Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Novel Unified Framework for Automated Generation and Multimodal Validation of UML Diagrams

1 Faculty of Information Technology, Thai Nguyen University of Information and Communication Technology, Thai Nguyen, 250000, Viet Nam

2 Distance Learning Center, Thai Nguyen University, Thai Nguyen, 250000, Viet Nam

3 Faculty of Arts and Communications, Thai Nguyen University of Information and Communication Technology, Thai Nguyen, 250000, Viet Nam

* Corresponding Author: The-Vinh Nguyen. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 33 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.075442

Received 31 October 2025; Accepted 18 December 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

It remains difficult to automate the creation and validation of Unified Modeling Language (UML) diagrams due to unstructured requirements, limited automated pipelines, and the lack of reliable evaluation methods. This study introduces a cohesive architecture that amalgamates requirement development, UML synthesis, and multimodal validation. First, LLaMA-3.2-1B-Instruct was utilized to generate user-focused requirements. Then, DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-32B applies its reasoning skills to transform these requirements into PlantUML code. Using this dual-LLM pipeline, we constructed a synthetic dataset of 11,997 UML diagrams spanning six major diagram families. Rendering analysis showed that 89.5% of the generated diagrams compile correctly, while invalid cases were detected automatically. To assess quality, we employed a multimodal scoring method that combines Qwen2.5-VL-3B, LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct and Aya-Vision-8B, with weights based on MMMU performance. A study with 94 experts revealed strong alignment between automatic and manual evaluations, yielding a Pearson correlation ofKeywords

Since the emergence of the Transformer architecture [1], modern software engineering has transformed tremendously in terms of scale and complexity. As such, communicating efficiently among stakeholders is becoming vital to ensuring robust programs. Traditionally, the Unified Modeling Language (UML) has been widely used to fulfill this role and has been an important component of communication in software design [2,3]. However, its presence has been less emphasized in the last decade due to the need for quick and runnable software (via the Agile approach, which used only lightweight UML diagrams) [4,5]. As the number of deep learning models keeps growing, their ability to generate code is increasing in size and complexity. Thus, modern software is more complex and costly to maintain due to the lack of traceability. In this context, UML has re-emerged as a new analytical software engineering design component [6,7]. The core value of UML is that it represents both structural and behavioral aspects of systems, thus providing a standard view among stakeholders and guiding implementation. However, crafting UML diagrams is an extremely tedious task, requiring labor-intensive processes, domain experts, and maintaining consistency across multiple diagrams [8,9]. Furthermore, the prevalence of UML diagrams as static image files adds to the challenge, as they are not directly machine-readable (unlike textual code, which can be parsed and analyzed by compilers), making it difficult to integrate them into automated toolchains. Based on the aforementioned points, modern software engineering is interested in automated design and modeling tools that assist engineers in generating, interpreting, and verifying UML diagrams with minimal manual effort.

Recent advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly Large Language Models (LLMs), offer a promising avenue for automating the modeling process. However, the current approach lacks an overall pipeline that can operate independently and ensure consistency across stages. Specifically, current systems still rely heavily on manually written requirements descriptions, which lack standardization and often do not accurately reflect the perspective of the end user or product owner’s perspective [9]. In addition, no method effectively leverages the combination of instruction models and reasoning LLMs to transform requirements descriptions into TypeScript (such as PlantUML code) in a logical, consistent, and generalizable manner. Furthermore, unlike other domains (e.g., text, common programming languages) that have rich ground truth; high-quality datasets for UML diagrams are remarkably scarce [4]. The amount of available data is important for data-driven approaches, as they are essential for training AI models. To alleviate this issue, previous efforts have compiled UML diagram datasets from various sources [4], but these are limited in size and often contain duplicate or mislabeled diagrams [4,10]. Most available datasets focus narrowly on structural elements such as class diagrams, while behavioral perspectives, including sequence diagrams, activity diagrams, and state machine diagrams, are either underrepresented or absent [10]. This imbalance limits the ability of AI/ML models to reason about the interplay between system structure and behavior, a capability crucial for realistic system design and verification. The first core research problem, therefore, is: How can we automatically generate a comprehensive UML dataset that captures both structural and behavioral aspects in a scalable and semantically coherent manner? Manual dataset construction approaches have proven insufficient due to their time-consuming nature and susceptibility to inconsistency [9]. While semi-automated techniques have emerged, they often fail to ensure diversity and completeness across multiple UML diagram types [11]. Addressing this gap requires the design of algorithmic pipelines capable of producing syntactically valid and semantically consistent UML models across heterogeneous diagram categories. A second, equally critical research problem concerns the validation of dataset correctness and utility. In contrast to natural language or image datasets, where labeling accuracy can often be validated at the instance score, UML datasets present an additional layer of complexity: correctness depends not only on individual diagrams but also on the relationships between multiple diagram types (e.g., alignment between class and sequence diagrams). Current validation methods are limited to either syntactic checks or manual expert review, both of which are insufficient to ensure large-scale consistency [4]. Thus, the second research problem can be stated as: How can we systematically validate the correctness, consistency, and usefulness of automatically generated UML datasets, particularly when integrating structural and behavioral models with cross-diagram relationships? Addressing this challenge calls for novel frameworks that combine multimodal reasoning, visual-semantic validation, and automated integrity checking, ensuring that generated datasets are not only syntactically valid but also semantically robust and practically useful for downstream AI applications. However, the literature underscores the need for further advances in creating comprehensive, high-quality UML datasets [11,12].

In addition to data collection, researchers are also interested in automating the generation of UML diagrams and other modeling artifacts. One significant challenge is to translate unstructured information into formal UML models. Natural language processing (NLP) techniques have been used to derive UML class diagrams directly from requirements specifications [13]. However, these NLP-based methods face difficulties in accurately interpreting language nuances. Studies have found that existing approaches often produce incomplete or incorrect UML diagrams from complex requirement texts [13]. Recently, Jahan et al. [14] experimented with a generative large language model (ChatGPT) to automatically generate UML sequence diagrams from user stories. They found that ChatGPT sometimes generated overly complex sequence diagrams (out of scope from user stories). This implies that controlling the semantic consistency and relevance of auto-generated diagrams remains an open problem even though recent AI can generate UML content. Thus, it is not just the ability to generate UML diagrams but to validate them. Previously, the evaluation of generated UML diagrams was still primarily based on manual inspection and qualitative criteria, leading to inaccuracies, limited scalability, and difficulty in reproducibility in research. Although Vision-Language Models have proven effective in many multimodal tasks, they have not been exploited for image-level UML diagram quality assessment–an increasingly important need for software design automation systems. Therefore, the question is: How can we build a complete, automated pipeline that combines a requirements-generation model, a reasoning model, and a multimodal evaluation model to create and evaluate UML diagrams in a unified, reliable, and scalable way? Automated validation encompasses consistency checking (ensuring no internal contradictions within or between diagrams) and conformance checking (ensuring the model meets specific requirements or design rules). Conventional approaches for this task used description logic and ontology-based techniques to formalize UML semantics [15]. However, these early intuitions required heavy setup (translating models to logical form) and were computationally intensive. One promising direction is the use of multimodal AI to evaluate UML diagrams [8,16]. This suggests that future AI could monitor and evaluate design models for errors or deviations.

The aforementioned analysis demonstrated that early prototypes for generating UML diagrams from text and images had been made, initial datasets to train models were crafted, and emerging AI techniques for validating diagrams were proposed. However, significant gaps remain in the state of the art, including high-quality UML datasets [4] for training AI models, automated generation of diverse UML diagrams, multimodal reasoning, and validation of UML models. As noted by Conrardy & Cabot [11], current AI converters still depend on a human-in-the-loop for verification. Thus, there is a clear need for an integrated approach that can refine and ensure the quality of the models.

To address this gap, this paper introduces a novel framework for automated UML dataset generation and multimodal validation. Our contributions are threefold: (1) an algorithmic pipeline for automatically generating both structural and behavioral UML models, (2) a conversion method that transforms these models into comprehensive datasets, and (3) a multimodal visual validation framework that leverages AI-driven reasoning to ensure accuracy and consistency across representations.

This study makes several significant contributions to advancing automated UML dataset generation and validation. First, it presents an end-to-end framework that can automatically generate several types of UML diagrams, including class, object, component, use case, sequence, and state diagrams, while maintaining semantic integrity and inter-model consistency. Second, it presents a structured methodology for transforming the generated UML models into machine-readable, well-organized datasets that support downstream AI and machine learning applications, effectively connecting software modeling with data-centric learning. Third, the paper presents an innovative multimodal vision validation framework that integrates structural and behavioral evaluations using quantitative metrics and expert-informed qualitative assessment, ensuring reliable and scalable model validation. Finally, it releases a large-scale synthetic UML dataset encompassing a wide range of system scenarios, providing a valuable open benchmark for future research in automated modeling, AI-driven software engineering, and multimodal reasoning.

Research on UML datasets remains relatively limited compared to other domains such as natural language processing or computer vision. A few notable efforts have attempted to compile UML diagram repositories, but these are often narrow in scope, small in scale, or lacking in behavioral coverage. ModelSet provides a labeled collection of software models for ML applications. However, it is primarily restricted to structural diagrams and does not fully capture relationships across multiple UML types, generating UML for class diagrams only [17]. Using natural language models to extract class, use case, and activity diagrams has been explored in both semi-automatic approaches [18–20] and systematic reviews of NLP in requirements engineering [21]. However, some techniques require aspect orientation [22]. Similarly, while curated collections of UML diagram images [23] with careful annotation and duplication control exist, these resources are often image-based rather than model-based, which limits their direct usability for AI training [4]. Overall, current UML datasets lack the scale, diversity, and multimodal representation needed to support advanced AI/ML research. While recent exploratory studies have demonstrated the potential of Deep Learning [24] and Large Language Models (LLMs) [25,26] in aiding novice analysts and modeling class diagrams, they typically lack a unified framework for large-scale generation.

In contrast, other fields have seen rapid progress through the construction of large-scale, automatically generated datasets. In computer vision, resources like ImageNet enabled significant advances by providing deep learning models with millions of labeled examples, sufficient in variety to learn from [27]. Similarly, in natural language processing, benchmark datasets such as GLUE and SuperGLUE have provided structured corpora for systematic evaluation of model performance [28]. These successes highlight the transformative role of dataset availability, and they suggest that analogous approaches leveraging algorithmic generation pipelines and Vision-Language Models (VLMs) could be applied to UML modeling, as seen in recent surveys and engineering applications [29,30]. Although emerging techniques have attempted to generate code from diagram images [31] or to automate assessment using LLMs [16], UML poses unique challenges due to the need to capture cross-diagram consistency (coherence between class and sequence diagrams), making the direct adaptation of existing dataset-generation techniques non-trivial.

Parallel to dataset construction, a body of work has explored automatic or semi-automatic tools for generating models. Techniques such as natural language-to-UML transformation [19], NLP to automatically extract object-oriented elements from textual specifications [32], or image-to-UML conversion [11] demonstrate the feasibility of automating parts of the modeling process. However, these methods are often task-specific and limited in generalizability, focusing either on structural modeling or on diagram recognition rather than on holistic dataset generation. Moreover, while model-driven engineering tools provide semi-automated support for generating UML diagrams from specifications, they typically require significant human intervention and lack scalability when applied to dataset score synthesis.

Taken together, prior research underscores two critical gaps: (1) the absence of comprehensive, large-scale UML datasets that encompass both structural and behavioral diagrams, and (2) the need for automated frameworks that not only generate diverse UML artifacts but also validate their correctness and consistency. Addressing these gaps forms the foundation of our work.

The integration of AI and machine learning (ML) into software engineering has accelerated significantly in recent years, enabling automation across a broad range of tasks. One central area of application is automatic code generation, where large language models (LLMs) such as Codex and Code LLaMA have demonstrated strong capabilities for transforming natural-language requirements into executable source code [33–36]. Similarly, AI-driven tools have advanced bug detection and program repair, leveraging deep learning to identify anomalous code patterns and suggest fixes [37]. Another promising direction is model transformation, where machine learning methods are used to convert high-score system specifications into formal models such as UML, or to migrate existing models into different representations [11]. Collectively, these applications highlight the transformative potential of AI/ML to reduce manual effort and improve the reliability of software engineering processes.

A critical enabler of these advances is the availability of high-quality datasets. For example, code-generation models are usually trained on billions of lines of source code from platforms like GitHub. This gives the models the variety they need to work across languages and fields [38]. Bug detection frameworks similarly rely on curated corpora of buggy and fixed code snippets to train supervised models [37]. In natural language processing, benchmark datasets like GLUE and SuperGLUE have served as standard evaluation platforms, catalyzing rapid innovation by providing structured, diverse, and challenging examples [28].

Translating these lessons to UML and model-driven engineering highlights a pressing challenge: unlike source code or text, UML datasets remain scarce, fragmented, and limited in scope [37], UML code generation from diagram images [31]. The complexity of UML arises not only from individual diagrams but also from the semantic dependencies across diagram types, which impose additional requirements on dataset design. Thus, for AI/ML methods to effectively support UML generation, validation, and transformation, there is a clear need for comprehensive, large-scale, and multimodally validated datasets that parallel ImageNet [39] in vision or CodeSearchNet in programming tasks.

In summary, two significant research gaps persist in the current literature. First, there is a notable lack of a comprehensive UML dataset that simultaneously incorporates both structural and behavioral diagrams while explicitly preserving their relationships. Second, existing studies lack an integrated validation framework that systematically ensures the correctness, coherence, and consistency of generated UML datasets. This paper addresses these challenges by introducing a unified framework for automated UML dataset generation and multimodal validation, establishing a robust foundation for scalable AI and ML-driven advancements in software modeling and analysis.

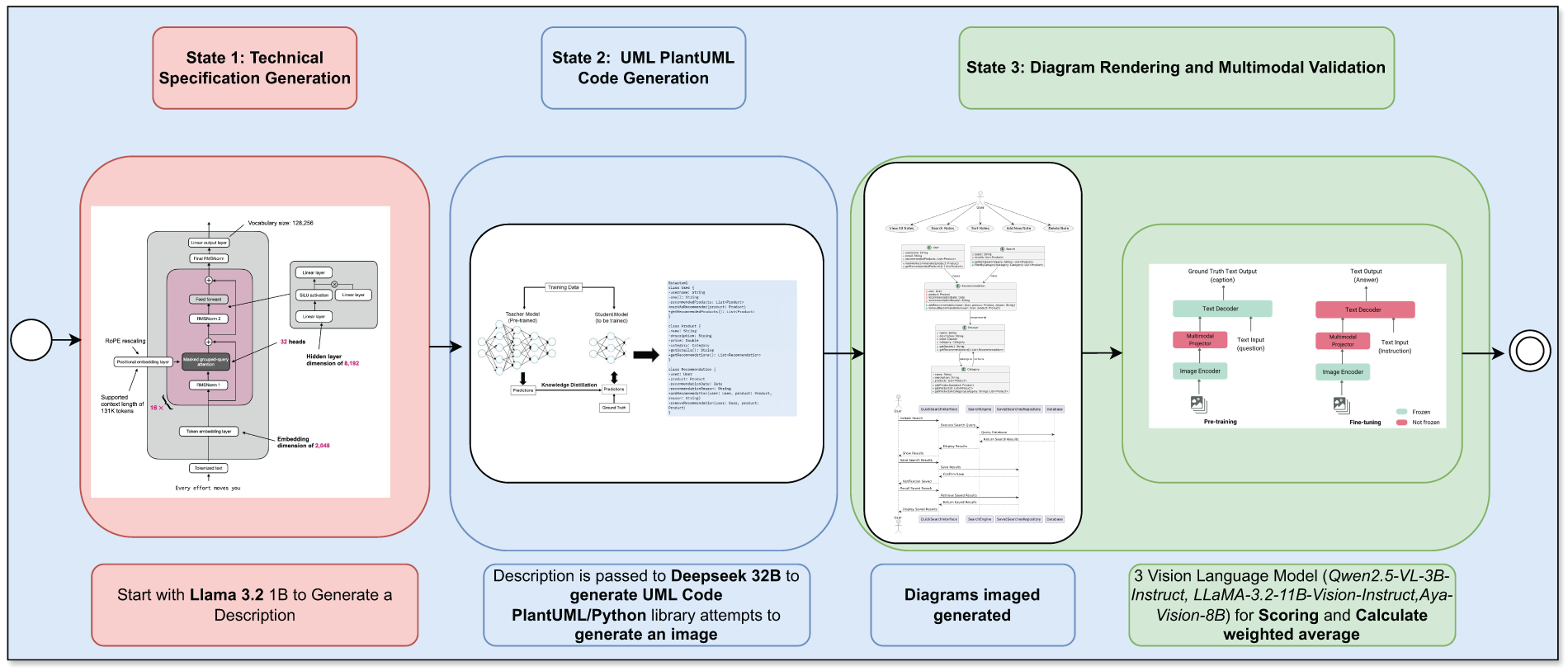

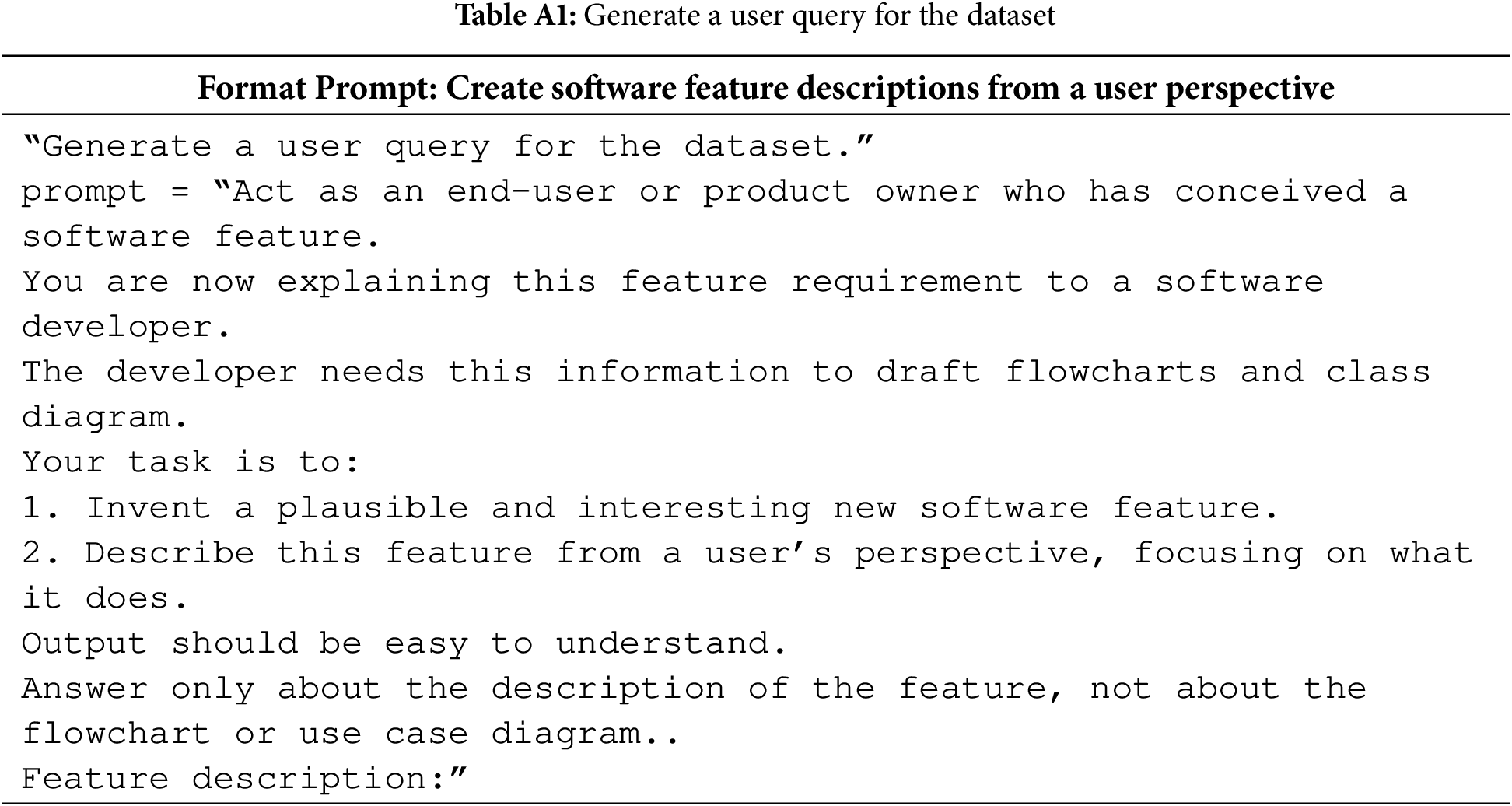

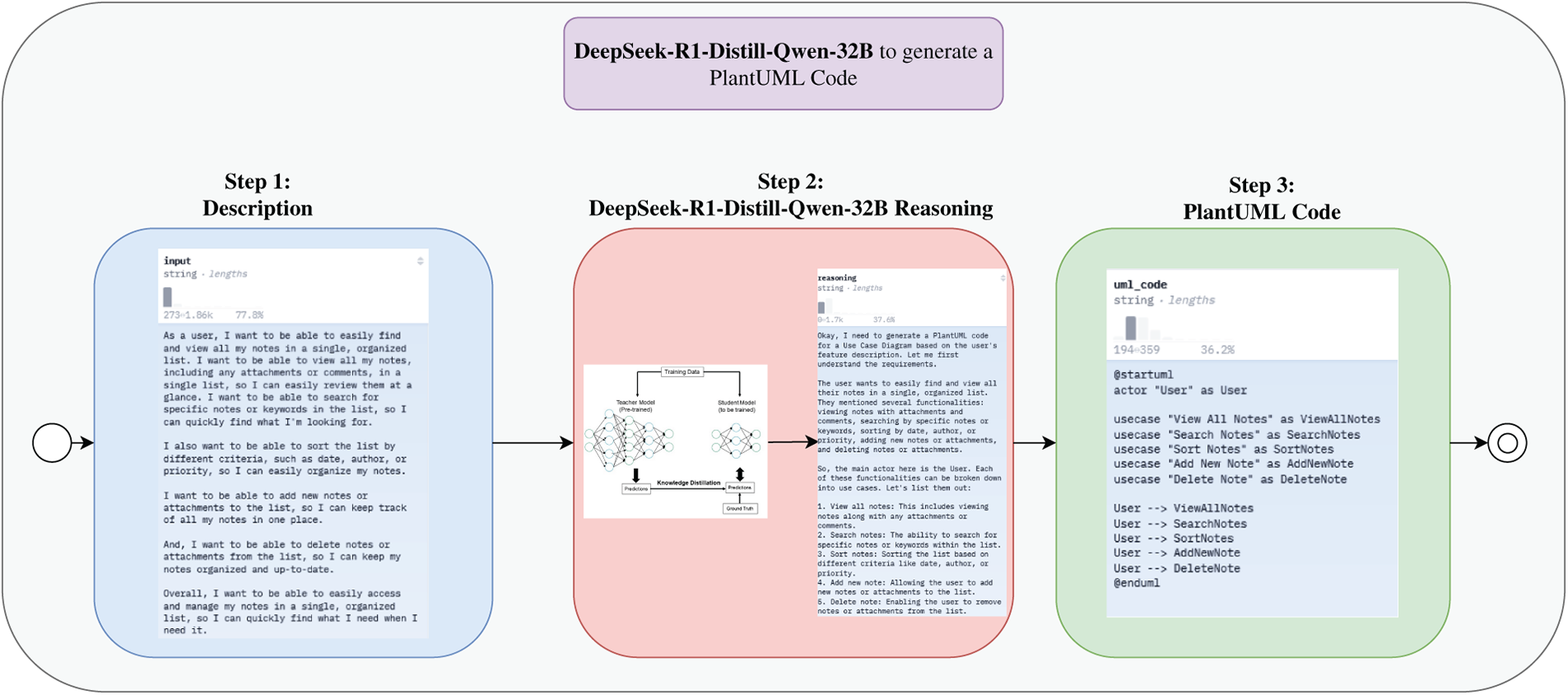

The proposed framework implements a unified and fully automated pipeline for generating and validating UML diagrams from natural-language descriptions. The pipeline consists of three sequential modules: (i) feature description synthesis from an end-user perspective, (ii) reasoning-augmented PlantUML generation, and (iii) multimodal diagram validation using an ensemble of Vision–Language Models (VLMs). Fig. 1 illustrates the complete workflow.

Figure 1: Unified pipeline for UML diagram generation and multimodal scoring

3.2 Module 1: Feature Description Generation

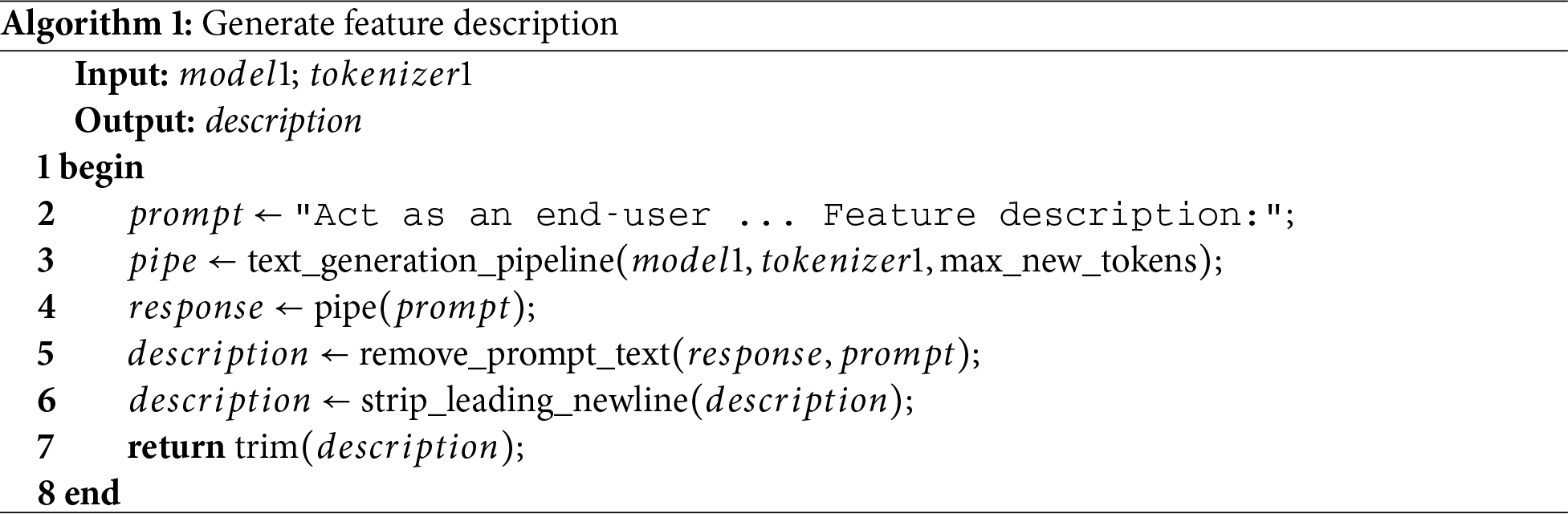

The first module aims to produce diverse and coherent feature descriptions that reflect realistic end-user needs. We employ LLaMA 3.2 1B-Instruct [40], a lightweight instruction-tuned small language model designed for high-quality natural-language generation. With a size of only about 1 billion parameters, the model achieves high performance on text generation, question answering, and light logical reasoning tasks, while remaining resource-efficient enough for edge applications or compute-constrained environments. The “Instruct” version of LLaMA 3.2 1B is fine-tuned on a high-quality instruction dataset, allowing it to accurately follow input requests and generate consistent, concise responses. With its balance between efficiency and performance, LLaMA 3.2 1B-Instruct is a potential choice for research on small language models (SLMs) applications in specialized tasks such as code generation, natural language processing, and intelligent education. To ensure naturalistic phrasing, the model is explicitly instructed to “act as an end-user” and provide domain-relevant requirements without relying on any predefined templates (prompt structure in Table A1 and Fig. A1, Appendix A). The algorithm’s core function is to prompt the model for a feature description and then refine the raw output by removing artifacts (such as the initial prompt text and extraneous whitespace). The outcome is a clean, domain-relevant feature description that serves as the standardized input for the next stage. The complete procedure is illustrated in Algorithm 1.

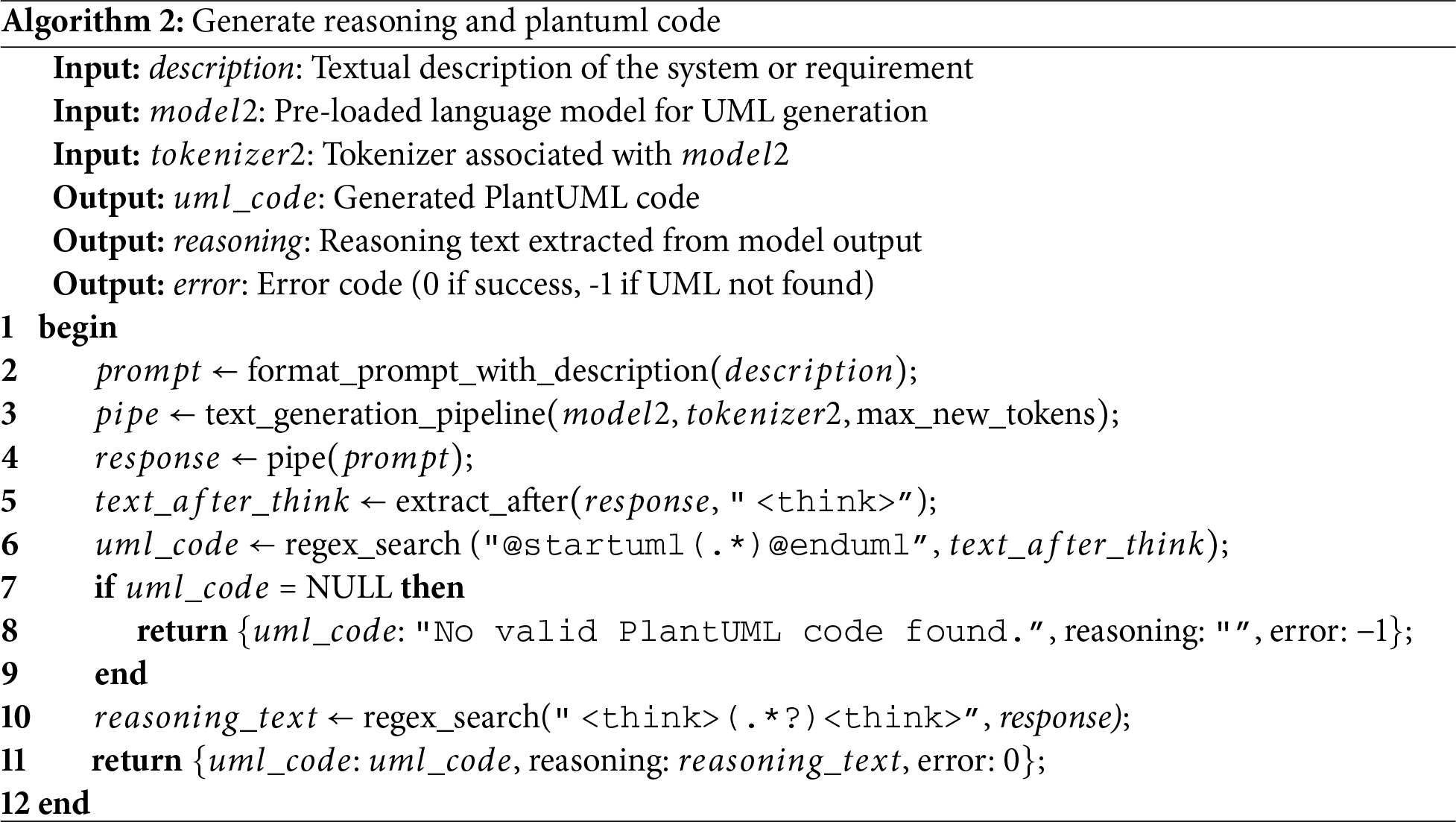

3.3 Module 2: Reasoning-Augmented PlantUML Synthesis

This module translates each feature description into a UML diagram represented in PlantUML format, while simultaneously generating an explicit reasoning trace. We adopt DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-32B [41], which has been optimized for structured reasoning and code generation through large-scale distillation from Qwen-72B. DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-32B is a distilled version of the powerful Qwen-72B model, specifically optimized by the DeepSeek team to enhance reasoning and code generation capabilities while significantly reducing inference costs. By leveraging a large-scale distillation process from Qwen’s original base, the model retains high-quality language understanding and generation abilities with only 32 billion parameters, making it suitable for complex tasks such as multi-hop reasoning, code synthesis, and technical question answering. DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-32B is trained on a curated mixture of natural language and programming datasets, incorporating both open-source code and instruction-following corpora. According to DeepSeek’s open model release [41], this distilled model shows comparable performance to larger LLMs while being more efficient for deployment in practical environments. Its strong reasoning capacity and compatibility with multimodal prompting make it a promising foundation for research in AI code generation and automated software modeling. Given a description, the model receives a structured prompt and produces a dual output consisting of:

• executable PlantUML code, and;

• a structured chain-of-thought explaining the mapping between textual requirements and UML constructs.

Regular-expression parsing is used to extract valid UML blocks (‘@startuml... @enduml’) and isolate the reasoning trace enclosed in <think> tags. If no valid diagram is detected, an error flag is returned. The complete workflow is shown in Algorithm 2 and detailed in Fig. A2.

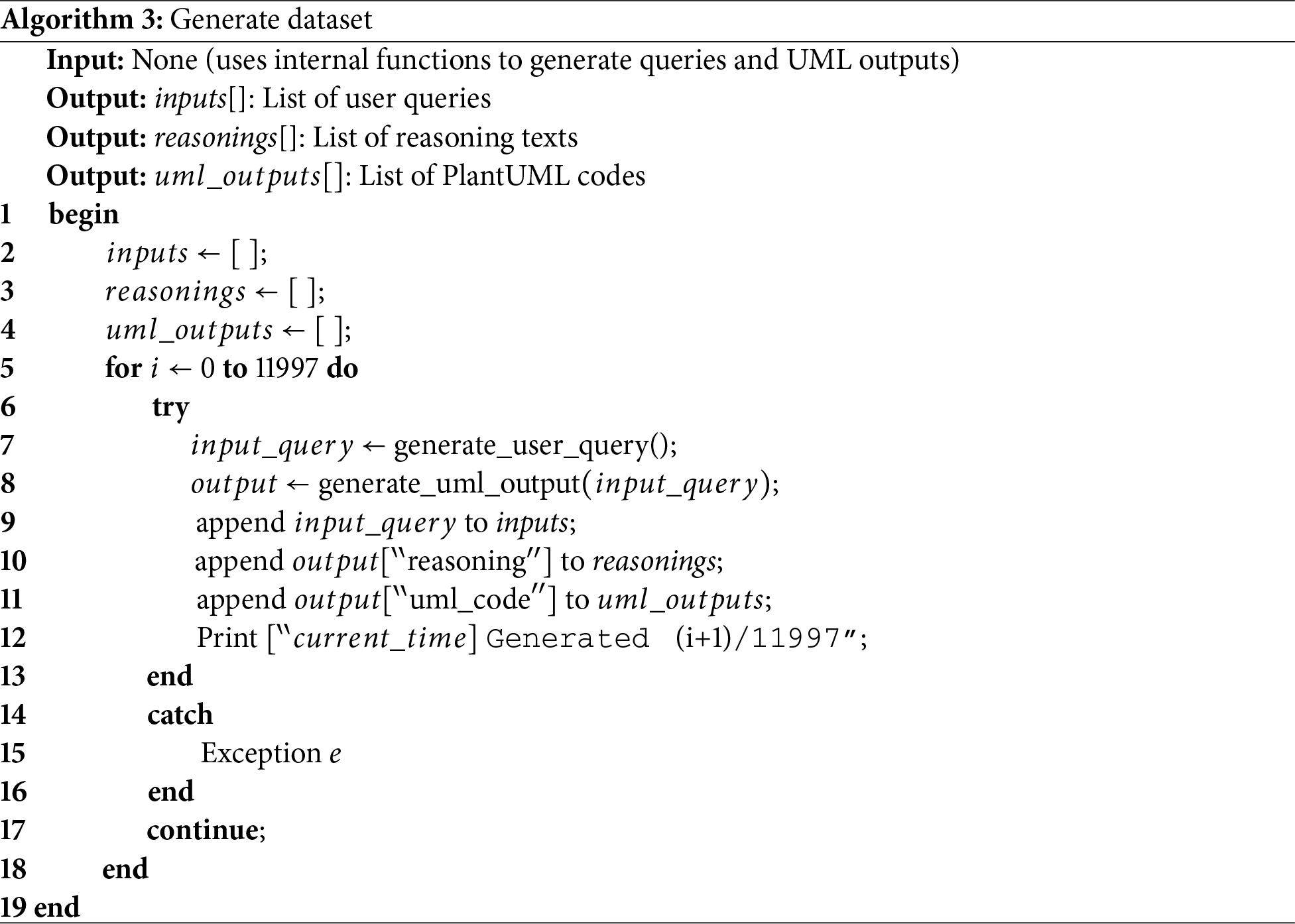

3.4 Module 3: Large-Scale Dataset Construction

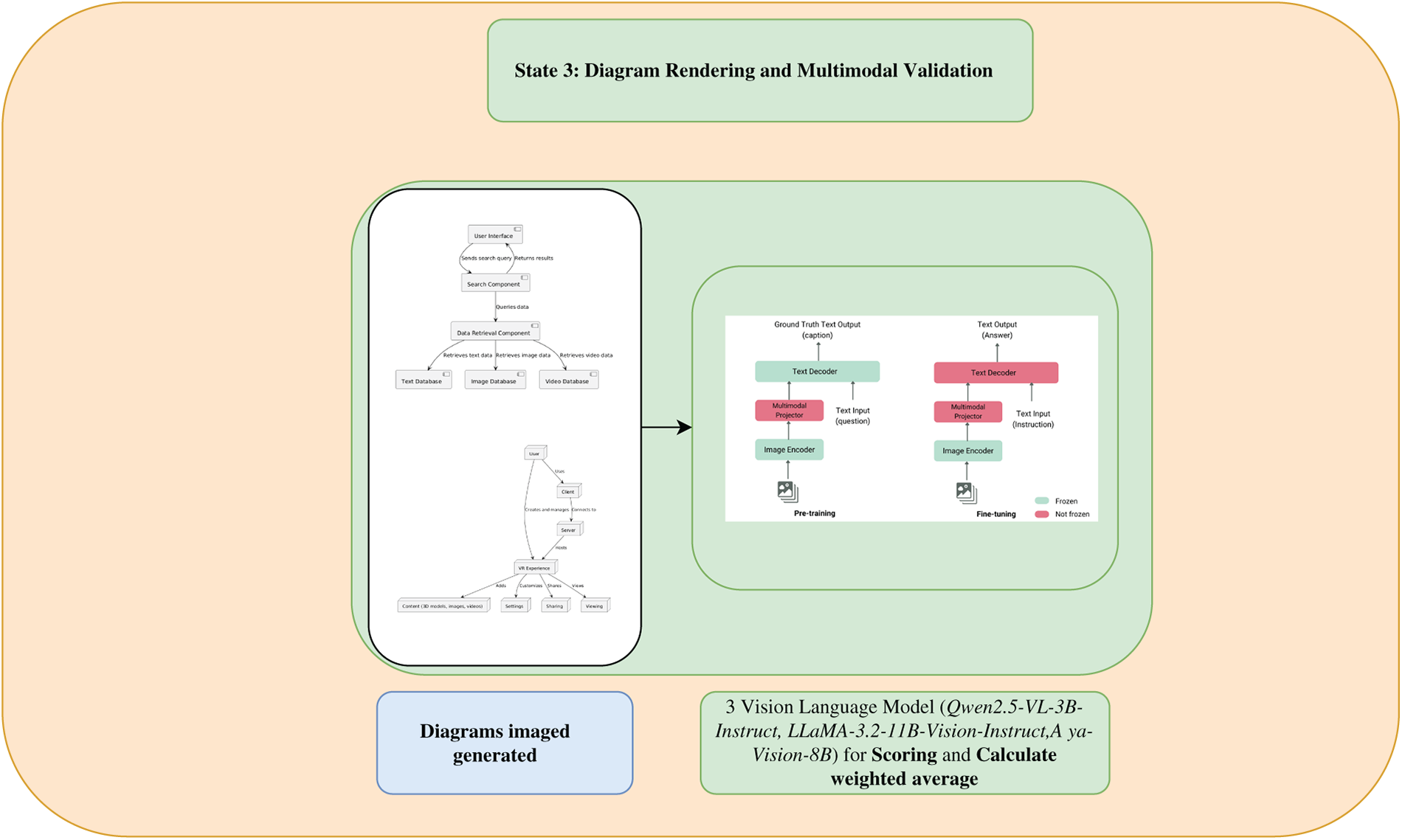

The third module operationalizes Modules 1 and 2 into a scalable data-generation engine. In each iteration, it calls Algorithm 1 to generate a user query, which is then passed to Algorithm 2 to retrieve the PlantUML code and corresponding inference traces. The resulting triple (query, inference, code) is then stored. To ensure completeness and reliability, the algorithm includes robust exception handling, allowing the process to continue uninterrupted even if only one error occurs. This systematic approach transforms the process of generating a single instance into a scalable factory for generating a comprehensive benchmark dataset. The graphs will then be imaged and three vision-language models will be used to evaluate the model quality. Algorithm 3 summarizes this process.

3.5 Automated Multimodal Validation Framework

To automate quality assessment, we employ three open source Vision-Language Models (VLMs), each with different architectures and training philosophies, to provide a multi-perspective evaluation. Qwen2.5-VL-3B-Instruct developed by Alibaba’s Qwen team, is a lightweight multimodal model based on Qwen2.5 architecture with only 3 billion parameters, yet it supports high-resolution image understanding and instruction-following tasks efficiently. It integrates a vision encoder and a pre-trained language decoder with cross-modal attention for flexible reasoning and fast inference [42]. LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct an extended variant of Meta’s LLaMA 3 series, incorporates a 11B-parameter text model with vision capabilities via a learned projection layer. The model is fine-tuned using vision-text instruction datasets and demonstrates competitive performance in complex visual reasoning tasks while maintaining high language fluency [40]. Aya-Vision-8B introduced by the Cohere for AI initiative under the Aya project, is a globally inclusive multilingual vision-language model. With 8 billion parameters, Aya-Vision-8B is optimized not only for multilingual visual understanding but also for alignment with open instruction datasets [43].

The selection of these models allows us to leverage diverse “opinions” to mitigate the bias of any single model. Their reasoning capabilities are benchmarked using MMMU [44] to inform our weighted scoring mechanism.

In this step, the framework integrates the outputs of three Vision-Language Models (VLMs) Qwen2.5-VL-3B-Instruct, LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct, and Aya-Vision-8B by computing a weighted ensemble score for each prediction position. As the algorithm iterates over the triplets of model outputs, it first checks whether all three models produce a value of zero; in such cases, a final score of zero is assigned, indicating the absence of meaningful signals. Otherwise, only models generating valid (non-zero) outputs contribute to the final score. Each contributing output is weighted by a model-specific reliability coefficient: 53.1 for Qwen2.5-VL-3B, 50.7 for LLaMA-3.2-VL-11B, and 39.9 for Aya-Vision-8B. The weighted contributions are accumulated and normalized by the sum of active weights to produce a stable aggregated score. This strategy ensures that more reliable models exert greater influence while still leveraging complementary information from the entire model ensemble.

Rendering: The generated PlantUML code is passed to the PlantUML library. If rendering fails due to syntax errors, the sample is automatically assigned a score of 0.

Validation: Successfully rendered diagrams are paired with their original technical descriptions. This (image, text) pair is evaluated by each of the three VLMs (Qwen2.5-VL-3B, LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct, Aya-Vision-8B). Each VLM is prompted to assess the diagram’s fidelity on a 6-point scale, evaluating the correctness of entities, relationships, and overall structure against the text.

Scoring: The individual scores from the VLMs are aggregated into a final composite score using a conditional weighted average. Specifically, the weight distribution is set as 53.1 for Qwen2.5-VL-3B-Instruct, 50.7 for LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct and 39.9 for Aya-Vision-8B, reflecting their relative reliability and prior performance in evaluation tasks. These weights are taken directly from the models’ scores on the MMMU benchmark [44], a standard benchmark for assessing multimodal inference performance.

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of our proposed framework’s performance in generating and validating three distinct types of UML diagrams: Use Case, Class, and Sequence. The experiments were conducted on a large-scale, synthetic dataset of approximately 12,000 samples, with each diagram type representing a different score of structural and semantic complexity. Our analysis focuses on two primary aspects: (1) the efficacy of the dual-LLM generation pipeline and (2) the comparative performance of the multimodal validation system across these varied tasks.

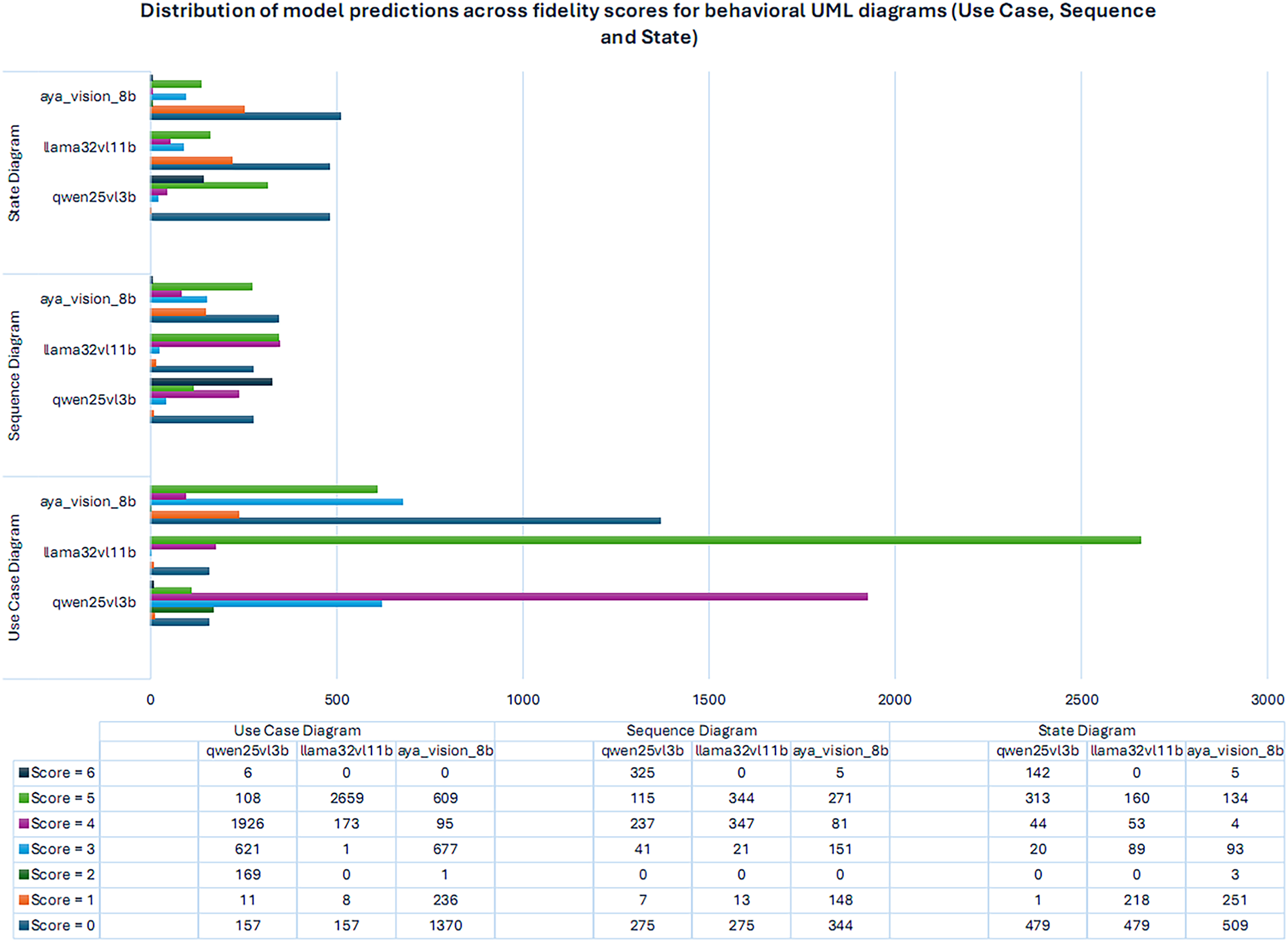

Behavioral UML Diagrams Fig. 2 presents the distribution of model predictions across fidelity scores for behavioral UML diagrams (Use Case, Sequence, and State). The results reveal substantial variability among models. For Use Case diagrams, LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct demonstrates the highest concentration at Scores 5, reflecting strong syntactic fidelity but limited diversity across correctness Scores. Qwen2.5-VL-3B produces a more balanced distribution, with a significant proportion at Scores 3–4 and a moderate peak at Score 5, suggesting more generalized behavioral reasoning. Aya-Vision-8B, however, shows dispersed outputs with higher counts at lower scores (0–3), indicating difficulty in capturing coherent actor–system relationships.

Figure 2: Distribution of model predictions across fidelity scores for behavioral UML diagrams (Use Case, Sequence and State)

For Sequence diagrams, Qwen2.5-VL-3B achieves a spread across scores 4–6, highlighting its robustness in modeling dynamic interaction flows. LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct concentrates predictions at scores 4 and 5 but fails to produce outputs at the highest scores (6), suggesting partial correctness with a ceiling effect. Aya-Vision-8B underperforms, with most predictions clustering at scores 0–3, reflecting difficulty in reasoning about temporal ordering and message dependencies.

Regarding State diagrams, Qwen2.5-VL-3B again shows the strongest performance, with a high number of predictions at scores 5 and 6, demonstrating capability in reasoning about system transitions. LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct produces a spread between lower (scores 1) and mid-range (scores 3–5), suggesting inconsistent performance. Aya-Vision-8B remains skewed toward scores 0–2, confirming its struggles with behavioral abstraction.

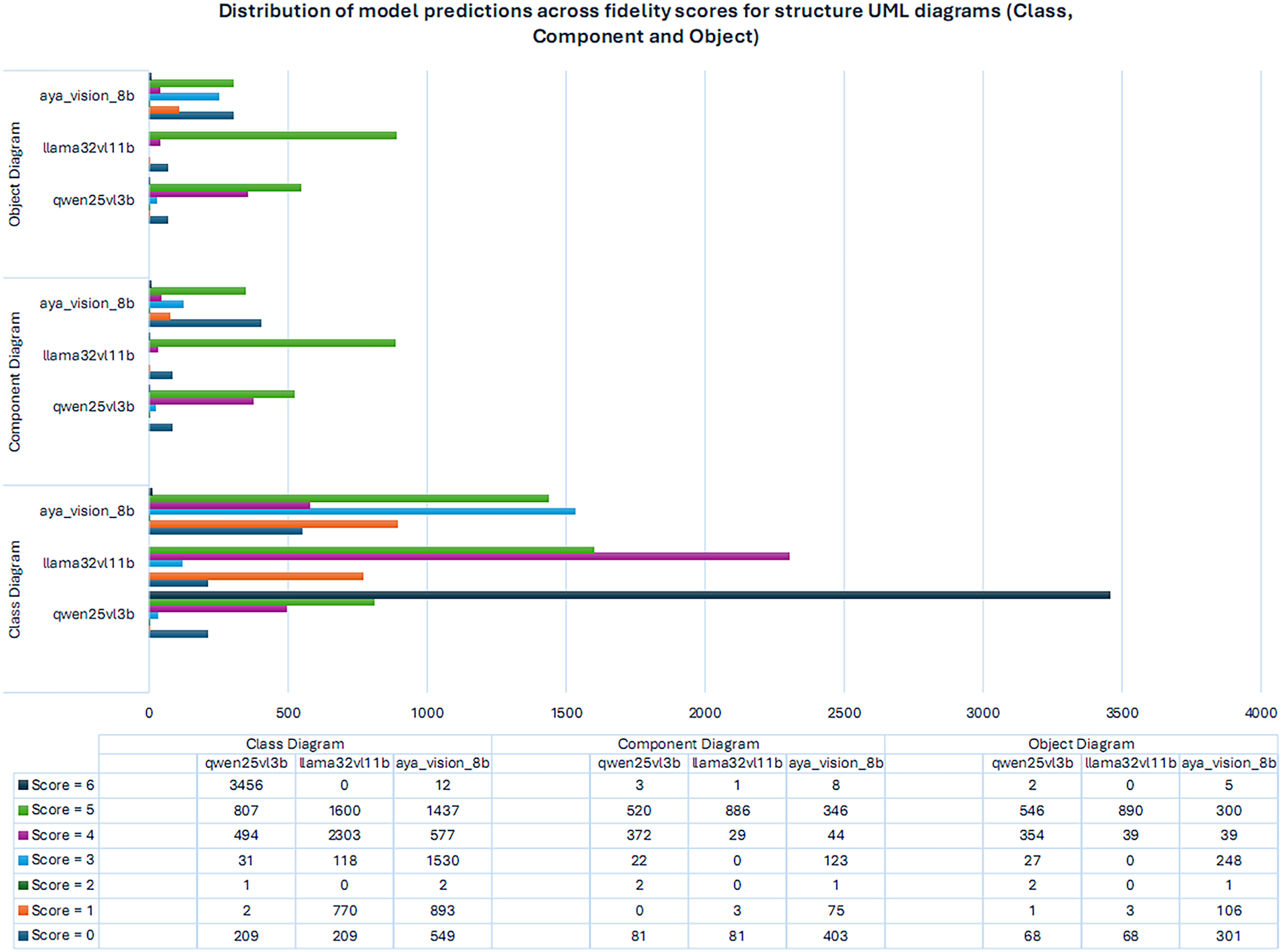

Structural UML Diagrams Fig. 3 illustrates the results for structural UML diagrams (Class, Component, and Object). The findings show a clearer hierarchy of performance across models. For Class diagrams, Qwen2.5-VL-3B significantly outperforms others with the majority of predictions concentrated at score 6, indicating high-fidelity capture of class relationships and attributes. LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct, in contrast, distributes predictions between scores 4 and 5 but produces none at score 6, pointing to consistent partial correctness. Aya-Vision-8B performs weaker overall, with predictions spread across lower score and only limited accuracy at score 5.

Figure 3: Distribution of model predictions across fidelity scores for structure UML diagrams (Class, Component and Object)

Component diagrams, Qwen2.5-VL-3B again demonstrates balanced performance with strong results at scores 4 and 5. LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct achieves its highest concentration at score 5, confirming its syntactic precision but lack of full structural fidelity. Aya-Vision-8B continues to struggle, with outputs skewed toward scores 0–3.

For Object diagrams, Qwen2.5-VL-3B yields consistent mid-to-high-score predictions, particularly at scores 4 and 5, capturing instance-score relationships with reasonable accuracy. LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct focuses overwhelmingly at score 5, reflecting reliable but incomplete mappings. Aya-Vision-8B once again clusters at lower scores, showing weak alignment with object semantics.

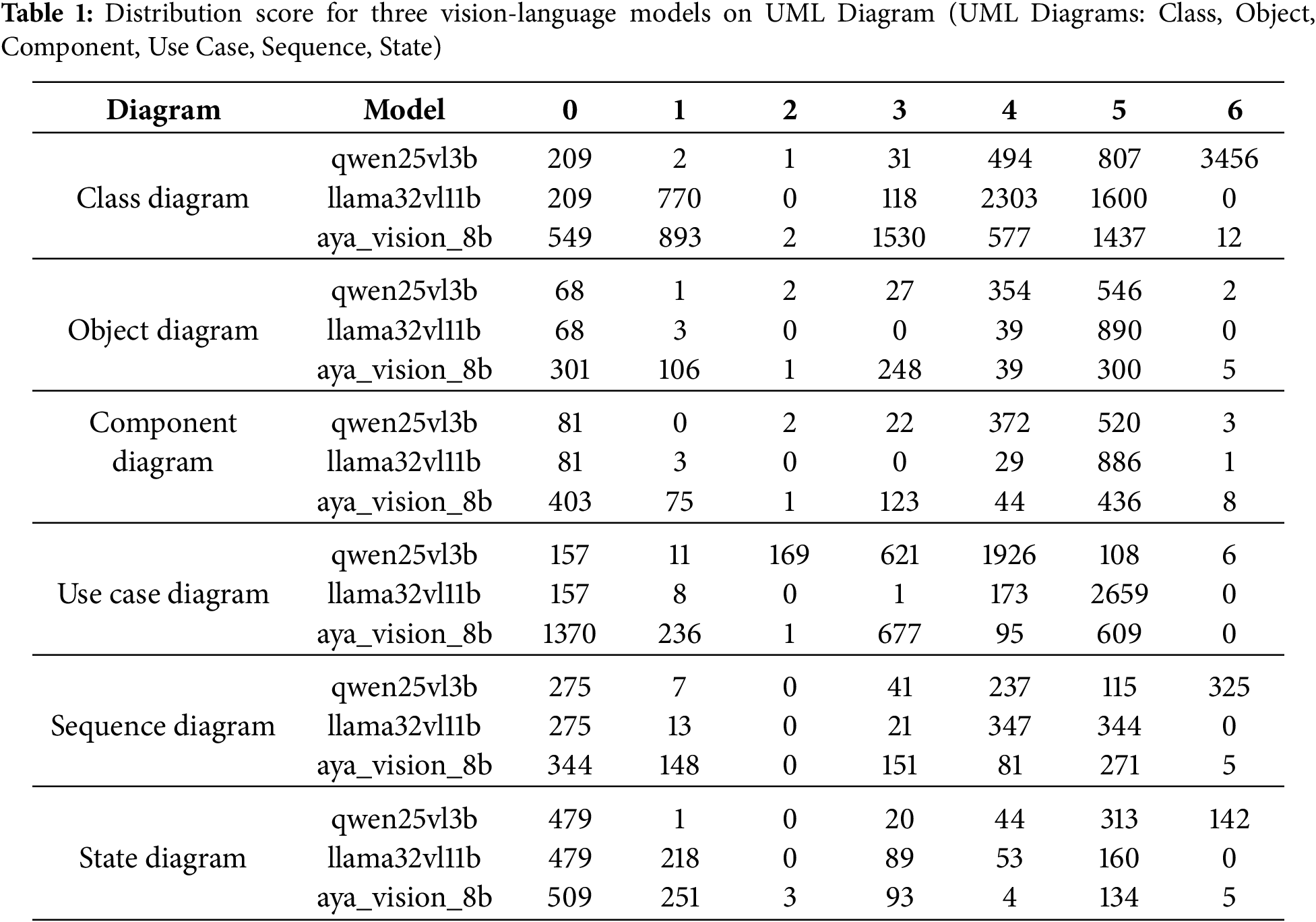

The comparative evaluation underscores a structural–behavioral asymmetry in UML modeling in Table 1. Structural diagrams, particularly class diagrams, are more tractable for current AI/ML models, with Qwen2.5-VL-3B achieving near-complete fidelity. Behavioral diagrams, however, remain a significant challenge, where models either plateau at partial correctness (LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct) or struggle with abstraction (Aya-Vision-8B). These findings validate the need for richer datasets and multimodal validation frameworks to bridge the gap between structural and behavioral reasoning in automated UML synthesis.

4.2 Quantitative Code Generation Analysis

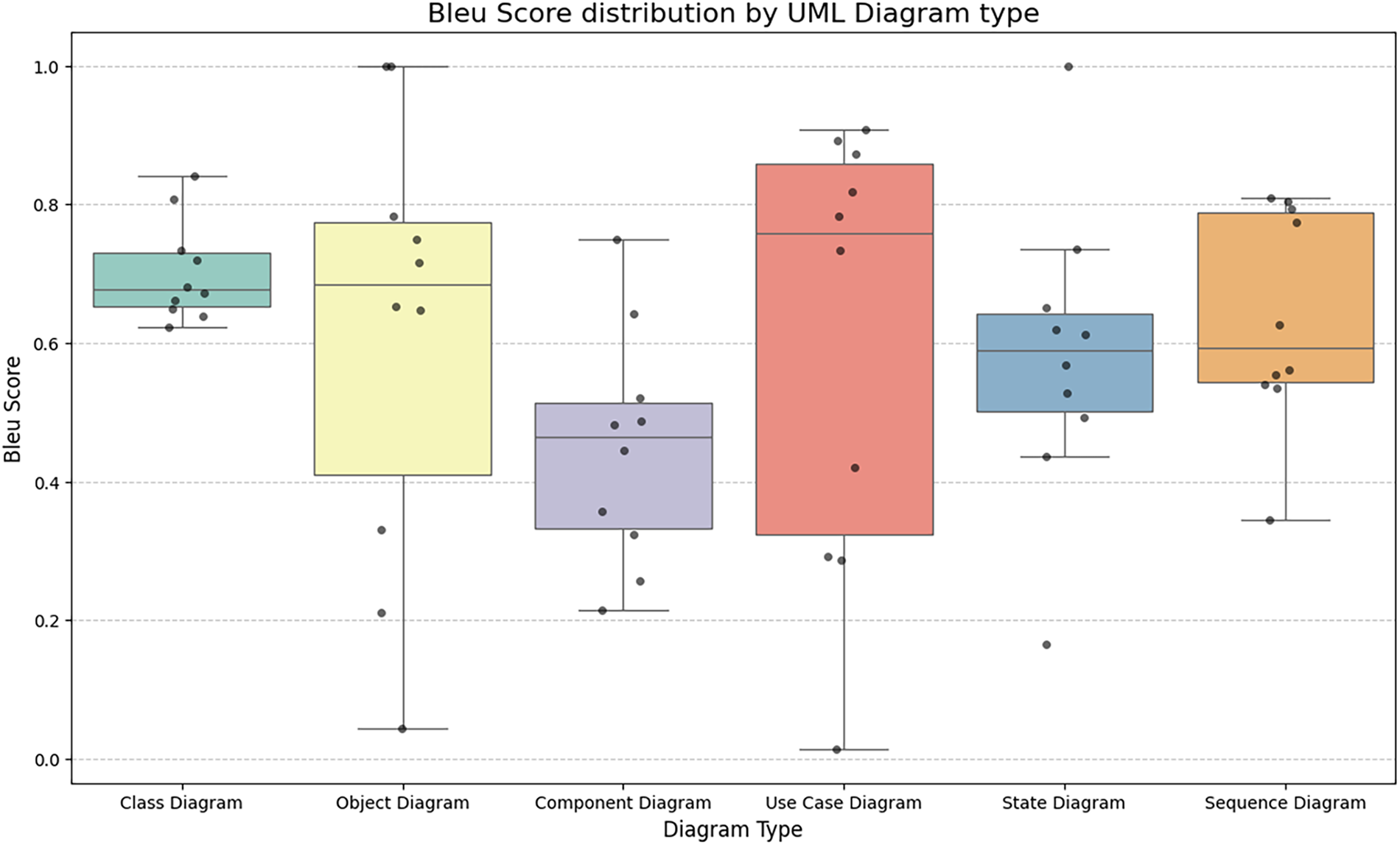

A subset of 60 samples was selected from the dataset for Human Expert Validation. In this process, experts carefully revised the PlantUML code to ensure correctness and consistency according to their professional judgment. To quantitatively evaluate the generated diagrams against the expert-refined versions, we employed the BLEU metric, which measures the similarity between the model-generated output and the expert-adjusted reference. This approach allows us to assess the alignment of automated generation with domain-specific expert knowledge.

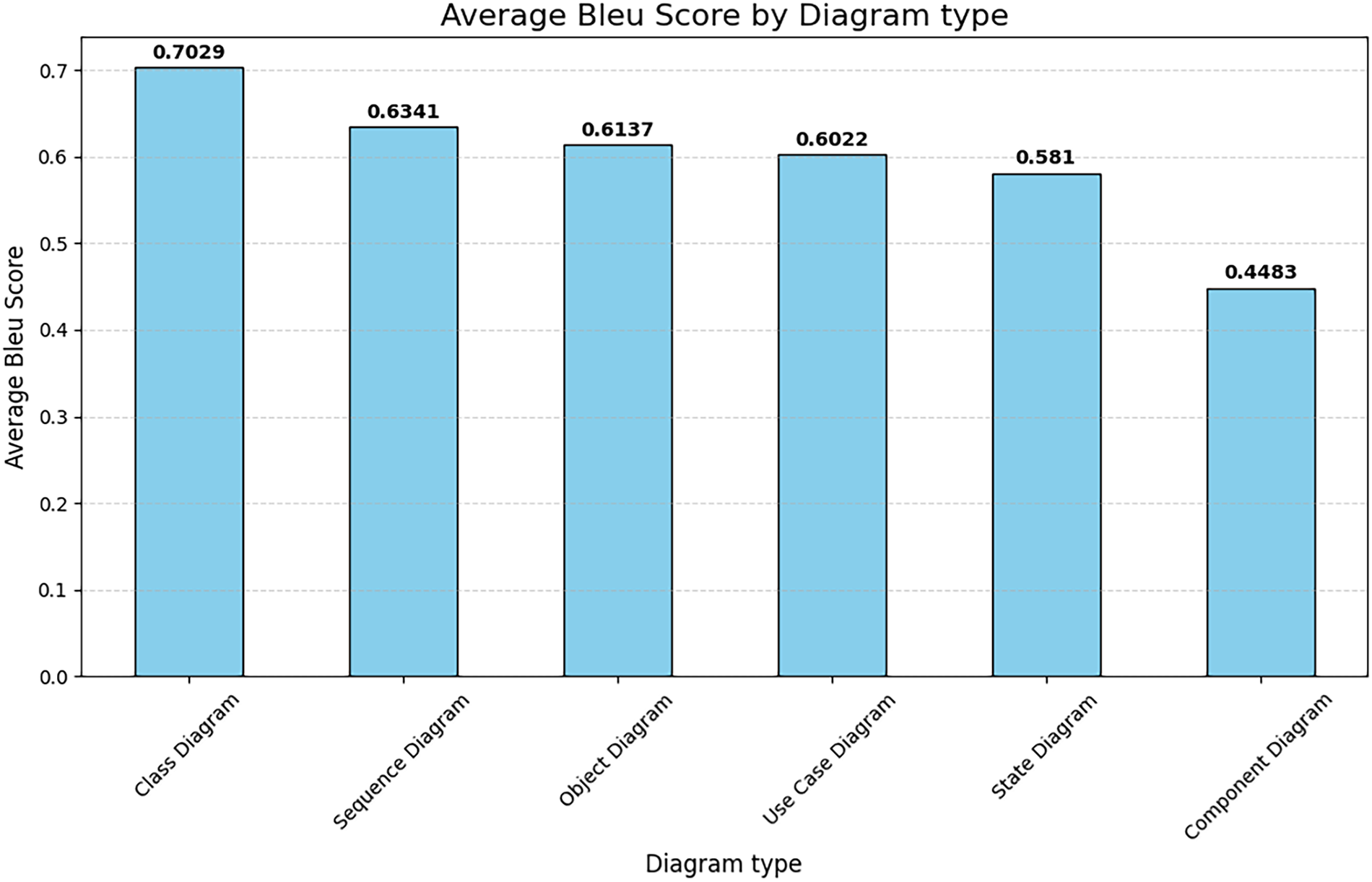

To complement the multimodal visual validation, we conducted a text-based quantitative analysis using the BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy) metric to measure the syntactic similarity between the PlantUML code generated by DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-32B and the ground truth references (Details about BLEU at Appendix B). The distribution of BLEU scores across the six diagram families is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Bleu score distribution by UML diagram type

The analysis reveals distinct performance characteristics across diagram types:

High stability in structural and interaction models: Class Diagrams and Sequence Diagrams demonstrate the most consistent performance, with average BLEU scores typically ranging from 0.60 to 0.80. Notably, Sequence Diagrams (Sequence diagram, scores > 0.80) demonstrate the model’s ability to accurately capture message order and interaction syntax, reinforcing the high visual fidelity scores observed in the above section.

Variance in Object and State Diagrams: Object Diagrams and State Diagrams displayed significant variance. While perfect matches were recorded ( Object diagram), there were instances of notably low scores (<0.1). This discrepancy suggests that for diagrams requiring specific instance naming or complex state transitions, the model may generate valid structures with divergent variable identifiers compared to the reference, heavily penalizing the BLEU score despite potential semantic correctness.

Use Case Efficacy: Use Case Diagrams achieved exceptional scores in several instances (Use case and Sequence diagrams), indicating strong alignment in translating actor-action requirements into code. However, the presence of outliers highlights the sensitivity of n-gram-based metrics to the ordering of declarations in PlantUML.

The integration of BLEU metrics addresses the limitation of relying solely on visual scoring. It confirms that the proposed pipeline not only generates visually coherent diagrams but also maintains high syntactic fidelity in the underlying source code, ensuring the practical utility of the generated artifacts for software engineering tasks.

Fig. 5 presents the average BLEU scores across the evaluated UML diagram types, revealing a distinct hierarchy in generation fidelity. Class Diagrams significantly outperform other categories with the highest average score of 0.7029, suggesting that the model is particularly effective at synthesizing static structural definitions. A consistent performance tier is observed among Sequence (0.6341), Object (0.6137), and Use Case (0.6022) diagrams, indicating balanced capabilities in modeling interactions and requirements. However, Component Diagrams exhibit a notable drop in performance, achieving the lowest score of 0.4483, which highlights potential challenges in generating the specific component-interface dependencies required for this format.

Figure 5: Average bleu score by diagram type

4.3.1 Interpretation of the Results

Discussion on Behavioral Diagram Evaluation:

Use Case Diagrams The evaluation of use case diagrams highlights substantial differences in behavioral reasoning across the three models. Qwen2.5-VL-3B demonstrates a relatively balanced distribution, with a strong concentration at scores 4 and 3 (1926 and 621 instances, respectively), suggesting moderate-to-high semantic alignment in actor–use case interactions. In contrast, LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct shows a sharp skew toward score 5 (2659 instances), indicating its strength in capturing actor–system relationships at near-correct scores but with reduced diversity across intermediate scores. Aya-Vision-8B, however, displays a more dispersed distribution with significant counts at scores 0, 1, and 3 (1370, 236, and 677, respectively). This pattern suggests sensitivity to low-score structural recognition while struggling with higher-order behavioral coherence. Overall, the results underscore that while larger models like LLaMA achieve high syntactic fidelity [45], mid-scale models (Qwen2.5) appear to generalize behavioral structures more evenly, and vision-centric models (Aya) face difficulty in abstracting actor–system dynamics.

Sequence Diagrams Behavioral reasoning for sequence diagrams shows a different trend. Qwen2.5-VL-3B produces a relatively even distribution across scores 4, 5, and 6 (237, 115, and 325 instances), reflecting an ability to model interaction flows with incremental behavioral depth. LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct performs similarly, with 347 and 344 instances at scores 4 and 5, but lacks higher-score (6) predictions, revealing a ceiling effect in capturing complete interaction fidelity. Aya-Vision-8B, by contrast, allocates more predictions at lower scores (344 at 0 and 148 at 1) and fewer at the higher spectrum, suggesting difficulty in mapping sequential dependencies when reasoning from visual features. Collectively, these findings reveal that sequence modeling is more demanding in terms of behavioral reasoning, with only Qwen2.5 showing robustness across all scores, whereas LLaMA converges to partial correctness and Aya underperforms in interaction depth.

State Diagrams For state diagrams, which require capturing system dynamics over transitions, all models show varying scores of behavioral understanding. Qwen2.5-VL-3B demonstrates a strong mid-to-high distribution, with 313 instances at score 5 and 142 at score 6, reflecting its ability to reason about state transitions with relatively high accuracy. LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct, however, distributes predictions more at lower and mid scores (218 at score 1, 89 at score 3, and 160 at score 5), suggesting that while it captures basic transition structures, it struggles to sustain behavioral depth across full state flows. Aya-Vision-8B, once again, shows a tendency toward lower scores (509 at 0 and 251 at 1), indicating a reliance on surface-score recognition with limited behavioral abstraction. Importantly, the concentration of Qwen2.5 at higher scores suggests that smaller models, when well-tuned, may outperform larger or vision-centric counterparts in tasks demanding explicit behavioral reasoning. Recent work has started to explore direct code generation from UML diagram images using large multimodal models [31], suggesting that our evaluation pipeline could be integrated into end-to-end modeling workflows.

Taken together, the comparative analysis demonstrates that behavioral modeling presents a distinct challenge across UML diagram types. Use case diagrams favor larger models that capture actor–system mappings, sequence diagrams highlight the robustness of mid-scale models in capturing dynamic interactions, and state diagrams emphasize the importance of fine-grained transition reasoning, where smaller yet well-aligned models outperform. These results suggest that future datasets and pipelines should emphasize behavioral annotation granularity and multimodal reasoning [46], as these remain the bottlenecks in automated UML synthesis. Our findings complement emerging work evaluating VLMs on UML diagrams [47], but extend it by introducing a dual text–visual validation pipeline with fine-grained scoring.

Discussion on Structural Diagram Evaluation:

The evaluation of class diagrams shows a clear divergence in structural reasoning across the three models. This aligns with recent deep learning approaches that successfully extract class diagrams from software artifacts [24], reinforcing the relative tractability of structural UML tasks. Qwen2.5-VL-3B yields a strong concentration at the highest fidelity scores (3456 instances at scores 6), indicating its effectiveness in capturing structural relationships such as inheritance, associations, and class attributes with high precision. LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct, on the other hand, produces a bimodal distribution: 2303 predictions at score 4 and 1600 at score 5, but no predictions at score 6. This pattern suggests that while the model can capture partial or near-correct structures, it struggles to achieve fully accurate class specifications. Aya-Vision-8B displays the widest spread, with considerable counts at low scores (549 at score 0 and 893 at score 1) and moderate presence at higher scores (1437 at score 5). This indicates that vision-centric reasoning is sensitive to surface-score features but lacks robustness in abstracting complete structural correctness. Our findings are complementary to prior work on automatic class-diagram generation from text [13], which primarily focuses on structural correctness rather than multimodal visual evaluation.

For component diagrams, Qwen2.5-VL-3B again shows balanced performance with strong results at scores 4 and 5 (372 and 520 instances), suggesting proficiency in modeling dependencies and modular boundaries. LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct demonstrates a pronounced skew toward score 5 (886 instances), confirming high syntactic accuracy but limited diversity across correctness scores, with very few reaching complete fidelity (only 1 at score 6). Aya-Vision-8B continues to exhibit high counts at lower scores (403 at score 0 and 75 at score 1), suggesting difficulty in identifying architectural partitions, though it achieves moderate alignment at score 5 (346 instances). This reinforces the view that multimodal alignment is challenging when higher-order abstraction of the software architecture is required.

For Object diagrams, which demand capturing instances and their concrete relationships, show patterns similar to component diagrams. Qwen2.5-VL-3B produces consistent results with a balanced distribution, particularly at scores 4 and 5 (354 and 546 instances), indicating reasonable accuracy in mapping objects to their class definitions. LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct, however, concentrates heavily at score 5 (890 instances) with negligible predictions at higher scores, reflecting its reliance on partial correctness rather than complete alignment. Aya-Vision-8B again clusters at the lower scores (301 at 0, 106 at 1), with limited high-fidelity predictions (only 5 at score 6). This suggests that while vision-based reasoning can identify object instances, it often misaligns them with the structural semantics of the system model.

Interestingly, we observed a divergence between BLEU scores and VLM visual scores in Object Diagrams. While BLEU scores penalized deviations in variable naming conventions (resulting in lower text metrics), the VLM evaluation often rated these diagrams highly (Score 5-6) because the visual topology and relationships remained correct. This reinforces the necessity of our dual-validation approach: BLEU ensures syntactic adherence to specifications, while VLMs assess semantic and visual correctness.

Overall, the evaluation of structural diagrams demonstrates that Qwen2.5-VL-3B consistently achieves the best balance between accuracy and distribution, excelling particularly in class diagram fidelity. Graph-based approaches such as UML common graph provide fine-grained topological similarity for multiple diagram types [48], which complements our current score-based evaluation. LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct shows strong partial correctness but rarely achieves full structural accuracy, highlighting a ceiling effect similar to its performance on behavioral diagrams. Aya-Vision-8B, while capable of identifying basic entities, struggles to generalize abstract structural rules, reinforcing the necessity of multimodal fine-tuning. These findings emphasize that structural UML tasks benefit most from models optimized for symbolic and relational reasoning, whereas vision-centric approaches require additional alignment strategies to capture software design abstractions.

Comparative Analysis: Structural and Behavioral Diagrams:

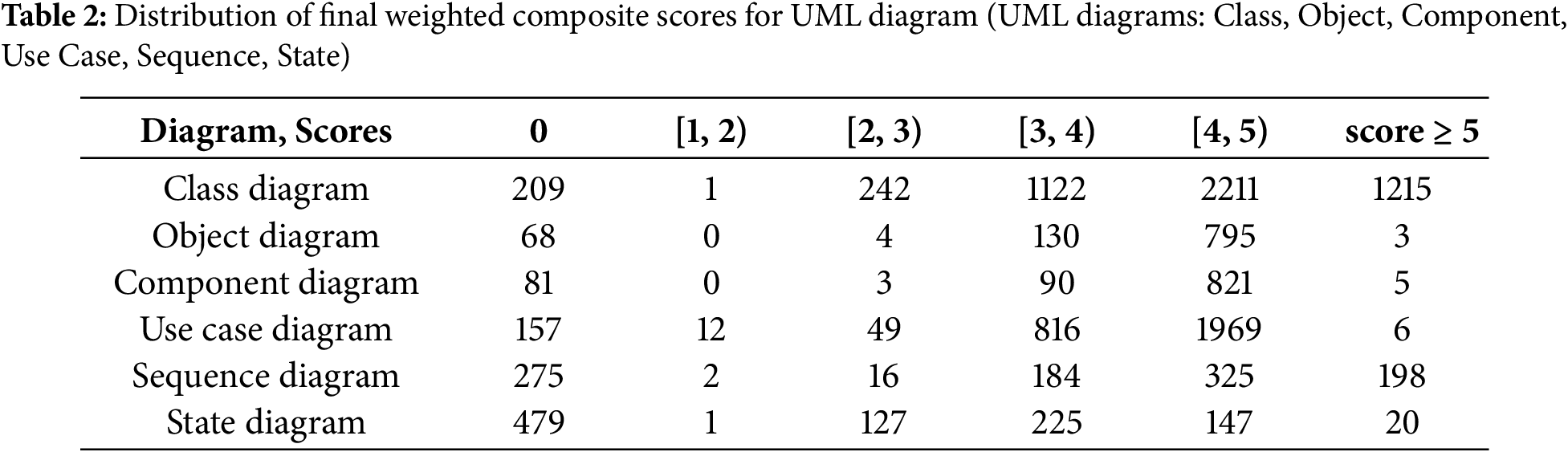

When comparing structural and behavioral modeling tasks, a distinct divergence in model performance emerges in Table 2. For structural diagrams (class, component, and object), Qwen2.5-VL-3B consistently demonstrates superior fidelity, with strong accuracy at higher scores most notably in class diagrams where it achieves a majority of predictions at score 6. This indicates that smaller, well-tuned models are highly effective at capturing static system elements such as classes, components, and object instances. LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct, while performing reliably at mid-to-high scores (4–5), rarely reaches full structural correctness, suggesting a plateau in its abstraction capability. Aya-Vision-8B, in contrast, tends to misallocate predictions toward lower scores, reflecting challenges in abstracting symbolic relationships from visual input.

In contrast, behavioral diagrams (use case, sequence, and state) present a greater challenge across all models [49]. While LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct excels in syntactic fidelity for use case diagrams (skewing toward score 5), it struggles to sustain behavioral reasoning in sequence and state diagrams, failing to produce higher-score predictions. Qwen2.5-VL-3B offers a more balanced distribution, particularly in sequence and state diagrams, indicating robustness in capturing dynamic interactions and system transitions. Aya-Vision-8B underperforms across behavioral tasks, often clustering at lower scores, suggesting that behavioral abstraction requires reasoning capabilities beyond surface-score recognition.

Taken together, these results highlight a critical asymmetry in UML modeling tasks: structural reasoning appears more tractable for AI/ML models, especially smaller transformer-based architectures, whereas behavioral reasoning remains an open challenge requiring more nuanced datasets, multimodal integration, and reasoning-oriented training objectives. This demonstrates the value of the proposed pipeline in bridging the structural–behavioral gap by enabling comprehensive dataset generation and multimodal validation.

Error Analysis for Zero-Score Cases.

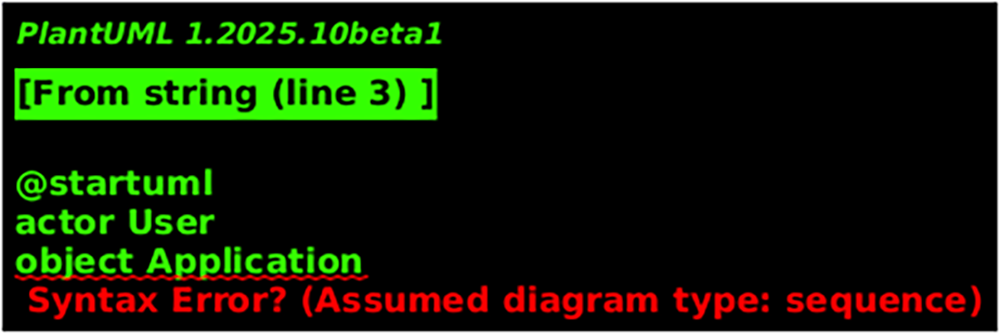

During the rendering phase, approximately 10.5% of the generated PlantUML codes failed to compile successfully, resulting in a score of 0. These failures were primarily due to syntactic or structural inconsistencies in the automatically generated code, as shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Example of a rendering failure resulting in a zero score. The PlantUML parser reports a syntax error

The “Syntax Error?” message is a consequence of providing a syntactically incomplete definition for an inferred diagram type. While the individual statements (actor, object) were correct, their combination without a corresponding message flow failed to constitute a valid sequence diagram according to the PlantUML grammar.

This case highlights a key design aspect of domain-specific languages (DSLs) like PlantUML: the trade-off between flexibility (implicit typing) and strictness. While type inference enhances usability for simple cases, it can lead to seemingly cryptic errors when the script provides insufficient context for a complete structural definition. For developers and technical writers, the key takeaway is that when defining interaction-based diagrams, it is imperative to include at least one interaction to ensure syntactic validity.

The parser successfully processes actor User and object Application as valid participant definitions. However, upon reaching the end of the script (or @enduml), it has not encountered any message-passing statements (e.g., User -> Application). This lack of interaction constitutes a violation of the expected structure for a sequence diagram, leading the parser to report a syntax error at the last successfully parsed, yet ultimately insufficient, line.

An illustrative error message is presented in Fig. 6, where the PlantUML compiler returns a “Syntax Error? (Assumed diagram type: sequence)” message. This indicates that the model failed to follow the correct sequence-diagram grammar, producing an invalid action label or missing transition. Such cases were automatically assigned a zero score and later analyzed to refine prompt constraints and post-processing filters in future iterations.

Despite the promising results, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the evaluation relies on a finite set of UML diagram types (class, component, object, use case, sequence and state), leaving other important diagram families such as activity, deployment, or communication diagrams unexplored. This partial coverage may constrain the generalizability of the findings to the full UML specification. Second, the dataset, while diverse, remains limited in size and annotation depth compared to established benchmarks in computer vision or natural language processing. As a consequence, behavioral reasoning tasks, particularly in sequence and state diagrams, still expose weaknesses across all tested models. Third, model evaluation is restricted to three representative architectures (Qwen2.5-VL-3B, LLaMA-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct and Aya-Vision-8B), which may not fully capture the broader landscape of vision–language and code-oriented models. Prior studies on multimodal prompting show that evaluation performance can be highly sensitive to prompt design [50]; a systematic study of prompting strategies for UML diagrams is left as future work. Fourth, while this study incorporates BLEU scores to assess syntactic fidelity, other complementary structural metrics such as graph edit distance or execution-based validation were not fully explored. Prior work has shown that graph edit distance is effective for matching and comparing UML class models [51], but we leave its integration into our evaluation pipeline as future work. The absence of these measures may restrict the ability to capture fine-grained topological discrepancies that syntactic metrics might miss. A limitation is that our study prioritizes the framework’s accuracy and reliability over a formal evaluation of its computational performance. Specifically, the reliance on multiple large models (LLMs and VLMs) introduces considerable computational overhead. Future work should address a detailed analysis of metrics such as inference time per stage, overall throughput, and resource utilization to provide a clearer picture of the feasibility of integrating this framework into real-time modeling tools. Finally, the scoring framework emphasizes syntactic and structural fidelity but provides only partial insight into semantic correctness, which is critical for ensuring executable and functionally valid UML representations.

Building upon these limitations, several avenues for future research emerge. Expanding the dataset to cover the complete spectrum of UML diagram types and increasing annotation granularity for behavioral semantics will be crucial to advancing automated UML synthesis. Incorporating execution-based evaluation metrics and formal verification mechanisms can enhance the assessment of semantic validity, complementing the current focus on structural fidelity. Furthermore, extending the benchmark to include a wider range of foundation models such as reasoning-optimized LLMs, multimodal transformers, and domain specific code models will provide a more comprehensive comparison across architectures. Another promising direction is the integration of hybrid multimodal reasoning pipelines, where symbolic, textual, and visual features are jointly optimized to reduce the structural behavioral gap. Finally, expanding the dataset to include additional UML diagram types particularly Activity, Deployment and Package diagrams would help capture a fuller spectrum of software design semantics and longitudinal studies on real-world industrial datasets and collaborative validation with software engineers can strengthen the practical relevance and adoption of automated UML generation frameworks.

4.4 Human Expert Validation and Correlation Analysis

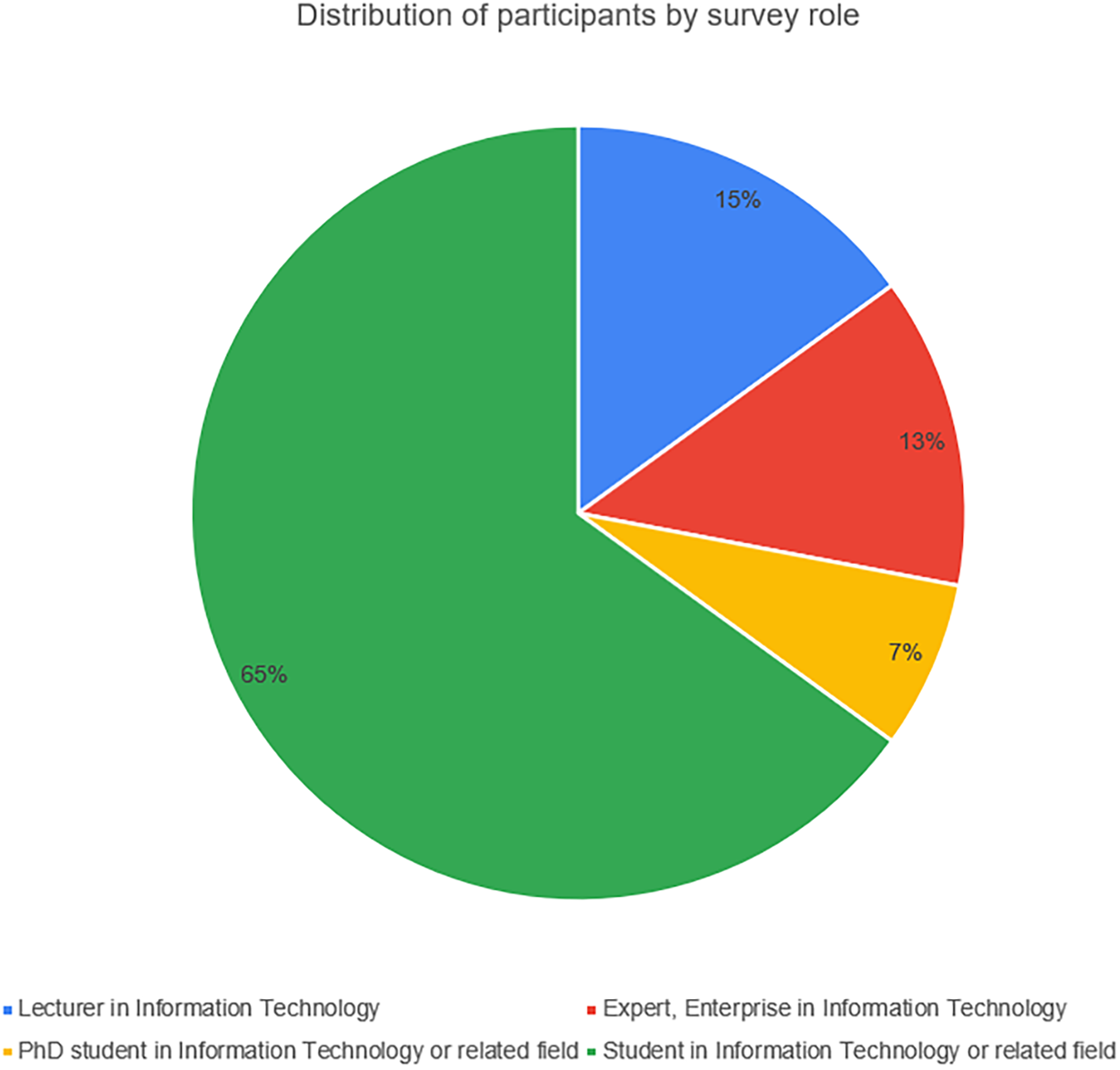

To validate the reliability of our automated multi-VLM evaluation framework, we conducted a human evaluation study. The primary goal was to measure the correlation between the composite scores generated by our VLM ensemble and the quality ratings provided by human experts in Fig. 7. A subset of 60 UML diagrams was randomly sampled from the dataset we generated, ensuring balanced representation across all nine diagram types. These diagrams, along with their corresponding textual specifications, were presented to a panel of four subjects for evaluation. The panel consisted of: Lecturer in Information Technology; Expert, Enterprise in Information Technology; PhD student in Information Technology or related field; Student in Information Technology or related field.

Figure 7: Distribution of participants by survey role

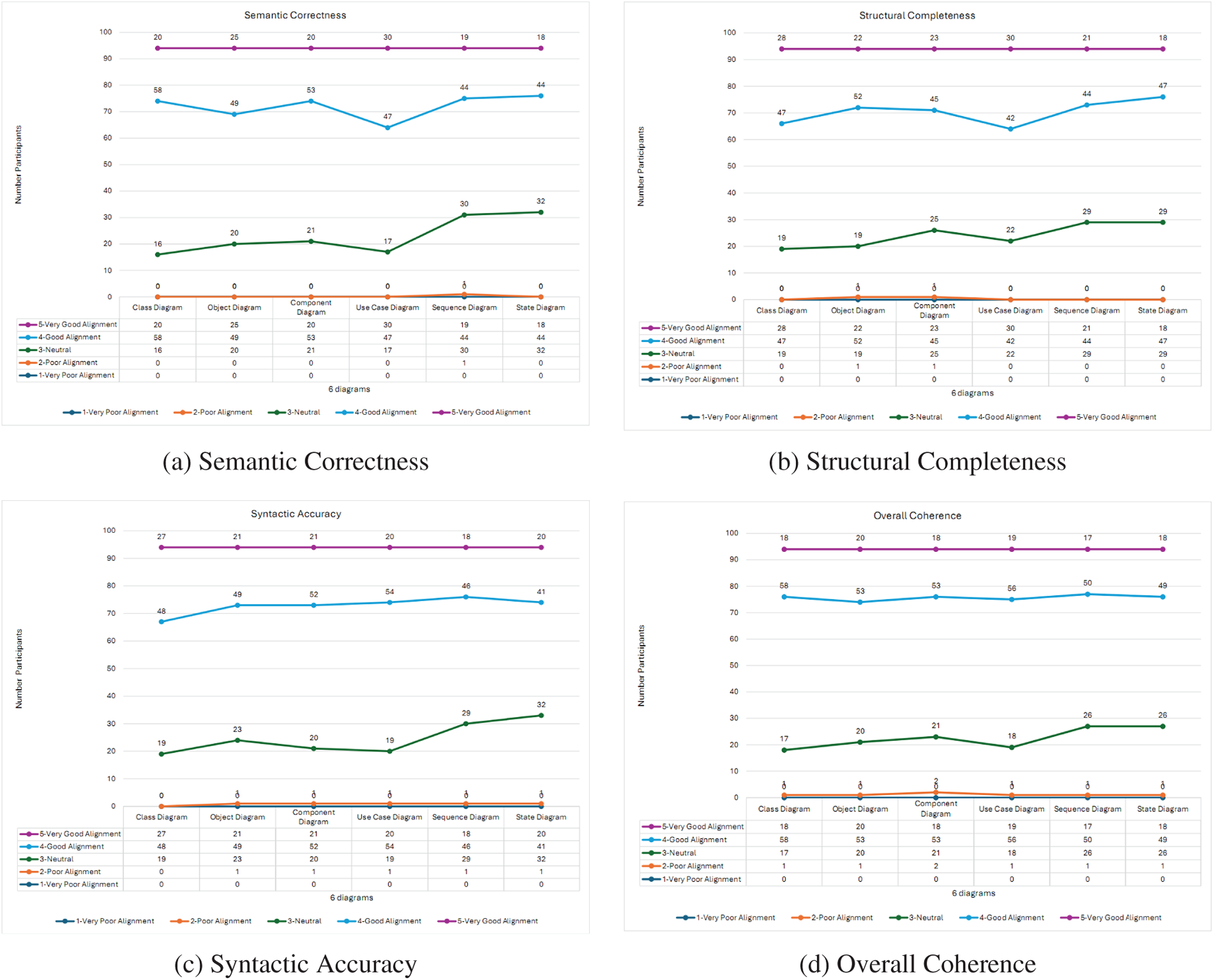

Figure 8: Human expert evaluation scores for UML diagrams across four quality criteria

Participants: We recruited 94 participants from four distinct groups based on their expertise in software engineering and UML modeling. The group comprised 14 universities Lecturer in Information Technology; 12 experts, Enterprise in Information Technology; 7 PhD students in Information Technology; 61 students in Information Technology. All participants confirmed proficiency across both structural and behavioral UML diagrams.

A stratified random sample of 60 diagrams was selected from our generated dataset of nearly 12,000. The sample was balanced to include 10 diagrams from each of the six types (Class, Object, Component, Use Case, Sequence, State) to ensure representative coverage.

Evaluation Protocol and Criteria

The experts were asked to rate the quality of each UML diagram on the same 1-to-5 Likert scale used by the VLMs, where 1 represents “very poor alignment” and 5 represents “Very Good Alignment” with the textual specification. To ensure consistency, a detailed evaluation rubric was provided. The key criteria included:

1. Semantic Correctness: Does the diagram accurately represent the entities, relationships, and processes described in the text?

2. Structural Completeness: Are all major components (classes, actors, states, etc.) from the specification present in the diagram?

3. Syntactic Accuracy: Does the diagram adhere to the standard conventions and syntax of the specific UML type (e.g., correct use of arrows for inheritance vs. association)?

4. Overall Coherence: Is the diagram logically organized, clear, and easy to understand?

The final expert score for each diagram was calculated as the average of the “Overall Fidelity” scores from the 94 experts.

To ensure the consistency and objectivity of the expert judgments, we calculated Fleiss’ Kappa, a robust statistical measure for assessing the reliability of agreement between multiple raters. The raw scores from the 94 experts across the 60 sampled diagrams were aggregated to determine the level of consensus. The resulting Kappa value was K = 0.78. According to the widely accepted interpretation scale by Landis and Koch, this value falls into the “Substantial Agreement” range (0.61–0.80). This high level of inter-rater reliability confirms that our human-generated ground truth is consistent and provides a solid baseline for validating the performance of the VLM-based evaluation framework.

To quantitatively validate the reliability of our VLM-based evaluation framework, we performed a correlation analysis comparing the VLM-generated composite scores against the mean overall fidelity ratings provided by the 94 human experts for the 60-diagram subset. The analysis yielded a strong, statistically significant positive correlation, with a Pearson correlation coefficient (r) of 0.82 (

In this paper, we propose a unified and scalable framework for automatically generating, validating, and evaluating UML diagrams using large language models (LLMs). The approach integrates a dual modeling process for requirements understanding and UML code generation, coupled with a multi-modal scoring mechanism that leverages vision-language models to assess both structural accuracy and semantic fidelity. The framework has been applied to a diverse set of UML diagrams, covering structural diagrams: Class (5000 samples), Object (1000 samples) and Component (1000 samples). Behavioral Diagrams: Use Case (2998), Sequence (1000), and State (999) resulting in six large-scale annotated datasets aligned with 12,000 natural language specifications. Our findings show that while LLMs are capable of producing plausible and often structurally correct UML diagrams, challenges remain in modeling complex interrelationships and nuanced semantics across diagram types. To mitigate this, we introduce a feedback loop mechanism that iteratively refines low quality outputs based on evaluation scores, alongside a multi perspective validation system employing vision-language models (LLaMA 3.2-Vision, Qwen2.5-VL, Aya-Vision) with a weighted aggregation scheme for reliable and reproducible assessment across UML tasks. Overall, the proposed framework not only addresses the scarcity of comprehensive UML datasets but also establishes a reusable pipeline for future research in automated system modeling, LLM benchmarking, and reasoning-aware diagram generation, with potential extensions to additional diagram families ( Activity, Deployment diagrams...) and integration of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) modules for improved contextual grounding during synthesis.

This research establishes a robust foundation for automated UML dataset construction and multimodal verification; however, several avenues remain open for further exploration. Future work will extend the framework to encompass additional UML diagram types beyond the current scope, including both structural diagrams (Class, Component, Object) and behavioral diagrams (Use Case, Sequence, State), as well as Package and Deployment diagrams, thereby broadening its applicability across different stages of software modeling. A key challenge lies in enhancing temporal reasoning capabilities, particularly for Sequence Diagram synthesis where correct ordering of interactions and lifeline consistency are critical, which may require the integration of temporal constraint solvers or hybrid neuro-symbolic reasoning approaches. In addition, fine-tuning and domain adaptation of both generation and evaluation models using large scale, domain-specific corpora will be explored to improve structural fidelity and semantic precision, with retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) serving as a promising strategy to inject contextual knowledge during synthesis. The automated evaluation pipeline can also be enriched with multimodal metrics such as graph-structural similarity and ontology-based alignment to complement the vision-language scoring system and provide deeper diagnostic insights. Finally, incorporating human-in-the-loop feedback mechanisms could enable iterative refinement of both diagram generation and scoring, fostering adaptive, self-improving AI-assisted modeling tools that enhance the accuracy, robustness, and industrial adoption of AI-driven design automation.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the ĐH2025-TN07-07 project conducted at the Thai Nguyen University of Information and Communication Technology, Thai Nguyen, Vietnam, with additional support from the AI in Software Engineering Lab.

Author Contributions: Study conceptualization: Van-Viet Nguyen, Huu-Khanh Nguyen,The-Vinh Nguyen, Duc-Quang Vu, Kim-Son Nguyen, Thi Minh-Hue Luong; data collection and experiment: Van-Viet Nguyen, Huu-Khanh Nguyen, The-Vinh Nguyen; analysis and interpretation of results: Van-Viet Nguyen, The-Vinh Nguyen, Duc-Quang Vu, Trung-Nghia Phung; draft manuscript preparation: Vinh Nguyen, Duc-Quang Vu,Trung-Nghia Phung; Van-Viet Nguyen and The-Vinh Nguyen served as the corresponding authors for this manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the repository: https://huggingface.co/nguyenvanviet/datasets (accessed on 17 December 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript

| UML | Unified Modeling Language |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| VLM | Vision-Language Models |

| BPMN | Business Process Model and Notation |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| SysML | Systems Modeling Language |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| LLaMA | Large Language Model Meta AI |

| MMMU | Massive Multi-discipline Multimodal Understanding |

| RAG | Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| PhD | Doctor of Philosophy |

| BLEU | Bilingual Evaluation Understudy |

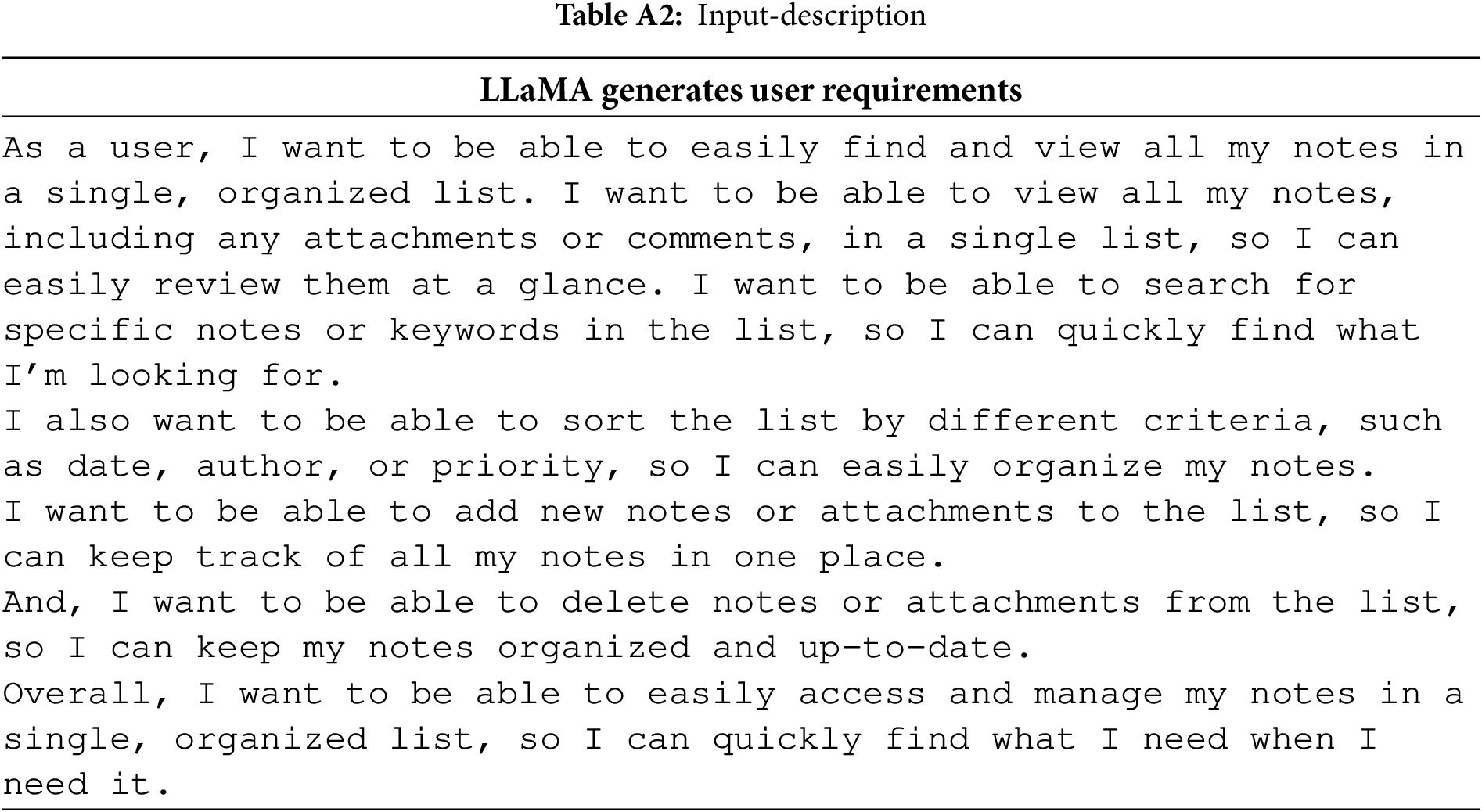

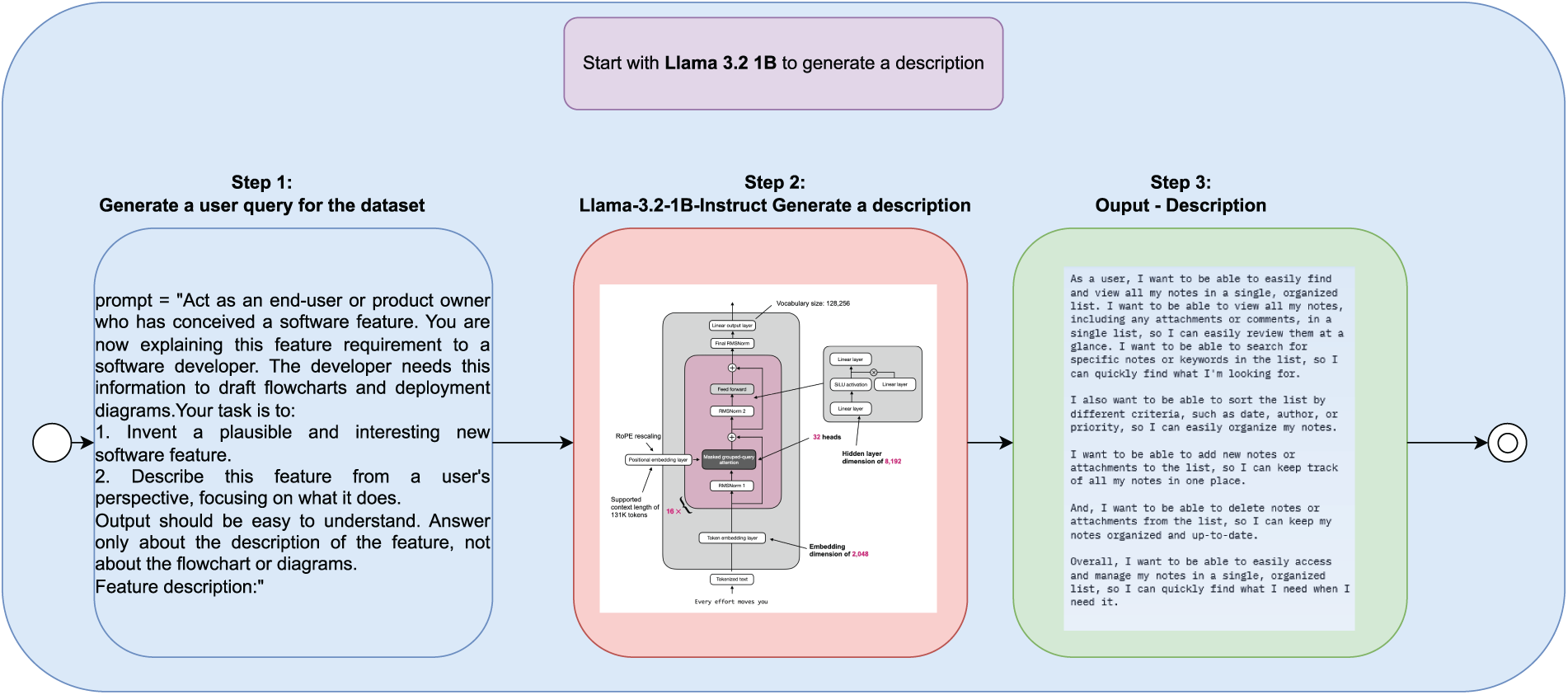

Table A1 illustrates the structured prompt templates designed for the two main stages of the proposed training process. The first format prompt, “Create software feature descriptions from a user perspective,” guides the model to simulate the behavior of an end-user or product owner. The goal is to generate coherent and human-like descriptions of hypothetical software features. These descriptions serve as high-quality textual inputs that reflect real-world software requirement expressions. The prompt explicitly instructs the model to (1) invent a plausible software feature, (2) describe its functionality from a user’s point of view and (3) avoid any discussion of implementation details such as as Class, Use case diagrams and more.

Fig. A1 shows about Llama 3.2 1B to generate a description.

Figure A1: Llama 3.2 1B to generate a description

Fig. A2 shows how DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-32B to generate a PlantUML Code.

Figure A2: DeepSeek-R1-distill-qwen-32B to generate a plantUML code

Fig. A3 is Diagram Rendering and Multimodal Validation.

Figure A3: Diagram rendering and multimodal validation

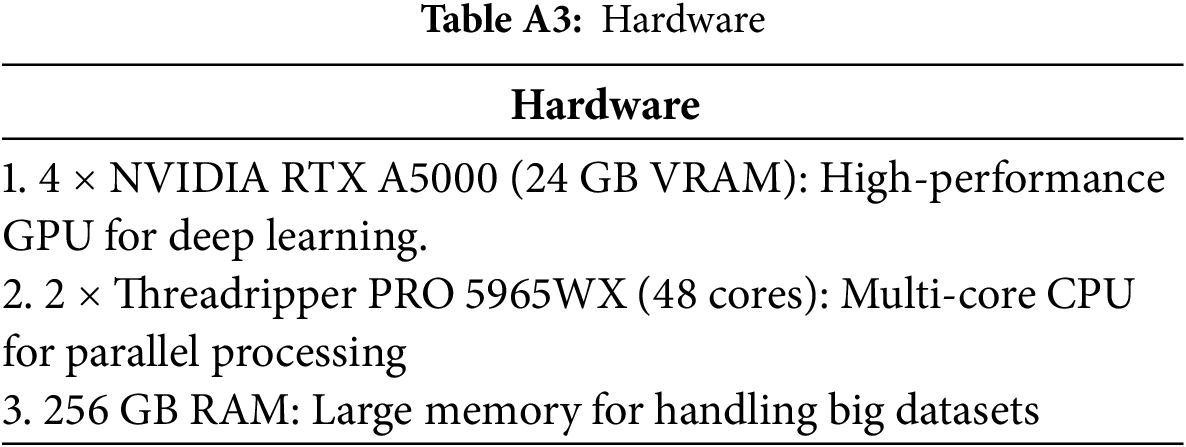

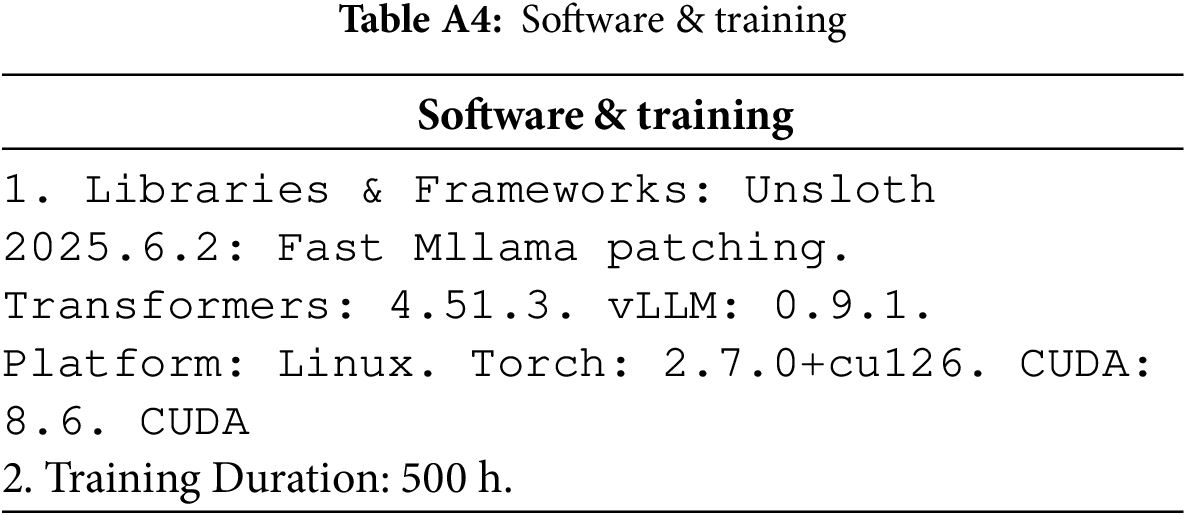

Experiment Environment: Table A3 for Hardware and Table A4 for Software-Training.

BLEU scores were computed using the sentence-level BLEU implementation from the NLTK library. By default, BLEU-4 was employed with uniform weights over 1- to 4-grams. A simple whitespace-based tokenization was applied, and smoothing method 1 proposed by Chen and Cherry (2014) was used to mitigate zero scores for short sequences. Each generated diagram was evaluated against a single reference.

References

1. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing System; 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 6000–10. [Google Scholar]

2. Booch G, Rumbaugh J, Jacobson I. The unified modeling language user guide. 2nd ed. Boston, MA, USA: Addison-Wesley; 2005. [Google Scholar]

3. Holt J, Perry S. SysML for systems engineering. Vol. 7. Institution of Engineering and Technology; 2008. [Google Scholar]

4. Torcal J, Moreno V, Llorens J, Granados A. Creating and validating a ground truth dataset of unified modeling language diagrams using deep learning techniques. Appl Sci. 2024;14(23):10873. doi:10.3390/app142310873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Whittle J, Hutchinson J, Rouncefield M. The state of practice in model-driven engineering. IEEE Softw. 2013;31(3):79–85. doi:10.1109/MS.2013.65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Alenezi M, Akour M. Ai-driven innovations in software engineering: a review of current practices and future directions. Appl Sci. 2025;15(3):1344. doi:10.3390/app15031344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Nguyen VV, Nguyen HK, Nguyen KS, Luong Thi Minh H, Nguyen TV, Vu DQ. A novel pipeline for automatic UML sequence diagram synthesis and multimodal scoring. In: Thai-Nghe N, Do TN, Benferhat S, editors. Intelligent systems and data science. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2026. p. 473–85. doi:10.1007/978-981-95-3355-8_34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Shehzadi N, Ferzund J, Fatima R, Riaz A. Automatic complexity analysis of UML class diagrams using visual question answering (VQA) techniques. Software. 2025;4(4):22. doi:10.3390/software4040022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ahmed S, Ahmed A, Eisty NU. Automatic transformation of natural to unified modeling language: a systematic review. In: 2022 IEEE/ACIS 20th International Conference on Software Engineering Research, Management and Applications (SERA); 2022 May 25–27; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 112–9. doi:10.1109/SERA54885.2022.9806783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. López JAH, Cánovas Izquierdo JL, Cuadrado JS. ModelSet: a dataset for machine learning in model-driven engineering. Software Syst Model. 2022;21(3):967–86. doi:10.1007/s10270-021-00929-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Conrardy A, Cabot J. From image to UML: first results of image-based UML diagram generation using LLMs. arXiv:2404.11376. 2024. [Google Scholar]

12. Rouabhia D, Hadjadj I. Behavioral augmentation of UML class diagrams: an empirical study of large language models for method generation. arXiv:2506.00788. 2025. [Google Scholar]

13. Meng Y, Ban A. Automated UML class diagram generation from textual requirements using NLP techniques. JOIV: Int J Inf Vis. 2024;8(3–2):1905–15. doi:10.62527/joiv.8.3-2.3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Jahan M, Hassan MM, Golpayegani R, Ranjbaran G, Roy C, Roy B, et al. Automated derivation of UML sequence diagrams from user stories: unleashing the power of generative AI vs. a rule-based approach. In: Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 27th International Conference on Model Driven Engineering Languages and Systems. MODELS ’24; 2024 Sep 22–27; Linz, Austria. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2024. p. 138–48. doi:10.1145/3640310.3674081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Simmonds J, Bastarrica MC. A tool for automatic UML model consistency checking. In: Proceedings of the 20th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering. ASE ’05; 2005 Nov 7–11; Long Beach, CA, USA. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2005. p. 431–2. doi:10.1145/1101908.1101989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Bouali N, Gerhold M, Rehman TU, Ahmed F. Toward automated UML diagram assessment: comparing LLM-generated scores with teaching assistants. In: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU–Volume 1; 2025 Apr 1–3; Porto, Portugal. p. 158–69. doi:10.5220/0013481900003932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Babaalla Z, Jakimi A, Oualla M. LLM-driven MDA pipeline for generating UML class diagrams and code. IEEE Access. 2025;13:171266–86. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3615828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Deeptimahanti DK, Kumar D, Babar MA. Semi-automatic generation of UML models from natural language requirements. ACM SIGSOFT Software Eng Notes. 2011;36(4):1–8. doi:10.1145/1953355.1953378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Abdelnabi EA, Maatuk AM, Abdelaziz TM, Elakeili S. Generating UML class diagram using NLP techniques and heuristic rules. In: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Sciences and Techniques of Automatic Control and Computer Engineering (STA); 2020 Dec 20–22; Monastir, Tunisia. p. 277–82. doi:10.1109/STA50679.2020.9329301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Maatuk AM, Abdelnabi EA. Generating UML use case and activity diagrams using NLP techniques and heuristics rules. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Science, E-learning and Information Systems 2021; 2021 Apr 5–7; Ma’an, Jordan. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2021. p. 271–7. doi:10.1145/3460620.3460768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Necula SC, Dumitriu F, Greavu-Şerban V. A systematic literature review on using natural language processing in software requirements engineering. Electronics. 2024;13(11):2055. doi:10.3390/electronics13112055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Alshareef S, Maatuk AM, Abdelaziz T. Aspect-oriented requirements engineering: approaches and techniques. In: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Data Science, E-learning and Information Systems; 2018 Oct 1–2; Madrid, Spain. p. 1–7. doi:10.1145/3279996.3280009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Metzner A. Systematic teaching of UML and behavioral diagrams. In: 2024 36th International Conference on Software Engineering Education and Training (CSEE&T); 2024 Jul 29–Aug 1; Würzburg, Germany. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/CSEET62301.2024.10663036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Babaalla Z. Extraction of UML class diagrams using deep learning: comparative study and critical analysis. Procedia Comput Sci. 2024;232(1):110–9. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2024.05.053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. De Bari D, Garaccione G, Coppola R, Torchiano M, Ardito L. Evaluating large language models in exercises of UML class diagram modeling. In: Proceedings of the 18th ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement. ESEM ’24; 2024 Oct 24–25; Barcelona, Spain. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2024. p. 393–9. doi:10.1145/3674805.3690741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang B, Wang C, Liang P, Li B, Zeng C. How LLMs Aid in UML modeling: an exploratory study with novice analysts. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Software Services Engineering (SSE); 2024 Jul 7–13; Shenzhen, China. p. 249–57. doi:10.1109/SSE62657.2024.00046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Deng J, Dong W, Socher R, Li LJ, Li K, Fei-Fei L. ImageNet: a large-scale hierarchical image database. In: 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2009 Jun 20–25; Miami, FL, USA. p. 248–55. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2009.5206848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wang A, Singh A, Michael J, Hill F, Levy O, Bowman SR. GLUE: a multi-task benchmark and analysis platform for natural language understanding. In: Proceedings of the 2018 EMNLP Workshop BlackboxNLP: Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP; 2018 Nov 1; Brussels, Belgium. p. 353–5. [Google Scholar]

29. Danish S, Ali M, Khan T. A comprehensive survey of Vision-Language Models: pretrained models, fine-tuning, prompt engineering, adapters, and benchmark datasets. Inf Fusion. 2025;108(9):102300. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2025.103623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Picard C, Thomas E, Zhao L. From concept to manufacturing: evaluating vision-language models for engineering design. Artifi Intell Rev. 2025;58(6):2451–76. doi:10.1007/s10462-025-11290-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Bates A, Singh R, Shah A. Unified modeling language code generation from diagram images using multimodal large language models. SoftwareX. 2025;23(1):101580. doi:10.1016/j.mlwa.2025.100660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Shinde SK, Bhojane V, Mahajan P. NLP based object oriented analysis and design from requirement specification. Int J Comput Appl. 2012;47(21):30–4. [Google Scholar]

33. Xu FF, Alon U, Neubig G, Hellendoorn VJ. A systematic evaluation of large language models of code. In: Proceedings of the 6th ACM SIGPLAN International Symposium on Machine Programming. MAPS 2022; 2022 Jun 13; San Diego, CA, USA. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2022. p. 1–10. doi:10.1145/3520312.3534862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang Y, Le H, Gotmare A, Bui N, Li J, Hoi S. Codet5+: open code large language models for code understanding and generation. In: Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2023 Dec 6–10; Singapore. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2023. p. 1069–88. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.emnlp-main.68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Viet NV, Vinh NT. Large language models in software engineering A systematic review and vision.2024;2(2):146–56. doi:10.56916/jesi.v2i2.968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Dehaerne E, Dey B, Halder S, De Gendt S, Meert W. Code generation using machine learning: a systematic review. IEEE Access. 2022;10:82434–55. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3196347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Padhye R, Lemieux C, Sen K. JQF: coverage-guided property-based testing in Java. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis (ISSTA 2019); 2019 Jul 15–19; Beijing China. p. 398–401. doi:10.1145/3293882.3339002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Chen M, Tworek J, Jun H, Yuan Q, Pondé H, Kaplan J, et al. Evaluating large language models trained on code. arXiv:2107.03374. 2021. [Google Scholar]

39. Recht B, Roelofs R, Schmidt L, Shankar V. Do imagenet classifiers generalize to imagenet? In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 398–401. [Google Scholar]

40. Touvron H, Lavril T, Izacard G, Martinet X, Lachaux MA, Lacroix T, et al. LLaMA: open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv:2302.13971. 2023. [Google Scholar]

41. DeepSeek-AI. DeepSeek-R1: incentivizing reasoning capability in LLMs via reinforcement learning. arXiv:2501.12948. 2025. [Google Scholar]

42. Wang P, Bai S, Tan S, Wang S, Fan Z, Bai J, et al. Qwen2-VL: enhancing vision-language model’s perception of the world at any resolution. arXiv:2409.12191. 2024. [Google Scholar]

43. Üstün A, Aryabumi V, Yong Z, Ko WY, D’souza D, Onilude G, et al. Aya model: an instruction finetuned open-access multilingual language model. In: Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024 Aug 11–16; Bangkok, Thailand. p. 15894–939. [Google Scholar]

44. Yue X, Ni Y, Zhang K, Zheng T, Liu R, Zhang G, et al. MMMU: a massive multi-discipline multimodal understanding and reasoning benchmark for expert AGI. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 9556–67. doi:10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.00913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. King’ori AW, Muketha GM, Ndia JG. A framework for analyzing UML behavioral metrics based on complexity perspectives. Int J Software Eng (IJSE). 2024;11(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

46. Singh D, Sidhu H. Optimizing the software metrics for uml structural and behavioral diagrams using metrics tool. Asian J Comput Sci Technol. 2018;7(2):11–7. doi:10.51983/ajcst-2018.7.2.1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Munde AR. Evaluation of vision language model on UML diagrams; 2025 [cited 2025 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388499054_Evaluation_of_Vision_Language_Model_on_UML_Diagrams/citations. [Google Scholar]

48. Fauzan R, Siahaan D, Rochimah S, Triandini E. Structural similarity assessment for multiple UML diagrams measurement with UML common graph. AIP Conf Proc. 2024;2927:060001. doi:10.1063/5.0192102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Arifin MN, Siahaan D. Structural and semantic similarity measurement of UML use case diagram. Lontar Komputer: Jurnal Ilmiah Teknologi Informasi. 2020;11(2):88. doi:10.24843/LKJITI.2020.v11.i02.p03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Keskar A, Perisetla S, Greer R. Evaluating multimodal vision-language model prompting strategies for visual question answering in road scene understanding. In: Proceedings of the Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision; 2025 Feb 28–Mar 4; Tucson, AZ, USA. p. 1027–36. [Google Scholar]

51. Čech P. Matching UML class models using graph edit distance. Expert Syste Appl. 2019;130:206–24. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2019.04.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools