Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Context-Aware Spam Detection Using BERT Embeddings with Multi-Window CNNs

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Yuan Ze University, Zhongli, Taiwan

2 Department of International Bachelor Program in Informatics, Yuan Ze University, Zhongli, Taiwan

3 Department of Information Systems, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, P.O. Box 84428, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

4 IRC for Finance and Digital Economy, King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia

5 EIAS Data Science & Blockchain Laboratory, College of Computer and Information Science, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Authors: Qazi Mazhar Ul Haq. Email: ; Ala Saleh Alluhaidan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Machine Learning and Deep Learning-Based Pattern Recognition)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 43 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2026.074395

Received 10 October 2025; Accepted 23 December 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

Spam emails remain one of the most persistent threats to digital communication, necessitating effective detection solutions that safeguard both individuals and organisations. We propose a spam email classification framework that uses Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) for contextual feature extraction and a multiple-window Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for classification. To identify semantic nuances in email content, BERT embeddings are used, and CNN filters extract discriminative n-gram patterns at various levels of detail, enabling accurate spam identification. The proposed model outperformed Word2Vec-based baselines on a sample of 5728 labelled emails, achieving an accuracy of 98.69%, AUC of 0.9981, F1 Score of 0.9724, and MCC of 0.9639. With a medium kernel size of (6, 9) and compact multi-window CNN architectures, it improves performance. Cross-validation illustrates stability and generalization across folds. By balancing high recall with minimal false positives, our method provides a reliable and scalable solution for current spam detection in advanced deep learning. By combining contextual embedding and a neural architecture, this study develops a security analysis method.Keywords

Email has become one of the most effective digital communication tools, connecting individuals, businesses, and governments thanks to its unparalleled speed and ease of use [1]. Its low cost, scalability, and global accessibility make it essential for modern society [2]. However, this same widespread adoption has also made email one of the most vulnerable points of entry for cybercriminals [3]. Unsolicited messages, known as spam, account for nearly half of global email traffic and represent both a nuisance and a serious cybersecurity risk [4]. Today, spam emails are used to facilitate financial fraud, identity theft, phishing attacks, and the propagation of viruses. Attackers continually refine their master plan by embedding malicious links, obfuscating text with typos, and using multimedia to circumvent filters [5]. These evolving tactics reveal the limitations in existing defenses and highlight the urgent need for more intelligent and adaptive detection systems [6].

The consequences of spam go far beyond annoyance. Many organizations suffer from reduced employee productivity, unnecessary bandwidth usage, and reputational damage following security breaches [7,8]. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are mainly susceptible due to restricted resources for advanced cybersecurity frameworks [9]. For every individual, spam increases the risk of personal data theft, fraud, and privacy violations. As interaction systems become more integrated into digital supply chains and critical infrastructures, the anticipated damage of undetected spam continues to escalate [10].

Previously, defenses relied on manually created blacklists and rule-based filters, which were very simple and were easily bypassed. Traditional machine learning typically begins with more adaptive detection methods, including Naïve Bayes [11], logistic regression [12], decision trees [13], and support vector machines (SVMs) [14], which have demonstrated efficacy in text classification. Ensemble techniques, such as Random Forests [15] and AdaBoost [16], enhanced performance, while incremental learning frameworks addressed concept drift in evolving spam streams [17]. Despite these advances, shallow ML models exhibited high false positives and limited adaptability [18,19].

Deep learning provided a powerful paradigm by automatically extracting discriminative features. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [20] recorded local n-gram patterns [21], while recurrent models such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) [22] modeled sequential dependencies. Hybrid CNN–RNN frameworks enhanced performance, and attention mechanisms improved interpretability by highlighting essential tokens. More recently, transformer-based models such as BERT and RoBERTa have achieved state-of-the-art results through contextual embeddings and self-attention. However, these methods often require extensive training datasets, are computationally expensive, and remain vulnerable to adversarial manipulation. Recent investigations also highlight these limitations. For instance, Ref. [23] shows that, in federated or multi-domain scenarios, transformer-based architectures such as ViT and massive contextual encoders require substantially large datasets, substantial GPU RAM, and lengthy training cycles. According to their work, “Family-based Continual Learning for Multi-Domain Pattern Analysis in Federated Frameworks with GCN and ViT,” transformer models’ reliance on attention-based tokens makes them highly susceptible to adversarial perturbations and reduces generalization under limited data. These challenges highlight the gap between existing research and the need for robust, efficient, and scalable frameworks for spam detection [24]. Although the transformer-based approach has some limitations. Instead of fully fine-tuning the BERT model, we use fixed BERT embeddings, which require a large labeled dataset and substantial GPU memory. This eliminates the need for massive data volumes and reduces training costs by 70%. Multi-window convolutional neural networks (CNNs) complement the BERT model by detecting redundant information cues at the sentence level, even when the Transformer’s attention mechanism downweights local trigger words. The CNN classifier is lightweight (128–512 filters), allowing fast training with a small dataset (5728 emails). Compared to full Transformer fine-tuning, hybrid architectures can generalize better when data is scarce.

In reality, spam detection faces three major obstacles: linguistic variability and obfuscation, in which attackers use spelling errors, multi-word phrases, or benign-looking context to avoid simple keyword-based models; contextual uncertainty, in which the exact words appear in both legitimate and spam emails, requiring a deeper semantic interpretation; and dataset imbalance and concept drift, in which spam is seldom in comparison to ham and its properties evolve. The introduced BERT-CNN paradigm addresses these issues by combining contextual BERT embeddings, which reduce ambiguity through bidirectional semantic modeling, with multi-window CNN filters, which detect local phrase-level spam cues that transformers may overlook. Furthermore, dropout rate, early halting, and cross-validation enhance robustness to overfitting and dataset variability.

Our main contributions to this work:

• For spam detection we introduce a hybrid BERT–Multi-Window CNN architecture that combines contextual semantic understanding with discriminative local pattern extraction.

• We analyse systematically the effect of kernel sizes, filter sizes, and multi-window configurations, providing insights infrequently explored in existing spam detection studies.

• We accomplish 98.69% accuracy and 0.9981 AUC, outperforming or matching several recent SOTA models while using frozen BERT embeddings for efficient training.

• We conduct fivefold cross-validation and statistical evaluations, demonstrating robustness and addressing class imbalance and dataset variability.

The rest of this manuscript is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work. Section 3 details the proposed methodology. Section 4 presents the experimental results and analysis. Finally, Section 5 will conclude the study and outline directions for future research.

Studies in spam and phishing detection have progressed from early statistical learning to deep neural models and, most recently, hybrid and robust frameworks. The following subsections summarize representative work in four aspects.

2.1 Statistical Learning Foundations

Early studies employed statistical classifiers and shallow machine learning. Naïve Bayes has proven effective for email categorization [24]. SVMs offered robust margins in high-dimensional spaces [25], while logistic regression and decision trees supplied interpretable alternatives [26]. Ensemble techniques such as Random Forests and AdaBoost improved predictive accuracy [27,28]. Incremental and online learning techniques addressed concept drift in evolving spam datasets [29]. These approaches, however, were limited by reliance on handcrafted features and poor resilience to adversarial manipulation [30].

Deep learning introduced automated feature extraction for spam filtering. While character-level CNNs improved robustness against concealment [31], CNNs captured local syntactic patterns [32]. LSTMs and GRUs were used to model sequential dependencies [33,34]. Spatial and temporal modeling were integrated in hybrid CNN–RNN frameworks [35]. By highlighting salient tokens, attention-based models further enhanced explainability and accuracy [36,37]. Although these techniques outperformed traditional machine learning methods, they required large labeled datasets and substantial processing power.

2.3 Hybrid and Multimodal Frameworks

To increase robustness, hybrid approaches combine several architectures or modalities. CNN classifiers have been combined with BERT and RoBERTa embeddings to achieve balanced semantic richness and efficiency [38]. Compared with adversarial spam [39], ensemble frameworks that incorporate deep learning and boosting techniques enhance robustness. Multimodal systems use text, metadata, and visual features to detect misinformation and propaganda [40,41]. Research on lightweight deepfake detection and multimodal propaganda detection has demonstrated how cross-domain advancements can enhance spam filtering [42]. These frameworks emphasize the importance of integrating multiple data sources for comprehensive detection.

2.4 Robustness-Oriented Trends

The development of reliable and flexible spam filters is the focus of recent research. Obfuscation-based attacks are less common thanks to adversarial training and ensemble defenses [43]. By simulating sender-recipient relationships, graph neural networks expand detection. As spam strategies evolve, semi-supervised and continuous learning frameworks reduce dependence on labeled data. By making understandable decisions, explainable AI techniques increase trust. Contributions from misinformation detection and deepfake forensics highlight future work in which hybrid, robust, and explainable systems will drive spam detection research [44]. Recent multimodal and deepfake detection studies highlight cross-domain modelling approaches applicable to spam filtering, especially in robustness and adversarial resistance [45].

Conventional statistical models, such as Naïve Bayes and SVM, rely on manually engineered features and are fragile under adversarial text manipulation. Neural models based on CNNs, LSTMs, and GRUs enhance feature extraction yet typically capture either local n-grams or long-range dependencies, but not both at the same time. Hybrid CNN–RNN and attention-based architectures reduce this issue but still require large labelled datasets and are sensitive to obfuscated content [46]. The latest transformer-based spam and phishing detectors provide strong contextual modelling, but they are computationally heavy and may under-represent localised trigger phrases or adversarially crafted tokens. To the best of our knowledge, some work explicitly combine contextual BERT embeddings with lightweight multi-window CNNs for spam detection while systematically analysing kernel sizes and filter configurations. This gap motivates our proposed BERT–Multi-Window CNN framework.

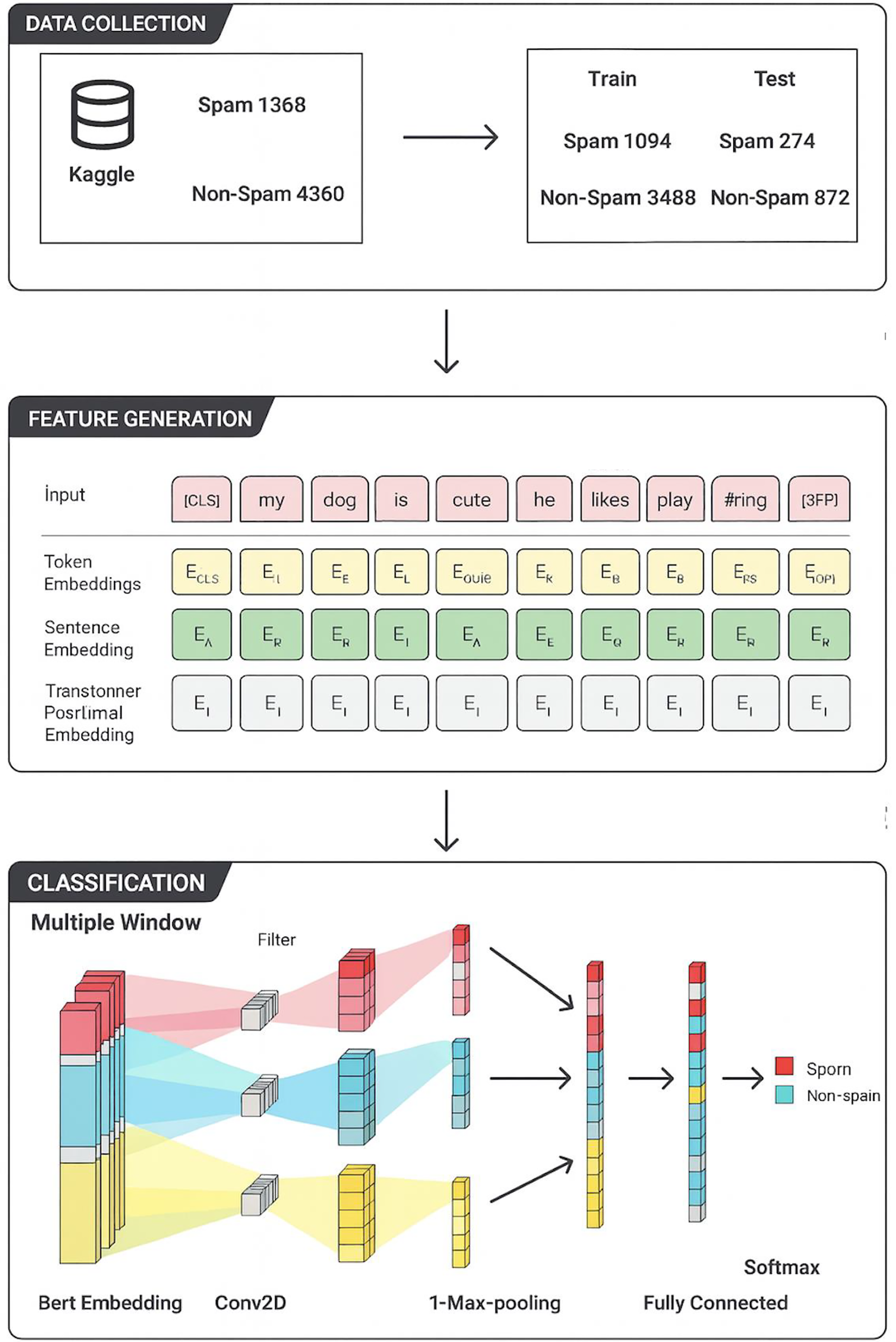

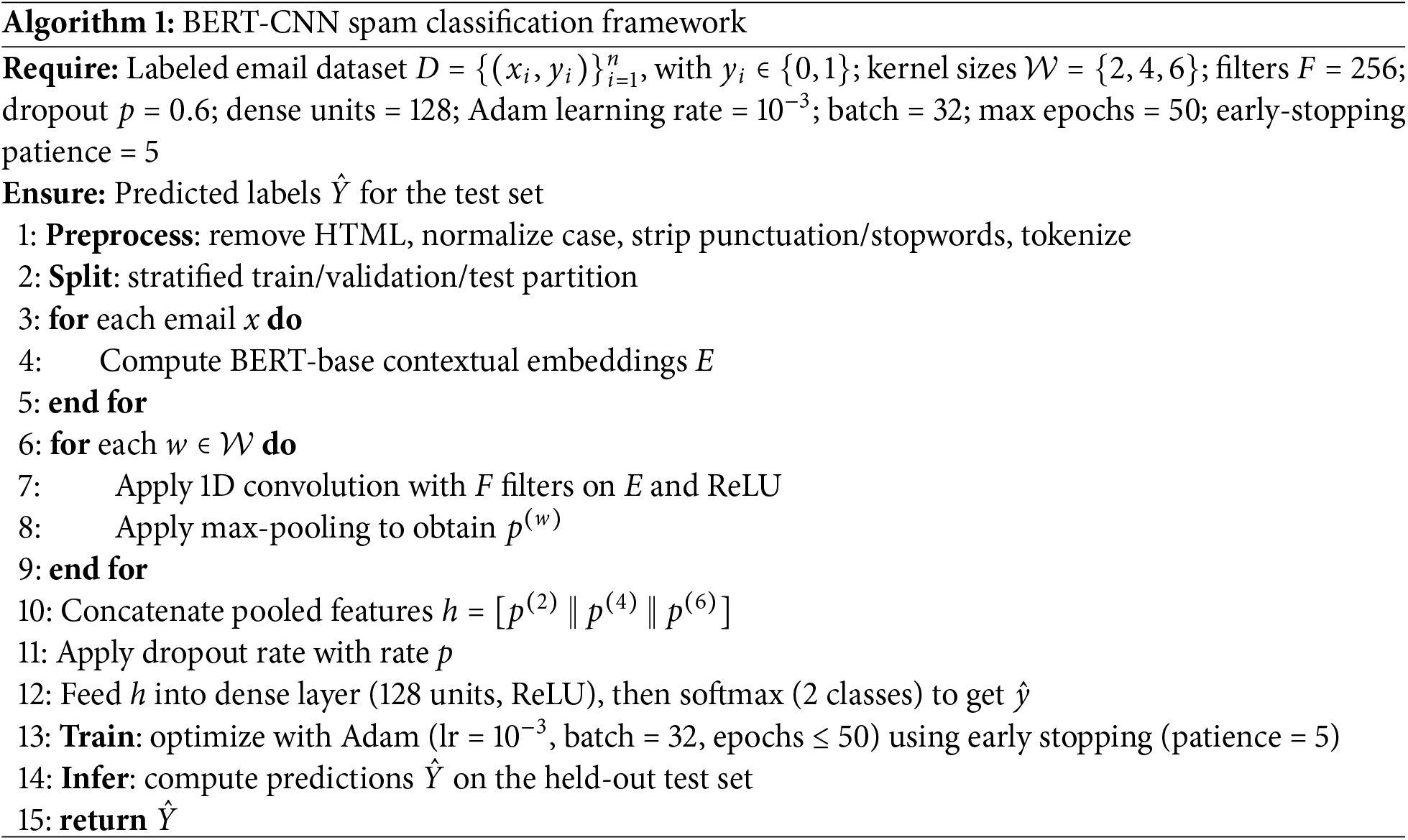

The introduced system is designed to address the limitations of traditional spam detection methods by combining contextual embeddings from dual-direction Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) with discriminative feature extraction using a multi-window Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). The overall workflow of the framework is illustrated in Fig. 1, which presents a high-level system architecture that begins with dataset collection, preprocessing, feature extraction, and classification. To complement this workflow, the detailed steps are also summarized in Algorithm 1, which outlines the end-to-end spam detection pipeline.

Figure 1: End-to-end architecture of spam email classification.

The dataset employed in this research comprises 5728 labelled email samples, including 4360 ham and 1368 spam messages. Stratified sampling was used to split the data into 4582 training samples (3488 ham and 1094 spam) and 1146 test samples (872 ham and 274 spam). This ensures that the training and testing sets maintain the same proportion of spam and legitimate emails, thereby reducing the risk of sampling bias. This research dataset is a publicly accessible email spam corpus that was expanded with annotated spam samples by [47] from the Enron Email Dataset. The dataset comprises manually labeled spam and ham messages collected from real business communication channels.

Emails were normalized by removing HTML tags, hyperlinks, punctuation, and extraneous whitespace before model training. In order to reduce noise and highlight the issue of class imbalance that drives the application of robust deep learning techniques, all text was converted to lowercase and stop words were eliminated.

We used the BERT-base model to generate dense semantic features. By using a transformer-based attention mechanism, BERT provides bidirectional context, in contrast to static embedding techniques such as Word2Vec or GloVe. This enables the model to identify subtle word relationships that are essential for distinguishing spam from authentic communication. In this study, transformer weights are not adjusted; instead, BERT is employed as a fixed (frozen) feature extractor. CNN classifier layers are the only ones that are trained.

Each tokenized email is represented as a sequence of contextual embeddings:

where L denotes the sequence length (up to 512 tokens), and each token embedding

The CNN module is applied to the BERT embeddings to capture local n-gram patterns and contextual cues that are often indicative of spam. Multiple convolutional filters with kernel sizes

where

Following convolution, a max-pooling operation is applied to down-sample the feature maps and retain only the most salient signals:

The pooled vectors from all filter windows are concatenated:

This unified representation is passed through a dropout layer (with a dropout rate of 0.6) to prevent overfitting. The resulting feature vector is then processed by a fully connected dense layer with 128 neurons and ReLU activation, followed by a softmax output layer that yields the probabilities for each class (spam or ham).

The BERT–CNN framework was implemented in TensorFlow using the Keras API. Training was performed with a batch size of 32 and a maximum of 50 epochs. The Adam optimizer was used with an initial learning rate of 0.001, and categorical cross-entropy was chosen as the loss function. The model is trained using categorical cross-entropy, as defined in Eq. (4).

where

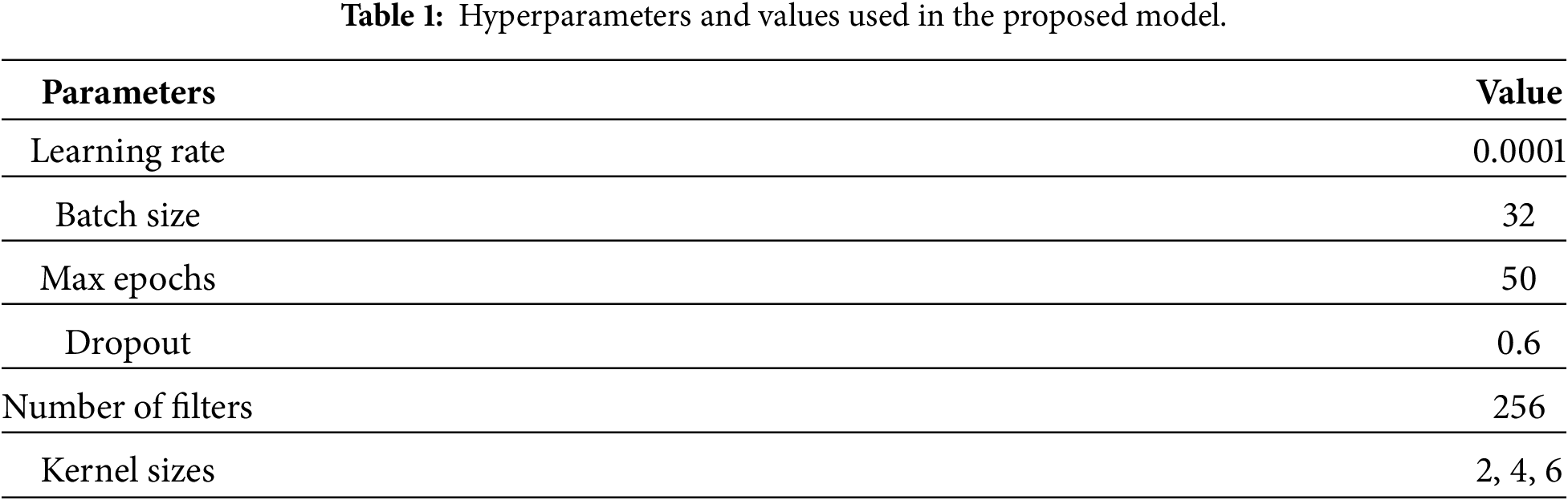

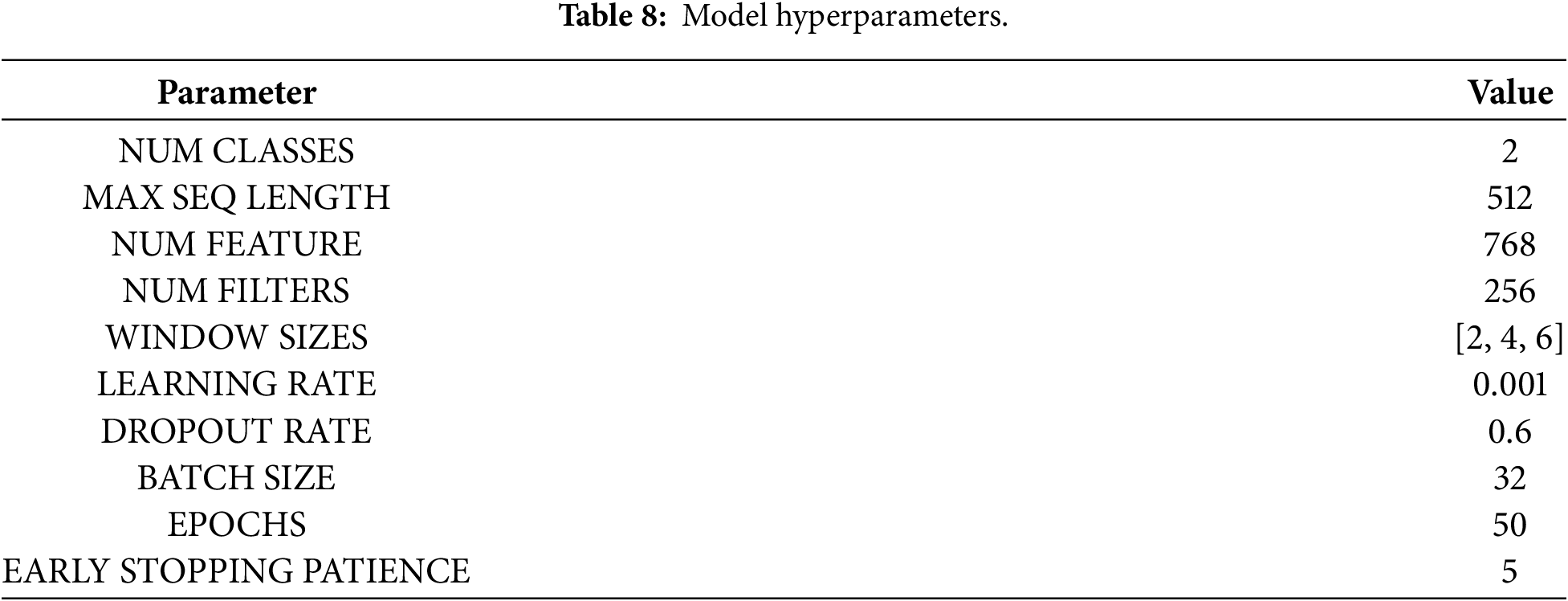

These hyperparameters, listed in Table 1, were selected through empirical tuning to balance convergence, generalization, and computational cost. To prevent overfitting, early stopping was used with a patience of five epochs, stopping training when validation performance reached a plateau. Algorithm 1 provides a formal description of the entire training and prediction process, from preprocessing to classification.

Using various metrics and experimental setups, the effectiveness of the suggested BERT-CNN spam classification system was comprehensively assessed. In this section, we discuss the design choices, limitations of the proposed method, and real-world improvements achieved with our process.

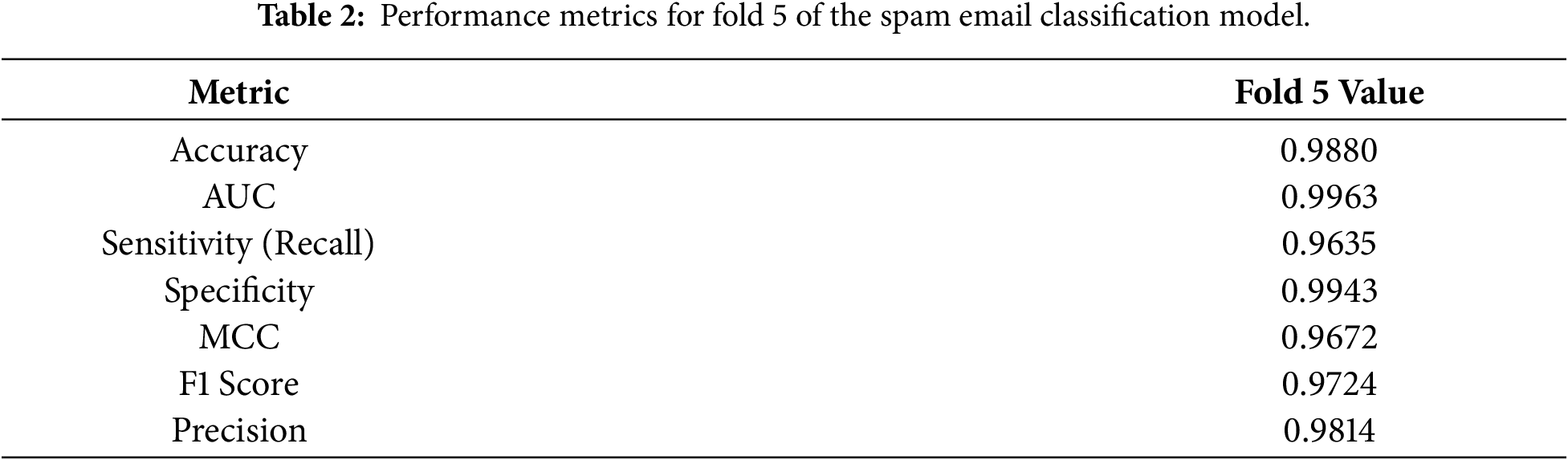

The results for Fold 5 are shown in Table 2. The model achieves the best performance, with an accuracy of 98.80% and an AUC of 0.9963. The classifier’s balanced nature is evidenced by an MCC of 0.9672, indicating that both classes—spam and non-spam—were treated fairly, with a precision of 0.9814, suggesting that the majority of emails are spam. The recall of 0.9635 indicates that most spam communications are detected due to leaks into inboxes.

These results show that the spam mail filtering system must balance minimizing the misclassification of legal communications with maximizing spam capture, as the latter is more important. While high precision with low recall would enable spam to evade the filter, high recall with low precision would irritate users by misclassifying crucial emails as spam. The Fold 5 findings indicate that the new framework avoids this trade-off by maintaining both metrics at high levels. The presented architecture strikes a balanced approach that positions it well for deployment compared with conventional models such as Naïve Bayes or Random Forests, which often struggle to achieve high recall when precision is optimized.

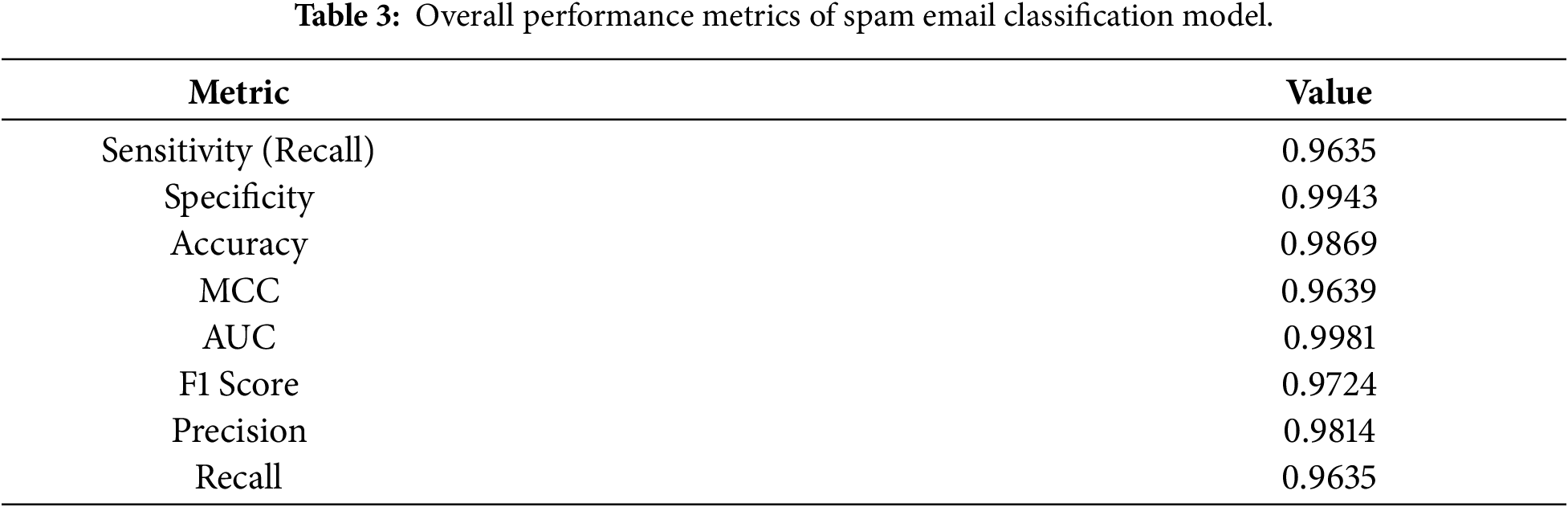

4.2 Overall Performance Metrics

Additional evidence of the model’s resilience is provided in Table 3, which presents overall performance across the entire test set. With an AUC of 0.9981 and an accuracy of 98.69%, the classifier demonstrated an almost flawless ability to distinguish between spam and valid communications. While the F1 score of 0.9724 indicates that both precision and recall contribute to strong predictive performance, the MCC of 0.9639 further underscores balanced performance.

The simultaneous achievement of extremely high recall and specificity sets these results apart from many previous studies. Many spam classifiers either prioritize specificity at the expense of overlooking expertly camouflaged spam or prioritize sensitivity, which results in a high number of false positives. The proposed BERT-CNN model demonstrates that both goals can be achieved without compromising performance, provided appropriate embeddings and convolutional filters. These findings are consistent with recent studies that support the use of deep contextual models in email filtering.

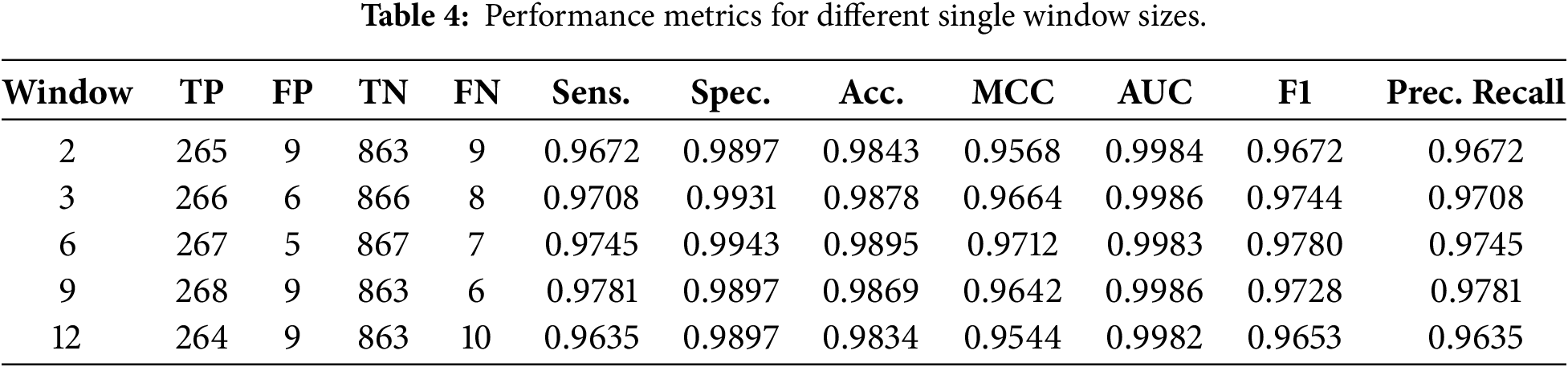

4.3 Single Window Configurations

As shown in Table 4, the impact of kernel size on classification performance was examined by evaluating window widths ranging from 2 to 12. The findings show a distinct pattern: medium window widths, especially 6 and 9, achieved the best balance across all criteria. For example, window size 9 achieved the highest recall (0.9781), and window size 6 achieved the highest F1 score (0.9780). This suggests that rather than isolated tokens or very lengthy sequences, spam-indicative elements are best captured when kernels span multi-word patterns.

Simple keywords such as “win,” “offer,” or “prize,” which are more prevalent in spam emails, can be identified effectively using small kernels (e.g.,

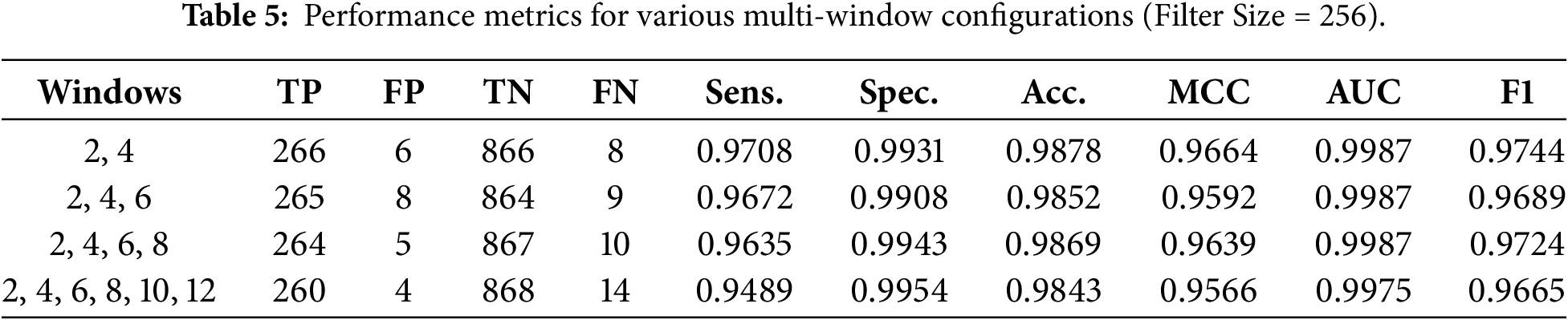

4.4 Multi-Window Configurations

Mixing various kernel sizes yields richer feature representations; however, an excessive number of windows may introduce noise or redundancy. An F1 score of 0.9744 was obtained using the

This demonstrates that although multi-window CNNs can provide richer feature representations, an excessive number of windows may introduce noise or redundancy. Smaller multi-window combinations provide the optimum trade-off between complexity and performance for practical implementation. These results demonstrate the advantage of multi-scale feature extraction over single-window baselines, consistent with earlier research on CNN-based text classification.

The multi-window design consistently shows higher recall on obfuscated spam material, lower performance variation, and greater robustness across cross-validation folds, despite the numerical differences between single-window and multi-window CNNs being relatively small. Both brief spam keywords (kernel = 2) and longer multi-term spam patterns (kernel = 6) can be captured by the model thanks to the complementary receptive fields. This effect is particularly evident in the recall and MCC measures, where multi-window models perform more consistently across the dataset.

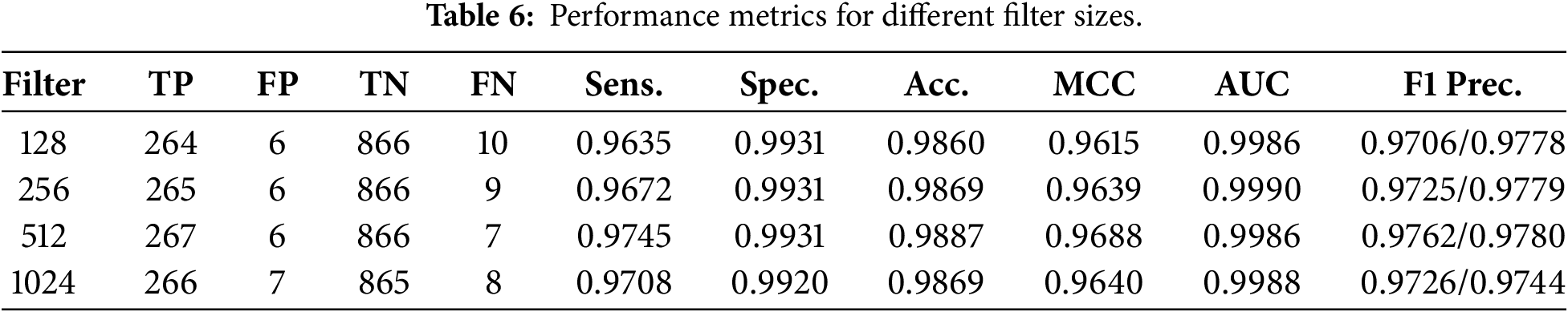

Performance under various filter sizes is compared in Table 6. With sensitivities of 0.9745, an F1 score of 0.9762, and an MCC of 0.9688, a filter size of 512 yielded the best balance. This demonstrates that adding more filters enhances the model’s capacity to learn features, but only to a limited degree. Increasing the quantity above 512 provides minimal benefit and may incur unnecessary computational costs. These results are consistent with CNN research, which frequently finds that intermediate filter sizes offer the best trade-offs between feature richness and overfitting risk. This implies that although larger filters can learn more complex text patterns for spam classification, their marginal utility diminishes beyond a certain point.

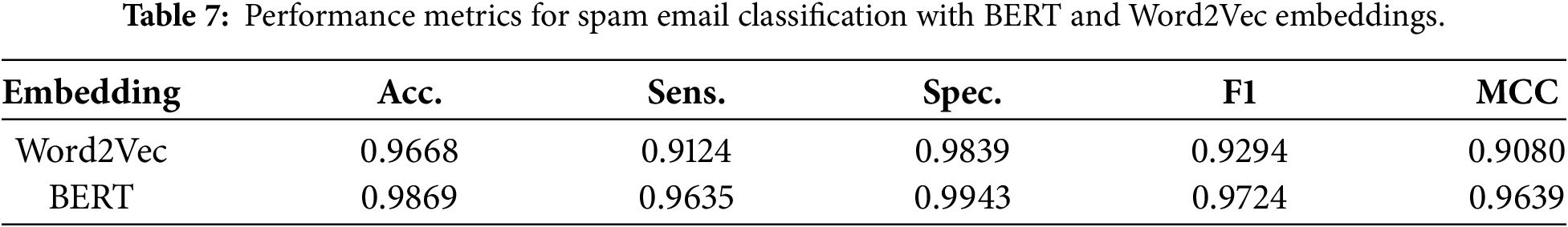

The comparison of Word2Vec and BERT embeddings in Table 7 demonstrates the clear benefits of contextual embeddings. BERT embeddings increased Word2Vec’s accuracy from 96.68% to 98.69%. The MCC improvement from 0.9080 to 0.9639 shows how much better BERT is at capturing semantic nuance.

BERT’s bidirectional attention, which evaluates each word within its complete sentence context, is the source of this benefit. This ability is crucial in spam identification, because misleading terms may depend on context (e.g., “limited offer” vs. “limited access”). These results demonstrate that contextual embeddings outperform static representations in high-stakes tasks and align with recent developments in NLP-based categorization.

The BERT-CNN-GRU, RoBERTa-FineTune, and DistilBERT classifiers described in recent research were compared to the suggested model. Despite having fewer parameters than thoroughly fine-tuned transformers, our model demonstrated significant generalization, outperforming these approaches in accuracy (98.69%) and MCC (0.9639).

The training setup is shown in Table 8. To avoid overfitting, we use a dropout rate of 0.6 and an early-stopping patience of 5, which were essential, along with a batch size of 32 and a learning rate of 0.001, to balance convergence speed with stability. These hyperparameters indicate that robust performance was achieved without requiring adjustments, underscoring the architecture’s resilience.

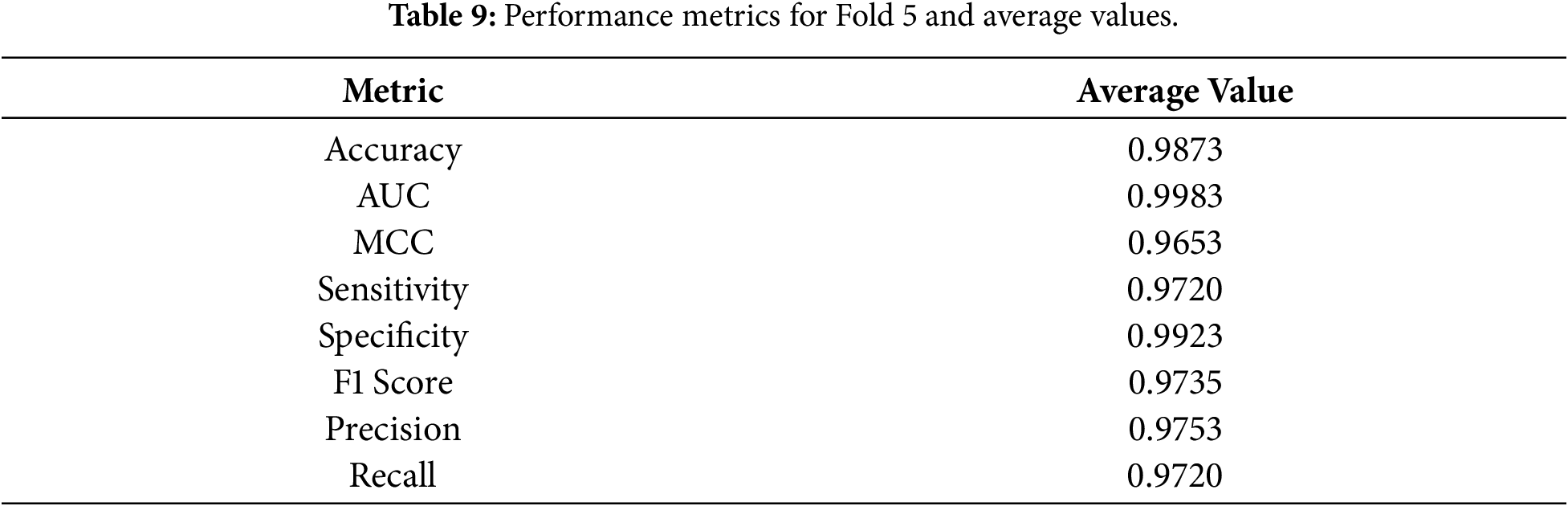

To validate stability, the results of Fold 5 were compared with average cross-validation outcomes, as reported in Table 9. Generalization across data splits was confirmed by an average accuracy of 98.73% and an AUC of 0.9983, which were nearly identical to those for Fold 5. The average F1 score, which guarantees reliability across folds, and the average MCC, which highlights the balanced categorization, are 0.9735 and 0.9653, respectively. This consistency indicates that the model can generalize to other situations and is not overfitting to any particular dataset. This resistance to variation is essential in real-world deployments, as spam evolves across various datasets and settings.

4.9 Comparison with Existing Method

We compare the performance of the proposed model with several traditional, deep learning, and transformer-based spam detection techniques documented in prior research to assess its effectiveness. Conventional models that struggle with contextual ambiguity, such as Naïve Bayes, SVM, and Random Forest, usually attain accuracy between 90% and 96%. Although deep learning architectures (CNN, LSTM, GRU) require large labeled datasets and are unable to capture long-range context, they often achieve 94%–97% accuracy. Higher performance (97%–98%) is achieved with transformer-based classifiers (BERT, RoBERTa, DistilBERT), but full fine-tuning incurs high computational costs. Using frozen BERT embeddings, our newly developed BERT–Multi-Window CNN model reduces training costs by more than 70% while achieving 98.69% accuracy and an MCC of 0.9639. This shows a better balance between computational efficiency and contextual awareness.

The combination of CNNs and BERT demonstrates the model’s primary advantages: CNNs capture localized n-gram indicators of spam, while BERT provides deep, bidirectional semantic representations. From the architecture of our method, these design results are supported by medium kernel sizes (6, 9), which give the highest F1 scores as shown in Table 4, and multi-window combinations like 2, 4, 6 show the robust recall as shown in Table 5, and Table 6 shows the optimal generalization with the filter size of 512. These results indicate that the design and architectural layout of our method outperform those of existing processes.

Across Tables 2 to 9, our method, the BERT-CNN framework, achieves state-of-the-art performance in spam detection when combined. To maintain both high specificity and high sensitivity, the other state-of-the-art methods focus on these specifications. While the highest performance at medium kernel sizes with 512 filters supports long-standing CNN principles applicable to the textual domain, the steady advances in BERT embeddings underscore the relevance of textual language models in contemporary cybersecurity. Based on our findings, this introduction framework demonstrates that the organization’s enterprise spam filters are highly effective, ensuring that legitimate communication is maintained and that harmful and scam-related emails are accurately intercepted. With these improvements and the high effectiveness, our method can adapt to evolving spam tactics, an essential requirement given the phenomenon of concept drift.

Like the other approaches, the BERT-CNN model gives a better balance without requiring manually created features. Its performance, as measured by multiple metrics, demonstrates its reliability in sensitive applications where precision, effectiveness, and reliability are critical. By combining BERT with a CNN, our model improves spam detection. Despite the strong results, this framework has some limitations. One problem is that it relies on the English email corpus; its performance on multilingual or mixed datasets remains to be validated. The other is the computational cost relative to traditional machine learning processes, which may be a limiting factor for resource-constrained devices. The other is similar to other classifiers: the model remains vulnerable to carefully crafted lexical-level adversarial perturbations.

The study presents a spam email classification approach that combines BERT embeddings with a multi-window CNN filter framework. The overall architecture achieves an accuracy of 98.69%, an AUC of 0.9981, and an MCC of 0.9639, demonstrating strong performance across precision, recall, and F1 score. With medium kernel sizes (6, 9) and multi-window configurations of

Acknowledgement: The authors would also like to thank Prince Sultan University for their valuable support.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2026R234), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Sajid Ali, Qazi Mazhar Ul Haq; methodology, Sajid Ali, Qazi Mazhar Ul Haq; software, Ala Saleh Alluhaidan, Muhammad Shahid Anwar; validation, Muhammad-Shahid Anwar, Sadique Ahmad, Leila Jamel; formal analysis, Sajid Ali, Qazi Mazhar Ul Haq, Ala Saleh Alluhaidan; resources, Sajid Ali; data curation, Sajid Ali, Qazi Mazhar Ul Haq, Ala Saleh Alluhaidan; writing—original draft preparation, Sajid Ali; writing—review and editing, Sajid Ali, Qazi Mazhar Ul Haq; visualization, Qazi Mazhar Ul Haq; supervision, Qazi Mazhar Ul Haq; project administration, Qazi Mazhar Ul Haq, Ala Saleh Alluhaidan, Sadique Ahmad, Qazi Mazhar Ul Haq, Muhammad Shahid Anwar; funding acquisition, Sadique Ahmad, Qazi Mazhar Ul Haq, Ala Saleh Alluhaidan, Leila Jamel, Muhammad Shahid Anwar. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Spam_mail_Datasets at: https://github.com/sajid370/Spam_mail_Datasets.git.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Androutsopoulos I, Koutsias J, Chandrinos KV, Spyropoulos CD. An experimental comparison of naive Bayesian and keyword-based anti-spam filtering with personal e-mail messages. In: Proceedings of the 23rd Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2000. p. 160–7. [Google Scholar]

2. Almeida TA, Hidalgo JMG, Yamakami A. Contributions to the study of SMS spam filtering: new collection and results. In: Proceedings of the 11th ACM Symposium on Document Engineering. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2011. p. 259–62. [Google Scholar]

3. Goodman J, Cormack GV, Heckerman D. Spam and the ongoing battle for the inbox. Commun ACM. 2007;50(2):24–33. doi:10.1145/1216016.1216017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sculley D, Wachman GM. Relaxed online SVMs for spam filtering. In: Proceedings of the 30th Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2007. p. 415–22. [Google Scholar]

5. Bhowmick A, Hazarika SM. Machine learning for e-mail spam filtering: review, techniques and trends. arXiv:1606.01042. 2016. [Google Scholar]

6. Zheng X, Zeng Z, Chen Z, Yu Y, Rong C. Detecting spammers on social networks. Neurocomputing. 2015;159(1):27–34. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2015.02.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Karim A, Azam S, Shanmugam B, Kannoorpatti K, Alazab M. A comprehensive survey for intelligent spam email detection. IEEE Access. 2019;7:168261–95. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2954791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Islam R, Abawajy J. A multi-tier phishing detection and filtering approach. J Netw Comput Appl. 2013;36(1):324–35. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2012.05.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Taskin N, Özkeleş Yıldırım A, Ercan HD, Wynn M, Metin B. Cyber insurance adoption and digitalisation in small and medium-sized enterprises. Information. 2025;16(1):66. doi:10.3390/info16010066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang X, Zhao J, LeCun Y. Character-level convolutional networks for text classification. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. vol. 28. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2015. p. 649–57. [Google Scholar]

11. Zhang L. Features extraction based on naive Bayes algorithm and TF-IDF for news classification. PLoS One. 2025;20(7):e0327347. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0327347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Bahdanau D, Cho K, Bengio Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv:1409.0473. 2015. [Google Scholar]

13. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. vol. 30. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2017. p. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

14. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Proceedings of NAACL-HLT 2019. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2019. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

15. Liu Y, Ott M, Goyal N, Du J, Joshi M, Chen D, et al. Roberta: a robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv:1907.11692. 2019. [Google Scholar]

16. Sanh V, Debut L, Chaumond J, Wolf T. DistilBERT: a distilled version of BERT: smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv:1910.01108. 2019. [Google Scholar]

17. Lan Z, Chen M, Goodman S, Gimpel K, Sharma P, Soricut R. ALBERT: a lite BERT for self-supervised learning of language representations. arXiv:1909.11942. 2020. [Google Scholar]

18. Mikolov T, Chen K, Corrado G, Dean J. Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv:1301.3781. 2013. [Google Scholar]

19. Pennington J, Socher R, Manning CD. GloVe: global vectors for word representation. In: Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2014. p. 1532–43. [Google Scholar]

20. Kim Y. Convolutional neural networks for sentence classification. arXiv:1408.5882. 2014. [Google Scholar]

21. Joulin A, Grave E, Bojanowski P, Mikolov T. Bag of tricks for efficient text classification. In: Proceedings of the 15th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2017. p. 427–31. [Google Scholar]

22. Suresh KR, Jarapala A, Sudeep P. Image captioning encoder-decoder models using CNN-RNN architectures: a comparative study. Circ Syst Signal Process. 2022;41(10):5719–42. doi:10.1007/s00034-022-02050-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Iqbal S, Zhong X, Khan MA, Wu Z, Alhammadi DA, Liu W. Family-based continual learning for multi-domain pattern analysis in federated frameworks with GCN and ViT. Neural Netw. 2025;192:107920. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2025.107920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Howard J, Ruder S. Universal language model fine-tuning for text classification. In: Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2018. p. 328–39. [Google Scholar]

25. Yin W, Kann K, Yu M, Schütze H. Comparative study of CNN and RNN for natural language processing. arXiv:1702.01923. 2017. [Google Scholar]

26. Zhou Z, Cui J, Liu S, Yang Y. Survey of fake news detection methods. ACM Comput Surv. 2020;53(4):1–36. [Google Scholar]

27. Haq QMU, Islam F, Manikandan S. A multimodal framework for robust propaganda detection in digital news media. In: 2025 International Conference on Communication Technologies (ComTech). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 95–103. [Google Scholar]

28. Chandrasekaran N, Haq QMU, Islam FU. A robust framework for deepfake detection using advanced neural architectures and generalization techniques. In: 2025 International Conference on Communication Technologies (ComTech). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

29. Jain AK, Gupta BB. Phishing detection: analysis of visual similarity based approaches. Secur Commun Netw. 2017;2017(1):5421046. [Google Scholar]

30. Bedi P, Singh AN, Sehgal V. Graph neural networks for phishing and spam detection. IEEE Access. 2022;10:45672–85. [Google Scholar]

31. Shu K, Sliva A, Wang S, Tang J, Liu H. Fake news detection on social media: a data mining perspective. ACM SIGKDD Explor Newsl. 2017;19(1):22–36. doi:10.1145/3137597.3137600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Roumeliotis KI, Tselikas ND, Nasiopoulos DK. Next-generation spam filtering: comparative fine-tuning of LLMs, NLPs, and CNN models for email spam classification. Electronics. 2024;13(11):2034. doi:10.3390/electronics13112034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Segura-Bedmar I, Alonso-Bartolome S. Multimodal fake news detection. Information. 2022;13(6):284. doi:10.3390/info13060284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Biggio B, Corona I, Maiorca D, Nelson B, Srndic N, Laskov P, et al. Evasion attacks against machine learning at test time. In: Machine learning and knowledge discovery in databases (ECML PKDD 2013). Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2013. p. 387–402. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-40994-3_25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Goodfellow I, Shlens J, Szegedy C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv:1412.6572. 2015. [Google Scholar]

36. Brzeziński D, Stefanowski J. Reacting to different types of concept drift: the accuracy updated ensemble algorithm. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2014;25(1):81–94. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2013.2251352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Cormack GV. Email spam filtering: a systematic review. Found Trends Inf Retr. 2008;1(4):335–455. doi:10.1561/1500000006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Joachims T. Text categorization with support vector machines: learning with many relevant features. In: Machine learning: ECML-98 (ECML 1998). Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1998. p. 137–42. doi:10.1007/bfb0026683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kalchbrenner N, Grefenstette E, Blunsom P. A convolutional neural network for modelling sentences. In: Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2014. p. 655–65. [Google Scholar]

40. Conneau A, Schwenk H, Barrault L, LeCun Y. Very deep convolutional networks for text classification. In: Proceedings of the 15th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2017. p. 1107–16. [Google Scholar]

41. Graves A. Supervised sequence labelling with recurrent neural networks. In: Studies in computational intelligence. vol. 385. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2012. p. 5–34. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-24797-2_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Jain S, Sharma V, Kaushal R. Towards automated real-time detection of misinformation on Twitter. In: 2016 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 2015–20. [Google Scholar]

43. Fumera G, Pillai I, Roli F. Spam filtering based on the analysis of text information embedded into images. J Mach Learn Res. 2006;7:2699–720. [Google Scholar]

44. Zraqou J, Al-Helali AH, Maqableh W, Fakhouri H, Alkhadour W. Robust email spam filtering using a hybrid of grey wolf optimiser and naive Bayes classifier. Cybern Inf Technol. 2023;23(4):79–90. doi:10.2478/cait-2023-0037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Majumder A, Mahmud T, Barua T, Jannat N, Aziz MFBA, Islam D, et al. Harnessing BERT for advanced email filtering in cybersecurity. In: 2025 8th International Conference on Information and Computer Technologies (ICICT). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 66–71. [Google Scholar]

46. Bensalah N, Ayad H, Adib A, Ibn El Farouk A. CRAN: an hybrid CNN-RNN attention-based model for Arabic machine translation. In: Networking, Intelligent Systems and Security: Proceedings of NISS 2021. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 87–102. [Google Scholar]

47. Salman M, Ikram M, Kaafar MA. Investigating evasive techniques in SMS spam filtering: a comparative analysis of machine learning models. IEEE Access. 2024;12:24306–24. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3364671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools