Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Computational Analysis of Thermal Buckling in Doubly-Curved Shells Reinforced with Origami-Inspired Auxetic Graphene Metamaterials

Faculty of Engineering, Mahallat Institute of Higher Education, Mahallat, P.O. Box 37811-51958, Iran

* Corresponding Authors: Ehsan Arshid. Email: ,

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 8 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.074898

Received 21 October 2025; Accepted 10 December 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

In this work, a computational modelling and analysis framework is developed to investigate the thermal buckling behavior of doubly-curved composite shells reinforced with graphene-origami (G-Ori) auxetic metamaterials. A semi-analytical formulation based on the First-Order Shear Deformation Theory (FSDT) and the principle of virtual displacements is established, and closed-form solutions are derived via Navier’s method for simply supported boundary conditions. The G-Ori metamaterial reinforcements are treated as programmable constructs whose effective thermo-mechanical properties are obtained via micromechanical homogenization and incorporated into the shell model. A comprehensive parametric study examines the influence of folding geometry, dispersion arrangement, reinforcement weight fraction, curvature parameters, and elastic foundation support on the critical buckling temperature (CBT). The results reveal that, under optimal folding geometry and reinforcement alignment with principal stress trajectories, the CBT can increase by more than 150%. Furthermore, the combined effect of G-Ori reinforcement and elastic foundation substantially enhances thermal buckling resistance. These findings establish design guidelines for architected composite shells in applications such as aerospace thermal skins, morphing structures, and thermally-responsive systems, and illustrate the potential of auxetic graphene metamaterials for multifunctional, lightweight, and thermally robust structural components.Keywords

Thermal buckling has long posed a fundamental challenge to the stability of thin-walled engineering structures. As modern designs increasingly demand lightweight and thermally reliable components, shells have become essential due to their efficiency yet remain highly susceptible to thermally induced instability. Recent studies illustrate the breadth of this challenge: Avey et al. [1] modeled thermoelastic stability in functionally graded (FG) nanocomposite cylinders, highlighting the influence of nanoscale reinforcement; Quan et al. [2] analyzed nonlinear buckling in eccentrically stiffened double-curved sandwich shells, emphasizing geometric and stiffener effects; Cong et al. [3] examined temperature-dependent dynamic responses of FG-carbon nanotubes reinforced composite (FG-CNTRC) laminated shallow shells, showing the role of material distribution on stability; and Sankar et al. [4] investigated carbon nanotube (CNT)-reinforced sandwich spherical and conical shells, demonstrating improved thermal resistance through nanoscale enhancement. Together, these works underscore the need for more accurate predictive models to ensure reliable performance of next-generation lightweight structures in severe thermal environments.

Thermal buckling in shell structures is often initiated by non-uniform temperature fields or restricted thermal expansions that generate compressive stresses capable of driving the structure into a new deformed state without any change in external loading. Because this form of instability arises purely from temperature variations, it becomes especially critical in environments with high or cyclic thermal exposure. Many recent studies highlight this sensitivity: Duc et al. [5] showed how oblique stiffeners and temperature jointly influence the nonlinear response of FG cylindrical panels; Duc et al. [6] analyzed thermally induced buckling in thick circular cylindrical shells with metal–ceramic–metal layering on elastic foundations; Anh et al. [7] examined stability of thin FG spherical shells under combined thermal and pressure loading; and Trabelsi et al. [8] introduced an improved finite shell element to better predict thermal buckling in functionally graded plates and cylindrical shells. These works collectively demonstrate the inherent vulnerability of shell systems to thermally driven instability.

Thermal buckling becomes even more critical when structural components are made from materials with high thermal expansion coefficients or appear in multilayered or FG assemblies, where differential thermal expansion can generate significant in-plane compression. In aerospace applications, this issue is intensified by extreme thermal gradients experienced during atmospheric re-entry or prolonged solar exposure, making thermal buckling a key design consideration for ensuring structural reliability and mission safety. Numerous studies have examined how thermal and multiphysics couplings reshape the stability of advanced shell systems. For instance, Tounsi et al. [9] developed a quasi-3D model for hygro-thermal wave propagation in imperfect FG sandwich plates, offering insight into thermally driven instability; Liu and Chen [10] provided a foundational description of porous material behavior relevant to thermomechanical response; Cao et al. [11] used synchrotron X-ray tomography to reveal deformation mechanisms in imperfect shell cylinders; Fu et al. [12] investigated sound insulation and stability in sandwich doubly curved shells with specialized cellular cores under varying thermal and mechanical fields; Bagheri et al. [13] analyzed free vibration of conical shells supported by intermediate rings, showing how geometric features affect thermal stability; and Guo et al. [14] proposed a simplified model for buckling and post-buckling of nanobeams under compression, illustrating key thermomechanical interactions. Recent studies further show that thermal fields can strongly modify nonlinear dynamic behavior in shells: nonlinear forced vibrations in FG piezoelectric shells with micro-voids were shown to be highly sensitive to electric–thermal–mechanical coupling [15], while rotating composite cylindrical shells with porosity displayed multiple internal resonances affected by temperature variations [16]. These findings collectively emphasize the strong interplay between thermal fields and material heterogeneity, reinforcing the motivation for examining thermally driven buckling in architected, metamaterial-reinforced curved panels as pursued here. The influence of geometry on thermal buckling is also widely documented: Esmaeili and Kiani [17] demonstrated the effect of graphene platelet reinforcement under thermal shock; Mirzaei and Kiani [18] investigated thermal buckling of temperature-dependent FG-CNTRC plates; Park and Kwan Seo [19] presented analytical simulations for buckling and post-buckling of curved plates; and Huang et al. [20] optimized buckling resistance of curved stiffeners using level-set-based density methods. Many other studies have also addressed thermal buckling in composite and architected shells [21–24], examining effects ranging from nanocomposite reinforcement in confined arches to experimental buckling of carbon fiber cylinders and graphene platelets-reinforced graded shells. Additionally, reliability assessments such as the comparative fatigue analysis of ball grid arrays older joints under thermally coupled vibration loading [25] highlight how even modest variations in material architecture can significantly modify stress distributions and stability margins, underscoring the broader importance of understanding thermally induced instability in advanced engineered systems.

Advanced composite structures have recently been introduced to address challenges posed by thermal environments, and several studies have demonstrated their potential. For instance, Liu et al. [26] examined size effects in cracked functional composite micro-plates; Sarafraz et al. [27] analyzed vibration and buckling in sandwich plates with auxetic honeycomb cores; Sofiyev et al. [28] explored buckling of FG-CNTRC conical shells under combined loading; Eskandary et al. [29] investigated buckling in FG-CNTRC conical shells with agglomeration effects; and Ali Mohammadimehr et al. [30] studied vibration behavior in double-curved sandwich panels with auxetic cores and CNT-reinforced facesheets.

Recent studies on advanced composite materials have demonstrated that microstructural architecture and heterogeneous reinforcement layouts play a decisive role in controlling stiffness, damping, and deformation patterns under coupled loading environments. For instance, magnetically tunable composites reinforced with graphene nanoplatelets have shown that even small changes in internal architecture can meaningfully modify dynamic stiffness and vibration characteristics [31]. Similarly, heterogeneous graphene-based structures have exhibited enhanced interfacial polarization and broadband absorption capabilities, illustrating how spatial variation in reinforcement can reshape multi-physics responses [32]. Multilayer pyrocarbon composites with heterogeneous microstructures have also demonstrated significant improvements in toughness and load-transfer efficiency, reinforcing the broader principle that engineered material gradients directly influence stability behavior [33]. Furthermore, the evolution of microscopic irreversible deformation in fiber-reinforced thermoplastics under cyclic loading has revealed strong sensitivity to reinforcement distribution, emphasizing the importance of microstructural tailoring in stability-critical components [34].

These insights align closely with the emerging role of metamaterials. Architected microstructures have been shown to fundamentally alter wave propagation, energy dissipation, and instability limits across a wide range of physical domains. Ultra-broadband absorbers based on biomimetic gradient resonators, for example, demonstrate how engineered mesoscale architecture can redirect energy pathways and suppress undesirable responses [35], while omni-directional acoustic metamaterials have exhibited controlled absorption performance across varying incidence angles [36]. Underwater ultra-thin metamaterials featuring bubble-based layers further highlight how tailored microstructures can be used to achieve unconventional energy attenuation mechanisms [37]. Experimental studies on composite metamaterials have likewise revealed enhanced energy-absorption and vibration-damping characteristics across thermal and mechanical fields [38]. More complex behaviors, such as Moiré-induced flat bands in twisted metasurfaces, underscore the potential of microstructural periodicity in controlling nonlinear dynamic responses [39]. Complementary efforts in dual-functional metamaterials show that integrated architectures can simultaneously achieve vibration isolation and energy harvesting, indicating the possibility of designing multi-purpose structural systems that leverage controlled buckling behaviors [40]. Together, these findings provide strong foundational motivation for exploring auxetic and origami-inspired architected reinforcements in thermally loaded composite shells. They demonstrate that tailored microstructures and heterogeneous reinforcement strategies can significantly influence stiffness pathways, redistribution of internal stresses, and overall stability margins—concepts that lie at the core of the present investigation. Some of the most recent contributions in this area include nonlinear vibration analysis of multiscale hybrid nanocomposite sandwich plates with auxetic cores reported by Mahinzare et al. [41], energy-absorbing behavior of re-entrant auxetic metamaterials demonstrated by Zhang et al. [42], and free vibration characteristics of FG-CNTRC spherical shell panels examined by Kiani [43].

In the analysis of thermal buckling behavior, particularly in shells, mathematical modeling plays a pivotal role. Traditional linear elastic theories have been extended to include temperature-dependent material properties, geometric nonlinearities, and interactions with foundation models such as Winkler or Pasternak types. Semi-analytical approaches have provided closed-form solutions under specific boundary conditions, while numerical methods such as finite element analysis have enabled the study of complex geometries and advanced material configurations. Several recent contributions illustrate this progress: Ghadiri and Hosseini [44] examined nonlinear forced vibration in graphene–piezoelectric sandwich nanoplates under mechanical shock; Sadeghian et al. [45] formulated a nonlocal strain gradient model for nonlinear static behavior of circular and annular nanoplates; Bellal et al. [46] investigated the buckling of graphene sheets on viscoelastic media using a nonlocal integral framework; and Guellil et al. [47] analyzed how porosity distribution and boundary conditions influence bending in FG plates on Pasternak foundation. The issue becomes further complicated by the inherent imperfection sensitivity of shells. Even minor geometric irregularities can severely reduce buckling resistance, especially under thermal loads, necessitating conservative safety factors unless additional stiffening or optimized support layouts are introduced. Representative studies include Esmailpoor Hajilak et al. [48], who explored mechanics of FG nanoshells; Pham et al. [49], who optimized vibration characteristics of stiffened sandwich shells with auxetic cores; Fu et al. [50], who analyzed impact response in doubly curved FGM shells with re-entrant honeycomb cores; and Jing et al. [51], who proposed an optimization-based buckling design for laminated shallow shells. Recent analytical studies on non-local FG nanoplates have shown that graded material distributions and small-scale effects can notably alter the vibrational response of nanoscale structures [52], while studies on CNT-reinforced composite beams have demonstrated how reinforcement content and distribution strongly influence stiffness and dynamic behavior under excitation [53]. Similar efforts are reported in the broader literature: Arshid et al. [54] examined vibrational behavior of variable-thickness sandwich beams with FG cellular cores and CNT-reinforced patches in thermal environments; Babaei et al. [55] studied the dynamic response of lightweight porous plates with nanocomposite facesheets on elastic foundations; Arshid et al. [56] analyzed aerodynamic stability and vibration in FG porous microplates under supersonic flow; Uzun et al. [57] introduced a hardening nonlocal method for vibration of axially loaded nanobeams with deformable boundaries; and Kaveh et al. [58] investigated flexoelectric and porous-FG effects in sandwich microplates. The integration of thermal buckling considerations into early-stage design has consequently become essential, especially for multidisciplinary applications such as hypersonic vehicles, space habitats, and high-efficiency thermal storage systems, where thermal–mechanical interactions dictate system reliability. Controlled buckling has even been harnessed for beneficial functions in morphing structures and energy absorption devices. Physics-based understanding of thermal buckling thus enables more efficient material allocation, improved thermal management, and rational safety margins. With the advent of additive manufacturing and architected materials, designers now have greater freedom to tailor buckling responses through topology, gradient materials, and programmable deformation pathways, as evidenced in numerous recent studies such as nonlinear flexural analysis of laminated composites under hygro-thermal–mechanical loading by Mahapatra et al. [59], semi-analytical modeling of vibration in FG porous doubly curved shells by Zhao et al. [60], vibration and bending analyses of graphene nanoplatelet reinforced nanocomposite shells by Wang et al. [61], nonlinear vibration of magneto-electro-elastic CNT-reinforced shells by Vinyas and Harursampath [62], large-amplitude vibration of FG orthotropic double-curved shells studied by Sofiyev et al. [63], buckling of steel cylindrical shells reinforced with fiber-reinforced polymer layers by Tănase and Lvov [64], and vibration of rotating FG porous discs with nanocomposite coatings analyzed by Rasooli Jazi et al. [65].

Despite notable progress in the study of thermal buckling, most previous investigations have concentrated on conventional composite or isotropic materials, frequently employing idealized geometries and simplified boundary or thermal loading conditions. Such simplifications often neglect the unique mechanical characteristics of architected materials (particularly auxetic and origami-inspired structures) whose programmable deformation and negative Poisson’s ratio responses can significantly alter stability behavior under thermomechanical loading. Moreover, critical factors such as folding topology, reinforcement dispersion patterns, and the coupling between the structure and elastic foundation are commonly oversimplified or excluded, reducing the predictive capability and generality of existing models. To bridge these gaps, the present study develops a comprehensive and physically consistent computational framework for analyzing the thermal buckling response of doubly-curved composite shells reinforced with graphene-origami (G-Ori) auxetic metamaterials. The formulation integrates micromechanical homogenization of G-Ori reinforcements with a semi-analytical model based on First-Order Shear Deformation Theory (FSDT) and the principle of virtual displacements, enabling the evaluation of the critical buckling temperature (CBT) under various folding configurations, reinforcement patterns, and foundation stiffnesses. This framework provides a predictive tool for the design and optimization of thermally stable architected shells with tunable stiffness, offering valuable insights for the development of next-generation aerospace panels, morphing skins, reconfigurable structures, and other thermally adaptive systems.

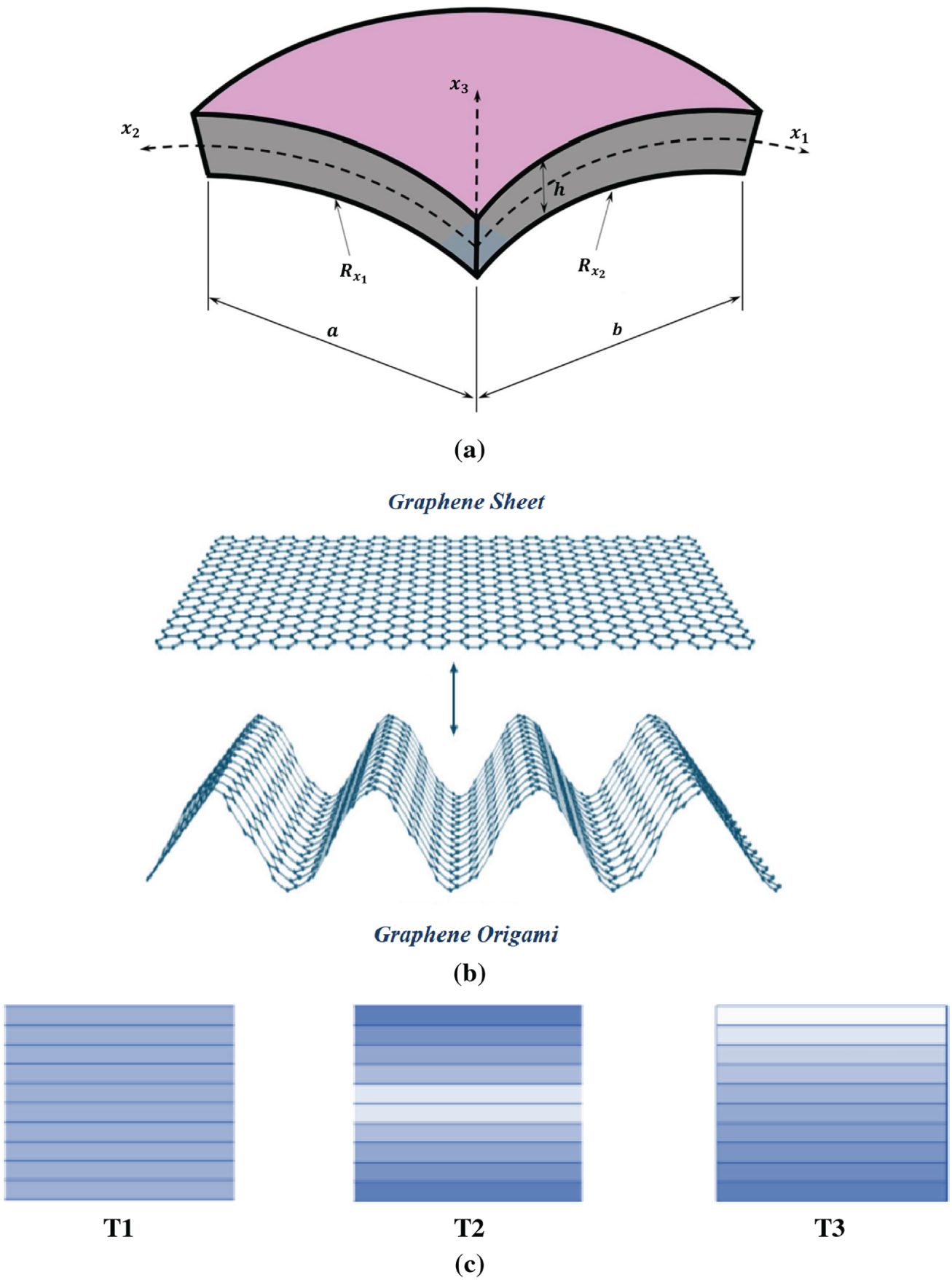

This study investigates a novel composite doubly curved panel composed of a copper matrix reinforced with auxetic G-Ori metamaterials. The panel is assumed to rest on a Pasternak elastic foundation, which is modeled by incorporating both linear spring elements and a shear interaction layer to more realistically capture the subgrade response. The geometric details of the structure are illustrated in Fig. 1, where the in-plane dimensions are denoted by the length a and width b. In Fig. 1 the coordinates x1 and x2 follow the curved mid surface of the shell along the directions associated with the principal radii of curvature

Figure 1: Schematics of the (a) Doubly-curved panel; (b) Convertion of 2D graphene sheet to 3D G-Ori structure; (c) Different configurations of VG-Ori [66]

As a first step, the effective thermo-mechanical properties of the doubly curved panel are determined. In the presence of a thermal environment, the constitutive equations governing the panel’s coupled thermo-mechanical response can be expressed as follows [67]:

In this formulation, the stress and strain tensors are denoted by

In which

In addition, Eq. (1) includes the stiffness components, thermal expansion coefficient, and temperature variation, which are denoted by

G-Ori auxetic metamaterials represent a new class of architected materials that synergistically combine the remarkable mechanical and thermal properties of graphene with the structural adaptability of origami-inspired designs and the counterintuitive behavior of auxetic systems. These metamaterials are typically constructed by embedding patterned graphene sheets into folded configurations capable of exhibiting a negative Poisson’s ratio. This auxetic effect results in lateral expansion under tensile loading and lateral contraction under compression—an unconventional deformation mechanism linked to enhanced shear strength, greater indentation resistance, and improved energy dissipation characteristics. Due to their foldable geometry, G-Ori structures exhibit tunable mechanical responses that can be precisely controlled by adjusting folding angles, spatial distribution, and unit cell configurations. Such geometric programmability enables designers to tailor stiffness and deformation modes to meet specific functional requirements. The exceptional intrinsic properties of graphene, particularly its high strength and stiffness, also contribute to an impressive strength-to-weight ratio, making G-Ori metamaterials highly attractive for lightweight structural components in advanced engineering applications, including aerospace and high-performance mechanical systems. In addition to their mechanical advantages, these materials offer excellent thermal conductivity and stability, allowing them to perform reliably in elevated temperature environments while supporting passive thermal management. The integration of graphene’s multifunctionality with the auxetic and reconfigurable nature of origami geometry positions G-Ori metamaterials as promising candidates for smart materials, adaptive structures, and thermally responsive systems. Their direction-dependent stiffness and thermal tunability make them especially well-suited for incorporation into curved shell structures subjected to complex thermomechanical conditions. Consequently, G-Ori auxetic metamaterials are gaining increasing attention for applications in aerospace engineering, soft robotics, bioinspired systems, and multifunctional metamaterial design.

The effective mechanical properties of the G-Ori auxetic metamaterials incorporated into the proposed structural system are evaluated in the subsequent formulation. To estimate the equivalent Young’s modulus—which represents the overall in-plane stiffness of the metamaterial-enhanced panel—the following expression is utilized [69]:

In this context,

As the reinforcement and matrix phases collectively occupy the full volume of the composite system, their respective volume fractions must sum to unity, regardless of the modeling approach or formulation adopted. Based on this constraint, the volume fraction of the G-Ori auxetic metamaterial phase, denoted by

here,

in which NL is the number of layers. In this formulation, the dispersion function in Eq. (9) represents how the density of G-Ori units varies gradually through the shell thickness, with higher function values corresponding to regions containing a greater concentration of folded microstructures.

To evaluate the overall thermo-mechanical performance of composite structures, the rule of mixtures is frequently employed as a micromechanical modeling technique. This method approximates the effective properties of the composite as weighted averages of the individual constituents’ properties, typically based on their corresponding volume fractions. Despite its simplicity, the rule of mixtures serves as an effective tool for estimating key material parameters such as elastic modulus, thermal conductivity, and the coefficient of thermal expansion—particularly when phase interactions are relatively uniform and ideal bonding conditions are assumed. While the approach involves certain idealizations, it remains widely used due to its versatility and its ability to produce reasonably accurate predictions during the early stages of design, analysis, and material optimization. Accordingly, to accurately estimate the remaining thermo-mechanical properties relevant to the proposed model, the following expressions are utilized [73]:

Furthermore, the correction functions applied in Eqs. (6), (10) and (11) are defined as follows [74]:

here,

In this study, four different distribution patterns of the metamaterial are examined. The mathematical formulations corresponding to each distribution mode are presented as follows:

In these expressions,

In the present homogenized formulation, the folding degree of the G-Ori construct influences the material properties not merely through local softening but through coordinated modifications of the effective Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and thermal expansion coefficient. The corrective functions introduced for these quantities cause the G-Ori architecture to exhibit enhanced in-plane stiffness within the parameter range considered. This behavior originates from the auxetic nature of the metamaterial, where lateral expansion under tensile loading produces a densification of load paths and an overall increase in effective membrane rigidity. As a result, the folding degree acts as a stiffness-enhancing mechanism in this particular architected system, which directly affects the thermal stress field and the onset of thermal buckling.

The principle of virtual displacements is a foundational concept in structural mechanics and continuum analysis. It states that a mechanical system is in equilibrium if the virtual work performed by internal forces is exactly counterbalanced by the virtual work of external forces, for any kinematically admissible virtual displacement. Rather than relying directly on Newton’s laws, this energy-based approach enables the derivation of equilibrium equations through variational methods. In structural analysis, small hypothetical (virtual) displacements are assumed, consistent with the boundary conditions of the system. The variation of the total potential energy—which comprises the strain energy stored in the structure and the work performed by external loads—is then set to zero. This condition yields the differential equations governing the system’s equilibrium. The virtual displacement method is particularly advantageous for analyzing complex configurations such as doubly curved shells, layered composites, and structures resting on elastic foundations, where traditional force-based formulations may become analytically cumbersome.

In the present work, the governing equations are derived by applying the virtual displacement principle, incorporating variations in both the internal strain energy and the external work. The external virtual work includes two primary components: the reaction forces induced by the Pasternak elastic foundation and the thermal loads acting on the structure. Enforcing the condition that the total virtual work vanishes leads directly to the equilibrium equations of the system [75]:

To derive the governing equations, it is first necessary to formulate the strain energy of the system. The total strain energy stored in the structure is expressed using the following relation:

By taking the variation of the strain energy expression and combining it with the corresponding variation of the external work, the following governing equation is obtained:

The virtual work contribution from the Pasternak elastic foundation is given by the following expression [76]:

In this expression, K1 and K2 denote the stiffness coefficients of the spring elements and the shear layer, respectively, within the Pasternak foundation model.

To evaluate the virtual work induced by thermal loading, the following expression is utilized [77]:

In this relation, the thermal loads acting along the x1 and x2 directions are represented by

By substituting the strain components in terms of the displacement field and applying variational calculus, the governing equilibrium equations are derived. These equations are formulated as follows:

The integral coefficients appearing in the preceding expressions are defined as follows:

The equilibrium equations derived for thermal analysis of composite shells can be solved using a range of analytical and numerical techniques, depending on the complexity of the geometry, material behavior, and boundary conditions involved. In general, two major categories of solution strategies are employed: analytical and numerical methods. Numerical methods are widely adopted when dealing with complex geometries, heterogeneous materials, and general boundary or loading conditions. In these approaches, the problem domain is discretized into smaller subregions, and the governing differential equations are approximated using algebraic forms. Among these, the finite element method has been most extensively used due to its flexibility and robustness. However, numerical approaches often require considerable computational effort and may involve challenges in mesh generation, especially for curved shell structures. On the other hand, analytical and semi-analytical methods have been developed to address idealized configurations, providing closed-form or approximate solutions that satisfy the governing equations and boundary conditions under simplified assumptions. Although such methods are restricted to regular geometries and standard boundary conditions, they offer valuable insights into the underlying mechanics of the system and are often used to validate numerical results or conduct parametric studies. In the present study, the Navier method has been employed to obtain an analytical solution to the governing equilibrium equations. This method is based on the assumption that displacement fields can be expressed as double Fourier series, which inherently satisfy simply supported boundary conditions along all edges of the shell. By substituting the assumed series expansions into the equilibrium equations and applying the orthogonality conditions of trigonometric functions, the original partial differential system is transformed into an algebraic eigenvalue problem. Navier’s method provides several advantages in the context of thermal buckling analysis. Since the boundary conditions are exactly satisfied by the chosen solution functions, high accuracy can be achieved with relatively simple mathematical formulation. Moreover, the method enables direct evaluation of the influence of key design parameters (including material distribution, geometric curvature, and metamaterial reinforcement patterns) on the thermal stability behavior of the shell. Specifically, for doubly curved composite panels, Navier’s method allows the critical buckling temperatures (CBTs) to be determined analytically by solving the resulting eigenvalue problem. The smallest eigenvalue corresponds to the temperature difference at which the structure becomes unstable. This approach is particularly effective when the curvature is constant and the panel edges are simply supported, which is the case considered in this work. Through this method, the impact of folding degree, dispersion patterns of G-Ori auxetic metamaterials, and thermo-elastic coupling can be systematically investigated with high computational efficiency. In accordance with Navier’s solution technique, the displacement fields are constructed to inherently satisfy the simply supported boundary conditions along the shell’s edges. As a result, the displacement components can be expressed in the following form [78]:

where:

In this formulation, m and n represent the longitudinal and transverse wavenumbers, respectively. By substituting the Fourier series expressions defined in Eqs. (29)–(32) into the governing equilibrium equations, and incorporating the thermal load in the form of

In this context, the matrix [Ke] denotes the elastic stiffness matrix, whereas [KT] represents the geometric stiffness matrix associated with thermal loading. The vector {X} contains the displacement amplitude coefficients obtained from the assumed Fourier series expansions.

The present study focused on the thermal buckling analysis of doubly curved composite panels reinforced with G-Ori auxetic metamaterials. The FSDT was employed to model the mechanical behavior of the structure, while the governing equilibrium equations were derived using the principle of virtual displacements. The thermo-mechanical properties of the composite system were estimated through micromechanical modeling based on the rule of mixtures and modified by appropriate correction functions. Navier’s method was then applied to obtain a semi-analytical solution for panels with simply supported boundary conditions, leading to an eigenvalue problem whose non-trivial solutions correspond to the CBTs of the structure.

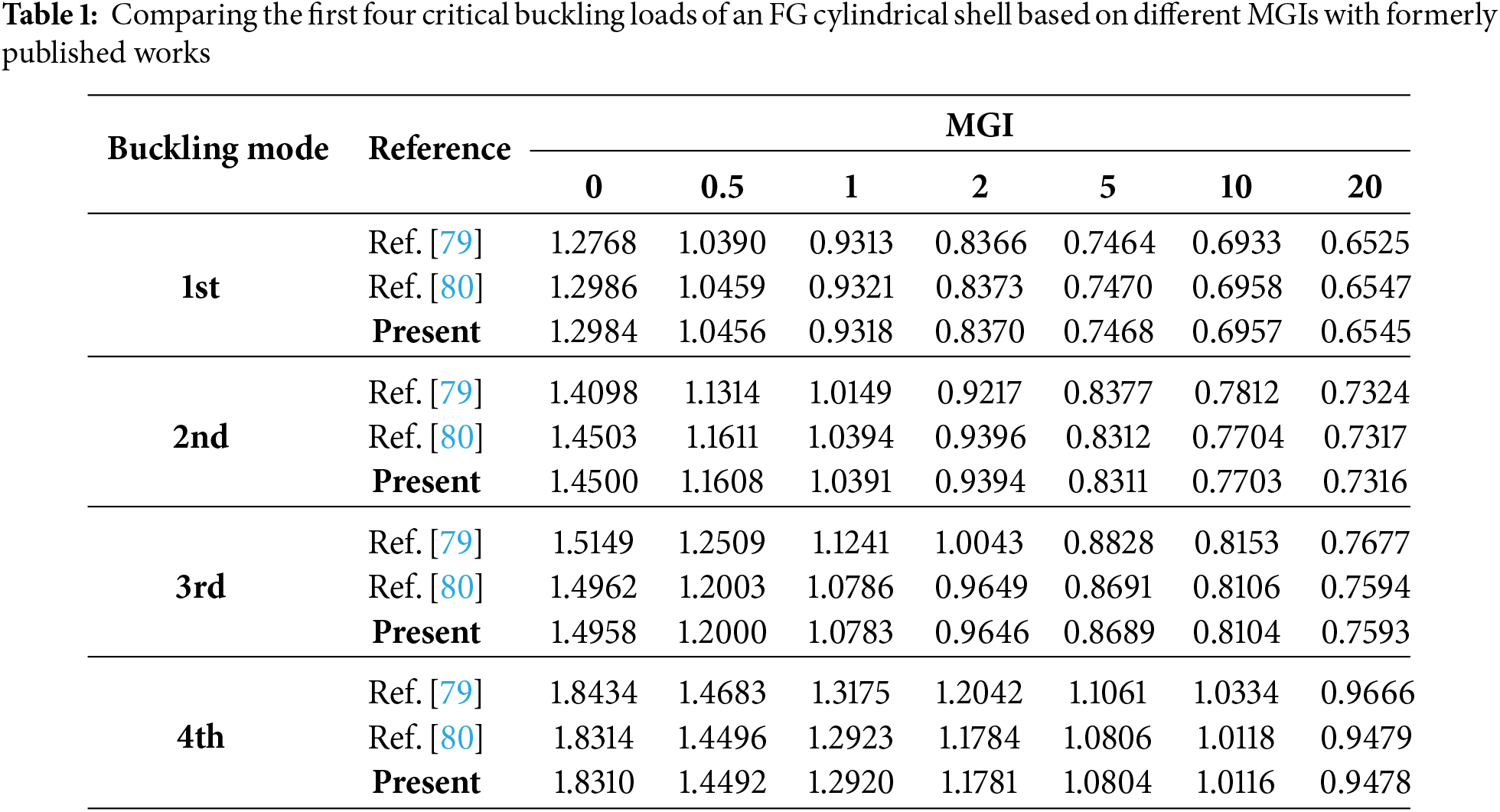

Given the novelty of the structural configuration analyzed in this study, and the lack of prior investigations on thermal buckling behavior of panels reinforced with G-Ori metamaterials, it was essential to verify the validity of the developed model. To evaluate the accuracy of the proposed model, the first four critical buckling loads of a functionally graded (FG) cylindrical shell were calculated and compared with the corresponding results reported in two previously published studies, referred to as Refs. [79,80]. The comparison was carried out across a wide range of material gradient indices (MGI), from 0 (fully ceramic) to 20 (nearly fully metallic), and the results are summarized in Table 1. The normalized critical buckling load of this table is defined as

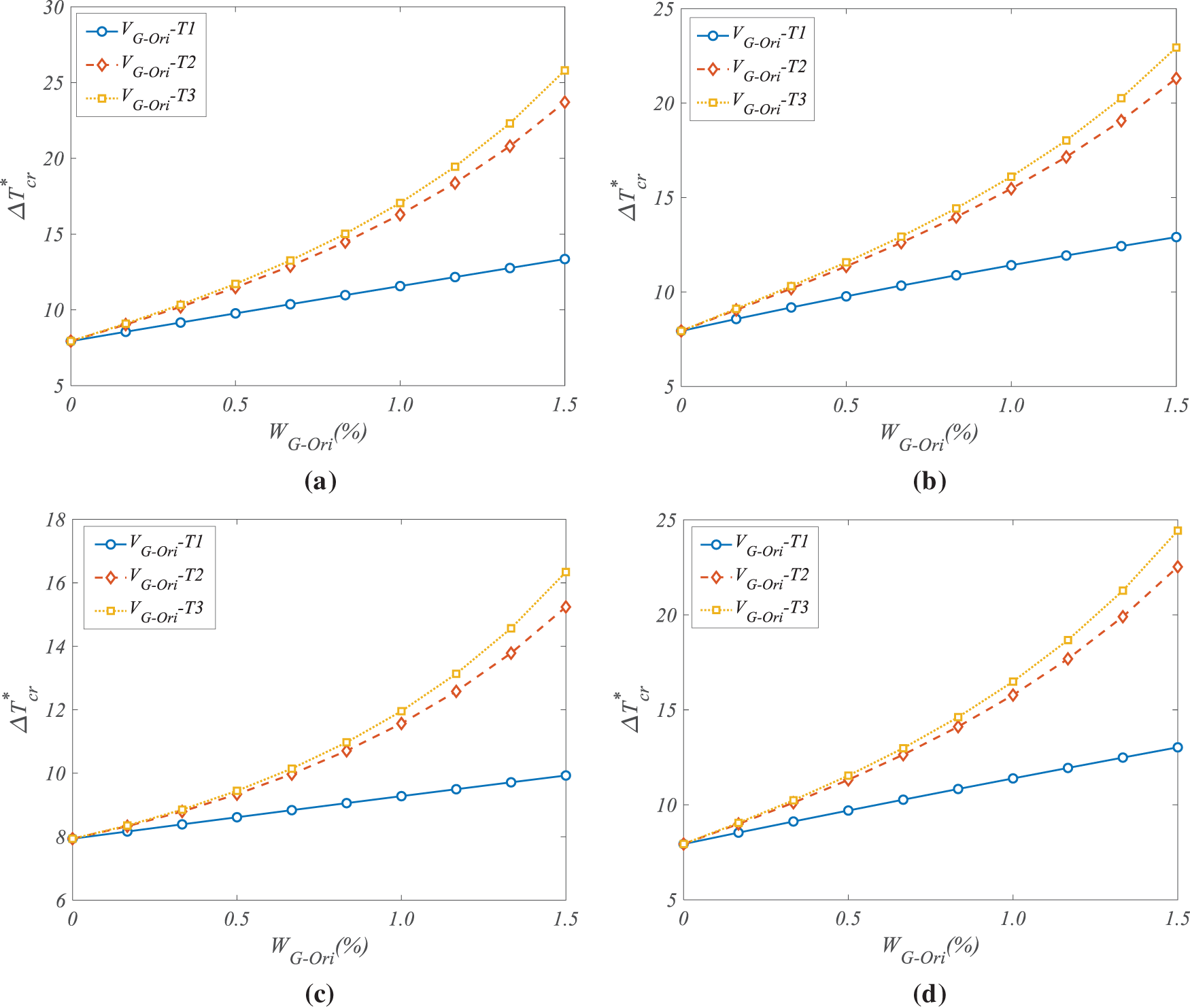

Following model validation, a detailed parametric investigation was carried out to assess the influence of the G-Ori auxetic metamaterial distribution on the thermal buckling response of the doubly curved panel. It should be noted that all of the following CBTs are normalized via

Figure 2: Effect of weight fraction of G-Ori auxetic metamaterials and dispersion types on the CBTs for (a) P1; (b) P2; (c) P3; (d) P4 configurations of HG-Ori

In order to further assess the influence of structural configuration on thermal buckling resistance, the effect of folding degree (HG-Ori) and folding layout on the normalized CBTs was investigated, as shown in Fig. 3. The analysis was conducted for three types of volume fraction distributions: T1 (uniform), T2 (X-shaped), and T3 (A-shaped), which are represented in subfigures (a)–(c), respectively. In each case, four folding configurations (P1 to P4) were considered, and the folding degree was varied to examine its impact on thermal stability.

Figure 3: Effect of folding degree and configurations of G-Ori auxetic metamaterials on the CBTs for (a) T1; (b) T2; (c) T3 types of VG-Ori

Across all dispersion types, an increase in HG-Ori—representing the extent of folding—leads to a consistent rise in the normalized CBT. This behavior highlights the role of geometrical reconfiguration in enhancing the overall stiffness and thermal resistance of the metamaterial-reinforced shell. As the folding degree increases, the effective mechanical interlocking and auxetic response of the structure are improved, resulting in greater resistance to deformation under thermal loads. For the T1 (uniform) distribution, the increase in CBT due to folding is noticeable but moderate. As the folding degree rises from its minimum to maximum value, the normalized CBT increases by approximately 15.2% for P1, 17.8% for P2, 19.5% for P3, and 20.6% for P4. The A-shaped folding configuration (P4) provides the highest thermal stability, indicating that even with uniform material distribution, geometrical tailoring of the folding pattern significantly affects performance. In the T2 distribution (X-shaped), the effect of folding degree becomes more pronounced. The CBT enhancements between minimum and maximum folding degrees are approximately 16.7%, 20.3%, 22.9%, and 24.1% for P1 through P4, respectively. These results confirm that aligning both the dispersion and folding configurations amplifies the effectiveness of G-Ori metamaterials in resisting buckling. The most substantial impact is observed under the T3 (A-shaped) distribution. In this case, the normalized CBT increases by more than 27% for the P4 configuration as the folding degree is maximized, whereas gains of 18.4%, 21.5%, and 24.8% are recorded for P1, P2, and P3, respectively. The T3–P4 combination, which aligns both the volume distribution and folding configuration in an A-shaped pattern, delivers the highest thermal resistance among all examined cases. This synergistic interaction between material arrangement and geometric configuration results in more efficient stress redistribution and energy dissipation during thermal loading. These findings highlight the critical role of folding degree as a tunable design parameter. In addition to increasing the G-Ori content, manipulating the folding geometry and coordinating it with dispersion patterns enables precise control over the shell’s thermal buckling performance. This level of programmability makes G-Ori-based systems particularly attractive for adaptive and thermally demanding environments, such as aerospace structures and morphing components.

Noted that the trend observed in Fig. 3, where the CBT increases with the folding degree, reflects the intrinsic mechanical behavior of the G-Ori auxetic architecture. Although conventional folded structures often experience stiffness reduction with increasing fold amplitude, the present metamaterial displays the opposite effect due to its negative Poisson’s ratio and the consequent expansion of the structural lattice under in-plane loading. This mechanism strengthens the effective membrane stiffness along the principal stress paths, which in turn raises the resistance of the shell against thermally induced compressive stresses. The results therefore originate directly from the homogenized thermo-mechanical model and reveal how the tunable geometry of the G-Ori reinforcement can be exploited to enhance thermal buckling resistance in doubly curved shells.

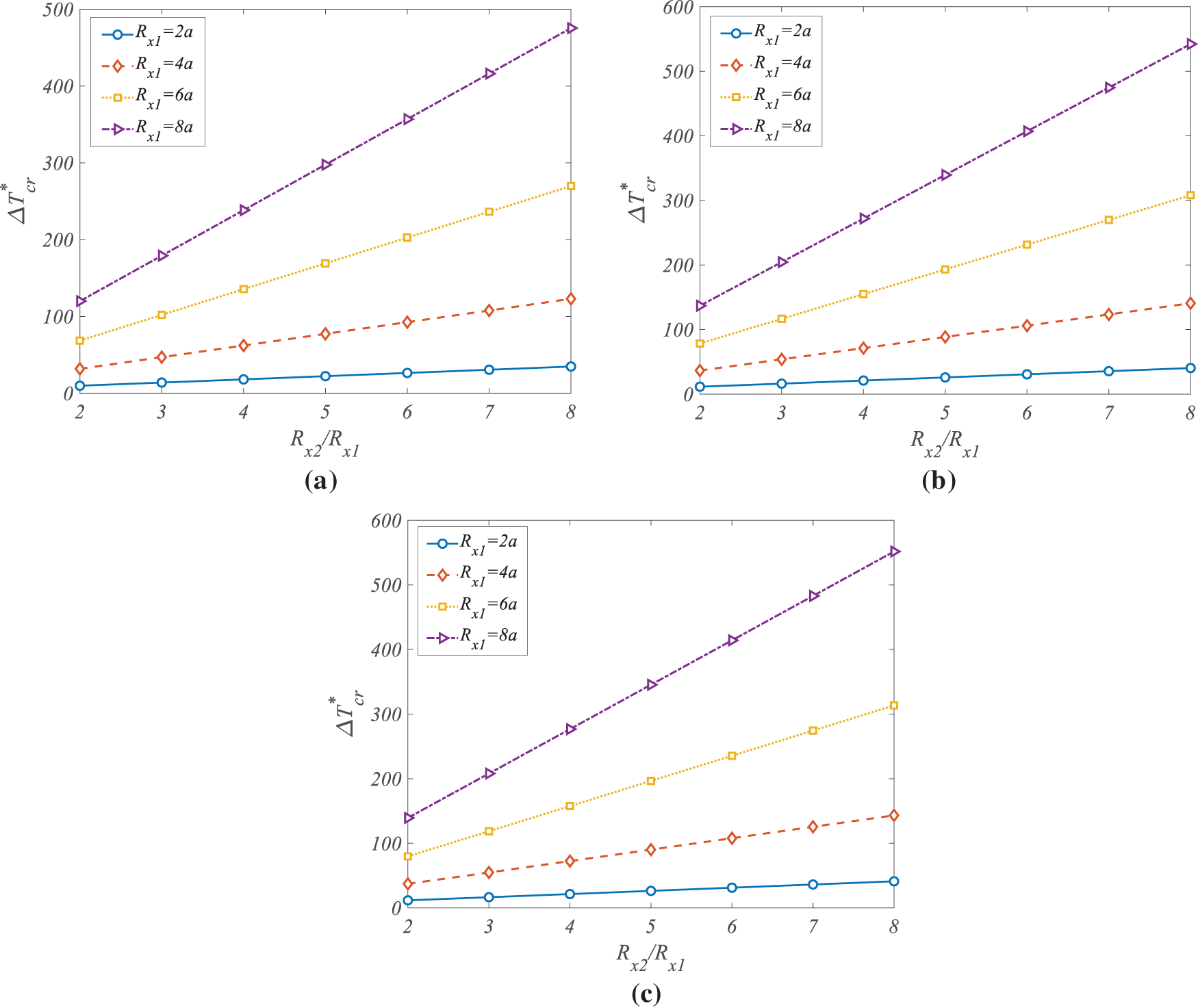

To assess the influence of geometric properties on thermal buckling behavior, Fig. 4 presents the variation of normalized CBTs with respect to the normalized curvature ratio Rx1/a, where Rx1 denotes the shell’s longitudinal radius of curvature and a is its length. The analysis is conducted for three different dispersion patterns of G-Ori auxetic metamaterials: T1 (uniform), T2 (X-shaped), and T3 (A-shaped), shown in subfigures (a)–(c), respectively. The transverse radius of curvature Rx2 is kept constant during the analysis to isolate the influence of Rx1/a. The results indicate a clear and consistent trend: as the value of Rx1/a increases, the normalized CBT decreases across all dispersion types. Physically, this trend corresponds to a flattening of the shell geometry in the longitudinal direction. As the curvature becomes less pronounced (i.e., larger Rx1), the inherent geometric stiffness provided by the double curvature diminishes, making the panel more vulnerable to thermally induced buckling. For the T1 configuration, the normalized CBT drops by approximately 19% as Rx1/a increases over the considered range. In comparison, the T3 pattern shows a slightly reduced sensitivity, with a CBT decrease of around 15%, suggesting improved resistance to curvature loss due to its optimized material placement. The X-shaped dispersion pattern (T2) performs intermediate between T1 and T3. Its normalized CBT decreases by roughly 17%, highlighting that non-uniform, patterned reinforcement plays a significant role in mitigating geometric effects. The A-shaped dispersion (T3) consistently outperforms the other configurations, especially at lower curvature ratios, where geometric stiffening is more dominant and where strategically placed auxetic reinforcement proves most effective. These results underscore the critical interaction between shell curvature and metamaterial architecture in determining thermal buckling behavior. While larger values of Rx1/a inherently reduce structural resistance due to diminished curvature, this effect can be partially offset through intelligent design of the G-Ori reinforcement layout. In particular, matching the auxetic reinforcement pattern to curvature-induced stress pathways enhances energy absorption and deformation control under thermal loads, enabling the design of more stable and resilient curved composite structures.

Figure 4: Effect of geometric properties of the doubly-curved panel on the CBTs for (a) T1; (b) T2; (c) T3 types of VG-Ori

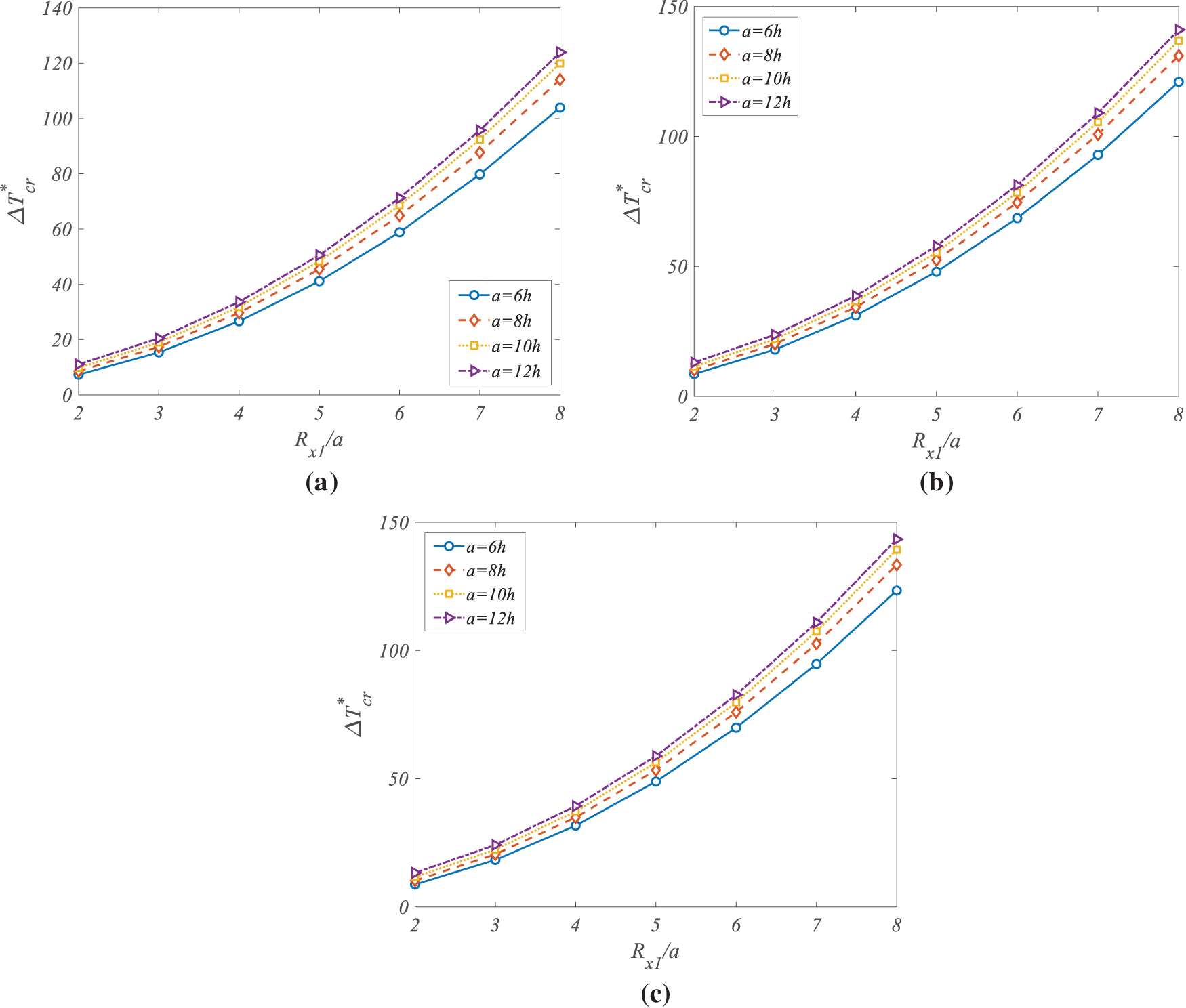

To further evaluate the geometric sensitivity of the thermal buckling behavior, Fig. 5 presents the combined influence of panel thickness and longitudinal curvature radius on the normalized CBT. The analysis is performed for three G-Ori auxetic metamaterial dispersion patterns: T1 (uniform), T2 (X-shaped), and T3 (A-shaped), shown in subfigures (a)–(c), respectively. In all cases, the panel length is denoted by h, and the effect of varying panel thickness is studied while considering different values of the curvature radius Rx1. The results demonstrate that an increase in panel thickness leads to a consistent rise in the normalized CBT across all dispersion types. This is a direct consequence of increased structural rigidity associated with thicker panels, which enhances resistance to thermally induced deformation. In the T1 case, increasing the thickness from its minimum to maximum considered value results in a CBT enhancement of approximately 23%, while in T2 and T3 configurations, the increases are approximately 26% and 29%, respectively. The greater improvement in the patterned distributions (particularly T3) reflects their enhanced ability to localize stiffness where it is most effective. In contrast, an increase in the curvature radius Rx1—which corresponds to a reduction in curvature—leads to a decrease in the normalized CBT. This geometric flattening reduces the natural stiffness advantage of the shell’s curved form, thereby making it more susceptible to thermal buckling. The CBT reduction in T1 due to increasing Rx1 is observed to be about 17%, while in T3, it is limited to around 13%, demonstrating that well-optimized dispersion of G-Ori reinforcement can partially counteract the geometric stiffness loss caused by reduced curvature. Among the three dispersion types, the T3 (A-shaped) pattern consistently produces the highest CBTs for all combinations of thickness and curvature radius. This superior performance is attributed to the strategic placement of auxetic material in high-stress regions, which allows more efficient absorption and redistribution of thermal stresses. The T1 pattern, by contrast, shows the least sensitivity to thickness variation but also yields the lowest overall buckling resistance. These observations emphasize that panel thickness and curvature radius interact strongly with the material dispersion strategy to influence thermal buckling behavior. While thicker structures inherently exhibit greater thermal stability, the use of G-Ori auxetic metamaterials—particularly with optimized dispersion such as the A-shaped layout—can further amplify this stability. Moreover, carefully selected reinforcement layouts can mitigate the adverse effects of reduced curvature, offering a valuable design strategy for thermally loaded curved structures where geometric constraints are imposed by application requirements. It should be noted that for the doubly curved shell considered here, enlarging the side lengths increases the dominance of membrane action relative to bending, which elevates the critical thermal stress required for buckling. Combined with the stiffness-enhancing effect of the G-Ori auxetic reinforcement, this causes the CBT to increase rather than decrease as the panel dimensions grow.

Figure 5: Effect of thickness and curvature radius of the doubly-curved panel on the CBTs for (a) T1; (b) T2; (c) T3 types of VG-Ori

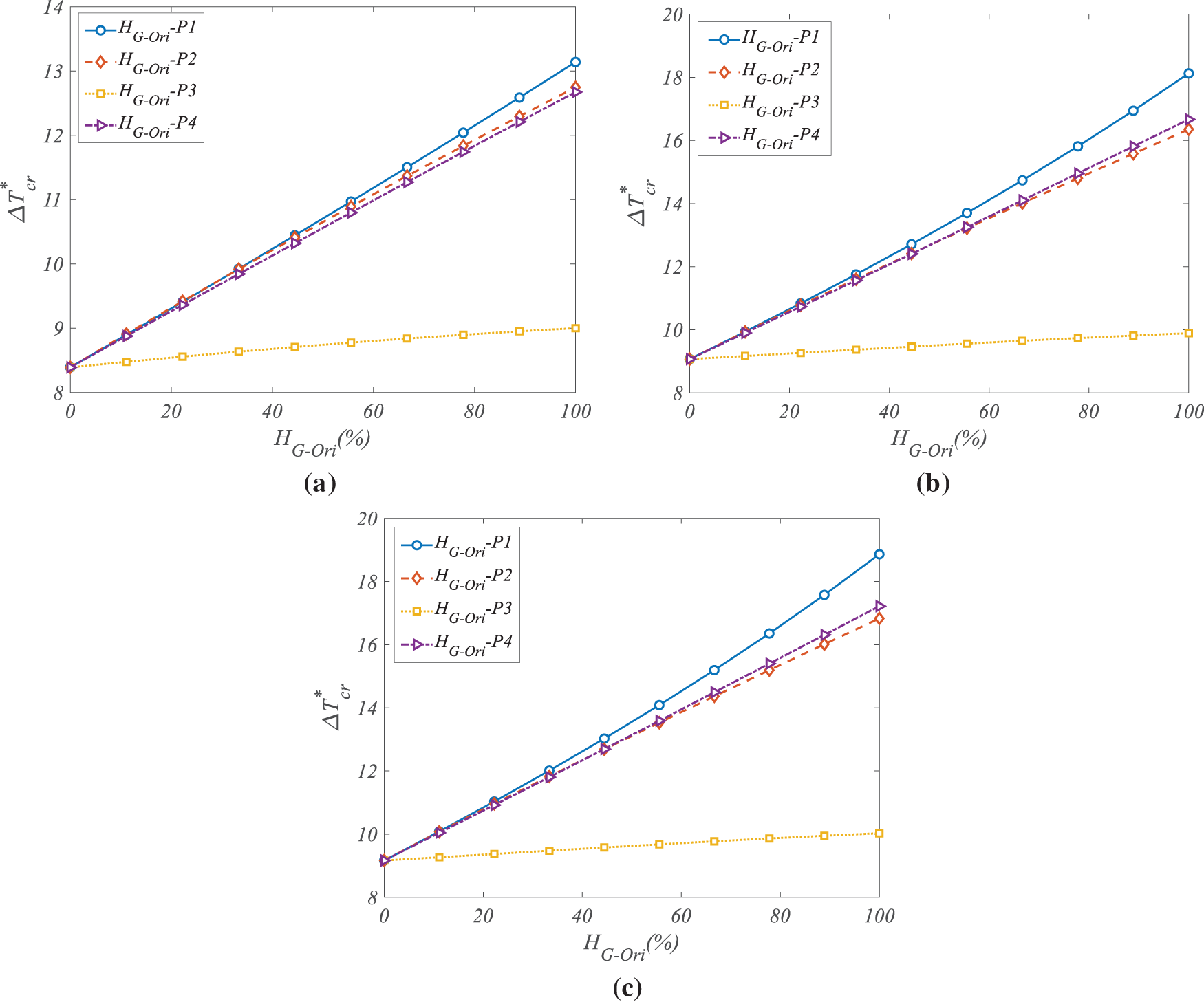

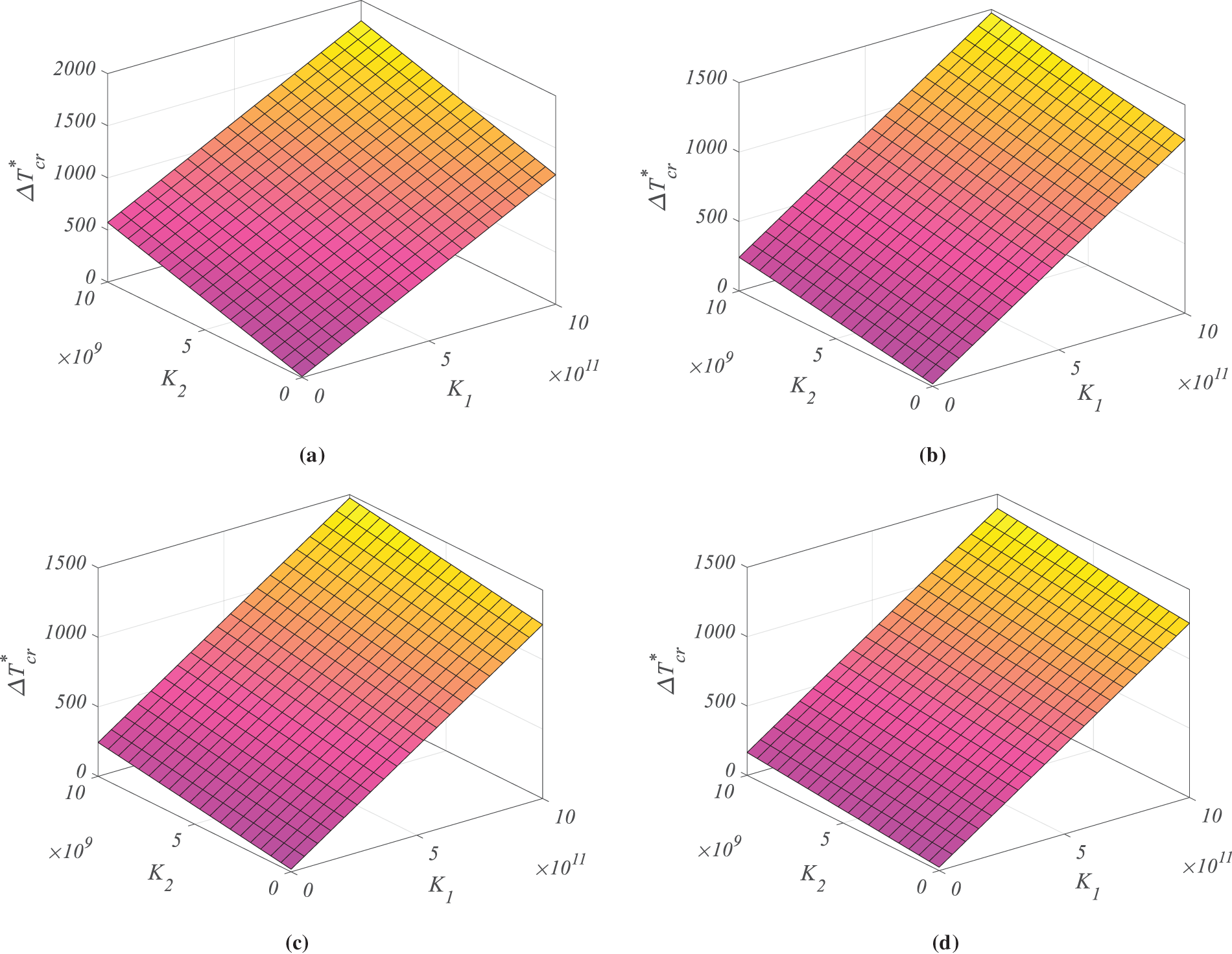

To evaluate the role of foundation support on thermal buckling behavior, Fig. 6 illustrates the effect of Pasternak elastic foundation parameters on the normalized CBTs of the doubly curved G-Ori-reinforced panel. The influence is assessed across the first four buckling modes, shown respectively in subfigures (a)–(d). Two parameters govern the behavior of the Pasternak foundation: the spring stiffness K1, which resists vertical displacements, and the shear layer stiffness K2, which provides resistance to shear deformation of the foundation layer. The results indicate that increasing either K1 or K2 leads to a clear and consistent enhancement in the normalized CBT across all buckling modes. This improvement can be attributed to the additional support and restoring forces introduced by the elastic foundation, which effectively suppress out-of-plane deformations and delay the onset of thermal instability. The stabilizing effect is especially pronounced when both stiffness components are simultaneously increased.

Figure 6: Effect of Pasternak foundation parameters on the CBTs for (a) 1st; (b) 2nd; (c) 3rd; (d) 4th buckling mode

In the first buckling mode (Fig. 6a), the normalized CBT rises sharply with increasing K1 and K2. For example, compared to the unsupported case, an increase in both parameters leads to a CBT enhancement of approximately 28%, reflecting the significant impact of foundation stiffness on the most flexible deformation mode. The second and third modes (Fig. 6b,c) exhibit similar trends, though with slightly reduced sensitivity; CBT increases of 24% and 21% are observed, respectively. These reductions are expected as higher-order buckling modes involve more complex deformation shapes with localized curvature, which are less uniformly influenced by foundation stiffness. In the fourth buckling mode (Fig. 6d), while the trend remains upward, the relative increase in CBT tapers off to approximately 18%. This diminishing effect suggests that for higher modes, the interaction between localized buckling shapes and foundation stiffness becomes less dominant, though still beneficial. Importantly, the shear layer parameter K2 plays a particularly influential role in enhancing thermal stability for curved panels, due to its ability to resist lateral shear distortions that commonly accompany thermal gradients. The combined use of K1 and K2 ensures both vertical and shear constraints, creating a more robust mechanical environment for buckling suppression. These results confirm that embedding the curved shell structure within a Pasternak-type elastic foundation can significantly elevate its thermal buckling resistance. Moreover, the effectiveness of the foundation is mode-dependent, being most impactful in lower-order global buckling responses. This finding supports the use of elastic foundation models in engineering applications where structural stability under thermal loading is critical, such as buried pipelines, layered aerospace panels, and insulated structural skins.

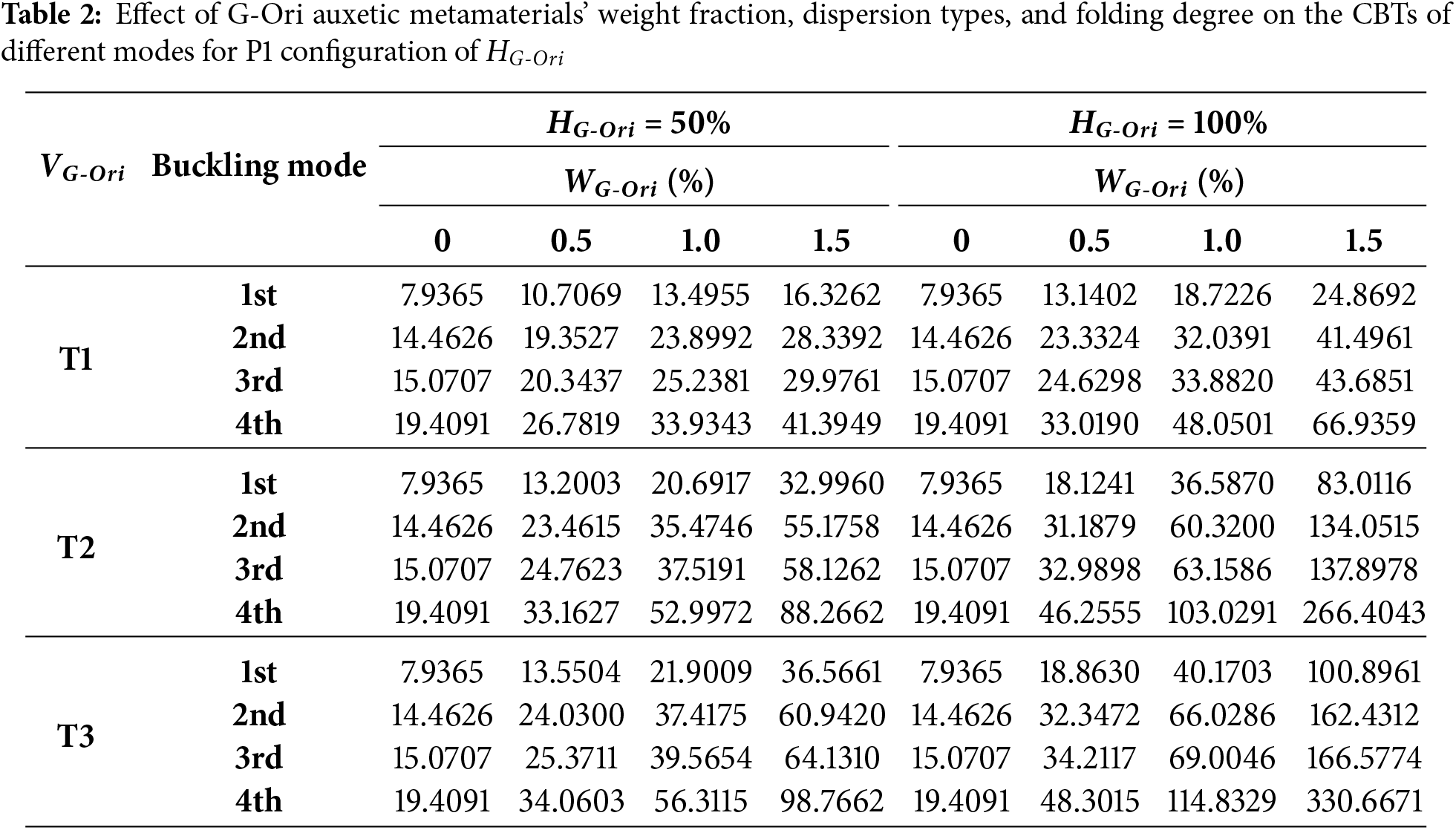

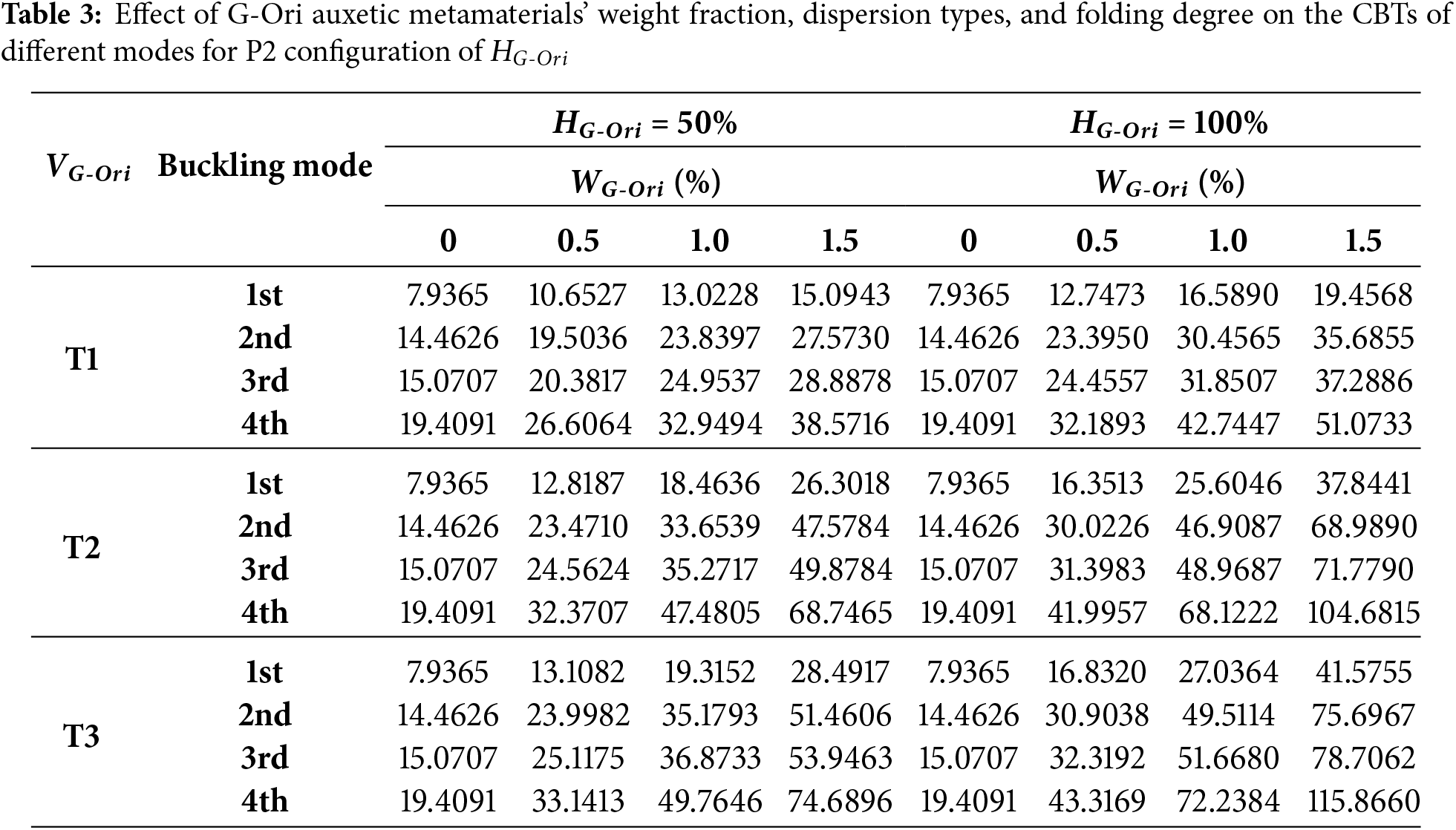

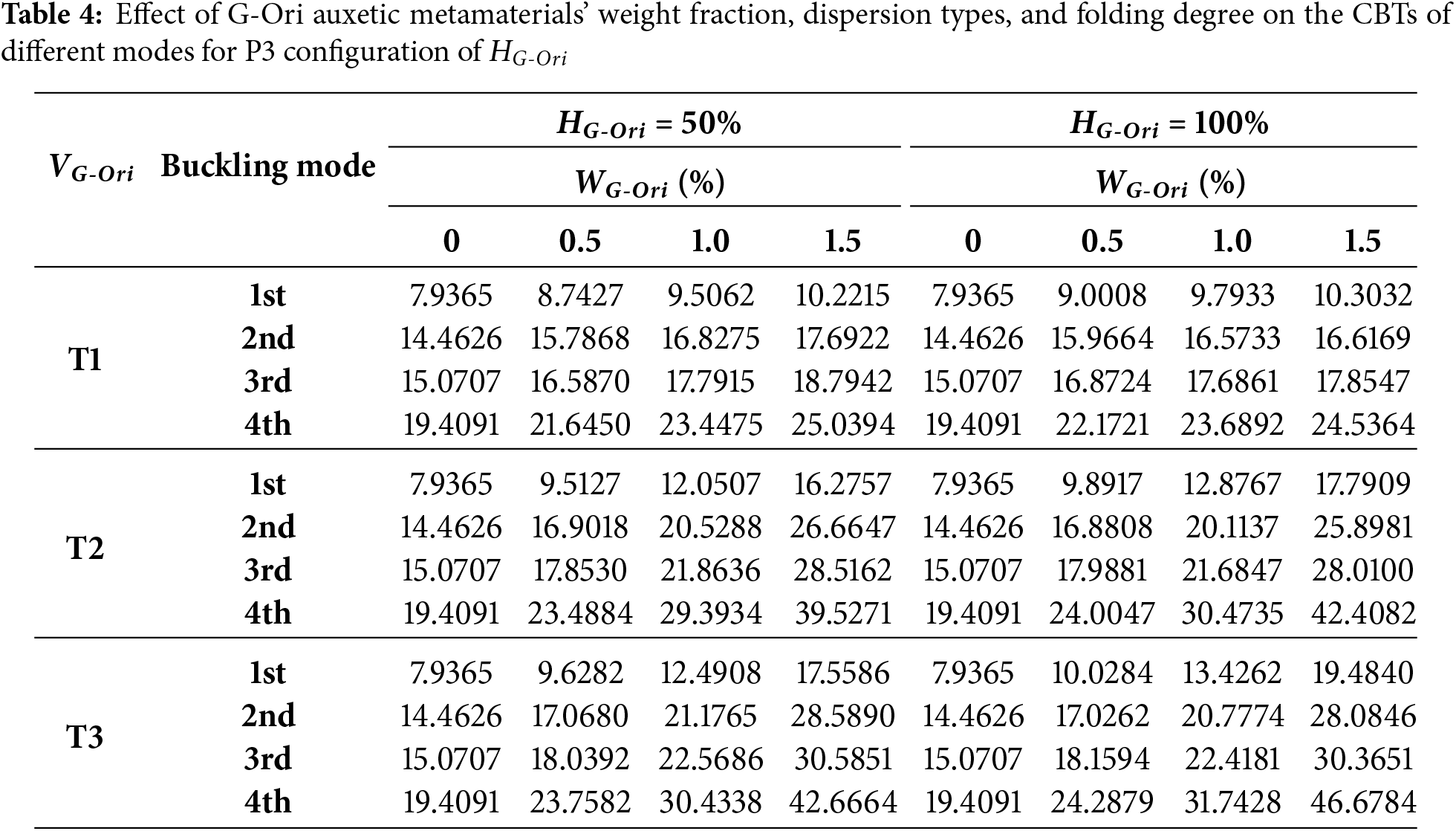

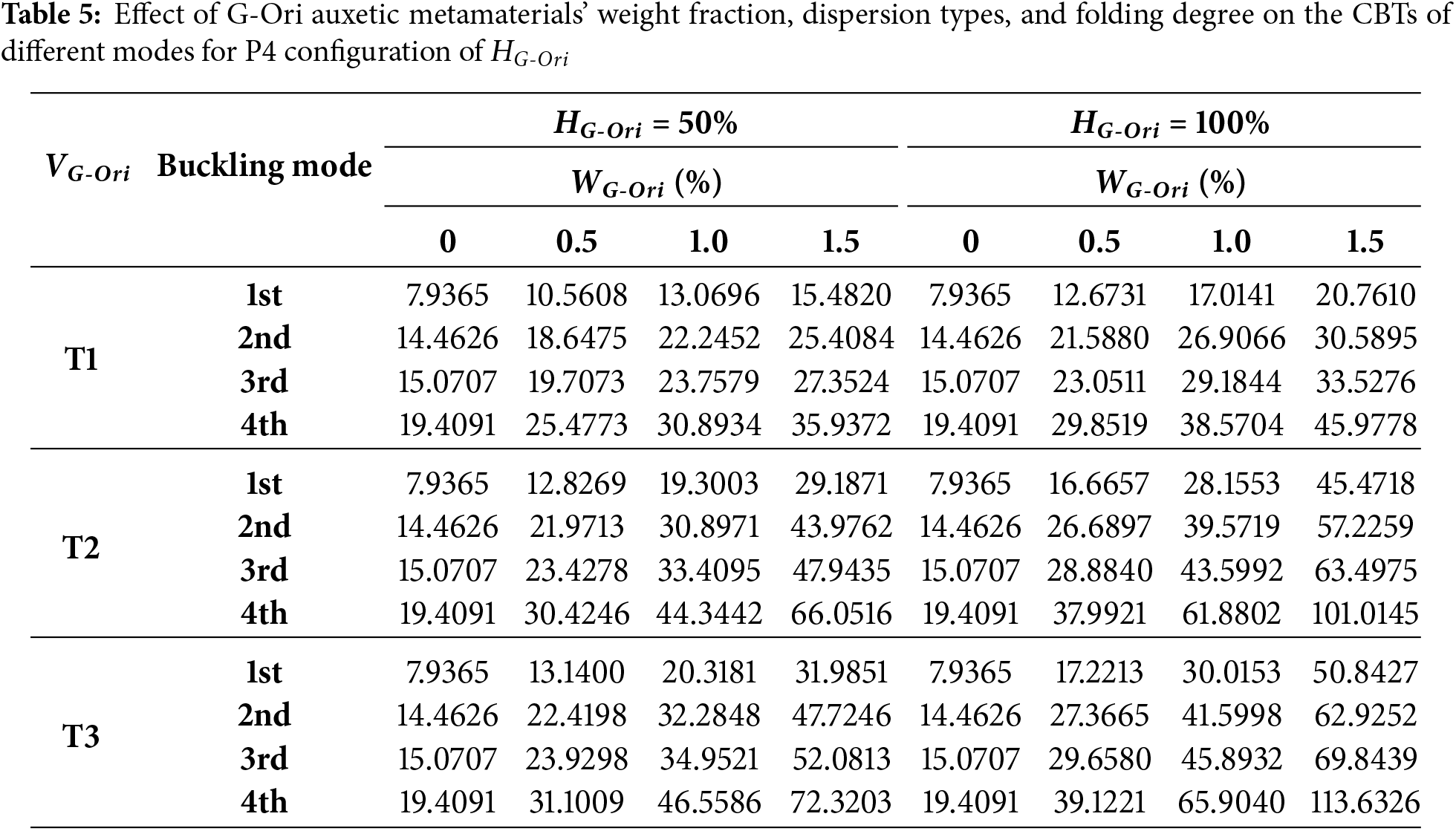

The combined influence of G-Ori auxetic metamaterial weight fraction, dispersion pattern, and folding degree on the thermal buckling response of the doubly-curved panel is presented in Tables 2–5 for four different folding configurations (P1 to P4). The data are categorized by buckling mode (first to fourth) and show the normalized CBTs for increasing values of WG-Ori (0% to 1.5%) under two folding degrees: 50% and 100%. Across all configurations, several consistent trends emerge. An increase in the weight fraction of G-Ori metamaterials significantly enhances CBTs due to the superior stiffness, thermal conductivity, and auxetic behavior of the reinforcement phase. Likewise, increasing the folding degree from 50% to 100% improves thermal stability by amplifying the mechanical response of the folded structure, especially in configurations aligned with the dispersion pattern. Among the dispersion strategies, the A-shaped pattern (T3) consistently delivers the highest CBTs, particularly in higher buckling modes, by efficiently placing auxetic material along the primary deformation zones. These trends confirm the synergistic impact of material content, structural patterning, and geometric configuration on buckling resistance under thermal loading. In the Table 2, i.e., P1 (uniform folding) layout, CBTs increase markedly with both WG-Ori and folding degree. For the first mode, CBT increases from 7.94 (no reinforcement) to 24.87 at 100% folding and 1.5% WG-Ori for T1, and up to 100.90 and 83.01 for T3 and T2, respectively—reflecting an increase of over 1150% in the best-performing case. The fourth buckling mode shows the most dramatic gains: CBT rises from 19.41 (T1, no reinforcement) to 330.67 (T3, 100%, 1.5%), an increase of over 1600%. These results emphasize the P1 layout’s compatibility with non-uniform dispersion, especially under high reinforcement and folding conditions.

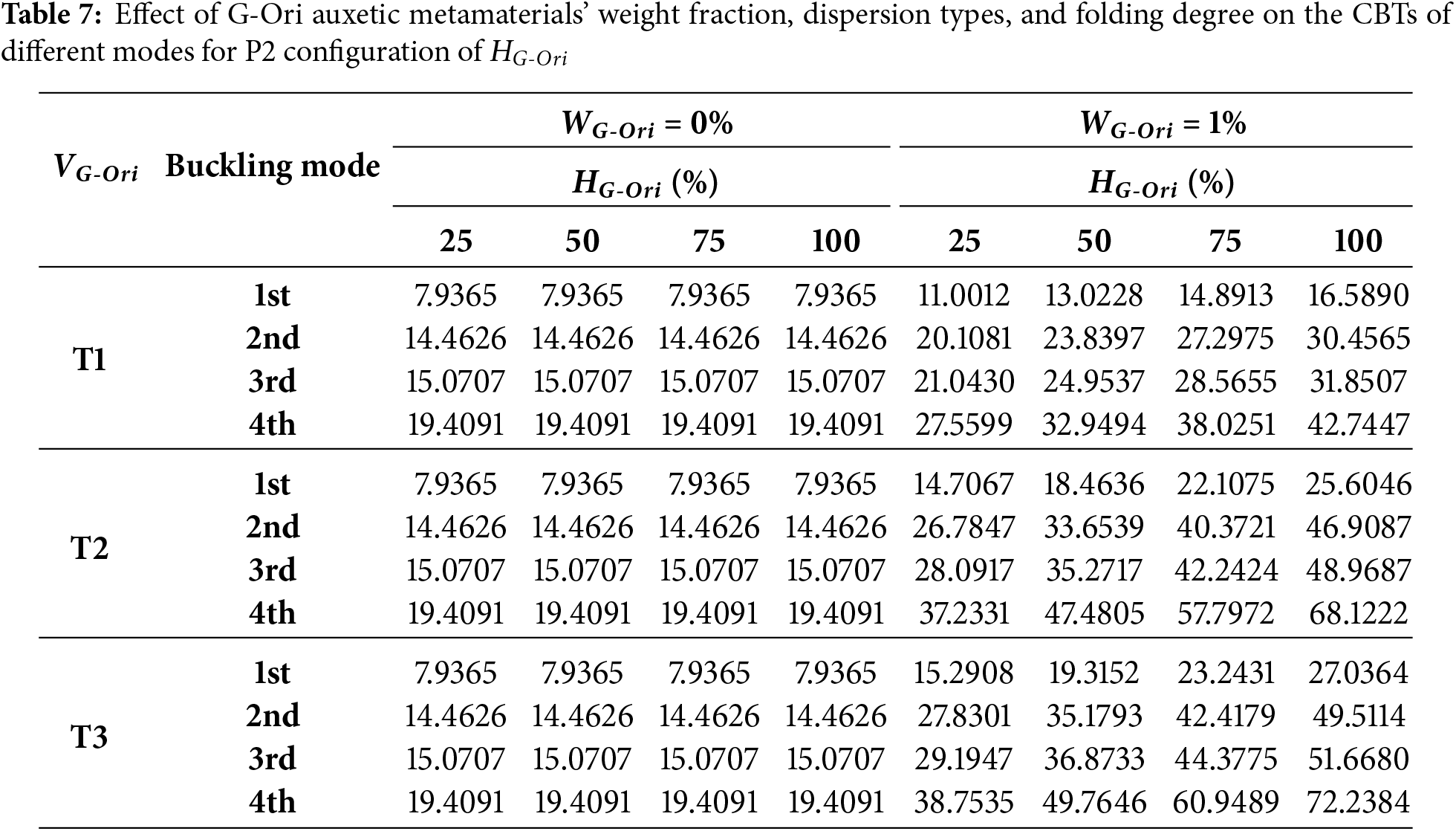

The Table 3, i.e., P2 (X-shaped) configuration shows slightly lower absolute CBTs than P1 but follows similar trends. For the first mode, CBT increases from 7.94 to 41.58 for T3 at 100% folding and 1.5% weight fraction—a 423% increase. For the fourth mode under the same conditions, CBT reaches 115.87, compared to 19.41 at the baseline—an increase of nearly 497%. The T3 dispersion again outperforms T2 and T1, with better reinforcement alignment in this configuration enhancing thermal stability across all modes.

In the Table 4, i.e., P3 (O-shaped) configuration, the CBTs are lower than those in P1 and P2, particularly under T1. For instance, in the first buckling mode, CBT grows from 7.94 to only 10.30 (T1, 100%, 1.5%), a modest 29% increase. However, for T3, the CBT reaches 19.48, representing a 145% improvement over the baseline. For the fourth mode, T3 provides a CBT of 46.68, nearly 141% higher than the unreinforced case. These results show that while the P3 configuration is less effective for uniformly dispersed reinforcements, it still benefits significantly from patterned layouts such as T2 and T3.

The Table 5, i.e., P4 (A-shaped folding) configuration exhibits the highest overall performance across all modes. For the first buckling mode, CBT increases from 7.94 (no reinforcement) to 50.84 (T3, 100%, 1.5%)—a 540% increase. For the fourth mode, the CBT reaches 113.63 (T3, 100%, 1.5%), up from 19.41, corresponding to a 485% improvement. Notably, even under the uniform dispersion (T1), the increases remain substantial, confirming that folding pattern and material alignment in P4 are ideally suited for maximizing thermal buckling resistance.

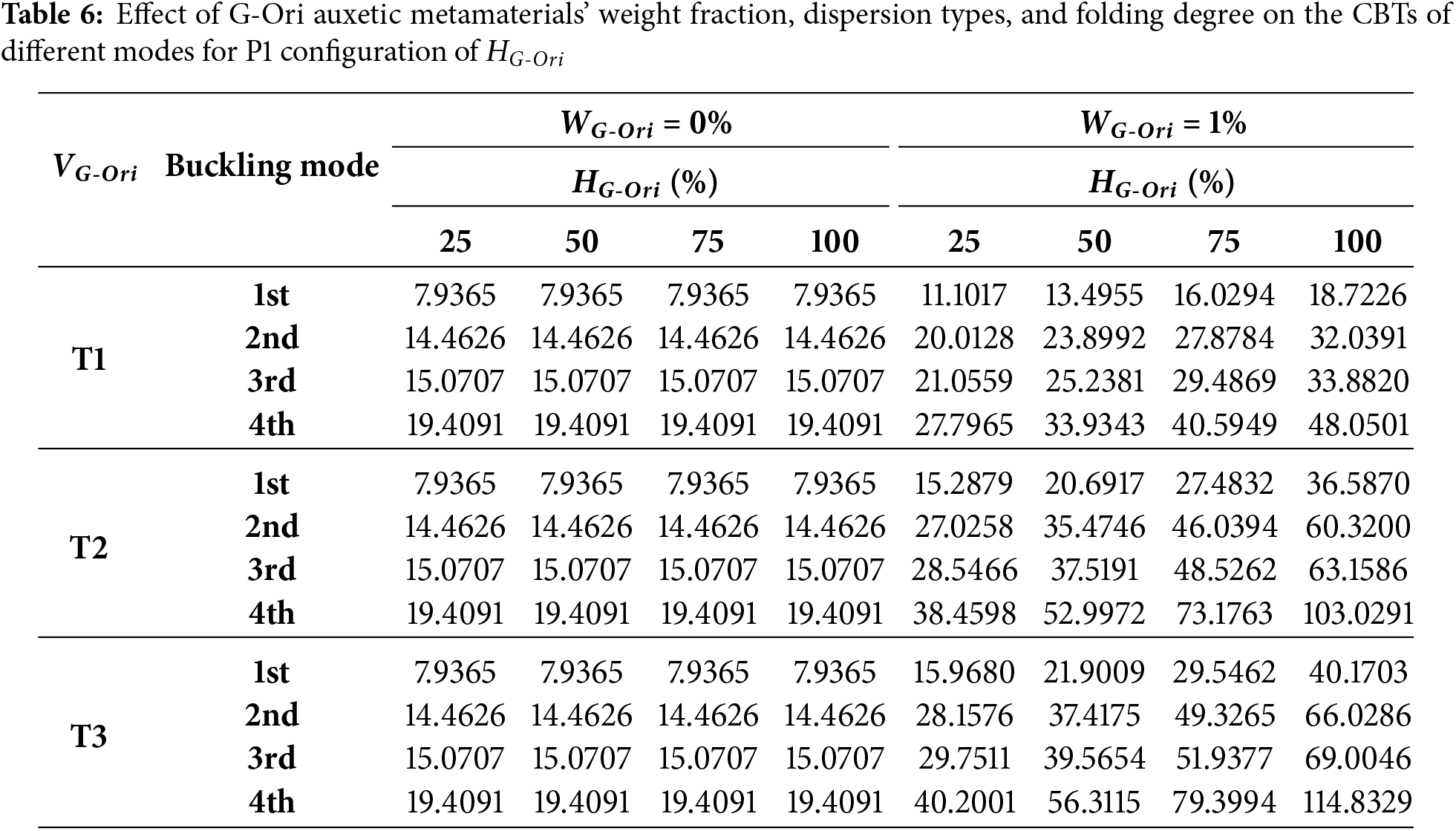

The data presented in Tables 6–9 investigate the combined effects of folding degree HG-Ori, dispersion type, and folding configuration on the thermal buckling behavior of the doubly curved G-Ori-reinforced panel. While the weight fraction of G-Ori metamaterials is kept constant at 1%, the folding degree varies from 25% to 100%, allowing the progressive engagement of the origami geometry to be analyzed. Across all configurations and modes, the normalized CBT increases monotonically with higher folding degrees and becomes especially sensitive when the dispersion strategy (T1, T2, or T3) is coordinated with an effective folding layout. This behavior can be attributed to the geometric stiffening and auxetic response induced by increased folding, which enhances energy absorption and redistribution during thermally induced deformation. Particularly for non-uniform patterns (T2 and T3), greater folding activation allows the metamaterial to develop localized stiffness and deformation pathways aligned with the buckling mode shapes. Consequently, folding degree acts as a tunable design parameter that significantly boosts thermal stability without altering material content.

In the Table 6, i.e., P1 (uniform folding) case, the CBTs rise steadily with increasing folding degree. For the first mode, the CBT increases from 11.10 (25%) to 18.72 (100%) under T1, reflecting a 68.6% improvement. Under T3, this gain is more dramatic—from 15.97 to 40.17, a 151.4% increase. The fourth mode experiences even stronger improvements under T3, with CBT rising from 40.20 to 114.83, representing a 186% enhancement over the 25% case. These results emphasize that higher folding degrees, especially when combined with T3 dispersion, dramatically enhance thermal buckling resistance in uniform folding layouts.

In the Table 7, i.e., X-shaped folding layout (P2), the enhancements follow a similar pattern but with slightly smaller gains. For the first mode, CBT under T3 increases from 15.29 (25%) to 27.04 (100%)—a 76.8% increase. The fourth mode, however, shows more substantial improvement, rising from 38.75 to 72.24 (T3), a 86.3% gain. Although the initial values are lower than those in P1, the folding degree still exerts a strong effect, particularly when coordinated with patterned dispersion strategies.

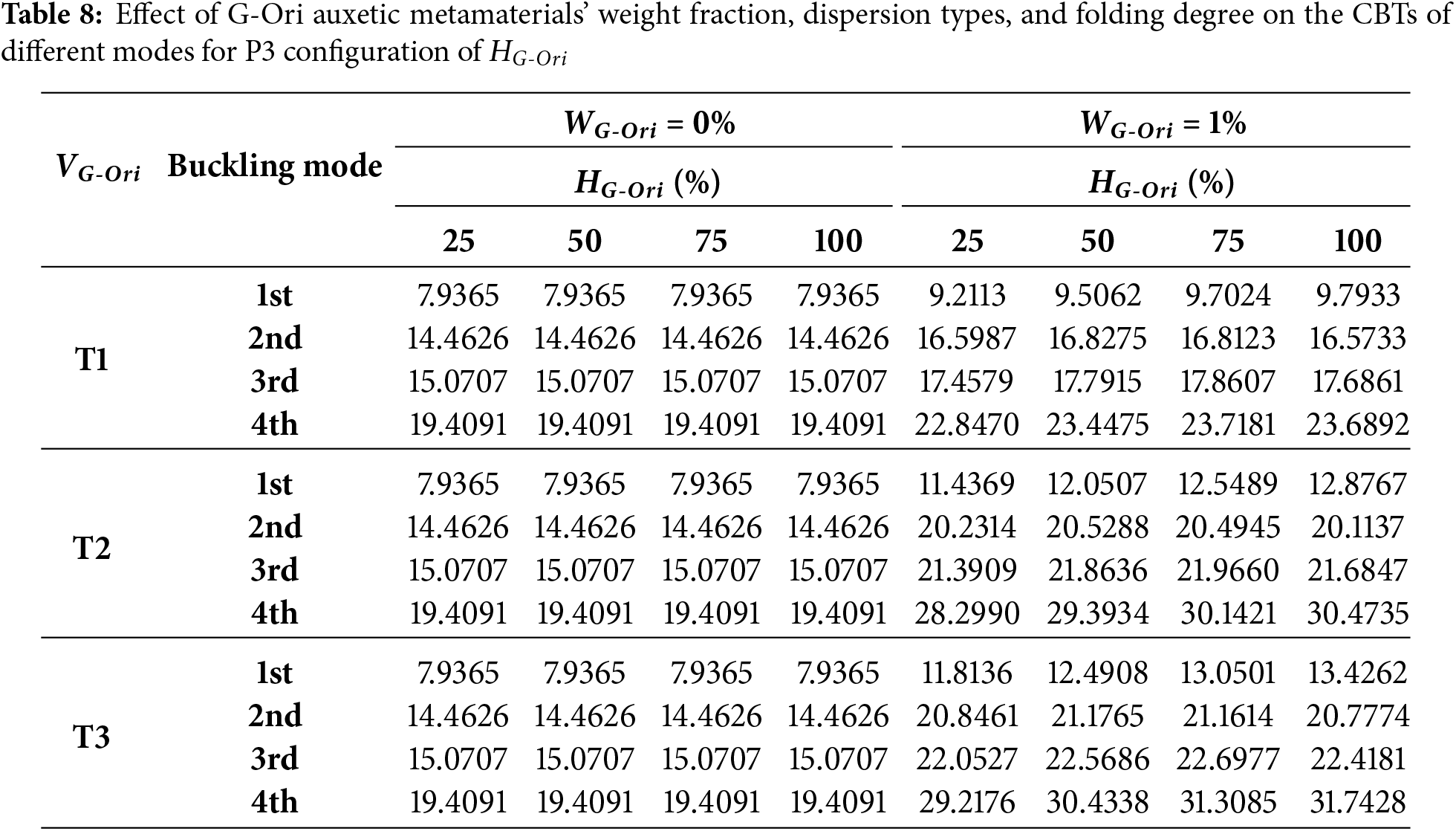

In the Table 8, i.e., P3 (O-shaped folding) configuration, the CBT values and folding sensitivity are comparatively lower. For example, the first mode under T1 increases only slightly from 9.21 to 9.79, representing an increase of just 6.2%. Even for the more efficient T3 pattern, the CBT in the first mode increases from 11.81 to 13.43—a 13.7% improvement. The fourth mode, however, still shows a moderate enhancement under T3, increasing from 29.22 to 31.74, a 8.6% rise. These results indicate that in the P3 configuration, the geometry of the fold layout is less aligned with the dominant stress paths during buckling, thus limiting the effectiveness of increased folding.

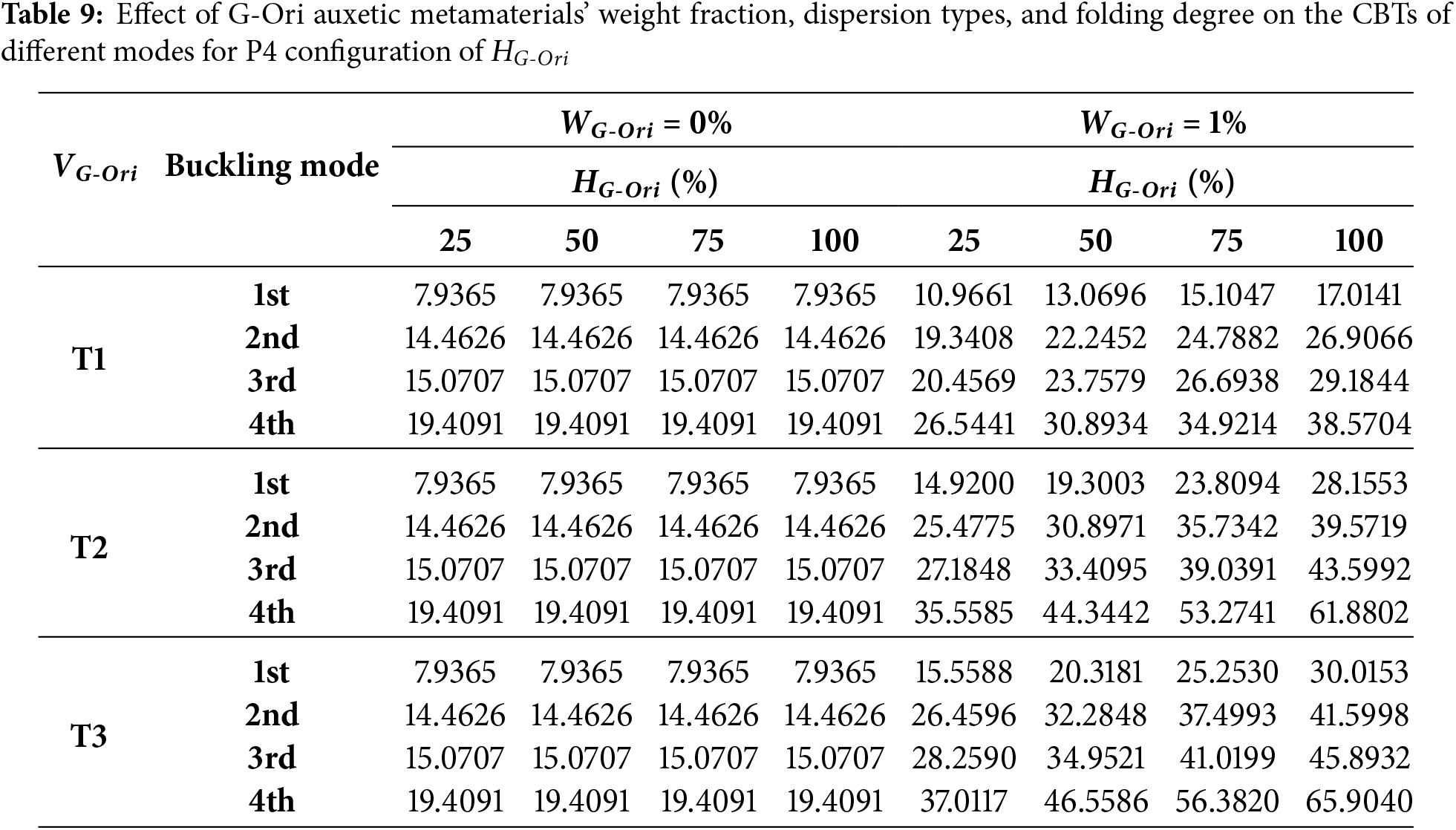

In the Table 9, i.e., P4 (A-shaped folding) configuration, the influence of folding degree is most prominent. Under T3, the first buckling mode CBT increases from 15.56 to 30.02—a 92.8% enhancement. The fourth mode shows even more striking gains, with CBT rising from 37.01 at 25% folding to 65.90 at 100%, representing a 78.1% improvement. The A-shaped dispersion (T3) aligns optimally with the A-shaped folding configuration, creating a highly synergistic effect that maximizes structural resistance against thermal buckling.

This study examined the thermal buckling behavior of doubly curved composite panels reinforced with G-Ori auxetic metamaterials through a semi-analytical formulation constructed within the framework of first-order shear deformation theory. The approach combined closed-form Navier solutions with a micromechanical description of the thermo-elastic properties, in which the influence of the G-Ori weight fraction, dispersion profile and folding degree was represented through a homogenized material model. Validation against established results for functionally graded cylindrical shells demonstrated that the proposed formulation accurately captures the structural response over a wide range of gradient indices and buckling modes. The validated framework enabled a systematic exploration of the role played by the auxetic microarchitecture, geometric parameters and elastic foundation characteristics. The results showed that increasing the proportion of G-Ori reinforcement enhances the critical buckling temperature by strengthening the effective membrane response through the combined action of graphene stiffness and origami-induced auxetic mechanisms. The folding degree was identified as a key parameter, since stronger folding intensifies the re-entrant behavior and supports more efficient alignment between the auxetic deformation field and the principal stress trajectories of the shell. The dispersion pattern also proved influential, with graded distributions producing higher thermal resistance when their spatial variation was compatible with the underlying stress landscape. Geometric curvature, panel thickness and foundation stiffness contributed additional stabilizing effects, each operating through distinct interactions between membrane action, geometric stiffness and thermal compressive fields. Taken together, the findings show that G-Ori reinforcement can substantially improve thermal stability when its distribution and folding geometry are tailored to the mechanical environment of a doubly curved shell. The proposed formulation offers a structured analytical basis for exploring these interactions and for guiding the design of lightweight shell components that exploit auxetic microarchitectures to achieve enhanced thermal resistance. At the same time, the scope of the present study is bounded by the simplifying assumptions required to obtain closed-form solutions, including the use of a homogenized micromechanical representation and simply supported boundary conditions. The results should therefore be interpreted within this analytical framework, while future work may extend the methodology to more detailed micromechanical models, additional boundary conditions and fully nonlinear thermal environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, [Ehsan Arshid], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Avey M, Fantuzzi N, Sofiyev A. Mathematical modeling and analytical solution of thermoelastic stability problem of functionally graded nanocomposite cylinders within different theories. Mathematics. 2022;10(7):1081. doi:10.3390/math10071081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Quan TQ, Cuong NH, Duc ND. Nonlinear buckling and post-buckling of eccentrically oblique stiffened sandwich functionally graded double curved shallow shells. Aerosp Sci Technol. 2019;90:169–80. doi:10.1016/j.ast.2019.04.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cong PH, Trung VD, Khoa ND, Duc ND. Vibration and nonlinear dynamic response of temperature-dependent FG-CNTRC laminated double curved shallow shell with positive and negative Poisson’s ratio. Thin Walled Struct. 2022;171:108713. doi:10.1016/j.tws.2021.108713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sankar A, Natarajan S, Merzouki T, Ganapathi M. Nonlinear dynamic thermal buckling of sandwich spherical and conical shells with CNT reinforced facesheets. Int J Str Stab Dyn. 2017;17(9):1750100. doi:10.1142/s0219455417501000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Duc ND, Kim SE, Manh DT, Nguyen PD. Effect of eccentrically oblique stiffeners and temperature on the nonlinear static and dynamic response of S-FGM cylindrical panels. Thin Walled Struct. 2020;146:106438. doi:10.1016/j.tws.2019.106438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Duc ND, Thang PT, Dao NT, Tac HV. Nonlinear buckling of higher deformable S-FGM thick circular cylindrical shells with metal-ceramic-metal layers surrounded on elastic foundations in thermal environment. Compos Struct. 2015;121(1):134–41. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2014.11.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Anh VTT, Bich DH, Duc ND. Nonlinear stability analysis of thin FGM annular spherical shells on elastic foundations under external pressure and thermal loads. Eur J Mech A. 2015;50:28–38. doi:10.1016/j.euromechsol.2014.10.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Trabelsi S, Frikha A, Zghal S, Dammak F. A modified FSDT-based four nodes finite shell element for thermal buckling analysis of functionally graded plates and cylindrical shells. Eng Struct. 2019;178:444–59. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2018.10.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Tounsi A, Tahir SI, Al-Osta MA. An integral quasi-3D computational model for the hygro-thermal wave propagation of imperfect FGM sandwich plates. Comput Concr. 2023;32:61. [Google Scholar]

10. Liu PS, Chen GF. Porous materials: processing and applications. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2014. doi:10.1016/C2012-0-03669-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Cao X, Huang Z, He C, Wu W, Xi L, Li Y, et al. In-situ synchrotron X-ray tomography investigation of the imperfect smooth-shell cylinder structure. Compos Struct. 2021;267:113926. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2021.113926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Fu T, Wang X, Rabczuk T. Broadband low-frequency sound insulation of stiffened sandwich PFGM doubly-curved shells with positive, negative and zero Poisson’s ratio cellular cores. Aerosp Sci Technol. 2024;147:109049. doi:10.1016/j.ast.2024.109049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Bagheri H, Kiani Y, Eslami MR. Free vibration of conical shells with intermediate ring support. Aerosp Sci Technol. 2017;69:321–32. doi:10.1016/j.ast.2017.06.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Guo J, Xu Y, Jiang Z, Liu X, Cai Y. A simplified model for buckling and post-buckling analysis of Cu nanobeam under compression. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2020;125(2):611–23. doi:10.32604/cmes.2020.011148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Liu Y, Qin Z, Chu F. Nonlinear forced vibrations of functionally graded piezoelectric cylindrical shells under electric-thermo-mechanical loads. Int J Mech Sci. 2021;201:106474. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2021.106474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Liu Y, Wang J, Hu J, Qin Z, Chu F. Multiple internal resonances of rotating composite cylindrical shells under varying temperature fields. Appl Math Mech Engl Ed. 2022;43(10):1543–54. doi:10.1007/s10483-022-2904-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Esmaeili HR, Kiani Y. On the response of graphene platelet reinforced composite laminated plates subjected to instantaneous thermal shock. Eng Anal Bound Elem. 2022;141:167–80. doi:10.1016/j.enganabound.2022.05.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Mirzaei M, Kiani Y. Thermal buckling of temperature dependent FG-CNT reinforced composite conical shells. Aerosp Sci Technol. 2015;47:42–53. doi:10.1016/j.ast.2015.09.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Park JS, Kwan Seo J. Analytical method for simulation of buckling and post-buckling behaviour of curved pates. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2015;106:291–308. [Google Scholar]

20. Huang Z, Tian Y, Zhang Y, Shi T, Xia Q. Buckling optimization of curved grid stiffeners through the level set based density method. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;140(1):711–33. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.045411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Xiao X, Bu G, Ou Z, Li Z. Nonlinear in-plane instability of the confined FGP arches with nanocomposites reinforcement under radially-directed uniform pressure. Eng Struct. 2022;252:113670. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.113670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Guan W, Zhu Y, Wang W, Wang F, Zhang J, Wu Y, et al. Experimental and numerical buckling analysis of carbon fiber composite cylindrical shells under external pressure. Ocean Eng. 2023;275:114134. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2023.114134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Wang Y, Feng C, Zhao Z, Yang J. Eigenvalue buckling of functionally graded cylindrical shells reinforced with graphene platelets (GPL). Compos Struct. 2018;202:38–46. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2017.10.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Arshid E, Maraghi ZK. Dynamic analysis of prismatic auxetic trigonometric rotating blades integrated by GNPs-reinforced layers. Mech Based Des Struct Mach. 2025;13:1–28. doi:10.1080/15397734.2025.2527206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ferdowsi SB, Doranga S, Li Y. Comparison of the reliability of SAC305 and innolot-based solder alloy in a board-level BGA package considering harmonic and random vibration environment. Electronics. 2025;14(2):292. doi:10.3390/electronics14020292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Liu S, Yu T, Van Lich L, Yin S, Bui TQ. Size effect on cracked functional composite micro-plates by an XIGA-based effective approach. Meccanica. 2018;53(10):2637–58. doi:10.1007/s11012-018-0848-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Sarafraz M, Seidi H, Kakavand F, Viliani NS. Free vibration and buckling analyses of a rectangular sandwich plate with an auxetic honeycomb core and laminated three-phase polymer/GNP/fiber face sheets. Thin Walled Struct. 2023;183:110331. doi:10.1016/j.tws.2022.110331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sofiyev AH, Tornabene F, Dimitri R, Kuruoglu N. Buckling behavior of FG-CNT reinforced composite conical shells subjected to a combined loading. Nanomater. 2020;10(3):419. doi:10.3390/nano10030419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Eskandary K, Shishesaz M, Moradi S. Buckling analysis of composite conical shells reinforced by agglomerated functionally graded carbon nanotube. Arch Civ Mech Eng. 2022;22(3):132. doi:10.1007/s43452-022-00440-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ali Mohammadimehr M, Loghman A, Amir S, Mohammadimehr M, Arshid E. Vibration behavior of a thick double-curved sandwich panel with auxetic core and carbon nanotube reinforced composite based on TSDDCT and NSGT. Acta Mech. 2025;236(5):2967–3000. doi:10.1007/s00707-025-04302-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang P, Wang Z, Tian H, Xi X, Liu X. On the magnetically tunable free damped-vibration of L-shaped composite spherical panels made of GPL-reinforced magnetorheological elastomers: an element-based GDQ approach. Thin Walled Struct. 2026;218:113987. doi:10.1016/j.tws.2025.113987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Liang J, Ye F, Song Q, Cao Y, Hui S, Qin Y, et al. In-plane heterogeneous structure-boosted interfacial polarization in graphene for wide-band and wide-temperature microwave absorption. Chem Eng J. 2024;497:154307. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2024.154307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Xiao C, Peng J, Jiao Y, Shen Q, Zhao Y, Zhao F, et al. Strong and tough multilayer heterogeneous pyrocarbon based composites. Adv Funct Materials. 2024;34(51):2409881. doi:10.1002/adfm.202409881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhang C, Lou M, Wang Y, Shao Y, Yang D, Sui T. Mechanical responses and microscopic irreversible deformation evolution of thermoplastic fiber-reinforced composites under cyclic loading. Int J Fatigue. 2026;203:109327. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2025.109327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ren Z, Yang Z, Mu W, Liu T, Liu X, Wang Q. Ultra-broadband perfect absorbers based on biomimetic metamaterials with dual coupling gradient resonators. Adv Mater. 2025;37(11):e2416314. doi:10.1002/adma.202416314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Bai X, Xiao Z, Shi H, Zhang K, Luo Z, Wu Y. Omnidirectional sound wave absorption based on the multi-oriented acoustic meta-materials. Appl Acoust. 2025;228:110344. doi:10.1016/j.apacoust.2024.110344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Gao N, Huang Q, Pan G. Ultra-broadband sound absorption characteristics in underwater ultra-thin metamaterial with three layer bubbles. Eng Rep. 2024;6(11):e12939. doi:10.1002/eng2.12939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Gao N, Yu H, Liu J, Deng J, Huang Q, Chen D, et al. Experimental investigation of composite metamaterial for underwater sound absorption. Appl Acoust. 2023;211:109466. doi:10.1016/j.apacoust.2023.109466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Fan S, Han C, He K, Bai L, Chen LQ, Shi H, et al. Acoustic moiré flat bands in twisted heterobilayer metasurface. Adv Mater. 2025;37(29):e2418839. doi:10.1002/adma.202418839. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Lu ZQ, Zhao L, Ding H, Chen LQ. A dual-functional metamaterial for integrated vibration isolation and energy harvesting. J Sound Vib. 2021;509:116251. doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2021.116251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Mahinzare M, Rastgoo A, Ebrahimi F. On nonlinear vibration of piezo-electrically multiscale hybrid nanocomposite sandwich plate including an auxetic core based on HSDT. Int J Str Stab Dyn. 2024;24(5):2450069. doi:10.1142/s021945542450069x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zhang X, Hao H, Tian R, Xue Q, Guan H, Yang X. Quasi-static compression and dynamic crushing behaviors of novel hybrid re-entrant auxetic metamaterials with enhanced energy-absorption. Compos Struct. 2022;288:115399. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2022.115399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Kiani Y. Free vibration of FG-CNT reinforced composite spherical shell panels using Gram-Schmidt shape functions. Compos Struct. 2017;159:368–81. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2016.09.079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Ghadiri M, Hosseini SSH. Nonlinear forced vibration of graphene/piezoelectric sandwich nanoplates subjected to a mechanical shock. J Sandw Struct Mater. 2021;23(3):956–87. doi:10.1177/1099636219849647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Sadeghian M, Palevicius A, Janusas G. Nonlocal strain gradient model for the nonlinear static analysis of a circular/annular nanoplate. Micromachines. 2023;14(5):1052. doi:10.3390/mi14051052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Bellal M, Hebali H, Heireche H. Buckling behavior of a single-layered graphene sheet resting on viscoelastic medium via nonlocal four-unknown integral model. Steel Compos Struct. 2020;34:643–55. [Google Scholar]

47. Guellil M, Saidi H, Bourada F, Bousahla AA, Tounsi A, Al-Zahrani MM, et al. Influences of porosity distributions and boundary conditions on mechanical bending response of functionally graded plates resting on Pasternak foundation. Steel Compos Struct. 2021;38:1–15. doi:10.12989/SCS.2021.38.1.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Esmailpoor Hajilak Z, Pourghader J, Hashemabadi D, Sharifi Bagh F, Habibi M, Safarpour H. Multilayer GPLRC composite cylindrical nanoshell using modified strain gradient theory. Mech Based Des Struct Mach. 2019;47(5):521–45. doi:10.1080/15397734.2019.1566743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Pham HA, Tran HQ, Tran MT, Nguyen VL, Huong QT. Free vibration analysis and optimization of doubly-curved stiffened sandwich shells with functionally graded skins and auxetic honeycomb core layer. Thin Walled Struct. 2022;179:109571. doi:10.1016/j.tws.2022.109571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Fu T, Hu X, Yang C. Impact response analysis of stiffened sandwich functionally graded porous materials doubly-curved shell with re-entrant honeycomb auxetic core. Appl Math Model. 2023;124:553–75. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2023.08.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Jing Z, Li X, Sun Q, Liang K, Zhang Y, Duan L. A 2D-sampling optimization method for buckling layup design of doubly-curved laminated composite shallow shells. Compos Struct. 2022;297:115934. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2022.115934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Hosseini-Hashemi S, Bedroud M, Nazemnezhad R. An exact analytical solution for free vibration of functionally graded circular/annular Mindlin nanoplates via nonlocal elasticity. Compos Struct. 2013;103:108–18. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2013.02.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Civalek Ö, Akbaş ŞD, Akgöz B, Dastjerdi S. Forced vibration analysis of composite beams reinforced by carbon nanotubes. Nanomaterials. 2021;11(3):571. doi:10.3390/nano11030571. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Arshid E, Maraghi ZK, Civalek Ö. Variable-thickness higher-order sandwich beams with FG cellular core and CNT-RC patches: vibrational analysis in thermal environment. Arch Appl Mech. 2024;95(1):2. doi:10.1007/s00419-024-02716-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Babaei H, Zavari S, Kaveh A, Arshid E, Civalek Ö. Dynamic response of advanced lightweight porous plates integrated with nanocomposite face sheets resting on elastic substrate. Int J Str Stab Dyn. 2025;25(12):2550132. doi:10.1142/s0219455425501329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Arshid E, Amir S, Loghman A, Civalek Ö. Aerodynamic stability and free vibration of FGP-reinforced nano-fillers annular sector microplates exposed to supersonic flow. Thin Walled Struct. 2024;197:111610. doi:10.1016/j.tws.2024.111610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Uzun B, Civalek Ö, Yaylı MÖ. A hardening nonlocal approach for vibration of axially loaded nanobeam with deformable boundaries. Acta Mech. 2023;234(5):2205–22. doi:10.1007/s00707-023-03490-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Kaveh A, Babaei H, Zavari S, Arshid E, Civalek Ö. Vibrational response of a sandwich microplate considering the impact of flexoelectricity and based on a novel porous-FGM formulation. Mech Based Des Struct Mach. 2024;52(11):9122–43. doi:10.1080/15397734.2024.2337913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Mahapatra TR, Panda SK, Kar VR. Nonlinear flexural analysis of laminated composite panel under hygro-thermo-mechanical loading—a micromechanical approach. Int J Comput Methods. 2016;13(3):1650015. doi:10.1142/s0219876216500158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Zhao J, Xie F, Wang A, Shuai C, Tang J, Wang Q. Vibration behavior of the functionally graded porous (FGP) doubly-curved panels and shells of revolution by using a semi-analytical method. Compos Part B Eng. 2019;157:219–38. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.08.087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Wang A, Chen H, Hao Y, Zhang W. Vibration and bending behavior of functionally graded nanocomposite doubly-curved shallow shells reinforced by graphene nanoplatelets. Results Phys. 2018;9:550–9. doi:10.1016/j.rinp.2018.02.062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Vinyas M, Harursampath D. Nonlinear vibrations of magneto-electro-elastic doubly curved shells reinforced with carbon nanotubes. Compos Struct. 2020;253:112749. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.112749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Sofiyev AH, Turan F, Zerin Z. Large-amplitude vibration of functionally graded orthotropic double-curved shallow spherical and hyperbolic paraboloidal shells. Int J Press Vessels Pip. 2020;188:104235. doi:10.1016/j.ijpvp.2020.104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Tănase M, Lvov G. Analytical and numerical study of the buckling of steel cylindrical shells reinforced with internal and external FRP layers under axial compression. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;144(1):717–37. doi:10.32604/cmes.2025.067891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Rasooli Jazi F, Amir S, Arshid E. Vibration analysis of asymmetric sandwich rotating FG porous discs coated with agglomerated nanocomposite facesheets. Arch Civ Mech Eng. 2024;24(4):201. doi:10.1007/s43452-024-01009-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Ezzati H, Ebrahimi F, Salari E. Exploring graphene origami-enabled metamaterials: a review. J Comput Appl Mech. 2025;56:249–63. [Google Scholar]

67. Li W, Gao X, Ma L. Bending and buckling analysis of functionally graded graphene origami-enabled auxetic metamaterials plates with arbitrary distribution of Kerr elastic foundation based on the three-variable simplified plate theory. ZAMM J Appl Math Mech/Z Für Angew Math Und Mech. 2025;105(7):e70145. doi:10.1002/zamm.70145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Aminipour H, Janghorban M, Civalek O. Analysis of functionally graded doubly-curved shells with different materials via higher order shear deformation theory. Compos Struct. 2020;251:112645. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.112645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Yao Y, Arshid E. Effects of folding degree and mass fraction on the static and natural frequency characteristics of functionally graded graphene origami-enabled auxetic metamaterials annular plates. Int J Str Stab Dyn. 2025:2650128. doi:10.1142/s0219455426501282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Mohamed SA, Eltaher MA, Mohamed N, Abo-bakr R. Nonlinear post-buckling stability of graphene origami-enabled auxetic metamaterials plates. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;143(1):515–38. doi:10.32604/cmes.2025.061897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Arshid E, Civalek Ö. Analytical vibration analysis of thermally loaded doubly curved shells reinforced with graphene origami metamaterials on Kerr foundation. Compos Struct. 2026;377:119847. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2025.119847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Gao XY, Wang ZZ, Ma LS. Free vibration and buckling analysis of FG graphene origami-enabled auxetic metamaterial beams in a thermal environment. Acta Mech. 2025;236(2):1265–87. doi:10.1007/s00707-024-04197-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Arshid E. Thermomechanical stability of hyperbolic shells incorporating graphene origami auxetic metamaterials on elastic foundation: applications in lightweight structures. J Compos Sci. 2025;9(11):594. doi:10.3390/jcs9110594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Jin Z, Huo W, Habibi M, Albaijan I. Thermo-foldable bending analysis of tunable shells using a higher-order modeling. Mech Adv Mater Struct. 2025;32(8):1707–20. doi:10.1080/15376494.2024.2369263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Askari M, Saidi AR, Rezaei AS. An investigation over the effect of piezoelectricity and porosity distribution on natural frequencies of porous smart plates. J Sandw Struct Mater. 2020;22(7):2091–124. doi:10.1177/1099636218791092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Song M, Chen L, Yang J, Zhu W, Kitipornchai S. Thermal buckling and postbuckling of edge-cracked functionally graded multilayer graphene nanocomposite beams on an elastic foundation. Int J Mech Sci. 2019;161–162:105040. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2019.105040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Arshid E, Amir S, Dadoo I, Civalek Ö. Thermo-dependent dynamic analysis of imperfect shear-deformable nanocomposite conical micro shells. Arch Civ Mech Eng. 2025;25(5):271. doi:10.1007/s43452-025-01328-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Bourada F, Bousahla AA, Tounsi A. Stability and dynamic analyses of SW-CNT reinforced concrete beam resting on elastic-foundation. Comput Concr. 2020;25:485–95. [Google Scholar]

79. Zhao X, Liew KM. A mesh-free method for analysis of the thermal and mechanical buckling of functionally graded cylindrical shell panels. Comput Mech. 2010;45(4):297–310. doi:10.1007/s00466-009-0446-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Arshid E, Ghorbani MA, Nia MJM, Civalek Ö, Kumar A. Thermo-elastic buckling behaviors of advanced fluid-infiltrated porous shells integrated with GPLs-reinforced nanocomposite patches. Mech Adv Mater Struct. 2024;31(26):7853–69. doi:10.1080/15376494.2023.2251015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools