous data sources. Intermediate regions link target domain, source domain, and pre-trained—key bridging terms that represent how TL frameworks translate knowledge from one operational setting to another.

By combining linguistic frequency with geometric proximity, Fig. 11 complements the hierarchical patterns shown in Fig. 10. It illustrates how TL research forms a continuous semantic field rather than isolated topical fragments, demonstrating strong internal consistency across applications and methodologies. Such an integrated representation assists readers in recognizing conceptual neighborhoods, helping identify which approaches share transferable principles and which remain domain-specific.

In PV forecasting, Zhang et al. [96] showed that effective weight transfer enables PV forecasting models to adapt from stable to highly variable regions such as Nottingham, UK. Transfer learning significantly cuts training time and data needs while maintaining high accuracy, highlighting its value for robust solar forecasting across diverse climates.

In wind energy, Tang et al. [93] tackled temporal domain shifts in wind power forecasting by combining adversarial training with a temporal convolutional network (DA-TCN). Their approach, which splits training data into temporal domains and jointly optimizes for forecasting and domain discrimination, achieved robust generalization and outperformed benchmarks on real turbine data, showing superior accuracy and stability under changing temporal distributions.

Zhu et al. [100] proposed the error compensation transfer learning echo state network (ETL-ESN) model, which combines error compensation with transfer learning to improve wind power prediction. On the Spatial Dynamic Wind Power Forecasting (SDWPF) dataset, ETL-ESN reduced MAE by up to 98% vs. LSTM and other benchmarks and consistently achieved lower RMSE, demonstrating strong adaptability and reliability for large-scale wind farms.

Across other domains, TL continues to prove versatile. Studies on energy efficiency prediction in petrochemical processes have applied partial layer freezing to balance accuracy and training speed [101]. Digital twin-based transformers can learn domain-invariant features for PV [91], and energy-aware pruning in water metering tasks achieves substantial computational savings without loss of accuracy [98]. Even in zero-shot scenarios (e.g., N-BEATS forecasting of electricity prices with no target data), TL-based initializations deliver competitive MAPE values [87]. Collectively, these cases underscore the adaptability of TL across modalities, time scales, and sensor resolutions. Whether minimizing training costs, accelerating inference, or bridging domain shifts, TL provides a consistent performance benefit, especially in cold-start and resource-constrained environments [102].

4.3 When and Why Transfer Learning Excels

Although meta-learning frameworks (e.g., MAML) provide elegant solutions for fast adaptation, they may not consistently align with the constraints of real-world energy systems [69]. Scenarios involving sparse labels, limited computational budgets, or nonstationary environments often favor TL due to its operational simplicity and adaptability, as TL handles asymmetric data availability more naturally [103]. When only a single rich source corpus is available (e.g., a national SCADA archive), TL can apply it directly, whereas MAML may struggle to generalize with insufficient task diversity. In domains where broad environmental shifts (e.g., seasonal climate changes) are more significant than per-site idiosyncrasies, TL enables explicit distribution alignment via adversarial or similarity-based methods, bypassing the assumption of shared task support that is often embedded in meta-learning [104].

Moreover, TL is well-suited for edge deployment because it requires only a single forward-backward pass per update [105]. Parameter-efficient techniques (e.g., LoRA or adapter modules) can be added with minimal overhead, typically less than 1% of the original parameter count. This lightweight nature contrasts with the memory and computational demands of MAML, which must retain inner- and outer-loop gradients and often requires second-order optimization. Moreover, TL simplifies model maintenance. Fine-tuning can be scheduled as a routine task using cron jobs, without the need for specialized task construction or nested learning rate tuning.

Recent meta-learning approaches for few-shot fault diagnosis highlight this trade-off between adaptability and efficiency. For instance, Zhang et al. [106] proposed an MAML framework for few-shot bearing fault diagnosis, achieving up to 25% higher accuracy than Siamese-network benchmarks and demonstrating strong generalization to new and real faults. Similarly, Zheng et al. [107] developed an improved meta-relation network (IMRN) that leverages multiscale feature encoding and relation-based metric learning; tested on three public datasets, IMRN outperformed other few-shot methods, offering robust and adaptable fault classification with limited data.

The TL method continues to evolve in tandem with broader trends in DL, offering exciting opportunities for the energy domain. One emerging direction is applying foundation models for time series, where large-scale self-supervised pretraining across multiple domains is followed by lightweight task-specific adaptation. For instance, the LLaMA-LoRA–integrated autoregressive model (LLIAM) [90] showed that foundation models pretrained on diverse data can be efficiently adapted for time-series forecasting using lightweight methods such as LoRA. This approach achieves high accuracy and strong generalization with minimal tuning, underscoring the potential of large-scale pretraining followed by efficient adaptation for energy forecasting tasks.

Cross-modal transfer is another promising method. For example, Nie et al. [92] demonstrated that pretraining solar forecasting models on large, multi-location sky image datasets and fine-tuning with limited local data enables robust irradiance prediction, even with 80% less local data than conventional methods. Likewise, Moosbrugger et al. [89] found that transferring from synthetic to real load profiles in energy communities can substantially reduce prediction error (lowering MSE from 0.34 to 0.13), enabling accurate forecasts despite scarce real data. These findings underscore the value of leveraging information across modalities or domains to improve forecasting accuracy and data efficiency.

The TL method prioritizes practicality over complexity, avoiding nested optimization loops in favor of a single, scalable pipeline. This method requires fewer hyperparameters, fits on smaller devices, and begins generating useful forecasts from Day 1. When task diversity is scarce but unlabeled or synthetic data are abundant, TL often outperforms meta-learning in accuracy and deployment speed. The following layered strategy is recommended:

• Begin with zero-shot TL at system commissioning, using a pretrained backbone;

• Begin few-shot fine-tuning after accumulating a week of local data;

• Transition to meta-learning or full retraining once seasonal shifts or operational scaling justify a deeper adaptation.

This hybrid pipeline balances accuracy, speed, and feasibility, providing a robust framework for real-world energy forecasting under evolving data conditions.

5 Graph-Based Spatiotemporal Learning for Cold-Start Forecasting

Many energy infrastructures (from wind farms to power distribution grids) naturally form spatially structured networks [108]. In such systems, the behavior of one node (e.g., a turbine or smart meter) is often shaped by its neighbors, reflecting physical couplings or shared environmental influences. Cold-start forecasting in this context presents a dual challenge: local data are sparse and the topological context may be incomplete or rapidly evolving [11,109]. Recent advances in graph-based spatiotemporal DL address this challenge by integrating two powerful priors: (1) graph topology that captures how entities interact across space and (2) temporal dynamics learned via temporal convolutional networks (TCNs), LSTM networks, or transformers. Together, these models (typically instantiated as ST-GNNs) embed structured domain knowledge directly into the architecture, enabling strong generalization even with minimal local training data [15].

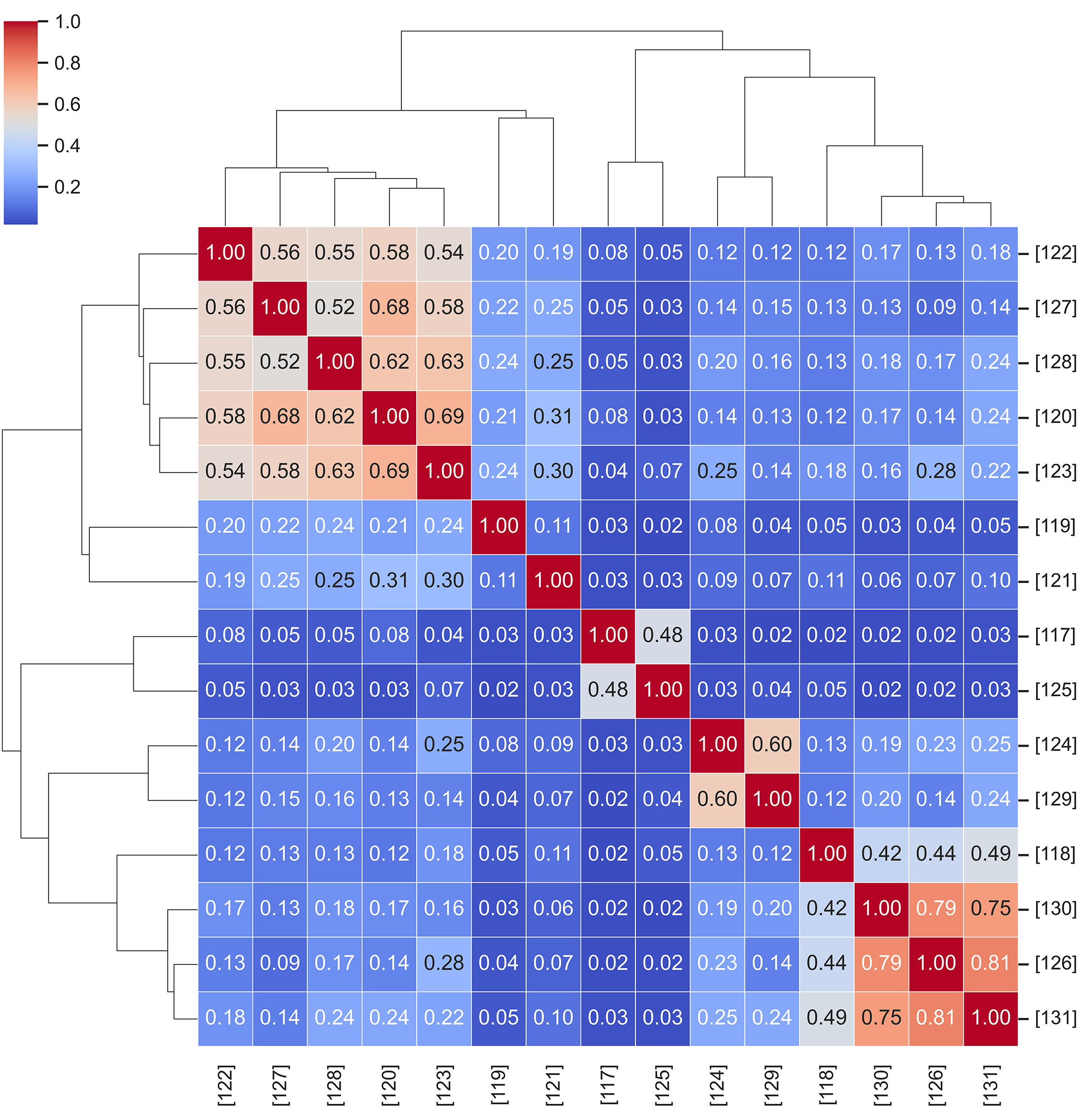

This framework offers two benefits under cold-start conditions. First, it offers relational inductive bias: by encoding who influences whom, the model avoids relearning basic correlations at every site [110]. Second, it offers edge learning modules: dynamic graph-structure learning (GSL) techniques can infer or revise connectivity patterns in real time, easing deployment in sensor-rich or rapidly changing environments [111]. Before addressing representative studies, we contrast the inductive nature of ST-GNNs with the adaptive mechanisms of MAML and TL, as introduced in the previous sections. In contrast to MAML and TL, which focus on optimizing initialization or parameter reuse, ST-GNNs derive generalization directly from the graph-aware architecture [112]. This section conceptually contrasts these approaches, and Table 7 summarizes their cold-start capabilities, focusing on spatial priors, computational efficiency, and adaptability to unseen nodes.

5.1 Spatiotemporal Propagation: Equation and Application

The ST-GNN is a class of models designed to capture spatial dependencies jointly between entities (e.g., PV sites, wind turbines, or distribution feeders) and temporal dynamics in their measurements [113]. By encoding the network topology and time-series history, ST-GNNs provide a rich inductive prior that is suitable for cold-start energy forecasting [114]. With little or no local data, forecasts remain feasible by drawing on information from neighboring nodes. In practice, the input to an ST-GNN comprises a feature matrix Xt for each time step t (e.g., lagged load, irradiance, and calendar features), paired with a graph structure A that describes the inter-node relationships [115]. The output is typically a multivariate forecast vector (e.g., load or generation for the next 1 to 24 h) for each node. Crucially, even if one node has no history, it can still participate in the prediction process via message passing from its neighbors.

A standard layer in these models integrates spatial and temporal components. Many architectures apply a TCN over past measurements to extract local trends and combine this with graph-based aggregation across nodes [115,116]. This layered operation is expressed in Eq. (4):

where

The first term in Eq. (4),

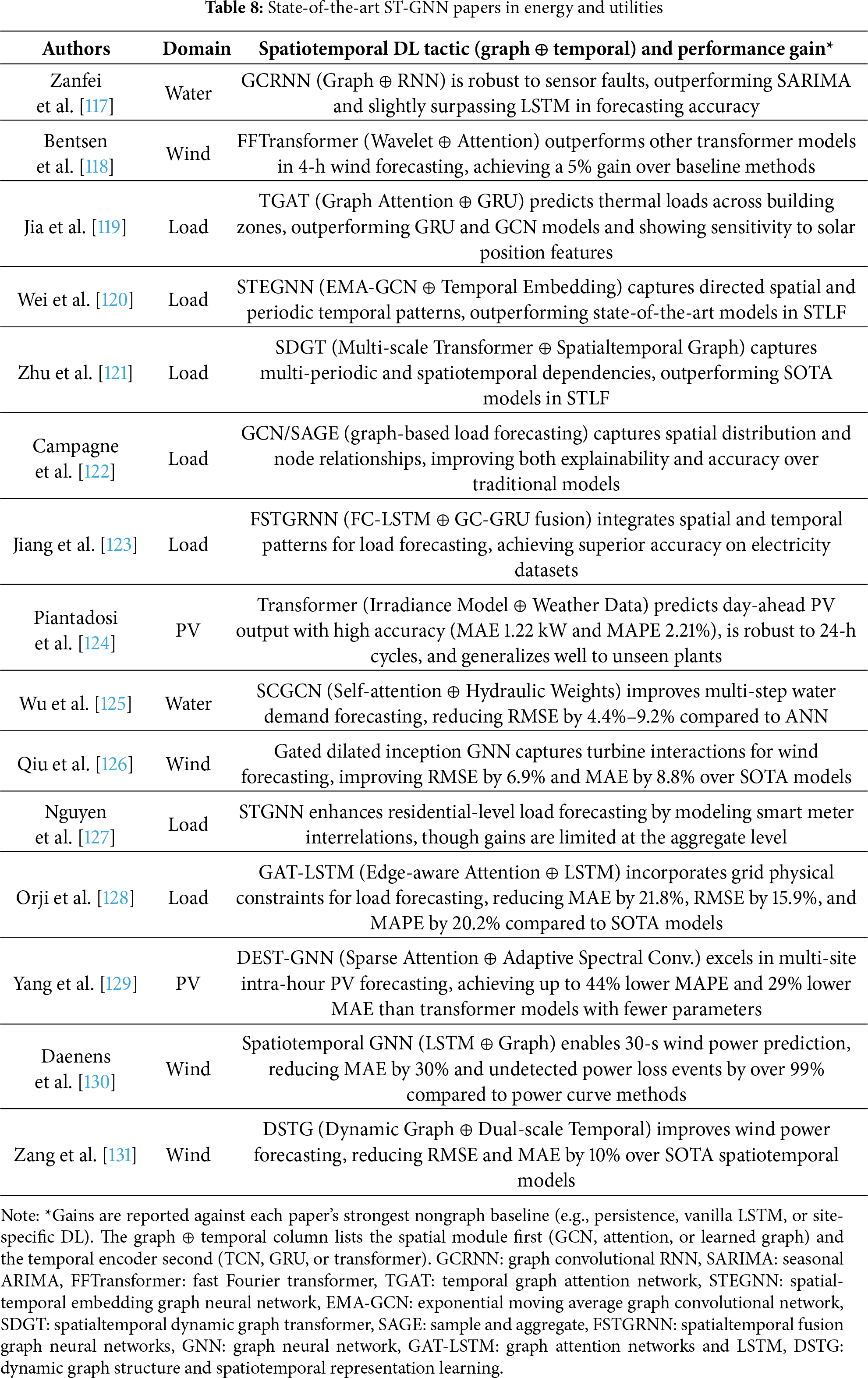

5.2 Representative Spatiotemporal Graph Neural Network Case Studies

The studies summarized in Table 8 describe recent advances that integrate graph-based relational priors with deep temporal encoders to improve cold-start forecasting across domains, including PV generation, wind power, grid load, and urban water demand. Each model applies spatial relationships derived from physical proximity, electrical topology, or data-driven edge inference to enable predictive reasoning across nodes, even when local labels are sparse or unavailable. These architectures exemplify the potential of spatiotemporal graph learning to generalize in low-data regimes by embedding the structural context directly into the model design.

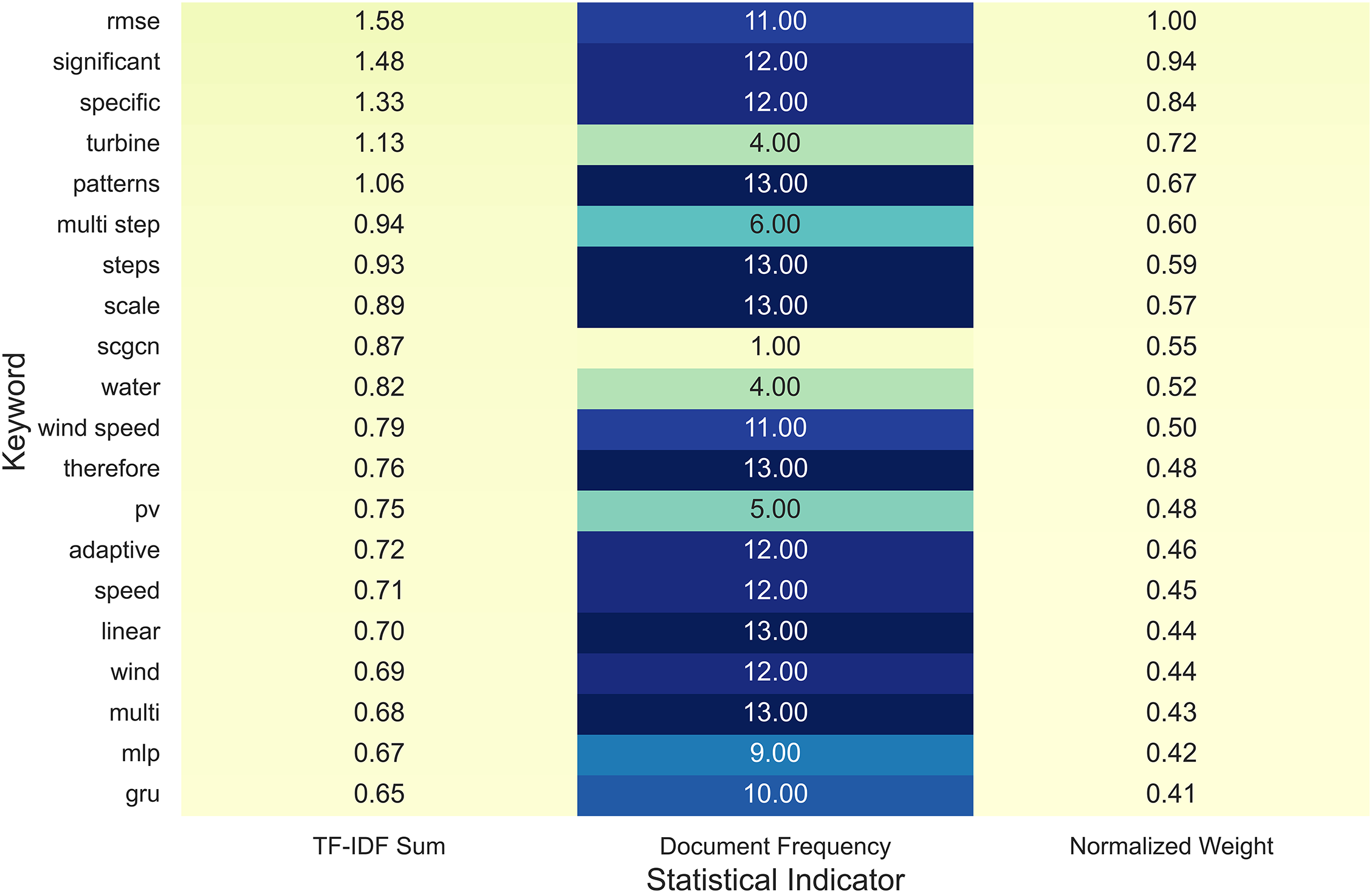

To highlight emerging trends in graph-based spatiotemporal learning for cold-start forecasting, Fig. 12 presents a statistical summary of the twenty most dominant keywords identified from recent literature. The results reveal how research priorities have shifted from purely temporal architectures toward graph-aware models that encode spatial structure and relational dynamics.

Figure 12: Quantitative summary of dominant keywords in graph-based spatiotemporal learning for cold-start forecasting

Among the leading terms, RMSE, significant, and specific exhibit the highest normalized weights, indicating the community’s increasing focus on quantitative error minimization and statistically interpretable performance metrics. Meanwhile, patterns, multi-step, and scale frequently appear in studies that model hierarchical temporal sequences within spatially coupled sensor networks, suggesting that multi-horizon prediction remains central to ST-GNN design. Notably, SCGCN, wind speed, and PV appear alongside adaptive and linear, signifying the convergence of graph convolution, temporal adaptation, and energy-domain specialization within a unified spatiotemporal framework.

This distribution supports the conceptual contrast outlined in Table 7—showing that, unlike meta- or transfer learning approaches that rely on parameter reuse, graph-based models derive generalization directly from encoded topology and message passing. The quantitative evidence in Fig. 12 thus substantiates the dual inductive bias of modern ST-GNNs: (1) relational coupling among spatial entities and (2) temporal pattern extraction across dynamic contexts. Together, these properties explain why graph-based architectures achieve superior adaptability in data-scarce or rapidly evolving energy systems.

To examine how recent graph-based spatiotemporal forecasting studies relate to one another conceptually, Fig. 13 presents a hierarchical similarity map derived from the cosine similarity of their TF-IDF representations. This analysis quantifies the directional alignment among papers by comparing the linguistic composition of each study, with darker red blocks indicating higher textual coherence and methodological overlap.

Figure 13: Hierarchical similarity map of graph-based spatiotemporal forecasting studies

The dendrogram structure in Fig. 13 reveals two main clusters. The upper-left branch groups studies [120,122,123,127,128] that emphasize static or semi-dynamic adjacency modeling, where spatial priors are either predefined or updated infrequently. In contrast, the lower-right cluster (e.g., [126,130,131]) aggregates works integrating GSL or attention-based edge refinement, highlighting adaptive graph construction as a key research trajectory. Intermediate clusters (e.g., [117,125]) represent hybrid configurations that combine temporal convolutional encoders with partially learnable connectivity, bridging the gap between predefined topology and fully data-driven edge inference.

These textual proximities mirror the methodological trends summarized in Table 8, suggesting that recent advances in dynamic message passing, multi-scale temporal aggregation, and edge-aware learning are increasingly interrelated across application domains such as wind, PV, and load forecasting. By embedding linguistic similarity into a hierarchical structure, Fig. 13 provides readers with a systematic guide to navigate related works—clarifying which models share comparable architectural assumptions and which diverge through novel spatiotemporal adaptations.

To visualize the conceptual structure of graph-based spatiotemporal learning, Fig. 14 depicts a two-dimensional keyword landscape projected by PCA over cosine similarity embeddings. Each point represents a high-frequency term extracted from the reviewed corpus, with color denoting its cluster membership and size reflecting relative TF-IDF weight.

Figure 14: Keyword landscape of graph-based spatiotemporal learning in cold-start forecasting

Fig. 14 separates the underlying vocabularies that shape current research trajectories. In the visualization, the orange cluster consolidates terms associated with physical system components—such as turbine and irradiance—whereas the blue cluster groups concepts tied to computational modeling, including adaptive and scale. This spatial differentiation underscores the inherently hybrid character of ST-GNNs: their effectiveness stems from weaving together physical domain insight with data-driven optimization techniques, thereby narrowing the semantic divide between engineering intuition and algorithmic learning. This side of the map highlights studies that focus on generic learning structures such as GRU, MLP, and graph aggregation, aiming to refine computational efficiency and predictive generalization under cold-start conditions.

Collectively, the spatial arrangement in Fig. 14 illustrates how energy-specific and method-oriented vocabularies converge within the modern ST-GNN framework. It visually reinforces the dual emphasis discussed in Section 5: (1) capturing spatial relationships through graph topology, and (2) leveraging adaptive temporal modules for robust, low-data forecasting. Such conceptual clustering provides empirical support for the field’s transition toward unified, cross-domain spatiotemporal learning paradigms.

The following contributions in this area are the most notable. Yang et al. [129] introduced double-explored spatiotemporal graph neural network (DEST-GNN), a graph neural network (GNN) that predicts intra-hour PV output for multiple sites by modeling spatiotemporal correlations with undirected graphs and sparse attention. On NREL datasets from Alabama and California, DEST-GNN achieved MAEs of 0.49 and 0.42, outperforming independent and fixed-graph baselines for multi-site PV forecasting.

Yu et al. [115] offered a comprehensive review in 2025, tracing how DL has reshaped time-series and spatiotemporal forecasting across sectors such as energy, weather, transportation, and healthcare. Their analysis showed that advanced models—particularly spatiotemporal GNNs and transformers—were driving clear improvements in predictive performance. The review also emphasized practical considerations, including the need for high-quality datasets, thoughtful allocation of computational resources, and attention to model scalability.

Collectively, these studies highlight a critical advantage of the ST-GNNs, their ability to embed spatial coupling directly into the model architecture, enabling meaningful predictions in low-data regimes. Rather than relying solely on fine-tuning or meta-initialization, these models use “reason over neighbors” via learned or structured graph edges, making them a suitable option for forecasting tasks where data are sparse, delayed, or partially missing.

5.3 Cold-Start Deployment Strategies with Spatiotemporal Graph Neural Networks

The ST-GNN introduces a unique architectural bias. By jointly employing a spatial structure and temporal dynamics, these types of networks bypass the need for extensive local labels during deployment, which is useful in energy applications where new sites often lack sufficient telemetry but are surrounded by well-instrumented neighbors [113]. Unlike TL or MAML, which emphasize parameter reuse or fast adaptation, respectively, ST-GNNs directly produce useful forecasts via relational reasoning encoded in graph edges [132].

In a zero-shot setup, the model employs an initial adjacency matrix derived from geographic proximity, electrical topology, or turbine layout to propagate signals via a fixed graph. Eq. (4) handles spatiotemporal aggregation without local gradient updates. As soon as a few samples are gathered, few-shot updates can refine the edge weights or temporal filters using lightweight backpropagation, avoiding the full-network fine-tuning typically required in TL. The following hybrid strategy may also be deployed: 1) initialize global parameters via TL and 2) re-weight edges via ST-GNN message passing to handle local climate or operational differences.

5.4 When and How to Integrate Spatiotemporal Graph Neural Networks

The ST-GNN outperforms TL or MAML under specific cold-start conditions. If a new node has rich neighbors (e.g., a newly added rooftop PV near existing arrays), relational message passing enables useful forecasting without meta-updates. When label scarcity is combined with stable network geometry, which is common in microgrids or industrial feeders, shared edge weights facilitate supervision transfer. Moreover, temporal convolutions allow ST-GNNs to handle subminute ramps that traditional models miss, making them suitable for high-resolution SCADA streams.

Explainability is another strength of such models. Edge attention scores in models (e.g., DEST-GNN or GAT-LSTM) reveal which nodes most influence predictions, enhancing model transparency [128,129]. These features position ST-GNNs as the middle ground between zero-shot TL and few-shot meta-learners. A layered deployment may proceed as follows: Day 0, deploy a zero-shot TL model; Hour 1, switch to a ST-GNN with a fixed graph; Week 1, initiate edge-level fine-tuning; and Season 1, consider full meta-retraining if long-term data justifies the cost. This strategy balances adaptation speed, computational efficiency, and long-term accuracy in real-world systems.

6 Synthetic-Data Generation for Cold-Start Energy Forecasting

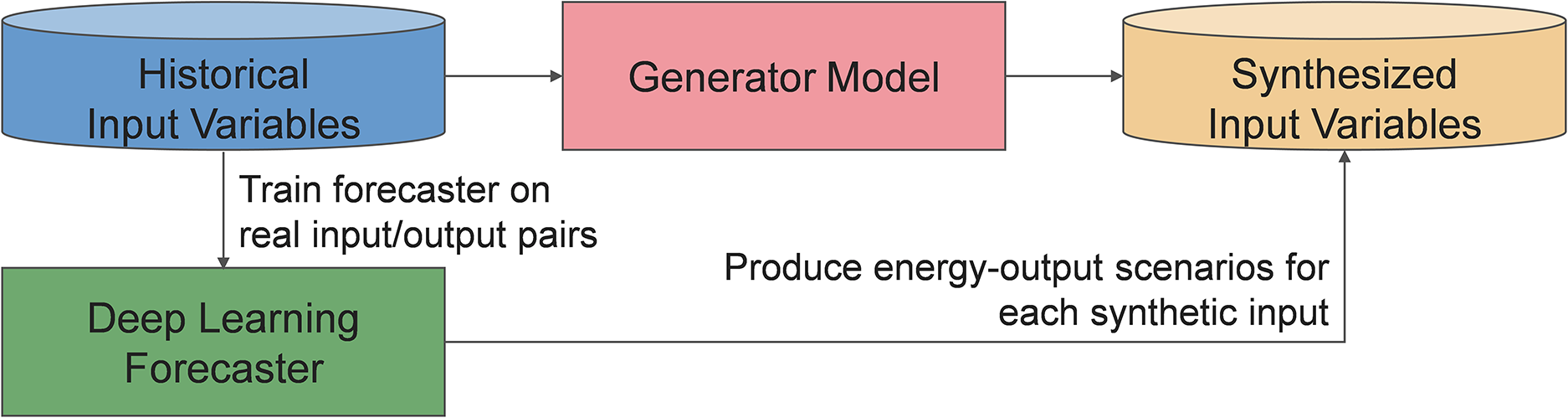

In cold-start scenarios (e.g., when a new PV site comes online and only a few hours of sensor data are logged), generative learning enhances model training by enriching the data space rather than optimizing the architecture or weights [133]. When only a single, small dataset is available and no access to related tasks or domains exists, relying solely on these limited observations causes severe overfitting. Instead, generative models synthesize plausible pseudo-data that mirror the statistical structure of the target distribution, expanding coverage before the forecaster even observes real-world samples [16].

This approach is formalized in Eq. (5), where a generative model

The resulting synthetic dataset

Figure 15: Synthetic-data pipeline for cold-start energy forecasting

This approach allows forecasting models to perform meaningfully even with minimal observed data, a critical advantage in domains (e.g., solar output, wind power, and smart-grid demand) where the ground truth is often delayed or expensive to collect. The sections below introduce critical frameworks, including generative adversarial networks (GANs), TimeGAN, diffusion, and graph-based generators, summarizing recent studies that validate these methods in energy-sector deployments [135–138].

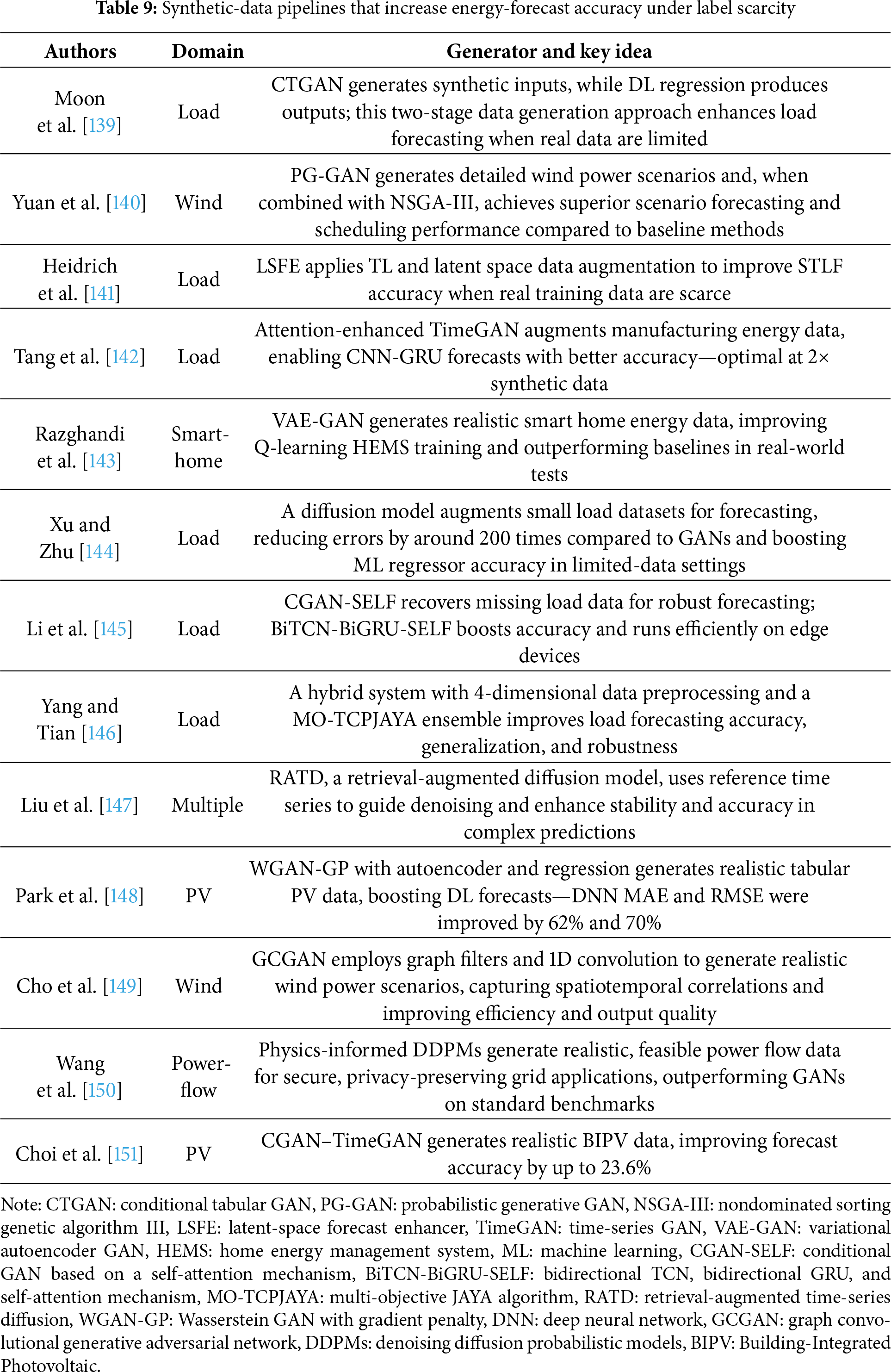

Recent literature has demonstrated the practical value of this strategy across diverse energy applications. Table 9 synthesizes 15 notable studies that apply GANs, diffusion models, and hybrid architectures to domains including PV forecasting, wind power prediction, grid load estimation, and power-flow reconstruction. Each paper quantifies the gains relative to strong nonaugmented baselines, underscoring that, even without dense telemetry, synthetic augmentation can substantially reduce forecast errors and enhance model robustness.

These recent studies collectively highlight the following five notable trends that are reshaping the role of generative learning in cold-start energy forecasting:

• Foundational evidence for GANs in tabular energy data: Early studies have established that generative models (e.g., conditional tabular GAN) can significantly reduce forecasting errors in short-term load forecasting, providing a baseline for advances in synthetic augmentation.

• Integration of physical constraints: Recent work has combined diffusion models with domain-specific knowledge, embedding power-system feasibility into generative architectures. This trend enhances the realism and operational applicability of synthetic data.

• Synergy with TL: Augmentation is increasingly employed to enrich TL pipelines. By populating latent spaces with plausible pseudo-samples, generative methods can help pretrained models generalize more quickly in cold-start settings.

• Privacy-aware augmentation: Generative techniques are also effective in privacy-sensitive contexts. For instance, synthetic consumption traces can replace raw smart-home telemetry during model training without compromising performance.

• Lightweight fallback options: Even simple hybrid schemes combining a few synthetic samples with interpolated data offer measurable improvements, especially when computation or data access is limited. This result makes generative augmentation practical even for edge deployments.

Taken together, these studies chart the progression of generative augmentation in energy forecasting, from initial gains achieved with tabular GANs to recent advances in physics-informed diffusion models and integrated hybrid pipelines that complement TL. These studies substantiate the conceptual foundations of Section 6 and provide actionable references for practitioners, modelers, and energy systems architects aiming to address data scarcity in real-world deployments.

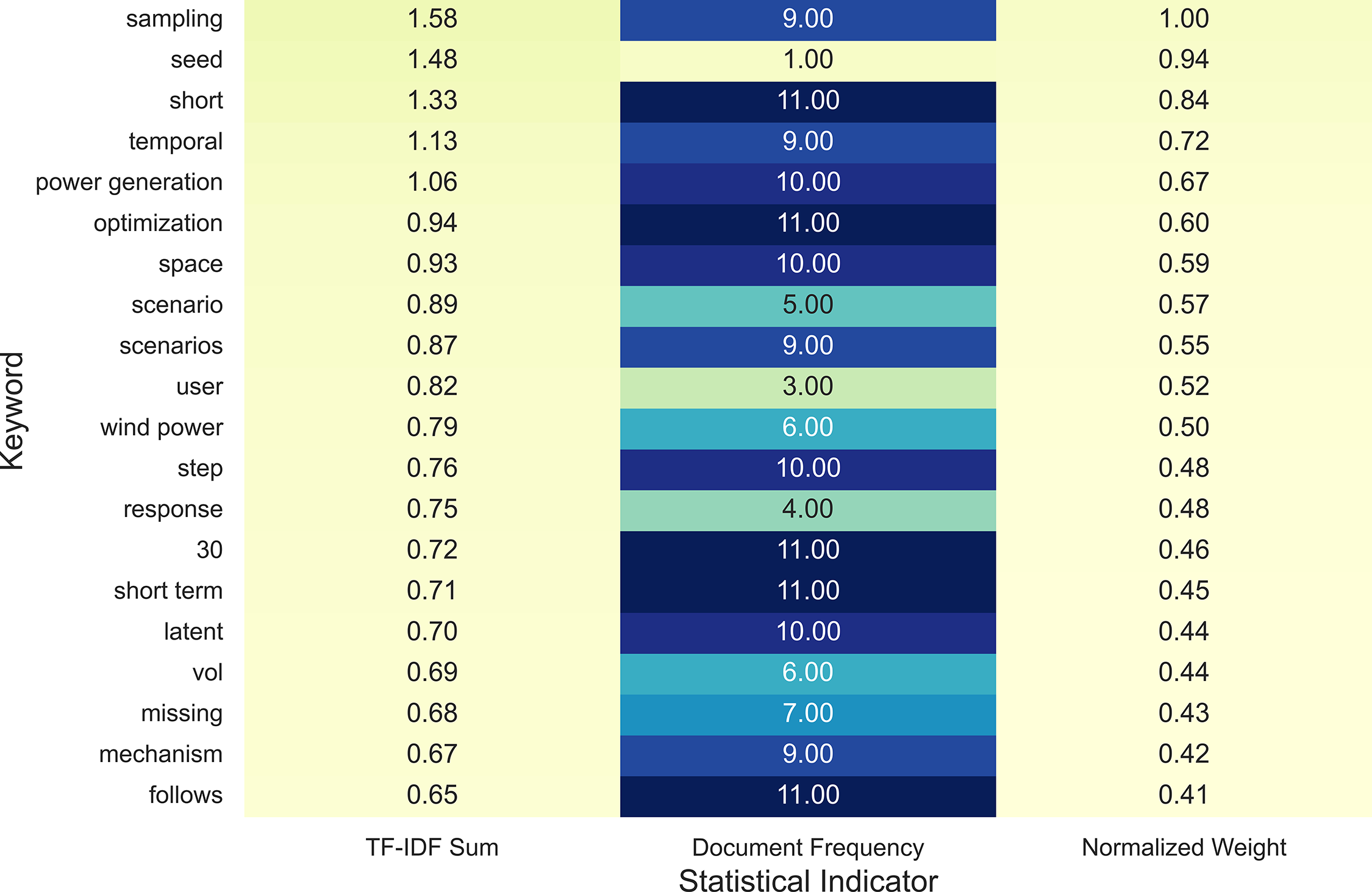

To highlight the linguistic and conceptual structure of recent research on synthetic-data generation for cold-start energy forecasting, Fig. 16 summarizes the twenty most significant keywords extracted from relevant studies. The visualization integrates three statistical dimensions—TF-IDF sum, document frequency, and normalized weight—to capture how core methodological terms recur across the literature.

Figure 16: Quantitative summary of dominant keywords in synthetic-data generation for cold-start energy forecasting

The most dominant terms, such as sampling, seed, short, and temporal, emphasize the focus on data scarcity mitigation and short-term forecasting horizons, where synthetic augmentation compensates for limited real-world observations. Keywords like power generation, optimization, and scenario appear with high statistical relevance, indicating a shift toward scenario-based modeling and physically consistent data synthesis, often combining generative and constraint-driven approaches. Terms such as response, latent, and missing reflect the emergence of latent-space modeling and data-imputation mechanisms, both essential for constructing realistic yet privacy-safe synthetic datasets.

Collectively, these linguistic patterns correspond to the practical developments outlined in Table 9, where techniques such as GAN-based tabular augmentation, diffusion-driven denoising, and retrieval-guided synthesis demonstrate measurable forecasting improvements under sparse conditions. The quantitative distribution in Fig. 16 thus reinforces the view that generative learning expands the usable data space rather than altering the predictive architecture itself, positioning it as a complementary paradigm alongside transfer and meta-learning in addressing data scarcity challenges.

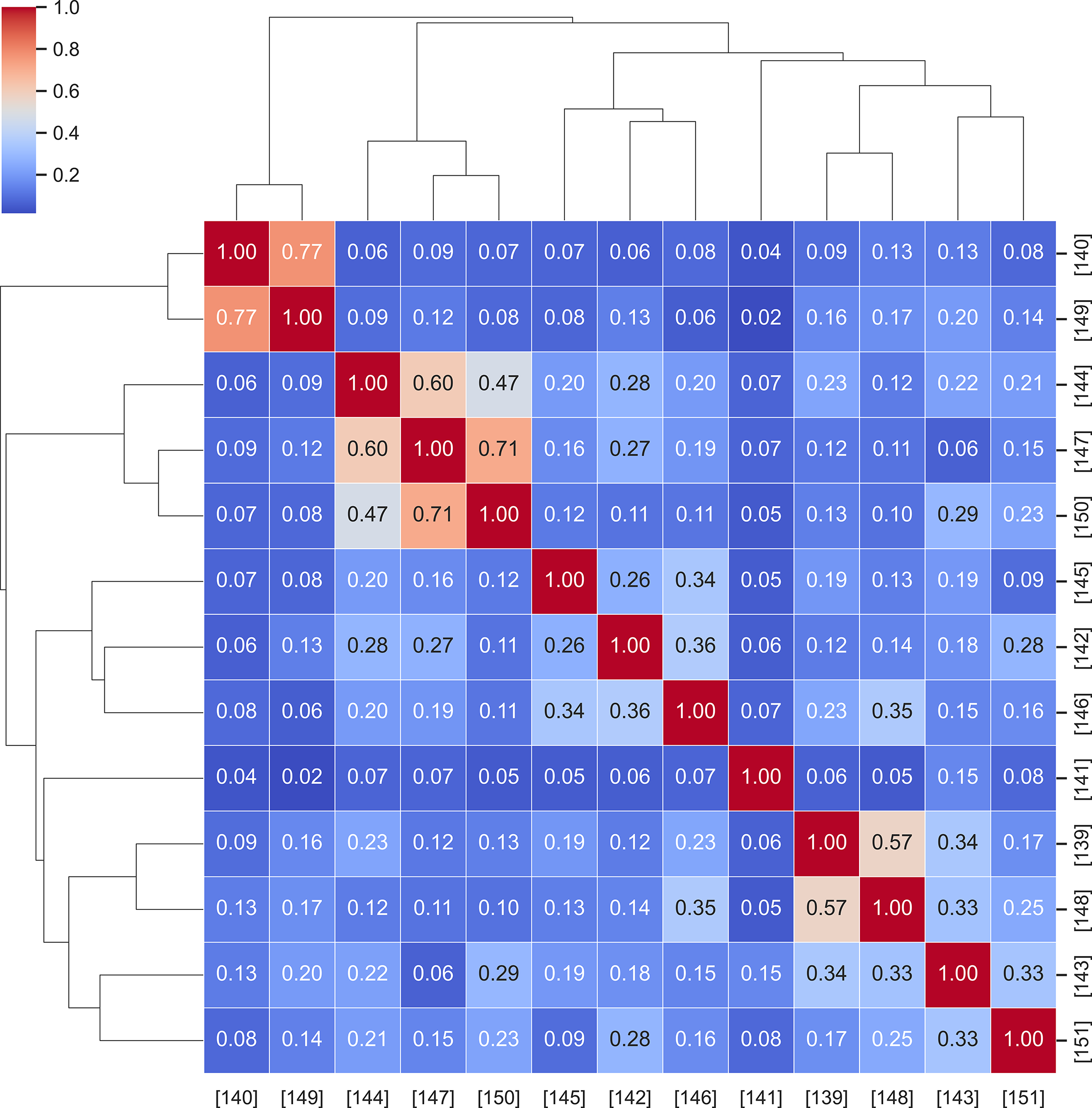

To examine the conceptual proximity among recent studies on synthetic-data generation in energy forecasting, Fig. 17 presents a hierarchical similarity map derived from TF-IDF cosine similarity. Each matrix cell quantifies the directional alignment between two studies, while the dendrograms at the top and left illustrate how they cluster according to shared methodological or domain-specific language.

Figure 17: Hierarchical similarity map among synthetic-data generation studies

The hierarchical dendrogram in Fig. 17 outlines the methodological progression that has shaped recent developments in generative modeling. The upper-left branch (e.g., [140,149]) coalesces early adversarial approaches, where conditional generator designs such as PG-GAN formed the initial foundation for synthetic augmentation. Moving toward the center of the hierarchy, a separate cluster (e.g., [144,147,150]) captures the emergence of diffusion-based architectures, making visible the field’s gradual pivot toward more stable, physics-aware denoising processes. Meanwhile, the lower-right region (e.g., [143,148,151]) brings together domain-oriented adaptations—from smart-home simulation to BIPV forecasting—illustrating how these generative frameworks are being reshaped to meet practical deployment requirements.

This hierarchical arrangement mirrors the methodological progression summarized in Table 9: from early GAN-based tabular synthesis toward diffusion-driven hybrid frameworks that integrate domain constraints, privacy preservation, and transferability. By capturing these relationships through textual similarity, Fig. 17 helps readers identify which works share underlying design principles and which extend the generative paradigm into new data modalities. Such a structural view reinforces the interpretive goal of Section 6—showing how synthetic-data generation has matured into a coherent research direction that complements transfer and meta-learning in addressing data scarcity.

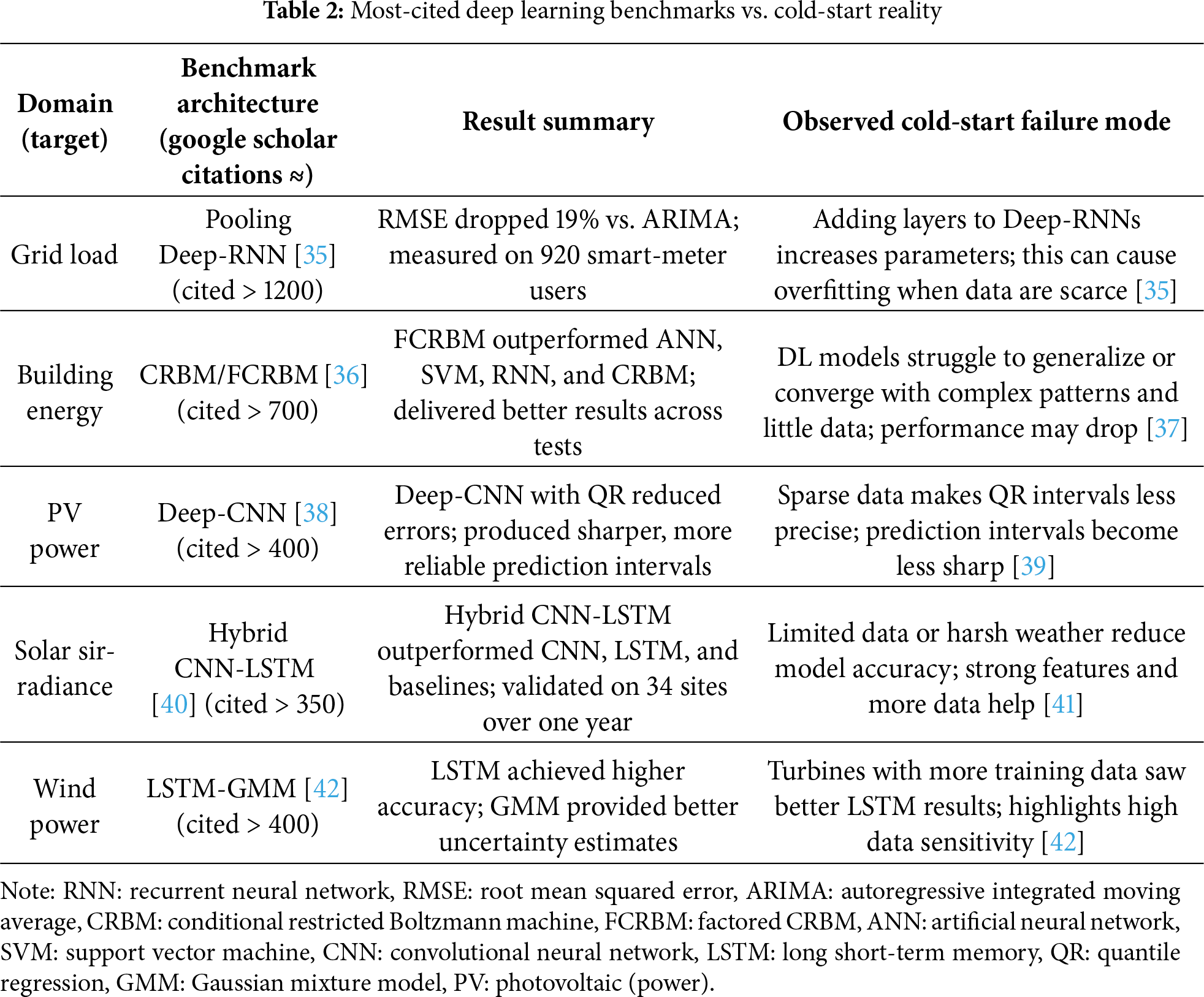

To visualize how recent generative-learning studies organize conceptually across the cold-start forecasting domain, Fig. 18 maps the high-frequency keywords in a two-dimensional PCA projection derived from cosine-similarity embeddings. Each color represents a distinct cluster of research emphasis, while the circle size indicates each term’s relative TF-IDF weight within the corpus.

Figure 18: Hierarchical similarity map among synthetic-data generation studies

Five primary conceptual regions emerge. The blue cluster (Cluster 0) groups structural and operational terms—optimization, response, and user—reflecting studies focused on algorithmic stability, model tuning, and feedback-driven control in energy forecasting frameworks. The orange cluster (Cluster 1) centers on sampling, seed, and noise, signifying data-generation mechanics and stochastic training pipelines found in GAN-based and diffusion-based synthesis. The red cluster (Cluster 3) encompasses temporal, power generation, and GAN, pointing to time-series-driven generation models (e.g., TimeGAN, conditional GANs) that simulate dynamic energy behavior. The green cluster (Cluster 2) collects mechanism, state, and follows, aligning with rule-constrained or physics-informed architectures that embed domain feasibility into synthetic data. Finally, the purple cluster (Cluster 4) connects scenario and wind power, representing application-level scenario modeling for renewable-energy systems and grid-planning studies.

The spatial separation among clusters reveals how the field has diversified from early GAN-centric augmentation toward hybrid and domain-integrated generation pipelines that combine temporal dynamics, physical realism, and optimization feedback. Thus, the conceptual landscape in Fig. 18 complements the hierarchical similarity structure in Fig. 17 by showing the underlying semantic relationships among core methodological vocabularies. Together, these analyses demonstrate that generative augmentation is evolving into an independent yet interoperable pillar of data-driven energy forecasting.

6.2 Using Generative Learning under Cold-Start Constraints

Although TL and meta-learning frameworks have demonstrated notable efficacy in adapting models across tasks, these frameworks remain contingent upon the availability of labeled data at the target site. However, the initiation of energy systems often occurs in environments devoid of telemetry or with only a limited number of labeled samples available. Generative learning circumvents this bottleneck by generating statistically coherent pseudo-samples prior to supervised training [152]. In scenarios where local labels are unavailable, GANs or diffusion-based models can be applied to generate realistic inputs, enabling training to commence from Day 0. Conversely, substantial adaptation by TL and MAML necessitates a minimum of 5 to 30 examples.

Furthermore, generative pipeline implementation has great potential for accentuating rare yet critical events (e.g., extreme solar ramps or grid faults), which are commonly underrepresented in historical records. By deliberately oversampling these outlier cases, models can be rendered more robust in their ability to predict extreme behavior. Privacy and deployment constraints favor this strategy [153]. In residential or commercial settings where data sharing is prohibited, pretrained generators (rather than raw logs) can be transferred across domains. Furthermore, synthetic augmentation can be executed off-line, preserving the lightweight nature of the deployed inference model, which is critical in edge computing environments, where resources (e.g., random access memory and power) are constrained [154].

6.3 Canonical Formulation and Forecasting Integration

In scenarios where historical telemetry data are limited (e.g., for newly installed PV systems or emerging microgrids), the cold-start problem substantially impedes accurate energy forecasting. A promising remedy is applying generative models, particularly those trained under a Wasserstein-style objective, which enhances the training stability and output realism. The optimization problem is formulated as in Eq. (6):

where

From the cold-start perspective, generator

7 Conversational Natural Language Processing and Explainable-AI Interfaces

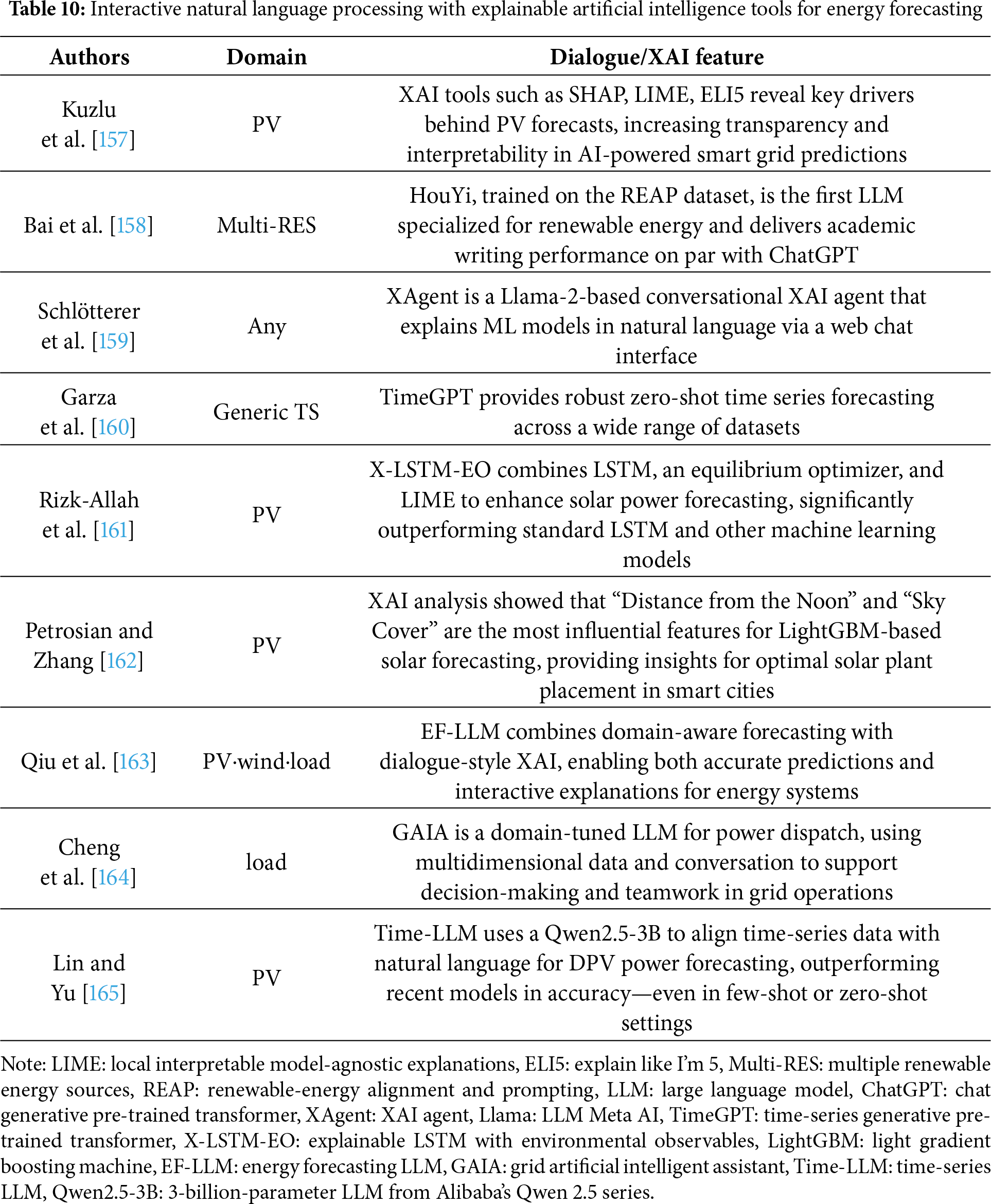

The importance of transparency and human interpretability increases as these forecasting systems scale and influence critical infrastructure decisions [155]. Integrating XAI modules helps stakeholders understand how synthetic data affect model outcomes, building trust [156]. Furthermore, chatbot interfaces driven by natural language processing enable nonexperts (e.g., grid operators or policymakers) to query models interactively, audit decisions, and interpret forecasts in real time [31]. Such interfaces democratize access to complex AI systems, ensuring ethical, auditable, and inclusive decision-making in data-scarce energy contexts.

7.1 Bridging Cold-Start Forecasts to the Control-Room Operator