Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

MCPSFOA: Multi-Strategy Enhanced Crested Porcupine-Starfish Optimization Algorithm for Global Optimization and Engineering Design

1 School of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Hainan University, Haikou, China

2 Engineering Management Department, Hainan Provincial Water Conservancy and Hydropower Group Co., Ltd., Haikou, China

3 Department of Engineering Mechanics, State Key Laboratory of Structural Analysis Optimization and CAE Software for Industrial Equipment, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China

* Corresponding Authors: Dabo Xin. Email: ; Changting Zhong. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: AI-Enhanced Computational Mechanics and Structural Optimization Methods)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 16 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2026.075792

Received 08 November 2025; Accepted 31 December 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

Optimization problems are prevalent in various fields of science and engineering, with several real-world applications characterized by high dimensionality and complex search landscapes. Starfish optimization algorithm (SFOA) is a recently optimizer inspired by swarm intelligence, which is effective for numerical optimization, but it may encounter premature and local convergence for complex optimization problems. To address these challenges, this paper proposes the multi-strategy enhanced crested porcupine-starfish optimization algorithm (MCPSFOA). The core innovation of MCPSFOA lies in employing a hybrid strategy to improve SFOA, which integrates the exploratory mechanisms of SFOA with the diverse search capacity of the Crested Porcupine Optimizer (CPO). This synergy enhances MCPSFOA’s ability to navigate complex and multimodal search spaces. To further prevent premature convergence, MCPSFOA incorporates Lévy flight, leveraging its characteristic long and short jump patterns to enable large-scale exploration and escape from local optima. Subsequently, Gaussian mutation is applied for precise solution tuning, introducing controlled perturbations that enhance accuracy and mitigate the risk of insufficient exploitation. Notably, the population diversity enhancement mechanism periodically identifies and resets stagnant individuals, thereby consistently revitalizing population variety throughout the optimization process. MCPSFOA is rigorously evaluated on 24 classical benchmark functions (including high-dimensional cases), the CEC2017 suite, and the CEC2022 suite. MCPSFOA achieves superior overall performance with Friedman mean ranks of 2.208, 2.310 and 2.417 on these benchmark functions, outperforming 11 state-of-the-art algorithms. Furthermore, the practical applicability of MCPSFOA is confirmed through its successful application to five engineering optimization cases, where it also yields excellent results. In conclusion, MCPSFOA is not only a highly effective and reliable optimizer for benchmark functions, but also a practical tool for solving real-world optimization problems.Keywords

Optimization has grown increasingly pivotal in modern science and engineering, driven by the necessity for efficient and effective solutions to a vast spectrum of practical problems [1,2]. These challenges, which encompass complex engineering design, resource allocation, and data analysis, often feature non-linear, high-dimensional, and multi-modal objective functions, rendering them intractable for traditional deterministic methods [3,4]. Consequently, there is a persistent and pressing demand for robust and versatile optimization algorithms capable of navigating such complex search spaces to yield optimal or near-optimal results within a computationally viable timeframe [5].

Metaheuristic algorithms provide a powerful alternative to classical optimization methods, leveraging stochastic strategies inspired by natural processes to systematically search for and locate global optima [6]. Notable examples include particle swarm optimization (PSO) [7,8], genetic algorithm (GA) [9], and differential evolution (DE) [10], whose efficacy has been extensively validated through widespread adoption in real-world scenarios. The appeal of metaheuristic algorithms stems from their simplicity, gradient-free nature, and robust global search capabilities [11]. Driven by the diversity of natural phenomena, several high-performance bio-inspired, nature-inspired, and human-inspired metaheuristic algorithms have emerged in recent decades to address complex optimization challenges, such as biogeography-based optimization [12], bat algorithm [13], teaching-learning-based optimization [14], grey wolf optimizer (GWO) [15], JAYA [16], Harris hawks optimization [17], seagull optimization algorithm [18], equilibrium optimizer [19], marine predator algorithm [20,21], beluga whale optimization [22], crayfish optimization algorithm [23], special relatively search [24], alpha evolution [25], crested porcupine optimizer [26], phototropic growth algorithm [27], and so on. Some of them have attracted much attention in the optimization field [28].

Although these metaheuristic algorithms are widely used in the optimization field, they still suffer from some limitations when addressing complex optimization problems, such as local convergence, premature, limited diversity within the population, and so on. To mitigate these issues, researchers often employ hybridization methods. For instance, Bai and Li [29] developed a hybrid cuckoo search-GWO algorithm for parameter identification of a solid oxide fuel cell. Han et al. [30] incorporated PSO with the marine predator algorithm to enhance the population diversity. Gupta et al. [31] integrated DE into other metaheuristic algorithms and have shown promising results in tackling high-dimensional problems and the optimal power flow problem. Some effective strategies include the incorporation of chaotic maps for population initialization, dynamic mutation mechanisms, and adaptive learning strategies to balance exploration and exploitation [6]. Besides, a variety of other hybrid metaheuristic algorithms apply to a spectrum of optimization challenges, including the hybrid salp swarm-simulate annealing algorithm [32], arithmetic optimization-aquila optimizer [33], hybrid GA-GWO for mixed-fleet bus scheduling [34], salp swarm-Kepler optimization [35], hybrid Harris hawks-equilibrium optimization [36], Gaussian quantum PSO-GA [37], etc.

Furthermore, a more effective approach to complex optimization problems involves combining multiple ensemble operators. By leveraging their combined advantages, this method achieves more robust and efficient search performance than single-method strategies. For example, Lynn and Suganthan [38] developed an ensemble PSO incorporating different strategies to enhance the robustness and reliability of PSO. Gupta et al. [39] developed a Harris hawks optimization algorithm enhanced by opposition-based learning to solve optimization problems. Zhong et al. [40] augmented the equilibrium optimizer with opposition-based learning, Lévy flight and other operators, achieving superior high-dimensional performance. The hybrid grey wolf optimizer enhanced with mechanisms for memory, evolutionary operations, and local search was verified in many ways [41]. Hamad et al. [42] used Q-learning to strengthen the sine cosine algorithm’s global optimization capability. Song et al. [43] investigated the reinforcement learning strategies for enhancing optimization algorithms, showing that the reinforcement learning operator is useful for continuous and combinatorial optimization problems, which can be expanded for various phases such as multi-agents, algorithmic mechanism design, population and local search, training methods, theoretical analysis, and so on. Deng and Liu [44] introduced a hybrid sine cosine algorithm, in which an elite pool strategy was incorporated to enhance performance. Yu et al. [45] developed a teaming behavior-assisted PSO for optimization. Other developments of advanced metaheuristic algorithms include chaotic-quasi-oppositional-phasor hybrid gorilla troop algorithm [46], quantum encoding whale optimization algorithm [47], fractional order dung beetle optimizer [48], step gravitational search algorithm [49], chaotic modified black-winged kite optimization [50], reflection imaging learning seagull optimization [51], synergistic learning snake optimizer [52], and so on. These enhancements work to enrich the population, thereby optimizing the defects of the original algorithm.

Although these meta-heuristic algorithms have achieved widespread success in many fields, according to the No Free Lunch theorem, no single algorithm can be competent for all optimization problems [53]. The theorem states that no single algorithm is guaranteed to be superior for every possible optimization problem. Therefore, the development of specialized algorithms through continuous research is imperative to address the distinct characteristics of various problem domains [54]. This demand drives researchers to continuously explore new optimization strategies, including structural enhancements of existing algorithms, the construction of hybrid frameworks with complementary advantages, and the conduct of rigorous empirical validations tailored to specific application scenarios.

Motivated by this need, Zhong et al. [55] introduced the starfish optimization algorithm (SFOA). SFOA models arm coordination and population interaction to maintain sustained performance improvement. It has demonstrated high competitiveness against 100 metaheuristic algorithms based on the criteria of convergence and solution accuracy. In addition, SFOA demonstrates a slightly reduced computational complexity relative to PSO [56]. Thus, SFOA has attracted some researchers to use it for optimization in various fields, such as optimal energy management of microgrid [57], solar radiation forecasting [58], economic emission dispatch [59], quantification in fresh sweet potato roots [60], and temperature regulation of a continuous stirred-tank heater [61]. However, like other recent metaheuristic algorithms, SFOA’s performance on complex problems can be hampered by premature convergence and limited diversity. Enhancing the algorithm, therefore, requires strategies that bolster its ability to escape local optima, perform more intensive local searches, and dynamically manage population distribution—key advancements for achieving greater robustness and broader applicability.

Inspired by the need for continuous algorithmic improvement, this paper presents the multi-strategy enhanced crested porcupine-starfish optimization algorithm, called MCPSFOA, to address the shortcomings of the standard SFOA. The proposed MCPSFOA enhances the original SFOA by four key strategies: the crested porcupine optimizer’s update rules for balanced search, Lévy flight and Gaussian mutation for improved convergence, and a diversity enhancement operator. The effectiveness of the MCPSFOA algorithm has been proven through extensive tests in standard benchmark functions and engineering optimization problems. The research contributions of this article are as follows:

(1) A hybrid multi-strategy enhanced crested porcupine-starfish optimization algorithm (MCPSFOA) is proposed for global optimization and complex practical challenges to overcome the limitations of SFOA.

(2) MCPSFOA is enhanced by the crested porcupine optimizer, Lévy flight, Gaussian mutation, and population diversity operator, to achieve a better exploration-exploitation balance;

(3) The proposed MCPSFOA is rigorously evaluated using classic benchmarks, the CEC2017/2022 test suites, and five real-world engineering optimization problems. Compared with 11 other metaheuristic algorithms, the results demonstrate its superior optimization performance and robust convergence characteristics, underscoring its efficacy and viability for complex practical applications.

The following framework organizes this paper: Section 2 presents related work and provides background on classical and modern metaheuristics, including the original SFOA and CPO. Section 3 details the architecture and components of the proposed MCPSFOA. Section 4 outlines the experimental setup and benchmark suite, and presents a comparative analysis of the results. Section 5 discusses the algorithm’s efficacy on practical engineering problems. Finally, Section 6 concludes with a summary and future research directions.

2 Starfish Optimization Algorithm (SFOA)

The starfish optimization algorithm is a novel metaheuristic algorithm proposed by Siddiqui et al. in 2025 [54]. The algorithm is inspired by starfish, with simpler structures and lower computational cost. The following is a detailed elaboration of the mechanisms at each stage:

During exploration, starfish searches over a large area with five arms. According to the different problem dimensions (D), the following two strategies are adopted:

(1) When D > 5, adopt a cooperative search strategy among the five arms. At this point, the following position update method is adopted:

where the new and current positions of the starfish are denoted as

where T and Tmax denote the current and maximum iteration counts, respectively.

(2) When D ≤ 5, use one arm to explore for food:

where

The exploitation stage of SFOA also consists of two sub-stages, each mirroring a key biological behavior.

(1) In predation behavior, SFOA employs a concurrent two-way search method. First, calculate the distance separating the global optimum and the other five starfish:

Among them, the distance from the optimum to each of the other 5 agents is denoted as dm. To update the position, two values, dm1 and dm2, are randomly selected from this set of distances and employed in the calculation:

where, r1, r2 ∈ (0, 1) are random numbers. According to the parallel bidirectional search strategy, in each iteration, a portion of the starfish is randomly selected to move towards the current optimal solution, while the other portion moves in the opposite direction for exploration. This mechanism ensures that all starfish have the same ability to search outside the local optimum.

(2) Regeneration behavior: A small-scale random update is performed only on the last individual (i = N) in the population:

To enhance and maintain the population diversity of SFOA and the ability to solve realistic optimization problems, this paper proposes the multi-strategy enhanced crested porcupine-starfish optimization algorithm (MCPSFOA). The algorithm establishes a hybrid CPO-SFOA update framework, further empowers it with Lévy flight and Gaussian mutation for superior global exploration and local exploitation, and enhances search with a population diversity enhancement mechanism to prevent premature convergence.

3.1 Crested Porcupine Optimizer (CPO)

To boost the effectiveness of SFOA for optimization tasks, the population updating mechanism from the crested porcupine optimizer is utilized in MCPSFOA. In this framework, the execution of SFOA or CPO is selected through probability Psc, which is calculated by:

where Psi represents the initial probability to use SFOA’s update mechanism, and Psf represents the final probability to use SFOA’s update mechanism. Psi and Psf are set to 0.8 and 0.2, respectively.

Crested porcupine optimizer is a swarm-inspired metaheuristic developed by Gao and Zhang [25] to simulate the behaviors of the crested porcupine for optimization, including four different defensive strategies in exploration and exploitation phases. The main mathematical models are illustrated as follows.

Upon encountering a predator, the crested porcupine activates its first defense mechanism: it erects and fans its quills, attempting to scare off the predators. Predators may either be deterred or continue their attack. This model simulates both of these behavioral patterns:

where, rn, r1 and r are random numbers. rn is generated using a normal distribution, r1 ∈ [0,1], and r ∈ [1, N]. When r ∈ [−1, 1], the simulated intimidation by the crested porcupine is ineffective. In this case, the predator continues to approach, reducing the distance between them. This mechanism helps accelerate the exploration of the region between the two agents, thereby improving the algorithmic convergence efficiency. When r is not within the interval, the simulated intimidation takes effect, increasing the distance between the predator and the crested porcupine. This strategy encourages the predator to search uncharted regions of the solution space, which aids in identifying promising candidate solutions.

The second defensive strategy of the crested porcupine is to use sound warnings and to drive away predators. This defense strategy can produce three possible effects depending on the volume of the sound and the choice of the predator: continuing to move towards the crested porcupine, standing still, or leaving out of fear. Through simulation of this behavior:

where U1 is a randomly generated parameter containing only two values of 0 and 1. When U1 = 0, the predator remains stationary; otherwise, the predator may either approach or move away from the porcupine. The random numbers r2 and r3 are respectively between [1, N] and [0,1].

The secretion of foul odors is another defense strategy employed by the crested porcupine. The following equation simulates this defense behavior:

where U1 is the same as the formula and is used to simulate the distance between the crowned porcupine and its predator. Parameter δ governs the search direction, γt serves as a defensive parameter, and Si controls the odor diffusion. The calculation method is as follows:

Attack can also be considered a form of defense, representing the porcupine’s counterattack via a unidimensional inelastic collision:

where Cα is the convergence rate factor, taken as 0.2; The random values r4, r5 and r6 all fall within the range of [0, 1]. Fi refers to the inelastic collision law and quantifies the average force the crested porcupine exerts on a predator:

As a bio-inspired stochastic search paradigm, Lévy flight draws its inspiration from the foraging patterns of numerous animal species, including albatrosses and spider monkeys. These animals exhibit a characteristic mix of short, intensive search patterns near a food source interspersed with long, sweeping trajectories in search of new, richer foraging grounds [62,63]. This dual-mode strategy is mathematically modeled by a heavy-tailed Lévy distribution, which yields step lengths with a high probability of being small, but also a non-negligible chance of being exceptionally large. This inherent randomness and occasional large jumps are instrumental in mitigating premature convergence to local optima, thus substantially bolstering global search performance.

Within the MCPSFOA framework, Lévy flight is not applied to every individual in every iteration; rather, its application is a probabilistic event governed by two parameters: Pe and Pl. If an individual is selected for this enhancement, its position update is realized by superimposing a Lévy-distributed step vector upon its current position Xi. This step vector, denoted as sL, is generated using Mantegna’s algorithm [64].

The update mechanism strategically integrates the stochasticity of Lévy flight with a directional heuristic bias. Specifically, the term (Xi − Xbest) imparts a convergence pressure toward the current global optimum, thereby governing the Lévy flight trajectories. This configuration ensures that while the search leverages the heavy-tailed, exploratory dynamics of Lévy flight, it remains anchored toward the promising regions of the search space. The infinitesimal scaling factor α, modulates the step size, mitigating the risk of the individual overshooting potential optima. This synergetic integration effectively reconciles the requirement for extensive exploration to bypass local optima with the imperative of intensified exploitation toward the global best solution.

The updating rule by the Lévy flight mechanism is expressed as:

where αL is a small constant factor equals to 0.01 in the algorithm, sL means the Lévy step vector:

where u and v are random variables drawn from normal distributions u~N (0, σu2) and v~N (0, 1) to control the properties of the Lévy distribution.

Gaussian mutation is a widely utilized local exploitation operator in metaheuristic algorithms [65,66]. It’s designed to introduce a small, random perturbation to a solution vector. This perturbation is drawn from a Gaussian (or normal) distribution, which is characterized by its bell-shaped curve. The key property of a Gaussian distribution is that values close to the mean (in this case, zero) are much more likely to be generated than values far from it. This ensures that the mutation primarily produces new candidate solutions that are in the immediate vicinity of the parent solution, making it ideal for performing a refined, localized search.

Within the MCPSFOA, Gaussian mutation is employed as a complementary enhancement operator when Lévy flight is not selected. Its primary role is to enhance the algorithm’s exploitation capacity, helping it to fine-tune promising solutions. The operator works by adding a vector of Gaussian-distributed noise to the current individual’s position Xi.

A crucial aspect of this mechanism is the Gaussian scale parameter σ. It determines the magnitude of the perturbation. In this algorithm, σg is not static; it is dynamically scaled based on the initial range of the search space, (ub − lb). This approach ensures that the mutation’s intensity is proportional to the problem’s scale, allowing for a more effective and context-aware local search. By adding this controlled, random noise, the algorithm can explore the neighborhood of a promising solution without making drastic changes that might move it away from a good region, thereby facilitating a more precise search for the optimum.

The updating rule of Gaussian mutation in MCPSFOA is given by:

where σGf is the constant factor equals to 0.05 to control the mutation’s intensity, Gn represents a random vector drawn from a standard normal distribution N ∈ (0, 1).

3.4 Population Diversity Enhancement

The preservation of population diversity is a fundamental principle in the design and success of metaheuristic algorithms. Historically, the challenges of maintaining diversity have been central to the field, dating back to early evolutionary algorithms. Strategies for diversity enhancement emerged as a direct response to the problem of premature convergence, where a population quickly loses its genetic variation and all individuals converge to a suboptimal solution, trapping the algorithm in a local minimum. Techniques such as mutation in GA were early attempts to reintroduce diversity, but more advanced mechanisms were developed to specifically address stagnation. These include crowding [67], niching [68], and, more recently, re-initialization techniques [69].

The necessity of a population diversity enhancement mechanism is rooted in the exploration-exploitation dilemma, a core challenge in optimization [70]. Without sufficient diversity, a metaheuristic algorithm risks premature stagnation, characterized by the population becoming trapped in a local minimum, thereby neglecting a wider, potentially more optimal search space. This mechanism acts as a theoretical safeguard against this issue. By proactively re-initializing a portion of the population’s worst-performing individuals, the algorithm breaks out of a stagnated state and reintroduces new genetic material. This not only forces the search to re-engage in exploration but also replaces unpromising solutions with new, randomly generated individuals, thereby increasing the chances of discovering a new, more promising search trajectory.

The population diversity enhancement mechanism in the MCPSFOA algorithm is a condition-based logical process. It relies on monitoring the algorithm’s progress to detect a state of stagnation before taking corrective action. For stagnation detection, a stagnation counter is used to monitor the global best fitness value. If the fitness of the current best solution fails to improve a set number of iterations, the mechanism is triggered. Then, for the identification of individuals, the algorithm identifies the worst-performing search agents. This is achieved by sorting the population fitness in descending order and selecting the top a specific fraction of individuals for re-initialization. For re-initialization, the positions of these selected individuals are then re-initialized by sampling new points within the defined bounds. This process introduces new individuals with different search directions and potentially better fitness values, effectively pulling the population out of stagnation. The primary mathematical model for this mechanism in the re-initialization of selected individuals can be written as:

The number of individuals Nre to be re-initialized is calculated as Npop × σre, σre is a constant factor 0.1 to control the number of population diversity enhancement.

The multi-strategy enhanced crested porcupine-starfish optimization algorithm (MCPSFOA) is a hybrid metaheuristic that integrates a suite of specialized operators to improve search performance. The SFOA, inspired by starfish foraging, primarily facilitates global exploration by leveraging a parallel search strategy, thereby enabling efficient exploration of extensive solution spaces. The CPO complements this by contributing a distinct strategy that balances both exploration and exploitation, helping the algorithm locate promising regions and refine solutions. To address the potential for inadequate global exploration and the risk of becoming trapped in local optima, a Lévy flight mechanism is incorporated. Additionally, Gaussian mutation is employed to bolster local exploitation, facilitating fine-grained searches for precise solution refinement. Finally, the population diversity enhancement mechanism serves as a crucial safeguard against premature convergence; it actively re-initializes a portion of the worst-performing individuals to overcome stagnation and re-engage in exploration, thereby improving the overall robustness of the algorithm.

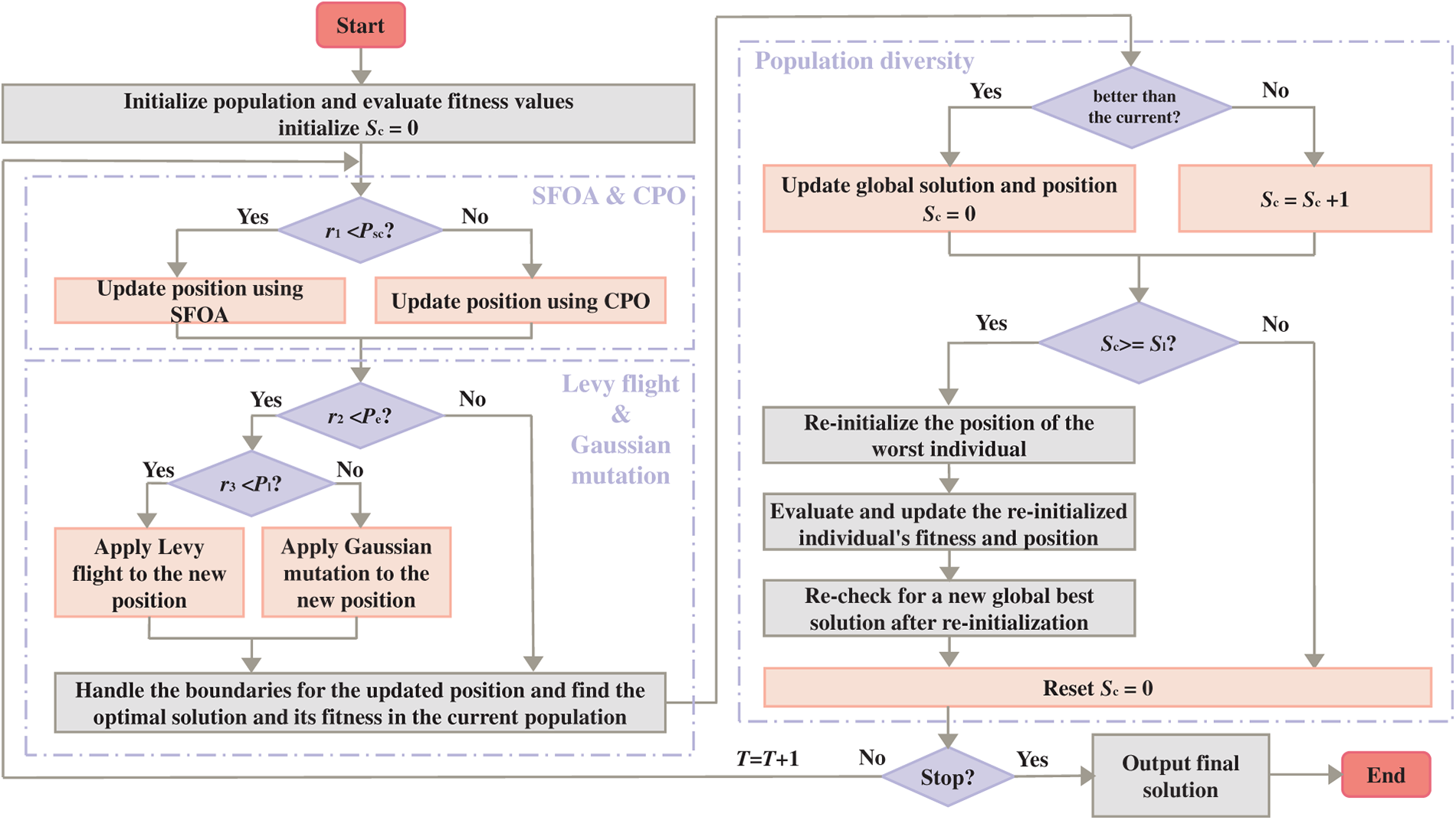

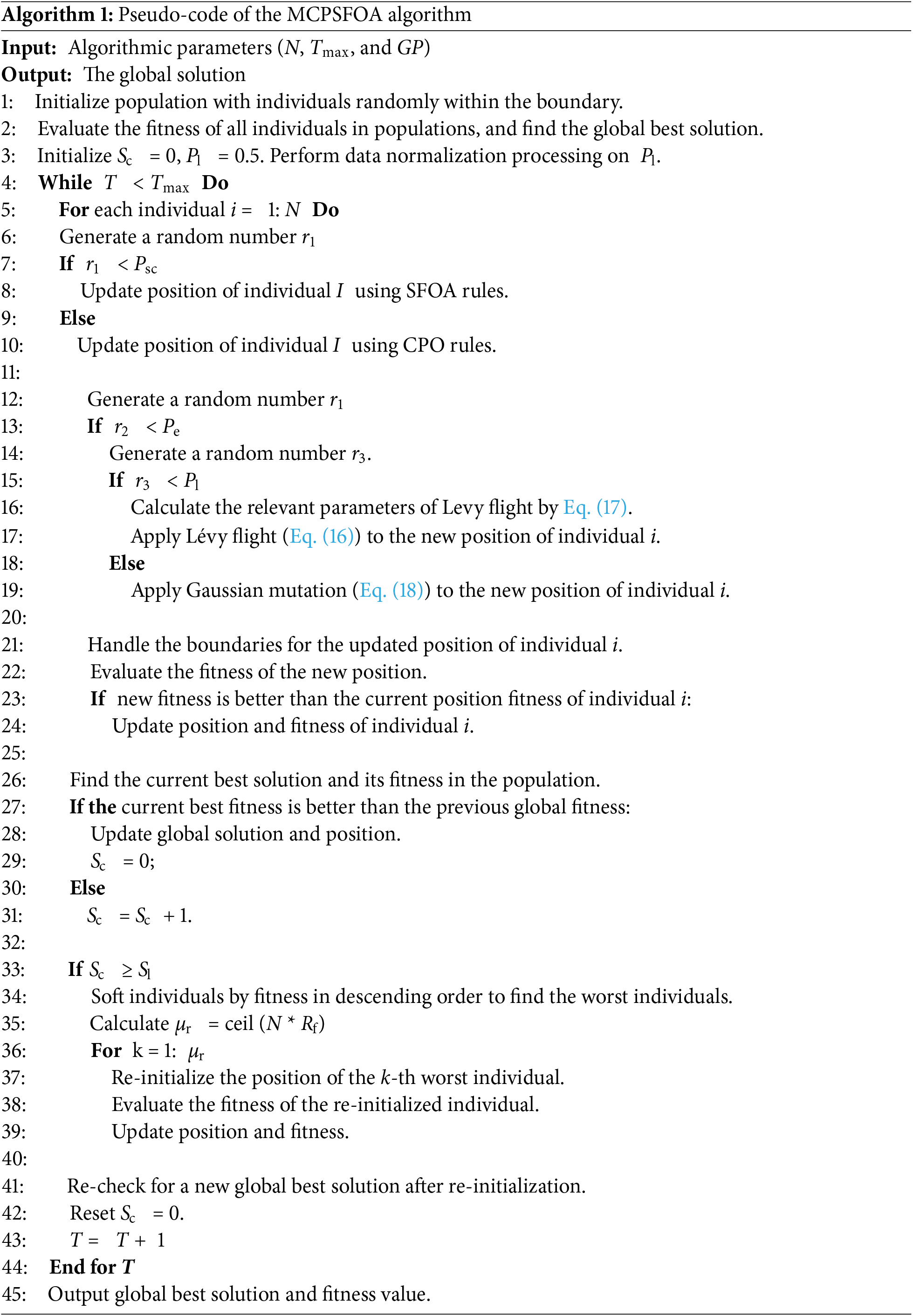

The implementation of the MCPSFOA is presented below:

1. Initialization: The algorithm commences with the initialization of a population of N individuals, deployed via stochastic initialization within the predefined search boundaries (lb and ub). The fitness of each individual is evaluated, and the best-performing one is designated as the initial global best solution.

2. Main Loop Iteration: The algorithm enters an iterative loop that runs for a maximum of Tmax iterations. Within each iteration, the following steps are performed:

3. Parallel Core Update Strategies (CPO and SFOA): For each individual, the algorithm probabilistically decides whether to apply the update rules of the CPO or the SFOA. This parallel approach ensures a dynamic and diverse search behavior.

4. Enhancement Operator Application: After an individual’s position has been updated by either CPO or SFOA, it undergoes a further refinement step. The algorithm probabilistically selects either the Lévy flight operator (for global exploration) or the Gaussian mutation operator (for local exploitation) to modify the individual’s new position.

5. Boundary Handling: Following the position updates, all dimensions of the individual’s position vector are checked to maintain their positions within the defined boundaries. Any values exceeding these bounds are reset to the respective boundary limits.

6. Fitness Evaluation and Global Best Update: The fitness of the new positions is re-evaluated. The new fitness values are compared with the current global best fitness. Upon discovery of a superior solution, the global best position and fitness are updated.

7. Population Diversity Enhancement Mechanism: After all individuals have been processed, the algorithm checks for stagnation. If the global best fitness has not improved for a set number of iterations (Sl), the mechanism is triggered. The algorithm identifies a specific fraction of the worst-performing individuals and re-initializes their positions with new random values, thereby introducing fresh diversity and helping the population escape local minima.

8. Termination: The iterative process continues until the iteration limit is met, at which point the final incumbent solution and its objective function value are yielded.

The pseudo-code of MCPSFOA is outlined in Algorithm 1, with the corresponding flowchart presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Flowchart of MCPSFOA

This section discusses the computational complexity of MCPSFOA. In this process, the maximum number of iterations T, population size N, and problem dimension D are the key factors determining the computational complexity of MCPSFOA.

During every iteration, MCPSFOA selects the update tactic of executing SFOA or CPO through a dynamic probability mechanism. Among them, the complexity of a single update for SFOA is approximately O(N × D), and the complexity of a single update for CPO is O(D). The probability of choosing SFOA is Psc, and the probability of choosing CPO is 1 − Psc. Therefore, the single computational complexity of this part is Psc × O(N × D) + (1 − Psc) × O(D). The total computational complexity can be expressed as: O(T × [(1 − Psc) × D + Psc × N × D]) = O(T × N × D × Psc).

In the preservation of population diversity strategy adopted by MCPSFOA, the number of iterations without global best improvement to trigger reinitialization is set to 10, and the fraction of the population to reinitialize is set to 0.1. So the computational complexity of this part is O(0.1 × T × NlogN + 0.01 × T × N × D). However, the Lévy flight operator and Gaussian mutation operator do not increase the computational complexity.

During the entire operation process, the computational complexity is: O(MCPSFOA) = O(T × [(1 − Psc) × D + Psc × N × D] + 0.1 × T × NlogN + 0.01 × T × N × D) = O(1.01 × T × N × D × Psc + 0.1 × T × NlogN). Analysis shows that the added operator has a relatively small impact on the overall computational complexity. Moreover, the complexity of MCPSFOA lies between that of SFOA and CPO, and it can be flexibly adjusted through probability Psc, thus having a potential advantage in computational efficiency.

4 Experimental Results for Benchmark Functions

4.1 Introduction to Benchmark Functions and Comparative Algorithms

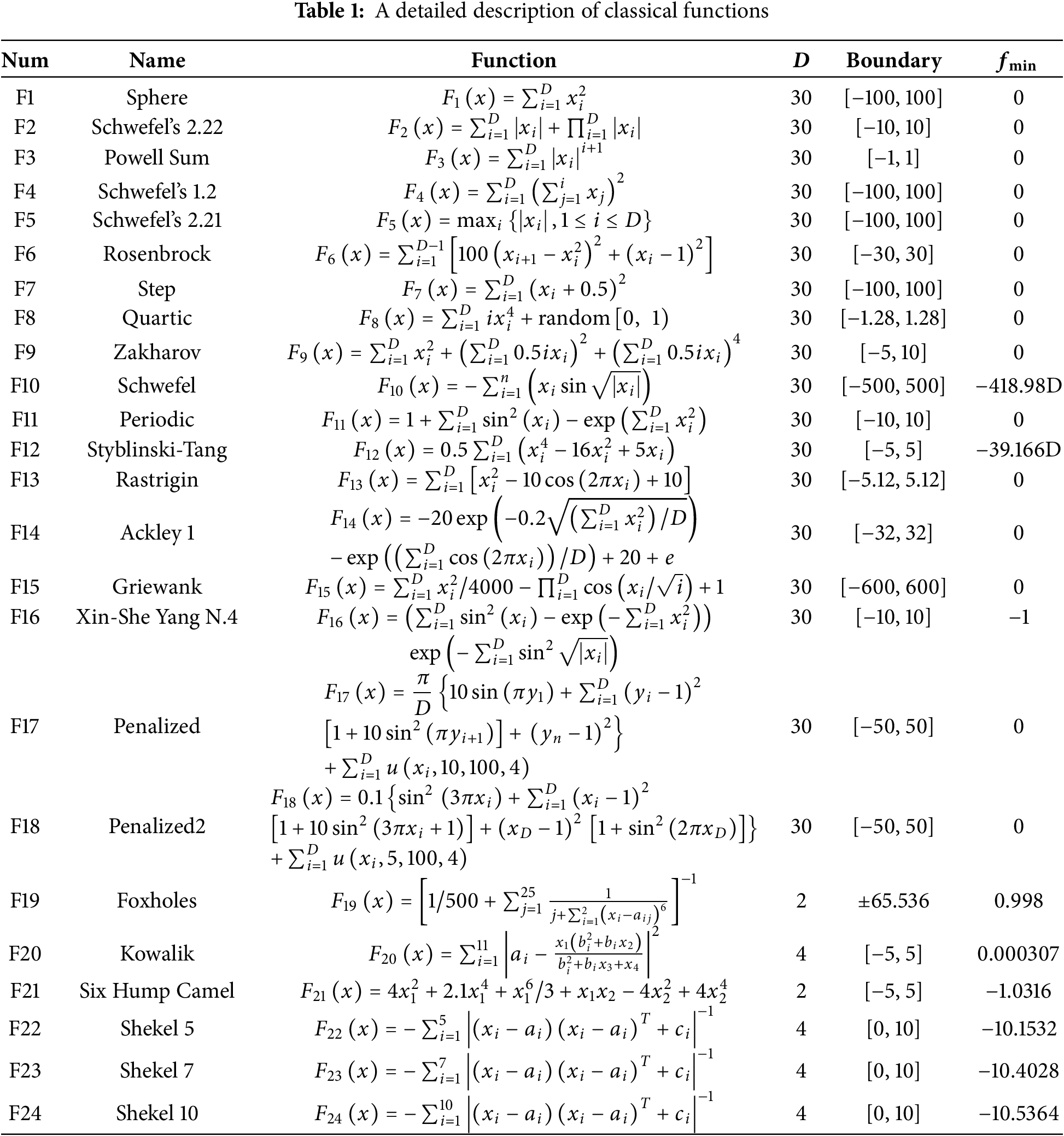

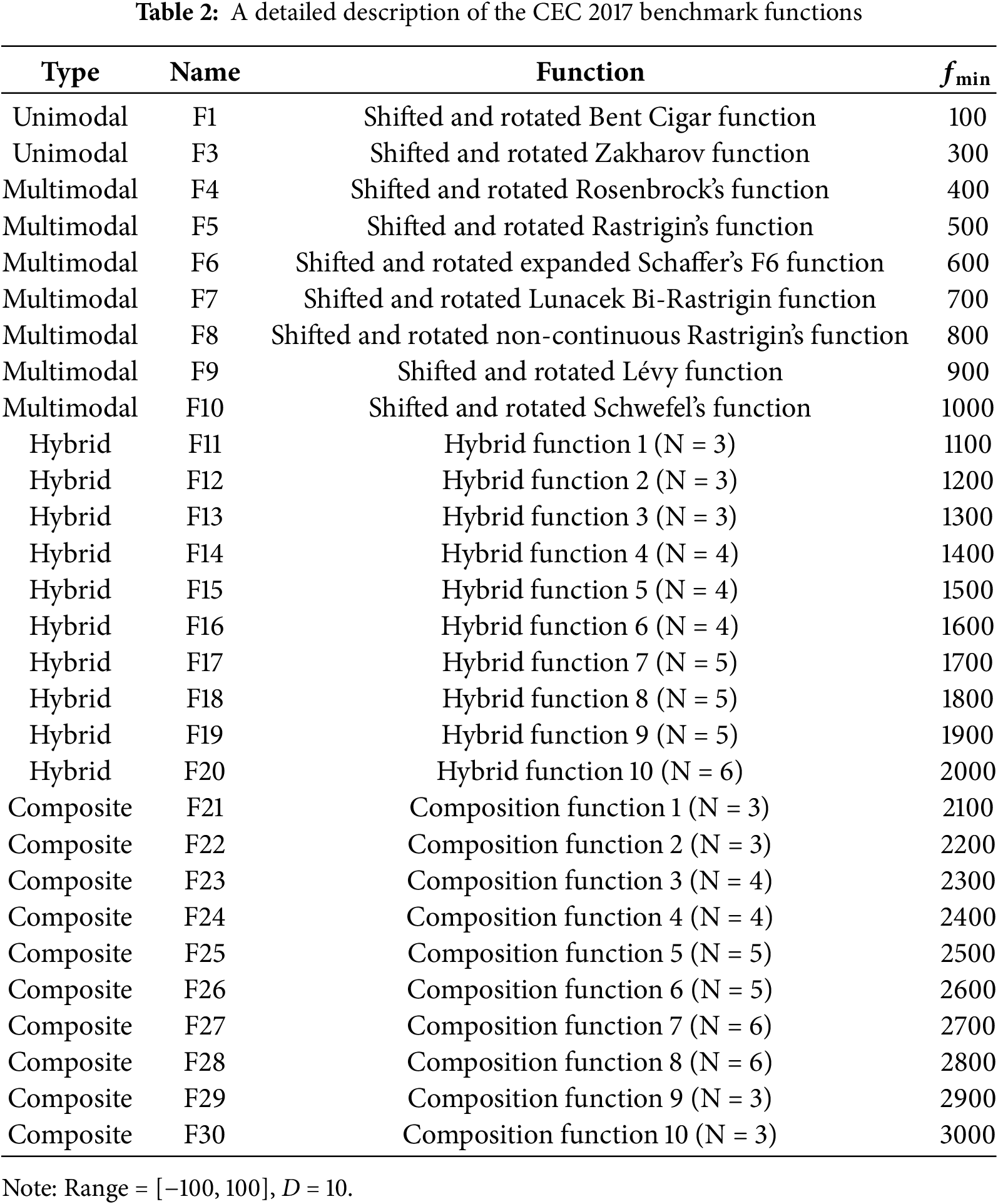

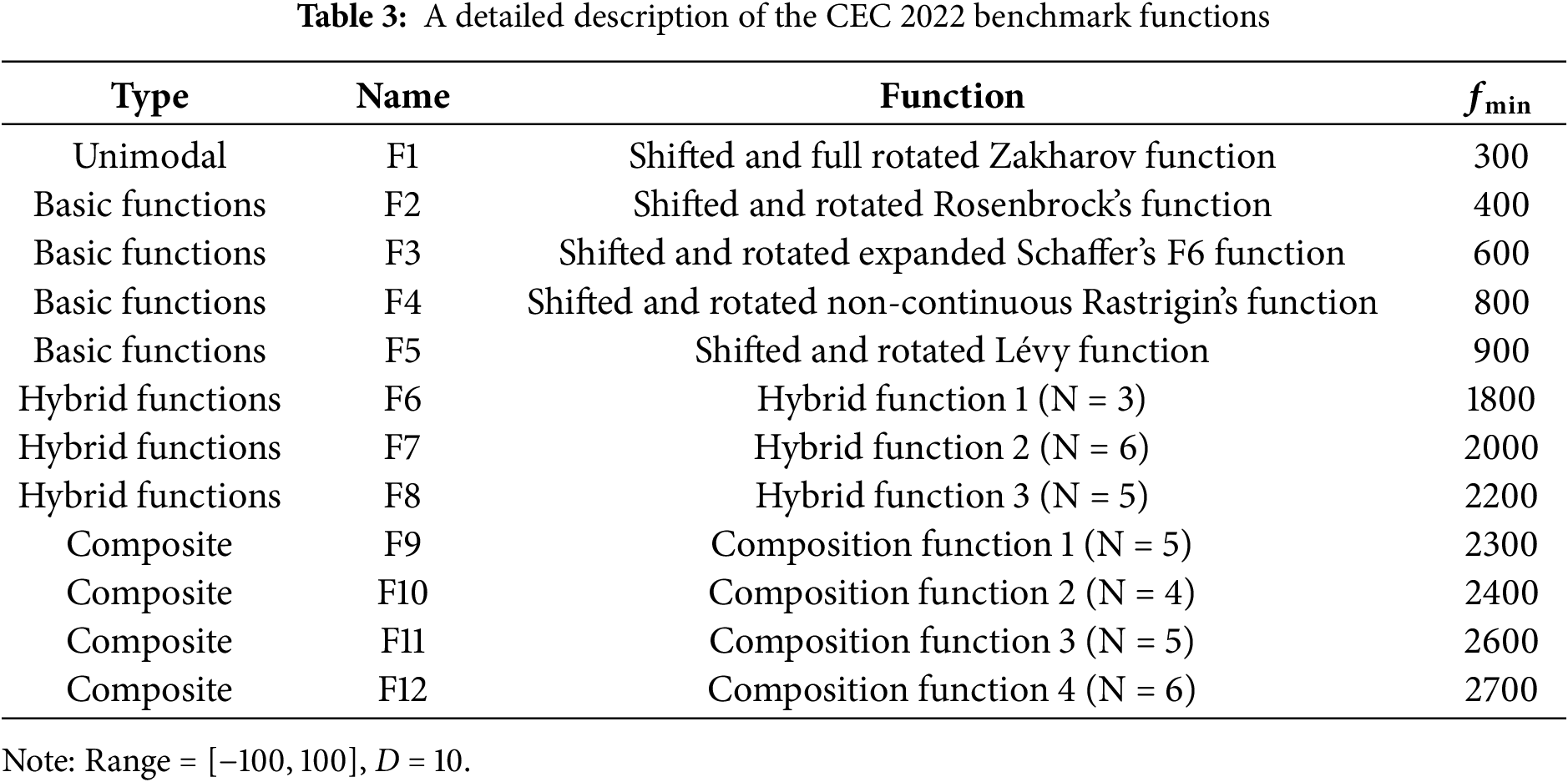

This paper presents a systematic performance evaluation of MCPSFOA, using comparative experiments on multiple benchmark functions. Benchmark functions are vital for testing the effectiveness of metaheuristic algorithms providing standardized testing environments that reveal algorithmic advantages and disadvantages. This section employs three benchmark suites: classical functions, the CEC 2017 test suite, and the CEC 2022 test suite. Classical functions [71] introduce 24 test functions, including unimodal functions to assess exploitation and convergence speed, multimodal functions to validate the effectiveness and efficiency of the algorithm’s exploration process, and fix-dimension functions with complex landscapes. The CEC 2017 test suite [72] introduces 29 functions (excluding F2) which categorized as unimodal, simple multimodal, hybrid and composite types, incorporating transformations like shifting and rotation to create non-separable variables and deceptive landscapes, preventing algorithms from relying on simple symmetry assumptions or coordinate-wise strategies. The CEC 2022 benchmark [73] introduces 12 test functions with asymmetric search spaces, heterogeneous variable transformations, and enhanced hybrid/composition functions. The above 65 benchmark functions give a rigorous framework for evaluating the algorithm’s capability in managing the exploration-exploitation trade-off, handling non-separability and maintaining performance in diverse and scalable problem domains. Tables 1–3 summarize the details of these benchmark functions.

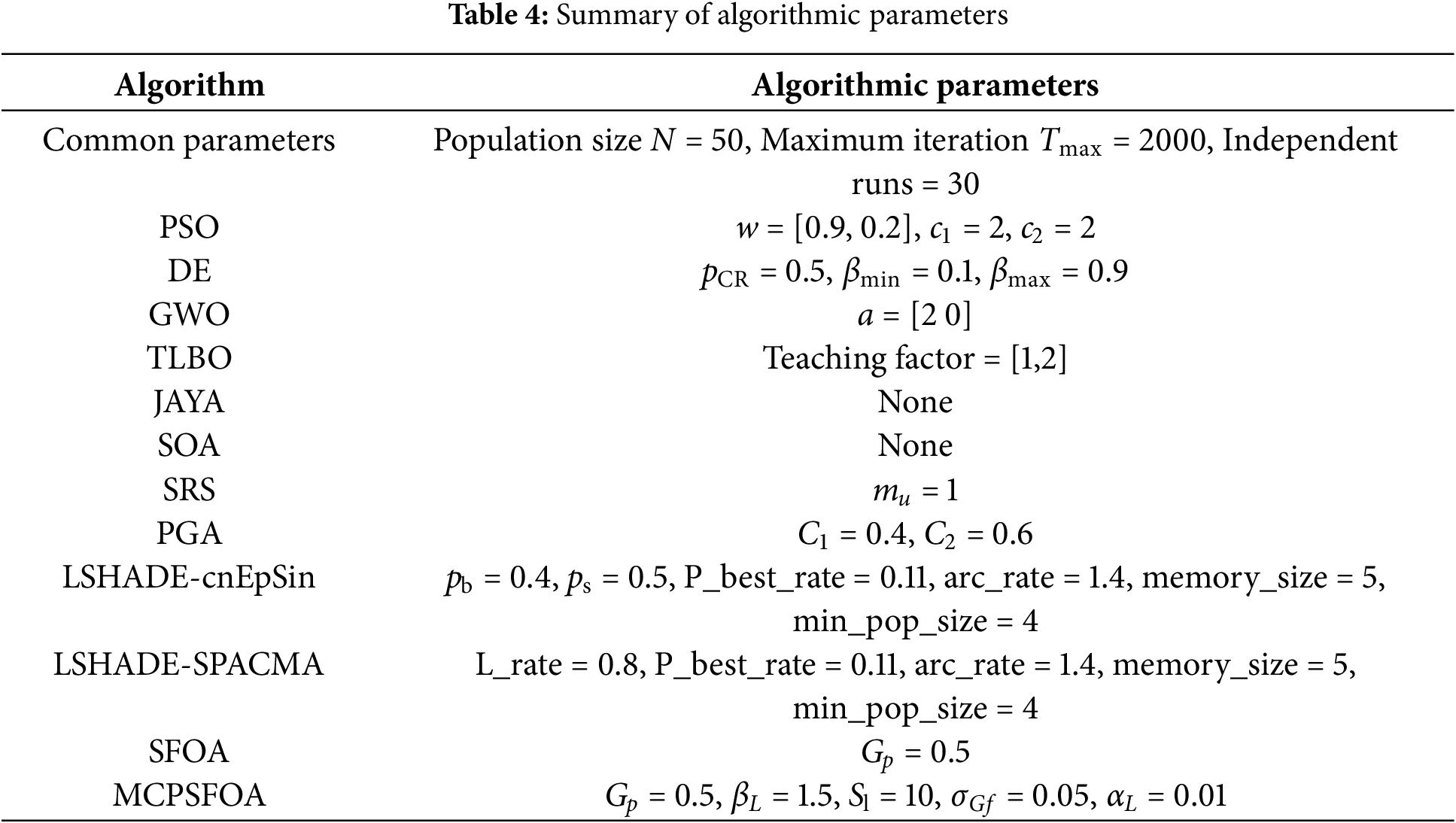

To validate the performance of MCPSFOA, 11 optimization algorithms are selected for comparison. Well-established classical algorithms, including particle swarm optimization (PSO) [8], differential evolution (DE) [10], grey wolf optimizer (GWO) [15], and teaching-learning-based optimization (TLBO) [14], serve as foundational benchmarks. Recently proposed metaheuristics, such as JAYA [16], the seagull optimization algorithm (SOA) [18], special relativity search (SRS) [24], and phototropic growth algorithm (PGA) [27], represent modern advancements in the field. High-performing CEC competition winners, namely LSHADE with covariance matrix adaptation and episodic sinusoidal inertia (LSHADE-cnEpSin) [74], LSHADE with space transformation and cma-es (LSHADE-SPACMA) [75], are included as state-of-the-art benchmarks. Finally, the original starfish optimization algorithm (SFOA) [55] is used as a baseline to directly quantify the improvements afforded by our proposed modifications. Table 4 presents the summary of algorithmic parameters. For each algorithm, the population size N is set at 50, and the maximum iteration Tmax is defined as 2000. Each algorithm independently performs 30 independent runs for each test function. Metrics including mean and standard deviation (Std), are calculated separately to evaluate, respectively for algorithmic performance assessment and mean ranking calculation, with leading benchmark values emphasized in bold. To evaluate the statistical difference between the MCPSFOA and other comparative methods, we employed the Wilcoxon rank-sum test [76] and the Friedman rank test. For the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, the significance level (α) was set to 0.05. If the p-value for a given test problem is less than 0.05, it indicates that the performance of MCPSFOA is significantly superior to the competitor algorithm; conversely, a p-value greater than 0.05 suggests that MCPSFOA performed worse than its counterpart. In the results, the NaN denotes no significant difference between the two algorithms. Furthermore, the symbols “+/ = /−” are used to represent the win, tie, and loss scenarios, respectively, of MCPSFOA in comparison to the benchmark algorithms.

Based on the statistical results, the proposed MCPSFOA achieves the best ranking and obtains the best mean values on 16 out of 24 functions. Specifically, on the unimodal functions F1 to F9, the mean and Std values obtained by MCPSFOA are zero in F1, F2, F3, F4, F5, and F9 functions, which are equal to the theoretical optimum. In contrast, SFOA, TLBO, LSHADE-cnEpSin, SRS, and GWO achieve the best values in 6, 2, 2, 2, and 1 functions, respectively, and other algorithms do not obtain the best values among all unimodal functions. On the multimodal functions F10 to F24, MCPSFOA achieves the best values and theoretical optimums in F11, F13, F14, F15, F16, F19, F21, F22, F23, F24 functions, and achieves the second best in F10, F12, F18 functions. In comparison, SFOA achieves the best values in 10 functions, DE, SRS, LSHADE-cnEpSin, TLBO, PGA, LSHADE-SPACMA, and GWO obtain the best values in 6, 5, 5, 3, 3, 2, 1 functions, respectively. According to the Friedman mean rank values for classical functions, the top five algorithms are as follows: MCPSFOA (2.208), SFOA (2.542), TLBO (3.667), PGA (4.500) and LSHADE-cnEpSin (4.500). Moreover, observations from the third and fourth rows from the bottom of Table 5 indicate that, across the classical benchmark functions, the p-values of MCPSFOA from the Wilcoxon rank-sum test are significantly superior to those of the majority of comparative optimization algorithms. Notably, only SFOA showed no significant difference when compared to MCPSFOA.

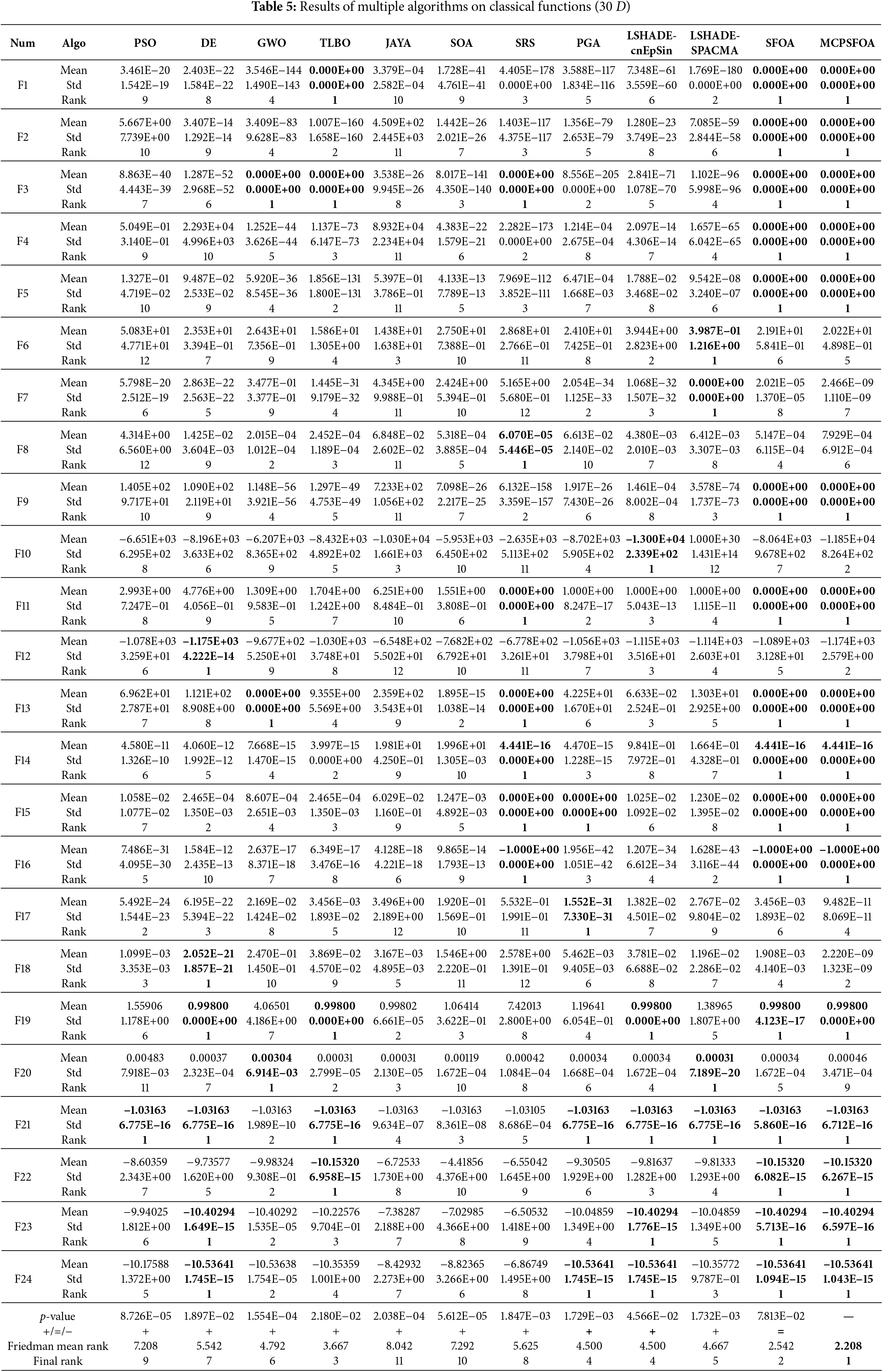

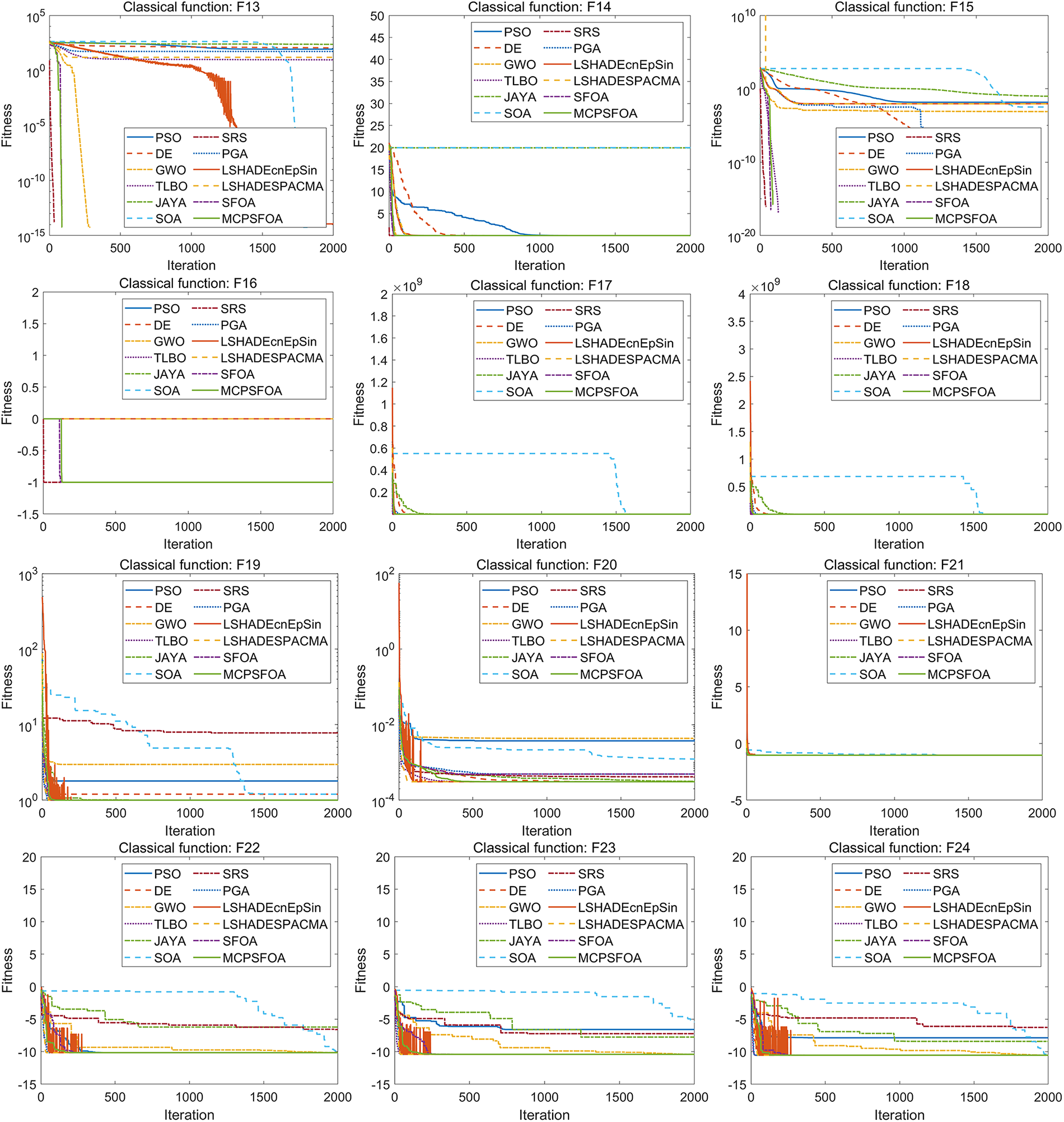

Fig. 2 illustrates the convergence curves of twelve metaheuristic algorithms on a set of classical benchmark functions. The proposed MCPSFOA demonstrates strong overall performance by achieving rapid convergence across multiple functions. Specifically, on functions F1–F5, F9, F13–F16, F19 and F21–F24, it attains either the fastest or the second-fastest convergence speed. In these cases, MCPSFOA consistently reaches the optimal solution well before the 500th iteration. This behavior indicates an effective balance between exploration and exploitation, which allows the algorithm to maintain strong convergence capacity without premature stagnation.

Figure 2: Convergence curves of multiple algorithms on the classical functions (30 D)

4.2 Classical Functions Test Results

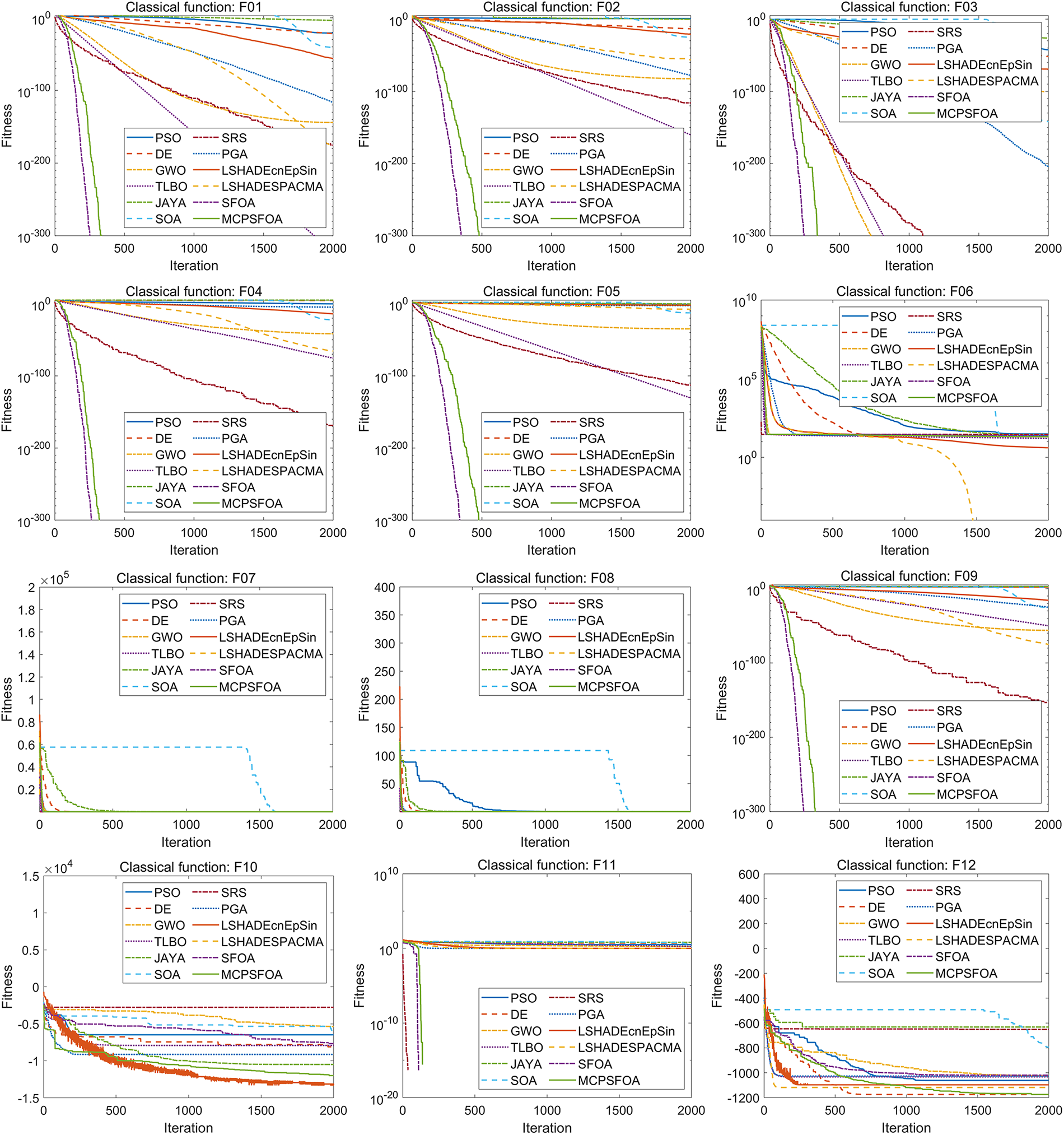

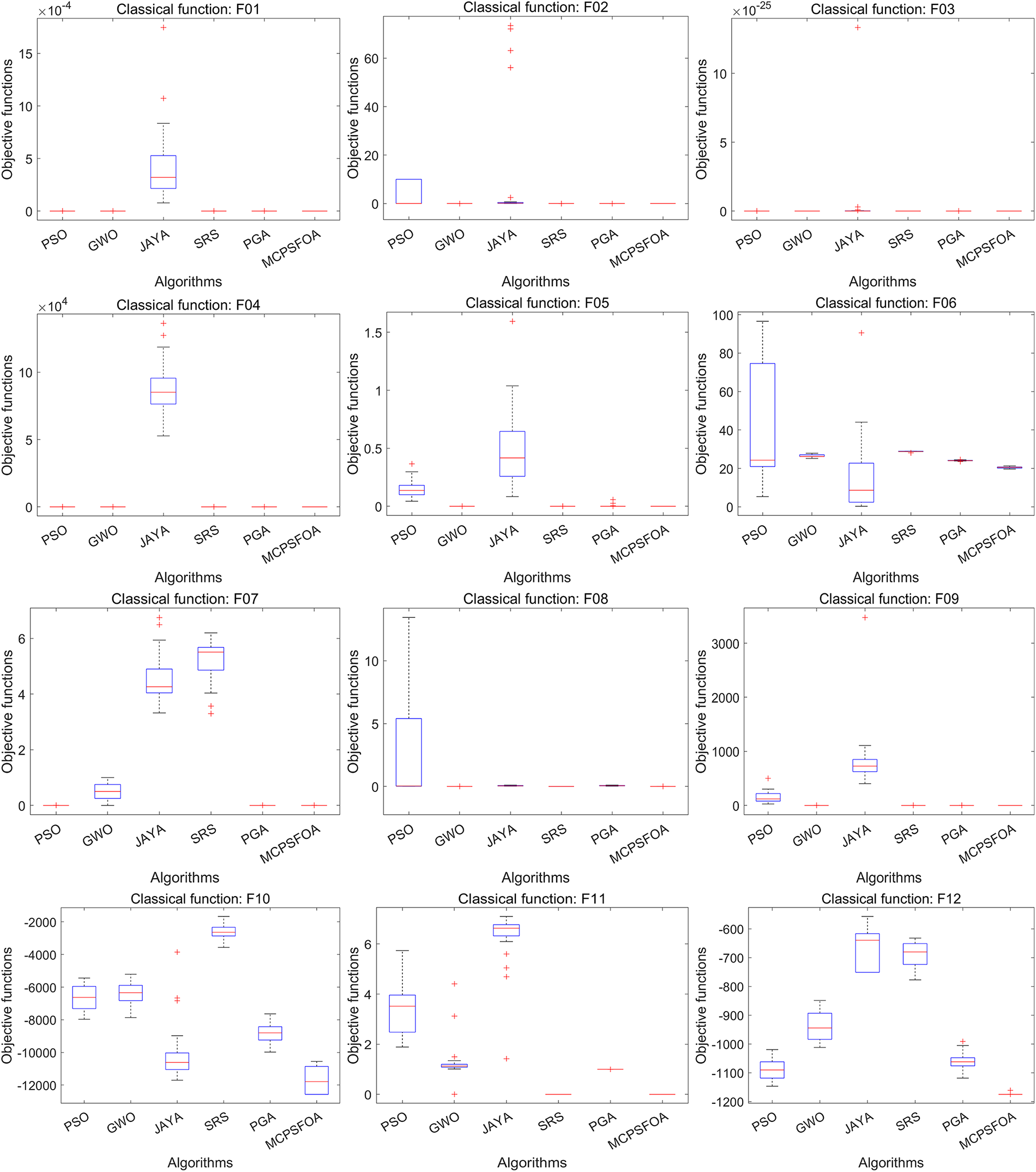

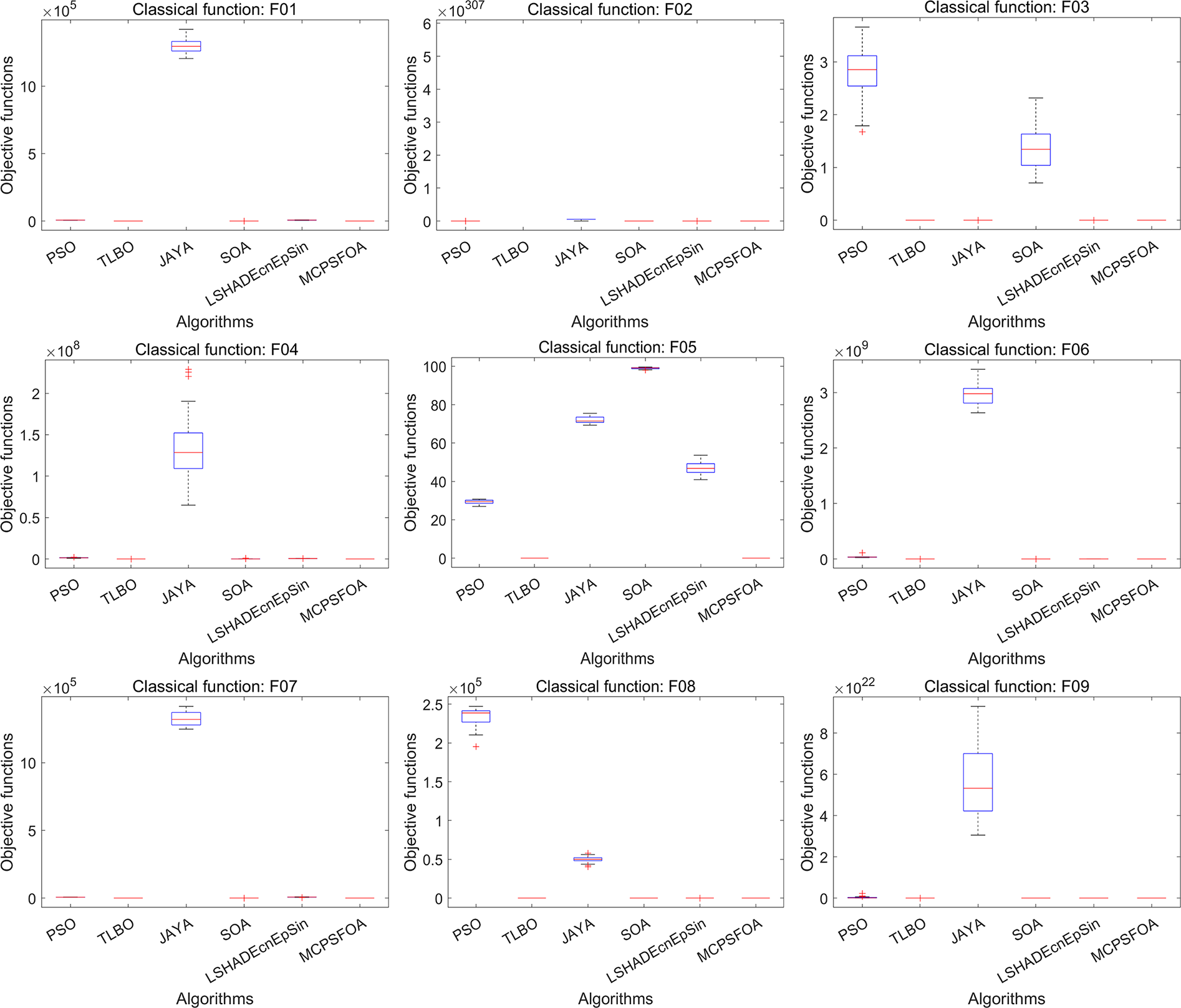

The MCPSFOA is evaluated on 24 classical functions and judged against 11 excellent metaheuristic algorithms. Table 5 summarizes the statistical results, including mean values (Mean), standard deviation (Std), and rank of each algorithm (Rank), while the best mean and Std are emphasized in bold on each function. Fig. 2 presents the convergence curves of the various algorithms, where the MCPSFOA is highlighted with a solid green line. Fig. 3 shows the corresponding boxplots, with the MCPSFOA positioned on the far right.

Figure 3: Boxplots of multiple algorithms on the classical functions (30 D)

Fig. 3 presents a comparative analysis of result distributions through boxplots for six algorithms, including PSO, GWO, JAYA, SRS, PGA, and the proposed MCPSFOA. Visually, the boxes for MCPSFOA are consistently lower, narrower, and contain fewer outliers than those of other algorithms. These traits collectively signify superior solution accuracy and remarkable stability. Quantitatively, MCPSFOA exhibits a smaller interquartile range on most functions. This directly reflects its reduced performance variance and stronger robustness across different problem landscapes.

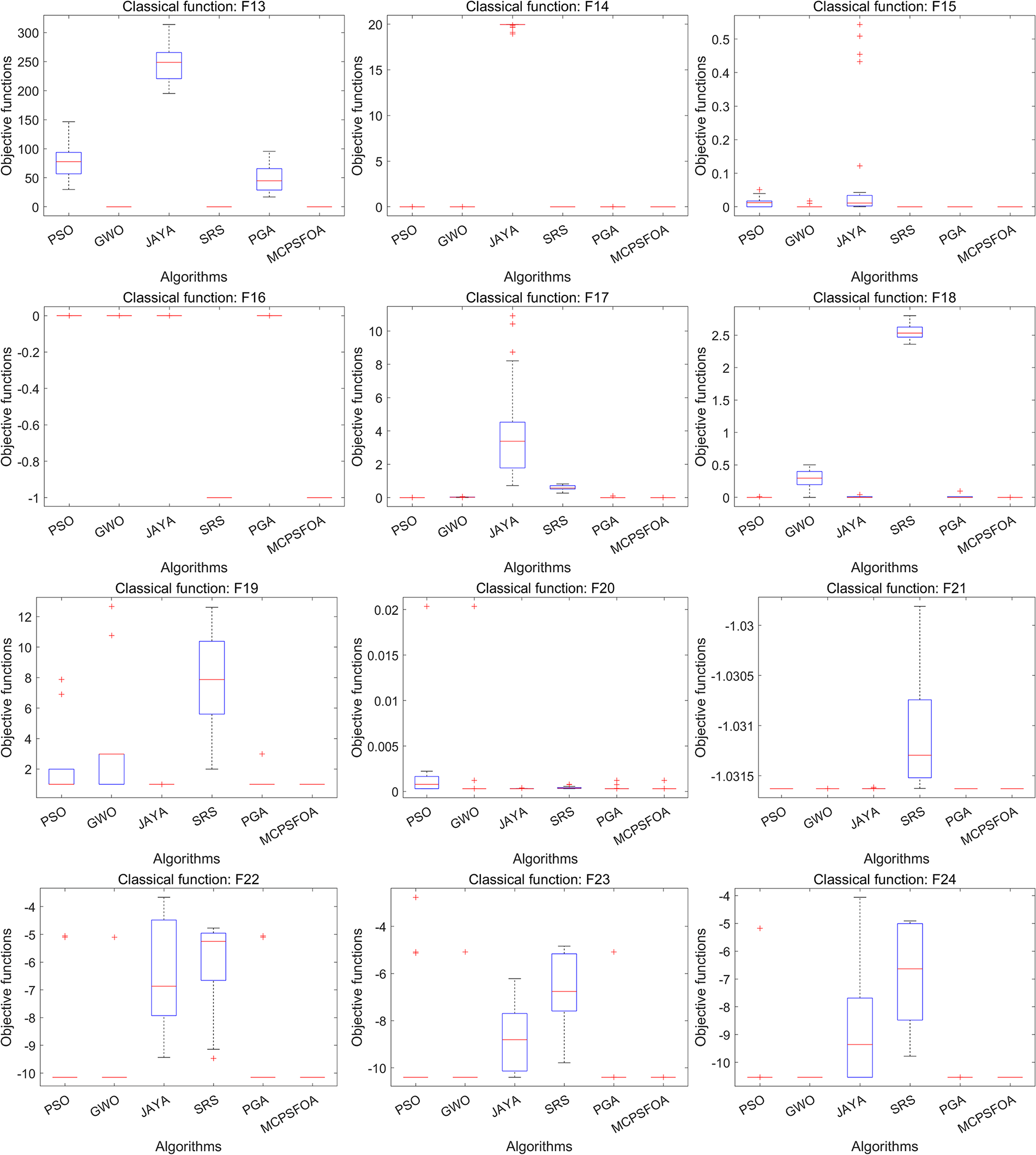

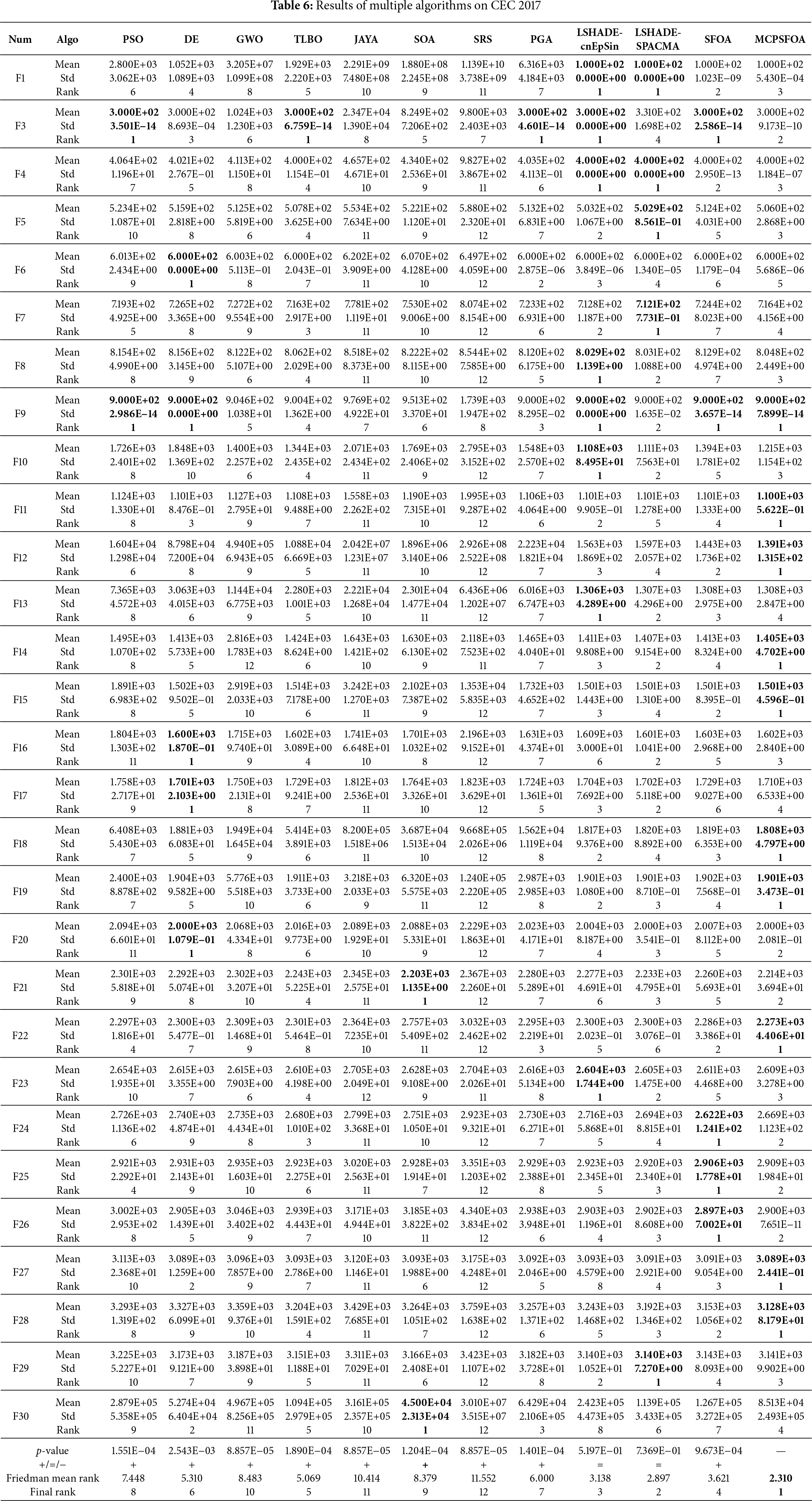

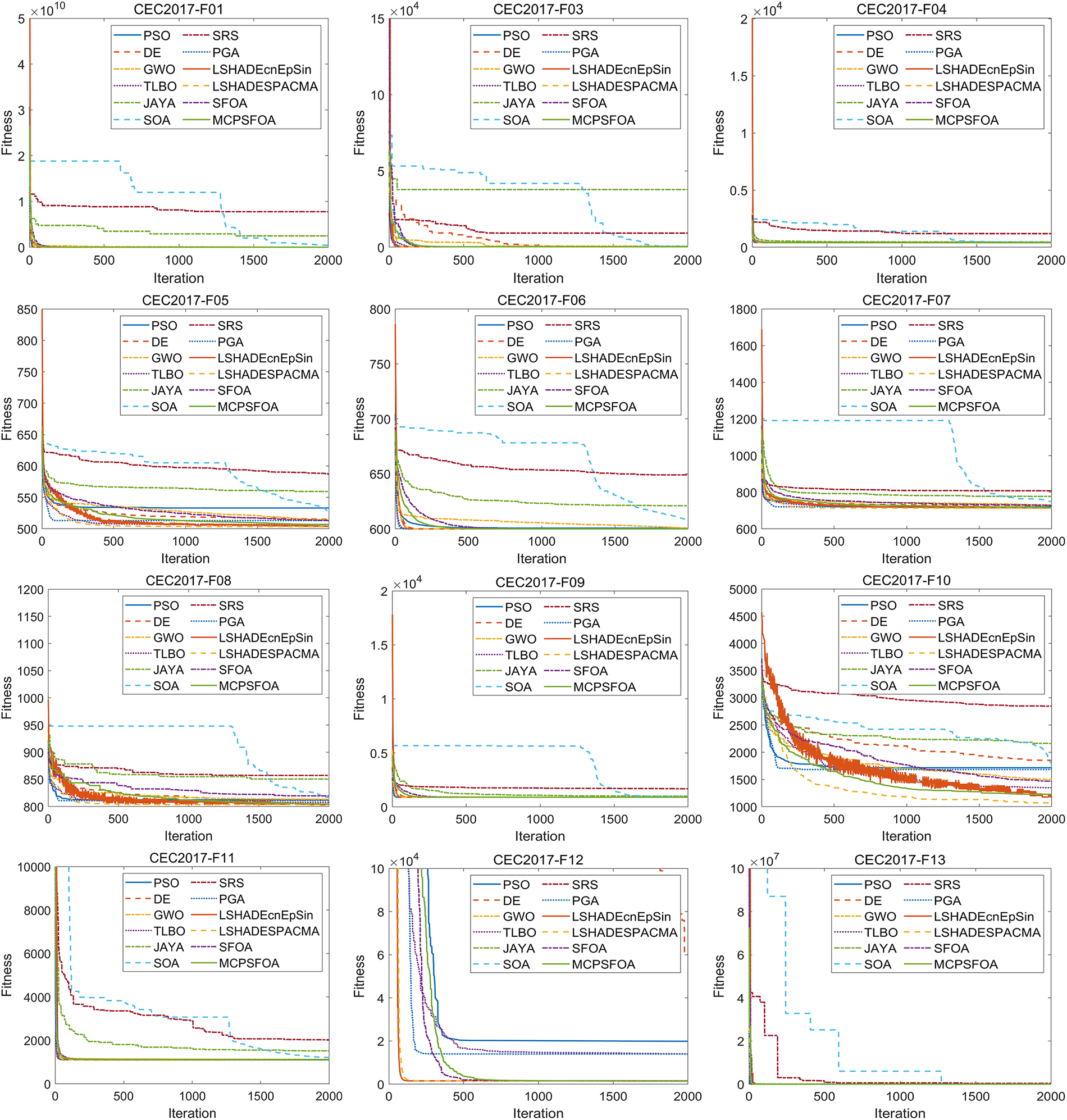

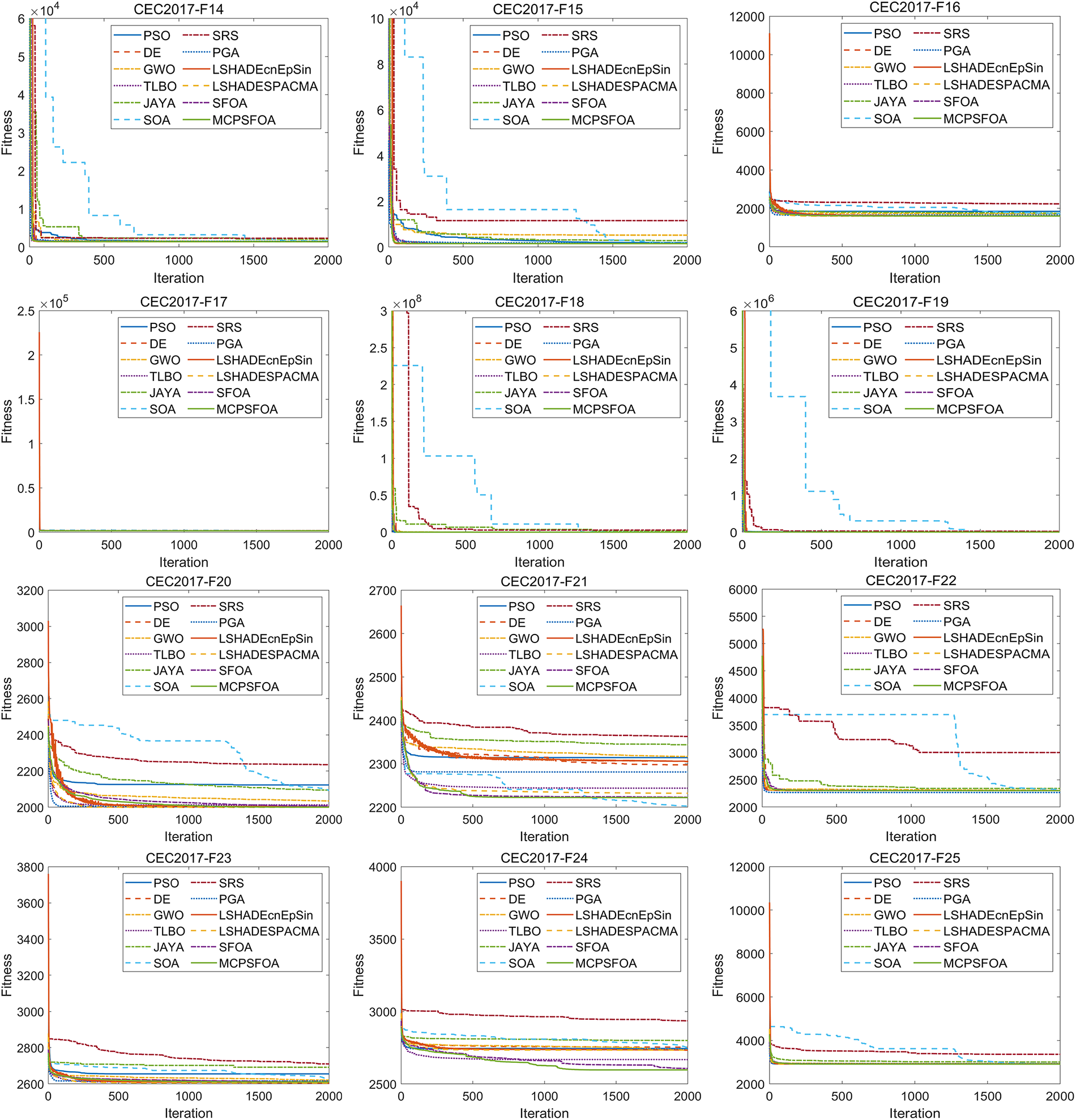

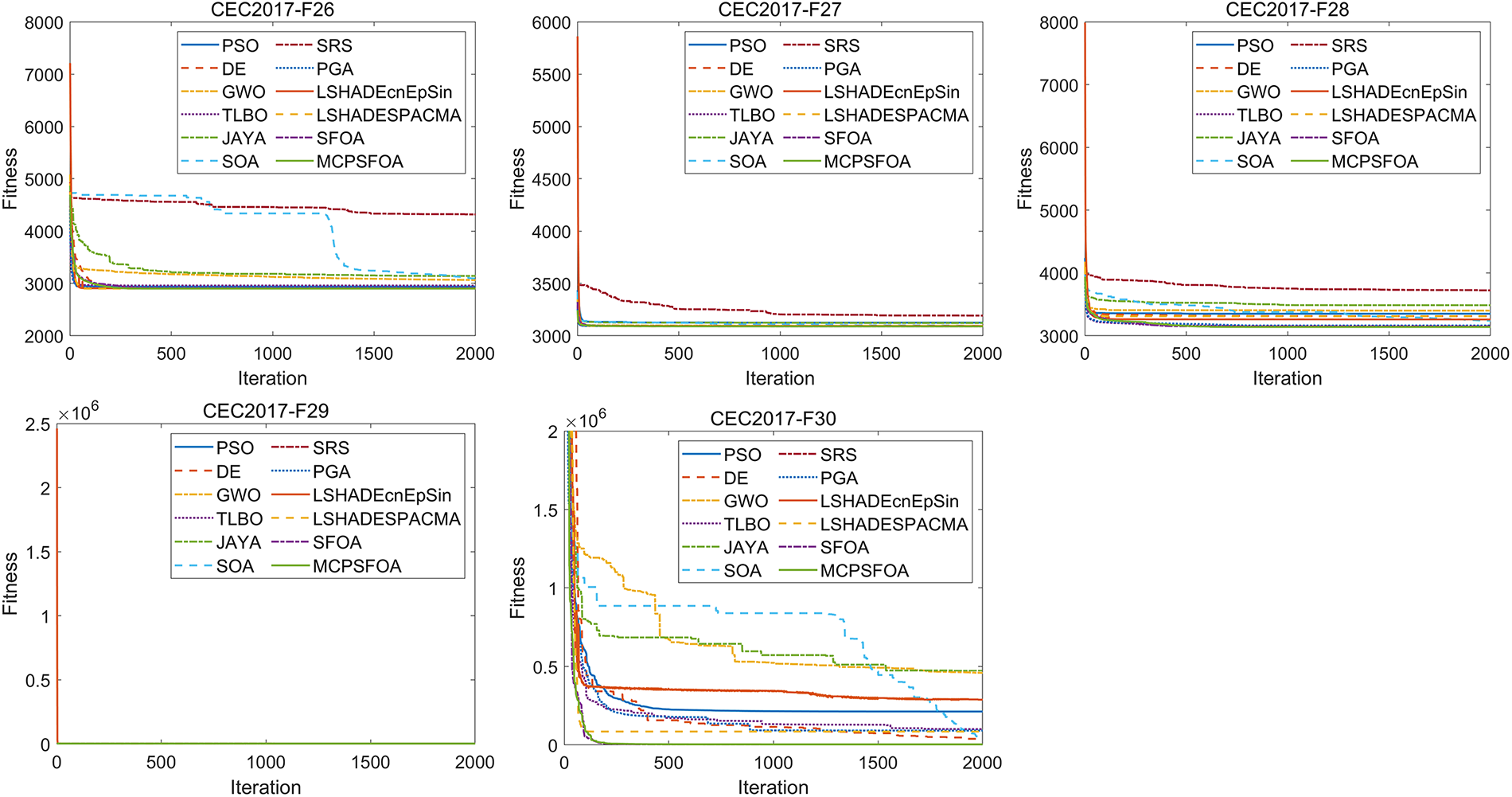

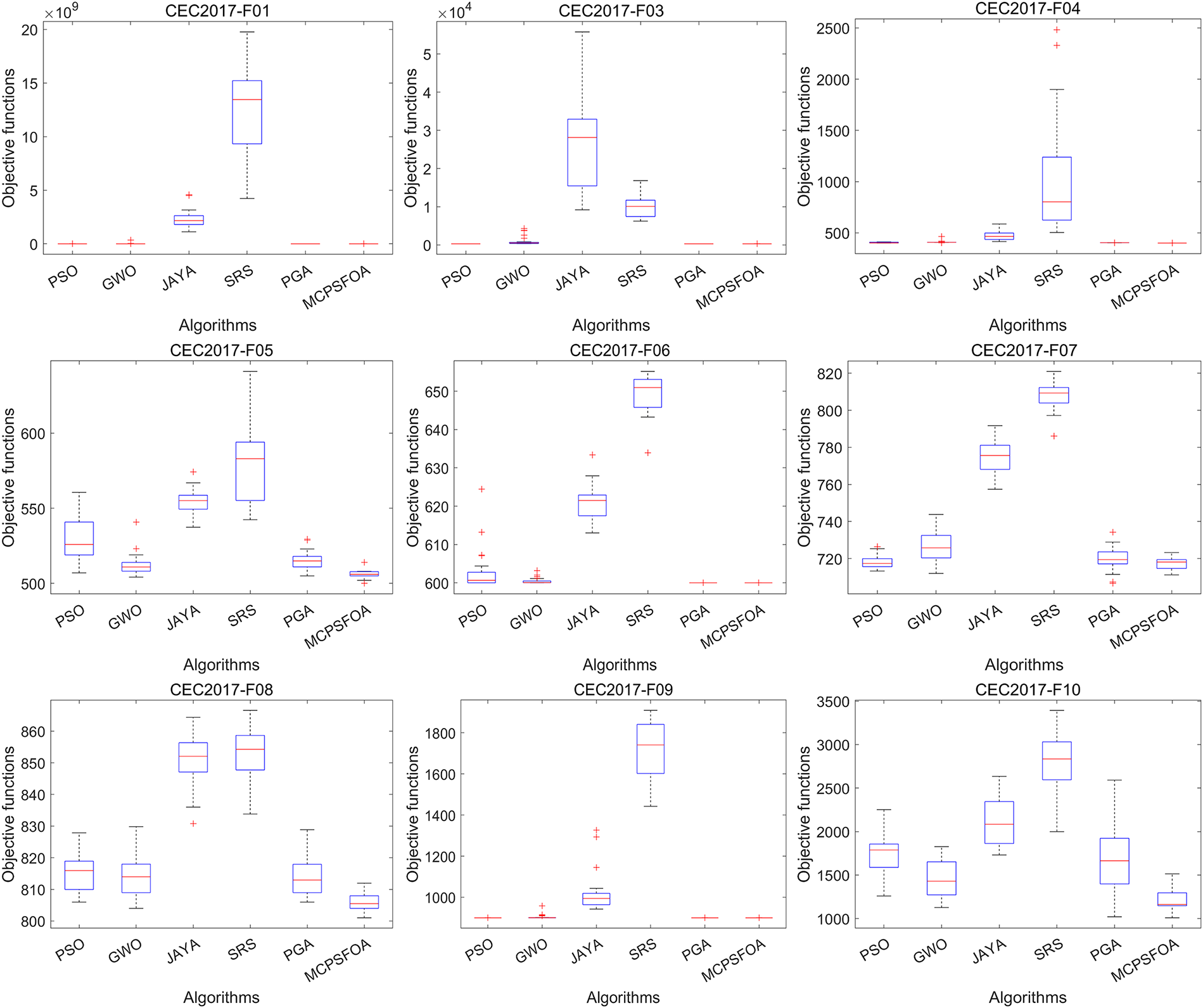

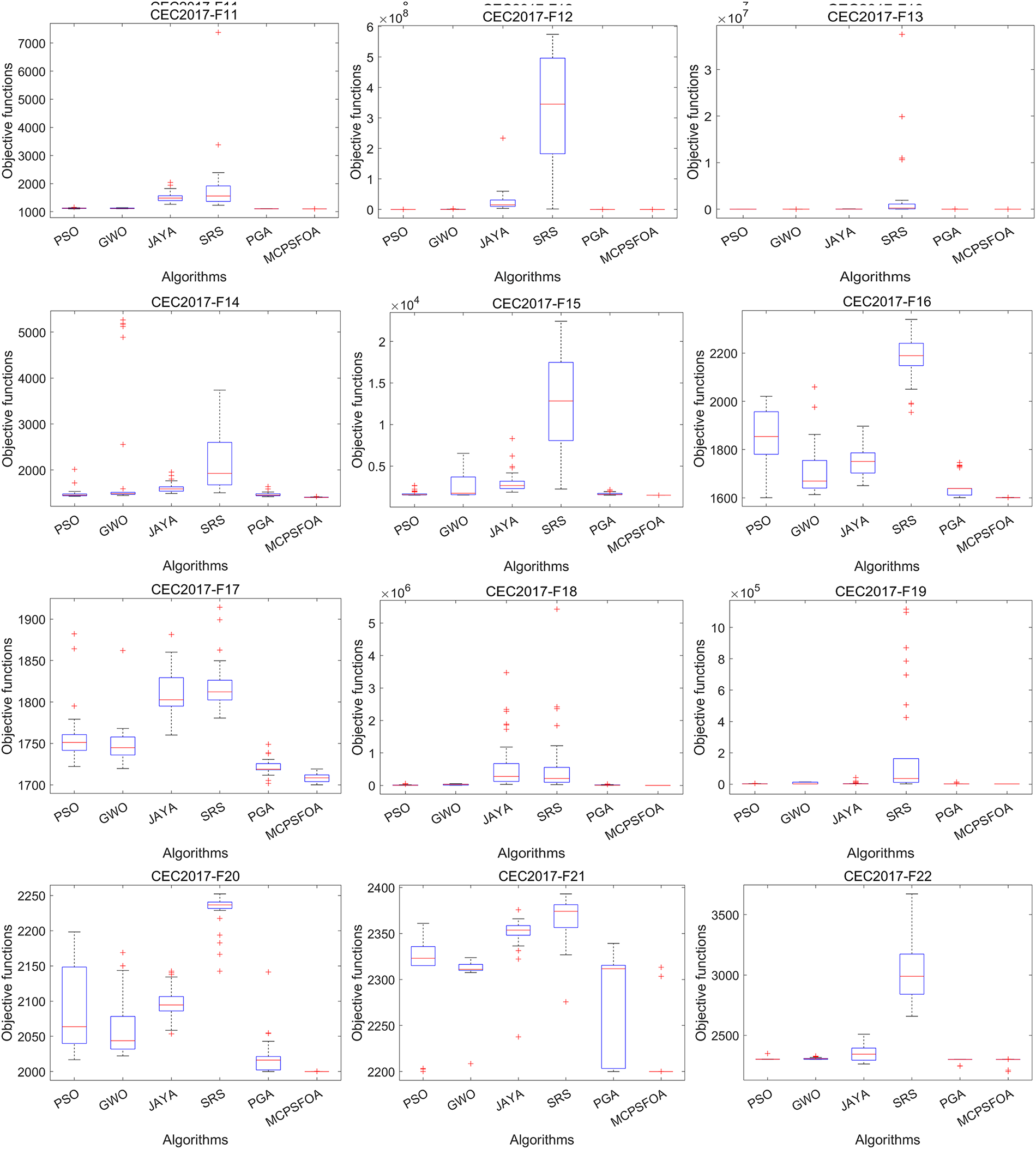

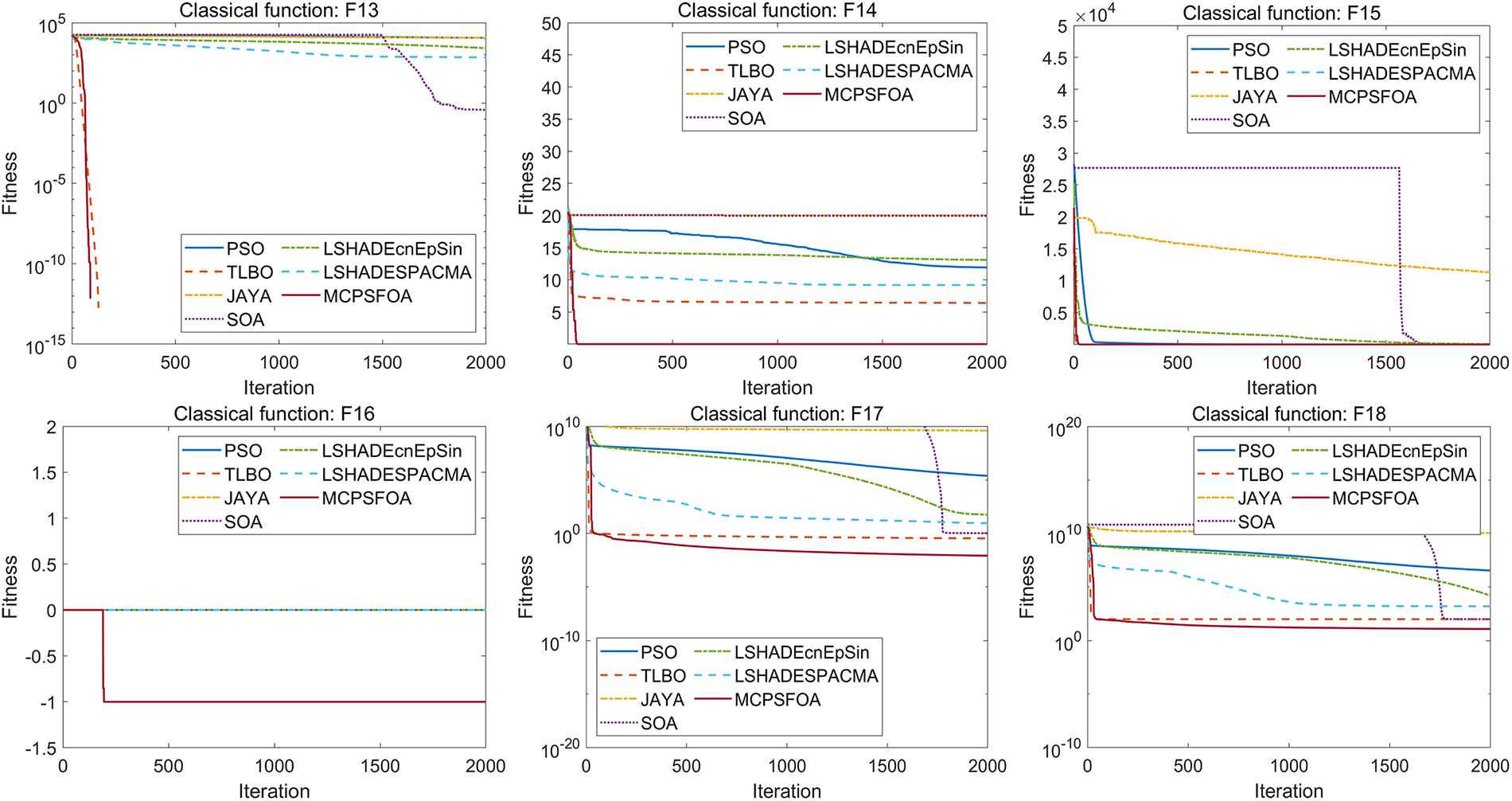

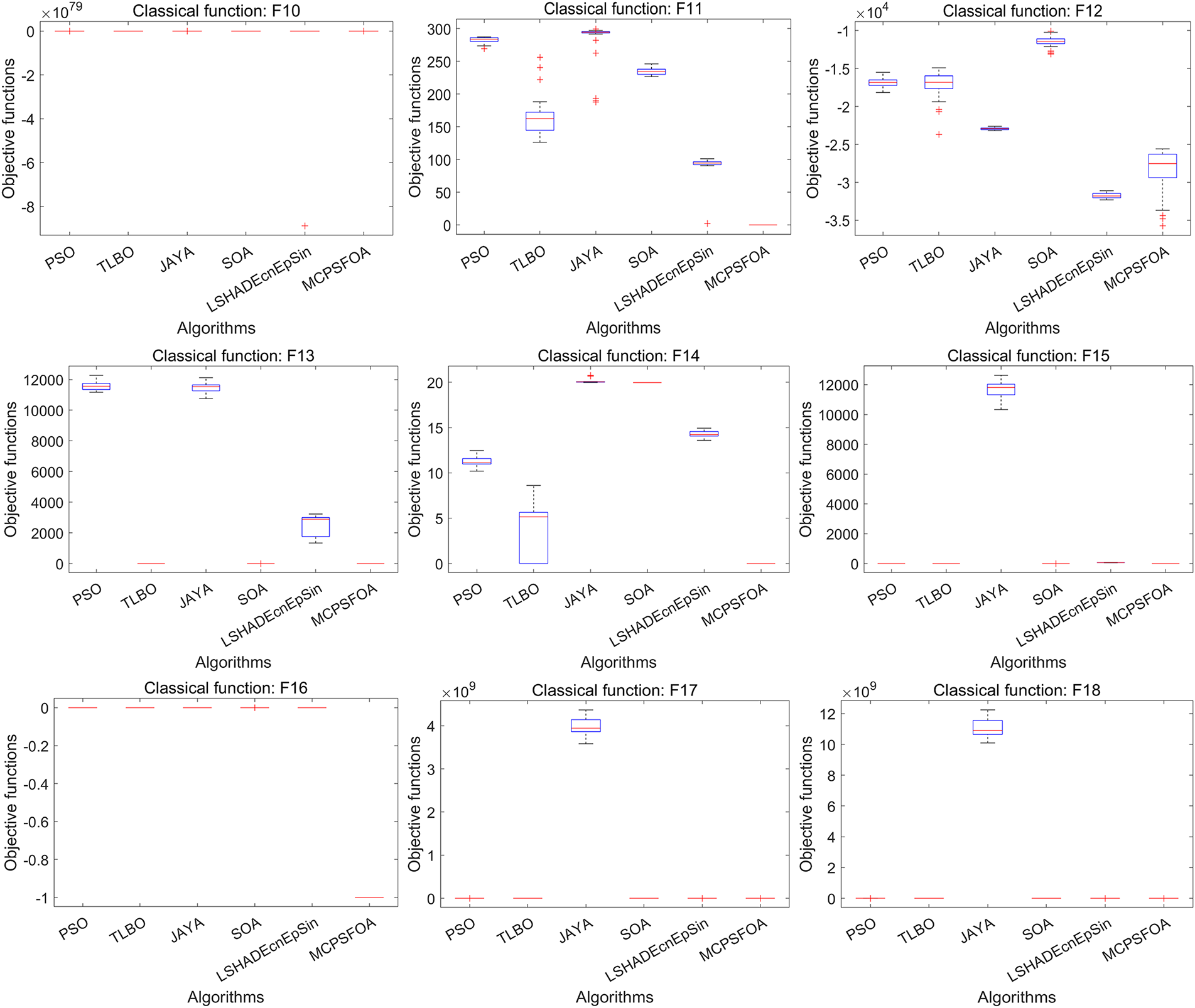

In the testing of the CEC2017 test, MCPSFOA was challenged with 29 test functions. The mean, Std, and rank of all algorithms are summarized in Table 6. The convergence performance of the algorithms is illustrated in Fig. 4 and the proposed MCPSFOA is represented by the solid green line. Fig. 5 illustrates the statistical distribution via boxplots, where the result for MCPSFOA corresponds to the rightmost box.

Figure 4: Convergence curves of multiple algorithms on the CEC 2017

Figure 5: Boxplots of multiple algorithms on the CEC 2017

The results show that MCPSFOA (2.345) outperforms the original SFOA (3.655) in the Friedman mean rank, proving the effectiveness of the proposed optimization strategy. From the results of each function, MCPSFOA achieved the best ranking in 10 out of 29 functions, ranked second in 6 functions, and third in 7 functions. In other words, MCPSFOA ranked among the top three in 79.31% of the functions, demonstrating its strong competitiveness. On relatively easy functions, MCPSFOA can achieve a better average value with high convergence accuracy, which highlights the algorithm’s powerful ability in fine search and can rapidly and precisely converge to the global optimum. In more challenging functions, MCPSFOA also performs well, indicating that its global search capability is equally outstanding and can effectively escape the traps of numerous local optima. Furthermore, observations from the third and fourth rows from the bottom of Table 6 reveal that, across the CEC 2017 benchmark function set, the p-values of MCPSFOA from the Wilcoxon rank-sum test are significantly superior to those of the majority of comparative optimization algorithms. Only LSHADE-cnEpSin and LSHADE-SPACMA showed no significant difference when compared to MCPSFOA.

The convergence curves results indicate that MCPSFOA demonstrates strong global convergence capability on functions F1, F3, F4, F9, F11–F20, F22–F25, and F27–F29 of the CEC2017 test set. In 20 functions, MCPSFOA reached or approached the global optimum within the first 500 iterations. Its convergence speed outperforms most of the compared algorithms. Some algorithms, such as SOA and PSO, exhibit significant oscillations on the CEC2017 multimodal test functions and struggle to converge to the global optimum. In comparison with SFOA, MCPSFOA shows better convergence curves in 22 functions, comparable performance in 3 functions, and inferior results in only 4 functions. These convergence results confirm that MCPSFOA possesses a strong ability to escape local optima and locate the global optimum.

The box plot comparison results in Fig. 5 show that the solution distribution of MCPSFOA is the most compact, with the smallest fluctuation range and fewer outliers, fully demonstrating its excellent stability. Although it leads in overall performance, in some specific functions, MCPSFOA still has room for improvement. For example, in function F25, the box plot of MCPSFOA is longer and higher than that of GWO, indicating that the performance of MCPSFOA is not as good as GWO in achieving higher accuracy and stability on this F25 function. This observation is consistent with the No Free Lunch theorem, which suggests that no single algorithm can outperform all others across every function. Overall, thanks to its effective update and convergence mechanisms, MCPSFOA achieves superior performance in the boxplot comparisons.

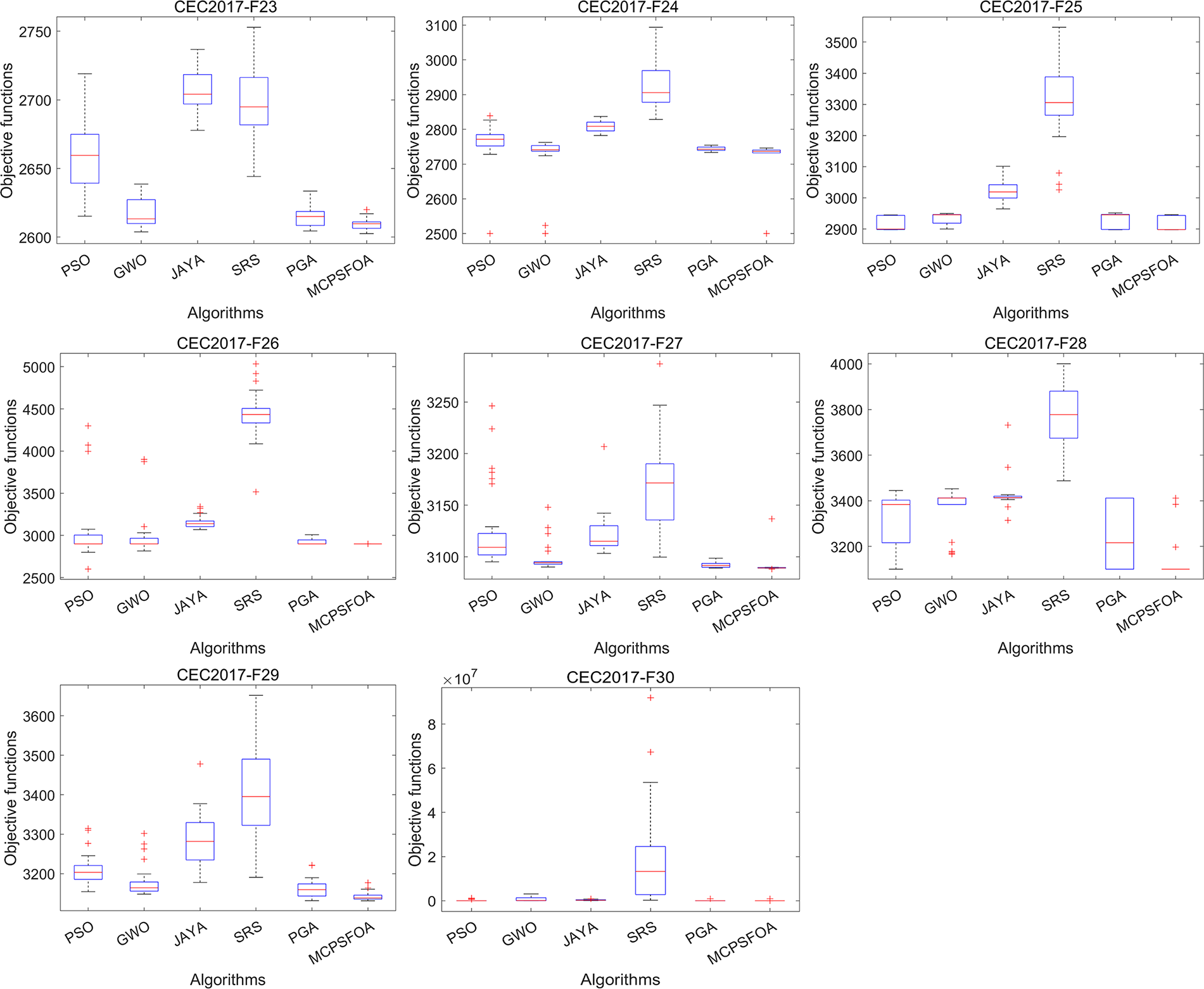

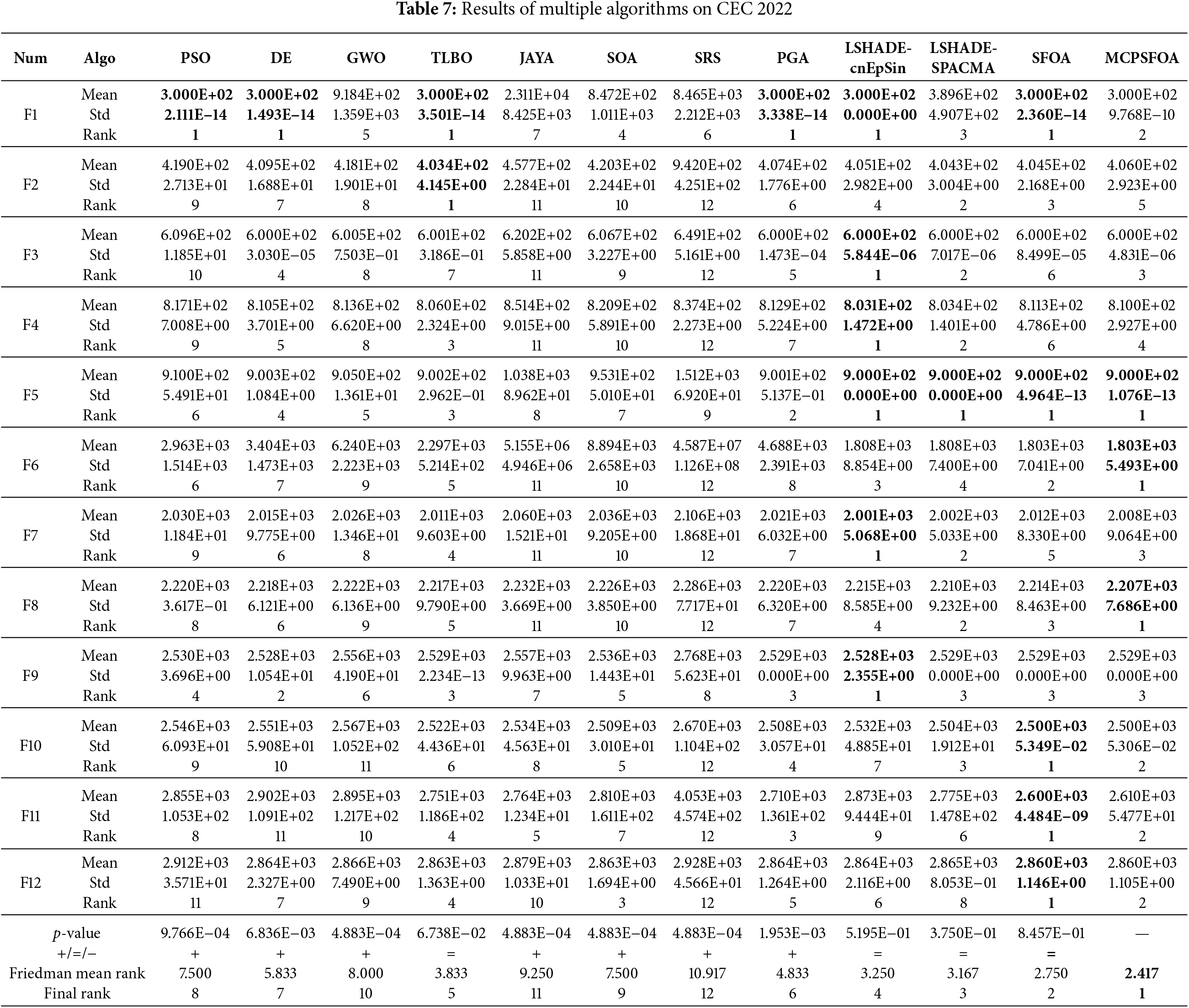

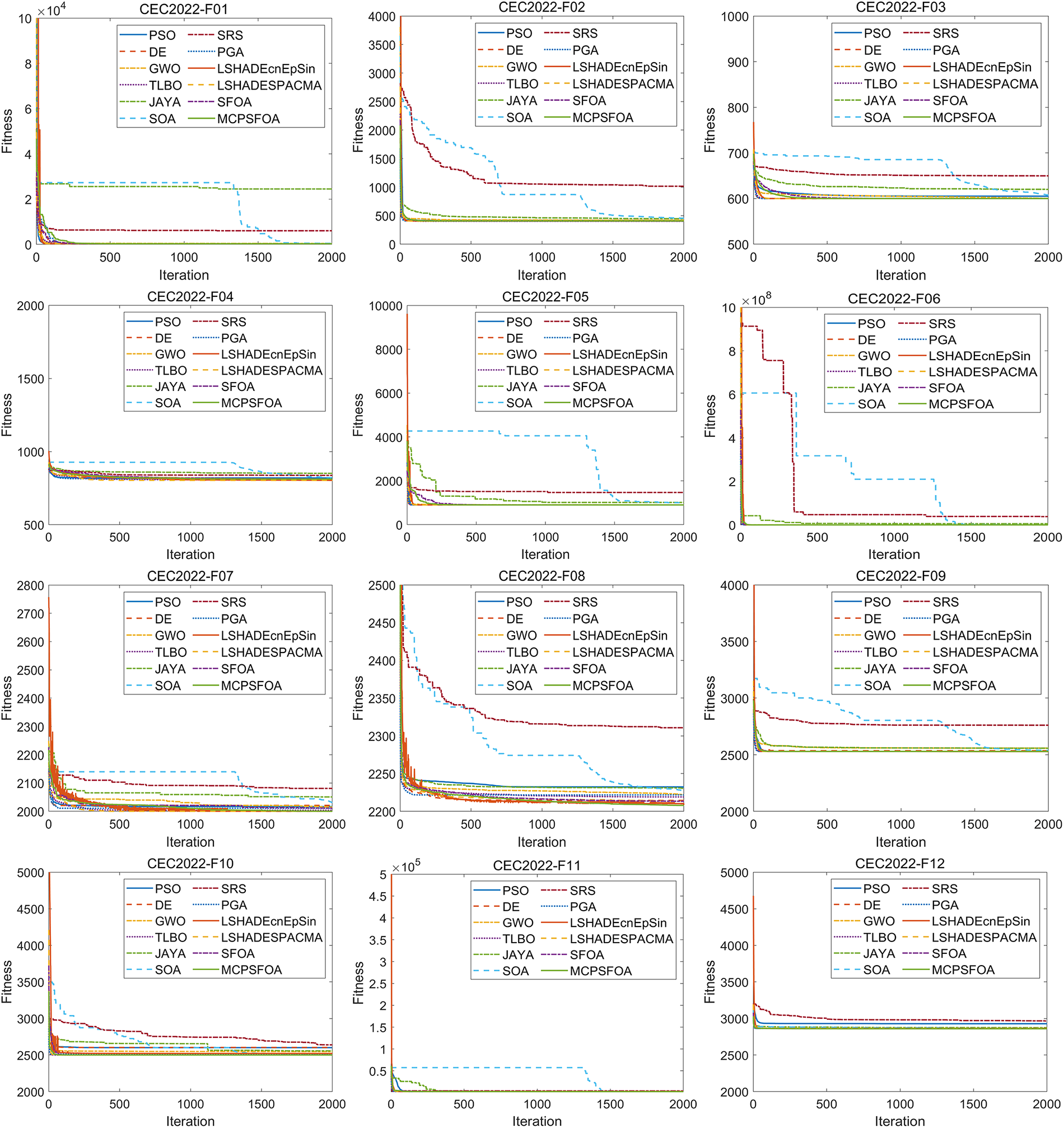

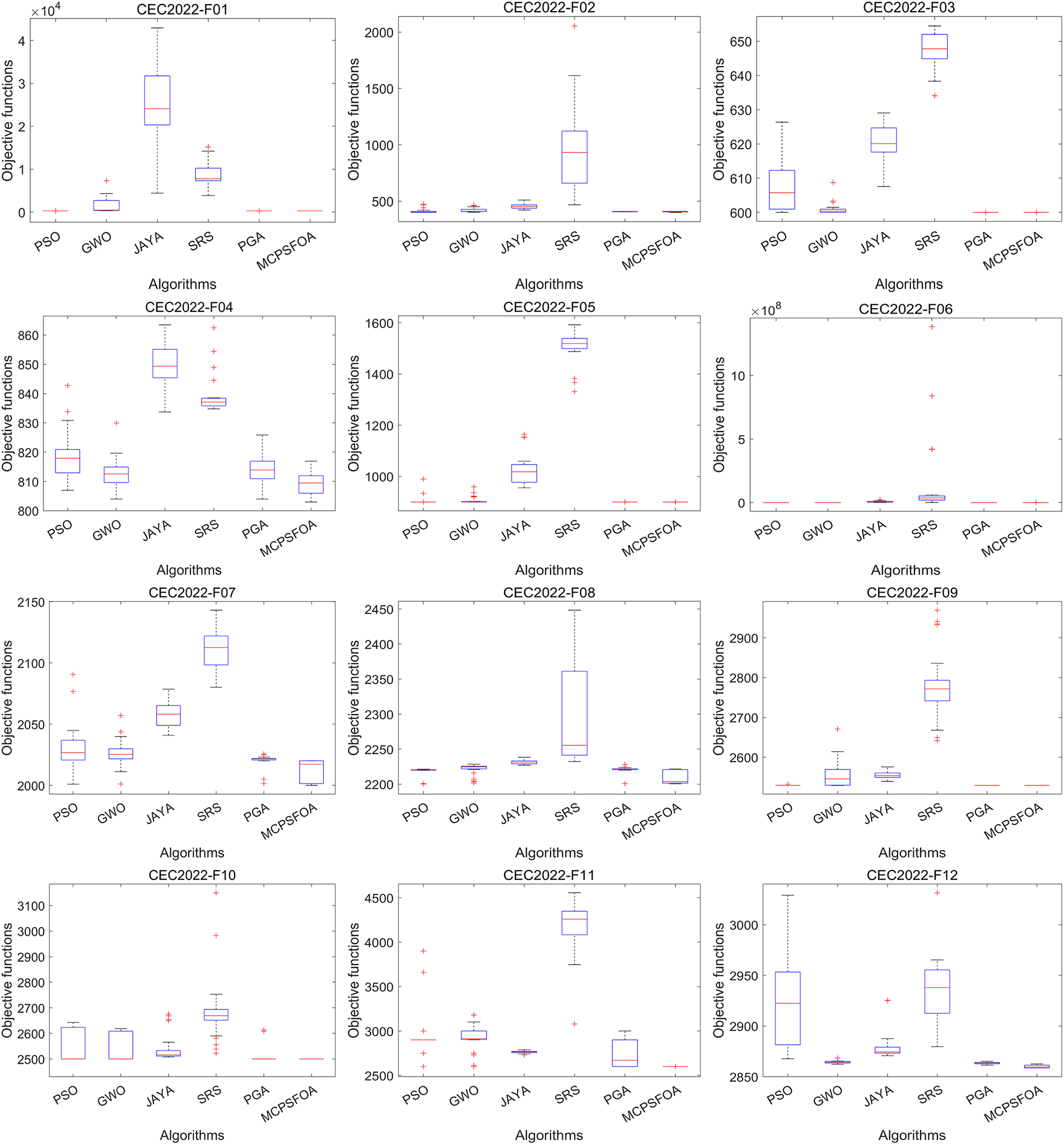

We tested MCPSFOA’s performance with the more challenging CEC2022 test. The CEC2022 test set introduces a more complex function structure, a more challenging search landscape, and a higher problem dimension in its design, aiming to simulate the tricky optimization fields encountered in current real-world applications. All algorithms are calculated with the same number of runs, and the results are presented in Table 7. Fig. 6 depicts the convergence curves for all algorithms, with the proposed MCPSFOA plotted as a solid green line. In Fig. 7, which provides the boxplots, MCPSFOA appears on the right-hand side.

Figure 6: Convergence curves of multiple algorithms on the CEC 2022

Figure 7: Boxplots of multiple algorithms on the CEC 2022

As evidenced by Table 7 that in the Friedman mean rank, the first place is MCPSFOA (2.417), the second place is SFOA (2.750), and the third place is LSHADE-SPACMA (3.167), which reflects the positive effect of optimizing SFOA. For each function being solved, MCPSFOA ranks first among F5, F6, and F8 with the smallest Std, second among F1, F10, F11, and F12, and third among F3, F7, and F9. It indicates that MCPSFOA ranks among the top three in 10 out of 12 functions, accounting for 83.33% of the total functions. The functions of CEC2022 have put forward higher requirements for the learning and adaptability of algorithms. MCPSFOA achieves better average values and lower Std on these functions, which indicates that the operator of MCPSFOA is very finely designed to effectively handle complex variable interactions and rugged search space. The more complex the problem is, the greater the difficulty for the algorithm to maintain stability. The fact that MCPSFOA achieves a lower Std indicates that it can provide reliable solutions for new types of problems with strong uncertainties. Furthermore, observations from the third and fourth rows from the bottom of Table 7 reveal that, with respect to the CEC 2022 benchmark function set, the p-values of MCPSFOA from the Wilcoxon rank-sum test are significantly superior to those of most comparative optimization algorithms. Specifically, only TLBO, LSHADE-cnEpSin, LSHADE-SPACMA, and SFOA showed no significant difference in performance when compared to MCPSFOA.

As illustrated in the convergence curves, MCPSFOA consistently exhibits the fastest or a relatively fast convergence speed, achieving favorable results on most test functions. Moreover, its convergence process remains smooth and stable throughout the iterations, without the abnormal fluctuations observed in algorithms such as LSHADE-cnEpSin. In comparison, the performance of other algorithms reveals areas for improvement. SOA exhibits a slower convergence rate on functions F1 to F3 and F5 to F11. PSO shows a tendency to converge prematurely, especially on functions F6 through F8. DE occasionally encounters difficulties in escaping local optima, particularly on F6 and F11. SRS fails to reach the global solution on multiple functions, including F2, F3 and F7 to F12.

The boxplots analysis further confirmed the outstanding performance of MCPSFOA across most of the test functions. Compared with algorithms such as SRS, JAYA, PSO, and GWO, the output results of MCPSFOA exhibit smaller fluctuations, demonstrating stronger robustness and consistency. In contrast to the comparison algorithms, they present a slender box structure in multiple CEC 2022 functions, indicating high result dispersion and poor stability. This intuitive visual comparison clearly shows that under the same experimental conditions, MCPSFOA possesses more stable and efficient global optimization capabilities.

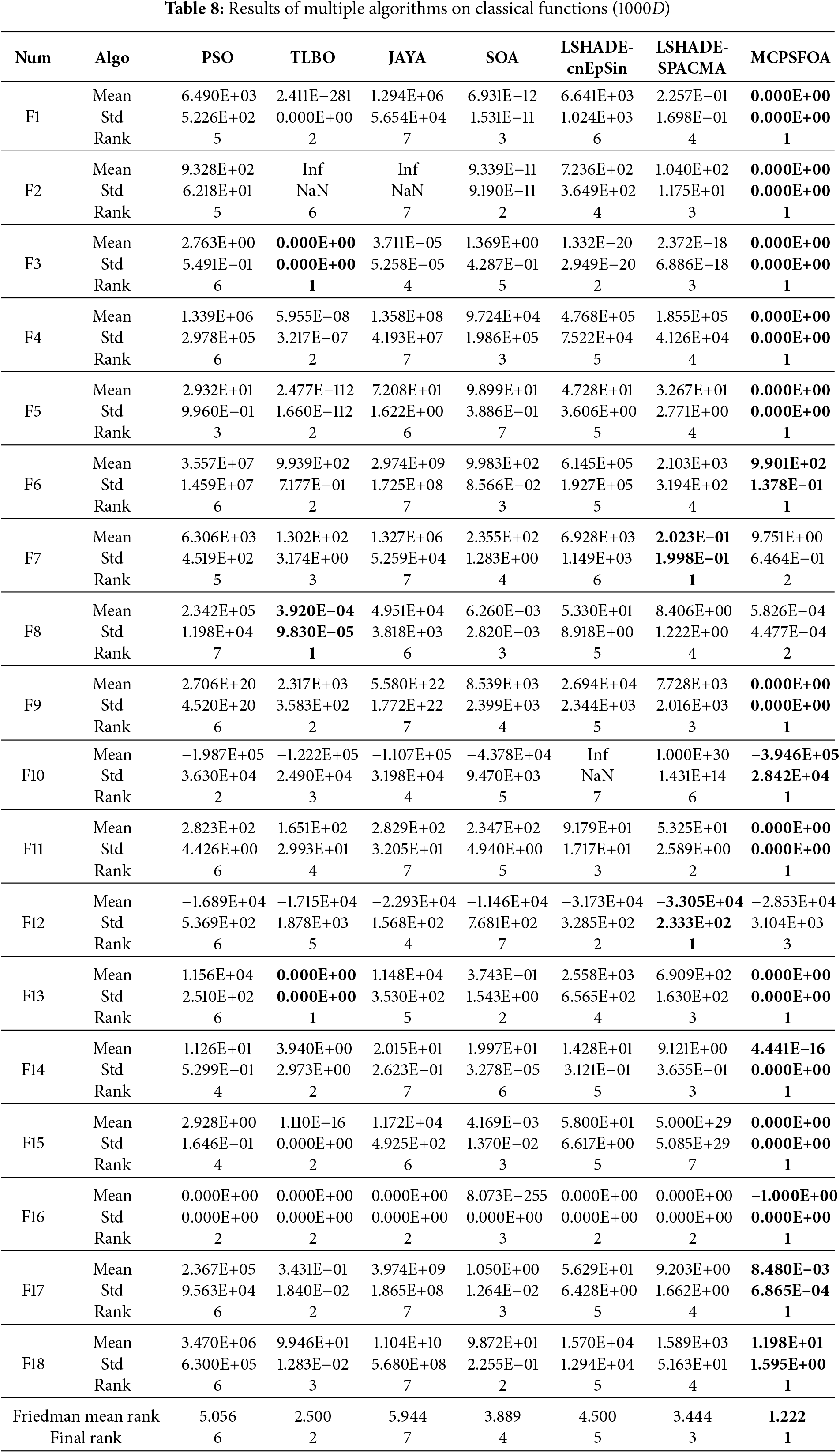

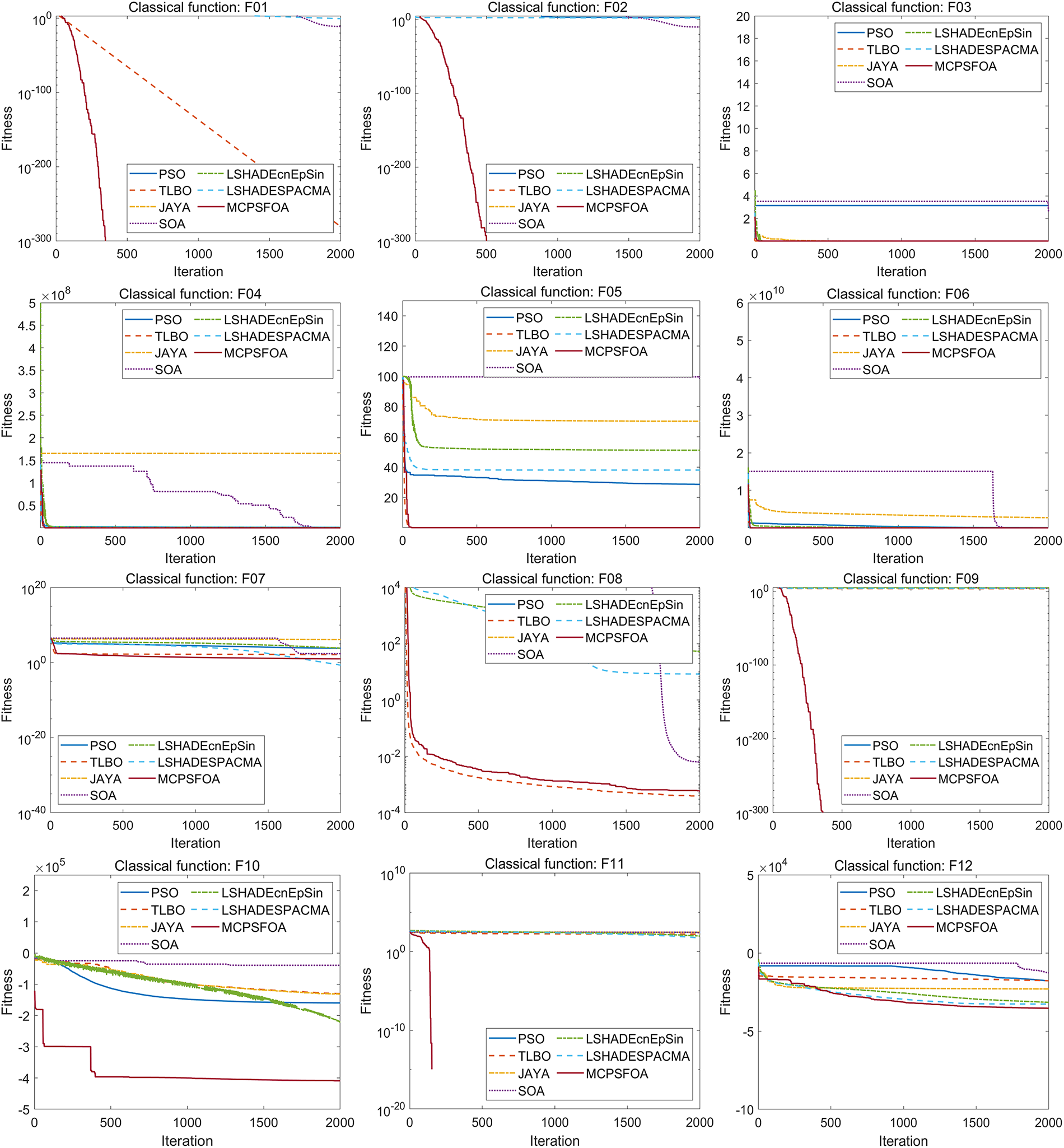

4.5 Results for High-Dimensional Benchmark Functions

Furthermore, this study validates the MCPSFOA using high-dimensional benchmark functions (D = 1000) from classical functions F1–F18, to indicate the searching capacity of MCPSFOA for a high-dimensional search space. For simplicity, MCPSFOA is compared with PSO, TLBO, JAYA, SOA, LSHADE-cnEpSin, and LSHADE-SPACMA. The relevant parameters are the same in Table 4.

The findings from the statistical analysis conducted on high-dimensional functions are summarized in Table 8. These results suggest that MCPSFOA provides superior performance for high-dimensional functions, ranking first at 15 out of 18 functions, ranking second in functions F7 and F8, and ranking third in function F12. In comparison, TLBO and LSHADE-SPACMA achieve the first rank in 3, 2 functions, respectively; whereas the other algorithms did not rank first on any function. The Friedman mean ranks by algorithms are 1.222 (MCPSFOA, 1st), 2.500 (TLBO, 2nd), 3.500 (LSHADE-SPACMA, 3rd), 3.944 (SOA, 4th), 4.556 (LSHADE-cnEpSin, 5th), 5.111 (PSO, 6th), 6.000 (JAYA, 7th).

Fig. 8 illustrates the convergence curves of MCPSFOA and compared algorithms for high-dimensional functions. MCPSFOA (shown in crimson solid line) exhibits the most rapid and precise convergence on functions F1–F6, F9–F11, F13–F18, reaching near-optimal regions early and continuing to refine solution accuracy in later iterations. Some limitations are observed on F7, F12 by MCPSFOA, where convergence accuracy is comparatively reduced. Nonetheless, the overall convergence performance of MCPSFOA exceeds that of the compared algorithms. Fig. 9 displays the resulting boxplots for high-dimensional functions, where the result for MCPSFOA corresponds to the rightmost box. MCPSFOA still has the smallest interquartile range on the majority of test functions, reflecting the reduced result variance and stronger robustness even within the context of high-dimensional optimization. In all, the statistical, convergence, and distributional analyses demonstrate that MCPSFOA can provide strong global search capacity, higher solution precision, and better stability for high-dimensional benchmark functions.

Figure 8: Convergence curves for high-dimensional classical functions (1000D)

Figure 9: Boxplots for high-dimensional classical functions (1000D)

The above analysis shows that the MCPSFOA algorithm, due to its outstanding update mechanism, demonstrates excellent performance in all benchmark functions, including high-dimensional problems. The proposed algorithm combines the update mechanisms of CPO and SFOA, which can well balance the exploration and development capabilities. By integrating the Lévy flight technology, it can quickly jump and thus avoid local optimal solutions. Additionally, it introduces Gaussian mutation to achieve more accurate optimal solutions. Moreover, it breaks the stagnation state through the population diversity enhancement mechanism, thereby preventing premature convergence. In conclusion, the multi-strategy update mechanism further enhances the global convergence and exploration capabilities of the algorithm, enabling it to perform exceptionally well in the benchmark function.

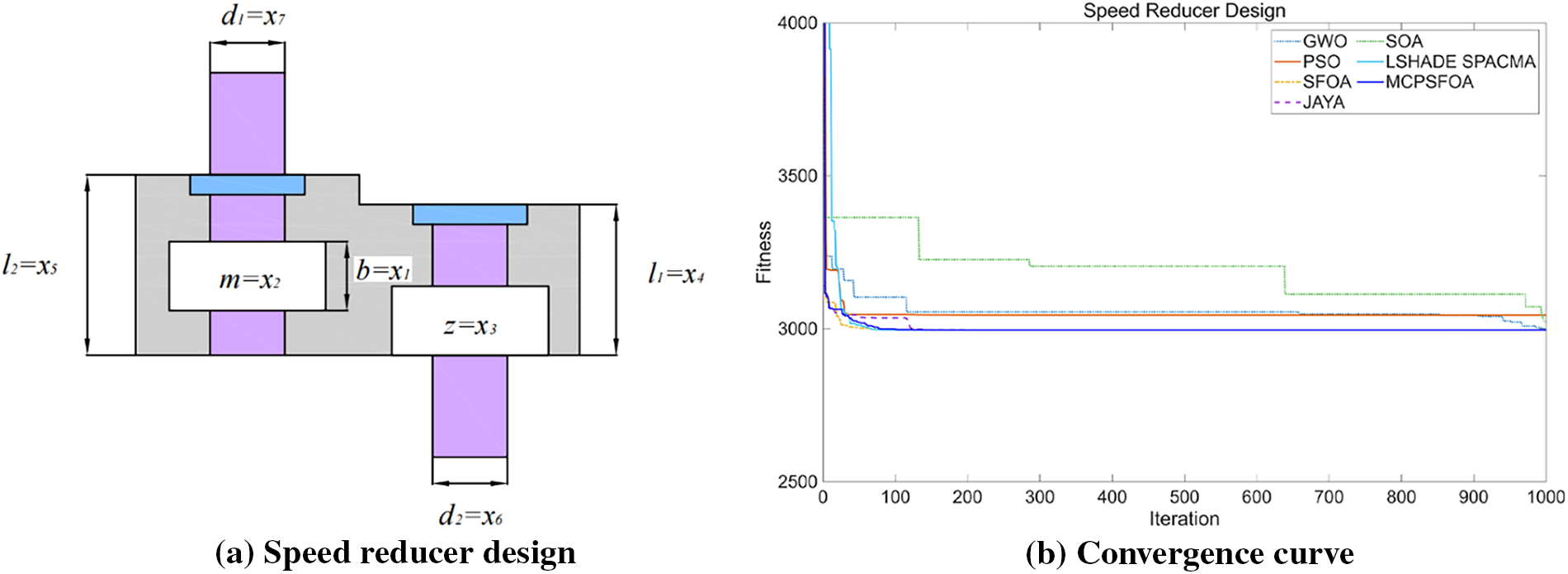

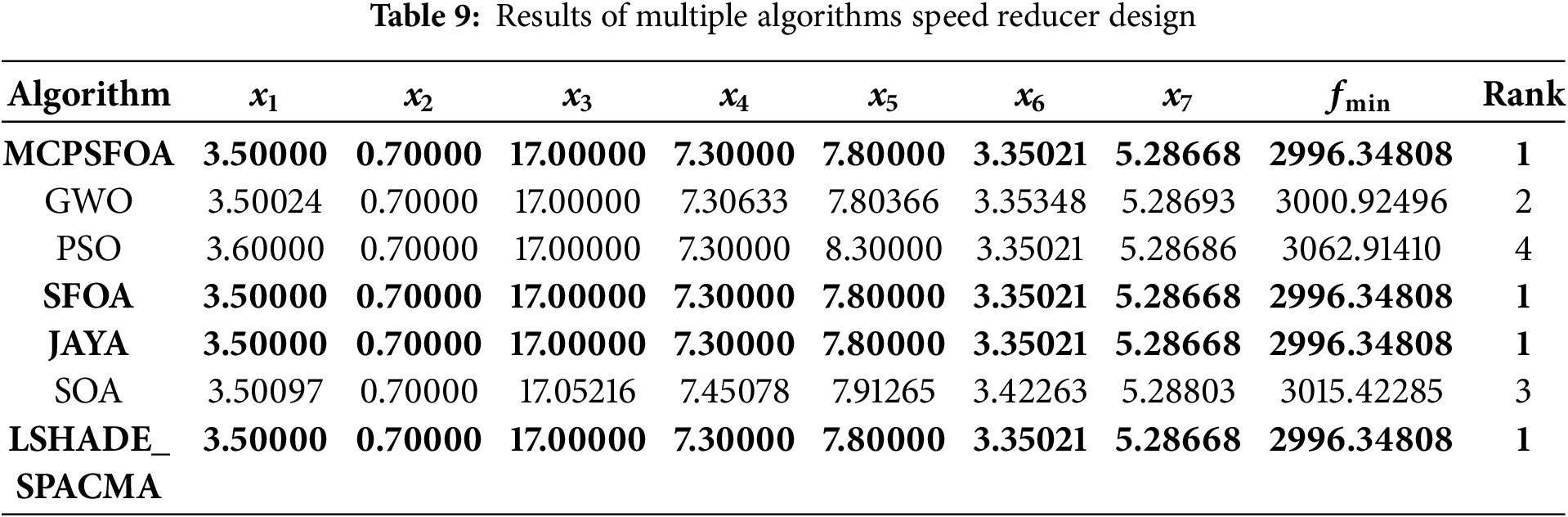

To examine the ability of MCPSFOA to solve practical challenges, we selected 5 real optimization problems for testing. Including speed reducer design, car side impact design, multiple disk clutch brake design, 25-bar truss and tension/compression spring design. All algorithms were compared under the experimental configuration with a population size of 50 and a maximum of 1000 iterations and the operation was repeated 10 times. The algorithms involved in the performance comparison include GWO, PSO, SFOA, JAYA, SOA, and LSHADE_SPACMA.

The speed reducer design problem (Fig. 10) is a well-established benchmark in engineering optimization, characterized by mixed variable types and multiple nonlinear constraints. This problem tests an algorithm’s ability to handle constrained, mixed-variable search spaces. The objective is to minimize the weight of the reducer, with seven design variables: Tooth surface width (b = x1), gear module (m = x2), number of pinion teeth (z = x3), lengths of the first and second shafts between the two bearings (l1 = x4, l2 = x5), and diameters of the two shafts (d1 = x6, d2 = x7), where x3 is a discrete design variable. Moreover, this model also contains 11 constraints, whose mathematical expressions are as follows:

Figure 10: (a) Speed reducer design and (b) the convergence curve

As summarized in Table 9, MCPSFOA achieved a globally competitive solution with a minimum weight of fmin = 2996.34808, at x = (3.5, 0.7, 17, 7.3, 7.8, 3.35021, 5.28668). This result outperforms several established algorithms, including GWO, PSO, and SOA. The convergence behavior further reveals that MCPSFOA maintains a balance between exploration and exploitation, efficiently navigating the constrained design space without premature convergence. This case demonstrates the algorithm’s robustness in solving mixed-integer nonlinear programming problems typical in mechanical design.

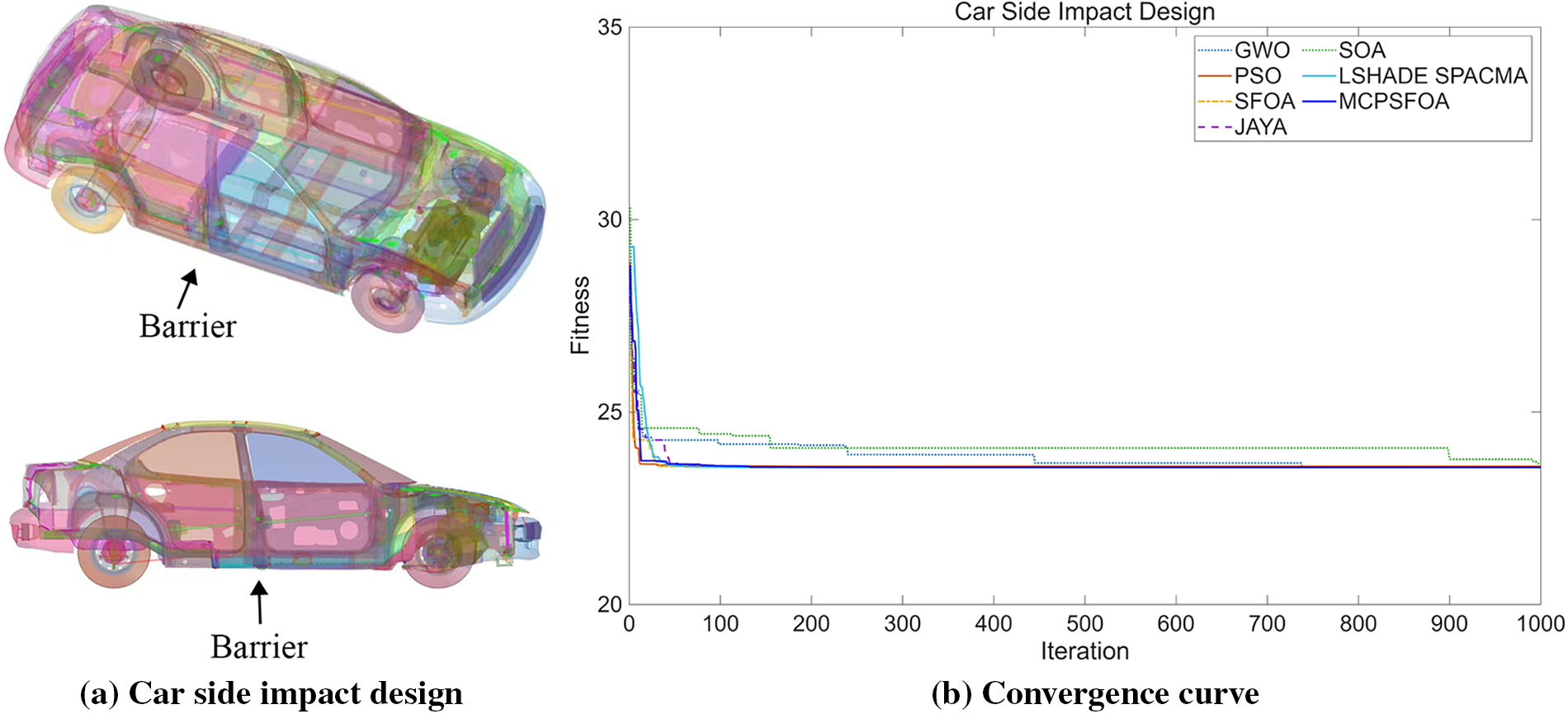

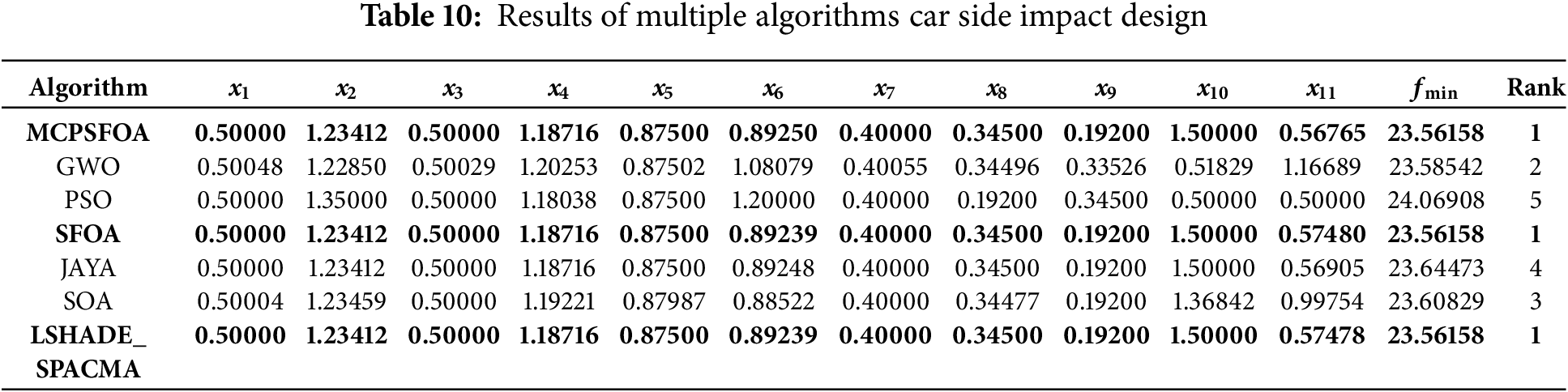

This problem optimizes the side crashworthiness of the car, as shown in Fig. 11. This problem is representative of high-dimensional, constrained industrial design challenges. Eleven design variables are defined in the problem: the thickness of the B-pillar inner panel (x1), the B-pillar reinforcement plate (x2), the floor side inner panel (x3), the crossmember (x4), the door anti-intrusion beam (x5), the door waistline reinforcement (x6), and the roof rail (x7), in addition to the material of the B-pillar inner panel (x8), the material of the floor side inner panel (x9), the obstacle height (x10), and the impact location (x11). Coupled with ten constraint conditions must also be met. This design is formulated as:

Figure 11: (a) Car side impact design and (b) the convergence curve

From an analysis of the globally best solutions for this problem presented in Table 10, MCPSFOA obtained solution (fmin = 23.56158, x = 0.5, 1.23412, 0.5, 1.18716, 0.875, 0.8925, 0.4, 0.345, 0.192, 1.5, 0.5676) is optimal. Compared with algorithms such as GWO, PSO, JAYA, and SOA, MCPSFOA demonstrates more advantageous optimization capabilities in this issue. The convergence curve also reflects the high accuracy of MCPSFOA. The algorithm’s probabilistic strategy selection effectively navigates the highly constrained feasible region, while Lévy flight assists in escaping local optima commonly encountered in crashworthiness simulations. This case validates MCPSFOA’s applicability to safety-critical automotive design problems.

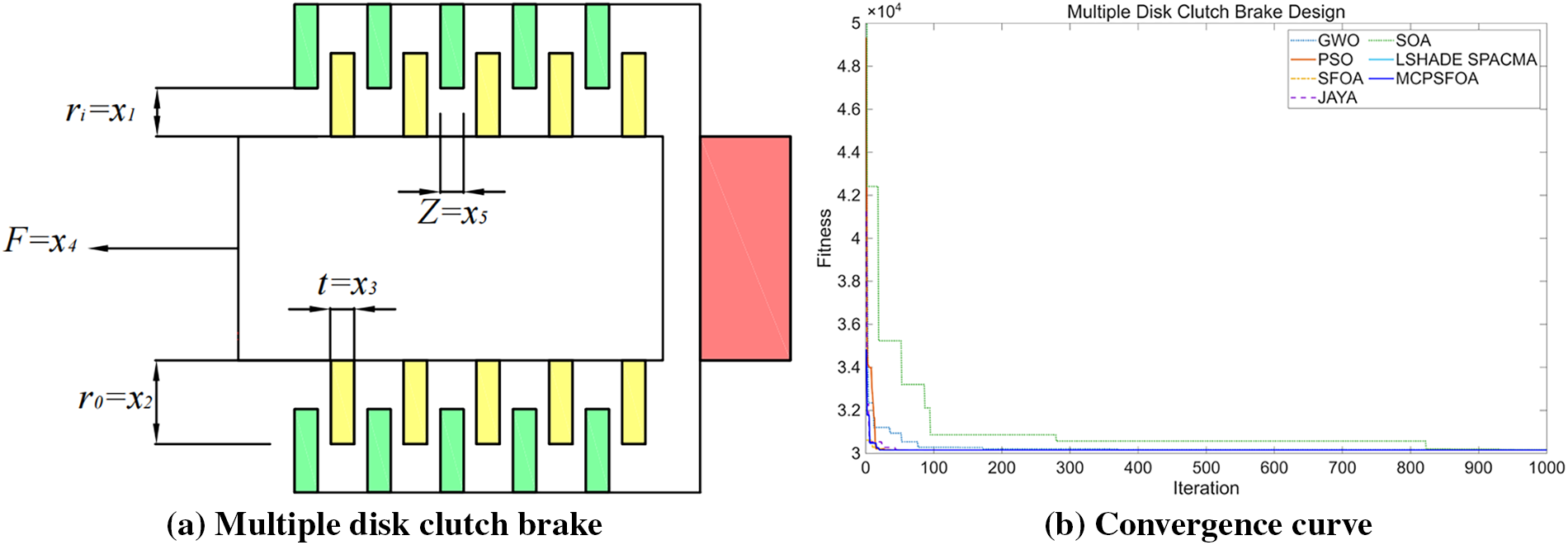

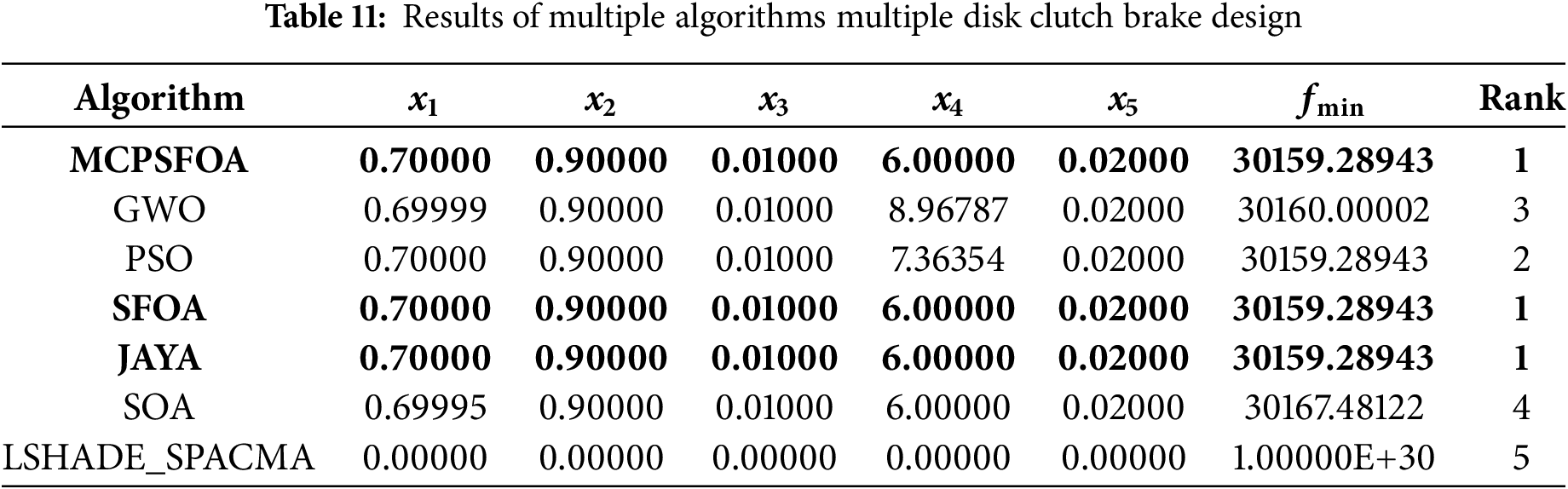

5.3 Multiple Disc Clutch Brake Design

As shown in Fig. 12, the design problem involves continuous and discrete variables and aims to minimize the mass of a clutch brake under nine nonlinear constraints. Its five design variables include the inner radius (ri = x1), outer radius (r0 = x2), disc thickness (t = x3), operating force (F = x4), and the number of friction surfaces (Z = x5). This is a mass-minimization problem for the brake design, while also satisfying nine nonlinear constraints regarding radius, length, pressure and bending moment. The mathematical expression of this problem is:

Figure 12: (a) Multiple disk clutch brake and (b) the convergence curve

In this problem, MCPSFOA obtains the best global solution among the 7 comparison algorithms, and its objective function value fmin is 3015.28943. The design variable combination is x = (0.7, 0.9, 0.01, 6, 0.02). The solutions of all the algorithms are summarized in Table 11. This result proves that the performance of MCPSFOA is superior to that of GWO, PSO, SOA and LSHADE_SPACMA. The algorithm’s Gaussian mutation operator facilitates fine-tuning in the later stages of search, improving solution precision. Moreover, the convergence profile confirms that MCPSFOA achieves rapid and stable convergence, highlighting its effectiveness in handling hybrid-variable, constrained design tasks.

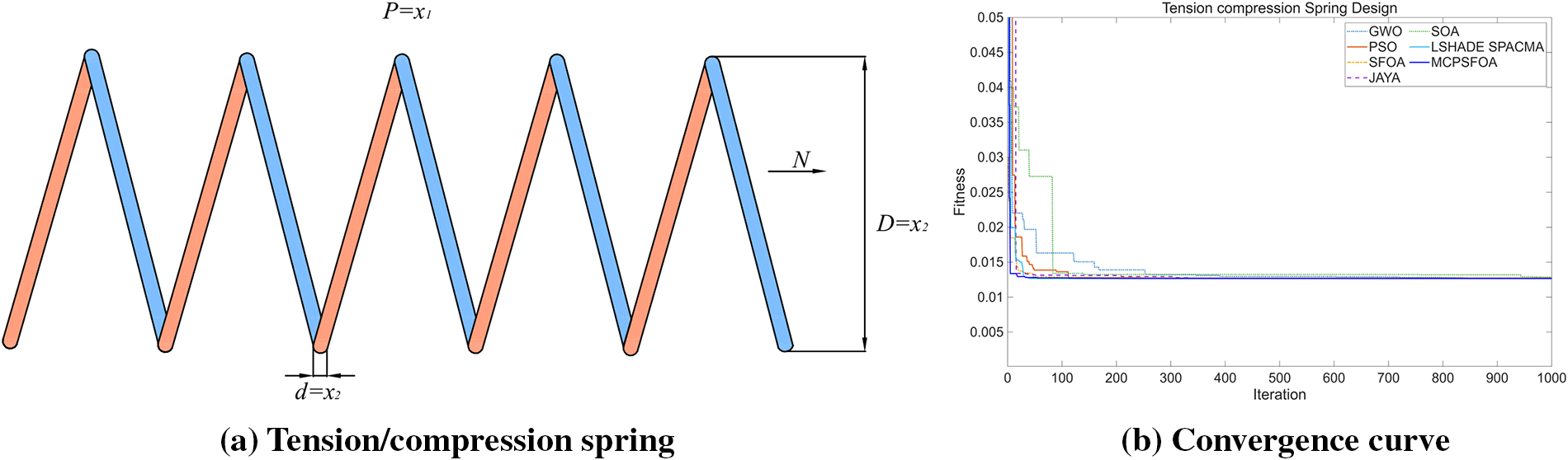

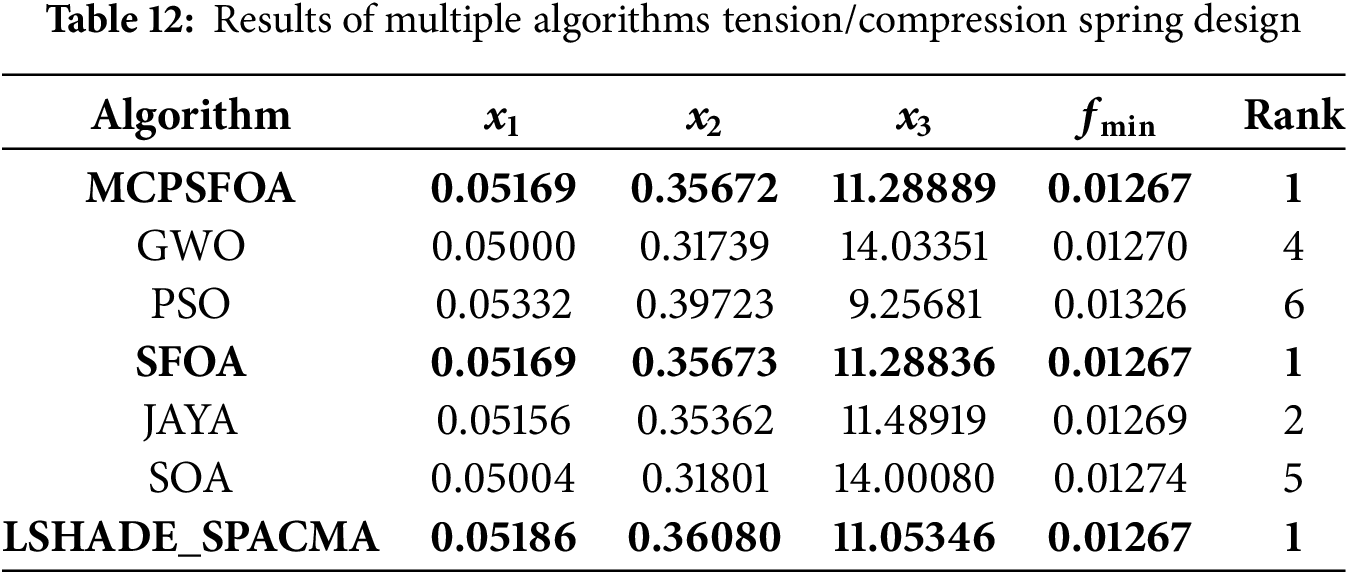

5.4 Tension/Compression Spring Design

This is a classic structural optimization problem. Fig. 13 shows that the optimization objective is to reduce the weight as much as possible while ensuring performance. Therefore, it is necessary to comprehensively optimize three design variables. These are defined as: the number of spring coils (P = x1), the coil diameter (D = x2), and the wire diameter (d = x3), which create a non-convex search space with narrow feasible regions. Moreover, the problem also needs to meet the constraints of shear stress, fluctuation frequency and deflection to ensure the strength and stability of the spring. This design is governed by the following equations:

Figure 13: (a) Tension/compression spring and (b) the convergence curve

According to Table 12, the comparative results of the algorithms for solving the problem are given. MCPSFOA ranked first with the optimal value of fmin = 0.01267 and the corresponding design variable x = (0.05169, 0.35672, 11.28889). The algorithm outperformed GWO, PSO, JAYA, and SOA, largely due to its adaptive diversity preservation mechanism, which prevents stagnation in local basins. The convergence curve further illustrates MCPSFOA’s consistent performance in both convergence speed and final solution quality, underscoring its reliability for weight-sensitive structural design.

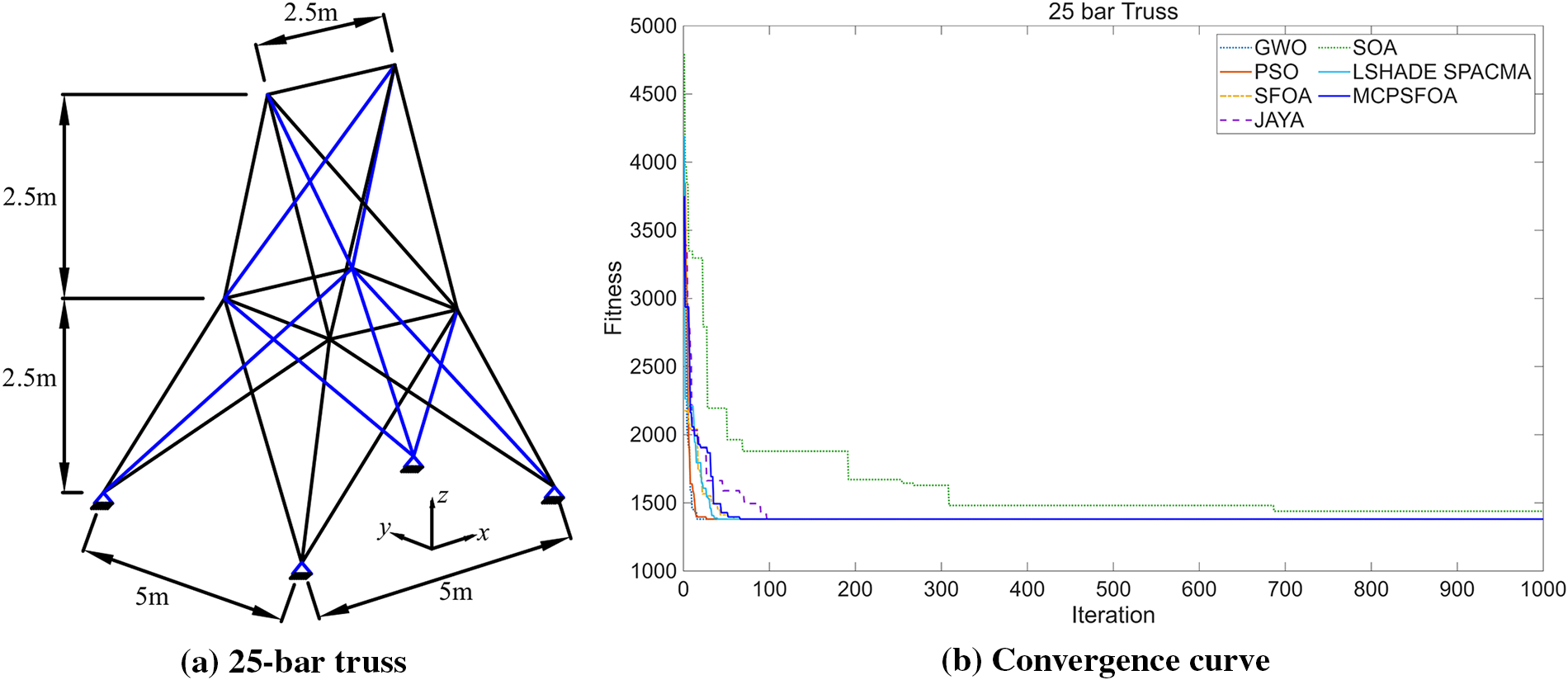

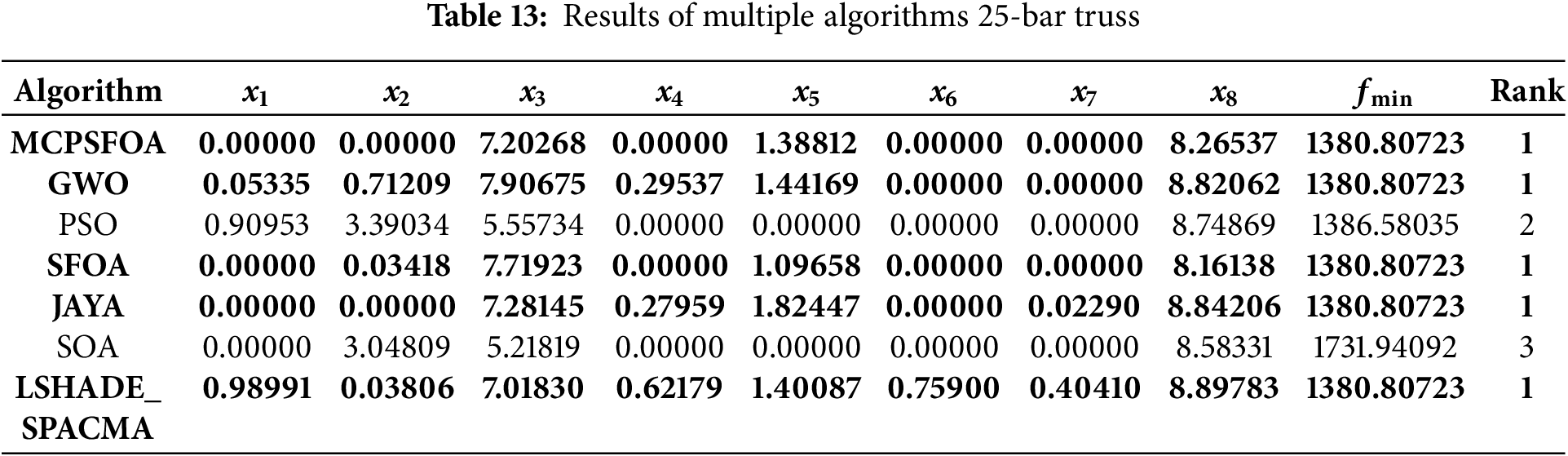

The engineering problem shown in Fig. 14 is about the optimization of a 25-bar truss, which is a structural optimization task involving stress constraints and grouped design variables. The material parameters of this truss are as follows: the density is 7850 kg/m3, the elastic modulus is 200 GPa, and the tensile stress in each member is constrained to be less than or equal to 400 MPa. The optimization objective is to minimize structural mass by optimizing cross-sectional areas grouped into eight variables.

Figure 14: (a) 25-bar truss and (b) the convergence curve

Table 13 summarizes the outcomes for the 25-bar truss optimization. It is evident that MCPSFOA obtains the best result of fmin = 1380.80723, and the result of the design variable is x = (0, 0, 7.20268, 0, 1.38812, 0, 0, 8.26537). The proposed algorithm surpasses GWO and SOA in terms of solution quality. Further evidence of MCPSFOA’s superiority is provided by the convergence curve. The algorithm’s ability to efficiently explore discrete variable combinations while respecting stress constraints demonstrates its strength in solving combinatorial-structural optimization problems. The convergence behavior further confirms its superiority in balancing exploration with exploitation across complex truss design.

6 Conclusions and Future Works

To enhance the performance of SFOA and address its limitations in maintaining population diversity, this paper presents a hybrid metaheuristic algorithm called MCPSFOA that enhances the crested porcupine-starfish optimizer with multiple strategies. MCPSFOA uses the exploration and exploitation of SFOA or CPO updates via a probabilistic mechanism as the algorithm’s core, and combines Lévy flight and Gaussian mutation to achieve more effective coordination. To maintain population diversity, a diversity enhancement mechanism is utilized that identifies and randomly reinitializes stagnant individuals. These improvements enable MCPSFOA to achieve better optimization performance in practical engineering problems while ensuring high performance in benchmark function tests.

We designed a comprehensive experiment to evaluate MCPSFOA. The algorithm was tested on multiple benchmark suites, including 24 classical functions, 29 from CEC2017, and 12 from CEC2022, and compared with 11 other prominent algorithms, demonstrating strong competitiveness. MCPSFOA exhibited robust and excellent performance in classical function tests at both 30 and 1000 dimensions, confirming its scalability and effectiveness across different problem scales. In the more challenging CEC2017 and CEC2022, MCPSFOA ranked among the top three in 79.31% and 83.33% of the test functions respectively. The results show that MCPSFOA achieved the highest overall ranking across the three test suites. Moreover, as observed from the convergence curves and boxplots, MCPSFOA exhibits good convergence accuracy, stability, and robustness.

To further assess its performance on real-world engineering problems, MCPSFOA was tested on five classical constrained optimization problems. The results demonstrate its superiority over seven other algorithms. For these problems, MCPSFOA was able to consistently find feasible optimal solutions that satisfy all constraints and outperformed most of the compared algorithms. This indicates that MCPSFOA not only demonstrates high performance on benchmarks but also offers outstanding practical value for real-world engineering problems characterized by complex constraints and nonlinear characteristics.

Future work could focus on expanding its application domains, such as extreme value prediction, power system dispatch, image processing, and hyperparameter optimization for deep learning models. Additionally, further research may explore its integration with other optimization algorithms or its adaptation for large-scale problems.

Acknowledgement: The first author would like to acknowledge Yuquan Lin for providing the model diagram of car side impact design (Fig. 11a).

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12402139, No. 52368070), supported by Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 524QN223), Scientific Research Startup Foundation of Hainan University (Grant No. RZ2300002710), State Key Laboratory of Structural Analysis, Optimization and CAE Software for Industrial Equipment, Dalian University of Technology (Grant No. GZ24107), the Horizontal Research Project (Grant No. HD-KYH-2024022), Innovative Research Projects for Postgraduate Students in Hainan Province (Grant No. Hys2025-217).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Hao Chen, Tong Xu, Dabo Xin and Changting Zhong; methodology, Hao Chen, Tong Xu, Yutian Huang, Dabo Xin and Changting Zhong; software, Hao Chen, Tong Xu and Changting Zhong; validation, Hao Chen, Tong Xu, Yutian Huang, Dabo Xin and Changting Zhong; resources, Hao Chen, Tong Xu, Yutian Huang, Dabo Xin and Changting Zhong; writing—original draft preparation, Hao Chen, Tong Xu and Changting Zhong; writing—review and editing, Hao Chen, Tong Xu, Yutian Huang, Dabo Xin and Changting Zhong; funding acquisition, Dabo Xin, Tong Xu and Changting Zhong. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| SFOA | Starfish optimization algorithm |

| CPO | Crested porcupine optimizer |

| PSO | Particle swarm optimization |

| DE | Differential evolution |

| GWO | Grey wolf optimizer |

| TLBO | Teaching-learning-based optimization |

| JAYA | JAYA algorithm |

| SOA | Seagull optimization algorithm |

| SRS | Special relativity search |

| PGA | Phototropic growth algorithm |

| LSHADE-cnEpSin | LSHADE with covariance matrix adaptation and episodic sinusoidal inertia |

| LSHADE-SPACMA | LSHADE with space transformation and cma-es |

References

1. Zhang G, Wang L, Deng Z, Liu X, Su X, Li H, et al. Landing scheduling for carrier aircraft fleet considering bolting probability and aerial refueling. Def Technol. 2025;50:1–19. doi:10.1016/j.dt.2025.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Cho S, Lee Y, Yoon C. Enhancing ITS reliability and efficiency through optimal VANET clustering using grasshopper optimization algorithm. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;143(3):3769–93. doi:10.32604/cmes.2025.066298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liu J, Sarker R, Elsayed S, Essam D, Siswanto N. Large-scale evolutionary optimization: a review and comparative study. Swarm Evol Comput. 2024;85:101466. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2023.101466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhu R, Zhang X, Zhang S, Dai Q, Qin Z, Chu F. Modeling and topology optimization of cylindrical shells with partial CLD treatment. Int J Mech Sci. 2022;220:107145. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2022.107145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Machaček J, Siegel S, Zachert H. DEEM—differential evolution with elitism and multi-populations. Swarm Evol Comput. 2025;92:101818. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2024.101818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Abdel-Salam M, Ali Alomari S, Yang J, Lee S, Saleem K, Smerat A, et al. Harnessing dynamic turbulent dynamics in parrot optimization algorithm for complex high-dimensional engineering problems. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2025;440:117908. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2025.117908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Houssein EH, Saber E, Abdel Samee N. An improved animated oat optimization algorithm with particle swarm optimization for dry eye disease classification. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;144(2):2445–80. doi:10.32604/cmes.2025.069184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kennedy J, Eberhart RC. Particle swarm optimization. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks; 1995 Nov 27–Dec 1; Perth, Australia. p. 1942–8. doi:10.1109/MHS.1995.494215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Holland J. Adaptation in natural and artificial systems. Ann Arbor, MI, USA: University of Michigan Press; 1975. p. 29–41. [Google Scholar]

10. Storn R, Price K. Differential evolution-a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J Glob Optim. 1997;11(4):341–59. doi:10.1023/A:1008202821328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Gölcük İ, Ozsoydan FB, Durmaz ED. Reinforcement and opposition-based learning enhanced weighted mean of vectors algorithm for global optimization and feature selection. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;319:113626. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2025.113626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Simon D. Biogeography-based optimization. IEEE Trans Evol Computat. 2008;12(6):702–13. doi:10.1109/tevc.2008.919004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yang XS, Hossein Gandomi A. Bat algorithm: a novel approach for global engineering optimization. Eng Comput. 2012;29(5):464–83. doi:10.1108/02644401211235834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Rao RV, Savsani VJ, Vakharia DP. Teaching-learning-based optimization: a novel method for constrained mechanical design optimization problems. Comput Aided Des. 2011;43(3):303–15. doi:10.1016/j.cad.2010.12.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Mirjalili S, Mirjalili SM, Lewis A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv Eng Softw. 2014;69:46–61. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2013.12.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Rao RV. Jaya: a simple and new optimization algorithm for solving constrained and unconstrained optimization problems. Int J Ind Eng Comput. 2016:19–34. doi:10.5267/j.ijiec.2015.8.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Heidari AA, Mirjalili S, Faris H, Aljarah I, Mafarja M, Chen H. Harris Hawks optimization: algorithm and applications. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2019;97:849–72. doi:10.1016/j.future.2019.02.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Dhiman G, Kumar V. Seagull optimization algorithm: theory and its applications for large-scale industrial engineering problems. Knowl Based Syst. 2019;165:169–96. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2018.11.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Faramarzi A, Heidarinejad M, Stephens B, Mirjalili S. Equilibrium optimizer: a novel optimization algorithm. Knowl Based Syst. 2020;191:105190. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2019.105190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Faramarzi A, Heidarinejad M, Mirjalili S, Gandomi AH. Marine predators algorithm: a nature-inspired metaheuristic. Expert Syst Appl. 2020;152:113377. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Abdel-Basset M, Mohamed R, Elhoseny M, Chakrabortty RK, Ryan M. A hybrid COVID-19 detection model using an improved marine predators algorithm and a ranking-based diversity reduction strategy. IEEE Access. 2020;8:79521–40. doi:10.1109/access.2020.2990893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhong C, Li G, Meng Z. Beluga whale optimization: a novel nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm. Knowl Based Syst. 2022;251(1):109215. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.109215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Jia H, Rao H, Wen C, Mirjalili S. Crayfish optimization algorithm. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56(2):1919–79. doi:10.1007/s10462-023-10567-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Goodarzimehr V, Talatahari S, Shojaee S, Hamzehei-Javaran S. Special Relativity Search for applied mechanics and engineering. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2023;403:115734. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2022.115734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Gao H, Zhang Q. Alpha evolution: an efficient evolutionary algorithm with evolution path adaptation and matrix generation. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;137:109202. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.109202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Abdel-Basset M, Mohamed R, Abouhawwash M. Crested Porcupine Optimizer: a new nature-inspired metaheuristic. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;284:111257. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2023.111257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Bohat VK, Hashim FA, Batra H, Abd Elaziz M. Phototropic growth algorithm: a novel metaheuristic inspired from phototropic growth of plants. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;322:113548. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2025.113548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Lee SW, Haider A, Rahmani AM, Arasteh B, Gharehchopogh FS, Tang S, et al. A survey of Beluga whale optimization and its variants: statistical analysis, advances, and structural reviewing. Comput Sci Rev. 2025;57(1):100740. doi:10.1016/j.cosrev.2025.100740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Bai Q, Li H. The application of hybrid cuckoo search-grey wolf optimization algorithm in optimal parameters identification of solid oxide fuel cell. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2022;47(9):6200–16. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.11.216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Han B, Li B, Qin C. A novel hybrid particle swarm optimization with marine predators. Swarm Evol Comput. 2023;83:101375. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2023.101375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Gupta S, Bilal M, Zuhaib M, Srivastava L, Malik H, García Márquez FP, et al. Optimal power flow solution using novel optimization technique: a case study. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;287:128163. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.128163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kassaymeh S, Al-Laham M, Al-Betar MA, Alweshah M, Abdullah S, Makhadmeh SN. Backpropagation Neural Network optimization and software defect estimation modelling using a hybrid Salp Swarm optimizer-based Simulated Annealing Algorithm. Knowl Based Syst. 2022;244:108511. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.108511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ahmadipour M, Murtadha Othman M, Bo R, Sadegh Javadi M, Mohammed Ridha H, Alrifaey M. Optimal power flow using a hybridization algorithm of arithmetic optimization and Aquila optimizer. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;235:121212. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Sadrani M, Tirachini A, Antoniou C. Bus scheduling with heterogeneous fleets: formulation and hybrid metaheuristic algorithms. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;263:125720. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Güven AF. A novel hybrid Salp Swarm Kepler optimization for optimal sizing and energy management of renewable microgrids with EV integration. Energy. 2025;334(1):137696. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.137696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhong C, Li G. Comprehensive learning Harris Hawks-equilibrium optimization with terminal replacement mechanism for constrained optimization problems. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;192(1):116432. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2021.116432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Xu Y, Zhang M, Wang D, Yang M, Liang C. Hybrid Gaussian quantum particle swarm optimization and adaptive genetic algorithm for flexible job-shop scheduling problem. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2025;154:110882. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2025.110882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Lynn N, Suganthan PN. Ensemble particle swarm optimizer. Appl Soft Comput. 2017;55:533–48. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2017.02.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Gupta S, Deep K, Heidari AA, Moayedi H, Wang M. Opposition-based learning Harris Hawks optimization with advanced transition rules: principles and analysis. Expert Syst Appl. 2020;158:113510. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhong C, Li G, Meng Z, He W. Opposition-based learning equilibrium optimizer with Levy flight and evolutionary population dynamics for high-dimensional global optimization problems. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;215:119303. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.119303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ahmed R, Rangaiah GP, Mahadzir S, Mirjalili S, Hassan MH, Kamel S. Memory, evolutionary operator, and local search based improved Grey Wolf Optimizer with linear population size reduction technique. Knowl Based Syst. 2023;264:110297. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2023.110297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Hamad QS, Samma H, Suandi SA, Mohamad-Saleh J. Q-learning embedded sine cosine algorithm (QLESCA). Expert Syst Appl. 2022;193:116417. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2021.116417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Song Y, Wu Y, Guo Y, Yan R, Suganthan PN, Zhang Y, et al. Reinforcement learning-assisted evolutionary algorithm: a survey and research opportunities. Swarm Evol Comput. 2024;86:101517. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2024.101517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Deng L, Liu S. A sine cosine algorithm guided by elite pool strategy for global optimization. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;164:111946. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Yu YF, Wang Z, Chen X, Feng Q. Particle swarm optimization algorithm based on teaming behavior. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;318:113555. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2025.113555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Jamal R, Zhang J, Men B, Khan NH, Ebeed M, Jamal T, et al. Chaotic-quasi-oppositional-phasor based multi populations Gorilla troop optimizer for optimal power flow solution. Energy. 2024;301:131684. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.131684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Zhang J, Liu W, Zhang G, Zhang T. Quantum encoding whale optimization algorithm for global optimization and adaptive infinite impulse response system identification. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(5):158. doi:10.1007/s10462-025-11120-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Xia H, Ke Y, Liao R, Zhang H. Fractional order dung beetle optimizer with reduction factor for global optimization and industrial engineering optimization problems. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(10):308. doi:10.1007/s10462-025-11239-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Fan C, Yang LT, Xiao L. A step gravitational search algorithm for function optimization and STTM’s synchronous feature selection-parameter optimization. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(6):179. doi:10.1007/s10462-025-11193-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Mansouri H, Elkhanchouli K, Elghouate N, Bencherqui A, Tahiri MA, Karmouni H, et al. A modified black-winged kite optimizer based on chaotic maps for global optimization of real-world applications. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;318:113558. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2025.113558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Long W, Jiao H, Yang Y, Xu M, Tang M, Wu T. Planar-mirror reflection imaging learning based seagull optimization algorithm for global optimization and feature selection. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;317:113420. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2025.113420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Wang Y, Ping F, Li Y, Gu T, Wang T. Estimation of photovoltaic parameters by dynamic updating and selecting a snake optimizer based on multi-directional optimization. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(9):286. doi:10.1007/s10462-025-11272-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Wolpert DH, Macready WG. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans Evol Computat. 1997;1(1):67–82. doi:10.1109/4235.585893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Siddiqui AM, Abbas H, Asim M, Ateya AA, Abdallah HA. SGO-DRE: a squid game optimization-based ensemble method for accurate and interpretable skin disease diagnosis. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;144(3):3135–68. doi:10.32604/cmes.2025.069926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Zhong C, Li G, Meng Z, Li H, Yildiz AR, Mirjalili S. Starfish optimization algorithm (SFOAa bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization compared with 100 optimizers. Neural Comput Appl. 2025;37(5):3641–83. doi:10.1007/s00521-024-10694-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Kumar N, Kumar H. A fuzzy clustering technique for enhancing the convergence performance by using improved Fuzzy c-means and Particle Swarm Optimization algorithms. Data Knowl Eng. 2022;140:102050. doi:10.1016/j.datak.2022.102050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Fathy A. Optimal energy management framework of microgrid in Aljouf area considering demand response and renewable energy uncertainty. Energy. 2025;330:136963. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.136963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Şener İF, Tuğal İ. Optimized CNN-LSTM with hybrid metaheuristic approaches for solar radiation forecasting. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2025;72:106356. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2025.106356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Mohanachandran DK, Krishna Reddy YV, Tambe-Jagtap SN, Manjunath TC, Swarnkar KK, Bhuria V. Starfish optimization algorithm for economic emission dispatch with chance constraints and wind power integration. J Inf Syst Eng Manag. 2025;10(4s):327–37. doi:10.52783/jisem.v10i4s.510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. He HJ, Zhang C, Xing L, Qiao H, Bi J, Niu S, et al. Machine learning-driven pocket-sized NIR analysis for non-invasive quantification of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin and pectin in sweet potato roots. LWT. 2025;226:117973. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2025.117973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Izci D, Ekinci S, Jabari M, Bajaj M, Blazek V, Prokop L, et al. A new intelligent control strategy for CSTH temperature regulation based on the starfish optimization algorithm. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):12327. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-96621-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Chawla M, Duhan M. Levy flights in metaheuristics optimization algorithms—a review. Appl Artif Intell. 2018;32(9–10):802–21. doi:10.1080/08839514.2018.1508807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Qu S, Liu H, Zhang H, Li Z. Application of Lévy and sine cosine algorithm hunger game search in machine learning model parameter optimization and acute appendicitis prediction. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;269:126413. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.126413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Mantegna RN. Fast, accurate algorithm for numerical simulation of Lévy stable stochastic processes. Phys Rev E. 1994;49(5):4677–83. doi:10.1103/physreve.49.4677. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Higashi N, Iba H. Particle swarm optimization with Gaussian mutation. In: Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE Swarm Intelligence Symposium. SIS’03 (Cat. No. 03EX706); 2003 Apr 26; Indianapolis, IN, USA. p. 72–9. doi:10.1109/SIS.2003.1202250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Xu H, Zhang A, Bi W, Xu S. Dynamic Gaussian mutation beetle swarm optimization method for large-scale weapon target assignment problems. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;162:111798. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Zhao W, Zhang Z, Mirjalili S, Wang L, Khodadadi N, Mirjalili SM. An effective multi-objective artificial hummingbird algorithm with dynamic elimination-based crowding distance for solving engineering design problems. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2022;398:115223. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2022.115223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Bala I, Yadav A. Niching comprehensive learning gravitational search algorithm for multimodal optimization problems. Evol Intell. 2022;15(1):695–721. doi:10.1007/s12065-020-00547-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Ibrahim AW, Xu J, Al-Shamma’a AA, Hussein Farh HM, Dagal I. Intelligent adaptive PSO and linear active disturbance rejection control: a novel reinitialization strategy for partially shaded photovoltaic-powered battery charging. Comput Electr Eng. 2025;123:110037. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.110037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Osuna-Enciso V, Cuevas E, Morales Castañeda B. A diversity metric for population-based metaheuristic algorithms. Inf Sci. 2022;586:192–208. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2021.11.073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Suganthan PN, Hansen N, Liang JJ, Deb K, Chen YP, Auger A, et al. Problem definitions and evaluation criteria for the CEC, 2005 special session on real-parameter optimization. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2005. p. 1–50 p. [Google Scholar]

72. Fu S, Ma C, Li K, Xie C, Fan Q, Huang H, et al. Modified LSHADE-SPACMA with new mutation strategy and external archive mechanism for numerical optimization and point cloud registration. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(3):72. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-11053-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Luo W, Lin X, Li C, Yang S, Shi Y. Benchmark functions for CEC, 2022 competition on seeking multiple optima in dynamic environments. arXiv:2201.00523. 2022. [Google Scholar]

74. Awad NH, Ali MZ, Suganthan PN. Ensemble sinusoidal differential covariance matrix adaptation with Euclidean neighborhood for solving CEC2017 benchmark problems. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC); 2017 Jun 5–8; Donostia, Spain. doi:10.1109/cec.2017.7969336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Mohamed AW, Hadi AA, Fattouh AM, Jambi KM. LSHADE with semi-parameter adaptation hybrid with CMA-ES for solving CEC, 2017 benchmark problems. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC); 2017 Jun 5–8; Donostia, Spain. doi:10.1109/cec.2017.7969307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]