Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Trajectory-Guided Diffusion Model for Consistent and Realistic Video Synthesis in Autonomous Driving

School of Mechatronics Engineering, Harbin Institute of Technology, Weihai, China

* Corresponding Author: Dafang Wang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Recent Advances in Signal Processing and Computer Vision)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 35 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2026.076439

Received 20 November 2025; Accepted 06 January 2026; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

Scalable simulation leveraging real-world data plays an essential role in advancing autonomous driving, owing to its efficiency and applicability in both training and evaluating algorithms. Consequently, there has been increasing attention on generating highly realistic and consistent driving videos, particularly those involving viewpoint changes guided by the control commands or trajectories of ego vehicles. However, current reconstruction approaches, such as Neural Radiance Fields and 3D Gaussian Splatting, frequently suffer from limited generalization and depend on substantial input data. Meanwhile, 2D generative models, though capable of producing unknown scenes, still have room for improvement in terms of coherence and visual realism. To overcome these challenges, we introduce GenScene, a world model that synthesizes front-view driving videos conditioned on trajectories. A new temporal module is presented to improve video consistency by extracting the global context of each frame, calculating relationships of frames using these global representations, and fusing frame contexts accordingly. Moreover, we propose an innovative attention mechanism that computes relations of pixels within each frame and pixels in the corresponding window range of the initial frame. Extensive experiments show that our approach surpasses various state-of-the-art models in driving video generation, and the introduced modules contribute significantly to model performance. This work establishes a new paradigm for goal-oriented video synthesis in autonomous driving, which facilitates on-demand simulation to expedite algorithm development.Keywords

The rapid growth of autonomous driving technology has intensified the critical need for comprehensive safety validation. However, real-world testing is often prohibitively expensive, difficult to replicate, and limited in its ability to capture rare and crucial corner cases and hazardous scenarios. Thus, simulation has emerged as a highly promising alternative for vehicle testing.

A fundamental objective in real-world simulation is the dynamic generation of new scenes in response to vehicle movement, which supplies tested vehicles with evolving driving visual signals to accurately replicate the driving process. Researchers have investigated 3D reconstruction techniques, such as Neural Radiance Fields (NeRFs) [1] and 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) [2], to reconstruct the environments and novel viewpoints. Mars [3] and EmerNeRF [4] have to separate background and dynamic instances for the simulation, while NeuRas [5] and DGNR [6] improve the technique to realize real-time rendering. DrivingGaussian [7] rebuilds scenarios by applying LiDAR priors in dynamic-aware Gaussian splatting, and HO-Gaussian [8] achieves good robustness by addressing initialization problems, which introduces a hybrid Gaussian splatting pipeline. Although these advanced methods excel at producing imagery and 3D scenes with intricate details from numerous viewpoints, they are inherently limited by the generalization ability and the typical demand for substantial inputs.

Recently, the use of diffusion models to generate realistic driving videos has become increasingly popular. Wovogen [9] integrates a diffusion model with a 4D volume to reform rendering-based methods. Refs. [10–12] modifies Stable Video Diffusion (SVD) [13] for conditioned video synthesis. Moreover, [14–17] extend scene prediction to forecasting future actions or trajectories. These methods expand pre-trained diffusion models from text-conditioned general video generation tools into multiple-constraint-based world models and achieve remarkable progress. Nevertheless, they frequently struggle with maintaining temporal consistency, which is shown by the gradually degraded quality of the subsequent frames.

To address the issues mentioned above, we propose a diffusion-model-based method for generating realistic driving videos under the conditions of the first frame and a set of trajectories. The ordinary temporal attention modules in world models [17–20] only take one pixel from each frame into account, while our novel proposal in GenScene, the Global Attention Module (GAM), processes videos by extracting global contexts of each frame and utilizing them to upgrade each other. This design enables comprehensive information integration, where every pixel in the video sequence can contribute to the representation of each frame, thereby ensuring complete preservation of temporal and spatial information throughout the refinement process. Additionally, we design a Window-enhanced Module (WEM) to improve the quality of subsequent frames. For every pixel, we integrate all the pixels in the same frame with the pixels in a corresponding window range in the first frame to compute the attention, which injects the information in the initial frame explicitly into the generation of later frames and provides definite constraints.

In general, the contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

• We propose a world model containing a diffusion model backbone and two new modules. The model takes the first frame and planned trajectories as conditions to synthesize consistent and realistic videos. The pre-trained SVD [13] is used as a strong prior to accelerate training and to provide prior knowledge. Furthermore, the two new modules collect global contexts and appearance priors to enhance the performance.

• This work develops a Global Attention Module (GAM) that first extracts frame-level global contextual representations and then sequentially injects them to refine the original frame features. Unlike existing temporal attention modules that model cross-frame dependencies through spatially aligned positions, GAM removes explicit position correspondence constraints by allowing all pixels within each frame to participate in global attention. As a result, GAM captures scene-level global structures and long-range dependencies, which are particularly beneficial for maintaining long-horizon consistency in autonomous driving video generation.

• A Window-enhanced Module (WEM) is presented. Existing self-attention mechanisms operate only within a single frame and do not impose explicit constraints. Our contribution is not a re-use of standard self-attention, but a structural extension that introduces a reference-frame–anchored attention pathway. For each pixel, attention is computed not only over the current frame but also over a fixed spatial window at the corresponding location in the reference frame. This design explicitly injects deterministic reference content into the generation of all subsequent frames, which is fundamentally different from frame-wise self-attention and effectively improves both per-frame image quality and long-horizon temporal consistency.

• Extensive experiments carried out on NuScenes illustrate that our method outperforms various cutting-edge methods, and the proposed modules contribute to the promotion of generation quality.

2.1 Real World Video Generation

Recent progress in reconstructing urban environments has been mainly driven by Neural Radiance Fields (NeRFs) [1] and 3DGS [2]. The pioneering work S-NeRF [21] creates a unified framework that combines both static and dynamic elements within a single neural network. However, these methods still face fundamental challenges, such as limited viewing angles and high computational demands, that restrict their practical use. Later studies [22–24] aim to extend NeRFs to large-scale urban street scenes with dynamic objects, by introducing enhanced scene parameterization, tri-branch scene representations, and crowd-sourced data collection strategies, respectively, to improve realism and scalability. NeRF On-the-go [25] enhances NeRFs robustness in unconstrained dynamic scenes by using uncertainty estimation to suppress distractors. Global SfM-Enhanced NeRF [26] leverages global structure-from-motion information to improve the geometric and texture reconstruction quality of NeRFs, especially under sparse-view settings. Despite these improvements, long rendering times and the need for diverse data inputs remain inherent limitations that continue to hinder their real-world application.

To address limitations in efficiency, 3DGS [2] has become an attractive alternative that offers faster processing. Refs. [7,27] expand the Gaussian representation to 4D, which speeds up the reconstruction. Subsequent methods like [28,29] developed ways to automatically separate static and dynamic elements while incorporating visual odometry that helps initialize camera positions. Meanwhile, ref. [30] proposed a two-stage approach that uses geometric constraints to reduce visual artifacts under limited viewpoints. Ref. [31] employs a streamlined Gaussian system that can recreate environments directly from various multi-camera arrangements. In addition, ref. [32] combines 3DGS with neural field technology, which enhances its ability to represent moving objects. Although improvements are continually made, there are still obstacles, such as sensor calibration, rapid movements handling, ensuring structural consistency, and unseen scenarios synthesis.

In contrast, 2D generative models require fewer inputs and have better generalization ability. Earlier approaches [33,34] explore the video generation potential of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [35]. Nowadays, diffusion models [36] have emerged as a powerful alternative, which demonstrate exceptional capabilities in multimodal modeling and conditional video generation. SVD [13] implements the diffusion mechanism within a latent space, making it possible to generate videos with larger resolutions. Ref. [37] leverages ControlNet [38] to enable stronger condition enforcement, whereas [39] enhances temporal consistency by embedding attention modules throughout both the primary network and its ControlNet [38] adapter. Moreover, ref. [40] introduces a reference-based noise initialization technique that helps maintain visual coherence across frames, while [41] projects the initial noise with a pair of direction parameters to improve consistency. Overall, diffusion models present a naturally suitable framework for driving video synthesis due to their robust prior knowledge, creative generalization capacity, and high output quality. Nevertheless, difficulties in preserving inter-frame stability and the noticeable decline in quality during extended sequence generation highlight the need for continued methodological improvements.

2.2 2D Generative World Models

Recently, significant advances have been made in autonomous driving video generation using diffusion models. TERRA [42] generates videos with trajectories using an autoregressive framework. Drivinggpt [43] establish a closed-loop pipeline by predicting both trajectory and visual scenes. However, inherent limitations of autoregressive approaches, including error accumulation, global inconsistency, and training complexity, have constrained their effectiveness. In this case, DriveDreamer [14] firstly modifies the diffusion model into a world model with action control. Later methods like [12] adopt transformer-based diffusion architectures to support multi-task and multi-condition vehicle simulation. Despite these innovations, they have not fully overcome the fundamental constraints above. Parallel efforts have explored hybrid approaches. Refs. [9,16,44] bring 3DGS into the diffusion process to form extra geometric control. While effective in certain aspects, these methods introduce new challenges like increased computational demands and also have persistent long-sequence inconsistencies. Significant attention has also been directed toward temporal attention improvements. DreamForge [10] uses a dedicated motion encoder that feeds into a motion-aware temporal module to guide video generation. Refs. [45–47] decomposed conventional spatio-temporal attention into multi-directional attention mechanisms to enhance multi-view coherence. Delphi [48] developed local feature correlation between adjacent frames to improve moving object consistency, while Vista [18] incorporated dynamic priors from three reference frames to govern future motion, supplemented by specialized losses for dynamics enhancement and structure preservation. Although these contributions represent substantial progress in consistent video generation, opportunities for improvement remain, particularly in addressing temporal inconsistency and frame quality degradation, which are key focus areas of our proposed architectural modules.

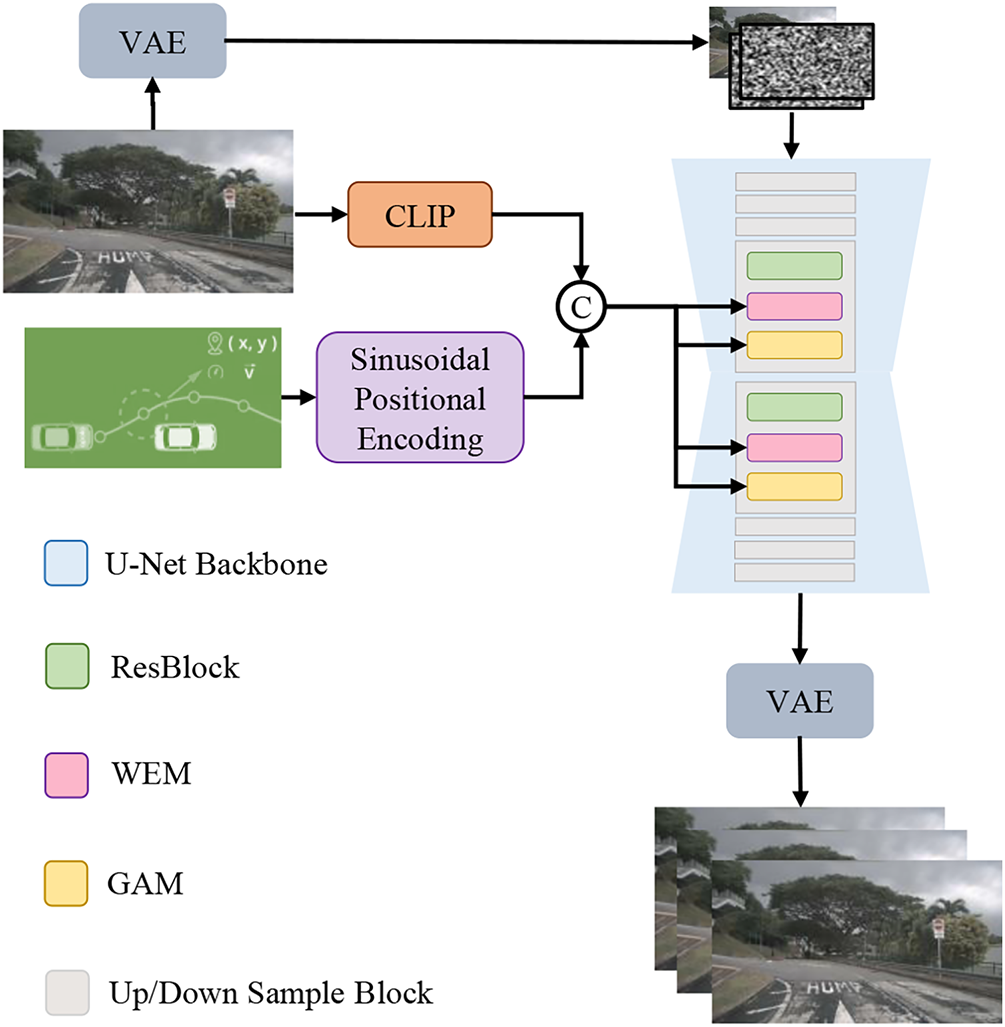

GenScene utilizes SVD [13] as the backbone due to its possession of rich prior from the pre-trained checkpoints trained on large-scale data. Global Attention Module (GAM) is one of our novel designs incorporated in the model. Unlike ordinary temporal attention modules, GAM extracts frame representations from every frame, computes frame relationships, and updates frames with these global attentions. This approach takes all pixels in a frame into account yet avoids computational explosion. The other new module in this work is the Window-enhanced Module (WEM). In order to fully utilize the only known appearance condition, the first frame of the video, WEM not only computes self-attention in a frame, but also takes the relevance between the target pixel and those in the corresponding window of the initial frame into account. The overall architecture of the proposed model is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Architecture of the proposed GenScene

One of the conditions in GenScene is the first frame of the video, namely the reference image. There are two paths for injecting it into the model. Firstly, the reference image is sent into the encoder of the Variational Autoencoder (VAE) to be encoded as a latent feature

As for the trajectories, they are represented as a sequence of coordinates and are first embedded into a compact trajectory feature using a lightweight encoder. Suppose

Then,

This trajectory feature is then concatenated with the reference image’s context feature

3.3 Global Attention Module (GAM)

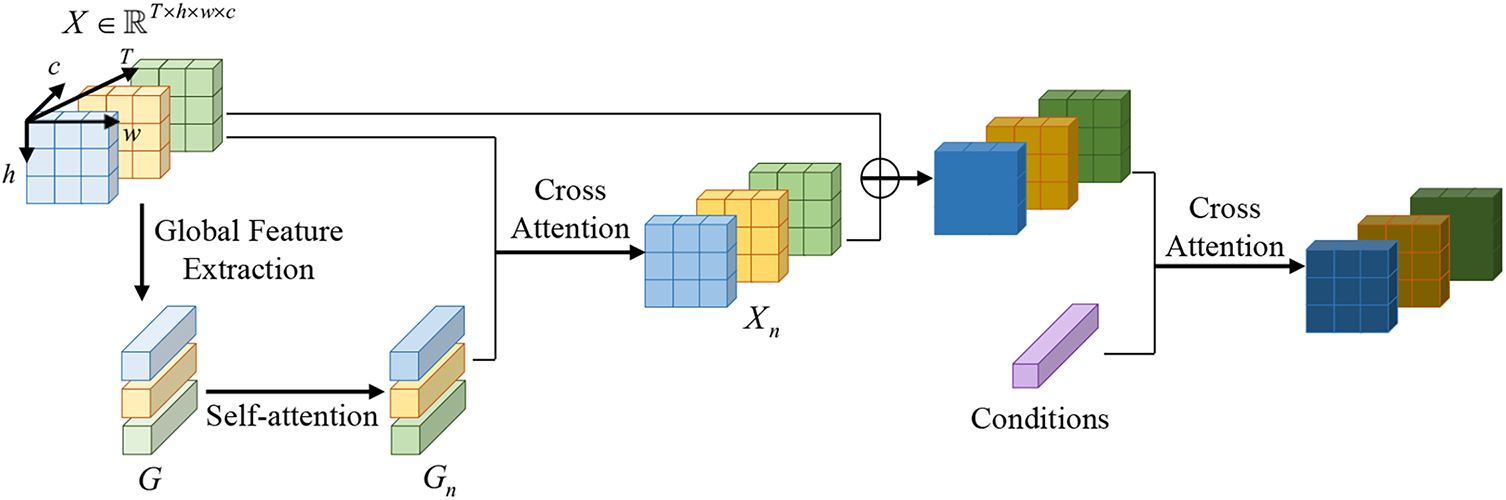

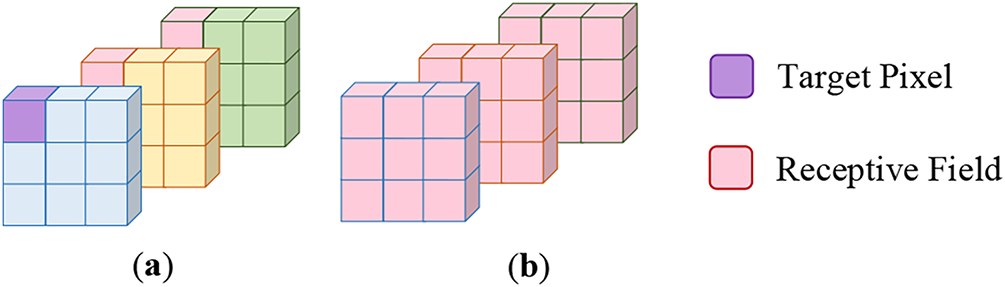

Conventional temporal attention typically establishes relationships between corresponding pixels across frames, processing only a single pixel position from each frame within the temporal dimension. Since this design represents a practical compromise between temporal coherence and computational efficiency, it fundamentally limits the model’s capacity to capture comprehensive scene dynamics. Our approach addresses this limitation by extracting and processing global representations of each frame, thereby enabling holistic temporal optimization that significantly enhances frame-to-frame consistency while simultaneously reducing computational overhead. The global representation extracted by GAM serves as a frame-level scene descriptor, summarizing global appearance and layout information shared across frames, rather than encoding explicit geometry or motion. This integrated processing strategy facilitates more efficient cross-frame information exchange, which proves particularly crucial for obtaining temporal coherence. The structure of GAM is visualized in Fig. 2, and the receptive field comparison is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 2: Structure of GAM

Figure 3: Comparison of the receptive fields: (a) Common temporal attention module; (b) GAM

Suppose

where

where

where

To retain the condition injection, cross-attention between the conditions and the frames is settled at the end of GAM.

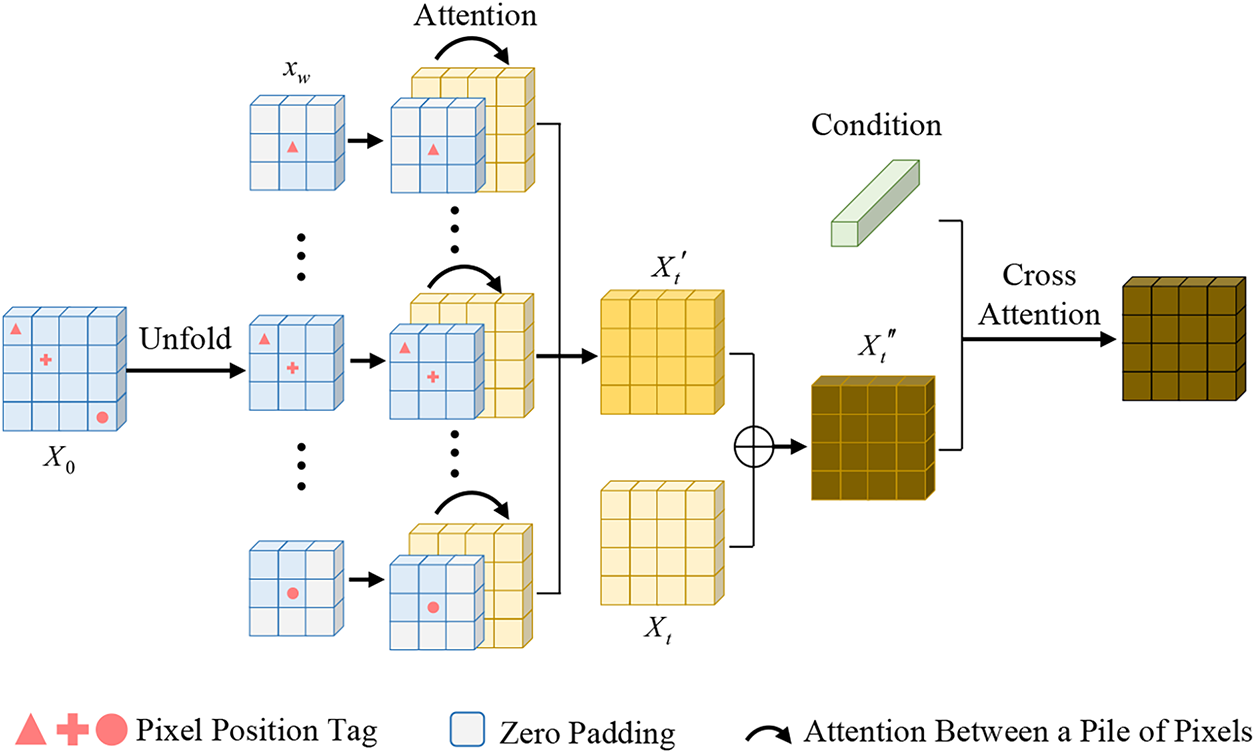

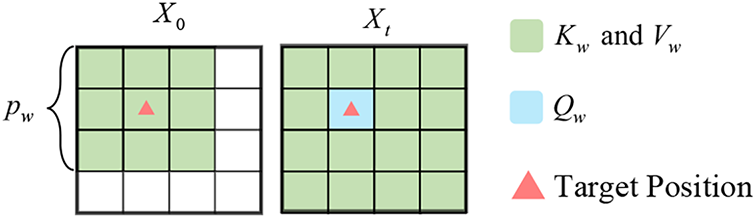

3.4 Window-Enhanced Module (WEM)

In the common process of SVD [13], there are two paths for the initial frame to constrain the generation. One of them is the concatenation with the noise followed by temporal attention to update one pixel of each frame, and the other is the cross-attention to guide the content synthesis. However, one pixel of the first frame can’t pass enough contexts to subsequent frames, let alone the movement of the ego vehicle may lead to irrelevance between the one pixel and the pixels in other frames, which makes the former path inefficient. Moreover, since the features sent into the cross-attention are obtained by CLIP, which are aligned text contexts, the guidance of the first frame is implicit in the later path. To address these problems, WEM combines pixels in a corresponding window of the reference frame with other pixels to be upgraded in the target frame and computes attentions between them, which will provide explicit control of appearance for the generation. The windowed area has richer contexts, can cover the motion interference, and prevents computational explosion. The structure of WEM is demonstrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Structure of WEM

Given the first frame

where

In order to keep the original information,

Same as GAM, we place the original cross attention at the end to retain the original constraint.

Figure 5: Demonstration of the query, key, and vector of the window-enhanced attention in WEM

For the fair comparisons with [14,18,42], GenScene is estimated on a large-scale driving dataset named NuScenes [49]. We take training and testing data from the official GitHub repository of Vista [18], which comprise 20,000 and 5369 video clips containing 25 frames each, respectively. According to Vista [18], these videos are sampled from NuScenes [49] at 10 Hz. As for the comparison of zero-shot generalization, the Waymo validation dataset, containing 600 videos, is utilized. Waymo is also a large-scale urban scene dataset that consists of multiple annotations, but the camera parameters and data distribution are different from those of NuScenes [49], which makes it suitable for the zero-shot test. Additionally, we use the testing data from ACT-Bench [42], which is a subset of NuScenes [49] validation set, to evaluate the trajectory controllability of GenScene.

Following [14,18,42,45], Fréchet Image Distance (FID) [50], Fréchet Video Distance (FVD) [51], Average Displacement Error (ADE) [52], and Final Displacement Error (FDE) [52] are utilized to validate the effectiveness of GenScene. FID and FVD measure the Fréchet distance between the ground truth and the synthesis to evaluate the generation quality. Meanwhile, ADE and FDE calculate the frame-average and final-frame L2 errors, respectively, between the conditioning trajectories and the predicted trajectories coming from the generated videos. They can estimate the trajectory controllability of GenScene.

Notably, since baselines for generation quality comparison only report results of FID and FVD in their original papers, with Vista [18] and TERRA [42] being the exceptions, we compare with them on FID and FVD, but not ADE or FDE.

The model is implemented on the basis of the architecture of Vista [18] and trained for 40 epochs with a batch size of 8. The training is optimized by AdamW with a learning rate of 5 × 10−5. And other optimization settings and learning rate schedules are the same as those of Vista [18], which guarantee a stable training behavior. In the comparisons with state-of-the-art models, the videos are generated in a resolution of 320 × 576 and 512 × 1024 by the Denoising Diffusion Implicit Model (DDIM) sampler with 50 steps. Additionally, the videos are synthesized in a resolution of 128 × 192 by the DDIM sampler with 15 steps. The results in Section 4.4 are from their public papers to fulfill fair comparisons. In order to control the computational complexity, we set

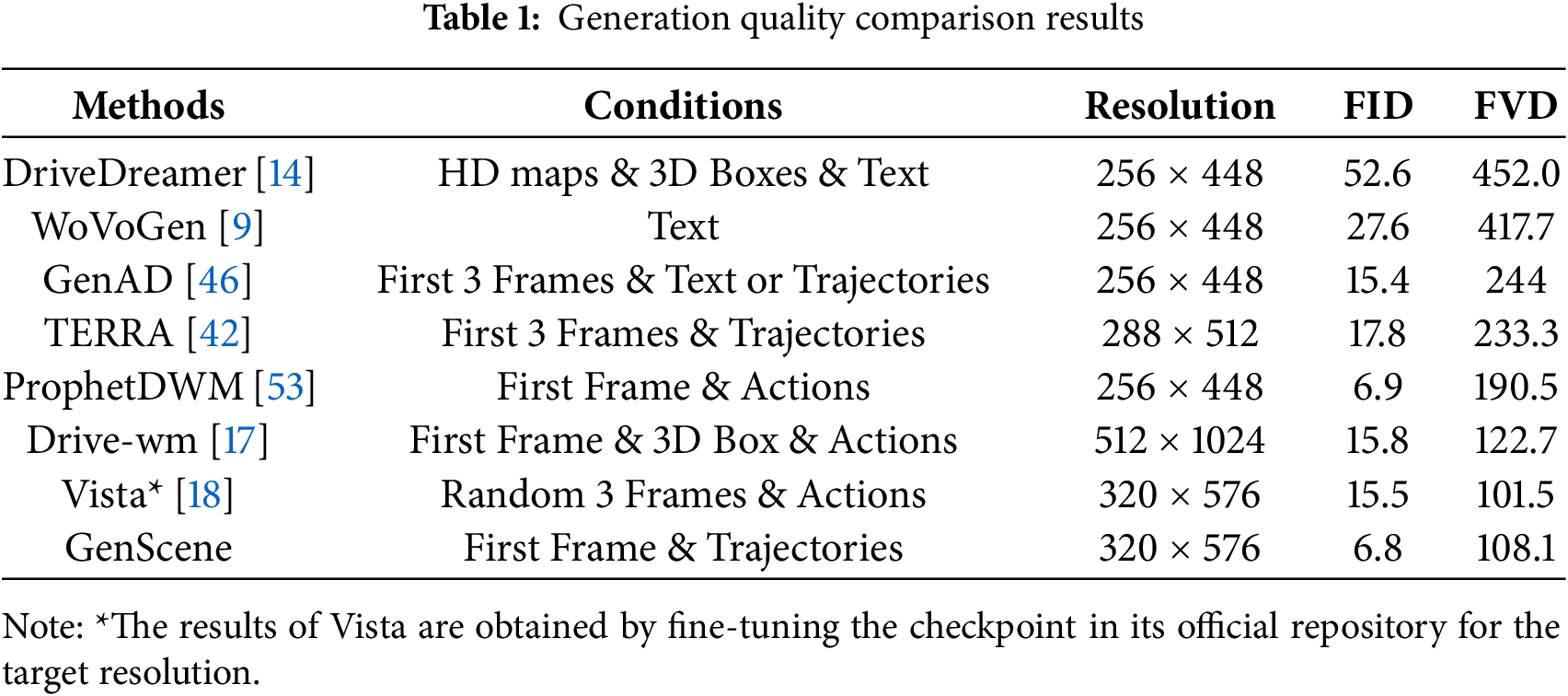

4.4 Generation Quality Comparison

FID and FVD results of various state-of-the-art models, which are referenced from their public papers, are displayed in Table 1. GenScene gets 6.8 in FID, which is the best in all the competitors. Even though our model gets 108.1 in FVD, which is higher than the only model Vista [18] by 6.6, the number of the reference frames of GenScene is one, yet that of Vista [18] is three. Other than that, GenScene obtains a lower FVD than the others, which require more complex conditions. Moreover, FID and FVD of GenScene are 0.1 and 82.4, respectively, lower than those of ProphetDWM [53], which requires the same condition as GenScene. These results prove that GenScene is superior in synthesizing realistic and consistent videos under simple conditions.

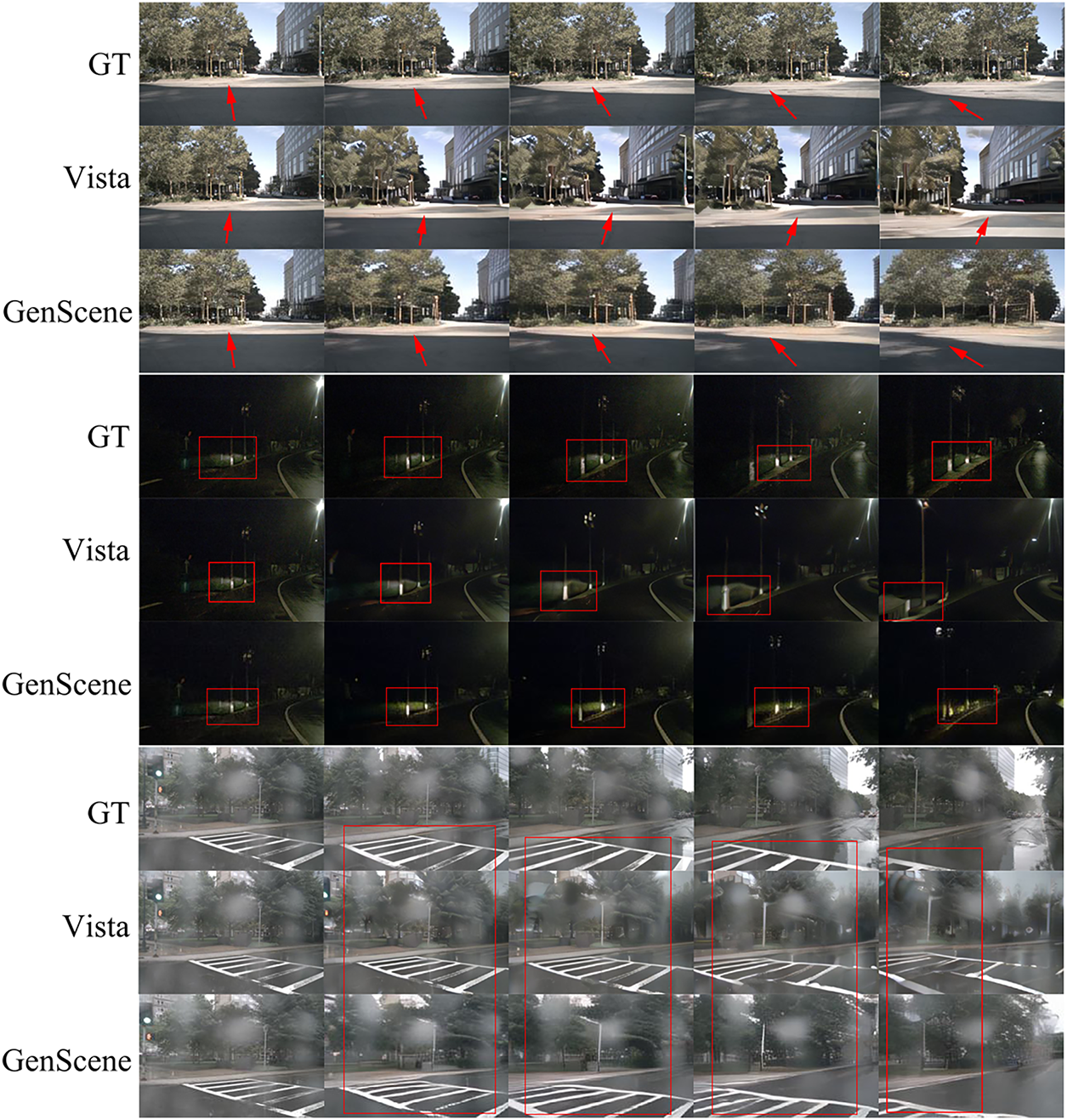

Fig. 6 shows the qualitative comparisons between Vista [18] and GenScene in red rectangles. In the first set, it is observed that the route in the ground truth is turning left, which is followed by GenScene, while Vista [18] generates scenes displaying the opposite direction. Additionally, the ego-vehicle-lighted area in the ground truth of the second set is almost in the same position, but that in Vista’s generation is obviously moving gradually towards the bottom left. In contrast, the lighting status of GenScenes synthesis is more in line with reality. Comparing the frames in the third set, we can find that the frames generated by Vista [18] can’t align with the trajectories, and the synthesized crosswalk is clearly deformed. On the other hand, GenScene follows the trajectories very well and maintains a reasonable view change of the crosswalk. These observations prove that GenScene generates videos with higher quality and better alignment with the given trajectories.

Figure 6: Appearance comparisons between Vista and GenScene

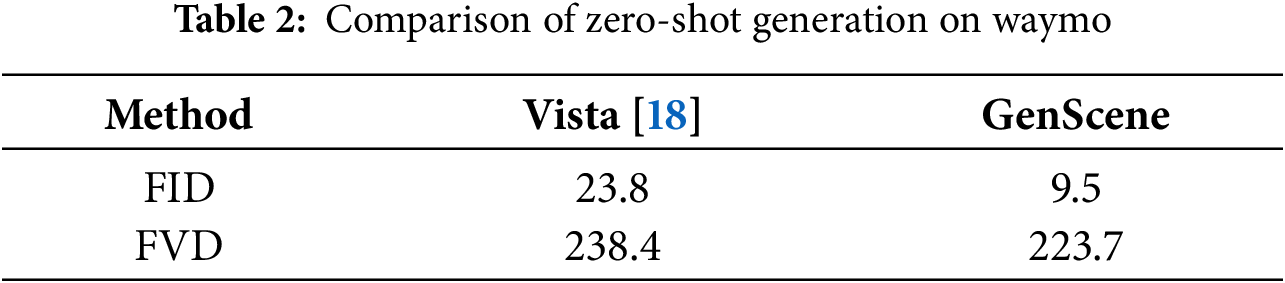

4.5 Zero-Shot Generalization Comparison

In order to evaluate the generalization capability of GenScene, we conduct a comparison experiment on the Waymo validation dataset with the model trained on NuScenes [49], which is not fine-tuned on the Waymo training dataset. Since only Vista [18] releases its pre-trained checkpoint, among the baselines in Table 1, we test it on Waymo directly and show the comparison in Table 2. It is observed that GenScene outperforms Vista [18] by 14.3 in FID and 14.7 in FVD, respectively, demonstrating better performance in the visual quality and coherence of the synthesis. These results prove that GenScene generates more authentic frames because it involves the pixels from the reference frame in the relationship-building process. Moreover, due to the frame modification dominated by global contexts, inter-frame consistency is significantly improved. This means that GenScene has great generalizability to synthesize high-fidelity videos in unseen domains.

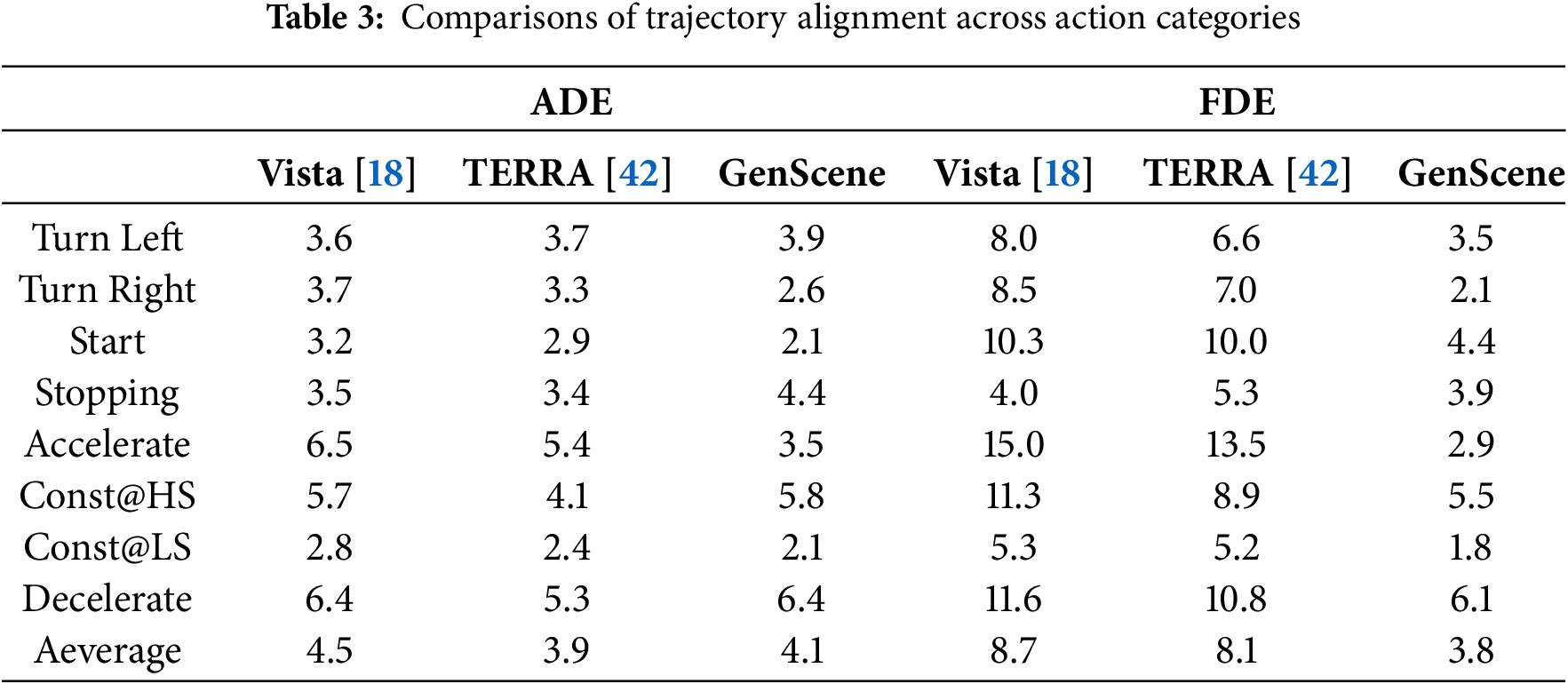

4.6 Trajectory Controllability

Trajectory alignment is compared among Vista [18], TERRA [42], and GenScene in Table 3, from which we can find that GenScene gets the lowest ADE in half of the categories, and TERRA [42] gets the lowest ADE on average, which is better than that of GenScene by 0.2. In terms of FDE, GenScene obtains the lowest values in all the categories, and on average, which is better than that of TERRA [42] by 4.3. These outcomes reveal that although GenScene has a slight imperfection in aligning trajectories in an individual frame, it takes care of the destination very well, which reflects excellent long-distance trajectory alignment. GenScene’s minor deficiency in the ADEs for some classes and the average ADE can be caused by the difference in the training data scale. TERRA [42] is trained on OpenDV-YouTube with 1.67 million clips, NuScenes [49] with 25,000 clips, and CoVLA with 230,000 clips. While GenScene is trained by 20,000 clips from NuScenes [49], which amounts to less data than the portion of the NuScenes [49] dataset used in TERRA [42], not to mention TERRA‘s entire training dataset. Even though with less training data, GenScene is superior to TERRA [42] in generation quality and long-distance trajectory controllability.

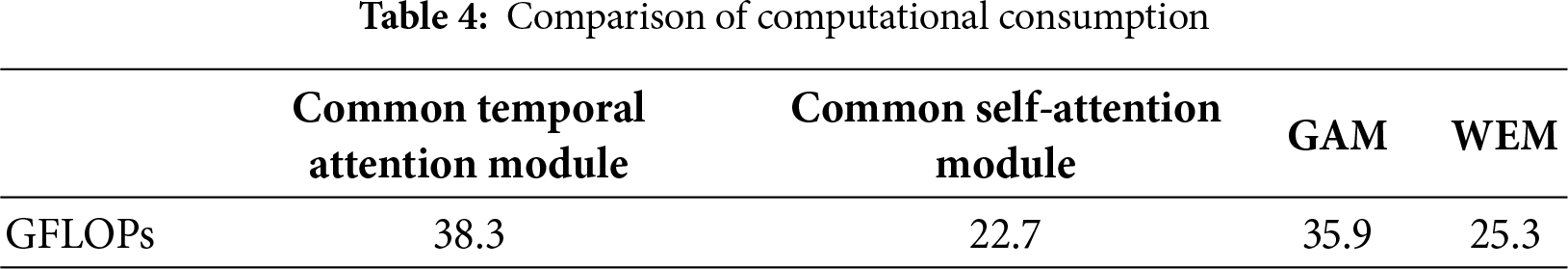

4.7 Computational Consumption Comparison

Since WEM and GAM are designed to replace common self-attention modules and common temporal modules, respectively, it is necessary to explore the change in computational consumption. Giga Floating Point Operations (GFLOPs) measures the total computational cost in the forward process of a model, and is a commonly used metric. Therefore, we calculate the GFLOPs of each module by using a video with a resolution of 128 × 192 as the input in an inference stage. As listed in Table 4, compared to a common temporal attention module, GAM decreases the computational cost by 2.4 GFLOPs. It means that even though GAM involves all pixels in each frame, it needs fewer computing resources, which demonstrates that GAM’s collection of global contexts is efficient. On the other hand, WEM requires 2.6 GFLOPs more computing resources than a common self-attention module. Due to the extra pixels in the anchored windows in the reference frame, more calculations are needed, yet this results in better generation quality.

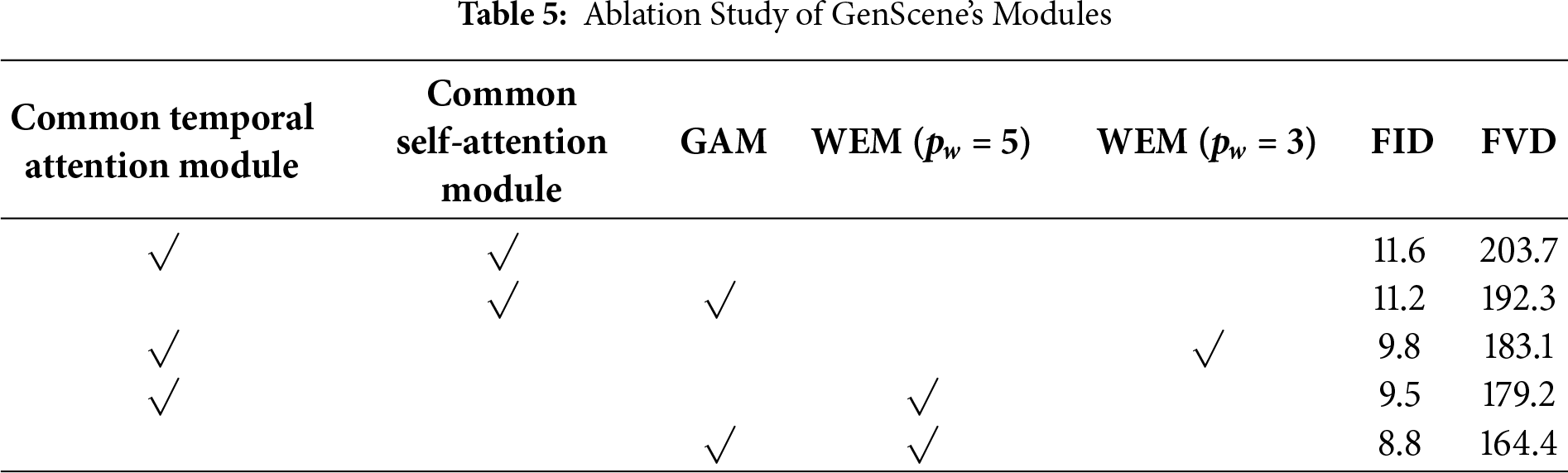

4.8 Ablation Study of Novel Modules

To estimate the effectiveness of the presented modules, ablation studies are conducted in this section, and the results are shown in Table 5. The baseline is a conventional video generation diffusion model containing common self-attention modules and common temporal attention modules, which WEM and GAM are supposed to replace, respectively. Note that configurations without attention modeling modules are not included, as they lead to degenerate video generation and do not provide meaningful baselines.

As demonstrated in Rows 2 and 3, replacing the commonly used temporal attention modules with the proposed GAM leads to a reduction of 0.4 in FID and 11.4 in FVD, indicating that GAM contributes to improved generation consistency. This improvement mainly stems from GAM’s ability to extract global representations of each frame and use them to regulate feature updates, which helps maintain scene-level structure and semantic coherence across time.

Moreover, a more substantial performance gain is observed when substituting the common self-attention modules with the proposed WEM. As reported in Rows 2 and 5, employing WEM with a window size of 5 reduces FID by 2.1 and FVD by 24.5, demonstrating that WEM improves both visual fidelity and temporal coherence simultaneously. This larger improvement can be attributed to the fact that WEM introduces a pixel-wise and spatially explicit constraint without discarding local context. Each pixel in the target frame is refined not only by intra-frame context but also by a fixed spatial window at the corresponding location in the reference frame, resulting in stronger and more direct constraints on frame generation. In contrast, the global representations used in GAM are obtained through global pooling, which aggregates frame-level semantics in a coarse manner. While this is effective for capturing overall scene layout, it may overlook fine-grained spatial details in complex driving environments. Consequently, WEM exhibits a larger performance improvement than GAM.

Furthermore, Rows 4 and 5 show that increasing the window size in WEM from 3 to 5 further reduces FID and FVD by 0.3 and 3.9, respectively, suggesting that a larger window provides richer contextual information from the reference frame and thus yields better generation quality. This trend indicates that incorporating broader spatially anchored reference contexts is beneficial for long-horizon video synthesis. Larger window sizes may further improve performance at the cost of increased computation, which we leave for future exploration. Regarding the situation of

Finally, when both GAM and WEM are applied simultaneously to replace the original modules in Row 6, FID and FVD are further reduced by 2.8 and 39.3, respectively, compared to the baseline in Row 2. This result indicates that GAM and WEM play complementary roles, where GAM stabilizes global scene semantics, while WEM enforces fine-grained spatial alignment. Together, they lead to the best overall synthesis performance.

4.9 Limitations and Discussion

Despite the effectiveness of the proposed GenScene, we observe representative limitations that help clarify its scope and design trade-offs.

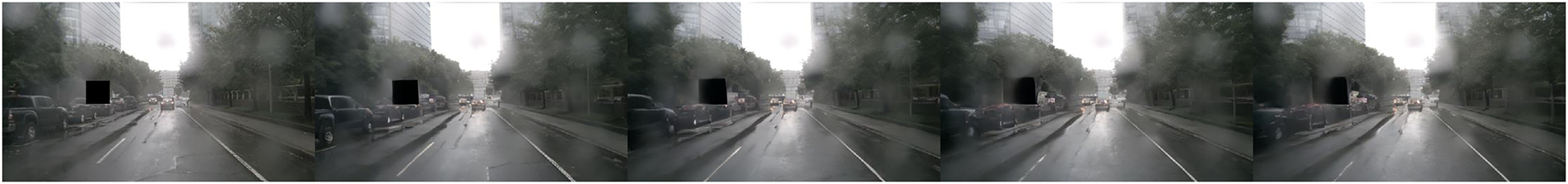

Firstly, GenScene is sensitive to the quality of the reference frame. Our method conditions video generation on the first frame to establish a stable appearance and structural reference. Consequently, when the reference frame contains occlusions, these imperfections may propagate to subsequent frames, leading to degraded visual quality over time, as is shown in Fig. 7. This behavior is expected, as the first frame provides essential visual cues that guide the denoising process throughout the entire video sequence.

Figure 7: Occluded first frame affects subsequent frames

Secondly, GenScene has limited fidelity for small-scale text details. As shown in Fig. 8, the words on the signage in the red rectangle are fading through the subsequent frames. In scenes containing small signage or fine-grained textual elements, the generated videos may exhibit reduced text readability. This limitation arises from the design of GAM, which emphasizes scene-level global context and layout rather than preserving high-frequency local details. While this design choice improves overall spatial–temporal consistency, it may smooth out small text regions that are not dominant in the global attention distribution.

Figure 8: The words on the signage are fading through the subsequent frames

Addressing these limitations by incorporating explicit mechanisms for reference frame robustness or local-detail preservation is an interesting direction for future work.

In this paper, we propose GenScene to improve the fidelity and consistency of driving video generation, which is useful for scalable autonomous vehicle simulation. GenScene is composed of a pre-trained video diffusion backbone and two novel modules named Global Attention Module (GAM) and Window-enhanced Module (WEM), respectively. GAM first extracts global features of each frame and computes attentions to update them. Then the relationships between the global representations and the original frames are calculated to produce the refined frame. Unlike the common temporal attention modules, GAM involves all the pixels in each frame to measure the inter-frame relevance instead of one, which can collect more contexts for information exchange. In addition, WEM combines each subsequent frame with a windowed area in the first frame corresponding to every target pixel and calculates self-attention, which leverages the reference frame explicitly to inject the only appearance guidance into the generation. Extensive experiments demonstrated that GenScene outperforms various state-of-the-art methods with better visual quality and trajectory alignment. Moreover, ablation studies prove that the present GAM and WEM can truly contribute to the improvement of generation performance. The efficacy of our method in driving video generation not only highlights its practical value but also establishes a scalable framework for visual signals synthesis. Combining with a simulation platform, GenScene is instrumental for accelerating autonomous vehicle testing.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was financially supported by the Cultivation Program for Major Scientific Research Projects of Harbin Institute of Technology (ZDXMPY20180109).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, Beike Yu; supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, Dafang Wang. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Dafang Wang, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Mildenhall B, Srinivasan PP, Tancik M, Barron JT, Ramamoorthi R, Ng R. Nerf: representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis. Commun Acm. 2021;65(1):99–106. [Google Scholar]

2. Kerbl B, Kopanas G, Leimkühler T, Drettakis G. 3D gaussian splatting for real-time radiance field rendering. Acm Trans Graph. 2023;42(4):1–14. doi:10.1145/3592433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wu Z, Liu T, Luo L, Zhong Z, Chen J, Xiao H editors, et al. Mars: an instance-aware, modular and realistic simulator for autonomous driving. In: CAAI International Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2023. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-8850-1_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Yang J, Ivanovic B, Litany O, Weng X, Kim SW, Li B, et al. EmerNeRF: emergent spatial-temporal scene decomposition via self-supervision. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2024 May 7–11; Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

5. Liu JY, Chen Y, Yang Z, Wang J, Manivasagam S, Urtasun R. Real-time neural rasterization for large scenes. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

6. Li Z, Wu C, Zhang L, Zhu J. DGNR: density-guided neural point rendering of large driving scenes. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2024;22:4394–407. doi:10.1109/tase.2024.3410891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhou X, Lin Z, Shan X, Wang Y, Sun D, Yang MH editors. Drivinggaussian: composite gaussian splatting for surrounding dynamic autonomous driving scenes. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr52733.2024.02044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li Z, Zhang Y, Wu C, Zhu J, Zhang L. HO-Gaussian: hybrid Optimization of 3D Gaussian splatting for urban scenes. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2024. [Google Scholar]

9. Lu J, Huang Z, Yang Z, Zhang J, Zhang L editors. Wovogen: world volume-aware diffusion for controllable multi-camera driving scene generation. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2024. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-72989-8_19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. DreamForge: motion-aware autoregressive video generation for multiview driving scenes. In: Proceedings of the ECCV 2024 2024 European Conference on Computer Vision; 2024 Sep 29–Oct 4; Milan, Italy. [Google Scholar]

11. Wang Y, Cheng K, He J, Wang Q, Dai H, Chen Y editors, et al. DrivingDojo dataset: advancing interactive and knowledge-enriched driving world model. In: Proceedings of Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2024 Dec 10–15; Vancouver, BC, Canada. doi:10.52202/079017-0414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Russell L, Hu A, Bertoni L, Fedoseev G, Shotton J, Arani E, et al. Gaia-2: a controllable multi-view generative world model for autonomous driving. arXiv:250320523. 2025. [Google Scholar]

13. Blattmann A, Dockhorn T, Kulal S, Mendelevitch D, Kilian M, Lorenz D, et al. Stable video diffusion: scaling latent video diffusion models to large datasets. arXiv:2311.15127. 2023. [Google Scholar]

14. Wang X, Zhu Z, Huang G, Chen X, Zhu J, Lu J. Drivedreamer: towards real-world-driven world models for autonomous driving. In: Proceedings of European Conference on Computer Vision; 2024 Sep 29–Oct 4; Milan, Italy. [Google Scholar]

15. Zhao G, Wang X, Zhu Z, Chen X, Huang G, Bao X, et al. Drivedreamer-2: LLM-enhanced world models for diverse driving video generation. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2025 Feb 25–Mar 4; Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

16. Zhao G, Ni C, Wang X, Zhu Z, Zhang X, Wang Y editors, et al. Drivedreamer4D: world models are effective data machines for 4D driving scene representation. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference; 2025 Jun 11–15; Nashville, TN, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr52734.2025.01122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang Y, He J, Fan L, Li H, Chen Y, Zhang Z editors. Driving into the future: multiview visual forecasting and planning with world model for autonomous driving. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. [Google Scholar]

18. Gao S, Yang J, Chen L, Chitta K, Qiu Y, Geiger A, et al. Vista: a generalizable driving world model with high fidelity and versatile controllability. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2024;37:91560–96. doi:10.52202/079017-2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Liang D, Zhang D, Zhou X, Tu S, Feng T, Li X, et al. Seeing the future, perceiving the future: a unified driving world model for future generation and perception. arXiv:250313587. 2025. [Google Scholar]

20. Xie B, Liu Y, Wang T, Cao J, Zhang X editors. Glad: a streaming scene generator for autonomous driving. arXiv:2503.00045. 2025. [Google Scholar]

21. Xie Z, Zhang J, Li W, Zhang F, Zhang L editors. S-NeRF: neural radiance fields for street views. arXiv:2303.00749. 2023. [Google Scholar]

22. Chen Y, Zhang J, Xie Z, Li W, Zhang F, Lu J, et al. S-nerf++: autonomous driving simulation via neural reconstruction and generation. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2025;47(6):4358–76. doi:10.1109/tpami.2025.3543072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Turki H, Zhang JY, Ferroni F, Ramanan D editors. Suds: scalable urban dynamic scenes. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. doi:10.1109/cvpr52729.2023.01191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Qin T, Li C, Ye H, Wan S, Li M, Liu H, et al. Crowd-sourced nerf: collecting data from production vehicles for 3D street view reconstruction. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(11):16145–56. doi:10.1109/tits.2024.3415394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ren W, Zhu Z, Sun B, Chen J, Pollefeys M, Peng S. Nerf on-the-go: exploiting uncertainty for distractor-free nerfs in the wild. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 June 16–24; Seattle, WA, USA. [Google Scholar]

26. Ye T, Huang H, Liu Y, Yang J. Global structure-from-motion enhanced neural radiance fields 3D reconstruction. Int Arch Photogramm Remote Sens Spat Inf Sci. 2024;48:199–204. doi:10.5194/isprs-archives-xlviii-4-w10-2024-199-2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yan Y, Lin H, Zhou C, Wang W, Sun H, Zhan K, et al. Street gaussians for modeling dynamic urban scenes. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2024. [Google Scholar]

28. Huang N, Wei X, Zheng W, An P, Lu M, Zhan W, et al. S3Gaussian: self-supervised street gaussians for autonomous driving [Internet]. CoRR; 2024 [cited 2026 Jan 5]. Available from: https://openreview.net/forum?id=BPmg2LtliZ. [Google Scholar]

29. Li H, Li J, Zhang D, Wu C, Shi J, Zhao C, et al. VDG: vision-only dynamic gaussian for driving simulation. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2025;10(5):5138–45. doi:10.1109/lra.2025.3555938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Peng C, Zhang C, Wang Y, Xu C, Xie Y, Zheng W editors, et al. Desire-gs: 4D street gaussians for static-dynamic decomposition and surface reconstruction for urban driving scenes. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference; 2025 Jun 11–15; Nashville, TN, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr52734.2025.00636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Tian Q, Tan X, Xie Y, Ma L editors. Drivingforward: feed-forward 3D gaussian splatting for driving scene reconstruction from flexible surround-view input. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2025 Feb 25–Mar 4; Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

32. Fischer T, Kulhanek J, Bulò SR, Porzi L, Pollefeys M, Kontschieder P. Dynamic 3D gaussian fields for urban areas. In: Proceedings of Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2024 Dec 10–15; Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

33. Yu S, Tack J, Mo S, Kim H, Kim J, Ha J-W editors, et al. Generating videos with dynamics-aware implicit generative adversarial networks. arXiv:2202.10571. 2022. [Google Scholar]

34. Tulyakov S, Liu M-Y, Yang X, Kautz J. Mocogan: decomposing motion and content for video generation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. [Google Scholar]

35. Goodfellow I, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S editors, et al. Generative adversarial nets. Commun ACM. 2020;63(11):139–44. doi:10.1145/3422622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ho J, Jain A, Abbeel P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2020;33:6840–51. [Google Scholar]

37. Zhang Y, Wei Y, Jiang D, ZHANG X, Zuo W, Tian Q. ControlVideo: training-free controllable text-to-video generation. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2024 May 7–11; Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

38. Zhang L, Rao A, Agrawala M editors. Adding conditional control to text-to-image diffusion models. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2023 Oct 4–6; Paris, France. doi:10.1109/iccv51070.2023.00355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Chen W, Ji Y, Wu J, Wu H, Xie P, Li J, et al. Control-a-video: controllable text-to-video generation with diffusion models. arXiv:2305.13840. 2023. [Google Scholar]

40. Zhang Z, Long F, Pan Y, Qiu Z, Yao T, Cao Y editors, et al. Trip: temporal residual learning with image noise prior for image-to-video diffusion models. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr52733.2024.00828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Khachatryan L, Movsisyan A, Tadevosyan V, Henschel R, Wang Z, Navasardyan S editors, et al. Text2video-zero: text-to-image diffusion models are zero-shot video generators. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. doi:10.1109/iccv51070.2023.01462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Arai H, Ishihara K, Takahashi T, Yamaguchi Y. ACT-bench: towards action controllable world models for autonomous driving. In: ICLR 2025 Workshop on World Models: Understanding, Modelling and Scaling; 2025 Apr 24–28; Singapore. [Google Scholar]

43. Chen Y, Wang Y, Zhang Z. Drivinggpt: unifying driving world modeling and planning with multi-modal autoregressive transformers. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2025 Oct 19–23; Honolulu, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

44. Ni C, Zhao G, Wang X, Zhu Z, Qin W, Huang G editors, et al. ReconDreamer: crafting world models for driving scene reconstruction via online restoration. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference; 2025 Jun 3–7; Nashville, CO, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr52734.2025.00153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Li X, Zhang Y, Ye X editors. DrivingDiffusion: layout-guided multi-view driving scenarios video generation with latent diffusion model. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2024. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-73229-4_27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Yang J, Gao S, Qiu Y, Chen L, Li T, Dai B editors, et al. Generalized predictive model for autonomous driving. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr52733.2024.01389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Wen Y, Zhao Y, Liu Y, Jia F, Wang Y, Luo C editors, et al. Panacea: panoramic and controllable video generation for autonomous driving. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr52733.2024.00659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Ma E, Zhou L, Tang T, Zhang Z, Han D, Jiang J, et al. Unleashing generalization of end-to-end autonomous driving with controllable long video generation. arXiv:2406.01349. 2024. [Google Scholar]

49. Caesar H, Bankiti V, Lang AH, Vora S, Liong VE, Xu Q editors, et al. Nuscenes: a multimodal dataset for autonomous driving. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.01164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Heusel M, Ramsauer H, Unterthiner T, Nessler B, Hochreiter S. Gans trained by a two time-scale update rule converge to a local nash equilibrium. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2017;30(1):25–34. doi:10.18034/ajase.v8i1.9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Unterthiner T, Van Steenkiste S, Kurach K, Marinier R, Michalski M, Gelly S. Towards accurate generative models of video: a new metric & challenges. arXiv:1812.01717. 2018. [Google Scholar]

52. Phong T, Wu H, Yu C, Cai P, Zheng S, Hsu D. What truly matters in trajectory prediction for autonomous driving? Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2023;36:71327–39. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4921566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Wang X, Peng P. Prophetdwm: a driving world model for rolling out future actions and videos. arXiv:2505.18650. 2025. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools