Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Real-Time Mouth State Detection Based on a BiGRU-CLPSO Hybrid Model with Facial Landmark Detection for Healthcare Monitoring Applications

1 Department of Electronic Engineering, National Kaohsiung University of Science and Technology, Kaohsiung, 807618, Taiwan

2 Faculty of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, Nha Trang University, Nha Trang, 650000, Vietnam

3 Department of Sports Medicine, College of Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, 807378, Taiwan

4 Program in Biomedical Engineering, College of Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, 807378, Taiwan

* Corresponding Authors: Thanh-Tuan Nguyen. Email: ; Chin-Shiuh Shieh. Email:

# These authors contributed equally as co-first authors

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Artificial Intelligence Models in Healthcare: Challenges, Methods, and Applications)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 42 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.075064

Received 24 October 2025; Accepted 19 December 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

The global population is rapidly expanding, driving an increasing demand for intelligent healthcare systems. Artificial intelligence (AI) applications in remote patient monitoring and diagnosis have achieved remarkable progress and are emerging as a major development trend. Among these applications, mouth motion tracking and mouth-state detection represent an important direction, providing valuable support for diagnosing neuromuscular disorders such as dysphagia, Bell’s palsy, and Parkinson’s disease. In this study, we focus on developing a real-time system capable of monitoring and detecting mouth state that can be efficiently deployed on edge devices. The proposed system integrates the Facial Landmark Detection technique with an optimized model combining a Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU) and Comprehensive Learning Particle Swarm Optimization (CLPSO). We conducted a comprehensive comparison and evaluation of the proposed model against several traditional models using multiple performance metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, cosine similarity, ROC–AUC, and the precision–recall curve. The proposed method achieved an impressive accuracy of 96.57% with an excellent precision of 98.25% on our self-collected dataset, outperforming traditional models and related works in the same field. These findings highlight the potential of the proposed approach for implementation in real-time patient monitoring systems, contributing to improved diagnostic accuracy and supporting healthcare professionals in patient treatment and care.Keywords

Swallowing disorders and neuromuscular dysfunctions in the orofacial region, such as facial paralysis, Parkinson’s disease, or cranial nerve injury, significantly impair patients’ ability to eat and communicate, thereby reducing their quality of life and increasing the risk of respiratory complications. Several studies have reported that the prevalence of dysphagia in the elderly ranges from 13% to 38% [1] and can reach up to 78% in stroke patients [2]. This highlights the urgent need for effective monitoring of oral motor functions in rehabilitation. Continuous observation of mouth movements not only enables clinicians to objectively assess neuromuscular conditions but also facilitates timely adjustments in treatment plans. In particular, real-time and remote monitoring systems have opened new opportunities in telemedicine, allowing patients to be supervised and guided directly at home. Such systems can reduce follow-up visits, alleviate the workload on healthcare facilities, and extend medical services to regions with limited professional resources [3,4]. However, there remains a lack of lightweight and reliable solutions that can operate stably on common edge devices, such as IP cameras or wearable sensors, which are typically constrained in energy consumption and computational resources [5].

The real-time mouth-state detection problem faces multiple technical challenges. On edge platforms, CPU power, memory, and bandwidth are limited, whereas the system demands low latency and high stability for immediate response. Deep learning models with heavy architectures, such as multi-layer CNNs, though capable of achieving high accuracy, often fail to maintain consistent performance and reasonable energy efficiency under edge-deployment conditions. Conversely, handcrafted feature-based methods, such as those using the Mouth Aspect Ratio (MAR) with fixed thresholds, are lightweight and easy to implement but lack adaptability. They tend to degrade in sensitivity or produce high false-positive rates under variations in individual anatomy and environmental conditions, such as lighting, head pose, or occlusion [6]. Here, the MAR threshold can be understood as a relative ratio between the vertical and horizontal dimensions of the mouth. When the mouth opens, the vertical distance increases while the horizontal distance tends to decrease. However, fixed-threshold MAR systems are difficult to generalize in practice, as they cannot dynamically adapt across groups of patients differing in gender, age, or ethnicity.

To overcome these limitations, this study proposes an optimized pipeline composed of several coordinated components designed to balance accuracy, sensitivity, and processing speed. First, mouth landmarks are extracted from a lightweight facial-landmark detector, yielding a total of 68 spatial coordinates per video frame. The 2D spatial coordinates of these landmarks are then used as input features for deep learning models to classify mouth states as open or closed. The learning models automatically extract key intermediate features, such as distances and geometric ratios between landmarks, without relying on manually defined parameters. In this framework, a Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (Bi-GRU) serves as the primary model for processing sequential data and identifying mouth states [7]. Finally, the Comprehensive Learning Particle Swarm Optimization (CLPSO) algorithm is employed to perform hyperparameter tuning for the Bi-GRU network. This optimization strategy aims to achieve an optimal configuration within resource constraints, reducing inference latency while improving sensitivity and accuracy compared with baseline approaches [8].

Compared with previous studies, this approach differs by introducing a landmark-coordinate-based mouth-state detection method that replaces MAR thresholds while maintaining a lightweight model architecture suitable for edge deployment. The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

(i) Proposing the use of 2D spatial coordinates of facial landmarks as model input for mouth-state recognition, replacing MAR thresholds that are often sensitive to inter-subject variations.

(ii) Introducing a lightweight hybrid BiGRU-CLPSO architecture for mouth-state detection from sequential landmark data.

(iii) Successfully deploying the proposed system on common edge devices with low latency, suitable for home-based monitoring scenarios using only CPU and standard cameras.

(iv) Conducting cross-validation on our self-collected dataset to evaluate model robustness and compare with multiple machine learning models such as MLP, CNN, LSTM, and XGBoost. Experimental results show that landmark-based geometric models achieve high accuracy and sensitivity with stable real-time inference. Furthermore, the BiGRU-CLPSO model demonstrates superior stability and overall performance compared with other methods under real-world operating conditions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the related works; Section 3 describes the proposed BiGRU-CLPSO method and feature design; Section 4 presents the experiments, multi-source evaluation, and discussion; and Section 5 concludes the study and outlines future research directions.

2.1 Clinical Applications of Mouth-State Monitoring

Monitoring the open–close states of the mouth holds significant clinical value across multiple medical domains. In the management of dysphagia, detecting abnormal oral movements or prolonged mouth opening can serve as an early indicator of swallowing difficulty or aspiration risk, allowing timely intervention to prevent complications such as aspiration pneumonia [9]. Continuous monitoring also enables the detection of subtle deviations from normal swallowing patterns, which are often overlooked during brief or periodic clinical assessments [4]. In fatigue detection, particularly in driver monitoring and neurological evaluation, the frequency of yawning or prolonged mouth opening can provide a reliable indicator of drowsiness or reduced alertness, thereby supporting timely safety warnings [10,11]. Another important application is rehabilitation compliance monitoring: patients recovering from facial nerve paralysis, stroke, or temporomandibular joint disorders can be remotely supervised to ensure correct execution and frequency of prescribed oral exercises [12,13]. Moreover, assistive communication systems for individuals with severe motor impairments can employ mouth-state recognition as a control signal, enhancing accessibility to assistive technologies [14].

Despite these promising applications, current “gold-standard” clinical tools, such as video fluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) and fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES), remain limited by their discontinuous nature, high cost, and dependence on specialized equipment and trained personnel [15,16]. These constraints highlight the need for affordable, continuous, and remote patient monitoring (RPM) solutions that are compatible with commonly available consumer cameras, thereby extending care beyond hospital settings, particularly for patients in remote areas or with mobility limitations.

However, deploying mouth-state monitoring systems outside laboratory conditions faces several constraints. Target platforms are typically resource-constrained edge devices, with restricted memory, computational power, and battery capacity, making the deployment of heavy neural models challenging [17,18]. Environmental variability, including changes in lighting, head posture, or partial occlusion by masks or hands, further challenges system robustness [6]. In addition, privacy requirements demand minimizing the storage and processing of raw facial images, while model interpretability remains critical in medical contexts where clinicians must understand and trust algorithmic decisions [19,20].

Regarding evaluation metrics, medical applications typically prioritize f1-score and recall to ensure high sensitivity in detecting clinically relevant events, while also considering median inference latency, model size, and cross-subject or cross-session stability as indicators of overall system reliability [21]. To meet these demands, recent studies have increasingly focused on developing lightweight, stable, and interpretable processing pipelines capable of being deployed on edge devices and operating reliably in real-world, non-laboratory environments [20].

2.2 Deep Learning Approaches for Mouth-State Detection

In recent years, there has been a rapid growth in the use of deep learning techniques for mouth-state recognition, with various approaches leveraging the power of spatiotemporal feature extraction models [22,23]. Two-dimensional convolutional neural networks (2D-CNNs) focus on learning static shape features from still images or individual video frames, often adopting lightweight architectures such as MobileNet or EfficientNet to enhance deployability on mobile or embedded devices [24,25]. Three-dimensional convolutional neural networks (3D-CNNs) extend this capability into the temporal domain, extracting both spatial and motion features from frame sequences. Architectures such as C3D, I3D, and S3D have achieved high performance in classifying mouth-related behaviors, such as swallowing, chewing, or speaking, but they demand substantial computational resources [26,27].

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and their variants, LSTM and GRU, have been widely employed to model sequential temporal features, enabling the detection of dynamic mouth patterns such as open–close cycles or repetitive swallowing phases [28]. More recently, Transformer-based architectures, including lightweight variants such as Video Swin Transformer and TimeSformer, have been applied to video data. By leveraging the self-attention mechanism, they can learn long-range temporal dependencies between frames and improve robustness under noisy or varying environmental conditions [27]. Notably, in the domain of facial analysis, novel architectures such as the Reference Heatmap Transformer have set new benchmarks for precise landmark localization [29]. However, most of these models still require high-end hardware and large memory capacity to make them unsuitable for edge deployment on resource-limited hardware platforms. To address this limitation, several lightweight approaches have emerged, combining facial landmark features with compact recurrent networks to reduce input dimensionality and computational cost. These studies have shown that when geometric features are well designed, lightweight sequential models can achieve performance close to that of heavier end-to-end architectures [22]. Nevertheless, feature selection and hyperparameter tuning in these models are often based on manual or empirical heuristics, leading to suboptimal results and limited adaptability to multi-source or cross-subject datasets [30,31].

In this study, we adopt the Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (Bi-GRU) as the core component. Bi-GRU retains the lightweight structure of GRU with a bidirectional mechanism, enabling the model to capture both past and future contextual information at each step. Specifically, the sequence is encoded by two parallel GRU branches named as forward and backward, and their hidden states are concatenated or combined to form context-rich representations. This design is particularly effective for distinguishing short transitions, such as quick swallows, and lip compressions. With landmark coordinates as input, Bi-GRU can exploit inter-frame dynamics more effectively than static geometric descriptors [30].

To overcome the limitations of manual hyperparameter tuning, we integrate Comprehensive Learning Particle Swarm Optimization (CLPSO), an enhanced swarm intelligence algorithm, to optimize the Bi-GRU hyperparameters and simultaneously perform feature selection for geometric descriptors. CLPSO is particularly well-suited for hybrid search spaces, combining binary dimensions for feature selection with continuous or integer dimensions for network parameters. It balances exploration and exploitation, avoids premature convergence, and supports multi-objective optimization goals: maximizing f1-score and recall, while minimizing median latency and model size [32].

The proposed integration of Bi-GRU and CLPSO with spatial landmark coordinates has been initially explored in prior researches, especially within the context of simultaneous optimization of lightweight sequential models and geometric-feature pipelines for edge devices. This study, therefore, addresses this research gap by developing a solution that is computationally efficient for real-time edge deployment to maintain the accuracy and the sensitivity required for clinical monitoring applications.

3 Real-Time Mouth State Detection Based on a BiGRU-CLPSO Hybrid Model with Facial Landmark

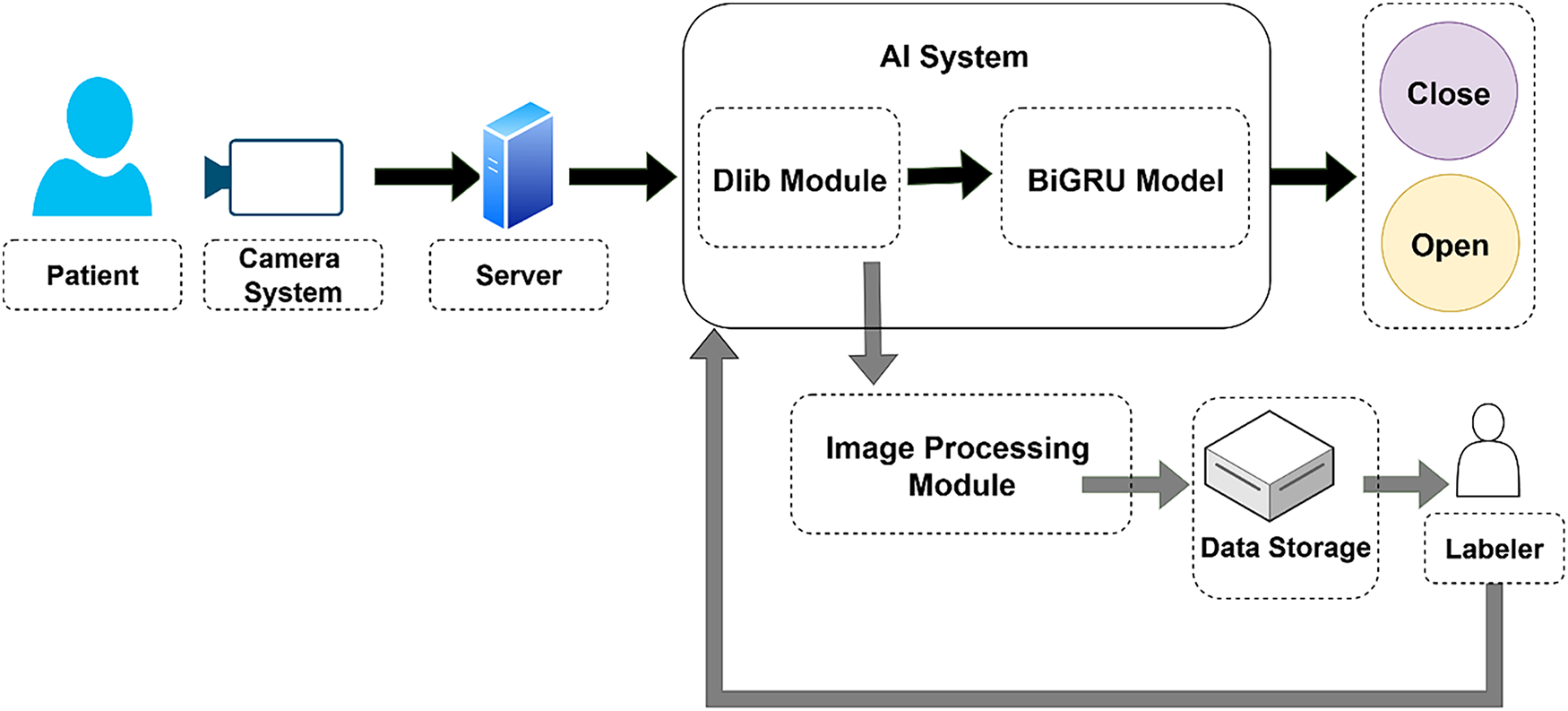

In this study, we develop a patient monitoring system designed to track changes in mouth movements, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Overall architecture of the proposed system

In this system, a camera module is installed to capture and transmit patient images to a central server system. The AI module processes the incoming video by extracting individual frames and detecting facial landmarks with the Dlib library. The spatial coordinates of the detected landmarks are then fed into a BiGRU model to determine the mouth state, open or closed. In addition, the system includes a mechanism to store video frames along with the corresponding landmark information. These images are forwarded to human annotators for manual labeling of mouth states. This process helps expand and refine the mouth-state dataset of patients, enabling further training to improve model accuracy over time.

As mentioned earlier, this study employs the BiGRU model in combination with the heuristic optimization algorithm CLPSO as the primary approach for mouth-state classification. Furthermore, we compare the proposed method with several other representative deep learning algorithms, including CNN, MLP, LSTM, and XGBoost. Multiple algorithms are evaluated to highlight the superior performance of deep learning models trained on facial landmark coordinates, as opposed to traditional approaches that rely on fixed MAR thresholds. Thehe deep learning models utilized in this study are introduced later.

3.1 Facial Landmark Detection Using Dlib

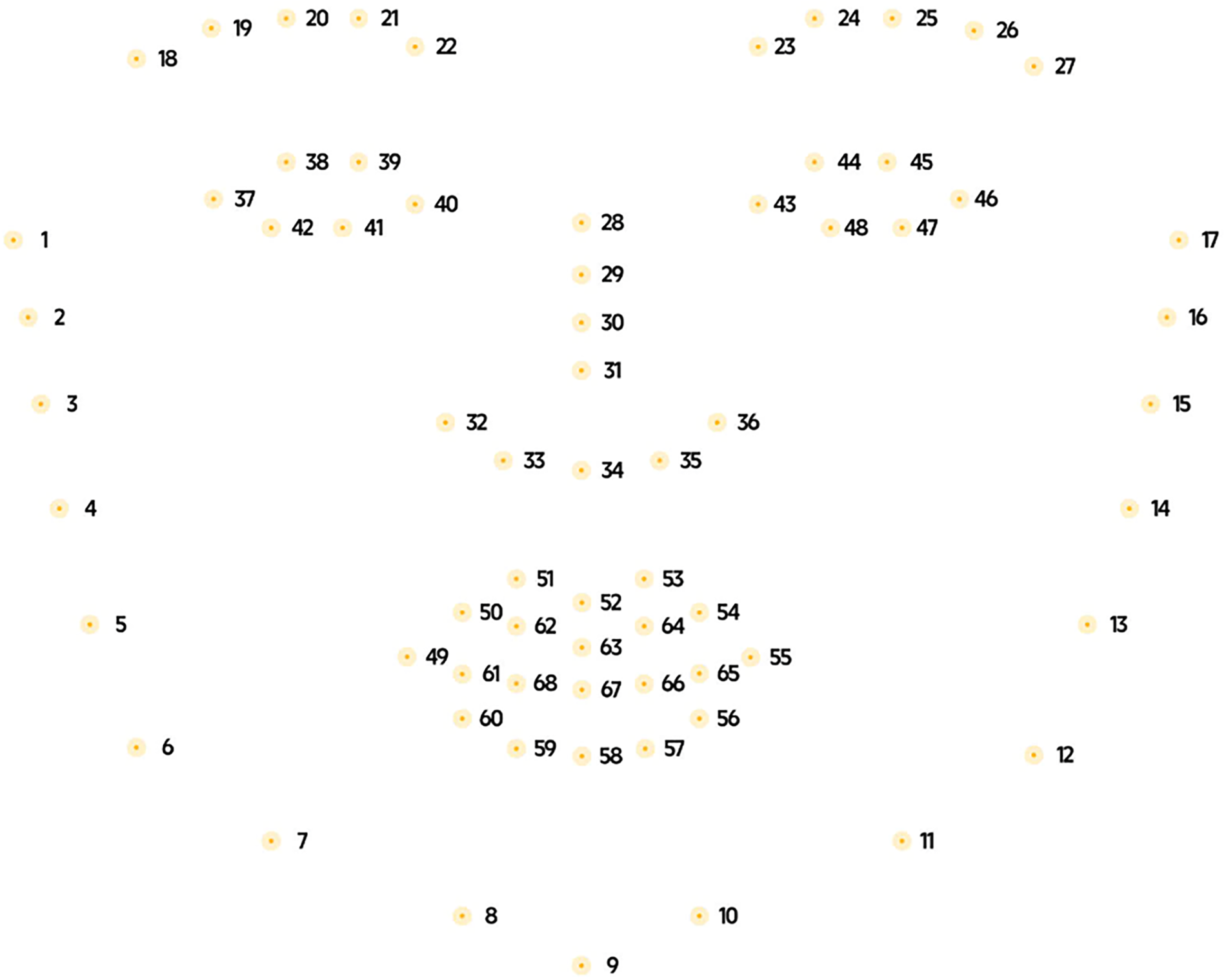

In the overall pipeline, the Dlib module performs two key functions: face detection using the Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG)+ SVM method and landmark localization using Ensemble of Regression Trees (ERT). Dlib is an open-source C++ library that integrates multiple optimized modules for computer vision and machine learning applications. In this study, we utilize built-in face detection and facial landmark localization capabilities of Dlib library [23]. The detection mechanism combines HOG and Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifiers [5]. Once a face bounding box is detected, the Ensemble of Regression Trees (ERT) module predicts the facial landmark points [24]. The landmark predictor used in this study was trained on the 300 Faces In-the-Wild Challenge (300-W) dataset [25–27]. Fig. 2 illustrates the standard set of 68 facial landmark points identified by the algorithm.

Figure 2: Position the 68 facial landmarks detected by Dlib on the face

In the grayscale image, the gradient components are approximated as:

where

where

where

where

where

where

where

where

where

where

3.2 BiGRU Model for Mouth State Classification

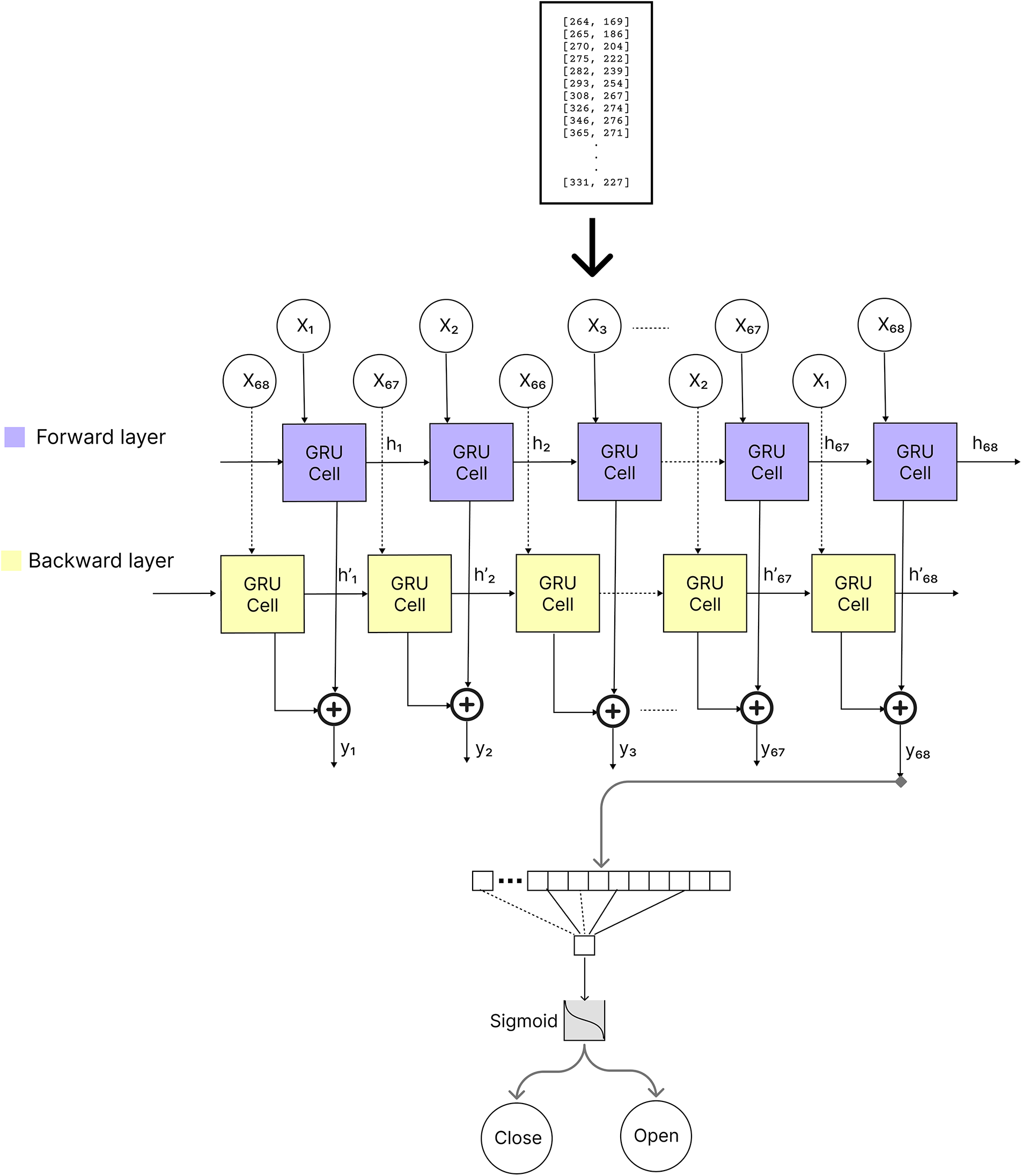

The overall architecture of the proposed BiGRU attention, is presented in Fig. 3, which was applied in the proposed model.

Figure 3: The architecture of our BiGRU model

The time-normalized landmark sequence

here,

where

From (14),

To form a compact sequence descriptor aligned with our downstream classifier and latency constraints, we apply additive attention. This mechanism emphasizes frames near state transitions rather than averaging uniformly:

where

where

with label

where

where

3.3 Multi-Objective CLPSO for Feature Selection and Hyperparameter Tuning

To satisfy the real-time constraint without sacrificing accuracy, we cast model configuration as a joint search over a sparse feature set derived from the landmark sequence and the BiGRU hyperparameters. We employ Comprehensive Learning Particle Swarm Optimization (CLPSO), which mitigates premature convergence by letting each coordinate learn from different exemplars. We encode each candidate as a concatenation of a binary feature mask and continuous hyperparameters is

From (21),

To reduce variance in accuracy estimation during the search, we average Recall across folds with early stopping inside each fold:

where

From (23),

where

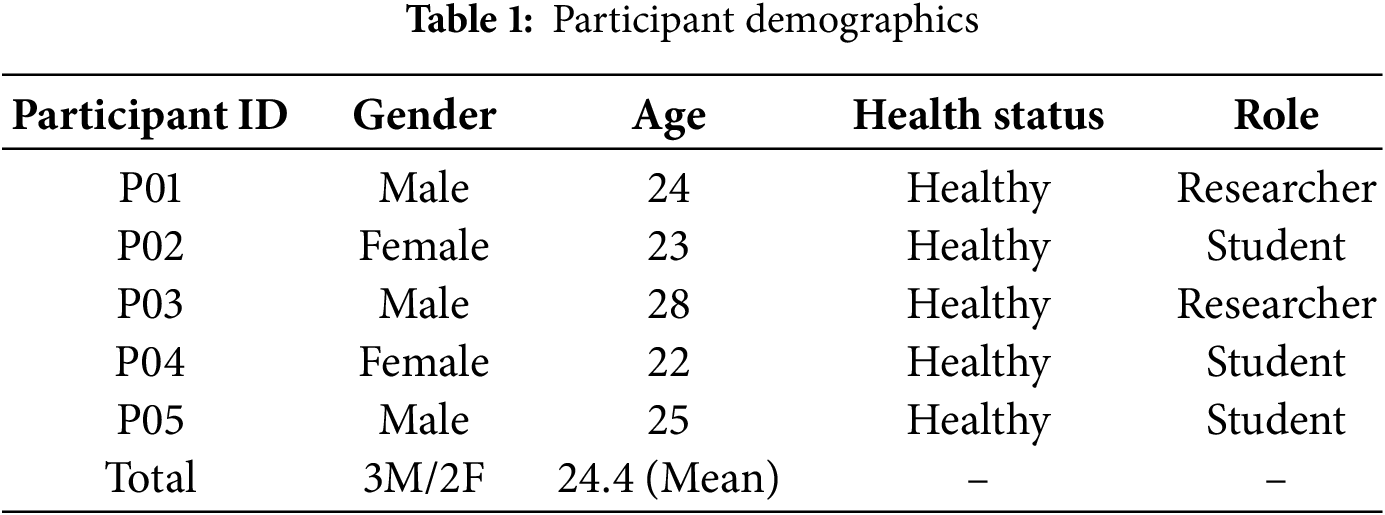

The dataset was collected from 5 healthy volunteers (3 males and 2 females) aged between 22 and 28 years. All participants were recruited from the university research laboratory. None of the participants had a history of neuromuscular disorders or facial paralysis. They were instructed to simulate slow mouth movements under controlled laboratory lighting conditions. The demographic details of the participants are summarized in Table 1. This study serves as a pre-clinical pilot to validate the feasibility of the proposed algorithm before deploying it on patients with dysphagia.

To ensure the reliability of the dataset, a rigorous manual labeling process was implemented. Two independent annotators were trained to classify mouth states based on standard visual criteria: the mouth was labeled as “Open” if there was a visible separation between the lips or teeth exceeding 2 mm; otherwise, it was labeled as “Closed” [15]. Any discrepancies between the two annotators were reviewed and resolved by a third senior researcher to reach a final consensus. This cross-verification process minimizes subjective bias and ensures high inter-rater agreement for the binary classification task. We established an experimental environment to record mouth movement images. Participants were asked to sit in front of the camera module in the Raspberry Pi 4 and perform the actions as follows:

• The participant sat approximately one meter away from the recording camera.

• The participant looked straight ahead and opened and closed their mouth at least three times while maintaining a forward gaze.

• The participant turned their face to the left and opened and closed their mouth at least three times.

• The participant turned their face to the right and opened and closed their mouth at least three times.

• The participant tilted their head upward and opened and closed their mouth at least three times.

• The participant tilted their head downward and opened and closed their mouth at least three times.

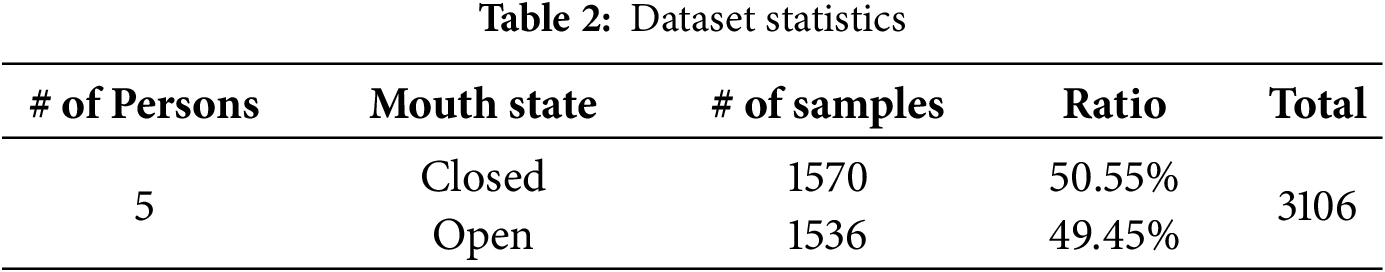

After the recording, video frames were extracted for analysis. Each frame was manually labeled to determine whether the participant’s mouth was open or closed based on the visual appearance in the image. Table 2 summarizes the dataset used in this study.

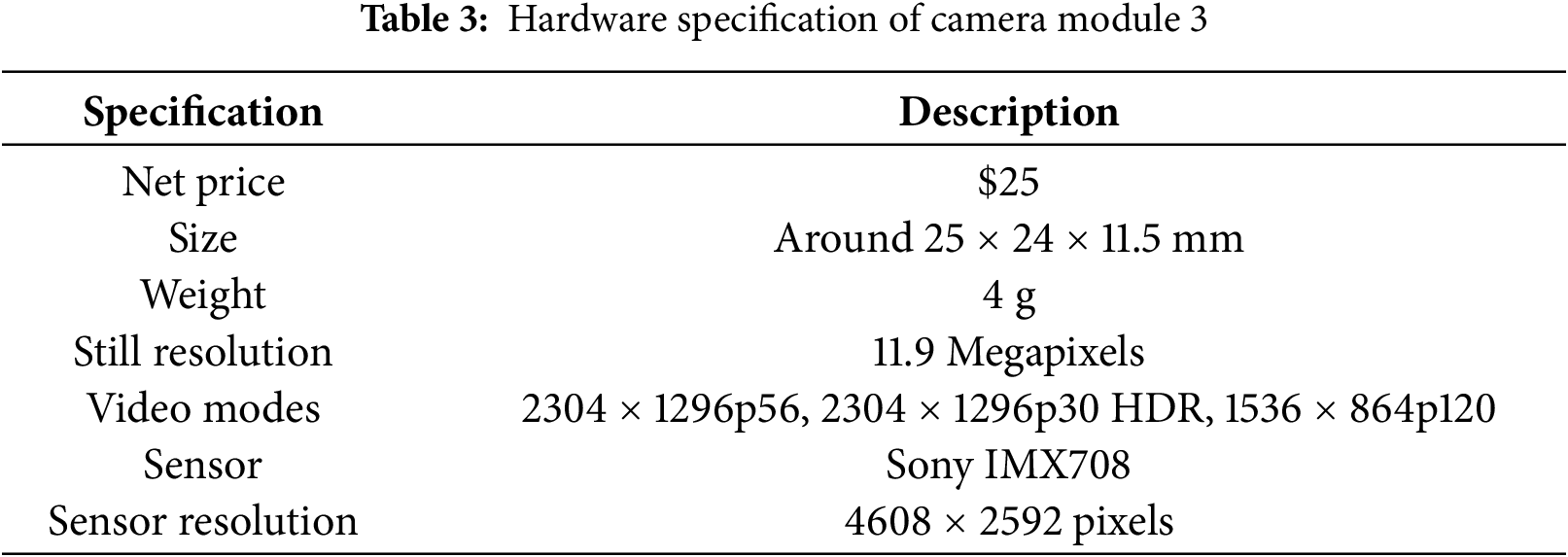

In this experiment, the environment has been designed with two architectures the first is composed of a workstation with Windows 10 Pro and the second is a light weight Raspberry Pi 4. The workstation was equipped with an Intel Core i5-10500 processor operating at 3.1 GHz, featuring six cores and twelve threads, along with 24.0 GB of DDR4 memory. In addition, an NVIDIA RTX 3070 GPU was employed to accelerate parallel computations through CUDA (Compute Unified Device Architecture). The lightweight solution includes Raspberry Pi 4 board and the Camera Module 3. The Raspberry Pi 4 Model B represents the latest generation of the Raspberry Pi microcomputer series, powered by the Broadcom BCM2711 SoC, which integrates a quad-core ARM Cortex-A72 (ARM v8, 64-bit) CPU running at 1.5 GHz. The board supports 4 GB of LPDDR4 RAM and offers modern connectivity options such as USB 3.0, Gigabit Ethernet, Bluetooth 5.0, and dual-band Wi-Fi. Notably, it includes two micro-HDMI ports capable of 4K video output and a VideoCore VI GPU that provides strong graphics processing performance. Fig. 4 illustrates the Raspberry Pi 4 Model B board.

Figure 4: Raspberry Pi 4 model B board

The hardware specifications of the Camera Module 3 is presented in Table 3.

4.3 Model Preprocessing and Training

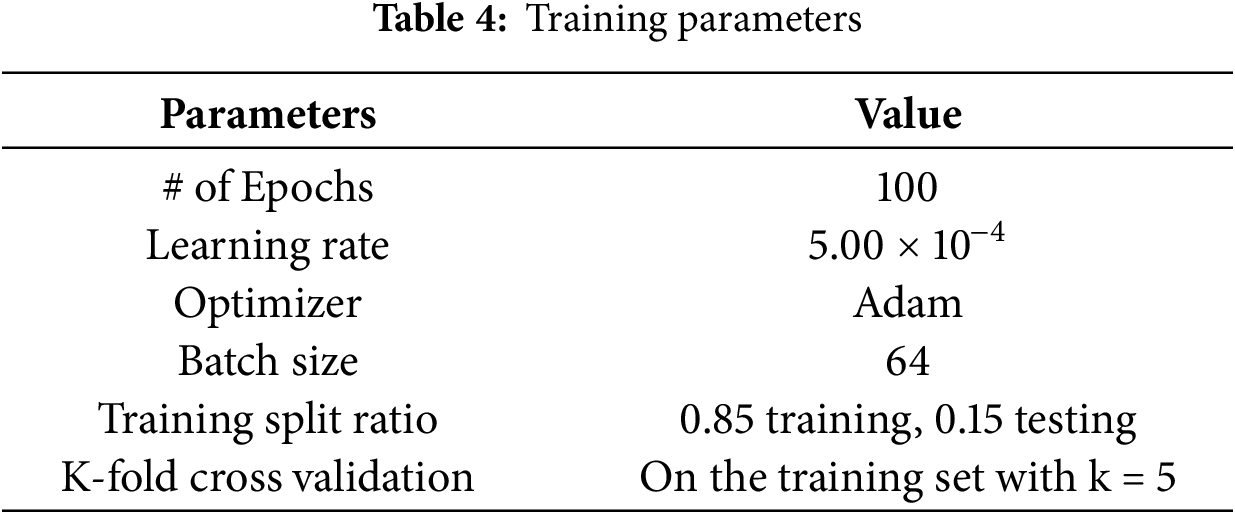

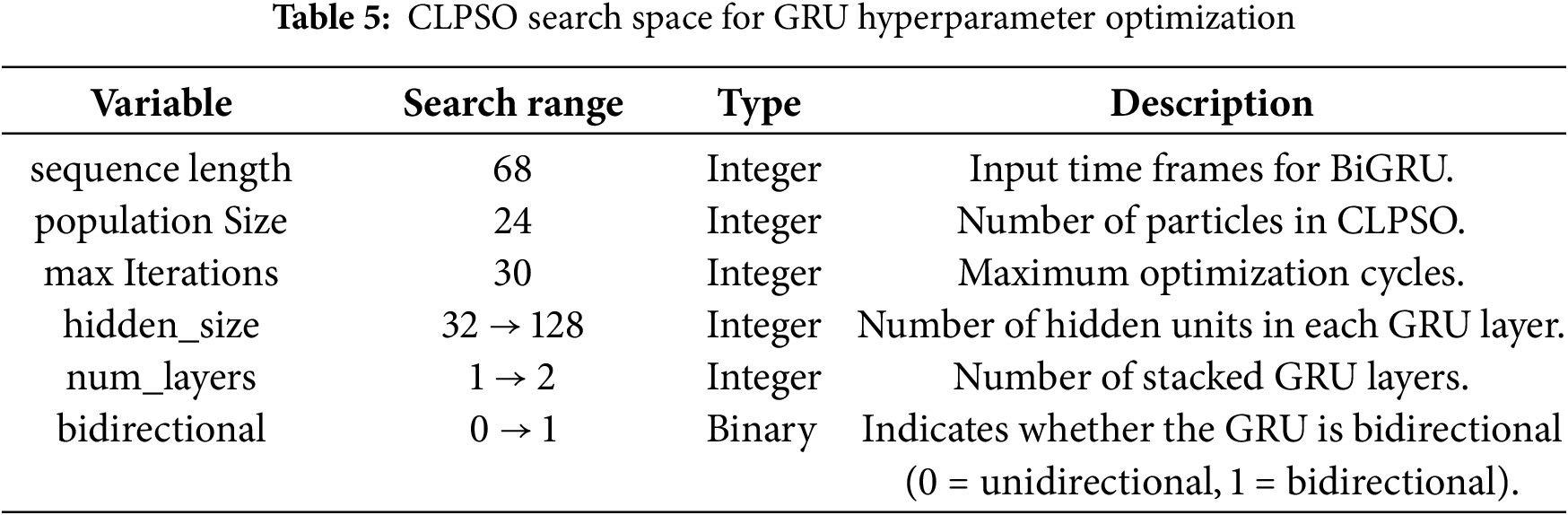

In this study, we set up the Camera Module 3 of the Raspberry Pi 4 board as an edge device. The Dlib library was then employed to detect 68 facial landmark points in each image. The two-dimensional coordinates of these landmarks were directly used to train the machine learning models. The dataset was divided into 85% for training and 15% for testing. During training, we applied the k-fold cross-validation technique with k equal to 5. Table 4 summarizes the training configuration parameters. We also employed the heuristic optimization algorithm CLPSO to search for the optimal parameters of the GRU model. Table 5 summarizes the search space of the CLPSO algorithm.

To standardize the temporal input, the sequence length was fixed at T = 68. At each time step, the BiGRU receives a 2-D feature vector

In machine learning and pattern recognition, evaluation metrics serve as quantitative indicators for measuring the performance and effectiveness of a model. These metrics are used to assess and compare how well a model performs on a given task or problem. In the context of this study, we employed the following metrics:

• Accuracy: Measures the overall correctness of the model’s predictions.

• Precision: Evaluates the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples among all samples predicted as positive.

• Recall: Measures the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples among all actual positive samples.

• F1 score: A comprehensive measure that combines both precision and recall.

• Cosine Similarity: Assesses the similarity between the predicted labels vector and the true labels vector by computing the cosine of the angle between them, reflecting their closeness in vector space.

• ROC AUC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve): Measures the model’s ability to distinguish between classes by considering all possible classification thresholds.

• Precision–Recall (Average Precision—AP): Summarizes the relationship between precision and recall across multiple thresholds, particularly useful in cases of class imbalance.

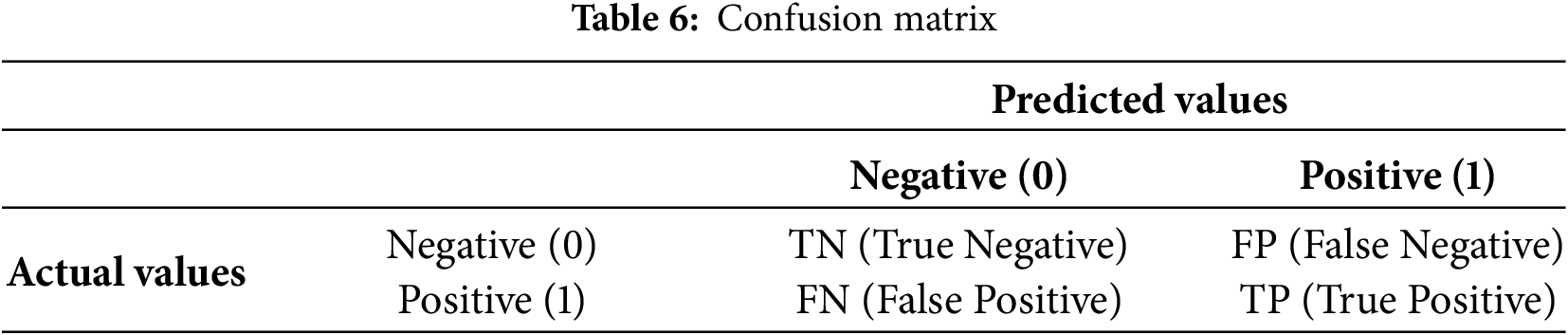

These metrics collectively reflect the model’s performance in distinguishing between different classes. Table 6 presents the definition of the confusion matrix used in machine learning.

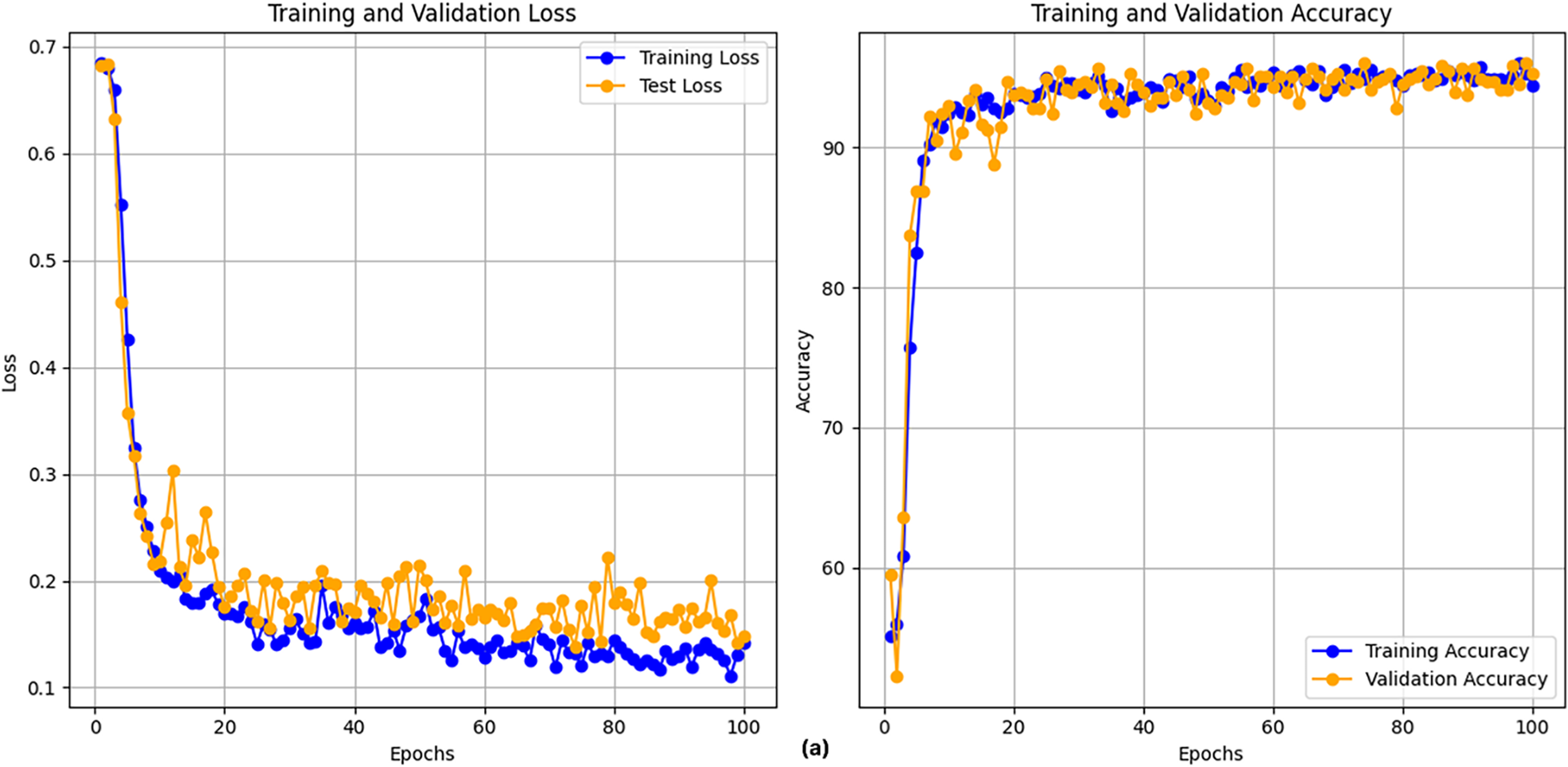

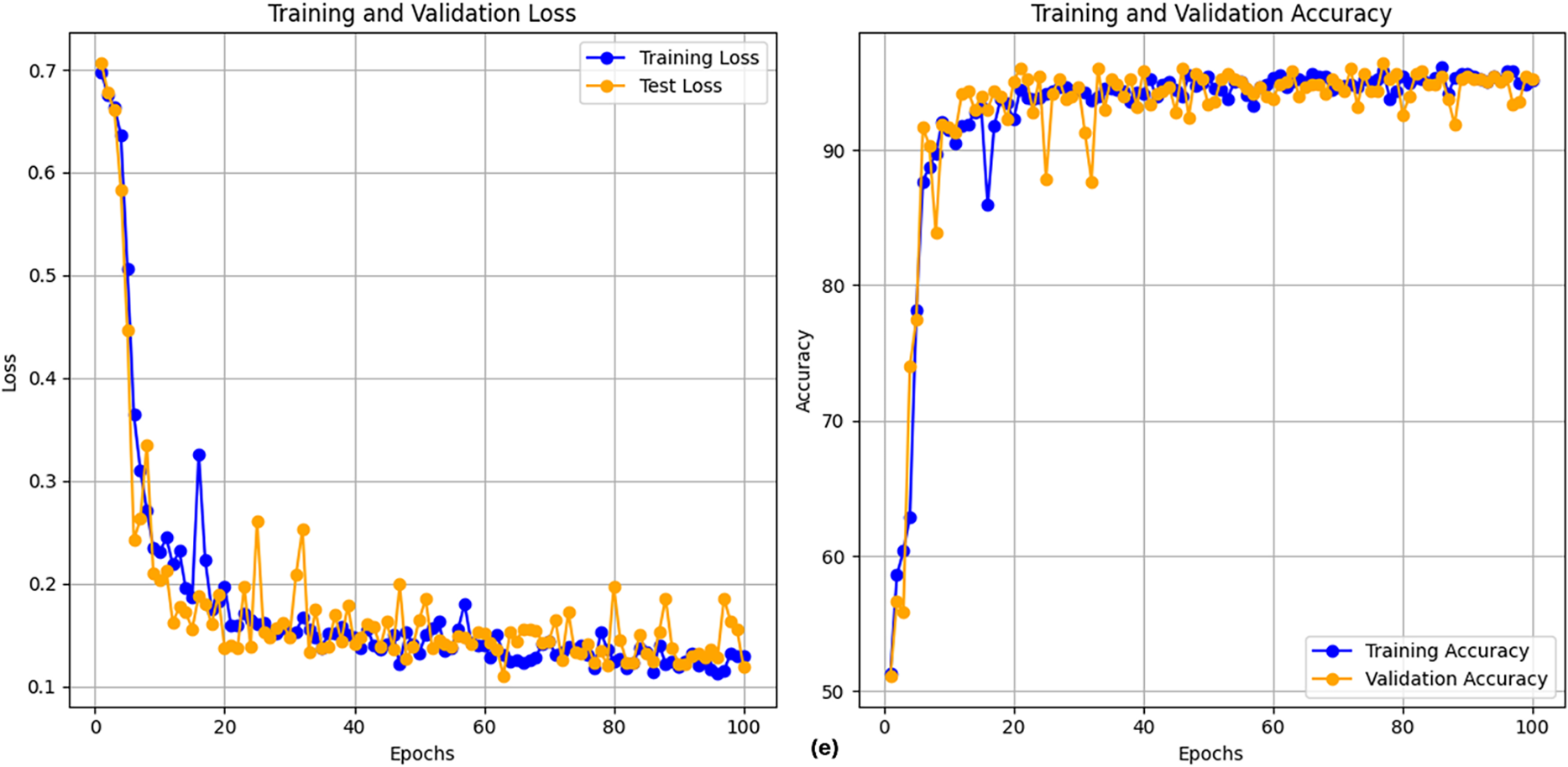

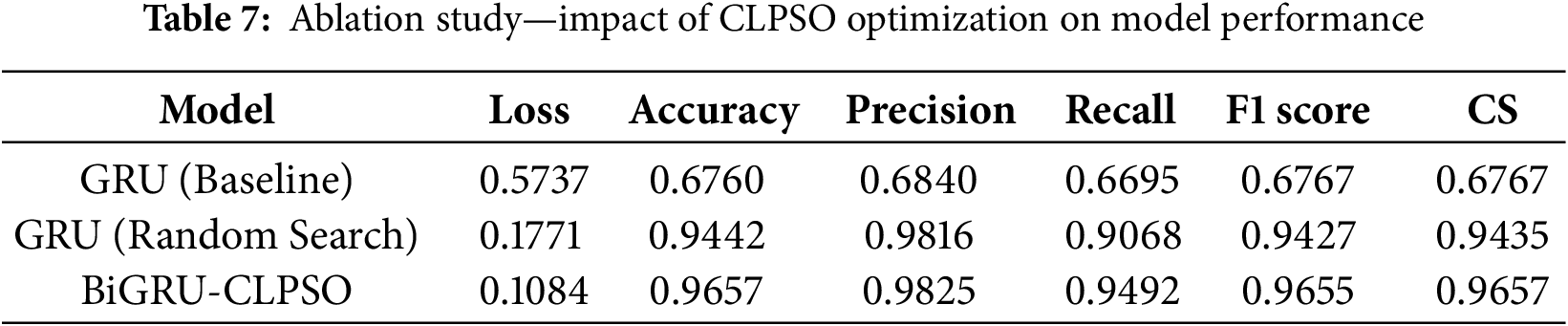

After executing the CLPSO algorithm to search for the optimal configuration, we obtained the best setup for the GRU model with parameters: hidden_size = 128, num_layers = 2, bidir = True. Fig. 5 shows the training plot of the BiGRU-CLPSO model during k-fold cross-validation. To further analyze the contribution of CLPSO-based optimization, we conducted comparative experiments using a baseline GRU model configured with hidden_size = 32, num_layers = 1, and bidirectional = True. In addition, the GRU was further tuned using the Random Search algorithm. The optimal GRU configuration obtained by Random Search was hidden_size = 101, num_layers = 1, and bidirectional = True. Table 7 summarizes the performance comparison among the baseline GRU, the GRU optimized by Random Search, and the proposed BiGRU-CLPSO model on the testing dataset.

Figure 5: Training plot with cross-validation of of BiGRU-CLPSO model

Table 7 serves as an ablation study to quantify the specific contribution of the CLPSO component. When the GRU model is used without optimization (Baseline), the accuracy is limited to 67.60%. Applying a standard Random Search improves performance significantly to 94.42%. However, the proposed BiGRU-CLPSO integration yields the highest accuracy of 96.57% and an F1-score of 0.9657. This incremental improvement demonstrates that the CLPSO algorithm effectively navigates the hyperparameter search space to locate a global optimum that manual or random tuning might miss, thereby validating the necessity of the optimization module in the proposed architecture.

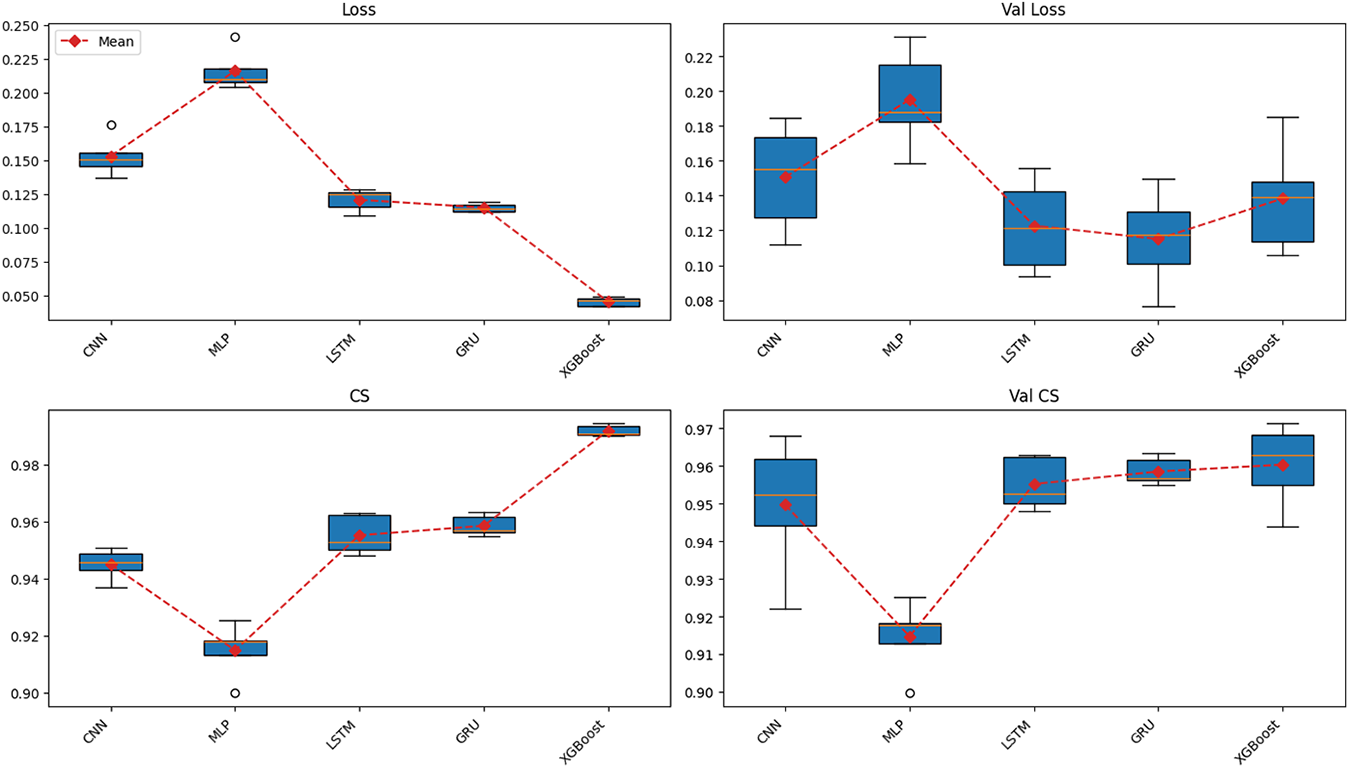

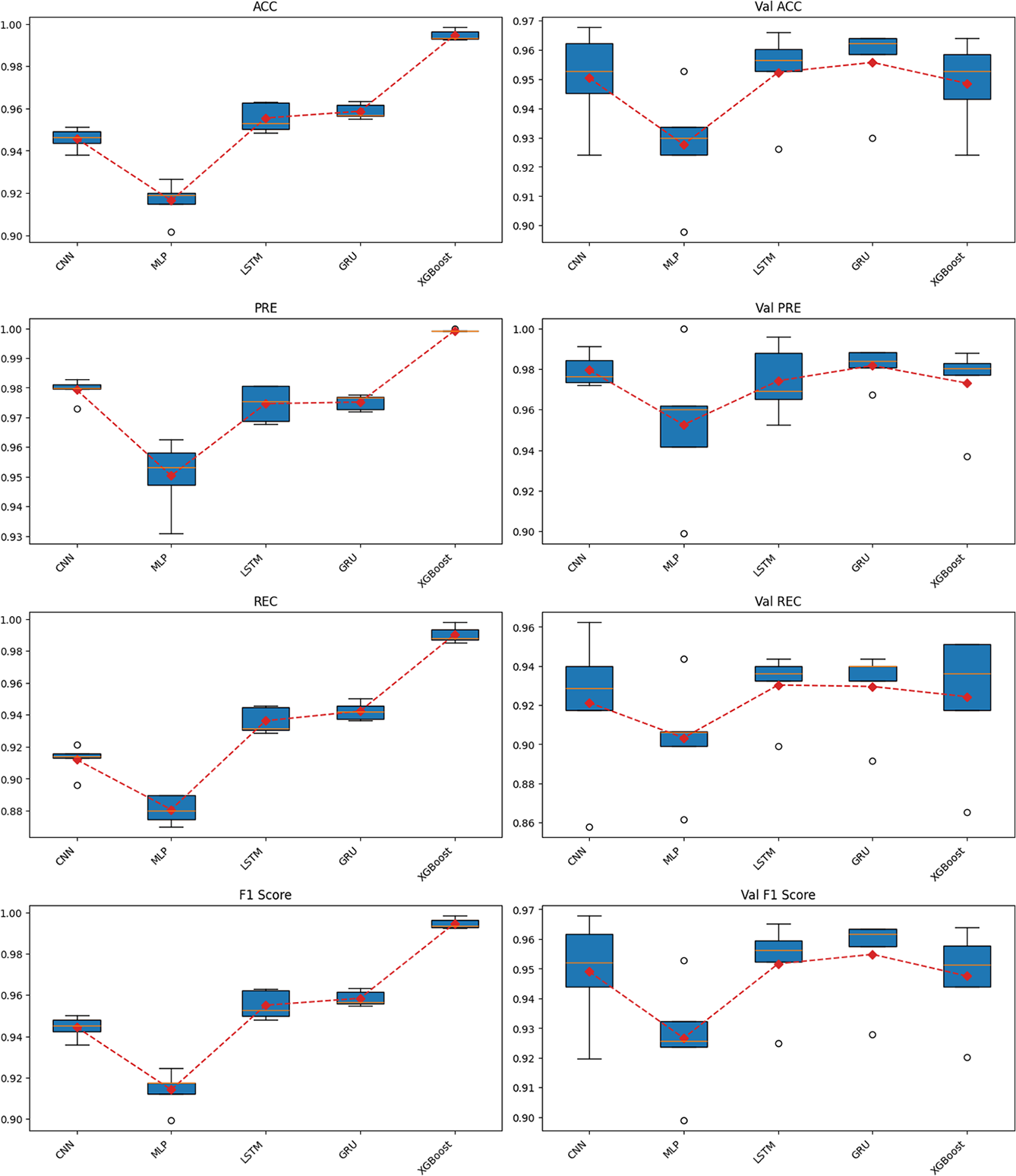

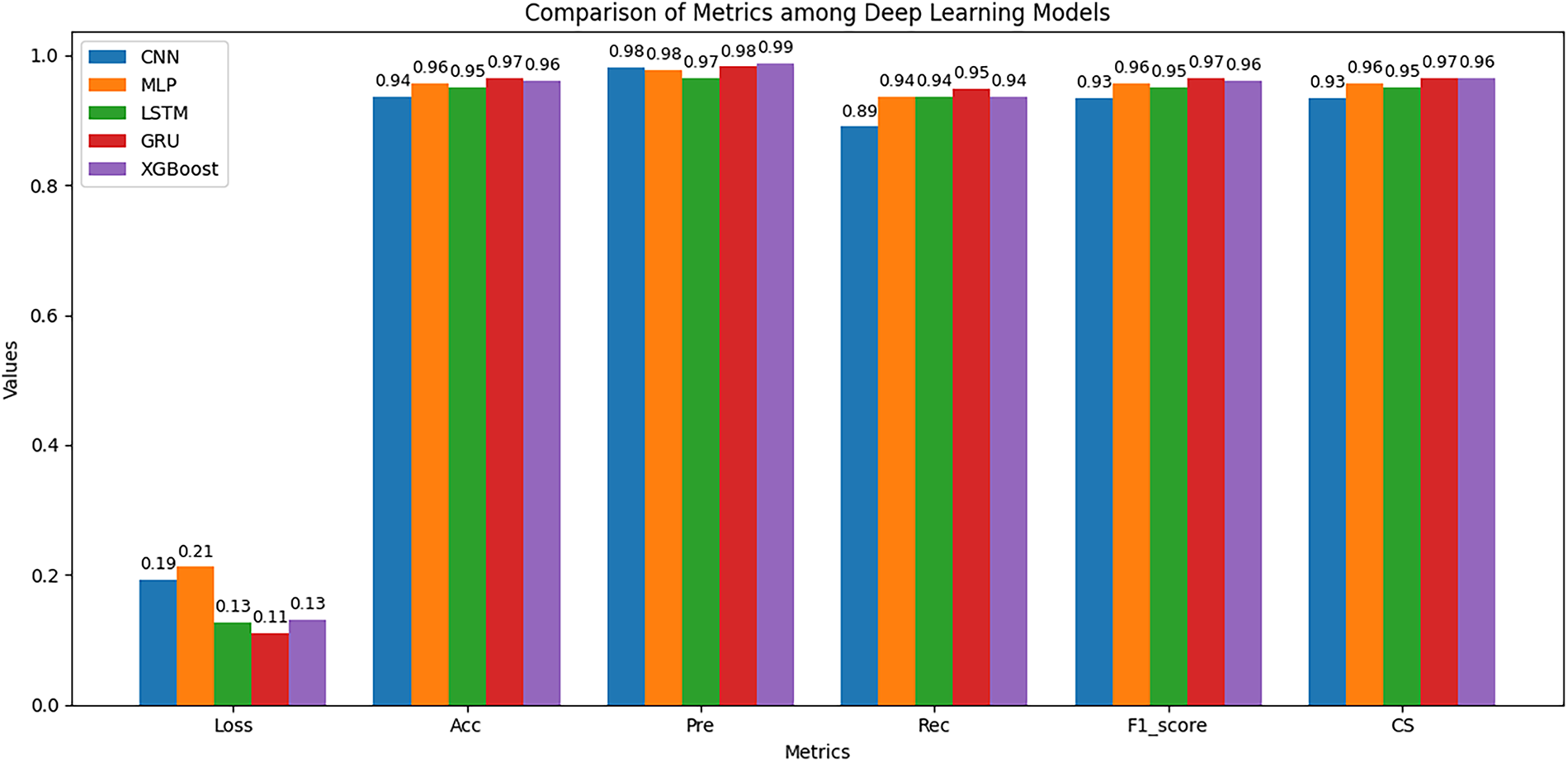

The cross-validation results on the training dataset, as shown in Fig. 6, reveal clear performance differences among the models in the binary classification task based on sequences of two-dimensional coordinate features.

Figure 6: Cross-validation results across multiple models on the training dataset

Starting with the loss function values, when trained for 100 epochs, XGBoost achieved the lowest training loss but showed clear signs of overfitting, ranking only third out of five algorithms in validation loss. In contrast, both LSTM and GRU maintained stable loss values across training and validation phases. Notably, GRU achieved the second-lowest loss during training and the lowest loss during validation. Conversely, CNN exhibited relatively high loss values, while MLP had the highest loss in both training and validation phases.

Overall, GRU achieved the highest and most stable performance across all evaluation metrics, including Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Cosine Similarity. The model maintained a high median value with a narrow range across folds, reflecting strong generalization capability. Importantly, the evaluation emphasized not only the training phase but also the validation phase, where overfitting was evident in models such as XGBoost. LSTM followed GRU in terms of stability and performance, ranking second on most metrics, including Accuracy, Recall, and F1-score. However, GRU outperformed LSTM in stability, as reflected by the smallest gap between training and validation results.

CNN demonstrated moderate performance, with relatively high precision but significantly lower recall, leading to a reduced F1-score. This suggests that CNN tended to minimize false positives at the expense of missing many true positives. XGBoost exhibited typical overfitting behavior, performing almost perfectly on the training set with near-zero loss and an F1-score close to 1.0. However, its validation performance did not remain consistent and was lower than that of LSTM, and notably inferior to GRU. Finally, MLP showed the weakest performance, with uniformly low results across most metrics, indicating its limitation in capturing the sequential structure of temporal data.

Regarding the precision–recall relationship, LSTM and GRU maintained a good balance, resulting in high and stable F1-scores. CNN favored precision, while XGBoost achieved high precision but showed large fluctuations in recall across folds, and MLP performed poorly in both metrics. For Cosine Similarity, LSTM and GRU again outperformed other models, indicating that the logit distributions of these two models were more closely aligned with the true label distribution.

From these findings, it can be concluded that GRU and LSTM are the two best-performing models on the training dataset. In particular, GRU stands out as the optimal choice due to its superior stability and slightly better generalization compared to LSTM. CNN and XGBoost may be considered for specific use cases but are not suitable as primary models, while MLP demonstrated the weakest performance overall.

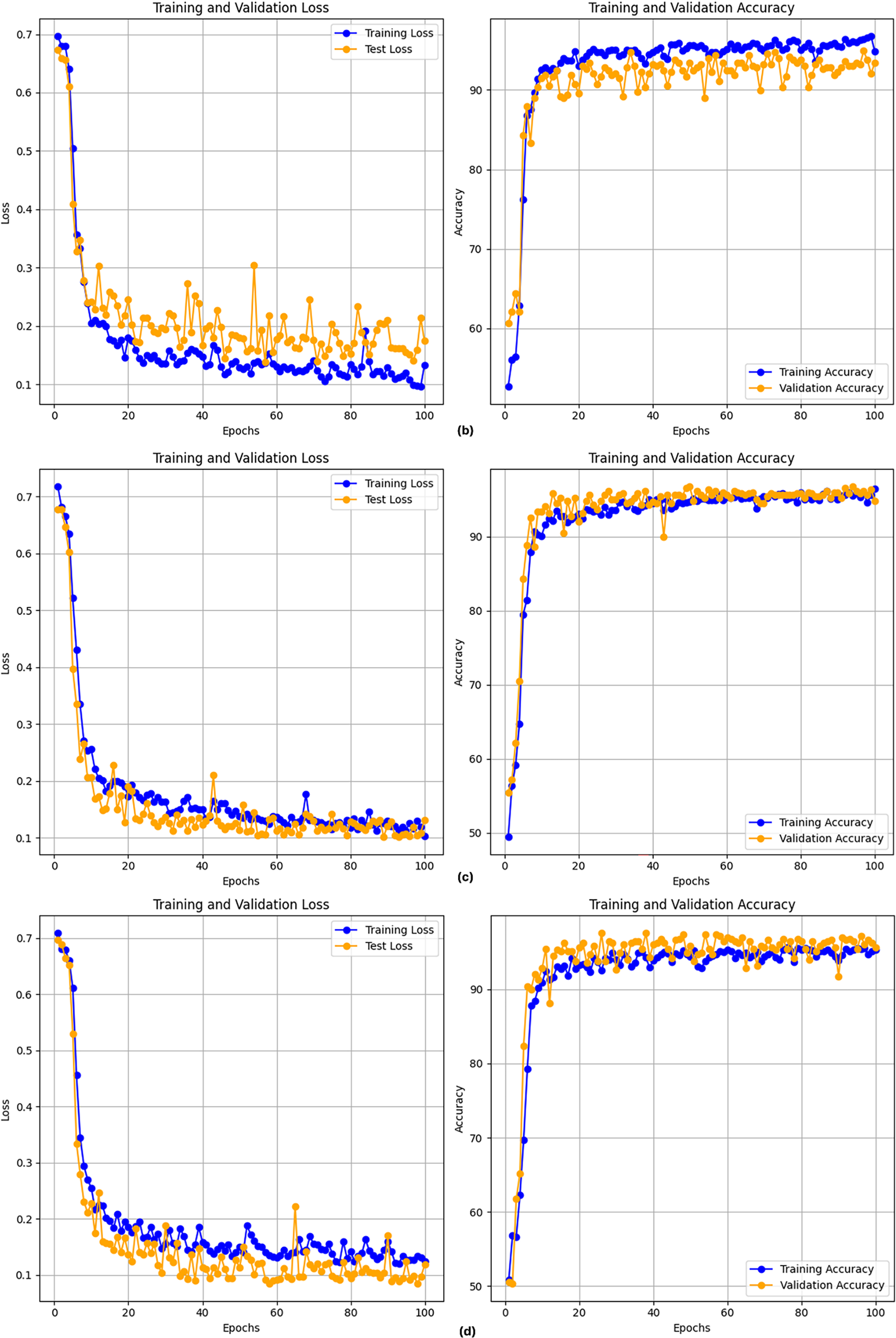

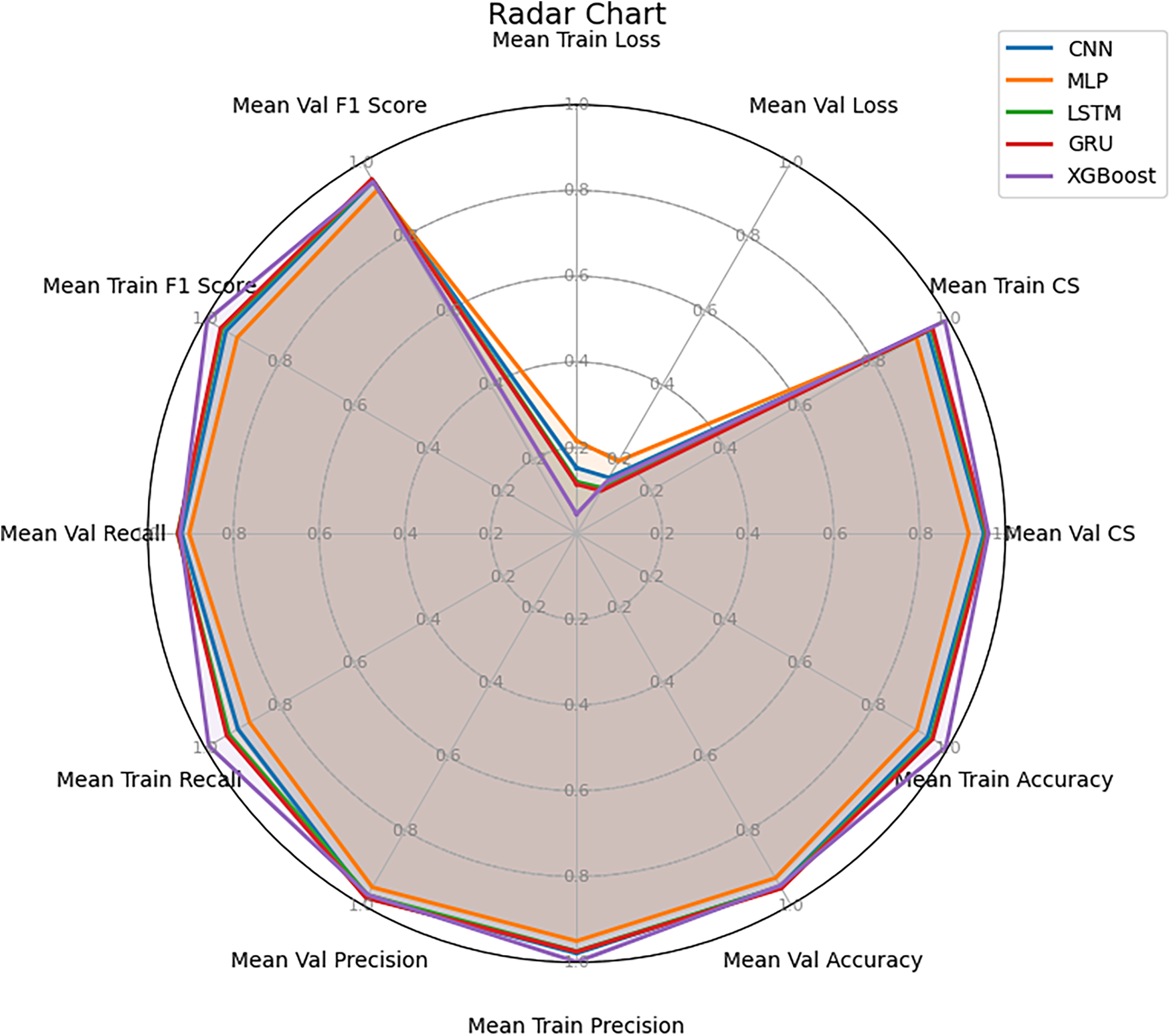

Fig. 7 illustrates the average values of all evaluation metrics obtained during cross-validation on the training dataset, presented in the form of a radar chart. This visualization provides an overview of the comparative performance among the models. The results clearly show that GRU and LSTM lead with high and well-balanced average scores across most criteria, including Loss, Cosine Similarity, Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score. The radar boundaries of these two models are broader and more stable than those of the others, with GRU consistently outperforming LSTM. This further reinforces the conclusion drawn from Fig. 6 that GRU is the optimal choice on the training dataset.

Figure 7: Radar chart of mean performance across multiple models

CNN achieved moderate overall performance, showing a relatively strong result in Precision; however, its lower Recall reduced the overall balance of the model. XGBoost, despite achieving very high values on the training set, demonstrated considerable discrepancies when compared with validation results, clearly reflecting the overfitting tendency previously discussed. Lastly, MLP was the weakest model, with all average metrics remaining low and its radar boundary concentrated near the center of the chart, indicating limited capability in capturing sequential data features.

Fig. 7 not only confirms the findings from Fig. 6 but also provides an intuitive view of the overall comprehensiveness of each model. GRU and LSTM demonstrate superiority in both accuracy and balance across evaluation metrics.

After training all models, we proceeded to evaluate their performance on the testing dataset.

Fig. 8 presents the performance of the models on the independent test dataset, which directly reflects their generalization ability. The results show that the GRU model continues to lead, achieving the lowest Loss value of 0.11, while maintaining Accuracy, Precision, F1-score, and Cosine Similarity values above 0.97. Notably, GRU demonstrates a well-balanced relationship between Precision and Recall, resulting in the highest F1-score of 0.97. This indicates that the model remains stable and reliable when applied to previously unseen data.

Figure 8: Performance comparison on the testing set

XGBoost ranks second, also exhibiting competitive performance, particularly in Precision, which reached 0.99. This suggests that XGBoost is effective at minimizing false positive predictions. However, its lower Recall compared to GRU indicates that it missed some true positive cases, leading to less balanced overall performance. In remote patient monitoring scenarios, the primary priority is to detect abnormal behaviors such as difficulty swallowing, swallowing errors, or prolonged mouth opening as early as possible. Therefore, any unusual inability of a patient to close the mouth must trigger an immediate alert. For such systems, Recall is the most critical metric. The high Recall and F1-score values achieved by GRU clearly demonstrate its superior performance and robustness for remote dysphagia monitoring applications.

Unlike the results observed during cross-validation on the training dataset, the LSTM model performed near the bottom on most evaluation metrics in this test phase. CNN yielded the lowest overall performance, with a Loss exceeding 0.19 and the lowest Recall value of 0.89, resulting in a reduced F1-score of 0.93. This outcome highlights the limitations of CNN in capturing the sequential dependencies inherent in temporal data. MLP ranked third, performing slightly better than CNN and LSTM but still falling short of GRU and XGBoost.

Overall, the results on the test dataset reinforce and extend the earlier analyses. GRU stands out as the most effective and suitable model for this task, excelling not only during cross-validation but also when evaluated on entirely new data. XGBoost may be considered as a supplementary model in applications that prioritize Precision, whereas LSTM, CNN, and MLP exhibit limited performance and are not yet suitable as primary models.

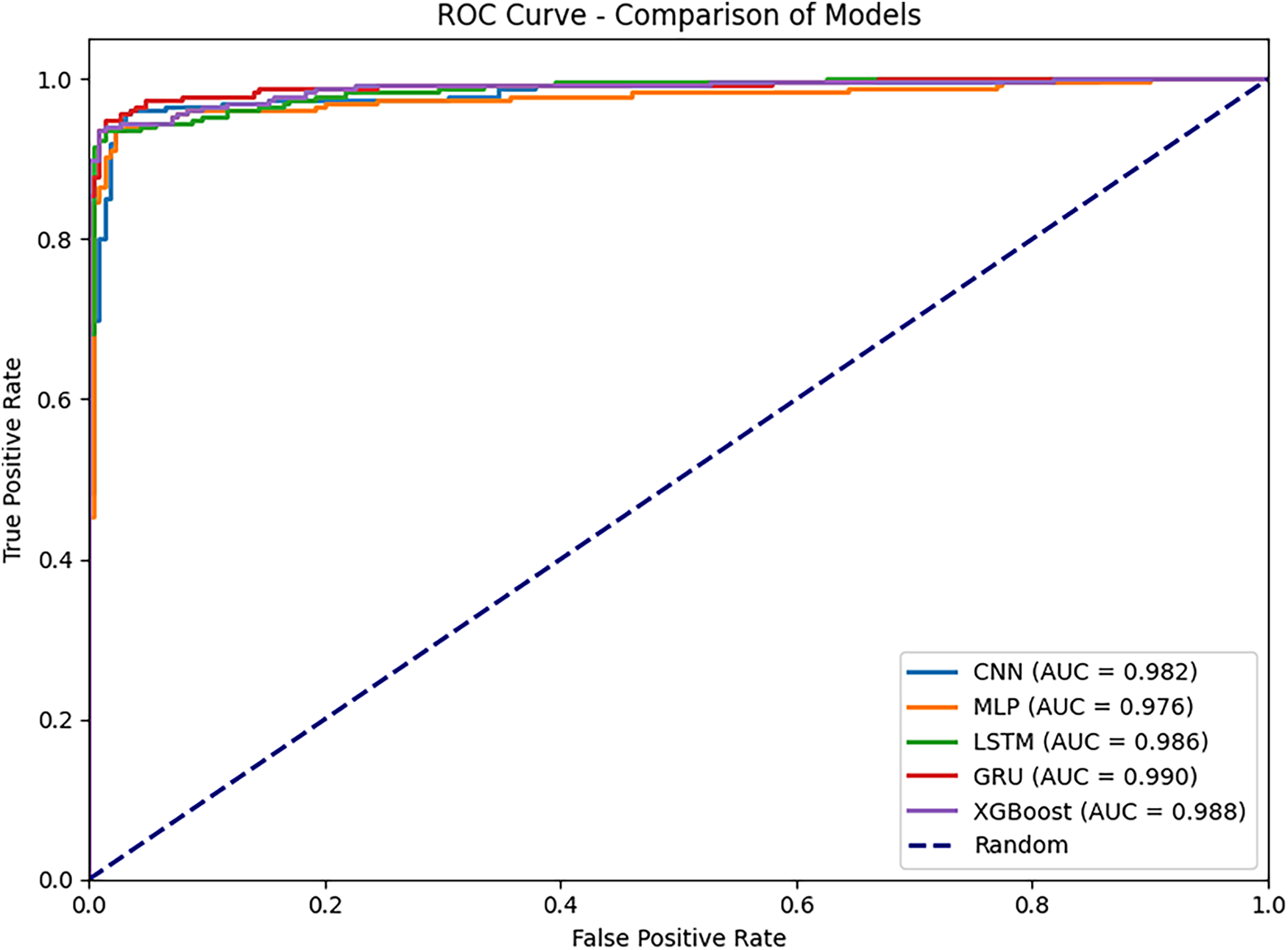

Fig. 9 presents the ROC curves and AUC values of the models on the test dataset. The results show that all models achieved very high AUC values above 0.976, indicating strong capability in distinguishing between the two classes. Among them, the GRU model obtained the highest AUC value of 0.990, confirming its superior classification performance compared with the other models. XGBoost with a value of 0.988 and LSTM with a value of 0.986 followed closely, both exhibiting ROC curves that lie near the upper-left corner, demonstrating their ability to maintain a high true positive rate even at low false alarm rates. CNN achieved an AUC of 0.982, which is relatively high; however, its overall performance was weaker due to the lower Recall observed in Fig. 8. Finally, MLP recorded the lowest AUC value of 0.976, consistent with its weaker performance on both the training and test datasets. Thus, the ROC–AUC analysis reinforces the previous findings, confirming that GRU is the most comprehensive and stable model on the test dataset.

Figure 9: ROC-AUC comparison across multiple models

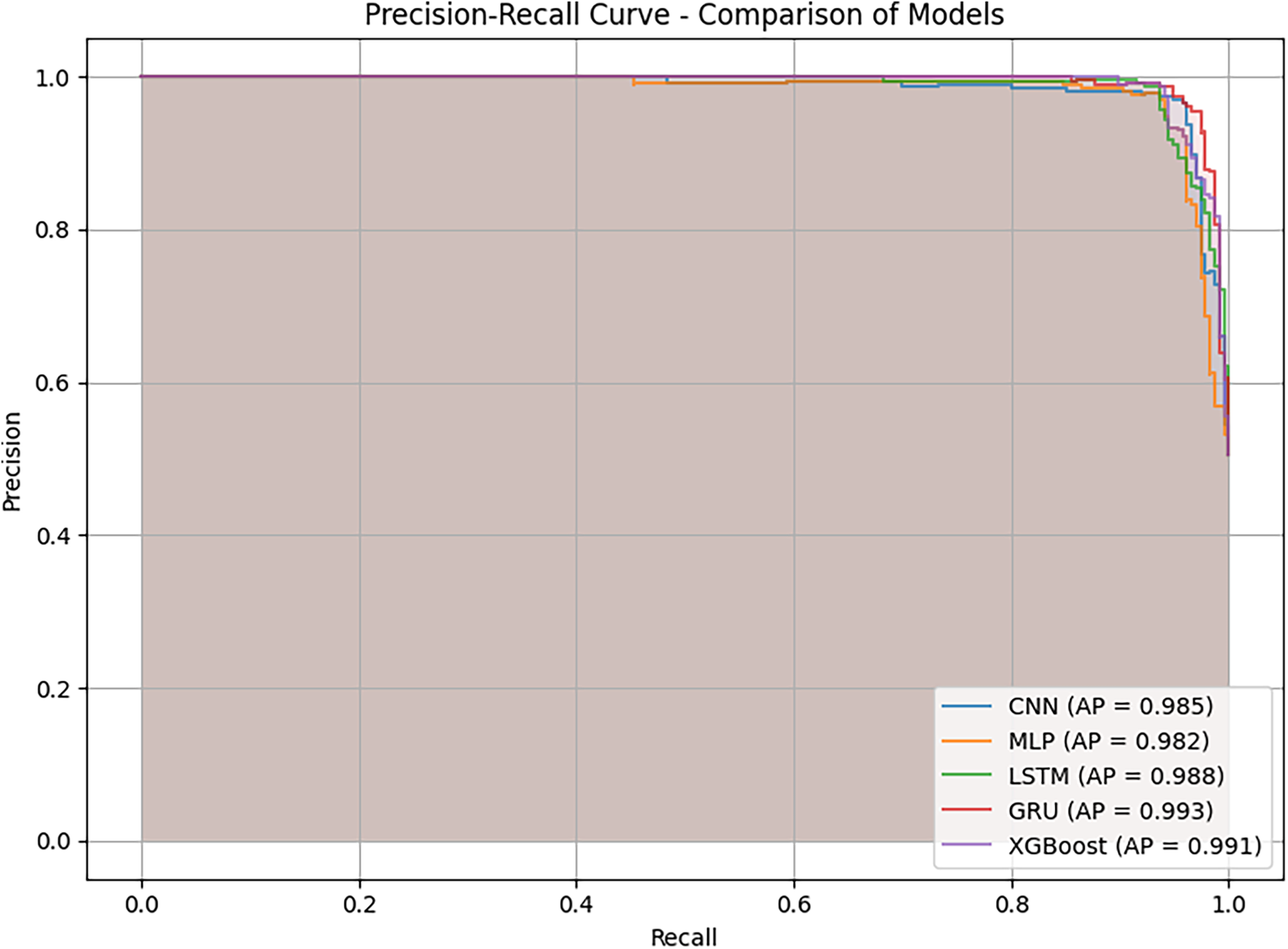

Fig. 10 presents the Precision–Recall (PR) curves and the Average Precision (AP) values of the models on the test dataset. This metric is particularly important for assessing the trade-off between precision and recall across different decision thresholds. The results show that all models achieved very high AP values, with values equal to or exceeding 0.982, confirming their stable classification capability. GRU achieved the highest AP of 0.993, with a PR curve closely following the upper boundary and maintaining stability in the high-recall region. This demonstrates the model’s ability to sustain high precision while minimizing missed positive cases. XGBoost also exhibited highly competitive performance, with an AP of 0.991, approaching GRU’s result and maintaining consistently high precision across the recall range. LSTM achieved an AP of 0.988, showing a good balance between precision and recall, though its curve was slightly lower than those of GRU and XGBoost in the high-recall region. CNN with AP value of 0.985 and MLP with AP value of 0.982 also achieved reasonably high results. However, their PR curves declined as recall approached 1.0, reflecting limitations in detecting all positive cases. This observation aligns with the analysis in Figs. 7 and 9, where both models exhibited lower recall compared to the top-performing group.

Figure 10: Precision–recall (PR) curves and average precision (AP) values comparison across multiple models

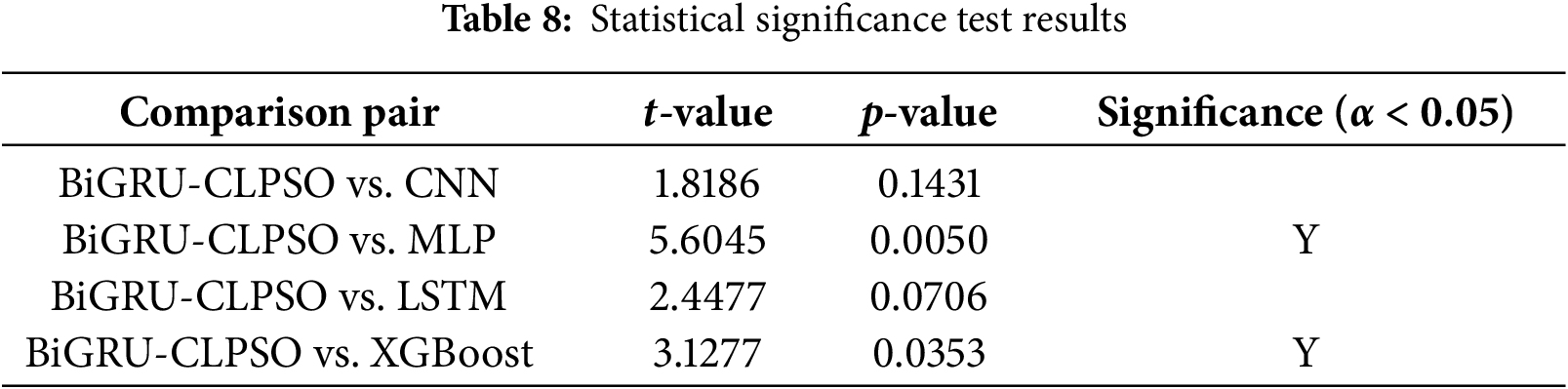

To validate the reliability of the performance improvements observed in the figures, we conducted paired t-tests (at a significance level of α = 0.05) comparing the F1-scores of the proposed BiGRU-CLPSO model against the other classifiers. Table 8 summarizes these statistical results.

First, the analysis confirms that BiGRU-CLPSO statistically outperforms the traditional machine learning baselines, specifically MLP (p = 0.005 < 0.01) and XGBoost (p = 0.0353 < 0.05). This statistically significant difference provides robust evidence that the proposed deep learning architecture generalizes far better than shallow models. While XGBoost demonstrated high training accuracy, its significantly lower validation stability indicates a tendency toward overfitting on limited datasets. In contrast, the BiGRU model effectively captures the temporal dependencies in landmark sequences that MLP and XGBoost fail to model adequately. Second, regarding the deep learning comparisons, the performance differences against CNN (p = 0.1431) and LSTM (p = 0.0706) were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The p-value for LSTM, while marginally close to the threshold, suggests that both RNN variants (LSTM and BiGRU) possess comparable predictive power for this specific task. However, in the context of edge computing, statistical accuracy is not the sole criterion for model selection; computational complexity is equally critical. The BiGRU architecture is structurally simpler, utilizing only two gating mechanisms (reset and update) compared to the three-gate structure (input, output, and forget) of the LSTM. This architectural difference translates to fewer trainable parameters and reduced matrix operations during inference. Consequently, since BiGRU-CLPSO achieves a statistically equivalent level of accuracy to LSTM but with greater computational efficiency, it is verified as the optimal choice for deployment on resource constrained platforms like Raspberry Pi.

The experimental results on both the training dataset via cross-validation and the independent test dataset demonstrate consistent performance patterns across models. The training analyses from Figs. 5 and 6 identified GRU and LSTM as the leading models, characterized by low loss values, high accuracy, and an optimal balance between precision and recall. CNN and MLP showed less stability, with CNN favoring precision but lacking recall, and MLP producing the lowest overall results. XGBoost achieved very high training accuracy but showed signs of overfitting, though it still maintained competitive test performance. The test results presented in Figs. 7–9 further supported these findings. GRU stood out as the most comprehensive and stable model, achieving the lowest loss, the highest F1-score, and excellent AUC and AP scores of 0.990 and 0.993, respectively. LSTM and XGBoost also demonstrated strong performance, with LSTM maintaining a good balance and XGBoost excelling in precision. Although CNN and MLP achieved high AUC and AP scores exceeding 0.97, they lacked the balance and stability exhibited by the leading models.

In conclusion, these experimental results demonstrate that BiGRU-CLPSO is the optimal model for classifying mouth states based on sequential coordinate data. The model not only outperforms the baseline GRU and the GRU optimized using the Random Search algorithm but also exhibits greater stability and superior performance compared with traditional models such as CNN, MLP, LSTM, and XGBoost. These improvements are consistent across multiple evaluation metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, cosine similarity, ROC–AUC, and the precision–recall curve. These findings highlight the robustness of BiGRU in handling sequential data and the effectiveness of CLPSO in searching for the optimal hyperparameter configuration for the BiGRU model.

4.6 Real-Time Performance on Edge Device

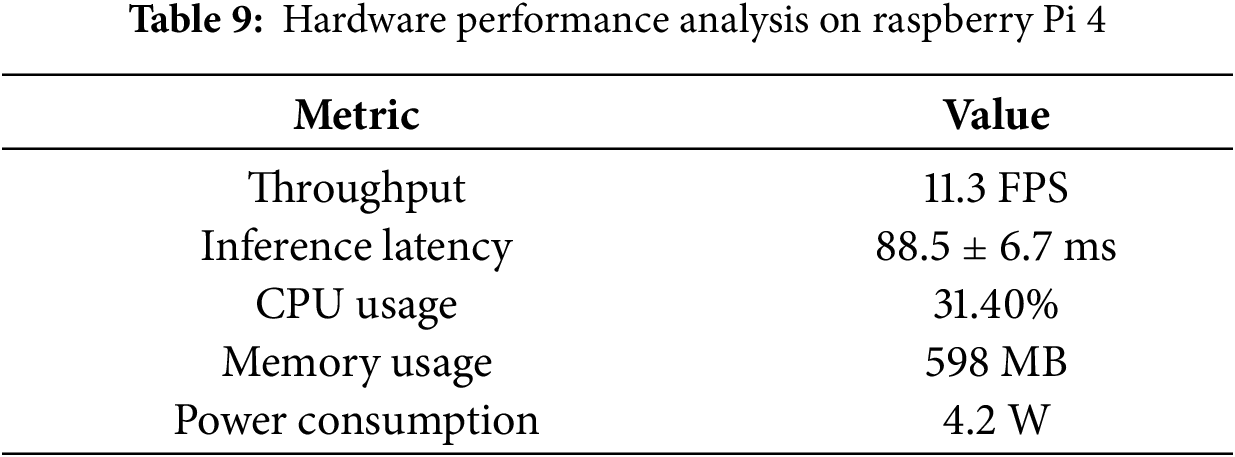

Beyond algorithmic accuracy, the practical viability of a healthcare monitoring system depends on its operational efficiency on resource-constrained hardware. To validate this, we monitored the system performance directly on the Raspberry Pi 4 device under continuous inference load. The hardware metrics derived from system resource analysis are summarized in Table 9.

As detailed in Table 9, the system achieves a stable throughput of approximately 11.3 FPS, corresponding to an average inference latency of 88.5 ms. While this frame rate is lower than standard video streaming (30 FPS), it is highly effective for patient monitoring applications. Physiological mouth movements, such as opening for feeding or yawning, typically occur over durations of 2 to 5 s. With a sampling rate of ~11 times per second, the system captures sufficient temporal granularity to reconstruct the motion dynamics without missing critical state transitions. The low latency variance (±6.7 ms) further confirms the temporal stability of the pipeline, which is crucial for real time alerting. Regarding computational resources, the system demonstrates exceptional efficiency. The memory usage is 598 MB, only up to 15% of the devicecapacity. Notably, the system-wide CPU user load is approximately 31.4%. Since the Raspberry Pi 4 utilizes a Quad-core Cortex-A72 processor, this moderate load profile indicates that the lightweight BiGRU architecture is computationally efficient, leaving substantial headroom (~68%) for concurrent background tasks. This is a critical feature for IoT deployment, as it allows the device to simultaneously handle data encryption, wireless transmission, and system health checks without experiencing thermal throttling or performance degradation.

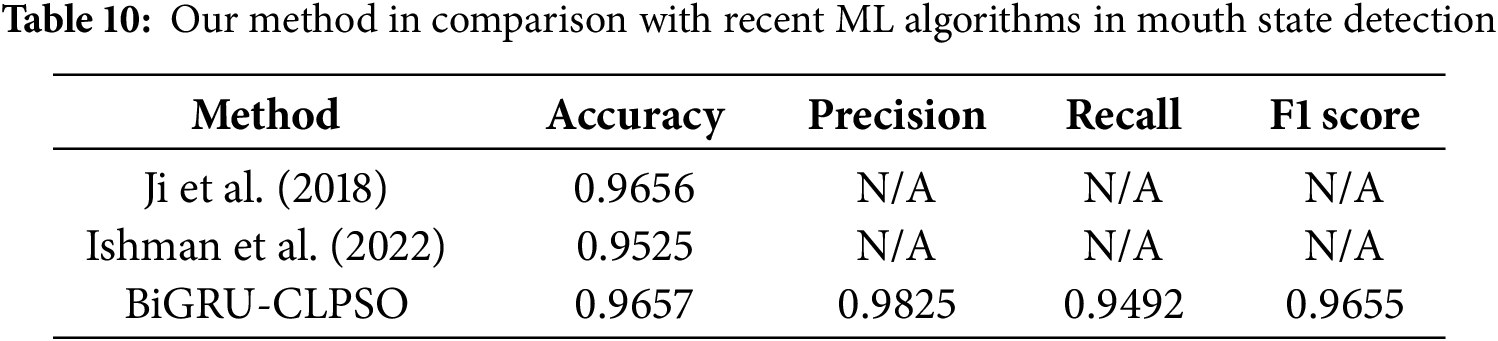

We compared the results of this study with several recent prominent works in the same field of mouth-state recognition. The selected studies include Ji et al. (2018) [33] and Ishmam et al. (2022) [34]. Ji et al. (2018) proposed a contour-based algorithm to detect whether the eyes and mouth are open or closed, aiming to identify driver fatigue states. Ishmam et al. (2022) introduced two lightweight CNN models for recognizing lip states, open or closed, to support non-verbal communication for individuals with hearing impairment. Instead of using raw images directly, the authors employed landmark detection tools (DLIB and MediaPipe) to extract six key feature points around the lips and then computed pairwise distances between these points as input to the CNN model. In our comparison, we refer to the results of the model developed by Ishmam et al. based on the Dlib landmark detector.

At present, comparisons with recent studies are not fully standardized because all datasets were self-collected. The main reason is that there is currently no publicly available benchmark dataset specifically designed for monitoring mouth-opening and closing states in patients. Some existing facial expression datasets, such as emotion recognition datasets (e.g., CK+, MUGFE, or AFEW), can be partially repurposed to construct mouth-state datasets. However, the mapping between emotional expressions and mouth-opening states is not always consistent, and therefore, the conversion rate cannot reach 100% accuracy. For example, in the study by Ji et al. (2018) [33], only a small subset of the FERET database (418 images) was selected for analysis. Consequently, comparisons with prior work can only serve as qualitative references, as the evaluations were performed on different datasets. However, the results summarized in Table 10 indicate that the proposed method achieved high and competitive performance in identifying mouth-opening states. This demonstrates that the present study provides a promising tool for remotely monitoring patients with conditions involving impaired oral motor control.

4.8 Discussion and Limitations

The experimental results provide several important implications for practical model deployment. First, GRU and LSTM not only achieved superior performance on both the training and test datasets but also maintained high stability, making them the most suitable candidates for implementation in real-time monitoring systems or embedded applications. In particular, GRU, with its more compact architecture, offers advantages in inference speed and resource efficiency, making it ideal for hardware-constrained environments such as embedded cameras or mobile devices. Second, although XGBoost exhibited signs of overfitting during training, it achieved very high accuracy and precision on the testing set. This suggests that XGBoost may serve as an effective alternative in scenarios with limited data or when rapid deployment is needed, offering lower computational cost compared to deep learning models. Finally, while CNN and MLP were not the optimal choices in this study, their results indicate potential for improvement through techniques such as data augmentation, architectural optimization, or integration into hybrid models. These enhancements could help leverage the simplicity and fast training capability of CNN and MLP in practical applications where short development cycles are required. In establishing the baseline for this study, we focused on learning based approaches (CNN, LSTM, MLP) rather than static geometric thresholds like the MAR. As noted in previous studies [6], fixed-threshold metrics are susceptible to variations in head pose and perspective, which are inherent in our multi-view dataset (frontal, tilted, and rotated orientations). Therefore, we prioritized the BiGRU architecture to automatically learn robust, pose-invariant features from the temporal landmark sequences, ensuring stable performance across the simulated head movements described in Section 4.1.

It is also worth noting why recent heavy architectures, such as Transformer-based models, were not prioritized in this specific comparative analysis. While Transformers have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in video understanding, they typically demand substantial computational resources due to the quadratic complexity of self-attention mechanisms. In the context of this research, our primary objective was to develop an ultra-lightweight solution capable of operating on CPU-based edge devices (Raspberry Pi) with minimal latency. Furthermore, our input data consists of low-dimensional geometric vectors rather than high-dimensional raw pixel data. Applying complex Transformer encoders to such compact feature sets often results in computational redundancy without proportional gains in accuracy, particularly on smaller datasets where Transformers are prone to overfitting. Therefore, the BiGRU-CLPSO architecture was selected as the optimal balance between data efficiency, inference speed, and predictive accuracy for this specific edge-health monitoring orientation.

The proposed system demonstrates strong potential for real-world healthcare applications. In remote patient monitoring systems, accurate detection of mouth dynamics can provide valuable support for diagnosing neuromuscular disorders such as dysphagia, Bell’s palsy, and Parkinson’s disease [35]. In addition, it can assist in evaluating fatigue, drowsiness, and respiratory abnormalities, particularly in elderly or bedridden individuals. The high recall achieved by the BiGRU–CLPSO model indicates its suitability for early-warning tasks, where minimizing false negatives is critical. The system can be integrated into edge devices such as Raspberry Pi modules for on-device inference, thereby reducing transmission latency and protecting data privacy. Furthermore, the proposed system is highly convenient for expanding training data sources, facilitating continuous improvement of model performance, and enabling remote updates to maintain real-time operation of the system.

In addition, the developed system is designed to facilitate future data expansion through hardware integration with edge devices, enabling scalable and real-time data acquisition. This feature distinguishes our work from several previous studies that rely on specialized equipment, trained medical staff, and high-cost procedures such as VFSS and FEES [15,16], highlighting the practical potential of our approach. However, strict interpretation of these results requires acknowledging certain limitations. First, the dataset used in this study is relatively small, involving 5 healthy participants with approximately 3100 samples, and currently lacks diversity in terms of age, ethnicity, and pathological conditions. Consequently, this work represents a pre-clinical pilot investigation aimed at demonstrating the algorithmic effectiveness of the BiGRU–CLPSO model on geometric inputs, rather than a large-scale clinical assessment. It is worth noting that, despite the limited sample size, data collection was conducted under rigorous, well-controlled conditions, where each participant performed mouth-opening actions in multiple fundamental orientations (frontal, right-tilted, left-tilted, upward, and downward) to ensure initial algorithmic robustness. Future work will focus on validating the system in uncontrolled environments and expanding the dataset to include patients with actual neuromuscular disorders to ensure broader clinical generalization.

This study proposes a BiGRU–CLPSO model for detecting the mouth-open and mouth-close states of patients, which is suitable for deployment in real-time systems on edge devices. The proposed model was also compared with traditional algorithms, including CNN, LSTM, MLP, and XGBoost. Through experiments involving cross-validation on the training dataset and independent testing on a held-out dataset, the models were thoroughly analyzed using several evaluation metrics, including Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, Cosine Similarity, ROC–AUC, and the Precision–Recall Curve.

The experimental results show that the proposed BiGRU–CLPSO model consistently achieved the highest performance, demonstrating an optimal balance between accuracy and coverage while maintaining stability across both training and testing datasets. BiGRU–CLPSO was particularly outstanding due to its compact structure and strong generalization ability, making it the optimal choice for real-time applications and edge deployment. Although more complex, LSTM maintained competitive performance and served as a reliable alternative. XGBoost also performed well, especially in terms of precision, though it exhibited a clear tendency toward overfitting during training. CNN and MLP showed noticeably lower performance. CNN favored precision but lacked recall, while MLP produced the weakest and least stable results.

Finally, the proposed model can be effectively integrated into real-time patient monitoring systems using cameras or edge devices. Such systems have the potential to enhance the processes of monitoring, diagnosis, and treatment of disorders related to the oral muscles and the corresponding neural mechanisms.

For future work, we plan to enrich and diversify the data sources to expand the dataset. In addition, more comprehensive analyses will be conducted to further refine and optimize the current system, with the goal of improving its accuracy and responsiveness to the demands of real-time applications. Specifically, we plan to enhance the interpretability of the proposed model using Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) techniques to better understand the feature contributions and decision-making process. This will help identify which facial regions contribute most to mouth-state classification. Furthermore, real-time latency assessment will be conducted on edge devices to validate the model’s suitability for continuous monitoring scenarios. Finally, ethical considerations such as informed consent, data anonymization, and bias mitigation across demographic groups will be integrated into the future deployment framework.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, for funding this research.

Funding Statement: This research was partly supported by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, with grant numbers NSTC 114-2622-8-992-007-TD1 and 112-2811-E-992-003-MY3.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Thanh-Lam Nguyen and Mong-Fong Horng; data collection: Thanh-Lam Nguyen; analysis and interpretation of results: Thanh-Tuan Nguyen and Chin-Shiuh Shieh; draft manuscript preparation: Thanh-Tuan Nguyen and Thanh-Lam Nguyen; supervision: Chin-Shiuh Shieh and Mong-Fong Horng; validation: Chen-Fu Hung and Lan-Yuen Guo; critical review: Chun-Chih Lo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Doan TN, Ho WC, Wang LH, Chang FC, Nhu NT, Chou LW. Prevalence and methods for assessment of oropharyngeal dysphagia in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2022;11(9):2605. doi:10.3390/jcm11092605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. González-Fernández M, Ottenstein L, Atanelov L, Christian AB. Dysphagia after stroke: an overview. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep. 2013;1(3):187–96. doi:10.1007/s40141-013-0017-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Moritoyo R, Nakagawa K, Yoshimi K, Yamaguchi K, Nagasawa Y, Yanagida R, et al. Effects of telemedicine on dysphagia rehabilitation in patients requiring home care: a retrospective study. Dysphagia. 2025;40(6):1468–78. doi:10.1007/s00455-025-10844-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Yang W, Du Y, Chen M, Li S, Zhang F, Yu P, et al. Effectiveness of home-based telerehabilitation interventions for dysphagia in patients with head and neck cancer: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25(6):e47324. doi:10.2196/47324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Meuser T, Lovén L, Bhuyan M, Patil SG, Dustdar S, Aral A, et al. Revisiting edge AI: opportunities and challenges. IEEE Internet Comput. 2024;28(4):49–59. doi:10.1109/mic.2024.3383758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Albadawi Y, Takruri M, Awad M. A review of recent developments in driver drowsiness detection systems. Sensors. 2022;22(5):2069. doi:10.3390/s22052069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Cho K, van Merrienboer B, Gulcehre C, Bahdanau D, Bougares F, Schwenk H, et al. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder–decoder for statistical machine translation. In: Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2014 Oct 25–29; Doha, Qatar. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; p. 1724–34. doi:10.3115/v1/d14-1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang YE, Song X. A multi-strategy adaptive comprehensive learning PSO algorithm and its application. Entropy. 2022;24(7):890. doi:10.3390/e24070890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Karunaratne TB, Clavé P, Ortega O. Complications of oropharyngeal dysphagia in older individuals and patients with neurological disorders: insights from Mataró hospital, Catalonia, Spain. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1355199. doi:10.3389/fneur.2024.1355199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Florez R, Palomino-Quispe F, Alvarez AB, Coaquira-Castillo RJ, Herrera-Levano JC. A real-time embedded system for driver drowsiness detection based on visual analysis of the eyes and mouth using convolutional neural network and mouth aspect ratio. Sensors. 2024;24(19):6261. doi:10.3390/s24196261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Majeed F, Shafique U, Safran M, Alfarhood S, Ashraf I. Detection of drowsiness among drivers using novel deep convolutional neural network model. Sensors. 2023;23(21):8741. doi:10.3390/s23218741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. de Sire A, Marotta N, Agostini F, Drago Ferrante V, Demeco A, Ferrillo M, et al. A telerehabilitation approach to chronic facial paralysis in the COVID-19 pandemic scenario: what role for electromyography assessment? J Pers Med. 2022;12(3):497. doi:10.3390/jpm12030497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Machetanz K, Lins M, Roder C, Naros G, Tatagiba M, Hurth H. Innovative mobile app solution for facial nerve rehabilitation: a usability analysis. Front Digit Health. 2024;6:1471426. doi:10.3389/fdgth.2024.1471426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. MacLellan LE, Stepp CE, Fager SK, Mentis M, Boucher AR, Abur D, et al. Evaluating Camera Mouseas a computer access system for augmentative and alternative communication in cerebral palsy: a case study. Assist Technol. 2024;36(3):217–23. doi:10.1080/10400435.2023.2242893. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Helliwell K, Hughes VJ, Bennion CM, Manning-Stanley A. The use of videofluoroscopy (VFS) and fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) in the investigation of oropharyngeal dysphagia in stroke patients: a narrative review. Radiography. 2023;29(2):284–90. doi:10.1016/j.radi.2022.12.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Ferrari de Castro MA, Dedivitis RA, Luongo de Matos L, Baraúna JC, Kowalski LP, de Carvalho Moura K, et al. Endoscopic and videofluoroscopic evaluations of swallowing for dysphagia: a systematic review. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2025;91(5S):101598. doi:10.1016/j.bjorl.2025.101598. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Xu Y, Khan TM, Song Y, Meijering E. Edge deep learning in computer vision and medical diagnostics: a comprehensive survey. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(3):93. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-11033-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Singh R, Gill SS. Edge AI: a survey. Internet Things Cyber Phys Syst. 2023;3(5):71–92. doi:10.1016/j.iotcps.2023.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Khalid N, Qayyum A, Bilal M, Al-Fuqaha A, Qadir J. Privacy-preserving artificial intelligence in healthcare: techniques and applications. Comput Biol Med. 2023;158(3):106848. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.106848. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Sadeghi Z, Alizadehsani R, Cifci MA, Kausar S, Rehman R, Mahanta P, et al. A review of explainable artificial intelligence in healthcare. Comput Electr Eng. 2024;118(5):109370. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.109370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hicks SA, Strümke I, Thambawita V, Hammou M, Riegler MA, Halvorsen P, et al. On evaluation metrics for medical applications of artificial intelligence. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):5979. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-09954-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Friji R, Chaieb F, Drira H, Kurtek S. Geometric deep neural network using rigid and non-rigid transformations for landmark-based human behavior analysis. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(11):13314–27. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2023.3291663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Bertasius G, Wang H, Torresani L. Is space-time attention all you need for video understanding?. In: Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2021 Jul 18–24; Virtual. 2021. p. 813–24. [Google Scholar]

24. Tan M, Le QV. EfficientNetV2: smaller models and faster training. In: Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2021 Jul 18–24; Virtual. p. 10096–106. [Google Scholar]

25. Vasu PKA, Gabriel J, Zhu J, Tuzel O, Ranjan A. MobileOne: an improved one millisecond mobile backbone. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada, p. 7907–17. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Huang X, Cai Z. A review of video action recognition based on 3D convolution. Comput Electr Eng. 2023;108(1):108713. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2023.108713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu Z, Ning J, Cao Y, Wei Y, Zhang Z, Lin S, et al. Video swin transformer. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 3202–11. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.00320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhu T, Zhang C, Wu T, Ouyang Z, Li H, Na X, et al. Research on a real-time driver fatigue detection algorithm based on facial video sequences. Appl Sci. 2022;12(4):2224. doi:10.3390/app12042224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wan J, Liu J, Zhou J, Lai Z, Shen L, Sun H, et al. Precise facial landmark detection by reference heatmap transformer. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2023;32(3):1966–77. doi:10.1109/tip.2023.3261749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Lu Y, Li K. Research on lip recognition algorithm based on MobileNet + attention-GRU. Math Biosci Eng. 2022;19(12):13526–40. doi:10.3934/mbe.2022631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Easwaran S, Venugopal JP, Subramanian AAV, Sundaram G, Naseeba B. A comprehensive learning based swarm optimization approach for feature selection in gene expression data. Heliyon. 2024;10(17):e37165. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Liang JJ, Qin AK, Suganthan PN, Baskar S. Comprehensive learning particle swarm optimizer for global optimization of multimodal functions. IEEE Trans Evol Computat. 2006;10(3):281–95. doi:10.1109/tevc.2005.857610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ji Y, Wang S, Lu Y, Wei J, Zhao Y. Eye and mouth state detection algorithm based on contour feature extraction. J Electron Imag. 2018;27(5):051205. doi:10.1117/1.jei.27.5.051205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ishmam A, Hasan M, Hassan Onim MS, Roy K, Hoque Akif MA, Nyeem H. Modelling lips state detection using CNN for non-verbal communications. In: Proceedings of International Conference on Fourth Industrial Revolution and Beyond 2021. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 59–70. doi:10.1007/978-981-19-2445-3_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Hung CF, Hsu M, Liu HY, Horng MF, Yang CC, Guo LY. Development of a non-contact screening approach for identifying oral function high-risk older adults using jaw movement and diadochokinetic performance. BMC Oral Health. 2025;25(1):1568. doi:10.1186/s12903-025-06725-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools